SELF-CONSCIOUS EMOTIONS: ANTICIPATORY AND CONSEQUENTIAL REACTIONS TO THE SELF

“Moral Emotions and Moral Behavior”

by June Price Tangney, Jeff Stuewig, and Debra J. Mashek

“Shame, guilt, embarrassment, and pride are members of a family of “self-conscious emotions” that are evoked by self-reflection and self-evaluation. This self-evaluation may be implicit or explicit, consciously experienced or transpiring beneath the radar of our awareness. But importantly, the self is the object of these self-conscious emotions. As the self-reflects upon the self, moral self-conscious emotions provide immediate punishment (or reinforcement) of behavior. In effect, shame, guilt, embarrassment, and pride function as an emotional moral barometer, providing immediate and salient feedback on our social and moral acceptability. When we sin, transgress, or err, aversive feelings of shame, guilt, or embarrassment are likely to ensue. When we “do the right thing,” positive feelings of pride and self-approval are likely to result. Moreover, actual behavior is not necessary for the press of moral emotions to have an effect. People can anticipate their likely emotional reactions (e.g., guilt versus pride/self-approval) as they consider behavioral alternatives. Thus, the self-conscious moral emotions can exert a strong influence on moral choice and behavior by providing critical feedback regarding both anticipated behavior (feedback in the form of anticipatory shame, guilt, or pride) and actual behavior (feedback in the form of consequential shame, guilt, or pride). In our view, people’s anticipatory emotional reactions are typically inferred based on history—that is, based on their past consequential emotions in reaction to similar actual behaviors and events. Ref

Think there is no objective morality?

So, if I can show one simple objective morality fact then there is at least the possibility of objective morality right?

Humans/feeling beings/life are to be protected over dirt/garbage/non-life, and to care for the harm of dirt/garbage/non-life over the harm of Humans/feeling beings/life is unethical and of course a possibility of objective morality right? Are there objective facts about or in the world? Yes, then we indeed can evaluate them objectively. So yes, then we can say what is a better or worse choice objectively in relation to the objective facts. “Morality Confusion” doesn’t start at the dilemma but the value judgments of the parts. Morality is not just the final conclusion reached or offered but all the parts that are involved and the most responsible and reasonable based on the assumption that there are a set of things not just one thing involved and this an assessment of the “value” of what’s involved and thus what would be a “most responsible and reasonable choice. So, are there objective facts? Is there such thing as objective methods? Can we objectively conclude the value of objective facts with objective methods to conclude objective conclusions of value of or in relation to objective facts? To me, it is an answer of yes and thus morality is not a special thing it to can involve objective facts and objective methods and thus can involve objectively conclusions about the value of objective facts with the objective methods to conclude objective conclusions of value, of or in relation to objective facts. To me, morality is a pro-social behavioral response. Therefore, it is involving the moralizer, saying that somehow means there is no objective is a nonsense skepticism confusion, as with such a thinking one can not objectively even say there is anything objective as one is always limited to their mind perceiving what it believes is an outside world. saying we should think beyond ourselves is hard but not at all impossible. I hold that morality is a human invented judgment, but so is “reason” and that does not mean we can not tell the difference from unreason right?

Why care? Because we are Dignity Beings.

*Axiological Dignity Being Theory*

“Dignity is an internal state of peace that comes with the recognition and acceptance of the value and vulnerability of all living things.” – Donna Hicks (2011). Dignity: The Essential Role It Plays in Resolving Conflict

I am inspired by philosophy, enlightened by archaeology and grounded by science that religious claims, on the whole, along with their magical gods, are but Dogmatic-Propaganda, myths and lies. Kindness beats prayers every time, even if you think prayer works, you know kindness works. Think otherwise, do both without telling people and see which one they notice. Aspire to master the heavens but don’t forget about the ones in need still here on earth. You can be kind and never love but you cannot love and never be kind. Therefore, it is this generosity of humanity, we need the most of. So, if you can be kind, as in the end some of the best we can be to others is to exchange kindness. For too long now we have allowed the dark shadow of hate to cloud our minds, while we wait in silence as if pondering if there is a need to commiserate. For too long little has been done and we too often have been part of this dark clouded shame of hate. Simply, so many humans now but sadly one is still left asking, where is the humanity?

Why Ought We Care?

Because kindness is like chicken soup to the essence of who we are, by validating the safety needs of our dignity. When the valuing of dignity is followed, a deep respect for one’s self and others as dignity beings has become one’s path. When we can see with the eyes of love and kindness, how well we finally see and understand what a demonstrates of a mature being of dignity when we value the human rights of others, as we now see others in the world as fellow beings of dignity. We need to understand what should be honored in others as fellow dignity beings and the realization of the value involved in that. As well as strive to understand how an attack to a person’s “human rights” is an attack to the value and worth of a dignity being.

Yes, I want to see “you” that previous being of dignity worthy of high value and an honored moral weight to any violation of their self-ownership. And this dignity being with self-ownership rights is here before you seeking connection. what will you do, here you are in the question ever present even if never said aloud, do you see me now or are you stuck in trying to evaluate my value and assess worth as a fellow being of dignity. A violation of one’s dignity (Which it the emotional, awareness or the emotional detection of the world) as a dignity being can be quite harmful, simply we must see how it can create some physiological disturbance in the dignity being its done to. I am a mutualistic thinker and to me we all are in this life together as fellow dignity beings.

Therefore, I want my life to be of a benefit to others in the world. We are natural evolutionary derived dignity beings not supernatural magic derived soul/spirit beings. Stopping lying about who we are, as your made-up magic about reality which is forced causing a problem event (misunderstanding of axiological valuations) to the natural wonder of reality. What equals a dignity worth being, it is the being whose species has cognitive awareness and the expense of pain. To make another dignity being feel pain is to do an attack to their dignity as well as your own. What equals a dignity worth being, it is the being whose species has cognitive awareness and the expense of pain. When I was younger I felt proud when I harmed those I did not like now I find it deserving even if doing it was seen as the only choice as I now see us for who we are valuable beings of dignity. I am not as worried about how I break the box you believe I need to fit as I am worried about the possibility of your confining hopes of hindering me with your limits, these life traps you have decided about and for me are as owning character attacks to my dignity’s needs which can be generalized as acceptance, understanding, and support.

As I see it now, how odd I find it to have prejudice or bigotry against other humans who are intact previous fellow beings of dignity, we too often get blinded by the external packaging that holds a being of dignity internally. What I am saying don’t judge by the outside see the worth and human value they have as a dignity being. Why is it easier to see what is wrong then what is right? Why do I struggle in speaking what my heart loves as thorough and as passionate as what I dislike or hate? When you say “an act of mercy” the thing that is being appealed to or for is the proposal of or for the human quality of dignity. May my lips be sweetened with words of encouragement and compassion. May my Heart stay warm in the arms kindness. May my life be an expression of love to the world. Dignity arises in our emotional awareness depending on cognition. Our dignity is involved when you feel connected feelings with people, animals, plants, places, things, and ideas. Our dignity is involved when we feel an emotional bond “my family”, “my pet”, “my religion”, “my sport’s team” etc.

Because of the core sensitivity of our dignity, we feel that when we connect, then we are also acknowledging, understanding, and supporting a perceived sense of dignity. Even if it’s not actually a dignity being in the case of plants, places, things, and ideas; and is rightly interacting with a dignity being in people and animals. We are trying to project “dignity developing motivation” towards them somewhere near equally even though human and animals don’t have the same morality weight to them. I am anthropocentric (from Greek means “human being center”) as an Axiological Atheist. I see humans value as above all other life’s value. Some say well, we are animals so they disagree with my destination. But how do the facts play out? So, you don’t have any difference in value of life?

Therefore, a bug is the same as a mouse, a mouse is the same as a dolphin, a dolphin is the same as a human, all to you have exactly the same value? You fight to protect the rights of each of them equally? And all killing of any of them is the same crime murder? I know I am an animal but you also know that we do have the term humans which no other animal is classified. And we don’t take other animals to court as only humans and not any other animals are like us. We are also genetically connected to plants and stars and that still doesn’t remove the special class humans removed from all other animals. A society where you can kill a human as easily as a mosquito would simply just not work ethically to me and it should not to any reasonable person either. If you think humans and animals are of equal value, are you obviously for stronger punishment for all animals to the level of humans?

If so we need tougher laws against all animals including divorce and spousal or child support and we will jail any animal parent (deadbeat animal) who does not adequately as we have been avoiding this for too long and thankfully now that in the future the ideas about animals being equal we had to create a new animal police force and animal court system, not to mention are new animal jails as we will not accept such open child abuse and disregard for responsibilities? As we don’t want to treat animals as that would be unjust to some humans, but how does this even make sense? To me it doesn’t make sense as humans a different from all other animals even though some are similar in some ways. To further discuss my idea of *dignity developing motivation” can be seen in expressions like, I love you and I appreciate you. Or the behavior of living and appreciating.

However, this is only true between higher cognitive aware beings as dignity and awareness of selfness is directly related to dignity awareness. The higher the dignity awareness the higher the moral weight of the dignity in the being’s dignity. What do you think are the best ways to cultivate dignity? Well, to me dignity is not a fixed thing and it feels honored or honoring others as well as help self-helping and other helping; like ones we love or those in need, just as our dignity is affected by the interactions with others. We can value our own dignity and we can and do grow this way, but as I see it because we are a social animals we can usually we cannot fully flourish with our dignity. Thus, dignity is emotionally needy for other dignity beings that is why I surmise at least a partially why we feel empathy and compassion or emotional bonds even with animals is a dignity awareness and response.

Like when we say “my pet” cat one is acknowledging our increased personal and emotional connecting. So, when we exchange in experience with a pet animal what we have done is we raze their dignity. Our dignity flourishes with acceptance, understanding and support. Our dignity withers with rejection, misunderstanding, and opposition. Dignity: is the emotional sensitivity of our sense of self or the emotional understanding about our sense of self. When you say, they have a right to what they believe, what I hear is you think I don’t have a right to comment on it. Dignity is the emotional sensitivity of our sense of self or the emotional understanding about our sense of self. To me when we say it’s wrong to kill a human, that person is appealing to our need to value the dignity of the person.’ The person with whom may possibly be killed has a life essence with an attached value and moral weight valuations.

And moral weight,’ which is different depending on the value of the dignity being you are addressing understanding moral weight as a kind of liability, responsibility, or rights is actualized. So, it’s the dignity to which we are saying validates the right to life. But I believe all living things with cognitively aware have a dignity. As to me dignity is the name I home to the emotional experience, emotional expression, emotional intelligence or sensitivity at the very core of our sense of self the more aware the hire that dignity value and thus worth. Dignity is often shredded similar to my thinking: “Moral, ethical, legal, and political discussions use the concept of dignity to express the idea that a being has an innate right to be valued, respected, and to receive ethical treatment. In the modern context dignity, can function as an extension of the Enlightenment-era concepts of inherent, inalienable rights.

English-speakers often use the word “dignity” in prescriptive and cautionary ways: for example, in politics it can be used to critique the treatment of oppressed and vulnerable groups and peoples, but it has also been applied to cultures and sub-cultures, to religious beliefs and ideals, to animals used for food or research, and to plants. “Dignity” also has descriptive meanings pertaining to human worth. In general, the term has various functions and meanings depending on how the term is used and on the context.” Dignity, authenticity and integrity are of the highest value to our experience, yet ones that we must define for ourselves. People of hurt and harm, you are not as free to attack other beings of dignity without any effect on you as you may think. So, I am sorry not sorry that there is no such thing in general, as hurting or harming other beings of dignity without psychological destruction to the dignity being in us. This is an understanding that once done hunts and harm of other beings of dignity emotionally/psychologically hurts and harms your life as an acceptance needy dignity being, as we commonly experience moral discuss involuntary as on our deepest level as dignity beings. Disgust is deeply related to our sense of morality.

Is the choice of morality truly all subjective or all objective?

As an axiological thinker I don’t see morality as an all or nothing endeavor, i.e. all subjective or all objective but do think we can come to objective truths to some extent, even in a seeming subjective situation. I think in a way morality is both an emergent reasoning expressed in cognitive capacities of highly developed minds. However, morality is also a behavioral and social interaction not always requiring highly developed minds. Why would I say that, is because there is not one moral choice we can make but many different moral behaviors, some simple and some very complex. But morality is not just limited to what I have already stated either as to me, it’s also better understood in a biopsychosocial thinking view that variable interactions of biological factors, psychological factors (mood, personality, behavior, etc), and social factors (cultural, familial, socioeconomic, medical, etc) affect morally and or ability to engage in or process moral reasoning. To me such absolute propositions as all subjective or all objective are odd as if one universal idea can label all and every moral thought, behavior and moral agent or moral property is all or nothing terms is confusing or applying a too simplistic box to a very complicated often positional shifting riddle, not an unsolvable one but varying in complexity.

I believe in realism, thus that there are real facts about the world as well as that humans can learn or know them or assess and quantify them with a value realism and that human interactions are behavioral actions in the world which can also be learned or known to some extent or another. I think the conception of morality is limited to behavioral actions with others there is not an immoral action we do to ourselves as we cannot violate our own consent. Can one defend themselves? And is there any choice in this self-defense morality that is truly all subjective or all objective to all situations and all peoples? Is this act of self-defense that harms or attacks another always subjective or always objective in itself? Do you need more facts positional to a given situation to know or make a reasoned moral choice? Do you think there is some fact or facts which can be known that make it always objective to defend oneself? Or do you think self-defense is always subjective and no facts can turn such a moral choice of self-defense into anything else than always a subjective moral choice? Is any of the thousands of choices one could make in any given situation limited to all or nothing morality under the cloak of nothing but always a subjective morality? To me, I reject an all or nothing endeavor to every moral action or by every moral agent in every situation instead see it often as more a sliding set of factors among a myriad of element or choices not all subjective or all objective in every way, at all times, to every moral agent, in every situation.

Think even if I say it’s an objective fact that self-defense is always morally defensible, does that mean any action I or someone else does is morally excusable in such a moral endeavor? As in does it matter the threat and is that always subjective or always objective? Or is the chosen response in the act of self-defense always subjective or always objective? I.e. if a baby hits an adult, can the adult beat them to death and if you make a moral judgment on this would you say it was always subjective or always objective? If a parent hits a small child can the small child shoot them to death and if you make a moral judgment on this would you say it was always subjective or always objective? If an adult of lesser size, strength, or power and means hits an adult of greater size, strength, or power and means, can the greater size adult beat them to death and if you make a moral judgment on this would you say it was always subjective or always objective? If an adult of greater size, strength, or power and means hits an adult of lesser size, strength, or power and means, can the lesser size adult shoot them to death and if you make a moral judgment on this would you say it was always subjective or always objective?

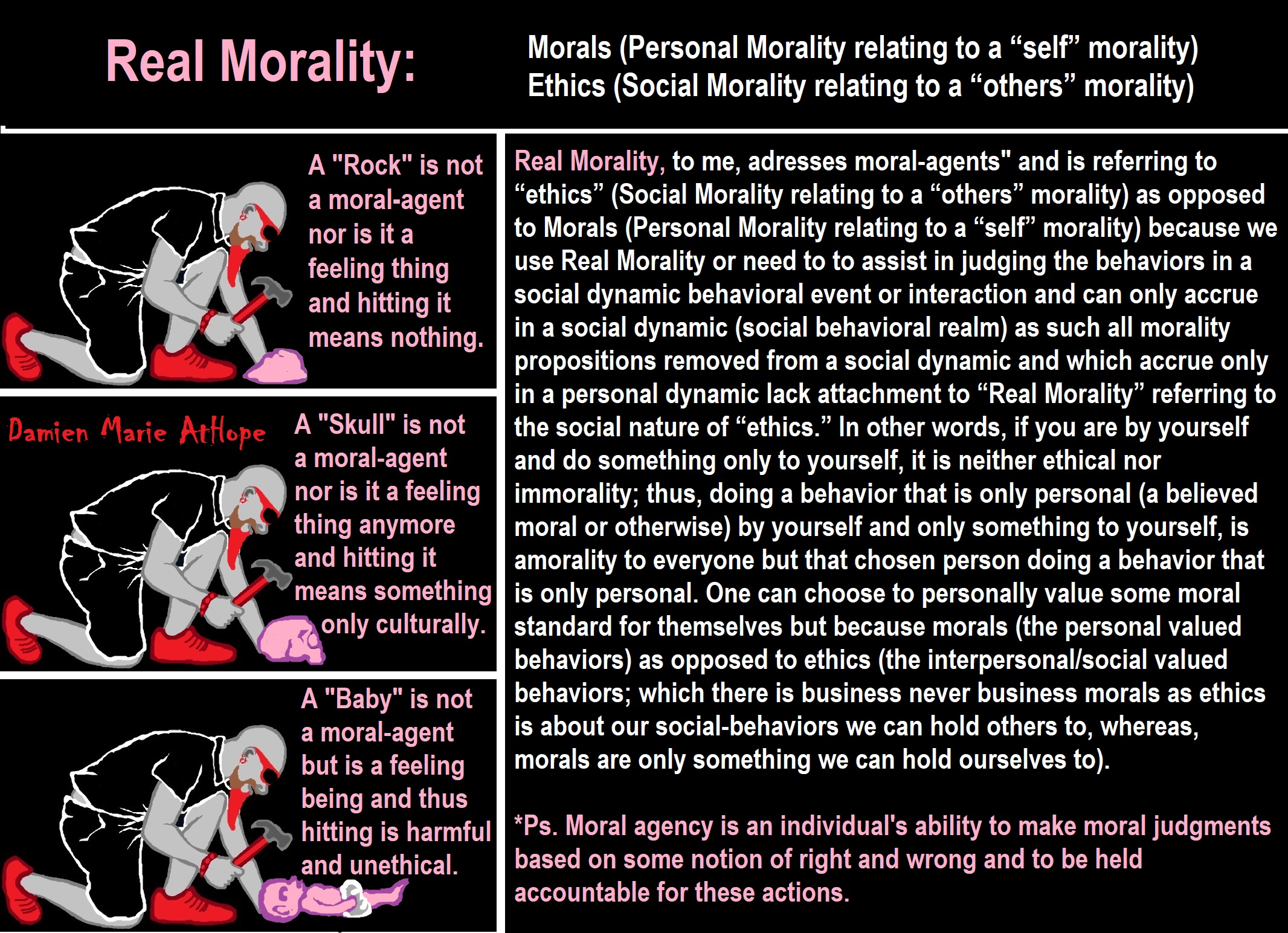

I as an axiological (value theory or value science) thinker I don’t see morality as an all or nothing endeavor, i.e. all subjective or all objective but do think we can come to objective truths to some extent even in a seeming subjective situation. I think it is in a way morality is an emergent cognitive capacities of highly developed minds but is also a behavioral and social interaction not always requiring highly developed minds. To me , rue morality is not starting with a us or me focused morality as morality is a social interaction exchange thus it must be other focused. “treating others as they should be treated” To me, I see everyone as owning themselves all equal in this right as humans. Moreover, to me morality is behavioral and a social property, there is no immoral thing one can do to themselves as one cannot violate themselves or their own consent as they choose their own actions.

Thus, to me all morality is about others and our interactions with them and them with us. So, morality arises in a social context with all things not that all things have the same moral weight. Therefore, moral relationships with life outside humans has a different moral weight or value. Such as killing 100 humans is not the same as killing 100 dogs, killing 100 fish, killing 100 flies, etc. Of course, the method of killing used should inflict the least amount of suffering to the animal or plant. And to not do that could make it immoral. Such as torturing them to death is immoral even if the killing was not. And this understanding can be applied to theism. Every child born with horrific deformities shows that those who believe in a loving god who is in control and values every life is not just holding a ridicules belief it is an offensive belief to the compassion for life and a loving morality.

I am a Realist in Many ways.

I have a positive epistemic attitude (belief) towards or in philosophical realism that there is a real external world and that is can be know or substantially approximated by humans objectively. I have a positive epistemic attitude towards or in scientific realism that the content of the best scientific theories, models, and aspects of the world described by the sciences can be know or substantially approximated by humans objectively. I have a positive epistemic attitude towards or in logical realism such as that logic is the means of discovering the structure of facts and its projection in the language such as the Law of Non-Contradiction or logical fallacies which represent logical truths pertaining to aspects of the world and can be know or substantially approximated by humans objectively. I have a positive epistemic attitude towards or in mathematical realism such as that 2 + 2 equals 4 even if there are no intelligences or minds. Because math is in a sense a method of communication or description of and or about aspects of the world quantifying what can be know or substantially approximated by humans objectively.

I have a positive epistemic attitude towards or in value realism roughly speaking “axiological realism,” is that value claims (such as, nurturing a baby is good and abusing a baby is bad) can be literally true or false; that some such claims are indeed true; that their truth can be know or substantially approximated by humans objectively. I have a positive epistemic attitude towards or in epistemological realism roughly speaking, is that what you know about an object exists independently of your mind. Relating directly to the correspondence theory of truth, which claims that the world exists independently and innately to our perceptions of it. Our sensory data then reflect or correspond to the innate world and that such truths can be know or substantially approximated by humans objectively. I have a positive epistemic attitude towards or in moral realism roughly speaking, is that some moral claims do purport to report facts and are true if they get the facts right. Moreover, wile not all at least some moral claims actually are true or have connection to additional commitments which the truth can be reached, and those facts in some specified way can be know or substantially approximated by humans objectively.

(Rachels, James. Ethical Theory) a moral theory must be able to solve:

The ontological problem: an adequate theory must account for ethics without assuming the existence of anything that does not actually exist. The epistemological problem: if we have knowledge of right and wrong, an adequate theory must explain how we acquire such knowledge. The experience problem: An adequate theory about ethics must account for the phenomenology of moral experience. The supervenience problem: An adequate theory must be consistent with the supervenient character of evaluative concepts. The motivation problem: an adequate theory must account for the internal connection between moral belief and motivation (or if there is no such connection, it must offer an alternative account of how morality guides action). The reason problem: An adequate theory must account for the place of reason in ethics. The disagreement problem: An adequate theory must explain the nature of ethical disagreement. Ref

Sociological and Psychological Ontology of Morality in Relation to

The Objective and Subjective Correspondence to Reality.

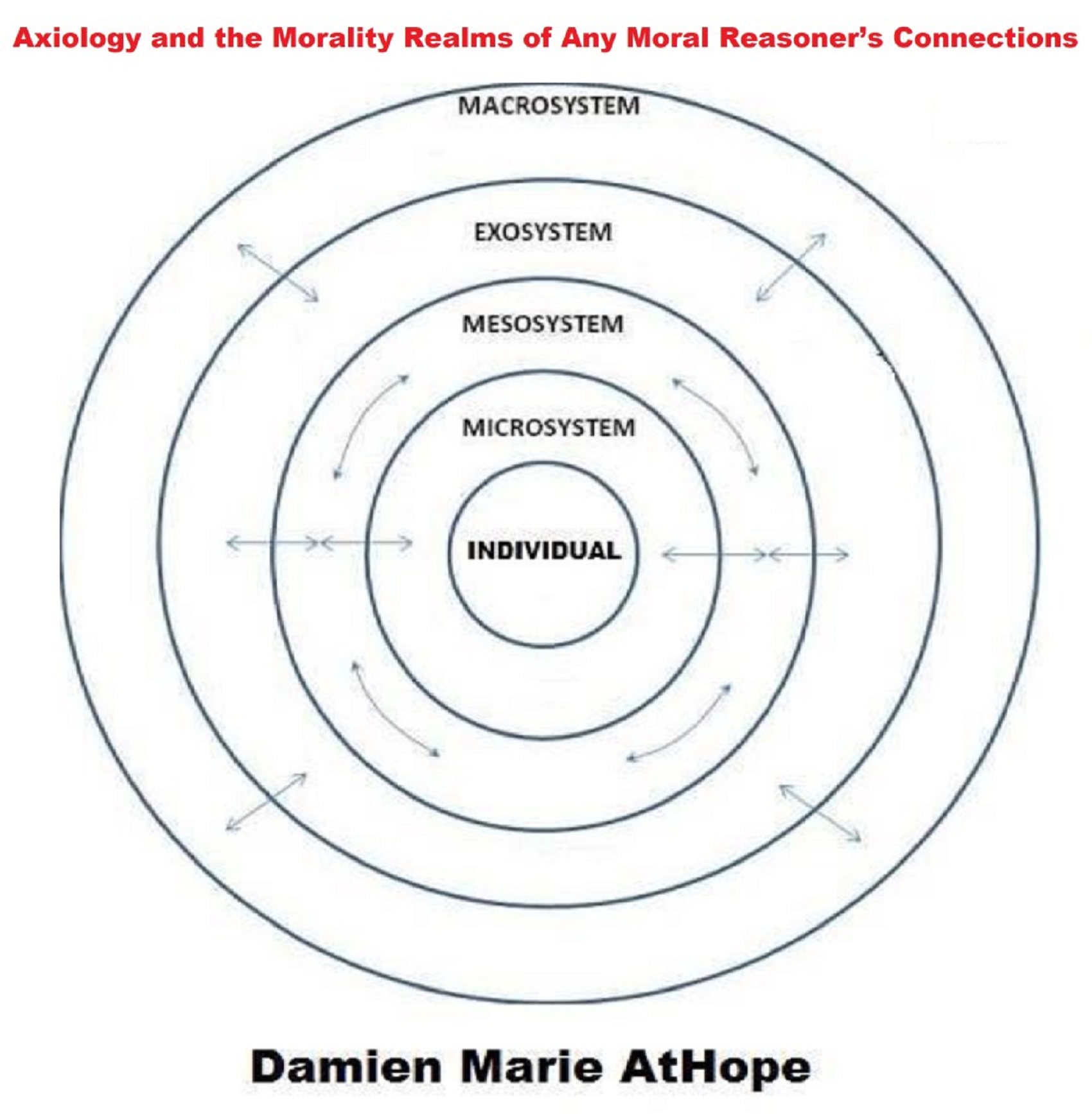

To me, morality (relatively involves moral actors, moral reasoning, moral capital, moral concerns and moral compulsions) is a thinking in relation of behavior to or with “other” and is involved in a cognitive aware (psychological development of, pertaining to, or affecting the mind, especially as a function of awareness, feeling, or motivation) interaction (most commonly social interaction) by humans and thus is both a subjective aspect in the world as it is only positioned to cognitive aware interaction of humans and objective to impacts on the moral actors, moral reasoning, moral capital, moral concerns and moral compulsions choices positioned to cognitive aware interactions of humans. Nonhuman animals are not doing or held accountable for this thing/things we label morality, though this does not remove all moral capital they hold or moral weight in our relations to them, because what happens to nonhuman animals can be attached to moral relevant interactions with them or some indirect secondary connections to other factors (i.e. someone’s pet). I feel that morality and the morally relevant choices only relates to occurrences linked to thinking in the relation of behavior involved in relation to or with “other” in a cognitive aware interaction of humans. Thus feel with no interaction relation to or with “other” then there is no such thing as morality occurring. In a sense to me when nothing of interaction is happening to an external “other” even if, the internal self in question is a cognitive aware human. Such as, if one is by them self and only do things to themselves there is no morality involved. I feel morality in a sense cannot happen to you by you, it is your interacting with others, other things, or their relation to “other” but to me, this is likely an unavoidable reality that corresponds to morality.

Axiology, Realism, and the Problem of Evil (THOMAS L. CARSON)

Although moral realism is the subject of lively debate in contemporary philosophy, it would seem almost all standard discussions of the problem of evil presupposes the truth of moral realism. So, if nonrealism is true, then it would seem we need to rethink and/or re-frame the entire discussion about the problem of evil. Ref

Evolutionary Morality?

If evolutionary critics of morality seek to critique by revealing the unreliability of evolutionary origins by showing that they have generated moral beliefs we know to be false. Indeed, this sort of critique would be self-defeating, for if we were able to sort true moral beliefs from false ones, then we could rely on that knowledge to correct for any epistemically harmful effect, especially in a gradual or subtle way evolutionary influence on the formation of our moral beliefs.

Moral disagreement (Geoff Sayre-McCord)

The mere fact of disagreement does not raise a challenge for moral realism. Disagreement is to be found in virtually any area, even where no one doubts that the claims at stake purport to report facts and everyone grants that some claims are true. But disagreements differ and many believe that the sort of disagreements one finds when it comes to morality are best explained by supposing one of two things: (i) that moral claims are not actually in the business of reporting facts, but are rather our way of expressing emotions, or of controlling others’ behavior, or, at least, of taking a stand for and against certain things or (ii) that moral claims are in the business of reporting facts, but the required facts just are not to be found. Taking the first line, many note that people differ in their emotions, attitudes, and interests and then argue that moral disagreements simply reflect the fact that the moral claims people embrace are (despite appearances) really devices for expressing or serving their different emotions, attitudes, and interests. Taking the second line, others note that claims can genuinely purport to report facts and yet utterly fail (consider claims about phlogiston or astrological forces or some mythical figure that others believed existed) and then argue that moral disagreements take the form they do because the facts that would be required to give them some order and direction are not to be found. On either view, the distinctive nature of “moral disagreement” is seen as well explained by the supposition that moral realism is false, either because cognitivism is false or because an error theory is true. Interestingly, the two lines of argument are not really compatible. If one thinks that moral claims do not even purport to report facts, one cannot intelligibly hold that the facts such claims purport to report do not exist. Nonetheless, in important ways, the considerations each mobilizes might be used to support the other. For instance, someone defending an error theory might point to the ways in which moral claims are used to express or serve peoples’ emotions, attitudes, and interests, to explain why people keep arguing as they do despite there being no moral facts. And someone defending noncognitivism might point to the practical utility of talking as if there were moral facts to explain why moral claims seem to purport to report facts even though they do not. Moreover, almost surely each of these views is getting at something that is importantly “right” about some people and their use of what appear to be moral claims. No one doubts that often peoples’ moral claims do express their emotions, attitudes, and do serve their interests and it is reasonable to suspect that at least some people have in mind as moral facts a kind of fact we have reason to think does not exist.

I am a Moral Realist?

Moral realists are committed to holding, though, that to whatever extent moral claims might have other uses and might be made by people with indefensible accounts of moral facts, some moral claims, properly understood, are actually true. To counter the arguments that appeal to the nature of moral disagreement, moral realists need to show that the disagreements are actually compatible with their commitments. An attractive first step is to note, as was done above, that mere disagreement is no indictment. Indeed, to see the differences among people as disagreements—rather than as mere differences—it seems as if one needs to hold that they are making claims that contradict one another and this seems to require that each side sees the other as making a false claim. To the extent there is moral disagreement and not merely difference, moral realists argue, we need at least to reject noncognitivism (even as we acknowledge that the views people embrace might be heavily influenced by their emotions, attitudes, and interests). While this is plausible, noncognitivists can and have replied by distinguishing cognitive disagreement from other sorts of disagreement and arguing that moral disagreements are of a sort that does not require cognitivism. Realists cannot simply dismiss this possibility, though they can legitimately challenge noncognitivists to make good sense of how moral arguments and disagreements are carried on without surreptitiously appealing to the participants seeing their claims as purporting to report facts.

In any case, even if the nature of disagreements lends some plausibility to cognitivism, moral realists need also to respond to the error theorist’s contention that the arguments and disagreements all rest on some false supposition to the effect that there are actually facts of the sort there would have to be for some of the claims to be true. And, however moral realists respond, they need to avoid doing so in a way that then makes a mystery of the widespread moral disagreement (or at least difference) that all acknowledge. Some moral realists argue that the disagreements, widespread as they are, do not go very deep—that to a significant degree moral disagreements play out against the background of shared fundamental principles with the differences of opinion regularly being traceable to disagreements about the non-moral facts that matter in light of the moral principles. On their view, the explanation of moral disagreements will be of a piece with whatever turns out to be a good explanation of the various nonmoral disagreements people find themselves in. Other moral realists, though, see the disagreements as sometimes fundamental.

On their view, while moral disagreements might in some cases be traceable to disagreements about non-moral matters of fact, this will not always be true. Still, they deny the anti-realist’s contention that the disagreements that remain are well explained by noncognitivism or by an error theory Instead, they regularly offer some other explanation of the disagreements. They point out, for example, that many of the disagreements can be traced to the distorting effects of the emotions, attitudes, and interests that are inevitably bound up with moral issues. Or they argue that what appear to be disagreements are really cases in which the people are talking past each other, each making claims that might well be true once the claims are properly understood (Harman 1975, Wong 1984). And they often combine these explanatory strategies holding that the full range of moral disagreements are well explained by some balanced appeal to all of the considerations just mentioned, treating some disagreements as not fundamentally moral, others as a reflection of the distorting effects of emotion and interest, and still others as being due to insufficiently subtle understandings of what people are actually claiming. If some combination of these explanations works, then the moral realist is on firm ground in holding that the existence of moral disagreements, such as they are, is not an argument against moral realism. Of course, if no such explanation works, then an appeal either to noncognitivism or an error theory (i.e. to some form of anti-realism) may be the best alternative. Ref

Benefit of Seeing Morality as a Matter of Objective Facts

(Liane Young & A.J. Durwin) getting people to think about morality as a matter of objective facts rather than subjective preferences may lead to improved moral behavior, Boston College researchers report in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. Ref

Wish to Reject Moral Realism?

(Geoff Sayre-McCord) those who reject moral realism are usefully divided into (i) those who think moral claims do not purport to report facts in light of which they are true or false (noncognitivists) and (ii) those who think that moral claims do carry this purport but deny that any moral claims are actually true (error theorists). It is worth noting that, while moral realists are united in their cognitivism and in their rejection of error theories, they disagree among themselves not only about which moral claims are actually true but about what it is about the world that makes those claims true. Moral realism is not a particular substantive moral view nor does it carry a distinctive metaphysical commitment over and above the commitment that comes with thinking moral claims can be true or false and some are true. Still, much of the debate about moral realism revolves around either what it takes for claims to be true or false at all (with some arguing that moral claims do not have what it takes) or what it would take specifically for moral claims to be true (with some arguing that moral claims would require something the world does not provide). The debate between moral realists and anti-realists assumes, though, that there is a shared object of inquiry—in this case, a range of claims all involved are willing to recognize as moral claims—about which two questions can be raised and answered: Do these claims purport to report facts in light of which they are true or false? Are some of them true? Moral realists answer ‘yes’ to both, non-cognitivists answer ‘no’ to the first (and, by default, ‘no’ to the second) while error theorists answer ‘yes’ to the first and ‘no’ to the second. (With the introduction of “minimalism” about truth and facts, things become a bit more complicated. See the section on semantics, below.) To note that some other, non-moral, claims do not (or do) purport to report facts or that none (or some) of them are true, is to change the subject. That said, it is strikingly hard to nail down with any accuracy just which claims count as moral and so are at issue in the debate. For the most part, those concerned with whether moral realism is true are forced to work back and forth between an intuitive grasp of which claims are at issue and an articulate but controversial account of what they have in common such that realism either is, or is not, defensible about them. By all accounts, moral realism can fairly claim to have common sense and initial appearances on its side. That advantage, however, might easily outweighed, however; there are a number of powerful arguments for holding that it is a mistake to think of moral claims as true. Ref

Moral Judgments?

(Shin Kim) the cognitivist understanding of moral judgments is at the center of moral realism. For the cognitivist, moral judgments are mental states; moral judgments are of the same kind as ordinary beliefs, that is, cognitive states. But how are we to know this? One manageable way is to focus on what we intend to do when we make moral judgments, and also on how we express them. Moral judgments are intended to be accurate descriptions of the world, and statements express moral judgments (as opposed to command or prescription) just as statements express ordinary beliefs. That is, statements express moral language. The statements that express moral judgments are either true or false just as the statements that express ordinary beliefs are. Moral truths occur when our signs match the world. Language allows us to communicate with one another, typically using sentences and utterances. A large part of language involves, among many other things, influencing others and us. Normative language, in contrast with descriptive language, includes moral language (that is, moral language is part of evaluative or normative language). It is even more important not to be swayed by moral language because moral reality grips us. It is bad that others try to deceive us, but it is worse that we deceive ourselves into accepting moral facts simply because of the language that we use. That is, moral language — if it is not to describe the world —must not be mistaken as descriptive. Moral language binds us in a certain manner, and the manner in which it binds us is important. If it is noncognitivism that provides the antirealist a way of rejecting moral truth, moral knowledge, and moral objectivity, the denial of noncognitivism (that is, cognitivism) must be necessary for the realist to properly claim them. Cognitivism is the view that moral judgments are cognitive states just like ordinary beliefs. It is part of their function to describe the world accurately. The realist argument that stems from cognitivism — as we saw from the above argument— is oftentimes guided by the apparent difficulties that the noncognitivist analysis of moral judgments faces. For instance, there is the famous Frege-Geach problem, namely, the noncognitivist difficulty of rendering emotive, prescriptive or projective meaning for embedded moral judgments. Geach (1965) uses the “the Frege point,” according to which “a proposition may occur in discourse now asserted, now unasserted, and yet be recognizably the same proposition,” to establish that no noncognitivist (“the anti-descriptive theorist”) analysis of moral sentences and utterances can be adequate. Consider a simple moral sentence: “Setting a kitten on fire is wrong.” Suppose that the simple sentence means, “Boo to setting a kitten on fire!” The Frege point dictates that the antecedent of “if setting a kitten on fire is wrong, then getting one’s friends to help setting a kitten on fire is also wrong” must mean the same as the simple sentence. But this cannot be because the antecedent of the conditional makes no such assertions while the simple moral sentence does. In other words, the noncognitivist analysis of moral sentences cannot be given to the conditional sentences with the embedded simple moral sentence. The problem can be generally applied to cases of other compound sentences such as “It is wrong to set a kitten on fire, or it is not.” Even if the noncognitivist analysis of the simple sentence were correct, compound sentences within which a simple moral sentence is embedded should be given an analysis independently of the noncognitivist analysis of it. This seems unacceptable to many. For the following argument is valid: “It is wrong to set a kitten on fire, or it is not; it is not ‘not wrong’; hence, it is wrong to set a kitten on fire.” If the argument is valid, then the conclusion must mean the same as one of the disjuncts of its first premise. The argument would be otherwise invalid because of an equivocation, and the noncognitivist seems to be forced to say that the argument is invalid.

The Frege-Geach problem demonstrates the noncognitivists’ requirement of adequately rendering the emotive, prescriptive, expressive, or projective meaning of those moral sentences that are embedded within compound moral sentences. (For more on the Frege-Geach problem, see Non-Cognitivism in Ethics. See also Darwall, Gibbard, and Railton 1992: 151-52.) Ref

What do Professional Philosophers Believe?

What are the philosophical views of 1,972 contemporary professional philosophers?

On God: atheism 72.8%; theism 14.6%; other 12.6%.

Meta-ethics: moral realism 56.4%; moral anti-realism 27.7%; other 15.9%.

Moral judgment: cognitivism 65.7%; non-cognitivism 17.0%; other 17.3%.

Moral motivation: internalism 34.9%; externalism 29.8%; other 35.3%

Science: scientific realism 75.1%; scientific anti-realism 11.6%; other 13.3%.

Truth: correspondence 50.8%; deflationary 24.8%; epistemic 6.9%; other 17.5%.

It should be acknowledged that this target group has a strong (although not exclusive) bias toward analytic or Anglocentric philosophy. As a consequence, the results of the survey are a much better guide to what analytic/Anglocentric philosophers (or at least philosophers in strong analytic/Anglocentric departments) believe than to what philosophers from other traditions believe. Ref

Consider the Judgment (Shin Kim)

“Suffering from lack of food is bad.” The judgment is usually expressed with the statement “suffering from lack of food is bad.” Call it a “B-statement.” Sometimes, we find it necessary to express it with “it is true that suffering from lack of food is bad.” Call it a “T-statement.” (To complete it, there are “F-statements” like “it is false that suffering from lack of food is bad.”) We use T-statements to emphasize partiality toward “being true to the world.” However, regardless of what motivates us to use T-statements, the explicit ascription of truth in T-statements commands our attention. Does the T-statement add anything extra to the B-statement? If so, what is it that the T-statement says over and above the B-statement? There are two broad ways to answer the question: deflationism and various forms of substantial theory (or what we called above “inflationist theory”). Substantial theorists deny that the B-statement and the T-statement are exactly the same while the deflationist maintains that the difference is merely stylistic. If the deflationist has her way, then it is obvious that antirealists could have truth in moral judgments. (David Brink argues against the coherentist theory of truth with respect to moral constructivism. See Brink 1989, 106-7 and 114; see Tenenbaum, 1996, for the deflationist approach.) Antirealist moral truths would seem irrelevant in marking the realist territory. If some form of substantial theory is true, then the T-statement adds something to what the B-statements say. Here are two alternatives. Letting a coherence theory of truth stand in for the range of “modified theories” (namely, the inflationist theories of truth that are different from the correspondence theory of truth), and the “B-proposition” for what the B-statement describes the world, the T-statement adds that: (1) The B-proposition corresponds to an actual state of affairs. (2) The B-proposition belongs to a maximally coherent system of belief. It is worth noting also that even the non-descriptivist may say that the T-statement adds to the B-statement, insofar as the B-statement expresses something other than the B-proposition. The non-descriptivist has two alternatives as well. The T-statement adds that (letting a coherence theory of truth stand in for the range of “modified theories,” and the “B-feeling-proposition” stand in for the range of non-descriptivism, for example, the speaker dislikes suffering from lack of food): (3) The B-feeling-proposition corresponds to an actual state of affairs. (4) The B-feeling-proposition belongs to a maximally coherent system of belief. We may say that the T-statement specifies truth conditions for the B-proposition or for the B-feeling-proposition. It could be objected that the non-descriptivist must deny that there are truth-conditions for moral language. Nonetheless, she need not object to moral language describing something about the world figuratively. If option (1) were true, then there would have to be an actual state of affairs that makes the B-statement true. That is, there must be a truth-maker for the statement, “suffering from lack of food is bad,” and the truth-maker is the fact that suffering from lack of food is bad. But no other alternatives require the existence of the fact for them to be true. If one ignores deflationism, truth in moral judgments gives rise to exactly four alternative theories of truth. Realists cannot embrace options (3) and (4) because, as we saw, non-descriptivism is sufficient for moral antirealism. The remaining option (2), although it is a viable option for the realist, falls short of guaranteeing that there are moral facts. In other words, moral realists must find other ways to establish the existence of moral facts, even if option (2) allows a way of maintaining moral truths for the realists. Modified theories, for example, the coherence theory of truth are simply silent about whether there are B-facts. That is, option (2) could be maintained even if there were no B-facts such as suffering from lack of food is bad. Thus, the most direct option for realists in marking her territory from the above list of alternatives is (1). It appears then that the correspondence truth in moral judgments properly marks the realist territory. This is captured in C2: (C2) S is a moral realist if and only if S is a descriptivist; S believes that moral judgments express truth, and S believes that the moral judgments are true when they correspond to the world. Is C2 true? No, it is not. For the antirealist may choose to deny that moral judgments literally describe the world. Ref

Axiology (value science) & Neuroscience (brain science)

(Demarest, Peter D.; Schoof, Harvey J. ) Axiogenics™ is, “the mind-brain science of value generation.” It is a practical life-science based on applied neuro-axiology1 — the integration of neuroscience (brain science) and axiology (value science). Neuroscience is the study of the biochemical mechanics of how the brain works. We are, of course, primarily interested in the human brain, which, owing to our genetics, is one of the most complex and magnificent creations in the known universe. Axiology is the study of how Value, values and value judgments affect the subjective choices and motivations of the mind—both conscious and sub-conscious. Formal axiology is the mathematical study of value—the nature and measurement of value and people’s perception of value. Both axiology and neuroscience have existed separately for years. In many ways, the two sciences have approached the same question (What makes people tick?) from opposite directions. Neuroscience, a relatively young science, seeks to understand brain function and explain human behavior from a neuro-biological perspective. In contrast, for 2500 years, axiologists have sought to understand and explain human behavior and motivation from the perspective of the moral, ethical, and value-based judgments of the mind. Many human sciences, including neuroscience and axiology, have come to the realization that the mind-brain is value-driven. That is, Value, values, and value judgments drive many, if not most or even all, of the processes of both the brain and the mind, including our sub-conscious habits of mind. Think about it—have you ever made a conscious choice that wasn’t, at that moment, an attempt to add greater value at some level? Unfortunately, to our knowledge, the neuroscientists and axiologists have not been comparing notes. Consequently, until now, the amazing value-based connection between the mind and brain has been overlooked. This book makes that connection and more. Axiogenics is not some rehashed mystical, moral, or religious philosophy, nor is it a newfangled twist on the rhetoric of so-called “success gurus.” It is a fresh, new paradigm for personal, leadership and organizational development. It is a science-driven technology for deliberately creating positive changes in how we think, how we perceive, the kinds of choices we make, and the actions we take. Life is about adding value. Whether you realize it yet or not, your entire life is about one thing: creating value. Virtually every thought, action, choice, and reaction you have is an attempt to create or preserve value. Success in life, love and leadership requires making good value judgments. Real personal power is in knowing which choices and actions will create the greatest net value.

Axiogenics is based on four core principles. They are:

1. Value drives success in all endeavors.

2. Your mind-brain is already value-driven.

3. There is an objective, universal Hierarchy of Value.

4. Accurately answering The Central Question is the key to maximizing your success.

Demarest, Peter D.; Schoof, Harvey J. (2011-06-24). Answering The Central Question (Kindle Locations 130-136). Heartlead Publishing, LLC. Kindle Edition.

Moral Reasoning & Crime (Carey Goldberg)

People who commit crimes are dumb, but what happens is, in the moment, that information about costs and consequences can’t get into their decision-making. Research shows that brain biology governs not just our choices but also our moral judgments about what is right and wrong. Using new technology, brain researchers are beginning to tease apart the biology that underlies our decisions to behave badly or do good deeds. They’re even experimenting with ways to alter our judgments of what is right and wrong and our deep gut feelings of moral conviction. One thing is certain: We may think in simple terms of “good” and “evil,” but that’s not how it looks in the brain at all. In past years, as neuroscientists and psychologists began to delve into morality, “Many of us were after a moral center of the brain, or a particular system or circuit that was responsible for all of morality,” says assistant professor Liane Young, who runs The Morality Lab at Boston College. But “it turns out that morality can’t be located in any one area, or even set of areas — that it’s all over, that it colors all aspects of our life, and that’s why it takes up so much space in the brain.” So there’s no “root of all evil.” Rather, says Buckholtz, “When we do brain studies of moral decision-making, what we are led into is an understanding that there are many different paths to antisocial behavior.” If we wanted to build antisocial offenders, he says, brain science knows some of the recipe: They’d be hyper-responsive to rewards like drugs, sex and status — and the more immediate, the better. “Another thing we would build in is an inability to maintain representations of consequences and costs,” he says. “We would certainly short-circuit their empathic response to other people. We would absolutely limit their ability to regulate their emotions, particularly negative emotions like anger and fear.” If it’s all just biology at work, are we still to blame if we commit a crime? And the correlate: Can we still take credit when we do good? Daniel Dennett a professor of philosophy at Tufts University who incorporates neuroscience into his thinking and is a seasoned veteran of the debates around free will. He says it’s not news that our morality is based in our brains, and he doesn’t have much patience for excuses like, “My brain made me do it.” “Of course my brain made me do it!” he says. “What would you want, your stomach to make you do it!?” The age-old debate around free willis still raging on in philosophical circles, with new brain science in the mix. But Dennett argues that science doesn’t change the basic facts: “If you do something on purpose and you know what you’re doing, and you did it for reasons good, bad or indifferent, then your brain made you do it,” he says. “Of course. And it doesn’t follow that you were not the author of that deed. Why? Because you are your embodied brain.” Ref

Antisocial Personality; Not a Lack of Intelligence

Sociopaths and psychopaths, or the catch-all clinical diagnosis of Antisocial personality disorder, fall under the above description, except intelligence is often high. Consequences do not seem to devour them, so definitely something not right in the mind/brain, however, this is not lack of intelligence. Here are some books relating to this: The gift of fear, by Gavin Debecker. Without conscience, by Robert Hare, Men who hate women and the Woman who love them, and the Sociopath Next Door. Link, Link, Link, Link

Too quick to condemn?

However, But don’t be too quick to condemn all Sociopaths and psychopaths, or those with the clinical diagnosis of Antisocial personality disorder, because just having Mental Health Issues does not mean you cannot be moral. A scientist who studies psychopaths found out he was one by accident — and it completely changed his life. Around 2005, Fallon started to notice a pattern in the scans of some of the criminals who were thought to be psychopaths, which led him to develop a theory: All of them appeared to have low levels of activity in a region of the brain located towards its center at the base of the frontal and temporal lobes. Scientists believe this region, called the orbital cortex, is involved in regulating our emotions and impulses and also plays a role in morality and aggression. One day, Fallon’s technician brought him a stack of brain scans from an unrelated Alzheimer’s study. As he was going through the scans of healthy participants, they all looked normal — no surprises. But then he got to the last one. “It looked just like those of the murderers.” The identity of the brains in the scans had deliberately been masked so as not to bias the results. But Fallon couldn’t leave it alone. “I said, we’ve got to check the [source] of that scan,” Fallon recalled recently to Business Insider. “It’s probably a psychopath… someone who could be a danger to society.” Turns out, the image wasn’t a scan of just any random participant — it was a scan of his own brain. Ref

Axiological Realism (Joel J. Kupperman)

Many would consider the lengthening debate between moral realists and anti-realists to be draw-ish. Plainly new approaches are needed. Or might the issue, which most broadly concerns realism in relation to normative judgments, be broken down into parts or sectors? Physicists have been saying, in relation to a similarly longstanding debate, that light in some respects behaves like waves and in some respects like particles. Might realism be more plausible in relation to some kinds of normative judgments than others? Ref

Are we born with a moral core? The Baby Lab says ‘yes’ Moreover, Studies have shown babies are good judges of character in fact, Even Babies Think Crime Deserves Punishment thins should make you consider The Case for Objective Morality.

Animals and Morality?

5 Animals With a Moral Compass Moreover, Animals can tell right from wrong: Scientists studying animal behaviour believe they have growing evidence that species ranging from mice to primates are governed by moral codes of conduct in the same way as humans. Likewise, in the book: Wild Justice: The Moral Lives of Animals: Scientists have long counseled against interpreting animal behavior in terms of human emotions, warning that such anthropomorphizing limits our ability to understand animals as they really are. Yet what are we to make of a female gorilla in a German zoo who spent days mourning the death of her baby? Or a wild female elephant who cared for a younger one after she was injured by a rambunctious teenage male? Or a rat who refused to push a lever for food when he saw that doing so caused another rat to be shocked? Aren’t these clear signs that animals have recognizable emotions and moral intelligence? With Wild Justice Marc Bekoff and Jessica Pierce unequivocally answer yes. Marrying years of behavioral and cognitive research with compelling and moving anecdotes, Bekoff and Pierce reveal that animals exhibit a broad repertoire of moral behaviors, including fairness, empathy, trust, and reciprocity. Underlying these behaviors is a complex and nuanced range of emotions, backed by a high degree of intelligence and surprising behavioral flexibility. Animals, in short, are incredibly adept social beings, relying on rules of conduct to navigate intricate social networks that are essential to their survival. Ultimately, Bekoff and Pierce draw the astonishing conclusion that there is no moral gap between humans and other species: morality is an evolved trait that we unquestionably share with other social mammals.

Moral Naturalism (James Lenman)

While “moral naturalism” is sometimes used to refer to any approach to metaethics intended to cohere with naturalism in metaphysics more generally, the label is more usually reserved for naturalistic forms of moral realism according to which there are objective moral facts and properties and these moral facts and properties are natural facts and properties. Views of this kind appeal to many as combining the advantages of naturalism and realism. Ref

Realism, Naturalism, and Moral Semantics (David O. Brink)

He prospects for moral realism and ethical naturalism have been important parts of recent debates within metaethics. As a first approximation, moral realism is the claim that there are facts or truths about moral matters that are objective in the sense that they obtain independently of the moral beliefs or attitudes of appraisers. Ethical naturalism is the claim that moral properties of people, actions, and institutions are natural, rather than occult or supernatural, features of the world. Though these metaethical debates remain unsettled, several people, myself included, have tried to defend the plausibility of both moral realism and ethical naturalism. I, among others, have appealed to recent work in the philosophy of language—in particular, to so-called theories of “direct reference” —to defend ethical naturalism against a variety of semantic worries, including G. E. Moore’s “open question argument.” In response to these arguments, critics have expressed doubts about the compatibility of moral realism and direct reference. In this essay, I explain these doubts, and then sketch the beginnings of an answer—but understanding both the doubts and my answer requires some intellectual background. Ref

Formal Axiology: Efficiency of good?

“I thought to myself if evil can be organized so efficiently [by the Nazis] why cannot good? Is there any reason for efficiency to be monopolized by the forces for evil in the world? Why have good people in history never seemed to have had as much power as bad people? I decided I would try to find out why and devote my life to doing something about it.” – Robert S. Hartman http://www.hartmaninstitute.org/resources/journal-formal-axiology/

Formal Axiology?

Formal Axiology is a specific branch of the science of Axiology. The late Dr. Robert S. Hartman developed this science between 1930 and 1973. It is a unique social science because it is the only social science that has a one to one relationship between a field of mathematics (transfinite set calculus) and its dimensions. More About Formal Axiology Ref More About Dr. Robert S. Hartman http://www.cleardirection.com/docs/articles/drhartman.asp

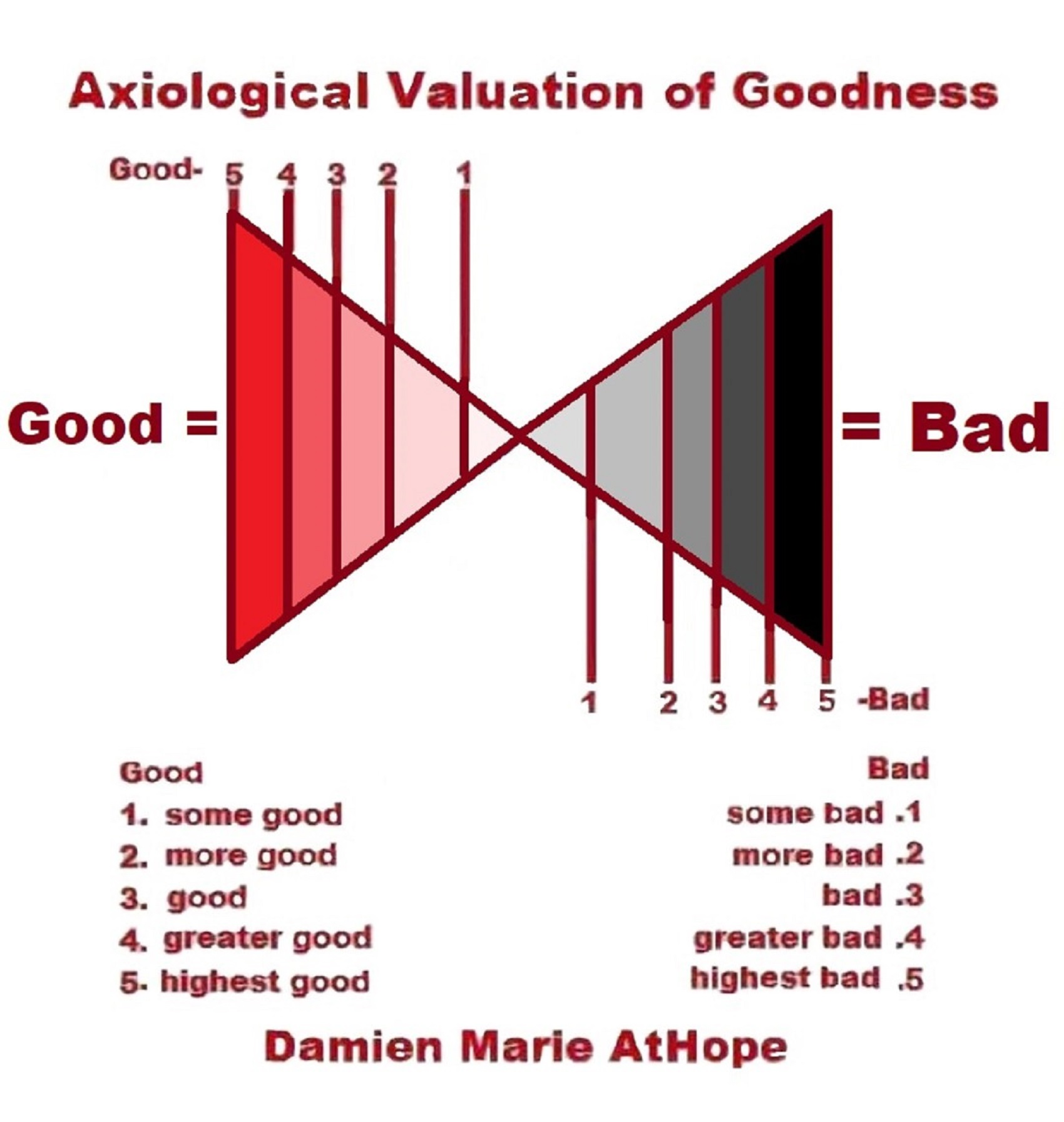

The Dimensions of Value

Dr. Hartman identified three dimensions of reality, which he called the Dimensions of Value. We value everything in one of these three ways or in a combination of these dimensions. The Dimensions of Value are Systemic, Extrinsic, and Intrinsic. More About The Dimensions of Value: http://www.cleardirection.com/docs/dimensions.asp

Formal Axiology – Another Victim in Religion’s War on Science (William J. Kelleher)

Formal Axiology is R.S. Hartman’s foundation for the development of value science. In order to properly discuss Rem’s book we will first summarize Hartman’s understanding of Formal Axiology and his hopes for a science of values. What are “values”? “Values” are the ideas and feelings of people about such matters as likes/dislikes, right/wrong, good/bad, beautiful/ugly, and other preferences. Clearly, it is a fact that people have values. But a science which can raise our knowledge of values above that of ideas, feelings, and opinion has yet to be developed. Robert S. Hartman was a philosopher of science who believed he had found a way to place the study of values on a footing that is every bit as precise and above mere opinion as are physics, chemistry, and the other natural sciences. Indeed, he presented his “Formal Axiology” as the foundation upon which a “Second Scientific Revolution” would be launched. This foundation consists primarily of three parts. These are his Value Axiom, the three dimensions of value, and his Value Calculus. While it may seem difficult to understand at first, due to its unfamiliarity, upon sufficient reflection, the reader will come to see that Hartman’s system truly can make researching and analyzing values as precise and illuminating of value reality as any natural science is about its subject matter. Just as the chemical formula for “water” is H2O, so Formal Axiology has the capacity to make the structure of values and of valuing equally as precise. Let us consider the three elements of Formal Axiology before turning to Rem’s treatment of the subject.

The Three Elements of Formal Axiology

The first part of Formal Axiology is the Value Axiom, or the definition of “good. ”Hartman defines “good” as conceptual fulfillment. That is, a thing is a good such thing if it fulfills the definition of its concept or classification. For example, suppose we define a “chair” as an object with a back, a seat, and four legs. Then we look around the room and find just such an object. By matching the thing with our conception of it, we know at once that it is a chair. Beyond the initial identification of the object, we can also formulate a judgment as to how good of a chair the thing is. We can add to our specifications for the goodness of a chair by requiring that it has padding, or can rock, or can be folded and stored away. One chair can be compared to others. Then, using our conception of a good chair, we can make an assessment about which chairs are “better,” or “worse,” or “average,” and “best,” etc. We can assign a numbered scale to the predicates in our definition, and measure exactly how much better or worse one chair is compared to another. Suppose we say that on a scale from 1 to 10, a three-foot high seat is worth 5 points. A tilted back is worth 6 points, while a straight back is only worth 2, etc. To illustrate, suppose that newlyweds, Mary and John, go shopping at a furniture store, using the criteria we have discussed. They compare several sets of chairs, adding up the points for each set. Then Mary spots a set of chairs that not only measure up, but that she just loves, and must have. As to the second element of Formal Axiology, this Mary and John scenario illustrates what Hartman calls the three dimensions of value. These are the extrinsic, systemic, and intrinsic. In the extrinsic dimension, object and conception are matched together. As we have seen, this process can result in measurable degrees of goodness. In the systemic dimension of value, only identity is considered. An object is a “chair” or it isn’t. Beds and tables weren’t on John and Mary’s shopping list today. The systemic entails the process of classification or taxonomy. Identifying a thing is the first step taken before the more elaborate measurement of degrees can be undertaken. The intrinsic dimension of values is in the realm of feeling rather than in the more rational realm of measuring degrees or of making either/or judgments. Mary’s love of the set of chairs she and John bought can’t be quantified or even fully explained. The chairs just fit her aesthetic sensibility and the vision of how she wanted to decorate her living room. They also remind her of her happy childhood and her holiday visits to Aunt Jane’s house. The third element of Formal Axiology is the more formal part, the Value Calculus. Here is the computational aspect that makes precise value sciences possible. Hartman developed a system of notation using the letters S (systemic), E (extrinsic), and I (intrinsic) to represent the three dimensions of value as categories, and using the same letters as ways of notating how the object in the categories is being valued. To illustrate this computational system, let us continue to follow John and Mary as they shop. When Mary was shopping she first scanned the store’s inventory to identify which objects are chairs or not. Since chairs are things, they are in the extrinsic value category. Her classifying of things as chairs or non-chairs is a systemic valuation of them. In the Value Calculus, this would be notated as E S. This is read as “E power S,” or the systemic valuation of an extrinsic value. Mary’s love of the chairs she and John bought can be notated as E I; or, E power I. That is, the intrinsic valuation of an extrinsic value. Most of the chairs she saw, she felt indifferent to; hence, there was no valuation beyond the quick systemic valuations she made to identify the objects as chairs or not. Some of the chairs were so ugly, in her estimation, that she just hated them. This valuation would be notated as E I; or, E sub I – the intrinsic disvaluation of an extrinsic value.

Value Calculus Realism

Hartman’s Value Calculus takes a realistic, or fact-based, view of the world. People have and act upon values. Value scientists will seek to understand what those values are, and to analyze their structure. That empirical orientation is why the Value Calculus can serve as the formal side of the yet to be developed value sciences. To illustrate this realism, suppose that after church on Sunday Mary comments to her friend, Jane, that there are three things she loves most in the world. These are God, her new husband John, and her old dog Fido (no kids yet).How would a value scientist notate these value situations, or instances of valuing? Since the science of value has an empirical orientation, God is seen as a conception in Mary’s mind; hence, notated as S. Since she loves God, the valuation is intrinsic, or I. The Value Calculus formula for this is S I – read as S power I; or, as the intrinsic valuation of a systemic value. As to Mary’s valuation of John, the Value Calculus has a special rule: persons, and only persons, are always notated as I in the initial position of the Value Calculus formula. So her love of John is notated as I I – I power I; or, the intrinsic valuation of an intrinsic value. Since Fido is a non-human organism, or a thing in the world, his initial value category is E, an extrinsic value. Hence, E I – read as E power I; or, as the intrinsic valuation of an extrinsic value. Comparing value structures and trying to account for the similarities and differences will one day be a regular part of practicing value science. Instances of valuing can be far more complex than this illustration of Mary’s feelings. So, the Value Calculus uses “nesting” to notate further permutations of value. For example, notice that the formula for Mary’s love of Fido has the same value structure as her love of her new chairs: E I. But suppose Mary protests that she loves Fido even more than her chairs because he is a living thing, and the chairs are inanimate objects. So Mary’s love of Fido as a living organism requires a different value structure than her love of the chairs. Since “life” is a principle, or conception, which adds value to Fido, a different formula can be used: [E S] I; or, the intrinsic valuation of the systemic valuation of an extrinsic value. Take another example: Mary has surgery to remove the mole on her nose, and is delighted with the results. From the value scientist’s point of view, the value structure of this situation is, [I E] I. The doctor operating on Mary to improve her looks is marked as I power E, because Mary is an intrinsic value being acted upon, and action is an extrinsic value. Mary’s delight with the results is an intrinsic valuation of the doctor’s extrinsic valuation of her. So, this more complex formula is read as I power E power I; or, the intrinsic valuation of the extrinsic valuation of an intrinsic value. In the future, computers will be able to workout extremely complex value structures. In the Value Calculus, superscripts represent what Hartman calls “compositions”(positives) while subscripts are for “transpositions” (negatives) of value. For example, Mary hated that mole on her nose. The mole is an extrinsic value, and her hate for it an intrinsic disvaluation. The formula: E I; read as E sub I, or an intrinsic disvaluation of an extrinsic value. This is the same value structure as her disdain of the ugly chairs in the furniture store.

The Threat to Religion-based Morality

In a nutshell, then, this is Hartman’s Formal Axiology. It is the foundation, or computational framework, for the development of value sciences, but it is not value science in itself. Particular value sciences will have to be founded by pioneering thinkers. Hartman wrote that a new science of “ethics” will be developed unlike any of the existing ethical theories that philosophers and religious partisans have been arguing over for centuries. Value science, he hoped, would “secularize ethics,” and displace religion, superstition, and the current variety of ethical philosophies with an empirically based scientific method of thinking about ethical values. Hartman was fully aware of the threat Formal Axiology is to religion as a moral authority in the world today. He wrote that just as Galileo’s use of a formal system brought “revolutionary changes … in [pre-scientific] natural philosophy… the transition to moral science [will bring] radical changes in moral philosophy.” Hartman envisioned a scientific ethics that would eventually displace religion as an authoritative, but not authoritarian, source of moral advice. He was aware, as we all are, of the shameful wars that dogmatic and fanatical religions some times engage in against one another. Each side believes itself in possession of The One Truth, and therefore Morally Superior to apostates, infidels, and the heretics in the opposed religions. In the value structure of such deadly conflicts, ideas and doctrines are regarded as more important than the real human beings who are murdered in the name of such “Truths.” Indeed, such murder is often considered “morally good” by the Believers. But the Value Calculus can expose this hypocrisy. Killing a person in the name of a religion is formulated as [I E] S; or, the systemic valuation of the extrinsic disvaluation of an intrinsic value. The religious warriors think it is “good,” or morally honorable, to kill folks with different views. But the formal structure shows that no matter how good one sees such killing, the disvaluation of a person is contained in the self-delusion that the act was a purely positive act. Thus are religious warriors confronted with the Real Truth, the Truth of Formal Axiology. Using the Value Calculus, ideas are never more important than people. Hartman wrote that Formal Axiology “thus helps expose the real evils – the disvalues posing as values – of our civilization … which are chronic diseases of the so-called Christian world and which arise from its inverted hierarchy of values.” Hartman predicted that among the coming value sciences would be a new form of political science which could become an authoritative, but not authoritarian, a source of political wisdom. It would analyze the value structures of laws, policies, and government practices. Indeed, he outlined 18 different branches of the value sciences. Among these are a new form of aesthetics, economics, psychology, sociology, epistemology, jurisprudence, and literary criticism – all yet to be developed. Formal Axiology is intended to provide the formal system for the value sciences like mathematics provides the formal system for the natural sciences, such as astronomy, biology, chemistry, and physics. Hartman predicted that just as the natural sciences have produced amazing and revolutionary benefits for humanity, when the value sciences develop and mature, so they will enrich the quality of human life beyond what is currently thought achievable. Hartman introduced his Formal Axiology, and discussed his hopes for it, in his1967 book,

The Structure of Value

Unfortunately, the book was slow to catch on, and tragically, Hartman died in 1973. A group calling itself “The Hartman Institute,” headquartered in Knoxville, Tennessee was given possession of Hartman’s voluminous unpublished writings, by his grieving widow, Rita, and in exchange they pledged to make his work known to the world. Rem Edwards was one of the founding members of that group, and the book we are reviewing here’s hows how they have gone about fulfilling their pledge to Rita Hartman (who is now deceased.)

The Augustinian Plot

Rem’s book presents itself as an explanation of R.S. Hartman’s Formal Axiology. But it is not that at all. Unhappily, it is a rambling, repetitious, screed bent upon so mutilating and misrepresenting Hartman’s work that no one will be interested in learning more about it. It is, in short, not a difference of opinion, but an act of sabotage. A little history will put this poison pill in its proper context. In the Fifth Century, Saint Augustine formulated Church doctrine with such books as The City of God, which, among other things, disparaged Pagan beliefs and the study of nature. Philosopher Michael Polanyi notes that Augustine “denied the value of a natural science which contributed nothing to the pursuit of salvation. His ban destroyed interest in science all over Europe for a thousand years.” As interest in science began to re-emerge with the Renaissance, one of the major challenges to Christian beliefs was brought by Copernicus. He claimed that the universe did not revolve around Earth, as Church officials taught, but that Earth revolved around the sun. Galileo used a telescope to gather evidence which, among other things, supported Copernicus. In the 1630s the blessed Bishops of the Catholic Church threatened Galileo with torture and prison if he didn’t recant some of his more offensive findings. Mindful of what happened to Giordano Bruno, Galileo complied. The astronomer Bruno went even further than Copernicus, and asserted that our sun was just one among many in the universe. In 1600 he was burned at the stake after the Inquisition declared him guilty of heresy. Over the years, many other scientists, as well as witches, heretics, Pagans, and suspected or known nonbelievers suffered imprisonment, torture, and death for their independence of mind. But religion’s war on science didn’t stop in ancient Europe. It has continued well in to modern times. For example, Christian Fundamentalists had a law passed in Tennessee prohibiting the teaching of Darwin’s theory of evolution in public schools, because they said such teachings contradicted the Bible. The Scopes Trial was conducted in that Bible Belt state in 1925, and high school teacher John Scopes was convicted and fined $100 for “teaching Darwin.” (A new Model T Ford, then, cost around $300.) Now, if Rem and his group of True Believers in the Scope’s Trial sub-culture have their way, value science will suffer a fate like that of natural science under Augustine, and be neglected for the next 1000 years. They have already let Hartman’s main book, The Structure of Value, go out of print, even as they publish a stream of their own works on “Christian Values.” They have kept Hartman’s papers locked up in Tennessee, not put online, inaccessible to the world for nearly 40 years. Their Augustinian plot is well on its way towards success.

Hartman’s Unitary Vision