Genetic history of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas

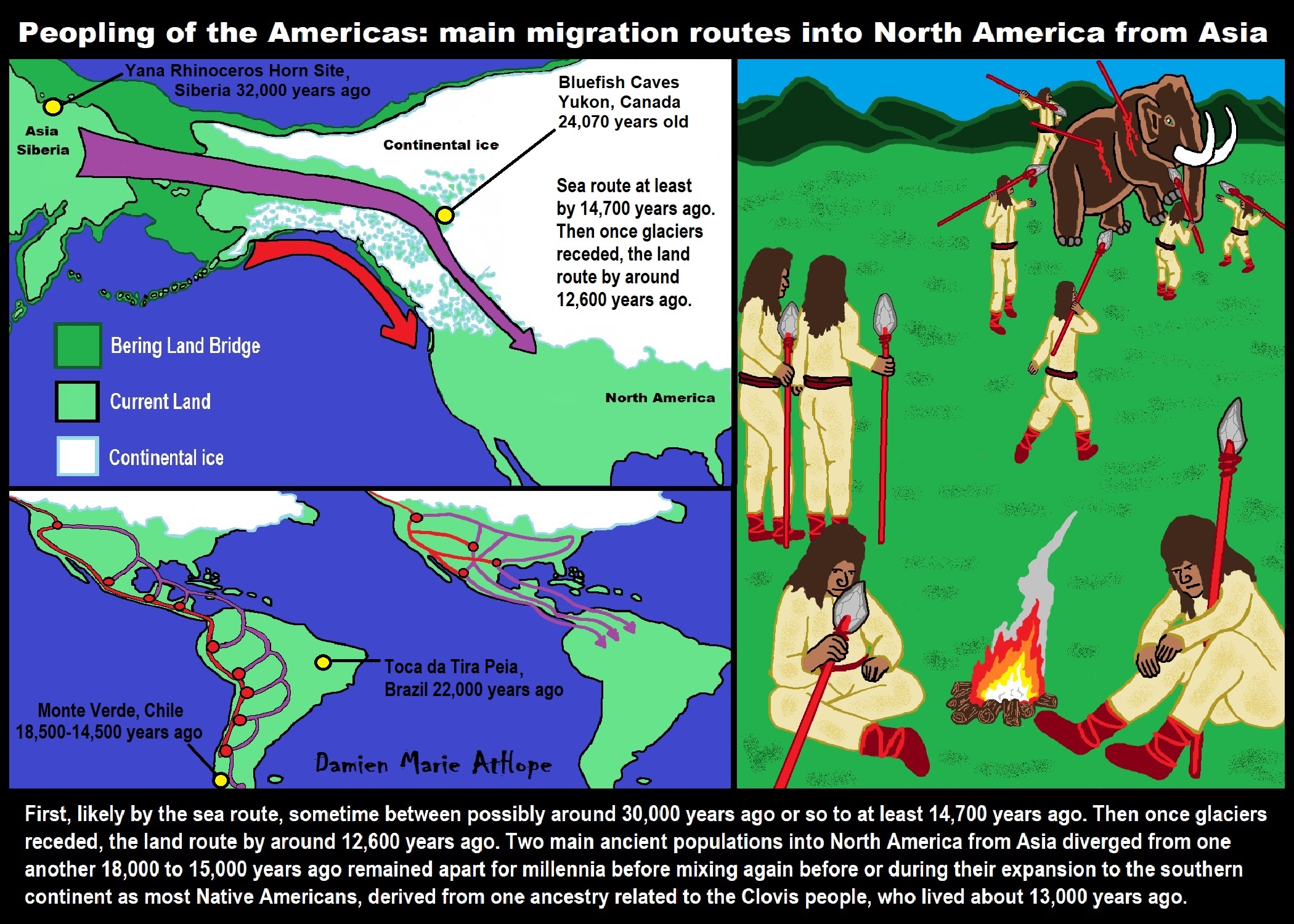

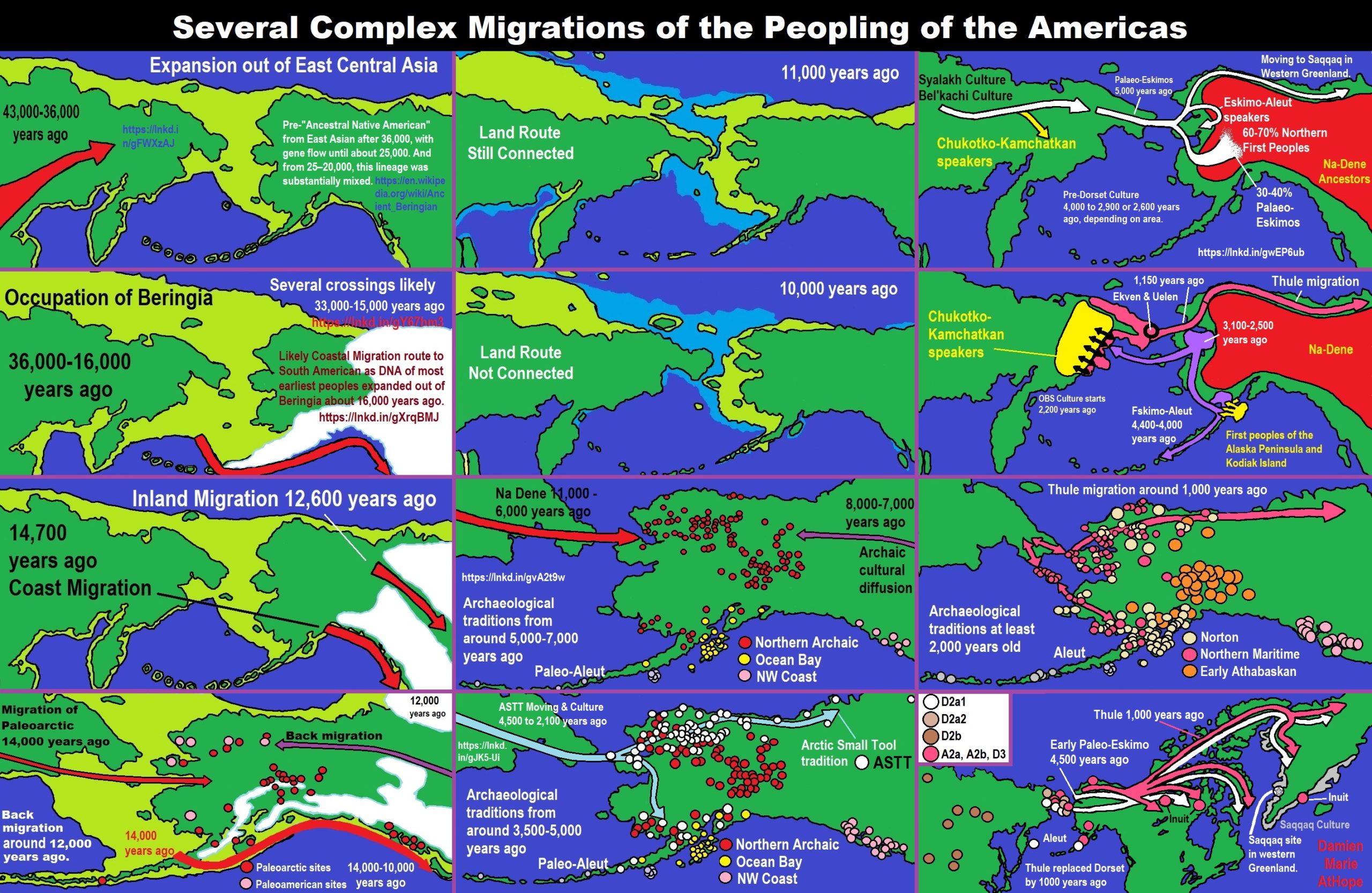

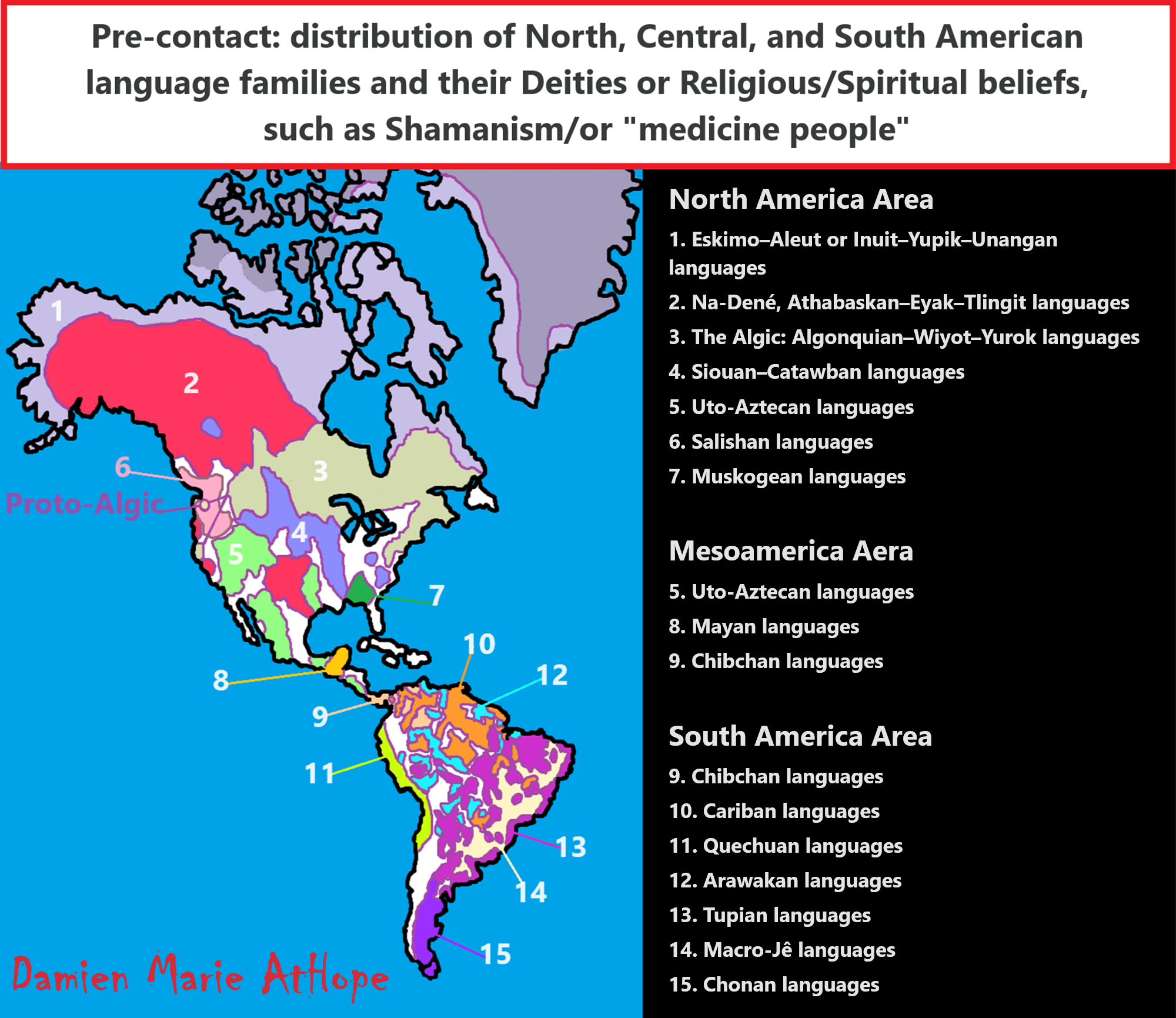

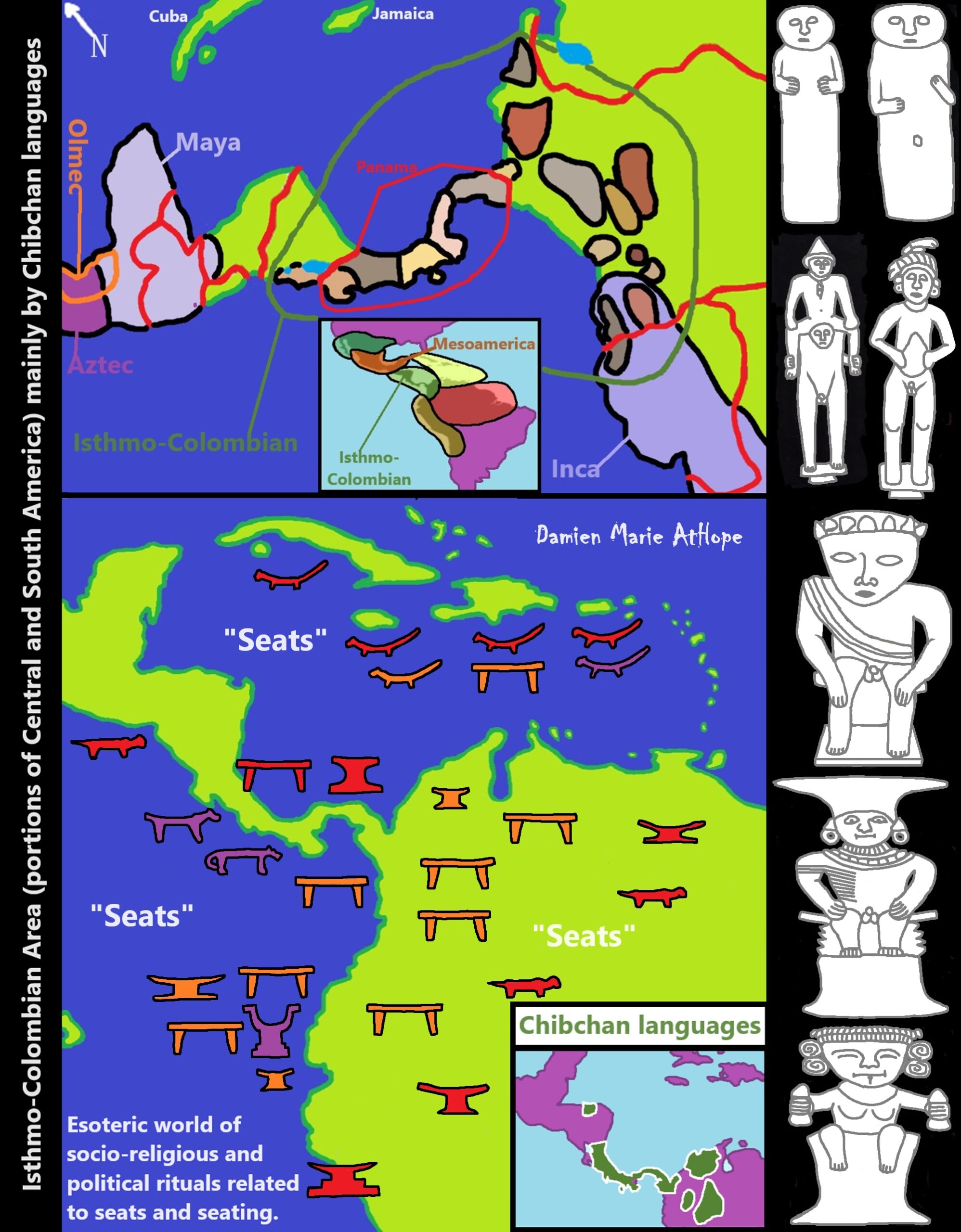

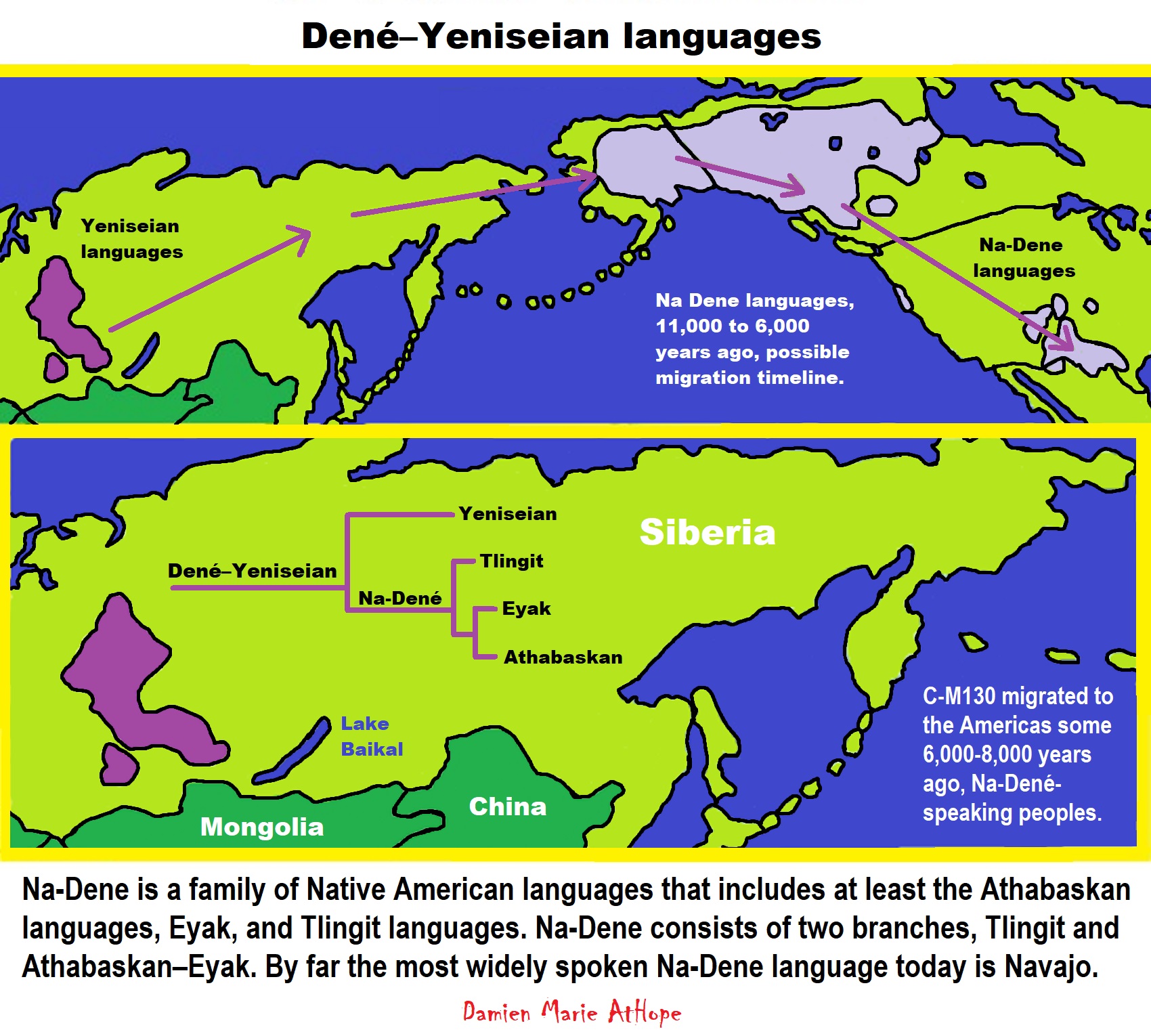

“According to an autosomal genetic study from 2012, Indigenous Americans descend from at least three main migrant waves from East Asia. Most of it is traced back to a single ancestral population, called ‘First Americans’. However, those who speak Inuit languages from the Arctic inherited almost half of their ancestry from a second East Asian migrant wave. And those who speak Na-Dene, on the other hand, inherited a tenth of their ancestry from a third migrant wave. The initial settling of the Americas was followed by a rapid expansion southwards along the west coast, with little gene flow later, especially in South America. One exception to this are the Chibcha speakers of Colombia, whose ancestry comes from both North and South America. A study published in the Nature journal in 2018 concluded that Indigenous Americans descended from a single founding population which initially divided from East Asians about ~36,000 BCE or around 38,000 years ago, with gene flow between Ancestral Indigenous Americans and Siberians persisting until ~25,000 BCE, before becoming isolated in the Americas at ~22,000 BCE or around 24,000 years ago. Northern and Southern American Indigenous sub-populations split from each other at ~17,500 BCE or around 19,500 years ago. There is also some evidence for a back-migration from the Americas into Siberia after ~11,500 BCE or around 13,500 years ago.” ref

