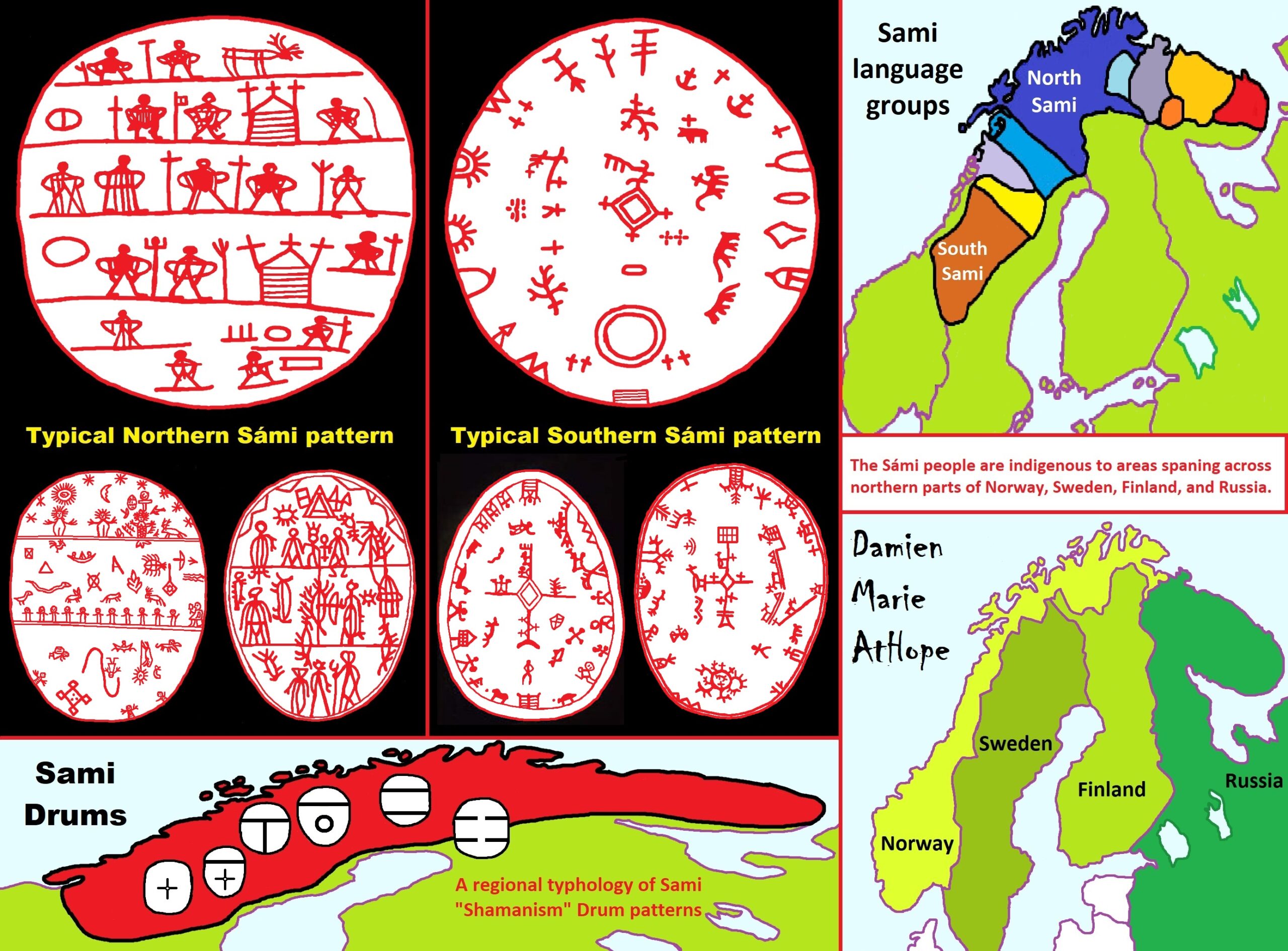

“The drum of Anders Paulsen (top left) and the Bindal drum (top right) represent variations in Sami drums, their shape, decoration and history. Paulsen’s drum was confiscated in Vadsø in 1691, while the Bindal drum was bought by a museum official in 1925; Vadsø and Bindal being in opposite corners of the Sami world. Paulsens’s drum has a typical Northern Sámi pattern, with several separate levels representing the different layers of spiritual worlds. The Bindal drum has a typical Southern Sami decoration: a rhombus-shaped sun symbol in the center, with other symbols around the sun, representing people, animals, landscape and deities.” ref

Anders Paulsen

“Anders Poulsen (died 1692), was a Sami “noaidi/shaman,” who was the last victim of the many Vardø witch trials, which took place between 1621 and 1692. In Sámi form his name was Poala-Ánde. He was born in Torne Lappmark in Sweden, married and lived in Varanger. He was active as a noaidi, and as such used a Sámi drum. The drum was taken from him by force on 7 December 1691 during the Christianization of the Sámi people, and he was put on trial for idolatry for being a follower of the Pagan Sami shamanism religion. The law used to persecute him was however formally the witchcraft law. Poulsen explained the drum’s use during his trial in February 1692. The case was considered significant and the local authorities sent a request to Copenhagen about how to deal with it. Before a sentence could be reached, however, he was killed by a fellow prisoner who suffered from insanity.” ref

“Poulsen’s drum became part of the Danish royal collection after his death and eventually entered the collections of the National Museum of Denmark. It was on loan to the Sámi Museum in Karasjok, northern Norway from 1979 but it took “a 40-year struggle” for it to be officially handed back to the Sámi people in 2022, according to Jelena Porsanger, director of the museum, following an appeal by Norway’s Sámi president to Queen Margrethe of Denmark.” ref

- African Back Migrations and the Status of Shamanism Origins as well as its Spreading

- Women/Feminine-Natured people as the first Shamans from around 30,000 to 7,000 years ago?

- Sky Father/Sky Mother “High Gods” or similar gods/goddesses of the sky more loosely connected, seeming arcane mythology across the earth seen in Siberia, China, Europe, Native Americans/First Nations People and Mesopotamia, etc.

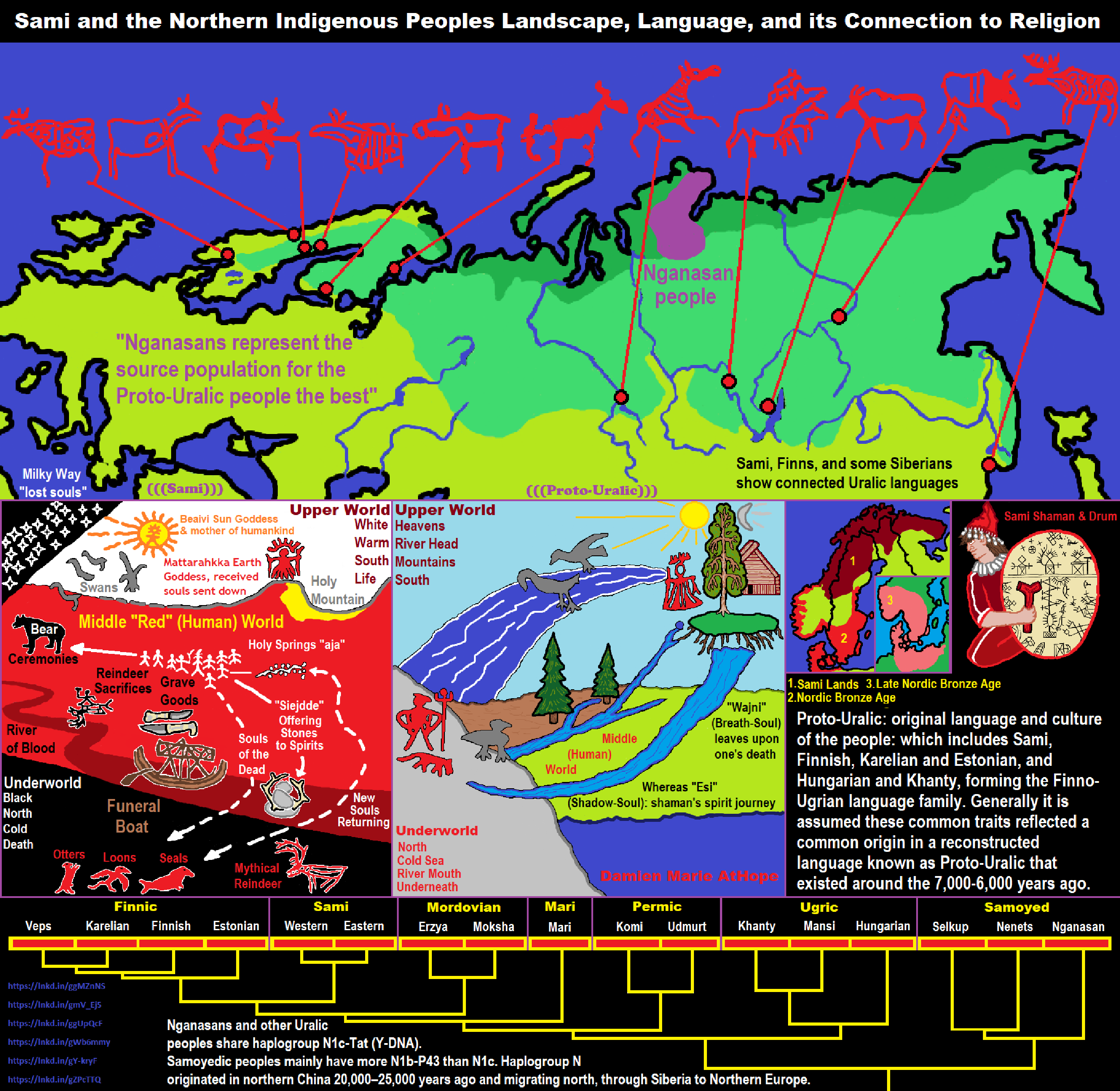

- Sami and the Northern Indigenous Peoples Landscape, Language, and its Connection to Religion

- Sacred Land, Hills, and Mountains: Sami Mythology (Paganistic Shamanism)

