[Antireligionist] My blogs that address Religion: Archaeology, Anthropology, Philosophy and History

“The A Priori Argument Fallacy (also, Rationalization; Dogmatism, Proof Texting.): A corrupt argument from logos, starting with a given, pre-set belief, dogma, doctrine, scripture verse, “fact” or conclusion and then searching for any reasonable or reasonable-sounding argument to rationalize, defend or justify it. Certain ideologues and religious fundamentalists are proud to use this fallacy as their primary method of “reasoning” and some are even honest enough to say so.” http://utminers.utep.edu/omwilliamson/engl1311/fallacies.htm

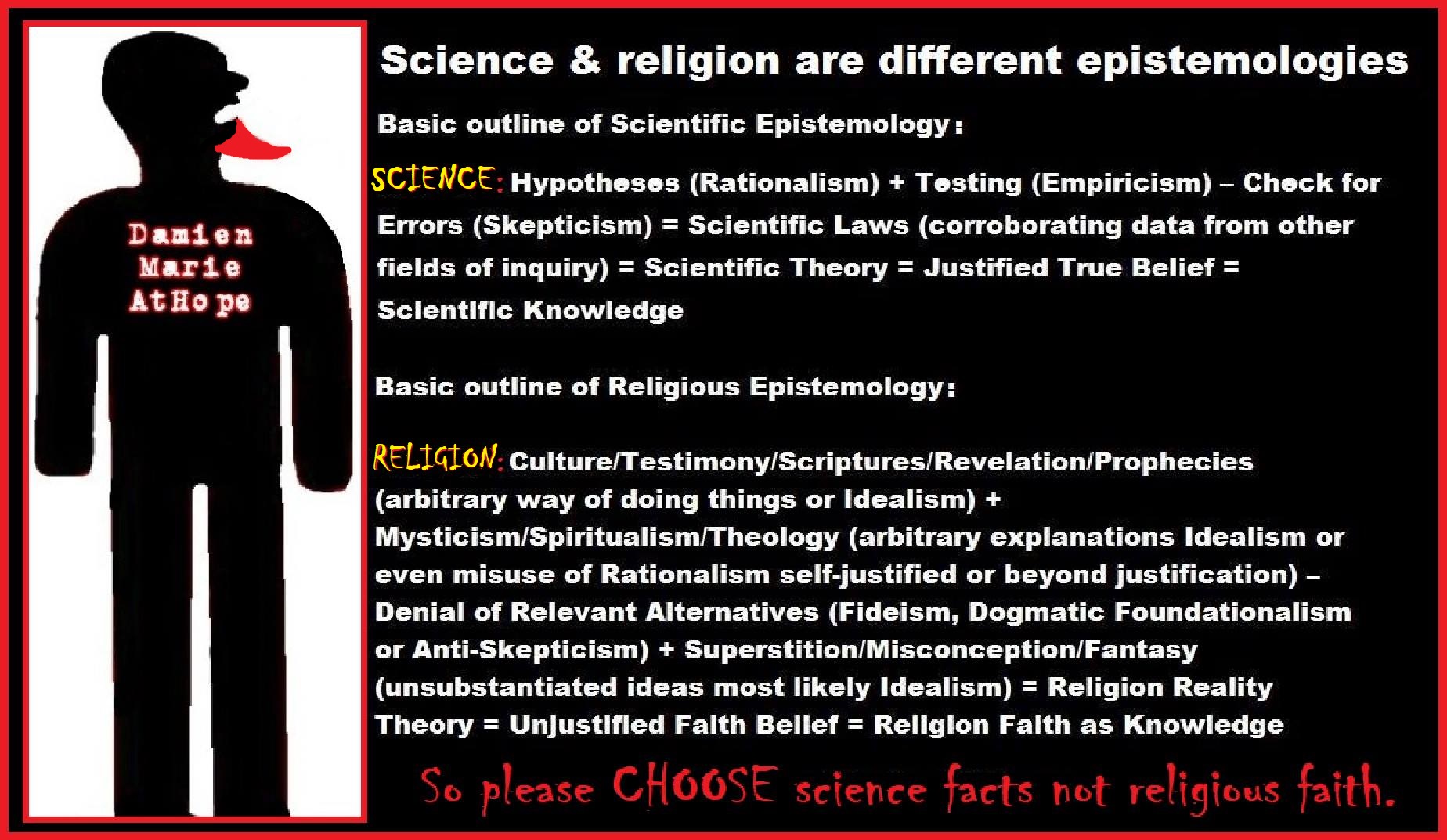

Religion vs. Science, Don’t Confuse Beliefs

It is widely believed that you can’t prove a negative. Some people even think that it is a law of logic—you can’t prove that Santa Claus, unicorns, the Loch Ness Monster, God, pink elephants, WMD in Iraq and Bigfoot don’t exist. This widespread belief is flatly, 100% wrong. In this little essay, I show precisely how one can prove a negative, to the same extent that one can prove anything at all. Ref

Thinking Tools is a regular feature that introduces tips and pointers on thinking clearly and rigorously. A principle of folk logic is that one can’t prove a negative. Dr. Nelson L. Price, a Georgia minister, writes on his website that ‘one of the laws of logic is that you can’t prove a negative.’ Julian Noble, a physicist at the University of Virginia, agrees, writing in his ‘Electric Blanket of Doom’ talk that ‘we can’t prove a negative proposition.’ University of California at Berkeley Professor of Epidemiology Patricia Buffler asserts that ‘The reality is that we can never prove the negative, we can never prove the lack of effect, we can never prove that something is safe.’ A quick search on Google or Lexis-Nexis will give a mountain of similar examples. But there is one big, fat problem with all this. Among professional logicians, guess how many think that you can’t prove a negative?

That’s right: zero. Yes, Virginia, you can prove a negative, and it’s easy, too. For one thing, a real, actual law of logic is a negative, namely the law of non-contradiction. This law states that that a proposition cannot be both true and not true. Nothing is both true and false. Furthermore, you can prove this law. It can be formally derived from the empty set using provably valid rules of inference. (I’ll spare you the boring details).

One of the laws of logic is a provable negative?

“Wait… this means we’ve just proven that it is not the case that one of the laws of logic is that you can’t prove a negative. So we’ve proven yet another negative! In fact, ‘you can’t prove a negative’ is a negative, so if you could prove it true, it wouldn’t be true! Uh-oh. Not only that, but any claim can be expressed as a negative, thanks to the rule of double negation. This rule states that any proposition P is logically equivalent to not-not-P. So pick anything you think you can prove. Think you can prove your own existence? At least to your own satisfaction? Then, using the exact same reasoning, plus the little step of double negation, you can prove that you aren’t nonexistent. Congratulations, you’ve just proven a negative. The beautiful part is that you can do this trick with absolutely any proposition whatsoever. Prove P is true and you can prove that P is not false. Some people seem to think that you can’t prove a specific sort of negative claim, namely that a thing does not exist. So it is impossible to prove that Santa Claus, unicorns, the Loch Ness Monster, God, pink elephants, WMD in Iraq, and Bigfoot don’t exist. Of course, this rather depends on what one has in mind by ‘prove.’ Can you construct a valid deductive argument with all true premises that yields the conclusion that there are no unicorns? Sure.– Steven Hales is professor of philosophy at Bloomsburg University, Pennsylvania.

“Here’s one, using the valid inference procedure of modus tollens:

1. If unicorns had existed, then there is evidence in the fossil record.

2. There is no evidence of unicorns in the fossil record.

3. Therefore, unicorns never existed. Someone might object that that was a bit too fast, after all, I didn’t prove that the two premises were true. I just asserted that they were true.” – Steven Hales is professor of philosophy at Bloomsburg University, Pennsylvania.

“Well, that’s right. However, it would be a grievous mistake to insist that someone prove all the premises of any argument they might give. Here’s why. The only way to prove, say, that there is no evidence of unicorns in the fossil record, is by giving an argument to that conclusion. Of course one would then have to prove the premises of that argument by giving further arguments, and then prove the premises of those further arguments, ad infinitum. Which premises we should take on credit and which need payment up front is a matter of long and involved debate among epistemologists. But one thing is certain: if proving things requires that an infinite number of premises get proved first, we’re not going to prove much of anything at all, positive or negative. Maybe people mean that no inductive argument will conclusively, indubitably prove a negative proposition beyond all shadow of a doubt.– Steven Hales is professor of philosophy at Bloomsburg University, Pennsylvania.

“For example, suppose someone argues Hales Thinking tools • Think summer 2005 • that we’ve scoured the world for Bigfoot, found no credible evidence of Bigfoot’s existence, and therefore there is no Bigfoot. A classic inductive argument. A Sasquatch defender can always rejoin that Bigfoot is reclusive, and might just be hiding in that next stand of trees. You can’t prove he’s not! (until the search of that tree stand comes up empty too). The problem here isn’t that inductive arguments won’t give us certainty about negative claims (like the nonexistence of Bigfoot), but that inductive arguments won’t give us certainty about anything at all, positive or negative. All observed swans are white, therefore all swans are white looked like a pretty good inductive argument until black swans were discovered in Australia. The very nature of an inductive argument is to make a conclusion probable, but not certain, given the truth of the premises. That just what an inductive argument is.” – Steven Hales is professor of philosophy at Bloomsburg University, Pennsylvania.

