ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

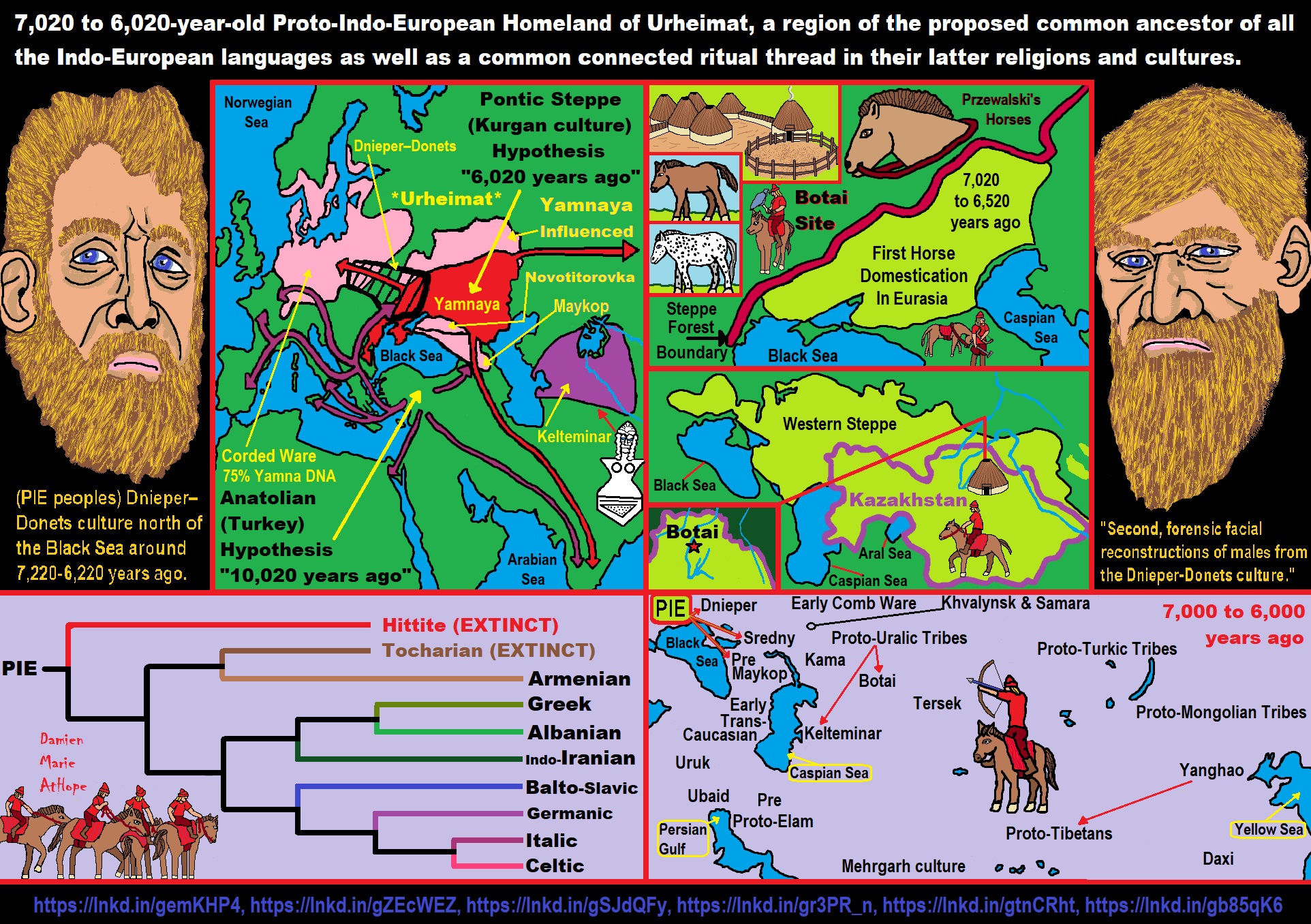

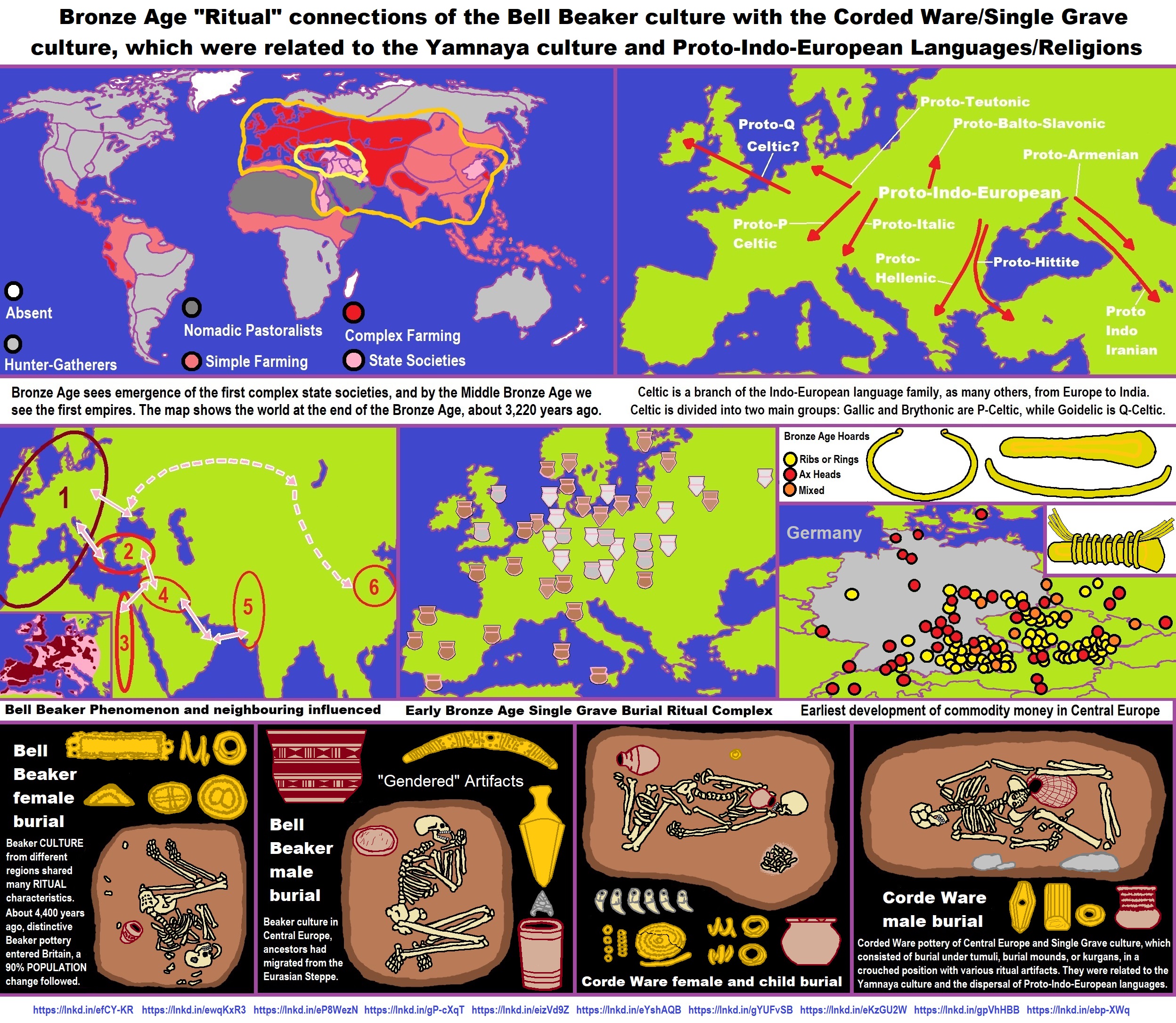

5th millennium BC (around 7,000-6,000 years ago) Events

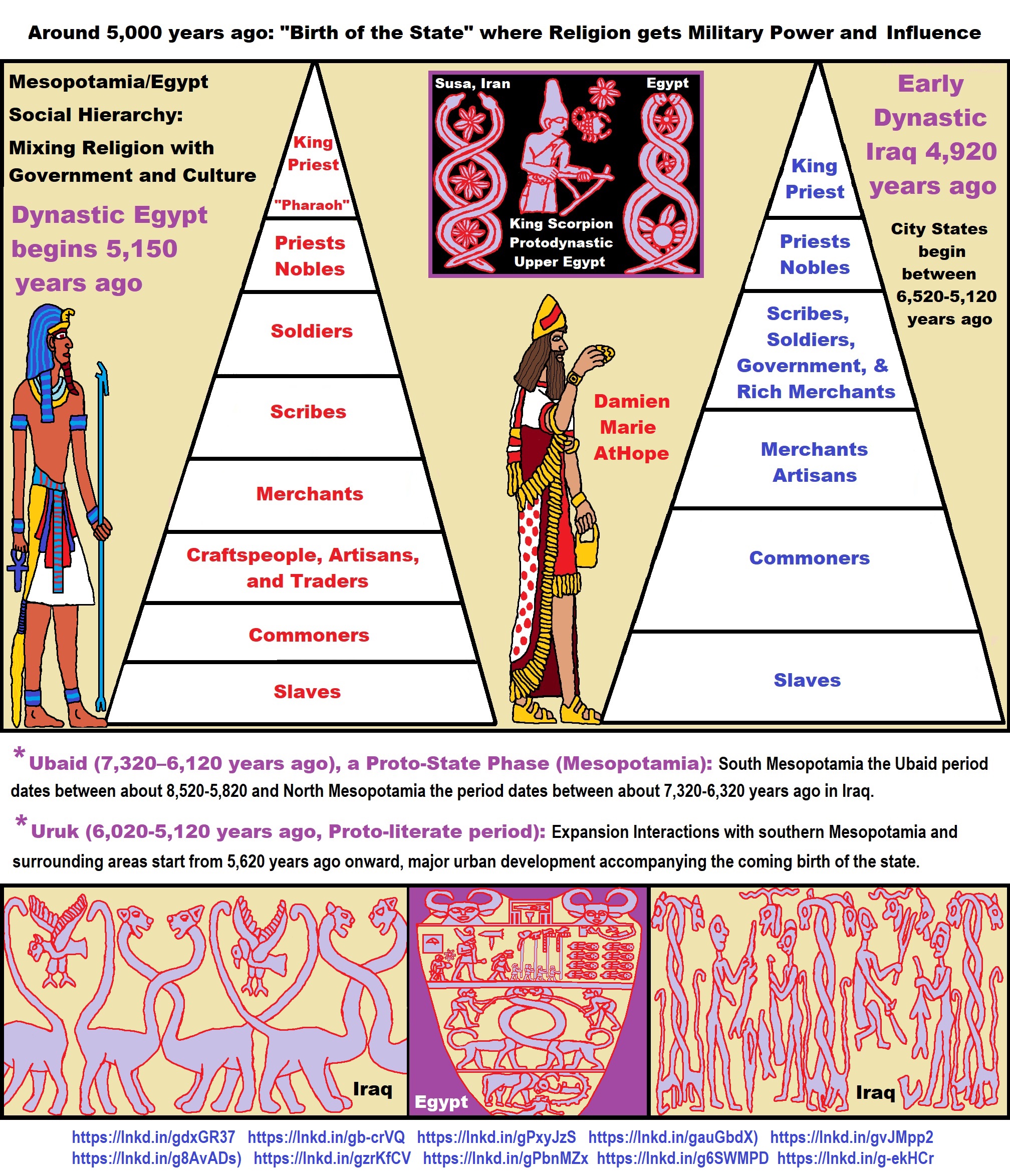

This was a time of great development along with the spread of agriculture from Western Asia throughout Southern and Central Europe. Urban cultures in Mesopotamia and Anatolia flourished, developing the wheel. Copper ornaments became more common, marking the beginning of the Chalcolithic. Animal husbandry spread throughout Eurasia, reaching China. World population grew slightly throughout the millennium, possibly from 5 to 7 million people. ref

Inventions, discoveries, introductions

- Farming reaches Atlantic coast of Europe from Ancient Near East (around 7,000 years ago)

- Maize is cultivated in Mexico (around 7,000 years ago)

