Can mathematical theorems be proved with 100% certainty?

Here is why “Reason is my only master”

The most Base Presupposition begins in reason. Reason is needed for logic (logic is realized by the aid of reason enriching its axioms). Logic is needed for axiology/value theory (axiology is realized by the aid of logic). Axiology is needed for epistemology (epistemology is realized by aid of axiology value judge and enrich its value assumptions as valid or not). Epistemology is needed for a good ontology (ontology is realized by the aid of epistemology justified assumptions/realizations/conclusions). Then when one possesses a good ontology (fortified with valid and reliable reason and evidence) they can then say they know the ontology of that thing.

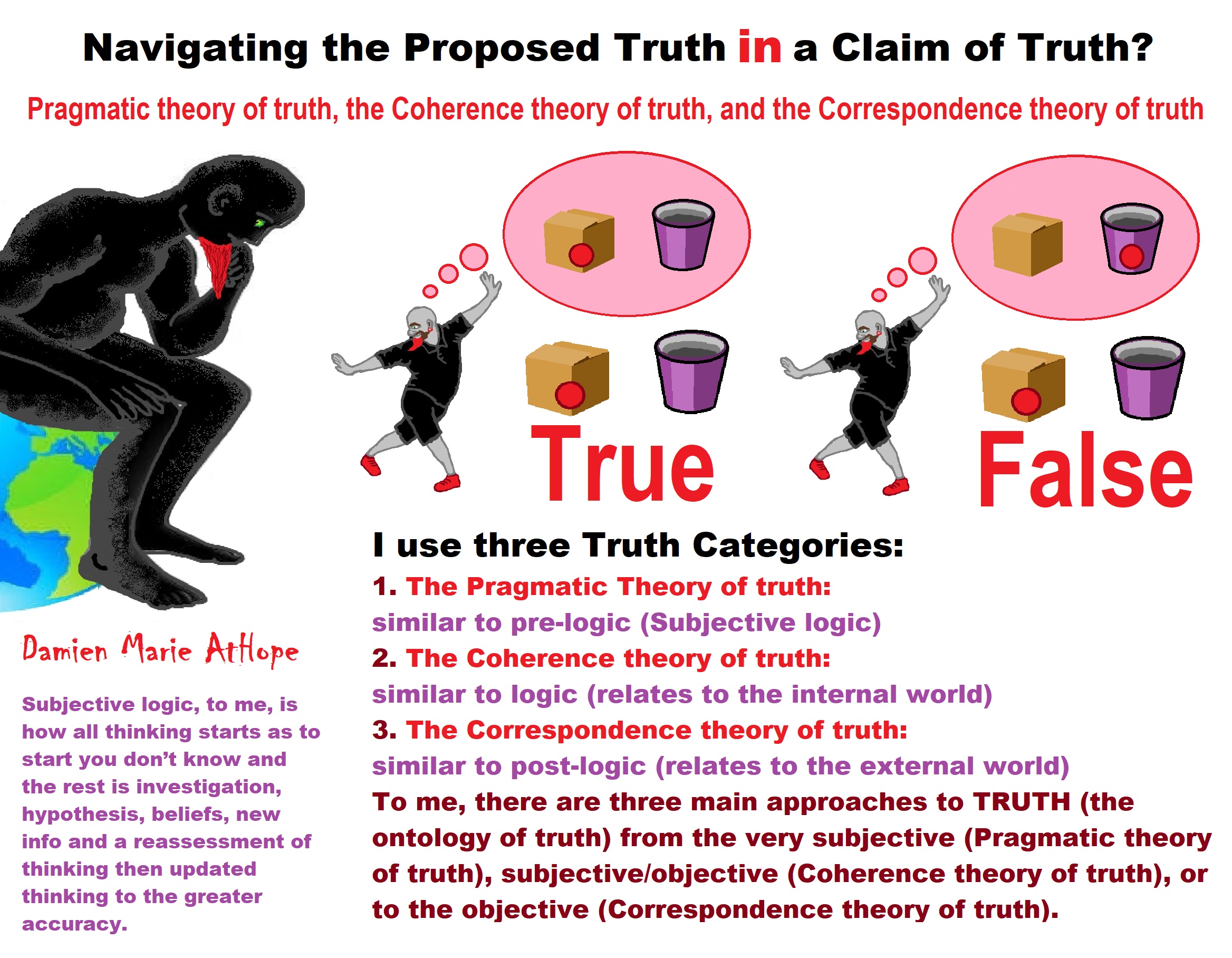

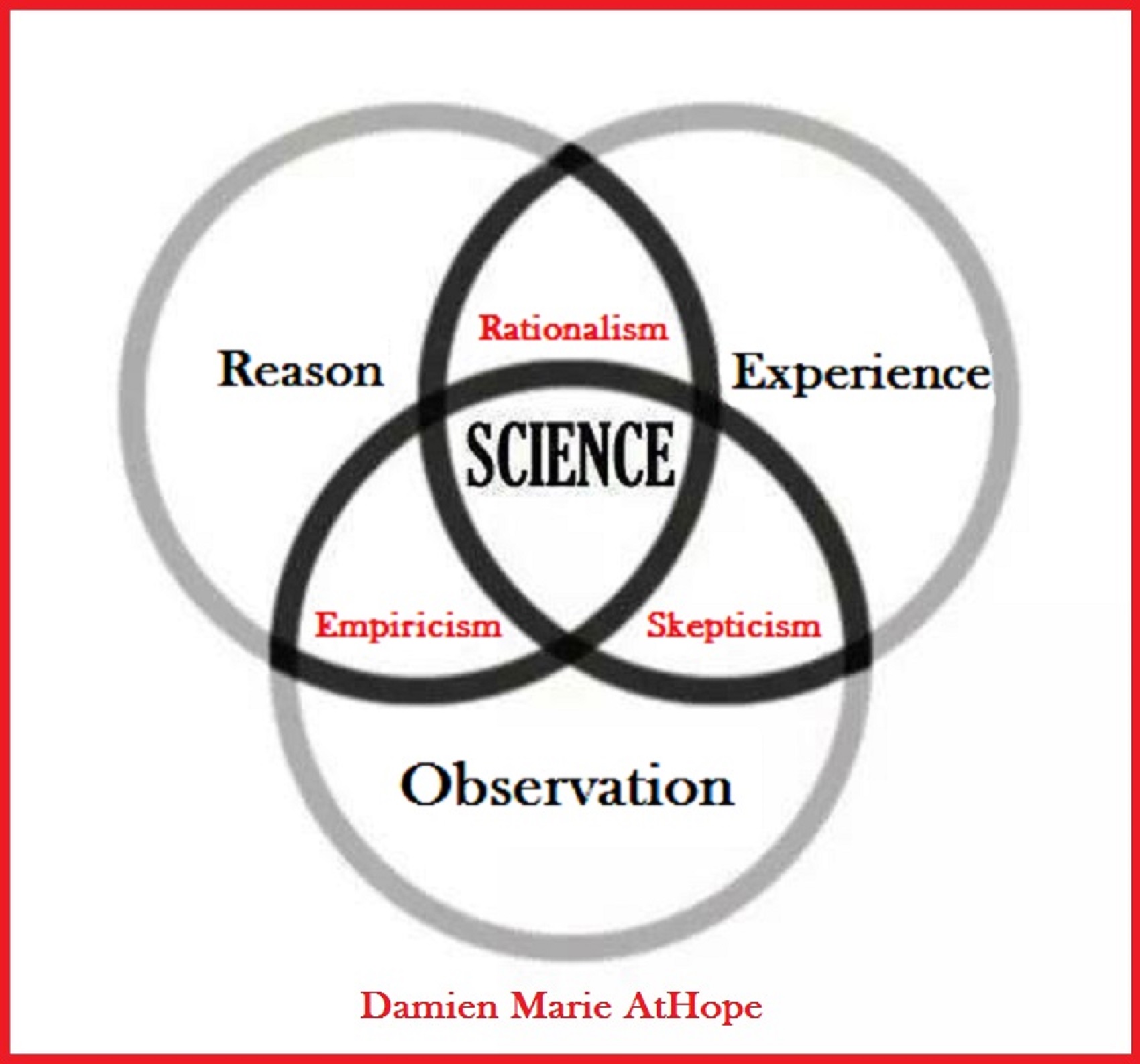

So, I think, right thinking is reason. Right reason is logic. Right logic, can be used for mathematics and from there we can get to science. And, by this methodological approach, we get one of the best ways of knowing the scientific method. Activating experience/event occurs, eliciting our feelings/scenes. Then naive thoughts occur, eliciting emotions as a response. Then it is our emotional intelligence over emotional hijacking, which entrance us but are unavoidable and that it is the navigating this successfully in a methodological way we call critical thinking or as In just call right thinking. So, to me, could be termed “Right” thinking, that is referring to a kind of methodological thinking. Reason is at the base of everything and it builds up from pragmatic approaches. And, to me, there are three main approaches to truth (ontology of truth) from the very subjective (Pragmatic theory of truth), to subjective (Coherence theory of truth), then onto objective (Correspondence theory of truth) but remember that this process as limited as it can be, is the best we have and we build one truth ontop another like blocks to a wall of truth.

Pragmatic theory of truth, Coherence theory of truth, and Correspondence theory of truth

In a general way, all reality, in a philosophic sense, is an emergent property of reason, and knowing how reason accrues does not remove its warrant. Feelings are experienced then perceived, leading to thinking, right thinking is reason, right reason is logic, right logic is mathematics, right mathematics is physics and from there all science.

Science is quite the opposite of just common sense. To me, common sense in a relative way as it generally relates to the reality of things in the world, will involve “naive realism.” Whereas, most of those who are scientific thinkers, generally hold more to scientific realism or other stances far removed from the limited common sense naive realism. Science is a multidisciplinary methodological quest for truth. Science is understanding what is, while religion is wishing on what is not.

Absolute Certainty?

According to the writers of the philosophy website LESSWRONG, possessing absolute certainty in a fact, or Bayesian probability of 1, isn’t a good idea. Losing an epistemic bet made with absolute certainty corresponds to receiving an infinite negative payoff, according to the logarithmic proper scoring rule. The same principle applies to mathematical truths. Confidence levels inside and outside an argument Not possessing absolute certainty in math doesn’t make the math itself uncertain, the same way that an uncertain map doesn’t cause the territory to blur out. The world, and the math, are precise, while knowledge about them is incomplete. The impossibility of justified absolute certainty is sometimes used as a rationalization for the fallacy of gray. Here is a link for Infinite Certainty. ref

Advancing Certainty?

According to the writers of the philosophy website LESSWRONG, and Related: Horrible LHC Inconsistency, The Proper Use of Humility But Overconfidence, is a big fear around these parts. Well, it is a known human bias, after all, and therefore something to be guarded against. But what is going to argue is that, at least in aspiring-rationalist circles, people are too afraid of overconfidence, to the point of overcorrecting — which, not surprisingly, causes problems. (Some may detect implications here for the long-standing Inside View vs. Outside View debate.)

Here’s Eliezer, voicing the typical worry:

[I]f you asked me whether I could make one million statements of authority equal to “The Large Hadron Collider will not destroy the world”, and be wrong, on average, around once, then I would have to say no.

Moreover, according to the writers of LESSWRONG, there may be a reason to now suspect that misleading imagery may be at work here. A million statements — that sounds like a lot, doesn’t it? If you made one such pronouncement every ten seconds, a million of them would require you to spend months doing nothing but pontificating, with no eating, sleeping, or bathroom breaks. Boy, that would be tiring, wouldn’t it? At some point, surely, your exhausted brain would slip up and make an error. In fact, it would surely make more than one — in which case, poof!, there goes your calibration. No wonder, then, that people claim that we humans can’t possibly hope to attain such levels of certainty. Look, they say, at all those times in the past when people — even famous scientists! — said they were 99.999% sure of something, and they turned out to be wrong. My own adolescent self would have assigned high confidence to the truth of Christianity; so where do I get the temerity, now, to say that the probability of this is 1-over-oogles-and-googols? A probability estimate is not a measure of “confidence” in some psychological sense. Rather, it is a measure of the strength of the evidence: how much information you believe you have about reality. So, when judging calibration, it is not really appropriate to imagine oneself, say, judging thousands of criminal trials, and getting more than a few wrong here and there (because, after all, one is human and tends to make mistakes). Let me instead propose a less misleading image: picture yourself programming your model of the world (in technical terms, your prior probability distribution) into a computer, and then feeding all that data from those thousands of cases into the computer — which then, when you run the program, rapidly spits out the corresponding thousands of posterior probability estimates. That is, visualize a few seconds or minutes of staring at a rapidly-scrolling computer screen, rather than a lifetime of exhausting judicial labor. When the program finishes, how many of those numerical verdicts on the screen are wrong?

According to the writers of LESSWRONG, don’t know about you, but modesty seems less tempting when one thinks about it in this way. One can say I have a model of the world, and it makes predictions. For some reason, when it’s just me in a room looking at a screen, I don’t feel the need to tone down the strength of those predictions for fear of unpleasant social consequences. Nor do I need to worry about the computer getting tired from running all those numbers. In the vanishingly unlikely event that Omega was to appear and tell me that, say, Amanda Knox was guilty, it wouldn’t mean that I had been too arrogant and that I had better not trust my estimates in the future. What it would mean is that my model of the world was severely stupid with respect to predicting reality. In which case, the thing to do would not be to humbly promise to be more modest henceforth, but rather, to find the problem and fix it. (computer programmers call this “debugging”.) A “confidence level” is a numerical measure of how stupid your model is, if you turn out to be wrong.

Furthermore, according to the writers of the philosophy website LESSWRONG, the fundamental question of rationality is: why do you believe what you believe? As a rationalist, you can’t just pull probabilities out of your rear end. And now here’s the kicker: that includes the probability of your model being wrong. The latter must, paradoxically but necessarily, be part of your model itself. If you’re uncertain, there has to be a reason you’re uncertain; if you expect to change your mind later, you should go ahead and change your mind now. This is the first thing to remember in setting out to dispose of what I call “quantitative Cartesian skepticism”: the view that even though science tells us the probability of such-and-such is 10-50, well, that’s just too high of a confidence for mere mortals like us to assert; our model of the world could be wrong, after all — conceivably, we might even be brains in vats. Now, it could be the case that 10-50 is too low of a probability for that event, despite the calculations; and it may even be that that particular level of certainty (about almost anything) is in fact beyond our current epistemic reach. But if we believe this, there have to be reasons we believe it, and those reasons have to be better than the reasons for believing the opposite.

According to the writers of the philosophy website LESSWRONG, one can expect that if you probe the intuitions of people who worry about 10-6 being too low of a probability that the Large Hadron Collider will destroy the world — that is, if you ask them why they think they couldn’t make a million statements of equal authority and be wrong on average once — they will cite statistics about the previous track record of human predictions: their own youthful failures and/or things like Lord Kelvin calculating that evolution by natural selection was impossible.