“We’d better not dismiss induction because we’re not getting certainty out of it, though. Why do you think that the sun will rise tomorrow? Not because of observation (you can’t observe the future!), but because that’s what it has always done in the past. Why do you think that if you turn on the kitchen tap that water will come out instead of chocolate? Why do you think you’ll find your house where you last left it? Why do you think lunch will be nourishing instead of deadly? Again, because that’s the way things have always been in the past. In other words, we use inferences — induction — from past experiences in every aspect of our lives. As Bertrand Russell pointed out, the chicken who expects to be fed when he sees the farmer approaching, since that is what had always happened in the past, is in for a big surprise when instead of receiving dinner, he becomes dinner. But if the chicken had rejected inductive reasoning altogether, then every appearance of the farmer would be a surprise. So why is it that people insist that you can’t prove a negative? I think it is the result of two things. (1) an acknowledgement that induction is not bulletproof, airtight, and infallible, and (2) a desperate desire to keep believing whatever one believes, even if all the evidence is against it.” – Steven Hales is professor of philosophy at Bloomsburg University, Pennsylvania.

“That’s why people keep • believing in alien abductions, even when flying saucers always turn out to be weather balloons, stealth jets, comets, or too much alcohol. You can’t prove a negative! You can’t prove that there are no alien abductions! Meaning: your argument against aliens is inductive, therefore not incontrovertible, and since I want to believe in aliens, I’m going to dismiss the argument no matter how overwhelming the evidence against aliens, and no matter how vanishingly small the chance of extraterrestrial abduction. If we’re going to dismiss inductive arguments because they produce conclusions that are probable but not definite, then we are in deep doo-doo. Despite its fallibility, induction is vital in every aspect of our lives, from the mundane to the most sophisticated science. Without induction we know basically nothing about the world apart from our own immediate perceptions. So we’d better keep induction, warts and all, and use it to form negative beliefs as well as positive ones. You can prove a negative — at least as much as you can prove anything at all.” – Steven Hales is professor of philosophy at Bloomsburg University, Pennsylvania.

You Can Prove a Negative

“Well, no it isn’t philosophically impossible… read on: It is commonly thought that one cannot prove a negative, but of course I can. If I say “there are no weasels in my right pocket”, all I need to do is enumerate the objects in my right pocket and find a dearth of weasels among them to prove that negative claim. So why do people think one can’t prove a negative?

Negative claims are of the form

?∃(x)(Fx)

Or, in English, “NOT There is an x such that x Fs”… oh, OK, it asserts that no x is F.

Now to prove this claim, you need something that logicians call “the Universe of Discourse”, or “the Domain”. That is, the totality of the world or worlds that the claim ranges across. In the pocket example, that is my right pocket. If the domain or universe is small enough, and all the objects in it accessible in a reasonable time, we certainly do think that we can make proof claims. Consider the extinction of the Yellow River dolphin. Pretty well all areas in which that animal can exist are under constant observation by a very large population that has the means to report its existence. So we can safely say that it no longer exists. So why is it a common claim? This has to do with the development of the medieval logics, and ambiguity (errors in logic are nearly always due to ambiguity in some way or another). The medievals had what they called “the Square of Opposition”. It went like this: Propositions of the form E are negative claims. But if the universe is not defined, as it wasn’t (the medievals thought that logical possibility ranged across all the universe and possible universes unrestrictedly), one cannot find out if something is false until one encounters an existing contradiction to the claim (an x that is F). Because they had an unrestricted domain, they could never prove that negative if none were ever encountered. I suspect, though, that it is easier to prove that Obama is not a Muslim or a terrorist than to prove that no gods are green, for example. The domain is smaller, and more manageable.” Ref

Myth: One can’t prove a negative.

Proving Negatives and Dealing With Absence of Evidence and Evidence of Absence

Factmyth.com

Factmyth.com

The saying “you can’t prove a negative” isn’t accurate. Proving negatives is a foundational aspect of logic (ex. the law of contradiction).[1][2][3]

An Example of Proving a Negative in the Sense that People Mean it When they Say the Phrase

Putting aside negatives we can prove with certainty for a second, consider the following: To “prove” a something we simply have to provide sufficient evidence that a proposition (statement or claim) is true. In other words, we have to show that it is very likely the case, we don’t have to show it is true with absolute certainty. Thus, to prove a negative, we only have to show that it is very likely the case. To do this, there must not be compelling evidence that it is the case and there must instead be compelling evidence that it is not the case. We DO NOT have to observe empirically that which cannot be observed (for example, we don’t have to see a Unicorn not existing to know it doesn’t exist, we just have to show compelling evidence of its non-existence). Thus, proving a negative in this sense can be accomplished by providing evidence of absence (not argument from ignorance, but scientific evidence of absence gathered from scientific research). For example, a strong argument that proves that it is very likely Unicorns don’t exist involves showing that there is no evidence of Unicorns existing (no fossils, no eye witness accounts, no hoofprints, nothing). If we did a serious scientific inquiry, searching for Unicorn fossils, and turned up nothing, it would be a type of evidence for the non-existence of Unicorns. If no one could show scientific data pointing toward unicorns to combat this, then at a point it would become a good theory and we could put forth a scientific theory, based on empirical data, that says “Unicorns don’t exist.” At that point, the burden of proof would be on those who believe in Unicorns to prove that Unicorns do in fact exist (the burden would be on them to prove the theory of non-existent Unicorns false by providing a better theory). This is just one of many ways to prove a negative, below we list others including using the law of contradiction and using double negatives. TIP: Science can’t actually prove anything with 100% certainty. Essentially “all we know for sure is that we know nothing for sure.” This is because all testing of the outside world involves inductive reasoning(comparing specific observations to other specific observations). Meanwhile, logically certain truths are generally pure analytic a priori (they are generally tautologically redundant and necessarily true facts like “since A is A” therefore “A is not B.”) Does this prove God does or doesn’t exist? Proving the existence of God (or the non-existence) is loosely related to this line of reasoning, but it is sort of outside of the sphere of what we are talking about here. If one claims, “all that is is, but God exists outside of that” then the argument for God becomes ontological, theological, metaphysic, and faith-based. Faith-based metaphysical arguments don’t require scientific empirical evidence… unless they try to posit something that can be debunked by empirical science (in that case, arguments for faith instead of reason tend to be logically “weak,” in that they lack supporting evidence). An Introduction to Proving Negatives With Necessary Logical Truths and the Inductive Evidence of Absence. To clarify the above, in terms of proving negatives with certainty and uncertainty, we can prove some negatives with certainty (like necessary logical truths such as “A is not B” and double negatives like “I don’t not not exist”), but generally “proving negatives” means providing compelling evidence that shows it is very likely that something isn’t the case (it means “proving” probable truths, not certain ones). This type of “inductive” reasoning can produce scientific truths using evidence of absence (it can show that it is likely that something isn’t the case via scientific observation and measurement that shows a lack of evidence), but the reality is there isn’t much we can actually prove true or false for certain (negative or positive) using evidence or a lack-there-of. For example, all empirical data points to me sitting at my desk writing this, but maybe “I’m in a virtual simulation and my senses are tricking me?” Yet, despite any confusion we may have in terms of certainty, “everything is ultimately either true or it isn’t despite our inability to know for sure.” Below we explain all the above and more in detail, including the ways in which proving negatives is and isn’t possible. First, here are some examples related to proving negatives:

- The Law of Contradiction itself is a negative: “Nothing can be A and not A.” Ex. Ted can’t be in Room A and not in Room A (and therefore, if Ted is in Room A, then Ted is not in Room B; or if Ted is in Room A, then Ted is not not in Room A). This is a rule used in deductive reasoning and is a necessarily true logical rule.

- The Modus Tollens also proves a negatives: “If P, then Q. Not Q. Therefore, not P.” Ex. “If the cake is made with sugar, then the cake is sweet. The cake is not sweet. Therefore, the cake is not made with sugar.” This is also a logical rule that relates to deductive reasoning.[4]

- Proving a negative with certainty using double negatives: Any true positive statement can be made negative and proved that way. Ex. I do not not exist; or Every A is A, nothing can be A and not A, everything is either A or not A, therefore A is not not A. These prove a negative with certainty, but are somewhat redundant (rephrasing “A is A” as “A is not not A” is tautological).

- Proving a negative with probability using induction: We can show something is highly certain using evidence of absence, but we can’t know for sure (that said, the same is true for proving positives with evidence; this is the nature of induction). Ex. Santa cannot be real and not real at the same time. There is no evidence to suggest Santa is real. Therefore it is highly likely Santa is not real. Simply put, induction doesn’t prove negatives with certainty; but it can produce highly certain scientific and logical conclusions.