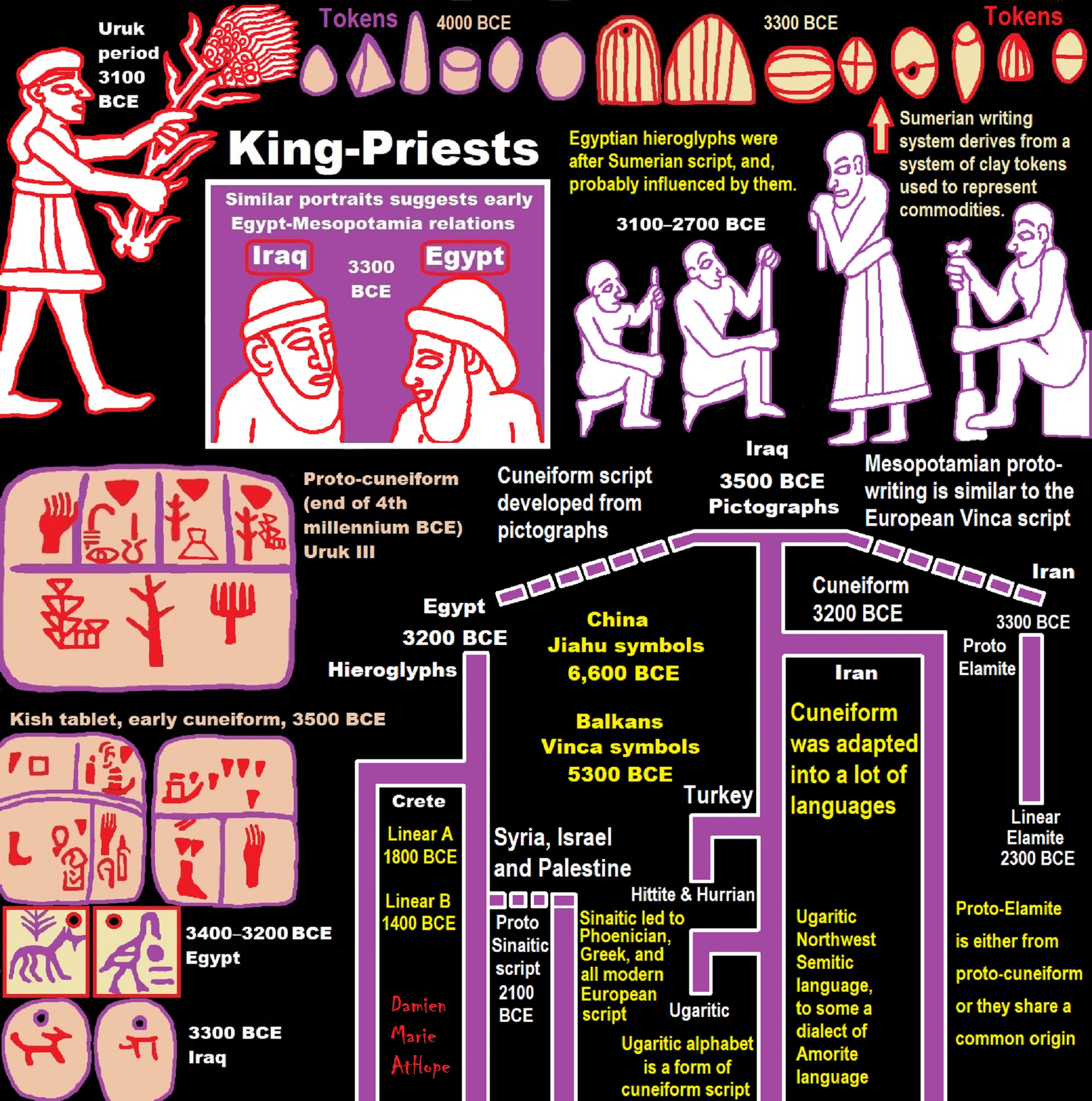

- Proto-writing, such as ideographic Vinča symbols, Tartaria tablets (around 7,000 years ago)

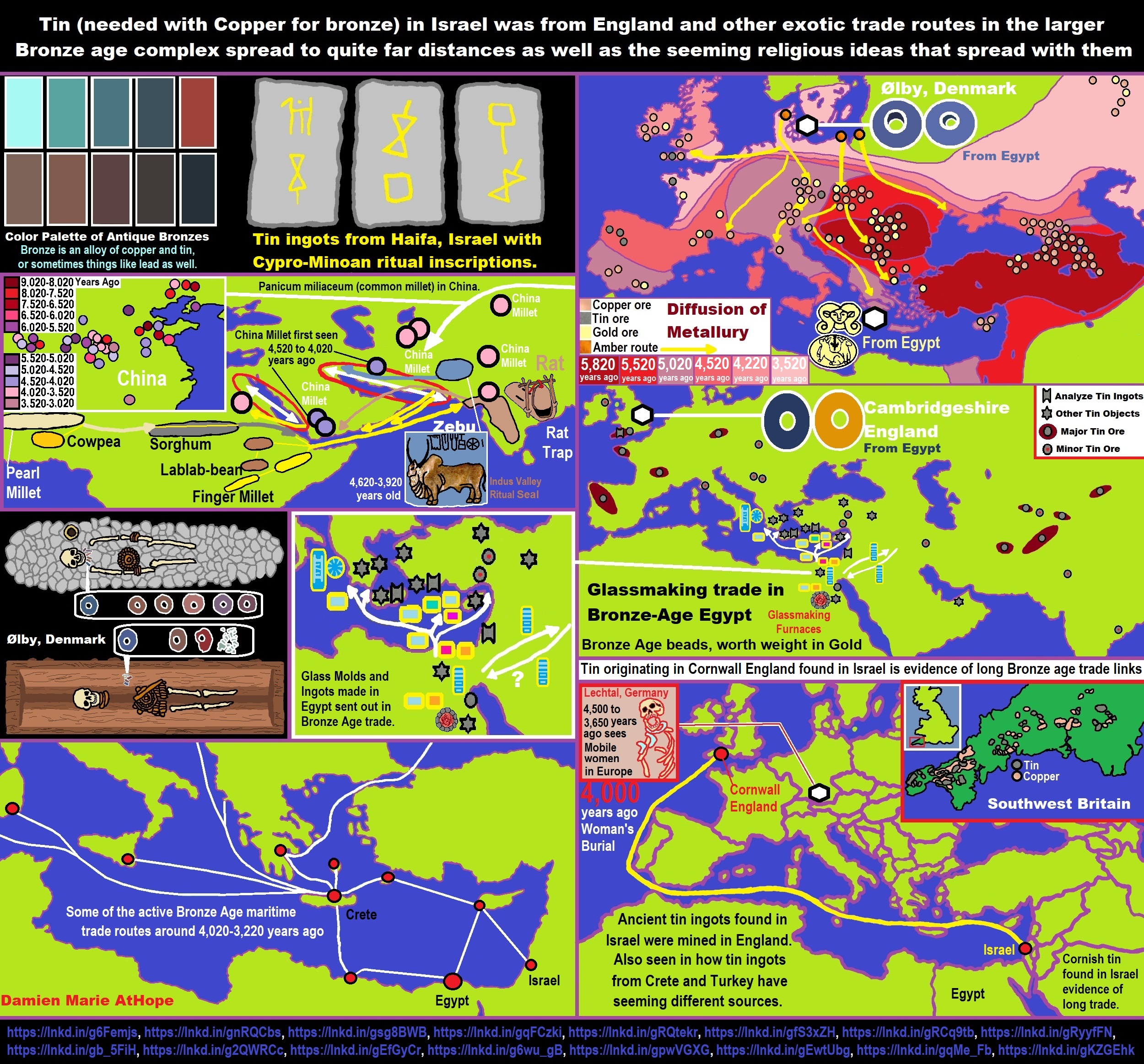

- around 7,000 years ago, Metallurgy during the Copper Age in Europe

- around 7,000 years ago, agriculture starts in Ancient Japan; beans and gourds are cultivated

- Plough is introduced in Europe (around 6,500 years ago)

- Copper pins dating to around 6,000 years ago found in Egypt

- Water buffalo are domesticated in China

- Beer brewing is developed

- Wheel is developed in Mesopotamia and India. ref

Fertile Crescent

- Ubaid culture around 8,500 – 5,800 tears ago in Mesopotamia, derives from Tell al-`Ubaid

- Yumuktepe and Gözlükule cultures in south Anatolia/Turkey. ref

- 1. (Yumuktepe had 23 archaeological levels of occupation dating from ca 6300 BCE. In his book, Prehistoric Mersin, Garstang lists the tools unearthed in the excavations. The earliest tools are made of either stone or ceramic. Both agriculture and animal husbandry (sheep, cattle, goats, and pigs) were among the economic activities in Yumuktepe. In the layer which corresponds to roughly 4500 BCE, one of the earliest fortifications in human history exists. According to Isabella Caneva, during the chalcolithic age, an early copper blast furnace was in use in Yumuktepe. ref)

- 2. (Gözlükule Höyüğü is located to the south of the Gülek Bosphorus, which passes through the Taurus Mountains in Çukurova (ancient Cilicia), located on the northeastern shore of the Mediterranean. The site Gözlü Kule is the ancient city of Tarsus, the Hittite Terussa or Tarsa dating to around 5,000 years ago, the with monumental buildings, houses, and Northern Syria characteristic potteries.

- Towards 4,500 years ago, aligned houses and streets intersecting at right angles resemble those of the Minoans. Some destructions are observed from 4,400 years ago culminating in the construction of a fortified wall and the potteries and jewelry are similar to what has been found to Troy.

- During 4,100 years ago, further destruction are observed. The characteristics of the occupants of the houses appear, again, be those of Syria. Under the Hittites (dated to around 3,600 – 3,178 years ago), Tarsus is a major town or even the regional capital. 65 seals or seals footprints, Hittite hieroglyphics, were found. Fragments of alabaster and lapis lazuli, gold work molds, and a statuette attest of the prosperity of the city. Many specialists think, on the base of these excavations, that Tarsus was a local capital. ref, ref)

- The earliest representations of culture in Anatolia were Stone Age artifacts. The remnants of Bronze Age civilizations such as the Hattian, Akkadian, Assyrian, and Hittite peoples provide us with many examples of the daily lives of its citizens and their trade. After the fall of the Hittites, the new states of Phrygia and Lydia stood strong on the western coast as Greek civilization began to flourish. They, and all the rest of Anatolia were relatively soon after incorporated into the Achaemenid Persian Empire. ref

Egypt

- Badari culture on the Nile (around 6,400 – 6,000 years ago)

- Merimde culture on the Nile in Prehistoric Egypt (around 6,570 – 6,250 years ago). ref

China

- Yangshao culture around 7,000 – 5,000 years ago on the Yellow River

- Proto-Austronesian culture is based on the south coast of China; they combine extensive maritime technology, fishing with hooks and nets and gardening (7,000 years ago) ref

Europe

- Cycladic culture—a distinctive Neolithic culture amalgamating Anatolian and mainland Greek elements arose in the western Aegean before 6,000 years ago

