ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

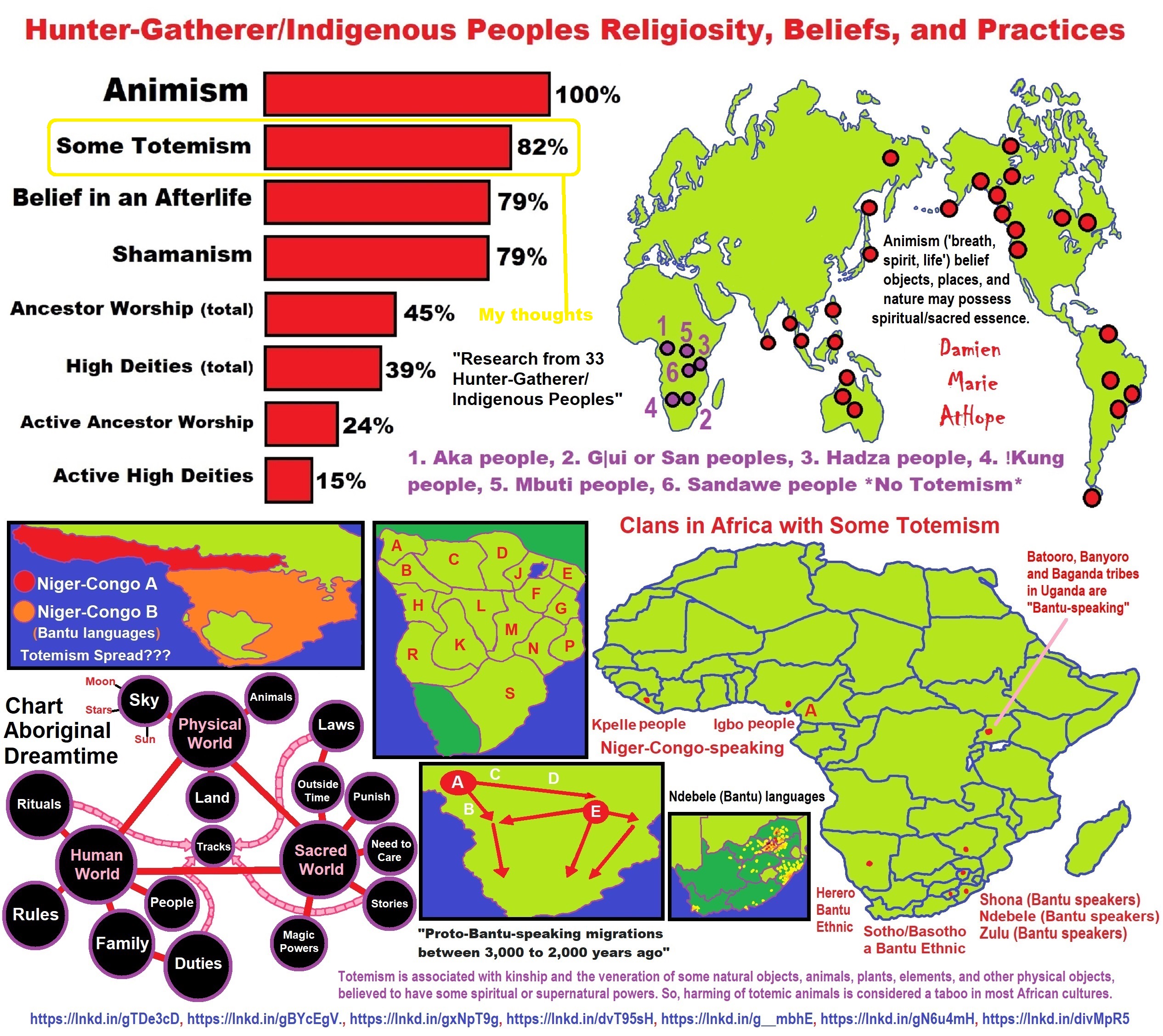

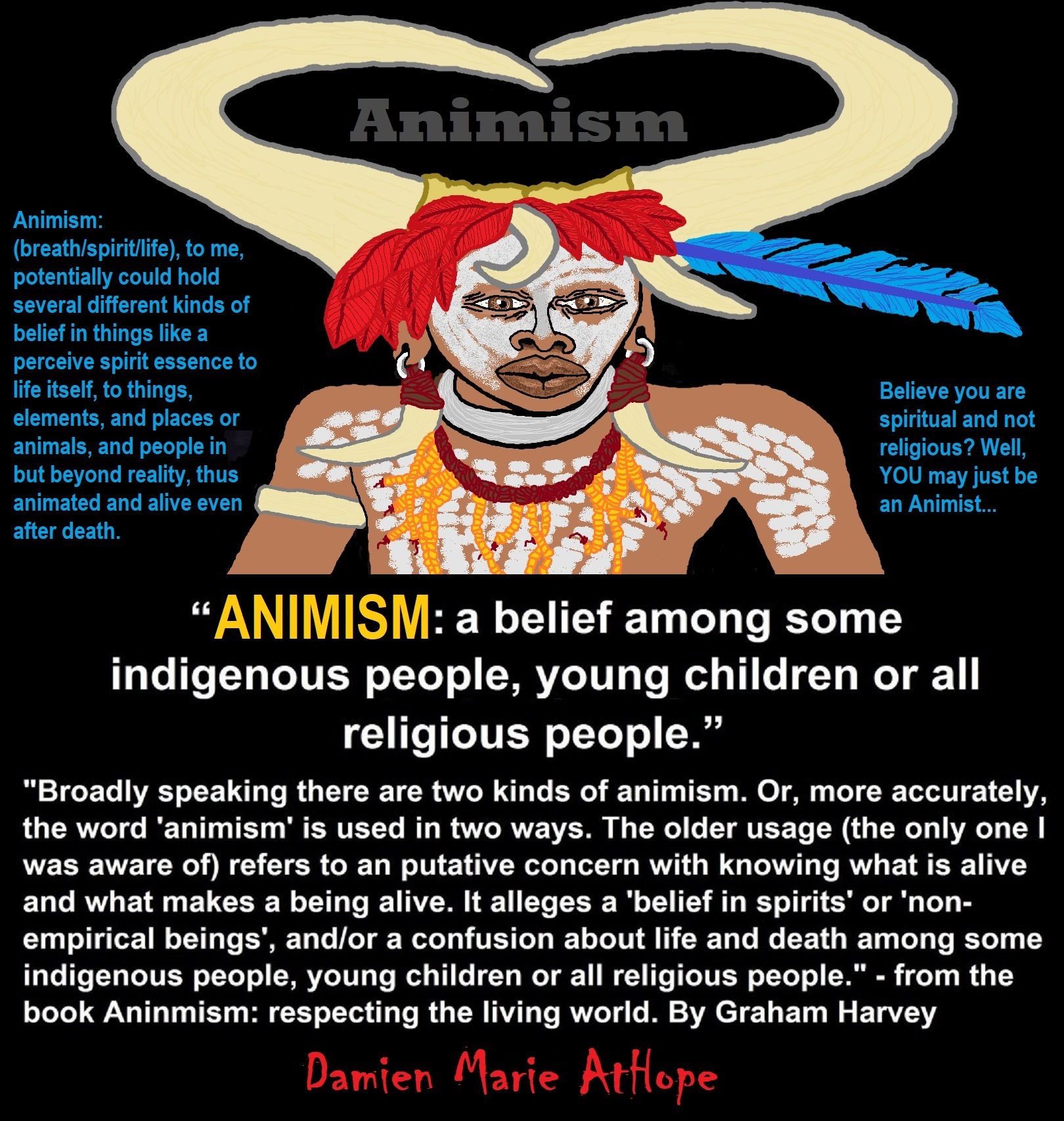

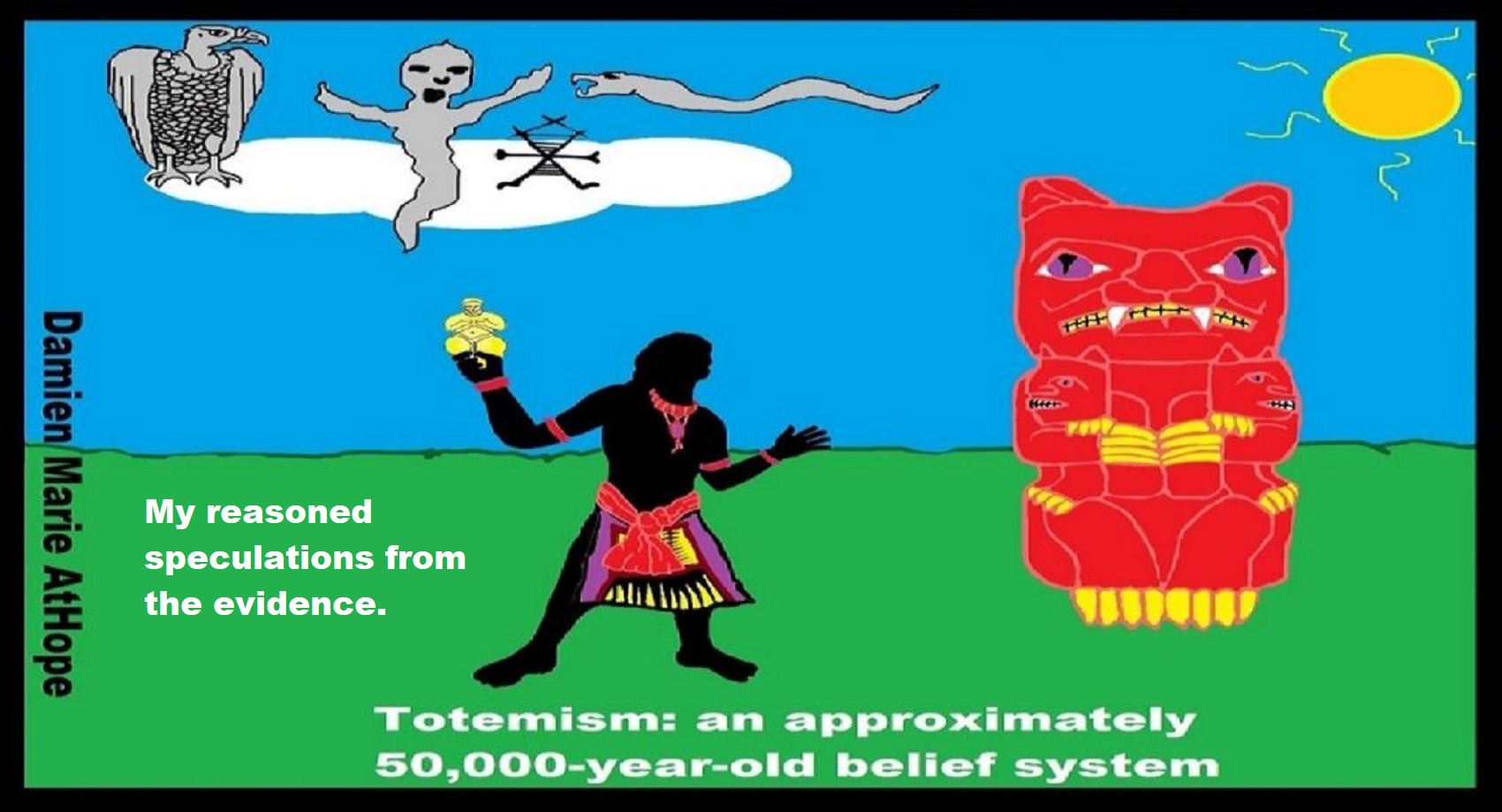

Totemism is associated with kinship and the veneration of some natural objects, animals, plants, elements, and other physical objects, believed to have some spiritual or supernatural powers. So, harming of totemic animals is considered a taboo in most African cultures. Animism (‘breath, spirit, life’) belief objects, places, and nature may possess spiritual essence spirit.

