@ Vincent Rowlatt. (Peasant) – “My take on this ‘stuff’. Way back, some ape\human got smashed on natural fermenting fruit or ate some ‘shrooms’, and ‘he’ began to think, became conscious, and ask questions. “What the feck is the sun?” sort of thing. Sometime later… Along came a ‘priest’ and told him what to think.”

My response, The Drunken Monkey hypothesis (Ps. I don’t think it actually is an important factor in evolution, nor religion)

@ Vincent Rowlatt. (Peasant) – “The question, for example, “What the feck is the sun?” was exploited by those who called themselves ‘priests’. At some point in time, ‘humans’ did not ask such questions… What changed and why?”

My response, My take on religious evolution (bellow).

The Unifying theme of Unreliability?

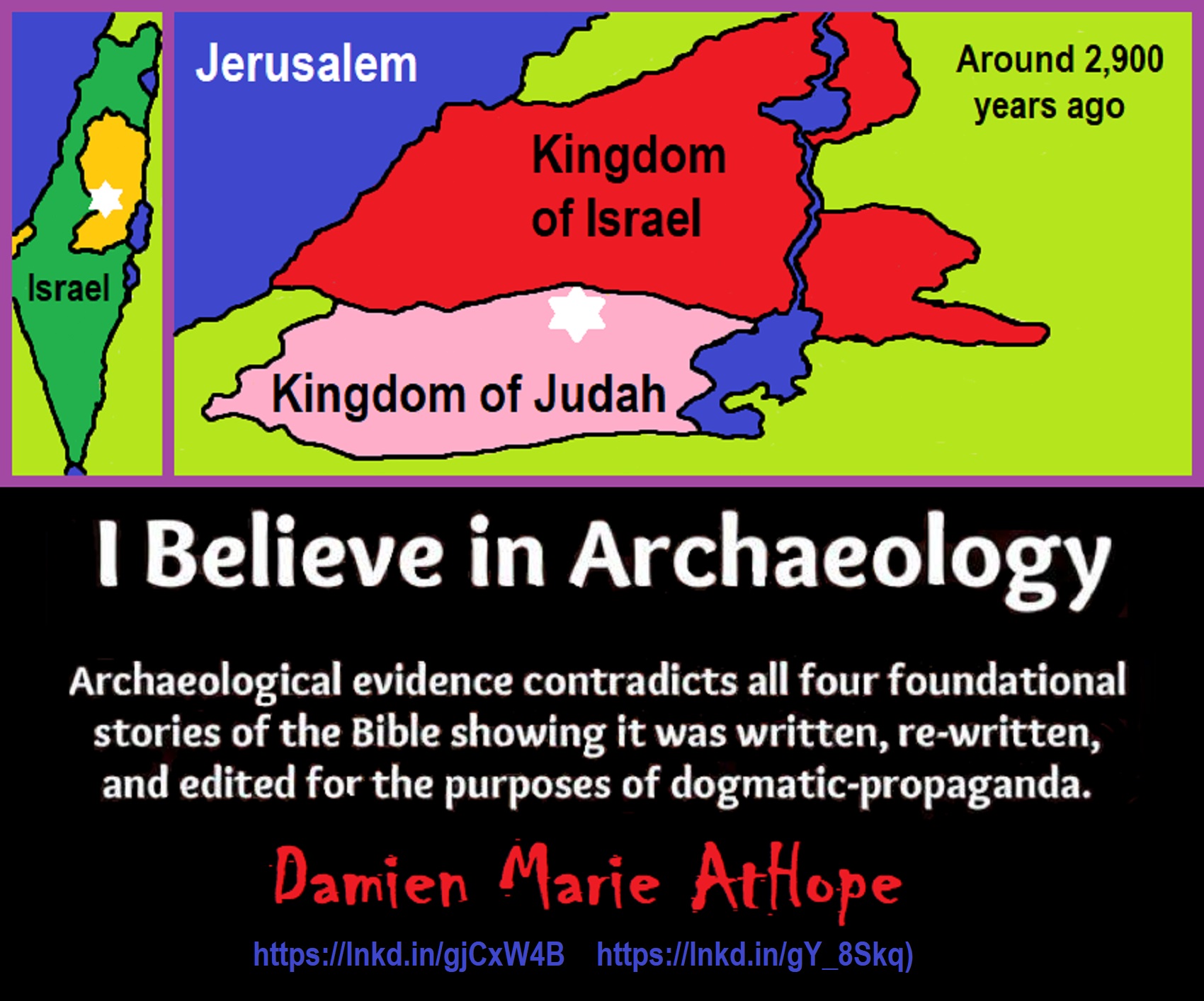

You know one common problem several major religions have? They were not written by the person they claim to represent the main figure. The Torah, was not written by Moses. The claimed sacred texts of Buddhism were not written by Buddha (also known as Siddhārtha Gautama). And of course, not even one written word was put in the Christian Bible authored by Jesus, let me make this fully clear for the students in the back, not any part of the bible was written by Jesus, think long and hard on this. Jesus came according to most Christians it seems, to save the world, and create a new religion “Christianity”, one would assume as well, but then why did he not just simply write the books himself? Oh, let’s not forget the late bloomer, the Koran not written by Muhammad, not even one word. Nor did he say to write a Koran either, strange, right? But the shit show must go on, I guess. Neither was the Taoism or Daoism “Tao Te Ching” written by Lao-Tzu, so you see the theme I see, right?

My response, Here is my blog post for: Sexism in Bahaism

“According to Latter Day Saint belief, the golden plates are the source from which Joseph Smith translated the Book of Mormon, a sacred text of the faith. Smith said that he returned the plates to the angel and their authenticity cannot be determined by physical examination.” ref

“The “lost 116 pages” were the original manuscript pages of what Joseph Smith, founder of the Latter Day Saint movement, said was the translation of the Book of Lehi, the first portion of the golden plates revealed to him by an angel in 1827.” ref

Jim Davis @commonismnow – “Reform Mormons believe he just wrote it as religious fiction with some good ideas. The thing about Mormonism is that the process of revelation is always open, and the Mormon God is open to change. I suspect the LDS people will follow the Community of Christ Mormons and accept queer folks within the next decade.”

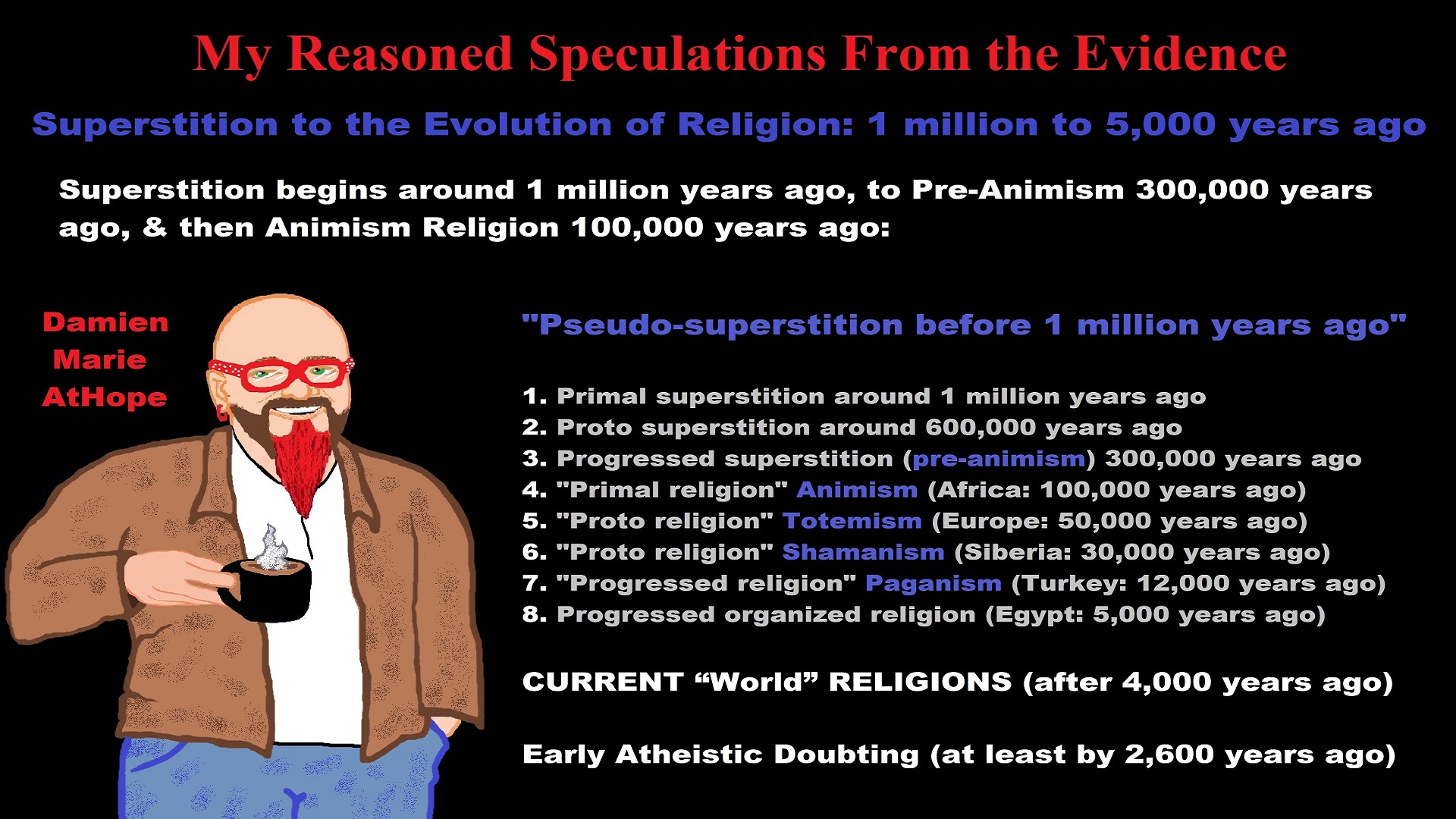

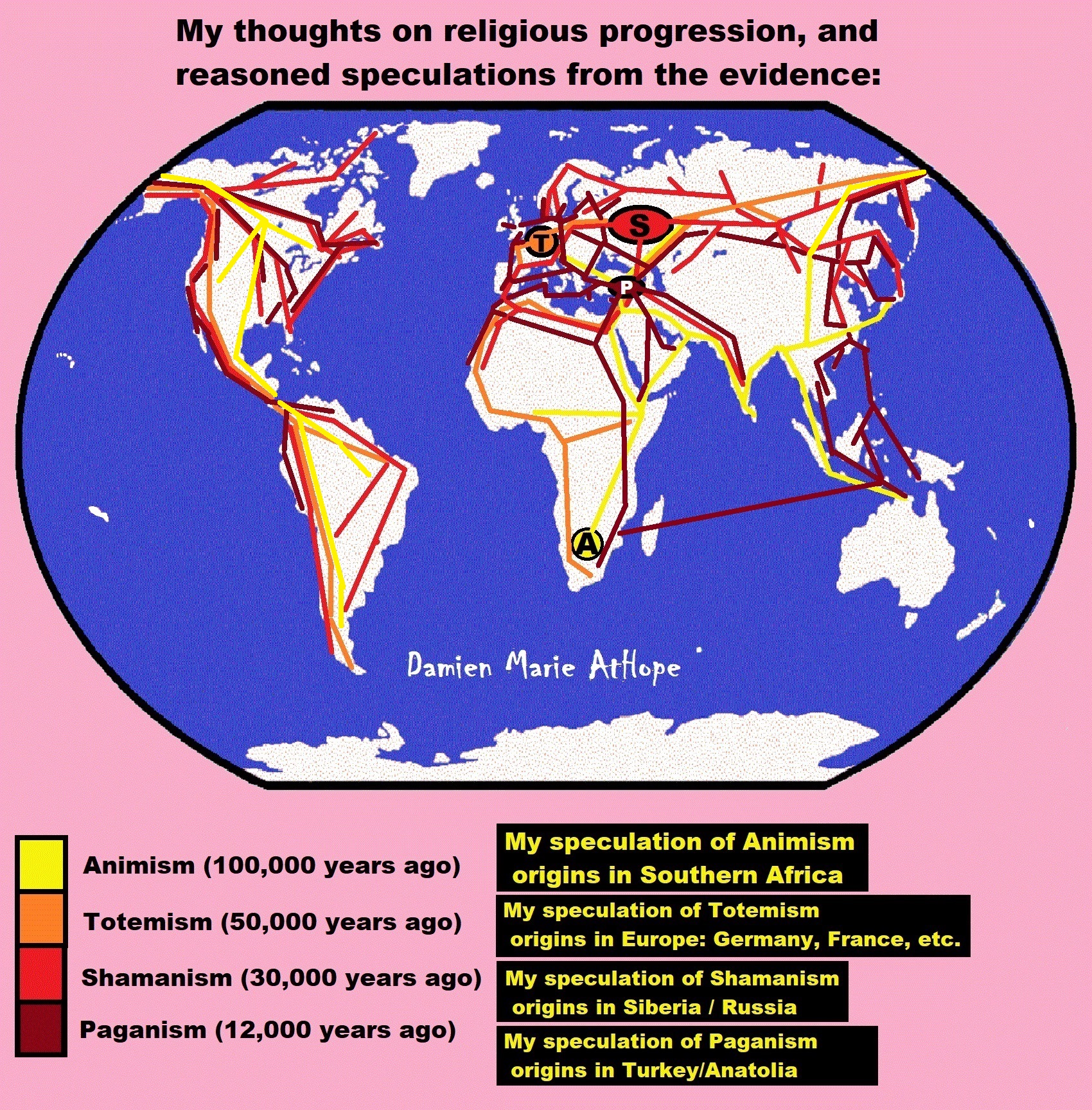

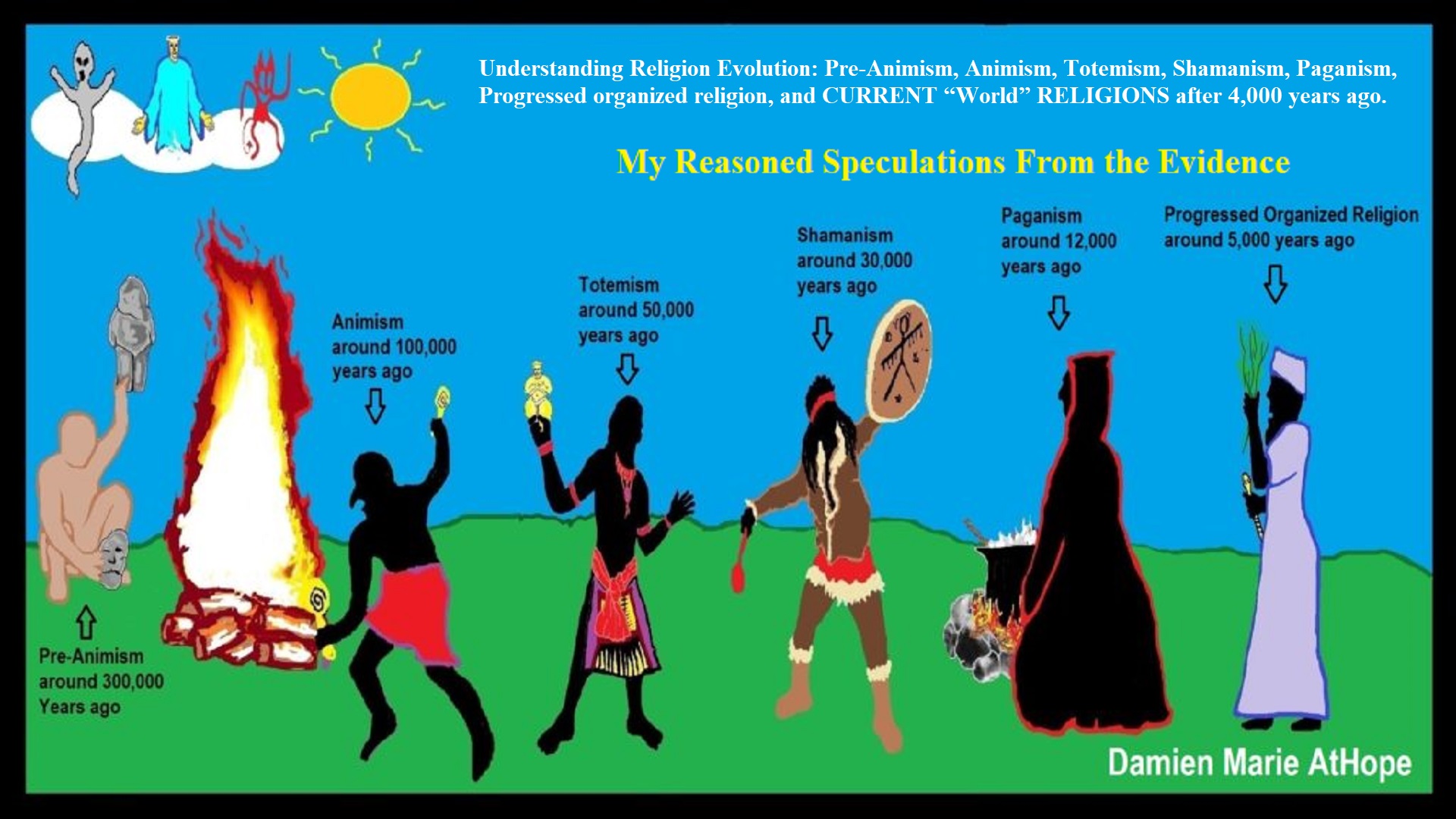

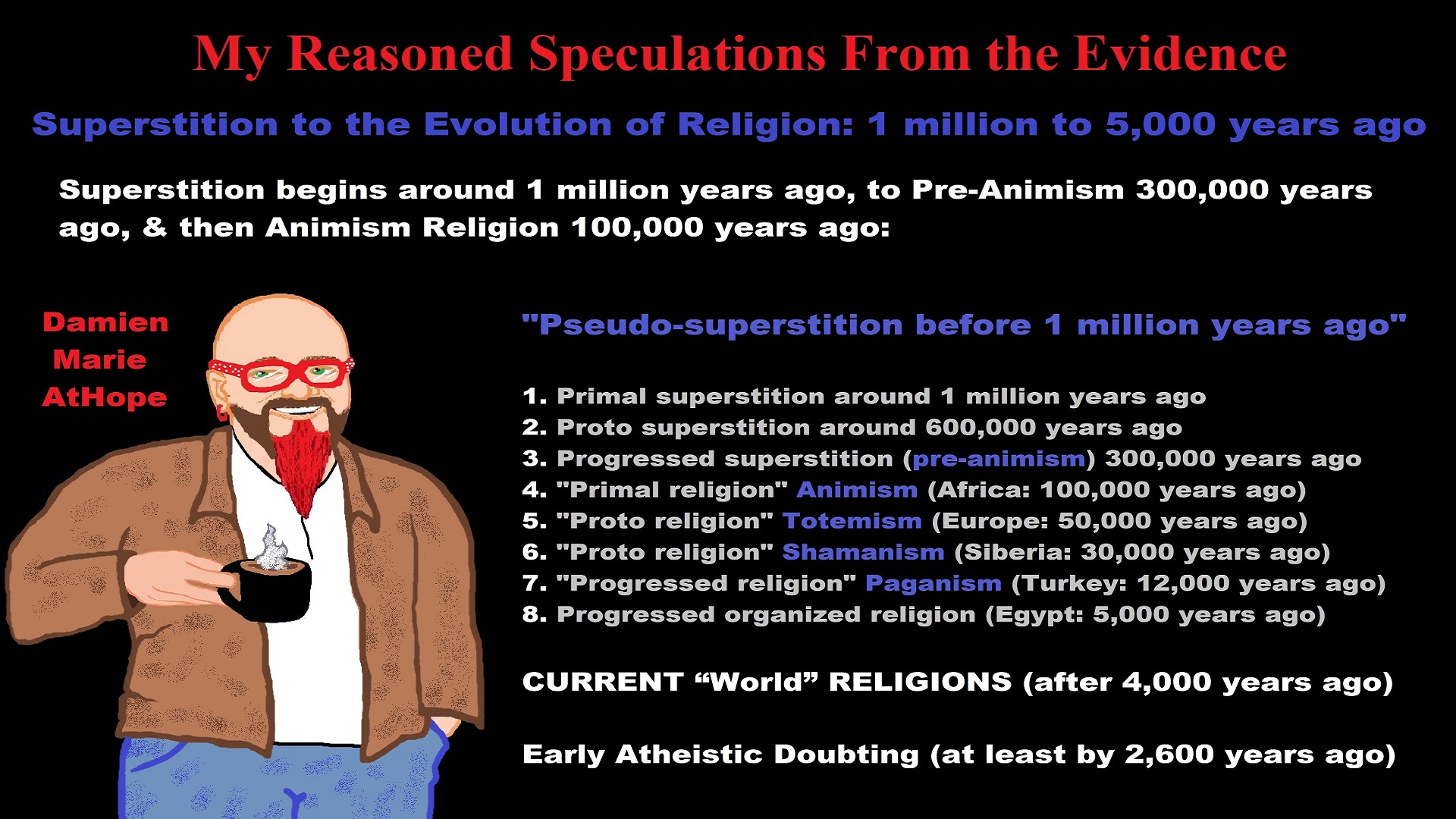

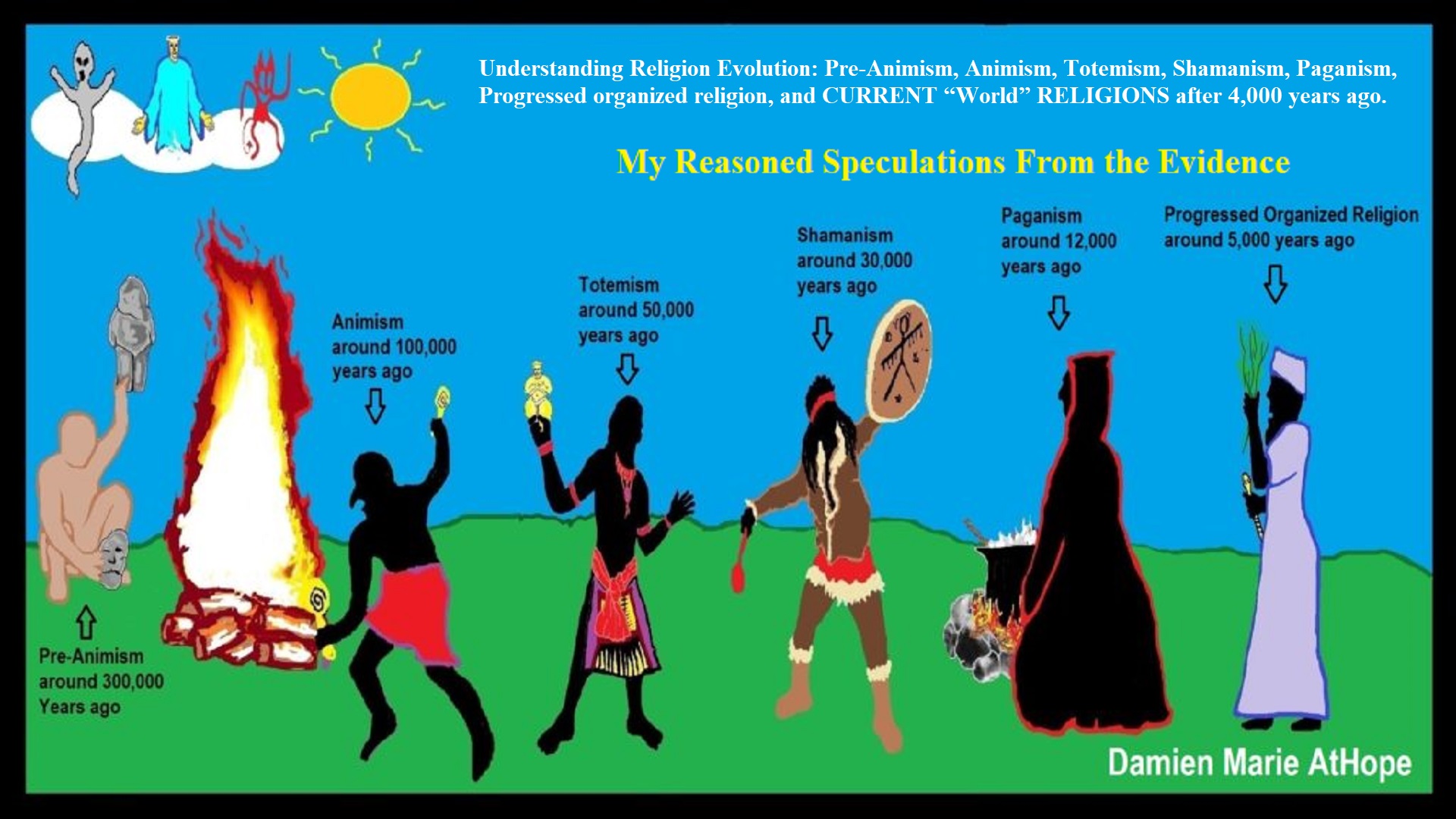

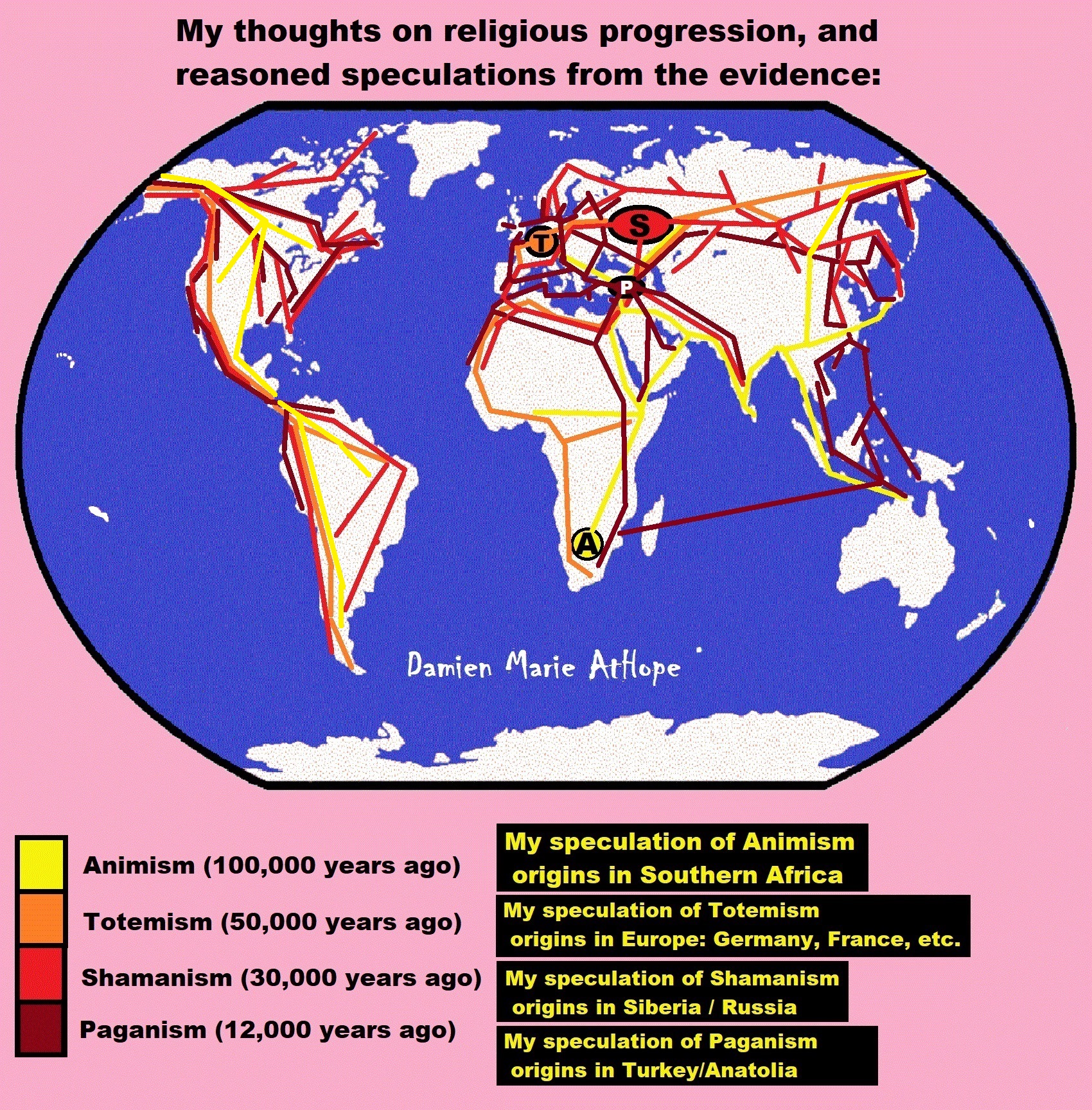

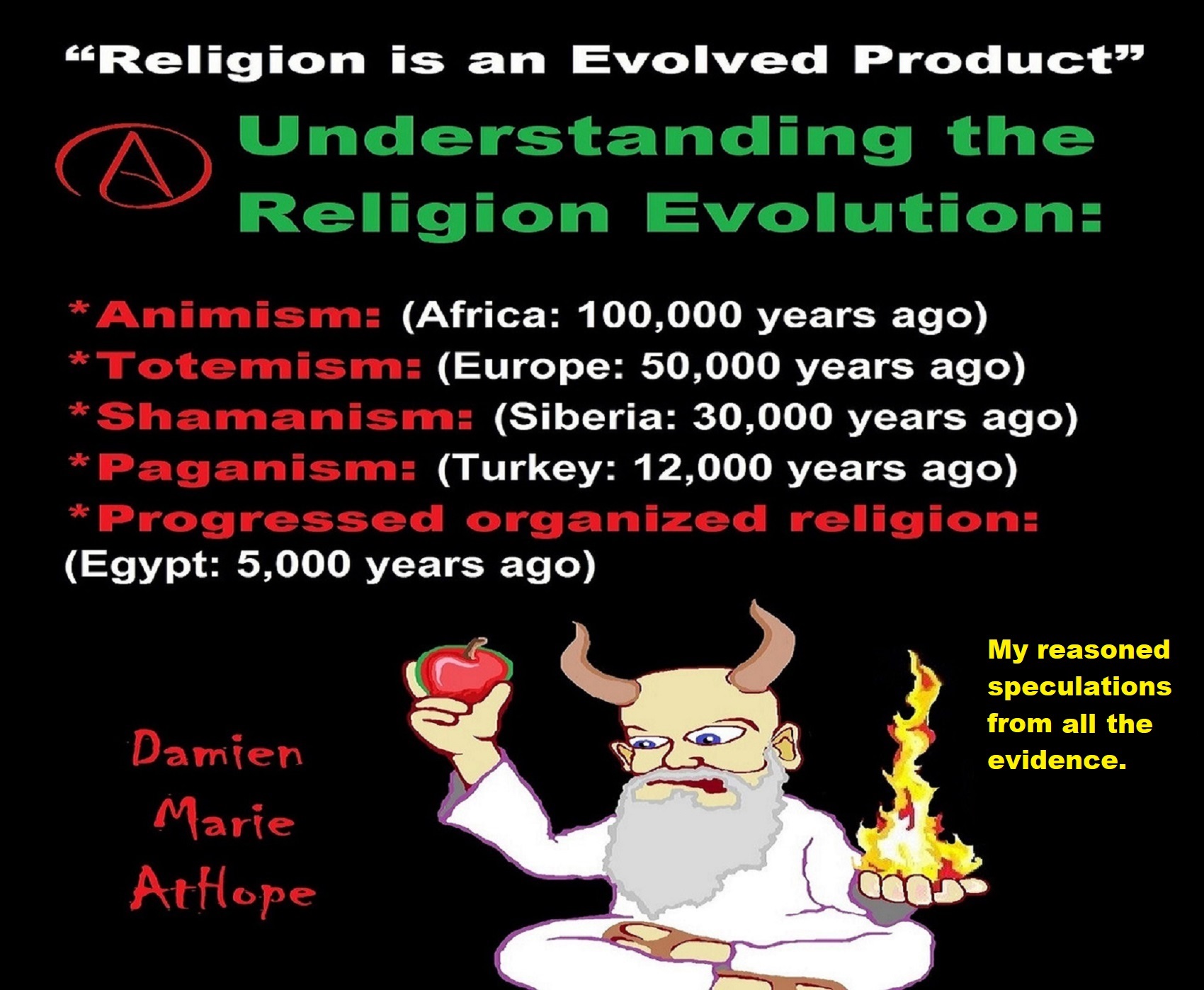

My thoughts on religious progression, and reasoned speculations from the evidence:

