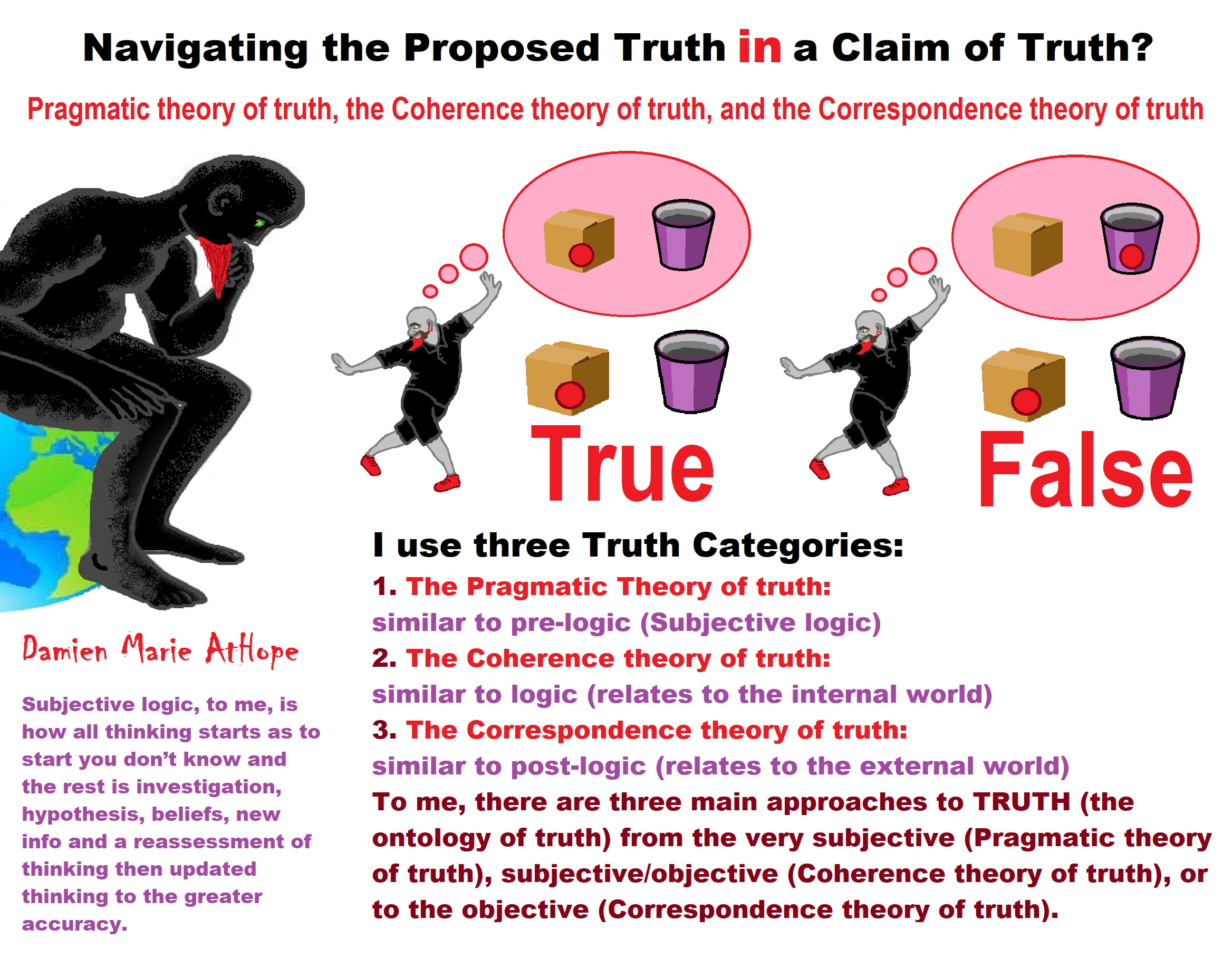

Grasping the status of truth (ontology of truth)

Authoritarian Truth Seekers and Anti-Authoritarian Truth Seekers?

I understand that there are truth seekers and non-truth seekers (because of disinterest, dogma “false sense of truth” and/or delusion).

But I also realize there are two types of truth seekers: Authoritarian Truth Seekers and Anti-Authoritarian Truth Seekers.

Authoritarian Truth Seekers: to me use an Authoritarian Personality to understand, analyze, confirm truth, and limit what is thought of as truth.

Authoritarian personality is a state of mind or attitude that is characterized by belief in absolute obedience or submissive to authority and possibly even one’s own authority, as well as the administration of that belief through the oppression of one’s subordinates. It is an ideology which entails accepting authority or hierarchical organization in the conduct of intellectual or human relations that includes authoritative, strict, or oppressive personality in truth acquisition and adherence to values or beliefs that are perceived as endorsed by followed leadership, authority of holy books, authority of gods, authority of beliefs held by someone who is favored or idolized, and authority of one’s own beliefs.

Anti-Authoritarian Truth Seekers: to me use an Anti-Authoritarian Personality to understand, analyze and confirm truth.

Anti-Authoritarian personality is a state of mind or attitude that is characterized by a cognitive application of freethought known as “freethinking” and is a philosophical viewpoint that holds that opinions should be formed on the basis of logic, reason, and empiricism, rather than authority, tradition, or other dogmas. Anti-Authoritarian personality is an opposition to authoritarianism, favoring instead full equality and open thinking in the conduct of intellectual or human relations, including democratic, flexible, or accessible personality in truth acquisition and adherence to values or beliefs perceived as endorsed by critical thinking and right reason which entails opposing authority as the means of conformation in truth attainment.

To me Anti-Authoritarian Truth Seekers are the only real seekers of truth.

To value faith as a means to know reality or the truth or something, is a mental weakness of wanting one’s beliefs about reality to matter more than the actual reality. Faith in relation of truth is at best just wishful emotions over rational understanding. 1, 2

I posted my Authoritarian Truth Seekers vs. Anti-Authoritarian Truth Seekers on facebook and this is a sample of what transpired:

Challenger #1, I think this blog post presents a false dichotomy: either one seeks truth through Authoritarian or Anti-authoritarian means. I think most of us have sought truth through the authority of our teachers and text books as kids in school; as we’ve grown older we tend to rely less on those authorities, but in some cases we still seek via Authoritarian means. For me, truth seeking is a Bayesian process of weighing hypothesis against reality. However, there are many subjects which may impact ones Bayesian reasoning for which one does not have the time/energy to investigate so we rely on the knowledge of “experts” who have spent time and energy investigating those matters.

