ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

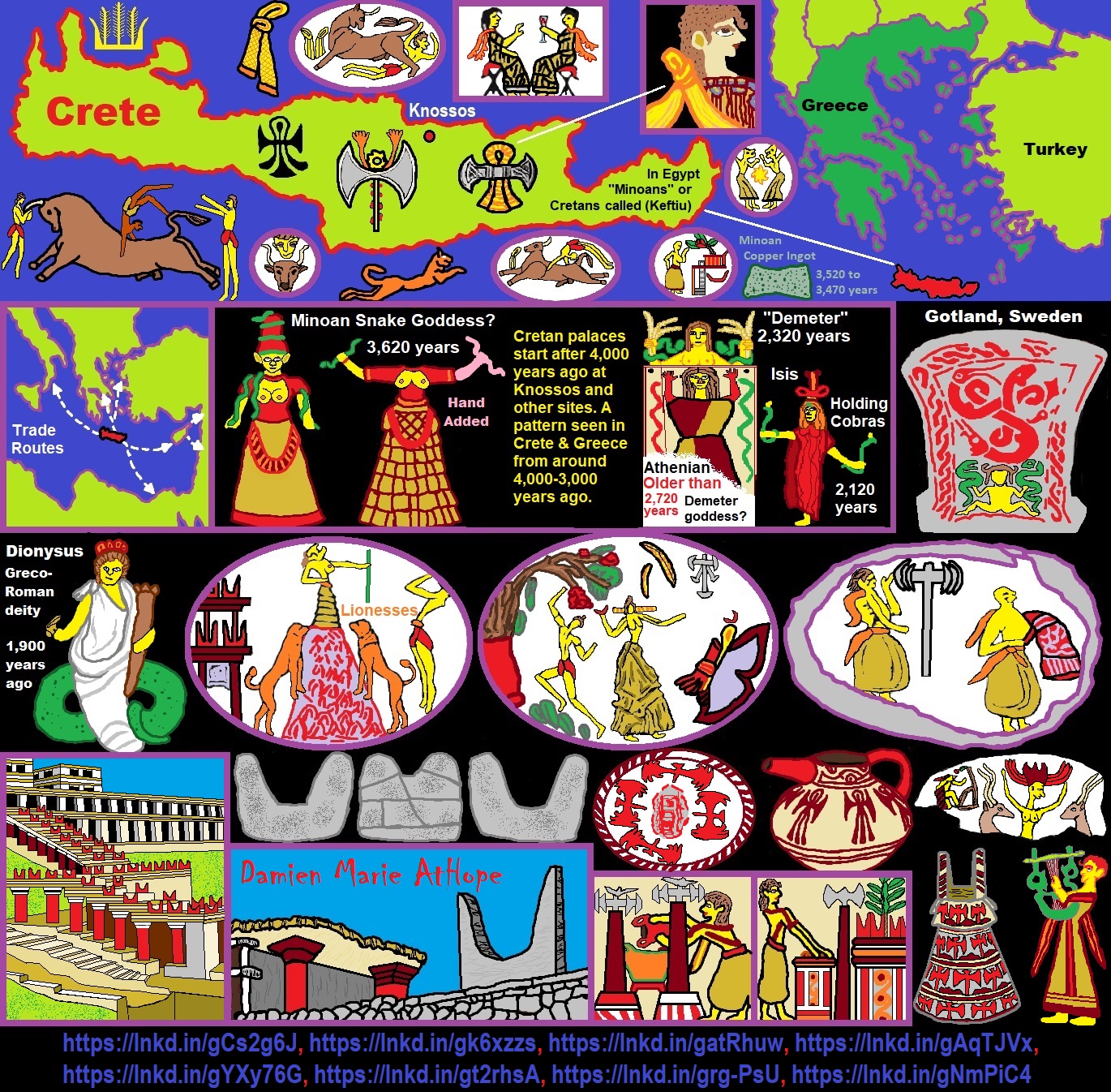

Cretan palaces start sometime after around 4,000 years ago at Knossos and other sites. A pattern seen in Crete & Greece from around 4,000-3,000 years ago.

“The Minoan civilization was a Bronze Age Aegean civilization on the island of Crete and the other Aegean Islands, flourishing from around 3000 BC to 1450 BC until a late period of decline, finally ending around 1100 BC. It represents the first advanced civilization in Europe, leaving behind massive building complexes, tools, artwork, writing systems, and a massive network of trade. The civilization was rediscovered at the beginning of the 20th century through the work of British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans. The name “Minoan” derives from the mythical King Minos and was coined by Evans, who identified the site at Knossos with the labyrinth and the Minotaur. The Minoan civilization has been described as the earliest of its kind in Europe,[2] and historian Will Durant called the Minoans “the first link in the European chain”. The Minoan civilization is particularly notable for its large and elaborate palaces up to four stories high, featuring elaborate plumbing systems and decorated with frescoes. The most notable Minoan palace is that of Knossos, followed by that of Phaistos. The Minoan period saw extensive trade between Crete, Aegean, and Mediterranean settlements, particularly the Near East. Through their traders and artists, the Minoans’ cultural influence reached beyond Crete to the Cyclades, the Old Kingdom of Egypt, copper-bearing Cyprus, Canaan, and the Levantine coast, and Anatolia. Some of the best Minoan art is preserved in the city of Akrotiri on the island of Santorini, which was destroyed by the Minoan eruption. The Minoans primarily wrote in the Linear A and also in Cretan hieroglyphs, encoding a language hypothetically labeled Minoan. The reasons for the slow decline of the Minoan civilization, beginning around 1550 BC, are unclear; theories include Mycenaean invasions from mainland Greece and the major volcanic eruption of Santorini.” ref

“The term “Minoan” refers to the mythical King Minos of Knossos. Its origin is debated, but it is commonly attributed to archeologist Arthur Evans (1851–1941). Minos was associated in Greek mythology with the labyrinth. However, Karl Hoeck had already used the title Das Minoische Kreta in 1825 for volume two of his Kreta; this appears to be the first known use of the word “Minoan” to mean “ancient Cretan”. Evans probably read Hoeck’s book, and continued using the term in his writings and findings: “To this early civilization of Crete as a whole I have proposed—and the suggestion has been generally adopted by the archaeologists of this and other countries—to apply the name ‘Minoan’.” Evans said that he applied it, not invented it. Hoeck, with no idea that the archaeological Crete had existed, had in mind the Crete of mythology. Although Evans’ 1931 claim that the term was “unminted” before he used it was called a “brazen suggestion” by Karadimas and Momigliano, he coined its archaeological meaning. And Cretans (Keftiu) are seen in art bringing gifts to Egypt, in the Tomb of Rekhmire, under Pharaoh Thutmosis III (c. 1479-1425 BC).” ref

“Crete is a mountainous island with natural harbors. There are signs of earthquake damage at many Minoan sites, and clear signs of land uplifting and submersion of coastal sites due to tectonic processes along its coast. According to Homer, Crete had 90 cities. Judging by the palace sites, the island was probably divided into at least eight political units at the height of the Minoan period. The vast majority of Minoan sites are found in central and eastern Crete, with few in the western part of the island. There appears to be four major palaces on the island: Knossos, Phaistos, Malia, and Kato Zakros. The north is thought to have been governed from Knossos, the south from Phaistos, the central-eastern region from Malia, the eastern tip from Kato Zakros. Smaller palaces have been found elsewhere on the island.” ref

Major settlements

- “Knossos – the largest Bronze Age archaeological site on Crete. Knossos had an estimated population of 1,300 to 2,000 in 2500 BC, 18,000 in 2000 BC, 20,000 to 100,000 in 1600 BC and 30,000 in 1360 BC.

- Phaistos – the second-largest palatial building on the island, excavated by the Italian school shortly after Knossos

- Malia – the subject of French excavations, a palatial center which provides a look into the proto-palatial period

- Kato Zakros – sea-side palatial site excavated by Greek archaeologists in the far east of the island, also known as “Zakro” in archaeological literature

- Galatas – confirmed as a palatial site during the early 1990s

- Agia Triada – administrative center near Phaistos which has yielded the largest number of Linear A tablets.