Animism

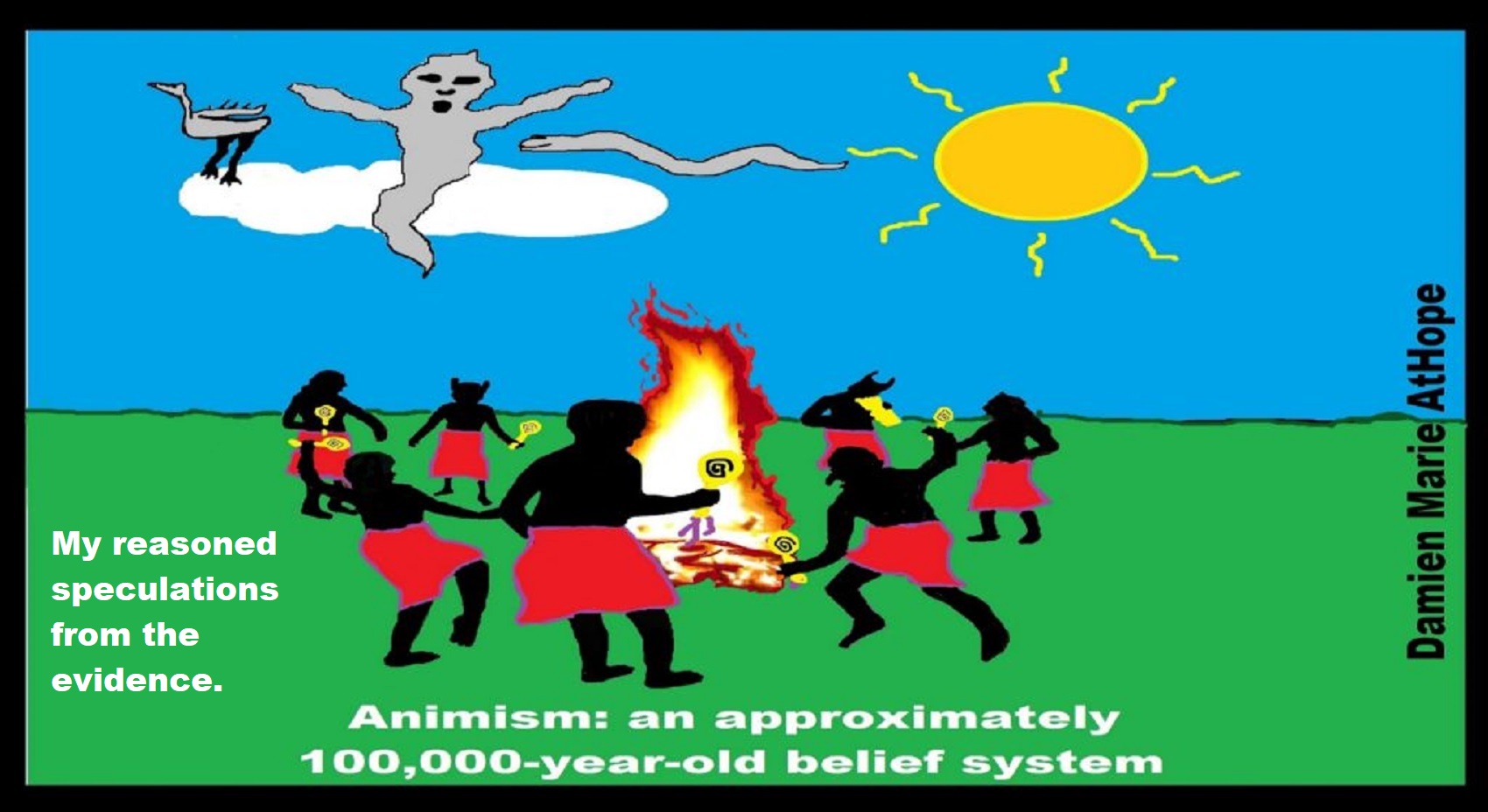

“Animism (from Latin: anima, ‘breath, spirit, life‘) is the belief that objects, places, and creatures all possess a distinct spiritual essence. Potentially, animism perceives all things—animals, plants, rocks, rivers, weather systems, human handiwork, and perhaps even words—as animated and alive. Animism is used in the anthropology of religion as a term for the belief system of many indigenous peoples, especially in contrast to the relatively more recent development of organised religions. Although each culture has its own different mythologies and rituals, animism is said to describe the most common, foundational thread of indigenous peoples’ “spiritual” or “supernatural” perspectives. The animistic perspective is so widely held and inherent to most indigenous peoples that they often do not even have a word in their languages that corresponds to “animism” (or even “religion”); the term is an anthropological construct.” ref

“Aka people” Central African nomadic Mbenga pygmy people (Animist)

“Aka are very warm and hospitable. Relationships between men and women are extremely egalitarian. Men and women contribute equally to a household’s diet, either a husband or wife can initiate divorce, and violence against women is very rare. No cases of rape have been reported. The Aka are fiercely egalitarian and independent. No individual has the right to force or order another individual to perform an activity against his or her will. Aka have a number of informal methods for maintaining their egalitarianism. First, they practice “prestige avoidance”; no one draws attention to his or her own abilities. Individuals play down their achievements.” ref

Mbuti People of the Congo (Animist)

“The Mbuti hunter-gatherers in the Congo’s Ituri Forest have traditionally lived in stateless communities with gift economies and largely egalitarian gender relations. They were a people who had found in the forest something that made life more than just worth living, something that made it, with all its hardships and problems and tragedies, a wonderful thing full of joy and happiness and free of care. Pygmies, like the Inuit, minimize discrimination based upon sex and age differences. Adults of all genders make communal decisions at public assemblies. The Mbuti do not have a state, or chiefs or councils.” ref

Hadza people of East Africa (Animist)

“The Hadza of Tanzania in East Africa are egalitarian, meaning there are no real status differences between individuals. While the elderly receive slightly more respect, within groups of age and sex all individuals are equal, and compared to strictly stratified societies, women are considered fairly equal. This egalitarianism results in high levels of freedom and self-dependency. When conflict does arise, it may be resolved by one of the parties voluntarily moving to another camp. Ernst Fehr and Urs Fischbacher point out that the Hadza people “exhibit a considerable amount of altruistic punishment” to organize these tribes. The Hadza live in a communal setting and engage in cooperative child-rearing, where many individuals (both related and unrelated) provide high-quality care for children. Having no tribal or governing hierarchy, the Hadza trace descent bilaterally (through paternal and maternal lines), and almost all Hadza can trace some kin tie to all other Hadza people. ” ref

1. Yukaghir people

2. Nivkh or Gilyak people

3. Ainu people

4. Aeta or Agta people

5. Andamanese peoples

6. Batek or Bateq people

7. Bajau Tawi or Sama-Bajau people

8. Tiwi people

9. Vedda people

10. Warlpiri or Walbiri people

11. Arrernte or Aranda people

12. Aka people

13. Mbuti people

14. Hadza people

15. Sandawe people

16. ǃKung people

17. Gǀui or San peoples

18. Copper Eskimo or Inuit

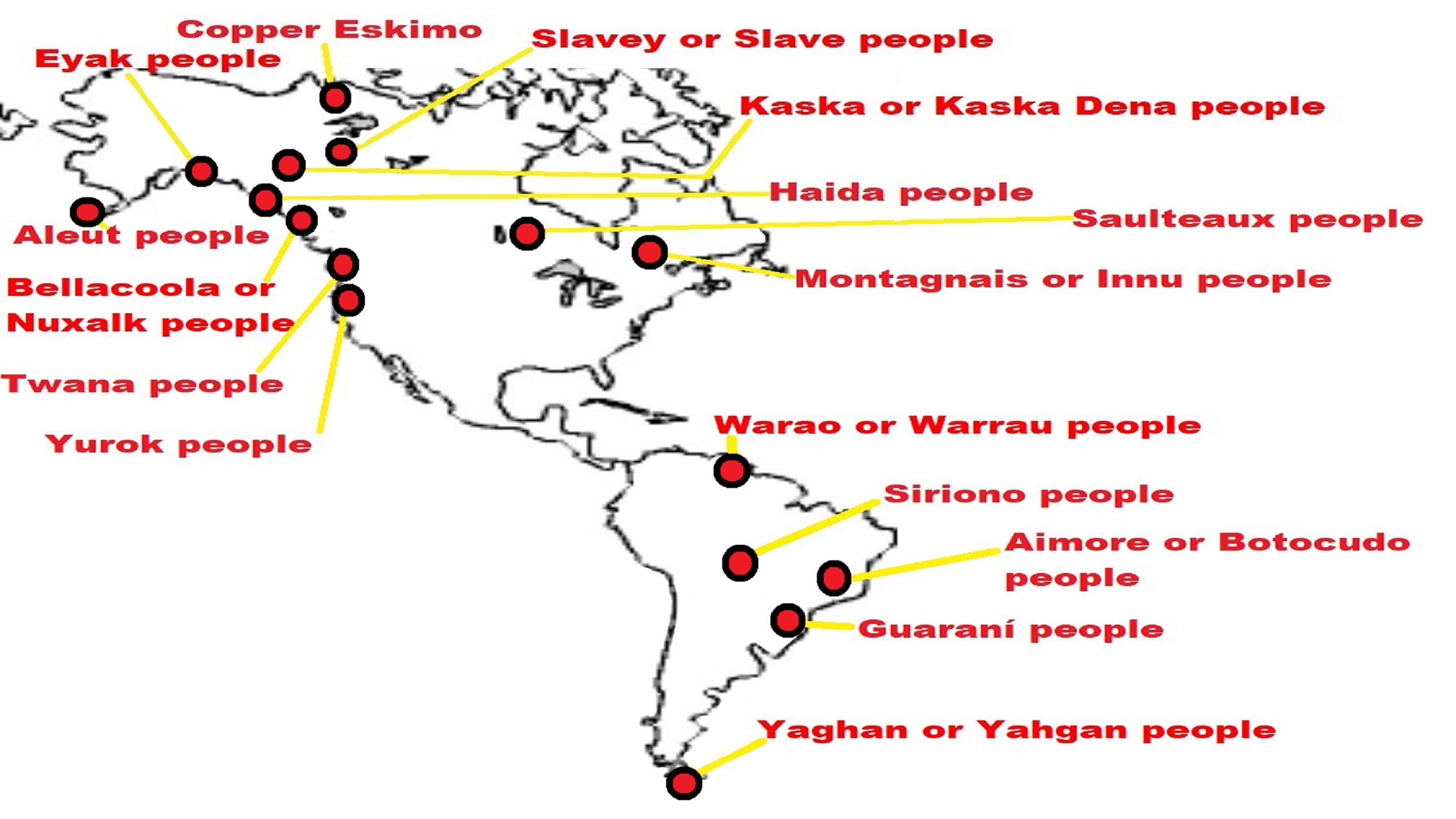

19. Slavey or Slave people

20. Eyak people

21. Kaska or Kaska Dena people

22. Haida people

23. Aleut people

24. Bellacoola or Nuxalk people

25. Twana people

26. Yurok people

27. Saulteaux people

28. Montagnais or Innu people

29. Warao or Warrau people

30. Siriono people

31. Aimore or Botocudo people

32. Guaraní people

33. Yaghan or Yahgan people

6 out of 33 have no discernable trait of totemism so those that do come to 82%.

