No I don’t believe in goddess(es) or god(s). I cannot believe in the possibility of any deity and definitely not the even more preposterous idea of a psychopathic deity that would create hell with an eternity of torture.

Any being so malevolent would not play with the nonsense of staying so invisible to the extreme that there is not even the slightest bit of evidence of any kind that such a being exists. If this deity is so all-powerful and malevolent who wants to create a mass amount of fear and terror which could be done immediately by proving it exist in the real external world, by not proving or even allowing some evidence for the possibility of it to be true then it has to be false.

Moreover, many say this all-invisible god is all benevolent, but if so, why would such a god create a psychopathic deity’s hell with its eternity of torture. By doing so, it would no longer be a benevolent god. In addition, if god were all-benevolent, it would not stay so invisible to the extreme that there is not even the slightest bit of evidence of any kind that such a being exists. If this deity is so all-powerful and benevolent who wants to create a mass amount of hope and peace which could be done immediately by proving it exist in the real external world, by not proving or even allowing some evidence for the possibility of it to be true then it has to be false.

Then some may say god plays the biggest game of hide and seek by staying invisible to evidence in every way because god wants belief without evidence. However, what about the proposed evidence in holy books? Are they not a reference of when gods (always so long ago) supposedly provided evidence you are not to believe even if it is disproved by science or archaeology evidence? In addition, what about gods reported enemy the devil, why does the devil also stay so invisible to such an extreme that there is not even the slightest bit of evidence of any kind such a being exists in an external world reality.

Well my simple answer is because both gods and devils are myths that are not worthy of justified true belief and actually, not reasonable for any belief at all when one accepts the reality of the external world as in supernatural free.

Lastly, any god that threatens with the human horror of injustice that would be hell cannot be also called a god of love, because a just loving god would not torture anyone for eternity, especially people not guilty of grievously harming others.

Then “hell god” supports say, but god does not torture you for eternity, it is you, who puts yourself there by your own choices, “aka” people’s own free will. For a true ethically minded individual “hell god” as a “loving god” is absurd. A loving god would appreciate our reason, skepticism, and freethought. A true “loving god” would totally get that faith devoid of evidence and contrary to evidence is not only not enough it’s rationally repugnant.

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

Sumerian religion/ Mesopotamian mythology

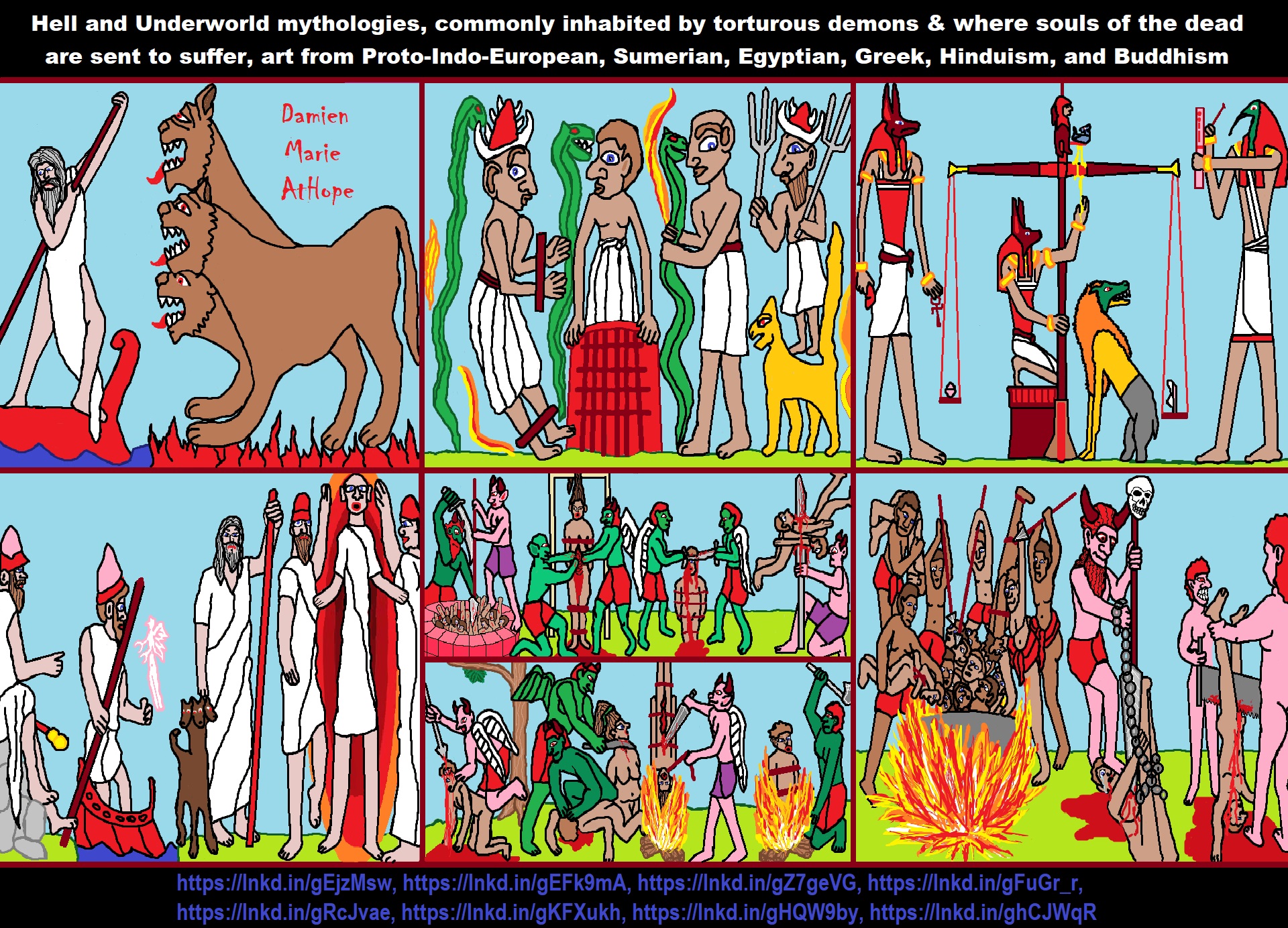

Hell and Underworld mythologies, commonly inhabited by torturous demons and the souls of dead sent to suffer, from Proto-Indo-European, Sumerian, Egyptian, Greek, Hinduism, and Buddhism

“Hell appears in several mythologies and religions. And in religion as well as folklore, Hell is an afterlife location in which evil souls are subjected to punitive suffering, often torture as eternal punishment after death. Religions with a linear divine history often depict hells as eternal destinations, the biggest examples of which are Christianity and Islam, whereas religions with reincarnation usually depict a hell as an intermediary period between incarnations, as is the case in the dharmic religions. Religions typically locate hell in another dimension or under Earth‘s surface. Other afterlife destinations include Heaven, Paradise, Purgatory, Limbo, and the underworld. Other religions, which do not conceive of the afterlife as a place of punishment or reward, merely describe an abode of the dead, the grave, a neutral place that is located under the surface of Earth (for example, see Kur, Hades, and Sheol). Such places are sometimes equated with the English word hell, though a more correct translation would be “underworld” or “world of the dead”. The ancient Mesopotamian, Greek, Roman, and Finnic religions include entrances to the underworld from the land of the living.” ref

“The modern English word hell is derived from Old English hel, helle (first attested around 725 AD to refer to a nether world of the dead) reaching into the Anglo-Saxon pagan period. The word has cognates in all branches of the Germanic languages, including Old Norse hel (which refers to both a location and goddess-like being in Norse mythology), Old Frisian helle, Old Saxon hellia, Old High German hella, and Gothic halja. All forms ultimately derive from the reconstructed Proto-Germanic feminine noun *xaljō or *haljō (‘concealed place, the underworld’). In turn, the Proto-Germanic form derives from the o-grade form of the Proto-Indo-European root *kel-, *kol-: ‘to cover, conceal, save’. Indo-European cognates include Latin cēlāre (“to hide”, related to the English word cellar) and early Irish ceilid (“hides”). Upon the Christianization of the Germanic peoples, extension of Proto-Germanic *xaljō were reinterpreted to denote the underworld in Christian mythology, for which see Gehenna. Related early Germanic terms and concepts include Proto-Germanic *xalja-rūnō(n), a feminine compound noun, and *xalja-wītjan, a neutral compound noun. This form is reconstructed from the Latinized Gothic plural noun *haliurunnae (attested by Jordanes; according to philologist Vladimir Orel, meaning ‘witches‘), Old English helle-rúne (‘sorceress, necromancer‘, according to Orel), and Old High German helli-rūna ‘magic’. The compound is composed of two elements: *xaljō (*haljō) and *rūnō, the Proto-Germanic precursor to Modern English rune.[4] The second element in the Gothic haliurunnae may however instead be an agent noun from the verb rinnan (“to run, go”), which would make its literal meaning “one who travels to the netherworld”. Proto-Germanic *xalja-wītjan (or *halja-wītjan) is reconstructed from Old Norse hel-víti ‘hell’, Old English helle-wíte ‘hell-torment, hell’, Old Saxon helli-wīti ‘hell’, and the Middle High German feminine noun helle-wīze. The compound is a compound of *xaljō (discussed above) and *wītjan (reconstructed from forms such as Old English witt ‘right mind, wits’, Old Saxon gewit ‘understanding’, and Gothic un-witi ‘foolishness, understanding’).” ref