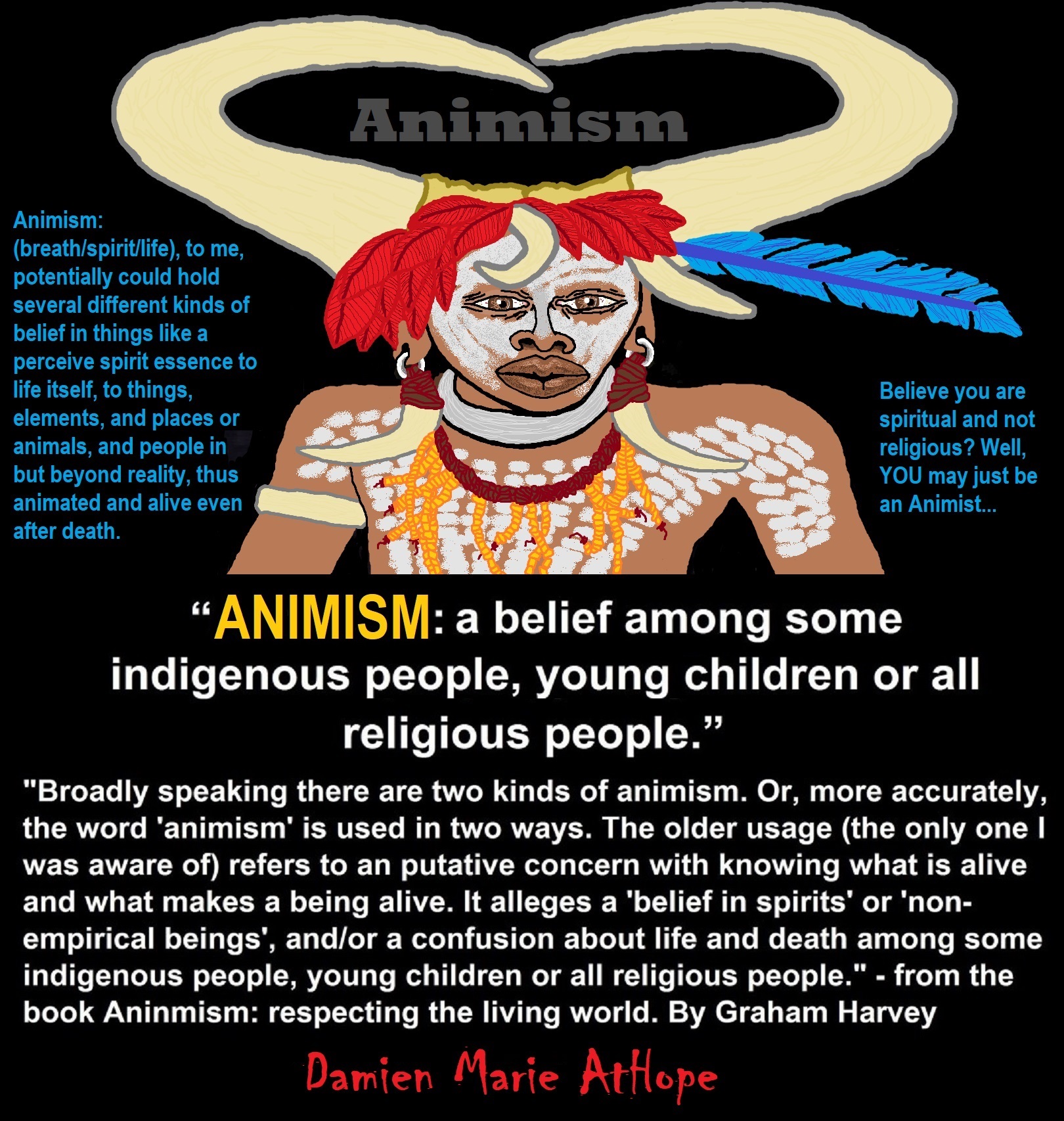

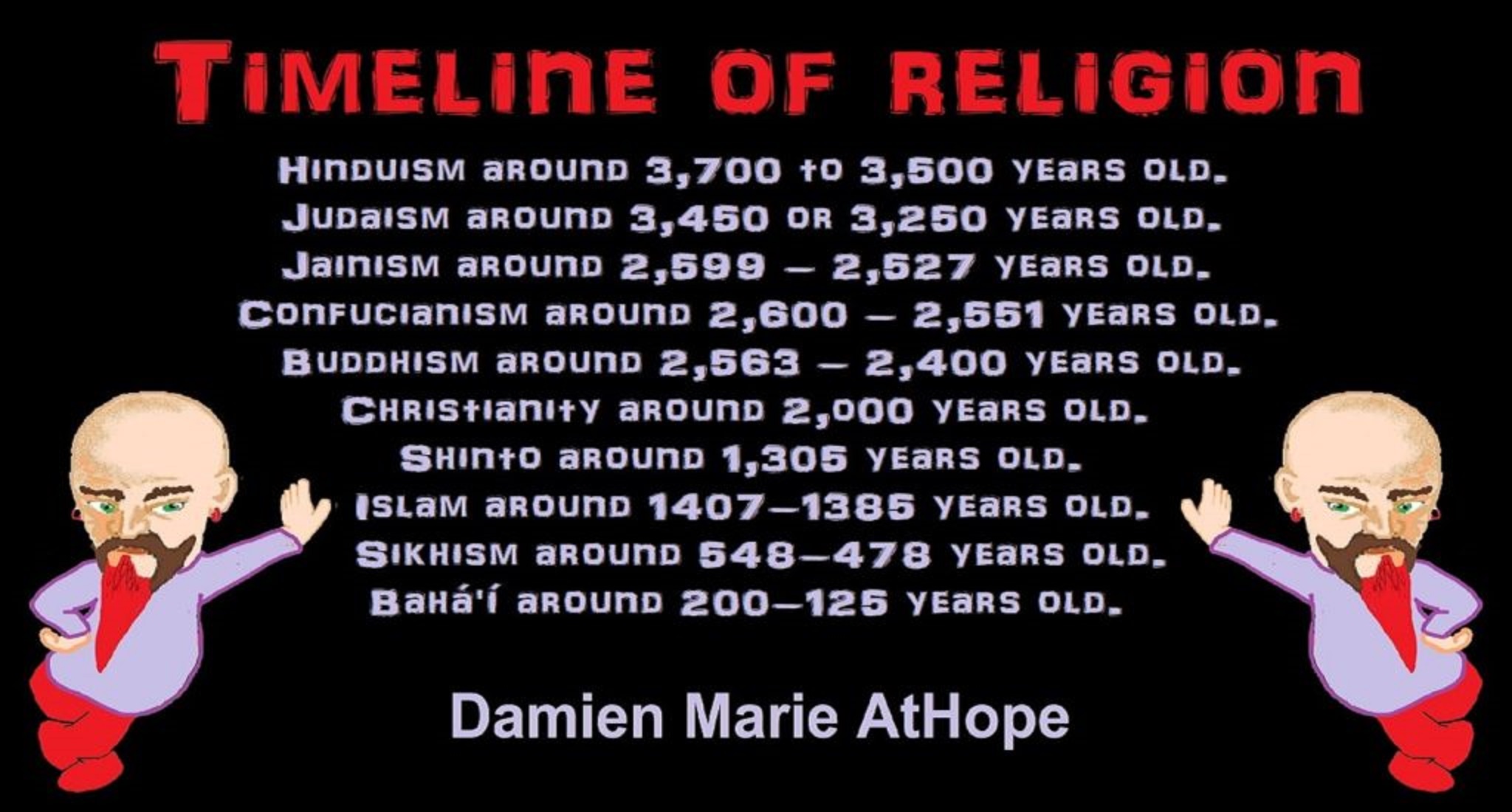

Animism (100,000 years ago)

Totemism (50/45,000 years ago)

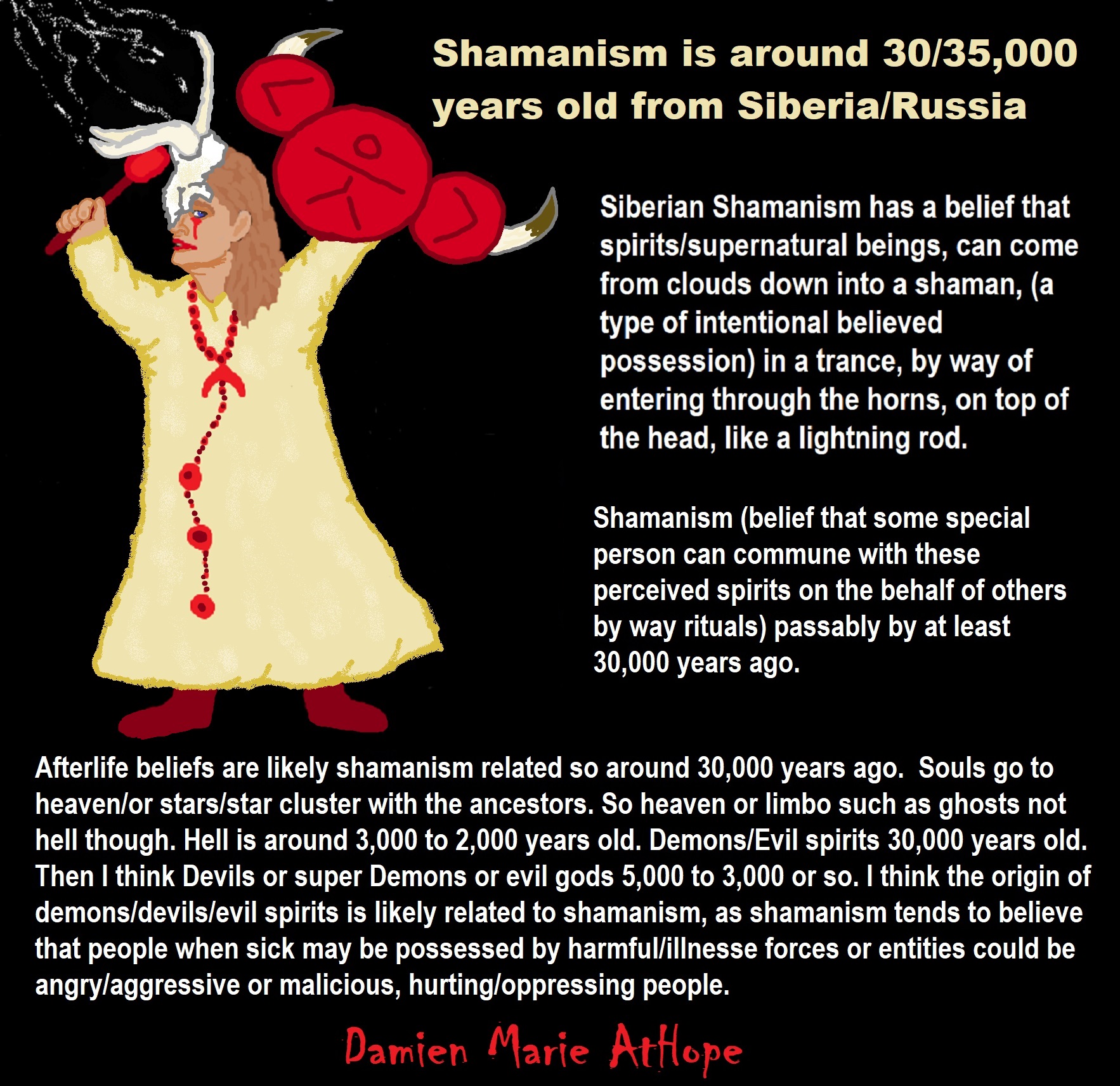

Shamanism (30/35,000 years ago)

Paganism (13/12,000 years ago)

“Institutional” Progressed Organized Religion (5,000 years ago)

Present world religions are under 4,000 years ago.

“Since I believe that all cults/religions are made up for profit of the few, and fooling of the many – how did they profit from animism? Any guesses?” – Questioner

My response, Anamism allows unscientific thinking/magical thinking to believe one understands what can seem like mysteries, such as how you feel air yet there is nothing there, “it is a spirit then” they may think, or have thought in our ancient past.

“I would guess selling to the unwashed, magic talismans to ward off the evil (Ie. was the beginning of religions involving selling)?” – Questioner

My response, Evil is likely something that relates to shamanism, ie. sicknesses were seen as things like evil spirits the shaman can heal you from. Then you make things such as magic talismans to ward off the evil.

“Animism is intrinsic to hunter-gatherer societies which are/were mostly egalitarian – ‘the many’ profits. Animism features a system of related taboos that help enforce the egalitarian/sharing culture.” – Get Starmer @davidjohnc

My response, I agree, there are behavior modifiers like “prestige avoidance” which is the practice of not bringing lots of attention to yourself and being humble, being just one worth of all the other people who have equal worth.

What I do not like about religion in one idea, religions as a group are “Conspiracy Theories of Reality,” usually filled with Pseudoscience, Pseudohistory, along with Pseudomorality, and other harmful aspects.

“Anti-theist ancom (Anarchist Communist) rting my post ab the smallpox epidemic here is so funny. Anti-theists would participate in the extortion of the Wei Wai Kai cultural & historical artifacts actually.” – lythra @nukedpuppy

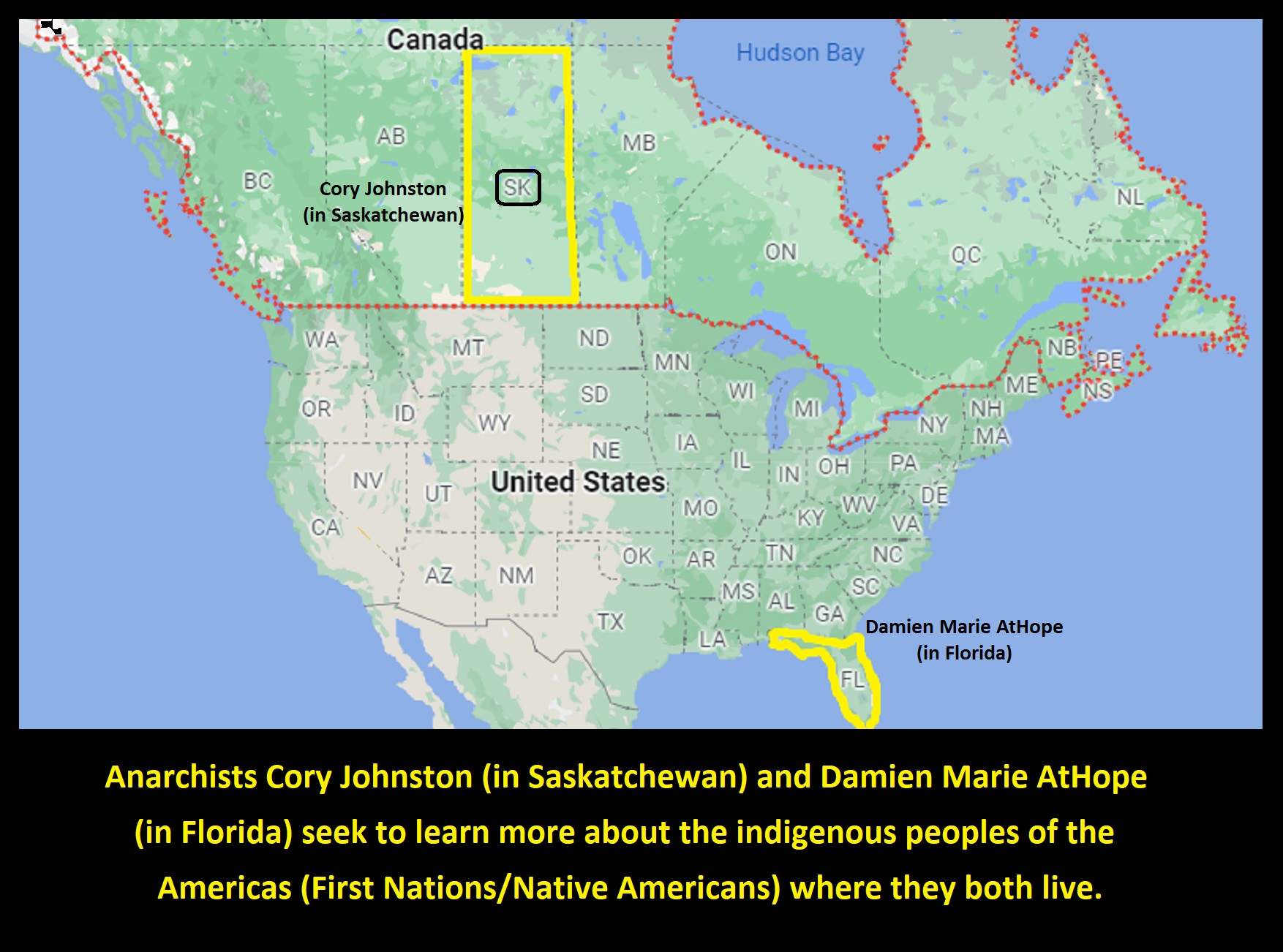

My response, I enjoy your posts and I am an antitheist and ancom. Antitheist is my dislike of theism it is not a removal of my secularist thinking or humanist endeavors. I respect people even if I don’t like religion or gods. One can dislike things and not be a bigot. I followed you as well.

“istg I will never hear a white person say “Kwakiutl” the right way, I’ve seen a lot of videos on general Kwakwaka’wakw history lately & every single white person has pronounced it the same wrong way.” – lythra @nukedpuppy

My response, I hear you and I feel bad as I talk on prehistory a lot and I am terrible at pronouncing names. I wish I was better at saying names correctly. I know it matters and I do try to improve. It would have been better if America was not so bigoted, and used more indigenous words as a rule.

“I’m not bigoted, I just vehemently oppose & demonize a core aspect of your culture.” – lythra @nukedpuppy

My response, I am not opposed to your culture. I am not opposed to someone choosing religion or gods, I do believe in them (people, not their religions or gods) and think religion teaches mythology as truth. I respect people’s rights to beliefs but not that those beliefs have to be respected.

“How anti-theists say this shit seriously is baffling.” – lythra @nukedpuppy

My response, Well it seems many people seem to strawman or be in error what antitheist means and then think this error makes antitheist bad. “Antitheism is the philosophical position that theism should be opposed.” I do oppose gods and theism, I do this by writing thinking about theism.

“Could you explain Ligwilda’xw culture, to me, without the aspect of gods & spirituality?” – lythra @nukedpuppy

My response, So everything in culture is related to religion? Or theism? There are many things in cultures of non-religious or nontheism in cultures that are merged with religion and theism. If I oppose the belief in a religion that is not the same as thinking I want to remove others’ rights.

“Could you explain your fundamental criticisms of the Ligwilda’xw religion?” – lythra @nukedpuppy

My response, I have some knowledge of some Indigenous peoples of the Americas but I don’t know anything about Ligwilda’xw. I am open to learning about it. I don’t attack Indigenous religions, I address beliefs and how I see lots of connections. I see religion as a cultural product, like that of languages.

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

“These ideas are my speculations from the evidence.”

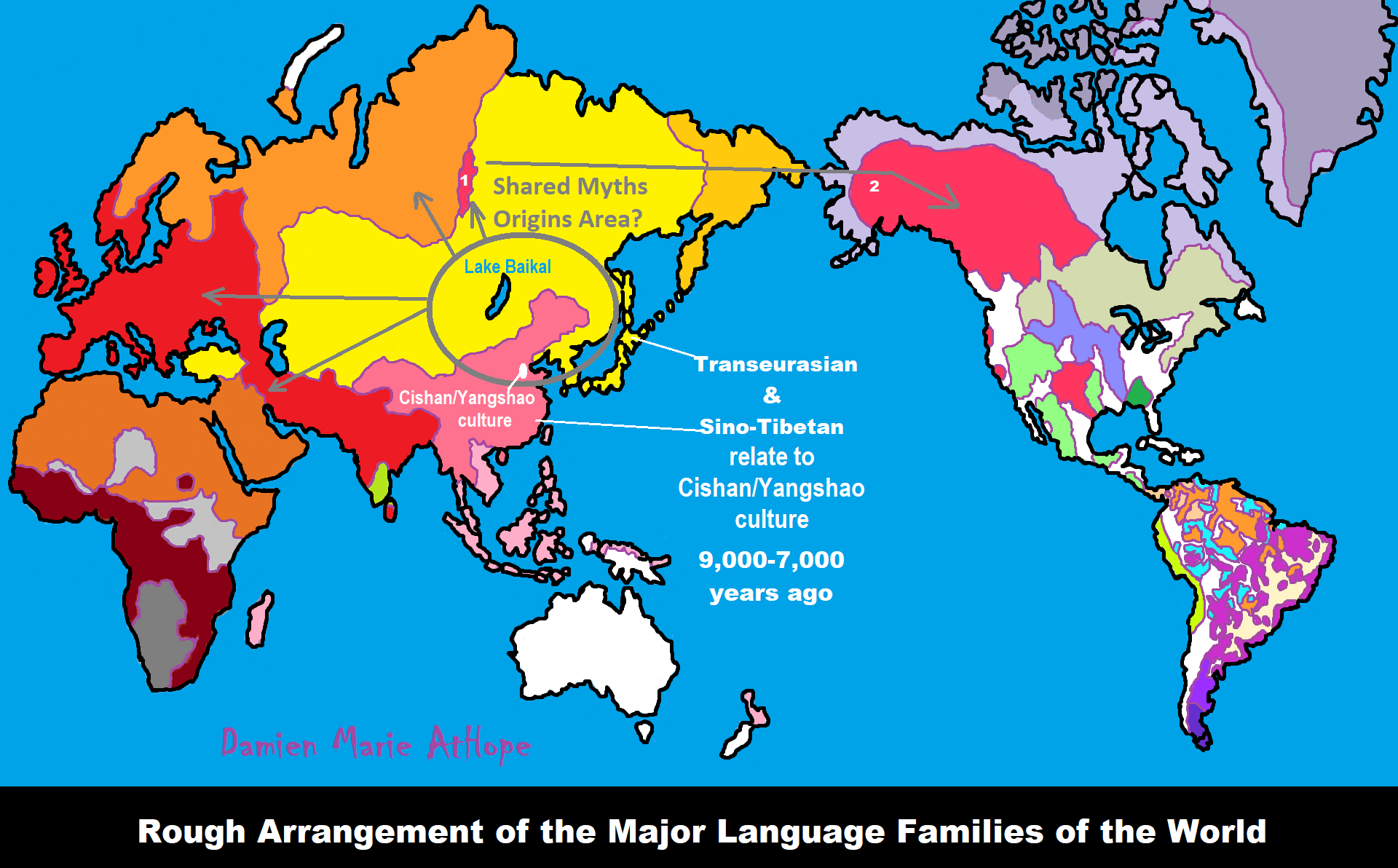

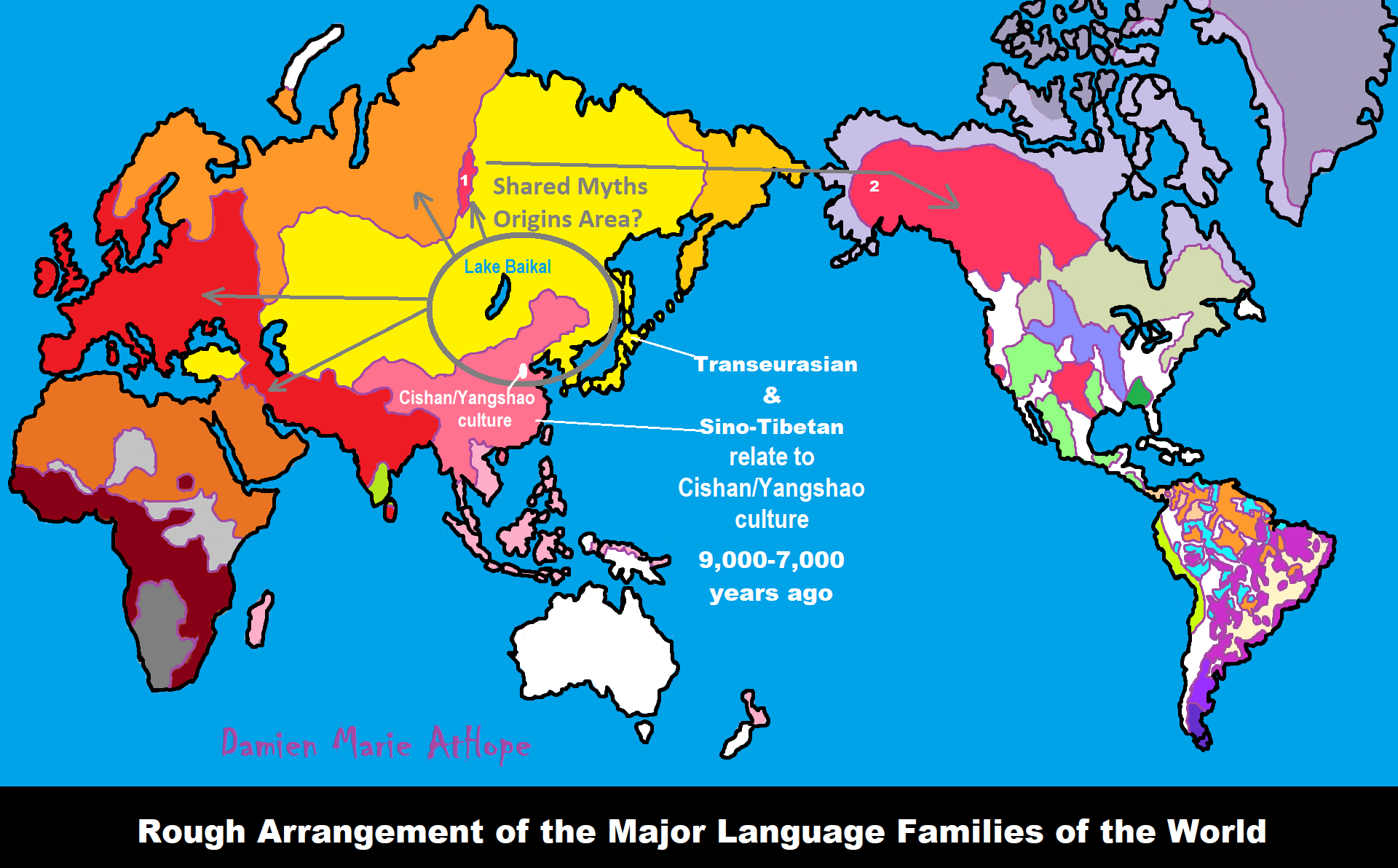

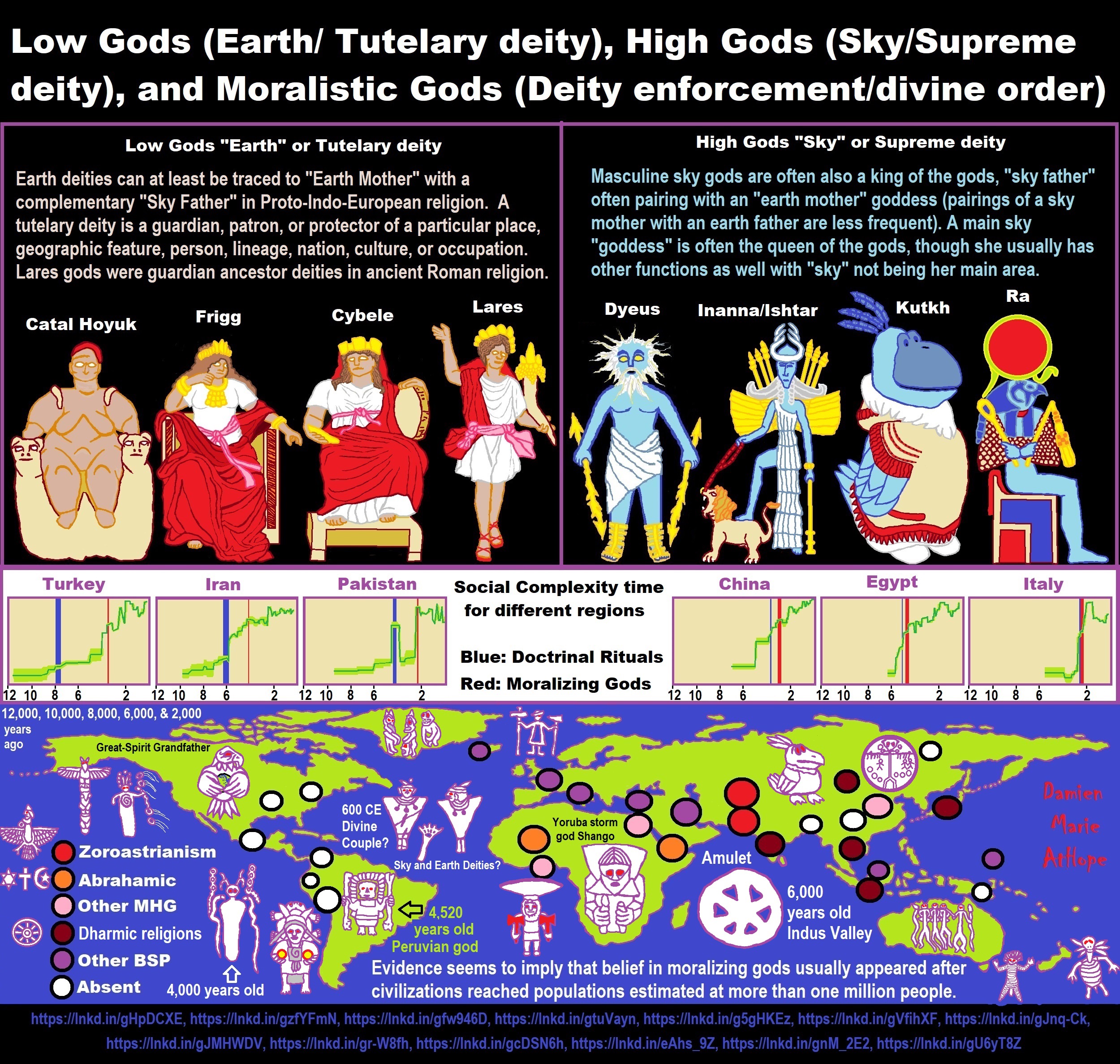

I am still researching the “god‘s origins” all over the world. So you know, it is very complicated but I am smart and willing to look, DEEP, if necessary, which going very deep does seem to be needed here, when trying to actually understand the evolution of gods and goddesses. I am sure of a few things and less sure of others, but even in stuff I am not fully grasping I still am slowly figuring it out, to explain it to others. But as I research more I am understanding things a little better, though I am still working on understanding it all or something close and thus always figuring out more.

