ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

#Japan #Jōmon #Torii #Skyburial #Shinto #Buddhism #Yayoi #Confucian #Zen

Japanese Paleolithic

“The Japanese Paleolithic period is the period of human inhabitation in Japan predating the development of pottery, generally before 10,000 BCE. The starting dates commonly given to this period are from around 40,000 BCE; although any date of human presence before 35,000 BCE is controversial, with artifacts supporting a pre-35,000 BCE human presence on the archipelago being of questionable authenticity. The period extended to the beginning of the Mesolithic Jōmon period, or around 14,000 BCE. The earliest human bones were discovered in the city of Hamamatsu in Shizuoka Prefecture, which were determined by radiocarbon dating to date to around 18,000–14,000 years ago.” ref

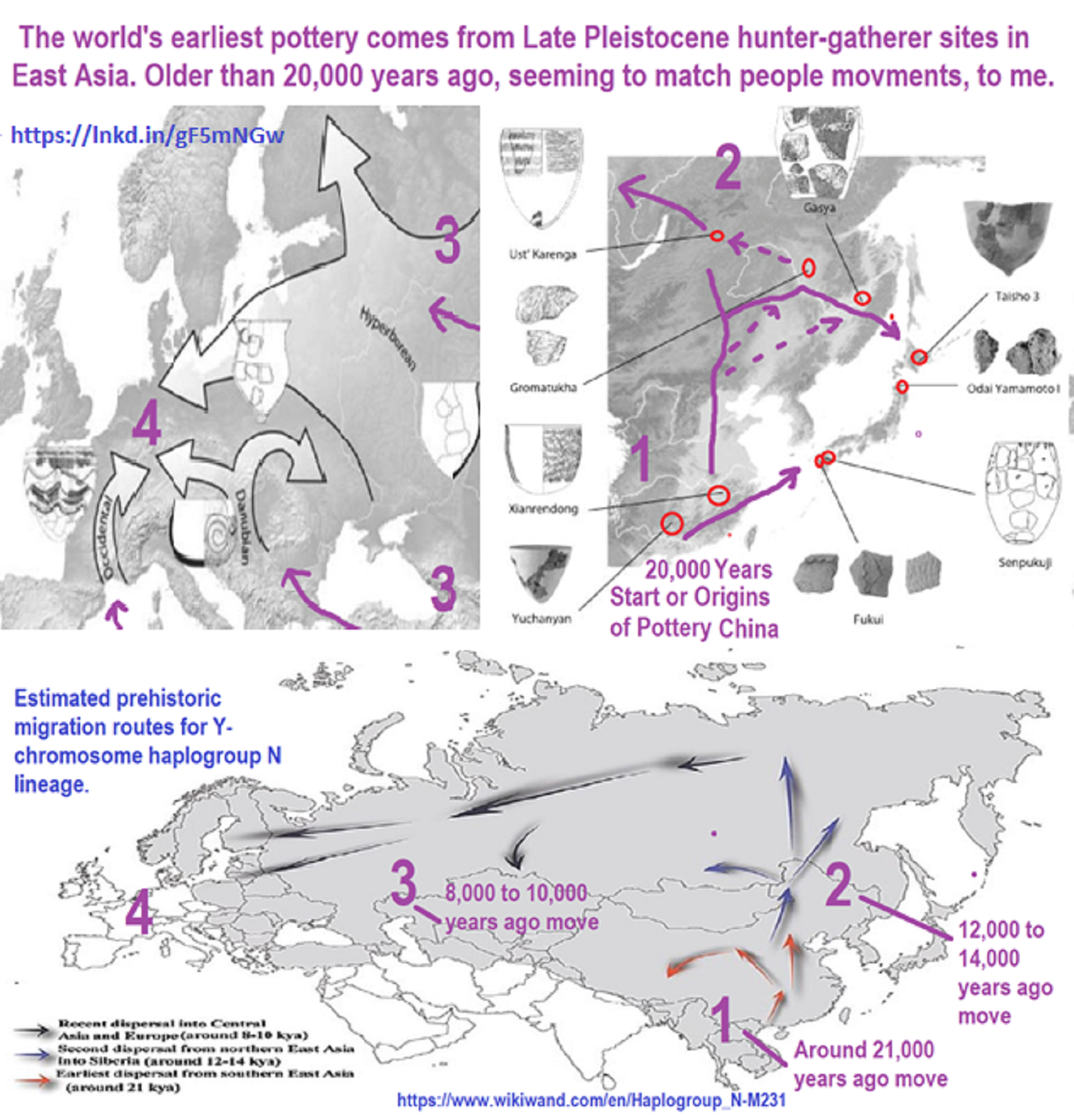

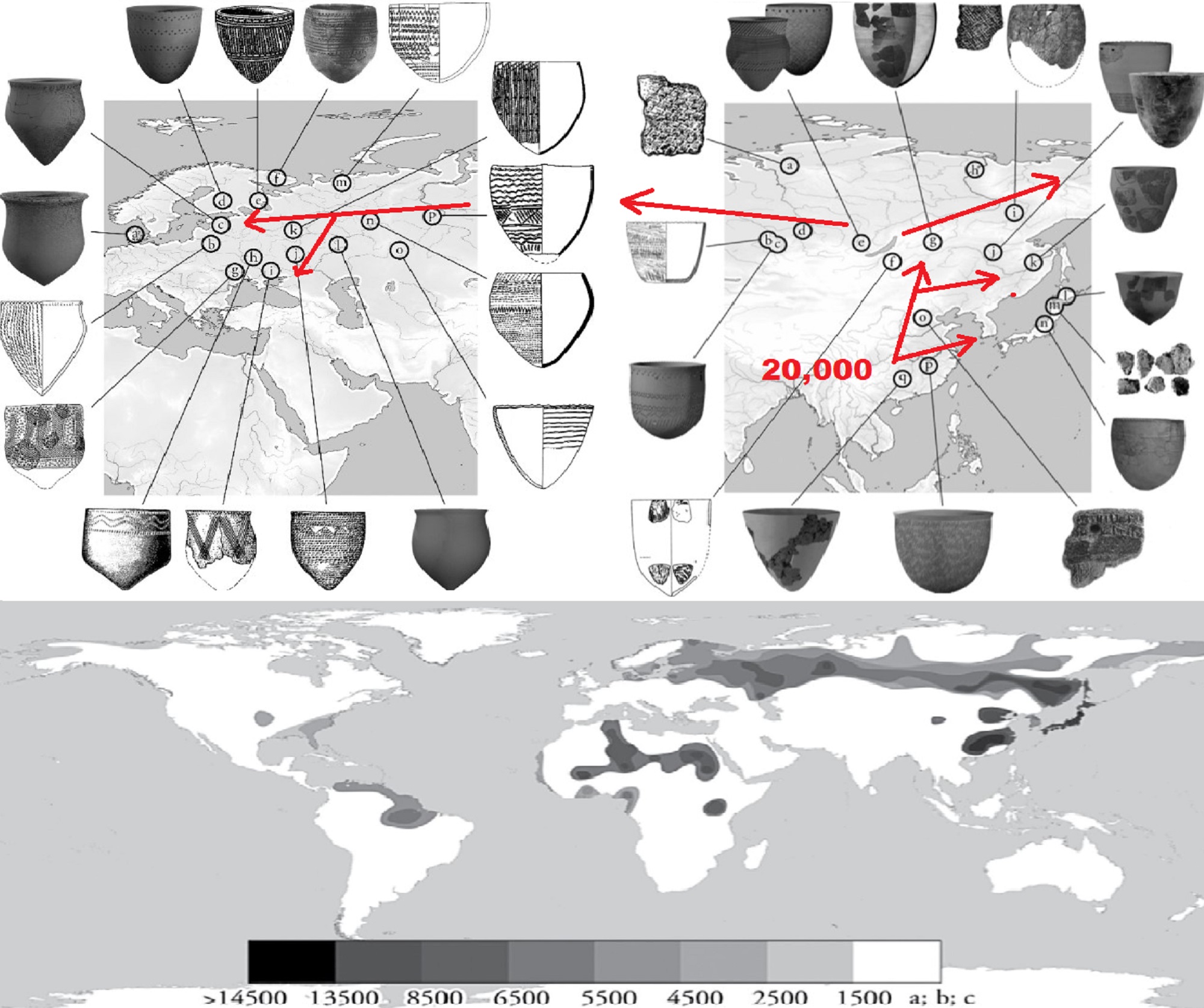

“The Japanese Paleolithic is unique in that it incorporates one of the earliest known sets of ground stone and polished stone tools in the world, although older ground stone tools have been discovered in Australia. The tools, which have been dated to around 30,000 BCE, are a technology associated in the rest of the world with the beginning of the Neolithic around 10,000 BCE or around 12,000 years ago. It is not known why such tools were created so early in Japan. Because of this originality, the Japanese Paleolithic period in Japan does not exactly match the traditional definition of Paleolithic based on stone technology (chipped stone tools). Japanese Paleolithic tool implements thus display Mesolithic and Neolithic traits as early as 30,000 BCE.” ref

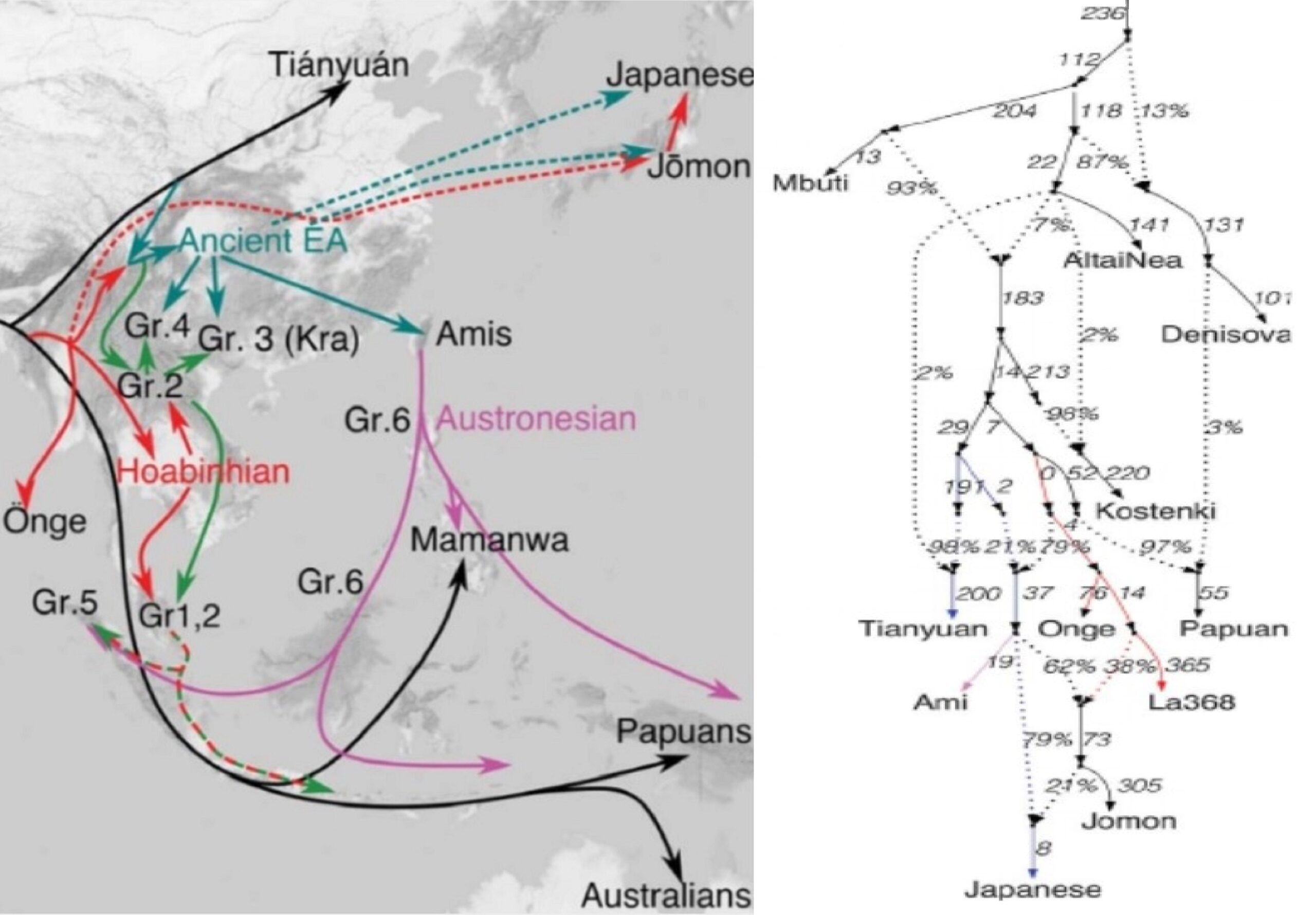

“The Paleolithic populations of Japan, as well as the later Jōmon populations, appear to relate to an ancient Paleo-Asian group which occupied large parts of Asia before the expansion of the populations characteristic of today’s people of China, Korea, and Japan. During much of this period, Japan was connected to the Asian continent by land bridges due to lower sea levels. Skeletal characteristics point to many similarities with other aboriginal people of the Asian continent. Dental structures are distinct but generally closer to the Sundadont than to the Sinodont group, which points to an origin among groups in Southeast Asia or the islands south of the mainland. Skull features tend to be stronger, with comparatively recessed eyes.” ref

