ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

-

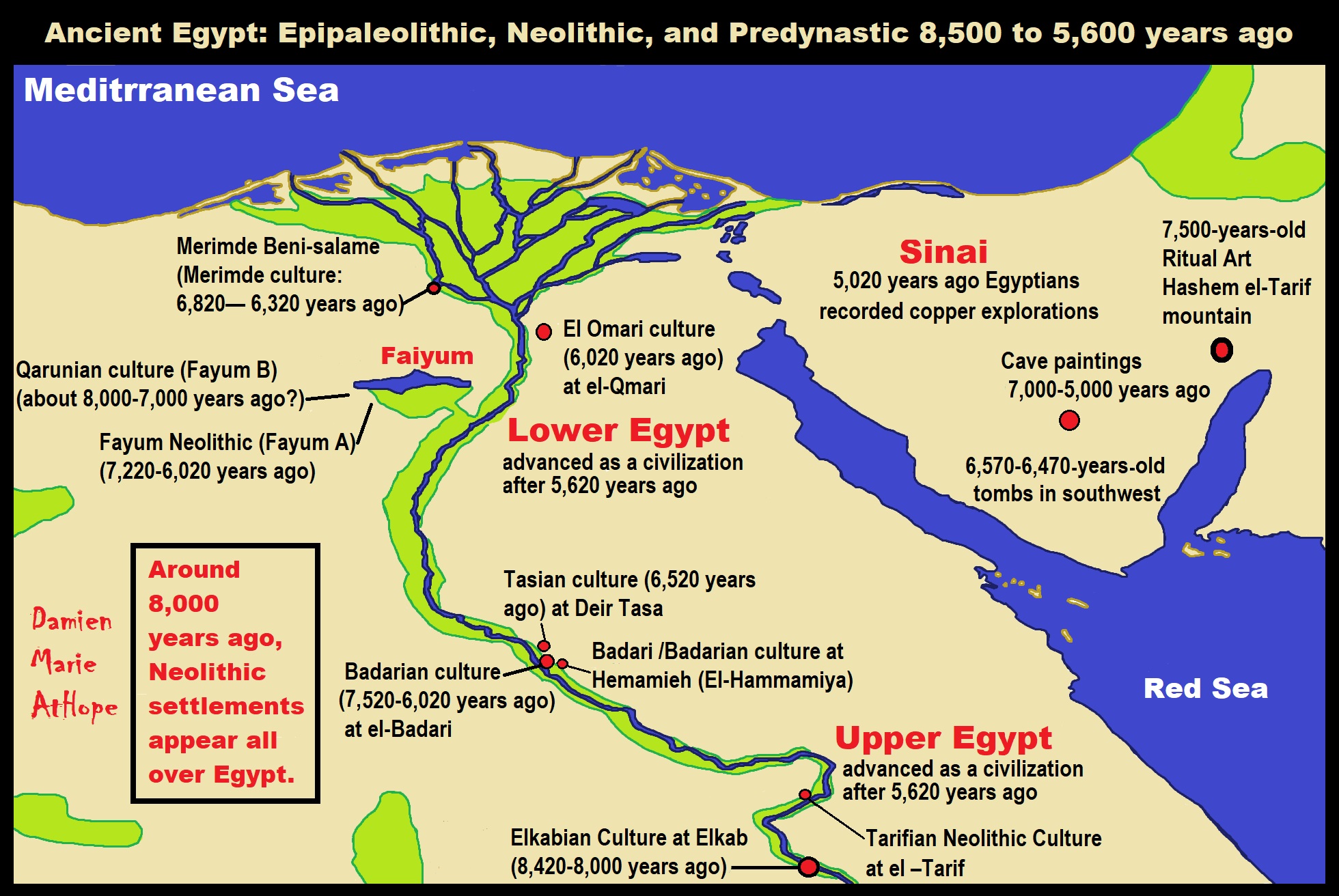

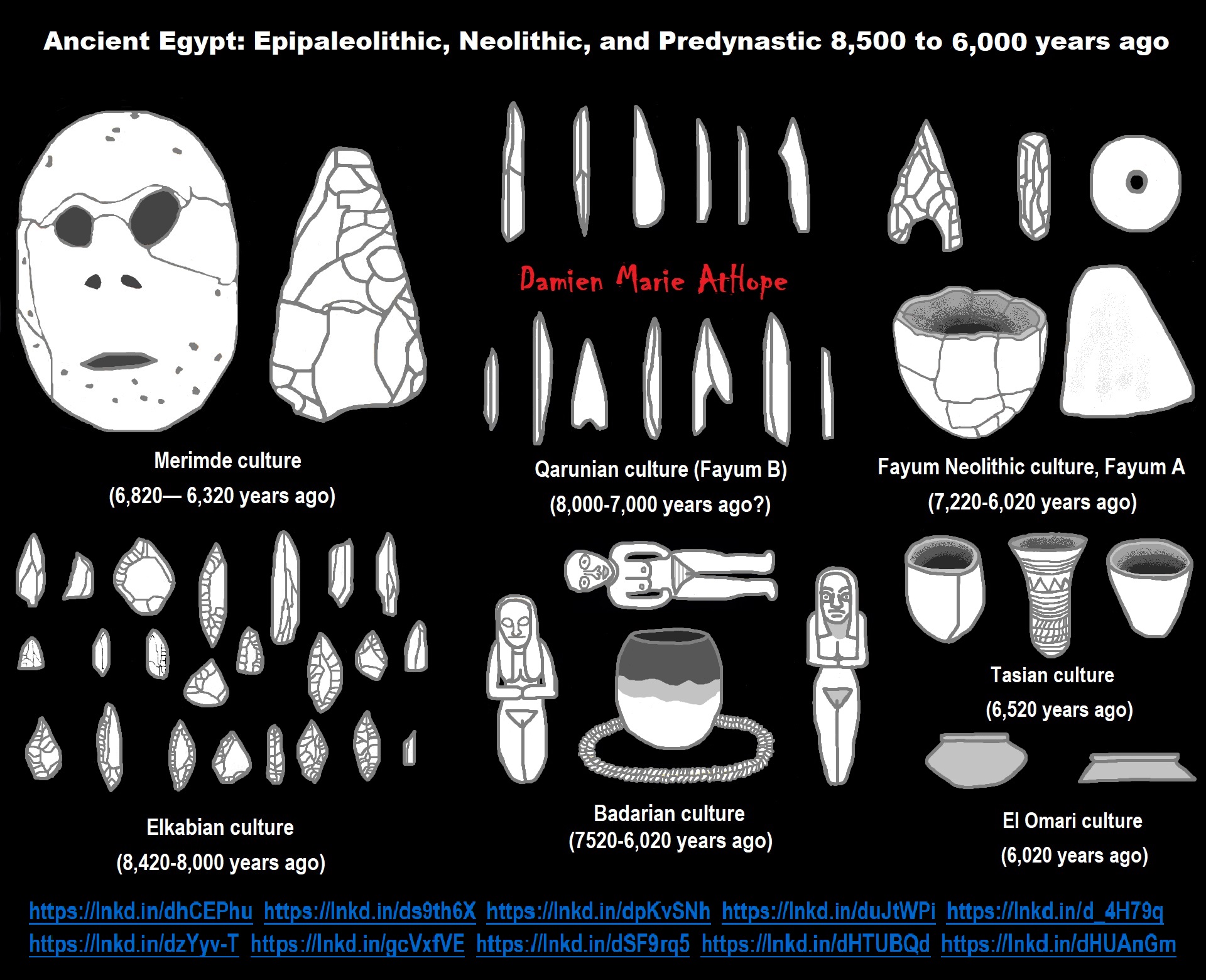

Fayum Neolithic (Fayum A) (7,220-6,020 years ago) is similar to Qarunian culture and contemporary with the Neolithic culture of Merimde as well as connected with it in many ways. ref

-

Epipaleolithic Egypt: Two main cultural groups have been found that date to the Epipaleolithic (or final Paleolithic) Period; the Qarunian culture in the Faiyum, and the Elkabian culture in Upper Egypt. The Qarunian people (also designated as Faiyum B) hunted gazelle, hippo, waterfowl, and hartebeest and fished extensively. Evidence of their campsites along the banks of the marshland dater to between 6240 and 5480 BC. They used small-backed microlithic blades, often formed from chert. When the Faiyum was cut off from the Nile by lower floods (around 5480 BC), their culture disappeared, and the area was not repopulated for around 300 years. The Elkabian site consists of a lower level of occupation (around 6400 BC), a middle level (at 6040 BC), and an upper level (at around 5980 BC). As well as plentiful evidence of fishing (some of which suggests there may have been seasonal fishing outposts), there is some indication that they used reed boats to fish in deeper waters. Archaeologists also found numerous ostrich shell beads. ref

-

Tarifian Neolithic Culture at el –Tarif: At the sites of el –Tarif and Armant, archeologists found some remains pointing to an intermediate industry bridging the gap between Epipaleolithic and Neolithic cultures, which was roughly contemporary with the Faiyum A culture of Lower Egypt. There is no evidence that this culture domesticated animals or farmed food, but it is difficult to be certain of this as the excavation of tombs during the New Kingdom all but destroyed any settlements in the area. ref

-

Badari /Badarian culture (7520-6,020 years ago) at el-Badari ref

-

Sites at El Badari (an El Matmar, El Etmanieh, El Hammamiya, and El Mostagedda) offer the first clear evidence of Neolithic industry in Upper Egypt. Located south of the Faiyum, on the eastern bank of the Nile, the Badari were a semi-nomadic people, who formed small settlements and began to cultivate grain and domesticate animals. The exact chronological range of their culture is still debated. A period of 4400 to 4000 BC is certain, but they may have been established as early as 5000 BC. They were originally considered to have emerged from the south (in part because of their relatively simplistic tool use), but it is generally suggested that agriculture and animal husbandry originated not in the south, but in the East. It would seem likely that their origins are to be found in the Merimde culture of Lower Egypt and the Neolithic cultures of the Western Desert. The culture was first identified by its characteristic pottery made from red Nile clay, often with a black interior and rim and a decorative rippled effect on the surface created by combing and polishing. Black beakers with incised decorations that were originally ascribed to an earlier culture labeled as Tasian are now considered to be imported goods from Sudan and the people of the Deir Tasa site are now considered to be part of the Badarian culture. Although their tools were fairly basic, the quality of the pottery is notable. In some cases, the walls of the vessels are thinner than any other example from a predynastic site. No remains of dwellings have been found, only storage pits and postholes suggestive of light structures perhaps made of reeds, skins, or mats. They farmed emmer wheat, barley, lentil, and flax and kept sheep, goats, and cattle. Fishing supplemented their diet, but there is little evidence of hunting. Copper awls and pins, steatite beads, shells, and turquoise found at Badari sites are thought to have been traded goods from the Red Sea and Palestine. However, it is possible that the Badarian people obtained their own copper and malachite, and the culture may have been more technically advanced than previously thought. They buried their dead in small cemeteries on the outskirts of these settlements and also conducted ceremonial burials for some of their domesticated animals. Pits were oval or rectangular. The body was generally interred in contracted position on the left side, facing west with the head to the south. A reed mat or hide was often placed over the body. Although the graves themselves were simple, the deceased was buried with fine ceramics, jewelry, cloth, and fur, and they sometimes included a finely crafted figurine of a female fertility idol and a cosmetic palette. Trigger has described Badari culture as predominantly egalitarian with little social stratification. However, Bard, Hendrickx, and Vermeersch have challenged this view, pointing to the evidence of differing social status displayed by the grave goods found in the cemeteries at Armant and Nagada. ref