- Gournia – town site excavated in the first quarter of the 20th century

- Pyrgos – early Minoan site in southern Crete

- Vasiliki – early eastern Minoan site which gives its name to distinctive ceramic ware

- Fournou Korfi – southern site

- Pseira – island town with ritual sites

- Mount Juktas – the greatest Minoan peak sanctuary, associated with the palace of Knossos

- Arkalochori – site of the Arkalochori Axe

- Karfi – refuge site, one of the last Minoan sites

- Akrotiri – settlement on the island of Santorini (Thera), near the site of the Thera Eruption

- Zominthos – mountainous city in the northern foothills of Mount Ida” ref

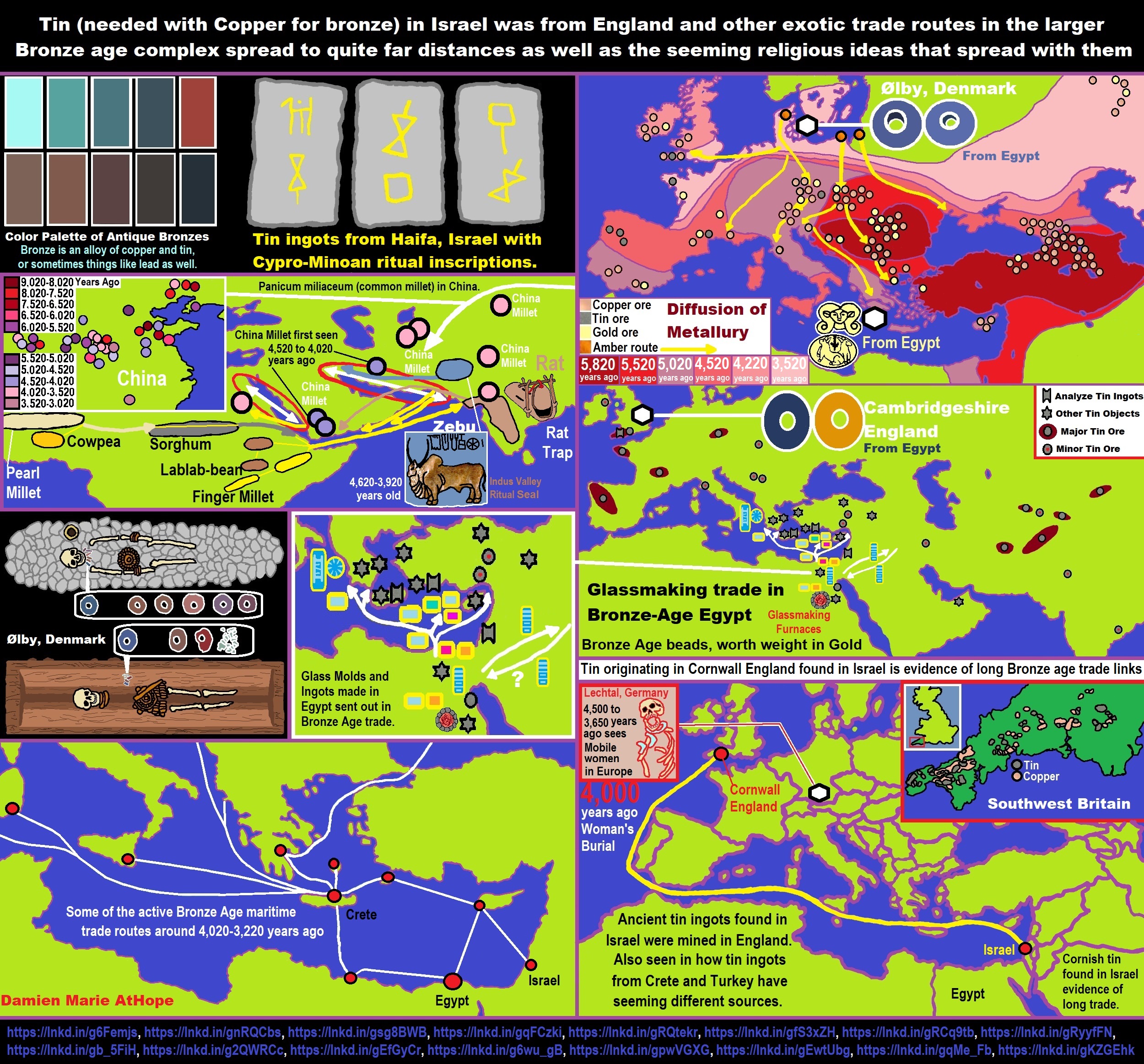

MINOAN TRADE ROUTES

“Minoan influence in the Bronze Age can be traced through archaeology. On the island of Melos, there are architectural remnants, pottery, and frescoes in Cretan style, similar to those on Thera. Farther north, there is evidence of Minoan settlement i on the island of Kea. In the eastern Aegean, Minoan pottery has been found in Rhodes. Minoan artifacts and cooking equipment have been found at Miletus, a city in Anatolia that would have attracted the Cretans for its proximity to sources of metal. Thucydides’ vision of ancient Crete was a thalassocracy, from the Greek words thalassa, meaning “sea,” and kratos, meaning “power.” This notion may well reflect the historian’s concerns with naval power in the region in his own day more than the reality of ancient Crete. Modern historians tend to view Crete as a less aggressive power that used its naval expertise to dominate trade rather than to conquer. Despite the importance of Crete to ancient Greek civilization, the archaeological study of its culture is relatively recent. Some of the earliest traces of a powerful, Bronze Age civilization were uncovered in the 19th century. British archaeologist Arthur Evans discovered extensive ruins on Crete in the early 1900s. In honor of the legendary King Minos, he termed the civilization he uncovered “Minoan.” Archaeological evidence shows that during the third millennium B.C. Crete lay at the center of an extensive trading network dealing in copper from the Cyclades and tin from Asia Minor. These materials were essential for producing bronze, a commodity that brought power and prestige to the Minoans. In the second millennium B.C., great palaces began to be built on Crete during the period known as the Neopalatial (circa 1700-1490 B.C.). Evans excavated several of these structures, including the magnificent Palace of Knossos, seat of the legendary King Minos. More recent archaeological digs have demonstrated that Crete was widely urbanized during this period and that Knossos exercised some kind of hegemony over other Cretan cities. The mid-second millennium B.C. seemed a time of great prosperity. Although many Minoan structures have been given the secular term “palace,” researchers believe their role was not a royal one. It has never been firmly established whether Minoan Crete had a true royal dynasty, so these lavish palaces may have had mixed secular and religious roles. Some archaeologists interpret these palaces more as civic centers from which to control and distribute raw materials, carry out rituals, mete out justice, maintain water distribution, and also organize festivals for the populace. Daily life was, for the majority, simple but comfortable. Islanders lived in houses made of stone, mud brick, and wood, and the domestic economy was based on viticulture and olive farming. The surrounding cypress forests provided timber for shipbuilding for the important Minoan fleet.” ref

“During the Late Minoan period (1570-1425 B.C.), nautical decorations were popular on pottery It was common to cover the whole surface of a vessel with paintings of creatures such as octopuses, fish, or dolphins. The Aegina Treasure is a trove of gold artifacts, like this two-headed pendant, featuring strong Minoan characteristics. Dating to between 1850 and 1550 B.C., it is named for the island. As the Minoan upper classes grew increasing wealthy, they imported luxuries—jewelry and precious stones—which provided extra incentive to develop new trading routes for Crete’s exports: timber, pottery, and textiles. Little evidence has been found of city walls or fortifications built on ancient Crete during this time. This finding seems to suggest that either there were no serious threats to the island or—more likely—that patrolling ships were enough to guard its coastlines. A maritime force would have also protected the trading routes, harbors, and strategic points, such as Amnisos, the port that served the capital, Knossos. As Minoan culture and trade radiated across the Aegean, communities on the islands of the Cyclades and the Dodecanese (near the coast of modern-day Turkey) were radically changed through contact with Crete. Cretan fashions became very popular in the eastern Mediterranean. Local island elites first acquired Cretan pottery and textiles as a symbol of prestige. Later, the presence of Minoan merchants also prompted island communities far from Knossos to adopt Crete’s standard system of weights and measures.” ref

“Perhaps the clearest sign of Minoan influence was the appearance of its writing system in the languages of later cultures. Characteristics of Crete’s letters appear to have used several forms. One of the oldest was discovered by Arthur Evans and is now known as Linear A. Despite not yet being deciphered, scholars believe it is the local language of Minoan Crete. But it must have been an important regional common language of its day, as Linear A has been found inscribed on many of the clay vessels discovered on islands across the Aegean. The other script, called Linear B, evolved from Linear A. Deciphered in the 1950s, Linear B is recognized as the oldest known Greek dialect. The Minoans also maintained trading relationships with Egypt, Syria, and the Greek mainland. Their trade routes may have extended as far west as Italy and Sicily. Certain locations had especially close ties with Crete and its sailors. These included Miletus on the Anatolian peninsula on Crete’s eastern trading route. The city of Akrotiri on the island of Thera (modern-day Santorini) is one of the best preserved of these Minoan settlements. A volcanic eruption around the 16th century B.C. buried Akrotiri under ash, preserving its ruins which were excavated in the 19th and 20th centuries. Digs in the 1960s and ’70s unearthed a wealthy city with many distinctive Minoan features. Its walls boasted stunning murals of brightly colored, stylized images of sparring boxers, climbing monkeys, swimming dolphins, and flying birds. The quality of the paintings uncovered at Akrotiri suggests that artists either from Crete or influenced by its culture had set up workshops in this city.” ref