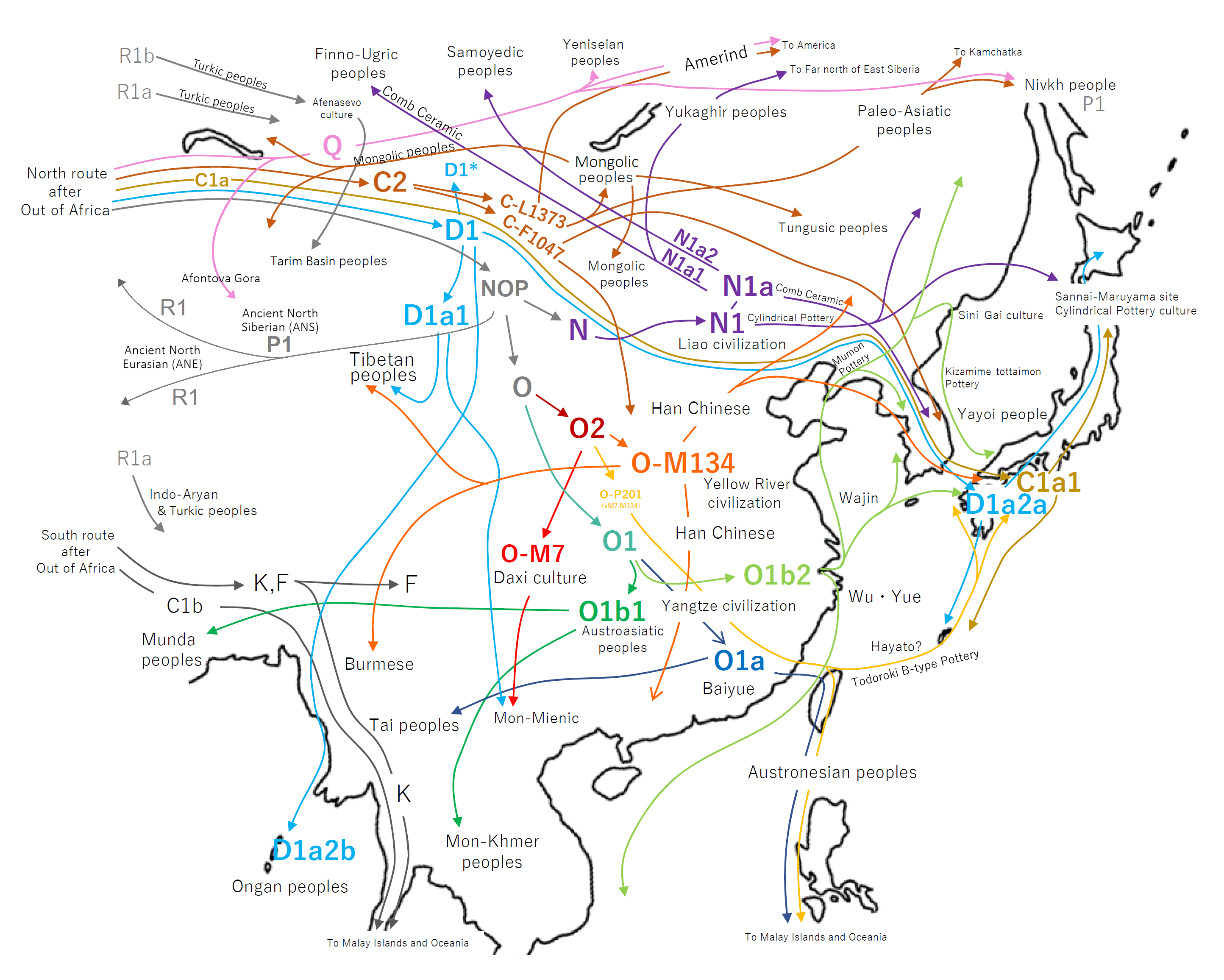

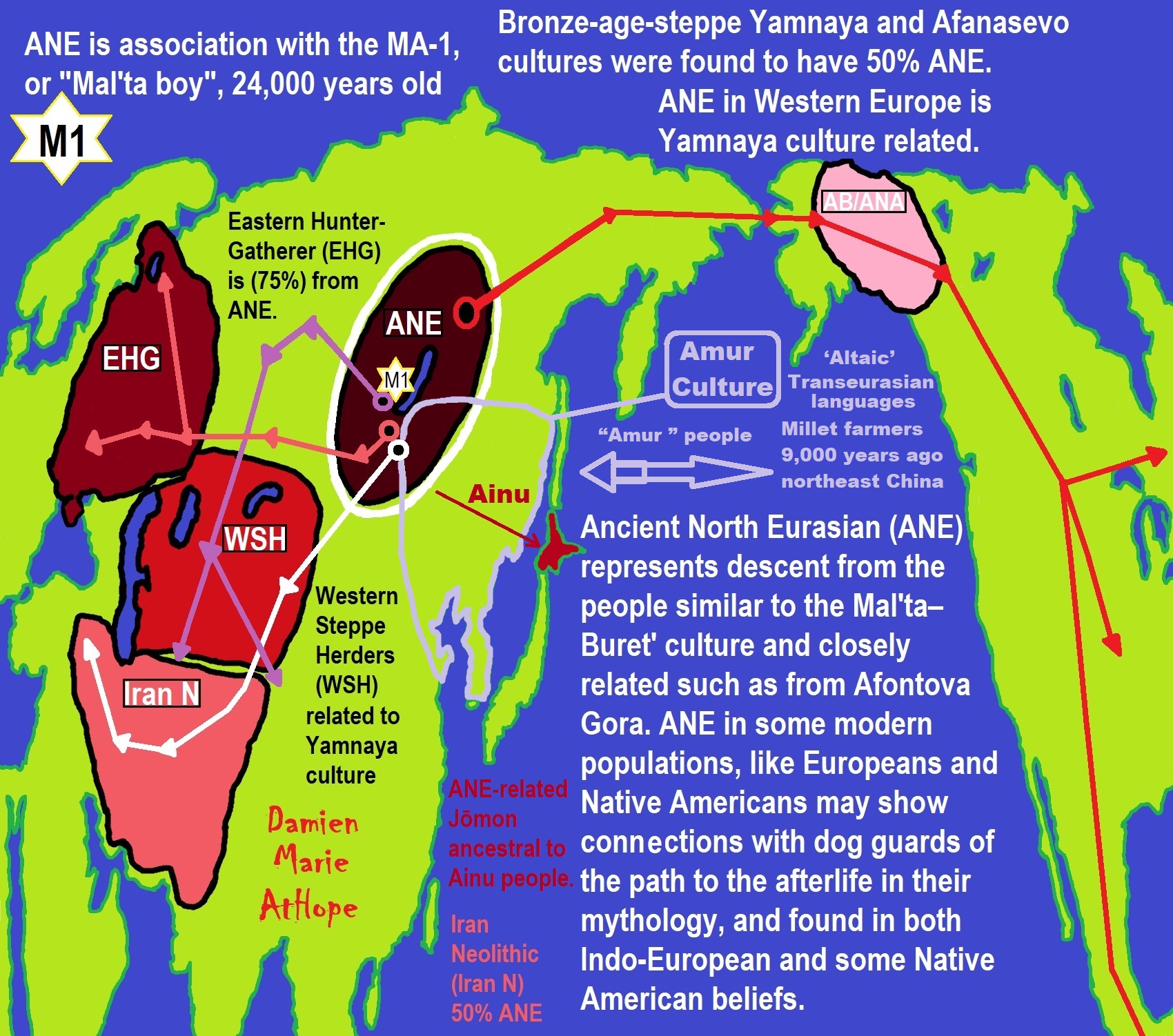

“According to “Jōmon culture and the peopling of the Japanese archipelago” by Schmidt and Seguchi, the prehistoric Jōmon people descended from a paleolithic populations of Siberia (in the area of the Altai Mountains). Other cited scholars point out similarities between the Jōmon and various paleolithic and Bronze Age Siberians. There were likely multiple migrations into ancient Japan. According to Mitsuru Sakitani, the Jōmon people were an admixture of two distinct ethnic groups: A more ancient group (carriers of Y chromosome D1a) that were present in Japan since more than 30,000 years ago and a more recent group (carriers of Y chromosome C1a) that migrated to Japan about 13,000 years ago (Jomon). Genetic analysis on today’s populations is not clear-cut and tends to indicate a fair amount of genetic intermixing between the earliest populations of Japan and later arrivals (Cavalli-Sforza). It is estimated that modern Japanese have about 10% Jōmon ancestry.” ref

“Jōmon people were found to have been very heterogeneous. Jōmon samples from the Ōdai Yamamoto I Site differ from Jōmon samples of Hokkaido and geographically close eastern Honshu. Ōdai Yamamoto Jōmon were found to have C1a1 and are genetically close to ancient and modern Northeast Asian groups but noteworthy different to other Jōmon samples such as Ikawazu or Urawa Jōmon. Similarly, the Nagano Jōmon from the Yugora cave site are closely related to contemporary East Asians but genetically different from the Ainu people, which are direct descendants of the Hokkaido Jōmon. One study, published in the Cambridge University Press in 2020, suggests that the Jōmon people were rather heterogeneous, and that many Jōmon groups were descended from an ancient “Altaic-like” population (close to modern Tungusic-speakers, represented by Oroqen), which established itself over the local hunter gatherers.” ref

“This “Altaic/Transeurasian-like” population migrated from Northeast Asia in about 6,000 BCE, and coexisted with other unrelated tribes and or intermixed with them, before being replaced by the later Yayoi people. C1a1 and C2 are linked to the “Tungusic-like people“, which arrived in the Jōmon period archipelago from Northeast Asia in about 6,000 BCE and introduced the Incipient Jōmon culture, typified by early ceramic cultures such as the Ōdai Yamamoto I Site. Another study, published in Nature in 2021, combined linguistic, archaeological, and genetic evidence to suggest that the Transeurasian, or “Altaic”, population, originated in the West Liao basin of northeastern China, and farmed millet around 9,000 years ago. The study concluded that this population spread through Korea to Japan, bringing their agricultural practices, and triggering a genetic shift from the Jōmon to the Yayoi people, as well as a shift to the Japonic language.” ref

“The origins of the Japanese people is not entirely clear yet. It is common for Japanese people to think that Japan is not part of Asia since it is an island, cut off from the continent. This tells a lot about how they see themselves in relation to their neighbours. But in spite of what the Japanese may think of themselves, they do not have extraterrestrial origins, and are indeed related to several peoples in Asia.” ref