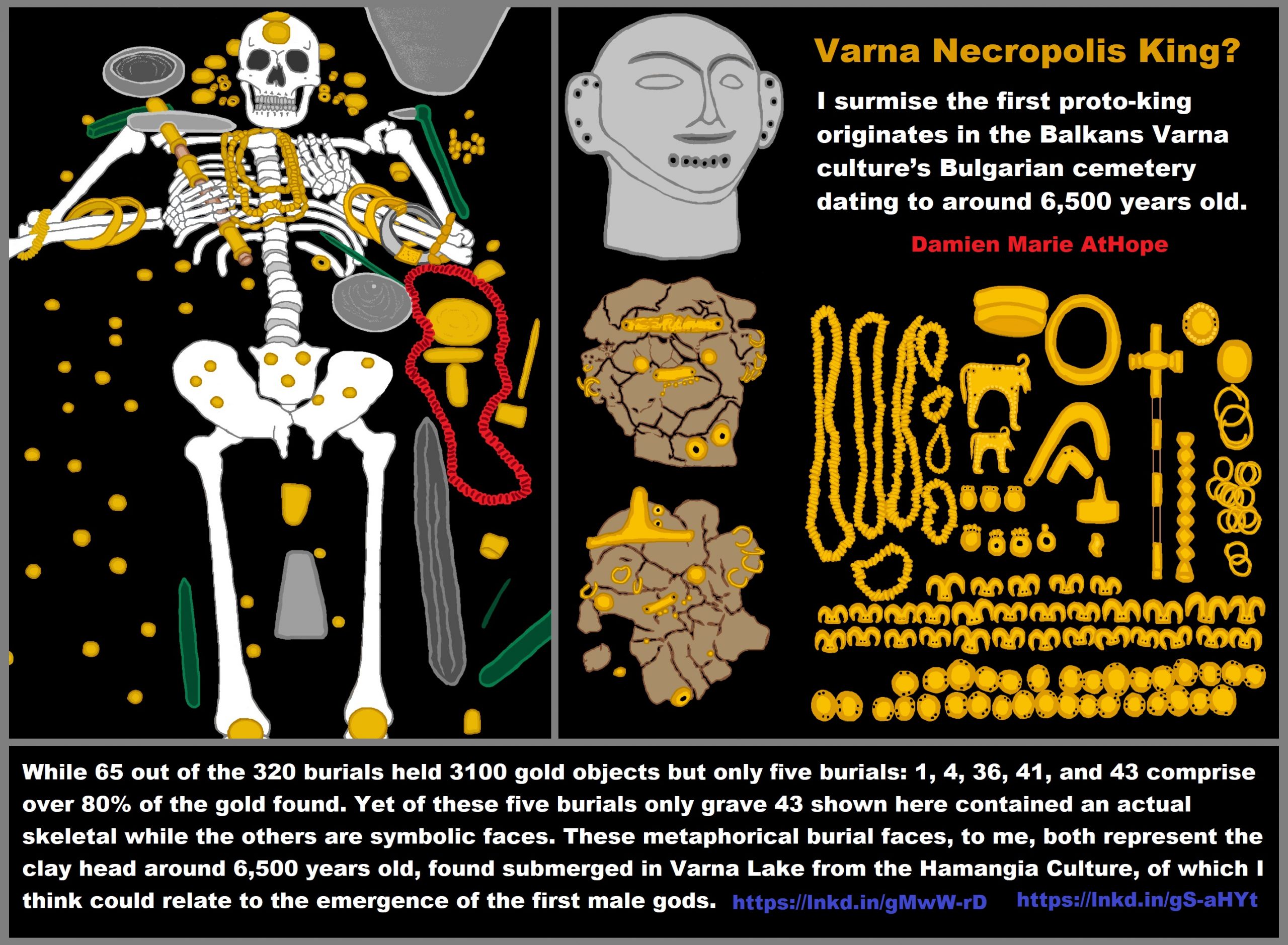

- Varna culture in the Balkans possibly starting at 7,700 years ago, it is attested to around 6,400-6,100 years ago but seems to possibly endured until around 5,000 years ago)

- Comb Ceramic culture in northeast Europe 6,200 to 4,350 years ago

- Stentinello culture (Sicilian Neolithic Temple Builders around 6,000 years ago probably part of an influx of Neolithic farmers, identified genetically with Y Haplogroup J2 (M172), and some of their pottery has been dated to around 7,200 years ago and may relate to the earliest known inhabitants of Malta arrived from Sicily sometime before 7,200 years ago. ref)

- Samara culture around 7,200–6,200 years ago on the Volga river that flows through central Russia

- Sredny Stog culture on the Dnieper that flows through Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine to the Black Sea. The Sredny Stog culture is a pre-kurgan culture around 7,000 years ago, relating to Ukraine, where it was first located. (It is thought by some this Sredny Stog culture pre-kurgan archaeological culture could represent the Urheimat (homeland) of the Proto-Indo-European language. Moreover, it seems to have had contact with the agricultural Cucuteni-Trypillian culture in the west and was a contemporary of the Khvalynsk culture. In its three largest cemeteries, Alexandria (39 individuals), Igren (17), and Dereivka (14), evidence of inhumation in flat graves (ground level pits) has been found. This parallels the practice of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture, and is in contrast with the later Yamna culture, which practiced tumuli burials, according to the Kurgan hypothesis. In Sredny Stog culture, the deceased was laid to rest on their backs with the legs flexed. The use of ochre in the burial was practiced, as with the Kurgan cultures. ref)

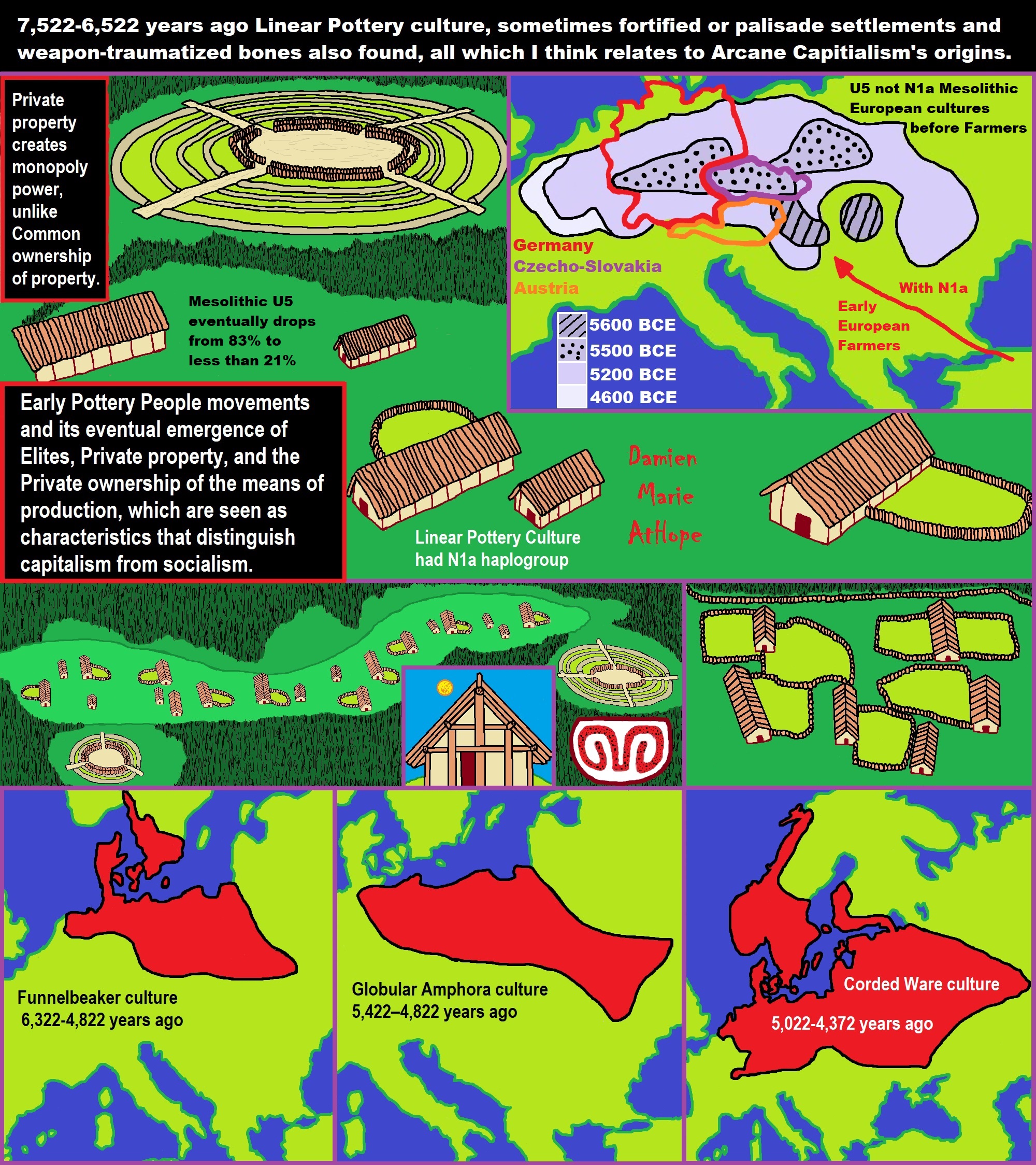

- Lengyel culture centered on the Middle Danube in Central Europe around 7,000-5,400 years ago (preceded by the Linear Pottery culture and succeeded by the Corded Ware culture. In its northern extent, overlapped the somewhat later but otherwise approximately contemporaneous Funnelbeaker culture. Also closely related are the Stroke-ornamented ware and Rössen cultures, adjacent to the north and west, respectively. ref) ref

Events around 7,000-6,000 years ago

- 7,000–6,500 years ago: Għar Dalam phase of Neolithic farmers on Malta, possibly immigrant farmers from the Agrigento region of Sicily Cucuteni-Trypillian culture

- 7,000–6,000 years ago: Bowl, from Banpo, near Xi’an, Shaanxi, is made; Neolithic period; Yangshao culture; now kept at Banpo Museum

- 7,000–4,000 years ago: Neolithic period in China

- 6,900–6,600 years ago: Arrangements of circular ditches are built in Central Europe (the Goseck circle was constructed around 6,900 years ago)

- 6,800 years ago: Dimini culture replaces the Sesklo culture in Thessaly, Greece (4800–4000 BC)

- 6,500 years ago: Settlement of Chirokitia in Cyprus dates from this period

- 6,500 years ago: Ending of Neolithic IA (the Aceramic) in Cyprus

- 6,350 years ago: Kikai Caldera in Japan forms in a massive VEI7 eruption

- 6,300 years ago: First Funnelbeaker Culture in north and east Germany

- 6,300 years ago: Theta Boötis became the nearest visible star to the celestial north pole; it remained the closest until 5,942 years ago when it was replaced by Thuban

- 6,250–5,750 years ago: Menhir alignments at Menec, Carnac, France are made

- 6,200 years ago: Date of Mesolithic examples of Naalebinding found in Denmark, marking spread of technology to Northern Europe

- 6,100–5,500 years ago: New wave of immigration to Malta from Sicily leads to the Żebbuġ and Mġarr phases, and to the Ġgantija phase of temple builders. ref

Is gender inequality man-made?

People have long accepted that political power is man-made rather than god-given. But it’s been different for gender equality. History, religion, science, everything, in fact, have seemed to condemn feminism for being against the natural order. Are there examples of true gender equality in the history of mankind? And if so, how far do we have to go back?

Catalhöyük – aggressively egalitarian?

“It’s hard to get one’s 21st-century head around the Catalhöyük settlement, which existed from approximately 7500 – 5700 BCE or 9,520-7,720 years ago. Its early inhabitants lived at the dawn of agriculture. They had semi-domesticated animals and were learning to sow crops. Not only did women have the same diets as men and inhabit the same physical space, but there were no wider hierarchies in the community. Professor Ian Hodder explains, ‘there is no evidence of a big ceremonial center or a chiefly house. We see these houses that look like they could produce more and could become quite dominant but there seems to be a cap that stops them doing it.” ref

The Mother Goddess

“Catalhöyük has a special significance for anyone interested in women’s history. It is the lynchpin in the Mother Goddess argument. According to this theory, Stone Age society was matriarchal, peaceful, spiritual, and sexually uninhibited. Women were respected for their life-giving powers, and the feminine mysteries were worshipped. In the 1960s, the swashbuckling archaeologist James Mellaart found at Catalhöyük one of the most powerful representations ever made of female divinity. Known as the ‘Seated Woman of Catalhöyük’, or more popularly the ‘Mother Goddess’, it is a clay figurine of a corpulent woman sitting on a throne, flanked by two large leopards, who appears to be giving birth. As he continued his excavations Mellaart unearthed a treasury of female imagery and figurines.” ref

For Mellaart, and many others, this was the confirmation they sought for the Mother Goddess theory. Catalhöyük was proof that patriarchy was no more ‘natural’ than the pyramids. When Professor Hodder took over the site, it wasn’t his intention to be controversial. Nevertheless, his findings have been revolutionary. His team dug through 18 levels, covering about 1,200 years of uninterrupted habitation. They found no evidence to support the claim that Catalhöyük was a matriarchy or that female fertility was worshipped over and above that of phallic or animal spiritualism. But, Hodder insists, the question should never have been posed as an either-or issue. He argues that his team’s discoveries are so much more significant than anything previously imagined. Catalhöyük was a place were true gender equality flourished.” ref

“In ancient Sumer – now modern-day southern Iraq – women enjoyed the same privileges as men in both society and commerce. But when the Akkadian King Sargon conquered, and Sumer became a Vassall state, the outlook for women drastically changed.” ref

The patriarchy promoted by law

“When civilizations begin to write down their laws, this is when the patriarchy becomes enshrined. There is a phrase on the Enmetena and Urukagina cones – the earliest known law codes from circa 2400 BCE – that says “If a woman speaks out of turn, then her teeth will be smashed by a brick.” Later, the Code of Hammurabi (circa 1754 BCE) of ancient Mesopotamia proved a mixed blessing for women. The laws recognized the right for women to own property, while also forbidding arbitrary ill-treatment or neglect. In widowhood, wives were allowed to use their husband’s estates for their lifetime. However, the code was a blow to women’s sexual freedom. Husbands and fathers now owned the sexual reproduction of their wives and daughters. This meant that women could be put to death for adultery and that virginity was now a condition for marriage.” ref

