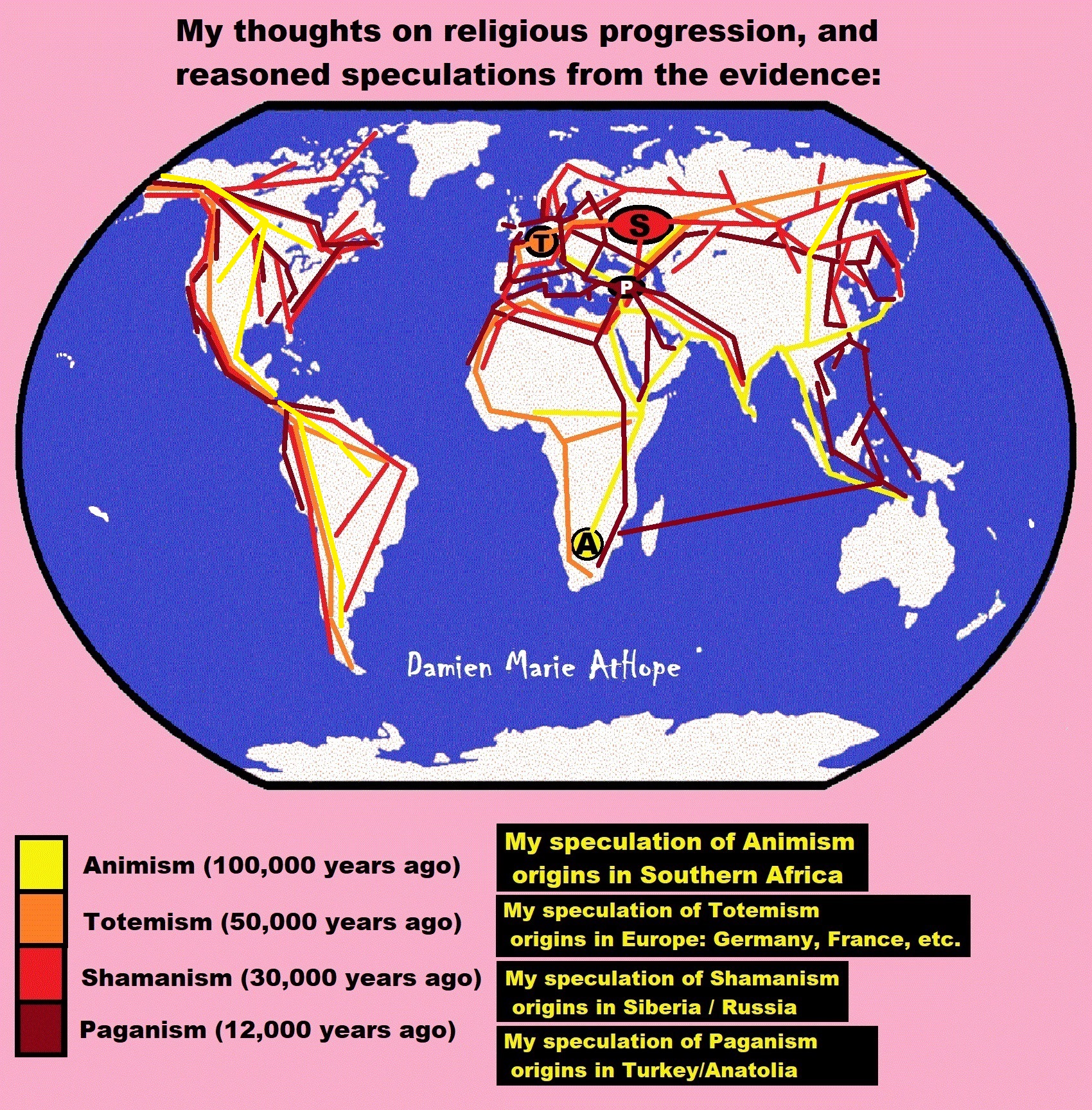

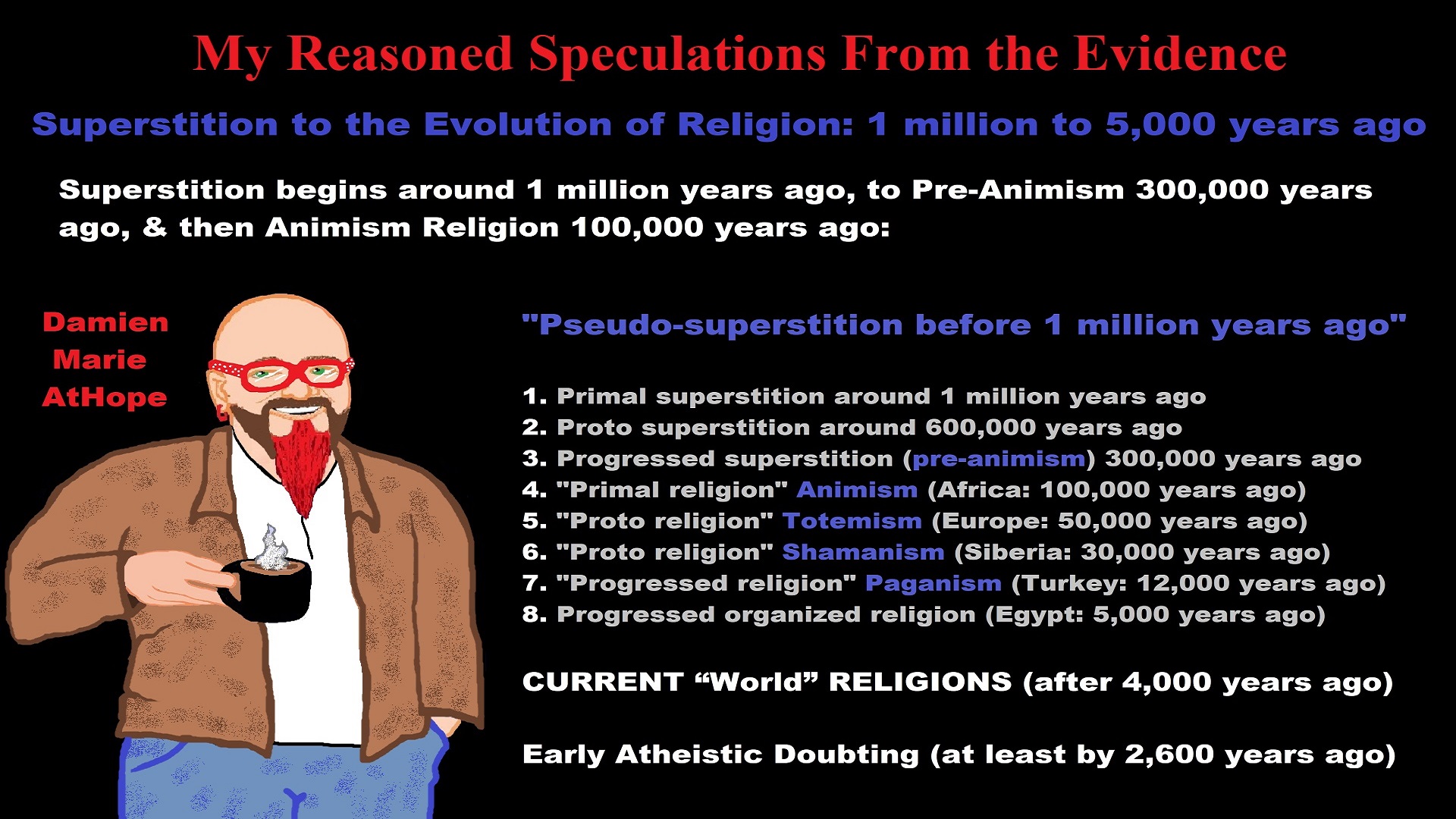

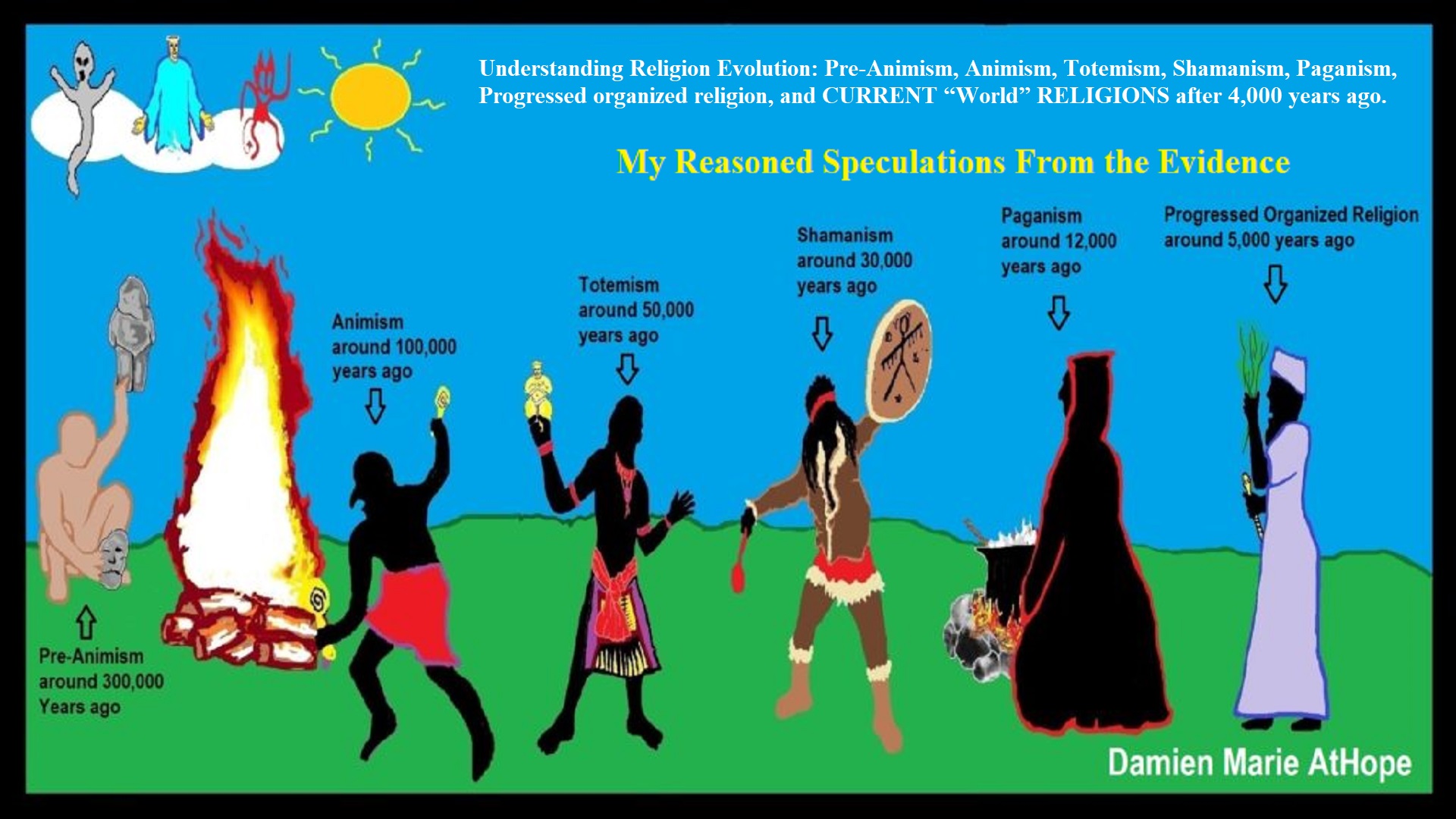

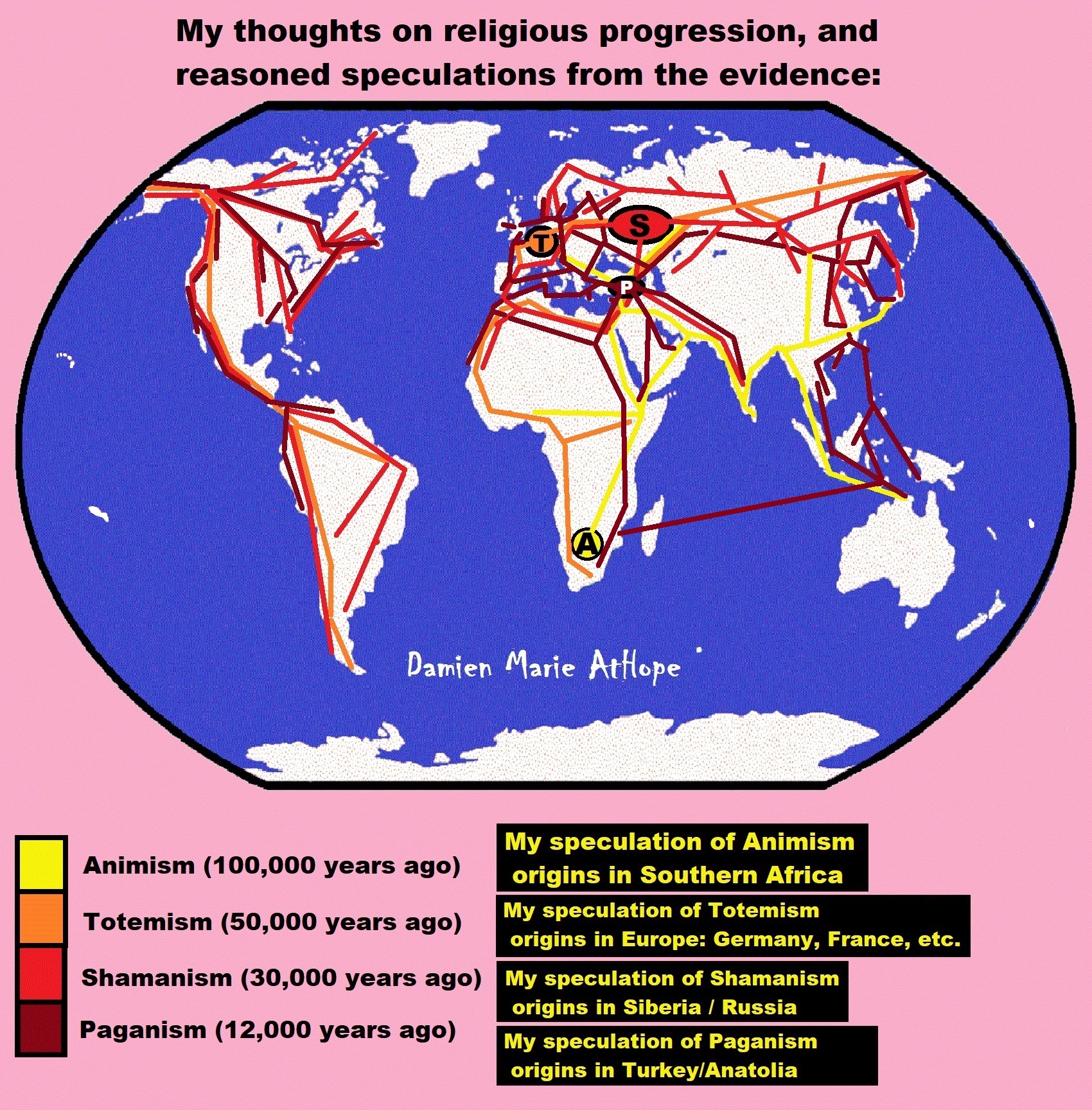

Understanding Religion Evolution per Damien’s speculations from the evidence:

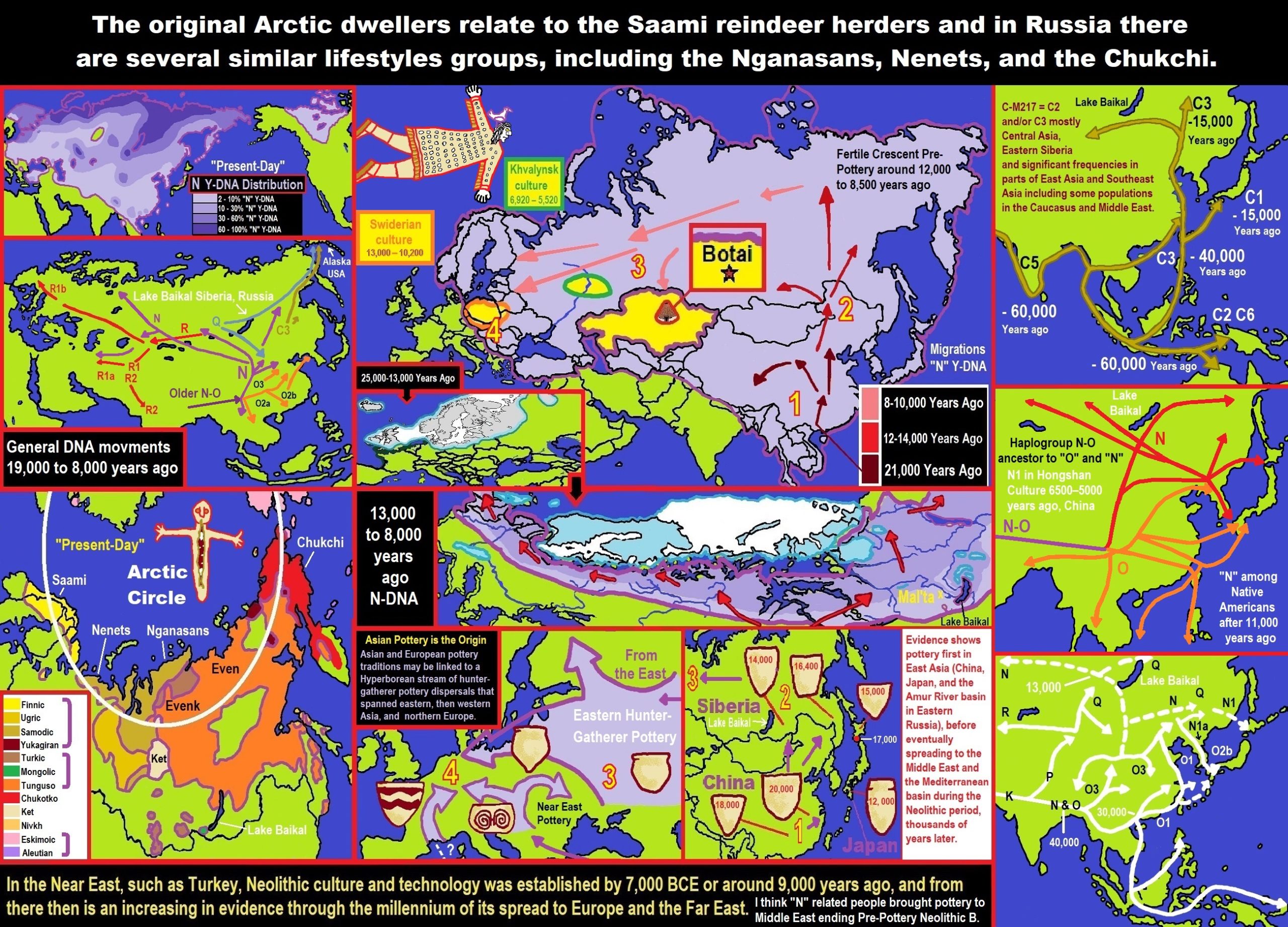

Pre-Animism (at least 300,000 years ago) possibly Africa, Middle East, and Eurasia

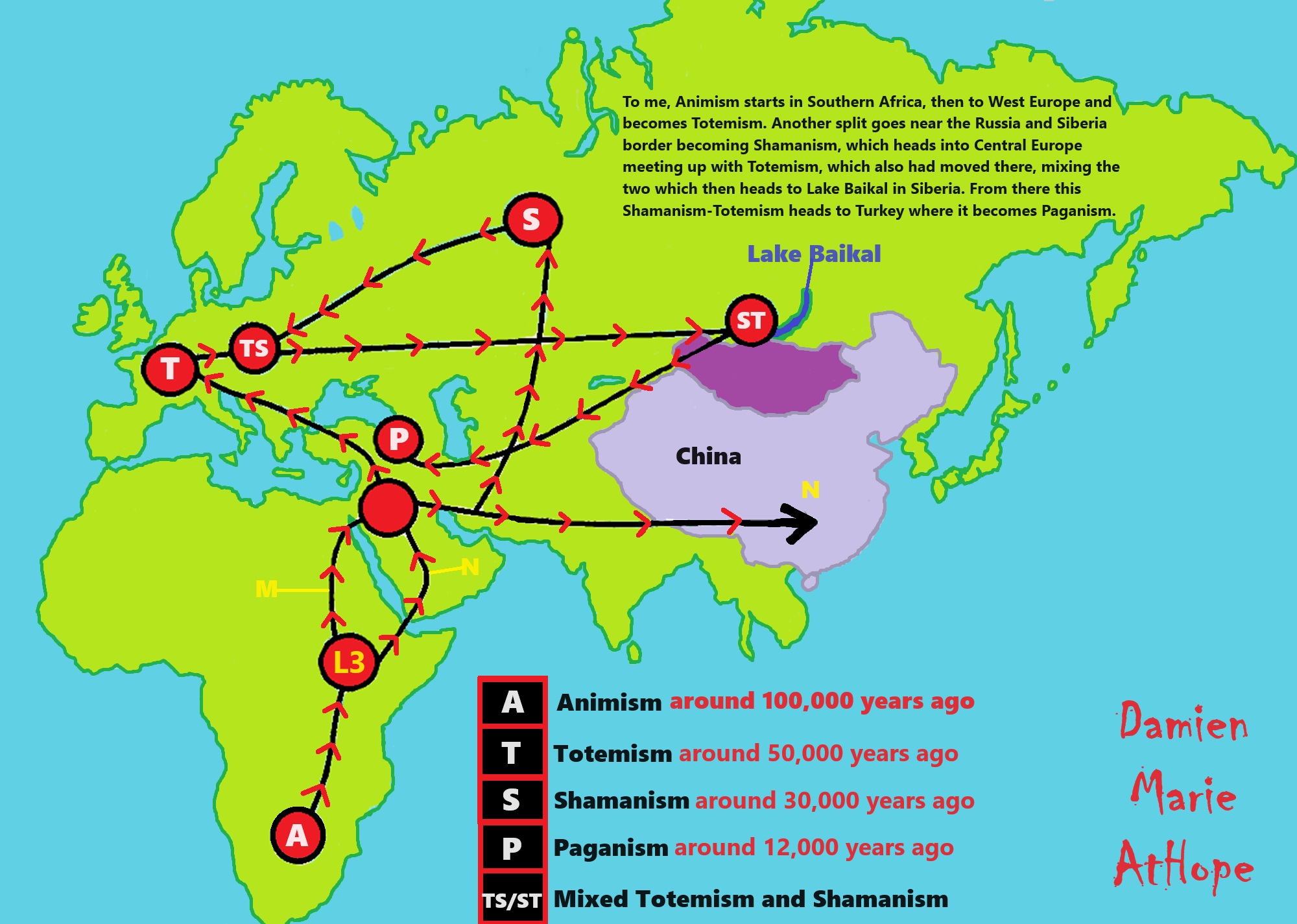

Animism (at least 100,000 years ago) possibly Southern Africa or maybe Central Africa

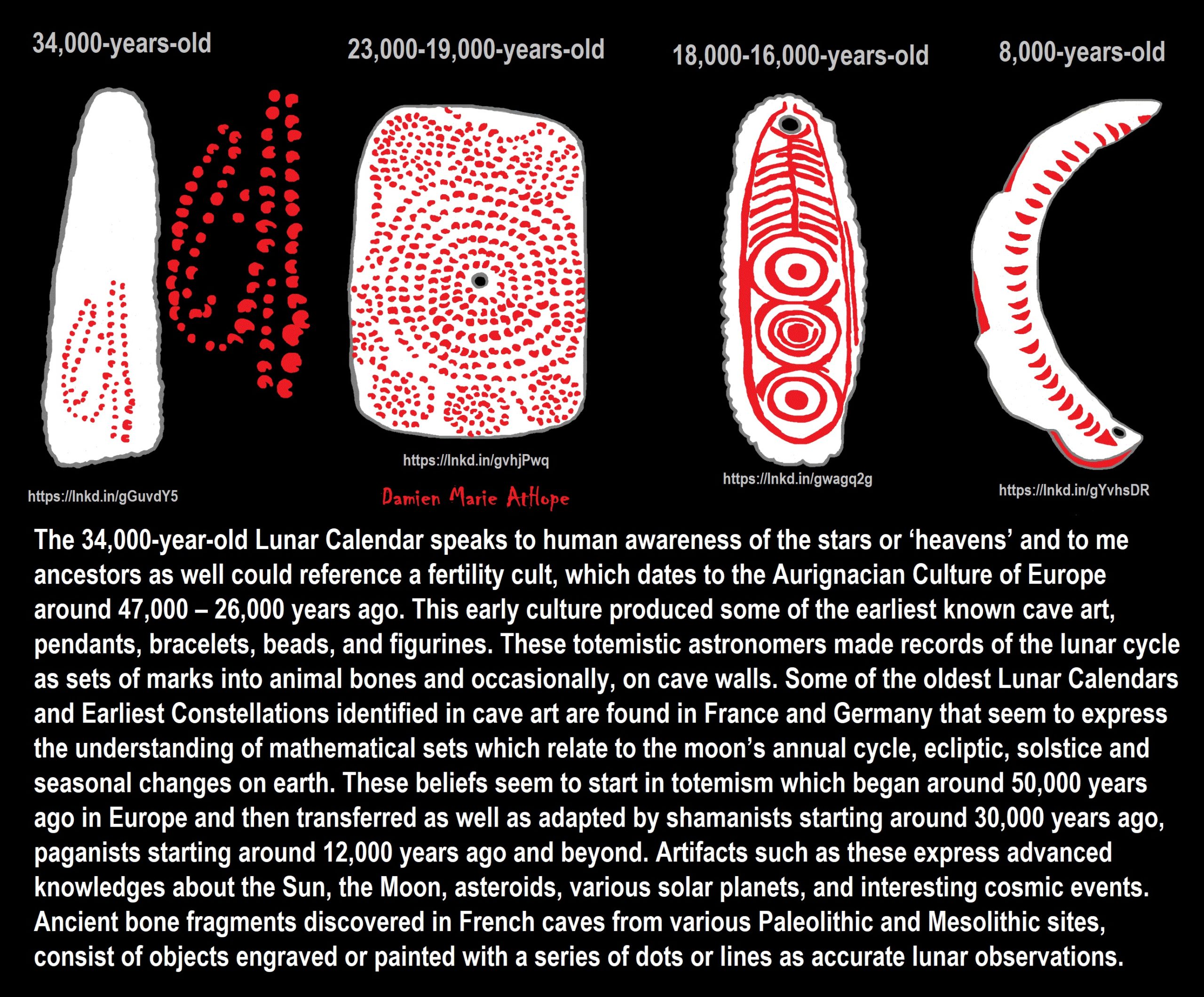

Totemism (at least 50,000/45,000 years ago) possibly around Germany, France, or somewhere in West Europe