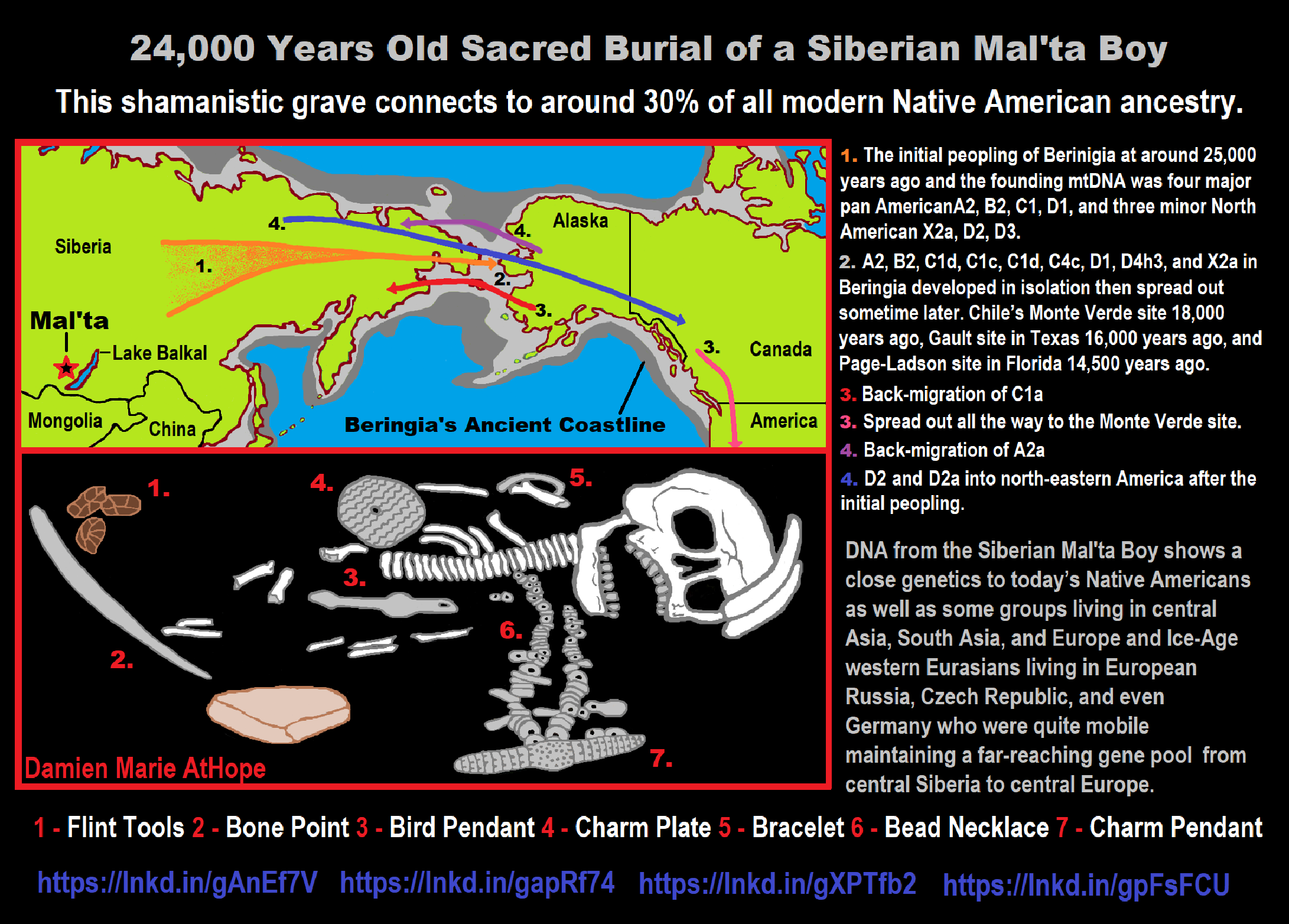

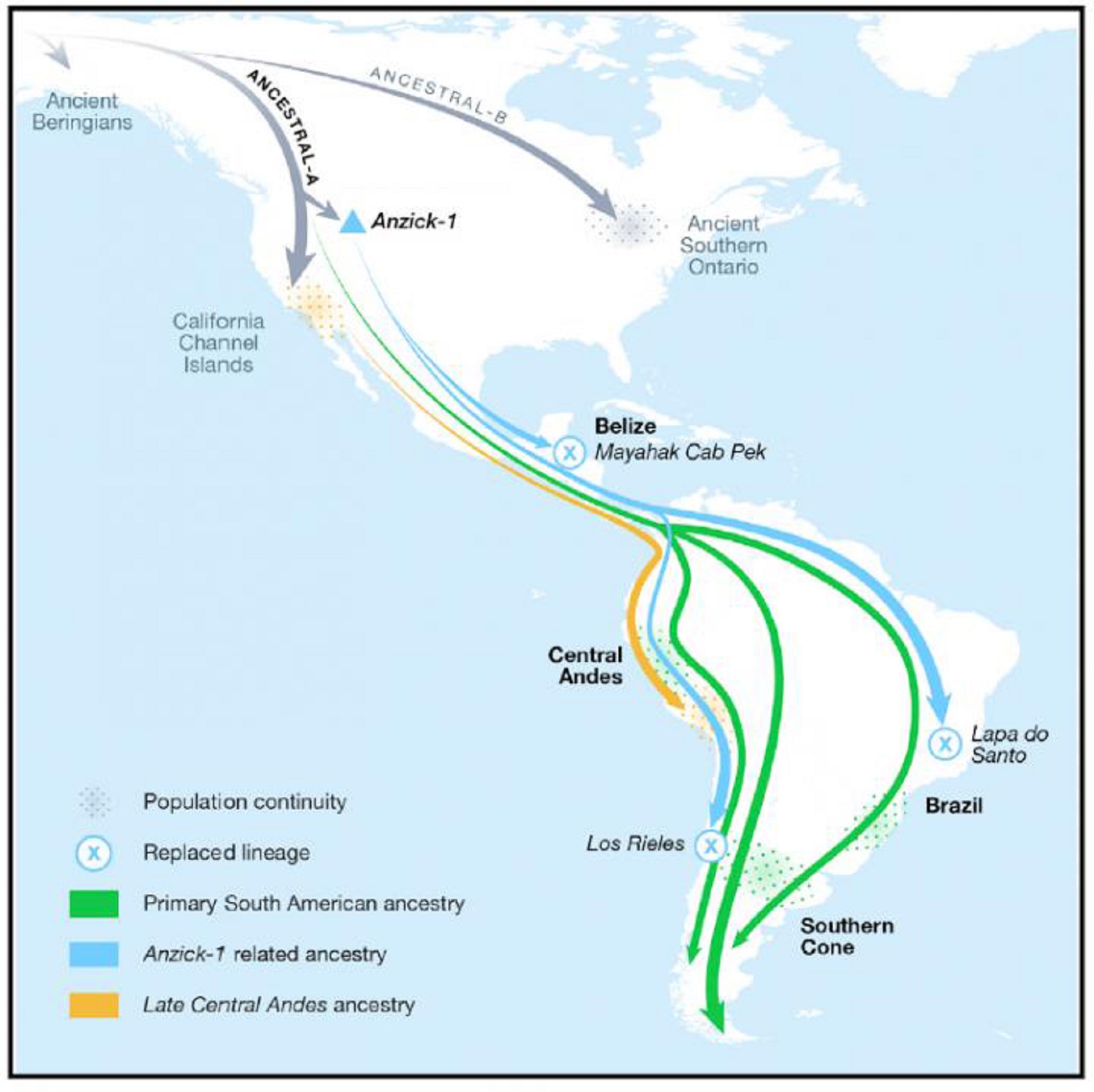

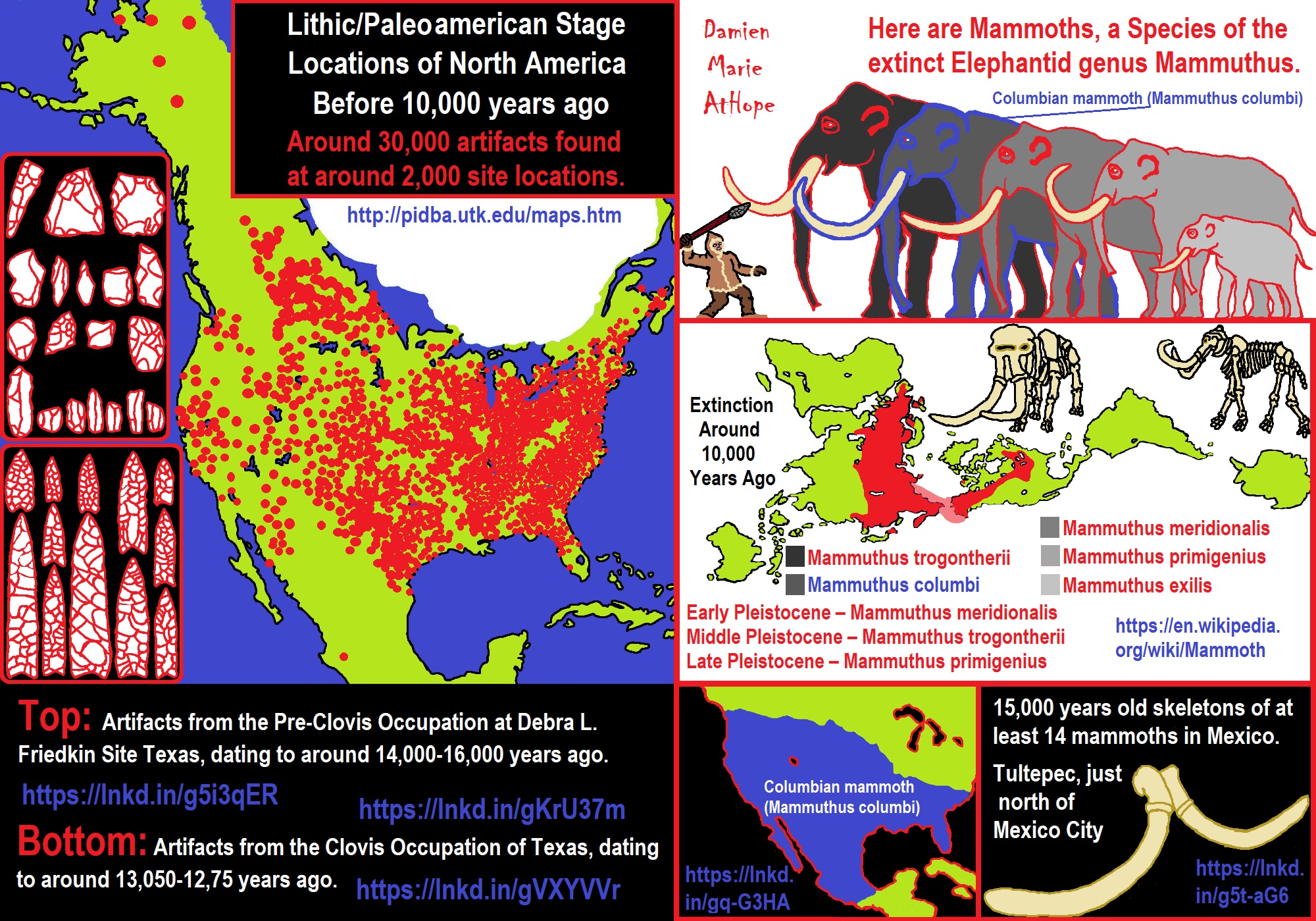

“In 2014, the autosomal DNA of a 12,500+ year-old infant from Montana was sequenced. The DNA was taken from a skeleton referred to as Anzick-1, found in close association with several Clovis artifacts. Comparisons showed strong affinities with DNA from Siberian sites, and virtually ruled out that particular individual had any close affinity with European sources (the “Solutrean hypothesis“). The DNA also showed strong affinities with all existing Indigenous American populations, which indicated that all of them derive from an ancient population that lived in or near Siberia. Linguistic studies have reinforced genetic studies, with relationships between languages found among those spoken in Siberia and those spoken in the Americas. Two 2015 autosomal DNA genetic studies confirmed the Siberian origins of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. However, an ancient signal of shared ancestry with Australasians (Indigenous peoples of Australia, Melanesia and the Andaman Islands) was detected among the Indigenous peoples of the Amazon region. The migration coming out of Siberia would have happened 23,000 years ago.” ref

“A 2018 study analyzed ancient Indigenous samples. The genetic evidence suggests that all Indigenous Americans ultimately descended from a founding population that combined East Asian and Ancient North Eurasian ancestry. The authors also provided evidence that the basal northern and southern Indigenous American branches, to which all other Indigenous peoples belong, diverged around 16,000 years ago. An Indigenous American sample from 16,000 BCE or around 18,000 years ago in Idaho, which is craniometrically similar to modern Indigenous Americans as well as Paleosiberians, was found to have been largely East-Eurasian genetically, and showed high affinity with contemporary East Asians, as well as Jōmon period samples of Japan, confirming that Ancestral Indigenous Americans split from an East-Eurasian source population somewhere in eastern Siberia.” ref

“A review article published in the Nature journal in 2021, which summarized the results of previous genomic studies, similarly concluded that all Indigenous Americans descended from the movement of people from Northeast Asia into the Americas. These Ancestral Americans, once south of the continental ice sheets, spread and expanded rapidly, and branched into multiple groups, which later gave rise to the major subgroups of Indigenous American populations. The study also dismissed the existence, inferred from craniometric data, of a hypothetical distinct non-Indigenous American population (suggested to have been related to Indigenous Australians and Papuans), sometimes called “Paleoamerican”. Overall, the ‘Ancestral Native Americans’ formed from an ‘Ancient Paleo-Siberian‘ lineage which formed from the admixture between East Asian people and a distinct Paleolithic Siberian population known as Ancient North Eurasians, closer related to modern Europeans, giving rise to both Indigenous peoples of Siberia and Native Americans. Around 67% of the ancestry of Native Americans is derived from East Asian sources, while c. 33% is derived from an Ancient West Eurasian (Ancient North Eurasian-like) source.” ref