Damien Marie AtHope, Thanks for your thoughts, you address interesting ideas but the issue you are addressing sounds a bit different that I was trying to say is doing an appeal to authority is a logical fallacy, so to limit one’s thinking to an appeal to authority is thinking strategy as a logical fallacy.

Challenger #2, it’s only a fallacy of the authority to which one is appealing is Not an authority in the field in question. For instance, if one’s argument is that, “Well even Richard Dawkins says the Big Bang proves the universe had a finite beginning,” (I’m making up the quote), that would be an appeal to authority fallacy because Dawkins is not an astrophysicist. However, if one quoted Krauss on this issue, it would not be fallacious. in a field for which I have no training, it’s perfectly reasonable for me to rely on experts and the consensus among experts.

Damien Marie AtHope, But even if I as an anti-authoritarianist were to accept an appeal to the scholarly articles on any scientific studies are valid only on the evidence and have nothing to do with the scientists or researchers. Just as if one wants to overturn any previous believed scientific theory it’s the evidence not in any way the person presenting it.

Challenger #1, Hmmm, I never got the impression that this post was about the logical fallacy known as: appeal to authority. However, when regarding the appeal to authority as a fallacy: if the the authority in question has made statements of an opinionated matter then I have to agree with Damien. However, if the appeal is to something the authority claimed based on the evidence and the current body of knowledge then I don’t think that would be considered a fallacy.

New respondent, Very succinct explanation of what divides believers from non-believers.

An argument from authority (Latin: argumentum ad verecundiam), also called an appeal to authority, is a common type of argument which can be fallacious, such as when an authority is cited on a topic outside their area of expertise or when the authority cited is not a true expert.[1]

Carl Sagan wrote of arguments from authority:

One of the great commandments of science is, “Mistrust arguments from authority.” … Too many such arguments have proved too painfully wrong. Authorities must prove their contentions like everybody else.[2]

Appeal to Authority Fallacy

Historically, opinion on the appeal to authority has been divided – it has been held to be a valid argument about as often as it has been considered an outright fallacy. John Locke, in his 1690 Essay Concerning Human Understanding, was the first to identify argumentum ad verecundiam as a specific category of argument. Although he did not call this type of argument a fallacy, he did note that it can be misused by taking advantage of the “respect” and “submission” of the reader or listener to persuade them to accept the conclusion. Over time, logic textbooks started to adopt and change Locke’s original terminology to refer more specifically to fallacious uses of the argument from authority. By the mid-twentieth century, it was common for logic textbooks to refer to the “Fallacy of appealing to authority,” even while noting that “this method of argument is not always strictly fallacious.” In the Western rationalistic tradition and in early modern philosophy, appealing to authority was generally considered a logical fallacy. More recently, logic textbooks have shifted to a less blanket approach to these arguments, now often referring to the fallacy as the “Argument from Unqualified Authority” or the “Argument from Unreliable Authority”. However, these are still not the only recognized forms of appeal to authority. For example, a 2012 guidebook on philosophical logic describes appeals to authority not merely as arguments from unqualified or unreliable authority, but as arguments from authority in general. In addition to appeals lacking evidence of the authority’s reliability, the book states that arguments from authority are fallacious if there is a lack of “good evidence” that the authorities appealed to possess “adequate justification for their views.” And there are other recognized fallacious arguments from authority. Among them, the “Fallacies” entry by Bradley Dowden in The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy states that “appealing to authority as a reason to believe something is fallacious […] when authorities disagree on this subject (except for the occasional lone wolf)” The “Fallacies” entry by Hans Hansen in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy similarly states that “when there is controversy, and authorities are divided, it is an error to base one’s view on the authority of just some of them.” However, Hansen’s entry in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy does not appear to share Dowden’s exception regarding “lone wolf” dissenting authorities.

Fallacious arguments from authority can also be the result of citing a non-authority as an authority. These arguments assume that a person without status or authority is inherently reliable. The appeal to poverty for example is the fallacy of thinking a conclusion is more likely to be correct because the one who holds or is presenting it is poor. When an argument holds that a conclusion is likely to be true precisely because the one who holds or is presenting it lacks authority, it is a fallacious appeal to the common man. A common example of the fallacy is appealing to an authority in one subject to pontificate on another – for example citing Albert Einstein as an authority on religion when his expertise was in physics. The attributed authority might not even welcome that authority, as with the “More Doctors Smoke Camels” ad campaign. However, it is also a fallacious ad hominem argument to argue that a person presenting statements lacks authority and thus their arguments do not need to be considered. As appeals to a perceived lack of authority, these types of argument are fallacious for much the same reasons as an appeal to authority.

Notable examples

Inaccurate chromosome number

In 1923, leading American zoologist Theophilus Painter declared, based on poor data and conflicting observations he had made, that humans had 24 pairs of chromosomes. From the 1920s to the 1950s, this continued to be held based on Painter’s authority, despite subsequent counts totaling the correct number of 23. Even textbooks with photos showing 23 pairs incorrectly declared the number to be 24 based on the authority of the then-consensus of 24 pairs. This seemingly established number created confirmation bias among researchers, and “most cytologists, expecting to detect Painter’s number, virtually always did so”. Painter’s “influence was so great that many scientists preferred to believe his count over the actual evidence”, to the point that “textbooks from the time carried photographs showing twenty-three pairs of chromosomes, and yet the caption would say there were twenty-four”. Scientists who obtained the accurate number modified or discarded their data to agree with Painter’s count.

Psychological basis

An integral part of the appeal to authority is the cognitive bias known as the Asch effect. In repeated and modified instances of the Asch conformity experiments, it was found that high-status individuals create a stronger likelihood of a subject agreeing with an obviously false conclusion, despite the subject normally being able to clearly see that the answer was incorrect. Further, humans have been shown to feel strong emotional pressure to conform to authorities and majority positions. A repeat of the experiments by another group of researchers found that “Participants reported considerable distress under the group pressure”, with 59% conforming at least once and agreeing with the clearly incorrect answer, whereas the incorrect answer was much more rarely given when no such pressures were present. Scholars have noted that the academic environment produces a nearly ideal situation for these processes to take hold, and they can affect entire academic disciplines, giving rise to groupthink. One paper about the philosophy of mathematics for example notes that, within mathematics,

If…a person accepts our discipline, and goes through two or three years of graduate study in mathematics, he absorbs our way of thinking, and is no longer the critical outsider he once was…If the student is unable to absorb our way of thinking, we flunk him out, of course. If he gets through our obstacle course and then decides that our arguments are unclear or incorrect, we dismiss him as a crank, crackpot, or misfit. Ref

Challenged or Challenging? (questions of ontology)