TIP: Learn about how induction and deduction work. The certain proofs are deductive, the likely proofs are inductive. The Absence of Evidence and the Evidence of Absence – What Do People Mean When they Say “You Can’t Prove a Negative”? In general, and putting aside those who misunderstand the concept, when people use the phrase “you can’t prove a negative” they mean: we can’t prove negatives with certainty based on the absence of evidence alone (the absence of evidence is not necessarily the evidence of absence). For example, having no proof of Bigfoot doesn’t prove that he isn’t real with certainty. Likewise, it is hard to provide proof that a giant flying invisible pink unicorn name Terry-corn isn’t… because it isn’t and thus our best evidence is the absolute lack of evidence. We can only “prove” that which there is no evidence for with a high degrees of probability (by considering the lack of evidence and some rules of logic). With that in mind, and as noted above, we can’t actually prove positives very well either. Most proofs (positive or negative) rely on inductive evidence, and induction necessarily always produces probable conclusions. In other words, if we had Santa on tape admitting he was Santa it would still only be very strong evidence (it wouldn’t prove he Santa was real with certainty; our senses could be tricking us, the video could be fake, we might be in the Matrix, etc). Absence of evidence and the evidence of absence: Absence of evidence is an ambiguous term. If it is absence from ignorance, in that no one has ever carefully studied the matter, then it means next to nothing. If it is absence despite careful empirical study done in-line with the scientific method, then the absence of evidence itself can be considered a type of scientific evidence. If we inspect the room over and over and there is never any mice in the room, we can conclude with a high degree of certainty from the absence of mice that the room is not infested with mice. Here absence of evidence (or “the evidence of absence despite our looking for it” more specifically) is a type of evidence. If we keep checking and don’t see evidence of Santa, we can be highly confident that there is no Santa. See “Evidence of absence.” The Bottom Line on Proving Negatives, The bottom line here is:

- We can actually prove some negatives with certainty (using deduction), and generally speaking this type of proof is a foundational aspect of logic.

- “The Absence of Evidence is not the Evidence of Absence”… although it is often a really, really, strong hint (the same works for correlation and causation). In other words, a lack of evidence is a sort of evidence, but it doesn’t prove anything with certainty.

- As far as induction goes, “really strong hints” with “lots of logical truths backing them up”… are types of “proofs” (putting aside the definition of mathematic proof and treating proof as ” sufficient evidence or a sufficient argument for the truth of a proposition.”)[5]

For one last example before moving on: If we know Ted must be in Room A or Room B, and we have always seen Ted in Room A, and Ted never has gone into Room B and doesn’t have a key to Room B, and no person in the history of humankind has ever provided evidence of Ted being in Room B, we can be very confident in a logical inductive argument that concludes with a very high degree of certainty that Ted is in Room A. In these ways, “we can prove a negative… just not with certainty in some cases” (although, again, we can’t prove much with certainty outside of “tautological and analytic statements a priori” anyway). TIP: For more reading, see: “You Can Prove a Negative ” Steven D. Hales Think Vol. 10, Summer 2005 pp. 109-112.

RELATED FACTOIDS: Potentially, Everything is Light

There are No Straight Lines or Perfect Circles

There is No Such Thing as Objective Truth

The Term “Computer” Used to Refer to Humans

There are Different Types of Tyranny

Democracy is a Form of Government Where Power Originates With the Citizens

People Tend to Act Out of Perceived Self Interest

Life is all About “Trade-offs”

Logically, After You Die Will Be Like Before You Were Born

we should understand the truth behind the “you can’t prove a negative” idea.

What Does Proving a Negative Mean?

With the above introduction covered, let’s start at the beginning again and cover some details.So first, “what does proving a negative mean?”It means proving something isn’t true. For example, “proving Santa Claus doesn’t exist.”If Santa did exist, you could find evidence and prove it, but because [spoiler] he doesn’t, you can’t find evidence to prove it. There is an “absence of evidence.”

How to Prove a Negative

Now that we know the task and have the basics down, let’s discuss how to prove a negative and the ways in which we can and can’t prove negatives.To do that, let’s answer an important related question, “what is the law of contradiction / non-contradiction?”The law of contradiction / non-contradiction states that a proposition (statement) cannot be both true and not true (that nothing can be both true and false).…in other words, one of the fundamental laws of logic (the laws of thought featured below) is a provable negative proposition (and is thus an example of proving a negative).The rule of contradiction is saying that a statement CANNOT be both true and not true (unlike the positive rule of identity that says “whatever is, is.”)To help that sink in, here are the laws of thought.

- The Law of Identity: Whatever is, is; or, in a more precise form, Every A is A. Ex. Whatever is true about Santa is true about Santa.

- The Law of Contradiction: Nothing can both be and not be; Nothing can be A and not A. Ex. Santa cannot be real and not real at the same time.

- The Law of Excluded Middle: Everything must either be or not be; Everything is either A or not A. Ex. Santa must be real or not real.

In other words, Santa is either real or not real, there is no in-between. So the following logic works:

- If Santa was real there would likely be some evidence of Santa (not certain).

- There is no evidence of Santa (we should assume this as certain for the example).

- Therefore we can reasonably infer that Santa is not real (a likely truth inferred using induction).

Now, to be fair, that is an inductive argument (a very strong and cogent one, but an inductive argument none-the-less). What that means is that we didn’t produce a certainty, we produced a probability.In other words, we can “prove a negative” (we do it all the time), but we can’t prove something with certainty without direct proof…… with that in mind, almost all arguments are inductive and therefore probable.If we find a person hovering over a dead body with the murder weapon and they say “I did it” we still don’t know for sure that they did it.If we find zero proof of Santa ever, we still don’t know for sure he doesn’t exist.However, in both cases we can be very certain of our conclusions, and we can prove our conclusions using logic.If to prove something is to prove absolute certainty, then only tautological forms of deduction are valid and induction (and all other reasoning methods are useless). <— This creates a very strange and existential world where we can’t trust our senses and theories are meaningless.If we on the other hand can consider overwhelming evidence that draws a highly certain conclusion as proof until better evidence comes along, then we can prove negatives. <— This is how science works.With all that said, details aside, the blanket statement “we can’t prove a negative” is wrong either way.In mathematics and logic, when we replace empirical evidence for numbers and symbols, we can prove negatives all day.Of course, even in the way it is meant, that lack of evidence doesn’t imply lack of existence, even that isn’t exactly right. No one ever in the history of mankind having evidence of Santa is itself… pretty strong evidence. MYTH One can’t prove a negative. Ref

Science is the thing people do when they require evidence.

Whereas faith is the thing people do when they do not require evidence.

There is NO supernatural, thus, there is no god nor ghosts; just as there are no goblins. Nor Unicorns or Dragons for that matter and don’t get me started on Santa or the Easter bunny as of course all this nonsense is completely unjustified to believe as real. I would imagine not too many atheists epistemologists would feel a need to start believing claims of gods after establishing high standards of epistemic rationality. Whereas, I would imagine many theistic epistemologists (if they are intellectually honest: slaves to reason not faith) would feel a need to stop believing claims of gods after establishing high standards of epistemic rationality.

Empiricism atheism: empiricism is an epistemological theory which argues that that all knowledge must be acquired a posteriori and that nothing can be known a priori. Another way of putting it is that empiricism denies the existence of purely intellectual knowledge and argues that only sense-knowledge can exist. Empiricism is a common philosophical belief among many atheists. They believe that empirical science is the only true path to understanding. If you cannot see it, smell it, taste it, hear it, etc., it cannot be known. Empiricism atheists say that if you cannot prove something empirically, such as the existence of God, you are irrational for believing it. 1 2

Epistemological atheism: highlights a branch of philosophy that deals with determining what is and what is not true, and why we believe or disbelieve what we or others do. On one hand, this is begging the question of having the ability to measure “truth” – as though there is an “external” something that one measures against. Epistemology is the analysis of the nature of knowledge, how we know, what we can and cannot know, and how we can know that there are things we know we cannot know. In Greek episteme, meaning “knowledge, understanding”, and logos, meaning “discourse, study, ratio, calculation, reason. Epistemology is the investigation of what distinguishes justified belief from opinion. In other words, it is the academic term associated with study of how we conclude that certain things are true. Epistemology: the theory of knowledge, especially with regard to its methods, validity, and scope. From this atheist orientation, there is no, nor has there ever been, nor will there ever be, any “external” something so there can be no god-concept. Many debates between atheist and theists revolve around fundamental issues which people don’t recognize or never get around to discussing. Many of these are epistemological in nature: in disagreeing about whether it’s reasonable to believe in the existence of a god something, to believe in miracles, to accept revelation and scriptures as authoritative, and so forth, atheists and theists are ultimately disagreeing about basic epistemological principles. Without understanding this and understanding the various epistemological positions, people will just end up talking past each other. it’s common for Epistemological atheism to differ in what they consider to be appropriate criteria for truth and, therefore, the proper criteria for a reasonable disbelief. Atheists demand proof and evidence for other worldviews, yet there is no proof and evidence that atheism is true. Also, despite the abundant evidence for Christianity and the lack of proof and evidence for atheism, atheist reject the truth of Christianity.

