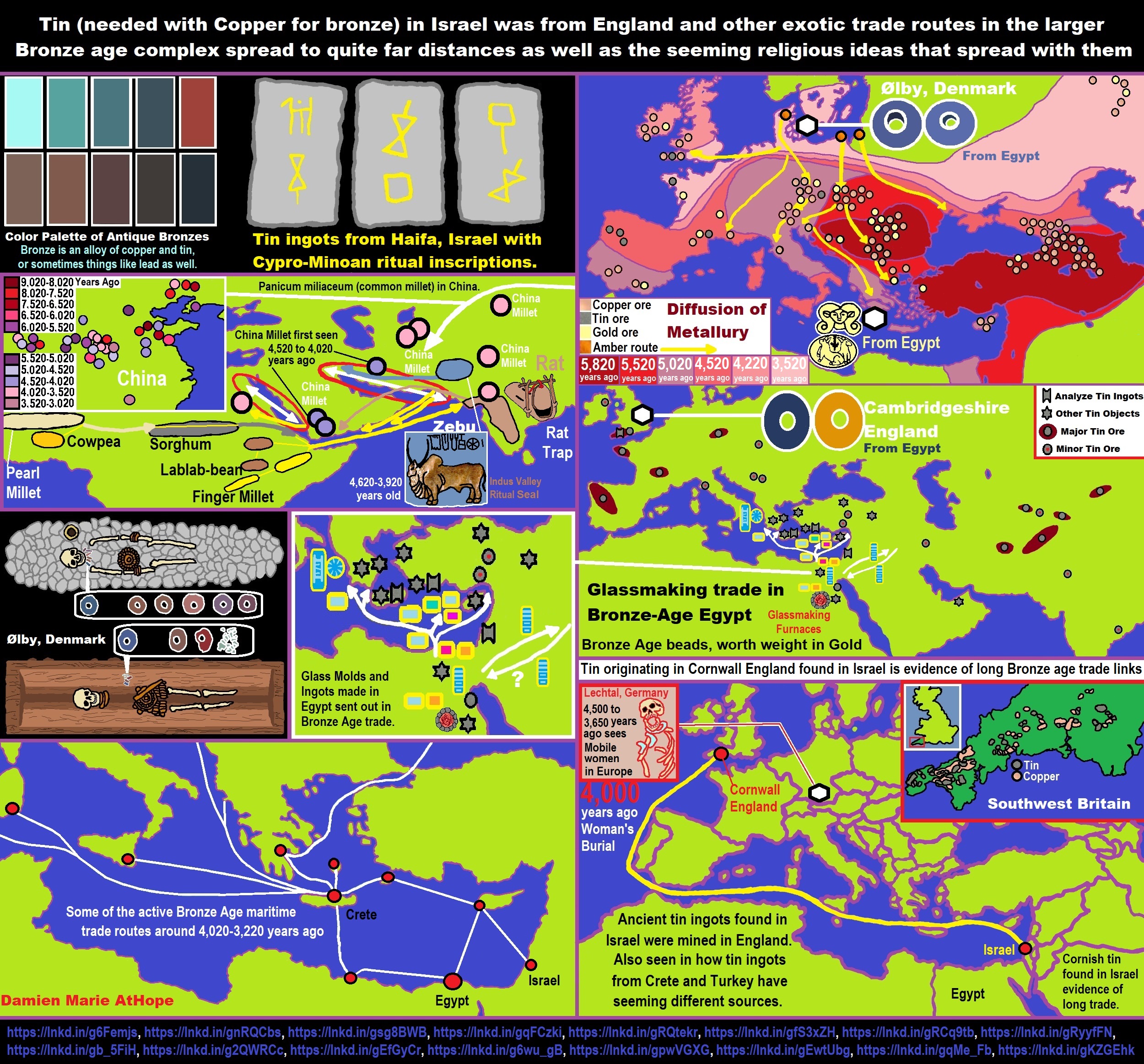

Tin (needed with Copper for bronze) in Israel was from England, and other exotic trade routes in the larger Bronze age complex spread to quite far distances as well as the seeming religious ideas that spread with them

“The ancient civilizations in Mesopotamia didn’t have their own copper sources. Copper mined from mines in the hills around Wadi Jizzi near Sohar in Oman were exported at least as early as 2200 B.C. by the Magan to the Sumerian empire and Elam, another ancient civilization. As other copper sources were discovered and exploited, the influence of the Magan waned. The Bronze Age in Mesopotamia (roughly 3200 B.C. to 1000 B.C.) has been characterized as a time of vibrant economic expansion when the earliest Sumerian cities and the first great Mesopotamian empires grew and prospered. John Noble Wilford wrote in the New York Times, “After thousands of years in which copper was the only metal in regular use, the rising civilizations of Mesopotamia set off a revolution in metallurgy when they learned to combine tin with copper — in proportions of about 5 to 10 percent tin and the rest copper — to produce bronze.” ref

Cornish tin found in Israel is hard evidence of earliest trade links

“Tin ingots from Haifa with Cypro-Minoan inscriptions were assumed to have come from central Asia. Tin ingots found in Israel that are more than 3,000 years old are of Cornish origin and probably reached the Middle East by way of Greece, experts say. Chemical analysis done provided the first hard evidence for the trading of the metal, which is used in making bronze, between the west of Britain and the most famous Bronze Age civilizations — over networks covering thousands of miles.” ref

Ancient tin ingots found in Israel were mined in England. Seen in how tin ingots from Crete and Turkey have a different source.

“Tin deposits on the Eurasian continent and distribution of tin finds in the area studied dating from 2500-1000 BCE or 4,520-3,020 years ago. The arrow does not indicate the actual trade route but merely illustrates the assumed origin of the Israeli tin based on the data. The “age” of the tin is important for excluding other previous leading mine contenders — tin deposits in Anatolia, central Asia, and Egypt — “since they formed either much earlier or later,” write the authors. Tin is a moderately rare essential metal that is found sporadically in sites spread out around the globe. Having excluding the close-by sites through the tin’s age, with the new study of the tin isotope composition, the authors state that they were also able to exclude several of the European sources as the origin mine for the Israeli ingots. Interestingly, the tin ingots from coastal Crete and Turkey appear to have a different source.” ref

The Colour Palette of Antique Bronzes: An Experimental Archaeology Project

“Bronze is an alloy of copper and tin, with lead also added. Hellenistic and Roman bronze objects have a variable percentage of metals, and because of this, the color of the alloy will differ depending on the proportions. The color of the alloy can be maintained by polishing, but it is also possible to give a patina to the surface of bronze using a reagent. Other metals and alloys (copper, silver, gold, Corinthian bronze) can be inlaid by damascening, or by plating to create polychrome decorations. Unfortunately, copper alloy materials recovered from archaeological sites suffer from the effects of time and deposition, which may lead to corrosion and discoloring of the surface, often appearing green or brown. Archaeological bronzes also may suffer from overly aggressive restorations that scour original surfaces or cover them with a layer of paint imitating green corrosion. The collection of swatches I created gathers the spectrum of colors of antique bronzes and allows for a restoration of the original colors of the objects of my study: Greco-Roman bronze furniture. This study combines the processes of the lost wax method and the addition of polychrome bronze surfaces (patina, inlay, and gilding). Some platelet samples from this collection of swatches have also been analyzed to determine their elemental composition and their patina, so as to compare them to archaeological materials. Initial results suggest that the colors of bronze luxury furniture vary greatly and that the spectrum of colors is a product of bronze alloy composition, and of the techniques used in finishing the surface, either polishing or patina application. The initial results clearly show a spectrum of colors for bronze. Colors change depending on the composition of the alloy involved, but also in the creation of a patina. A polychromatic effect can be added by inlaying metals or gilding to accentuate some details. Greco-Roman bronze furniture was enriched with colors and shine. The present article is based on the various steps required for the manufacture and decoration of bronze platelet samples of the collection of color swatches.” ref

Tin sources and trade in ancient times

“Tin is an essential metal in the creation of tin bronzes, and its acquisition was an important part of ancient cultures from the Bronze Age onward. Its use began in the Middle East and the Balkans around 3000 BC. Tin is a relatively rare element in the Earth’s crust, with about two parts per million (ppm), compared to iron with 50,000 ppm, copper with 70 ppm, lead with 16 ppm, arsenic with 5 ppm, silver with 0.1 ppm, and gold with 0.005 ppm. Ancient sources of tin were therefore rare, and the metal usually had to be traded over very long distances to meet demand in areas that lacked tin deposits. Known sources of tin in ancient times include the southeastern tin belt that runs from Yunnan in China to the Malay Peninsula; Devon and Cornwall in England; Brittany in France; the border between Germany and the Czech Republic; Spain; Portugal; Italy; and central and South Africa. Syria and Egypt have been suggested as minor sources of tin, but the archaeological evidence is inconclusive.” ref

Tin Early use

“Tin extraction and use can be dated to the beginning of the Bronze Age around 3000 BCE or around 5,020 years ago, during which copper objects formed from polymetallic ores had different physical properties. The earliest bronze objects had tin or arsenic content of less than 2% and are therefore believed to be the result of unintentional alloying due to trace metal content in copper ores such as tennantite, which contains arsenic. The addition of a second metal to copper increases its hardness, lowers the melting temperature, and improves the casting process by producing a more fluid melt that cools to a denser, less spongy metal. This was an important innovation that allowed for the much more complex shapes cast in closed molds of the Bronze Age. Arsenical bronze objects appear first in the Middle East where arsenic is commonly found in association with copper ore, but the health risks were quickly realized and the quest for sources of the much less hazardous tin ores began early in the Bronze Age (Charles 1979, p. 30). This created the demand for rare tin metal and formed a trade network that linked the distant sources of tin to the markets of Bronze Age cultures.” ref