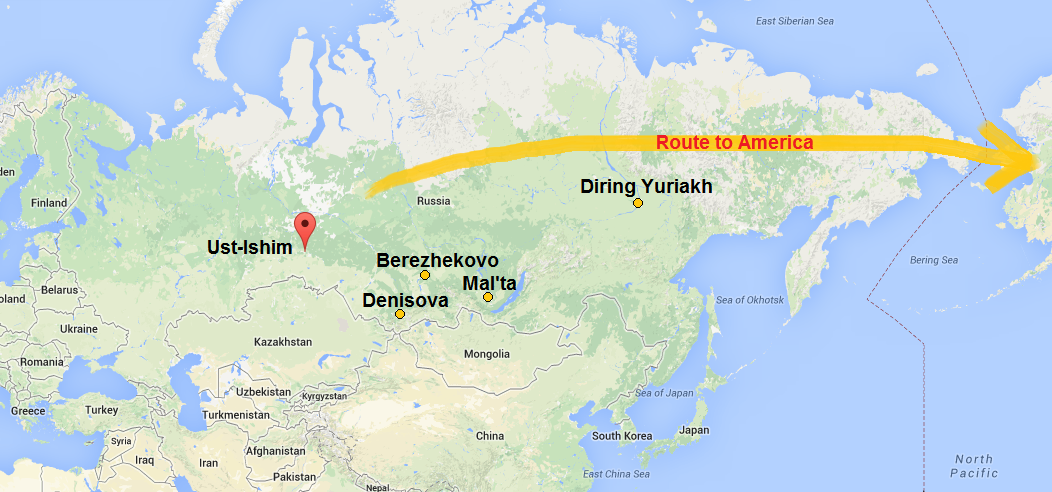

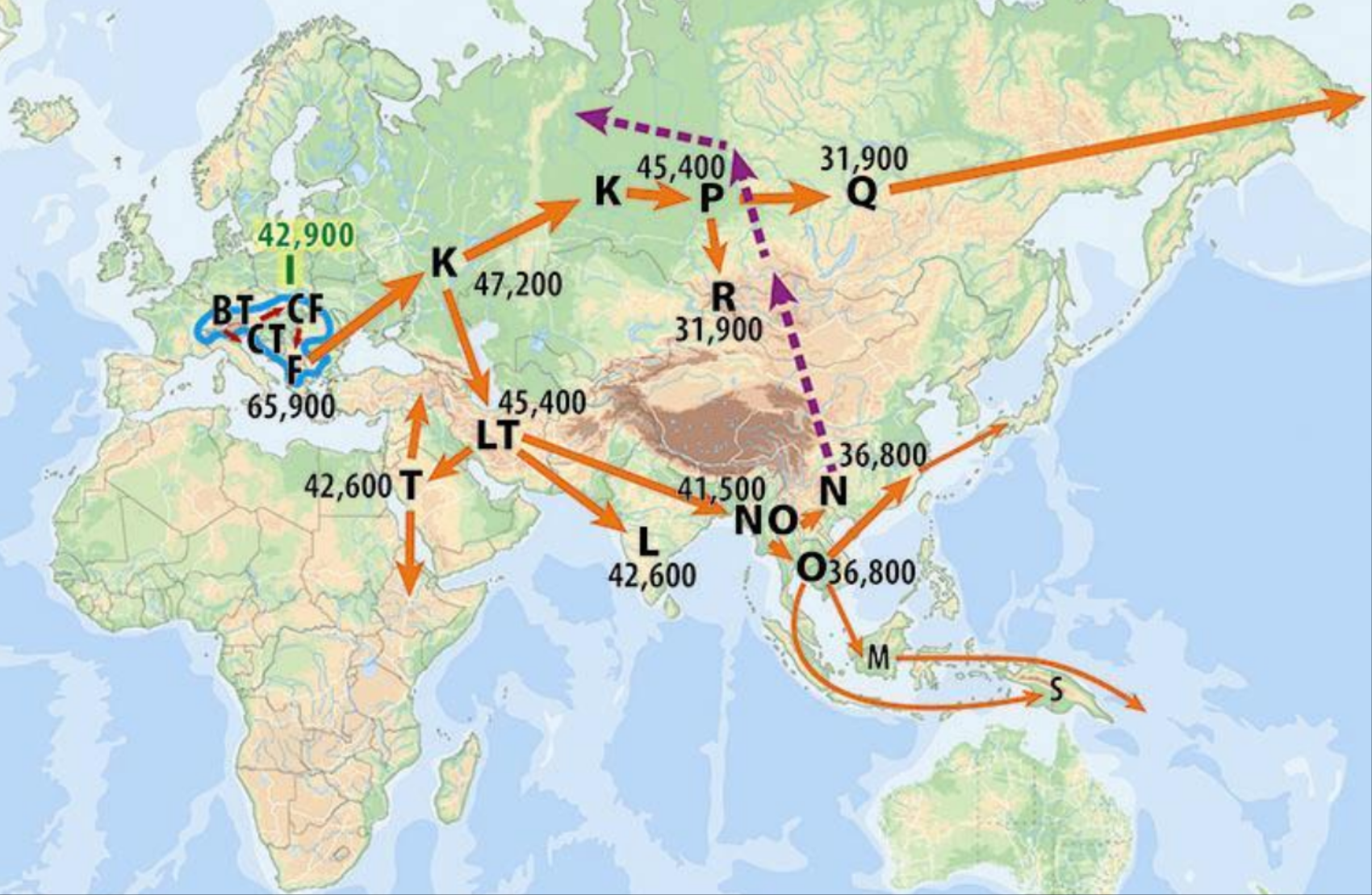

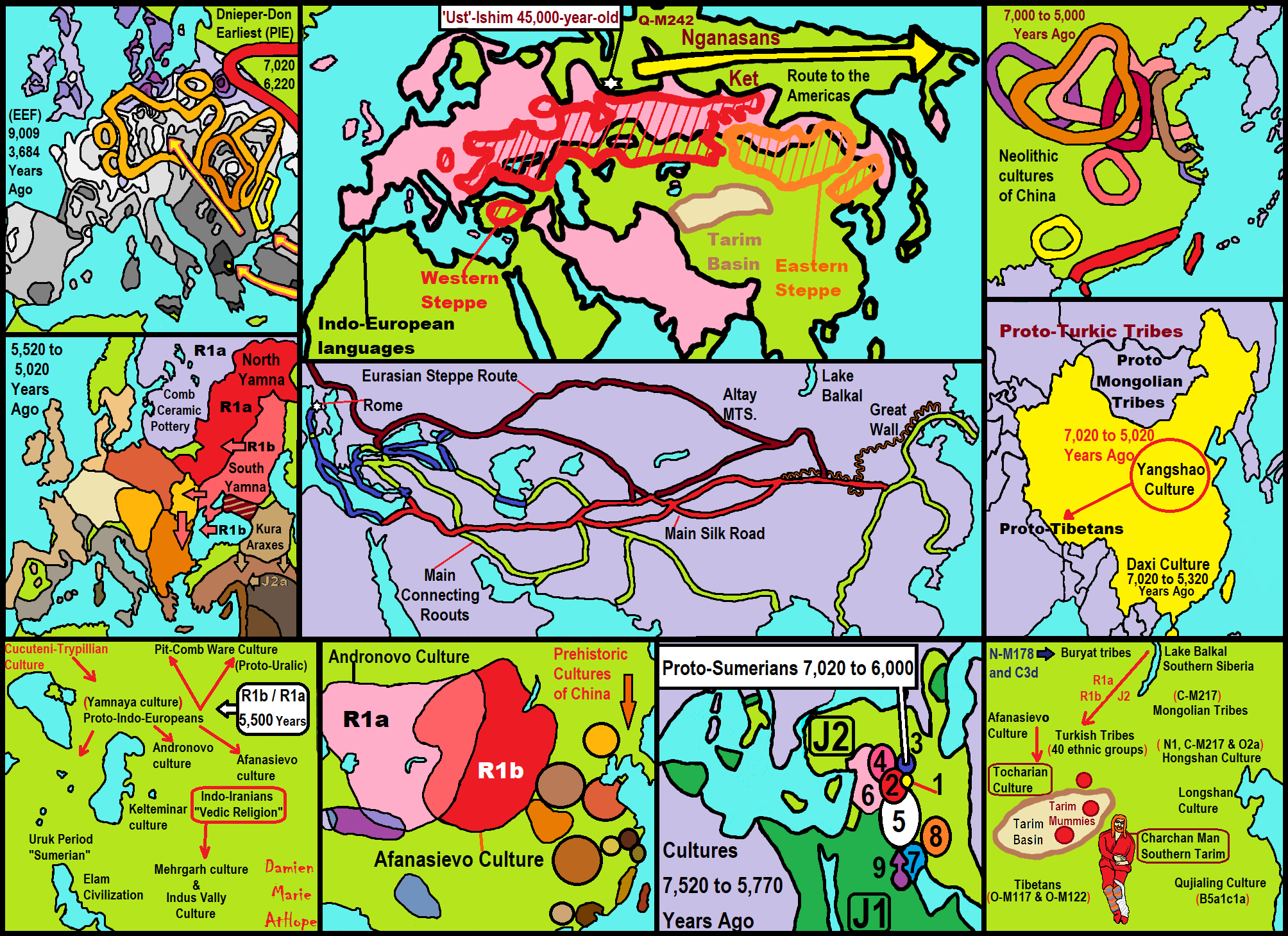

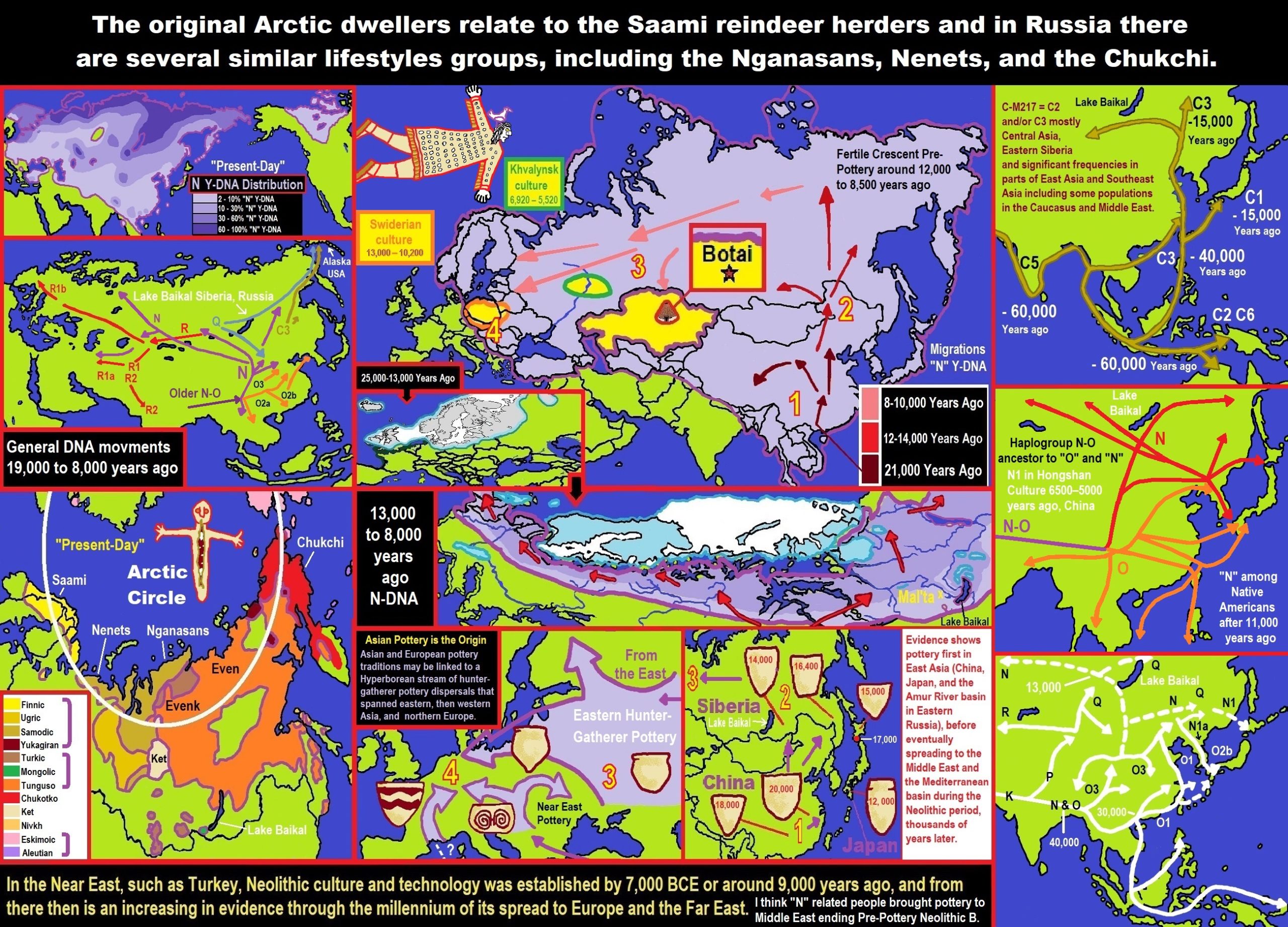

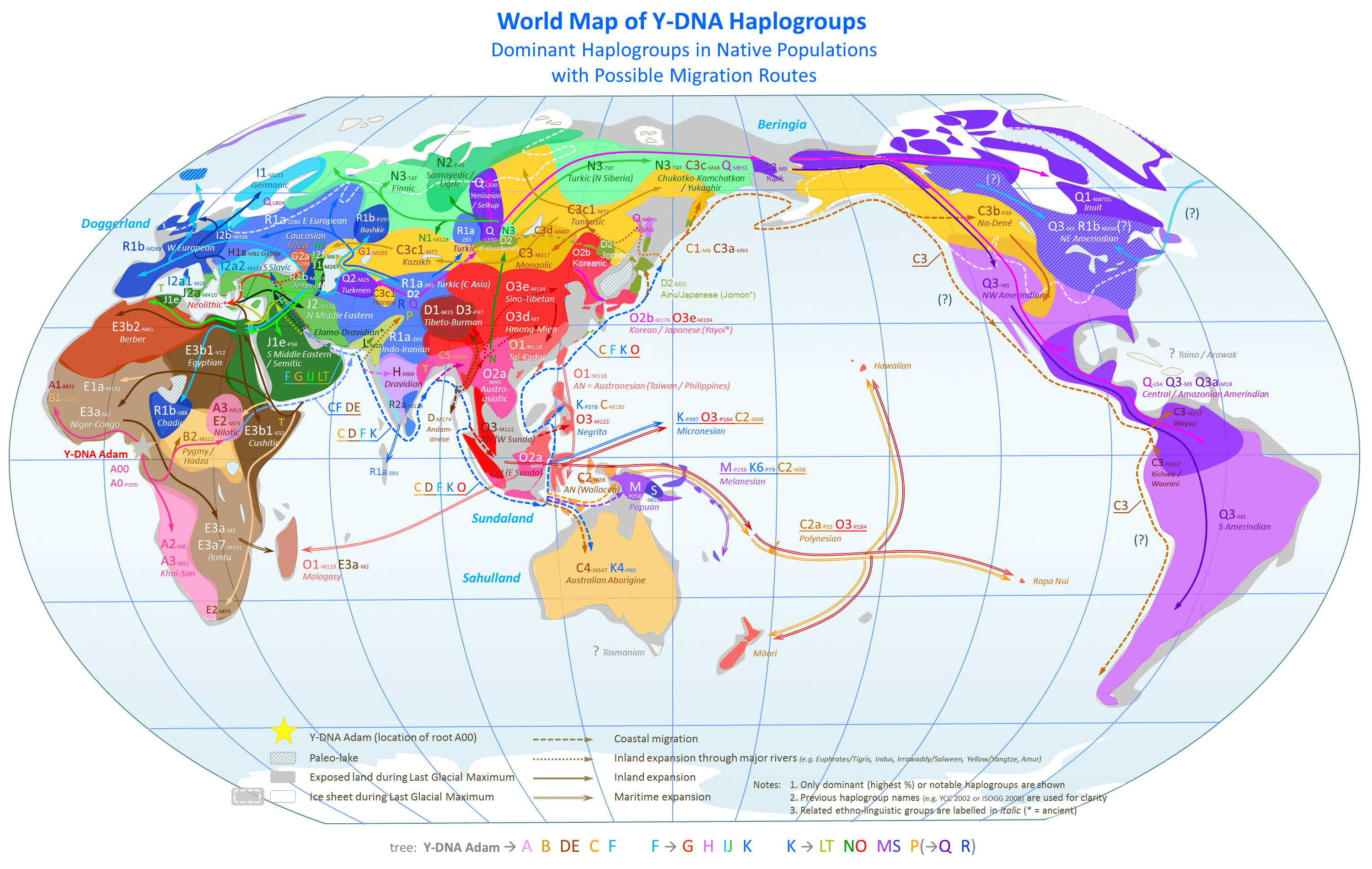

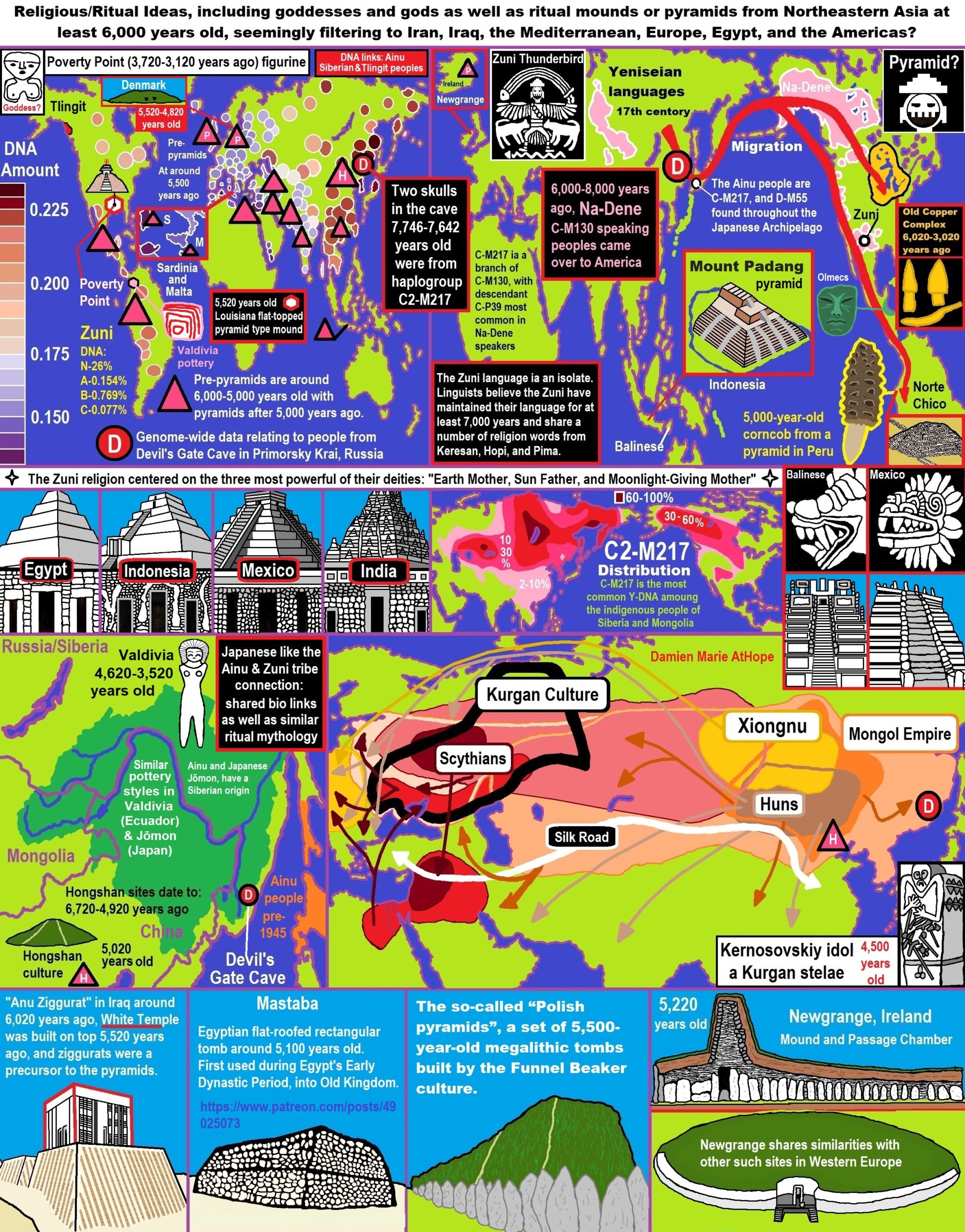

“A “Central Siberian” origin has been postulated for the paternal lineage of the source populations of the original migration into the Americas. Membership in haplogroups Q and “C3b” (now called Haplogroup C-M217, also known as C2 and previously as C3), is a Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup. It is the most frequently occurring branch of the wider Haplogroup C (M130) implies Indigenous American patrilineal descent. The haplogroup C-M217 is now found at high frequencies among Central Asian peoples, indigenous Siberians, and some Native peoples of North America. In particular, males belonging to peoples such as the Buryats, Evens, Evenks, Itelmens, Kalmyks, Kazakhs, Koryaks, Mongolians, Negidals, Nivkhs, Udege, and Ulchi have high levels of M217. According to Sakitani et al., haplogroup C-M130 originated in Central Asia and spread from there into other parts of Eurasia and into parts of Australia. It is suggested that C-M130 was found in Eastern Eurasian hunter gatherers as well as in ancient samples of East and Southeast Asia and Europe. Genetic testing also showed that the haplogroup C3b1a3a2-F8951 of the Aisin Gioro family came to southeastern Manchuria after migrating from their place of origin in the Amur river’s middle reaches, originating from ancestors related to Daurs in the Transbaikal area. The Tungusic-speaking peoples mostly have C3c-M48 as their subclade of C3 which drastically differs from the C3b1a3a2-F8951 haplogroup of the Aisin Gioro which originates from Mongolic speaking populations like the Daur. Jurchen (Manchus) are a Tungusic people. In an early study of Japanese Y-chromosomes, haplogroup C-M217 was found relatively frequently among Ainus (2/16=12.5% or 1/4=25%) and among Japanese of the Kyūshū region (8/104=7.7%). However, in other samples of Japanese, the frequency of haplogroup C-M217 was found to be only about one to three percent.” ref, ref

“More precisely, haplogroup C2-M217 is now divided into two primary subclades: C2a-L1373 (sometimes called the “northern branch” of C2-M217) and C2b-F1067 (sometimes called the “southern branch” of C2-M217). The oldest sample with C2-M217 is AR19K in the Amur River basin (19,587-19,175 years ago). The micro-satellite diversity and distribution of a Y lineage specific to South America suggest that certain Indigenous American populations became isolated after the initial colonization of their regions. The Na-Dene, Inuit, and Native Alaskan populations exhibit haplogroup Q (Y-DNA) mutations, but are distinct from other Indigenous Americans with various mtDNA and autosomal DNA (atDNA) mutations. This suggests that the earliest migrants into the northern extremes of North America and Greenland derived from later migrant populations. C2a1-F3447 includes all extant Eurasian members of C2a-L1373, whereas C2a2-BY63635/MPB374 contains extant South American members of C2a-L1373 as well as ancient archaeological specimens from South America and Chertovy Vorota Cave in Primorsky Krai. Haplogroup C-M217 is the modal haplogroup among Mongolians and most indigenous populations of the Russian Far East, such as the Buryats, Northern Tungusic peoples, Nivkhs, Koryaks, and Itelmens. The subclade C-P39 is common among males of the indigenous North American peoples whose languages belong to the Na-Dené phylum.” ref

“Haplogroup C is found in ancient populations on every continent except Africa and is the predominant Y-DNA haplogroup among males belonging to many peoples indigenous to East Asia, Central Asia, Siberia, North America, and Australia as well as as some populations in Europe, the Levant, and later Japan. Also found with moderate to low frequency among many present-day populations of Southeast Asia, South Asia, and Southwest Asia. C2 (previously C3) M217 Typical of Mongolians, Kazakhs, Buryats, Daurs, Kalmyks, Hazaras, Afghan Uzbeks, Evenks, Evens, Oroqen, Ulchi, Udegey, Manchus, Sibes, Nivkhs, Koryaks, and Itelmens, with a moderate distribution among other Tungusic peoples, Ainus, Koreans, Han, Vietnamese, Altaians, Tuvinians, Uyghurs, Uzbeks, Kyrgyzes, Nogais, and Crimean Tatars. It is found in moderate to low frequencies among Japanese, Tai peoples, North Caucasian peoples, Abazinians, Adygei, Tabassarans, Kabardians, Tajiks, Pashtuns, etc. C2b L1373* Ecuador (Bolívar Province),USA. C2b1a1a P39 Canada, USA (Found in several indigenous peoples of North America, including some Na-Dené-, Algonquian-, or Siouan-speaking populations). Males carrying C-M130 are believed to have emigrated to the Americas some 6,000-8,000 years ago, and was carried by Na-Dené-speaking peoples into the northwest Pacific coast of North America.” ref, ref

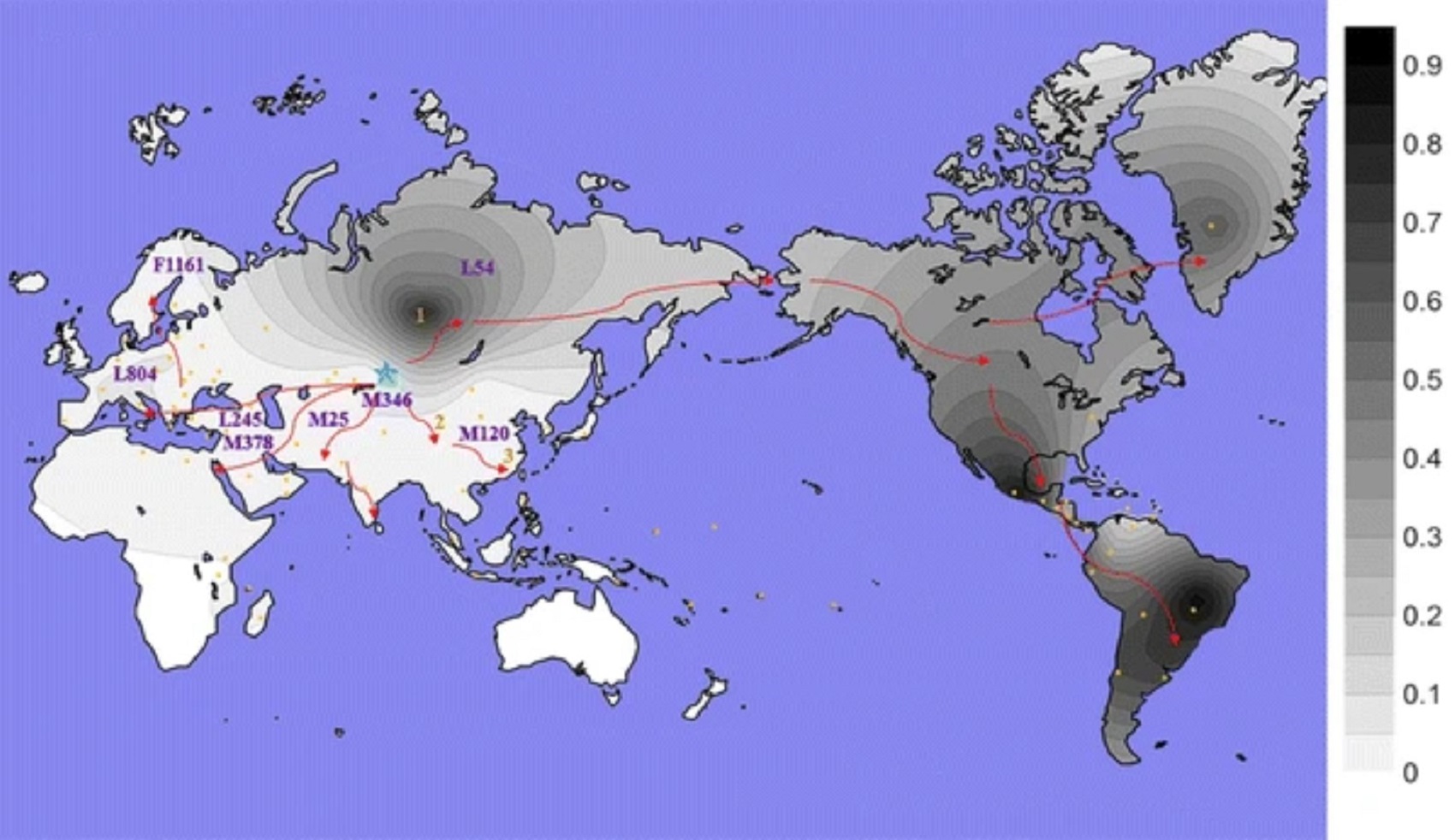

“Worldwide distribution of haplogroup Q-M242. The blue star is the original place of haplogroup Q-M242, around Central Asia and Siberia. The brown number one is Russian sample location in the Krasnoyarsk Region. The brown number two is Chinese sample location in Gansu province. The brown number three is Chinese sample location in Zhejiang province. The red arrows are the expansion routes of haplogroup Q-M242. The purple words show the locations of subclades of haplogroup Q used in this study.” ref

“The human Y-chromosome has proven to be a powerful tool for tracing the paternal history of human populations and genealogical ancestors. The human Y-chromosome haplogroup Q is the most frequent haplogroup in the Americas. Previous studies have traced the origin of haplogroup Q to the region around Central Asia and Southern Siberia. Although the diversity of haplogroup Q in the Americas has been studied in detail, investigations on the diffusion of haplogroup Q in Eurasia and Africa are still limited. In this study, we collected 39 samples from China and Russia, investigated 432 samples from previous studies of haplogroup Q, and analyzed the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) subclades Q1a1a1-M120, Q1a2a1-L54, Q1a1b-M25, Q1a2-M346, Q1a2a1a2-L804, Q1a2b2-F1161, Q1b1a-M378, and Q1b1a1-L245. Through NETWORK and BATWING analyses, we found that the subclades of haplogroup Q continued to disperse from Central Asia and Southern Siberia during the past 10,000 years. Apart from its migration through the Beringia to the Americas, haplogroup Q also moved from Asia to the south and to the west during the Neolithic period, and subsequently to the whole of Eurasia and part of Africa.” ref

“The human Y-chromosome haplogroup Q (also named Q-M242 in accordance with its defining mutation) probably originated in Central Asia and Southern Siberia during the time period of 15,000–25,000 years ago, then subsequently diffused in the eastward, westward, and southward directions. Haplogroup Q has several subclades defined by single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), and it reaches its highest frequency of 70–100% in the Americas. Although the diversity of haplogroup Q in the Americas has been studied in detail, investigations on the diffusion of haplogroup Q in Eurasia and Africa are still limited. Consequently, we studied samples of haplogroup Q in Eurasia to explore how it expanded from Central Asia and Southern Siberia during the Neolithic period. The ancestors of present-day Native Americans migrated to the Americas from Siberia via the Beringia around 16,000 years ago. Q1a2a1-L54 and its subclade Q1a2a1a1-M3 are the two predominant subclades of haplogroup Q found on both sides of the Bering Strait. Q1a2a1-L54 has spread throughout Northern Asia, the Americas, and Western and Central Europe. An ancient individual of the Clovis culture belonged to Q1a2a1-L54 (xQ1a2a1a1-M3).” ref

