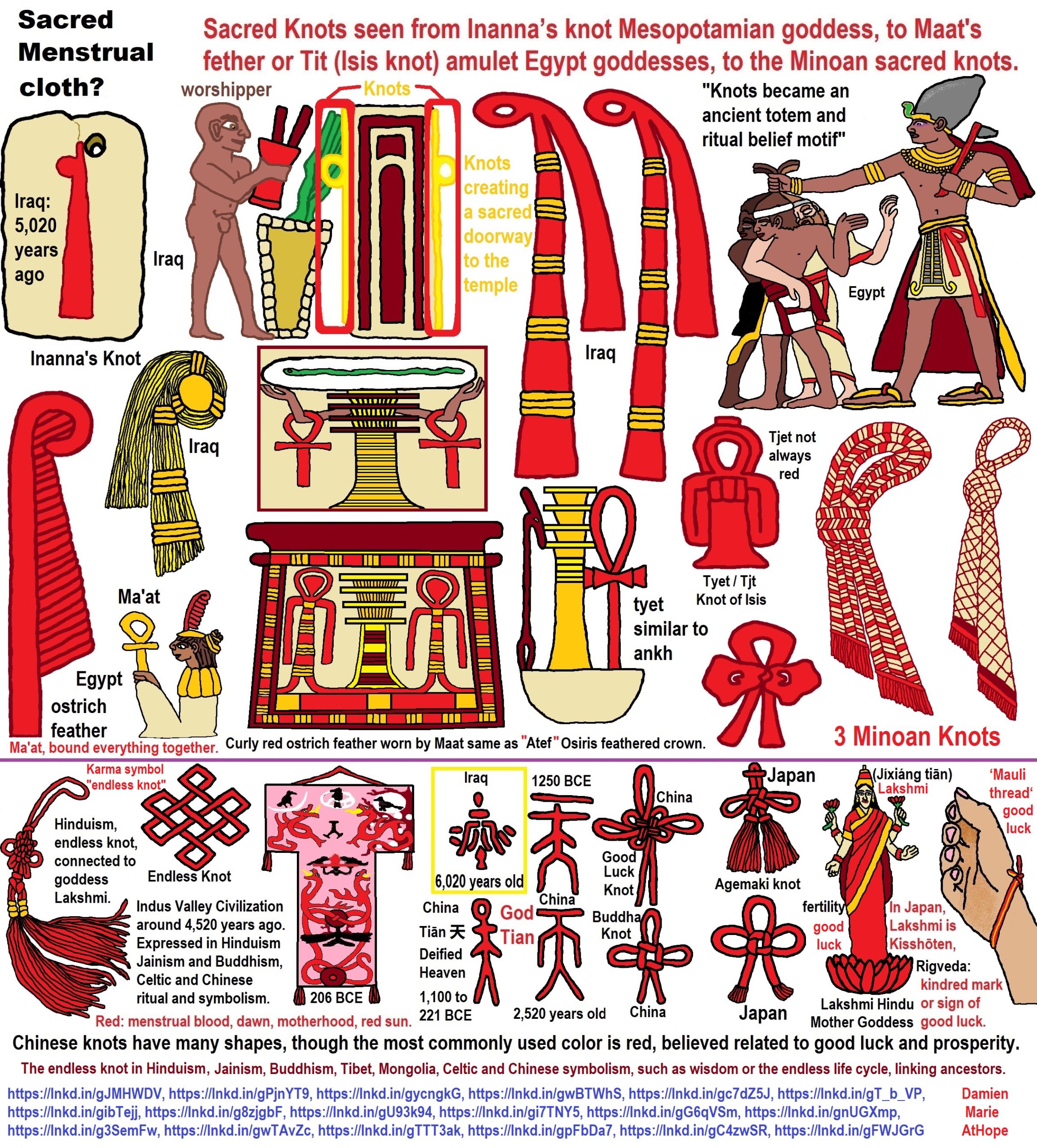

Sacred Menstrual cloth?

Sacred Knots were seen from Inanna’s knot, a Mesopotamian goddess, to Maat’s feather or Tit/Tyet (Isis knot), amulet Egypt goddesses, to the Minoan sacred knots.

“Knots became an ancient totem and ritual belief motif” ref

Inanna’s knot (Symbol of protection, fertility)

“Inanna was an ancient Mesopotamian goddess. She was associated with beauty, love, desire, and fertility. Innana’s cuneiform ideogram was a hook-shaped knot of reeds. The knot represented the doorpost of a storehouse which is a symbol of fertility. Inanna represents the power of creation and divine feminism. The knot is an agricultural symbol for her. It represents the reed boat Inanna built to save humankind after Eniki caused a great flood to try and wipe out humankind. Reeds are a symbol of provision, life, and structure. Reeds were a highly coveted crop and were used daily in Mesopotamian life.” ref

“As early as the Uruk period (c. 4000 – 3100 BCE or 6,020-5,120 years ago), Inanna was already associated with the city of Uruk. During this period, the symbol of a ring-headed doorpost was closely associated with Inanna. The famous Uruk Vase (found in a deposit of cult objects of the Uruk III period) depicts a row of naked men carrying various objects, including bowls, vessels, and baskets of farm products, and bringing sheep and goats to a female figure facing the ruler. The female stands in front of Inanna’s symbol of the two twisted reeds of the doorpost, while the male figure holds a box and stack of bowls, the later cuneiform sign signifying the En, or high priest of the temple.” ref

“Ring posts of Inanna on each side of a temple door, with naked devotee offering libations. Inanna’s symbol is a ring post made of reed, an ubiquitous building material in Sumer. It was often beribboned and positioned at the entrance of temples, and marked the limit between the profane and the sacred realms. The design of the emblem was simplified between 3000-2000 BCE to become the cuneiform logogram for Inanna. Individuals who went against the traditional gender binary were heavily involved in the cult of Inanna.” ref

“Inanna/Ishtar’s most common symbol was the eight-pointed star, though the exact number of points sometimes varies. Six-pointed stars also occur frequently, but their symbolic meaning is unknown. The eight-pointed star seems to have originally borne a general association with the heavens, but, by the Old Babylonian Period (c. 1830 – c. 1531 BCE), it had come to be specifically associated with the planet Venus, with which Ishtar was identified. Starting during this same period, the star of Ishtar was normally enclosed within a circular disc. During later Babylonian times, slaves who worked in Ishtar’s temples were sometimes branded with the seal of the eight-pointed star. On boundary stones and cylinder seals, the eight-pointed star is sometimes shown alongside the crescent moon, which was the symbol of Sin (Sumerian Nanna) and the rayed solar disk, which was a symbol of Shamash (Sumerian Utu).” ref

“Inanna’s cuneiform ideogram was a hook-shaped twisted knot of reeds, representing the doorpost of the storehouse, a common symbol of fertility and plenty. The rosette was another important symbol of Inanna, which continued to be used as a symbol of Ishtar after their syncretism. During the Neo-Assyrian Period (911 – 609 BCE), the rosette may have actually eclipsed the eight-pointed star and become Ishtar’s primary symbol. The temple of Ishtar in the city of Aššur was adorned with numerous rosettes.” ref

“In many respects, the Tyet resembles an Ankh, except that its arms curve down. Its meaning is also reminiscent of the ankh, as it is often translated to mean “welfare” or “life”. The tyet resembles a knot of cloth and may have originally been a bandage used to absorb menstrual blood.” ref

“Early examples of the ankh sign date to the First Dynasty (c. 3,000 to 2,900 BCE). There is little agreement on what physical object the sign originally represented. Many scholars believe the ankh sign is a knot formed of a flexible material such as cloth or reeds, as early versions of the sign show the lower bar of the ankh as two separate lengths of flexible material that seem to correspond to the two ends of the knot. These early versions bear a resemblance to the tyet symbol, a sign that represented the concept of “protection”. For these reasons, the Egyptologists Heinrich Schäfer and Henry Fischer thought the two signs had a common origin, and they regarded the ankh as a knot that was used as an amulet rather than for any practical purpose.” ref

The red looped sash: an enigmatic element of royal regalia in ancient Egypt

“What message is the looped sash worn at the king’s waist meant to convey? Why is it almost always painted red, and what meaning does that facet add to the inherent significance of the sash itself? The first discussing sashes in general and the usage of this regalia element in Ramesside royal tombs and the second focused on the meanings of the color red in ancient Egypt) have suggested a range of possible implications for the red looped sash. The associations of the color with the aggressive Eyes of Re and the morning and evening ordeals of the solar god, when he passed through the dangerous liminal zone, connect this attribute to a powerful form of apotropaic protection.” ref

“The similarity of the looped red sash to the girdle ties worn by goddesses and queens, combined with the connection between both types of ties and the tyet and ankh, suggests that this ritual knot was not only protective but also contained significant creative potential. It is also quite likely that the particular meaning inherent in the red looped sash may vary considerably depending upon the king’s context. There are 72 examples of the looped sash appearing at the memorial temple of Ramses III at Medinet Habu. They appear in all areas of the temple and in a variety of scene types.” ref

Chinese knotting

“Chinese knotting is a decorative handcraft art that began as a form of Chinese folk art in the Tang and Song dynasty (960–1279 CE) in China. The technique was later popularized in the Ming dynasty and subsequently spread to Japan, Korea, Singapore, and other parts of Asia. This art is also called “Chinese traditional decorative knots”. In other cultures, it is known as “decorative knots”. Chinese knots are usually lanyard-type arrangements where two cords enter from the top of the knot and two cords leave from the bottom. The knots are usually double-layered and symmetrical.” ref

“A few examples of prehistoric Chinese knotting exist today. Some of the earliest evidence of knotting have been preserved on bronze vessels of the Warring States period (481–221 BCE), Buddhist carvings of the Northern Dynasties period (317–581), and on silk paintings during the Western Han period (206 BCE–9 CE). Based on the archaeology and literature evidence, before 476 BCE, the knots in China had a specific function: recording and ruling method, similar to the Inca Quipu.” ref

“According to ‘Zhouyi·Xi Ci II’, from the ancient times of Bao-xi ruling era, except the use for fishing, knots were used to record and govern the community. The Eastern Han (25-220 CE) scholar Zheng Xuan annotated The Book of Changes that “Big events were recorded with complicated knots, and small events were recorded with simple knots.” Moreover, the chapter of Tubo (Tibet) in the New Book of Tang recorded that “the government makes the agreement by tie cords due to lack of characters.” ref

“Simultaneously, additional to the use of recording and ruling, knots became an ancient totem and belief motif. In the ancient time, Chinese brought knots a lot of good meanings from the pictograms, quasi-sound, to the totem worship. An example is the double coin knot pattern painting on the T-shape silk banner discovered by archaeologists in Mawangdui tombs (206 BCE – CE 9). The pattern is in the form of intertwined dragons as a double coin knot in the middle of the fabric painting. In the upper part, the fabric painting illustrates the ancient deities Fuxi and Nüwa who are also the initiator of marriage in China that derived the meaning of love for double coin knot in many ancient poems. The tangible evidence has been excavated that 3000 years ago on the Yinxu Oracle bone script, knots recognized as the use of symbol rather than functional use.” ref

“According to Lydia Chen, the earliest tangible evidence of using knots as a decorative motif is on a high stem small square pot in Spring and Autumn Period (770-476 BCE) which now are displayed in Shanxi Museum. However, the archaeology research in the latest decade confirmed that the earliest artifact of the decorative knot in China can trace back 4000 years ago when a three-row rattan knotting of double coin knot was excavated from Liangzhu Ruins.” ref

“With gradually developing, the knots became a distinctive decorative art in China starting from the Spring and Autumn Period to use the ribbon knotting and the decorative knots on the clothing. Written in Zuo zhuan: “The collar has an intersection, and the belt is tied as knots“. It then deriving the Lào zi (Chinese: 络子) culture. The word Lao is the ancient appellation in China of the knot, and it was a tradition to tie a knot at the waist by silk or cotton ribbon.” ref

“The first peak of Lào zi culture was during the Sui Dynasty and Tang Dynasty (581-906 CE), when numbers basic knots, such as Sauvastika knot and Round brocade knot, generated the Lào zi vogue on the garments and the common folk art in the palace and home. Therefore, knots were cherished not only as symbols and tools but also as an essential part of everyday life to decorate and express thoughts and feelings.” ref

“In Tang and Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE), the love-based knot is a unique element as evidenced in many of the poem, novel, and painting. For example, in the memoir, Dongjing Meng Hua Lu written by Meng Yuanlao noticed that in the traditional wedding custom, a Concentric knot (Chinese: 同心结 ) or the knot made like a Concentric knot was necessary to be held by the bride and groom. Other ancient poems mentioned the Concentric knot to portray love such as Luo Binwang‘s poem: Knot the ribbon as the Concentric knot, interlock the love as the clothes. Huang Tingjian‘s poem: We had a time knotting together, loving as the ribbon tied. The most famous poem about the love knot was written by Meng Jiao Knotting love.” ref

“The phenomenon of knot tying continued to steadily evolve over thousands of years with the development of more sophisticated techniques and increasingly intricate woven patterns. During Song and Yuan Dynasties (960-1368), Pan Chang knot, today’s most recognizable Chinese knot started popularly. There are also many artwork evidence showed the knots as clothing decoration in Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), for instance from Tang Yin‘s beautiful paintings, knotting ribbon is clearly shown.” ref

“During the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911) knotting finally broke from its pure folklore status, becoming an acceptable art form in Chinese society and reached the pinnacle of its success. The culture of Lào zi then caught a second peak during the period of Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). During that time, basic knots became widely used to grace objects such as Ruyi, sachets, wallets, fan tassels, spectacle cases, and rosaries, in daily use, and extended the single knot technique into complicated knots. According to the Chinese classical novel Dream of the Red Chamber, Lào zi was developed and spread between the middle and higher hierarchy, making Lào zi was a way to express love and lucky within family members, lovers, and friends in Qing Dynasty. It is also honourable craftsmanship studied and created by maids in the Imperial Palace, written in Gongnv Tan Wang lu that when knotting, the maids amusing for Ci Xi were able to quickly produce objects of various kinds proficient.” ref

knotwork in China

“Historically knotwork is divided into cords and knots. In the dynastic periods, a certain number of craftsmen were stationed in the court and outside the court to produce cords and knots in order to meet the increasing demand for them at various places of the court. Cord, knot, and tassels were made separated and combined later. Around the times of Chinese new year festival, Chinese knot decorations can be seen hanging on walls, doors of homes, and as shop decorations to add some festival feel. Usually, these decorations are in red, which traditional Chinese regard it as “luck.” ref

knotwork in Japan

“The tying knots tradition in Japan is called hanamusubi (hana means “flower” and musubi which means “knot”). It is a legacy of the China’s Tang dynasty when a Japanese Emperor in the 7th century was so impressed by Chinese knots which were used to tie a gift from the Chinese that he started to encourage Japanese people to adopt the tying knots practice. Japanese knots are more austere and formal, simple, structurally looser than the Chinese knots. In function, Japanese knots are more decorative than functional. With a greater emphasis on the braids that are used to create the knots, Japanese knotting tends to focus on individual knots.” ref