“Cassiterite (SnO2), oxidized tin, most likely was the original source of tin in ancient times. Other forms of tin ores are less abundant sulfides such as stannite that require a more involved smelting process. Cassiterite often accumulates in alluvial channels as placer deposits due to the fact that it is harder, heavier, and more chemically resistant than the granite in which it typically forms (Penhallurick 1986). These deposits can be easily seen in river banks, because cassiterite is usually black or purple or otherwise dark, a feature exploited by early Bronze Age prospectors. It is likely that the earliest deposits were alluvial and perhaps exploited by the same methods used for panning gold in placer deposits. The importance of tin to the success of Bronze Age cultures and the scarcity of the resource offers a glimpse into that time period’s trade and cultural interactions, and has therefore been the focus of intense archaeological studies. However, a number of problems have plagued the study of ancient tin such as the limited archaeological remains of placer mining, the destruction of ancient mines by modern mining operations, and the poor preservation of pure tin objects due to tin disease or tin pest. These problems are compounded by the difficulty in provenancing tin objects and ores to their geological deposits using isotopic or trace element analyses. The current archaeological debate is concerned with the origins of tin in the earliest Bronze Age cultures of the Near East.” ref

Mining in Cornwall and Devon

“Mining in Cornwall and Devon, in the southwest of England, began in the early Bronze Age, around 2150 BC, and ended with the closure of South Crofty tin mine in Cornwall in 1998. Tin, and later copper, were the most commonly extracted metals. Some tin mining continued long after the mining of other metals had become unprofitable. Historically, tin and copper as well as a few other metals (e.g. arsenic, silver, and zinc) have been mined in Cornwall and Devon. As of 2007, there are no active metalliferous mines remaining. However, tin deposits still exist in Cornwall, and there has been talk of reopening the South Crofty tin mine. In addition, work has begun on re-opening the Hemerdon tungsten and tin mine in south-west Devon. Tin is one of the earliest metals to have been exploited in Britain. Chalcolithic metal workers discovered that by putting a small proportion of tin (5 – 20%) in molten copper, the alloy bronze was produced. The alloy is harder than copper. The oldest production of tin-bronze is in Turkey about 3500 BCE or around 5,520 years ago, but exploitation of the tin resources in Britain is believed to have started before 2000 BC, with a thriving tin trade developing with the civilizations of the Mediterranean. The strategic importance of tin in forging bronze weapons brought the southwest of Britain into the Mediterranean economy at an early date. Later tin was also used in the production of pewter.” ref

“Mining in Cornwall has existed from the early Bronze Age Britain around 2150 BCE or 4,170 years ago. Cornwall was traditionally thought to have been visited by Phoenician metal traders from the eastern Mediterranean, but this view changed during the 20th century, and Timothy Champion observed in 2001 that “The direct archaeological evidence for the presence of Phoenician or Carthaginian traders as far north as Britain is non-existent”. Britain is one of the places proposed for the Cassiterides, that is “Tin Islands”, first mentioned by Herodotus. The tin content of the bronze from the Nebra Sky Disc dating from 1600 BCE, was found to be from Cornwall. Originally it is likely that alluvial deposits in the gravels of streams were exploited, but later underground mining took root. Shallow cuttings were then used to extract ore.” ref

Expansion of trade

“As demand for bronze grew in the Middle East, the accessible local supplies of tin ore (cassiterite) were exhausted and searches for new supplies were made over all the known world, including Britain. Control of the tin trade seems to have been in Phoenician hands, and they kept their sources secret. The Greeks understood that tin came from the Cassiterides, the “tin islands”, of which the geographical identity is debated. By 500 BC Hecataeus knew of islands beyond Gaul where tin was obtained. Pytheas of Massalia traveled to Britain in about 325 BC where he found a flourishing tin trade, according to the later report of his voyage. Posidonius referred to the tin trade with Britain around 90 BC but Strabo in about 18 AD did not list tin as one of Britain’s exports. This is likely to be because Rome was obtaining its tin from Hispania at the time.” ref

Diodorus Siculus’s account

“In his Bibliotheca historica, written in the 1st century BC, Diodorus Siculus described ancient tin mining in Britain. “They that inhabit the British promontory of Belerion by reason of their converse with strangers are more civilized and courteous to strangers than the rest are. These are the people that prepare the tin, which with a great deal of care and labor, they dig out of the ground, and that being done the metal is mixed with some veins of earth out of which they melt the metal and refine it. Then they cast it into regular blocks and carry it to a certain island near at hand called Ictis for at low tide, all being dry between there and the island, tin in large quantities is brought over in carts.” Pliny, whose text has survived in eroded condition, quotes Timaeus of Taormina in referring to “insulam Mictim“, “the island of Mictim” [sic], where the m of insulam has been repeated. Several locations for “Ictin” or “Ictis”, signifying “tin port” have been suggested, including St. Michael’s Mount, but, as a result of excavations, Barry Cunliffe has proposed that this was Mount Batten near Plymouth. A shipwreck site with ingots of tin was found at the mouth of the River Erme not far away, which may represent trade along this coast during the Bronze Age, although dating the site is very difficult. Strabo reported that British tin was shipped from Marseille.” ref

Iron Age archaeology

“There are few remains of prehistoric tin mining in Cornwall or Devon, probably because later workings have destroyed early ones. However, shallow cuttings used for extracting ore can be seen in some places such as Challacombe Down, Dartmoor. There are a few stone hammers, such as those in the Zennor Wayside Museum. It may well be that mining was mostly undertaken with shovels, antler picks, and wooden wedges. An excavation at Dean Moor on Dartmoor, at a site dated at 1400 – 900 BC from pottery, yielded a pebble of tin ore and tin slag. Rocks were used for crushing the ore and stones for this were found at Crift Farm. There have been finds of tin slag on the floors of Bronze Age houses, for example at Trevisker. Tin slag was found at Caerloges with a dagger of the Camerton-Snowhill type. In the Iron Age bronze continued to be used for ornaments though not for tools and weapons, so tin extraction seems to have continued. An ingot from Castle Dore is probably of Iron Age date.” ref

Panicum miliaceum from China

“A model for the domestication of Panicum miliaceum (common, proso, or broomcorn millet) in China. The location of the 43 sites used within this analysis. The inset shows sites of the Ying and Lou Valley in Henan.” ref

“Major Bronze Age translocations between South Asia, Arabia, and Africa including the distribution of archaeobotanical evidence of broomcorn millet (Panicum miliaceum) of Chinese origin, suggesting dispersal from South Asia to Arabia and Nubia via the sea. Inset lower right: map of the distribution of sites in South Asia with archaeobotanical evidence for one or more crops of African origin.” ref

Across the Indian Ocean: The Prehistoric Movement of Plants and Animals

“Major research shows that is peopling the Indian Ocean with prehistoric seafarers exchanging native crops and stock between Africa and India. Not the least exciting part of the work is the authors’ contention that the prime movers of this maritime adventure were not the great empires but a multitude of small-scale entrepreneurs. The study of prehistory resembles a complex jigsaw and for much of the last half-century, Peter Bellwood has been at work finding and fitting pieces together, especially as they pertain to the island worlds of the western Pacific. His work has been pre-eminent in generating new understanding and fresh debate about the origins of Austronesian language speakers and the spread of agriculture and languages through Island Southeast Asia and the Pacific. Austronesian is the most geographically dispersed of any global language family in pre-modern times and the inclusion of the Malagasy language in it implies that — complementary to the eastward spread of Austronesian into the Pacific —a westward extension of Austronesian speaking seafarers was involved in the peopling of Madagascar. ” ref

“In this paper, researchers explore the wider Indian Ocean context of this western Austronesian expansion and highlight how current research, including our Sea links project, is helping to reveal processes of cultural contact, trade and biological translocations in the Indian Ocean in later prehistory, from what can be termed the Bronze Age (in western Asian chronologies) through to the Iron Age and later. This research is inherently interdisciplinary and thus follows in the footsteps of Peter Bellwood’s pioneering archaeology of island cultures. We also draw upon another strand of Bellwood’s work, namely his focus on small-scale societies as major forces of cultural history. The actors in the drama of Austronesian and Polynesian origins, who created new worlds in Island Southeast Asia and the Pacific, and seafaring technologies of unparalleled sophistication, were not the river valley civilizations or literate cities that so often capture the archaeological imagination, and dominate the public image of archaeology. Instead, it was small-scale, village or lineage groups of farmers and seafarers who played the key role in the peopling of the Pacific and the cultural transformation of Neolithic Island Southeast Asia.” ref

“Similarly, there is mounting evidence that small-scale coastal societies were often the pioneers in creating cross-cultural contacts and translocating plants and animals in the early Indian Ocean. In this paper, they sketch the emerging picture of a dynamic prehistoric Indian Ocean, in which links were created between societies in East Africa, Arabia, South Asia, and Southeast Asia, all prior to the development of the better-documented trade of later periods, including the famous spice trade of the Roman and subsequent eras. This picture emerges from archaeological evidence, and particularly the evidence of translocated crop plants, as well as from historical linguistics, most notably relating to tree crops and boat technology, with a growing contribution from genetic studies of animals, including domesticated and commensal species.” ref

The Bronze Age inter-savannah translocations (c. 2000–1500 BC): north-east Africa, India, Arabia

“The connections between Africa and India, which constitute the first act of the narrative of transoceanic connections in the north-western part of Indian Ocean, took place as the hitherto separate trading spheres of the Persian/Arabian Gulf and the Red Sea/Gulf of Aden became interlinked, probably at the end of the third millennium BC. Trade and contact in the southern part of the Red Sea began as early as the Neolithic, as indicated by the movement of obsidian from Ethiopia to Yemen, and from the fourth millennium BCE or around 6,020-5,020 years ago stretched northward to Egypt as well, when incense and other goods were no doubt also part of the increasing flow of commodities across the region. The much later expeditions of the Egyptian state southwards towards Punt, in search of incense and other exotica, were likely built on these earlier Neolithic contacts, which began in an era prior to local cereal agriculture, in which settlements are still mainly dominated by early to mid-Holocene shell middens. From c. 2000 BCE or 4,020 years ago, elements of the Red Sea/Gulf of Aden sphere appear to have been brought within the remit of an extended India-Gulf trading network, presumably through the activities of the coastal societies of southern Arabia and/or the agency of Gujarati seafarers, as well as the involvement of an undetermined source in Africa.” ref

