ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

Hongshan culture

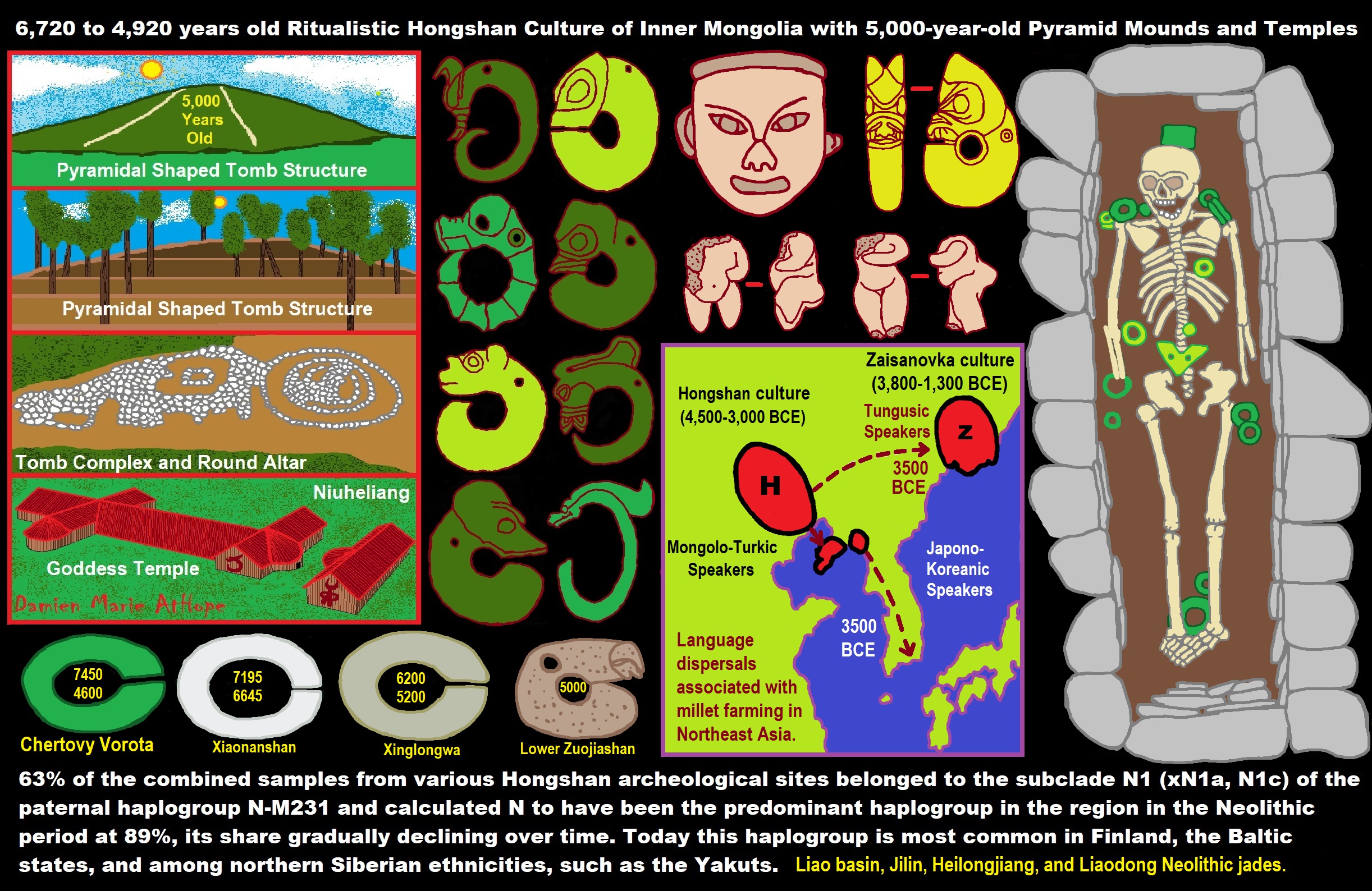

“The Hongshan culture was a Neolithic culture in the Liao river basin in northeast China. Hongshan sites have been found in an area stretching from Inner Mongolia to Liaoning, and dated from about 4700 to 2900 BCE. In northeast China, Hongshan culture was preceded by Xinglongwa culture (6200–5400 BCE), Xinle culture (5300–4800 BCE), and Zhaobaogou culture, which may be contemporary with Xinle and a little later. Yangshao culture was in the larger area and contemporary with Hongshan culture. These two cultures interacted with each other.” ref

“A study by Yinqiu Cui et al. from 2013 found that 63% of the combined samples from various Hongshan archeological sites belonged to the subclade N1 (xN1a, N1c) of the paternal haplogroup N-M231 and calculated N to have been the predominant haplogroup in the region in the Neolithic period at 89%, its share gradually declining over time. Today this haplogroup is most common in Finland, the Baltic states, and among northern Siberian ethnicities, such as the Yakuts. Other paternal haplogroups identified in the study were C and O3a (O3a3), both of which predominate among the present-day inhabitants. Nelson et al. 2020 attempts to link the Hongshan culture to a “Transeurasian” linguistic context (see Altaic).” ref

“The archaeological site at Niuheliang is a unique ritual complex associated with the Hongshan culture. Excavators have discovered an underground temple complex—which included an altar—and also cairns in Niuheliang. The temple was constructed of stone platforms, with painted walls. Archaeologists have given it the name Goddess Temple due to the discovery of a clay female head with jade inlaid eyes. It was an underground structure, 1m deep. Included on its walls are mural paintings.” ref

Housed inside the Goddess Temple are clay figurines as large as three times the size of real-life humans.[6] The exceedingly large figurines are possibly deities, but for a religion not reflective in any other Chinese culture. The existence of complex trading networks and monumental architecture (such as pyramids and the Goddess Temple) point to the existence of a “chiefdom” in these prehistoric communities.” ref

“Painted pottery was also discovered within the temple. Over 60 nearby tombs have been unearthed, all constructed of stone and covered by stone mounds, frequently including jade artifacts. Cairns were discovered atop two nearby two hills, with either round or square stepped tombs, made of piled limestone. Entombed inside were sculptures of dragons and tortoises. It has been suggested that religious sacrifice might have been performed within the Hongshan culture.” ref

“Just as suggested by evidence found at early Yangshao culture sites, Hongshan culture sites also provide the earliest evidence for feng shui. The presence of both round and square shapes at Hongshan culture ceremonial centers suggests an early presence of the gaitian cosmography (“round heaven, square earth”). Early feng shui relied on astronomy to find correlations between humans and the universe.” ref

“Some Chinese archaeologists such as Guo Da-shun see the Hongshan culture as an important stage of early Chinese civilization. Whatever the linguistic affinity of the ancient denizens, Hongshan culture is believed to have exerted an influence on the development of early Chinese civilization. The culture also have contributed to the development of settlements in ancient Korea.” ref

5,200 years old Walled City Unearthed in Central China

“HUBEI PROVINCE, CHINA—Xinhua reports that a section of wall and a moat estimated to be 5,200 years old have been unearthed at the Fenghuangzui site in central China. “The discovery gave us a basic idea about the ancient city’s rise and demise,” said archaeologist Shan Siwei. The excavation also revealed the remains of houses, pits, ditches, tombs, and pottery. “Based on the construction style and unearthed items, we believe the site used to be a regional center in the past and also served important military functions,” Shan added.” ref

Remains of an ancient wall section, moat found in central China

“The remains were found in the Fenghuangzui site located in the city of Xiangyang, after more than seven months of excavation. Archaeologists believe the remains belong to several cultural phases of Chinese history ranging from 3,900 to 5,200 years old. The Fenghuangzui site is the site of a Neolithic city on a roughly square-shaped area measuring about 140,000 square meters. A joint archaeological team started excavation work at the site in August last year covering an area of more than 450 square meters. The excavation confirmed the existence of the ancient city walls and the moat, as well as their structure, said Shan Siwei, one of the leading archaeologists from the excavation team. “The discovery gave us a basic idea about the ancient city’s rise and demise.” In addition to the wall section and the moat, they also found remains of some houses, pits, ditches, tombs, coffins, and clays. “Based on the construction style and unearthed items, we believe the site used to be a regional center in the past and also served important military functions,” Shan added.” ref

“Xiangyang is located at a strategic site on the middle reaches of the Han River, and has witnessed several major battles in Chinese history. Xiangyang County was first established at the location of modern Xiangcheng in the early Western Han dynasty and the name had been used continuously for more than 2,000 years until the 20th century.” ref

“In the final years of Eastern Han dynasty, Xiangyang became the capital of Jing Province (ancient Jingzhou). The warlord Liu Biao governed his territory from here. Under Liu’s rule, Xiangyang became a major destination of the northern elite fleeing warfare in the Central Plain. In the Battle of Xiangyang in 191 AD, Sun Jian, who was a rival warlord and the father of Sun Quan, founder of Eastern Wu, was defeated and killed. The area passed to Liu Bei after Liu Biao’s death. Two decades later, Battle of Fancheng, one of the most important battles in late Han-Three Kingdoms period was fought here, resulting in Liu Bei‘s loss of Jingzhou.” ref

“During the early years of Jin dynasty, Xiangyang was on the frontier between Jin and Eastern Wu. Yang Hu, the commander in Xiangyang, was remembered for his policy of “border peace”. Cross-border commerce was allowed, and the pressure on the Jin army was greatly relieved. Eventually, Xiangyang accumulated sufficient supplies for 10 years, which played a key role in Jin’s conquest of Wu.” ref

“In Southern Song dynasty, after the Treaty of Shaoxing, Xiangyang became a garrison city on the northern frontier of Song. During Mongol conquest of the Song dynasty, Xiangyang together with Fancheng formed one of the greatest obstacles against the expansion of Mongol Empire. They were able to resist for six years before finally surrendering in the Siege of Xiangyang.” ref

“In 1796, Xiangyang was one of the centers of the White Lotus Rebellion against the Qing dynasty. Here, rebel leader Wang Cong’er successfully organized an rebel army of 50,000 and joined the main rebel forces in Sichuan. The revolt lasted for nearly 10 years and marked a turning point in the history of Qing dynasty. In 1950, Xiangyang and Fancheng were merged to form Xiangfan City. In the later 20th century, it became a major transport hub as Handan, Jiaoliu, and Xiangyu railways intersect in Fancheng. The city’s current boundaries were established in 1983 when Xiangyang Prefecture was incorporated into Xiangfan City. The city was renamed to Xiangyang in 2010.” ref

“Xiangyang has a latitude range of 31° 14’−32° 37′ N, or 154 km (96 mi), and longitude range of 110° 45’−113° 43′ E, or 220 km (137 mi), and is located on the middle reaches of the Hanshui, a major tributary of the Yangtze River. The urban area, however, has a latitude range of 31° 54’−32° 10′ N, or 29 km (18 mi), and longitude range of 112° 00’−112° 14′ E, or 21 km (13 mi). It borders Suizhou to the east, Jingmen and Yichang to the south, Shennongjia and Shiyan to the west, and Nanyang (Henan) to the north. Its administrative border has a total length of 1,332.8 km (828.2 mi).” ref

“Xiangyang has a monsoon-influenced, four-season humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa), with cold, damp (but comparatively dry), winters, and hot, humid summers. Xiangyang possesses large water energy resources whilst its mineral deposits include rutile, ilmenite, phosphorus, barite, coal, iron, aluminum, gold, manganese, nitre, and rock salt. The reserves of rutile and ilmenite rank highly in China.” ref