1. Aka people, 2. Gǀui or San peoples, 3. Hadza people, 4. ǃKung people, 5. Mbuti people, 6. Sandawe people *No Totemism*

TOTEMISM IN AFRICA: A PHILOSOPHICAL EVALUATION OF ITS SIGNIFICANCE IN A WORLD OF CHANGE

Abstract

“Totemism has to do with the veneration of some natural objects, namely, animals, plants, and other physical objects. Totems are believed to have some spiritual or supernatural powers. In this regard, the mishandling or killing of totemic animals is considered a taboo in most African cultures. Belief in totems is a common practice in the traditional African society. African people have deep sense of reverence for either their personal or group totems. This study focuses on Igbo society. The study is guided by the following questions: What is the rational basis for belief in totems? Does belief in totems have any significance in Igbo society in the world of change? Or can we say that belief in totems is now obsolete and without any practical significant value? Therefore, employing the philosophical methods of critical analysis and hermeneutics, the study argues that totems in themselves have no inherent powers and as such, belief in them can best be regarded as irrational and superstitious. However, it further concludes from a functional perspective that totemism has some significance in the areas of ecology and tourism.” ref

Introduction

“The idea of the sacred in African society is as old as the African. Faced with the puzzles, wonders, and mysteries in nature, the African had no choice but to consider certain objects and plants as sacred. These objects and places are seen from the perspective of the divine. And as such, they are not to be toyed with; they are given special reverence especially as objects of worship. “The sacred”, in the understanding of Roberston, “is to be treated with a certain specific attitude of respect.”1Africans believe that spirits inhabit the sacred objects and places. This understanding also gave rise to the reality of totems in African ontology. For sure, belief in totems is an existential fact among African people. Certain trees, animals, places, and individuals are regarded as totems. They are seen as sacred objects that symbolize something real for the people that entertain such belief. Totems are also believed to possess some spiritual and supernatural powers. The thrust of this study is to expose the belief and practice of totemism in Africa and also to ascertain the significance of such belief and practice in a world of change. The focus of this study is on Igbo – African society.” ref

Totemism: A Brief Exposé

“Generally, the notion of “totem” is associated with the idea of kinship between certain animals, animate or inanimate beings, and a particular individual or group of individuals in a given society. it shows that there is a spiritual link between a totemic object and the person or persons concern. The concept, totem, is derived from the Ojibwa word ototeman which simply means a brother – sister blood tie. The grammatical root ote actually signifies a blood relationship between brothers and sisters who have the same mother and who, according to custom, may not marry each other.3The Dictionary of Beliefs and Religion sees totems as objects that serve as a representation of a society or person, and from which the members of that society are thought to descend. This implies that totems are symbolic in nature. Various scholars have varied views on the concept of totem. In the understanding of Burton as cited in Nwashindu and Ihediwa, “totems are used to designate those things whose names the clan or family bears or revers.”4In this sense, the kind of name of a person or a particular clan or community can be traced to their totems. Amirthalingam observes that “totemism denotes a mystical or ritual relationship among members of a specific social group and specie, of animals or plants.” Theoderson sees the notion of totems as a kind of spiritual bond that exists between a particular animal and a tribe that accounts for the wellbeing of the people.6One thing to note from the various views of scholars is that totemism is an expression of a relationship that exists between particular human beings and their natural environment.” ref

“This relationship could be between the people and a particular animal, plant, or place. For the simple fact of the relationship that exists between a totemic group and the totem, there is a deep reverence for the totemic being. There are rules and regulations to ensure the protection, preservation, and reverence of the totemic beings. In most African societies, it is a taboo and a violation of cultural and spiritual life to hurt, mishandle, or kill a totemic animal. Totems are handled with utmost respect and care. “Totemism implies respect for and prohibition against the killing and eating of the totemic animals or plants. Underlying this practice is the belief that the members of the group are descendants from a common totemic ancestor and thus are related.” Nwashindu and Ihediwa related that a survey of Igboland shows the ubiquity of totemic laws, deification of animals and trees, sanctions, and retributive actions guiding men, animals, and trees.8The point here is that totems are very much respected by the totemic group. This deep respect may also stem from the belief that totems protect the totemic group from enemies and dangers.” ref

Totemism in Africa

“The reality of totems or the belief in totems among Africans is not something that is new to the African. Africa is well known for the belief and practice of totemism. The African people believe that the human person can be related in two ways. First, a person can have blood relationship. This type of relationship shows that the persons in question have the same father or mother. This is a type of relationship that can be traced by blood. The second understanding of relationship is the totemic relationship. This means that the people in question share the same totems. This can be seen from the perspective of a clan, village, or a whole community or even people from different communities with the same totemic being. So human relationship in African perspective can be consanguineous or totemic. Without mincing words, belief and practice of totemism is a well-known fact in African thought and culture. The world of the African is not only the world of human beings alone; it includes both living and nonliving things. This position is amplified by Onwubiko: “Ideologically speaking, the African world is a world of inanimate, animate and spiritual beings. The African is conscious of the influence of each category of these beings in the universe. Their existence, for the African, is reality; so also is the fact that they interact as co-existent beings in the universe.”9 Totemism in Africa constitutes part of the cherished cultural values of the African people. The nature of this study will not allow us to expose everything about the belief and practice of totemism in Africa. However, we shall focus on totemism in Igboland as a unit of African society.” ref

Totemism in Igbo Worldview

“The Igbo people are an ethnic group native to the present-day southeast and south-south Nigeria. Igbo people constitute one of the largest ethnic groups in Africa.10As one of the ethnic groups in Africa, there are many totemic animals and plants in Igboland. These animals and plants are seen as sacred and as such, are accorded deep reverence. Below are some of the totemic animals and plants in some parts of Igboland: Python: A python is a large reptile found in many communities of the Igbo cultural area. Some clans and communities see python as a totem. Among those communities are Idemili, Enugwu Ukwu, Abagana, Nnewi, Ogidi, Oguta, Mgbidi, Njaba, Urualla, Awo-Omamma, etc. In these communities, python is very much revered and cared for. Nwashindu and Ihediwa observed that “deification of python is a common heritage and religion in Idemili area of Anambra state”11 In the communities that have python as a totem, it is a taboo (Sacrad/Supernatural Law), to hurt or kill a python. If consciously or unconsciously one kills a python, the person is expected to carry out burial rites for the python as if it is a human being. This view is in line with the submission of Adibe as cited in I. A. Kanu: “No one makes the mistakes of killing it [python] voluntarily or involuntarily. When it is done accidentally, it is buried with the appropriate religious rituals and rites accorded to it. If it is killed knowingly, it is considered an abomination.”12 Monkey: This is another totemic animal in Igboland. The people Awka in Anambra state do not joke with monkey. It is a taboo, to hurt or kill a monkey in Awka. It is believed among the people that monkeys possess some spiritual and supernatural powers and they were quite instrumental to Awka people in the time of war. Following the instrumentality of the black monkeys in helping Awka people defeat their enemies, there is an annual Imoka festival in Awka which is linked to the myth of the black monkey. Also brown monkeys are seen as totems in Ezioha in Mgbowo community of Enugu state. The people “are forbidden to harm, eat or kill a specie of brown monkey called Utobo. It is the family’s belief that Utobo are representatives of the kindred, and bear a direct link between the living and the dead.” ref

“Among the people of Akpugoeze in Enugu state, monkeys are also seen as totems. They are regarded as sacred and no one dares challenge them. Any attempt to hunt or kill a monkey in Akpugoeze is seen as abomination. Ram: This is another totemic animal in some parts of Igboland. The people of Umuanya Nwoko kindred of Itungwa in Abia state regard ram as a totemic animal. Every member of the community is forbidden from hurting, killing or eating ram. The people can have rams as domestic animals but they are not allowed to eat it. Anyone who eats the meat of a ram automatically falls sick which will certainly lead to the person’s death. Tortoise and Crocodile: These reptiles are regarded as totemic animals in Agulu community of Anambra state. Also most communities in riverine Ogbaru local government area of Anambra state treat tortoise and crocodile as sacred animals. Tiger: This is an animal that is generally dreaded by people. But in Umulelu in Obingwa of Abia state, tiger is a sacred animal. It is not harmful to the people. As a totemic animal among the people, tiger is neither eaten nor killed among the people of Umulelu. Oral history has it that some members of the community transformed themselves occasionally into tigers and performed some assignments as tigers and later changed back to human beings. There is a close tie between the people and tiger. There is a story of a man who quarreled with his wife; but when the wife, out of annoyance, parked her baggage to go back to her father’s house, the husband did not resist. But no sooner had she left his house than the husband transformed into a tiger and pounced on her along the road and in the process, the woman, out of fear, changed her mind and returned to her husband’s house. It is a taboo to shoot, harm or kill a tiger among the people of Umulelu. It is important to note at this point that there are many totemic animals in Africa generally and Igboland in particular. The above are simply highlighted as a foundation for this study. We have also to note that totemism in African is not all about animals; there are some plants and trees that are regarded as totemic in Igbo – African ontology, namely, ogilisi, akpu, ofo, udala, ngwu, oji, etc.14 F. C. Ogbalu opines that “some species of plants are held sacred or are actually worshiped or sacrifices offered to them. Example of such trees held sacred in some places are Akpu (silk-cotton tree), Iroko, Ngwu, Ofo, Ogirisi, etc. Such plants are used in offering worship to the idols” ref

