ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

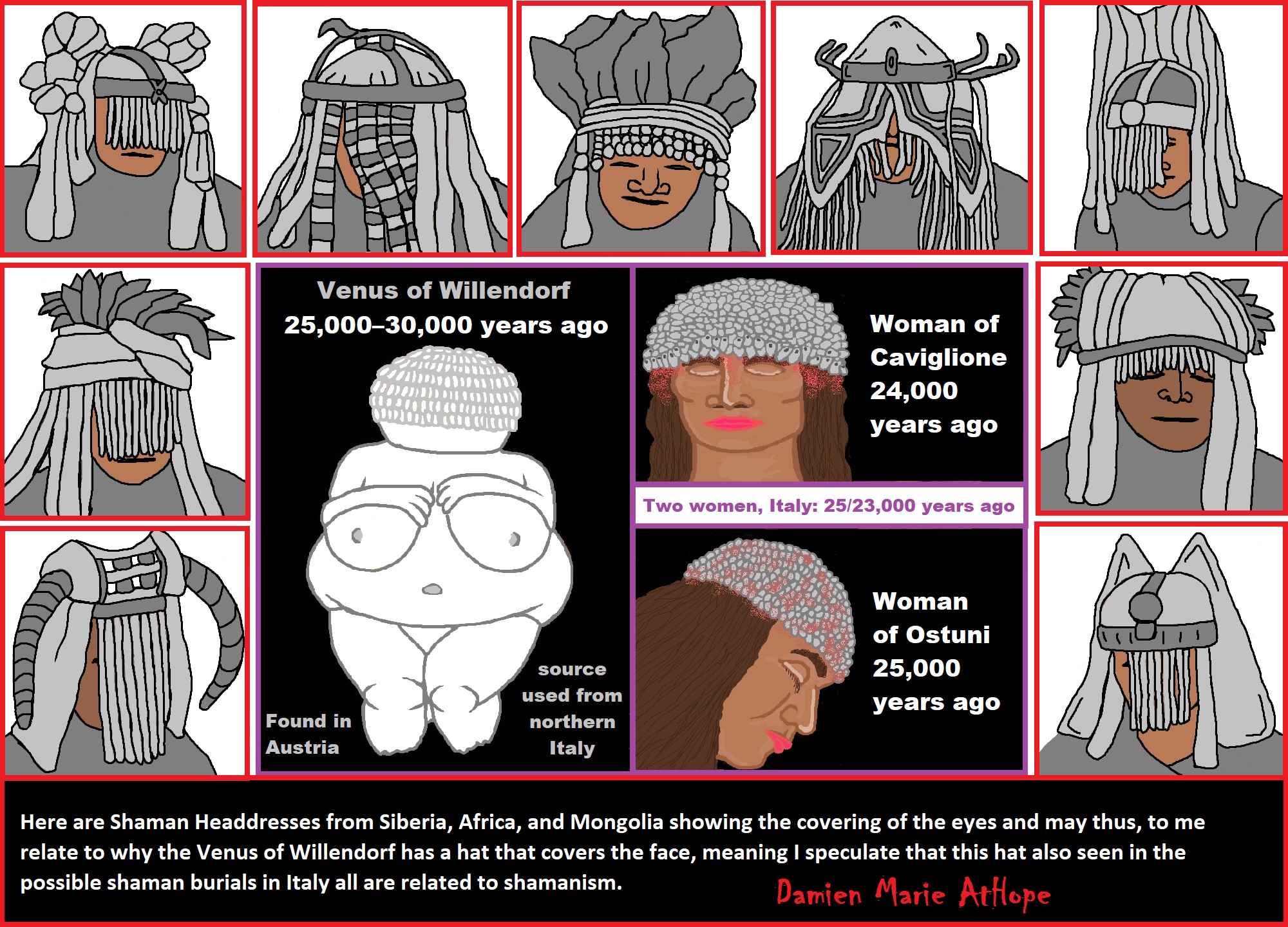

Here are Shaman Headdresses from Siberia, Africa, and Mongolia showing the covering of the eyes and may thus, to me relate to why the Venus of Willendorf has a hat that covers the face, meaning I speculate that this hat, also seen in the possible shaman burials in Italy all are related to shamanism.

“Venus figurines have been unearthed in Europe, Siberia, and much of Eurasia.

Most date from the Gravettian period but start in the Aurignacian era, and lasts to the Magdalenian time.” ref

Venus of Willendorf: Shamanism Headdresses that Cover the Eyes?

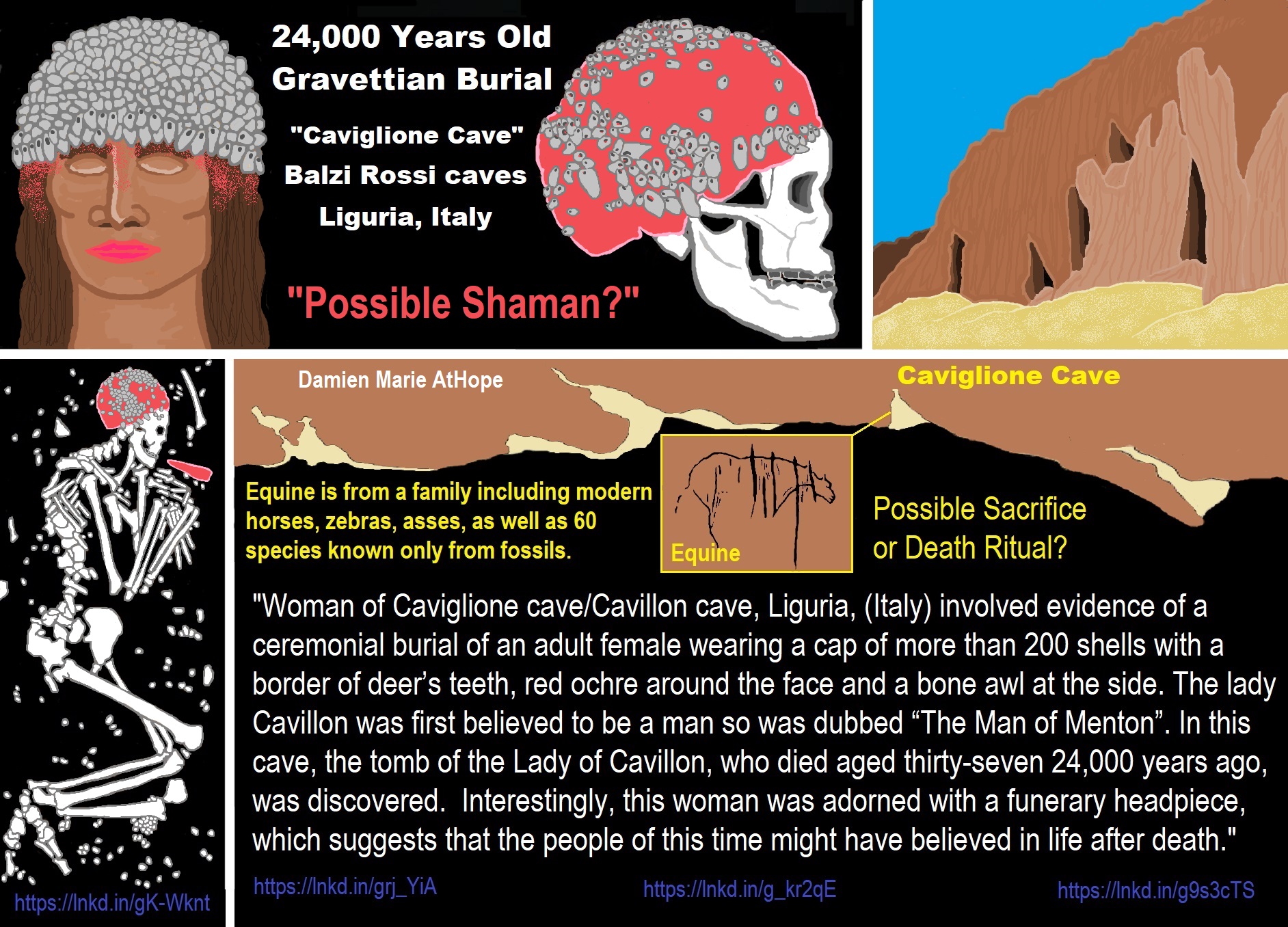

“Woman of Caviglione cave/Cavillon cave, Liguria, (Italy) involved evidence of a ceremonial burial of an adult female wearing a cap of more than 200 shells with a border of deer’s teeth, red ochre around the face and a bone awl at the side. The lady Cavillon was first believed to be a man so was dubbed “The Man of Menton”. In this cave, the tomb of the Lady of Cavillon, who died aged thirty-seven 24,000 years ago, was discovered. Interestingly, this woman was adorned with a funerary headpiece, which suggests that the people of this time might have believed in life after death.” Ref, Ref, Ref, Ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