Sámi shamanism

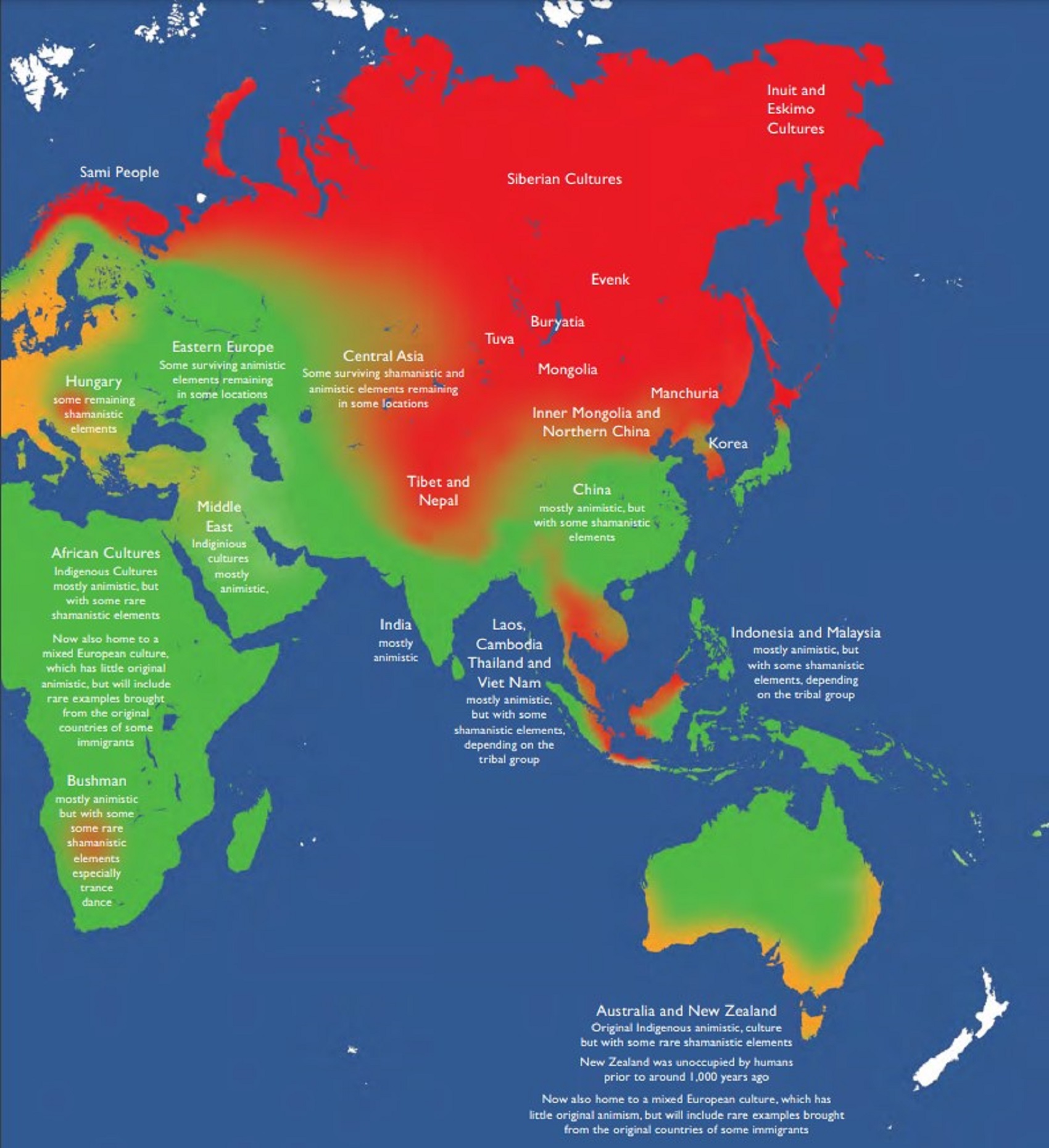

“Traditional Sámi spiritual practices and beliefs are based on a type of animism, polytheism, and what anthropologists may consider shamanism. The religious traditions can vary considerably from region to region within Sápmi. Traditional Sámi religion is generally considered to be Animism. The Sámi belief that all significant natural objects (such as animals, plants, rocks, etc.) possess a soul, and from a polytheistic perspective, traditional Sámi beliefs include a multitude of spirits. Sámi traditional beliefs and practices commonly emphasizes veneration of the dead and of animal spirits. The relationship with the local animals that sustain the people, such as the reindeer, are very important to the kin-group.” ref

Sámi drum

“A Sámi drum is a shamanic ceremonial drum used by the Sámi people of Northern Europe. Sámi ceremonial drums have two main variations, both oval-shaped: a bowl drum in which the drumhead is strapped over a burl, and a frame drum in which the drumhead stretches over a thin ring of bentwood. The drumhead is fashioned from reindeer hide. In Sámi shamanism, the noaidi used the drum to get into a trance, or to obtain information from the future, or other realms. The drum was held in one hand, and beaten with the other. While the noaidi was in trance, his “free spirit” was said to leave his body to visit the spirit-world. When used for divination, the drum was beaten with a drum hammer; a vuorbi (‘index’ or ‘pointer’), a kind of die made of brass or horn, would move around on the drumhead when the drum was struck. Future events would be predicted according to the symbols upon which the vuorbi stopped on the membrane.” ref

“The patterns on the drum membrane reflect the worldview of the owner and his family, both in religious and worldly matters, such as reindeer herding, hunting, householding, and relations with their neighbors and the non-Sámi community. Many drums were taken out of Sámi ownership and use during the Christianization of the Sámi people in the 17th and 18th centuries. Many drums were confiscated by Sámi missionaries and other officials as a part of an intensified Christian mission towards the Sámi. Other drums were bought by collectors. Between 70 and 80 drums are preserved; the largest collection of drums is at the Nordic Museum in Stockholm.” ref

“The Northern Sámi terms for the drum are goavddis, gobdis and meavrresgárri, while the Lule Sámi and Southern Sámi terms are goabdes and gievrie, respectively. Norwegian: runebomme, Swedish: nåjdtrumma; In English it is also known as a rune drum or Sámi shamanic drum. The Northern Sámi name goavddis describes a bowl drum, while the Southern Sámi name gievrie describes a frame drum, corresponding to the distribution of these types of drums. Another Northern Sámi name, meavrresgárri, is a cross-language compound word: Sámi meavrres, from meavrit and Finnish möyriä (‘dig, roar, mess’), plus gárri from Norwegian kar (‘cup, bowl’).” ref

“The common Norwegian name for the drum, runebomme, is based on an earlier misunderstanding of the symbols on the drum, which interpreted them as runes. Suggested new names in Norwegian are sjamantromme (“shaman drum”) or sametromme (‘Sámi drum’). The original Swedish name, trolltrumma, comes from the Christian perception of Sámi religion as witchcraft (trolldom), and it is now considered derogatory. In his Fragments of Lappish Mythology (ca 1840) Læstadius used the term divination drum (“spåtrumma”). In Swedish today, the term that’s commonly used is samiska trumman (‘the Sámi drum’).” ref

“There are four categories of sources for the history of the drums. First are the drums themselves, and what might be interpreted from them. Secondly, there are reports and treatises on Sámi subjects from the 17th and 18th centuries, written by Swedish and Dano-Norwegian priests, missionaries, or other civil servants, like Johannes Schefferus. The third category are statements from Saami themselves, given to legal courts or other official representatives. The fourth are the sporadic references to drums and Sámi shamanism in other sources, such as Historia Norvegiæ (late 12th century).” ref

“The oldest mention of a Sámi drum and shamanism is in the anonymous Historia Norvegiæ (late 12th century). It mentions a drum with symbols of marine animals, a boat, reindeer and snowshoes. There is also a description of a shaman healing an apparently dead woman by moving his spirit into a whale. Peder Claussøn Friis describes a noaidi’sspirit leaving the body in his Norriges oc omliggende Øers sandfærdige Bescriffuelse (1632). The oldest description by a Sámi is by Anders Huitlok of the Pite Sámi in 1642 about a drum that he owned. Huitlok also made a drawing; his story was written down by the German-Swedish bergmeister Hans P. Lybecker. Huitlok’s drum represents a worldview where deities, animals and the living and the dead are working together within a given landscape. The court protocols from the trials against Anders Paulsen in Vadsø in 1692 and against Lars Nilsson in Arjeplog in 1691 are also sources.” ref

“During the 17th century, the Swedish government commissioned a work to gain more knowledge of the Sámi and their culture. During the Thirty Years’ War (1618–48) rumours were spread that the Swedes won their battles with the help of Sámi witchcraft. Such rumours were part of the background for the research that lead to Johannes Schefferus‘ book Lapponia, published in Latin in 1673. For Schefferus, a number of “priests’ correspondences” (prästrelationer) were written by vicars within the Sámi districts of Sweden. Treatises by Samuel Rheen, Olaus Graan, Johannes Tornæus and Nicolai Lundius were the sources used by Schefferus.” ref

“In Norway, the main source are writings from the mission of Thomas von Westen and his colleagues from 1715 until 1735. Authors were Hans Skanke, Jens Kildal, Isaac Olsen, and Johan Randulf (the Nærøy manuscript). These books were, in part, instructions for the missionaries and their co-workers, and part documentation, intended for the government in Copenhagen. Late books within this tradition are Pehr Högström‘s Beskrifning Öfwer de til Sweriges Krona lydande Lapmarker (1747) in Sweden and Knud Leem‘s Beskrivelse over Finmarkens Lapper (1767) in Denmark-Norway. Notable is especially Læstadius‘ Fragments of Lappish Mythology (1839–45), which both discusses earlier treatises with a critical approach, and builds upon Læstadius’ own experience.” ref

“The drums are always oval; the exact shape of the oval would vary with the kind of wood used. Drums which still exist are of four different types, and can be divided into two main groups: bowl drums and frame drums:

- In bowl drums, the wood consists of a burl shaped into a bowl. The burl usually comes from pine, but sometimes from spruce. The membrane is attached to the wood with a sinew.

- Frame drums are shaped by wet or heat bending; the wood is usually pine, and the membrane is sewn to holes in the frame with sinew.

- Ring drums are made from a naturally grown piece of pine wood. There is only one known drum of this type.

- Angular-cut frame drums are made from one piece of wood cut from a tree. To bend the wood into an oval, angular cuts are made in the bottom and the side of the frame. Only two such drums are preserved, both from Kemi Sámi districts in Finland. The partly preserved drum from Bjørsvik in Nordland is also an angular-cut frame drum.” ref

“In his major work on Sámi drums, Die lappische Zaubertrommel, Ernst Manker lists 41 frame drums, one ring drum, two angular-cut frame drums and 27 bowl drums. Given these numbers, many tend to divide the drums into two main groups: bowl drums and frame drums, seeing the others as variations. Judged by these remaining drums and their known provenance, frame drums seem to be more common in the Southern Sámi areas, and bowl drums seem to be common in the Northern Sámi areas. The bowl drum is sometimes regarded as a local adjustment of the basic drum type, this being the frame drum. The frame drum type is more reminiscent of other ceremonial drums used by the indigenous peoples of Siberia.” ref

“The membrane is made of untanned reindeer hide. Lars Olsen, who described his uncle’s drum, the Bindal drum, in 1885, said that the hide was usually taken from the neck of a reindeer calf because of its thickness. The symbols were painted with a paste made from alder bark. The motifs on a drum reflect the worldview of the owner and his family, both in terms of religious beliefs and in their modes of subsistence. A world is depicted via images of reindeer, both domesticated and wild, and of carnivorous predators that pose a threat to the herd. The modes of subsistence are presented by scenes of wild game hunting, boats with fishing nets, and reindeer herding.” ref

“Additional imagery on the drum consists of mountains, lakes, people, deities, as well as the camp-site with tents and storage-houses. Symbols of foreign civilizations, such as churches and houses, represent the threats from the surrounding and expanding non-Sámi community. Each owner chose his set of symbols; there are no two drums with identical sets of symbols. The drum mentioned in the medieval Latin tome Historia Norvegiæ, with motifs such as whales, reindeer, skis and a boat would have belonged to a coastal Sámi. The Lule Sámi drum reflects an owner who found his mode of subsistence chiefly through hunting, rather than herding.” ref

“A typology based on the structure of the patterns can be divided into three main categories:

- Southern Sámi, characterized by the rhombus-shaped sun cross in the center

- Central Sámi, where the membrane is divided in two by a horizontal line, often with a solar symbol in the lower section