“Other Aegean settlements bearing clear evidence of Minoan influence include the Cycladi islands of Melos and Kea, and islands in the Dodecanese, such as Rhodes. The settlement of Kastri, on the island of Cythera, south of the Peloponnesian peninsula of the Greek mainland, is another example of Cretan cultural power. Built to exploit the local stocks of murex—a mollusk highly prized for its purple ink used for dyeing cloth—Kastri is purely Minoan in its urban planning. But even this town was not a colony. There is no evidence that these places were politically subject to Crete, as it is not believed that they paid any kind of tribute beyond the money exchanged when trading goods. Minoan civilization declined by the late 15th century B.C., but the exact cause is unknown. One theory is that the volcanic eruption on Thera damaged other cities along Minoan trade routes, which hurt Crete economically. Taking all the evidence available, the volcano did not directly affect life on Crete—about 70 miles to the south. No damage from the eruption has been found there. Crete’s cities seemed unaffected for at least a few generations after the volcano. Archaeologists have uncovered evidence of an invasion in the mid-15th century B.C. Many sites, including several large palaces in central and southern Crete were burned, and many settlements were abandoned shortly thereafter. The invaders most likely overthrew the Minoan government and took control of the island, ending the era of Crete’s dominance. Despite its abrupt ending, the influence of Crete survived. Its vibrant culture made a major impact on the rising new regional power: the Mycenaean Greeks, who lauded King Minos and Crete in their mythology. Linear B, the Cretan writing system adopted by the Mycenaeans, would be the basis for the Greek in which the poet Homer would write his two masterpieces.” ref

“Soles explores the fact that many Pre-Palatial tombs were “maintained in good condition for centuries”. “The distribution and ownership of land in ancestor-worshipping societies is widespread. This is because the land belongs to the ancestors, and is held in trust to be passed down.” And, Soles adds, “The erection of actual buildings at specific locations in order to house, honor and provide access to ancestors is a common phenomenon in the ethnographic record.” “Death and renewal remained linked in cult through all the periods of Minoan history,” Marinatos notes. Hence in her view, the ceremonies on the Agia Triada larnax “preserve the essence of Minoan ritual as it was established already in the Pre-Palatial period” (31; dated to the end of Late Minoan III or after 1370). The details present these relationships such as, a priestess (wearing blue) who pours a sacrificed bull’s blood into a blue vessel, and its contents will be “soaked up by the earth” for the person joining the ancestors. The dead must be propitiated to ensure a bountiful return from nature, the regeneration of crops, and human life. Or a priestess fulfills this reciprocity before a doubled Labrys and a doubled pair of horns, with a green tree centered between them. With the blood offerings made, the vessel for drink (which is sometimes a symbol of rain: Evans Palace 4: 453) and the fruit-bowl before her eyes seem to register a hoped-for agricultural return. The motif repeated on the priestess’ skirt is similar to Linear B writing-signs for “cereals” (for examples see Evans Palace 4: 624-5). On these practical and religious bases, the generations who made Knossos the center of Minoan cosmology were “likely to have enjoyed [an] egalitarian society…in which the small farms and country villas and townhouses that [in time, came to] dot the landscape in the New Palace period were not so much manifestations of a landed aristocracy as they were evidence for the existence of a large middle class of free, land-owning people.” In a phrase, Crete was what Schoep’s 2002 “Palace State” called a religion-centered heterarchy; meaning, a fiercely diverse and fluidly factional civilization with many centers and shared religious ways. If theocratic signifies central and compelling religious ideas, heterarchic suggests secular “real world” understandings about them, among proudly different and independent parties.” ref

“A third ancient continuity cannot be ignored. Minoans mounted over 1000 years of bull-leaping games, events surrounded from Early to Late with timely festivals and, above all, feasting. The volumes of Aegaeum are replete with generations of feasts across a time when Egyptians devoted about 100 days per year to their banquets and pastimes, as MacGillivray notes. He dates these events in Crete as early as 2600 BCE, and they point to annual cycles of Festival whose religious and practical functions were central parts of life. Perhaps our guide forward should be the “time line for what happened next” provided in the Abstract published with Driessen and Macdonald’s 1997 Troubled Island—although debated, still one of the most detailed comprehensive studies of these last Minoan periods. Early forms that seem to address or anticipate an 8½-year lunar/solar cycle, Island is based in a view of “complete cultural continuity” from Middle into Late Minoan times.” ref

“Wiener details many apparent political changes, most in Knossos’ favor, through and after the Middle Minoan III (or circa 1700) destructions that ended their Old Palace period. Plenitude brought increases in population, expansions of old living-places (Crete’s many “villas”), and new settlements including “palatial style” buildings. Scholars of the villa system note “social structure but not, in view of the integration of house and village, social division”. Driessen and Macdonald look back into Middle Minoan times (roughly 1700-1600), and then examine the New Palace era, or what happened after the ensuing 1600 “tectonic earthquake” (which was to be only the first half of Thera’s eruption). Hence, toward the middle of the next period (1600-1480, or Late Minoan I A), they find the explosion of the volcano, its ash-fall, tsunamis, and after-effects: in their view, between the 1550s and 1530s. (Moody points out that for all the studies of ash-fall and more, the eruption’s date is no more “absolute” than 1650-1150. After that, the damaged landscape’s “limited capacity” and other factors reduced Crete’s population.” ref

“Their Abstract’s time line, slightly clarified below, begins with events that next unfolded after the 1480 dawn of Late Minoan I B—the period that culminated in clear Mycenaean domination of Crete, and which along the way brought wholesale destruction everywhere except Knossos. Here is their outline of the times in which the Bull Leap fresco and Great Year calendar possibly played their parts: …A severe economic dislocation…appears to have been triggered, first, by a tectonic earthquake [1600], and shortly afterwards, by the eruption of Thera [1550-1530]. The situation gradually worsened, accompanied by a general feeling of uncertainty caused by the eruption and its effects. The tectonic earthquake led to abandonments at some sites, or to an effort to rebuild at others, in an attempt to reestablish normal economic and social life. The results of these two natural disasters gave local centers greater independence from the traditional “Palaces.” The natural events that proved to be the catalysts for change presaged the end of the traditional ruling elites, who appeared to have lost their assumed divine support. They tried in vain to maintain their special status.” ref

“But, with major problems in the production and distribution of food, the existing system disintegrated. [This was] a process of decentralization, with an increase in the regional exploitation of land, chiefly for local consumption. Numerous lesser elites may well have prospered in this environment. However…the fragmentation of Crete into many small centers may have led to internal Cretan conflict. A massive wave of fire destructions [swept through the period from 1480-1425, or Late Minoan IB], indicating a state of anarchy by the end of the period. This fragmentation of Minoan Crete brought about the end of the most highly developed economic system in the Aegean. It was somewhat resurrected…during the succeeding Mycenaean period [1425 through the late 1300s; or, Late Minoan II and III]; during which only the palace at Knossos seems to have functioned as a major center. There was a gradual but general decrease in the sophistication of architecture and arts. This period may perhaps be regarded as the final phase of the decline that began [after 1480, with the widespread destruction of main Minoan sites]. Some major centers suffered destruction once again. [As of about 1425], a new Knossian elite or dynasty appears to have taken control, and installed a modified socio-political and economic system….” ref

“These conditions—a spirited creative resilience, followed by one disintegrative stress after another—might signify, or demand, focused efforts toward improved calendric precision. Timing underwrites agriculture and the rhythms of ceremonial life that foster effective organization. As noted from Wright (1995: 68), “uncontrolled variables” had to make “ritual activities” a “major concern”; and according to Wiener’s estimates, “the numbers [were] vast everywhere,” with more people than before “participating in mass rituals” and/or “larger work forces”. Island notes that Crete’s transition-years from Middle to Late periods had seen about 33% less-centralized storage of foodstuffs, “perhaps related to a better monitoring of agricultural production”. An inspired beginning might grow the more determined in a deepening crisis.” ref

“Although that food-storage trend reversed when the later problems arose, the century between the 1700 and 1600 earthquakes saw three or four Minoan generations building on their inheritance before the main disasters; then, five generations trying to respond to crises before the destructions began around 1480. Altogether, that is a period as long as United States history. Whichever generation may have created the Bull Leap fresco and brought together elements of a Great Year calendar, all of them had motive, means and opportunity before the time of outright “anarchy” began. Some research since Island has disputed some of its central characterizations of these times. J. S. Soles, for example (in his 1999 “Collapse”), finds that through the harshest decades after 1480, “food remained plentiful,” although because of more intense and “well-documented” land-cultivation. At worst, to quote one of Soles’ sources in volcanology, “Minoans had to tighten their belts for a year or two”. This largely agreed with Sewell’s 2001 evaluation of all Thera’s aspects (Section 8.3). According to Warren’s 2001 Island review, the eruption presented “challenges” for years, but few that Minoans had not faced before.” ref

“Soles rejected Island’s account of Thera’s impact on Crete, meaning near-famine, reduced population and the “fragmentation” of Late Minoan life. He judged that Minoan “reverence” was “too pervasive and too intense in all periods” for them to have desecrated and destroyed their own religious centers. Soles instead saw “alien intruders,” Mycenaeans, raiding Crete through the decades after Thera, across “one or two generations” whose elders had never before known such insecurity. Warren’s review could not reconcile Island’s account with a Minoan realm simultaneously at a new height of multiple powers. Stresses, however, might have turned the central strength of the Minoan system—its ability to respond to challenges “because of its dispersal of power into a number of quasi-autonomous palatial centers” (Soles)—into a liability. For Soles, a gradual collapse occurred between the pressure to feed a rising population, the need to turn farm-laborers into warriors for defense, and the eventual conquest of Crete’s main centers including Knossos, where “the large supplies of food [were] stored”. As Haysom notes also, more evidence is needed.” ref

