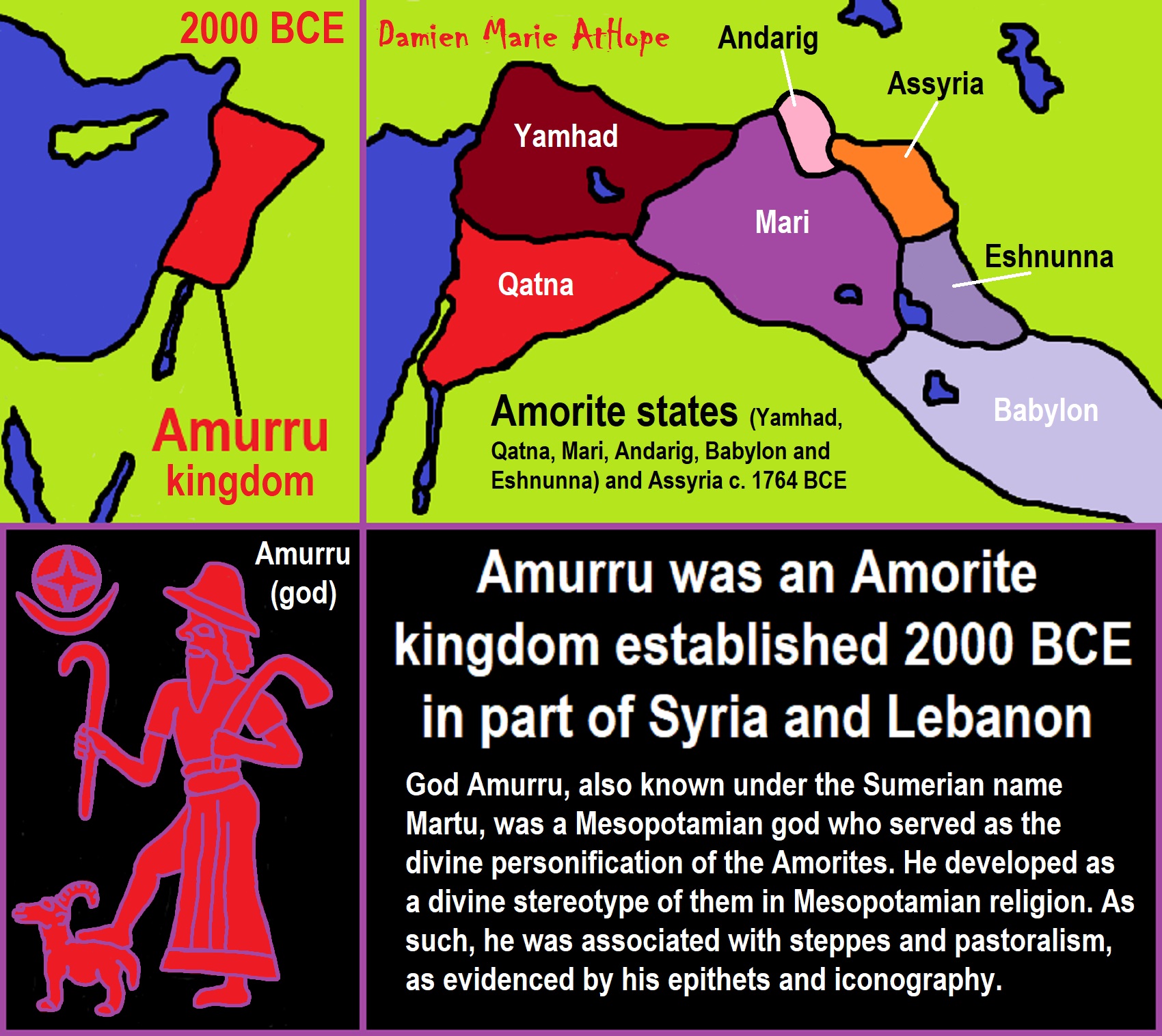

Amorites

“The Amorites were an ancient Northwest Semitic-speaking people from the Levant who also occupied large parts of southern Mesopotamia from the 21st century BCE to the end of the 17th century BCE, where they established several prominent city-states in existing locations, such as Isin, Larsa and later notably Babylon, which was raised from a small town to an independent state and a major city. The term Amurru in Akkadian and Sumerian texts refers to the Amorites, their principal deity, and an Amorite kingdom. The Amorites are also mentioned in the Bible as inhabitants of Canaan both before and after the conquest of the land under Joshua. In the earliest Sumerian sources concerning the Amorites, beginning about 2400 BCE, the land of the Amorites (“the Mar.tu land”) is associated not with Mesopotamia but with the lands to the west of the Euphrates, including Canaan and what was to become Syria by the 3rd century BC, then known as The land of the Amurru, and later as Aram and Eber-Nari.” ref

“They appear as an uncivilized and nomadic people in early Mesopotamian writings from Sumer, Akkad, and Assyria, to the west of the Euphrates. The ethnic terms Mar.tu (“Westerners”), Amurru (suggested in 2007 to be derived from aburru, “pasture”) and Amor were used for them in Sumerian, Akkadian, and Ancient Egyptian respectively. From the 21st century BCE, possibly triggered by a long major drought starting about 2200 BCE, a large-scale migration of Amorite tribes infiltrated southern Mesopotamia. They were one of the instruments of the downfall of the Third Dynasty of Ur, and Amorite dynasties not only usurped the long-extant native city-states such as Isin, Larsa, Eshnunna, and Kish, but also established new ones, the most famous of which was to become Babylon, although it was initially a minor insignificant state.” ref

“Known Amorites wrote in a dialect of Akkadian found on tablets at Mari dating from 1800–1750 BCE. Since the language shows northwest Semitic forms, words, and constructions, the Amorite language is a Northwest Semitic language, and possibly one of the Canaanite languages. The main sources for the extremely limited extant knowledge of the Amorite language are the proper names, not Akkadian in style, that are preserved in such texts. The Akkadian language of the native Semitic states, cities, and polities of Mesopotamia (Akkad, Assyria, Babylonia, Isin, Kish, Larsa, Ur, Nippur, Uruk, Eridu, Adab, Akshak, Eshnunna, Nuzi, Ekallatum, etc.), was from the east Semitic, as was the Eblaite of the northern Levant.” ref

“There is a wide range of views regarding the Amorite homeland. One extreme is the view that kur mar.tu/māt amurrim covered the whole area between the Euphrates and the Mediterranean Sea, the Arabian Peninsula included. The most common view is that the “homeland” of the Amorites was a limited area in central Syria identified with the mountainous region of Jebel Bishri. Since the Amorite language is closely related to the better-studied Canaanite languages, both being branches of the Northwestern Semitic languages, as opposed to the South Semitic languages found in the Arabian Peninsula, they are usually considered native to the region around Syria and Transjordan.” ref

“As the centralized structure of the Third Dynasty slowly collapsed, the component regions, such as Assyria in the north and the city-states of the south such as Isin, Larsa, and Eshnunna, began to reassert their former independence, and the areas in southern Mesopotamia with Amorites were no exception. Elsewhere, the armies of Elam, in southern Iran, were attacking and weakening the empire, making it vulnerable. Many Amorite chieftains in southern Mesopotamia aggressively took advantage of the failing empire to seize power for themselves. There was not an Amorite invasion of southern Mesopotamia as such, but Amorites ascended to power in many locations, especially during the reign of the last king of the Neo-Sumerian Empire, Ibbi-Sin. Leaders with Amorite names assumed power in various places, usurping native Akkadian rulers, including in Isin, Eshnunna, and Larsa. The small town of Babylon, unimportant both politically and militarily, was raised to the status of a minor independent city-state, under Sumu-abum in 1894 BCE.” ref

“The Elamites finally sacked Ur in c. 2004 BCE. Some time later, the Old Assyrian Empire (c. 2050 – 1750 BCE) became the most powerful entity in Mesopotamia immediately preceding the rise of the Amorite king Hammurabi of Babylon. The new Assyrian monarchic line was founded by c. 2050 BCE; their kings repelled attempted Amorite incursions, and may have countered their influence in the south as well under Erishum I, Ilu-shuma ,and Sargon I. However, even Assyria eventually found its throne usurped by an Amorite in 1809 BCE: the last two rulers of the Old Assyrian Empire period, Shamshi-Adad I and Ishme-Dagan, were Amorites who originated in Terqa (now in northeastern Syria).

“Amorite presence in Egypt was inevitable since at least the First Intermediate Period. The Levantine-blooded Fourteenth Dynasty of Egypt, centered in the Nile Delta, had rulers bearing Amorite names, such as Yakbmu. Furthermore, increasing evidence suggests that the succeeding Hyksos of Egypt were an amalgam of Asiatic peoples from Syria, of which the Amorites were also part of. Based on temple architecture, Manfred Bietak argues for strong parallels between the religious practices of the Hyksos at Avaris with those of the area around Byblos, Ugarit, Alalakh, and Tell Brak, defining the “spiritual home” of the Hyksos as “in northernmost Syria and northern Mesopotamia”, areas typically associated with Amorites at the time. In 1650 BCE, the Hyksos went on to establish the Fifteenth Dynasty of Egypt and rule most of Lower and Middle Egypt contemporaneously with the Sixteenth and Seventeenth dynasties of Thebes.” ref

“The era ended in northern Mesopotamia, with the defeat and expulsion of the Amorites and Amorite-dominated Babylonians from Assyria by Puzur-Sin and king Adasi between 1740 and 1735 BCE, and in the far south, by the rise of the native Sealand Dynasty c. 1730 BCE. The Amorites clung on in a once-more small and weak Babylon until the Hittites‘ sack of Babylon (c. 1595 BCE), which ended the Amorite presence, and brought new ethnic groups, particularly the Kassites, to the forefront in southern Mesopotamia. From the 15th century BCE onward, the term Amurru is usually applied to the region extending north of Canaan as far as Kadesh on the Orontes River in northern Syria.” ref

“Amorite presence in Egypt was supplanted by Ahmose I, the founder of the Eighteenth Dynasty, when he kicked out the wider group of Asiatic Hyksos back into the Levant in 1550 BCE, putting an end to Levantine political influence in Egypt. After their expulsion from Mesopotamia, the Amorites of Syria came under the domination of first the Hittites and, from the 14th century BCE, the Middle Assyrian Empire (1365–1050 BCE). They appear to have been displaced or absorbed by a new wave of semi-nomadic West Semitic-speaking peoples, known collectively as the Ahlamu during the Late Bronze Age collapse. The Arameans rose to be the prominent group amongst the Ahlamu, and from c. 1200 BCE on, the Amorites disappeared from the pages of history. From then on, the region that they had inhabited became known as Aram (“Aramea”) and Eber-Nari.” ref