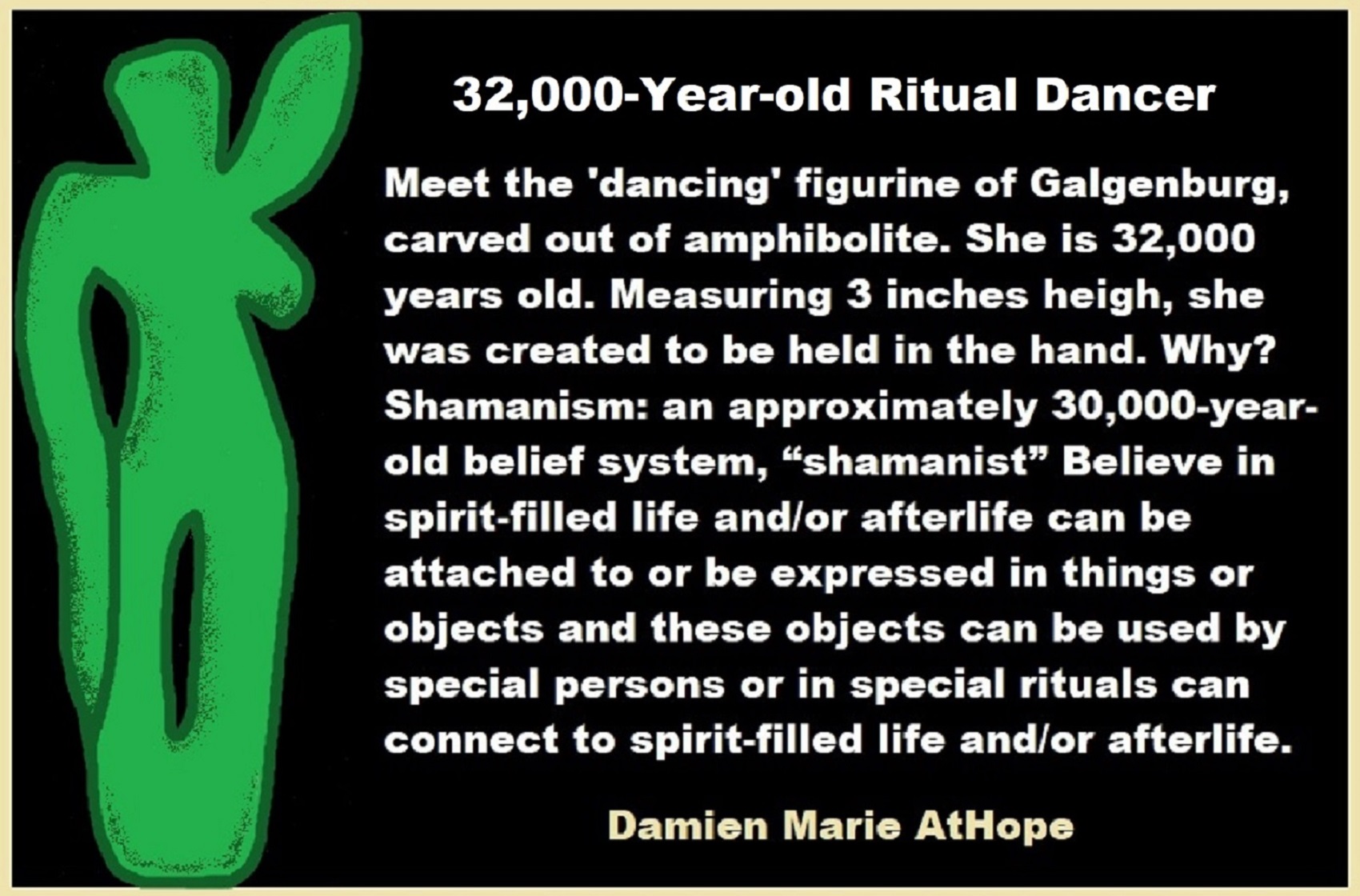

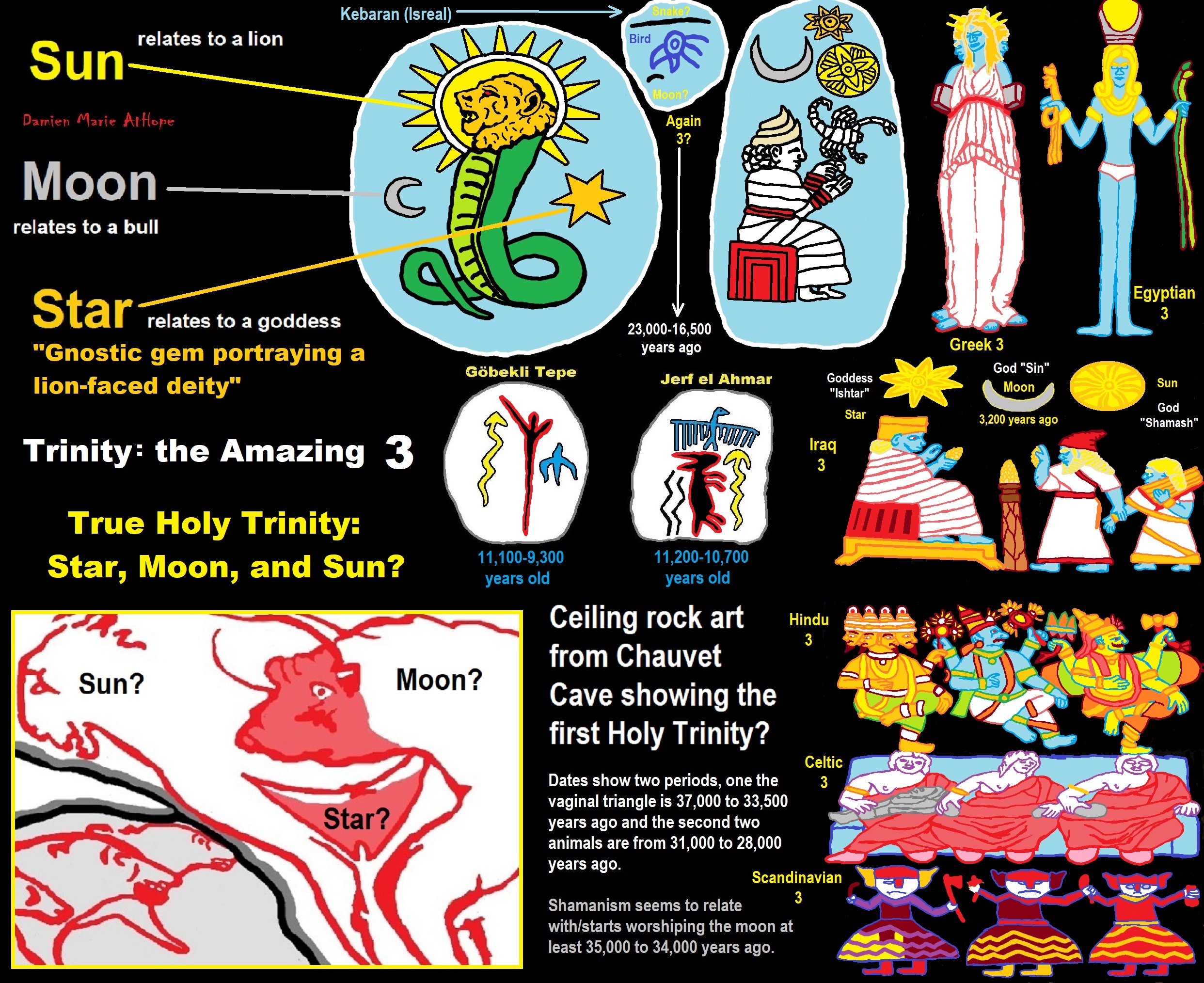

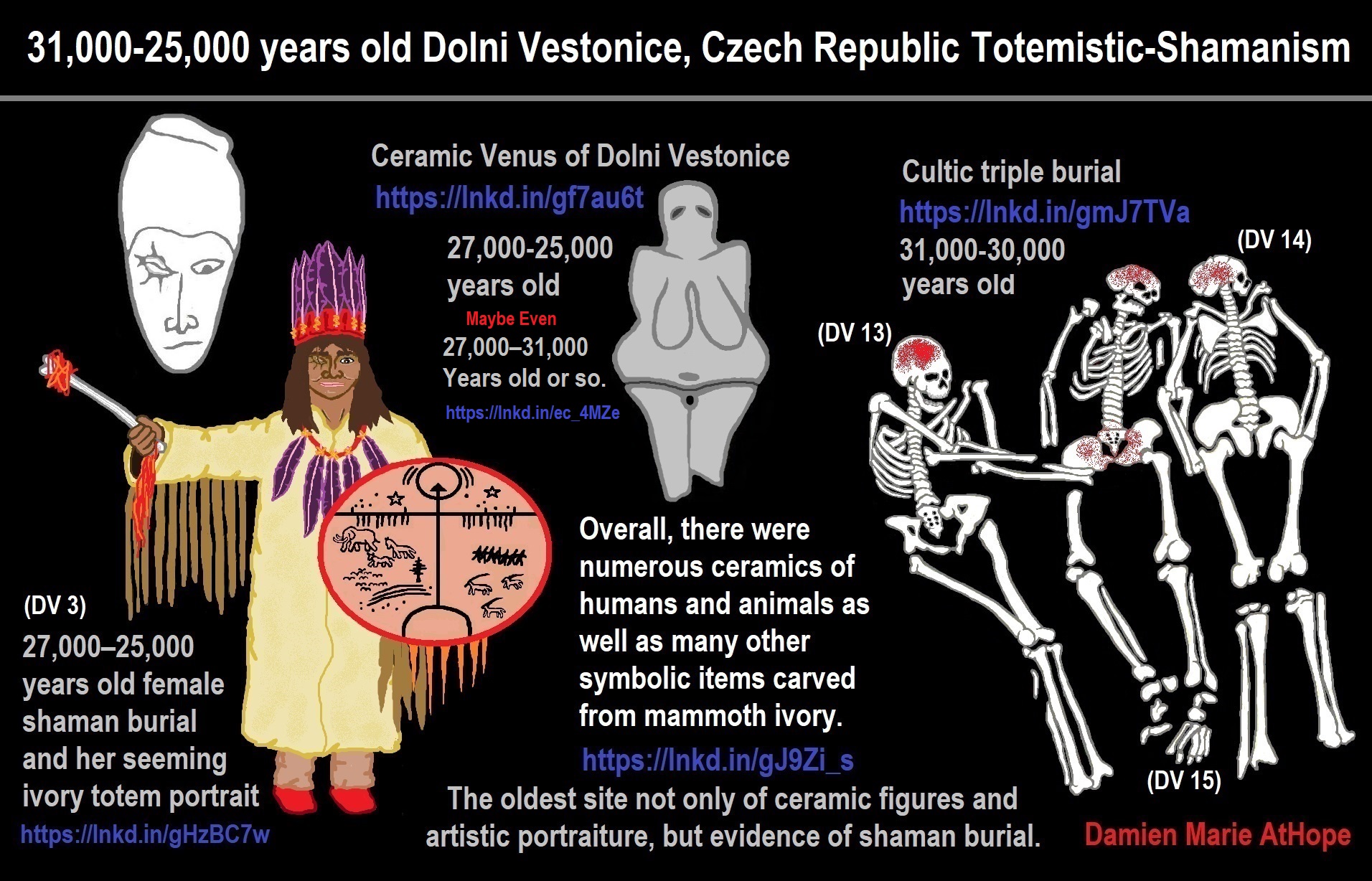

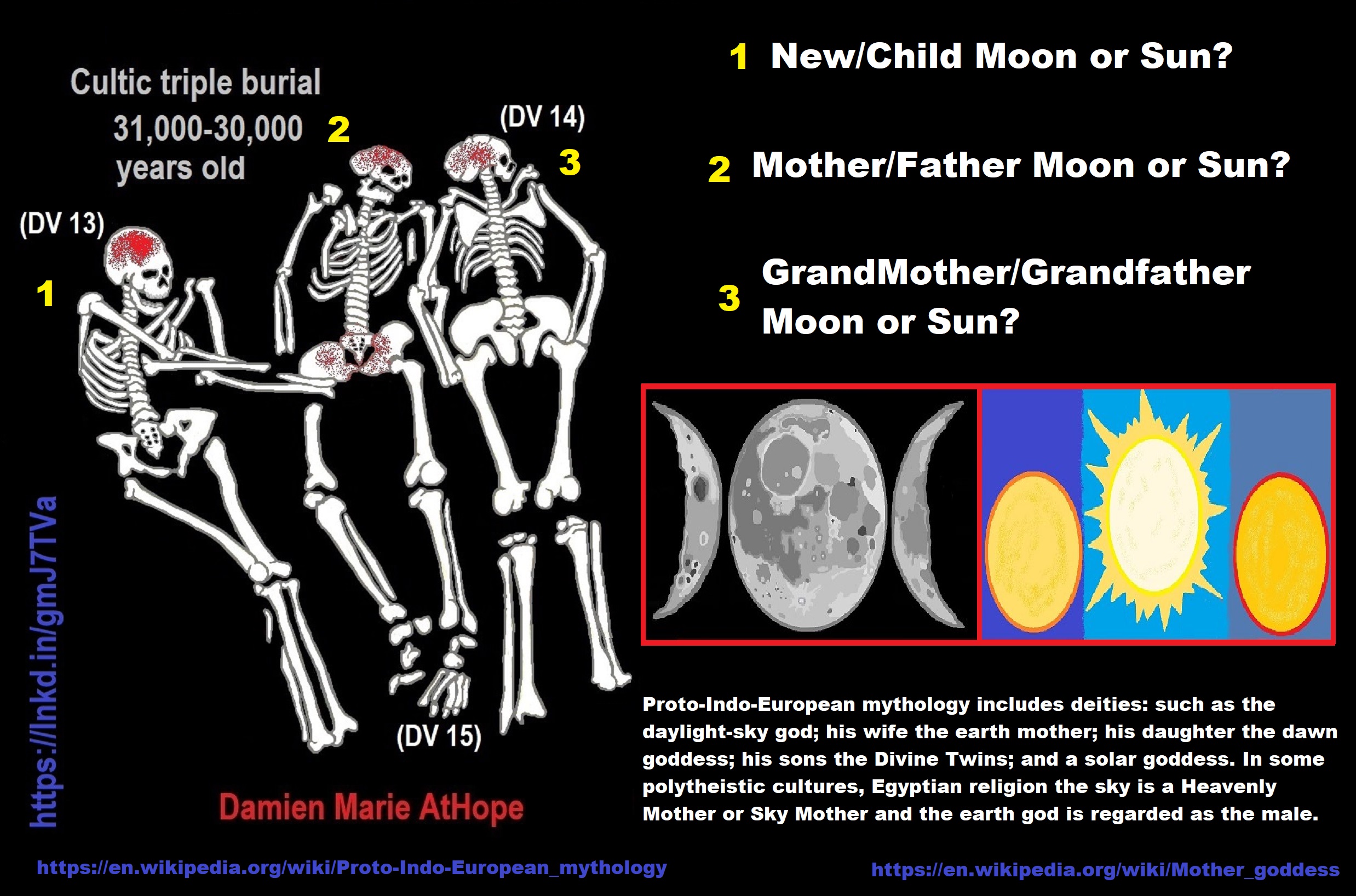

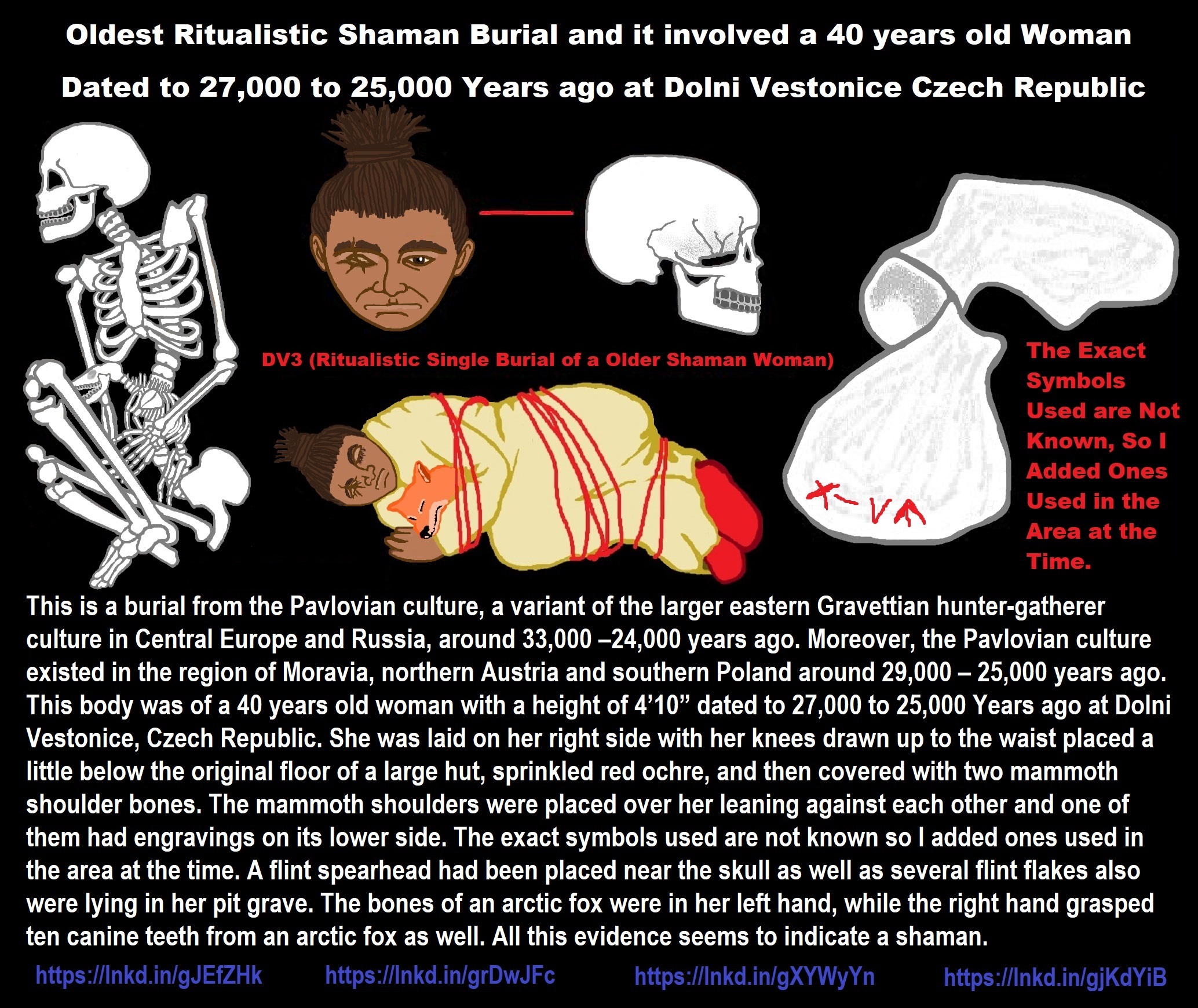

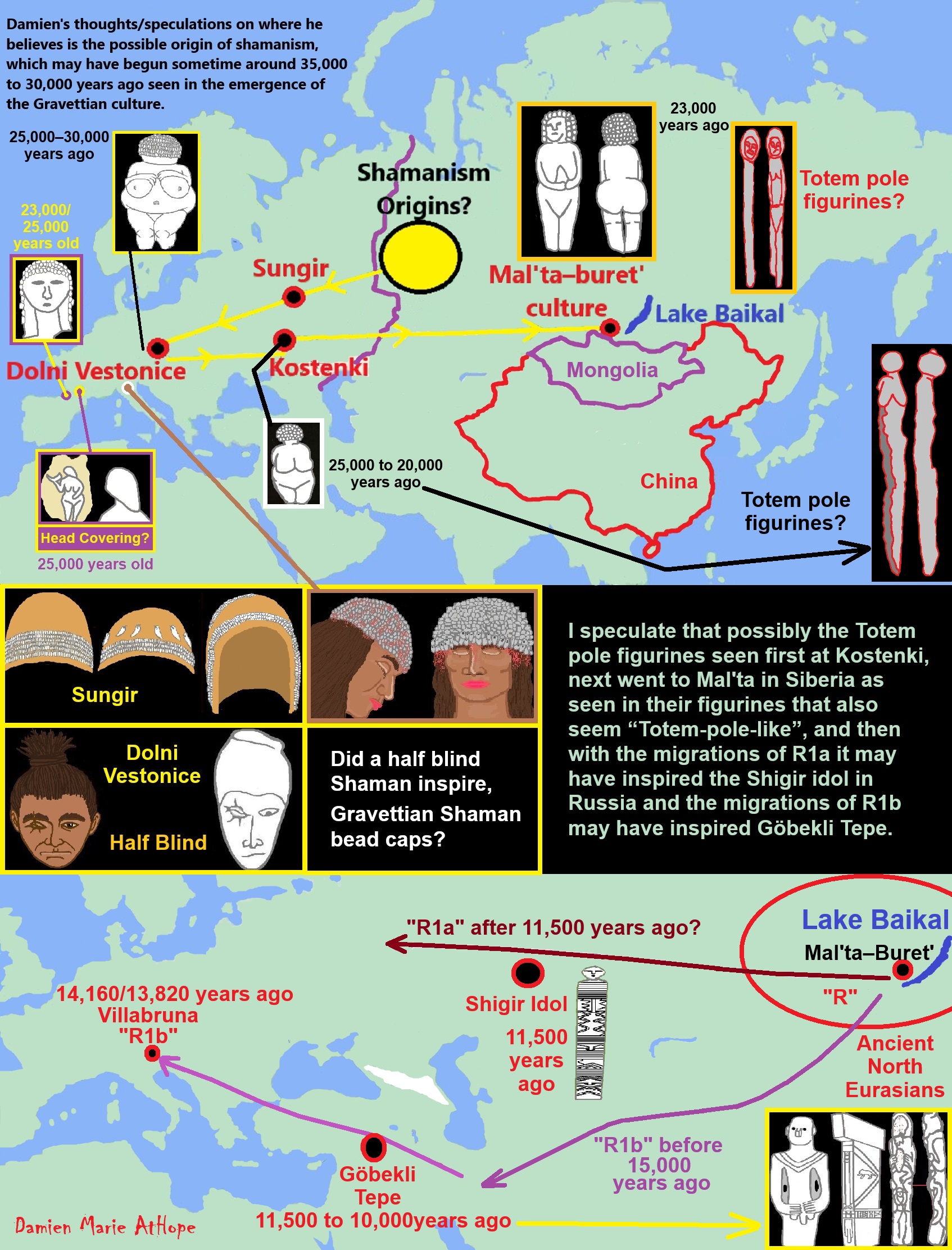

Here are my thoughts/speculations on where I believe is the possible origin of shamanism, which may have begun sometime around 35,000 to 30,000 years ago seen in the emergence of the Gravettian culture, just to outline his thinking, on what thousands of years later led to evolved Asian shamanism, in general, and thus WU shamanism as well. In both Europe-related “shamanism-possible burials” and in Gravettian mitochondrial DNA is a seeming connection to Haplogroup U. And the first believed Shaman proposed burial belonged to Eastern Gravettians/Pavlovian culture at Dolní Věstonice in southern Moravia in the Czech Republic, which is the oldest permanent human settlement that has ever been found. It is at Dolní Věstonice where approximately 27,000-25,000 years ago a seeming female shaman was buried and also there was an ivory totem portrait figure, seemingly of her.

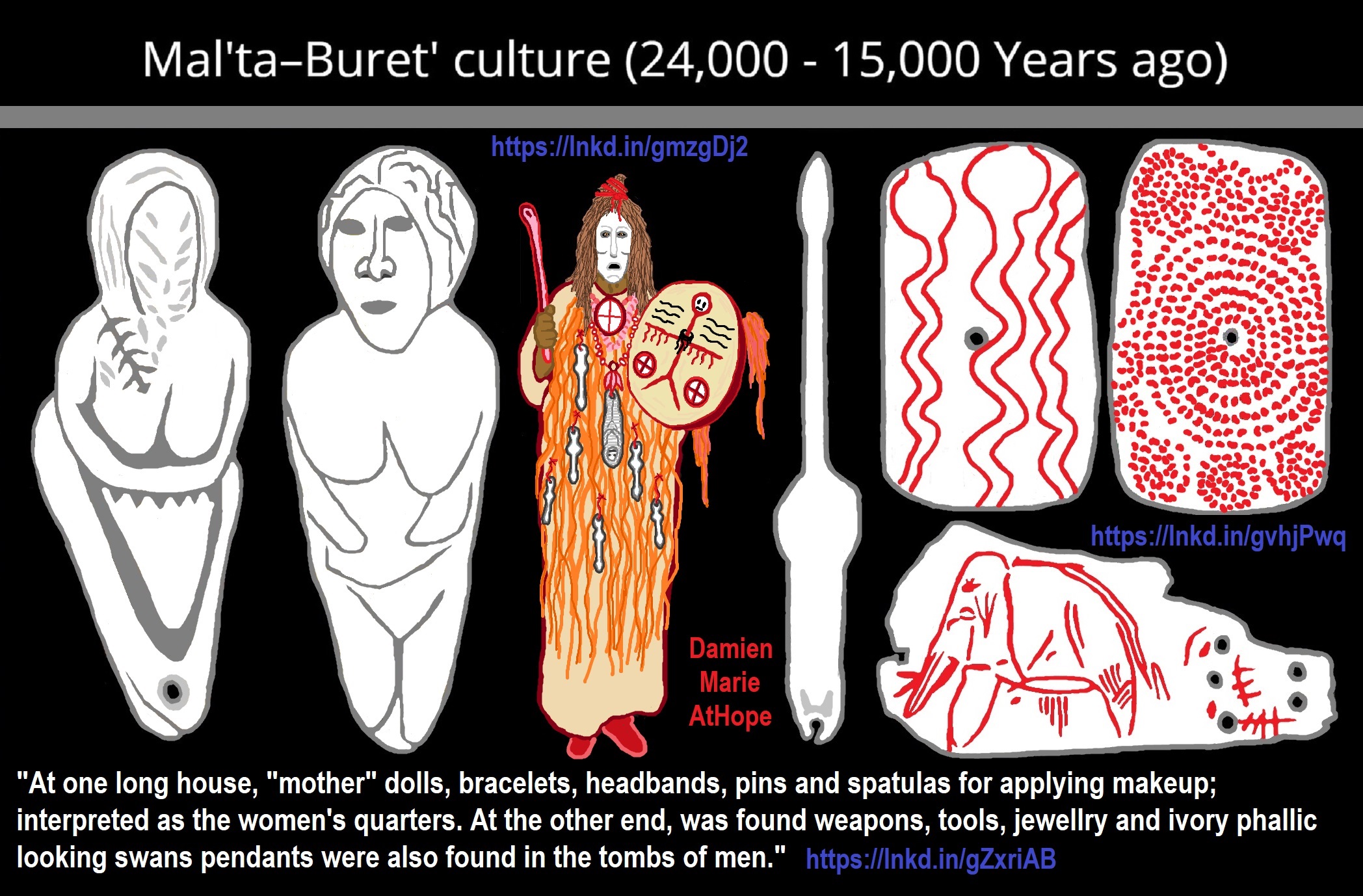

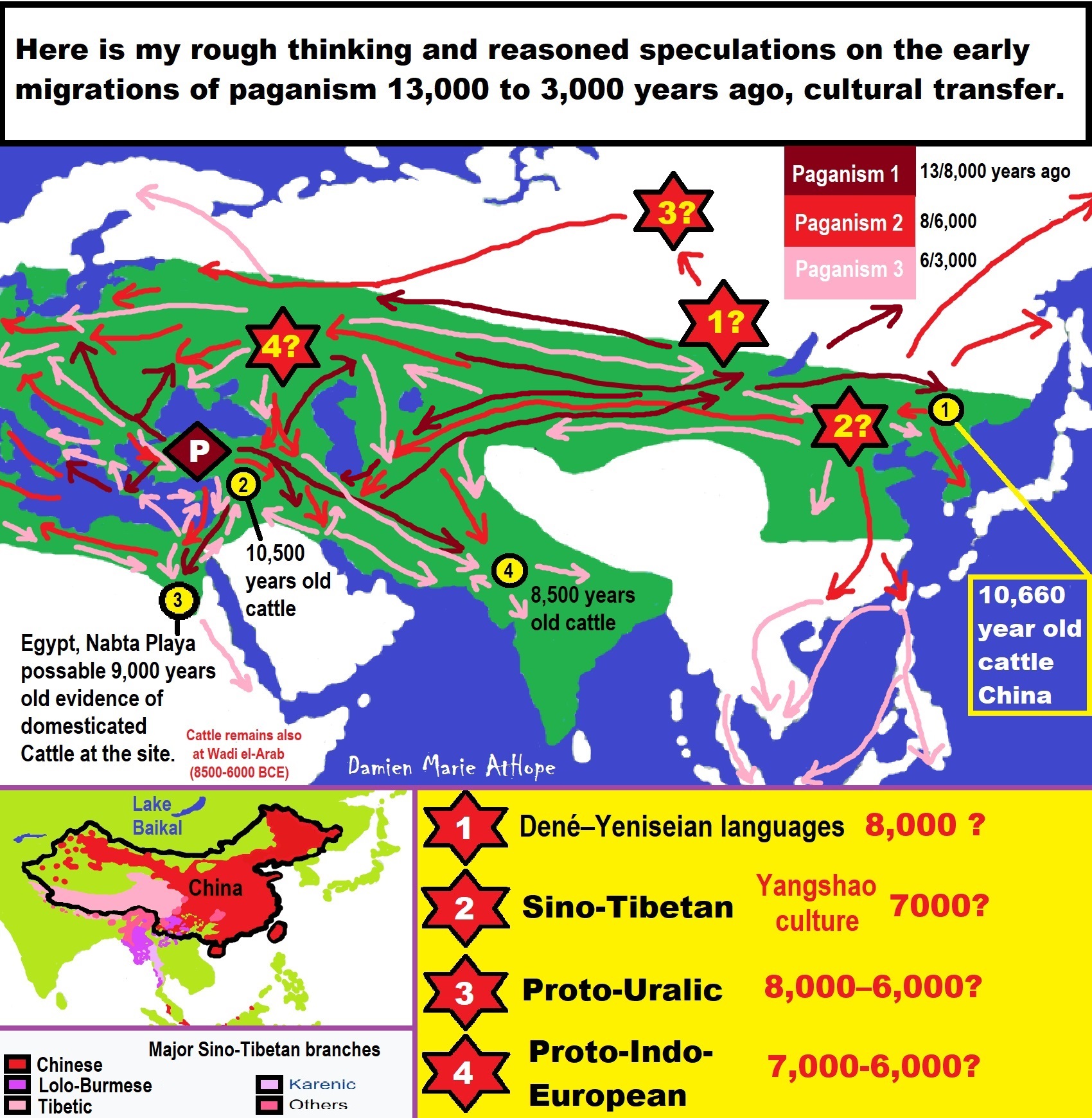

And my thoughts on how cultural/ritual aspects were influenced in the area of Göbekli Tepe. I think it relates to a few different cultures starting in the area before the Neolithic. Two different groups of Siberians first from northwest Siberia with U6 haplogroup 40,000 to 30,000 or so. Then R Haplogroup (mainly haplogroup R1b but also some possible R1a both related to the Ancient North Eurasians). This second group added its “R1b” DNA of around 50% to the two cultures Natufian and Trialetian. To me, it is likely both of these cultures helped create Göbekli Tepe. Then I think the female art or graffiti seen at Göbekli Tepe to me possibly relates to the Epigravettians that made it into Turkey and have similar art in North Italy. I speculate that possibly the Totem pole figurines seen first at Kostenki, next went to Mal’ta in Siberia as seen in their figurines that also seem “Totem-pole-like”, and then with the migrations of R1a it may have inspired the Shigir idol in Russia and the migrations of R1b may have inspired Göbekli Tepe.