Q Haplogroup South American settlement pre-18,000 years ago

“Increasing archaeological evidence proves the early human presence in the American continent. Recent archaeological excavations in the Chiquihuite cave in Northern Mexico demonstrate human occupation dating from ~26,500 years ago, and there is even earlier evidence in this country. This evidence joins several documented archaeological sites in Northeastern and Central Brazil that have yielded dates between 20,000 and 30,000 years ago for human occupation in this region. Reserchers estimated a temporal depth of 19,300 years ago (17,000–21,900 years ago) for Q-Z780 and Q-Z781. This temporal depth and the presence of these lineages in Mexico and Brazil are consistent with the dates estimated for the human presence from the archaeological sites mentioned in Mexico and in Northeastern and Central-Western Brazil. As seen in Fig 2, Q-Z781 could be found widely distributed among individuals from Mesoamerica and South America since 19,300 years ago (17,000–21,900 years ago). Furthermore, Q-Z781 seems to have undergone a characteristic regional differentiation from Q-Y2816 and Q-Z782 for individuals from Mexico (uncertain dates), Q-YP937 among individuals from Peru, Brazil, and Argentina since 18,700 years ago (16,500–21,200 years ago), and Q-GMP73 among individuals from the Central Andes and Central West of Argentina since 18,200 years ago (16,100–20,600 years ago). This study provides genetic evidence that supports an early human settlement for Mesoamerica and South America, before 18,000 years ago. Environmental alterations could potentially have affected human populations genomes at the time in a number of ways: the extinction of primary food sources could have drastically altered their diet, perhaps exposing them to new mutagens for which humans had not yet evolved to avoid or metabolize.” ref

“Q-Z780 and Q-Z781 sub-lineages, autochthonous of the Americas, presented a wide distribution in Mesoamerica and South America since ~19,300 years ago. This contributed to a regional differentiation from Q-Y2816 and Q-Z782 for individuals from Mexico, Q-YP937 among individuals from Peru, Brazil, and Argentina since ~18,700 years, and Q-GMP73 among individuals from the Central Andes and Central West of Argentina since ~18,200 years ago. Moreover, it provided genetic support for South American settlement before 18,000 years ago, in agreement with a long chronology scenario and the dates of Meso- and South American archaeological sites. The Q-Z780 lineage, and perhaps Q-F4674, could have suffered a substantial drop due to the environmental events occurred during the YD, which could be the main reason for its current low frequency. For the Q-M848 lineage the YD environmental events could have acted as a driving force for its expansion and diversification, and while they could have also caused a substantial decrease, this lineage survived more successfully than Q-Z780.” ref

“The upper and lower limits of all divergence times for Q-M848 sub-lineages cover the YD period or later. The spatial structure of the South American male population at ~12,300 years ago, and the archaeological intensity signal peak at ~12,500 years ago could represent those human groups that managed to survive the environmental events that occurred during the Younger Dryas period (~12,800 years ago), in full process of expansion and diversification. Understanding the relationship between the Eurasian and American Q-M242 lineages becomes more complex when population changes during the YD period are included. Since there was no population decline in the Middle East during the YD period but it rather served as a refuge for humans of the time, then, Q Haplogroup lineages prior to ~12,900 years ago (such as Q-L275) could have been preserved to a greater extent during the YD event in the Middle East region and after this disperse and differentiate until reaching the diversity that exists today for Q Haplogroup in Euro-Asia. However, Q Haplogroup Native American sub-lineages older than ~12,900 years ago would have suffered a drastic decline in the YD period, altering the ancient spatial structure (before 12,900 cal BP) of the human populations of the Americas and causing the extinction of lineages and loss of part of the gene pool. Further studies should include ancient Native American sub-lineages (before 12,900 years ago) in order to understand and estimate the origin of Q-M242.” ref

“Human Y chromosome sequences from Q Haplogroup reveal a South American settlement pre-18,000 years ago and a profound genomic impact during the Younger Dryas. Q-M848 is known to be the most frequent autochthonous sub-haplogroup of the Americas. The present is the first genomic study of Q Haplogroup in which current knowledge on Q-M848 sub-lineages is contrasted with the historical, archaeological, and linguistic data available. The divergence times, spatial structure, and the SNPs found here as novel for Q-Z780, a less frequent sub-haplogroup autochthonous of the Americas, provide genetic support for a South American settlement before 18,000 years ago. We analyzed how environmental events that occurred during the Younger Dryas period may have affected Native American lineages, and found that this event may have caused a substantial loss of lineages. This could explain the current low frequency of Q-Z780 (also perhaps of Q-F4674, a third possible sub-haplogroup autochthonous of the Americas). These environmental events could have acted as a driving force for the expansion and diversification of the Q-M848 sub-lineages, which show a spatial structure that developed during the Younger Dryas period.” ref

“Q Haplogroup in the Y chromosome is the only Pan-American haplogroup and represents virtually all Native American lineages in Mesoamerica and South America. The autochthonous Q-M3 sub-haplogroup of Amerindians has been previously described at high frequency and with a star-shaped phylogenetic topology that has been interpreted as the initial colonization of South America with a rapid expansion ~15,000 years ago. Furthermore, it has been observed that Q-M848 sub-lineages (within Q-M3) present a spatial structure in South America that arose as early as ~12,300 years ago. Q-Z780 is another Native American autochthonous sub-haplogroup that occurs at low frequency and is still little studied from genomic data due to its low availability in sequence databases. A recent report using high coverage complete sequences has dated this lineage ~17,000 years ago, which was explained as a more complex settlement scenario in the Americas where the deep branches could reflect a separate out-of-Beringia dispersal after the melting of the glaciers at the end of the Pleistocene.” ref

“Q-M346 was dated 25 years ago (22,000–28,300 years ago) in the present work, within the range previously reported in literature. It has been described in Eastern Europe, Middle East, Central Asia, Eastern Asia, Southern Siberia, and in the Americas. The most prevalent Native American lineages, Q-Z780 and Q-M3, are derived from Q-M346. Q-Z780 haplogroup is recognized as a Y chromosome founding lineage in the Americas at low frequency. It is widely distributed, with representatives from Mexico, Peru, Bolivia, Brazil, and Argentina in this study, but its presence has been also reported for Central America, Colombia, and Paraguay. Given its low frequency and scarce sequence availability in databases, little is known about its sub-lineages. According to the best known markers, it can be classified into Q-Z781 and Q-FGC47532, the latter characterizing the ancient Anzick-1 Y chromosome (with a 14C calibrated age of 12,600 years ago). Four new SNPs parallel to Q-Z780 not described in ISOGG were found; one of them was validated and named Q-GMP10 (see S2 and S4 Tables). Two samples incorporated in this study to Q-Z780 (Z8ZMY and S8BAL) allowed adjust its temporal depth, showing values of 19,300 years ago (17,000–21,900 years ago), older than those reported in the literature of 17,000 years ago (15,000–19,300 years ago).” ref

“Q-Z781 is the most represented sub-lineage of Q-Z780. Given the similar number of Q-Z780 and Q-Z781 sequences, the dates found for both are equal, though older than those found by other authors with values of 16,000 years ago (14,100–18,100 years ago) for Q-Z781. However, older dates as 22,900 years ago (18,300–27,500 years ago) have been found from STRs for a great number of samples for this sub-lineage. Q-Z781 branches into Q-Y2816 and Q-YP937. Q-Y2816 is distributed mainly in individuals of Mexican origin, and also in an individual from the United States without a defined origin. We found 3 individuals of Mexican origin in this sub-lineage, 2 of which also share Q-Z782. Q-YP937 is characteristic of South America with a wide distribution from Peru and Argentina to Brazil. We found 3 new SNPs parallel to Q-YP937 (S2 Table). The dating for this sub-lineage is 18,700 years ago (16,500–21,200 years ago), which is older than that of 12,500 years ago (11,000–14,000 years ago) reported in literature. We found a new sub-lineage, not described in ISOGG, supported by 2 SNPs named Q-GMP73 and Q-GMP74 (see S6 Fig, S2 and S4 Tables) with a dating of 18,200 years ago (16,100–20,600 years ago). The phylogenetic association found for this new sub-lineage evidences a link between Andean individuals and Central-West Argentina with dates for which there are no archaeological records showing such temporal depth for human groups from this region. Further analysis of these findings is provided in the Hypothesis of the American Settlement section.” ref

“Q-M3 haplogroup has been previously described as a founder lineage of the Y chromosome in the Americas and is the most frequent sub-lineage among present-day Native Americans. Although its presence has also been described for some populations from Siberia, it is not known whether these are remains of the founding lineage or evidence of regressive migrations from Beringia to East Asia. The dating found for this marker in the present work is 15,400 years ago (13,600–17,400 years ago), within the range previously reported in the literature. In recent decades, the internal resolution of Q-M3 has expanded and this lineage is now known to be subdivided into two branches, Q-M848 and Q-Y4308. Although Q-Y4308 is still underrepresented, it is widely distributed. Its presence has been reported for individuals from the United States in association with those who speak the Algonquian language, Eskimo peoples from the extreme Northeast of Asia, Mexican individuals, and a Tupi-Guarani individual from Southern Brazil reported in this work (S5 Fig), this latter in agreement with previously reported data. Q-M848 is the most represented sub-lineage of the Q Haplogroup in the Americas, and more frequent in South America than in North America. It has been previously described with a star-shaped topology where many short branches are connected in the same internal node (S5 Fig). Given the high Q-M848 and poor Q-Y4308 representativeness of the samples studied in this work, the datings for Q-M848 and Q-M3 show the same values, within ranges estimated in the literature. The fossil remains of Kennewick man, found on the banks of the Columbia River in the United States, belong to Q-M848 haplogroup and have been dated 8,300–9,200 years ago.” ref

“The Q-MPB118 sub-lineage was found here defining the same Aranã samples from Southeast Brazil and Xavante from West Brazil (S6 Fig and S1 Table), in agreement with previous reports. For the moment, this lineage is restricted to Brazilian individuals. We found 6 new SNPs not validated, provided in this work as new information to this lineage (S2 Table). The dating found here for this node is 9,700 years ago (8,500–11,000 years ago) (S5 Table), similar to previously reported estimates. Since the aim of the present study is to reconstruct the history of the lineages belonging to Q-M848, in section 6 of S1 Text, we present further information for each of these sub-lineages regarding the history of their ethnic groups, linguistic family, and the region they inhabit or inhabited. Q-MPB118 supports a lineage ancestry shared between native Xavante and Aranã groups, both of the Macro-Jê linguistic trunk. Since its differentiation (~9,700 years ago), this lineage is present among human groups from Central-West and Southeast Brazil, although further study on its distribution is still necessary. For a schematic representation of the geographic distribution of Q-MPB118, see S4B Fig. Q-SK281 is currently presented as a restricted lineage for Peruvian individuals (S6 Fig), dated 12,600 years ago (12,100–13,100 years ago). This study provides 19 new SNPs for its sub-lineage defined by Q-Z35727 (S2 Table). For a schematic representation of the geographic distribution of Q-SK281, see S2C Fig.” ref

“Uro samples from Peru and Pasto from Ecuador were found here supported by Q-MPB139 in agreement with previous reports. The dating found in the present study was 14,000 years ago (12,400–15,900 years ago), similar to the one previously reported. Q-MPB139 shows a shared lineage ancestry between the Uros of Peruvian Altiplano and the Pasto of the Ecuadorian Altiplano, evidencing a great temporal depth and vast movements of human groups between the Central and North Andean Areas, near 14,000 years ago (12,400–15,900 years ago). For a schematic representation of the geographic distribution of Q-MPB139, see S1A Fig. In this lineage the Uro individual is separated from other characteristic lineages of Peruvians and individuals of the Central Andes (such as: Q-SK281, Q-Z6658, Q-Y788, Q-Z5908, Q-Z35841, and Q-Z5906), providing genetic support to anthropological and linguistic hypotheses that consider the Uro ethnic group different from neighboring ethnic groups (such as Aymara and Quechua), with its own language, traditions, beliefs, and ways of hunting, fishing, gathering and farming. Previous studies carried out with Y chromosome microsatellites found that the Uros have exclusive lineages different from Aymara, Quechua, and Arawak haplotypes, whom they have been associated with in other studies. According to some researchers, the Uros were the first settlers of the Andean Altiplano; however, their origin is unknown and is currently subject of academic debate.” ref

“So far, the Q-B43 sub-lineage has been described by other authors in Wichi individuals from Salta, Argentina, and in individuals from Paraguay and Brazil. The present study includes an individual from the Paresí community, from Mato Grosso, Brazil, obtained from the databases, as well as another individual from Salta, from our collection. The phylogenetic relationship found in this work for 3 individuals from East Salta, Argentina, was supported by Q-Z35505, parallel to Q-B43. Moreover, one of these samples from the East of Salta, from our collection, shares 26 SNPs with the individual from the Paresí community, out of which Q-Z35497 is also parallel to the 2 markers mentioned above. We contribute 5 new SNPs to this sub-lineage (S2 Table), 4 of them validated as Q-GMP26 to Q-GMP29 (S4 Table). We also found 50 new private SNPs for our Salta sample of this lineage (S2 Table), 4 of them validated as Q-GMP30 to Q-GMP33 (S4 Table). The dotted line in S5 Fig for this sub-lineage means that further studies are required for its better definition; here we have found some difficulties due to the large amount of missing data present in samples for which complete sequences are not available and are in VCF format (see Section 3 in S1 Text and S1 Table). The dating of this lineage had been previously estimated as 1,500 years ago (900–2,100 years ago), calculated only between 2 samples (GS000016946-ASM and GS000016945-ASM) for which the complete sequence is not available and comes from VCF files (see section 3 in S1 Text and S1 Table). The dating found in this work, calculated only between two samples for which the complete sequence is available and present greater sequencing coverage (N87FK8 and GRC14349596_S) (see section 2 in S1 Text and S1 Table), is 9,600 years ago (8,400–10,800 years ago). We believe that our results could be reflecting a temporal estimate more in line with the greater geographic distribution found here for this lineage. On the other hand, the estimate of ~1.500 years ago could reflect some internal sub-lineage with regional differentiation in Argentina’s Northwest and also characteristic of the Wichi community; this could be better defined in the future with the incorporation of more samples to this lineage.” ref

“In this study, researchers present genetic evidence that associates within the same sub-lineage (Q-Z35505/Q-Z35497) Mataguayan-speaking individuals from Gran Chaco and Arawak-speaking individuals from the Mato Grosso region, bordering the Gran Chaco (for more information see section 6 in S1 Text). In this regard, it has been previously argued that Mataguayan-speaking population may have moved to the Southeast due to pressure from Amazonian groups, speaking Arawak languages. In fact, some sort of exchange must have taken place between Mataguayos and local Arawak farmers before their settling in the area, since some archaeological sites in the Gran Chaco reveal similar but more rudimentary decorated pottery. We present genetic support for these hypotheses, adding a temporal depth for Q-Z35505/Q-Z35497 of ~9,600 years ago. We cannot determine whether Mataguayan-speaking and Arawak-speaking communities have a common origin or if both groups have different origins and then linked and admixed leaving shared genetic traits. The dates found suggest that Gran Chaco could have been inhabited earlier than estimated. This lineage is currently restricted to individuals from Peru and has been previously described. A dating of 12,000 years ago (9,500–14,700 years ago) was found in literature.” ref

“The marker Q-B42 has been previously described as ancestral to Q-B43 (parallel to Q-Z35505) and Q-B46. Q-B42 is known to be a recurrent mutation that is used to describe another sub-lineage belonging to the European R haplogroup (R1b1a1b1a1a2c1a3a2a1d3). Given this characteristic, the ISOGG platform does not include this marker within Q Haplogroup, but it is still used in current works on the phylogenetic reconstruction of Q Haplogroup. In the present study, Q-B42 is present among individuals belonging to the sub-lineages Q-B46, Q-Z35505, and Q-Z6658 (discussed above) but it is absent in some individuals within the last two sub-lineages (see S1 Table). S5 Fig proposes the position of Q-B42 based on these results, which is represented with a dotted line suggesting that findings should be further studied. The contribution of two new high coverage complete sequences provided in this work belonging to Q-B42 allows their dating to be adjusted to values of 14,200 years ago (12,600–16,200 years ago), older than those of 10,100 years ago (8,400–11,800 years ago) found in the literature. Q-B42 occurs among individuals from Peru, Northwest Argentina, and Central Chaco. For the Huaca Prieta archaeological site located near the Pacific coast in Northern Peru, radiocarbon dating indicates intermittent human presence between ~15,000 and 8,000 years ago. In Northwestern Argentina, several sites date from ~12,000 years ago and possibly as early as ~12,800 years ago.” ref

“As proof of the influence of the first civilizations of the Andean highlands on Northwestern Argentina, such as the pre-Inca culture of Tiwanaku located near Titicaca Lake within the current territory of Bolivia, cultural legacy has been found in Peru, Chile, and elsewhere Northwestern Argentina. The Collasuyu was part of the Inca Empire (Tawantinsuyu) and expanded to the Argentine Northwest. Q-B42 could have differentiated in the central Andean region and could be one of the oldest Q-M848 sub-lineages with 14,200 years ago (12,600–16,200 years ago), being part of the gene pool of cultures that settled in this region. This sub-lineage shows links and gene flow among Andean, Chaco, and Amazonian groups, in accordance with archaeological studies that have found cultural evidence showing that Chaco human groups have received peripheral influence, both Andean and Amazonian. The phylogenetic relationships found in the present study for Q-B42 and Q-Z35497 provides genetic support to these findings. The characteristics of the Chaco territory, with fluctuating seasonality in relation to the flood levels of the land, may have not been an obstacle for a constant interrelation among the human groups of these regions. For a schematic representation of the geographic distribution of Q-B42 and its sub-lineages, see S1C Fig.” ref

“The Q-CTS2731 lineage is currently restricted to native populations of the United States and Mexico. We have found this lineage in 4 Mexican samples from the databases (S1 Table), in agreement with previous reports. The estimates found in the literature for this lineage are 12,400 years ago (10,600–14,300 years ago). We contribute 2 new SNPs parallel to Q-CTS2731; 2 new SNPs parallel to the Q-CTS8571 sub-lineage; and 43 new SNPs parallel to the Q-Y26467 sub-lineage, absent in ISOGG (S2 Table). Q-Y26467 has been described as characteristic of the Zapotec male population of Mexico, which has also been observed in the present study (S1 Table). The dating found in this work for this node is 600 years ago (530–680 years ago), within the range previously reported. The timing found for the first human occupation in Mexico is currently under discussion. Archaeological studies consider that Mexico shows consistent evidence of human occupation from at least 40,000–30,000 years ago, but dating for that period is controversial. Yet, there is not so much discussion about the common scattered sites in Mexico for the 10.5–13 kya period. It is known that the writing style used in the Central Valleys of Oaxaca, belonging to the Zapotec scribal tradition, constitutes the earliest evidence of writing in the American continent. The first tangible manifestations of the graphic system can be dated to approximately 600 years ago. These archaeological dates are consistent with those found for the Zapotec sub-lineage Q-Y26467. For a schematic representation of the geographic distribution of Q-CTS2731 and its sub-lineages, see S2A Fig.” ref

“This lineage is known to have a wide distribution beginning at Southwest United States and extending through Mexico, Central America, and South America. In the present study, Q-CTS11357 is widely represented by 7 individuals from Mexico, 2 from Colombia, and one from Brazil, in accordance with previously reported data. The dating found in this work for this lineage is 11,300 years ago (10,300–13,200 years ago), close to that found by other authors. We contributed 4 new SNPs to Q-CTS11357 sub-lineages, absent in ISOGG (S2 Table). Q-CTS11330 has been described in this and other research works as characteristic of Mexican individuals though has been also found in one individual from San Salvador de Jujuy. The dating found in this study for Q-CTS11330 is 8,400 years ago (7,400–9,600 years ago), close to the literature estimates. The Q-CTS11357 lineage is represented by individuals of the Pima and Nahua, speakers of the Uto-Aztecan language, and Karitiana ethnic groups, speakers of the only remnant of the Arikém linguistic family, being a sub-family of the Tupí linguistic trunk (see S1 Table and section 6 in S1 Text). For a schematic representation of the geographic distribution of Q-CTS11357 and its sub-lineages, see S3B Fig.” ref

“The Q-CTS11357 lineage shows that approximately 11,300 years ago (10,300–13,200 years ago) there was a population focus in Mexico that extended to Southwest United States, Central America, reaching Colombia and the Brazilian Amazon. At present, this lineage finds greater representation and differentiation in Mexico, with Uto-Aztecan speaking representatives (See S1 Table). This evidence could provide genetic support to previous hypotheses suggesting that the Proto-Uto-Aztecan speaking community could have formed in Central Mexico, being one of the drivers of the primary domestication of maize. Its expansion towards North America and the Amazon could have been driven by demographic pressure resulting from a growing commitment to the cultivation of this gramineous. The phylogenetic links found for this lineage are also in agreement with studies on the genetic diversity of corn using contemporary and archaeological maize samples, showing that corn used by Brazilian indigenous populations, including those from the Amazon, is genetically closer to corn samples from Mexico, as compared to other regions such as the Andes. Q-CTS11357 evidences a shared lineage ancestry between Uto-Aztecan- and Arikém-speaking human groups; given its temporal depth it is likely that this lineage has formed part of the gene pool of both the proto-Uto-Aztecan and proto-Tupí speakers. It is not possible to define whether both groups have a common origin or, having different origins, left shared genetic traits due to their geographic expansion.” ref

“Currently, this lineage has been reported for individuals from Mexico and Argentina. The ISOGG platform defines Q-Y27993 and Q-Y27992 as parallel; we have found Q-Y27993 in a Mexican sample from the databases and an Argentine individual belonging to the Chané ethnic group from Salta (S1 Table). Q-Y27992 occurs in a Mixtec individual from Oaxaca, but we have not found any marker shared by the three samples; therefore, in Fig 1 and S5 Fig it is represented with dotted lines since further study is needed to determine this link. The time estimate found for this lineage is 16,100 years ago (14,200–18,200 years ago) (see S5 Table), older than that found in the literature. We consider that the current dating calculations for this lineage are subject to biases due to low sample size and lineage resolution. If the three samples were not a monophyletic group and therefore Q-Y27992 and Q-Y27993 would not belong to the same sub-lineage, then the dating found in this study would be an error. On the contrary, if they really are a monophyletic group, our results could indicate that it is one of the oldest lineages of Q-M848, and this would lead to question its dating. However, given that the status of Q-Y27993/Q-Y27992 still requires further studies and higher resolution, in S5 Fig we consider the dating calculated in the literature as 12,600 years ago (12,100–13,100 years ago). For a schematic representation of the geographic distribution of Q-Y27993/Q-Y27992, see S2B Fig.Q-Y27993 occurs among individuals from Mexico and Chané from Northern Argentina. The language spoken by the Chané belongs to the Arawak linguistic group, one of the largest and most dispersed linguistic families in the Americas. Q-Y27993 provide genetic support to the links found between Arawak-speaking individuals and Mexican communities, though further studies would be necessary to determine the ethnic relationship found between these regions.” ref