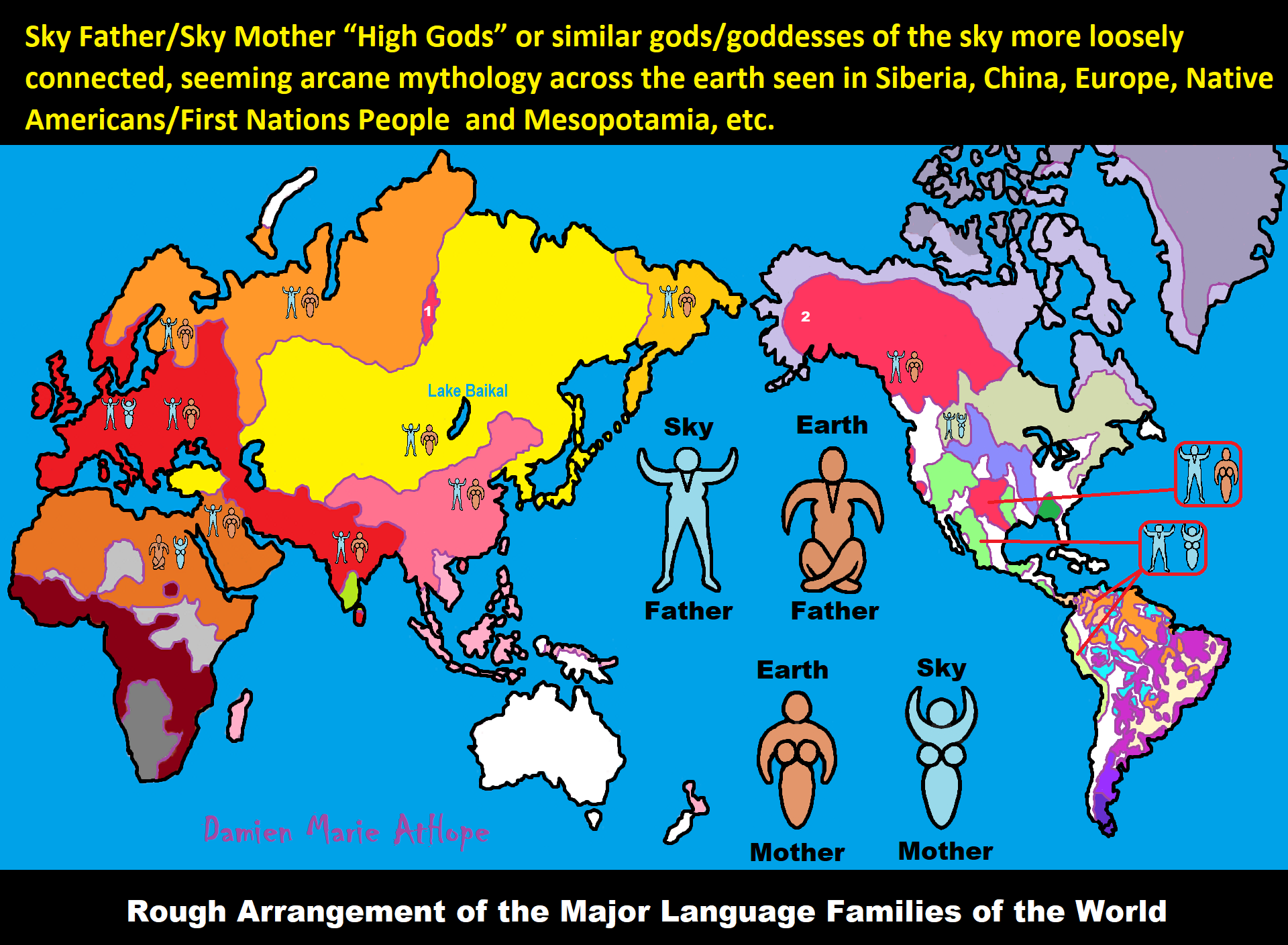

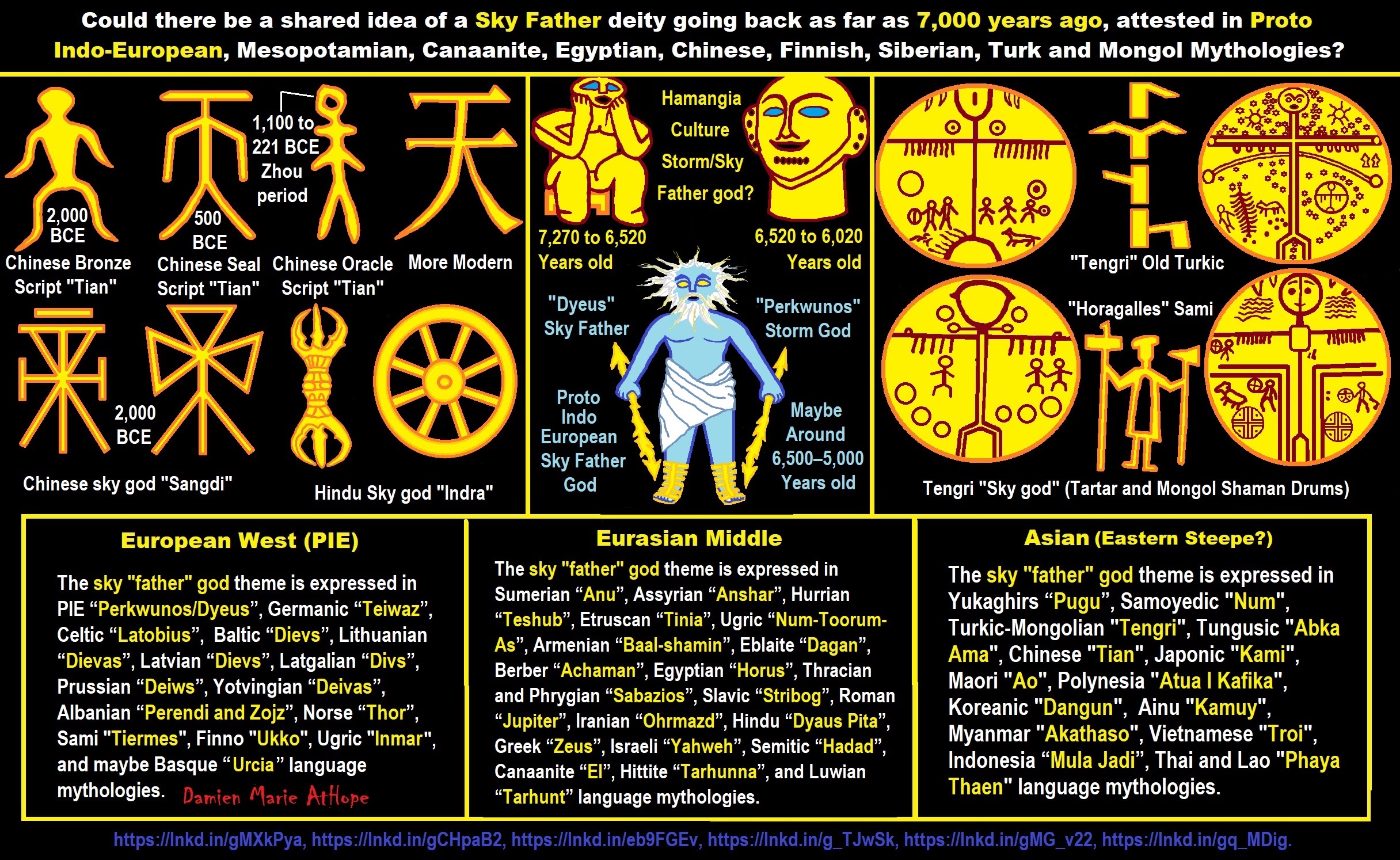

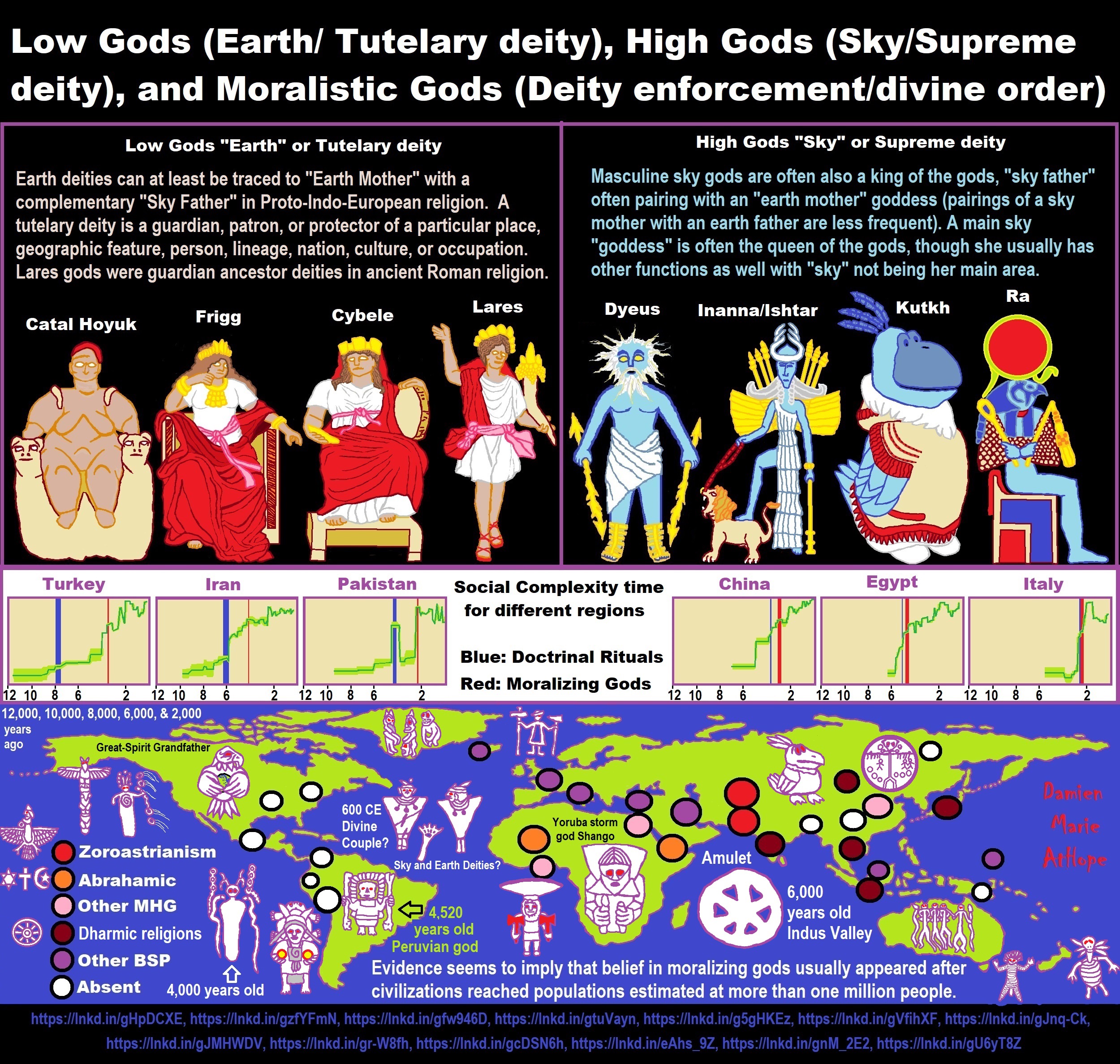

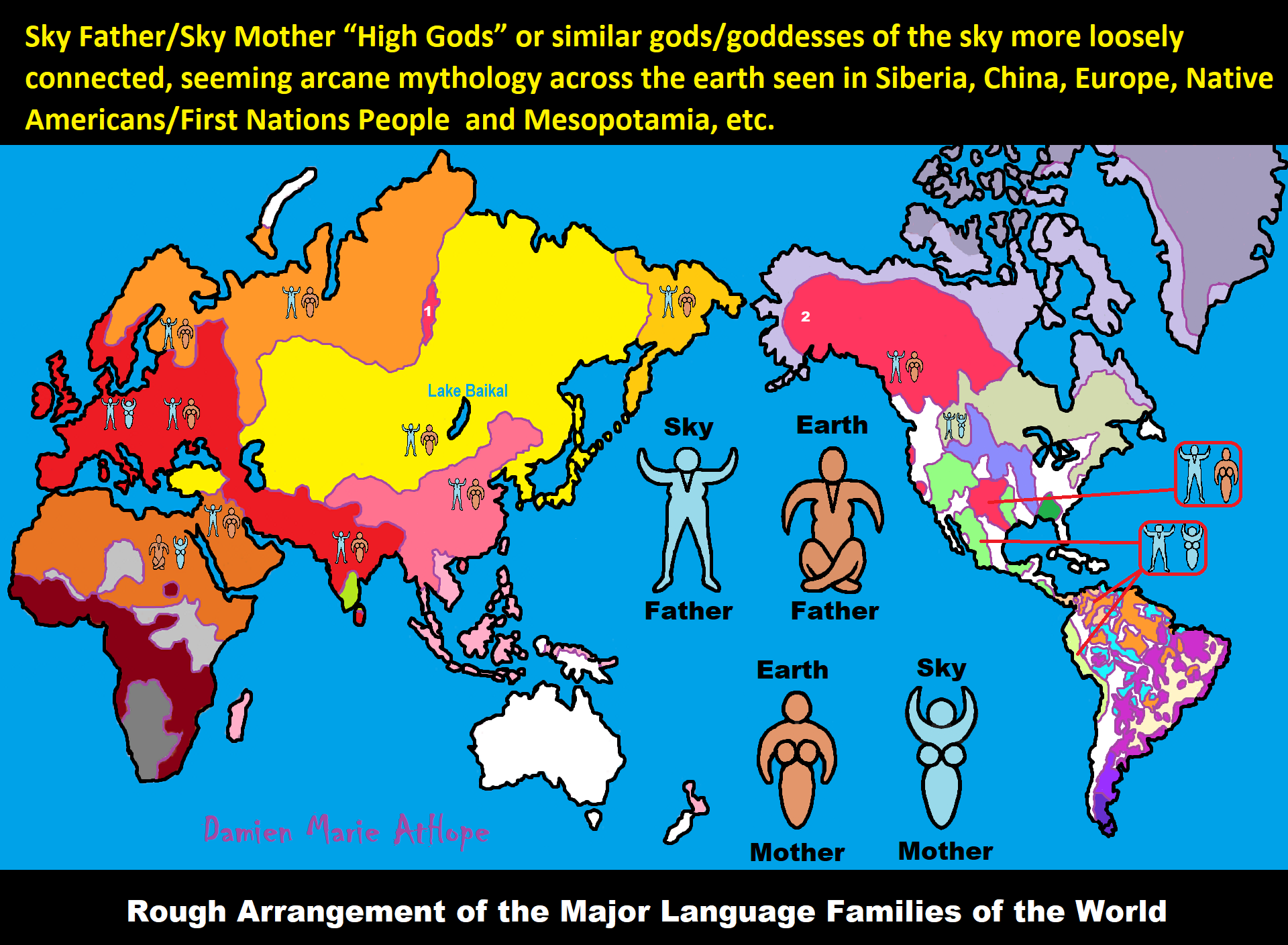

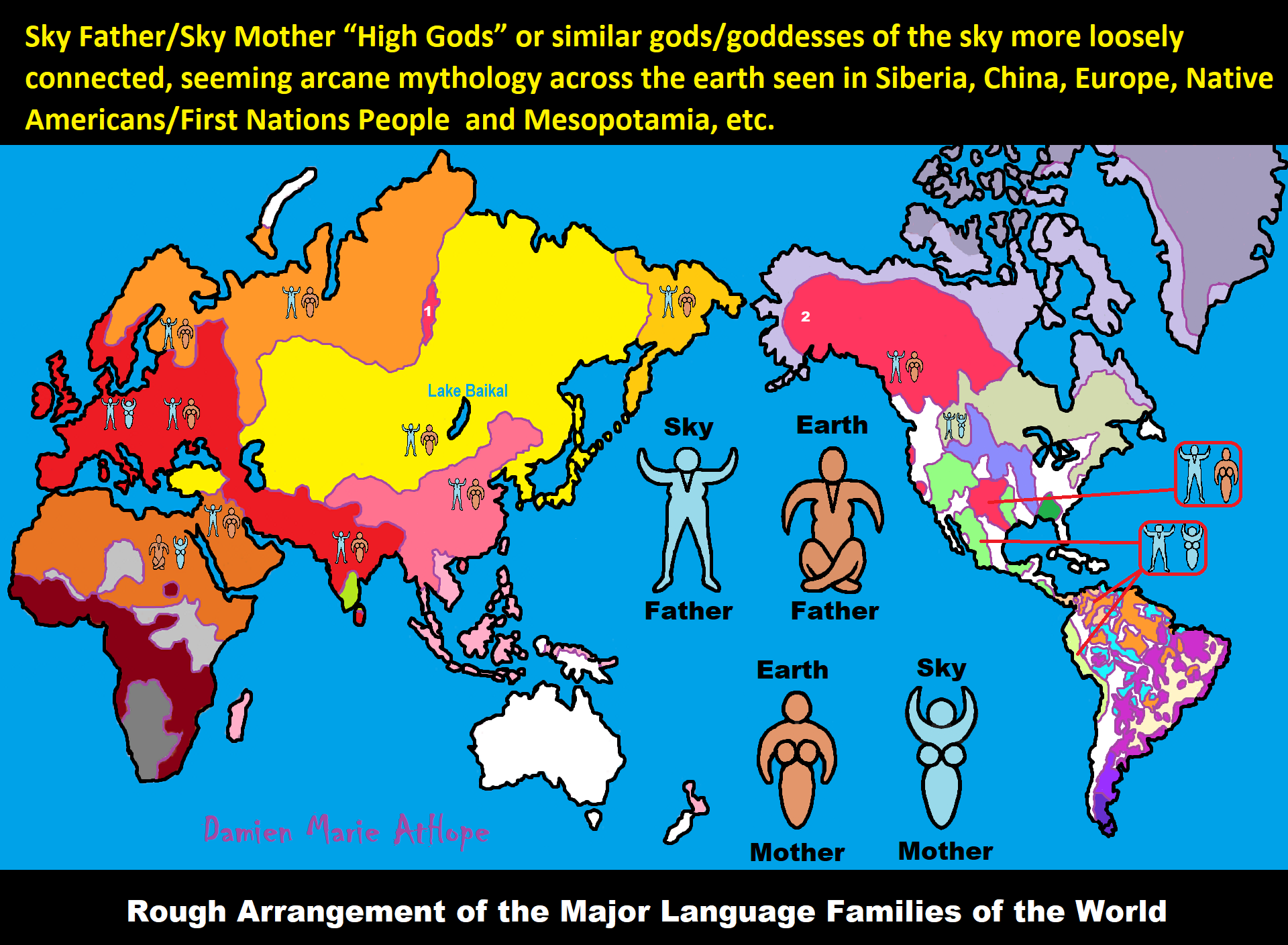

Sky Father/Sky God?

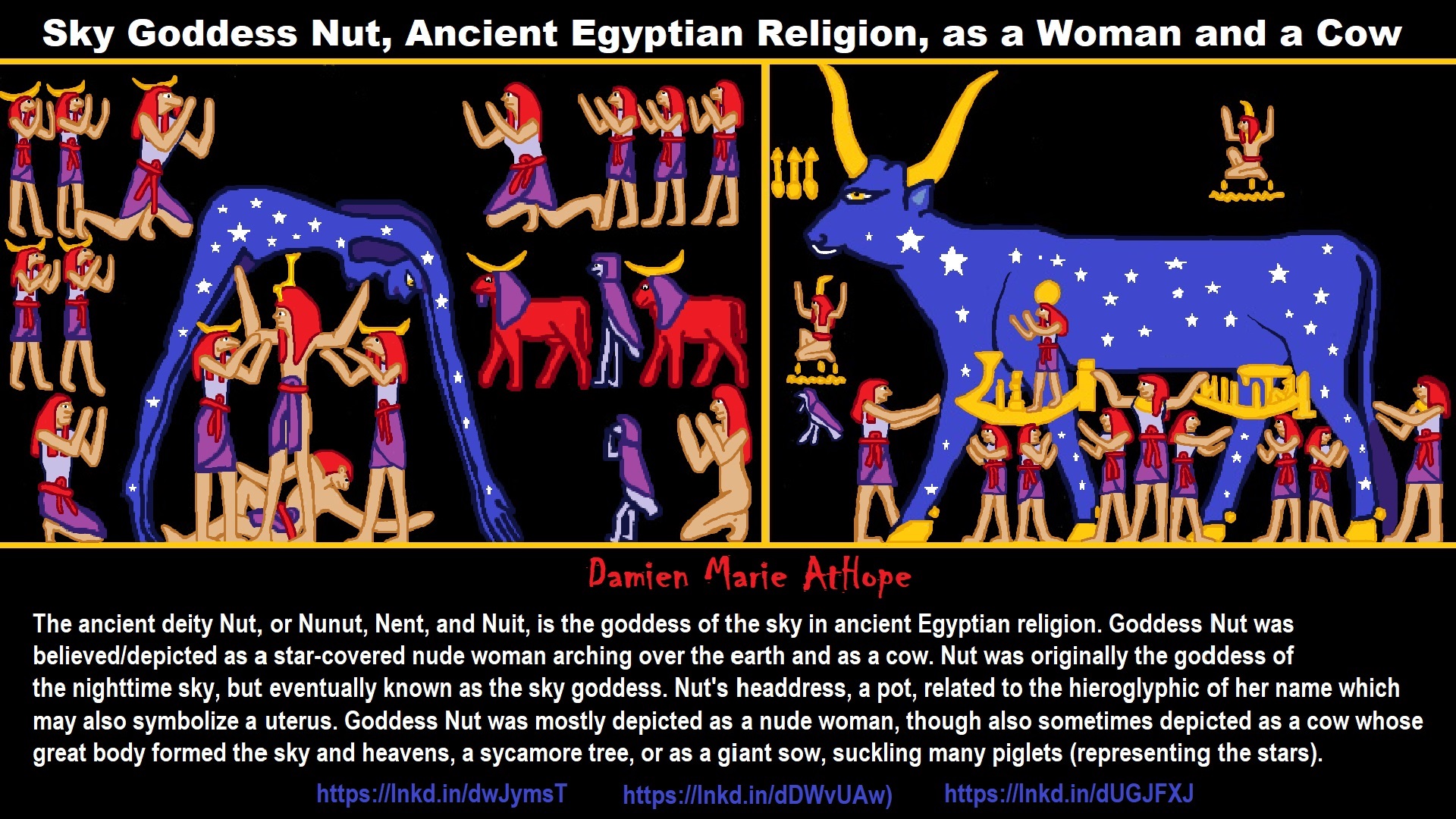

“Egyptian: (Nut) Sky Mother and (Geb) Earth Father” (Egypt is different but similar)

Turkic/Mongolic: (Tengri/Tenger Etseg) Sky Father and (Eje/Gazar Eej) Earth Mother *Transeurasian*

Hawaiian: (Wākea) Sky Father and (Papahānaumoku) Earth Mother *Austronesian*

New Zealand/ Māori: (Ranginui) Sky Father and (Papatūānuku) Earth Mother *Austronesian*

Proto-Indo-European: (Dyḗus/Dyḗus ph₂tḗr) Sky Father and (Dʰéǵʰōm/Pleth₂wih₁) Earth Mother

Indo-Aryan: (Dyaus Pita) Sky Father and (Prithvi Mata) Earth Mother *Indo-European*

Italic: (Jupiter) Sky Father and (Juno) Sky Mother *Indo-European*

Etruscan: (Tinia) Sky Father and (Uni) Sky Mother *Tyrsenian/Italy Pre–Indo-European*

Hellenic/Greek: (Zeus) Sky Father and (Hera) Sky Mother who started as an “Earth Goddess” *Indo-European*

Nordic: (Dagr) Sky Father and (Nótt) Sky Mother *Indo-European*

Slavic: (Perun) Sky Father and (Mokosh) Earth Mother *Indo-European*

Illyrian: (Deipaturos) Sky Father and (Messapic Damatura’s “earth-mother” maybe) Earth Mother *Indo-European*

Albanian: (Zojz) Sky Father and (?) *Indo-European*

Baltic: (Perkūnas) Sky Father and (Saulė) Sky Mother *Indo-European*

Germanic: (Týr) Sky Father and (?) *Indo-European*

Colombian-Muisca: (Bochica) Sky Father and (Huythaca) Sky Mother *Chibchan*

Aztec: (Quetzalcoatl) Sky Father and (Xochiquetzal) Sky Mother *Uto-Aztecan*

Incan: (Viracocha) Sky Father and (Mama Runtucaya) Sky Mother *Quechuan*

China: (Tian/Shangdi) Sky Father and (Dì) Earth Mother *Sino-Tibetan*

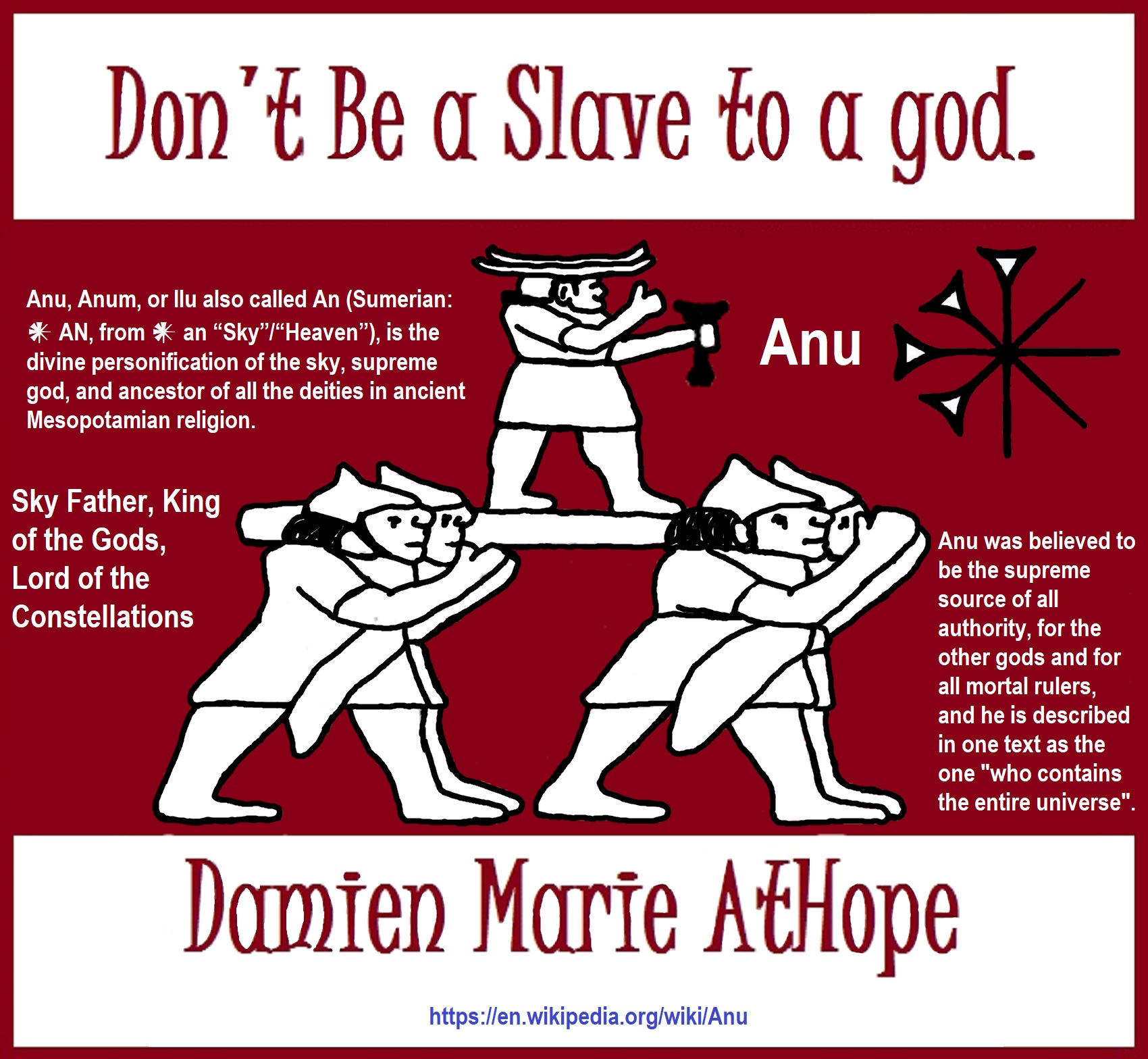

Sumerian, Assyrian and Babylonian: (An/Anu) Sky Father and (Ki) Earth Mother

Finnish: (Ukko) Sky Father and (Akka) Earth Mother *Finno-Ugric*

Sami: (Horagalles) Sky Father and (Ravdna) Earth Mother *Finno-Ugric*

Puebloan-Zuni: (Ápoyan Ta’chu) Sky Father and (Áwitelin Tsíta) Earth Mother

Puebloan-Hopi: (Tawa) Sky Father and (Kokyangwuti/Spider Woman/Grandmother) Earth Mother *Uto-Aztecan*

Puebloan-Navajo: (Tsohanoai) Sky Father and (Estsanatlehi) Earth Mother *Na-Dene*

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

“Mf said I straw-manned, then said this. And how do you define “arcane?” – lythra @nukedpuppy

My response, Thank you for the question. I generally see “arcane” as obscure presently (hard to get information about), not well-known, or mostly forgotten.

“These ideas are my speculations from the evidence.”

