Taxonomy of Race? Construct or a biological reality?

Axiological Dignity Being Theory

Why are lies more appealing than the truth?

Charlottesville, hate crimes are public health issue, experts say

BY CNN WIRE,

CHARLOTTESVILLE, Va. — As a white nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, turned deadly on Saturday, doctors and public health leaders were among those watching events unfold on their television screens and social media. Dr. Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association, was at a car dealership getting his vehicle inspected when he saw news reports of a car plowing into a group of counterprotesters. “I was horrified,” he said. Dr. Elizabeth Samuels, an emergency physician in New Haven, Connecticut, and Providence, Rhode Island, was closely following the events in Charlottesville from home. “I had actually been following the news, went out for a run and saw (counterprotester) Heather (Heyer) had been killed when I got back home,” she said. Dr. Jack Ende, president of the American College of Physicians and a professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine, also was watching from home. “I was shocked to see what was going on,” he said. “I was shocked and saddened.” Benjamin, Samuels and Ende all agree that the expressions of hate seen in Charlottesville over the weekend were a public health problem.

‘This is a public health issue’

Hate crimes directed at people based on their race, ethnicity, gender, nationality, sexual orientation, religion or other characteristics are a public health issue, according to a policy statement from the American College of Physicians that was posted on its website Monday. “Is it appropriate for a medical organization to take a stance on hate crimes? The American College of Physicians said, ‘Yes, it was,’ ” Ende said. “There are data indicating the public health ramifications of both the hate crime itself but also of the stigma of bias, the stigma of prejudice and hatred directed against somebody because of their sexual orientation, because of their race, because of their ethnicity or their country of origin,” he said. “For that reason, we felt that this is a public health issue, and we joined with other medical organizations to take a stance against hate crimes.” The American Psychological Association, the American Medical Association and the American Academy of Family Physicians also have issued policy statements on hate crime as a public health concern. The American Public Health Association has a site devoted to racism’s negative impact on public health and launched a national campaign against racism, including hate crimes. “We studied the statements of our sister groups before we came out with our own,” Ende said. “There is a consensus within the medical societies that this really needs to be kept on our radar.” The American College of Physicians’ statement, which its board of regents approved last month, calls for more research on the impact of hate crimes, the understanding and prevention of hate crimes and interventions to address the needs of hate crime survivors and their communities. “By identifying discrimination and hate crimes as public health issues, the ACP not only acknowledges the impact these factors have on our patients but also our role and responsibility to address them as part of our professional dedication to the health of our patients and the public,” said Samuels, who was not involved in the policy statement but attended a vigil in Providence on Sunday where people reflected on the violence. “When I have cared for patients assaulted because of their race, religion, gender, sexual orientation, age or disability, what has stood out to me is not so much the physical injuries inflicted — which are not to be minimized — but the psychological harm,” she said. “Hate-based violence and systemic racism are detrimental to public health.”

How hate hurts public health

Several studies suggest that experiences of racism or discrimination raise the risk of emotional and physical health problems, including depression, hypertension, cardiovascular disease and even death. A study of 1,016 Arab-Americans found that their reports of abuse and discrimination after September 11, 2001, were associated with higher levels of distress, lower levels of happiness and worse overall health. The study was published in the American Journal of Public Health in 2010. As for hate crimes in particular, a study found that lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender high school students living in neighborhoods with higher rates of LGBT assault hate crimes were significantly more likely to report having suicidal thoughts or suicide attempts than students in neighborhoods with lower rates of hate crime. That study was published in the American Journal of Public Health in 2014. “Bottom line is that hate has physical and mental health consequences and should be considered within the remit of public health,” said Dr. Sandro Galea, dean and professor at the Boston University School of Public Health, who was not involved in the American College of Physicians’ latest policy statement. In other words, being considered within the remit of public health means that hate crimes have significant public health consequences, such as being associated with mental and physical problems. Galea said that he agreed with the policy statement, adding that what appears to be a recent rise in divisive language and outward expressions of hate is “deeply troubling” both as a citizen and as a doctor. He pointed to the weekend’s rally in Charlottesville as an example of that expression of hate. “The escalation to outright violence, including the killing of one person, are the tip of the iceberg, the ultimate manifestation of the consequences of hate,” Galea said. The American College of Physicians is not the first health organization to recognize hate crimes as a public health concern — and Charlottesville certainly is not the first city to see hateful rhetoric sweep its streets. Nor will it be the last, with rallies planned in other cities this weekend. America’s narrative includes not only the Civil Rights Act of 1968, the first federal statute to recognize hate crimes, but a haunting history of violent Ku Klux Klan gatherings and lynch mobs. As for why the American College of Physicians and other health organizations are only now recognizing hate crimes as a public health issue, Ende said the health community has evolved and become more “sophisticated in our sensitivity” to determinants of illness and social issues. Now, some medical groups are seeking out public health solutions.

‘We have the capacity as a nation to … fix this’

The American Academy of Family Physicians points to educational programs directed at the prevention of hate crimes as a possible solution, and such programs could be implemented in community centers and schools. The American Psychological Association cites research suggesting that getting people from conflicting groups in the same room in a peaceful way to hear each other’s perspectives, such as in a town hall meeting, or teaching the history of hate in America — such as how there was prejudice against German culture during World War I — are both approaches to turning bias around and possibly preventing hate. The American Medical Association even urges the expedient passage of appropriate hate crimes legislation. The American Public Health Association’s campaign against racism includes three potential public health solutions to hate crimes and racism, Benjamin said. They mostly focus on public discussions. “The first one is naming it. Identifying it. That is a very, very important first step, you know, putting it on the agenda,” Benjamin said. In other words, he said, calling out a hate crime or racism by name can initiate public discussions. Then, as part of that discussion, the second step would be to identify how racism is driving policies, practices or social norms, he said. For instance, “when you have two societies that live on different sides of the railroad tracks and there’s differences in their economic well-being and health … was that constructed?” Benjamin asked. The third step would be taking action, such as promoting or facilitating research and interventions through educational programs or community forums, to address racism and hate crimes from a public health perspective. “The public health community is good at understanding the data, thinking about the population-based impact of it and then working with others, because we don’t do this alone. We work across many sectors to find solutions,” Benjamin said. “I think we need to recognize Charlottesville is an overt expression of something that has been going on for a long time in our country,” he said. “That is a stain and a terrible, terrible situation in our country that we have to fix, and we need to do it now. We have the capacity as a nation to come together and fix this.” Ref

Can Racism Cause PTSD? Implications for DSM-5

By Monnica T. Williams, Ph.D.

Monnica T. Williams, is a licensed clinical psychologist and associate professor

at the University of Connecticut in the department of Psychological Sciences.

Allen was a young African American man working at a retail store. Although he enjoyed and valued his job, he struggled with the way he was treated by his boss. He was frequently demeaned, given menial tasks, and even required to track African American customers in the store to make sure they weren’t stealing. He began to suffer from symptoms of depression, generalized anxiety, low self-esteem, and feelings of humiliation. After filing a complaint, he was threatened by his boss and then fired. Allen’s symptoms worsened. He had intrusive thoughts, flashbacks, difficulty concentrating, irritability, and jumpiness – all hallmarks of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Allen later sued his employer for job-related discrimination, and five employees supported his allegations. Allen was found to be suffering from race-based trauma (from Carter & Forsyth, 2009)

Epidemiology of PTSD in Minorities

PTSD is a severe and chronic condition that may occur in response to any traumatic event. The National Survey of American Life (NSAL) found that African Americans show a prevalence rate of 9.1% for PTSD versus 6.8% in non-Hispanic Whites, indicating a notable mental health disparity (Himle et al., 2009). Incresed rates of PTSD have been found in other groups as well, including Hispanic Americans, Native Americans, Pacific Islander Americans. and Southeast Asian refugees (Pole et al., 2008). Furthermore, PTSD may be more disabling for minorities; for example, African Americans with PTSD experience significantly more impairment at work and carrying out everyday activities (Himle, et al. 2009).