The knot called “agemaki” (総角) and auspiciously symbolizes the four directions. It is hung above sumo rings, and was used on samurai armor both for decoration and as a structural component.(Samurai Weapons) For these reasons and its graphical simplicity, it makes a lot of sense as a samurai mon. Slightly more stylized depictions continue to be used in mon today,(Kamon Composition Maker) albeit rarely.” ref

knotwork in Korea

See also: Korean knots

“In Korea, decorative knotwork is known as maedeup (매듭), often called Korean knotwork or Korean knots. Korean knotting techniques is believed to originate from China, but Korean knots evolved into its own rich culture as to design, color, and incorporation of local characteristics. The origins of Maedeup date back to the Three Kingdoms of Korea in the first century CE. Maedeup articles were first used at religious ceremonies. Inspired by Chinese knotwork, a wall painting found in Anak, Hwanghae Province, now in North Korea, dated 357 CE, indicates that the work was flourishing in silk at that time. Decorative cording was used on silk dresses, to ornament swords, to hang personal items from belts for the aristocracy, in rituals, where it continues now in contemporary wedding ceremonies. Korean knotwork is differentiated from Korean embroidery. Maedeup is still a commonly practiced traditional art, especially among the older generations.” ref

“The most basic knot in Maedeup is called the Dorae or double connection knot. The Dorae knot is used at the start and end of most knot projects. There are approximately 33 basic Korean knots which vary according to the region they come from. The Bong Sool tassel is noteworthy as the most representative work familiar to Westerners, and often purchased as souvenirs for macramé-style wall-hangings.” ref

“Chinese knots have many shapes, though the most commonly used color is red, believed related to good luck and prosperity.” ref

Good luck knot

“The Good luck knot can be seen in images of the carved on a statue of the Asian Goddess of Mercy, Guanyin, which was created between CE 557 and 588, and later found in a cave in northwest China.” ref

“Tiān (天) is one of the oldest Chinese terms for heaven and a key concept in Chinese mythology, philosophy, and religion. During the Shang dynasty (17th―11th century BCE), the Chinese referred to their supreme god as Shàngdì (上帝, “Lord on High”) or Dì (帝,”Lord”). During the following Zhou dynasty, Tiān became synonymous with this figure. Before the 20th century, Heaven worship was an orthodox state religion of China.” ref

“In Taoism and Confucianism, Tiān (the celestial aspect of the cosmos, often translated as “Heaven“) is mentioned in relationship to its complementary aspect of Dì (地, often translated as “Earth“). These two aspects of Daoist cosmology are representative of the dualistic nature of Taoism. They are thought to maintain the two poles of the Three Realms (三界) of reality, with the middle realm occupied by Humanity (人, Rén), and the lower world occupied by demons; (魔, Mó) and “ghosts,” the damned, specifically (鬼, Guǐ).” ref

“The Modern Standard Chinese pronunciation of 天 “sky, heaven; heavenly deity, god” is tiān in level first tone. The character is read as Cantonese tin1; Taiwanese thiN1 or thian1; Vietnamese thiên; Korean cheon or ch’ŏn (천); and Japanese ten in On’yomi (borrowed Chinese reading) and ama- (bound), ame (free), or sora in Kun’yomi (native Japanese reading).” ref

“Tiān 天 reconstructions in Middle Chinese (ca. 6th–10th centuries CE) include t’ien (Bernhard Karlgren), t’iɛn (Zhou Fagao), tʰɛn > tʰian (Edwin G. Pulleyblank), and then (William H. Baxter, Baxter & Sagart). Reconstructions in Old Chinese (ca. 6th–3rd centuries BCE) include *t’ien (Karlgren), *t’en (Zhou), *hlin (Baxter), *thîn (Schuessler), and *l̥ˤin (Baxter & Sagart). For the etymology of tiān, a suggested link with the Mongolian word tengri “sky, heaven, heavenly deity” or the Tibeto-Burman words taleŋ (Adi) and tǎ-lyaŋ (Lepcha), both meaning “sky”. A suggested link is likely in the connection between Chinese tiān 天, diān 巔 “summit, mountaintop”, and diān 顛 “summit, top of the head, forehead”, which have cognates such as Zemeic Naga tiŋ “sky”.” ref

“Tengri, the Turkic-Mongolic sky God, Tengri is one of the names for the primary chief deity of the early Turkic and Mongolic peoples. Worship of Tengri is Tengrism. The core beings in Tengrism are the Heavenly-Father (Tengri/Tenger Etseg) and the Earth Mother (Eje/Gazar Eej). It involves shamanism, animism, totemism, and ancestor worship.” ref

“The oldest form of the name is recorded in Chinese annals from the 4th century BC, describing the beliefs of the Xiongnu. It takes the form 撑犁/Cheng-li, which is hypothesized to be a Chinese transcription of Tängri. (The Proto-Turkic form of the word has been reconstructed as *Teŋri or *Taŋrɨ.) Alternatively, a reconstructed Altaic etymology from *T`aŋgiri (“oath” or “god”) would emphasize the god’s divinity rather than his domain over the sky.” ref

“The Turkic form, Tengri, is attested in the 8th century Orkhon inscriptions as the Old Turkic form ???????????????? Teŋri. In modern Turkish, the derived word “Tanrı” is used as the generic word for “god”, or for the Abrahamic God, and is used today by Turkish people to refer to any god. The supreme deity of the traditional religion of the Chuvash is Tură. Other reflexes of the name in modern languages include Mongolian: Тэнгэр (“sky”), Bulgarian: Тангра, Azerbaijani: Tanrı.” ref

“Earlier, the Chinese word for “sky” 天 (Mandarin: tiān < Old Chinese *thīn or *thîn) has been suggested to be related to Tengri, possibly a loan into Chinese from a prehistoric Central Asian language. However, this proposal is unlikely in light of recent reconstructions of the Old Chinese pronunciation of the character “天”, such as *qʰl’iːn (Zhengzhang) or *l̥ˤi[n] (Baxter-Sagart),, which propose for 天 a voiceless lateral onset, either a cluster or single consonant, respectively. Baxter & Sagart (2014:113-114) pointed to attested dialectal differences in Eastern Han Chinese, the use of 天 as a phonetic component in phono-semantic compound Chinese characters, and the choice of 天 to transcribe foreign syllables, all of which prompted them to conclude that, around 200 CE, 天’s onset had two pronunciations: coronal *tʰ & dorsal *x, both of which likely originated from an earlier voiceless lateral *l̥ˤ.” ref

Confucianism and Tiān 天

“Confucianism, also known as Ruism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China. Variously described as tradition, a philosophy, a religion, a humanistic or rationalistic religion, a way of governing, or simply a way of life, Confucianism developed from what was later called the Hundred Schools of Thought from the teachings of the Chinese philosopher Confucius (551–479 BCE). Confucius considered himself a transmitter of cultural values inherited from the Xia (c. 2070–1600 BCE), Shang (c. 1600–1046 BCE), and Zhou dynasties (c. 1046–256 BCE).” ref

“Confucianism transcends the dichotomy between religion and humanism, considering the ordinary activities of human life—and especially human relationships—as a manifestation of the sacred, because they are the expression of humanity’s moral nature (xìng 性), which has a transcendent anchorage in Heaven (Tiān 天). While Tiān has some characteristics that overlap the category of godhead, it is primarily an impersonal absolute principle, like the Dào (道) or the Brahman. Confucianism focuses on the practical order that is given by a this-worldly awareness of the Tiān. Confucian liturgy (called 儒 rú, or sometimes simplified Chinese: 正统; traditional Chinese: 正統; pinyin: zhèngtǒng, meaning ‘orthopraxy‘) led by Confucian priests or “sages of rites” (礼生; 禮生; lǐshēng) to worship the gods in public and ancestral Chinese temples is preferred on certain occasions, by Confucian religious groups and for civil religious rites, over Taoist or popular ritual.” ref

“Olden versions of the grapheme 儒 rú, meaning “scholar”, “refined one”, “Confucian”. It is composed of 人 rén (“man”) and 需 xū (“to await”), itself composed of 雨 yǔ (“rain”, “instruction”) and 而 ér (“sky”), graphically a “man under the rain”. Its full meaning is “man receiving instruction from Heaven”. According to Kang Youwei, Hu Shih, and Yao Xinzhong, they were the official shaman-priests (wu) experts in rites and astronomy of the Shang, and later Zhou, dynasty.” ref

Red Mystic Knot

“This is a classic Feng Shui protection symbol, and the mystic knot is known by other names: the lucky diagram, the eternal knot, the endless knot, the glorious knot, and so forth. It is also called shrivasta in Sanskrit. The mystic knot originated in India as an emblem of Lakshmi on Vishnu’s chest. Lakshmi is the Vedic goddess of wealth, so this symbol brings abundance and good fortune. This mystic knot is a symbol that is said to swallow its own tail, and symbolizes the eternal nature of wisdom and compassion.” ref

“In Buddhism, the mystic knot is the sixth of the eight auspicious symbols. The eight together symbolize offerings that are said to have been presented to the Buddha when he attained enlightenment. The other seven offerings are the parasol, treasure vase, lotus flower, conch shell, victory banner, and finally a golden wheel. Asian culture brings the mystic knot into many of their decorative charms. An endless knot of red cord is often paired with another Asian symbol. The color of red is the most auspicious color in feng shui.” ref

Karma and the Endless knot

“Karma symbols such as the endless knot are common cultural motifs in Asia. Endless knots symbolize interlinking of cause and effect, a Karmic cycle that continues eternally. The endless knot is visible in the center of the prayer wheel.” ref

“Karma means action, work, or deed. The term also refers to the spiritual principle of cause and effect, often descriptively called the principle of karma, wherein intent and actions of an individual (cause) influence the future of that individual (effect): good intent and good deeds contribute to good karma and happier rebirths, while bad intent and bad deeds contribute to bad karma and bad rebirths.” ref

“The philosophy of karma is closely associated with the idea of rebirth in many schools of Indian religions (particularly Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism), as well as Taoism. In these schools, karma in the present affects one’s future in the current life, as well as the nature and quality of future lives—one’s saṃsāra. This idea is also commonly implemented in Western popular culture, in which the events which happen after a person’s actions may be considered natural consequences.” ref

“Difficulty in arriving at a definition of karma arises because of the diversity of views among the schools of Hinduism; some, for example, consider karma and rebirth linked and simultaneously essential, some consider karma but not rebirth to be essential, and a few discuss and conclude karma and rebirth to be flawed fiction. Buddhism and Jainism have their own karma precepts. Thus, karma has not one, but multiple definitions and different meanings. It is a concept whose meaning, importance, and scope varies between the various traditions that originated in India, and various schools in each of these traditions. Wendy O’Flaherty claims that, furthermore, there is an ongoing debate regarding whether karma is a theory, a model, a paradigm, a metaphor, or a metaphysical stance.” ref

“The third common theme of karma theories is the concept of reincarnation or the cycle of rebirths (saṃsāra). Rebirth is a fundamental concept of Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism. Rebirth, or saṃsāra, is the concept that all life forms go through a cycle of reincarnation, that is, a series of births and rebirths. The rebirths and consequent life may be in a different realm, condition, or form. The karma theories suggest that the realm, condition, and form depends on the quality and quantity of karma. In schools that believe in rebirth, every living being’s soul transmigrates (recycles) after death, carrying the seeds of Karmic impulses from life just completed, into another life and lifetime of karmas. This cycle continues indefinitely, except for those who consciously break this cycle by reaching moksa. Those who break the cycle reach the realm of gods, those who don’t continue in the cycle.'” ref

“The theory of ‘karma and rebirth’ raises numerous questions—such as how, when, and why did the cycle start in the first place, what is the relative Karmic merit of one karma versus another and why, and what evidence is there that rebirth actually happens, among others. Various schools of Hinduism realized these difficulties, debated their own formulations, some reaching what they considered as internally consistent theories, while other schools modified and de-emphasized it, while a few schools in Hinduism such as Charvakas (or Lokayata) abandoned the theory of ‘karma and rebirth’ altogether. Schools of Buddhism consider karma-rebirth cycle as integral to their theories of soteriology.” ref

“The Vedic Sanskrit word kárman- (nominative kárma) means ‘work’ or ‘deed’, often used in the context of Srauta rituals. In the Rigveda, the word occurs some 40 times. In Satapatha Brahmana 1.7.1.5, sacrifice is declared as the “greatest” of works; Satapatha Brahmana 10.1.4.1 associates the potential of becoming immortal (amara) with the karma of the agnicayana sacrifice. The earliest clear discussion of the karma doctrine is in the Upanishads. For example, causality and ethicization is stated in Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad 3.2.13: Truly, one becomes good through good deeds, and evil through evil deeds.” ref

“Some authors state that the samsara (transmigration) and karma doctrine may be non-Vedic, and the ideas may have developed in the “shramana” traditions that preceded Buddhism and Jainism. Others state that some of the complex ideas of the ancient emerging theory of karma flowed from Vedic thinkers to Buddhist and Jain thinkers. The mutual influences between the traditions is unclear, and likely co-developed.” ref

“Many philosophical debates surrounding the concept are shared by the Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist traditions, and the early developments in each tradition incorporated different novel ideas. For example, Buddhists allowed karma transfer from one person to another and sraddha rites, but had difficulty defending the rationale. In contrast, Hindu schools and Jainism would not allow the possibility of karma transfer.” ref

“The endless knot or eternal knot was seen in the Indus Valley Civilization around 4,520 years ago. Expressed in Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism, Celtic, and Chinese as ritual and symbolism.” ref

“The endless knot or eternal knot is a symbolic knot and one of the Eight Auspicious Symbols. It is an important symbol in Hinduism Jainism and Buddhism. It is an important cultural marker in places significantly influenced by Tibetan Buddhism such as Tibet, Mongolia, Tuva, Kalmykia, and Buryatia. It is also found in Celtic and Chinese symbolism.” ref

“In Hinduism, Srivatsa is mentioned as connected to Shree .i.e, the goddess Lakshmi. It is a mark on the chest of Vishnu where his consort Lakshmi resides. According to the Vishnu purana, the tenth avatar of Vishnu, Kalki, will bear the Shrivatsa mark on his chest. It is one of the names of Vishnu in the Vishnu Sahasranamam. Srivatsa is considered to be an auspicious symbol in Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Tamil Nadu, and Karnataka. In Jainism it is one of the eight auspicious items, an asthamangala, however, found only in the Svetambara sect. It is often found marking the chests of the 24 Saints, the tirthankaras. It is more commonly referred to as the Shrivatsa.” ref