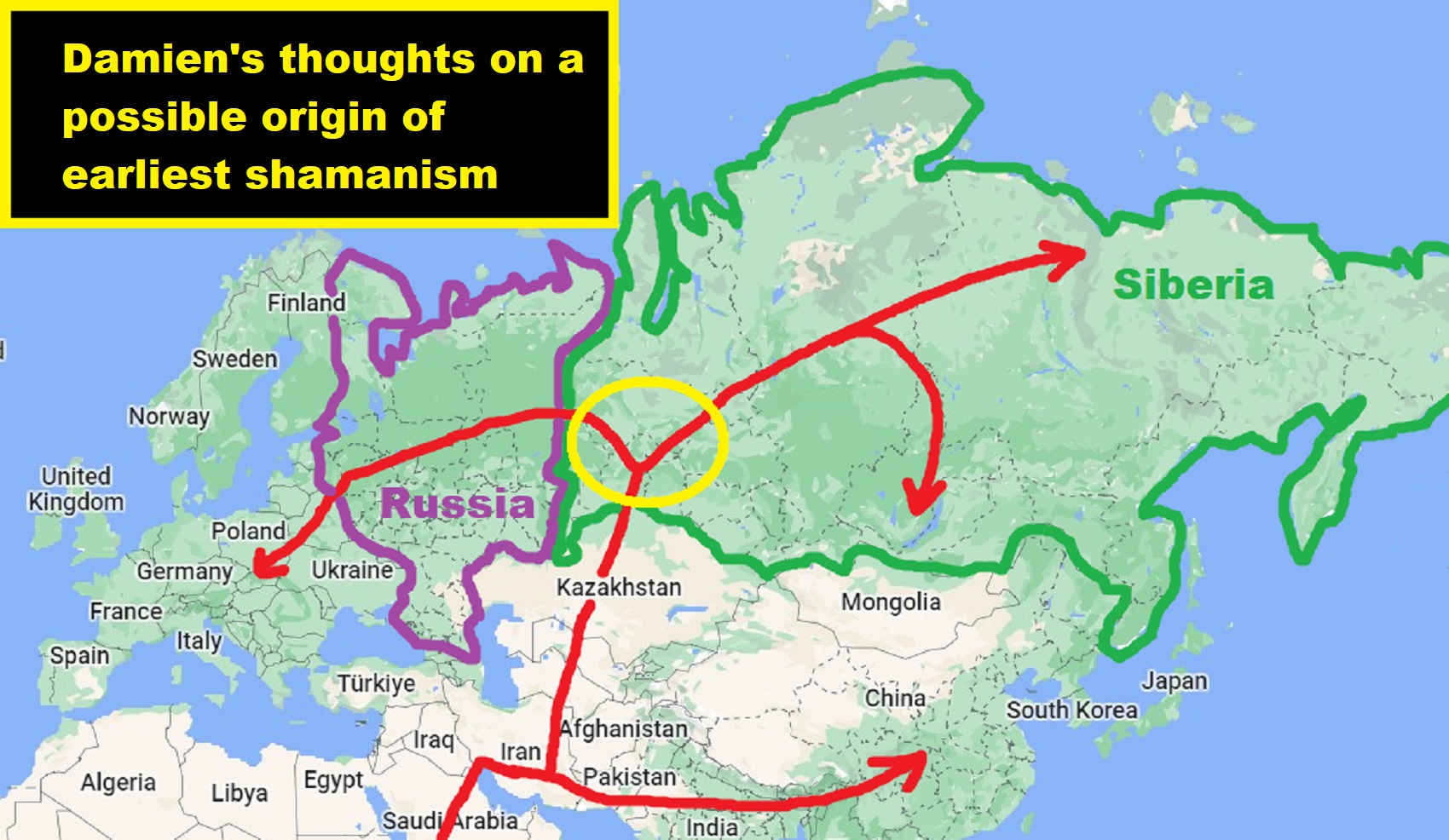

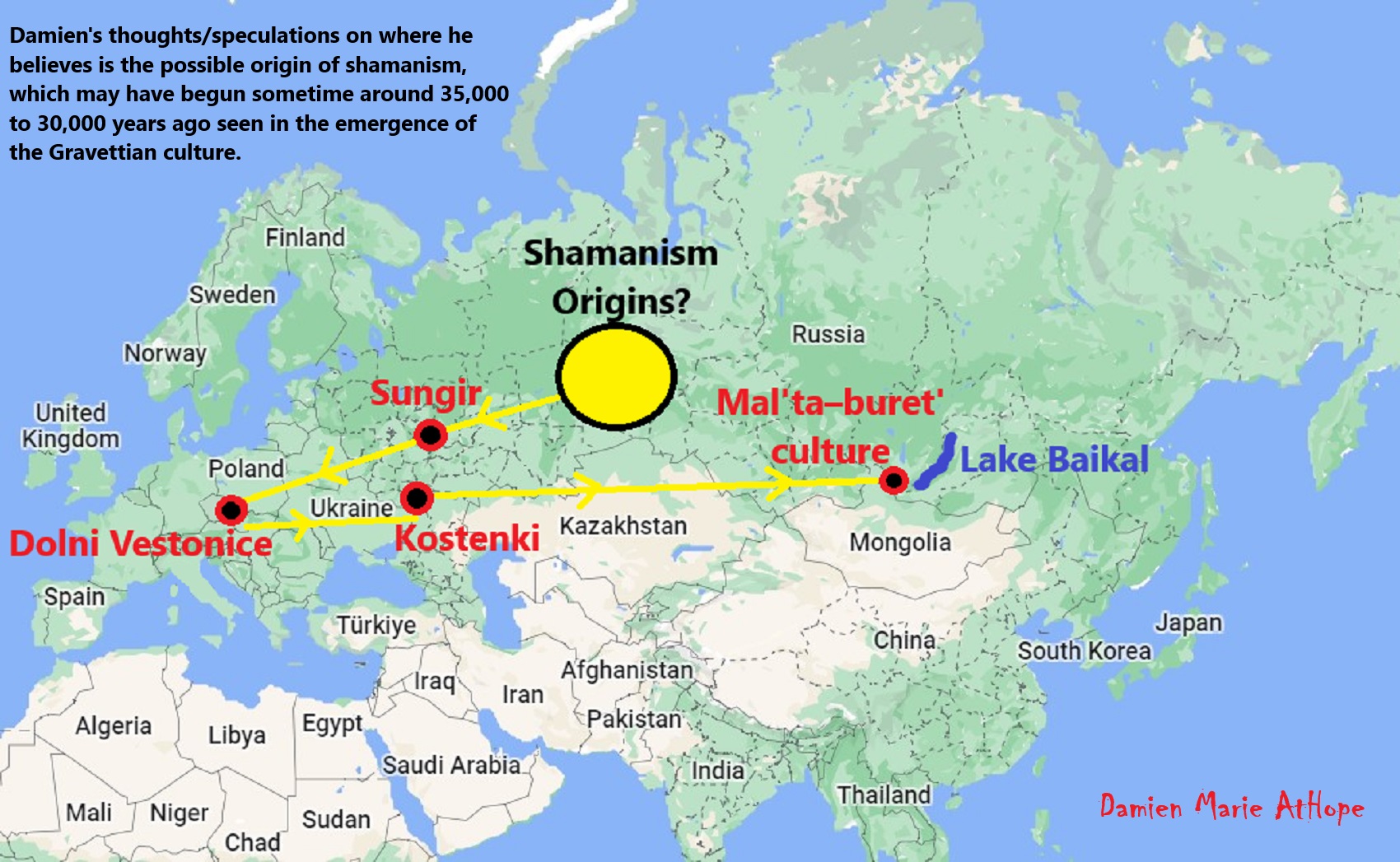

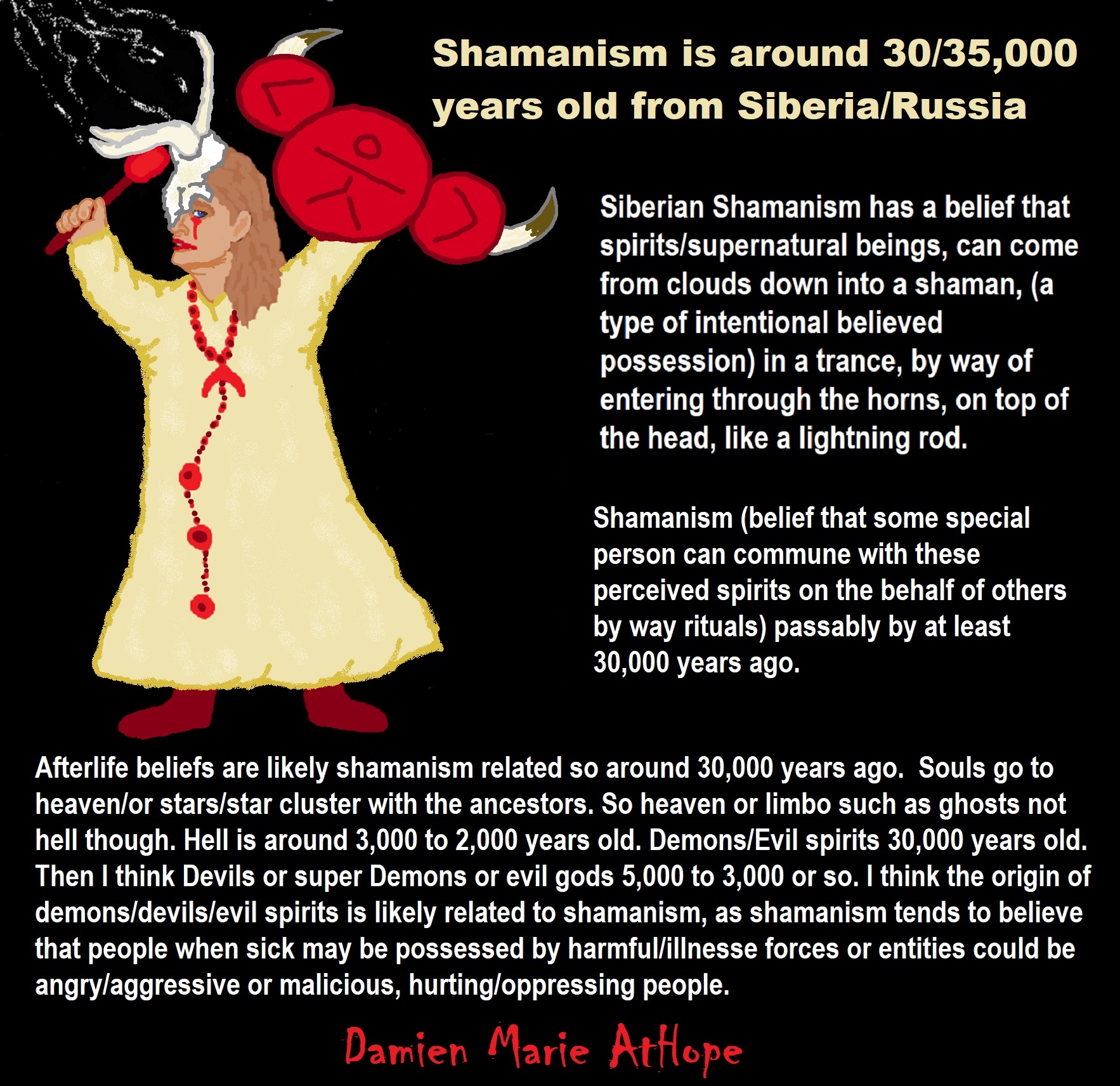

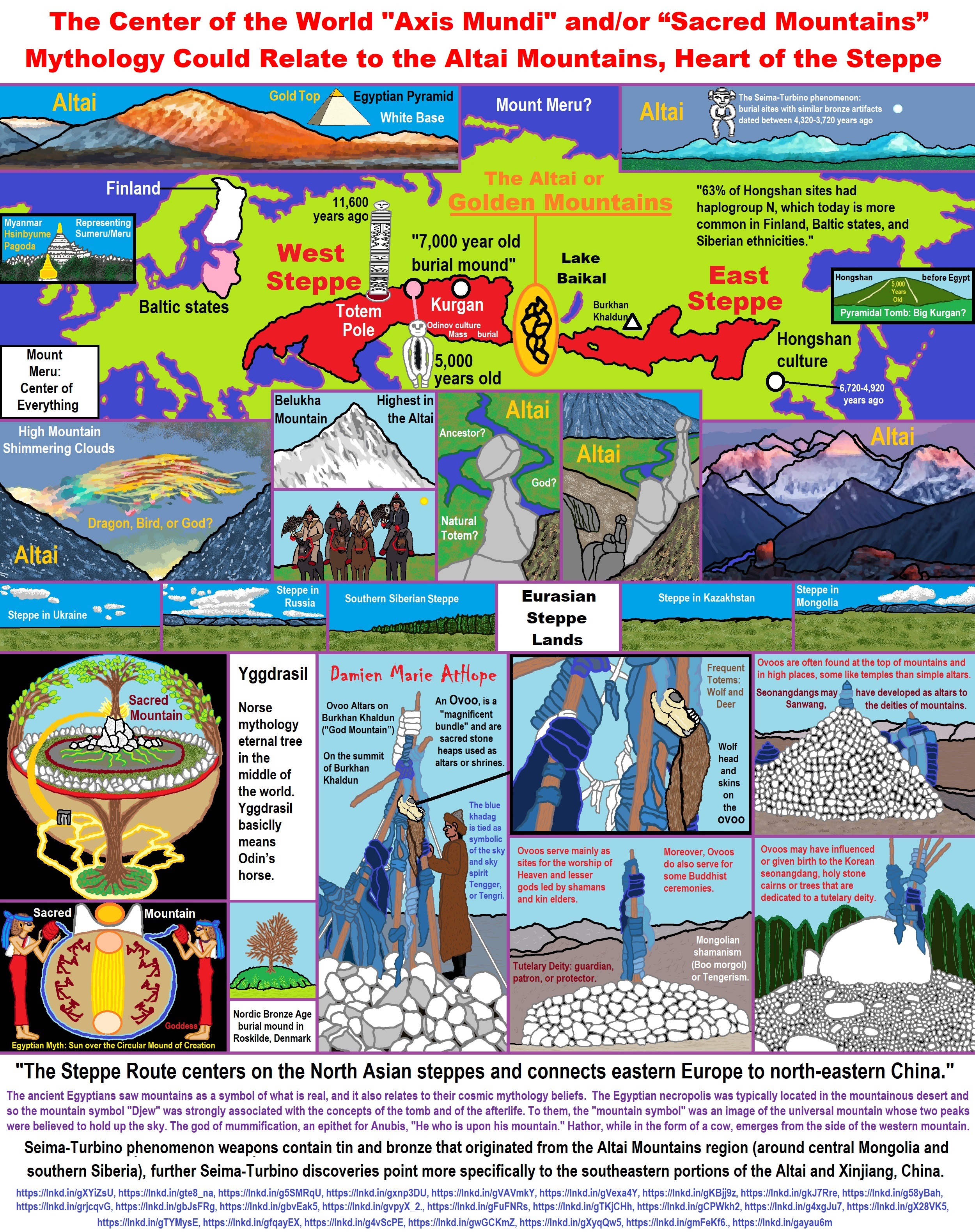

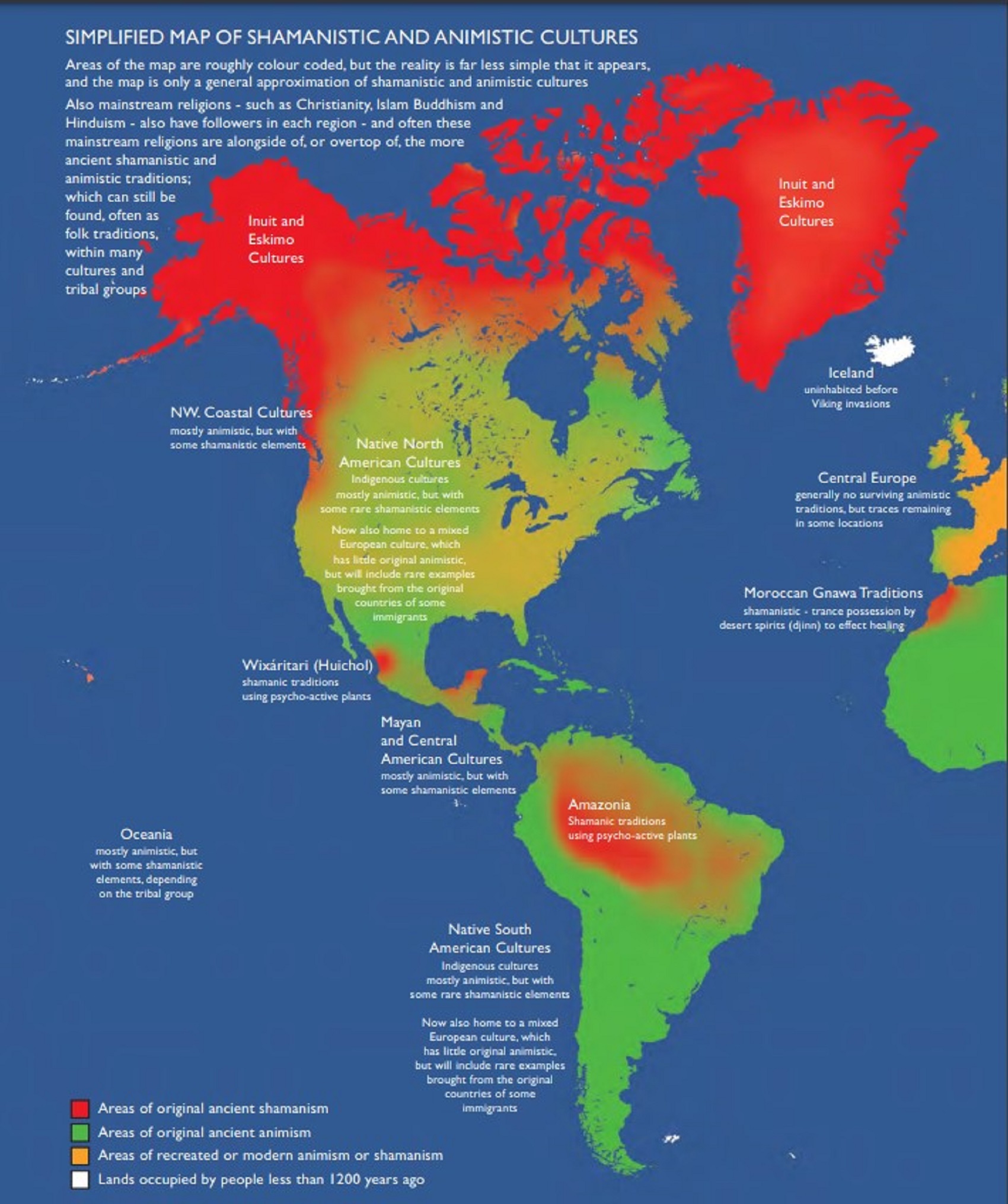

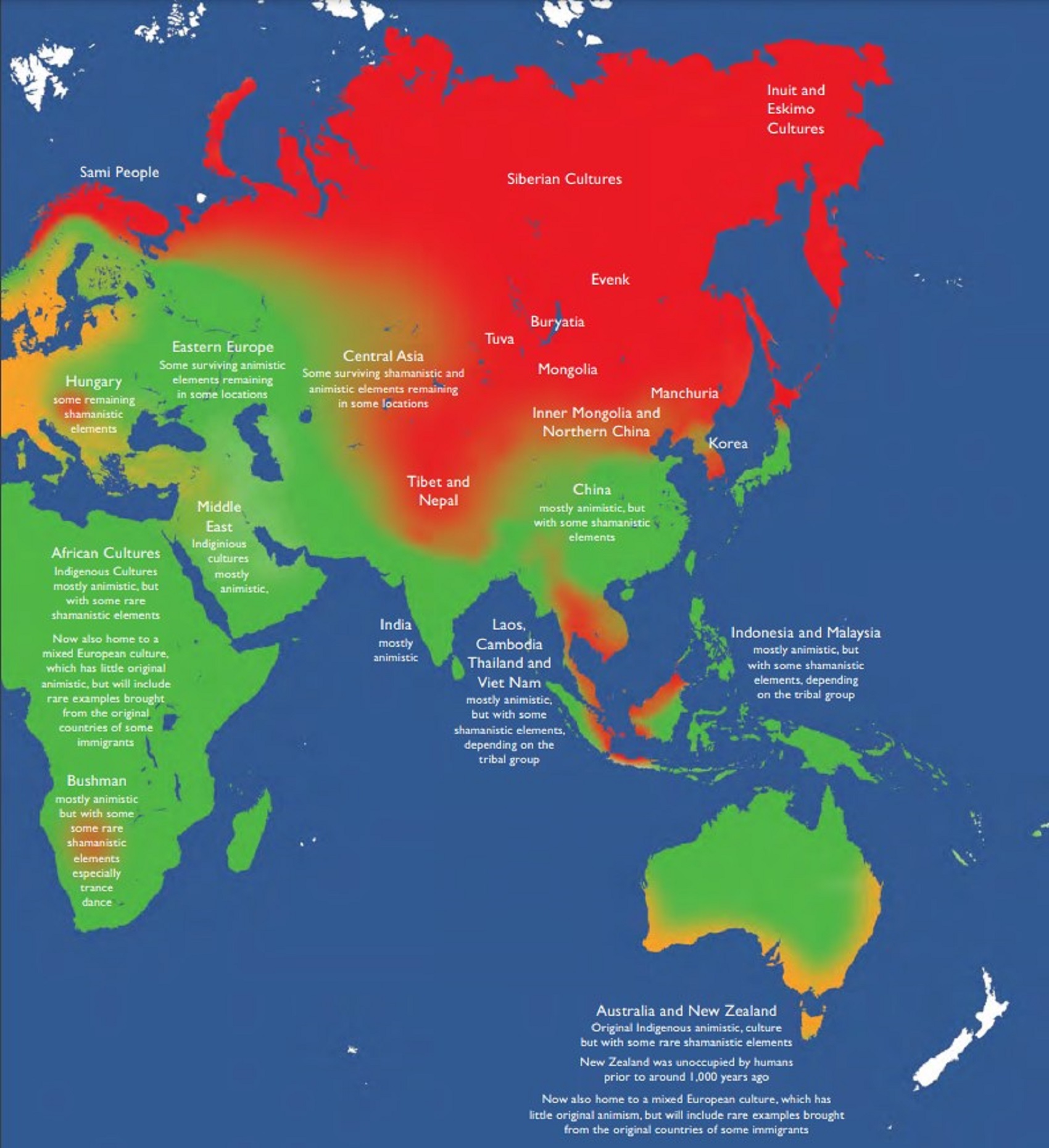

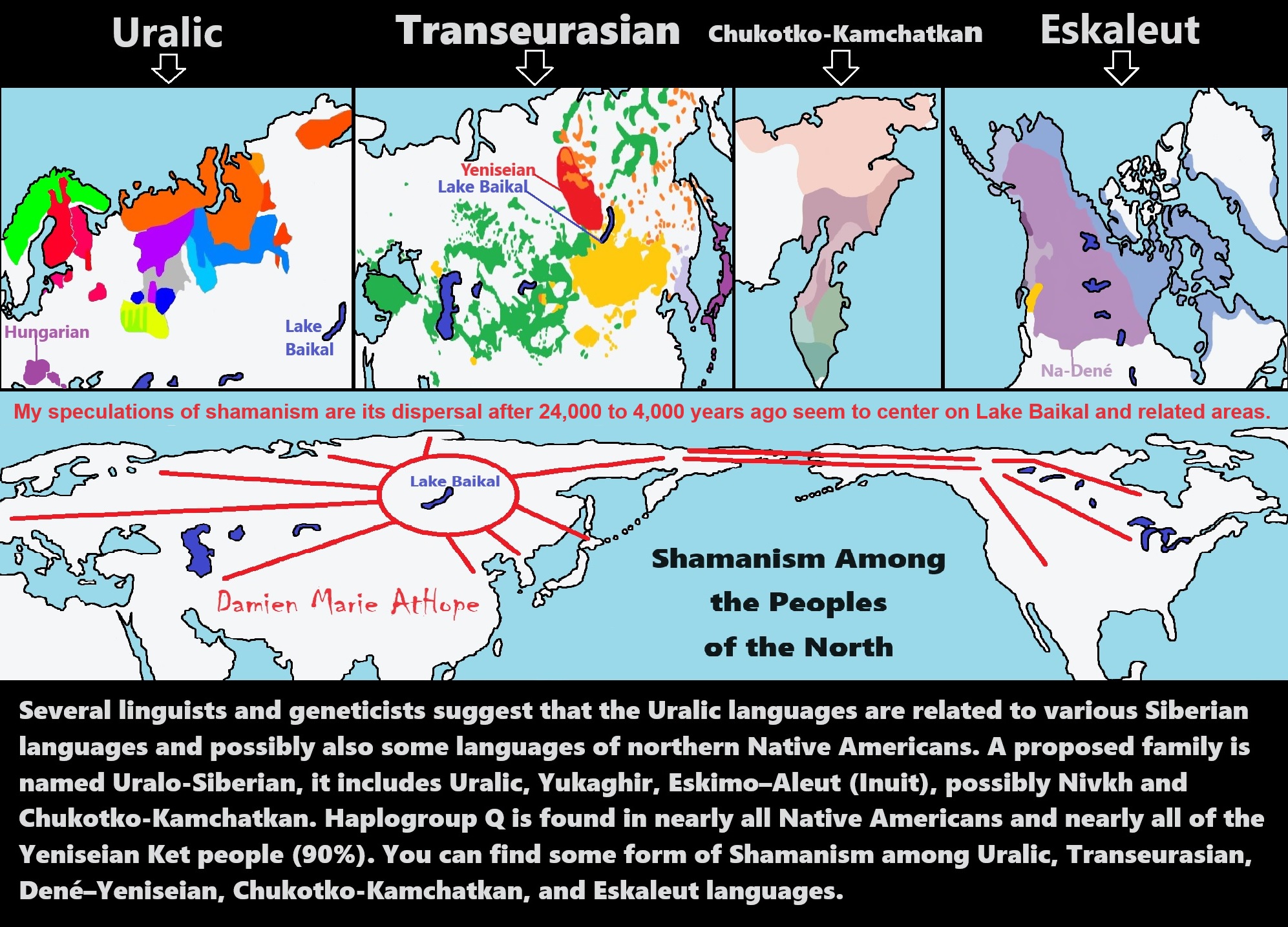

Shamanism (at least 30,000/35,000 years ago) possibly West Siberia or East Russia

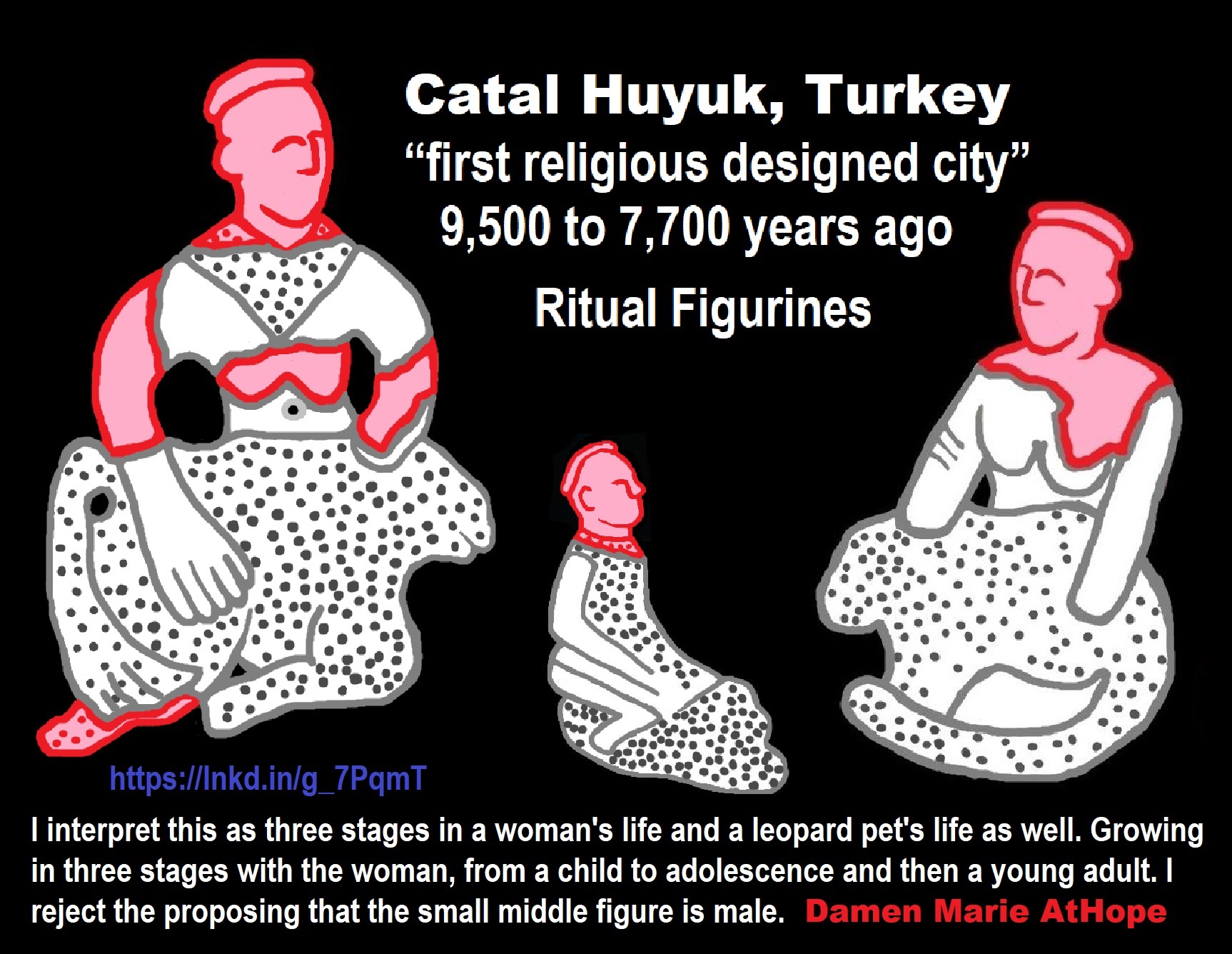

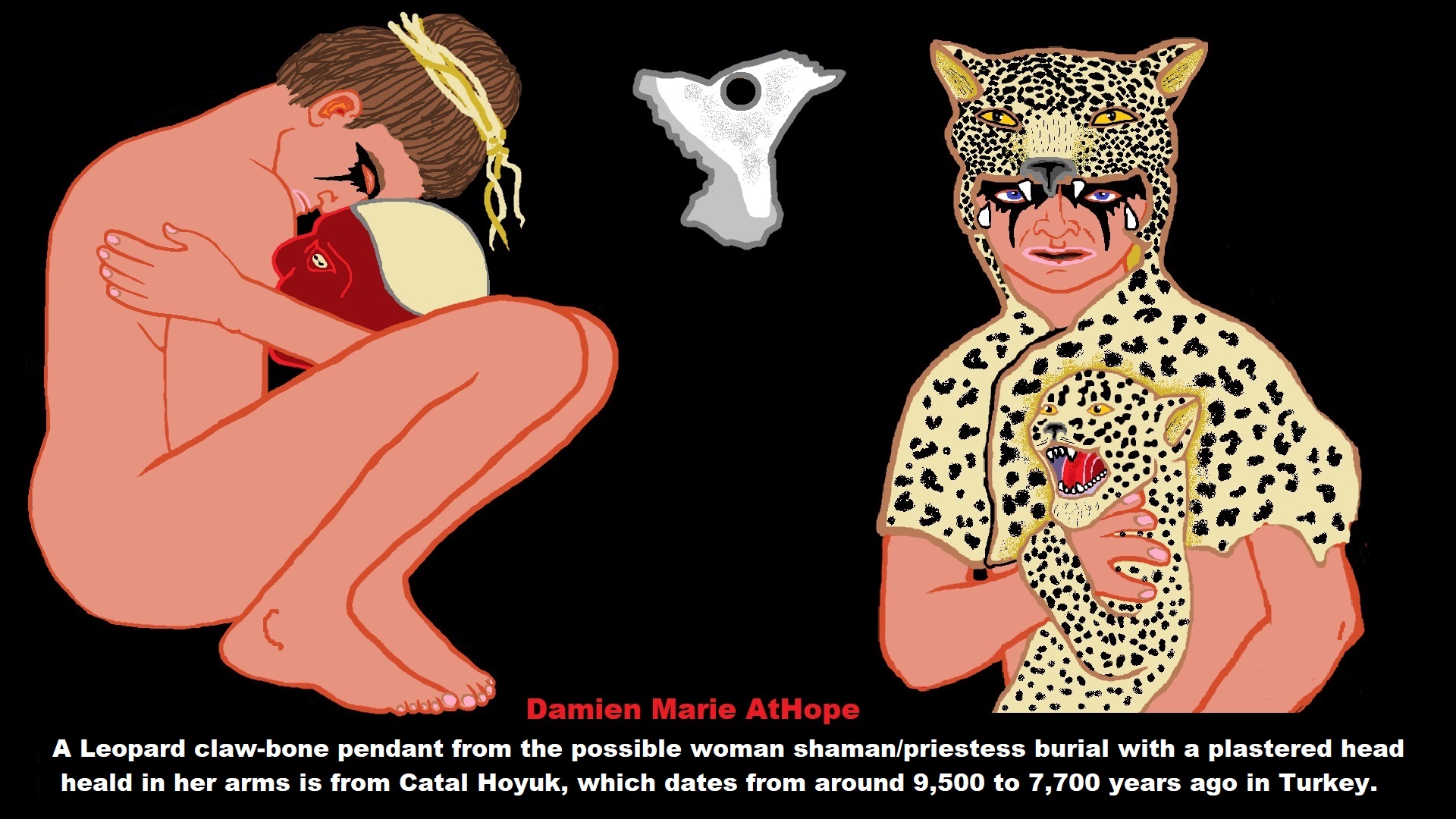

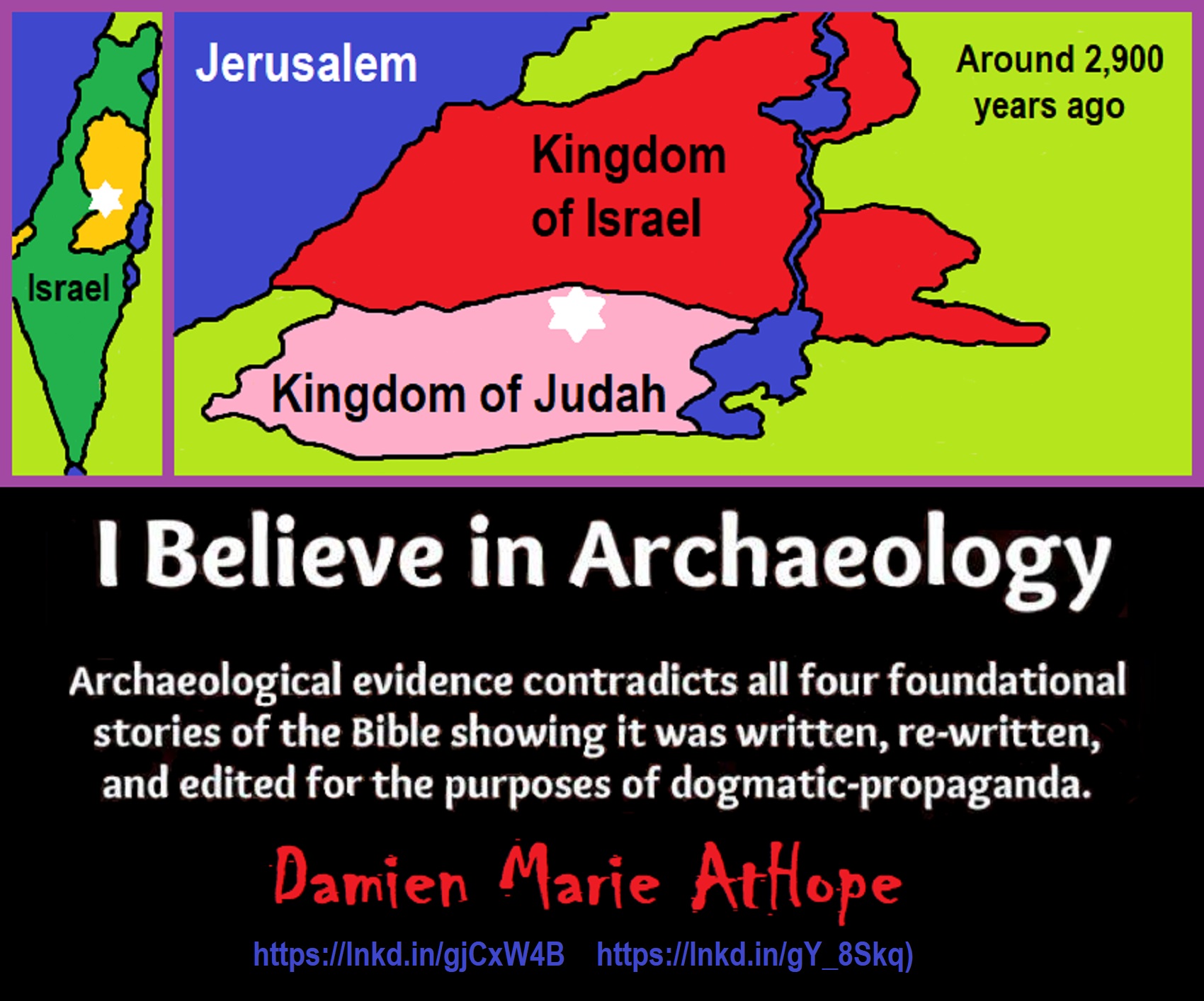

Paganism (at least 12,000/13,000 years ago) Turkey And/or Levant: “Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, Syria”

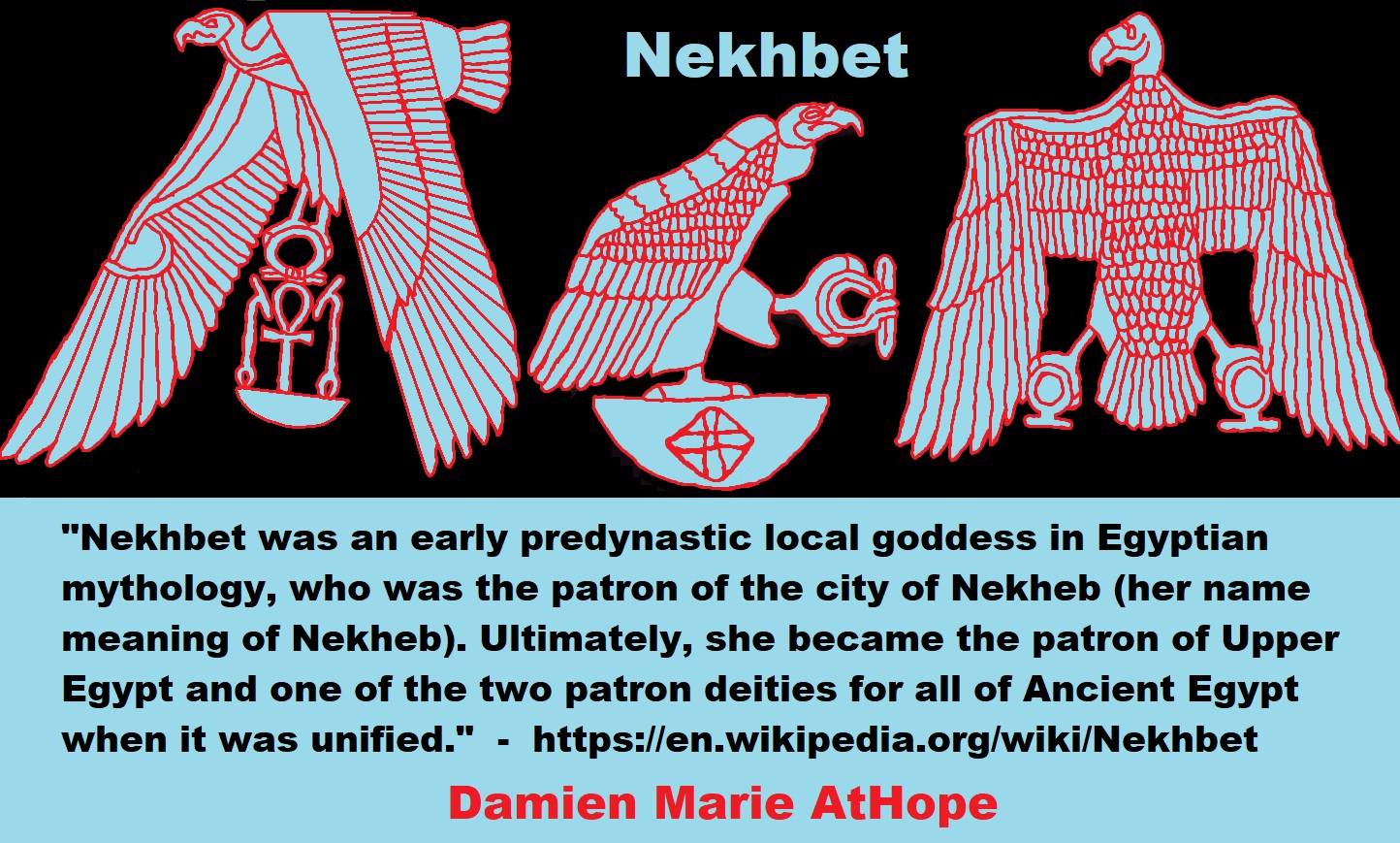

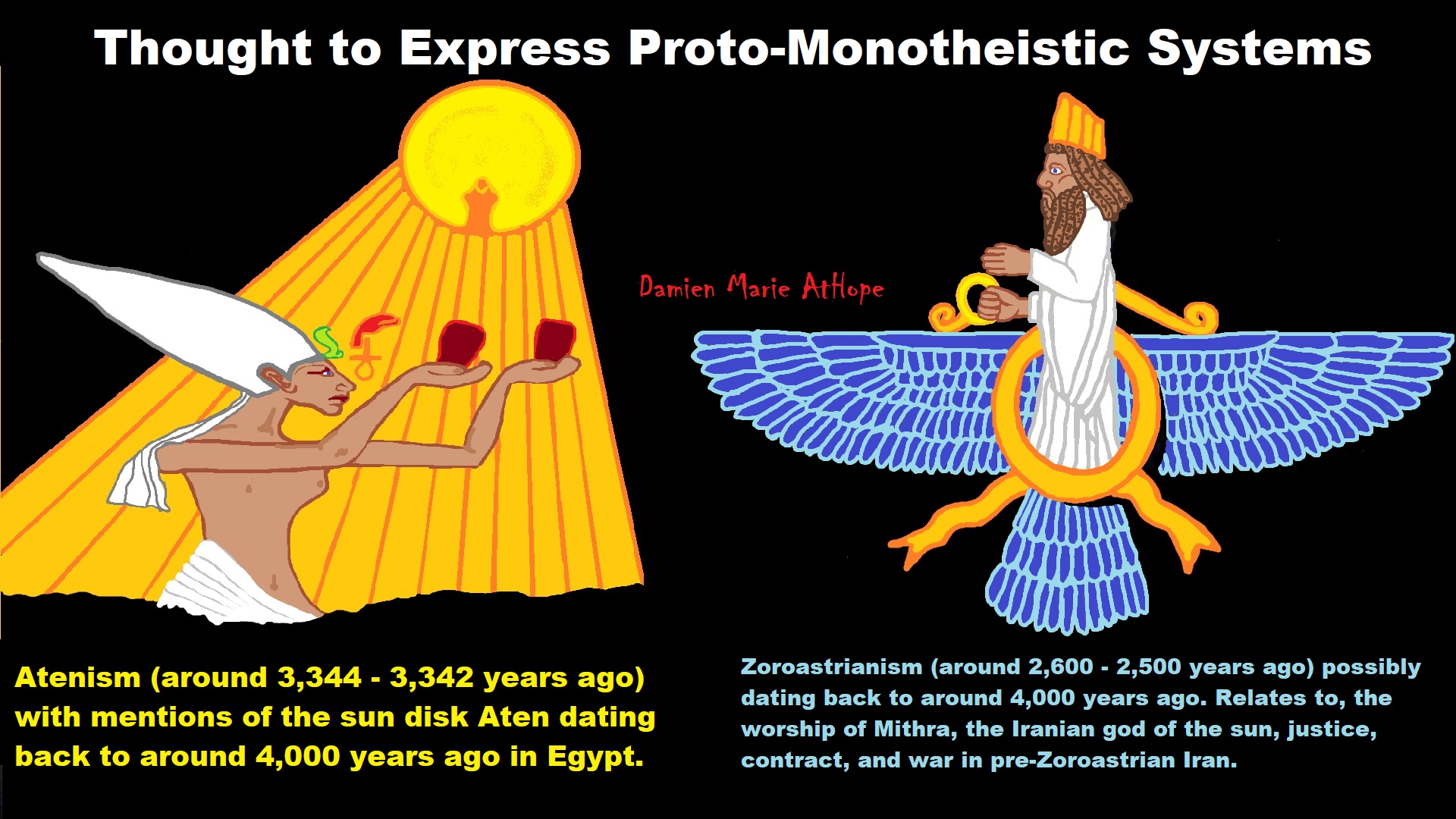

Progressed organized religion (at least 5,000 years ago), (Egypt, the First Dynasty 5,150 years ago)

I think animism started 100,000 years ago, totemism 50,000-45,000 years ago, and shamanism 30,000-35,000 years ago.

Animism (simplified to me as a belief in a perceived spirit world) passably by at least 100,000 years ago “the primal stage of early religion” To me, Animistic Somethingism: You just feel/think there has to be something supernatural/spirit-world or feel/think things are supernatural/spirit-filled.

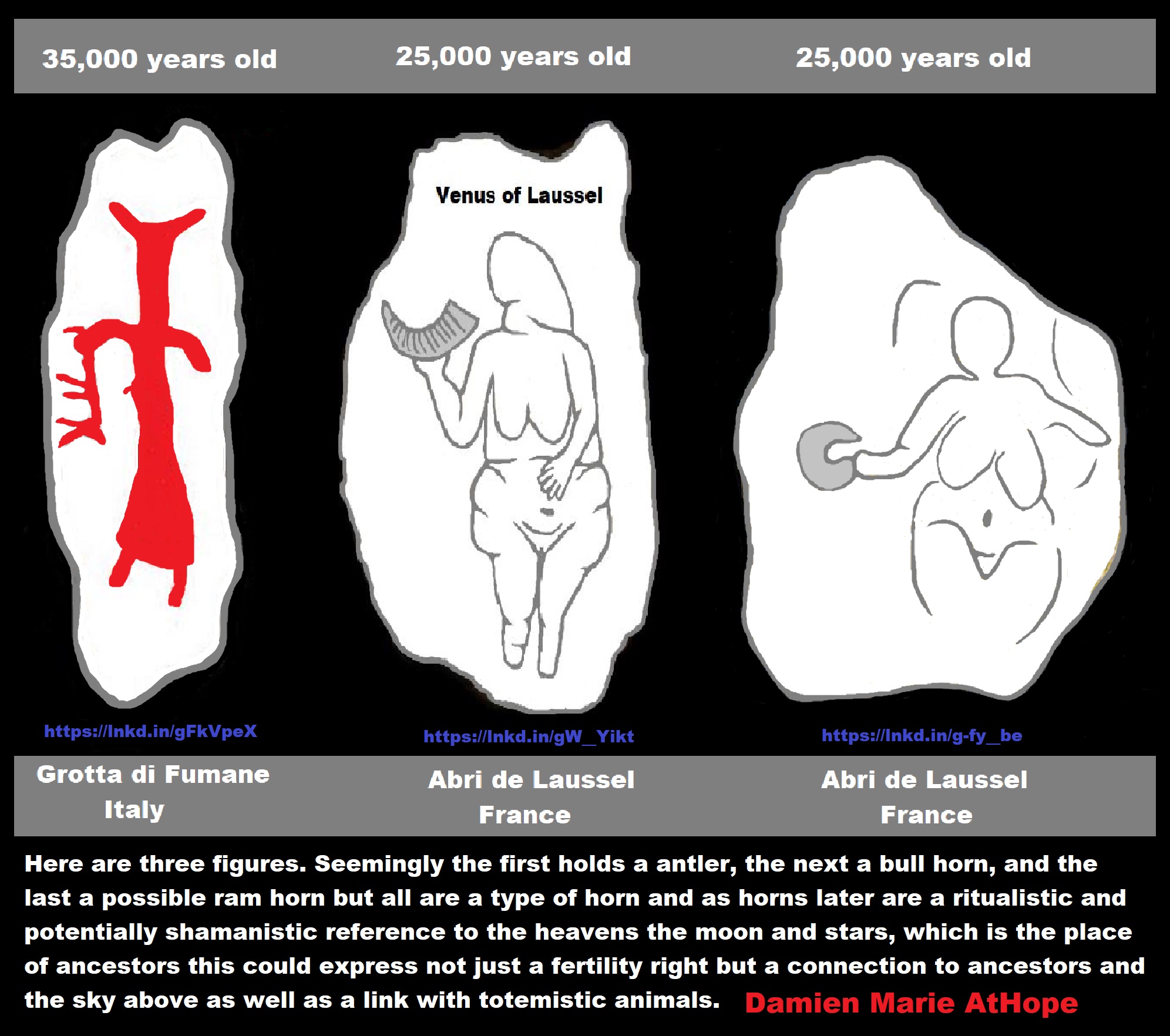

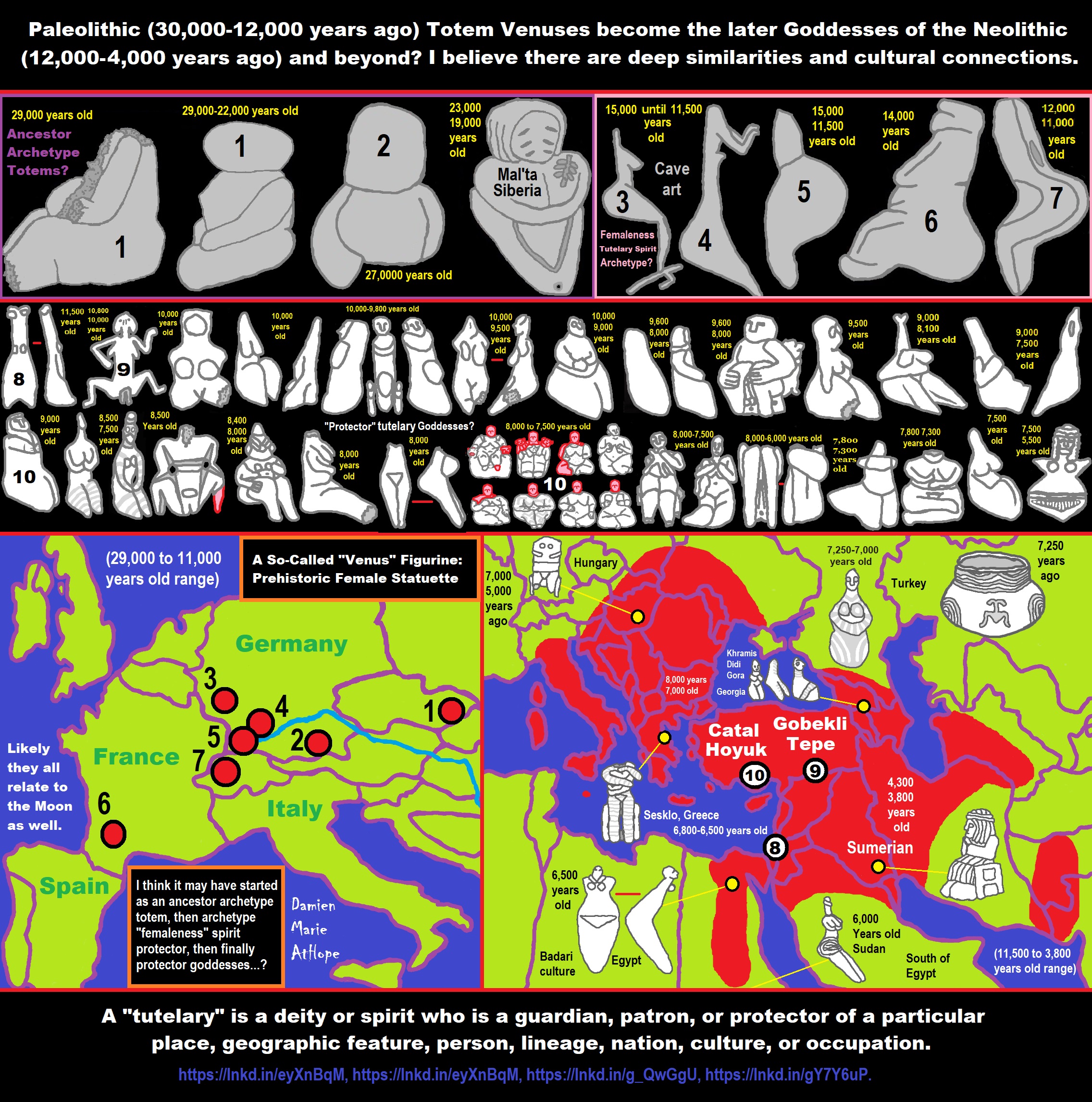

Totemism (simplified to me, as a belief that these perceived spirits could be managed or related with by created physical expressions) passably by at least 50,000 years ago “progressed stage of early religion” A totem is a representational spirit being, a sacred object, or symbol of a group of people, clan, or tribe.

