Taoism and the Championing of Woo-Woo Nonsense?

Taoism has a high potential for woo abuse, especially by those who don’t really know much about the religion, and by martial artists. Many of these can be found in books with the title “The Tao of…” There are a few good ones out there, like Bruce Lee’s Tao of Jeet Kune Do, but most resemble Fritjof Capra’s 1975 book The Tao of Physics, which has been criticized in its efforts to link mystical philosophy and quantum mechanics and for its use of outdated physics. ref

Popularly, a distinction is drawn between philosophical and religious Taoism. Philosophical Taoism, called 道家 daojia, treats the Tao Te Ching as a guide to help one’s actions conform with the way of nature. Religious Taoism, called 道教 daojiao, is focused on obtaining physical immortality and avoiding evil spirits. In reality, this distinction is completely fictional and merely serves as a method for fans of the Tao Te Ching or the Zhuangzi to separate out the ideas they find most palatable, and discard the rest as superstition. One critic states, “[M]ost scholars who have seriously studied Taoism, both in Asia and in the West, have finally … abandoned the simplistic dichotomy of tao-chia and tao-chiao – ‘philosophical Taoism’ and ‘religious Taoism.'” Nonetheless, most popular interpretations and high-school summaries of Taoism make this division into “philosophical Taoism,” which provides a way to understand the world and which is fully compatible with other religious traditions, and “religious Taoism,” which includes elements of ancestor worship, animism, and alchemy. Taoist Xian![]() (not to be confused with the X-Men or Xians), have super powers

(not to be confused with the X-Men or Xians), have super powers![]() , like the Siddhi

, like the Siddhi![]() s of Hinduism. According to Victor H. Mair, “They are immune to heat and cold, untouched by the elements, and can fly, mounting upward with a fluttering motion. They dwell apart from the chaotic world of man, subsist on air and dew, are not anxious like ordinary people, and have the smooth skin and innocent faces of children. The transcendents live an effortless existence that is best described as spontaneous. They recall the ancient Indian ascetics and holy men known as ṛṣi who possessed similar traits.” The term refers to both supernatural humans and animals dwelling in the sacred mountains. In the early part of the 21st century, a new text was discovered, called the Nei-yeh (lit. Inward training), which dated to roughly the same period of the Laozi and Zhuangzi texts. The Nei-yehis a manual for personal betterment, largely through meditative practices, and much of the more obscure language in the foundational texts can now be deciphered as references to this work. This discovery has further destabilized the belief that there is any real separation between philosophical and religious Taoism, since the fundamental distinction, that philosophical Taoism does not partake in or advocate monastic-type practices, has now been effectively disproven. ref

s of Hinduism. According to Victor H. Mair, “They are immune to heat and cold, untouched by the elements, and can fly, mounting upward with a fluttering motion. They dwell apart from the chaotic world of man, subsist on air and dew, are not anxious like ordinary people, and have the smooth skin and innocent faces of children. The transcendents live an effortless existence that is best described as spontaneous. They recall the ancient Indian ascetics and holy men known as ṛṣi who possessed similar traits.” The term refers to both supernatural humans and animals dwelling in the sacred mountains. In the early part of the 21st century, a new text was discovered, called the Nei-yeh (lit. Inward training), which dated to roughly the same period of the Laozi and Zhuangzi texts. The Nei-yehis a manual for personal betterment, largely through meditative practices, and much of the more obscure language in the foundational texts can now be deciphered as references to this work. This discovery has further destabilized the belief that there is any real separation between philosophical and religious Taoism, since the fundamental distinction, that philosophical Taoism does not partake in or advocate monastic-type practices, has now been effectively disproven. ref

Taoism (/ˈdaʊɪzəm/ or /ˈtaʊɪzəm/), also known as Daoism, is a religious or philosophical tradition of Chinese origin which emphasizes living in harmony with the Tao (道, literally “Way”, also romanized as Dao). The Tao is a fundamental idea in most Chinese philosophical schools; in Taoism, however, it denotes the principle that is the source, pattern and substance of everything that exists. Taoism differs from Confucianism by not emphasizing rigid rituals and social order. Taoist ethics vary depending on the particular school, but in general tend to emphasize wu wei (effortless action), “naturalness”, simplicity, spontaneity, and the Three Treasures: 慈 “compassion”, 儉 “frugality”, and 不敢為天下先 “humility”. The roots of Taoism go back at least to the 4th century BCE. Early Taoism drew its cosmological notions from the School of Yinyang (Naturalists), and was deeply influenced by one of the oldest texts of Chinese culture, the Yijing, which expounds a philosophical system about how to keep human behavior in accordance with the alternating cycles of nature. The “Legalist” Shen Buhai may also have been a major influence, expounding a realpolitik of wu wei. The Tao Te Ching, a compact book containing teachings attributed to Laozi (Chinese: 老子; pinyin: Lǎozǐ; Wade–Giles: Lao Tzu), is widely considered the keystone work of the Taoist tradition, together with the later writings of Zhuangzi. By the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), the various sources of Taoism had coalesced into a coherent tradition of religious organizations and orders of ritualists in the state of Shu (modern Sichuan). In earlier ancient China, Taoists were thought of as hermits or recluses who did not participate in political life. Zhuangzi was the best known of these, and it is significant that he lived in the south, where he was part of local Chinese shamanic traditions. Women shamans played an important role in this tradition, which was particularly strong in the southern state of Chu. Early Taoist movements developed their own institution in contrast to shamanism, but absorbed basic shamanic elements. Shamans revealed basic texts of Taoism from early times down to at least the 20th century. Institutional orders of Taoism evolved in various strains that in more recent times are conventionally grouped into two main branches: Quanzhen Taoism and Zhengyi Taoism. After Laozi and Zhuangzi, the literature of Taoism grew steadily and was compiled in form of a canon—the Daozang—which was published at the behest of the emperor. Throughout Chinese history, Taoism was nominated several times as a state religion. After the 17th century, however, it fell from favor. Taoism has had a profound influence on Chinese culture in the course of the centuries, and Taoists (Chinese: 道士; pinyin: dàoshi, “masters of the Tao”), a title traditionally attributed only to the clergy and not to their lay followers, usually take care to note distinction between their ritual tradition and the practices of Chinese folk religion and non-Taoist vernacular ritual orders, which are often mistakenly identified as pertaining to Taoism. Chinese alchemy (especially neidan), Chinese astrology, Chan (Zen) Buddhism, several martial arts, traditional Chinese medicine, feng shui, and many styles of qigong have been intertwined with Taoism throughout history. Beyond China, Taoism also had influence on surrounding societies in Asia. Today, the Taoist tradition is one of the five religious doctrines officially recognized in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) as well as Taiwan and although it does not travel readily from its East Asian roots, it claims adherents in a number of societies. It particularly has a presence in Hong Kong, Macau, and in Southeast Asia. Ref

Yin and Yang is sexist with an ORIGIN around 2,300 years ago?

The Tao sees the world as male (yang) and female (yin) which is very sexist. Some think the yin and yang are just good and bad. Never heard of it as sexist. But the white is male and the black is female. Chinese literature beginning with the classic cannon Yijing (book of Changes) we see sexism as we find the male (yang) symbolized as day or the sun embodying everything good and positive, and this status is identified with heaven. Whereas the female (yin) is symbolized as night or the moon embodying everything negative, evil and lowly. Ref

Sexism in Taoism

Some scholars make sharp distinctions between moral or ethical usage of the word “Tao” that is prominent in Confucianism and religious Taoism and the more metaphysical usage of the term used in philosophical Taoism and most forms of Mahayana Buddhism; others maintain that these are not separate usages or meanings, seeing them as mutually inclusive and compatible approaches to defining the principle. The original use of the term was as a form of praxis rather than theory – a term used as a convention to refer to something that otherwise cannot be discussed in words – and early writings such as the Tao Te Ching and the I Ching make pains to distinguish between conceptions of the Tao (sometimes referred to as “named Tao”) and the Tao itself (the “unnamed Tao”), which cannot be expressed or understood in language. Liu Da asserts that the Tao is properly understood as an experiential and evolving concept, and that there are not only cultural and religious differences in the interpretation of the Tao, but personal differences that reflect the character of individual practitioners. The Tao was shared with Confucianism, Chán, and Zen Buddhism and more broadly throughout East Asian philosophy and religion in general. In Taoism, Chinese Buddhism and Confucianism, the object of spiritual practice is to ‘become one with the Tao’ (Tao Te Ching) or to harmonise one’s will with Nature (cf. Stoicism) in order to achieve ‘effortless action’ (Wu wei). This involves meditative and moral practices. Important in this respect is the Taoist concept of De (德; virtue). In Confucianism and religious forms of Taoism, these are often explicitly moral/ethical arguments about proper behavior, while Buddhism and more philosophical forms of Taoism usually refer to the natural and mercurial outcomes of action (comparable to karma). The Tao is intrinsically related to the concepts yin and yang (pinyin: yīnyáng), where every action creates counter-actions as unavoidable movements within manifestations of the Tao, and proper practice variously involves accepting, conforming to, or working with these natural developments. ref

Confucianism’s Tiān (Shangdi god 4,000 years old): Supernaturalism, Pantheism or Theism?