Five African crops

Five African crops reached South Asia shortly thereafter. It has been known for many years that some of the major crops of the drier regions of India, such as sorghum (Sorghum bicolor), pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum) and finger millet (Eleusine coracana), originated in Africa and arrived in India at some point in prehistory. A popular argument has been that these crops arrived in the “Indus Vally” Harappan urban period (2600–2000 BCE or 4,620-4,020 years ago), brought by Harappan ‘seafarers’, but there is little firm evidence to support this. Recent re-assessments, of both botanical identifications and archaeological context, leave reason to doubt the few grains reported from the Harappan urban period; in contrast, there is now a large accumulation of evidence for these crops in India from the second millennium BC, including finds from 33 sites.” ref

“What the dating evidence currently suggests is that this transfer of African crops took place at the end of the Harappan era, perhaps as the urban Harappan civilization was undergoing its transformative de-urbanisation process. Given the lack of any other material evidence for Harappan or South Asian contacts with the Red Sea or Africa before 2000 BC, we have argued that this transfer took place primarily between north-east Africa and/or Yemen and western India, probably outside of the context of the Bronze Age trade between major civilizations. It is, of course, well documented that the Harappan civilization was involved in maritime trade with Oman, Bahrain, and Mesopotamia in the second half of the third millennium BCE or 5,020-4,020 years ago. But this trade was between urban actors, and increasingly appears to have been built on earlier regional contacts between small-scale coastal fishing and agropastoral societies.” ref

“Moving in the other direction was the Asian broomcorn millet (Panicum miliaceum), ultimately of Chinese origin, which had left China on westward trade routes by c. 2200 BCE. Broomcorn millet is known from other central Asian sites from around 2000 BCE and is found in Pakistan at c. 1900 BCE, Yemen at around 2000 BC, and in Sudanese Nubia by c. 1700 BCE, while being absent from intervening regions such as Egypt and Mesopotamia. Zebu cattle may also have moved from India to Yemen and East Africa starting at this time, although this was presumably the first stage in an ongoing process of gene flow through introduced bulls which made the genetic landscape of south Arabian and African cattle one of hybridity between African taurine and Indian zebu stocks, with evidence for interbreeding most marked at the margins of the Indian Ocean. These zebu-hybrid cattle played an important role in the long-term success and southernmost spread of cattle pastoralists in eastern Africa.” ref

The Arabian Sea corridor, which led to early species exchange between the savannahs of Africa and India, was in some ways a precursor to the later pepper route of the spice trade. The first hint of this spice trade comes from the findings of valued black peppercorns that were used to fragrance the nostrils of the deceased Pharaoh Ramses II (c. 1200 BCE). This spice is endemic only to the wet forests of southern India, and in all likelihood was supplied by hunter-gatherer groups to coastal groups. At this date, it is unclear whether any farming was practiced along the coastal plains of southern India, with rice agriculture in the far south of India normally dated after 1000 BCE, and it may be the case that the earliest pepper was moved between coastal hunter-fisher groups into the emerging network of Arabian Sea voyaging and exchange.” ref

“In this link is a map detailing some of the active maritime trade routes in the Aegean during the Middle and Late Bronze Age.” ref

Exotic foods reveal contact between South Asia and the Near East during the second millennium BCE.

Abstract

“Although the key role of long-distance trade in the transformation of cuisines worldwide has been well-documented since at least the Roman era, the prehistory of the Eurasian food trade is less visible. In order to shed light on the transformation of Eastern Mediterranean cuisines during the Bronze Age and Early Iron Age, we analyzed microremains and proteins preserved in the dental calculus of individuals who lived during the second millennium BCE in the Southern Levant. Our results provide clear evidence for the consumption of expected staple foods, such as cereals (Triticeae), sesame (Sesamum), and dates (Phoenix). We additionally report evidence for the consumption of soybean (Glycine), probable banana (Musa), and turmeric (Curcuma), which pushes back the earliest evidence of these foods in the Mediterranean by centuries (turmeric) or even millennia (soybean). We find that, from the early second millennium onwards, at least some people in the Eastern Mediterranean had access to food from distant locations, including South Asia, and such goods were likely consumed as oils, dried fruits, and spices. These insights force us to rethink the complexity and intensity of Indo-Mediterranean trade during the Bronze Age as well as the degree of globalization in early Eastern Mediterranean cuisine.” ref

‘Globalized’ early Bronze Age Levantines consumed exotic Asian nosh, study shows

“Analysis of dental tartar from skeletons excavated at Megiddo and Tel Erani shows first evidence in the region from the 2nd millennium BCE (4,020-3,020 years ago) of foods such as bananas, soybeans, turmeric. Proving a network of elusive Bronze Age trade routes is like pulling teeth for scholars. Taking that quite literally, the lead authors of a new scientific paper analyzed ancient Southern Levant dental tartar and uncovered a cornucopia of minuscule last suppers — the exotic ingredients of which shore up an increasingly recognized academic theory of a “globalized” 2nd millennium BCE Bronze Age. As part of a multi-year, interdisciplinary project, a team of researchers led by Harvard University Prof. Christina Warinner and University of Munich Prof. Philipp Stockhammer microscopically examined tooth tartar taken from 13 skeletal remains excavated at northern Israel’s Megiddo site, which was largely populated by Canaanites. Three more skeletal samples were taken from an Iron Age cemetery at Tel Erani, located near Kiryat Gat, which dates to circa 500 years after Megiddo and is thought to have been populated by Philistines.” ref

“With the microscopic remains that were preserved over the millennia by the “skin” of the skeletons’ teeth, the scientists discovered non-native, outlier foodstuffs such as soybeans, turmeric, and bananas, which were not previously known to exist in the Southern Levant at this time. Anyone who does not practice good dental hygiene will still be telling us, archaeologists, what they have been eating thousands of years from now,” said Stockhammer in a press release. The study, “Exotic foods reveal contact between South Asia and the Near East during the second millennium BCE,” was published this week in the prestigious Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) journal. It outlines compelling evidence of a wide-ranging trade route, spanning from South Asia to Egypt, and posits it was part of an even larger Bronze Age “globalized” network.” ref

“This increasingly studied idea of a connected ancient world led scholar Helle Vandkilde to coin the term “Bronzization” in a 2016 paper explaining how the pursuit of the components of bronze created a web of routes. A recently published example of a trade route in pursuit of bronze production is found in a study that concluded that ancient tin ingots discovered in Israel were mined in England. Now, say the PNAS authors, “Although named for a metal that is highly visible in the archaeological record, the process of Bronzization was likely a much broader phenomenon that also linked cuisines and economies across Eurasia.” Among the previously known exotic cuisine, evidence of vanilla, most likely collected from South Asia vanilla orchid pods, was already uncovered at Megiddo in a tomb dated to the later phase of the Middle Bronze Age (around 1700-1600 BCE). Likewise, the earliest citrus within the Mediterranean, dated to circa 2,500 years ago, probably came from Southeast Asia, according to a study by Tel Aviv University Prof. Dafna Langgut.” ref

“Tel Aviv University Prof. Israel Finkelstein, who is an author in the study, believes this new paper goes much farther to shore up the idea of an ancient spice route. “This is clear evidence of trade with southeast Asia as early as the 16th century BCE – much earlier than previously assumed,” said Finkelstein in a press release. Finkelstein has led excavations at Megiddo since 1994 and most of the samples in the present study came from tombs and other burials there. “Several years ago, we found similar evidence of long-distance trade: molecular traces of vanilla in ceramic vessels from the same period at Megiddo. Yet very little is known about the trade routes or how the goods were delivered,” said Finkelstein.” ref

Looking a gift horse in the mouth

“This issue of delivery is addressed by co-lead author Stockhammer in his massive collaborative project, “FoodTransforms: Transformations of Food in the Eastern Mediterranean Late Bronze Age.” As emphasized in the PNAS study, what makes its methodology notable is that unlike tried and true “macro-archaeological” methods such as digging and sifting, it drills down into the issue through micro-testing of dental calculus. “Although there are numerous ways to investigate the food and drink consumed in antiquity, perhaps the most powerful evidence is based on material obtained from inside the mouth,” reads Stockhammer’s project website. “One such material is dental calculus (tartar), a calcified microbial biofilm that builds up in layers over the years. HDC is an abundant, nearly ubiquitous, and long-term reservoir of the ancient oral microbiome, preserving not only microbial and host biomolecules but also dietary and environmental debris,” he writes.” ref

“According to his co-author, Harvard University’s Warinner, the ancient tooth tartar is “like a time capsule… It’s the single richest source of ancient DNA in the archaeological record. There are so many things we can learn from it — everything from pollution in the environment to people’s occupations to aspects of health. It’s all in there,” she said in a 2019 interview. When using these Palaeoproteomic methodologies to analyze the “microremains” and proteins preserved in the dental calculus of the 16 skeletons’ samples, the authors found examples of expected staple foods such as cereals, sesame, and dates, according to a PNAS press release. It was the unexpected edibles that bit into their intellectual curiosity and pushed back the clocks on these foodstuffs’ appearance in the Middle East.” ref

“Our results provide clear evidence for the consumption of expected staple foods, such as cereals (Triticeae), sesame (Sesamum), and dates (Phoenix). We additionally report evidence for the consumption of soybean (Glycine), probable banana (Musa), and turmeric (Curcuma), which pushes back the earliest evidence of these foods in the Mediterranean by centuries (turmeric) or even millennia (soybean),” they write. “In fact, we can now grasp the impact of globalization during the second millennium BCE on East Mediterranean cuisine,” said Stockhammer in a press release. “Mediterranean cuisine was characterized by intercultural exchange from an early stage.” ref

