Life is short but not as short as the times we smile or laugh and even shorter are the times our heart smiles or we are filled with bliss, love, and joy. It is this realization that reminds me, to not just fill my life with them, but to likewise do what I can, so others around me can experience them too.

I was challenged on the idea of justice.

Questioner: but what is “justice”? Like, what do you mean by that? What is justice other than “just us”. Sure it’s a cute idea. Maybe we could agree that it’s just a bullshit term meant to incur emotional feeling, the silent suppressor of logic.

My response: For to me justice or injustice are moral sentiments’ which apply to an inclination to assess condemn or praise someone or something.

Justice is not limited to law it can be an expression of other shared values being achieved like having access to human rights. To question justice is to likewise deny its opposite injustice, to do so is to remove meaning of humanitarian experience. Which would be unnecessarily subversive to the voice it brings to meaning in reality. There will be the experience of both injustice and acts of justice whether you remove or replace the words words are just packages to give voice to meaning.

There is never universal justice to all people in the world or for all time likewise it is also a over generalization to hint that there has never been justice or will be justice for lots of people. And it should be the goal for all people of the world whether it ever universally happens. If we question justice and injustice like they have no meaning we also have to ask what kinds of reasoning should count in the assessment of ethical concepts such as as a what they express as a whole.

In what way can a diagnosis of of ethical violation be comprised denying injustice thus a need for justice, or the identification of what would reduce or eliminate it, be objective? Does this demand impartiality in some particular sense, such as detachment from one’s own vested interests? Does it also demand re-examination of some attitudes even if they are not related to vested interests, but reflect local preconceptions and prejudices, which may not survive reasoned confrontation with others not restricted by the same parochialism?

What is the role of rationality and of reasonableness in understanding the demands of justice? Judgments about justice are based (whether freedoms, capabilities, resources, happiness, well-being or something else), the special relevance of diverse considerations that figure under the general headings of equality and liberty, the evident connection between pursuing justice and human dignity.

Justice is ultimately connected with the way people’s lives go, and not merely with the nature of the institutions surrounding them. What got this challenge of justice started was I stated to me No act of justice is without value and no act of care is without meaning to a better humanity. We are limited but our thoughtfulness has a group effect like a signal of hope with the ability to inspire others. The difference we make is a difference shared. So if you want to make a different world start with you and be the difference.

I support justice….

Three Theories of Justice

I will discuss three theories of justice: Mill’s Utilitarianism, Rawls’s Justice as Fairness, and Nozick’s libertarianism. Much of my understanding of theories of justice comes from Business Ethics (Third Edition) by Willian H. Shaw. I will expand my discussion of justice by considering objections to each of these theories, but I do not necessarily endorse any of the objections and there could be good counterarguments against them.

What is justice? Justice can be used to mean any number of things, like the importance of having rights, fairness, and equality (87-88). People will think it’s unjust to have their rights violated (like being thrown in prison without being found guilty in a court of law); or being unfairly harmed by someone unwilling to pay compensation for the harm done; or being unfairly treated as an inferior (unequal) who isn’t hired for a job despite being the most qualified person for the job. Theories of justice are not necessarily “moral” theories because “justice” is a bit more specific and could even be separate from morality entirely.

Mill’s utilitarian theory of justice

Utilitarians tend to be among those who see no major divide between justice and morality. Utilitarians see justice as part of morality and don’t see justice to have a higher priority than any other moral concern. In particular, utilitarians think that we should promote goodness (things of value), and many think that goodness can be found in a single good; such as happiness, flourishing, well-being, or desire satisfaction. Utilitarian ideas of justice connect morality to the law, economic distribution, and politics. What economic or political principles will utilitarians say we should accept? That is not an easy question to answer and is still up in the air. We have to discover the best economic and political systems for ourselves by seeing the effects they produce (90).

Utilitarians often advocate for social welfare because everyone’s well-being is of moral interest and social welfare seems like a good way to make sure everyone flourishes to a minimal extent. On the other hand utilitarians often advocate free trade because (a) free trade can help reward people for hard work and encourage people to be productive, (b) the free market allows for a great deal of freedom, (c) freedom has a tendency to lead to more prosperity, and (d) taking away freedom has a tendency to cause suffering.

One conception of utilitarian justice can be found in the work Utilitarianism by John Stuart Mill (91). Mill said that justice was a subset of morality—“injustice involves the violation of the rights of some identifiable individual” (ibid.). Mill suggests, “Justice implies something which is not only right to do, and wrong not to do, but which some individual person can claim from us as his moral right” (ibid.). Morality is larger than justice because it’s plausible that we can be heroic or act beyond the call of duty to help others and such acts would not be best described as examples of “justice.”

When do we (or should we) have a right? When we can legitimately make demands on society based on utilitarian grounds. “To have a right, then, is… to have something which society ought to defend me in the possession of. If the objector goes on to ask why it ought, I can give him no other reason than general utility” (ibid.). Rights are rules society can make for everyone that could help people flourish and prosper in general, and we should have rights given the assumption that they are likely to increase goodness in the long run.

Mill’s conception of rights can include both positive rights (for public education, food, shelter, medical assistance, etc.) and negative rights (to be allowed to say what we want, to be allowed to have any religion, etc.) Both of these sorts of rights can potentially help people have greater well being.

Concrete utilitarian suggestions

Utilitarians have suggestions for improving economic systems. For example:

- Mill argued that we should reduce the division between workers and owners (92-94). Workers and owners often engage in class warfare or other hostile relations. There might be a way for workers and owners to blend together rather than be sharply divided groups, which could reduce class warfare and hostile relations. For example, profits could be shared with the workers.