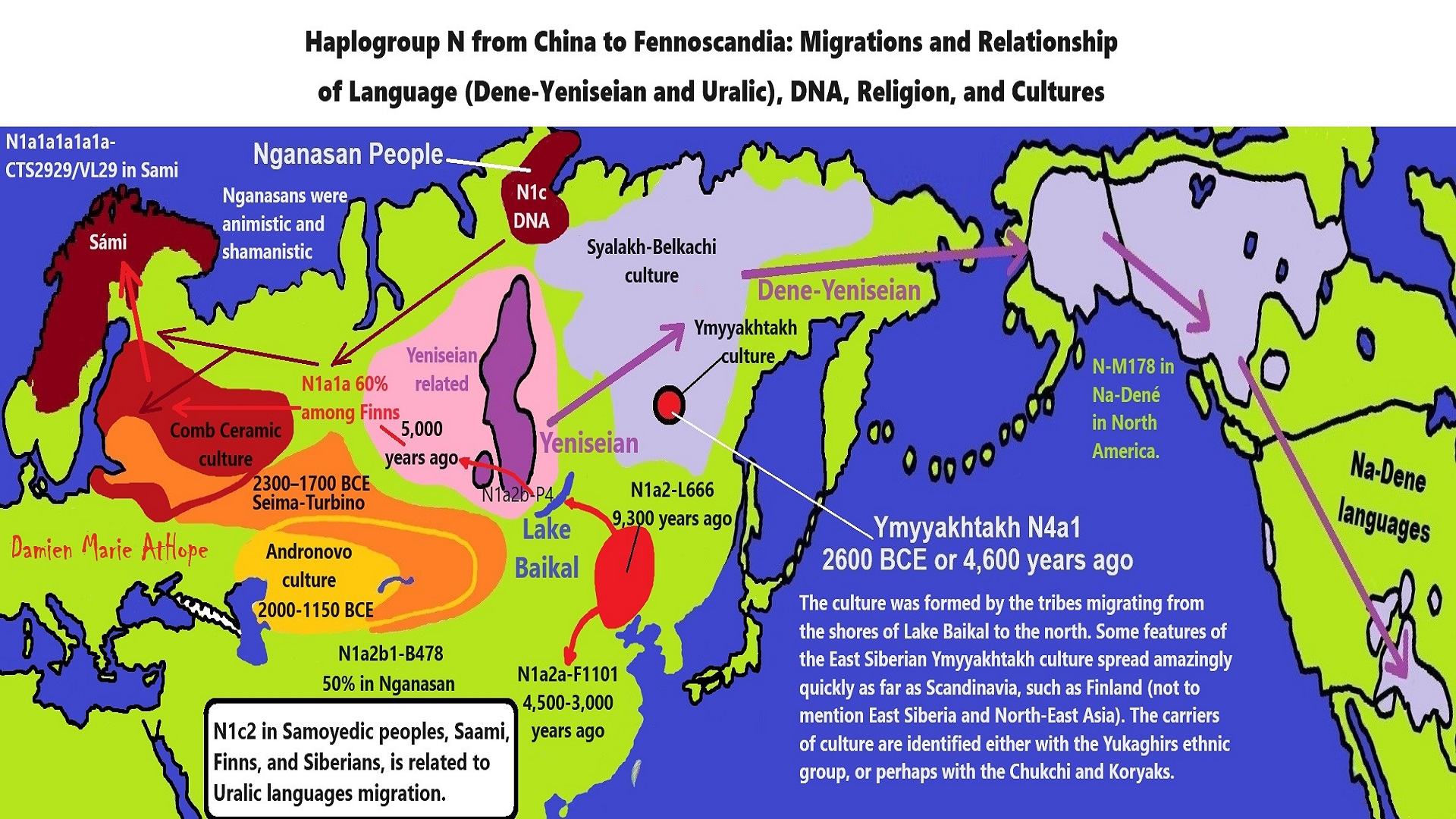

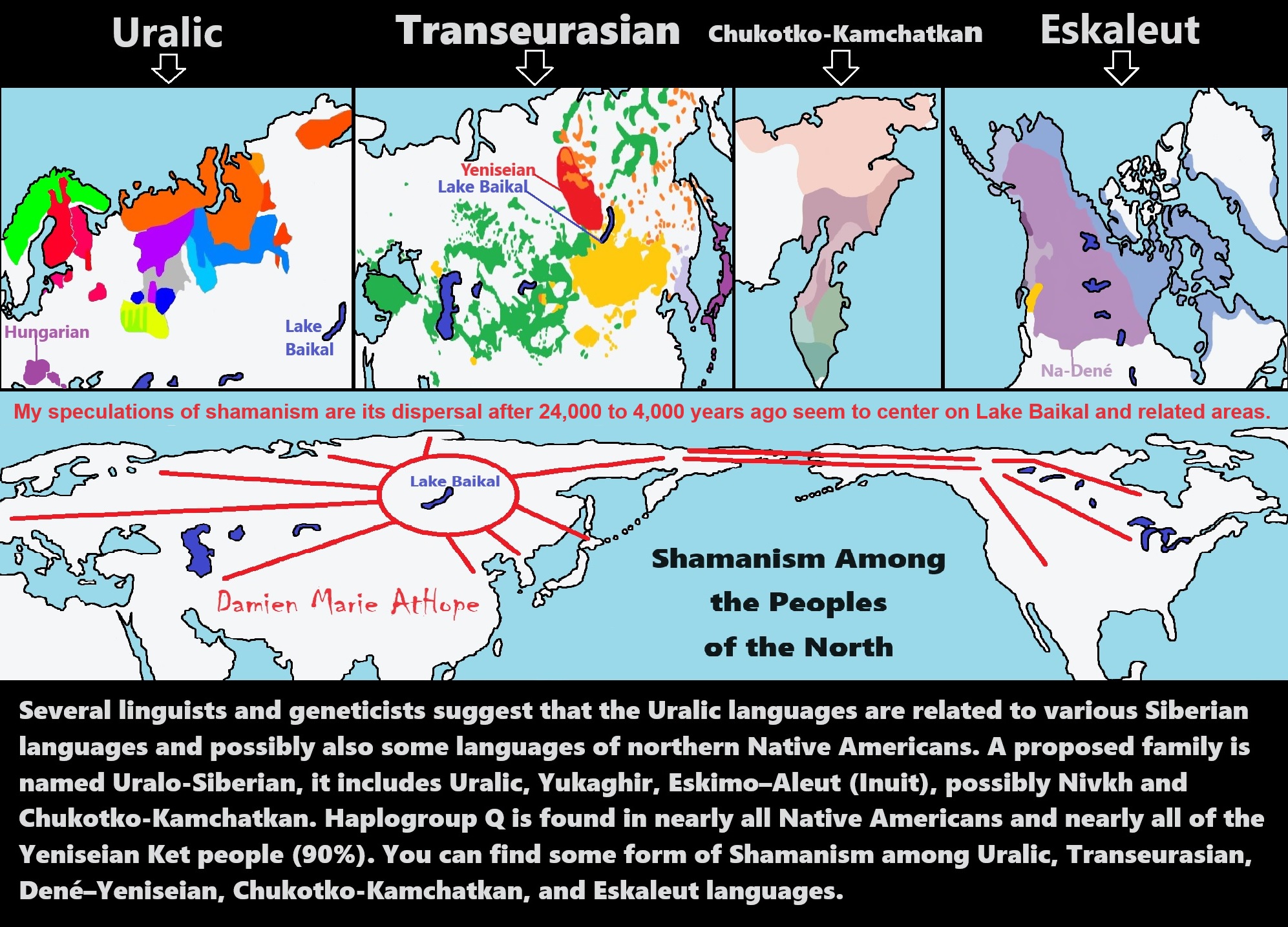

“1 central Eurasian Neolithic individual from Tajikistan (around 8,000 years ago) and approximately 8,200 years ago Yuzhniy Oleniy Ostrov group from Karelia in western Russia formed by 19 genomes affinity to Villabruna ancestry than all the other Eastern Hunter-Gatherer groups” https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-023-05726-0

Postglacial genomes from foragers across Northern Eurasia reveal prehistoric

mobility associated with the spread of the Uralic and Yeniseian languages

Abstract

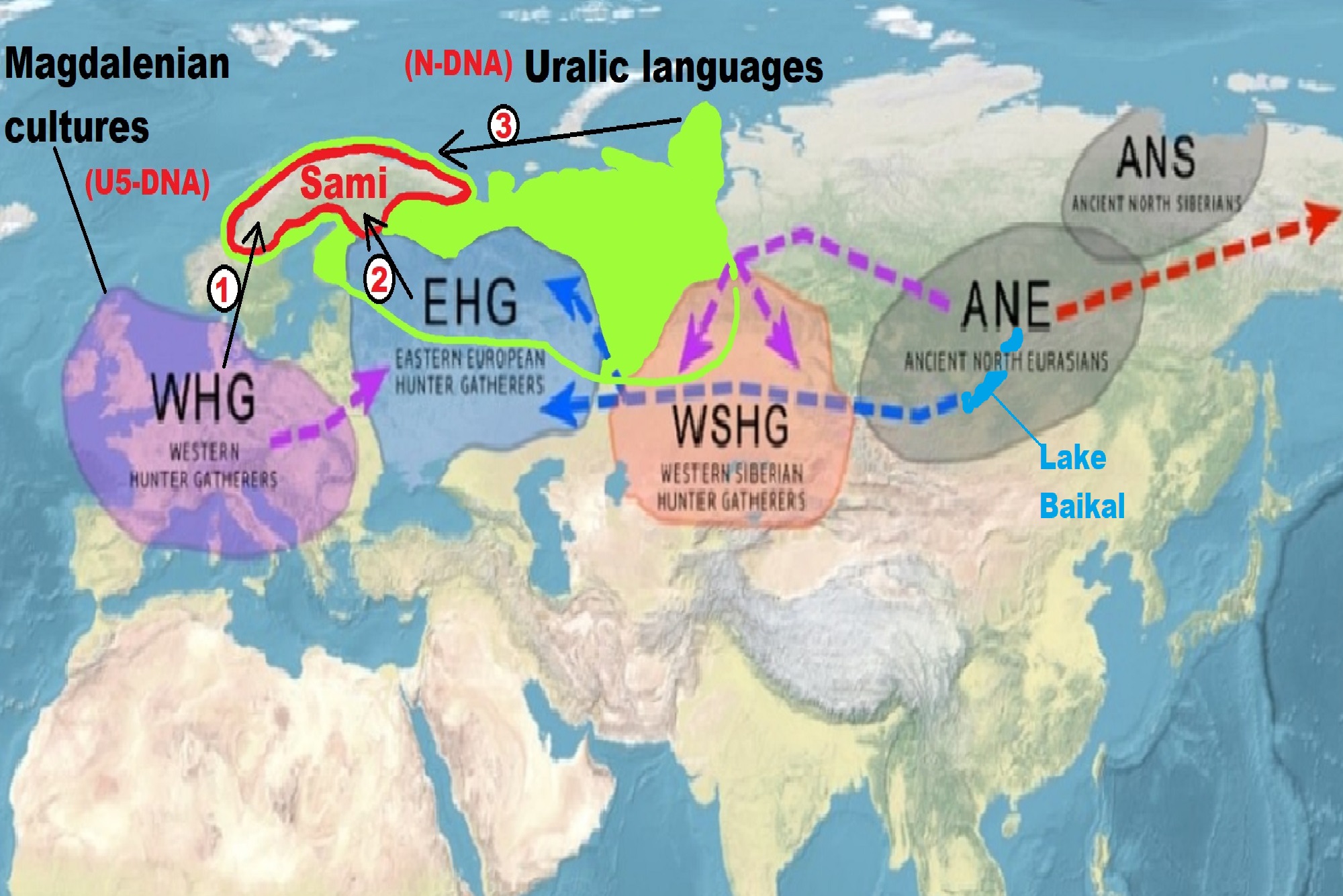

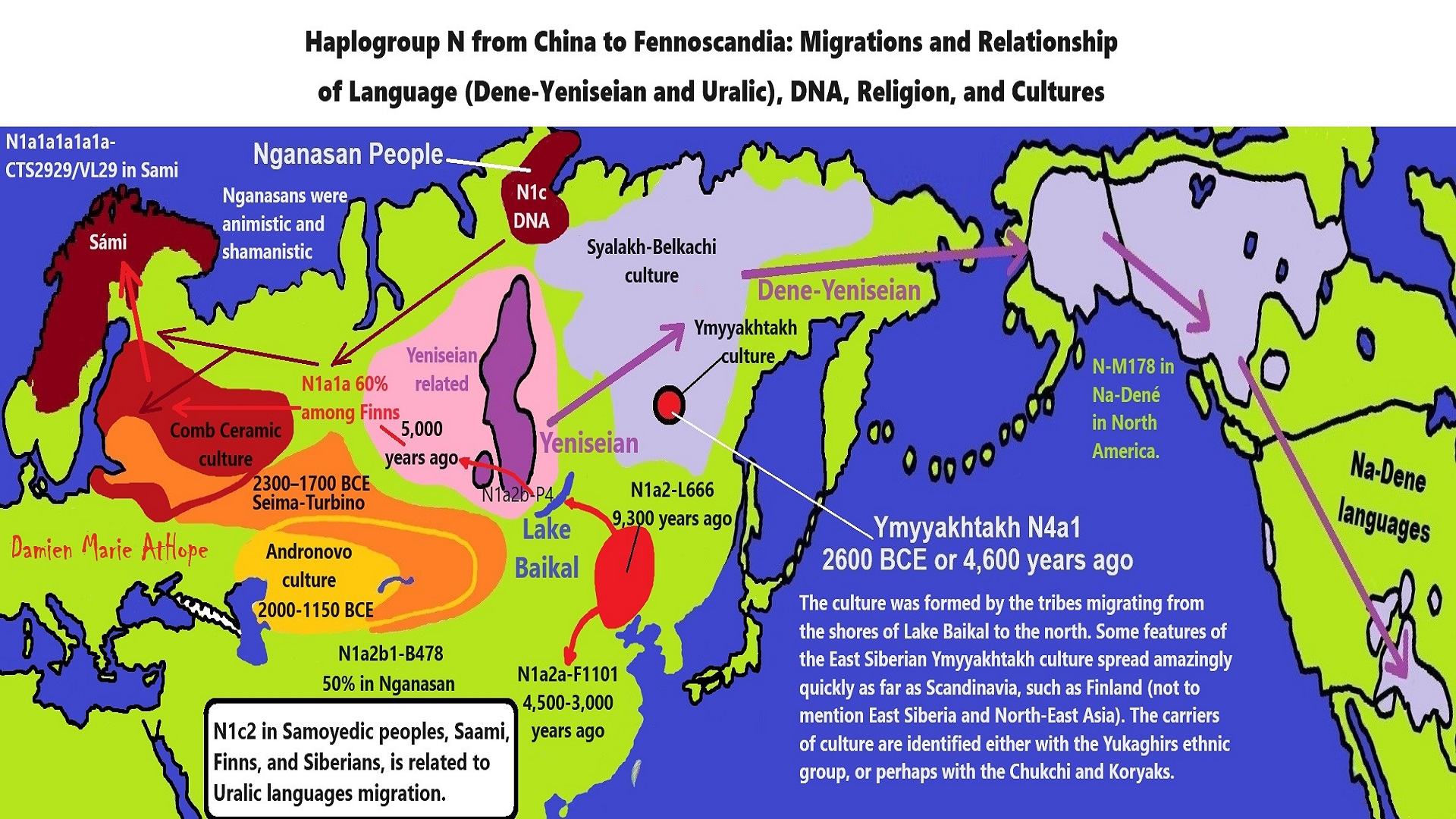

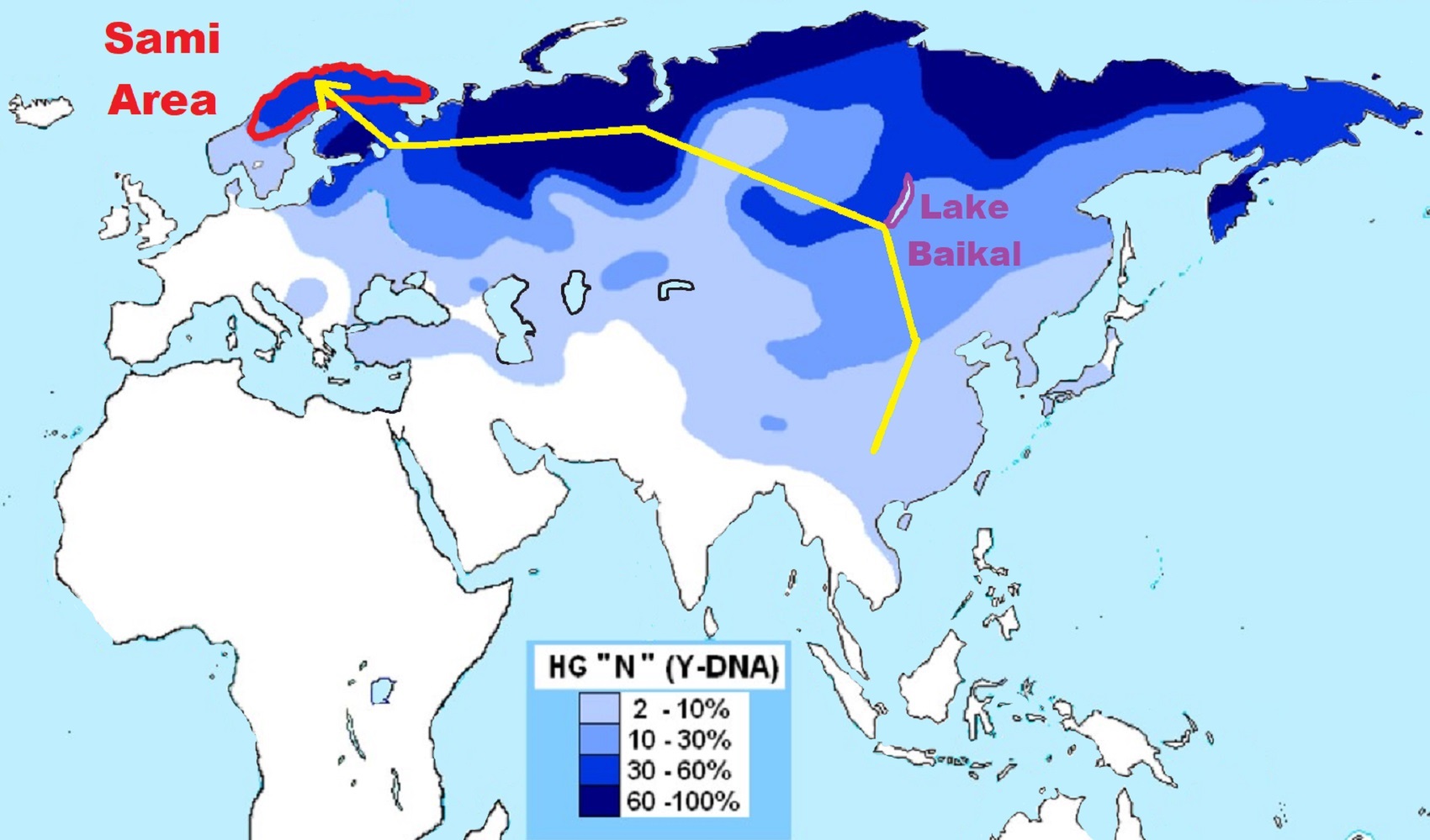

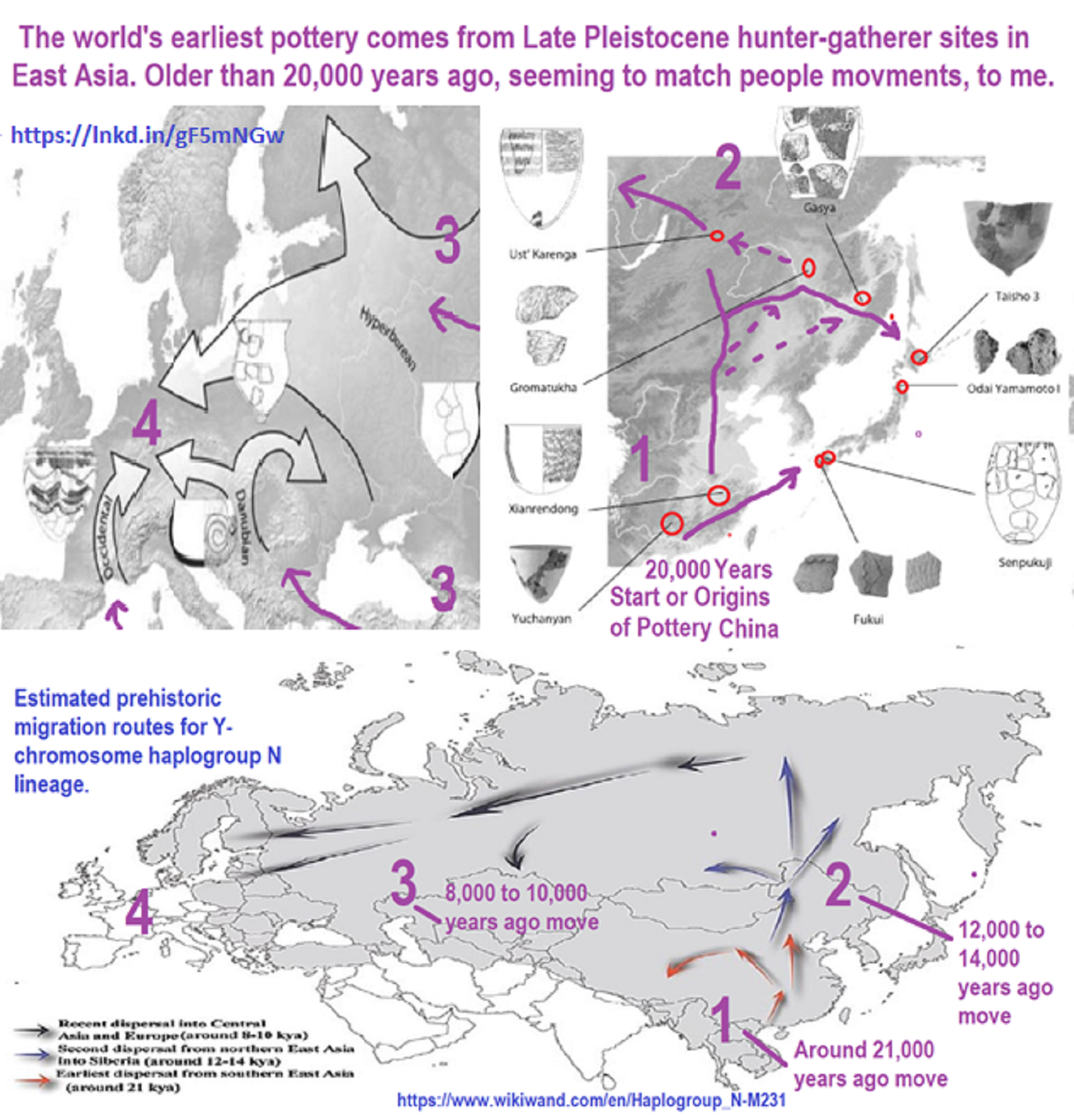

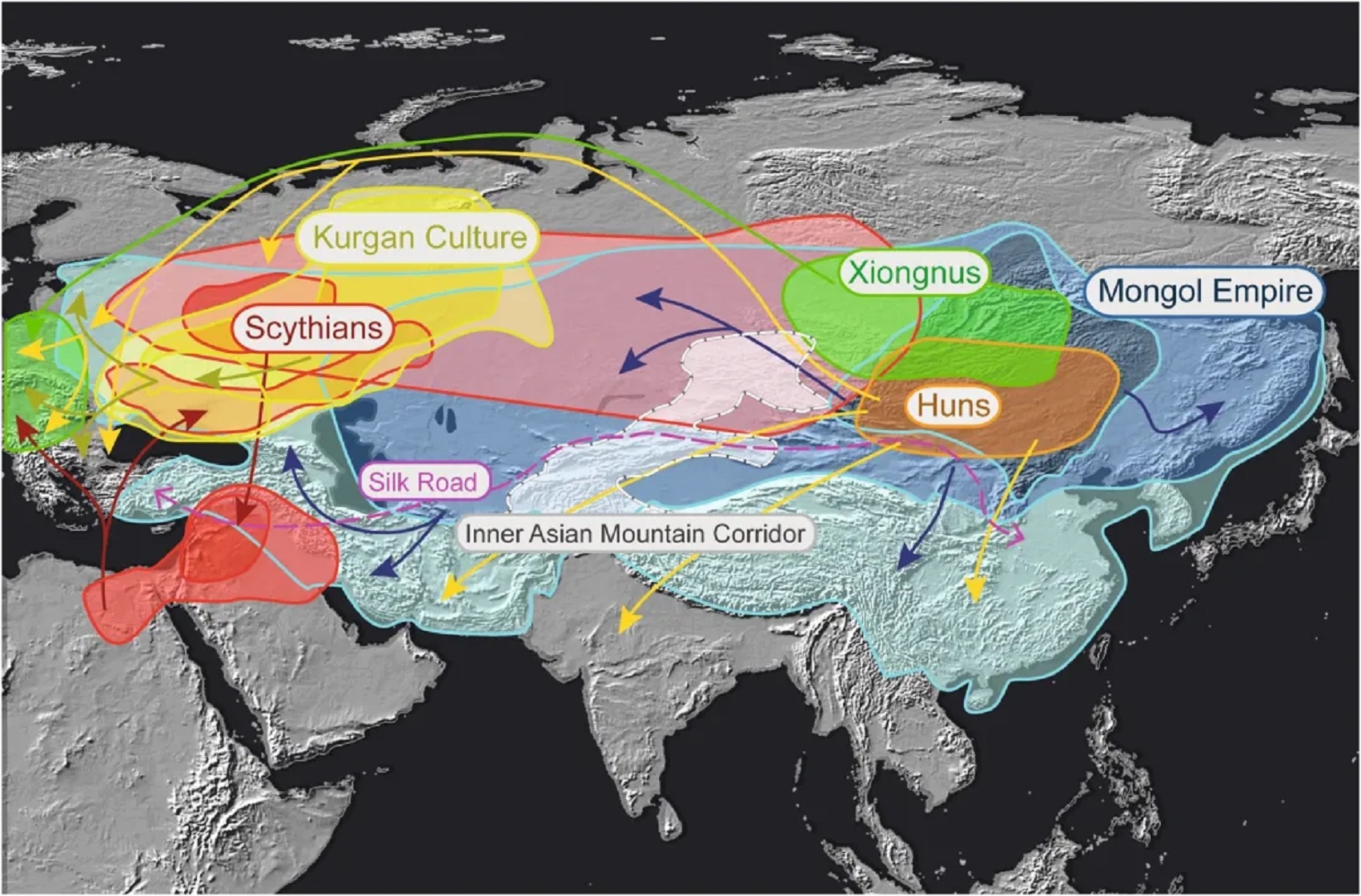

“The North Eurasian forest and forest-steppe zones have sustained millennia of sociocultural connections among northern peoples. We present genome-wide ancient DNA data for 181 individuals from this region spanning the Mesolithic, Neolithic, and Bronze Age. We find that Early to Mid-Holocene hunter-gatherer populations from across the southern forest and forest-steppes of Northern Eurasia can be characterized by a continuous gradient of ancestry that remained stable for millennia, ranging from fully West Eurasian in the Baltic region to fully East Asian in the Transbaikal region. In contrast, cotemporaneous groups in far Northeast Siberia were genetically distinct, retaining high levels of continuity from a population that was the primary source of ancestry for Native Americans. By the mid-Holocene, admixture between this early Northeastern Siberian population and groups from Inland East Asia and the Amur River Basin produced two distinctive populations in eastern Siberia that played an important role in the genetic formation of later people. Ancestry from the first population, Cis-Baikal Late Neolithic-Bronze Age (Cisbaikal_LNBA), is found substantially only among Yeniseian-speaking groups and those known to have admixed with them. Ancestry from the second, Yakutian Late Neolithic-Bronze Age (Yakutia_LNBA), is strongly associated with present-day Uralic speakers. We show how Yakutia_LNBA ancestry spread from an east Siberian origin ~4.5kya, along with subclades of Y-chromosome haplogroup N occurring at high frequencies among present-day Uralic speakers, into Western and Central Siberia in communities associated with Seima-Turbino metallurgy: a suite of advanced bronze casting techniques that spread explosively across an enormous region of Northern Eurasia ~4.0kya. However, the ancestry of the 16 Seima-Turbino-period individuals–the first reported from sites with this metallurgy–was otherwise extraordinarily diverse, with partial descent from Indo-Iranian-speaking pastoralists and multiple hunter-gatherer populations from widely separated regions of Eurasia. Our results provide support for theories suggesting that early Uralic speakers at the beginning of their westward dispersal where involved in the expansion of Seima-Turbino metallurgical traditions, and suggests that both cultural transmission and migration were important in the spread of Seima-Turbino material culture.” ref

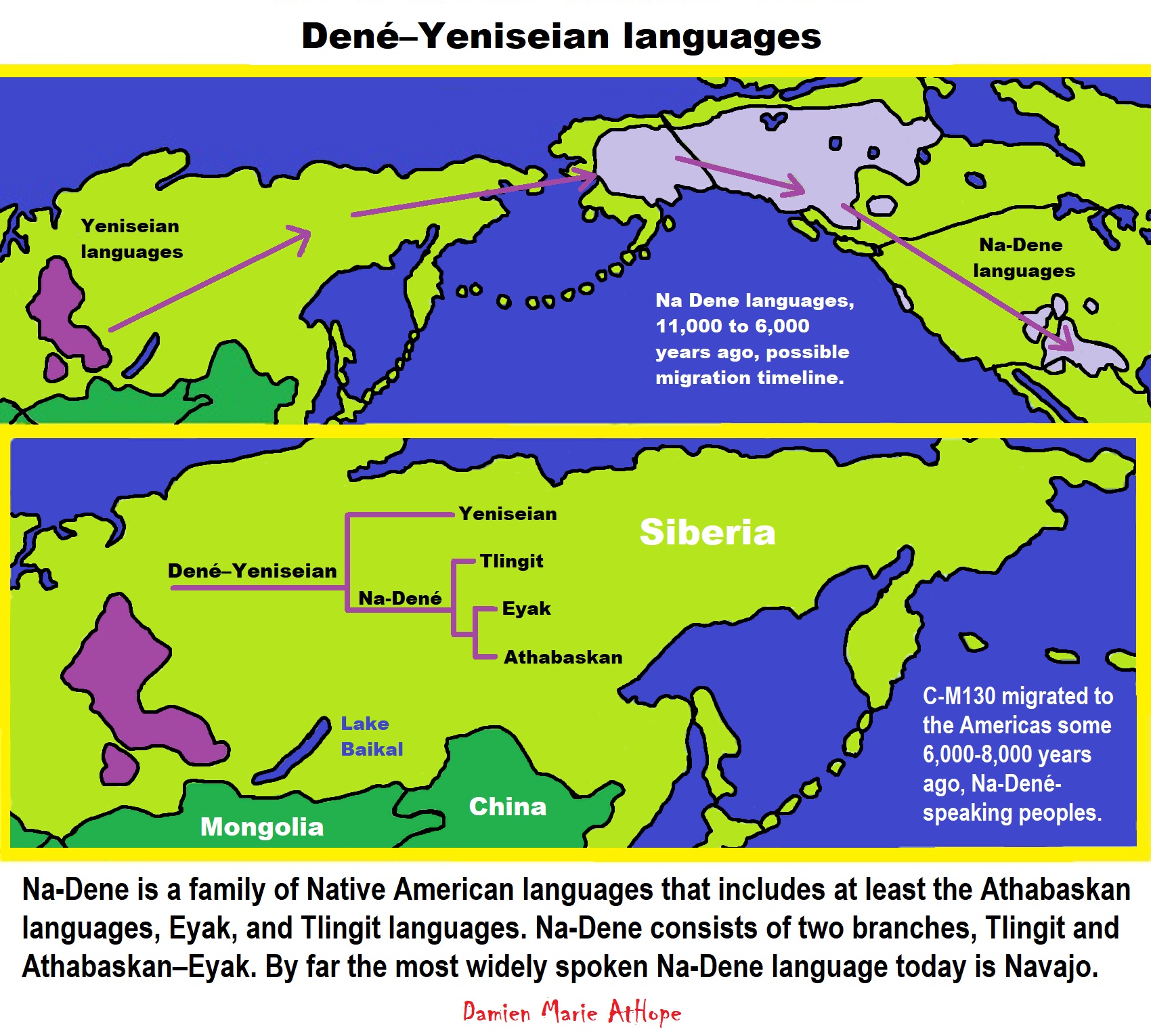

Dené–Yeniseian languages

“Dené–Yeniseian is a proposed language family consisting of the Yeniseian languages of central Siberia and the Na-Dené languages of northwestern North America. Reception among experts has been somewhat favorable; thus, Dené–Yeniseian has been called “the first demonstration of a genealogical link between Old World and New World language families that meets the standards of traditional comparative–historical linguistics“, besides the Eskaleut languages spoken in far eastern Siberia and North America.” ref

“In his 2012 presentation, Vajda also addressed non-linguistic evidence, including analyses of Y-chromosome and mitochondrial DNA haplogroups, which are passed unchanged down the male and female lines, respectively, except for mutations. His most compelling DNA evidence is the Q1 Y-chromosomal haplogroup subclade, which he notes arose c. 15,000 years ago and is found in nearly all Native Americans and nearly all of the Yeniseian Ket people (90%), but almost nowhere else in Eurasia except for the Selkup people (65%), who have intermarried with the Ket people for centuries. In his 2012 reply to George Starostin, Vajda clarifies that Dené-Yeniseian “as it currently stands is a hypothesis of language relatedness but not yet a proper hypothesis of language taxonomy”. He leaves “open the possibility that either Yeniseian or ND (or both) might have a closer relative elsewhere in Eurasia.” ref

“Using this and other evidence, he proposes a Proto-Dené-Yeniseian homeland located in eastern Siberia around the Amur and Aldan Rivers. These people would have been hunter-gatherers, as are the modern Yeniseians, but unlike, as Vajda incorrectly claims, nearly all other Siberian groups (except for some Paleosiberian peoples located around the Pacific Rim of far eastern Siberia, who appear genetically unrelated to the Yeniseians). Eventually all descendants in Eurasia were eliminated by the spread of reindeer-breeding pastoralist peoples (e.g. the speakers of the so-called Altaic languages) except for the modern Yeniseians, who were able to survive in swampy refuges far to the west along the Yenisei River because it is too mosquito-infested for reindeer to survive easily. Contrarily, the caribou (the North American reindeer population) were never domesticated, and thus the modern Na-Dené people were not similarly threatened. In fact, reindeer herding spread throughout Siberia rather recently and there were many other hunter-gatherer peoples in Siberia in modern times.” ref

“Instead of forming a separate family, Starostin believes that both Yeniseian and Na-Dené are part of a much larger grouping called Dene-Caucasian. Starostin states that the two families are related in a large sense, but there is no special relationship between them that would suffice to create a separate family between these two language families. In 2015, linguist Paul Kiparsky endorsed Dené–Yeniseian, saying that “the morphological parallelism and phonological similarities among corresponding affixes is most suggestive, but most compelling evidence for actual relationship comes from those sound correspondences which can be accounted for by independently motivated regular sound changes.” ref