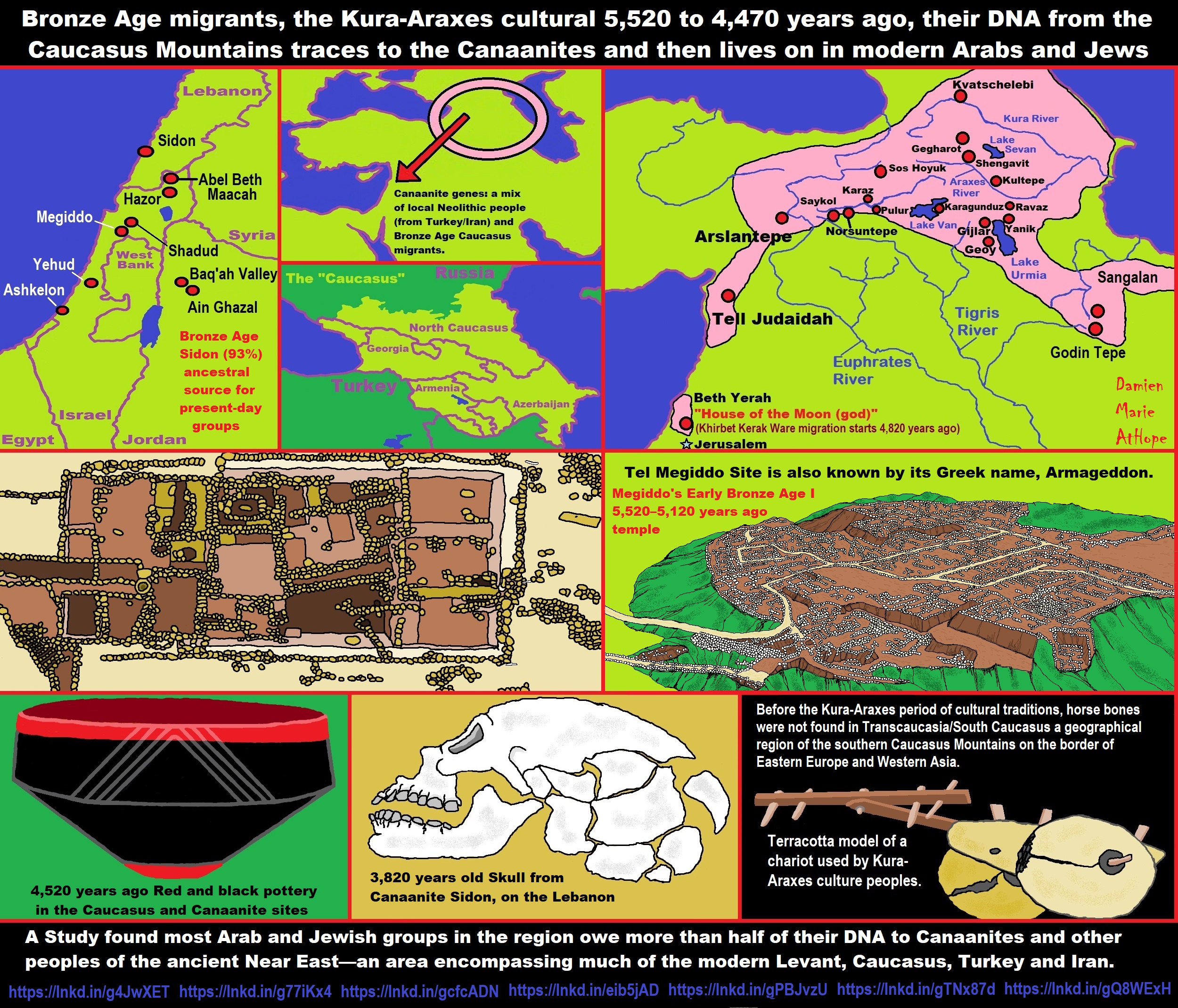

“Skourtanioti et al. (2020) conducted ancient DNA analysis on 28 human remains dating to the Middle and Late Bronze age from Tell Atchana, ancient Alalakh, a city which was founded by Amorites and contained a Hurrian minority later on, which the authors called an Amorite cultural assemblage. The analysis found that the inhabitants of Alalakh were a mixture of Copper age Levantines and Mesopotamians, and were genetically similar to contemporary Levantines from Syria (Ebla) and Lebanon (Sidon).” ref

Amurru (god)

“Amurru and Martu are names given in Akkadian and Sumerian texts to the god of the Amorite/Amurru people, often forming part of personal names. He is sometimes called Ilu Amurru (DMAR.TU). He was the patron god of the Mesopotamian city of Ninab, whose exact location is unknown. He was occasionally called “lord of the steppe” or “lord of the mountain.” ref

“Amurru/Martu was probably a western Semitic god originally. He is sometimes described as a ‘shepherd’ or as a storm god, and as a son of the sky-god Anu. He is sometimes called bêlu šadī or bêl šadê, ‘lord of the mountain’; dúr-hur-sag-gá sikil-a-ke, ‘He who dwells on the pure mountain’; and kur-za-gan ti-[la], ‘who inhabits the shining mountain’. In Cappadocian Zinčirli inscriptions he is called ì-li a-bi-a, ‘the god of my father‘.” ref

“Bêl Šadê could also have become the fertility-god ‘Ba’al‘, possibly adopted by the Canaanites, a rival and enemy of the Hebrew God YHWH, and famously combatted by the Hebrew prophet Elijah.” ref

“Amurru also has storm-god features. Like Adad, Amurru bears the epithet ramān ‘thunderer’, and he is even called bāriqu ‘hurler of the thunderbolt’ and Adad ša a-bu-be ‘Adad of the deluge’. Yet his iconography is distinct from that of Adad, and he sometimes appears alongside Adad with a baton of power or throwstick, while Adad bears a conventional thunderbolt.” ref

“Amurru’s wife is usually the goddess Ašratum (see Asherah) who in northwest Semitic tradition and Hittite tradition appears as wife of the god El which suggests that Amurru may indeed have been a variation of that god. If Amurru was identical with Ēl, it would explain why so few Amorite names are compounded with the name Amurru, but so many are compounded with Il; that is, with El.” ref

“Another tradition about Amurru’s wife (or one of Amurru’s wives) gives her name as Belit-Sheri, ‘Lady of the Desert’. A third tradition appears in a Sumerian poem in pastoral style, which relates how the god Martu came to marry Adg̃ar-kidug the daughter of the god Numushda of the city of Inab. It contains a speech expressing urbanite Sumerian disgust at uncivilized, nomadic Amurru life which Adg̃ar-kidug ignores, responding only: “I will marry Martu!.” ref

“Amorite (Sumerian ???????? MAR.TU, Akkadian Tidnum or Amurrūm, Egyptian Amar, Hebrew ’emōrî אמורי) refers to a Semitic people who occupied large parts of Mesopotamia from at least the second half of the third millennium BCE. The term Amurru refers to them, as well as to their principal deity.” ref

“In the earliest Sumerian sources, beginning about 2400 BCE, the land of the Amorites (“the Mar.tu land”) is associated with the West, including Syria and Canaan. They appear as nomadic people in the Mesopotamian sources, and they are especially connected with the mountainous region of Jebel Bishri in Syria called as the “mountain of the Amorites”. The ethnic terms Amurru and Amar were used for them in Assyria and Egypt respectively.” ref

“From the 21st century BCE and likely triggered by the 22nd century BCE drought, a large-scale migration of Amorite tribes infiltrated Mesopotamia, precipitating the downfall of the Neo-Sumerian Third Dynasty of Ur, and acquiring a series of powerful kingdoms, culminating in the triumph under Hammurabi of one of them, that of Babylon.” ref

“Known Amorites (mostly those of Mari) wrote in a dialect of Akkadian found on tablets dating from 1800–1750 BCE showing many northwest Semitic forms and constructions. The Amorite language was presumably a northwest Semitic dialect. The main sources for our extremely limited knowledge about the language are proper names, not Akkadian in style, that are preserved in such texts.” ref

“In early inscriptions, all western lands, including Syria and Canaan, were known as “the land of the Amorites”. “The MAR.TU land” appears in the earliest Sumerian texts, such as Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta, as well as early tablets from Ebla; and for the Akkadian kings Mar.tu was one of the “Four Quarters” surrounding Akkad, along with Subartu, Sumer, and Elam. The Akkadian king Naram-Sin records campaigns against them in northern Syria ca. 2240 BCE, and his successor Shar-Kali-Sharri followed suit.” ref

“By the time of the Neo-Sumerian Ur-III empire, immigrating Amorites had become such a force that kings such as Shu-Sin were obliged to construct a 170-mile wall from the Tigris to the Euphrates to hold them off. These Amorites appear as nomadic clans ruled by fierce tribal chiefs, who forced themselves into lands they needed to graze their herds. Some of the Akkadian literature of this era speaks disparagingly of the Amorites, and implies that the neo-Sumerians viewed their nomadic way of life with disgust and contempt, for example:

“The MAR.TU who know no grain…. The MAR.TU who know no house nor town, the boors of the mountains…. The MAR.TU who digs up truffles… who does not bend his knees (to cultivate the land), who eats raw meat, who has no house during his lifetime, who is not buried after death…They have prepared wheat and gú-nunuz (grain) as a confection, but an Amorite will eat it without even recognizing what it contains!” ref

“As the centralized structure of the neo-Sumerian empire of Ur slowly collapsed, the component regions began to reassert their former independence, and places, where Amorites resided, were no exception. Elsewhere, armies of Elam were attacking and weakening the empire, making it vulnerable. Some Amorites aggressively took advantage of the failing empire to seize power for themselves. There was not an Amorite invasion as such, but Amorites did ascend to power in many locations, especially during the reign of the last king of the Ur-III Dynasty, Ibbi-Sin. Leaders with Amorite names assumed power in various places, including Isin, Larsa, and Babylon. The Elamites finally sacked Ur in ca. 2004 BC. Sometime later, the most powerful ruler in Mesopotamia (immediately preceding the rise of Hammurabi of Babylon) was Shamshi-Adad I, another Amorite.” ref

Effects on Mesopotamia

“The rise of the Amorite kingdoms in Mesopotamia brought about deep and lasting repercussions in its political, social, and economic structure. The division into kingdoms replaced the Sumerian city-state. Men, land, and cattle ceased to belong physically to the gods or to the temples and the king. The new monarchs gave, or let out for an indefinite period, numerous parcels of royal or sacerdotal land, freed the inhabitants of several cities from taxes and forced labor, and seem to have encouraged a new society to emerge, a society of big farmers, free citizens, and enterprising merchants which was to last throughout the ages. The priest assumed the service of the gods, and cared for the welfare of his subjects, but the economic life of the country was no longer exclusively (or almost exclusively) in their hands.” ref

“In general terms, Mesopotamian civilization survived the arrival of Amorites, as it had survived the Akkadian domination and the restless period that had preceded the rise of the Third Dynasty of Ur. The religious, ethical, and artistic directions in which Mesopotamia had been developing since earliest times, were not greatly impacted by the Amorites’ hegemony. They continued to worship the Sumerian gods, and the older Sumerian myths and epic tales were piously copied, translated, or adapted, generally with only minor alterations. As for the scarce artistic production of the period, there is little to distinguish it from the preceding Ur-III era.” ref

“The era of the Amorite kingdoms, ca. 2000–1600 BCE, is sometimes known as the “Amorite period” in Mesopotamian history. The principal Amorite dynasties arose in Mari, Yamkhad, Qatna, Assur (under Shamshi-Adad I), Isin, Larsa, and Babylon. This era ended with the Hittite sack of Babylon (c. 1595 BCE) which brought new ethnic groups—particularly Kassites and Hurrians—to the forefront in Mesopotamia. From the 15th century BC onward, the term Amurru is usually applied to the region extending north of Canaan as far as Kadesh on the Orontes.” ref

Biblical Amorites

“The term Amorites is used in the Bible to refer to certain highland mountaineers who inhabited the land of Canaan, described in Gen. 10:16 as descendants of Canaan, son of Ham. They are described as a powerful people of great stature “like the height of the cedars,” who had occupied the land east and west of the Jordan; their king, Og, being described as the last “of the remnant of the giants” (Deut. 3:11). The terms Amorite and Canaanite seem to be used more or less interchangeably, Canaan being more general, and Amorite a specific component among the Canaanites who inhabited the land.” ref

“The Biblical Amorites seem to have originally occupied the region stretching from the heights west of the Dead Sea (Gen. 14:7) to Hebron (13:8; Deut. 3:8; 4:46-48), embracing “all Gilead and all Bashan” (Deut. 3:10), with the Jordan valley on the east of the river (4:49), the land of the “two kings of the Amorites,” Sihon and Og (Deut. 31:4; Josh. 2:10; 9:10). Both Sihon and Og were independent kings.” ref

“These Amorites seem to have been linked to the Jerusalem region, and the Jebusites may have been a subgroup of them. The southern slopes of the mountains of Judea are called the “mount of the Amorites” (Deut. 1:7, 19, 20). Five kings of the Amorites were first defeated with great slaughter by Joshua (10:10). They were said to have been utterly destroyed at the waters of Merom by Joshua (Josh. 11:8).” ref

“It is mentioned that in the days of Samuel, there was peace between them and the Israelites (1 Sam. 7:14). The Gibeonites were said to be their descendants, being an offshoot of the Amorites that made a covenant with the Hebrews; when Saul would break that vow and kill some of the Gibeonites, God sent a famine to Israel.” ref

Indo-European Amorites

“The view that Amorites were fierce tall nomads led to an idiosyncratic theory among some writers in the 19th Century that they were a tribe of “Germanic” warriors who at one point dominated the Israelites. This was because the evidence fitted then-current models of Indo-European migrations. This theory originated with Felix von Luschan, who later abandoned it.” ref