“Either conception of Late Crete’s conditions can inform the examples ahead were elements of a possible Great Year calendar came into play. In both conceptions, food and the control of public food supplies were increasingly the base of power and a decisive element leading to “desperate choices” (Island 54, 103). A calendar attuned to ecology (maximizing food production), and to astronomy (yielding apparent “command of nature”), would be an instrument of power. Let us look further into social and other contexts based in the central, agreed Late evidence of what happened. Island and Soles’ “Reverence” agree that after 1600 (into New Palace times), elements of Crete’s “large middle class of free, land-owning people” were emerging as “new elites.” Their families comprised “a new managerial and redistributive bureaucracy,” with close kinship, reciprocal relations, and obligations to Crete’s “secondary elite,” the families established in the country villa system.” ref

“Together they raised new centers and grand residences along the coasts and fertile river-valleys, besides repairing the New Palace. “Never before had such tremendous effort been put into devising architectural schemes that gave sophistication and lightness to a building” (Island 41). While so much creative labor may have gone toward the “legitimization of certain elites,” it went into projects that stressed “group identity and prestigious labor” (45): a spirit not unlike that which built Egypt’s public monuments and Pyramids. Ceremonial practices anchored by the ancestors, festivals, and bull-leaping had given independent Minoans strong values in common. As conditions worsened with each Late decade, changes in social patterns measured them. It appears that some of these families raised houses encroaching on Knossos precincts. The masons’ marks on the best “ashlar” buildings included Labrys and star (41), while the lack of their own food-stores might also have signaled palace connection and dependency (53). Others built or developed old sites into “near-palaces” that signaled (in Soles’ conception) more of the same “dispersed” power; or, in Island’s view, increasing “fragmentation.” ref

“The New Labyrinth reflected new divisions, a new inequality and/or insecurity (Island)—well before the destructions began around 1480. These changes, visible above in this Old vs. New Palace comparison (in Moody’s 1987 “Prestige”), reduced and restricted access. In a Driessen/Macdonald phrase describing Vathypetrou, “permeability became linear and locked”. At the same time, Marinatos noted a marked increase of public pomp and ritual: “perhaps,” according to Hatzaki, “reducing social tensions among the many,” and reinforcing “the leading role of the few, who would have been closely linked to the ideological and economic supremacy of the Palace.” Island characterized these new programs as “propaganda”—again, to legitimize the new generation(s) of Knossos’ “managers,” whose “redistributive” powers of course concerned food and wealth. In a sense, these elites were simultaneously separating from the general population, and reaching out to them.” ref

“Reassuring symbols, ceremonies, and festivals might blunt the new divisions while imposing them. Perhaps this double aspect reflected a conflict of loyalties inside Knossos: one strongly traditional toward Cretans, and one less so. Because the pieces of evidence of Mycenaean roles and influences in these changes must be understood in Minoan contexts, let us first look further into Crete. Possibly, amid Knossos’ increasing affiliations with the mainland, Crete’s main population-based in their ancestors, in kinship, general equality, and independence—were as much the people “separating,” in some ways, from a Knossos that was failing them; and failing them in regard to more than warding off Thera’s eruption and its effects. Propaganda is a body of statements—claims and promises—from people who want to be believed about them. What remains to discover is the substance of this Late propaganda’s message. How did a few central symbols from Knossos present Minoans with the suggestion that their elites might have divine sanction? Seals, painted ritual vases, ceremonial equipment, jewelry, textiles: these were some of the central media carrying Knossos’ message into daily life, ceremonies, and socio-political practice.” ref

“According to studies of Crete’s scores of peak sanctuaries, all but 8 of these high-country ceremonial centers were abandoned in the midst of Knossos’ Late-period efforts at consolidation of religious and social power. Calendric efforts in the wind, inspired perhaps by the actual and consistent Great Year cycles in the sky, would have to be broadcast through the culture. Promises had to concern things ardently desired by people at that time. Whatever Knossos’ motives, their efforts had to speak in familiar Minoan terms to have a chance of broad adoption in a culture devoted to continuity. If part of the Knossos response to Late crises was in calendric terms, the forms they selected for their divine propaganda should reflect it. As Frankel and Webb note about the distribution of “distinctive” artifacts that “imply restricted access to esoteric knowledge,” such forms were “likely to have been closely linked to the dynamics of identity negotiation”.” ref

“For some people, riches and status themselves prove divine sanction and powers. Yet, this propaganda’s substantive content has remained as opaque as Labrys. In fact, along with some few surviving stone vessels in the shapes of Bull and Lion (Island 66), and the cults of Snake that Evans and Nilsson termed “canonical” through Late times, we find Labrys a main element among these Late signs of power—as noted, literally elevated to new heights of display and levels of distribution. The pair of vases above, dated to the last Middle period (about 1650-1600), show that Late Knossos had already created variations of Labrys that could speak to its most-troubled times (more below). Three other preexisting symbols most commonly deployed were the Sacral Knot, Marine Style pottery, and “horns of consecration.” Troubled Island’s chapters, charts, and its Gazetteer are packed with details showing these artifacts’ discoveries together. Marine Style vessels, for example, reached 23 settlements, and D’Agata studied “horns” at 12 sites.” ref

“Why would a Knossos elite, trying to re-negotiate their Minoan identity, calculate that these particular symbols might better unite, reassure and/or reconcile people toward a new political order? Let us look at each and at all together in their ways, and see how they might relate to a Minoan Great Year calendar. If we remember how important a calendar was/is to the most efficient production of food, then Labrys as its possible prime symbol would be key to the promises within Late Knossos propaganda. We have seen how, in MacGillivray’s words, Labrys “could symbolize the marriage of the sun and moon, perhaps the union of the solar and lunar calendar” (“Astral Labyrinth”). Like the powers that came with the throne itself, built from its solar alignment and lunar symbol (and from which, more appears below), Labrys might have embodied a natural cycle whose forms were adapted into religious, social, and political practices; in order to promote and ensure the smooth, perhaps-cyclical transitions of executive power (Chapter 8). Relating Bull (as part of the “horns” complex of meanings) to forms of power, Nikoloudis notes the ancient links between tauros and the Indo-European verbal root “to stand”—with senses suggesting “steadfast” and “sturdy”. Such was one meaning also of Egypt’s Djed Pillar.” ref

“The forms of Labrys that become most common in Late times have vegetal features—visual signs that it lives, and perhaps that through conformity with its (calendric) principles, the world of nature can be renewed and sustained at levels of abundance. Evans noted a Minoan “tendency to link themselves with vegetable forms”. Given the ways already shown that Labrys points from the underworld to this life and Beyond, we might call these promises the big three, for the power they have exerted in propaganda throughout history: A) food in plenty, B) ceremonial, social and political order, and C) a way to the afterlife. With the clear Middle-period “anticipations” of vegetal Labrys forms, Island dates the example at right to a time after Knossos suffered west wing fire-damage, near the very start of the destructions all over Crete (after 1480). The 4-point wheel and doublings (8 points) round a central sphere present Great Year forms, while adding 12 vegetal points in 3’s (possibly, moons and seasons). The links between natural cycles (crops and food), orderly production, social balance, and religion seem apparent in this form, the vegetal aspect an appealing practical and spiritual one in an environment either increasingly short of food, or more concerned with its storage and security for other reasons (ahead). Evans considered Labrys intimately connected with the cult of the dead, and this chapter’s final shreds of evidence will suggest how. These Late examples seem to suggest Labrys as the flower and center of nature, while connecting the double ax also to the throne’s disc-and-crescent. How—the meaning of these “promises”—will appear, again, through the final pieces of evidence.” ref

“Evans noted that Sacral Knots were parts of Minoan tradition as old as Labrys, dating many examples to at least Middle Minoan III (circa 1700); but their precise meanings have remained obscure. We saw New Palace seals which, as “knots” held together by Snake, perhaps embodied the four calendric beasts. According to Rutter’s Internet resources, Sacral Knots were a “popular” feature in the troubled times after 1480 (Late Minoan IB), and they too were sometimes fused with Labrys, as shown below. What can we learn of their meanings and functions as part of Late Knossos’ “divine propaganda”? How might Sacral Knots connect with the needs and claims of a new Minoan elite, and (if at all) with a Great Year calendar? Let us look at the best available clues. Sacral Knots had several forms: perhaps first in the hair of women, priestesses and deities, and those worn by Minoan sailors.” ref

“In Egypt, “she-knots” denoted women’s “holy mysteries” (Budge Dwellers 189, 250): Isis cut a lock of her hair to safeguard the soul of dead Osiris. When she unbound her hair and shook it out over him, his resurrection began (Budge Gods of Egypt). Later Greece’s Three Fates or Moerae spun, measured, and cut every person’s life-thread from their hair. And the power of a knot to bind or control forces was evident in Homer’s Odyssey when sailors untied the knotted bag from wind-god Aiolos (X, I), and in “Circe of the braided tresses.” Binding and unleashing power, protection through a bond, transformation, and resurrection might be reasonable associations to explore. Some Knots were made of costly ivory or faience, and painted or physically mounted on a wall, as if produced and posted to the purpose of some social meaning. They also often appeared with figure-8 shields. While shields are sometimes read as “thunder” signs, they are as frequently literal shields, another possible connection to Minoan “men in the service” on land and sea. This was, after all, the period of Crete’s greatest influence in the Aegean and Mediterranean. If these Knots were almost the one sign of a cultural practice on Minoan sailors, they must have borne important meanings.” ref