*Epistemology (knowledge of things) questions to explode or establish and confirm knowledge. Epistemology “Truth” questions/assertion: Lawyer searches for warrant or justification for the claim. Epistemology, (understanding what you know or can know; as in you do have and thing in this reality to know anything about this term you call god, and no way of knowing if there is anything non-naturalism beyond this universe and no way to state any about it if there where). -How do know your claim? -How reliable or valid must aspects be for your claim? -How does the source of your claim make it different than other similar claims? I may respond, “how do you know that, what is your sources and how reliable they are” (asking to find the truth or as usual expose the lack of a good Epistemology) Atheists refuse to go where the evidence clearly leads. In addition, when atheist make claims related to naturalism, make personal claims or make accusations against theists, they often employ lax evidential standards instead of employing rigorous evidential standards. For the most part, atheists have presumed that the most reasonable conclusions are the ones that have the best evidential support. And they have argued that the evidence in favor of a god something’s existence is too weak, or the arguments in favor of concluding there is no a god something are more compelling. Traditionally the arguments for a god something’s existence have fallen into several families: ontological, teleological, and cosmological arguments, miracles, and prudential justifications. For detailed discussion of those arguments and the major challenges to them that have motivated the atheist conclusion, the reader is encouraged to consult the other relevant sections of the encyclopedia. Arguments for the non-existence of a god something are deductive or inductive. Deductive arguments for the non-existence of a god something are either single or multiple property disproofs that allege that there are logical or conceptual problems with one or several properties that are essential to any being worthy of the title “GOD.” Inductive arguments typically present empirical evidence that is employed to argue that a god something’s existence is improbable or unreasonable. Briefly stated, the main arguments are: a god something’s non-existence is analogous to the non-existence of Santa Claus. The existence of widespread human and non-human suffering is incompatible with an all powerful, all knowing, all good being. Discoveries about the origins and nature of the universe, and about the evolution of life on Earth make the a god something hypothesis an unlikely explanation. Widespread non-belief and the lack of compelling evidence show that a god something who seeks belief in humans does not exist. Broad considerations from science that support naturalism, or the view that all and only physical entities and causes exist, have also led many to the atheism conclusion. 1 2 3 4

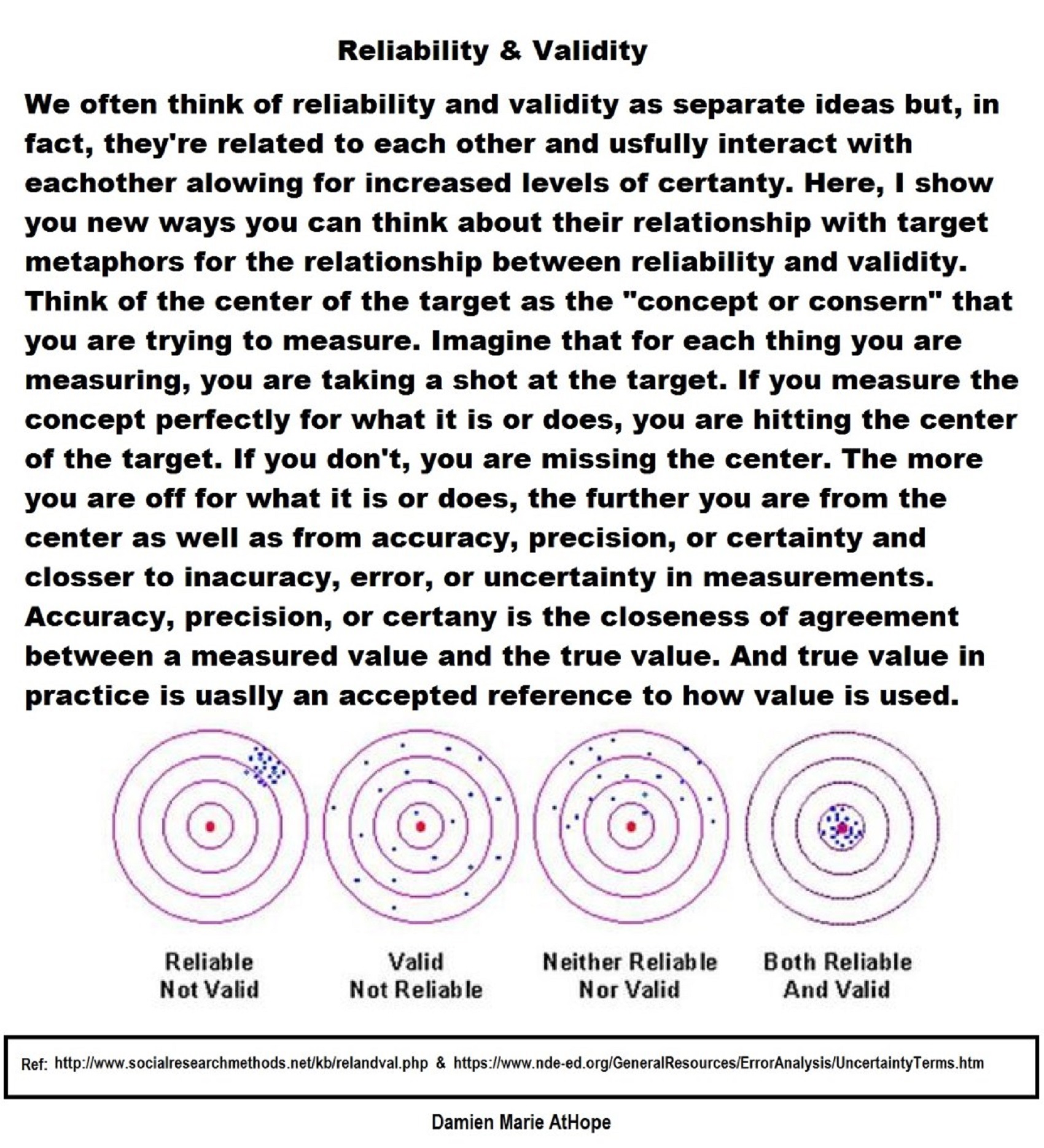

Ethical atheism: heavily involved and utilizes ethical thought and standards to navigate atheism or the humanism that is likely to follow such an ethical awareness. Ethical atheism strives to utilize the strong force of ethics and ethical challenge to address the many issues that not only arise in combating the fanatical promotion of harmful myths but ethical ways to positively navigate all of life’s real struggles or options to behave in interactions with others. God claims all totally lack a standard of meeting any warrant or justification in their burden of proof, thus the claim as offered debunks itself as any kind of viable claim. Would you be intellectually honest enough to want to know if your belief was completely false, and once knowing it was an unjustified belief, realize it lacks warrant and the qualities needed for belief-retention, as well as grasp the rationality that certain beliefs are epistemically unfounded which compels belief-relinquishment due to the beliefs insufficient supporting reason and evidence, realizing that belief. To me, belief in gods is intellectually flawed and dishonest compared to the evidence of the natural world being not only explainable on every level as only natural, but also there is not a shred of anything supernatural and every claim tested ever has time and again debunked such nonsense. If anything supernatural or paranormal was provable, the believers would have taken James Randi’s famous million-dollar challenge, or they would have gone and got their Nobel Prize in proving the supernatural or open up a 100% faith-based prayer and miracles hospital. Where the cure for anything and everything is guaranteed because “prayer and miracles works” and the only education was being a religious or spiritual leader. Prove it or it is not really worthy for true belief and if there was actual scientific proof it would silence us rationalists, atheists, and skeptics forever. However, nothing of the sort has ever happened. List of prizes for evidence of the paranormal or supernatural woo-woo go back to at least 1922 with Scientific American. But it did not stop there instead there has been many individuals and groups have offered similar monetary awards for proof of the paranormal or supernatural with some reaching over a million dollars yet as of February 2016, not one prizes have been claimed. Therefore, belief in supernatural or paranormal are not realistic nor are they reasonable. And what’s even crazier is it’s nonsense and they act like it is us rationalists, atheists, and skeptics that have to disprove something they have never proved. I do think critical thinkers and thinkers who are intellectually honest should follow something close to “The Ethics of Belief” or they are likely not honest thinkers. “The Ethics of Belief” was published in 1877 by philosopher William Kingdon Clifford outlined the famous principle “It is wrong always, everywhere, and for anyone to believe anything on insufficient evidence.” Arguing that it was immoral to believe things for which one lacks evidence, in direct opposition to religious thinkers for whom “blind faith” (i.e. belief in things in spite of the lack of evidence for them) was seen as a virtue. To me, it comes down to the question, would you be intellectually honest enough to want to know if your belief was completely false? And once knowing it was an unjustified belief, realize it lacks warrant and the qualities needed for belief-retention, as well as grasp the rationality that compels belief-relinquishment due to the beliefs insufficient supporting reason and evidence. The act of believing, just because one wants to believe, when everything contradicts the belief is intellectually unethical or deluded. Beliefs are directly connected to behavior, behavior is directly involved in ethics, and ethics requires involvement in social thinking which requires us to mature or discipline our beliefs. Ethics of Belief: sufficient evidence to support belief. An honest thinker would want to know what is sufficient evidence for the reliability and validity to support belief. According to the legal decision in 1950, evidence is sufficient when it satisfies an unprejudiced mind. Sufficient evidence can be said to reference the evidence of such value as to support the belief. The word sufficient does not mean conclusive. Conclusive evidence is evidence that serves to establish a fact or the proven truth of something. To me, the test for belief analysis in relation to the offered evidence attempting to affirm the belief, would be is it sufficient evidence such as, could any rational addresser of the belief in question to find the essential elements of the issue sufficiency evidence is beyond a reasonable doubt. it is reasonable to require a greater level of evidence proportional to the importance of the belief or the external effects of the belief. – IN THE MATTER OF THE ESTATE OF LUCILLE CRUSON STATE LAND BOARD V. LONG, ADM’R, ET AL. OREGON SUPREME COURT. ARGUED JUNE 13, 1950 REVERSED AUGUST 29, 1950 *538538 APPEAL FROM CIRCUIT COURT, LINN COUNTY, VICTOR OLLIVER, JUDGE. Someone asked why would a critical thinker follow another old book from 1877? Well the age of evidence or thinking is relevant if it is reasonable. Saying it’s age is old is not a refutation of its arguments. Moreover, it could be said that for ethical atheism applied logically “to me” in general ethics must be equally applied or the concept of ethics has no ethical meaning to begin with. Ethical atheism could be seen as thinking that if the idea of god implies the abdication of human reason and justice; it is the most decisive negation against of human rights, dignity, and liberty. Therefore ethical atheism holds a necessarily requirement to disbelief in order to end such unethical thinking and to end a god only morality enslavement of mankind. Ethical atheism holds all to ethical standards therefor if god did exist, it would be necessary to abolish him so we could be freely utilize human rights, dignity, reason and justice. Ethical atheism promotes atheism because it is both the logical and the ethical position to take in a world where religious people fly planes into skyscrapers, blow themselves up on crowded busses, and do all sorts of horrible things in the name of an imaginary sky monster. As an atheist ethicist, I am not just an Atheist (disbelieving claims of gods), an Antitheist (seeing theism as harmful) and an Antireligionist (seeing religion as untrue and/or harmful). Also as an atheist ethicist I value and require reason and evidence to support beliefs or propositions as well as am against all pseudohistory, pseudoscience, and pseudomorality. Why are gods even concerned with belief, as if they truly wanted it so bad they would be real and being more than just mental projections of which they are now they would show themselves and we all would believe. Therefore we can rightly conclude with no evidence of them at all, that belief in god(s) is the thing people do when playing at reality is valued more than understanding the actual natural only nature of reality. 1 2 3 4 5 6