History of China

ANCIENT China

Neolithic c. 8500 – 2070 BCE

Xia c. 2070 – 1600 BCE

Shang c. 1600 – 1046 BCE

Zhou c. 1046 – 256 BCE

IMPERIAL China

Qin 221–207 BCE

Han 202 BCE – 220 CE

“The earliest known written records of the history of China date from as early as 1250 BCE, from the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE), during the king Wu Ding‘s reign, who was mentioned as the twenty-first Shang king by the same. Ancient historical texts such as the Book of Documents (early chapters, 11th century BCE), the Records of the Grand Historian (c. 100 BCE) and the Bamboo Annals (296 BCE) mention and describe a Xia dynasty (c. 2070–1600 BCE) before the Shang, but no writing is known from the period, and Shang writings do not indicate the existence of the Xia. The Shang ruled in the Yellow River valley, which is commonly held to be the cradle of Chinese civilization. However, Neolithic civilizations originated at various cultural centers along both the Yellow River and Yangtze River. These Yellow River and Yangtze civilizations arose millennia before the Shang. With thousands of years of continuous history, China is one of the world’s oldest civilizations and is regarded as one of the cradles of civilization.” ref

“The Zhou dynasty (1046–256 BCE) supplanted the Shang, and introduced the concept of the Mandate of Heaven to justify their rule. The central Zhou government began to weaken due to external and internal pressures in the 8th century BC, and the country eventually splintered into smaller states during the Spring and Autumn period. These states became independent and fought with one another in the following Warring States period. Much of traditional Chinese culture, literature, and philosophy first developed during those troubled times.” ref

“In 221 BCE, Qin Shi Huang conquered the various warring states and created for himself the title of Huangdi or “emperor” of the Qin, marking the beginning of imperial China. However, the oppressive government fell soon after his death, and was supplanted by the longer-lived Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE). Successive dynasties developed bureaucratic systems that enabled the emperor to control vast territories directly. In the 21 centuries from 206 BCE until CE 1912, routine administrative tasks were handled by a special elite of scholar-officials. Young men, well-versed in calligraphy, history, literature, and philosophy, were carefully selected through difficult government examinations. China’s last dynasty was the Qing (1644–1912), which was replaced by the Republic of China in 1912, and then in the mainland by the People’s Republic of China in 1949. The Republic of China retreated to Taiwan in 1949. Hong Kong and Macau transferred sovereignty to China in 1997 and 1999.” ref

“Chinese history has alternated between periods of political unity and peace, and periods of war and failed statehood—the most recent being the Chinese Civil War (1927–1949). China was occasionally dominated by steppe peoples, most of whom were eventually assimilated into the Han Chinese culture and population. Between eras of multiple kingdoms and warlordism, Chinese dynasties have ruled parts or all of China; in some eras control stretched as far as Xinjiang and Tibet, as at present. Traditional culture, and influences from other parts of Asia and the Western world (carried by waves of immigration, cultural assimilation, expansion, and foreign contact), form the basis of the modern culture of China.” ref

Neolithic China

List of Neolithic cultures of China

Further information: Yellow river civilization, Yangtze civilization, and Liao civilization

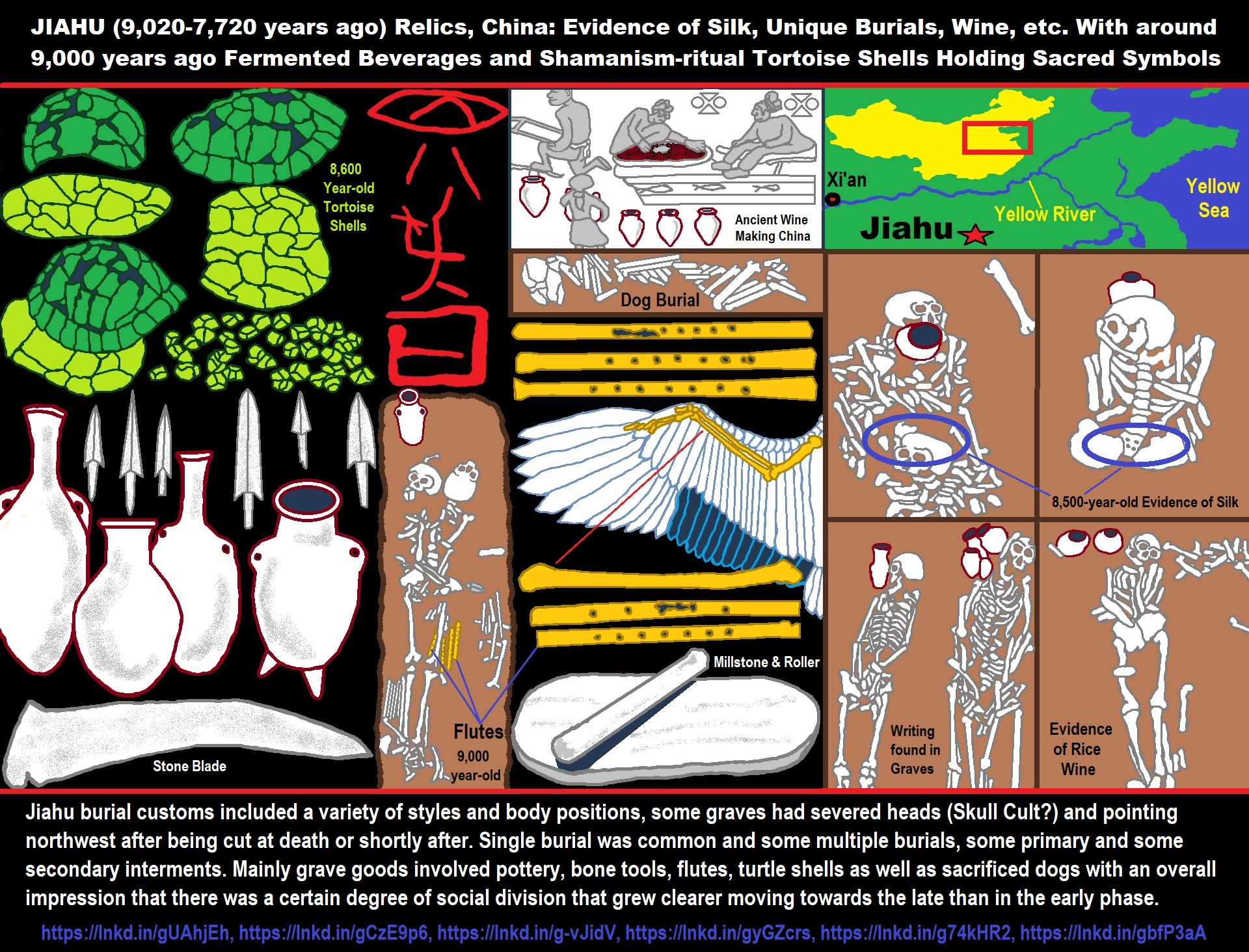

“The Neolithic age in China can be traced back to about 10,000 BCE The earliest evidence of cultivated rice, found by the Yangtze River, is carbon-dated to 8,000 years ago. Early evidence for proto-Chinese millet agriculture is radiocarbon-dated to about 7000 BCE. Farming gave rise to the Jiahu culture (7000 to 5800 BCE). At Damaidi in Ningxia, 3,172 cliff carvings dating to 6000–5000 BCE have been discovered, “featuring 8,453 individual characters such as the sun, moon, stars, gods, and scenes of hunting or grazing”. These pictographs are reputed to be similar to the earliest characters confirmed to be written Chinese.” ref

“Chinese proto-writing existed in Jiahu around 7000 BCE, Dadiwan from 5800-5400 BCE, Damaidi around 6000 BCE, and Banpo dating from the 5th millennium BCE. Some scholars have suggested that Jiahu symbols (7th millennium BCE) were the earliest Chinese writing system. Excavation of a Peiligang culture site in Xinzheng county, Henan, found a community that flourished in 5,500-4,900 BCE, with evidence of agriculture, constructed buildings, pottery, and burial of the dead. With agriculture came an increased population, the ability to store and redistribute crops, and the potential to support specialist craftsmen and administrators. In late Neolithic times, the Yellow River valley began to establish itself as a center of Yangshao culture (5000-3000 BCE), and the first villages were founded; the most archaeologically significant of these was found at Banpo, Xi’an. Later, Yangshao culture was superseded by the Longshan culture, which was also centered on the Yellow River from about 3000-2000 BCE.” ref

Bronze Age

See also: List of Bronze Age sites in China

“Bronze artifacts have been found at the Majiayao culture site (between 3100-2700 BCE). The Bronze Age is also represented at the Lower Xiajiadian culture (2200–1600 BCE) site in northeast China. Sanxingdui located in what is now Sichuan province is believed to be the site of a major ancient city, of a previously unknown Bronze Age culture (between 2000-1200 BCE). The site was first discovered in 1929 and then re-discovered in 1986. Chinese archaeologists have identified the Sanxingdui culture to be part of the ancient kingdom of Shu, linking the artifacts found at the site to its early legendary kings.” ref

“Ferrous metallurgy begins to appear in the late 6th century in the Yangzi Valley. A bronze tomahawk with a blade of meteoric iron excavated near the city of Gaocheng in Shijiazhuang (now Hebei province) has been dated to the 14th century BCE. For this reason, authors such as Liana Chua and Mark Elliott have used the term “Iron Age” by convention for the transitional period of c. 500-100 BCE, roughly corresponding to the Warring States period of Chinese historiography. An Iron Age culture of the Tibetan Plateau has tentatively been associated with the Zhang Zhung culture described in early Tibetan writings.” ref

Ancient China

Xia dynasty (2070 – 1600 BCE)

Main article: Xia dynasty

“The Xia dynasty of China (from c. 2070-1600 BC) is the first dynasty to be described in ancient historical records such as Sima Qian‘s Records of the Grand Historian and Bamboo Annals. The dynasty was considered mythical by historians until scientific excavations found early Bronze Age sites at Erlitou, Henan in 1959. With few clear records matching the Shang oracle bones, it remains unclear whether these sites are the remains of the Xia dynasty or of another culture from the same period. Excavations that overlap the alleged time period of the Xia indicate a type of culturally similar groupings of chiefdoms. Early markings from this period found on pottery and shells are thought to be ancestral to modern Chinese characters. According to ancient records, the dynasty ended around 1600 BCE as a consequence of the Battle of Mingtiao.” ref

Shang dynasty (1600 – 1046 BCE)

Main article: Shang dynasty

Further information: Chinese Bronze Age

“Archaeological findings providing evidence for the existence of the Shang dynasty, c. 1600–1046 BCE, are divided into two sets. The first set, from the earlier Shang period, comes from sources at Erligang, Zhengzhou, and Shangcheng. The second set, from the later Shang or Yin (殷) period, is at Anyang, in modern-day Henan, which has been confirmed as the last of the Shang’s nine capitals (c. 1300–1046 BCE). The findings at Anyang include the earliest written record of the Chinese so far discovered: inscriptions of divination records in ancient Chinese writing on the bones or shells of animals—the “oracle bones“, dating from around 1250 BCE.” ref

“A series of thirty-one kings reigned over the Shang dynasty. During their reign, according to the Records of the Grand Historian, the capital city was moved six times. The final (and most important) move was to Yin in around 1300 BCE which led to the dynasty’s golden age. The term Yin dynasty has been synonymous with the Shang dynasty in history, although it has lately been used to refer specifically to the latter half of the Shang dynasty. Chinese historians in later periods were accustomed to the notion of one dynasty succeeding another, but the political situation in early China was much more complicated. Hence, as some scholars of China suggest, the Xia and the Shang can refer to political entities that existed concurrently, just as the early Zhou existed at the same time as the Shang.” ref