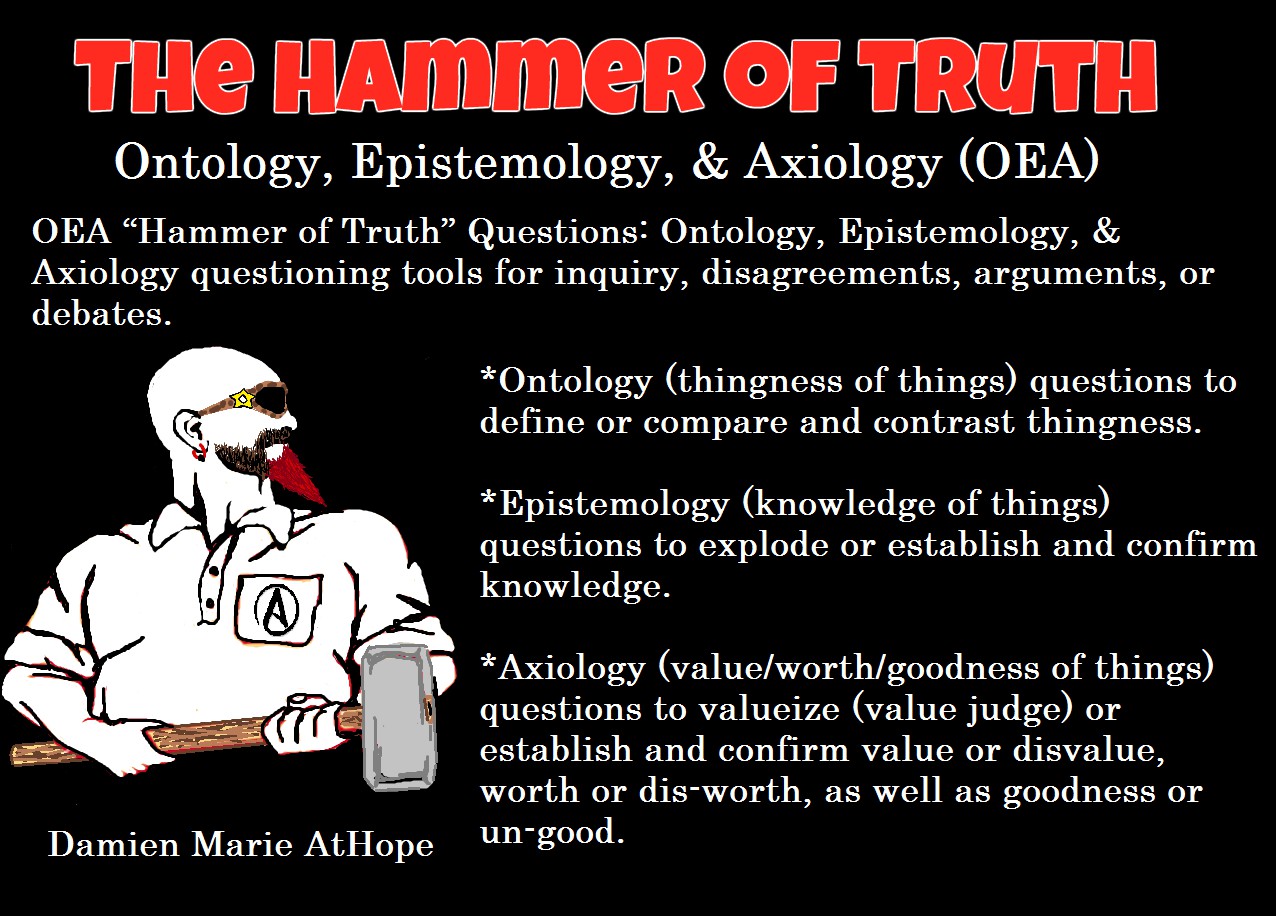

All thinkers should know that ontological (thingness) definition require answers and that need to answers in can we confirm or conclude what a god even is could be to as well as if god exists, what is a god, and how or where/how did you acquire such definitions; impossible or possible for a god to exist. “From a confirmed or concluded” you have or do not have well definite if a god to the reality of a god. When anyone talks of challenges they are generally in some way even if only a unstated presupposition will include or involve three things: 1. the ontology (the thingness of things), 2. the epistemology ( how you know what you think you believe or know) and 3. the axiology (what and why of value/worth/good)? The ontology is of core importance to require it by asking for ontological definition or definition. This would make a good first act of fighting without having to fight, by always try starting by making them define the details of any claims but it can be done just as easily for attacks as well. Ontology attacks: slow down and unpack any claims, “you said you know god is real.” What do you mean by the qualities, attribution, or thingness of the things involved in the term god or what do you know about the term god and is an estimate for the faith reality you agree to believe in. Ontology defense: slow down and unpack any attacks, “you said I can’t be moral or good without god.” What do you mean by the qualities, attribution, or thingness of the things involved in the term god or morality? Simply, ontology is a universal investigation pinpoint. Ontology is likely what is being addressed or is involved when the reality confirmed by science, and the scientific method is generally employs several philosophy tools realized or not and they are mainly rationalism, empiricism and skepticism/fallibilism and/or falsificationism.

Ontology, Epistemology, & Axiology argument/challenge protocol: https://damienmarieathope.com/2016/10/13/ontology-epistemology-axiology-argumentchallenge-protocol/

To me belief ontologies address the conceptual schemas involved, at the intersection of three elements: a belief is a thinking system with a susceptibility to flaws, use ontological challenging or ontological disproofs which are logical arguments against by attacker/challenger access to the flaw, and attacker capability to exploit the flaw. Ontological disproofs, are sophisticated ontological arguments, ontological challenges or ontological disproofs accusations that demand equally sophisticated responses, to which, many people are unprepared. Belief or argument forms should be valid, to prove them sound or unsound, strong/weak, or well defined/undefined, as weak premises must be shown to be false. By use ontological challenging, you are shining a light on its ways claimed or points proposed, outlined or arranged which equals a thing or its qualities to define it that makes the depth and fullness to a being or thing, like just what is provisional about the thing in question or offer, are the characteristics of adequate development structure and infrastructure of the ontology involved in claims or propositions as truth, fact, or knowledge? One ontological criticism focuses on the semantics that are given for quantifiers qualities used or involved as the notation of the language representations of the contents of belief talk, proposing that the qualities offered are fully alike (unequivocal) when the items or properties identified to you are likely one of the three partly unlike (equivocal). To me, ontologies are like an adequate way or web of elements involved in the thingness of things or ideas. Point by slow methodological point, is the most effective way to use ontological challenging. Ontologically challenge needs to be done, in order to develop in the other person, an ontological insecurity about what the person, place, thing, or idea are construction of and just what is being claimed, portrayed or proposed as truth, fact, or knowledge? A belief or set of beliefs, likely have a relationship between ideas of the thing expose the cracks and fissure in the conceptualizations divided up or overlap but often while a belief or set of beliefs are offered with assurance, they instead ontologically inadequate or almost completely ontologically empty. By exposing ontological volnurniblities or weakness in a belief or set of beliefs can rise person’s sense of ontological Insecurity as the thinker realized they may not know that that know. In my way of thinking as ontological insecurity refers or relates to in an existential sense a person’s sense of “belief” deflation, discrediting, or disproving. Such an ontologically insecure thinker, may be so ontologically desperate, to stop/lower believing/accepting the level of “reality or existence” of the things or ideas they were just referring to. In contrast, the ontologically secure thinker, may be so ontologically stable in relation to ontological commitment of their fragments involved to feel a high level. Ontological arguments or Ontological commitment need to demonstrate or require demonstration of the disciplined or disordered structures but, a priori and necessary premises to the conclusion