Evidential atheism: thinks that whether or not belief in a divine being is epistemically acceptable will be determined by the evidence. I intend to treat “evidence” in a broad sense including a priori arguments, arguments to the best explanation, inductive and empirical reasons, as well as deductive and conceptual premises. (Also note that one could be an evidentialist theist.) The evidentialist theist and the evidentialist atheist may have a number of general epistemological principles concerning evidence, arguments, implication in common, but then disagree about what the evidence is, how it should be understood, and what it implies. They may disagree, for instance, about whether the values of the physical constants and laws in nature constitute evidence for intentional fine tuning, but agree that whether God exists is a matter that can be explored empirically. 1

Grasping the status of truth (ontology of truth)

Authoritarian Truth Seekers and Anti-Authoritarian Truth Seekers?

I understand that there are truth seekers and non-truth seekers (because of disinterest, dogma “false sense of truth” and/or delusion).

But I also realize there are two types of truth seekers: Authoritarian Truth Seekers and Anti-Authoritarian Truth Seekers.

Authoritarian Truth Seekers: to me use an Authoritarian Personality to understand, analyze, confirm truth, and limit what is thought of as truth.

Authoritarian personality is a state of mind or attitude that is characterized by belief in absolute obedience or submissive to authority and possibly even one’s own authority, as well as the administration of that belief through the oppression of one’s subordinates. It is an ideology which entails accepting authority or hierarchical organization in the conduct of intellectual or human relations that includes authoritative, strict, or oppressive personality in truth acquisition and adherence to values or beliefs that are perceived as endorsed by followed leadership, authority of holy books, authority of gods, authority of beliefs held by someone who is favored or idolized, and authority of one’s own beliefs.

Anti-Authoritarian Truth Seekers: to me use an Anti-Authoritarian Personality to understand, analyze and confirm truth.

Anti-Authoritarian personality is a state of mind or attitude that is characterized by a cognitive application of freethought known as “freethinking” and is a philosophical viewpoint that holds that opinions should be formed on the basis of logic, reason, and empiricism, rather than authority, tradition, or other dogmas. Anti-Authoritarian personality is an opposition to authoritarianism, favoring instead full equality and open thinking in the conduct of intellectual or human relations, including democratic, flexible, or accessible personality in truth acquisition and adherence to values or beliefs perceived as endorsed by critical thinking and right reason which entails opposing authority as the means of conformation in truth attainment.

To me Anti-Authoritarian Truth Seekers are the only real seekers of truth.

To value faith as a means to know reality or the truth or something, is a mental weakness of wanting one’s beliefs about reality to matter more than the actual reality. Faith in relation of truth is at best just wishful emotions over rational understanding. 1, 2

Damien Marie AtHope, Thanks for your thoughts, you address interesting ideas but the issue you are addressing sounds a bit different than I was trying to say is doing an appeal to authority is a logical fallacy, so to limit one’s thinking to an appeal to authority is thinking strategy as a logical fallacy.

Challenger #2, it’s only a fallacy of the authority to which one is appealing is Not an authority in the field in question. For instance, if one’s argument is that, “Well even Richard Dawkins says the Big Bang proves the universe had a finite beginning,” (I’m making up the quote), that would be an appeal to authority fallacy because Dawkins is not an astrophysicist. However, if one quoted Krauss on this issue, it would not be fallacious. in a field for which I have no training, it’s perfectly reasonable for me to rely on experts and the consensus among experts.

Damien Marie AtHope, But even if I as an anti-authoritarianist were to accept an appeal to the scholarly articles on any scientific studies are valid only on the evidence and have nothing to do with the scientists or researchers. Just as if one wants to overturn any previous believed scientific theory it’s the evidence not in any way the person presenting it.

Challenger #1, Hmmm, I never got the impression that this post was about the logical fallacy known as: appeal to authority. However, when regarding the appeal to authority as a fallacy: if the the authority in question has made statements of an opinionated matter then I have to agree with Damien. However, if the appeal is to something the authority claimed based on the evidence and the current body of knowledge then I don’t think that would be considered a fallacy.

New respondent, Very succinct explanation of what divides believers from non-believers.

An argument from authority (Latin: argumentum ad verecundiam), also called an appeal to authority, is a common type of argument which can be fallacious, such as when an authority is cited on a topic outside their area of expertise or when the authority cited is not a true expert.[1]

Carl Sagan wrote of arguments from authority:

One of the great commandments of science is, “Mistrust arguments from authority.” … Too many such arguments have proved too painfully wrong. Authorities must prove their contentions like everybody else.[2]

Historically, opinion on the appeal to authority has been divided – it has been held to be a valid argument about as often as it has been considered an outright fallacy. John Locke, in his 1690 Essay Concerning Human Understanding, was the first to identify argumentum ad verecundiam as a specific category of argument. Although he did not call this type of argument a fallacy, he did note that it can be misused by taking advantage of the “respect” and “submission” of the reader or listener to persuade them to accept the conclusion. Over time, logic textbooks started to adopt and change Locke’s original terminology to refer more specifically to fallacious uses of the argument from authority. By the mid-twentieth century, it was common for logic textbooks to refer to the “Fallacy of appealing to authority,” even while noting that “this method of argument is not always strictly fallacious.” In the Western rationalistic tradition and in early modern philosophy, appealing to authority was generally considered a logical fallacy. More recently, logic textbooks have shifted to a less blanket approach to these arguments, now often referring to the fallacy as the “Argument from Unqualified Authority” or the “Argument from Unreliable Authority”. However, these are still not the only recognized forms of appeal to authority. For example, a 2012 guidebook on philosophical logic describes appeals to authority not merely as arguments from unqualified or unreliable authority, but as arguments from authority in general. In addition to appeals lacking evidence of the authority’s reliability, the book states that arguments from authority are fallacious if there is a lack of “good evidence” that the authorities appealed to possess “adequate justification for their views.” And there are other recognized fallacious arguments from authority. Among them, the “Fallacies” entry by Bradley Dowden in The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy states that “appealing to authority as a reason to believe something is fallacious […] when authorities disagree on this subject (except for the occasional lone wolf)” The “Fallacies” entry by Hans Hansen in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy similarly states that “when there is controversy, and authorities are divided, it is an error to base one’s view on the authority of just some of them.” However, Hansen’s entry in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy does not appear to share Dowden’s exception regarding “lone wolf” dissenting authorities.