“Although written records found at Anyang confirm the existence of the Shang dynasty, Western scholars are often hesitant to associate settlements that are contemporaneous with the Anyang settlement with the Shang dynasty. For example, archaeological findings at Sanxingdui suggest a technologically advanced civilization culturally unlike Anyang. The evidence is inconclusive in proving how far the Shang realm extended from Anyang. The leading hypothesis is that Anyang, ruled by the same Shang in the official history, coexisted and traded with numerous other culturally diverse settlements in the area that is now referred to as China proper.” ref

“The Zhou dynasty (1046 BCE to approximately 256 BCE) is the longest-lasting dynasty in Chinese history. By the end of the 2nd millennium BCE, the Zhou dynasty began to emerge in the Yellow River valley, overrunning the territory of the Shang. The Zhou appeared to have begun their rule under a semi-feudal system. The Zhou lived west of the Shang, and the Zhou leader was appointed Western Protector by the Shang. The ruler of the Zhou, King Wu, with the assistance of his brother, the Duke of Zhou, as regent, managed to defeat the Shang at the Battle of Muye.” ref

“The king of Zhou at this time invoked the concept of the Mandate of Heaven to legitimize his rule, a concept that was influential for almost every succeeding dynasty. Like Shangdi, Heaven (tian) ruled over all the other gods, and it decided who would rule China. It was believed that a ruler lost the Mandate of Heaven when natural disasters occurred in great number, and when, more realistically, the sovereign had apparently lost his concern for the people. In response, the royal house would be overthrown, and a new house would rule, having been granted the Mandate of Heaven. The Zhou initially moved their capital west to an area near modern Xi’an, on the Wei River, a tributary of the Yellow River, but they would preside over a series of expansions into the Yangtze River valley. This would be the first of many population migrations from north to south in Chinese history.” ref

Spring and Autumn period (722 – 476 BCE)

“In the 8th century BCE, power became decentralized during the Spring and Autumn period, named after the influential Spring and Autumn Annals. In this period, local military leaders used by the Zhou began to assert their power and vie for hegemony. The situation was aggravated by the invasion of other peoples from the northwest, such as the Qin, forcing the Zhou to move their capital east to Luoyang. This marks the second major phase of the Zhou dynasty: the Eastern Zhou. The Spring and Autumn period is marked by a falling apart of the central Zhou power. In each of the hundreds of states that eventually arose, local strongmen held most of the political power and continued their subservience to the Zhou kings in name only. Some local leaders even started using royal titles for themselves. China now consisted of hundreds of states, some of them only as large as a village with a fort.” ref

“As the era continued, larger and more powerful states annexed or claimed suzerainty over smaller ones. By the 6th century BCE, most small states had disappeared by being annexed and just a few large and powerful principalities dominated China. Some southern states, such as Chu and Wu, claimed independence from the Zhou, who undertook wars against some of them (Wu and Yue). Many new cities were established in this period and Chinese culture was slowly shaped.” ref

“Once all these powerful rulers had firmly established themselves within their respective dominions, the bloodshed focused more fully on interstate conflict in the Warring States period, which began when the three remaining élite families in the Jin state—Zhao, Wei, and Han—partitioned the state. Many famous individuals such as Laozi, Confucius, and Sun Tzu lived during this chaotic period.” ref

“The Hundred Schools of Thought of Chinese philosophy blossomed during this period, and such influential intellectual movements as Confucianism, Taoism, Legalism, and Mohism were founded, partly in response to the changing political world. The first two philosophical thoughts would have an enormous influence on Chinese culture.” ref

Warring States period (476 – 221 BCE)

Main article: Warring States period

“After further political consolidation, seven prominent states remained by the end of the 5th century BCE, and the years in which these few states battled each other are known as the Warring States period. Though there remained a nominal Zhou king until 256 BCE, he was largely a figurehead and held little real power.” ref

“Numerous developments were made during this period in culture and mathematics. Examples include an important literary achievement, the Zuo zhuan on the Spring and Autumn Annals, which summarizes the preceding Spring and Autumn period, and the bundle of 21 bamboo slips from the Tsinghua collection, which was invented during this period dated to 305 BCE, are the world’s earliest example of a two-digit decimal multiplication table, indicating that sophisticated commercial arithmetic was already established during this period.” ref

“As neighboring territories of these warring states, including areas of modern Sichuan and Liaoning, were annexed, they were governed under the new local administrative system of commandery and prefecture. This system had been in use since the Spring and Autumn period, and parts can still be seen in the modern system of Sheng and Xian (province and county). The final expansion in this period began during the reign of Ying Zheng, the king of Qin. His unification of the other six powers, and further annexations in the modern regions of Zhejiang, Fujian, Guangdong, and Guangxi in 214 BCE, enabled him to proclaim himself the First Emperor (Qin Shi Huang).” ref

Imperial China

“Empire of China” and “Chinese Empire” redirect here. For the empire founded by Yuan Shikai, see Empire of China (1915–1916).

See also: Political systems of Imperial China

“The Imperial China Period can be divided into three sub-periods: Early, Middle, and Late. Major events in the Early sub-period include the Qin unification of China and their replacement by the Han, the First Split followed by the Jin unification, and the loss of north China. The Middle sub-period was marked by the Sui unification and their supplementation by the Tang, the Second Split, and the Song unification. The Late sub-period included the Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties.” ref

Qin dynasty (221 – 206 BCE)

Main article: Qin dynasty

“Historians often refer to the period from the Qin dynasty to the end of the Qing dynasty as Imperial China. Though the unified reign of the First Qin Emperor lasted only 12 years, he managed to subdue great parts of what constitutes the core of the Han Chinese homeland and to unite them under a tightly centralized Legalist government seated at Xianyang (close to modern Xi’an). The doctrine of Legalism that guided the Qin emphasized strict adherence to a legal code and the absolute power of the emperor. This philosophy, while effective for expanding the empire in a military fashion, proved unworkable for governing it in peacetime. The Qin Emperor presided over the brutal silencing of political opposition, including the event known as the burning of books and burying of scholars. This would be the impetus behind the later Han synthesis incorporating the more moderate schools of political governance.” ref

“Major contributions of the Qin include the concept of a centralized government, and the unification and development of the legal code, the written language, measurement, and currency of China after the tribulations of the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods. Even something as basic as the length of axles for carts—which need to match ruts in the roads—had to be made uniform to ensure a viable trading system throughout the empire. Also as part of its centralization, the Qin connected the northern border walls of the states it defeated, making the first, though rough, version of the Great Wall of China.” ref

“The tribes of the north, collectively called the Wu Hu by the Qin, were free from Chinese rule during the majority of the dynasty. Prohibited from trading with Qin dynasty peasants, the Xiongnu tribe living in the Ordos region in northwest China often raided them instead, prompting the Qin to retaliate. After a military campaign led by General Meng Tian, the region was conquered in 215 BCE and agriculture was established; the peasants, however, were discontented and later revolted. The succeeding Han dynasty also expanded into the Ordos due to overpopulation, but depleted their resources in the process. Indeed, this was true of the dynasty’s borders in multiple directions; modern Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, Tibet, Manchuria, and regions to the southeast were foreign to the Qin, and even areas over which they had military control were culturally distinct.” ref

“After Emperor Qin Shi Huang’s unnatural death due to the consumption of mercury pills, the Qin government drastically deteriorated and eventually capitulated in 207 BCE after the Qin capital was captured and sacked by rebels, which would ultimately lead to the establishment of a new dynasty of a unified China. Despite the short 15-year duration of the Qin dynasty, it was immensely influential on China and the structure of future Chinese dynasties.” ref

Han dynasty (206 BC – CE 220)

Main article: Han dynasty

Further information: History of the Han dynasty

“The Han dynasty was founded by Liu Bang, who emerged victorious in the Chu–Han Contention that followed the fall of the Qin dynasty. A golden age in Chinese history, the Han dynasty’s long period of stability and prosperity consolidated the foundation of China as a unified state under a central imperial bureaucracy, which was to last intermittently for most of the next two millennia. During the Han dynasty, territory of China was extended to most of the China proper and to areas far west. Confucianism was officially elevated to orthodox status and was to shape the subsequent Chinese civilization.” ref

“Art, culture, and science all advanced to unprecedented heights. With the profound and lasting impacts of this period of Chinese history, the dynasty name “Han” had been taken as the name of the Chinese people, now the dominant ethnic group in modern China, and had been commonly used to refer to Chinese language and written characters. The Han dynasty also saw many mathematical innovations being invented such as the method of Gaussian elimination which appeared in the Chinese mathematical text Chapter Eight Rectangular Arrays of The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art. Its use is illustrated in eighteen problems, with two to five equations. The first reference to the book by this title is dated to 179 CE, but parts of it were written as early as approximately 150 BCE, more than 1500 years before a European came up with the method in the 18th century.” ref

“After the initial laissez-faire policies of Emperors Wen and Jing, the ambitious Emperor Wu brought the empire to its zenith. To consolidate his power, Confucianism, which emphasizes stability and order in a well-structured society, was given exclusive patronage to be the guiding philosophical thoughts and moral principles of the empire. Imperial Universities were established to support its study and further development, while other schools of thought were discouraged.” ref

“Major military campaigns were launched to weaken the nomadic Xiongnu Empire, limiting their influence north of the Great Wall. Along with the diplomatic efforts led by Zhang Qian, the sphere of influence of the Han Empire extended to the states in the Tarim Basin, opened up the Silk Road that connected China to the west, stimulating bilateral trade and cultural exchange. To the south, various small kingdoms far beyond the Yangtze River Valley were formally incorporated into the empire.” ref

“Emperor Wu also dispatched a series of military campaigns against the Baiyue tribes. The Han annexed Minyue in 135 BCE and 111 BC, Nanyue in 111 BCE, and Dian in 109 BCE. Migration and military expeditions led to the cultural assimilation of the south. It also brought the Han into contact with kingdoms in Southeast Asia, introducing diplomacy and trade.” ref

“After Emperor Wu, the empire slipped into gradual stagnation and decline. Economically, the state treasury was strained by excessive campaigns and projects, while land acquisitions by elite families gradually drained the tax base. Various consort clans exerted increasing control over strings of incompetent emperors and eventually, the dynasty was briefly interrupted by the usurpation of Wang Mang.” ref

Xin dynasty

Main article: Xin dynasty

“In CE 9, the usurper Wang Mang claimed that the Mandate of Heaven called for the end of the Han dynasty and the rise of his own, and he founded the short-lived Xin dynasty. Wang Mang started an extensive program of land and other economic reforms, including the outlawing of slavery and land nationalization and redistribution. These programs, however, were never supported by the landholding families, because they favored the peasants. The instability of power brought about chaos, uprisings, and loss of territories. This was compounded by mass flooding of the Yellow River; silt buildup caused it to split into two channels and displaced large numbers of farmers. Wang Mang was eventually killed in Weiyang Palace by an enraged peasant mob in CE 23.” ref

Cishan culture

“The Cishan culture (6500–5000 BCE) was a Neolithic culture in northern China, on the eastern foothills of the Taihang Mountains. The Cishan culture was based on the farming of broomcorn millet, the cultivation of which on one site has been dated back 10,000 years. The people at Cishan also began to cultivate foxtail millet around 8700 years ago. However, these early dates have been questioned by some archaeologists due to sampling issues and lack of systematic surveying. There is also evidence that the Cishan people cultivated barley and, late in their history, a japonica variety of rice.” ref

“Common artifacts from the Cishan culture include stone grinders, stone sickles, and tripod pottery. The sickle blades feature fairly uniform serrations, which made the harvesting of grain easier. Cord markings, used as decorations on the pottery, were more common compared to neighboring cultures. Also, the Cishan potters created a broader variety of pottery forms such as basins, pot supports, serving stands, and drinking cups.” ref