According to the writers of LESSWRONG, the reply is: hindsight is 20/20 — so how about taking advantage of this fact? Previously, the phrase “epistemic technology” was used in reference to our ability to achieve greater certainty through some recently-invented methods of investigation than through others that are native unto us. This, I confess, was an almost deliberate foreshadowing of my thesis here: we are not stuck with the inferential powers of our ancestors. One implication of the Bayesian-Jaynesian-Yudkowskian view, which marries epistemology to physics, is that our knowledge-gathering ability is as subject to “technological” improvement as any other physical process. With effort applied over time, we should be able to increase not only our domain knowledge but also our meta-knowledge. As we acquire more and more information about the world, our Bayesian probabilities should become more and more confident. If we’re smart, we will look back at Lord Kelvin’s reasoning, find the mistakes, and avoid making those mistakes in the future. We will, so to speak, debug the code. Perhaps we couldn’t have spotted the flaws at the time; but we can spot them now. Whatever other flaws may still be plaguing us, our score has improved. In the face of precise scientific calculations, it doesn’t do to say, “Well, science has been wrong before”. If science was wrong before, it is our duty to understand why science was wrong, and remove known sources of stupidity from our model. Once we’ve done this, “past scientific predictions” is no longer an appropriate reference class for second-guessing the prediction at hand, because the science is now superior. (Or anyway, the strength of the evidence of previous failures is diminished.)

According to the writers of LESSWRONG, that is why, with respect to Eliezer’s LHC dilemma — which amounts to a conflict between avoiding overconfidence and avoiding hypothesis-privileging — coming down squarely on the side of hypothesis-privileging as the greater danger. Psychologically, you may not “feel up to” making a million predictions, of which no more than one can be wrong; but if that’s what your model instructs you to do, then that’s what you have to do — unless you think your model is wrong, for some better reason than a vague sense of uneasiness. Without, ultimately, trusting science more than intuition, there’s no hope of making epistemic progress. At the end of the day, you have to shut up and multiply — epistemically as well as instrumentally. ref

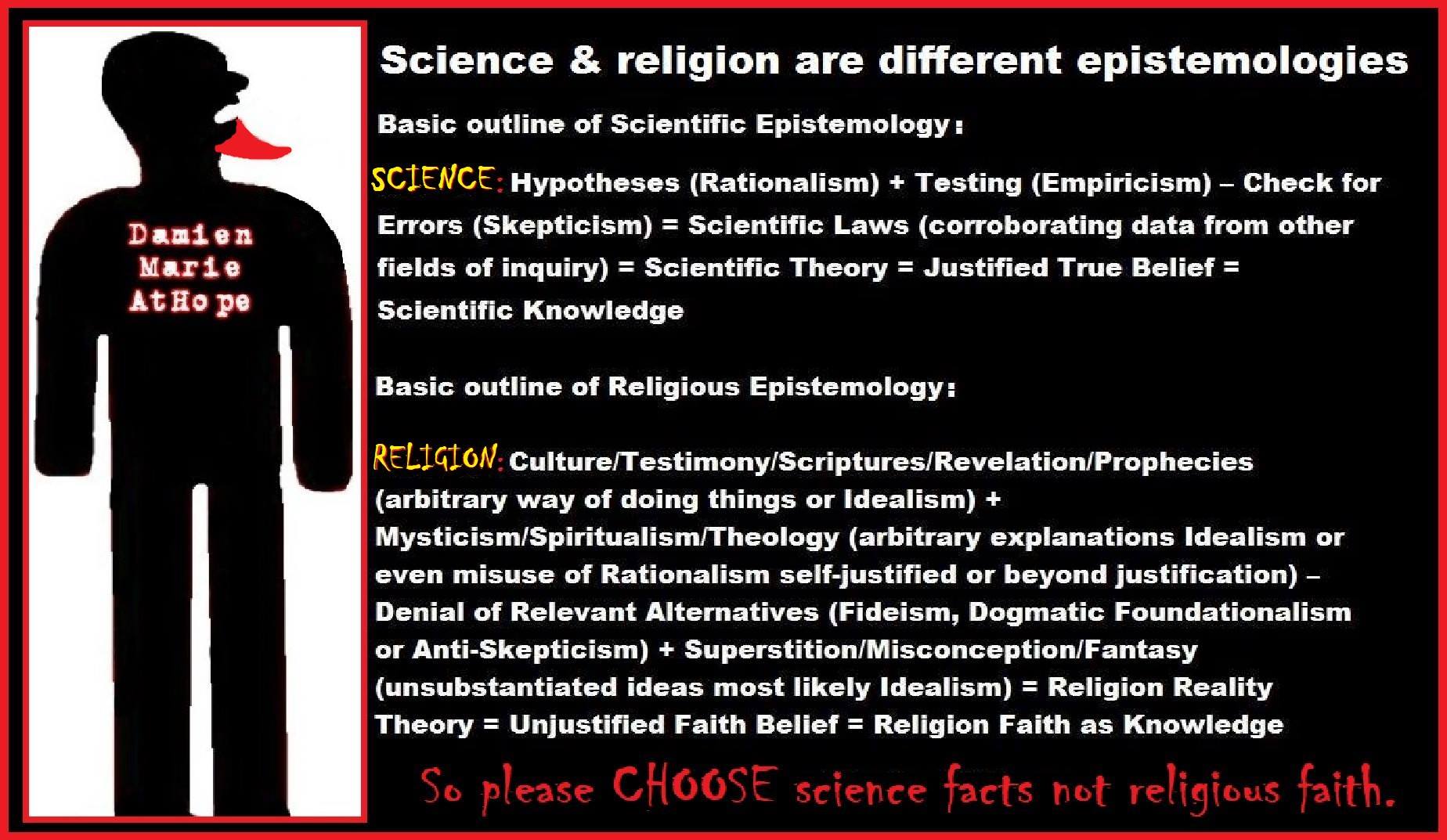

Problems in the Basic outline of One’s Epistemology?

“Incorporating a prediction into future planning and decision making is advisable only if we have judged the prediction’s credibility. This is notoriously difficult and controversial in the case of predictions of future climate. By reviewing epistemic arguments about climate model performance, we discuss how to make and justify judgments about the credibility of climate predictions. Possibly proposing arguments that justify basing some judgments on the past performance of possibly dissimilar prediction problems. This encourages a more explicit use of data in making quantitative judgments about the credibility of future climate predictions, and in training users of climate predictions to become better judges of value, goodness, credibility, accuracy, worth or usefulness.” Ref

Definition of epistemic,

of or relating to knowledge or knowing

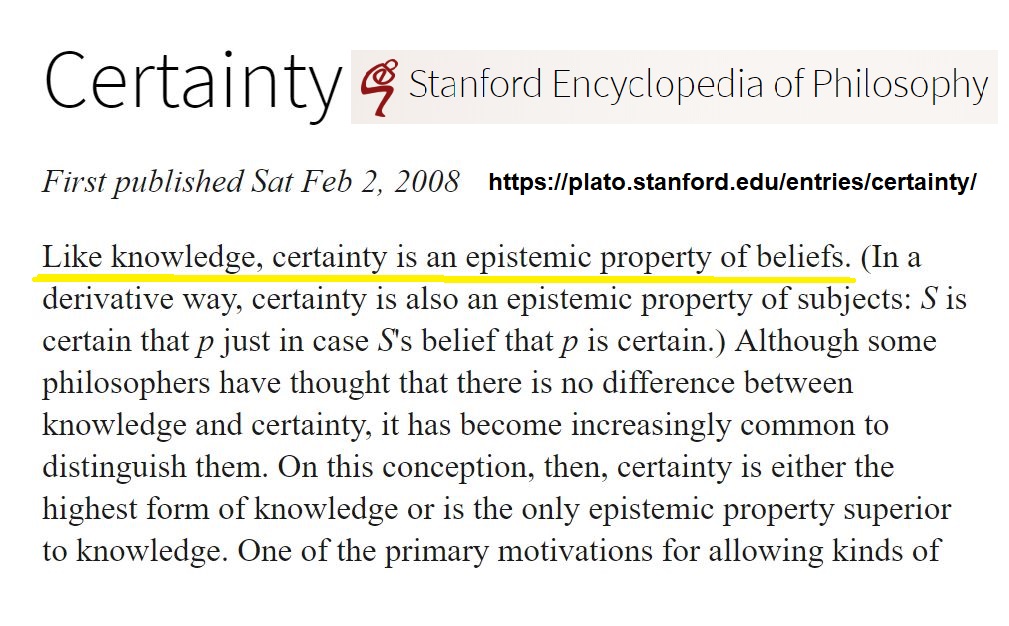

Certainty: “I know” vs “I believe”

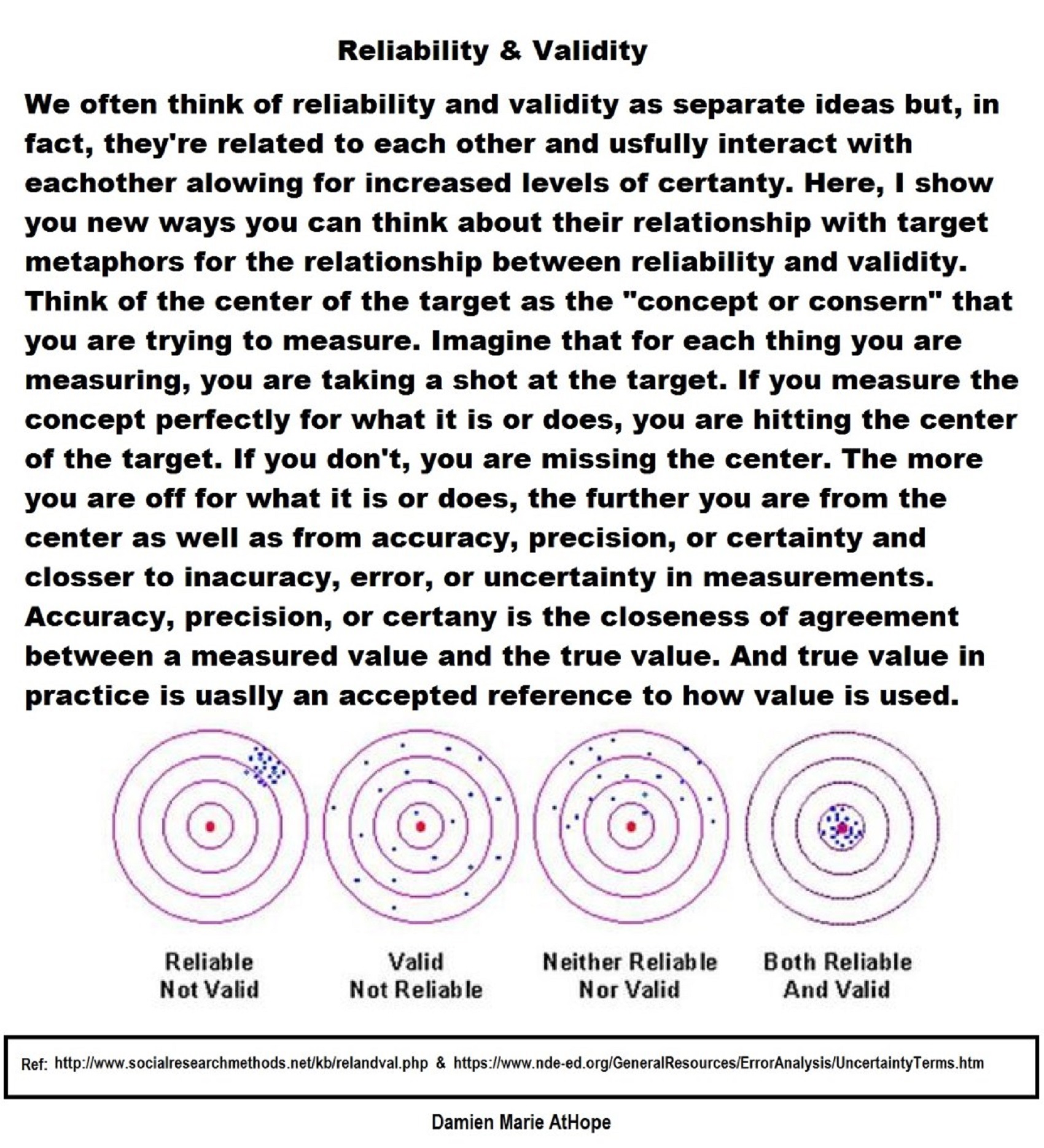

“Certainty is often explicated in terms of indubitability. What makes possible doubting is “the fact that some propositions are exempt from doubt, are as it were like hinges on which those turn.” Do you certainty that you are reading this in English? I would think all are comfortable accepting that this is written in English you would likely say you have knowledge of this. But like knowledge, certainty is an epistemic property of beliefs. Although some philosophers have thought that there is no difference between knowledge and certainty, it has become increasingly common to distinguish them. On this conception, then, certainty is either the highest form of knowledge or is the only epistemic property superior to knowledge. One of the primary motivations for allowing kinds of knowledge less than certainty is the widespread sense that skeptical arguments are successful in showing that we rarely or never have beliefs that are certain (a kind of skeptical argument) but do not succeed in showing that our beliefs are altogether without epistemic worth, there is an argument that skepticism undermines every epistemic status a belief might have and there is an argument that knowledge requires certainty, which we are capable of having. As with knowledge, it is difficult to provide an uncontentious analysis of certainty. There are several reasons for this. One is that there are different kinds of certainty, which are easy to conflate. Another is that the full value of certainty is surprisingly hard to capture. A third reason is that there are two dimensions to certainty: a belief can be certain at a moment or over some greater length of time. There are various kinds of certainty. A belief is psychologically certain when the subject who has it is supremely convinced of its truth. Certainty in this sense is similar to incorrigibility, which is the property a belief has of being such that the subject is incapable of giving it up. But psychological certainty is not the same thing as incorrigibility. A belief can be certain in this sense without being incorrigible; this may happen, for example, when the subject receives a very compelling bit of counterevidence to the (previously) certain belief and gives it up for that reason. Moreover, a belief can be incorrigible without being psychologically certain. For example, a mother may be incapable of giving up the belief that her son did not commit a gruesome murder, and yet, compatible with that inextinguishable belief, she may be tortured by doubt. A second kind of certainty is epistemic. Roughly characterized, a belief is certain in this sense when it has the highest possible epistemic status. Epistemic certainty is often accompanied by psychological certainty, but it need not be. It is possible that a subject may have a belief that enjoys the highest possible epistemic status and yet be unaware that it does. In such a case, the subject may feel less than the full confidence that her epistemic position warrants. I will say more below about the analysis of epistemic certainty and its relation to psychological certainty. Some philosophers also make use of the notion of moral certainty. For example, in the Latin version of Part IV of the Principles of Philosophy, Descartes says that “some things are considered as morally certain, that is, as having sufficient certainty for application to ordinary life, even though they may be uncertain in relation to the absolute power of god”. Thus characterized, moral certainty appears to be epistemic in nature, though it is a lesser status than epistemic certainty. In the French version of this passage, however, Descartes says that “moral certainty is certainty which is sufficient to regulate our behaviour, or which measures up to the certainty we have on matters relating to the conduct of life which we never normally doubt, though we know that it is possible, absolutely speaking, that they may be false”. Understood in this way, it does not appear to be a species of knowledge, given that a belief can be morally certain and yet false. Rather, on this view, for a belief to be morally certain is for it to be subjectively rational to a high degree. Although all three kinds of certainty are philosophically interesting, it is epistemic certainty that has traditionally been of central importance. In what follows, then, I shall focus mainly on this kind of certainty. In general, every indubitability account of certainty will face a similar problem. The problem may be posed as a dilemma: when the subject finds herself incapable of doubting one of her beliefs, either she has good reasons for being incapable of doubting it, or she does not. If she does not have good reasons for being unable to doubt the belief, the type of certainty in question can be only psychological, not epistemic, in nature. On the other hand, if the subject does have good reasons for being unable to doubt the belief, the belief may be epistemically certain. But, in this case, what grounds the certainty of the belief will be the subject’s reasons for holding it, and not the fact that the belief is indubitable. A second problem for indubitability accounts of certainty is that, in one sense, even beliefs that are epistemically certain can be reasonably doubted. According to a second conception, a subject’s belief is certain just in case it could not have been mistaken—i.e., false. Alternatively, the subject’s belief is certain when it is guaranteed to be true. This is “truth-evaluating” sense of certainty. As with the claim of knowing that a proposition is certain, which entails that such a proposition is a true proposition or the claim of knowing is inacurate. Certainty is, significantly stronger than lesser forms of knowledge.” Ref

Epistemic Uncertainty?