“Sometimes in textile form, Knots were tied around a pillar, an act Evans related to a later ritual “sleeping-in” within sight of them. To bind a circle around a symbol for life itself, evoking the image of a snake entwined around it, and then to seek out a visionary dream in its presence might connect to traditions (at Neolithic Malta and Catal Huyuk) of women or priestesses sleeping in proximity to tombs and snakes, both embodiments of the dead. In the seal images just above, the probably-dead bull-leaper and doubled Sacral Knots might be one image for “binding prayers” for the resurrection of people lost in many life-threatening endeavors. Below, we see how Labrys and the Sacral Knot at times became one sign, which Marinatos reads as “life” because of its similarity to the Egyptian ankh. It seems significant that this bound-together sign should be found in Minoan skies, as above (though the object was found at Mycenae). Beside it we see likely signs for rain (the vessel), for grain (the stalk descending), and a magnificent tree, toward which a man reaches while climbing upward and the central female whirls in a cosmic dance. To the right, a “chrysalis” with a Sacral Knot behind it unfolds the potential new or reborn creature still within. Lowe Fri found “a” butterfly along with “a” Sacral Knot (and bulls’ heads) incised on double axes.” ref

“Labrys in the sky” might not surprise us, but why fused with a Sacral Knot? In times of increasing stress on communities, rich offerings to collective causes are called for and/or come forward in recognition of common threats and interests. Sailors and warriors were sons of families and clans. Supporting them in their services in both practical and religious terms might have been a reason for “civilians” to obtain a Sacral Knot—the right to wear one or to post one in public and ceremonial form. Defense of Crete and its trade required all the labor and manpower that Soles (above) saw being drained from Minoan agriculture in its post-1480 crescendo of violence. Watrous recently found evidence of a large wall and “tower” defending Gournia from seaborne (not inland) attack. A Knossos elite had to be bound by the same reciprocal relations governing Crete’s classes, and had to bestow the rewards at its command in respect for crucial contributions, including children. Such relations and political strategies may have informed Mycenaean life as well, given the examples above and below-right.” ref

“Clearly, “binding forces together” was a message old in Crete before its “twilight,” and an appealing one as their Late fortunes declined. Enlistments of family-members, contributions of labor and wealth in exchange for the status rewards of posting civic participation, solidarity in the midst of cultural crises and struggles—and a hope of reunion with the ancestors, waiting in the astral afterlife Beyond, as reward for maximum effort and contribution here. To post a Sacral Knot in the sky around Labrys (in conjunction with the above-listed other signs) might represent another part of Knossos’ Late propaganda-promises: food, order, and afterlife. If these efforts “failed” as Island says, or seemed to fail in the face of increasing violence, they might have turned in “a generation or two” into motives for widespread resentment and rebellion. As Island argues, the pressures of living more closely together than before, and of having to devote formerly public ritual space to domestic service and food-storage, would have degraded the bond-supportive meanings of those places; and, in turn, many human bonds. Again, however, Labrys in this connection seems to be deployed in Late forms as the core of a hopeful, proffered formula for plenitude, security, order, and rebirth.” ref

“Those would be the levels of cultural work where we might expect to find a calendar and cosmology: enabling a society to sustain and empower its connections with nature, through a set of observations (like the Great Year cycle) mixed with “beliefs” or propositions for making the most of them, in practical, social, political and religious affairs. A Late Knossos elite whose best option meant pouring gold into mainland Shaft Graves needed to appropriate multiple home traditions. Wedding Sacral Knots to Labrys in the sky, they might have promised eternal care over Minoan sons and family interests; and so tried to enlist the powers of family bonds to their own “divine” benefit. The gestures at least seem visible in relation to the central sign of the Bull Leap fresco calendar. The Marine Style element of Late Knossos’ “divine propaganda” was in part a new kind of Minoan recognition of the sea, which had mothered their race, made them rich, and then done them so much damage through Thera and its tsunamis. Evans found “some” Marine Style in the last Middle period, a rise to importance after 1600, and then its “rush” to production through the destructive decades after 1480—along with another increase in the appearance of “horns of consecration” (Island), to explore last here.” ref

“Perhaps people demanded ceremonial recognitions of the powers that had struck them by sea and air. Some attribute Marine Style vessels to the influence of refugee artists from Thera. Or, Knossos had begun to recognize or appropriate a Mycenaean sea-deity, Potidan, Poseidon (Island). Evans showed that Marine elements such as shells were known as early as any other religious aspect. He also speculated (2: 542) that while Minoans were including pumice, shells, and other sea-objects in ritual places (Island 97), they built “many” new pillar crypts into the Little Palace next to Knossos, as if with some “expiatory” motive that, implicitly, relates to Minoan ancestors and cosmology. Was this a sign of Minoan feeling that, given their disasters and increasing mainland pressures, they had gone astray from reliable ways? While the Snake Goddesses seem to have been “put away” in some further adaptation of central ceremony, it is probably a coincidence that Marine Style included an “8 or 9” Great Year feature in its forms of octopi. Labrys’ other new aspects as part of this will appear. As one measure of its ascendancy, by the time Crete’s destructions had subsided into Mycenaean domination (circa 1425), it was the substance of a Labyrinth ceiling pattern (at left below); possibly as protection, from above, against seismic forces. Before long (circa 1400), Marine Style mingled with a vegetal form of Labrys between horns, below at right. Marinatos reads this combination as “a mini-model of the universe,” showing Labrys’ reach into “the upper and lower worlds.” ref

“While no calendric element seems appreciable among Marine Style motifs, the final element in Late Knossos “propaganda,” “horns of consecration,” returns us first by way of Mount Ida to the Knossos throne. Mount Ida with its pair of horns is the peak at right. Close to the center of Ida’s northern face is the Idaean Cave (long one of Crete’s most important, along with Dikte). Yet, we do not have to think of Mount Ida to see, below, the twin peaks of the mountain in the face of the throne, below its disc and crescent. Banou’s comprehensive history of expert debate (over “horns of consecration” as references mainly to Bull, or something more) reflects new contemporary opinion—that Minoan “horns” were at least as connected with the concepts of “mountain[s]” and “horizon”). As forms, sun, moon and horned mountain are seamlessly part of one another in the Knossos throne. Given all that we (may) know about the calendric connections built into this central artifact, let us see if we can read why it presents moon and sun centered above a horned mountain.” ref

“Two other examples of this mountain come from an Akkadian seal, and from an Egyptian tomb-painting. At left, Babylon’s “Shamash,” a god of justice, mounts upward from the horned mountain toward sun, moon, and likely Pole Star. At right, the djew sign for mountain is used to express a massive Egyptian harvest of grain—and grain, as on the Agia Triada larnax where we began this chapter, was always the primary gift returned to mortals by the dead after receipt of their proper ceremonial offerings and honors. Plenitude, steadfast social order through the honor of the ancestors, and the afterlife appear entwined in the mountain’s many meanings. A basic one was that the djew (or “mountain,”) denoted in part The Land of the Dead, the necropolis of tombs that Egyptians had made of their “wilderness” lands east and west of the Nile. And we saw similarities between the akhet (or “horizon of the sun,” above right) and the widespread, long-held, and many-formed figure of a person or divinity “with upraised arms,” including New Year and rebirth.” ref

“Horns as a figure of a mountain do not dispense with their relations to Bull, or with D’Agata’s and the Hallagers’ views of them as “a clear symbol of territorial power.” In Late times, horns were important aspects of 12 sites from Knossos to Zakros. As in the model shrine and seal-impression above (and, by wide agreement in research), horns pointed to the sanctity and authority of sites where they were posted (Marinatos “Kingship”). Again above, horns—their ancestral meanings, their referents in cycles of astronomy and hence their doublings–date from at least the last period of the Old or Proto-Palatial Knossos. In Rethemiotakis’ 2009 reconstruction of a very Late “model” from a peak sanctuary, a doubled pair of horns also flank the central point. On the Agia Triada larnax we found a tree in the central place: in these “models” as at left above, a niche or door. Both connect this world and Beyond. (Marinatos 2010, 194 notes that “Minoans deliberately played with the form: horns look like mountain peaks” and vice-versa.) For Hitchcock, horns marked “transitional spaces” in the architecture of ceremonial places. Troubled Island is clear that Knossos never “dominated” Crete except in symbolic terms. It seems we have to look beyond a Bull’s brute force to understand this “horned mountain” better, and what it might have offered for so long to a society of families rooted in kinship.” ref