“Since the culture shared many similarities with its southern neighbor, the Peiligang culture, both cultures were sometimes previously referred to together as the Cishan-Peiligang culture or Peiligang-Cishan culture. The Cishan culture also shared several similarities with its eastern neighbor, the Beixin culture. However, the contemporary consensus among archaeologists is that the Cishan people were members of a distinct culture that shared many characteristics with its neighbors. This culture has been linked to the origin of the Sino-Tibetan language family. ” ref

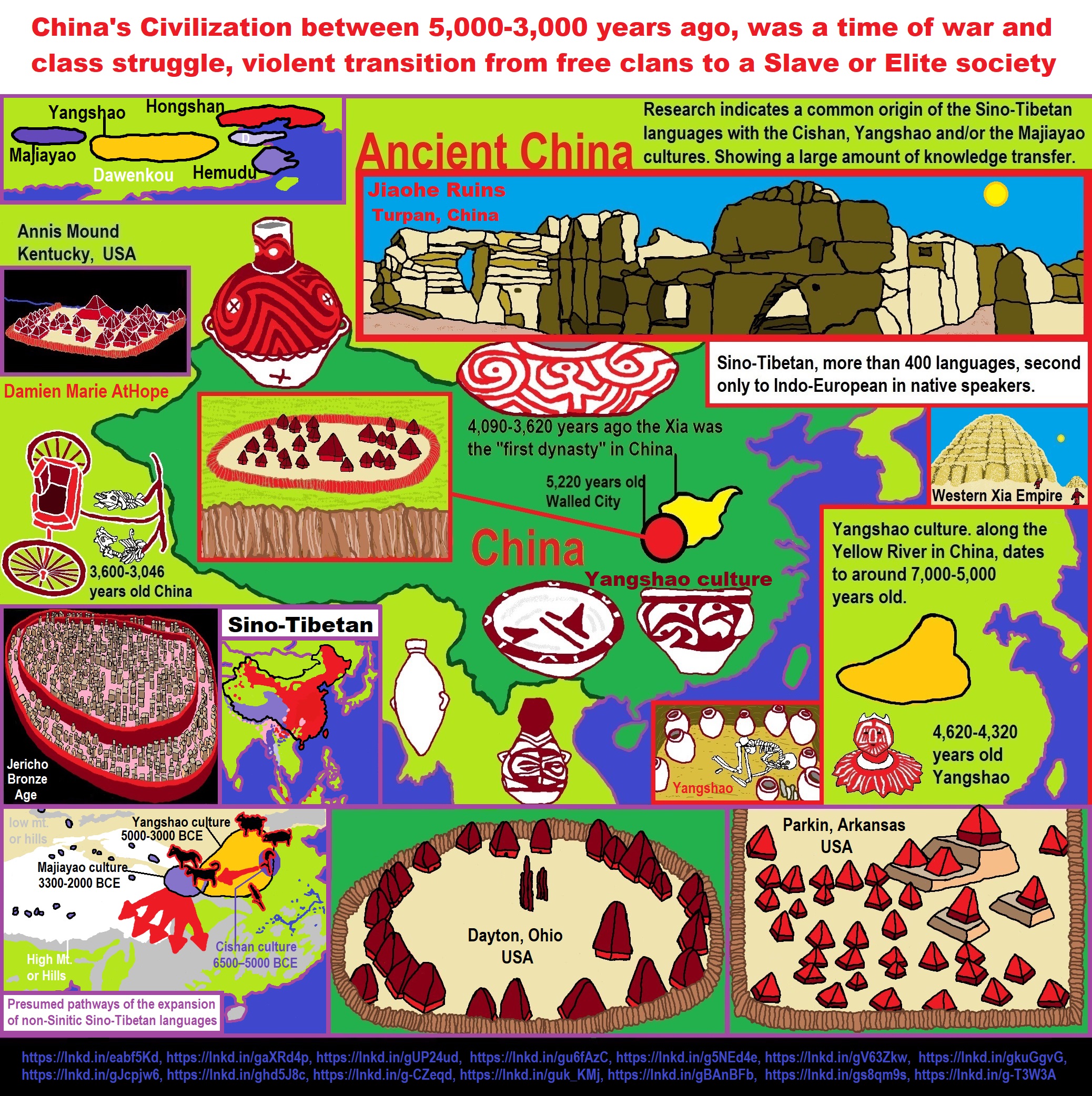

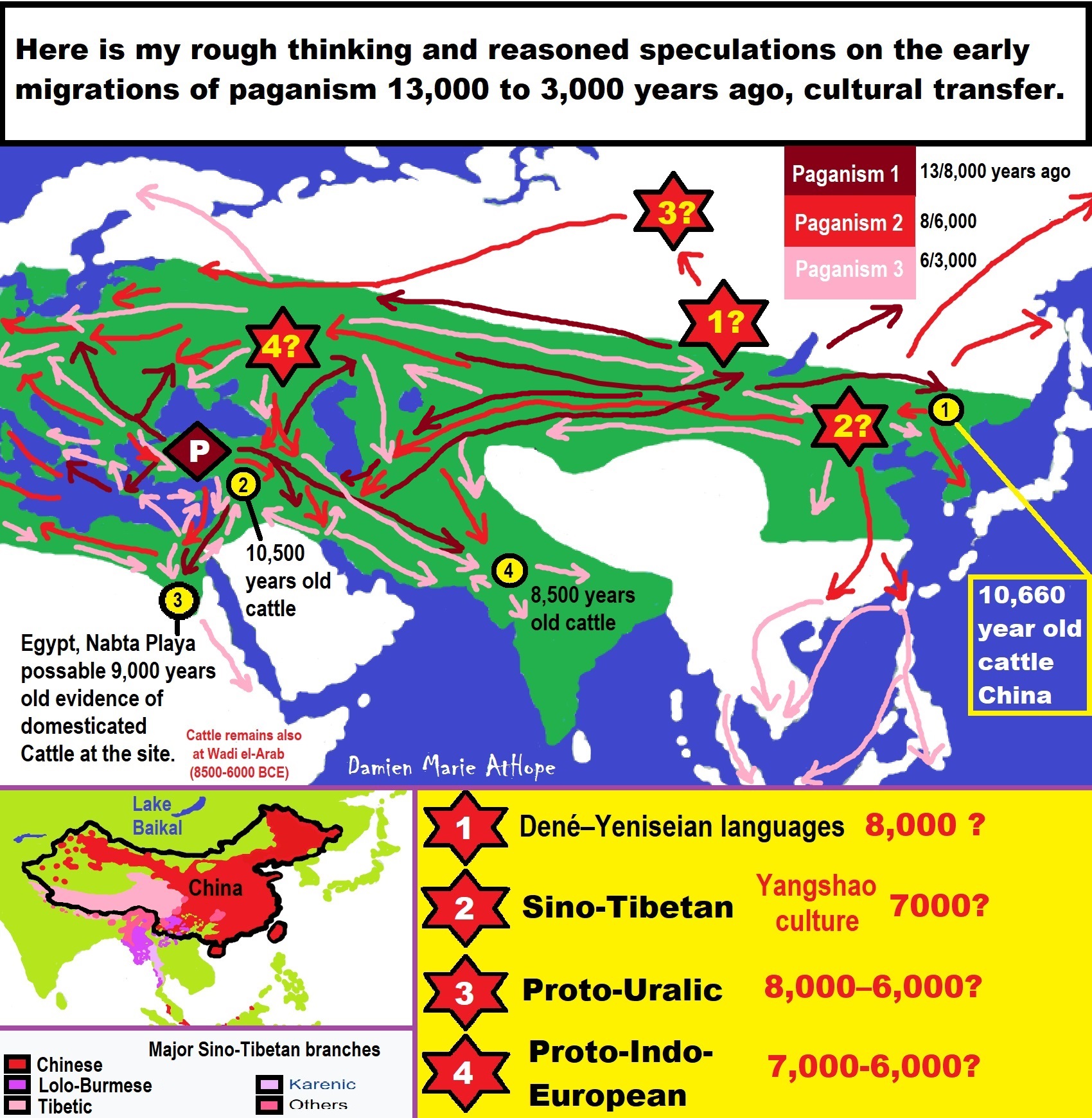

“Yangshao culture. along the Yellow River in China, dates to around 7,000-5,000 years old. Research indicates a common origin of the Sino-Tibetan languages with the Cishan, Yangshao, and/or the Majiayao cultures. Showing a large amount of knowledge transfer.” ref

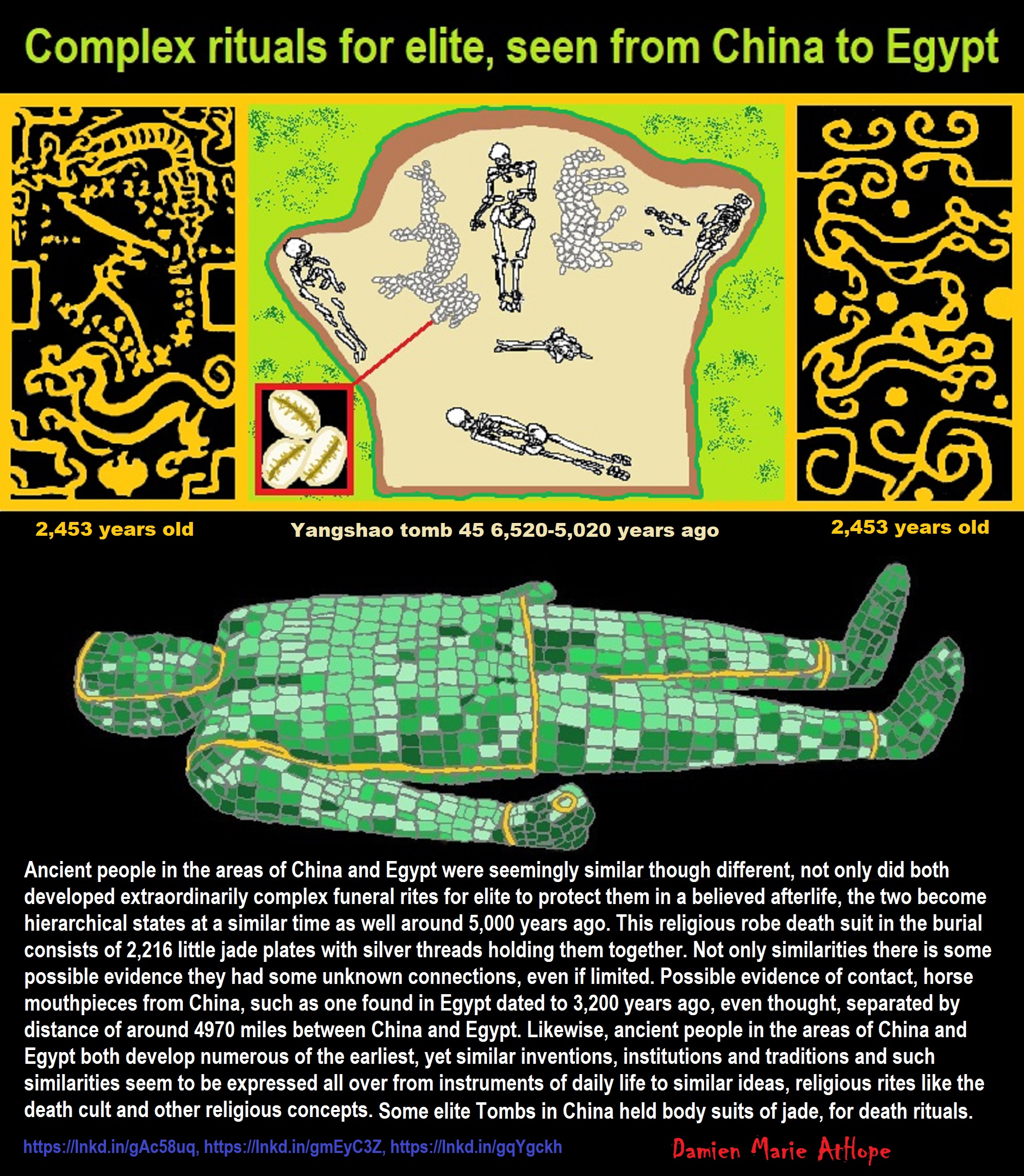

Yangshao culture

“The Yangshao culture was a Neolithic culture that existed extensively along the Yellow River in China. It is dated from around 5000-3000 BCE. The culture is named after the Yangshao site, the first excavated site of this culture, which was discovered in 1921 in Yangshao town, Mianchi County, Henan Province by the Swedish geologist Johan Gunnar Andersson (1874–1960). The culture flourished mainly in the provinces of Henan, Shaanxi, and Shanxi. Recent research indicates a common origin of the Sino-Tibetan languages with the Cishan, Yangshao, and/or the Majiayao cultures.” ref

“The main food of the Yangshao people was millet, with some sites using foxtail millet and others proso millet, though some evidence of rice has been found. The exact nature of Yangshao agriculture, small-scale slash-and-burn cultivation versus intensive agriculture in permanent fields, is currently a matter of debate. Once the soil was exhausted, residents picked up their belongings, moved to new lands, and constructed new villages.