Significance of Totemism in Africa in a World of Change

“There is no doubt about the belief and practice of totemism among the African people. It is part of the everyday experience of the Traditional African. In the Traditional African Society, no one ever toyed with totems of a given community. This is not the case in our cotemporary African society. In this regard, some questions disturb the questioning mind of the researcher: What is the significance of totemism in Africa in a world of change? Put differently, what is the place of totems in our ever-changing world? Experience has shown that belief and practice of totemism does not have the original meaning and understanding in our contemporary society as against what existed in the Traditional Africa society. Kanu submits that the influence of western education, cross-cultural influence, Christianity, and Islamic influence has actually brought about a decline in the original way and manner our people accorded reverence to totems in Igbo – African ontology. He noted that some totemic animals are being killed while totemic plants are being cut down for economic purposes.16However, one can say without mincing words that belief in totems can have some significance in the areas of ecology and tourism. There is no gainsaying the fact that the belief and practice of totemism can foster the growth and preservation of totemic animals and plants in the areas where they are considered as sacred. It is an existential truism that animals relax, procreate, and survive more in the areas where they are not treated with hostility. The friendly expression makes it possible for the different species of the animal to multiply within the totemic community. In this regard, one can say that the preservation of totemic animals and plants is a way of maintaining the ecosystem.” ref

“It is the responsibility of every person within the totemic society to care and feed the totemic animal. This is a traditional way of environmental conservation. This is actually what is needed in our contemporary society. Chemhuru and Masaka as cited in Chakanaka Zinyemba are of the view that the belief and practice of totemism have been institutional wildlife conservation measures to preserve various animal species so that they could be saved from extinction due unchecked hunting.17 Furthermore, the belief and practice of totemism can be said to be very significant in the area of tourism. Tourism is a good source of revenue for many countries of the world. People like to travel for fun and also for sight-seeing. Tourism attracts both local and international tourists. This is what the preservation of totemic animals and plants brings to a totemic community. There are certain animals that are going into extinction in some communities because the people engage in hunting and killing of animals without restrictions. Also, in some places, people engage in cutting down trees without any form of restrictions. But as we have state earlier, the belief and practice of totemism brings deep reverence for the totemic beings coupled with rules and regulations to that effect. And so with the preservation of totemic beings, it will certainly bring about large amount of income to the local economy since the community will be the centre of attraction for both local and international tourists. Concluding Reflections The belief and practice of totemism in Africa has to do with the culture and tradition of the African people. However, the idea that totemic beings possess some spiritual and supernatural powers can best be described as superstitious. The claim cannot stand before the Court of Reason.” ref

“The researcher witnessed in a community where python was regarded as a totem but was killed by a man in that community. The man was asked to carry out the burial rites as demanded by their custom or else he will be visited with strange sickness and die. The man refused and till today he is still hale and hearty. There are instances of this kind in many other places as experience has shown. In this regard, one can say that there is no rational basis for totemic practice. It is simply a matter of belief without any rational justification for its claim. On another note, this paper submits that in our ever-changing world, the basis for the belief and practice of totemism can only be viewed from its ecological and tourist significance. There is need for people to be encouraged to preserve animals and plants. Indiscriminate hunting and cutting of trees should be highly frowned at. Forest reserves and game villages should be encouraged by both the governments and nongovernmental organizations. Governments in Africa should step up their lukewarm attitude in this regard. The media should also be involved in sensitizing our people about the need for preservation of animals and plants in order to maintain the ecosystem and more so to ensure tourist attraction. The federal and state ministries of culture and tourism should set up monitoring agencies to ensure the protection of animal rights. There should be stringent penalty for those that violate the rights of animals and forest reserve. In sum, this paper submits that totems have no inherent spiritual and supernatural powers in themselves. The belief and practice of totemism in Africa in a world of change can only be encouraged on the basis of its significant roles in maintaining the ecosystem and also bringing about revenue generation through tourist activities.” ref

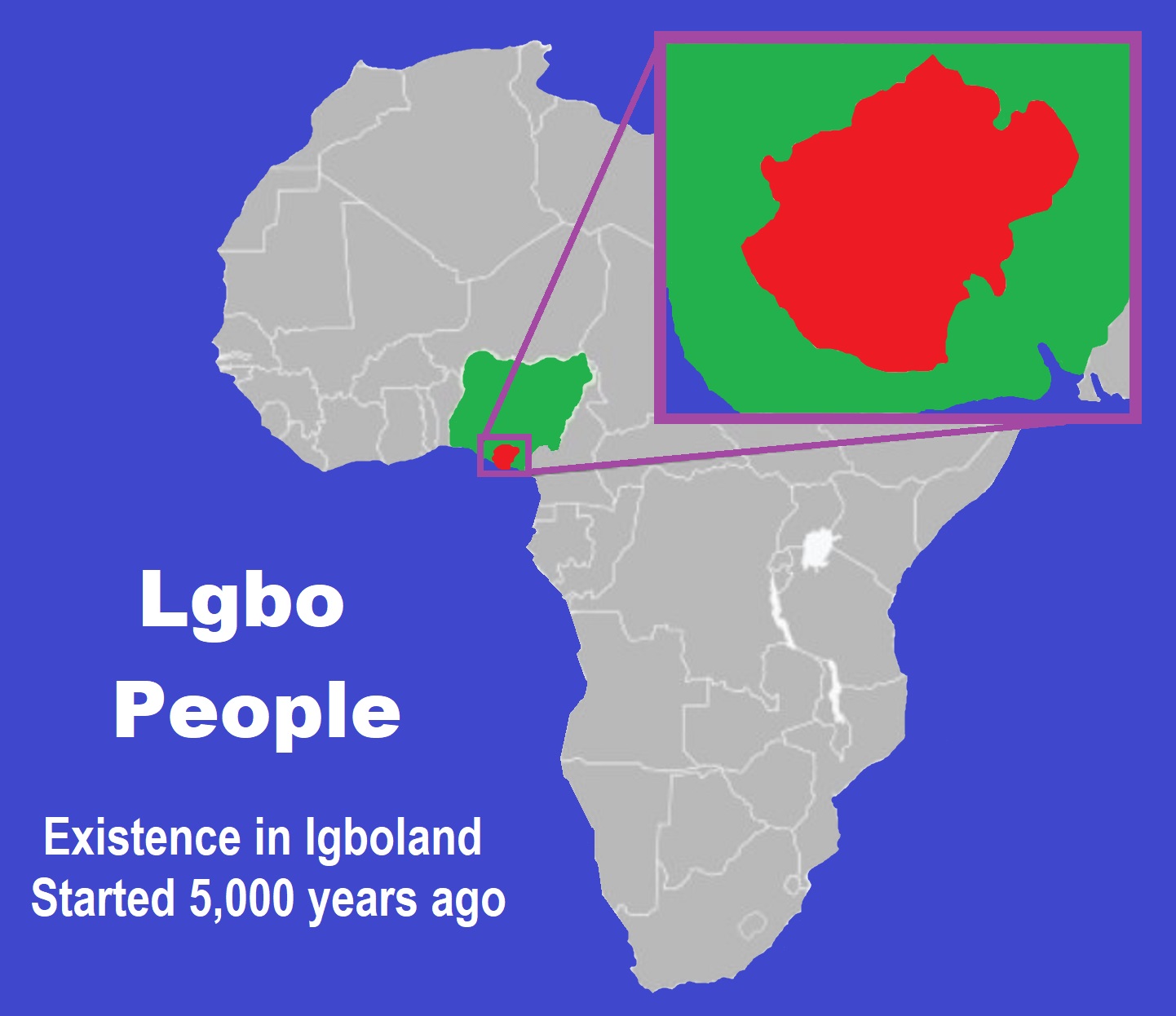

Lgbo People

“3000 BCE Neolithic peoples existence in Igboland. c. CE 850 Bronzes found at the town of Igbo-Ukwu are created, among them iron swords, bronze and copper vases and ornaments, and terracotta sculptures are made.” ref

Estimated geographical frequency distribution of the Y-DNA haplogroup E-M2. Black dots show sampling locations.

“Genetic studies have shown the Igbo to cluster most closely with other Niger-Congo-speaking peoples. The predominant Y-chromosmoal haplogroup is E1b1a1-M2. Haplogroup E-M2 is a human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup. It is primarily distributed in Sub-Saharan Africa. E-M2 is the predominant subclade in Western Africa, Central Africa, Southern Africa, and the African Great Lakes, and occurs at moderate frequencies in North Africa and Middle East. E-M2 has several subclades, but many of these subhaplogroups are included in either E-L485 or E-U175. E-M2 is especially common in native Africans speaking Niger-Congo languages and was spread to Southern and Eastern Africa through the Bantu expansion.” ref

Totemism and Human–Animal Relations in West Africa

Book Description

“This book explores human-animal relations amongst the Bebelibe of West Africa, with a focus on the establishment of totemic relationships with animals, what these relationships entail and the consequences of abusing them. Employing and developing the concepts of ‘presencing’ and ‘the ontological penumbra’ to shed light on the manner in which people make present and engage in the world around them, including the shadowy spaces that have to be negotiated in order to make sense of the world, the author shows how these concepts account for empathetic and intersubjective encounters with non-human animals. Grounded in rich ethnographic work, Totemism and Human–Animal Relations in West Africa offers a reappraisal of totemism and considers the implications of the ontological turn in understanding human-animal relations. As such, it will appeal to anthropologists, sociologists, and anthrozoologists concerned with human-animal interaction.” ref

African Totems: Cultural Heritage for Sustainable Environmental Conservation

Abstract

“Sustainable development, a development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs, has eluded most developing nations in the world today. The world’s countries inlude the developed and developing nations where most African nations fit into the latter category. Attempts have been made to explain the circumstances under which African countries are striving to develop, but the role of Indigenous Knowledge System (IKS) in the entire process has not been exhaustively explored. Indigenous people have responded to ecological and development challenges by using the cultures and knowledge systems transmitted through their indigenous languages. The aim of this paper was to investigate how totems, as cultural belief systems, have been used in Africa to promote the conservation of natural resources. Qualitative methods (based on literature) were used to explore the values and perceptions that underlie the use of totems. The information was collected by reviewing some literature on African culture and totems from Kenya and South Africa. The literature reviewed concentrated on the cultural symbolism attached to totems among different tribes which were randomly selected from the two countries. Data was analyzed through content analysis and presented thematically. It was found that animal, plant, and insect totems in Kenya and South Africa have symbolic meanings attached to them. The symbolic meanings are usually accompanied by taboos believed to have special spiritual and cultural associations. Due to these cultural associations and taboos, totems are protected against harm by the respective tribes, conserving species diversity, and ecosystem diversity. The study recommends that there is a need to appreciate the cultural values and beliefs that help in sustainable development. Findings of the study could add value to the existing body of knowledge on Indigenous Knowledge Systems (IKS) relating to the management and preservation of indigenous knowledge produced in Africa for sustainable development.” ref