-

Tasian culture (6,520 years ago) at Deir Tasa ref

-

El Omari culture (6,020 years ago) at el-Qmari

-

The El Omari culture is known from a small settlement near modern Cairo. People seem to have lived in huts, but only postholes and pits survive. The pottery is undecorated. Stone tools include small flakes, axes, and sickles. Metal was not yet known. Their sites were occupied from 4000 BC to the Archaic Period. ref

-

Lower Egypt advanced civilization after 5,620 years ago. ref

-

Upper Egypt advanced civilization after 5,620 years ago. ref

-

Around 6000 BC, Neolithic settlements appear all over Egypt. ref

-

5,020 years ago ancient Egyptians recorded their explorations to the Sinai Peninsula in search of copper. ref

-

6,570-6,470-years-old tombs in southwest Sinai. ref

-

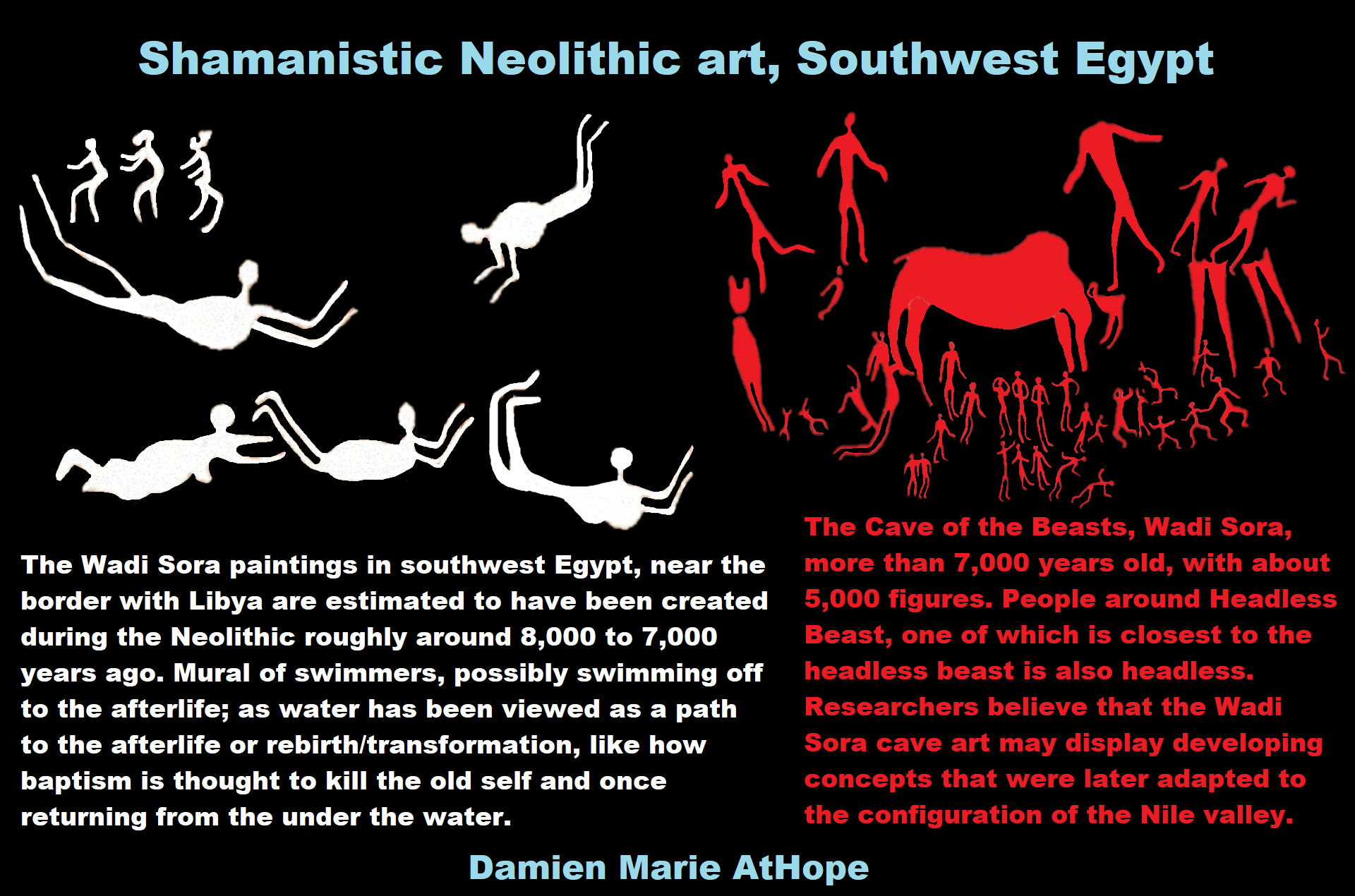

Ritual Art made with stones northeast Egyptian, Sinai, Hashem el-Tarif mountain site of Jebe Hashem alTaref where “stone drawings”, also found in a few other sites (best known- Uvda valley), reflect mythological stories told and acted out some 3000 years before the emergence of writing that dates around 7,500 years ago or about the mid 6th millennium BCE. ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

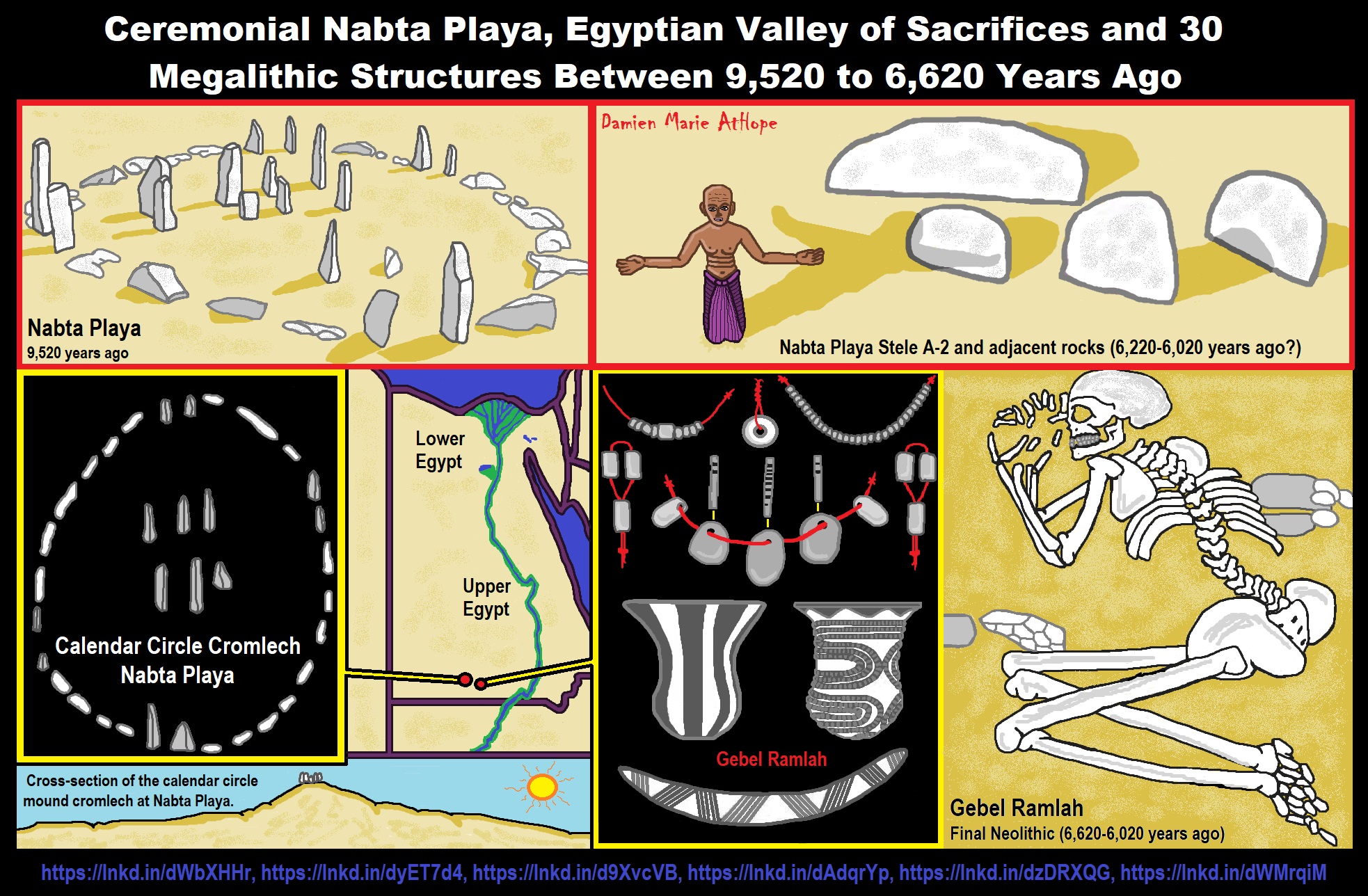

Ceremonial Nabta Playa, Egyptian Valley of Sacrifices and 30 Megalithic Structures Between 9,520 to 6,620 Years Ago

9,520 years ago shows the beginning of early occupation that started to spread throughout the Western Desert of Egypt, such as in Nabta Playa which is just 12 miles northwest of Gebel Ramlah, and findings from the two regions are often compared. Circular stone or pebbles arrangements (interpreted as fireplaces) occur widely in the Sahara with more than 50 dates, ranging from around 9,070 to 3,570 years ago, with a maximum occurrence at 5870–5070 years ago. The first cattle tumuli (evidence of cattle worship) marks Nabta Playa as a key site in the question of evolving complexity with a Saharan cultural mosaic. Cattle tumuli at Nabta Playa are identified as a potential source of evidence on the origins of cattle worship in the ancient Egyptian belief system.

Furthermore, cattle seem to have arrived with the rest of the Neolithic package from Anatolia, into Egypt about 7,700 years ago. By the 6th millennium BCE (8,000-7,000 years ago), evidence of a prehistoric cultic religion appears, with several sacrificed cattle buried in stone-roofed chambers lined with clay. It has been suggested that the associated cattle cult indicated in Nabta Playa marks an early evolution of Ancient Egypt’s Hathor cult. For example, Hathor was worshipped as a nighttime protector in desert regions (Serabit el-Khadim, Temple of Hathor). Overall, there seem to be many aspects of political and ceremonial life in prehistoric Egypt and the Old Kingdom that reflects connections to the Saharan cattle pastoralists like those at Nabta Playa. As rituals progressed around 8,520 years ago with some of the earliest known burials being found at Gebel Ramlah.

Moreover, burials dating to the Middle and Late Neolithic (7,520-6,670 years ago) are scattered throughout the area as well. These are individual burials or sometimes burial clusters, predating the use of large-scale cemeteries in the region. Such individuals were some of the last to inhabit the Western Desert before drought drove them out. Some traveled up the Nile into northern Africa, potentially setting the stage for Ancient Egyptian civilizations. There are cultural elements found in the Final Neolithic of Gebel Ramlah which overlap with or are potential precursors for Ancient Egyptian elements, such as astronomical knowledge and the production of amulets. Additionally, it has been argued that the evidence for passive burial conservation in Gebel Ramlah cemeteries could be a precursor for Ancient Egyptian mummification, perhaps being based in similar protective beliefs. ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

Epipaleolithic Egypt: Two main cultural groups; the Qarunian culture in the Faiyum, and the Elkabian culture in Upper Egypt.