- Northern Sámi, where the membrane is divided by horizontal lines into three or five separate levels representing different worlds: the heavens, the world of the living and an underworld.” ref

“In Manker’s overview of 71 known drums, there are 42 Southern Sámi drums, 22 Central Sámi drums and seven Northern Sámi drums. The Bindal drum is a typical Southern Sámi drum, with the sun-symbol in its center. Its last owner also explained that the symbols on the membrane were organized according to the four cardinal directions around the sun. South is described as the “summer side” or “the direction of life,” and contains symbols of the Sámi’s life in the fells during summer: the goahti, the storehouse or njalla, the herd of reindeer, and their pastures. North is described as “the side of death,” and contains symbols of sickness, death and wickedness.” ref

“Kjellström and Rydving have summarised the symbols of the drums in the following categories: nature, reindeer, bears, elk, other mammals (wolf, beaver, small fur animals), birds, fish, hunting, fishing, reindeer-herding, the camp site – with goahti, njalla and other storehouses, the non-Sámi village – often represented by the church, people, travel (skiing, reindeer with pulk, boats), and deities and their worlds. Sometimes even the use of the drum itself is depicted.” ref

“The reindeer-herding is mainly depicted with a circular symbol for the reindeer corral that was used to gather, mark and milk the flock. This symbol is found on 75% of the Southern Sámi drums, but not on any northern or eastern drums. The symbol for the corral is always placed in the lower half of the drum. Reindeer are represented as singular line figures, as fully modeled figures or by their antlers. The campsite is usually shown as a triangle symbolizing the tent/goahti. The Sámi storehouse (njalla) is depicted on many drums from different areas. The njalla is a small hut in bear cache style, built on top of a cut tree. It is usually depicted with its ladder in front.” ref

“Sámi deities are shown on several drum membranes. These are the high god Ráðði, the demiurge and sustainer Varaldi olmmai, the thunder and fertility god Horagallis, the weather god Bieggolmmái, the hunting god Leaibolmmái, the sun god Beaivi / Biejjie, the mother goddesses Máttaráhkká, Sáráhkká, Juoksáhkká og Uksáhkká, the riding Ruto spirit who brought sickness and death, and Jábmeáhkká – the empress of the underworld. Some subjects from the non-Sámi world also appears on several drums. These are interpreted as attempts to understand and master the new influences interacting with the Sámi society. Churches, houses and horses appear on several drums, and drums from Torne and Kemi districts show both the city, the church and the lapp commissary.” ref

“Interpretation of the drums’ symbols might be difficult, and different explanations have been proposed for several of the symbols. It has often been assumed that the Sámi deliberately gave misleading explanations when they presented their drums to missionaries and other Christian audiences, in order to downplay the pagan elements and emphasise the Christian impact on Sámi culture. However, it has also been proposed that some of the symbols have been over-interpreted as religious motifs, when they actually represented matters of everyday life.” ref

“Håkan Rydving evaluated the drum symbols from a perspective of source criticism, and divides them into four categories:

- Preserved drums that were explained by their owners. These are only two such drums: Anders Paulsen‘s drum and the Freavnantjahke gievrie.

- Preserved drums that were explained by other people, contemporary to the owners. These are five such drums, four Southern Sami and one Ume Sami.

- Lost drums that were explained by contemporaries, either the owner or other people. There are four of these drums.

- Preserved drums without a contemporary explanation. These make up the majority of the 70 known drums.” ref

“Rydving and Kjellström have demonstrated that both Olov Graan’s drum fra Lycksele and the Freavnantjahke gievrie have been spiritualized through Manker‘s interpretations: When the explanations are compared, it appears as if Graan relates the symbols to household life and modes of subsistence, where Manker sees deities and spirits. This underlines the problems of interpretation. Symbols that Graan explains as snowy weather, a ship, rain and squirrels in the trees, are interpreted by Manker as the wind god Bieggolmai/Biegkålmaj, a boat sacrifice, a weather god and – among other suggestions – as a forest spirit.” ref

“At the Freavnantjahke gievrie there is a symbol explained by the owner as “a Sámi riding in his pulk behind his reindeer”, while Manker suggests that “this might be an ordinary sleigh ride, but we might as well assume that this is the noaidi, the drum owner, going on an important errand into the spiritual world”. On the other hand, one might suggest that the owner of the Freavnantjahke gievrie, Bendik Andersen, is de-emphasising the spiritual content of the drum when the symbols usually recognized as the three mother goddesses are explained away by him as “men guarding the reindeer.” ref

“The primary tools used when working with the drum are mainly the drum hammer and one or two vuorbi for each drum. The drums also had different kinds of cords as well as “bear nails”. The drum hammer (Northern Sami: bállin) was usually made of horn and was T- or Y-shaped, with two symmetric heads, and with geometric decorations. Some hammers have tails made of leather straps, or have leather or tin wires wrapped around the shaft. Manker (1938) knew and described 38 drum hammers. The drum hammer was used for both trance drumming and, together with the vuorbi, for divination. The vuorbi (‘index’ or ‘pointer’; Northern Sámi vuorbi, bajá or árpa; Southern Sámi viejhkie) used for divination was made of brass, horn or bone, and sometimes of wood.” ref

“The cords are leather straps nailed or tied to the frame, or to the bottom of the drum. They had pieces of bone or metal tied to them. The owner of the Freavnantjahke gievrie, Bendix Andersen Frøyningsfjell, explained to Thomas von Westen in 1723 that the leather straps and their decorations of tin, bone and brass were offers of gratitude to the drum, given by the owner as a response to good luck gained via the messages the shaman received when using the drum. The frame of the Freavnantjahke gievrie also had 11 tin nails in it, in a cross shape. Bendix explained them as an indicator of the number of bears killed thanks to instructions given by the drum. Manker found similar bear nails in 13 drums. Other drums had a baculum from a bear or a fox among the cords.” ref

“Ernst Manker summarized the use of the drum, regarding both trance and divination:

- before use, the membrane was tightened by holding the drum close to the fire

- the user stood on his knees, or sat with his legs crossed, holding the drum in his left hand

- the vuorbi was placed on the membrane, either in a fixed starting place or one chosen at random

- the hammer was held in the right hand; the membrane was struck either with one of the hammer heads, or with the flat side of the hammer

- the drumming started at a slow pace, and grew wilder

- if the drummer fell into a trance, his drum was placed upon him, with the painted membrane facing downwards

- the route of the vuorbi across the membrane, and the places where it stopped, were interpreted as significant” ref

“Samuel Rheen, who was a priest in Kvikkjokk 1664–1671, was one of the first to write about Sámi religion. His impression was that many Sámi, but not all, used the drum for divination. Rheen mentioned four kinds of things the drum could give:

- knowledge about what was happening elsewhere

- knowledge about luck, misfortune, health, and illness

- curing diseases

- advice on which deity one should sacrifice unto” ref

“Of these four things mentioned by Rheen, other sources state that the first of them was only performed by the noaidi. Based on the sources, one might get the impression that the use of the drum was gradually “democratized”, so that there in some regions there was a drum in each household, and that the father of the household could use it to seek advice. Yet the original use of the drum, inducing trance work, seems to have remained a specialty of the shaman.” ref

“Sources seem to agree that in Southern Sámi districts in the 18th century, each household had its own drum. These were mostly used for divination. The types and the configurations of the motifs on the Southern Sámi drums suggest it was, indeed, used for divination. On the other hand, the configurations of the Northern Sámi drum motifs, with their hierarchical structures of the worlds, represent a mythological universe in which it was the noaidi’s privilege to wander.” ref

“The drum was usually carried along on nomadic wanderings. There are also reports of drums being hidden close to regular campsites. Inside the lavvu and the goahti, the drum was always placed in the boaššu, the space behind the fireplace that was considered the “holy room” of the goahti. Several contemporary sources describe a dual view of the drums: they were seen both as occult devices and as divination tools for practical purposes. Drums were inherited. Not all of those who owned drums in the 18th century described themselves as active users of their drum–at least that was what they insisted when the drums were confiscated.” ref

“There is no known evidence of the drum or the noaidi having had any role in childbirth or funeral rituals. Some sources suggest that the drum was manufactured with the aid of secret rituals. However, Manker made a photo documentary describing the drum-making process. The selection of the motifs for the membrane, or the philosophy behind it, are not described in any sources. It is known that the dedication of a new drum featured rituals that involved the whole household.” ref

“The noaidi used the drum to induce a state of trance. He hit the drum with an intense rhythm until he went into a trance or sleep-like state. While in this tate, his free spirit could travel into the spirit-worlds, or to other places in the material world. The episode mentioned in Historia Norvegiæ tells about a noaidi who traveled to the spirit-world and fought against enemy spirits in order to heal the sick. The writings of Peder Claussøn Friis (1545–1614) describe a Sámi in Bergen who could supposedly travel in the material world while he was in a trance: a Sámi named Jakob made his spirit-journey to Germany to learn about the health of a German merchant’s family.” ref

“Both Nicolai Lundius (ca 1670), Isaac Olsen (1717) and Jens Kildal (ca. 1730) describe noaidis traveling to spirit-worlds where they negotiated with death deities, especially Jábmeáhkka–the queen of the realm of the dead–regarding people’s health and lives. This journey involved risks to the noaidi’s own life and health. In the writings of both Samuel Rheen and Isaac Olsen, the drum is mentioned as a part of the preparations for a bear hunt. Rheen says that the noaidi could give information about hunting fortune, while Olsen suggests that the noaidi was able to manipulate the bear to move into the hunters’ range. The noaidi–or the drum’s owner–was a member of the group of hunters, following on the heels of the spear bearer. The noaidi also sat at a prominent place during the feast after the hunting.” ref

“In Fragments of Lappish Mythology (1840–45), Lars Levi Læstadius writes that the Sámi used his drum as an oracle, and consulted it when some important matter was at hand. “Just like any other kind of fortune-telling with cards or dowsing. One should not consider every drum owner a magician.” A common practice was to let the vuorbi move across the membrane, visiting the different symbols. The noaidi would interpret the will of the gods by the route taken by the vuorbi. Such practices are described in conjunction with the Bindal drum, the Freavnantjahke gievrie and the Velfjord drum.” ref

“Whether women were allowed to use the drum has been debated, but no consensus has yet been reached. On one hand, some sources say that women were not even allowed to touch the drum, and during herd migration, women should follow another route than the sleigh that carried the drum. On the other, the whole family was involved in the initiation of the drum. Also, the participation of joiking women was of importance for a successful spirit-journey.” ref

“May-Lisbeth Myrhaug has reinterpreted the sources from the 17th and 18th century, and suggests that there is evidence of female noaidi, including spirit-travelling female noaidi. In contrast to the claim that only men could be noaidi and use the drum, there are examples of Sami women who did use the drum. Kirsten Klemitsdotter (d. 1714), Rijkuo-Maja of Arvidsjaur (1661-1757) and Anna Greta Matsdotter of Vapsten, known as Silbo-gåmmoe or Gammel-Silba (1794-1870), are examples of women noted to have used the drum.” ref