Amorite Jesus and David

“Houston Stewart Chamberlain, claimed that King David and Jesus were both Aryans of Amorite extraction. This argument was repeated by the Nazi ideologist Alfred Rosenberg.” ref

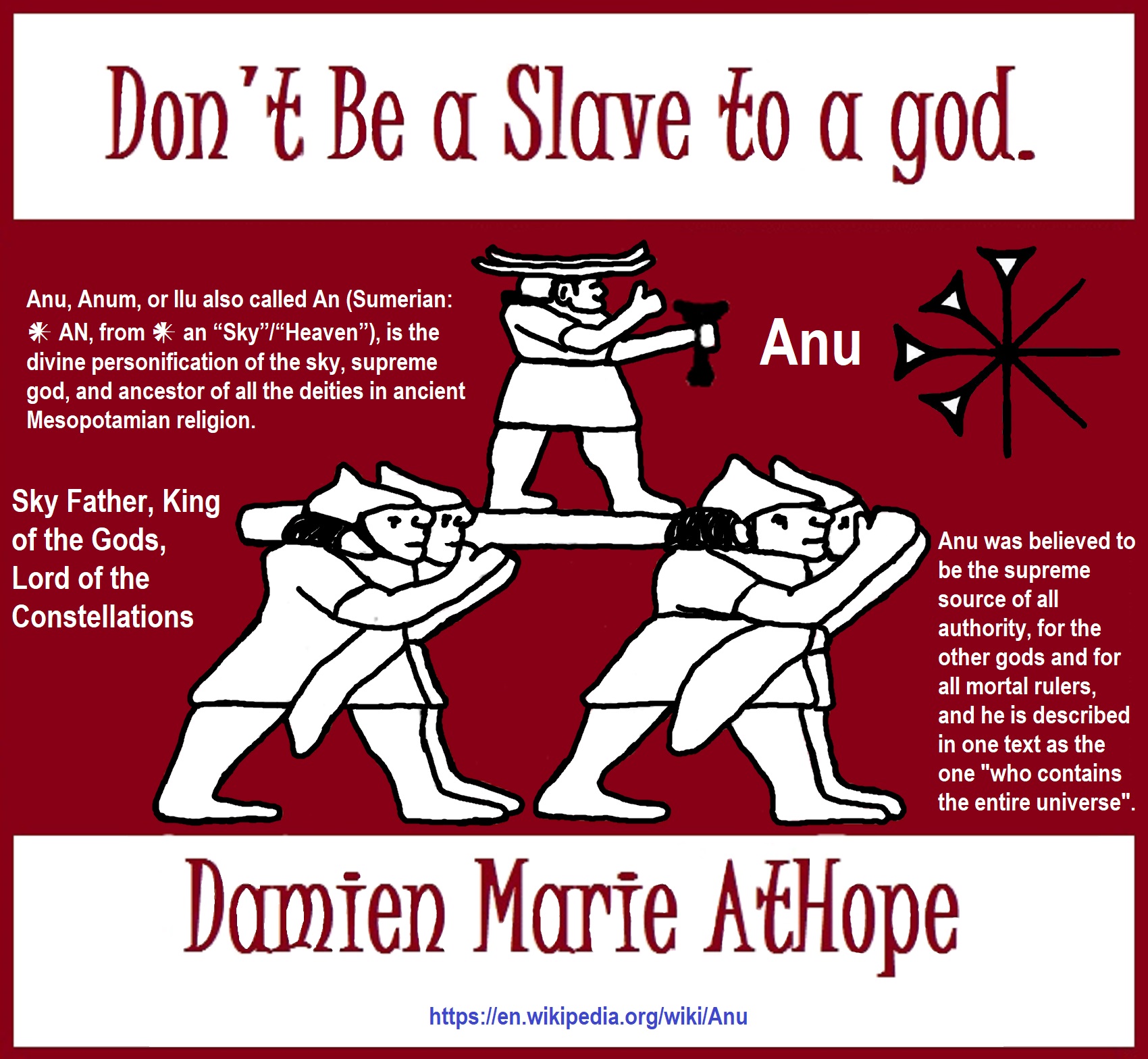

God Amurru’s father sky God Anu

“Anu, Anum, or Ilu (Akkadian: ???????? DAN), also called An (Sumerian: ???? AN, from ???? an “Sky”, “Heaven”), is the divine personification of the sky, supreme god, and ancestor of all the deities in ancient Mesopotamian religion. Anu was believed to be the supreme source of all authority, for the other gods and for all mortal rulers, and he is described in one text as the one “who contains the entire universe”. He is identified with the part of the sky located between +17° and -17° declination which contains 23 constellations. Along with his sons Enlil and Enki, Anu constitutes the highest divine triad personifying the three bands of constellations of the vault of the sky. By the time of the earliest written records, Anu was rarely worshipped, and veneration was instead devoted to his son Enlil. But, throughout Mesopotamian history, the highest deity in the pantheon was always said to possess the anûtu, meaning “Heavenly power”. Anu’s primary role in myths is as the ancestor of the Anunnaki, the major deities of Sumerian religion. His primary cult center was the Eanna temple in the city of Uruk, but, by the Akkadian Period (c. 2334–2154 BCE), his authority in Uruk had largely been ceded to the goddess Inanna, the Queen of Heaven.” ref

“Anu’s consort in the earliest Sumerian texts is the goddess Uraš, but she is later the goddess Ki and, in Akkadian texts, the goddess Antu, whose name is a feminine form of Anu. Anu briefly appears in the Akkadian Epic of Gilgamesh, in which his daughter Ishtar (the East Semitic equivalent to Inanna) persuades him to give her the Bull of Heaven so that she may send it to attack Gilgamesh. The incident results in the death of Enkidu. In another legend, Anu summons the mortal hero Adapa before him for breaking the wing of the south wind. Anu orders for Adapa to be given the food and water of immortality, which Adapa refuses, having been warned beforehand by Enki that Anu will offer him the food and water of death. In ancient Hittite religion, Anu is a former ruler of the gods, who was overthrown by his son Kumarbi, who bit off his father’s genitals and gave birth to the storm god Teshub. Teshub overthrew Kumarbi, avenged Anu’s mutilation, and became the new king of the gods. This story was the later basis for the castration of Ouranos in Hesiod‘s Theogony.” ref

“In Mesopotamian religion, Anu was the personification of the sky, the utmost power, the supreme god, the one “who contains the entire universe”. He was identified with the north ecliptic pole centered in Draco. His name meant the “One on High”, and together with his sons Enlil and Enki (Ellil and Ea in Akkadian), he formed a triune conception of the divine, in which Anu represented a “transcendental” obscurity, Enlil the “transcendent” and Enki the “immanent” aspect of the divine. The three great gods and the three divisions of the heavens were Anu (the ancient god of the heavens), Enlil (son of Anu, god of the air and the forces of nature, and lord of the gods), and Ea (the beneficent god of earth and life, who dwelt in the abyssal waters). The Babylonians divided the sky into three parts named after them: The equator and most of the zodiac occupied the Way of Anu, the northern sky was the Way of Enlil, and the southern sky was the Way of Ea. The boundaries of each Way were at 17°N and 17°S.” ref

“Though Anu was the supreme god, he was rarely worshipped, and, by the time that written records began, the most important cult was devoted to his son Enlil. Anu’s primary role in the Sumerian pantheon was as an ancestor figure; the most powerful and important deities in the Sumerian pantheon were believed to be the offspring of Anu and his consort Ki. These deities were known as the Anunnaki, which means “offspring of Anu”. Although it is sometimes unclear which deities were considered members of the Anunnaki, the group probably included the “seven gods who decree”: Anu, Enlil, Enki, Ninhursag, Nanna, Utu, and Inanna.” ref

“Anu’s main cult center was the Eanna temple, whose name means “House of Heaven” (Sumerian: e2-anna; Cuneiform: ???????? E2.AN), in Uruk. Although the temple was originally dedicated to Anu, it was later transformed into the primary cult center of Inanna. After its dedication to Inanna, the temple seems to have housed priestesses of the goddess.” ref

“Anu was believed to be a source of all legitimate power; he was the one who bestowed the right to rule upon gods and kings alike. According to scholar Stephen Bertman, Anu “… was the supreme source of authority among the gods, and among men, upon whom he conferred kingship. As heaven’s grand patriarch, he dispensed justice and controlled the laws known as the meh that governed the universe.” In inscriptions commemorating his conquest of Sumer, Sargon of Akkad, the founder of the Akkadian Empire, proclaims Anu and Inanna as the sources of his authority. A hymn from the early second millennium BCE professes that “his utterance ruleth over the obedient company of the gods.” ref

“Anu’s original name in Sumerian is An, of which Anu is a Semiticized form. Anu was also identified with the Semitic god Ilu or El from early on. The functions of Anu and Enlil frequently overlapped, especially during later periods as the cult of Anu continued to wane and the cult of Enlil rose to greater prominence. In later times, Anu was fully superseded by Enlil. Eventually, Enlil was, in turn, superseded by Marduk, the national god of ancient Babylon. Nonetheless, references to Anu’s power were preserved through archaic phrases used in reference to the ruler of the gods. The highest god in the pantheon was always said to possess the anûtu, which literally means “Heavenly power”. In the Babylonian Enûma Eliš, the gods praise Marduk, shouting “Your word is Anu!” ref

“Although Anu was a very important deity, his nature was often ambiguous and ill-defined; he almost never appears in Mesopotamian artwork and has no known anthropomorphic iconography. During the Kassite Period (c. 1600—1155 BCE) and Neo-Assyrian Period (911—609 BCE), Anu was represented by a horned cap. The Amorite god Amurru was sometimes equated with Anu. Later, during the Seleucid Empire (213—63 BCE), Anu was identified with Enmešara and Dumuzid.” ref

Family

“The earliest Sumerian texts make no mention of where Anu came from or how he came to be the ruler of the gods; instead, his preeminence is simply assumed. In early Sumerian texts from the third millennium BC, Anu’s consort is the goddess Uraš; the Sumerians later attributed this role to Ki, the personification of the earth. The Sumerians believed that rain was Anu’s seed and that, when it fell, it impregnated Ki, causing her to give birth to all the vegetation of the land. During the Akkadian Period, Ki was supplanted by Antu, a goddess whose name is probably a feminine form of Anu. The Akkadians believed that rain was milk from the clouds, which they believed were Antu’s breasts.” ref

“Anu is commonly described as the “father of the gods”, and a vast array of deities were thought to have been his offspring over the course of Mesopotamian history. Inscriptions from Lagash dated to the late third millennium BC identify Anu as the father of Gatumdug, Baba, and Ninurta. Later literary texts proclaim Adad, Enki, Enlil, Girra, Nanna-Suen, Nergal, and Šara as his sons and Inanna-Ishtar, Nanaya, Nidaba, Ninisinna, Ninkarrak, Ninmug, Ninnibru, Ninsumun, Nungal, and Nusku as his daughters. The demons Lamaštu, Asag, and the Sebettu were thought to have been Anu’s creations.” ref

Sumerian

Sumerian creation myth

Main article: Sumerian creation myth

“The main source of information about the Sumerian creation myth is the prologue to the epic poem Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld, which briefly describes the process of creation: at first, there is only Nammu, the primeval sea. Then, Nammu gives birth to An (the Sumerian name for Anu), the sky, and Ki, the earth. An and Ki mate with each other, causing Ki to give birth to Enlil, the god of the wind. Enlil separates An from Ki and carries off the earth as his domain, while An carries off the sky.” ref

“In Sumerian, the designation “An” was used interchangeably with “the heavens” so that in some cases it is doubtful whether, under the term, the god An or the heavens is being denoted. In Sumerian cosmogony, heaven was envisioned as a series of three domes covering the flat earth; Each of these domes of heaven was believed to be made of a different precious stone. An was believed to be the highest and outermost of these domes, which was thought to be made of reddish stone. Outside of this dome was the primordial body of water known as Nammu. An’s sukkal, or attendant, was the god Ilabrat.” ref

Inanna myths

“Inanna and Ebih, otherwise known as Goddess of the Fearsome Divine Powers, is a 184-line poem written in Sumerian by the Akkadian poetess Enheduanna. It describes An’s granddaughter Inanna’s confrontation with Mount Ebih, a mountain in the Zagros mountain range. An briefly appears in a scene from the poem in which Inanna petitions him to allow her to destroy Mount Ebih. An warns Inanna not to attack the mountain, but she ignores his warning and proceeds to attack and destroy Mount Ebih regardless.” ref