“The authors conclude that incredibly perishable bananas discovered in samples from at Tel Erani were likely either eaten by the male subject — perhaps a merchant — prior to his arrival and death, or were transported as a dried fruit. At Megiddo, the scholars discovered a plethora of soybean samples, which they conclude was transported there as oil. Oil was a highly desired commodity during this era and had uses ranging from embalming the dead to cooking and medicine to personal body care. The idea that the soybean remnants came in oil may explain the lack of soybeans in the archaeological record, although they were cultivated in China since at least the 7th century BCE. Soybean cultivation is only documented in Israel from the 20th century CE onwards. Unlike soybeans, the turmeric spice is known within the Near East since the 7th century BCE from Assyrian cuneiform medical texts in Nineveh. However, the first archaeological evidence is only from the Islamic period during the 11th to 13th centuries CE. From the Megiddo evidence, the authors surmise that the spice was already available in the Levant from the mid-2nd millennium BCE.” ref

“The broader body of evidence for exotic goods, which also includes zebu cattle, chickens, citron, melon, cloves, millet, vanillin, peppercorns, monkeys, and beetles, points to a pattern of established trade,” write the authors. The broader body of evidence for exotic goods, which also includes zebu cattle, chickens, citron, melon, cloves, millet, vanillin, peppercorns, monkeys, and beetles, points to a pattern of established trade. All of these perishable goods — and potentially many more — may have been trafficked through a widespread early spice route. But only through a consistent use of microscopic Palaeoproteomic methods will they continue to be detected, the authors emphasize. “The recovery and identification of diverse foodstuffs using molecular and microscopic techniques enables a new understanding of the complexity of early trade routes and nascent globalization in the ancient Near East and raises questions about the long-term maintenance and continuity of this trade system into later periods,” write the authors.” ref

Food trade with South Asia revealed by Near East food remains

“Exotic Asian spices such as turmeric and fruits like the banana had already reached the Mediterranean more than 3000 years ago, much earlier than previously thought. A team of researchers working alongside archaeologist Philipp Stockhammer at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität in Munich (LMU) has shown that even in the Bronze Age, long-distance trade in food was already connecting distant societies. Imagine this scene from a market in the city of Megiddo in the Levant 3700 years ago: The market traders are hawking not only wheat, millet or dates, which grow throughout the region, but also carafes of sesame oil and bowls of a bright yellow spice that has recently appeared among their wares. This is how Philipp Stockhammer imagines the bustle of the Bronze Age market in the eastern Mediterranean.” ref

“Working with an international team to analyze food residues in tooth tartar, the LMU archaeologist has found evidence that people in the Levant were already eating turmeric, bananas, and even soy in the Bronze and Early Iron Ages. “Exotic spices, fruits, and oils from Asia had thus reached the Mediterranean several centuries, in some cases even millennia, earlier than had been previously thought,” says Stockhammer. “This is the earliest direct evidence to date of turmeric, banana, and soy outside of South and East Asia.” It is also direct evidence that as early as the second millennium BCE there was already a flourishing long-distance trade in exotic fruits, spices, and oils, which is believed to have connected South Asia and the Levant via Mesopotamia or Egypt. While substantial trade across these regions is amply documented, later on, tracing the roots of this nascent globalization has proved to be a stubborn problem. The findings of this study confirm that long-distance trade in culinary goods has connected these distant societies since at least the Bronze Age. People obviously had a great interest in exotic foods from very early on.” ref

“For their analyses, Stockhammer’s international team examined 16 individuals from the Megiddo and Tel Erani excavations, which are located in present-day Israel. The region in the southern Levant served as an important bridge between the Mediterranean, Asia, and Egypt in the 2nd millennium BCE. The aim of the research was to investigate the cuisines of Bronze Age Levantine populations by analyzing traces of food remnants, including ancient proteins and plant microfossils, that have remained preserved in human dental calculus over thousands of years. The human mouth is full of bacteria, which continually petrify and form calculus. Tiny food particles become entrapped and preserved in the growing calculus, and it is these minute remnants that can now be accessed for scientific research thanks to cutting-edge methods. For the purposes of their analysis, the researchers took samples from a variety of individuals at the Bronze Age site of Megiddo and the Early Iron Age site of Tel Erani. They analyzed which food proteins and plant residues were preserved in the calculus on their teeth. “This enables us to find traces of what a person ate,” says Stockhammer. “Anyone who does not practice good dental hygiene will still be telling us, archaeologists, what they have been eating thousands of years from now.” ref

“Palaeoproteomics is the name of this growing new field of research. The method could develop into a standard procedure in archaeology, or so the researchers hope. “Our high-resolution study of ancient proteins and plant residues from human dental calculus is the first of its kind to study the cuisines of the ancient Near East,” says Christina Warinner, a molecular archaeologist at Harvard University and the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History and co-senior author of the article. “Our research demonstrates the great potential of these methods to detect foods that otherwise leave few archaeological traces. Dental calculus is such a valuable source of information about the lives of ancient peoples.” ref

“Our approach breaks new scientific ground,” explains LMU biochemist and lead author Ashley Scott. That is because assigning individual protein remnants to specific foodstuffs is no small task. Beyond the painstaking work of identification, the protein itself must also survive for thousands of years. “Interestingly, we find that allergy-associated proteins appear to be the most stable in human calculus”, says Scott, a finding she believes may be due to the known thermostability of many allergens. For instance, the researchers were able to detect wheat via wheat gluten proteins, says Stockhammer. The team was then able to independently confirm the presence of wheat using a type of plant microfossil known as phytoliths. Phytoliths were also used to identify millet and date palm in the Levant during the Bronze and Iron Ages, but phytoliths are not abundant or even present in many foods, which is why the new protein findings are so groundbreaking—paleoproteomics enables the identification of foods that have left few other traces, such as sesame. Sesame proteins were identified in dental calculus from both Megiddo and Tel Erani. “This suggests that sesame had become a staple food in the Levant by the 2nd millennium BCE,” says Stockhammer.” ref

Two additional protein findings are particularly remarkable, explains Stockhammer. In one individual’s dental calculus from Megiddo, turmeric and soy proteins were found, while in another individual from Tel Erani banana proteins were identified. All three foods are likely to have reached the Levant via South Asia. Bananas were originally domesticated in Southeast Asia, where they had been used since the 5th millennium BCE, and they arrived in West Africa 4000 years later, but little is known about their intervening trade or use. “Our analyses thus provide crucial information on the spread of the banana around the world. No archaeological or written evidence had previously suggested such an early spread into the Mediterranean region,” says Stockhammer, although the sudden appearance of banana in West Africa just a few centuries later has hinted that such a trade might have existed. “I find it spectacular that food was exchanged over long distances at such an early point in history.” ref

“Stockhammer notes that they cannot rule out the possibility, of course, that one of the individuals spent part of their life in South Asia and consumed the corresponding food only while they were there. Even if the extent to which spices, oils, and fruits were imported is not yet known, there is much to indicate that trade was indeed taking place, since there is also other evidence of exotic spices in the Eastern Mediterranean—Pharaoh Ramses II was buried with peppercorns from India in 1213 BCE. They were found in his nose. The results of the study have been published in the journal PNAS. The work is part of Stockhammer’s project “FoodTransforms—Transformations of Food in the Eastern Mediterranean Late Bronze Age,” which is funded by the European Research Council. The international team that produced the study encompasses scientists from LMU Munich, Harvard University, and the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena. The fundamental question behind his project—and thus the starting point for the current study—was to clarify whether the early globalization of trade networks in the Bronze Age also concerned food. “In fact, we can now grasp the impact of globalization during the second millennium BCE on East Mediterranean cuisine,” says Stockhammer. “Mediterranean cuisine was characterized by intercultural exchange from an early stage.” ref

Sweet-toothed Canaanites imported exotic food to Israel 3,600-years ago

“Analysis of teeth of individuals who lived in Megiddo then shows that the Canaanites imported exotic food from India and Southeast Asia. Bronze Age cuisine in Israel included exotic foodstuffs, such as bananas, soybeans, and turmeric, according to a new study published in the journal PNAS. It pushes back the evidence for these foods by centuries. The conclusion is based on an analysis of micro-remains and proteins preserved in the tooth tartar of individuals who lived in Megiddo and Tel Erani during the Bronze Age and the Iron Age. The study was carried out by an international team of experts from LMU Munich, Harvard University, and the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, Germany. The authors show that in addition to Levantine plants, such as chickpeas, lentils, barley, wheat, grapes, figs, and dates, the Canaanite inhabitants also ate bananas, soybeans, sesame, turmeric, and other exotic spices – typical ingredients of Middle Eastern cuisine today (except for soybeans and bananas). The research proves that Mediterranean cuisine was diverse and that exotic foods from Asia had arrived several centuries, and sometimes millennia, earlier than had been previously thought.” ref

“The origin of the fruits and plants was proven by detailed analysis of the remains of 18 individuals found in Megiddo and Tel Erani excavations, including plant remains and proteins that have remained preserved in human dental calculus over thousands of years. The human mouth is full of bacteria that continually petrify and form calculus. Tiny food particles become entrapped and preserved in the growing calculus, and these remnants can be accessed for scientific research. “This enables us to find traces of what a person ate,” Stockhammer said. “Anyone who does not practice good dental hygiene will still be telling us, archaeologists, what they have been eating thousands of years from now.” ref

Turmeric in Megiddo

“Previously, researchers thought the Middle Eastern diet contained mostly bread. In fact, archaeologists excavating in Jericho found that the most abundant item in the destruction apart from pottery was grain. As a result, they concluded that Canaanites ate a lot of grain. Bread was such an important part of the diet that in Hebrew, the expression to “eat a meal” literally meant to “eat bread.” Cereals used to make bread, such as wheat, barley, oats, spelt, and millet, made up a large portion of the Bronze Age Canaanite diet. Researchers estimate that a person would consume some 200 kg. of cereals a year, providing about half of their needed calories. The international team of archaeologists and experts was surprised to find that sesame had become a staple food in the Levant by the second millennium BCE. Two additional protein findings were particularly remarkable. Turmeric and soy proteins were found in the dental calculus of one individual from Megiddo in the 16th-15th century BCE, while banana proteins were identified in another individual from Tel Erani 500 years later.” ref