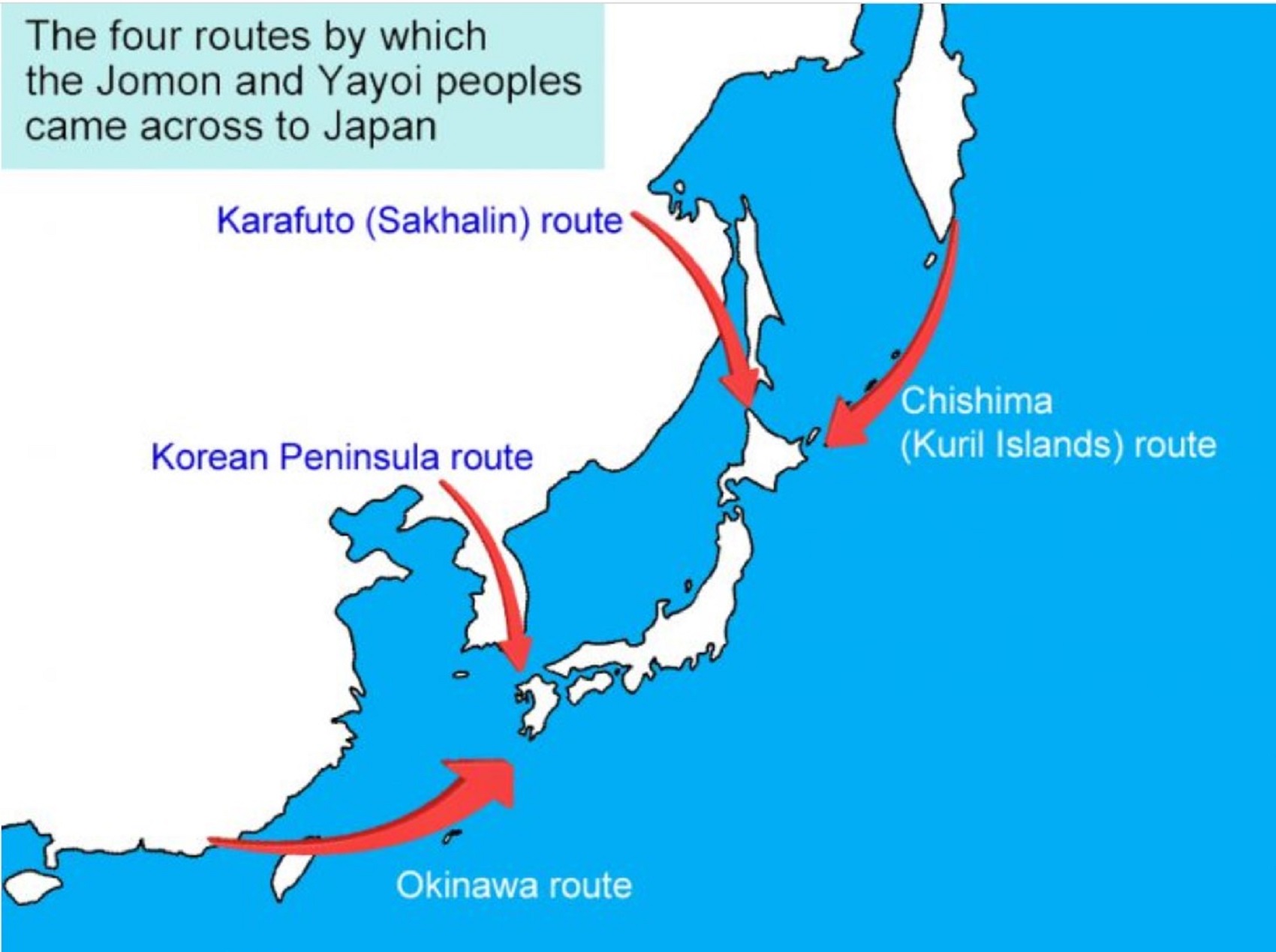

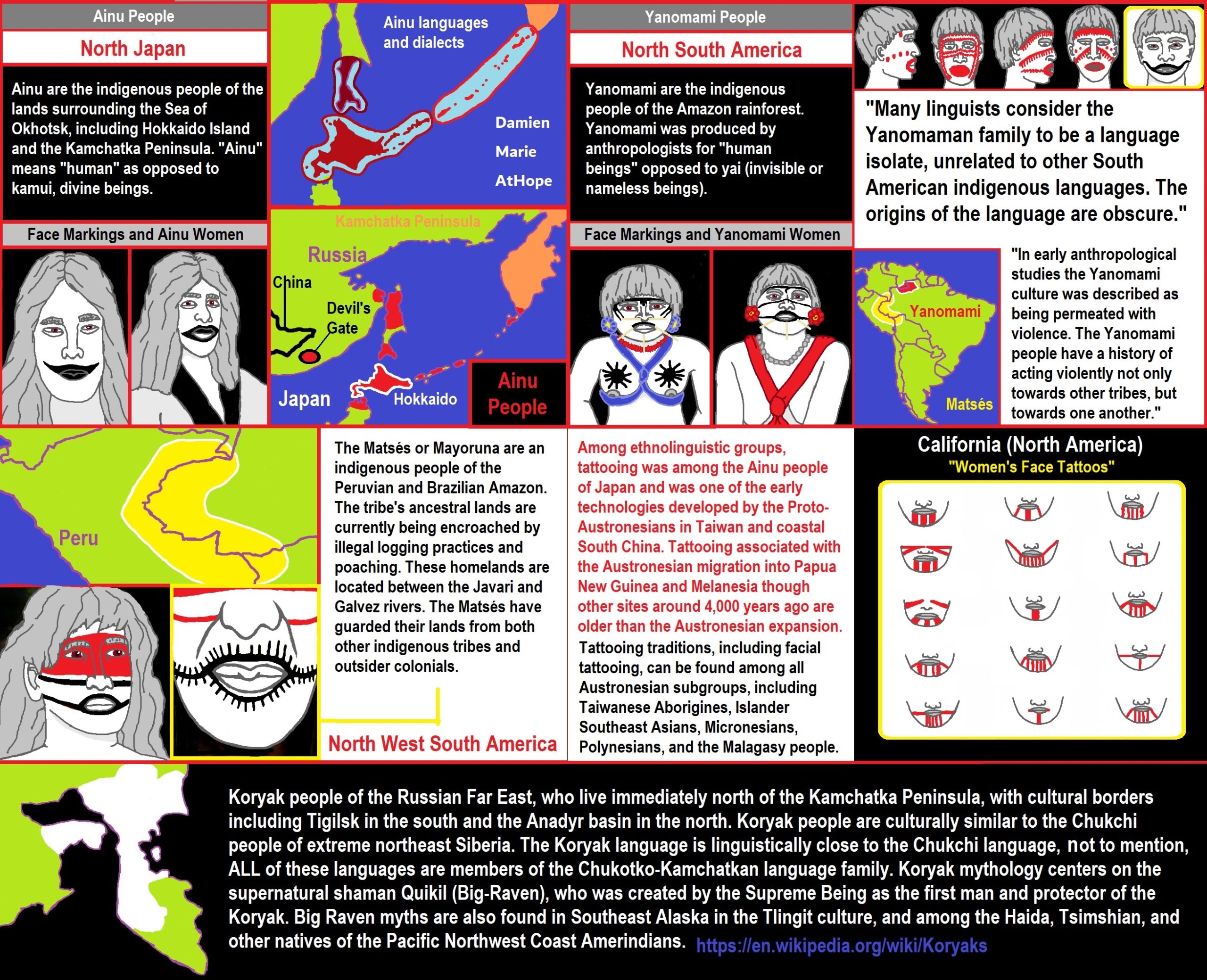

“During the last Ice Age, which ended approximately 15,000 years ago, Japan was connected to the continent through several land bridges, notably one linking the Ryukyu Islands to Taiwan and Kyushu, one linking Kyushu to the Korean peninsula, and another one connecting Hokkaido to Sakhalin and the Siberian mainland. In fact, the Philippines and Indonesia were also connected to the Asian mainland. This allowed migrations from China and Austronesia towards Japan, about 35,000 years ago. These were the ancestors of the modern Ryukyuans (Okinawans), and the first inhabitants of all Japan. The Ainu came from Siberia and settled in Hokkaido and Honshu some 15,000 years ago, just before the water levels started rising again. Nowadays the Ryukuyans, the Ainus and the Japanese are considered three ethnically separate groups. We will see why.” ref

Mitochondrial haplogroups A, B and G originated about 50,000 years ago, and bearers subsequently colonized Siberia, Korea, and Japan, by about 35,000 years ago. Several phenotypical traits associated with Mongoloids with a single mutation of the EDAR gene, dated to c. 35,000 years ago. A Paleolithic site on the Yana River, Siberia, at 71°N, lies well above the Arctic Circle and dates to 27,000 radiocarbon years before present, during glacial times. This site shows that people adapted to this harsh, high-altitude, Late Pleistocene environment much earlier than previously thought. ref

Ust’-Ishim man has been classified as belonging to Y-DNA haplogroup K2a*, belonged to mitochondrial DNA haplogroup R*. Before 2016 they had been classified as U*. Both of these haplogroups and descendant subclades are now found among populations throughout Eurasia, Oceania and The Americas. When compared to other ancient remains, Ust’-Ishim man is more closely related, in terms of autosomal DNA to Tianyuan man, found near Beijing and dating from 42,000 to 39,000 years ago; Mal’ta boy (or MA-1), a child who lived 24,000 years ago along the Bolshaya Belaya River near today’s Irkutsk in Siberia, or; La Brañaman – a hunter-gatherer who lived in La Braña (modern Spain) about 8,000 years ago. ref

“Whole-genome studies reveal a split between Europeans and Asians dating to around 17,000 to 43,000 years ago. The rise of modern Asians dates to around 25,000 to 38,000 years ago.” ref

“Comparing the DNA sequences of these individuals revealed that, between 15,000 to 34,000 years ago, the humans living in Eurasia had genetic profiles similar to either Europeans or Asians — that is, they had become distinct. This hinted to Fu and Yang that a genetic separation between Asians and Europeans likely happened well before that, around 40,000 years ago. But in younger Eurasian fossils, those from around 7,500 to 14,000 years ago, the genetic gap appeared to have shrunk again, showing humans with genetic similarities to both Asians and Europeans. This suggests that, during this time, the once-distinct Asian and European populations had interacted once again, thereby complicating the genetic history of these groups.” ref

From a cave in South Korea have found evidence that suggests human beings were using sophisticated techniques to catch fish as far back as 29,000 years ago. Pryor to the South Korean find, the oldest fishing implements were believed to be fishing hooks, made from the shells of sea snails, that was found on a southern Japanese island and said to date back some 23,000 years. ref

The Korea Strait was, however, quite narrow at the Last Glacial Maximum from 25,000 to 20,000 years BP. The earliest firm evidence of human habitation is of early Upper Paleolithic hunter-gatherers from 40,000 years ago, when Japan was separated from the continent. Edge-ground axes dating to 32–38,000 years ago found in 224 sites in Honshu and Kyushu are unlike anything found in neighbouring areas of continental Asia, and have been proposed as evidence for the first Homo sapiens in Japan; watercraft appear to have been in use in this period. Radiocarbon dating has shown that the earliest fossils in Japan date back to around 32,000-27,000 years ago; for example in the case of Yamashita Cave 32,100 years ago, in Sakitari Cave cal 31,000–29,000 years ago, in Shiraho Saonetabaru Cave c. 27,000 years ago among others. ref

Jōmon period

The Jōmon period of prehistoric Japan spans from about 14,000 years ago (in some cases dates as early as 16,500 years ago are given) to about 2,800 years ago. Japan was inhabited by a hunter-gatherer culture that reached a considerable degree of sedentism and cultural complexity. The name “cord-marked” was first applied by the American scholar Edward S. Morse who discovered shards of pottery in 1877 and subsequently translated it into Japanese as jōmon. The pottery style characteristic of the first phases of Jōmon culture was decorated by impressing cords into the surface of wet clay. ref

Jōmon mtDNA

“At present, 131 Jōmon-period skeletons have been tested in several separate studies, with samples from Kanto (n=54), Tohoku (n=23) and Hokkaido (n=54). The haplogroups identified in Tohoku and Hokkaido were D4h2, M7a and N9b, with also D1a and G1 in Hokkaido.” ref

“Haplogroup N9b was clearly dominant in northern Japan during the Jōmon period, making up over 60% of the matrilineal lineages. Today, N9b is also found among the Udege people of eastern Siberia, just north of the islands of Hokkaido and Sakhalin.” ref

“Haplogroup G1 is a typically Siberian lineage, completely absent from China, and found only at low frequencies in Korea (2.5%). It most common in eastern Siberia, particularly among the Negidals in the Khabarovsk Krai, among the Chuvans of Chukotka, where it exceeds 25% of the female lineages, and among the Itelmens and the Koryaks of the Kamchatka Peninsula, who have over 50% of G1 lineages. G1 has a frequency of 2.5% in Japan, but 22% among the Ainu, who have intermarried over the centuries with tribes from eastern Siberia via Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands. It is therefore not surprising to find in in ancient Hokkaido as well as among modern Ainu.” ref

“Haplogroup D4h seems to be native to Japan, while D1 is not normally found among East Asians but among Native Americans. How did D1 end up in Palaeolithic Hokkaido is still unknown. D1 might first appeared in Siberia then migrated to the Americas, and that a few women carrying these lineages married into other Siberian tribes that eventually came into contact with the Ainu, after many generations of geographic drift. It should be said, however, that D1 now extremely rare in the modern Japanese population and may even have become extinct since the Jōmon period. Samples from Kantō were more varied and suggests that migrations from the continent might have happened before the Yayoi period. They included haplogroups A (7.4%), B (9.3%), D4h (18.5%), F(1.9%), G2 (1.9%), M7a (3.7%), M7b (1.9%), M8a (9.3%), M10 (33%) and N9b (5.6%).” ref

“Like N9b, haplogroups M7 and M10 are extremely ancient lineages that are associated with the some of the earliest migrations of Homo sapiens to East Asia over 50,000 years ago. M7b, M7c and M7e have been found in southern China, Indochina, and the Philippines. M7a, M7b and M7c were all found during the Jōmon period and are still found in modern Japan. However, about 60% of Japanese M7 members belong to M7a, which is really specific to Japan. M10 is considerably more common in China and Korea than in Japan.” ref

“Haplogroup G2 is found in 5% of the Japanese population, but only 4% of the Ainu. It has a very different geographic distribution, being absent from eastern Siberia, but relatively common in Korea (6%), northern China (6.5%), Mongolia (10%), Tibet (11%), Nepal (14%) and even Central Asia.” ref

Did South Chinese Neolithic farmers colonise Japan during the Jōmon period?

“It is not clear at present why typically Chinese mtDNA haplogroups like A, B, F, M8a and M10 were already present in the Kanto during the Late Jōmon period (1500–300 BCE). These may represent early migration of farmers from the continent, many centuries or millennia before the Yayoi invasion. Catherine D’Andrea reported evidence for Late Jōmon rice, foxtail millet, and broomcorn millet dating to the first millennium BCE in Tohoku. However, there is evidence of plant cultivation in Japan long before that. Arboriculture was practiced by Jōmon people in the form of tending groves of nut- and lacquer-producing trees (see Matsui and Kanehara 2006 and Transitions to Agriculture in Japan, Gary W. Crawford). A domesticated variety of peach, apparently from China, appeared very early at Jōmon sites circa 4700–4400 BCE. Several sites (including Torihama, Sannai Maruyama and Mawaki in central and northern Honshu) of the Early Jōmon (4,000–2500 BCE) and Middle Jōmon (2500–1500 BCE) periods show evidence of cultivated plants, including barley, barnyard millet, buckwheat, rice, bean, soybean, burdock, hemp, egoma and shiso mint, mountain potato, taro potato, and bottle gourd. Many archeologists believe that these cultivated plants were only used to supplement the Jōmon diet, which still relied heavily on hunting, fishing and gathering.” ref

“Most of these domesticated plants, including rice and millet, are very unlikely to have been domesticated independently by the Jōmon hunter-gatherers, and almost certainly required the migration of farmers from China or Korea. The hundreds of ancient DNA samples from the Middle East and Europe have confirmed that the spread of agriculture always involved the migration of farmers and did not propagate purely by cultural diffusion. Consequently, it is extremely likely that Chinese Neolithic farmers brought these crops to Japan, perhaps in several waves of migration which would have taken place between 4500 and 2500 BCE.” ref

“The presence of typically South Chinese paternal (D1a1, O1a, O2a, O3a1, O3a2) and maternal lineages (M7b, M7c, M9, M12) strongly suggests that at least one of these Neolithic migrations originated in South China. These specifically South Chinese haplogroups represent approximately 5-10% of the modern Japanese maternal lineages and up to 15% of paternal ones. However, South Chinese farmers would have also carried haplogroups shared by the Yayoi people, such as other Y-DNA O3 subclades, and mtDNA A, B D4, D5 and F. Late Jomon mtDNA samples from the Kanto region shows that Chinese lineages made up about 65 to 75% of the maternal lineages at the time. A fairer approximation of the share of modern lineage of Neolithic South Chinese origin might be anywhere between 5 and 35% for maternal lineages, and perhaps around 10 to 20% for paternal ones. More data would be needed to give a more accurate estimation.” ref

“It remains to be confirmed how South Chinese Neolithic farmers reached Japan, but the easiest and safest route is via Taiwan and the Ryukyu Islands. Agriculture appears to have taken root in Taiwan between 4000 and 3500 BCE. The The southern Ryukyu Islands were re-settled by around 2300 BCE as part of the Neolithic Austronesian expansion from Taiwan (Austronesian and Jōmon identities in the Neolithic of the Ryukyu Islands, Mark J. Hudson (2012)), and could have reached Kyushu by 2000 BCE. However, this does not account for the evidence of crops during the Early Jōmon period, which might have come through another route, either following the coastline until the Korean peninsula, or crossing directly from China to Kyushu. A third possibility is that the first migration from Southeast China followed the chain of islands from Taiwan to Kyushu without stopping along the way and only settling in Japan itself, while Taiwan and the Ryukyus were settled by another later migration from mainland China. In fact, these

“Anatomically modern humans expanded into Southeast Asia(SEA) at least 65,000 years ago, leading to the formation of the Hòabìnhian hunter-gatherer tradition first recognized by ~44,000 years ago. Though Hòabìnhian foragers are considered the ancestors of present-day hunter-gatherers from mainland Southeast Asia (MSEA), the East Asian phenotypic affinities of the majority of Present-day Southeast Asian populations suggest that diversity was influenced by later migrations involving rice and millet farmers from the north. These observations have generated two competing hypotheses: One states that the Hòabìnhian hunter-gatherers adopted agriculture without substantial external gene flow, and the other (the “two-layer” hypothesis) states that farmers from East Asia (EA) replaced the indigenous Hòabìnhian inhabitants ~4,000 years ago. Studies of present-day populations have not resolved the extent to which migrations from East Asia affected the genetic makeup of Southeast Asia.” ref

“Outgroup f3 statistics show that group 1 shares the most genetic drift with all ancient mainland samples and Jōmon. All other ancient genomes share more drift with present-day East Asian and Southeast Asian populations than with Jōmon. This is apparent in the fastNGSadmix analysis when assuming six ancestral components (K= 6), where the Jōmon sample contains East Asian components and components found in group 1. Finally, the Jōmon individual is best-modeled as a mix between a population related to group 1/Önge and a population related to East Asians (Amis), whereas present-day Japanese can be modeled as a mixture of Jōmon and an additional East Asian component. The remaining ancient individuals are modeled in fastNGSadmix as containing East Asian and Southeast Asian components present in high proportions in present-day Austroasiatic, Austronesian, and Hmong-Mien speakers, along with a broad East Asian component. A principal component analysis including only East Asian and Southeast Asian populations that did not show considerable Papuan or Önge-like ancestry separates the present-day speakers of ancestral language families in the region: Trans-Himalayan (formerly Sino-Tibetan), Austroasiatic, and Austronesian/Kradai. The ancient individuals form five slightly differentiated clusters (groups 2 to 6), in concordance with fastNGSadmix and f3 results.” ref