Yin and Yang ORIGIN around 2,300 years ago?

The concept of Yin and Yang became popular with the work of the Chinese school of Yinyang which studied philosophy and cosmology in the 3rd century BCE. The principal proponent of the theory was the cosmologist Zou Yan (or Tsou Yen) who believed that life went through five phases (wuxing) – fire, water, metal, wood, earth – which continuously interchanged according to the principle of Yin and Yang.

WHAT IS YIN?

Yin is:

- feminine

- black

- dark

- north

- water (transformation)

- passive

- moon (weakness and the goddess Changxi)

- earth

- cold

- old

- even numbers

- valleys

- poor

- soft

- and provides spirit to all things.

Yin reaches it’s height of influence with the winter solstice. Yin may also be represented by the tiger, the colour orange and a broken line in the trigrams of the I Ching (or Book of Changes).

WHAT IS YANG?

Yang is:

- masculine

- white

- light

- south

- fire (creativity)

- active

- sun (strength and the god Xihe)

- heaven

- warm

- young

- odd numbers

- mountains

- rich

- hard

- and provides form to all things.

Yang reaches it’s height of influence with the summer solstice. Yang may also be represented by the dragon, the color blue, and a solid line trigram. ref

The idea of balancing male and female energies is fundamental to Taoism, and applies to women as well as to men. One early practice was ritual sexual intercourse between men and women who were not married to one another. These rituals followed strict guidelines, and the goal was the union of yin and yang energies. In the Taode jing offers a females role is made clear in passages like this one from Chapter 61: “The Feminine always conquers the Masculine by her quietness, by lowering herself through her quietness. The general stance on gender is there are attitudes expected of women, such as keeping a cheerful attitude or speaking in quiet tones. Divine marriages with deities were one very ancient version of this practice. Ref

On particular holidays, street parades take place. These are lively affairs which invariably involve firecrackers and flower-covered floats broadcasting traditional music. They also variously include lion dances and dragon dances; human-occupied puppets (often of the “Seventh Lord” and “Eighth Lord“); tongji (童乩 “spirit-medium; shaman”) who cut their skin with knives; Bajiajiang, which are Kungfu-practicing honor guards in demonic makeup; and palanquins carrying god-images. The various participants are not considered performers, but rather possessed by the gods and spirits in question. There is also, ancestor worship ceremony led by Taoists. In terms of Ceremonial Taoism, we find a pantheon that is huge, and that includes many important female Gods. Two notable examples are Xiwangmu (Queen of the Immortals) and Shengmu Yuanjun (Mother of the Tao). Similar to the Hindu tradition, then, Ceremonial Taoism offers the possibility of seeing our Divinity represented in female as well as in male forms. In terms of the practice of Neidan (Inner Alchemy), there are places where techniques for men and for women are different. In the introduction to Nourishing the Essence of Life, Eva Wong provides a general outline of these differences: In males, blood is weak and vapor is strong; therefore the male practitioner must refine the vapor and use it to strengthen the blood. … In females, blood is strong and vapor is weak; therefore the female practitioner must refine the blood and use it to strengthen the vapor. (page 22-23) If “dual cultivation” sexual practices are part of our path, there obviously will be differences that correspond to the differences between male and female sexual anatomy. The roots of Taoism lie in the tribal and shamanic cultures of ancient China, which settled along the Yellow River. The wu – the shamans of these cultures – were able to communicate with the spirits of plants, minerals and animals; enter trance-states in which they traveled (in their subtle bodies) to distant galaxies, or deep into the earth; and mediate between the human and supernatural realms. Many of these practices would find expression, later, in the rituals, ceremonies and Inner Alchemy techniques of various Taoist lineages. THE EASTERN HAN DYNASTY (25-220 CE). In this period we see the emergence of Taoism as an organized religion (Daojiao). In 142 CE, the Taoist adept Zhang Daoling – in response to a series of visionary dialogues with Laozi – established the “Way of the Celestial Masters” (Tianshi Dao). Practitioners of Tainshi Dao trace their lineage through a succession of sixty-four Masters, the first being Zhang Daoling, and the most recent, Zhang Yuanxian. It is during the Tang Dynasty that Taoism becomes the official “state religion” of China, and as such is integrated into the imperial court system. It was also the time of the “second Daozang” – an expansion of the official Taoist canon, ordered (in CE 748) by Emperor Tang Xuan-Zong. The emergence of the Shangqing Taoist (Way of Highest Clarity) lineage. This lineage was founded by Lady Wei Hua-tsun, and propagated by Yang Hsi. Shangqing is a highly mystical form of practice, which includes communication with the Five Shen (the spirits of the internal organs), spirit-travel to celestial and terrestrial realms, and other practices to realize the human body as the meeting-place of Heaven and Earth. According to Taoist Cosmology, the first movement into manifestation happens via Yang Qi and Yin Qi – the primordial masculine and feminine energies. At this level, then, there is equality between the masculine and the feminine. They are understood to simply be two sides of the same coin: one could not exist without the other, and it is their “dance” which gives birth to the Five Elements, which in their various combinations produce the Ten Thousand Things, i.e. everything arising within the fields of our perception. In terms of Chinese Medicine, each human body is understood to contain both Yang Qi and Yin Qi. Yang Qi is symbolically “masculine,” and Yin Qi is symbolically“feminine.” In terms of Chinese Medicine, each human body is understood to contain both Yang Qi and Yin Qi. Yang Qi is symbolically “masculine,” and Yin Qi is symbolically“feminine.” The balanced functioning of these two is an important aspect of maintaining health. In terms of Inner Alchemy practice, however, there frequently is a bias of sorts in the direction of Yang Qi. As we progress along the path, little by little we replace Yin Qi with Yang Qi, becoming more and more light and subtle. An Immortal, it is said, is a being (a man or a woman) whose body has been transformed largely or completely into Yang Qi, en route to transcending the Yin/Yang polarity entirely, and merging ones body-mind back into the Tao. Ref, Ref

“Taoists traditionally have had a somewhat positive view of women. Nonetheless, the Tao de Jing was written by men for men, at a time when conflict was a common part of life, presumably written to try to end the perpetual conflicts by teaching men to be more feminine. A central part of Taoism is the concept of yin and yang. Yin and yang are male and female, they cannot exist without one another, are unified and equal but represent different things. Yin, the female part of the symbol which is black is calmer and cooler and is often represented by still water. Hence, Taoist women are expected to conform to this ideal of being peaceful and quiet. This is clearly represented in the image of He XianGu, one of the Eight Immortals in Taoist beliefs, the Eight Immortals being humans who are true followers of the Tao. She is the only woman of the Eight Immortals and her symbol is the lotus which signifies modesty, purity and love. In reality, the expectation for women to be peaceful, beautiful and respectful like He XianGu and the Yin, is often abused by the loud, fiery Yang counterparts. Taoist women can be very reserved and restricted because of their gender stereotype. There have been very few female Taoists who have risen to prominence. This is due to the way Taoist women are expected to behave. The result is the loss of a great female contribution to Taoism. Nonetheless, the Tao De Jing written by Lao Tzu aims to teach society how to live peacefully by describing ‘feminine’ characteristics for people to follow.” Ref

Taoism is the personification of “woo woo” bullshit nonsense offered as wisdom: “I confess that there is nothing to teach: on religion, on science, on body of information, which will lead your mind back to the tao. Today I speak in this fashion, tomorrow in another, but the integral way is beyond words and beyond mind.” Ref

In Taoism, the two sexes should be united like the two colors in the T’ai-chi T’u (“Yin-Yang symbol”) to make one rounded and fully human whole in an individual marriage and in society.