“The Dene-Yeniseian hypothesis regards the Ket language spoken in the Yenisei River Basin as genetically related to the widespread Na-Dene language family in North America. Na-Dene comprises Tlingit and the recently extinct Eyak in Alaska, along with over thirty Athabaskan languages spoken from the western North American Subarctic to pockets in California (Hupa), Oregon (Tolowa) and the American Southwest (Navajo, Apache) (Krauss 1976). Pre-Proto-Na-Dene is believed to have spread from Alaska ca. 3000-2500 BCE.” ref

“Sampled Ancient Athabaskans from Alaska (ca. CE 1200) show a 30-40% contribution from Paleo-Eskimo ancestry – complementing the pre-existing ancestry of Northern First Peoples – in an admixture event estimated to have happened roughly during the formation of the Proto-Na-Dene community. To complicate things, these two Ancient Athabascan samples (together with a 19th-century one of hg. Q1b-Y4276) suggest a Y-chromosome bottleneck under Q1b-FGC8436 lineages, in common with an ancient sample (ca. AD 880) from a likely Uto-Aztecan-speaking population from San Nicolas Island, in California.” ref

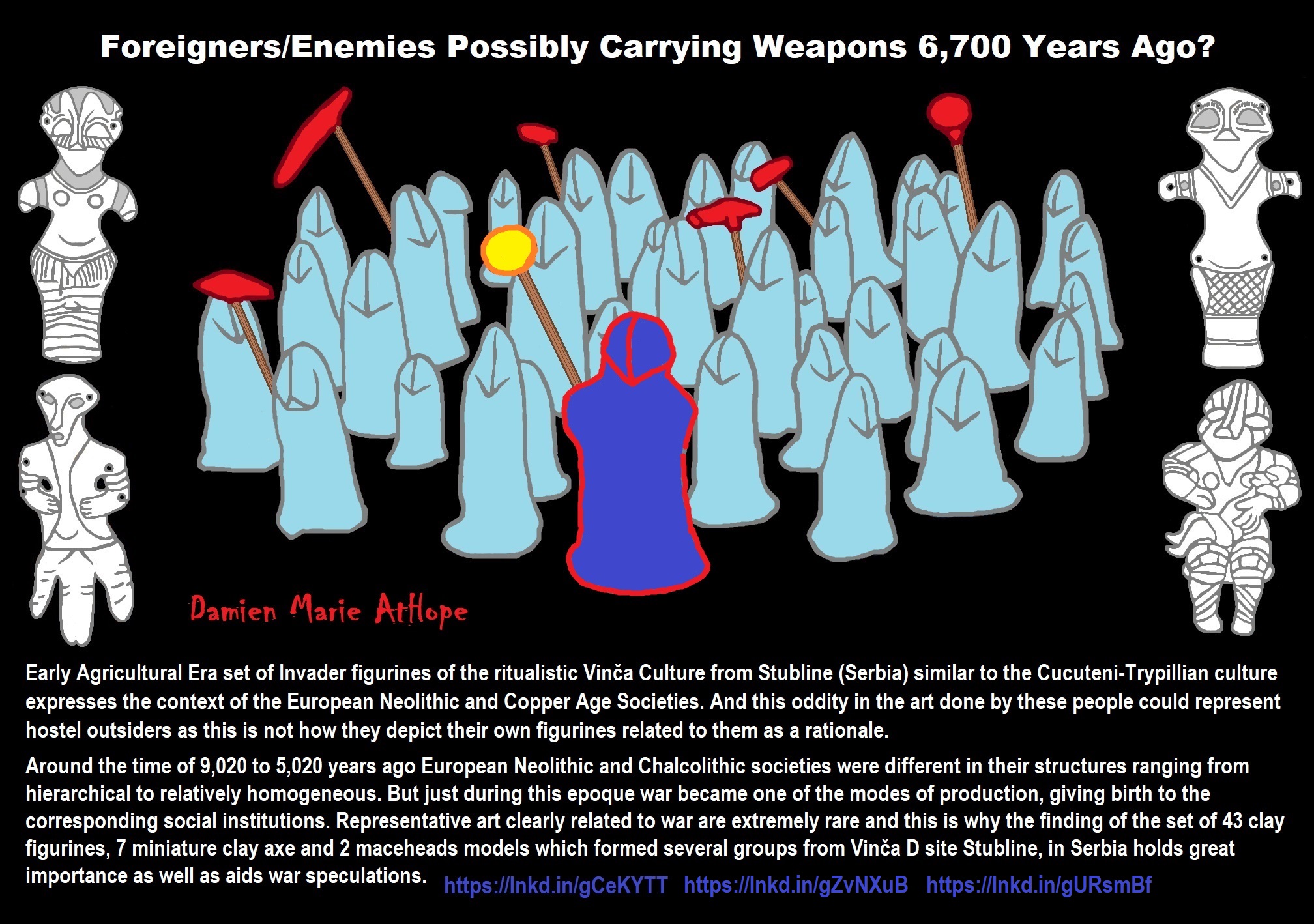

The art above is from the blog post: What is a god? Just an Empty Label.

“War became one of the modes of production during that epoch”, this is very good to know. Thank you. And lovely work. I really like the depiction of the warriors. It’s very thought-provoking and insightful.” – Commenter

My response, Those are my art of clay figurines found. Did you like the blog post, I explained a lot?

“I just clicked through just now. Wow! The effort you’ve put in is overpowering. And inspiring! I’ll be sure to start my reading with this post. And explore the rest as time permits. Thank you.” – Commenter

My response, I am honored. We rise by helping each other.

Here is me doing antitheism in public. I used to do a little atheism activism out on the street.

Religion: “Sacred Falsehoods” (untrue statements)

“How do you respond when someone condescendingly says, ‘I will pray for you’?” – Questioner

My response, I sometimes say, “Don’t waste your prayers on me, pray for all the children starving throughout the world, that your “God” seems to not care about.”

“Damien, you seem to think god is antiscience but we did call the Higgs Boson the God particle?” – Commenter

My response, The media called it that, it is not somehow proof of anything, but human superstitious language is still used because of religions giving evidenceless terms meaning they don’t deserve.

“Damian, do people from the opposite opinion talk to you?”

My response, I don’t challenge people who believe unless they claim true or ask me a question. I attack thinking not people. I just sit there with a sign and let others come to me, which they do. In all kinds of ways. It is like 80% of the people who try to talk to you during atheist activism are theists.

“Damien, what has come of your atheist activism?”

My response, I have had people lose faith, doubt their faith, still think they will use faith, or a few seemed to want to clutch faith harder. Most people who talk with me for a while, start thinking more before leaving me. I use the Hammer of Truth questions (Hammer of Truth: Investigate (ONTOLOGY), Expose (EPISTEMOLOGY), and Judge (AXIOLOGY)) to show errors in thinking and help others think better.

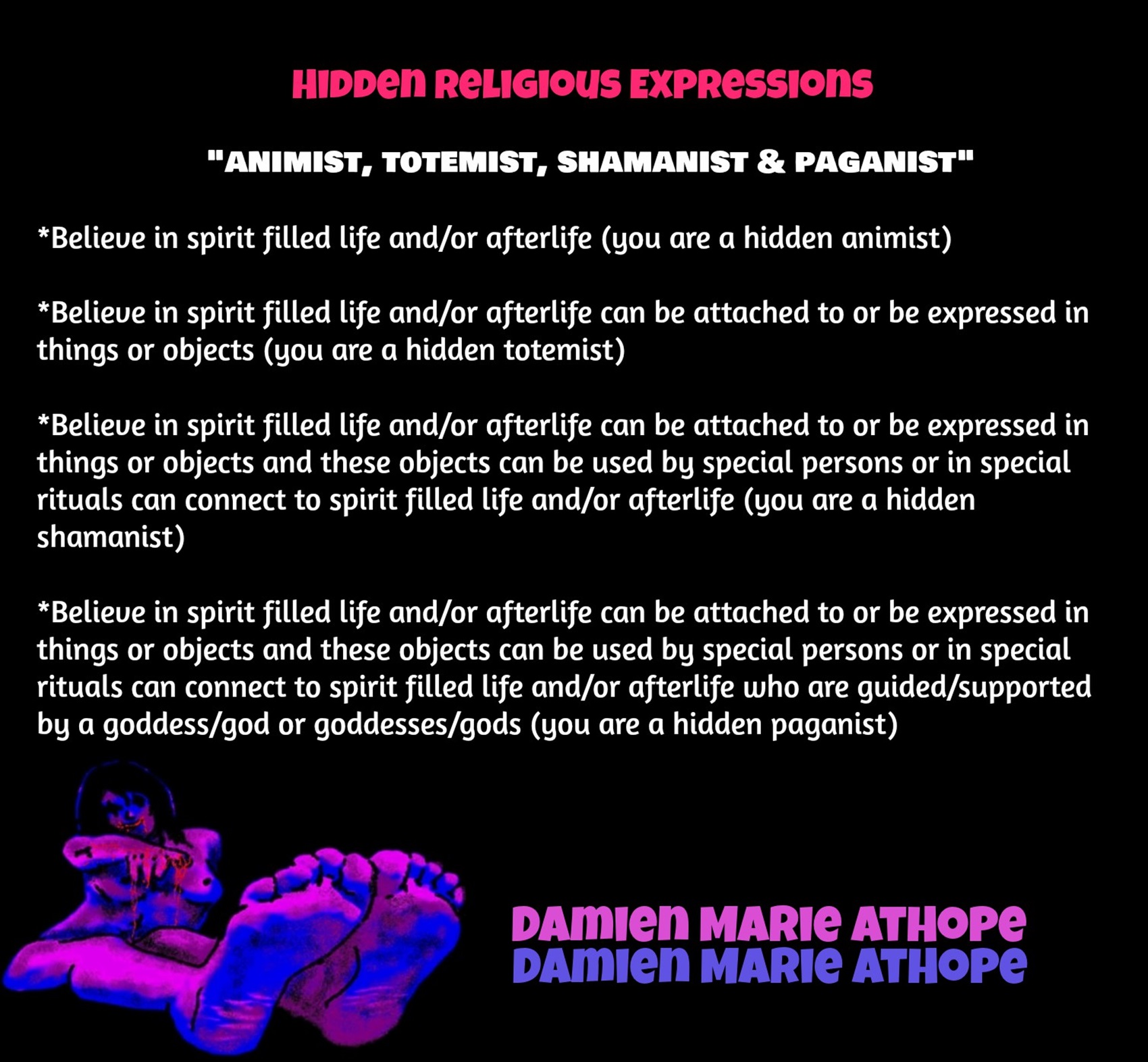

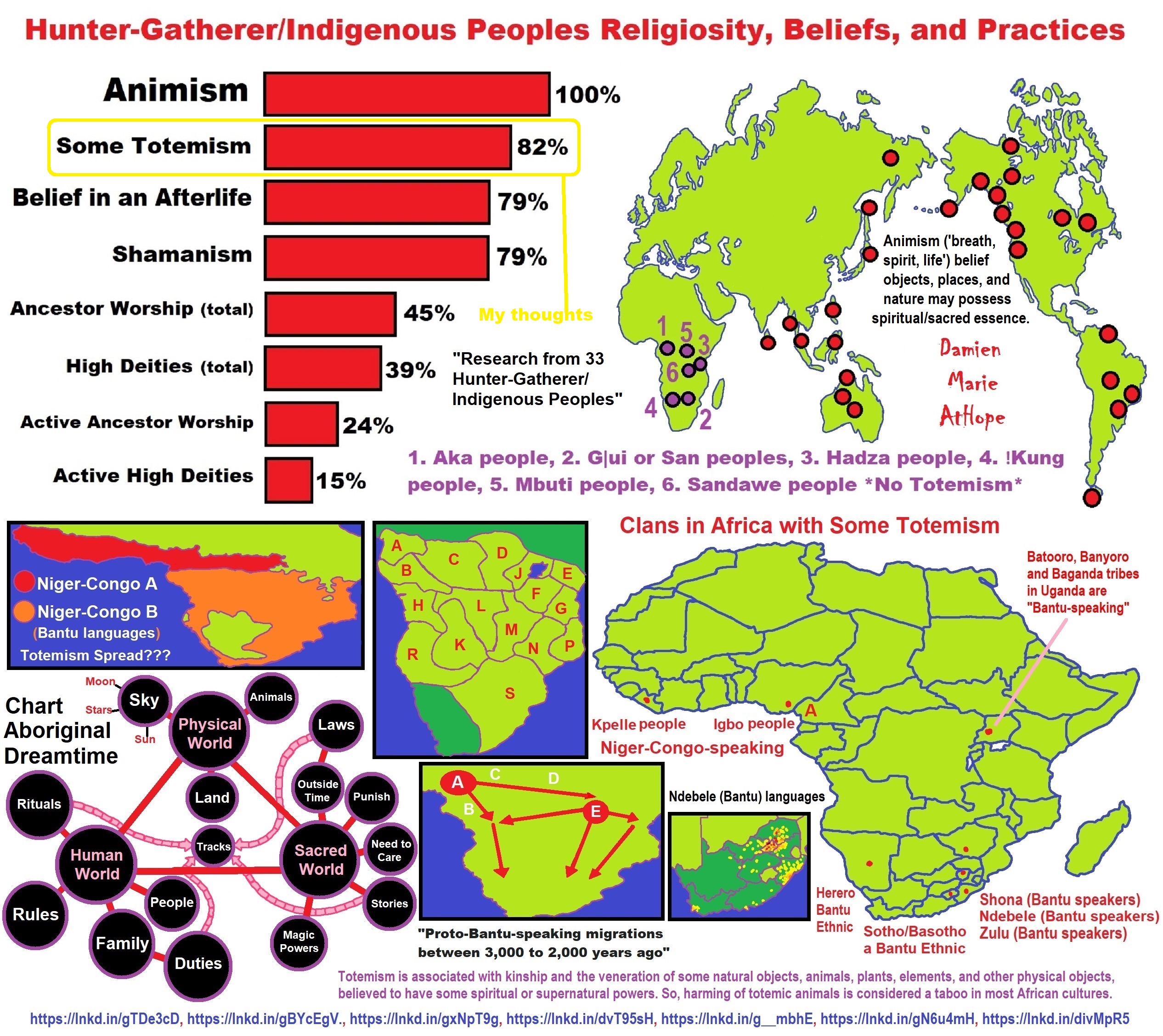

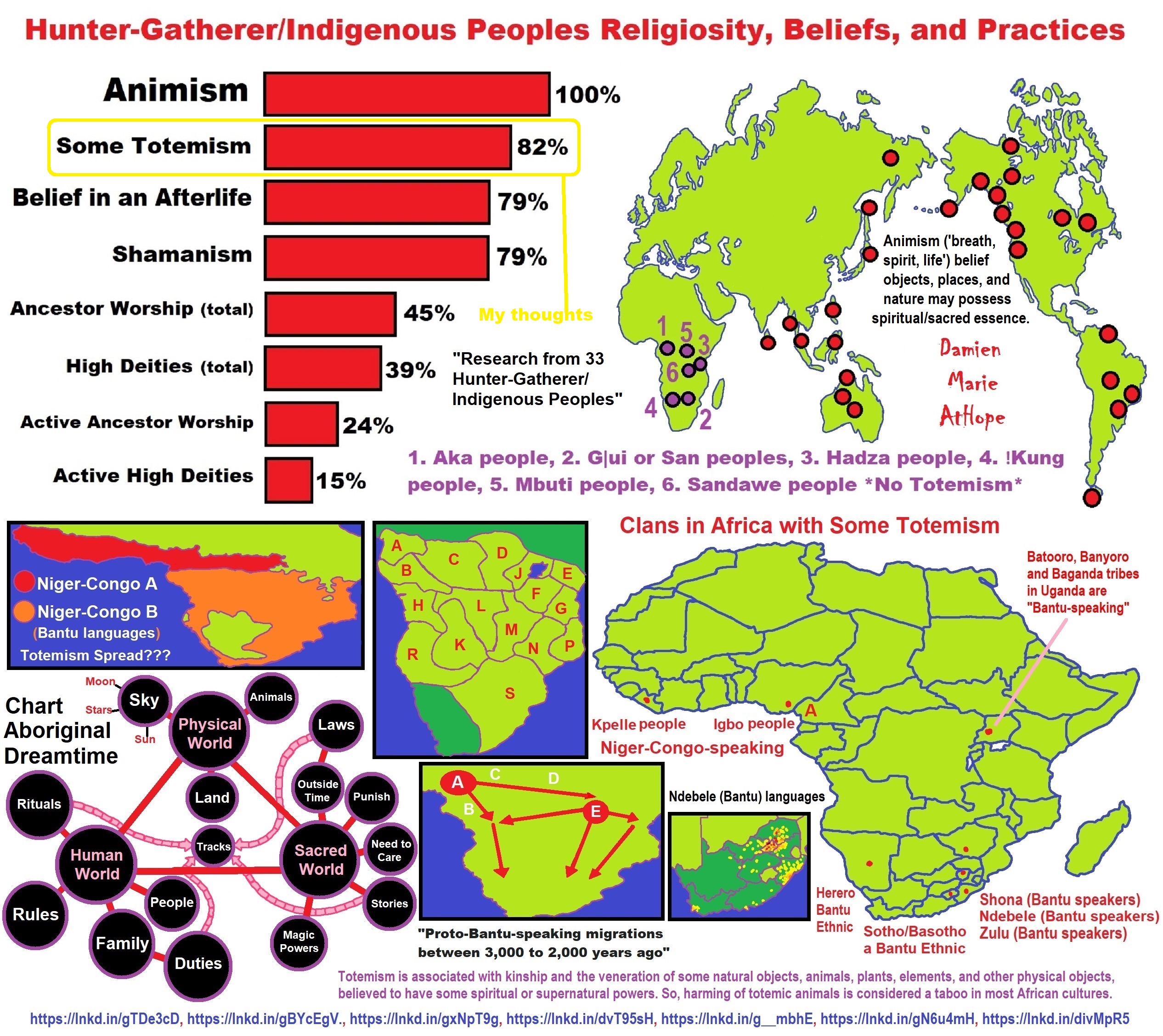

I don’t see religious terms like Animism, Totemism, Shamanism, or Paganism as primitive, but original or core elements that are different parts of world views and their supernatural/non-natural beliefs or thinking. I see all religions as having shared or similar features or core elements that relate to religious terms Animism, Totemism, Shamanism, or Paganism including Abrahamic (Judaism, Christianity, or Islam) religious thinking. I don’t class any religious thinking as primitive but in error to what I see as a natural-only world, that religious thinking then makes up a myriad of non-natural/non-empirical themes/beings, stories, and myths about which group together are called religions.

I was asked what is my favorite putdown of religious believers. Well, I don’t worry about putting anyone down, my goal is to offer info to challenge what believers think they know, hoping to change their minds. Truth rather than some fixed thing is at times but a guess, later shown accurate thus labeled knowledge or possibly seen as wrong in the sunlight of new information, requiring correction.

As an atheist, I don’t believe in gods, as an antitheist I oppose theism, and as an antireligionist, I oppose religions.

“Oppose: disapprove of and attempt to prevent, especially by argument.”

I am intelligent but don’t use it against people as some seem to do,

rather I strive to use my abilities to empower others.

I want to make a difference in the world if I can.

“Did you ever try to understand religion? Did you ever try to find superstition in it? I am tired of “atheists” giving childish descriptions of faith.” – Angel de Plata@toyman0806@mastodon.social

My response, I am more informed about religion than most people. If you want to understand what I know about religion you can check out my blog post: An Archaeological/Anthropological Understanding of Religion Evolution

My response, Please feel free to give what you see as a non-childish version of faith. “Faith: a firm belief in something for which there is no proof.” If you support faith: What makes faith reasonable or unreasonable, valuable or disvaluable, and how do you navigate between contradictory faith assumptions?

My response, “A superstition is any belief or practice considered by non-practitioners to be irrational or supernatural, attributed to fate or magic, perceived supernatural influence, or fear of that which is unknown. The word superstition is also used to refer to a religion not practiced by the majority of a given society regardless of whether the prevailing religion contains alleged superstitions or to all religions by the antireligious. The Oxford English Dictionary describes them as “irrational, unfounded”, Merriam-Webster as “a false conception about causation or belief or practice. Stuart Vyse proposes that a superstition’s “presumed mechanism of action is inconsistent with our understanding of the physical world”, and Dale Martin says they “presuppose an erroneous understanding about cause and effect, that have been rejected by modern science.” Both Vyse and Martin argue that what is considered superstitious varies across cultures and time. For Vyse, “if a culture has not yet adopted science as its standard, then what we consider magic or superstition is more accurately the local science or religion. Vyse proposes that in addition to being irrational and culturally dependent, superstitions have to be instrumental; an actual effect is expected by the person holding a belief.” ref

“Religious practices that differ from commonly accepted religions in a given culture are sometimes called superstitious; similarly, new practices brought into an established religious community can also be labeled as superstitious in an attempt to exclude them. Also, an excessive display of devoutness has often been labeled as superstitious behavior. According to Michael David Bailey, it was with Pliny’s usage that Magic came close to superstition; and charges of being superstitious were first leveled by Roman authorities on their Christian subjects. In turn, early Christian writers pronounced all Roman and Pagan cults to be superstitious, worshipping false Gods, fallen angels, and demons. It is with Christian usage that almost all forms of magic started being described as forms of superstition. In the classical era, the existence of gods was actively debated both among philosophers and theologians, and opposition to superstition arose consequently. From a simpler perspective, natural selection will tend to reinforce a tendency to generate weak associations or heuristics that are overgeneralized. If there is a strong survival advantage to making correct associations, then this will outweigh the negatives of making many incorrect, “superstitious” associations. It has also been argued that there may be connections between OCD and superstition. It is stated that superstition is at the end of the day long-held beliefs that are rooted in coincidence and/or cultural tradition rather than logic and facts.” ref

“How interesting. I just translated from English to Russian the book of Randall Price on archaeology. He is a Christian, archaeologist, and professor of archaeology at university (don’t remember what university, Wikipedia knows). I know that there are several schools of thought in modern archaeology and I am not impressed with high criticism. I can’t say much about anthropology, I haven’t met a good scholar in that field. Sorry, I don’t have time to watch your video.” – Angel de Plata@toyman0806@mastodon.social

Laich-kwil-tach

“Laich-kwil-tach (also spelled Ligwilda’xw), is the Anglicization of the Kwak’wala autonomy by the “Southern Kwakiutl” people of Quadra Island and Campbell River in British Columbia, Canada. There are today two main groups (of perhaps five original separate groups): the Wei Wai Kai (Cape Mudge Band) and Wei Wai Kum just across on the Vancouver Island “mainland” in the town of Campbell River. In addition to these two main groups there are the Kwiakah (Kwiakah Band / Kwiakah First Nation) originally from Phillips Arm and Frederick Arm and the Discovery Islands, the Tlaaluis (Laa’luls) between Bute and Loughborough Inlets—after a great war between the Kwakiutl and the Salish peoples they were so reduced in numbers that they joined the Kwiakah—and the Walitsima / Walitsum Band of Salmon River (also called Hahamatses or Salmon River Band).” ref

“So great was the power of the Southern Kwakiutl that the Comox people of the Courtenay–Comox came to speak Kwak’wala instead of K’omox, which today remains spoken by their kin the Sliammon and Homalhko on the other side of Georgia Strait around Powell River. Many of the Wewaykum in Campbell River are of Comox descent, while the Weewaikai of the Cape Mudge Band retain noble lineages and ceremonies going back centuries to their roots in the Queen Charlotte Strait. The great potlatches of the Cape Mudge chiefs are celebrated in the book Chiefly Feasts: The Enduring Kwakiutl Potlatch (A. Donaitis, U. Wash Press).” ref

“The Southern Kwakiutl remain politically separate from their distant kin, the Kwakwaka’wakw, whose name means speakers of Kwak’wala who remained in the Queen Charlotte Strait. The Kwagu’ł or Northern Kwakiutl of Fort Rupert are more closely allied and related to the Southern Kwakiutl than are the Kwakwaka’wakw. The term “Kwakiutl” has different political and historical associations with each of these groups, and has associations with one band in particular over all others, which is one reason why Kwakwaka’wakw evolved as the collective name for the main group of Queen Charlotte Strait Kwak’wala-speakers. The Southern Kwakiutl have always called themselves Laich-kwil-tach, at least since moving into the Georgia Strait.” ref

“Laich-kwil-tach raids on the southern Georgia Strait, Puget Sound, and even up the Fraser River and out into the Strait of Juan de Fuca, and northwards, are described in the annals of the early non-First Nations explorers and traders. There was one notable incident shortly after the founding of Fort Langley in which the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) staff repelled a siege by the Euclataws (i.e. the Laich-kwil-tach) with cannonades (much earning the appreciation of the beleaguered local Kwantlens). Despite the presence of Fort Langley the Laich-kwil-tach continued to raid other Sto:lo communities farther up the river.” ref

“The Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw (IPA: [ˈkʷakʷəkʲəʔwakʷ]), also known as the Kwakiutl (/ˈkwɑːkjʊtəl/; “Kwakʼwala-speaking peoples”), are one of the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast. Their current population, according to a 2016 census, is 3,665. Most live in their traditional territory on northern Vancouver Island, nearby smaller islands including the Discovery Islands, and the adjacent British Columbia mainland. Some also live outside their homelands in urban areas such as Victoria and Vancouver. They are politically organized into 13 band governments. Their language, now spoken by only 3.1% of the population, consists of four dialects of what is commonly referred to as Kwakʼwala. These dialects are Kwak̓wala, ʼNak̓wala, G̱uc̓ala and T̓łat̓łasik̓wala.” ref

“The name Kwakiutl derives from Kwaguʼł—the name of a single community of Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw located at Fort Rupert. The anthropologist Franz Boas had done most of his anthropological work in this area and popularized the term for both this nation and the collective as a whole. The term became misapplied to mean all the nations who spoke Kwakʼwala, as well as three other Indigenous peoples whose language is a part of the Wakashan linguistic group, but whose language is not Kwakʼwala. These peoples, incorrectly known as the Northern Kwakiutl, were the Haisla, Wuikinuxv, and Heiltsuk. Each Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw nation has its own clans, chiefs, history, culture, and peoples, but remains collectively similar to the rest of the Kwak̓wala-Speaking nations.” ref

“Many people who others call “Kwakiutl” consider that name a misnomer. They prefer the name Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw, which means “Kwakʼwala-speaking-peoples”. One exception is the Laich-kwil-tach at Campbell River—they are known as the Southern Kwakiutl, and their council is the Kwakiutl District Council. Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw oral history says their ancestors (ʼnaʼmima) came in the forms of animals by way of land, sea, or underground. When one of these ancestral animals arrived at a given spot, it discarded its animal appearance and became human. Animals that figure in these origin myths include the Thunderbird, his brother Kolas, the seagull, orca, grizzly bear, or chief ghost. Some ancestors have human origins and are said to come from distant places.” ref

“Historically, the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw economy was based primarily on fishing, with the men also engaging in some hunting, and the women gathering wild fruits and berries. Ornate weaving and woodwork were important crafts, and wealth, defined by slaves and material goods, was prominently displayed and traded at potlatch ceremonies. These customs were the subject of extensive study by the anthropologist Franz Boas. In contrast to most non-native societies, wealth and status were not determined by how much you had, but by how much you had to give away. This act of giving away your wealth was one of the main acts in a potlatch.” ref

“The first documented contact with Europeans was with Captain George Vancouver in 1792. Disease, which developed as a result of direct contact with European settlers along the West Coast of Canada, drastically reduced the Indigenous Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw population during the late 19th-early 20th century. Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw population dropped by 75% between 1830 and 1880. The 1862 Pacific Northwest smallpox epidemic alone killed over half of the people. Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw dancers from Vancouver Island performed at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago.” ref

“An account of experiences of two founders of early residential schools for Aboriginal children was published in 2006 by the University of British Columbia Press. Good Intentions Gone Awry – Emma Crosby and the Methodist Mission On the Northwest Coast by Jan Hare and Jean Barman contains the letters and account of the life of the wife of Thomas Crosby the first missionary in Lax Kwʼalaams (Port Simpson). This covers the period from 1870 to the turn of the 20th century.” ref

“A second book was published in 2005 by the University of Calgary Press, The Letters of Margaret Butcher – Missionary Imperialism on the North Pacific Coast edited by Mary-Ellen Kelm. It picks up the story from 1916 to 1919 in Kitamaat Village and details of Butcher’s experiences among the Haisla people. A review article entitled Mothers of a Native Hell about these two books was published in the British Columbia online news magazine The Tyee in 2007.” ref

“Restoring their ties to their land, culture and rights, the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw have undertaken much in bringing back their customs, beliefs and language. Potlatches occur more frequently as families reconnect to their birthright, and the community uses language programs, classes and social events to restore the language. Artists in the 19th and 20th centuries, such as Mungo Martin, Ellen Neel, and Willie Seaweed have taken efforts to revive Kwakwakaʼwakw art and culture.” ref

“Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw kinship is based on a bilinear structure, with loose characteristics of a patrilineal culture. It has large extended families and interconnected community life. The Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw are made up of numerous communities or bands. Within those communities they are organized into extended family units or naʼmima, which means ‘of one kind’. Each naʼmima had positions that carried particular responsibilities and privileges. Each community had around four naʼmima, although some had more, some had less.” ref

“Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw follow their genealogy back to their ancestral roots. A head chief who, through primogeniture, could trace his origins to that naʼmima‘s ancestors delineated the roles throughout the rest of his family. Every clan had several sub-chiefs, who gained their titles and position through their own family’s primogeniture. These chiefs organized their people to harvest the communal lands that belonged to their family.” ref

“Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw society was organized into four classes: the nobility, attained through birthright and connection in lineage to ancestors, the aristocracy who attained status through connection to wealth, resources or spiritual powers displayed or distributed in the potlatch, commoners, and slaves. On the nobility class, “the noble was recognized as the literal conduit between the social and spiritual domains, birthright alone was not enough to secure rank: only individuals displaying the correct moral behavior [sic] throughout their life course could maintain ranking status.” ref

“As in other Northwest Coast peoples, the concept of property was well developed and important to daily life. Territorial property such as hunting or fishing grounds was inherited, and from these properties material wealth was collected and stored. A trade and barter subsistence economy formed the early stages of the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw economy. Trade was carried out between internal Kwakwakaʼwakw nations, as well as surrounding Indigenous nations such as the Tsimshian, Tlingit, the Nuu-chah-nulth, and Coast Salish peoples.” ref

“Over time, the potlatch tradition created a demand for stored surpluses, as such a display of wealth had social implications. By the time of European colonialism, it was noted that wool blankets had become a form of common currency. In the potlatch tradition, hosts of the potlatch were expected to provide enough gifts for all the guests invited. This practice created a system of loan and interest, using wool blankets as currency. As with other Pacific Northwest nations, the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw highly valued copper in their economy and used it for ornament and precious goods.” ref

“Scholars have proposed that prior to trade with Europeans, the people acquired copper from natural copper veins along riverbeds, but this has not been proven. Contact with European settlers, particularly through the Hudson’s Bay Company, brought an influx of copper to their territories. The Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw nations also were aware of silver and gold, and crafted intricate bracelets and jewellery from hammered coins traded from European settlers. Copper was given a special value amongst the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw, most likely for its ceremonial purposes. This copper was beaten into sheets or plates, and then painted with mythological figures. The sheets were used for decorating wooden carvings or kept for the sake of prestige.” ref

“Individual pieces of copper were sometimes given names based on their value. The value of any given piece was defined by the number of wool blankets last traded for them. In this system, it was considered prestigious for a buyer to purchase the same piece of copper at a higher price than it was previously sold, in their version of an art market. During potlatch, copper pieces would be brought out, and bids were placed on them by rival chiefs. The highest bidder would have the honor of buying said copper piece. If a host still held a surplus of copper after throwing an expensive potlatch, he was considered a wealthy and important man. Highly ranked members of the communities often have the Kwakʼwala word for “copper” as part of their names.” ref