Racism and PTSD

One major factor in understanding PTSD in ethnoracial minorities is the impact of racism on emotional and psychological well-being. Racism continues to be a daily part of American culture, and racial barriers have an overwhelming impact on the oppressed. Much research has been conducted on the social, economic, and political effects of racism, but little research recognizes the psychological effects of racism on people of color (Carter, 2007).Chou, Asnaani, and Hofmann (2012) found that perceived racial discrimination was associated with increased mental disorders in African Americans, Hispanic Americans, and Asian Americans, suggesting that racism may in itself be a traumatic experience.

PTSD in the DSM-IV

Currently, the DSM recognizes racism as trauma only when an individual meets DSM criteria for PTSD in relation to a discrete racist event, such as an assault. This is problematic given that many minorities experience cumulative experiences of racism as traumatic, with perhaps a minor event acting as “the last straw” in triggering trauma reactions (Carter, 2007). Thus, current conceptualizations of trauma as a discrete event may be limiting for diverse populations. Moreover, existing PTSD measures aimed at identifying an index trauma typically fail to include racism among listed choice response options, leaving such events to be reported as “other” or squeezed into an existing category that may not fully capture the nature of the trauma. This can be especially problematic as minorities may be reluctant to volunteer experiences of racism to White therapists, who comprise the majority of mental health clinicians. Clients may worry that the therapist will not understand, feel attacked, or express disbelief. Additionally, minority clients also may not link current PTSD symptoms to cumulative experiences of discrimination if queried about a single event.

Implications for Treatment

Racism is not typically considered a PTSD Criterion A event, i.e., a qualifying trauma. Mental health difficulties attributed to racist incidents are often questioned or downplayed, a response that only perpetuates the victim’s anxieties (Carter, 2007). Thus, clients who seek out mental healthcare to address race-based trauma may be further traumatized by microaggressions — subtle racist slights — from their own therapists (Sue et al., 2007). Mental health professionals must be willing and able to assess race-based trauma in their minority clients. Psychologists assessing ethnoracial minorities are encouraged to directly inquire about the client’s experiences of racism when determining trauma history. Some forms of race-based trauma may include racial harassment, discrimination, witnessing ethnoviolence or discrimination of another person, historical or personal memory of racism, institutional racism, microaggressions, and the constant threat of racial discrimination (Helms et al., 2012). The more subtle forms of racism mentioned may be commonplace, leading to constant vigilance, or “cultural paranoia,” which may be a protective mechanism against racist incidents. However subtle, the culmination of different forms of racism may result in victimization of an individual parallel to that induced by physical or life-threatening trauma. Bryant-Davis and Ocampo (2005) noted similar courses of psychopathology between rape victims and victims of racism. Both events are an assault on the personhood and integrity of the victim. Similar to rape victims, race-related trauma victims may respond with disbelief, shock, or dissociation, which can prevent them from responding to the incident in a healthy manner. The victim may then feel shame and self-blame because they were unable to respond or defend themselves, which may lead to low self-concept and self-destructive behaviors. In the same study, a parallel was drawn between race-related trauma victims and victims of domestic violence. Both survivors are made to feel shame over allowing themselves to be victimized. For instance, someone who may have experienced a racist incident may be told that if they are polite, work hard, and/or dress in a certain way, they will not encounter racism. When these rules are followed yet racism persists, powerlessness, hyper vigilance, and other symptoms associated with PTSD may develop or worsen (Bryant-Davis & Ocampo, 2005).

Changes in the DSM-5

Proposed changes to PTSD criteria in the DSM-5 have been made to improve diagnostic accuracy in light of current research (Friedman et al., 2011). The first section involving the experienced trauma has changed moderately, reflecting findings in clinical experience as well as empirical research. If a person has learned about a traumatic event involving a close friend or family member, or if a person is repeatedly exposed to details about trauma, they may now be eligible for a PTSD diagnosis. These changes were made to include those exposed in their occupational fields, such as police officers or emergency medical technicians. However, this could be applicable to those suffering from the cumulative effects of racism as well. The requirement of responding to the event with intense fear, helplessness, or horror has been removed. It was found that in many cases, such as soldiers trained in combat, emotional responses are only felt afterward, once removed from the traumatic setting. The most notable change to the criterion is from a three to a four-factor model. The proposed factors are intrusion symptoms, persistent avoidance, alterations in cognition and mood, and hyperarousal/reactivity symptoms. Three new symptoms have been added – persistent distorted blame of self or others, persistent negative emotional state, and reckless or self-destructive behavior. All of these symptoms may be also seen in those victimized by race-based trauma.

Summary

The changes to the DSM increase the potential for better recognition of race-based trauma, although more research will be needed to understand the mechanism by which this occurs. Additionally, current instruments should be expanded and a culturally competent model of PTSD must be developed to address how culture may differentially influence traumatic stress. In the meantime, clinicians should educate themselves about the impact of racism in lives of their ethnic minority clients, specifically the connection between racist events and trauma (Williams et al., 2014). Ref

The Link Between Racism and PTSD

Our screens and feeds are filled with news and images of black Americans dying or being brutalized. A brief and yet still-too-long list: Trayvon Martin, Tamir Rice, Walter Scott, Eric Garner, Renisha McBride. The image of a white police officer straddling a black teenager on a lawn in McKinney, Tex., had barely faded before we were forced to grapple with the racially motivated shooting in Charleston, S.C. I’ve had numerous conversations with friends and colleagues who are stressed out by the recent string of events; our anxiety and fear is palpable. A few days ago, a friend sent a text message that read, “I’m honestly terrified this will happen to us or someone we know.” Twitter and Facebook are teeming with anguish, and within my own social network (which admittedly consists largely of writers, academics and activists), I’ve seen several ad hoc databases of clinics and counselors crop up to help those struggling to cope. Instagram and Twitter have become a means to circulate information about yoga, meditation and holistic treatment services for African-Americans worn down by the barrage of reports about black deaths and police brutality, and I’ve been invited to several small gatherings dedicated to discussing these events. A handful of friends recently took off for Morocco for a few months with the explicit goal of escaping the psychic weight of life in America. It was against this backdrop that I first encountered the research of Monnica Williams, a psychologist, professor and the director of the University of Louisville’s Center for Mental Health Disparities. Several years ago, Williams treated a “high-functioning patient, with two master’s degrees and a job at a company that anyone would recognize.” The woman, who was African-American, had been devastated by racial harassment by a director within her company. Williams recalls being stunned by how drastically her patient’s condition deteriorated as a result of the treatment. “She completely withdrew and was suffering from extreme emotional anxiety,” she told me. “And that’s what made me say, ‘Wow, we have to focus on this.’ ” In a 2013 Psychology Today article, Williams wrote that “much research has been conducted on the social, economic and political effects of racism, but little research recognizes the psychological effects of racism on people of color.” Williams now studies the link between racism and post-traumatic stress disorder, which is known as race-based traumatic stress injury, or the emotional distress a person may feel after encountering racial harassment or hostility. Although much of Williams’s work focuses on individuals who have been directly targeted by racial discrimination or aggression, she says race-based stress reactions can be triggered by events that are experienced vicariously, or externally, through a third party — like social media or national news events. She argues that racism should be included as a cause of PTSD in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (D.S.M.). Williams is in the process of opening a clinical program that will exclusively treat race-based stress and trauma, in a predominantly black neighborhood in Louisville. Shortly after the Charleston shooting, I called Williams to discuss her work; what follows is a lightly edited and condensed transcript of our conversation.