“Punishment in Hell typically corresponds to sins committed during life. Sometimes these distinctions are specific, with damned souls suffering for each sin committed (see for example Plato’s myth of Er or Dante’s The Divine Comedy), but sometimes they are general, with condemned sinners relegated to one or more chamber of Hell or to a level of suffering. In many religious cultures, including Christianity and Islam, Hell is often depicted as fiery, painful, and harsh, inflicting suffering on the guilty. Despite these common depictions of Hell as a place of fire, some other traditions portray Hell as cold. Buddhist – and particularly Tibetan Buddhist – descriptions of Hell feature an equal number of hot and cold Hells. Among Christian descriptions, Dante‘s Inferno portrays the innermost (9th) circle of Hell as a frozen lake of blood and guilt. But cold also played a part in earlier Christian depictions of Hell, beginning with the Apocalypse of Paul, originally from the early third century; the “Vision of Dryhthelm” by the Venerable Bede from the seventh century; “St Patrick’s Purgatory“, “The Vision of Tundale” or “Visio Tnugdali“, and the “Vision of the Monk of Eynsham“, all from the twelfth century; and the “Vision of Thurkill” from the early thirteenth century.” ref

Proto-Indo-European

“The hells of Europe include Breton mythology’s “Anaon”, Celtic mythology‘s “Uffern”, Slavic mythology‘s “Peklo”, the hell of Sami mythology and Finnish “tuonela” (“manala”).” ref

“The Indo-European languages are a large language family native to western Eurasia. It comprises most of the languages of Europe together with those of the northern Indian Subcontinent and the Iranian Plateau. A few of these languages, such as English and Spanish, have expanded through colonialism in the modern period and are now spoken across all continents. The Indo-European family is divided into several branches or sub-families, the largest of which are the Indo-Iranian, Germanic, Romance, and Balto-Slavic groups. The most populous individual languages within them are Spanish, English, Hindustani (Hindi/Urdu), Portuguese, Bengali, Punjabi, and Russian, each with over 100 million speakers. German, French, Marathi, Italian, and Persian have more than 50 million each. In total, 46% of the world’s population (3.2 billion) speaks an Indo-European language as a first language, by far the highest of any language family. There are about 445 living Indo-European languages, according to the estimate by Ethnologue, with over two thirds (313) of them belonging to the Indo-Iranian branch. All Indo-European languages are descendants of a single prehistoric language, reconstructed as Proto-Indo-European, spoken sometime in the Neolithic era. Its precise geographical location, the Indo-European urheimat, is unknown and has been the object of many competing hypotheses; the most widely accepted is the Kurgan hypothesis, which posits the urheimat to be the Pontic–Caspian steppe, associated with the Yamnaya culture around 3000 BC. By the time the first written records appeared, Indo-European had already evolved into numerous languages spoken across much of Europe and south-west Asia. Written evidence of Indo-European appeared during the Bronze Age in the form of Mycenaean Greek and the Anatolian languages, Hittite and Luwian. The oldest records are isolated Hittite words and names – interspersed in texts that are otherwise in the unrelated Old Assyrian language, a Semitic language – found in the texts of the Assyrian colony of Kültepe in eastern Anatolia in the 20th century BC. Although no older written records of the original Proto-Indo-Europeans remain, some aspects of their culture and religion can be reconstructed from later evidence in the daughter cultures. The Indo-European family is significant to the field of historical linguistics as it possesses the second-longest recorded history of any known family, after the Afroasiatic family in the form of the Egyptian language and the Semitic languages.” ref

“The Proto-Indo-Europeans were a hypothetical prehistoric ethnolinguistic group of Eurasia who spoke Proto-Indo-European (PIE), the ancestor of the Indo-European languages according to linguistic reconstruction. Knowledge of them comes chiefly from that linguistic reconstruction, along with material evidence from archaeology and archaeogenetics. The Proto-Indo-Europeans likely lived during the late Neolithic, or roughly the 4th millennium BC. Mainstream scholarship places them in the Pontic–Caspian steppe zone in Eastern Europe (present-day Ukraine and southern Russia). Some archaeologists would extend the time depth of PIE to the middle Neolithic (5500 to 4500 BC) or even the early Neolithic (7500 to 5500 BC), and suggest alternative location hypotheses. By the early second millennium BC, descendants of the Proto-Indo-Europeans had reached far and wide across Eurasia, including Anatolia (Hittites), the Aegean (the ancestors of Mycenaean Greece), the north of Europe (Corded Ware culture), the edges of Central Asia (Yamnaya culture), and southern Siberia (Afanasievo culture).” ref

“Using linguistic reconstruction from old Indo-European languages such as Latin and Sanskrit, hypothetical features of the Proto-Indo-European language are deduced. Assuming that these linguistic features reflect the culture and environment of the Proto-Indo-Europeans, the following cultural and environmental traits are widely proposed:

- pastoralism, including domesticated cattle, horses, and dogs

- agriculture and cereal cultivation, including technology commonly ascribed to late-Neolithic farming communities, e.g., the plow

- transportation by or across water

- the solid wheel, used for wagons, but not yet chariots with spoked wheels[8]

- worship of a sky god, *Dyḗus Ph2tḗr (lit. “sky father”; > Vedic Sanskrit Dyáuṣ Pitṛ́, Ancient Greek Ζεύς (πατήρ) / Zeus (patēr)), vocative *dyeu ph2ter (> Latin Iūpiter, Illyrian Deipaturos)

- oral heroic poetry or song lyrics that used stock phrases such as imperishable fame (*ḱléwos ń̥dʰgʷʰitom) and the wheel of the sun (*sh₂uens kʷekʷlos).

- a patrilineal kinship-system based on relationships between men. ref

“The Kurgan hypothesis, as of 2017 the most widely held theory, depends on linguistic and archaeological evidence but is not universally accepted. It suggests PIE origin in the Pontic-Caspian steppe during the Chalcolithic. A minority of scholars prefer the Anatolian hypothesis, suggesting an origin in Anatolia during the Neolithic. Other theories (Armenian hypothesis, Out of India theory, Paleolithic Continuity Theory, Balkan hypothesis) have only marginal scholarly support. According to some archaeologists, PIE speakers cannot be assumed to have been a single, identifiable people or tribe, but were a group of loosely related populations ancestral to the later, still partially prehistoric, Bronze Age Indo-Europeans. This view is held especially by those archaeologists who posit an original homeland of vast extent and immense time depth. However, this view is not shared by linguists, as proto-languages, like all languages before modern transport and communication, occupied small geographical areas over a limited time span, and were spoken by a set of close-knit communities—a tribe in the broad sense. Researchers have put forward a great variety of proposed locations for the first speakers of Proto-Indo-European. Few of these hypotheses have survived scrutiny by academic specialists in Indo-European studies sufficiently well to be included in modern academic debate.” ref

“Proto-Indo-European mythology is the body of myths and deities associated with the Proto-Indo-Europeans, the hypothetical speakers of the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European language. Although the mythological motifs are not directly attested – since Proto-Indo-European speakers lived in prehistoric societies – scholars of comparative mythology have reconstructed details from inherited similarities found among Indo-European languages, leading to the assumption that parts of the Proto-Indo-Europeans’ original belief systems survived in the daughter traditions. The Proto-Indo-European pantheon includes a number of securely reconstructed deities such as *Dyḗws Ph₂tḗr, the daylight-sky god; his consort *Dʰéǵʰōm, the earth mother; his daughter *H₂éwsōs, the dawn goddess; his sons the Divine Twins; and *Seh₂ul, a solar goddess. Some deities, like the weather god *Perkʷunos or the herding-god *Péh₂usōn, are only attested in a limited number of traditions–Western (European) and Graeco-Aryan, respectively–and could, therefore, represent late additions that did not spread throughout the various Indo-European dialects. Some myths are also securely dated to Proto-Indo-European times, since they feature both linguistic and thematic evidence of an inherited motif: a story portraying a mythical figure associated with thunder and slaying a multi-headed serpent to release torrents of water that had previously been pent up; a creation myth involving two brothers, one of whom sacrifices the other in order to create the world; and probably the belief that the Otherworld was guarded by a watchdog and could only be reached by crossing a river. Various schools of thought exist regarding possible interpretations of the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European mythology. The main mythologies used in comparative reconstruction are Vedic, Roman, and Norse, often supported with evidence from the Baltic, Celtic, Greek, Slavic, Hittite, Armenian, and Albanian traditions as well.” ref