“The Megiddo individual who revealed evidence for soybeans and turmeric was buried in an elaborate family burial, stone built, meaning that he was probably a member of the city’s elite,” said Prof. Israel Finkelstein, who is co-director of the Megiddo excavation along with Dr. Mario M. Martin of Tel Aviv University. In another recent study from Megiddo, evidence of vanilla was discovered in the elite tomb there. “These foods were clearly something special and priced as such,” Martin said. “The evidence for far-distance trade is not altogether unexpected. It is certainly exciting to be able to prove the actual existence of these foodstuffs in the southern Levant.” While the elites of Megiddo could afford luxury goods, such as turmeric, the individual from Tel Erani, where the banana proteins were identified, seemed to have belonged to the rural population.” ref

“The Erani individual was only buried in one flask, a standard vessel, nothing special with regard to the archaeological context and no indication for elevated status,” Stockhammer said. Other evidence, such as cinnamon, was verified several years ago and is found considerably later during the Iron Age, he said. Nonetheless, all three foods are likely to have reached the Levant via South Asia. Bananas were originally domesticated in Southeast Asia, where they had been used since the fifth millennium BCE, arriving in West Africa 4,000 years later. But little is known about their intervening trade or use. “Our analyses thus provide crucial information on the spread of the banana around the world,” Stockhammer said. “No archaeological or written evidence had previously suggested such an early spread into the Mediterranean region.” The sudden appearance of bananas in West Africa just a few centuries later indicated that such a trade might have existed, he added. “I find it spectacular that food was exchanged over long distances at such an early point in history,” Stockhammer said.” ref

Milk, Honey, and Bananas

Until now, there has been little evidence regarding these culinary descriptions painted in ancient sources. The variety of foods, such as grapes, pistachios, almonds, pomegranates, and figs, found in Canaan during the Bronze Age is highlighted in the Bible (Genesis 43:11, Numbers 13:23) and in second-millennium textual sources from the Near East. For instance, Assyrian cuneiform tablets record donkey caravans between the Mesopotamian city of Aššur and the Anatolian trade post of Kaneš in the 19th century BCE and in the 15th century BCE during the reign of Amenhotep IV, commonly referred to as Akhenaten. The flow of exotic goods, such as ivory, ostrich eggshells, ebony, and frankincense, flourished, as indicated by clay tablets from el-Amarna, Egypt, priceless letters that contain correspondence from the city kings of Canaan to the foreign office of the Pharaoh, which throw light on the conditions in Canaan in the 14th century BCE.” ref

“Among the most well-known of these accounts is an expedition initiated by Egypt’s Queen Hatshepsut to the land of Punt (probably located in the Horn of Africa region) in the 15th century BCE. In addition, seals, stone weights, lapis lazuli, and carnelian jewelry weights provide evidence for long-distance trade between the Near East and the Indian subcontinent. “In fact, we can now grasp the impact of globalization during the second millennium BCE on East Mediterranean cuisine,” Stockhammer said. “Mediterranean cuisine was characterized by intercultural exchange from an early stage,” The extent to which spices, oils, and fruits were imported is not yet known. But there is much to indicate that trade was taking place. There is other evidence of exotic spices in the Eastern Mediterranean. For example, Pharaoh Ramses II was buried with peppercorns from India in 1213 BCE. They were found in his nose.” ref

Glassmaking in Bronze-Age Egypt: Long trade links of Molds and Ingots with their Glassmaking Furnaces

“Glass production and trade around the Mediterranean in seen in the Late Bronze Age. Evidence presented by Rehren and Pusch strengthens the case for primary glass production in Egypt.” ref

“Ever since Sir Flinders Petrie[HN1] discovered evidence for Bronze-Age glass production in Tell el-Amarna, Egypt [HN2], in the late 19th century, controversy has surrounded his findings. Does the evidence represent primary glass production (raw materials were mixed to produce glass) or secondary working (ready-made glass was imported and reworked into artifacts)? The answer has important implications for understanding trade and exchange in the Mediterranean during the late second millennium B.C. On page 1756 of this issue, Rehren and Pusch [HN3] provide evidence in favor of primary production in Egypt. In the Late Bronze Age, glass [HN5] was a high-status commodity. Any group that controlled its production or consumption would have occupied a powerful position. Archaeological evidence of a rise in trade and consumption indicates that this was a period of political change throughout the Near and Middle East and the Mediterranean area. This transformation may be explained by the rise of elite groups who chose to express allegiances through competitive gift exchange of prestigious artifacts. Glass—being difficult to work, complicated to produce, and available in vivid, symbolically significant colors—was favored for use in such artifacts. Understanding the evidence from Amarna will help to define the role of prestige goods and how elites used them to enhance their position.” ref

“The first glass vessels found in Egypt were stylistically indistinguishable from the earlier Mesopotamian glasses. The only contemporary written accounts of glasses are from the Amarna tablets [HN6]. These small, sun-dried clay tablets document dispatches to and from the Egyptian courts and, in the case of glass, record a request by the pharaoh Akhenaten [HN7] (∼14th century BCE or 3,420 years ago) for glass to be brought to Egypt. These strands of evidence suggest that glass was not produced in Egypt, but only reworked there. However, stylistic analysis and analysis of textual accounts are not the only ways to understand the trade in, and manufacture of, glass. The composition of a glass [HN8] will vary when different raw materials and recipes are used, in principle allowing both technology and provenance to be investigated with chemical fingerprinting. Egyptian glasses were produced from silica (probably from quartz pebbles) and a sodarich plant ash flux, which should vary in composition depending on where the raw materials were procured. Therefore, glasses with similar compositions would suggest that they were produced with similar raw materials and technology and were made at the same production center. Ideally, we may expect to see different chemical fingerprints of glasses made at different factories, or at least differentiate glasses with respect to broad geographical areas such as Egypt and Mesopotamia.” ref

“This concept can be applied to the Amarna controversy. If the chemical fingerprint of glass production debris found by Petrie at Amarna differed from that of Mesopotamian glasses, then, with the support of secure archaeological evidence, we could suggest that Amarna was a primary production center. In practice, chemical analysis of artifacts has both expanded and complicated our knowledge in this area. For example, such analysis has shown that contemporary glasses from Egypt and Mesopotamia cannot be unequivocally distinguished on the basis of their chemistry, giving no real clue as to possible provenance. Rehren has attributed this finding to the method by which the glass was produced, rather than to the use of raw materials with a similar composition or adherence to a strict recipe. By only partially melting the glass, the glass composition with the lowest melting point would be obtained; any unfused raw material would be removed from the melt. This approach would produce glasses of similar compositions, irrespective of slight differences in the raw materials, because it depends on temperature rather than raw material composition.” ref

“This partial-melting model is not contradicted by compositional differences observed between glasses of differing colors. Different concentrations of potassium in cobalt- and copper-colored blue glasses are attributed to the use of different plant ashes in their production. This observation has led Rehren to propose that Egyptian glasses were made at a few large glassmaking centers, each specializing in a particular color. These ideas can only really be tested against archaeological evidence. In the 1990s, excavations were undertaken at Amarna, the royal city of Akhenaten, to locate Petrie’s glass-production site. Two large circular furnaces were discovered, and the associated vitrified mud-brick suggested that they had reached temperatures adequate for primary glass production from raw materials. This interpretation was confirmed by experimental reconstruction. [HN9] Supporting evidence that the furnaces were used for glassmaking rather than reworking comes in two forms: fragmentary lumps of deep-blue “frit,” currently thought to be the remains of an intermediate, low-temperature stage of the glassmaking process (5), and fragments of cylindrical ceramic vessels, coated on the outside with drips of dark-blue cobalt glass and on the inside with a calcareous liner.” ref

Our understanding of Egypt’s role in glass production and trade at this time hinges on the function of these ceramic vessels. It is assumed that they were used as ingot molds, in which glass, produced from raw materials, was cast into ingots and traded around the Mediterranean (see the figure). Support for this interpretation comes from cobalt blue glass ingots fitting the dimensions of the cylindrical vessels from Amarna, which have been found in a Late Bronze Age shipwreck off the coast of Turkey at Uluburun [HN10], near Kas. Such evidence argues against the stylistic and documentary evidence referred to earlier. This is where the report by Rehren and Pusch becomes highly significant. They present evidence for primary glassmaking from the 19th-dynasty Ramesside capital at Qantir [HN11] (∼13th century BCE or 3,320 years ago). This evidence is extremely important in two respects. First, it provides a key to glass technology at the site that is missing from other production centers. Evidence of cylindrical vessels filled with partially fused glasses and jars indicates a two-stage glassmaking process. The first stage involved heating the glass at low temperatures in ovoid jars. The resulting material was then removed from the jars, the non-fused insoluble material discarded, and more flux and a colorant added. The second stage involved melting these components to form glass ingots, in cylindrical molds similar to those found at Amarna.” ref

“Most of the glass found at Qantir is red, produced with copper in a reducing atmosphere. Red glasses are relatively difficult to produce, requiring a high level of technical know-how, whereas cobalt blue glasses, probably produced at Amarna, require no special regulation of redox conditions. Whether production of cobalt glasses follows a similar two-stage process remains to be seen, because evidence for filled ingot molds is absent from Amarna. Aside from the number of stages in glass production, both sites have yielded cylindrical vessels and semifused raw materials, implying that a similar technology was practiced at both centers. Second, these finds also address the question of provenance. Rehren and Pusch convincingly show that the Egyptians were making their own glass in large specialized facilities that were under royal control. At Qantir, production was linked specifically to the use of copper to color the glasses either red or blue, and glass was manufactured in the form of ingots to be reworked elsewhere.” ref