“The Qarunian people (also designated as Faiyum B) hunted gazelle, hippo, waterfowl, hartebeest and fished extensively. Faiyum is a city in Middle Egypt. 62 miles southwest of Cairo, in the Faiyum Oasis. Evidence of their campsites along the banks of the marshland dater to between around 8,240-7,480 years ago. They used small-backed microlithic blades, often formed from chert. When the Faiyum was cut off from the Nile by lower floods (around 7,480 years ago), their culture disappeared and the area was not repopulated for around 300 years.” ref

“Qarunian (Fayum B) culture, well attested at a number of sites in the Fayum (a late Capsian culture which was centered in the Maghreb mainly in modern Tunisia and Algeria, with some lithic sites attested from southern Spain to Sicily and their burial methods suggest a belief in an afterlife. Decorative art is widely found at their sites, including figurative and abstract rock art, and ochre is found coloring both tools and corpses. Ostrich eggshells were used to make beads and containers; seashells were used for necklaces; ref). The stone industry is different to Fayum Neolithic, and characterized by small tools (‘microliths’). However there are some types common to both cultures (the arrowheads), suggestive of connections between them. Knives and scrapers are common. There is no pottery. The settlement site labelled Z by the excavators is thought to have been located about 5 m above the lake level at the time of its use. Not much survived from the settlement, but there is a ‘hearth of ashes’. People must have lived from fishing, hunting and food gathering. The sites are small and were most likely only seasonal and perhaps short-lived.” ref

“The Elkabian site consists of a lower level of occupation (around 8,400 years ago), a middle level (at 8,040 years ago) and an upper level (at around 7,980 years ago). As well as plentiful evidence of fishing (some of which suggests these may have been seasonal fishing outposts), there is some indication that they used reed boats to fish in deeper waters. Archaeologists also found numerous ostrich shell beads.” ref

Elkab, 1937-2007: seventy years of Belgian archaeological research: LINK

“And El-Kab was called Nekheb in Egyptian, a name that refers to Nekhbet, the goddess depicted as a white vulture. First is a series of well-stratified Epipaleolithic campsites dated to 8,400-7,980 years ago, these are the type-sites of the Elkabian microlithic industry, a prehistoric cultural sequence of Egypt before the earliest Neolithic (7,500 years ago).” ref

Introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt

Epipaleolithic (Final Paleolithic)

“With warmer weather globally in the early Holocene, glaciers in the northern hemisphere began to melt and sea levels rose worldwide. In the Nile Valley, many occupation sites of the last Paleolithic hunter-gatherers are probably deeply buried under alluvium. Consequently, little evidence of the Epipaleolithic has been recovered from within the Nile Valley. Only two Epipaleolithic cultures have been found, both dating to around 9,000 years ago or less and after: the Qarunian culture with sites in the Faiyum region, where a much larger lake existed than the present one, and the Elkabian, in southern Upper Egypt.” ref

“At some Epipaleolithic sites in the Middle East, such as Abu Hureyra in Syria and Natufian sites in Israel, there is evidence of transitional cultures which led to the important inventions of the Neolithic. But such evidence, especially the transition from harvesting wild cereals to cultivating domesticated ones, is lacking in Egypt because the innovations of a Neolithic economy were introduced into Egypt and not invented there.” ref

“While Epipaleolithic hunter-gatherers at Natufian sites (12,,000–10,,000 years ago) were living in permanent villages occupied year round, such evidence is missing in Egypt until much later, in the Predynastic Period, and even then the evidence of permanent villages and towns is ephemeral. Working in the Faiyum, Gertrude Caton Thompson (see 1.4) identified two Neolithic cultures, which she termed Faiyum A and Faiyum B. The latter was thought to be a degenerated culture that followed Faiyum A.” ref

“Investigations in the Faiyum have identified Faiyum B as the Epipaleolithic Qarunian culture, ca. 1,000 years before the Neolithic Faiyum A. The Qarunian people were hunter-gatherers-fishers who lived near the shore of the lake. There is no evidence to suggest that they were experimenting with the domestication of plants and animals. They hunted large mammals such as gazelle, hartebeest, and hippopotamus, and fishing of catfish and other species provided a major source of protein.” ref

“The tool kit was microlithic, with many small chert blades. Fishing was also important for the Epipaleolithic peoples at Elkab, and they may have used (reed?) boats for deep-water fishing in the main Nile. Originally these sites were located next to a channel of the Nile. The evidence has been relatively well preserved because the sites were later accidentally protected by a huge enclosure built at Elkab in the Late Period, long after the Nile channel had silted up. Like the Qarunian, the tools at these Elkab sites are microlithic, with many small burins (chisel-like stone tools). Grinding stones are also present.” ref

“These were probably used to grind pigment, still in evidence on the stone, not to process cereals or other wild plants for consumption. Mammals, such as dorcas gazelle and barbery sheep, were also hunted. The sites were camps with no evidence of permanent occupation, and the hunters may have gone out of the Valley for seasonal hunting in the desert, which in the early Holocene had become a less arid environment.” ref

Saharan Neolithic

“Although there is evidence in southwest Asia of early Neolithic villages practicing some agriculture and herding of domesticated animals by 10,000 years ago, contemporary Neolithic sites in Egypt are found only in the Western Desert, where the evidence for subsistence practices is quite different from that in southwest Asia. Occupation of the Western Desert sites was only possible during periods when there was rain, as a result of northward shifts in the monsoon belt. In the early Holocene there was not enough rainfall in the desert for agriculture, which in any event had not yet been invented or introduced into Egypt.” ref

“Permanent villages are unknown in the earliest phase and the sites are like the seasonal camps of hunter-gatherers. While there may have been permanent settlements later, these were not villages increasing in size and population, and after about 7,000 years ago, they were gradually abandoned, as the Western Desert became more and more. The Saharan Neolithic sites do not represent a true Neolithic economy. They have been classified as Neolithic because of the possible domestication of cattle, which seem to have been herded, and the presence of pottery.” ref

“Three periods of the Saharan Neolithic have been identified in the Western Desert: Early (12,800–10,800 years ago), Middle (10,500–9,100 years ago), and Late (7,100–6,700 years ago). Excavated by Fred Wendorf, Neolithic sites in the Western Desert have been found in a number of localities, especially Bir Kiseiba (more than 250 km west of the Nile in Lower Nubia) and Nabta Playa (ca. 90 km southeast of Bir Kiseiba). Neolithic sites are also found farther north in Dakhla and Kharga Oases.” ref

“At Early Neolithic sites Wendorf has evidence of small amounts of cattle bones and argues that cattle could not have survived in the desert without human intervention, that is, herding and watering. Whether these herded cattle were fully domesticated, or were still morphologically wild, is problematic. By 9,500 years ago there is evidence of excavated wells, which may have provided water for people and cattle, thus making longer stays in the desert possible.” ref

“But hare and gazelle were also hunted, and cattle may have been kept for milk and blood, rather than primarily for meat, as is still practiced by many cattle pastoralists in East Africa. Early Neolithic tools include backed bladelets (with one side intentionally blunted), some of which are pointed and were probably used for hunting. Grinding stones were used to process wild grass seeds and wild sorghum, which have been preserved at one Nabta Playa site. Later evidence at the same site includes the remains of several rows of stone huts, probably associated with temporary lake levels, as well as underground storage pits and wells.” ref

“The Nabta Playa is one of the earliest of the Egyptian Neolithic Period, is dated to 9,500 years ago in the Nubian Desert. By the 6th millennium BCE/8,000-7,000 years old evidence of a prehistoric religion or cult appears, with a number of sacrificed cattle buried in stone-roofed chambers lined with clay. It has been suggested that the associated cattle cult indicated in Nabta Playa marks an early evolution of Ancient Egypt‘s Hathor cult. For example, Hathor was worshipped as a nighttime protector in desert regions (see Serabit el-Khadim). There are thought to be many aspects of political and ceremonial life in prehistoric Egypt and the Old Kingdom that reflects a strong impact from Saharan cattle pastoralists. Other subterranean complexes are also found in Nabta Playa, one of which included evidence of perhaps the oldest known sculpture in Egypt. By the 5th millennium BCE/7,000-6,000 years ago these peoples had fashioned what may be among the world’s earliest known archeoastronomical devices (roughly contemporary to the Goseck circle in Germany and the Mnajdra megalithic temple complex in Malta). These include alignments of stones that may have indicated the rising of certain stars and a “calendar circle” that indicates the approximate direction of summer solstice sunrise. “Calendar circle” may be a misnomer as the spaces between the pairs of stones in the gates are a bit too wide, and the distances between the gates are too short for accurate calendar measurements.” An inventory of Egyptian archaeoastronomical sites for the UNESCO World Heritage Convention evaluated Nabta Playa as having “hypothetical solar and stellar alignments.” ref

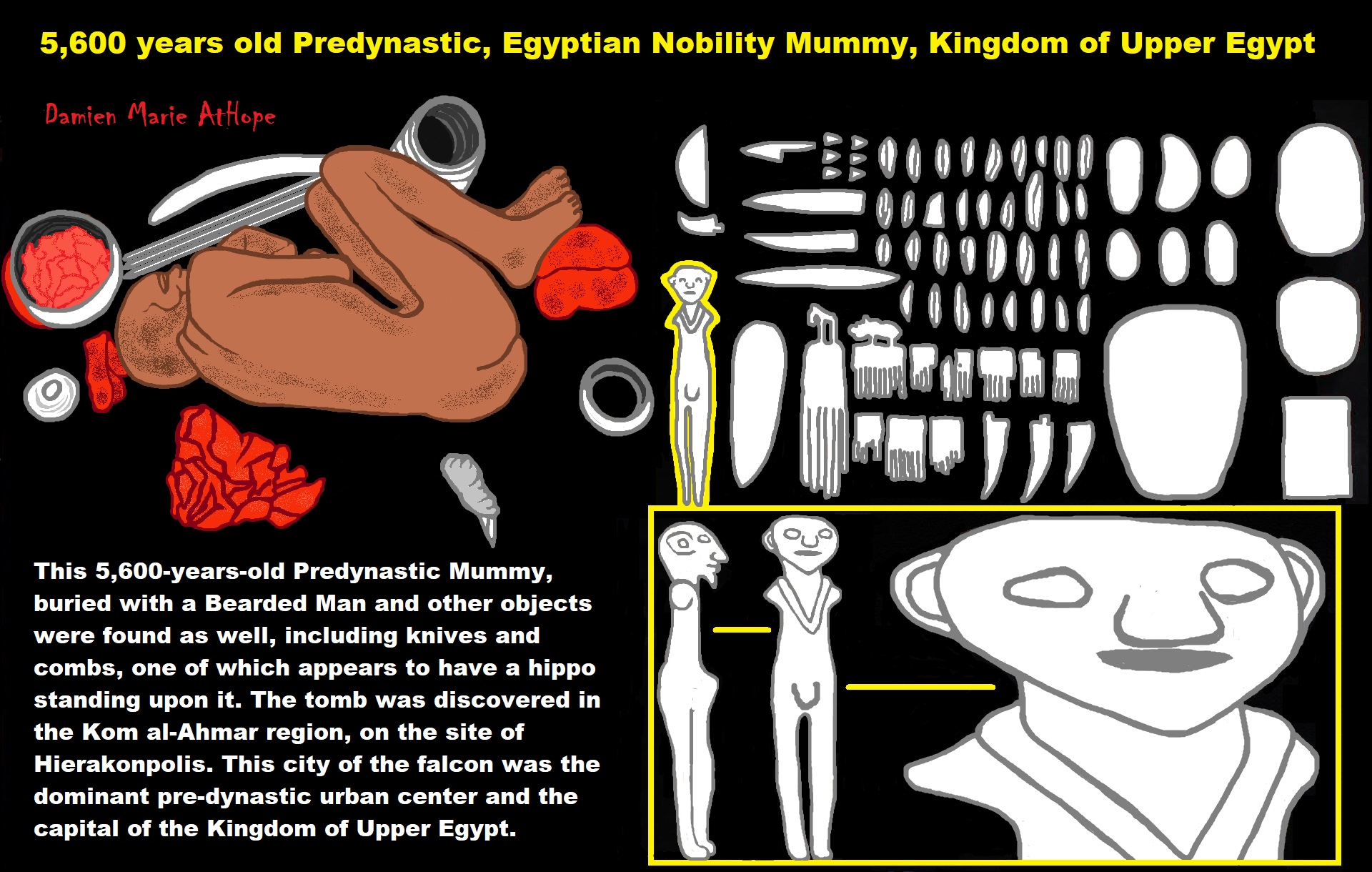

“Similar to one found in Upper Egypt, El-Badari made of Hippopotamus ivory carved into the figure of woman; incised eyes and pubic-triangle, dated to around 6,400-6,000 years ago mortuary figure.” ref

Goddess Nut

“Nut, in older sources as Nunut, Nent, and Nuit, is the goddess of the sky in the Ennead of ancient Egyptian religion. She was seen as a star-covered nude woman arching over the earth, or as a cow. She was originally the goddess of the nighttime sky, but eventually became referred to as simply the sky goddess. Her headdress was the hieroglyphic of part of her name, a pot, which may also symbolize the uterus. Mostly depicted in nude human form, Nut was also sometimes depicted in the form of a cow whose great body formed the sky and heavens, a sycamore tree, or as a giant sow, suckling many piglets (representing the stars). A sacred symbol of Nut was the ladder used by Osiris to enter her heavenly skies. This ladder-symbol was called maqet and was placed in tombs to protect the deceased, and to invoke the aid of the deity of the dead. Nut was the goddess of the sky and all heavenly bodies, a symbol of protecting the dead when they enter the afterlife. According to the Egyptians, during the day, the heavenly bodies—such as the sun and moon—would make their way across her body. Then, at dusk, they would be swallowed, pass through her belly during the night, and be reborn at dawn.” ref

Some of the titles of Nut were:

- “Coverer of the Sky: Nut was said to be covered in stars touching the different points of her body.