“One of the earliest attested and thus most important of all Indo-European mythologies is Vedic mythology, especially the mythology of the Rigveda, the oldest of the Vedas. Early scholars of comparative mythology such as Friedrich Max Müller stressed the importance of Vedic mythology to such an extent that they practically equated it with Proto-Indo-European myth. Modern researchers have been much more cautious, recognizing that, although Vedic mythology is still central, other mythologies must also be taken into account. Another of the most important source mythologies for comparative research is Roman mythology. Contrary to the frequent erroneous statement made by some authors that “Rome has no myth”, the Romans possessed a very complex mythological system, parts of which have been preserved through the characteristic Roman tendency to rationalize their myths into historical accounts. Despite its relatively late attestation, Norse mythology is still considered one of the three most important of the Indo-European mythologies for comparative research, simply due to the vast bulk of surviving Icelandic material. Baltic mythology has also received a great deal of scholarly attention, as it is linguistically the most conservative and archaic of all surviving branches, but has so far remained frustrating to researchers because the sources are so comparatively late. Nonetheless, Latvian folk songs are seen as a major source of information in the process of reconstructing Proto-Indo-European myth. Despite the popularity of Greek mythology in western culture, Greek mythology is generally seen as having little importance in comparative mythology due to the heavy influence of Pre-Greek and Near Eastern cultures, which overwhelms what little Indo-European material can be extracted from it. Consequently, Greek mythology received minimal scholarly attention until the first decade of the 21st century. Although Scythians are considered relatively conservative in regards to Proto-Indo-European cultures, retaining a similar lifestyle and culture, their mythology has very rarely been examined in an Indo-European context and infrequently discussed in regards to the nature of the ancestral Indo-European mythology. At least three deities, Tabiti, Papaios, and Api, are generally interpreted as having Indo-European origins, while the remaining have seen more disparate interpretations. Influence from Siberian, Turkic, and even Near Eastern beliefs, on the other hand, are more widely discussed in the literature.” ref

“There was a fundamental opposition between the never-ageing gods dwelling above in the skies, and the mortal humans living beneath on earth. The earth *dʰéǵʰōm was perceived as a vast, flat, and circular continent surrounded by waters (“the Ocean”). Although they may sometimes be identified with mythical figures or stories, the stars (*h₂stḗr) were not bound to any particular cosmic significance and were perceived as ornamental more than anything else. Linguistic evidence has led scholars to reconstruct the concept of an impersonal cosmic order,*h₂értus, denoting “what is fitting, rightly ordered” and ultimately deriving from the root *h₂er-, “to fit” : Hittite āra (“right, proper”); Sanskrit ṛta (“divine/cosmic law, force of truth, or order”); Avestan arəta- (“order”); Greek artús (“arrangement”), possibly arete (“excellence”) via the root *h₂erh₁ (“please, satisfy”); Latin artus (“joint”); Tocharian A ārtt- (“to praise, be pleased with”); Armernian ard (“ornament, shape”); Middle High German art (“innate feature, nature, fashion”). The cosmic order embodies a superordinate passive principle, similar to a symmetry or balancing principle. Interwoven with the root *h₂er- is the root *dʰeh₁-, which means “to put, lay down, sit down, produce, make, speak, say, bring back”. The Greek thémis and Sanskrit dhāman, both meaning “law”, derive from *dʰeh₁-men-/i- (‘that which is established’). This notion of “law” includes an active principle, which denotes an activity in obedience to the cosmic order and in a social context is interpreted as a lawful conduct. In the Greek daughter culture, the Titaness Themis personifies the cosmic order and the rules of lawful conduct which derived from it. In the Vedic daughter culture, the etymology of the Buddhist code of lawful conduct, the Dharma, can also be traced back to the PIE root *dʰeh₁-. In proto-Indo-European mythology, the universe was represented by a World Tree. Reflexes of this most fundamental symbolism for the universe can be seen in all Indo-European daughter cultures, compare the article World Tree.” ref

There is no scientific consensus which of the many variants is the ‘true’ reconstruction of the proto-Indo-European cosmogonic myth. John Grigsby lists three variants of reconstructions :

- Twin and Man

- The World Parents

- Near Eastern Cosmogonies ref

“The following paragraph is a detailed summary of Bruce Lincoln‘s reconstruction of the proto-Indo-European cosmogonic myth (Manu – Twin – Trito), which is supported by other scholars like J. P. Mallory and Douglas Q. Adams : The comparative analysis of different Indo-European tales has led some scholars to reconstruct an original Proto-Indo-European creation myth involving twin brothers, *Manu- (“Man”) and *Yemo- (“Twin”), as the progenitors of the world and mankind, and a hero named *Trito (“Third”) who ensured the continuity of the original sacrifice. Although some thematic parallels can be made with Ancient Near East (the twin Abel and Cain and their brother Seth), and even Polynesian or South American legends, the linguistic correspondences found in descendant cognates of *Manu and *Yemo make it very likely that the myth discussed here has a Proto-Indo-European origin. Since its modern reconstruction, the cosmogonical motifs of Manu and Yemo and, to a lesser extent, that of Trito, have been generally accepted among scholars. The Vedic, Germanic and, partially, the Greek traditions give evidence of a primordial state where the cosmological elements were not present: “neither non-being was nor being was at that time; there was not the air, nor the heaven beyond it…” (Rigveda), “…there was not sand nor sea nor the cool waves; earth was nowhere nor heaven above; Ginnunga Gap there was, but grass nowhere…” (Völuspá), “…there was Chasm and Night and dark Erebos at first, and broad Tartarus, but earth nor air nor heaven there was…” (The Birds). The concept of the Cosmic Egg, symbolizing the primordial state from which the universe arises, is also found in many Indo-European creation myths.” ref

“The first man Manu and his giant twin Yemo are crossing the cosmos, accompanied by the primordial cow. To create the world, Manu sacrifices his brother and, with the help of heavenly deities (the Sky-Father, the Storm-God, and the Divine Twins), forges both the natural elements and human beings from his remains. Manu thus becomes the first priest after initiating sacrifice as the primordial condition for the world order, and his deceased brother Yemo the first king as social classes emerge from his anatomy (priesthood from his head, the warrior class from his breast and arms, and the commoners from his sexual organs and legs). Although the European and Indo-Iranian versions differ on this matter, the primeval cow was most likely sacrificed in the original myth, giving birth to the other animals and vegetables.” ref

“To the third man Trito, the celestial gods then offer cattle as a divine gift, which is stolen by a three-headed serpent named *Ngʷhi (“serpent”; and the Indo-European root for negation). Trito first suffers at his hands, but the hero eventually manages to overcome the monster, fortified by an intoxicating drink and aided by the Sky-Father. He eventually gives the recovered cattle back to a priest for it to be properly sacrificed. Trito is now the first warrior, maintaining through his heroic actions the cycle of mutual giving between gods and mortals.” ref

Ancient Mesopotamia

My art is of an Ancient Sumerian cylinder seal impression showing the god Dumuzid being tortured in the Underworld by galla demons. ref

“The Sumerian afterlife was a dark, dreary cavern located deep below the ground, where inhabitants were believed to continue “a shadowy version of life on earth”. This bleak domain was known as Kur, and was believed to be ruled by the goddess Ereshkigal. All souls went to the same afterlife, and a person’s actions during life had no effect on how the person would be treated in the world to come. The souls in Kur were believed to eat nothing but dry dust and family members of the deceased would ritually pour libations into the dead person’s grave through a clay pipe, thereby allowing the dead to drink. Nonetheless, funerary evidence indicates that some people believed that the goddess Inanna, Ereshkigal’s younger sister, had the power to award her devotees with special favors in the afterlife. During the Third Dynasty of Ur, it was believed that a person’s treatment in the afterlife depended on how he or she was buried those that had been given sumptuous burials would be treated well:58 but those who had been given poor burials would fare poorly.” ref

“The entrance to Kur was believed to be located in the Zagros mountains in the far east. It had seven gates, through which a soul needed to pass. The god Neti was the gatekeeper, Ereshkigal’s sukkal, or messenger, was the god Namtar, Galla were a class of demons that were believed to reside in the underworld; their primary purpose appears to have been to drag unfortunate mortals back to Kur. They are frequently referenced in magical texts, and some texts describe them as being seven in number. Several extant poems describe the galla dragging the god Dumuzid into the underworld. The later Mesopotamians knew this underworld by its East Semitic name: Irkalla. During the Akkadian Period, Ereshkigal’s role as the ruler of the underworld was assigned to Nergal, the god of death. The Akkadians attempted to harmonize this dual rulership of the underworld by making Nergal Ereshkigal’s husband.” ref

Ancient Egypt

My art is of 1275 BCE Book of the Dead scene the dead scribe Hunefer‘s heart is weighed on the scale of Maat against the feather of truth, by the canine-headed Anubis. The ibis-headed Thoth, scribe of the gods, records the result. If his heart is lighter than the feather, Hunefer is allowed to pass into the afterlife. If not, he is eaten by the crocodile-headed Ammit. ref

“With the rise of the cult of Osiris during the Middle Kingdom the “democratization of religion” offered to even his humblest followers the prospect of eternal life, with moral fitness becoming the dominant factor in determining a person’s suitability. At death a person faced judgment by a tribunal of forty-two divine judges. If they had led a life in conformance with the precepts of the goddess Maat, who represented truth and right living, the person was welcomed into the heavenly reed fields. If found guilty the person was thrown to Ammit, the “devourer of the dead” and would be condemned to the lake of fire. The person taken by the devourer is subject first to terrifying punishment and then annihilated. These depictions of punishment may have influenced medieval perceptions of the inferno in hell via early Christian and Coptic texts. Purification for those considered justified appears in the descriptions of “Flame Island”, where humans experience the triumph over evil and rebirth. For the damned complete destruction into a state of non-being awaits but there is no suggestion of eternal torture; the weighing of the heart in Egyptian mythology can lead to annihilation. The Tale of Khaemwese describes the torment of a rich man, who lacked charity when he dies and compares it to the blessed state of a poor man who has also died. Divine pardon at judgment always remained a central concern for the ancient Egyptians.” ref