“This lineage has been reported before in Peru and in Argentine individuals of the Colla ethnic group from Salta province. In this study, researchers corroborate this previous distribution and add a Brazilian individual from a database belonging to Maxakalí ethnic group from Minas Gerais, as a new contribution to this sub-lineage (S1 Table and S5 Fig). For a schematic representation of the geographic distribution of Q-Z19357 and its sub-lineages, see S3C Fig. Q-Z19357 provides evidence of a shared lineage ancestry among individuals from Andean Peru, Northwestern Argentina, and the Brazilian Maxakalí ethnic group with a temporal depth of 8,100 years ago (9,500–6,700 years ago), as reported in the literature. We cannot determine whether these groups have a common origin or have different origins and were later linked and admixed leaving shared genetic traits. The greatest current diversity for this lineage occurs among Andean individuals, so it is likely that this sub-lineage has differentiated among Andean human groups, perhaps within the current territory of Peru, a region known for being the cradle of great South American civilizations, expanding its ties with the Macro-Jê-speaking communities of Brazil, native language of Maxakalí groups. These people have probably also established relationships with Chaco human groups because this area relates the Andean region with the Brazilian Cerrado Ecoregion, which was extensively inhabited by Macro-Jê speakers in times previous to European colonization. In this regard, linguistic studies on languages of the Guaicurú family (spoken by Mocovíes, Toba, Pilagás, and Caduveos), typical of the Chaco region and Mato Grosso do Sul, have shown some grammatical morphemes similar to elements of languages belonging to the Macro-Jê linguistic trunk, widely spread throughout the Central and Eastern regions of Brazil. A higher amount of Chaco samples should be analyzed in Y chromosome genomic studies to better understand the human links among these regions.” ref

“The phylogenetic relationship found in this work between an Ecuadorian individual of the Cañari ethnic group and a Brazilian individual of the Hupda ethnic group agrees with that previously described. In the present work we contribute 7 new SNPs shared between both samples, not described in the literature and absent in ISOGG (see S2 Table). The dating found in this study for this sub-lineage is 11,200 years ago (9,900–12,700 years ago), within the range estimated before. Q-MPB016 provides evidence of a shared lineage ancestry among human groups of the Cañari ethnic group of Ecuador and the Hupda ethnic group of Northwestern Amazonia of Brazil with a temporal depth of 11,200 years ago (9,900–12,700 years ago). We cannot define whether these groups have a common origin, or if they had different origins and were then linked and admixed leaving shared genetic traits, but genetic evidence of separation of the Cañari lineage from the characteristic lineages of Peru (such as Q-SK281or Q-Z6658) would indicate that the Cañaris managed to preserve their ancestral lineage despite the Inca and Spanish conquest processes. The same is observed for the Hupda ethnic group, which presents a differentiated lineage from those found for neighboring Amazonian ethnic groups such as Arawak (such as Q-Z35497 or Y27993). The links between Cañari and Hupda groups could also be useful for the reconstruction of their ancient history. For a schematic representation of the geographic distribution of Q-MPB016, see S3C Fig.” ref

“Q-Z5908 was found in the present study shared among 6 individuals from Peru, as previously reported, 2 individuals from the Province of Salta, Argentina, 1 individual belonging to the Colla ethnic group, and another one from the town of Cachi, also previously described for this lineage. A new Argentine sample in our collection from La Quiaca, Jujuy Province, is added to this sub-lineage as a novelty in this study (S1 Table and S5 Fig). We have found 69 new SNPs for this lineage, absent in ISOGG (S2 Table), one of which is equivalent for Q-Z5912 and another one is equivalent for Q-Z5910. We have also described a new sub-lineage derived from Q-Z5908 defined by Q-GMP51 (S4 Table and S5 Fig). The remaining 66 SNPs are private for the new sample in our collection, and 7 named Q-GMP52 to Q-GMP58 were validated (see S2 and S4 Tables). Furthermore, the incorporation of a new high coverage complete sequence to this sub-lineage allows a new estimate of its dating, with values of 13.6 kya (12.0–15.4), older than those reported in the literature. The phylogenetic relationships found for Q-Z5908 show links among human groups from the Central Andes, extending through the territories that today are part of Peru and Northwestern Argentina, with a regional differentiation and defined spatial structure (~13,600 years ago). These links resemble what was previously discussed for the Q-B42 lineage in human groups of these regions. For a schematic representation of the geographic distribution of Q-Z5908, see S1B Fig.” ref

“The Q-Z5906 sub-lineage includes 11 individuals, out of which 5 are Peruvians and 6 are individuals from Northwestern Argentina (S1 Table and S6 Fig). This lineage has been described in the literature as characteristic among members of Peru, Bolivia, Calchaquí communities, and Colla ethnic groups of Argentina. In the present study, 2 new sequences of Argentine individuals are contributed to this sub-lineage, both from La Quiaca, province of Jujuy (see S1 Table and Table A in S1 Text). We have found 30 new SNPs for this lineage, absent in ISOGG, out of which 8 are equivalent for Q-B35 and 5 were validated as Q-GMP65 to Q-GMP69; downstream, we found a new sub-lineage validated as Q-GMP70, with other 3 SNPs equivalents, 2 of which were validated as Q-GMP71 to Q-GMP72 (see S2 and S4 Tables). We also detected 2 Q-Z5907 equivalents and the remaining 16 were private of the new samples of this lineage (S2 Table). The gene flow between Andean human groups of Peru and Northwestern Argentina is reflected once again by Q-Z5906 and its sub-lineages Q-B35, Q-GMP70, and Q-Z5907 (S6 Fig), similar to the links found for Q-Z35841, Q-Z5908, and Q-B42 lineages, discussed above for human groups of these regions. This lineage was found in literature with an estimated dating of 12,880 years ago (11.38–14.57). The present study determined datings of 2,400 years ago (2,100–2.700 years ago) and 1,700 years ago (1,500–1,900 years ago) for the derived sub-lineages Q-GMP70 and Q-Z5907respectively (S5 Table). This indicates a great temporal depth for this lineage but with more recent regional differentiation covering the great extension between Peru and Northwestern Argentina, which shows the constant interaction and gene flow of these groups for thousands of years. For a schematic representation of the geographic distribution of Q-Z5906 and its sub-lineages, see S2A Fig.” ref

“Migrations to the Americas from North Asia by way of Alaska are well known. Haplogroup Q-M242 is one of the two branches of P-P226 (M45), the other being R-M207. Q-M242 is the predominant Y-DNA haplogroup among Native Americans and several peoples of Central Asia and Northern Siberia. Q-M242 is believed to have arisen around the Altai Mountains area (or South Central Siberia), approximately 17,000 to 31,700 years ago. However, the matter remains unclear due to limited sample sizes and changing definitions of Haplogroup Q: early definitions used a combination of the SNPs M242, P36.2, and MEH2 as defining mutations.” ref

“Here are the Haplogroup Q migrations. Highest frequencies: Kets (Yeniseian-speaking people in Siberia) 93.8%, South American Indians 92%, Turkmens from Karakalpakstan (mainly Yomut: Western and Central Asia), 73%, Selkups 66.4%., Altaians 63.6%., Tuvans (from Xinjiang: Uygur Autonomous Region, China) 62.5%., Chelkans 60.0%., Greenlandic Inuit 54%, Tubalar 41%, Siberian Tatars(Ishtyak-Tokuz Tatars) 38%, Inuit, the indigenous peoples of the Americas, Akha people of northern Thailand, Mon-Khmer people, and some tribes of Assam.” ref

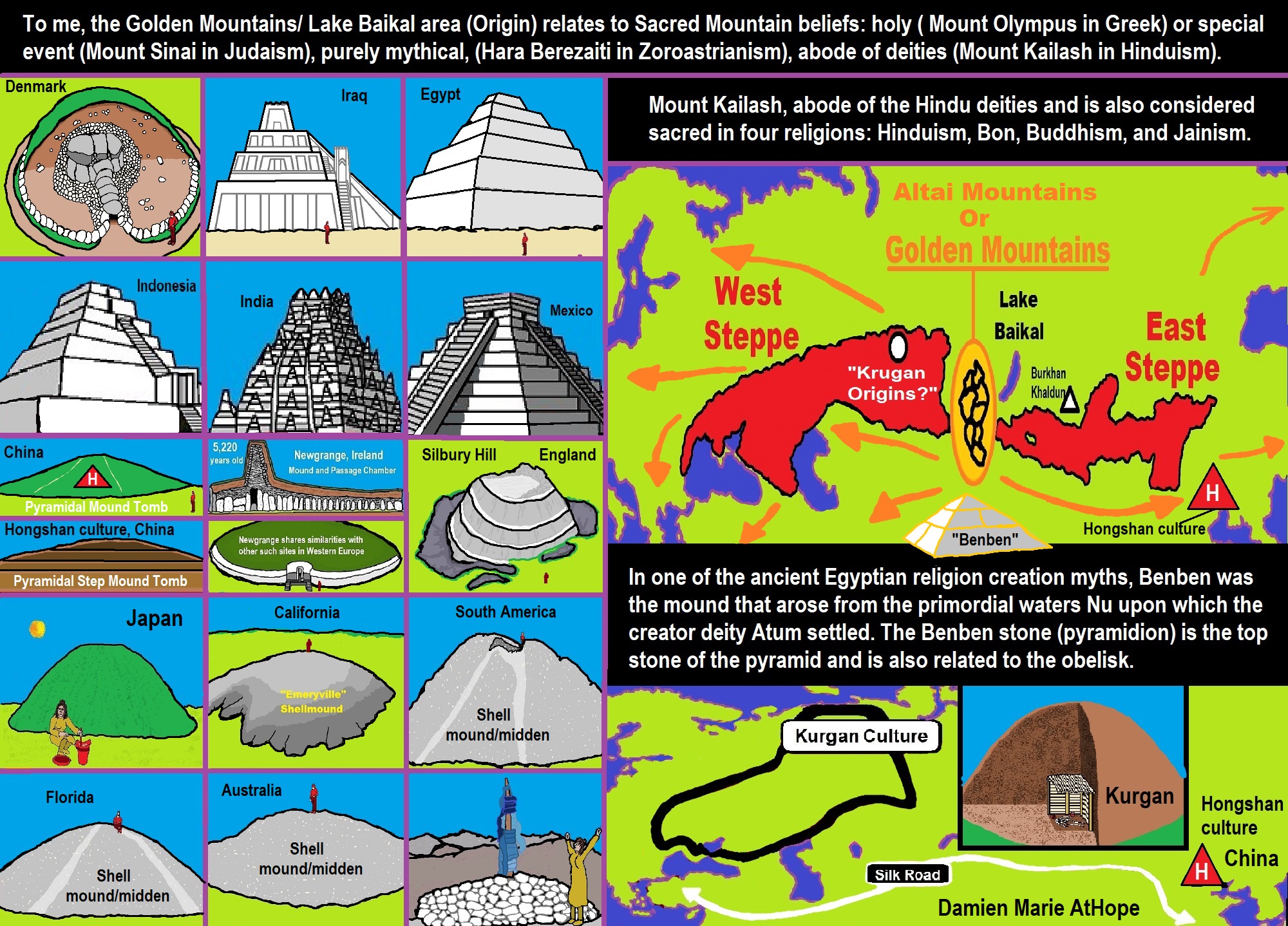

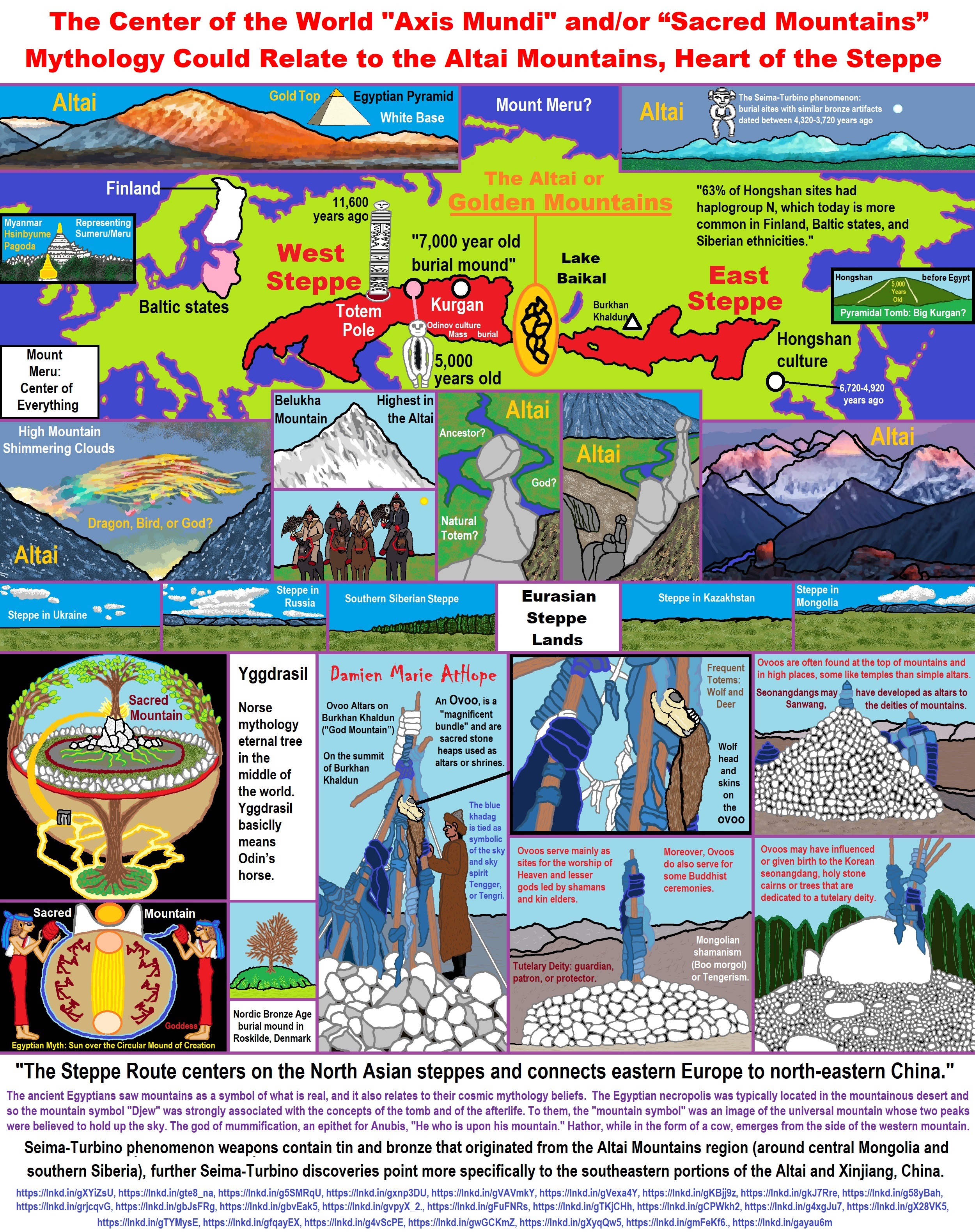

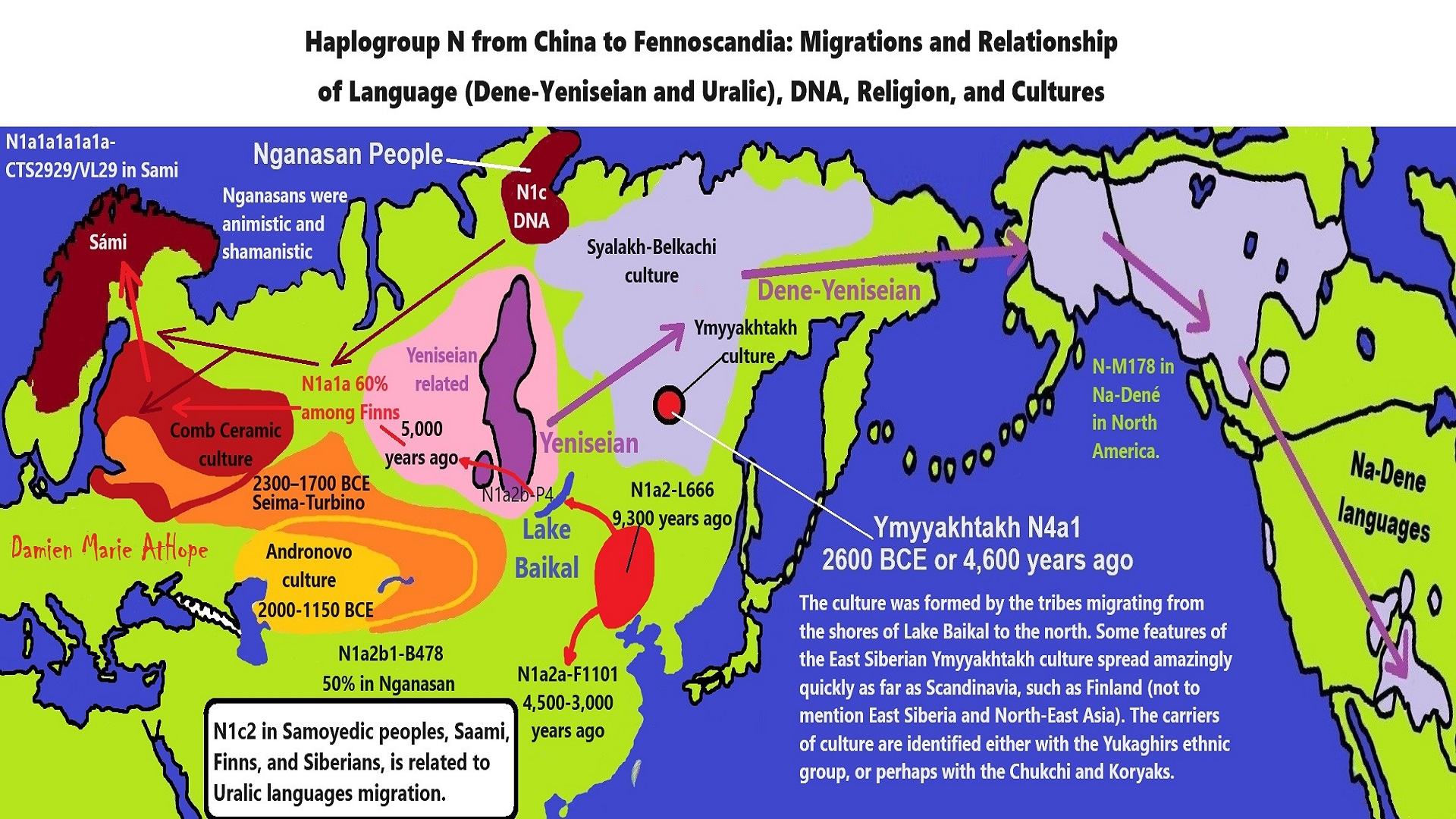

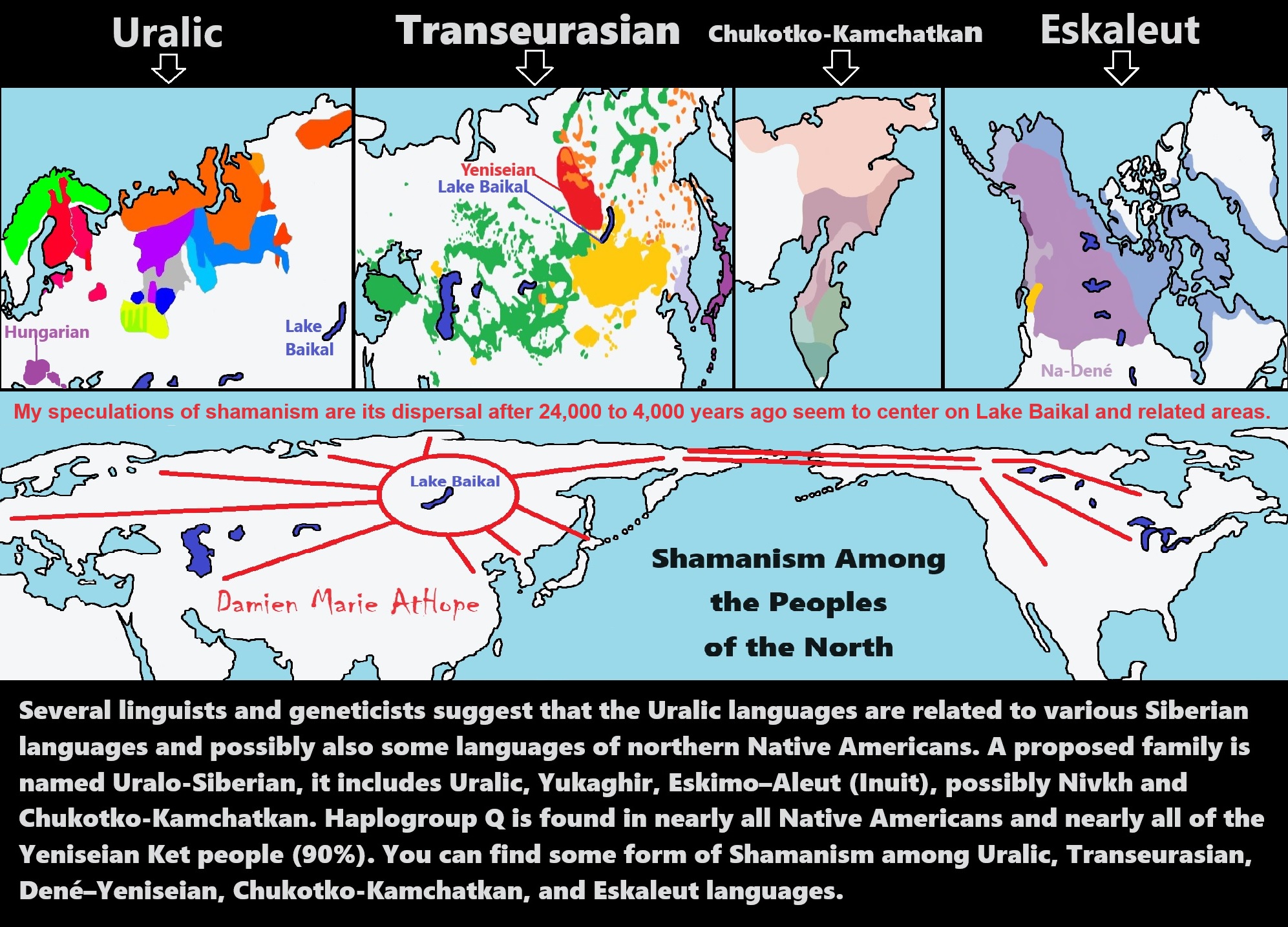

“The Ket people share their origin with other Yeniseian people and are closely related to other Indigenous people of Siberia and Indigenous peoples of the Americas. They belong mostly to Y-DNA haplogroup Q-M242. The Ket language has been linked to the Na-Dené languages of North America in the Dené–Yeniseian language family. This link has led to some collaboration between the Ket and northern Athabaskan peoples. According to a 2016 study, the Ket and other Yeniseian people originated likely somewhere near the Altai Mountains or near Lake Baikal. It is suggested that parts of the Altaians are predominantly of Yeniseian origin and closely related to the Ket people. The Ket people are also closely related to several Native American groups. According to this study, the Yeniseians are linked to the Paleo-Eskimo groups.” ref