- She Who Protects: Among her jobs was to envelop and protect Ra, the sun god.

- Mistress of All or “She who Bore the Gods”: Originally, Nut was said to be lying on top of Geb (Earth) and continually having intercourse. During this time she birthed four children: Osiris, Isis, Set, and Nephthys. A fifth child named Arueris is mentioned by Plutarch. He was the Egyptian counterpart to the Greek god Apollo, who was made syncretic with Horus in the Hellenistic era as ‘Horus the Elder’. The Ptolemaic temple of Edfu is dedicated to Horus the Elder and there he is called the son of Nut and Geb, brother of Osiris.

- She Who Holds a Thousand Souls: Because of her role in the re-birthing of Ra every morning and in her son Osiris’ resurrection, Nut became a key god in many of the myths about the afterlife.” ref

Woman like Figures in Pre-Dynastic

and

Early-Dynastic Periods

“Small figures commonly showing naked women are already among the earliest depictions of human figure in Egypt. They come from the Badarian period ( around 6,400-6,000 years ago). It is possible that they are intended as fertility figures. Sexual organs are often shown very explicitly. These figures might have different functions: the wish for many children and fertility in agriculture may well have been inseparable. Figures of naked men are also known but not so common. The connection to fertility is not certain. However, already at the end of the Predynastic Period the god of male procreative power, Min was important and already shown ithypallic.” ref

“Figurine evidence for the Old Kingdom (about 4,686-4,181 years ago) is not very abundant. This might reflect the change in burial customs; fertility figures were no longer placed into tombs. There are also not many excavated settlement sites of the period. However, several funerary statues placed in tombs show the (male) tomb owner naked. At the end of the Old Kingdom figures of naked women appear in tombs. However, now they are often interpreted as ‘concubines’ for the tomb-owner who wished to continue a sexual life in the afterworld.” ref

“In the Middle Kingdom small often very stylized figures of naked women were placed in tombs; they have also been found at settlement sites. They seem to have a strong connection to fertility. Their function might have been to guarantee safe childbirth in this life, or regeneration (and sexual activity) in the next world. Nothing similar is known on this (more private) level for male sexuality; though the cult of Min was still one of the main state cults.” ref

“In the New Kingdom record is similar to that of the Middle Kingdom. There are many (female) figures known from settlement sites, evidence for a more domestic fertility cult. A typical new form is the naked woman lying on a bed, sometimes with child by the legs. Votive offerings to the goddess Hathor, found at several of her chapels might also have had a fertility function.” ref

“Early Neolithic pottery is decorated with patterns of lines and points, often made by impressing combs or cords. The pottery (and that of the following Middle Neolithic) is related to ceramics of the “Khartoum” or “Saharo-Sudanese” tradition farther south in northern Sudan. Since potsherds are few at Early Neolithic sites, water was probablyalso stored in ostrich egg shells, of which more have been found (or possibly also in animal skins that have not been preserved).” ref

“Middle and Late Neolithic occupation sites in the Western Desert are more numerous. There are more living structures and wells, as well as the earliest evidence of wattle-and-daub houses, made of plants plastered with mud. Some of these sites may have been occupied year round, while the smaller ones may still represent temporary camps of pastoralists. Sheep and goat, originally domesticated in southwest Asia, are found for the first time in the Western Desert, but hunting wild animals still provided most of the animal protein.” ref

“Bifacially worked stone tools called foliates and points (arrowheads) with concave bases become more frequent. There are also grinding stones, smaller ground stone tools (palettes and ungrooved ax-like tools called celts), and beads. In the Late Neolithic at Nabta Playa and Bir Kiseiba a new ceramic ware appears that is smoothed on the surface. Some of this pottery is black-topped, which becomes a characteristic ware of the early Predynastic in the Nile Valley.” ref

“The appearance of this new pottery in the Western Desert, and later in Upper Egypt, may be evidence for movements of people, but other forms of contact and exchange (of pottery, technology, ideas, etc.) are also possible. After 6,900 years ago more arid conditions prevailed in the Western Desert, making life for pastoralists there increasingly difficult except in the oases, where Neolithic cultures continued into Dynastic times.” ref

“Some very unusual Late Neolithic evidence has been excavated by Wendorf at Nabta Playa, including two tumuli covered by stone slabs, one of which had a pit containing the burial of a bull. Also found there were an alignment of ten large stones, ca. 2 meters × 3 meters, which had been brought from 1.5 kilometers or more away, and a circular arrangement of smaller stone slabs, ca. 4 meters in diameter.” ref

“It has been suggested that the stone alignments had calendrical significance based on astronomical/celestial movements (as is known for more complex stone alignments, the most famous of which is Stonehenge in southern England). Such a specific explanation for the Nabta Playa stone alignments is difficult to demonstrate, but they appear to have had no utilitarian purpose. They should probably be understood as related to the belief system of these Neolithic pluralists.” ref

BOX 4-C

“Although the term “Neolithic” means “New Stone Age,” the technological and social changes that occurred during the Neolithic were some of the most fundamental ones in the evolution of human culture and society. Archaeologist V. Gordon Childe termed this development the “Neolithic revolution.” The technological changes included many more tools used by farmers, which had originally developed in late Paleolithic cultures to collect and process wild plants, including sickle blades as well as axes, to clear areas for farming. More importantly, the Neolithic was the period of transition from a subsistence based on hunting, gathering, and fishing, with people living in small temporary camps, to an economy based on farming and herding domesticated plants and animals, as well as the beginning of village life, which could properly be called the “Neolithic economy.” ref

“Pottery, which was useful for cooking and storage of cultivated cereals, was invented in the Neolithic, although it is also associated with sedentary villages of some earlier (Mesolithic) cultures that did not practice agriculture. Village life would forever change human societies, laying the social and economic foundations for the subsequent rise of towns and cities, which has been termed the “urban revolution.” Some of the changes the Neolithic brought were beneficial: the potential for a permanent supply of food provided by farming and herding, and permanent shelter. Hunting and gathering is physically difficult for child-bearing women, and there was a rise in population associated with the Neolithic. More women of child-bearing years survived to bear more children, and more children were useful for farming activities, especially harvesting.” ref

“But with the Neolithic came new problems. As agriculture and herding spread, large numbers of wild species (and their environments) were replaced by domesticated ones. With a decrease in biodiversity, there was a greater possibility of crop failure and famine, as a result of low floods (in Egypt) and droughts, as well as insect pests and diseases that prey on cultivated plants. Domesticated animals carry diseases that are contagious to humans, especially anthrax and tuberculosis. In dense human populations living in permanent villages infectious diseases also increase: smallpox, cholera, chicken pox, influenza, polio, et cetera. Unsanitary conditions of more people living together can also create an environment that encourages parasites (bacilli and streptococci).” ref

“Human waste and animals that are attracted to villages (rodents, cockroaches, etc.) can carry the bacteria of bubonic plague, leprosy, dysentery, et cetera. Without socially acceptable outlets, the psychological effect of more people living together in permanent settlements can also lead to increased tension and violence. The advantages of the Neolithic economy and village life in Egypt laid the foundations for pharaonic civilization.” ref

“The Egyptian Nile Valley was an almost ideal environment for cereal agriculture, with the potential of large surpluses, which were the economic base of pharaonic society. The population increased greatly during pharaonic times. Fishing remained an important source of protein in the pharaonic diet, while fowling and hunting also continued, mainly as an elite pastime. As the habitats of wild birds and mammals decreased through time, older subsistence strategies acquired new meanings.” ref

Neolithic in the Nile Valley: Faiyum A and Lower Egypt

“In the Egyptian Nile Valley farming and herding were just beginning to be established in the later 6th millennium bc. Since this major cultural transition had occurred much earlier in southwest Asia, with permanent villages in existence in the Epipaleolithic, it seems strange that the Neolithic economy (see Box 4-C) appeared much later in Egypt, and of a very different type there – without permanent villages.” ref

Several explanations for the late development of the Neolithic in the Egyptian Nile Valley have been suggested:

(1) “None of the species of wild plants or animals that later became domesticated, with the possible exception of cattle, were present in Egypt.” ref

(2) “Some of these species (6-row barley, sheep) did not appear in the southern Levant until close to 8,000 years ago, so they could not have appeared in Egypt until after that time. In addition, the Sinai Peninsula, which was too dry for farming, provided an effective barrier for the flow of farming technology between Egypt and the southern Levant.” ref

(3) “The Nile Valley was such a resource-rich environment for hunter-gatherer-fishers that the need to supplement this subsistence with farming and herding did not develop until much later than in southwest Asia.” ref

(4) “Much archaeological information from the Epipaleolithic, when technological developments were taking place which led to the invention of agriculture and herding of domesticated animals in some parts of the Old World, is missing for geological reasons in the Egyptian Nile Valley – especially if such settlements were located next to the river.” ref

“Although none of these is a satisfactory explanation by itself, in combination they help to clarify some of the problems surrounding the lack of evidence for the transition to a Neolithic economy in Egypt. In the Faiyum region there is a gap of about 1,000 years between the Epipaleolithic Qarunian culture and the Faiyum A Neolithic sites are the earliest known Neolithic ones in (or near) the Nile Valley, dating to 7,500–6,500 years ago.” ref

“The sites contain evidence of domesticated cereals (emmer wheat and 6-row barley) and domesticated sheep/goat, all of which were first domesticated in different parts of southwest Asia. Cattle bones were also found, only some of which are domesticated. But there is no evidence of houses or permanent villages, and the Faiyum A sites resemble camps of hunter-gatherers with scatters of lithics and potsherds.” ref

Ancient Egyptian Cattle’s Origin?