Fallacious arguments from authority can also be the result of citing a non-authority as an authority. These arguments assume that a person without status or authority is inherently reliable. The appeal to poverty for example is the fallacy of thinking a conclusion is more likely to be correct because the one who holds or is presenting it is poor. When an argument holds that a conclusion is likely to be true precisely because the one who holds or is presenting it lacks authority, it is a fallacious appeal to the common man. A common example of the fallacy is appealing to an authority in one subject to pontificate on another – for example citing Albert Einstein as an authority on religion when his expertise was in physics. The attributed authority might not even welcome that authority, as with the “More Doctors Smoke Camels” ad campaign. However, it is also a fallacious ad hominem argument to argue that a person presenting statements lacks authority and thus their arguments do not need to be considered. As appeals to a perceived lack of authority, these types of argument are fallacious for much the same reasons as an appeal to authority.

Notable examples

Inaccurate chromosome number

In 1923, leading American zoologist Theophilus Painter declared, based on poor data and conflicting observations he had made, that humans had 24 pairs of chromosomes. From the 1920s to the 1950s, this continued to be held based on Painter’s authority, despite subsequent counts totaling the correct number of 23. Even textbooks with photos showing 23 pairs incorrectly declared the number to be 24 based on the authority of the then-consensus of 24 pairs. This seemingly established number created confirmation bias among researchers, and “most cytologists, expecting to detect Painter’s number, virtually always did so”. Painter’s “influence was so great that many scientists preferred to believe his count over the actual evidence”, to the point that “textbooks from the time carried photographs showing twenty-three pairs of chromosomes, and yet the caption would say there were twenty-four”. Scientists who obtained the accurate number modified or discarded their data to agree with Painter’s count.

Psychological basis

An integral part of the appeal to authority is the cognitive bias known as the Asch effect. In repeated and modified instances of the Asch conformity experiments, it was found that high-status individuals create a stronger likelihood of a subject agreeing with an obviously false conclusion, despite the subject normally being able to clearly see that the answer was incorrect. Further, humans have been shown to feel strong emotional pressure to conform to authorities and majority positions. A repeat of the experiments by another group of researchers found that “Participants reported considerable distress under the group pressure”, with 59% conforming at least once and agreeing with the clearly incorrect answer, whereas the incorrect answer was much more rarely given when no such pressures were present. Scholars have noted that the academic environment produces a nearly ideal situation for these processes to take hold, and they can affect entire academic disciplines, giving rise to groupthink. One paper about the philosophy of mathematics for example notes that, within mathematics,

If…a person accepts our discipline, and goes through two or three years of graduate study in mathematics, he absorbs our way of thinking, and is no longer the critical outsider he once was…If the student is unable to absorb our way of thinking, we flunk him out, of course. If he gets through our obstacle course and then decides that our arguments are unclear or incorrect, we dismiss him as a crank, crackpot, or misfit. Ref

Challenged or Challenging? (questions of ontology)

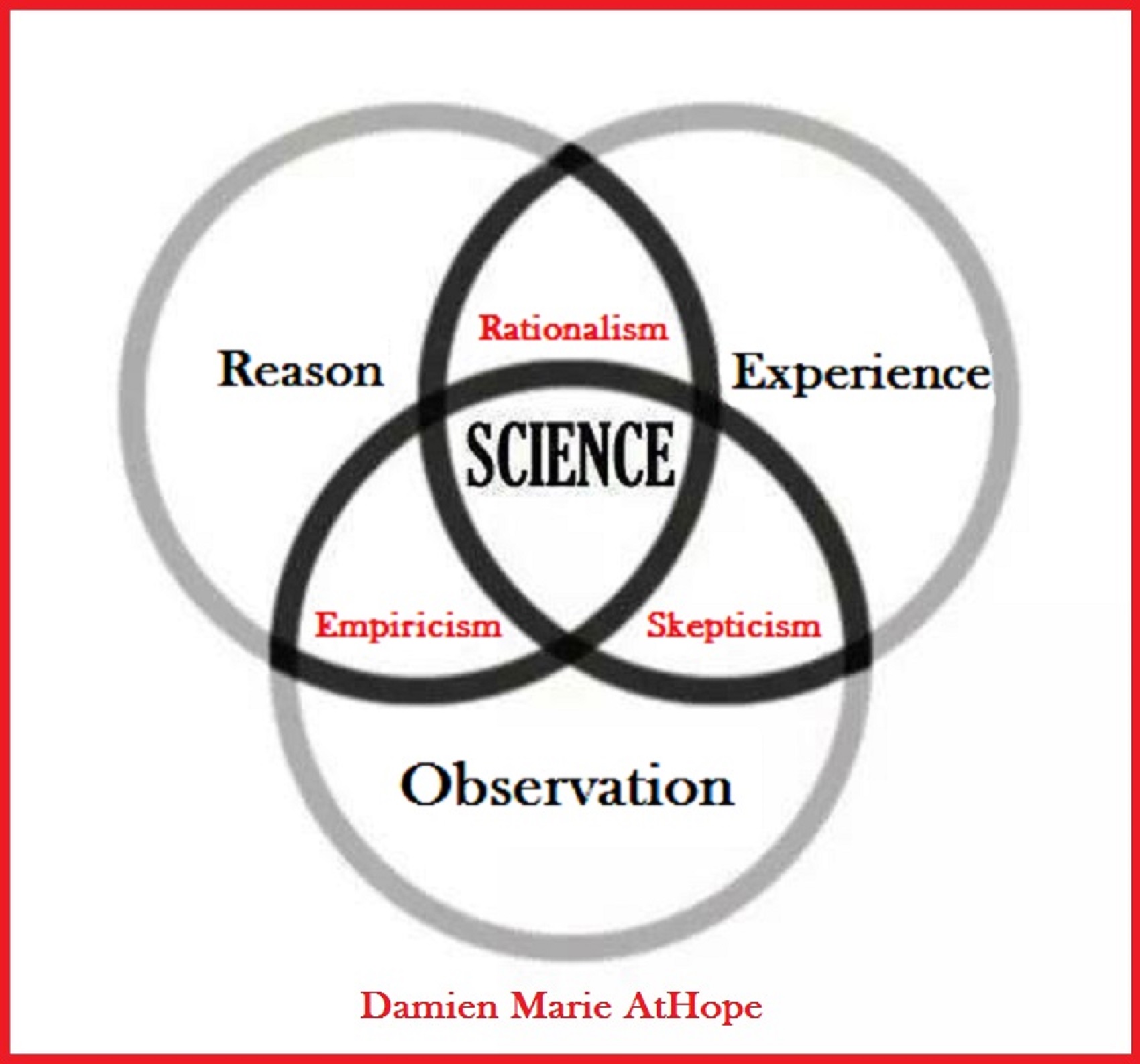

All thinkers should know that ontological (thingness) definition require answers and that need to answers in can we confirm or conclude what a god even is could be to as well as if god exists, what is a god, and how or where/how did you acquire such definitions; impossible or possible for a god to exist. “From a confirmed or concluded” you have or do not have well definite if a god to the reality of a god. When anyone talks of challenges they are generally in some way even if only a unstated presupposition will include or involve three things: 1. the ontology (the thingness of things), 2. the epistemology ( how you know what you think you believe or know) and 3. the axiology (what and why of value/worth/good)? The ontology is of core importance to require it by asking for ontological definition or definition. This would make a good first act of fighting without having to fight, by always try starting by making them define the details of any claims but it can be done just as easily for attacks as well. Ontology attacks: slow down and unpack any claims, “you said you know god is real.” What do you mean by the qualities, attribution, or thingness of the things involved in the term god or what do you know about the term god and is an estimate for the faith reality you agree to believe in. Ontology defense: slow down and unpack any attacks, “you said I can’t be moral or good without god.” What do you mean by the qualities, attribution, or thingness of the things involved in the term god or morality? Simply, ontology is a universal investigation pinpoint. Ontology is likely what is being addressed or is involved when the reality confirmed by science, and the scientific method is generally employs several philosophy tools realized or not and they are mainly rationalism, empiricism and skepticism/fallibilism and/or falsificationism.