“Lakshmi, lit. ‘she who leads to one’s goal’), also known as Shri is one of the principal goddesses in Hinduism. She is the goddess of wealth, fortune, power, health, love, beauty, joy, and prosperity, and associated with Maya (“Illusion”). Along with Parvati and Saraswati, she forms the trinity of Hindu goddesses (Tridevi).” ref

“Within the Goddess-oriented Shaktism, Lakshmi is venerated as a principal aspect of the Mother goddess. Lakshmi is both the wife and divine energy (shakti) of the Hindu god Vishnu, the Supreme Being of Vaishnavism; she is also the Supreme Goddess in the sect and assists Vishnu to create, protect and transform the universe. Whenever Vishnu descended on the earth as an avatar, Lakshmi accompanied him as consort, for example as Sita and Radha or Rukmini as consorts of Vishnu’s avatars Rama and Krishna respectively. The eight prominent manifestations of Lakshmi, the Ashtalakshmi symbolize the eight sources of wealth.” ref

“Lakshmi is depicted in Indian art as elegantly dressed, in both red and golden color, shown as a woman standing or sitting in padmasana on a lotus throne, while holding a lotus in her hand, symbolizing fortune, self-knowledge, and spiritual liberation. Her iconography shows her with four hands, which represent the four aspects of human life important to Hindu culture: dharma, kāma, artha, and moksha. Archaeological discoveries and ancient coins suggest the recognition and reverence for Lakshmi existing by 1,000 BCE or 3,020 years ago.” ref

“Many Hindus worship Lakshmi on Diwali, the festival of lights. It is celebrated in autumn, typically October or November every year. The festival spiritually signifies the victory of light over darkness, knowledge over ignorance, good over evil, and hope over despair. This festival dedicated to Lakshmi is considered by Hindus to be one of the most important and joyous festivals of the year.” ref

“Before Diwali night, people clean, renovate and decorate their homes and offices. On Diwali night, Hindus dress up in new clothes or their best outfits, light up diyas (lamps and candles) inside and outside their home, and participate in family puja (prayers) typically to Lakshmi. After puja, fireworks follow, then a family feast including mithai (sweets), and an exchange of gifts between family members and close friends. Diwali also marks a major shopping period, since Lakshmi connotes auspiciousness, wealth, and prosperity.” ref

“Gaja Lakshmi Puja is another autumn festival celebrated on Sharad Purnima in many parts of India on the full-moon day in the month of Ashvin (October). Sharad Purnima, also called Kojaagari Purnima or Kuanr Purnima, is a harvest festival marking the end of monsoon season. There is a traditional celebration of the moon called the Kaumudi celebration, Kaumudi meaning moonlight. On Sharad Purnima night, goddess Lakshmi is thanked and worshipped for the harvests. Vaibhav Lakshmi Vrata is observed on Friday for prosperity.” ref

“The octagram, or eight-pointed star polygon (Schläfli {8/2} or 2{4}), is used in Hinduism to symbolize Ashtalakshmi, the eight forms of wealth. The rise in popularity of the Ashta Lakshmi can be linked with the rising popularity of the Ashta Lakshmi Stotram.” ref

“Around the 1970s, a leading Sri Vaishnava theologian, Sri U. Ve. Vidvan Mukkur Srinivasavaradacariyar Svamikal, published a poem called Ashta Lakshmi Stotram dedicated to the eight Lakshmis. Narayanan comments, “Although these attributes (which represent the wealths bestowed by the Ashta Lakshmi) of Sri (Lakshmi) can be found in traditional literature, the emergence of these eight (Ashta Lakshmi goddesses) in precisely this combination is, as far as I can discern, new.” ref

“The Ashta Lakshmi are now widely worshipped both by Sri Vaishnava and other Hindu communities in South India. Occasionally, the Ashta Lakshmi are depicted together in shrines or in “framing pictures” within an overall design and are worshipped by votaries of Lakshmi who worship her in her various manifestations. In addition to emergence of Ashta Lakshmi temples since the 1970s, traditional silver articles used in home worship as well as decorative jars (‘Kumbha’) now appear with the Ashta Lakshmi group molded on their sides. Books, popular prayers manuals, pamphlets sold outside temples in South India; ritual worship, and “a burgeoning audiocassette market” are also popularizing these eight forms of Lakshmi.” ref

Tit/Tyet (Isis knot) amulet: Blood was life, and death, the trinity is bull cat and woman, or girl, mother, old woman. Blood is the meaning of sacred knots and that Ankh symbol, all, is related to female “sensitive area” blood, like that one worn around the neck of Ancient Egyptian Kings in battle as protection.” ref

“The Tit/Tyet (Isis knot) resembles a knot of cloth and may have originally been a bandage used to absorb menstrual blood. The tyet (Ancient Egyptian: tjt), sometimes called the knot of Isis or girdle of Isis, is an ancient Egyptian symbol that came to be connected with the goddess Isis. Its hieroglyphic depiction is cataloged as V39 in Gardiner’s sign list. And, the sacred knots are in Crete too, influenced by Egyptian trade.” ref

“The Tit/Tyet (Isis knot) symbol illustrates a knotted piece of cloth whose early meaning is unknown, but in the New Kingdom, it was clearly associated with the goddess Isis, the great magician, and wife of Osiris. By this time, the tit was also associated with the blood of Isis. The tit sign was considered a potent symbol of protection in the afterlife and the Book of the Dead specifies that the tit be made of blood-red stone, like this example, and placed at the deceased’s neck. Knots were widely used as amulets because the Egyptians believed they bound and released magic.” ref

Djed

“The djed (“pillar”) is one of the more ancient and commonly found symbols in ancient Egyptian religion. It is a pillar-like symbol in Egyptian hieroglyphs representing stability. It is associated with the creator god Ptah and Osiris, the Egyptian god of the afterlife, the underworld, and the dead. Isis asked for the pillar in the palace hall, and upon being granted it, extracted the coffin from the pillar. She then consecrated the pillar, anointing it with myrrh and wrapping it in linen. This pillar came to be known as the pillar of djed.” ref

The djed may originally have been a fertility cult-related pillar made from reeds or sheaves or a totem from which sheaves of grain were suspended or grain was piled around. Erich Neumann remarks that the djed pillar is a tree fetish, which is significant considering that Egypt was primarily treeless. He indicates that the myth may represent the importance of the importation of trees by Egypt from Syria. The djed came to be associated with Seker, the falcon god of the Memphite Necropolis, then with Ptah, the Memphite patron god of craftsmen. Ptah was often referred to as “the noble djed“, and carried a scepter that was a combination of the djed symbol and the ankh, the symbol of life. Ptah gradually came to be assimilated into Osiris. By the time of the New Kingdom, the djed was firmly associated with Osiris.” ref

The djed hieroglyph was a pillar-like symbol that represented stability. It was also sometimes used to represent Osiris himself, often combined “with a pair of eyes between the crossbars and holding the crook and flail.” The djed hieroglyph is often found together with the tyet (also known as Isis knot) hieroglyph, which is translated as life or welfare. The djed and the tiet used together may depict the duality of life. The tyet hieroglyph may have become associated with Isis because of its frequent pairing with the djed.” ref

The Djed Parallels in other cultures

“Parallels have also been drawn between the djed pillar and various items in other cultures. Sidney Smith in 1922, first suggested a parallel with the Assyrian “sacred tree” when he drew attention to the presence of the upper four bands of the djed pillar and the bands that are present in the center of the vertical portion of the tree. He also proposed a common origin between Osiris and the Assyrian god Assur with whom he said, the sacred tree might be associated. Cohen and Kangas suggest that the tree is probably associated with the Sumerian god of male fertility, Enki and that for both Osiris and Enki, an erect pole or polelike symbol stands beneath a celestial symbol. They also point out that the Assyrian king is depicted in proximity to the sacred tree, which is similar to the depiction of the pharaoh in the raising of the djed ceremony. Additionally, the sacred tree and the Assyrian winged disk, which are generally depicted separately, are combined in certain designs, similar to the djed pillar which is sometimes surmounted with a solar disk. Katherine Harper and Robert Brown also discuss a possible strong link between the djed column and the concept of kundalini in yoga.” ref

Ankh

“The ankh or key of life is an ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic symbol that was most commonly used in writing and in Egyptian art to represent the word for “life” and, by extension, as a symbol of life itself. The ankh has a cross shape but with a teardrop-shaped loop in place of an upper bar. The origins of the symbol are not known, although many hypotheses have been proposed. It was used in writing as a triliteral sign, representing a sequence of three consonants, Ꜥ-n-ḫ. This sequence was found in several Egyptian words, including the words meaning “mirror”, “floral bouquet”, and “life.” ref

“In art, the symbol often appeared as a physical object representing either life or substances such as air or water that are related to it. It was especially commonly held in the hands of ancient Egyptian deities, or being given by them to the pharaoh, to represent their power to sustain life and to revive human souls in the afterlife. The ankh was one of the most common decorative motifs in ancient Egypt and was also used decoratively by neighboring cultures.” ref

“Early examples of the ankh sign date to the First Dynasty (c. 30th to 29th century BCE). There is little agreement on what physical object the sign originally represented. Many scholars believe the sign is a knot formed of a flexible material such as cloth or reeds, as early versions of the sign show the lower bar of the ankh as two separate lengths of flexible material that seem to correspond to the two ends of the knot. These early versions bear a resemblance to the tyet symbol, a sign that represented the concept of “protection”. For these reasons, the Egyptologists Heinrich Schäfer and Henry Fischer thought the two signs had a common origin, and they regarded the ankh as a knot that was used as an amulet rather than for any practical purpose.” ref

“Hieroglyphic writing used pictorial signs to represent sounds, so that, for example, the hieroglyph for a house could represent the sounds p-r, which were found in the Egyptian word for “house”. This practice, known as the rebus principle, allowed the Egyptians to write the words for things that could not be pictured, such as abstract concepts. Gardiner believed the ankh originated in this way. He pointed out that the sandal-strap illustrations on Middle Kingdom coffins resemble the hieroglyph, and he argued that the sign originally represented knots like these and came to be used in writing all other words that contained the consonants Ꜥ-n-ḫ. Gardiner’s list of hieroglyphic signs labels the ankh as S34, placing it within the category for items of clothing and just after S33, the hieroglyph for a sandal. Gardiner’s hypothesis is still current; James P. Allen, in an introductory book on the Egyptian language published in 2014, assumes that the sign originally meant “sandal strap” and uses it as an example of the rebus principle in hieroglyphic writing. Various authors have argued that the sign originally represented something other than a knot.” ref

“In Egyptian belief, life was a force that circulated throughout the world. Individual living things, including humans, were manifestations of this force and fundamentally tied to it. Life came into existence at the creation of the world, and cyclical events like the rising and setting of the sun were thought of as reenactments of the original events of creation that maintained and renewed life in the cosmos. Sustaining life was thus the central function of the deities who governed these natural cycles. Therefore, the ankh was frequently depicted being held in gods’ hands, representing their life-giving power.” ref

“The Egyptians also believed that when they died, their individual lives could be renewed in the same manner as life in general. For this reason, the gods were often depicted in tombs giving ankh signs to humans, usually the pharaoh. As the sign represented the power to bestow life, humans other than the pharaoh were rarely shown receiving or holding the ankh before the end of the Middle Kingdom, although this convention weakened thereafter. The pharaoh to some extent represented Egypt as a whole, so by giving the sign to him, the gods granted life to the entire nation.” ref

“By extension of the concept of “life”, the ankh could signify air or water. In artwork, gods hold the ankh up to the nose of the king: offering him the breath of life. Hand fans were another symbol of air in Egyptian iconography, and the human servants who normally carried fans behind the king were sometimes replaced in artwork by personified ankh signs with arms. In scenes of ritual purification, in which water was poured over the king or a deceased commoner, the zigzag lines that normally represented water could be replaced by chains of ankh signs.” ref

“The ankh may have been used decoratively more than any other hieroglyphic sign. Mirrors, mirror cases, and floral bouquets were made in its shape, given that the sign was used in writing the name of each of these objects. Some other objects, such as libation vessels and sistra, were also shaped like the sign. The sign appeared very commonly in the decoration of architectural forms such as the walls and shrines within temples.” ref

“In contexts such as these, the sign often appeared together with the was and djed signs, which together signified “life, dominion, and stability”. In some decorative friezes in temples, all three signs, or the ankh and was alone, were positioned above the hieroglyph for a basket that represented the word “all”: “all life and power” or “all life, power, and stability”. Some deities, such as Ptah and Osiris, could be depicted holding a was scepter that incorporated elements of the ankh and djed. Amulets made in the shape of hieroglyphic signs were meant to impart to the wearer the qualities represented by the sign.” ref

“The Egyptians wore amulets in daily life as well as placing them in tombs to ensure the well-being of the deceased in the afterlife. Ankh-shaped amulets first appeared late in the Old Kingdom (c. 2700 to 2200 BCE) and continued to be used into the late first millennium BCE, yet they were rare, despite the importance of the symbol. Amulets shaped like a composite sign that incorporated the ankh, was, and djed were more widespread. Ankh signs in two-dimensional art were typically painted blue or black. The earliest ankh amulets were often made of gold or electrum, a gold and silver alloy. Egyptian faience, a ceramic that was usually blue or green, was the most common material for ankh amulets in later times, perhaps because its color represented life and regeneration.” ref

Minoan Sacral Knots

“Fragment of a mural depicting a “sacral knot”, a religious apotropaic symbol. From Nirou Chani, (1600-1450 BCE) An ivory inlay in the shape of a sacral knot, and a fragment from a stone lid depicting a knot (in a group of finds from Knossos, Zakros, and Hagia Triada). The famous Minoan mural fragment “La Parisienne” possibly wears the same knot.” ref

“The Knossos figurines, both significantly incomplete, date to near the end of the neo-palatial period of Minoan civilization, around 1600 BCE. It was Evans who called the larger of his pair of figurines a “Snake Goddess”, the smaller a “Snake Priestess”; since then, it has been debated whether Evans was right, or whether both figurines depict priestesses, or both depict the same deity or distinct deities.” ref

“The combination of elaborate clothes that leave the breasts completely bare, and “snake-wrangling”, attracted considerable publicity, not to mention various fakes, and the smaller figure, in particular, remains a popular icon for Minoan art and religion, now also generally referred to as a “Snake Goddess”. But archaeologists have found few comparable images, and a snake goddess plays little part in current thinking about the cloudy topic of Minoan religion.” ref

“The two Knossos snake goddess figurines were found by Evans’s excavators in one of a group of stone-lined and lidded cists Evans called the “Temple Repositories”, since they contained a variety of objects that were presumably no longer required for use, perhaps after a fire. The figurines are made of faience, a crushed quartz-paste material which after firing gives a true vitreous finish with bright colors and a lustrous sheen. This material symbolized the renewal of life in old Egypt, therefore it was used in the funeral cult and in the sanctuaries.” ref