“However, Middle Yangshao settlements such as Jiangzhi contain raised-floor buildings that may have been used for the storage of surplus grains. Grinding stones for making flour were also found. The Yangshao people kept pigs and dogs. Sheep, goats, and cattle are found much more rarely. Much of their meat came from hunting and fishing with stone tools. Their stone tools were polished and highly specialized. They may also have practiced an early form of sericulture.” ref

“The Yangshao culture crafted pottery. Yangshao artisans created fine white, red, and black painted pottery with human facial, animal, and geometric designs. Unlike the later Longshan culture, the Yangshao culture did not use pottery wheels in pottery-making. Excavations found that children were buried in painted pottery jars. The Yangshao culture produced silk to a small degree and wove hemp. Men wore loin clothes and tied their hair in a top knot. Women wrapped a length of cloth around themselves and tied their hair in a bun.” ref

“Houses were built by digging a rounded rectangular pit a few feet deep. Then they were rammed, and a lattice of wattle was woven over it. Then it was plastered with mud. The floor was also rammed down. Next, a few short wattle poles would be placed around the top of the pit, and more wattle would be woven to it. It was plastered with mud, and a framework of poles would be placed to make a cone shape for the roof.” ref

“Poles would be added to support the roof. It was then thatched with millet stalks. There was little furniture; a shallow fireplace in the middle with a stool, a bench along the wall, and a bed of cloth. Food and items were placed or hung against the walls. A pen would be built outside for animals. Yangshao villages typically covered ten to fourteen acres and were composed of houses around a central square.” ref

“Although early reports suggested a matriarchal culture, others argue that it was a society in transition from matriarchy to patriarchy, while still others believe it to have been patriarchal. The debate hinges on differing interpretations of burial practices. The discovery of a dragon statue dating back to the fifth millennium BC in the Yangshao culture makes it the world’s oldest known dragon depiction, and the Han Chinese continue to worship dragons to this day.” ref

The Yangshao culture is conventionally divided into three phases:

· The early period or Banpo phase, c. 5000–4000 BCE) is represented by the Banpo, Jiangzhai, Beishouling, and Dadiwan sites in the Wei River valley in Shaanxi.” ref

· The middle period or Miaodigou phase, c. 4000–3500 BCE) saw an expansion of the culture in all directions, and the development of hierarchies of settlements in some areas, such as western Henan.” ref

· The late period (c. 3500–3000 BCE) saw a greater spread of settlement hierarchies. The first wall of rammed earth in China was built around the settlement of Xishan (25 ha) in central Henan (near modern Zhengzhou).” ref

The Majiayao culture (c. 3300–2000 BCE) to the west is now considered a separate culture that developed from the middle Yangshao culture through an intermediate Shilingxia phase.” ref

· List of Neolithic cultures of China

· Beifudi

Origin of Sino-Tibetan language family revealed to be from North China, around 7,200 years ago

“The Sino-Tibetan language family includes early literary languages, such as Chinese, Tibetan, and Burmese, and is represented by more than 400 modern languages spoken in China, India, Burma, and Nepal. It is one of the most diverse language families in the world, spoken by 1.4 billion speakers. Although the language family has been studied since the beginning of the 19th century, scholars’ knowledge of the origin of these languages is still severely limited. An interdisciplinary study published in PNAS, led by scientists of the Centre des Recherches Linguistiques sur l’Asie Orientale (Paris), the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History (Jena), and the Centre de Recherches en Mathématiques de la Décision (Paris), now sheds new light on the place and date of the origin of these languages. Based on a phylogenetic study of 50 ancient and modern Sino-Tibetan languages, the scholars conclude that the Sino-Tibetan languages originated among millet farmers, located in North China, around 7,200 years ago.” ref

“During the past 10,000 years, two of the world’s largest language families emerged, one in the west and one in the east of Eurasia. Together, these families account for nearly 60 percent of the world’s population: Indo-European (3.2 billion speakers), and Sino-Tibetan (1.4 billion). The Sino-Tibetan family comprises about 500 languages spoken across a wide geographic range, from the west coast of the Pacific to Nepal, India, and Pakistan. Speakers of these languages have played a major role in human prehistory, giving rise to early high cultures China, Tibet, Burma, and Nepal. However, while archaeogeneticists, phylogeneticists, and linguists have energetically discussed the origins of the Indo-European language family, the formation of Sino-Tibetan languages has previously received little attention.” ref

Evolutionary trees suggest that the language family originated about 7200 years ago

“Using powerful computational phylogenetic methods, the team inferred the most probable relationships between these languages and then estimated when these languages might have originated in the past. “We find clear evidence for seven major subgroups with a complex pattern of overlapping signals beyond that level,” says Simon J. Greenhill of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. “Our estimates suggest that the ancestral language has arisen around 7,200 years ago.” ref

An agricultural analysis reveals the most likely origin and expansion scenario of the language family

“To further resolve the complex pathways of the evolution of the Sino-Tibetan languages, the authors looked at related words describing domesticates, because they may reveal how agricultural knowledge spread through the region. This agricultural analysis suggests an origin of the Sino-Tibetan family in Northern Chinese communities of millet farmers of the Neolithic cultures of late Cishan and early Yangshao. “The most likely expansion scenario of the languages involves an initial separation between an Eastern group, from which the Chinese dialects evolved, and a Western group, which is ancestral to the rest of the Sino-Tibetan languages,” summarizes Laurent Sagart of the Centre des Recherches Linguistiques sur l’Asie Orientale, co-first author of the study, who carried out the agricultural analysis.” ref

One of the world’s most diverse language families

“The Sino-Tibetan language family is one of the most diverse families in the world. It includes all of the different types of morphological systems, ranging from isolating languages, such as Chinese, Burmese, and Tujia, to polysynthetic languages, such as Gyalrongic and Kiranti languages,” explains Guillaume Jacques of the Centre des Recherches Linguistiques sur l’Asie Orientale, co-first author of the study. “While our knowledge of how to compare these languages linguistically is improving, important aspects of the development of their sound systems and their grammar remain poorly understood.” ref

Sino-Tibetan languages

“Sino-Tibetan, also known as Trans-Himalayan in a few sources, is a family of more than 400 languages, second only to Indo-European in number of native speakers. The vast majority of these are the 1.3 billion native speakers of Chinese languages. Other Sino-Tibetan languages with large numbers of speakers include Burmese (33 million) and the Tibetic languages (six million). Other languages of the family are spoken in the Himalayas, the Southeast Asian Massif, and the eastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau. Most of these have small speech communities in remote mountain areas, and as such are poorly documented.” ref

“Several low-level subgroups have been securely reconstructed, but reconstruction of a proto-language for the family as a whole is still at an early stage, so the higher-level structure of Sino-Tibetan remains unclear. Although the family is traditionally presented as divided into Sinitic (i.e. Chinese) and Tibeto-Burman branches, a common origin of the non-Sinitic languages has never been demonstrated. While Chinese linguists generally include Kra–Dai, and Hmong–Mien languages within Sino-Tibetan, most other linguists have excluded them since the 1940s. Several links to other language families have been proposed, but none has broad acceptance.” ref

“A genetic relationship between Chinese, Tibetan, Burmese, and other languages was first proposed in the early 19th century and is now broadly accepted. The initial focus on languages of civilizations with long literary traditions has been broadened to include less widely spoken languages, some of which have only recently, or never, been written. However, the reconstruction of the family is much less developed than for families such as Indo-European or Austroasiatic. Difficulties have included the great diversity of the languages, the lack of inflection in many of them, and the effects of language contact. In addition, many of the smaller languages are spoken in mountainous areas that are difficult to access, and are often also sensitive border zones.” ref

“Most of the current spread of Sino-Tibetan languages is the result of historical expansions of the three groups with the most speakers – Chinese, Burmese and Tibetic – replacing an unknown number of earlier languages. These groups also have the longest literary traditions of the family. The remaining languages are spoken in mountainous areas, along the southern slopes of the Himalayas, the Southeast Asian Massif, and the eastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau.” ref

“By far the largest branch are the Sinitic languages, with 1.3 billion speakers, most of whom live in the eastern half of China. The first records of Chinese are oracle bone inscriptions from c. 1200 BCE, when Old Chinese was spoken around the middle reaches of the Yellow River. Chinese has since expanded throughout China, forming a family whose diversity has been compared with the Romance languages. Diversity is greater in the rugged terrain of southeast China than in the North China Plain.” ref

“Burmese is the national language of Myanmar, and the first language of some 33 million people. Burmese speakers first entered the northern Irrawaddy basin from what is now western Yunnan in the early 9th century, when the Pyu city-states had been weakened by an invasion by Nanzhao. Other Burmish languages are still spoken in Dehong Prefecture in the far west of Yunnan. By the 11th century, their Pagan Kingdom had expanded over the whole basin. The oldest texts, such as the Myazedi inscription, date from the early 12th century.” ref

“The Tibetic languages are spoken by some 6 million people on the Tibetan Plateau and neighboring areas in the Himalayas and western Sichuan. They are descended from Old Tibetan, which was originally spoken in the Yarlung Valley before it was spread by the expansion of the Tibetan Empire in the 7th century. Although the empire collapsed in the 9th century, Classical Tibetan remained influential as the liturgical language of Tibetan Buddhism.” ref

“The remaining languages are spoken in upland areas. Southernmost are the Karen languages, spoken by 4 million people in the hill country along the Myanmar–Thailand border, with the greatest diversity in the Karen Hills, which are believed to be the homeland of the group. The highlands stretching from northeast India to northern Myanmar contain over 100 high-diverse Sino-Tibetan languages. Other Sino-Tibetan languages are found along the southern slopes of the Himalayas, southwest China and northern Thailand.” ref

“There have been a range of proposals for the Sino-Tibetan urheimat, reflecting the uncertainty about the classification of the family and its time depth. Three major hypotheses for the place and time of Sino-Tibetan unity have been presented:” ref

- “The most commonly cited hypothesis associates the family with Neolithic cultures of the upper and middle reaches of the Yellow River, such as the Yangshao culture (7000–5000 years ago) or the Majiayao culture (5300–4000 years ago), with an expansion driven by millet agriculture. This scenario is associated with a primary split between Sinitic and the rest, the Tibeto-Burman languages. For example, James Matisoff proposes a split around 6000 years ago, with Chinese-speakers settling along the Yellow River and other groups migrating south down the Yangtze, Mekong, Salween, and Brahmaputra rivers.” ref