“The best model for present-day Dai populations is a mixture of group 2 individuals and a pulse of admixture from East Asians. Group 6 individuals (1,880 to 299 years ago) originate from Malaysia and the Philippines and cluster with present-day Austronesians. Group 6 also contains Ma554, having the highest amounts of Denisovan-like ancestry relative to the other ancient samples, although we observe little variation in this archaic ancestry in our samples from mainland Southeast Asia. Group 5 (2,304 to 1,818 years ago) contains two individuals from Indonesia, modeled by fastNGSadmix as a mix of Austronesian- and Austroasiatic-like ancestry, similar to present-day western Indonesians, a finding consistent with their position in the principal component analysis. Indeed, after Mlabri and Htin, the present-day populations sharing the most drift with group 2 are western Indonesian samples from Bali and Java previously identified as having mainland Southeast Asian ancestry. Treemix models the group 5 individuals as an admixed population receiving ancestry related to group 2 and Amis.” ref

‘Despite the clear relationship with the mainland group 2 seen in all analyses, the small ancestry components in group 5 related to Jehai and Papuans visible in fastNGSadmix may be remnants of ancient Sundaland ancestry. These results suggest that group 2 and group 5 are related to mainland migration that expanded southward across mainland Southeast Asia by 4,000 years ago and into island Southeast Asia (ISEA) by 2,000 years ago. A similar pattern is detected for Ma555 in Borneo (505 to 326 years ago, group 6), although this may be a result of recent gene flow. Group 3 is composed of several ancient individuals from northern Vietnam (2,378 to 2,041 years ago ) and one individual from Long Long Rak (LLR), Thailand (1,691 to 1,537 ,000 years ago ). They cluster in the principal component analysis with the Dai, Amis, and Kradai speakers from Thailand, consistent with an Austro-Tai linguistic phylum, comprising both the Kradai and Austronesian language families. Group 4 contains the remaining ancient individuals from LLR in Thailand (1,570 to 1,815 years ago), and Vt778 from inland Vietnam (2,750 to 2,500 years ago).” ref

“These samples cluster with present-day Austroasiatic speakers from Thailand and China, in support of a South China origin for Long Long Rak. Present-day Southeast Asian populations derive ancestry from at least four ancient populations. The oldest layer consists of mainland Hòabìnhians (group 1), who share ancestry with present-day Andamanese Önge, Malaysian Jehai, and the ancient Japanese Ikawazu Jōmon. Consistent with the two-layer hypothesis in mainland Southeast Asia, researchers observed a change in ancestry by ~4,000 years ago, supporting a demographic expansion from East Asia into Southeast Asia during the Neolithic transition to farming. However, despite changes in genetic structure coinciding with this transition, evidence of admixture indicates that migrations from East Asia did not simply replace the previous occupants. Additionally, late Neolithic farmers share ancestry with present-day Austroasiatic-speaking hill tribes, in agreement with the hypotheses of an early Austroasiatic farmer expansion. By 2,000 years ago, Southeast Asian individuals carried additional East Asian ancestry components absent in the late Neolithic samples, much like present-day populations. One component likely represents the introduction of ancestral Kradai languages in mainland Southeast Asia, and another is the Austronesian expansion into island Southeast Asia reaching Indonesia by 2,100 years ago and the Philippines by 1,800 years ago. The evidence described here favors a complex model including a demographic transition in which the original Hòabìnhians admixed with multiple incoming waves of East Asian migration associated with the Austroasiatic, Kradai, and Austronesian language speakers.” ref

The Origins of Japanese Culture Uncovered Using DNA

“The Jomon people were not homogeneous”

“Samples discovered at the Odake shell mound dig in Toyama City, a site from around 6,000 years ago (Early Jomon period), but an enormous amount of artifacts have been unearthed. Although the total amount of Early Jomon period human remains excavated nationwide up to that point had been around only eighty sets of remains altogether, a further ninety-one sets of remains came from just this one site. As luck would have it, we ended up in charge of analyzing the “mitochondrial DNA” of those remains. Let me explain simply what we can tell from this analysis.” ref

“Mitochondria are organelles (tiny organs) contained in the cytoplasm in the cells of the human body. Because mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is passed genetically from mother to child, if we analyze a certain person’s mtDNA we can trace the maternal line of that person’s ancestry. By comparing different people’s DNA, we can tell in what kind of order branching occurred from a common ancestral line. There are two things that became clear from the analysis of the human remains found at the Odake shell mound. The first is that none of the D4 type mtDNA that one-in-three modern day Japanese people possesses was detected whatsoever. In other words, it reinforces the theory—as has been said conventionally—that the D4 type comes from immigrant-type Yayoi peoples.” ref

“It’s reasonable to think that a group of rice-growing farmers from the continent became one of the fundamental bases for the modern Japanese people. Only, this D4 group is classified down more finely from “a” to “n”—for example, D4b occurs frequently in the indigenous peoples of Siberia, and so on—and there are many aspects of the roots of these that have yet to be explained. In actual fact, type D4 DNA has been found in the remains of other Jomon people that we have examined. What we can say at this point in time is that it (the D4 type) was born on the continent around 20,000–30,000 years ago, and that later it gave birth to various other types, some of which also came to Japan during the Jomon period. But the main group is that which came to Japan together with rice farming during the Yayoi period.” ref

The second distinguishing feature of the Odake shell mound site is that a mixture of the Southern “M7a” type and the Northern “N9b” type was found there. Although the former type (M7a) is possessed by between 7 and 8% of modern day Japanese, in Okinawa as high as around 24% has been detected—so it is considered that this is the oldest group, which came to the Japanese archipelago first from the south. However, since there is nobody in Taiwan with this type and it is limited exclusively to the Japanese islands, the route by which it entered has yet to be identified. In contrast to this, remains containing the latter type (N9b) have been found in quite large numbers at shell mounds from Hokkaido, along the Tohoku (north-eastern Japan) coast and in the Kanto area; and given the fact that it is found frequently in the indigenous peoples of the Primorsky Krai (Maritime Province) area of Russia it is thought that this is a group that entered Japan from the north at a time not too different from that of the former (M7a) group.” ref

“The southern M7a type is a type that is unique to Japan. If somewhere in the world we examine some DNA and we find this type, we can judge that it is the DNA of someone who is related to a Japanese person or people in some shape or form. Actually, there are around 2 or 3% in the Korean Peninsula, but we think that there is a high probability that they are the descendants of a group that entered there from Japan. In any case, what we can say from the characteristics of the human remains found at the Odake shell mound is that it’s unreasonable to suppose that the people who were living in Japan before the Yayoi people came were “homogenous” Jomon people.” ref

“Since some time ago, in the world of archeology too, it has been pointed out—from the differences in the shapes of pottery and stone tools and so on—that Jomon culture was not uniform. For example, in the case of the earliest Jomon period pottery, there is Chinsenmon pottery, which is often found in eastern Japan, and Oshigatamon pottery, which is distributed around western Japan, and it has been acknowledged that there are clear differences in the patterns. When we tried analyzing the DNA—in other words the genome—of the Jomon people using the latest technology, we found that the Jomon people are not similar to anyone, in any period in history, anywhere else in the world. If we look at it another way, they are also slightly similar in small ways to each of the various peoples of regions across a wide area of Asia. What this means is that the Jomon people were probably born within the Japanese archipelago. In other words, in Japanese history there is an extremely long Paleolithic (stone age) period (between 40,000 and 15,000 years ago) leading up to the Jomon period, but during that period—roughly speaking—various different peoples came to the Japanese archipelago from the north and south. What I’m saying is, I wonder if it wasn’t that the Jomon people were born out of the progressive mixing/blending amongst the group brought about by this influx.” ref

“Haplogroup M7 (mtDNA)– found in East Asia and Southeast Asia, especially in Japan, southern China, Vietnam, Laos, and Thailand; also found with low frequency in Central Asia and Siberia

- Haplogroup M7a

- Haplogroup M7a* – Japan

- Haplogroup M7a1

- Haplogroup M7a1* – Japan, Jiangsu, Shandong

- Haplogroup M7a1a

- Haplogroup M7a1a* – Japan, Korea, Beijing, Hebei, Henan, Sichuan, Shanghai, Shandong

- Haplogroup M7a1a1

- Haplogroup M7a1a1* – Japan, Korea, Jiangsu, Shandong, Liaoning, Henan

- Haplogroup M7a1a1a – Japan

- Haplogroup M7a1a2

- Haplogroup M7a1a2* – Japan, Jiangsu

- Haplogroup M7a1a2a – Japan

- Haplogroup M7a1a3 – Japan

- Haplogroup M7a1a4

- Haplogroup M7a1a4* – Japan, Zhejiang

- Haplogroup M7a1a4a – Japan

- Haplogroup M7a1a5

- Haplogroup M7a1a5* – Japan

- Haplogroup M7a1a5a – Japan, Korea, Tianjin

- Haplogroup M7a1a6

- Haplogroup M7a1a6* – Japan, Philippines, Jiangsu, Shanxi, Shandong

- Haplogroup M7a1a6a – Japan

- Haplogroup M7a1a7

- Haplogroup M7a1a7* – Japan, Korea

- Haplogroup M7a1a7a – Uyghur

- Haplogroup M7a1a8 – Japan, Jiangsu

- Haplogroup M7a1a9 – Japan, Korea, Tianjin

- Haplogroup M7a1a10 – Japan

- Haplogroup M7a1b

- Haplogroup M7a1b1

- Haplogroup M7a1b1* – Japan, China (Minnan Han)

- Haplogroup M7a1b1a – Japan

- Haplogroup M7a1b2 – Japan

- Haplogroup M7a1b1

- Haplogroup M7a2

“Haplogroup N9b – Japan, Udegey, Nanai, Korea [time to most recent common ancestor 14,885 years ago]

-

- Haplogroup N9b1 – Japan [time to most recent common ancestor 11,859 years ago]

- Haplogroup N9b1a – Japan [time to most recent common ancestor 10,645 years ago]

- Haplogroup N9b1b – Japan [time to most recent common ancestor 2,746 years ago]

- Haplogroup N9b1c – Japan [time to most recent common ancestor 6,987 years ago]

- Haplogroup N9b1c1 – Japan

- Haplogroup N9b2 – Japan [time to most recent common ancestor 13,369 years ago]

- Haplogroup N9b2a – Japan

- Haplogroup N9b3 – Japan [time to most recent common ancestor 7,629 years ago]

- Haplogroup N9b4 – Japan, Ulchi” ref

- Haplogroup N9b1 – Japan [time to most recent common ancestor 11,859 years ago]

Prehistoric Japan’s Migrations

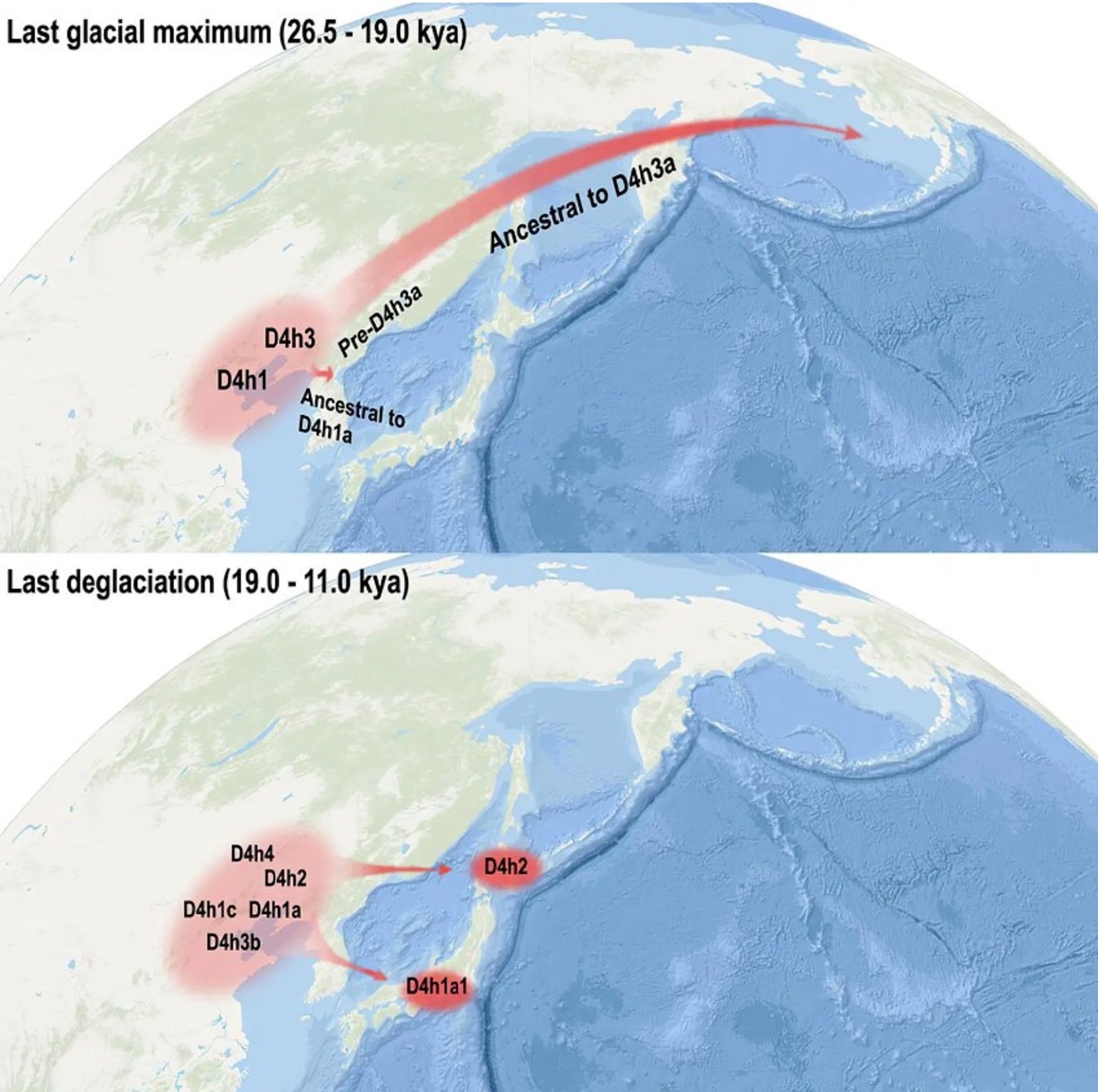

Maps showing ice age migration routes from northern coastal China to the Americas and Japan.