Shamanism in Siberia

“A large minority of people in North Asia, particularly in Siberia, follow the religio-cultural practices of shamanism. Some researchers regard Siberia as the heartland of shamanism. The people of Siberia comprise a variety of ethnic groups, many of whom continue to observe shamanistic practices in modern times. Many classical ethnographers recorded the sources of the idea of “shamanism” among Siberian peoples.” ref

Terminology in Siberian languages

- “shaman’: saman (Nedigal, Nanay, Ulcha, Orok), sama (Manchu). The variant /šaman/ (i.e., pronounced “shaman”) is Evenk (whence it was borrowed into Russian).

- ‘shaman’: alman, olman, wolmen (Yukagir)

- ‘shaman’: [qam] (Tatar, Shor, Oyrat), [xam] (Tuva, Tofalar)

- The Buryat word for shaman is бөө (böö) [bøː], from early Mongolian böge. Itself borrowed from Proto-Turkic *bögü (“sage, wizard”)

- ‘shaman’: ńajt (Khanty, Mansi), from Proto-Uralic *nojta (c.f. Sámi noaidi)

- ‘shamaness’: [iduɣan] (Mongol), [udaɣan] (Yakut), udagan (Buryat), udugan (Evenki, Lamut), odogan (Nedigal). Related forms found in various Siberian languages include utagan, ubakan, utygan, utügun, iduan, or duana. All these are related to the Mongolian name of Etügen, the hearth goddess, and Etügen Eke ‘Mother Earth’. Maria Czaplicka points out that Siberian languages use words for male shamans from diverse roots, but the words for female shaman are almost all from the same root. She connects this with the theory that women’s practice of shamanism was established earlier than men’s, that “shamans were originally female.” ref

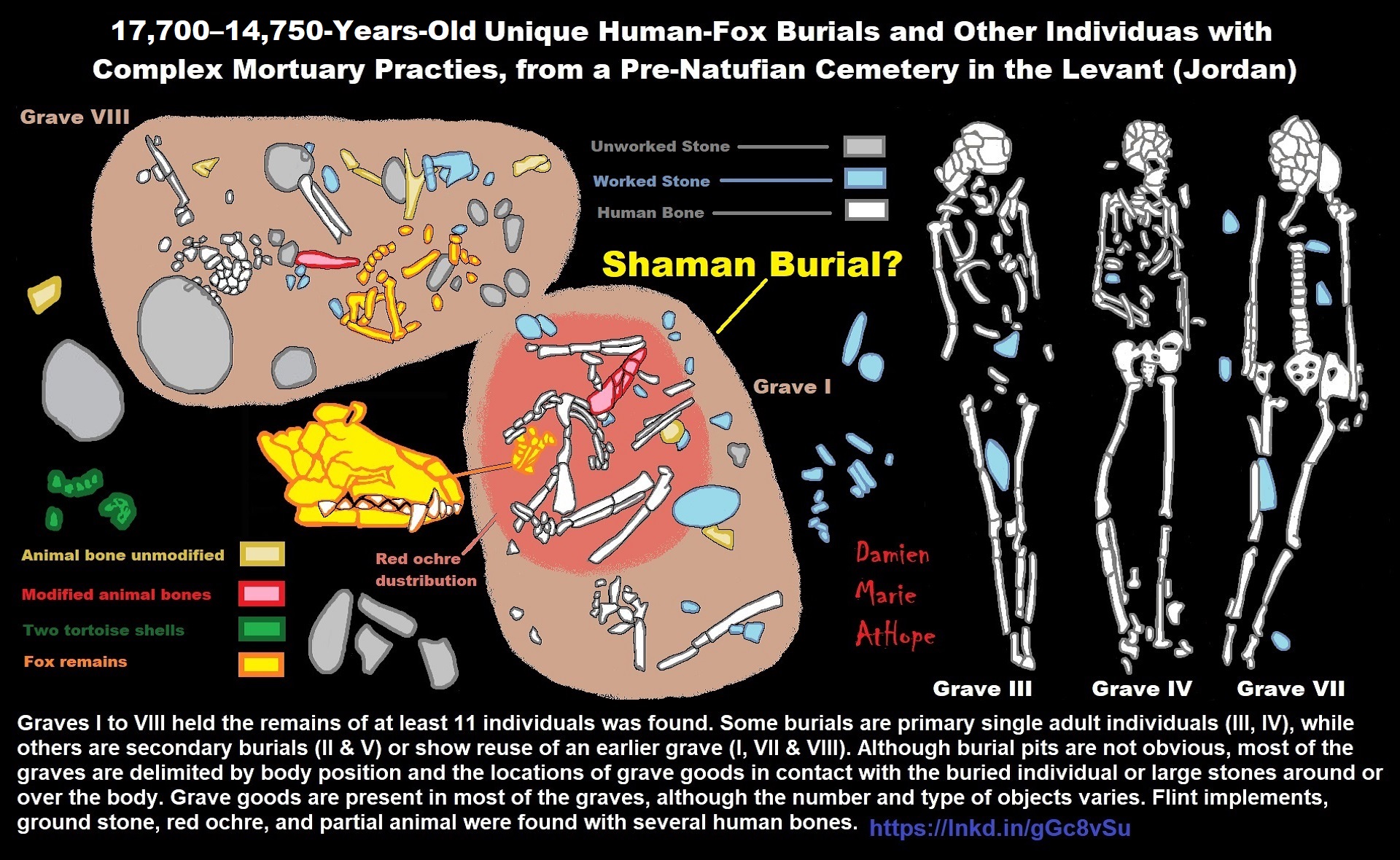

“Grave VIII also included very fragmentary tibia and fibula, in articulation, and a left humerus, scapula, radius and ulna, representing an articulated arm of an adult. Discriminant analysis of humeral metrics suggests that these elements represent an adult female.” ref

A Unique Human-Fox Burial from a Pre-Natufian Cemetery in the Levant (Jordan)

“Among the skeletal elements preserved, the pelvis from Burial A provides the only reliable sexually dimorphic traits, and is identified as a probable female on the basis of having broad sciatic notches. Discriminant function analysis of osteometric data collected from long-bones, including bone lengths, and diaphyseal and articular dimensions was used to further attempt sex determination (Supporting Information S1). Comparative samples included Levantine Epipalaeolithic skeletons where sex had been determined from pelvic morphology. The discriminant analysis provided ambiguous and male classifications of the two femora of Burial A, while all long bones in Grave I were classified as male. While this is not a conclusive sex determination, given the evidence from the Burial A pelvis, the results suggests that Grave I likely contains interments of one adult female (Burial A) and one adult male (Burial B). None of the individuals show signs of interpersonal violence or obvious pathologies that may indicate cause of death. Although burial pits are not obvious, most of the graves are delimited by body position and the locations of grave goods in contact with the buried individual or large stones around or over the body. Grave goods are present in most of the graves, although the number and type of objects varies. Flint implements, ground stone, red ochre, and partial animal skeletons were found associated with several of the skeletons. Since the burials are dug into pre-existing Epipalaeolithic deposits, the attribution of items as grave goods is conservative—only items in meaningful association or direct contact with the skeletons are included and, therefore, it is possible that we have underestimated the actual number of grave goods in each burial.” ref

“The archaeological record of the Epipalaeolithic period in the southern Levant (ca. 23,000–11,600 years ago) exhibits considerable variability across time and space. A wealth of archaeological investigations suggest dramatic disparities in material culture between earlier and later phases, explained in terms of pre-adaptive thresholds necessary for the development of subsequent Neolithic farming communities. The Late Epipalaeolithic Natufian culture is well-known for its stone architecture, organized site structures, portable art and decoration, and human burials, some of which display grave goods and personal ornaments. Formalized cemeteries, totaling more than 400 interments, appear for the first time. These burials document a wide variety of mortuary practices, with treatments of the dead including stone and organic burial containers and installations, worked stone and bone grave goods and, notably, animal inclusions such as early domesticated dog. Elucidating the social meanings of these variable burial customs is challenging due to the limitations of the material culture record and the limitations of ethnographic comparisons. However, contextual examination of items accompanying human remains permits preliminary interpretations of this mortuary behavior. For example, Grossman et al. interpret an elderly female Natufian burial containing a unique array of grave goods as the first shaman burial.” ref

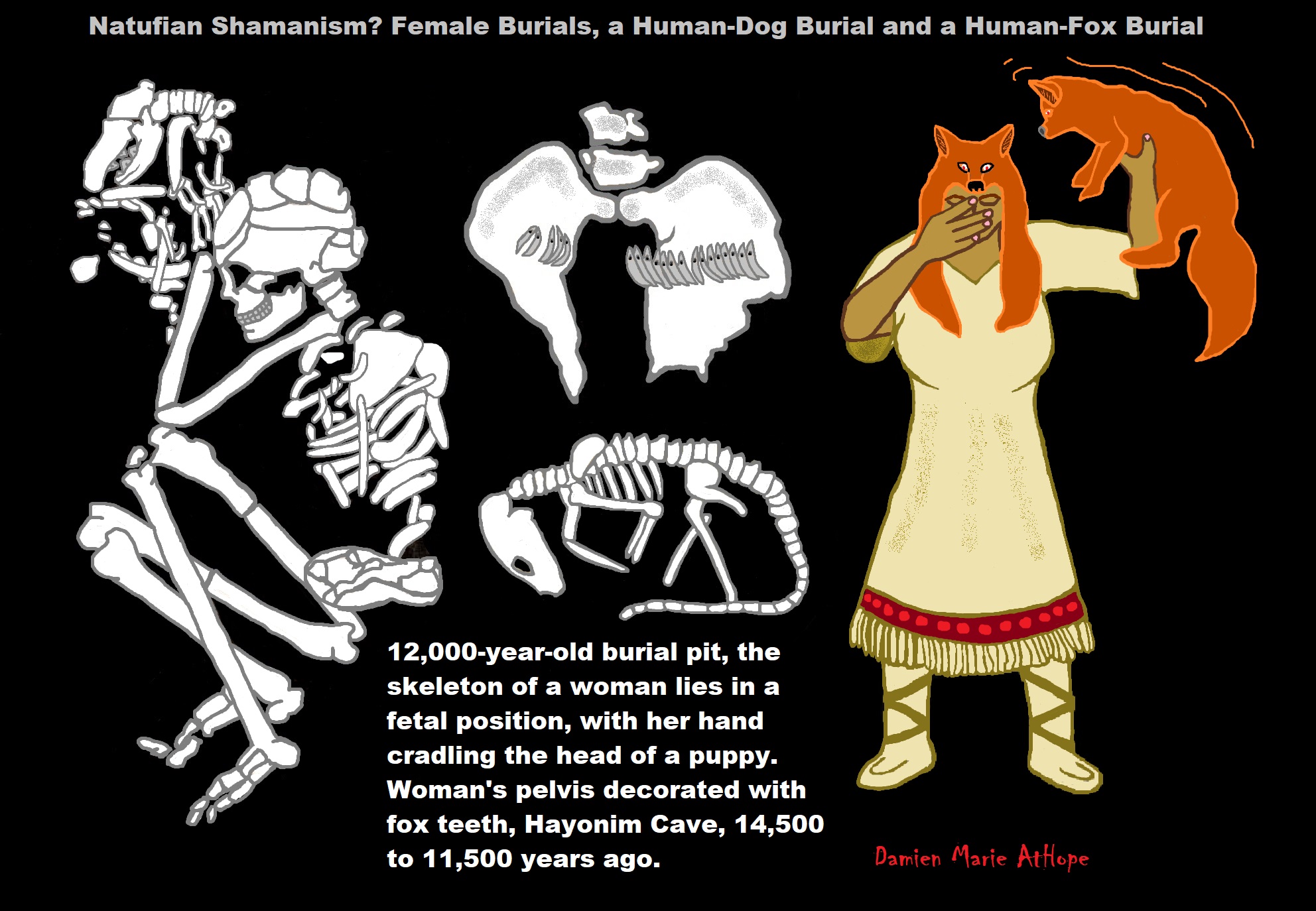

“Despite early work that seemed to indicate a behavioral break between Early/Middle Epipalaeolithic and later, socially-complex Natufian sites, new excavations suggest an earlier emergence of some of the features characteristic of the Natufian period. Key features used to differentiate Natufian from preceding Epipalaeolithic groups include the appearance of formalized burial grounds and the origin of mortuary traditions that become characteristic of Neolithic symbolic and ideological life. Two key mortuary practices demonstrate ideological continuity between the Natufian and Neolithic, while highlighting a break between the Natufian and earlier EP groups a) the movement or removal of skulls and, b) special human-animal relationships. For example, the burial of an adult female with a juvenile domestic dog is well-known from ‘Ain Mallaha (‘Eynan), while another human-dog burial comes from Hayonim Terrace. Also, a unique burial from the Late Natufian site of Hilazon Tachtit features an elderly female buried with over 50 tortoise carapaces, several articulated raptor wings, the pelvis of a leopard, and the mandible of a wolf. These unmodified animal parts could be viewed as evidence for changing human-animal interactions or domestication yet to come.” ref

“Uyun al-Hammam is a pre-Natufian burial ground, with elaborate human burials that include evidence for unique human-animal relationships, demonstrating that these features are not unique to the Natufian. The remains of at least eleven individuals, interred in eight graves, represent the earliest known cemetery in the southern Levant and more than double the number of human burials for the entire Early and Middle Epipalaeolithic periods. Recent discoveries at ‘Uyun al-Hammam demonstrate a unique collection (in abundance and diversity) of grave goods and varied patterns of interment associated with the human remains. Two adjacent graves contain the articulated remains of several individuals, and include the following elements: 1) the earliest human-fox burial, 2) the movement of human and animal (fox) body parts between graves and, 3) the presence of red ochre, worked bone implements, chipped and ground stone tools, and the remains of deer, gazelle, aurochs and tortoise – grave goods that together became common among later Natufian and Neolithic burials. The ‘Uyun al-Hammam burials thus demonstrate intriguing human-animal relationships earlier than the first domesticated animal in the region. In light of the significance recently given to the Natufian “shaman” of Hilazon Tachtit, our findings provide strong evidence that key aspects of these complex mortuary traditions occurred earlier in the Epipalaeolithic of the Near East than previously thought.” ref

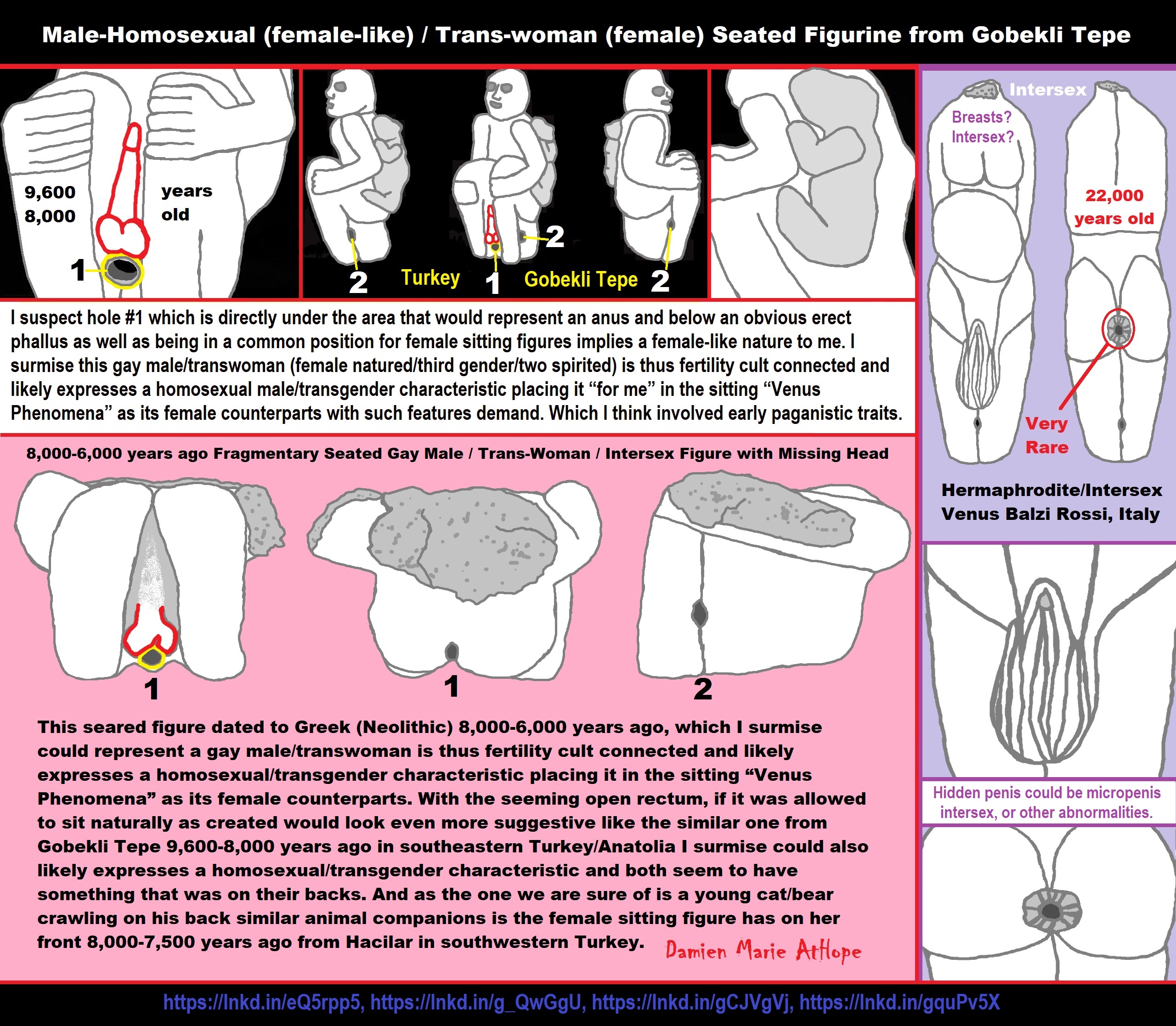

Shamanic Gender Identities

“Shamanic behavior necessitates a broadening of the notion of gender to be more fluid and dynamic, to include not only male and female but also various mediating identities.” ref