“Cattle are attested already in the eighth millennium BC/10,000-9,000 years ago in domestic contexts in Western Asia (Tell Mureybit, Syria). The earliest undisputed cattle remains in Africa were found at Capeletti, Algeria (about 6,500 years ago). In Egypt they appear first in the cultures of Fayum and Merimde, although it is not entirely certain if the remains found are from wild or domestic animals. The bones found at Merimde seem to come from domestic animals. There is much discussion over the origin of cattle in Egypt and Africa in general: are Egyptian cattle originally from the Near East or Africa?” ref

“Studies of ancient Egyptian religion have examined texts for evidence of cattle worship, but the picture given by the texts is incomplete. Mortuary patterns, ceremonial buildings, grave goods, ceramics and other remains also contain evidence of cattle worship and underline its importance to early Egypt. The recently discovered cattle tumuli at Nabta Playa in the Western Desert are identified here as a potential source of evidence on the origins of cattle worship in the ancient Egyptian belief system.” ref

“The desiccation of the Western Desert over the course of the Late Neolithic occurred about the same time as a drop in the flood levels of the Nile River. The tempered, black-topped and red-slipped pottery found in the Late Neolithic layers of Nabta Playa sites E-75-8 and E-94-2 are similar to that of the Badarians in the Nile Valley, suggestive of an interaction between the two areas. And while there is evidence for Eastern Desert influence on the Badarian culture there is a strong element of Saharan culture, which means that we cannot exclude the possibility that the semicircle formed by the Bahariya, Farafra, Dakhla and Kharga oases might have been the point of origin of populations who perhaps already pursued a pastoral mode of subsistence; these people might have been pushed eastwards by increasing aridity and would eventually have settled in the region of Asyut and Tahta.” ref

“[It] might even be suggested that the Neolithic cultures of the oases and the Faiyum could be regarded as the eastern fringes of the Sahara Neolithic groups. And thus, taken together, the two indications above suggest that the population which arrived in Nabta after 7,500 years ago – apparently pastoralists from the Sahara with a new and higher level of organisation – influenced the developments in the nearby Nile Valley. So it could be that the primary external stimulus for the rise of social complexity in Upper Egypt was contact with the pastoralists of the Western Desert. If this view is correct, social complexity in the Nile Valley was the end product.” ref

“Not only of numerous differentiating factors associated with the rise of craft specialisation, but also of the dynamic interaction between two contrasting lifestyles, pastoral and centralized agricultural economies, existing in close proximity. The Nile Valley and desert economies were characterized by structural and functional differentiation providing mutual support for each. Yet a tense harmony would also have been present, as well as diffusion of ideas and practices. Rock art from the Predynastic to the east and west of Armant, situated on the west bank of the Nile River, depicts domesticated cattle with artificially deformed horns, indicative of pastoralism.” ref

“Genetic studies support the scenario that Bos taurus domestication occurred in the Near East during the Neolithic transition about 10,000 years ago, with the likely exception of a minor secondary event in Italy. However, despite the proven effectiveness of whole mitochondrial genome data in providing valuable information concerning the origin of taurine cattle, until now no population surveys have been carried out at the level of mitogenomes in local breeds from the Near East or surrounding areas. Egypt is in close geographic and cultural proximity to the Near East, in particular the Nile Delta region, and was one of the first neighboring areas to adopt the Neolithic package. Thus, a survey of mitogenome variation of autochthonous taurine breeds from the Nile Delta region might provide new insights on the early spread of cattle rearing outside the Near East. The domestication of the wild aurochs (Bos primigenius) was a major element of the Neolithic transition. Archeozoological evidence indicates that taurine cattle were initially domesticated somewhere in the upper Euphrates Valley (likely Turkey or maybe Syria) between 11,000 to 10,000 years ago.” ref

“Initially it was suggested that haplogroup Q might have derived from European aurochsen, while later a parallel history was instead hypothesized for haplogroups Q and T, with Q representing an additional lineage that was domesticated in the Near East and spread with trade and human migrations. Interestingly, a recent survey of prehistoric domestic cattle control-regions has identified haplogroup Q in Middle/Late Neolithic remains from Anatolia/Turkey, and also at extremely high frequencies in skeletal remains from Bulgaria and Romania dated 7,000–4,000 years ago. Overall these findings highlight a growing complexity in the geographic distribution of Q, and lend support to the conclusion of Achilli and colleagues who stated that the parallel history and source of haplogroups Q and T needed to be tested by acquiring coding-region data from a wide range of B. taurus populations, especially from the Near East.” ref

Ancient Egypt: Epipaleolithic, Neolithic, and Predynastic 8,500 to 6,020 years ago

The ancient Egypt most think of today is the culminations of advancing lifestyles and cultural innovations which started to be arranged by some of Egypt’s mysterious Neolithic peoples involving a time from around 11,320 to 6,020 years ago. However, this is especially so from around 8,500 to 6,020 years ago and this provided the foundation for the advanced civilizations to come. The Late Neolithic (7,520-6,670 years ago) with domesticated cattle and goats, wild plant processing and cattle burials moving these successes further in the Final Neolithic (6,620-6,020 years ago), which culminated in the making of structures on the road to latter megaliths, as well as shrines and even calendar circles, something similar to other standing stone circles. During the final part of the Egyptian Neolithic period, people started burying the dead in formal cemeteries. An analysis of grave-pit funerary wrappings with an embalming “recipe” from the Badarian grave at the Mostagedda cemetery site in Upper Egypt shows growing elaborate treatment of the bodies as early as between 6,336 years ago is an early Pharaonic forerunner to more complex processes. Therefore, it was the development of complexity within the predynastic period ending around 5,220 years ago that led to the emergence of the ancient Egyptian religion and its empire state. ref, ref, ref

“One of Egypt’s earliest temples was the shrine of Nekhbet at Nekheb (also referred to as El Kab). It was the companion city to Nekhen, the religious and political capital of Upper Egypt at the end of the Predynastic period (5,200–5,100 years ago) and probably, also during the Early Dynastic Period (5,100–4,686 years ago). The original settlement on the Nekhen site dates from Naqada I or the late Badarian cultures. At its height, from about 5,400 years ago, Nekhen had at least 5,000 and possibly as many as 10,000 inhabitants. Nekhbet was the tutelary deity of Upper Egypt. Nekhbet and her Lower Egyptian counterpart Wadjet often appeared together as the “Two Ladies“. One of the titles of each ruler was the Nebty name, which began with the hieroglyphs for [s/he] of the Two Ladies…. In art, Nekhbet was depicted as a vulture. Alan Gardiner identified the species that was used in divine iconography as a griffon vulture. Arielle P. Kozloff, however, argues that the vultures in New Kingdom art, with their blue-tipped beaks and loose skin, better resemble the lappet-faced vulture.” ref

Picture Link: link

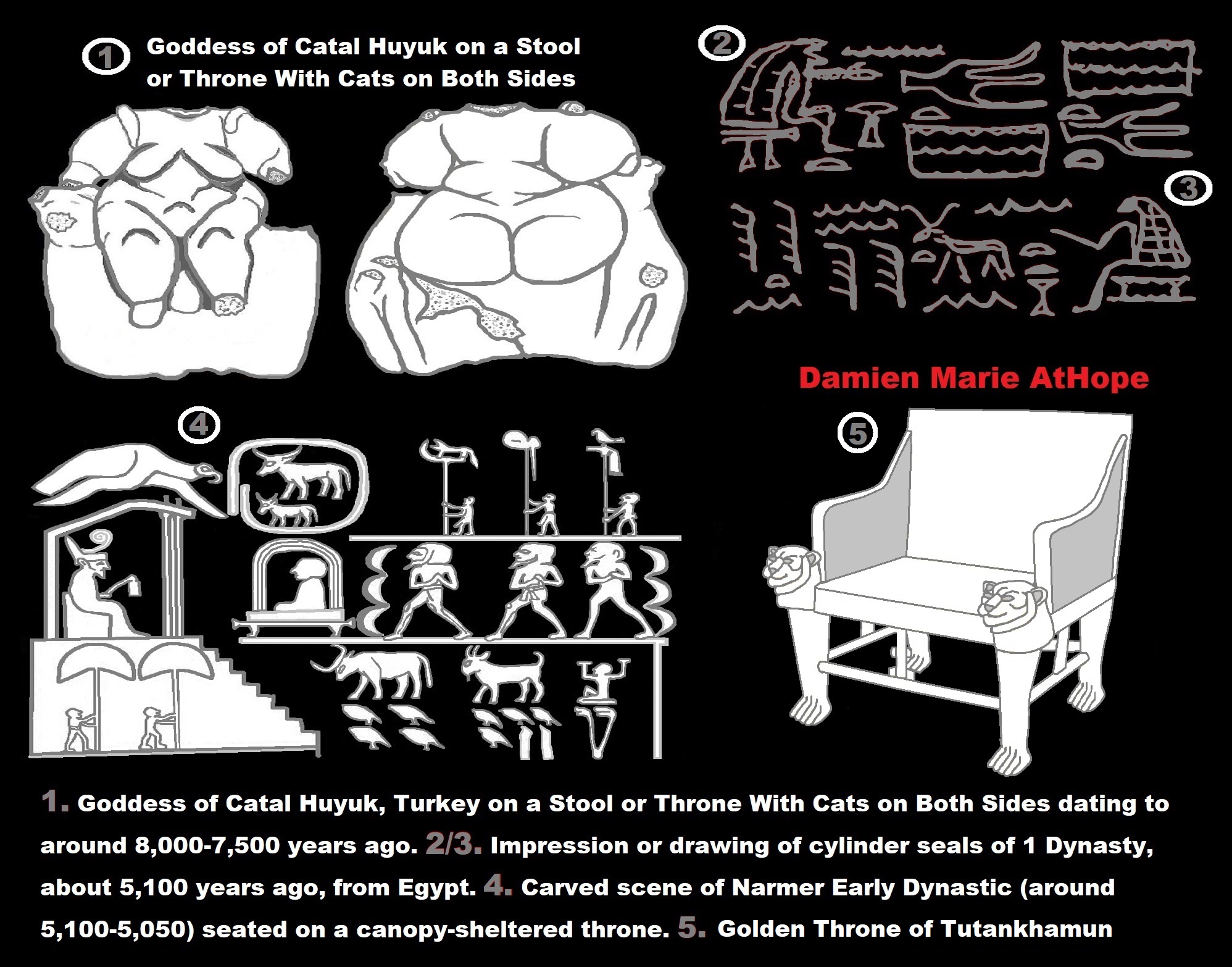

The bull shrine E VI,8 also from a site of Çatal Hüyük, Turkey.

“SVI.B.8, east and west walls, showing modelled splayed figure above a modelled bull’s head on the west wall, with bucrania arranged in front of the east wall at Çatalhöyük.” ref

Egypt, the tomb of King Uadji (after Conrad 1959.Fig. p. 75).