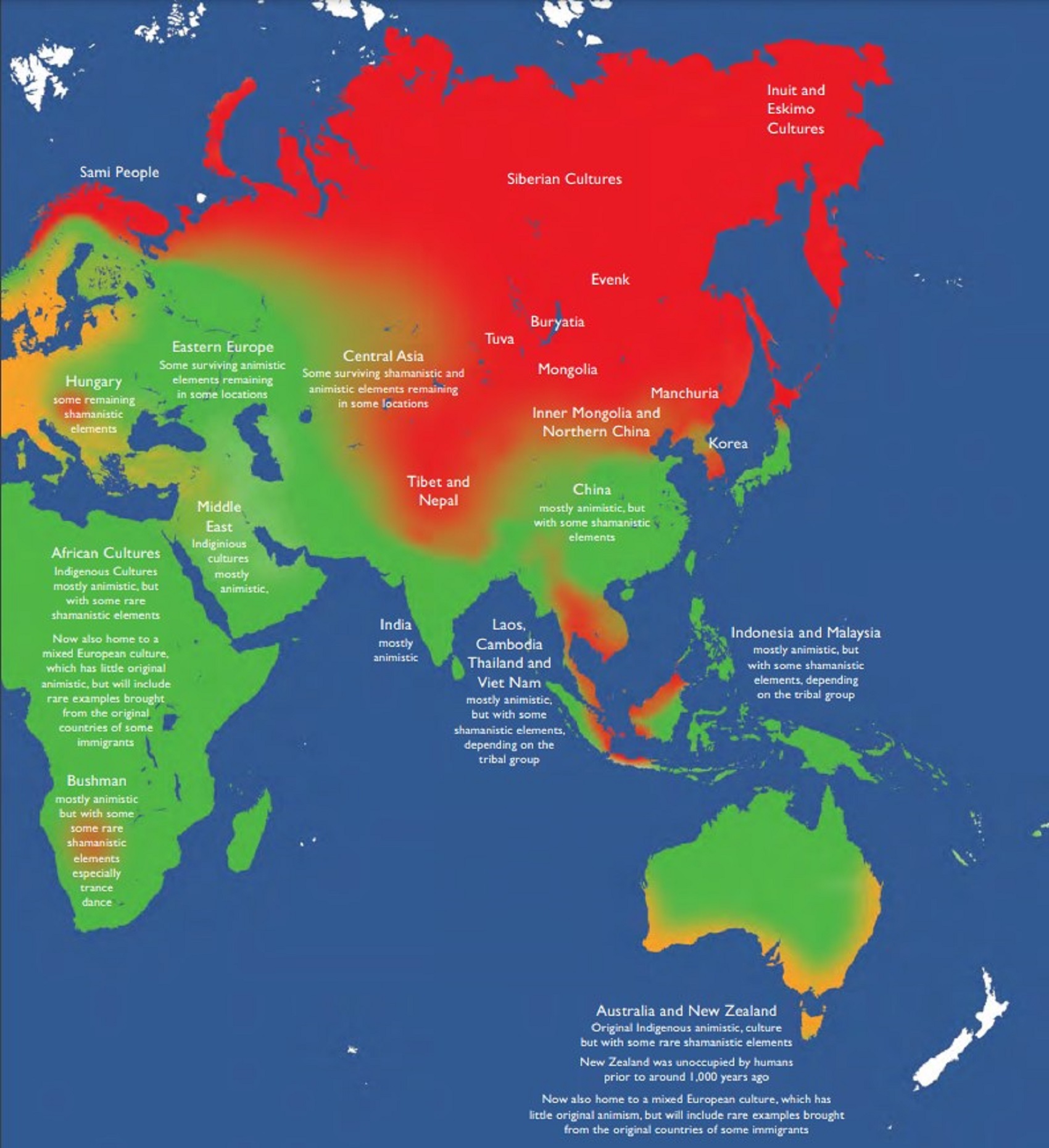

“The Kets have a rich and varied culture, filled with an abundance of Siberian mythology, including shamanistic practices and oral traditions. The shamans of the Ket people have been identified as practitioners of healing as well as other local ritualistic spiritual practices. Supposedly, there were several types of Ket shamans, differing in function (sacral rites, curing), power, and associated animals (deer, bear). Also, among Kets, (as with several other Siberian peoples such as the Karagas) there are examples of the use of skeleton symbolics. Hoppál interprets it as a symbol of shamanic rebirth, although it may also symbolize the bones of the loon (the helper animal of the shaman, joining the air and underwater worlds, just like the story of the shaman who traveled both to the sky and the underworld). The skeleton-like overlay represented shamanic rebirth among some other Siberian cultures as well.” ref

“Of great importance to Kets are spirit images, described as “an animal shoulder bone wrapped in a scrap of cloth simulating clothing.” One adult Ket, who had been careless with a cigarette, said, “It’s a shame I don’t have my doll. My house burnt down together with my dolls.” Kets regard their spirit images as household deities, which sleep in the daytime and protect them at night. Edward J. Vajda, a professor of Modern and Classical languages, spent a year in Siberia studying the Ket people, and found a relationship between the Ket language and the Na-Dene languages, of which Navajo is the most prominent and widely spoken. Vyacheslav Ivanov and Vladimir Toporov compared Ket mythology with those of speakers of Uralic languages, assuming in the studies that they are modeling semiotic systems in the compared mythologies. They have also made typological comparisons.” ref

“Among other comparisons, possibly from Uralic mythological analogies, the mythologies of Ob-Ugric peoples and Samoyedic peoples are mentioned. Other authors have discussed analogies (similar folklore motifs, purely typological considerations, and certain binary pairs in symbolics) may be related to a dualistic organization of society – some dualistic features can be found in comparisons with these peoples. However, for Kets, neither dualistic organization of society nor cosmological dualism have been researched thoroughly. If such features existed at all, they have either weakened or remained largely undiscovered. There are some reports of a division into two exogamous patrilinear moieties, folklore on conflicts of mythological figures, and cooperation of two beings in the creation of the land, the motif of the earth-diver. This motif is present in several cultures in different variants. In one example, the creator of the world is helped by a waterfowl as the bird dives under the water and fetches earth so that the creator can make land out of it. In some cultures, the creator and the earth-fetching being (sometimes called a devil, or taking the shape of a loon) compete with one another; in other cultures (including the Ket variant), they do not compete at all, but rather collaborate.” ref

Haplogroup Q and the Americas

“Several branches of haplogroup Q-M242 have been predominant pre-Columbian male lineages in indigenous peoples of the Americas. Most of them are descendants of the major founding groups who migrated from Asia into the Americas by crossing the Bering Strait. These small groups of founders must have included men from the Q-M346, Q-L54, Q-Z780, and Q-M3 lineages. In North America, two other Q-lineages also have been found. These are Q-P89.1 (under Q-MEH2) and Q-NWT01. They may have not been from the Beringia Crossings but instead come from later immigrants who traveled along the shoreline of Far East Asia and then the Americas using boats. It is unclear whether the current frequency of Q-M242 lineages represents their frequency at the time of immigration or is the result of the shifts in a small founder population over time. Regardless, Q-M242 came to dominate the paternal lineages in the Americas.” ref

North America

“In the indigenous people of North America, Q-M242 is found in Na-Dené speakers at an average rate of 68%. The highest frequency is 92.3% in Navajo, followed by 78.1% in Apache, 87% in SC Apache, and about 80% in North American Eskimo (Inuit, Yupik)–Aleut populations. (Q-M3 occupies 46% among Q in North America). On the other hand, a 4000-year-old Saqqaq individual belonging to Q1a-MEH2* has been found in Greenland. Surprisingly, he turned out to be genetically more closely related to Far East Siberians such as Koryaks and Chukchi people rather than Native Americans. Today, the frequency of Q runs at 53.7% (122/227: 70 Q-NWT01, 52 Q-M3) in Greenland, showing the highest in east Sermersooq at 82% and the lowest in Qeqqata at 30%.” ref

Mesoamerica and South America

“Haplogroup Q-M242 has been found in approximately 94% of Indigenous peoples of Mesoamerica and South America. The frequencies of Q among the whole male population of each country reach as follows:

- 61% in Bolivia.

- 51% in Guatemala,

- 40.1% (159/397) to 50% in Peru

- 37.6% in Ecuador,

- 37.3% (181/485) in Mexico (30.8% (203/659) among the specifically Mestizo segment)

- 31.2% (50/160) in El Salvador,

- 15.3% (37/242) to 21.8% (89/408) in Panama,

- 16.1% in Colombia,

- 15.2% (25/165) in Nicaragua,

- 9.7% (20/206) in Chile,

- 5.3% (13/246 in 8 provinces in northeastern, central, southern regions) to 23.4% (181/775 in 8 provinces in central-west, central, northwest regions) in Argentina,

- 5% in Costa Rica,

- 3.95% in Brazil, and so on.” ref

Y-DNA Q samples from ancient sites

- South Central Siberia (near Altai)

- Afontova-Gora-2, Yenisei River Bank, Krasnoyarsk (South Central Siberia of Russia), 17,000 years ago: Q1a1-F1215 (mtDNA R)

- North America

- Anzick-1, Clovis culture, western Montana, 12,600 years ago: Q1a2-L54* (not M3, mtDNA D4h3a)

- Kennewick Man, Washington, 8,500 years ago: Q1a2-M3 (mtDNA X2a)

- Altai (West Mongolia)

- Tsagaan Asga and Takhilgat Uzuur-5 Kurgan sites, westernmost Mongolian Altai, 2,900-4,800 years ago: 4 R1a1a1b2-Z93 (B.C. 10C, B.C. 14C, 2 period unknown), 3 Q1a2a1-L54 (period unknown), 1 Q-M242 (B.C. 28C), 1 C-M130 (B.C. 10C)

- Greenland

- Saqqaq (Qilakitsoq), Greenland, 4,000 years ago: Q1a-YP1500 (mtDNA D2a1)

- China

- Hengbei site (Peng kingdom cemetery of Western Zhou period), Jiang County, Shanxi, 2,800-3,000 years ago: 9 Q1a1-M120, 2 O2a-M95, 1 N, 4 O3a2-P201, 2 O3, 4 O*

- In another paper, the social status of those human remains of ancient Peng kingdom(倗国) are analyzed. aristocrats: 3 Q1a1 (prostrate 2, supine 1), 2 O3a (supine 2), 1 N (prostrate) / commoners: 8 Q1a1 (prostrate 4, supine 4), 3 O3a (prostrate 1, supine 2), 3 O* (supine 3) / slaves: 3 O3a, 2 O2a, 1 O*

- (cf) Pengbo (倗伯), Monarch of Peng Kingdom is estimated as Q-M120.

- Pengyang County, Ningxia, 2,500 years ago: all 4 Q1a1-M120 (with a lot of animal bones and bronze swords and other weapons, etc.)

- Heigouliang, Xinjiang, 2,200 years ago: 6 Q1a* (not Q1a1-M120, not Q1a1b-M25, not Q1a2-M3), 4 Q1b-M378, 2 Q* (not Q1a, not Q1b: unable to determine subclades):

- In a paper (Lihongjie 2012), the author analyzed the Y-DNAs of the ancient male samples from the 2nd or 1st century BCE cemetery at Heigouliang in Xinjiang – which is also believed to be the site of a summer palace for Xiongnu kings – which is east of the Barkol basin and near the city of Hami. The Y-DNA of 12 men excavated from the site belonged to Q-MEH2 (Q1a) or Q-M378 (Q1b). The Q-M378 men among them were regarded as hosts of the tombs; half of the Q-MEH2 men appeared to be hosts and the other half as sacrificial victims.

- Xiongnu site in Barkol, Xinjiang, all 3 Q-M3

- In L. L. Kang et al. (2013), three samples from a Xiongnu) site in Barkol, Xinjiang were found to be Q-M3 (Q1a2a1a1). And, as Q-M3 is mostly found in Yeniseians and Native Americans, the authors suggest that the Xiongnu had connections to speakers of the Yeniseian languages. These discoveries from the above papers (Li 2012, Kang et al., 2013) have some positive implications on the not as yet clearly verified theory that the Xiongnu were precursors of the Huns.

- Mongolian noble burials in the Yuan dynasty, Shuzhuanglou Site, northernmost Hebei China, 700 years ago: all 3 Q (not analyzed subclade, the principal occupant Gaodangwang Korguz (高唐王=趙王 阔里吉思)’s mtDNA=D4m2, two others mtDNA=A)

- (cf) Korguz was a son of a princess of Kublai Khan (元 世祖), and was the king of the Ongud tribe. He died in 1298 and was reburied in Shuzhuanglou in 1311 by his son. (Do not confuse this man with the Uyghur governor, Korguz who died in 1242.) The Ongud tribe (汪古部) was a descendant of the Shatuo tribe (沙陀族) which was a tribe of Göktürks (Western Turkic Khaganate) and was prominent in the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period of China, building three dynasties. His two queens were all princesses of the Yuan dynasty (Kublai Khan’s granddaughters). It was very important for the Yuan dynasty to maintain a marriage alliance with Ongud tribe which had been a principal assistant since Genghis Khan‘s period. About 16 princesses of the Yuan dynasty married kings of the Ongud tribe.” ref

- Hengbei site (Peng kingdom cemetery of Western Zhou period), Jiang County, Shanxi, 2,800-3,000 years ago: 9 Q1a1-M120, 2 O2a-M95, 1 N, 4 O3a2-P201, 2 O3, 4 O*

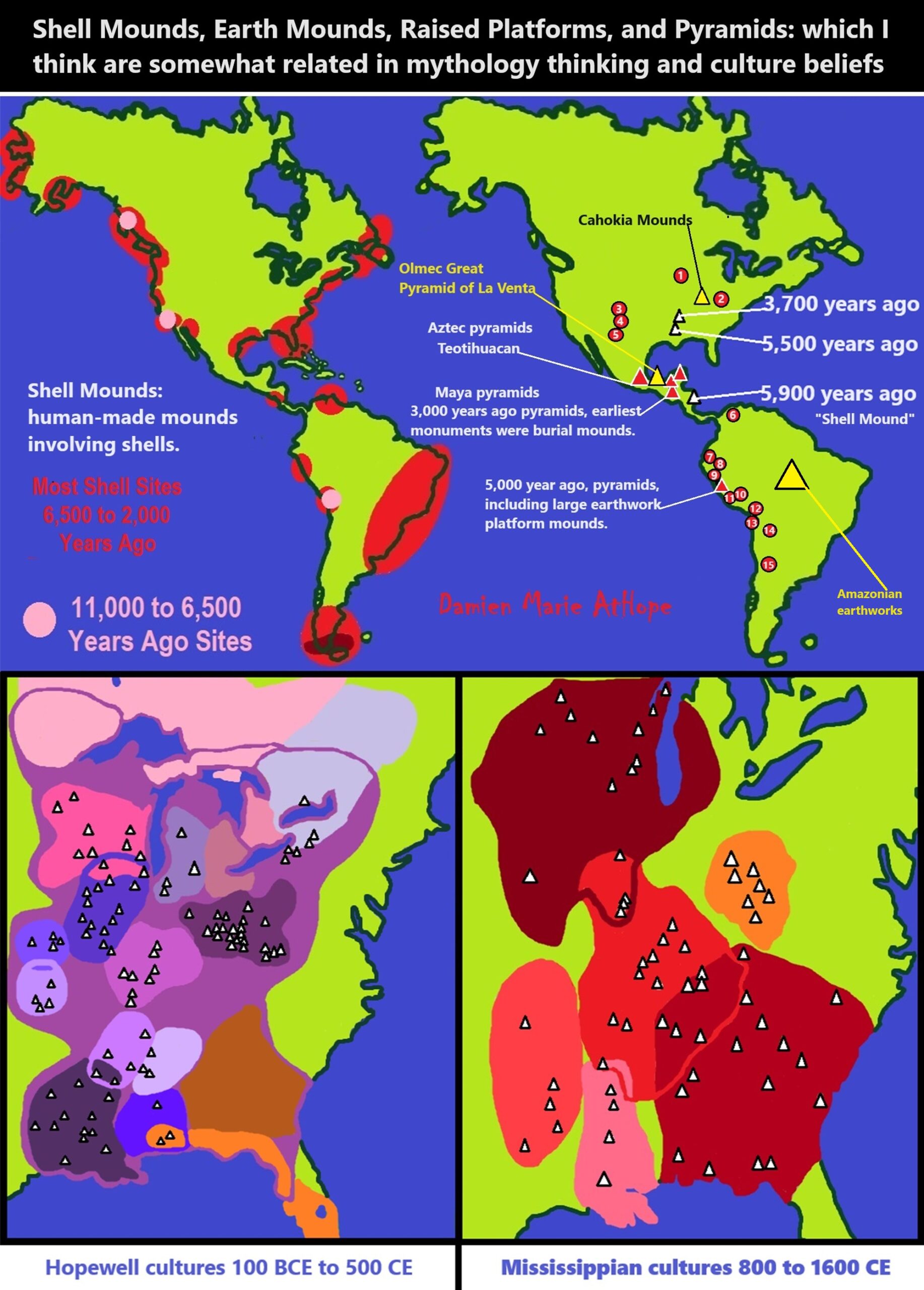

“The first humans to settle the Amazon Basin arrived around 13,000 years ago as part of a mass migration that quickly swept across the Americas, researchers have discovered.” ref

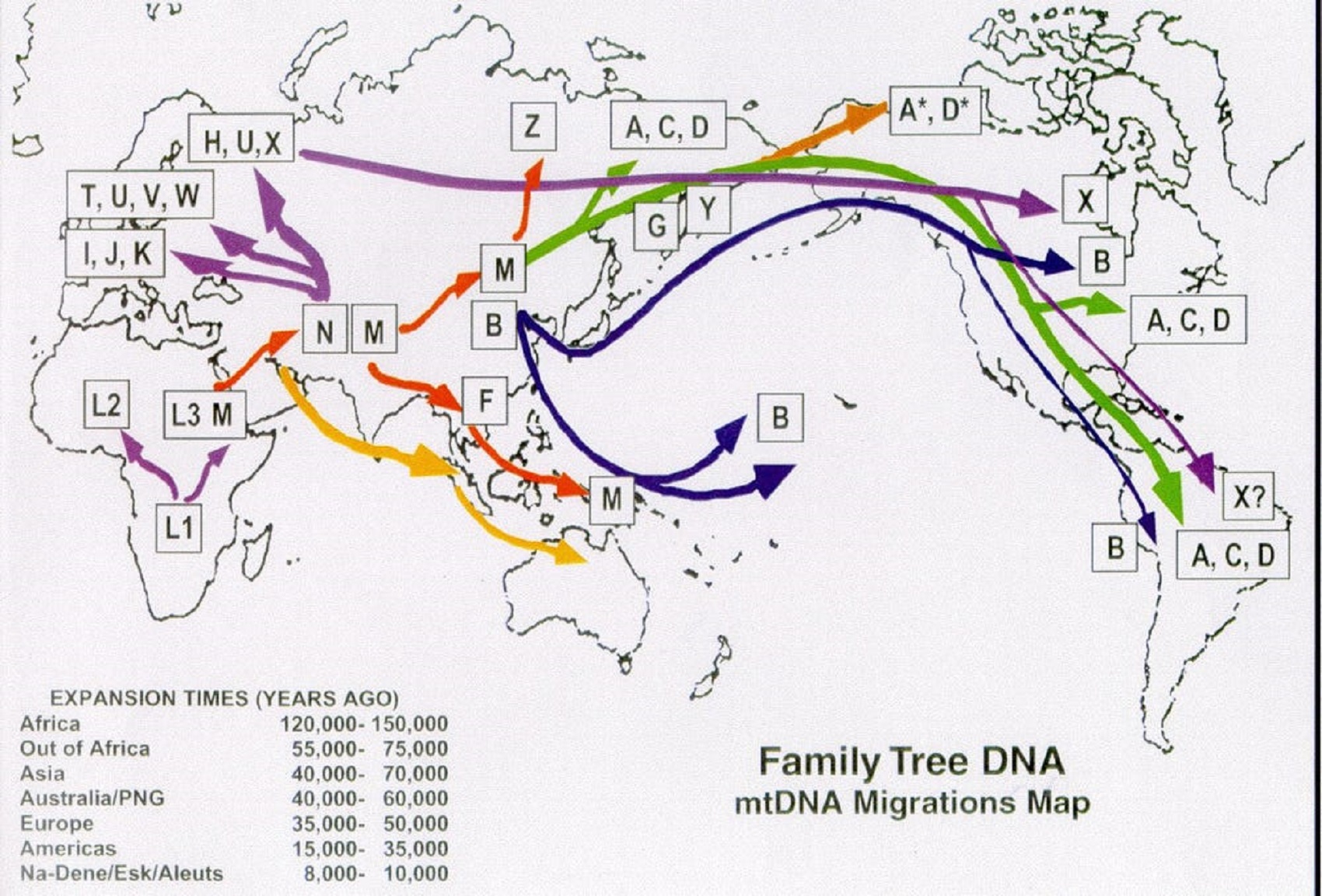

Source Populations for the Peopling of the Americas

“Genetic studies have used high-resolution analytical techniques applied to DNA samples from modern Native Americans and Asian populations regarded as their source populations to reconstruct the development of human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroups (yDNA haplogroups) and human mitochondrial DNA haplogroups (mtDNA haplogroups) characteristic of Native American populations. Models of molecular evolution rates were used to estimate the ages at which Native American DNA lineages branched off from their parent lineages in Asia and to deduce the ages of demographic events. One model (Tammetal 2007) based on Native American mtDNA Haplotypes (Figure 2) proposes that migration into Beringia occurred between 30,000 and 25,000 years ago, with migration into the Americas occurring around 10,000 to 15,000 years after isolation of the small founding population. Another model (Kitchen et al. 2008) proposes that migration into Beringia occurred approximately 36,000 years ago, followed by 20,000 years of isolation in Beringia. A third model (Nomatto et al. 2009) proposes that migration into Beringia occurred between 40,000 and 30,000 years ago, with a pre-LGM migration into the Americas followed by isolation of the northern population following the closure of the ice-free corridor. Evidence of Australo-Melanesians admixture in Amazonian populations was found by Skoglund and Reich (2016).” ref