- We can promote greater equality of income (93). The more money you get, the less that additional money can help your well being. People who have billions of dollars don’t get as much of a benefit from each dollar they own than others would. The poor often die from medical neglect, but everyone else can pretty much attain everything needed for survival. The luxuries enjoyed by the rich are much less important to their well being than the necessities that could be enjoyed by others if that wealth is shared. If we tax the rich to help the poor, than we could expect that greater goodness would result.

Applying Mill’s theory of justice

Mill thinks that we should have rights, laws, and government intervention when doing so will best maximize the good, which he finds to be happiness, and minimize evil in the form of suffering. We often say that utilitarianism asks us to “maximize happiness” for short, and it’s implied that suffering is incompatible and destructive to happiness. He thinks something’s just if it doesn’t violate any rights, and there are ideal rights that would maximize happiness. His utilitarian theory of justice doesn’t tell us what the ideal rights are.

How can we apply Mill’s utilitarian theory of justice to our lives? First, we need to figure out what rights will probably lead to greater happiness. Second, we have to figure out whether those rights are being violated in a given situation.

What rights will likely lead to greater happiness? – One proposed list of rights that seem like they could be justified through Mill’s utilitarianism are those listed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Let’s consider three of those rights:

1. Right to property – “No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his property” (Article 17). People ought to have a right to property for at least four reasons. One, because we have various needs and property is very helpful to fulfill those needs. We need food and shelter, and we can become ill or die when people take our food and shelter from us. Two, we make plans throughout the day concerning our future (e.g. retirement) and property rights are needed to have the stability required for these plans. Three, it often makes people upset when they are robbed, even when only luxuries are stolen. Four, the right to make a profit from one’s labor can be an incentive to work hard and be productive, which can help create greater prosperity for society at large.

2. Right to social welfare – “Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control” (Article 25). The right to the necessities of life requires the redistribution of wealth, but it can help many people who need help the most and thus increases happiness (the grater good) despite the fact that it can harm certain people. The greater happiness given to the poor can justify sacrificing some welfare of everyone else. As I said before, utilitarianism can justify greater income equality, and redistributing wealth can lead to greater income equality.

One could object that the right to social welfare violates property rights, but it is quite possible for people’s rights to conflict. Sometimes we think one right can override another. Utilitarians can justify when one right overrides another if we know that greater happiness will result from the violation. For example, I can attack someone in self-defense to protect myself, even though we have a right against being harmed. My own well being might justify the act of harming another when that other person is a danger to me.

It’s also possible for moral concerns that require us to violate people’s rights in utilitarianism. Perhaps we don’t have a right to social welfare, but the need for redistribution of wealth could still be a moral priority that overrides property rights in some contexts. The alternatives to coerced redistribution of wealth could be greater crime rates—the poor might have no better rational option than to steal from the rich—or even revolution when the poor think their current state is totally unacceptable.

Mill doesn’t make it entirely clear when we have an “obligation” to help other people, but redistribution of wealth certainly seems to imply that we can have such obligations because people can be punished if they refuse to pay their taxes and so forth.

3. Right to education – “Everyone has the right to education. Education shall be free, at least in the elementary and fundamental stages. Elementary education shall be compulsory. Technical and professional education shall be made generally available and higher education shall be equally accessible to all on the basis of merit” (Article 26). Widespread education can help society in many ways, but I will just discuss a couple. First, it can help people know how to be better productive and attain higher positions in society. Increased education not only improves opportunity, but it can help motivate people to be productive knowing that they have an opportunity to improve their lives by attaining better positions. Two, without a right to education many people could be stuck being poor without much of a chance at attaining a better position in society, and that could destroy their motivation to be productive. The poor could even be motivated to commit crimes if it’s the only way for them to attain a better position in life. Better opportunities diminish the desire to commit crime because there are often more efficient and less risky ways to try to improve one’s life than crime has to offer.

When are rights violated? – Consider the following six situations and whether or not any rights are being violated:

- A corporation sells TV sets that don’t work and scams people out of their money because people assume that the TV sets work when they buy them. Is this a violation of anyone’s rights? Mill can argue, yes, because a person’s property rights entail that property is transferred given an agreement and no one agreed to buy a broken TV set. Buying a TV set implies that it works unless it’s explicitly made clear that the TV set is broken.

- Samantha was born in a poor family and she could never afford an education. She couldn’t afford food and couldn’t find a job, so she starves to death. Meanwhile there is an abundance of food and wealth that is almost exclusively owned by the wealthiest members of society. Was any right being violated? Mill could argue, yes, because (a) she should have been given a free education and (b) she has a right to social welfare and redistributing wealth could have helped her survive. People have duties to help one another and they can’t just let others die of starvation.

- The government taxes all profits 10% to help poor families buy the necessities of life. Anyone who doesn’t pay their taxes can be punished. Was any right being violated? It seems obvious that the right to property was violated in this case, but Mill could argue that such a violation is necessary for ethical reasons—either because of conflicting rights or other moral considerations to the “greater good.” It is possible that a utilitarian could argue that taxing profits by 10% isn’t enough, or there’s some better way to redistribute wealth, but we will leave that concern aside for now.

- The government subsidizes the big bank industry by using tax money to give the big banks billions of dollars to help them avoid bankruptcy. Was any right being violated? Yes, property rights are being violated in this case because people are coerced to pay taxes to fund a bailout. Is it just to violate property rights in this case? It depends whether the big bank industry getting loads of free money will lead to the greater good. This seems unlikely considering that businesses that go bankrupt are often either not conducting business properly or aren’t providing a service people want, but some people might argue that “saving the banks” will prevent a huge disaster to the economy—and absolutely no other alternative course of action would be better.

- A corporation hires hit men to kill the competition. Was any right being violated? Mill will argue, yes, because we have a right not to be harmed and it will probably not serve the greater good. The happiness of the “competition” (and their family and friends) matters just as much as everyone else’s happiness.