Ontological commitment structures:

*similarity vs logic: this is the difference between matchings (predicating about the similarity of ontology terms), and mappings (logical axioms, typically expressing logical equivalence or inclusion among ontology terms)

*atomic vs complex: whether the alignments we considered are one-to-one, or can involve more terms in a query-like formulation (e.g., LAV/GAV mapping)

*homogeneous vs heterogeneous: do the alignments predicate on terms of the same type (e.g., classes are related only to classes, individuals to individuals, etc.) or we allow heterogeneity in the relationship?

*type of alignment: the semantics associated to an alignment, assumption, equivalence, discontinues, part-of or any user-specified relationship. Ref

Many arguments fall under the category of the ontological, and they tend to involve arguments about the state of being or existing. More specifically, ontological arguments tend to start with an a priori theory about the organization of the universe. If that organizational structure is true, the argument will provide reasons why God must exist. Ontological disproofs are logical arguments against of the existence of a thing based on what it would be if it existed. These arguments are very important because they do not simply purport to prove that god(s) does not exist (like, say, the Easter Bunny or Martians), but that God cannot exist (like a square circle or a married bachelor). The basic form of these arguments is something like this:

If God exists, he must be like ‘X’. [Here ‘X’ = some attribute(s) of God, e.g., he must be good, loving, omnipotent, etc.].

‘X’ is actually impossible.

Therefore, god(s) cannot exist.

The traditional definition of an ontological argument contrasted the ontological argument (literally any argument “concerned with being”) with the cosmological and physio-theoretical arguments. According to the Kantian view, ontological arguments are those founded on a priori reasoning. Graham Oppy, who holds the view that he “see[s] no urgent reason” to depart from the traditional definition, defined ontological arguments as those that begin with “nothing but analytic, a priori and necessary premises” and conclude that God exists. Oppy admitted, however, that not all of the “traditional characteristics” of an ontological argument (analyticity, necessity, and a priority) are found in all ontological arguments and, in his 2007 work Ontological Arguments and Belief in God, suggested that a better definition of an ontological argument would employ only considerations “entirely internal to the theistic worldview”. Oppy subclassified ontological arguments into definitional, conceptual (or hyperintensional), modal, Meinongian, experiential, mereological, higher-order, or Hegelian categories, based on the qualities of their premises. He defined these qualities as follows: definitional arguments invoke definitions; conceptual arguments invoke “the possession of certain kinds of ideas or concepts”; modal arguments consider possibilities; Meinongian arguments assert “a distinction between different categories of existence”; experiential arguments employ the idea that God exists solely to those who have had experience of him; and Hegelian arguments are from Hegel. He later categorized mereological as arguments that “draw on… the theory of the whole-part relation”. William Lane Craig criticized Oppy’s study as too vague for useful classification. Craig argued that an argument can be classified as ontological if it attempts to deduce the existence of God, along with other necessary truths, from his definition. He suggested that proponents of ontological arguments would claim that, if one fully understood the concept of God, one must accept his existence. William L. Rowe defined ontological arguments as those that start from the definition of God and, using only a priori principles, conclude with God’s existence. Ref

In information science, an upper, top-level, or foundation ontology is an ontology which consists of very general terms (such as “object”, “property”, “relation”) that are common across all domains. An important function of an upper ontology is to support broad semantic interoperability among a large number of domain-specific ontologies by providing a common starting point for the formulation of definitions. Terms in the domain ontology are ranked “under” the terms in the upper ontology, and the former stand to the latter in subclass relations. A number of upper ontologies proposed, each with its own proponents. Each upper ontology can be considered as a computational implementation of natural philosophy, which itself is a more empirical method for investigating the topics within the philosophical discipline of physical ontology. Arguments for the infeasibility of an upper ontology: Historically, many attempts in many societies have been made to impose or define a single set of concepts as more primal, basic, foundational, authoritative, true or rational than all others. A common objection to such attempts points out that humans lack the sort of transcendent perspective – or God’s eye view – that would be required to achieve this goal. Humans are bound by language or culture, and so lack the sort of objective perspective from which to observe the whole terrain of concepts and derive any one standard. Another objection is the problem of formulating definitions. Top level ontologies are designed to maximize support for interoperability across a large number of terms. Such ontologies must therefore consist of terms expressing very general concepts, but such concepts are so basic to our understanding that there is no way in which they can be defined, since the very process of definition implies that a less basic (and less well understood) concept is defined in terms of concepts that are more basic and so (ideally) more well understood. Very general concepts can often only be elucidated, for example by means of examples, or paraphrase.

There is no self-evident way of dividing the world up into concepts, and certainly no non-controversial one

There is no neutral ground that can serve as a means of translating between specialized (or “lower” or “application-specific”) ontologies

Human language itself is already an arbitrary approximation of just one among many possible conceptual maps. To draw any necessary correlation between English words and any number of intellectual concepts we might like to represent in our ontologies is just asking for trouble. (WordNet, for instance, is successful and useful precisely because it does not pretend to be a general-purpose upper ontology; rather, it is a tool for semantic / syntactic / linguistic disambiguation, which is richly embedded in the particulars and peculiarities of the English language.) Any hierarchical or topological representation of concepts must begin from some ontological, epistemological, linguistic, cultural, and ultimately pragmatic perspective. Such pragmatism does not allow for the exclusion of politics between persons or groups, indeed it requires they be considered as perhaps more basic primitives than any that are represented. Those who doubt the feasibility of general purpose ontologies are more inclined to ask “what specific purpose do we have in mind for this conceptual map of entities and what practical difference will this ontology make?” This pragmatic philosophical position surrenders all hope of devising the encoded ontology version of “everything that is the case.” Finally, there are objections similar to those against artificial intelligence. Technically, the complex concept acquisition and the social / linguistic interactions of human beings suggests any axiomatic foundation of “most basic” concepts must be cognitive, biological or otherwise difficult to characterize since we don’t have axioms for such systems. Ethically, any general-purpose ontology could quickly become an actual tyranny by recruiting adherents into a political program designed to propagate it and its funding means, and possibly defend it by violence. Historically, inconsistent and irrational belief systems have proven capable of commanding obedience to the detriment or harm of persons both inside and outside a society that accepts them. How much more harmful would a consistent rational one be, were it to contain even one or two basic assumptions incompatible with human life? Many of those who doubt the possibility of developing wide agreement on a common upper ontology fall into one of two traps:

they assert that there is no possibility of universal agreement on any conceptual scheme; but they argue that a practical common ontology does not need to have universal agreement, it only needs a large enough user community (as is the case for human languages) to make it profitable for developers to use it as a means to general interoperability, and for third-party developer to develop utilities to make it easier to use; and

they point out that developers of data schemes find different representations congenial for their local purposes; but they do not demonstrate that these different representation are in fact logically inconsistent.

In fact, different representations of assertions about the real world (though not philosophical models), if they accurately reflect the world, must be logically consistent, even if they focus on different aspects of the same physical object or phenomenon. If any two assertions about the real world are logically inconsistent, one or both must be wrong, and that is a topic for experimental investigation, not for ontological representation. In practice, representations of the real world are created as and known to be approximations to the basic reality, and their use is circumscribed by the limits of error of measurements in any given practical application. Ontologies are entirely capable of representing approximations, and are also capable of representing situations in which different approximations have different utility. Objections based on the different ways people perceive things attack a simplistic, impoverished view of ontology. The objection that there are logically incompatible models of the world are true, but in an upper ontology those different models can be represented as different theories, and the adherents of those theories can use them in preference to other theories, while preserving the logical consistency of the necessary assumptions of the upper ontology. The necessary assumptions provide the logical vocabulary with which to specify the meanings of all of the incompatible models. It has never been demonstrated that incompatible models cannot be properly specified with a common, more basic set of concepts, while there are examples of incompatible theories that can be logically specified with only a few basic concepts. Many of the objections to upper ontology refer to the problems of life-critical decisions or non-axiomatized problem areas such as law or medicine or politics that are difficult even for humans to understand. Some of these objections do not apply to physical objects or standard abstractions that are defined into existence by human beings and closely controlled by them for mutual good, such as standards for electrical power system connections or the signals used in traffic lights. No single general metaphysics is required to agree that some such standards are desirable. For instance, while time and space can be represented many ways, some of these are already used in interoperable artifacts like maps or schedules. Objections to the feasibility of a common upper ontology also do not take into account the possibility of forging agreement on an ontology that contains all of the primitive ontology elements that can be combined to create any number of more specialized concept representations. Adopting this tactic permits effort to be focused on agreement only on a limited number of ontology elements. By agreeing on the meanings of that inventory of basic concepts, it becomes possible to create and then accurately and automatically interpret an infinite number of concept representations as combinations of the basic ontology elements. Any domain ontology or database that uses the elements of such an upper ontology to specify the meanings of its terms will be automatically and accurately interoperable with other ontologies that use the upper ontology, even though they may each separately define a large number of domain elements not defined in other ontologies. In such a case, proper interpretation will require that the logical descriptions of domain-specific elements be transmitted along with any data that is communicated; the data will then be automatically interpretable because the domain element descriptions, based on the upper ontology, will be properly interpretable by any system that can properly use the upper ontology. In effect elements in different domain ontologies can be *translated* into each other using the common upper ontology. An upper ontology based on such a set of primitive elements can include alternative views, provided that they are logically compatible. Logically incompatible models can be represented as alternative theories, or represented in a specialized extension to the upper ontology. The proper use of alternative theories is a piece of knowledge that can itself be represented in an ontology. Users that develop new domain ontologies and find that there are semantic primitives needed for their domain but missing from the existing common upper ontology can add those new primitives by the accepted procedure, expanding the common upper ontology as necessary. Most proponents[who?] of an upper ontology argue that several good ones may be created with perhaps different emphasis. Very few are actually arguing to discover just one within natural language or even an academic field. Most are simply standardizing some existing communication. Another view advanced is that there is almost total overlap of the different ways that upper ontologies have been formalized, in the sense that different ontologies focus on a different aspect of the same entities, but the different views are complementary and not contradictory to each other; as a result, an internally consistent ontology that contains all the views, with means of translating the different views into the other, is feasible. Such an ontology has not thus far been constructed, however, because it would require a large project to develop so as to include all of the alternative views in the separately developed upper ontologies, along with their translations. The main barrier to construction of such an ontology is not the technical issues, but the reluctance of funding agencies to provide the funds for a large enough consortium of developers and users. Several common arguments against upper ontology can be examined more clearly by separating issues of concept definition (ontology), language (lexicons), and facts (knowledge). For instance, people have different terms and phrases for the same concept. However, that does not necessarily mean that those people are referring to different concepts. They may simply be using different language or idiom. Formal ontologies typically use linguistic labels to refer to concepts, but the terms that label ontology elements mean no more and no less than what their axioms say they mean. Labels are similar to variable names in software, evocative rather than definitive. The proponents of a common upper ontology point out that the meanings of the elements (classes, relations, rules) in an ontology depend only on their logical form, and not on the labels, which are usually chosen merely to make the ontologies more easily usable by their human developers. In fact, the labels for elements in an ontology need not be words – they could be, for example, images of instances of a particular type, or videos of an action that is represented by a particular type. It cannot be emphasized too strongly that words are *not* what are represented in an ontology, but entities in the real world, or abstract entities (concepts) in the minds of people. Words are not equivalent to ontology elements, but words *label* ontology elements. There can be many words that label a single concept, even in a single language (synonymy), and there can be many concepts labeled by a single word (ambiguity). Creating the mappings between human language and the elements of an ontology is the province of Natural Language Understanding. But the ontology itself stands independently as a logical and computational structure. For this reason, finding agreement on the structure of an ontology is actually easier than developing a controlled vocabulary, because all different interpretations of a word can be included, each *mapped* to the same word in the different terminologies. A second argument is that people believe different things, and therefore can’t have the same ontology. However, people can assign different truth values to a particular assertion while accepting the validity of certain underlying claims, facts, or way of expressing an argument with which they disagree. (Using, for instance, the issue/position/argument form.) This objection to upper ontologies ignores the fact that a single ontology can represent different belief systems, representing them as different belief systems, without taking a position on the validity of either. Even arguments about the existence of a thing require a certain sharing of a concept, even though its existence in the real world may be disputed. Separating belief from naming and definition also helps to clarify this issue, and show how concepts can be held in common, even in the face of differing belief. For instance, wiki as a medium may permit such confusion but disciplined users can apply dispute resolution methods to sort out their conflicts. It is also argued that most people share a common set of “semantic primitives”, fundamental concepts, to which they refer when they are trying to explain unfamiliar terms to other people. An ontology that includes representations of those semantic primitives could in such a case be used to create logical descriptions of any term that a person may wish to define logically. That ontology would be one form of upper ontology, serving as a logical “interlingua” that can translate ideas in one terminology to its logical equivalent in another terminology. Advocates[who?] argue that most disagreement about the viability of an upper ontology can be traced to the conflation of ontology, language and knowledge, or too-specialized areas of knowledge: many people, or agents or groups will have areas of their respective internal ontologies that do not overlap. If they can cooperate and share a conceptual map at all, this may be so very useful that it outweighs any disadvantages that accrue from sharing. To the degree it becomes harder to share concepts the deeper one probes, the more valuable such sharing tends to get. If the problem is as basic as opponents of upper ontologies claim, then, it also applies to a group of humans trying to cooperate, who might need machine assistance to communicate easily. If nothing else, such ontologies are implied by machine translation, used when people cannot practically communicate. Whether “upper” or not, these seem likely to proliferate. Ref