Taoist sexual (and sexist) practices

Sex and the concept of Yin and yang is important in Taoism. Man and Woman were the equivalent of heaven and earth, but became disconnected. Therefore, while heaven and earth are eternal, man and woman suffer a premature death. Every interaction between Yin and Yang had significance. Because of this significance, every position and action in lovemaking had importance. Taoist texts described a large number of special sexual positions that served to cure or prevent illness. The basis of all Taoist thinking is that qi is part of everything in existence. Qi is related to another energetic substance contained in the human body known as jing (精), and once all this has been expended the body dies. Jing can be lost in many ways, but most notably through the loss of body fluids. Taoists may use practices to stimulate/increase and conserve their bodily fluids to great extents. The fluid believed to contain the most Jing is semen. Women were often given a position of inferiority in sexual practice. Many of the texts discuss sex from a male point of view, and avoid discussing how sex could benefit women. Men were encouraged to not limit themselves to one woman, and were advised to have sex only with the woman who was beautiful and had not had children. While the man had to please the woman sexually, she was still just an object. At numerous points during the Ishinpō, the woman is referred to as the “enemy”; this was because the woman could cause him to spill semen and lose vitality. In later sexual texts from the Ming, women had lost all semblance of being human and were referred to as the “other,” “crucible”, or “stove” from which to cultivate vitality. The importance of pleasing the woman was also diminished in later texts. The practice was known as Caibu (採補), as a man enters many women without ejaculation. Women were also considered to be a means for men to extend men’s lives. Many of the ancient texts were dedicated explanation of how a man could use sex to extend his own life. But, his life was extended only through the absorption of the woman’s vital energies (jing and qi). Some Taoists called the act of sex “The battle of stealing and strengthening.” These sexual methods could be correlated with Taoist military methods. Instead of storming the gates, the battle was a series of feints and maneuvers that would sap the enemy’s resistance. Some Ming dynasty Taoist sects believed that one way for men to achieve longevity or ‘towards immortality’ is by having intercourse with virgins, particularly young virgins. Taoist sexual books, such as the Hsuan wei Hshin (“Mental Images of the Mysteries and Subtleties of Sexual Techniques”) and San Feng Tan Cheueh (“Zhang Sanfeng’s Instructions in the Physiological Alchemy”), written, respectively, by Zhao Liangpi and Zhang Sanfeng (not to be confused with semi-mythical Zhang Sanfeng who lived in an earlier period), call the woman sexual partner ding (鼎) and recommend sex with premenarche virgins. Zhao Liangpi concludes that the ideal ding is a premenarche virgin just under 14 years of age and women older than 18 should be avoided. Zhang Sanfeng went further and divided ding into three ranks: the lowest rank, 21- to 25-year-old women; the middle rank, 16- to 20-year-old menstruating virgins; the highest rank, 14-year-old premenarche virgins. Ref

“The principle of Yin and Yang is a fundamental concept in Chinese philosophy and culture in general dating from the third century BCE or even earlier. This principle is that all things exist as inseparable and contradictory opposites, for example, female-male, dark-light and old-young. The concept of yin and yang became popular with the work of the Chinese school of Yinyang which studied philosophy and cosmology in the 3rd century BCE. The principal proponent of the theory was the cosmologist Zou Yan (or Tsou Yen) who believed that life went through five phases (wuxing) – fire, water, metal, wood, earth – which continuously interchanged according to the principle of yin and yang. Yin is feminine, black, dark, north, water (transformation), passive, moon (weakness and the goddess Changxi), earth, cold, old, even numbers, valleys, poor, soft, and provides spirit to all things. Yin reaches it’s height of influence with the winter solstice. Yin may also be represented by the tiger, the color orange and a broken line in the trigrams of the I Ching(or Book of Changes). Yang is masculine, white, light, south, fire (creativity), active, sun (strength and the god Xihe), heaven, warm, young, odd numbers, mountains, rich, hard, and provides form to all things. Yang reaches it’s height of influence with the summer solstice. Yang may also be represented by the dragon, the color blue and a solid line trigram.” Ref

Taoism can be defined as pantheistic, given its philosophical emphasis on the formlessness of the Tao and the primacy of the “Way” rather than anthropomorphic concepts of God. This is one of the core beliefs that nearly all the sects share. Taoist orders usually present the Three Pure Ones at the top of the pantheon of deities, visualizing the hierarchy emanating from the Tao. Laozi (Laojun, “Lord Lao”), is considered the incarnation of one of the Three Purities and worshipped as the ancestor of the philosophical doctrine. Different branches of Taoism often have differing pantheons of lesser deities, where these deities reflect different notions of cosmology. Lesser deities also may be promoted or demoted for their activity. Some varieties of popular Chinese religion incorporate the Jade Emperor, derived from the main of the Three Purities, as a representation of the most high God. Persons from the history of Taoism, and people who are considered to have become immortals (xian), are venerated as well by both clergy and laypeople. Despite these hierarchies of deities, traditional conceptions of Tao should not be confused with the Western theism. Being one with the Tao does not necessarily indicate a union with an eternal spirit in, for example, the Hindu sense. English speakers continue to debate the preferred romanization of the words “Daoism” and “Taoism”. The root Chinese word 道 “way, path” is romanized taoin the older Wade–Giles system and dào in the modern Pinyin system. In linguistic terminology, English Taoism/Daoism is formed from the Chinese loanword tao/dao 道 “way; route; principle” and the native suffix -ism. The debate over Taoism vs. Daoism involves sinology, phonemes, loanwords, and politics – not to mention whether Taoism should be pronounced /ˈtaʊ.ɪzəm/ or /ˈdaʊ.ɪzəm/. Ref

The word “Taoism” is used to translate different Chinese terms which refer to different aspects of the same tradition and semantic field:

- “Taoist religion” (Chinese: 道教; pinyin: dàojiào; lit. “teachings of the Tao”), or the “liturgical” aspect — A family of organized religious movements sharing concepts or terminology from “Taoist philosophy”; the first of these is recognized as the Celestial Masters school.

- “Taoist philosophy” (Chinese: 道家; pinyin: dàojiā; lit. “school or family of the Tao”) or “Taology” (Chinese: 道學; pinyin: dàoxué; lit. “learning of the Tao”), or the “mystical” aspect — The philosophical doctrines based on the texts of the I Ching, the Tao Te Ching (or Daodejing, Chinese: 道德經; pinyin: dàodéjīng) and the Zhuangzi (Chinese: 莊子; pinyin: zhuāngzi). These texts were linked together as “Taoist philosophy” during the early Han Dynasty, but notably not before. It is unlikely that Zhuangzi was familiar with the text of the Daodejing, and Zhuangzi would not have identified himself as a Taoist as this classification did not arise until well after his death. Ref

However, the discussed distinction is rejected by the majority of Western and Japanese scholars. It is contested by hermeneutic(interpretive) difficulties in the categorization of the different Taoist schools, sects and movements. Taoism does not fall under an umbrella or a definition of a single organized religion like the Abrahamic traditions; nor can it be studied as a mere variant of Chinese folk religion, as although the two share some similar concepts, much of Chinese folk religion is separate from the tenets and core teachings of Taoism. Sinologists Isabelle Robinet and Livia Kohn agree that “Taoism has never been a unified religion, and has constantly consisted of a combination of teachings based on a variety of original revelations.” Chung-ying Cheng, a Chinese philosopher, views Taoism as a religion that has been embedded into Chinese history and tradition. “Whether Confucianism, Daoism, or later Chinese Buddhism, they all fall into this pattern of thinking and organizing and in this sense remain religious, even though individually and intellectually they also assume forms of philosophy and practical wisdom.” Chung-ying Cheng also noted that the Daoist view of heaven flows mainly from “observation and meditation, [though] the teaching of the way (dao) can also include the way of heaven independently of human nature”. In Chinese history, the three religions of Buddhism, Daoism and Confucianism stand on their own independent views, and yet are “involved in a process of attempting to find harmonization and convergence among themselves, so that we can speak of a ‘unity of three religious teaching’ (sanjiao heyi)”. Ref

The term “Taoist”, and Taoism as a “liturgical framework”