Conceptions of Certainty?

*In a general way a Fallibilistic Conception of Certainty (“Self-presenting/Self-evident”) could be stated as one’s belief is guaranteed to be true when attempting to provide an account of fallibilistic knowledge (i.e., knowledge that is less than certain). According to the standard account, the subject has fallibilistic knowledge that a proposition is true when she knows that a proposition is true on the basis of some justification, and yet the subject’s belief could have been false while still held on the basis of their justification offered. Alternatively, the subject knows that a proposition is true on the basis of some justification offered, but that justification offered does not entail the truth that a proposition is true. The problem with the standard account, in either version, is that it does not allow for fallibilistic knowledge of necessary truths. If it is necessarily true that a proposition is true, then the subject’s belief that a proposition is true could not have been false, regardless of what their justification for it may be like. And, if it is necessarily true that a proposition is true, then everything—including the subject’s justification for their belief—will entail or guarantee that a proposition is true. Our attempt to account for certainty encounters the opposite problem: it does not allow for a subject to have a belief regarding a necessary truth that does not count as certain. If the belief is necessarily true, it cannot be false—even when the subject has come to hold the belief for a very bad reason (say, as the result of guessing or wishful thinking). And, given that the beliefs are necessarily true, even these bad grounds for holding the belief will entail or guarantee that it is true. The best way to solve the problem for the analysis of fallibilistic knowledge is to focus, not on the entailment relation, but rather on the probabilistic relation holding between the subject’s justification and the proposition believed. When the subject knows that a proposition is true (claims) on the basis of justification from an offered justification is less than required for full confirmation, the subject’s knowledge is fallibilistic. (Although epistemologists will disagree about what the appropriate conception of probability is, here is a crude example of how probability may figure in a fallibilistic epistemology. Ref

*In a general way a Falsificationism Conception of Certainty (“Self-presenting/Self-evident”) could be stated as one’s belief is guaranteed to be true (if falsifiable, ie. testable) if it is possible to conceive of an observation or an argument which could negate them, thus synonymous to testability. Statements, hypotheses, or theories have falsifiability or refutability if there is the inherent possibility that they can be proven false. They are falsifiable if it is possible to conceive of an observation or an argument which could negate them. In this sense, falsify is synonymous with nullify, meaning to invalidate or “show to be false”. For example, by the problem of induction, no number of confirming observations can verify a universal generalization, such as All swans are white, since it is logically possible to falsify it by observing a single black swan. Thus, the term falsifiability is sometimes synonymous to testability. Some statements, such as It will be raining here in one million years, are falsifiable in principle, but not in practice. The concern with falsifiability gained attention by way of philosopher of scienceKarl Popper‘s scientific epistemology “falsificationism“. Popper stresses the problem of demarcation—distinguishing the scientific from the unscientific—and makes falsifiability the demarcation criterion, such that what is unfalsifiable is classified as unscientific, and the practice of declaring an unfalsifiable theory to be scientifically true is pseudoscience. Ref

Epistemically Rational Beliefs

Which is more epistemically rational, believing that which by lack of evidence could be false or disbelieving that which by insufficient evidence could be true?

Incapable of making a decision on if there is or not a god?

“Epistemic rationality is part of rationality involving, achieving accurate beliefs about the world. It involves updating on receiving new evidence, mitigating cognitive biases, and examining why you believe what you believe.” Ref

Being Epistemically Rational

Knowledge without Belief? Justified beliefs or disbeliefs worthy of Knowledge?

Justifying Judgments: Possibility and Epistemic Utility theory

To me the choice is to use the “Ethics of Belief” and thus the more rational approach one would be more motivated is to disbelieve, rather than “Believing that which by lack of evidence could be false”, otherwise you would accept any statement or claim as true no matter how at odds with other verified facts. The ethics of belief refers to a cluster of related issues that focus on standards of rational belief, intellectual excellence, and conscientious belief-formation as well as norms of some sort governing our habits of belief-formation, belief-maintenance, and belief-relinquishment. Contemporary discussions of the ethics of belief stem largely from a famous nineteenth-century exchange between the British mathematician and philosopher W. K. Clifford and the American philosopher William James. . In 1877 Clifford published an article titled “The Ethics of Belief” in a journal called Contemporary Review. There Clifford argued for a strict form of evidentialism that he summed up in a famous dictum: “It is wrong always, everywhere, and for anyone to believe anything on insufficient evidence.” As Clifford saw it, people have intellectual as well as moral duties, and both are extremely demanding. People who base their beliefs on wishful thinking, self-interest, blind faith, or other such unreliable grounds are not merely intellectually slovenly; they are immoral. Such bad intellectual habits harm both themselves and society. We sin grievously against our moral and intellectual duty when we form beliefs on insufficient evidence, or ignore or dismiss evidence that is relevant to our beliefs. 1, 2

Addressing The Ethics of Belief

Rationalist through and through

Don’t Talk About Beliefs, Without Justifying They are True and How You Know This.

“I have no beliefs”, is a Confusion (about beliefs) I Hear Some Atheists Say

Basics of my Methodological Rationalism Epistemology Approach

Agnosticism Beliefs Involve “FOLK LOGIC” Thinking?

Yes, We All Have Beliefs; But What Does That Mean?

Solipsism?

Philosophical Skepticism, Solipsism and the Denial of Reality or Certainty

I want to clarify that I am an an Ignostic, Axiological Atheist and Rationalist who uses methodological skepticism. I hold that there is valid and reliable reason and evidence to warrant justified true belief in the knowledge of the reality of external world and even if some think we don’t we do have axiological and ethical reasons to believe or act as if so.

Thinking is occurring and it is both accessible as well as guided by what feels like me; thus, it is rational to assume I have a thinking mind, so, I exist.

But, some skeptics challenge reality or certainty (although are themselves appealing to reason or rationality that it self they seem to accept almost a priori themselves to me). Brain in a vat or jar, Evil Demon in your mind, Matrix world as your mind, & Hologram world as your reality are some arguments in the denial or challenge of reality or certainty.

The use of “Brain in a vat” type thought experiment scenarios are common as an argument for philosophical skepticism and solipsism, against rationalism and empiricism or any belief in the external world’s existence.

Such thought experiment arguments do have a value are with the positive intent to draw out certain features or remove unreasoned certainty in our ideas of knowledge, reality, truth, mind, and meaning. However, these are only valuable as though challenges to remember the need to employ Disciplined-Rationality and the ethics of belief, not to take these thought experiment arguments as actual reality. Brain in a vat/jar, Evil Demon, Matrix world, and Hologram world are logical fallacies if assumed as a reality representations.

First is the problem that they make is a challenge (alternative hypotheses) thus requiring their own burden of proof if they are to be seen as real.

Second is the problem that they make in the act of presupposition in that they presuppose the reality of a real world with factual tangible things like Brains and that such real things as human brains have actual cognition and that there are real world things like vats or jars and computers invented by human beings with human real-world intelligence and will to create them and use them for intellectually meaningful purposes.

Third is the problem of valid and reliable slandered as doubt is an intellectual professes needing to offer a valid and reliable slandered to who, what, why, and how they are proposing Philosophical Skepticism, Solipsism and the Denial of Reality or Certainty. Though one cannot on one had say I doubt everything and not doubt even that. One cannot say nothing can be known for certain, as they violate this very thought, as they are certain there is no certainty. The ability to think of reasonable doubt (methodological Skepticism) counteracts the thinking of unreasonable doubt (Philosophical Skepticism’s external world doubt and Solipsism). Philosophical skepticism is a method of reasoning which questions the possibility of knowledge is different than methodological skepticism is a method of reasoning, which questions knowledge claims with the goal finding what has warrant, justification to validate the truth or false status of beliefs or propositions.

Fourth is the problem that external world doubt and Solipsism creates issues of reproducibility, details and extravagancy. Reproducibility such as seen in experiments, observation and real world evidence, scientific knowledge, scientific laws, and scientific theories. Details such as the extent of information to be contained in one mind such as trillions of facts and definable data and/or evidence. And extravagancy such as seen in the unreasonable amount of details in general and how that also brings the added strain to reproducibility and memorability. Extravagancy in the unreasonable amount of details also interacts with axiological and ethical reasoning such as why if there is no real world would you create rape, torture, or suffering of almost unlimited variations. Why not just rape but child rape not just torture but that of innocent children who would add that and the thousands of ways it can and does happen in the external world. Extravagancy is unreasonable, why a massive of cancers and infectious things, millions of ways to be harmed, suffer and die etc. There is a massive amount of extravagancy in infectious agents if the external world was make-believe because of infectious agents come in an unbelievable variety of shapes, sizes and types like bacteria, viruses, fungi, protozoa, and parasites. Therefore, the various types of pleasure and pain both seem an unreasonable extravagancy in a fake external world therefore the most reasonable conclusion is the external world is a justified true belief.

Fifth is the problem that axiological or ethical thinking would say we only have what we understand and must curtail behavior ethically to such understanding. Think of ability to give consent having that reasoning ability brings with it the requirement of being responsible for our behaviors. If one believes the external world is not real, they remove any value (axiology) in people, places or things and if the external world is not real there is no behavior or things to interact with (ethics) so nothing can be helped or harmed by actions as there is no actions or ones acting them or having them acting for or against. In addition, if we do not know is we are actually existing or behaving in the real world we also are not certain we are not either, demanding that we must act as if it is real (pragmatically) do to ethical and axiological concerns which could be true. Because if we do act ethically and the reality of the external world is untrue we have done nothing but if we act unethical as if the reality of the external world is untrue and it is in fact real we have done something to violate ethics. Then the only right way to navigate the ethics of belief in such matters would say one should behave as though the external world is real. In addition, axiological or ethical thinking and the cost-benefit analysis of belief in the existence of the external world support and highly favors belief in the external world’s existence.

Solipsism (from Latin solus, meaning “alone”, and ipse, meaning “self”) is the philosophical idea that only one’s own mind is sure to exist. To me, solipsism is trying to limit itself to rationalism only to, of, or by itself. Everyone, including a Solipsist, as the mind to which all possible knowledge flows; consider this, if you think you can reject rational thinking as the base of everything, what other standard can you champion that does not at its core return to the process of mind as we do classify people by intelligence. If you cannot use rationalism what does this mean, irrationalism? A Solipsist, is appealing to rationalism as we only have our mind or the minds of others to help navigate the world accurately as possible.

I am a Rationalist?

Pragmatic theory of truth, Coherence theory of truth, and Correspondence theory of truth?

People don’t commonly teach religious history, even that of their own claimed religion. No, rather they teach a limited “pro their religion” history of their religion from a religious perspective favorable to the religion of choice.

Do you truly think “Religious Belief” is only a matter of some personal choice?

Do you not see how coercive one’s world of choice is limited to the obvious hereditary belief, in most religious choices available to the child of religious parents or caregivers? Religion is more commonly like a family, culture, society, etc. available belief that limits the belief choices of the child and that is when “Religious Belief” is not only a matter of some personal choice and when it becomes hereditary faith, not because of the quality of its alleged facts or proposed truths but because everyone else important to the child believes similarly so they do as well simply mimicking authority beliefs handed to them. Because children are raised in religion rather than being presented all possible choices but rather one limited dogmatic brand of “Religious Belief” where children only have a choice of following the belief as instructed, and then personally claim the faith hereditary belief seen in the confirming to the belief they have held themselves all their lives. This is obvious in statements asked and answered by children claiming a faith they barely understand but they do understand that their family believes “this or that” faith, so they feel obligated to believe it too. While I do agree that “Religious Belief” should only be a matter of some personal choice, it rarely is… End Hereditary Religion!