“Copper’s importance as an indicator of status also led to its use in a Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw shaming ritual. The copper cutting ceremony involved breaking copper plaques. The act represents a challenge; if the target cannot break a plaque of equal or greater value, he or she is shamed. The ceremony, which had not been performed since the 1950s, was revived by chief Beau Dick in 2013, as part of the Idle No More movement. He performed a copper cutting ritual on the lawn of the British Columbia Legislature on February 10, 2013, to ritually shame the Stephen Harper government.” ref

“The Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw are a highly stratified bilineal culture of the Pacific Northwest. They are many separate nations, each with its own history, culture and governance. The Nations commonly each had a head chief, who acted as the leader of the nation, with numerous hereditary clan or family chiefs below him. In some of the nations, there also existed Eagle Chiefs, but this was a separate society within the main society and applied to the potlatching only.” ref

“The Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw are one of the few bilineal cultures. Traditionally the rights of the family would be passed down through the paternal side, but in rare occasions, the rights could pass on the maternal side of their family also. Within the pre-colonization times, the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw were organized into three classes: nobles, commoners, and slaves. The Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw shared many cultural and political alliances with numerous neighbors in the area, including the Nuu-chah-nulth, Heiltsuk, Wuikinuxv, and some Coast Salish.” ref

“The Kwakʼwala language is a part of the Wakashan language group. Word lists and some documentation of Kwakʼwala were created from the early period of contact with Europeans in the 18th century, but a systematic attempt to record the language did not occur before the work of Franz Boas in the late 19th and early 20th century. The use of Kwakʼwala declined significantly in the 19th and 20th centuries, mainly due to the assimilationist policies of the Canadian government. Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw children were forced to attend residential schools, which enforced English use and discouraged other languages. Although Kwakʼwala and Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw culture have been well-studied by linguists and anthropologists, these efforts did not reverse the trends leading to language loss. According to Guy Buchholtzer, “The anthropological discourse had too often become a long monologue, in which the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw had nothing to say.” ref

“As a result of these pressures, there are relatively few Kwakʼwala speakers today. Most remaining speakers are past the age of child-rearing, which is considered a crucial stage for language transmission. As with many other Indigenous languages, there are significant barriers to language revitalization. Another barrier separating new learners from the native speaker is the presence of four separate orthographies; the young are taught Uʼmista or NAPA, while the older generations generally use Boaz, developed by the American anthropologist Franz Boas. A number of revitalization efforts are underway. A 2005 proposal to build a Kwakwakaʼwakw First Nations Centre for Language Culture has gained wide support. A review of revitalization efforts in the 1990s showed that the potential to fully revitalize Kwakʼwala still remained, but serious hurdles also existed.” ref

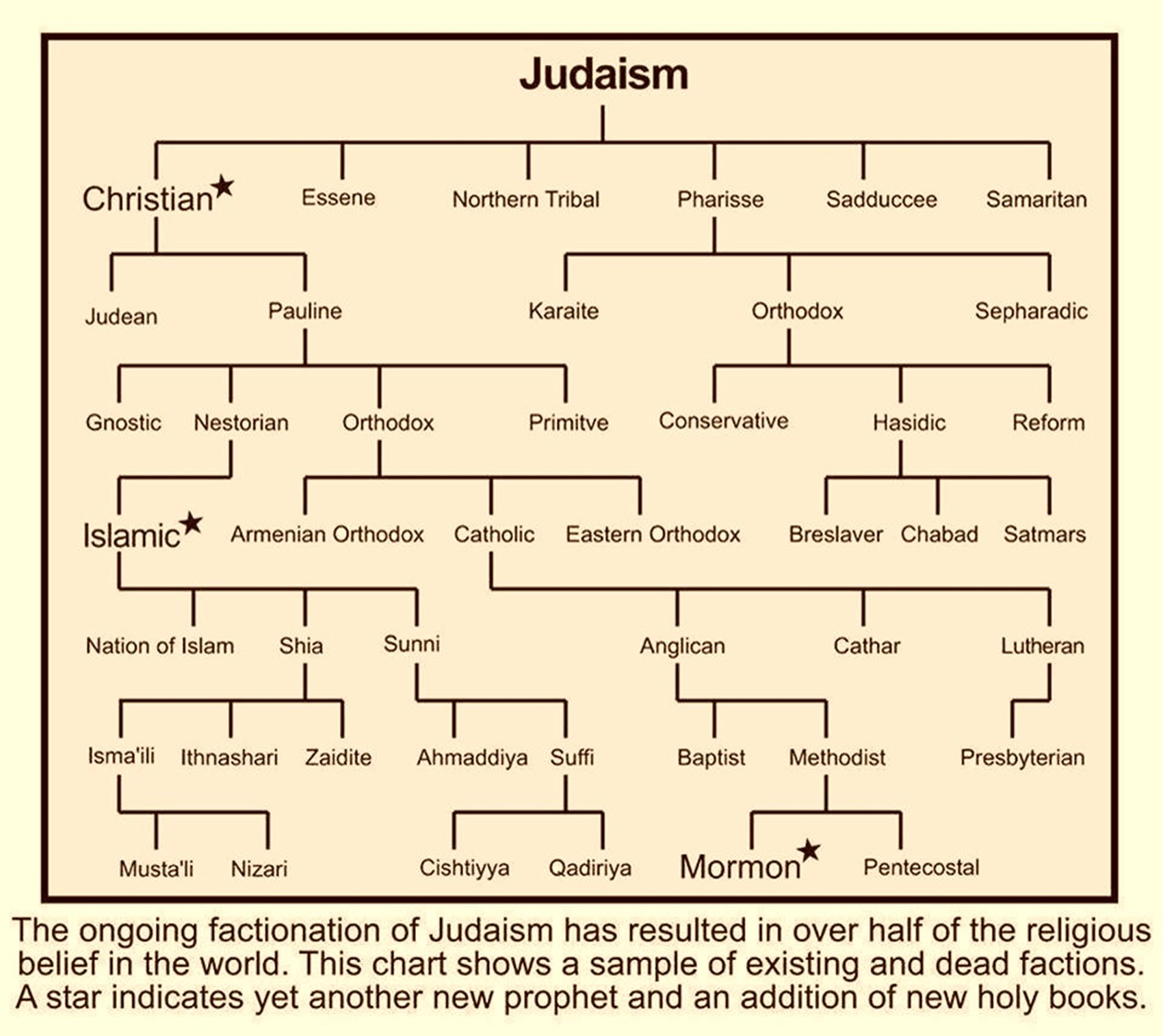

What branch of Judaism are you or were you? I was a Christian but am now an atheist. lol

“So, who created god?” – Atheist Girl @iamAtheistGirl

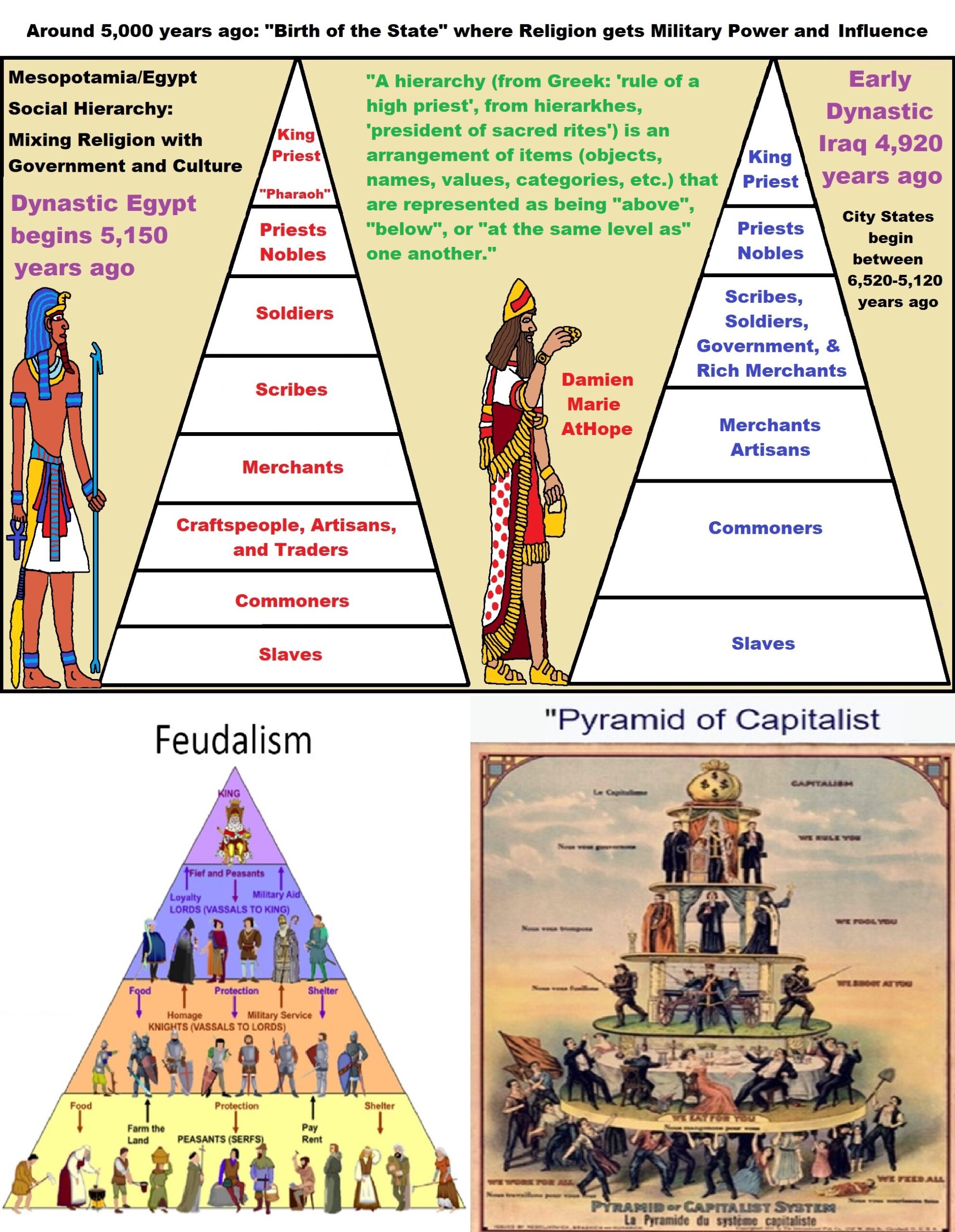

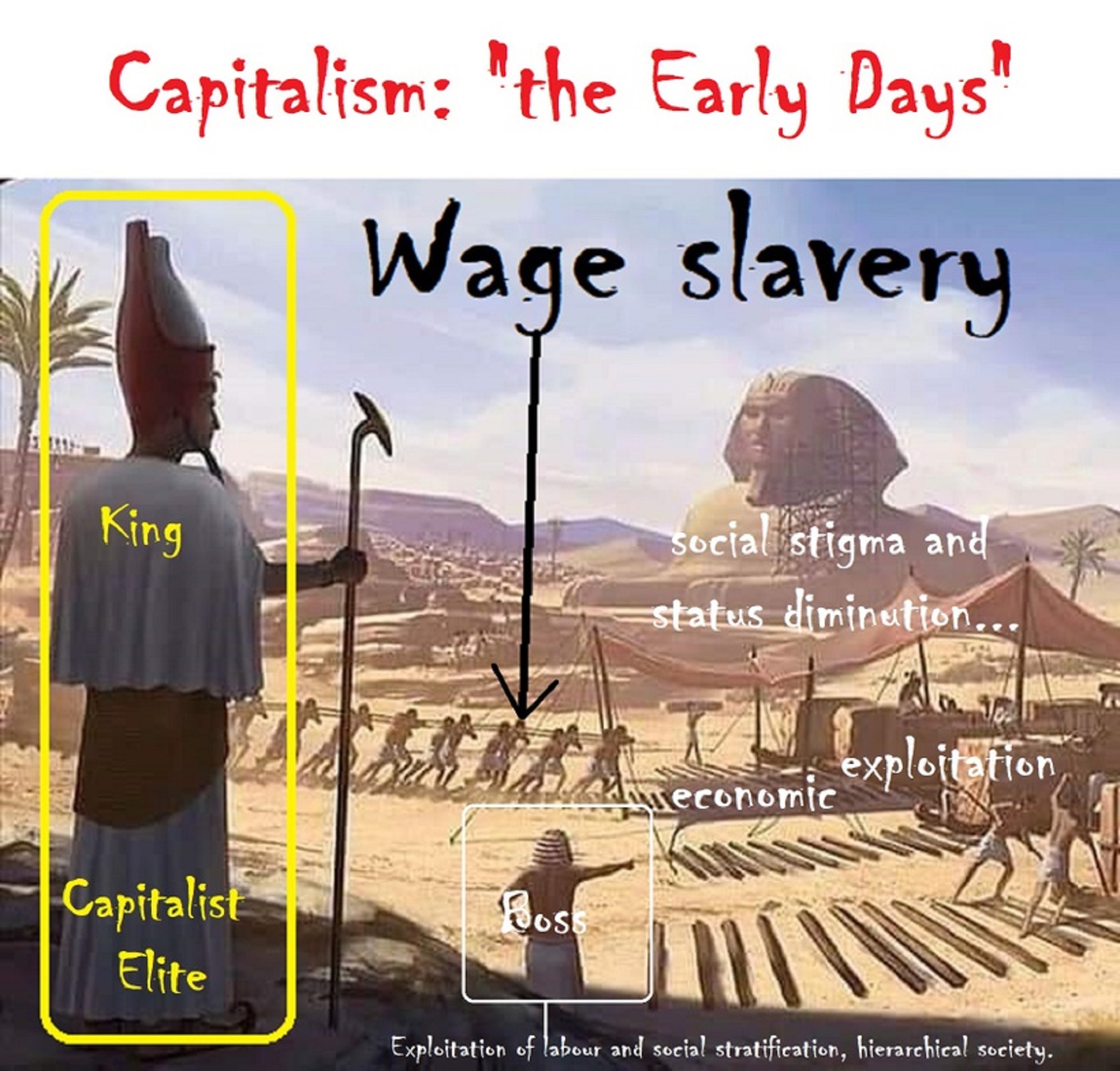

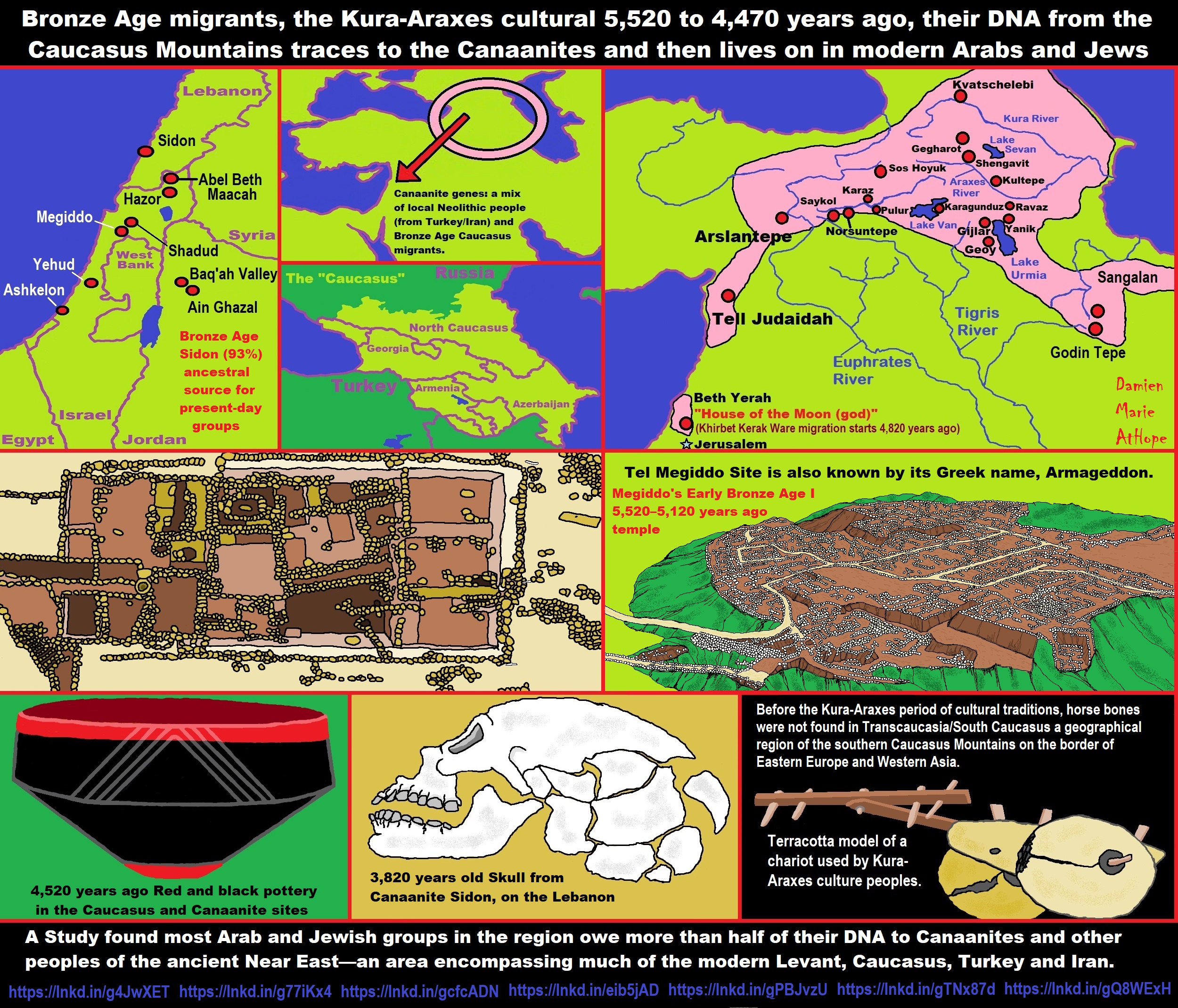

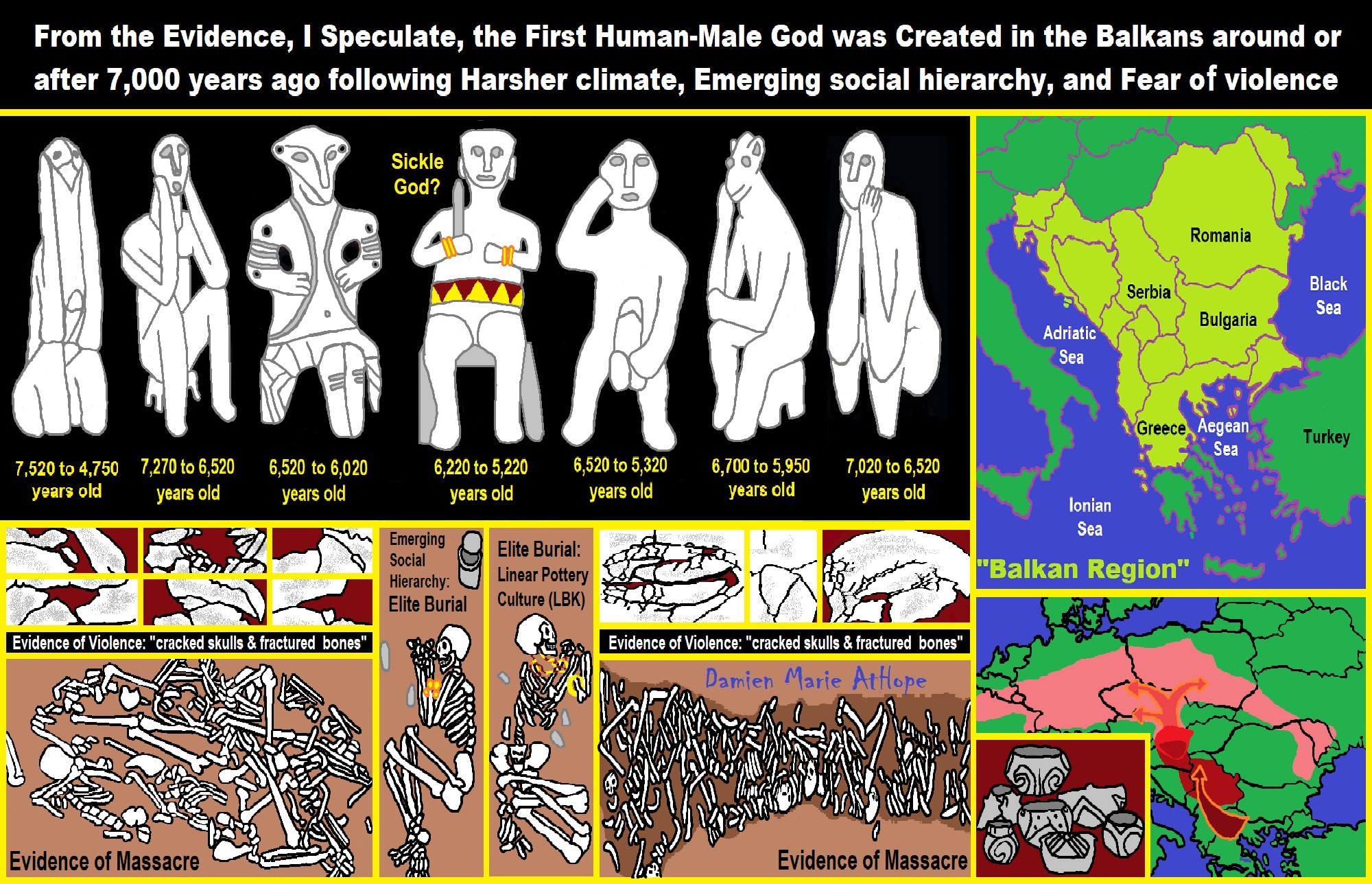

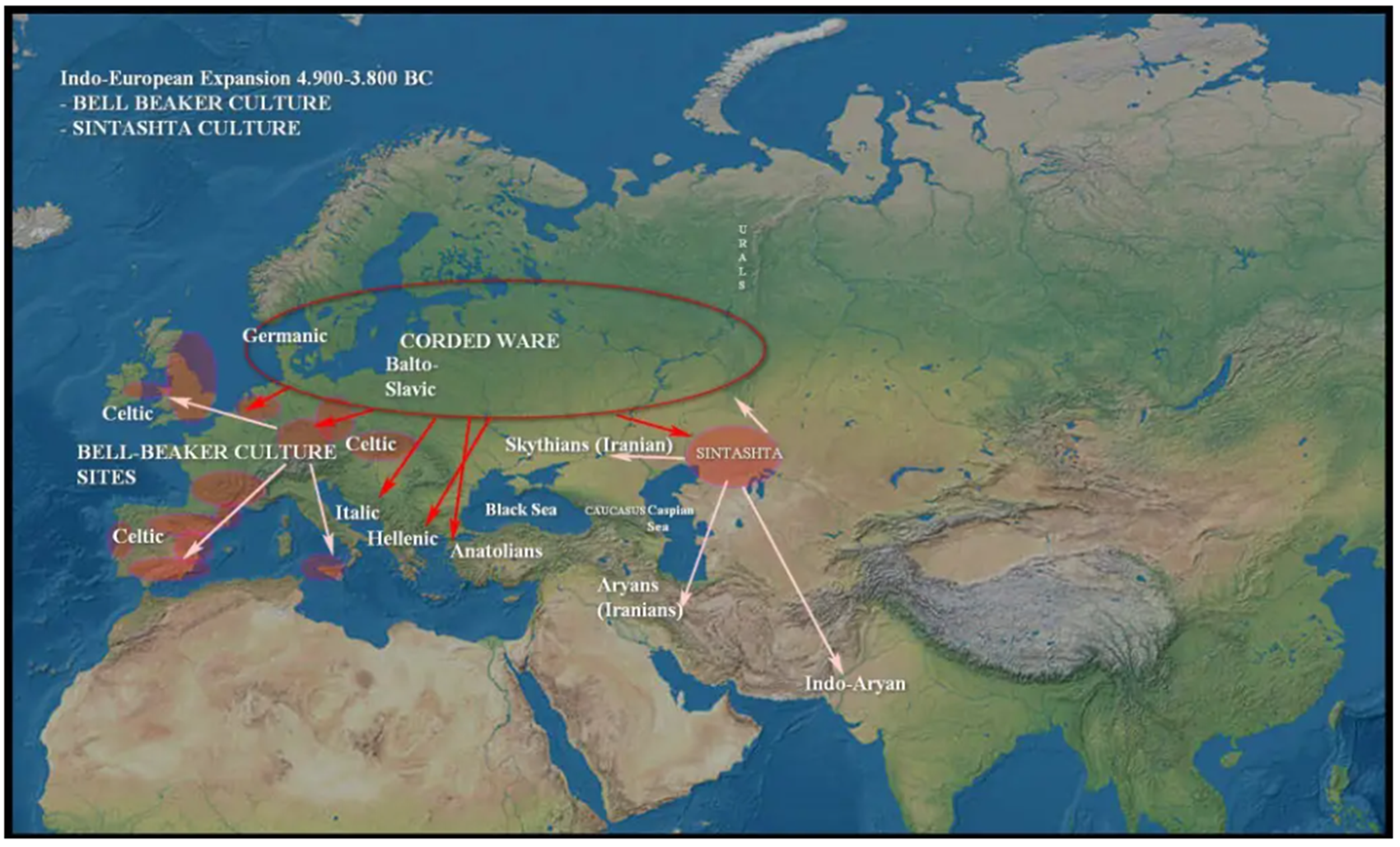

My response, Male clan wars around 7,000 years ago likely inspired the rise of the male god, sexism, organized slavery, and mass murder. These wars went from 7,000 to 5,000 years ago, ending in the birth of the State when religion got a military and extreme power.

Anarchist Schools/Anarchist Education?

“In 1904, the anarchist activist Francisco Ferrer established the Escuela Moderna (Modern School) in Barcelona. In the school’s prospectus, he declared: ‘I will teach them only the simple truth. I will not ram a dogma into their heads. I will not conceal from them one iota of fact. I will teach them not what to think but how to think’.” ref

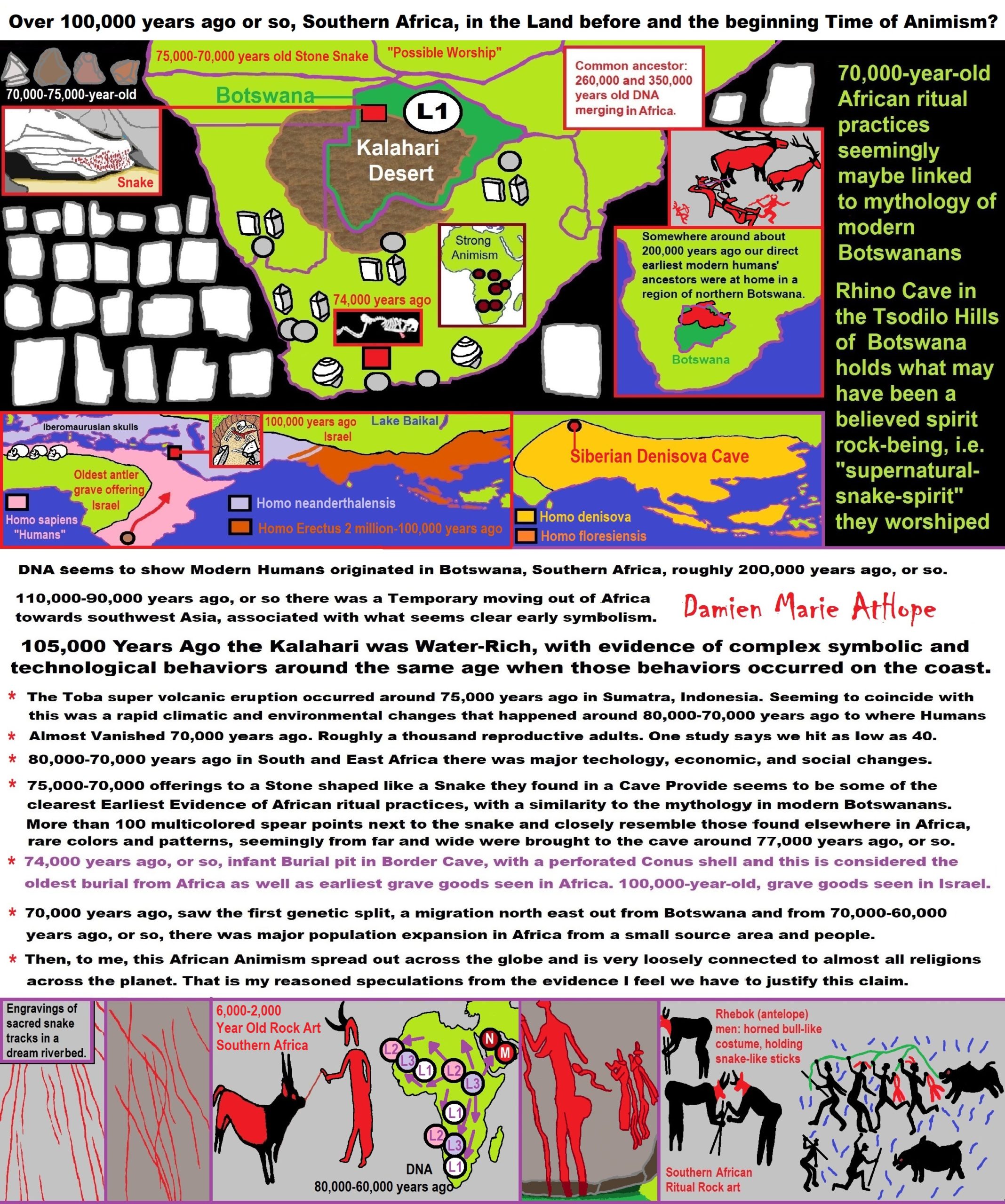

My response, Religion, to me, started in Animism around 100,000 years ago. Animism is basically the belief that non-alive things have lifelike qualities/spirits and are therefore maybe capable of having feelings, intentions, and emotions.

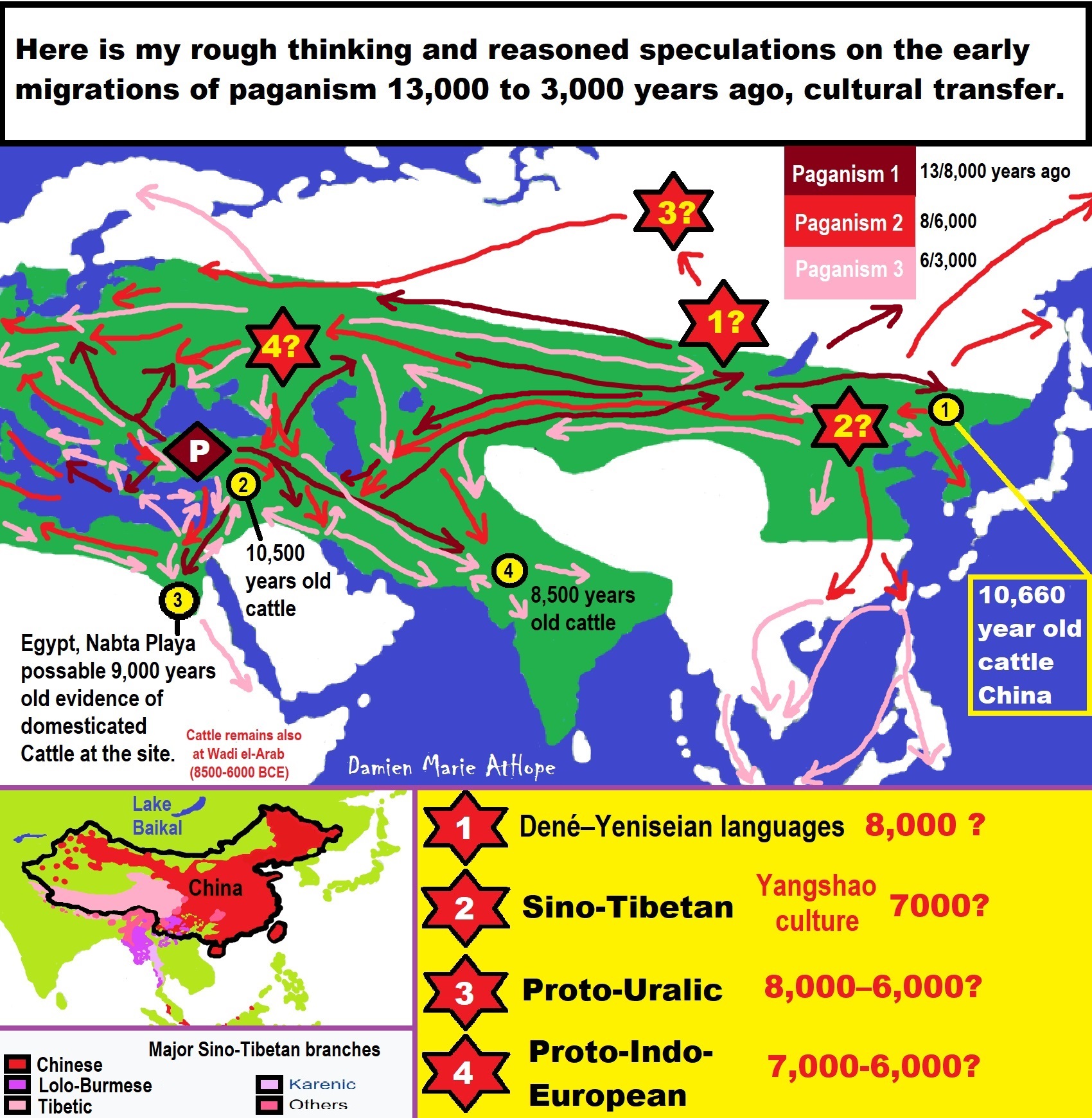

In a general way, it all starts with Animism (a theoretical belief in supernatural powers/spirits) and this is physically expressed in or with Totemism (a theoretical belief in a mythical relationship with powers/spirits through a totem item), which then enlists a full-time specific person to perform this worship and believed interaction as Shamanism (a theoretical belief in access and influence with spirits through rituals). In addition, there is the further employment of myths and gods added to all the above, which is Paganism and is often a lot more nature-based than most current top world religions, thus hinting to their close link to more ancient religious thinking from which it stems.