Traditionally, the Chinese language does not have terms defining lay people adhering to the doctrines or the practices of Taoism, who fall instead within the field of folk religion. “Taoist”, in Western sinology, is traditionally used to translate daoshi (道士, “master of the Tao”), thus strictly defining the priests of Taoism, ordained clergymen of a Taoist institution who “represent Taoist culture on a professional basis”, are experts of Taoist liturgy, and therefore can employ this knowledge and ritual skills for the benefit of a community. This role of Taoist priests reflects the definition of Taoism as a “liturgical framework for the development of local cults”, in other words a scheme or structure for Chinese religion, proposed first by the scholar and Taoist initiate Kristofer Schipper in The Taoist Body(1986). Daoshi are comparable to the non-Taoist fashi (法師, “ritual masters”) of vernacular traditions (the so-called “Faism“) within Chinese religion. The term dàojiàotú (Chinese: 道教徒; literally: “follower of Taoism”), with the meaning of “Taoist” as “lay member or believer of Taoism”, is a modern invention that goes back to the introduction of the Western category of “organized religion” in China in the 20th century, but it has no significance for most of Chinese society in which Taoism continues to be an “order” of the larger body of Chinese religion. Laozi is traditionally regarded as the founder of religious Taoism and is closely associated in this context with “original” or “primordial” Taoism. Whether he actually existed is disputed; however, the work attributed to him – the Tao Te Ching – is dated to the late 4th century BCE. Taoism draws its cosmological foundations from the School of Naturalists(in the form of its main elements – yin and yang and the Five Phases), which developed during the Warring States period (4th to 3rd centuries BC). Ref

Robinet identifies four components in the emergence of Taoism:

- Philosophical Taoism, i.e. the Tao Te Ching and Zhuangzi

- techniques for achieving ecstasy

- practices for achieving longevity or immortality

- exorcism. Ref

Some elements of Taoism may be traced to prehistoric folk religions in China that later coalesced into a Taoist tradition. In particular, many Taoist practices drew from the Warring-States-era phenomena of the wu (connected to the shamanic culture of northern China) and the fangshi (which probably derived from the “archivist-soothsayers of antiquity, one of whom supposedly was Laozi himself”), even though later Taoists insisted that this was not the case. Both terms were used to designate individuals dedicated to “… magic, medicine, divination,… methods of longevity and to ecstatic wanderings” as well as exorcism; in the case of the wu, “shamans” or “sorcerers” is often used as a translation. The fangshi were philosophically close to the School of Naturalists, and relied much on astrological and calendrical speculations in their divinatory activities. The first organized form of Taoism, the Tianshi (Celestial Masters’) school (later known as Zhengyi school), developed from the Five Pecks of Rice movement at the end of the 2nd century CE; the latter had been founded by Zhang Daoling, who claimed that Laozi appeared to him in the year 142. The Tianshi school was officially recognized by ruler Cao Cao in 215, legitimizing Cao Cao’s rise to power in return. Laozi received imperial recognition as a divinity in the mid-2nd century BCE. Taoism, in form of the Shangqing school, gained official status in China again during the Tang dynasty (618–907), whose emperors claimed Laozi as their relative. The Shangqing movement, however, had developed much earlier, in the 4th century, on the basis of a series of revelations by gods and spirits to a certain Yang Xi in the years between 364 and 370. Between 397 and 402, Ge Chaofu compiled a series of scriptures which later served as the foundation of the Lingbao school, which unfolded its greatest influence during the Song dynasty (960–1279). Several Song emperors, most notably Huizong, were active in promoting Taoism, collecting Taoist texts and publishing editions of the Daozang. In the 12th century, the Quanzhen School was founded in Shandong. It flourished during the 13th and 14th century and during the Yuan dynasty became the largest and most important Taoist school in Northern China. The school’s most revered master, Qiu Chuji, met with Genghis Khan in 1222 and was successful in influencing the Khan towards exerting more restraint during his brutal conquests. By the Khan’s decree, the school also was exempt from taxation. Aspects of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism were consciously synthesized in the Neo-Confucian school, which eventually became Imperial orthodoxy for state bureaucratic purposes under the Ming (1368–1644). The Qing Dynasty (1644–1912), however, much favored Confucian classics over Taoist works. During the 18th century, the imperial library was constituted, but excluded virtually all Taoist books. By the beginning of the 20th century, Taoism had fallen much from favor (for example, only one complete copy of the Daozang still remained, at the White Cloud Monastery in Beijing). Today, Taoism is one of five religions recognized by the People’s Republic of China. The government regulates its activities through the Chinese Taoist Association. Taoism is freely practiced in Taiwan, where it claims millions of adherents. Ref

Yes, Karma is also just the Same Old Nonsense

Women and Femininity in Early Chinese Philosophy

“Conclusion”

Is that where there are such rigid hierarchical relationships based on sex, practiced and codified in the society, that this would never be possible. The Odes make it plain that women in ancient China were not choosing a patriarchal social order, it was imposed on them and they just had to live with it. It is also obvious that yin and yang were more than sex distinctions in the Laozi: they were also gendered concepts in the human realm as they were seen to be available to men. There is no mention of women adopting yang qualities; the Laozi does not appear to have any view on this issue. Since this is the case, the Confucian justification of its rigid patriarchy by reference to yin/yang as complementary sex differences rather than gendered qualities is not a true reflection of what ying/yang really appears to be; it is open to interpretation as are all concepts of gender rather than sex. In Chinese philosophy it would seem that sex and gender are looked at in a more holistic interrelated way than in the western tradition although the Confucian patriarchal tendencies do amount to systematic sexism in my view; therein lies the problem. In the conflation of sex and gender it was possible to establish sexism as the natural order of things rather than as a social convention. Laozi had a lot to say about yin characteristics but nothing about actual women and how they could have any kind of different but equal complementarity with men in society apart from the fact that they were already yin Laoz is potential sages were still operating within patriarchy and hierarchy even when they purported to reject them. It was not the hierarchy of the Confucians because they rejected the primary Confucian values, but it is not quite clear how they would deal with 22 women released from these societal constraints or even if women would be released from them. The sage was still male and adopted feminine qualities; the mother was a metaphor, not a woman as a fully realized person in society. This is not to say that the yin/yang concept is at all a hindrance to women having equal status to men but different experiences of their humanity. In fact there is great potential in the concept to further explore and articulate a complementarity of the sexes without the entrenched social relations of sexual domination or gendered stereotypes. It would make a good topic for a future comparative study of Eastern and Western ideas about sex and gender; there are aspects in each tradition that together would make for a more complete understanding and articulation of true equality for men and women. The Laozi opens the way to celebrating difference in sex equality that is dynamic. The fluidity of gendered qualities in Laozi demonstrates that the potential for people and societies to reinvent what they perceive to be masculine and feminine is just that, a matter of perception. Ref

Yin and Yang is sexist with an ORIGIN around 2,300 years ago?

In a general way, Taoism philosophy is symbolized by the yin-yang symbol.

By Lijuan Shen, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, China

and Paul D’Ambrosio, East China Normal University, China

“Laozi, values the inseparability of yin and yang, which is equated with the female and male.”