Modern understanding of Egyptian notions of hell relies on six ancient texts:

- The Book of Two Ways (Book of the Ways of Rosetau)

- The Book of Amduat (Book of the Hidden Room, Book of That Which Is in the Underworld)

- The Book of Gates

- The Book of the Dead (Book of Going Forth by Day)

- The Book of the Earth

- The Book of Caverns ref

“Duat (Ancient Egyptian: dwꜣt, Egyptological pronunciation “do-aht”, Coptic: ⲧⲏ, also appearing as Tuat, Tuaut or Akert, Amenthes, Amenti, or Neter-khertet) is the realm of the dead in ancient Egyptian mythology. It has been represented in hieroglyphs as a star-in-circle: ????. The god Osiris was believed to be the lord of the underworld. He was the first mummy as depicted in the Osiris myth and he personified rebirth and life after death. The underworld was also the residence of various other gods along with Osiris. The Duat was the region through which the sun god Ra traveled from west to east each night, and it was where he battled Apophis, who embodied the primordial chaos which the sun had to defeat in order to rise each morning and bring order back to the earth. It was also the place where people’s souls went after death for judgment, though that was not the full extent of the afterlife. Burial chambers formed touching-points between the mundane world and the Duat, and the ꜣḫ (Egyptological pronunciation: “akh”) “the effectiveness of the dead”, could use tombs to travel back and forth from the Duat.” ref

“Each night through the Duat the sun god Ra traveled, signifying revivification as the main goal of the dead. Ra traveled under the world upon his Atet barge from west to east, and was transformed from its aged Atum form into Khepri, the new dawning sun. The dead king, worshipped as a god, was also central to the mythology surrounding the concept of Duat, often depicted as being one with Ra. Along with the sun god the dead king had to travel through the Kingdom of Osiris, the Duat, using the special knowledge he was supposed to possess, which was recorded in the Coffin Texts, that served as a guide to the hereafter not just for the king but for all deceased. According to the Amduat, the underworld consists of twelve regions signifying the twelve hours of the sun god’s journey through it, battling Apep in order to bring order back to the earth in the morning; as his rays illuminated the Duat throughout the journey, they revived the dead who occupied the underworld and let them enjoy life after death in that hour of the night when they were in the presence of the sun god, after which they went back to their sleep waiting for the god’s return the following night.” ref

“Just like the dead king, the rest of the dead journeyed through the various parts of the Duat, not to be unified with the sun god but to be judged. If the deceased was successfully able to pass various demons and challenges, then he or she would reach the weighing of the heart. In this ritual, the heart of the deceased was weighed by Anubis against the feather of Maat, which represents truth and justice. Any heart that is heavier than the feather was rejected and eaten by Ammit, the devourer of souls, as these people were denied existence after death in the Duat. The souls that were lighter than the feather would pass this most important test, and would be allowed to travel toward Aaru, the “Field of Rushes”, an ideal version of the world they knew of, in which they would plough, sow, and harvest abundant crops. What is known of the Duat derives principally from funerary texts such as the Book of Gates, the Book of Caverns, the Coffin Texts, the Amduat, and the Book of the Dead. Each of these documents fulfilled a different purpose and give a different conception of the Duat, and different texts could be inconsistent with one another. Surviving texts differ in age and origin, and there likely was never a single uniform conception of the Duat, as is the case of many theological concepts in ancient Egypt.” ref

“The geography of Duat is similar in outline to the world the Egyptians knew. There are realistic features like rivers, islands, fields, lakes, mounds, and caverns, but there were also fantastic lakes of fire, walls of iron, and trees of turquoise. In the Book of Two Ways, one of the Coffin Texts, there is even a map-like image of the Duat. The Book of the Dead and Coffin Texts were intended to guide people who had recently died through the Duat‘s dangerous landscape and to a life as an ꜣḫ. Emphasized in some of these texts are mounds and caverns, inhabited by gods, demons or supernatural animals, which threatened the deceased along their journey. The purpose of the books is not to lay out a geography, but to describe a succession of rites of passage that the dead would have to pass to reach eternal life. In spite of the many demon-like inhabitants of the Duat, it is not equivalent to the conceptions of Hell in the Abrahamic religions, in which souls are condemned with fiery torment; the absolute punishment for the wicked, in ancient Egyptian thought, was the denial of an afterlife to the deceased, ceasing to exist in ꜣḫ form. The grotesque spirits of the underworld were not evil, but under the control of the gods, being present as various ordeals that the deceased had to face. The Duat was also a residence for various gods, including Osiris, Anubis, Thoth, Horus, Hathor, and Maat, who all appear to the dead soul as it makes its way toward judgment.” ref

Greek and Roman

“In classic Greek mythology, below Heaven, Earth, and Pontus is Tartarus, or Tartaros (Greek Τάρταρος, deep place). It is either a deep, gloomy place, a pit or abyss used as a dungeon of torment and suffering that resides within Hades (the entire underworld) with Tartarus being the hellish component. In the Gorgias, Plato (c. 400 BC) wrote that souls of the deceased were judged after they payed for crossing the river of the dead, and those who received punishment were sent to Tartarus. As a place of punishment, it can be considered a hell. The classic Hades, on the other hand, is more similar to Old Testament Sheol. The Romans later adopted these views.” ref

“In mythology, the Greek underworld is an otherworld where souls go after death. The original Greek idea of afterlife is that, at the moment of death, the soul is separated from the corpse, taking on the shape of the former person, and is transported to the entrance of the underworld. Good people and bad people would then separate. The underworld itself—sometimes known as Hades, after its patron god—is described as being either at the outer bounds of the ocean or beneath the depths or ends of the earth. It is considered the dark counterpart to the brightness of Mount Olympus with the kingdom of the dead corresponding to the kingdom of the gods. Hades is a realm invisible to the living, made solely for the dead.” ref

“In Greek mythology, Tartarus (/ˈtɑːrtərəs/; Ancient Greek: Τάρταρος, Tártaros) is the deep abyss that is used as a dungeon of torment and suffering for the wicked and as the prison for the Titans. Tartarus is the place where, according to Plato‘s Gorgias (c. 400 BC), souls are judged after death and where the wicked received divine punishment. Tartarus is also considered to be a primordial force or deity alongside entities such as the Earth, Night, and Time. Tartarus is both a deity and a place in the underworld. In ancient Orphic sources and in the mystery schools, Tartarus is also the unbounded first-existing entity from which the Light and the cosmos are born.” ref

Deity

“In the Greek poet Hesiod‘s Theogony (c. late 8th century BC), Tartarus was the third of the primordial deities, following after Chaos and Gaia (Earth), and preceding Eros, and was the father, by Gaia, of the monster Typhon. According to Hyginus, Tartarus was the offspring of Aether and Gaia.” ref

Place

“As for the place, Hesiod asserts that a bronze anvil falling from heaven would fall nine days before it reached the earth. The anvil would take nine more days to fall from earth to Tartarus. In the Iliad (c. 8th century BC), Zeus asserts that Tartarus is “as far beneath Hades as heaven is above the earth.” Similarly, the mythographer Apollodorus, describes Tartarus as “a gloomy place in Hades as far distant from the earth as earth is distant from the sky.” ref

“While according to Greek mythology the realm of Hades is the place of the dead, Tartarus also has a number of inhabitants. When Cronus came to power as the King of the Titans, he imprisoned the one-eyed Cyclopes and the hundred-armed Hecatonchires in Tartarus and set the monster Campe as its guard. Zeus killed Campe and released these imprisoned giants to aid in his conflict with the Titans. The gods of Olympus eventually triumphed. Cronus and many of the other Titans were banished to Tartarus, though Prometheus, Epimetheus, and female Titans such as Metis were spared (according to Pindar, Cronus somehow later earned Zeus’ forgiveness and was released from Tartarus to become ruler of Elysium). Another Titan, Atlas, was sentenced to hold the sky on his shoulders to prevent it from resuming its primordial embrace with the Earth. Other gods could be sentenced to Tartarus as well. Apollo is a prime example, although Zeus freed him. The Hecatonchires became guards of Tartarus’ prisoners. Later, when Zeus overcame the monster Typhon, he threw him into “wide Tartarus”.” ref

Residents

“Originally, Tartarus was used only to confine dangers to the gods of Olympus. In later mythologies, Tartarus became a space dedicated to the imprisonment and torment of mortals who had sinned against the gods, and each punishment was unique to the condemned.” ref

For example:

- “King Sisyphus was sent to Tartarus for killing guests and travelers to his castle in violation to his hospitality, seducing his niece, and reporting one of Zeus’ sexual conquests by telling the river god Asopus of the whereabouts of his daughter Aegina (who had been taken away by Zeus). But regardless of the impropriety of Zeus’ frequent conquests, Sisyphus overstepped his bounds by considering himself a peer of the gods who could rightfully report their indiscretions. When Zeus ordered Thanatos to chain up Sisyphus in Tartarus, Sisyphus tricked Thanatos by asking him how the chains worked and ended up chaining Thanatos; as a result there was no more death. This caused Ares to free Thanatos and turn Sisyphus over to him. Sometime later, Sisyphus had Persephone send him back to the surface to scold his wife for not burying him properly. Sisyphus was forcefully dragged back to Tartarus by Hermes when he refused to go back to the Underworld after that. In Tartarus, Sisyphus was forced to roll a large boulder up a mountainside which when he almost reached the crest, rolled away from Sisyphus and rolled back down repeatedly. This represented the punishment of Sisyphus claiming that his cleverness surpassed that of Zeus, causing the god to make the boulder roll away from Sisyphus, binding Sisyphus to an eternity of frustration.