“The poem Inanna Takes Command of Heaven is an extremely fragmentary, but important, account of Inanna’s conquest of the Eanna temple in Uruk. It begins with a conversation between Inanna and her brother Utu in which Inanna laments that the Eanna temple is not within their domain and resolves to claim it as her own. The text becomes increasingly fragmentary at this point in the narrative, but appears to describe her difficult passage through a marshland to reach the temple, while a fisherman instructs her on which route is best to take. Ultimately, Inanna reaches An, who is shocked by her arrogance, but nevertheless concedes that she has succeeded and that the temple is now her domain. The text ends with a hymn expounding Inanna’s greatness. This myth may represent an eclipse in the authority of the priests of An in Uruk and a transfer of power to the priests of Inanna.” ref

Akkadian

Epic of Gilgamesh

“In a scene from the Akkadian Epic of Gilgamesh, written in the late second millennium BC, Anu’s daughter Ishtar, the East Semitic equivalent to Inanna, attempts to seduce the hero Gilgamesh. When Gilgamesh spurns her advances, Ishtar angrily goes to heaven and tells Anu that Gilgamesh has insulted her. Anu asks her why she is complaining to him instead of confronting Gilgamesh herself. Ishtar demands that Anu give her the Bull of Heaven and swears that if he does not give it to her, she will break down the gates of the Underworld and raise the dead to eat the living. Anu gives Ishtar the Bull of Heaven, and Ishtar sends it to attack Gilgamesh and his friend Enkidu.” ref

Adapa myth

“In the myth of Adapa, which is first attested during the Kassite Period, Anu notices that the south wind does not blow towards the land for seven days. He asks his sukkal Ilabrat the reason. Ilabrat replies that is because Adapa, the priest of Ea (the East Semitic equivalent of Enki) in Eridu, has broken the south wind’s wing. Anu demands that Adapa be summoned before him, but, before Adapa sets out, Ea warns him not to eat any of the food or drink any of the water the gods offer him, because the food and water are poisoned. Adapa arrives before Anu and tells him that the reason he broke the south wind’s wing was because he had been fishing for Ea and the south wind had caused a storm, which had sunk his boat. Anu’s doorkeepers Dumuzid and Ningishzida speak out in favor of Adapa. This placates Anu’s fury and he orders that, instead of the food and water of death, Adapa should be given the food and water of immortality as a reward.” ref

“Adapa, however, follows Ea’s advice and refuses the meal. The story of Adapa was beloved by scribes, who saw him as the founder of their trade and a vast plethora of copies and variations of the myth have been found across Mesopotamia, spanning the entire course of Mesopotamian history. The story of Adapa’s appearance before Anu has been compared to the later Jewish story of Adam and Eve, recorded in the Book of Genesis. In the same way that Anu forces Adapa to return to earth after he refuses to eat the food of immortality, Yahweh in the biblical story drives Adam out of the Garden of Eden to prevent him from eating the fruit from the tree of life. Similarly, Adapa was seen as the prototype for all priests; whereas Adam in the Book of Genesis is presented as the prototype of all mankind.” ref

Erra and Išum

“In the epic poem Erra and Išum, which was written in Akkadian in the eighth century BC, Anu gives Erra, the god of destruction, the Sebettu, which are described as personified weapons. Anu instructs Erra to use them to massacre humans when they become overpopulated and start making too much noise (Tablet I, 38ff).” ref

Hittite (indo-europian)

“In Hittite mythology, Anu overthrows his father Alalu and proclaims himself ruler of the universe. He himself is later overthrown by his own son Kumarbi; Anu attempts to flee, but Kumarbi bites off Anu’s genitals and swallows them. Kumarbi then banishes Anu to the underworld, along with his allies, the old gods, whom the Hittites syncretized with the Anunnaki. As a consequence of swallowing Anu’s genitals, Kumarbi becomes impregnated with Anu’s son Teshub and four other offspring. After he grows to maturity, Teshub overthrows his father Kumarbi, thus avenging his other father Anu’s overthrow and mutilation.” ref

Later influence

“The series of divine coups described in the Hittite creation myth later became the basis for the Greek creation story described in the long poem Theogony, written by the Boeotian poet Hesiod in the seventh century BCE. In Hesiod’s poem, the primeval sky-god Ouranos is overthrown and castrated by his son Kronos in much the same manner that Anu is overthrown and castrated by Kumarbi in the Hittite story. Kronos is then, in turn, overthrown by his own son Zeus. In one Orphic myth, Kronos bites off Ouranos’s genitals in exactly the same manner that Kumarbi does to Anu in the Hittite myth. Nonetheless, Robert Mondi notes that Ouranos never held mythological significance to the Greeks comparable with Anu’s significance to the Mesopotamians. Instead, Mondi calls Ouranos “a pale reflection of Anu”, noting that “apart from the castration myth, he has very little significance as a cosmic personality at all and is not associated with kingship in any systematic way.” ref

“According to Walter Burkert, an expert on ancient Greek religion, direct parallels also exist between Anu and the Greek god Zeus. In particular, the scene from Tablet VI of the Epic of Gilgamesh in which Ishtar comes before Anu after being rejected by Gilgamesh and complains to her mother Antu, but is mildly rebuked by Anu, is directly paralleled by a scene from Book V of the Iliad. In this scene, Aphrodite, the later Greek development of Ishtar, is wounded by the Greek hero Diomedes while trying to save her son Aeneas. She flees to Mount Olympus, where she cries to her mother Dione, is mocked by her sister Athena, and is mildly rebuked by her father Zeus. Not only is the narrative parallel significant, but so is the fact that Dione’s name is a feminization of Zeus’s own, just as Antu is a feminine form of Anu. Dione does not appear throughout the rest of the Iliad, in which Zeus’s consort is instead the goddess Hera. Burkert therefore concludes that Dione is clearly a calque of Antu.” ref

“The most direct equivalent to Anu in the Canaanite pantheon is Shamem, the personification of the sky, but Shamem almost never appears in myths and it is unclear whether the Canaanites ever regarded him as a previous ruler of the gods at all. Instead, the Canaanites seem to have ascribed Anu’s attributes to El, the current ruler of the gods. In later times, the Canaanites equated El with Kronos rather than with Ouranos, and El’s son Baal with Zeus. A narrative from Canaanite mythology describes the warrior-goddess Anat coming before El after being insulted, in a way that directly parallels Ishtar coming before Anu in the Epic of Gilgamesh.” ref

“El is characterized as the malk olam (“the eternal king”) and, like Anu, he is “consistently depicted as old, just, compassionate, and patriarchal”. In the same way that Anu was thought to wield the Tablet of Destinies, Canaanite texts mentions decrees issued by El that he alone may alter. In late antiquity, writers such as Philo of Byblos attempted to impose the dynastic succession framework of the Hittite and Hesiodic stories onto Canaanite mythology, but these efforts are forced and contradict what most Canaanites seem to have actually believed.” ref

Most Canaanites seem to have regarded El and Baal as ruling concurrently:

“El is king, Baal becomes king. Both are kings over other gods, but El’s kingship is timeless and unchanging. Baal must acquire his kingship, affirm it through the building of his temple, and defend it against adversaries; even so he loses it, and must be enthroned anew. El’s kingship is static, Baal’s is dynamic.” ref

El (deity)?

“Ēl (also ʼIl, Ugaritic: ????????; Phoenician: ????????; Hebrew: אֵל; Syriac: ܐܠ; Arabic: إيل or إله; cognate to Akkadian: ????, romanized: ilu) is a Northwest Semitic word meaning “god” or “deity“, or referring (as a proper name) to any one of multiple major ancient Near Eastern deities. A rarer form, ʼila, represents the predicate form in Old Akkadian and in Amorite. The word is derived from the Proto-Semitic *ʔil-, meaning “god”. Specific deities known as ʼEl or ʼIl include the supreme god of the ancient Canaanite religion and the supreme god of East Semitic speakers in Mesopotamia’s Early Dynastic Period.” ref

Linguistic forms and meanings

“Cognate forms are found throughout the Semitic languages. They include Ugaritic ʾilu, pl. ʾlm; Phoenician ʾl pl. ʾlm; Hebrew ʾēl, pl. ʾēlîm; Aramaic ʾl; Akkadian ilu, pl. ilānu. In northwest Semitic use, Ēl was both a generic word for any god and the special name or title of a particular god who was distinguished from other gods as being “the god”. Ēl is listed at the head of many pantheons. In some Canaanite and Ugaritic sources, Ēl played a role as father of the gods or of creation.” ref

“However, because the word sometimes refers to a god other than the great god Ēl, it is frequently ambiguous as to whether Ēl followed by another name means the great god Ēl with a particular epithet applied or refers to another god entirely. For example, in the Ugaritic texts, ʾil mlk is understood to mean “Ēl the King” but ʾil hd as “the god Hadad“.” ref

“The Semitic root ʾlh (Arabic ʾilāh, Aramaic ʾAlāh, ʾElāh, Hebrew ʾelōah) may be ʾl with a parasitic h, and ʾl may be an abbreviated form of ʾlh. In Ugaritic the plural form meaning “gods” is ʾilhm, equivalent to Hebrew ʾelōhîm “powers”. In the Hebrew texts this word is interpreted as being semantically singular for “god” by biblical commentators. However the documentary hypothesis developed originally in the 1870s, identifies these that different authors – the Jahwist, Elohist, Deuteronomist, and the Priestly source – were responsible for editing stories from a polytheistic religion into those of a monotheistic religion. Inconsistencies that arise between monotheism and polytheism in the texts are reflective of this hypothesis.” ref

“The stem ʾl is found prominently in the earliest strata of east Semitic, northwest Semitic, and south Semitic groups. Personal names including the stem ʾl are found with similar patterns in both Amorite and Sabaic – which indicates that probably already in Proto-Semitic ʾl was both a generic term for “god” and the common name or title of a single particular god.” ref

Proto-Sinaitic, Phoenician, Aramaic, and Hittite texts

“The Egyptian god Ptah is given the title ḏū gitti ‘Lord of Gath‘ in a prism from Tel Lachish which has on its opposite face the name of Amenhotep II (c. 1435–1420 BCE). The title ḏū gitti is also found in Serābitṭ text 353. Cross (1973, p. 19) points out that Ptah is often called the Lord (or one) of eternity and thinks it may be this identification of ʼĒl with Ptah that lead to the epithet ’olam ‘eternal’ being applied to ʼĒl so early and so consistently. (However, in the Ugaritic texts, Ptah is seemingly identified rather with the craftsman god Kothar-wa-Khasis.) Yet another connection is seen with the Mandaean angel Ptahil, whose name combines both the terms Ptah and Il.” ref

“In an inscription in the Proto-Sinaitic script, William F. Albright transcribed the phrase ʾL Ḏ ʿLM, which he translated as the appellation “El, (god) of eternity”.The name Raphael or Rapha-El, meaning ‘God has healed’ in Ugarit, is attested to in approximately 1350 BCE in one of the Amarna Letters EA333, found in Tell-el-Hesi from the ruler of Lachish to ‘The Great One’ ” ref

“A Phoenician inscribed amulet of the seventh century BCE from Arslan Tash may refer to ʼĒl. The text was translated by Rosenthal (1969, p. 658) as follows:

An eternal bond has been established for us.

Ashshur has established (it) for us,

and all the divine beings

and the majority of the group of all the holy ones,

through the bond of heaven and earth for ever, …” ref

“However, Cross (1973, p. 17) translated the text as follows:

The Eternal One (‘Olam) has made a covenant oath with us,

Asherah has made (a pact) with us.

And all the sons of El,

And the great council of all the Holy Ones.