The concept of gender is foundational to the general approach of Chinese thinkers. Yin and yang, core elements of Chinese cosmogony, involve correlative aspects of “dark and light,” “female and male,” and “soft and hard.” These notions, with their deeply-rooted gender connotations, recognize the necessity of interplay between these different forces in generating and carrying forward the world. The major thinkers of China’s first philosophic flourishing—traditionally referred to as the Hundred Schools, c. 500s-200s B.C.E.—inherited and further developed this comprehensively gendered view of the world. These concepts continue to shape contemporary Chinese thought, as well. Historically, the most influential Chinese perspectives on the issue of gender come from what are commonly referred to as Confucian and Daoist traditions of thought, which take somewhat opposing positions. Many texts associated with Confucianism emphasize yang’s dominant, male-related characteristics, whereas those linked to Daoism, especially the Laozi, reverse this view, finding value in yin’s subordinate, female characteristics. However, it should be noted that Chinese thinkers, regardless of their classification as Confucian or Daoist, generally see the opposing qualities of yin and yang as integral parts of a whole that complement one another. Accordingly, the closest word to “gender” in modern Chinese is xingbie, which can be quite literally understood as a difference (bie) of individual nature or tendencies (xing). The word generally, however, refers to the physiological characteristics that then provide the basis for corresponding social identities. The genders, in terms of social roles, are not defined absolutely or theoretically, but rather through the mutually reciprocal, physical, generative relationship between male and female. They are understood correlatively, and determined by their context and dynamic tendencies as they interact with one another. There is a debate in contemporary Chinese academic circles about whether or not the idea of “gender” or “gender concepts” actually applies to traditional Chinese thought. Chinese scholars argue about the presence of “male” (xiong) and “female” (ci) characteristics, differences, and relations in the context of ancient Chinese philosophy. Although affirming this interpretation would provide a space for comparative studies with Western traditions, some thinkers believe that doing so distorts traditional Chinese thought. Zhang Xianglong is a prominent representative of those who think that Chinese philosophy and culture have long been influenced by concepts of gender. For him, Chinese thinking is fundamentally gendered as it takes the interaction between male and female as the basic model for philosophical investigations. He further argues that it is one of the core aspects of mainstream thought in China. Zhang demonstrates that yin and yang strongly connote ideas of female and male, and identifies such gendered thought in works as early as the Zhouyi, or Yijing (Book of Changes), a traditional Chinese divinatory text of uncertain antiquity consisting of hexagrams and their interpretations, as well as throughout the later traditions of Confucianism, Daoism, and Chinese Buddhism. Accordingly, he argues that yin and women have “in principle never been doomed to be inferior” and “discrimination against women in ancient Chinese culture is neither deterministic nor universal” (Zhang 2002:5). Such a claim is dubious, as the dualistic dynamic of yin and yang, while positing both aspects as essential to existence and in this way ontologically equal, has been generally presented as inherently hierarchical. Chen Jiaqi opposes Zhang’s broader position, arguing that yin and yang are not necessarily related to gender. For Chen, yin and yangprimarily involve social relationships, political forms, and weighing advantages and disadvantages. He holds that gender characteristics are too abstract to be practically relevant in this context, and do not apply directly to social forms (Chen 2003). From a historical perspective, Chen’s interpretation is less convincing than Zhang’s. There are numerous Chinese texts where yin and yang are broadly associated with gender. While yang and yin are not exclusively defined as “male” and “female,” and either sex can be considered yin or yang within a given context, in terms of their most general relation to one another, yin references the female and yang the male. For example, the Daoist text known as the Taipingjing (Scripture of Great Peace) records that “the male and female are the root of yin and yang.” The Han dynasty Confucian thinker Dong Zhongshu (195-115 B.C.E.) also writes, “Yin and yang of the heavens and the earth [which together refer to the cosmos] should be male and female, and the male and female should be yin and yang. Thereby, yin and yang can be called male and female, and male and female can be called yin and yang.” These and other texts draw a strong link between yin as female and yang as male. However, it is important to also recognize that gender itself is not as malleable as yin and yang, despite this connection. While gender remains fixed, their coupling with yin and yang is not. This close and complex relationship means yin and yang themselves require examination if their role in Chinese gender theory is to be properly understood. The original meaning of yin and yang had little to do with gender differences. Some of the earliest uses of yin and yang are found in the Shangshu (Book of Documents). Here, the word yang is employed six times, and five times it denotes the southern side of mountains, which receives the most sunlight. The term yin appears three times in the text, and refers to the shadier northern side of mountains. These examples are characteristic of how yin and yang function throughout Chinese intellectual history; they do not refer to particular objects, but act as correlative categorizations. In most instances yin and yang are used to indicate a specific relationship within a determined context. The way sunshine falls on a mountain is the context, and the difference between the northern and southern sides, where the latter receives more light and warmth, determines their association, which is understood as yin and yang. The terms are thereby an expression of the function of the sun on a particular place, but they do not speak to the actual substance of the objects (the sun or mountain) themselves. The specific traits of the objects can only be designated yin and yang in their functional correlation to one another. Within this matrix, yin things share commonalities when viewed in relation to yang things. In this way, the early association of yin and yang with gender can be seen as speaking to the relationship between genders, and not to their essential or substantial natures. Yin and yang traits were thus seen as able to accurately describe broad differences between males and females as they interact with one another. Fixing the link between these categorizations, having men be yang in relation to women, who are yin, only works in a highly abstract or broad sense. For example, the Book of Changes states that the emperor is supposed to have six male ministers at the south palace (a yang position) and six wives or concubines at the north palace (a yin position). Like the southern and northern sides of a mountain, men and women are yang and yin in the way they serve the emperor. Social positions are linked to gender and understood through yin and yang. The Liji (Record of Rituals) states that “the male is outside, and the wife inside the home. The sun starts in the east and the moon starts in the west. This is the distinction of yin and yang, the positions of husband and wife.” However, in specific contexts, it is possible for the association to be reversed. For instance, in Dong Zhongshu’s Chunqiu Fanlu (Spring and Autumn Annals), we also find that “the sovereign is yang, the minister is yin; the father is yang, the son is yin.” Here males, such as ministers or sons, can also be considered yin. The entire pattern can be overturned, as well, such as in the relationship between an empress and her male ministers, where the woman is yangand the men are considered yin. However, such a situation was often considered something that should be approached with caution, as it violated natural patterns. For example, Wang Bi (226-249 C.E.), who did not care much for Dong Zhongshu’s cosmological interpretation, still argued that a woman who was too strong was not to be married. In terms of actual practice, the more generalized and stable affiliation between yin as female and yang as male often won out, as exemplified by Wang’s idea. It was commonly appropriated as an ideological tool for backing the oppression of women, especially after Dong Zhongshu’s theories took hold. Dong, whose version of Confucianism won imperial backing during the Han dynasty, was also responsible for promoting the official establishment of a formal cosmology based on yinand yang, which became quite influential in the Chinese tradition. While he allows for men to be understood as yin and women as yang in certain contexts, overall he sought to limit the scope of such reversals. For Dong, males are dominant, powerful, and moral, and therefore yang. Women, on the other hand, are precisely the opposite—subservient, weak, selfish, and jealous—and best described as yin. As a result, female virtues became largely oriented toward social roles, especially women’s duties as wives (for example, the female virtues of chastity and compliancy). Against this biased intellectual background, oppressive practices were supported and initiated. For instance, the widespread acceptance of concubinage and female foot binding in Chinese social history expressed the inequality between genders. However, this social inequality did not accurately reflect its culture’s philosophical thought. Most Chinese thinkers were very attentive to the advantageousness of the complementary nature of male and female characteristics. In fact, in many texts considered Confucian that are predominant for two millennia of Chinese thought, the political system and gender roles are integrated (Yang 2013). This integration is based on understanding yin and yang as fundamentally affixed to gender and thereby permeating all aspects of social life. Sinologists such as Joseph Needham have identified a “feminine symbol” in Chinese culture, rooted in the Daoist concentration on yin. Roger Ames and David Hall similarly argue that yin and yang indicate a “difference in emphasis rather than difference in kind” and should be viewed as a whole, and that therefore their relationship can be likened to that of male and female traits (Ames and Hall 1998: 90-96). Overall, while the complementary understanding of yin and yang did not bring about gender equality in traditional Chinese society, it remains a key factor for comprehending Chinese conceptions of gender. As Robin Wang has noted, “on the one hand, yinyang seems to be an intriguing and valuable conceptual resource in ancient Chinese thought for a balanced account of gender equality; on the other hand, no one can deny the fact that the inhumane treatment of women throughout Chinese history has often been rationalized in the name of yinyang” (Wang 2012: xi). Gender issues play an important role in the history of Chinese thought. Many thinkers theorized about the significance of gender in a variety of areas. The precondition for this discussion is an interpretation of xing, “nature” or “tendencies.” The idea of “differences of xing” constitutes the modern term for “gender,” xingbie (literally “tendency differences”) making xing central to this discussion. It should be noted that the Chinese understanding of xing, including “human xing,” is closer to “tendency” or “propensity” than traditional Western conceptions of human “nature.” This is mainly because xing is not seen as something static or unchangeable. (It is for this reason that Ames and Hall, in the quote above, highlight the difference between “emphasis” and “kind.”) The way xing is understood greatly contributes to the way arguments about gender unfold. The term xing first became an important philosophical concept in discussions about humanity and eventually human tendency, or renxing. In terms of its composition, the character xing is made up of a vertical representation of xin, “heart-mind” (the heart was thought to be the organ responsible for both thoughts and feelings/emotions) on the left side. This complements the character sheng, to the right, which can mean “generation,” “grow,” or “give birth to.” In many cases, the way shengis understood has a significant impact on interpreting xing and gender. As a noun, sheng can mean “natural life,” which gives rise to theories about “original nature” or “foundational tendencies” (benxing). It thereby connotes vital activities and physiological desires or needs. It is in this sense that Mengzi (372-289 B.C.E.) describes human tendencies (renxing) as desiring to eat and have sex. He also says that form and color are natural characteristics, or