- “George van Driem (2005) proposes that Sino-Tibetan originated in the Sichuan Basin before 9000 years years, with an early migration into northeast India, and a later migration north of the predecessors of Chinese and Tibetic.” ref

- “Roger Blench and Mark Post (2014) have proposed that the Sino-Tibetan homeland is Northeast India, the area of greatest diversity, around 9000 years ago. Roger Blench (2009) argues that agriculture cannot be reconstructed for Proto-Sino-Tibetan, and that the earliest speakers of Sino-Tibetan were not farmers but highly diverse foragers.” ref

“Zhang et al. (2019) performed a computational phylogenetic analysis of 109 Sino-Tibetan languages to suggest a Sino-Tibetan homeland in northern China near the Yellow River basin. The study further suggests that there was an initial major split between the Sinitic and Tibeto-Burman languages approximately 4,200 to 7,800 years ago (with an average of 5,900 years ago), associated with the Yangshao or Majiayao cultures. Sagart et al. (2019) also performed another phylogenetic analysis based on different data and methods to arrive at the same conclusions with respect to the homeland and divergence model, but proposed an earlier root age of approximately 7,200 years ago, associating its origin with millet farmers of the late Cishan and early Yangshao culture.” ref

“Yangshao culture. along the Yellow River in China, dates to around 7,000-5,000 years old. Research indicates a common origin of the Sino-Tibetan languages with the Cishan, Yangshao, and/or the Majiayao cultures. Showing a large amount of knowledge transfer. Sino-Tibetan, more than 400 languages, second only to Indo-European in native speakers.” ref, ref

Majiayao culture

“The Majiayao culture was a group of neolithic communities who lived primarily in the upper Yellow River region in eastern Gansu, eastern Qinghai, and northern Sichuan, China. The culture existed from 3300-2000 BCE. The Majiayao culture represents the first time that the upper Yellow River region was widely occupied by agricultural communities and it is famous for its painted pottery, which is regarded as a peak of pottery manufacturing at that time.” ref

“This culture developed from the middle Yangshao (Miaodigou) phase, through an intermediate Shilingxia phase. The culture is often divided into three phases: Majiayao (3300–2500 BCE), Banshan (2500–2300 BCE), and Machang (2300–2000 BCE). At the end of the 3rd millennium BCE, the Qijia culture succeeded the Majiayao culture at sites in three main geographic zones: eastern Gansu, central Gansu, and western Gansu/eastern Qinghai.” ref

Hemudu culture

“The Hemudu culture (5500-3300 BCE) was a Neolithic culture that flourished just south of the Hangzhou Bay in Jiangnan in modern Yuyao, Zhejiang, China. The culture may be divided into early and late phases, before and after 4000 BCE respectively. The site at Hemudu, 22 km northwest of Ningbo, was discovered in 1973. Hemudu sites were also discovered at Tianluoshan in Yuyao city, and on the islands of Zhoushan. Hemudu are said to have differed physically from inhabitants of the Yellow River sites to the north. Some authors propose that the Hemudu Culture was a source of the pre-Austronesian cultures.” ref

“Some scholars assert that the Hemudu culture co-existed with the Majiabang culture as two separate and distinct cultures, with cultural transmissions between the two.[citation needed] Other scholars group Hemudu in with Majiabang subtraditions. Two major floods caused the nearby Yaojiang River to change its course and inundated the soil with salt, forcing the people of Hemudu to abandon its settlements. The Hemudu people lived in long, stilt houses. Communal longhouses were also common in Hemudu sites, much like the ones found in modern-day Borneo.” ref

“The Hemudu culture was one of the earliest cultures to cultivate rice. Recent excavations at the Hemudu period site of Tianluoshan has demonstrated rice was undergoing evolutionary changes recognized as domestication. Most of the artifacts discovered at Hemudu consist of animal bones, exemplified by hoes made of shoulder bones used for cultivating rice. The culture also produced lacquer wood. A red lacquer wood bowl at the Zhejiang Museum is dated to 4000-5000 BCE. It is believed to be the earliest such object in the world.” ref

“The remains of various plants, including water caltrop, Nelumbo nucifera, acorns, melon, wild kiwifruit, blackberries, peach, the foxnut, or Gorgon euryale, and bottle gourd, were found at Hemudu and Tianluoshan. The Hemudu people likely domesticated pigs but practiced extensive hunting of deer and some wild water buffalo. Fishing was also carried out on a large scale, with a particular focus on crucian carp. The practices of fishing and hunting are evidenced by the remains of bone harpoons and bows and arrowheads. Music instruments, such as bone whistles and wooden drums, were also found at Hemudu. Artifact design by Hemudu inhabitants bears many resemblances to those of Insular Southeast Asia.” ref

“The culture produced a thick, porous pottery. This distinctive pottery was typically black and made with charcoal powder. Plant and geometric designs were commonly painted onto the pottery; the pottery was sometimes also cord-marked. The culture also produced carved jade ornaments, carved ivory artifacts, and small clay figurines.” ref

“Hemudu’s inhabitants worshiped a sun spirit as well as a fertility spirit. They also enacted shamanistic rituals to the sun and believed in bird totems. A belief in an afterlife and ghosts is thought to have been widespread as well. People were buried with their heads facing east or northeast and most had no burial objects. Infants were buried in urn-casket-style burials, while children and adults received earth-level burials. They did not have a definite communal burial ground, for the most part, but a clan communal burial ground has been found from the later period. Two groups in separate parts of this burial ground are thought to be two intermarrying clans. There were noticeably more burial goods in this communal burial ground.” ref

Dawenkou culture

“The Dawenkou culture was a Chinese Neolithic culture primarily located in the eastern province of Shandong, but also appearing in Anhui, Henan, and Jiangsu. The culture existed from 4100 to 2600 BCE, and co-existed with the Yangshao culture. Turquoise, jade, and ivory artifacts are commonly found at Dawenkou sites. The earliest examples of alligator drums appear at Dawenkou sites. Neolithic signs, perhaps related to subsequent scripts, such as those of the Shang Dynasty, have been found on Dawenkou pottery.” ref

“Archaeologists commonly divide the culture into three phases: the early phase (4100–3500 BCE), the middle phase (3500–3000 BCE), and the late phase (3000–2600 BCE). Based on the evidence from grave goods, the early phase was highly egalitarian. The phase is typified by the presence of individually designed, long-stemmed cups. Graves built with earthen ledges became increasingly common during the latter parts of the early phase. During the middle phase, grave goods began to emphasize quantity over diversity.” ref

“During the late phase, wooden coffins began to appear in Dawenkou burials. The culture became increasingly stratified, as some graves contained no grave goods while others contained a large quantity of grave goods. The type site at Dawenkou, located in Tai’an, Shandong, was excavated in 1959, 1974, and 1978. Only the middle layer at Dawenkou is associated with the Dawenkou culture, as the earliest layer corresponds to the Beixin culture and the latest layer corresponds to the early Shandong variant of the Longshan culture.” ref

“The term “chiefdom” seems to be appropriate in describing the political organization of the Dawenkou. A dominant kin group likely held sway over Dawenkou village sites, though power was most likely manifested through religious authority rather than coercion. Unlike the Beixin culture from which they descend, the people of the Dawenkou culture were noted for being engaged in violent conflict. Scholars suspect that they may have engaged in raids for land, crops, livestock, and prestigious goods.” ref

“The warm and wet climate of the Dawenkou area was suitable for a variety of crops, though they primarily farmed millet at most sites. Their production of millet was quite successful and storage containers have been found that could have contained up to 2000 kg of millet, once decomposition is accounted for, have been found. For some of the southern Dawenkou sites, rice was a more important crop, however, especially during the late Dawenkou period. Analysis done on human remains at Dawenkou sites in southern Shandong revealed that the diet of upper-class Dawenkou individuals consisted mainly of rice, while ordinary individuals ate primarily millet.” ref

“The Dawenkou people successfully domesticated chicken, dogs, pigs, and cattle, but no evidence of horse domestication was found. Pig remains are by far the most abundant, accounting for about 85% of the total, and are thought to be the most important domesticated animal. Pig remains were also found in Dawenkou burials also highlighting their importance. Seafood was also an important staple of the Dawenkou diet. Fish and various shellfish mounds have been found in the early periods indicating that they were important food sources.” ref

“Although these piles became less frequent in the later stages, seafood remained an important part of the diet. Dawenkou’s inhabitants were one of the earliest practitioners of trepanation in prehistoric China. A skull of a Dawenkou man dating to 3000 BCE was found with severe head injuries which appeared to have been remedied by this primitive surgery. Alligator hide drums have also been found in Dawenkou sites.” ref

“The Dawenkou interacted extensively with the Yangshao culture. “For two and a half millennia of its existence, the Dawenkou was, however, in a dynamic interchange with the Yangshao Culture, in which process of interaction it sometimes had the lead role, notably in generating Longshan. Scholars have also noted similarities between the Dawenkou and the Liangzhu culture as well as the related cultures of the Yantze River basin. According to some scholars, the Dawenkou culture may have a link with a pre-Austronesian language. Other researchers also note a similarity between Dawenkou inhabitants and modern Austronesian people in cultural practices such as tooth avulsion and architecture.” ref

“The physical similarity of the Jiahu people to the later Dawenkou (2600-4300 BCE) indicates that the Dawenkou might have descended from the Jiahu, following a slow migration along the middle and lower reaches of the Huai river and the Hanshui valley. Other scholars have also speculated that the Dawenkou originates in nearby regions to the south. The Dawenkou culture descends from the Beixin culture, but is deeply influenced by the northward expanding Longqiuzhuang culture located between the Yangtze and Huai rivers. The people of Dawenkou exhibited a primarily Sinodont dental pattern. The Dawenkou were also physically dissimilar to the neolithic inhabitants of Hemudu, Southern China, and Taiwan. DNA testing revealed that neolithic inhabitants of Shandong were closer to northern East Asians.” ref

Why was a splendid civilization created in all parts of China more than 5,000 years ago?

The truth is climate

Temperature can change the course of history, it can create the necessary conditions for the birth of civilization, and the fall of a civilization is also closely related to temperature. So today, let’s take a look at from the perspective of climate, in the early days of the birth of Chinese civilization, what influence and effect climate had on the evolution of civilization.

Before the establishment of the Xia Dynasty, a starry civilization appeared in China, the Yangshao and Longshan cultures in the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River, the Qijia and Majiayao cultures in the upper reaches of the Yellow River, and the Liangzhu and Liangzhu cultures in the Yangtze River. Hemudu culture, the emergence of these cultures is not unrelated to the changes in the climate at that time.

5000 years ago, China experienced a relatively warm period, with rising temperatures and adequate precipitation, which laid the foundation for the development of Neolithic agriculture. The Chinese historical geography calls this period “Yangshao Warm Period”.

The Warm Time transition

“Between 5000 – 3000 years ago, was the period of transition from the Neolithic Age to a slave society, accompanied by it The temperature is rising, much warmer than many parts of China today.” ref

4,090-3,620 years ago, the Xia was the “first dynasty” in China.