- King Tantalus also ended up in Tartarus after he cut up his son Pelops, boiled him, and served him as food when he was invited to dine with the gods. He also stole the ambrosia from the Gods and told his people its secrets. Another story mentioned that he held onto a golden dog forged by Hephaestus and stolen by Tantalus’ friend Pandareus. Tantalus held onto the golden dog for safekeeping and later denied to Pandareus that he had it. Tantalus’ punishment for his actions (now a proverbial term for “temptation without satisfaction”) was to stand in a pool of water beneath a fruit tree with low branches. Whenever he reached for the fruit, the branches raised his intended meal from his grasp. Whenever he bent down to get a drink, the water receded before he could get any. Over his head towered a threatening stone like that of Sisyphus.

- Ixion was the king of the Lapiths, the most ancient tribe of Thessaly. Ixion grew to hate his father-in-law and ended up pushing him onto a bed of coal and wood committing the first kin-related murder. The princes of other lands ordered that Ixion be denied of any sin-cleansing. Zeus took pity on Ixion and invited him to a meal on Olympus. But when Ixion saw Hera, he fell in love with her and did some under-the-table caressing until Zeus signaled him to stop. After finding a place for Ixion to sleep, Zeus created a cloud-clone of Hera named Nephele to test him to see how far he would go to seduce Hera. Ixion made love to her, which resulted in the birth of Centaurus, who mated with some Magnesian mares on Mount Pelion and thus engendered the race of Centaurs (who are called the Ixionidae from their descent). Zeus drove Ixion from Mount Olympus and then struck him with a thunderbolt. He was punished by being tied to a winged flaming wheel that was always spinning: first in the sky and then in Tartarus. Only when Orpheus came down to the Underworld to rescue Eurydice did it stop spinning because of the music Orpheus was playing. Ixion being strapped to the flaming wheel represented his burning lust.

- In some versions, the Danaides murdered their husbands and were punished in Tartarus by being forced to carry water in a jug to fill a bath which would thereby wash off their sins. But the tub was filled with cracks, so the water always leaked out.

- The giant Tityos attempted to rape Leto on Hera’s orders but was slain by Apollo and Artemis. As punishment, Tityos was stretched out in Tartarus and tortured by two vultures who fed on his liver. This punishment is extremely similar to that of the Titan Prometheus.

- King Salmoneus was also mentioned to have been imprisoned in Tartarus after passing himself off as Zeus, causing the real Zeus to smite him with a thunderbolt.” ref

“Greek mythology also mentions Arke, Ocnus, Phlegyas, the Aloadaes, and the Titans as inhabitants of Tartarus. According to Plato (c. 427 BC), Rhadamanthus, Aeacus, and Minos were the judges of the dead and chose who went to Tartarus. Rhadamanthus judged Asian souls, Aeacus judged European souls and Minos was the deciding vote and judge of the Greek. Souls regarded as unjust or perjured would go to Tartarus. Those who committed crimes seen as curable would be purified there, while those who committed crimes seen as uncurable would be eternally damned, and demonstrate a warning example for the living. In Gorgias, Plato writes about Socrates telling Callicles, who believes Might makes right, that doing injustice to others is worse than suffering injustice, and most uncurable inhabitants of Tartarus were tyrants who might gave them the opportunity to commit huge crimes. Archelaus I of Macedon is mentioned as a possible example of this, while Thersites is said to be curable, because of his lack of might. According to Plato’s Phaedo, the uncurable consisted of temple robbers and murderers, while sons who killed one of their parents during a status of rage but regretted this their whole live long, and involuntary manslaughterers, would be taken out of Tartarus after one year, so they could ask their victims for forgiveness. If they should be forgiven, they were liberated, but if not, would go back and stay there until they were finally pardoned. In the Republic, Plato mentions the Myth of Er, who is said to have been a fallen soldier who resurrected from the dead, and saw their realm. According to this, the length of a punishment an adult receives for each crime in Tartarus, who is responsible for a lot of deaths, betrayed states or armies and sold them into slavery or had been involved in similar misdeeds, corresponds to ten times out of a hundred earthly years (while good deeds would be rewarded in equal measure). There were a number of entrances to Tartarus in Greek mythology. One was in Aornum.” ref

Roman mythology

“In Roman mythology, Tartarus is the place where sinners are sent. Virgil describes it in the Aeneid as a gigantic place, surrounded by the flaming river Phlegethon and triple walls to prevent sinners from escaping from it. It is guarded by a hydra with fifty black gaping jaws, which sits at a screeching gate protected by columns of solid adamantine, a substance akin to diamond – so hard that nothing will cut through it. Inside, there is a castle with wide walls, and a tall iron turret. Tisiphone, one of the Erinyes who represents revenge, stands guard sleepless at the top of this turret lashing a whip. There is a pit inside which is said to extend down into the earth twice as far as the distance from the lands of the living to Olympus. At the bottom of this pit lie the Titans, the twin sons of Aloeus, and many other sinners. Still, more sinners are contained inside Tartarus, with punishments similar to those of Greek myth.” ref

“In Greek mythology and Roman mythology, Charon or Kharon (/ˈkɛərɒn, -ən/; Greek Χάρων) is a psychopomp, the ferryman of Hades who carries souls of the newly deceased across the rivers Styx and Acheron that divided the world of the living from the world of the dead. A coin to pay Charon for passage, usually, an obolus or danake, was sometimes placed in or on the mouth of a dead person. Some authors say that those who could not pay the fee, or those whose bodies were left unburied, had to wander the shores for one hundred years until they were allowed to cross the river. In the catabasis mytheme, heroes – such as Aeneas, Dionysus, Heracles, Hermes, Odysseus, Orpheus, Pirithous, Psyche, Theseus, and Sisyphus – journey to the underworld and return, still alive, conveyed by the boat of Charon.” ref

“Hades in the ancient Greek religion and myth, is the god of the dead and the king of the underworld, with which his name became synonymous. Hades was the eldest son of Cronus and Rhea, although the last son regurgitated by his father. He and his brothers, Zeus and Poseidon, defeated their father’s generation of gods, the Titans, and claimed rulership over the cosmos. Hades received the underworld, Zeus the sky, and Poseidon the sea, with the solid earth, long the province of Gaia, available to all three concurrently. Hades was often portrayed with his three-headed guard dog Cerberus.” ref

“In Greek mythology, Cerberus often referred to as the hound of Hades, is a multi-headed dog that guards the gates of the Underworld to prevent the dead from leaving. Cerberus was the offspring of the monsters Echidna and Typhon, and is usually described as having three heads, a serpent for a tail, and snakes protruding from multiple parts of his body. Cerberus is primarily known for his capture by Heracles, one of Heracles’ twelve labours. Descriptions of Cerberus vary, including the number of his heads. Cerberus was usually three-headed, though not always. Cerberus had several multi-headed relatives. His father was the multi snake-headed Typhon, and Cerberus was the brother of three other multi-headed monsters, the multi-snake-headed Lernaean Hydra; Orthrus, the two-headed dog who guarded the Cattle of Geryon; and the Chimera, who had three heads: that of a lion, a goat, and a snake. And, like these close relatives, Cerberus was, with only the rare iconographic exception, multi-headed. In the earliest description of Cerberus, Hesiod‘s Theogony (c. 8th – 7th century BC), Cerberus has fifty heads, while Pindar (c. 522 – c. 443 BC) gave him one hundred heads. However, later writers almost universally give Cerberus three heads. An exception is the Latin poet Horace‘s Cerberus which has a single dog head and one hundred snakeheads. Perhaps trying to reconcile these competing traditions, Apollodorus‘s Cerberus has three dog heads and the heads of “all sorts of snakes” along his back, while the Byzantine poet John Tzetzes (who probably based his account on Apollodorus) gives Cerberus fifty heads, three of which were dog heads, the rest being the “heads of other beasts of all sorts”.” ref