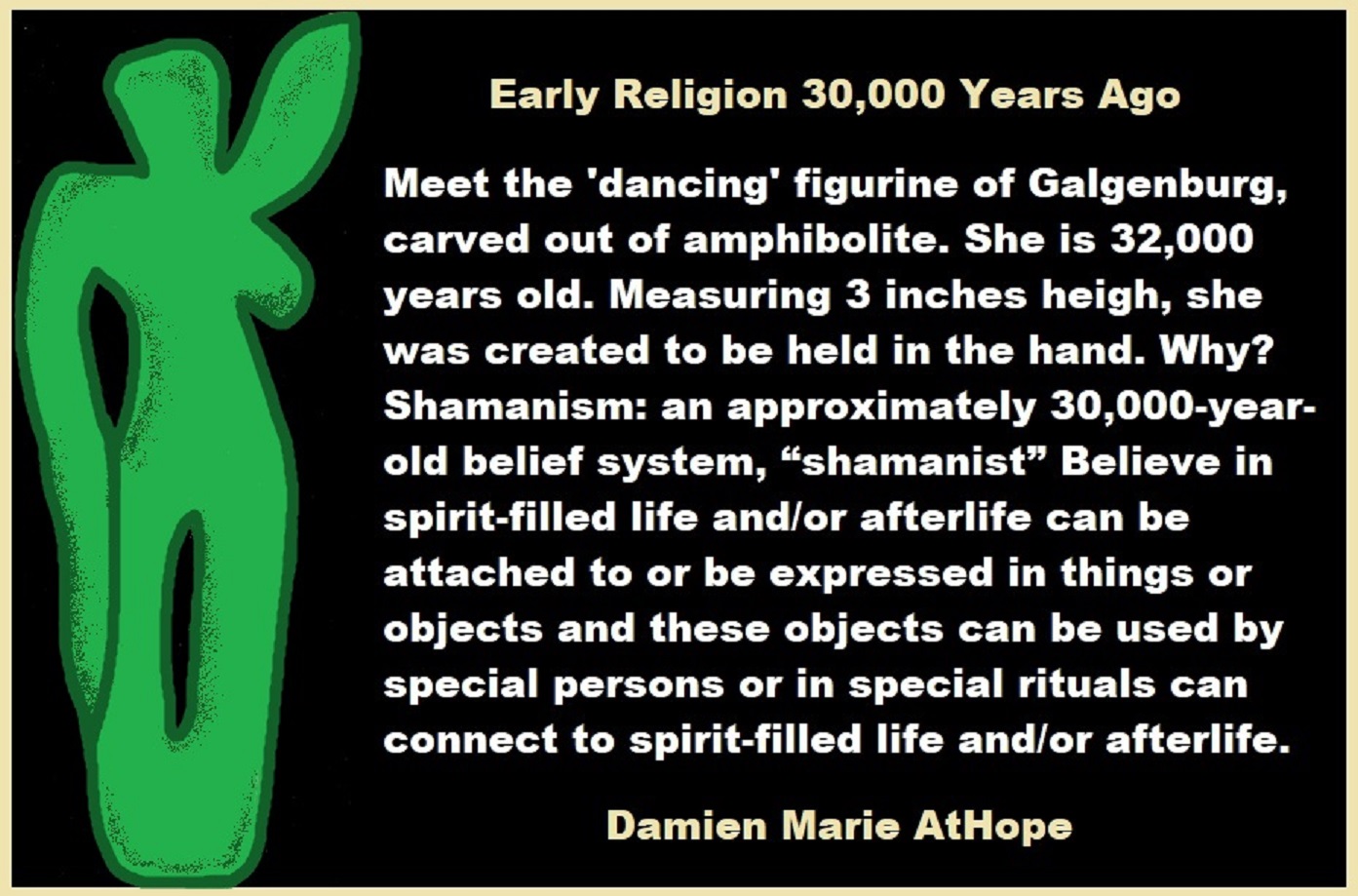

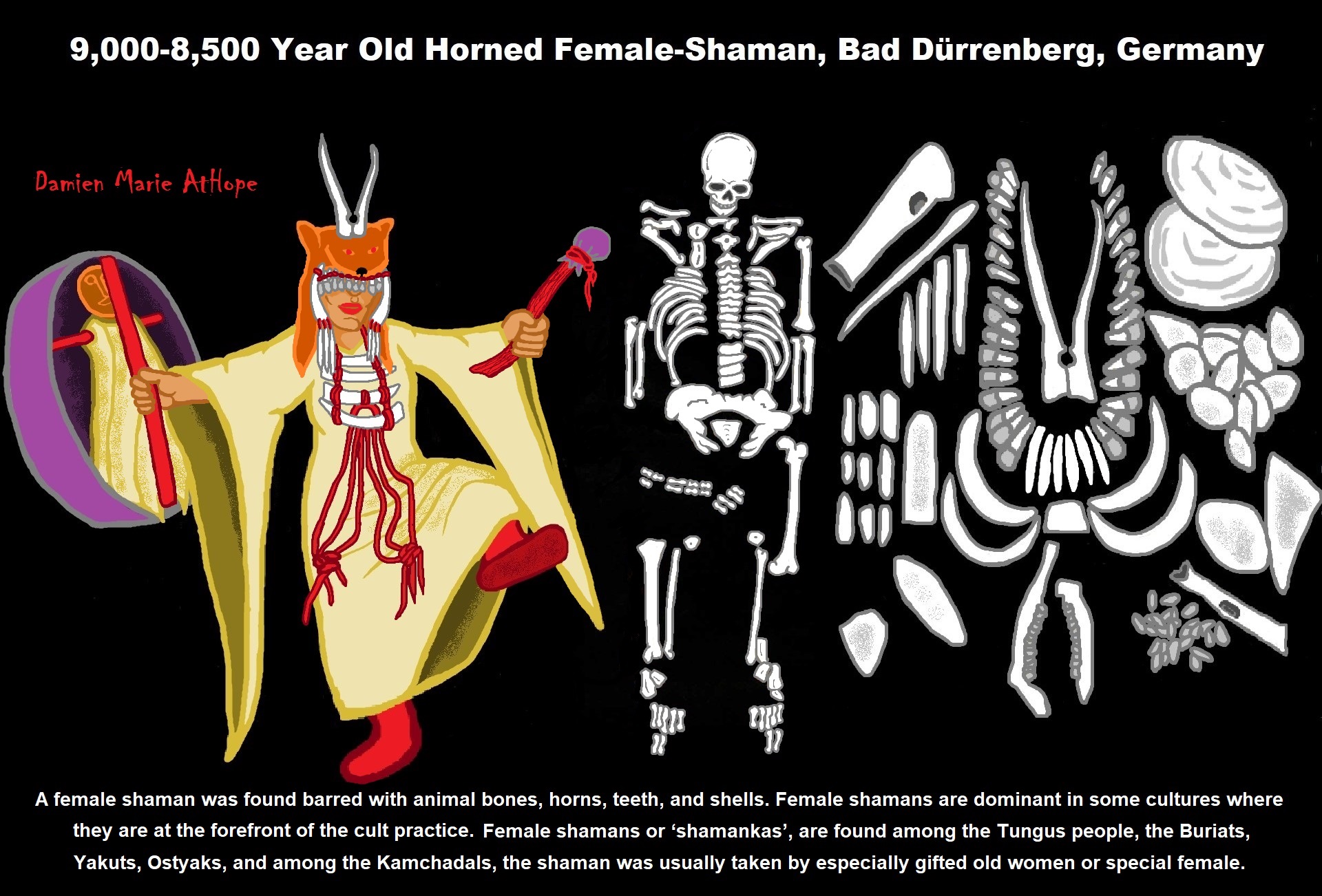

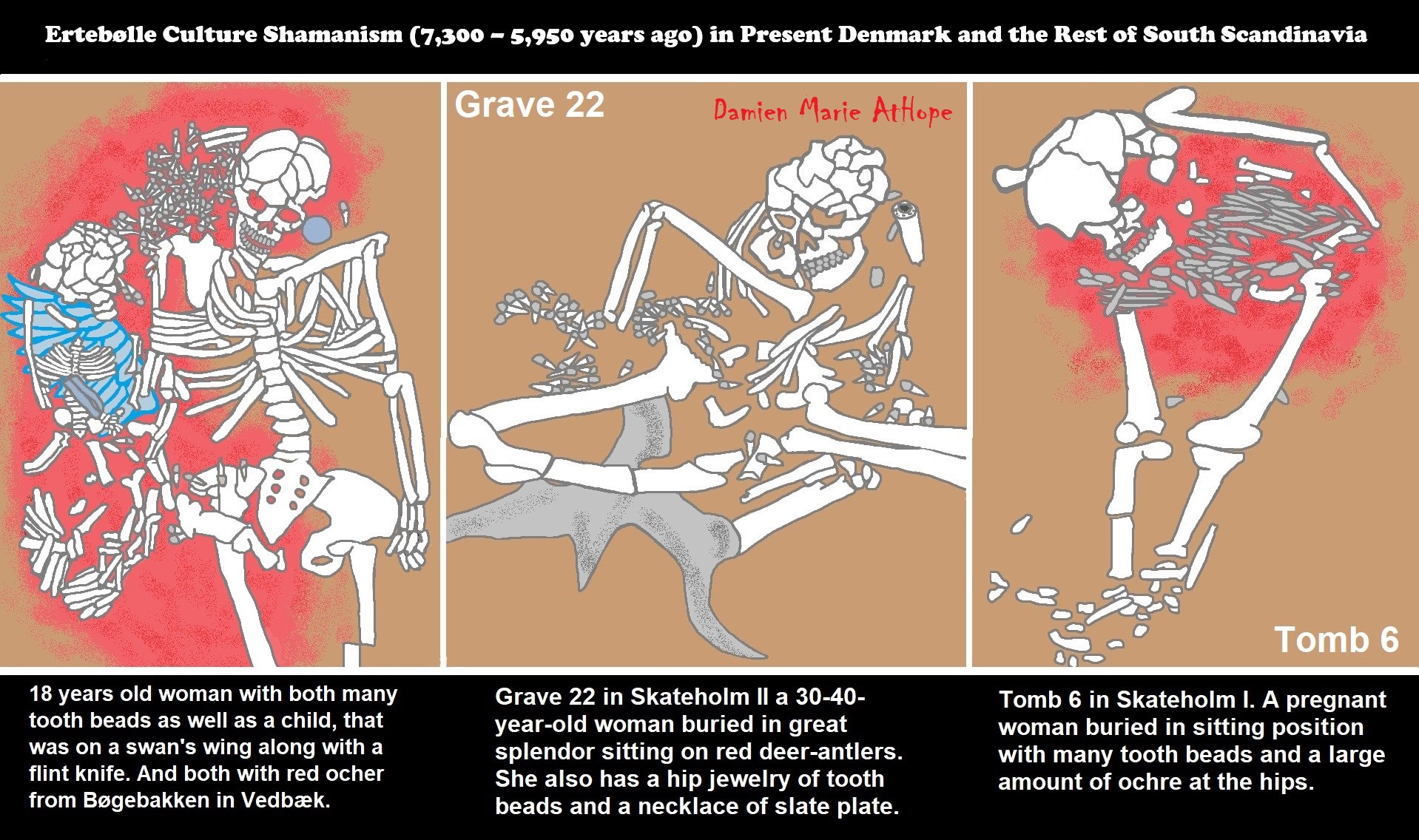

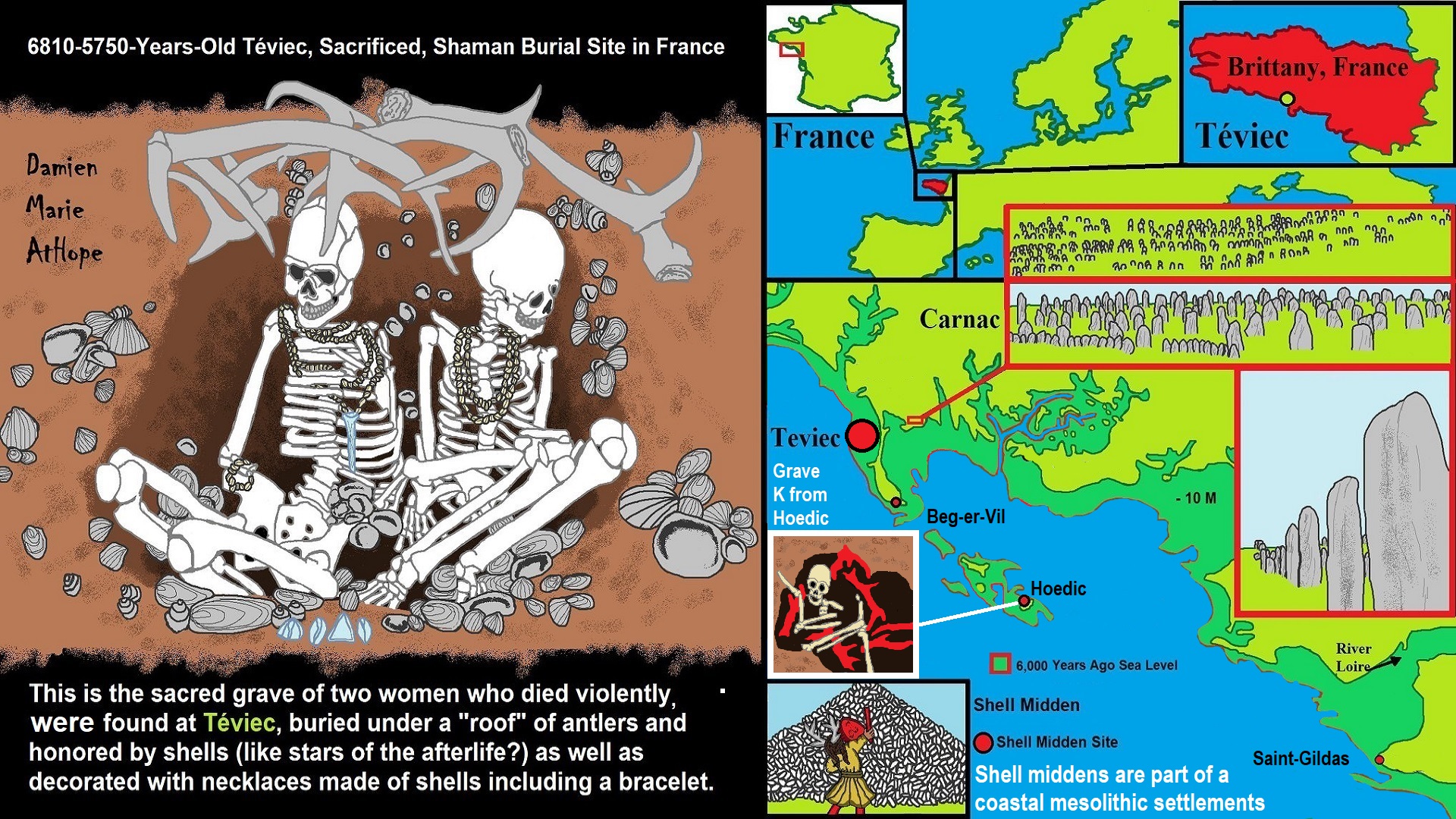

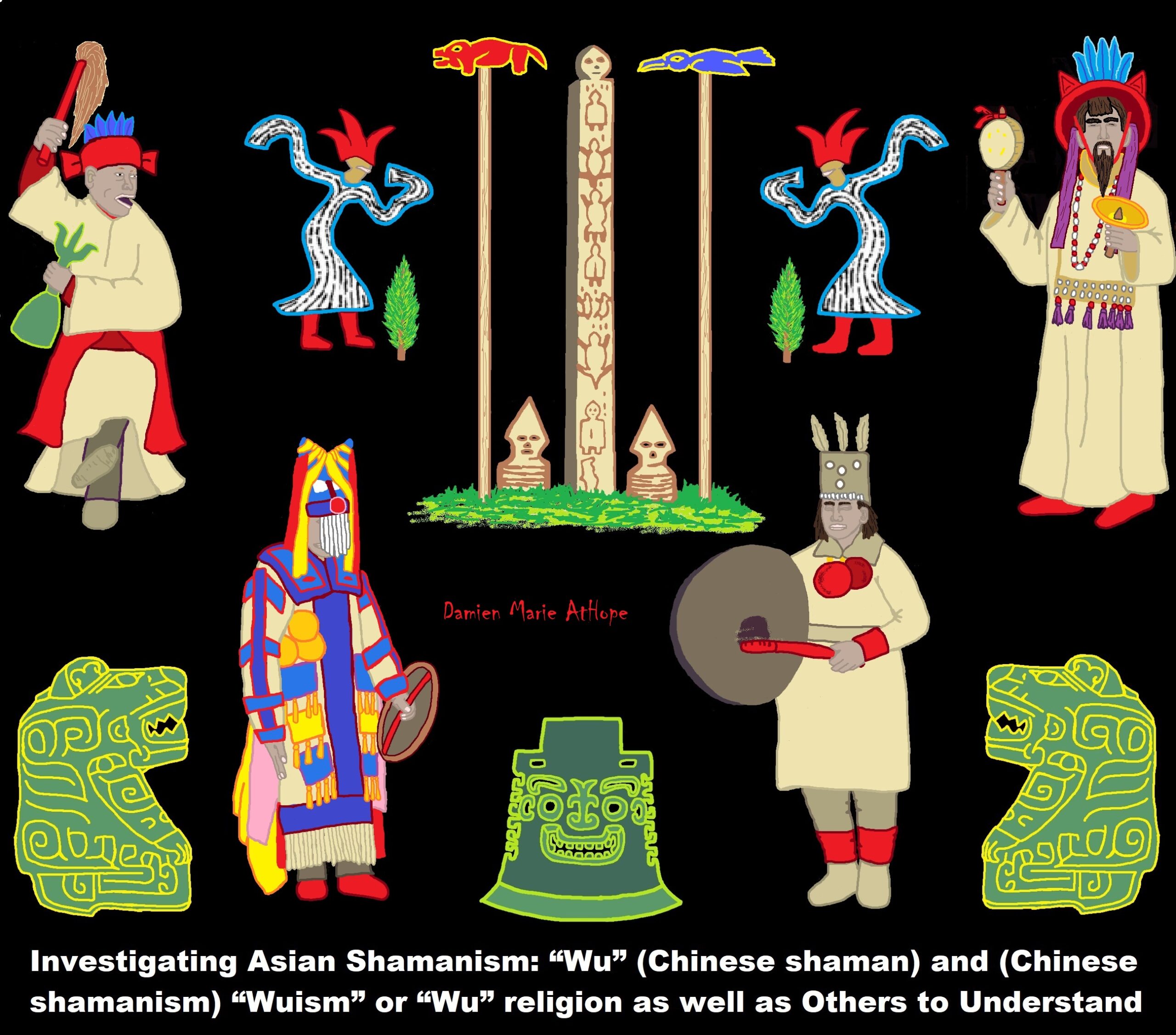

Shamanism (simplified to me as a belief that some special person can commune with these perceived spirits on the behalf of others by way of rituals) passably by at least 30,000 years ago Shamanism is an otherworld connection belief thought to heal the sick, communicate with spirits/deities, and escort souls of the dead.

- African Back Migrations and the Status of Shamanism Origins as well as its Spreading

- Women/Feminine-Natured people as the first Shamans from around 30,000 to 7,000 years ago?

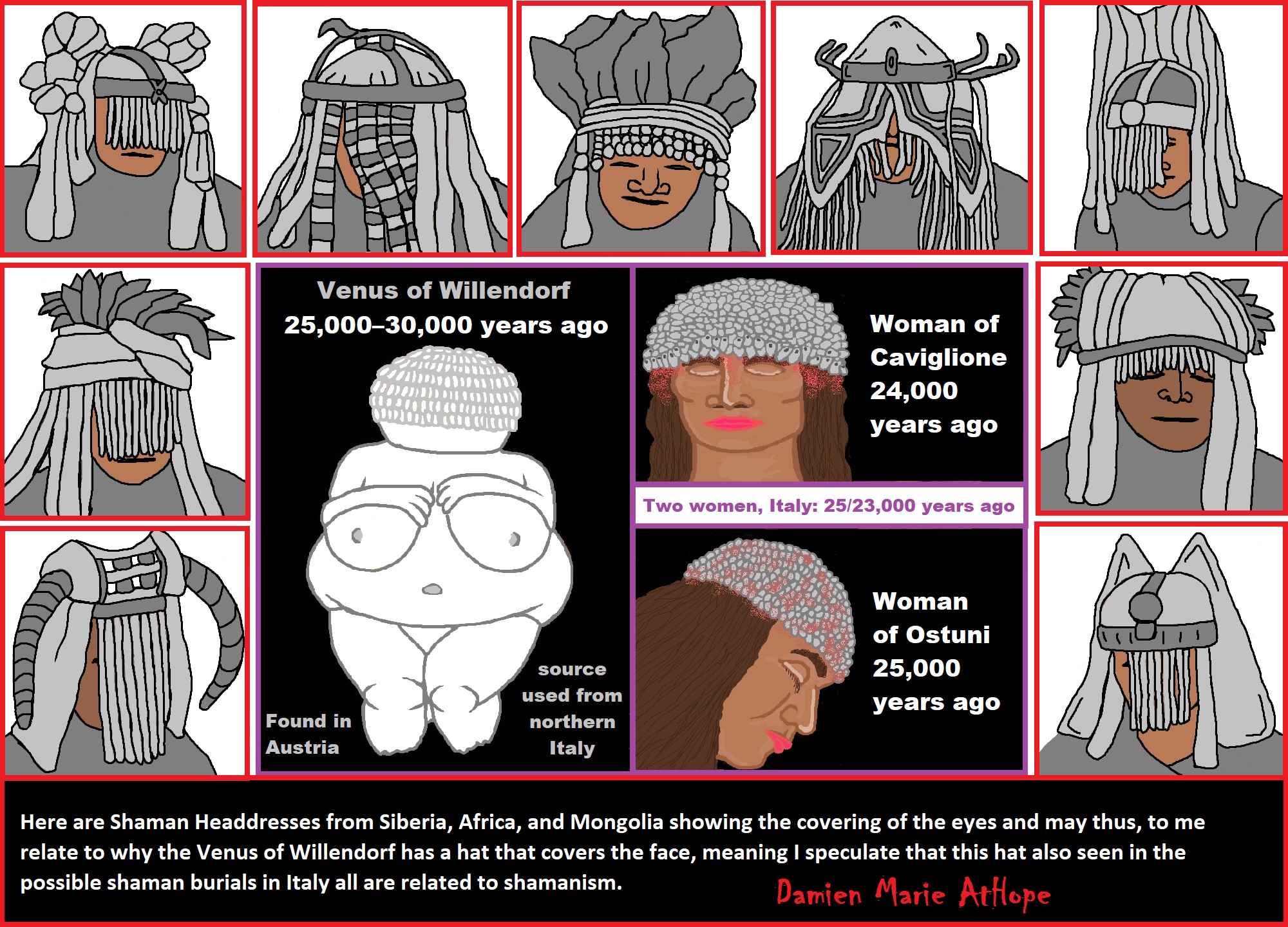

- Venus of Willendorf: Shamanism Headdresses that Cover the Eyes?

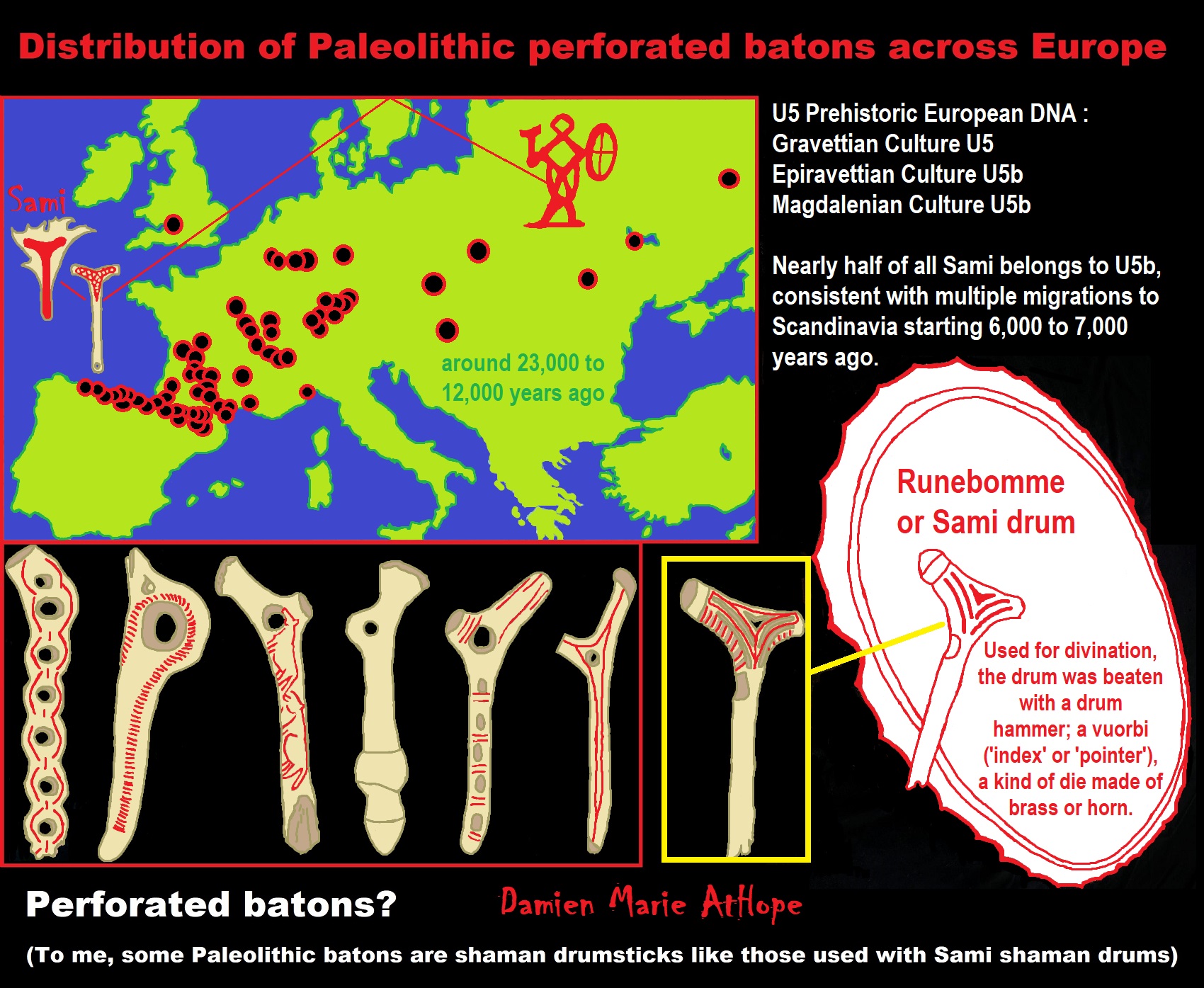

- Some Paleolithic Batons from 23,000 to 12,000 years ago are/maybe Shaman Drumsticks like Those Used with Sami Shaman Drums?

Shamanism: an approximately

30,000-year-old belief system

Shamanism (beginning around 30,000 years ago)

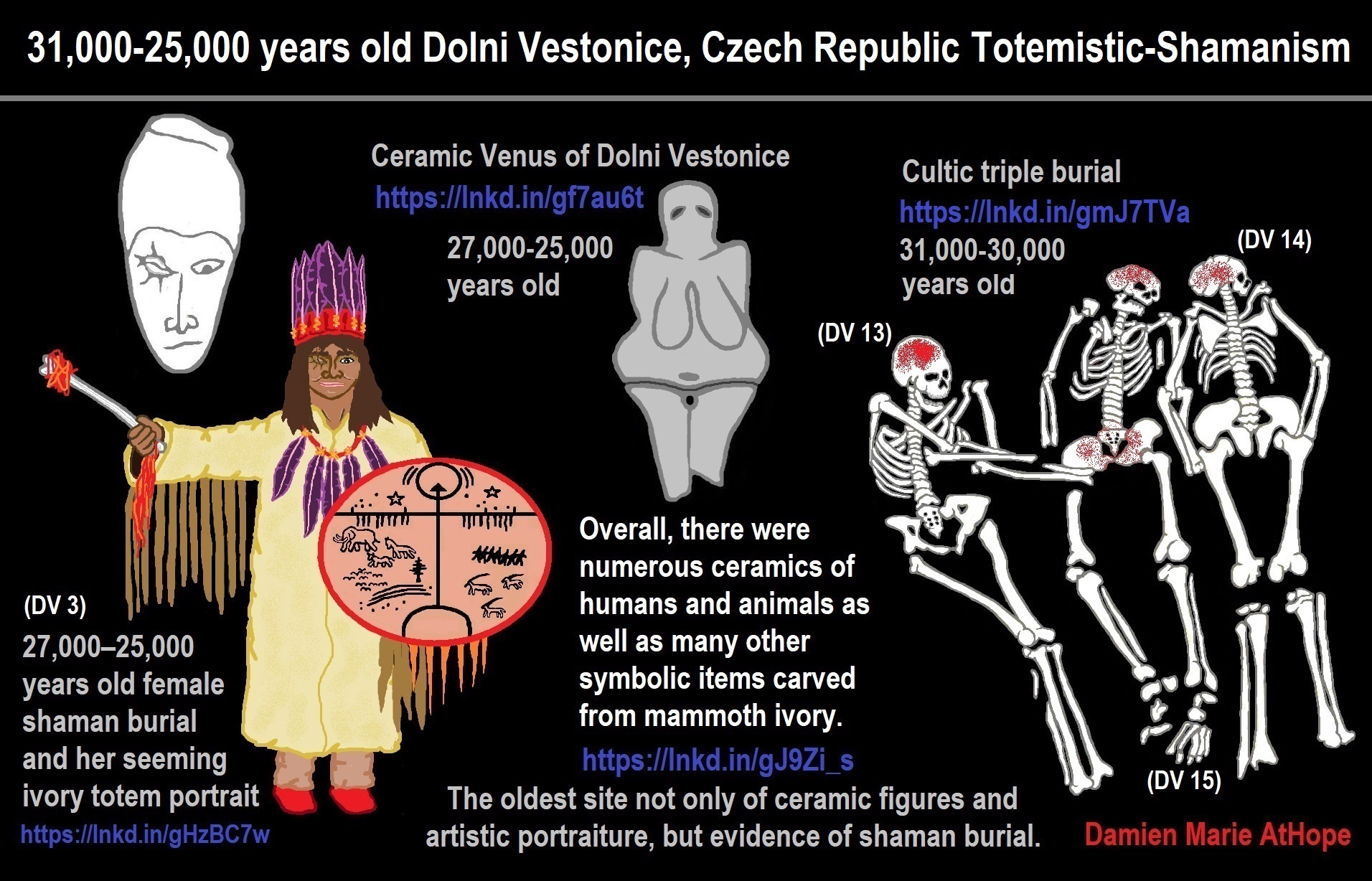

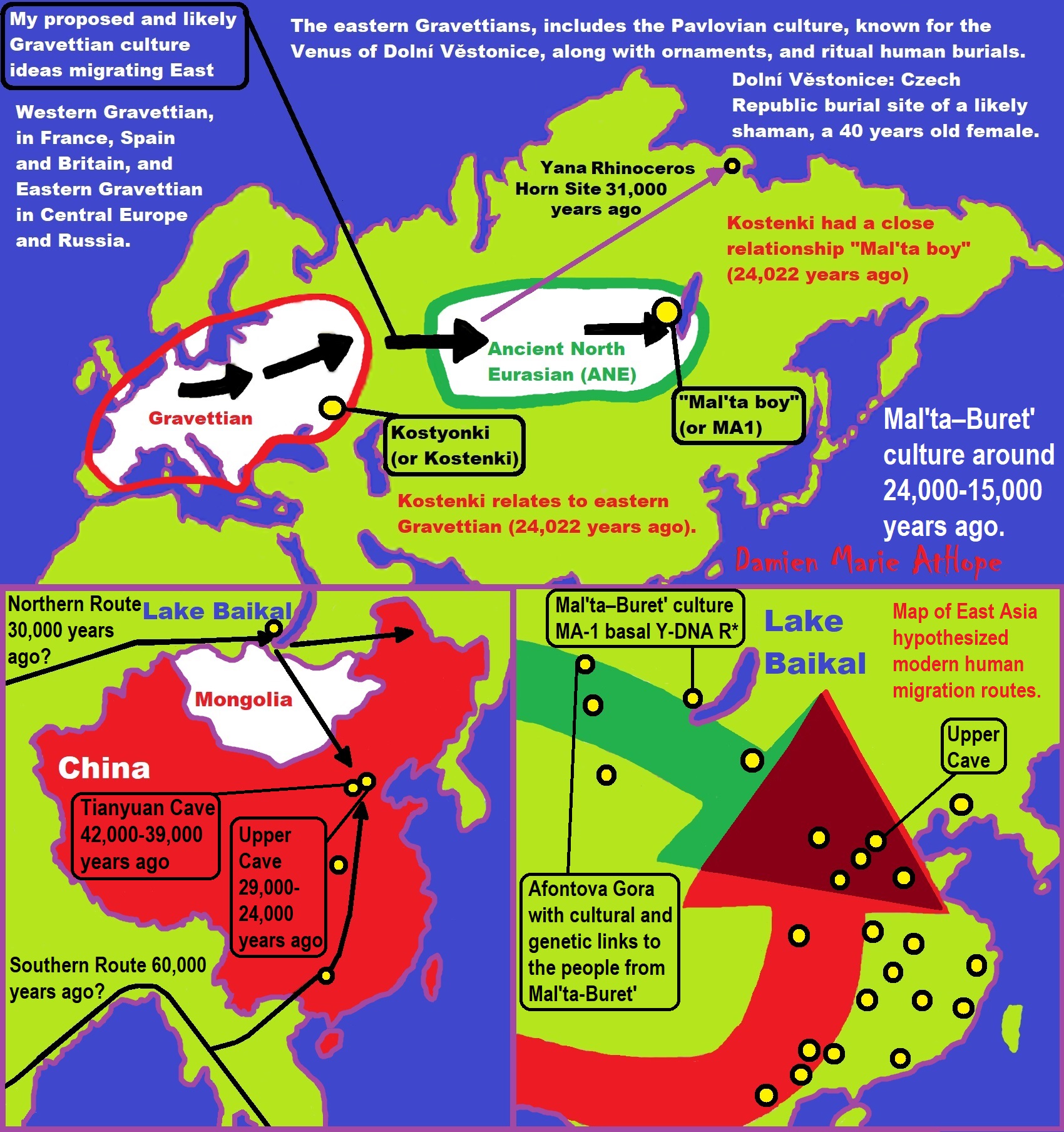

Shamanism (such as that seen in Siberia Gravettian culture: 30,000 years ago). Gravettian culture (34,000–24,000 years ago; Western Gravettian, mainly France, Spain, and Britain, as well as Eastern Gravettian in Central Europe and Russia. The eastern Gravettians, which include the Pavlovian culture). And, the Pavlovian culture (31,000 – 25,000 years ago such as in Austria and Poland). 31,000 – 20,000 years ago Oldest Shaman was Female, Buried with the Oldest Portrait Carving.