“The Xia dynasty is the first dynasty in traditional Chinese historiography. According to tradition, the Xia dynasty was established by the legendary Yu the Great, after Shun, the last of the Five Emperors, gave the throne to him. In traditional historiography, the Xia was later succeeded by the Shang dynasty. There are no contemporaneous records of the Xia, and they are not mentioned in the oldest Chinese texts, since the earliest oracle bone inscriptions date from the late Shang period (13th century BCE). The earliest mentions occur in the oldest chapters of the Book of Documents, which report speeches from the early Western Zhou period, and are accepted by most scholars as dating from that time. These speeches justify the Zhou conquest of the Shang as the passing of the Mandate of Heaven, likening it to the succession of the Xia by the Shang.” ref

Evidence for early dispersal of domestic sheep into Central Asia

“The development and dispersal of agropastoralism transformed the cultural and ecological landscapes of the Old World, but little is known about when or how this process first impacted Central Asia. Here, we present archaeological and biomolecular evidence from Obishir V in southern Kyrgyzstan, establishing the presence of domesticated sheep by ca. 6,000 BCE. Zooarchaeological and collagen peptide mass fingerprinting show exploitation of Ovis and Capra, while cementum analysis of intact teeth implicates possible pastoral slaughter during the fall season. Most significantly, ancient DNA reveals these directly dated specimens as the domestic O. aries, within the genetic diversity of domesticated sheep lineages. Together, these results provide the earliest evidence for the use of livestock in the mountains of the Ferghana Valley, predating previous evidence by 3,000 years and suggesting that domestic animal economies reached the mountains of interior Central Asia far earlier than previously recognized.” ref

NEOLITHIC CHINA: BEFORE THE SHANG DYNASTY

Genitalia, Totems and Painted Pottery: New Ceramic Discoveries in Gansu and Surrounding Areas

Ancient China From the Neolithic Period to the Han Dynasty

Religion, Violence, and Emotion: Modes of Religiosity in the Neolithic and Bronze Age of Northern China

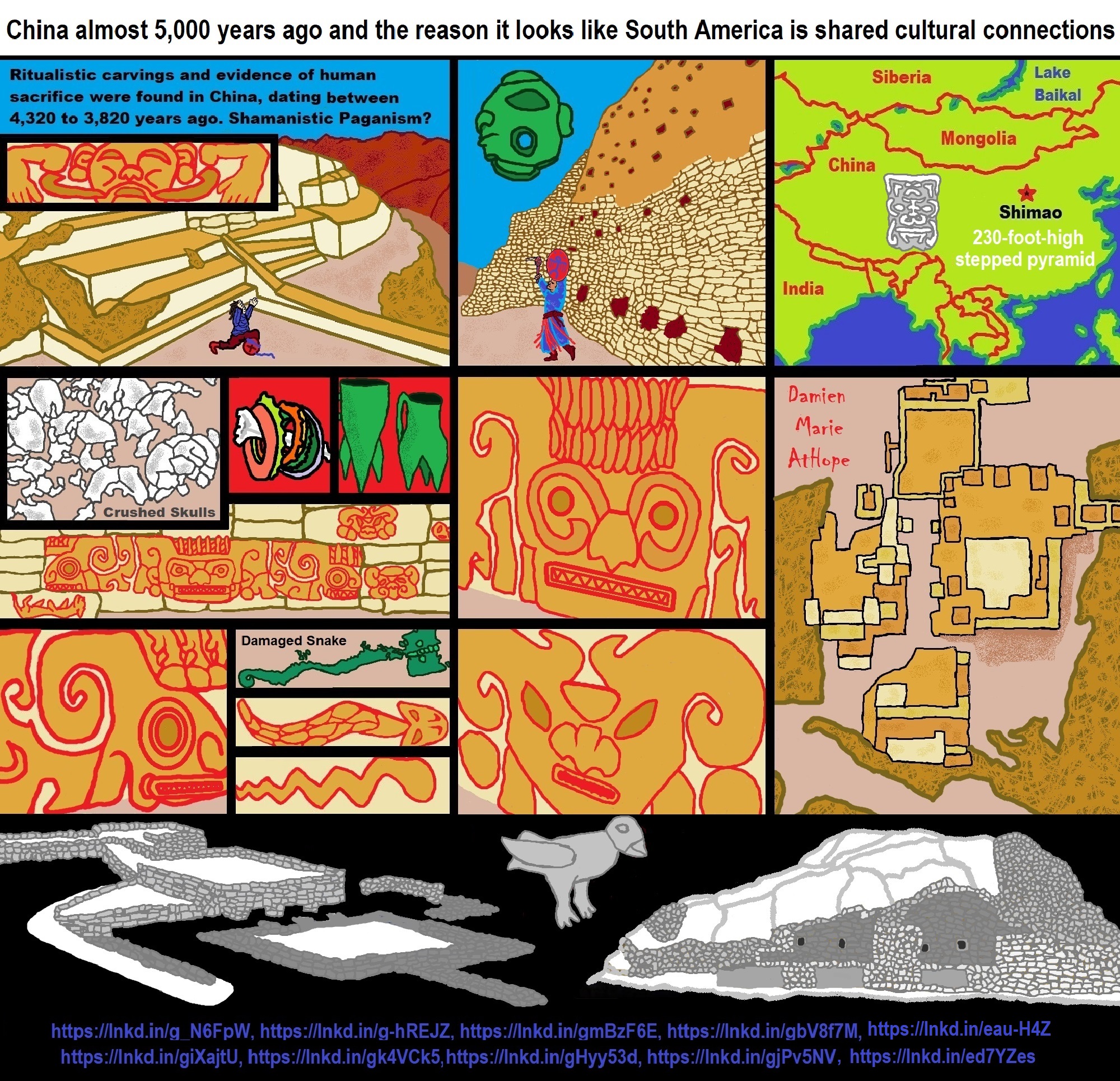

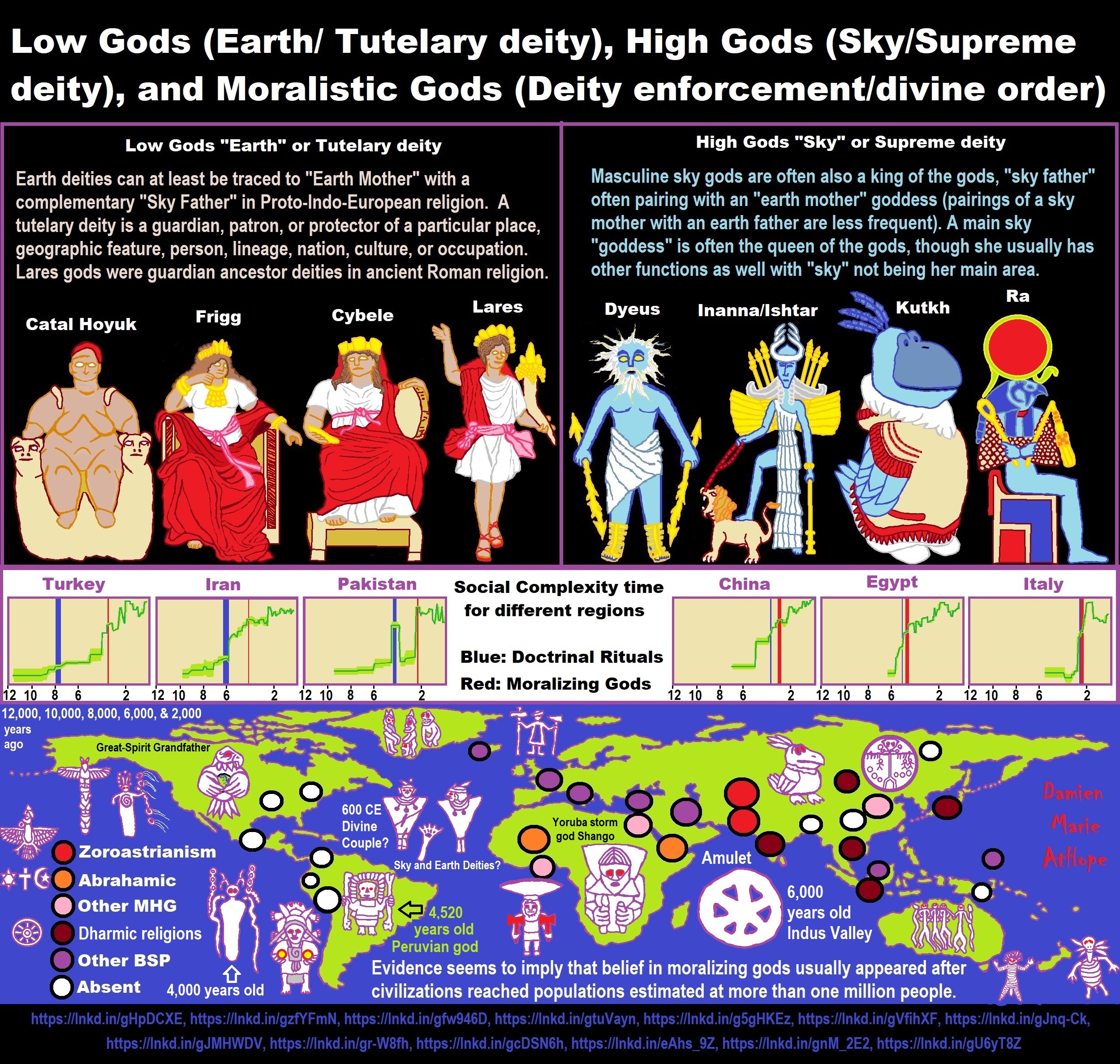

“This paper explores the development of religious traditions in the Neolithic and Bronze Age of northern China. It applies the cognitive anthropological theory of Divergent Modes of Religiosity (DMR) for the first time in this part of the world. DMR theory frames ritual behavior in two distinct modes, one that is more traumatic/emotional and occurs less frequently (imagistic rituals) and another that is more placid and occurs more frequently (doctrinal rituals). Various archaeological and historic sources indicate that violent imagistic rituals involving human sacrifice and feasting began deep in the Neolithic; but religion did not become more tame when societies entered the Bronze Age, as predicted by DMR theory. Instead, violent imagistic rituals continued and became arguably more brutal. The application of DMR theory here is a useful means to explore the challenging topic of religious violence and to reveal biases in the treatment of ritual and religion in Shang studies.” ref

Beginnings of Indian Astronomy with Reference to a Parallel Development in China

Kot Diji phase steatite button seal from Harappa

“Hypotheses of a Mesopotamian origin for the Vedic and Chinese star calendars are unfounded. The Yangshao culture burials discovered at Puyang in 1987 suggest that the beginnings of Chinese astronomy go back to the late fourth millennium. The instructive similarities between the Chinese and Indian luni-solar calendrical astronomy and cosmology therefore with great likelihood result from convergent parallel development and not from diffusion.” ref

“It is proposed that the first Indian stellar calendar, perhaps restricted to the quadrant stars, was created by Early Harappans around 3000 BCE, and that the heliacal rise of Aldebaran at vernal equinox marked the new year. The grid-pattern town of Rahman Dheri was oriented to the cardinal directions, defined by observing the place of the sunrise at the horizon throughout the year, and by geometrical means, as evidenced by the motif of intersecting circles. Early Harappan seals and painted pottery suggest that the sun and the center of the four directions symbolized royal power.” ref

Human evolutionary history in Eastern Eurasia using insights from ancient DNA

“Advances in ancient genomics are providing unprecedented insight into modern human history. Here, we review recent progress uncovering prehistoric populations in Eastern Eurasia based on ancient DNA studies from the Upper Pleistocene to the Holocene. Many ancient populations existed during the Upper Pleistocene of Eastern Eurasia—some with no substantial ancestry related to present-day populations, some with an affinity to East Asians, and some who contributed to Native Americans. By the Holocene, the genetic composition across East Asia greatly shifted, with several substantial migrations. Three are southward: an increase in northern East Asian-related ancestry in southern East Asia; movement of East Asian-related ancestry into Southeast Asia, mixing with Basal Asian ancestry; and movement of southern East Asian ancestry to islands of Southeast Asia and the Southwest Pacific through the expansion of Austronesians. We anticipate that additional ancient DNA will magnify our understanding of the genetic history in Eastern Eurasia.” ref