“The larger of these figures has snakes crawling over her arms and up to her “tall cylindrical crown”, at the top of which a snake’s head rears up. The figure lacked the body below the waist, one arm, and part of the crown. She has prominent bare breasts, with what seems to be one or more snakes winding round them. Because of the missing pieces, it is not clear if it is one or more snakes around her arms. Her dress includes a thick belt with a “sacred knot.” ref

“The Minoan sacral knot seems to have had a life of its own separate from being worn (always by women in the examples we have found so far) since it was often depicted hovering by itself in midair. Several seal rings show one or two sacral knots hanging near a bull or a stag. The images of the knot with the bulls include illustrations of men in what might be depictions of the famed bull-leaping activity, which was probably done in a sacred or ritual context.” ref

“Perhaps in these cases, the knot symbolizes the presence of the goddess who was invoked during the bull-leaping rituals. This would identify the knot with the Moon-Cow aspect of the Minoan goddess, the partner of the Moon-Bull (Minotauros). The Moon-Cow is known in later mythology as Pasiphae or Europa, but we don’t know what the Minoans called her or her consort in their native language. I find it interesting that the Minoan sacral knot is shown in pairs in several instances. I have to wonder about the significance of that depiction. Is it just for emphasis or does it have some sort of specific meaning? Perhaps the goddess the knot symbolizes had two faces or functions in these rituals (Life and death? Death and rebirth? Something else entirely?).” ref

Thread of Mauli

“The religious significance of tying Mauli thread, in Hinduism, every cultural fest is followed by tying of Mauli. According to scriptures, putting Mauli thread on hand’s wrist makes you ideal for the blessing of Tridev ‘Bramha, Vishnu, and Mahesh and the three goddesses. It also gifts you proper health. According to legends, the ritual of tying Mauli was started by Goddess Lakshmi and King Bali. It is a simple thread but makes it eligible to get the blessings of Almighty God.” ref

“The correct way of putting Mauli: According to Hindu scriptures, Men should tie mauli in right hand and unmarried girls should tie mauli on their left hand. While tying Mauli your fist should be tightening and the other hand should be on your head.” ref

Kautuka

“A Kautuka is a red-yellow colored ritual protection thread, sometimes with knots or amulets, found on the Indian subcontinent. It is sometimes called as kalava, mauli, moui, raksasutra, pratisara (in North India), kaapu, kayiru or charandu (in South India). A kautuka is a woven thread, cord, or ribbon, states the Indologist Jan Gonda, which is traditionally believed to be protective or apotropaeic. The pratisara and kautuka in a ritual thread context appear in the Vedic text Atharvaveda Samhita section 2.11. An even earlier reference to ritual “red and black” colored thread with a dual function, one of driving away “fiends” and the other “binding of bonds” between the bride and the groom by one’s relatives appears in hymn 10.85.28 of the Rigveda, states Gonda.” ref

“A pratisara or kautuka serves a ritual role in Hinduism, and is tied by the priest or oldest family member on the wrist of a devotee, patron, loved one, or around items such as kalasha or lota (vessel) for a rite-of-passage or yajna ritual. It is the woven thread in the poja thali. It is typically colored a shade of red, sometimes orange, saffron, yellow, or is a mixture of these colors. However, it may also be white or wreathe or just stalks of a grass of the types found in other cultures and believed to offer similar apotropaic value. It is typically tied to the wrist or worn like a necklace, but occasionally it may be worn in conjunction with a headband or turban-like gear. Similar threads are tied to various items and the neck of vessels during a Hindu puja ceremony.” ref

“The ritual thread is traditionally worn on the right wrist or arm by the males and on the left by the females. This thread also plays a role in certain familial and marital ceremonies. For example, a red or golden or similarly colored thread is offered by a sister to her brother at Raksha Bandhan. This thread, states the Indologist Jack Goody, is at once a “protection against misfortune for the brother, a symbol of mutual dependence between the sister and brother, and a mark of mutual respect”. In a Hindu marriage ceremony, this thread is referred to as kautuka in ancient Sanskrit texts. It is tied to both the bride and the groom, as well as household items such as grinding stone, clay pots, and fertility symbols. In South India, it is the priest who ties the kaapu (kautuka) on the groom’s wrist, while the groom ties the colored thread on the bride’s wrist as a part of the wedding rituals.” ref

“In regional Vaishnavism tradition of Hinduism such as those found in Maharashtra, the red-colored thread symbolizes Vishnu for men, and Lakshmi for women, states the Indologist Gudrun Bühnemann. The string typically has no knots or fourteen knots and it is tied to the wrist of the worshipper or garlanded as a necklace. If worn by the wife, it is without knots and is identified with Lakshmi-doraka or Anantī. To the husband, the thread has knots and it symbolizes Ananta (Vishnu).” ref

“The Shaivism tradition of Hinduism similarly deploys auspicious kautuka (pratisara) threads in puja and consecration rituals. For example, during temple construction and worship rituals, the shilpa Sanskrit texts recommend that the first bricks and the Shiva linga be ritually tied with red-, golden-, saffron- or similarly hued threads. The Shaiva temple architecture texts generally use the term kautuka for this auspicious thread, while Vaishnava texts refer to it as pratisara.” ref

“The raksasutra (kautuka, pratisara) is also a part of festive ceremonies and processions, where the protective thread is tied to the wrist of festival icons and human participants. It is mentioned in verses 27.206-207 of the Ajitagama, states the Indologist Richard Davis. Some Hindu texts mention these threads to be a part of the rakshabandhana rite for a temple procession and festive celebrations, recommending woven gold, silver, or cotton threads, with some texts specifying the number of threads in a kautuka.” ref

“In Jainism, protective threads with amulets are called raksapotli. Typically red and worn of the wrist, they may sometimes come with a rolled up red fabric that has been blessed by a Jain mendicant using mantras, according to the Indologist M. Whitney Kelting. If worn on the neck, states Kelting, the Jain tradition names the protective amulet after the Jain deity whose blessing is believed to be tied into the knot. The ritual significance of a protective thread between the sisters and brothers as well as during Jain weddings is similar to those in Hinduism.” ref

Bloodletting in Mesoamerica

“Bloodletting was the ritualized self-cutting or piercing of an individual’s body that served a number of ideological and cultural functions within ancient Mesoamerican societies, in particular the Maya. When performed by ruling elites, the act of bloodletting was crucial to the maintenance of sociocultural and political structure. Bound within the Mesoamerican belief systems, bloodletting was used as a tool to legitimize the ruling lineage‘s socio-political position, and when enacted, was important to the perceived well-being of a given society or settlement.” ref

“Ritualized bloodletting was typically performed by elites, settlement leaders, and religious figures (e.g., shamans) within contexts visible to the public. The rituals were enacted on the summits of pyramids or on elevated platforms that were usually associated with broad and open plazas or courtyards (where the masses could congregate and view the bloodletting). This was done so as to demonstrate the connection the person performing the auto-sacrifice had with the sacred sphere and, as such, a method used to maintain political power by legitimizing their prominent social, political, and/or ideological position.” ref

“While usually carried out by a ruling male, prominent females are also known to have performed the act. The El Perú tomb of a female (called the “Queen’s Tomb”) contains among its many grave goods a ceremonial stingray spine associated with her genital region.” ref

“Among all the Mesoamerican cultures, sacrifice, in whatever form, was a deeply symbolic and highly ritualized activity with strong religious and political significance. Various kinds of sacrifice were performed within a range of sociocultural contexts and in association with a variety of activities, from mundane everyday activities to those performed by the elites and ruling lineages with the aim of maintaining social structure. The social structure was maintained by showing that ruler’s blood sacrifice to the gods showed the power they had.” ref

“At its core, the sacrifice symbolized the renewal of divine energy and, in doing so, the continuation of life. Its ability of bloodletting to do this is based on two intertwined concepts that are prevalent in the Maya belief system. The first is the notion that the gods had given life to humankind by sacrificing parts of their own bodies. The second is the central focus of their mythology on human blood, which signified life among the Maya. Within their belief system, human blood was partially made up of the blood of the gods, who sacrificed their own divine blood in creating life in humans. Thus, in order to continually maintain the order of their universe, the Maya believed that blood had to be given back to the gods. The rulers are giving their blood to empower the gods in return for giving them life.” ref

“Unlike later cultures, there is no representation of actual bloodletting in Olmec art. However, solid evidence for its practice exists in the jade and ceramic replicas of stingray spines and shark teeth as well as representations of such paraphernalia on monuments and stelae and in iconography. A proposed translation of the Epi-Olmec culture‘s La Mojarra Stela 1, dated to roughly CE 155, tells of the ruler’s ritual bloodletting by piercing his penis and his buttocks, as well as what appears to be a ritual sacrifice of the ruler’s brother-in-law.” ref

“Bloodletting permeated Maya life. Kings performed bloodletting at every major political event. Building dedications, burials, marriages, and births all required bloodletting. As demonstrated by Yaxchilan Lintels 24 and 25, and duplicated in Lintels 17 and 15, bloodletting in Maya culture was also a means to a vision quest, where fasting, loss of blood, and perhaps hallucinogenics lead to visions of ancestors or gods. Contemporaneous with the Maya, the south-central panel at the Classic era South Ballcourt at El Tajín shows the rain god piercing his penis, the blood from which flows into and replenishes a vat of the alcoholic ritual drink pulque.” ref

Knot theory?

“Archaeologists have discovered that knot tying dates back to prehistoric times. Besides their uses such as recording information and tying objects together, knots have interested humans for their aesthetics and spiritual symbolism. Knots appear in various forms of Chinese artwork dating from several centuries BC (see Chinese knotting). The endless knot appears in Tibetan Buddhism, while the Borromean rings have made repeated appearances in different cultures, often representing strength in unity. The Celtic monks who created the Book of Kells lavished entire pages with intricate Celtic knotwork.” ref

Gordian Knot

“The Gordian Knot is a legend of Phrygian Gordium associated with Alexander the Great. It is often used as a metaphor for an intractable problem (untying an impossibly tangled knot) solved easily by finding an approach to the problem that renders the perceived constraints of the problem moot (“cutting the Gordian knot”):

Turn him to any cause of policy,

The Gordian Knot of it he will unloose,

Familiar as his garter— Shakespeare, Henry V, Act 1 Scene 1. 45–47″ ref

“The Phrygians were without a king, but an oracle at Telmissus (the ancient capital of Lycia) decreed that the next man to enter the city driving an ox-cart should become their king. A peasant farmer named Gordias drove into town on an ox-cart and was immediately declared king. Out of gratitude, his son Midas dedicated the ox-cart to the Phrygian god Sabazios (whom the Greeks identified with Zeus) and tied it to a post with an intricate knot of cornel bark (Cornus mas). The knot was later described by Roman historian Quintus Curtius Rufus as comprising “several knots all so tightly entangled that it was impossible to see how they were fastened.” ref

“Phrygians in the regions of Asia Minor/Anatolia or modern-day Turkey, spoke the Phrygian language, a member of the Indo-European linguistic family. Modern consensus regards Greek as its closest relative. The ox-cart still stood in the palace of the former kings of Phrygia at Gordium in the fourth century BCE when Alexander the Great arrived, at which point Phrygia had been reduced to a satrapy, or province, of the Persian Empire. An oracle had declared that any man who could unravel its elaborate knots was destined to become ruler of all of Asia. Alexander the Great wanted to untie the knot but struggled to do so. He then reasoned that it would make no difference how the knot was loosed, so he drew his sword and sliced it in half with a single stroke. In an alternative version of the story, Alexander the Great loosed the knot by pulling the linchpin from the yoke.” ref, ref

“Sources from antiquity agree that Alexander the Great was confronted with the challenge of the knot, but his solution is disputed. Both Plutarch and Arrian relate that, according to Aristobulus, Alexander the Great pulled the knot out of its pole pin, exposing the two ends of the cord and allowing him to untie the knot without having to cut through it. Some classical scholars regard this as more plausible than the popular account. Literary sources of the story include propagandist Arrian (Anabasis Alexandri 2.3), Quintus Curtius (3.1.14), Justin‘s epitome of Pompeius Trogus (11.7.3), and Aelian‘s De Natura Animalium 13.1. Alexander the Great later went on to conquer Asia as far as the Indus and the Oxus, thus fulfilling the prophecy.” ref

“The knot may have been a religious knot-cipher guarded by priests and priestesses. Robert Graves suggested that it may have symbolized the ineffable name of Dionysus that, knotted like a cipher, would have been passed on through generations of priests and revealed only to the kings of Phrygia. Unlike the popular fable, genuine mythology has few completely arbitrary elements. This myth taken as a whole seems designed to confer legitimacy to dynastic change in this central Anatolian kingdom: thus Alexander’s “brutal cutting of the knot … ended an ancient dispensation.” ref

“The ox-cart suggests a longer voyage, rather than a local journey, perhaps linking Alexander the Great with an attested origin-myth in Macedon, of which Alexander is most likely to have been aware. Based on this origin myth, the new dynasty was not immemorially ancient, but had widely remembered origins in a local, but non-priestly “outsider” class, represented by Greek reports equally as an eponymous peasant or the locally attested, authentically Phrygian in his ox-cart. Roller (1984) separates out authentic Phrygian elements in the Greek reports and finds a folk-tale element and a religious one, linking the dynastic founder ( with the cults of “Zeus” and Cybele.” ref

“Other Greek myths legitimize dynasties by right of conquest (compare Cadmus), but in this myth, the stressed legitimizing oracle suggests that the previous dynasty was a race of priest-kings allied to the unidentified oracular deity. The ox-cart is often depicted in works of art as a chariot, which made it a more readily legible emblem of power and military readiness. His position had also been predicted earlier by an eagle landing on his cart, a sign to him from the gods.” ref

Maʽat Goddess

“Maʽat refers to the ancient Egyptian concepts of truth, balance, order, harmony, law, morality, and justice. Maat was also the goddess who personified these concepts, and regulated the stars, seasons, and the actions of mortals and the deities who had brought order from chaos at the moment of creation. Her ideological opposite was Isfet (Egyptian jzft), meaning injustice, chaos, violence, or to do evil.” ref

“The earliest surviving records indicating that Maat is the norm for nature and society, in this world and the next, were recorded during the Old Kingdom of Egypt, the earliest substantial surviving examples being found in the Pyramid Texts of Unas (ca. 2375 BCE and 2345 BCE). Later, when most goddesses were paired with a male aspect, her masculine counterpart was Thoth, as their attributes are similar. In other accounts, Thoth was paired off with Seshat, goddess of writing and measure, who is a lesser-known deity.” ref

“After her role in the creation and continuously preventing the universe from returning to chaos, her primary role in ancient Egyptian religion dealt with the Weighing of the Heart that took place in the Duat. Her feather was the measure that determined whether the souls (considered to reside in the heart) of the departed would reach the paradise of the afterlife successfully. In other versions, Maat was the feather as the personification of truth, justice, and harmony.” ref

“Pharaohs are often depicted with the emblems of Maat to emphasise their roles in upholding the laws and righteousness. From the Eighteenth Dynasty (1550 – 1295 BCE) Maat was described as the daughter of Ra, indicating that pharaohs were believed to rule through her authority. Maat represents the ethical and moral principle that all Egyptian citizens were expected to follow throughout their daily lives. They were expected to act with honor and truth in matters that involve family, the community, the nation, the environment, and the god.