“Graphical abstract showing ice age migration routes from northern coastal China to the Americas and Japan. A team of scientists discovered that Native Americans share a female lineage with ancient populations from northern coastal China, adding complexity to the ancestry of Native Americans. By analyzing mitochondrial DNA, the researchers found evidence of two migrations from northern coastal China to the Americas during the last ice age and the subsequent melting period. Another branch of the same lineage migrated to Japan during the second migration, which may explain archeological similarities between the Americas, China, and Japan. This study broadens the understanding of Native American ancestry, which was previously thought to have come mainly from Siberia, Australo-Melanesia, and Southeast Asia.” ref

“Scientists have used mitochondrial DNA to trace a female lineage from northern coastal China to the Americas. By integrating contemporary and ancient mitochondrial DNA, the team found evidence of at least two migrations: one during the last ice age, and one during the subsequent melting period. Around the same time as the second migration, another branch of the same lineage migrated to Japan, which could explain Paleolithic archeological similarities between the Americas, China, and Japan. Though it was long assumed that Native Americans descended from Siberians who crossed over the Bering Strait’s ephemeral land bridge, more recent genetic, geological, and archeological evidence suggests that multiple waves of humans journeyed to the Americas from various parts of Eurasia.” ref

“To shed light on the history of Native Americans in Asia, a team of researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences followed the trail of an ancestral lineage that might link East Asian Paleolithic-age populations to founding populations in Chile, Peru, Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, Mexico, and California. The lineage in question is present in mitochondrial DNA, which can be used to trace kinship through the female line. The first radiation event occurred between 19,500 and 26,000 years ago during the Last Glacial Maximum, when ice sheet coverage was at its greatest and conditions in northern China were likely inhospitable for humans. The second radiation occurred during the subsequent deglaciation or melting period, between 19,000 and 11,500 years ago. There was a rapid increase in human populations at this time, probably due to the improved climate, which may have fueled expansion into other geographical regions. Mitogenome evidence shows two radiation events and dispersals of matrilineal ancestry from Northern Coastal China to the Americas and Japan.” ref

The emergence of writing in Japan artifacts from the second century BCE

“The emergence of writing in Japan has been dated based on pottery from the period decorated with written characters that ink stone manufacturing. Which was likely underway in the second and first centuries BCE in present-day Fukuoka and Saga prefectures in southwestern Japan. Stone artifacts from the second century BCE Uruujitokyu ruins in Itoshima, Fukuoka Prefecture, Nakabaru ruins in Karatsu, in neighboring Saga Prefecture, and the first century B.C. Higashi Oda Mine ruins in the town of Chikuzen, Fukuoka Prefecture.” ref

“Among the artifacts are thin stones with fan-shaped ends, polished on one side and left rough on the other — typical features of ink stones. However, the items appear to have been broken before they were finished. The artifacts also include unfinished stone files for making ink from the ink stones, and stone saws. The collection of items together led Yanagida to conclude the people in the area had been making ink stones. Ink stones are thought to have first been made in China in the third century BCE, toward the end of the Warring States period, and flat, rectangular stones became widespread during the Western Han dynasty. Many Yayoi period stones have been found in recent years, primarily in northern Kyushu where Fukuoka and Saga prefectures are now, but it was unknown whether they had been made in Japan.” ref

“Furthermore, even the oldest of the artifacts dated to about the first century. Yanagida’s findings put the start of ink stone manufacturing in Japan at least 100 years earlier than that, and in nearly the same period as the rectangular stones were being made in China. “There is nothing to say but that the stones were used by Wajin (Yayoi period Japanese people),” Yanagida said of the artifacts he analyzed. “There was a demand for the written word, and that’s why (the ink stones) were being made. I suspect (Japanese producers) copied Chinese stones and began making them domestically,” Professor Yasuo Yanagida from Kokugakuin University added after research.” ref

“The inkstone is Chinese in origin and is used in calligraphy and painting. Extant inkstones date from early antiquity in China. The device evolved from a rubbing tool used for rubbing dyes dating around 6000 to 7000 years ago. The earliest excavated inkstone is dated from the 3rd century BCE and was discovered in a tomb located in modern Yunmeng, Hubei. Usage of the inkstone was popularized during the Han Dynasty. Stimulated by the social economy and culture, the demand for inkstones increased during the Tang Dynasty (618–905) and reached its height in the Song Dynasty (960–1279).” ref

“Song Dynasty inkstones can be of great size and often display a delicacy of carving. Song Dynasty inkstones can also exhibit a roughness in their finishing. Dragon designs of the period often reveal an almost humorous rendition; the dragons often seem to smile. From the subsequent Yuan Dynasty, in contrast, dragons display a ferocious appearance. The Qianlong Emperor had his own imperial collection of inkstones catalogued into a twenty-four chapter compendium entitled Xiqingyanpu (Hsi-ch’ing yen-p’u). Many of these inkstones are housed in the National Palace Museum collection in Taipei.” ref

Genetic evidence

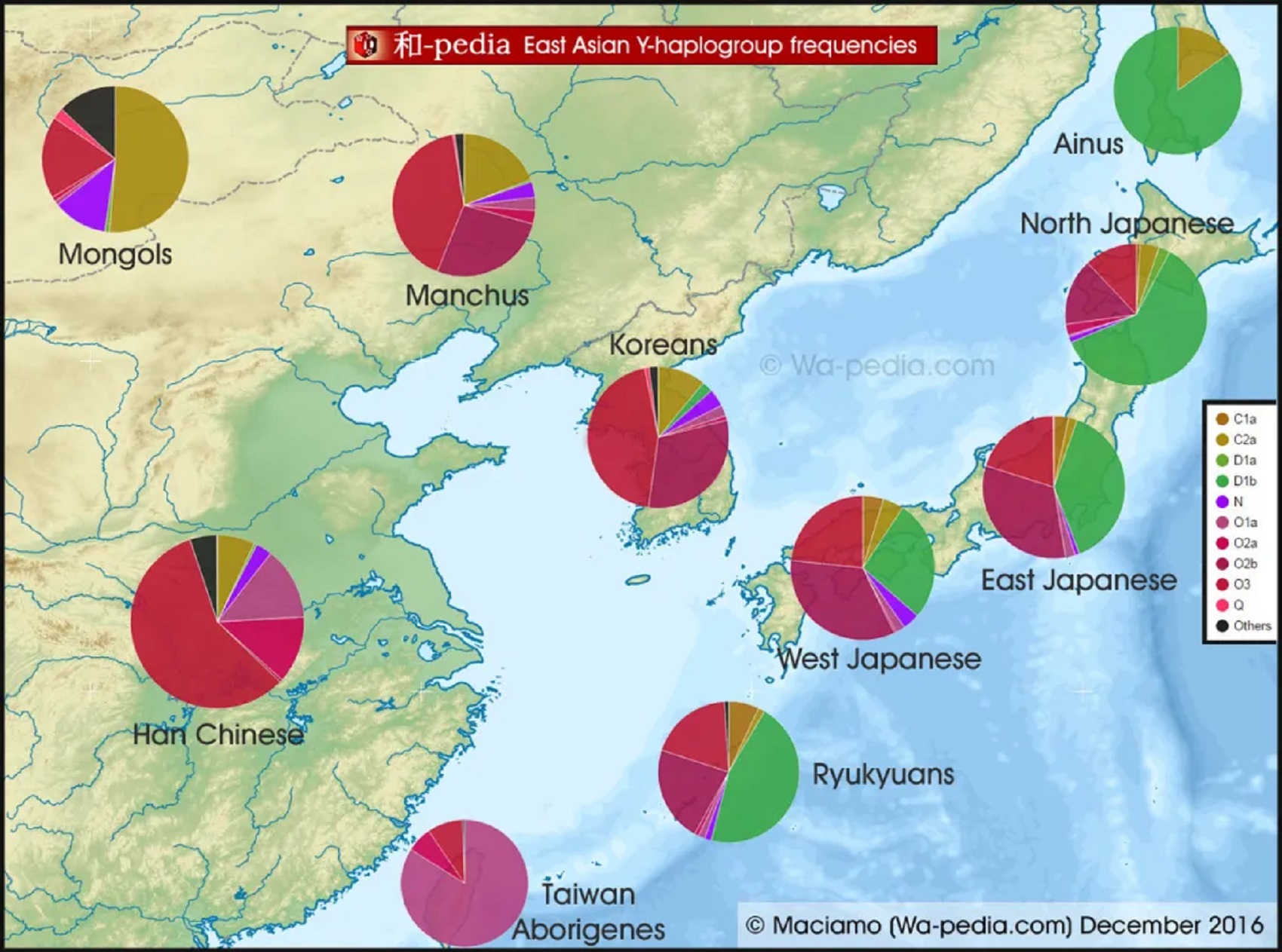

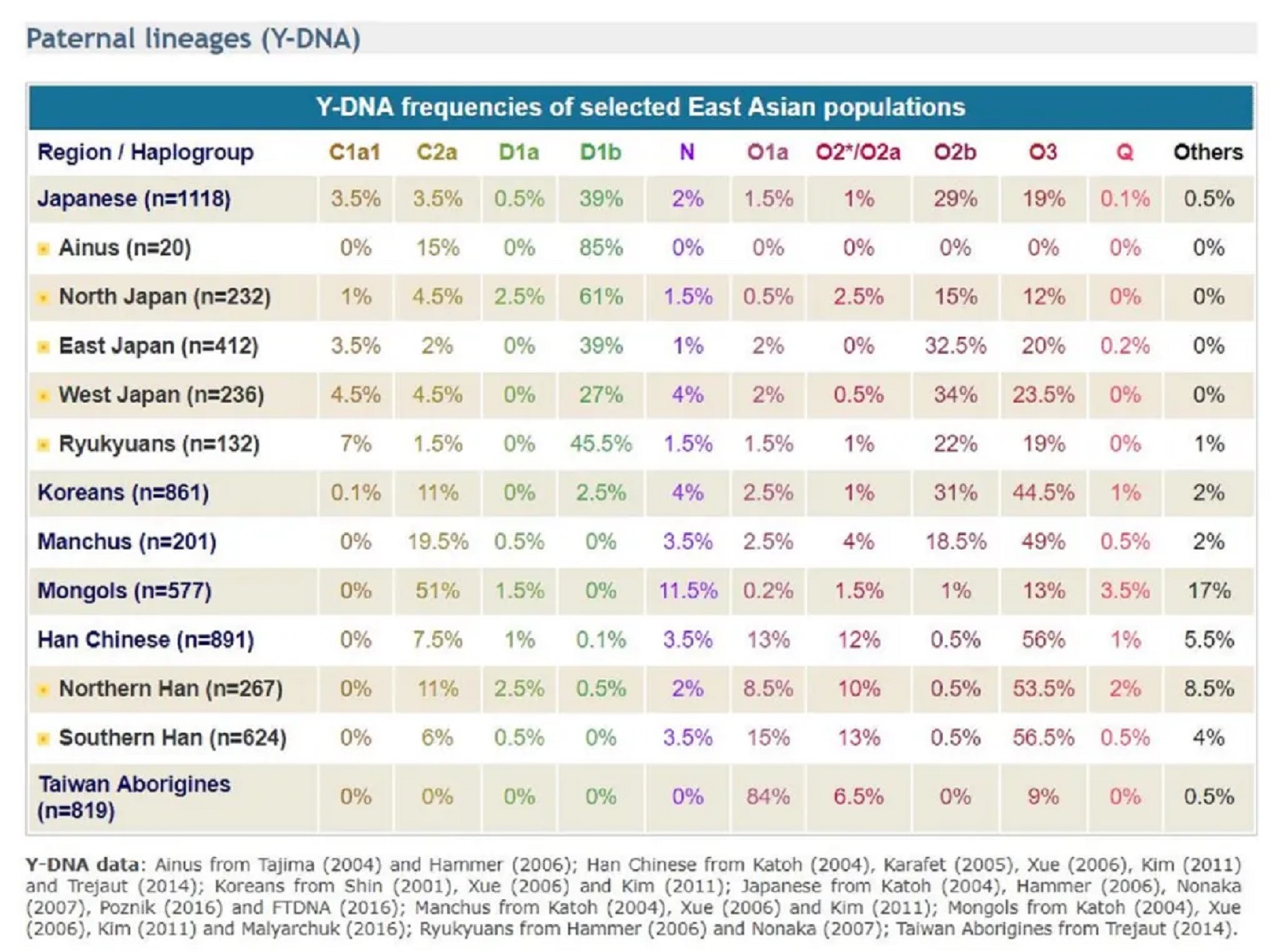

“It is now believed that the modern Japanese descend mostly from the interbreeding of the Jōmon Era people (15,000-500 BCE), composed of the above Ice Age settlers, and a later arrival from China and/or Korea. Around 500 BCE, the Yayoi people crossed the see from Korea to Kyushu, bringing with them a brand new culture, based on wet rice cultivation and horses. As we will see below, DNA tests have confirmed the likelihood of this hypothesis. About 54% of paternal lineages and 66% the maternal lineages have been identified as being of Sino-Korean origin.” ref

“Evidence has emerged from ancient DNA testing that there may have been two major waves of migration from the continent to Japan. The Iron Age Yayoi invasion from Korea was only the most recent of them. Kenichi Shinoda (2003) found Chinese-looking maternal lineages (haplogroups A, B, F, M8a and M10) in the Kanto region dating from the late Jōmon period mixed with typical Jōmon lineages (M7a, N9b). Although this hasn’t been completely confirmed yet, this could indicate that farmers from mainland China colonised Japan several millennia before the Yayoi invasion, which would explain why the Japanese also possess typically South Chinese Y-haplogroups not found in Korea, such as O1a, O2a, O3a1c (JST002611) and O3a2 (P201).” ref