Ontology, Epistemology, & Axiology argument/challenge protocol: https://damienmarieathope.com/2016/10/13/ontology-epistemology-axiology-argumentchallenge-protocol/

To me, belief ontologies address the conceptual schemas involved, at the intersection of three elements: a belief is a thinking system with a susceptibility to flaws, use ontological challenging or ontological disproofs which are logical arguments against by attacker/challenger access to the flaw, and attacker capability to exploit the flaw. Ontological disproofs, are sophisticated ontological arguments, ontological challenges or ontological disproofs accusations that demand equally sophisticated responses, to which, many people are unprepared. Belief or argument forms should be valid, to prove them sound or unsound, strong/weak, or well-defined/undefined, as weak premises must be shown to be false. By use ontological challenging, you are shining a light on its ways claimed or points proposed, outlined or arranged which equals a thing or its qualities to define it that makes the depth and fullness to a being or thing, like just what is provisional about the thing in question or offer, are the characteristics of adequate development structure and infrastructure of the ontology involved in claims or propositions as truth, fact, or knowledge? One ontological criticism focuses on the semantics that are given for quantifiers qualities used or involved as the notation of the language representations of the contents of belief talk, proposing that the qualities offered are fully alike (unequivocal) when the items or properties identified to you are likely one of the three partly unlike (equivocal). To me, ontologies are like an adequate way or web of elements involved in the thingness of things or ideas. Point by slow methodological point, is the most effective way to use ontological challenging. Ontologically challenge needs to be done, in order to develop in the other person, an ontological insecurity about what the person, place, thing, or idea are construction of and just what is being claimed, portrayed or proposed as truth, fact, or knowledge? A belief or set of beliefs, likely have a relationship between ideas of the thing expose the cracks and fissure in the conceptualizations divided up or overlap but often while a belief or set of beliefs are offered with assurance, they instead ontologically inadequate or almost completely ontologically empty. By exposing ontological volnurniblities or weakness in a belief or set of beliefs can rise person’s sense of ontological Insecurity as the thinker realized they may not know that that know. In my way of thinking as ontological insecurity refers or relates to in an existential sense a person’s sense of “belief” deflation, discrediting, or disproving. Such an ontologically insecure thinker, maybe so ontologically desperate, to stop/lower believing/accepting the level of “reality or existence” of the things or ideas they were just referring to. In contrast, the ontologically secure thinker, maybe so ontologically stable in relation to ontological commitment of their fragments involved to feel a high level. Ontological arguments or Ontological commitment need to demonstrate or require demonstration of the disciplined or disordered structures but, a priori and necessary premises to the conclusion

Ontological commitment structures:

*similarity vs logic: this is the difference between matchings (predicating about the similarity of ontology terms), and mappings (logical axioms, typically expressing logical equivalence or inclusion among ontology terms)

*atomic vs complex: whether the alignments we considered are one-to-one, or can involve more terms in a query-like formulation (e.g., LAV/GAV mapping)

*homogeneous vs heterogeneous: do the alignments predicate on terms of the same type (e.g., classes are related only to classes, individuals to individuals, etc.) or we allow heterogeneity in the relationship?

*type of alignment: the semantics associated to an alignment, assumption, equivalence, discontinues, part-of or any user-specified relationship. Ref

Many arguments fall under the category of the ontological, and they tend to involve arguments about the state of being or existing. More specifically, ontological arguments tend to start with an a priori theory about the organization of the universe. If that organizational structure is true, the argument will provide reasons why God must exist. Ontological disproofs are logical arguments against of the existence of a thing based on what it would be if it existed. These arguments are very important because they do not simply purport to prove that god(s) does not exist (like, say, the Easter Bunny or Martians), but that God cannot exist (like a square circle or a married bachelor). The basic form of these arguments is something like this:

If God exists, he must be like ‘X’. [Here ‘X’ = some attribute(s) of God, e.g., he must be good, loving, omnipotent, etc.].

‘X’ is actually impossible.

Therefore, god(s) cannot exist.

The traditional definition of an ontological argument contrasted the ontological argument (literally any argument “concerned with being”) with the cosmological and physio-theoretical arguments. According to the Kantian view, ontological arguments are those founded on a priori reasoning. Graham Oppy, who holds the view that he “see[s] no urgent reason” to depart from the traditional definition, defined ontological arguments as those that begin with “nothing but analytic, a priori and necessary premises” and conclude that God exists. Oppy admitted, however, that not all of the “traditional characteristics” of an ontological argument (analyticity, necessity, and a priority) are found in all ontological arguments and, in his 2007 work Ontological Arguments and Belief in God, suggested that a better definition of an ontological argument would employ only considerations “entirely internal to the theistic worldview”. Oppy subclassified ontological arguments into definitional, conceptual (or hyperintensional), modal, Meinongian, experiential, mereological, higher-order, or Hegelian categories, based on the qualities of their premises. He defined these qualities as follows: definitional arguments invoke definitions; conceptual arguments invoke “the possession of certain kinds of ideas or concepts”; modal arguments consider possibilities; Meinongian arguments assert “a distinction between different categories of existence”; experiential arguments employ the idea that God exists solely to those who have had experience of him; and Hegelian arguments are from Hegel. He later categorized mereological as arguments that “draw on… the theory of the whole-part relation”. William Lane Craig criticized Oppy’s study as too vague for useful classification. Craig argued that an argument can be classified as ontological if it attempts to deduce the existence of God, along with other necessary truths, from his definition. He suggested that proponents of ontological arguments would claim that, if one fully understood the concept of God, one must accept his existence. William L. Rowe defined ontological arguments as those that start from the definition of God and, using only a priori principles, conclude with God’s existence. Ref

In information science, an upper, top-level, or foundation ontology is an ontology which consists of very general terms (such as “object”, “property”, “relation”) that are common across all domains. An important function of an upper ontology is to support broad semantic interoperability among a large number of domain-specific ontologies by providing a common starting point for the formulation of definitions. Terms in the domain ontology are ranked “under” the terms in the upper ontology, and the former stand to the latter in subclass relations. A number of upper ontologies proposed, each with its own proponents. Each upper ontology can be considered as a computational implementation of natural philosophy, which itself is a more empirical method for investigating the topics within the philosophical discipline of physical ontology. Arguments for the infeasibility of an upper ontology: Historically, many attempts in many societies have been made to impose or define a single set of concepts as more primal, basic, foundational, authoritative, true or rational than all others. A common objection to such attempts points out that humans lack the sort of transcendent perspective – or God’s eye view – that would be required to achieve this goal. Humans are bound by language or culture, and so lack the sort of objective perspective from which to observe the whole terrain of concepts and derive any one standard. Another objection is the problem of formulating definitions. Top level ontologies are designed to maximize support for interoperability across a large number of terms. Such ontologies must therefore consist of terms expressing very general concepts, but such concepts are so basic to our understanding that there is no way in which they can be defined, since the very process of definition implies that a less basic (and less well understood) concept is defined in terms of concepts that are more basic and so (ideally) more well understood. Very general concepts can often only be elucidated, for example by means of examples, or paraphrase.

There is no self-evident way of dividing the world up into concepts, and certainly no non-controversial one

There is no neutral ground that can serve as a means of translating between specialized (or “lower” or “application-specific”) ontologies

Human language itself is already an arbitrary approximation of just one among many possible conceptual maps. To draw any necessary correlation between English words and any number of intellectual concepts we might like to represent in our ontologies is just asking for trouble. (WordNet, for instance, is successful and useful precisely because it does not pretend to be a general-purpose upper ontology; rather, it is a tool for semantic / syntactic / linguistic disambiguation, which is richly embedded in the particulars and peculiarities of the English language.) Any hierarchical or topological representation of concepts must begin from some ontological, epistemological, linguistic, cultural, and ultimately pragmatic perspective. Such pragmatism does not allow for the exclusion of politics between persons or groups, indeed it requires they be considered as perhaps more basic primitives than any that are represented. Those who doubt the feasibility of general purpose ontologies are more inclined to ask “what specific purpose do we have in mind for this conceptual map of entities and what practical difference will this ontology make?” This pragmatic philosophical position surrenders all hope of devising the encoded ontology version of “everything that is the case.” Finally, there are objections similar to those against artificial intelligence. Technically, the complex concept acquisition and the social / linguistic interactions of human beings suggests any axiomatic foundation of “most basic” concepts must be cognitive, biological or otherwise difficult to characterize since we don’t have axioms for such systems. Ethically, any general-purpose ontology could quickly become an actual tyranny by recruiting adherents into a political program designed to propagate it and its funding means, and possibly defend it by violence. Historically, inconsistent and irrational belief systems have proven capable of commanding obedience to the detriment or harm of persons both inside and outside a society that accepts them. How much more harmful would a consistent rational one be, were it to contain even one or two basic assumptions incompatible with human life? Many of those who doubt the possibility of developing wide agreement on a common upper ontology fall into one of two traps:

they assert that there is no possibility of universal agreement on any conceptual scheme; but they argue that a practical common ontology does not need to have universal agreement, it only needs a large enough user community (as is the case for human languages) to make it profitable for developers to use it as a means to general interoperability, and for third-party developer to develop utilities to make it easier to use; and

they point out that developers of data schemes find different representations congenial for their local purposes; but they do not demonstrate that these different representation are in fact logically inconsistent.

In fact, different representations of assertions about the real world (though not philosophical models), if they accurately reflect the world, must be logically consistent, even if they focus on different aspects of the same physical object or phenomenon. If any two assertions about the real world are logically inconsistent, one or both must be wrong, and that is a topic for experimental investigation, not for ontological representation. In practice, representations of the real world are created as and known to be approximations to the basic reality, and their use is circumscribed by the limits of error of measurements in any given practical application. Ontologies are entirely capable of representing approximations, and are also capable of representing situations in which different approximations have different utility. Objections based on the different ways people perceive things attack a simplistic, impoverished view of ontology. The objection that there are logically incompatible models of the world are true, but in an upper ontology those different models can be represented as different theories, and the adherents of those theories can use them in preference to other theories, while preserving the logical consistency of the necessary assumptions of the upper ontology.