The Veil

“Some of the starkest double standards exist within the Assyrian laws from the 12th century BCE. Husbands could abuse (and even pawn) their wives freely, with the only restriction being they couldn’t kill them without cause. Women in Assyria had no rights and many burdens. If they have an abortion they can be executed, if they commit adultery they can be executed. And if their husband commits a crime, they can be punished in his place.” ref

“Within these laws, there are the earliest examples of enforcing the veil, long before it was adopted by the Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, Christians, and Muslims. However, not all women are required to wear one. The laws specify that wives, daughters, and, indeed, concubines of the upper classes should not go outside uncovered. On the other hand, prostitutes were not entitled to wear the veil, and any man seeing a prostitute wear the veil is to arrest her and she will receive ’50 lashes with a bamboo cane’. If a slave-girl is seen to be wearing a veil, she too is to be arrested; in this case, her ears will be cut off and the man who arrested her may take her clothes.” ref

How the Gender Binary Limits Archaeological Study

“One case study demonstrates how contemporary assumptions about gender in ancient societies risk obscuring the larger picture.” ref

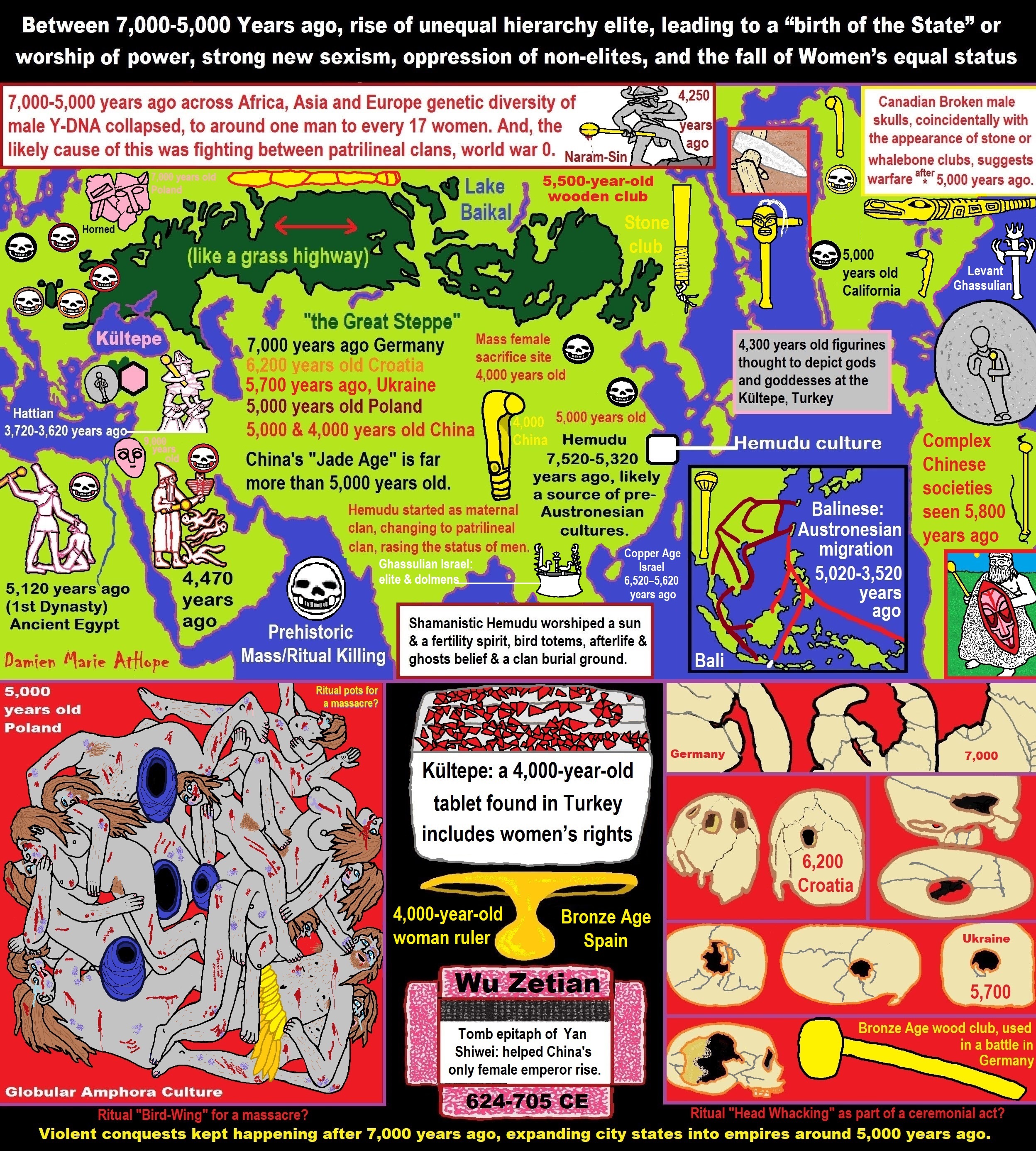

7,000-5,000 years ago, across Africa, Asia and Europe genetic diversity of male Y-DNA collapsed, to around one man to every 17 women. And the likely cause of this was fighting between patrilineal clans, world war 0.

“Around 7,000 years ago – all the way back in the Neolithic – something really peculiar happened to human genetic diversity. Over the next 2,000 years, and seen across Africa, Europe, and Asia, the genetic diversity of the Y chromosome collapsed, becoming as though there was only one man for every 17 women. Now, through computer modeling, researchers believe they have found the cause of this mysterious phenomenon: fighting between patrilineal clans. Drops in genetic diversity among humans are not unheard of, inferred based on genetic patterns in modern humans. But these usually affect entire populations, probably as the result of a disaster or other event that shrinks the population and therefore the gene pool.” ref

But the Neolithic Y-chromosome bottleneck, as it is known, has been something of a puzzle since its discovery in 2015. This is because it was only observed on the genes on the Y chromosome that get passed down from father to son – which means it only affected men. This points to a social, rather than an environmental, cause, and given the social restructures between 12,000 and 8,000 years ago as humans shifted to more agrarian cultures with patrilineal structures, this may have had something to do with it. In fact, a drop in genetic diversity doesn’t mean that there was necessarily a drop in population. The number of men could very well have stayed the same, while the pool of men who produced offspring declined.” ref

This was one of the scenarios proposed by the scientists who penned the 2015 paper.

“Instead of ‘survival of the fittest’ in a biological sense, the accumulation of wealth and power may have increased the reproductive success of a limited number of ‘socially fit’ males and their sons,” computational biologist Melissa Wilson Sayres of Arizona State University explained at the time. Tian Chen Zeng, a sociologist at Stanford, has now built on this hypothesis. He and colleagues point out that, within a clan, women could have married into new clans, while men stayed with their own clans their entire lives. This would mean that, within the clan, Y chromosome variation is limited.” ref

“However, it doesn’t explain why there was so little variation between different clans. However, if skirmishes wiped out entire clans, that could have wiped out many male lineages – diminishing Y chromosome variance. Computer modeling have verified the plausibility of this scenario. Simulations showed that wars between patrilineal clans, where women moved around but men stayed in their own clans, had a drastic effect on Y chromosome diversity over time. It also showed that a social structure that allowed both men and women to move between clans would not have this effect on Y chromosome diversity, even if there was conflict between them.” ref

“This means that warring patrilineal clans are the most likely explanation, the researchers said. “Our proposal is supported by findings in archaeogenetics and anthropological theory,” the researchers wrote in their paper. “First, our proposal involves an episode in human prehistory when patrilineal descent groups were the socially salient and major unit of intergroup competition, bracketed on either side by periods when this was not the case,” This hypothesis is also supported by a finding in the European DNA samples – shallow coalescence of the Y chromosome, a feature that indicates high levels of relatedness between males.” ref

“Groups of males in European post-Neolithic agropastoralist cultures appear to descend patrilineally from a comparatively smaller number of progenitors when compared to hunter-gatherers, and this pattern is especially pronounced among pastoralists,” they explained. “Our hypothesis would predict that post-Neolithic societies, despite their larger population size, have difficulty retaining ancestral diversity of Y-chromosomes due to mechanisms that accelerate their genetic drift, which is certainly in accord with the data.” ref

“Interestingly, there were variations in the intensity of the bottleneck. It is less pronounced in East and Southeast Asian populations than in European, West, or South Asian populations. This could be because pastoral cultures were much more important in the latter regions. The team are excited to apply their methodology, which combines sociology, biology, and mathematics, to other cultures, to observe how kinship links and genetic variation between cultural groups correlates with political history.” ref

“An investigation into the patterns of uniparental variation among, for example, the Betsileo highlanders of Madagascar, who may have undergone an entry and an exit from the ‘bottleneck period’ very recently, could reveal phenomena relevant to such history,” the researchers wrote. “Cultural changes in political and social organization – phenomena that are unique to human beings – may extend their reach into patterns of genetic variation in ways yet to be discovered.” ref

The truth of 7300-Year-Old Violence Uncovered in the Spanish Pyrenees

“An examination of human remains found in a cave in the Spanish Pyrenees, that date to almost 7300 years ago has provided proof of the brutality of life in the Stone Age . It is believed that the remains are those of adults and children who were massacred. This Stone Age massacre is helping researchers to understand the nature of human violence and they believe it shows that we are ‘hardwired’ to be violent.” ref

“The remains were found in the Els Trocs cave in the Spanish mountain range, which is set in an area of outstanding natural beauty. Archaeologists have uncovered 13 skeletons, from three burials, and also evidence of material culture in the cave. Els Trocs was inhabited in three phases during the Neolithic period. Researchers focused on nine individuals “five adults and four children from the earliest occupation,” according to Real Clear Science . They are some 1000 years older than the other skeletons found in the cave.” ref

Neolithic Massacre in Spanish Pyrenees

“The remains were examined by a multidisciplinary team of experts, who also carbon-dated the skeletons. They made the gruesome discovery that it appears the “five adults and four children between the ages of three and seven were brutally murdered around 5300 BCE or 7,320 years ago,” reports Real Clear Science . They were the victims of a massacre. The team stated that “the violent events in Els Trocs are without parallel either in Spain or in the rest of Europe at that time,” according to Scientific Reports. It appears that they were shot with arrows, apart from one skeleton found in a perpendicular position. The researchers also stated in Scientific Reports, “the children and adults furthermore show traces of similar blunt violence to the skull and entire skeleton.” The victims of the massacre had been shot by arrows and hacked to death showing evidence of overkill.” ref

Stone Age Warfare

“Support for the view that these individuals were the victims of violence and even warfare comes from previous archaeological finds in the Iberian Peninsula. At another Stone Age settlement in Spain, a number of arrows were found, and at Les Dogues rock shelter a battle scene depicts acts of often horrifying violence and conflict. According to the Scientific Reports, the evidence of a massacre at Els Trocs “raises two fundamental questions: on the one hand about the assailants and the other hand the motive for such a seemingly uninhibited excess of violence.” There is little physical evidence indicating who were the perpetrators of the massacre. However, genetic testing has established that the dead were related to the first Neolithic farmers in the Iberian Peninsula. Based on the remote location, they were probably herders who engaged in transhumance.” ref

Motives for the Massacre

“It has been speculated that the killers of the individuals were either new migrants to the area or possibly a group that had maintained a traditional hunter-gatherer lifestyle. A motive for the attack was “the terrain on which the violent events took place is a plateau offering manifold resources,” according to Scientific Reports. Quite simply the victims were killed by a group for control of the resources of the area by a new or previously settled group.” ref

“However, the brutality of the killings would indicate that there was another motive. Scientific Reports states that, “Els Trocs probably documents an early escalation of inter-group violence between people of conceivably different origins and worldviews, between natives and migrants or between economic or social rivals.” This massacre was possibly also prompted by tribal or xenophobic beliefs elated to a long-standing conflict between two groups.” ref