Shamanism is approximately a 30,000-year-old belief system and believe in spirit-filled life and/or afterlife that can be attached to or be expressed in things or objects and these objects can be used by special persons or in special rituals that can connect to spirit-filled life and/or afterlife. If you believe like this, regardless of your faith, you are a hidden shamanist.

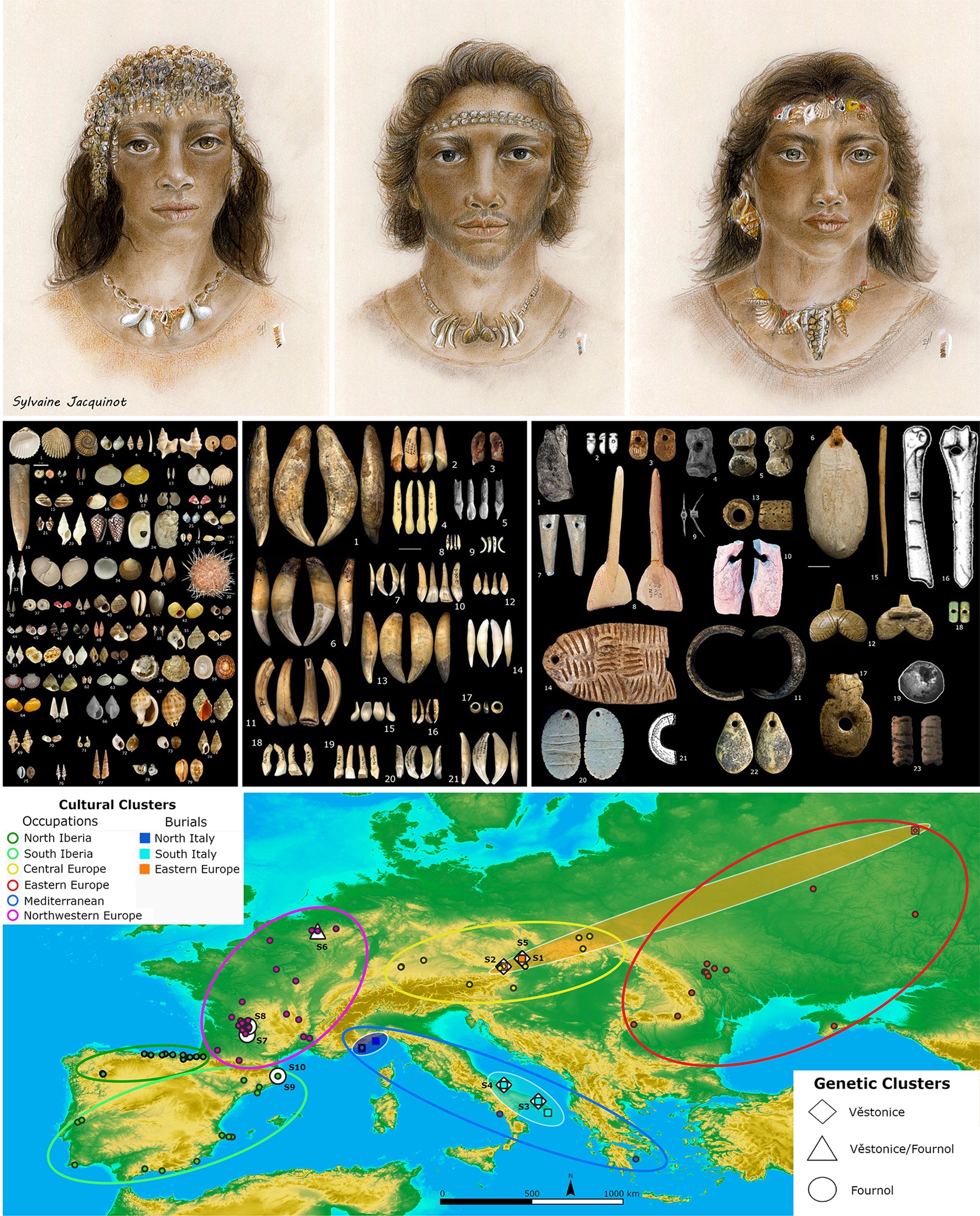

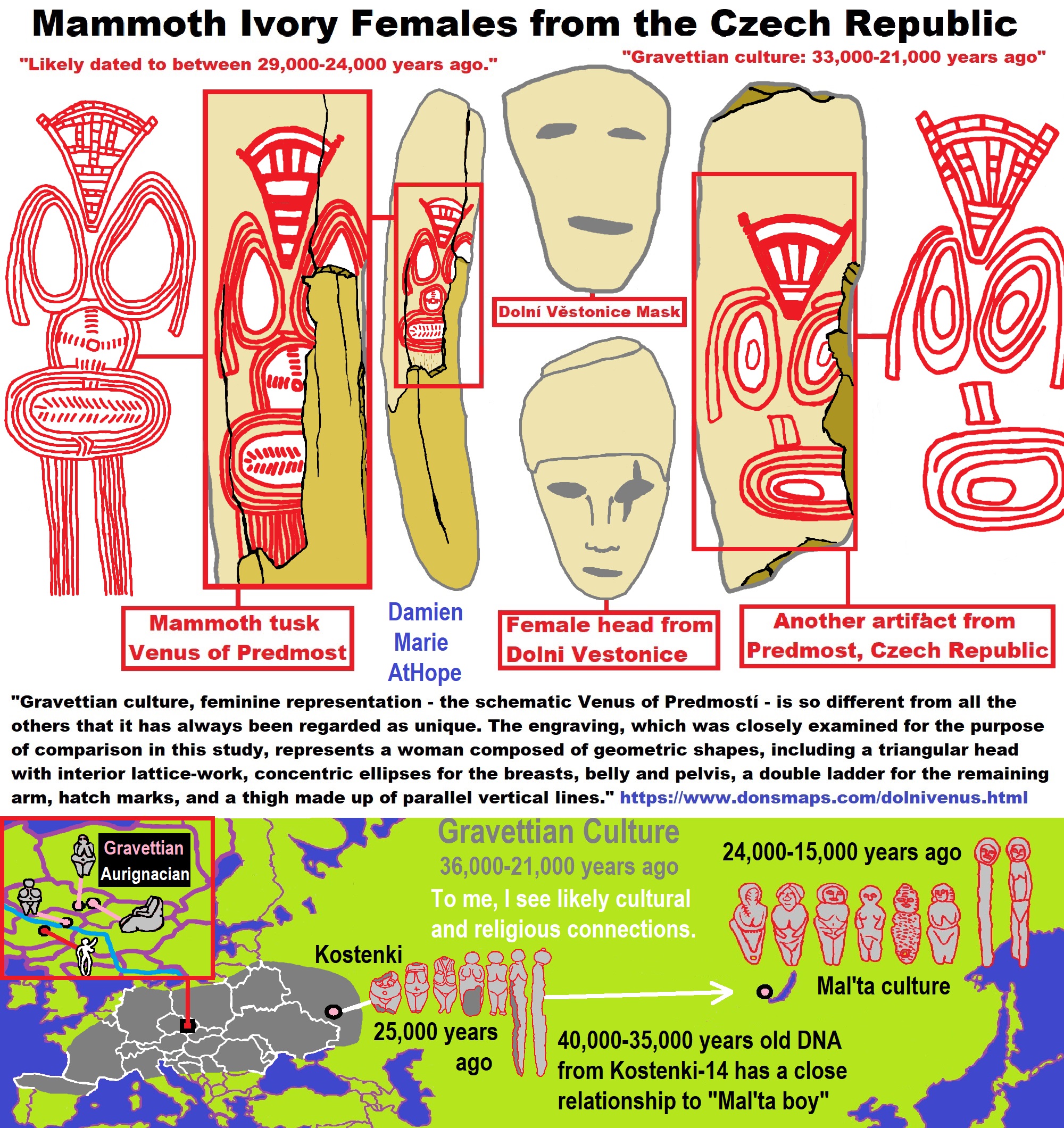

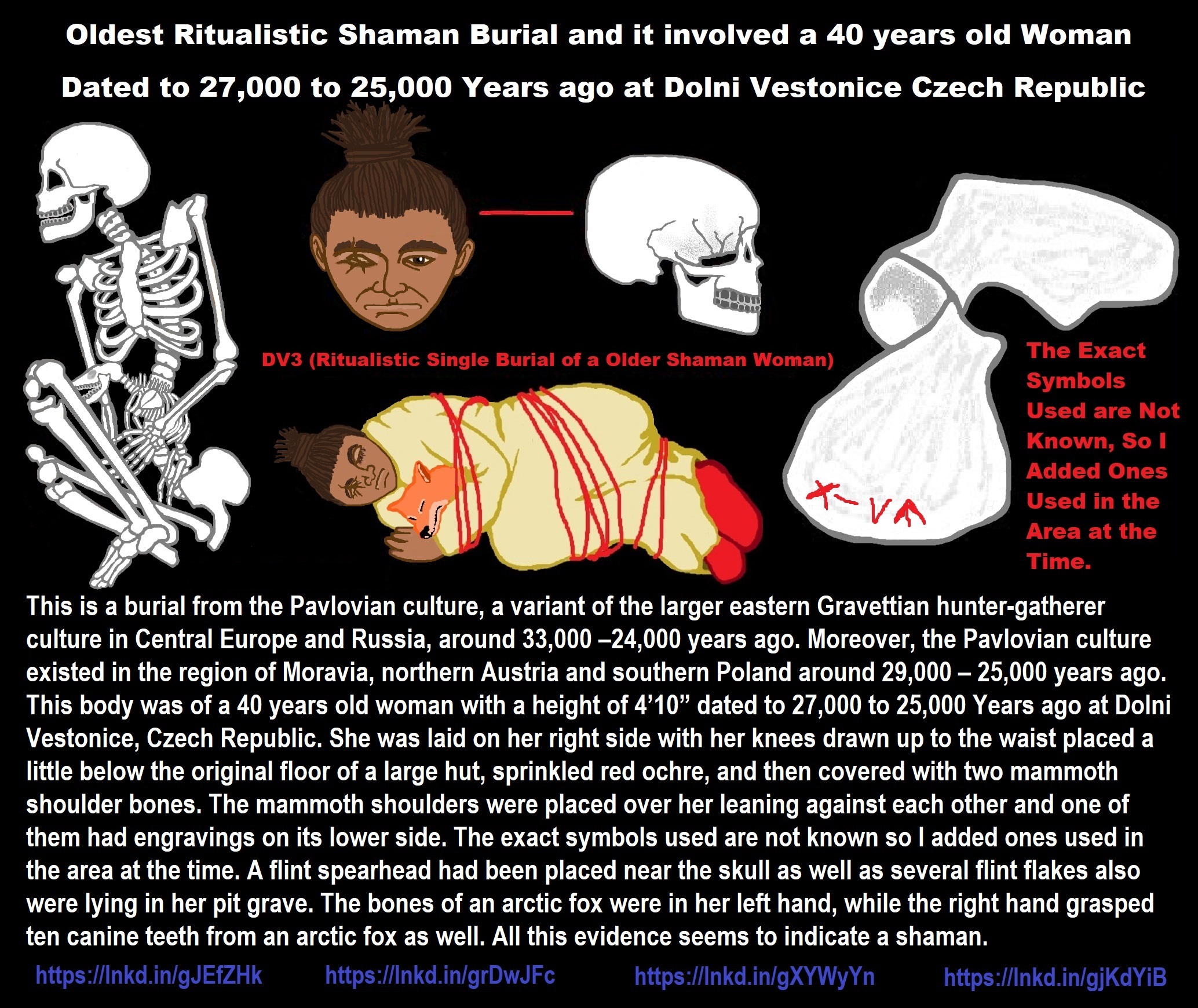

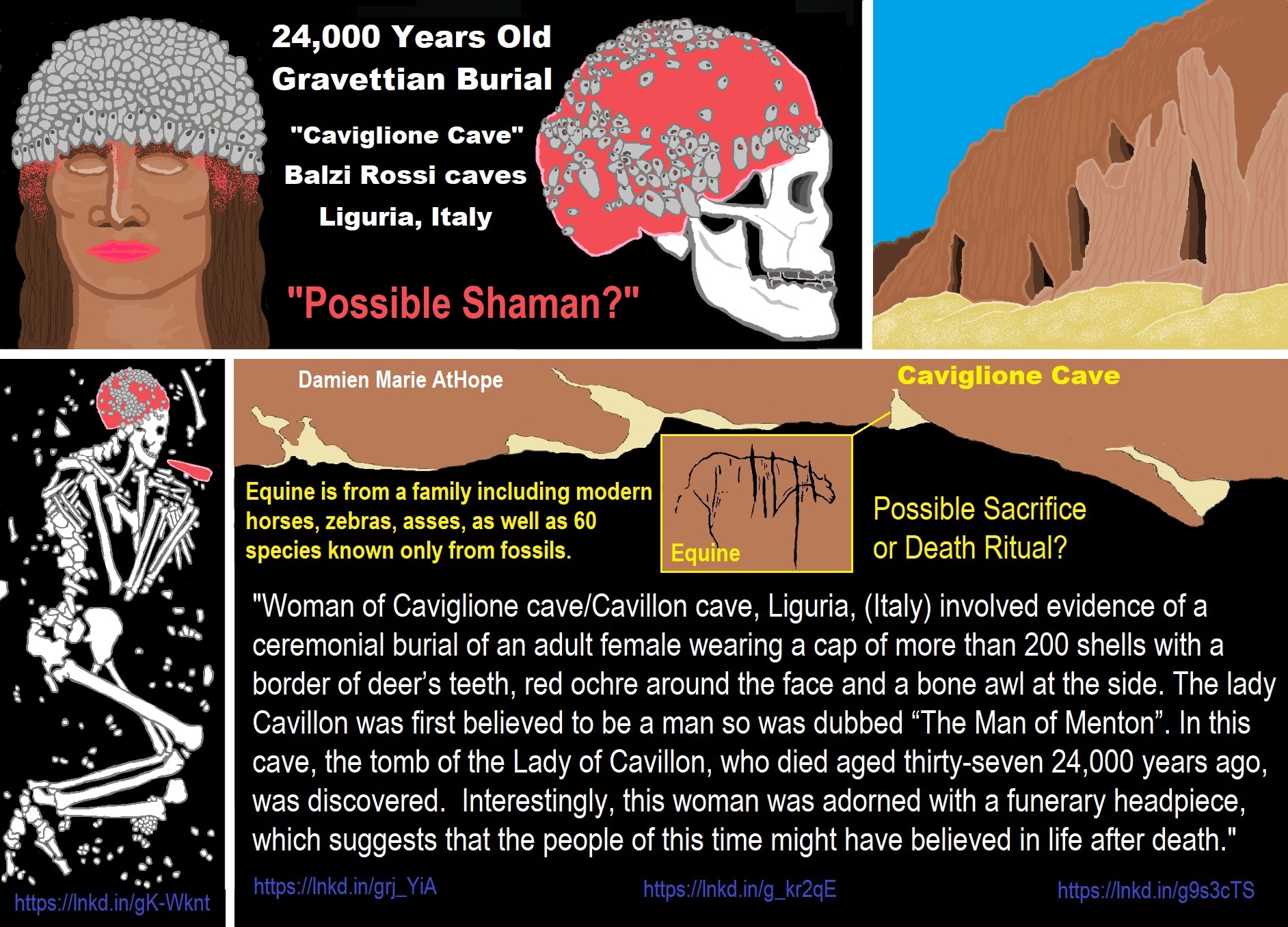

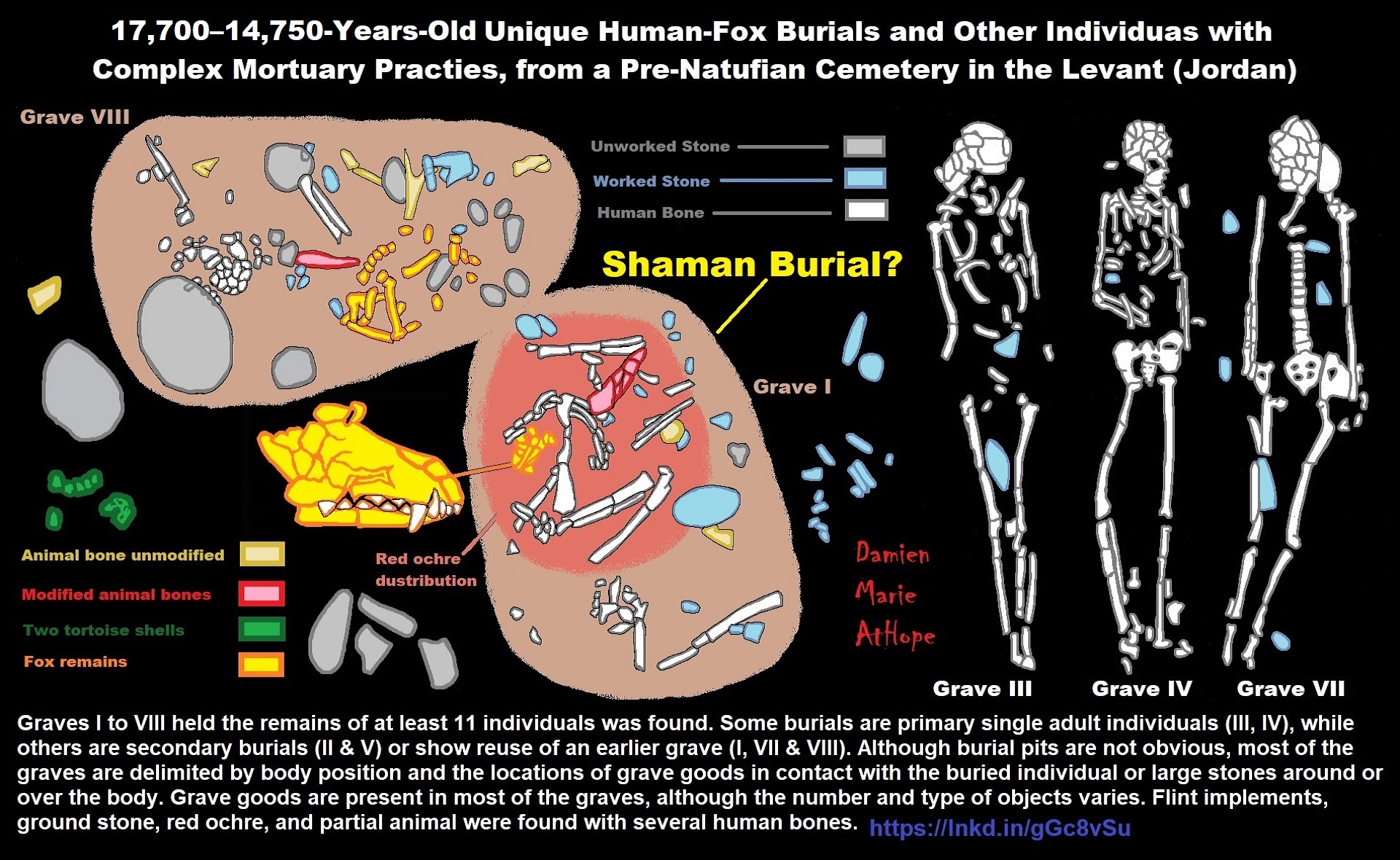

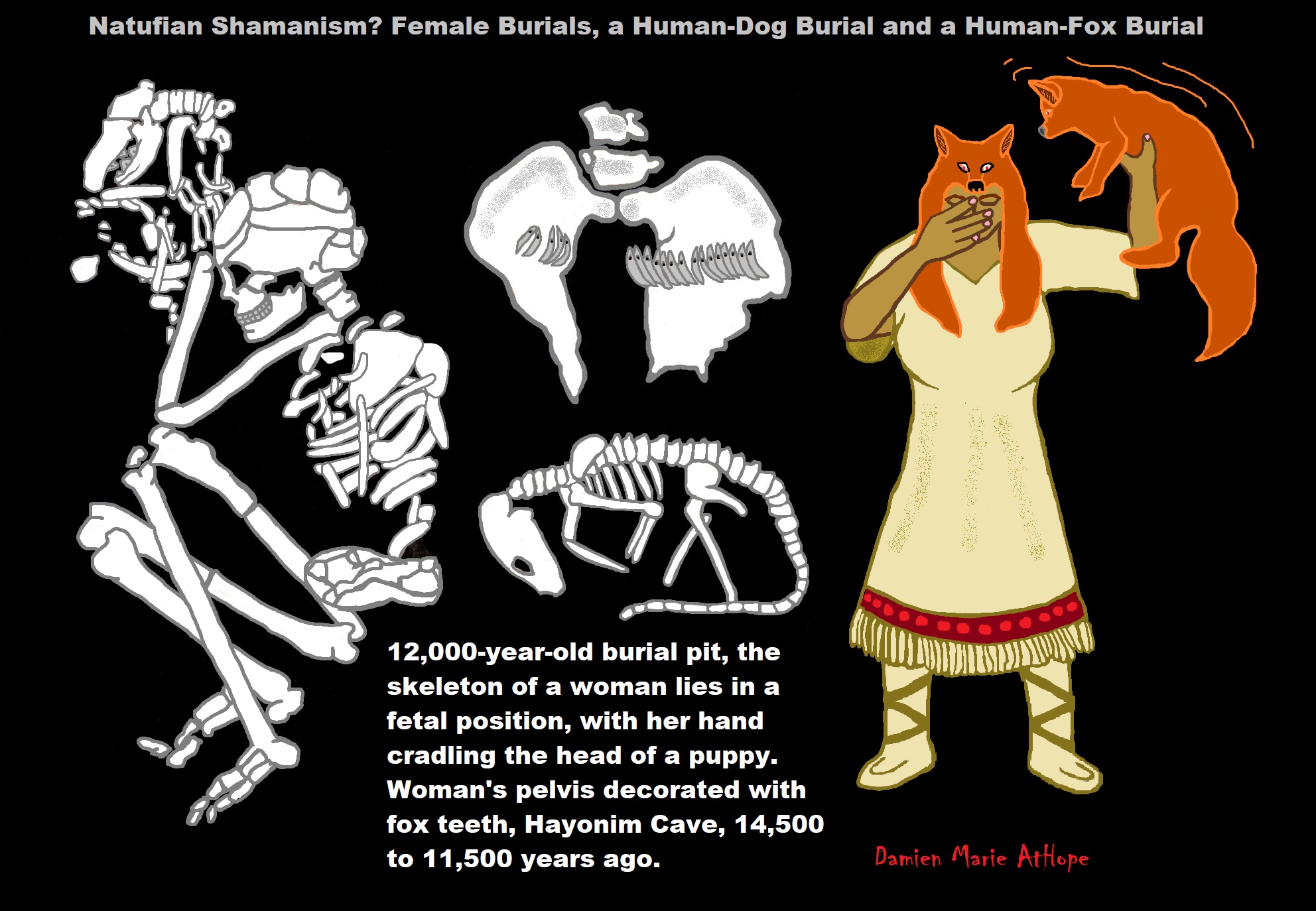

Around 29,000 to 25,000 years ago in Dolní Vestonice, Czech Republic, the oldest human face representation is a carved ivory female head that was found nearby a female burial and belong to the Pavlovian culture, a variant of the Gravettian culture. The left side of the figure’s face was a distorted image and is believed to be a portrait of an elder female, who was around 40 years old. She was ritualistically placed beneath a pair of mammoth scapulae, one leaning against the other. Surprisingly, the left side of the skull was disfigured in the same manner as the aforementioned carved ivory figure, indicating that the figure was an intentional depiction of this specific individual. The bones and the earth surrounding the body contained traces of red ocher, a flint spearhead had been placed near the skull, and one hand held the body of a fox. This evidence suggests that this was the burial site of a shaman. This is the oldest site not only of ceramic figurines and artistic portraiture but also of evidence of early female shamans. Before 5,500 years ago, women were much more prominent in religion.

Archaeologists usually describe two regional variants: the western Gravettian, known namely from cave sites in France, Spain, and Britain, and the eastern Gravettian in Central Europe and Russia. The eastern Gravettians include the Pavlovian culture, which were specialized mammoth hunters and whose remains are usually found not in caves but in open air sites. The origins of the Gravettian people are not clear, they seem to appear simultaneously all over Europe. Though they carried distinct genetic signatures, the Gravettians and Aurignacians before them were descended from the same ancient founder population. According to genetic data, 37,000 years ago, all Europeans can be traced back to a single ‘founding population’ that made it through the last ice age. Furthermore, the so-called founding fathers were part of the Aurignacian culture, which was displaced by another group of early humans members of the Gravettian culture. Between 37,000 years ago and 14,000 years ago, different groups of Europeans were descended from a single founder population. To a greater extent than their Aurignacian predecessors, they are known for their Venus figurines. ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, & ref

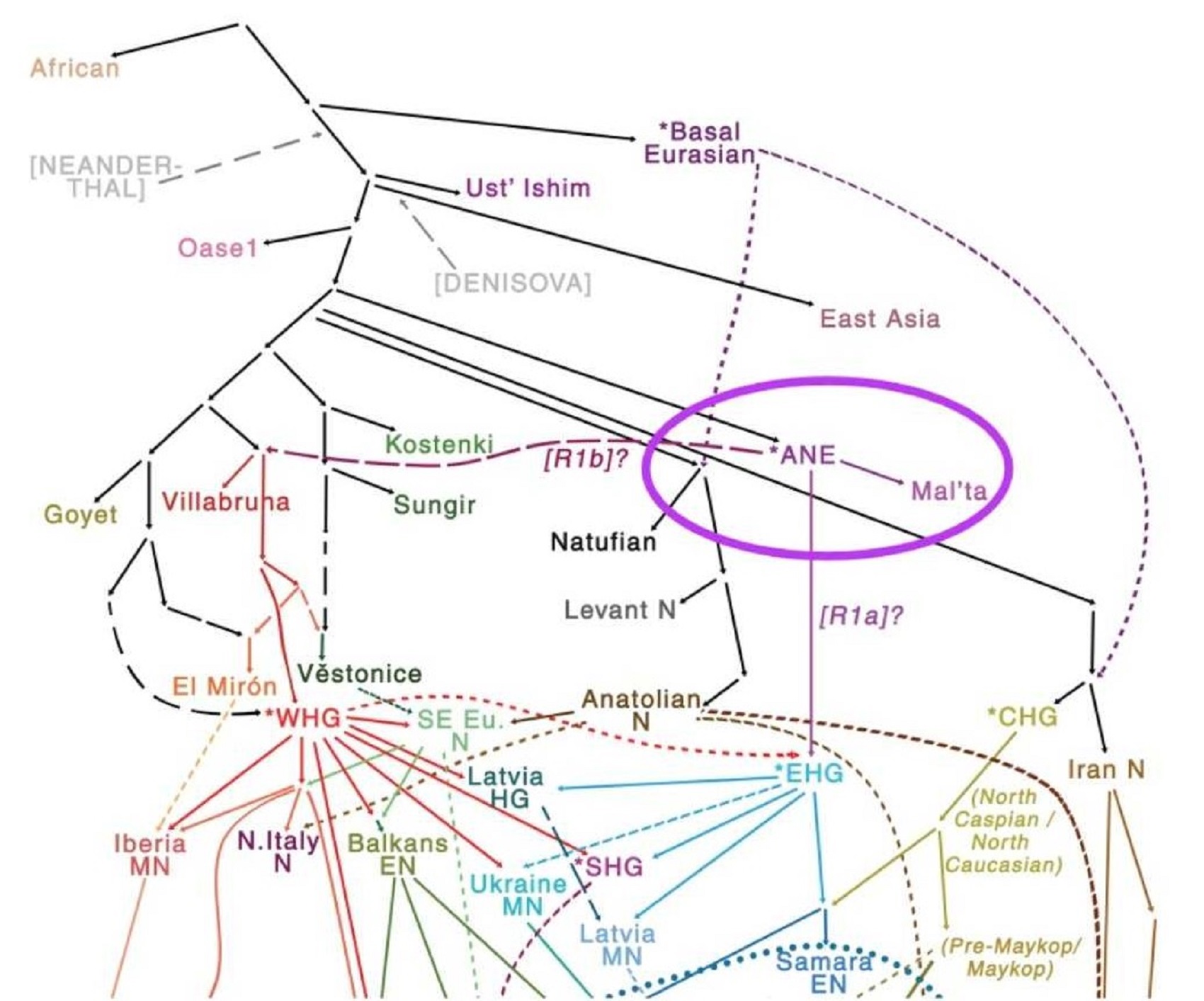

Haplogroup R is seen in several cultures

Haplogroup R possible time of origin about 27,000 years in Central Asia, South Asia, or Siberia:

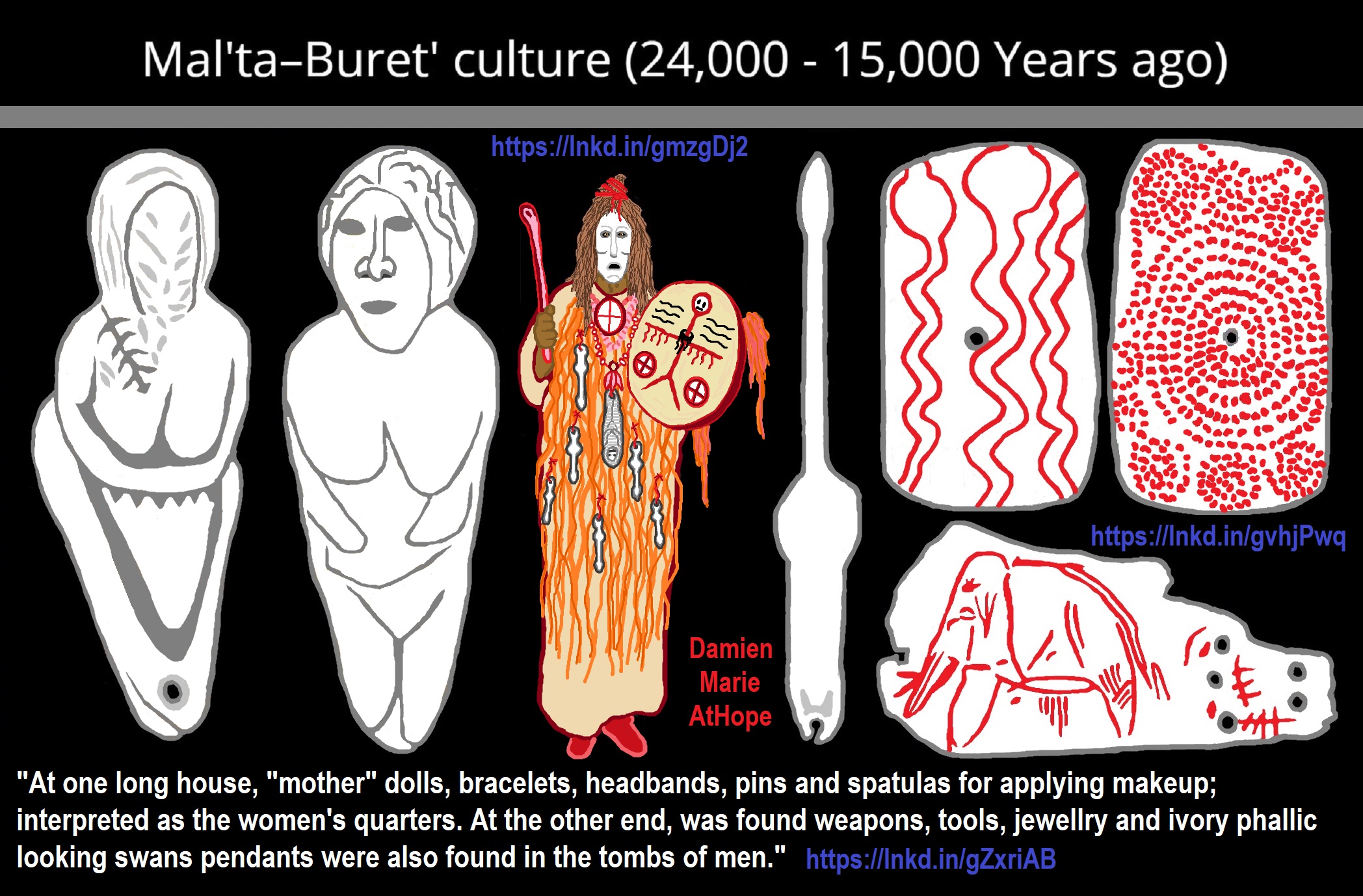

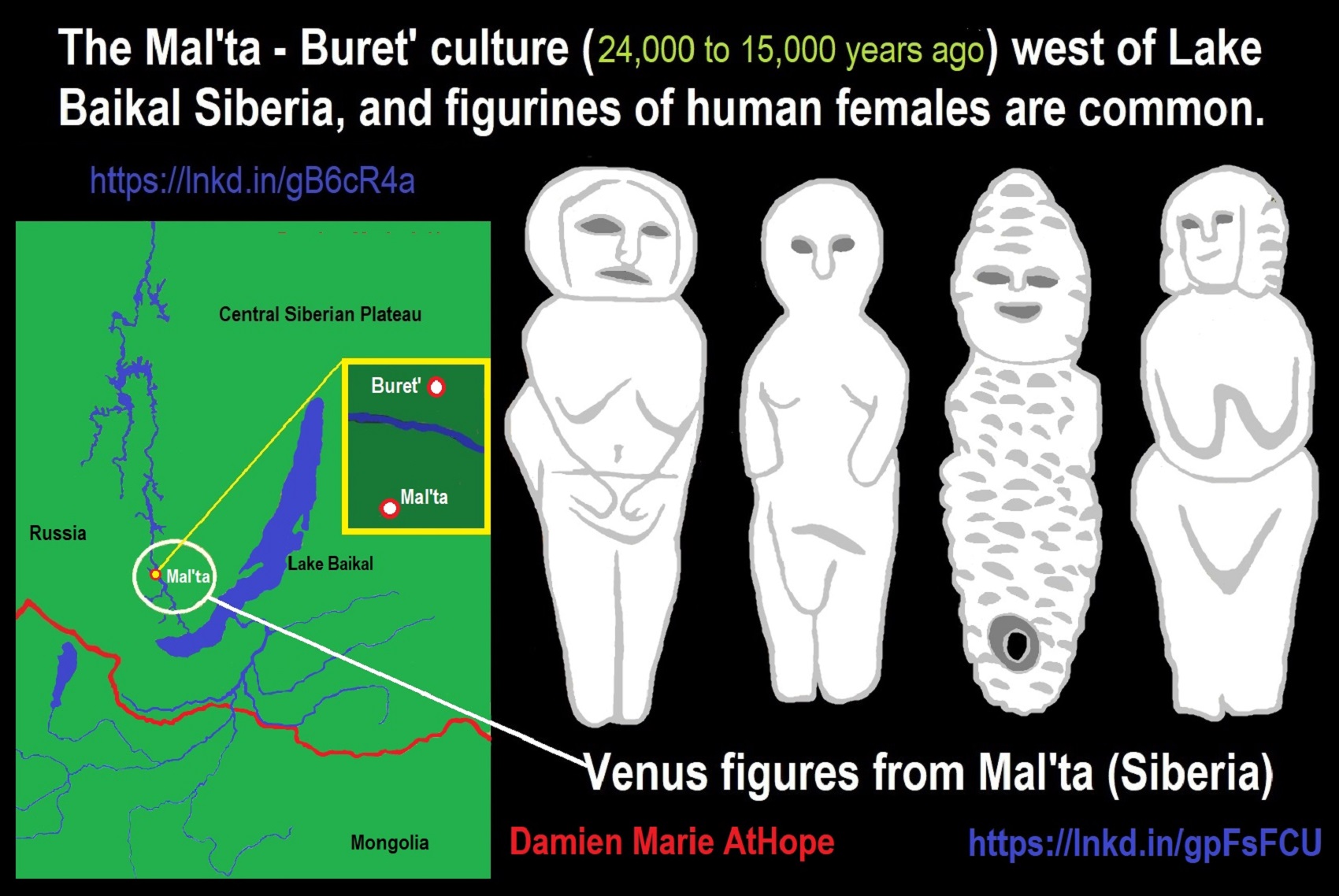

- Mal’ta–Buret’ culture (24,000-15,000 years ago)

- Afontova Gora culture (21,000-12,000 years ago)

- Trialetian culture (16,000–8000 years ago)

- Samara culture (7,000-6,500 years ago)

- Khvalynsk culture (7,000-6,500 years ago)

- Afanasievo culture (5,300-4,500 years ago)

- Yamna/Yamnaya Culture (5,300-4,500 years ago)