Totemism and Tribes: A Study of the Concept and Practice

Abstract

“Totem, the spirit or sacred object, or symbol or emblem of a group of people, such as family, clan, lineage, or tribe, has special significance in the tribal life. They believe that totemic character, sign, mark, letter, ideogram, or any other identity, etc. serve as a reminder of the ancestry or mythic past of them. It signifies a spiritual, religious, social, and cultural association between a clan or lineage and a bird, animal, or a natural phenomenon. India is the home to large number of indigenous people, who are still untouched by the lifestyle and beliefs. Of the 8.6% of the total population of the country, the diversified tribal groups of tribal of the country are scattered across the country. The tribal people have their own physical, cultural, religious, and spiritual identity. Most of the tribes living in India believe in the concept and practice of totem. The idea, concept, and message that totemism communicates has spiritual connection or kinship with creatures or objects of nature. The totemic belief of the tribal people is not only an integral part of their social-cultural, religious, and spiritual behavior. The objective of this study is to understand and document the significance of totemic belief of the tribal people of India.” ref

Introduction

“According to Webster’s dictionary, totem means “A natural object, usually an animal that serves as a distinctive, often venerated emblem or symbol. It is a means of personal or spiritual identity.” Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary defines Totem as “A natural object or animal that is believed by a particular society to have spiritual significance and that is adopted by it as an emblem.” According to Emile Durkheim, a renowned French sociologist, social psychologist, and philosopher, the word totem is originated from Ojibwe, an Algonquin tribe of Northern America, and it refers to an object of an animal or a plant. Some experts believe that Ojibwa word ototeman, meaning “one’s brother-sister kin” is origin of the word totem. The grammatical root, ote, denotes a blood relationship between brothers and sisters of having the same mother, and marriage between them is not permitted. In kinship and descent, if the apical ancestor of a clan is nonhuman, it is called a totem. Sigmund Freud, known as the father of psychoanalysis, in his collection of essays for the book ‘Totem and Taboo’ analyzes the socio-ethnographic perspective of totem.” ref

“In the essay, ‘The Horror of Incest’ he examines the system Totemism among the Australian Aborigines. It is the prevailing practice among them that prevents against incest. E.A. Hoebel, a renowned professor of Anthropology, defined totem “an object, often an animal or a plant, held in special regard by the members of a social group who feel that there is a peculiar bond of emotional identity between themselves and the Totem”. G. Van Der Leeuw, the Dutch historian and philosopher of religion, summarized the concept and definition of totem as: (a) group bears the name of the totem (b) totem denotes its ancestor (c) totem involves taboos, such as (i) prohibition against killing or eating the totem, except in specific circumstances or under special conditions and (ii) prohibition against intermarriage within the same totem. The belief in tutelary spirits and deities is not restricted to indigenous peoples but prevalent to a several cultures across the world. It is found in Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe, and the Arctic region. The spirit or sacred object, or symbol or emblem of a group of people, such as family, clan, lineage, or tribe, is termed as totem. Totems are considered as emblems of tribes that reflect the lineage of a tribe. The totemic character, sign, mark, letter, ideogram, or any other identity, etc. serve as a reminder of the ancestry or mythic past of such groups of people.” ref

“It signifies a spiritual, religious, social and cultural association between a clan or lineage and a bird, animal or a natural phenomenon. Each totem of the tribal clans has distinct identity with regard to their habitat and physiology. Anthropologists classified them into different types such as (1) land animal totem (2) water nimal totem, (3) air animal totem, (4) reptile totem, (5) insect totem, and (6) vegetable or plant totem. In general, the land animal totems includes beaver, otter, bobcat, bear, deer, fox, horse, cow, ram, lion, tiger, panther, wolf, bear etc. and the water animal totems comprise of the dragon, fish, frog, seahorse, turtle, etc. The birds like eagle, crow, bat, hawk, dove, etc. comes under air animal totems. The reptile totems include salamander, chameleon, turtle, etc. The insect totems include firefly, praying mantis, dragonfly, spider, butterfly, etc.” ref

Significance of Totems in Tribal Life

“There is no distinct or universally accepted theory to understand the origin of religion among the tribes across the world. But totemic belief, the concept of taboo, the philosophy of rebirth, and the immortality of soul, in whatever rudimentary forms that existed or prevails, are common in all tribal religions all over the world. The primitive form of religion is observed in Totemism, Mana, Animism, Animation, and taboo belief. Such forms of religion have a dominant influence on tribal populations across the world. They find their origin mainly from objects like animal and plants.” ref

Totem and Spirituality

“The mystical animal from which a tribe relates its origin is its totem. The totem animal is believed to be the beginner of life of the tribe. The tribal people believe that there is some supernatural and mystic relationship among the member of the same totem. The animal totems are believed to be animal spirits by different clans of indigenous people living across the world. They think that totem animals always stay with them for life both in physical and spiritual world. Many tribes believe that an offense against the totems can produce a corresponding decrease in the size of the clan. Totem and Culture All animal totems included as supernatural creatures of mythology and legend in the tribal culture and literature had special meaning, characteristics, and significance. Totems find special significance in dance, drama, motifs, handicraft, artifacts, painting, etc. of the ingredients of performing and visual tribal art.” ref

Totem and Religion

“For every tribe, totem is very sacred. A totem has religious significance in tribal life. Many tribes inscribe the sign or figure of totem on some specific location of their body or on the wall of their home or prayer room. Even the shape or figure of the totem is developed and kept at their sacred places. It is perceived that blessings of the totem animals protect the tribal people in all difficult situations and at all hard times. It warns the members about the any possible danger and predicts about the future.” ref

Totem and Taboo

“They do not kill their totem animal except on special occasion or sacred situation. In certain tribes, the prohibitions or taboos are sometimes cultivated to such an extreme degree that they believe eating, killing, or destroying them may lead to occur unrecoverable loss to the clan. Its skin is worn out during important occasions and used with care. Some tribes take out funerals for the death of their totemic animals as mark of respect for the totem.” ref

Totem and Social behavior

“From a sociological perspective, the totem animals keep the tribal people in bonds of unity and brotherhood. It brings social and community consciousness among the tribal people. They consider that totem protects the clan of the tribe in difficult times. Mourning is observed on the death of the totemic animal. As the members of the same totemic clan consider themselves to be bound by blood relationship and strictly follow the rule of exogamy.” ref

Totem and Tribal Life

“Several tribes across the globe believe that totem animal of a clan guides them in every walk of life. They consider that totemic animals teach and protect them in different situations of life. The life with totemic consideration is essential for most of the indigenous people in the world. Indian Tribes and Totems The area covering, central Indian states of Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh, Eastern Indian states of Odisha and Jharkhand, and west India states of Maharashtra and Rajasthan, has the largest population of tribal people. The study of the totems of the tribes of North, North East, and South India could not be included in the study due highly diversified population of tribes in those areas. The totemic believe among the tribes of the area is a significant part of their spiritual, religious, social, and culture lifestyle. The Birhor, an indigenous group of people lives mainly in Jharkhand, believes that there is a temperamental or physical similarity between the members of the clan and their totems. They are socially organized into patrilineal exogamous totem groups. A list of 37 clans, 12 are based on animals, 10 on plants, 8 on Hindu castes and localities, and the rest on objects, believed to be prevalent among the Birhor tribe. There are tales of the birth and classification of totemic objects among the tribe. Each totem had a fortuitous connection with the birth of the ancestor of the clan.” ref

“The Ho tribe of Jharkhand believes in the totemic significance in every walk of their life. Every Killis, means clans in their language, bears a totemic object that is sacred to them. They have more than 50 Killis that includes Hansda (a wild goose), Bage (tiger), Jamuda (spring) and Tiyu (fox). Every clan of Ho tribe has to undergo rituals of fast to worship its totemic object. One of the largest tribe of central Indian tribe, the Gond believes in social recognition of their population on the basis of clans with totemic animals or plants. Some of them have the clan names after the fauna and flora of their immediate habitat. Similarly, the Oraon and Munda tribes of Jharkhand and Odisha are classified on totemic clans. Out of more than 64 totems, the Munda tribe of Jharkand and Odisha has some popular totemic objects like Sol fish, Nag (serpant), Hassa (goose). Similarly, among the Santhals, there are more than 100 totems. It includes some popular totems like Murmu (a forest based wild cow), Chande (a lizard) and Boyar (a fish). The Bhil tribe of Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh believe in more than 25 totemic objects based on clans. Every geographical region is known for trees and animals that grow and inhabit there. The totemic animals of Chota Nagpur region of Jharkhand includes mainly of those animals that are found in the plateau. The totemic clans of the tribes of the region include Toppo (a small bird), Kerketta (the quail), Khalko ( a fish), Ekka (tortoise), Gidhi (the eagle), Tatenga (the lizard) Dhidma (a bird), Karkha (the cow), Tirki (a young mouse), Lakra (the tiger), Kindu (the ‘Saur’ fish), Lapoung (a small bird), Minz ( Eel), Barwa (wild hog), Kachhap ( tortoise), Xaxa (crow), Xess (corn), Bakula (crane), Kokro ( cock), Bando (fox), Tiga (the field mouse), Alia ( the dog), Hartu (the monkey) Rawna (vulture), Orgoda ( the hawk), Godo (name of a water creature), Kuhu (Cuckoo), Kannhar (vulture bird), Baghwar (the tiger), Beshra (a name of tree), Ckigalo (Jackal), Khoya ( jackal), etc. In fact, some castes of Orissa, not considered as tribe and rather have advanced social and cultural lifestyle such as the Kurmi, the Kumhar etc. have totems such as serpent, pumpkin, jackal, etc.” ref

Totem: A Significant Identity

“The study of totem in different levels and aspects suggest that totemic significance of tribal life still prevails among the tribes of India. The classification of a tribal population has spiritual, religious, social, and cultural significance. The method of classification based on totems and prohibitions related to totemic objects make the tribal people disciplined and sincere to their belief. The modern anthropologists look at totemism as a recurring way of conceptualizing relationships between different clans of a tribal group and the natural world. It communicates their love for the nature and efforts to preserve the environment, animals, and birds around them. Other than totemic animals, many Indian tribes consider trees as their totemic spirits. Such strong connections of totemism with nature help to protect the equilibrium of the biodiversity. The idea, concept, and message that totemism communicates has spiritual connection or kinship with creatures or objects of nature, similar to the thought and practice of Animism. In Animism, the central concept is based on the spiritual idea that the universe, and all natural objects within the universe, has souls or spirits. The spiritual perception behind the totemism communicates the strong belief of the tribal people on the existence of souls or spirits that exist not only in humans but also in animals, plants, trees, rocks, and all natural elements. It speaks about the strong boding of the tribes with animal and plants around them. With the changing times, proliferation of the mediums of communication, varied sources of entertainment, and spreading of knowledge, the totemic belief among the new generation of tribal groups is gradually decreasing. Those tribal people, who still stick to the ideological, mystical, emotional, reverential, and genealogical relationships with totemic objects, keep them away from the self-centric modern world. Moreover, the totemic belief is not only an integral part of their social-cultural, religious, and spiritual behavior but also a message of living in coexistence with nature.” ref