“Shamanism, like many other “isms,” is a Western construct, and issues of gender and sexuality play into this construct in various ways. Shamanism has been used since the eighteenth century to describe various people in indigenous (“tribal”) communities who might also be termed “medicine men,” “witch doctors,” “healers,” and “sorcerers”; those people who engage with “spirits” for certain socially sanctioned tasks. Shamans may be identified as such from birth, through an initiatory sickness, or a calling from the spirits; only rarely is the vocation taken up voluntarily. Shamanic practices may include healing the sick, controlling game, altering consciousness, journeying to other worlds, speaking to spirits or becoming possessed by them, even forming marriages and sexual relationships with powerful “spirit-helpers.” While the term derives from the Tungus-speaking Evenk in Siberia, shamanism is often regarded as a global and archaic phenomenon, even the origin of religion. But such a generalizing perspective is misleading. Moreover, an “ism” suggests something coherent and systematic; but in the case of shamanism no such thing exists. Consequently, it is difficult to arrive at a discrete definition; indeed, it would be naïve to attempt a monolithic, all-encompassing definition, or even to arrive at a list of defining characteristics of shamans without sacrificing cultural variety and nuance. A more sensitive approach acknowledges shamanisms’ historicity and foregrounds the diversity of shamans.” ref

“The theorizing of shamanism has marked important intellectual developments. Shamanism has been held to be the “oldest,” most “primitive,” even the “origin” of religion (whatever this may mean), but it is misleading to associate contemporary indigenous practices with a fixed and unchanging past. Prehistoric shamans, however, have been innovatively theorized by archaeologists. Rock art researchers have interpreted various cave paintings and rock engravings as originating in the altered consciousness of shamans. More recently, anthropologists have attended to the nature of shamanism in nuanced fashion, broadening our understanding away from “the shaman” in a society with a “shamanic worldview” to consider the specificity of relationships and wider epistemological concerns. The “old animism,” as presented by Tylor, assumed that indigenous peoples were mistaken in their belief in “spirits” and that “inanimate objects” had “souls.” More recently, scholars theorizing a “new animism” have foregrounded the sophisticated nature of animisms (there is no single “animism” but rather culture-specific animisms).” ref

“For animists, the world is filled with “persons” only some of whom are human. An ongoing system of relationships and regulated behavior steers engagements between human persons and such “other-thanhuman-persons” as tree-people, seal-people, and stone-people. Shamans are often key figures in these relationally-driven ontologies, acting as mediators, working to maintain harmony: for example, if a hunter offends an animal by using inappropriate etiquette, resulting in

the hunter falling ill, a shaman negotiates between the offended “spirit” of the dead animal in order to return the stolen “soul” of the hunter and so restore social harmony between the affected “persons.” Among the Ojibwe and speakers of cognate Algonkian language, a grammatical distinction is made between animate and inanimate genders, not between male and female genders. Persons and personal actions are talked about in a different way from objects and impersonal events. As demonstrated in the work of such scholars as Marjorie Balzer, Marie Czaplicka, and Bernard Saladin D’Anglure, these and other indigenous conceptions of gender, sex, and sexual orientation, tend to disrupt Western binary conventions of “male” and “female,” conflations of sex and gender, and heterosexuality as normative.” ref

“Shamanic behavior necessitates a broadening of the notion of gender to be more fluid and dynamic, to include not only male and female but also various mediating identities. Czaplicka, for example, notes that Siberian shamans are a “third class,” separate from males and females, and Saladin D’Anglure proposes a “ternary” model for Inuit shamans wherein shamans are “in-between” persons (by persuasion or initiation) who embody a “third gender” due to their ability to mediate. The “third gender” status of Inuit shamans is part of wider gender concepts: children are understood to have

decided which gender to be before or at birth, their genitalia adapting to their decision. Other children are given the name of a deceased relative of the opposite gender, performing that gender identity for the time that they hold the name. “Third gender” (shamans in other instances may have a fourth or even multiple gender identity) overlaps in some examples with homosexuality, with the marriage of some shamans to same-sex “spirit” partners involving, in some examples, homosexual marriages in the “ordinary world.” Shamans’ costumes may combine features peculiar to the dress of both men and women. Early explorers assumed biological males dressed in women’s clothing (some of whom were shamans) were transvestites, and the pejorative French term berdache (“male prostitute,” “transvestite”) entered anthropological literature. The more sensitive “two-spirit” was proposed by Native Americans in the 1990s, referring to the individual having two spirits, although “changing ones” more successfully avoids reproducing a Western binary opposition.” ref

“Cross-dressing may indicate shamans’ difference from the rest of the community or show that they have formed an intimate, sexual and/or marital relationship with a nonhuman person of the same gender. Transvestitism may be temporary, a part of specific performances, or permanent as a sign of a distinctive everyday identity. Shamans may undertake marriage to non-human persons of the same gender as themselves and, for example, a female shaman may sometimes be “male” in relation to a spirit wife: a Sora shaman of the Indian subcontinent marries a man, and the “spirit son” of her predecessor, who is her own aunt. The tightly bound relationship between shamans and their other world helpers, especially those with whom they form sexual and/or marital relationships, may mean that secrets are kept, and the revealing of such secrets may lead to the withdrawal of assistance from a nonhuman helper, thus compromising the shaman’s ability to shamanize. Sex has been theorized as key to understanding shamanism by Roberte Hamayon, who attends to shamans, sex, and gender in Siberian shamanism. She argues that shamanic séances among the Evenk and Buryats are “sexual encounters” in themselves. She views the “marriage” between shamans and their non-human helpers

as more significant in understanding what these shamans do than the “ecstasy,” “mastery of spirits,” “altered states” or “journeying” emphasized by other scholars.” ref

“Conclusion: Early work on Siberian shamans by Sergei Shirokogoroff demonstrated that shamans may be either (or both)

“hostages to the spirits” and their sexual and/or marital partners. Shamans might, then, be defined as people who welcome “possession” as an embodiment of (sexual and/or marital) relationship with otherthan-human-persons. As the most effective mediators, then–between genders, between humans and nonhumans, the living and dead, and so on–shamans mediate between all the many constituent elements, beings, and situations of the cosmos. They thereby actively accomplish meanings through the construction of relations between human and other-than-human worlds.” ref

There are other clothing resembling miniskirts that have been identified by archaeologists and historians as far back as 3,390–3,370 years ago. But this is much older. ref

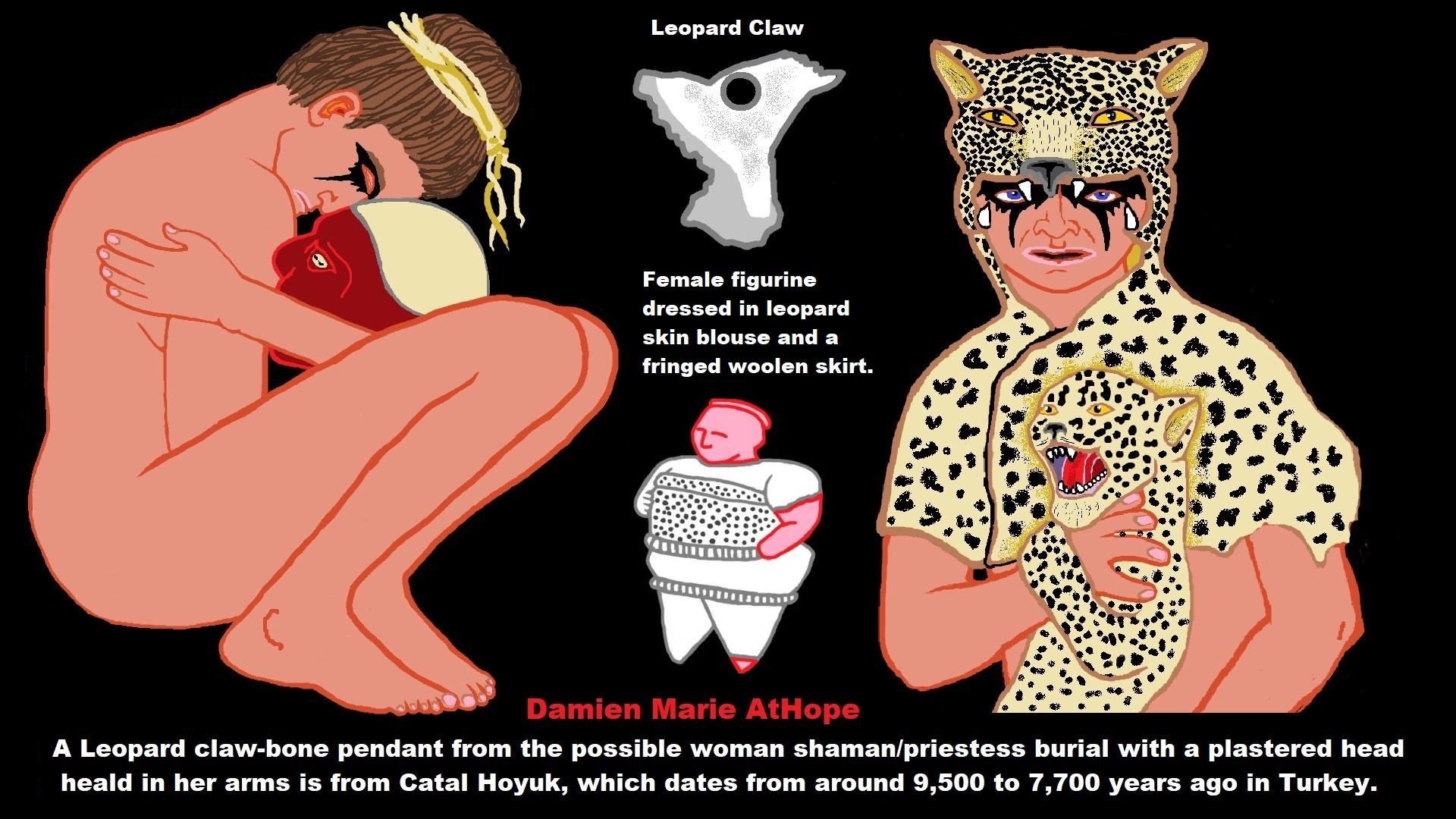

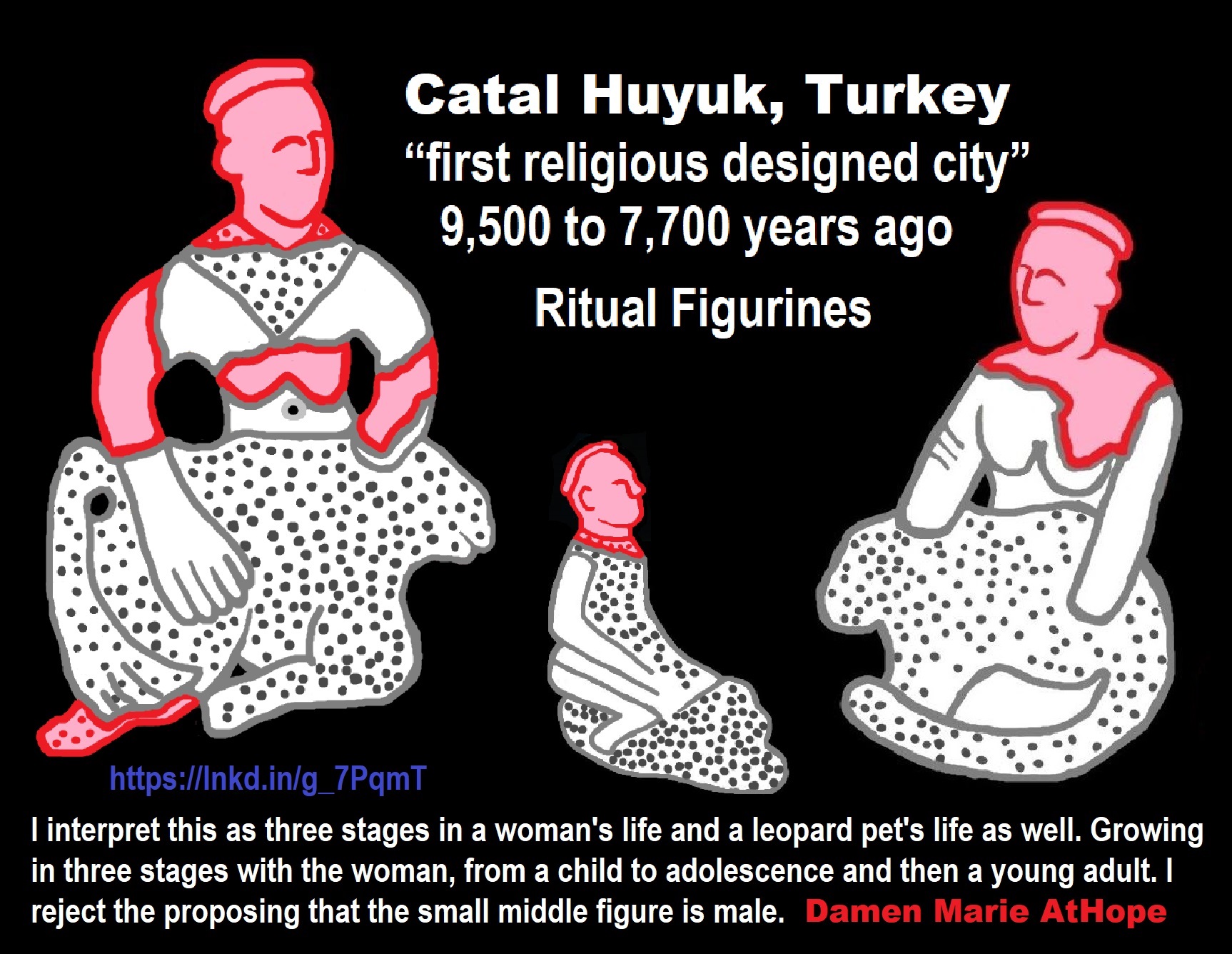

Leopard claw-bone pendant from the Possible Woman Shaman/Priestess burial with the plastered and painted woman’s head in her arms that is several generations removed. She was buried under the floor of the history house (house with multiple burials beyond that of the connected family) with the twin facing leopards at Catal Huyuk. Ref

“From about 7500 B.C.E to 5700 B.C.E., early farmers grew wheat, barley, and peas, and raised sheep, goats, and cattle. At its height, some 10,000 people lived there. Among its more noteworthy features, Çatalhöyük’s inhabitants were obsessed with plaster, lining their walls with it, using it as a canvas for artwork, and even coating the skulls of their dead to recreate the lifelike countenances of their loved ones.” ref