Talheim Death Pit

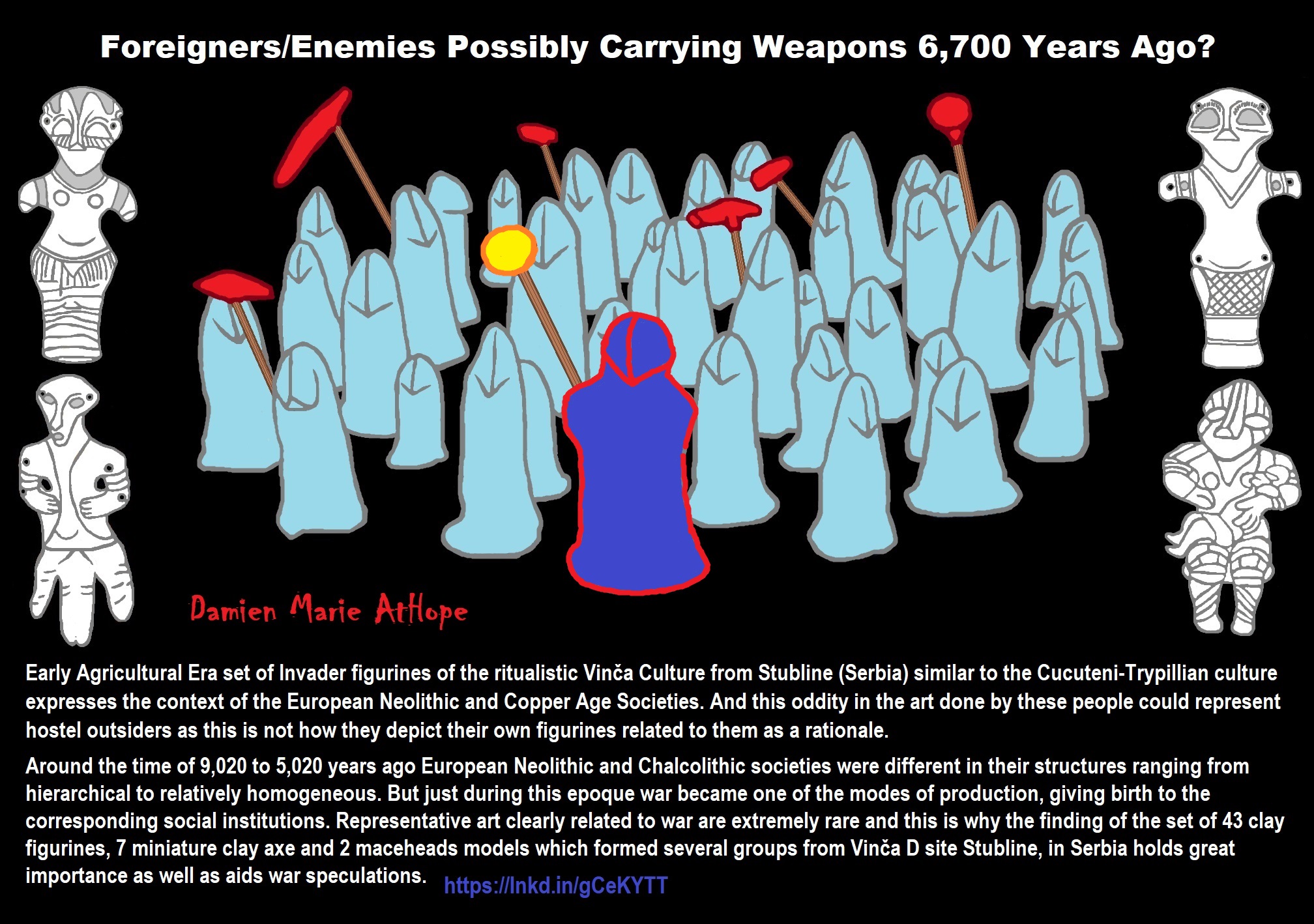

“The Talheim Death Pit (German: Massaker von Talheim), discovered in 1983, was a mass grave found in a Linear Pottery Culture settlement, also known as a Linearbandkeramik (LBK) culture. It dates back to about 5000 BCE or 7,000 years ago. The pit takes its name from its site in Talheim, Germany. The pit contained the remains of 34 bodies, and evidence points towards the first signs of organized violence in Early Neolithic Europe.” ref

Evidence of violence

“Warfare is thought to have been more prevalent in primitive, ungoverned regions than in civilized states. The massacre at Talheim supports this idea by giving evidence of habitual warfare between Linearbandkeramik settlements. It is most likely that the violence occurred among LBK populations since the head wounds indicate the use of weapons from LBK cultures and all skeletons found to resemble those of LBK settlers.” ref

“The Talheim grave contained a total of 34 skeletons, consisting of 16 children, nine adult males, seven adult women, and two more adults of indeterminate sex. Several skeletons of this group exhibited signs of repeated and healed-over trauma, suggesting that violence was a habitual or routine aspect of the culture. Not all of the wounds, however, were healed at the time of death. All of the skeletons at Talheim showed signs of significant trauma that were likely the cause of death. Broken down into three categories, 18 skulls were marked with wounds indicating the sharp edge of adzes of the Linearbandkeramik or Linear Pottery culture (LBK); 14 skulls were similarly marked with wounds produced from the blunt edge of adzes, and 2–3 had wounds produced by arrows. The skeletons did not exhibit evidence of defensive wounds, indicating that the population was fleeing when it was killed.” ref

Reasons for violence

“Investigation of the Neolithic skeletons found in the Talheim death pit suggests that prehistoric men from neighboring tribes were prepared to fight and kill each other in order to capture and secure women. Researchers discovered that there were women among the immigrant skeletons, but within the local group of skeletons there were only men and children. They concluded that the absence of women among the local skeletons meant that they were regarded as somehow special, thus they were spared execution and captured instead. The capture of women may have indeed been the primary motive for the fierce conflict between the men. Other speculations as to the reasons for violence between settlements include vengeance, conflicts over land, resources, poaching, demonstration of superiority, and kidnapping slaves. Some of these theories related to the lack of resources are supported by the discovery that various LBK fortifications bordering indigenously inhabited areas appear to have not been in use for very long.” ref

Similar occurrences

Mass burial at Schletz-Asparn

“The mass grave near Schletz, part of Asparn an der Zaya, was located about 33 kilometres (roughly 20 miles) to the north of Vienna, Austria, and dates back about 7,500 years. Schletz, just like the Talheim death pit, is one of the earliest known sites in the archaeological record that shows proof of genocide in Early Neolithic Europe, among various LBK tribes. The site was not entirely excavated, but it is estimated that the entire ditch could contain up to 300 individuals. The remains of 67 people have been uncovered, all showing multiple points of trauma. Scientists have concluded that these people were also victims of genocide. Since the weapons used were characteristic of LBK peoples, the attackers are believed to be members of other LBK tribes. In similar proportions to those found at Talheim, fewer young women were found than men at Schletz. Because of this scarcity of young women among the dead, it is possible that other women of the defeated group were kidnapped by the attackers. The site was enclosed, or fortified, which serves as evidence of violent conflict among tribes and means that these fortifications were built as a form of defense against aggressors. The people who lived there had built two ditches to counter the menace of other LBK communities.” ref

Mass burial at Herxheim

Main article: Herxheim (archaeological site)

“Another Early Neolithic mass grave was found at Herxheim, near Landau in the Rhineland-Palatinate. The site, unlike the mass burials at Talheim and Schletz, serves as proof of ritual cannibalism rather than of the first signs of violence in Europe. Herxheim contained 173 skulls and skull-plates, and the scattered remains of at least 450 individuals. Two complete skeletons were found inside the inner ditch. The crania from these bodies were discovered at regular intervals in the two defensive ditches surrounding the site. After the victims were decapitated, their heads were either thrown into the ditch or placed on top of posts that later collapsed inside the ditch. The heads showed signs of trauma from axes and one other weapon. Moreover, the organized placing of the skulls suggests a recurrent ritual act, instead of a single instance. Herxheim also contained various high-quality pottery artifacts and animal bones associated with the human remains. Unlike the mass burial at Talheim, scientists have concluded that instead of being a fortification, Herxheim was an enclosed center for ritual.” ref

Mass burial at Schöneck-Kilianstädten

“This Neolithic mass grave, also in modern-day Germany, may exhibit signs of deliberate mutilation and/or torture. Skeletal analysis of the interred remains showed a remarkably high percentage of long bones (especially in the lower leg) which were broken around the time of the individuals’ deaths, which insinuates a deliberate targeting of these areas of the body, possibly as the victims were still alive.” ref

Herxheim (archaeological site)

“The archaeological site of Herxheim, located in the municipality of Herxheim in southwest Germany, was a ritual center and a mass grave formed by people of the Linear Pottery culture (LBK) culture in Neolithic Europe. The site is often compared to that of the Talheim Death Pit and Schletz-Asparn, but is quite different in nature. The site dates from between 5300 to 4950 BCE or 7,320-6,970 years ago.” ref

Discovery

“Herxheim was discovered in 1996 on the site of a construction project when locals reported finds of bones, including human skulls. The excavation was considered a salvage or rescue dig, as parts of the site were destroyed by the construction.” ref

Culture

Main article: Linear Pottery culture

“The people at Herxheim were part of the LBK culture. Styles of LBK pottery, some of a high quality, were discovered at the site from local populations as well as from distant lands from the north and east, even as far as 500 kilometers (310 mi) away. Local flint, as well as flints from distant sources, were also found.” ref

Settlement

“The structures at Herxheim suggested that of a large village spanning up to 6 hectares (15 acres) surrounded by a sequence of ovoid pits dug over a duration of several centuries. These pits eventually cut into one another, forming a triple, semi-circular enclosure ditch split into three sections. The way the pits were dug over such a length of time, in addition to their use, suggests a pre-determined layout. The structures within the enclosure eroded over time, and “yielded only a small number of settlement pits and a few graves”. These pits were either trapezoidal or triangular in nature.” ref

Mass grave

“The enclosure ditches around the settlement comprise at least 80 ovoid pits containing the remains of humans and animals, and material goods such as pottery (some rare and high-quality), bone and stone tools, and “rare decorative artifacts”. The remains of dogs, often found intact, were also recovered. The human remains were primarily shattered and dispersed within the pits, rarely intact or in anatomical position. Using a quantification process known as “minimum number of individuals” (MNI), researchers concluded that the site contained at least 500 individual humans ranging from newborns to the elderly. However, “since the area excavated corresponds to barely half the enclosure, we can assume that in fact more than 1000 individuals were involved”. The deposition of the human remains occurred only within the final 50 years of occupation at the site.” ref

Mortuary practices

“The people at Herxheim practiced a type of burial known as secondary burial, which consists of the removal of the corpse or partial corpse and subsequent placement elsewhere. This is evident due to the lack of complete, articulated skeletons in the majority of the burials. Another possibility is that of sky burial, in which the corpse is exposed to the elements and many bones are carried off by scavengers.” ref

“A 2006 study revealed the intentional breakage and cutting of various human elements, particularly skulls. Bones were broken with stone tools in a peri-mortem state, as is evident by the fragmentation patterns on the bones, which differ between fresh and dry (old) conditions. The conclusion reached from this study was that the site of Herxheim was a ritual mortuary center – a necropolis – where the remains of the dead were not just buried, but for reasons unknown, destroyed.” ref

“A 2009 study confirmed many findings from the 2006 study, but added new information. In just one pit deposit, this study found 1906 bones and bone fragments from at least 10 individuals ranging from newborns to adults. At least 359 individual skeletal elements were identified. This in-depth study revealed many more cut, impact, and bite marks made upon the skulls and post-cranial skeletal elements. It was apparent that parts of the humans’ bodies were singled out for their marrow content, suggesting cannibalization (see Hypotheses). Note that due to the fractures present on the bones being peri-mortem, the blows to the bones could have been made immediately prior (including as cause of) or soon after death. However, because of their precision placement, a peri-mortem “Cause of Death” is not likely, and rather the impacts were placed after the bone was defleshed.” ref

Skull cult practices

“Of particular note from both studies was the peculiar treatment of the humans’ skulls. Many skulls were treated in a similar manner: skulls were struck on “the sagittal line, splitting faces, mandibles, and skull caps into symmetrical halves”. A few skulls were clearly skinned prior to being struck, again, all in the same manner: “horizontal cuts above the orbits, vertical cuts along the sagittal suture, and oblique cuts in the parietals“. The vault of the skull was preserved and shaped into what is referred to as a calotte (calvarium). During this process, the brain, which is a source of dietary fat, may have been extracted. Additionally, a later study revealed that the tongues of humans were removed.” ref