Error Crushing Force of the Dialectic Questions and the Hammer of Truth

Error Crushing Force of the Dialectic Questions and the Hammer of Truth

*(Ontology) What are you talking about, please slow down and give me each specific detail individually?

*(Epistemology) How do you know that and why do you think it is justified or warranted?

*(Axiology) What is its value if any and why do you value that or why would anyone?

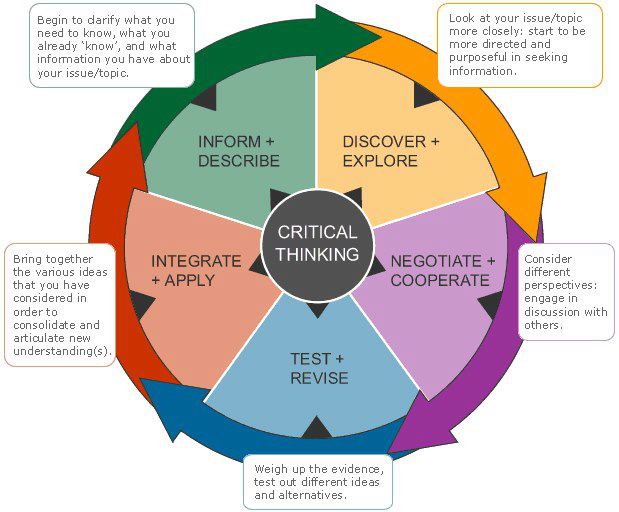

If you don’t already know, Dialectic is the art of investigating or discussing the truth of opinions.

What I am trying to say in this message of Dialectic Questions in order to find truth by giving people three questions that can be put towards almost anything and it help remove error and thus improved accuracy.

Ontology, Epistemology, & Axiology argument/challenge protocol

Grasping the status of truth (ontology of truth)

The Ontology of Humanistic Economics in Society?

Strong vs Weak Thinkers?

A strong thinker can deeply analyze their own positions removing all that are unworthy and updating to the most currently accurate. Whereas a weak thinker can only offer deep attacks to the positions of others that differ in thinking.

Just think, are your beliefs further supporting rhetoric or accuracy to the facts and are you ready to change if you have it the other way around?

Believer vs Thinker?

When you can, with all honesty, say that you put a similar voracity to one’s own ideas as they demand for others then they are a thinker not just a believer. And when you can quickly and eagerly relinquish any and all ideas, even the most cherished if they were not true; yes a willingness to discuss or discard if required, even if you like them is being a thinker and not just a unthinking believer.

We Love Generalizations (even if wrong)

We don’t like slow clear accurate thinking, no, we are bias irrational compulsive disordered hasty generalizations thinking beings.

We build our “belief” of the accuracy of our hasty generalizations one assertion at a time. In other words we add undue increasing assurance because we keep saying it over and over again, not because it’s actually accurate to the facts. We may cherry pick a few facts to support this error in thinking but that is intellectual dishonestly, as if it can be destroyed by the truth it should be. – Damien Marie AtHope

Here is my blog on rhetoric and stereotypes: Rhetoric & Stereotypes: Rethinking How We Think.

And, here is some information on hasty generalizations (also known as: argument from small numbers, statistics of small numbers, insufficient statistics, unrepresentative sample [form of], argument by generalization, faulty generalization, hasty conclusion [form of], inductive generalization, insufficient sample, lonely fact fallacy, over generality, over generalization)

Description: Drawing a conclusion based on a small sample size, rather than looking at statistics that are much more in line with the typical or average situation.

Logical Form:

Sample S is taken from population P.

Sample S is a very small part of population P.

Conclusion C is drawn from sample S.

Example #1:

My father smoked four packs of cigarettes a day since age fourteen and lived until age sixty-nine. Therefore, smoking really can’t be that bad for you.

Explanation: It is extremely unreasonable (and dangerous) to draw a universal conclusion about the health risks of smoking by the case study of one man.

Example #2:

Four out of five dentists recommend Happy Glossy Smiley toothpaste brand. Therefore, it must be great.

Explanation: It turns out that only five dentists were actually asked. When a random sampling of 1000 dentists were polled, only 20% actually recommended the brand. The four out of five result was not necessarily a biased sample or a dishonest survey, it just happened to be a statistical anomaly common among small samples.

Exception: When statistics of a larger population are not available, and a decision must be made or opinion formed if the small sample size is all you have to work with, then it is better than nothing. For example, if you are strolling in the desert with a friend, and he goes to pet a cute snake, gets bitten, then dies instantly, it would not be fallacious to assume the snake is poisonous.

Tip: Don’t base decisions on small sample sizes when much more reliable data exists.

Variation: The hasty conclusion is leaping to a conclusion without carefully considering the alternatives — a tad different than drawing a conclusion from too small of a sample. Ref

“The First Moral Humans”

By Jersey Flight

The first self-conscious moral human beings had to become an example!

We must show people how to interact. We must show them what a moral human looks like, most people have never seen one before. How are they supposed to know, they can only mimic what they can see? By interacting together as thinkers, by showing the world how we do collective philosophy, how we interact with people in general, we can train the next generation of thinkers. We are here to leave a moral imprint, an example that can be celebrated and held up for future generations to emulate.

I am not an ego-thinker, I am a caring-thinker.