“The earliest mentions of Cerberus (c. 8th – 7th century BC) occur in Homer‘s Iliad and Odyssey, and Hesiod‘s Theogony. Homer does not name or describe Cerberus, but simply refers to Heracles being sent by Eurystheus to fetch the “hound of Hades”, with Hermes and Athena as his guides, and, in a possible reference to Cerberus’ capture, that Heracles shot Hades with an arrow. According to Hesiod, Cerberus was the offspring of the monsters Echidna and Typhon, was fifty-headed, ate raw flesh, and was the “brazen-voiced hound of Hades”, who fawns on those that enter the house of Hades, but eats those who try to leave. Stesichorus (c. 630 – 555 BC) apparently wrote a poem called Cerberus, of which virtually nothing remains. However, the early-sixth-century BC-lost Corinthian cup from Argos, which showed a single head, and snakes growing out from many places on his body, was possibly influenced by Stesichorus’ poem. The mid-sixth-century BC cup from Laconia gives Cerberus three heads and a snake tail, which eventually becomes the standard representation. Pindar (c. 522 – c. 443 BC) apparently gave Cerberus one hundred heads. Bacchylides (5th century BC) also mentions Heracles bringing Cerberus up from the underworld, with no further details. Sophocles (c. 495 – c. 405 BC), in his Women of Trachis, makes Cerberus three-headed, and in his Oedipus at Colonus, the Chorus asks that Oedipus be allowed to pass the gates of the underworld undisturbed by Cerberus, called here the “untamable Watcher of Hades”. Euripides (c. 480 – 406 BC) describes Cerberus as three-headed, and three-bodied, says that Heracles entered the underworld at Tainaron, has Heracles say that Cerberus was not given to him by Persephone, but rather he fought and conquered Cerberus, “for I had been lucky enough to witness the rites of the initiated”, an apparent reference to his initiation into the Eleusinian Mysteries, and says that the capture of Cerberus was the last of Heracles’ labors. The lost play Pirthous (attributed to either Euripides or his late contemporary Critias) has Heracles say that he came to the underworld at the command of Eurystheus, who had ordered him to bring back Cerberus alive, not because he wanted to see Cerberus, but only because Eurystheus thought Heracles would not be able to accomplish the task, and that Heracles “overcame the beast” and “received favor from the gods”.” ref

Asia

“The hells of Asia include the Bagobo “Gimokodan” (which is believed to be more of an otherworld, where the Red Region is reserved who those who died in battle, while ordinary people go to the White Region) and ancient Indian mythology‘s “Kalichi” or “Naraka“. According to a few sources, hell is below ground and described as an uninviting wet or fiery place reserved for sinful people in the Ainu religion, as stated by missionary John Batchelor. However, belief in hell does not appear in oral tradition of the Ainu. Instead, there is a belief within the Ainu religion that the soul of the deceased (ramat) would become a kamuy after death. There is also a belief that the soul of someone who has been wicked during a lifetime, committed suicide, got murdered, or died in great agony would become a ghost (tukap) who would haunt the living, to come to fulfillment from which it was excluded during life. In Tengrism, it was believed that the wicked would get punished in Tamag before they would be brought to the third floor of the sky. In Taoism, hell is represented by Diyu.” ref

Naraka (Hinduism)

My art relates to a panel that portrays Yama, aided by Chitragupta and Yamadutas, judging the dead. Other panels depict various realms/hells of Naraka. ref

“Early Vedic religion does not have a concept of Hell. Ṛg-veda mentions three realms, bhūr (the earth), svar (the sky) and bhuvas or antarikṣa (the middle area, i.e. air or atmosphere). In later Hindu literature, especially the law books and Puranas, more realms are mentioned, including a realm similar to Hell, called naraka (in Devanāgarī: नरक). Yama as the first born human (together with his twin sister Yamī), by virtue of precedence, becomes ruler of men and a judge on their departure. Originally he resides in Heaven, but later, especially medieval, traditions mention his court in naraka. In the law-books (smṛtis and dharma-sūtras, like the Manu-smṛti), naraka is a place of punishment for sins. It is a lower spiritual plane (called naraka-loka) where the spirit is judged and the partial fruits of karma affect the next life. In Mahabharata there is a mention of the Pandavas and the Kauravas both going to Heaven. At first Yudhisthir goes to heaven where he sees Duryodhana enjoying heaven; Indra tells him that Duryodhana is in heaven as he did his Kshatriya duties. Then he shows Yudhisthir hell where it appears his brothers are. Later it is revealed that this was a test for Yudhisthir and that his brothers and the Kauravas are all in heaven and live happily in the divine abode of gods. Hells are also described in various Puranas and other scriptures. The Garuda Purana gives a detailed account of Hell and its features; it lists the amount of punishment for most crimes, much like a modern-day penal code. There is belief that people who commit sins go to Hell and have to go through punishments in accordance with the sins they committed. The god Yamarāja, who is also the god of death, presides over Hell. Detailed accounts of all the sins committed by an individual are kept by Chitragupta, who is the record keeper in Yama’s court. Chitragupta reads out the sins committed and Yama orders appropriate punishments to be given to individuals. These punishments include dipping in boiling oil, burning in fire, torture using various weapons, etc. in various Hells. Individuals who finish their quota of the punishments are reborn in accordance with their balance of karma. All created beings are imperfect and thus have at least one sin to their record; but if one has generally led a pious life, one ascends to svarga, a temporary realm of enjoyment similar to Paradise, after a brief period of expiation in Hell and before the next reincarnation, according to the law of karma. With the exception of Hindu philosopher Madhva, time in Hell is not regarded as eternal damnation within Hinduism. According to Brahma Kumaris, the iron age (Kali Yuga) is regarded as hell.” ref

“Naraka (Sanskrit: नरक) is the Hindu equivalent of Hell, where sinners are tormented after death. It is also the abode of Yama, the god of Death. It is described as located in the south of the universe and beneath the earth. The number and names of hells, as well as the type of sinners sent to a particular hell, varies from text to text; however, many scriptures describe 28 hells. After death, messengers of Yama called Yamadutas bring all beings to the court of Yama, where he weighs the virtues and the vices of the being and passes a judgement, sending the virtuous to Svarga (heaven) and the sinners to one of the hells. The stay in Svarga or Naraka is generally described as temporary. After the quantum of punishment is over, the souls are reborn as lower or higher beings as per their merits (the exception being Hindu philosopher Madhva, who believes in the eternal damnation of the Tamo-yogyas in Andhatamas).” ref

“The Bhagavata Purana describes Naraka as beneath the earth: between the seven realms of the underworld (Patala) and the Garbhodaka Ocean, which is the bottom of the universe. It is located in the South of the universe. Pitrloka, where the dead ancestors (Pitrs) headed by Agniṣvāttā reside, is also located in this region. Yama, the Lord of Naraka, resides in this realm with his assistants. The Devi Bhagavata Purana mentions that Naraka is the southern part of the universe, below the earth but above Patala. The Vishnu Purana mentions that it is located below the cosmic waters at the bottom of the universe. The Hindu epics agree that Naraka is located in the South, the direction which is governed by Yama, and is often associated with Death. Pitrloka is considered as the capital of Yama, from where Yama delivers his justice.” ref

“The god of Death, Yama, employs Yama-dutas (messengers of Yama) or Yama-purushas, who bring souls of all beings to Yama for judgment. Generally, all living beings, including humans and beasts, go to Yama’s abode upon death where they are judged. However, very virtuous beings are taken directly to Svarga (heaven). People devoted to charity, especially donors of food, and eternal truth speakers are spared the justice of Yama’s court. War-heroes who sacrifice their life and people dying in holy places like Kurukshetra are also described as avoiding Yama. Those who get moksha (salvation) also escape from the clutches of yamadutas. Those who are generous and ascetics are given preferential treatment when entering Naraka for judgment. The way is lighted for those who donated lamps, while those who underwent religious fasting are carried by peacocks and geese. Yama, as Lord of Justice, is called Dharma-raja. Yama sends the virtuous to Svarga to enjoy the luxuries of paradise. He also assesses the vices of the dead and accords judgment, assigning them to appropriate hells as a punishment commensurate with the severity and nature of their sins. A person is not freed of samsara (the cycle of birth-death-rebirth) and must take birth again after his prescribed pleasure in Svarga or punishment in Naraka is over. Yama is aided by his minister Chitragupta, who maintains a record of all good and evil actions of every living being. Yama-dhutas are also assigned the job of executing the punishments on sinners in the various hells.” ref

Number and names

“Naraka, as a whole, is known by many names conveying that it is the realm of Yama. Yamālaya, Yamaloka, Yamasādana, and Yamalokāya mean the abode of Yama. Yamakṣaya (the akṣaya of Yama) and its equivalents like Vaivasvatakṣaya use pun for the word kṣaya, which can be mean abode or destruction. It is also called Saṃyamanī, “where only truth is spoken, and the weak torment the strong”, Mṛtyulokāya – the world of Death or of the dead and the “city of the king of ghosts”, Pretarājapura. The Agni Purana mentions only 4 hells. Some texts mention 7 hells: Put (“childless”, for the childless), Avichi (“waveless”, for those waiting for reincarnation), Samhata (“abandoned”, for evil beings), Tamisra (“darkness”, where the darkness of hells begin), Rijisha (“expelled”, where torments of hell begin), Kudmala (“leprous”, the worst hell for those who are going to be reincarnated) and Kakola (“black poison”, the bottomless pit, for those who are eternally condemned to hell and have no chance of reincarnation).” ref