“The Serapeum (a temple or other sacred religious place) of Saqqara is located north west of the Pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara, a necropolis near Memphis in Lower Egypt. It was also a burial place of Apis bulls, sacred bulls that were incarnations of the ancient Egyptian deity Ptah.” ref

Bull Worship at Saqqara – (The facade of tomb 3504)

“The superstructure of the tomb shows evidence of 30 niches and 34 projections along its periphery. The structure was built on a wide platform on which, placed at reguar intervals, were clay bovine heads with real horns. At the rate of 7 to each niche and 4 on the facade, there would have been a total of 346. The bull played a considerable role in the Old kingdom, and in the pyramid texts the King is often called ‘The Bull of the Sky’. But because of its horns the bull was also related to the moon. Thus it is tempting to note that the number of bull heads here approximates to that of 12 lunations (354 days), and extremely close to the number of days which Sir Fred Hoyle related to the periodic return of eclipses.” ref

“Bucrania, or bull skulls, were used as a decorative motif in the architecture of First Dynasty Egypt. There is both archaeological and icongraphic evidence for this – bucrania have been excavated in the mastabas of Saqqara, and there artifacts from the period with depictions of buildings surmounted by bucrania. Comparative material, such as the bucrania found in situ at the burials of Kermaand the practice of human sacrifice during the Egyptian First Dynasty, can beexamined to gain insight into the significance and deeper meaning of the bucrania. This article will study the available evidence in an attempt to answerhow and why bucrania were used in the architecture of First Dynasty Egypt. In architecture, a bucranium (pl. bucrania) is a “carved decorative motif depicting theskull of a bull.” It can also refer to the skull and horncones of a real animal, or to a head modelled entirely from clay or plaster with realhorn cones. Bucrania have been found at sites across the ancient world, and their usein architecture is particularly famous at the Neolithic site of Çatalhöyük in modern-day Turkey. While the evidence for the use of bucrania islimited during later periods, there are examples from the First Dynasty from both the archaeological and iconographic records. The First Dynasty only lasted about 200 years, and based on the amount of evidence for the use of bucrania in the architecture of this period, it follows that bucrania were especially important during the First Dynasty.” ref

“Bucrania were used to decorate mastabas in the First Dynasty necropolis at Saqqara. The most elaborate decoration belonged to Tomb 3504. A low bench ran along the base of the mastaba. Approximately 300 life-size bulls’ heads, modeled from clay and with large natural horns, were mounted upon this platform. The bulls’ heads were arranged in a symmetrical pattern, each head held in place by two wooden pegs. There were traces of blue and red paint on the bulls’ heads, but it is uncertain if the heads were painted, or if these were splashes of paint from when the structure itself was painted.Tomb 3504 can be dated to the reign of Djet, the fourth pharaoh of the First Dynasty, by the labels and sealing impressions found within. The burial chamber was restored and remodeled towards the end of the First Dynasty, which led Emery to suggest that it was the burial place of “Uadji or some other important member of his family” and, because of its grandeur, it was thought to belong to Djet himself. It has also been identified as belonging to Djet’s predecessor, Djer. However, it cannot be the tomb of a pharaoh, because the pharaohs of the First Dynasty were buried in the Umm el-Qa’ab.” ref

“SVI.10 east wall, with modelled bull’s head and open breasts each containing the skull of a griffon vulture (Gyps fulva) with beak protruding from red-painted areola.” ref

Cattle burials in Nabta Playa and the Nile Valley

“On the western edge of the largest wadi to the north of Nabta is the first of two differing types of stone-covered tumuli marking the burial sites of cattle. Seven out of the nine tumuli examined have been excavated. At E-94-1n, at the northern end of the Late Neolithic ceremonial complex, the stones covered the articulated remains of a young cow in a clay-lined chamber. Radiocarbon tests on the wood from the roof returned a date of 7,400 years ago.” ref

“The poorly preserved cow is around 125 cm. in height, with the spine oriented north-south and its head facing south. The second type of tumulus consists of disarticulated Bos bones scattered between unshaped rocks. Sites E-94-1s, E-96-4, E-97-4, E-97-6 and E-97-16 are associated with the remains of 3, 4 (2 sub-adult, 2 young adults), 2 (1 juvenile, 1 sub-adult), 1 and 1 (sub-adult) bovines respectively. No particular body part was deliberately selected for deposition. A similar emphasis on the cattle cult can be observed in Egypt. The Nabta cattle burials are paralleled somewhat by the Badarian animal graves. Certain animals, including Bos, were revered during Badarian times as witnessed by their burials in select sections of different cemeteries either on their own, or in association with human burials or within human graves.” ref

“This does not presuppose that each species was buried for the same purpose, since pattern variation within the burials is well documented by Flores. Some graves had linen and matting which may have covered the animal. Cow remains are present in numbers at Hammamiya. Human and Bos remains were also sometimes found buried together. The latter practice continued down into late Old Kingdom times, as evidenced by the ox burials at Qau. These later burials show signs that the cattle had been carefully dismembered before burial. A Bos burial from Tomb 19 at Hierakonpolis Locality Hk6 and the tomb dates either to the end of Nagada I or to the beginning of Nagada II.” ref

“Its occupant is a specimen of Bos primigenius (the wild ancestor of the domestic cow Bos taurus). Reed matting and resin were utilised in the burial of the whole corpse, as indeed they were with human burials in the same locality. Remains of cattle have also been uncovered at localities Hk11, Hk29 and Hk29A at Hierakonpolis. Many of the Bos from Hk11 were of mature age, which is indicative of animal husbandry and possibly this reflects their use for purposes other than to supply meat (e.g. dairy products, draft animals, religious or social symbols). Locality Hk29 also displays strong signs of animal husbandry but it is at Hk29A, a ceremonial complex dating to late Nagada II, where something unusual occurs in the faunal patterns.” ref

“There is a discrepancy between the cranial and post-cranial age profiles, wherein the younger Bos crania are under-represented. The implication of ritual activities involving cattle at Hk29A is given additional weight by Friedman (1996: 30), who states that “representations [on Predynastic seals and vessels] of fences topped with the impaled heads (mainly cattle) may explain the head to torso discrepancy among the faunal remains at HK29A”. From the Terminal Predynastic period, cattle burials have been found at the Nubian A-Group cemetery at Qustul and again at Hierakonpolis. There is one burial at Hierakonpolis of particular interest, that of Tomb 7 in Locality Hk6.” ref

“By contrast with Nagada II tombs, this cattle burial grave has an almost square shape. It has a length of 2.5 m., a width of 2.1 m. and a depth of 0.65-0.75 m. It had been lined with stone slabs during the original construction. The community had placed grass matting over the bones of three dead animals, which were each buried in one piece. An intriguing aspect of this burial was the presence of a dark organic substance that sheathed a few of the bones. It has been hypothesized that since this organic substance was associated with only the ribs and was tightly packed around them, the possibility exists that it was used to fill out the animal’s eviscerated abdomen – a practice foreshadowing the mummification of later time.” ref

“It has a parallel in the earlier Bos burial from Tomb 19, mentioned above. This is the first known Bos burial triad. Bos triads are also known through representations on predynastic Nagada ceramics. It is possible that the cattle beliefs of the dynastic Egyptians had their origins in the Saharan pastoralists in the predynastic period and stemmed from the Saharan pastoralists, which in essence is also the hypothesis of this article. However, Hassan proposes a fertility-women-cattle ideology, which in the view of the present writer is based on several unfounded assumptions.” ref

“This is assuming that only women were associated with fertility and the provisioning of the essential ingredients of life, water and food, but there is no solid evidence to back up this claim. It has also been suggests that it was the women amongst the Saharan pastoralists who herded the cattle, but the ethnographic records of, for example, the Nuer of the Sudan reveal that teenage males herd the cattle. According to a proposed hypothesis, the predynastic male king drew power from his association with the female goddesses and the very status of women within Predynastic society – but there is a lack of data for the latter claim.” ref

“An integral part of such a hypothesis are the Nagada female figurines shown with their arms curved above their heads in a posture which he has interpreted as representing the bovine horns of a mother goddess. However, this does not account for the presence of male figurines, or the absence of figurines representing a mother and a son as could be expected in a “Mother Goddess” cult, or the lack of exaggerated features (breasts, buttocks) suggesting fertility and divinity, or alternative explanations of the curved arms, such as the invocation of a bird deity.” ref

“In short, there is little reason to directly connect the cattle burials, or cattle symbolism in general, with a “Mother Goddesses” cult, although there certainly are important symbols that have to do with a cow goddess in relation to the king. Whether the frequent occurrence of separated heads of cow goddesses (humanised or not), often on pillars or poles, in the Predynastic Nile Valley has any relation with the impaled cattle heads at Hierakonpolis (Hk29A) is hard to say.” ref

“But it is certain that the cow’s head seen front face, associated with a goddess, is an important bovine motif in early Egyptian art. Dating to the Terminal Predynastic is a sculptured palette that has been found at Gerzeh. Oval-shaped, it has one blank side with a flat relief covering the whole of the other side. The relief is of a cow’s head reduced to a geometrical form with ears and horns curving outwards, all embellished with five stars. It is identical to the Hathor Bowl dating from the 1st Dynasty at Hierakonpolis. The stars might suggest that the palette refers to the Heavenly Cow and to the epithet “Mistress of the Stars”, which in the later “Tale of Sinuhe” is applied to Hathor.” ref

“Also on the Narmer Palette, on either side of the top of the palette (as if looking down on the scenes from heaven), there are two frontal, humanised, cow heads. It has been argued for the identification of these heads with the goddess Bat. Bat was a local goddess of the seventh nome in Upper Egypt, where the bA.t fetish appears often on official pendants. One of the earliest written occurrences of the goddess’ name is from the 6th Dynasty: “I [Menenre] am Bзt with her two faces. (Pyramid Text §1096). It is possible that the first occurrence of Bat’s name is on a diorite vase excavated at Hierakonpolis and dated to the 1st Dynasty. The vase displays a human face with cow ears and horns. A jabiru stork was found near the vase. The vase and the jabiru stork (bз) has been regarded as representing a hieroglyphic construction, so that together they make up bз.t. This word is the same as that represented on the shrine of Sesostris I at Karnak.” ref

“A gold amulet from the archaic period at Naga ed-Deir displays in it a pendant of the bз.t fetish. As the classic representation of Hathor is with an outward curving pair of horns, It has been argued that, if Bat were a later offshoot of Hathor, then she should be expected initially to have adopted Hathor’s elegant and outward curving horns, instead of the heavy, ribbed, and inward curving horns that appear in some of the Predynastic cow heads.” ref

“These heavy archaic horn forms are therefore ascribed to Bat, who supposedly lost this bovine horn structure over time, replacing it with antennae with spiral tips that likewise curl inwards. Based on these arguments, It is thus possible that the Predynastic representations of cow heads are that of Bat, who consequently also appears at the top of the Narmer Palette, and that Hathor is first mentioned in the 4th Dynasty, a time in which she becomes connected with the bз.t fetish.” ref

“However, we cannot forget the Armant rock art, as has already been noted, horn manipulation is a mark of early pastoralism in the Nile Valley. Therefore it seems likely or warranted to identify the goddess depicted on the Narmer Palette as Hathor. Noteworthy is Pyramid Text §546, “My kilt which is on me is Hathor”, which reminds one of the four cow heads on Narmer’s kilt, identical to the ones on top of the Palette. A statue of Djoser displays a similar belt which has been identified as displaying Hathor’s head. Fisher’s idea that Hathor appeared relatively late can also not be maintained: a temple of Hathor at Gebelein dates from the late 2nd dynasty.” ref

“While it could be accurate in saying “it seems likely that, in this area, Egyptian theology was characterized by ‘a common substratum of ideas which lent the two goddesses a somewhat similar character”, it is Hathor who is consistently connected with the pharaoh, not Bat. In the Valley Temple of Mycerinus there are triads of Hathor, Mycerinus and a nome diety. Hathor stands in the middle of the figures in two of the triads, with her arm around Mycerinus as if in a protective stance and showing that she is related to him. The connection of the pharaoh with bovines is apparent from the beginnings of dynastic Egypt.” ref

“On the Narmer Palette, a bull breaking down the enemy’s fortifications symbolises the conquering pharaoh. The name Menes (mni) is usually linked with either the pharaohs Narmer or Hor-Aha and Fairservis hypothesises it has a possible origin in mniw, meaning “herdsman”. Hor-Aha’s name is proof of a close relationship between the pharaoh and the god Horus, who is sometimes depicted in bull form. It is during the late Predynastic that Horus (and by extension the king) adopts the cow goddess as his mother, formalized in the form of Hathor (Hw.t-Hr, “House of Horus”). This event is also evidenced by the dedication of the Narmer Palette in the temple of Horus at Hierakonpolis.” ref

“The Narmer Macehead has many features in common with the ceremonial complex Hk29A and also displays the pharaoh in association with bovines. The end products of the codification of such traditions are commemorative objects like the Narmer Palette, which built on the works of earlier commemorative pieces. It was a combination of formal commemorative hieroglyphic writing with the basic iconography of the evolving kingship.” ref