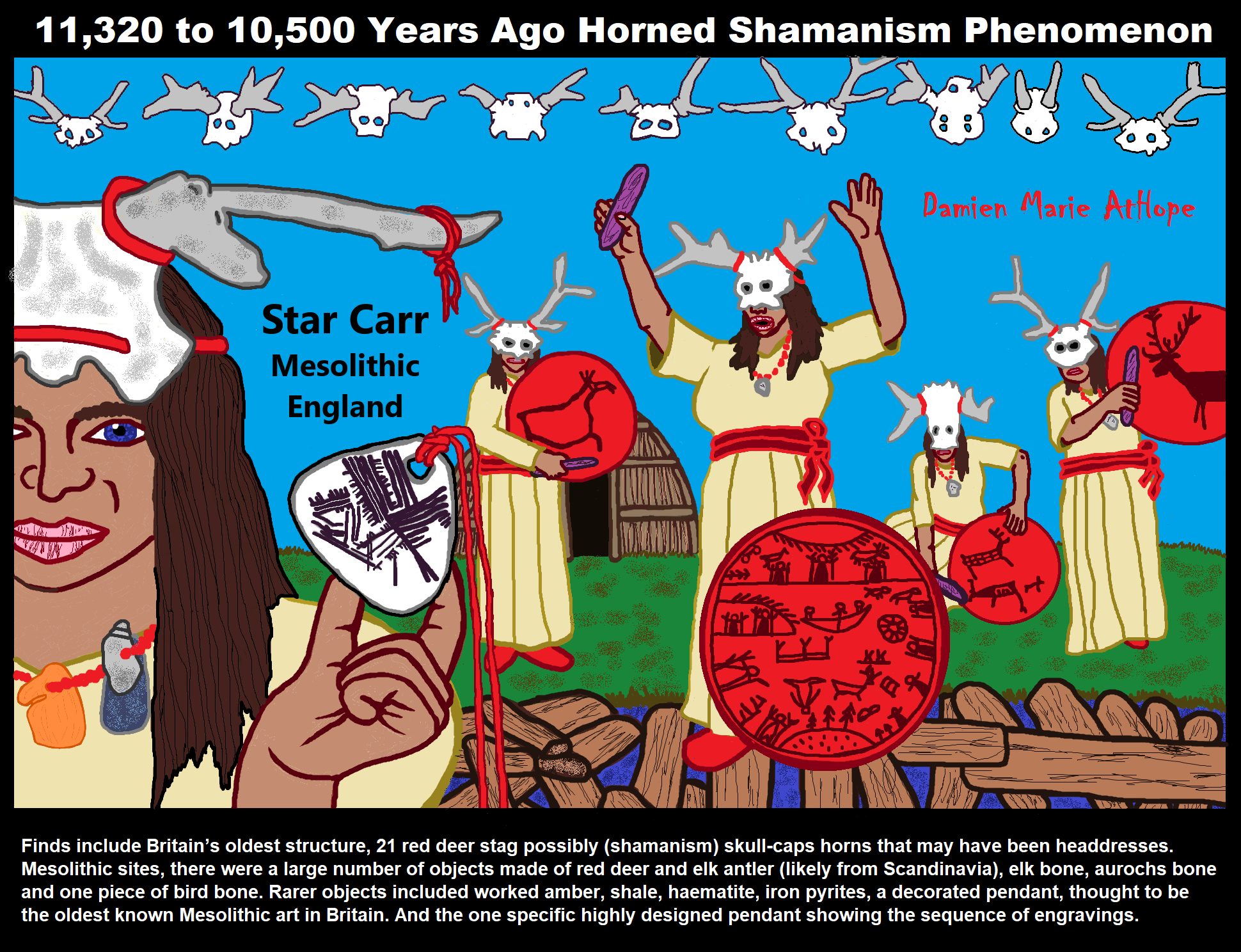

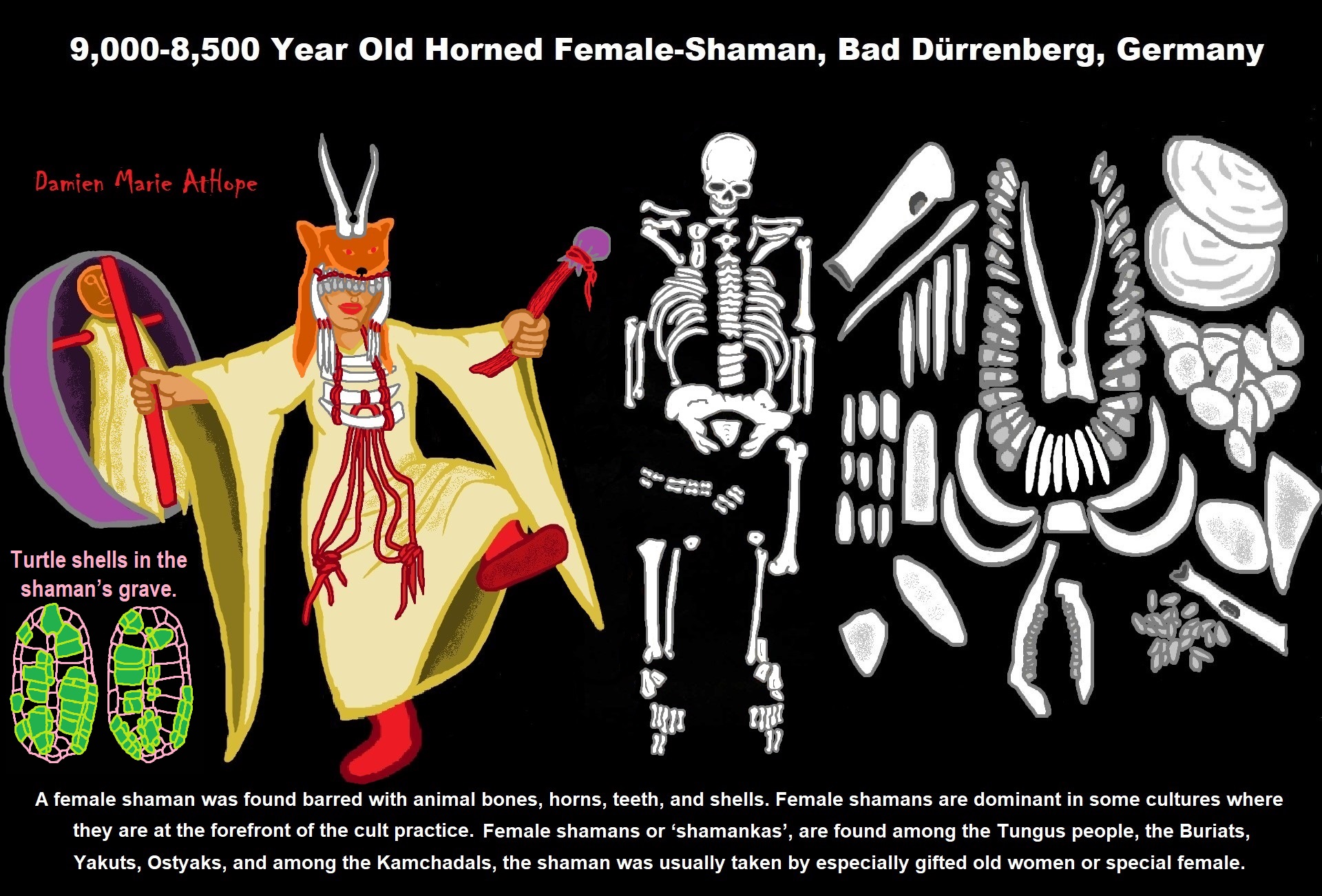

“Bad Dürrenberg is a modest spa town in eastern Germany, perched on a bluff overlooking the Saale River. Among the finds that emerged from the grave that afternoon was a second, tiny skull belonging to an infant of less than a year old, found between the thighs of the adult burial. Other unusual items included the delicate antlers of a roe deer, still attached to part of the skull, that could have been worn as a headdress. Henning also unearthed a polished stone ax similar to a type known from other sites in the area and 31 microliths, small flint blades barely an inch long.” ref

“In the 1950s, researchers reexamined the skeleton and, based on the shape of the pelvis and other bones, suggested that they belonged to a woman. The copious grave goods—in addition to the antler headdress, blades, mussel shells, and boar tusks there were hundreds of other artifacts, including boars’ teeth, turtle shells, and bird bones—clearly marked the burial as special. The flints and other finds were firmly rooted in the world of Mesolithic hunter-gatherers who lived between 12,000 and 6,000 years ago. The few Mesolithic graves that had been unearthed in Europe contained a flint blade or two, at most. In comparison, the Bad Dürrenberg grave was uniquely rich for the period.” ref

“It wasn’t until the late 1970s that radiocarbon dating showed that the bones were 9,000 years old, predating farming in central Europe by about 2,000 years and confirming earlier suspicions that the grave dated to the Mesolithic period. Surrounded by tall steel shelves storing artifacts and remains from other graves in the region, they set about excavating the blocks. They worked slowly, sieving the soil from the original dig, and recovered hundreds of additional artifacts. The new finds included dozens more microliths, and additional bird, mammal, and reptile bones. The team also found missing pieces of the woman’s skeleton and more tiny bones belonging to the baby buried with her.” ref

“The shaman lived at a pivotal point in Europe’s past when the climate was changing, pushing people to adapt. People adapted quickly, becoming less mobile and more specialized in response to the changing environment. In the absence of herds of mammoth and reindeer to hunt, such specialization let them wrest more fish and game out of rivers and forests while remaining in a smaller territory. Meller believes that the Bad Dürrenberg burial is proof that human spirituality became more specialized at this time, too, with specific people in the community delegated to interact with the spirit world, often with the help of trances or psychoactive substances. Combined with the earlier analysis of the woman’s grave, the team’s new finds and meticulous look at her bones painted a more complete picture of the shaman. They conjectured that, from an early age, she had been singled out as different from other members of her community.” ref

“Even in death, her unusually rich grave marked her as exceptional. Earlier scholars, including Grünberg, had speculated that she was a shaman who served as an intermediary between her community and the spirit world, and Meller says that the new finds prove it beyond a doubt. In her role as a shaman, the woman would have interceded with supernatural powers on behalf of the sick and injured or to ensure success in the hunt. “You travel in other worlds on behalf of your people with the help of your spirit animal,” says Meller. Just as some people in the Mesolithic specialized in fishing or carving, the Bad Dürrenberg woman specialized in accessing the spirit world. “She must have had talents or skills that were highly esteemed in society,” Jöris says.” ref

“As part of the new archaeological project that started with the reexcavation of the grave in 2019, researchers took yet another look at the woman’s skeleton. A closer examination of her teeth showed that they had been deliberately filed down, exposing the pulp inside. This would have been extremely painful and would have produced a steady flow of blood as the pulp died. The woman would have had to keep the now hollow teeth scrupulously clean to avoid deadly infections. This excruciating procedure, Meller says, might have been a pain ritual to establish her as an interlocutor with the spirit world. Upon close inspection, the woman’s spine revealed a deformity that may have further enhanced her mystical aura.” ref

“According to Orschiedt and Walter Wohlgemuth, head of radiology at Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg, the woman had an unusual nub of bone on the inside of her second cervical vertebra that would have compressed a vital artery when she tilted her head back and to the left, cutting off blood flow to her brain. The result was likely an extremely rare condition called nystagmus, a rhythmic twitch of the eyeball that is impossible to deliberately reproduce and would have appeared uncanny to the people in her community. She would have been able to switch it off by angling her head forward to relieve pressure on the artery. “She could deliberately put her head back and induce nystagmus,” Meller says. “It must have added greatly to her credibility as a shaman.” ref

“The woman’s skeleton and the remains of the baby she cradled also contain invisible clues to their identities. Techniques of ancient DNA analysis unavailable just a decade ago have made it possible to answer other questions. Among the finds recovered from the soil by Meller’s team was an inner ear bone belonging to the baby. Not much bigger than a fingernail, this pyramid-shaped bone, which protects fragile parts of the ear, is unusually dense and preserves genetic material particularly well. The shaman’s inner ear bone, too, was preserved along with her skull, which was found during the original excavation. DNA analysis conducted by geneticist Wolfgang Haak of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology confirmed that the shaman was female, as had first been suggested by researchers in the 1950s, and added color to her portrait. Genes for skin pigmentation and hair and eye color showed she was probably dark-skinned, dark-haired, and light-eyed, a far cry from the blond Aryan man imagined by the original excavators. The baby, the researchers found, was a boy.” ref

“DNA extracted from the inner ear bones of the woman and the baby also helped establish their relationship to each other, which was more complex than supposed. They were not, in fact, mother and child, as archaeologists had expected. “It was always assumed the baby was hers,” says Haak. “And it turns out that he’s not.” Instead, the two were distantly related on the mother’s side, second cousins, perhaps, or the woman may have been the baby’s great-great grandmother. Because she was only in her 30s when she died, the latter would mean the baby was placed inside the grave long after her death. “Maybe she took care of the baby in her role as a healer,” Meller says, and was buried with him after they both died at the same time.” ref

“The grave itself, along with the objects deposited inside, provided the final clues to understanding the power of the shaman’s mystical abilities. Researchers believe that the animal remains placed in the burial might have had symbolic meaning. Prey species such as deer and bison or aurochs may have been meant to evoke shamanic rituals intended to provide luck in the hunt. Marsh birds such as cranes, whose bones were also found in the grave, were the ultimate boundary-crossers, capable of flying in the heavens, nesting on the ground, and swimming underwater—a power the shaman might have called upon in her efforts to cross into the spirit world. The birds’ annual migration might also have had mystical significance, as they disappeared in winter and returned each spring. Turtles, whose shells were found by the dozen among the grave offerings, also cross from land to water. “It’s mind-boggling the spectrum of animal remains there are,” Haak says. “It’s a bit of a zoo.” ref

“The team’s analysis of the grave goods further showed that the shaman was connected to a wider community. The flints they found in the block were fashioned from more than 10 different rock sources, some located more than 50 miles away. “What goes in the grave is about how highly regarded she was and how big her community was,” Jöris says. “There were probably people who came from a long distance away for her burial.” During the reexcavation of the shaman’s grave, the team also turned their attention to the area surrounding the burial. As part of preparations for planting trees for the garden show, researchers dug dozens of test holes, but unearthed no other bones or Mesolithic artifacts.” ref

“Barely three feet away from the location of the shaman’s carefully arranged grave, however, they did uncover another small pit containing a pair of red deer antler headdresses. Both headdresses were pointed toward the shaman’s grave, a position scholars believe is unlikely to have been accidental. The fact that an offering had been made to the departed shaman came as no surprise. But radiocarbon dates the team gathered in 2022 indicate that these gifts are around 600 years younger than the woman’s grave, meaning they were placed there more than 20 generations after her death. This antler offering was made around 8,400 years ago and coincided with a dramatic cold spell in prehistoric Europe. Perhaps, Meller says, later shamans called on their distant ancestor for help in troubled times.” ref

“That a preliterate society may have preserved not only the woman’s memory but also recalled the precise location of her grave for so long is a display of sophistication not usually associated with hunter-gatherers. Meller believes that the idea that Mesolithic peoples lacked social complexity does these cultures a great disservice. The impressive level of attention to her grave, in her own time as well as centuries later, speaks to the significance of the shaman herself. “She was so charismatic and powerful,” Meller says, “that people were still talking about this woman six centuries after she died.” With a book on the team’s research published last year and plans for an updated exhibition in the museum in the works, people are talking about her nearly 10,000 years later, too.” ref

Women/Feminine-Natured (Intersex/Genderqueer/Transgender/LGBTQI+ (or non-heteronormative) people)

As the first Shamans at lest 30,000 years ago?

- Around 500,000 – 233,000 years ago, Oldest Anthropomorphic art (Pre-animism) is Related to Female

- Pre-Animism: Portable Rock Art at least 300,000-year-old

- Modern Humans start around 50,000 years ago Helped by Feminisation

- Totemism: an approximately 50,000-year-old belief system?

- Totemism and Shamanism Dispersal Theory Expressed around 50,000 to 30,000 years ago

- 45,000-Year-Old Bone Pinpoints Era of Human-Neanderthal Sex

- Possible Religion Motivations in the First Cave Art at around 43,000 years ago?

- 40,000 years ago “first seeming use of a Totem” ancestor, animal, and possible pre-goddess worship?

- Religious Art: “Venus” More Than Sex or Motherhood

- Yes, Your Male God is Ridiculous

- Me and My Gender Diversity: Genderqueer, Intersex, and Male.

- Homophobia, Transphobia, and Genderqueerphobia Hurts Us All

- Prehistoric Child Burials Begin Around 34,000 Years Ago

- Early Shamanism around 34,000 to 20,000 years ago: Sungar (Russia) and Dolni Vestonice (Czech Republic)

- 31,000 – 20,000 years ago Oldest Shaman was Female, Buried with the Oldest Portrait Carving

- Shamanism: an approximately 30,000-year-old belief system

oldest Saman burrials

31,000 – 20,000 years ago Oldest Shaman was Female, Buried with the Oldest Portrait Carving