This summarizes what’s wrong with most thinkers, in a very swift fashion: they are ego-thinkers. This means their ego disrupts the intelligence of their thought, it puts the thinker on an ego-mission, not a caring-mission or truth-mission. The thinker is most often derailed by the ego, not other people!

What is my secret to powerful writing? Short sentences of fact and common sense, the more self-evident the better! My writing is almost like a correspondence between words and reality, I try to mold my words to the bare ontology I see. I simply try to state what I perceive to be the case, in the simplest (most primitive) words possible. Because my main goal is to communicate effectively. Do we want to deal in words that move people, or words that impress people? Do I want someone to read what I write and say, “look how brilliant he is,” or do I want what I write to impart brilliance? This is my secret. jerseyflight.com

Addressing The Ethics of Belief

Yes, We All Have Beliefs; But What Does That Mean?

Critical or Analytical Thinking and Suspension of Judgment, Disbelief or Belief

“Theists, there has to be a god, as something can not come from nothing.”

Well, thus something (unknown) happened and then there was something. This does not tell us what the something that may have been involved with something coming from nothing. A supposed first cause, thus something (unknown) happened and then there was something is not an open invitation to claim it as known, neither is it justified to call or label such an unknown as anything, especially an unsubstantiated magical thinking belief born of mythology and religious storytelling.

While hallucinogens are associated with shamanism, it is alcohol that is associated with paganism.

The Atheist-Humanist-Leftist Revolutionaries Shows in the prehistory series:

Show two: Pre-animism 300,000 years old and animism 100,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism”

Show tree: Totemism 50,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism”

Show four: Shamanism 30,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism”

Show five: Paganism 12,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism”

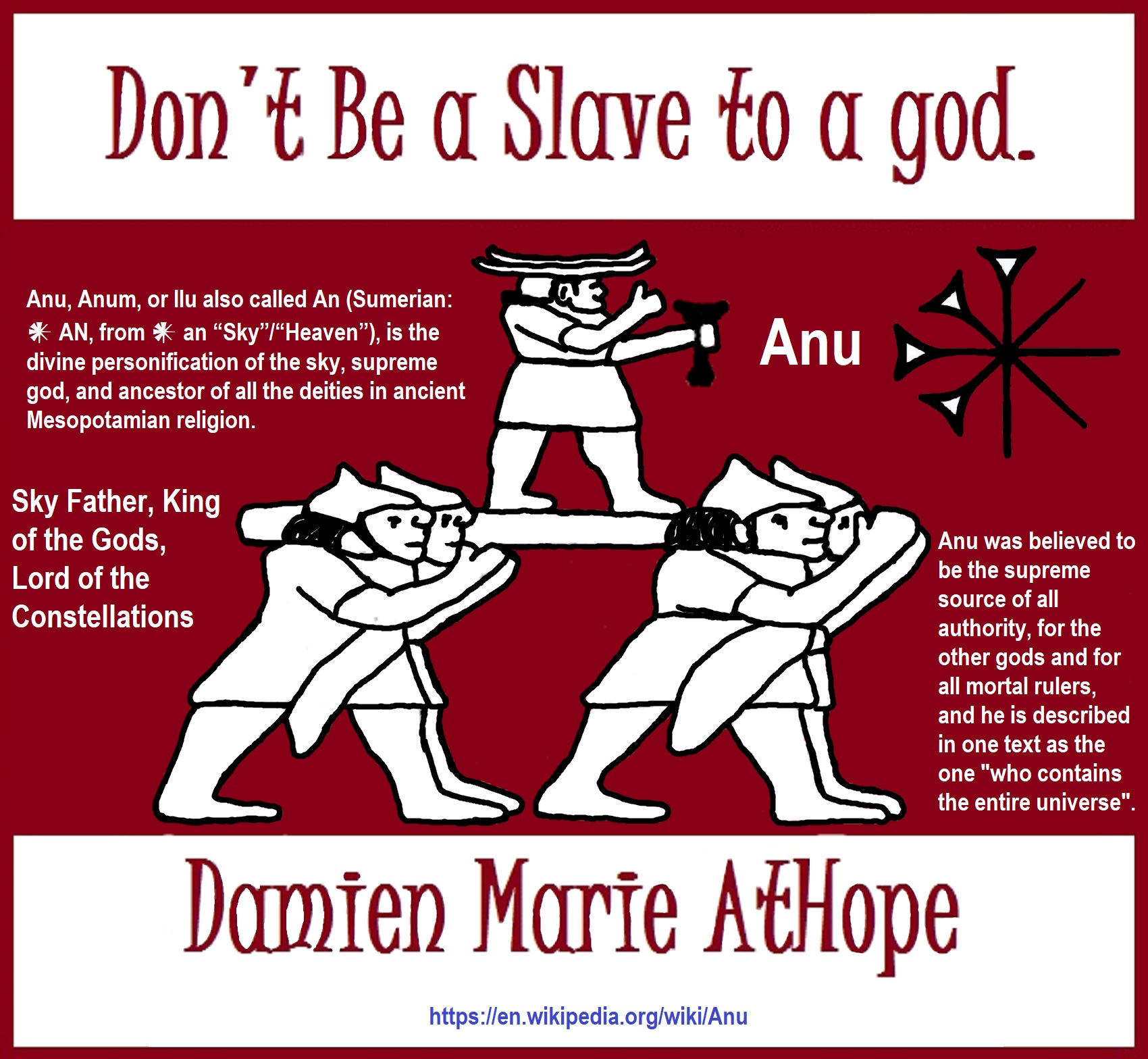

Show six: Emergence of hierarchy, sexism, slavery, and the new male god dominance: Paganism 7,000-5,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism” (Capitalism) (World War 0) Elite and their slaves!

Prehistory: related to “Anarchism and Socialism” the division of labor, power, rights, and recourses: VIDEO

Pre-animism 300,000 years old and animism 100,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism”: VIDEO

Totemism 50,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism”: VIDEO

Shamanism 30,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism”: VIDEO

Paganism 12,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism” (Pre-Capitalism): VIDEO

Paganism 7,000-5,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism” (Capitalism) (World War 0) Elite and their slaves: VIEDO

Paganism 5,000 years old: progressed organized religion and the state: related to “Anarchism and Socialism” (Kings and the Rise of the State): VIEDO

Paganism 4,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism” (First Moralistic gods, then the Origin time of Monotheism): VIEDO

I do not hate simply because I challenge and expose myths or lies any more than others being thought of as loving simply because of the protection and hiding from challenge their favored myths or lies.

The truth is best championed in the sunlight of challenge.

An archaeologist once said to me “Damien religion and culture are very different”

My response, So are you saying that was always that way, such as would you say Native Americans’ cultures are separate from their religions? And do you think it always was the way you believe?