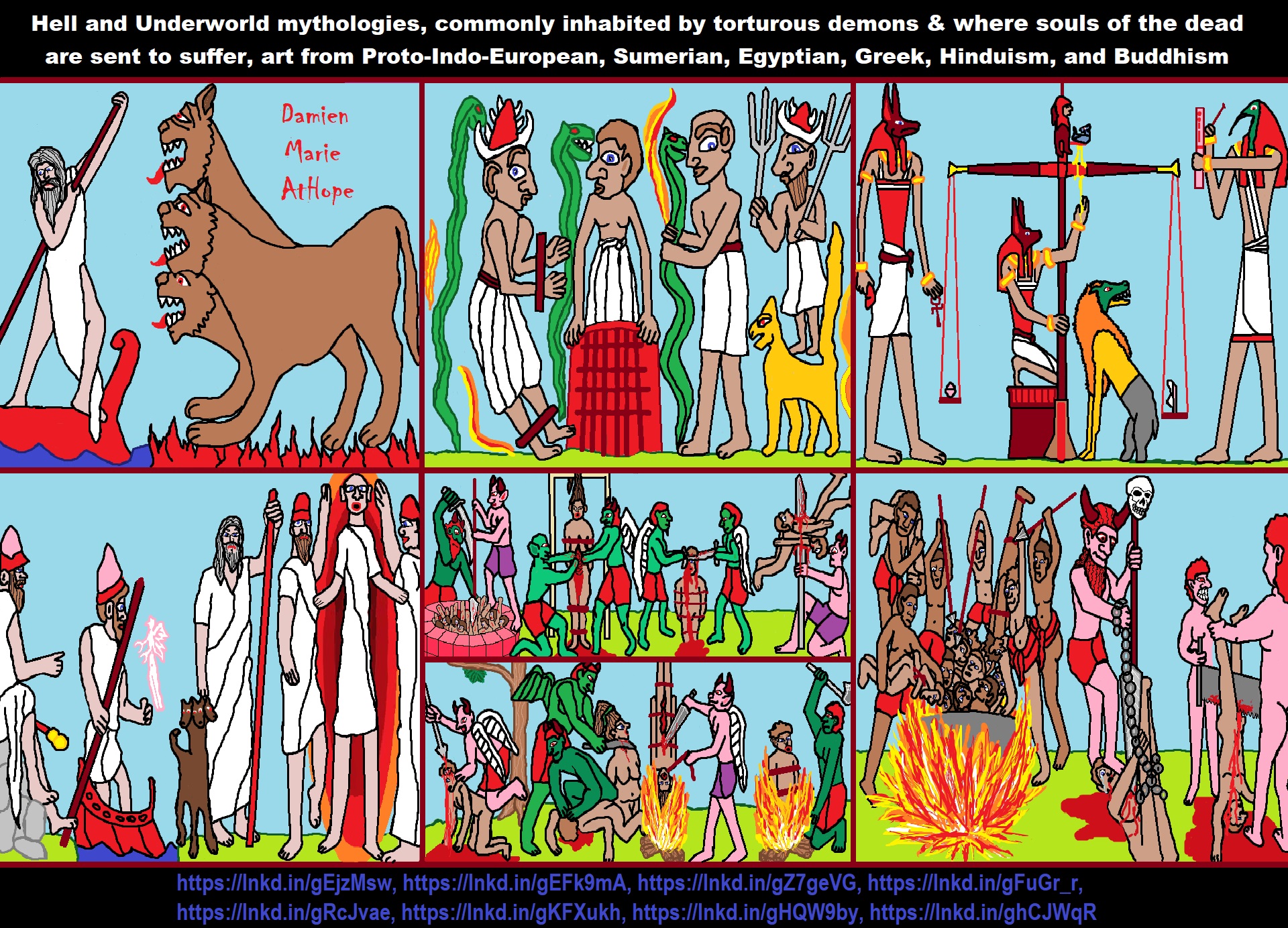

My hypothesis is expressed with an explanation of the building of a theoretical house (modern religions development). It seems ancient peoples had to survived amazing threats in a “dangerous universe by superstition perceived as good and evil”, and human “immorality or imperfection of the soul”, which was thought to affect the still living and led to ancestor worship. Presumably, this ancestor worship led to the belief in supernatural beings, which some of these were turned into the belief in gods. This feeble myth called gods were just a human conceived idea that was “made from nothing into something over and over, changing again and again, taking on more as they evolve, and all the while, they are thought to be special.” However, it is just supernatural animistic spirit-belief perceived as sacred.

Historically, around 5,000 years ago, in large city-state societies such as Egypt or Iraq culminated to make religion into something kind of new, a sociocultural-governmental-religious monarchy, where all or at least many of the people of such large city-state societies seem familiar with and committed to the existence of “religion” as the integrated life identity package of control dynamics with a fixed closed magical doctrine. However, this juggernaut integrated religion identity package of Dogmatic-Propaganda certainly did not exist or if developed to an extent, it was highly limited in most smaller prehistoric societies as they seem to lack most of the strong control dynamics with a fixed closed magical doctrine. These magical beliefs could be at times be added or removed and many people just want to see developed religious dynamics everywhere, even if it is not. Instead, all that is found is largely fragments until the domestication of religion.

Religions, as we think of them today, are a new fad, even if they go back to around 6,000 years in the timeline of human existence. This amounts to almost nothing when seen in the long slow evolution of religion that started at least around 70,000 years ago with one of the oldest ritual worship. This message of how religion and gods are intertwined with humans is clearly a man-made idea that was developed slowly as it was invented, reinvented, and implemented piece by piece, which discredits them all. This seems to be a simple point, which some are just not grasping how devastating this is to any claims of truth when we can see the lie clearly in the archeological sites.

“Religion is an Evolved Product”

“The worst thing that RELIGION has done is to make people believe that men are superior to women. That was INTENTIONALLY done by the men who wrote those holy books. You can’t keep women down unless they feel like they deserve to be kept down. Very effective.” – Michelle @Michell33650674

My response, Sexism was not always part of religion, religion to me, begins with animism (spiritual not religion per say) around 100,000 years ago. Sexism in religion really gets going around 7,000 years ago and institutionalised by 5,000 years ago and monotheistic thinking 4,000 years ago.

My response, Monotheism is actually “man-o-theism” as it is all just men. There is no single female Monotheism that I know of. And monotheism is only around 4,000 years old.

“The broader definition of monotheism characterizes the traditions of Bábism, the Bahá’í Faith, Balinese Hinduism, Cao Dai (Caodaiism), Cheondoism (Cheondogyo), Christianity, Deism, Eckankar, Hindu sects such as Shaivism and Vaishnavism, Islam, Judaism, Mandaeism, Rastafari, Seicho no Ie, Sikhism, Tengrism (Tangrism), Tenrikyo (Tenriism), Yazidism, and Zoroastrianism, and elements of pre-monotheistic thought are found in early religions such as Atenism, ancient Chinese religion, and Yahwism.” ref

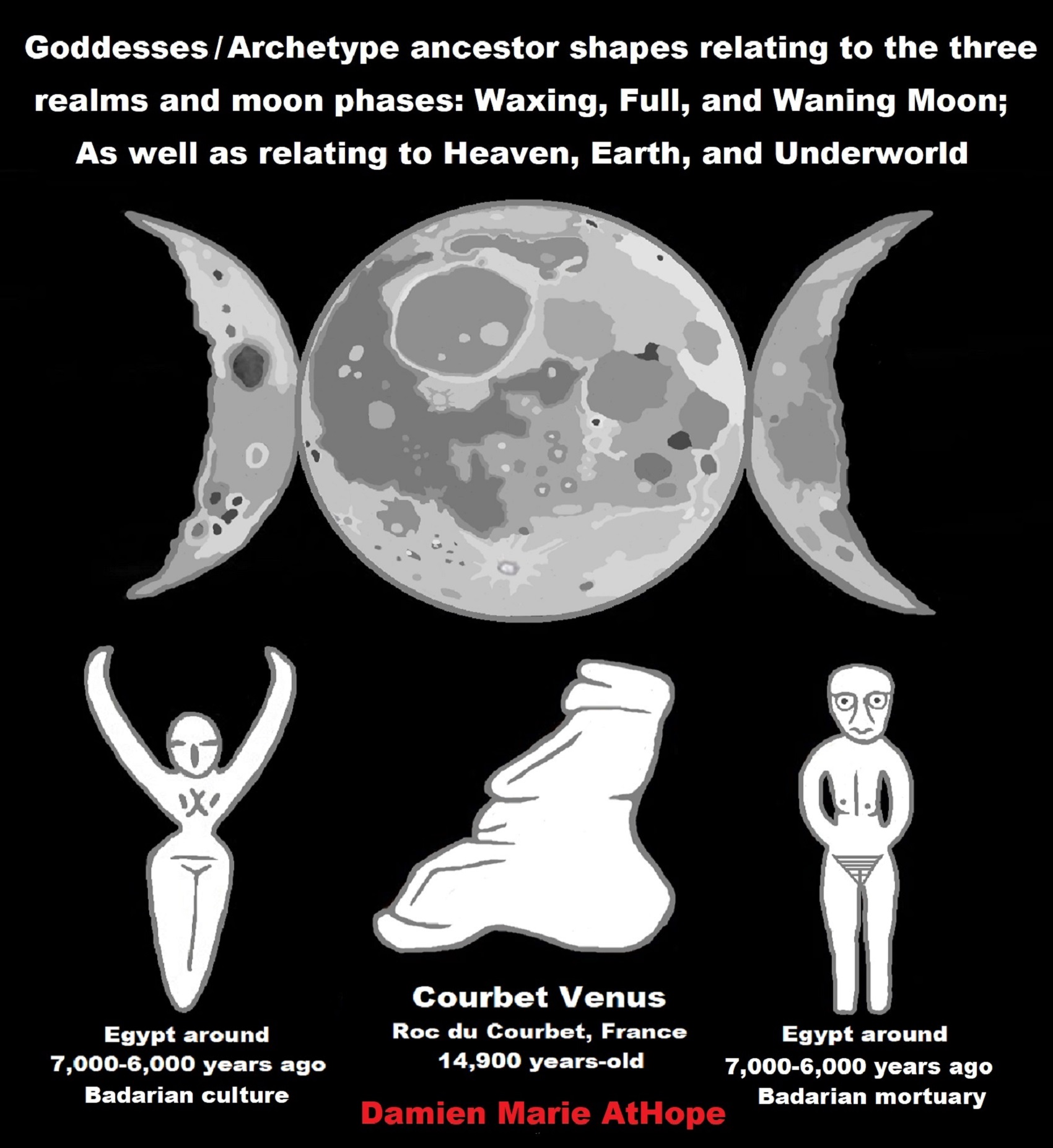

“Why does the majority of the world worship MALE DEITIES instead of FEMALE DEITIES? I think worship is ridiculous, but if ANYONE should be worshipped, it should be WOMEN. We are the backbone of society. We are the life bringers. We don’t go around murdering and raping.” – Michelle @Michell33650674

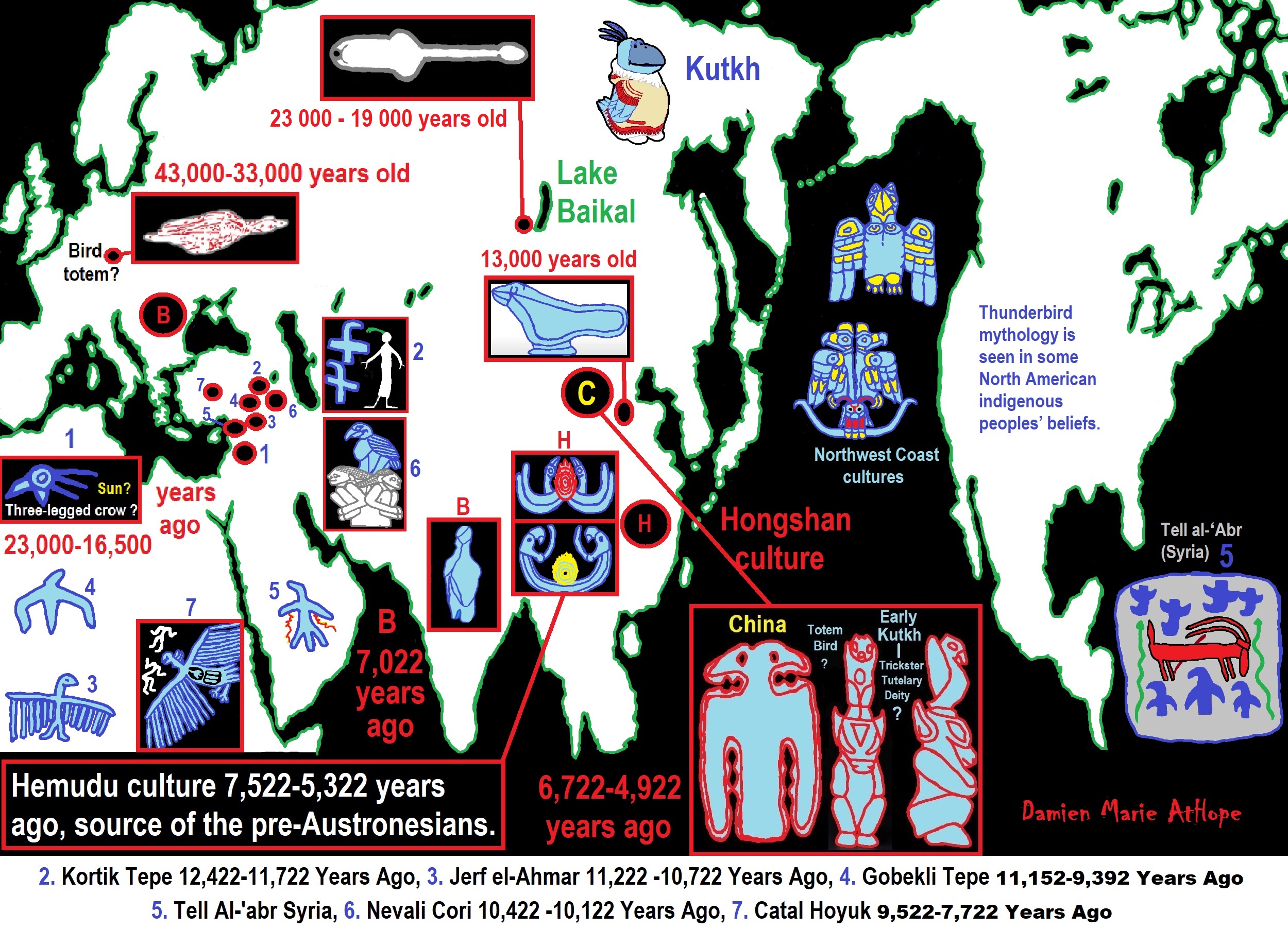

My response, To me, animal deities are first at 13,000/12,000 years ago at emergence of agriculture. Women as deities, to me, come next at around 11,000/10,000 years ago possibly related with domestication of plants/animals. Male deities about 8,000/7,000 years ago, with waring male clans.

Origins of Agriculture: 13,000-12,000 years ago

“Localised climate change is the favored explanation for the origins of agriculture in the Levant. When major climate change took place after the last ice age (c. 13,000 years ago), much of the earth became subject to long dry seasons. These conditions favoured annual plants which die off in the long dry season, leaving a dormant seed or tuber. An abundance of readily storable wild grains and pulses enabled hunter-gatherers in some areas to form the first settled villages at this time. The development of agriculture about 12,000 years ago changed the way humans lived. They switched from nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyles to permanent settlements and farming.” ref

Domestication of Animals: 11,000-10,000 years ago

“The domestication of plants began around 13,000–11,000 years ago with cereals such as wheat and barley in the Middle East, alongside crops such as lentil, pea, chickpea, and flax. In the Fertile Crescent 10,000-11,000 years ago, zooarchaeology indicates that goats, pigs, sheep, and taurine cattle were the first livestock to be domesticated.” ref, ref

“A fertility deity is a god or goddess associated with fertility, sex, pregnancy, childbirth, and crops. in some cases these deities are directly associated with these experiences; in others, they are more abstract symbols. Fertility rites may accompany their worship. The following is a list of fertility deities. Fertility rites or fertility cults are religious rituals that are intended to stimulate reproduction in humans or in the natural world. Such rites may involve the sacrifice of “a primal animal, which must be sacrificed in the cause of fertility or even creation. Fertility rites may occur in calendric cycles, as rites of passage within the life cycle, or as ad hoc rituals….Commonly fertility rituals are embedded within larger-order religions or other social institutions.” ref, ref

Male Clan Wars: 7,000 to 5,000 years ago

“Ancient Clan War Explains Genetic Diversity Drop. Some 5,000 to 7,000 years ago, the diversity of Y chromosomes plummeted. A new analysis suggests clan warfare may have been the cause. Christopher Intagliata reports. “It seemed to us that the 17-to-1 sex ratio was just too extreme to be real.” Imagine a single deadly battle knocking out a whole clan of men with the same Y chromosomes. Then repeat that unpleasant scenario a few times. You’d get a huge drop in the diversity of Y chromosomes, as the victorious clans won battles and expanded. The details are in the journal Nature Communications. [Tian Chen Zeng, Alan J. Aw & Marcus W. Feldman, Cultural hitchhiking and competition between patrilineal kin groups explain the post-Neolithic Y-chromosome bottleneck]” ref

“Believe it or not, ancient Egypt was not an oppressive slavery-based civilization. You’re thinking of Rome and Christian nations.” – R. Shane Clayton @ShaneMontane

My response, “Slavery in ancient Egypt existed at least since the Old Kingdom period. There were three types of enslavement in Ancient Egypt: chattel slavery, bonded labor, and forced labor.” ref

“I did not claim that it didn’t exist. I said that the civilization was not oppressive and based on slavery. As early as the Old Kingdom, the pyramids were built by working citizens. The only real slaves were criminals or enemy combatants, as your linked wiki article explains. Chattel laborers and other indentured servants were essentially just as free as most workers today.” – R. Shane Clayton @ShaneMontane

My response, Thanks, I appreciate your responses.

Religions continuing in our modern world, full of science and facts, should be seen as little more than a set of irrational conspiracy theories of reality. Nothing more than a confused reality made up of unscientific echoes from man’s ancient past. Rational thinkers must ask themselves why continue to believe in religions’ stories. Religion myths which are nothing more than childlike stories and obsolete tales once used to explain how the world works, acting like magic was needed when it was always only nature. These childlike religious stories should not even be taken seriously, but sadly too often they are.

Often without realizing it, we accumulate beliefs that we allow to negatively influence our lives. In order to bring about awareness, we need to be willing to alter skewed beliefs. Rational thinkers must examine the facts instead of blindly following beliefs or faith. Below is a collection of researched information such as archaeology, history, linguistics, genetics, art, science, sociology, geography, psychology, philosophy, theology, biology, and zoology. It will make you question your beliefs with information, inquiries, and ideas to ponder and expand on. The two main goals are to expose the evolution of religion starting by around 100,000 years ago and to offer challenges to remove the rationale of faith. It is like an intervention for belief in myths that have plagued humankind for way too long. We often think we know what truth is nevertheless this can be but a vantage point away from losing credibility if we are not willing to follow valid and reliable reason and evidence.

The door of reason opens not once but many times. Come on a journey to free thought where the war is against ignorance and the victor is a rational mind. Understanding Religion Evolution: Pre-Animism (at least 300,000 years ago), * Animism (such as that seen in Africa: 100,000 years ago), *Totemism (Europe: 50,000 years ago), * Shamanism (beginning around 30,000 years ago), *Paganism (beginning around 12,000 years ago), * Progressed organized religion (around 5,000 years ago), * CURRENT “World” RELIGIONS (after 4,000 years ago), and * Early Atheistic Doubting (at least by around 2,600 Years Ago)

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

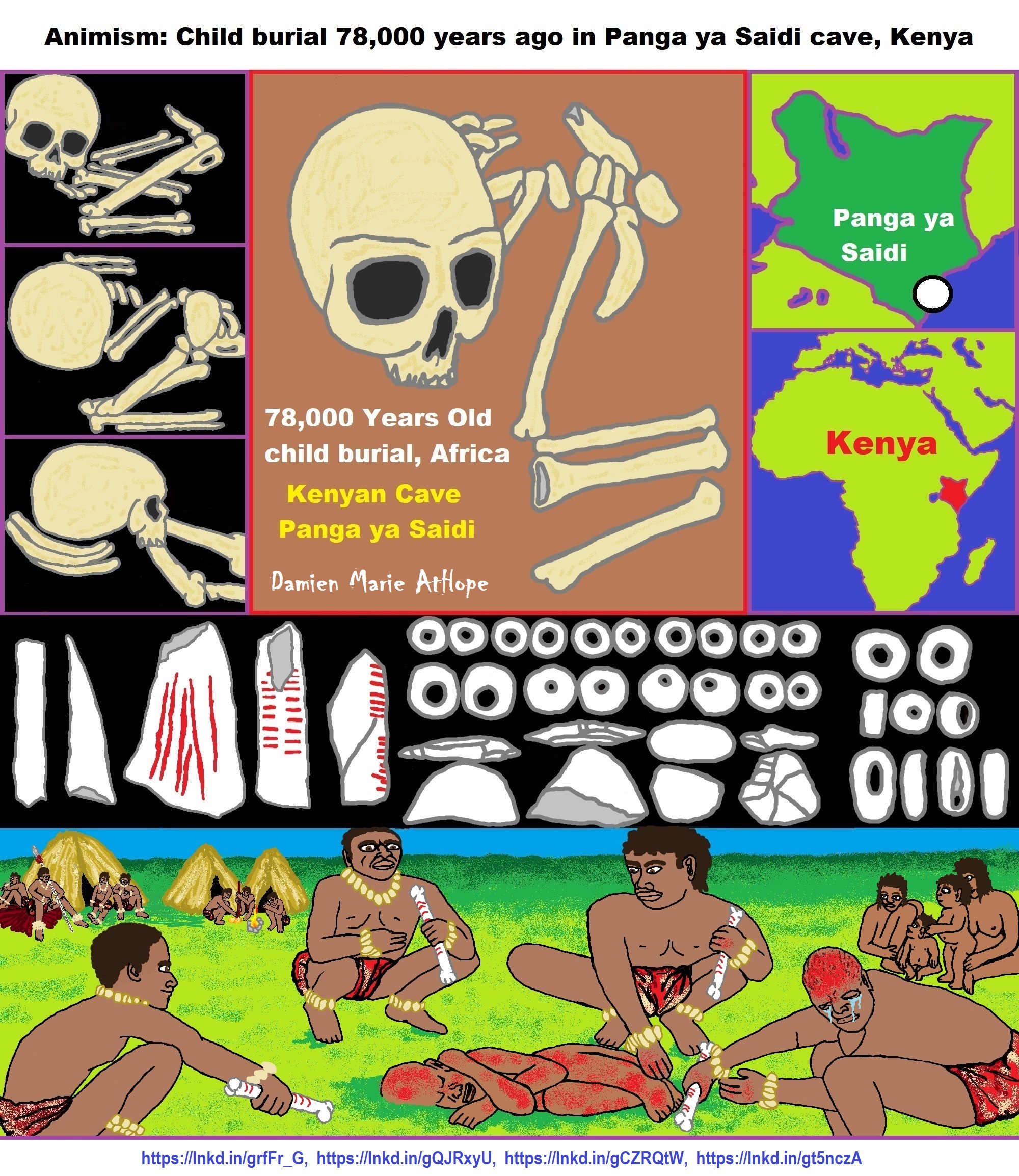

Animism: a belief among some indigenous people, young children, or all religious people!

78,000 Years Ago

“Mtoto’s burial, to experts it is believed the child was around three years old when they died and was likely wrapped in a shroud and had their head on a pillow. Besides the seemingly deliberate position of the body, the team noticed a few clues that suggested the child was swaddled in cloth, possibly with the intention of preserving the corpse. They also speculate the body was placed in a cave fissure — known as funerary caching — before being covered with sediment.” ref, ref

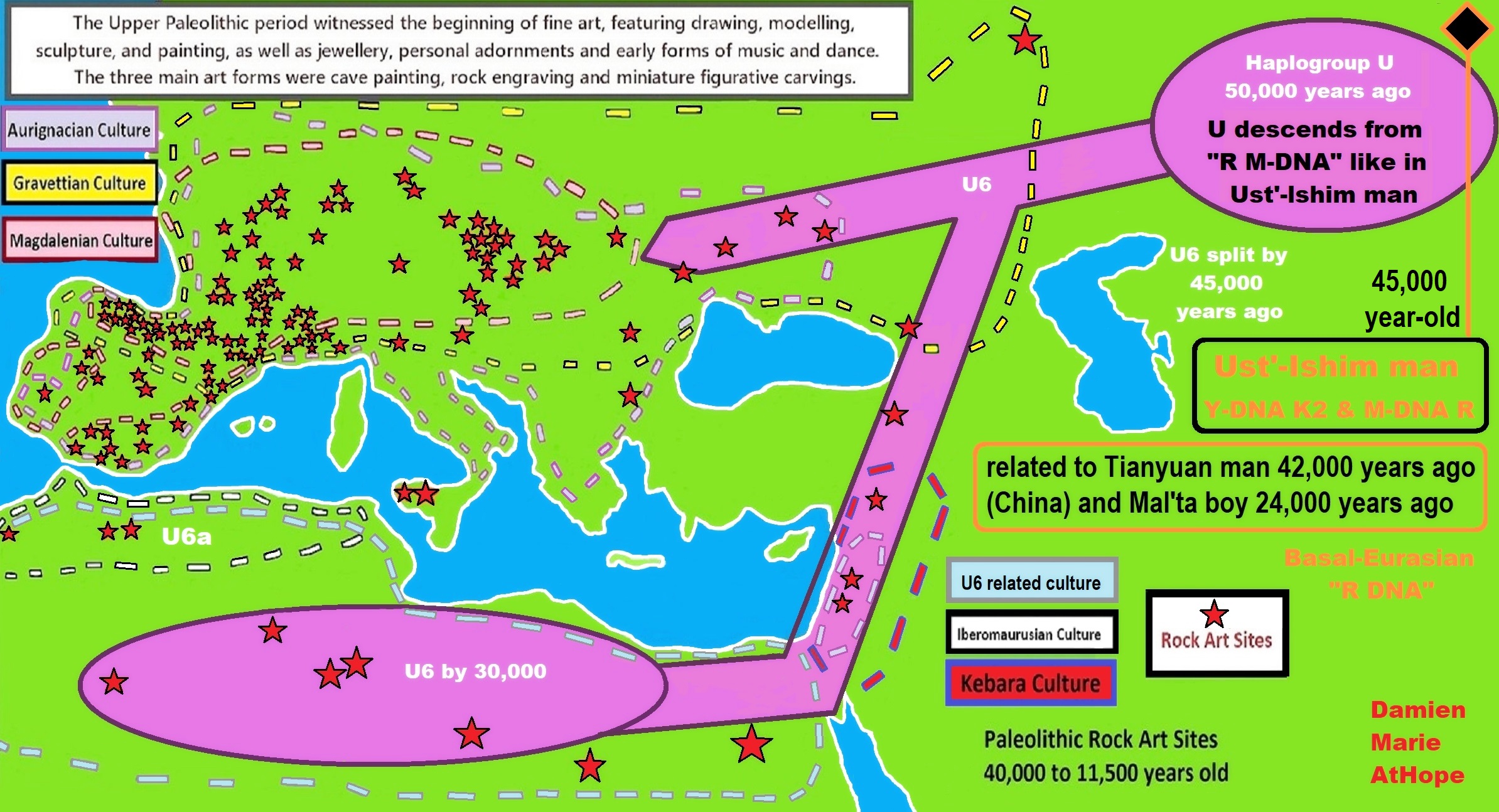

“Ust’-Ishim man is the term given to the 45,000-year-old remains of one of the early modern humans to inhabit western Siberia. He belonged to mitochondrial DNA haplogroup R*, differing from the root sequence of R by a single mutation. Ust’-Ishim man belongs to Y-DNA haplogroup K2. The two subclades of K2 are K2a and K2b. Haplogroup K is believed to have originated in the mid-Upper Paleolithic. It is the most common subclade of haplogroup U8b. The haplogroup U8b’s most common subclade is haplogroup K, and makes up a sizeable fraction of European and West Asian mtDNA lineages.” ref, ref, ref

“Both of these haplogroups and descendant subclades are now found among populations throughout Eurasia, Oceania, and The Americas, although no direct descendants of Ust Ishim man’s specific lineages are known from modern populations. Examination of the sequenced genome indicates that Ust’-Ishim man lived at a point in time (270,000 to 45,000 years ago) between the first wave of anatomically modern humans that migrated out of Africa and the divergence of that population into distinct populations, in terms of autosomal DNA in different parts of Eurasia. Consequently, Ust’-Ishim man is not more closely related to the first two major migrations of Homo Sapiens eastward from Africa into Asia: a group that migrated along the coast of South Asia, or a group that moved north-east through Central Asia. When compared to other ancient remains, Ust’-Ishim man is more closely related, in terms of autosomal DNA to Tianyuan man, found near Beijing and dating from 42,000 to 39,000 years ago; Mal’ta boy (or MA-1), a child who lived 24,000 years ago along the Bolshaya Belaya River near today’s Irkutsk in Siberia, or; La Braña man – a hunter-gatherer who lived in La Braña (modern Spain) about 8,000 years ago.” ref

“Ust’-Ishim was equally related to modern East Asians, Oceanians, and West Eurasian populations, such as the ancient Europeans. Modern Europeans are more closely related to other ancient remains. “The finding that the Ust’-Ishim individual is equally closely related to present-day Asians and to 8,000- to 24,000-year-old individuals from western Eurasia, but not to present-day Europeans, is compatible with the hypothesis that present-day Europeans derive some of their ancestry from a population that did not participate in the initial dispersals of modern humans into Europe and Asia.”In a 2016 study, modern Tibetans were identified as the modern population that has the most alleles in common with Ust’-Ishim man. According to a 2017 study, “Siberian and East Asian populations shared 38% of their ancestry” with Ust’-Ishim man. A 2021 study found that “the Ust’Ishim and Oase1 individuals showed no more affinity to western than to eastern Eurasian populations, suggesting that they did not contribute ancestry to later Eurasian populations, as previously shown.” ref

Paleolithic Y-chromosomal haplogroups by chronological period

- Proto-Aurignacian (47,000 to 43,000 years before present; eastern Europe): F

- Aurignacian Culture (43,000 to 28,000 ybp ; all ice-free Europe): CT, C1a, C1b, I

- Gravettian Culture (31,000 to 24,000 ybp ; all ice-free Europe): BT, CT, F, C1a2

- Epiravettian Culture (22,000 to 8,000 ybp ; Italy): R1b1a

- Magdalenian Culture 17,000 to 12,000 ybp ; Western Europe): IJK, I

- Epipaleolithic France (13,000 to 10,000 ybp): I

- Azilian Culture (12,000 to 9,000 ybp ; Western Europe): I2 ref

Paleolithic mitochondrial haplogroups by chronological period

- Proto-Aurignacian (47,000 to 43,000 years before present ; eastern Europe): N, R*

- Aurignacian Culture (43,000 to 28,000 ybp ; all ice-free Europe): M, U, U2, U6

- Gravettian Culture (31,000 to 24,000 ybp ; all ice-free Europe): M, U, U2’3’4’7’8’9, U2 (x5), U5 (x5), U8c (x2)

- Solutrean Culture (22,000 to 17,000 ybp ; France, Spain): U

- Epiravettian Culture (22,000 to 8,000 ybp ; Italy): U2’3’4’7’8’9, U5b2b (x2)

- Magdalenian Culture 17,000 to 12,000 ybp ; Western Europe): R0, R1b, U2’3’4’7’8’9, U5b (x2), U8a (x5)

- Epipaleolithic France (13,000 to 10,000 ybp): U5b1, U5b2a, U5b2b (x2)

- Epipaleolithic Germany (13,000 to 11,000 ybp): U5b1 (x2)

- Azilian Culture (12,000 to 9,000 ybp ; Western Europe): U5b1h ref

Mesolithic Y-chromosomal haplogroups by country

- Ireland: I2a1b, I2a2

- Britain: IJK, I2a2 (x2)

- France: I (x3), I2a1b2

- Luxembourg: I2a1b

- Germany: I2a2a

- Spain: C1a2

- Italy: I, I2a2

- Sweden: I2a1 (x2), I2a1a1a*, I2a1b (x2), I2c2

- Estonia: R1a-YP1272

- Latvia: I2a1 (x2), I2a1b, I2a2a1, I2a2a1b (x2), Q1a2, R1b1a1a-P297 (x7)

- Lithuania: I2a1b, I2a1a2a1a-L233

- Serbia: I, I2 (x2), I2a1, I2a2, I2a2a-M223, I2a2a-Z161 (x2), R, R1b1a-L794 (x8)

- Romania: R, R1, R1b

- Ukraine: IJ, I (x4), I2, I2a1, I2a2, I2a2a, I2a2a1b1-L702 (x2), R1a, R1b1a-L794

- Russia: J, R1a1* (x3), R1a1-YP1301, R1b1a, R1b1a1a-P297 ref

Mesolithic mitochondrial haplogroups by country

Note that the very late Mesolithic Pitted Ware culture (c. 3200–2300 BCE) in Sweden is listed separately as it is possible that intermarriages with Neolithic or Chalcolithic neighbors took place.