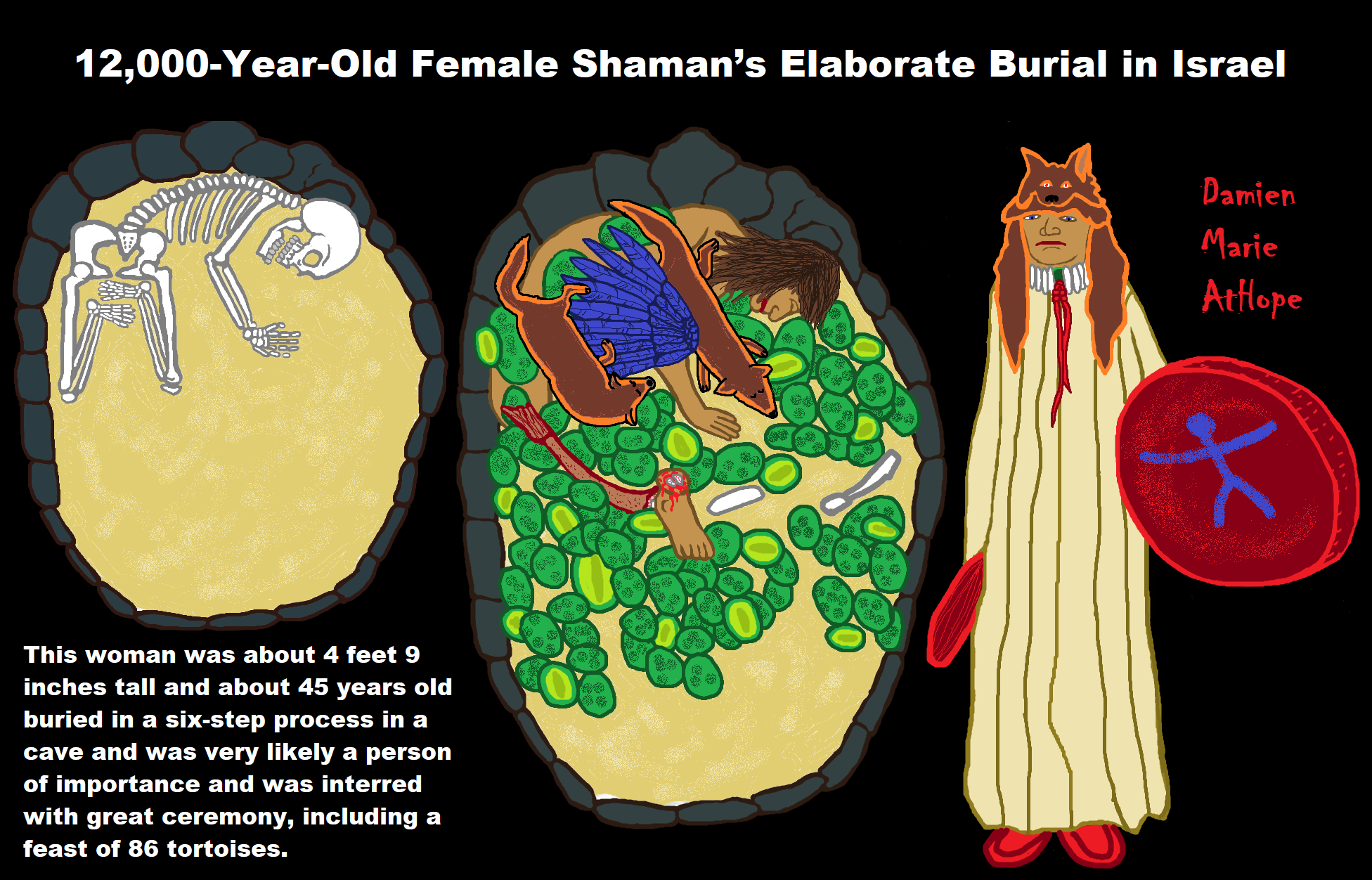

Shaman burial in Israel 12,000 years ago and the Shamanism Phenomena

9,000-8,500 year old Female shaman Bad Dürrenberg Germany

Human Religion Stage #3: Shamanism

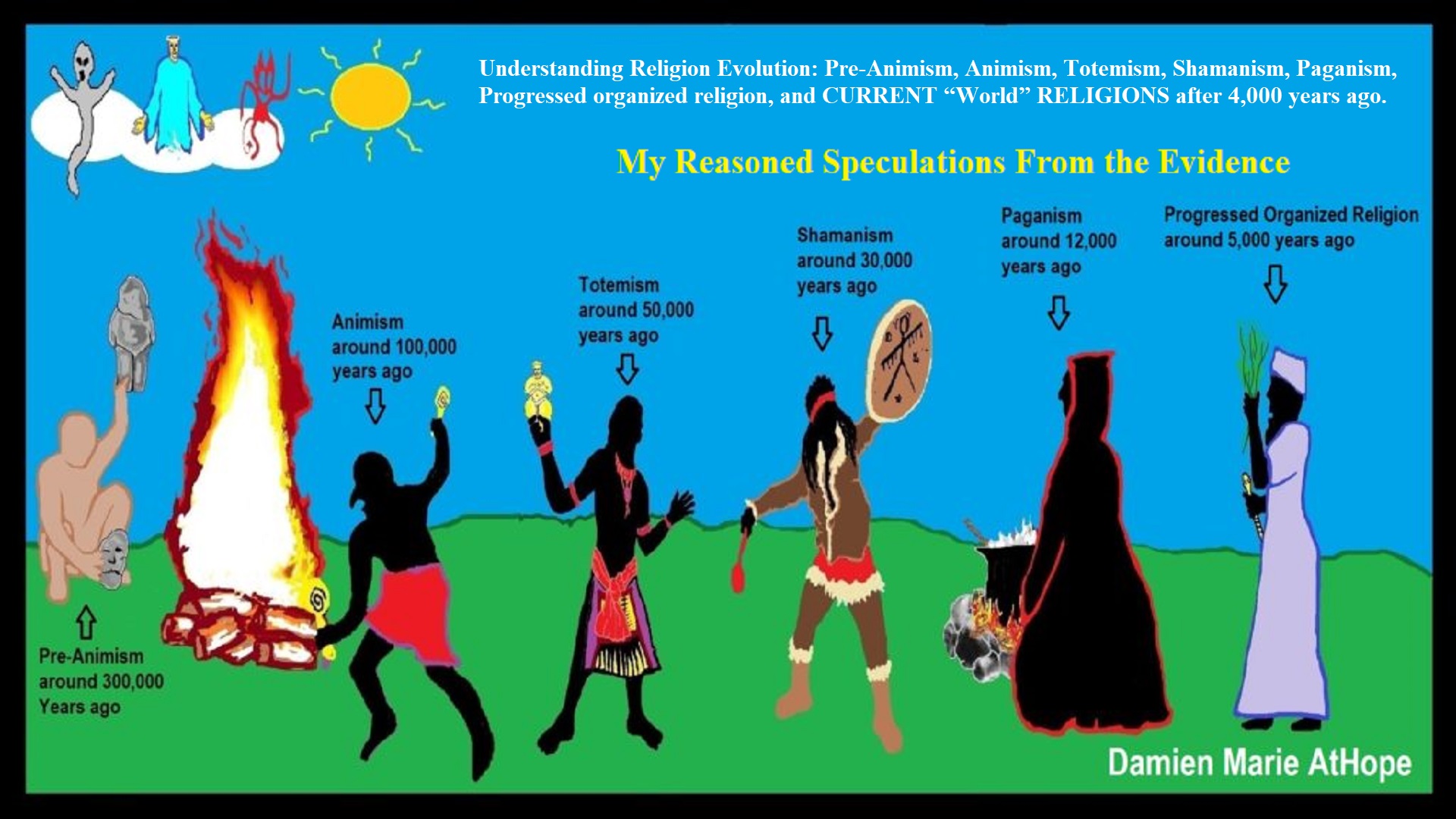

Shamanism to me, is semi-holistic, between Animism and Totemism. Shamanism is somewhat neofeminine, referring to “new”‘ forms of femininistic style in nature compared to Totemism, tending to go slightly back to a more animalistic sensibility than a totemistic one. Though it has elements if totemism as well where a shaman evokes animal images as spirit guides, omens, and message-bearers including throw bones/runes. Things in nature can be accessed by a shaman who is believed to have sacred access to, and influence in, the world of benevolent and malevolent spirits. Most believe in spirits, existing somewhere on the animism/pantheism spectrum, they actively pursue contact with the “spirit-world” in altered states of consciousness by drumming, dance, or the use of sacred plants some with euphoric or hallucinatory effect. Pantheism is the belief that all reality is identical with divinity, or that everything composes an all-encompassing, immanent god. Pantheists do not believe in a personal or anthropomorphic god and hold a broad range of doctrines differing with regards to the forms of and relationships between divinity and reality. Though there are a variety of definitions of pantheism, ranging from a theological and philosophical position concerning God on one side as a religious position in this way, is expressed as a polar opposite of atheism. Whereas on the other hand, some hold that pantheism is a non-religious philosophical position that can be compatible with science. To them, according to the World Pantheist Movement, Scientific pantheism is the only form of spirituality we know of which fully embraces science as part of the human exploration of Earth and Cosmos. And, such pantheism, in general, may hold the view that the Universe (in the sense of the totality of all existence) and God are identical (implying a denial of the personality and transcendence of God). They assert that scientific pantheism respects the rights not just of humans, but of all living beings. It focuses on saving the planet rather than “saving” souls. To them, it encourages you to make the most and best of your one life here. It values reason and the scientific method over adherence to ancient scriptures. Scientific pantheism moves beyond “God” and defines itself by positives. Shamanism may have something like deities, though they tend to be more like pantheism or metaphorical deism/polytheism. Deism is a philosophical position that posits that God (or in some cases, gods) does not interfere directly with the world; conversely it can also be stated as a system of belief which posits God’s existence as the cause of all things, and admits His perfection (and usually the existence of natural law and Providence) but rejects Divine revelation or direct intervention of God in the universe by miracles. It also rejects revelation as a source of religious knowledge and asserts that reason and observation of the natural world are sufficient to determine the existence of a single creator or absolute principle of the universe. Shamanism may have many supernatural beings both animal and human-like Animism animal deities are common but the more anthropomorphic ones that are human like have a different level of power. Anthropomorphic human-like ones can be both somewhat personal and nonpersonal with a shared metaphorical ancestor grandmother/grandfather or great grandmother/grandfather deism/polytheism, not as much of what we think about like a god today. The wounded healer is an archetype, such as a shamanistic crisis, a rite of passage for shamans-to-be, commonly involving physical illness (pushes them to the brink of death, thought to give them access to the spirit world) and/or psychological crisis but can also involve a disformity or abnormality. My art of the bird could be a chicken, and the shake is viewed as dangerous but also useful, in fact, the usefulness of animals is sacralized, even including animals as a sacrificial use in shamanic rituals for at least around 5,000 years ago, using animals with great respect. ref, ref, ref

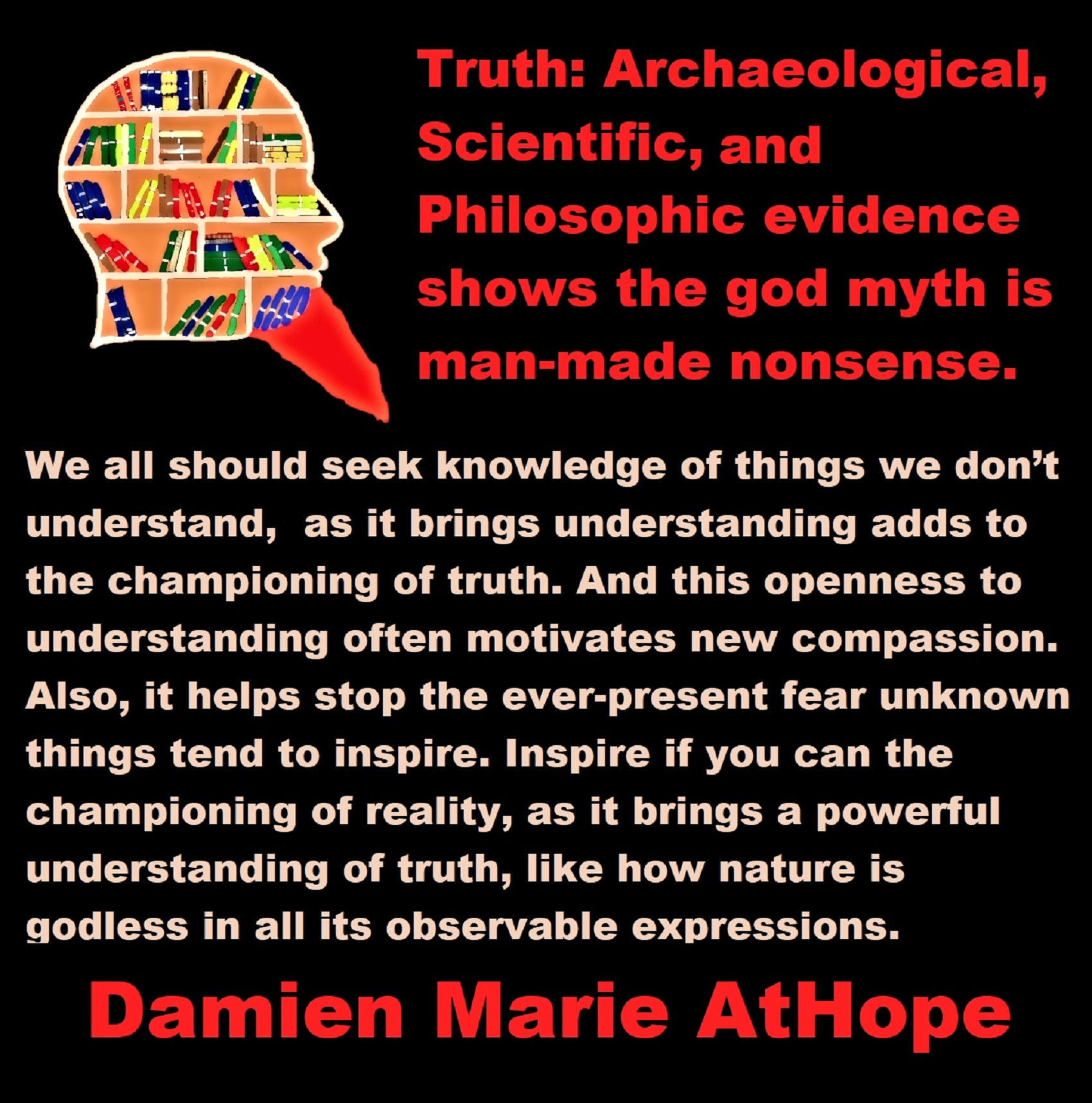

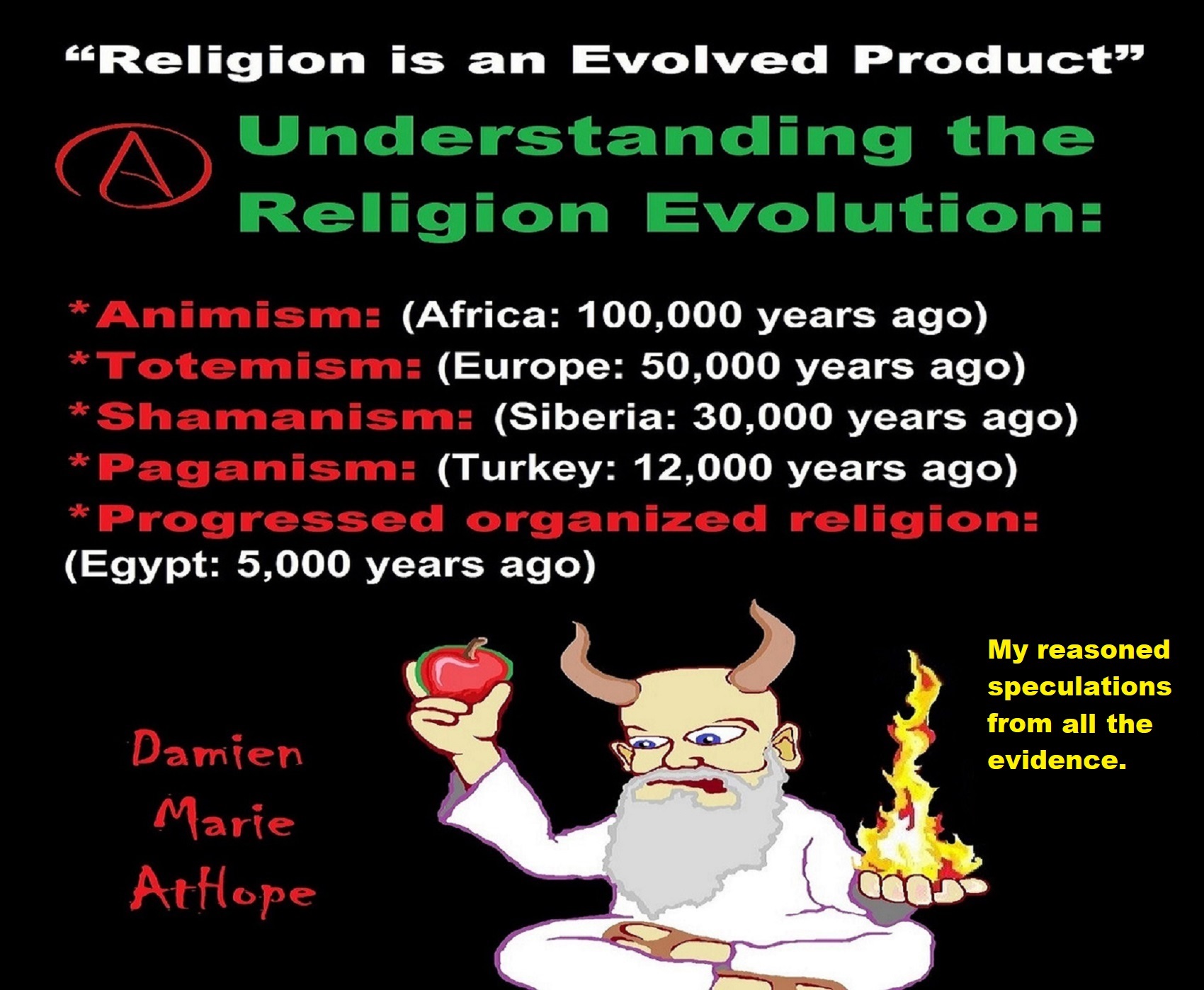

“Religion is an Evolved Product”

Neanderthals ‘kept our early ancestors out of Europe’

Two Paleolithic harpoons, at least 60,000 years old, decorated with geometric figures discovered at Veyrier near Geneva. Which is younger than a beautifully-carved 90,000-year-old bone harpoon used to hunt giant catfish in present-day the Democratic Republic of the Congo. ref

Our ancestors had interbred with Neanderthals 55,000 years ago, possibly in the Middle East.

Modern humans and Neanderthals interbred in Europe, an analysis of 40,000-year-old DNA suggests. ref

50,000-year-old Skull May Show Human-Neanderthal Hybrids Originated in Levant, not Europe as Thought

- Research into ancient genomics and archaeology has shed light into the first humans in Europe, who appear in the record approximately 45,000 years ago. Neanderthals disappeared from the region 5,000 years later. The nature of their relationship is being revealed with every new discovery and breakthrough. ref

- Neanderthals and modern humans belong to the same genus (Homo) and inhabited the same geographic areas in Asia for 30,000–50,000 years; genetic evidence indicate while they may have interbred with non-African modern humans, they are separate branches of the human family tree (separate species). ref

- So, around the time we fully interact with Neanderthals in Europe Totemism emerges about 50,000 years ago. And, around the time all interact with Neanderthals is over we see Shamanism emerge about 30,000 years ago, could this just be a coincidence, I don’t really think so.

Upper Paleolithic (totemism in Europe between 50,000 and 30,000 years ago)

“Cultures Aurignacian Associated with Paleo-humans/Paleolithic lifestyle“

Ust’-Ishim man 45,000-year-old remains of a male hunter-gatherer,

(I presume a totemist or connected to the firsts totemic peoples by around 50,000 years ago

then by 30,000 years ago are shamanistic-totemists)

one of the early modern humans to inhabit western Siberia.

Ust’-Ishim man has been classified as belonging to Y-DNA haplogroup K2a*, belonged to mitochondrial DNA haplogroup R*. Before 2016 they had been classified as U*. Both of these haplogroups and descendant subclades are now found among populations throughout Eurasia, Oceania and The Americas. When compared to other ancient remains, Ust’-Ishim man is more closely related, in terms of autosomal DNA to Tianyuan man, found near Beijing and dating from 42,000 to 39,000 years ago; Mal’ta boy (or MA-1), a child who lived 24,000 years ago along the Bolshaya Belaya River near today’s Irkutsk in Siberia, or; La Braña man – a hunter-gatherer who lived in La Braña (modern Spain) about 8,000 years ago. ref

- Grave of the Middle East’s Oldest Witch/Female Shaman

- Asian Shamanism

- Australian Aboriginal Shamanism

- Austronesia, beliefs such as ancestor worship, animism, and shamanism are also practiced. ref