- Andronovo culture (4,000–2,900 years ago) ref

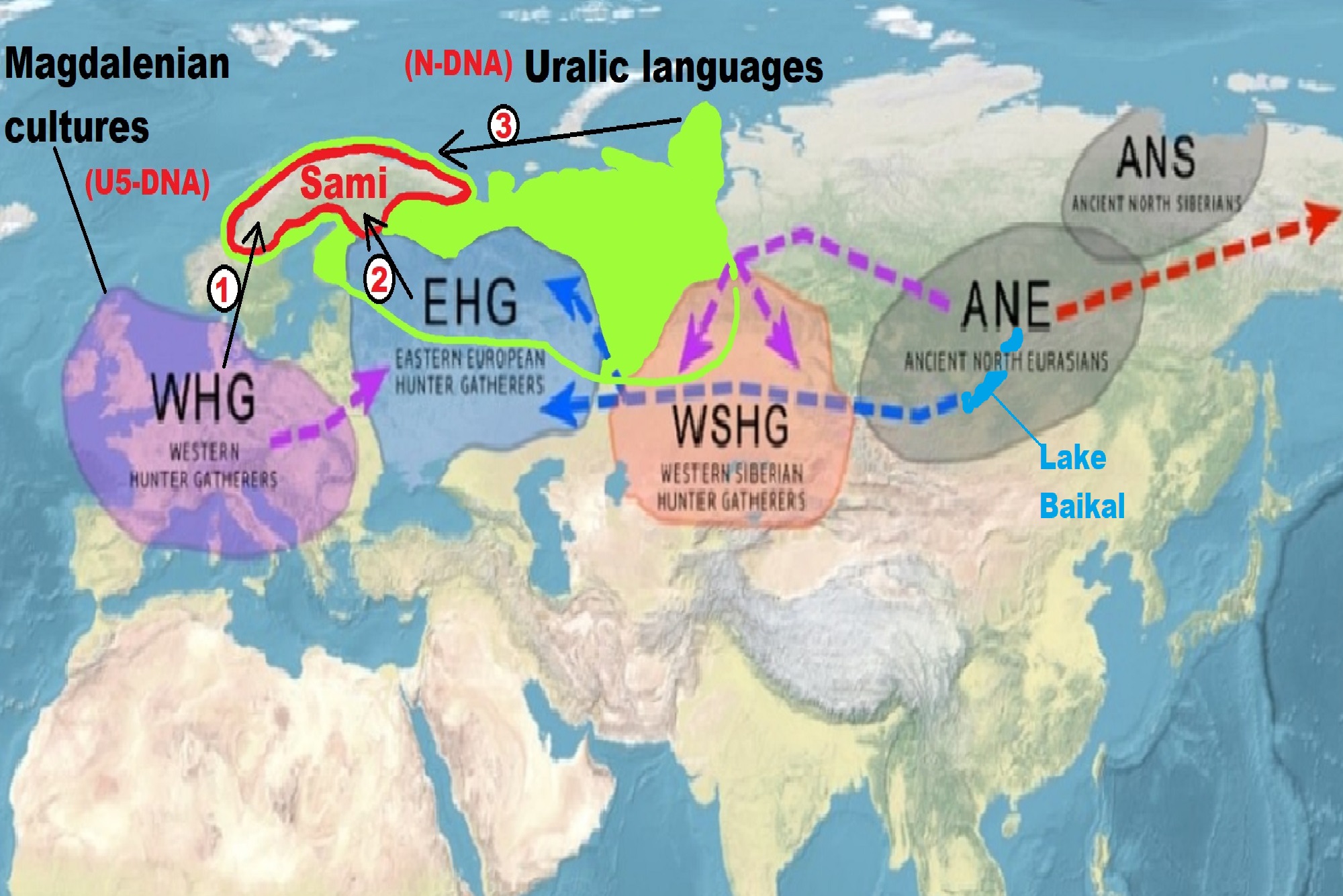

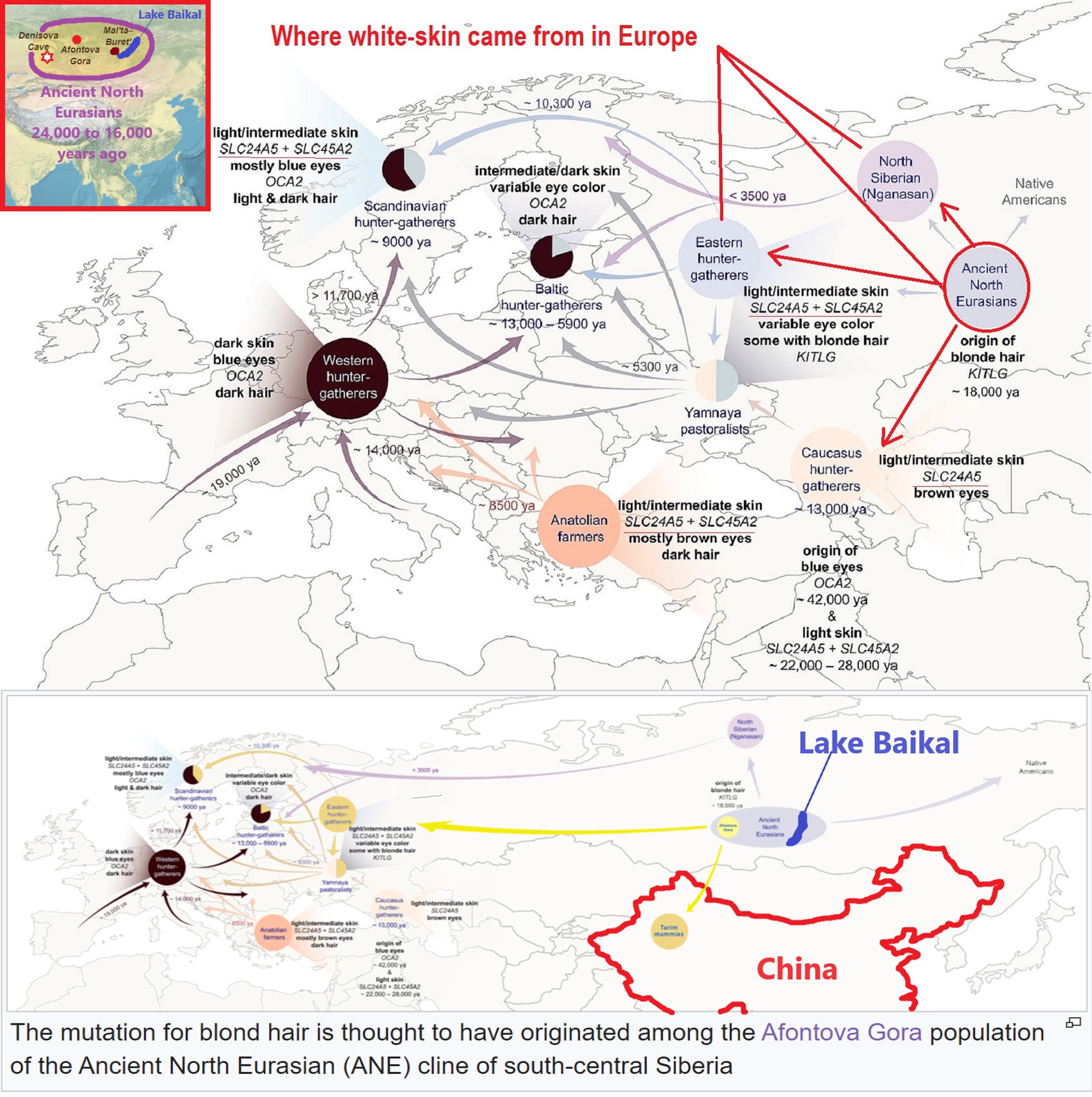

“Haplogroup U is a human mitochondrial DNA haplogroup (mtDNA). The clade arose from haplogroup R, likely during the early Upper Paleolithic. Basal U was found in the 26,000 years old remains of Ancient North Eurasian, Mal’ta boy (MA1 24,000 years old). Its various subclades (labelled U1–U9, diverging over the course of the Upper Paleolithic) are found widely distributed across Northern and Eastern Europe, Central, Western and South Asia, as well as North Africa, the Horn of Africa, and the Canary Islands. In a 2013 study, all but one of the ancient modern human sequences from Europe belonged to maternal haplogroup U, thus confirming previous findings that haplogroup U was the dominant type of Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) in Europe before the spread of agriculture into Europe and the presence and the spread of the Indo-Europeans in Western Europe. The age of U5 is estimated at between 25,000 and 35,000 years old, roughly corresponding to the Gravettian culture. Approximately 11% of Europeans (10% of European-Americans) have some variant of haplogroup U5. U5 was the predominant mtDNA of mesolithic Western Hunter Gatherers (WHG).” ref

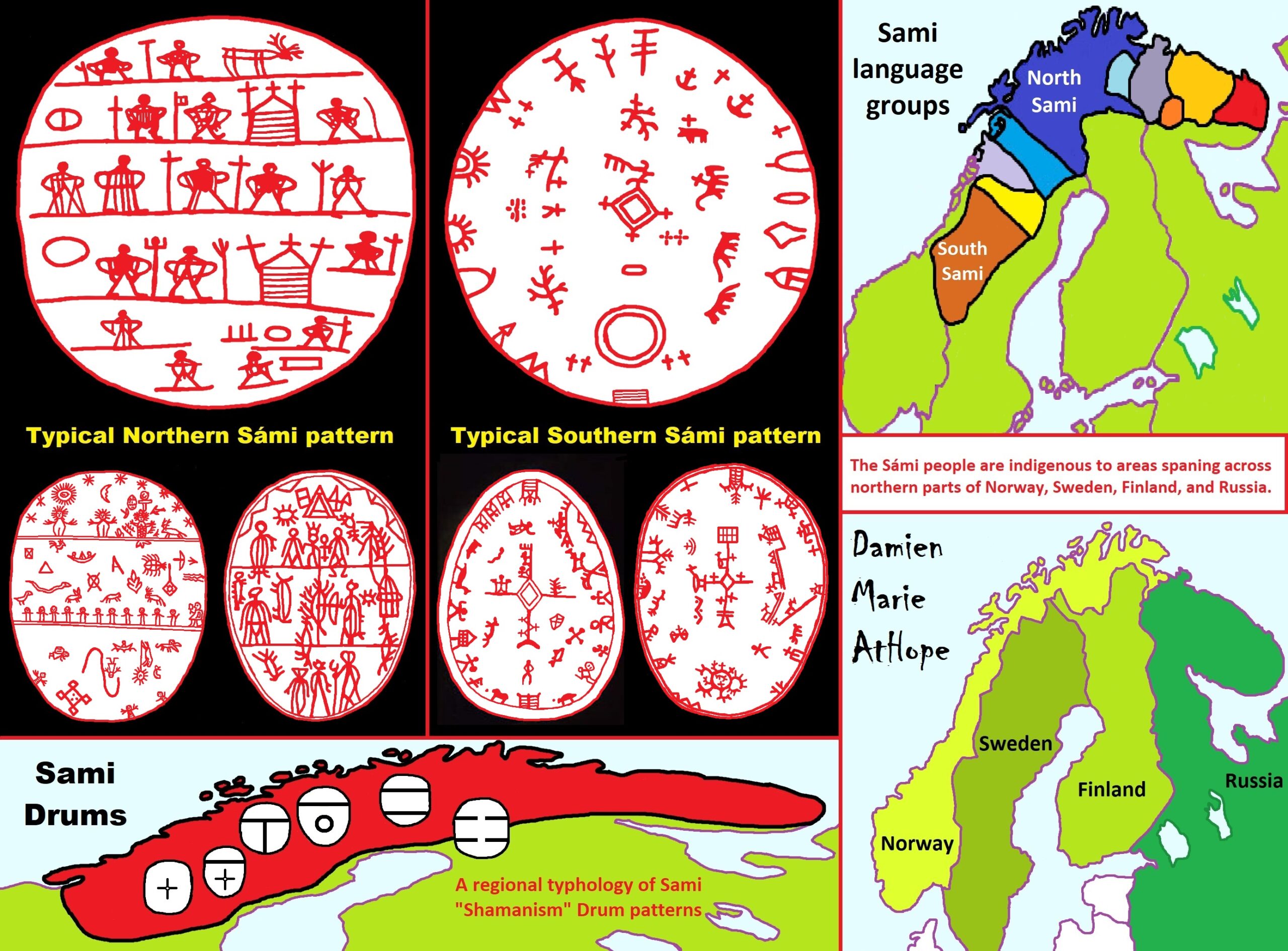

“U5 has been found in human remains dating from the Mesolithic in England, Germany, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal, Russia, Sweden, France and Spain. Neolithic skeletons (around 7,000 years old or so) that were excavated from the Avellaner cave in Catalonia, northeastern Spain included a specimen carrying haplogroup U5. Haplogroup U5 and its subclades U5a and U5b today form the highest population concentrations in the far north, among Sami, Finns, and Estonians. However, it is spread widely at lower levels throughout Europe. This distribution, and the age of the haplogroup, indicate individuals belonging to this clade were part of the initial expansion tracking the retreat of ice sheets from Europe around 10,000 years ago. U5b1b: has been found in Saami of Scandinavia, Finnish and the Berbers of North Africa, which were found to share an extremely young branch, aged merely around 9,000 years old or so. U5b1b was also found in Fulbe and Papel people in Guinea-Bissau and Yakuts people of northeastern Siberia. It arose around 11,000 years ago.” ref

Gravettian Culture “last European culture many consider unified” (33/35,000–24/20,000 years ago). Which Damien thinks expresses the first earliest shamanism. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gravettian

Pavlovian Culture “variant of the Gravettian” as seen in Czech Republic, Austria, and Poland (29,000–25,000 years ago). Which Damien thinks expresses the earliest burial of a shaman. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pavlovian_culture

Epigravettian Culture (Greek: epi “above, on top of”, and Gravettian, because they likely continued a lot of the Gravettian Culture) as seen in Southern and Eastern Europe (20,000–10,000 years ago) Which Damien thinks may have brought/influenced the people in the Middle East/Turkey to add belief in goddesses and female art/figurine themes to their early paganism emerging out or older shamanism 11,000/10,000 years ago. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Epigravettian

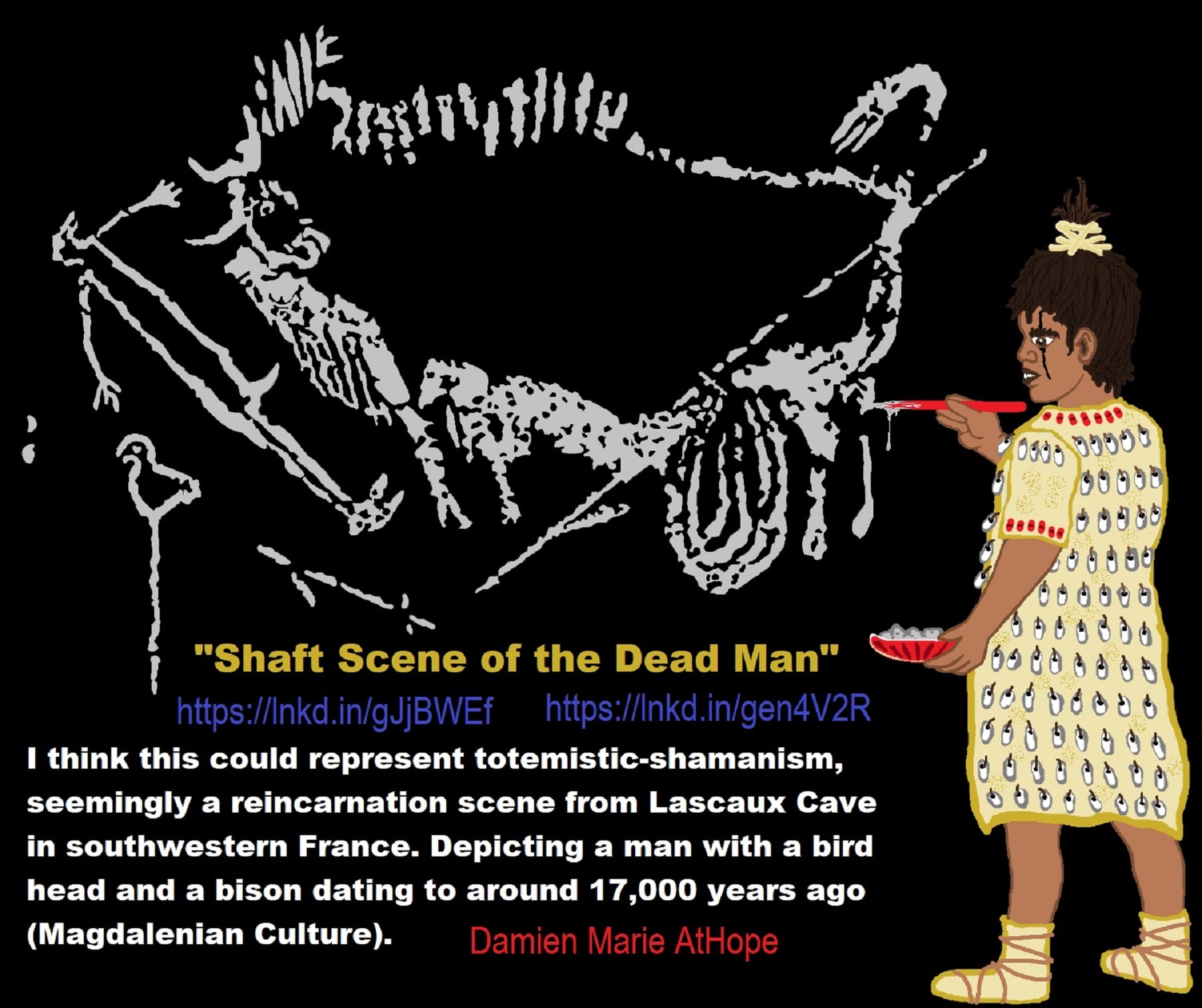

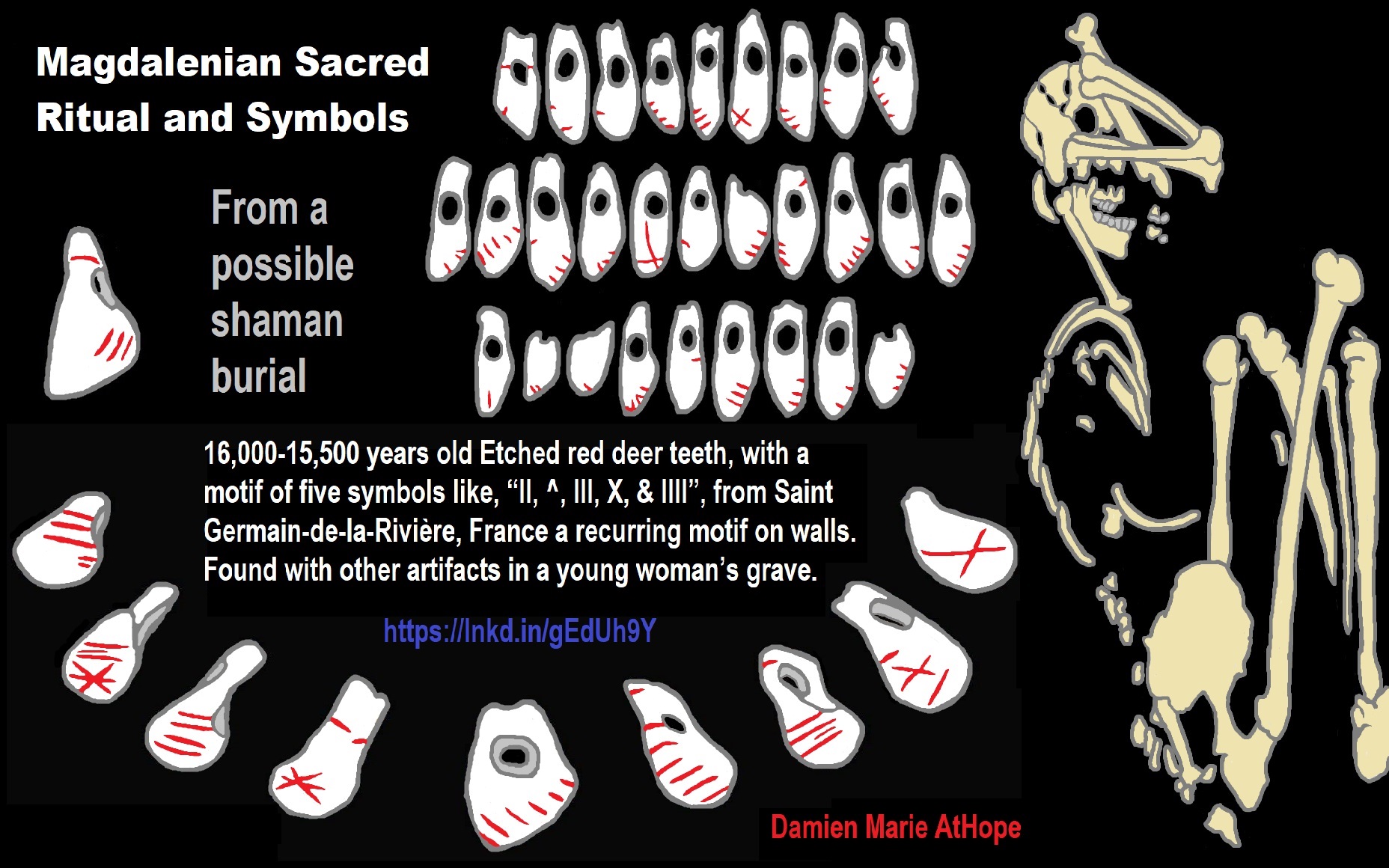

Magdalenian Culture as seen in Western Europe: “The earliest Magdalenian sites are in France and the Epigravettian is a similar culture appearing around the same time” (17,000–12,000 years ago) Which Damien thinks started to evolve Western Eurasian shamanism. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magdalenian

“The Magdalenian constitutes a civilization in the full meaning of the term, with its unique metaphysics, social rules, exchanges codified with nature via its art and weaponry. Before any climatic improvement then, daring was enough to both distinguish these populations from those that disappeared on a European scale and to invent facultative weapons, a conquering mythology, appropriate displacements, episodic ruptures, long-distance relays, flexibility in control over all kinds of environments, ritual delegation by shamanism, the “descent” of mythical decoration of rock walls in favor of mobile supports, such as modern crucifixes or portable altars.” https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1040618212001450

The Evidence of Shamanism Rituals in Early Prehistoric Periods of Europe and Anatolia

“Shamanism Rituals in Palaeolithic Siberian shamans (Eastern Eurasian Shamanism) believe that shamanism emerged in the period when hunting and gathering was the main means to support. Ethnographic evidence suggests that hunter-gatherer groups would have seen the environment as giving and reciprocating, and that their spirit worlds would have consisted largely of animals and natural features with which shaman-like figures may have mediated. From this point of view, it is best to begin investigating prehistoric shamanism in Palaeolithic rituals and related cave paintings of Europe. The shamanic hypothesis that cave art is based on a fusion of direct evidence from the caves themselves with observations of more recent hunter-gatherer societies that still produce rock art. However, not all cultures have specific shamanic ritual locations, and even when they are present, shamans will perform some rituals away from them. Ritual areas are typically viewed as the literal doorway between the spiritual and physical worlds, and are often an opening into the earth, like caves or springs, or elevated spaces such as mountains and even caves in mountains.” ref

“The Gravettian (30,000 to 20,000 years) is drawn in black and white; the subsequent Magdalenian (17,000 to 10,000 years) and Hamburgian (13,000-11,750 years) are in light blue and red. It is not known whether the spread of the Gravettian was a result of the diffusion of people or cultures.” ref

Gravettian culture

“The Gravettian was an archaeological industry of the European Upper Paleolithic that succeeded the Aurignacian circa 33,022 years ago. It is archaeologically the last European culture many consider unified, and had mostly disappeared by c. 22,022 years ago, close to the Last Glacial Maximum, although some elements lasted until c. 17,022 years ago. In Spain and France, it was succeeded by the Solutrean, and developed into or continued as the Epigravettian in Italy, the Balkans, Ukraine, and Russia. The Gravettian culture is known for Venus figurines, which were typically carved from either ivory or limestone. The culture was first identified at the site of La Gravette in the southwestern French department of Dordogne.” ref

“The Gravettians were hunter-gatherers who lived in a bitterly cold period of European prehistory, and the Gravettian lifestyle was shaped by the climate. Pleniglacial environmental changes forced them to adapt. West and Central Europe were extremely cold during this period. Archaeologists usually describe two regional variants: the western Gravettian, known mainly from cave sites in France, Spain, and Britain, and the eastern Gravettian in Central Europe and Russia. The eastern Gravettians, which include the Pavlovian culture, were specialized mammoth hunters, whose remains are usually found not in caves but in open-air sites.” ref

“Gravettian culture thrived on their ability to hunt animals. They utilized a variety of tools and hunting strategies. Compared to theorized hunting techniques of Neanderthals and earlier human groups, Gravettian hunting culture appears much more mobile and complex. They lived in caves or semi-subterranean or rounded dwellings which were typically arranged in small “villages”. Gravettians are thought to have been innovative in the development of tools such as blunted-back knives, tanged arrowheads, and boomerangs. Other innovations include the use of woven nets and oil lamps made of stone. Blades and bladelets were used to make decorations and bone tools from animal remains.” ref

“Gravettian culture extends across a large geographic region, as far as Estremadura in Portugal. but is relatively homogeneous until about 27,022 years ago. They developed burial rites, which included the inclusion of simple, purpose-built offerings and/or personal ornaments owned by the deceased, placed within the grave or tomb. Surviving Gravettian art includes numerous cave paintings and small, portable Venus figurines made from clay or ivory, as well as jewelry objects. The fertility deities mostly date from the early period; there are over 100 known surviving examples. They conform to a very specific physical type, with large breasts, broad hips, and prominent posteriors. The statuettes tend to lack facial details, and their limbs are often broken off. During the post-glacial period, evidence of the culture begins to disappear from northern Europe but was continued in areas around the Mediterranean.” ref

“Physical remains of people of the Gravettian have revealed that they were tall and relatively slender people. The male height of the Gravettian culture ranged between 179 and 188 centimeters (5 ft 10 in and 6 ft 2 in) tall with an average of 183.5 centimeters (6 ft 0.2 in), which is exceptionally tall not only for that period of prehistory but for all periods of history. They were fairly slender and normally weighed between 67–73 kilograms (148–161 lb), although they would likely have had a higher ratio of lean muscle mass compared to body fat in comparison to modern humans as a result of a very physically active and demanding lifestyle. The females of the Gravettian were much shorter, standing 158 centimeters (5 ft 2 in) on average, with an average weight of 54 kilograms (119 lb). Examinations of Gravettian skulls reveal that high cheekbones were common among them.” ref

“Clubs, stones, and sticks were the primary hunting tools during the Upper Paleolithic period. Bone, antler, and ivory points have all been found at sites in France; but proper stone arrowheads and throwing spears did not appear until the Solutrean period (~20,000 years ago). Due to the primitive tools, many animals were hunted at close range. The typical artifact of the Gravettian tool industry, once considered diagnostic, is the small pointed blade with a straight blunt back. They are today known as the Gravette point, and were used to hunt big game. Gravettians used nets to hunt small game, and are credited with inventing the bow and arrow.” ref

“Gravettian settlers tended towards the valleys that pooled migrating prey. Examples found through discoveries in Gr. La Gala, a site in Southern Italy, shows a strategic settlement based in a small valley. As the settlers became more aware of the migration patterns of animals like red deer, they learned that prey herd in valleys, thereby allowing the hunters to avoid traveling long distances for food. Specifically in Gr. La Gala, the glacial topography forced the deer to pass through the areas in the valley occupied by humans. Additional evidence of strategically positioned settlements include sites like Klithi in Greece, also placed to intercept migrating prey.” ref

“Discoveries in the Czech Republic suggest that nets were used to capture large numbers of smaller prey, thus offering a quick and consistent food supply and thus an alternative to the feast/famine pattern of large game hunters. Evidence comes in the form of 4 mm (0.16 in) thick rope preserved on clay imprints. Research suggests that although no larger net imprints have been discovered, there would be little reason for them not to be made as no further knowledge would be required for their creation. The weaving of nets was likely a communal task, relying on the work of both women and children.” ref

“The Gravettian era landscape is most closely related to the landscape of present-day Moravia. Pavlov I in southern Moravia is the most complete and complex Gravettian site to date, and a perfect model for a general understanding of Gravettian culture. In many instances, animal remains indicate both decorative and utilitarian purposes. In the case of, for example, Arctic foxes, incisors, and canines were used for decoration, while their humeri and radii bones were used as tools. Similarly, the skeletons of some red foxes contain decorative incisors and canines as well as ulnas used for awls and barbs.” ref

“Some animal bones were only used to create tools. Due to their shape, the ribs, fibulas, and metapodia of horses were good for awl and barb creation. In addition, the ribs were also implemented to create different types of smoothers for pelt preparation. The shapes of hare bones are also unique, and as a result, the ulnas were commonly used as awls and barbs. Reindeer antlers, ulnas, ribs, tibias, and teeth were utilized in addition to a rare documented case of a phalanx. Mammoth remnants are among the most common bone remnants of the culture, while long bones and molars are also documented. Some mammoth bones were used for decorative purposes. Wolf remains were often used for tool production and decoration.” ref

“In a genetic study published in Nature in May 2016, the remains of fourteen Gravettians were examined. The eight samples of Y-DNA analyzed were determined to be three samples of haplogroup CT, one sample of I, one sample of IJK, one sample of BT, one sample of C1a2, and one sample of F. Of the fourteen samples of mtDNA, there were thirteen samples of U and one sample of M. The majority of the sample of U belonged to the U5 and U2. In a genetic study published in Nature in November 2020, the remains of one adult male and two twin boys from a Gravettian site were examined. The Y-DNA analysis revealed that all 3 individuals belonged to haplogroup I. The 3 individuals had the same mtDNA, U5.” ref

Shamanism (such as that seen in Siberia Gravettian culture: 30,000 years ago)

- Gravettian culture (34,000–24,000 years ago; Western Gravettian, mainly France, Spain, and Britain, as well as Eastern Gravettian in Central Europe and Russia. The eastern Gravettians, which include the Pavlovian culture)

- Pavlovian culture (31,000 – 25,000 years ago such as in Austria and Poland)

- Prehistoric Child Burials Begin Around 34,000 Years Ago

- Early Shamanism around 34,000 to 20,000 years ago: Sungar (Russia) and Dolni Vestonice (Czech Republic)

- 31,000 – 20,000 years ago Oldest Shaman was Female, Buried with the Oldest Portrait Carving

- Shamanism: an approximately 30,000-year-old belief system

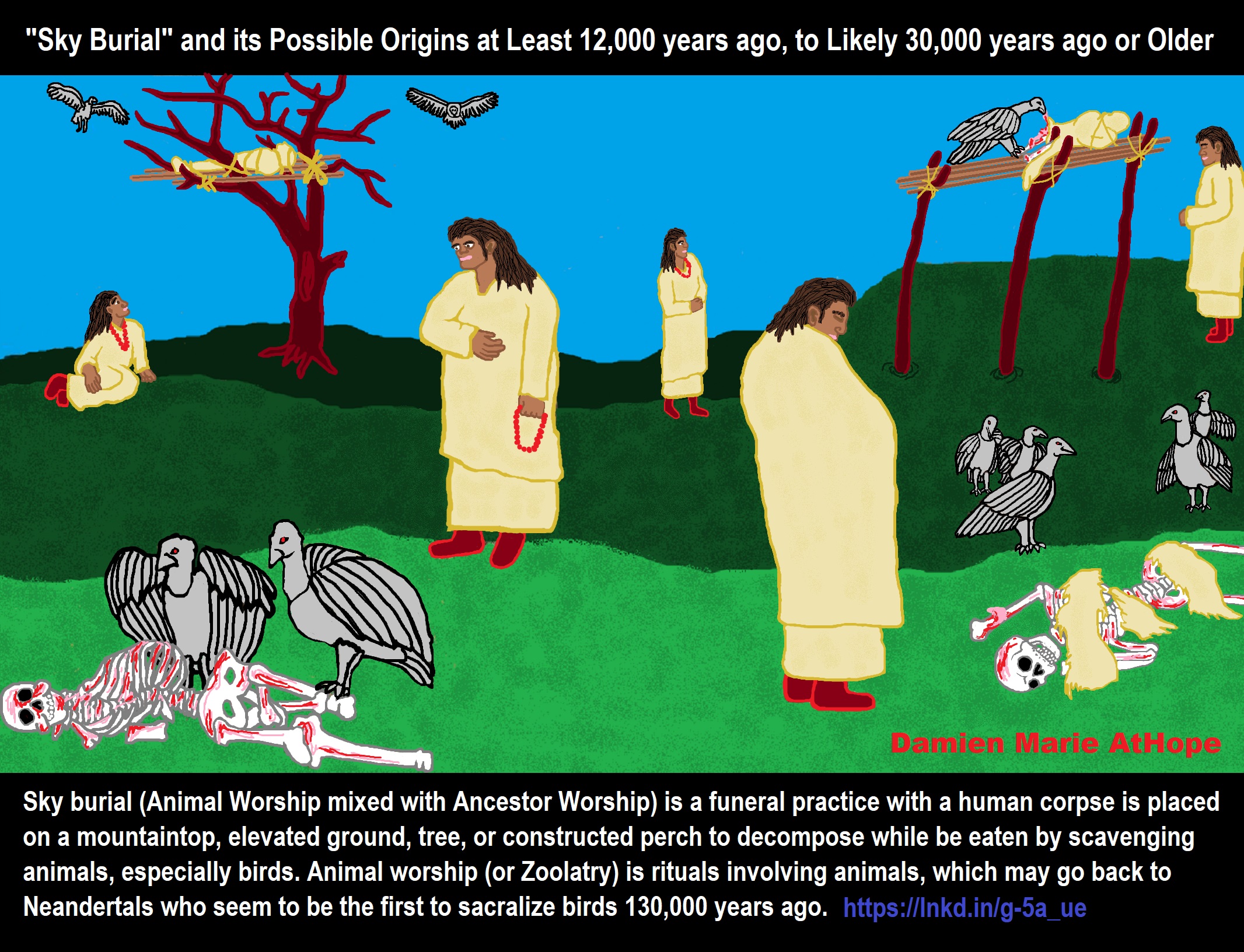

- ‘Sky Burial’ theory and its possible origins at least 12,000 years ago to likely 30,000 years ago or older.

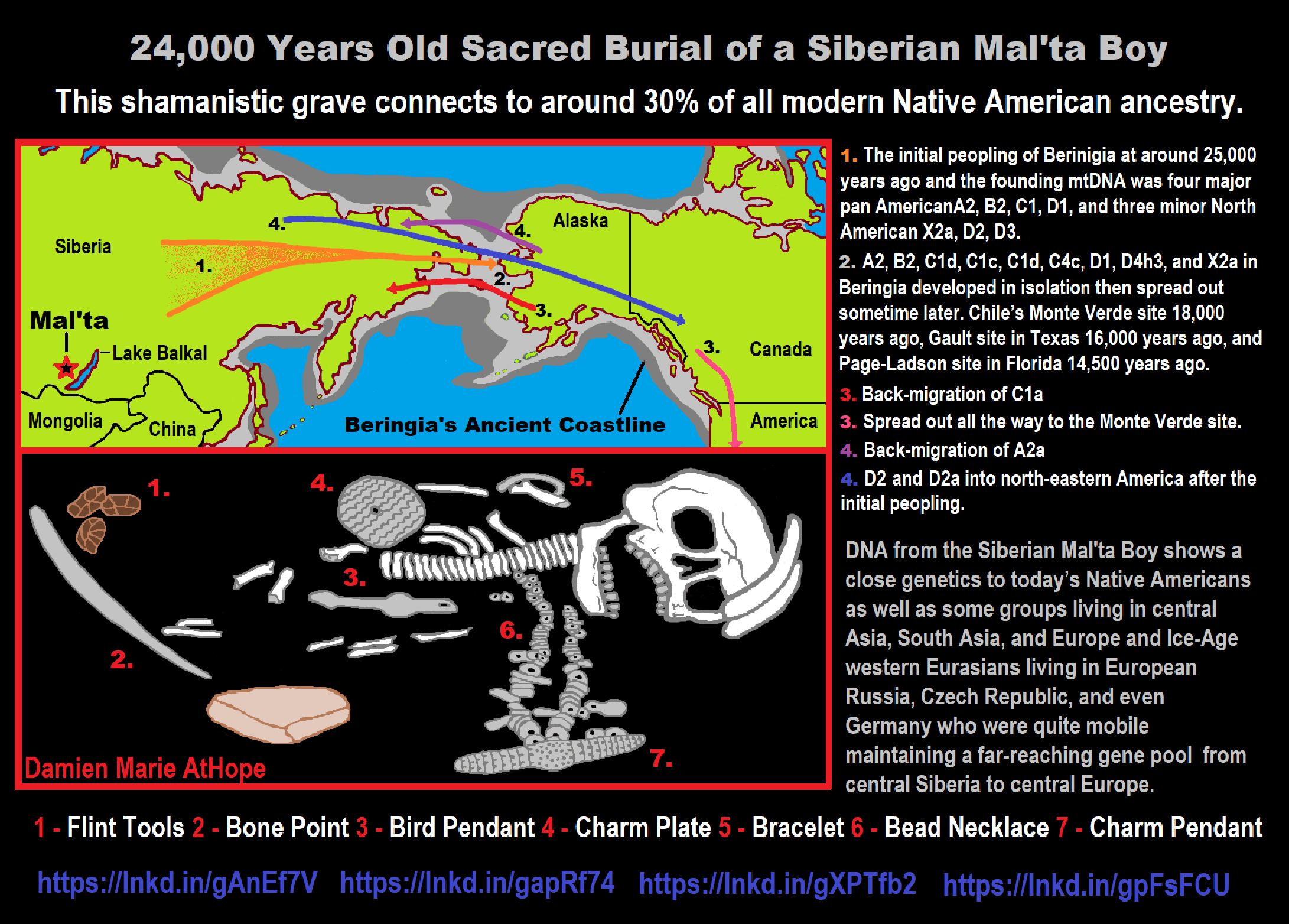

- The Peopling of the Americas Pre-Paleoindians/Paleoamericans around 30,000 to 12,000 years ago

- Similarity in Shamanism?

- Black, White, and Yellow Shamanism?

- Possible Clan Leader/Special “MALE” Ancestor Totem Poles At Least 13,500 years ago?

- Fertile Crescent 12,500 – 9,500 Years Ago: fertility and death cult belief system?

- 12,400 – 11,700 Years Ago – Kortik Tepe (Turkey) Pre/early-Agriculture Cultic Ritualism

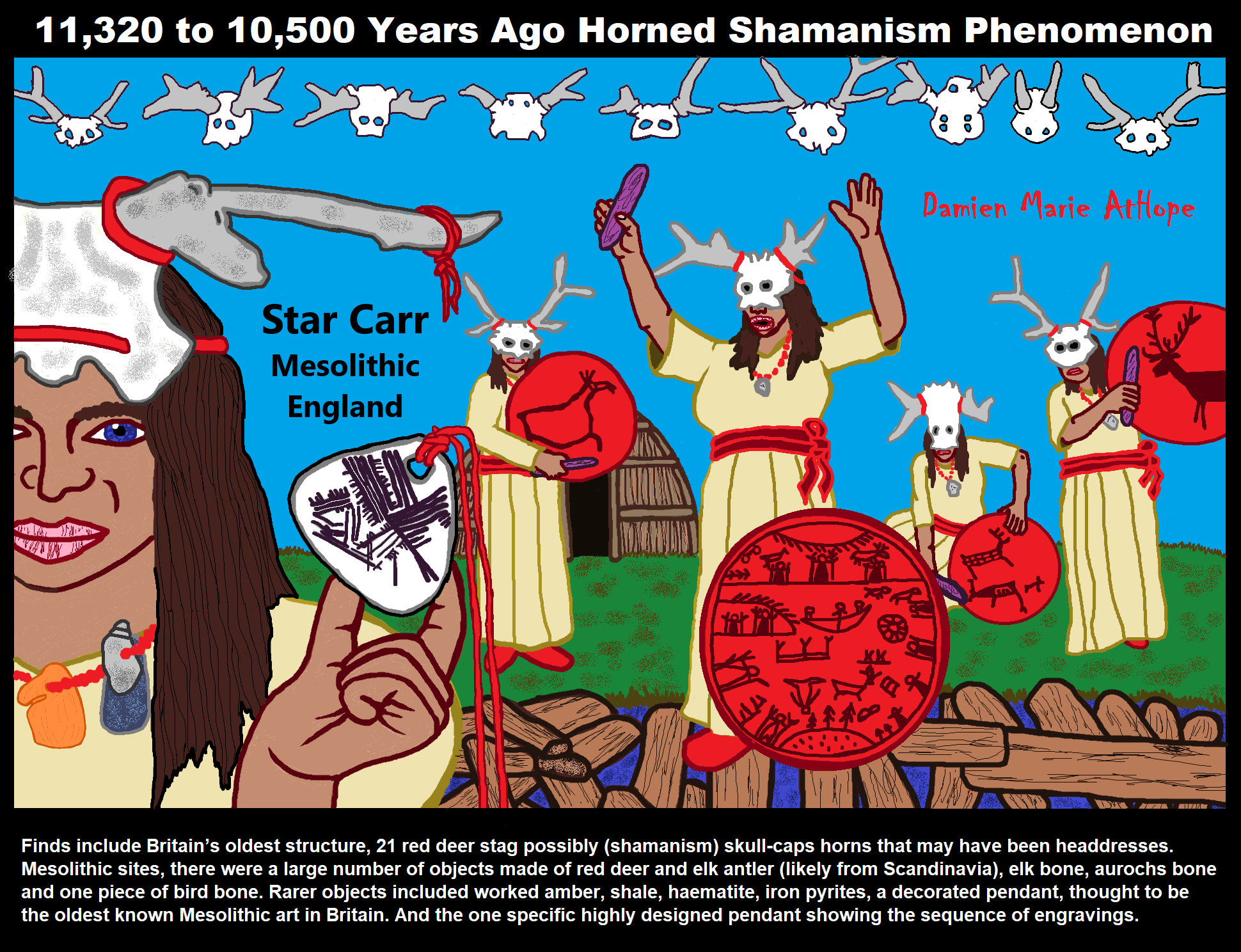

- Horned female shamans and Pre-satanism Devil/horned-god Worship? at least 10,000 years ago.