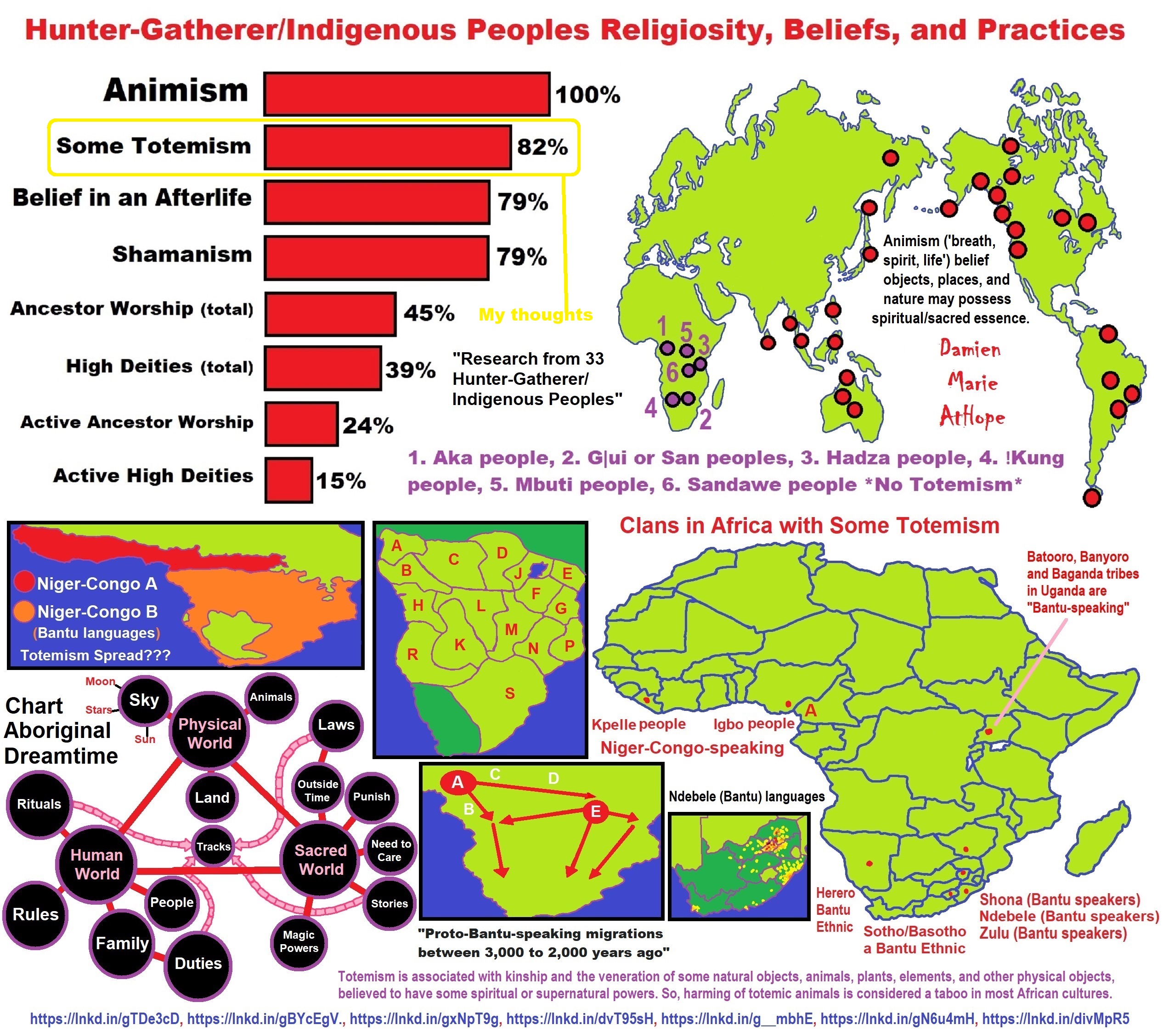

Animism: Respecting the Living World by Graham Harvey

“How have human cultures engaged with and thought about animals, plants, rocks, clouds, and other elements in their natural surroundings? Do animals and other natural objects have a spirit or soul? What is their relationship to humans? In this new study, Graham Harvey explores current and past animistic beliefs and practices of Native Americans, Maori, Aboriginal Australians, and eco-pagans. He considers the varieties of animism found in these cultures as well as their shared desire to live respectfully within larger natural communities. Drawing on his extensive casework, Harvey also considers the linguistic, performative, ecological, and activist implications of these different animisms.” ref

We are like believing machines we vacuum up ideas, like Velcro sticks to almost everything. We accumulate beliefs that we allow to negatively influence our lives, often without realizing it. Our willingness must be to alter skewed beliefs that impend our balance or reason, which allows us to achieve new positive thinking and accurate outcomes.

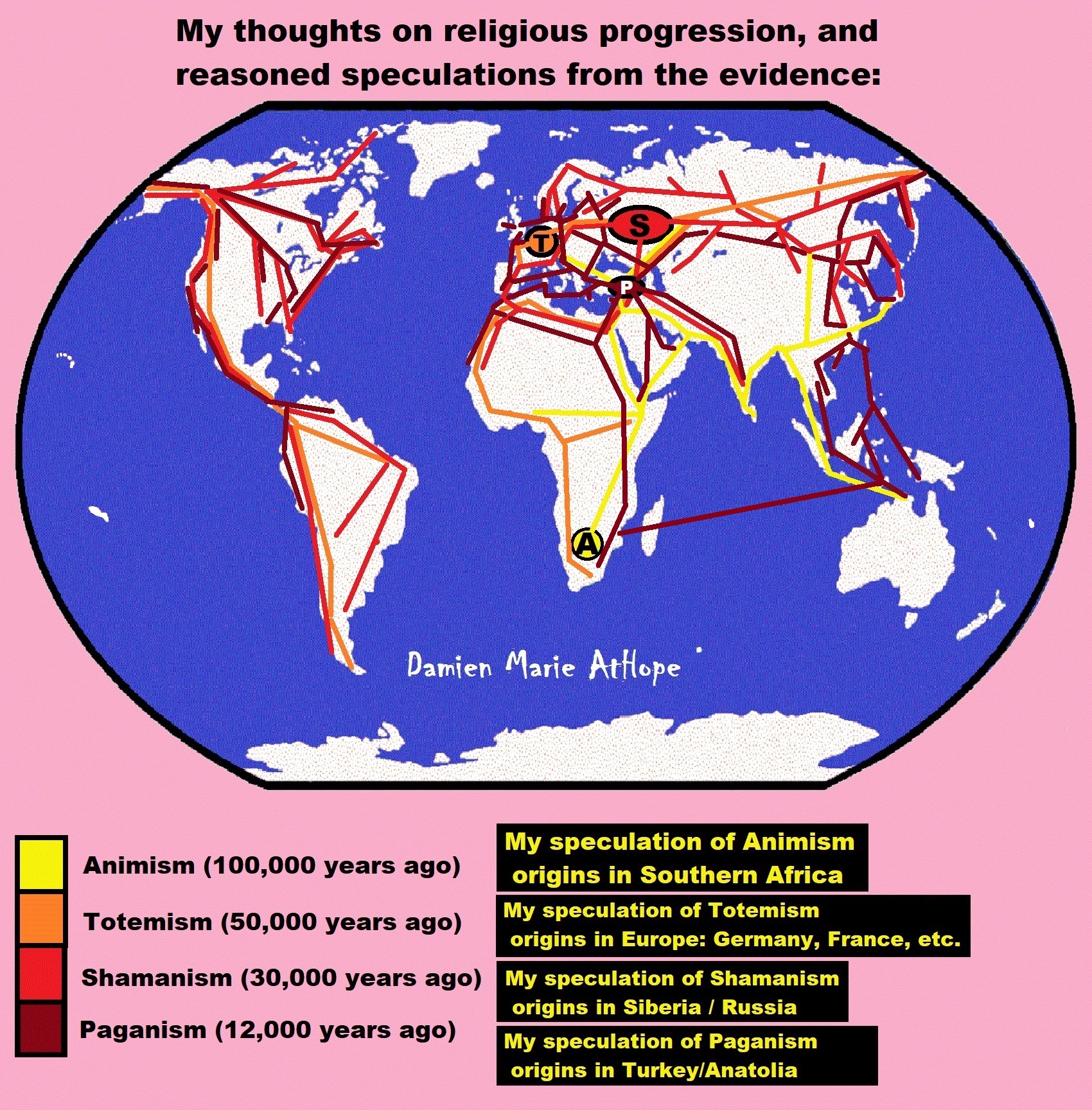

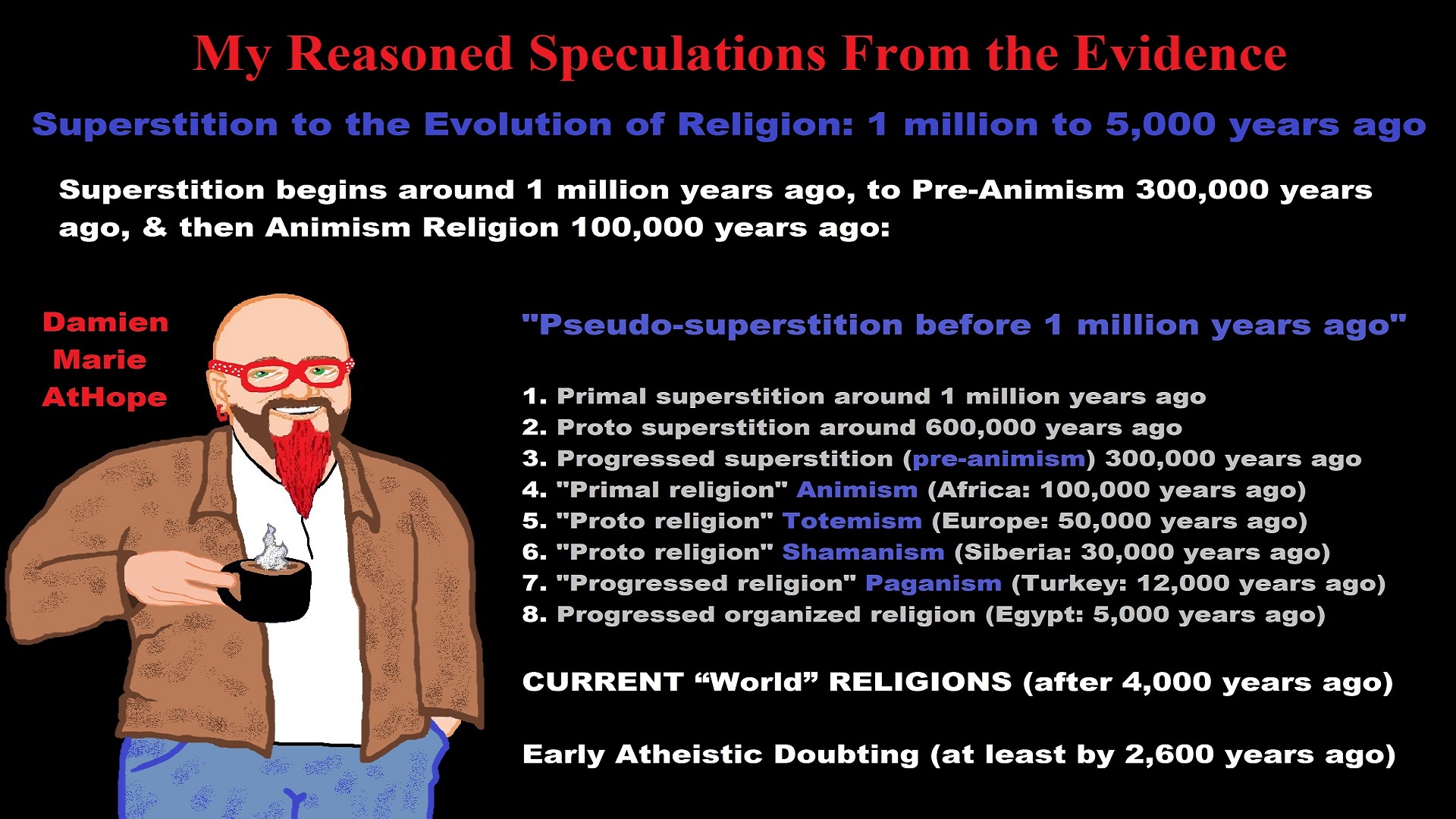

My thoughts on Religion Evolution with external links for more info:

- (Pre-Animism Africa mainly, but also Europe, and Asia at least 300,000 years ago), (Pre-Animism – Oxford Dictionaries)

- (Animism Africa around 100,000 years ago), (Animism – Britannica.com)

- (Totemism Europe around 50,000 years ago), (Totemism – Anthropology)

- (Shamanism Siberia around 30,000 years ago), (Shamanism – Britannica.com)

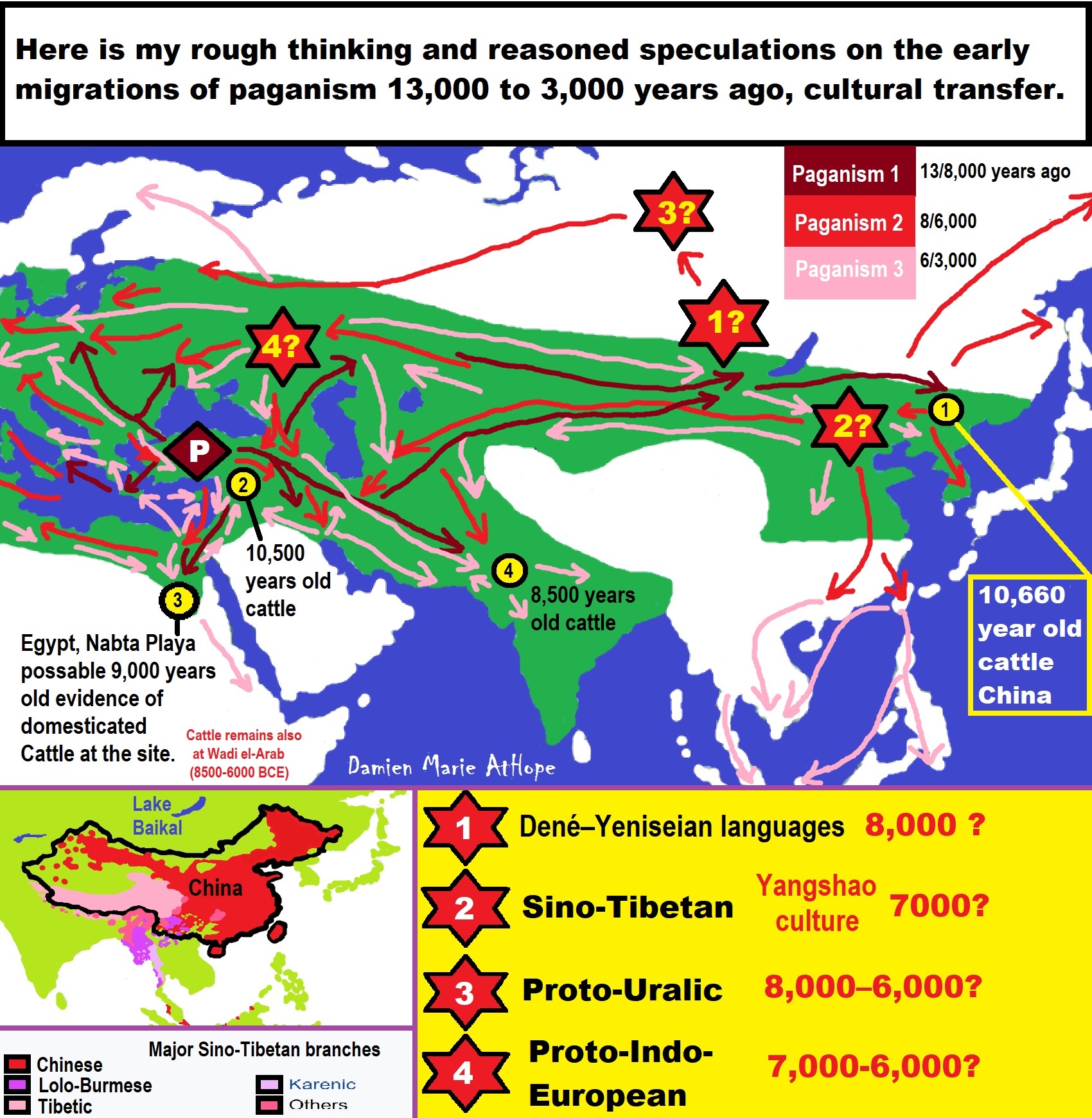

- (Paganism Turkey around 12,000 years ago), (Paganism – BBC Religion)

- (Progressed Organized Religion “Institutional Religion” Egypt around 5,000 years ago), (Ancient Egyptian Religion – Britannica.com)

- (CURRENT “World” RELIGIONS after 4,000 years ago) (Origin of Major Religions – Sacred Texts)

- (Early Atheistic Doubting at least by 2,600 years ago) (History of Atheism – Wikipedia)

“Religion is an Evolved Product” and Yes, Religion is Like Fear Given Wings…

Atheists talk about gods and religions for the same reason doctors talk about cancer, they are looking for a cure, or a firefighter talks about fires because they burn people and they care to stop them. We atheists too often feel a need to help the victims of mental slavery, held in the bondage that is the false beliefs of gods and the conspiracy theories of reality found in religions.