African Totemism Expressed

African Totems, Kinship and Conservation

“Rukariro Katsande explores the intricate and fascinating African culture of totems and kinship in relation to conservation… In traditional African culture, kinship is two-pronged and can be established on either bloodline or a totem. Extended family is made up of intricate kinship, with parents, children, uncles, aunts, nieces, nephews, brothers and sisters, all regarding each other as closely related. The word “cousin” does not exist in sub-Saharan languages/dialects, and kinship ends at the nephew and niece level. On a father’s side (which is more important being traditionally a patrilineal society) there is the actual father and big and small fathers, brothers and sisters. On the maternal side are uncles, younger and older mothers, nephews, and nieces. Totems protect against taboos such as incest among like totems. The concept of using totems demonstrated the close relationship between humans, animals, and the lived environment. Anthropologists believe that totem use was a universal phenomenon among early societies. Pre-industrial communities had some form of totem that was associated with spirits, religion, and success of community members. Early documented forms of totems in Europe can be traced to the Roman Empire, where symbols were used as coats of arms, a practice which continues today.” ref

In Africa, chiefs decorated their stools and other court items with their personal totems, or with those of the tribe or of the clans making up the larger community. It was a duty of each community member to protect and defend the totem. This obligation ranged from not harming that animal or plant, to actively feeding, rescuing, or caring for it as needed. African tales are told of how men became heroes for rescuing their totems. This has continued in some African societies, where totems are treasured and preserved for the community’s good. Totems have also been described as a traditional environmental conservation method besides being for kinship. Totemism can lead to environmental protection due to some tribes having multiple totems. For example, over 100 plant and animal species are considered totems among the Batooro (omuziro), Banyoro, and Baganda (omuzilo) tribes in Uganda, a similar number of species are considered totems among tribes in Congo (DRC) and the Central African Republic, (CAR). In Zimbabwe, totems (mitupo) have been in use among the Shona groupings since the initial development of their culture. Totems identify the different clans among the Shona that historically made up the dynasties of their ancient civilization. Today, up to 25 different totems can be identified among the Shona ethnic grouping, and similar totems exist among other South African groups, such as the Zulu, the Ndebele, and the Herero in Botswana and Namibia.” ref

“Those who share the same totem regard each other as being related even though they are not blood relatives and will find difficulty in finding approval to marry. Through totem use one can practically establish some form of kinship with anyone else in the region. Establishing relationships this way made it easier for a traveller or stranger to find social support. Totems are also essential to cast a curse. Today, the Uganda Wildlife Education Centre uses a community-based approach for animal protection. Individuals are encouraged to donate funds for feeding animals in the former zoo. Donations are applied to the donor’s totem; such a donation is considered an act of “feeding one’s brother” who is unable to feed himself. By taking their cue from such activities, environmental activists can use knowledge of totems and their cultural significance to revitalize environmental awareness, especially where animal protection laws are weak and unimplemented, and where the community has become detached from the environment.” ref

Kpelle People

“Among the Kpelle people of Liberia there is not only group totemism but also individual totemism. Both kinds of totems are referred to variously as “thing of possession,” “thing of birth,” or “thing of the back of men.” These phrases express the idea that the totem always accompanies, belongs to, and stands behind one as a guide and warner of dangers. The totem also punishes the breach of any taboo. Kpelle totems include animals, plants, and natural phenomena. The kin groups that live in several villages were matrilineal at an earlier time, but during the 20th century they began to exhibit patrilineal tendencies. The group totems, especially the animal totems, are considered as the residence of the ancestors; they are respected and are given offerings. Moreover, a great role is played by individual totems that, in addition to being taboo, are also given offerings. Personal totems that are animals can be transmitted from father to son or from mother to daughter; on the other hand, individual plant totems are assigned at birth or later. The totem also communicates magical powers. It is even believed possible to alter one’s own totem animal; further, it is considered an alter ego. Persons with the same individual totem prefer to be united in communities. The well-known leopard confederation, a secret association, seems to have grown out of such desires. Entirely different groups produce patrilineal taboo communities that are supposedly related by blood; they comprise persons of several tribes. The animals, plants, and actions made taboo by these groups are not considered as totems. In a certain respect, the individual totems in this community seem to be the basis of group totemism.” ref

Kpelle people

“The Kpelle or Guerze lived in North Sudan during the sixteenth-century, before fleeing to other parts of Northwest Africa into what is now Mali. Their flight was due to internal conflicts between the tribes from the crumbling Sudanic empire. Some migrated to Liberia, Mauritania, and Chad. They still maintained their traditional and cultural heritage despite their migration. A handful are still of Kpelle origin in North Sudan. Traditionally organized under several paramount chiefs who serve as mediators for the public, preserve order and settle disputes, the Kpelle are arguably the most rural and conservative of the major ethnic groups in Liberia. The Kpelle people are also referred to as Gberese, Gbese, Gbeze, Gerse, Gerze, Kpelli, Kpese, Kpwele, Ngere, and Nguere.” ref

Origin of the Kpelle

“The Kpelle ethnic group of Liberia is a member of the Niger-Congo ethnic group who migrated from western Sudan. Thus, their language falls in the Mande group of Niger-Congo. Some Liberian historians believe that the Kpelle, like the Loma, Gbandi, Mahn, and Mende ethnic groups, began immigrating from Kumba, present-day Ghana where they were builders of the empire by the early 1500. The Liberia-bound migration took them through the Songhai Empire which replaced the Mali Empire to central Liberia in the early 1600s.” ref

Shona People

“In Zimbabwe, totems (mitupo) have been in use among the Shona people ever since the initial stages of their culture. The Shona use totems to identify the different clans that historically made up the ancient civilizations of the dynasties that ruled over them in the city of Great Zimbabwe, which was once the center of the sprawling Munhumutapa Empire. Clans, which consist of a group of related kinsmen and women who trace their descent from a common founding ancestor, form the core of every Shona chiefdom. Totemic symbols chosen by these clans are primarily associated with animal names. The purposes of a totem are: 1) to guard against incestuous behavior, 2) to reinforce the social identity of the clan, and, 3) to provide praise to someone through recited poetry. In contemporary Shona society there are at least 25 identifiable totems with more than 60 principal names (zvidawo). Every Shona clan is identified by a particular totem (specified by the term mitupo) and principal praise name (chidawo). The principal praise name in this case is used to distinguish people who share the same totem but are from different clans. For example, clans that share the same totem Shumba (lion) will identify their different clansmanship by using a particular praise name like Murambwe, or Nyamuziwa. The foundations of the totems are inspired in rhymes that reference the history of the totem.” ref

“When the term “Shona” was created during the early-19th-century Mfecane (possibly by the Ndebele king Mzilikazi), it was used as a pejorative for non-Nguni people; there was no awareness of a common identity by the tribes and peoples which make up the present-day Shona. The Shona people of the Zimbabwe highlands, however, retained a vivid memory of the ancient kingdom often identified with the Kingdom of Mutapa. The terms “Karanga”, “Kalanga” and “Kalaka”, now the names of discrete groups, seem to have been used for all Shona before the Mfecane. Ethnologue notes that the language of the Bakalanga is mutually intelligible with the main dialects of Karanga and other Bantu languages in central and eastern Africa, but counts them separately. The Kalanga and Karanga are believed to be one clan who built the Mapungubwe, Great Zimbabwe, and Khami, and were assimilated by the Zezuru. Although many Karanga and Kalanga words are interchangeable, Kalanga is different from Zezuru. Dialect groups have many similarities. Although “standard” Shona is spoken throughout Zimbabwe, the dialects help identify a speaker’s town (or village) and ethnic group. Each Shona dialect is specific to a certain ethnic group.” ref

“The religion of Shona people is centred on Mwari (God), also known as Musikavanhu (Creator) or Nyadenga (one who lives high up). God communicates with his people on earth directly or through chosen holy people. At times God uses natural phenomena and the environment to communicate with his people. Some of the chosen people have powers to prophecy, heal, and bless. People can also communicate with God directly through prayer. When someone dies, according to Shona religion, they join the spiritual world. In the spiritual world, they can enjoy their afterlife or become bad spirits. No one ones to be a bad spirit, so during life, people are guided by a culture of unhu so that when they die, they enjoy their afterlife. Colonial white missionaries as well as anthropologists like Gelfand and political colonialists did not interpret this religion in good light because they wanted to undermine it in favor of Christianity. Initially, they said the Shona did not have a God, but this was a lie. They denigrated the way the Shona had communicated with their God, the Shona way of worship, and chosen people among the Shona. They could not distinguish the living and the dead. The chosen people were regarded as unholy and Shona prayer was regarded as pagan. Of course, the agenda was to colonise. When compared with Christianity, the Shona religion perspective of afterlife, holiness, worship and rules of life (unhu) have similar goals, they are only separated by cultures (African versus European) and values (unhu versus western). Although sixty to eighty percent of the Shona people converted to Christians as a result of colonial missionaries, and at times by force, Shona religious beliefs are still very strong.” ref

“Most of the Christian churches and beliefs have been blended with Shona religion. This was done to guard against European and western cultures that dominate Christianity. A small number of the population practice the Muslim faith, often brought about by immigrants from predominantly Malawi who practice Islam. There is also a small population of Jews. An example of a colonially constructed meaning of the Shona religion is found in the works of Gelfand, an anthropologist. Gelfand said the afterlife in Shona religion is not another world (like the Christian heaven and hell) but another form of existence in this world. This is not true. When people die, they join another world, and that world is not on earth, although like in Christianity, some of those people can interact with living beings in different ways. He further wrongly concluded that the Shona attitude towards dead ancestors is very similar to their attitude towards living parents and grandparents. The Bira ceremony, which often lasts all night, summons spirits for guidance and help in the same manner daily, weekly or all night Christian ceremonies summon spirits for guidance and help. In this analysis, Gelfand, and Hannan, both whites, and part of the colonial establishment, forgot that the Christian doctrine treats dead prophets, biblical figures, and living ‘holy people’ in much the same way. In fact in the Christian community, some of the prophets, figures, and ‘holy people’ are revered more than biological parents. In fact, in colonial Zimbabwe, converts were taught to disrespect their families and tribes, because of a promise of a new family and tribe in Christianity. This is ironical.” ref