The production of ingots at Qantir, presumably for export, shows that at this period, Egypt exported rather than imported glass. The chemical composition of fully formed vessels, inlays, and plaques from other high-status sites throughout the Mediterranean and particularly the Aegean, at least in the case of cobalt blue glass, is indistinguishable from that of the ingots, indicating that it was produced from Egyptian glass. Hence, elites in other societies were supplied with raw glass from Egypt for reworking. The location of glass manufacturing at the royal sites of Amarna and Qantir suggests that it was a controlled activity, which is not surprising, because glass was a “royal” medium used to enhance power, status, and political allegiances. The evidence from Amarna and Qantir suggests that in the Late Bronze Age there was an Egyptian monopoly not just on the exchange of luxury glass but also on the diplomatic currency that the control of such technologies offered the elite. The evidence from Qantir presented by Rehren and Pusch reinforces and reappraises the role of glass both within Egyptian society and as an elite material that was exported from Egypt to the Mediterranean world.” ref

Mobile women were key to cultural exchange in Stone Age and Bronze Age Europe

“4,000 years ago, European women traveled far from their home villages to start their families, bringing with them new cultural objects and ideas. Credit: Stadtarchäologie Augsburg. At the end of the Stone Age and in the early Bronze Age, families were established in a surprising manner in the Lechtal, south of Augsburg, Germany. The majority of women came from outside the area, probably from Bohemia or Central Germany, while men usually remained in the region of their birth. This so-called patrilocal pattern combined with individual female mobility was not a temporary phenomenon, but persisted over a period of 800 years during the transition from the Neolithic to the Early Bronze Age.” ref

“The findings, published today in PNAS, result from a research collaboration headed by Philipp Stockhammer of the Institute of Pre- and Protohistoric Archaeology and Archaeology of the Roman Provinces of the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München. In addition to archaeological examinations, the team conducted stable isotope and ancient DNA analyses. Corina Knipper of the Curt-Engelhorn-Centre for Archaeometry, as well as Alissa Mittnik and Johannes Krause of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena and the University of Tuebingen jointly directed these scientific investigations. “Individual mobility was a major feature characterizing the lives of people in Central Europe even in the 3rd and early 2nd millennium,” states Philipp Stockhammer. The researchers suspect that it played a significant role in the exchange of cultural objects and ideas, which increased considerably in the Bronze Age, in turn promoting the development of new technologies.” ref

“For this study, the researchers examined the remains of 84 individuals using genetic and isotope analyses in conjunction with archeological evaluations. The individuals were buried between 2500 and 1650 BC in cemeteries that belonged to individual homesteads, and that contained between one and several dozen burials made over a period of several generations. “The settlements were located along a fertile loess ridge in the middle of the Lech valley. Larger villages did not exist in the Lechtal at this time,” states Stockhammer. 4,000 years ago, European women traveled far from their home villages to start their families, bringing with them new cultural objects and ideas.” ref

“We see a great diversity of different female lineages, which would occur if over time many women relocated to the Lech Valley from somewhere else,” remarks Alissa Mittnik on the genetic analyses and Corina Knipper explains, “Based on analysis of strontium isotope ratios in molars, which allows us to draw conclusions about the origin of people, we were able to ascertain that the majority of women did not originate from the region.” The burials of the women did not differ from that of the native population, indicating that the formerly foreign women were integrated into the local community. From an archaeological point of view, the new insights prove the importance of female mobility for cultural exchange in the Bronze Age. They also allow us to view the immense extent of early human mobility in a new light. “It appears that at least part of what was previously believed to be migration by groups is based on an institutionalized form of individual mobility,” declares Stockhammer.” ref

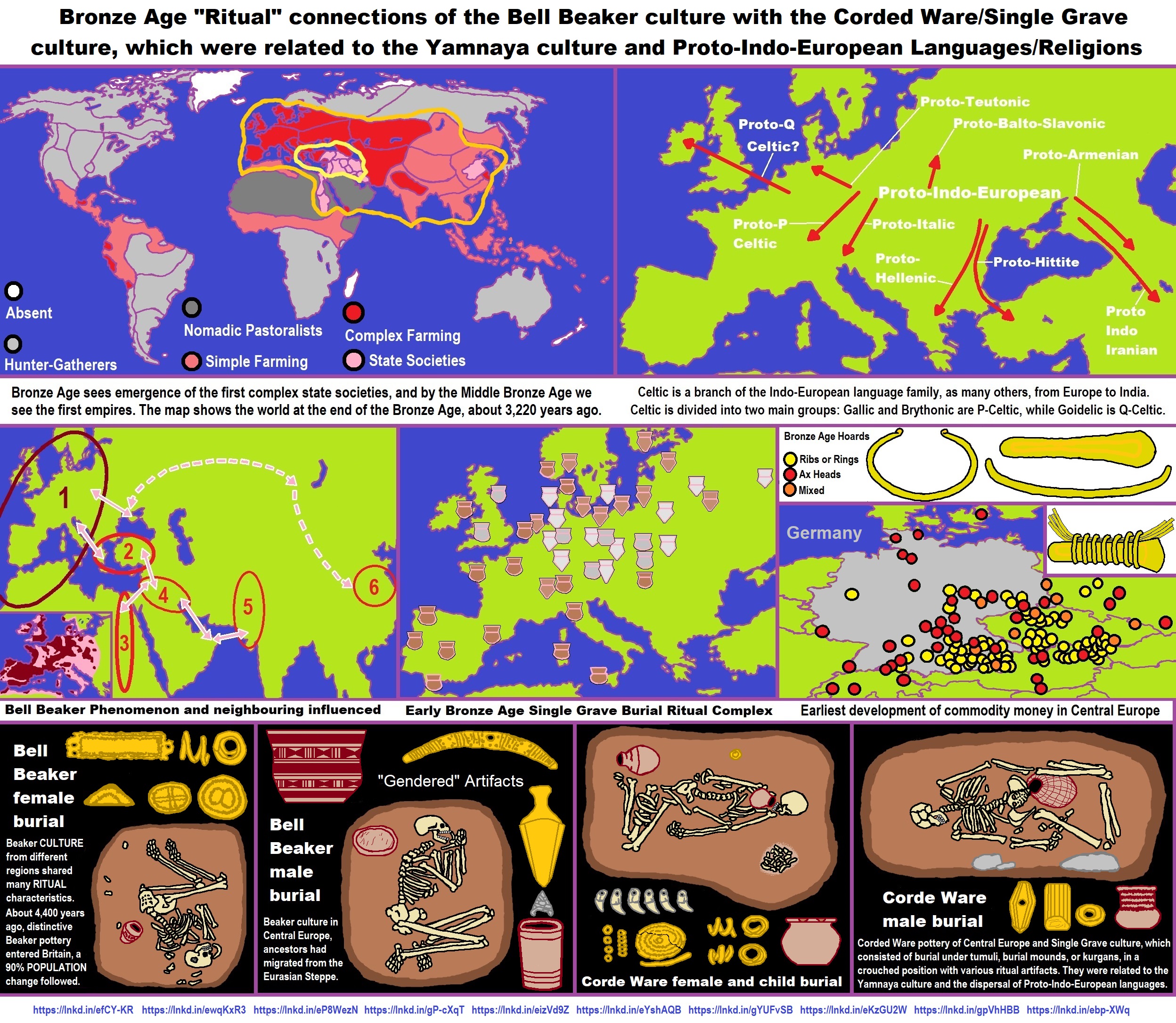

“Bronze is the defining metal of the European Bronze Age and has been at the center of archaeological and science-based research for well over a century. Archaeometallurgical studies have largely focused on determining the geological origin of the constituent metals, copper and tin, and their movement from producer to consumer sites. More recently, the effects of recycling, both temporal and spatial, on the composition of the circulating metal stock have received much attention. Also, discussions of the value and perception of bronze, both as individual objects and as hoarded material, continue to be the focus of scholarly debate. Here, we bring together the sometimes-diverging views of several research groups on these topics in an attempt to find common ground and set out the major directions of the debate, for the benefit of future research. The paper discusses how to determine and interpret the geological provenance of new metal entering the system; the circulation of extant metal across time and space, and how this is seen in changing compositional signatures; and some economic aspects of metal production. These include the role of metal-producing communities within larger economic settings, quantifying the amount of metal present at any one time within a society, and aspects of hoarding, a distinctive European phenomenon that is less prevalent in the Middle Eastern and Asian Bronze Age societies.” ref

Bronze Age bling!

“Was ‘Pompeii of the Fens’ a hub of international trade? Axes, textiles, and rings at 3,000-year-old settlement reveal treasures from the Middle East. Final finds from a 10-month excavation of the site in Cambridgeshire provide a rare glimpse into Bronze Age life. Artifacts from the site include bowls containing intact food, textiles, wild animal remains as well as weapons. Researchers say there are signs of how houses were constructed, what goods people had, and what they ate. The boggy marshland and waterways around Cambridgeshire were once home to a bustling, wealthy Bronze Age community, in what has become known as the ‘Pompeii of the Fens’, say archaeologists. While the community was destroyed in a fire 800-1,000 years ago, sinking beneath the water and into the thick mud, a 10-month excavation at the site has revealed phenomenal details of what life was like in Bronze Age Britain almost 3,000 years ago. Finds at the site give a sense of daily life, including how houses were constructed, what household goods the inhabitants had, what they ate, and how their clothes were made. But the findings also suggest the community had several international goods, from both Europe and the Middle East.” ref

“The team believes the buildings were set ablaze nearly a century after they were first built but have yet to discover if the fire was set deliberately or was an accident. They say it is possible the fire may have been started carried out by attackers +11. At least five houses were found at the Must Farm settlement, each one built very closely together for a small community of people. Archaeologists have spent 10 months excavating at least five ancient circular wooden houses that had been built on stilts in the East Anglian fens. The team working at the site, known as ‘Must Farm’ at Whittlesey in Cambridgeshire, has uncovered a collection of Bronze Age fabrics and one of the largest collections of Bronze Age glass ever found in Britain.” ref

“Known as Pompeii of the Fens, the Cambridgeshire site is the best-preserved Bronze Age settlement ever excavated in Britain, and is believed to have been destroyed by a major fire that caused the dwellings to collapse into a river. However, the river acted in a beneficial way, preserving many of the artifacts which would otherwise have been destroyed in the fire. Evidence, including tree-ring analysis of the oak structures, suggests that at the time of the fire, the structures were still new and had only been lived in for a few months, despite being well-equipped with household goods. Duncan Wilson, chief executive of Historic England, who joint-funded the excavation, said: ‘Over the past 10 months, Must Farm has given us an extraordinary window into how people lived 3,000 years ago.” ref