Necropolis

“Due to the transportation of distant pottery and flint, it was the conclusion of the 2006 study that Herxheim served as a necropolis for the LBK people of the area. “The projection of the number of individuals present (…) to a probable total of 1,300 to 1,500 rules out the possibility of a local graveyard — and points a regional center at Herxheim to which human remains were transported for the purpose of reburial. (…) To organize the transport not only of stone tools and pottery but also of human bones and partial or maybe even complete corpses implies an efficient organizational and communication system.” ref

Ritual cannibalism

“Whether for religious purpose or war, it is apparent from the 2009 study that the humans at the site of Herxheim were butchered and eaten. Not only were cut marks found on locations of the skeleton that are made during the dismemberment and filleting process, bones were also crushed for the purposes of marrow extraction, and chewed. Besides the fresh-bone fractures present on many bones, “[processing] for marrow is also documented by the presence of scrape marks in the marrow cavity on two fragments.” Skeletal representation analysis revealed that many of the “spongy bone” elements – such as the spinal column, patella, ilium, and sternum – were underrepresented compared to what would be expected in a mass grave. “All these observations are similar to those observed in animal butchery.” Additionally, preferential chewing of the metapodials and hand phalanges “speak strongly in favor of human choice rather than more or less random action by carnivores”.” ref

“The number of people concerned at Herxheim obviously suggests that cannibalism for the simple purpose of survival is highly improbable, all the more so as the characteristics of the deposits show a standard, repetitive, and strongly ritualized practice”. Although a concrete conclusion has yet to be made, the archaeology does not rule out the possibility of deliberate travel to the complex with pottery, flint, and dead bodies (or partial bodies), with the intent to have the dead cannibalized and/or ritually destroyed. It also does not rule out the idea of human sacrifice. Other archeologists reject the cannibalism hypothesis, however, maintaining the evidence better fits a scenario in which the dead were reburied following dismemberment and removal of flesh from bones. “Evidence of ceremonial reburial practices has been reported for many ancient societies.” ref

The Verteba Cave: A Subterranean Sanctuary of the Cucuteni-Trypillia Culture in Western Ukraine

Abstract and Figures

“In Eneolithic Europe, the complexity of mortuary differentiation increased with the complexity of the society at large. Human remains from the Verteba Cave provide a unique opportunity to study the lives, deaths, and cultural practices of the Cucuteni-Trypillia culture in Western Ukraine. The subterranean sanctuary of Verteba was without a doubt a rallying point of both religious and social significance. Therefore, this investigation focuses on the role and character of ritual activities, the diversity and variety of religious orientations in the Eneolithic period, and the question of how and for what reason this particular cave was modified from a natural space to a sacred place. We also seek to clarify the research potential of the site in relation to highly developed and relatively wide-spread religion with direct implications for the Cucuteni-Trypillia social structure.” ref

Site location

“Situated atop a loess plateau, Verteba Cave is located approximately two kilometers southeast of the site of Ogród near Bilcze Złote village, Borshchiv district, Ternopil province, Ukraine. Set within Precambrian granites and gneisses, beneath Meso-zoic and Cenozoic deposits, Verteba Cave is situated in the Volhyni-an-Podolian Upland. The Podolian Upland is comprised of rich and thick loess topsoil. In the surrounding landscape, tributaries of the Dniester, owing from north to south, reveal a sequence of geological deposits discernible in the deep ravines.” ref

“One such tributary is the Seret River, with Bilcze Złote located on its eastern bank. The village is located on grey-leached loess soils. The climate is warm and temperate, but with greater temperature ranges between winter and summer than usual for Eastern Europe. Verteba Cave (Fig. 2) is found within a larger complex of gyp-sum caves in the karst region, incorporating various karst formations such as caves, sinkholes, and pits. This region stretches along the northern bank of the Dniester, over an area of ca. 8,000 km2. In congruence with many other gypsum caves near the Dniester, Verteba Cave was formed in the Neogene. During the Mio-cene, the whole area was under a shallow sea and therefore gypsums, up to 35 m thick, precipitated in the same epoch. The cave itself has a floor area of 23,000 m2 and a capacity of 47,000 m3, with the combined length of all the passageways inside the cave totaling 8 km.” ref

“A comprehensive chronological and taxonomic overview of the ceramic materials from Verteba Cave has been proposed by Taras Tkachuk, who has analyzed the entire available assemblage. Traces of settlement in Verteba Cave are represented by a specific chronological sequence: a) BZ WI, the oldest horizon, related to the Shipentsy group and dated to the late CI phase; b) BZ WII, related to the Koshilivtsy group and dated to the early CII phase; and c) BZ WIII, associated with the Kasperivtsy group and dated to the younger phase of the CII period. This was confirmed by the stratigraphic relationships, and in congruence with radiocarbon dating (3700–2700 BCE) of selected materials. Recent data and research reinforce the debate that the local populations maintained regular and frequent contacts with surrounding groups of the Trypillia culture as well as more remotely located Eneolithic cultures from Central Europe. Moreover, a modern understanding of the Verteba phenome-non includes the discussion regarding its cultic function. Vertebra Cave has long been interpreted as a refuge settlement. However, it has also been suggested that the cave may have had an undetermined cultic function – a theory that currently seems to be gaining popularity.” ref

The cultural background and Trypillian pottery from Verteba cave

“The sites in Bilcze Złote lie in a settlement area, which was densely populated by groups of the Triypillia culture, primarily settling on the Strypa, Seret and Zbruch Rivers, left-bank tributaries of the Dniester River. The oldest traces of human activity in the Verteba Cave come from the late CI phase and are associated with the Shipentsy group, living near the Badrazhy group on the Central Dniester Plateau (Fig. 3). In the following period, the beginning of phase CII, the cave was visited by members of the Koshilivtsy group, which developed simultaneously with the Branzeni group. In the final stage, dated to the late CII phase, the area was populated by the Kasperivtsy group, which coincided chronologically with the Gordineşti group. The largest portion of the ceramic material recovered from Bilcze Złote is related to the Verteba I assemblage (BZ WI). Stylistic and typological analysis of the assemblage has shown that the material is affiliated with the late phase of the Shipentsy group and dated to the close of the CI phase of the Trypillia culture.” ref

“The assemblage consists of almost 2500 painted ceramics and over 200 ceramic cooking vessels. In total, the Verteba I ceramic assemblage is comprised of twenty-seven vessels imported from the Badrazhy group of the Tripillian culture (ca. 1 % of the total volume of painted ceramics from the sites). Imported goods consist mainly of bowls of various shapes, including, e.g., S-shaped bowls, semispherical bowls, and conical bowls. Foreign items are also represented by nine fragments of large amphora-like vessels with round bodies, two vessels with high conical necks, and one crater. The Verteba I ceramic assemblage includes items clearly associated with Badrazhy pottery-making traditions, for example, a vessel with an image of a cow placed between elements of the Tangentenkreis-band pattern pottery of the Shipentsy group of the Trypillia culture at Verteba Cave in Bilcze Złote from phase WI. Moreover, on one large amphora-like vessel, these decorative elements are separated by S-shaped lines. Wavy stripes within the Tan-gentenkreisband pattern have often been recorded for Badrazhy ceramics, while they are entirely unfamiliar in the Shipentsy group (Tkachuk 2013, 38).” ref

“The Shipentsy ceramics from the late chronological phase are also decorated with other ornamental motifs, which are atypical for that group, and reassemble patterns used by the Badrazhy group. Among them we encounter: 1) vertical and oblique lines crossed by perpendicular strokes (on pyriform vessels or semispherical-conical vessels); 2) empty or filled in black circles with short lines; and 3) filled in red circles (Tkachuk 2013, 38). Among beakers belonging to the Verte-ba I assemblage, one fragment is particularly noteworthy. It is decorated with a metopic motif of horizontal half ovals combined with a stripe of red vertical lines. The stripe, having double oblique strokes at the base, is flanked by elongated vertical half ovals.” ref

“Such decorations have parallels in Petreny mugs found in Varvarovka III. Amongst the serving vessels in the Verteba I ceramic assemblage, one may distinguish a group of thin-walled vessels made of adobe clay, often tempered with crushed pottery (nearly a hundred items – comprising almost 4 % of the whole assemblage). The vessels are usually undecorated, occasionally with small handles pierced horizontally. Most fragments of large and medium vessels have the pro-portions of half-barrel-shaped vessels or vases; there are also a few handles preserved in this class. Semi-spherical bowls form the second largest group, whereas fragments of vessels with high, smooth cylindrical necks are even less frequent. These vessels may be viewed as imports, or alternatively, as local adaptations produced in the late phase of the Lublin-Volhynia culture (numerous half-barrel-shaped vessels) and the Bodrogkeresztúr culture (handled vessels).” ref

“The Verteba II ceramic assemblage from Bilcze Złote is comprised of nearly 800 painted vessels in various stages of preservation. They were all demonstrably related to the Koshilivtsy group from the early CII phase of the Trypillia culture. The Verteba II painted ceramics attributed to the Koshilivtsy group have some ornamental patterns which are not known from Koshili-vtsy traditions, e.g., long or short wavy lines recorded on eleven items in the assemblage. The lines, quite often doubled, have been found: 1) on rims; 2) between lenticular figures; 3) inside the vessels; 4) on the outer and inner walls of bowls; and 5) in the middle of stripes. Double wavy lines are characteristic of settlement assemblages of the Badrazhy population and of the Branzeni group in the CII phase of the Trypillia culture. Vessels produced by the Koshilivtsy group were influenced by the Branzeni group and therefore took on more rounded shapes with higher necks and slight mouths. Ornamental motifs used by the Koshilivtsy group are mainly represented by big, vertical lenticular figures linked to one another by diagonal stripes (some with hooks) and lenticular figures arranged in cruciform patterns on the inner surfaces of conical bowls. Less frequently, we encounter semi-spherical motifs also found in the Branzeni group.” ref

“The predominance of semi-spherical bowls, decorated on the inner and outer walls, is another typical feature of that group. The Verteba II assemblage includes thirty-six imports and vessels inspired by the Branzeni group, nearly 5 % of the painted ceramics in the assemblage. Only a small portion of the ceramic material from Verteba Cave may purport to the Kasperivtsy population from the last phase of the Tripillian culture (fragments of 68 vessels; the late CII phase). Unlike the vessels described so far, the Verteba III assemblage is dominated by ceramics mainly used for cooking. They constitute 72 % of the whole assemblage (49 items). The clay of these vessels is tempered mainly with crushed mollusk shells (25 vessels) or, less often, with an admixture of fire clay, grit, or sand. The Verteba III assemblage includes only 4 sherds of painted vessels, 7.3 % of the whole assemblage. Ceramics produced by the Kas-perivtsy group in the late CII phase of the Tripillian culture had complex characteristics. At that time, Trypillian decorative patterns were gradually influenced by the Funnel Beaker culture and, to a lesser degree, the Baden culture (Tkachuk 2013, 43).” ref

“Cord impressions on vessels with their rims obliquely cut o inwards are a typical feature of the Kasperivtsy group of the Trypillia culture in Verteba. Similar motifs can be found on Funnel Beaker pottery from SE Poland on sites such as Majdan Nowy and Tominy, site 12. This kind of decorative motif is associated and inspired by Anatolian traditions and the eastern Balkan cultural background (culture complexes Sitagroi Va-Radomir I-II-Yunacite XIII-IX traditions), as well as the cultural impact of the Pontic steppes. Decorative motifs of pottery found in Verteba Cave show a wide range of cultural links between this region and surrounding territories, including the Pontic zone, the Eastern Balkans, Anatolia, Volhynia, and Lesser Poland. The collection of anthropomorphic and zoomorphic plastic art (kept at the Archaeological Museum in Kraków) is comprised of 79 and 36 items, respectively. The analysis of these artifacts confirms the chronological timeline of Verteba Cave. There are no major differences to be found between the anthropomorphic and zoomorphic plastic art from Verteba and that of neighboring, contemporary settlements around Bilcze Złote.” ref

Ritual practice in Verteba Cave

“Neolithic populations are often argued to have had a complex burial program; combining rites such as primary burial, secondary burial, excarnation, and the ceremonial manipulation of bones. Archaeologists have interpreted these funerary rites either as expressions of territoriality, ideological masks of inequality, ethnicity or ritual ways of creating relationships between the living, the dead and dwellings.” ref