I had said that religion was a cultural product. That is still how I see it and there are other archaeologists that think close to me as well. Gods too are the myths of cultures that did not understand science or the world around them, seeing magic/supernatural everywhere.

I personally think there is a goddess and not enough evidence to support a male god at Çatalhöyük but if there was both a male and female god and goddess then I know the kind of gods they were like Proto-Indo-European mythology.

This series idea was addressed in, Anarchist Teaching as Free Public Education or Free Education in the Public: VIDEO

Our 12 video series: Organized Oppression: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of power (9,000-4,000 years ago), is adapted from: The Complete and Concise History of the Sumerians and Early Bronze Age Mesopotamia (7000-2000 BC): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=szFjxmY7jQA by “History with Cy“

Show #1: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power (Samarra, Halaf, Ubaid)

Show #2: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power

Show #3: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power (Uruk and the First Cities)

Show #4: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power (First Kings)

Show #5: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power (Early Dynastic Period)

Show #6: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power

Show #7: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power (Sargon and Akkadian Rule)

Show #9: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power (Gudea of Lagash and Utu-hegal)

Show #12: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power (Aftermath and Legacy of Sumer)

The “Atheist-Humanist-Leftist Revolutionaries”

Cory Johnston ☭ Ⓐ Atheist Leftist @Skepticallefty & I (Damien Marie AtHope) @AthopeMarie (my YouTube & related blog) are working jointly in atheist, antitheist, antireligionist, antifascist, anarchist, socialist, and humanist endeavors in our videos together, generally, every other Saturday.

Why Does Power Bring Responsibility?

Think, how often is it the powerless that start wars, oppress others, or commit genocide? So, I guess the question is to us all, to ask, how can power not carry responsibility in a humanity concept? I know I see the deep ethical responsibility that if there is power their must be a humanistic responsibility of ethical and empathic stewardship of that power. Will I be brave enough to be kind? Will I possess enough courage to be compassionate? Will my valor reach its height of empathy? I as everyone, earns our justified respect by our actions, that are good, ethical, just, protecting, and kind. Do I have enough self-respect to put my love for humanity’s flushing, over being brought down by some of its bad actors? May we all be the ones doing good actions in the world, to help human flourishing.

I create the world I want to live in, striving for flourishing. Which is not a place but a positive potential involvement and promotion; a life of humanist goal precision. To master oneself, also means mastering positive prosocial behaviors needed for human flourishing. I may have lost a god myth as an atheist, but I am happy to tell you, my friend, it is exactly because of that, leaving the mental terrorizer, god belief, that I truly regained my connected ethical as well as kind humanity.

Cory and I will talk about prehistory and theism, addressing the relevance to atheism, anarchism, and socialism.

At the same time as the rise of the male god, 7,000 years ago, there was also the very time there was the rise of violence, war, and clans to kingdoms, then empires, then states. It is all connected back to 7,000 years ago, and it moved across the world.

Cory Johnston: https://damienmarieathope.com/2021/04/cory-johnston-mind-of-a-skeptical-leftist/?v=32aec8db952d

The Mind of a Skeptical Leftist (YouTube)

Cory Johnston: Mind of a Skeptical Leftist @Skepticallefty

The Mind of a Skeptical Leftist By Cory Johnston: “Promoting critical thinking, social justice, and left-wing politics by covering current events and talking to a variety of people. Cory Johnston has been thoughtfully talking to people and attempting to promote critical thinking, social justice, and left-wing politics.” http://anchor.fm/skepticalleft

Cory needs our support. We rise by helping each other.

Cory Johnston ☭ Ⓐ @Skepticallefty Evidence-based atheist leftist (he/him) Producer, host, and co-host of 4 podcasts @skeptarchy @skpoliticspod and @AthopeMarie

Damien Marie AtHope (“At Hope”) Axiological Atheist, Anti-theist, Anti-religionist, Secular Humanist. Rationalist, Writer, Artist, Poet, Philosopher, Advocate, Activist, Psychology, and Armchair Archaeology/Anthropology/Historian.

Damien is interested in: Freedom, Liberty, Justice, Equality, Ethics, Humanism, Science, Atheism, Antiteism, Antireligionism, Ignosticism, Left-Libertarianism, Anarchism, Socialism, Mutualism, Axiology, Metaphysics, LGBTQI, Philosophy, Advocacy, Activism, Mental Health, Psychology, Archaeology, Social Work, Sexual Rights, Marriage Rights, Woman’s Rights, Gender Rights, Child Rights, Secular Rights, Race Equality, Ageism/Disability Equality, Etc. And a far-leftist, “Anarcho-Humanist.”

I am not a good fit in the atheist movement that is mostly pro-capitalist, I am anti-capitalist. Mostly pro-skeptic, I am a rationalist not valuing skepticism. Mostly pro-agnostic, I am anti-agnostic. Mostly limited to anti-Abrahamic religions, I am an anti-religionist.

To me, the “male god” seems to have either emerged or become prominent around 7,000 years ago, whereas the now favored monotheism “male god” is more like 4,000 years ago or so. To me, the “female goddess” seems to have either emerged or become prominent around 11,000-10,000 years ago or so, losing the majority of its once prominence around 2,000 years ago due largely to the now favored monotheism “male god” that grow in prominence after 4,000 years ago or so.

My Thought on the Evolution of Gods?

Animal protector deities from old totems/spirit animal beliefs come first to me, 13,000/12,000 years ago, then women as deities 11,000/10,000 years ago, then male gods around 7,000/8,000 years ago. Moralistic gods around 5,000/4,000 years ago, and monotheistic gods around 4,000/3,000 years ago.

To me, animal gods were likely first related to totemism animals around 13,000 to 12,000 years ago or older. Female as goddesses was next to me, 11,000 to 10,000 years ago or so with the emergence of agriculture. Then male gods come about 8,000 to 7,000 years ago with clan wars. Many monotheism-themed religions started in henotheism, emerging out of polytheism/paganism.

Damien Marie AtHope (Said as “At” “Hope”)/(Autodidact Polymath but not good at math):

Axiological Atheist, Anti-theist, Anti-religionist, Secular Humanist, Rationalist, Writer, Artist, Jeweler, Poet, “autodidact” Philosopher, schooled in Psychology, and “autodidact” Armchair Archaeology/Anthropology/Pre-Historian (Knowledgeable in the range of: 1 million to 5,000/4,000 years ago). I am an anarchist socialist politically. Reasons for or Types of Atheism

My Website, My Blog, & Short-writing or Quotes, My YouTube, Twitter: @AthopeMarie, and My Email: damien.marie.athope@gmail.com