Drums after Christianisation

“In the 17th and 18th centuries, several raids were made to confiscate drums, both in Sweden and in Denmark-Norway, during the Christianization of the Sámi people. Thomas von Westen and his colleagues considered the drums to be “the Bible of the Sámi”, and wanted to eradicate what they saw as “idolatry” by destroying or removing the drums. Any uncontrolled, “idol-worshipping” Sámi were considered a threat to the government. The increased missionary efforts towards the Sámi in the early 18th century might be explained as a consequence of the government’s desire to controle the citizens under the era of absolute monarchy in Denmark-Norway, and also as a consequence of the increased emphasis on an individual Christian faith in pietism, popular at the time.” ref

“In Åsele, Sweden, 2 drums were collected in 1686, 8 drums in 1689 and 26 drums in 1725, mainly of the Southern Sámi type. Thomas von Westen collected about a hundred drums from the Southern Sámi district; 8 of them were collected at Snåsa in 1723. 70 of von Westen’s drums were lost in the Copenhagen Fire of 1728. von Westen found few drums during his journeys in the Northern Sámi districts between 1715 and 1730. This might be explained by the advanced Christianisation of the Sámi in the north, in that the drums had already been destroyed. It might also be explained through the differences in the ways the drums were used in Northern and Southern Sámi cultures, respectively. While the drum was a common household item in Southern Sámi culture, it might have been a rare object, reserved for the few educated noaidi in Northern Sámi culture.” ref

“Probably the best-known is the Linné Drum – a drum that was given to Carl Linnaeus during his visits to northern Sweden. He later gave it to a museum in France, and it was later brought back to the Swedish National Museum. Three Sámi drums can be found in the collections of the British Museum, including one bequeathed by Sir Hans Sloane, founder of the museum. Over 30 drums are held at the Nordiska Museet, Stockholm; with others held in Rome, Berlin, Leipzig and Hamburg. Cambridge University’s Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford and London’s Horniman Museum all hold examples of Sami drums.” ref

“Anders Poulsen’s drum became part of the Danish Royal Collection after his trial and death. It eventually entered the collections of the National Museum of Denmark and was on loan to the Sámi Museum in Karasjok, northern Norway, from 1979. Following “a 40-year struggle” it was officially returned to the Sámi people in 2022, according to Jelena Porsanger, director of the museum, following an appeal by Norway’s Sámi president to Queen Margrethe of Denmark.” ref

Noaidi (Shaman)

“A noaidi (Northern Sami: noaidi, Lule Sami: noajdde, Southern Sami: nåejttie, Skolt Sami: nōjjd, Ter Sami: niojte, Kildin Sami: noojd/nuojd, Pite Sami: nåjjde) is a shaman of the Sami people in the Nordic countries, playing a role in Sámi religious practices. Most noaidi practices died out during the 17th century, most likely because they resisted Christianization of the Sámi people and the king’s authority. Their actions were referred to in courts as “magic” or “sorcery” (cf. witchcraft). Several Sámi shamanistic beliefs and practices are similar to those of some Siberian cultures.” ref

“Noaidis, often referred to as the “Sámi shamans”, are the traditional healers and protectors of the Sami people. Noaidis are considered to have the role of mediator between humans and the spirits. To undertake this mediation, the noaidi are believed to be able to communicate with the spirit world, and to ask what sacrifice needed to be made by a person so that he might return to good health and be successful in the hunt for food. Sacrifices designed by the noaidi are understood to reestablish a kind of balance between the mortal and immortal worlds.” ref

“Using a traditional drum, which is the most important symbol and tool of the Sámi noaidi, they invoke assistance from benevolent spirits and conducted out-of-body travel via the “free soul” with the help of other siida members. The Sámi distinguish between the “free soul” versus the more mundane “body soul”; the “body soul” is unable to traverse the divide separating the spiritual netherworld from the more mundane, corporeal, real world. A noaidi can engage in any kind of affair that demands wisdom; it is said they take payments for their services. The activities include healing people, helping children, making decisions and protecting reindeer, which represents the most important source of food and are also used as tribute payment.” ref

“The sources from which we learn about noaidi are court protocols, tales, excavated tools such as belts, and missionary reports. That noaidis were punished and in some cases sentenced to death for their “sorcery” should perhaps rather be interpreted as an attempt to obliterate opposition to the crown. Prior to 1858, when the Conventicle Act was abolished, there was by law no freedom of religion, as the Lutheran Swedish church was the only allowed religion for Swedish citizens. Swedish priests supported conviction of noaidis for sorcery, and in 1693, Lars Nilsson was executed for this charge.” ref

“It has traditionally often been claimed that only men could become noaidi and use the drum, but both Rijkuo-Maja of Arvidsjaur (1661-1757) as well as Anna Greta Matsdotter of Vapsten, known as Silbo-gåmmoe or Gammel-Silba (1794-1870), were both noted to have done so. In the Sami shamanistic form of worship drumming and traditional chanting (joiking) is of singular importance. Some of joiks are sung on shamanistic rites; this memory is conserved also in a folklore text (a shaman story). Recently, joiks have been sung in two different styles, one of which is sung only by young people. The other joik may be identified with the “mumbling” joik, resembling chants or magic spells.” ref

“Several surprising characteristics of joiks can be explained by comparing the music ideals, as observed in joiks and contrasted to music ideals of other cultures. In some instances, joiks mimic natural sounds. This can be contrasted to other goals, namely overtone singing and bel canto, both of which exploit human speech organs to achieve “superhuman” sounds. Overtone singing and the imitation of sounds in shamanism are present in many other cultures as well. Sound imitation may serve other purposes such as games and other entertainment as well as important practical purposes such as luring animals during hunts. A noaidi is a mediator between the human world and saivo, the underworld, on the behalf of the community, usually using a Sámi drum and a domestic flute called a fadno in ceremonies.” ref, ref

Deities, Ancestors, and Animal Spirits

“Aside from bear worship, there are other animal spirits such as the Haldi who watch over nature. Some Sámi people have a thunder god called Horagalles. Rana Niejta is “the daughter of the green, fertile earth”. The symbol of the world tree or pillar, which reaches up to the North Star and is similar to that found in Finnish mythology, may also be present. Laib Olmai, the forest spirit of some of the Sámi people, is traditionally associated with forest animals, which are regarded as his herds, and he is said to grant either good or bad luck in hunting. His favor was so important that, according to one author, believers said prayers and made offerings to him every morning and every evening.” ref

“One of the most irreconcilable elements of the Sámi’s worldview from the missionaries’ perspective was the notion “that the living and the departed were regarded as two halves of the same family.” The Sámi regarded the concept as fundamental, while Protestant Christian missionaries absolutely discounted any possibility of the dead having anything to do with the living. Since this belief was not just a religion, but a living dialogue with their ancestors, their society was concomitantly impoverished.” ref

“The Sami religion differs somewhat between regions and tribes. Although the deities are similar, their names vary between regions. The deities also overlap: in one region, one deity can appear as several separate deities, and in another region, several deities can be united in to just a few. Because of these variations, the deities can be somewhat confused with each other.” ref

“The main deities of the Sami were as follows:

- Akka – a group of fertility goddesses, including Maderakka, Juksakka and Uksakka

- Beaivi – goddess of the sun, mother of human beings

- Bieggagallis – husband of the sun goddess, father of human beings

- Bieggolmai ‘Man of the Winds’ – god of the winds

- Biejjenniejte – goddess of healing and medicine, daughter of the Sun, Beaivi

- Horagalles – god of thunder. His name may mean “Thor-man”. He is also called “Grandfather”, Bajanolmmai, Dierpmis, Pajonn and Tordöm.

- Jahbme akka – the goddess of the dead, and mistress of the underworld and the realm of the dead

- Ipmil ‘God’ – adopted as a native name for the Christian God (see the related Finnish word Jumala), also used for Radien-attje

- Lieaibolmmai – god of the hunt and of adult men

- Madder-Attje – husband of Maderakka and father of the tribe. While his wife gives newborns their bodies, he gives them their souls.

- Mano, Manna, or Aske – god of the moon

- Mubpienålmaj – the god of evil, influenced by the Christian Satan

- Radien-attje – Creator and high god, the creator of the world and the head divinity. In Sámi religion, he is passive or sleeping and is not often included in religious practice. He created the souls of human beings with his spouse. He was also called Waralden Olmai.

- Raedieahkka – wife of the high god Radien-attje. She created the souls of human beings with her spouse.

- Rana Niejta – spring goddess, the daughter of Radien-attje and Raedieahkka. Rana, meaning “green” or by extension “fertile”, was a popular name for Sámi girls.

- Radien-pardne – the son of Radien-attje and Raedieahkka. He acts as the proxy of his passive father, performing his tasks and carrying out his will.

- Ruohtta – god of sickness and death. He was depicted riding a horse.

- Stallo – feared cannibal giants of the wilderness

- Tjaetsieålmaj – “the man of water”, god of water, lakes and fishing” ref

Sacred Landscape

“In the landscape throughout Northern Scandinavia, one can find sieidis, places that have unusual land forms different from the surrounding countryside, and that can be considered to have spiritual significance. Each family or clan has its local spirits, to whom they make offerings for protection and good fortune. The Storjunkare are described sometimes as stones, having some likeness to a man or an animal, that were set up on a mountain top, or in a cave, or near rivers and lakes. Honor was done to them by spreading fresh twigs under them in winter, and in summer leaves or grass. The Storjunkare had power over all animals, fish, and birds, and gave luck to those that hunted or fished for them. Reindeer were offered up to them, and every clan and family had its own hill of sacrifice.” ref

Mountain Sámi

“As the Sea Sámi settled along Norway’s fjords and inland waterways, pursuing a combination of farming, cattle raising, trapping, and fishing, the minority Mountain Sámi continued to hunt wild reindeer. Around 1500, they started to tame these animals into herding groups, becoming the well-known reindeer nomads, often portrayed by outsiders as following the traditional Sámi lifestyle. The Mountain Sámi had to pay taxes to three states, Norway, Sweden, and Russia, as they crossed each border while following the annual reindeer migrations; this caused much resentment over the years. Between 1635 and 1659, the Swedish crown forced Swedish conscripts and Sámi cart drivers to work in the Nasa silver mine, causing many Sámis to emigrate from the area to avoid forced labor. As a result, the population of Pite– and Lule-speaking Sámi decreased greatly.” ref