natural xing. The Record of Rituals similarly comments that food, drink, and relations between men and women are defining human interests. Xunzi (312-238 B.C.E.), generally regarded as the last great classical Confucian thinker, fundamentally disagreed with Mengzi’s claim that humans naturally tend toward what is good or moral. He did, however, similarly classify xing as the desire for food, warmth, and rest. Sheng can also be a verb, which gives xing a slightly different connotation. As a verb, shengindicates creation and growth, and thus supports the suggestion that xing should be understood as human growth through the development of one’s heart-mind, the root, or seat, of human nature or tendencies. The Mengzi expressly refers to this, stating that xing is understood through the heart-mind. This also marks the distinction between humans and animals. A human xing provides specific characteristics and enables a certain orientation for growth that is unique in that it includes a moral dimension. It is in this sense that Mengzi proposes his theory for natural human goodness, a suggestion that Xunzi later rebuts, albeit upon a similar understanding of xing. Texts classified as Daoist, such as the Laozi and Zhuangzi, similarly affirm that xing is what endows beings with their particular virtuousness (though it is not necessarily moral). It is on the basis of human nature/tendencies that their unique capacity for moral cultivation is given. The Xing Zi Ming Chu (Recipes for Nourishing Life), a 4th century B.C.E. text recovered from the Guodian archaeological site, comments that human beings are defined by the capacity and desire to learn. Natural human tendencies are thereby not simply inherent, they also need to be grown and refined. The Mengzi argues that learning is nothing more than developing and cultivating aspects of one’s own heart-mind. The Xunzi agrees, adding that too much change or purposeful change can bring about falsity—which often results in immoral thoughts, feelings, or actions. These texts agree in their argument that there are certain natural patterns or processes for each thing, and deviating from these is potentially dangerous. Anything “false” or out of accordance with these patterns is likely to be immoral and harmful to oneself and society, so certain restrictions are placed on human practice to promote moral growth. These discussions look at human tendencies as largely shaped in the context of society, and can be taken as a conceptual basis for understanding gender as a natural tendency that is steered through social institutions. For example, when Mengzi is asked why the ancient sage-ruler Shun lied to his parents in order to marry, Mengzi defends Shun as doing the right thing. Explaining that otherwise Shun would have remained a bachelor, Mengzi writes, “The greatest of human relations is that a man and a woman live together.” Thus Mengzi argues that Shun’s moral character was based on proper cultivation of his natural tendencies according to social mores. One’s individual nature is largely influenced, and to some extent even generated, by one’s cultural surroundings. This also produces physiological properties that account for a wide variety of characteristics that are then reflected in aspects of gender, culture, and social status. Linked to the understanding of yin and yang as functionally codependent categorizations, differences between genders are characterized on the basis of their distinguishing features, and defined correlatively. This means that behavior and identity largely arise within the context of male-female relations. One’s natural tendencies include gender identity as either xiong xing (male tendencies) or ci xing (female tendencies), which one is supposed to cultivate accordingly. Thus there are more physiological and cultural aspects to human tendencies, as well. In these diverse ways, Chinese philosophy emphasizes the difference between males and females, believing that each has their own particular aspects to offer, which are complementary and can be unified to form a harmonious whole (though this does not necessarily imply their equality). The idea of gender as being fundamentally understood through respective dissimilarities (nan nü you bie) is based in the physiological differences between men and women, but also manifests in philosophic thought. In fact, in one of the earliest references to the distinction between men and women, the Record of Rituals asserts: Once there is a difference between males and females, then there can be love between fathers and sons. Once there is love between fathers and sons, obligations are generated. Once obligations are generated, rituals are made. Once rituals are made, all things can be at ease. The original difference between genders is—presumably through the generative power of their combination—the foundation for obligations (or morality) and thus ritual (or social moral patterns), which allows finally for harmony in the cosmos as a whole. Through the establishment of the concept that human tendencies are formed and act in line with nature, Chinese gender cosmology applies an analogous generative model of yin and yang to a general understanding of the world. Another early text, the 3rd century B.C.E. medical compendium Huangdi Neijing (Inner Scripture of the Yellow Emperor), offers one of the most comprehensive definitions of yin and yang: Yin and yang are the dao (“way”) of the heavens and earth, they provide the model for the net (gangji) of all beings, they are the parents of all change and transformation, and the origin of life and death, and the residence for spirit and insight. To heal illness [one] must seek its root. (Zhang 2002: 41) Here, yin and yang are taken as a pattern embedded in the existence of all beings, thus providing the foundation for a coherent worldview. This weaves together human beings, nature, and dao(way) in a manner that creates a dynamic wholeness pervaded by and mediated through the interaction of yin and yang. This Chinese cosmological view sees all things, including humans, as borne of both yin and yang and thus naturally integrated with one another. In essence, daorepresents the interaction between yin and yang, and it is in this respect that the Laozi tells us that dao is both the source and the model, or pattern, for all things (Laozi 25). More directly, the Laozi comments that all things in turn carry yin and embrace yang (Laozi 42). This shows that through yin and yang and their patterns of interaction dao provides the rhythm of the cosmos. From this perspective the genders also complement and nourish one another, and are even vital to one another. The idea that the interaction of yin and yang generates the myriad things in existence corresponds to intercourse between male and female as the only means for reproducing life. Therefore, the nature of men and women in Chinese philosophy is not only based on purely physiological characteristics and differences, but is also the embodiment of yin and yang forces in gender. The dao of men and women are linked to the dao of the universe in terms of reproducing life. This is systematically discussed in the Book of Changes, one of China’s most ancient and influential texts. There, eight trigrams are given, which represent eight natural phenomena and can further be combined to form sixty-four hexagrams. These are expressions of the function and movement of yin and yang. They are composed of two contrasting symbols: the yang-yao unbroken horizontal line, and the yin-yao broken horizontal line. Some scholars see these as referring to the male and female genitals respectively. In this sense, the first two hexagrams qian or “heaven” (which is six yang-yaos) and kun or “earth” (six yin-yaos) can be interpreted as representing pure yin and yang. They are also responsible for the formation of general gender stereotypes in Chinese thought. They provide the gateways for change, and are considered, quite literally, the father and mother of all other hexagrams (which equates to all things in the world). The broad system of the Book of Changes attempts to explain every type of change and existence, and is built upon an identification of yin and yang with the sexes as well as their interaction with one another. According to the “Xici Zhuan” (Commentary on the Appended Phrases) section of the Book of Changes, qian is equated with the heavens, yang, power, and creativity, while kun is identified with the earth, yin, receptivity, and preservation. Their interaction generates all things and events in a way that is similar to the intercourse between males and females, bringing about new life. The Commentary on the Appended Phrases makes the link to gender issues clear by stating that both qian and kun have their own daos (ways) that are responsible for the male and female respectively. The text goes on to discuss the interaction between the two, both cosmologically in terms of the heavens and earth and biologically in terms of the sexes. The conclusion is that their combination and interrelation is responsible for all living things and their changes. The intercourse between genders is a harmonization of yin and yang that is necessary not only for an individual’s well-being, but also for the proper functioning of the cosmos. Interaction between genders is thus the primary mechanism of life, which explains all forms of generation, transformation, and existence. Theoretically, the social order of gender in Chinese thought is broadly formed on the concepts of the heavens and earth and yin and yang. When these notions are applied to the social field, they are likened to the male and female genders. In the aforementioned Commentary on the Appended Phrases, heaven and yang are considered honorable, while the earth and yin are seen as lowly in comparison. Since the former are coupled with qian, which comprises maleness, and the latter with kun, which marks femaleness, these gender roles are valued similarly. The Inner Scripture of the Yellow Emperor says that yang’s maleness is meant for the outside, and yin’s femaleness for the inside. Men, being equated here with yang, are also associated with superiority, motion, and firmness, while women are coupled with yin and so seen as inferior, still, and gentle. Gender cosmology then largely replaced more dynamic views of gender roles with sharply defined unequal relationships, and these were generally echoed throughout the culture. The social order that emerged from this thought saw men as largely in charge of external affairs and superior to women. The specific operational mode for maintaining this social order and its gender distinctions is li, propriety or ritual. The Record of Rituals focuses much of its discourse on specific rules regarding distinct practices reserved for certain individuals through gender categorization. In this way, wedding ceremonies are the root of propriety. Marriage is especially important because it is politically valuable for establishing and sustaining social order through designated male-female relations. In the Record of Rituals, men and women are asked to observe strict separation in society and uphold the distinction between the outer and inner. (Men being responsible for the family’s “outer” dealings, including legal, economic, and political affairs, and women the “inner” ones, such as familial relations and housework.) Social roles were thereby moralized according to gender. The Record of Rituals also tells us that the rites as a couple begin with gender responsibilities. It states, for example, that when outside the home the husband is supposed to lead the way and that the wife should follow. However, within the home women were supposed to obey men as well, even boys. Before marriage, a girl was expected to listen to her father, and then after marriage to be obedient to her husband, or to their sons if he died. These general guidelines are commonly referred to in other texts as the sancong side or “three obediences and four virtues,” which dominated theories of proper social ordering for most of China’s history. The four virtues—women’s virtue (fude), women’s speech (fuyan), women’s appearance (furong), and women’s work (fugong)—were expounded on by Ban Zhao (45-120 C.E.) in her book Nüjie(Admonitions for Women). She believed that women should be conservative, humble, and quiet in expressing ritual or filial propriety as their virtue. In the same way, a women’s speech should not be “flowery” or persuasive, but yielding and circumspect. She should also pay close attention to her appearance, be clean and proper, and act especially carefully around guests and in public. Her work consists mainly in household practicalities, such as weaving and food preparation. The sancong (three obediences) can also be regarded as a forerunner to the san gang, or “three cardinal guides,” of the later Han dynasty (25-220 C.E.). The three cardinal guides were put forward by the aforementioned Dong Zhongshu and contributed greatly to integrating yin and yang gender cosmology into the framework of Confucian ethics. These guides are regulations about relationships—they are defined as the