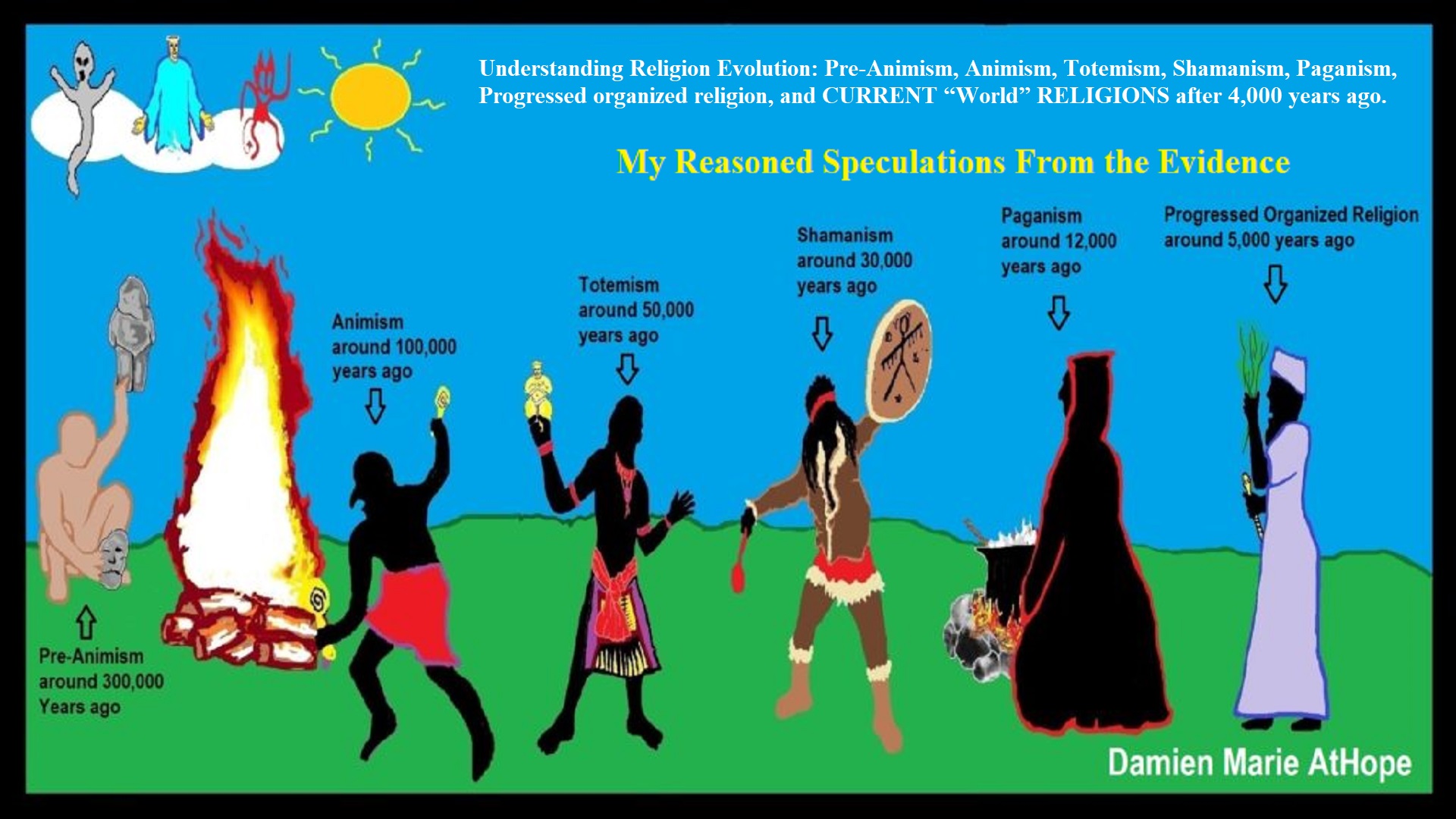

Understanding Religion Evolution:

- Pre-Animism (at least 300,000 years ago)

- Animism (Africa: 100,000 years ago)

- Totemism (Europe: 50,000 years ago)

- Shamanism (Siberia: 30,000 years ago)

- Paganism (Turkey: 12,000 years ago)

- Progressed organized religion (Egypt: 5,000 years ago), (Egypt, the First Dynasty 5,150 years ago)

- CURRENT “World” RELIGIONS (after 4,000 years ago)

- Early Atheistic Doubting (at least by 2,600 years ago)

“An Archaeological/Anthropological Understanding of Religion Evolution”

It seems ancient peoples had to survived amazing threats in a “dangerous universe (by superstition perceived as good and evil),” and human “immorality or imperfection of the soul” which was thought to affect the still living, leading to ancestor worship. This ancestor worship presumably led to the belief in supernatural beings, and then some of these were turned into the belief in gods. This feeble myth called gods were just a human conceived “made from nothing into something over and over, changing, again and again, taking on more as they evolve, all the while they are thought to be special,” but it is just supernatural animistic spirit-belief perceived as sacred.

Quick Evolution of Religion?

Pre-Animism (at least 300,000 years ago) pre-religion is a beginning that evolves into later Animism. So, Religion as we think of it, to me, all starts in a general way with Animism (Africa: 100,000 years ago) (theoretical belief in supernatural powers/spirits), then this is physically expressed in or with Totemism (Europe: 50,000 years ago) (theoretical belief in mythical relationship with powers/spirits through a totem item), which then enlists a full-time specific person to do this worship and believed interacting Shamanism (Siberia/Russia: 30,000 years ago) (theoretical belief in access and influence with spirits through ritual), and then there is the further employment of myths and gods added to all the above giving you Paganism (Turkey: 12,000 years ago) (often a lot more nature-based than most current top world religions, thus hinting to their close link to more ancient religious thinking it stems from). My hypothesis is expressed with an explanation of the building of a theatrical house (modern religions development). Progressed organized religion (Egypt: 5,000 years ago) with CURRENT “World” RELIGIONS (after 4,000 years ago).

Historically, in large city-state societies (such as Egypt or Iraq) starting around 5,000 years ago culminated to make religion something kind of new, a sociocultural-governmental-religious monarchy, where all or at least many of the people of such large city-state societies seem familiar with and committed to the existence of “religion” as the integrated life identity package of control dynamics with a fixed closed magical doctrine, but this juggernaut integrated religion identity package of Dogmatic-Propaganda certainly did not exist or if developed to an extent it was highly limited in most smaller prehistoric societies as they seem to lack most of the strong control dynamics with a fixed closed magical doctrine (magical beliefs could be at times be added or removed). Many people just want to see developed religious dynamics everywhere even if it is not. Instead, all that is found is largely fragments until the domestication of religion.

Religions, as we think of them today, are a new fad, even if they go back to around 6,000 years in the timeline of human existence, this amounts to almost nothing when seen in the long slow evolution of religion at least around 70,000 years ago with one of the oldest ritual worship. Stone Snake of South Africa: “first human worship” 70,000 years ago. This message of how religion and gods among them are clearly a man-made thing that was developed slowly as it was invented and then implemented peace by peace discrediting them all. Which seems to be a simple point some are just not grasping how devastating to any claims of truth when we can see the lie clearly in the archeological sites.

I wish people fought as hard for the actual values as they fight for the group/clan names political or otherwise they think support values. Every amount spent on war is theft to children in need of food or the homeless kept from shelter.

Here are several of my blog posts on history:

- To Find Truth You Must First Look

- (Magdalenian/Iberomaurusian) Connections to the First Paganists of the early Neolithic Near East Dating from around 17,000 to 12,000 Years Ago

- Natufians: an Ancient People at the Origins of Agriculture and Sedentary Life

- Possible Clan Leader/Special “MALE” Ancestor Totem Poles At Least 13,500 years ago?

- Jewish People with DNA at least 13,200 years old, Judaism, and the Origins of Some of its Ideas

- Baltic Reindeer Hunters: Swiderian, Lyngby, Ahrensburgian, and Krasnosillya cultures 12,020 to 11,020 years ago are evidence of powerful migratory waves during the last 13,000 years and a genetic link to Saami and the Finno-Ugric peoples.

- The Rise of Inequality: patriarchy and state hierarchy inequality

- Fertile Crescent 12,500 – 9,500 Years Ago: fertility and death cult belief system?

- 12,400 – 11,700 Years Ago – Kortik Tepe (Turkey) Pre/early-Agriculture Cultic Ritualism

- Ritualistic Bird Symbolism at Gobekli Tepe and its “Ancestor Cult”

- Male-Homosexual (female-like) / Trans-woman (female) Seated Figurine from Gobekli Tepe

- Could a 12,000-year-old Bull Geoglyph at Göbekli Tepe relate to older Bull and Female Art 25,000 years ago and Later Goddess and the Bull cults like Catal Huyuk?

- Sedentism and the Creation of goddesses around 12,000 years ago as well as male gods after 7,000 years ago.

- Alcohol, where Agriculture and Religion Become one? Such as Gobekli Tepe’s Ritualistic use of Grain as Food and Ritual Drink

- Neolithic Ritual Sites with T-Pillars and other Cultic Pillars

- Paganism: Goddesses around 12,000 years ago then Male Gods after 7,000 years ago

- First Patriarchy: Split of Women’s Status around 12,000 years ago & First Hierarchy: fall of Women’s Status around 5,000 years ago.

- Natufians: an Ancient People at the Origins of Agriculture and Sedentary Life

- J DNA and the Spread of Agricultural Religion (paganism)

- Paganism: an approximately 12,000-year-old belief system

- Paganism 12,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism” (Pre-Capitalism)

- Shaman burial in Israel 12,000 years ago and the Shamanism Phenomena

- Need to Mythicized: gods and goddesses

- 12,000 – 7,000 Years Ago – Paleo-Indian Culture (The Americas)

- 12,000 – 2,000 Years Ago – Indigenous-Scandinavians (Nordic)

- Norse did not wear helmets with horns?

- Pre-Pottery Neolithic Skull Cult around 11,500 to 8,400 Years Ago?

- 10,400 – 10,100 Years Ago, in Turkey the Nevail Cori Religious Settlement

- 9,000-6,500 Years Old Submerged Pre-Pottery/Pottery Neolithic Ritual Settlements off Israel’s Coast

- Catal Huyuk “first religious designed city” around 9,500 to 7,700 years ago (Turkey)

- Cultic Hunting at Catal Huyuk “first religious designed city”

- Special Items and Art as well as Special Elite Burials at Catal Huyuk

- New Rituals and Violence with the appearance of Pottery and People?

- Haplogroup N and its related Uralic Languages and Cultures

- Ainu people, Sámi people, Native Americans, the Ancient North Eurasians, and Paganistic-Shamanism with Totemism

- Ideas, Technology and People from Turkey, Europe, to China and Back again 9,000 to 5,000 years ago?

- First Pottery of Europe and the Related Cultures

- 9,000 years old Neolithic Artifacts Judean Desert and Hills Israel

- 9,000-7,000 years-old Sex and Death Rituals: Cult Sites in Israel, Jordan, and the Sinai

- 9,000-8500 year old Horned Female shaman Bad Dürrenberg Germany

- Neolithic Jewelry and the Spread of Farming in Europe Emerging out of West Turkey

- 8,600-year-old Tortoise Shells in Neolithic graves in central China have Early Writing and Shamanism

- Swing of the Mace: the rise of Elite, Forced Authority, and Inequality begin to Emerge 8,500 years ago?

- Migrations and Changing Europeans Beginning around 8,000 Years Ago

- My “Steppe-Anatolian-Kurgan hypothesis” 8,000/7,000 years ago

- Around 8,000-year-old Shared Idea of the Mistress of Animals, “Ritual” Motif

- Pre-Columbian Red-Paint (red ochre) Maritime Archaic Culture 8,000-3,000 years ago

- 7,522-6,522 years ago Linear Pottery culture which I think relates to Arcane Capitalism’s origins

- Arcane Capitalism: Primitive socialism, Primitive capital, Private ownership, Means of production, Market capitalism, Class discrimination, and Petite bourgeoisie (smaller capitalists)

- 7,500-4,750 years old Ritualistic Cucuteni-Trypillian culture of Moldova, Romania, and Ukraine

- Roots of a changing early society 7,200-6,700 years ago Jordan and Israel

- Agriculture religion (Paganism) with farming reached Britain between about 7,000 to 6,500 or so years ago and seemingly expressed in things like Western Europe’s Long Barrows

- My Thoughts on Possible Migrations of “R” DNA and Proto-Indo-European?

- “Millet” Spreading from China 7,022 years ago to Europe and related Language may have Spread with it leading to Proto-Indo-European

- Proto-Indo-European (PIE), ancestor of Indo-European languages: DNA, Society, Language, and Mythology

- The Dnieper–Donets culture and Asian varieties of Millet from China to the Black Sea region of Europe by 7,022 years ago

- Kurgan 6,000 years ago/dolmens 7,000 years ago: funeral, ritual, and other?

- 7,020 to 6,020-year-old Proto-Indo-European Homeland of Urheimat or proposed home of their Language and Religion

- Ancient Megaliths: Kurgan, Ziggurat, Pyramid, Menhir, Trilithon, Dolman, Kromlech, and Kromlech of Trilithons

- The Mytheme of Ancient North Eurasian Sacred-Dog belief and similar motifs are found in Indo-European, Native American, and Siberian comparative mythology

- Elite Power Accumulation: Ancient Trade, Tokens, Writing, Wealth, Merchants, and Priest-Kings

- Sacred Mounds, Mountains, Kurgans, and Pyramids may hold deep connections?

- Between 7,000-5,000 Years ago, rise of unequal hierarchy elite, leading to a “birth of the State” or worship of power, strong new sexism, oppression of non-elites, and the fall of Women’s equal status

- Paganism 7,000-5,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism” (Capitalism) (World War 0) Elite & their slaves

- Hell and Underworld mythologies starting maybe as far back as 7,000 to 5,000 years ago with the Proto-Indo-Europeans?