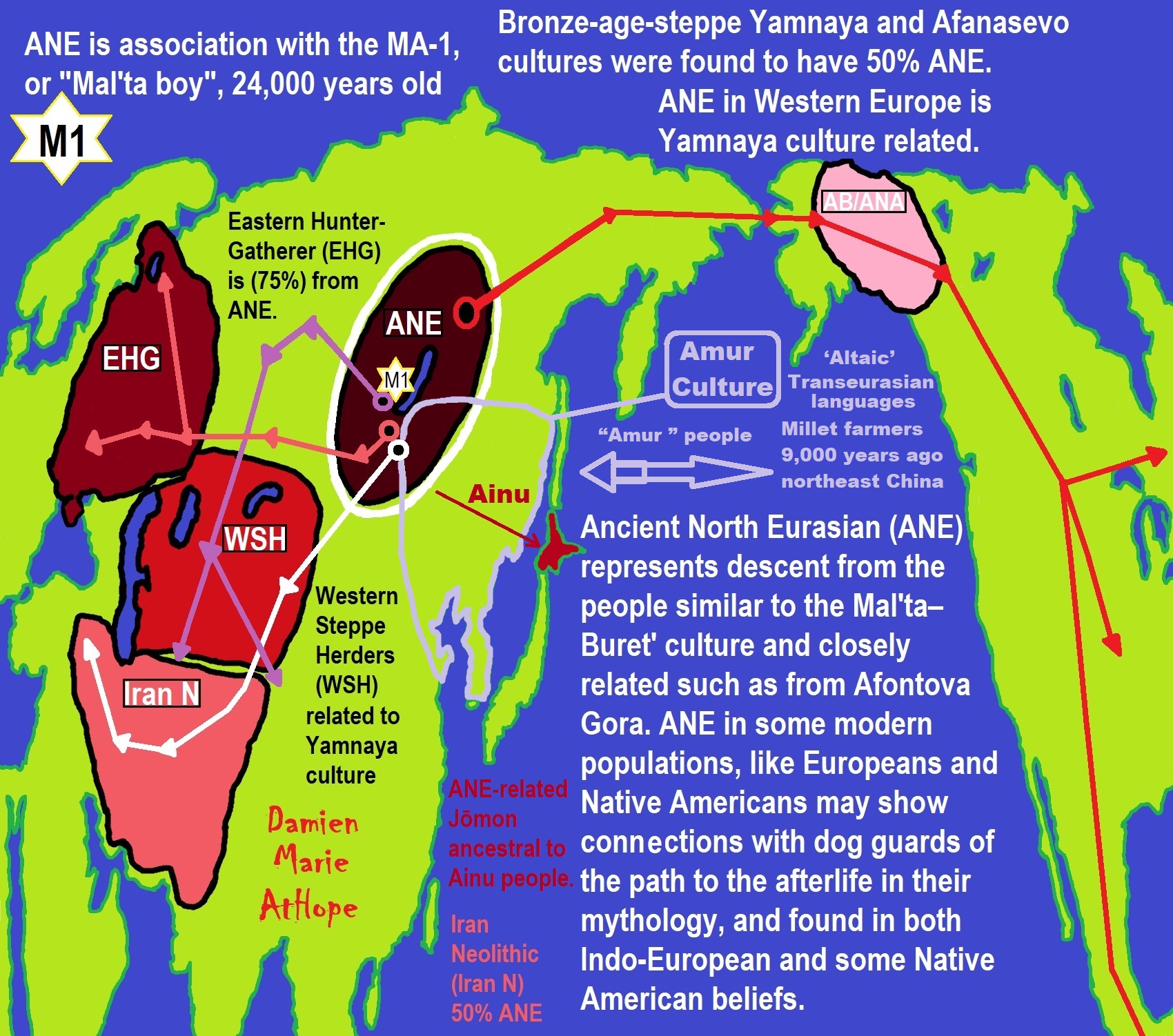

“A study of the diversification of mtDNA Haplogroups C and D from southern Siberia and eastern Asia, respectively, suggests that the parent lineage (Subhaplogroup D4h) of Subhaplogroup D4h3, a lineage found among Native Americans and Han Chinese, emerged around 20,000 years ago, constraining the emergence of D4h3 to post-LGM. Age estimates based on Y-chromosome micro-satellite diversity place origin of the American Haplogroup Q1a3a (Y-DNA) at around 15,000 to 10,000 years ago. Greater consistency of DNA molecular evolution rate models with each other and with archaeological data may be gained by the use of dated fossil DNA to calibrate molecular evolution rates. The Ancient Beringian (AB) is a specific archaeogenetic lineage, based on the genome of an infant found at the Upward Sun River site (dubbed USR1), dated to 11,500 years ago. The AB lineage diverged from the Ancestral Native American (ANA) lineage about 20,000 years ago. The ANA lineage was estimated as having been formed between 20,000 and 25,000 years ago by a mixture of East Asian and Ancient North Eurasian lineages, consistent with the model of the peopling of the Americas via Beringia during the Last Glacial Maximum.” ref

“The precise date for the peopling of the Americas is a long-standing open question, and while advances in archaeology, Pleistocene geology, physical anthropology, and DNA analysis have progressively shed more light on the subject, significant questions remain unresolved. The “Clovis first theory” refers to the hypothesis that the Clovis culture represents the earliest human presence in the Americas about 13,000 years ago. Evidence of pre-Clovis cultures has accumulated and pushed back the possible date of the first peopling of the Americas. Academics generally believe that humans reached North America south of the Laurentide Ice Sheet at some point between 15,000 and 20,000 years ago. Some new controversial archaeological evidence suggests the possibility that human arrival in the Americas may have occurred prior to the Last Glacial Maximum more than 20,000 years ago.

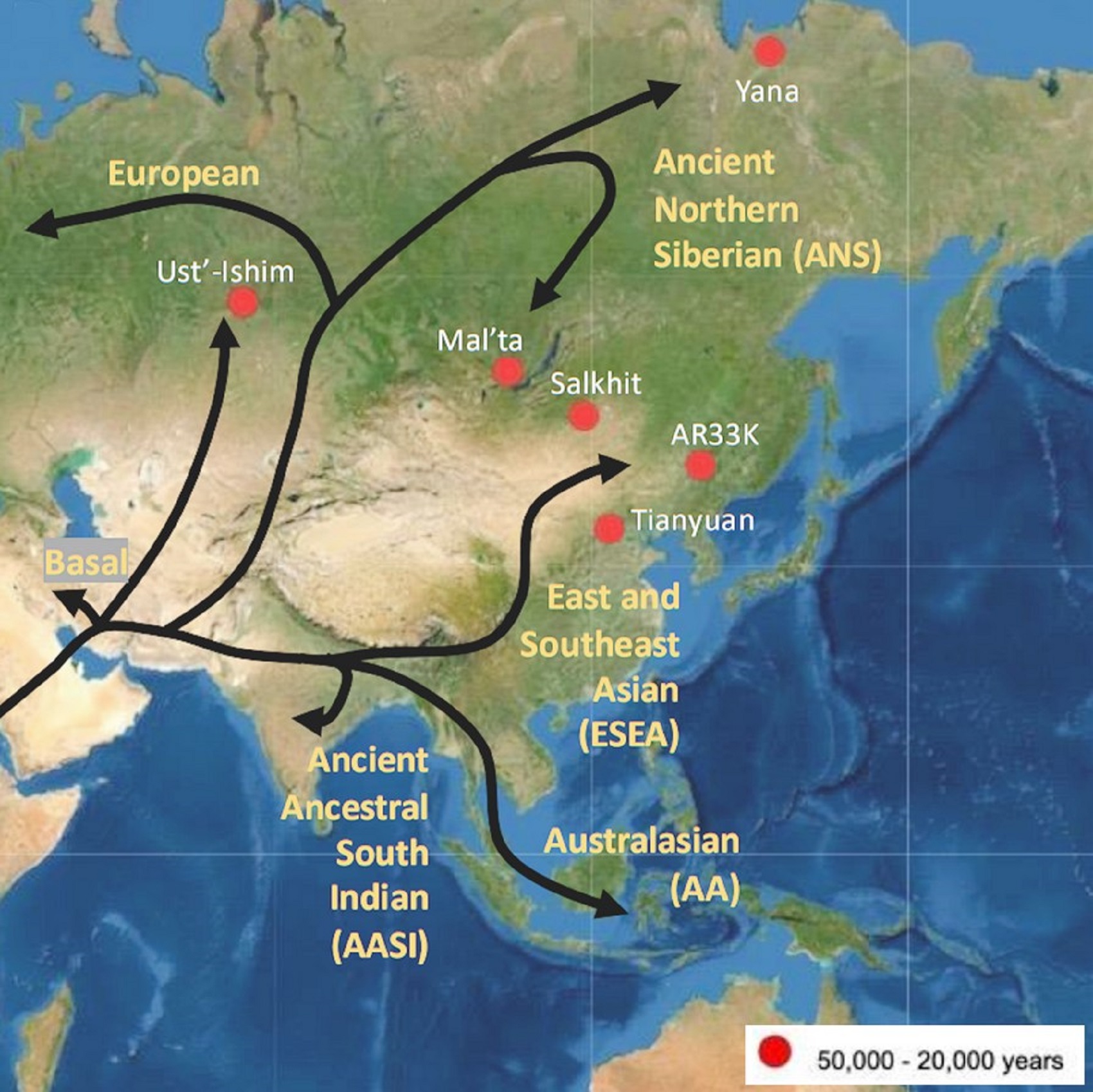

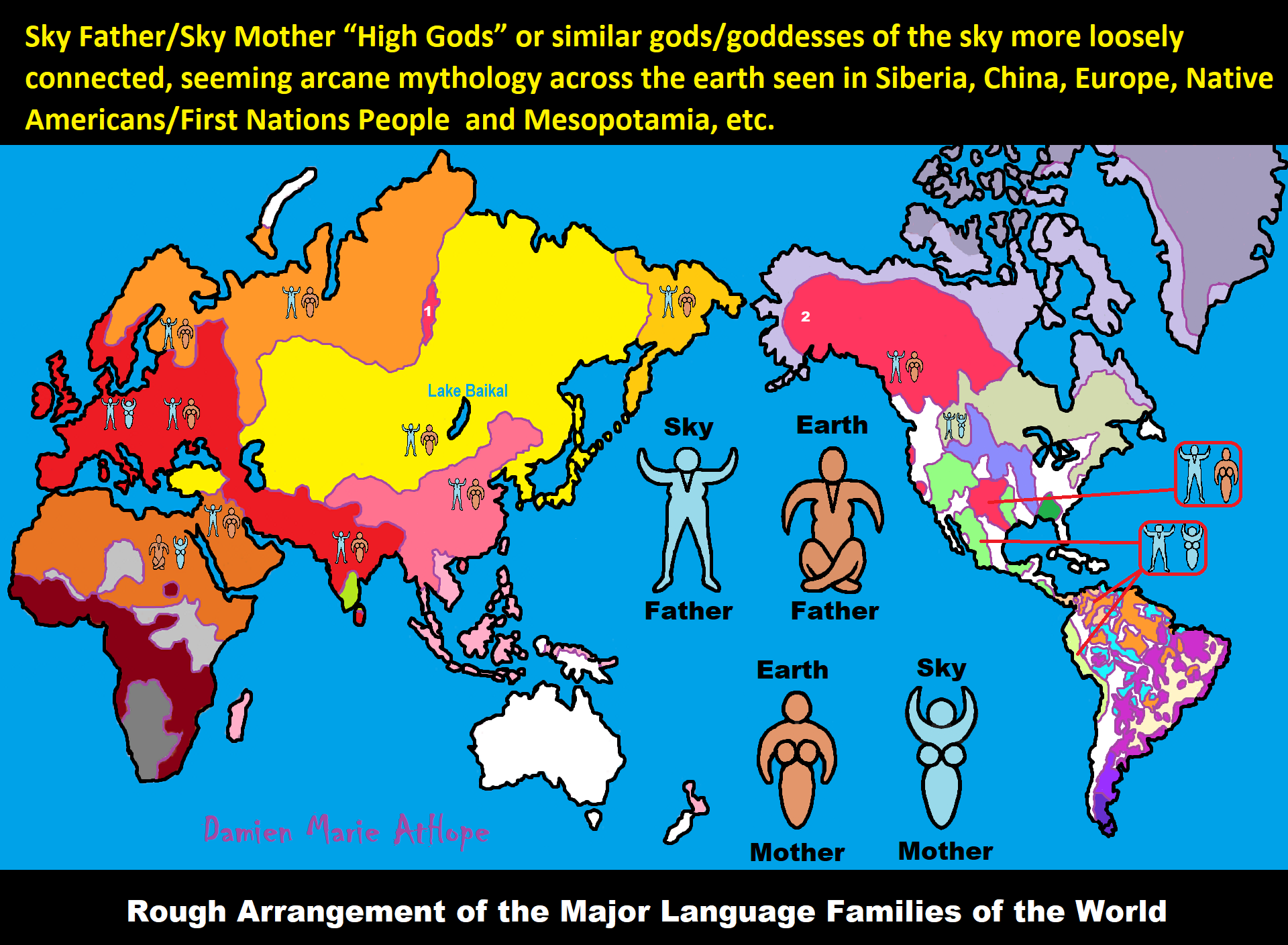

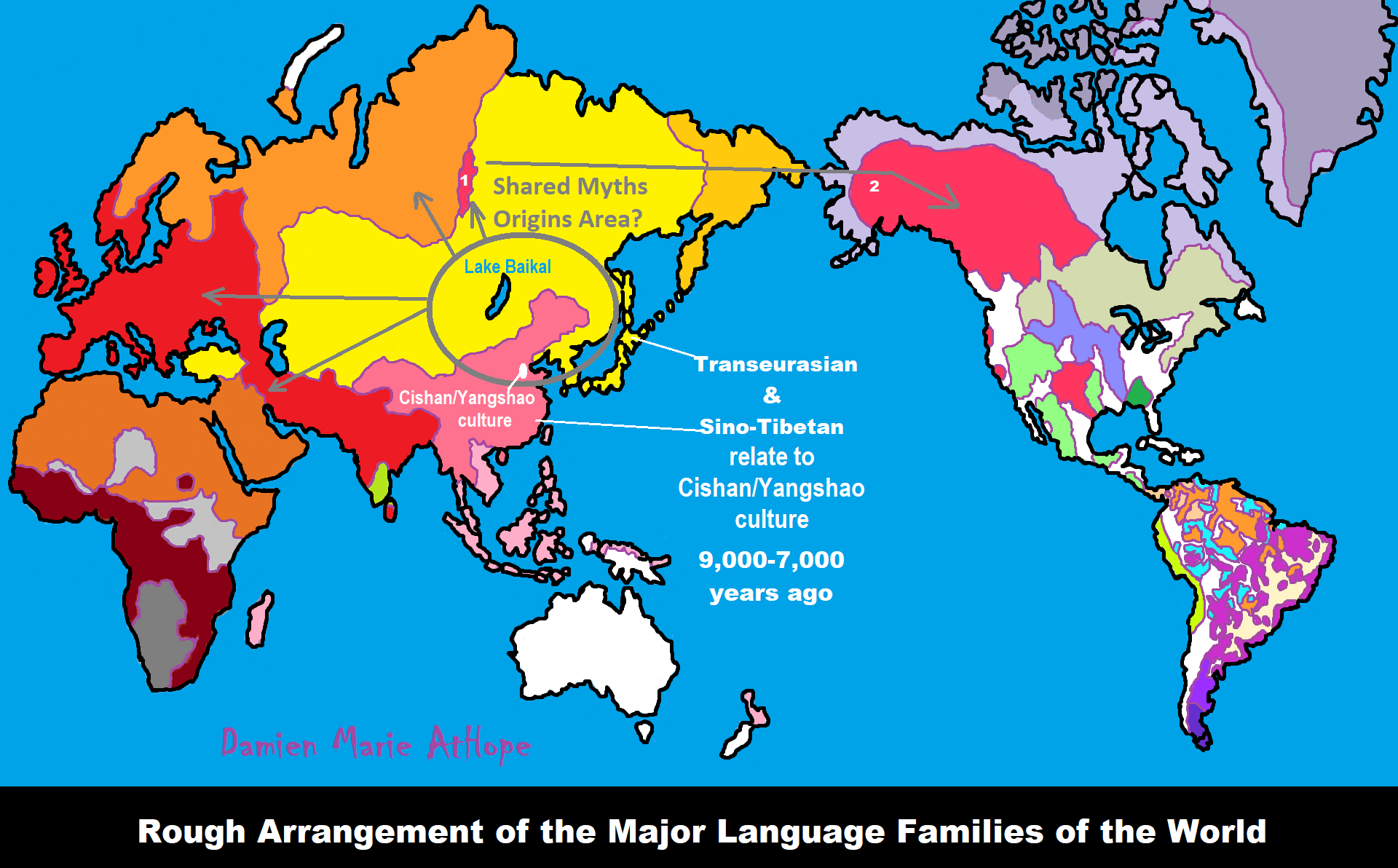

“The Native American source population was formed in Siberia by the mixing of two distinct populations: Ancient North Eurasians and an ancient East Asian (ESEA) population. According to Jennifer Raff, the Ancient North Eurasian population mixed with a daughter population of ancient East Asians, who they encountered around 25,000 years ago, which led to the emergence of Native American ancestral populations. However, the exact location where the admixture took place is unknown, and the migratory movements that united the two populations are a matter of debate. One theory supposes that Ancient North Eurasians migrated south to East Asia, or Southern Siberia, where they would have encountered and mixed with ancient East Asians. Genetic evidence from Lake Baikal in Mongolia supports this area as the location where the admixture took place. ” ref

“However, a third theory, the “Beringian standstill hypothesis”, suggests that East Asians instead migrated north to Northeastern Siberia, where they mixed with ANE, and later diverged in Beringia, where distinct Native American lineages formed. This theory is supported by maternal and nuclear DNA evidence. According to Grebenyuk, after 20,000 years ago, a branch of Ancient East Asians migrated to Northeastern Siberia, and mixed with descendants of the ANE, leading to the emergence of Ancient Paleo-Siberian and Native American populations in Extreme Northeastern Asia. However, the Beringian standstill hypothesis is not supported by paternal DNA evidence, which may reflect different population histories for paternal and maternal lineages in Native Americans, which is not uncommon and has been observed in other populations. A 2019 study suggested that Native Americans are the closest living relatives to 10,000-year-old fossils found near the Kolyma River in northeastern Siberia. A study published in July 2022 suggested that people in southern China may have contributed to the Native American gene pool, based on the discovery and DNA analysis of 14,000-year-old human fossils. The contrast between the genetic profiles of the Hokkaido Jōmon skeletons and the modern Ainu illustrates another uncertainty in source models derived from modern DNA samples: The development of high-resolution genomic analysis has provided opportunities to further define Native American subclades and narrow the range of Asian subclades that may be parent or sister subclades.” ref

“The common occurrence of the mtDNA Haplogroups A, B, C, and D among eastern Asian and Native American populations has long been recognized, along with the presence of haplogroup X. As a whole, the greatest frequency of the four Native-American-associated haplogroups occurs in the Altai–Baikal region of southern Siberia. Some subclades of C and D closer to the Native American subclades occur among Mongolian, Amur, Japanese, Korean, and Ainu populations. With further definition of subclades related to Native American populations, the requirements for sampling Asian populations to find the most closely related subclades grow more specific. Subhaplogroups D1 and D4h3 have been regarded as Native American specific based on their absence among a large sampling of populations regarded as potential descendants of source populations, over a wide area of Asia. Among the 3,764 samples, the Sakhalin–lower Amur region was represented by 61 Oroks.” ref