“The Manu Smriti mentions 21 hells: Tamisra, Andhatamisra, Maharaurava, Raurava, Kalasutra, Mahanaraka, Samjivana, Mahavichi, Tapana, Sampratapana, Samhata, Sakakola, Kudmala, Putimrittika, Lohasanku, Rijisha, Pathana, Vaitarani, Salmali, Asipatravana, and Lohadaraka. The Yajnavalkya Smriti also lists twenty-one: Tamisra, Lohasanku, Mahaniraya, Salamali, Raurava, Kudmala, Putimrittika, Kalasutraka, Sanghata, Lohitoda, Savisha, Sampratapana, Mahanaraka, Kakola, Sanjivana, Mahapatha, Avichi, Andhatamisra, Kumbhipaka, Asipatravana, and Tapana. The Bhagavata Purana, the Vishnu Purana and the Devi Bhagavata Purana enlist and describe 28 hells; however, they end the description by stating that there are hundreds and thousands of hells. The Bhagavata Purana enumerates the following 28: Tamisra, Andhatamisra, Raurava, Maharaurava, Kumbhipaka, Kalasutra, Asipatravana, Sukaramukha, Andhakupa, Krimibhojana, Samdamsa, Taptasurmi, Vajrakantaka-salmali, Vaitarani, Puyoda, Pranarodha, Visasana, Lalabhaksa, Sarameyadana, Avichi, Ayahpana, Ksharakardama, Raksogana-bhojana, Sulaprota, Dandasuka, Avata-nirodhana, Paryavartana and Suchimukha. The Devi Bhagavata Purana agrees with the Bhagavata Purana in most of names; however, a few names are slightly different. Taptasurmi, Ayahpana, Raksogana-bhojana, Avata-nirodhana, Paryavartana are replaced by Taptamurti, Apahpana, Raksogana-sambhoja, Avatarodha, Paryavartanataka respectively. The Vishnu Purana mentions the 28 in the following order: Raurava, Shukara, Rodha, Tala, Visasana, Mahajwala, Taptakumbha, Lavana, Vimohana, Rudhirandha, Vaitaraní, Krimiśa, Krimibhojana, Asipatravana, Krishna, Lalabhaksa, Dáruńa, Púyaváha, Pápa, Vahnijwála, Adhośiras, Sandansa, Kalasutra, Tamas, Avichi, Śwabhojana, Apratisht́ha, and another Avichi.” ref

Description of hells

“Early texts like the Rigveda do not have a detailed description of Naraka. It is simply a place of evil and a dark bottomless pit. The Atharvaveda describes a realm of darkness, where murderers are confined after death. The Shatapatha Brahmana is the first text to mention the pain and suffering of Naraka in detail, while the Manu Smriti begins naming the multiple hells. The epics also describe Hell in general terms as a dense jungle without shade, where there is no water and no rest. The Yamadutas torment souls on the orders of their master. The names of many of hells are common in Hindu texts; however, the nature of sinners tormented in particular hells varies from text to text.” ref

The summary of twenty-eight hells described in the Bhagavata Purana and the Devi Bhagavata Purana are as follows:

Tamisra (darkness): It is intended for a person who grabs another’s wealth, wife or children. In this dark realm, he is bound with ropes and starved without food or water. He is beaten and reproached by Yamadutas until he faints. ref

Andhatamisra (blind-darkness): Here, a man – who deceives another man and enjoys his wife or children – is tormented to the extent he loses his intelligence and sight. The torture is described as cutting the tree at its roots. ref

Raurava (fearful or hell of rurus): As per the Bhagavata Purana and the Devi Bhagavata Purana, it is assigned for a person who cares about his own and his family’s good, but harms other living beings and is always envious of others. The living beings hurt by such a man take the form of savage serpent-like beasts called rurus and torture this person. The Vishnu Purana deems this hell fit for a false witness or one who lies. ref

Maharaurava (great-fearful): A person who indulges at the expense of other beings is afflicted with pain by fierce rurus called kravyadas, who eat his flesh. ref

Kumbhipaka (cooked in a pot): A person who cooks beasts and birds alive is cooked alive in boiling oil by Yamadutas here, for as many years as there were hairs on the bodies of their animal victims. ref

Kalasutra (thread of Time/Death): The Bhagavata Purana assigns this hell to a murderer of a brahmin, while the Devi Bhagavata Purana allocates it for a person who disrespects his parents, elders, ancestors or brahmins. This realm is made entirely of copper and extremely hot, heated by fire from below, and the red hot sun from above. Here, the sinner burns from within by hunger and thirst and the smoldering heat outside, whether he sleeps, sits, stands, or runs. ref

Asipatravana/Asipatrakanana (forest of sword leaves): The Bhagavata Purana and the Devi Bhagavata Purana reserve this hell for a person who digresses from the religious teachings of the Vedas and indulges in heresy. The Vishnu Purana states that wanton tree-felling leads to this hell. Yamadutas beat them with whips as they try to run away in the forest where palm trees have swords as leaves. Afflicted with the injury of whips and swords, they faint and cry out for help in vain. ref

Shukaramukha (hog’s mouth): It houses kings or government officials who punish the innocent or grant corporal punishment to a Brahmin. Yamadutas crush him as sugar cane is crushed to extract juice. He will yell and scream in agony, just as the guiltless suffered. ref

Andhakupa (well with its mouth hidden): It is the hell where a person who harms others with the intention of malice and harms insects is confined. He is attacked by birds, mammals, reptiles, mosquitoes, lice, worms, flies, and others, who deprive him of rest and compel him to run hither and thither. ref

Krimibhojana/Krimibhaksha (worm-food): As per the Bhagavata Purana and the Devi Bhagavata Purana, it is where a person who does not share his food with guests, elders, children or the gods, and selfishly eats it alone, and he who eats without performing the five yajnas (panchayajna) is chastised. The Vishnu Purana states that one who loathes his father, Brahmins, or the gods and who destroys jewels is punished here. This hell is a 100,000 yojana lake filled with worms. The sinful person is reduced to a worm, who feeds on other worms, who in turn devour his body for 100,000 years. ref

Sandansa/Sandamsa (hell of pincers): The Bhagavata Purana and the Devi Bhagavata Purana state that a person who robs a Brahmin or steals jewels or gold from someone, when not in dire need, is confined to this hell. However, the Vishnu Purana tells the violators of vows or rules endure pain here. His body is torn by red-hot iron balls and tongs.

Taptasurmi/Taptamurti (red-hot iron statue): A man or woman who indulges in illicit sexual relations with a woman or man is beaten by whips and forced to embrace red-hot iron figurines of the opposite sex. ref

Vajrakantaka-salmali (the silk-cotton tree with thorns like thunderbolts/vajras): A person who has sexual intercourse with non-humans or who has excessive coitus is tied to the Vajrakantaka-salmali tree and pulled by Yamadutas so that the thorns tear his body. ref

Vaitarni/Vaitarna (to be crossed): It is a river that is believed to lie between Naraka and the earth. This river, which forms the boundary of Naraka, is filled with excreta, urine, pus, blood, hair, nails, bones, marrow, flesh, and fat, where fierce aquatic beings eat the person’s flesh. As per the Bhagavata Purana and the Devi Bhagavata Purana, a person born in a respectable family – kshatriya (warrior-caste), royal family or government official – who neglects his duty is thrown into this river of hell. The Vishnu Purana assigns it to the destroyer of a bee-hive or a town. ref

Puyoda (water of pus): Shudras (workmen-caste) and husbands or sexual partners of lowly women and prostitutes – who live like beasts devoid of cleanliness and good behavior – fall in Puyoda, the ocean of pus, excreta, urine, mucus, saliva, and other repugnant things. Here, they are forced to eat these disgusting things. ref

Pranarodha (obstruction to life): Some Brahmins, Kshatriyas, and Vaishyas (merchant caste) indulge in the sport of hunting with their dogs and donkeys in the forest, resulting in wanton killing of beasts. Yamadutas play archery sport with them as the targets in this hell. ref

Visashana (murderous): The Bhagavata Purana and the Devi Bhagavata Purana mention that Yamadutas whip a person, who has pride of his rank and wealth and sacrifices beasts as a status symbol, and finally kill him. The Vishnu Purana associates it with the maker of spears, swords, and other weapons. ref

Lalabhaksa (saliva as food): As per the Bhagavata Purana and the Devi Bhagavata Purana, a Brahmin, a Ksahtriya or a Vaishya husband, who forces his wife to drink his semen out of lust and to enforce his control, is thrown in a river of semen, which he is forced to drink. The Vishnu Purana disagrees stating that one who eats before offering food to the gods, the ancestors or guests is brought to this hell. ref

Sarameyadana (hell of the sons of Sarama): Plunderers who burn houses and poison people for wealth, and kings and other government officials who grab money of merchants, mass murder or ruin the nation, are cast into this hell. Seven hundred and twenty ferocious dogs, the sons of Sarama, with razor-sharp teeth, prey on them at the behest of Yamadutas. ref

Avici/Avicimat (waterless/waveless): A person, who lies on oath or in business, is repeatedly thrown head-first from a 100 yojana high mountain whose sides are stone waves, but without water. His body is continuously broken, but it is made sure that he does not die. ref

Ayahpana (iron-drink): Anybody else under oath or a Brahmin who drinks alcohol is punished here. Yamadutas stand on their chests and force them to drink molten-iron. ref

Ksarakardama (acidic/saline mud/filth): One who in false pride, does not honor a person higher than him by birth, austerity, knowledge, behavior, caste, or spiritual order, is tortured in this hell. Yamadutas throw him head-first and torment him. ref