- The First Expression of the Male God around 7,000 years ago?

- White (light complexion skin) Bigotry and Sexism started 7,000 years ago?

- Around 7,000-year-old Shared Idea of the Divine Bird (Tutelary and/or Trickster spirit/deity), “Ritual” Motif

- Nekhbet an Ancient Egyptian Vulture Goddess and Tutelary Deity

- 6,720 to 4,920 years old Ritualistic Hongshan Culture of Inner Mongolia with 5,000-year-old Pyramid Mounds and Temples

- First proto-king in the Balkans, Varna culture around 6,500 years ago?

- 6,500–5,800 years ago in Israel Late Chalcolithic (Copper Age) Period in the Southern Levant Seems to Express Northern Levant Migrations, Cultural and Religious Transfer

- KING OF BEASTS: Master of Animals “Ritual” Motif, around 6,000 years old or older…

- Around 6000-year-old Shared Idea of the Solid Wheel & the Spoked Wheel-Shaped Ritual Motif

- “The Ghassulian Star,” a mysterious 6,000-year-old mural from Jordan; a Proto-Star of Ishtar, Star of Inanna or Star of Venus?

- Religious/Ritual Ideas, including goddesses and gods as well as ritual mounds or pyramids from Northeastern Asia at least 6,000 years old, seemingly filtering to Iran, Iraq, the Mediterranean, Europe, Egypt, and the Americas?

- Maykop (5,720–5,020 years ago) Caucasus region Bronze Age culture-related to Copper Age farmers from the south, influenced by the Ubaid period and Leyla-Tepe culture, as well as influencing the Kura-Araxes culture

- 5-600-year-old Tomb, Mummy, and First Bearded Male Figurine in a Grave

- Kura-Araxes Cultural 5,520 to 4,470 years old DNA traces to the Canaanites, Arabs, and Jews

- Minoan/Cretan (Keftiu) Civilization and Religion around 5,520 to 3,120 years ago

- Evolution Of Science at least by 5,500 years ago

- 5,500 Years old birth of the State, the rise of Hierarchy, and the fall of Women’s status

- “Jiroft culture” 5,100 – 4,200 years ago and the History of Iran

- Stonehenge: Paganistic Burial and Astrological Ritual Complex, England (5,100-3,600 years ago)

- Around 5,000-year-old Shared Idea of the “Tree of Life” Ritual Motif

- Complex rituals for elite, seen from China to Egypt, at least by 5,000 years ago

- Around 5,000 years ago: “Birth of the State” where Religion gets Military Power and Influence

- The Center of the World “Axis Mundi” and/or “Sacred Mountains” Mythology Could Relate to the Altai Mountains, Heart of the Steppe

- Progressed organized religion starts, an approximately 5,000-year-old belief system

- China’s Civilization between 5,000-3,000 years ago, was a time of war and class struggle, violent transition from free clans to a Slave or Elite society

- Origin of Logics is Naturalistic Observation at least by around 5,000 years ago.

- Paganism 5,000 years old: progressed organized religion and the state: related to “Anarchism and Socialism” (Kings and the Rise of the State)

- Ziggurats (multi-platform temples: 4,900 years old) to Pyramids (multi-platform tombs: 4,700 years old)

- Did a 4,520–4,420-year-old Volcano In Turkey Inspire the Bible God?

- Finland’s Horned Shaman and Pre-Horned-God at least 4,500 years ago?

- 4,000-year-Old Dolmens in Israel: A Connected Dolmen Religious Phenomenon?

- Creation myths: From chaos, Ex nihilo, Earth-diver, Emergence, World egg, and World parent

- Bronze Age “Ritual” connections of the Bell Beaker culture with the Corded Ware/Single Grave culture, which were related to the Yamnaya culture and Proto-Indo-European Languages/Religions

- Low Gods (Earth/ Tutelary deity), High Gods (Sky/Supreme deity), and Moralistic Gods (Deity enforcement/divine order)

- The exchange of people, ideas, and material-culture including, to me, the new god (Sky Father) and goddess (Earth Mother) religion between the Cucuteni-Trypillians and others which is then spread far and wide

- Koryaks: Indigenous People of the Russian Far East and Big Raven myths also found in Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, and other Indigenous People of North America

- 42 Principles Of Maat (Egyptian Goddess of the justice) around 4,400 years ago, 2000 Years Before Ten Commandments

- “Happy Easter” Well Happy Eostre/Ishter

- 4,320-3,820 years old “Shimao” (North China) site with Totemistic-Shamanistic Paganism and a Stepped Pyramid

- 4,250 to 3,400 Year old Stonehenge from Russia: Arkaim?

- 4,100-year-old beaker with medicinal & flowering plants in a grave of a woman in Scotland

- Early European Farmer ancestry, Kelif el Boroud people with the Cardial Ware culture, and the Bell Beaker culture Paganists too, spread into North Africa, then to the Canary Islands off West Africa

- Flood Accounts: Gilgamesh epic (4,100 years ago) Noah in Genesis (2,600 years ago)

- Paganism 4,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism” (First Moralistic gods, then the Origin time of Monotheism)

- When was the beginning: TIMELINE OF CURRENT RELIGIONS, which start around 4,000 years ago.

- Early Religions Thought to Express Proto-Monotheistic Systems around 4,000 years ago

- Kultepe? An archaeological site with a 4,000 years old women’s rights document.

- Single God Religions (Monotheism) = “Man-o-theism” started around 4,000 years ago with the Great Sky Spirit/God Tiān (天)?

- Confucianism’s Tiān (Shangdi god 4,000 years old): Supernaturalism, Pantheism or Theism?

- Yes, Your Male God is Ridiculous

- Mythology, a Lunar Deity is a Goddess or God of the Moon

- Sacred Land, Hills, and Mountains: Sami Mythology (Paganistic Shamanism)

- Horse Worship/Sacrifice: mythical union of Ruling Elite/Kingship and the Horse

- The Amorite/Amurru people’s God Amurru “Lord of the Steppe”, relates to the Origins of the Bible God?

- Bronze Age Exotic Trade Routes Spread Quite Far as well as Spread Religious Ideas with Them

- Sami and the Northern Indigenous Peoples Landscape, Language, and its Connection to Religion

- Prototype of Ancient Analemmatic Sundials around 3,900-3,150 years ago and a Possible Solar Connection to gods?

- Judaism is around 3,450 or 3,250 years old. (“Paleo-Hebrew” 3,000 years ago and Torah 2,500 years ago)

- The Weakening of Ancient Trade and the Strengthening of Religions around 3000 years ago?

- Are you aware that there are religions that worship women gods, explain now religion tears women down?

- Animistic, Totemistic, and Paganistic Superstition Origins of bible god and the bible’s Religion.

- Myths and Folklore: “Trickster gods and goddesses”

- Jews, Judaism, and the Origins of Some of its Ideas

- An Old Branch of Religion Still Giving Fruit: Sacred Trees

- Dating the BIBLE: naming names and telling times (written less than 3,000 years ago, provable to 2,200 years ago)

- Did a Volcano Inspire the bible god?

- Dené–Yeniseian language, Old Copper Complex, and Pre-Columbian Mound Builders?

- No “dinosaurs and humans didn’t exist together just because some think they are in the bible itself”

- Sacred Shit and Sacred Animals?

- Everyone Killed in the Bible Flood? “Nephilim” (giants)?

- Hey, Damien dude, I have a question for you regarding “the bible” Exodus.

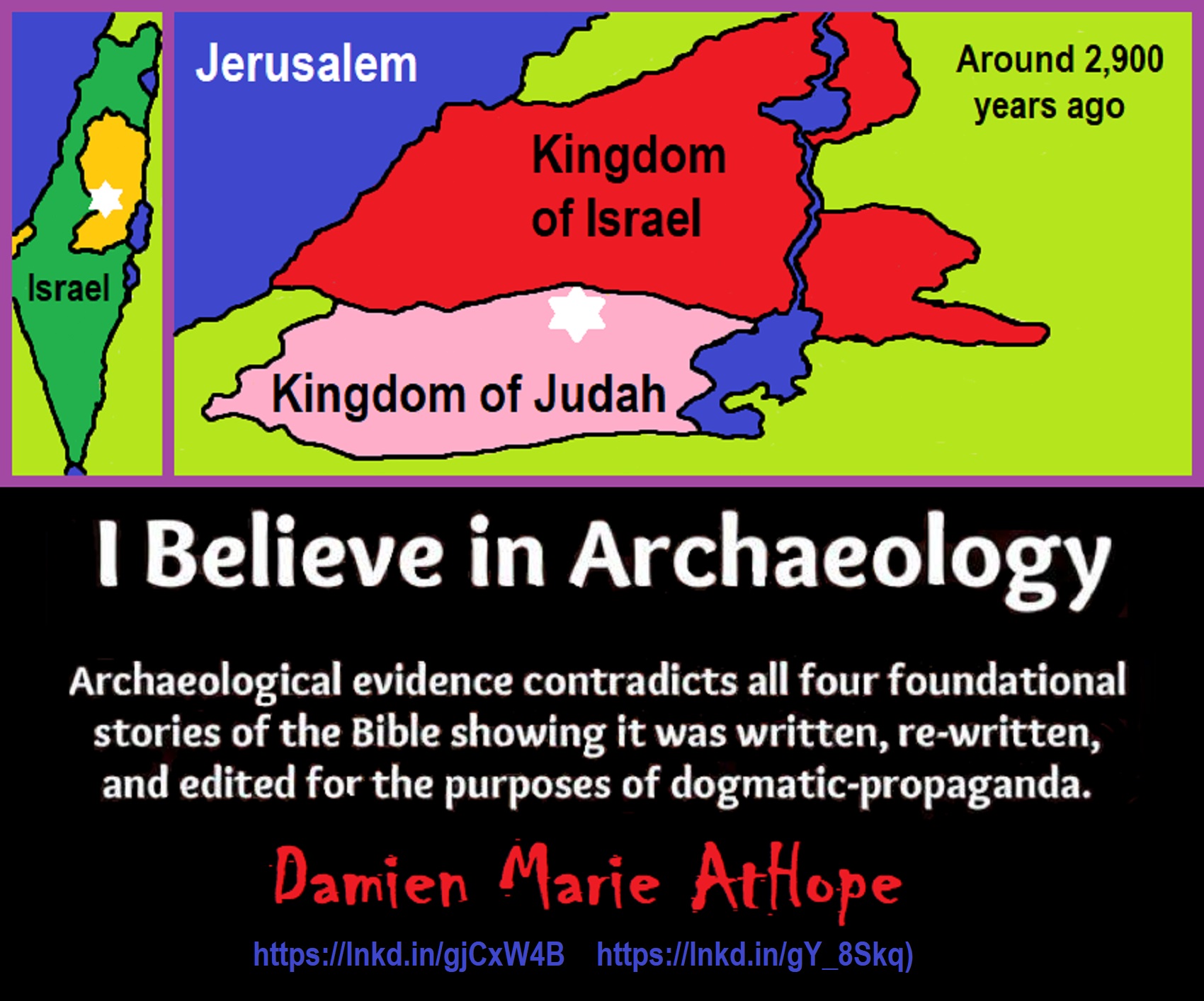

- Archaeology Disproves the Bible

- Bible Battle, Just More, Bible Babble

- The Jericho Conquest lie?

- Canaanites and Israelites?

- Accurate Account on how did Christianity Began?

- Let’s talk about Christianity.

- So the 10 commandments isn’t anything to go by either right?

- Misinformed christian

- Debunking Jesus?

- Paulism vs Jesus

- Ok, you seem confused so let’s talk about Buddhism.

- Unacknowledged Buddhism: Gods, Savior, Demons, Rebirth, Heavens, Hells, and Terrorism

- His Foolishness The Dalai Lama

- Yin and Yang is sexist with an ORIGIN around 2,300 years ago?

- I Believe Archaeology, not Myths & Why Not, as the Religious Myths Already Violate Reason!

- Archaeological, Scientific, & Philosophic evidence shows the god myth is man-made nonsense.

- Aquatic Ape Theory/Hypothesis? As Always, Just Pseudoscience.

- Ancient Aliens Conspiracy Theorists are Pseudohistorians

- The Pseudohistoric and Pseudoscientific claims about “Bakoni Ruins” of South Africa

- Why do people think Religion is much more than supernaturalism and superstitionism?

- Religion is an Evolved Product

- Was the Value of Ancient Women Different?

- 1000 to 1100 CE, human sacrifice Cahokia Mounds a pre-Columbian Native American site

- Feminist atheists as far back as the 1800s?

- Promoting Religion as Real is Mentally Harmful to a Flourishing Humanity

- Screw All Religions and Their Toxic lies, they are all fraud

- Forget Religions’ Unfounded Myths, I Have Substantiated “Archaeology Facts.”

- Religion Dispersal throughout the World

- I Hate Religion Just as I Hate all Pseudoscience

- Exposing Scientology, Eckankar, Wicca and Other Nonsense?

- Main deity or religious belief systems

- Quit Trying to Invent Your God From the Scraps of Science.

- Archaeological, Scientific, & Philosophic evidence shows the god myth is man-made nonsense.

- Ancient Alien Conspiracy Theorists: Misunderstanding, Rhetoric, Misinformation, Fabrications, and Lies

- Misinformation, Distortion, and Pseudoscience in Talking with a Christian Creationist

- Judging the Lack of Goodness in Gods, Even the Norse God Odin

- Challenging the Belief in God-like Aliens and Gods in General

- A Challenge to Christian use of Torture Devices?

- Yes, Hinduism is a Religion

- Trump is One of the Most Reactionary Forces of Far-right Christian Extremism

- Was the Bull Head a Symbol of God? Yes!

- Primate Death Rituals

- Christian – “God and Christianity are objectively true”

- Australopithecus afarensis Death Ritual?

- You Claim Global Warming is a Hoax?

- Doubter of Science and Defamer of Atheists?

- I think that sounds like the Bible?

- History of the Antifa (“anti-fascist”) Movements

- Indianapolis Anti-Blasphemy Laws #Free Soheil Rally

- Damien, you repeat the golden rule in so many forms then you say religion is dogmatic?

- Science is a Trustable Methodology whereas Faith is not Trustable at all!

- Was I ever a believer, before I was an atheist?

- Atheists rise in reason

- Mistrust of science?

- Open to Talking About the Definition of ‘God’? But first, we address Faith.

- ‘United Monarchy’ full of splendor and power – Saul, David, and Solomon? Most likely not.

- Is there EXODUS ARCHAEOLOGY? The short answer is “no.”

- Lacking Proof of Bigfoots, Unicorns, and Gods is Just a Lack of Research?

- Religion and Politics: Faith Beliefs vs. Rational Thinking

- Hammer of Truth that lying pig RELIGION: challenged by an archaeologist

- “The Hammer of Truth” -ontology question- What do You Mean by That?

- Navigation of a bad argument: Ad Hominem vs. Attack

- Why is it Often Claimed that Gods have a Gender?