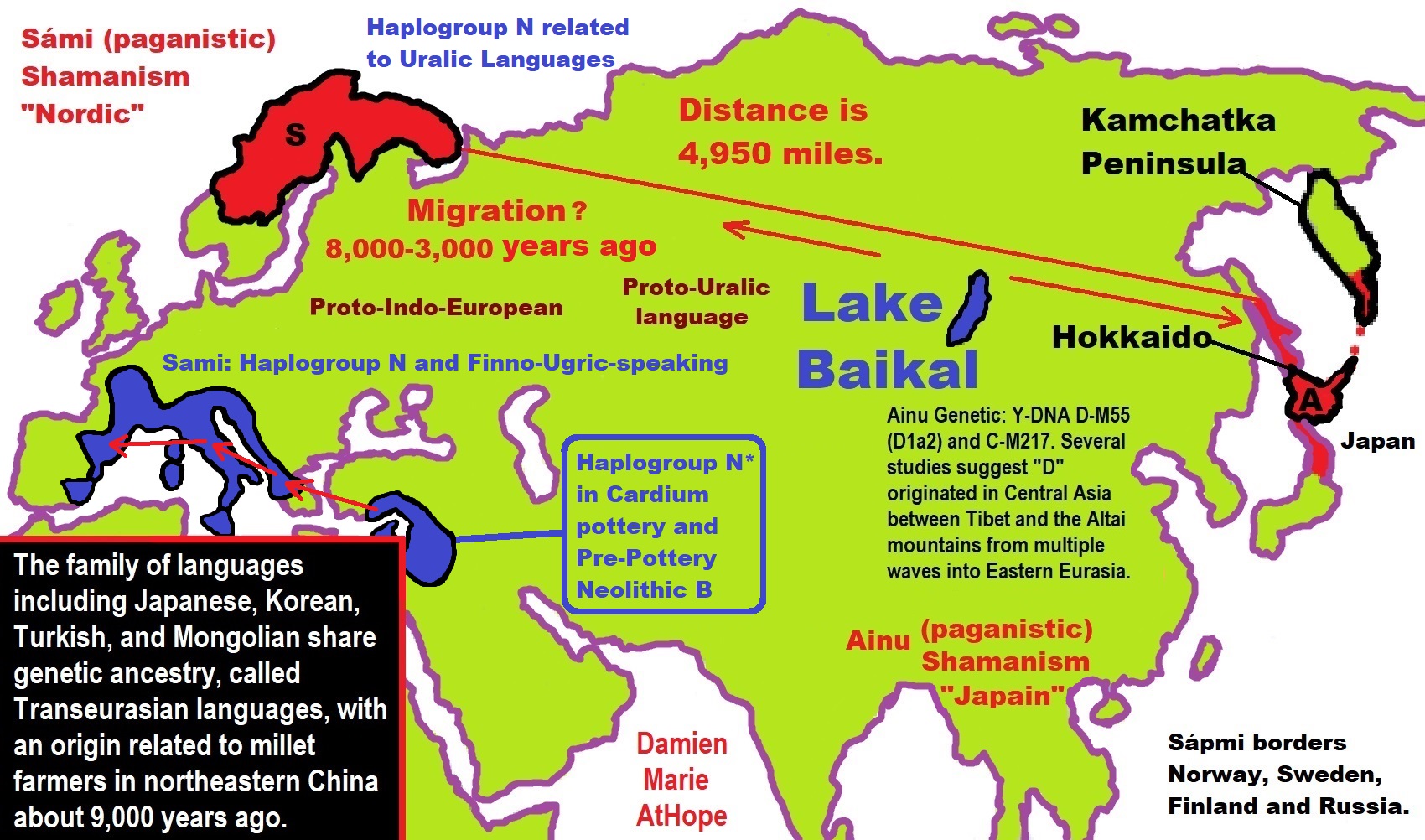

“The Sámi (/ˈsɑːmi/ SAH-mee; also spelled Sami or Saami) are the traditionally Sámi-speaking people inhabiting the region of Sápmi, which today encompasses large northern parts of Norway, Sweden, Finland, and of the Kola Peninsula in Russia. The region of Sápmi was formerly known as Lapland, and the Sámi have historically been known in English as Lapps or Laplanders, but these terms are regarded as offensive by the Sámi, who prefer the area’s name in their own languages, e.g. Northern Sámi Sápmi. Their traditional languages are the Sámi languages, which are classified as a branch of the Uralic language family.” ref

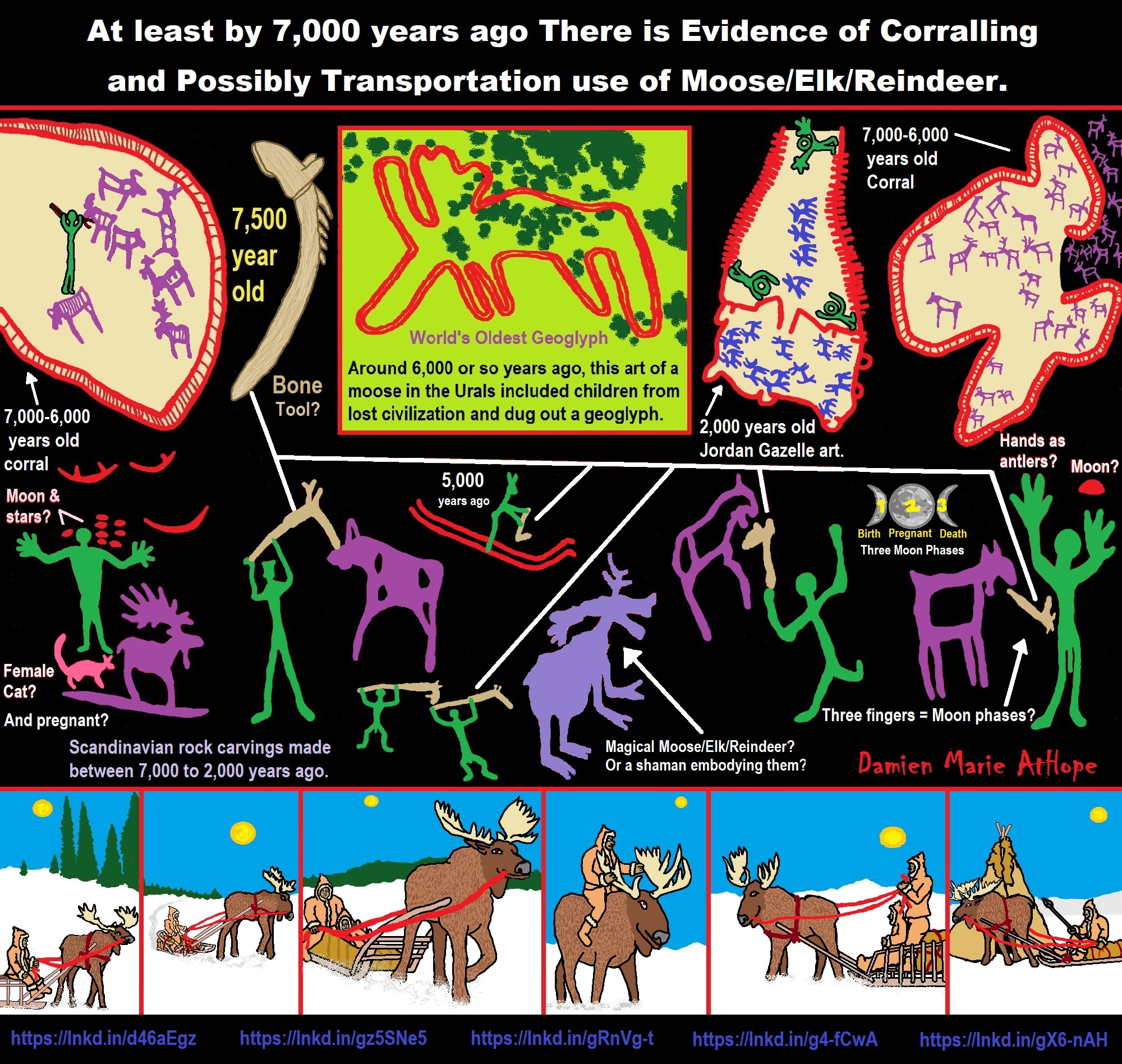

“Traditionally, the Sámi have pursued a variety of livelihoods, including coastal fishing, fur trapping, and sheep herding. Their best-known means of livelihood is semi-nomadic reindeer herding. As of 2007 about 10% of the Sámi were connected to reindeer herding, which provides them with meat, fur, and transportation; around 2,800 Sámi people were actively involved in reindeer herding on a full-time basis in Norway. For traditional, environmental, cultural, and political reasons, reindeer herding is legally reserved for only Sámi in some regions of the Nordic countries.” ref

“Speakers of Northern Sámi refer to themselves as Sámit (the Sámis) or Sápmelaš (of Sámi kin), the word Sápmi being inflected into various grammatical forms. Other Sámi languages use cognate words. As of around 2014, the current consensus among specialists was that the word Sámi was borrowed from the Proto-Baltic word *žēmē, meaning ‘land’ (cognate with Slavic zemlja (земля), of the same meaning).” ref

“The word Sámi has at least one cognate word in Finnish: Proto-Baltic *žēmē was also borrowed into Proto-Finnic, as *šämä. This word became modern Finnish Häme (Finnish for the region of Tavastia; the second ä of *šämä is still found in the adjective Hämäläinen). The Finnish word for Finland, Suomi, is also thought probably to derive ultimately from Proto-Baltic *žēmē, though the precise route is debated and proposals usually involve complex processes of borrowing and reborrowing.” ref

“Suomi and its adjectival form suomalainen must come from *sōme-/sōma-. In one proposal, this Finnish word comes from a Proto-Germanic word *sōma-, itself from Proto-Baltic *sāma-, in turn borrowed from Proto-Finnic *šämä, which was borrowed from *žēmē. The Sámi institutions—notably the parliaments, radio and TV stations, theatres, etc.—all use the term Sámi, including when addressing outsiders in Norwegian, Swedish, Finnish, or English. In Norwegian and Swedish, the Sámi are today referred to by the localized form Same.” ref

“The western Uralic languages are believed to spread from the region along the Volga, which is the longest river in Europe. The speakers of Finnic and Sámi languages have their roots in the middle and upper Volga region in the Corded Ware culture. These groups presumably started to move to the northwest from the early home region of the Uralic peoples in the second and third quarters of the 2nd millennium BC. On their journey, they used the ancient river routes of northern Russia. Some of these peoples, who may have originally spoken the same western Uralic language, stopped and stayed in the regions between Karelia, Ladoga and Lake Ilmen, and even further to the east and to the southeast. The groups of these peoples that ended up in the Finnish Lakeland from 1600 to 1500 BCE later “became” the Sámi. The Sámi people arrived in their current homeland some time after the beginning of the Common Era.” ref

“The Sámi language first developed on the southern side of Lake Onega and Lake Ladoga and spread from there. When the speakers of this language extended to the area of modern-day Finland, they encountered groups of peoples who spoke a number of smaller ancient languages (Paleo-Laplandic languages), which later became extinct. However, these languages left traces in the Sámi language (Pre-Finnic substrate). As the language spread further, it became segmented into dialects. The geographical distribution of the Sámi has evolved over the course of history. From the Bronze Age, the Sámi occupied the area along the coast of Finnmark and the Kola Peninsula.” ref

“This coincides with the arrival of the Siberian genome to Estonia and Finland, which may correspond with the introduction of the Finno-Ugric languages in the region. Petroglyphs and archeological findings such as settlements, dating from about 10,000 BCE can be found in Lapland and Finnmark, although these have not been demonstrated to be related to the Sámi people. These hunter-gatherers of the late Paleolithic and early Mesolithic were named Komsa by the researchers.” ref

“The Sámi have a complex relationship with the Scandinavians (known as Norse people in the medieval era), the dominant peoples of Scandinavia, who speak Scandinavian languages and who founded and thus dominated the kingdoms of Norway and Sweden in which most Sámi people live. While the Sámi have lived in Fennoscandia for around 3,500 years, Sámi settlement of Scandinavia does not predate Norse/Scandinavian settlement of Scandinavia, as sometimes popularly assumed. The migration of Germanic-speaking peoples to Southern Scandinavia happened independently and separate from the later Sámi migrations into the northern regions.” ref