“At Nabta Playa in the Western Desert, evidence of the domestication of cattle dates from the Middle Neolithic. This brought about socio-economic changes within the desert communities, which is later reflected in the Late Neolithic cattle tumuli and megalithic constructions at Nabta Playa. The Bos tumuli are indicative of cattle worship, and the Late Neolithic site as a whole displays evidence of a community with greater social complexity than its contemporaries in the Nile Valley. Prolonged contact with desert pastoralists led to the first socially complex society in the Nile Valley, the Badarian. It introduced a new religious and socio-economic element into the life of the Upper Egyptians, namely ownership and burial of domestic cattle. Bos burials are found in Nagada period settlements, in clearly ceremonial contexts. As pastoralism became increasingly fused in the Nile Valley economy with agriculture, religious associations evolved between the cow goddess and the king. These aspects became codified in the artefactual representations dating from the time of Unification.” ref

“The only permanent features are a great number of hearths and granaries – ca. 350 hearths at the site of Kom W, and 56 granaries, some lined with baskets, at nearby Kom K. Another 109 granaries were also excavated near Kom W, one of which contained a wooden sickle (for harvesting cereals) with chert blades still hafted to it. Although the domesticated cereals and sheep/goat at the Faiyum A sites were not indigenous to Egypt, the stone tools there argue for an Egyptian origin of this culture.” ref

“Lithics include grinding stones for processing cereals, but also concave-base arrowheads for hunting, which are found earlier in the Western Desert. Faiyum A ceramics are simple open pots of a crude, chaff-tempered clay. But there is also evidence of woven linen cloth (made from domesticated flax), and imported materials for jewelry, including seashells and beads of green feldspar (from the Eastern Desert), obtained by long distance trade or exchange. As elsewhere at early Neolithic sites in the ancient Near East, farming and herding in the Faiyum were in addition to hunting, gathering, and fishing, and cereals were probably stored for consumption in the drier months, when wild resources became scarce.” ref

“Unlike Neolithic evidence in the Nile Valley, the Fayium A culture did not become transformed into a society with full-time farming villages. In the 4th millennium bc/ 6,000-5,000 years ago when social complexity was developing in the Nile Valley, the Faiyum remained a cultural backwater. From around 6,000 years ago there are the remains of a few fishing/hunting camps in the Faiyum, but the region was probably deserted by farmers who took advantage of the much greater potential of floodplain agriculture in the Nile Valley.” ref

Somewhat later Neolithic sites have been excavated in Lower Egypt, at Merimde Beni-Salame near the apex of the Delta, and at el-Omari, a suburb south of Cairo. Radiocarbon dates for Merimde range from 6,750–6,250 years ago. The village was never that large at any one time, but that occupation shifted horizontally through time.” ref

In the earliest stratum (I) there was evidence of postholes for small round houses, with shallow pits and hearths, and pottery without temper. In the middle phase (stratum II) a new type of chaff-tempered ceramics appeared, which is also found at the site of el-Omari. Concave-based arrowheads were also new. In the later Merimde strata (III–V) a new and more substantial type of structure appeared that was semi-subterranean, about 1.5–3.0 meters in diameter, with mud walls (pisé) above.” ref

“The later ceramics occur in a variety of shapes, many with applied, impressed, or engraved decorations, and a dark, black burnished pottery is first seen. Granaries from this phase were associated with individual houses, suggesting less communal control of stored cereals, as was probably the case at the Faiyum A sites with granaries. Merimde represents a fully developed Neolithic economy. From the beginning there is evidence of ceramics, as well as farming and the herding of domesticated species, supplemented by hunting, gathering, and especially fishing.” ref

“While Merimde subsistence practices are similar to the Faiyum A Neolithic, the Merimde remains also include the earliest house structures. The Neolithic site at el-Omari, which was occupied 6,600–6,400 years ago, is contemporaneous with the latest phase at Merimde. el-Omari with evidence that points to a Neolithic economy similar to that at Merimde, except that storage pits and postholes for wattle-and-daub houses are the only evidence of structures.” ref

“In addition to tools that were used for farming and fishing (but very little hunting), there is evidence of stone and bone tools for craft activities, including the production of animal skins, textiles, baskets, beads, and simple stone vessels. Although contracted burials (in a fetal position) are known at both Merimde and el-Omari, they were within the settlements. Burials at Merimde were usually without grave goods; at el-Omari they frequently included only a small pot.” ref

“Specific cemetery areas for these sites may not have been found (or recognized) in the earlier excavations, but a lack of symbolic behavior concerning disposal of the dead is in great contrast to the type of burial symbolism that began to develop in the Neolithic Badarian culture in Middle Egypt, and which became much more elaborate in the later Predynastic Naqada culture of Upper Egypt.” ref

Neolithic in the Nile Valley: Middle and Upper Egypt

“In Upper Egypt there is evidence of a transitional culture contemporaneous with the Faiyum A. In western Thebes scatters of lithics with some organic-tempered ceramics have been found by Polish archaeologists at the site of el-Tarif, hence the name Tarifian culture. Another Tarifian site has been excavated at Armant to the south. The lithics, which are mainly flake tools with a few microliths, seem to be intermediate in typology between Epipaleolithic and Neolithic ones. There is no evidence of food production or domesticated animals.” ref

“In the New Kingdom this region of western Thebes was greatly disturbed by excavation of tombs for high status officials, so most of the evidence of this prehistoric culture has probably been destroyed. What is known about the Tarifian culture suggests that a Neolithic economy was to be found farther north in the Faiyum at this time, and not yet fully developed in the Nile Valley of Upper Egypt, where hunter-gatherers were making very small numbers of ceramics. South of the Faiyum, clear evidence of a Neolithic culture is first found at sites in the el-Badari district, located on desert spurs on the east bank in Middle Egypt.” ref

“Over 50 sites held a previously unknown type of pottery which was thought typologically earlier than the ceramics from Predynastic sites farther south. Made of red Nile clay, frequently with a blackened rim and thin walls in bowl and cup shapes, these vessels had a rippled surface achieved by combing and then polishing. This hypothesis was demonstrated to be correct by stratigraphic excavations at another el-Badari district site, Hammamiya, where there was found rippled Badarian potsherds in the lowest stratum, beneath strata with Predynastic wares.” ref

“Later investigations of el-Badari district sites were conducted and obtained radiocarbon dates of 6,500–6,000 years ago, also verifying the early date of the Badarian. Aside from cemeteries, there was mainly storage pits and associated artifacts, which were the only remains of Badarian settlements. At one site he found post-holes of some kind of light organic structure, but evidence of permanent houses and sedentism was lacking. Possibly the sites were outlying camps, once associated with larger and more permanent villages being sited within the floodplain and now destroyed.” ref

“Near Deir Tasa, some artifacts as coming from an earlier culture that was first called Tasian and is now thought that the black beakers with incised decoration classified as imports, probably from northern Sudan – hundreds of kilometers to the south. Thus there was no Tasian culture, but the so-called Tasian sites are Badarian ones, with imported beakers and mainly Badarian artifacts. Badarian peoples practiced farming and animal husbandry, of cattle, sheep, and goat. They cultivated emmer wheat, 6-row barley, lentils, and flax, and collected tubers. Fishing was definitely important, but hunting much less so. Bifacially worked tools include axes and sickle blades, which would have been used by farmers, but also concave-based arrowheads for hunting.” ref

Emmer Wheat?

“Wild emmer is native to the Fertile Crescent of the Middle East, growing in the grass and woodland of hill country from modern-day Israel to Iran. The origin of wild emmer has been suggested, without universal agreement among scholars, to be the Karaca Dag mountain region of southeastern Turkey. Emmer was collected from the wild and eaten by hunter gatherers for thousands of years before its domestication. Grains of wild emmer discovered at Ohalo II had a radiocarbon dating of around 20,000 years ago and at the Pre Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) site of Netiv Hagdud are 10,000-9,400 years old. The location of the earliest site of emmer domestication is still unclear and under debate. Some of the earliest sites with possible indirect evidence for emmer domestication during the Early Pre-Pottery Neolithic B include Tell Aswad, Çayönü, Cafer Höyük, Aşıklı Höyük, Kissonerga-Mylouthkia [de] and Shillourokambos. Definitive evidence for the full domestication of emmer wheat is not found until the Middle Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (10,200 to 9,500 years ago), at sites such as Beidha, Tell Ghoraifé, Jericho, Abu Hureyra, Tell Halula, Tell Aswad and Cafer Höyük. Emmer is found in a large number of Neolithic sites scattered around the fertile crescent. From its earliest days of cultivation, emmer was a more prominent crop than its cereal contemporaries and competitors, einkorn wheat and barley. Small quantities of emmer are present during Period 1 at Mehrgharh on the Indian subcontinent, showing that emmer was already cultivated there by 9,000-7,000 years ago. In the Near East, in southern Mesopotamia in particular, cultivation of emmer wheat began to decline in the Early Bronze Age, from about 5,000 years ago became a standard cereal crop. This has been related to increased salinization of irrigated alluvial soils. Emmer had a special place in ancient Egypt, where it was the main wheat cultivated in Pharaonic times, although cultivated einkorn wheat was grown in great abundance during the Third Dynasty, and large quantities of it were found preserved, along with cultivated emmer wheat, in the subterranean chambers beneath the Step Pyramid at Saqqara.” ref

Einkorn Wheat?

“Einkorn wheat commonly grows wild in the hill country in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent and Anatolia although it has a wider distribution reaching into the Balkans and south to Jordan near the Dead Sea. Einkorn wheat is one of the earliest cultivated forms of wheat, alongside emmer wheat. Hunter gatherers in the Fertile Crescent may have started harvesting einkorn as long as 30,000 years ago, according to archaeological evidence from Syria. Although gathered from the wild for thousands of years, einkorn wheat was first domesticated approximately 10,000 years BP in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) or B (PPNB) periods. Evidence from DNA fingerprinting suggests einkorn was first domesticated near Karaca Dağ in southeast Turkey, an area in which a number of PPNB farming villages have been found. ” ref

“Possibly from Naqada I (about 6,400–5,500 years ago), female figurines with painted decoration: 1 Naqada (?) provenance unknown.” ref

“Much of the knowledge of the early Naqada culture comes from 85 well-known cemeteries and 50 settlements, with research focused on tombs for a long time. The deceased were like those of Badari culture in Hocker- or fetal position facing west and grave goods in the form of ceramic buried and personal items. The settlements, as in other contemporary cultures, consisted of round rammed earth huts sunk into the ground , probably in reference to earlier nomadic tents. The ceramic of Naqada I culture consists of red bowls and cups made Nilton with a shiny black border, the so-called “black topped pottery”. Typical decoration pattern are white and cream-colored geometric pattern. Increasingly there are representations of animals, hunting scenes, cultic acts and battles. For the first time ships also appear as a symbol of trade. Unlike in earlier cultures, there are also human figures, both bearded men and women, who could be attached to ivory sticks or pendants.” ref

“Several Kemetuic statuettes of goddesses with vulture-shaped heads and upraised arms are known from around 6,200-5,400 years ago. Ancient ivory amulet of a bearded man “phallus” from the Gerzeh culture.” ref

“The stone tools made from side-blow flakes suggest origins in the Western Desert, and the rippled pottery may have developed from the burnished Neolithic pottery known in the Western Desert and Nile Valley, from Merimde to northern Sudan. True Badarian sites are not found in southern Egypt, where the subsequent Naqada culture began after 6,000 years ago, i.e., at the end of the known dates for the Badarian in Middle Egypt. According to Holmes’ investigations, there is a lack of Naqada I type artifacts at Badari district sites, although later Naqada II artifacts (beginning around 5,500 years ago) are definitely found there.” ref