“There has been surprisingly little osteological research to support this grand theoretical edifice, however, the discovery of disarticulated human remains in Verte-ba Cave provides a unique opportunity to study the lives, deaths, and cultural practices of the Tripillian culture. Osteological materials, curated at the Archaeological Museum in Kraków, derive from ear-ly excavations undertaken by Demetrykiewicz in 1898, 1904, and in 1906. Originally, the collection was comprised of probably 36 specimens (according to catalog numbers), however today it is represented by a minimum of 17 identifiable individuals. Nonetheless, the collection does include over 300 fully preserved large ceramic vessels (measuring ca. 1 m in height), 35,000 pottery sherds and fragments of vessels, 120 anthropomorphic idols, over 60 clay items of varied functions, ca. 200 bone tools, 300 stone tools, and implements as well as bone jewelry.” ref

“Some of these finds are of considerable archaeological value and importance, for instance, the spectacular ‘bull head’ palette with an engraved female figure, or a green hematite disk. Throughout the 19th century, dozens of clay idols of both genders have been discovered inside Verteba Cave. They were hanging from the ceiling or driven into the walls of the cave. These artifacts create the archaeological background and setting for cultural practices in this case. The full archaeological potential of this site remains to be realized. In recent years, until 2008, another 21 individuals were uncovered during excavations within the cave. It is likely that the volume of osteological remains will increase in the future. Tak-ing all this into consideration, the current study aims to investigate the materials using primary referents of mortuary variability: biological, cultural (pre-treatment of skulls, disposal modes), and location-al criteria. Skeletal remains from Verteba Cave can be divided into a few categories. Both human and animal remains exhibit similar levels of con-textual complexity. The vast majority of human bone is represented solely by crania and mandibles. Excluding two cases, a child and an unidentified adult (stored in Kraków), no other body parts were ever found. The deposition of crania, with or without mandibles, must be analyzed separately, as it may exhibit diversity with respect to the cultural phenomenon.” ref

“Today, all materials deriving from Verte-ba Cave are divided between museums in Kraków and Borshchiv, in more or less equal proportions, with the only difference being all child remains are stored in Poland. The excavated skulls form an unquantifiable sample of the de-ceased Tripillian population; the assemblage includes the remains of at least 5 (13 %) immature individuals and 33 adults (87 %; Fig. 12). All but 9 of the individuals were securely sexed, showing a much higher proportion of males (77 % adults) than females (23 % adults). The median age range for all adults is 35–45 years, there being little variation between the sexes. In an older collection, gathered by Demetrykiewicz, only two adult males were more than 40 years of age. There is a possibility of spatial separation based on the individual’s age and/or sex, creating a biased view of the dead population, al-though the remains appear to demonstrate a dispersed distribution.” ref

Brain removal and pigments

“The cultural practice of post-mortem brain removal has been recorded in 4 crania from Verteba. Specimens belong to 2 adult and 2 non-adult individuals. The recurring pattern covers four basic re-moval techniques: 1) brain tissue was extracted through the nose cavity; 2) through eye sockets; 3) through dilatation of the foramen magnum; and 4) through the large skull opening on the right or left side of the mainly temporal region (Fig. 13). The dilatation of the foramen magnum has been recorded in the cranium of an adult male (Verteba no. 21), which was additionally coated with red ochre pigments. A similar process was administered to cranium no. 15 (non-adult), where the brain was extracted through large openings in both the left and right temporal bones prior to the empty skull being covered with pigments.” ref

“Defleshing, including brain extraction via an opening in the temporal bones, and the use of ochre also reappear in cranium no. 18 (child, Infans I). Traseological evidence suggests that large stone hammers were used during the early stages of decomposition to open the skulls. Death separated the deceased from their social status. The period of preparing the dead for burial moved them into a transitional phase, when they were neither their past selves, nor yet what they would become. Such moments of ‘transition’ often involve uncertainty and potential danger. Some ceremonial acts or customs employed at the time of death in the Tripilllian culture seemed to encompass both ritual cleansing (defleshing) and apotropaic magic (red pigments). However, ritualization is a strategy of power, whereby status functions are collectively imposed on agents, objects, and events. Despite the fact that death rituals are essentially deceptive and manipulative, they employ characteristically eye-catching, costly, amplified, and stereotyped process-es and are prone to massive redundancy signals. Ritualized deesh-ing is also an embodied experience with the transformations of body surfaces playing a key role. Body painting and cosmetics are among the simplest forms of such transformational techniques.” ref

Excarnation and scalping

“Scalping and excarnation in the archaeological record are recognized by patterns of cut marks. Scalping marks occur on the cranium, as cuts or clusters of cuts, and typically form a rough circle around the superior aspect of the skull. At least two individuals from Verte-ba, an adult female (skull no. 4) and a child (Infants I, no. 18) have been subjected to such post-mortem treatment. The skull of the non-adult has been defleshed and subsequently covered with red pigments, indicating ritualistic cleansing. The incised marks were multiple, repetitive and of varying length, appearing to run vertically along the frontal bone. This leads to the conclusion that the manner of scalp re-moval was clearly different to that of the adult female. Marks attributed to scalping generally matched the exterior surface of the bone in color. If the scalper was skilled at the practice, no damage would occur to the underlying bone. While scalping was most often performed at death or the minutes preceding it, in some instances evidence indicates that the practice of scalping was also performed on living individuals.” ref

“If the removal of the scalp was not preceded by a circular incision outlining the perimeter of the scalp, the method was termed sabrage. In addition to the scalp, portions of the neck and face might also have been removed. This method involved making short, parallel cuts across the frontal bone, followed by short cuts around and behind one ear, then across the occipital bone near the nuchal crest and behind the other ear, and finally connecting the cut with the initial cuts on the victim’s frontal bone. It seems feasible that both defleshing and scalping in Eneolithic Ukraine were only performed with stone knives. Experiments on cadaver crania have elicited conclusive differences between cutting tools. In general, scalping cuts are not left on the cranial bones if the incisions of the soft tissues were made with metal knives. When stone implements were used, these tools often had irregular edges that left parallel incisions or cuts on the surface of the cranial bones. The two most likely behavioral interpretations of cut marks are scalping and ritual defleshing, however, scalping should be clearly separated from excarnation or defeating. The number, location, and placement of cuts can be used to distinguish between excarnated and scalped crania.” ref

“A greater number of cuts and cuts that are scattered across the frontal bone usually indicated a skull that was systematical defleshed, rather than scalped. The typical pattern of cuts on scalped skulls consists of fewer incisions, generally in clusters that form a distinctive circumferential configuration. Also, scalped frontals often show cuts that originate at the temporal line, extend to approximately halfway between the hairline and the brow ridges, and finally terminate at the opposite temporal line. Two contributing factors to the variation of scalping methods were cultural preference and the duration of time allotted for the removal of a trophy (Bueschgen/Case 1996). Ethnographic data indicates that scalping techniques utilized by different tribes were culturally transmitted behaviors passed down by each tribe’s ancestors. Scalping methods difiered in the amount of skin taken from the head, the number of scalps lifted from the same head, and the method of scalp removal. In both prehistoric and historic times, scalping by Native Americans was interpreted as a final insult or curse upon the victim.” ref

“The underlying idea of scalping was the desire to preserve a souvenir of the slain enemy, while simultaneously dishonoring his remains. Scalping, therefore, was a tangible symbol of physical and spiritual dominance. Among the Arikara tribes, for example, survival of scalping appeared to have strong cultural significance. In accordance with Ari-kara folklore, a male scalping survivor was forced into a solitary life outside of his village and had to stay hidden to avoid shocking or offending others. If scalped, only men were forced from their village. In the Northern American Plains and the South-West, burial patterns suggest that female scalping survivors were accepted back into their community and most often were buried with other members of their tribe. Re-burial practice Secondary mortuary practices, including re-burial and intention-al re-deposition of human remains, are relatively rare, especially in a prehistoric setting. The idea of re-interment is based on a certain set of cult practices and the intentionality of ritual cleansing procedures. A mortuary program, involving secondary disposal of the deceased, can be divided into two stages.” ref

“The initial phase of the treatment commenced with the death or imminent death of an individual and terminated with the initial disposal. The second stage was initiated by an event non-associated with the death of the person; it involved the removal of the deceased from the location of initial disposal, followed by either replacement in the initial disposal facility, or removal to a place of secondary disposal. Re-interment is probably among the most time-consuming religious practices in prehistory and it may take a few years to bury any given individual. Interestingly, this indicates, in turn, that in the Tripillian culture secondary body treatment was a socially sanctioned and approved method of handling the deceased. Ethnographic sources infer that tribal societies, which practice re-burial, usually demonstrate greater cognitive concern in connection with the bones. This may be communicated in the rich vocabulary used to describe the bones and/or decaying body; or it might form a key portion of the myths of the culture (Goodale 1985). The cranium of a reburied adult male individual discovered in Verteba Cave is shown in (Fig. 15). The bone surface in the frontal and parietal regions indicates plant rooting and scalping. It seems feasible that this male had been buried in a difierent location and his body was kept in the ground for at least two years prior to re-deposition in the cave. The knife marks suggest that some loose and partially decomposed fragments of tissue have been removed. His ‘cleansed’ skull was deposited in Verteba Cave as pars pro toto internment of the whole body.” ref

“Perimortem blunt force trauma In several cases of perimortem blunt force, injuries to the cranium have been recorded in Verteba assemblages. The morphology of these marks is a crucial factor that needs to be accurately described and accounted for in archaeological and forensic records. The evidence of violent death and the secondary treatment of the cadavers can be interpreted either as opportunistic votive burial, an actual sacrifice with a specific ritual pattern, or more traditionally, a deviant deposit in which the individuals were deprived of funerals and exposed to scavengers. Nasal septum deviation, probably caused by impact trauma, was found in the cranium belonging to an adult male (ca. 40 years of age, Verteba no. 19). This male had sustained a fracture to the inferior end of the nasal bone, slightly flattening and splaying both halves. The changes suggest a blow on the nose from directly in front of the individual, possibly accidental, but more likely deliberate, using a blunt implement. Moreover, the same individual sustained severe perimortem blunt force injury of the right eye (quite likely resulting from multiple blows). It is shown as a comminuted fracture to the left supraorbital margin with fracture lines measuring approx. 35 mm (mediolateral) x 22.5 mm (anteroposteriorly). Female skull no. 16 shows several distinctive marks of traumatic brain injury.” ref

“The occipital bone was crushed from behind by a large object, which left a circular depressed fracture to the parietal, probably in combination with a frontal fracture measuring ca. 9–10 mm. She died due to a severe brain-penetrating wound, caused by a high-velocity blow with a long and pointy implement from the back. In addition, two deep ante-mortem longitudinal grooves have been recorded on the parietal bone, presumably the marks of a stone hammer. Her nasal septum has been totally removed, probably post-mortem. Specific patterning of craniocerebral damage has been recognized in three male crania recently uncovered in Verteba Cave. In all 3 cases, we are dealing with a large sub-circular comminuted depressed fracture that penetrates the skull. The ectocranial margins are sharp. Bevelling along the endocranial margin indicates the central fragments were inwardly displaced. The direct primary impact caused intracranial hemorrhaging, cerebral contusions, lacerations, and deep brain hemorrhages. It may be asserted to a high degree of certainty that such a head injury would have been the sole cause of death. The full extent of the injuries suffered, however, cannot be precisely estimated due to a lack of other body parts. The discussed specimens have been compared with reference material deriving from medieval and Bronze Age warfare contexts.” ref

“Non-human biological agentsTaphonomic damage, specifically that created by rodent gnawing, root etching, and excavation damage, may also be misinterpreted as tool marks. Haglund et al. (1988) provide a brief account of forensic cases in which human remains were ravaged by carnivores. In his later publications, he distinguished rodents from carnivore damage. Excluding co-mingled human remains found in the cave, some attention should be paid to the causes and overall im-pact of non-human agents, such as rodent gnawing on Verteba cultural deposits. Three crania (curated in Kraków) show evidence of rodent activity, following similar patterns. In specimen no. 19, gnawing was recorded on the right temporal bone and supraorbital margin. Cranium no. 4 displays a comparable arrangement. Rodent activity affected the right supraorbital margin and the left side of the maxilla. Obvious traces of gnawing with deep marks have also been found on the right temporal bone along the superior temporal line (attachment of the temporalis muscle) of the same skull.” ref

“Due to specific alignments of gnaw marks, it seems credible to theorize that some parts of the skulls were deposited in the cave prior to any cleans-ing or processing. Some skulls were still covered with large parts of muscles, soft tissue, and possibly blood with mandibles present. Additionally, skull no. 19 shows a vestige of scalping as well. It seems possible that during ritual cleansing, mandibles were detached from the rest of the skull. Regular, at-bottomed groves indicate the presence of large rodents, possibly rats (Ratus ratus) in the cave. Like carnivores, rodents can move bones around, often carrying them over large distances to their dens, where they accumulate and modify them by chewing, which to some extent may explain the formation of co-mingled deposits of bone. In addition to displaying indicators of chewing by mammals, bones can be scarred by the action of feet. Trampling and polishing by the constant passage of carnivores in a lair may scratch and polish bone surfaces. Several skulls show randomly orientated superficial scratches and some bones in Verteba’s subterranean environment may have been relocated by animals.” ref

Conclusions

It should be highlighted that there are several larger karst caves in the Blicze Złote region.