Maternal genetic structure in ancient Shandong between 9500 and 1800 years ago

“Archaeological and ancient DNA studies revealed that Shandong, a multi-culture center in northern coastal China, was home to ancient populations having ancestry related to both northern and southern East Asian populations. However, the limited temporal and geographical range of previous studies have been insufficient to describe the population history of this region in greater detail. Here, we report the analysis of 86 complete mitochondrial genomes from the remains of 9500 to 1800-year-old humans from 12 archaeological sites across Shandong. For samples older than 4600 years ago, we found haplogroups D4, D5, B4c1, and B5b2, which are observed in present-day northern and southern East Asians.” ref

“For samples younger than 4600 years ago, haplogroups C (C7a1 and C7b), M9 (M9a1), and F (F1a1, F2a, and F4a1) begin to appear, indicating changes in the Shandong maternal genetic structure starting from the beginning of the Longshan cultural period. Within Shandong, the genetic exchange is possible between the coastal and inland regions after 3100 tears ago. We also discovered the B5b2 lineage in Shandong populations, with the oldest Bianbian individual likely related to the ancestors of some East Asians and North Asians. By reconstructing a maternal genetic structure of Shandong populations, we provide greater resolution of the population dynamics of the northern coastal East Asia over the past nine thousand years.” ref

Ancient genomes from northern China suggest links between subsistence changes and human migration

“Northern China harbored the world’s earliest complex societies based on millet farming, in two major centers in the Yellow (YR) and West Liao (WLR) River basins. Until now, their genetic histories have remained largely unknown. Here we present 55 ancient genomes dating to 7500-1700 years ago from the YR, WLR, and Amur River (AR) regions. Contrary to the genetic stability in the AR, the YR and WLR genetic profiles substantially changed over time. The YR populations show a monotonic increase over time in their genetic affinity with present-day southern Chinese and Southeast Asians. In the WLR, intensification of farming in the Late Neolithic is correlated with increased YR affinity while the inclusion of a pastoral economy in the Bronze Age was correlated with increased AR affinity. Our results suggest a link between changes in subsistence strategy and human migration, and fuel the debate about archaeolinguistic signatures of past human migration.” ref

“China is one of the earliest independent centers in the world for the domestication of cereal crops, second only to the Near East, with the rainfed rice agriculture in the Yangtze River Basin in southern China, and dryland millet agriculture in northern China. Northern China represents a large geographic region that encompasses the Central Plain in the middle-to-lower Yellow River (YR) basin, the birthplace of the well-known YR civilization since the Neolithic period. However, northern China extends far beyond the Central Plain and includes several other major river systems in distinct ecoregions.” ref

“Especially, it is now well-received that the West Liao River (WLR) region in northeast China played a critical role distinct from the YR region in the adoption and spread of millet farming. Both foxtail (Setaria italica) and broomcorn millets (Panicum miliaceum) were first cultivated in the WLR and lower reaches of the YR basins since at least 6000 BCE. In the ensuing five millennia, millets domesticated in northern China spread across east Eurasia and beyond. Millets had served as one of the main staple foods in northeast Asia, particularly until the introduction of maize and sweet potato in the 16–17th centuries.” ref

“Both the YR and the WLR are known for rich archeological cultures that relied substantially on millet farming. By the Middle Neolithic (roughly 4000 BCE), complex societies with a substantial reliance on millet farming had developed in the WLR (Hongshan culture; 4500–3000 BCE) and in the YR (Yangshao culture; 5000–3000 BCE) basins. For example, excavations of Hongshan societies in the WLR yielded public ceremonial platforms with substantial offerings including numerous jade ornaments, among which the “Goddess Temple” at the Niuheliang site is the most famous. The establishment of the Middle Neolithic complex societies appears to have been associated with rapid population growth and cultural innovation, and may have been linked to the dispersal of two major language families, Sino-Tibetan from the YR and Transeurasian from the WLR, although some scholars debate the genealogical unity of the latter.” ref

“Compared with the YR region where crop cultivation already took the status of the dominant subsistence strategy by the Middle Neolithic, the level of reliance on crops in the WLR region has changed frequently in association with changes in climate and archeological culture. For example, paleobotanical and isotopic evidence suggests that the contribution of millets to the diet of the WLR people steadily increased from the Xinglongwa to Hongshan to Lower Xiajiadian (2200–1600 BCE) cultures, but was partially replaced by nomadic pastoralism in the subsequent Upper Xiajiadian culture (1000–600 BCE).” ref

“Although many archeologists associated this subsistence switch with a response to the climate change, it remains to be investigated whether substantial human migrations mediated these changes. The WLR region adjoins the Amur River (AR) region to the northeast, in which people continued to rely on hunting, fishing, and animal husbandry combined with some cultivation of millet, barley, and legumes into the historic era. Little is known to what extent contacts and interaction between YR and WLR societies affected the dispersal of millet farming over northern China and surrounding regions.” ref

“More generally, given the limited availability of ancient human genomes so far, prehistoric human migrations and contacts as well as their impact on present-day populations are still poorly understood in this region. Researchers, here, present the genetic analysis of 55 ancient human genomes from various archeological sites representative of major archeological cultures across northern China since the Middle Neolithic. By the spatiotemporal comparison of their genetic profiles, we provide an overview of past human migration and admixture events in this region and compare them with changes in subsistence strategy.” ref

Genetic grouping of ancient individuals from northern China

“Principal component analysis (PCA) of 2077 present-day Eurasian individuals in the “HumanOrigins” dataset shows that the ancient individuals from northern China are separated into distinct groups. The ancient individuals fall within present-day eastern Eurasians along PC1. Likewise, they also harbor derived alleles characteristic of present-day East Asians and associated with potentially adaptive phenotypes. However, they fall on different positions on PC2, which separates eastern Eurasians in a largely north-south manner (northern Siberian Nganasan at the top and Austronesian-speaking populations in Taiwan at the bottom).” ref

“Ancient individuals from this study form three big clusters, with AR individuals to the top, YR individuals to the bottom, and WLR individuals in between, which largely reflected their geographic origin. To focus on variation within East Asians, we then used a panel of nine present-day East Asian populations in the “1240k-Illumina” dataset which includes highland Tibetans in large numbers. The first two PCs separate Tungusic-speakers (e.g. Oroqen, Hezhen, Xibo), Tibetans, and lowland East Asian populations (e.g. Han and Tujia). Here fine-scaled clustering of ancient individuals, especially those from the YR and WLR, are more visible than in the Eurasian PCA. Unsupervised ADMIXTURE analysis shows a similar pattern that all ancient individuals harbor three ancestral components, and ancient individuals from the same river basins share similar genetic compositions, consistent with their PCA positions.” ref

Long-term genetic stability of AR populations

“In both the Eurasian and East Asian PCA, two early Neolithic hunter-gatherers (“AR_EN”) and three Iron Age individuals (“AR_Xianbei_IA”; second century CE; Xianbei context) from the Upper AR, and one Bronze Age WLR individual from a nomadic pastoralist context (“WLR_BA_o”) form a tight cluster that falls within the range of present-day AR populations, who are mostly Tungusic speakers. One individual (AR_IA) falls outside of the AR cluster and slightly shifted in PCA along PC1 towards the Mongolic-speakers, but this is likely an artifact due to his low coverage (×0.068) and a small amount of contamination (6.3 ± 6.4%; point estimate ± 1 standard error measure, s.e.m.). Ancient and present-day AR populations also show similar genetic profiles in ADMIXTURE analysis.” ref

“Between pairs of AR populations, ancients as well as present-day samples from the lower AR, we observe large outgroup-f3 statistics supporting their close genetic affinity. Furthermore, we formally confirm that they are largely cladal to each other. First, the nonsignificant statistic f4(AR1, AR2; X, Mbuti) statistics are nonsignificant (Z < 3) for most outgroup populations (X’s) except for the two present-day Siberian populations (Nganasan and Itelmen) who may have experienced historical genetic exchanges with the AR-related gene pools. Second, the qpWave analysis cannot tell pairs of AR populations apart in terms of their affinity to the outgroups.” ref

Although the AR populations do not show a substantial change over time regarding their affinity to populations outside the AR, a published test of the genetic continuity in the strictest sense32 rejects the hypothesis that the ancient AR populations in this study are the direct ancestor of the present-day ones (Supplementary Table 3B). This suggests a stratification within the AR gene pool and presumably gene flows between the AR populations during the formation of the present-day populations.

Temporal changes in the YR genetic profile

“Ancient YR individuals from the Central Plain area form a cluster distinct from the AR individuals in the PCA and likewise share a similar genetic profile in the ADMIXTURE analysis. However, we also observe small but significant differences between them: Late Neolithic Longshan individuals (“YR_LN”) are genetically closer to present-day populations from southern China and Southeast Asia (“SC–SEA”) than earlier Middle Neolithic Yangshao ones (“YR_MN”), measured by positive f4(YR_LN, YR_MN; X, Mbuti). This provides a genetic parallel to our observation of a significant increase of rice farming in middle and lower YR between Middle Neolithic Yangshao and Late Neolithic Longshan periods. We detect no further change in later Bronze/Iron Age individuals (“YR_LBIA”), shown by nonsignificant f4(YR_LN, YR_LBIA; X, Mbuti) (|Z| < 3).” ref

“Unlike the AR region, we do not find present-day populations that form a clade with YR_LBIA. Han Chinese, a dominant ethnic group currently residing in the Central Plain, clearly show extra affinity with SC–SEA populations (max |Z| = 10.3 s.e.m.). Tibeto-Burman-speaking Naxi from southwest China show much reduced but still significant differences from ancient YR populations (max |Z| = 4.0 s.e.m.). These results suggest a long-term genetic connection between YR populations across time but with an important axis of exogenous genetic contribution that may be related to the northward expansion of rice farming by population migrations from south China (e.g. Yangtze river).” ref

“Neolithic genomes from the region surrounding the Central Plain show that the YR genetic profile had a wide geographic distribution. Genomes from Middle Neolithic Inner Mongolia (“Miaozigou_MN”) and Late Neolithic Shanxi province (“Shimao_LN”), both located between the YR and WLR, are genetically similar to each other and to ancient YR populations. Late Neolithic individuals from the upper YR (“Upper_YR_LN”), who are associated with the Qijia culture, also show a similar pattern. We model these groups as a mixture of YR farmers and AR hunter-gatherers, with a majority ancestry (~80%) coming from the YR. Iron Age genomes from the upper YR region (“Upper_YR_IA”) show an even higher YR contribution, compatible with 100% YR ancestry (94.7 ± 5.3%).” ref

“Archeological studies suggest a pivotal role of the mid-altitude region at the northeastern fringe of the Tibetan plateau, where the Qijia culture was located, in the permanent human occupation of the plateau after around 1600 BCE. More broadly, recent linguistic studies favor a northern origin of Sino-Tibetan languages, suggesting the Yangshao culture as their likely origin. We explored genetic connections between present-day Sino-Tibetan and ancient YR populations using admixture modeling. Tibetans are modeled as a mixture of Sherpa and Upper_YR_LN, although other sources also work. This provides a likely local source for the admixture signals previously reported. Among the other Sino-Tibetan-speaking populations in our data set, Naxi and Yi are indistinguishable from YR_MN to our resolution, while Lahu, Tujia, and Han show a prevailing influence from a gene pool related to the SC–SEA populations. Our results are compatible with the above-mentioned linguistic and archeological scenarios, although we find other models also marginally work due to resolution of our genetic data.” ref