“Maat as a principle was formed to meet the complex needs of the emergent Egyptian state that embraced diverse peoples with conflicting interests. The development of such rules sought to avert chaos and it became the basis of Egyptian law. From an early period, the king would describe himself as the “Lord of Maat” who decreed with his mouth the Maat he conceived in his heart.” ref

The significance of Maat developed to the point that it embraced all aspects of existence, including the basic equilibrium of the universe, the relationship between constituent parts, the cycle of the seasons, heavenly movements, religious observations and good faith, honesty, and truthfulness in social interactions.” ref

“The ancient Egyptians had a deep conviction of an underlying holiness and unity within the universe. Cosmic harmony was achieved by correct public and ritual life. Any disturbance in cosmic harmony could have consequences for the individual as well as the state. An impious king could bring about famine, and blasphemy could bring blindness to an individual. In opposition to the right order expressed in the concept of Maat is the concept of Isfet: chaos, lies, and violence.” ref

“In addition, several other principles within ancient Egyptian law were essential, including an adherence to tradition as opposed to change, the importance of rhetorical skill, and the significance of achieving impartiality and “righteous action”. In one Middle Kingdom (2062 to1664 BCE) text, the creator declares “I made every man like his fellow”. Maat called the rich to help the less fortunate rather than exploit them, echoed in tomb declarations: “I have given bread to the hungry and clothed the naked” and “I was a husband to the widow and father to the orphan.” ref

“To the Egyptian mind, Maat bound all things together in an indestructible unity: the universe, the natural world, the state, and the individual were all seen as parts of the wider order generated by Maat.” ref

“Ma’at, who is symbolized by an ostrich feather or shown with one in her hair, is both a goddess, the daughter of the sun god Ra (Re), and an abstract. To the ancient Egyptians, Ma’at, everlasting and powerful, bound everything together in order. Ma’at represented truth, right, justice, world order, stability, and continuity. Ma’at represents harmony and unending cycles, Nile flooding, and the king of Egypt. This cosmic outlook rejected the idea that the universe could ever be completely destroyed. Isft (chaos) is the opposite of Ma’at. Ma’at is credited with staving off Isft.” ref

“Humankind is expected to pursue justice and to operate according to the demands of Ma’at because to do otherwise is to encourage chaos. The king upholds the order of the universe by ruling well and serving the gods. From the fourth dynasty, pharaohs added “Possessor of Ma’at” to their titles. There is, however, no known temple to Ma’at prior to the New Kingdom. Ma’at is similar to the Greek goddess of justice, Dike.” ref

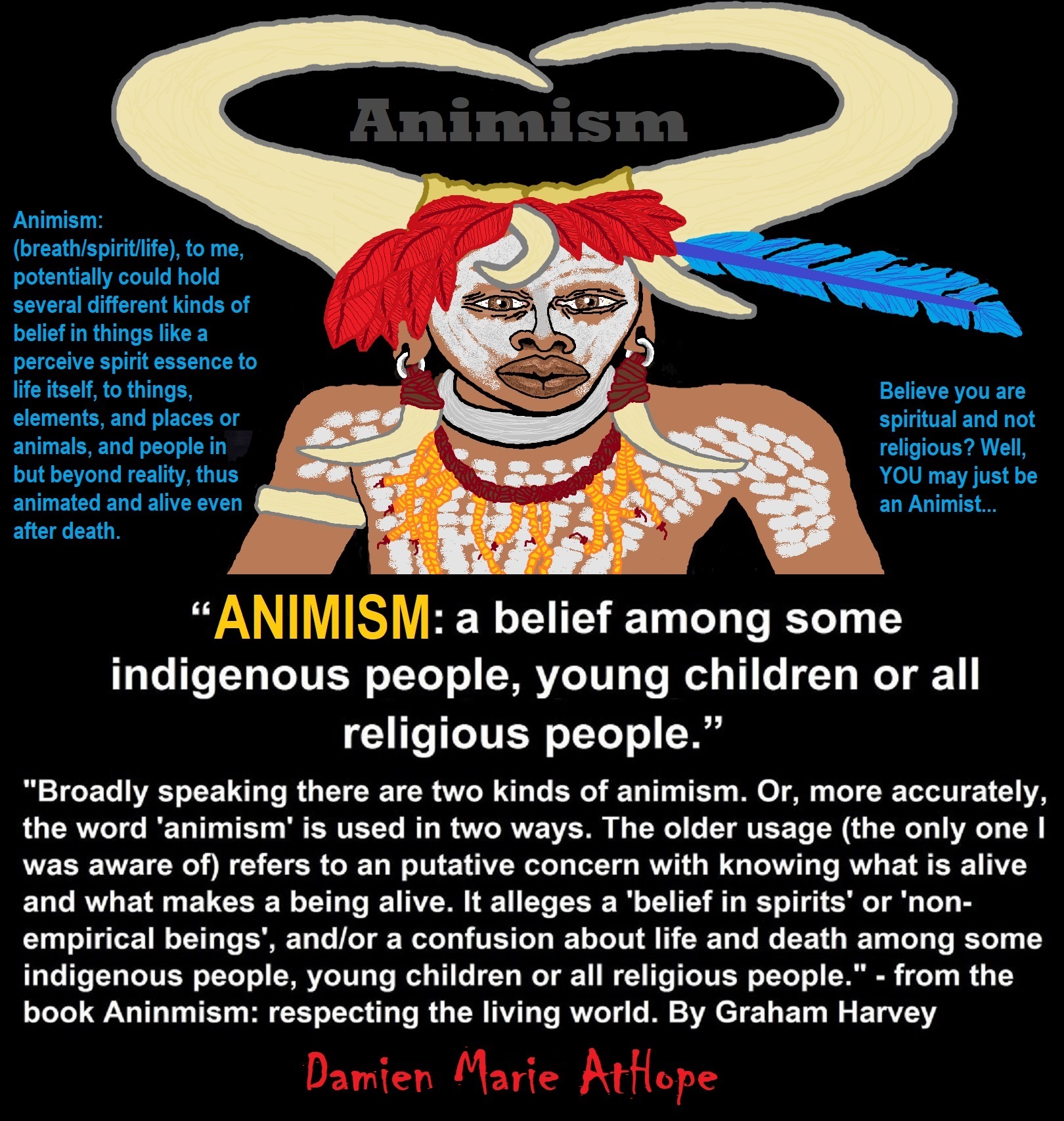

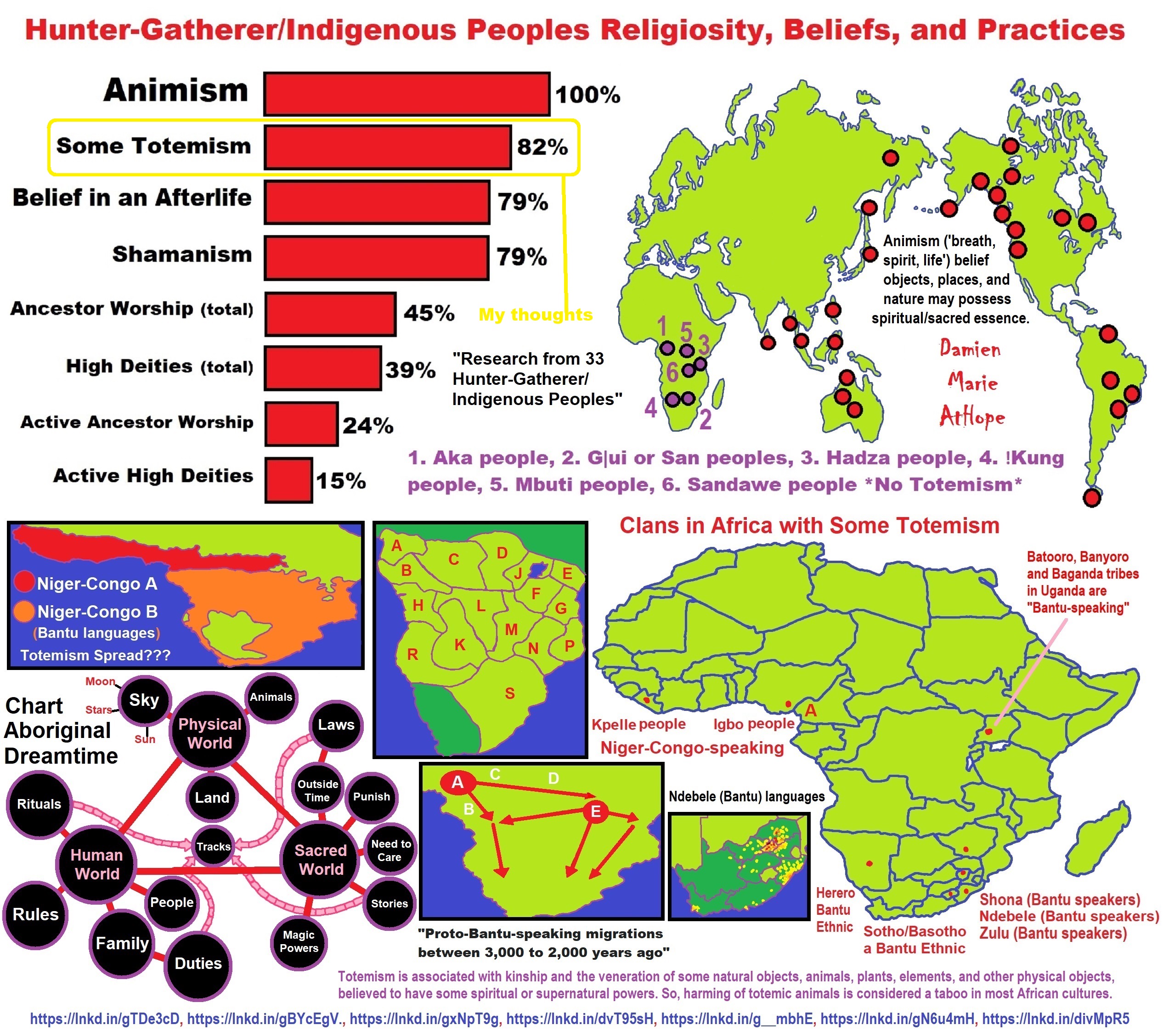

Animism: Respecting the Living World by Graham Harvey

“How have human cultures engaged with and thought about animals, plants, rocks, clouds, and other elements in their natural surroundings? Do animals and other natural objects have a spirit or soul? What is their relationship to humans? In this new study, Graham Harvey explores current and past animistic beliefs and practices of Native Americans, Maori, Aboriginal Australians, and eco-pagans. He considers the varieties of animism found in these cultures as well as their shared desire to live respectfully within larger natural communities. Drawing on his extensive casework, Harvey also considers the linguistic, performative, ecological, and activist implications of these different animisms.” ref

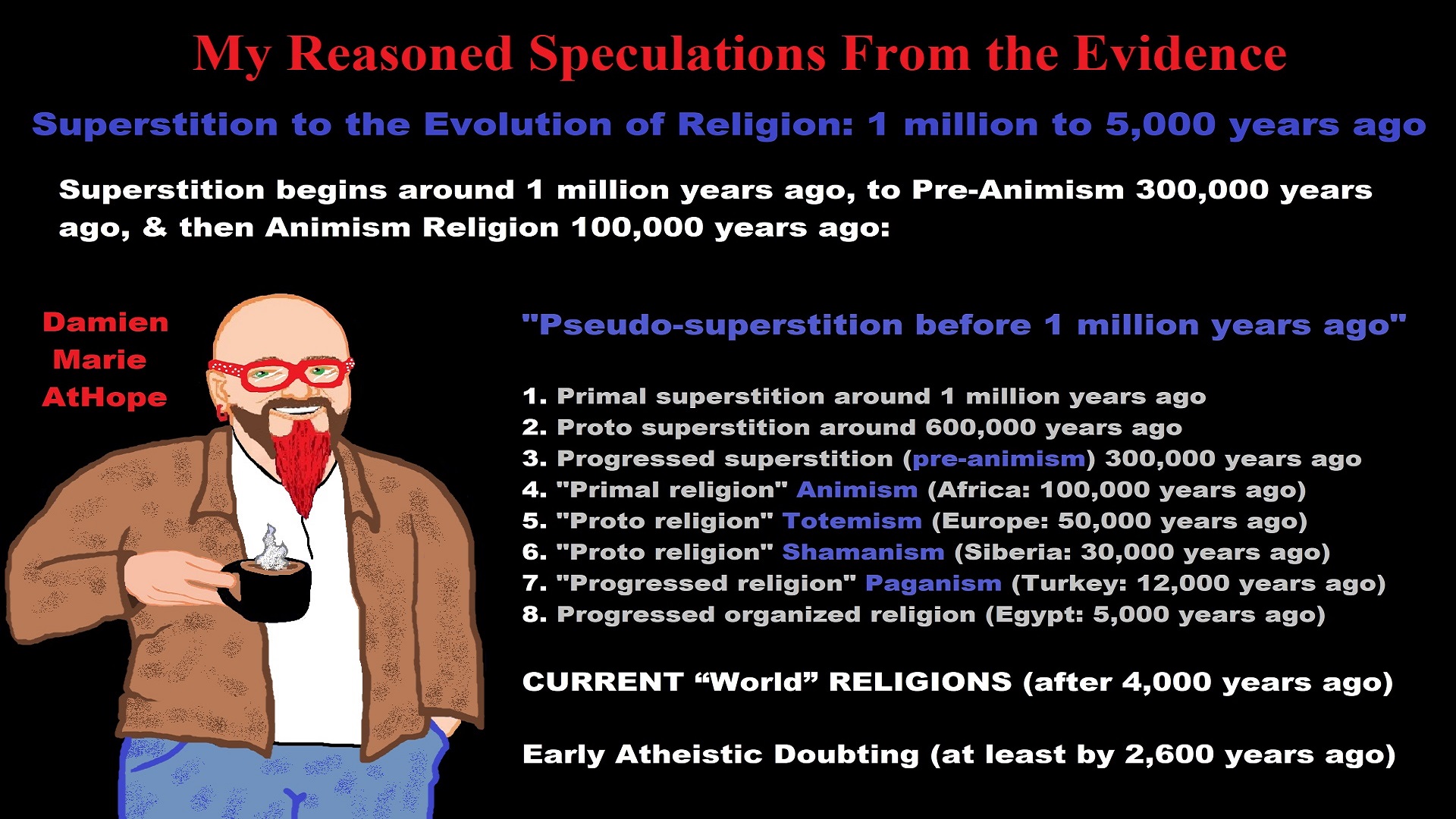

My thoughts on Religion Evolution with external links for more info:

- (Pre-Animism Africa mainly, but also Europe, and Asia at least 300,000 years ago), (Pre-Animism – Oxford Dictionaries)

- (Animism Africa around 100,000 years ago), (Animism – Britannica.com)

- (Totemism Europe around 50,000 years ago), (Totemism – Anthropology)

- (Shamanism Siberia around 30,000 years ago), (Shamanism – Britannica.com)

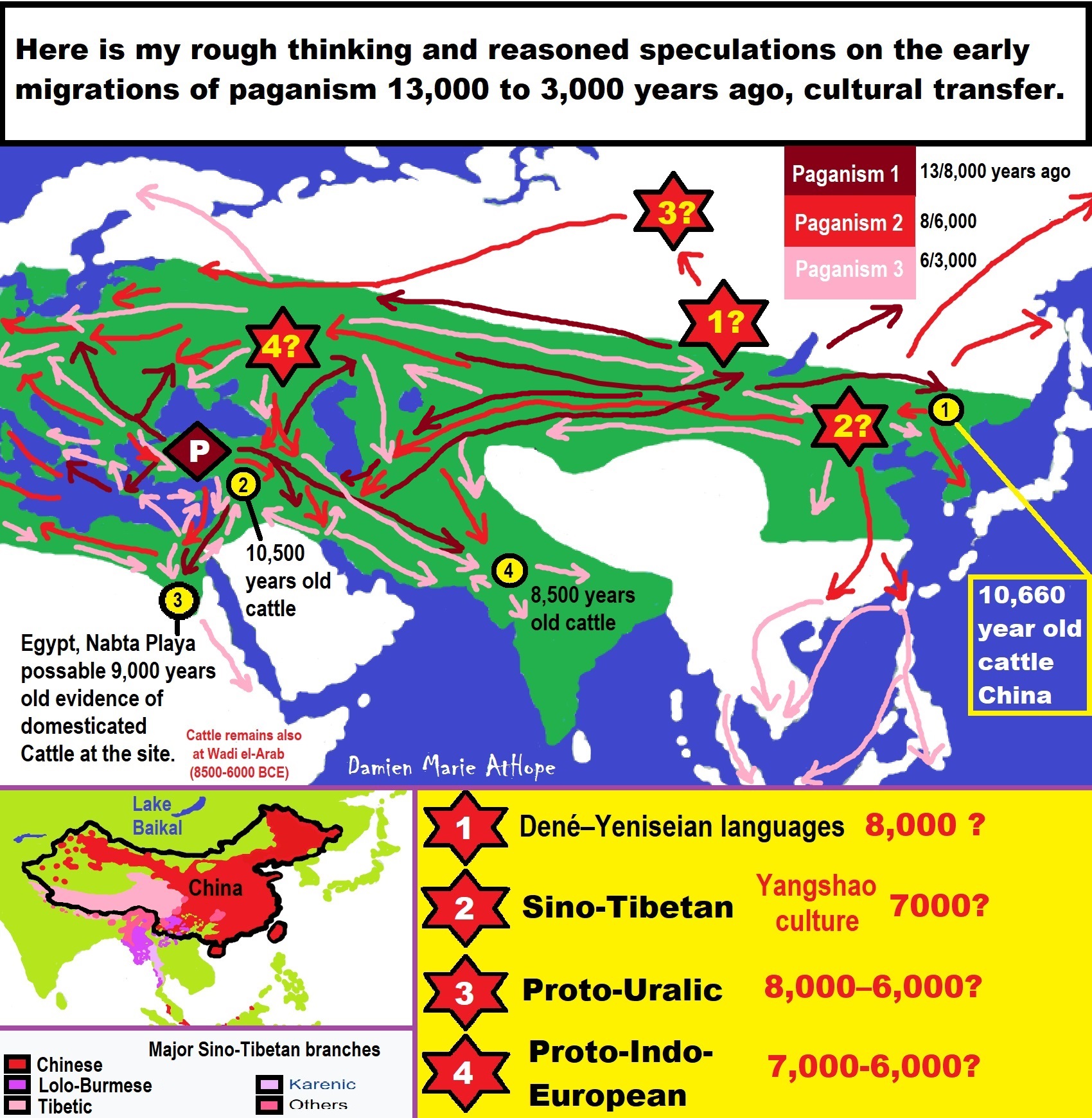

- (Paganism Turkey around 12,000 years ago), (Paganism – BBC Religion)

- (Progressed Organized Religion “Institutional Religion” Egypt around 5,000 years ago), (Ancient Egyptian Religion – Britannica.com)

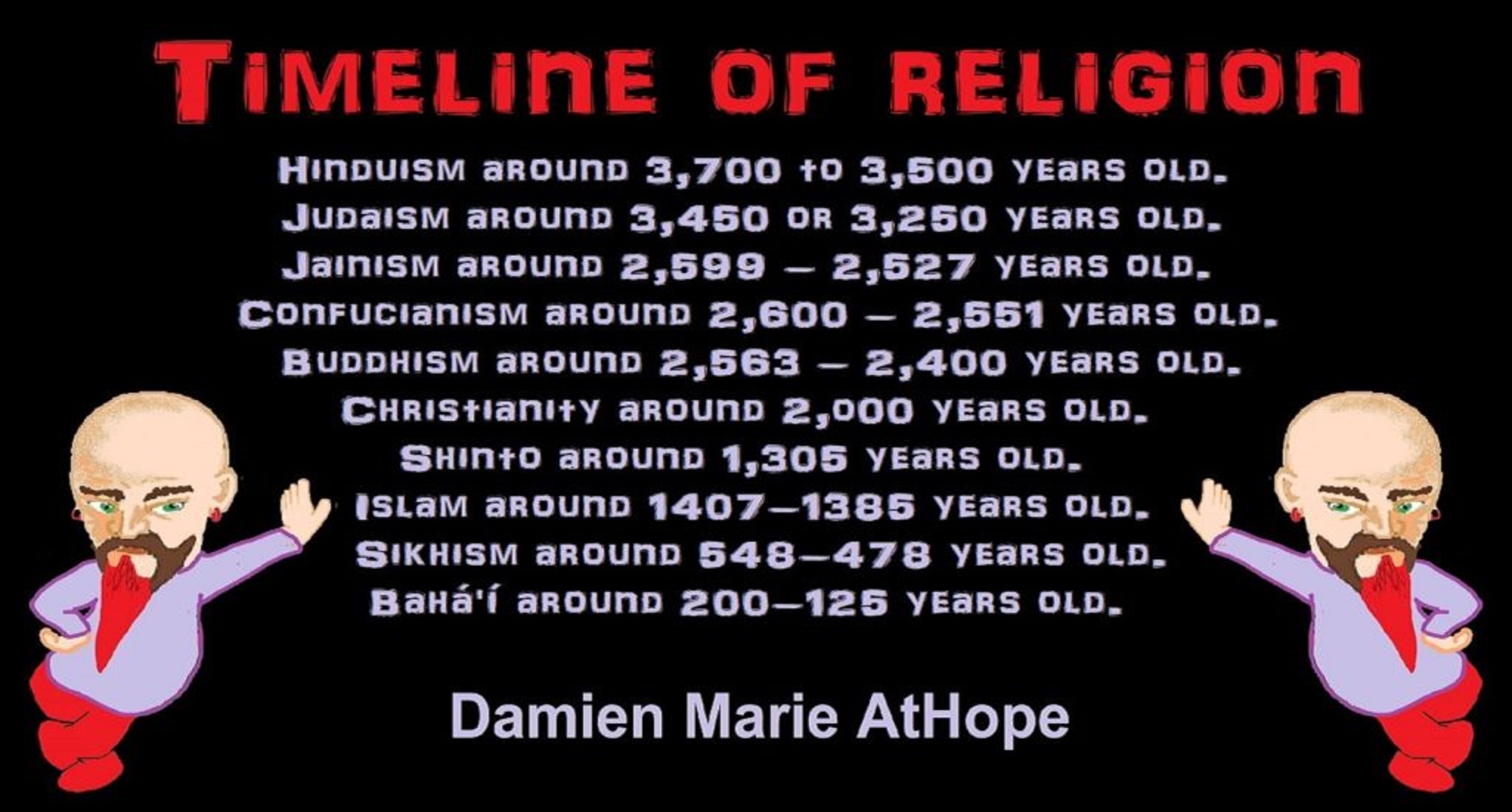

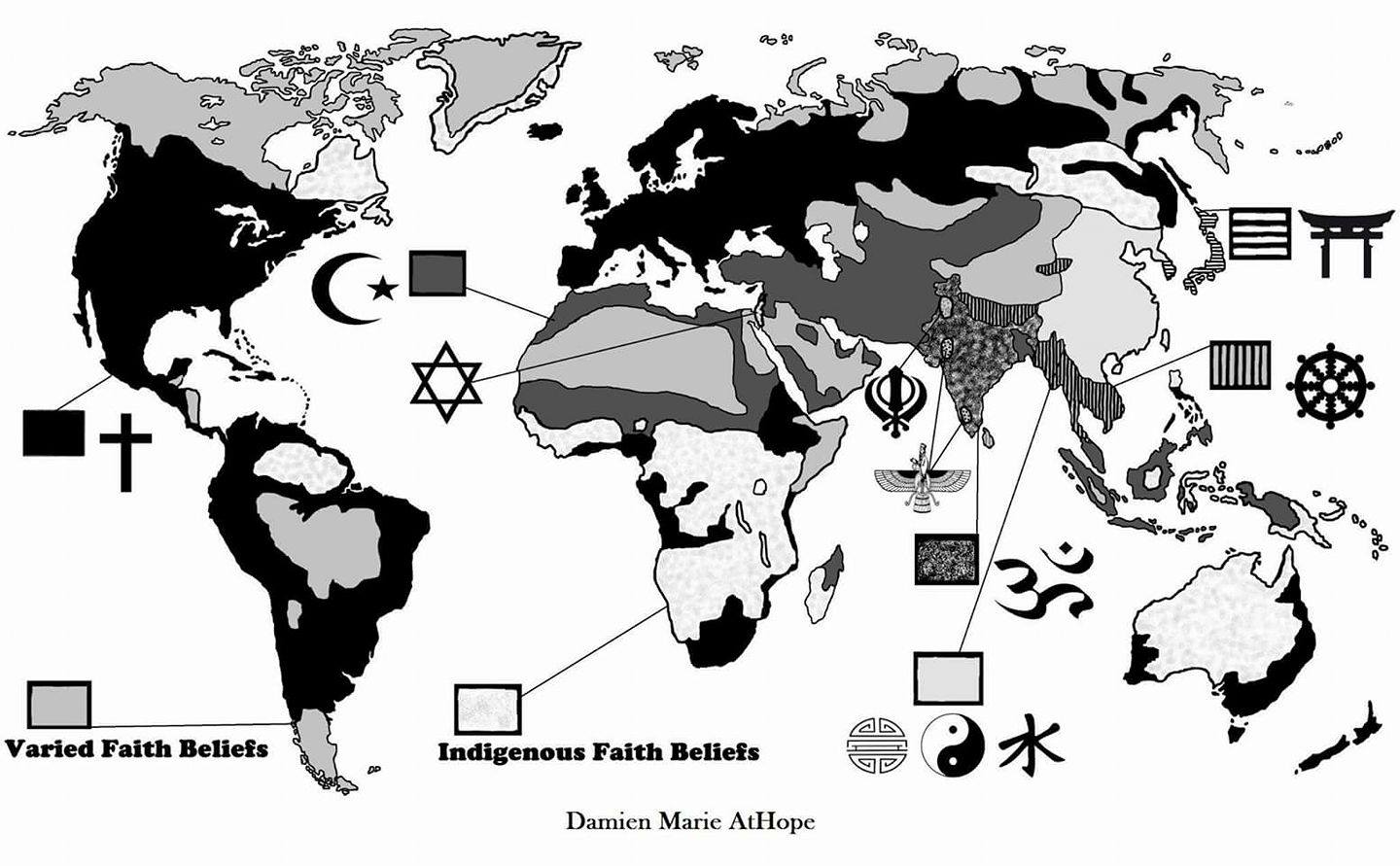

- (CURRENT “World” RELIGIONS after 4,000 years ago) (Origin of Major Religions – Sacred Texts)

- (Early Atheistic Doubting at least by 2,600 years ago) (History of Atheism – Wikipedia)