The necessary assumptions provide the logical vocabulary with which to specify the meanings of all of the incompatible models. It has never been demonstrated that incompatible models cannot be properly specified with a common, more basic set of concepts, while there are examples of incompatible theories that can be logically specified with only a few basic concepts. Many of the objections to upper ontology refer to the problems of life-critical decisions or non-axiomatized problem areas such as law or medicine or politics that are difficult even for humans to understand. Some of these objections do not apply to physical objects or standard abstractions that are defined into existence by human beings and closely controlled by them for mutual good, such as standards for electrical power system connections or the signals used in traffic lights. No single general metaphysics is required to agree that some such standards are desirable. For instance, while time and space can be represented many ways, some of these are already used in interoperable artifacts like maps or schedules. Objections to the feasibility of a common upper ontology also do not take into account the possibility of forging agreement on an ontology that contains all of the primitive ontology elements that can be combined to create any number of more specialized concept representations.

Adopting this tactic permits effort to be focused on agreement only on a limited number of ontology elements. By agreeing on the meanings of that inventory of basic concepts, it becomes possible to create and then accurately and automatically interpret an infinite number of concept representations as combinations of the basic ontology elements. Any domain ontology or database that uses the elements of such an upper ontology to specify the meanings of its terms will be automatically and accurately interoperable with other ontologies that use the upper ontology, even though they may each separately define a large number of domain elements not defined in other ontologies. In such a case, proper interpretation will require that the logical descriptions of domain-specific elements be transmitted along with any data that is communicated; the data will then be automatically interpretable because the domain element descriptions, based on the upper ontology, will be properly interpretable by any system that can properly use the upper ontology. In effect elements in different domain ontologies can be *translated* into each other using the common upper ontology. An upper ontology based on such a set of primitive elements can include alternative views, provided that they are logically compatible.

Logically incompatible models can be represented as alternative theories, or represented in a specialized extension to the upper ontology. The proper use of alternative theories is a piece of knowledge that can itself be represented in an ontology. Users that develop new domain ontologies and find that there are semantic primitives needed for their domain but missing from the existing common upper ontology can add those new primitives by the accepted procedure, expanding the common upper ontology as necessary. Most proponents[who?] of an upper ontology argue that several good ones may be created with perhaps different emphasis. Very few are actually arguing to discover just one within natural language or even an academic field. Most are simply standardizing some existing communication. Another view advanced is that there is almost total overlap of the different ways that upper ontologies have been formalized, in the sense that different ontologies focus on a different aspect of the same entities, but the different views are complementary and not contradictory to each other; as a result, an internally consistent ontology that contains all the views, with means of translating the different views into the other, is feasible. Such an ontology has not thus far been constructed, however, because it would require a large project to develop so as to include all of the alternative views in the separately developed upper ontologies, along with their translations.

The main barrier to construction of such an ontology is not the technical issues, but the reluctance of funding agencies to provide the funds for a large enough consortium of developers and users. Several common arguments against upper ontology can be examined more clearly by separating issues of concept definition (ontology), language (lexicons), and facts (knowledge). For instance, people have different terms and phrases for the same concept. However, that does not necessarily mean that those people are referring to different concepts. They may simply be using different language or idiom. Formal ontologies typically use linguistic labels to refer to concepts, but the terms that label ontology elements mean no more and no less than what their axioms say they mean. Labels are similar to variable names in software, evocative rather than definitive. The proponents of a common upper ontology point out that the meanings of the elements (classes, relations, rules) in an ontology depend only on their logical form, and not on the labels, which are usually chosen merely to make the ontologies more easily usable by their human developers.

In fact, the labels for elements in an ontology need not be words – they could be, for example, images of instances of a particular type, or videos of an action that is represented by a particular type. It cannot be emphasized too strongly that words are *not* what are represented in an ontology, but entities in the real world, or abstract entities (concepts) in the minds of people. Words are not equivalent to ontology elements, but words *label* ontology elements. There can be many words that label a single concept, even in a single language (synonymy), and there can be many concepts labeled by a single word (ambiguity). Creating the mappings between human language and the elements of an ontology is the province of Natural Language Understanding. But the ontology itself stands independently as a logical and computational structure. For this reason, finding agreement on the structure of an ontology is actually easier than developing a controlled vocabulary, because all different interpretations of a word can be included, each *mapped* to the same word in the different terminologies. A second argument is that people believe different things, and therefore can’t have the same ontology.

However, people can assign different truth values to a particular assertion while accepting the validity of certain underlying claims, facts, or way of expressing an argument with which they disagree. (Using, for instance, the issue/position/argument form.) This objection to upper ontologies ignores the fact that a single ontology can represent different belief systems, representing them as different belief systems, without taking a position on the validity of either. Even arguments about the existence of a thing require a certain sharing of a concept, even though its existence in the real world may be disputed. Separating belief from naming and definition also helps to clarify this issue, and show how concepts can be held in common, even in the face of differing belief. For instance, wiki as a medium may permit such confusion but disciplined users can apply dispute resolution methods to sort out their conflicts. It is also argued that most people share a common set of “semantic primitives”, fundamental concepts, to which they refer when they are trying to explain unfamiliar terms to other people. An ontology that includes representations of those semantic primitives could in such a case be used to create logical descriptions of any term that a person may wish to define logically.

That ontology would be one form of upper ontology, serving as a logical “interlingua” that can translate ideas in one terminology to its logical equivalent in another terminology. Advocates[who?] argue that most disagreement about the viability of an upper ontology can be traced to the conflation of ontology, language and knowledge, or too-specialized areas of knowledge: many people, or agents or groups will have areas of their respective internal ontologies that do not overlap. If they can cooperate and share a conceptual map at all, this may be so very useful that it outweighs any disadvantages that accrue from sharing. To the degree it becomes harder to share concepts the deeper one probes, the more valuable such sharing tends to get. If the problem is as basic as opponents of upper ontologies claim, then, it also applies to a group of humans trying to cooperate, who might need machine assistance to communicate easily. If nothing else, such ontologies are implied by machine translation, used when people cannot practically communicate. Whether “upper” or not, these seem likely to proliferate.

Error Crushing Force of the Dialectic Questions and the Hammer of Truth

Error Crushing Force of the Dialectic Questions and the Hammer of Truth

*(Ontology) What are you talking about, please slow down and give me each specific detail individually?

*(Epistemology) How do you know that and why do you think it is justified or warranted?

*(Axiology) What is its value if any and why do you value that or why would anyone?

If you don’t already know, Dialectic is the art of investigating or discussing the truth of opinions.

What I am trying to say in this message of Dialectic Questions in order to find truth by giving people three questions that can be put towards almost anything and it help remove error and thus improved accuracy.

Ontology, Epistemology, & Axiology argument/challenge protocol

Grasping the status of truth (ontology of truth)

The Ontology of Humanistic Economics in Society?

Strong vs Weak Thinkers?

A strong thinker can deeply analyze their own positions removing all that are unworthy and updating to the most currently accurate. Whereas a weak thinker can only offer deep attacks to the positions of others that differ in thinking.

Just think, are your beliefs further supporting rhetoric or accuracy to the facts and are you ready to change if you have it the other way around?

Believer vs Thinker?

When you can, with all honesty, say that you put a similar voracity to one’s own ideas as they demand for others then they are a thinker not just a believer. And when you can quickly and eagerly relinquish any and all ideas, even the most cherished if they were not true; yes a willingness to discuss or discard if required, even if you like them is being a thinker and not just a unthinking believer.

We Love Generalizations (even if wrong)

We don’t like slow clear accurate thinking, no, we are bias irrational compulsive disordered hasty generalizations thinking beings.

We build our “belief” of the accuracy of our hasty generalizations one assertion at a time. In other words we add undue increasing assurance because we keep saying it over and over again, not because it’s actually accurate to the facts. We may cherry pick a few facts to support this error in thinking but that is intellectual dishonestly, as if it can be destroyed by the truth it should be. – Damien Marie AtHope

Here is my blog on rhetoric and stereotypes: Rhetoric & Stereotypes: Rethinking How We Think.

And, here is some information on hasty generalizations (also known as: argument from small numbers, statistics of small numbers, insufficient statistics, unrepresentative sample [form of], argument by generalization, faulty generalization, hasty conclusion [form of], inductive generalization, insufficient sample, lonely fact fallacy, over generality, over generalization)

Description: Drawing a conclusion based on a small sample size, rather than looking at statistics that are much more in line with the typical or average situation.

Logical Form:

Sample S is taken from population P.

Sample S is a very small part of population P.

Conclusion C is drawn from sample S.

Example #1:

My father smoked four packs of cigarettes a day since age fourteen and lived until age sixty-nine. Therefore, smoking really can’t be that bad for you.

Explanation: It is extremely unreasonable (and dangerous) to draw a universal conclusion about the health risks of smoking by the case study of one man.

Example #2:

Four out of five dentists recommend Happy Glossy Smiley toothpaste brand. Therefore, it must be great.