Raksogana-bhojana (food of Rakshasas): Those who practise human-sacrifice and cannibalism are condemned to this hell. Their victims, in the form of Rakshasas, cut them with sharp knives and swords. The Rakshasas feast on their blood and sing and dance in joy, just as the sinners slaughtered their victims. ref

Shulaprota (pierced by sharp-pointed spear/dart): Some people give shelter to birds or animals pretending to be their saviors, but then harass them poking with threads, needles or using them like lifeless toys. Also, some people behave the same way to humans, winning their confidence and then killing them with sharp tridents or lances. The bodies of such sinners, fatigued with hunger and thirst, are pierced with sharp, needle-like spears. Ferocious carnivorous birds like vultures and herons tear and gorge their flesh. ref

Dandasuka (snakes): Filled with envy and fury, some people harm others like snakes. These are destined to be devoured by five or seven hooded serpents in this hell. ref

Avata-nirodhana (confined in a hole): People who imprison others in dark wells, crannies, or mountain caves are pushed into this hell, a dark well engulfed with poisonous fumes and smoke that suffocates them. ref

Paryavartana (returning): A householder who welcomes guests with cruel glances and abuses them is restrained in this hell. Hard-eyed vultures, herons, crows, and similar birds gaze on them and suddenly fly and pluck his eyes. ref

Sucimukha (needle-face): An ever-suspicious man is always wary of people trying to grab his wealth. Proud of his money, he sins to gain and to retain it. Yamadutas stitch thread through his whole body in this hell. ref

“The Hindu religion regards Hell not as a place of lasting permanence, but as an alternate domain from which an individual can return to the present world after crimes in the previous life have been compensated for. These crimes are eventually nullified through an equal punishment in the next life. The concept of Hell has provided many different opportunities for the Hindu religion including narrative, social and economic functions.” ref

Narrative

“A narrative rationale for the concept of Hell can be found in the Hindu epic Mahabharata. This narrative ends with Yudhishthira‘s visit to hell after being offered acceptance into heaven. This journey creates a scene for the audience that helps illustrate the importance of understanding hell as well as heaven before accepting either extreme. This idea provides an essential lesson regarding Dharma, a primary theme within the Mahabharata. Dharma is not a black and white concept, and all people are not entirely good or entirely evil. As such, tolerance is essential in order to truly understand the “right way of living”. We all must understand the worst to truly understand and appreciate the best just as we must experience the best before we can experience the worst. This narrative utilizes the Hindu religion in order to teach lessons on tolerance and acceptance of one another’s faults as well as virtues.” ref

Social

“A social rationale for the Hindu concept of rebirth in Hell is evident in the metric work of the Manusmrti: a written discourse focused on the “law of the social classes”. A large portion of it is designed to help people of the Hindu faith understand evil deeds (pätaka) and their karmic consequences in various hellish rebirths. The Manusmrti, however, does not go into explicit detail of each hell. For this we turn to the Bhagavata Purana. The Manusmrti lists multiple levels of hell in which a person can be reborn into. The punishments in each of these consecutive hells is directly related to the crimes (pätaka) of the current life and how these deeds will affect the next reincarnation during the cycle of Saṃsāra This concept provides structure to society in which crimes have exacting consequences. An opposite social facet to these hellish rebirths is the precise way in which a person can redeem himself/herself from a particular crime through a series of vows (such as fasting, water purification rituals, chanting, and even sacrifices). These vows must take place during the same life cycle that the crimes were committed in. These religious lessons assist the societal structure by defining approved and unapproved social behavior.” ref

Economic

“The last Hindu function for Hell-based reincarnations is the text Preta khanda in the Garuda Purana used by Hindu priests during Śrāddha rituals. During these rituals, the soul of a dying or deceased individual is given safe passage into the next life. This ritual is directly related to the economic prosperity of Hindu priests and their ability to “save” the dying soul from a hellish reincarnation through gifts given on behalf of the deceased to the priest performing the ritual. With each gift given, crimes committed during the deceased’s life are forgiven and the next life is progressively improved.” ref

Jainism

“In Jain cosmology, Naraka (translated as Hell) is the name given to realm of existence having great suffering. However, a Naraka differs from the hells of Abrahamic religions as souls are not sent to Naraka as the result of a divine judgment and punishment. Furthermore, the length of a being’s stay in a Naraka is not eternal, though it is usually very long and measured in billions of years. A soul is born into a Naraka as a direct result of his or her previous karma (actions of body, speech, and mind), and resides there for a finite length of time until his karma has achieved its full result. After his karma is used up, he may be reborn in one of the higher worlds as the result of an earlier karma that had not yet ripened.” ref

“The Hells are situated in the seven grounds at the lower part of the universe. The seven grounds are:

- Ratna prabha

- Sharkara prabha

- Valuka prabha

- Panka prabha

- Dhuma prabha

- Tamaha prabha

- Mahatamaha prabha” ref

“The hellish beings are a type of souls that are residing in these various hells. They are born in hells by sudden manifestation. The hellish beings possess vaikriya body (protean body which can transform itself and take various forms). They have a fixed life span (ranging from ten thousand to billions of years) in the respective hells where they reside. According to Jain scripture, Tattvarthasutra, following are the causes for birth in hell:

- Killing or causing pain with intense passion

- Excessive attachment to things and worldly pleasure with constantly indulging in cruel and violent acts

- Vowless and unrestrained life.” ref

Buddhism

“In “Devaduta Sutta”, the 130th discourse of the Majjhima Nikaya, Buddha teaches about hell in vivid detail. Buddhism teaches that there are five (sometimes six realms of rebirth, which can then be further subdivided into degrees of agony or pleasure. Of these realms, the hell realms, or Naraka, is the lowest realm of rebirth. Of the hell realms, the worst is Avīci (Sanskrit and Pali for “without waves”). The Buddha’s disciple, Devadatta, who tried to kill the Buddha on three occasions, as well as create a schism in the monastic order, is said to have been reborn in the Avici Hell. Like all realms of rebirth in Buddhism, rebirth in the Hell realms is not permanent, though suffering can persist for eons before being reborn again. In the Lotus Sutra, the Buddha teaches that eventually, even Devadatta will become a Pratyekabuddha himself, emphasizing the temporary nature of the Hell realms. Thus, Buddhism teaches to escape the endless migration of rebirths (both positive and negative) through the attainment of Nirvana. The Bodhisattva Ksitigarbha, according to the Ksitigarbha Sutra, made a great vow as a young girl to not reach Nirvana until all beings were liberated from the Hell Realms or other unwholesome rebirths. In popular literature, Ksitigarbha travels to the Hell realms to teach and relieve beings of their suffering.” ref

“Naraka is a term in Buddhist cosmology usually referred to in English as “hell” (or “hell realm”) or “purgatory“. The Narakas of Buddhism are closely related to diyu, the hell in Chinese mythology. A Naraka differs from the hell of Christianity in two respects: firstly, beings are not sent to Naraka as the result of a divine judgment or punishment; and secondly, the length of a being’s stay in a Naraka is not eternal, though it is usually incomprehensibly long, from hundreds of millions to sextillions (1021) of years. A being is born into a Naraka as a direct result of its accumulated actions (karma) and resides there for a finite period of time until that karma has achieved its full result. After its karma is used up, it will be reborn in one of the higher worlds as the result of karma that had not yet ripened. In the Devaduta Sutta, the 130th discourse of Majjhima Nikaya, the Buddha teaches about hell in vivid detail. Physically, Narakas are thought of as a series of cavernous layers that extend below Jambudvīpa (the ordinary human world) into the earth. There are several schemes for enumerating these Narakas and describing their torments. The Abhidharma-kosa (Treasure House of Higher Knowledge) is the root text that describes the most common scheme, as the Eight Cold Narakas and Eight Hot Narakas.” ref

Cold Narakas: Each lifetime in these Narakas is twenty times the length of the one before it.

- Arbuda (頞部陀), the “blister” Naraka, is a dark, frozen plain surrounded by icy mountains and continually swept by blizzards. Inhabitants of this world arise fully grown and abide lifelong naked and alone, while the cold raises blisters upon their bodies. The length of life in this Naraka is said to be the time it would take to empty a barrel of sesame seeds if one only took out a single seed every hundred years. Life in this Naraka is 2×1012 years long.

- Nirarbuda (刺部陀), the “burst blister” Naraka, is even colder than Arbuda. There, the blisters burst open, leaving the beings’ bodies covered with frozen blood and pus. Life in this Naraka is 4×1013 years long.

- Aṭaṭa (頞听陀) is the “shivering” Naraka. There, beings shiver in the cold, making an aṭ-aṭ-aṭ sound with their mouths. Life in this Naraka is 8×1014 years long.

- Hahava (臛臛婆;) is the “lamentation” Naraka. There, the beings lament in the cold, going haa, haa in pain. Life in this Naraka is 1.6×1016 years long.

- Huhuva (虎々婆), the “chattering teeth” Naraka, is where beings shiver as their teeth chatter, making the sound hu, hu. Life in this Naraka is 3.2×1017 years long.

- Utpala (嗢鉢羅) is the “blue lotus” Naraka. The intense cold there makes the skin turn blue like the colour of an utpala waterlily. Life in this Naraka is 6.4×1018 years long.