- The people who personally made the decision to hire hit men to kill the competition are thrown in prison after being found guilty in a court of law. Are any rights being violated? Yes, the rights not to be harmed are being violated here. The criminals have rights not to be harmed, just like everyone else, and being in prison is a violation of liberty—something that would ordinarily be considered to be unjust behavior against “innocent people.” However, a utilitarian could argue that it’s for the “greater good” to throw the criminals in prison because such use of coercion helps discourage and prevent further criminal acts and rights violations.

Objections

1. It’s too simple – Many philosophers who reject utilitarianism are “deontologists” who generally agree that utilitarianism has much to say about morality that’s relevant, but utilitarianism is too simple and ignores some moral principles. It’s possible that consequences (promoting goodness) is not the only thing of moral relevance.

2. Utilitarianism fails to account for the need to be respectful – It’s not clear that utilitarians can fully account for why we need to respect people. There are some “counterexamples” philosophers often give against utilitarianism, and they often argue that it might (sometimes) be wrong to hurt someone even if it promotes the greater good. For example, we wouldn’t think it’s right to kill someone and donate their organs to those who need them to survive, even if the person’s death lead to a “greater good.” Someone could argue that utilitarian governments would take away people’s rights whenever they decide that it will serve the “greater good” to do so; but such a dispensable view of rights could miss the point of having rights in the first place.

3. It ignores personal relationships – Some philosophers argue that personal relationships provide us with unique obligations that utilitarianism can’t account for. For example, parents have a duty to protect and feed their children; but they don’t have the same duty to all children that exist. They shouldn’t spend just as much time protecting and feeding the children of strangers as they spend to feed and protect their own children.

4. It’s too demanding – Some philosophers argue that utilitarianism implies that we have a duty to promote goodness as much as possible, but that’s too hard. Mill’s utilitarianism in particular says it’s wrong to do something that maximizes happiness less than an alternative course of action. It might be that you could be doing something better to promote goodness every second of your life. Maybe you could be curing cancer right now instead of reading this. There might be no limit to how much good we can do, and we would then be forever condemned for failing to live up to the unlimited demands of utilitarianism. This not only requires us to stop enjoying ourselves when we could be doing something better, but it implies that no actions are “above the call of duty” despite the fact that it seems intuitive that there are.

You can read more about Mill here. You can read Utilitarianism for free here or buy it for $2.50 here.

Nozick’s Libertarian Theory of Justice

Libertarians are people who favor negative rights (and the right to property in particular), small government, and a free market. Many libertarians ascribe to an extreme view that denies the existence of positive rights and favors a laissez-faire free market no matter how horrible the consequences are. This seems to entail no government regulation or public education.

Some utilitarians are libertarians because they think libertarianism will promote goodness best, but Robert Nozick developed his own theory of justice that finds utilitarianism completely irrelevant to justice, which was described in Anarchy, State, and Utopia. Nozick argues that we have “Lockean rights” by our very nature prior to any political institutions, such as the right to property (95). For Nozick these rights are absolute and can’t be violated for any reason—except perhaps if the only alternative action would directly violate even more rights.

Nozick thinks that we have property rights to keep our possessions as long as they were attained fairly—without violating other people’s rights, harming others, or defrauding them (95-96). The world’s natural resources are all up for grabs. They are the property of anyone who takes them. This conception of property rights are described by three principles of justice:

- A person who acquires a holding in accordance with the principle of justice in acquisition is entitled to that holding.

- A person who acquires a holding in accordance with the principle of justice in transfer, from someone else entitled to the holding, is entitled to the holding.

- No one is entitied to a holding except by (repeated) applications of 1 or 2. (97)

Nozick’s view seems to imply that taxation is a form of theft because it violates our property rights. People are coerced by governments to give up their property when they are being taxed. No one can take away our legitimately attained property without permission. Any public service funded by taxation would then also be illegitimate, such as public education or food for the poor.

Nozick argues for his theory of justice through a thought experiment, called the “Wilt Chamberlain example” (97-98). Imagine that your favorite form of economic justice is enacted and a basketball player, Wilt Chamberlain, agrees to play for a team by getting paid twenty five cents for each ticket sold. Everyone was entitled to their money (assuming your favorite form of economic justice is truly just), and that they therefore have a right to spend their money as they wish. Wilt Chamberlain also seems entitled to the money given to him (assuming that people have a right to spend their money as they wish after justly attaining it).

Applying Nozick’s theory of justice

Nozick’s theory of justice affirms that we have negative rights (to be left alone) but denies that we have positive rights (to social welfare or education). Nozick says taxation is a form of coerced redistribution of wealth and it’s unjust because we have a right to property and we don’t have a right to social welfare. We have no ethical obligations to help others—and even if we did, his theory of justice would override any other moral considerations there might be. Nozick says public education is one more form of redistributing wealth. I expect that Nozick’s government to be fully funded by donations and/or requires volunteers. It would be wrong to tax people to have a police department because that’s just one more unjust violation of our property rights. The police department, fire department, public schools, prisons, and everything else must either be “for profit,” exist from volunteers, and/or be funded by donations.

How do we apply Nozick’s theory of justice? First, we need to know what rights we have. He thinks we have “Lockean rights”—a right from being harmed, a right to property, freedom of speech, and so on. Second, we need to know how those rights apply to various contexts.

Consider how Nozick’s theory of justice could apply to the contexts mentioned earlier:

- A corporation sells TV sets that don’t work and scams people out of their money because people assume that the TV sets work when they buy them. Is this unjust? I expect that Nozick will agree with Mill here. As I stated before, a person’s property rights entail that property is transferred given an agreement and no one agreed to buy a broken TV set.