- Croatia: U5b2a5

- France: U5a2 (x2), U5b1, U5b1b

- Germany, Luxembourg: U2e, U4, U5a, U5a2c (x2), U5a2c3, U5b (x2), U5b1a, U5b1d1 (x2), U5b2a2, U5b2c1

- Greece: K1c (x2)

- Italy: U5b1

- Lithuania: U4, U5b (x3)

- Poland: U5a, U5b (x2), U5b1b

- Spain: U5b, U5b1, U5b2c1 (x2)

- Russia: C, C1g, C5d, D, H, U2e, U4 (x3), U4a, U4a1, U5a (x3), U5a1 (x2), U5a1d, T, Z1a (x2)

- Sweden: U2e1 (x2), U4b1, U5a1 (x3), U5a2, U5a2d (x2)

- Sweden (Pitted Ware): H, H1f, HV0 (x2), K1a, K1a1 (x3), T2b (x2), U, U4 (x8), U4a1, U4d (x3), U5a, U5a1a’g (x2), U5b (x2), U5b1, U5b2b1a ref

@ Vincent Rowlatt. (Peasant) – “The question, for example, “What the feck is the sun?” was exploited by those who called themselves ‘priests’. At some point in time, ‘humans’ did not ask such questions… What changed and why?”

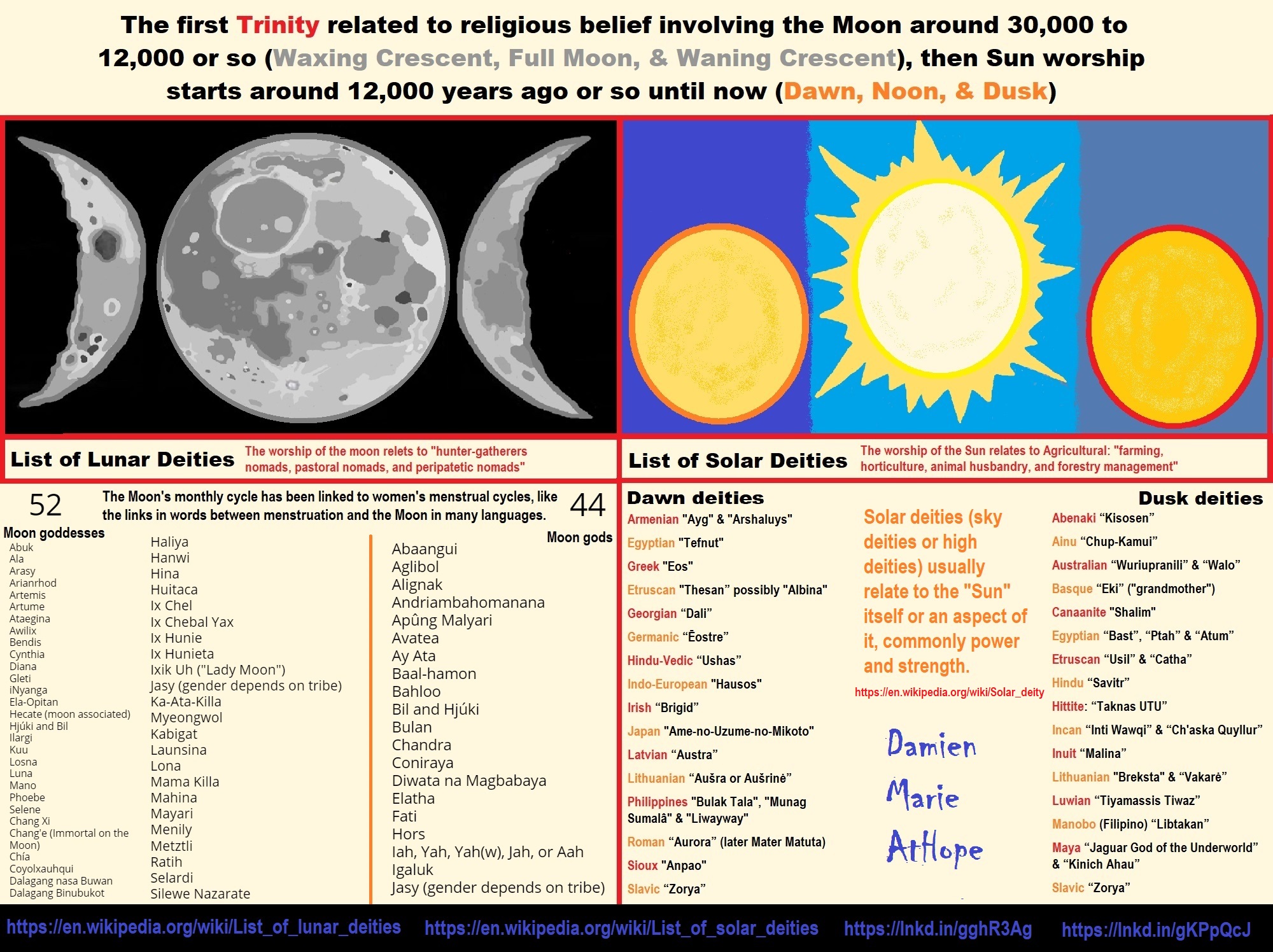

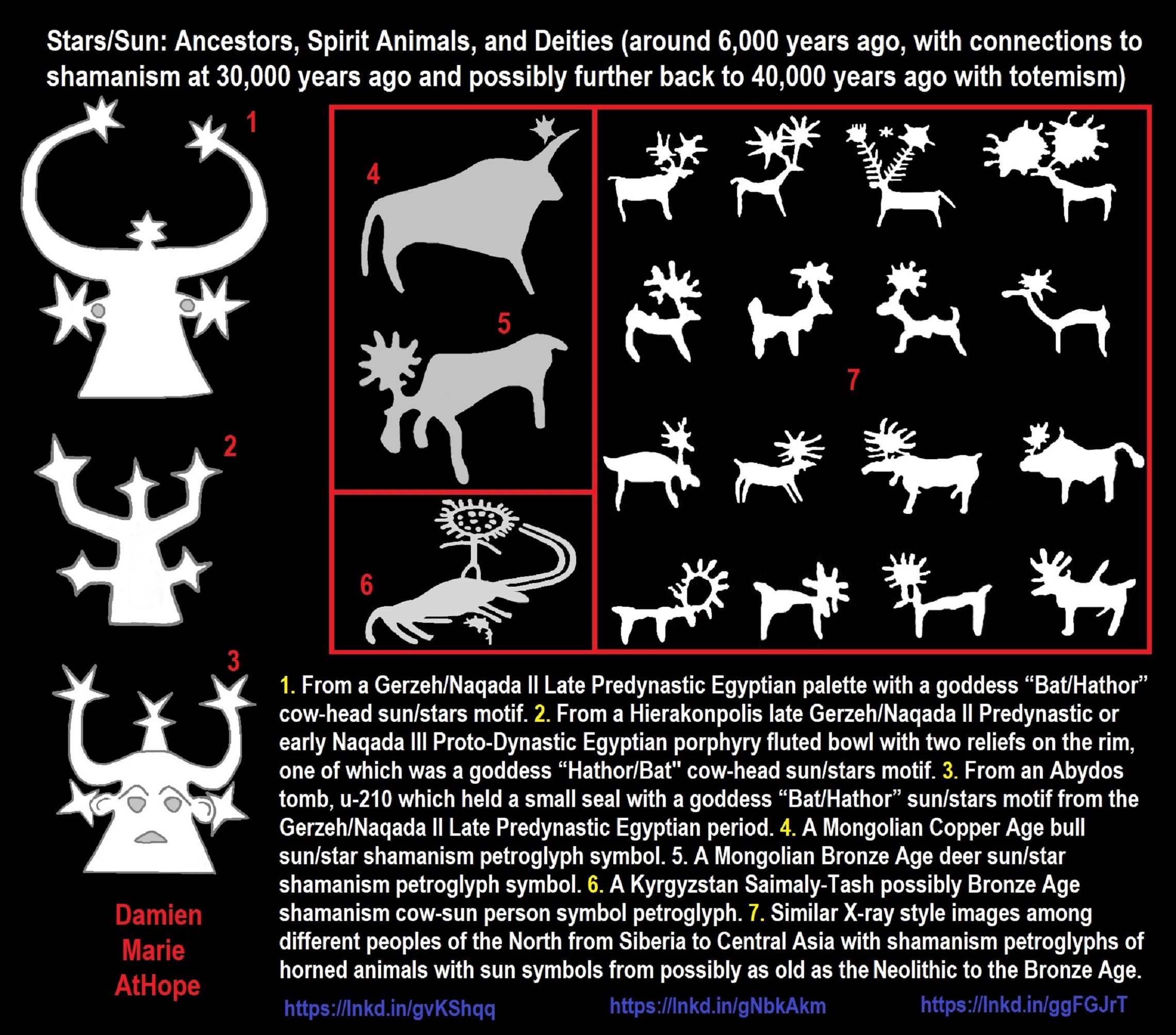

My response, There may have been some thoughts on the sun but it did not likely matter much until after agriculture had already gotten going I think like 8,000/7,000 years ago, and rain or thunder deities/sky spirits represented as birds came first at least 13,000/12,000 years ago.

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

1. Kebaran culture 23,022-16,522 Years Ago, 2. Kortik Tepe 12,422-11,722 Years Ago, 3. Jerf el-Ahmar 11,222 -10,722 Years Ago, 4. Gobekli Tepe 11,152-9,392 Years Ago, 5. Tell Al-‘abrUbaid and Uruk Periods, 6. Nevali Cori 10,422 -10,122 Years Ago, 7. Catal Hoyuk 9,522-7,722 Years Ago

@ Vincent Rowlatt. (Peasant) – “The sun was important long before agriculture. What changed, why did ‘we’ invent ‘gods and religion’?“

My response, The moon was more important first. For most of human evolution, we were on the move as migratory peoples in hunter-gatherer cultures. The moon is favored by migrating peoples and the sun by sedentary people.

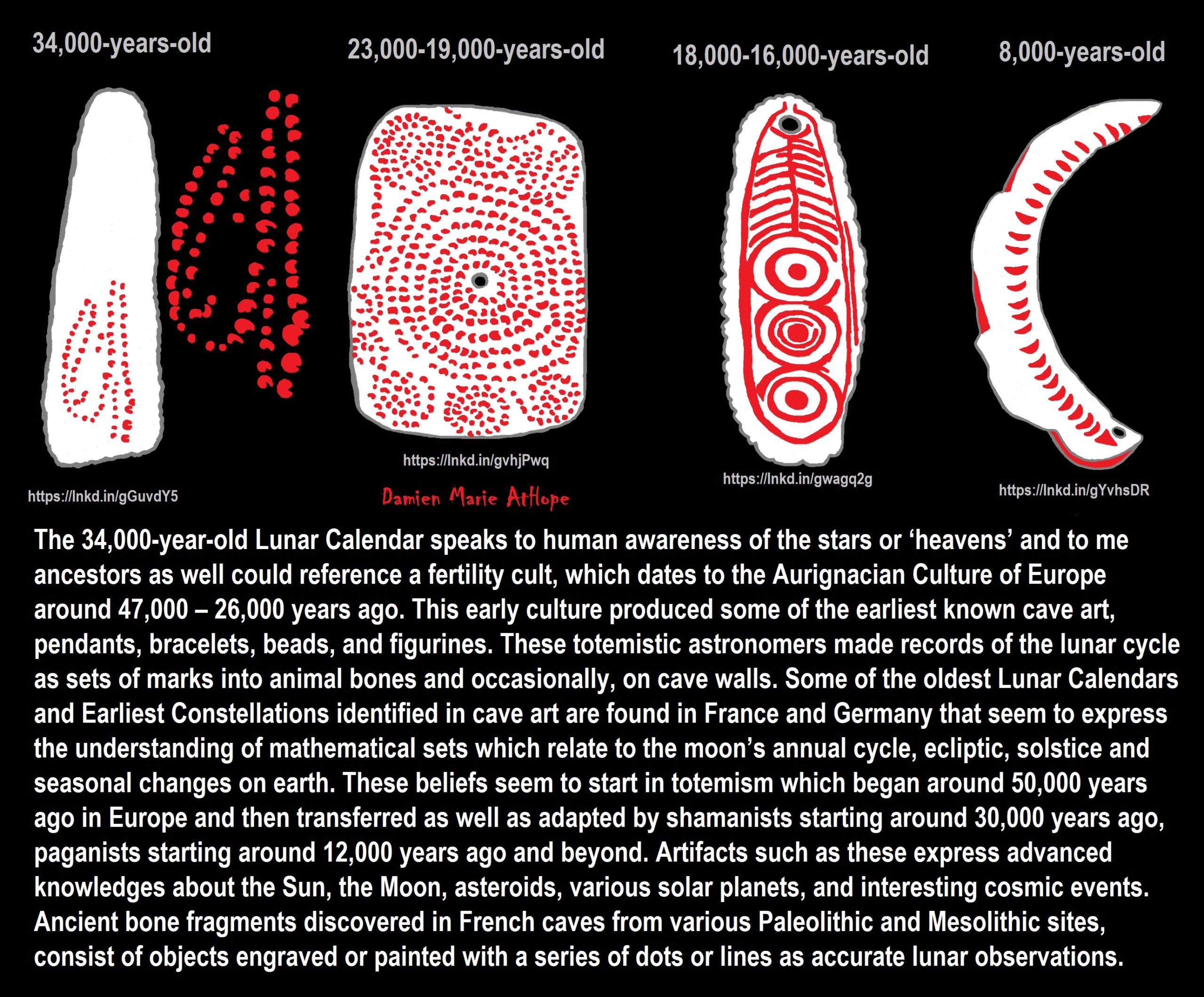

34,000 years ago Lunar Calendar Cave art around the Time Shift From Totemism to Early Shamanism?

“The Oldest Lunar Calendars and Earliest Constellations have been identified in cave art found in France and Germany. The astronomer-priests of these late Upper Paleolithic Cultures understood mathematical sets, and the interplay between the moon annual cycle, ecliptic, solstice and seasonal changes on earth. The archaeological record’s earliest data that speaks to human awareness of the stars and ‘heavens’ dates to the Aurignacian Culture of Europe, around 34,000 years ago. Between 1964 and the early 1990s, Alexander Marshack published breakthrough research that documented the mathematical and astronomical knowledge in the Late Upper Paleolithic Cultures of Europe. Marshack deciphered sets of marks carved into animal bones, and occasionally on the walls of caves, as records of the lunar cycle. These marks are sets of crescents or lines. Artisans carefully controlled line thickness so that a correlation with lunar phases would be as easy as possible to perceive. Sets of marks were often laid out in a serpentine pattern that suggests a snake deity or streams and rivers. Many of these lunar calendars were made on small pieces of stone, bone or antler so that they could be easily carried. These small, portable, lightweight lunar calendars were easily carried on extended journeys such as long hunting trips and seasonal migrations.” ref

“Hunting the largest animals was arduous, and might require hunters to follow herds of horses, bison, mammoth or ibex for many weeks. (Other big animals such as the auroch, cave bear and cave lion were well known but rarely hunted for food because they had a special status in the mythic realm. The Auroch is very important to the search for earliest constellations.) The phases of the moon depicted in these sets of marks are inexact. Precision was impossible unless all nights were perfectly clear which is an unrealistic expectation. The arithmetic counting skill implied by these small lunar calendars is obvious. The recognition that there are phases of the moon and seasons of the year that can be counted – that should be counted because they are important – is profound. “All animal activities are time factored, simply because time passes, the future is forever arriving. The reality of time factoring is objective physics and does not depend upon human awareness or consciousness. Until Marshack’s work, many archeologists believed the sets of marks he chose to study were nothing but the aimless doodles of bored toolmakers. What Marshack uncovered is the intuitive discovery of mathematical sets and the application of those sets to the construction of a calendar.” Bone is the preferred medium because it allows for easy transport and a long calendar lifetime. Mankind’s earliest astronomy brought the clan into the multi-dimensional universe of the gods. Objects used in the most potent rituals had the highest contextual, cultural value and were treated with great reverence.” ref

“Regarding the Aurignacian, between 43,000 and 35,000 years ago, the archaeological record from habitations is relatively poor in the Ardèche (Abri des Pécheurs, Grotte du Figuier) while appearing more abundant in the Languedoc (La Salpétrière, La Balauzière, Esquicho-Grapaou, La Laouza etc.). The same applies to the sites of the early phases of the Gravettian. During climatic fluctuations, and unlike the deep caves such as Chauvet, the porch and shelter fills seem to have better recorded the cold episodes than the humid phases. To date, 20 decorated caves are indexed in the gorges of the Ardèche and nearby; in other words as far as the valley of the Gardon (Baume-Latrone). This group includes several important caves (Ebbou, Oulen, Émilie etc.) which are not precisely dated and were judged to be of secondary importance until the discovery of the Chauvet Cave.” ref

“A 10,000-year-old engraved stone could be a lunar calendar. The rare pebble — found high up in the mountains near Rome, Italy, the hammer-stone was found on top of Monte Alta in the Alban Hills. It’s believed that our early ancestors would’ve used the stone to keep track of the moon’s cycles. Notches were engraved “as if they were being used to count, calculate or store the record of some kind of information. And these notches — which total either 27 or 28 — suggest the stone’s engraver used the pebble to track lunar cycles.” ref

“Archaeologists excavating in Scotland found a series of huge pits were dug by Mesolithic people to track the cycle of the Moon. They found a series of twelve huge, specially shaped pits designed to mimic the various phases of the Moon. The holes aligned perfectly on the midwinter solstice to help the hunter-gathers of Mesolithic Britain keep precise track of the passage of the seasons and the lunar cycle. The holes were dug in the shapes of various phases of the moon. “Waxing, waning, crescents, and gibbous, they’re all there and arranged in a 50-meter-long (164-foot) arc. The one representing the full moon is large and circular, approximately two meters (roughly seven feet) across, and placed right in the center. And this arc is arranged perfectly with a notch in the landscape where the sun would have risen on the day of the midwinter solstice about 10,000 years ago. Placing their calendar in the landscape the way they did would have let the people who built it to recalibrate the lunar months every winter to bring their lunar calendar in line with the solar year. This means that any effort to keep track of the seasons using the moon alone will slowly drift ever further from true. An observer needs to know when to add or subtract an extra month to make good the time or hit the reset button and start counting again.” ref

“A moon-shaped calendar was found in Smederevska Palanka, Serbia that dates back 8,000 years, and is made from a wild boar’s tusk engraved with markings to denote a lunar cycle. Farmers may have used the device to plan when to plant crops. It is made from the tusk of a wild boar and is marked with engravings thought to denote a lunar cycle of 28 days, as well as the four phases of the moon.” ref

“A lunisolar calendar was found at Warren Field in Scotland and has been dated to c. 8000 BCE, during the Mesolithic period. Some scholars argue for lunar calendars still earlier—Rappenglück in the marks on a c. 17,000-year-old cave painting at Lascaux and Marshack in the marks on a c. 27,000-year-old bone baton—but their findings remain controversial. Scholars have argued that ancient hunters conducted regular astronomical observations of the Moon back in the Upper Palaeolithic. Samuel L. Macey dates the earliest uses of the Moon as a time-measuring device back to 28,000–30,000 years ago.” ref

“A lunar calendar is a calendar based on the monthly cycles of the Moon‘s phases (synodic months, lunations), in contrast to solar calendars, whose annual cycles are based only directly on the solar year. The most commonly used calendar, the Gregorian calendar, is a solar calendar system that originally evolved out of a lunar calendar system. A purely lunar calendar is also distinguished from a lunisolar calendar, whose lunar months are brought into alignment with the solar year through some process of intercalation. The details of when months begin varies from calendar to calendar, with some using new, full, or crescent moons and others employing detailed calculations.” ref

“Since each lunation is approximately 29+1⁄2 days, it is common for the months of a lunar calendar to alternate between 29 and 30 days. Since the period of 12 such lunations, a lunar year, is 354 days, 8 hours, 48 minutes, 34 seconds (354.36707 days), purely lunar calendars are 11 to 12 days shorter than the solar year. In purely lunar calendars, which do not make use of intercalation, like the Islamic calendar, the lunar months cycle through all the seasons of a solar year over the course of a 33–34 lunar-year cycle.” ref

“Although the Gregorian calendar is in common and legal use in most countries, traditional lunar and lunisolar calendars continue to be used throughout the world to determine religious festivals and national holidays. Such holidays include Rosh Hashanah (Hebrew calendar); Easter (the Computus); the Chinese, Korean, Vietnamese, and Mongolian New Year (Chinese, Korean, Vietnamese, and Mongolian calendars, respectively); the Nepali New Year (Nepali calendar); the Mid-Autumn Festival and Chuseok (Chinese and Korean calendars); Loi Krathong (Thai calendar); Sunuwar calendar; Vesak/Buddha’s Birthday (Buddhist calendar); Diwali (Hindu calendars); Ramadan, Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha (Islamic calendar).” ref

“The Japanese Calendar formerly used both the lunar and lunisolar calendar before it was replaced by the Gregorian Calendar during the Meiji government in 1872. Holidays such as the Japanese New Year were simply transposed on top as opposed to being calculated like other countries that use the lunisolar and Gregorian calendars together, for example, the Japanese New Year now falls on January 1, creating a month delay as opposed to other East Asian Countries. See customary issues in modern Japan.” ref

“Most calendars referred to as “lunar” calendars are in fact lunisolar calendars. Their months are based on observations of the lunar cycle, with intercalation being used to bring them into general agreement with the solar year. The solar “civic calendar” that was used in ancient Egypt showed traces of its origin in the earlier lunar calendar, which continued to be used alongside it for religious and agricultural purposes. Present-day lunisolar calendars include the Chinese, Vietnamese, Hindu, and Thai calendars.” ref

“Synodic months are 29 or 30 days in length, making a lunar year of 12 months about 11 to 12 days shorter than a solar year. Some lunar calendars do not use intercalation, for example, the lunar Hijri calendar used by most Muslims. For those that do, such as the Hebrew calendar, and Buddhist Calendars in Myanmar, the most common form of intercalation is to add an additional month every second or third year. Some lunisolar calendars are also calibrated by annual natural events which are affected by lunar cycles as well as the solar cycle. An example of this is the lunar calendar of the Banks Islands, which includes three months in which the edible palolo worms mass on the beaches. These events occur at the last quarter of the lunar month, as the reproductive cycle of the palolos is synchronized with the moon.” ref

“Lunar and lunisolar calendars differ as to which day is the first day of the month. In some lunisolar calendars, such as the Chinese calendar, the first day of a month is the day when an astronomical new moon occurs in a particular time zone. In others, such as some Hindu calendars, each month begins on the day after the full moon. Others are based on the first sighting of the lunar crescent, such as the lunar Hijri calendar (and, historically, the Hebrew calendar).” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

List of Lunar Deities

“In mythology, a lunar deity is a god or goddess of the Moon, sometimes as a personification. These deities can have a variety of functions and traditions depending upon the culture, but they are often related. Some forms of moon worship can be found in most ancient religions. The Moon features prominently in art and literature, often with a purported influence in human affairs. Many cultures are oriented chronologically by the Moon, as opposed to the Sun. The Hindu calendar maintains the integrity of the lunar month and the moon god Chandra has religious significance during many Hindu festivals (e.g. Karwa Chauth, Sankashti Chaturthi, and during eclipses). The ancient Germanic tribes were also known to have a lunar calendar.” ref

“Many cultures have implicitly linked the 29.5-day lunar cycle to women’s menstrual cycles, as evident in the shared linguistic roots of “menstruation” and “moon” words in multiple language families. This identification was not universal, as demonstrated by the fact that not all moon deities are female. Still, many well-known mythologies feature moon goddesses, including the Greek goddess Selene, the Roman goddess Luna, and the Chinese goddess Chang’e. Several goddesses including Artemis, Hecate, and Isis did not originally have lunar aspects, and only acquired them late in antiquity due to syncretism with the de facto Greco-Roman lunar deity Selene/Luna. In traditions with male gods, there is little evidence of such syncretism, though the Greek Hermes has been equated with the male Egyptian lunar god Thoth.” ref

“Male lunar gods are also common, such as Sin of the Mesopotamians, Mani of the Germanic tribes, Tsukuyomi of the Japanese, Igaluk/Alignak of the Inuit, and the Hindu god Chandra. The original Proto-Indo-European lunar deity appears to have been male, with many possible derivatives including the Homeric figure of Menelaus. Cultures with male moon gods often feature sun goddesses. An exception is Hinduism, featuring both male and female aspects of the solar divine. The ancient Egyptians had several moon gods including Khonsu and Thoth, although Thoth is a considerably more complex deity. Set represented the moon in the Egyptian Calendar of Lucky and Unlucky Days.” ref

List of Solar Deities

“A solar deity is a god or goddess who represents the Sun, or an aspect of it, usually by its perceived power and strength. Solar deities and Sun worship can be found throughout most of recorded history in various forms. The following is a list of solar deities. A dawn god or goddess is a deity in a polytheistic religious tradition who is in some sense associated with the dawn. These deities show some relation with the morning, the beginning of the day, and, in some cases, become syncretized with similar solar deities.” ref, ref

Deity Artemis

“The Greek deity Artemis is the ancient Greek goddess of the hunt, wilderness, wild animals, chastity, and the Moon. She is the daughter of Zeus and Leto and the twin sister of Apollo. She would eventually be extensively syncretized with the Roman goddess Diana. Cynthia was originally an epithet of the Greek goddess Artemis, who according to legend was born on Mount Cynthus. Selene, the Greek personification of the Moon, and the Roman Diana were also sometimes called “Cynthia.” ref

“While associated with the Moon, Hecate is not actually considered a goddess of the moon.” ref

Lusitanian Deity Ataegina

“Diana is a goddess in Roman and Hellenistic religion, primarily considered a patroness of the countryside, hunters, crossroads, and the Moon. She is equated with the Greek goddess Artemis (see above), and absorbed much of Artemis’ mythology early in Roman history, including a birth on the island of Delos to parents Jupiter and Latona, and a twin brother, Apollo, though she had an independent origin in Italy.” ref

“Elatha was a king of the Fomorians in Irish mythology. He succeeded his father Delbáeth and was replaced by his son Bres, mothered by Ériu.” ref

Norse Deities Hjúki and Bil

African

“Goddess of fertility, morality, creativity, and love.” ref

“Protective goddess and wife of Apedemak, the lion-god. She was represented with a crown-shaped as a falcon, or with a crescent moon on her head on top of which a falcon was standing.” ref

Dahomean Deities Gleti and Mawu

Zulu Deity iNyanga

“Goddess of the Moon.” ref

“God of wisdom, the arts, science, and judgment.” ref

“The god of the moon. A story tells that Ra (the sun God) had forbidden Nut (the Sky goddess) to give birth on any of the 360 days of the calendar. In order to help her give birth to her children, Thoth (the god of wisdom) played against Khonsu in a game of senet. Khonsu lost to Thoth and then he gave away enough moonlight to create 5 additional days so Nut could give birth to her five children. It was said that before losing, the moonlight was on par with the sunlight. Sometimes, Khonsu is depicted as a hawk-headed god, however, he is mostly depicted as a young man with a side-lock of hair, like a young Egyptian. He was also a god of time. The center of his cult was at Thebes which was where he took place in a triad with Amun and Mut. Khonsu was also heavily associated with Thoth who also took part in the measurement of time and the moon.” ref

Yoruba Deity Ela-Opitan

Norse SOL AND MANI

“Sol (pronounced like the English word “soul”; Old Norse Sól, “Sun”) and Mani (pronounced “MAH-nee”; Old Norse Máni, “Moon”), are, as their names suggest, the divinities of the sun and the moon, respectively. Sol is female, and Mani male.” ref

“Sol and Mani form a sister and brother pair. When they first emerged as the cosmos was being created, they didn’t know what their powers were or what their role was in the new world. Then the gods met together and created the different parts of the day and year and the phases of the moon so that Sol and Mani would know where they fit into the great scheme of things.” ref

“They ride through the sky on horse-drawn chariots. The horses who pull Mani’s chariot are never named, but Sol’s horses are apparently named Árvakr (“Early Riser”) and Alsviðr (“Swift”). They ride “swiftly” because they’re pursued through the sky by the wolves Skoll (“Mockery”) and Hati (“Hate”), who will overtake them when the cosmos descends back into chaos during Ragnarok.” ref

“According to one of the poems in the Poetic Edda, a figure named Svalinn rides in the sun’s chariot and holds a shield between her and the earth below. If he didn’t do this, both the land and the sea would be consumed in flames. Elsewhere, the father of Sol and Mani is named as “Mundilfari,” about whom we know nothing. His name might mean “The One Who Moves According to Particular Times.” ref