DNA analysis of the Japanese people

“Two kinds of DNA tests allow to trace back prehistoric ancestry. The first one is mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), DNA found outside the cells’ nucleus and inherited through the mother’s line. The other is the Y-chromosome (Y-DNA), inherited exclusively from father to son (women do not have it). They are both inherited in an unaltered fashion for many generations, which allow geneticists to identify very old lineages and ancient ethnicities.” ref

| Did South Chinese Neolithic farmers colonize Japan during the Jōmon period? |

|---|

|

“It is not clear at present why typically Chinese mtDNA haplogroups like A, B, F, M8a, and M10 were already present in the Kanto during the Late Jōmon period (1500–300 BCE). These may represent the early migration of farmers from the continent, many centuries or millennia before the Yayoi invasion. Catherine D’Andrea reported evidence for Late Jōmon rice, foxtail millet, and broomcorn millet dating to the first millennium BCE in Tohoku. However, there is evidence of plant cultivation in Japan long before that. Arboriculture was practiced by Jōmon people in the form of tending groves of nut- and lacquer-producing trees (see Matsui and Kanehara 2006 and Transitions to Agriculture in Japan, Gary W. Crawford). A domesticated variety of peach, apparently from China, appeared very early at Jōmon sites circa 4700–4400 BCE. Several sites (including Torihama, Sannai Maruyama and Mawaki in central and northern Honshu) of the Early Jōmon (4,000–2500 BCE) and Middle Jōmon (2500–1500 BCE) periods show evidence of cultivated plants, including barley, barnyard millet, buckwheat, rice, bean, soybean, burdock, hemp, egoma and shiso mint, mountain potato, taro potato, and bottle gourd. Many archeologists believe that these cultivated plants were only used to supplement the Jōmon diet, which still relied heavily on hunting, fishing and gathering.” ref “Most of these domesticated plants, including rice and millet, are very unlikely to have been domesticated independently by the Jōmon hunter-gatherers, and almost certainly required the migration of farmers from China or Korea. The hundreds of ancient DNA samples from the Middle East and Europe have confirmed that the spread of agriculture always involved the migration of farmers and did not propagate purely by cultural diffusion. Consequently, it is extremely likely that Chinese Neolithic farmers brought these crops to Japan, perhaps in several waves of migration which would have taken place between 4500 and 2500 BCE.” ref “The presence of typically South Chinese paternal (D1a1, O1a, O2a, O3a1, O3a2) and maternal lineages (M7b, M7c, M9, M12) strongly suggests that at least one of these Neolithic migrations originated in South China. These specifically South Chinese haplogroups represent approximately 5-10% of the modern Japanese maternal lineages and up to 15% of paternal ones. However, South Chinese farmers would have also carried haplogroups shared by the Yayoi people, such as other Y-DNA O3 subclades, and mtDNA A, B D4, D5, and F. Late Jomon mtDNA samples from the Kanto region shows that Chinese lineages made up about 65 to 75% of the maternal lineages at the time. A fairer approximation of the share of modern lineage of Neolithic South Chinese origin might be anywhere between 5 and 35% for maternal lineages, and perhaps around 10 to 20% for paternal ones. More data would be needed to give a more accurate estimation.” ref “It remains to be confirmed how South Chinese Neolithic farmers reached Japan, but the easiest and safest route is via Taiwan and the Ryukyu Islands. Agriculture appears to have taken root in Taiwan between 4000 and 3500 BCE. The The southern Ryukyu Islands were re-settled by around 2300 BCE as part of the Neolithic Austronesian expansion from Taiwan (Austronesian and Jōmon identities in the Neolithic of the Ryukyu Islands, Mark J. Hudson (2012)), and could have reached Kyushu by 2000 BCE. However, this does not account for the evidence of crops during the Early Jōmon period, which might have come through another route, either following the coastline until the Korean peninsula, or crossing directly from China to Kyushu. A third possibility is that the first migration from Southeast China followed the chain of islands from Taiwan to Kyushu without stopping along the way and only settling in Japan itself, while Taiwan and the Ryukyus were settled by another later migration from mainland China. In fact, these Austrnesian Neolithic farmers reached the Philippines by 5000 BCE and the rest of Southeast Asia by 4000 BCE, so there is no reason they couldn’t have reached Japan by then. There is reliable evidence of a minor but very real linguistic connection between Austronesian languages (notably Malay) and Japanese (see Linguistic evidence below), and the Austronesian expansion from south-eastern China is the best way to explain it.” ref |

Shintoism

“Shinto (Japanese: 神道, romanized: Shintō) is a religion originating from Japan. Classified as an East Asian religion by scholars of religion, its practitioners often regard it as Japan’s indigenous religion and as a nature religion. Scholars sometimes call its practitioners Shintoists, although adherents rarely use that term themselves. There is no central authority in control of Shinto, with much diversity of belief and practice evident among practitioners. A polytheistic and animistic religion, Shinto revolves around supernatural entities called the kami (神). The kami are believed to inhabit all things, including forces of nature and prominent landscape locations. The kami are worshipped at kamidana household shrines, family shrines, and jinja public shrines. The latter are staffed by priests, known as kannushi, who oversee offerings of food and drink to the specific kami enshrined at that location. This is done to cultivate harmony between humans and kami and to solicit the latter’s blessing.” ref

“Other common rituals include the kagura dances, rites of passage, and seasonal festivals. Public shrines facilitate forms of divination and supply religious objects, such as amulets, to the religion’s adherents. Shinto places a major conceptual focus on ensuring purity, largely by cleaning practices such as ritual washing and bathing, especially before worship. Little emphasis is placed on specific moral codes or particular afterlife beliefs, although the dead are deemed capable of becoming kami. The religion has no single creator or specific doctrine, and instead exists in a diverse range of local and regional forms. Although historians debate at what point it is suitable to refer to Shinto as a distinct religion, kami veneration has been traced back to Japan’s Yayoi period (300 BCE to 300 CE). Buddhism entered Japan at the end of the Kofun period (300 to 538 CE) and spread rapidly. Religious syncretization made kami worship and Buddhism functionally inseparable, a process called shinbutsu-shūgō.” ref

“The kami came to be viewed as part of Buddhist cosmology and were increasingly depicted anthropomorphically. The earliest written tradition regarding kami worship was recorded in the 8th-century Kojiki and Nihon Shoki. In ensuing centuries, shinbutsu-shūgō was adopted by Japan’s Imperial household. During the Meiji era (1868 to 1912), Japan’s nationalist leadership expelled Buddhist influence from kami worship and formed State Shinto, which some historians regard as the origin of Shinto as a distinct religion. Shrines came under growing government influence, and citizens were encouraged to worship the emperor as a kami.” ref

“With the formation of the Japanese Empire in the early 20th century, Shinto was exported to other areas of East Asia. Following Japan’s defeat in World War II, Shinto was formally separated from the state. Shinto is primarily found in Japan, where there are around 100,000 public shrines, although practitioners are also found abroad. Numerically, it is Japan’s largest religion, the second being Buddhism. Most of the country’s population takes part in both Shinto and Buddhist activities, especially festivals, reflecting a common view in Japanese culture that the beliefs and practices of different religions need not be exclusive. Aspects of Shinto have been incorporated into various Japanese new religious movements. There is no universally agreed definition of Shinto. However, the authors Joseph Cali and John Dougill stated that if there was “one single, broad definition of Shinto” that could be put forward, it would be that “Shinto is a belief in kami“, the supernatural entities at the center of the religion.” ref

“Kami (Japanese: 神, [kaꜜmi]) are the deities, divinities, spirits, mythological, spiritual, or natural phenomena, or holy powers that are venerated in the Shinto religion. They can be elements of the landscape, forces of nature, beings and the qualities that these beings express, and/or the spirits of venerated dead people. Many kami are considered the ancient ancestors of entire clans (some ancestors became kami upon their death if they were able to embody the values and virtues of kami in life). Traditionally, great leaders like the Emperor could be or became kami. Kami is the Japanese word for a deity, divinity, or spirit. It has been used to describe mind, God, supreme being, one of the Shinto deities, an effigy, a principle, and anything that is worshipped. Although deity is the common interpretation of kami, some Shinto scholars argue that such a translation can cause a misunderstanding of the term.” ref

“Some etymological suggestions are:

- Kami may, at its root, simply mean spirit, or an aspect of spirituality. It is written with the kanji 神, Sino-Japanese reading shin or jin. In Chinese, the character means deity.

- In the Ainu language, the word kamuy refers to an animistic concept very similar to Japanese kami. The matter of the words’ origins is still a subject of debate; but it is generally suggested that the word kami was derived from Ainu word kamuy.

- In his Kojiki-den, Motoori Norinaga gave a definition of kami: “…any being whatsoever which possesses some eminent quality out of the ordinary, and is awe-inspiring, is called kami.” ref

“A kamuy (Ainu: カムィ; Japanese: カムイ, romanized: kamui) is a spiritual or divine being in Ainu mythology, a term denoting a supernatural entity composed of or possessing spiritual energy. The Ainu people have many myths about the kamuy, passed down through oral traditions and rituals. The stories of the kamuy were portrayed in chants and performances, which were often performed during sacred rituals. In concept, kamuy are similar to the Japanese kami but this translation misses some of the nuances of the term (the missionary John Batchelor assumed that the Japanese term was of Ainu origin). The usage of the term is very extensive and contextual among the Ainu, and can refer to something regarded as especially positive as well as something regarded as especially strong. Kamuy can refer to spiritual beings, including animals, plants, the weather, and even human tools. Guardian angels are called Ituren-Kamui. Kamuy are numerous; some are delineated and named, such as Kamuy Fuchi, the hearth goddess, while others are not. Kamuy often have very specific associations, for instance, there is a kamuy of the undertow. Batchelor compares the word with the Greek term daimon. Personified deities of Ainu mythology often have the term kamuy applied as part of their names.” ref

“The Ainu legend goes that at the beginning of the world, there was only water and earth mixed together in a sludge. Nothing existed except for the thunder demons in the clouds and the first self created kamuy. The first kamuy then sent down a bird spirit, moshiri-kor-kamuy, to make the world inhabitable. The water wagtail bird saw the swampy state of the earth and flew over the waters, and pounded down the earth with its feet and tail. After much work, areas of dry land appeared, seeming to float above the waters that surrounded them. Thus, the Ainu refer to the world as moshiri, meaning “floating earth”. The wagtail is also a revered bird due to this legend. Once the earth was formed, the first kamuy, otherwise known as kanto-kor-kamuy, the heavenly spirit, sent other kamuy to the earth. Of these kamuy was ape-kamuy (see also kamuy huchi, ape huchi), the fire spirit. Ape-kamuy was the most important spirit, ruling over nusa-kor-kamuy (ceremonial altar spirit), ram-nusa-kor-kamuy (low ceremonial altar spirit), hasinaw-kor-kamuy (hunting spirit), and wakka-us-kamuy (water spirit). As the most important kamuy, ape-kamuy’s permission/assistance is needed for prayers and ceremonies. She is the connection between humans and the other spirits and deities, and gives the prayers of the people to the proper spirits.” ref

“Though kamuy yukar is considered to be one of the oldest genres of Ainu oral performance, anthropologist Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney supposed that there are more than 20 types of genres. Originally, it seems kamuy yukar was performed solely for religious purposes by the women who took on the role of shamans. The shamans became possessed and recanted the chants, possibly explaining why kamuy yukar is performed with a first-person narrative. As time passed, kamuy yukar became less of a sacred ritual, serving as entertainment and as a way to pass down traditions and cultural stories. Today, the kamuy yukar is no longer performed in the Horobetsu tradition. The only hints of the traditional chants are in written records, including those of Yukie Chiri (1903-1922), a Horobetsu Ainu woman who wrote fragments of traditional chants that her grandmother performed. She compiled the historical chants from her aunt Imekanu in a book titled Ainu shin’yoshu.” ref

“The Ainu have rituals in which they “send back” the kamuy to the heavens with gifts. There are various rituals of this type, including the iomante, the bear ceremony. The rituals center around the idea of releasing the kamuy from their disguises, their hayopke, that they have put on to visit the human world in order to receive gifts from the humans. The kamuy in their hayopke choose the hunter that will hunt them, giving them the flesh of the animal in turn. Once the hayopke is broken, the kamuy are free to return to their world with the gifts from the humans. The iomante (see also iyomante), is a ritual in which the people “send-off” the guest, the bear spirit, back to its home in the heavens. A bear is raised by the ritual master’s wife as a cub. When it is time for the ritual, the men create prayer sticks (inau) for the altar (nusa-san), ceremonial arrows, liquor, and gifts for the spirit in order to prepare for the ritual. Prayers are then offered to ape-kamuy, and dances, songs, and yukar are performed.” ref

“The main part of the ritual is performed the next day, taking place at a ritual space by the altar outside. Prayers are offered to various kamuy, and then the bear is taken out of its cage with a rope around its neck. There is dancing and singing around the bear, and the bear is given food and a prayer. The men shoot the ceremonial decorated arrows at the bear, and the ritual master shoots the fatal arrow as the women cry for the bear. The bear is strangled with sticks and then taken to the altar where the people give gifts to the dead bear and pray to the kamuy again. The bear is dismembered, and the head brought inside. There is a feast with the bear’s boiled flesh, with performances of yukar, dances, and songs.” ref

“On the third and final day of the ritual, the bear’s head is skinned and decorated with inau and gifts. It is then put on a y-shaped stick and turned to face the mountains in the east. This part of the ritual is to send the bear off to the mountains. After another feast, the skull is turned back towards the village to symbolize the kamuy’s return to its world. In Ainu mythology, the kamuy are believed to return home after the ritual and find their houses filled with gifts from the humans. More gifts mean more prestige and wealth in the kamuy’s society, and the kamuy will gather his friends and tell them of the generosities of the humans, making the other kamuy wish to go to the human world for themselves. In this way, the humans express their gratitude for the kamuy, and the kamuy will continue to bring them prosperity.” ref

“Haplogroup C is another extremely old lineage that left Africa approximately 60,000 years ago and spread over most of Eurasia. Two subclades of C are found in Japan: C1a1 (aka C-M8, formerly C1) and C2a (aka C-M93, formerly C3). Both are likely to have been in the Japanese archipelago since the first human beings reached the region 35,000 years ago.” ref

“Haplogroup C1a seems to have split around 45,000 years ago in the middle of Eurasia, one group going west to Europe, and the other east to Japan. C1a2 was found among the first Palaeolithic Europeans (Cro-Magnons) during the Aurignacian period, and was still relatively common 7,000 years ago, both among Mesolithic West Europeans and Neolithic farmers from Anatolia. C1a2 is now nearly extinct in Europe. C1a1 is particularly common in Okinawa (7%), Shikoku (10%) and Tohoku (10%), but is apparently absent from Hokkaido and Kyushu.” ref

“Haplogroup C2a, representing also 3% of the population, is typically found among the Mongols, Manchus, Koreans and Siberians, which suggests a propagation by the Yayoi farmers. The last surviving tribes of ‘pure’ Ainu people, living on the island of Sakhalin in Russia, just north of Hokkaido, possess 15% of C2a (the remaining 85% being D1b). There is therefore a good chance that C2a could also have come to Japan from Siberia through Sakhalin and Hokkaido. C2a is indeed found at both extremities of the country, peaking in Kyushu (8%), Hokkaido (5%), but is rare in central Japan, which supports the theory of two separate points of entry.” ref

“Over 40% of Japanese men belong to haplogroup D, a paternal lineage thought to have originated in East Africa some 50,000 to 60,000 years ago. Its first carriers would have migrated along the coasts of the Indian Ocean, from the Arabian peninsula all the way to Indonesia, then following the chain of islands up through the Philippines and using the land bridge from Taiwan through the present-day Ryukyu islands to Japan. Korea and Sakhalin would have been connected to Japan during the Ice Age, allowing D tribes to continue their migration to eastern Siberia, Mongolia, northwest China, and ultimately ending up in Tibet. Nowadays haplogroup D only survives scattered in very specific regions of Asia: the Andaman Islands (between India and Myanmar), Indonesia (only a small minority), Southwest China, Mongolia (also a small minority) and Tibet.” ref