- Why are basically all monotheistic religions ones that have a male god?

- Shifting through the Claims in support of Faith

- Dear Mr. AtHope, The 20th Century is an Indictment of Secularism and a Failed Atheist Century

- An Understanding of the Worldwide Statistics and Dynamics of Terrorist Incidents and Suicide Attacks

- Intoxication and Evolution? Addressing and Assessing the “Stoned Ape” or “Drunken Monkey” Theories as Catalysts in Human Evolution

- Sacred Menstrual cloth? Inanna’s knot, Isis knot, and maybe Ma’at’s feather?

- Damien, why don’t the Hebrews accept the bible stories?

- Dealing with a Troll and Arguing Over Word Meaning

- Knowledge without Belief? Justified beliefs or disbeliefs worthy of Knowledge?

- Afrocentrism and African Religions

- Crecganford @crecganford offers history & stories of the people, places, gods, & culture

- Empiricism-Denier?

I am not an academic. I am a revolutionary that teaches in public, in places like social media, and in the streets. I am not a leader by some title given but from my commanding leadership style of simply to start teaching everywhere to everyone, all manner of positive education.

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

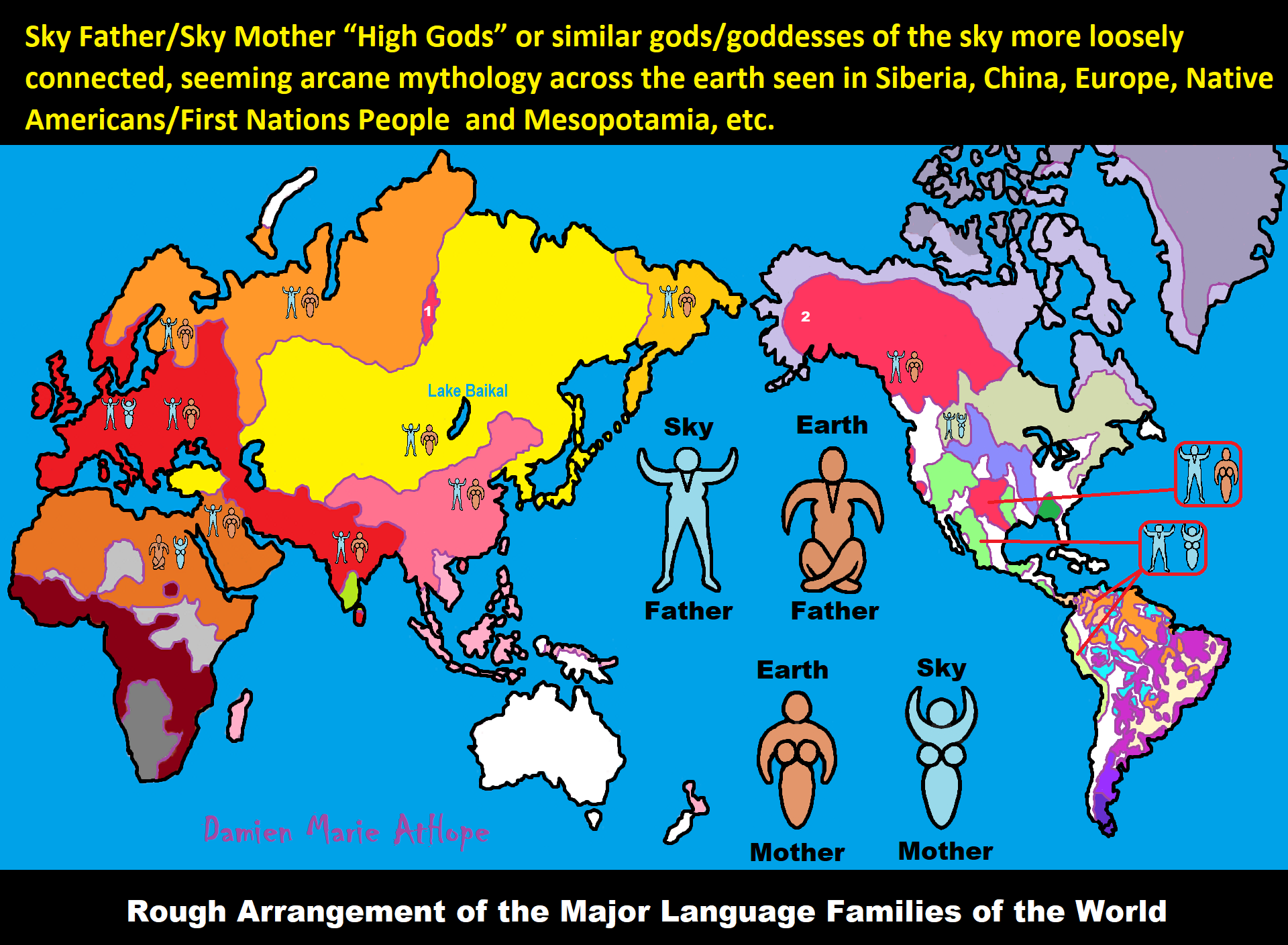

Low Gods “Earth” or Tutelary deity and High Gods “Sky” or Supreme deity

“An Earth goddess is a deification of the Earth. Earth goddesses are often associated with the “chthonic” deities of the underworld. Ki and Ninhursag are Mesopotamian earth goddesses. In Greek mythology, the Earth is personified as Gaia, corresponding to Roman Terra, Indic Prithvi/Bhūmi, etc. traced to an “Earth Mother” complementary to the “Sky Father” in Proto-Indo-European religion. Egyptian mythology exceptionally has a sky goddess and an Earth god.” ref

“A mother goddess is a goddess who represents or is a personification of nature, motherhood, fertility, creation, destruction or who embodies the bounty of the Earth. When equated with the Earth or the natural world, such goddesses are sometimes referred to as Mother Earth or as the Earth Mother. In some religious traditions or movements, Heavenly Mother (also referred to as Mother in Heaven or Sky Mother) is the wife or feminine counterpart of the Sky father or God the Father.” ref

“Any masculine sky god is often also king of the gods, taking the position of patriarch within a pantheon. Such king gods are collectively categorized as “sky father” deities, with a polarity between sky and earth often being expressed by pairing a “sky father” god with an “earth mother” goddess (pairings of a sky mother with an earth father are less frequent). A main sky goddess is often the queen of the gods and may be an air/sky goddess in her own right, though she usually has other functions as well with “sky” not being her main. In antiquity, several sky goddesses in ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the Near East were called Queen of Heaven. Neopagans often apply it with impunity to sky goddesses from other regions who were never associated with the term historically. The sky often has important religious significance. Many religions, both polytheistic and monotheistic, have deities associated with the sky.” ref

“In comparative mythology, sky father is a term for a recurring concept in polytheistic religions of a sky god who is addressed as a “father”, often the father of a pantheon and is often either a reigning or former King of the Gods. The concept of “sky father” may also be taken to include Sun gods with similar characteristics, such as Ra. The concept is complementary to an “earth mother“. “Sky Father” is a direct translation of the Vedic Dyaus Pita, etymologically descended from the same Proto-Indo-European deity name as the Greek Zeûs Pater and Roman Jupiter and Germanic Týr, Tir or Tiwaz, all of which are reflexes of the same Proto-Indo-European deity’s name, *Dyēus Ph₂tḗr. While there are numerous parallels adduced from outside of Indo-European mythology, there are exceptions (e.g. In Egyptian mythology, Nut is the sky mother and Geb is the earth father).” ref

Tutelary deity

“A tutelary (also tutelar) is a deity or spirit who is a guardian, patron, or protector of a particular place, geographic feature, person, lineage, nation, culture, or occupation. The etymology of “tutelary” expresses the concept of safety and thus of guardianship. In late Greek and Roman religion, one type of tutelary deity, the genius, functions as the personal deity or daimon of an individual from birth to death. Another form of personal tutelary spirit is the familiar spirit of European folklore.” ref

“A tutelary (also tutelar) in Korean shamanism, jangseung and sotdae were placed at the edge of villages to frighten off demons. They were also worshiped as deities. Seonangshin is the patron deity of the village in Korean tradition and was believed to embody the Seonangdang. In Philippine animism, Diwata or Lambana are deities or spirits that inhabit sacred places like mountains and mounds and serve as guardians. Such as: Maria Makiling is the deity who guards Mt. Makiling and Maria Cacao and Maria Sinukuan. In Shinto, the spirits, or kami, which give life to human bodies come from nature and return to it after death. Ancestors are therefore themselves tutelaries to be worshiped. And similarly, Native American beliefs such as Tonás, tutelary animal spirit among the Zapotec and Totems, familial or clan spirits among the Ojibwe, can be animals.” ref

“A tutelary (also tutelar) in Austronesian beliefs such as: Atua (gods and spirits of the Polynesian peoples such as the Māori or the Hawaiians), Hanitu (Bunun of Taiwan‘s term for spirit), Hyang (Kawi, Sundanese, Javanese, and Balinese Supreme Being, in ancient Java and Bali mythology and this spiritual entity, can be either divine or ancestral), Kaitiaki (New Zealand Māori term used for the concept of guardianship, for the sky, the sea, and the land), Kawas (mythology) (divided into 6 groups: gods, ancestors, souls of the living, spirits of living things, spirits of lifeless objects, and ghosts), Tiki (Māori mythology, Tiki is the first man created by either Tūmatauenga or Tāne and represents deified ancestors found in most Polynesian cultures). ” ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

Mesopotamian Tutelary Deities can be seen as ones related to City-States

“Historical city-states included Sumerian cities such as Uruk and Ur; Ancient Egyptian city-states, such as Thebes and Memphis; the Phoenician cities (such as Tyre and Sidon); the five Philistine city-states; the Berber city-states of the Garamantes; the city-states of ancient Greece (the poleis such as Athens, Sparta, Thebes, and Corinth); the Roman Republic (which grew from a city-state into a vast empire); the Italian city-states from the Middle Ages to the early modern period, such as Florence, Siena, Ferrara, Milan (which as they grew in power began to dominate neighboring cities) and Genoa and Venice, which became powerful thalassocracies; the Mayan and other cultures of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica (including cities such as Chichen Itza, Tikal, Copán and Monte Albán); the central Asian cities along the Silk Road; the city-states of the Swahili coast; Ragusa; states of the medieval Russian lands such as Novgorod and Pskov; and many others.” ref

“The Uruk period (ca. 4000 to 3100 BCE; also known as Protoliterate period) of Mesopotamia, named after the Sumerian city of Uruk, this period saw the emergence of urban life in Mesopotamia and the Sumerian civilization. City-States like Uruk and others had a patron tutelary City Deity along with a Priest-King.” ref

“Chinese folk religion, both past, and present, includes myriad tutelary deities. Exceptional individuals, highly cultivated sages, and prominent ancestors can be deified and honored after death. Lord Guan is the patron of military personnel and police, while Mazu is the patron of fishermen and sailors. Such as Tu Di Gong (Earth Deity) is the tutelary deity of a locality, and each individual locality has its own Earth Deity and Cheng Huang Gong (City God) is the guardian deity of an individual city, worshipped by local officials and locals since imperial times.” ref

“A tutelary (also tutelar) in Hinduism, personal tutelary deities are known as ishta-devata, while family tutelary deities are known as Kuladevata. Gramadevata are guardian deities of villages. Devas can also be seen as tutelary. Shiva is the patron of yogis and renunciants. City goddesses include: Mumbadevi (Mumbai), Sachchika (Osian); Kuladevis include: Ambika (Porwad), and Mahalakshmi. In NorthEast India Meitei mythology and religion (Sanamahism) of Manipur, there are various types of tutelary deities, among which Lam Lais are the most predominant ones. Tibetan Buddhism has Yidam as a tutelary deity. Dakini is the patron of those who seek knowledge.” ref

“A tutelary (also tutelar) The Greeks also thought deities guarded specific places: for instance, Athena was the patron goddess of the city of Athens. Socrates spoke of hearing the voice of his personal spirit or daimonion:

You have often heard me speak of an oracle or sign which comes to me … . This sign I have had ever since I was a child. The sign is a voice which comes to me and always forbids me to do something which I am going to do, but never commands me to do anything, and this is what stands in the way of my being a politician.” ref

“Tutelary deities who guard and preserve a place or a person are fundamental to ancient Roman religion. The tutelary deity of a man was his Genius, that of a woman her Juno. In the Imperial era, the Genius of the Emperor was a focus of Imperial cult. An emperor might also adopt a major deity as his personal patron or tutelary, as Augustus did Apollo. Precedents for claiming the personal protection of a deity were established in the Republican era, when for instance the Roman dictator Sulla advertised the goddess Victory as his tutelary by holding public games (ludi) in her honor.” ref

“Each town or city had one or more tutelary deities, whose protection was considered particularly vital in time of war and siege. Rome itself was protected by a goddess whose name was to be kept ritually secret on pain of death (for a supposed case, see Quintus Valerius Soranus). The Capitoline Triad of Juno, Jupiter, and Minerva were also tutelaries of Rome. The Italic towns had their own tutelary deities. Juno often had this function, as at the Latin town of Lanuvium and the Etruscan city of Veii, and was often housed in an especially grand temple on the arx (citadel) or other prominent or central location. The tutelary deity of Praeneste was Fortuna, whose oracle was renowned.” ref

“The Roman ritual of evocatio was premised on the belief that a town could be made vulnerable to military defeat if the power of its tutelary deity were diverted outside the city, perhaps by the offer of superior cult at Rome. The depiction of some goddesses such as the Magna Mater (Great Mother, or Cybele) as “tower-crowned” represents their capacity to preserve the city. A town in the provinces might adopt a deity from within the Roman religious sphere to serve as its guardian, or syncretize its own tutelary with such; for instance, a community within the civitas of the Remi in Gaul adopted Apollo as its tutelary, and at the capital of the Remi (present-day Rheims), the tutelary was Mars Camulus.” ref

Household deity (a kind of or related to a Tutelary deity)

“A household deity is a deity or spirit that protects the home, looking after the entire household or certain key members. It has been a common belief in paganism as well as in folklore across many parts of the world. Household deities fit into two types; firstly, a specific deity – typically a goddess – often referred to as a hearth goddess or domestic goddess who is associated with the home and hearth, such as the ancient Greek Hestia.” ref

“The second type of household deities are those that are not one singular deity, but a type, or species of animistic deity, who usually have lesser powers than major deities. This type was common in the religions of antiquity, such as the Lares of ancient Roman religion, the Gashin of Korean shamanism, and Cofgodas of Anglo-Saxon paganism. These survived Christianisation as fairy-like creatures existing in folklore, such as the Anglo-Scottish Brownie and Slavic Domovoy.” ref