- Shamanistic rock art 8,000 and 10,000 years ago from central Aboriginal Siberians and Aboriginal drums in the Americas.

Shamanism is approximately a 30,000-year-old belief system and believe in spirit-filled life and/or afterlife that can be attached to or be expressed in things or objects and these objects can be used by special persons or in special rituals that can connect to spirit-filled life and/or afterlife. If you believe like this, regardless of your faith, you are a hidden shamanist.

Around 29,000 to 25,000 years ago in Dolní Vestonice, Czech Republic, the oldest human face representation is a carved ivory female head that was found nearby a female burial and belong to the Pavlovian culture, a variant of the Gravettian culture. The left side of the figure’s face was a distorted image and is believed to be a portrait of an elder female, who was around 40 years old. She was ritualistically placed beneath a pair of mammoth scapulae, one leaning against the other. Surprisingly, the left side of the skull was disfigured in the same manner as the aforementioned carved ivory figure, indicating that the figure was an intentional depiction of this specific individual. The bones and the earth surrounding the body contained traces of red ocher, a flint spearhead had been placed near the skull, and one hand held the body of a fox. This evidence suggests that this was the burial site of a shaman. This is the oldest site not only of ceramic figurines and artistic portraiture but also of evidence of early female shamans. Before 5,500 years ago, women were much more prominent in religion.

Archaeologists usually describe two regional variants: the western Gravettian, known namely from cave sites in France, Spain, and Britain, and the eastern Gravettian in Central Europe and Russia. The eastern Gravettians include the Pavlovian culture, which were specialized mammoth hunters and whose remains are usually found not in caves but in open air sites. The origins of the Gravettian people are not clear, they seem to appear simultaneously all over Europe. Though they carried distinct genetic signatures, the Gravettians and Aurignacians before them were descended from the same ancient founder population. According to genetic data, 37,000 years ago, all Europeans can be traced back to a single ‘founding population’ that made it through the last ice age. Furthermore, the so-called founding fathers were part of the Aurignacian culture, which was displaced by another group of early humans members of the Gravettian culture. Between 37,000 years ago and 14,000 years ago, different groups of Europeans were descended from a single founder population. To a greater extent than their Aurignacian predecessors, they are known for their Venus figurines. ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, & ref

- “33,000 years ago: oldest known domesticated dog skulls show they existed in both Europe and Siberia by this time.

- 31,000–16,000 years ago: Last Glacial Maximum (peak at 26,500 years ago).

- 30,000 years ago: rock paintings tradition begins in Bhimbetka rock shelters in India, which presented as a collection is the densest known concentration of rock art. In an area about 10 km2, there are about 800 rock shelters of which 500 contain paintings.

- 29,000 years ago: The earliest ovens found.

- 28,500 years ago: New Guinea is populated by colonists from Asia or Australia.

- 28,000 years ago: the oldest known twisted rope.

- 28,000–24,000 years ago: some of the oldest known pottery—used to make figurines rather than cooking or storage vessels (Venus of Dolní Věstonice).

- 28,000–20,000 years ago: Gravettian period in Europe. Harpoons and saws invented.

- 26,000 years ago: people around the world use fibers to make baby carriers, clothes, bags, baskets, and nets.

- 25,000 years ago: a hamlet consisting of huts built of rocks and of mammoth bones is founded in what is now Dolní Věstonice in Moravia in the Czech Republic. This is the oldest human permanent settlement that has yet been found by archaeologists.

- 21,000 years ago: artifacts suggests early human activity occurred in Canberra, the capital city of Australia.

- 20,000 years ago: Kebaran culture in the Levant.

- 20,000 years ago: oldest pottery storage/cooking vessels from China.

- 20,000-10,000 years ago: Khoisanid expansion to Central Africa.

- 16,000-14,000 years ago: Minatogawa Man (Proto-Mongoloid phenotype) in Okinawa, Japan

- 16,000–13,000 years ago: the first colonization of North America.

- 16,000-11,000 years ago: Caucasian Hunter-Gatherer (Caucasoid phenotype) expansion to Europe.

- 16,000 years ago: Wisent sculpted in clay deep inside the cave now known as Le Tuc d’Audoubert in the French Pyrenees near what is now the border of Spain.

- 15,000–14,700 years ago: Earliest supposed date for the domestication of the pig.

- 14,800 years ago: The Humid Period begins in North Africa. The region that would later become the Sahara is wet and fertile, and the aquifers are full.

- 14,500-11,500: Red Deer Cave people in China, possible late survival of archaic or archaic-modern hybrid humans.

- 14,000-12,000 years ago: Oldest evidence for prehistoric warfare (Jebel Sahaba massacre, Natufian culture).

- 13,000–10,000 years ago: Late Glacial Maximum, end of the Last glacial period, climate warms, glaciers recede.

- 13,000 years ago: A major water outbreak occurs on Lake Agassiz, which at the time could have been the size of the current Black Sea and the largest lake on Earth. Much of the lake is drained in the Arctic Ocean through the Mackenzie River.

- 13,000–11,000 years ago: Earliest dates suggested for the domestication of the sheep.

- Approximately 13,000 years ago, the Younger Dryas ice age.” ref

“Haplogroup U is a human mitochondrial DNA haplogroup (mtDNA). The clade arose from haplogroup R, likely during the early Upper Paleolithic. Its various subclades (labeled U1–U9, diverging over the course of the Upper Paleolithic) are found widely distributed across Northern and Eastern Europe, Central, Western, and South Asia, as well as North Africa, the Horn of Africa, and the Canary Islands. Basal U was found in the 26,000-year-old remains of Ancient North Eurasian, Mal’ta boy (MA1). The age of U5 is estimated at between 25,000 and 35,000 years old, roughly corresponding to the Gravettian culture. and is the DNA associated with the seeming first Gravettian shaman burial seen in the Pavlovian culture, around Dolní Věstonice in southern Moravia. One of the Dolní Věstonice burials, located near the huts, revealed a human female skeleton aged to 40+ years old, ritualistically placed beneath a pair of mammoth scapulae, one leaning against the other. Surprisingly, the left side of the skull was disfigured in the same manner as the aforementioned carved ivory figure, indicating that the figure was an intentional depiction of this specific individual. The bones and the earth surrounding the body contained traces of red ocher, a flint spearhead had been placed near the skull, and one hand held the body of a fox. This evidence suggests that this was the burial site of a shaman. This is the oldest site not only of ceramic figurines and artistic portraiture, but also of evidence of female shamans.” ref, ref, ref, ref

“Approximately 11% of Europeans (10% of European-Americans) have some variant of haplogroup U5. U5 was the predominant mtDNA of mesolithic Western Hunter Gatherers (WHG). U5 has been found in human remains dating from the Mesolithic in England, Germany, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal, Russia, Sweden, France, and Spain. Neolithic skeletons (~7,000 years old) that were excavated from the Avellaner cave in Catalonia, northeastern Spain included a specimen carrying haplogroup U5. Haplogroup U5 and its subclades U5a and U5b today form the highest population concentrations in the far north, among Sami, Finns, and Estonians. However, it is spread widely at lower levels throughout Europe. This distribution, and the age of the haplogroup, indicate individuals belonging to this clade were part of the initial expansion tracking the retreat of ice sheets from Europe around 10,000 years ago. The modern Basques and Cantabrians possess almost exclusively U5b lineages (U5b1f, U5b1c1, U5b2).” ref

6 Ice Age Humans (30,000 Years Ago)

“Abstract: Starting about 35,000 years ago, humans seem to have made a great leap forward culturally. The authors argue that this wasn’t because of genetic changes that caused the human brain to have increased capacity. It was because some groups culturally evolved the “social tools” that allowed them to maintain connections and share information over long distances. The groups with the most effective social tools managed to stay connected and to survive, and their descendants inherited this culture of connectedness. It’s likely that forming greater connectedness and more complex culture was necessary in order to survive the periods of high climate variability that were a feature of the last ice age.” ref

“Archaeologists usually describe two regional variants: the western Gravettian, known mainly from cave sites in France, Spain, and Britain, and the eastern Gravettian in Central Europe and Russia. The eastern Gravettians, which include the Pavlovian culture, were specialized mammoth hunters, whose remains are usually found not in caves but in open air sites. Gravettian culture thrived on their ability to hunt animals. They utilized a variety of tools and hunting strategies. Compared to theorized hunting techniques of Neanderthals and earlier human groups, Gravettian hunting culture appears much more mobile and complex. They lived in caves or semi-subterranean or rounded dwellings which were typically arranged in small “villages”. Gravettians are thought to have been innovative in the development of tools such as blunted-back knives, tanged arrowheads, and boomerangs. Other innovations include the use of woven nets and oil lamps made of stone. Blades and bladelets were used to make decorations and bone tools from animal remains.” ref

“Gravettian culture extends across a large geographic region, as far as Estremadura in Portugal. but is relatively homogeneous until about 27,000 years ago. They developed burial rites, which included simple, purpose-built offerings and/or personal ornaments owned by the deceased, placed within the grave or tomb. Surviving Gravettian art includes numerous cave paintings and small, portable Venus figurines made from clay or ivory, as well as jewelry objects. The fertility deities mostly date from the early period; there are over 100 known surviving examples. They conform to a very specific physical type, with large breasts, broad hips and prominent posteriors. The statuettes tend to lack facial details, and their limbs are often broken off. During the post glacial period, evidence of the culture begins to disappear from northern Europe but was continued in areas around the Mediterranean. The Mal’ta Culture (c. 24,000 years ago) in Siberia is often considered as belonging to the Gravettian, due to its similar characteristics, particularly its Venus figurines, but any hypothetical connection would have to be cultural and not genetic: a 2016 genomic study showed that the Mal’ta people have no genetic connections with the people of the European Gravettian culture (the Vestonice Cluster).” ref

“Fu et al. (2016) examined the remains of fourteen Gravettians. The eight males included three samples of Y-chromosomal haplogroup CT, one of I, one IJK, one BT, one C1a2, and one sample of F. Of the fourteen samples of mtDNA, there were thirteen samples of U and one sample of M. The majority of the sample of U belonged to the U5 and U2. Teschler et al. (2020) examined the remains of one adult male and two twin boys from a Gravettian site in Austria. All belonged to haplogroup Y-Haplogroup I. and all had the same mtDNA, U5. According to Scorrano et al. (2022), “the genome of an early European individual from Kostenki 14, dated to around 37,000 years ago, demonstrated that the ancestral European gene pool was already established by that time.” ref

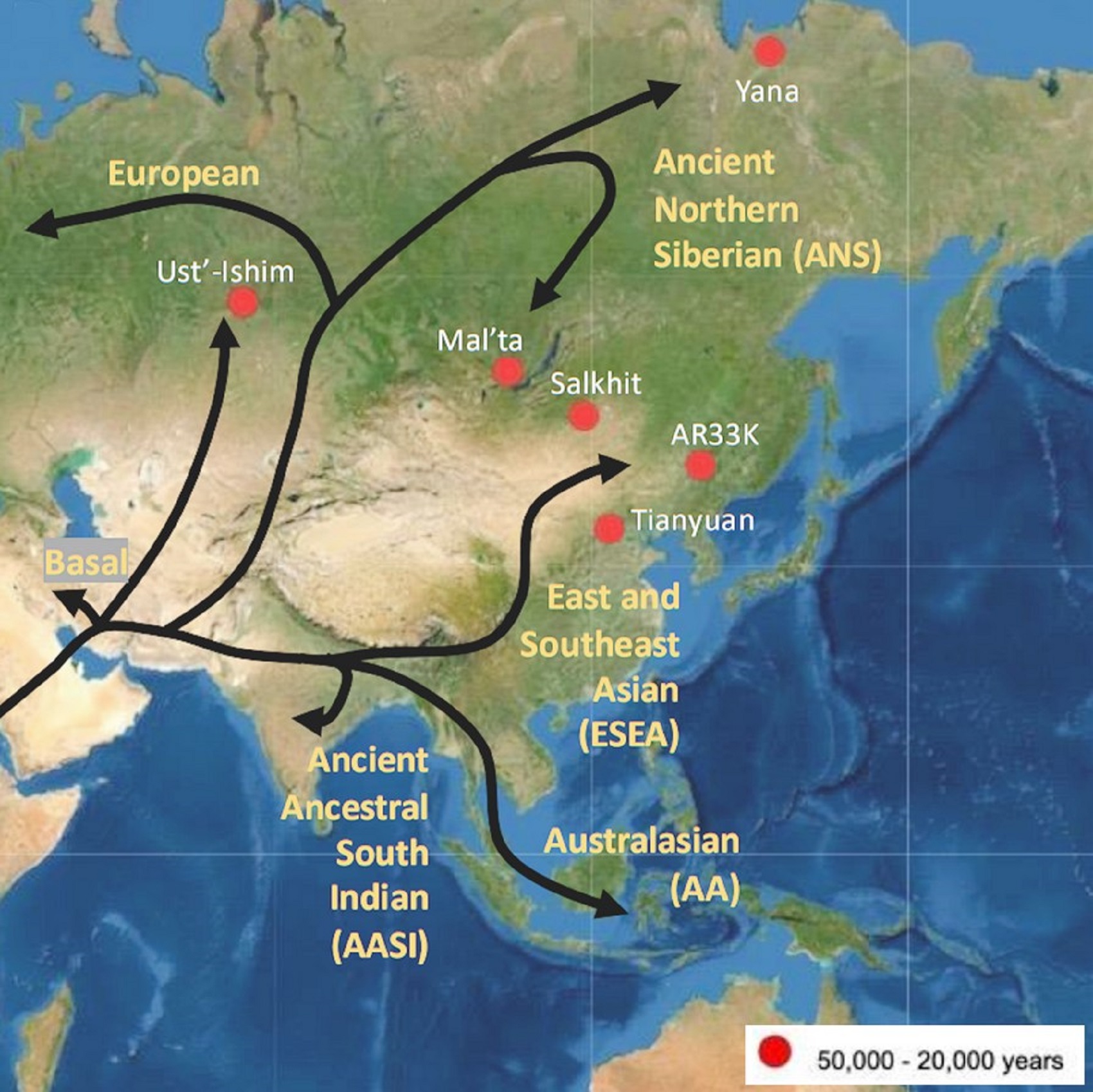

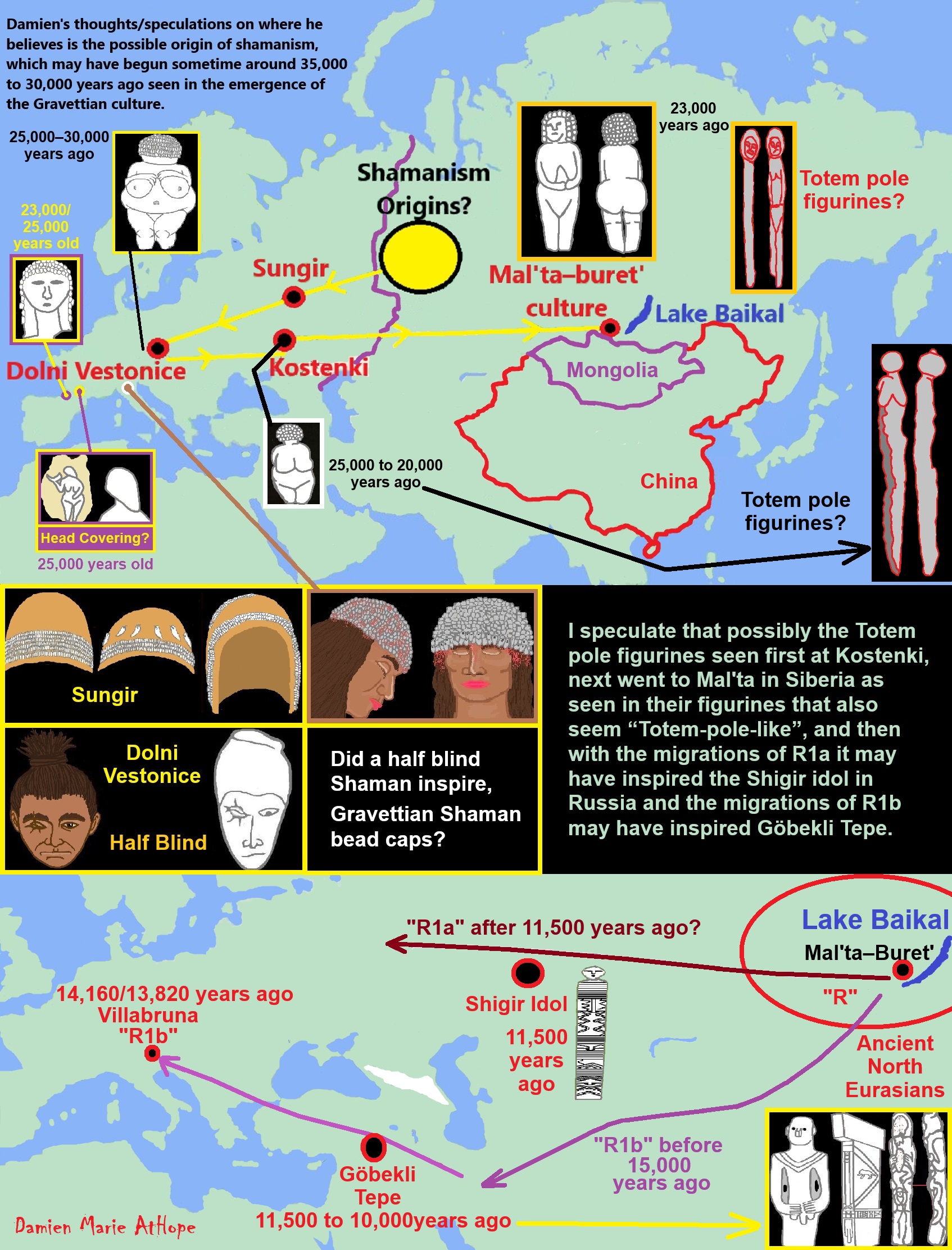

Here are Damien’s thoughts/speculations on where he believes is the possible origin of shamanism, which may have begun sometime around 35,000 to 30,000 years ago seen in the emergence of the Gravettian culture, just to outline his thinking, on what thousands of years later led to evolved Asian shamanism, in general, and thus WU shamanism as well. In both Europe-related “shamanism-possible burials” and in Gravettian mitochondrial DNA is a seeming connection to Haplogroup U. And the first believed Shaman proposed burial belonged to Eastern Gravettians/Pavlovian culture at Dolní Věstonice in southern Moravia in the Czech Republic, which is the oldest permanent human settlement that has ever been found. It is at Dolní Věstonice where approximately 27,000-25,000 years ago a seeming female shaman was buried and also there was an ivory totem portrait figure, seemingly of her.

“The Pavlovian is an Upper Paleolithic culture, a variant of the Gravettian, that existed in the region of Moravia, northern Austria, and southern Poland around 29,000–25,000 years ago. Its name is derived from the village of Pavlov, in the Pavlov Hills, next to Dolní Věstonice in southern Moravia. The culture used sophisticated stone age technology to survive in the tundra on the fringe of the ice sheets around the Last Glacial Maximum. Excavation has yielded flint implements, polished and drilled stone artifacts, bone spearheads, needles, digging tools, flutes, bone ornaments, drilled animal teeth, and seashells. Art or religious finds are bone carvings and figurines of humans and animals made of mammoth tusk, stone, and fired clay.” ref

“One of the burials, located near the huts, revealed a human female skeleton aged to 40+ years old, ritualistically placed beneath a pair of mammoth scapulae, one leaning against the other. Surprisingly, the left side of the skull was disfigured in the same manner as the aforementioned carved ivory figure, indicating that the figure was an intentional depiction of this specific individual. The bones and the earth surrounding the body contained traces of red ocher, a flint spearhead had been placed near the skull, and one hand held the body of a fox. This evidence suggests that this was the burial site of a shaman. This is the oldest site not only of ceramic figurines and artistic portraiture, but also of evidence of female shamans.” ref

“A burial of an approximately forty-year-old woman was found at Dolní Věstonice in an elaborate burial setting. Various items found with the woman have had a profound impact on the interpretation of the social hierarchy of the people at the site, as well as indicating an increased lifespan for these inhabitants. The remains were covered in red ochre, a compound known to have religious significance, indicating that this woman’s burial was ceremonial in nature. Also, the inclusion of a mammoth scapula and a fox are indicative of a high-status burial.” ref

“In the Upper Paleolithic, anatomically modern humans began living longer, often reaching middle age, by today’s standards. Rachel Caspari argues in “Human Origins: the Evolution of Grandparents,” that life expectancy increased during the Upper Paleolithic in Europe (Caspari 2011). She also describes why elderly people were highly influential in society. Grandparents assisted in childcare, perpetuated cultural transmission, and contributed to the increased complexity of stone tools (Caspari 2011). The woman found at Dolní Věstonice was old enough to have been a grandparent. Although human lifespans were increasing, elderly individuals in Upper Paleolithic societies were still relatively rare. Because of this, it is possible that the woman was attributed with great importance and wisdom, and revered because of her age. Because of her advanced age, it is also possible she had a decreased ability to care for herself, instead relying on her family group to care for her, which indicates strong social connections.” ref

“Furthermore, a female figurine was found at the site and is believed to be associated with the aged woman, because of remarkably similar facial characteristics. The woman was found to have deformities on the left side of her face. The special importance accorded with her burial, in addition to her facial deformity, makes it possible that she was a shaman in this time period, where it was “not uncommon that people with disabilities, either mental or physical, are thought to have unusual supernatural powers” (Pringle 2010).” ref

“In 1981, Patricia Rice studied a multitude of female clay figurines found at Dolní Věstonice, believed to represent fertility in this society. She challenged this assumption by analyzing all the figurines and found that, “it is womanhood, rather than motherhood that is symbolically recognized or honored” (Rice 1981: 402). This interpretation challenged the widely held assumption that all prehistoric female figurines were created to honor fertility. The fact is that we have no idea why these figurines proliferated nor of their purpose or usage.” ref

“Haplogroup U5 is estimated to be about 30,000 years old, and it is primarily found today in people with European ancestry. Both the current geographic distribution of U5 and testing of ancient human remains indicate that the ancestor of U5 expanded into Europe before 31,000 years ago. A 2013 study by Fu et al. found two U5 individuals at the Dolni Vestonice burial site in the Czech Republic that has been dated to 31,155 years ago. A third person from the same burial was identified as haplogroup U8. The Dolni Vestonice samples have only two of the five mutations ( C16192T and C16270T) that are found in the present day U5 population. This indicates that the U5-(C16192T and C16270T) mtDNA sequence is ancestral to the present day U5 population that includes the additional three mutations T3197C, G9477A and T13617C.” ref

“Haplogroup U5 is thought to have evolved in the western steppe region and then entered Europe around 30,000 to 55,000 years ago. Results support previous hypotheses that haplogroup U5 mtDNAs expanded throughout Northern, Southern, and Central Europe with more recent expansions into Western Europe and Africa. The results further allow us to explain how U5 mtDNAs are now found with high frequency in Northern Europe, as well as delineate the origins of the specific U5 subhaplogroups found in that part of Europe.” ref

“Haplogroup U5 is found throughout Europe with an average frequency ranging from 5% to 12% in most regions. U5a is most common in north-east Europe and U5b in northern Spain. Nearly half of all Sami and one fifth of Finnish maternal lineages belong to U5. Other high frequencies are observed among the Mordovians (16%), the Chuvash (14.5%) and the Tatars (10.5%) in the Volga-Ural region of Russia, the Estonians (13%), the Lithuanians (11.5%) and the Latvians in the Baltic, the Dargins (13.5%), Avars (13%) and the Chechens (10%) in the Northeast Caucasus, the Basques (12%), the Cantabrians (11%) and the Catalans (10%) in northern Spain, the Bretons (10.5%) in France, the Sardinians (10%) in Italy, the Slovaks (11%), the Croatians (10.5%), the Poles (10%), the Czechs (10%), the Ukrainians (10%) and the Slavic Russians (10%). Overall, U5 is generally found in population with high percentages of Y-haplogroups I1, I2, and R1a, three lineages already found in Mesolithic Europeans. The highest percentages are observed in populations associated predominantly with Y-haplogroup N1c1 (the Finns and the Sami), although N1c1 is originally an East Asian lineage that spread over Siberia and Northeast Europe and assimilated indigenous U5 maternal lineages.” ref

“The age of haplogroup U5 is uncertain at present. It could have arisen as recently as 35,000 years ago, or as early was 50,000 years ago. U5 appear to have been a major maternal lineage among the Paleolithic European hunter-gatherers, and even the dominant lineage during the European Mesolithic. In two papers published two months apart, Posth et al. 2016 and Fu et al. 2016 reported the results of over 70 complete human mitochondrial genomes ranging from 45,000 to 7,000 years ago. The oldest U5 samples all dated from the Gravettian culture (c. 32,000 to 22,000 years ago), while the older Aurignacian samples belonged to mt-haplogroups M, N, R*, and U2. Among the 16 Gravettian samples that yielded reliable results, six belonged to U5 – the others belonging mostly to U2, as well as isolated samples of M, U*, and U8c. Two Italian Epigravettian samples, one from the Paglicci Cave in Apulia (18,500 years ago), and another one from Villabruna in Veneto (14,000 years ago), belonged to U5b2b, as did two slightly more recent Epipaleolithic samples from the Rhône valley in France. U5b1 samples were found in Epipalaeolithic Germany, Switzerland (U5b1h in the Grotte du Bichon), and France. More 80% of the numerous Mesolithic European mtDNA tested to date belonged to various subclades of U5. Overall, it appears that U5 arrived in Europe with the Gravettian tool makers, and that it particularly prospered from the end of the glacial period (from 11,700 years ago) until the arrival of Neolithic farmers from the Near East (between 8,500 and 6,000 years ago).” ref

“Carriers of haplogroup U5 were part of the Gravettian culture, which experienced the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM, 26,000 to 19,000 years ago). During this particularly harsh period, Gravettian people would have retreated into refugia in southern Europe, from which they would have re-expanded to colonise the northern half of the continent during the Late Glacial and postglacial periods. For reasons that are yet unknown, haplogroup U5 seems to have resisted better to the LGM to other Paleolithic haplogroups like U*, U2 and U8. Mitochondrial DNA being essential for energy production, it could be that the mutations selected in early U5 subclades (U5a1, U5a2, U5b1, U5b2) conferred an advantage for survival during the coldest millennia of the LGM, which had for effect to prune less energy efficient mtDNA lineages.” ref

“It is likely that U5a and U5b lineages already existed prior to the LGM and they were geographically scattered to some extent around Europe before the growing ice sheet forced people into the refugia. Nonetheless, founder effects among the populations of each LGM refugium would have amplified the regional division between U5b and U5a. U5b would have been found at a much higher frequency in the Franco-Cantabrian region. We can deduce this from the fact that modern Western Europeans have considerably more U5b than U5a, but also because the modern Basques and Cantabrians possess almost exclusively U5b lineages. What’s more, all the Mesolithic U5 samples from Iberia whose subclade could be identified belonged to U5b.” ref

“Conversely, only U5a lineages have been found so far in Mesolithic Russia (U5a1) and Sweden (U5a1 and U5a2), which points at an eastern origin of this subclade. Mesolithic samples from Poland, Germany and Italy yielded both U5a and U5b subclades. German samples included U5a2a, U5a2c3, U5b2 and U5b2a2. The same observations are valid for the Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods too, with U5a1 being found in Russia and Ukraine, U5b in France (Cardium Pottery and Megalithic), U5b2 in Portugal. U5b1b1 arose approximately 10,000 years ago, over two millennia after the end of the Last Glaciation, when the Neolithic Revolution was already under way in the Near East. Despite this relatively young age, U5b1b1 is found scattered across all Europe and well beyond its boundaries. The Saami, who live in the far European North and have 48% of U5 and 42% of V lineages, belong exclusively to the U5b1b1 subclade. Amazingly, the Berbers of Northwest Africa also possess that U5b1b1 subclade and haplogroup V.” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

Here are my thoughts/speculations on where I believe is the possible origin of shamanism, which may have begun sometime around 35,000 to 30,000 years ago seen in the emergence of the Gravettian culture, just to outline his thinking, on what thousands of years later led to evolved Asian shamanism, in general, and thus WU shamanism as well. In both Europe-related “shamanism-possible burials” and in Gravettian mitochondrial DNA is a seeming connection to Haplogroup U. And the first believed Shaman proposed burial belonged to Eastern Gravettians/Pavlovian culture at Dolní Věstonice in southern Moravia in the Czech Republic, which is the oldest permanent human settlement that has ever been found. It is at Dolní Věstonice where approximately 27,000-25,000 years ago a seeming female shaman was buried and also there was an ivory totem portrait figure, seemingly of her.

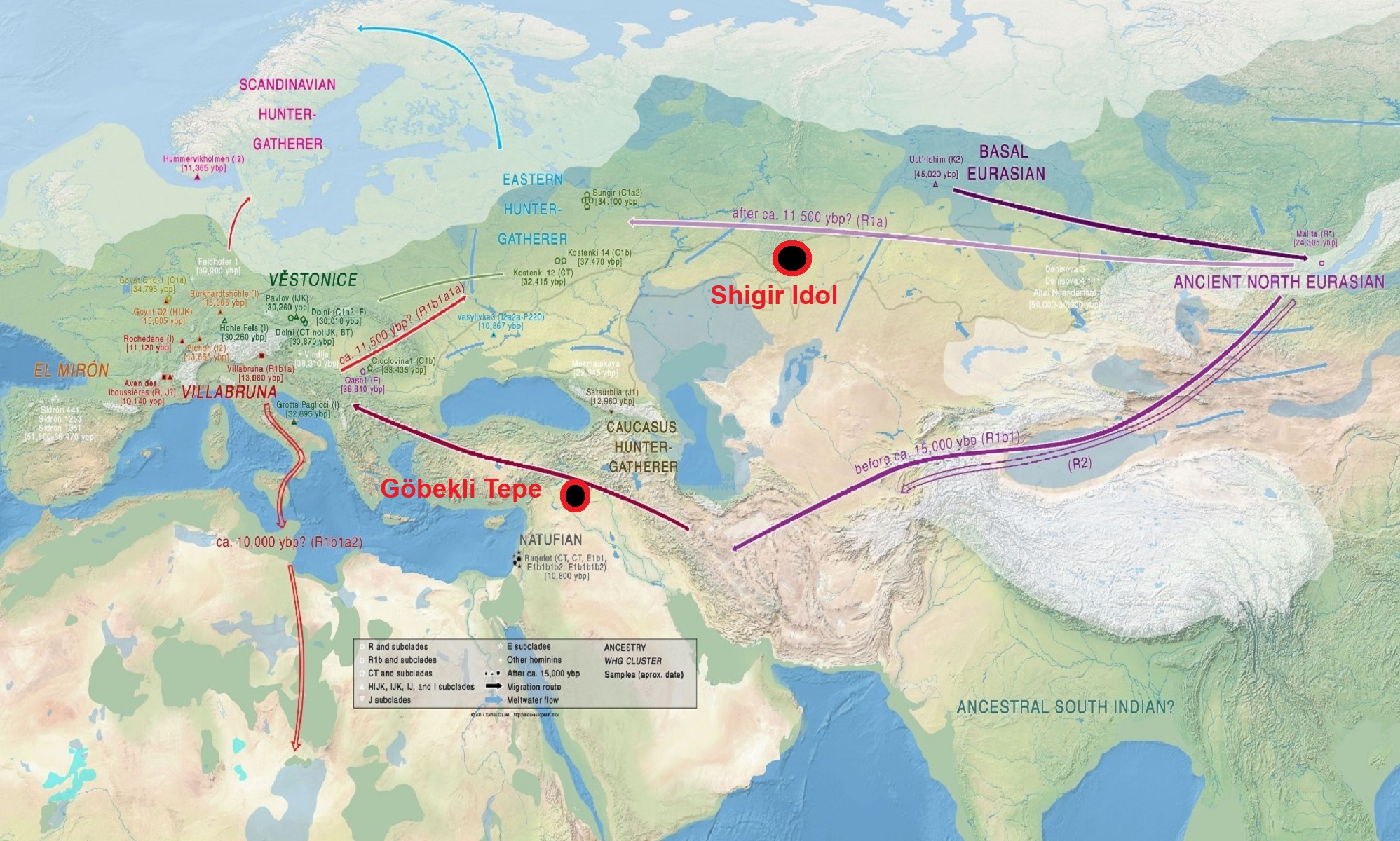

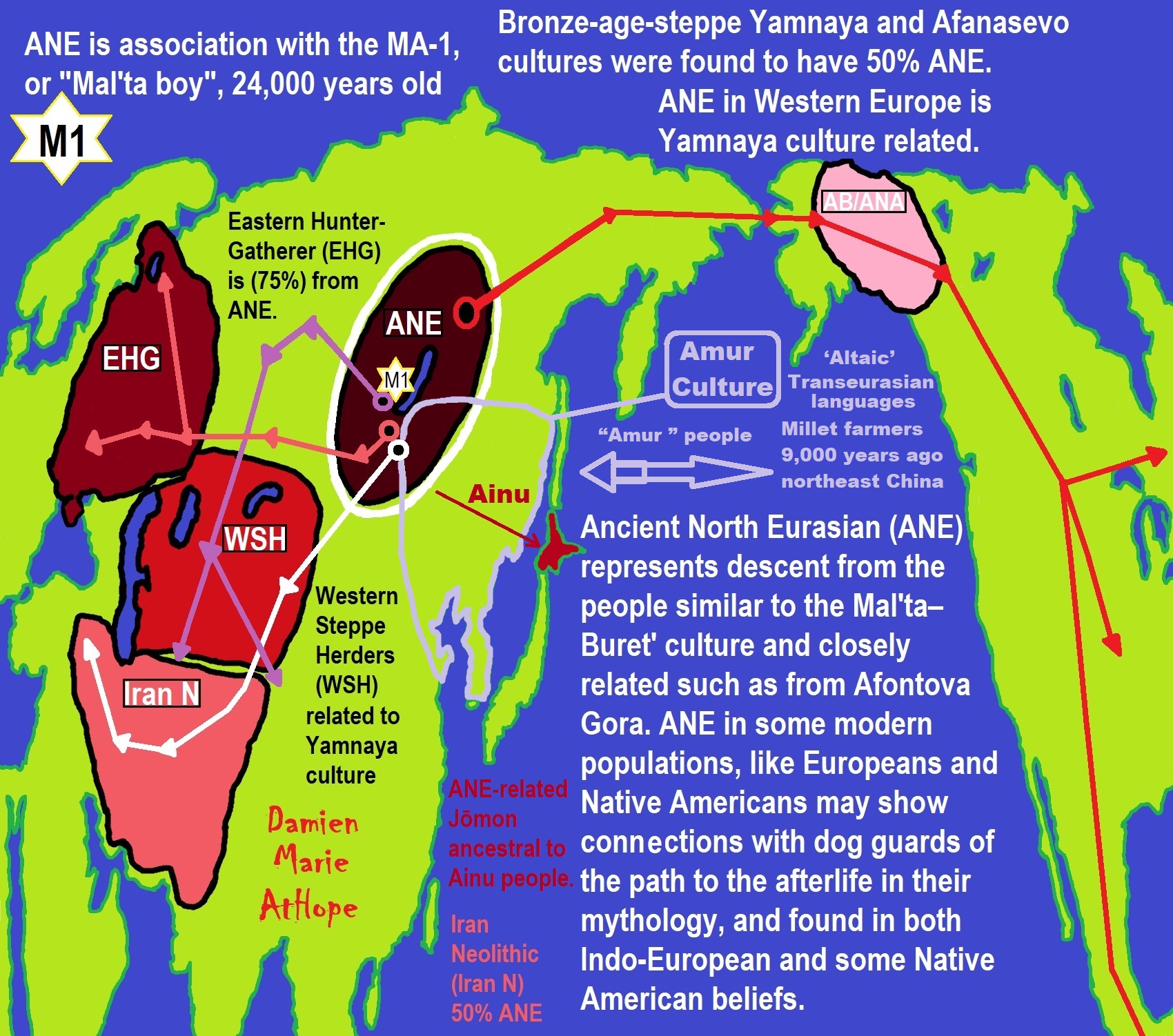

And my thoughts on how cultural/ritual aspects were influenced in the area of Göbekli Tepe. I think it relates to a few different cultures starting in the area before the Neolithic. Two different groups of Siberians first from northwest Siberia with U6 haplogroup 40,000 to 30,000 or so. Then R Haplogroup (mainly haplogroup R1b but also some possible R1a both related to the Ancient North Eurasians). This second group added its “R1b” DNA of around 50% to the two cultures Natufian and Trialetian. To me, it is likely both of these cultures helped create Göbekli Tepe. Then I think the female art or graffiti seen at Göbekli Tepe to me possibly relates to the Epigravettians that made it into Turkey and have similar art in North Italy. I speculate that possibly the Totem pole figurines seen first at Kostenki, next went to Mal’ta in Siberia as seen in their figurines that also seem “Totem-pole-like”, and then with the migrations of R1a it may have inspired the Shigir idol in Russia and the migrations of R1b may have inspired Göbekli Tepe.