With oaths of Heaven and Ancient Earth.” ref

“In some inscriptions, the name ’Ēl qōne ’arṣ (Punic: ???????? ???????? ???????????? ʾl qn ʾrṣ) meaning “ʼĒl creator of Earth” appears, even including a late inscription at Leptis Magna in Tripolitania dating to the second century. In Hittite texts, the expression becomes the single name Ilkunirsa, this Ilkunirsa appearing as the husband of Asherdu (Asherah) and father of 77 or 88 sons. In a Hurrian hymn to ʼĒl (published in Ugaritica V, text RS 24.278), he is called ’il brt and ’il dn, which Cross (p. 39) takes as ‘ʼĒl of the covenant’ and ‘ʼĒl the judge’ respectively.” ref

“Amorite inscriptions from Sam’al refer to numerous gods, sometimes by name, sometimes by title, especially by such titles as Ilabrat ‘God of the people'(?), ʾil abīka “God of your father”, ʾil abīni “God of our father” and so forth. Various family gods are recorded, divine names listed as belonging to a particular family or clan, sometimes by title and sometimes by name, including the name ʾil “God”. In Amorite personal names, the most common divine elements are ʾil “God”, Hadad/Adad, and Dagan. It is likely that ʾil is also very often the god called in Akkadian texts Amurru or ʾil ʾamurru.” ref

Ugarit and the Levant

“For the Canaanites and the ancient Levantine region as a whole, Ēl or Il was the supreme god, the father of mankind and all creatures. He also fathered many gods, most importantly Hadad, Yam, and Mot, each sharing similar attributes to the Greco-Roman gods: Zeus, Poseidon, and Hades respectively. As recorded on the clay tablets of Ugarit, El is the husband of the goddess Asherah.” ref

“Three pantheon lists found at Ugarit (modern Ras Shamrā—Arabic: رأس شمرا, Syria) begin with the four gods ’il-’ib (which according to Cross; is the name of a generic kind of deity, perhaps the divine ancestor of the people), Ēl, Dagnu (that is Dagon), and Ba’l Ṣapān (that is the god Haddu or Hadad). Though Ugarit had a large temple dedicated to Dagon and another to Hadad, there was no temple dedicated to Ēl.” ref

“Ēl is called again and again Tôru ‘Ēl (“Bull Ēl” or “the bull god”). He is bātnyu binwāti (“Creator of creatures”), ’abū banī ’ili (“father of the gods”), and ‘abū ‘adami (“father of man”). He is qāniyunu ‘ôlam (“creator eternal”), the epithet ‘ôlam appearing in Hebrew form in the Hebrew name of God ’ēl ‘ôlam “God Eternal” in Genesis 21.33. He is ḥātikuka (“your patriarch”). Ēl is the grey-bearded ancient one, full of wisdom, malku (“King”), ’abū šamīma (“Father of years”), ’El gibbōr (“Ēl the warrior”). He is also named lṭpn of unknown meaning, variously rendered as Latpan, Latipan, or Lutpani (“shroud-face” by Strong’s Hebrew Concordance).” ref

“El” (Father of Heaven / Saturn) and his major son: “Hadad” (Father of Earth / Jupiter), are symbolized both by the bull, and both wear bull horns on their headdresses. In Canaanite mythology, El builds a desert sanctuary with his children and his two wives, leading to speculation that at one point El was a desert god. The mysterious Ugaritic text Shachar and Shalim tells how (perhaps near the beginning of all things) Ēl came to shores of the sea and saw two women who bobbed up and down.” ref

“Ēl was sexually aroused and took the two with him, killed a bird by throwing a staff at it, and roasted it over a fire. He asked the women to tell him when the bird was fully cooked, and to then address him either as husband or as father, for he would thenceforward behave to them as they called him. They saluted him as husband. He then lay with them, and they gave birth to Shachar (“Dawn”) and Shalim (“Dusk”). Again Ēl lay with his wives and the wives gave birth to “the gracious gods”, “cleavers of the sea”, “children of the sea”. The names of these wives are not explicitly provided, but some confusing rubrics at the beginning of the account mention the goddess Athirat, who is otherwise Ēl’s chief wife, and the goddess Raḥmayyu (“the one of the womb”), otherwise unknown.” ref

“In the Ugaritic Ba‘al cycle, Ēl is introduced dwelling on (or in) Mount Lel (Lel possibly meaning “Night”) at the fountains of the two rivers at the spring of the two deeps. He dwells in a tent according to some interpretations of the text which may explain why he had no temple in Ugarit. As to the rivers and the spring of the two deeps, these might refer to real streams, or to the mythological sources of the salt water ocean and the fresh water sources under the earth, or to the waters above the heavens and the waters beneath the earth.” ref

“In the episode of the “Palace of Ba‘al”, the god Ba‘al Hadad invites the “seventy sons of Athirat” to a feast in his new palace. Presumably these sons have been fathered on Athirat by Ēl; in following passages they seem to be the gods (’ilm) in general or at least a large portion of them. The only sons of Ēl named individually in the Ugaritic texts are Yamm (“Sea”), Mot (“Death”), and Ashtar, who may be the chief and leader of most of the sons of Ēl. Ba‘al Hadad is a few times called Ēl’s son rather than the son of Dagan as he is normally called, possibly because Ēl is in the position of a clan-father to all the gods.” ref

“The fragmentary text R.S. 24.258 describes a banquet to which Ēl invites the other gods and then disgraces himself by becoming outrageously drunk and passing out after confronting an otherwise unknown Hubbay, “he with the horns and tail”. The text ends with an incantation for the cure of some disease, possibly hangover.” ref

Hebrew Bible

“The Hebrew form (אל) appears in Latin letters in Standard Hebrew transcription as El and in Tiberian Hebrew transcription as ʾĒl. El is a generic word for god that could be used for any god, including Hadad, Moloch, or Yahweh. In the Tanakh, ’elōhîm is the normal word for a god or the great God (or gods, given that the ‘im’ suffix makes a word plural in Hebrew).” ref

“But the form ’El also appears, mostly in poetic passages and in the patriarchal narratives attributed to the Priestly source of the documentary hypothesis. It occurs 217 times in the Masoretic Text: seventy-three times in the Psalms and fifty-five times in the Book of Job, and otherwise mostly in poetic passages or passages written in elevated prose. It occasionally appears with the definite article as hā’Ēl ‘the god’ (for example in 2 Samuel 22:31,33–48).” ref

“The theological position of the Tanakh is that the names Ēl and ’Ĕlōhîm, when used in the singular to mean the supreme god, refer to Yahweh, beside whom other gods are supposed to be either nonexistent or insignificant. Whether this was a long-standing belief or a relatively new one has long been the subject of inconclusive scholarly debate about the prehistory of the sources of the Tanakh and about the prehistory of Israelite religion. In the P strand, Exodus 6:3 may be translated:

I revealed myself to Abraham, to Isaac, and to Jacob as Ēl Shaddāi, but was not known to them by my name, YHVH.” ref

“However, it is said in Genesis 14:18–20 that Abraham accepted the blessing of El, when Melchizedek, the king of Salem and high priest of its deity El Elyon blessed him. One scholarly position is that the identification of Yahweh with Ēl is late, that Yahweh was earlier thought of as only one of many gods, and not normally identified with Ēl. Another is that in much of the Hebrew Bible the name El is an alternative name for Yahweh, but in the Elohist and Priestly traditions it is considered an earlier name than Yahweh. Mark Smith has argued that Yahweh and El were originally separate, but were considered synonymous from very early on. The name Yahweh is used in the Bible Tanakh in the first book of Genesis 2:4; and Genesis 4:26 says that at that time, people began to “call upon the name of the LORD”.” ref

“In some places, especially in Psalm 29, Yahweh is clearly envisioned as a storm god, something not true of Ēl so far as we know (although true of his son, Ba’al Haddad). It is Yahweh who is prophesied to one day battle Leviathan the serpent, and slay the dragon in the sea in Isaiah 27:1. The slaying of the serpent in myth is a deed attributed to both Ba’al Hadad and ‘Anat in the Ugaritic texts, but not to Ēl.” ref

“Such mythological motifs are variously seen as late survivals from a period when Yahweh held a place in theology comparable to that of Hadad at Ugarit; or as late henotheistic/monotheistic applications to Yahweh of deeds more commonly attributed to Hadad; or simply as examples of eclectic application of the same motifs and imagery to various different gods.” ref

“Similarly, it is argued inconclusively whether Ēl Shaddāi, Ēl ‘Ôlām, Ēl ‘Elyôn, and so forth, were originally understood as separate divinities. Albrecht Alt presented his theories on the original differences of such gods in Der Gott der Väter in 1929. But others have argued that from patriarchal times, these different names were in fact generally understood to refer to the same single great god, Ēl. This is the position of Frank Moore Cross (1973). What is certain is that the form ’El does appear in Israelite names from every period including the name Yiśrā’ēl (“Israel”), meaning “El strives”.” ref

“According to The Oxford Companion to World Mythology,

It seems almost certain that the God of the Jews evolved gradually from the Canaanite El, who was in all likelihood the “God of Abraham”… If El was the high God of Abraham—Elohim, the prototype of Yahveh—Asherah was his wife, and there are archaeological indications that she was perceived as such before she was in effect “divorced” in the context of emerging Judaism of the 7th century BCE. (See 2 Kings 23:15.)” ref

“The apparent plural form ’Ēlîm or ’Ēlim “gods” occurs only four times in the Tanakh. Psalm 29, understood as an enthronement psalm, begins:

A Psalm of David.

Ascribe to Yahweh, sons of Gods (bênê ’Ēlîm),

Ascribe to Yahweh, glory and strength” ref

“Psalm 89:6 (verse 7 in Hebrew) has:

For who in the skies compares to Yahweh,

who can be likened to Yahweh among the sons of Gods (bênê ’Ēlîm).” ref

“Traditionally bênê ’ēlîm has been interpreted as ‘sons of the mighty’, ‘mighty ones’, for ’El can mean ‘mighty’, though such use may be metaphorical (compare the English expression [by] God awful). It is possible also that the expression ’ēlîm in both places descends from an archaic stock phrase in which ’lm was a singular form with the m-enclitic and therefore to be translated as ‘sons of Ēl’.” ref

“The m-enclitic appears elsewhere in the Tanakh and in other Semitic languages. Its meaning is unknown, possibly simply emphasis. It appears in similar contexts in Ugaritic texts where the expression bn ’il alternates with bn ’ilm, but both must mean ‘sons of Ēl’. That phrase with m-enclitic also appears in Phoenician inscriptions as late as the fifth century BCE.” ref

“One of the other two occurrences in the Tanakh is in the “Song of Moses“, Exodus 15:11a:

Who is like you among the Gods (’ēlim), Yahweh?” ref

“The final occurrence is in Daniel 11:36:

And the king will do according to his pleasure; and he will exalt himself and magnify himself over every god (’ēl), and against the God of Gods (’El ’Elîm) he will speak outrageous things, and will prosper until the indignation is accomplished: for that which is decided will be done.” ref

“There are a few cases in the Tanakh where some think ’El referring to the great god Ēl is not equated with Yahweh. One is in Ezekiel 28:2, in the taunt against a man who claims to be divine, in this instance, the leader of Tyre:

Son of man, say to the prince of Tyre: “Thus says the Lord Yahweh: ‘Because your heart is proud and you have said: “I am ’ēl (god), in the seat of ’elōhîm (gods), I am enthroned in the middle of the seas.” Yet you are man and not ’El even though you have made your heart like the heart of ’elōhîm (‘gods’).” ref

“Here ’ēl might refer to a generic god, or to a highest god, Ēl. When viewed as applying to the King of Tyre specifically, the king was probably not thinking of Yahweh. When viewed as a general taunt against anyone making divine claims, it may or may not refer to Yahweh depending on the context.” ref

“In Judges 9:46 we find ’Ēl Bêrît ‘God of the Covenant’, seemingly the same as the Ba‘al Bêrît ‘Lord of the Covenant’ whose worship has been condemned a few verses earlier. See Baal for a discussion of this passage.” ref

“Psalm 82:1 says:

’elōhîm (“god”) stands in the council of ’ēl

he judges among the gods (Elohim).” ref

“This could mean that Yahweh judges along with many other gods as one of the council of the high god Ēl. However it can also mean that Yahweh stands in the Divine Council (generally known as the Council of Ēl), as Ēl judging among the other members of the council. The following verses in which the god condemns those whom he says were previously named gods (Elohim) and sons of the Most High suggest the god here is in fact Ēl judging the lesser gods.” ref