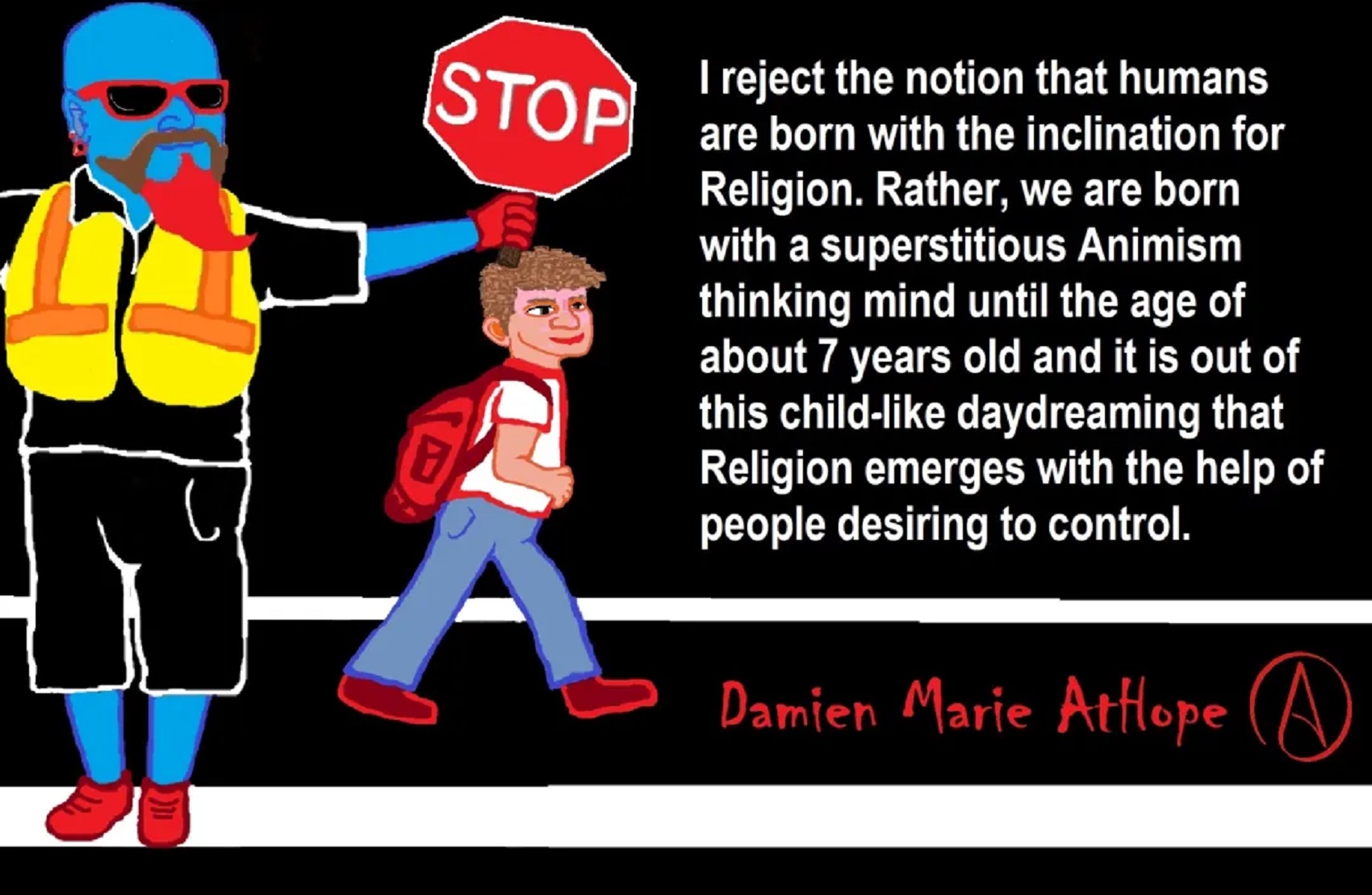

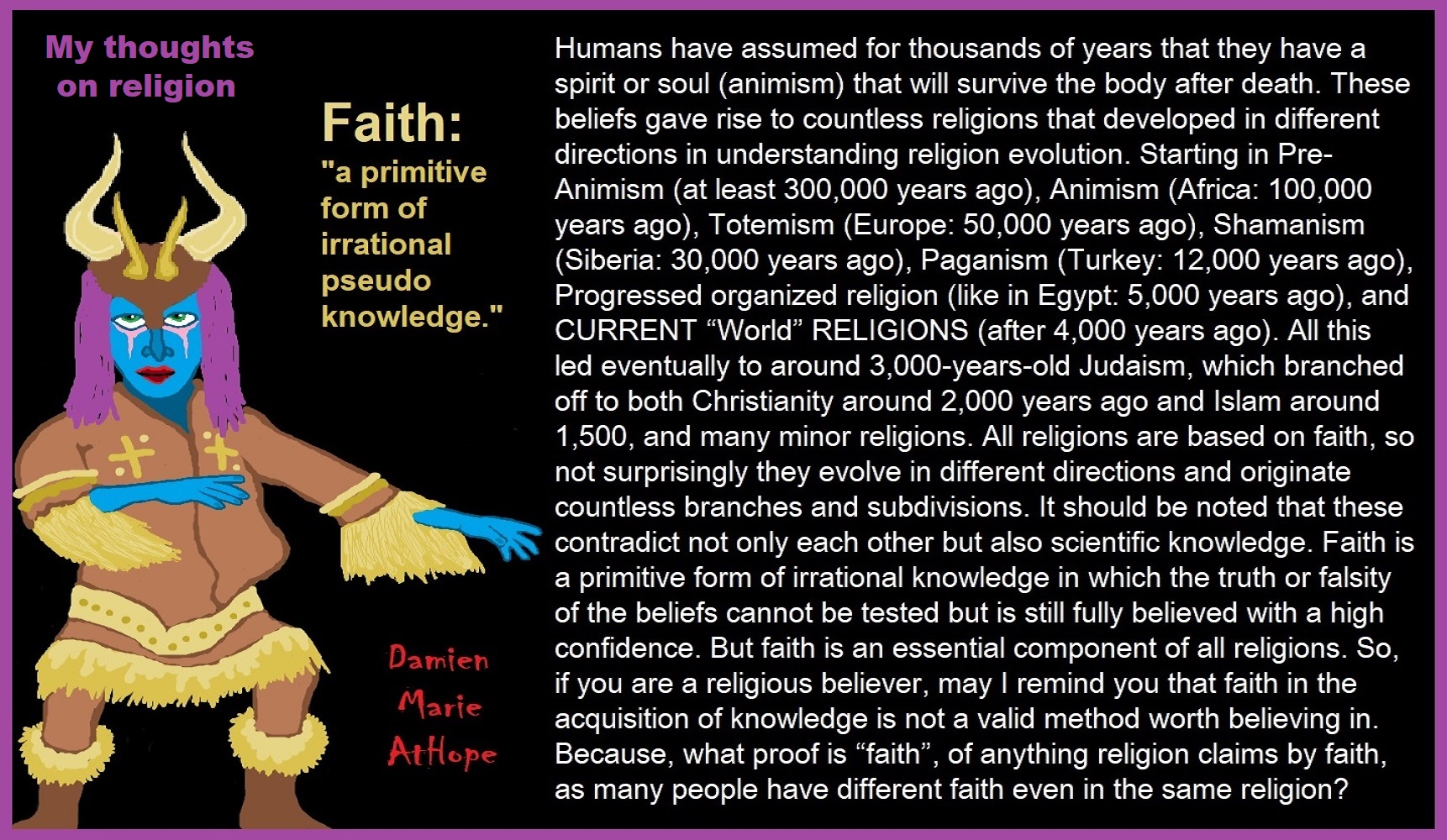

“Religion is an Evolved Product” and Yes, Religion is Like Fear Given Wings…

Atheists talk about gods and religions for the same reason doctors talk about cancer, they are looking for a cure, or a firefighter talks about fires because they burn people and they care to stop them. We atheists too often feel a need to help the victims of mental slavery, held in the bondage that is the false beliefs of gods and the conspiracy theories of reality found in religions.

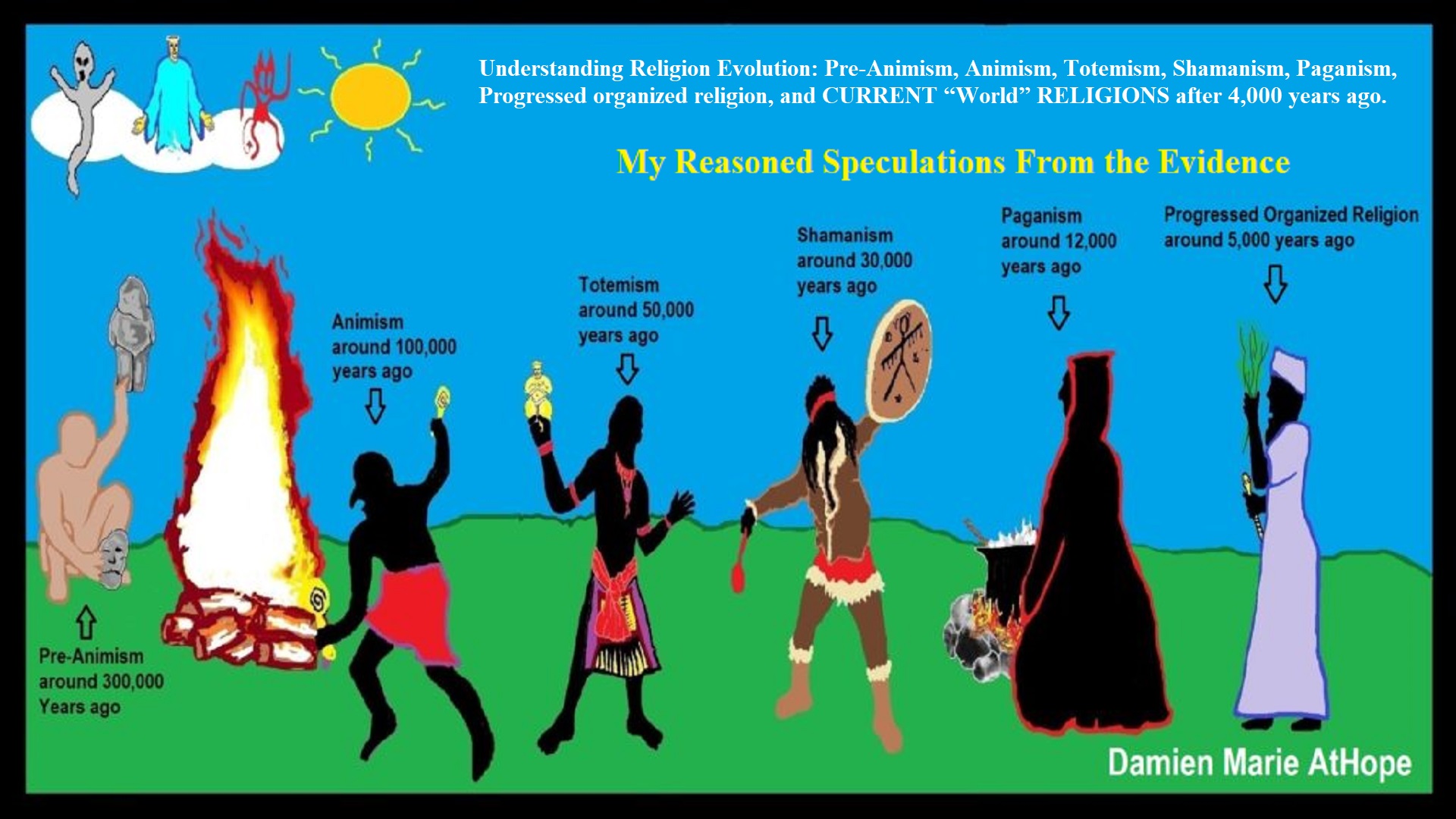

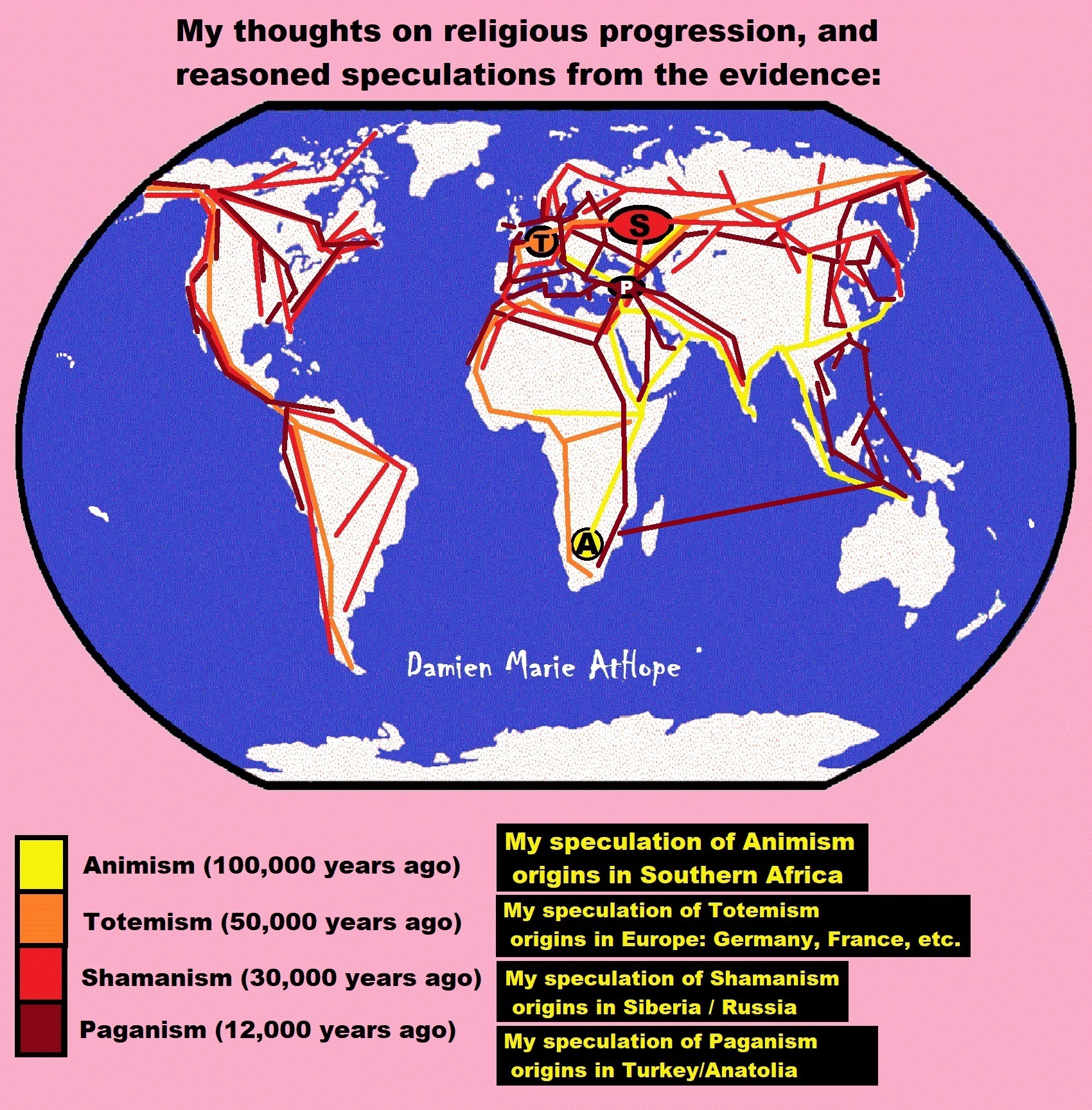

Understanding Religion Evolution:

- Pre-Animism (at least 300,000 years ago)

- Animism (Africa: 100,000 years ago)

- Totemism (Europe: 50,000 years ago)

- Shamanism (Siberia: 30,000 years ago)

- Paganism (Turkey: 12,000 years ago)