“However, traces of human occupation were only found in Verteba Cave. Regardless of this finding, the cave did not provide proper conditions for permanent inhabitancy per se. An obvious lack of an independent water source, poor ventilation, permanent darkness, and very dicult or near inaccessible entrances (steep funnel-like precipice), can be mentioned among few leading reasons. Nonetheless, the specific appearance of artifacts and a sig-nicant volume of selected human remains undoubtedly indicates the cultic function of this site. Data collected in this study evidently points towards a multidirectional exchange network amongst a few local populations. The simultaneous presence of imported goods and local wares suggests the significant trans-regional importance of the Verteba sanctuary and a long-distance network of connections. The same can be maintained about immaterial aspects of the Trypillian cult.” ref

“The study of mortuary practices reflects social phenomena. In order to assess the usefulness of mortuary data from Verteba for social modeling, two criteria are important: 1) the range of social information that can be derived from mortuary remains, and 2) the reliability of burial data as indicators of social phenomena. In the case of the Verteba subterranean sanctuary, mortuary rituals were more than ‘just’ a way of disposing of the dead. They provided a forum for remembrance and celebration of the deceased, for engaging with and potentially challenging cultural norms, and for integrating the social units in ways that can mimic, mask, or modify social relationships that exist in the non-ritual social structure.” ref

“While mortuary rituals are reproduced through acts of ritual performance and burial practices, each act offers opportunities to change the role of these rituals in society. Consequently, mortuary rituals could serve multiple roles that not only could but would change over time. The majority of Trypillian materials from the Verteba Cave indicate the presence of a highly developed eschatological vision of the afterlife and rites of passage. Mortuary rituals seem to combine ani-malistic beliefs and apotropaic magic. Nonetheless, certain evidence shows elements typical for warfare assemblages, trophy taking, or executions. In global terms, it can be hypothesized that Tripillian warfare grew out of a combination of economic and demographic variables. It emerged in association with some degree of territoriality and sedentism and with concentrations of resources.” ref

“The development of agriculture was probably not a necessary precondition for the onset of war, but it provides accommodating environments with-in which warfare could arise and spread. The level, intensity, and impact of warfare usually tend to increase as cultural systems become more complex, but in the case of Verteba Cave, this statement may be overrated. Assemblages of highly fragmented or extensively processed hu-man remains can derive from countless sources, including warfare, social control, cult, and preparation of the deceased. According to some authors, the overall context of Verteba’s skeletal assemblages can simply be seen as evidence of “trophy taking and cranial surgery and interpersonal violence” (Lillie et al. 2011). In fact, in this paper, we demonstrate that the complexity of Tripillian rituals goes way beyond that. All human remains recovered during archaeological prospects derive from the same location within the cave (Zawrat and the Great Hall). It seems feasible that ritual space was originally divided into sectors, with tools, ceramics, idols, and other artifacts being deposited in specific places. The practice of cult depositions probably lasted through centuries and involved more than one population inhabiting the region.” ref

Bilche-Zolote

“Bilche-Zolote is a Ukrainian village located within the Borshchiv Raion (district) of the Ternopil Oblast (province), about 460 kilometers (290 mi) driving distance southwest of Kyiv, and about 16 km (9.9 mi) west of the district seat of Borshchiv. This rural community is located in a small valley adjacent to the Seret River, which is surrounded by plateaus covered with farms, broken by occasional stands of mixed forest. Bilche-Zolote is home to a remarkable park of 1,800 hectares (4,400 acres), of which 11 hectares (27 acres) is covered with virgin timber, including some trees up to 400 years old. Bilche-Zolote is also the location of the large gypsum karst Verteba Cave, as well as a significant Neolithic Cucuteni-Trypillian culture archaeological site, and attracts tourist and spelunker visitors from many countries.” ref

Vertebra and Priest’s Grotto Caves

“The Verteba Cave located on the outskirts of Bilche-Zolote village gets its name from the Ukrainian word for “crib”. Verteba is one of the largest caves in Europe, measuring 7.8 kilometers (4.8 mi) in length, with a total of 6000 cubic meters. It consists of maze-like passageways, often separated by thin walls, as well as broad galleries. The walls of the cave are smooth and dark, with rare incrustations of calcium carbonate appearing. There are also small stalactites, and unusual stalagmites that have the appearance of barrels, all of which are coated in an opaque watery liquid known as moonmilk.” ref

Cucuteni-Trypillian settlement

“During a mundane excavation on the Sapyehy estate in 1884, workers stumbled upon the buried ruins of a prehistoric settlement near the mouth of the Verteba cave. Over the years, more than 300 intact ceramic containers have been unearthed from the floor of the cave and this Neolithic era settlement, which encompasses a total of 8 hectares (20 acres). Archaeologists identified the artifacts as belonging to the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture, with evidence of two separate periods of settlement activity dating from 4440-4100 BCE and 3800-3300 BCE. The members of this society plowed their farms, raised livestock, hunted and fished, created textiles, and developed a beautiful and highly refined style of pottery with very intricate designs. Their settlements, which with up to 15,000 inhabitants were among the largest on earth at the time, were built in oval or circular layouts, with concentric rows of houses that were interconnected to form rings around the center of the community, where often a sanctuary building would be found. They left behind a large number of clay figurines, many of which are regarded as Mother goddess fetishes. For over 2500 years the culture flourished with no evidence left behind that would indicate they experienced warfare. However, at the beginning of the Bronze Age their culture disappeared, the reasons for which are still debated, but possibly as a result of invaders coming from the Steppes to the east.” ref

“Over the years there have been a number of major archaeological explorations of this site, starting with excavations from 1889-1891 by Edward Pawłowicz and Gotfryd Ossowski. In 1898 Włodzimierz Demetrykiewicz conducted an excavation and analysis. In 1952 and 1956 V. N. Eravets, I. E. Svyshnikov, and G. M. Vlasova resumed the exploration of the site, which had been neglected during the turbulent first half of the 20th Century. Recently, in 2000, M. Sohatskyy conducted further excavations of the site. The evidence from the discoveries revealed that there had been a gap between when the settlement was occupied. The more recent settlement yielded ceramic finds that connected it to the Shypynetsk group (Ukrainian: шипинецької групи), a sub-group of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture that flourished in this region during the later Neolithic.” ref

“Along with the intact ceramic containers unearthed in the cave, archaeologists have also found more than 35,000 clay fragments, including many of the famous Cucuteni-Trypillian goddess figurines, 200 pieces of bone and antler remains, and an additional 300 tools and other objects crafted from bone and stone, including flint implements, bone awls, and a few small copper artifacts. Perhaps most importantly, archaeologists discovered one of the few burial sites of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture at this site, amounting to almost 120 individuals. One of the most famous artifacts from the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture was found at Bilche-Zolote by the first team of archaeologists in the 1890s: a bone plate from about 3500 BCE. was found inside the Verteba cave, which was incised with a beautiful silhouette of a Mother goddess, and which became one of the most recognized symbols of this culture.” ref

“Beginning in 1907, a collection of the archaeological finds from the Bilche-Zolote Cucuteni-Trypillian settlement made up the core collection of the local archaeological museum, which was housed in the palace located on the grounds of the Landscape Park. During the period of Polish occupation, these materials were removed to the Museum of Archeology in Krakow. More recent finds from archaeological excavations have been housed in the Lviv Historical Museum and the Borshchiv Regional Museum of Local Lore.” ref

New AMS Dates for Verteba Cave and Stable Isotope Evidence of Human Diet in The Holocene Forest-Steppe, Ukraine

Abstract

“Excavations at several locations in Verteba Cave have uncovered a large amount of human skeletal remains in association with faunal bones and Tripolye material culture. We aim to establish radiocarbon (14C) dates for eight sites and to evaluate whether these deposits are singular events, or slow accumulations over time. 14C measurements, along with stable carbon and nitrogen isotope data from human and faunal remains, were collected from 18 specimens. Stable isotope values were used to evaluate human and animal diet, and whether freshwater reservoir effects offset measured dates. We found diets of the sampled species had limited to no influence from freshwater resources. The human diet appears to be dominated by terrestrial plants and herbivores. Four new sites were identified as Eneolithic. Comparisons of dates from the top and bottom strata for two sites (7 and 20) reveal coeval dates, and we suggest that these deposits represent discrete events rather than slow continuous use. Lastly, we identified dates from the Mesolithic (8490±45 BP, 8765±30 BP), Iron Age (2505±20 BP), Slavic state era (1315±25 BP), and Medieval Period (585±15 BP), demonstrating periodic use of the cave by humans prior to and after the Eneolithic.” ref

Analysis of ancient human mitochondrial DNA from Verteba Cave, Ukraine: insights into the origins and expansions of the Late Neolithic-Chalcolithic Cututeni-Tripolye Culture

Abstract

Background

“The Eneolithic (~ 5,500 yrBP) site of Verteba Cave in Western Ukraine contains the largest collection of human skeletal remains associated with the archaeological Cucuteni-Tripolye Culture. Their subsistence economy is based largely on agro-pastoralism and had some of the largest and most dense settlement sites during the Middle Neolithic in all of Europe. To help understand the evolutionary history of the Tripolye people, we performed mtDNA analyses on ancient human remains excavated from several chambers within the cave.” ref

Results

“Burials at Verteba Cave are largely commingled and secondary in nature. A total of 68 individual bone specimens were analyzed. Most of these specimens were found in association with well-defined Tripolye artifacts. We determined 28 mtDNA D-Loop (368 bp) sequences and defined 8 sequence types, belonging to haplogroups H, HV, W, K, and T. These results do not suggest continuity with local pre-Eneolithic peoples, but rather a complete population replacement. We constructed maximum parsimonious networks from the data and generated population genetic statistics. Nucleotide diversity (π) is low among all sequence types and our network analysis indicates highly similar mtDNA sequence types for samples in chamber G3. Using different sample sizes due to the uncertainly in the number of individuals (11, 28, or 15), we found Tajima’s D statistic to vary. When all sequence types are included (11 or 28), we do not find a trend for demographic expansion (negative but not significantly different from zero); however, when only samples from Site 7 (peak occupation) are included, we find a significantly negative value, indicative of demographic expansion.” ref

Conclusions

“Our results suggest individuals buried at Verteba Cave had overall low mtDNA diversity, most likely due to increased conflict among sedentary farmers and nomadic pastoralists to the East and North. Early Farmers tend to show demographic expansion. We find different signatures of demographic expansion for the Tripolye people that may be caused by the existing population structure or the spatiotemporal nature of ancient data. Regardless, peoples of the Tripolye Culture are more closely related to early European farmers and lack genetic continuity with Mesolithic hunter-gatherers or pre-Eneolithic groups in Ukraine.” ref

“The Chalcolithic, a name derived from the Greek: χαλκός khalkós, “copper” and from λίθος líthos, “stone” or Copper Age, also known as the Eneolithic or Aeneolithic (from Latin aeneus “of copper”) is an archaeological period which researchers now regard as part of the broader Neolithic. Earlier scholars defined it as a transitional period between the Neolithic and the Bronze Age. In the context of Eastern Europe, archaeologists often prefer the term “Eneolithic” to “Chalcolithic” or other alternatives.” ref

“In the Chalcolithic period, copper predominated in metalworking technology. Hence it was the period before it was discovered that by adding tin to copper one could create bronze, a metal alloy harder and stronger than either component. The archaeological site of Belovode, on Rudnik mountain in Serbia, has the worldwide oldest securely-dated evidence of copper smelting at high temperature, from c. 5000 BC (7000 BP). The transition from Copper Age to Bronze Age in Europe occurs between the late 5th and the late 3rd millennia BCE. In the Ancient Near East the Copper Age covered about the same period, beginning in the late 5th millennium BCE and lasting for about a millennium before it gave rise to the Early Bronze Age.” ref

7,020-6,020 years old