“For centuries, the Sámi and the Scandinavians had relatively little contact; the Sámi primarily lived in the inland of northern Fennoscandia, while Scandinavians lived in southern Scandinavia and gradually colonised the Norwegian coast; from the 18th and especially the 19th century, the governments of Norway and Sweden started to assert sovereignty more aggressively in the north, and targeted the Sámi with Scandinavization policies aimed at forced assimilation from the 19th century.” ref

“Before the era of forced Scandinavization policies, the Norwegian and Swedish authorities had largely ignored the Sámi and did not interfere much in their way of life. While Norwegians moved north to gradually colonize the coast of modern-day Troms og Finnmark to engage in an export-driven fisheries industry prior to the 19th century, they showed little interest in the harsh and non-arable inland populated by reindeer-herding Sámi. Unlike the Norwegians on the coast who were strongly dependent on their trade with the south, the Sámi in the inland lived off the land. From the 19th century Norwegian and Swedish authorities started to regard the Sámi as a “backward” and “primitive” people in need of being “civilized”, imposing the Scandinavian languages as the only valid languages of the kingdoms and effectively banning Sámi language and culture in many contexts, particularly schools.” ref

“The Far North was a fabled territory to city dwellers in “civilized,” temperate Europe. Classical Greek and Roman geographers told their readers that north beyond civilized settlements roamed cannibals; dog-headed people who barked; people who hibernated half of the year or spent half the year underwater; people who had no notion of private property, marriage, or laws. Medieval travel writers including Marco Polo repeated the fantastic tales. Meanwhile, the Russian kingdoms of Novgorod and then Moscow developed a trade in expensive furs—sable, fox, and beaver—with northern hunters. By the end of the sixteenth century, Cossacks employed by Russian agents shattered Tatar rule in Sibir and extended the Czar’s sovereignty through a series of fortified trading posts where natives were obliged to pay tribute in the form of furs, receiving “gifts” from “the czar’s exalted hand” in return.” – Shamans and Religion, An Anthropological Exploration in Critical Thinking by Alice Beck Kehoe

“The “gifts” were axes and knives, cloth, beads, tea, sugar, and tobacco, presented with exotic food (Russian bread) and liquor. Superficially, it looked like the Western European trade with American Indians that would develop a century later, except that Russia considered the Siberian nations to be their subjects and enforced tribute with military campaigns. Siberia being an exceedingly large territory, it took Russia a good two centuries to push sovereignty eastward to the Pacific, and then the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 turned the Czar’s rule into Soviet domination.” – Shamans and Religion, An Anthropological Exploration in Critical Thinking by Alice Beck Kehoe

“Russian or Soviet, the conquering power officially classified the non-Russian people as “aliens.” A few “aliens” were formally educated town-dwellers or peasant farmers and could be treated like Russians, many were classified as “nomads” who moved with their herds regularly to seasonal pastures, and others were classified as “wanderers” who hunted and fished apparently (so far as the Russian officials noticed) without fixed movements. Nomads and wanderers were required to turn in annual fur tributes, but the Russian colonial officials let them continue their “alien” customs. “Aliens” who accepted Christian baptism were compelled to settle in Russian outposts. Native women who were married to, or kept as concubines by, Russians expected this, but for native men, it meant leaving their families and occupations of herding or hunting.” – Shamans and Religion, An Anthropological Exploration in Critical Thinking by Alice Beck Kehoe

“For the Russian enterprise, it meant these men ceased to pay fur tribute; therefore, there was little government effort to convert the Siberians until, in 1702, Peter the Great encouraged the Russian Orthodox missionaries to bring soldiers with them to persuade whole villages to accept baptism after the priests burned their shrines and images of spirits. Czar Peter protected the Crown’s revenue by rescinding the rule that converts were freed of fur tribute. Through the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Russian interventions in Siberia became increasingly onerous for the indigenous nations. Siberian families became accustomed to trade for metal kettles as well as axes, knives, and traps, and purchased flour, tea, and sugar that were regularly eaten. Liquor and tobacco remained important constituents of the fur trade.” – Shamans and Religion, An Anthropological Exploration in Critical Thinking by Alice Beck Kehoe

“The “aliens” were subject to labor taxes including road building, carting, providing firewood to heat the trading posts, and assisting officials. An 1822 law formally recognized a policy of indirect rule with Russian officials governing through designated male “clan elders” regardless of whether the people had clans. These appointees administered customary law and relieved some of the burdens of tribute collecting. A designated “clan elder” could be a shaman, or simply the oldest active responsible man in a district. Historian Yuri Slezkine (1994:88) considers this attitude toward the empire’s “aliens” to reflect nineteenth-century Western intellectuals’ belief that uncivilized (i.e., not living in cities) peoples are indicative of the early condition of human-kind, incapable of performing the obligations and rights of citizens. Superficially, the policy seems benign, but in fact, it was racist, denying the social achievements of the small nations adapted to the harsh environments of the north.” – Shamans and Religion, An Anthropological Exploration in Critical Thinking by Alice Beck Kehoe

“For long periods of time, the Sámi lifestyle thrived because of its adaptation to the Arctic environment. Indeed, throughout the 18th century, as Norwegians of Northern Norway suffered from low fish prices and consequent depopulation, the Sámi cultural element was strengthened, since the Sámi were mostly independent of supplies from Southern Norway.” ref

Christianization of the Sámi people

“The Christianization of the Sámi people in Norway and Sweden–Finland took place in stages during a several centuries long process. The Sámi were Christianized in a similar way in both Norway and Sweden–Finland. During the 19th century, the pressure of Christianization of the Sámi increased, with some Sámi adopting Laestadianism. With the introduction of seven compulsory years of school in 1889, the Sámi language and traditional way of life came increasingly under pressure from forced cultural normalization. Strong economic development of the north also ensued, giving Norwegian culture and language higher status.” ref, ref

“There were Christian missionaries in Sápmi already during the Roman Catholic middle ages, and Christianity co-existed with traditional Sámi shamanism. In 1389, the Sami Margareta (missionary) traveled south to request Christian missionaries. It was however not until the 17th-century, when the kingdoms of Denmark-Norway and Sweden started to colonize Sápmi, that Christianity truly made its presence known.” ref

“In the Kingdoms of Denmark-Norway, the Sami religion was banned on death penalty as witchcraft. During the 17th-century, the persecution of the followers of Sami religion were more intensely persecuted than before by Christian missionaries, and several Sami were persecuted for sorcery because they practiced the Sami religion. A fifth of all charged with sorcery in Norway are estimated to have been Pagan Sami. During the 17th-century, a more intense Christian mission was launched in Norway to convert the Sami people to Christianity.” ref

“However, there was an awareness’ that this campaign only caused the Sami to behave outwardly as Christians and kept practicing their own religion in secrecy. This fact was pointed out by the Sami missionaries, who stated that it would not be possible to truly convert the Sami people if the Sami religion could not even be discussed, which was not possible when Pagans were afraid to be accused of witchcraft if they admitted to be Pagans.” ref

“The Protestant church was hostile to Sámi shamanism, which it considered to be Pagan idolatry, and wished to exterminate it and Christianize the Sámi people, in parallel with the royal powers wishing to assert their political dominance over the territory and use its economic resources. In the first half of the 17th-century, churches were built in Sápmi by the order of king Charles IX of Sweden, and the Sámi people were compelled to subject themselves to the law of Sweden by attending them. They were however silently allowed to practice Sámi shamanism in private until the second half of the 17th-century, when Swedish authorities forced them to abandon their religion, burning their Sámi drums, banning the joik singing and forcing them to subject to the doctrine of the church both in public and private.” ref

“In the 18th-century, the Christian mission among the Sami in Norway achieved actual success, after the Christian missionaries convinced the authorities to grant the Sami amnesty from the witchcraft law, which made it possible for Pagans to openly discuss their religion without the risk of getting arrested for witchcraft. In parallel, the Pietist Mission in Copenhagen sent the missionary Thomas von Westen to the Norwegian Sami people in Finnmarken where he was active in 1716-1727. Thomas von Westen used a new method. Instead of doing as the previous missionaries and force the Sami to practice outward Christianity, such as to attend church, he focused on personal theological persuasion. It was he who convinced the authorities to grant declare the Sami religion no longer illegal: he then informed himself of the religion, and convinced the Sami to convert with a focus on the idea of personal conviction and confession, which proved very efficient.” ref

“The Sámi people still continued to practice Sámi shamanism in secrecy until the second half of the 18th-century, when missionaries of first the Pietism and then eventually the Laestadianism sect had true success in their mission and the Sámi people converted to Christianity. The mission of Thomas von Westen in Norway proved so efficient that the Swedish Pietists under Daniel Djurberg made use of it during their mission among the Sami in Sweden. In contrast to the coercive 17th-century mission, which forced the Sami to outward Christianity, the 18th-century Pietist mission appears to have been truly successful, although the conversion progressed slowly. Around the 1770s, the Sami people were reportedly Christian, talked about the Sami religion as the religion of their ancestors rather than their own, and were reported to have good knowledge about Christianity by the Sami priests. The Christian mission among the Sami did however continue until as late as the mid 19th-century, when Laestadianism became very successful among the Sami people.” ref

“On the Swedish and Finnish sides, the authorities were less militant, although the Sámi language was forbidden in schools and strong economic development in the north led to weakened cultural and economic status for the Sámi. From 1913 to 1920, the Swedish race-segregation political movement created a race-based biological institute that collected research material from living people and graves. Throughout history, Swedish settlers were encouraged to move to the northern regions through incentives such as land and water rights, tax allowances, and military exemptions.” ref

“The strongest pressure took place from around 1900 to 1940, when Norway invested considerable money and effort to assimilate Sámi culture. Anyone who wanted to buy or lease state lands for agriculture in Finnmark had to prove knowledge of the Norwegian language and had to register with a Norwegian name. This caused the dislocation of Sámi people in the 1920s, which increased the gap between local Sámi groups (something still present today) that sometimes has the character of an internal Sámi ethnic conflict.” ref

“In 1913, the Norwegian parliament passed a bill on “native act land” to allocate the best and most useful lands to Norwegian settlers. Another factor was the scorched earth policy conducted by the German army, resulting in heavy war destruction in northern Finland and northern Norway in 1944–45, destroying all existing houses, or kota, and visible traces of Sámi culture. After World War II, the pressure was relaxed, though the legacy was evident into recent times, such as the 1970s law limiting the size of any house Sámi people were allowed to build.” ref

“The controversy over the construction of the hydro-electric power station in Alta in 1979 brought Sámi rights onto the political agenda. In August 1986, the national anthem (“Sámi soga lávlla“) and flag (Sámi flag) of the Sámi people were created. In 1989, the first Sámi parliament in Norway was elected. In 2005, the Finnmark Act was passed in the Norwegian parliament giving the Sámi parliament and the Finnmark Provincial council a joint responsibility of administering the land areas previously considered state property. These areas (96% of the provincial area), which have always been used primarily by the Sámi, now belong officially to the people of the province, whether Sámi or Norwegian, and not to the Norwegian state.” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