- Samantha was born in a poor family and she could never afford an education. She couldn’t afford food and couldn’t find a job, so she starves to death. Meanwhile there is an abundance of food and wealth that is almost exclusively owned by the wealthiest members of society. Was any right being violated? Nozick would say, “No.” No one has a right to anything nor does anyone have an obligation to help others. To redistribute wealth using coercion would be a violation of our property rights and there is no conflicting right against our property rights in this situation.

- The government taxes all profits 10% to help poor families buy the necessities of life. Anyone who doesn’t pay their taxes can be punished. Was any right being violated? Nozick would say, “Yes,” because taxation is a violation of our property rights, just like any other form of coerced redistribution.

- The government subsidizes the big bank industry by using tax money to give the big banks billions of dollars to help the big bank industry avoid bankruptcy. Was any right being violated? Yes, property rights are being violated in this case—and there’s no rights that could possibly justify taxation or coerced redistribution of wealth.

- A corporation hires hit men to kill the competition. Was any right being violated? Nozick will answer, “Yes,” because we have a right not to be harmed and people were killed. There are no conflicting rights in this situation, so the corporation has done something unjust.

- The people who personally made the decision to hire hit men to kill the competition are thrown in prison after being found guilty in a court of law. Are any rights being violated? Nozick can argue, “Yes,” the rights not to be harmed are being violated here. However, there can be conflicting rights in this case. The criminals in question should be in prison assuming it’s necessary to protect the rights of others, and that seems like a fair assumption.

Objections

1. We have duties to each other – Many people argue that we have duties to each other, and Nozick isn’t justified to reject such a moral fact. We start the world as helpless infants; and almost everyone becomes incapacitated from illness, injury, or old age at some point in their age. If we have no duties to anyone; then we can let orphans die, we can let uninsured poor people die from illness and injury, and we can let the elderly die out in the streets. That doesn’t seem like acceptable behavior and could hardly be described as “moral behavior.”

One could argue that Nozick’s Wilt Chamberlain thought experiment is a good example of justice, but only accounts for one example of a just form of libertarianism rather than the unjust forms. In the scenario given, there is nothing unjust happening precisely when we assume that there is a “just distribution” of wealth that assures us that no one is suffering from extreme poverty. If a libertarian society donates to public service of its own free will, there is no problem with it. However, we can find fault with his libertarian ethics via a counterexample. Imagine a libertarian society where the poor all starve to death because there is no way for them to buy food and no job opportunities. The poor are seen as what Scrooge called the “excess population.” In that case Wilt Chamberlain’s wealth would be much better used to help the poor, and he is refusing to help them. We have reason to think that Wilt Chamberlain would have a duty to help the poor, and he is failing to fulfill his obligation. In that case we seem to have little choice but to tax him and therefore take a portion of his wealth to help the poor. The point is that Nozick’s libertarianism isn’t necessarily unjust, but that it might allow for unjust situations that should not be allowed in a proper theory of justice.

2. Freedom is more than negative rights – Nozick loves freedom and he thinks that his libertarian form of justice will be the best theory to support freedom. However, we can argue that Nozick isn’t justified to equate freedom with negative rights—rights to be left alone, like freedom of speech and a right to property. Freedom can also entail power. The slaves that were freed after the civil war could have negative rights, but they lacked positive rights—rights to food, to resources, to education, to medical attention, to opportunity, and so on. In some ways some freed slaves were worse off than when they were slaves. Many became sharecroppers and made barely enough money to survive and had little to no opportunity to improve their lives. The so-called choice to work under the same (and perhaps even worse) conditions as a slave or die doesn’t seem like the kind of freedom an economic system embodying justice could allow.

3. The free market can lead to exploitation and oppression – This is related to the last objection. Absolute property rights leads to a free market, but an unregulated free market can lead to exploitation—disrespectful and oppressive behavior towards others. Sharecropping is one example. One could also argue that the fact that we needed a minimum wage is evidence that a company would pay their poor workers even less if it was legal to do so. Nozick doesn’t think a worker deserves to make more money than companies will pay them. If workers have no choice but to work in horrible conditions for barely enough money to live, then that’s perfectly fine. It seems like the result of a completely free market is that company owners will often make tons of money while many of their workers will be forced to live in poverty without any hope for medical insurance or educational opportunities. Those who have attained the world’s resources (food, oil, etc.) and means of production (factories and machines) are holding all the cards and are “good enough chaps” to provide work for those in poverty while making a great deal of profit. Nozick seems to imply that such workers should be resigned to die young from a disease or poor working conditions rather than revolt against those who are wealthy.

4. Inheritance is unfair – Some people argue that Nozick’s libertarian justice allows for unlimited inheritance, but that allows children of the wealthy to be given an unfair amount of freedom, power, opportunity, and education while the children of the poor might almost be guaranteed to live a horrible life of no better quality than a slave (101).

5. The free market can lead to horrible consequences. Absolute property rights seems to lead to a free market, but that could hurt a lot of people. For example, lots of people can starve to death when they can’t get access to food, even when there’s a free market.

Professor Amartya Sen of Oxford University shows how, in certain circumstances, changing market entitlements—the economic dynamics of which he attempts to unravel—have led to mass starvation. Although the average person thinks of famine as caused simply by a shortage of food, Sen and other experts have pointed out that famines are frequently accompanied by no shortfall of food in absolute terms. Indeed even more food may be available during a famine than in nonfamine years—if one has the money to buy it. Famine occurs because large numbers of people lack the financial wherewithal to obtain the necessary food. (101)

In some cases a country would rather export its food to other countries for greater profits than sell them to their own people who are starving. In other cases a country would rather sell its fertile land to rich foreigners than sell it to its own starving people for less. Is there any reason to think that this couldn’t happen in a free market? Perhaps there is no reason for Nozick to criticize people for exporting all their country’s food to other countries.

You can read more about Nozick’s theory of justice here. You can buy Nozick’s Anarchy, State, and Utopia here.