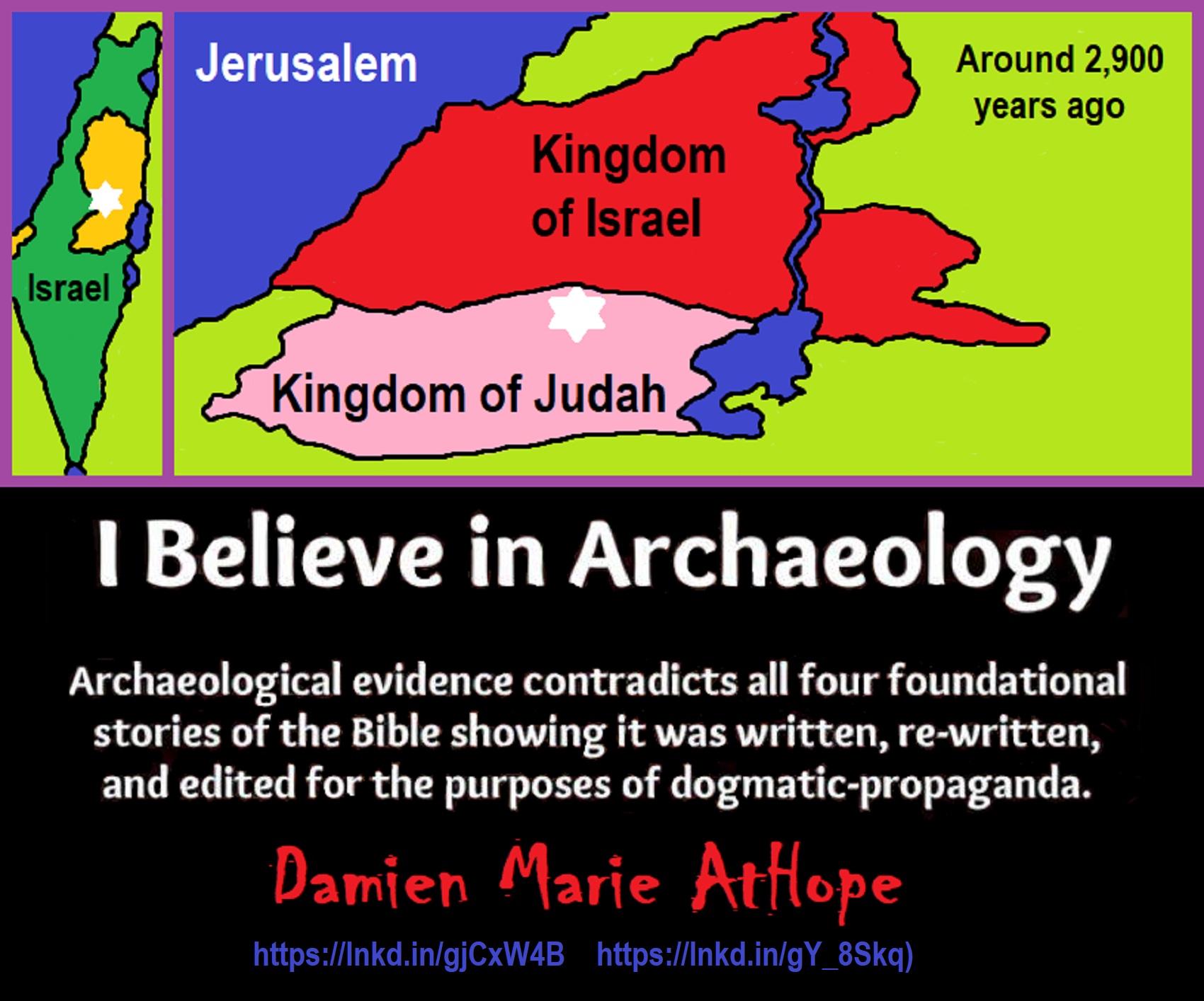

- Progressed organized religion (Egypt: 5,000 years ago), (Egypt, the First Dynasty 5,150 years ago)

- CURRENT “World” RELIGIONS (after 4,000 years ago)

- Early Atheistic Doubting (at least by 2,600 years ago)

“An Archaeological/Anthropological Understanding of Religion Evolution”

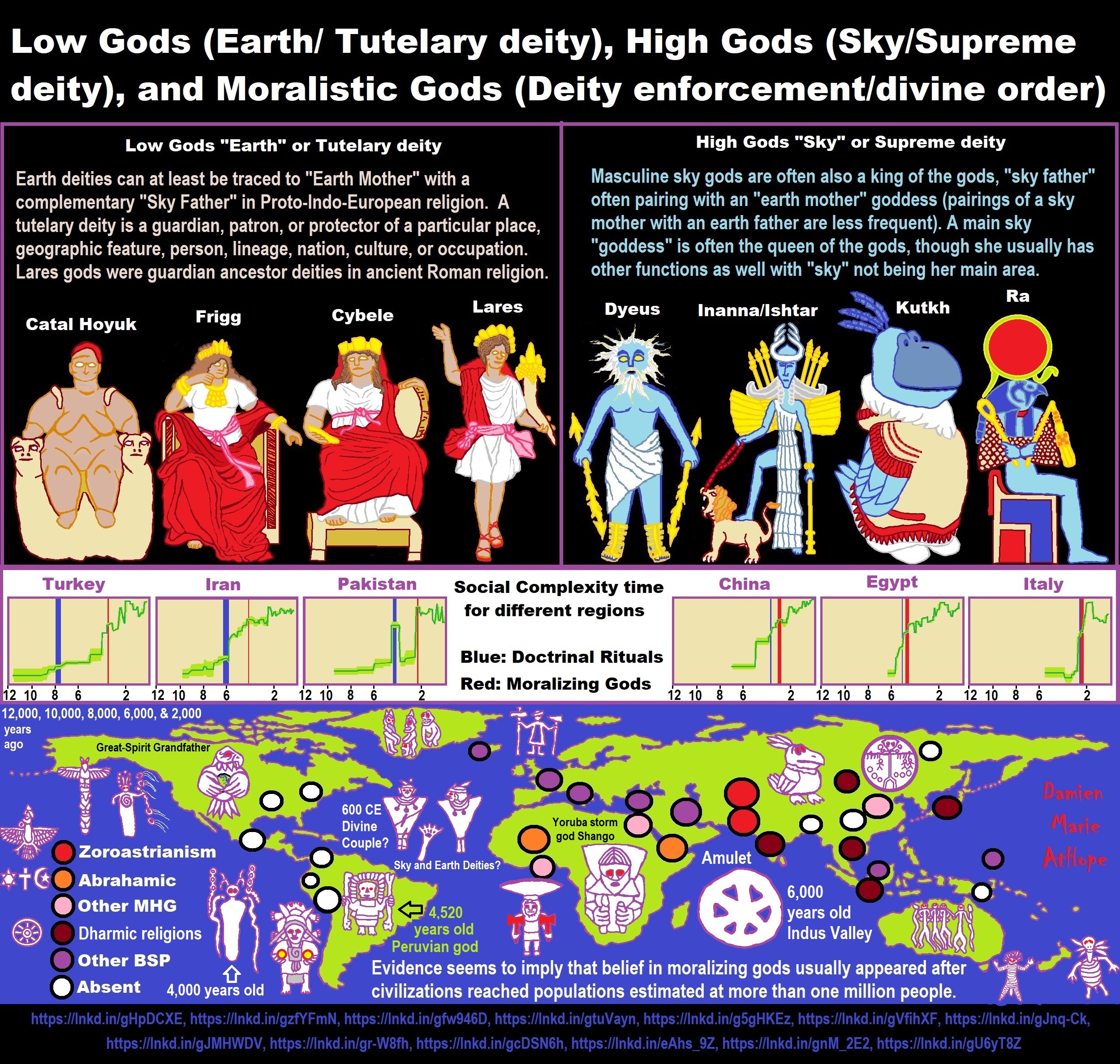

It seems ancient peoples had to survived amazing threats in a “dangerous universe (by superstition perceived as good and evil),” and human “immorality or imperfection of the soul” which was thought to affect the still living, leading to ancestor worship. This ancestor worship presumably led to the belief in supernatural beings, and then some of these were turned into the belief in gods. This feeble myth called gods were just a human conceived “made from nothing into something over and over, changing, again and again, taking on more as they evolve, all the while they are thought to be special,” but it is just supernatural animistic spirit-belief perceived as sacred.

Quick Evolution of Religion?

Pre-Animism (at least 300,000 years ago) pre-religion is a beginning that evolves into later Animism. So, Religion as we think of it, to me, all starts in a general way with Animism (Africa: 100,000 years ago) (theoretical belief in supernatural powers/spirits), then this is physically expressed in or with Totemism (Europe: 50,000 years ago) (theoretical belief in mythical relationship with powers/spirits through a totem item), which then enlists a full-time specific person to do this worship and believed interacting Shamanism (Siberia/Russia: 30,000 years ago) (theoretical belief in access and influence with spirits through ritual), and then there is the further employment of myths and gods added to all the above giving you Paganism (Turkey: 12,000 years ago) (often a lot more nature-based than most current top world religions, thus hinting to their close link to more ancient religious thinking it stems from). My hypothesis is expressed with an explanation of the building of a theatrical house (modern religions development). Progressed organized religion (Egypt: 5,000 years ago) with CURRENT “World” RELIGIONS (after 4,000 years ago).

Historically, in large city-state societies (such as Egypt or Iraq) starting around 5,000 years ago culminated to make religion something kind of new, a sociocultural-governmental-religious monarchy, where all or at least many of the people of such large city-state societies seem familiar with and committed to the existence of “religion” as the integrated life identity package of control dynamics with a fixed closed magical doctrine, but this juggernaut integrated religion identity package of Dogmatic-Propaganda certainly did not exist or if developed to an extent it was highly limited in most smaller prehistoric societies as they seem to lack most of the strong control dynamics with a fixed closed magical doctrine (magical beliefs could be at times be added or removed). Many people just want to see developed religious dynamics everywhere even if it is not. Instead, all that is found is largely fragments until the domestication of religion.

Religions, as we think of them today, are a new fad, even if they go back to around 6,000 years in the timeline of human existence, this amounts to almost nothing when seen in the long slow evolution of religion at least around 70,000 years ago with one of the oldest ritual worship. Stone Snake of South Africa: “first human worship” 70,000 years ago. This message of how religion and gods among them are clearly a man-made thing that was developed slowly as it was invented and then implemented peace by peace discrediting them all. Which seems to be a simple point some are just not grasping how devastating to any claims of truth when we can see the lie clearly in the archeological sites.

I wish people fought as hard for the actual values as they fight for the group/clan names political or otherwise they think support values. Every amount spent on war is theft to children in need of food or the homeless kept from shelter.

Here are several of my blog posts on history:

- To Find Truth You Must First Look

- (Magdalenian/Iberomaurusian) Connections to the First Paganists of the early Neolithic Near East Dating from around 17,000 to 12,000 Years Ago

- Natufians: an Ancient People at the Origins of Agriculture and Sedentary Life

- Possible Clan Leader/Special “MALE” Ancestor Totem Poles At Least 13,500 years ago?

- Jewish People with DNA at least 13,200 years old, Judaism, and the Origins of Some of its Ideas

- Baltic Reindeer Hunters: Swiderian, Lyngby, Ahrensburgian, and Krasnosillya cultures 12,020 to 11,020 years ago are evidence of powerful migratory waves during the last 13,000 years and a genetic link to Saami and the Finno-Ugric peoples.

- The Rise of Inequality: patriarchy and state hierarchy inequality

- Fertile Crescent 12,500 – 9,500 Years Ago: fertility and death cult belief system?

- 12,400 – 11,700 Years Ago – Kortik Tepe (Turkey) Pre/early-Agriculture Cultic Ritualism

- Ritualistic Bird Symbolism at Gobekli Tepe and its “Ancestor Cult”

- Male-Homosexual (female-like) / Trans-woman (female) Seated Figurine from Gobekli Tepe

- Could a 12,000-year-old Bull Geoglyph at Göbekli Tepe relate to older Bull and Female Art 25,000 years ago and Later Goddess and the Bull cults like Catal Huyuk?

- Sedentism and the Creation of goddesses around 12,000 years ago as well as male gods after 7,000 years ago.

- Alcohol, where Agriculture and Religion Become one? Such as Gobekli Tepe’s Ritualistic use of Grain as Food and Ritual Drink

- Neolithic Ritual Sites with T-Pillars and other Cultic Pillars

- Paganism: Goddesses around 12,000 years ago then Male Gods after 7,000 years ago

- First Patriarchy: Split of Women’s Status around 12,000 years ago & First Hierarchy: fall of Women’s Status around 5,000 years ago.

- Natufians: an Ancient People at the Origins of Agriculture and Sedentary Life

- J DNA and the Spread of Agricultural Religion (paganism)

- Paganism: an approximately 12,000-year-old belief system

- Paganism 12,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism” (Pre-Capitalism)

- Shaman burial in Israel 12,000 years ago and the Shamanism Phenomena

- Need to Mythicized: gods and goddesses

- 12,000 – 7,000 Years Ago – Paleo-Indian Culture (The Americas)

- 12,000 – 2,000 Years Ago – Indigenous-Scandinavians (Nordic)

- Norse did not wear helmets with horns?

- Pre-Pottery Neolithic Skull Cult around 11,500 to 8,400 Years Ago?

- 10,400 – 10,100 Years Ago, in Turkey the Nevail Cori Religious Settlement

- 9,000-6,500 Years Old Submerged Pre-Pottery/Pottery Neolithic Ritual Settlements off Israel’s Coast

- Catal Huyuk “first religious designed city” around 9,500 to 7,700 years ago (Turkey)

- Cultic Hunting at Catal Huyuk “first religious designed city”

- Special Items and Art as well as Special Elite Burials at Catal Huyuk

- New Rituals and Violence with the appearance of Pottery and People?

- Haplogroup N and its related Uralic Languages and Cultures

- Ainu people, Sámi people, Native Americans, the Ancient North Eurasians, and Paganistic-Shamanism with Totemism

- Ideas, Technology and People from Turkey, Europe, to China and Back again 9,000 to 5,000 years ago?

- First Pottery of Europe and the Related Cultures

- 9,000 years old Neolithic Artifacts Judean Desert and Hills Israel

- 9,000-7,000 years-old Sex and Death Rituals: Cult Sites in Israel, Jordan, and the Sinai

- 9,000-8500 year old Horned Female shaman Bad Dürrenberg Germany

- Neolithic Jewelry and the Spread of Farming in Europe Emerging out of West Turkey

- 8,600-year-old Tortoise Shells in Neolithic graves in central China have Early Writing and Shamanism

- Swing of the Mace: the rise of Elite, Forced Authority, and Inequality begin to Emerge 8,500 years ago?

- Migrations and Changing Europeans Beginning around 8,000 Years Ago

- My “Steppe-Anatolian-Kurgan hypothesis” 8,000/7,000 years ago

- Around 8,000-year-old Shared Idea of the Mistress of Animals, “Ritual” Motif

- Pre-Columbian Red-Paint (red ochre) Maritime Archaic Culture 8,000-3,000 years ago

- 7,522-6,522 years ago Linear Pottery culture which I think relates to Arcane Capitalism’s origins

- Arcane Capitalism: Primitive socialism, Primitive capital, Private ownership, Means of production, Market capitalism, Class discrimination, and Petite bourgeoisie (smaller capitalists)

- 7,500-4,750 years old Ritualistic Cucuteni-Trypillian culture of Moldova, Romania, and Ukraine

- Roots of a changing early society 7,200-6,700 years ago Jordan and Israel

- Agriculture religion (Paganism) with farming reached Britain between about 7,000 to 6,500 or so years ago and seemingly expressed in things like Western Europe’s Long Barrows

- My Thoughts on Possible Migrations of “R” DNA and Proto-Indo-European?