In Egypt, the original meaning of ka was “bull,” and its sign was a pair of upraised arms. It was often “the symbol of an embrace, a greeting, an act of worship, the protection of a man by his ka, or a sign of praise, although other interpretations are possible”. “When depicted with the arms squared off at the elbow and extended so as to embrace, it is thought to represent the life force being passed to an individual by gods or the creator” (Isler). For all the complexity of the term—the ka as one part of an Egyptian soul, and as the very source of being, in one’s ancestors—there might be ways to understand these relationships to the dead and to astronomy.“To return to one’s Ka” was to rejoin ancestors and family, the people from whom one received life. The way to access the ancestors was in many traditions through the use of a construction called a niche, or a “false door” threshold between the living and the dead: a transitional space encountered in the midst of ceremony. The Egyptian, Theran, and Minoan conceptions above are types of these structures. “Mountain” is clearly a part of the Aegean and Minoan examples shown here, including at its highest point (in the detail above from a Zakros stone rhyton), between the horns of wild goats, a shape that Marinatos (Religion) links to the Knossos throne. According to Isler’s study of niches and false doors (which agrees with Marinatos’ Religion), the dead, in turn, received revivifying effects from offerings, and as well from the alignments of these tomb-portals with the sun at chosen times of the year. As a Pyramid Text stated at the moment of the king’s “ascension to the celestial realm,” “The doors of the sky are opened” (Shafer).” ref

“And it was from such a mountain, through a door’s transitional space, that the goddess Hathor emerged as shown at left above, “showing forth” and manifesting new life born of the immortal dead. Egypt’s widely-popular cow-goddess and “daily companion” of the Solar Bull left evidence in Crete from Old Palace times in the sistrum; and Hathor appears in post-Minoan art in Egypt. It is she (or “Wazet of Buto,” Evans) emerging likewise from a “field of rushes,” welcoming the deceased to the afterlife. Hathor’s links to the protection of the dead, and to the stars and sky, articulate connections between the mountain, the dead in their underworld, and the Beyond. Banou noted a seal image showing a doubled pair of horns “in the sky” over a sacrificed Bull, and found them redundant unless they reflected a “wider abstract meaning” for ritual with “celestial” associations.” ref

“Not every Minoan peak sanctuary—the birthplaces of Minoan religion—included a “horned” mountain or a view of one. But while Krattenmaker notes that “the mountain” had “much to do with the character of Minoan kingship” and “the sources of its power,” neither she nor Marinatos seem to make the crucial connection between “the mountain” and the all-important Minoan ancestors. Peak sanctuaries fundamentally position their living celebrants between the sky with its moon, sun, and stars, and the ancestral underworld with its tombs, niches, caves, and pillars. “The mountain,” especially a horned one, seems to embody the realm of the dead protected by this deity (Marinatos Warrior); to manifest their “risen” status with its upraised points or “arms”; and as shown in Chapter 1, the dead were commonly believed to live on as well in the sky. “The mountain” thus points from and connects “below” to “above.” The “Snake Tube” above at right, from Gournia’s Late shrine, with its disc between horns at the top, presents a like configuration. While Cadogan suggests it should be called a “stand” because of uncertain connections with snakes, J. and M. Shaw, writing of excavations at Kommos, described the same functions and meanings in these objects, symbolically connecting earth (in the “snake handles”) and the sky (above, with the disc; and on other such tubes, birds).” ref

“Access to the ancestors and a share in their life-eternal—promised in “horns,” and in their mountain-form, graven into the Knossos throne—were central concerns for Minoan generations. Display-processions such as “the god-king going up the mountain of the ancestors” had been a convention of rulership since Babylon. As Watrous observed in exploring Minoan-Egyptian connections, one of the key tenets of a religion-centered society was that, by following the way of society, one gained a place in the Beyond. The ancestors promise back grain, plenitude, and life-eternal for their honors. Living boughs, Labrys, X-forms weave these meanings together between the horns. The Minoan mountain in the throne room, however, upholds and is crowned with the solar disc and crescent lunar horns. Hence, if a Great Year cycle was (or was trying to be) “the” Minoan organizing principle, a Great Year cosmos would be the visible capital principle of spiritual relationship and access to the ancestors. As Hitchcock observed, the only other truly “monumental” horns were found near Knossos, atop a mountain—Juktas, the tomb of a dying and resurrected god.” ref

According to Pietrovito, it was in these Late times that Labrys began to be “socketed” and “monumentalized” as never before: it was posted atop pillars and between horns, not as “a replacement of either, but [as] a new symbol of the two combined”. Briault’s 2007 study of long-term ritual practices focuses on the Minoan double ax, horns of consecration, and their combined ‘composite symbol’. Her careful chronological inventory finds double axes most prevalent ‘as a marker of temporary cult places inside settlements’ and, outside them, as a ‘votive offering’ at peak and cave sanctuaries. These findings coincide with others suggesting the double ax’s associations with mountains (peaks above, caves below) and the dead. A ‘temporary cult place,’ meanwhile, is a space made sacred at certain times by and for religious ritual—and the question of which times almost certainly points to the role of a calendar, symbolized in these chapters by Labrys. By the Late years in which these two symbols combined their similar functions, they still ‘had as much to do with funerary as with religious ritual’: the double ax on a horned mountain ‘was part of a wider re-inscription of traditional practices…[a] selective use of tradition as an actively shaping force’ that was ‘perhaps indicative of a deliberate reaching back to traditional meanings and values that still retained significance.’ (And as we’ll see, they continued to appear and function ‘long after elite groups’ had vanished as producers and users of both symbols).” ref

“Perhaps this emergent union of Labrys and horns of consecration can be read in terms consistent with Great Year pieces of evidence. As Pietrovito and Dietrich date “horns” to the Neolithic, this new symbol seemed to combine Crete’s oldest beliefs with calendric ones, which must have gradually become ascribed to Labrys from Middle into Late times. If horns had long been a sign of the ancestors and kinship, Labrys posted between horns of the World Mountain might have embodied and been intended to present a calendric, ceremonial, and cosmic way to them, in this life through annual and cyclic rites and festivals. What else might explain the ‘mason’s marks’ on many new constructions of this period that juxtaposed a double ax and a star—astral symbols of the calendric ‘way’ and its ‘Door’ to the Beyond? If that was what Knossos’ Late leaders were claiming and offering, it would only have been to repeat a strategy employed in the rise of the first palaces, whereby “elite groups…were successful in merging their own ideology with a long-standing tradition of beliefs and practices” (Schoep).” ref

“In this way, “Labrys between horns” might be read as a new form or configuration of the central traditional symbol on the Knossos throne, the sun-and-moon-over-mountain; as the sign of “a social group who exercised power in the economic, military and religious realms,” all of which depended on an orderly calendar, and who, like Labrys, were centered in but not confined to Knossos. This new combined symbol, appropriating old relationships with ancestors, appeared “without an exclusive control” over its use, and without Knossos “imposing a strict iconographic form” for either element. While there seems no better candidate for the centerpiece of the Late Labyrinth’s “propaganda”, two artifacts noted in Rehak might be examples of its varied echoes. A Late IIIA mirror-handle from a tomb presents a pair of Genii flanking a “mound,” or mountain-shape, like that of the throne; and below, this seal-image (dated contemporary with Knossos’ final years) shows a “snake-frame” headdress with a Labrys between its crescent horns, worn by a female from mainland Pylos. Both combine the ancestral and the astral in what appear to be Great Year terms.” ref

“Knossos as Calendar House: “the” horned threshold-place, “the” mountain, “the” door on its landscape to the ancestors and Beyond. Labrys—like the sun, but also like the moon and stars—pointing a path to eternity through time, constructed in cycles of lights and shadows. Perhaps for such cosmically-centering reasons, the “new symbol” continued through Knossos’ final decades (in the Shrine of the Double Ax), and reached into Cyprus. A Late-period distribution across the island, claiming for Knossos such a cosmic mediator’s role, might have begun in attempts to “standardize” solstices and equinoxes through the use of horns (MacGillivray “Astral”): calendric activities. Standardization, a many-sided and widespread conformity with Knossos detailed by Wiener, was a main Late-period trait, including the arranged “intervisibility at increasingly greater scales” among the 8 peak-sanctuaries still in use (Nixon). Blomberg and Henriksson see an “8 or 9”-year cycle connected with Minoan high office itself, as does Willetts.” ref

“With Labrys and other calendric and vegetal forms posted between horns at significant places and times, Great Year symbolism points again toward plenitude, earthly order, and eternity. In this detail (above) from Luce’s reconstruction of Knossos Labyrinth, shadows from the supposed upper stories happen to configure a djew-form in front of the throne room’s doorways. It grows easier to imagine many deliberate constructions like it, built to incorporate the ancient sacredness of peak sanctuaries and, in so doing, invest Knossos’ political ascendancy (and calendric system) with an aura of blessing and approval from the ancestors. In the light of these developments in Minoan iconography, Late-period social divisions between Crete’s larger kinship groups and a Knossos with perhaps-divided loyalties. A Late Knossos that had borrowed and then was seen to be corrupting ancient traditions might have needed to be building so many “expiatory” pillar crypts. O’Connor and Silverman noted in Ancient Egyptian Kingship (1995: 264) that a “palace” was “structured so as to be a vital link between Egypt [for example] and the cosmos. The plan, architectural form, ‘decorative’ scenes, and texts of the temple integrated the earthly reality of the rituals performed…with the supra-reality of the cosmic processes of creation and the renewal of creation. This integration ensured that ritual had meaning, authority, and effective power.” ref