“Haplogroup D1b (aka D-M55 or D-M64.1, formerly known as D2) is 23,000 years old and would have arrived in Japan around the time of the Last Glacial Maximum (c. 24,500 to 17,500 years before present), when a land bridge connected northern Japan to Siberia. D1b is found almost exclusively in Japan, with a small minority in places who have had historical ties with Japan, such as Korea. D1b is most common in Hokkaido (60-65%), followed by Tohoku and Kanto (40-50%), and its frequency declines as one moves towards western Japan (25-30% in Kyushu, Chugoku and Shikoku), which have higher percentages of Y-haplogroup O. Okinawans also have high levels of D1b (45%). If D1b colonized Japan from the north, it would explain why its frequency is highest in northern Japan and, conversely also why pre-LGM lineages like C1a1 survived better in southern Japan, notably Okinawa, and Shikoku.” ref

“The only other variety of D identified among the Japanese is D1a1 (D-M15), which only makes up 0.5% of the Japanese male population. This haplogroup is particularly common among some ethnic groups from Southwest China and Indochina, such as the Hmong and Ksingmul in Laos, the Qiang in Sichuan, and the Yao people in Guanxi and Vietnam. Tibetans carry about 54% of haplogroup D, including 15.5% of D1a1 and 30% of D1a2a (P47). D1a1 might have come to Japan with Neolithic farmers from southern China.” ref

“Andaman Islanders belong to the basal D*. It means that their most recent common ancestors goes back tens of thousands of years. In other words the genetic gap between these ethnic groups is immense, despite false appearances of belonging to a common haplogroup. Haplogroup D1b was formed 45,000 years ago, but the most recent common ancestor of Japanese D1b members lived 23,000 years ago, which means that other D1b branches may have become extinct outside Japan. Haplogroup D1b is found among the Ryukyuans as well as the Ainus, and is thought to have been the dominant paternal lineage of the Jōmon people.” ref

“Almost exactly half of Japanese men belong to haplogroup O, a paternal lineage of Paleolithic Sino-Korean origin that is now found all over East and Southeast Asia.” ref

“Haplogroup O2b (aka O-SRY465) is found especially in Manchuria, Korea, and Japan, and very probably came to Japan with the Yayoi people. It reaches its highest frequency in western Japan (35%) and is least common in Hokkaido (12.5%) and Okinawa (22%). In the rest of the country, its frequency is around 30%. Approximately two thirds of the Japanese O2b belong to the O2b1 subclade, which is much less common in Korea and Manchuria, possibly due to a founder effect among the Yayoi invaders.” ref

“Haplogroup O3 (aka O-M122) is the main Han Chinese paternal lineage. It is an extremely diverse lineage, with numerous subclades, including many associated with the expansion of agriculture from northern China. Most of them are found in Korea and would have been part of the Yayoi migration to Japan. However, some specific subclades, notably O3a1c (JST002611) and O3a2(P201) are considerably more common in southern China and among non-aboriginal Taiwanese (25%) than in Korea (6%). Within Japan, it reaches a maximum frequency in Okinawa (16%), a region with low Yayoi ancestry. Its frequency among non-Okinawan Japanese is of 10-15%, about twice higher than in Korea, a fact that cannot be explained by the Yayoi invasion. O3a1c and O3a2 could have come to Japan during the Jomon period with Neolithic farmers from southern China associated with the Austronesian expansion via Taiwan (see below). The most common O3 subclade in Korea is O3a2c1(M134, formerly known as O3e), which is found in 25-30% of the population. In Japan, its frequency ranges from 7.5% to 10%, except in Okinawa and Hokkaido where it is only 5%.” ref

“A negligible percentage of the Japanese belong to haplogroup O1a (aka O-M119), a lineage especially common in southern China, Taiwan, the Philippines, Malaysia, and Indonesia, and haplogroup O2a1 (aka O-M95), which is found in south-west China, Indochina, around Malaysia and in central-eastern India. Both of them might have also have come with South Chinese Neolithic farmers during the Jomon period.” ref

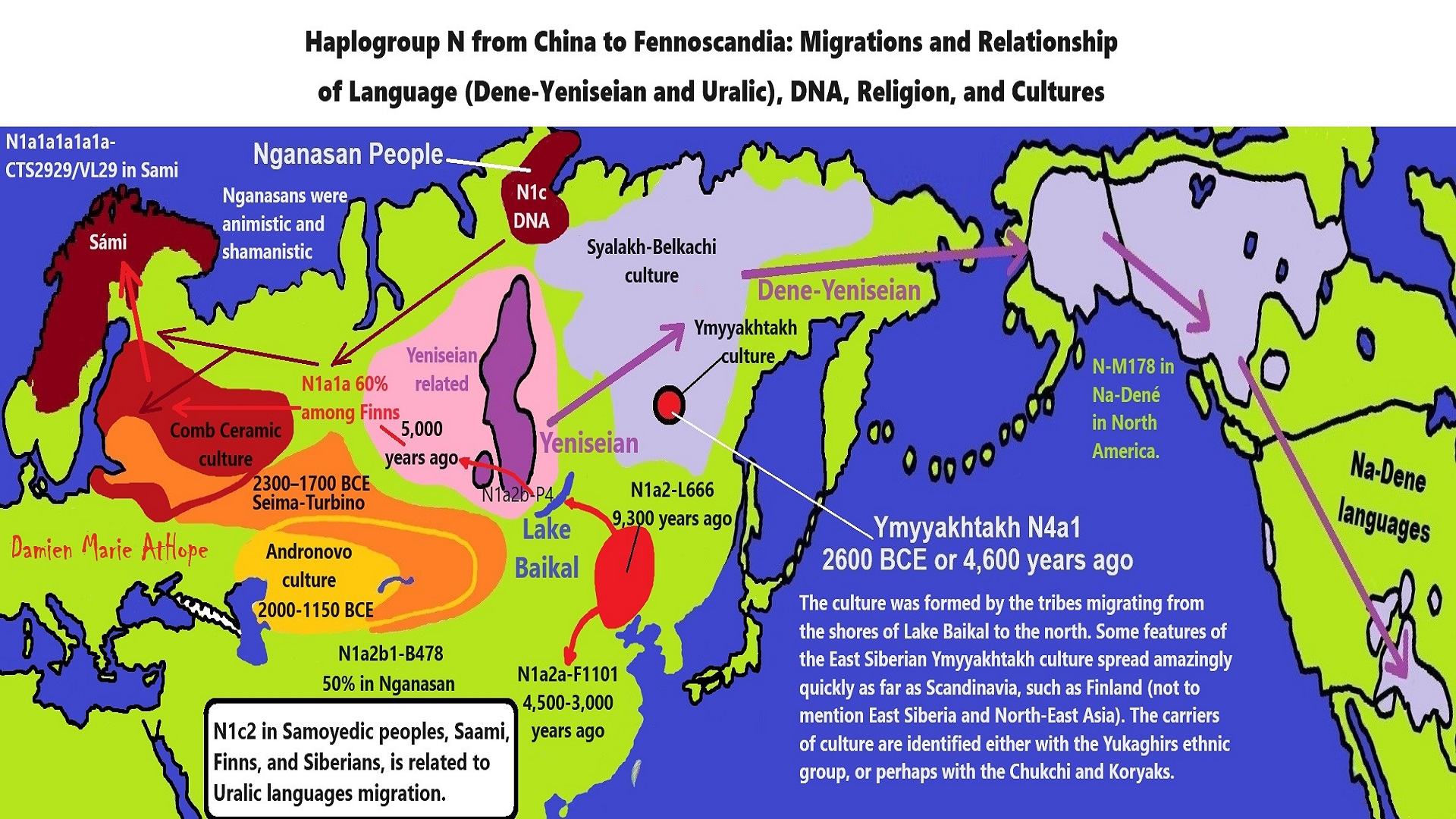

“Approximately 3% of Japanese men belong to haplogroup N, a lineage that is thought to have originated in China some 35,000 years ago, but underwent a serious population bottleneck during the Last Glacial Maximum, and re-expanded after that. Japanese people belong to N1, a subclade that is associated with the diffusion of the Neolithic lifestyle from northern China to Siberia. Haplogroup N1 was found at high frequency (26 out of 70 samples, or 37%) in Neolithic and Bronze Age remains (4500-700 BCE) from the West Liao River valley in Northeast China (Manchuria) by Yinqiu Cui et al. (2013). Among the Neolithic samples, haplogroup N1 represented two thirds of the samples from the Hongshan culture (4700-2900 BCE) and all the samples from the Xiaoheyan culture (3000-2200 BCE). Haplogroup N1c is found especially among Uralic and Turkic peoples nowadays, including among the Finns, Estonians, and Sami in Northeast Europe, and among the Turks in Central Asia and Turkey. It is found at low frequencies in Korea and could have arrived with the Yayoi people. Alternatively, N1 could also have entered Japan via Sakhalin and Hokkaido, as it is present among eastern Siberia tribes.” ref

“Haplogroup Q is the dominant lineage of Native Americans, but originated in Siberia. Nowadays it is found at varying, but generally low frequencies throughout Siberia, Central Asia, as well as parts of the Middle East and Europe. While haplogroup N1 seems to have propagated from northern China to Siberia, haplogroup Q would have spread the other way round, apparently only reaching northern China and Korea some 3,000 years ago with invasions from Mongolia. As this was before the Yayoi invasion of Japan, it is possible that the tiny fraction of Japanese Q lineages came with Yayoi farmers. It is unlikely to have entered Japan through Hokkaido as it is not found among tribes at the eastern extremity of Siberia, nor among the Ainus.” ref

“In conclusion, approximately 44% to 48% of modern Japanese men carry a Y-chromosome of Paleolithic Jōmon origin. The highest proportions of Y-DNA haplogroup C and D is found in northern Japan (over 60%) and the lowest in Western Japan (25%). This is concordant with the history of Japan, the Yayoi people of Sino-Korean origins having settled first and most heavily in Kyushu and Chūgoku, in Western Japan.” ref

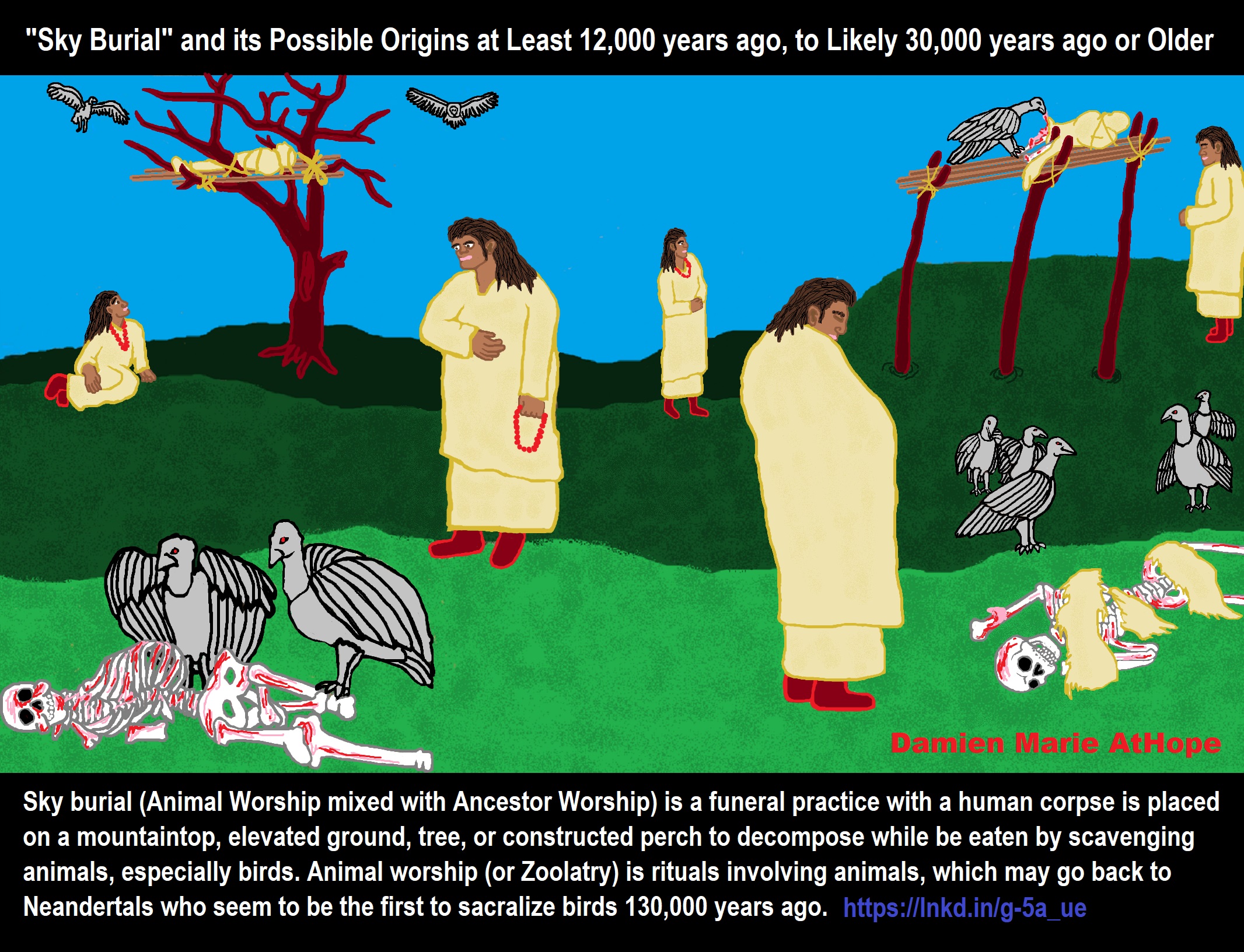

‘Sky Burial’ theory and its possible origins at least 12,000 years ago to likely 30,000 years ago or older.