Rawls’s theory of justice

Rawls described his theory of justice called “Justice as Fairness” in his book A Theory of Justice. Rawls agrees with Nozick that justice is quite separate from morality and he too rejects utilitarian forms of justice. He first suggests a new way to learn about principles of justice—the original position (103-105). The original position asks us to imagine that a group of people will get to decide the principles of justice. These people don’t know who they are (what he calls a ‘veil of ignorance’), they are self-interested, and they know everything science has to offer. He argues that in a veil of ignorance they couldn’t be as biased towards their profession, race, gender, age, or social status because they wouldn’t know which categories they belong to (104-105). As far as self-interest is concerned, Rawls argues that they will want principles of justice that will “fairly distribute” certain goods that everyone will value—what Rawls calls “primary social goods” (105). Rawls argues that the people in the original position will discuss which principles of justice are best before voting on them, and the best principles worth having will reach a “reflective equilibrium”—the most intuitive principles will be favored and incompatible less intuitive principles will have to be rejected in order to maintain coherence. He argues that two intuitive principles of justice in particular will reach reflective equilibrium:

- Each person is to have an equal right to the most extensive total system of equal basic liberties compatible with a similar system of liberty for all.

- Social and economic inequalities are to satisfy two conditions: first, they are to be attached to positions and offices open to all under conditions of fair equality of opportunity; and second, they are to be the greatest expected benefit of the least advantaged members of society (107).

Rawls says that the first principle has priority over the second, “at least for societies that have attained a moderate level of affluence” (ibid.). The liberties Rawls has in mind are negative rights, like the freedom of thought. The distribution of social goods can include education, food, and housing; which could be considered to be positive rights.

The second principle’s second restriction—that social and economic inequalities must benefit the worst off group—is known as the “difference principle” and seems to imply that total communism is automatically just if such a system has no economic or social inequalities because it’s only inequalities that require a rationale. Capitalism will only be justified if it benefits the least advantaged group—the poor, orphans, and so on. The assumption is that inequality can allow hard work to be rewarded to the point that people decide to be more productive and share their wealth with the poor. People won’t be allowed to be wealthier unless the wealth is shared with the poor.

Applying Raws’s theory of justice

Rawls agrees with Nozick that we have negative rights and no positive rights, but he argues that social and economic inequalities are unjust unless they meet certain requirements. In particular, there must be equal opportunity (public education) and greater inequality must benefit those who have the least social and economic goods (the worst off group). Rawls disagrees with utilitarians that economic inequality is justified if it maximizes happiness—by providing rewards to being productive members of society—if such inequality doesn’t help those who are the worst off. (A utilitarian could argue that some people living in poverty are a necessary for the “greater good” but Rawls would rather no one live in poverty.)

Rawls thinks that redistribution of wealth and taxes are justified if it is the best way for the “worst off” to benefit from social and economic inequalities. He thinks total economic equality is just (perhaps in a socialist state), but he thinks that a capitalistic system might actually be better and help the “worst off” by rewarding productive behavior to give an incentive to increase productivity and therefore prosperity.

How will Rawls’s theory of justice apply to the six above contexts?

- A corporation sells TV sets that don’t work and scams people out of their money because people assume that the TV sets work when they buy them. Is this unjust? I expect that Rawls will agree with Mill and Nozick here. As I stated before, a person’s property rights entail that property is transferred given an agreement and no one agreed to buy a broken TV set.

- Samantha was born in a poor family and she could never afford an education. She couldn’t afford food and couldn’t find a job, so she starves to death. Meanwhile there is an abundance of food and wealth that is almost exclusively owned by the wealthiest members of society. Was any right being violated? Rawls would likely say, “Yes” because the economic inequalities don’t seem to help the “worst off.” (Perhaps Rawls assumes that people won’t starve to death if we have economic equality.)

- The government taxes all profits 10% to help poor families buy the necessities of life. Anyone who doesn’t pay their taxes can be punished. Was any right being violated? Rawls would say, “Yes,” because taxation is a violation of our property rights—but he might still think this form of taxation is just if it’s the best way to redistribute wealth and make sure the “worst off” benefit from economic inequalities.

- The government subsidizes the big bank industry by using tax money to give the big banks billions of dollars to help the big bank industry avoid bankruptcy. Was any right being violated? Yes, property rights are being violated in this case, but is it also unjust? If this form of redistribution will help the “worst off,” then it is just. However, it seems likely that Rawls would agree that saving an incredibly powerful company from going bankrupt would somehow benefit those who are the “worst off.”

- A corporation hires hit men to kill the competition. Was any right being violated? Rawls will agree with utilitarians and Nozick here and will answer, “Yes,” because we have a right not to be harmed and people were killed.

- The people who personally made the decision to hire hit men to kill the competition are thrown in prison after being found guilty in a court of law. Are any rights being violated? Rawls can argue, “Yes,” the rights not to be harmed are being violated here. However, there can be conflicting ethical considerations in this context. Rawls can agree with Nozick that the criminals in question should be in prison assuming it’s necessary to protect the rights of others.

Objections

1. Basic liberties aren’t good enough – The first principle of justice equates freedom with some list of negative rights, but we can argue that freedom is and ought to be more than that. The idea of having a finite list of rights implies that we can restrict freedom and oppress people willy nilly as long as the specific freedom in question isn’t on some official list. Why not make freedom innocent until proven guilty? We shouldn’t be restricting any freedom until we have an overriding reason to do so.

2. Aren’t these people too risk averse? – It’s not entirely clear how Rawls knows what principles people will agree to in the original position nor is it entirely clear that the original position is going to help us discover the best principles of justice. In particular, some people argue that they wouldn’t agree the difference principle because so few people will be part of the least advantaged group. Why not take a risk by screwing over the poor to help everyone else as long as there’s a very low chance of being poor?