ruler guiding ministers, fathers guiding sons, and husbands guiding wives. Although these rules lack specific content, they do provide a general understanding for ordering society that is concentrated on proper relationships, which is the basic element for morality in many Confucian texts. Here a strong gender bias emerges. The partiality shown toward the elevated position of husbands is only further bolstered by the other two relationships being completely male-based. The only time females are mentioned they are last. Moreover, the ranking of the relationships themselves are hierarchical, relegating women to the lowest level of this order. Dong also elaborated on distinguishing goodness from evil based on elevating things associated with yang and its general characteristics as ultimately superior to yin, and at the same time emphasized their connections to gender characteristics. This further reinforces deep gender bias. The language of Dong’s Spring and Autumn Annals praises males and presents a negative view of females and all things feminine. The text explicitly argues that even if there are ways in which the husband is inferior to the wife, the former is still yang and therefore better overall. Even more drastically, it states that evilness and all things bad belong to yin, while goodness and all things good are associated with yang, which clearly implicitly links good and evil to male and female, respectively. There are places where, due to the interrelated correlative relationship between yinand yang, the female might be yang and therefore superior in certain aspects, but since she is mostly yin, she is always worse overall. The text even goes so far as to require that relationships between men and women be adjusted to strictly conform to the three cardinal guides. Rules require that subjects obey their rulers, children their fathers, and wives their husbands. In Dong’s other writings, he goes a step further, declaring that the three cardinal guides are a mandate of the heavens. This gives cosmological support to his social arrangement, equating male superiority with the natural ordering of all things. In the Baihutong (Philosophical Discussions in the White Tiger Hall), which is a collection of court debates from the later Han dynasty, discourse on Dong’s guidelines is taken further. During this time, Confucianism was established as the official state ideology and heavily influenced many areas of politics, including court functioning, policies, and education. This, in turn, provided the foundation for a Confucian society in which this ideology successfully penetrated the daily lives of the state’s entire populace. Dong’s interpretation of ancient texts, including his reading of gender cosmology, became especially powerful as Confucianism believes that the basis for social order and morality begins in human interaction, not individuals. In this context, people are mainly understood according to their roles in society or relationships with others, which were already established as naturally hierarchical in the Analects (the record of Confucius’s actions and words). Dong’s work added a distinct favoring of male over female that became increasingly established and widespread as Confucianism became increasingly influential. Conceived of as analogous to the relationship between rulers and ministers, teachers and students, or parents and children, the two sexes were generally assumed to be a natural ordering of the superior and inferior. Although these sexist trends are not found in earlier texts—at least not explicitly—they became quite common after the Han dynasty. (The most controversial exception to this is in Analects 17:25, where Confucius is recorded to have equated petty people and women; however, it is unclear exactly what he meant, and whether or not he was referring to women in general or just “petty” ones.) By the Song dynasty (960-1279 C.E.), mainstream political and intellectual discourse viewed both the ability and moral character of women as significantly inferior to males. The Confucian classic known as the Shijing (Book of Poetry) includes the controversial line “Male intellect builds states, female intellect topples states” (Zhou 2002: 489), which in the Song dynasty became understood as an argument for keeping women out of politics and state affairs. On this basis, the Neo-Confucian thinker Zhu Xi (1130-1200) criticized Wu Zetian, China’s only female emperor, arguing that failure to observe Dong’s three cardinal guides was ultimately responsible for the chaos, violence, and civil wars that had followed the Tang dynasty (618-907 C.E.). Later, during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644 C.E.), the Confucian thinker Zhang Dai (1597-1679 C.E.) developed the idea that males express virtuousness through their ability to debate and contend with one another, while women find virtuousness in lacking this skill. Although he did not expound much on this idea, it was taken to mean that women were both unable and ought not contend with others, including their husband. Their obedience was a display of morality. Similarly, men were expected to dominate their wives in a somewhat disrespectful manner in order to display their own ethical cultivation. In more extreme interpretations, Zhang’s notion was read as “a woman without talent is virtuous.” This was linked to the cosmological understanding of gender roles so that failure to follow these guides meant the betrayal of natural patterns—the traditional foundation for ethical norms. During this time, imperial law stated that any man over forty without a male heir must take on a concubine to aid him in producing one. The domination of these views in both culture and philosophy caused the Chinese tradition to attach great importance to hierarchical gender roles. Social order based itself on cosmological theories that were automatically normative and constituted guidelines for moral cultivation. Despite the Book of Changes and Laozi’s emphasis on the importance of the interaction between yin and yang as complementary and mutually constitutive, women were generally regarded as inferior. Ideal political and social order in the state was regarded as a replication of the family model on a larger scale. The way neighbors interacted, friends treated one another, and ministers served rulers were all based on models of familial relationships. Early Confucian texts provided the ideological foundation for this pattern by arguing that morality must be cultivated at home first before it could be adequately practiced in society. In terms of gender, the hierarchical relationships in socio-political spheres were simply extensions of the superiority of husbands in spousal relations. The Record of Rituals explains, “Just as two rulers cannot coexist in one country, a household cannot have two masters; only one can govern” (Zheng 2008: 2353). Dong Zhongshu’s three cardinal guides promoted this attitude by requiring that wives listen to their husbands in the same way that children should listen to fathers and then further placing the spousal relationship below that of father and son. Zhu Xi bolstered this order by arguing that children should respect both parents, but that the father should be absolutely superior to the mother. Zhu recognized that there were aspects of life, mostly household affairs (nei), that women were well suited for, but saw men’s duties as superior, and therefore advocated that males always dominate females. In line with the mutual relationship of yin and yang emphasized by the Book of Changes and Daoism, marriages were largely understood as being a deferential equivalence. The wedding rites in the Record of Rituals say that marriages are important for maintaining ancestral sacrifice and family lineages. The text describes that when a groom gives a salute, the bride can sit, and that during the ceremony they should eat at the same table and drink from the same bottle to display their mutual affection, trust, and support. This also aligns the woman, who had no official rank of her own, with her husband’s rank. The Record of Rituals further records that during China’s first dynasties, enlightened monarchs respected their wives and children, and that this is in line with natural order or dao. The Xiaojing (Classic of Filial Piety) also says that rulers should never insult even their concubines, let alone their wives. Although only leaders are mentioned, according to Chinese ethical systems people are supposed to emanate their superiors, so this deference would ideally be practiced in every household. However, such roles were largely based on function. For men this meant learning, working, and carrying on the ancestral line. Women were in charge of household affairs and principally responsible for producing a male heir. If they failed in the latter, their martial function was largely unfulfilled, which reflected poorly on the husband, as well. Since the women’s function was largely mechanistic, her status was much lower and she was essentially anonymous, without independent social standing. Men could take on concubines to produce heirs or simply for pleasure, and while wives were “in charge” of concubines, they could also be (albeit rarely) replaced by them, and would have to serve the sons of concubines if they produced none of their own. Legally, men owned their wives, and there was often little practical recourse for a woman against her husband, even though the laws of certain periods allowed for it. The Book of Poetry contains a large number of poems and songs describing marriage and love between men and women, some of which express the joys and sorrows of women. The collection includes lamentations of men going off on business or to war, and women’s complaints of being abandoned by their husbands after concubines are purchased. They are meant to remind husbands of social expectations and moral responsibilities. The Lienüzhuan (Biographies of Virtuous Women) and Xunzi both argue that the husband-wife relation is foundational for the family, and therefore for a stable society, as well. (The Zhongyong, or Doctrine of the Mean, adds that the sage’s virtue is found most simply in husband-wife relations.) Liu Xiang (77 B.C.E.-6 C.E.), the complier of the Lienüzhuan, firmly believed that morality starts in the family and reverberates out into society. He grouped virtuous women into six categories, or virtues: maternal rectitude (muyi), sage-like intelligence (xianming), humane wisdom (renzhi), purity and deference (zhenshun), chastity and dutifulness (jieyi), and skill in arguments and communication (biantong). Later editions of this text became less gender specific, but Liu emphasized women who were able to carry out certain female-related duties in role-specific conditions (including those of daughter, wife, daughter-in-law, and mother). Although Liu did not mention it, later texts argued that widows should not remarry or take on lovers. The Neo-Confucian thinker Cheng Yi (1033-1107) was one of the harshest interpreters of widow fidelity, claiming that they should rather starve to death than take on a second husband. Zhu Xi, who disagreed with Cheng on many issues, argued that this was not practical; yet it was generally regarded as virtuous, even if not widely practiced. Cheng’s proposal was also important because he did not restrict such devotion to women, which created a rare sense of equality (of which Zhu also disapproved). Analogous to yin and yang, the relationship of the wife and “inner” with the husband and “outer” is conceived of as complementary, not dualistic. According to the functional distinction of “inner” and “outer,” women were responsible for everything in the house, while men dominated external affairs. The most basic form of this division was given as “Men plow and women weave” (nan geng nü zhi). However, this distinction is not equivalent to the Western concepts of private and public. In fact, during the Wei-Jin period of national disunity (265-420 C.E.), it was common for women in northern Chinese states to handle family legal matters at court, go out to present gifts, and handle certain business matters. The woman’s role was not always marginalized, but it was focused on specific tasks. Chinese families often believed that educating their daughters well (though not necessarily in literary learning) was the precondition for improving the family and encouraging orderliness. Women were also often the primary caretakers and to some extent educators of all children, male or female—an invaluable role for the entire household. A couple’s shared goals, like obtaining wealth or educating children, were designated into separate spheres that either the wife or husband would control. The third-century B.C.E. philosophical miscellany known as Lüshi Chunqiu (Mr. Lü’s Spring and Autumn Annals) declares that husbands should have clothes to wear without weaving and wives have food to eat without farming because of their division of labor, which allows for a more efficacious family and society. Individual differences should be acknowledged so that the couple can support and assist one another. Ref