- Shamanism in Europe

- Shamanism Arctic polar region

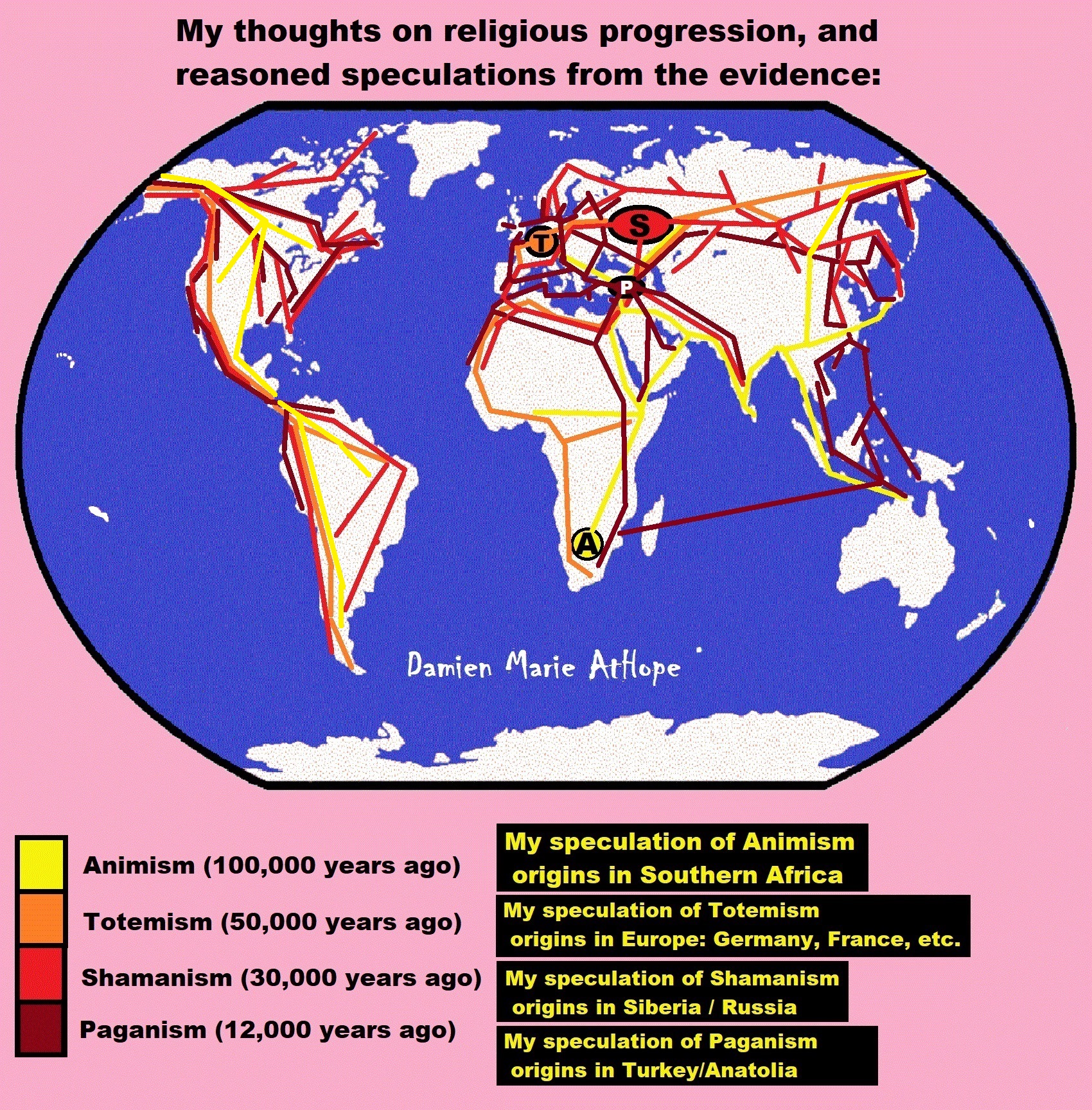

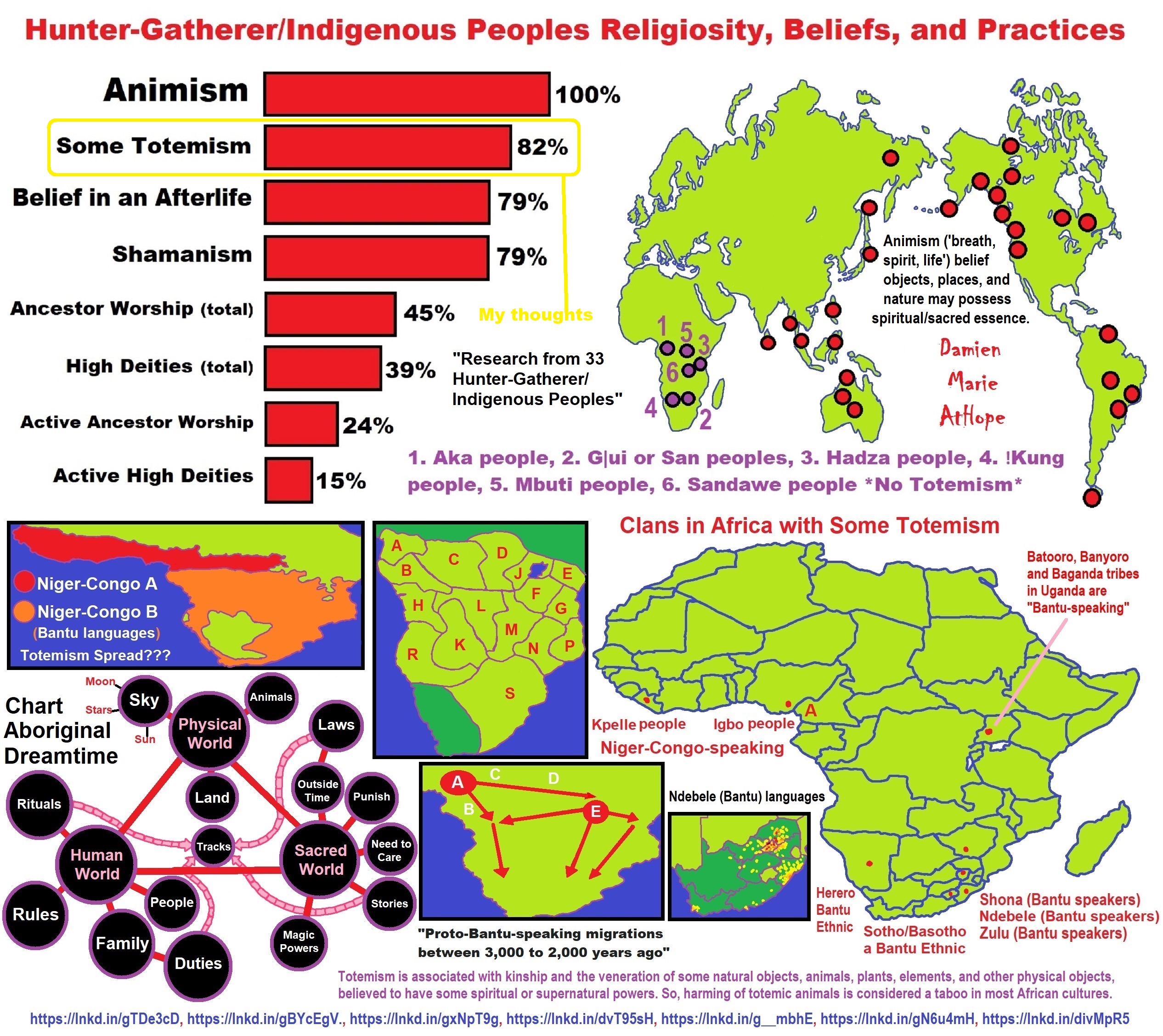

Totemism and Shamanism Dispersal Theory

To me, totemism seems to have fully developed in Europe (likely western) but could have further developed pre-totemism from Africa, such as seen in the Stone Snake of South Africa: “first human worship” 70,000 years ago. Thus, I am also not sure that the European Totemists could just have been ones that had left Africa or was formed when we interacted with Neandertals in the middle east then splitting from there as early totemists but or the northern peoples caring Desonivin DNA could have come from the north with my proposed Europe Totemism as it seems Totemism hit Indonesia around 30,000 ago or so and possibly then spread to Papua New Guinea and presumably Australia.

I hypothesize that both Totemism and Shamanism Disperse somewhat together as a complementary set of varied beliefs as either one of two main persuasions, totemistic-(female leaning, to me, more geared to “Group-totemism” Acephalous/Gynocentrism–Egalitarian–Equalitarian/Matrilineal–Matriarchy)-shamanism and/or shamanistic-(male leaning, to me, more geared to “Individual-Clan-totemism” Acephalous/Hierarchical–Heterarchy–Homoarchy/Patrilineal–Patriarchy)-Totemism which this must be thought of as only in a general kind of way, rather than only one-type each or that both where varied. I think, likely both held diversity almost from the beginning, so they latter becoming even more diverse through tome also seems logical, which after that became more area stylized or splitting of the two. Such as, a possibility that true totemism as I think fully developed in Europe, not Africa: approximately 50,000-year-old belief system and that Shamanism: an approximately 30,000-year-old belief system by way of Siberia only to later find its way I think through Turkey to the Middle East maybe by around 12,000 years ago, referenced in the shaman burial of that time than out from there to Africa by way of Neolithic farmers from western Eurasia who, about 8,000 years ago, brought agriculture to Europe then began to return to Africa aided by DNA info from a 4,500-year-old hunter-gatherer, known as Mota man, were found in a cave. ref And at least by 3,000 years ago this southern migrations had spread to Africa, as it was by 3,000 years ago Europen DNA took that long to get to southern Africa through “The widespread use of iron weapons which replaced bronze weapons rapidly disseminated throughout the Near East (North Africa, southwest Asia) by around 3,000 years ago.” ref As well as where both Early Shamanism around 30,000 to 20,000 years ago: Sungar (Russia) and Dolni Vestonice (Czech Republic) taken along with European totemism by way of Siberia through Austronesians migrations) all the way to Aboriginal Religion.

- Description of Matriarchy – Matriarchy.Info

- Matriarchy in China: mothers, queens, goddesses and shamans

- Medicine in Matriarchal Society

- Matriarchal Studies – Anthropology – Oxford Bibliographies

- Matriarchy | Rain Queens: Female leadership traditions of Africa

- China’s Last but one matriarchy: The Jino of Yunnan

- Matriarchal: Pre-Islam Arab cultures in Arabic Peninsula?

- List of matrilineal or matrilocal societies

- Shamans of the 20th Century

- 6 Modern Societies Where Women Rule

- 5 Latin American Matriarchal Societies You Never Knew About

- Setting the record straight: Matrilineal does not equal matriarchal

- Heterarchy and the Analysis of Complex Societies

- Gynocentrism & Matriarchal Societies

- Matrilineal society

Group totemism was traditionally common among peoples in Africa, India, Oceania (especially in Melanesia), North America, and parts of South America. These peoples include, among others, the Australian Aborigines, the African Pygmies, and various Native American peoples—most notably the Northwest Coast Indians (predominantly fishermen), California Indians, and Northeast Indians. Moreover, group totemism is represented in a distinctive form among the Ugrians and west Siberians (hunters and fishermen who also breed reindeer) as well as among tribes of herdsmen in North and Central Asia. ref

Group/Clan Totemism a clan is a group claiming common descent in the male or female line. They share a common relationship with 1 or more natural phenomena. For the members of this unit, the clan, the totem is a symbol of membership of the unit. It is recognised for the members of this clan and those of other clans. This totem has strong territorial and mythological ties associated with it, and it is believed that it can warn them of approaching danger. Some distinguish between matrilineal social clan totemism and patrilineal clan totemism. Matrilineal clan totemism is widespread throughout eastern Australia – Queensland, New South Wales, western Victoria and eastern South Australia. There is also a small area in the southwest of Western Australia. The genera translation of the word for this totem is ‘flesh’ or ‘meat’ – the person is ‘of one flesh’ with his totem. The totems connected with matrilineal phratries of western Arnhem Land are not the center of cult life, and the members of the phratry don’t have a special attitude towards it. The totems of the matrilineal social clans are the center of cult life. An example among the Dieri is the mardu. It is really an avunculineal (of the mother’s brother’s line) cult totem. Patrilineal clan cult totemism, bindara, is also found in this tribe. Patrilineal clan totemism was present in parts of Western Australia, the Northern Territory, Cape York, coastal areas of New South Wales and Queensland, central Victoria, along the lower Murray and the Coorong district and among the Lake Eyre groups. The best example was among the Jaraldi, Dangani, etc. and northeastern Arnhem Land. In eastern Arnhem Land a combination of aspects, including non-totemic, were associated with the clan. A clan has several totemic cults, and these can be associated with more than one linguistic group. In central Australia totemic combinations were apparent but less strongly so. ref

Individual totemism is widely disseminated. It is found not only among tribes of hunters and harvesters but also among farmers and herdsmen. Individual totemism is especially emphasized among the Australian Aborigines and the American Indians. Studies of shamanism indicate that individual totemism may have predated group totemism, as a group’s protective spirits were sometimes derived from the totems of specific individuals. To some extent, there also exists a tendency to pass on an individual totem as hereditary or to make taboo the entire species of animal to which the individual totem belongs. ref

Shamanism: an approximately 30,000-year-old belief system

37,000 years ago at the site of Kostenki 14 (also known as Markina Gora) in western Russia, genome of a man who was buried there shows, that once modern humans had dispersed out of Africa and into Eurasia, they separated at least sometime before 37,000-years ago into at least three populations, whose descendants would develop the unique features that reflect the core of the diversity of non-African modern humans. Moreover, after then, despite major climatic fluctuations, one of these groups – Palaeolithic Europeans – persisted as a population, ebbing and flowing by moments of contraction and expansion, but persisting intertwined until the arrival of farmers from the Middle East in the last 8,000 years, with whom they mixed extensively. The Kostyonki-Borshchyovo archaeological complex is an extended Upper Paleolithic (Aurignacian to Gravettian) site. The Kostenki burial and other ancient genomes show that for 30,000-years there was a single meta-population in Europe, consisting of Palaeolithic hunter-gatherer groups that split up, mixed, dispersed and changed. Only when farmers from the Near East arrived approximately 8,000 years ago, did the structure of the European population change significantly. DNA from a male hunter-gatherer from Kostenki-12 date to around 30,000 years ago and died aged 20–25. His maternal lineage was found to be mtDNA haplogroup U2. He was buried in an oval pit in a crouched position and covered with red ochre. Kostenki 12 was later found to belong to the patrilineal Y-DNA haplogroup C1* (C-F3393). A male from Kostenki-14 (Markina Gora), who lived approximately 35–40,000 BP, was also found to belong to mtDNA haplogroup U2. His Y-DNA haplogroup was C1b* (C-F1370). The Kostenki-14 genome represents early evidence for the separation of Western Eurasian and East Asian lineages. It was found to have a close relationship to both “Mal’ta boy” (24 ka) of central Siberia (Ancient North Eurasian) and to the later Mesolithic hunter-gatherers of Europe and western Siberia, as well as with a basal population ancestral to Early European Farmers, but not to East Asians. ref, ref

34,000-30,000-year-old to remains, carbon analysis dates between 34,050-30,550 and by DNA analysis at 34,000. The mortuary site contains a few extremely elaborate burials one of which involved a juvenile and an adolescent, approximately 10 and 12 years old, buried head to head. The children had the same mtDNA, which may indicate the same maternal lineage. The individuals at Sungir are genetically closest to each other and show closest genetic affinity to the individuals from Kostenki, while showing closer affinity to the individual from Kostenki 12 than to the individual from Kostenki 14. The Sungir individuals descended from a lineage that was related to the individual from Kostenki 14, but were not directly related. The individual from Kostenki 12 was also found to be closer to the Sungir individuals than to the individual from Kostenki 14. The Sungir individuals also show close genetic affinity to various individuals belonging to Vestonice Cluster buried in a Gravettian context, such as those excavated from Dolní Věstonice. And mtDNA analysis shows that the four individuals tested from Sungir belong to mtDNA Haplogroup U. ref

31,000 – 20,000 years ago Oldest Shaman was Female, Buried with the Oldest Portrait Carving

“Gravettian Cultures” (to me, connects to the birth of Shamanism)

Around, Dates: 33,000 to 21,000 BP

The Gravettian was an archaeological industry of the European Upper Paleolithic that succeeded the Aurignacian circa 33,000 years ago. They seem to dissipate or make transfer changes from 22,000 years ago, close to the Last Glacial Maximum, although some elements lasted until around 17,000 years ago. At this point, it was generally replaced abruptly by the Solutrean in France and Spain, and developed into or continued as the Epigravettian in Italy, the Balkans, Ukraine, and Russia. They are known for their Venus figurines, which were typically made as either ivory or limestone carvings. The Gravettian culture was first identified at the site of La Gravette in Southwestern France. The Gravettians were hunter-gatherers who lived in a bitterly cold period of European prehistory, and Gravettian lifestyle was shaped by the climate. Pleniglacial environmental changes forced them to adapt. West and Central Europe were extremely cold during this period. Archaeologists usually describe two regional variants: the western Gravettian, known mainly from cave sites in France, Spain and Britain, and the eastern Gravettian in Central Europe and Russia. The eastern Gravettians, which include the Pavlovian culture, were specialized mammoth hunters, whose remains are usually found not in caves but in open air sites. Gravettian culture thrived on their ability to hunt animals. They utilized a variety of tools and hunting strategies. Compared to theorized hunting techniques of Neanderthals and earlier human groups, Gravettian hunting culture appears much more mobile and complex. They lived in caves or semi-subterranean or rounded dwellings which were typically arranged in small “villages”. Gravettians are thought to have been innovative in the development of tools such as blunted black knives, tanged arrowheads , and boomerangs. Other innovations include the use of woven nets and stone-lamps.[9] Blades and bladelets were used to make decorations and bone tools from animal remains. Sites including CPM II, CPM III, Casal de Felipe, and Fonte Santa (all in Spain) have evidence the use of blade and bladelet technology during the period. The objects were often made of quartz and rock crystals, and varied in terms of platforms, abrasions, endscrapers and burins. They were formed by hammering bones and rocks together until they formed sharp shards, in a process known as lithic reduction. The blades were used to skin animals or sharpen sticks. ref

30,000 Years Ago – (Eurasia), found evidence that the earliest human burial practices varied widely, with some graves are ornate while the vast majority were fairly plain but it seems to be a more common ritual showing the further solidification of ritualizing was blooming. Overall, between 35,000 years ago and 10,000 years ago there is a wide variation in human burial customs. 1

29,000 – 25,000 years ago– (Eurasia), the Pavlovian is an Upper Paleolithic culture, a variant of the Gravettian, that existed in the region of Moravia, northern Austria and southern Poland around 29,000 – 25,000 years BP. The culture used sophisticated stone age technology to survive in the tundra on the fringe of the ice sheets around the Last Glacial Maximum. Its economy was principally based on the hunting of mammoth herds for meat, fat fuel, hides for tents and large bones and tusks for building winter shelters. Its name is derived from the village of Pavlov, in the Pavlov Hills, next to Dolní Věstonice in southern Moravia. The site was excavated in 1952 by the Czechoslovakian archaeologist Bohuslav Klima. Another important Pavlovian site is Předmostí, now part of the town of Přerov. Excavation has yielded flint implements, polished and drilled stone artifacts, bone spearheads, needles, digging tools, flutes, bone ornaments, drilled animal teeth, and seashells. Art or religious finds are bone carvings and figurines of humans and animals made of mammoth tusk, stone, and fired clay. Textile impression made into wet clay give the oldest proof of the existence of weaving by humans. ref

27,000 Years Ago – (Eurasia), Gravettian culture extends across a large geographic region but is relatively homogeneous until about 27,000 years ago. They developed burial rites, which included the inclusion of simple, purpose-built, offerings and or personal ornaments owned by the deceased, placed within the grave or tomb. Surviving Gravettian art includes numerous cave paintings and small, portable Venus figurines made from clay or ivory, as well as jewelry objects. The fertility deities mostly date from the early period, and consist of over 100 known surviving examples. They conform to a very specific physical type of large breasts, broad hips, and prominent posteriors. The statuettes tend to lack facial details, with limbs that are often broken off. During the ppost-glacialperiod, evidence of the culture begins to disappear from northern Europe but was continued in areas around the Mediterranean. ref

27,000 Years Ago – (Austria), Krems-Wachtberg in Lower Austria, Two separate pits, one containing the remains of two infants and the other of a single baby, were discovered at the same Stone Age camp. Infants may have been considered equal members of prehistoric society, according to an analysis of burial pits, as Both graves were decorated with beads and covered in red ochre, a pigment commonly used by prehistoric peoples as a grave offering when they buried adults. ref

12,707–12,556-year-old child remains at a burial site in North America. Anzick-1 is the name given to the remains of Paleo-Indian male infant found in western Montana, remains revealed Siberian ancestry and a close genetic relationship to modern Native Americans, including those of Central and South America. These findings support the hypothesis that modern Native Americans are descended from Asian populations who crossed Beringia between 32,000 and 18,000 years ago. buried under numerous tools: 100 stone tools and 15 remnants of tools made of bone. The site contained hundreds of stone projectile points, blades, and bifaces, as well as the remains of two juveniles. Some of the artifacts were covered in red ocher. The stone points were identified as part of the Clovis Complex because of their distinct shape and size. ref

11,500-year-old child remains of a six-week-old baby girl in a burial pit in central Alaska whos DNA indicated there was just a single wave of migration into the Americas across a land bridge, now submerged, that spanned the Bering Strait and connected Siberia to Alaska during the Ice Age. The girl was found alongside remains of an even-younger female infant, possibly a first cousin, whose genome the researchers could not sequence. Both were covered in red ochre and next to decorated antler rods. ref

“The Rainbow-Serpent (totemistic) Myth of Australia”

9,000 years ago – (Isreal) site discovered in Motza, at the foot of the Jerusalem hills. The site, featuring dozens of stone houses, grander buildings that may have been temples, and skeletal remains. Domestic houses in which the hoi polloi lived didn’t have particularly invested flooring beyond dirt or basic plaster. The public places in prehistoric Motza had better plastering, colored red. one thing they ate that may alude to cultural connections is sheep, which were only dometicated around 10,000 to 11,000 years ago and not exactly next door, but in Anatolia. The floors of the houses were made of tightly-packed plaster which seems to have been kept clean, leaving behind few clues from the inhabitants’ daily lives. But underneath the plaster floors at least 10 people were found buried, lying in fetal positions. A third were men. A third were women. And, a third were children and babies. Which shows, Khalaily explains, that for the first known time in human history, children were considered something other than disposable. “During the transitional time between hunting and gathering to settlement, the attitude towards children, in life and death, changed,” he explains the theory. No earlier burials of children have been found in the ariea. ref