“An archaic phrase appears in Isaiah 14:13, kôkkêbê ’ēl ‘stars of God’, referring to the circumpolar stars that never set, possibly especially to the seven stars of Ursa Major. The phrase also occurs in the Pyrgi Inscription as hkkbm ’l (preceded by the definite article h and followed by the m-enclitic). Two other apparent fossilized expressions are arzê-’ēl ‘cedars of God’ (generally translated something like ‘mighty cedars’, ‘goodly cedars’) in Psalm 80:10 (in Hebrew verse 11) and kêharrê-’ēl ‘mountains of God’ (generally translated something like ‘great mountains’, ‘mighty mountains’) in Psalm 36:7 (in Hebrew verse 6).” ref

“For the reference in some texts of Deuteronomy 32:8 to seventy sons of God corresponding to the seventy sons of Ēl in the Ugaritic texts, see `Elyôn.” ref

Sanchuniathon

“Philo of Byblos (c. 64–141 AD) was a Greek writer whose account Sanchuniathon survives in quotation by Eusebius and may contain the major surviving traces of Phoenician mythology. Ēl (rendered Elus or called by his standard Greek counterpart Cronus) is not the creator god or first god. Ēl is rather the son of Sky (Uranus) and Earth (Ge). Sky and Earth are themselves children of ‘Elyôn ‘Most High’. Ēl is brother to the God Bethel, to Dagon and to an unknown god, equated with the Greek Atlas and to the goddesses Aphrodite/’Ashtart, Rhea (presumably Asherah), and Dione (equated with Ba‘alat Gebal). Ēl is the father of Persephone and of Athena (presumably the goddess ‘Anat).” ref

“Sky and Earth have separated from one another in hostility, but Sky insists on continuing to force himself on Earth and attempts to destroy the children born of such unions. At last, with the advice of his daughter Athena and the god Hermes Trismegistus (perhaps Thoth), Ēl successfully attacks his father Sky with a sickle and spear of iron. He and his military allies the Eloim gain Sky’s kingdom.” ref

“In a later passage, it is explained that Ēl castrated Sky. One of Sky’s concubines (who was given to Ēl’s brother Dagon) was already pregnant by Sky. The son who is born of the union, called Demarûs or Zeus, but once called Adodus, is obviously Hadad, the Ba‘al of the Ugaritic texts who now becomes an ally of his grandfather Sky and begins to make war on Ēl.” ref

“Ēl has three wives, his sisters or half-sisters Aphrodite/Astarte (‘Ashtart), Rhea (presumably Asherah), and Dione (identified by Sanchuniathon with Ba‘alat Gebal the tutelary goddess of Byblos, a city which Sanchuniathon says that Ēl founded).” ref

“El is depicted primarily as a warrior; in Ugaritic sources, Baal has the warrior role and El is peaceful, and it may be that the Sanchuniathon depicts an earlier tradition that was more preserved in the southern regions of Canaan.” ref

“Eusebius, through whom the Sanchuniathon is preserved, is not interested in setting the work forth completely or in order. But we are told that Ēl slew his own son Sadidus (a name that some commentators think might be a corruption of Shaddai, one of the epithets of the Biblical Ēl) and that Ēl also beheaded one of his daughters.” ref

“Later, perhaps referring to this same death of Sadidus we are told:

But on the occurrence of a pestilence and mortality Cronus offers his only begotten son as a whole burnt-offering to his father Sky and circumcises himself, compelling his allies also to do the same.” ref

“A fuller account of the sacrifice appears later:

It was a custom of the ancients in great crises of danger for the rulers of a city or nation, in order to avert the common ruin, to give up the most beloved of their children for sacrifice as a ransom to the avenging daemons; and those who were thus given up were sacrificed with mystic rites. Cronus then, whom the Phoenicians call Elus, who was king of the country and subsequently, after his decease, was deified as the star Saturn, had by a nymph of the country named Anobret an only begotten son, whom they on this account called Iedud, the only begotten being still so called among the Phoenicians; and when very great dangers from war had beset the country, he arrayed his son in royal apparel, and prepared an altar, and sacrificed him.” ref

“The account also relates that Thoth:

also devised for Cronus as insignia of royalty four eyes in front and behind … but two of them quietly closed, and upon his shoulders four wings, two as spread for flying, and two as folded. And the symbol meant that Cronus could see when asleep, and sleep while waking: and similarly in the case of the wings, that he flew while at rest, and was at rest when flying. But to each of the other gods he gave two wings upon the shoulders, as meaning that they accompanied Cronus in his flight. And to Cronus himself again he gave two wings upon his head, one representing the all-ruling mind, and one sensation.” ref

“This is the form under which Ēl/Cronus appears on coins from Byblos from the reign of Antiochus IV Epiphanes (175–164 BCE) four spread wings and two folded wings, leaning on a staff. Such images continued to appear on coins until after the time of Augustus.” ref

Poseidon

Main article: Poseidon

“A bilingual inscription from Palmyra dated to the 1st century equates Ēl-Creator-of-the-Earth with the Greek god Poseidon. Going back to the 8th century BCE, the bilingual inscription at Karatepe in the Taurus Mountains equates Ēl-Creator-of-the-Earth to Luwian hieroglyphs read as da-a-ś, this being the Luwian form of the name of the Babylonian water god Ea, lord of the abyss of water under the earth. (This inscription lists Ēl in second place in the local pantheon, following Ba‘al Shamîm and preceding the Eternal Sun.)” ref

“Poseidon is known to have been worshipped in Beirut, his image appearing on coins from that city. Poseidon of Beirut was also worshipped at Delos where there was an association of merchants, shipmasters, and warehousemen called the Poseidoniastae of Berytus founded in 110 or 109 BCE. Three of the four chapels at its headquarters on the hill northwest of the Sacred Lake were dedicated to Poseidon, the Tyche of the city equated with Astarte (that is ‘Ashtart), and to Eshmun.” ref

“Also at Delos, that association of Tyrians, though mostly devoted to Heracles–Melqart, elected a member to bear a crown every year when sacrifices to Poseidon took place. A banker named Philostratus donated two altars, one to Palaistine Aphrodite Urania (‘Ashtart) and one to Poseidon “of Ascalon.” ref

“Though Sanchuniathon distinguishes Poseidon from his Elus/Cronus, this might be a splitting off of a particular aspect of Ēl in a euhemeristic account. Identification of an aspect of Ēl with Poseidon rather than with Cronus might have been felt to better fit with Hellenistic religious practice, if indeed this Phoenician Poseidon really is Ēl who dwells at the source of the two deeps in Ugaritic texts. More information is needed to be certain.” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

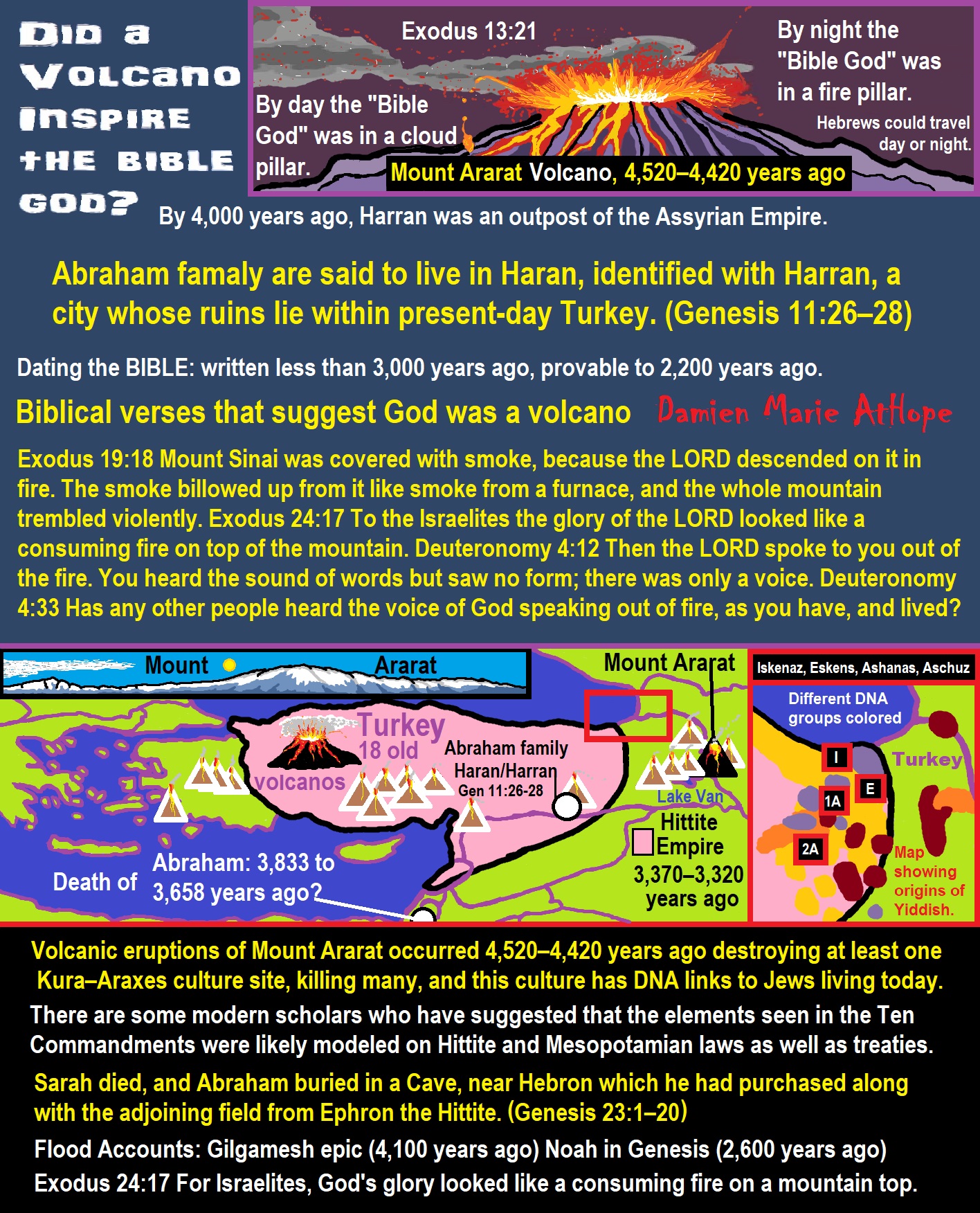

By day the LORD went ahead of them in a pillar of cloud to guide them on their way and by night in a pillar of fire to give them light, so that they could travel by day or night.

- By day the “Bible God” was in a cloud pillar.

- By night the “Bible God” was in a fire pillar.