‘Now we know what this small but wealthy Bronze Age community ate, how they made their homes, and where they traded. ‘This has transformed our knowledge of Bronze Age Britain, and there is more to come as we enter a post-excavation phase of research.’ At least five houses were found at the Must Farm settlement, each one built very closely together for a small community of people. Every house seems to have been planned in the same way, with an area for storing meat and another area for cooking or preparing food. The roundhouses were built on stilts above a small river, with conical roofs built of long wooden rafters covered in turf, clay, and thatch, and floors and walls made of wickerwork.” ref

“Within the houses, a huge array of household goods were found, including complete sets of pots – some with food still inside – wooden buckets and platters, decorative textiles, tweezers and loom weights. Amazingly, it also seems that the settlers engaged in international trade, as suggested by the finding of decorative beads made from glass, jet, and amber from the Mediterranean Basin and the Middle East. These findings suggest a materialism and sophistication never before seen in a British Bronze Age settlement. Many of the objects were still relatively pristine which suggests that they had only been used for a very short time before the settlement was engulfed by fire. While it was previously known that textiles were common in the Bronze Age, it is very rare for them to survive today. However, the excavators found a range of textiles on site, including balls of thread, twining, and bundles of plant fibres, as well as loom weights which were used to weave threads together.” ref

“The findings also give us clues into what people ate in the Bronze Age. Wild animal remains found in rubbish dumps outside the houses show they were eating wild boar, red deer, and freshwater fish such as pike. Additionally, inside the houses themselves, the remains of young lambs and calves were found, revealing a mixed diet. Plants and cereals were also an important part of the Bronze Age diet and the remains of porridge-type foods were found preserved in amazing detail, sometimes still inside the bowls they were served in. Speaking about the findings, David Gibson, archaeological manager at the Cambridge Archaeological Unit at the University of Cambridge, said: ‘The exceptional site of Must Farm allows you visit in exquisite detail everyday life in the Bronze Age. ‘Domestic activity within structures is demonstrated from clothing to household objects, to furniture and diet.’ The excavation has now come to a close, but the archaeological findings may soon be displayed for the public.” ref

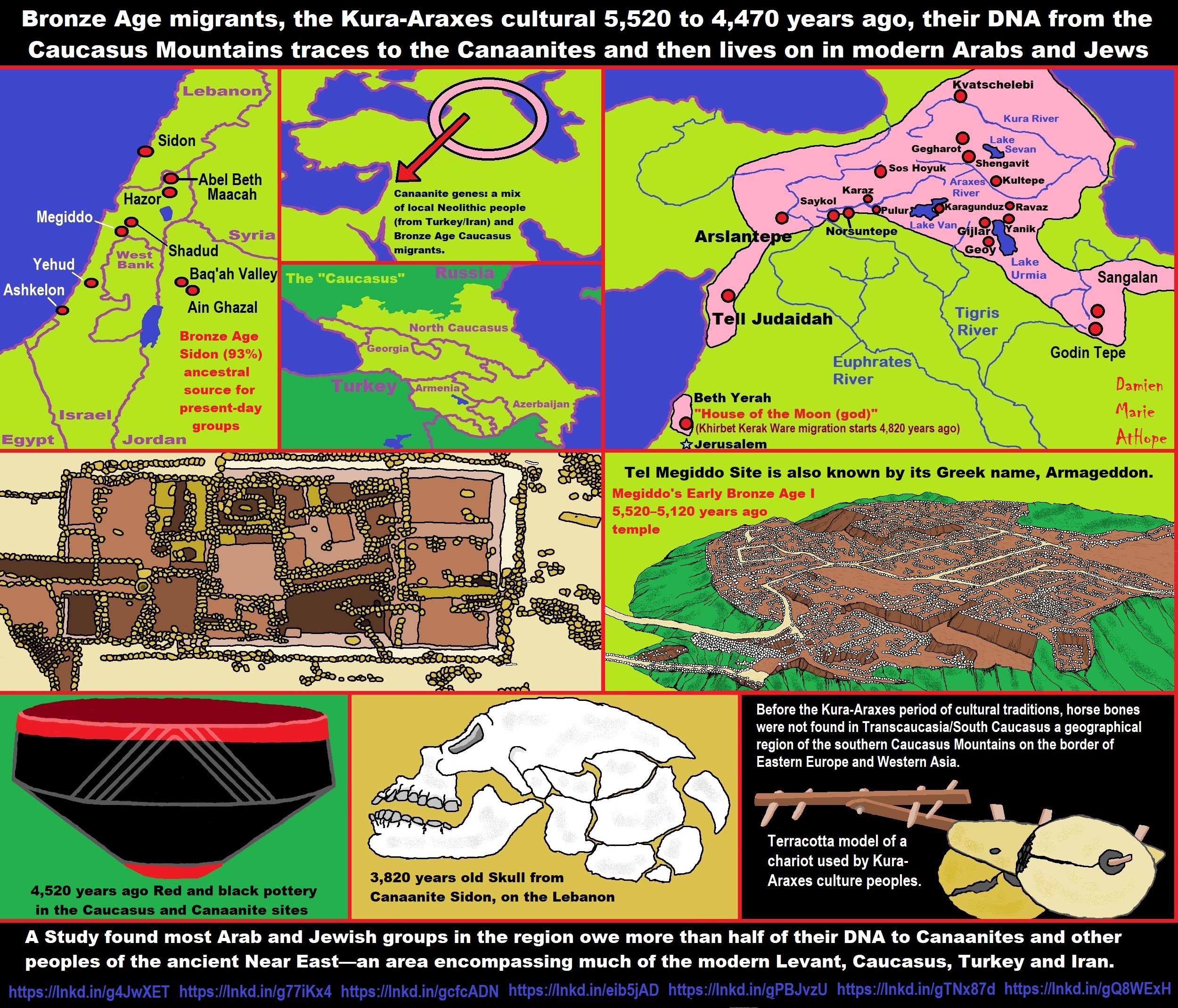

Bronze Age beads in Denmark are traced to EGYPT: Ancient Nordic jewelry matches the material used in Tutankhamun’s death mask

“Blue beads unearthed in an ancient Ølby grave, south of Copenhagen. They match material from Amarna in Egypt and Nippur in Mesopotamia. This suggests Egyptian glass was traded with amber 3,400 years ago. It also links the Egyptian sun cult with a Bronze Age Danish sun cult. Both civilizations valued material as the sun could penetrate its surface. Bronze Age beads found in Ølby, Denmark match the blue glass inlays found in Tutankhamun’s gold death mask, scientists claim. The discovery hints at some of the trade routes between Denmark and the ancient civilizations in Egypt and Mesopotamia 3,400 years ago. It also provides new details that could link the Egyptian cult of worshiping the sun with a similar sun cult that developed at the same time in Denmark. Twenty-three blue beads unearthed in an Ølby grave, south of Copenhagen, were analyzed using a technique known as plasma-spectrometry, according to a report in Science Nordic. The method allowed researchers to analyze the fragile bead and compare the chemical composition of trace elements with material from Amarna in Egypt and Nippur in Mesopotamia. The comparison showed that the chemicals matched exactly, marking the first time that Bronze Age Egyptian and Middle Eastern cobalt glass has been found outside the Mediterranean area. The blue beads were found in the grave of what is thought to have been a wealthy lady who lay in a hollowed-out oak trunk, wearing an overarm bracelet made of amber beads and other jewelry.” ref

4,000-year-old Bronze Age beads, and worth their weight in gold

“If you dug these up in your garden, you probably wouldn’t think twice about throwing them away. But the unassuming objects are 4,000-year-old Bronze Age beads and worth their weight in gold. Unearthed from a prehistoric burial chest on Dartmoor last year, they were heralded as one of the most significant historical finds in more than a century. Jane Marchand, the senior archaeologist from Dartmoor National Park, described the haul as one of the most important discoveries since the 19th century. She said: ‘The amber beads probably came from the Baltic – and meant they were long-distance trading 4,000 years ago. ‘These artifacts show Dartmoor wasn’t the isolated, hard-to-reach place we thought it was. This mystery is unfolding. ‘This has been fascinating to work on, but it’s just one piece in a puzzle. The story is only part-told.'” ref

“Scientists believe most of the beads were Mesopotamian and made from melted quartz sand and ash from Tigris river grass. Two of them came from Egypt. Previous studies had already shown that Bronze Age amber was exported from Nordic areas to Egypt, with Tutankhamun and other pharaohs burial chambers containing the material. Researchers from the National Museum in Denmark and the Institute of Archaeomaterials Research in France say the latest study shows that as well as amber, Denmark and Egypt traded glass 3,400 years ago. They also believe it links two ancient sun cults, based on the fact that sunlight is able to penetrate the surface of both amber and glass. The study claims that burying amber and glass may have constituted as a prayer to the sun, to ensure that the dead body would share its fate with the sun on an eternal journey.” ref

Ancient Egyptian Trade Routes

The ancient Egyptians most oftentimes visited the countries along the Mediterranean Sea and the Upper Nile River to the south because they were immediately connected to Egypt and contained materials that the Egyptians desired. At several times in their history, the ancient Egyptians set up trade paths to Cyprus, Crete, Greece, Syro-Palestine, Punt, and Nubia. Egyptian records as early as the Predynastic Period list some tokens that were worked into Egypt, taking leopard peels, giraffe tails, monkeys or baboons, cattle, ivory, ostrich plumes and eggs, and gold. Punt (whose location is variable) was a major source for incense, while Syro-Palestine provided cedar, oils and salves, and horses. Land travel was longitudinal and dangerous because of contingent attacks by nomadic peoples. Donkeys were the only transport and throng animals used by the Egyptians until horses were brought to Egypt in Dynasty XVIII (1539-1295 B.C.). Horses were valuable and used only for sitting or for pulling chariots. The domesticated camel was not enclosed in Egypt until after 500 BCE or around 2,520 years ago.” ref