Sacred Bird Shrine (to me this is now hidden but still Sky burial connected beliefs)

Sky burial (Animal worship mixed with ancestor worship) is a funeral practice in which a human corpse is placed on a mountaintop to decompose while exposed to the elements or to be eaten by scavenging animals, especially carrion birds. And, Animal worship (or zoolatry) refers to rituals involving animals, such as the glorification of animal deities or animal sacrifice. According to most accounts of the Sky burial practice, vultures are given the whole body. Then, when only the bones remain, these are broken up with mallets, ground with tsampa (barley flour with tea and yak butter, or milk), and given to the crows (possibly expressing a Sacred bull)and hawks that have waited for the vultures to depart. ref, ref

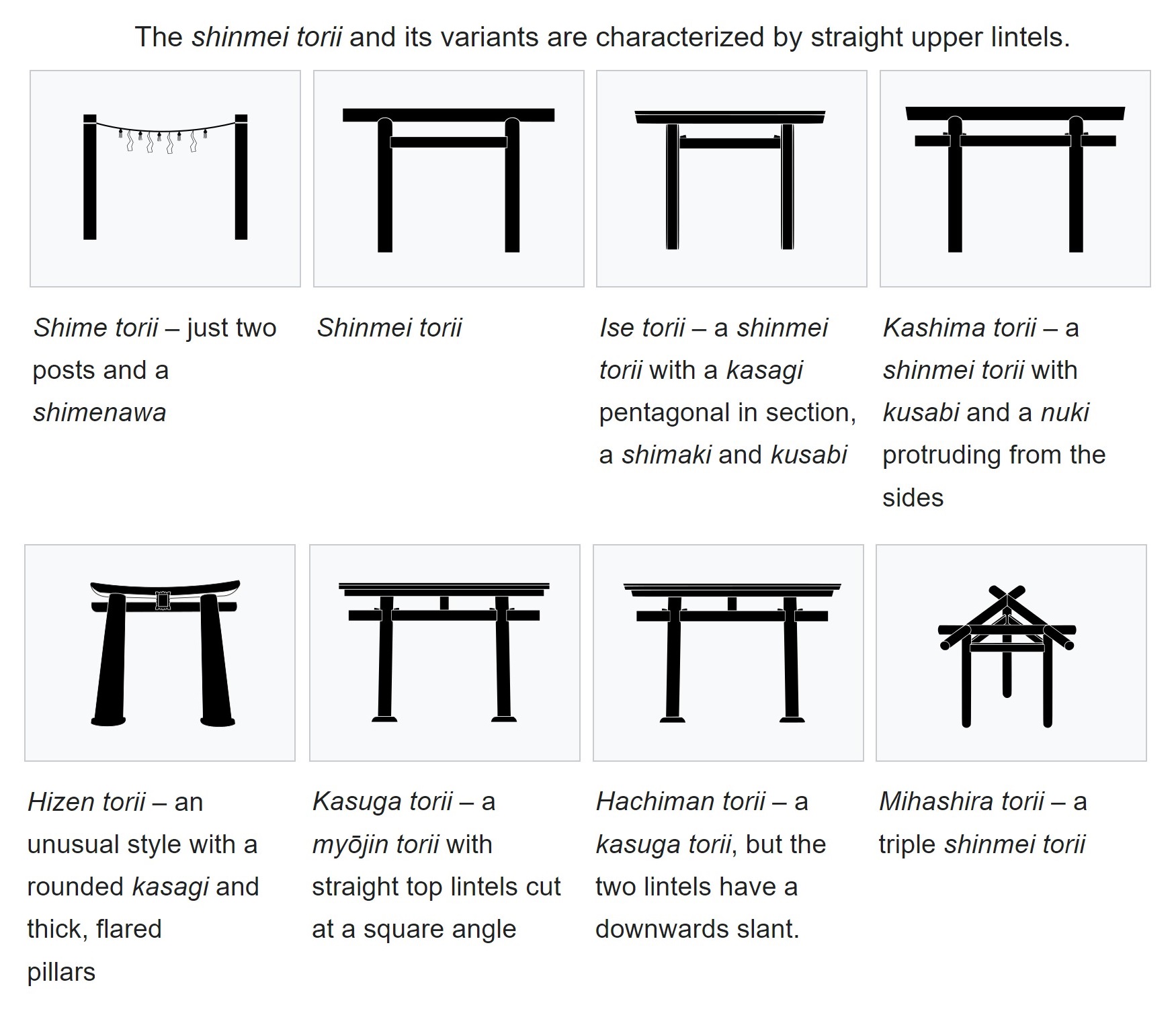

Torii Gates (Japanese 鳥居, literally bird abode )

A torii (鳥居, literally bird abode) is a traditional Japanese gate most commonly found at the entrance of or within a Shinto shrine, where it symbolically marks the transition from the profane to sacred. The presence of a torii at the entrance is usually the simplest way to identify Shinto shrines, and a small torii icon represents them on Japanese road maps. The first appearance of Torii gates in Japan can be reliably pinpointed to at least the mid-Heian period because they are mentioned in a text written in 922. The oldest existing stone torii was built in the 12th century and belongs to a Hachiman Shrine in Yamagata prefecture. The oldest wooden torii is a ryōbu torii (see description below) at Kubō Hachiman Shrine in Yamanashi prefecture built in 1535. Torii gates were traditionally made from wood or stone, but today they can be also made of reinforced concrete, copper, stainless steel or other materials. They are usually either unpainted or painted vermilion with a black upper lintel. Inari shrines typically have many torii because those who have been successful in business often donate in gratitude a torii to Inari, kami of fertility and industry. ref

Fushimi Inari-taisha in Kyoto has thousands of such torii, each bearing the donor’s name. The function of a torii is to mark the entrance to a sacred space. For this reason, the road leading to a Shinto shrine (sandō) is almost always straddled by one or more torii, which are therefore the easiest way to distinguish a shrine from a Buddhist temple. If the sandōpasses under multiple torii, the outer of them is called ichi no torii (一の鳥居, first torii). The following ones, closer to the shrine, are usually called, in order, ni no torii (二の鳥居, second torii) and san no torii (三の鳥居, third torii). Other torii can be found farther into the shrine to represent increasing levels of holiness as one nears the inner sanctuary (honden), core of the shrine. Also, because of the strong relationship between Shinto shrines and the Japanese Imperial family, a torii stands also in front of the tomb of each Emperor. Whether torii existed in Japan before Buddhism or, to the contrary, arrived with it (see section below) is, however, an open question. In the past torii must have been used also at the entrance of Buddhist temples. Even today, as prominent a temple as Osaka‘s Shitennō-ji, founded in 593 by Shōtoku Taishi and the oldest state-built Buddhist temple in the world (and country), has a torii straddling one of its entrances. ref

(The original wooden torii burned in 1294 and was then replaced by one in stone.)

Many Buddhist temples include one or more Shinto shrines dedicated to their tutelary kami (“Chinjusha“), and in that case a torii marks the shrine’s entrance. Benzaiten is a syncretic goddess derived from the Indian divinity Sarasvati which unites elements of both Shinto and Buddhism. For this reason halls dedicated to her can be found at both temples and shrines, and in either case in front of the hall stands a torii. The goddess herself is sometimes portrayed with a torii on her head (see photo below). Finally, until the Meiji period (1868–1912) torii were routinely adorned with plaques carrying Buddhist sutras. The association between Japanese Buddhism and the torii is therefore old and profound. Yamabushi, Japanese mountain ascetic hermits with a long tradition as mighty warriors endowed with supernatural powers, sometimes use as their symbol a torii. The torii is also sometimes used as a symbol of Japan in non-religious contexts. For example, it is the symbol of the Marine Corps Security Force Regiment and the 187th Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division and of other US forces in Japan. The origins of the torii are unknown and there are several different theories on the subject, none of which has gained universal acceptance. Because the use of symbolic gates is widespread in Asia—such structures can be found for example in India, China, Thailand, Korea, and within Nicobarese and Shompen villages—historians believe they may be an imported tradition. They may, for example, have originated in India from the torana gates in the monastery of Sanchi in central India. ref

According to this theory, the torana was adopted by Shingon Buddhism founder Kūkai, who used it to demarcate the sacred space used for the homa ceremony. The hypothesis arose in the 19th and 20th centuries due to similarities in structure and name between the two gates. Linguistic and historical objections have now emerged, but no conclusion has yet been reached. In Bangkok, Thailand, a Brahmin structure called Sao Ching Cha strongly resembles a torii. Functionally, however, it is very different as it is used as a swing. During ceremonies Brahmins swing, trying to grab a bag of coins placed on one of the pillars. Other theories claim torii may be related to the pailou of China. These structures however can assume a great variety of forms, only some of which actually somewhat resemble a torii. The same goes for Korea’s “hongsal-mun”. Unlike its Chinese counterpart, the hongsal-mun does not vary greatly in design and is always painted red, with “arrowsticks” located on the top of the structure (hence the name). Various tentative etymologies of the word torii exist. ref

According to one of them, the name derives from the term tōri-iru (通り入る, pass through and enter). Another hypothesis takes the name literally: the gate would originally have been some kind of bird perch. This is based on the religious use of bird perches in Asia, such as the Korean sotdae(솟대), which are poles with one or more wooden birds resting on their top. Commonly found in groups at the entrance of villages together with totem poles called jangseung, they are talismans which ward off evil spirits and bring the villagers good luck. “Bird perches” similar in form and function to the sotdae exist also in other shamanistic cultures in China, Mongolia and Siberia. Although they do not look like torii and serve a different function, these “bird perches” show how birds in several Asian cultures are believed to have magic or spiritual properties, and may therefore help explain the enigmatic literal meaning of the torii’s name (“bird perch”). Poles believed to have supported wooden bird figures very similar to the sotdae have been found together with wooden birds, and are believed by some historians to have somehow evolved into today’s torii. Intriguingly, in both Korea and Japan single poles represent deities (kami in the case of Japan) and hashira (柱, pole) is the counter for kami. ref

In Japan birds have also long had a connection with the dead, this may mean it was born in connection with some prehistorical funerary rite. Ancient Japanese texts like the Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki for example mention how Yamato Takeru after his death became a white bird and in that form chose a place for his own burial. For this reason, his mausoleum was then called shiratori misasagi (白鳥陵, white bird grave). Many later texts also show some relationship between dead souls and white birds, a link common also in other cultures, shamanic like the Japanese. Bird motifs from the Yayoi and Kofun periods associating birds with the dead have also been found in several archeological sites. This relationship between birds and death would also explain why, in spite of their name, no visible trace of birds remains in today’s torii: birds were symbols of death, which in Shinto brings defilement (kegare). Finally, the possibility that torii are a Japanese invention cannot be discounted. ref

The first toriicould have evolved already with their present function through the following sequence of events:

- Four posts were placed at the corners of a sacred area and connected with a rope, thus dividing sacred and mundane.

- Two taller posts were then placed at the center of the most auspicious direction, to let the priest in.

- A rope was tied from one post to the other to mark the border between the outside and the inside, the sacred and the mundane. This hypothetical stage corresponds to a type of torii in actual use, the so-called shime-torii (注連鳥居), an example of which can be seen in front of Ōmiwa Shrine‘s haiden in Kyoto (see also the photo in the gallery).

- The rope was replaced by a lintel.

- Because the gate was structurally weak, it was reinforced with a tie-beam, and what is today called shinmei torii (神明鳥居) or futabashira torii (二柱鳥居, two pillar torii) (see illustration at right) was born. This theory however does nothing to explain how the gates got their name. ref

The shinmei torii, whose structure agrees with the historians’ reconstruction, consists of just four unbarked and unpainted logs: two vertical pillars (hashira (柱)) topped by a horizontal lintel(kasagi (笠木)) and kept together by a tie-beam ( nuki (貫)). The pillars may have a slight inward inclination called uchikorobi (内転び) or just korobi (転び). Its parts are always straight. ref

- Torii may be unpainted or painted vermilion and black. The color black is limited to the

kasagi and thenemaki (根巻, see illustration). Very rarely torii can be found also in other colors. Kamakura‘s Kamakura-gūfor example has a white and red one. - The

kasagi may be reinforced underneath by a second horizontal lintel calledshimaki orshimagi (島木). - Kasagi and the

shimaki may have an upward curve calledsorimashi (反り増し). - The

nuki is often held in place by wedges (kusabi (楔)). Thekusabi in many cases are purely ornamental. - At the center of the

nuki gakuzuka (額束), sometimes covered by a tablet carrying the name of the shrine (see photo in the gallery). - The pillars often rest on a white stone ring called

kamebara (亀腹, turtle belly) ordaiishi (台石, base stone). The stone is sometimes replaced by a decorative black sleeve callednemaki (根巻, root sleeve). - At the top of the

pillars there may be a decorative ring calleddaiwa (台輪, big ring). - The gate has a purely symbolic function and therefore there usually are no doors or board fences, but exceptions exist, as for example in the case of Ōmiwa Shrine‘s triple-arched torii(

miwa torii, see below). ref

The Torii and Its Meaning in the Shinto Religion

“In order to understand the Torii, we must first know the basic belief of Shinto (神道) the shamanic religion, ethnic of the people of Japan. This religion is heavily based on its rituals and practices, held at the local shrines, built where the Shinto kami (神) are believed to reside. This is the key principle needed to understand the meaning of the Torii. Given this extremely basic introduction to the Shinto religion, we can finally explore the meaning of the Torii. The Torii is, in fact, a gateway, that signals the transition from the profane to the sacred, as it is usually located at the entrance to Shinto shrines, though it isn’t rare to find them even at the entrance of Buddhist temples. As a matter of fact, the first documentation of the Torii dates back to the mid-Heian period, in 922, when Buddhism had already been introduced in Japan. Because of this, and the existence of similar structures in the rest of Asia, typically associated with Buddhist sites, it is quite hard to find a clear-cut origin of the Torii, there are many theories, none of which seems to satisfy the question of its origin. However, it is a matter of fact that today, the Torii, though present in Buddhist sites as well, is more closely associated to Shinto, for instance, the Shinto shrines are signaled on maps with Torii icons. On a final note, it’s worth saying that the Torii doesn’t necessarily mark the entrance to a shrine, but is sometimes used to simply mark an area believed to have a deep religious meaning, such as the Torii of the Meoto Iwa.” The Meoto Iwa, is a particular complex, also called the Married Couple Rocks, as it features two rock stacks in the off of Futami, Mie, tied by a shimenawa, with a Torii places on top of the bigger stack.” ref

“Onehypothesis takes the name literally: the gate would originally have been some kind of bird perch. This is based on the religious use of bird perches in Asia, such as the Korean sotdae (솟대), which are poles with one or more wooden birds resting on their top. Commonly found in groups at the entrance of villages together with totem poles called jangseung, they are talismans which ward off evil spirits and bring the villagers good luck. “Bird perches” similar in form and function to the sotdae exist also in other shamanistic cultures in China, Mongolia, and Siberia. Although they do not look like torii and serve a different function, these “bird perches” show how birds in several Asian cultures are believed to have magic or spiritual properties, and may therefore help explain the enigmatic literal meaning of the torii’s name (“bird perch”). Poles believed to have supported wooden bird figures very similar to the sotdae have been found together with wooden birds, and are believed by some historians to have somehow evolved into today’s torii.” ref

“Intriguingly, in both Korea and Japan single poles represent deities (kami in the case of Japan) and hashira (柱, pole) is the counter for kami. In Japan birds have also long had a connection with the dead, this may mean it was born in connection with some prehistorical funerary rite. Ancient Japanese texts like the Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki for example mention how Yamato Takeru after his death became a white bird and in that form chose a place for his own burial. For this reason, his mausoleum was then called shiratori misasagi (白鳥陵, white bird grave). Many later texts also show some relationship between dead souls and white birds, a link common also in other cultures, shamanic like the Japanese. Bird motifs from the Yayoi and Kofun periods associating birds with the dead have also been found in several archeological sites. This relationship between birds and death would also explain why, in spite of their name, no visible trace of birds remains in today’s torii: birds were symbols of death, which in Shinto brings defilement (kegare).” ref

I think Torii Gates, rope between trees/hanging off trees, or an accompanying hammock of some sort, was still likely

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref