“Damien, Beliefs are not claims”

My response: Sounds to me, like you are making a claim, are you not? In epistemology, all claims have a truth-value, and beliefs are believed to hold a “value” of truth, or they would not be believed, as untrue things do not hold a truth-value, thus not supporting justified belief (so unworthy to be believed) and if one claims to believe in things they don’t believe are true sounds more like intellectual dishonesty or some other form of unvaluable thinking strategy.

“Damien, personal beliefs are not knowledge claims”

My response: Look, yet another claim. If you keep it as a belief, you claim it is believable, thus a claim. Or are you saying what you believe is not also reasonable to be believed? If you believe, you accept “its” truth-value claim.

“Damien, You wouldn’t have a belief, if it wasn’t reasonable to you. In fact, you would reject it.”

My response: I am glad you agree, with the architecture of belief. 🙂

Picture: ref

Eric Schwitzgebel – “Contemporary Anglophone philosophers of mind generally use the term “belief” to refer to the attitude we have, roughly, whenever we take something to be the case or regard it as true. To believe something, in this sense, needn’t involve actively reflecting on it: Of the vast number of things ordinary adults believe, only a few can be at the fore of the mind at any single time. Nor does the term “belief”, in standard philosophical usage, imply any uncertainty or any extended reflection about the matter in question (as it sometimes does in ordinary English usage). Forming beliefs is thus one of the most basic and important features of the mind, and the concept of belief plays a crucial role in both philosophy of mind and epistemology. Much of epistemology revolves around questions about when and how our beliefs are justified or qualify as knowledge. Most contemporary philosophers characterize belief as a “propositional attitude”. Propositions are generally taken to be whatever it is that sentences express (see the entry on propositions). For example, if two sentences mean the same thing (e.g., “snow is white” in English, “Schnee ist weiss” in German), they express the same proposition, and if two sentences differ in meaning, they express different propositions. (Here we are setting aside some complications about that might arise in connection with indexicals; see the entry on indexicals.) A propositional attitude, then, is the mental state of having some attitude, stance, take, or opinion about a proposition or about the potential state of affairs in which that proposition is true—a mental state of the sort canonically expressible in the form “S A that P”, where S picks out the individual possessing the mental state, A picks out the attitude, and P is a sentence expressing a proposition. For example: Ahmed [the subject] hopes [the attitude] that Alpha Centauri hosts intelligent life [the proposition], or Yifeng [the subject] doubts [the attitude] that New York City will exist in four hundred years. What one person doubts or hopes, another might fear, or believe, or desire, or intend—different attitudes, all toward the same proposition. Contemporary discussions of belief are often embedded in more general discussions of the propositional attitudes; and treatments of the propositional attitudes often take belief as the first and foremost example.” – The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

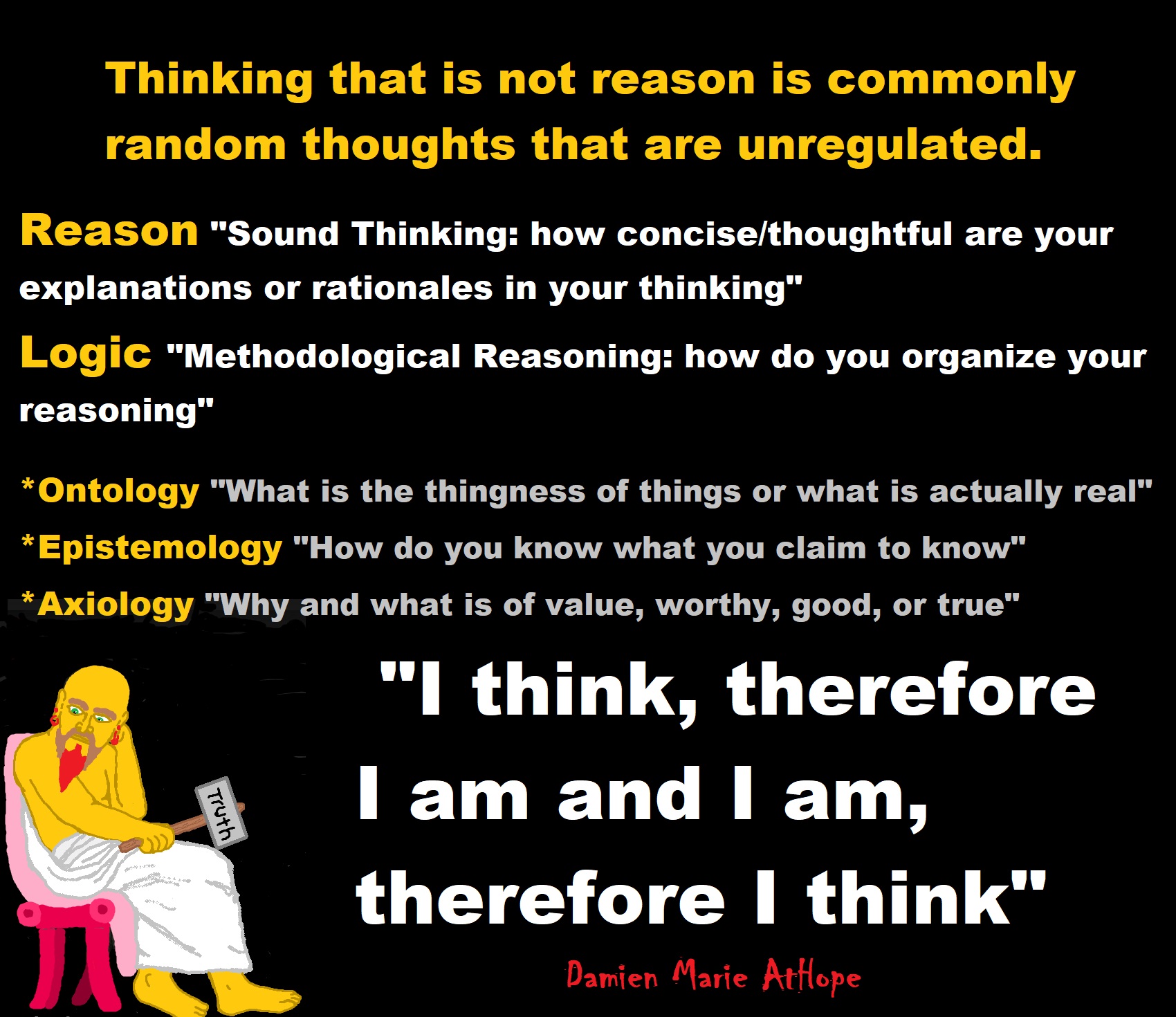

Epistemology

“From Greek ἐπιστήμη, epistēmē ‘knowledge’, and -logy) is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge. Epistemologists study the nature of knowledge, epistemic justification, the rationality of belief, and various related issues. Epistemology is considered one of the four main branches of philosophy, along with ethics, logic, and metaphysics/Ontology.” ref

Debates in epistemology are generally clustered around four core areas:

- The philosophical analysis of the nature of knowledge and the conditions required for a belief to constitute knowledge, such as truth and justification

- Potential sources of knowledge and justified belief, such as perception, reason, memory, and testimony

- The structure of a body of knowledge or justified belief, including whether all justified beliefs must be derived from justified foundational beliefs or whether justification requires only a coherent set of beliefs

- Philosophical skepticism, which questions the possibility of knowledge, and related problems, such as whether skepticism poses a threat to our ordinary knowledge claims and whether it is possible to refute skeptical arguments ref

“In these debates and others, epistemology aims to answer questions such as “What do we know?”, “What does it mean to say that we know something?”, “What makes justified beliefs justified?”, and “How do we know that we know?”. Epistemology largely came to the fore in philosophy during the early modern period, which historians of philosophy traditionally divide up into a dispute between empiricists (including John Locke, David Hume, and George Berkeley) and rationalists (including René Descartes, Baruch Spinoza, and Gottfried Leibniz). The debate between them has often been framed using the question of whether knowledge comes primarily from sensory experience (empiricism), or whether a significant portion of our knowledge is derived entirely from our faculty of reason (rationalism).” ref

Belief and Acceptance

“Philosophers have sometimes drawn a distinction between acceptance and belief. Generally speaking, acceptance is held to be more under the voluntary control of the subject than belief and more directly tied to a particular practical action in a context. For example, a scientist, faced with evidence supporting a theory, evidence acknowledged not to be completely decisive, may choose to accept the theory or not to accept it. If the theory is accepted, the scientist ceases inquiring into its truth and becomes willing to ground her own research and interpretations in that theory; the contrary if the theory is not accepted. If one is about to use a ladder to climb to a height, one may check the stability of the ladder in various ways. At some point, one accepts that the ladder is stable and climbs it. In both of these examples, acceptance involves a decision to cease inquiry and to act as though the matter is settled. This does not, of course, rule out the possibility of re-opening the question if new evidence comes to light or a new set of risks arise. The distinction between acceptance and belief can be supported by appeal to cases in which one accepts a proposition without believing it and cases in which one believes a proposition without accepting it. Van Fraassen (1980) has argued that the former attitude is common in science: the scientist often does not think that some particular theory on which her work depends is the literal truth, and thus does not believe it, but she nonetheless accepts it as an adequate basis for research. The ladder case, due to Bratman (1999), may involve belief without acceptance: One may genuinely believe, even before checking it, that the ladder is stable, but because so much depends on it and because it is good general policy, one nonetheless does not accept that the ladder is stable until one has checked it more carefully.” ref

“One of the core concepts in epistemology is belief. A belief is an attitude that a person holds regarding anything that they take to be true. For instance, to believe that snow is white is comparable to accepting the truth of the proposition “snow is white”. Beliefs can be occurrent (e.g. a person actively thinking “snow is white”), or they can be dispositional (e.g. a person who if asked about the color of snow would assert “snow is white”). While there is not universal agreement about the nature of belief, most contemporary philosophers hold the view that a disposition to express belief B qualifies as holding the belief B. There are various different ways that contemporary philosophers have tried to describe beliefs, including as representations of ways that the world could be (Jerry Fodor), as dispositions to act as if certain things are true (Roderick Chisholm), as interpretive schemes for making sense of someone’s actions (Daniel Dennett and Donald Davidson), or as mental states that fill a particular function (Hilary Putnam). Some have also attempted to offer significant revisions to our notion of belief, including eliminativists about belief who argue that there is no phenomenon in the natural world which corresponds to our folk psychological concept of belief (Paul Churchland) and formal epistemologists who aim to replace our bivalent notion of belief (“either I have a belief or I don’t have a belief”) with the more permissive, probabilistic notion of credence (“there is an entire spectrum of degrees of belief, not a simple dichotomy between belief and non-belief”). While belief plays a significant role in epistemological debates surrounding knowledge and justification, it also has many other philosophical debates in its own right. Notable debates include: “What is the rational way to revise one’s beliefs when presented with various sorts of evidence?”; “Is the content of our beliefs entirely determined by our mental states, or do the relevant facts have any bearing on our beliefs (e.g. if I believe that I’m holding a glass of water, is the non-mental fact that water is H2O part of the content of that belief)?”; “How fine-grained or coarse-grained are our beliefs?”; and “Must it be possible for a belief to be expressible in language, or are there non-linguistic beliefs?” ref

The Valued of Good Belief Etiquette

Hammer of Truth: Yes, you too, have lots of beliefs…

Yes, We All Have Beliefs; But What Does That Mean?

Epistemically Rational Beliefs: Evidence and Reason Warranted Beliefs, not Faith Beliefs

Atheists, please stop saying you have no beliefs.

Well, we all have beliefs it’s unavoidable. The issue is having justified true beliefs that hold warrants or are valid and reliable because of reason and evidence. I am not directing this at anyone, I am only stating this trying to help. Even saying I don’t have a belief is exhibiting a belief that you don’t have a belief. To me, beliefs are not what’s the problem it’s having justified true beliefs warranted on valid and reliable reason and evidence is the issue. Think of it like this: there are three belief states one is “lacking belief” which would stand for not having information or not making a decision, belief or disbelief.

Some unbelievers in faith, gods, or any other magical/supernatural nonsense say they only “lack belief” and do not have disbelief. So they are saying they have a disbelief in the idea that they have a disbelief as they are actively rejecting the concept of them having disbelief. I feel there is a confusion about the definition of disbelief, which is a feeling that you do not or cannot believe or accept that something is true or real. The act of disbelieving is the mental rejection of something as untrue. http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/disbelief

Thus disbelief is rendered to you do not or cannot believe.

Do we have to ‘believe’ that the scientific method yields qualified truths? You have to use rationalism to establish the rationale and yes it is a belief in a certain style of information possessing but it is a warranted justified true belief both before its use because of reason and after its use in the reliability as well as validating of evidence. At that point beliefs are no longer required as the reproducibility of conclusions makes the facts. I think I can see what the disconnect is for some atheists… Theists try to deflect from debates by saying that atheists “believe in science”. While many of us believe in scientific principles, it is not a belief system. As you said before, we believe things that there is evidence for. It’s not about faith. It’s about evidence, but theists try to call it faith because we didn’t necessarily come up with the ideas ourselves. This is stupid because belief in science is justified and warranted, as there is evidence to support the justified belief for the ideas whether or not we made them ourselves. I hear the I have no beliefs thinking but they need to read what philosophy, psychology and neurology to grasp what they state about beliefs or disbeliefs. I am sure they will be the most motivated by science so here is the Neurology of Belief.

The difference between believing and disbelieving a proposition is one of the most potent regulators of human behavior and emotion. When one accepts a statement as true, it becomes the basis for further thought and action; rejected as false, it remains nothing more than a string of words someone put together.

Functional Neuroimaging of Belief, Disbelief, and Uncertainty

A study was done to test the difference between believing and disbelieving a proposition is one of the most potent regulators of human behavior and emotion. When one accepts a statement as true, it becomes the basis for further thought and action; rejected as false, it remains a string of words. The purpose of these studies is to differentiate belief, disbelief, and uncertainty at the level of the brain. A study was done testing naïve Bayes classification of belief versus disbelief using event-related neuroimaging data. There were significant differences between blasphemous and non-blasphemous statements in both religious people and atheists. These are regions that show greater signal both when Christians reject stimuli contrary to their doctrine (e.g. “The Biblical god is a myth”) and when nonbelievers affirm their belief in those same statements (pc = paracingulate gyrus; mf = middle frontal gyrus; vs = ventral striatum; ip = inferior parietal lobe; fp = frontal pole). http://www.brainmapping.org/MarkCohen/research/Belief.html

According to Michael Shermer an American science writer, historian of science, founder of The Skeptics Society, and Editor in Chief of its magazine Skeptic, we form our beliefs for a variety of subjective, emotional, and psychological reasons in the context of environments created by family, friends, colleagues, culture, and society at large. After forming our beliefs, we then defend, justify and rationalize them with a host of intellectual reasons, cogent arguments, and rational explanations. Beliefs come first; explanations for beliefs follow. In Michael Shermer’s book The Believing Brain, Michael Shermer calls this process, wherein our perceptions about reality are dependent on the beliefs that we hold about it, belief-dependent realism. Reality exists independent of human minds, but our understanding of it depends on the beliefs we hold at any given time. Michael Shermer patterned belief-dependent realism after model-dependent realism, presented by physicists Stephen Hawking and Leonard Mlodinow in their book The Grand Design (click to download). There they argue that because no one model is adequate to explain reality, “one cannot be said to be more real than the other.” When these models are coupled to theories, they form entire worldviews. Once we form beliefs and make commitments to them, we maintain and reinforce them through a number of powerful cognitive biases that distort our percepts to fit belief concepts. Among them are:

Anchoring Bias. Relying too heavily on one reference anchor or piece of information when making decisions.

Authority Bias. Valuing the opinions of an authority, especially in the evaluation of something we know little about.

Belief Bias. Evaluating the strength of an argument based on the believability of its conclusion.

Confirmation Bias. Seeking and finding confirming evidence in support of already existing beliefs and ignoring or reinterpreting disconfirming evidence. http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-believing-brain/

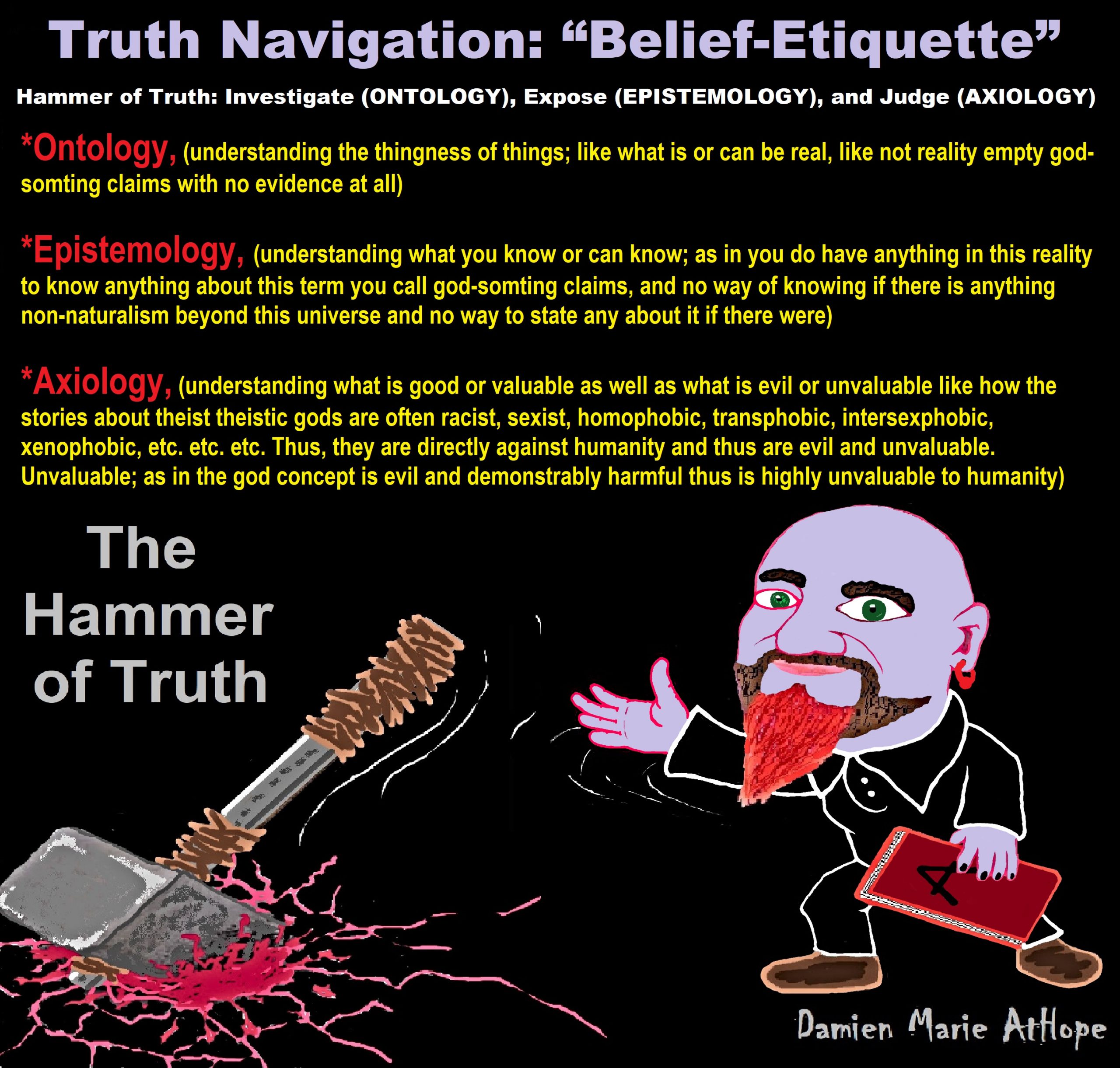

Justified True Beliefs?

I follow the standard in philosophy JTB Justified True Beliefs.

Justified / True / Beliefs

To established justification I use the philosophy called Reliabilism.

Reliabilism is a general approach to epistemology that emphasizes the truth-conduciveness of a belief-forming process, method, or other epistemologically relevant factor. The reliability theme appears both in theories of knowledge and theories of justification.

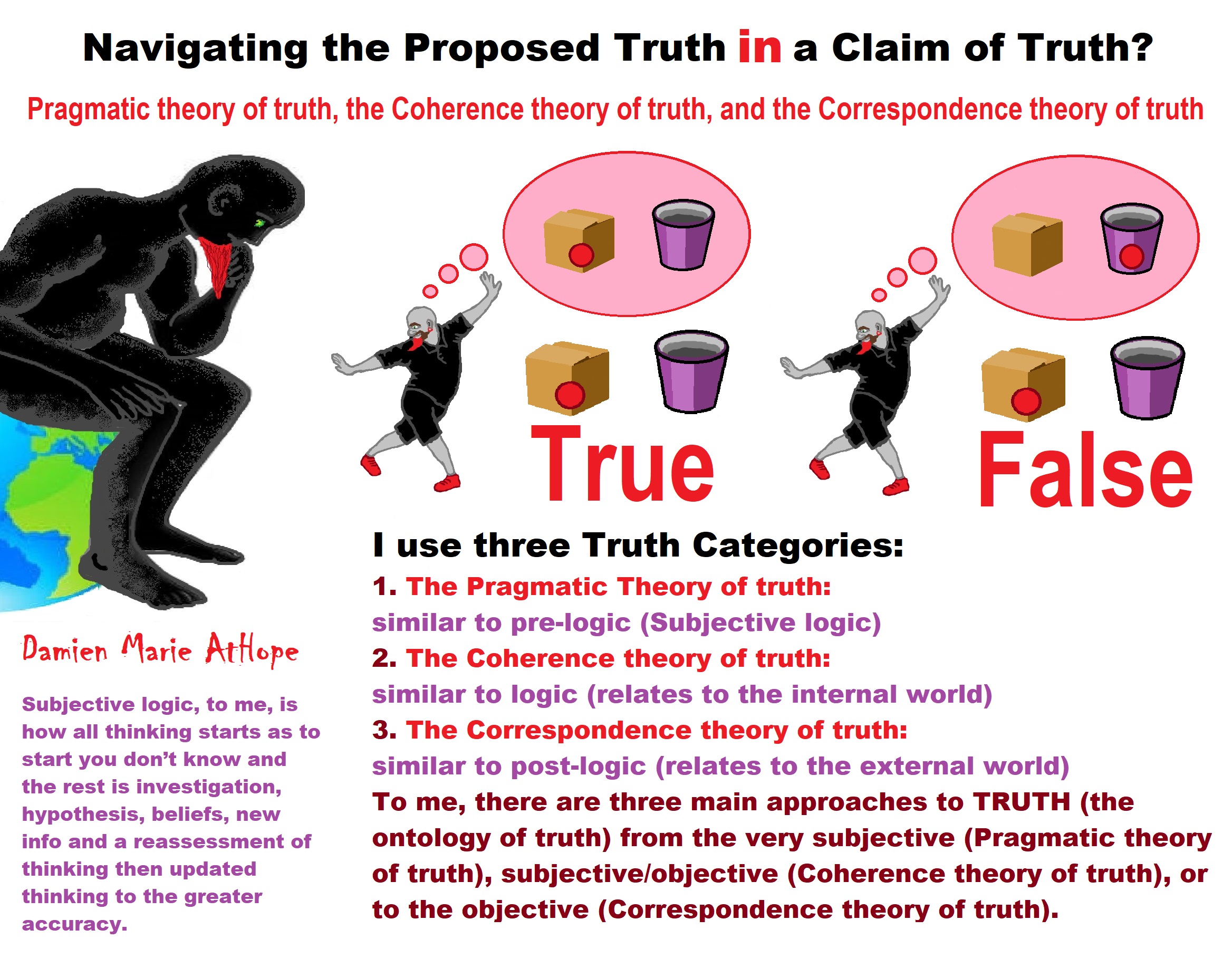

For the true part I use the philosophy called The Correspondence Theory of Truth.

The correspondence theory of truth states that the truth or falsity of a statement is determined only by how it relates to the world and whether it accurately describes (i.e., corresponds with) that world.

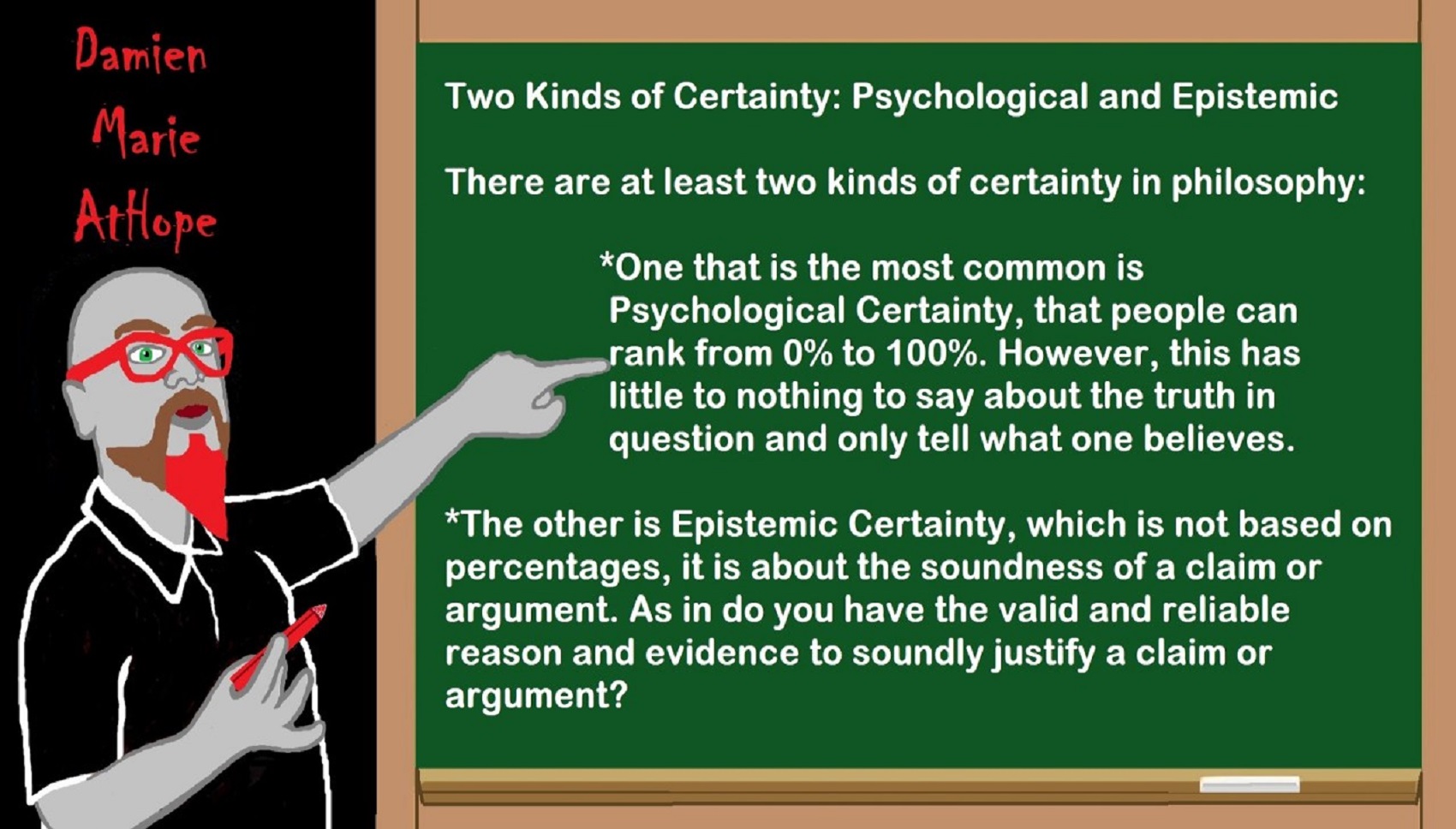

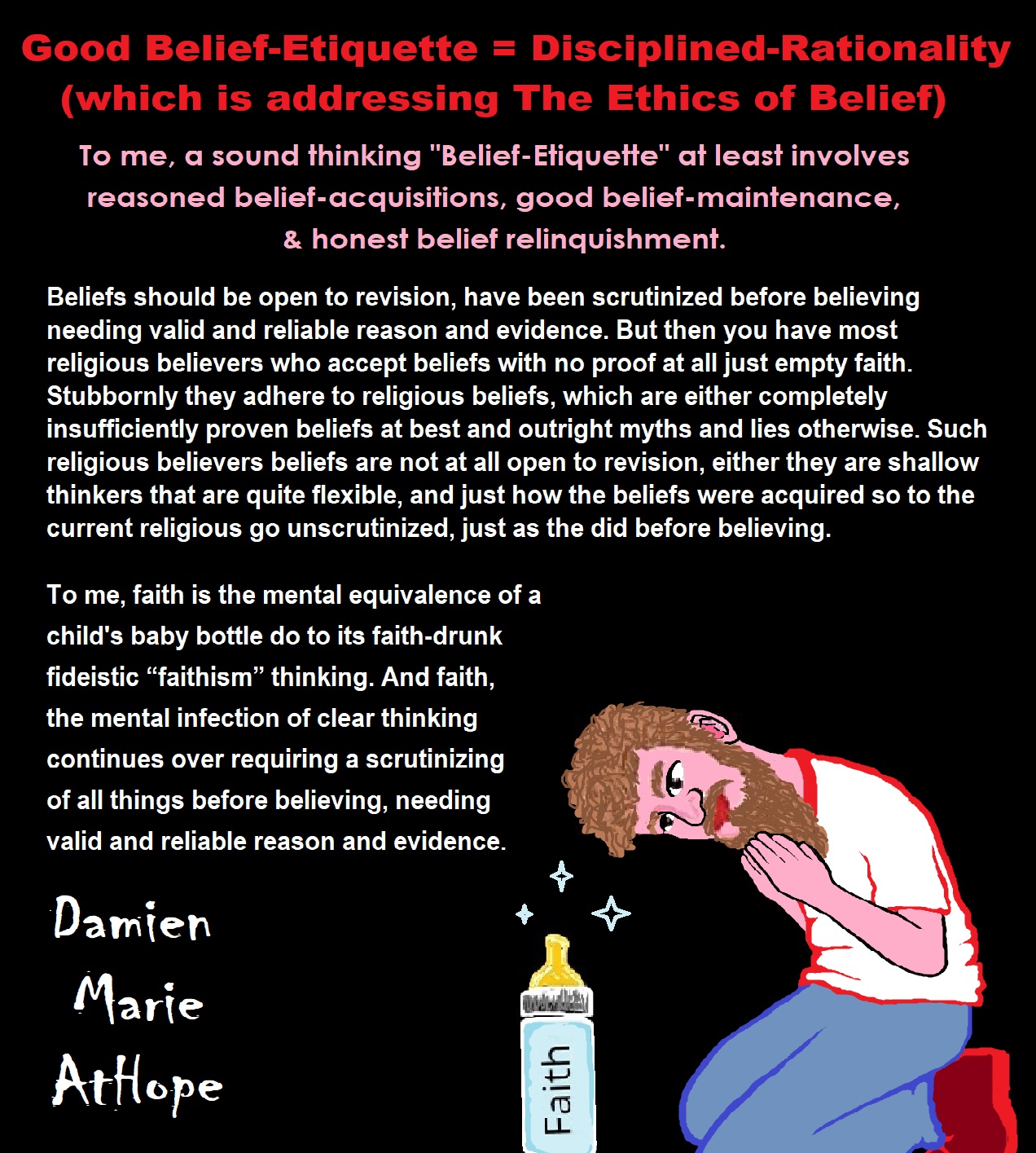

For the beliefs part I use what philosophy calls The Ethics of Belief.

The “ethics of belief” refers the intersection of epistemology, philosophy of mind, psychology, and ethics. The central is norms governing our habits of belief-formation, belief-maintenance, and belief-relinquishment. It morally wrong (or epistemically irrational, or imprudent) to hold a belief on insufficient evidence. It morally right (or epistemically rational, or prudent) to believe on the basis of sufficient evidence, or to withhold belief in the perceived absence of evidence. It always obligatory to seek out all available epistemic evidence for a belief.

What is belief? (philosophy)

“Belief” to refer to the attitude we have, roughly, whenever we take something to be the case or regard it as true. To believe something, in this sense, needn’t involve actively reflecting on it it seems so evident we just take it as so as such there are a vast number of things ordinary adults believe. Many of the things we all believe, in the relevant sense, are quite mundane: that there is a sun, that a there is a planet we call earth, that it revolves around that sun, and that there is some intelligent life on it; albeit some times this intelligent life believes unintelligent things. Forming beliefs is thus one of the most basic and important features of the mind, and the concept of belief plays a crucial role in both philosophy of mind and epistemology. Forming beliefs is thus one of the most basic and important features of the mind, and the concept of belief plays a crucial role in both philosophy of mind and epistemology. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/belief/

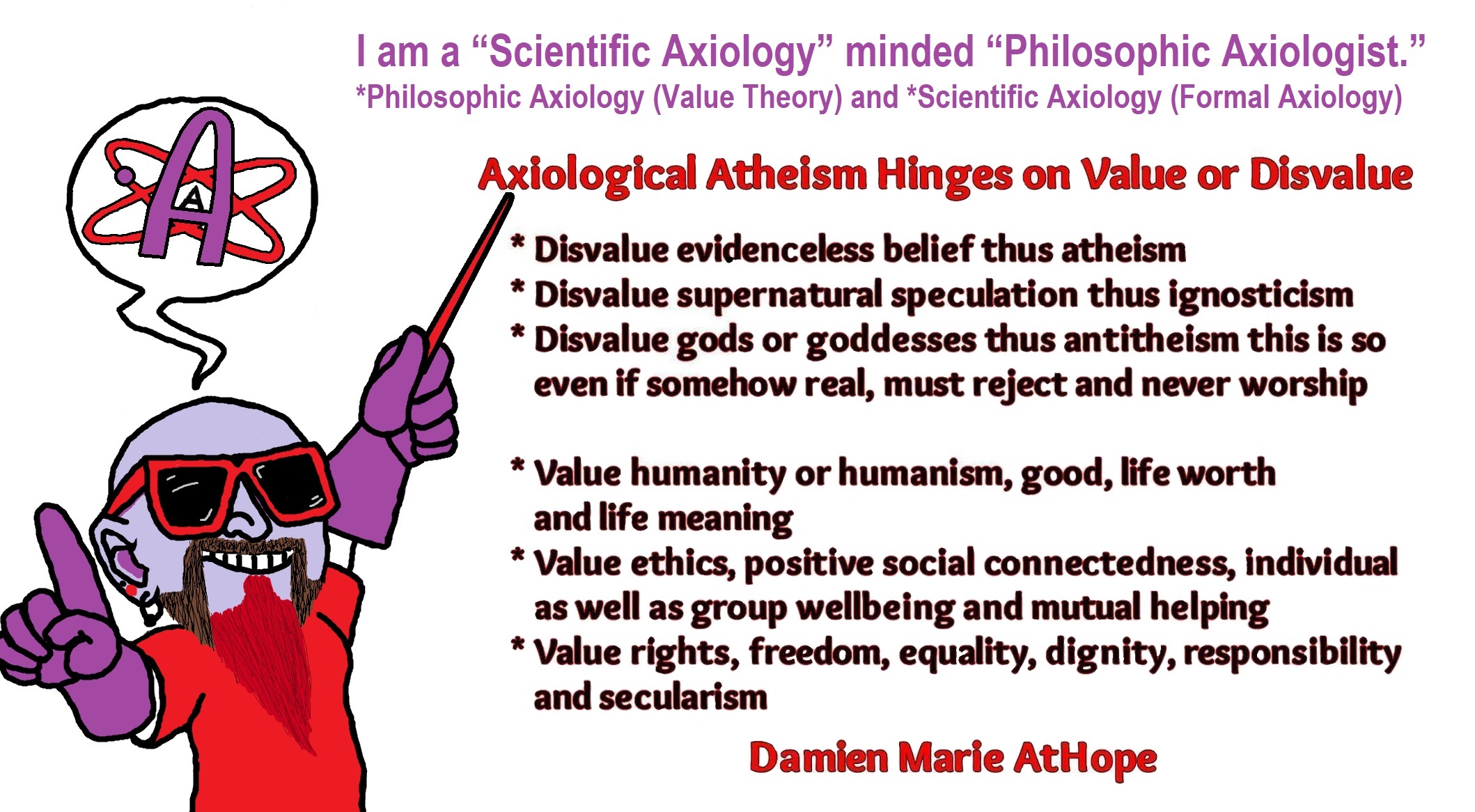

Some continue to try and call Atheism a belief system.

Ok, well I will humor you. If atheism is to be thought of as a belief system as religionists like to think then it’s the confirmation of two philosophies Rationalism (reason) and Empiricism (evidence) and in simple terms, it’s the method of only accepting valid as well as reliable reason and evidence. Since god hypothesis claims fail to substantiate with any “evidence” as well as are exposed to contain thinking errors, logical fallacies, and internal contradictions it has no warrant nor justification to support “reason” believing it to be in any way true. Thus, to your belief that Atheism is a belief but you have it backward, we have credible belief systems that lead us to the conclusion of Atheism which is stating I do not have a belief in gods, which because of the facts in evidence is the only rational choice.

What is belief? (Psychology)

“Simply, a belief defines an idea or principle which we judge to be true. When we stop to think about it, functionally this is no small thing: lives are routinely sacrificed and saved based simply on what people believe. Yet I routinely encounter people who believe things that remain not just unproven, but which have been definitively shown to be false. In fact, I so commonly hear people profess complete certainty in the truth of ideas with insufficient evidence to support them that the alarm it used to trigger in me no longer goes off. I’ll challenge a false belief when, in my judgment, it poses a risk to a patient’s life or limb, but I let far more unjustified beliefs pass me by than I stop to confront. If I didn’t, I wouldn’t have time to talk about anything else. What exactly is going on here? Why are we all (myself included) so apparently predisposed to believe false propositions? The answer lies in neuropsychology’s growing recognition of just how irrational our rational thinking can be, according to an article in Mother Jones by Chris Mooney. We now know that our intellectual value judgments—that is, the degree to which we believe or disbelieve an idea—are powerfully influenced by our brains’ proclivity for attachment. Our brains are attachment machines, attaching not just to people and places, but to ideas. And not just in a coldly rational manner. Our brains become intimately emotionally entangled with ideas we come to believe are true (however we came to that conclusion) and emotionally allergic to ideas we believe to be false. This emotional dimension to our rational judgment explains a gamut of measurable biases that show just how unlike computers our minds are: Confirmation bias, which causes us to pay more attention and assign greater credence to ideas that support our current beliefs. That is, we cherry-pick the evidence that supports a contention we already believe and ignore evidence that argues against it. Disconfirmation bias, which causes us to expend disproportionate energy trying to disprove ideas that contradict our current beliefs. Accuracy of belief isn’t our only cognitive goal. Our other goal is to validate our pre-existing beliefs, beliefs that we’ve been building block by block into a cohesive whole our entire lives. In the fight to accomplish the latter, confirmation bias and disconfirmation bias represent two of the most powerful weapons at our disposal, but simultaneously compromise our ability to judge ideas on their merits and the evidence for or against them.” https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/happiness-in-world/201104/the-two-kinds-belief

EVIDENCE VS. EMOTION:

“This isn’t to say we can’t become aware of our cognitive biases and guard against them—just that it’s hard work. But if we really do want to believe only what’s actually true, it’s necessary work. In fact, I would argue that if we want to minimize the impact of confirmation and disconfirmation bias, we need to reason more like infants than adults. Though many people think belief can occur only in self-aware species possessing higher intelligence, I would argue that both infants and animals also believe things, the only difference being they’re not aware they believe them. That is, they do indeed judge certain ideas “true”—if not with self-aware minds, with minds that act based on the truth of them nonetheless. Infants will learn that objects don’t cease to exist when placed behind a curtain around 8 to 12 months, a belief called object permanence (link is external), which scientists are able to determine from the surprise infants of this age exhibit when the curtain is lifted and the object has been removed. Animals will run from predators because they know—that is, believe—they will be eaten if they don’t. In this sense, even protozoa can be said to believe things (e.g., they will move toward energy sources rather than away because they know, or “believe,” engulfing such sources will continue their existence). Infants and animals, however, are free of the emotional biases that color the reasoning of adults because they haven’t yet developed (or won’t, in the case of animals) the meta-cognitive abilities of adults, i.e., the ability to look back on their conclusions and form opinions about them. Infants and animals are therefore forced into drawing conclusions I consider compulsory beliefs—”compulsory” because such beliefs are based on principles of reason and evidence that neither infants nor animals are actually free to disbelieve. This leads to the rather ironic conclusion that infants and animals are actually better at reasoning from evidence than adults. Not that adults are, by any means, able to avoid forming compulsory beliefs when incontrovertible evidence presents itself (e.g., if a rock is dropped, it will fall), but adults are so mired in their own meta-cognitions that few facts absorbed by their minds can escape being attached to a legion of biases, often creating what I consider rationalized beliefs—”rationalized” because adult judgments about whether an idea is true are so often powerfully influenced by what he or she wants to be true. This is why, for example, creationists continue to disbelieve in evolution despite overwhelming evidence in support of it and activist actors and actresses with autistic children continue to believe that immunizations cause autism despite overwhelming evidence against it. But if we look down upon people who seem blind to evidence that we ourselves find compelling, imagining ourselves to be paragons of reason and immune to believing erroneous conclusions as a result of the influence of our own pre-existing beliefs, more likely than not we’re only deceiving ourselves about the strength of our objectivity. Certainly, some of us are better at managing our biases than others, but all of us have biases with which we must contend. What then can be done to mitigate their impact? First, we have to be honest with ourselves in recognizing just how biased we are. If we only suspect that what we want to be true is having an influence on what we believe is true, we’re coming late to the party. Second, we have to identify the specific biases we’ve accumulated with merciless precision. And third, we have to practice noticing how (not when) those specific biases are exerting influence over the judgments we make about new facts. If we fail to practice these three steps, we’re doomed to reason, as Jonathan Haidt argues, often more like lawyers than scientists—that is, backward from our predetermined conclusions rather than forward from evidence. Some evidence suggests we’re less apt to become automatically dismissive of new ideas that contradict our current beliefs if those ideas are presented in a non-worldview-threatening manner or by someone who we perceive thinks as we do. As a society, therefore, we have critically important reasons to reject bad (untrue) ideas and promulgate good (true) ones. When we speak out, however, we must realize that reason alone will rarely if ever be sufficient to correct misconceptions. If we truly care to promote belief in what’s true, we need to first find a way to circumvent the emotional biases in ourselves that prevent us from recognizing the truth when we see it.” https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/happiness-in-world/201104/the-two-kinds-belief

What is belief? (neuroscience)

“Where belief is born: Scientists have begun to look in a different way at how the brain creates the convictions that mold our relationships and inform our behavior. “Belief has been a most powerful component of human nature that has somewhat been neglected,” says Peter Halligan, a psychologist at Cardiff University. “But it has been capitalized on by marketing agents, politics, and religion for the best part of two millennia.” That is changing. Once the preserve of philosophers alone, belief is quickly becoming the subject of choice for many psychologists and neuroscientists. Their goal is to create a neurological model of how beliefs are formed, how they affect people, and what can manipulate them. And the latest steps in the research might just help to understand a little more about why the world is so fraught with political and social tension. Matthew Lieberman, a psychologist at the University of California, recently showed how beliefs help people’s brains categorize others and view objects as good or bad, largely unconsciously. He demonstrated that beliefs (in this case prejudice or fear) are most likely to be learned from the prevailing culture. When Lieberman showed a group of people photographs of expressionless black faces, he was surprised to find that the amygdala – the brain’s panic button – was triggered in almost two-thirds of cases. There was no difference in the response between black and white people. The amygdala is responsible for the body’s fight or flight response, setting off a chain of biological changes that prepare the body to respond to danger well before the brain is conscious of any threat. Lieberman suggests that people are likely to pick up on stereotypes, regardless of whether their family or community agrees with them. The work, published last month in Nature Neuroscience, is the latest in a rapidly growing field of research called “social neuroscience”, a wide arena that draws together psychologists, neuroscientists, and anthropologists all studying the neural basis for the social interaction between humans. Traditionally, cognitive neuroscientists focused on scanning the brains of people doing specific tasks such as eating or listening to music, while social psychologists and social scientists concentrated on groups of people and the interactions between them. To understand how the brain makes sense of the world, it was inevitable that these two groups would have to get together. “In the West, most of our physical needs are provided for. We have a level of luxury and civilization that is pretty much unparalleled,” says Kathleen Taylor, a neuroscientist at Oxford University. “That leaves us with a lot more leisure and more space in our heads for thinking.” Beliefs and ideas, therefore, become our currency, says Taylor. Society is no longer a question of simple survival; it is about the choice of companions and views, pressures, ideas, options, and preferences. “It is quite an exciting development but for people outside the field, a very obvious one,” says Halligan. Understanding belief is not a trivial task, even for the seemingly simplest of human interactions. Take a conversation between two people. When one talks, the other’s brain is processing information through their auditory system at a phenomenal rate. That person’s beliefs act as filters for the deluge of sensory information and guide the brain’s response. Lieberman’s recent work echoed parts of earlier research by Joel Winston of the University of London’s Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience. Winston found that when he presented people with pictures of faces and asked them to rate the trustworthiness of each, the amygdalae showed a greater response to pictures of people who were specifically chosen to represent untrustworthiness. And it did not matter what each person actually said about the pictured faces. “Even people who believe to their core that they do not have prejudices may still have negative associations that are not conscious,” says Lieberman. Beliefs also provide stability. When a new piece of sensory information comes in, it is assessed against these knowledge units before the brain works out whether or not it should be incorporated. People do it when they test the credibility of a politician or hear about a paranormal event. Physically speaking, then, how does a belief exist in the brain? “My own position is to think of beliefs and memories as very similar,” says Taylor. Memories are formed in the brain as networks of neurons that fire when stimulated by an event. The more times the network is employed, the more it fires and the stronger the memory becomes. Halligan says that belief takes the concept of memory a step further. “A belief is a mental architecture of how we interpret the world,” he says. “We have lots of fluid things moving by – perceptions and so forth – but at the level of who our friends are and so on, those things are consolidated in crystallized knowledge units. If we did not have those, every time we woke up, how would we know who we are?” These knowledge units help to assess threats – via the amygdala – based on experience. Ralph Adolphs, a neurologist at the University of Iowa, found that if the amygdala was damaged, the ability of a person to recognize expressions of fear was impaired. A separate study by Adolphs with Simon Baron-Cohen at Cambridge University showed that amygdala damage had a bigger negative impact on the brain’s ability to recognize social emotions, while more basic emotions seemed unaffected. This work on the amygdala shows it is a key part of the threat-assessment response and, in no small part, in the formation of beliefs. Damage to this alarm bell – and subsequent inability to judge when a situation might be dangerous – can be life-threatening. In hunter-gatherer days, beliefs may have been fundamental to human survival. Neuroscientists have long looked at brains that do not function properly to understand how healthy ones work. Researchers of belief formation do the same thing, albeit with a twist. “You look at people who have delusions,” says Halligan. “The assumption is that a delusion is a false belief. That is saying that the content of it is wrong, but it still has the construct of a belief.” In people suffering from prosopagnosia, for example, parts of the brain are damaged so that the person can no longer recognize faces. In the Cotard delusion, people believe they are dead. Fregoli delusion is the belief that the sufferer is constantly being followed around by people in disguise. Capgras’ delusion, named after its discoverer, the French psychiatrist Jean Marie Joseph Capgras, is a belief that someone emotionally close has been replaced by an identical impostor. Until recently, these conditions were regarded as psychiatric problems. But closer study reveals that, in the case of Capgras’ delusion, for example, a significant proportion of sufferers had lesions in their brain, typically in the right hemisphere. “There are studies indicating that some people who have suffered brain damage retain some of their religious or political beliefs,” says Halligan. “That’s interesting because whatever beliefs are, they must be held in memory.” Another route to understanding how beliefs form is to look at how they can be manipulated. In her book on the history of brainwashing, Taylor describes how everyone from the Chinese thought reform camps of the last century to religious cults have used systematic methods to persuade people to change their ideas, sometimes radically.” http://www.theguardian.com/science/2005/jun/30/psychology.neuroscience

The first step is to isolate a person and control what information they receive. Their former beliefs need to be challenged by creating uncertainty. New messages need to be repeated endlessly. And the whole thing needs to be done in a pressured, emotional environment. “Beliefs are mental objects in the sense that they are embedded in the brain,” says Taylor. “If you challenge them by contradiction, or just by cutting them off from the stimuli that make you think about them, then they are going to weaken slightly. If that is combined with a very strong reinforcement of new beliefs, then you’re going to get a shift in emphasis from one to the other.” The mechanism Taylor describes is similar to the way the brain learns normally. In brainwashing though, the new beliefs are inserted through a much more intensified version of that process. This manipulation of belief happens every day. Politics is a fertile arena, especially in times of anxiety. “Stress affects the brain such that it makes people more likely to fall back on things they know well – stereotypes and simple ways of thinking,” says Taylor. “It is very easy to want to do that when everything you hold dear is being challenged. In a sense, it was after 9/11.” The stress of the terror attacks on the US in 2001 changed the way many Americans viewed the world, and Taylor argues that it left the population open to tricks of belief manipulation. A recent survey, for example, found that more than half of Americans thought Iraqis were involved in the attacks, despite the fact that nobody had come out and said it. This method of association uses the brain against itself. If an event stimulates two sets of neurons, then the links between them get stronger. If one of them activates, it is more likely that the second set will also fire. In the real world, those two memories may have little to do with each other, but in the brain, they get associated. Taylor cites an example from a recent manifesto by the British National Party, which argues that asylum seekers have been dumped on Britain and that they should be made to clear up rubbish from the streets. “What they are trying to do is to link the notion of asylum seekers with all the negative emotions you get from reading about garbage, [but] they are not actually coming out and saying asylum seekers are garbage,” she says. The 9/11 attacks highlight another extreme in the power of beliefs. “Belief could drive people to agree to premeditate something like that in the full knowledge that they would all die,” says Halligan of the hijacker pilots. It is unlikely that beliefs as wide-ranging as justice, religion, prejudice, or politics are simply waiting to be found in the brain as discrete networks of neurons, each encoding for something different. “There’s probably a whole combination of things that go together,” says Halligan. And depending on the level of significance of a belief, there could be several networks at play. Someone with strong religious beliefs, for example, might find that they are more emotionally drawn into certain discussions because they have a large number of neural networks feeding into that belief. “If you happen to have a predisposition, racism for example, then it may be that you see things in a certain way and you will explain it in a certain way,” says Halligan. He argues that the reductionist approach of social neuroscience will alter the way people study society. “If you are brain scanning, what are the implications for privacy in terms of knowing another’s thoughts? And being able to use those, as some governments are implying, in terms of being able to detect terrorists and things like that,” he says. “If you move down the line in terms of potential uses for these things, you have potential uses for education and for treatments being used as cognitive enhancers.” So far, social neuroscience has provided more questions than answers. Ralph Adolphs of the University of Iowa looked to the future in a review paper for Nature. “How can causal networks explain the many correlations between brain and behavior that we are discovering? Can large-scale social behavior, as studied by political science and economics, be understood by studying social cognition in individual subjects? Finally, what power will insights from cognitive neuroscience give us to influence social behavior, and hence society? And to what extent would such pursuit be morally defensible?” http://www.theguardian.com/science/2005/jun/30/psychology.neuroscience

A cognitive account of belief: a tentative road map

“Beliefs comprise more distributed and therefore less accessible central cognitive processes assumed to not really be like more established and accessible modular psychological process (e.g., vision, audition, face-recognition, language-processing, and motor-control systems). Belief can be defined as the mental acceptance or conviction in the truth or actuality of some idea (Schwitzgebel, 2010). Beliefs thus involve at least two properties: (i) representational content and (ii) assumed veracity (Stephens and Graham, 2004). It is important to note, however, that beliefs need not be conscious or linguistically articulated. It is likely that the majority of beliefs remain unconscious or outside of immediate awareness, and are of relatively mundane content: for example, that one’s senses reveal an environment that is physically real, that one has ongoing relationships with other people, and that one’s actions in the present can bring about outcomes in the future. Beliefs thus typically describeenduring, unquestioned ontological representations of the world and comprise primary convictions about events, causes, agency, and objects that subjects use and accept as veridical. Beliefs can be distinguished from other types of cognitive “representations” that are more frequently referred to in contemporary cognitive science, such as memory, knowledge, and attitudes. In contrast to memory, beliefs can apply to present and future events, as well as the past. In some cases, it may also be possible to distinguish between memories that are believed (as in the vast majority of memories) and memories that are not believed (as in false memories when a person recognises that the remembered event could not have occurred;Loftus, 2003). In contrast to knowledge, beliefs are, by definition, held with conviction and regarded as true (Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975; Eagly and Chaiken, 1993; Wyer and Albarracín, 2005). Beliefs also typically involve a large self-referential element that may not be present in knowledge. Finally, in contrast to attitudes (as understood in social psychology, rather than the broader philosophical usage), beliefs need not contain an evaluative component, which is a defining characteristic of attitudes in social psychology (Eagly and Chaiken, 1993). On the other hand, beliefs may provide a framework for understanding attitudes (e.g., the belief that an object has a particular property and the belief that this property should be evaluated in a particular way; for further discussion, see Kruglanski and Stroebe, 2005; Wyer and Albarracín, 2005). In all three cases, however, there is likely to be considerable overlap with belief and the different constructs may involve shared underpinnings. Semantic memory, for example, which involves memory for meaning, is likely to have many commonalities with belief.” http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4327528/

Beliefs come first, explanations for beliefs follow.

“In this book, The Believing Brain Michael Shermer is interested in more than just why people believe weird things, or why people believe this or that claim, but in why people believe anything at all. By assessing the neuroscience behind our beliefs. The brain is a belief engine. From sensory data flowing in through the senses, the brain naturally begins to look for and find patterns, and then infuses those patterns with meaning. The first process Michael Shermer calls patternicity: the tendency to find meaningful patterns in both meaningful and meaningless data. The second process he calls agenticity: the tendency to infuse patterns with meaning, intention, and agency. We can’t help believing. Our brains evolved to connect the dots of our world into meaningful patterns that explain why things happen. These meaningful patterns become beliefs. Once beliefs are formed the brain begins to look for and find confirmatory evidence in support of those beliefs, which adds an emotional boost of further confidence in the beliefs and thereby accelerates the process of reinforcing them, and round and round the process goes in a positive feedback loop of belief confirmation. Michael Shermer outlines the numerous cognitive tools our brains engage to reinforce our beliefs as truths and to ensure that we are always right. Interlaced with his theory of belief, Michael Shermer provides countless real-world examples of belief from all realms of life, and in the end, he demonstrates why science is the best tool ever devised to determine whether or not a belief matches reality.” http://www.michaelshermer.com/the-believing-brain/

Philosophies for Good Belief Formation

Philosophies for good belief formation: “Reliabilism” and “Correspondence Theory of Truth”

You if a reasoned thinker, YOU, likely use both of the philosophies I stated to some extent you just did not realize that you were doing so. If you reserve belief waiting for a large consensus you would be following “reliabilism” and withhold belief until evidence for that belief is established would be “correspondence theory of truth.”

Reliabilism would say before you even can assess if the evidence is warranted or justified it must come from a reliable source. In other words, a peer-reviewed journal is reliable or at least can be warranted to be reliable until shown otherwise. The bible with unknown authorship without corroborating facts and demonstrated lies and at least half-truths are unwarranted and unjustified as a reliable source, thus cannot be used as evidence until some part one was trying to uses was proven otherwise. Narrowly speaking, the correspondence theory of truth is the view that truth is correspondence to, or with, a fact—a view that was advocated by Russell and Moore early in the 20th century. But the label is usually applied much more broadly to any view explicitly embracing the idea that truth consists in a relation to reality, i.e., that truth is a relational property involving a characteristic relation (to be specified) to some portion of reality (to be specified). This basic idea has been expressed in many ways, giving rise to an extended family of theories and, more often, theory sketches. Members of the family employ various concepts for the relevant relation (correspondence, conformity, congruence, agreement, accordance, copying, picturing, signification, representation, reference, satisfaction) and/or various concepts for the relevant portion of reality (facts, states of affairs, conditions, situations, events, objects, sequences of objects, sets, properties, tropes). The resulting multiplicity of versions and reformulations of the theory is due to a blend of substantive and terminological differences. ref

The correspondence theory of truth is often associated with metaphysical realism.

Reliability theories of knowledge of varying stripes continue to appeal to many epistemologists. Here is a link: http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/reliabilism/

Be Careful What You Believe

We accumulate beliefs that we allow to negatively influence our lives often without realizing it. However, it is our willingness to alter skewed beliefs or assertions that impede our balance, which brings about a new caring, connected, and critical awareness.

Philosophical Skepticism, Solipsism and the Denial of Reality or Certainty

Agnosticism is a Belief about knowledge Built on Folk Logic

While hallucinogens are associated with shamanism, it is alcohol that is associated with paganism.

The Atheist-Humanist-Leftist Revolutionaries Shows in the prehistory series:

Show two: Pre-animism 300,000 years old and animism 100,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism”

Show tree: Totemism 50,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism”

Show four: Shamanism 30,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism”

Show five: Paganism 12,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism”

Show six: Emergence of hierarchy, sexism, slavery, and the new male god dominance: Paganism 7,000-5,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism” (Capitalism) (World War 0) Elite and their slaves!

Prehistory: related to “Anarchism and Socialism” the division of labor, power, rights, and recourses: VIDEO

Pre-animism 300,000 years old and animism 100,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism”: VIDEO

Totemism 50,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism”: VIDEO

Shamanism 30,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism”: VIDEO

Paganism 12,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism” (Pre-Capitalism): VIDEO

Paganism 7,000-5,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism” (Capitalism) (World War 0) Elite and their slaves: VIEDO

Paganism 5,000 years old: progressed organized religion and the state: related to “Anarchism and Socialism” (Kings and the Rise of the State): VIEDO

Paganism 4,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism” (First Moralistic gods, then the Origin time of Monotheism): VIEDO

I do not hate simply because I challenge and expose myths or lies any more than others being thought of as loving simply because of the protection and hiding from challenge their favored myths or lies.

The truth is best championed in the sunlight of challenge.

An archaeologist once said to me “Damien religion and culture are very different”

My response, So are you saying that was always that way, such as would you say Native Americans’ cultures are separate from their religions? And do you think it always was the way you believe?

I had said that religion was a cultural product. That is still how I see it and there are other archaeologists that think close to me as well. Gods too are the myths of cultures that did not understand science or the world around them, seeing magic/supernatural everywhere.

I personally think there is a goddess and not enough evidence to support a male god at Çatalhöyük but if there was both a male and female god and goddess then I know the kind of gods they were like Proto-Indo-European mythology.

This series idea was addressed in, Anarchist Teaching as Free Public Education or Free Education in the Public: VIDEO

Our 12 video series: Organized Oppression: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of power (9,000-4,000 years ago), is adapted from: The Complete and Concise History of the Sumerians and Early Bronze Age Mesopotamia (7000-2000 BC): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=szFjxmY7jQA by “History with Cy“

Show #1: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power (Samarra, Halaf, Ubaid)

Show #2: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power

Show #3: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power (Uruk and the First Cities)

Show #4: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power (First Kings)

Show #5: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power (Early Dynastic Period)

Show #6: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power

Show #7: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power (Sargon and Akkadian Rule)

Show #9: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power (Gudea of Lagash and Utu-hegal)

Show #12: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power (Aftermath and Legacy of Sumer)

The “Atheist-Humanist-Leftist Revolutionaries”

Cory Johnston ☭ Ⓐ Atheist Leftist @Skepticallefty & I (Damien Marie AtHope) @AthopeMarie (my YouTube & related blog) are working jointly in atheist, antitheist, antireligionist, antifascist, anarchist, socialist, and humanist endeavors in our videos together, generally, every other Saturday.

Why Does Power Bring Responsibility?

Think, how often is it the powerless that start wars, oppress others, or commit genocide? So, I guess the question is to us all, to ask, how can power not carry responsibility in a humanity concept? I know I see the deep ethical responsibility that if there is power their must be a humanistic responsibility of ethical and empathic stewardship of that power. Will I be brave enough to be kind? Will I possess enough courage to be compassionate? Will my valor reach its height of empathy? I as everyone, earns our justified respect by our actions, that are good, ethical, just, protecting, and kind. Do I have enough self-respect to put my love for humanity’s flushing, over being brought down by some of its bad actors? May we all be the ones doing good actions in the world, to help human flourishing.

I create the world I want to live in, striving for flourishing. Which is not a place but a positive potential involvement and promotion; a life of humanist goal precision. To master oneself, also means mastering positive prosocial behaviors needed for human flourishing. I may have lost a god myth as an atheist, but I am happy to tell you, my friend, it is exactly because of that, leaving the mental terrorizer, god belief, that I truly regained my connected ethical as well as kind humanity.

Cory and I will talk about prehistory and theism, addressing the relevance to atheism, anarchism, and socialism.

At the same time as the rise of the male god, 7,000 years ago, there was also the very time there was the rise of violence, war, and clans to kingdoms, then empires, then states. It is all connected back to 7,000 years ago, and it moved across the world.

Cory Johnston: https://damienmarieathope.com/2021/04/cory-johnston-mind-of-a-skeptical-leftist/?v=32aec8db952d

The Mind of a Skeptical Leftist (YouTube)

Cory Johnston: Mind of a Skeptical Leftist @Skepticallefty

The Mind of a Skeptical Leftist By Cory Johnston: “Promoting critical thinking, social justice, and left-wing politics by covering current events and talking to a variety of people. Cory Johnston has been thoughtfully talking to people and attempting to promote critical thinking, social justice, and left-wing politics.” http://anchor.fm/skepticalleft

Cory needs our support. We rise by helping each other.

Cory Johnston ☭ Ⓐ @Skepticallefty Evidence-based atheist leftist (he/him) Producer, host, and co-host of 4 podcasts @skeptarchy @skpoliticspod and @AthopeMarie

Damien Marie AtHope (“At Hope”) Axiological Atheist, Anti-theist, Anti-religionist, Secular Humanist. Rationalist, Writer, Artist, Poet, Philosopher, Advocate, Activist, Psychology, and Armchair Archaeology/Anthropology/Historian.

Damien is interested in: Freedom, Liberty, Justice, Equality, Ethics, Humanism, Science, Atheism, Antiteism, Antireligionism, Ignosticism, Left-Libertarianism, Anarchism, Socialism, Mutualism, Axiology, Metaphysics, LGBTQI, Philosophy, Advocacy, Activism, Mental Health, Psychology, Archaeology, Social Work, Sexual Rights, Marriage Rights, Woman’s Rights, Gender Rights, Child Rights, Secular Rights, Race Equality, Ageism/Disability Equality, Etc. And a far-leftist, “Anarcho-Humanist.”

I am not a good fit in the atheist movement that is mostly pro-capitalist, I am anti-capitalist. Mostly pro-skeptic, I am a rationalist not valuing skepticism. Mostly pro-agnostic, I am anti-agnostic. Mostly limited to anti-Abrahamic religions, I am an anti-religionist.

To me, the “male god” seems to have either emerged or become prominent around 7,000 years ago, whereas the now favored monotheism “male god” is more like 4,000 years ago or so. To me, the “female goddess” seems to have either emerged or become prominent around 11,000-10,000 years ago or so, losing the majority of its once prominence around 2,000 years ago due largely to the now favored monotheism “male god” that grow in prominence after 4,000 years ago or so.

My Thought on the Evolution of Gods?

Animal protector deities from old totems/spirit animal beliefs come first to me, 13,000/12,000 years ago, then women as deities 11,000/10,000 years ago, then male gods around 7,000/8,000 years ago. Moralistic gods around 5,000/4,000 years ago, and monotheistic gods around 4,000/3,000 years ago.

Damien Marie AtHope (Said as “At” “Hope”)/(Autodidact Polymath but not good at math):

Axiological Atheist, Anti-theist, Anti-religionist, Secular Humanist, Rationalist, Writer, Artist, Jeweler, Poet, “autodidact” Philosopher, schooled in Psychology, and “autodidact” Armchair Archaeology/Anthropology/Pre-Historian (Knowledgeable in the range of: 1 million to 5,000/4,000 years ago). I am an anarchist socialist politically. Reasons for or Types of Atheism

My Website, My Blog, & Short-writing or Quotes, My YouTube, Twitter: @AthopeMarie, and My Email: damien.marie.athope@gmail.com