“Figurines of bone and ivory. Predynastic, Naqada I. 6,000-5,600 years ago. Ivory and bone figures of this type first appeared in the Naqada I period and continued into Naqada II. The inlaid eyes in one example are of lapis-lazuli may be a later addition. (Photo by: Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images)” ref

“Male figurine from Egyptian Pre-Dynastic, Naqada II 5,650–5,300 years ago, from Abydos. So could this be an early god Horus often the ancient Egyptians’ national tutelary deity usually depicted as a falcon-headed man a symbol of kingship in Egypt?” ref, ref

“The earliest recorded form of Horus is the tutelary deity of Nekhen in Upper Egypt, who is the first known national god, specifically related to the ruling pharaoh who in time came to be regarded as a manifestation of Horus in life and Osiris in death. The most commonly encountered family relationship describes Horus as the son of Isis and Osiris, and he plays a key role in the Osiris myth as Osiris’s heir and the rival to Set, the murderer of Osiris. In another tradition Hathor is regarded as his mother and sometimes as his wife. Horus served many functions, most notably being a god of kingship and the sky.” ref

“Possibly in Middle Egypt after 6,000 years ago there was a transitional Badarian/Naqada I phase. Since Badarian artifacts are also found in Upper Egypt, but in small numbers, these artifacts could represent Badarian trade with Upper Egypt. Another possible interpretation is that the Badarian culture stretched from Middle to Upper Egypt, but the artifacts farther south represent regional variation. What may be seen at the Badarian sites is the earliest evidence in Egypt of pronounced ceremonialism surrounding burials, which become much more elaborate in the 6,000-5,000 years ago Naqada culture. Brunton excavated about 750 Badarian burials, most of which were contracted ones in shallow oval pits.” ref

“Most burials were placed on the left side, facing west with the head to the south. This later became the standard orientation of Naqada culture burials. Although the Badarian burials had few grave goods, there was usually one pot in a grave. Some burials also had jewelry, made of beads of seashell, stone, bone, and ivory. A few burials contained stone cosmetic palettes or chert tools. Burials such as the Badarian ones represent the material expression of important beliefs and practices in a society concerning the transition from life to death (see Box 5-B).” ref

“Burial evidence may symbolize roles and social status of the dead and commemoration of this by the living, expressions of grief by the living, and possibly also concepts of an afterlife. The elaborate process of burial, which would become profoundly important in pharaonic society for 3,000 years, is much more pronounced in the Neolithic Badarian culture of Middle Egypt than in the earlier Saharan Neolithic or the Neolithic in northern Egypt.” ref

The Colossus of Min Dynasty 0 (around 5,300 years ago). This big statue (in brown) is one of a pair found in the re- mains of the temple in Coptos in Upper Egypt. ref

“And the Min temple in the Early Dynastic Period, was likely placed in a packed town, very close to the surrounding houses. Such an inner urban location is attested at the few other sites with an early temple (Elephantine, Hierakonpolis, Tell Ibrahim Awad). The temple building is surrounded by a wall, as found at other early temples (Abydos, Elephantine). Next to the temple is placed a lettuce field. Cos lettuce is typically depicted beside Min in formal art of later periods.” ref

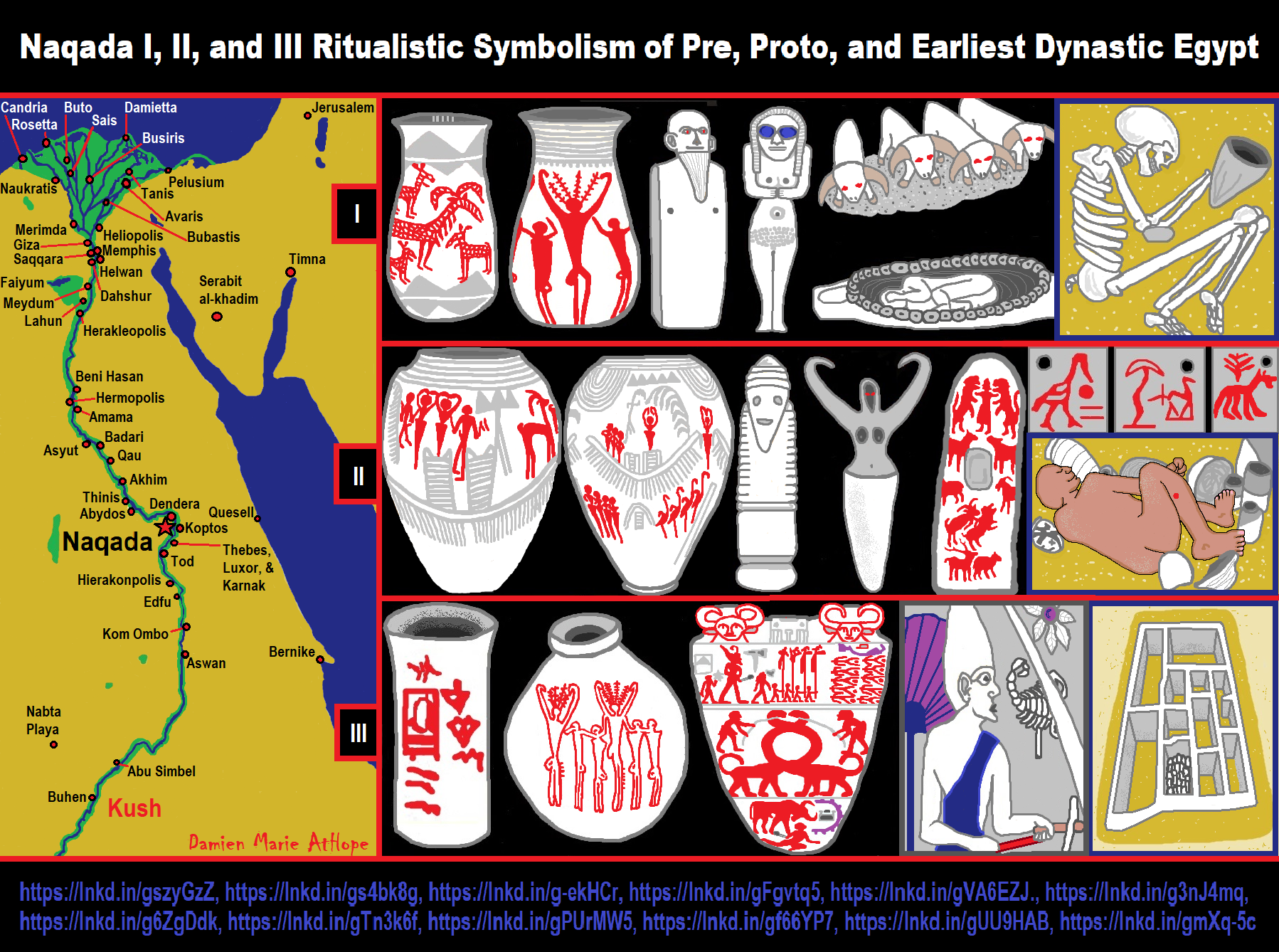

Nagada, also known as Naqada, is the type site of the prehistoric Egyptian Amratian culture (“Naqada I”), Gerzeh culture (“Naqada II”) and Naqada III (“Dynasty 0”) predynastic cultures. Naqada existed before and during the union of Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt, the Naqada III or “protodynastic” period. The process of unification apparently started from Nagada. ref

“The Predynastic Period is divided into four separate phases: the Early Predynastic, which ranges from the 6th to 5th millennium B.C.E. (approximately 7,500-6,000 years ago): Old Predynastic, Early Predynastic, Middle Predynastic, and Late Predynastic.” ref

“The Old Predynastic, which ranges from 6,500 to 5,500 years ago (the time overlap is due to diversity along the length of the Nile); the Middle Predynastic, which roughly goes form 5,500-5,200 years ago; and the Late Predynastic, which takes us up to the First Dynasty at around 5,100 years ago. The reducing size of the phases can be taken as an example of how social and scientific development was accelerating. The Old Predynastic is also known as the Amratian or Naqada I Phase — named for the Naqada site found near the center of the huge bend in the Nile, north of Luxor. A number of cemeteries have been discovered in Upper Egypt, as well as a rectangular house at Hierakonpolis, and further examples of clay pottery — most notably terra cotta sculptures. In Lower Egypt, similar cemeteries and structures have been excavated at Merimda Beni Salama and at el-Omari (south of Cairo).” ref

“The Early Predynastic, which is otherwise known as the Badrian Phase — named for the el-Badari region, and the Hammamia site in particular, of Upper Egypt. The equivalent Lower Egypt sites are found at Fayum (the Fayum A encampments) which are considered to be the first agricultural settlements in Egypt, and at Merimda Beni Salama. During this phase, the Egyptians began making pottery, often with quite sophisticated designs (a fine polished red wear with blackened tops), and constructing tombs from mud brick. Corpses were merely wrapped in animal hides.” ref

“The Middle Predynastic, which is also known as the Gerzean Phase — named for Darb el-Gerza on the Nile to the east of Fayum in Lower Egypt. It is also known as the Naqada II Phase for similar sites in Upper Egypt once again found around Naqada. Of particular importance is a Gerzean religious structure, a temple, found at Hierakonpolis which had early examples of Egyptian tomb painting. Pottery from this phase is often decorated with depictions of birds and animals as well as more abstract symbols for gods. The tombs are often quite substantial, with several chambers built out of mud bricks.” ref

“The Late Predynastic, which blends into the first Dynastic Period, is also known as the Protodynistic phase. Egypt’s population had grown considerably and there were substantial communities along the Nile which were politically and economically aware of each other. Goods were exchanged and a common language was spoken. It was during this phase that the process of wider political agglomeration began (archaeologists keep pushing back the date as more discoveries are made) and the more successful communities extended their spheres of influence to include nearby settlements. The process led to the development of two distinct kingdoms of Upper and Lower Egypt, the

Nile Valley and Nile Delta areas respectively.” ref

Predynastic Egypt

The Predynastic Period Egypt, 4th Millennium bc (around 6,000-5,100 years ago)

Lower Egypt: Buto-Ma’adi Culture (around 6,000–5,200 years ago)

Upper Egypt: Naqada Culture (around 6,000–5,200 years ago)

Naqada I (Amratian), 6,000–5,500 years ago; Naqada II (Gerzean), 5,500–5,200 years ago; Naqada III (Semainean)/Dynasty 0, 5,200–5,000 years ago. ref

Lower Nubia: A-Group Culture (around 6,000–5,200 years ago)

Early A-Group contemporary with Naqada I and early Naqada II Classic A-Group contemporary with Naqada IId–IIIa Terminal A-Group contemporary with Naqada IIIb/Dynasty 0, 1st Dynasty. ref

First Dynasty of Egypt

“The First Dynasty of ancient Egypt (Dynasty I) covers the first series of Egyptian kings to rule over a unified Egypt. It immediately follows the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt, possibly by Narmer, and marks the beginning of the Early Dynastic Period, a time at which power was centered at Thinis. The date of this period is subject to scholarly debate about the Egyptian chronology. It falls within the early Bronze Age and based on radiocarbon dates, the beginning of the First Dynasty—the accession of Hor-Aha—was placed at 5,100 years ago, give or take a century (3218–3035, with 95% confidence).” ref

“With the introduction of farming and herding in Egypt, and successful development of a Neolithic economy in the lower Nile Valley, the economic foundation of the pharaonic state was laid. But the Neolithic did not mean that the rise of Egyptian civilization was inevitable. Communities in Upper and Lower Egypt became more dependent on farming in the 4th millennium bc, but only in the Naqada culture of Upper Egypt did social and economic complexity follow the successful adaptation of a Neolithic economy.” ref

“By the mid-4th millennium bc Naqada culture began to spread northward through various mechanisms that are incompletely understood, and by the late 4th millennium it had replaced the ButoMa’adi culture in northern Egypt.” ref