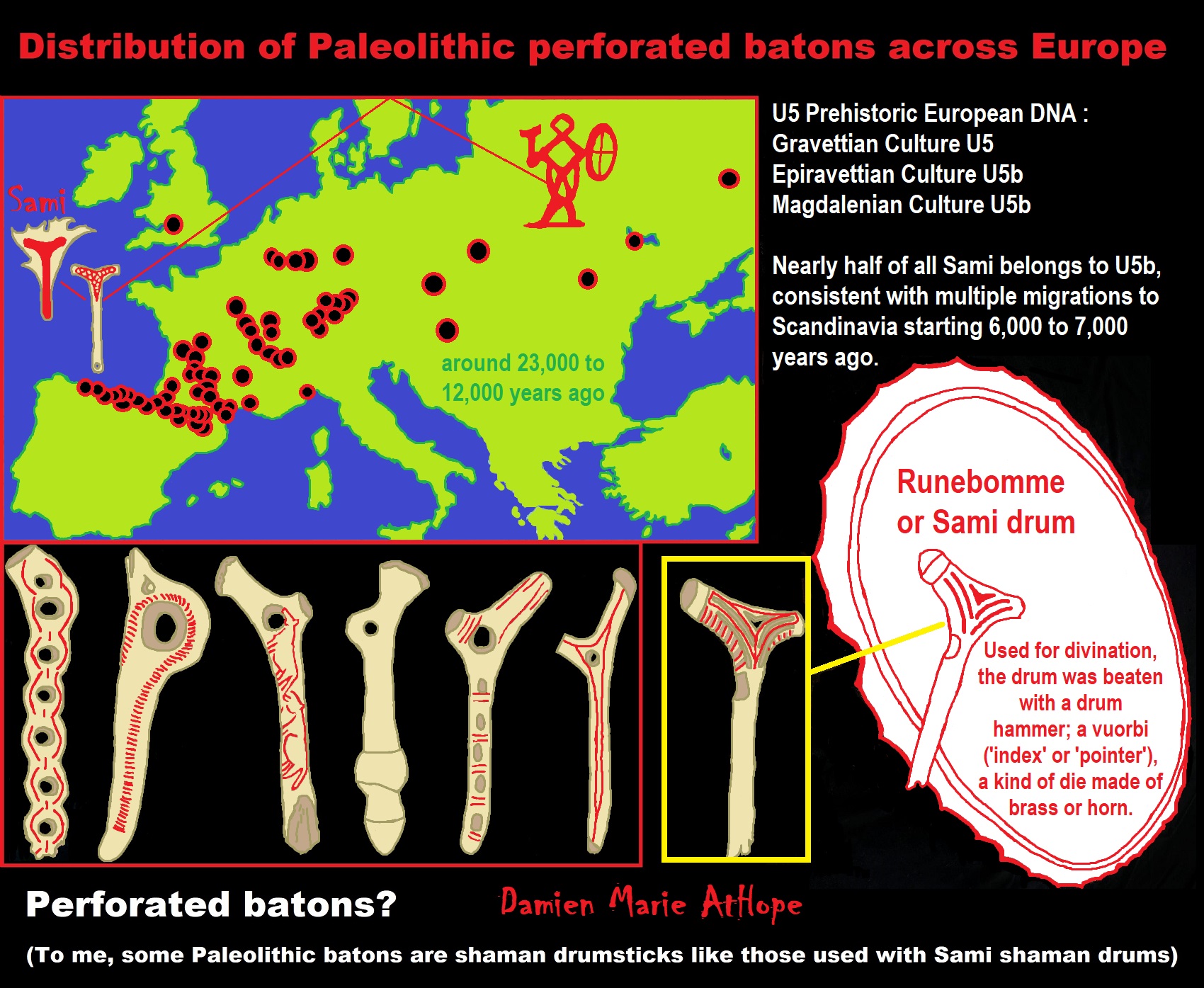

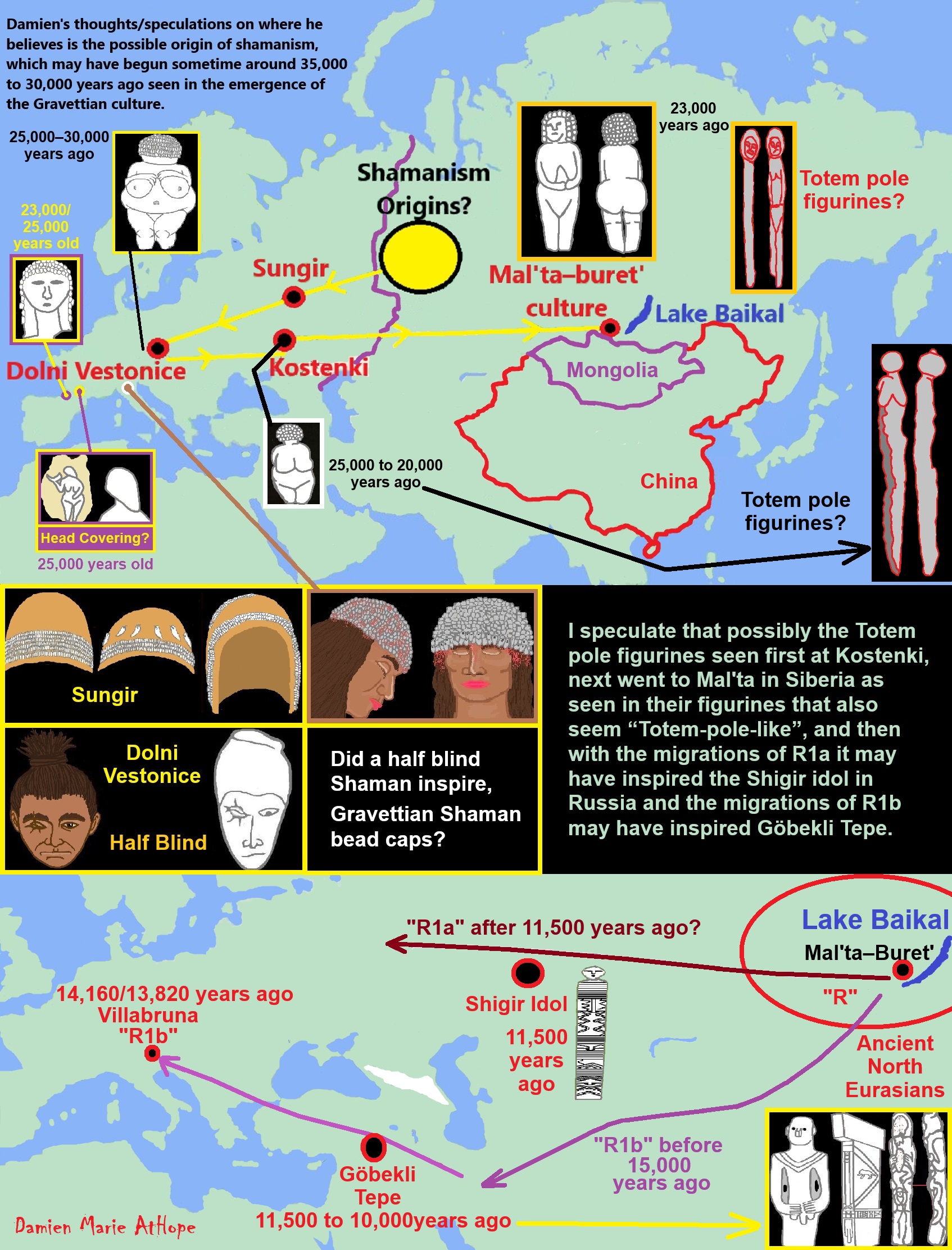

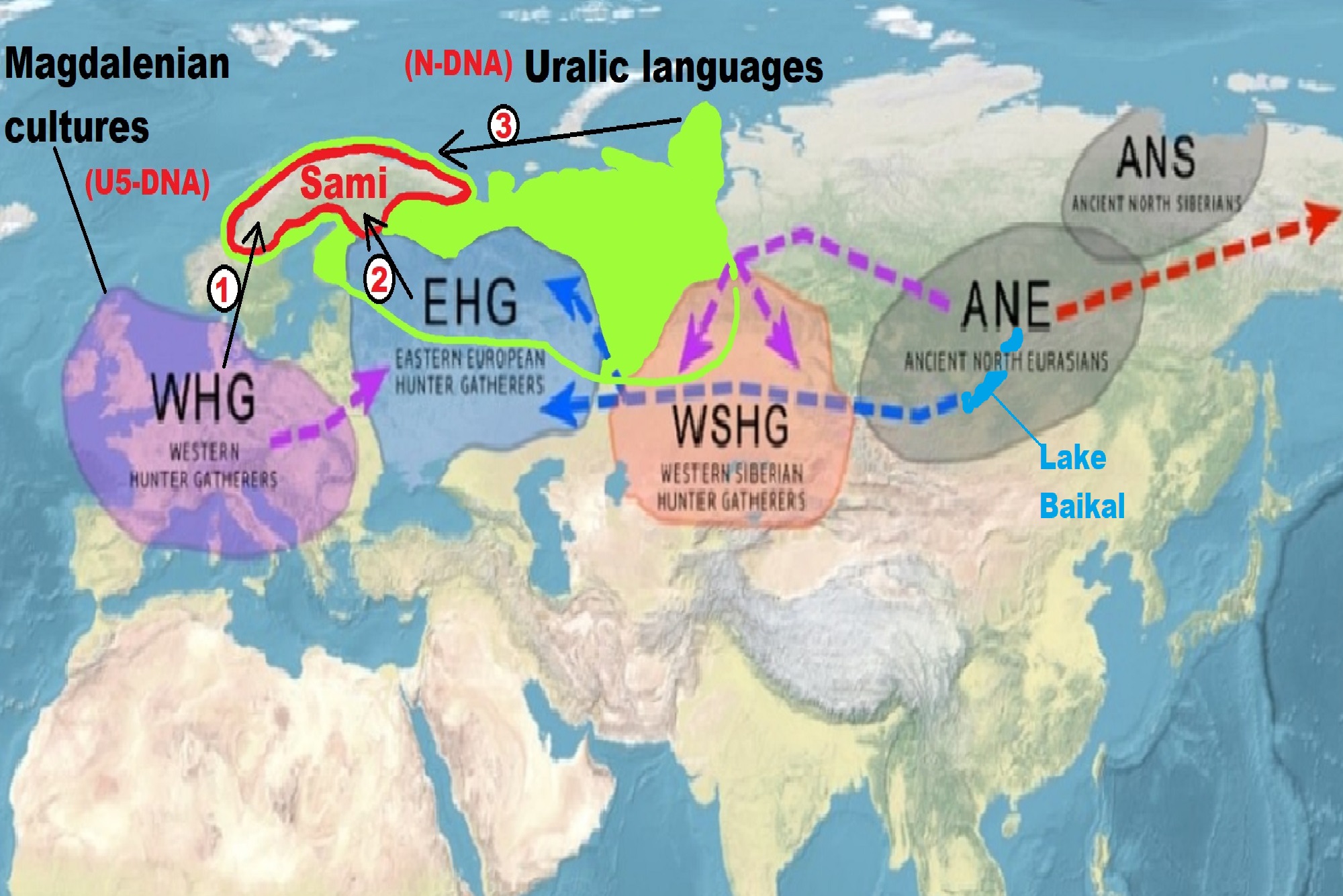