“Perpetuation of the Minoan world-order depended on the “incorporating practices” of participative ceremony; meaning “actions of the body [that] transmit information, including gestures, manners or etiquette [as well as] rituals, in which the body ‘performs’ the information” to be lived out and passed on (Lucas Archaeology of Time). The ceremonial inclusion of nature—turning its major powers, phases, and events into ritual backgrounds to confirm “elite esoteric knowledge” and power—would have been an advantage to reckon with, beyond the Late-period “light shows” that some scholars (Banou and Soles, for example) have inferred from various pieces of evidence. While those might have included uses of “bright objects” such as the “crescent crystal” below from the throne room (which Evans judged “part of a necklace”), rites at centers such as Mochlos must have been equally impressive, for awhile. Soles described “large numbers of conical cup lamps” there, perhaps for “luminary” rituals that ranged from pillar crypts to upper-floor “windows of appearance.” From “columnar rooms” above the crypts came “a clay boat and female figurine, which may have formed a three-dimensional religious tableau showing a goddess and a sacred boat, like the scene depicted on the famous Mochlos signet ring”.” ref

“A journey from below to above, culminating (in some related beliefs) in a guided boat-journey across the stellar void, might evidence an elite providing ritual reassurances about the afterlife. To many Minoans, a boat might have symbolized a farthest-imaginable journey: a dragon-headed guide might serve in traditional terms we have seen. Yet, in the decades that ended Crete’s independence, “shows” did not protect Mochlos or any other center from “desecration” (by Mycenaeans, Minoans, or both). Knossos alone withstood the times. Bull-leaping scenes expressed 1200 years of festival in the center of the fresco. For the central image of a central calendar there was hardly a more mainstream way to express and enlist Minoan life. “This kind of design was never more popular,” or perhaps calculated to be, “than in the Late epoch of the Palace”. This seems thoroughly consistent with Peter Warren’s detailed 2012 review of 25 years of studies on Minoan civilization. His finding is that Late Minoan Crete manifests two main political and social dynamics. First, a ‘shifting instability of factional competition,’ manifesting not in ‘military or coercive’ terms, but in monumentality, emulation, and great expenditures in ‘feasting and drinking ceremonies’—multiple elite locations, then, outdoing each other along a chain of probably-regular events. In a phrase, alternating places and times of high festivals, with the benefits of distributing prestige and thwarting full centralized power. (Long after the Minoans, alternation with those purposes was still a core aspect of Cretan political structure.” ref

“If this political rhythm was also important to the city-states later listed on the Antikythera Mechanism, then the second main Late Minoan condition that emerges in Warren’s study (an ‘organizing power’) may point to a Knossos with a similar function—as the timekeeping-piece among Crete’s shifting heterarchic factions. Again, the only throne in Crete is positioned in space according to time. To what purpose? The studies gathered by Warren also document some kind of ‘organizing power…a ruler or ruling family’ whose hierarchs were ‘engaged in traditional, stabilizing practices’ across the island’s independent groups. And yet, because there are no visible rulers or dynasties—the throne is inscribed with moon, sun, and mountain, not with a dynastic logo—the one supportable theory left standing for a viable mechanism of Minoan government (a central, but thoroughly limited ‘state’) can only be such a ‘family.’ I.e., an initiated elite mostly local to Knossos, refining and using knowledge of the cycles of time (through their sciences, traditions, arts, and assets) to turn nature into the platform of their influence, and hold Minoan space together. The centrality of Knossos—which began in the cooperation of groups, not in one faction’s entrenchment—must have anchored Crete’s time-based practical and political affairs, while it evolved to turn the sun’s journey into the soul’s.” ref

“After all, for a century of international research, what we clearly do have so far in the artifacts is not imperialism or ‘kings’ but a heterarchy held together by shared practical, political, and spiritual cycles. The great houses that imitated Knossos and took on its symbols must have been at least partial subscribers to its temporal frame. We can see their remains speak to each other, of sun, moon, mountain, star, and the Beyond, from the first Labrys to the Bull-Leap Fresco, in artifacts common and elite. How, finally, would actual Great Year lunar/solar anniversaries play out from beginning to end (and around again), and provide meaningful bases in time and nature for the structures of central unifying festivals? Altogether, we might conceive of a ceremonial life led by the most gifted and charismatic in religion, the arts and proto-sciences: what Frank called “ritual calendar-keepers, a class of proto-astronomers,” who studied nature and spiritual matters, and from their learning constructed life as a dramatic play; based in and structured by a cycle with ever-different episodes, new combinations of circumstances and individuals—on a scale we still find in Tibet and Bali.” ref

“Once the mainland’s Mycenaeans had a potent place in Crete, a Minoan calendar had to provide an inner benefit as well. Who, after all, would control and gain the most from a cultural movement toward a central cosmology? Minoans, or their “new elites”? In Late Knossos propaganda, kinship—founded in plenitude, social reciprocity, and a confident afterlife—was apparently being “appropriated” toward a cosmology and a new conception of political power. Long ages through which the only “kings and queens” had seemed to remain anonymous in their executive and/or ceremonial functions were coming to an end. Blakolmer found in the Knossos throne’s traditional “anonymity” a “strategy for equality of persons.” Minoan arts were serving “not king, but cult” (Davis “Missing Ruler”), in the elucidation of a “religious rather than secular ideology” (Marinatos “Divine”). Or as Driessen observed in “Crisis Cults”: “Whereas in Egypt and Mesopotamia, the Pharaoh and the En or Lugal guaranteed the link between mortals and gods, explaining their role in iconography and…the royal image, the link between the two worlds [in Minoan cosmology was] constituted by the rituals themselves. The acts were more important than the actors or mediators, and these actions seemed to constitute the political ideology”.” ref

Beyond Crete

“The Minoans were traders, and their cultural contacts reached the Old Kingdom of Egypt, copper-containing Cyprus, Canaan, and the Levantine coast and Anatolia. Minoan-style frescoes and other artifacts were discovered during excavations of the Canaanite palace at Tel Kabri, Israel, leading archaeologists to conclude that the Minoan influence was the strongest on the Canaanite city-state. These are the only Minoan artifacts which have been found in Israel. Minoan techniques and ceramic styles had varying degrees of influence on Helladic Greece. Along with Santorini, Minoan settlements are found at Kastri, Kythera, an island near the Greek mainland influenced by the Minoans from the mid-third millennium BC (EMII) to its Mycenaean occupation in the 13th century. Minoan strata replaced a mainland-derived early Bronze Age culture, the earliest Minoan settlement outside Crete. The Cyclades were in the Minoan cultural orbit and, closer to Crete, the islands of Karpathos, Saria, and Kasos also contained middle-Bronze Age (MMI-II) Minoan colonies or settlements of Minoan traders. Most were abandoned in LMI, but Karpathos recovered and continued its Minoan culture until the end of the Bronze Age. Other supposed Minoan colonies, such as that hypothesized by Adolf Furtwängler on Aegina, were later dismissed by scholars. However, there was a Minoan colony at Ialysos on Rhodes.” ref

“Minoan cultural influence indicates an orbit extending through the Cyclades to Egypt and Cyprus. Fifteenth-century BC paintings in Thebes, Egypt depict Minoan-appearing individuals bearing gifts. Inscriptions describing them as coming from keftiu (“islands in the middle of the sea”) may refer to gift-bringing merchants or officials from Crete. Some locations on Crete indicate that the Minoans were an “outward-looking” society. The neo-palatial site of Kato Zakros is located within 100 meters of the modern shoreline in a bay. Its large number of workshops and wealth of site materials indicate a possible entrepôt for trade. Such activities are seen in artistic representations of the sea, including the “Flotilla” fresco in room five of the West House at Akrotiri.” ref

Minoan/Cretan (Keftiu) women

“As Linear A, Minoan writing, has not been decoded yet, almost all information available about Minoan women is from various art forms. Most importantly, women are depicted in fresco art paintings within various aspects of society such as child rearing, ritual participation, and worshiping. Artistically, women were portrayed very differently compared to the representations of men. Most obviously, men were often artistically represented with dark skin while women were represented with lighter skin. Fresco paintings also portray three class levels of women; elite women, women of the masses, and servants. A fourth, smaller class of women are also included among some paintings; these women are those who participated in religious and sacred tasks. Evidence for these different classes of women not only comes from fresco paintings but from Linear B tablets as well. Elite women were depicted within paintings as having a stature twice the size of women in lower classes: artistically this was a way of emphasizing the important difference between the elite wealthy women and the rest of the female population within society. Within paintings women were also portrayed as caretakers of children, however, few frescoes portray pregnant women, most artistic representations of pregnant women are in the form of sculpted pots with the rounded base of the pots representing the pregnant belly. Additionally, no Minoan art forms portray women giving birth, breastfeeding, or procreating. Lack of such actions leads historians to believe that these actions would have been recognized by Minoan society to be either sacred or inappropriate. As public art pieces such as frescoes and pots do not illustrate these acts, it can be assumed that this part of a woman’s life was kept private within society as a whole.” ref