“Migration from Siberia behind the formation of Göbeklitepe: Expert states. People who migrated from Siberia formed the Göbeklitepe, and those in Göbeklitepe migrated in five other ways to spread to the world, said experts about the 12,000-year-old Neolithic archaeological site in the southwestern province of Şanlıurfa.“ The upper paleolithic migrations between Siberia and the Near East is a process that has been confirmed by material culture documents,” he said.” ref

“Semih Güneri, a retired professor from Caucasia and Central Asia Archaeology Research Center of Dokuz Eylül University, and his colleague, Professor Ekaterine Lipnina, presented the Siberia-Göbeklitepe hypothesis they have developed in recent years at the congress held in Istanbul between June 11 and 13. There was a migration that started from Siberia 30,000 years ago and spread to all of Asia and then to Eastern and Northern Europe, Güneri said at the international congress.” ref

“The relationship of Göbeklitepe high culture with the carriers of Siberian microblade stone tool technology is no longer a secret,” he said while emphasizing that the most important branch of the migrations extended to the Near East. “The results of the genetic analyzes of Iraq’s Zagros region confirm the traces of the Siberian/North Asian indigenous people, who arrived at Zagros via the Central Asian mountainous corridor and met with the Göbeklitepe culture via Northern Iraq,” he added.” ref

“Emphasizing that the stone tool technology was transported approximately 7,000 kilometers from east to west, he said, “It is not clear whether this technology is transmitted directly to long distances by people speaking the Turkish language at the earliest, or it travels this long-distance through using way stations.” According to the archaeological documents, it is known that the Siberian people had reached the Zagros region, he said. “There seems to be a relationship between Siberian hunter-gatherers and native Zagros hunter-gatherers,” Güneri said, adding that the results of genetic studies show that Siberian people reached as far as the Zagros.” ref

“There were three waves of migration of Turkish tribes from the Southern Siberia to Europe,” said Osman Karatay, a professor from Ege University. He added that most of the groups in the third wave, which took place between 2600-2400 BCE, assimilated and entered the Germanic tribes and that there was a genetic kinship between their tribes and the Turks. The professor also pointed out that there are indications that there is a technology and tool transfer from Siberia to the Göbeklitepe region and that it is not known whether people came, and if any, whether they were Turkish.” ref

“Around 12,000 years ago, there would be no ‘Turks’ as we know it today. However, there may have been tribes that we could call our ‘common ancestors,’” he added. “Talking about 30,000 years ago, it is impossible to identify and classify nations in today’s terms,” said Murat Öztürk, associate professor from İnönü University. He also said that it is not possible to determine who came to where during the migrations that were accepted to have been made thousands of years ago from Siberia. On the other hand, Mehmet Özdoğan, an academic from Istanbul University, has an idea of where “the people of Göbeklitepe migrated to.” ref

“According to Özdoğan, “the people of Göbeklitepe turned into farmers, and they could not stand the pressure of the overwhelming clergy and started to migrate to five ways.” “Migrations take place primarily in groups. One of the five routes extends to the Caucasus, another from Iran to Central Asia, the Mediterranean coast to Spain, Thrace and [the northwestern province of] Kırklareli to Europe and England, and one route is to Istanbul via [Istanbul’s neighboring province of] Sakarya and stops,” Özdoğan said. In a very short time after the migration of farmers in Göbeklitepe, 300 settlements were established only around northern Greece, Bulgaria, and Thrace. “Those who remained in Göbeklitepe pulled the trigger of Mesopotamian civilization in the following periods, and those who migrated to Mesopotamia started irrigated agriculture before the Sumerians,” he said.” ref

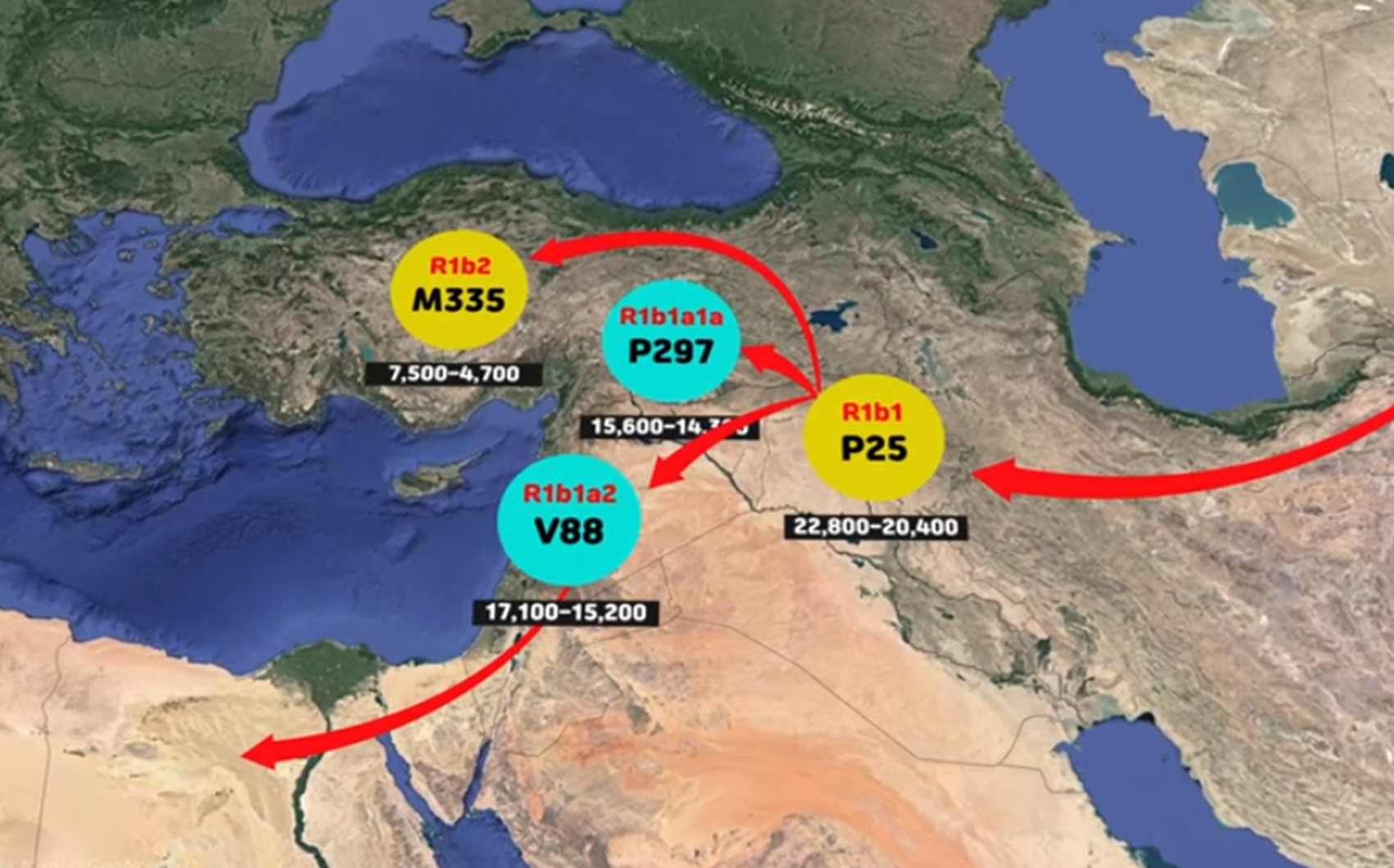

“Haplogroup R* originated in North Asia just before the Last Glacial Maximum (26,500-19,000 years ago). This haplogroup has been identified in the remains of a 24,000 year-old boy from the Altai region, in south-central Siberia (Raghavan et al. 2013). This individual belonged to a tribe of mammoth hunters that may have roamed across Siberia and parts of Europe during the Paleolithic. Autosomally this Paleolithic population appears to have contributed mostly to the ancestry of modern Europeans and South Asians, the two regions where haplogroup R also happens to be the most common nowadays (R1b in Western Europe, R1a in Eastern Europe, Central and South Asia, and R2 in South Asia).” ref

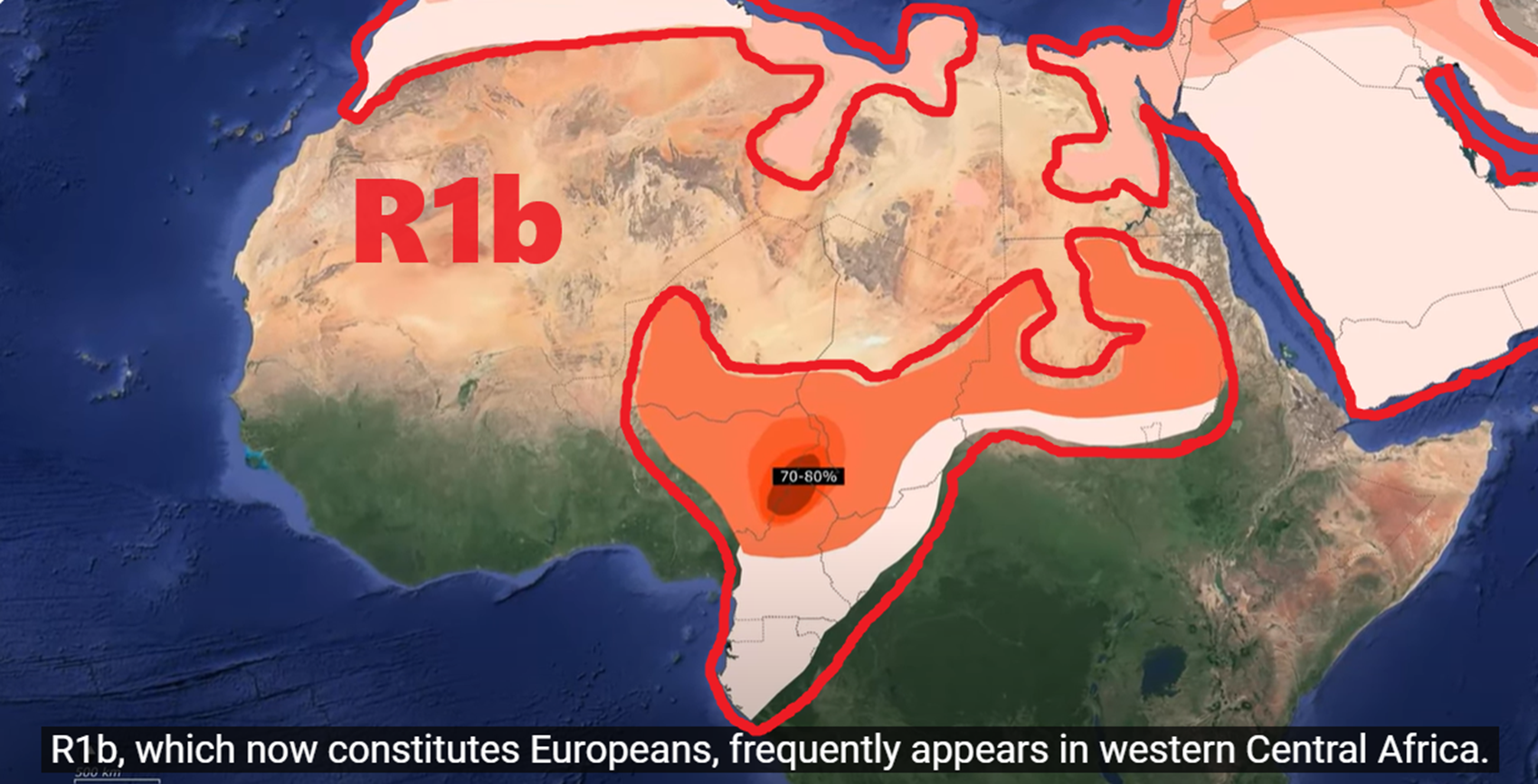

“The oldest forms of R1b (M343, P25, L389) are found dispersed at very low frequencies from Western Europe to India, a vast region where could have roamed the nomadic R1b hunter-gatherers during the Ice Age. The three main branches of R1b1 (R1b1a, R1b1b, R1b1c) all seem to have stemmed from the Middle East. The southern branch, R1b1c (V88), is found mostly in the Levant and Africa. The northern branch, R1b1a (P297), seems to have originated around the Caucasus, eastern Anatolia or northern Mesopotamia, then to have crossed over the Caucasus, from where they would have invaded Europe and Central Asia. R1b1b (M335) has only been found in Anatolia.” ref

“It has been hypothetised that R1b people (perhaps alongside neighbouring J2 tribes) were the first to domesticate cattle in northern Mesopotamia some 10,500 years ago. R1b tribes descended from mammoth hunters, and when mammoths went extinct, they started hunting other large game such as bisons and aurochs. With the increase of the human population in the Fertile Crescent from the beginning of the Neolithic (starting 12,000 years ago), selective hunting and culling of herds started replacing indiscriminate killing of wild animals. The increased involvement of humans in the life of aurochs, wild boars and goats led to their progressive taming. Cattle herders probably maintained a nomadic or semi-nomadic existence, while other people in the Fertile Crescent (presumably represented by haplogroups E1b1b, G and T) settled down to cultivate the land or keep smaller domesticates.” ref

“The analysis of bovine DNA has revealed that all the taurine cattle (Bos taurus) alive today descend from a population of only 80 aurochs. The earliest evidence of cattle domestication dates from circa 8,500 BCE in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic cultures in the Taurus Mountains. The two oldest archaeological sites showing signs of cattle domestication are the villages of Çayönü Tepesi in southeastern Turkey and Dja’de el-Mughara in northern Iraq, two sites only 250 km away from each others. This is presumably the area from which R1b lineages started expanding – or in other words the “original homeland” of R1b.” ref

“The early R1b cattle herders would have split in at least three groups. One branch (M335) remained in Anatolia, but judging from its extreme rarity today wasn’t very successful, perhaps due to the heavy competition with other Neolithic populations in Anatolia, or to the scarcity of pastures in this mountainous environment. A second branch migrated south to the Levant, where it became the V88 branch. Some of them searched for new lands south in Africa, first in Egypt, then colonising most of northern Africa, from the Mediterranean coast to the Sahel. The third branch (P297), crossed the Caucasus into the vast Pontic-Caspian Steppe, which provided ideal grazing grounds for cattle. They split into two factions: R1b1a1 (M73), which went east along the Caspian Sea to Central Asia, and R1b1a2 (M269), which at first remained in the North Caucasus and the Pontic Steppe between the Dnieper and the Volga. It is not yet clear whether M73 actually migrated across the Caucasus and reached Central Asia via Kazakhstan, or if it went south through Iran and Turkmenistan. In any case, M73 would be a pre-Indo-European branch of R1b, just like V88 and M335.” ref

“R1b-M269 (the most common form in Europe) is closely associated with the diffusion of Indo-European languages, as attested by its presence in all regions of the world where Indo-European languages were spoken in ancient times, from the Atlantic coast of Europe to the Indian subcontinent, which comprised almost all Europe (except Finland, Sardinia and Bosnia-Herzegovina), Anatolia, Armenia, European Russia, southern Siberia, many pockets around Central Asia (notably in Xinjiang, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan and Afghanistan), without forgetting Iran, Pakistan, northern India and Nepal. The history of R1b and R1a are intricately connected to each others.” ref

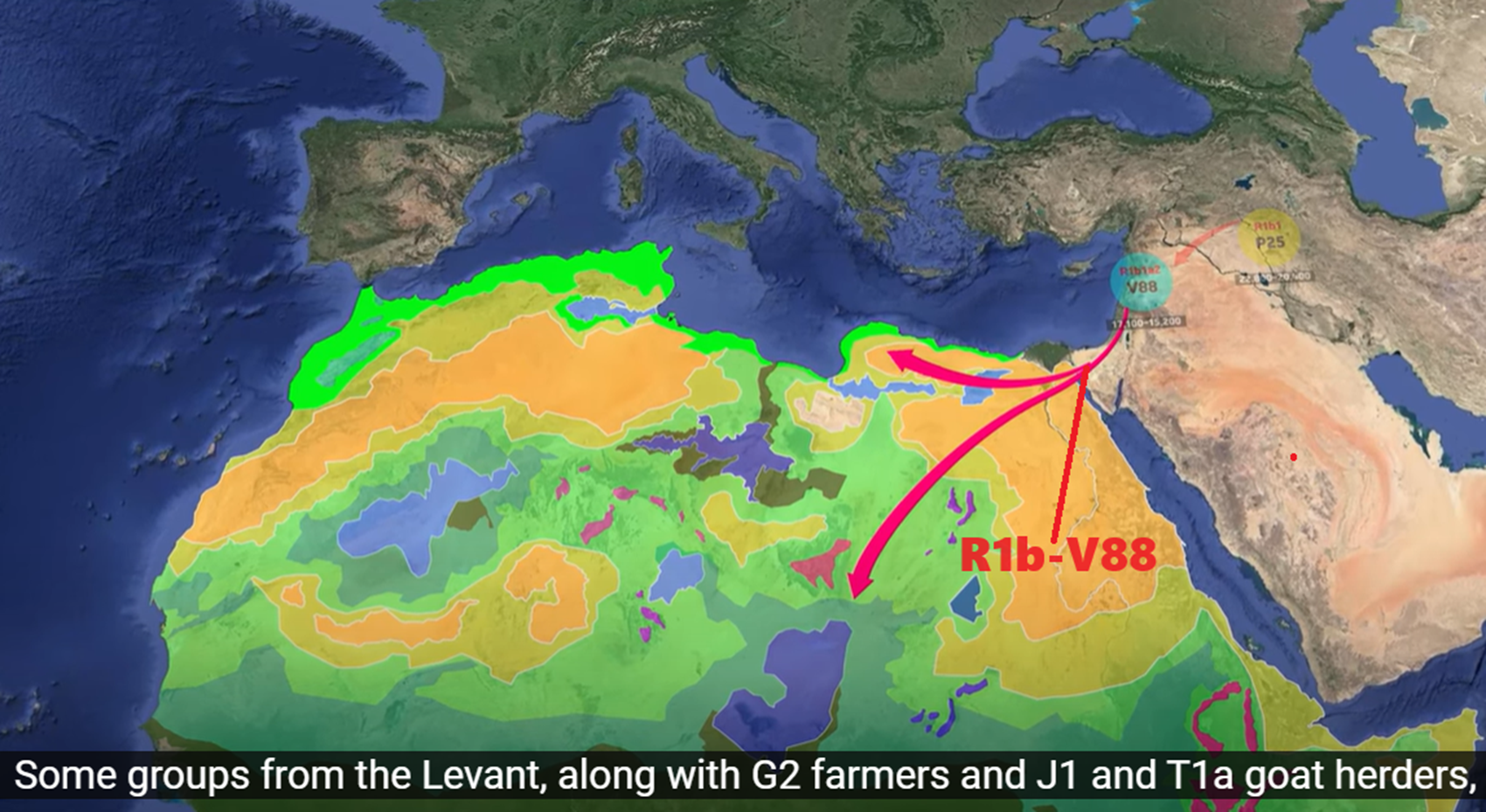

The Levantine & African branch of R1b (V88)

“Like its northern counterpart (R1b-M269), R1b-V88 is associated with the domestication of cattle in northern Mesopotamia. Both branches of R1b probably split soon after cattle were domesticated, approximately 10,500 years ago (8,500 BCE). R1b-V88 migrated south towards the Levant and Egypt. The migration of R1b people can be followed archeologically through the presence of domesticated cattle, which appear in central Syria around 8,000-7,500 BCE (late Mureybet period), then in the Southern Levant and Egypt around 7,000-6,500 BCE (e.g. at Nabta Playa and Bir Kiseiba). Cattle herders subsequently spread across most of northern and eastern Africa. The Sahara desert would have been more humid during the Neolithic Subpluvial period (c. 7250-3250 BCE), and would have been a vast savannah full of grass, an ideal environment for cattle herding.” ref

“Evidence of cow herding during the Neolithic has shown up at Uan Muhuggiag in central Libya around 5500 BCE, at the Capeletti Cave in northern Algeria around 4500 BCE. But the most compelling evidence that R1b people related to modern Europeans once roamed the Sahara is to be found at Tassili n’Ajjer in southern Algeria, a site famous pyroglyphs (rock art) dating from the Neolithic era. Some painting dating from around 3000 BCE depict fair-skinned and blond or auburn haired women riding on cows. The oldest known R1b-V88 sample in Europe is a 6,200 year-old farmer/herder from Catalonia tested by Haak et al. (2015). Autosomally this individual was a typical Near Eastern farmer, possessing just a little bit of Mesolithic West European admixture.” ref

“After reaching the Maghreb, R1b-V88 cattle herders could have crossed the Strait of Gibraltar to Iberia, probably accompanied by G2 farmers, J1 and T1a goat herders. These North African Neolithic farmers/herders could have been the ones who established the Almagra Pottery culture in Andalusia in the 6th millennium BCE.” ref

“Nowadays small percentages (1 to 4%) of R1b-V88 are found in the Levant, among the Lebanese, the Druze, and the Jews, and almost in every country in Africa north of the equator. Higher frequency in Egypt (5%), among Berbers from the Egypt-Libya border (23%), among the Sudanese Copts (15%), the Hausa people of Sudan (40%), the the Fulani people of the Sahel (54% in Niger and Cameroon), and Chadic tribes of northern Nigeria and northern Cameroon (especially among the Kirdi), where it is observed at a frequency ranging from 30% to 95% of men. According to Cruciani et al. (2010) R1b-V88 would have crossed the Sahara between 9,200 and 5,600 years ago, and is most probably associated with the diffusion of Chadic languages, a branch of the Afroasiatic languages. V88 would have migrated from Egypt to Sudan, then expanded along the Sahel until northern Cameroon and Nigeria. However, R1b-V88 is not only present among Chadic speakers, but also among Senegambian speakers (Fula-Hausa) and Semitic speakers (Berbers, Arabs).” ref

“R1b-V88 is found among the native populations of Rwanda, South Africa, Namibia, Angola, Congo, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, Ivory Coast, Guinea-Bissau. The wide distribution of V88 in all parts of Africa, its incidence among herding tribes, and the coalescence age of the haplogroup all support a Neolithic dispersal. In any case, a later migration out of Egypt would be improbable since it would have brought haplogroups that came to Egypt during the Bronze Age, such as J1, J2, R1a or R1b-L23. The maternal lineages associated with the spread of R1b-V88 in Africa are mtDNA haplogroups J1b, U5 and V, and perhaps also U3 and some H subclades (=> see Retracing the mtDNA haplogroups of the original R1b people).” ref

R1b-v88 haplogroup

“According to ancient DNA studies, most R1a and R1b lineages would have expanded from the Pontic Steppe along with the Indo-European languages. Analysis of ancient Y-DNA from the remains from early Neolithic Central and North European Linear Pottery culture settlements have not yet found males belonging to haplogroup R1b-M269. Olalde et al. (2017) trace the spread of haplogroup R1b-M269 in western Europe, particularly Britain, to the spread of the Beaker culture, with a sudden appearance of many R1b-M269 haplogroups in Western Europe ca. 5000–4500 years BP during the early Bronze Age. Two branches of R-V88, R-M18 and R-V35, are found almost exclusively on the island of Sardinia. As can be seen in the above data table, R-V88 is found in northern Cameroon in west central Africa at a very high frequency, where it is considered to be caused by a pre-Islamic movement of people from Eurasia.” ref

R1b1b (R-V88)

“R1b1b (PF6279/V88; previously R1b1a2) is defined by the presence of SNP marker V88, the discovery of which was announced in 2010 by Cruciani et al. Apart from individuals in southern Europe and Western Asia, the majority of R-V88 was found in the Sahel, especially among populations speaking Afroasiatic languages of the Chadic branch. Studies in 2005–08 reported “R1b*” at high levels in Jordan, Egypt and Sudan. Subsequent research by Myres et al. (2011) indicates that the samples concerned most likely belong to the subclade R-V88, which is now concentrated in Sub-Saharan Africa.” ref

“According to Myres et al. (2011), this may be explained by a back-migration from Asia into Africa by R1b-carrying people. Gonzales et al. (2013), using more advanced techniques, indicate that it is equally probable that V88 originated in Central Africa and spread northward towards Asia. The patterns of diversity in African R1b-V88 did not seem to fit with a movement of Chadic-speaking people from the North, across the Sahara to West-Central Africa, but was compatible with the reverse. An origin of V88 lineages in Central Africa, followed by a migration to North Africa. However, Shriner, D., & Rotimi, C. N. (2018), associate the introduction of R1b into Chad, with the more recent movements of Baggara Arabs.” ref

“D’Atanasio et al. (2018) propose that R1b-V88 originated in Europe about 12 000 years ago and crossed to North Africa by about 8000 years ago; it may formerly have been common in southern Europe, where it has since been replaced by waves of other haplogroups, leaving remnant subclades almost exclusively in Sardinia. It first radiated within Africa likely between 8000 and 7000 years ago – at the same time as trans-Saharan expansions within the unrelated haplogroups E-M2 and A-M13 – possibly due to population growth allowed by humid conditions and the adoption of livestock herding in the Sahara. R1b-V1589, the main subclade within R1b-V88, underwent a further expansion around 5500 years ago, likely in the Lake Chad Basin region, from which some lines recrossed the Sahara to North Africa.” ref

“Marcus et al. (2020) provide strong evidence for this proposed model of North to South trans-Saharan movement: The earliest basal R1b-V88 haplogroups are found in several Eastern European Hunter Gatherers close to 10,000 years ago. The haplogroup then seemingly further spread with the Neolithic Cardial Ware expansion, which established agriculture in the Western Mediterranean around 7500 years ago: R1b-V88 haplogroups were identified in ancient Neolithic individuals in central Italy, Iberia and, at a particularly high frequency, in Sardinia. A part of the branch leading to present-day African haplogroups (V2197) is already derived in some of these ancient Neolithic European individuals, providing further support for a North-to-South trans-Saharan movement.” ref

“Early human remains found to carry R1b include:

- Villabruna 1 (individual I9030), a Western Hunter-Gatherer (WHG), found in an Epigravettian culture setting in the Cismon valley (modern Veneto, Italy), who lived circa 14000 years ago and belonged to R1b1a.

- Several males of the Iron Gates Mesolithic in the Balkans buried between 11,200 to 8,200 years ago carried R1b1a1a. These individuals were determined to be largely of WHG ancestry, with slight Eastern Hunter-Gatherer (EHG) admixture.

- Several males of the Mesolithic Kunda culture and Neolithic Narva culture buried in the Zvejnieki burial ground in modern-day Latvia c. 9,500–6,000 years ago carried R1b1b. These individuals were determined to be largely of WHG ancestry, with slight EHG admixture.

- Several Mesolithic and Neolithic males buried at Deriivka and Vasil’evka in modern-day Ukraine c. 9500-7000 years ago carried R1b1a. These individuals were largely of EHG ancestry, with significant WHG admixture.

- A WHG male buried at Ostrovul Corbuli, Romania c. 8,700 years ago carried R1b1c.

- A male buried at Lepenski Vir, Serbia c. 8,200-7,900 years ago carried R1b1a.

- An EHG buried near Samara, Russia 7,500 years ago carried R1b1a1a.

- An Eneolithic male buried at Khvalynsk, Russia c. 7,200-6,000 years ago carried R1b1a.

- A Neolithic male buried at Els Trocs, Spain c. 7,178-7,066 years ago, who may have belonged to the Epi-Cardial culture, was found to be a carrier of R1b1.

- A Late Chalcolithic male buried in Smyadovo, Bulgaria c. 6,500 years ago carried R1b1a.

- An Early Copper Age male buried in Cannas di Sotto, Carbonia, Sardinia c. 6,450 years ago carried R1b1b2.

- A male of the Baalberge group in Central Europe buried c. 5,600 years ago carried R1b1a.

- A male of the Botai culture in Central Asia buried c. 5,500 years ago carried R1b1a1 (R1b-M478).

- 7 males that were tested of the Yamnaya culture were all found to belong to the M269 subclade of haplogroup R1b.” ref

“R1b is a subclade within the “macro-haplogroup“ K (M9), the most common group of human male lines outside of Africa. K is believed to have originated in Asia (as is the case with an even earlier ancestral haplogroup, F (F-M89). Karafet T. et al. (2014) “rapid diversification process of K-M526 likely occurred in Southeast Asia, with subsequent westward expansions of the ancestors of haplogroups R and Q.” ref

“Three genetic studies in 2015 gave support to the Kurgan hypothesis of Marija Gimbutas regarding the Proto-Indo-European homeland. According to those studies, haplogroups R1b-M269 and R1a, now the most common in Europe (R1a is also common in South Asia) would have expanded from the West Eurasian Steppe, along with the Indo-European languages; they also detected an autosomal component present in modern Europeans which was not present in Neolithic Europeans, which would have been introduced with paternal lineages R1b and R1a, as well as Indo-European languages.” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

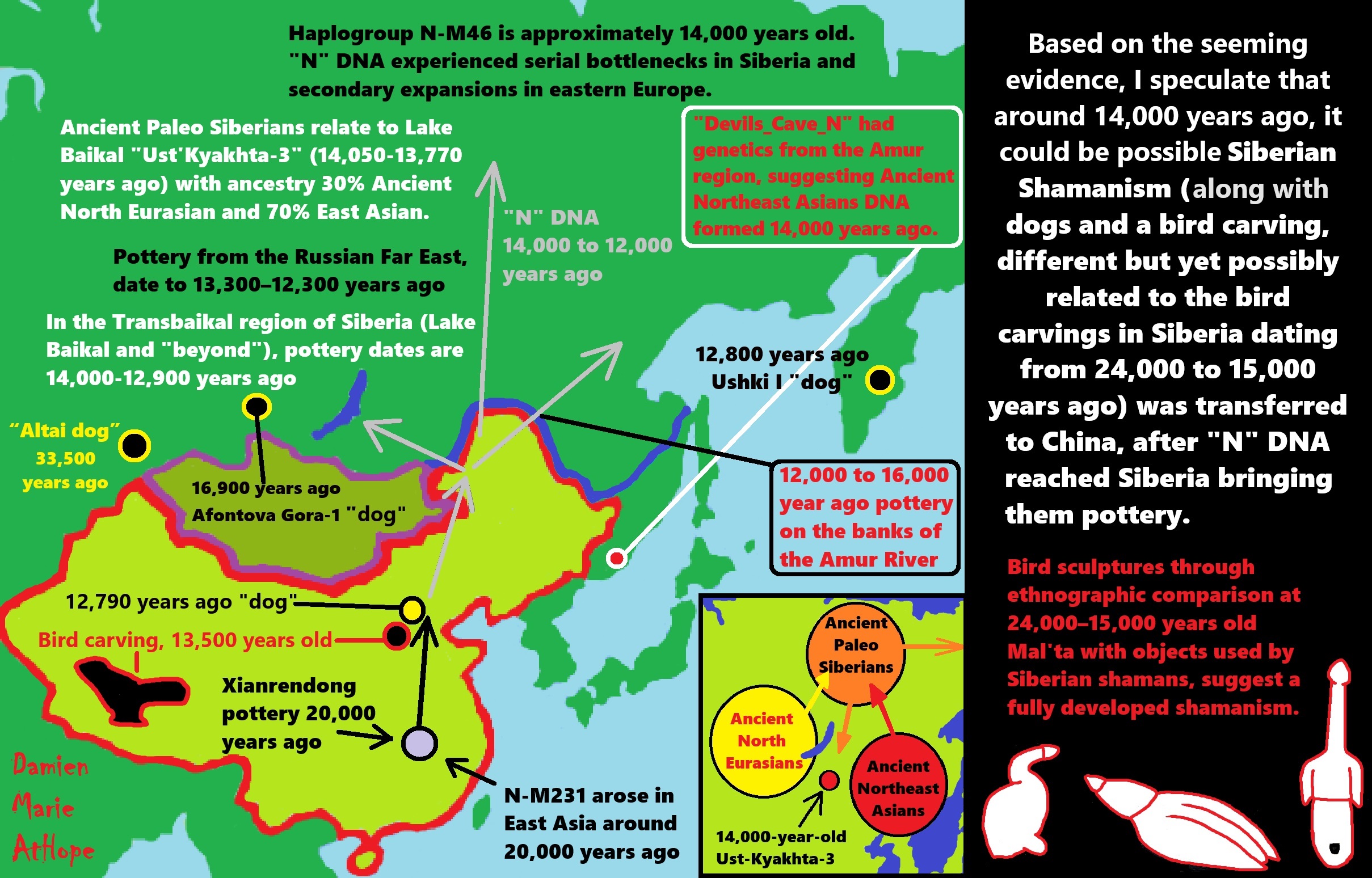

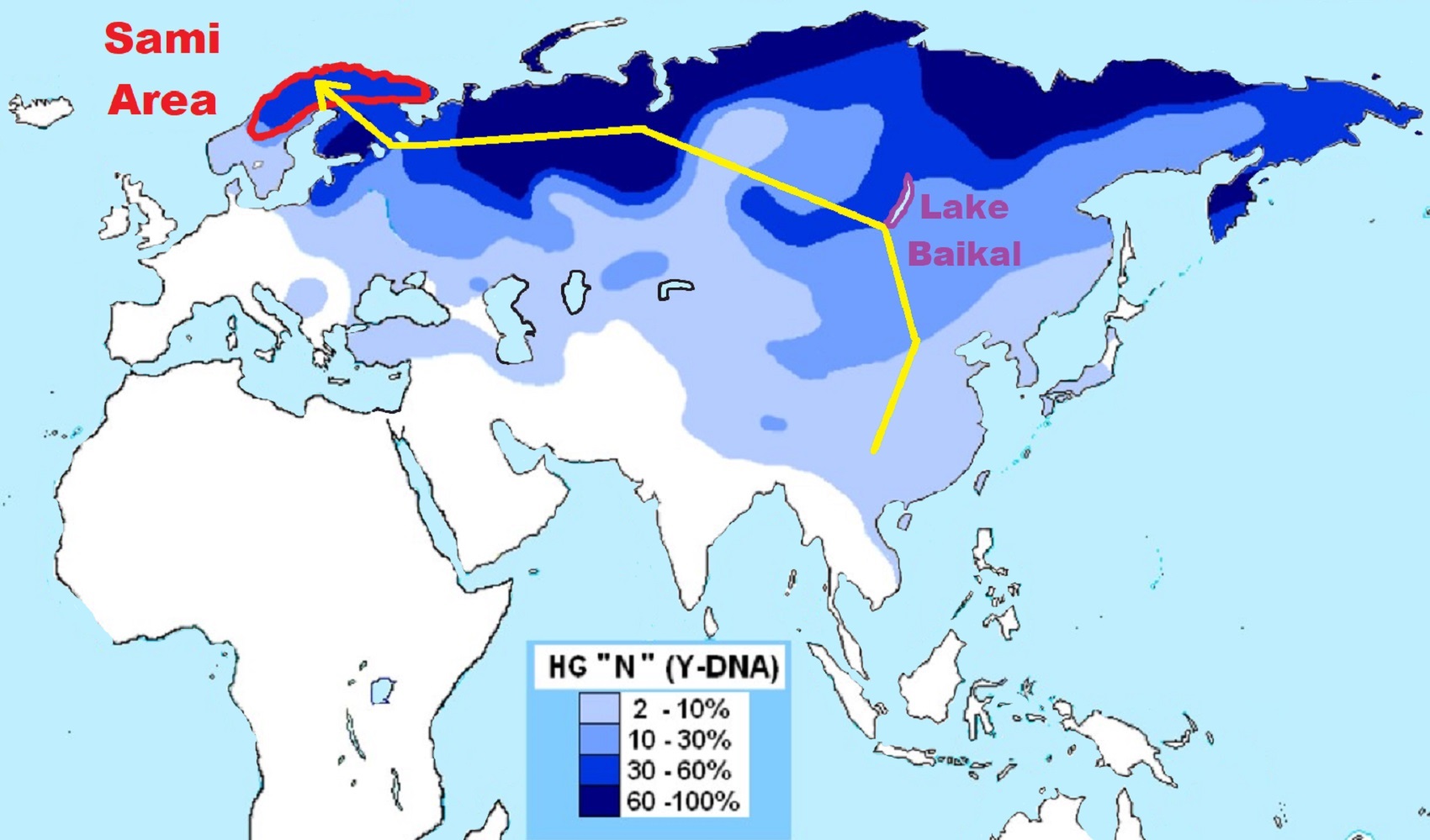

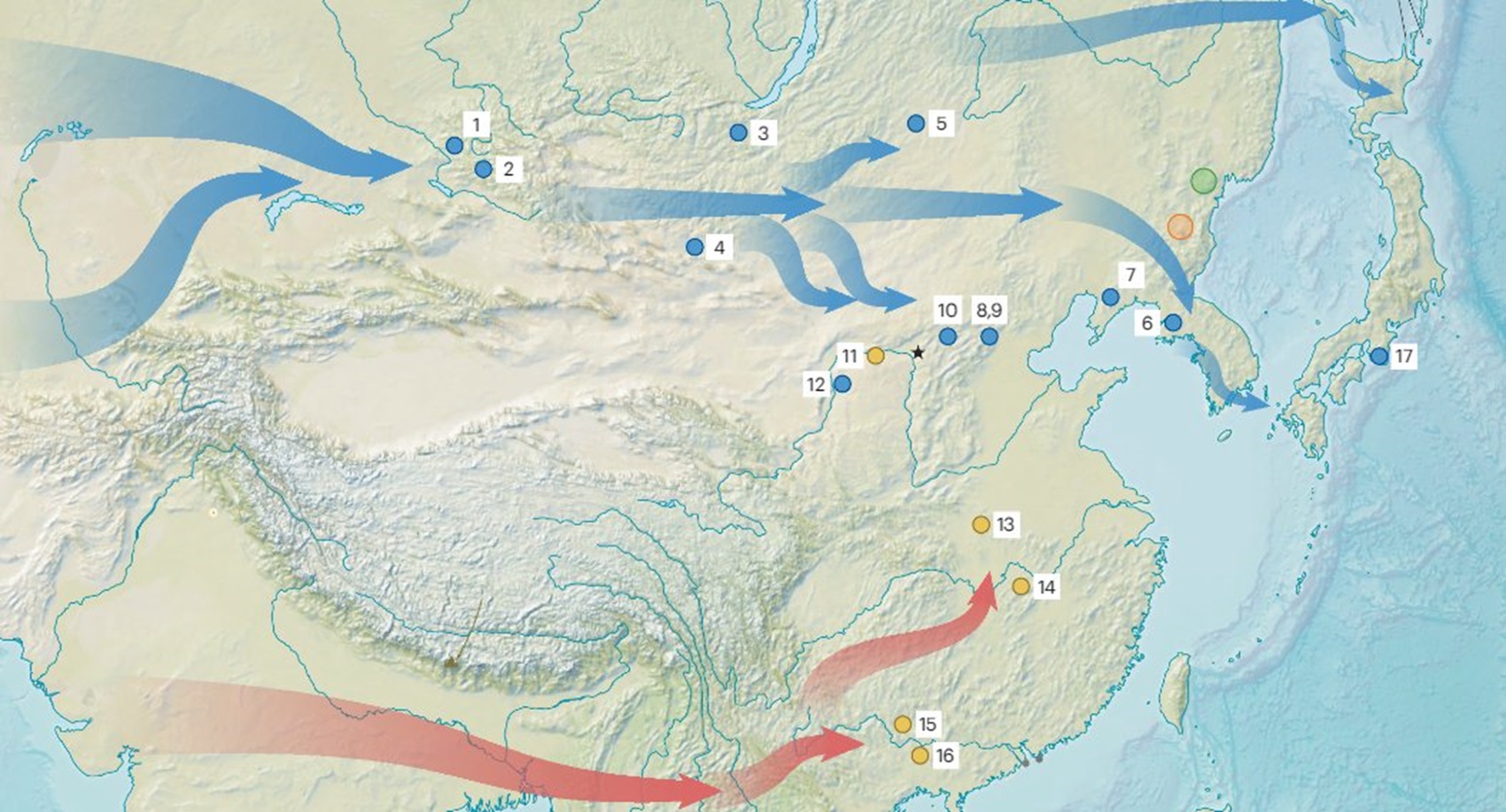

Based on the seeming evidence, I speculate that around 14,000 years ago, it could be possible Siberian Shamanism (along with dogs and a bird carving, different but yet possibly related to the bird carvings in Siberia dating from 24,000 to 15,000 years ago) was transferred to China, after “N” DNA reached Siberia bringing them pottery. Bird sculptures through ethnographic comparison at 24,000–15,000 years old Mal’ta with objects used by Siberian shamans, suggest a fully developed shamanism.