Ancient Egyptian trade

“Ancient Egyptian trade consisted of the gradual creation of land and sea trade routes connecting the ancient Egyptian civilization with the ancient India, Fertile Crescent, Arabia, and Sub-Saharan Africa.” ref

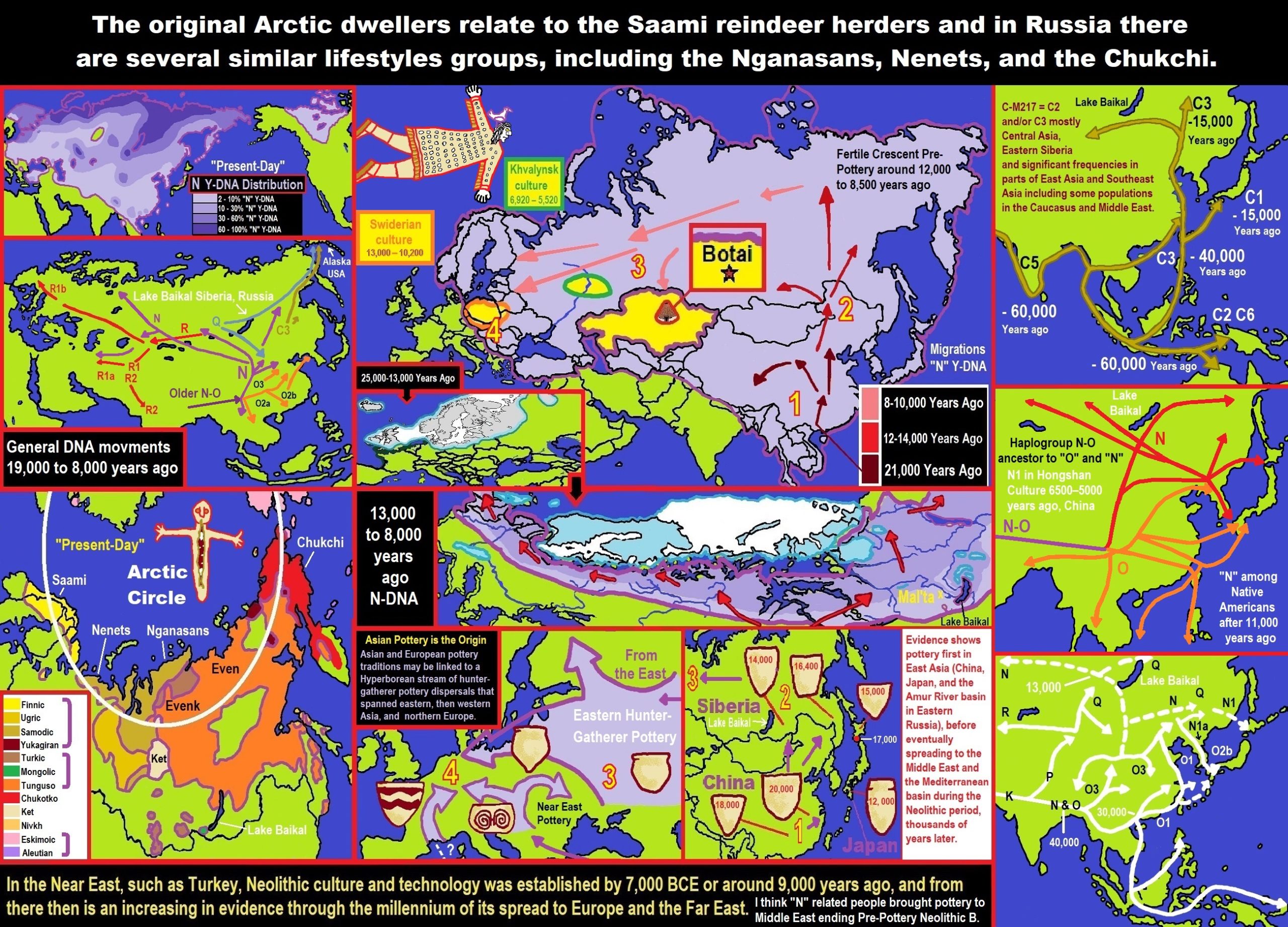

Prehistoric transport and trade

“Epipaleolithic Natufians carried parthenocarpic figs from Africa to the southeastern corner of the Fertile Crescent, c. 10,000 BCE or 12,020 years ago. Later migrations out of the Fertile Crescent would carry early agricultural practices to neighboring regions—westward to Europe and North Africa, northward to Crimea, and eastward to Mongolia. The ancient people of the Sahara imported domesticated animals from Asia between 6000 and 4000 BCE. In Nabta Playa by the end of the 7th millennium BCE, prehistoric Egyptians had imported goats and sheep from Southwest Asia. Foreign artifacts dating to the 5th millennium BCE in the Badarian culture in Egypt indicate contact with distant Syria. In predynastic Egypt, by the beginning of the 4th millennium BCE, ancient Egyptians in Maadi were importing pottery as well as construction ideas from Canaan.” ref

“By the 4th millennium BCE or around 6,020 to 5,020 years ago, shipping was well established, and the donkey and possibly the dromedary had been domesticated. Domestication of the Bactrian camel and use of the horse for transport then followed. Charcoal samples found in the tombs of Nekhen, which were dated to the Naqada I and II periods, have been identified as cedar from Lebanon. Predynastic Egyptians of the Naqada I period also imported obsidian from Ethiopia, used to shape blades and other objects from flakes. The Naqadans traded with Nubia to the south, the oases of the western desert to the west, and the cultures of the eastern Mediterranean to the east. Pottery and other artifacts from the Levant that date to the Naqadan era have been found in ancient Egypt. Egyptian artifacts dating to this era have been found in Canaan and other regions of the Near East, including Tell Brak and Uruk and Susa in Mesopotamia.” ref

By the second half of the 4th millennium BCE, the gemstone lapis lazuli was being traded from its only known source in the ancient world—Badakhshan, in what is now northeastern Afghanistan—as far as Mesopotamia and Egypt. By the 3rd millennium BCE, the lapis lazuli trade was extended to Harappa, Lothal, and Mohenjo-daro in the Indus Valley Civilization of modern-day Pakistan and northwestern India. The Indus Valley was also known as Meluhha, the earliest maritime trading partner of the Sumerians and Akkadians in Mesopotamia. The ancient harbor constructed in Lothal, India, around 2400 BCE or 4,420 years ago is the oldest seafaring harbor known.” ref

Trans-Saharan trade

“The overland route through the Wadi Hammamat from the Nile to the Red Sea was known as early as predynastic times; drawings depicting Egyptian reed boats have been found along the path dating to 4000 BCE or 6,020 years ago. Ancient cities dating to the First Dynasty of Egypt arose along both its Nile and Red Sea junctions, testifying to the route’s ancient popularity. It became a major route from Thebes to the Red Sea port of Elim, where travelers then moved on to either Asia, Arabia, or the Horn of Africa. Records exist documenting knowledge of the route among Senusret I, Seti, Ramesses IV, and also, later, the Roman Empire, especially for mining. The Darb el-Arbain trade route, passing through Kharga in the south and Asyut in the north, was used from as early as the Old Kingdom of Egypt for the transport and trade of gold, ivory, spices, wheat, animals, and plants. Later, Ancient Romans would protect the route by lining it with varied forts and small outposts, some guarding large settlements complete with cultivation. Described by Herodotus as a road “traversed … in forty days,” it became by his time an important land route facilitating trade between Nubia and Egypt. Its maximum extent was northward from Kobbei, 25 miles north of al-Fashir, passing through the desert, through Bir Natrum and Wadi Howar, and ending in Egypt.” ref

Maritime trade

“Shipbuilding was known to the Ancient Egyptians as early as 3000 BCE 5,020 years ago, and perhaps earlier. Ancient Egyptians knew how to assemble planks of wood into a ship hull, with woven straps used to lash the planks together, and reeds or grass stuffed between the planks helped to seal the seams. The Archaeological Institute of America reports that the earliest dated ship—75 feet long, dating to 3000 BCE—may have possibly belonged to Pharaoh Aha. An Egyptian colony stationed in southern Canaan dates to slightly before the First Dynasty. Narmer had Egyptian pottery produced in Canaan—with his name stamped on vessels—and exported back to Egypt, from regions such as Arad, En Besor, Rafiah, and Tel Erani. In 1994, excavators discovered an incised ceramic shard with the serekh sign of Narmer, dating to c. 3000 BCE. Mineralogical studies reveal the shard to be a fragment of a wine jar exported from the Nile valley to Palestine. Due to Egypt’s climate, wine was very rare and nearly impossible to produce within the limits of Egypt. In order to obtain wine, Egyptians had to import it from Greece, Phoenicia, and Palestine. These early friendships played a key role in Egypt’s ability to conduct trade and acquire goods that were needed.” ref

“The Palermo stone mentions King Sneferu of the Fourth Dynasty sending ships to import high-quality cedar from Lebanon. In one scene in the pyramid of Pharaoh Sahure of the Fifth Dynasty, Egyptians are returning with huge cedar trees. Sahure’s name is found stamped on a thin piece of gold on a Lebanon chair, and 5th dynasty cartouches were found in Lebanon stone vessels. Other scenes in his temple depict Syrian bears. The Palermo stone also mentions expeditions to Sinai as well as to the diorite quarries northwest of Abu Simbel. The oldest known expedition to the Land of Punt was organized by Sahure, which apparently yielded a quantity of myrrh, along with malachite and electrum. Around 1950 BCE, in the reign of Mentuhotep III, an officer named Hennu made one or more voyages to Punt. In the 15th century BCE, Nehsi conducted a very famous expedition for Queen Hatshepsut to obtain myrrh; a report of that voyage survives on a relief in Hatshepsut’s funerary temple at Deir el-Bahri. Several of her successors, including Thutmoses III, also organized expeditions to Punt.” ref

Canal construction: Canal of the Pharaohs