“In Zimbabwe, (mutupo) (plural mitupo) wrongly called totems by colonial missionaries and athropologists have been used by the Shona people since their culture developed. Mitupo are an elaborate was of identifying clans and sub-clans. They help to avoid incest, and they also build solidarity and identity. There are more than 25 mitupo in Zimbabwe. In marriage, mitupo help create a strong identity for children but it serves another function of ensuring that people marry someone they know. In shona this is explained by the proverb rooranai vematongo which means marry or have a relationship with someone that you know. However, as a result of colonisation, urban areas and migration resulted in people mixing and others having relationships of convenience with people they do not know. This results in unwanted pregnancy and also unwanted babies some of whom are dumbed or abandoned. This may end up with children without mutupo. This phenomena has resulted in numerous challenges for communities but also for the children who lacks part of their identity.” ref

“Villages consist of clustered mud and wattle huts, granaries, and common cattle kraals (pens) and typically accommodate one or more interrelated families. Personal and political relations are largely governed by a kinship system characterized by exogamous clans and localized patrilineages. Descent, succession, and inheritance, with the exception of a few groups in the north that are matrilineal, follow the male line. Chiefdoms, wards, and villages are administered by hereditary leaders. Shona traditional culture, now fast declining, was noted for its excellent ironwork, good pottery, and expert musicianship. There is belief in a creator-god, Mwari, and a concern to propitiate ancestral and other spirits to ensure good health, rain, and success in enterprise.” ref

“The Shona tribe is Zimbabwe’s largest indigenous group, their tribal language is also called Shona (Bantu) and their population is around 9 million. They are found in Zimbabwe, Botswana and southern Mozambique in Southern Africa and bordering South Africa. Representing over 80% of the population, the Shona tribe is culturally the most dominate tribe in Zimbabwe. There are five main Shona language groups: Korekore, Zeseru, Manyika, Ndau, and Karanga. The Ndebele largely absorbed the last of these groups when they moved into western Zimbabwe in the 1830s.” ref

Totemism: A symbolic representation of a clan with specific reference to the Basotho ba Leboa – An ethnographical approach

Abstract

(Northern Sotho people)

“The aim of this article is to share some views about the social significance of totems among the Basotho ba Leboa (Northern Sotho people). As reflected in history, totems are not restricted to any particular continent, but are found throughout the world, including Africa, the Arctic polar region, Australia, Eastern Europe, and Western Europe. To achieve the goal of this article, it will be shown how totemism reflects a connection between animals and human beings regarding power, wisdom, spirits, respect, trust, and understanding. In totemistic beliefs, symbolic representation plays a significant role as the human being seeks to imitate the animal totem’s traits. This shall be demonstrated by demystifying the classification of various animal totems, categorizing them into clans or groups, and evaluating their distinct features or characteristics and their impact on the human being. The fact that totems in the Northern Sotho culture are slowly dying out could perhaps be ascribed to the negative impact that formal education has had on the indigenous knowledge systems (IKS) of the African communities in South Africa. However, IKS is currently gaining popularity and is being incorporated into the formal education system to preserve indigenous knowledge for posterity. In this study, the ethnographic approach was used to collect data.” ref

“The Sotho people, or Basotho, are a Bantu ethnic group of Southern Africa who speak Sesotho. They are native to modern Lesotho and South Africa. The Basotho have inhabited the region since around the fifth century CE and are closely related to other Bantu peoples of the region. Bantu-speaking peoples had settled in what is now South Africa by about 500 CE. Separation from the Tswana is assumed to have taken place by the 14th century. The first historical references to the Basotho date to the 19th century. By that time, a series of Basotho kingdoms covered the southern portion of the plateau (Free State Province and parts of Gauteng). Basotho society was highly decentralized and organized on the basis of kraals, or extended clans, each of which was ruled by a chief. Fiefdoms were united into loose confederations.” ref

Batooro (omuziro), Banyoro and Baganda (omuzilo) tribes in Uganda

“Totems have also been described as a traditional environmental conservation method besides being for kinship. Totemism can lead to environmental protection due to some tribes having multiple totems. For example, over 100 plant and animal species are considered totems among the Batooro (omuziro), Banyoro, and Baganda (omuzilo) tribes in Uganda, a similar number of species are considered totems among tribes in Congo (DRC) and the Central African Republic, (CAR).” ref

Toro people (Batooro)

“The Toro people, Tooro people or Batooro are a Bantu ethnic group, native to the Tooro Kingdom, a subnational constitutional monarchy within Uganda.” ref

Banyoro people

“According to historian Wainwright. Kitara is derived from the Bantu prefix Ki– and the Merotic (old Egyptian script) word Tar which means a King, hence Kingdom. The Kingdom of Bunyoro-Kitara was a very prestigious, widespread, and a great kingdom at the peak of its power. The region enjoys the rich history spanning over 1000 years. The kingdom of Bunyoro is a remnant from the Empire of Kitara, when it was founded when Kyomya’s Twins, Insigoma Rukidi Mpuuga, and Kato Kimera came to take over power from their Bachwezi Ancestors in the early 14th century. Before that, it is claimed that Kitara, also known by other names, was a successor state to Meroe, Napata, Kush, and Aksum. When the Kingdom of Aksum disintegrated around 940 AD into kingdom of Makuria, the Zagwe kingdom, the Damot kingdom, and the Shewa kingdom in Northeast of Africa, another kingdom broke away in the south to form the Empire of Kitara. Kintu, his wife Kati, brought their cattle and a white cow(kitara). Kintu and Kati had three sons. The first son was called Kairu, the second Kahuma, and the third Kakama. Starting at the later date of the 9 century, as per oral history, three dynasties had ruled over the area, from the time when it was an Empire of Kitara till present-day kingdom of Bunyoro-Kitara.” ref

Origin of Bunyoro/Banyoro

“(a) Bahuma or pastoral cow-men were the Original people belived to have invated Kitara, there were mainly cattle keepers and mostly very light skinned and believed to be an off short of the Axum empire of modern day Ethiopia. (c) the Bahera, agricultural people and artisans, who were regarded as serfs and are believed to have came from Kumba saley in the present day Cameroon, also the batwa are believed to be the original inhabitants of the great lakes region before the Bantu and Bahuma. kuhuma is the sound made by a group cattle on the ground while moving in a large numbers. Bahera comes from kuhera meaning to scold, its class system of the agriculturalists. Bahera were agriculturalists who spoke various dialects of the Bantu language. Their heartland was the savannah and rain forest regions around the Niger River of southern West Africa (modern Nigeria, Cameroon, and Gabon), they are belived to have migrated into Kitara in between 200 BCE and 1500 CE before the Kitara was formed. The intermarriage between the Bahuma and the indigenous Bantu lead to Bahima.” ref

Okuhima means to darken.

“The Bachwezi is a clan comprising the Ancestors of Bahuma, Bahima whereas Bahuma, Bahima are just class system, not a clan. Bunyoro was an Empire-Kitara Empire far much beyond a nation with vast borders up to Rwanda, Wanga in Kenya, the entire northern Tanzania and entire eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).” ref

“The Banyoro or Bunyoro live in western Uganda to the east of Albert they inhabit the present districts of Hoima, Masindi, Kibale, Kiryandongo, Buliisa, Kagadi, and Kakumiro. They speak a Bantu language and their origins, like other Bantu can be traced to the Congo region. The Banyoro live in scattered settlements in the populated parts of their country. Traditionally, Banyoro are organized under a King (Omukama).” ref

“In Zimbabwe, totems (mitupo) have been in use among the Shona groupings since the initial development of their culture. Totems identify the different clans among the Shona that historically made up the dynasties of their ancient civilization. Today, up to 25 different totems can be identified among the Shona ethnic grouping, and similar totems exist among other South African groups, such as the Zulu, the Ndebele, and the Herero in Botswana and Namibia.” ref

Zulu people

“Zulu people (/zuːluː/; Zulu: amaZulu) are an Nguni ethnic group in Southern Africa. The Zulu people are the largest ethnic group and nation in South Africa with an estimated 10–12 million people living mainly in the province of KwaZulu-Natal. They originated from Nguni communities who took part in the Bantu migrations. As the clans integrated together, the rulership of Shaka brought success to the Zulu nation due to his perfected military policies. The Zulu people take pride in their ceremonies such as the Umhlanga, or Reed Dance, and their various forms of beadwork. The art and skill of beadwork takes part in the identification of Zulu people and acts as a form of communication. The men and women both serve different purposes in society in order to function as a whole. The Zulu were originally a major clan in what is today Northern KwaZulu-Natal, founded ca. 1709 by Zulu kaMalandela. In the Nguni languages, iZulu means heaven, or weather. At that time, the area was occupied by many large Nguni communities and clans (also called the isizwe people or nation, or were called isibongo, referring to their clan or family name). Nguni communities had migrated down Africa’s east coast over centuries, as part of the Bantu migrations. As the nation began to develop, the rulership of Shaka brought the clans together to build a cohesive identity for the Zulu.” ref

“The language of the Zulu people is “isiZulu”, a Bantu language; more specifically, part of the Nguni subgroup. Zulu is the most widely spoken language in South Africa, where it is an official language. More than half of the South African population are able to understand it, with over 9 million first-language and over 15 million second-language speakers. Many Zulu people also speak Xitsonga, Sesotho and others from among South Africa’s 11 official languages. Traditional Zulu religion includes belief in a creator God (uNkulunkulu) who is above interacting in day-to-day human life, although this belief appears to have originated from efforts by early Christian missionaries to frame the idea of the Christian God in Zulu terms. Traditionally, the more strongly held Zulu belief was in ancestor spirits (amaThongo or amaDlozi), who had the power to intervene in people’s lives, for good or ill. This belief continues to be widespread among the modern Zulu population. Traditionally, the Zulu recognize several elements to be present in a human being: the physical body (inyama yomzimba or umzimba); the breath or life force (umoya womphefumulo or umoya); and the “shadow,” prestige, or personality (isithunzi). Once the umoya leaves the body, the isithunzi may live on as an ancestral spirit (idlozi) only if certain conditions were met in life. Behaving with ubuntu, or showing respect and generosity towards others, enhances one’s moral standing or prestige in the community, one’s isithunzi. By contrast, acting in a negative way towards others can reduce the isithunzi, and it is possible for the isithunzi to fade away completely.” ref

Ngoni people

“The Ngoni people are an ethnic group living in the present-day Southern African countries of Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, and Zambia. The Ngoni trace their origins to the Nguni and Zulu people of kwaZulu-Natal in South Africa. The displacement of the Ngoni people in the great scattering following the Zulu wars had repercussions in social reorganization as far north as Malawi and Zambia.” ref

“Within the Nguni nations, the clan, based on male ancestry, formed the highest social unit. Each clan was led by a chieftain. Influential men tried to achieve independence by creating their own clan. The power of a chieftain often depended on how well he could hold his clan together. From about 1800, the rise of the Zulu clan of the Nguni, and the consequent Mfecane that accompanied the expansion of the Zulus under Shaka, helped to drive a process of an alliance between and consolidation among many of the smaller clans.” ref