3. The difference principle unjustly restrains freedom and power – Someone could argue that many of us want as much freedom and power as possible and the difference principle will deny the ability of the wealthy and powerful to attain more wealth or power, even when it doesn’t hurt anyone. What if the rich could attain a great deal more power and wealth without hurting anyone? It seems oppressive to stop them from doing so.

4. The difference principle can lead to poverty – First, it’s possible that communism might lead to mass poverty. Everyone can all be equally poor, but that doesn’t seem to imply that it’s a just economic system. Second, it’s logically possible that every economic system that leads to prosperity requires that the least off group to do very poorly. The difference principle would force us to reject prosperity and live in poverty just because economic differences might inevitably require that the worst off group do poorly compared to everyone else.

5. International responsibilities – Rawls’s Justice as Fairness doesn’t guarantee that a civilization will treat other civilizations with respect nor does it require civilizations to help other civilizations living in poverty and with many people who are starving to death. Utilitarians could argue that justice doesn’t stop within our borders, but it expands to everyone in the world and Rawls’s Justice as Fairness ignores this fact.

You can read more about Rawls here. You can buy Rawls’s A Theory of Justice here.

Conclusion

It’s possible that none of these theories of justice are true, but they have been the result of decades of philosophy. They could be the best philosophers have to offer at this time and they are certainly important to understand the history of the historical debate of justice. It’s possible that no theory of justice needs to be endorsed and we could reason about justice using intuitive assumptions rather than a systematic attempt to capture justice in its entirety. That doesn’t imply that justice is just a matter of opinion or meaningless. The fact that we are ignorant about justice neither implies that all beliefs concerning justice are equal nor does it imply that we know absolutely nothing about it. Ref

“Justice, in its broadest sense, is the principle that people receive that which they deserve, with the interpretation of what then constitutes “deserving” being impacted upon by numerous fields, with many differing viewpoints and perspectives, including the concepts of moral correctness based on ethics, rationality, law, religion, equity, and fairness.” ref

“Consequently, the application of justice differs in every culture. Early theories of justice were set out by the Ancient Greek philosophers Plato in his work The Republic, and Aristotle in his Nicomachean Ethics. Throughout history various theories have been established. Advocates of divine command theory have said that justice issues from God. In the 1600s, philosophers such as John Locke said that justice derives from natural law. Social contract theory said that justice is derived from the mutual agreement of everyone. In the 1800s, utilitarian philosophers such as John Stuart Mill said that justice is based on the best outcomes for the greatest number of people.” ref

“Theories of distributive justice study what is to be distributed, between whom they are to be distributed, and what is the proper distribution. Egalitarians have said that justice can only exist within the coordinates of equality. John Rawls used a social contract theory to say that justice, and especially distributive justice, is a form of fairness. Robert Nozick and others said that property rights, also within the realm of distributive justice and natural law, maximizes the overall wealth of an economic system. Theories of retributive justice say that wrongdoing should be punished to insure justice. The closely related restorative justice (also sometimes called “reparative justice”) is an approach to justice that focuses on the needs of victims and offenders.” ref

“In his dialogue Republic, Plato uses Socrates to argue for justice that covers both the just person and the just City State. Justice is a proper, harmonious relationship between the warring parts of the person or city. Hence, Plato’s definition of justice is that justice is the having and doing of what is one’s own. A just man is a man in just the right place, doing his best and giving the precise equivalent of what he has received. This applies both at the individual level and at the universal level. A person’s soul has three parts – reason, spirit, and desire. Similarly, a city has three parts – Socrates uses the parable of the chariot to illustrate his point: a chariot works as a whole because the two horses’ power is directed by the charioteer. Lovers of wisdom – philosophers, in one sense of the term – should rule because only they understand what is good.” ref

“If one is ill, one goes to a medic rather than a farmer, because the medic is expert in the subject of health. Similarly, one should trust one’s city to an expert in the subject of the good, not to a mere politician who tries to gain power by giving people what they want, rather than what’s good for them. Socrates uses the parable of the ship to illustrate this point: the unjust city is like a ship in open ocean, crewed by a powerful but drunken captain (the common people), a group of untrustworthy advisors who try to manipulate the captain into giving them power over the ship’s course (the politicians), and a navigator (the philosopher) who is the only one who knows how to get the ship to port. For Socrates, the only way the ship will reach its destination – the good – is if the navigator takes charge.” ref

“Social justice encompasses the just relationship between individuals and their society, often considering how privileges, opportunities, and wealth ought to be distributed among individuals. Social justice is also associated with social mobility, especially the ease with which individuals and families may move between social strata. Social justice is distinct from cosmopolitanism, which is the idea that all people belong to a single global community with a shared morality.” ref

“Social justice is also distinct from egalitarianism, which is the idea that all people are equal in terms of status, value, or rights, as social justice theories do not all require equality. For example, sociologist George C. Homans suggested that the root of the concept of justice is that each person should receive rewards that are proportional to their contributions. Economist Friedrich Hayek said that the concept of social justice was meaningless, saying that justice is a result of individual behavior and unpredictable market forces. Social justice is closely related to the concept of relational justice, which is about the just relationship with individuals who possess features in common such as nationality, or who are engaged in cooperation or negotiation.” ref

While hallucinogens are associated with shamanism, it is alcohol that is associated with paganism.