“Household deities were usually worshipped not in temples but in the home, where they would be represented by small idols (such as the teraphim of the Bible, often translated as “household gods” in Genesis 31:19 for example), amulets, paintings, or reliefs. They could also be found on domestic objects, such as cosmetic articles in the case of Tawaret. The more prosperous houses might have a small shrine to the household god(s); the lararium served this purpose in the case of the Romans. The gods would be treated as members of the family and invited to join in meals, or be given offerings of food and drink.” ref

“In many religions, both ancient and modern, a god would preside over the home. Certain species, or types, of household deities, existed. An example of this was the Roman Lares. Many European cultures retained house spirits into the modern period. Some examples of these include:

- Brownie (Scotland and England) or Hob (England) / Kobold (Germany) / Goblin / Hobgoblin

- Domovoy (Slavic)

- Nisse (Norwegian or Danish) / Tomte (Swedish) / Tonttu (Finnish)

- Húsvættir (Norse)” ref

“Although the cosmic status of household deities was not as lofty as that of the Twelve Olympians or the Aesir, they were also jealous of their dignity and also had to be appeased with shrines and offerings, however humble. Because of their immediacy they had arguably more influence on the day-to-day affairs of men than the remote gods did. Vestiges of their worship persisted long after Christianity and other major religions extirpated nearly every trace of the major pagan pantheons. Elements of the practice can be seen even today, with Christian accretions, where statues to various saints (such as St. Francis) protect gardens and grottos. Even the gargoyles found on older churches, could be viewed as guardians partitioning a sacred space.” ref

“For centuries, Christianity fought a mop-up war against these lingering minor pagan deities, but they proved tenacious. For example, Martin Luther‘s Tischreden have numerous – quite serious – references to dealing with kobolds. Eventually, rationalism and the Industrial Revolution threatened to erase most of these minor deities, until the advent of romantic nationalism rehabilitated them and embellished them into objects of literary curiosity in the 19th century. Since the 20th century this literature has been mined for characters for role-playing games, video games, and other fantasy personae, not infrequently invested with invented traits and hierarchies somewhat different from their mythological and folkloric roots.” ref

“In contradistinction to both Herbert Spencer and Edward Burnett Tylor, who defended theories of animistic origins of ancestor worship, Émile Durkheim saw its origin in totemism. In reality, this distinction is somewhat academic, since totemism may be regarded as a particularized manifestation of animism, and something of a synthesis of the two positions was attempted by Sigmund Freud. In Freud’s Totem and Taboo, both totem and taboo are outward expressions or manifestations of the same psychological tendency, a concept which is complementary to, or which rather reconciles, the apparent conflict. Freud preferred to emphasize the psychoanalytic implications of the reification of metaphysical forces, but with particular emphasis on its familial nature. This emphasis underscores, rather than weakens, the ancestral component.” ref

“William Edward Hearn, a noted classicist, and jurist, traced the origin of domestic deities from the earliest stages as an expression of animism, a belief system thought to have existed also in the neolithic, and the forerunner of Indo-European religion. In his analysis of the Indo-European household, in Chapter II “The House Spirit”, Section 1, he states:

The belief which guided the conduct of our forefathers was … the spirit rule of dead ancestors.” ref

“In Section 2 he proceeds to elaborate:

It is thus certain that the worship of deceased ancestors is a vera causa, and not a mere hypothesis. …

In the other European nations, the Slavs, the Teutons, and the Kelts, the House Spirit appears with no less distinctness. … [T]he existence of that worship does not admit of doubt. … The House Spirits had a multitude of other names which it is needless here to enumerate, but all of which are more or less expressive of their friendly relations with man. … In [England] … [h]e is the Brownie. … In Scotland this same Brownie is well known. He is usually described as attached to particular families, with whom he has been known to reside for centuries, threshing the corn, cleaning the house, and performing similar household tasks. His favorite gratification was milk and honey.” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

“These ideas are my speculations from the evidence.”

I am still researching the “god‘s origins” all over the world. So you know, it is very complicated but I am smart and willing to look, DEEP, if necessary, which going very deep does seem to be needed here, when trying to actually understand the evolution of gods and goddesses. I am sure of a few things and less sure of others, but even in stuff I am not fully grasping I still am slowly figuring it out, to explain it to others. But as I research more I am understanding things a little better, though I am still working on understanding it all or something close and thus always figuring out more.

Sky Father/Sky God?

“Egyptian: (Nut) Sky Mother and (Geb) Earth Father” (Egypt is different but similar)

Turkic/Mongolic: (Tengri/Tenger Etseg) Sky Father and (Eje/Gazar Eej) Earth Mother *Transeurasian*

Hawaiian: (Wākea) Sky Father and (Papahānaumoku) Earth Mother *Austronesian*

New Zealand/ Māori: (Ranginui) Sky Father and (Papatūānuku) Earth Mother *Austronesian*

Proto-Indo-European: (Dyḗus/Dyḗus ph₂tḗr) Sky Father and (Dʰéǵʰōm/Pleth₂wih₁) Earth Mother

Indo-Aryan: (Dyaus Pita) Sky Father and (Prithvi Mata) Earth Mother *Indo-European*

Italic: (Jupiter) Sky Father and (Juno) Sky Mother *Indo-European*

Etruscan: (Tinia) Sky Father and (Uni) Sky Mother *Tyrsenian/Italy Pre–Indo-European*

Hellenic/Greek: (Zeus) Sky Father and (Hera) Sky Mother who started as an “Earth Goddess” *Indo-European*

Nordic: (Dagr) Sky Father and (Nótt) Sky Mother *Indo-European*

Slavic: (Perun) Sky Father and (Mokosh) Earth Mother *Indo-European*

Illyrian: (Deipaturos) Sky Father and (Messapic Damatura’s “earth-mother” maybe) Earth Mother *Indo-European*

Albanian: (Zojz) Sky Father and (?) *Indo-European*

Baltic: (Perkūnas) Sky Father and (Saulė) Sky Mother *Indo-European*

Germanic: (Týr) Sky Father and (?) *Indo-European*

Colombian-Muisca: (Bochica) Sky Father and (Huythaca) Sky Mother *Chibchan*

Aztec: (Quetzalcoatl) Sky Father and (Xochiquetzal) Sky Mother *Uto-Aztecan*

Incan: (Viracocha) Sky Father and (Mama Runtucaya) Sky Mother *Quechuan*

China: (Tian/Shangdi) Sky Father and (Dì) Earth Mother *Sino-Tibetan*

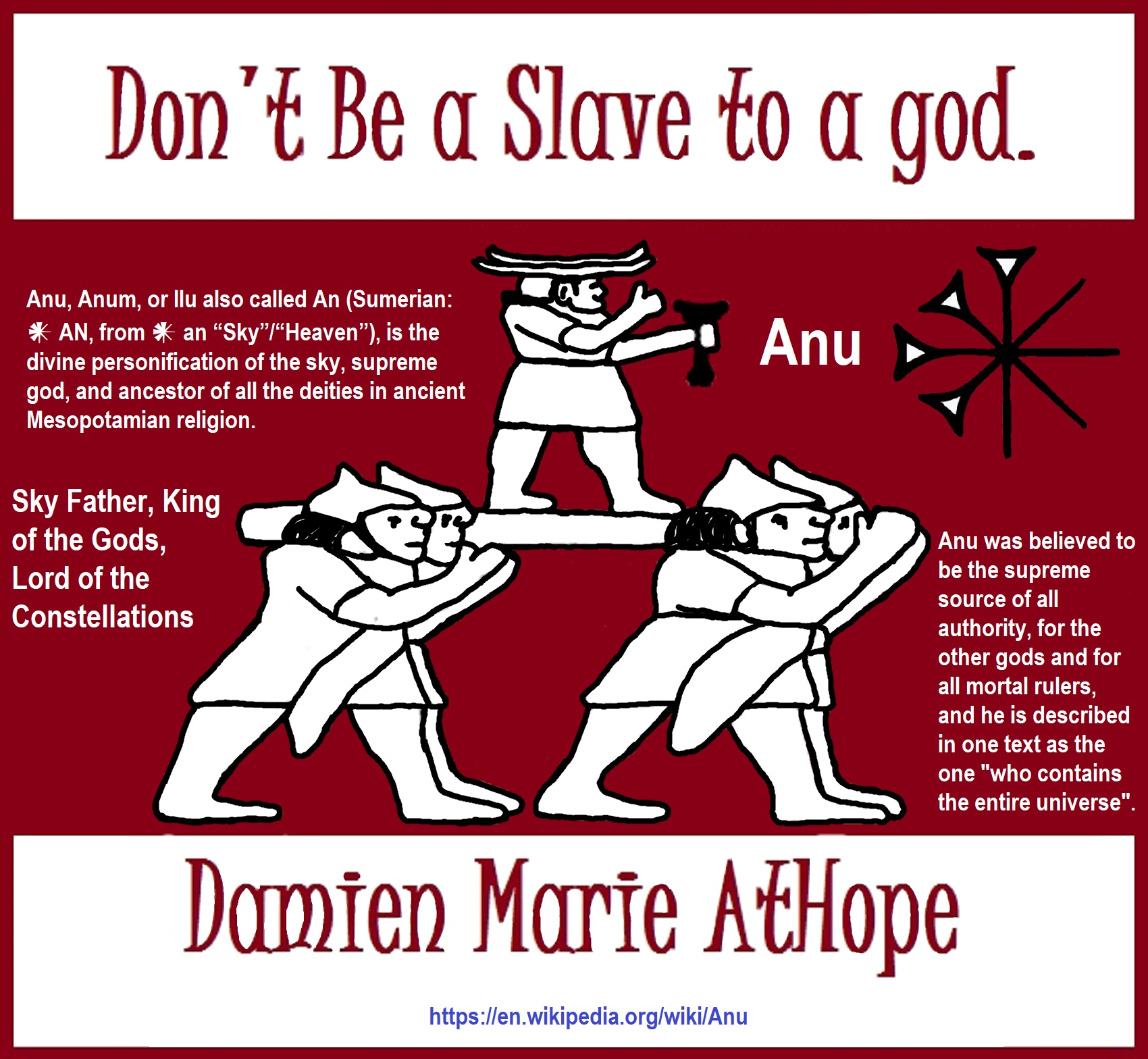

Sumerian, Assyrian and Babylonian: (An/Anu) Sky Father and (Ki) Earth Mother

Finnish: (Ukko) Sky Father and (Akka) Earth Mother *Finno-Ugric*

Sami: (Horagalles) Sky Father and (Ravdna) Earth Mother *Finno-Ugric*

Puebloan-Zuni: (Ápoyan Ta’chu) Sky Father and (Áwitelin Tsíta) Earth Mother

Puebloan-Hopi: (Tawa) Sky Father and (Kokyangwuti/Spider Woman/Grandmother) Earth Mother *Uto-Aztecan*

Puebloan-Navajo: (Tsohanoai) Sky Father and (Estsanatlehi) Earth Mother *Na-Dene*

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

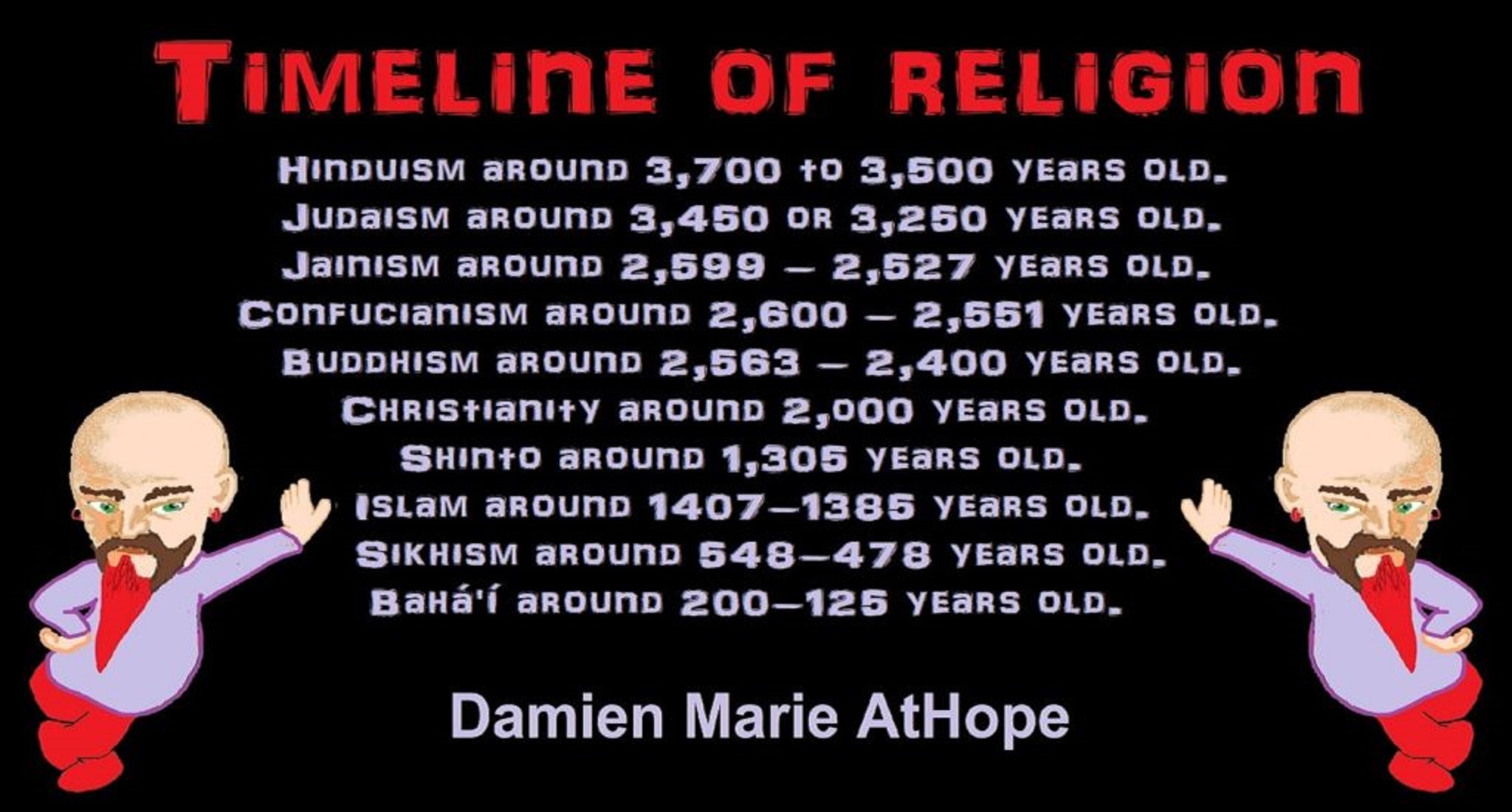

Hinduism around 3,700 to 3,500 years old. ref

Judaism around 3,450 or 3,250 years old. (The first writing in the bible was “Paleo-Hebrew” dated to around 3,000 years ago Khirbet Qeiyafa is the site of an ancient fortress city overlooking the Elah Valley. And many believe the religious Jewish texts were completed around 2,500) ref, ref