“Not only was childbirth a private subject within Minoan society but it was a dangerous process as well. Archeological sources have found numerous bones of pregnant women, identified as pregnant by the fetus bones within their skeleton found in the abdomen area. This leads to strong evidence that death during pregnancy and childbirth were common features within society. Further archeological evidence illustrates strong evidence for female death caused by nursing as well. Death of this population is attributed to the vast amount of nutrition and fat that women lost because of lactation which they often could not get back. As stated above childcare was a central job for women within Minoan society, evidence for this can not only be found within art forms but also within the Linear B found in Mycenaean communities. Some of these sources describe the child-care practices common within Minoan society which help historians to better understand Minoan society and the role of women within these communities. Other roles outside the household that have been identified as women’s duties are food gathering, food preparation, and household care-taking. Additionally, it has been found that women were represented in the artisan world as ceramic and textile craftswomen.” ref

“As women got older it can be assumed that their jobs taking care of children ended and transitions to more of a priority towards household management and job mentoring, teaching younger women the jobs that they themselves participated in. Minoan dress representation also clearly marks the difference between men and women. Minoan men were often depicted clad in little clothing while women’s bodies, specifically later on, were more covered up. While there is evidence that the structure of women’s clothing originated as a mirror to the clothing that men wore, fresco art illustrates how women’s clothing evolved to be more and more elaborate throughout the Minoan era. Throughout the evolutions of women’s clothing, a strong emphasis was placed on the women’s sexual characteristics, particularly the breasts. Female clothing throughout the Minoan era emphasized the breasts by exposing cleavage or even the entire breast. Similarly to the modern bodice women continue to wear today, Minoan women were portrayed with “wasp” waists. This means that the waist of women were constricted, made smaller by a tall belt or a tight lace bodice. Furthermore, not only women but men are illustrated wearing these accessories. Within Minoan society and throughout the Minoan era, numerous documents written in Linear B have been found documenting Minoan families. Interestingly, spouses and children are not all listed together, in one section, fathers were listed with their sons, while mothers were listed with their daughter in a completely different section apart from the men who lived in the same household. This signifies the vast gender divide that was present within all aspects of society. Minoan society was a highly gendered and divided society separating men from women in clothing, art illustration, and societal duties. Scholarship about Minoan women remains limited.” ref

“Minoan men wore loincloths and kilts. Women wore robes with short sleeves and layered, flounced skirts. The robes were open to the navel, exposing their breasts. Women could also wear a strapless, fitted bodice, and clothing patterns had symmetrical, geometric designs. The Minoans seem to have prominently worshiped a Great Goddess/or goddesses, which had previously led to the belief that their society was matriarchal. However it is now known that this was not the case; the Minoan pantheon featured many deities, among which a young, spear-wielding male god is also prominent. Some scholars see in the Minoan Goddess a female divine solar figure. Although some depictions of women may be images of worshipers and priestesses officiating at religious ceremonies (as opposed to deities), goddesses seem to include a mother goddess of fertility, a goddess of animals and female protectors of cities, the household, the harvest, and the underworld. They are often represented by serpents, birds, poppies, or an animal. Minoan horn-topped altars, which Arthur Evans called Horns of Consecration, are represented in seal impressions and have been found as far afield as Cyprus. Minoan sacred symbols include the bull (and its horns of consecration), the labrys (double-headed ax), the pillar, the serpent, the sun-disc, the tree, and even the Ankh.” ref

“According to Nanno Marinatos, “The hierarchy and relationship of gods within the pantheon is difficult to decode from the images alone.” Marinatos disagrees with earlier descriptions of Minoan religion as primitive, saying that it “was the religion of a sophisticated and urbanized palatial culture with a complex social hierarchy. It was not dominated by fertility any more than any religion of the past or present has been, and it addressed gender identity, rites of passage, and death. It is reasonable to assume that both the organization and the rituals, even the mythology, resembled the religions of Near Eastern palatial civilizations.” It even seems that the later Greek pantheon would synthesize the Minoan female deity and Hittite goddess from the Near East. Haralampos V. Harissis and Anastasios V. Harissis posit a different interpretation of these symbols, saying that they were based on apiculture rather than religion. A major festival was exemplified in bull-leaping, represented in the frescoes of Knossos and inscribed in miniature seals. Similar to other Bronze Age archaeological finds, burial remains constitute much of the material and archaeological evidence for the period. By the end of the Second Palace Period, Minoan burial was dominated by two forms: circular tombs (tholoi) in southern Crete and house tombs in the north and the east. However, much Minoan mortuary practice does not conform to this pattern. Burial was more popular than cremation. Individual burial was the rule, except for the Chrysolakkos complex in Malia. Evidence of possible human sacrifice by the Minoans has been found at three sites: at Anemospilia, in a MMII building near Mt. Juktas considered a temple; an EMII sanctuary complex at Fournou Korifi in south-central Crete, and in an LMIB building known as the North House in Knossos.” ref

Minoan snake goddess figurines

“Snake goddess” is a type of figurine depicting a woman holding a snake in each hand, as were found in Minoan archaeological sites in Crete. The first two of such figurines (both incomplete) were found by the British archaeologist Arthur Evans and date to the neo-palatial period of Minoan civilization, c. 1700–1450 BCE. It was Evans who called the larger of his pair of figurines a “Snake Goddess”, the smaller a “Snake Priestess”; since then, it has been debated whether Evans was right, or whether both figurines depict priestesses, or both depict the same deity or distinct deities. The figurines were found only in house sanctuaries, where the figurine appears as “the goddess of the household”, and they are probably (according to Burkert) related to the Paleolithic traditions regarding women and domesticity. The figurines have also been interpreted as showing a mistress of animals-type goddess and as a precursor to Athena Parthenos, who is also associated with snakes.” ref

“The first two snake goddess figurines to be discovered were found by Arthur Evans in 1903, in the temple repositories of Knossos. The figurines are made of faience, a technique for glazing earthenware and other ceramic vessels by using a quartz paste. After firing, this produces bright colors and a lustrous sheen. This material symbolized the renewal of life in old Egypt, therefore it was used in the funeral cult and in the sanctuaries. These two figurines are today exhibited at the Herakleion Archeological Museum in Crete. The larger of these figures has snakes crawling over her arms up to her tiara. The smaller figure holds two snakes in her raised hands, which seems to be the imitation of a panther. In particular, one of the “snake goddesses” was found in a few scattered pieces, and was later filled with a solution of paraffin to preserve it from further damage. The goddess is depicted just as in other statues (crown on head, hands grasping snakes etc.). The expression on her face is described as life like, and is also wearing the typical Minoan dress. Another figure found in Berlin, made of bronze, looks more like a snake charmer with the snakes on top of her head. Many Minoan statues and statuettes seem to express pride.” ref

“The snake goddess’s Minoan name may be related with A-sa-sa-ra, a possible interpretation of inscriptions found in Linear A texts. Although Linear A is not yet deciphered, Palmer relates tentatively the inscription a-sa-sa-ra-me which seems to have accompanied goddesses, with the Hittite išhaššara, which means “mistress”. The serpent is often symbolically associated with the renewal of life because it sheds its skin periodically. A similar belief existed in the ancient Mesopotamians and Semites, and appears also in Hindu mythology. The Pelasgian myth of creation refers to snakes as the reborn dead. However, Martin P. Nilsson noticed that in the Minoan religion the snake was the protector of the house, as it later appears also in Greek religion.[8] Within the Greek Dionysiac cult it signified wisdom and was the symbol of fertility. Barry Powell suggested that the “snake goddess” reduced in legend into a folklore heroine was Ariadne (whose name might mean “utterly pure” or “the very holy one”), who is often depicted surrounded by Maenads and satyrs. Some scholars relate the snake goddess with the Phoenician Astarte (virgin daughter). She was the goddess of fertility and sexuality and her worship was connected with an orgiastic cult. Her temples were decorated with serpentine motifs. In a related Greek myth Europa, who is sometimes identified with Astarte in ancient sources, was a Phoenician princess whom Zeus abducted and carried to Crete. Evans tentatively linked the snake goddess with the Egyptian snake goddess Wadjet but did not pursue this connection. Statuettes similar to the “snake goddess” type identified as “priest of Wadjet” and “magician” were found in Egypt.” ref

Sacral knot

“Both goddesses have a knot with a projecting looped cord between their breasts. Evans noticed that these are analogous to the sacral knot, his name for a knot with a loop of fabric above and sometimes fringed ends hanging down below. Numerous such symbols in ivory, faience, painted in frescoes or engraved in seals sometimes combined with the symbol of the double-edged ax or labrys which was the most important Minoan religious symbol. Such symbols were found in Minoan and Mycenaean sites. It is believed that the sacral knot was the symbol of holiness on human figures or cult-objects. ff Its combination with the double-ax can be compared with the Egyptian ankh (eternal life), or with the tyet (welfare/life) a symbol of Isis (the knot of Isis).” ref

Really a goddess?