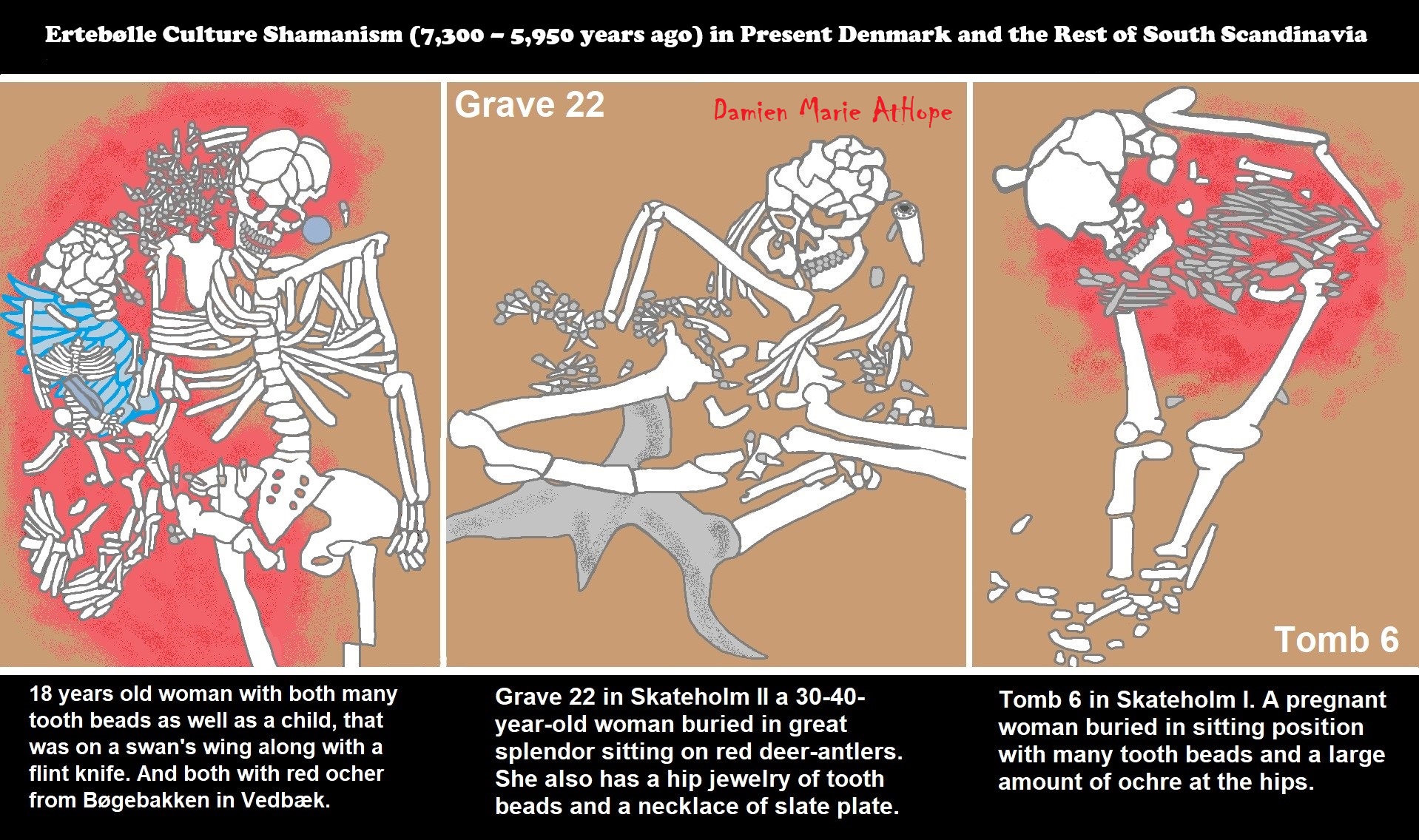

7,000 years ago – (Denmark) site at Vedbaek Denmark, the so-called Vedbæk Finds from the Bøgebakken archaeological site, a Mesolithic cemetery of the Ertebølle culture. An example of the findings of this culture cemetery include the bodies of a young woman with a necklace made of teeth and her newborn baby. The child is cradled in the wing of a swan with a flint knife at its hip. The brief statistical findings of the cemetery are as follows; 22 individual bodies (4 newborns), 17 of the adults buried could be aged – 8 died before reaching the age of 20. There were 9 men, 5 of them over the age of 50, and 8 women: 2 died before the age of 20, 3 living to over 40. Two women died in childbirth (including the young woman mention above) and were buried with their newborns beside them. ref

Grave of Siberian noblewoman with a child up to 4,500 years old

Around 3,950-3,539 years ago, at Sidon, Lebanon. From 19 discrete burial units a total of 31 individuals, included ‘warrior’ burials in constructed graves containing bronze weapons, with high mortality during infancy and early childhood and a peak in adult mortality during early adulthood. There is a conspicuous occurrence of unusual dental traits. Jar burials, all found with remains of sub-adult individuals, represent a burial practice applied to children of a wide age range. Many burials are associated with faunal remains, mostly of sheep or goats, but also of large ungulates. The burial jars found in copper-age Sidon had all contained adults. However, there is burial of a child that had been interred with a necklace around its neck. The fact of the child’s burial, with a funerary vessel and jewelry, could be indicative of status, or of the value attributed to children. ref, ref

3,500-Year-Old Child Burials Unearthed at Ancient Egyptian

Gender Identity

Gender Identity: Unlike biological sex—which is assigned at birth and based on physical characteristics—gender identity refers to a person’s innate, deeply felt sense of being male or female (sometimes even both or neither). While it is most common for a person’s gender identity to align with their biological sex, this is not always the case. A person’s gender identity can be different from their biological sex. Increased societal understanding and scientific research exploring the origins of gender are serving to expand formerly simplistic societal notions of limited gender categorization. Gender identity and other recently defined terms are ones that are more inclusive of these normal variations of gender. Because gender identity is internal and not always visible to others, it is something determined by the individual alone. Gender Variance/Gender Non-Conformity: Gender variance refers to behaviors and interests that fit outside of what we consider ‘normal’ for a child or adult’s assigned biological sex. We think of these people as having interests that are more typical of the “opposite” sex; in children, for example, a girl who insists on having short hair and prefers to play football with the boys, or a boy who wears dresses and wishes to be a princess. These are considered gender-variant or gender non-conforming behaviors and interests. It should be noted that gender nonconformity is a term not typically applied to children who have only a brief, passing curiosity in trying out these behaviors or interests. Gender “Non-Conformity” can be defined most simply as behavior and appearance that conforms to the social expectations for one’s assigned or believed/preserved gender. Gender non-conformity, then, is behaving and appearing in ways that are considered not typical for one’s gender. Gender non-conformity should not be confused sexual orientation. Gender nonconforming people are often assumed to also be lesbian, gay, or bisexual, etc. while gender conforming people are assumed to be heterosexual do to believed heteronormativity which can relate to heterocentricism. heteronormativity/heterocentricism assumes heterosexual unless something, like gender non-conformity, makes one think otherwise. Researchers have noted that there may be real differences in terms of gender between lesbian, gay, bisexual, pansexual, and heterosexual people. In particular, there are higher rates of gender non-conformity in both childhood and adulthood among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and pansexual people than among heterosexual people. Nevertheless, it is important to note that gender non-conformity is not universal among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and pansexual people, nor is it absent among heterosexuals.

Transgender refers to an individual whose gender identity does not match their assigned birth sex. For example, a transgender person may self-identify as a woman but was born biologically male. Being transgender does not imply any specific sexual orientation (attraction to people of a specific gender). Therefore, transgender people may additionally identify as straight, gay, lesbian, or bisexual. In its broadest sense, the term transgender can encompass anyone whose identity or behavior falls outside of stereotypical gender norms. Science has Proved That Being Transgender Is Not a Phase. Our culture is undeniably uneducated about transgender individuals. At worst, this ignorance results in violent hate crimes and murders. In its most benevolent form, transgenderism is viewed as a “phase” or transgender individuals are regarded as “confused.” A new study, however, pushes back on these misconceptions by finding that transgender children identify with their gender identity as consistently as their cisgender peers. The study’s findings support what trans advocates have been saying for years: Being transgender is not a phase or a choice, but a consistent gender identity. The study indicated that transgender children’s responses were indistinguishable from the two groups of cisgender children, suggesting that trans and cisgender children identify with their gender in the same consistent ways.

Gender Fluidity conveys a wider, more flexible range of gender expression, with interests and behaviors that may even change from day to day. Gender fluid people do not feel confined by restrictive boundaries of stereotypical expectations of women and men. For some people, gender fluidity extends beyond behavior and interests, and actually serves to specifically define their gender identity. In other words, a person may feel they are more female on some days and more male on others, or possibly feel that neither term describes them accurately. Their identity is seen as being gender fluid.

Genderqueer is a term that is growing in usage, representing a blurring of the lines surrounding society’s rigid views of both gender identity and sexual orientation. Genderqueer people embrace a fluidity of gender expression that is not limiting. They may not identify as male or female, but as both, neither, or as a blend. Similarly, genderqueer is a more inclusive term with respect to sexual orientation. It does not limit a person to identifying strictly as heterosexual or homosexual. (Note: This term is NOT typically used in connection with gender identity in pre-adolescent children).

Bigender, bi-gender or dual-gender is a gender identity where the person moves between feminine and masculine gender identities and behaviors, possibly depending on context.

Non-Binary gender is an umbrella term covering any gender identity that doesn’t fit within the gender binary. The label may also be used by individuals wishing to identify as falling outside of the gender binary without being any more specific about the nature of their gender.

Gender Identity has broader historical connections such as how early humans became more feminine, which led to the birth of culture. The first is an analysis of fossilized skulls of our ancestors has found that brow ridges became significantly less prominent and male facial shape became more similar to that of females. They referred to this as craniofacial feminization, meaning that as Homo sapiens slimmed down their skulls became flatter and more “feminine” in shape. It is proposed that what happened were lower levels of testosterone, as there is a strong relationship between levels of this hormone and long faces with extended brow ridges, which we may perceive today as very “masculine” features. The other large effect lower levels of testosterone impart is individuals are less likely to be violent and have enhanced social tolerance. This feminization through self-domestication may not only have made humans more peaceful and evenly sized, but may have also produced a more sexually equal society. A recent study showed that in hunter-gatherer groups in the Congo and the Philippines decisions about where to live and with whom were made equally by both genders. Despite living in small communities, this resulted in hunter-gatherers living with a large number of individuals with whom they had no kinship ties. Thus, the argument is that this may have proved an evolutionary advantage for early human societies who became more feminine, as it would have fostered wider-ranging social networks and closer cooperation between unrelated individuals. The frequent movement and interaction between groups also fostered the sharing of innovations, which may have helped the spread of culture.

Gender Expression

Gender Expression: In contrast to gender identity, gender expression is external and is based on individual and societal conceptions and expectations. It encompasses everything that communicates our gender to others: clothing, hairstyles, body language, mannerisms, how we speak, how we play, and our social interactions and roles. Most people have some blend of masculine and feminine qualities that comprise their gender expression, and this expression can also vary depending on the social context i.e.; attire worn at work rather than play, hobbies or interests, etc. Color is a cue that effects how people interact with a child. The response of others to gender-specific colors of attire encourage what is socially designated as gender-appropriate behavior by that child. Stone observed that dressing a newborn in either blue or pink in America begins a series of interactions. Norms governing gender-appropriate attire are powerful. Gender-specific attire enhances the internalization of expectations for gender-specific behavior. Through the subtle and frequently nonverbal interactions with children regarding both their appearance and behavior, parents either encourage or discourage certain behaviors often related to dress that lead to a child’s development of their gender identity. When a boy decides he wants to play dress-up in skirts or makeup or a daughter chooses to play aggressive sports only with the boys, it would not be surprising to find the parents redirecting the child’s behavior into a more socially “acceptable” and gender-specific activity. Even the most liberal and open-minded parents can be threatened by their child not conforming to appropriate gender behaviors. Research has shown that children as young as two years of age classify people into gender categories based on their appearance. A person or behavior that deviates from these scripts of gender can be defined as unnatural or pathological.

A few points about Being Non-Binary can be expressed, such as its okay for Androgynous/Non-Binary people to live as their assigned gender when or as long as it suits them. It’s okay if they realizing that they don’t fit into the gender boxes marked ‘male’ or ‘female’ and do absolutely nothing about it. It is completely, one-hundred-percent acceptable to know you are non-binary and do absolutely nothing about it. You are not obliged to appear androgynous as such you have your whole life to work out your gender identity.

The only clues we have of paleolithic trans individuals would be by considering the societies of aboriginal peoples still living with stone age technologies. The few left remaining on the earth, in the rain forests of South America, or the remaining unspoiled lands of Africa, all have reverential positions for the transsexuals that are born to them. In such societies, trans individuals are considered magical, kin to the gods or spirits, and possessed of shamanic powers. Almost every society in history has had some name, role, or way of relating to non-heteronormativity and/or trans individuals from ancient Mesopotamia, Canaan, and Turkey to India, even to the present day. Some scholars assert that her role in myths as a gender transgressor, as a woman in a man’s lifestyle, she outrageously crossed gender boundaries and was used to support this in others. Inanna’s myths and her professional cult personnel may have offered a safe ideological and social space for those crossing gender and sexuality roles. This would seem evident given the evidence for same-sex behavior, transvestism, same-sex ritual, same-sex prostitution, and varying degrees of non-heterononnativity in the larger Mesopotamian culture. In ancient Rome existed the ‘Gallae’, Phrygian worshipers of the Goddess Cybele. Once decided on their choice of gender and religion, physically male Gallae ran through the streets and threw their own severed genitalia into open doorways, as a ritualistic act. The household receiving these remains considered them a great blessing. In return, the household would nurse the Gallae back to health. The Gallae then ceremoniously received female clothes, and assumed a female identity. Commonly, they would be dressed as brides, or in other splendid clothing. In India, ritual practices for transsexual individuals continue to the present day. Called Hijiras, this sect also worships a Goddess, and undergo a primitive sort of sex reassignment surgery. The Hijiras are treated in a rather hypocritical fashion within Indian society, however, in that they are both despised and revered at the same time. Hijiras often are paid to attend a bless weddings, and to act as spiritual and social advisers, but are also shunned as less than worthy eunuchs. Yet in other circumstances, such as social situations, they are accorded the status of true females. The Dine, or Navajos of the southwest United States, recognize three sexes instead of only two. For the Dine, there are Males, Females, and Nadles, which are considered somewhat both and neither. While those born intersexed or hermaphroditic are automatically considered Nadle, physically ‘normal’ individuals may define as Nadle based on their own self-definition of gender identity. The Nadle once possessed far greater respect before the Navaho were conquered and their culture all but obliterated by the forced assumption of Catholicism. Among the Sioux, the Winkte served much the same function, and individuals could assume the complete role of their preferred gender. Physical females lived as male warriors, and had wives, while physical males lived their lives completely as women. In Sioux society no special magic was associated with this, it was just considered a way of correcting a mistake of nature. Winkte would also perform primitive reassignment operations of a sort, and history records the process used by physical males: riding for days on a special hard saddle to crush the testicles and thus effectively castrate the individual. Native American in general usually have what is called Two Spirits which were male, female, and sometimes intersexed individuals who combined activities of both men and women with traits unique to their status as two spirits. In most tribes, they were considered neither men nor women; they occupied a distinct, alternative gender status. In tribes where male and female two-spirits were referred to with the same term, this status amounted to a third gender. In other cases, female two spirits were referred to with a distinct term and, therefore, constituted a fourth gender. Although there were important variations in two-spirit roles across North America, they share some common traits:

Specialized work roles. Male and female two-spirits were typically described in terms of their preference for and achievements in the work of the “opposite” sex or in activities specific to their role. Two spirits were experts in traditional arts—such as pottery making, basket weaving, and the manufacture and decoration of items made from leather. Among the Navajo, male two-spirits often became weavers, usually women&srquo;s work, as well as healers, which was a male role. By combining these activities, they were often among the wealthier members of the tribe. Female two spirits engaged in activities such as hunting and warfare, and became leaders in war and even chiefs.

Gender variation. A variety of other traits distinguished two spirits from men and women, including temperament, dress, lifestyle, and social roles.

Spiritual sanction. Two-spirit identity was widely believed to be the result of supernatural intervention in the form of visions or dreams and sanctioned by tribal mythology. In many tribes, two-spirit people filled special religious roles as healers, shamans, and ceremonial leaders.

Same-sex relations. Two spirits typically formed sexual and emotional relationships with non-two-spirit members of their own sex. Male and female two-spirits were often sexually active, forming both short- and long-term relationships. Among the Lakota, Mohave, Crow, Cheyenne, and others, two spirits were believed to be lucky in love, and able to bestow this luck on others.

34,000 years old Paleolithic dog or wolf-dog hybrid skulls found in Razboinichya Cave, Siberia

Dogs were domesticated between 9,000 and 34,000 years ago, suggesting the earliest dogs most likely arose when humans were still hunting and gathering – before the advent of agriculture around 10,000 years ago, according to an analysis of individual genomes of modern dogs and gray wolves. An international team of researchers, who published their report in PLoS Genetics Jan. 16, studied genomes of three gray wolves, one each from China, Croatia, and Israel – all areas thought to be possible geographic centers of dog domestication. They also studied dog genomes from an African basenji and an Australian dingo; both breeds come from places with no history of wolves, where recent mixing with wolves could not have occurred. Their findings revealed the three wolves were more closely related to each other than to any of the dogs. Likewise, the two dog genomes and a third boxer genome resembled each other more closely than the wolves. This suggests that modern dogs and gray wolves represent sister branches on an evolutionary tree descending from an older, common ancestor. The results contrast with previous theories that speculated dogs evolved from one of the sampled populations of gray wolves.“The analysis revealed that domestication led to sizable pruning in population of early dogs and wolves.” ref

Dog Domestication and Emerging Sacred Mortuary Rituals around 16,500 to 12,000 years ago

Uyun al-Hammam, A Unique Human-Fox Burial from a Pre-Natufian Cemetery in Jordon Red ochre underlays the bones in a relatively continuous manner around the rib cage but occurred more as infrequent chunks around the other isolated bones. The Earliest Fox-Human Burial, Grave I included an articulated fox skull, lying on its right side, underneath the articulated human ribs of Burial B (link). Although distorted by post-depositional crushing, the skull is remarkably intact (link). The complete right humerus of a fox was found directly below and adhering to the right side of the mandible. Large pieces of red ochre were found adhering to the underside of the human ribs on both left and right sides, while ochre fragments adhered to the nasal bones, mandible and right side of the fox cranium, as well as in the sediment within the skull cavity. The red ochre here is dense and continuous, suggesting that fox skull and human rib cage were placed on top of a layer of red ochre (link) as part of the primary interment episode of Burial B. Isolated chunks of red ochre were also found in Grave VIII near the human remains and between the legs of the fox. Ochre has been documented at several other sites in the Levant in association with or staining art objects, human bones, shell, bone and flint ref

The first burial of red ochre, Use of red ochre by early Neandertals | PNAS

burial practices in jordan from the natufians to the persians