The Atheist-Humanist-Leftist Revolutionaries Shows in the prehistory series:

Show two: Pre-animism 300,000 years old and animism 100,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism”

Show tree: Totemism 50,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism”

Show four: Shamanism 30,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism”

Show five: Paganism 12,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism”

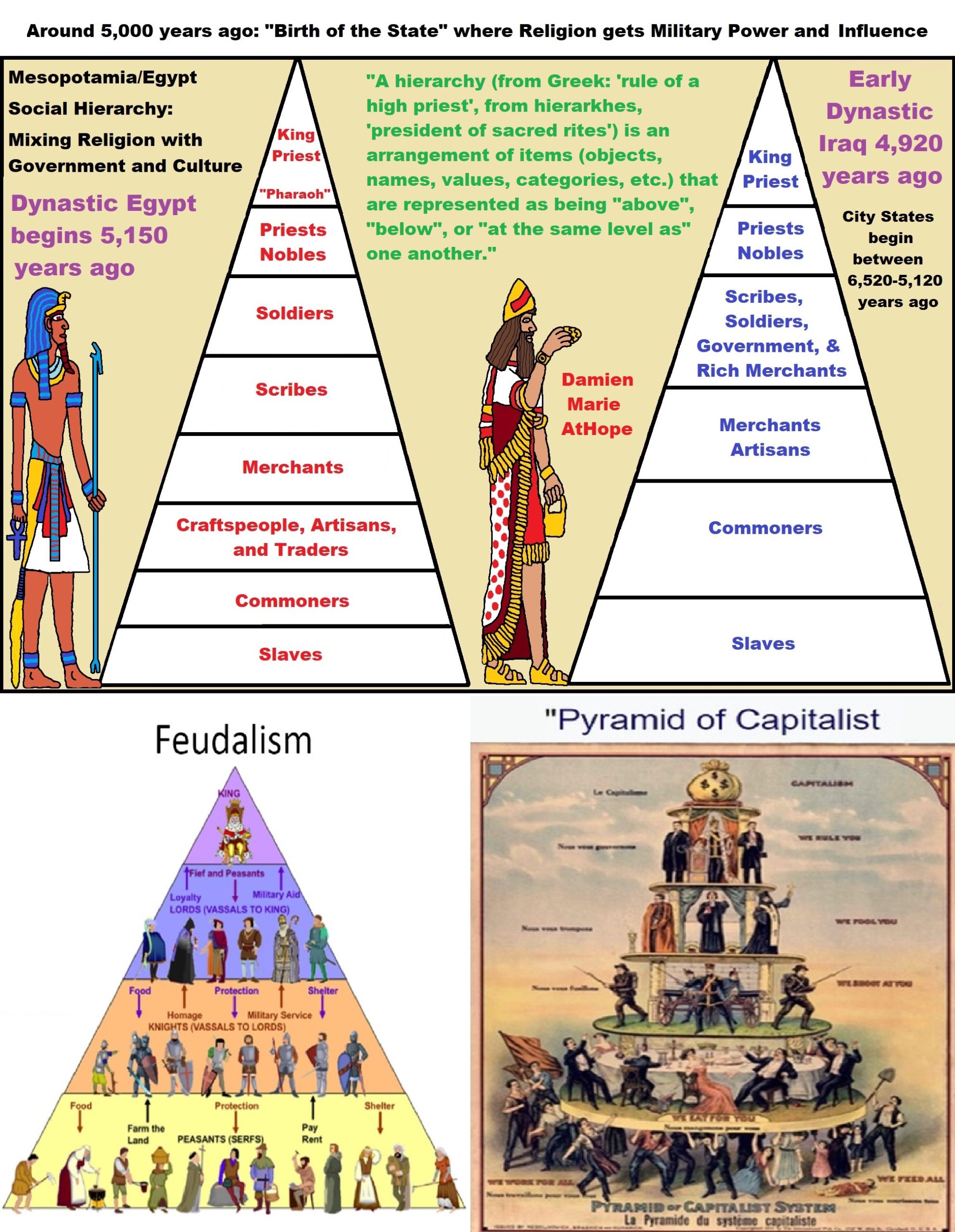

Show six: Emergence of hierarchy, sexism, slavery, and the new male god dominance: Paganism 7,000-5,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism” (Capitalism) (World War 0) Elite and their slaves!

Prehistory: related to “Anarchism and Socialism” the division of labor, power, rights, and recourses: VIDEO

Pre-animism 300,000 years old and animism 100,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism”: VIDEO

Totemism 50,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism”: VIDEO

Shamanism 30,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism”: VIDEO

Paganism 12,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism” (Pre-Capitalism): VIDEO

Paganism 7,000-5,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism” (Capitalism) (World War 0) Elite and their slaves: VIEDO

Paganism 5,000 years old: progressed organized religion and the state: related to “Anarchism and Socialism” (Kings and the Rise of the State): VIEDO

Paganism 4,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism” (First Moralistic gods, then the Origin time of Monotheism): VIEDO

I do not hate simply because I challenge and expose myths or lies any more than others being thought of as loving simply because of the protection and hiding from challenge their favored myths or lies.

The truth is best championed in the sunlight of challenge.

An archaeologist once said to me “Damien religion and culture are very different”

My response, So are you saying that was always that way, such as would you say Native Americans’ cultures are separate from their religions? And do you think it always was the way you believe?

I had said that religion was a cultural product. That is still how I see it and there are other archaeologists that think close to me as well. Gods too are the myths of cultures that did not understand science or the world around them, seeing magic/supernatural everywhere.

I personally think there is a goddess and not enough evidence to support a male god at Çatalhöyük but if there was both a male and female god and goddess then I know the kind of gods they were like Proto-Indo-European mythology.