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

Postglacial genomes from foragers across Northern Eurasia reveal prehistoric

mobility associated with the spread of the Uralic and Yeniseian languages

Abstract

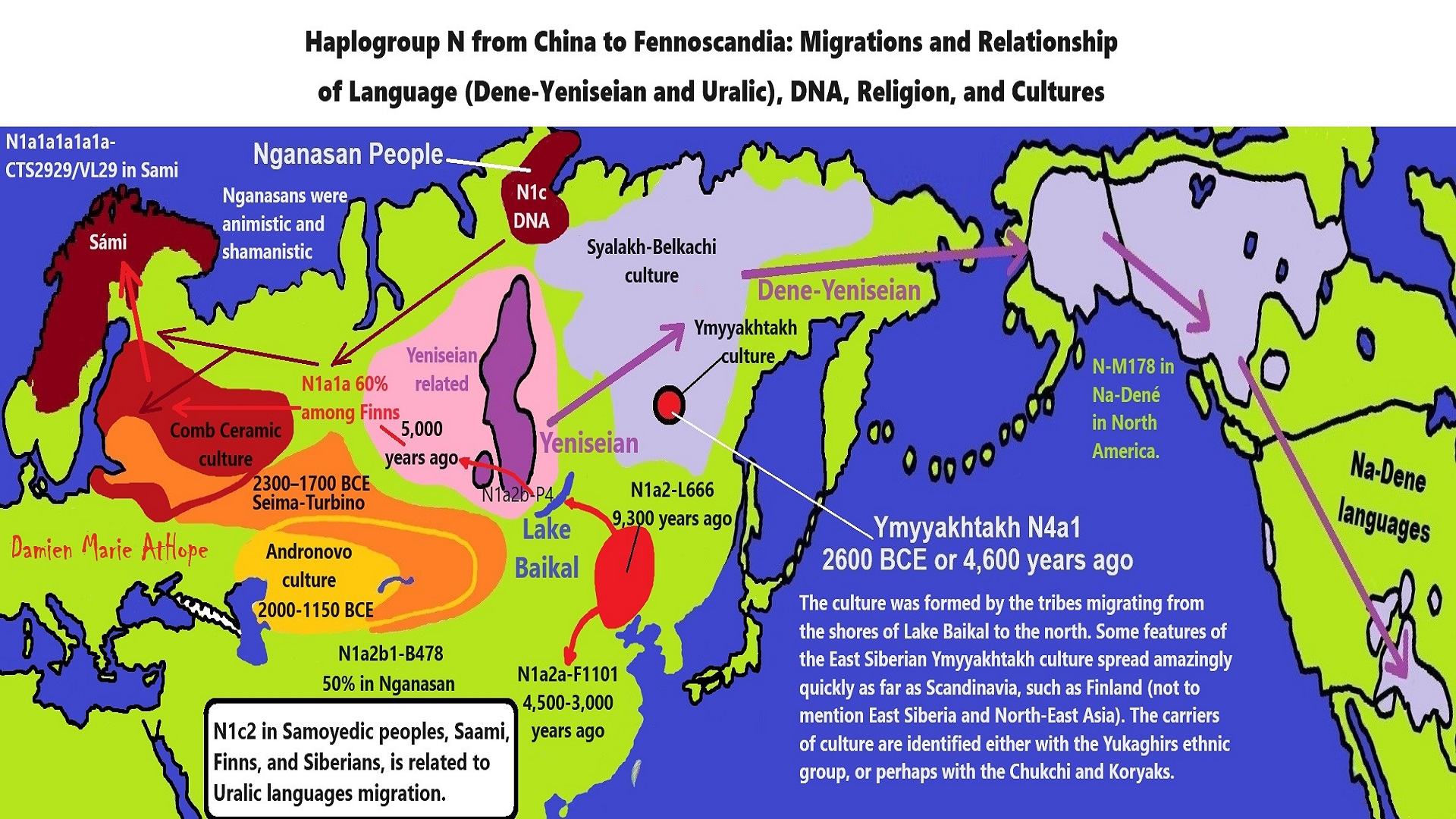

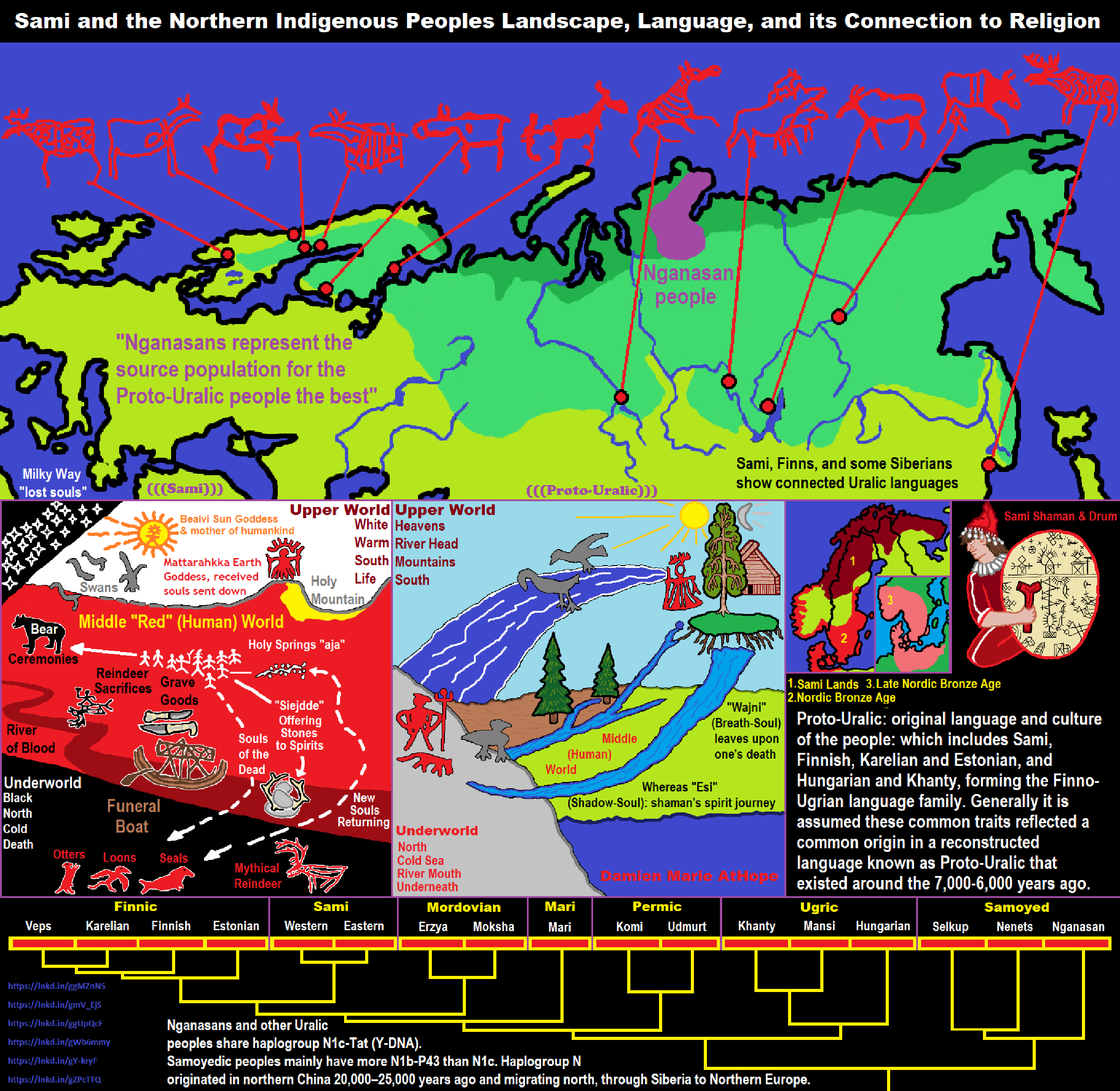

“The North Eurasian forest and forest-steppe zones have sustained millennia of sociocultural connections among northern peoples. We present genome-wide ancient DNA data for 181 individuals from this region spanning the Mesolithic, Neolithic, and Bronze Age. We find that Early to Mid-Holocene hunter-gatherer populations from across the southern forest and forest-steppes of Northern Eurasia can be characterized by a continuous gradient of ancestry that remained stable for millennia, ranging from fully West Eurasian in the Baltic region to fully East Asian in the Transbaikal region. In contrast, cotemporaneous groups in far Northeast Siberia were genetically distinct, retaining high levels of continuity from a population that was the primary source of ancestry for Native Americans. By the mid-Holocene, admixture between this early Northeastern Siberian population and groups from Inland East Asia and the Amur River Basin produced two distinctive populations in eastern Siberia that played an important role in the genetic formation of later people. Ancestry from the first population, Cis-Baikal Late Neolithic-Bronze Age (Cisbaikal_LNBA), is found substantially only among Yeniseian-speaking groups and those known to have admixed with them. Ancestry from the second, Yakutian Late Neolithic-Bronze Age (Yakutia_LNBA), is strongly associated with present-day Uralic speakers. We show how Yakutia_LNBA ancestry spread from an east Siberian origin ~4.5kya, along with subclades of Y-chromosome haplogroup N occurring at high frequencies among present-day Uralic speakers, into Western and Central Siberia in communities associated with Seima-Turbino metallurgy: a suite of advanced bronze casting techniques that spread explosively across an enormous region of Northern Eurasia ~4.0kya. However, the ancestry of the 16 Seima-Turbino-period individuals–the first reported from sites with this metallurgy–was otherwise extraordinarily diverse, with partial descent from Indo-Iranian-speaking pastoralists and multiple hunter-gatherer populations from widely separated regions of Eurasia. Our results provide support for theories suggesting that early Uralic speakers at the beginning of their westward dispersal where involved in the expansion of Seima-Turbino metallurgical traditions, and suggests that both cultural transmission and migration were important in the spread of Seima-Turbino material culture.” ref

Shamanism encompasses the premise that shamans are:

intermediaries or messengers between the human world and the spirit worlds.

A shaman is someone who is regarded as having access to, and influence in, the world of benevolent and malevolent spirits, who typically enters into a trance state during a ritual, and practices divination and healing. The word “shaman” probably originates from the Tungusic Evenki language of North Asia. According to ethnolinguist Juha Janhunen, “the word is attested in all of the Tungusic idioms” such as Negidal, Lamut, Udehe/Orochi, Nanai, Ilcha, Orok, Manchu and Ulcha, and “nothing seems to contradict the assumption that the meaning ‘shaman’ also derives from Proto-Tungusic” and may have roots that extend back in time at least two millennia. The term was introduced to the west after Russian forces conquered the shamanistic Khanate of Kazan in 1552. The term “shamanism” was first applied by Western anthropologists as outside observers of the ancient religion of the Turks and Mongols, as well as those of the neighbouring Tungusic and Samoyedic-speaking peoples. Upon observing more religious traditions across the world, some Western anthropologists began to also use the term in a very broad sense, to describe unrelated magico-religious practices found within the ethnic religions of other parts of Asia, Africa, Australasia and even completely unrelated parts of the Americas, as they believed these practices to be similar to one another. Mircea Eliade writes, “A first definition of this complex phenomenon, and perhaps the least hazardous, will be: shamanism = ‘technique of religious ecstasy‘.” Shamanism encompasses the premise that shamans are intermediaries or messengers between the human world and the spirit worlds. Shamans are said to treat ailments/illness by mending the soul. Alleviating traumas affecting the soul/spirit restores the physical body of the individual to balance and wholeness. The shaman also enters supernatural realms or dimensions to obtain solutions to problems afflicting the community. Shamans may visit other worlds/dimensions to bring guidance to misguided souls and to ameliorate illnesses of the human soul caused by foreign elements. The shaman operates primarily within the spiritual world, which in turn affects the human world. The restoration of balance results in the elimination of the ailment. Beliefs and practices that have been categorised this way as “shamanic” have attracted the interest of scholars from a wide variety of disciplines, including anthropologists, archaeologists, historians, religious studies scholars, philosophers and psychologists. Hundreds of books and academic papers on the subject have been produced, with a peer-reviewed academic journal being devoted to the study of shamanism.

Regional variations of Shamanism

- Asia

- Europe

- Circumpolar shamanism

- Americas

- Oceania

- Africa

- Contemporary Western shamanism

* “shamanist” Believe in spirit-filled life and/or afterlife can be attached to or be expressed in things or objects and these objects can be used by special persons or in special rituals can connect to spirit-filled life and/or afterlife (you are a hidden shamanist/Shamanism: an approximately 30,000-year-old belief system) there is what is believed to be a female shaman burial with a matching carved ivory female head belonging to the Pavlovian culture 29,000 to 25,000 a variant of the Gravettian/(Gravettian culture 33,000 to 22,000 years ago), dated to 29,000 to 25,000-years old Dolní Vestonice, Moravia, Czech Republic. A carved ivory figure in the shape of a female head was discovered near the huts. The left side of the figure’s face was distorted image is believed to be a description of elder female’s burial around 40 years old, she was ritualistically placed beneath a pair of mammoth scapulae, one leaning against the other. Surprisingly, the left side of the skull was disfigured in the same manner as the aforementioned carved ivory figure, indicating that the figure was an intentional depiction of this specific individual. The bones and the earth surrounding the body contained traces of red ocher, a flint spearhead had been placed near the skull, and one hand holding the body of a fox. This evidence suggests that this was the burial site of a shaman. This is the oldest site not only of ceramic figurines and artistic portraiture but also of evidence of early female shamans. Archaeologists usually describe two regional variants: the western Gravettian, known namely from cave sites in France, Spain and Britain, and the eastern Gravettian in Central Europe and Russia. The eastern Gravettians — they include the Pavlovian culture — were specialized mammoth hunters, whose remains are usually found not in caves but in open air sites. The origins of the Gravettian people are not clear, they seem to appear simultaneously all over Europe. Though they carried distinct genetic signatures, the Gravettians and Aurignacians before them were descended from the same ancient founder population. According to genetic data, 37,000 years ago, all Europeans can be traced back to a single ‘founding population’ that made it through the last ice age. Furthermore, the so-called founding fathers were part of the Aurignacian culture which was displaced by another group of early humans members of the Gravettian culture. Between 37,000 years ago and 14,000 years ago, different groups of Europeans were descended from a single founder population. To a greater extent than their Aurignacian predecessors, they are known for their Venus figurines. ref, ref, ref, ref

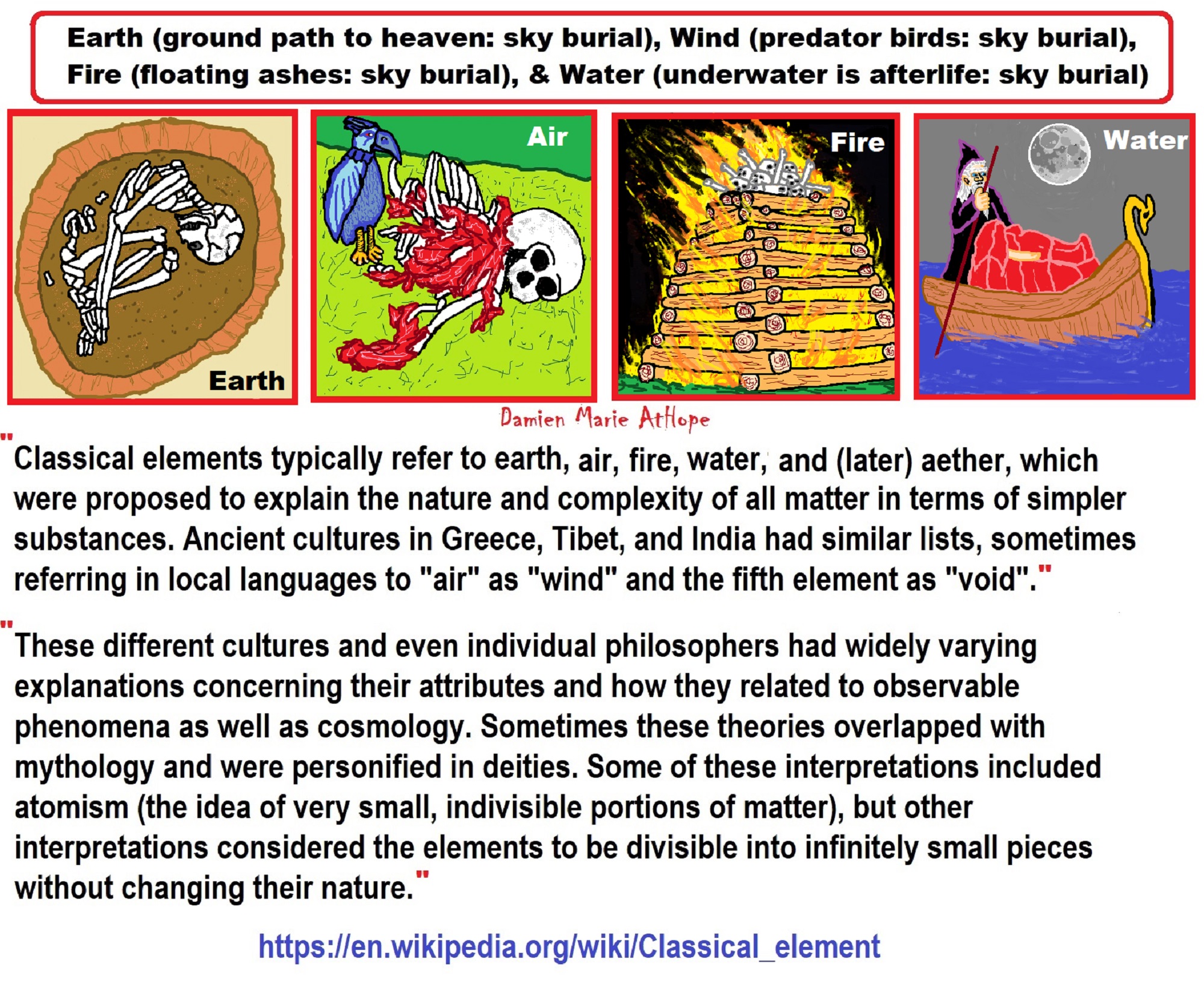

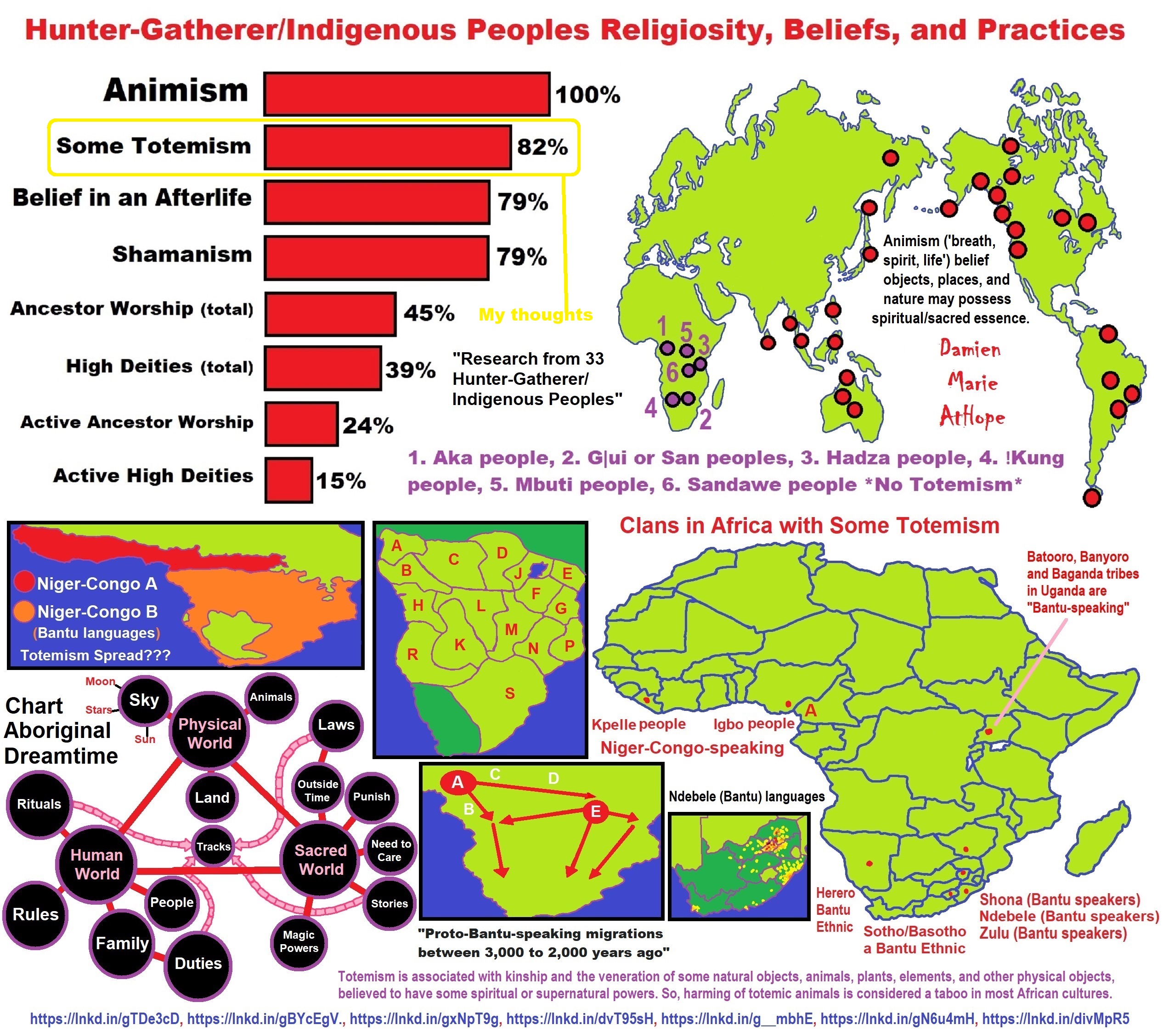

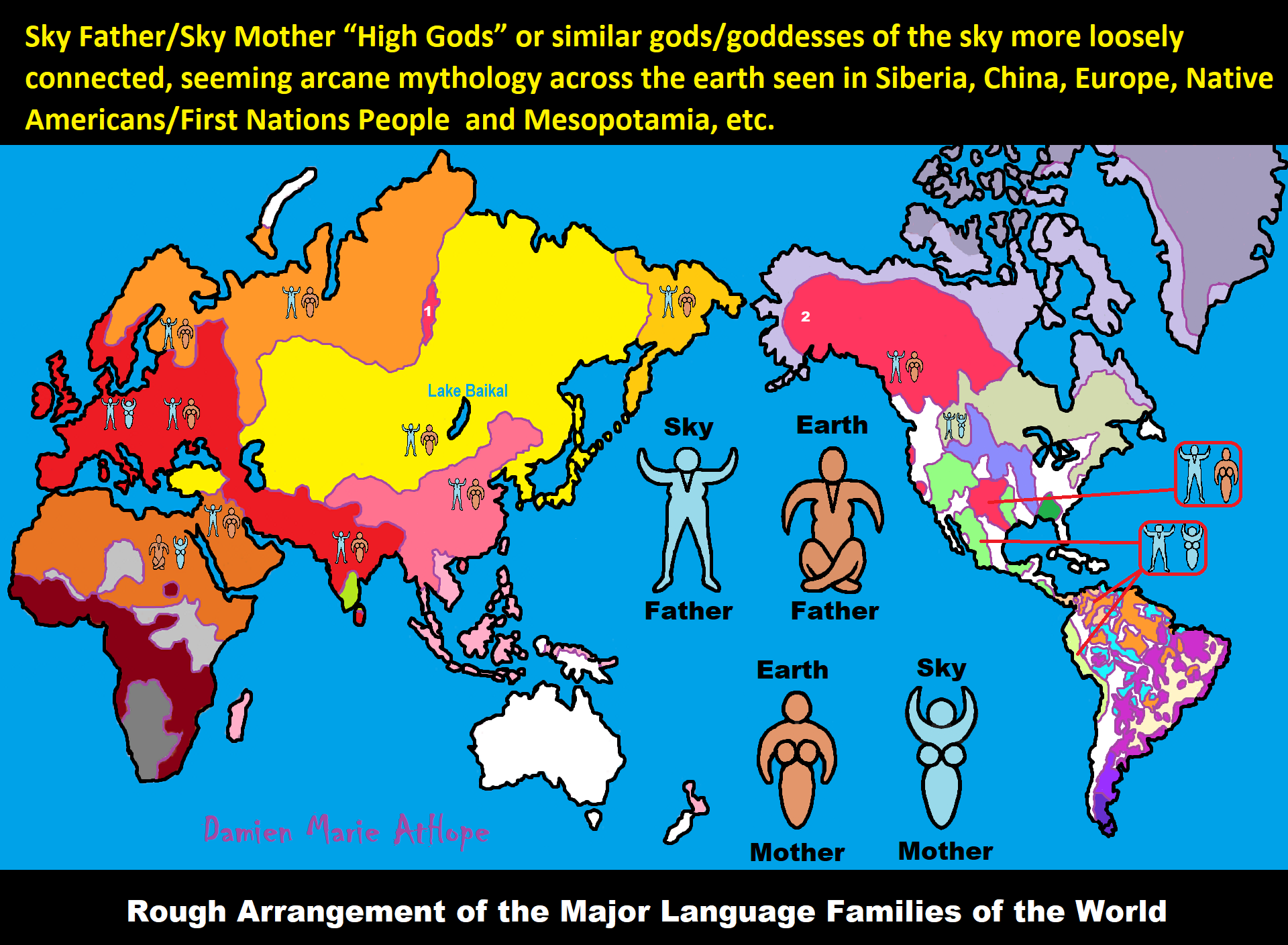

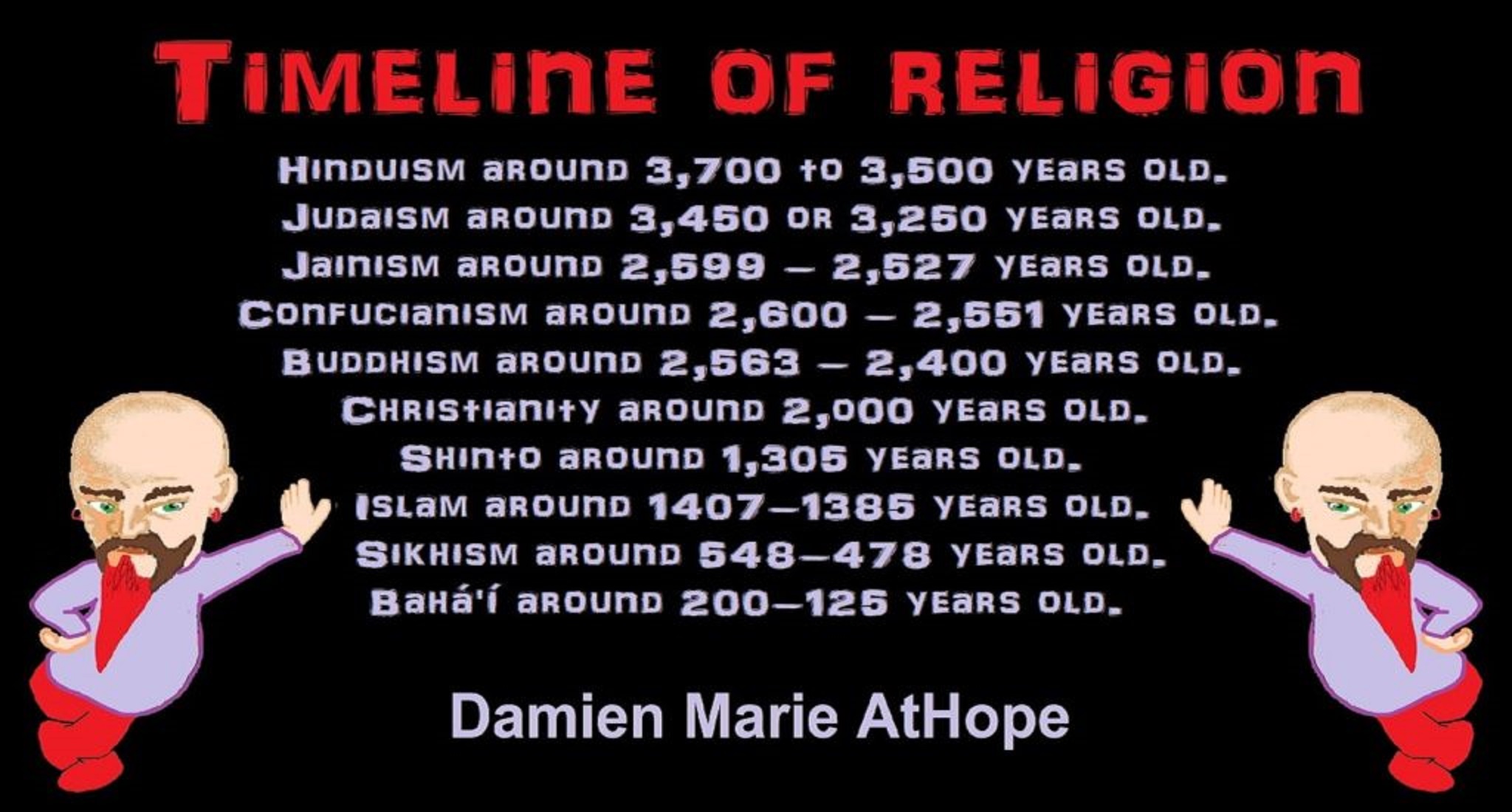

So, it all starts in a general way with Animism (theoretical belief in supernatural powers/spirits), then this is physically expressed in or with Totemism (theoretical belief in a mythical relationship with powers/spirits through a totem item), which then enlists a full-time specific person to do this worship and believed interacting Shamanism (theoretical belief in access and influence with spirits through ritual), and then there is the further employment of myths and gods added to all the above giving you Paganism (often a lot more nature-based than most current top world religions, thus hinting to their close link to more ancient religious thinking it stems from). My hypothesis is expressed with an explanation of the building of a theatrical house (modern religions development).

Sky Burials: Animism, Totemism, Shamanism, and Paganism

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

“The shaman is, above all, a connecting figure, bridging several worlds for his people, traveling between this world, the underworld, and the heavens. He transforms himself into an animal and talks with ghosts, the dead, the deities, and the ancestors. He dies and revives. He brings back knowledge from the shadow realm, thus linking his people to the spirits and places which were once mythically accessible to all.–anthropologist Barbara Meyerhoff” ref

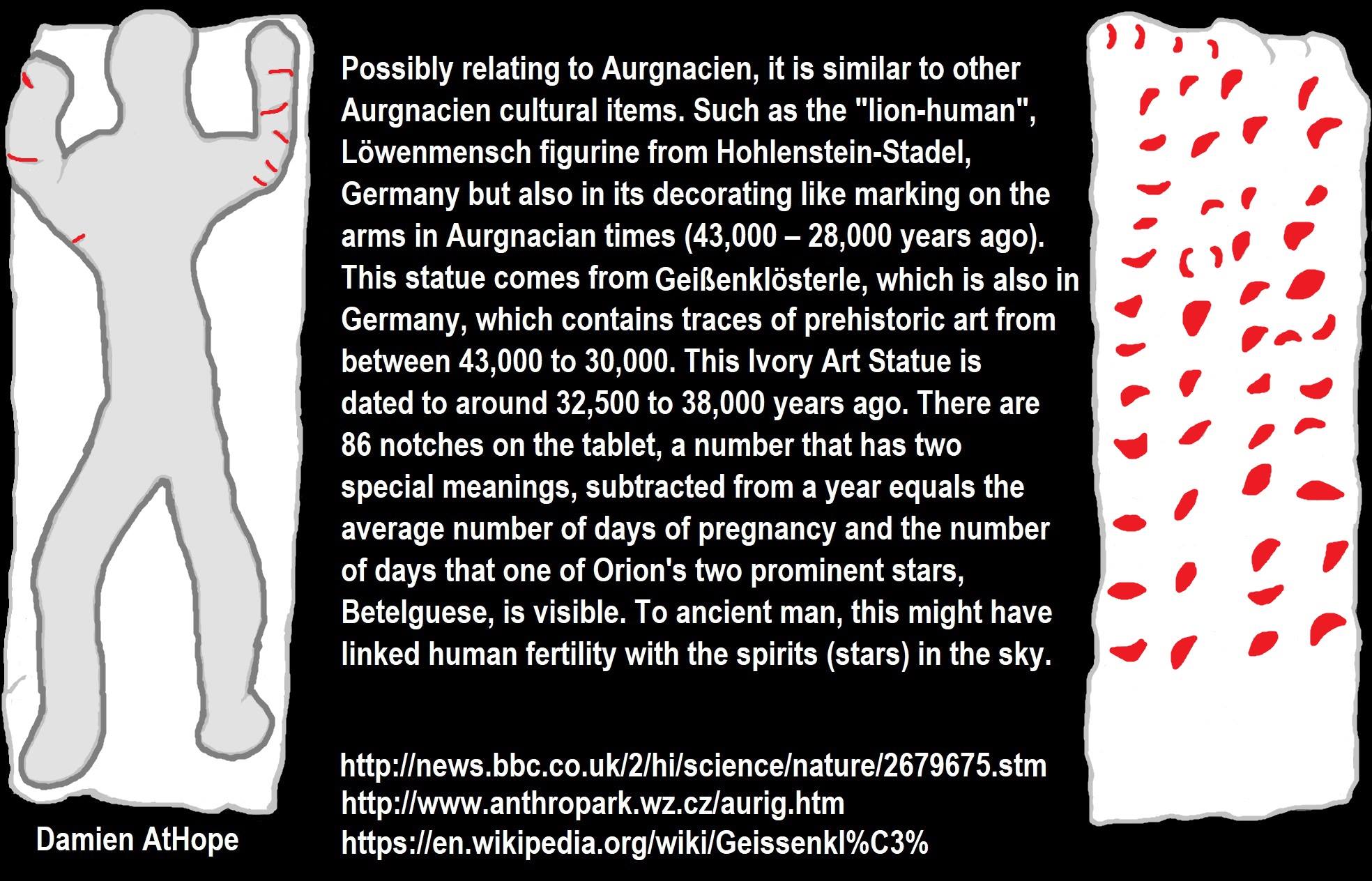

“Probably occupied from as much as around 38,900–32,630 years ago. It had previously been dated at a lower date as low as around 23,000-19,000 years ago which changed.” ref

Sungar “Gravettian culture” (Russia) and related Dolni Vestonice Pavlovian/Gravettian culture (Czech Republic).

Sungar (Russia), found posable evidence of shamanistic Gravettian culture burials and that seem to match the latter indigenous American shamanistic burials in Alaska at the Tanana River site with around 11,500 years old duel infant burial very similar shamanistic grave offerings like decorated stone weapons. To further a clear connection is the Bluefish Cave (Yukon Territory Canada) that held bones with cut marks which is possibly as old as 24,000 to 19,650 years ago and the youngest are around 12,000 years old seem to offer strong support for the “Beringian hypothesis” human population dispersed to North and South America. ref

To me, is seems Siberian is the general origin of native Americans at least by around 11,000 years ago, by the land bridge “Beringia” from Asia by way of Siberia in Russia over to Alaska in the Americas, which the Paleoindians had crossover on, finally flooded over by rising sea levels and was submerged. Siberia has a large variety of climate, vegetation, and landscape. Siberia’s Prehistory demonstrates several distinct cultures sometimes transferring ideas, other times not, and some split from earlier cultures creating new ones often in illation, mainly starting with hunter-gatherer nomadism. During glaciation around 115,000 to 15,000 years ago, the Siberia tundra extended south and an ice sheet covered area of Russia around the Ural Mountains that while some of the oldest mountains are more like large hills, and the area to the east of the lower Yenisei River basin, which in the general area of central and southern Siberia. ref

Some of the first nomadic peoples entered Siberia about 50,000 years ago. Ancient nomadic tribes such as the Ket people and the Yugh people a separate but similar group lived along its banks. Shamanism among Kets shares characteristics with those of Turkic and Mongolic peoples thus not at all homogeneous in expression though neither is shamanism in Siberia in general. As for shamanism among Kets had several types of Ket shamans and shared characteristics with those of Turkic and Mongolic peoples. The Yana River sites, in Siberia, demonstrate that modern human populations had reached Western Beringia by 32,000 years ago then engaging in an early dispersal possibly by 24,000 years ago. ref