“The Nguni religion is typically monotheistic. God is said to care for larger matters whilst the ancestors deal with miner tasks. The ancestors are revered and worshiped. Many are fearful of the wicked unleashed by witchdoctors. ‘Sangomas’ are frequently consulted to help individuals speak to or understand the wishes of ancestors. Nguni people will visit ‘nyangas’ who are herbal doctors although they do tend to opt for western doctors. The Nguni people are well-known for their love of bright colors and personal adornment. In general, they will wear western clothing, breaking out their traditional outfits during celebrations and important events. Animal skins, beads, and other objects are used in outfits. Colored beads in specific patterns act as an unspoken language representing status, clan, home village and are used as love letters.” ref

“The Drakensberg (Afrikaans: Drakensberge, Zulu: uKhahlamba, Sotho: Maluti) is the eastern portion of the Great Escarpment, which encloses the central Southern African plateau. The Great Escarpment reaches its greatest elevation – 2,000 to 3,482 metres (6,562 to 11,424 feet) within the border region of South Africa and Lesotho.” ref

“Southern Ndebele, also known as Transvaal Ndebele or South Ndebele, is an African language belonging to the Nguni group of Bantu languages, spoken by the Ndebele people of South Africa.” ref

Northern Ndebele, also called Ndebele, isiNdebele, Zimbabwean Ndebele or North Ndebele, and formerly known as Matabele, is an African language belonging to the Nguni group of Bantu languages, spoken by the Northern Ndebele people, or Matabele, of Zimbabwe. Northern Ndebele is related to the Zulu language, spoken in South Africa. This is because the Northern Ndebele people of Zimbabwe descend from followers of the Zulu leader Mzilikazi (one of Zulu King Shaka‘s generals), who left the Zulu Kingdom in the early 19th century, during the Mfecane, arriving in present-day Zimbabwe in 1839. Although there are some differences in grammar, lexicon, and intonation between Zulu and Northern Ndebele, the two languages share more than 85% of their lexicon. To prominent Nguni linguists like Anthony Cope and Cyril Nyembezi, Northern Ndebele is a dialect of Zulu. To others like Langa Khumalo, it is a language. Distinguishing between a language and a dialect for language varieties that are very similar is difficult, with the decision often being based not on linguistic but political criteria. Northern Ndebele and Southern Ndebele (or Transvaal Ndebele), which is spoken in South Africa, are separate but related languages with some degree of mutual intelligibility, although the former is more closely related to Zulu. Southern Ndebele, while maintaining its Nguni roots, has been influenced by the Sotho languages.” ref

Ndebele people

“The Southern African Ndebele are an Nguni ethnic group native to South Africa who speak Southern Ndebele, which is distinct from the Zimbabwean Ndebele language. Although sharing the same name, they should not be confused with (Mzilikazi‘s) Northern Ndebele people of modern Zimbabwe, a breakaway from the Zulu nation, with whom they came into contact only after Mfecane. Northern Ndebele people speak the Ndebele language. Mzilikazi’s Khumalo clan (later called the Ndebele) have a different history (see Zimbabwean Ndebele language) and their language is more similar to Zulu and Xhosa. The history of the Ndebele people begin with the Bantu Migrations southwards from the Great Lakes region of East Africa. Bantu speaking peoples moved across the Limpopo river into modern day South Africa and over time assimilated and conquered the indigenous San people in the North Eastern regions of South Africa. At the time of the collapse of the Kingdom of Zimbabwe in 1450, Two main groups had emerged south of the Limpopo River: the Nguni, who occupied the eastern coastal plains, and the Sotho–Tswana, who lived on the interior plateau. Between the 1400s and early 1800s saw these two groups split into smaller distinct cultures and people. The Ndebele were just such a people.” ref

Herero people

“The Herero, also known as Ovaherero, are a Bantu ethnic group inhabiting parts of Southern Africa. The majority reside in Namibia, with the remainder found in Botswana and Angola.[citation needed] There were an estimated 250,000 Herero people in Namibia in 2013. They speak Otjiherero, a Bantu language. Unlike most Bantu, who are primarily subsistence farmers, the Herero are traditionally pastoralists. They make a living tending livestock. Cattle terminology in use among many Bantu pastoralist groups testifies that Bantu herders originally acquired cattle from Cushitic pastoralists inhabiting Eastern Africa. After the Bantu settled in Eastern Africa, some Bantu nations spread south. Linguistic evidence also suggests that the Bantu borrowed the custom of milking cattle from Cushitic peoples; either through direct contact with them or indirectly via Khoisan intermediaries who had acquired both domesticated animals and pastoral techniques from Cushitic migrants. The Herero claim to comprise several sub-divisions, including the Himba, Tjimba (Cimba), Mbanderu, and Kwandu. Groups in Angola include the Mucubal Kuvale, Zemba, Hakawona, Tjavikwa, Tjimba and Himba, who regularly cross the Namibia/Angola border when migrating with their herds. However, the Tjimba, though they speak Herero, are physically distinct indigenous hunter-gatherers. It may be in the Hereros’ interest to portray indigenous peoples as impoverished Herero who do not own livestock.” ref

“The Herero have a bilateral descent system. A person traces their heritage through both their father’s lineage, or oruzo (plural: otuzo), and their mother’s lineage, or eanda (plural: omaanda). In the 1920s, Kurt Falk recorded in the Archiv für Menschenkunde that the Ovahimba retained a “medicine-man” or “wizard” status for homosexual men. He wrote, “When I asked him if he was married, he winked at me slyly and the other natives laughed heartily and declared to me subsequently that he does not love women, but only men. He nonetheless enjoyed no low status in his tribe.” The Holy Fire okuruuo (OtjikaTjamuaha) of the Herero is located at Okahandja. During immigration, the fire was doused and quickly relit. From 1923 to 2011, it was situated at the Red Flag Commando. On Herero Day 2011, a group around Paramount Chief Kuaima Riruako claimed that this fire was facing eastwards for the past 88 years, while it should be facing towards the sunset. They removed it and placed it at an undisclosed location, a move that has stirred controversy among the ovaherero community. Herero people believe in Okuruo (holy fire), which is a link to their ancestors to speak to God and Jesus Christ on their behalf. Modern-day Herero are mostly Christians, primarily Catholic, Lutheran, and Born-again Christian.” ref

“Proto-Bantu-speaking migrations between 3,000 to 2,000 years ago”

“The Bantu expansion was a major series of migrations of the original Proto-Bantu-speaking group, which spread from an original nucleus around West–Central Africa across much of sub-Saharan Africa. In the process, the Proto-Bantu-speaking settlers displaced or absorbed pre-existing hunter-gatherer and pastoralist groups that they encountered. The primary evidence for this expansion is linguistic – a great many of the languages which are spoken across Sub-Equatorial Africa are remarkably similar to each other, suggesting the common cultural origin of their original speakers. The linguistic core of the Bantu languages, which comprise a branch of the Niger–Congo family, was located in the adjoining regions of Cameroon and Nigeria. However, attempts to trace the exact route of the expansion, to correlate it with archaeological evidence and genetic evidence, have not been conclusive; thus although the expansion is widely accepted as having taken place, many aspects of it remain in doubt or are highly contested.” ref

“The expansion is believed to have taken place in at least two waves, between about 3,000 and 2,000 years ago (approximately 1,000 BCE to CE 1). Linguistic analysis suggests that the expansion proceeded in two directions: the first went across or along the Northern border of the Congo forest region (towards East Africa), and the second – and possibly others – went south along the African coast into Gabon, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Angola, or inland along the many south-to-north flowing rivers of the Congo River system. The expansion reached South Africa, probably as early as AD 300.” ref

“The Bantu languages (Proto-Bantu: *bantʊ̀) are a large family of languages spoken by the Bantu peoples throughout sub-Saharan Africa. The total number of Bantu languages ranges in the hundreds, depending on the definition of “language” versus “dialect”, and is estimated at between 440 and 680 distinct languages. For Bantuic, Linguasphere (Part 2, Transafrican phylosector, phylozone 99) has 260 outer languages (which are equivalent to languages, inner languages being dialects). McWhorter points out, using a comparison of 16 languages from Bangi-Moi, Bangi-Ntamba, Koyo-Mboshi, Likwala-Sangha, Ngondi-Ngiri, and Northern Mozambiqean, mostly from Guthrie Zone C, that many varieties are mutually intelligible. The total number of Bantu speakers is in the hundreds of millions, estimated around 350 million in the mid-2010s (roughly 30% of the total population of Africa or roughly 5% of world population). Bantu languages are largely spoken southeast of Cameroon, throughout Central Africa, Southeast Africa, and Southern Africa. About one-sixth of the Bantu speakers, and about one-third of Bantu languages, are found in the Democratic Republic of the Congo alone (c. 60 million speakers as of 2015).” ref

“The Bantu language with the largest total number of speakers is Swahili; however, the majority of its speakers use it as a second language (L1: c. 16 million, L2: 80 million, as of 2015). Other major Bantu languages include Zulu, with 27 million speakers (15.7 million L2), and Shona, with about 11 million speakers (if Manyika and Ndau are included). Ethnologue separates the largely mutually intelligible Kinyarwanda and Kirundi, which, if grouped together, have 20 million speakers.” ref

“Proto-Bantu is the reconstructed common ancestor of the Bantu languages, a subgroup of the Benue-Congo family. It is thought to have originally been spoken in West/Central Africa in the area of what is now Cameroon. Approximately 3000–4000 years ago, it split off from other Southern Bantoid languages when the Bantu expansion began to the south and east. Two theories have been put forward about the way the languages expanded: one is that the Bantu-speaking people moved first to the Congo region and then a branch split off and moved to East Africa; the other (more likely) is that the two groups split from the beginning, one moving to the Congo region, and the other to East Africa. Like other proto-languages, there is no record of Proto-Bantu. Its words and pronunciation have been reconstructed by linguists. From the common vocabulary which has been reconstructed on the basis of present-day Bantu languages, it appears that agriculture, fishing, and the use of boats were already known to the Bantu people before their expansion began, but iron-working was still unknown. This places the date of the start of the expansion somewhere between 3000 BCE and 800 BCE or around 5,020 to 2,820 years ago. Doubts continue to be raised as to whether Proto-Bantu, as a unified language, actually existed in the time before the Bantu expansion, or whether Proto-Bantu was not a single language but a group of related dialects. One scholar, Roger Blench, writes: “The argument from comparative linguistics which links the highly diverse languages of zone A to a genuine reconstruction is non-existent. Most claimed Proto-Bantu is either confined to particular subgroups, or is widely attested outside Bantu proper.” According to this view, Bantu is a polyphyletic group that combines a number of smaller language families which ultimately belong to the (much larger) Southern Bantoid language family.” ref