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

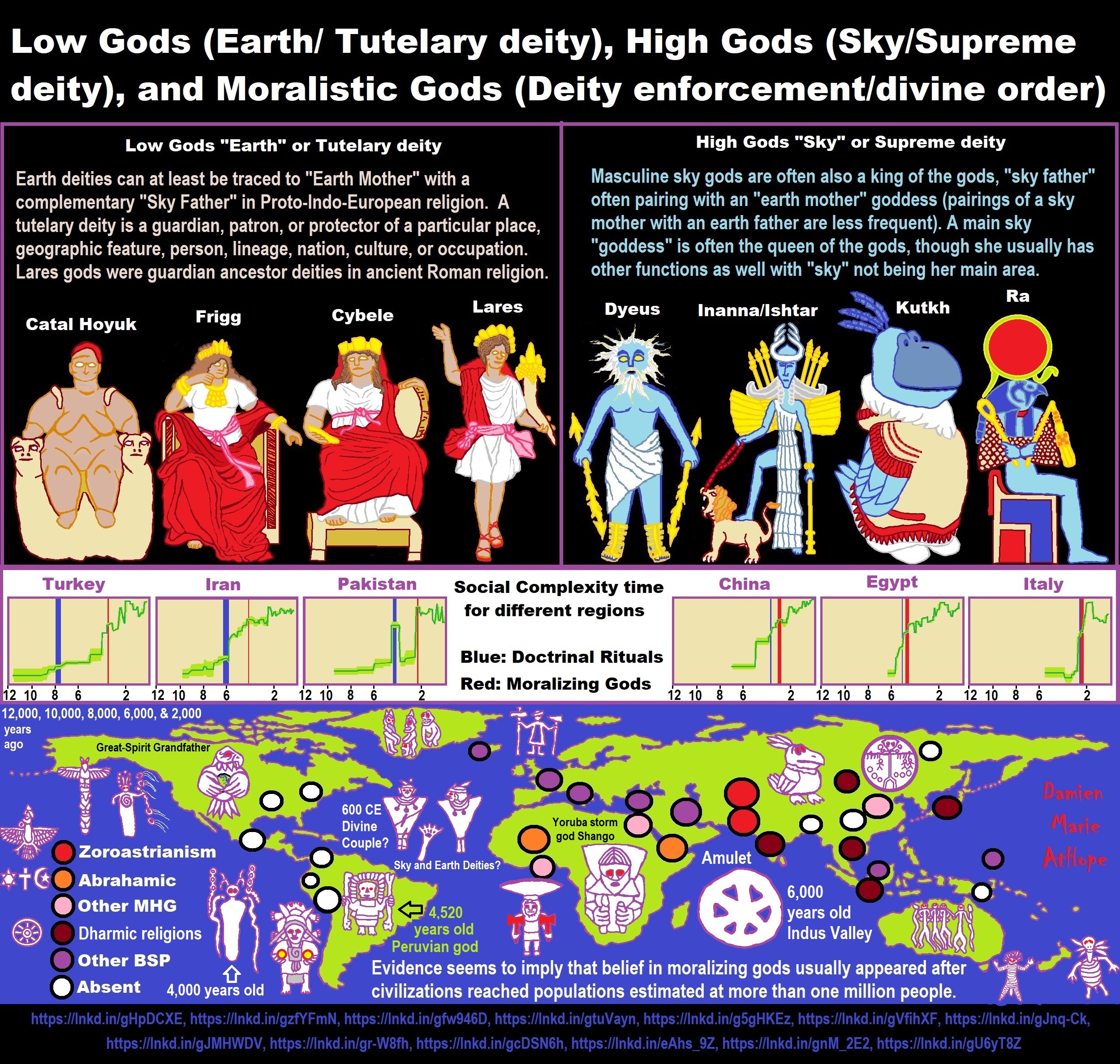

Low Gods “Earth” or Tutelary deity and High Gods “Sky” or Supreme deity

“An Earth goddess is a deification of the Earth. Earth goddesses are often associated with the “chthonic” deities of the underworld. Ki and Ninhursag are Mesopotamian earth goddesses. In Greek mythology, the Earth is personified as Gaia, corresponding to Roman Terra, Indic Prithvi/Bhūmi, etc. traced to an “Earth Mother” complementary to the “Sky Father” in Proto-Indo-European religion. Egyptian mythology exceptionally has a sky goddess and an Earth god.” ref

“A mother goddess is a goddess who represents or is a personification of nature, motherhood, fertility, creation, destruction or who embodies the bounty of the Earth. When equated with the Earth or the natural world, such goddesses are sometimes referred to as Mother Earth or as the Earth Mother. In some religious traditions or movements, Heavenly Mother (also referred to as Mother in Heaven or Sky Mother) is the wife or feminine counterpart of the Sky father or God the Father.” ref

“Any masculine sky god is often also king of the gods, taking the position of patriarch within a pantheon. Such king gods are collectively categorized as “sky father” deities, with a polarity between sky and earth often being expressed by pairing a “sky father” god with an “earth mother” goddess (pairings of a sky mother with an earth father are less frequent). A main sky goddess is often the queen of the gods and may be an air/sky goddess in her own right, though she usually has other functions as well with “sky” not being her main. In antiquity, several sky goddesses in ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the Near East were called Queen of Heaven. Neopagans often apply it with impunity to sky goddesses from other regions who were never associated with the term historically. The sky often has important religious significance. Many religions, both polytheistic and monotheistic, have deities associated with the sky.” ref

“In comparative mythology, sky father is a term for a recurring concept in polytheistic religions of a sky god who is addressed as a “father”, often the father of a pantheon and is often either a reigning or former King of the Gods. The concept of “sky father” may also be taken to include Sun gods with similar characteristics, such as Ra. The concept is complementary to an “earth mother“. “Sky Father” is a direct translation of the Vedic Dyaus Pita, etymologically descended from the same Proto-Indo-European deity name as the Greek Zeûs Pater and Roman Jupiter and Germanic Týr, Tir or Tiwaz, all of which are reflexes of the same Proto-Indo-European deity’s name, *Dyēus Ph₂tḗr. While there are numerous parallels adduced from outside of Indo-European mythology, there are exceptions (e.g. In Egyptian mythology, Nut is the sky mother and Geb is the earth father).” ref

Tutelary deity

“A tutelary (also tutelar) is a deity or spirit who is a guardian, patron, or protector of a particular place, geographic feature, person, lineage, nation, culture, or occupation. The etymology of “tutelary” expresses the concept of safety and thus of guardianship. In late Greek and Roman religion, one type of tutelary deity, the genius, functions as the personal deity or daimon of an individual from birth to death. Another form of personal tutelary spirit is the familiar spirit of European folklore.” ref

“A tutelary (also tutelar) in Korean shamanism, jangseung and sotdae were placed at the edge of villages to frighten off demons. They were also worshiped as deities. Seonangshin is the patron deity of the village in Korean tradition and was believed to embody the Seonangdang. In Philippine animism, Diwata or Lambana are deities or spirits that inhabit sacred places like mountains and mounds and serve as guardians. Such as: Maria Makiling is the deity who guards Mt. Makiling and Maria Cacao and Maria Sinukuan. In Shinto, the spirits, or kami, which give life to human bodies come from nature and return to it after death. Ancestors are therefore themselves tutelaries to be worshiped. And similarly, Native American beliefs such as Tonás, tutelary animal spirit among the Zapotec and Totems, familial or clan spirits among the Ojibwe, can be animals.” ref

“A tutelary (also tutelar) in Austronesian beliefs such as: Atua (gods and spirits of the Polynesian peoples such as the Māori or the Hawaiians), Hanitu (Bunun of Taiwan‘s term for spirit), Hyang (Kawi, Sundanese, Javanese, and Balinese Supreme Being, in ancient Java and Bali mythology and this spiritual entity, can be either divine or ancestral), Kaitiaki (New Zealand Māori term used for the concept of guardianship, for the sky, the sea, and the land), Kawas (mythology) (divided into 6 groups: gods, ancestors, souls of the living, spirits of living things, spirits of lifeless objects, and ghosts), Tiki (Māori mythology, Tiki is the first man created by either Tūmatauenga or Tāne and represents deified ancestors found in most Polynesian cultures). ” ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

Mesopotamian Tutelary Deities can be seen as ones related to City-States

“Historical city-states included Sumerian cities such as Uruk and Ur; Ancient Egyptian city-states, such as Thebes and Memphis; the Phoenician cities (such as Tyre and Sidon); the five Philistine city-states; the Berber city-states of the Garamantes; the city-states of ancient Greece (the poleis such as Athens, Sparta, Thebes, and Corinth); the Roman Republic (which grew from a city-state into a vast empire); the Italian city-states from the Middle Ages to the early modern period, such as Florence, Siena, Ferrara, Milan (which as they grew in power began to dominate neighboring cities) and Genoa and Venice, which became powerful thalassocracies; the Mayan and other cultures of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica (including cities such as Chichen Itza, Tikal, Copán and Monte Albán); the central Asian cities along the Silk Road; the city-states of the Swahili coast; Ragusa; states of the medieval Russian lands such as Novgorod and Pskov; and many others.” ref

“The Uruk period (ca. 4000 to 3100 BCE; also known as Protoliterate period) of Mesopotamia, named after the Sumerian city of Uruk, this period saw the emergence of urban life in Mesopotamia and the Sumerian civilization. City-States like Uruk and others had a patron tutelary City Deity along with a Priest-King.” ref

“Chinese folk religion, both past, and present, includes myriad tutelary deities. Exceptional individuals, highly cultivated sages, and prominent ancestors can be deified and honored after death. Lord Guan is the patron of military personnel and police, while Mazu is the patron of fishermen and sailors. Such as Tu Di Gong (Earth Deity) is the tutelary deity of a locality, and each individual locality has its own Earth Deity and Cheng Huang Gong (City God) is the guardian deity of an individual city, worshipped by local officials and locals since imperial times.” ref

“A tutelary (also tutelar) in Hinduism, personal tutelary deities are known as ishta-devata, while family tutelary deities are known as Kuladevata. Gramadevata are guardian deities of villages. Devas can also be seen as tutelary. Shiva is the patron of yogis and renunciants. City goddesses include: Mumbadevi (Mumbai), Sachchika (Osian); Kuladevis include: Ambika (Porwad), and Mahalakshmi. In NorthEast India Meitei mythology and religion (Sanamahism) of Manipur, there are various types of tutelary deities, among which Lam Lais are the most predominant ones. Tibetan Buddhism has Yidam as a tutelary deity. Dakini is the patron of those who seek knowledge.” ref

“A tutelary (also tutelar) The Greeks also thought deities guarded specific places: for instance, Athena was the patron goddess of the city of Athens. Socrates spoke of hearing the voice of his personal spirit or daimonion:

You have often heard me speak of an oracle or sign which comes to me … . This sign I have had ever since I was a child. The sign is a voice which comes to me and always forbids me to do something which I am going to do, but never commands me to do anything, and this is what stands in the way of my being a politician.” ref

“Tutelary deities who guard and preserve a place or a person are fundamental to ancient Roman religion. The tutelary deity of a man was his Genius, that of a woman her Juno. In the Imperial era, the Genius of the Emperor was a focus of Imperial cult. An emperor might also adopt a major deity as his personal patron or tutelary, as Augustus did Apollo. Precedents for claiming the personal protection of a deity were established in the Republican era, when for instance the Roman dictator Sulla advertised the goddess Victory as his tutelary by holding public games (ludi) in her honor.” ref

“Each town or city had one or more tutelary deities, whose protection was considered particularly vital in time of war and siege. Rome itself was protected by a goddess whose name was to be kept ritually secret on pain of death (for a supposed case, see Quintus Valerius Soranus). The Capitoline Triad of Juno, Jupiter, and Minerva were also tutelaries of Rome. The Italic towns had their own tutelary deities. Juno often had this function, as at the Latin town of Lanuvium and the Etruscan city of Veii, and was often housed in an especially grand temple on the arx (citadel) or other prominent or central location. The tutelary deity of Praeneste was Fortuna, whose oracle was renowned.” ref

“The Roman ritual of evocatio was premised on the belief that a town could be made vulnerable to military defeat if the power of its tutelary deity were diverted outside the city, perhaps by the offer of superior cult at Rome. The depiction of some goddesses such as the Magna Mater (Great Mother, or Cybele) as “tower-crowned” represents their capacity to preserve the city. A town in the provinces might adopt a deity from within the Roman religious sphere to serve as its guardian, or syncretize its own tutelary with such; for instance, a community within the civitas of the Remi in Gaul adopted Apollo as its tutelary, and at the capital of the Remi (present-day Rheims), the tutelary was Mars Camulus.” ref

Household deity (a kind of or related to a Tutelary deity)

“A household deity is a deity or spirit that protects the home, looking after the entire household or certain key members. It has been a common belief in paganism as well as in folklore across many parts of the world. Household deities fit into two types; firstly, a specific deity – typically a goddess – often referred to as a hearth goddess or domestic goddess who is associated with the home and hearth, such as the ancient Greek Hestia.” ref

“The second type of household deities are those that are not one singular deity, but a type, or species of animistic deity, who usually have lesser powers than major deities. This type was common in the religions of antiquity, such as the Lares of ancient Roman religion, the Gashin of Korean shamanism, and Cofgodas of Anglo-Saxon paganism. These survived Christianisation as fairy-like creatures existing in folklore, such as the Anglo-Scottish Brownie and Slavic Domovoy.” ref

“Household deities were usually worshipped not in temples but in the home, where they would be represented by small idols (such as the teraphim of the Bible, often translated as “household gods” in Genesis 31:19 for example), amulets, paintings, or reliefs. They could also be found on domestic objects, such as cosmetic articles in the case of Tawaret. The more prosperous houses might have a small shrine to the household god(s); the lararium served this purpose in the case of the Romans. The gods would be treated as members of the family and invited to join in meals, or be given offerings of food and drink.” ref

“In many religions, both ancient and modern, a god would preside over the home. Certain species, or types, of household deities, existed. An example of this was the Roman Lares. Many European cultures retained house spirits into the modern period. Some examples of these include:

- Brownie (Scotland and England) or Hob (England) / Kobold (Germany) / Goblin / Hobgoblin

- Domovoy (Slavic)