This series idea was addressed in, Anarchist Teaching as Free Public Education or Free Education in the Public: VIDEO

Our 12 video series: Organized Oppression: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of power (9,000-4,000 years ago), is adapted from: The Complete and Concise History of the Sumerians and Early Bronze Age Mesopotamia (7000-2000 BC): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=szFjxmY7jQA by “History with Cy“

Show #1: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power (Samarra, Halaf, Ubaid)

Show #2: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power

Show #3: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power (Uruk and the First Cities)

Show #4: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power (First Kings)

Show #5: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power (Early Dynastic Period)

Show #6: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power

Show #7: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power (Sargon and Akkadian Rule)

Show #9: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power (Gudea of Lagash and Utu-hegal)

Show #12: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power (Aftermath and Legacy of Sumer)

The “Atheist-Humanist-Leftist Revolutionaries”

Cory Johnston ☭ Ⓐ Atheist Leftist @Skepticallefty & I (Damien Marie AtHope) @AthopeMarie (my YouTube & related blog) are working jointly in atheist, antitheist, antireligionist, antifascist, anarchist, socialist, and humanist endeavors in our videos together, generally, every other Saturday.

Why Does Power Bring Responsibility?

Think, how often is it the powerless that start wars, oppress others, or commit genocide? So, I guess the question is to us all, to ask, how can power not carry responsibility in a humanity concept? I know I see the deep ethical responsibility that if there is power their must be a humanistic responsibility of ethical and empathic stewardship of that power. Will I be brave enough to be kind? Will I possess enough courage to be compassionate? Will my valor reach its height of empathy? I as everyone, earns our justified respect by our actions, that are good, ethical, just, protecting, and kind. Do I have enough self-respect to put my love for humanity’s flushing, over being brought down by some of its bad actors? May we all be the ones doing good actions in the world, to help human flourishing.

I create the world I want to live in, striving for flourishing. Which is not a place but a positive potential involvement and promotion; a life of humanist goal precision. To master oneself, also means mastering positive prosocial behaviors needed for human flourishing. I may have lost a god myth as an atheist, but I am happy to tell you, my friend, it is exactly because of that, leaving the mental terrorizer, god belief, that I truly regained my connected ethical as well as kind humanity.

Cory and I will talk about prehistory and theism, addressing the relevance to atheism, anarchism, and socialism.

At the same time as the rise of the male god, 7,000 years ago, there was also the very time there was the rise of violence, war, and clans to kingdoms, then empires, then states. It is all connected back to 7,000 years ago, and it moved across the world.

Cory Johnston: https://damienmarieathope.com/2021/04/cory-johnston-mind-of-a-skeptical-leftist/?v=32aec8db952d

The Mind of a Skeptical Leftist (YouTube)

Cory Johnston: Mind of a Skeptical Leftist @Skepticallefty

The Mind of a Skeptical Leftist By Cory Johnston: “Promoting critical thinking, social justice, and left-wing politics by covering current events and talking to a variety of people. Cory Johnston has been thoughtfully talking to people and attempting to promote critical thinking, social justice, and left-wing politics.” http://anchor.fm/skepticalleft

Cory needs our support. We rise by helping each other.

Cory Johnston ☭ Ⓐ @Skepticallefty Evidence-based atheist leftist (he/him) Producer, host, and co-host of 4 podcasts @skeptarchy @skpoliticspod and @AthopeMarie

Damien Marie AtHope (“At Hope”) Axiological Atheist, Anti-theist, Anti-religionist, Secular Humanist. Rationalist, Writer, Artist, Poet, Philosopher, Advocate, Activist, Psychology, and Armchair Archaeology/Anthropology/Historian.

Damien is interested in: Freedom, Liberty, Justice, Equality, Ethics, Humanism, Science, Atheism, Antiteism, Antireligionism, Ignosticism, Left-Libertarianism, Anarchism, Socialism, Mutualism, Axiology, Metaphysics, LGBTQI, Philosophy, Advocacy, Activism, Mental Health, Psychology, Archaeology, Social Work, Sexual Rights, Marriage Rights, Woman’s Rights, Gender Rights, Child Rights, Secular Rights, Race Equality, Ageism/Disability Equality, Etc. And a far-leftist, “Anarcho-Humanist.”

I am not a good fit in the atheist movement that is mostly pro-capitalist, I am anti-capitalist. Mostly pro-skeptic, I am a rationalist not valuing skepticism. Mostly pro-agnostic, I am anti-agnostic. Mostly limited to anti-Abrahamic religions, I am an anti-religionist.

To me, the “male god” seems to have either emerged or become prominent around 7,000 years ago, whereas the now favored monotheism “male god” is more like 4,000 years ago or so. To me, the “female goddess” seems to have either emerged or become prominent around 11,000-10,000 years ago or so, losing the majority of its once prominence around 2,000 years ago due largely to the now favored monotheism “male god” that grow in prominence after 4,000 years ago or so.

My Thought on the Evolution of Gods?

Animal protector deities from old totems/spirit animal beliefs come first to me, 13,000/12,000 years ago, then women as deities 11,000/10,000 years ago, then male gods around 7,000/8,000 years ago. Moralistic gods around 5,000/4,000 years ago, and monotheistic gods around 4,000/3,000 years ago.

To me, animal gods were likely first related to totemism animals around 13,000 to 12,000 years ago or older. Female as goddesses was next to me, 11,000 to 10,000 years ago or so with the emergence of agriculture. Then male gods come about 8,000 to 7,000 years ago with clan wars. Many monotheism-themed religions started in henotheism, emerging out of polytheism/paganism.

Damien Marie AtHope (Said as “At” “Hope”)/(Autodidact Polymath but not good at math):

Axiological Atheist, Anti-theist, Anti-religionist, Secular Humanist, Rationalist, Writer, Artist, Jeweler, Poet, “autodidact” Philosopher, schooled in Psychology, and “autodidact” Armchair Archaeology/Anthropology/Pre-Historian (Knowledgeable in the range of: 1 million to 5,000/4,000 years ago). I am an anarchist socialist politically. Reasons for or Types of Atheism

My Website, My Blog, & Short-writing or Quotes, My YouTube, Twitter: @AthopeMarie, and My Email: damien.marie.athope@gmail.com