“In another study, Subhaplogroup D1a has been identified among the Ulchis of the lower Amur River region (4 among 87 sampled, or 4.6%), along with Subhaplogroup C1a (1 among 87, or 1.1%). Subhaplogroup C1a is regarded as a close sister clade of the Native American Subhaplogroup C1b. Subhaplogroup D1a has also been found among ancient Jōmon skeletons from Hokkaido The modern Ainu are regarded as descendants of the Jōmon. The occurrence of the Subhaplogroups D1a and C1a in the lower Amur region suggests a source population from that region distinct from the Altai-Baikal source populations, where sampling did not reveal those two particular subclades. The conclusions regarding Subhaplogroup D1 indicating potential source populations in the lower Amur and Hokkaido areas stand in contrast to the single-source migration model. Subhaplogroup D4h3 has been identified among Han Chinese. Subhaplogroup D4h3 from China does not have the same geographic implication as Subhaplotype D1a from Amur-Hokkaido, so its implications for source models are more speculative. Its parent lineage, Subhaplotype D4h, is believed to have emerged in East Asia, rather than Siberia, around 20,000 years ago. Subhaplogroup D4h2, a sister clade of D4h3, has also been found among Jōmon skeletons from Hokkaido. D4h3 has a coastal trace in the Americas.” ref

“X is one of the five mtDNA haplogroups found in Indigenous Americans. Native Americans mostly belong to the X2a clade, which has never been found in the Old World. According to Jennifer Raff, X2a probably originated in the same Siberian population as the other four founding maternal lineages, and that there is no compelling reason to believe it is related to X lineages found in Europe or West Eurasia. The Kennewick man fossil was found to carry the deepest branch of the X2a haplogroup, and he did not have any European ancestry that would be expected for a European origin of the lineage. The Human T cell Lymphotrophic Virus 1 (HTLV-1) is a virus transmitted through exchange of bodily fluids and from mother to child through breast milk. The mother-to-child transmission mimics a hereditary trait, although such transmission from maternal carriers is less than 100%. The HTLV virus genome has been mapped, allowing identification of four major strains and analysis of their antiquity through mutations. The highest geographic concentrations of the strain HLTV-1 are in sub-Saharan Africa and Japan.” ref

“In Japan, it occurs in its highest concentration on Kyushu. It is also present among African descendants and native populations in the Caribbean region and South America. It is rare in Central America and North America. Its distribution in the Americas has been regarded as due to importation with the slave trade. The Ainu have developed antibodies to HTLV-1, indicating its endemicity to the Ainu and its antiquity in Japan. A subtype “A” has been defined and identified among the Japanese (including Ainu), and among Caribbean and South American isolates. A subtype “B” has been identified in Japan and India. In 1995, Native Americans in coastal British Columbia were found to have both subtypes A and B. Bone marrow specimens from an Andean mummy about 1500 years old were reported to have shown the presence of the A subtype. The finding ignited controversy, with contention that the sample DNA was insufficiently complete for the conclusion and that the result reflected modern contamination. However, a re-analysis indicated that the DNA sequences were consistent with, but not definitely from, the “cosmopolitan clade” (subtype A). The presence of subtypes A and B in the Americas is suggestive of a Native American source population related to the Ainu ancestors, the Jōmon.” ref

“Paleo-Indian skeletons in the Americas such as Kennewick Man (Washington State), Hoya Negro skeleton (Yucatán), Luzia Woman and other skulls from the Lagoa Santa site (Brazil), Buhl Woman (Idaho), Peñon Woman III, two skulls from the Tlapacoya site (Mexico City), and 33 skulls from Baja California have exhibited certain craniofacial traits distinct from most modern Native Americans, leading physical anthropologists to posit an earlier “Paleoamerican” population wave. The most basic measured distinguishing trait is the dolichocephaly of the skull. Some modern isolated populations such as the Pericúes of Baja California and the Fuegians of Tierra del Fuego exhibit that same morphological trait. Other anthropologists advocate an alternative hypothesis that evolution of an original Beringian phenotype gave rise to a distinct morphology that was similar in all known Paleoamerican skulls, followed by later convergence towards the modern Native American phenotype.” ref

“Archaeogenetic studies do not support a two-wave model or the Paleoamerican hypothesis of an Australo-Melanesian origin, and firmly assign all Paleo-Indians and modern Native Americans to one ancient population that entered the Americas in a single migration from Beringia. Only in one ancient specimen (Lagoa Santa) and a few modern populations in the Amazon region, a small Australasian ancestry component of c. 3% was detected, which remains unexplained by the current state of research (as of 2021), but may be explained by the presence of the more basal Tianyuan-related ancestry, a deep East Asian lineage which did not directly contribute to modern East Asians but may have contributed to the ancestors of Native Americans in Siberia, as such ancestry is also found among previous Paleolithic Siberians (Ancient North Eurasians).” ref

“A report published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology in January 2015 reviewed craniofacial variation focusing on differences between early and late Native Americans and explanations for these based on either skull morphology or molecular genetics. Arguments based on molecular genetics have in the main, according to the authors, accepted a single migration from Asia with a probable pause in Beringia, plus later bi-directional gene flow. Some studies focusing on craniofacial morphology have previously argued that Paleoamerican remains have been described as closer to Australo-Melanesians and Polynesians than to the modern series of Native Americans, suggesting two entries into the Americas, an early one occurring before a distinctive East Asian morphology developed (referred to in the paper as the “Two Components Model”). Another “third model”, the “Recurrent Gene Flow” (RGF) model, attempts to reconcile the two, arguing that circumarctic gene flow after the initial migration could account for morphological changes. It specifically re-evaluates the original report on the Hoya Negro skeleton which supported the RGF model, the authors disagreed with the original conclusion which suggested that the skull shape did not match those of modern Native Americans, arguing that the “skull falls into a subregion of the morphospace occupied by both Paleoamericans and some modern Native Americans.” ref

“Stemmed points are a lithic technology distinct from Beringian and Clovis types. They have a distribution ranging from coastal East Asia to the Pacific coast of South America. The emergence of stemmed points has been traced to Korea during the upper Paleolithic. The origin and distribution of stemmed points have been interpreted as a cultural marker related to a source population from coastal East Asia. The Indigenous peoples of the Americas have ascertained archaeological presence in the Americas dating back to about 15,000 years ago. More recent research, however, suggests a human presence dating to between 18,000 and 26,000 years ago, during the Last Glacial Maximum. There remain uncertainties regarding the precise dating of individual sites and regarding conclusions drawn from population genetics studies of contemporary Native Americans.” ref

“Genetic diversity and population structure in the American land mass using DNA micro-satellite markers (genotype) sampled from North, Central, and South America have been analyzed against similar data available from other Indigenous populations worldwide. The Amerindian populations show a lower genetic diversity than populations from other continental regions. Decreasing genetic diversity with increasing geographic distance from the Bering Strait can be seen, as well as a decreasing genetic similarity to Siberian populations from Alaska (genetic entry point). A higher level of diversity and lower level of population structure in western South America compared to eastern South America is observed. A relative lack of differentiation between Mesoamerican and Andean populations is a scenario that implies coastal routes were easier than inland routes for migrating peoples (Paleo-Indians) to traverse. The overall pattern that is emerging suggests that the Americas were recently colonized by a small number of individuals (effective size of about 70–250), and then they grew by a factor of 10 over 800–1,000 years.” ref

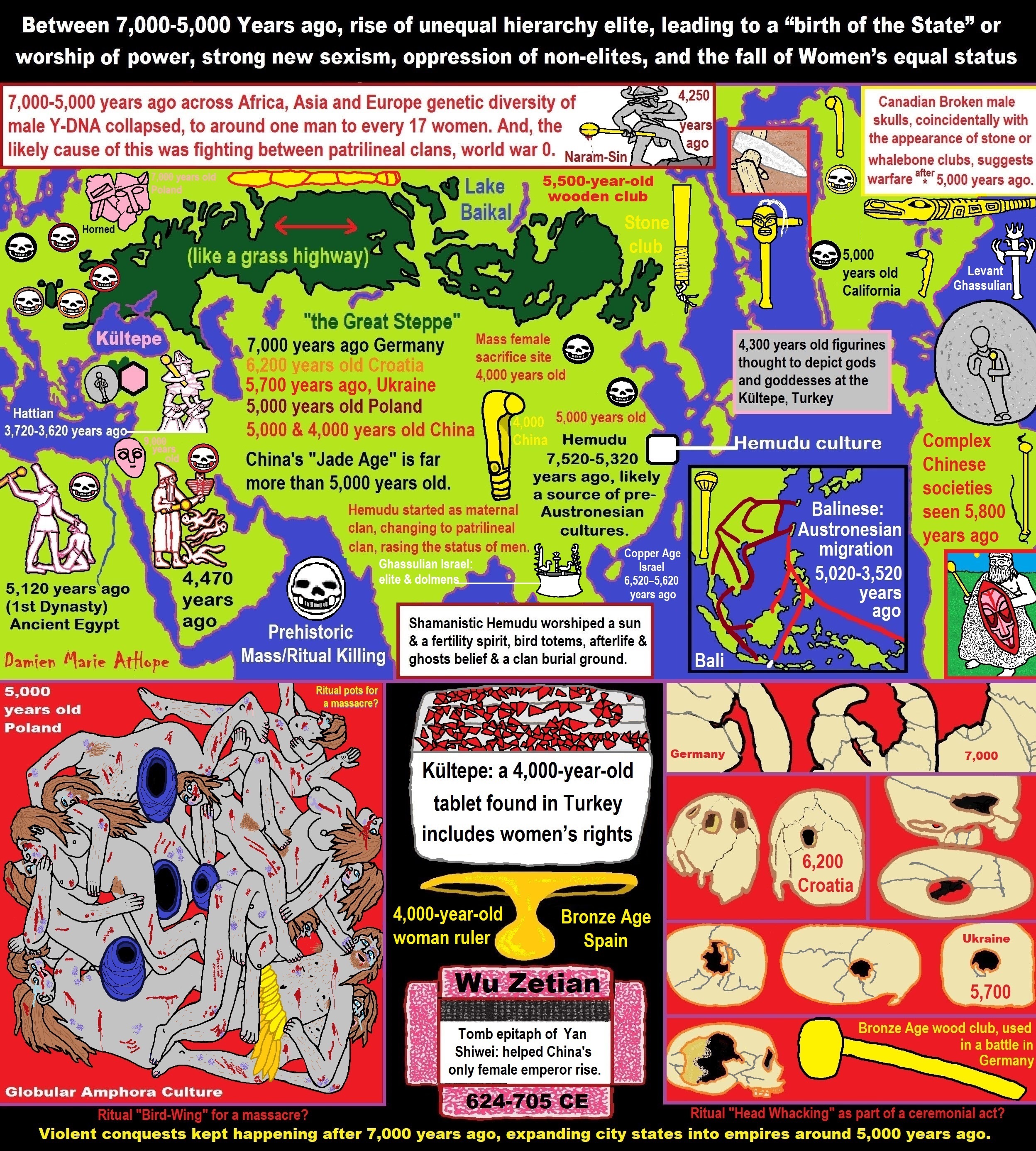

“The data also show that there have been genetic exchanges between Asia, the Arctic, and Greenland since the initial peopling of the Americas. A new study in early 2018 suggests that the effective population size of the original founding population of Native Americans was about 250 people. “Pre-Columbian population figures are difficult to estimate due to the fragmentary nature of the evidence. Estimates range from 8–112 million. Scholars have varied widely on the estimated size of the Indigenous populations prior to colonization and on the effects of European contact. Estimates are made by extrapolations from small bits of data. A 2020 genetic study suggests that prior estimates for the pre-Columbian Caribbean population may have been at least tenfold too large. Historian David Stannard estimates that the extermination of Indigenous peoples took the lives of 100 million people: “…the total extermination of many American Indian peoples and the near-extermination of others, in numbers that eventually totaled close to 100,000,000.” ref

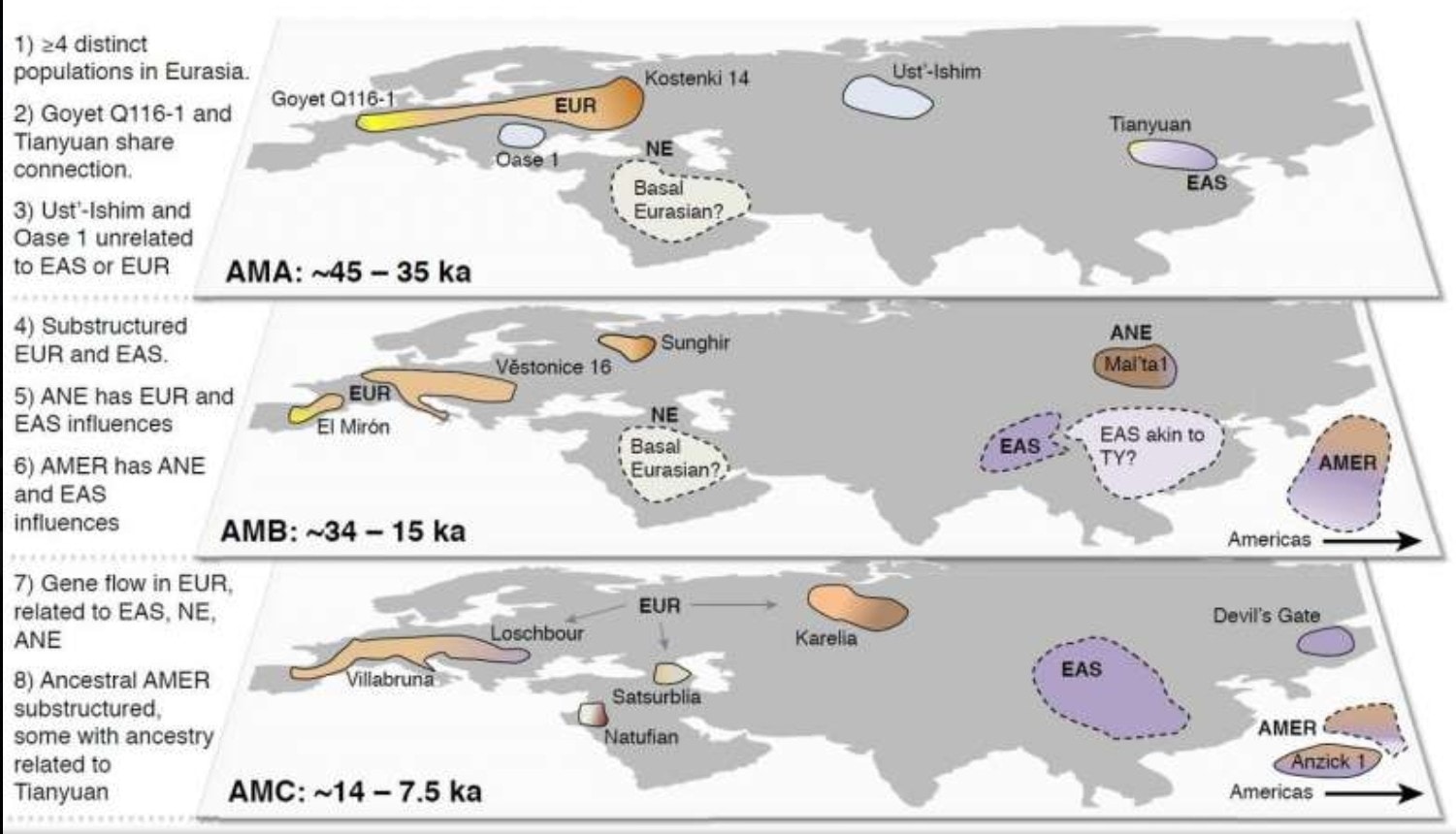

Abstract: “The dispersal of Homo sapiens in Siberia and Mongolia occurred by 45,000 to 40,000 years ago; however, the climatic and environmental context of this event remains poorly understood. We reconstruct a detailed vegetation history for the Last Glacial period based on pollen spectra from Lake Baikal. While herb and shrub taxa including Artemisia and Alnus dominated throughout most of this period, coniferous forests rapidly expanded during Dansgaard-Oeschger (D-O) events 14 (55,000 years ago) and 12 to 10 (48,000 to 41,000 years ago), with the latter presenting the strongest signal for coniferous forest expansion and Picea trees, indicating remarkably humid conditions. These abrupt forestation events are consistent with obliquity maxima, so that we interpret last glacial vegetation changes in southern Siberia as being driven by obliquity change. Likewise, we posit that major climate amelioration and pronounced forestation precipitated H. sapiens dispersal into Baikal Siberia 45,000 years ago, as chronicled by the appearance of the Initial Upper Paleolithic.” ref

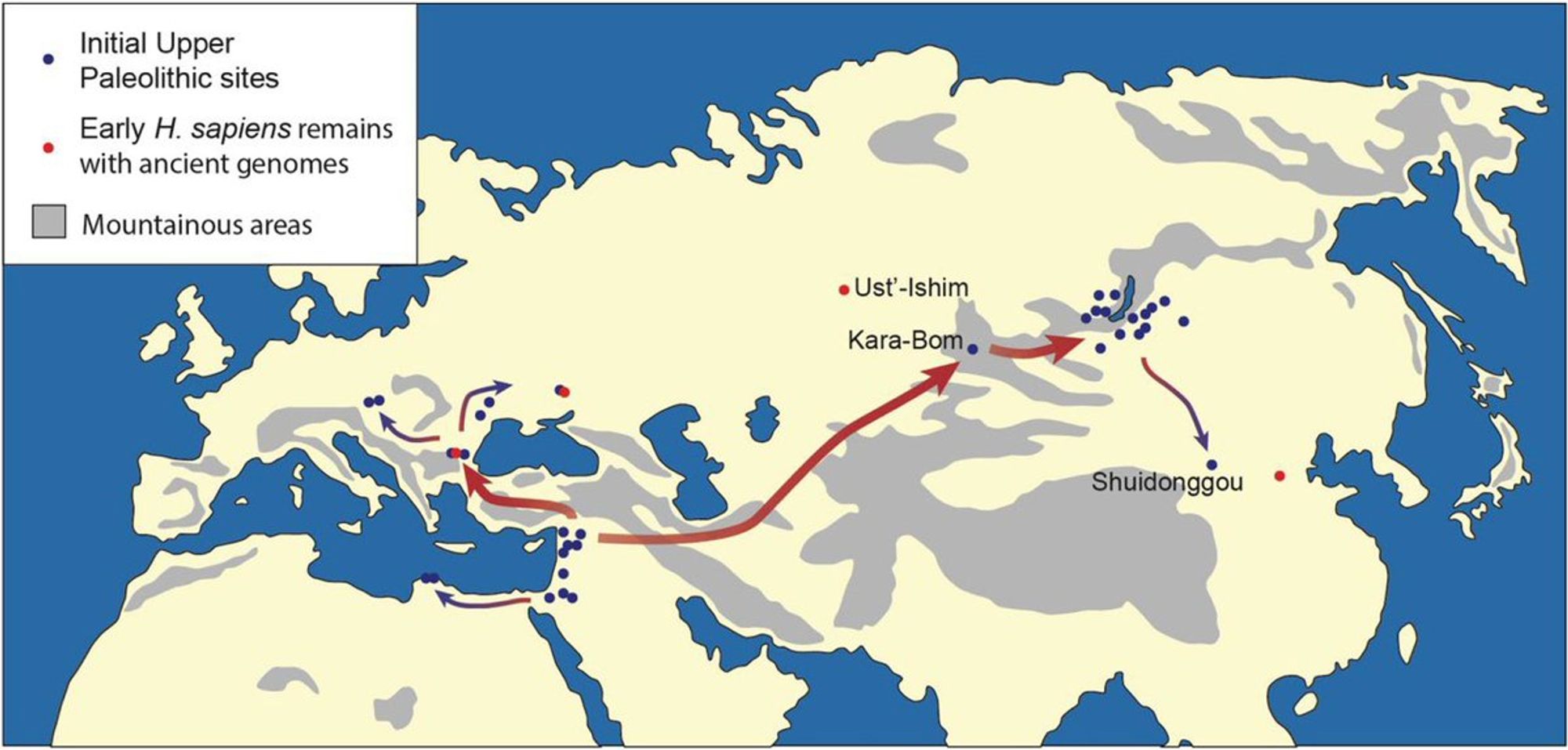

“The Yana Rhinoceros Horn Site (Yana RHS) is an Upper Palaeolithic archaeological site located near the lower Yana river in northeastern Siberia, Russia, north of the Arctic Circle in the far west of Beringia. It was discovered in 2001, after thawing and erosion exposed animal bones and artifacts. The site features a well-preserved cultural layer due to the cold conditions, and includes hundreds of animal bones and ivory pieces and numerous artifacts, which are indicative of sustained settlement and a relatively high level of technological development. With an estimated age of around 32,000 years ago, the site provides the earliest archaeological evidence for human settlement in this region, or anywhere north of the Arctic Circle, where people survived extreme conditions and hunted a wide range of fauna before the onset of the Last Glacial Maximum. The Yana site is perhaps the earliest unambiguous evidence of mammoth hunting by humans. A 2019 genetic study found that the remains of two young male humans discovered at the site, dating to c. 31,600 years ago, represent a distinct archaeogenetic lineage, named ‘Ancient North Siberians‘ (ANS). The Yana RHS site is preceded in Siberia by a few Initial Upper Paleolithic archaeological sites such as Ust-Ischim (with modern human remains, 45,000 years ago), or Kara-Bom (dating to 46,620 +/-1,750 cal years ago), Kara-Tenesh, Kandabaevo, and Podzvonskaya.” ref

“A model of differentiation after dispersal out of Africa in the Early Upper Paleolithic (45,000–20,000 years ago) (“The tree diagram shows divergence patterns and is not meant to depict migration routes from the branches or geographic origins of ancestral populations”). The genetic proximity of Yana with Ancient North Eurasian populations (Mal’ta, Afontova Gora), but also Ust-Ishim and Sunghir and to a lesser extent Tianyuan, within a principal component analysis of ancient and present-day individuals from worldwide populations. Human teeth, dated to around 31,630 calibrated years before present, were found at the site, at the Northern Point locality. DNA extracted from two of these teeth, which were found to be from two unrelated males, were found to represent a distinct archaeogenetic lineage which can be modeled as a mixture of early West Eurasian with significant contribution (c. 22% to 50%) from early East Asians (represented by Tianyuan man), an ancestral lineage that the authors have named ‘Ancient North Siberian’ (ANS), thought to have diversified around 38,000 years ago. Both individuals from the Yana site were found to belong to mitochondrial haplogroup U, and Y chromosome haplogroup P1. This is currently the oldest human genetic material retrieved from Siberia.” ref