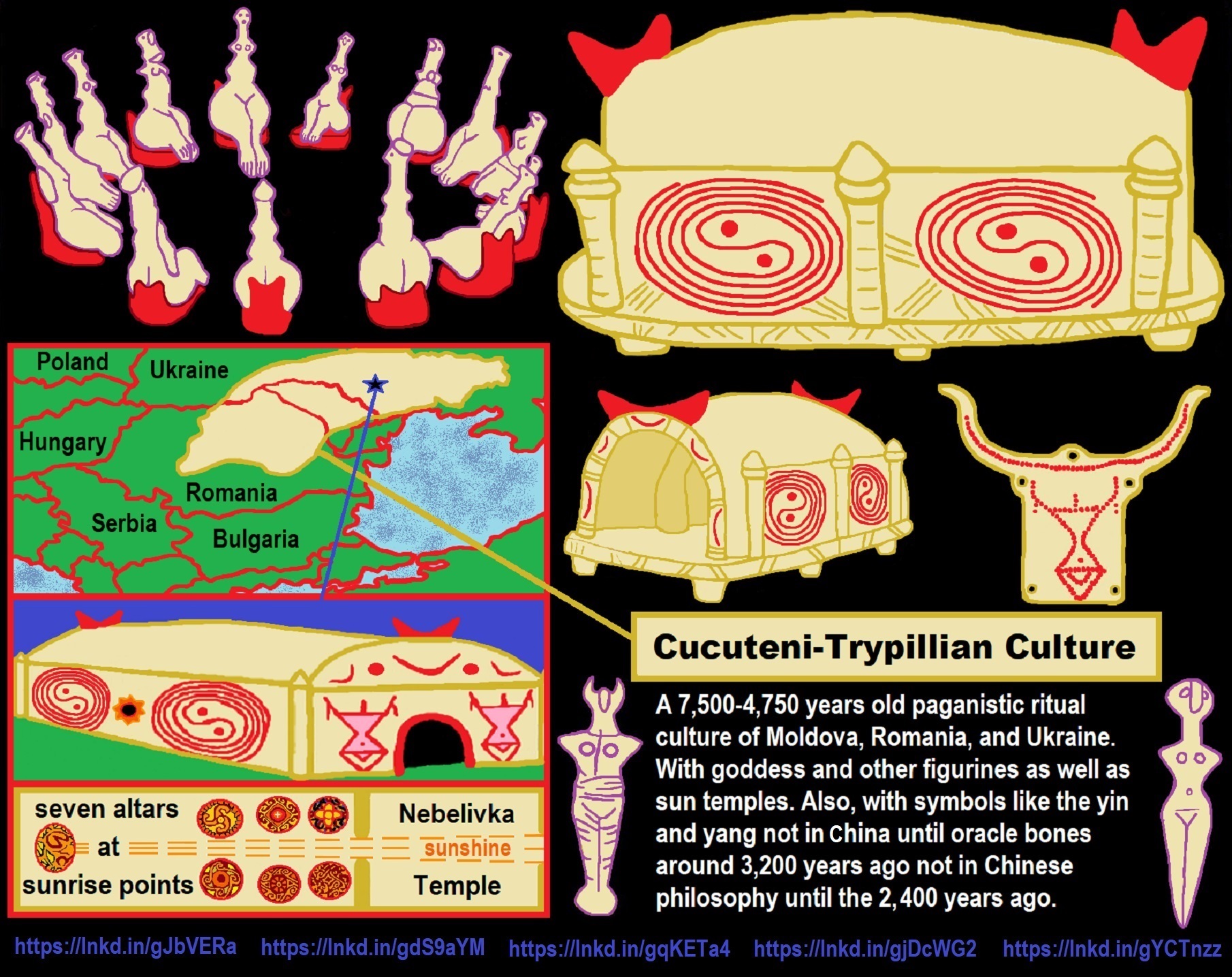

Cucuteni–Trypillia Culture

“The Cucuteni–Trypillia culture (Romanian: Cultura Cucuteni and Ukrainian: Трипільська культура), also known as the Tripolye culture (Russian: Трипольская культура), is a Neolithic–Eneolithic archaeological culture (c. 5500 to 2750 BCE) of Eastern Europe. It extended from the Carpathian Mountains to the Dniester and Dnieper regions, centered on modern-day Moldova and covering substantial parts of western Ukraine and northeastern Romania, encompassing an area of 350,000 km2 (140,000 sq mi), with a diameter of 500 km (300 mi; roughly from Kyiv in the northeast to Brașov in the southwest).” ref

“The majority of Cucuteni–Trypillia settlements consisted of high-density, small settlements (spaced 3 to 4 kilometers apart), concentrated mainly in the Siret, Prut, and Dniester river valleys. During the Middle Trypillia phase (c. 4000 to 3500 BCE), populations belonging to the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture built the largest settlements in Neolithic Europe, some of which contained as many as three thousand structures and were possibly inhabited by 20,000 to 46,000 people.” ref

“One of the most notable aspects of this culture was the periodic destruction of settlements, with each single-habitation site having a lifetime of roughly 60 to 80 years.[7] The purpose of burning these settlements is a subject of debate among scholars; some of the settlements were reconstructed several times on top of earlier habitational levels, preserving the shape and the orientation of the older buildings. One particular location; the Poduri site in Romania, revealed thirteen habitation levels that were constructed on top of each other over many years.” ref