- Nisse (Norwegian or Danish) / Tomte (Swedish) / Tonttu (Finnish)

- Húsvættir (Norse)” ref

“Although the cosmic status of household deities was not as lofty as that of the Twelve Olympians or the Aesir, they were also jealous of their dignity and also had to be appeased with shrines and offerings, however humble. Because of their immediacy they had arguably more influence on the day-to-day affairs of men than the remote gods did. Vestiges of their worship persisted long after Christianity and other major religions extirpated nearly every trace of the major pagan pantheons. Elements of the practice can be seen even today, with Christian accretions, where statues to various saints (such as St. Francis) protect gardens and grottos. Even the gargoyles found on older churches, could be viewed as guardians partitioning a sacred space.” ref

“For centuries, Christianity fought a mop-up war against these lingering minor pagan deities, but they proved tenacious. For example, Martin Luther‘s Tischreden have numerous – quite serious – references to dealing with kobolds. Eventually, rationalism and the Industrial Revolution threatened to erase most of these minor deities, until the advent of romantic nationalism rehabilitated them and embellished them into objects of literary curiosity in the 19th century. Since the 20th century this literature has been mined for characters for role-playing games, video games, and other fantasy personae, not infrequently invested with invented traits and hierarchies somewhat different from their mythological and folkloric roots.” ref

“In contradistinction to both Herbert Spencer and Edward Burnett Tylor, who defended theories of animistic origins of ancestor worship, Émile Durkheim saw its origin in totemism. In reality, this distinction is somewhat academic, since totemism may be regarded as a particularized manifestation of animism, and something of a synthesis of the two positions was attempted by Sigmund Freud. In Freud’s Totem and Taboo, both totem and taboo are outward expressions or manifestations of the same psychological tendency, a concept which is complementary to, or which rather reconciles, the apparent conflict. Freud preferred to emphasize the psychoanalytic implications of the reification of metaphysical forces, but with particular emphasis on its familial nature. This emphasis underscores, rather than weakens, the ancestral component.” ref

“William Edward Hearn, a noted classicist, and jurist, traced the origin of domestic deities from the earliest stages as an expression of animism, a belief system thought to have existed also in the neolithic, and the forerunner of Indo-European religion. In his analysis of the Indo-European household, in Chapter II “The House Spirit”, Section 1, he states:

The belief which guided the conduct of our forefathers was … the spirit rule of dead ancestors.” ref

“In Section 2 he proceeds to elaborate:

It is thus certain that the worship of deceased ancestors is a vera causa, and not a mere hypothesis. …

In the other European nations, the Slavs, the Teutons, and the Kelts, the House Spirit appears with no less distinctness. … [T]he existence of that worship does not admit of doubt. … The House Spirits had a multitude of other names which it is needless here to enumerate, but all of which are more or less expressive of their friendly relations with man. … In [England] … [h]e is the Brownie. … In Scotland this same Brownie is well known. He is usually described as attached to particular families, with whom he has been known to reside for centuries, threshing the corn, cleaning the house, and performing similar household tasks. His favorite gratification was milk and honey.” ref

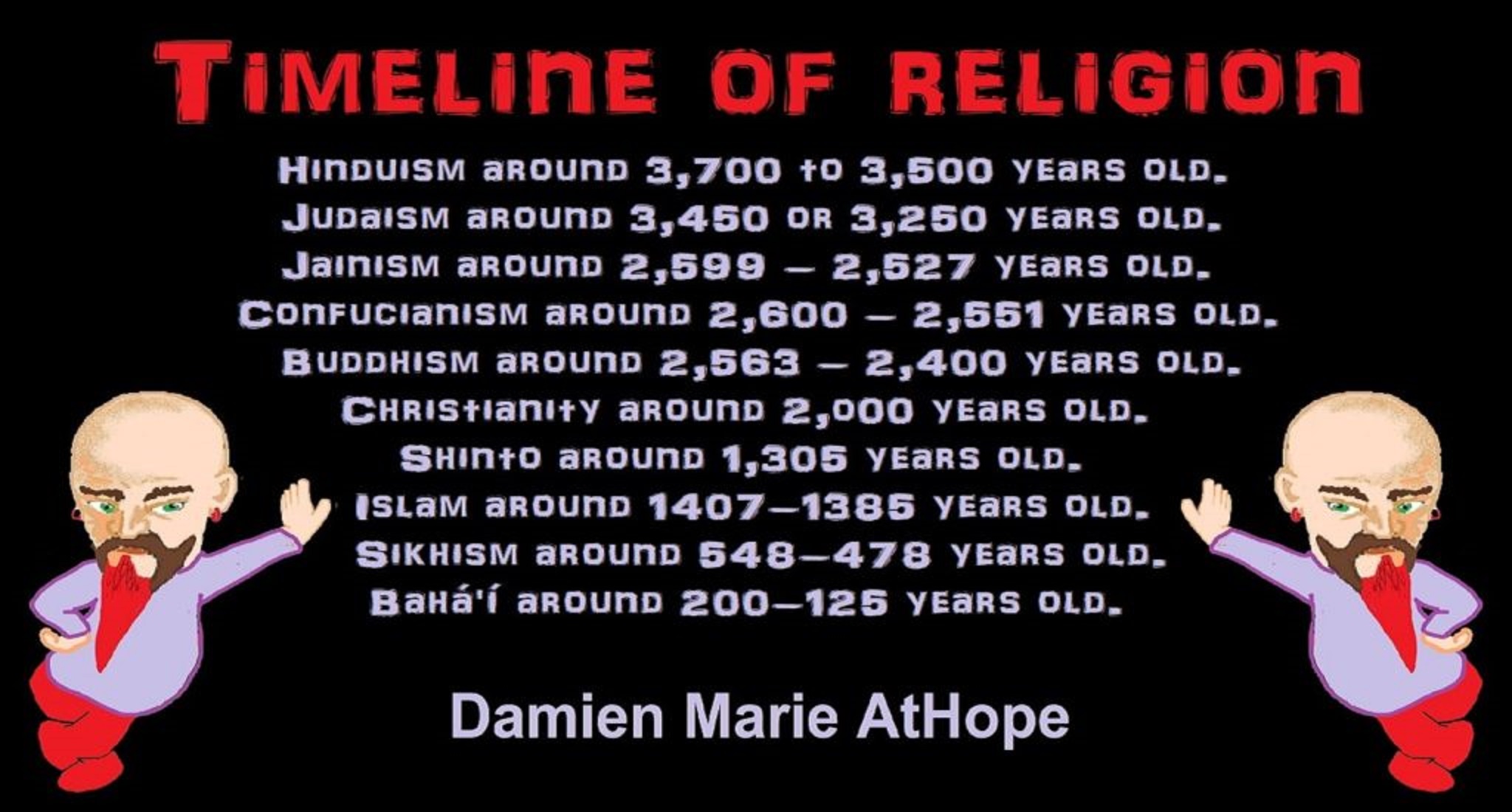

Hinduism around 3,700 to 3,500 years old. ref

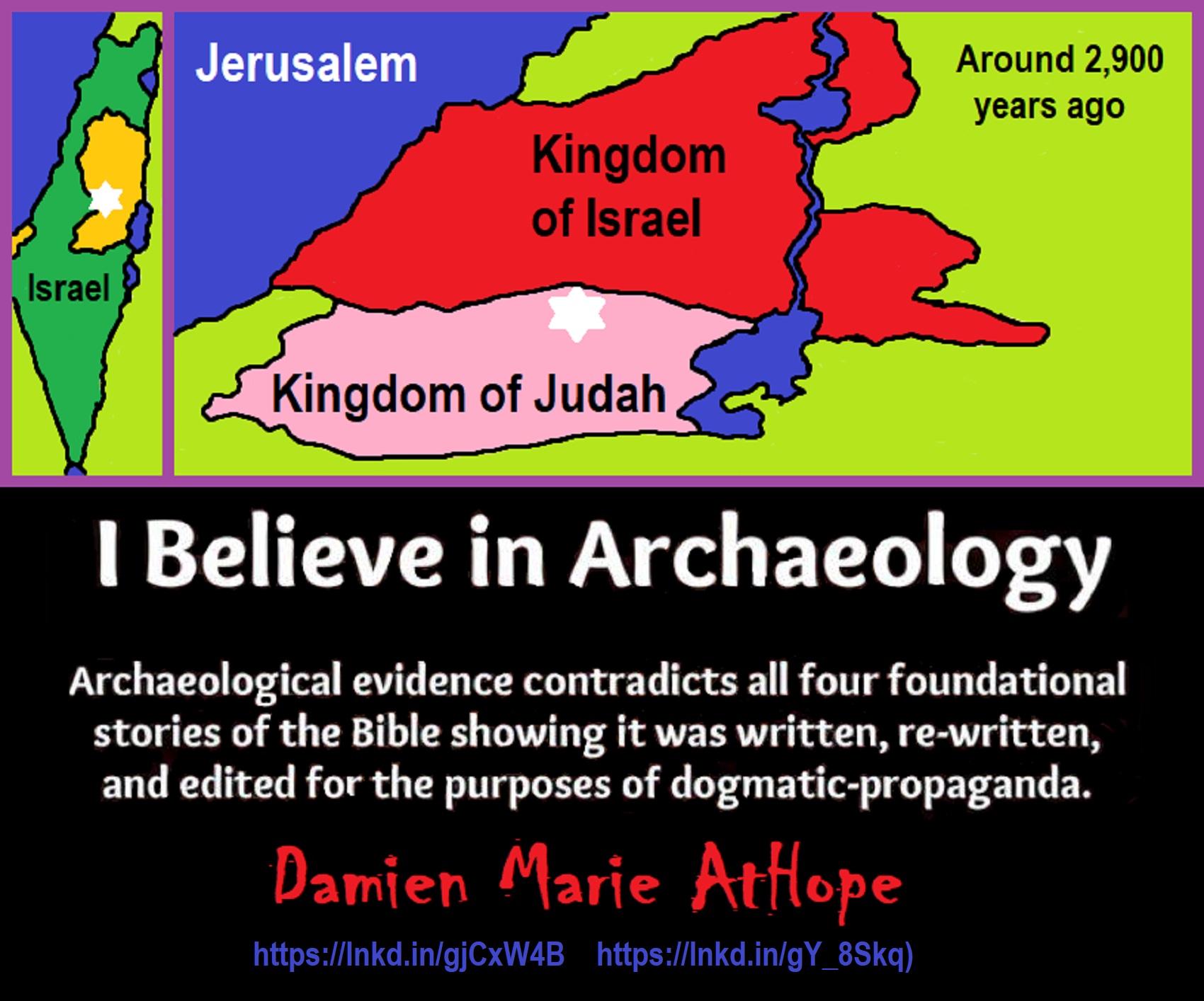

Judaism around 3,450 or 3,250 years old. (The first writing in the bible was “Paleo-Hebrew” dated to around 3,000 years ago Khirbet Qeiyafa is the site of an ancient fortress city overlooking the Elah Valley. And many believe the religious Jewish texts were completed around 2,500) ref, ref

Judaism is around 3,450 or 3,250 years old. (“Paleo-Hebrew” 3,000 years ago and Torah 2,500 years ago)

“Judaism is an Abrahamic, its roots as an organized religion in the Middle East during the Bronze Age. Some scholars argue that modern Judaism evolved from Yahwism, the religion of ancient Israel and Judah, by the late 6th century BCE, and is thus considered to be one of the oldest monotheistic religions.” ref

“Yahwism is the name given by modern scholars to the religion of ancient Israel, essentially polytheistic, with a plethora of gods and goddesses. Heading the pantheon was Yahweh, the national god of the Israelite kingdoms of Israel and Judah, with his consort, the goddess Asherah; below them were second-tier gods and goddesses such as Baal, Shamash, Yarikh, Mot, and Astarte, all of whom had their own priests and prophets and numbered royalty among their devotees, and a third and fourth tier of minor divine beings, including the mal’ak, the messengers of the higher gods, who in later times became the angels of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Yahweh, however, was not the ‘original’ god of Israel “Isra-El”; it is El, the head of the Canaanite pantheon, whose name forms the basis of the name “Israel”, and none of the Old Testament patriarchs, the tribes of Israel, the Judges, or the earliest monarchs, have a Yahwistic theophoric name (i.e., one incorporating the name of Yahweh).” ref