What is race-based stress and trauma?

It’s a natural byproduct of the types of experiences that minorities have to deal with on a regular basis. I would argue that it is pathological, which means it is a disorder that we can assess and treat. To me, that means these are symptoms that are a diagnosable disorder that require a clinical intervention. It goes largely unrecognized in most people, and that’s based on my experience as a clinician.

What are the symptoms?

Depression, intrusion (the inability to get the thoughts about what happened out of one’s mind), vigilance (an inability to sleep, out of fear of danger), anger, loss of appetite, apathy and avoidance symptoms and emotional numbing. My training and study has been on post-traumatic stress disorder for a long time, and the two look very much alike. Over the weekend, I received several distressing emails and texts from friends who were suffering from feelings of anxiety and depression. Do you think we should all be in treatment? I think everyone could benefit from psychotherapy, but I think just talking to someone and processing the feelings can be very effective. It doesn’t have to be with a therapist; it could be with a pastor, family, friends and people who understand it and aren’t going to make it worse by telling you to stop complaining. What do you think about the #selfcare hashtags on social media and the role of “Black Twitter” as resources for people who may not have the resources they need to help process this? Are online interactions like that more meaningful than they initially might seem? Ref

Within the context of immigration (particularly from the Caribbean), author Joan Wilkinson examines racism and emotional abuse. The findings reveal the need for more cultural sensitivity and awareness. Canadian Statistics tells us that 29% of women have been victims of wife abuse. The immigrant woman is not excluded from this group. Frequently women who immigrate to Canada from the Caribbean are vulnerable to emotional abuse to the extent that it affects their ability to seek social support. They often find themselves in abusive situations in their home, at their place of employment or even in their churches. Incapable of finding a safe way to escape their violent circumstances, many women blame themselves or may even rationalize the abuse they are experiencing, which, over time, results in significant impact on the self-esteem, self-confidence and/or the parenting capacity of these women. Unfortunately, due to a lack of cultural awareness and systemic racism, those who are placed in positions of power aimed at protecting society, for instance in the legal and judiciary system, may react with indifference or ignorance. For example, a woman may be told that women from her culture are known to prefer men who abuse them. This lack of knowledge regarding abuse and its impact on the victim only serve to contribute to the immigrant woman’s fear of reporting the various forms of abuse that have been inflicted upon her. As such, poor responses strengthen the feelings of distrust an immigrant woman has about various institutions, such as social work practitioners, the education and judicial systems. From another perspective, the failure to establish a supportive workable intervention with an abused woman should be viewed as revictimizing her. The response to immigrant women is often buttressed by racial stereotypes specific to a certain culture, and by societal norms that state women are supposed to be submissive. Often an immigrant woman is not aware of the societal support systems and is therefore unable to use them. The emotional abuse may also undermine her ability to seek economic independence. Unfortunately, she may soon forget her own inner resources and the resilience that helped her to migrate to begin a new life. Service providers such as counselors, police and settlement workers must consider the complexity of the issues facing immigrant women. They should possess knowledge of the woman’s culture and understand each woman individually within her own cultural context culture in order to be effective, while avoiding stereotypes when dealing with women of colour. This awareness would facilitate a more effective intervention with this often hidden and misunderstood client group. Ref

Emotional violence

Emotional violence and controlling behaviour is behaviour which does not give equal importance and respect to another person’s feelings and experiences. It is often the most difficult to pinpoint or identify. Emotional violence includes the refusal to listen to, or denial of, another person’s feelings, telling people what they do or do not feel and ridiculing or shaming of their feelings. It happens when one person believes they have a right to control or dominate another person. Bullying ![]() , threatening, harassing, isolating and name calling are all forms of control. They can make people feel bad and worry about what is going to happen next. Emotional violence can also make people feel powerless, fearful or angry about the violence. Ref

, threatening, harassing, isolating and name calling are all forms of control. They can make people feel bad and worry about what is going to happen next. Emotional violence can also make people feel powerless, fearful or angry about the violence. Ref

What Is Psychological Violence?

Violence is a central concept for describing social relationships among humans, a concept loaded with ethical and political significance. Yet, what is violence? What forms can it take? Can human life be void of violence, and should it be? These are some of the hard questions that a theory of violence shall address. In this article we shall address psychological violence, which will be kept distinct from physical violence and verbal violence. Other questions, such as Why are humans violent?, or Can violence ever be just?, or Should humans aspire to non-violence? will be left for another occasion.

PSYCHOLOGICAL VIOLENCE

In a first approximation, psychological violence may be defined as that sort of violence which involves a psychological damage on the part of the agent who is being violated. You do have psychological violence, that is, any time that an agent voluntarily inflicts some psychological distress on an agent. Psychological violence is compatible with physical violence or verbal violence. The damage done to a person that has been the victim of a sexual assault is not only the damage deriving from the physical injuries to her or his body; the psychological trauma the event may provoke is part and parcel of the violence perpetrated, which is a psychological sort of violence.

THE POLITICS OF PSYCHOLOGICAL VIOLENCE

Psychological violence is of the utmost importance from a political point of view. Racism and sexism have been indeed analyzed as forms of violence that a government, or a sect of society, was inflicting on some individuals. From a legal perspective, to recognize that racism is a form of violence even when no physical damage is provoked to the victim of a racist behavior, is an important instrument for putting some pressure (that is, exercising some form of coercion) on those whose behavior is racist. On the other hand, as it is often difficult to assess a psychological damage (who can tell whether a woman is really suffering because of the sexist behavior of her acquaintances rather than because of her own personal issues?), the critics of psychological violence often try to find an easy apologetic way out. While disentangling causes in the psychological sphere is difficult, however, there is little doubt that discriminatory attitudes of all sorts do put some psychological pressure on agents: such a sensation is quite familiar to all human beings, since childhood.

REACTING TO PSYCHOLOGICAL VIOLENCE

Psychological violence poses also some important and difficult ethical dilemmas. First and foremost, is it justified to react with physical violence to an act of psychological violence? Can we, for instance, excuse bloody or physically violent revolts that were perpetrated as a reaction to situations of psychological violence? Consider even a simple case of mobbing, which (at least in part) involves some dose of psychological violence: can it be justified reacting in a physically violent manner to mobbing? The questions just raised divide harshly those who debate violence. On one hand stand those who regard physical violence as a higher variant of violent behavior: reacting to psychological violence by perpetrating physical violence means to escalateviolence. On the other hand, some maintain that certain forms of psychological violence may be more atrocious than any form of physical violence: it is indeed the case that some of the worst forms of torture are psychological and may involve no direct physical damage be inflicted on the tortured.

UNDERSTANDING PSYCHOLOGICAL VIOLENCE

While the majority of human beings may have been victim of some form of psychological violence at some point of their life, without a proper notion of a self it is difficult to devise effective strategies for coping with the damages inflicted by those violent acts. What does it take to heal from a psychological trauma or damage? How to cultivate the well-being of a self? Those may possibly be among the most difficult and central questions that philosophers, psychologists, and social scientists have to answer in order to cultivate the well-being of individuals. Ref

What You Can Do?

- Gun Violence PreventionSee research on gun violence and learn how to help people in an emotional crisis.

- Abuse of Women with DisabilitiesWomen with disabilities may experience unique forms of abuse that are difficult to recognize — making it even harder to get the kind of help they need.

- Abuso de Mujeres con DiscapacidadLas mujeres con discapacidad pueden experimentar formas únicas de abuso que son difíciles de reconocer.

- Warning signs of youth violenceLearn how to recognize danger signs and keep anger from escalating out of control.

- Raising children to resist violence: What you can doChildren learn aggressive behavior early in life. Several strategies can help parents and others teach kids to manage their emotions without using violence.

- Partner Violence: What Can You Do?This brochure briefly describes violence in the home and provides advice for victims, abusers, and family and friends.

- What makes kids care? Teaching gentleness in a violent worldIn a world where violence and cruelty seem to be common and almost acceptable, many parents wonder what they can do to help their children to become kinder and gentler — to develop a sense of caring and compassion for others.

- Understanding and Preventing Violence Directed Against TeachersInformation to help K-12 teachers to cope with and prevent the occurrence and threat of violent incidents in their classrooms.

Getting Help

- Talking to your children about the recent spate of school shootingsEvery child will respond to trauma differently. Some will have no ill effects; others may suffer an immediate and acute effect. Still others may not show signs of stress until sometime after the event.

- How to find help through seeing a psychologistThis brief question-and-answer guide provides some basic information to help individuals take advantage of outpatient (non-hospital) psychotherapy.

- Managing your distress in the aftermath of a shootingYou may be struggling to understand how a shooting rampage could take place in a community, even a workplace or military base, and why such a terrible thing would happen.

- Intimate Partner ViolenceNearly half of all women in the United States have experienced at least one form of psychological aggression by an intimate partner.

- Violencia en Contra de la ParejaMujeres con discapacidades tienen 40 por ciento mayor riesgo de sufrir violencia por parte de la pareja, principalmente violencia severa, en comparación con mujeres sin discapacidades.

I strive to be a good human ethical in both my thinking and behaviors thus I strive to be:

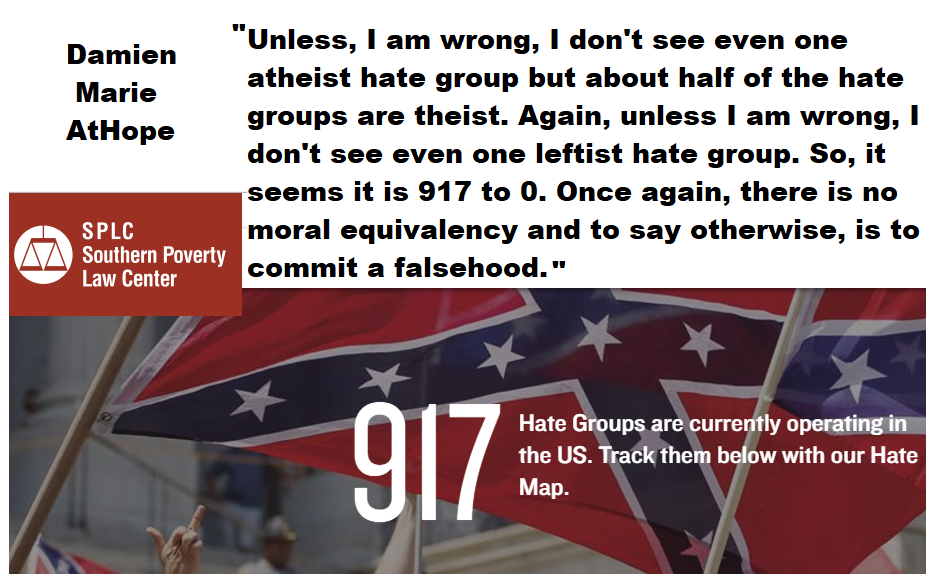

Anti-racist, Anti-sexist, Anti-homophobic, Anti-biphobic. Anti-transphobic, Anti-classist, Anti-ablest, Anti-ageist, and as Always Antifascist!

In fact, I want to strive to avoid as much as I can bigoted thinking towards others based on their perceived membership or classification based on that person’s perceived political affiliation (Well: within reason, justice, and ethics), sex/gender, beliefs (Well: within reason, justice, and ethics), social class (Well: within reason, justice, and ethics), age, disability, religion (Well: within reason, justice, and ethics), sexuality (Well: within reason, justice, and ethics), race, ethnicity, language (Well: within reason, justice, and ethics), nationality, beauty, height, occupation (Well: within reason, justice, and ethics), wealth (Well: within reason, justice, and ethics), education, sport-team affiliation, music tastes or other personal characteristics (Well: within reason, justice, and ethics).

Although, I am a “very”, yes, VERY strong atheist, antitheist as well as antireligionist, My humanity is just as strong and I value it above my disbeliefs. My kind of people are those who champion humanity, the one’s who value kindness, love justice, and support universal empowerment for all humans, we are all equal in dignity, and all deserve human rights, due self-sovereignty.

My Antireligionism?

I will grant you some religious mythology is quite interesting but I never forget it is simple stories of hope, fear, and magical thinking arising from human ignorance fueled by imagination and presto people believe in things never seen. I hate religion as I hate harm, oppression, bigotry, and love equality, self-ownership, self-empowerment, self-actualization including self-mastery, as well as truth and not only does religion lie, it is a conspiracy theory of reality. I know that god-something is is an unjustified and debunked claim of super supernatural when no supernatural any has ever been found to even start such claims.

I don’t think antireligionism is really anti-friendly-atheism, as it can involve being friendly to people even if it is harsh to religion, positive antireligionism or Anti-Accommodationism is attacking bad thinking and bad behaviors, not just people who believe. Not just an atheist and antitheist, I am a proud anti-religionist. I have greater confidence in science as they often admit errors and I have greater mistrust of religion as they often refuse to accept or admit errors.

What I do not like about religion in one idea, religions as a group are “Conspiracy Theories of Reality,” usually filled with Pseudoscience, Pseudohistory, along with Pseudomorality, and other harmful aspects. An antireligionist generally means opposition to religion, this includes all, every religion or pseudo-religion, YES, I am an atheist and antitheist, who is “Anti” ALL RELIGIONS. But I am against the ideas, not people. We regrettably pay our life debt in our time lost living one moment at a time which seem to group together into what we call a life, so live as there just went another lost moment.

“But Damien, Souls are real because energy does not die!”

My response, That is a logical fallacy as it is not a reasoned jump in logic. Energy leaves all once alive bodies by dissipating heat in the environment then is gone as the once related energy in a now dead body.

My thoughts on religious progression, and reasoned speculations from the evidence:

Animism (100,000 years ago)

Totemism (50,000 years ago)

Shamanism (30,000 years ago)

Paganism (13,000 years ago)

“Institutional” Progressed Organized Religion (5,000 years ago)

Religion Progression

- Animism (belief in a perceived spirit world) passably by at least 100,000 years ago “the primal stage of early religion”

- Totemism (belief that these perceived spirits could be managed with created physical expressions) passably by at least 50,000 years ago “progressed stage of early religion”

- Shamanism (belief that some special person can commune with these perceived spirits on the behalf of others by way rituals) passably by at least 30,000 years ago

- Paganism “Early organized nature-based religion” mainly like an evolved shamanism with gods (passable by at least 13,000 years ago).

- Institutional religion developed stage of “Progressed Organized Type Religion” as a social institution with official dogma usually set in a hierarchical/bureaucratic structure that contains strict rules and practices dominating the believer’s life.

I classify Animism (animated ‘spirit‘ or “supernatural” perspectives).

I see all religious people as at least animists, so, all religions have at least some amount, kind, or expression of animism as well.

I want to make something clear as I can, as simple as I can, even though I classify Animism (animated and alive from Latin: anima, ‘breath, spirit, life‘ or peoples’ “spiritual” or “supernatural” perspectives. Potentially, in some animism perceives, all things may relate to some spiritual/supernatural/non-natural inclinations, even a possible belief that objects, places, and/or creatures all possess a distinct spiritual essence, and/or thinking things like all things—animals, plants, rocks, rivers, weather systems, human handiwork, and perhaps even words— could be as animated and alive ref) as the first expression of religious thinking or religion, it is not less than, nor is it not equal to any other religion, or religious thinking. I see all religious people as at least animists any way, so everyone is at least animist, how could it be less than other religions as all other religions have at least some amount, kind, or expression of animism. Animism, +? is what I think about all that say they are spiritual or religious in thinking. Regardless if they know it, understand it, or claim it, they all, to me, an animistic-thinker, plus a paganistic, totemistic, and shamanistic-monotheist, calling themselves a Christian, Jew, or Muslim, as an example of my thinking. Animism (is the other-then-reality thinking relates to, thus it is in all such non-reality thinking generally.

Furthermore, I actually am impressed by animist cultures in Africa, others have seen them as primitive or something, help with that, they are revolutionaries with women’s rights, child rights. I mean if I had to choose a religion it would be animism only like in Africa so I don’t look down on them nor any indigenous peoples, who I care about, as well as I am for “humanity for all.” I challenge religious Ideas, and this is not meant to be an attack on people, but rather a challenge to think or rethink ideas, I want what is actually true. May we all desire a truly honest search for what is true even if we have to update what we believe or know. I even have religious friends, as I am not a bigot.

I class religious thinking in “time of origin” not somehow that any are better or worse or more reasoned than others. No, I am trying to help others understand how things happened, so they understand, and for themselves can finally think does the religion they say they believe in, still seems true, as they believed before learning my information and art. I am hoping I inspire freedom of thought and development of heart as well as mind as we need such a holistic approach in our quest for a humanity free for all and supportive of all. Until then, train your brain to think ethically. We are responsible for the future, we are the future, living in the present, soon to be passed, so we must act with passion, because life is over just like that. I am just another fellow dignity being. May I be a good human.

Your embracing and supporting “white privilege” makes me sick!!!

Hell YES, America is a Racist Country!!!

For the love of Hillbillies and Teachers?

Less Imperialism Worship in Prehistory/History, PLEASE

I love when people of Statism-worship persuasion, love saying, things are so bad and we need to lower the struggle,

I think what the delusion are you talking about, it has always been class war, crazy fucker, you know, for about 7,000 years ago of oppressions forced on us at the end.

Between 7,000-5,000 Years ago, rise of unequal hierarchy elite, leading to a “birth of the

State” or worship of power, strong new sexism, oppression of non-elites,

Here are a few of what I see as “Animist only” Cultures:

“Aka people” Central African nomadic Mbenga pygmy people. PRONUNCIATION: AH-kah

“The Aka people are very warm and hospitable. Relationships between men and women are extremely egalitarian. Men and women contribute equally to a household’s diet, either a husband or wife can initiate divorce, and violence against women is very rare. No cases of rape have been reported. The Aka people are fiercely egalitarian and independent. No individual has the right to force or order another individual to perform an activity against his or her will. Aka people have a number of informal methods for maintaining their egalitarianism. First, they practice “prestige avoidance”; no one draws attention to his or her own abilities. Individuals play down their achievements.” ref

“Mbuti People”

“The Mbuti people are generally hunter-gatherers who commonly are in the Congo’s Ituri Forest have traditionally lived in stateless communities with gift economies and largely egalitarian gender relations. They were a people who had found in the forest something that made life more than just worth living, something that made it, with all its hardships and problems and tragedies, a wonderful thing full of joy and happiness and free of care. Pygmies, like the Inuit, minimize discrimination based upon sex and age differences. Adults of all genders make communal decisions at public assemblies. The Mbuti people do not have a state, or chiefs or councils.” ref

“Hadza people”

“The Hadza people of Tanzania in East Africa are egalitarian, meaning there are no real status differences between individuals. While the elderly receive slightly more respect, within groups of age and sex all individuals are equal, and compared to strictly stratified societies, women are considered fairly equal. This egalitarianism results in high levels of freedom and self-dependency. When conflict does arise, it may be resolved by one of the parties voluntarily moving to another camp. Ernst Fehr and Urs Fischbacher point out that the Hadza people “exhibit a considerable amount of altruistic punishment” to organize these tribes. The Hadza people live in a communal setting and engage in cooperative child-rearing, where many individuals (both related and unrelated) provide high-quality care for children. Having no tribal or governing hierarchy, the Hadza people trace descent bilaterally (through paternal and maternal lines), and almost all Hadza people can trace some kin tie to all other Hadza people.” ref

- First, there is the foundation: Superstitionism and Symbolism/Ritualism.

- Second, is the frame and walls: Supernaturalism and Sacralizism/Spiritualism.

- Third, is the roof and finishing elements of the structure: Dogmatism and Myths.

- Fourth, is the window dressing and stylings to the house: decorated with the webs religious Dogmatic-Propaganda.

In the stage of organized religion, one important aspect that is often overlooked because of male-only thinking or by some over-emphasized because of extreme feminism is gender. There are some obvious gender associations in artifacts and possible gender-involved religious beliefs but thoughtful feminist archaeologists do not pounce on every representation of a woman and pronounce that it is a goddess. Around 5,000 years ago there are the full elements seem to be grouping together with its connected set of Dogmatic-Propaganda-Closure belief strains of sacralized superstitionism that took different forms of behavior in different areas of the world.

Interconnectedness of religious thinking Animism, Totemism, Shamanism, and Paganism

So, it all starts in a general way with Animism (theoretical belief in supernatural powers/spirits), then this is physically expressed in or with Totemism (theoretical belief in mythical relationship with powers/spirits through a totem item), which then enlists a full-time specific person to do this worship and believed interacting Shamanism (theoretical belief in access and influence with spirits through ritual), and then there is the further employment of myths and gods added to all the above giving you Paganism (often a lot more nature-based than most current top world religions, thus hinting to their close link to more ancient religious thinking it stems from). My hypothesis is expressed with an explanation of the building of a theatrical house (modern religions development ending with Institutional religion/organized religion).

Primal early superstition starts around 1 million years ago with. Then the development of religion increased around 600,000 years ago with proto superstition and then even to a greater extent around 300,000 years ago with progressed superstition. Around 100,000 years ago, is the primal stage of early religion, the proto stage of religion is around 75,000 years ago, or less, the progressed stage of early religion is around 50,000 years ago and finally after 13,500 years ago, begins with the evolution of organized religion. The set of stages for the development of organized religion is subdivided into the following: the primal stage of early organized religion is 13,000 years ago, the proto stage of organized religion is around 10,000 years ago, and finally the progressed stage of organized religion is around 7,000 years ago with the forming of mythology and its connected set of Dogmatic-Propaganda-Closure belief strains of sacralized superstitionism. In the stage of organized religion, one important aspect that is often overlooked because of male-only thinking or by some over-emphasized because of extreme feminism is gender. There are some obvious gender associations in artifacts and possible gender-involved religious beliefs but thoughtful feminist archaeologists do not pounce on every representation of a woman and pronounce that it is a goddess. Around 5,000 years ago elements seem to be grouping together with its connected set of Dogmatic-Propaganda-Closure belief strains of sacralized superstitionism that took different forms of behavior in different areas of the world.

Promoting Religion as Real is Harmful?

Sometimes, when you look at things, things that seem hidden at first, only come clearer into view later upon reselection or additional information. So, in one’s earnest search for truth one’s support is expressed not as a one-time event and more akin to a life’s journey to know what is true. I am very anti-religious, opposing anything even like religion, including atheist church. but that’s just me. Others have the right to do atheism their way. I am Not just an Atheist, I am a proud antireligionist. I can sum up what I do not like about religion in one idea; as a group, religions are “Conspiracy Theories of Reality.” These reality conspiracies are usually filled with Pseudo-science and Pseudo-history, often along with Pseudo-morality and other harmful aspects and not just ancient mythology to be marveled or laughed at. I regard all this as ridiculous. Promoting Religion as Real is Mentally Harmful to a Flourishing Humanity To me, promoting religion as real is too often promotes a toxic mental substance that can divide a person from who they are shaming them for being human. In addition, religion is a toxic mental substance that can divide a person from real history, real science or real morality to pseudohistory, pseudoscience, and pseudomorality. Moreover, religion is a toxic mental substance that can divide a person from rational thought, critical thinking, or logic. Likewise, religion is a toxic mental substance that can divide a person from justice, universal ethics, equality, and liberty. Yes, religion is a toxic mental substance that can divide a person from loved ones, and religion is a toxic mental substance that can divide a person from humanity. Therefore, to me, promoting religion as real is too often promote a toxic mental substance that should be rejected as not only false but harmful as well even if you believe it has some redeeming quality. To me, promoting religion as real is mentally harmful to a flourishing humanity. Religion may have once seemed great when all you had or needed was to believe. Science now seems great when we have facts and need to actually know.

A Rational Mind Values Humanity and Rejects Religion and Gods

A truly rational mind sees the need for humanity, as they too live in the world and see themselves as they actually are an alone body in the world seeking comfort and safety. Thus, see the value of everyone around them as they too are the same and therefore rationally as well a humanistically we should work for this humanity we are part of and can either dwell in or help its flourishing as we are all in the hands of each other. You are Free to think as you like but REALITY is unchanged. While you personally may react, or think differently about our shared reality (the natural world devoid of magic anything), We can play with how we use it but there is still only one communal reality (a natural non-supernatural one), which we all share like it or not and you can’t justifiably claim there is a different reality. This is valid as the only one of warrant is the non-mystical natural world around us all, existing in or caused by nature; not made or caused by superstitions like gods or other monsters, too many sill fear irrationally.

I know that god-something is is an unjustified and debunked claim of super supernatural when no supernatural any has ever been found to even start such claims. I am quite familiar with a general when and why gods were created. Gods are not in all religions nor their thinking. I believe that all claims of God will fail epistemic qualities need for belief and instead require disbelief in all of them, unless shown real epistemic value.

Every child born with horrific deformities shows that those who believe in a loving god who is in control and values every life is not just holding a ridiculous belief; it is an offensive belief to the compassion for life and a loving morality. Prayer is nothing like hope, as prayer is the Belief in magic and a thing one is believed they are praying to is magical things or beings. Hope is a desire or aspiration, not a Belief in magical things or you have additional beliefs added in that hope.

Religion removed? All its pseudo meaning as well as pseudoscience, pseudohistory, and pseudo-morality. We have real science, realistic history and can access real morality with a blend of philosophy, anthropology, psychology, sociology, and cognitive science. I do not hate simply because I challenge and expose myths or lies any more than others being thought of as loving simply because of the protection and hiding from challenge their favored myths or lies.

Can we do better?

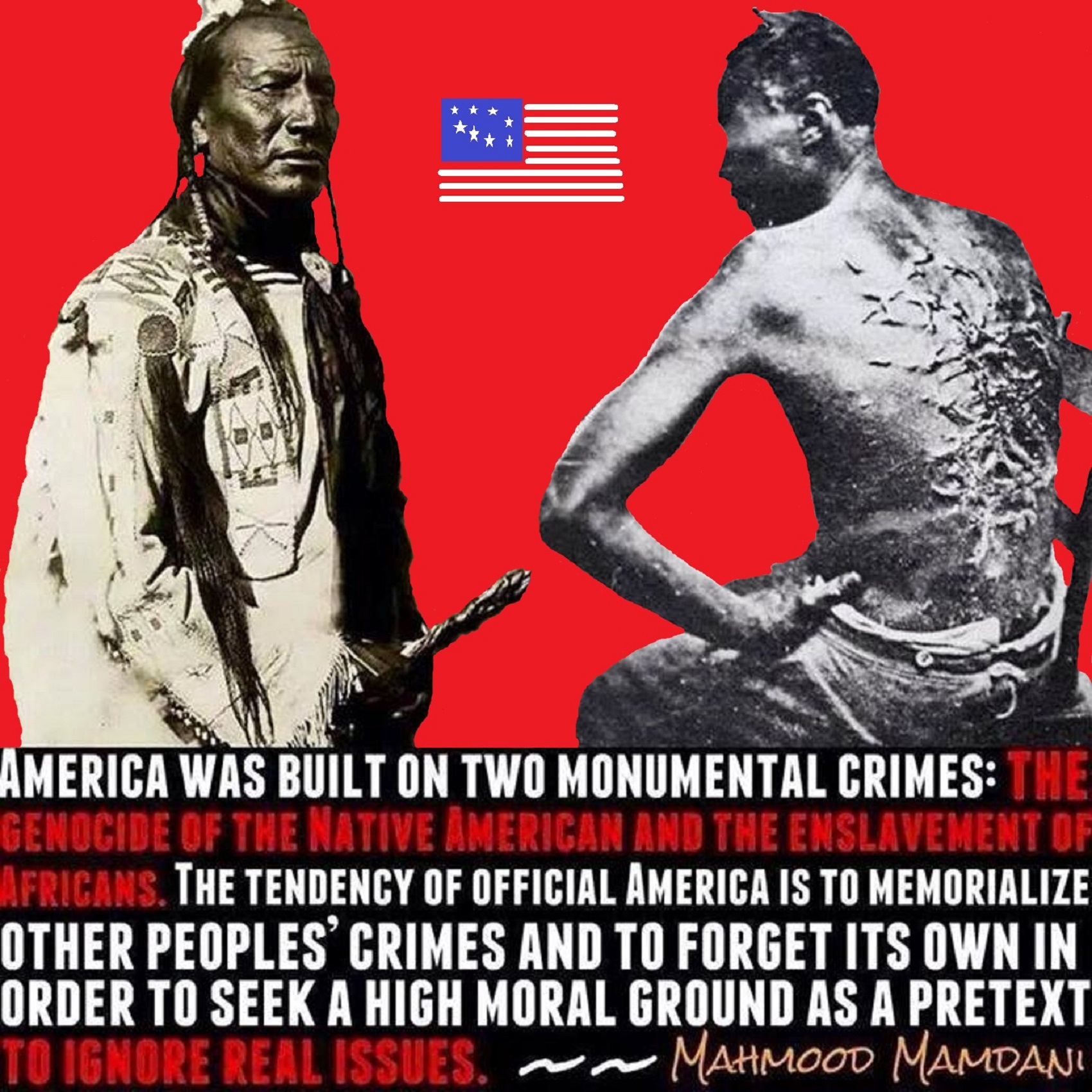

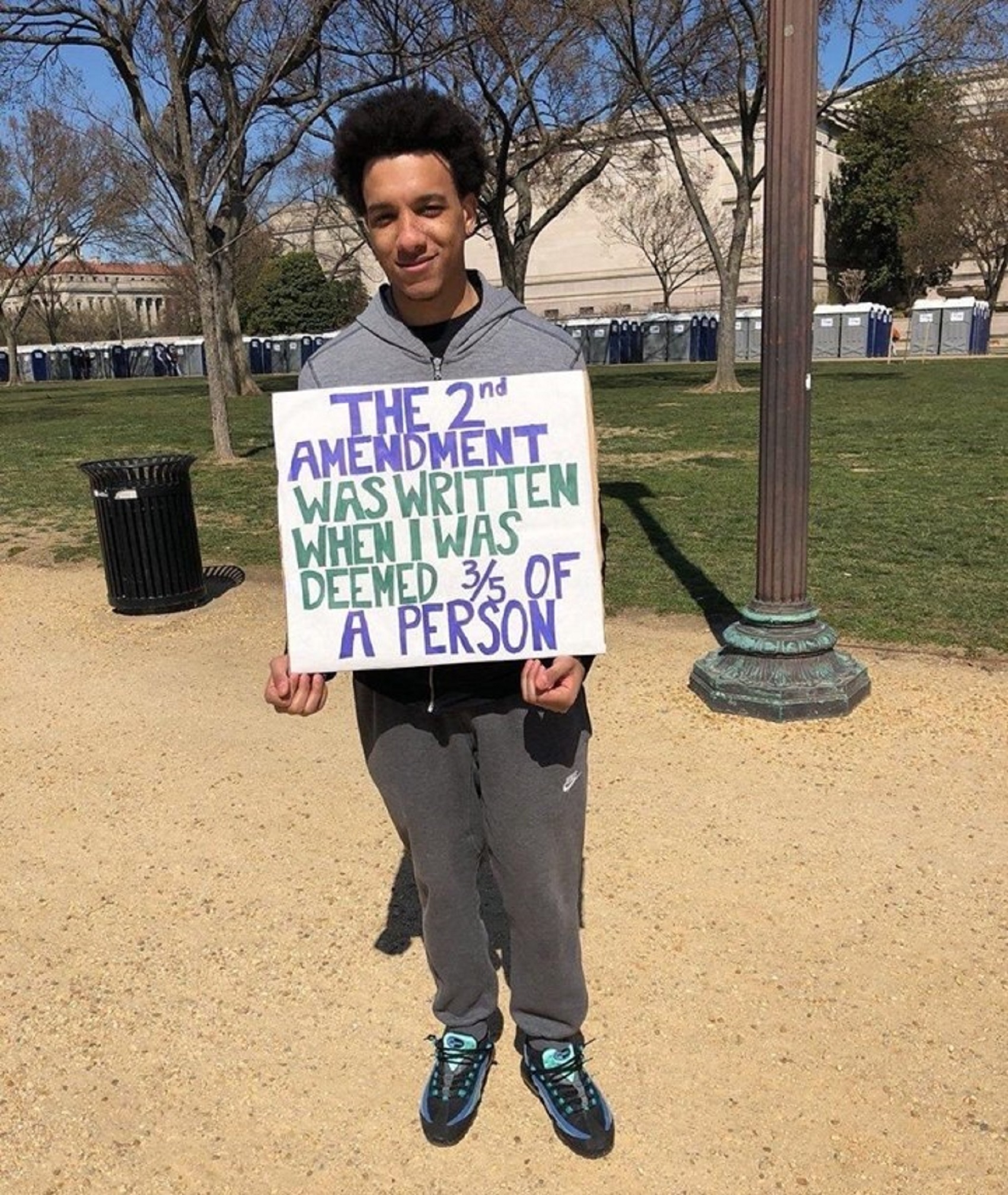

Reparations for Slavery, American Terrorism?

Reparations for Jim Crow, American Terrorism?

Reparations for Red Lining, American Terrorism?

Reparations for Lynchings, American Terrorism?

Reparations for Unarmed Shootings, American Terrorism?

Yes, I believe we should!

A Study Finds 4,000 Lynchings in Jim Crow South, Will U.S. Address Legacy of Racial Terrorism?

Such vile American-Terrorism, So horrific, I totally support reparations.

I have learned about one racist group that also supports atheism.

While hallucinogens are associated with shamanism, it is alcohol that is associated with paganism.

The Atheist-Humanist-Leftist Revolutionaries Shows in the prehistory series:

Show two: Pre-animism 300,000 years old and animism 100,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism”

Show tree: Totemism 50,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism”

Show four: Shamanism 30,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism”

Show five: Paganism 12,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism”

Show six: Emergence of hierarchy, sexism, slavery, and the new male god dominance: Paganism 7,000-5,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism” (Capitalism) (World War 0) Elite and their slaves!

Prehistory: related to “Anarchism and Socialism” the division of labor, power, rights, and recourses: VIDEO

Pre-animism 300,000 years old and animism 100,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism”: VIDEO

Totemism 50,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism”: VIDEO

Shamanism 30,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism”: VIDEO

Paganism 12,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism” (Pre-Capitalism): VIDEO

Paganism 7,000-5,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism” (Capitalism) (World War 0) Elite and their slaves: VIEDO

Paganism 5,000 years old: progressed organized religion and the state: related to “Anarchism and Socialism” (Kings and the Rise of the State): VIEDO

Paganism 4,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism” (First Moralistic gods, then the Origin time of Monotheism): VIEDO

I do not hate simply because I challenge and expose myths or lies any more than others being thought of as loving simply because of the protection and hiding from challenge their favored myths or lies.

The truth is best championed in the sunlight of challenge.

An archaeologist once said to me “Damien religion and culture are very different”

My response, So are you saying that was always that way, such as would you say Native Americans’ cultures are separate from their religions? And do you think it always was the way you believe?

I had said that religion was a cultural product. That is still how I see it and there are other archaeologists that think close to me as well. Gods too are the myths of cultures that did not understand science or the world around them, seeing magic/supernatural everywhere.

I personally think there is a goddess and not enough evidence to support a male god at Çatalhöyük but if there was both a male and female god and goddess then I know the kind of gods they were like Proto-Indo-European mythology.

This series idea was addressed in, Anarchist Teaching as Free Public Education or Free Education in the Public: VIDEO

Our 12 video series: Organized Oppression: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of power (9,000-4,000 years ago), is adapted from: The Complete and Concise History of the Sumerians and Early Bronze Age Mesopotamia (7000-2000 BC): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=szFjxmY7jQA by “History with Cy“

Show #1: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power (Samarra, Halaf, Ubaid)

Show #2: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power

Show #3: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power (Uruk and the First Cities)

Show #4: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power (First Kings)

Show #5: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power (Early Dynastic Period)

Show #6: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power

Show #7: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power (Sargon and Akkadian Rule)

Show #9: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power (Gudea of Lagash and Utu-hegal)

Show #12: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power (Aftermath and Legacy of Sumer)

The “Atheist-Humanist-Leftist Revolutionaries”

Cory Johnston ☭ Ⓐ Atheist Leftist @Skepticallefty & I (Damien Marie AtHope) @AthopeMarie (my YouTube & related blog) are working jointly in atheist, antitheist, antireligionist, antifascist, anarchist, socialist, and humanist endeavors in our videos together, generally, every other Saturday.

Why Does Power Bring Responsibility?

Think, how often is it the powerless that start wars, oppress others, or commit genocide? So, I guess the question is to us all, to ask, how can power not carry responsibility in a humanity concept? I know I see the deep ethical responsibility that if there is power their must be a humanistic responsibility of ethical and empathic stewardship of that power. Will I be brave enough to be kind? Will I possess enough courage to be compassionate? Will my valor reach its height of empathy? I as everyone, earns our justified respect by our actions, that are good, ethical, just, protecting, and kind. Do I have enough self-respect to put my love for humanity’s flushing, over being brought down by some of its bad actors? May we all be the ones doing good actions in the world, to help human flourishing.

I create the world I want to live in, striving for flourishing. Which is not a place but a positive potential involvement and promotion; a life of humanist goal precision. To master oneself, also means mastering positive prosocial behaviors needed for human flourishing. I may have lost a god myth as an atheist, but I am happy to tell you, my friend, it is exactly because of that, leaving the mental terrorizer, god belief, that I truly regained my connected ethical as well as kind humanity.

Cory and I will talk about prehistory and theism, addressing the relevance to atheism, anarchism, and socialism.

At the same time as the rise of the male god, 7,000 years ago, there was also the very time there was the rise of violence, war, and clans to kingdoms, then empires, then states. It is all connected back to 7,000 years ago, and it moved across the world.

Cory Johnston: https://damienmarieathope.com/2021/04/cory-johnston-mind-of-a-skeptical-leftist/?v=32aec8db952d

The Mind of a Skeptical Leftist (YouTube)

Cory Johnston: Mind of a Skeptical Leftist @Skepticallefty

The Mind of a Skeptical Leftist By Cory Johnston: “Promoting critical thinking, social justice, and left-wing politics by covering current events and talking to a variety of people. Cory Johnston has been thoughtfully talking to people and attempting to promote critical thinking, social justice, and left-wing politics.” http://anchor.fm/skepticalleft

Cory needs our support. We rise by helping each other.

Cory Johnston ☭ Ⓐ @Skepticallefty Evidence-based atheist leftist (he/him) Producer, host, and co-host of 4 podcasts @skeptarchy @skpoliticspod and @AthopeMarie

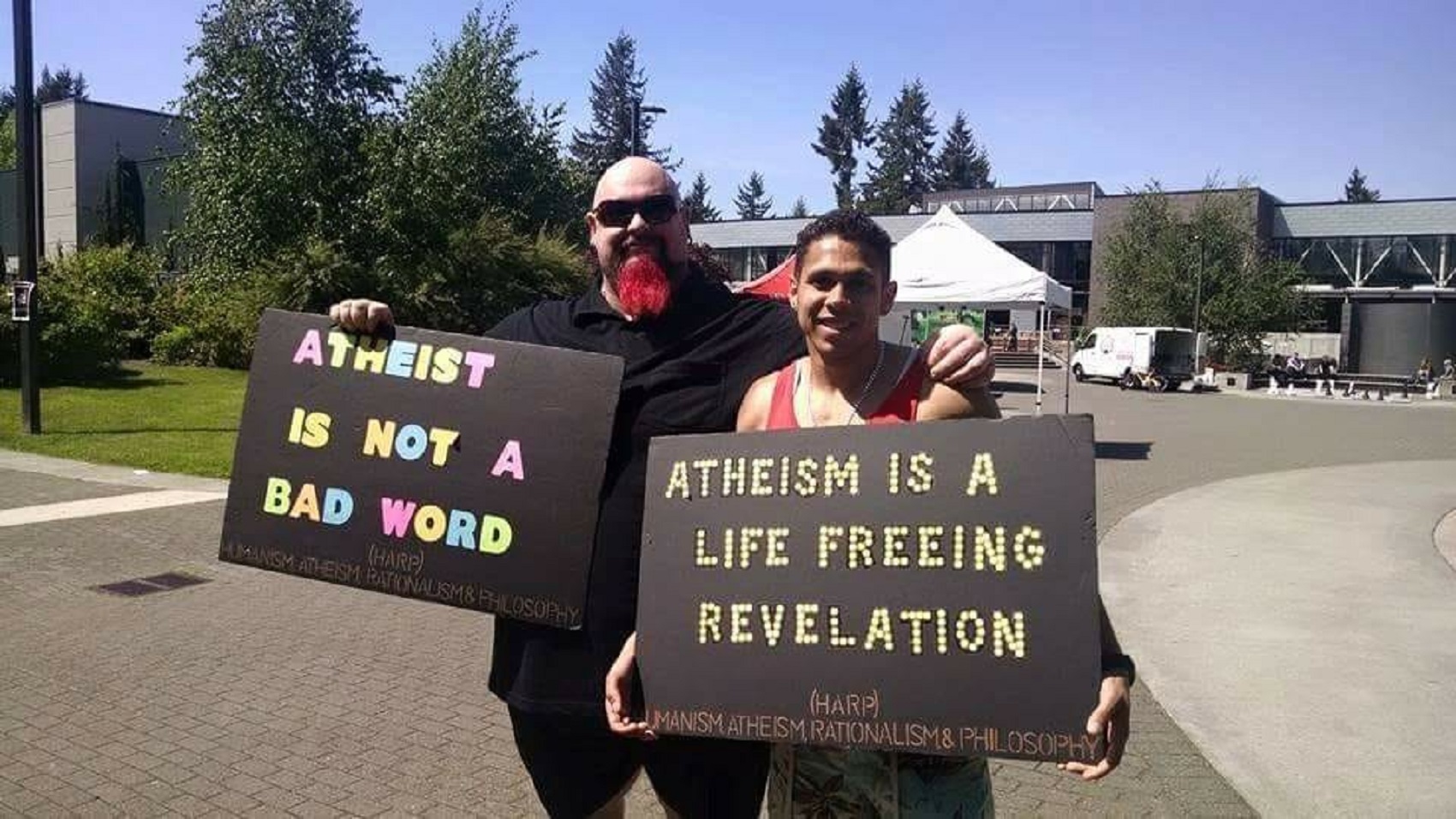

Damien Marie AtHope (“At Hope”) Axiological Atheist, Anti-theist, Anti-religionist, Secular Humanist. Rationalist, Writer, Artist, Poet, Philosopher, Advocate, Activist, Psychology, and Armchair Archaeology/Anthropology/Historian.

Damien is interested in: Freedom, Liberty, Justice, Equality, Ethics, Humanism, Science, Atheism, Antiteism, Antireligionism, Ignosticism, Left-Libertarianism, Anarchism, Socialism, Mutualism, Axiology, Metaphysics, LGBTQI, Philosophy, Advocacy, Activism, Mental Health, Psychology, Archaeology, Social Work, Sexual Rights, Marriage Rights, Woman’s Rights, Gender Rights, Child Rights, Secular Rights, Race Equality, Ageism/Disability Equality, Etc. And a far-leftist, “Anarcho-Humanist.”

I am not a good fit in the atheist movement that is mostly pro-capitalist, I am anti-capitalist. Mostly pro-skeptic, I am a rationalist not valuing skepticism. Mostly pro-agnostic, I am anti-agnostic. Mostly limited to anti-Abrahamic religions, I am an anti-religionist.

To me, the “male god” seems to have either emerged or become prominent around 7,000 years ago, whereas the now favored monotheism “male god” is more like 4,000 years ago or so. To me, the “female goddess” seems to have either emerged or become prominent around 11,000-10,000 years ago or so, losing the majority of its once prominence around 2,000 years ago due largely to the now favored monotheism “male god” that grow in prominence after 4,000 years ago or so.

My Thought on the Evolution of Gods?

Animal protector deities from old totems/spirit animal beliefs come first to me, 13,000/12,000 years ago, then women as deities 11,000/10,000 years ago, then male gods around 7,000/8,000 years ago. Moralistic gods around 5,000/4,000 years ago, and monotheistic gods around 4,000/3,000 years ago.

To me, animal gods were likely first related to totemism animals around 13,000 to 12,000 years ago or older. Female as goddesses was next to me, 11,000 to 10,000 years ago or so with the emergence of agriculture. Then male gods come about 8,000 to 7,000 years ago with clan wars.

Damien Marie AtHope (Said as “At” “Hope”)/(Autodidact Polymath but not good at math):

Axiological Atheist, Anti-theist, Anti-religionist, Secular Humanist, Rationalist, Writer, Artist, Jeweler, Poet, “autodidact” Philosopher, schooled in Psychology, and “autodidact” Armchair Archaeology/Anthropology/Pre-Historian (Knowledgeable in the range of: 1 million to 5,000/4,000 years ago). I am an anarchist socialist politically. Reasons for or Types of Atheism

My Website, My Blog, & Short-writing or Quotes, My YouTube, Twitter: @AthopeMarie, and My Email: damien.marie.athope@gmail.com