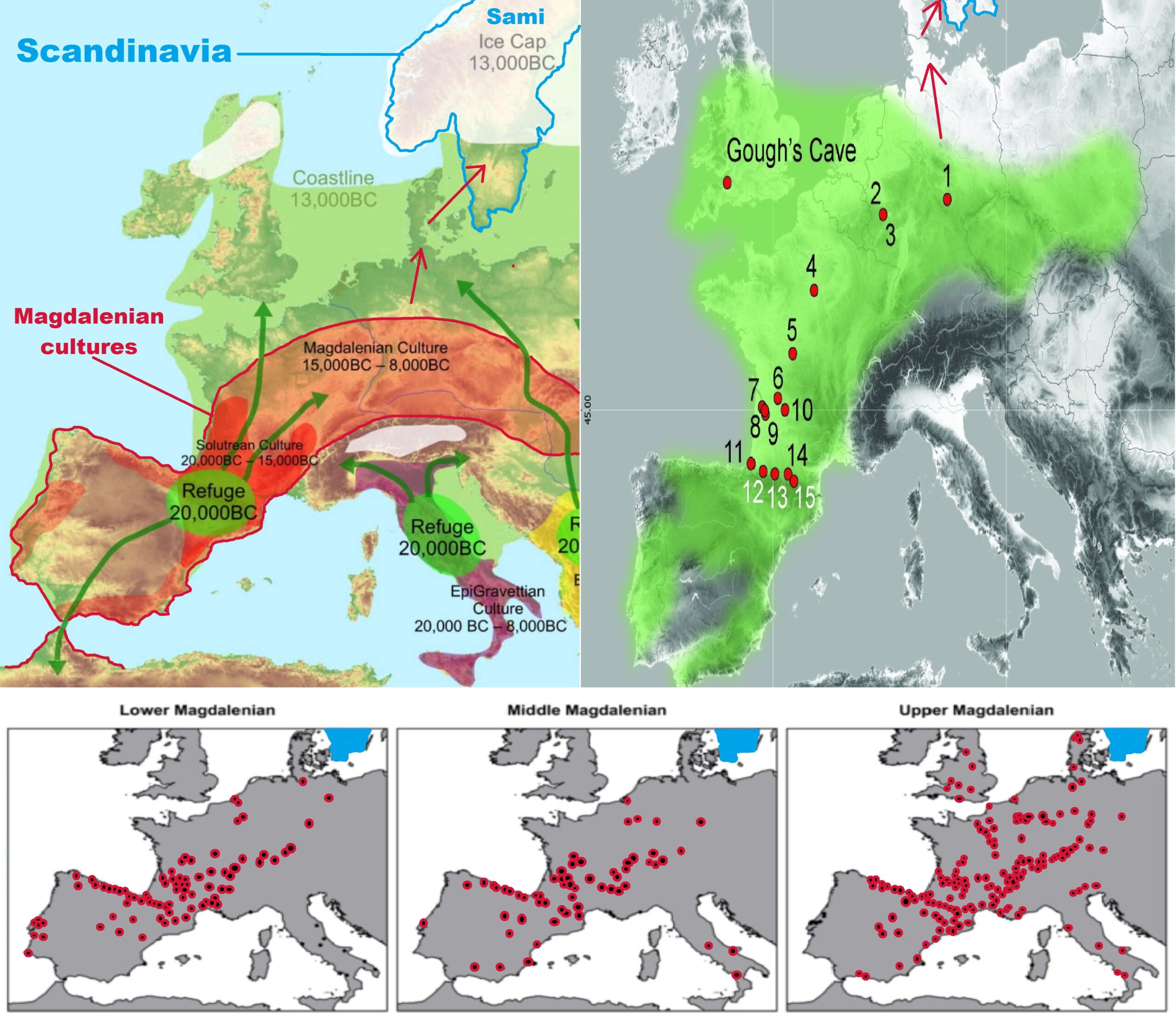

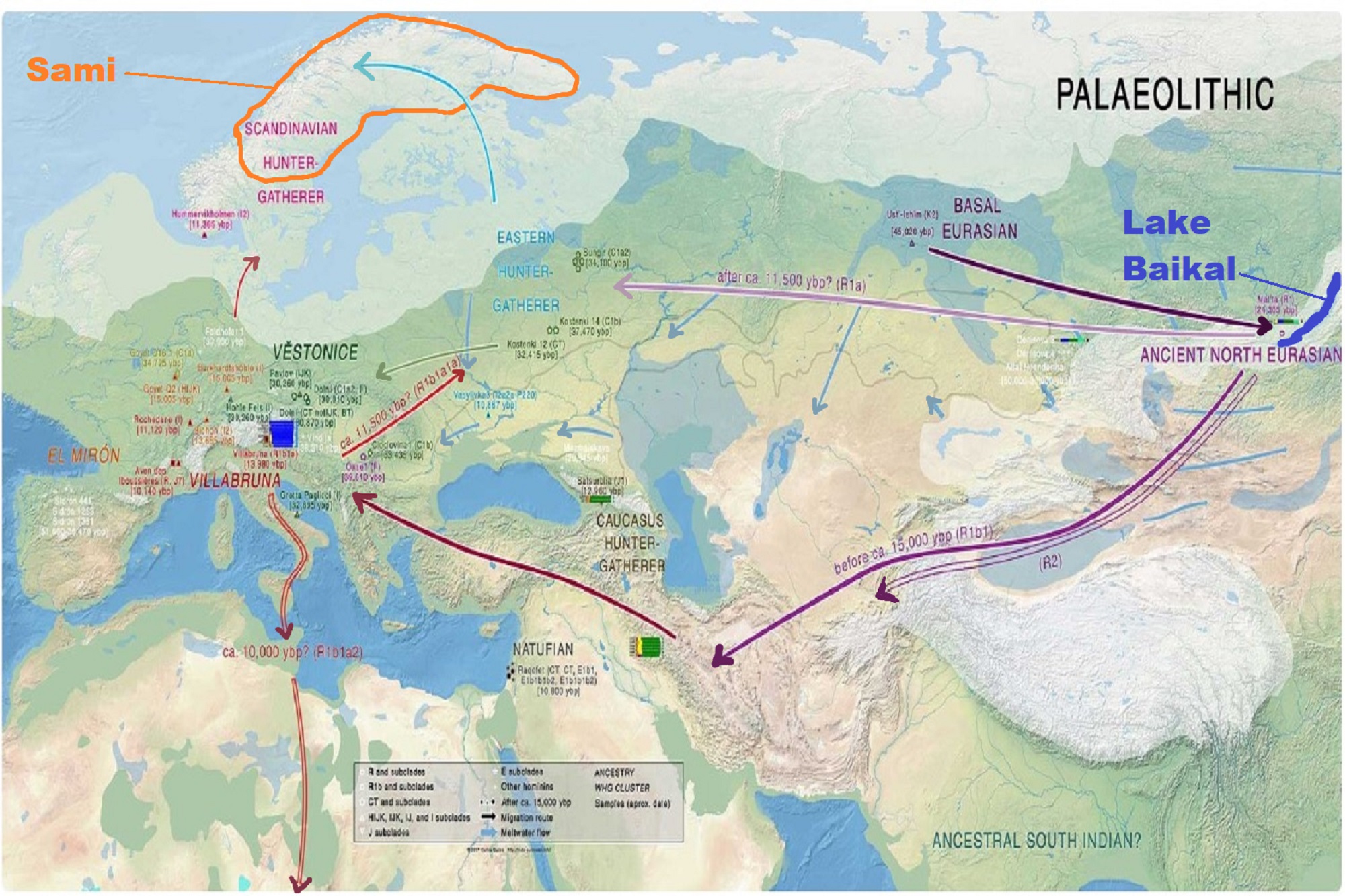

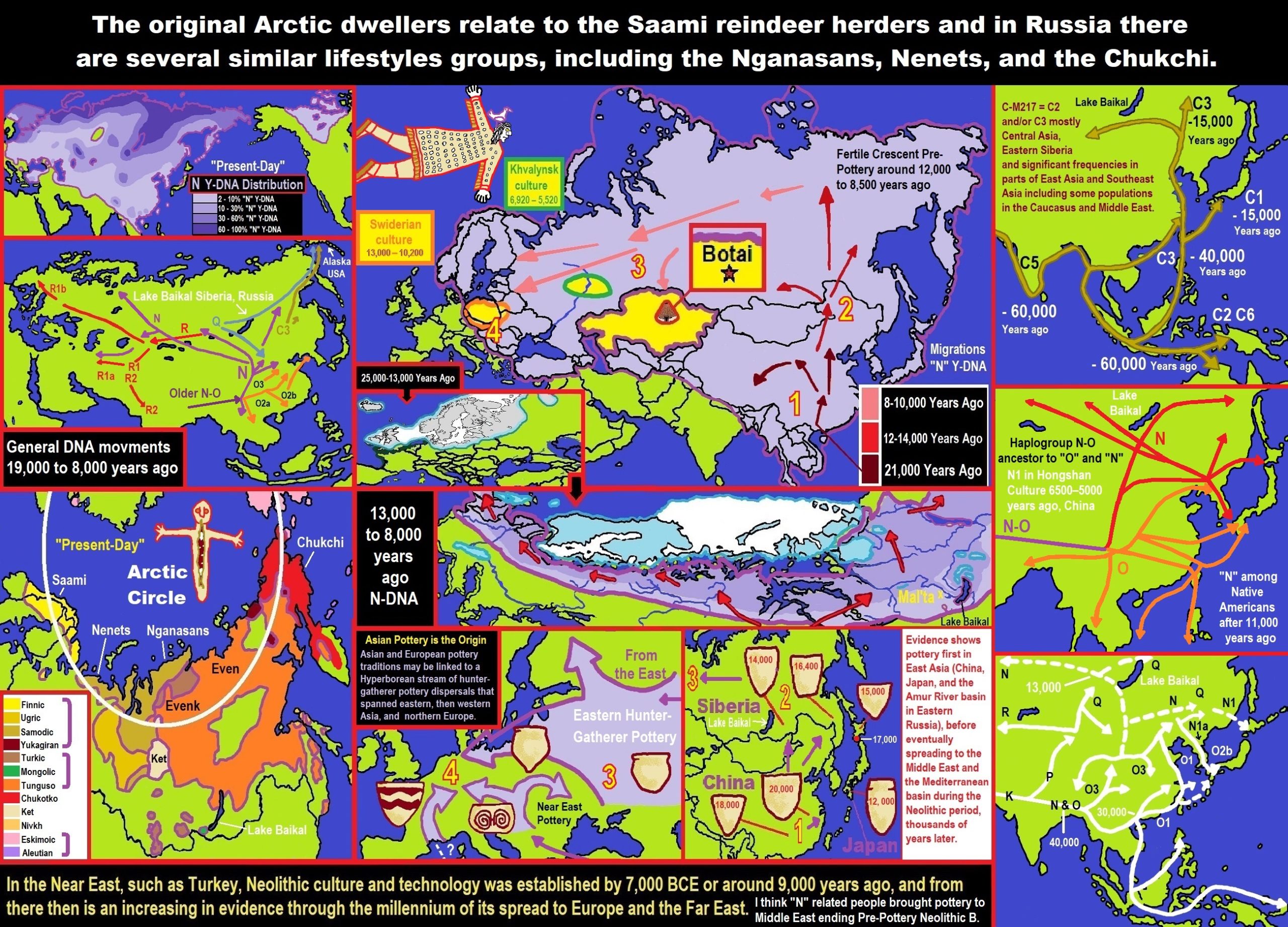

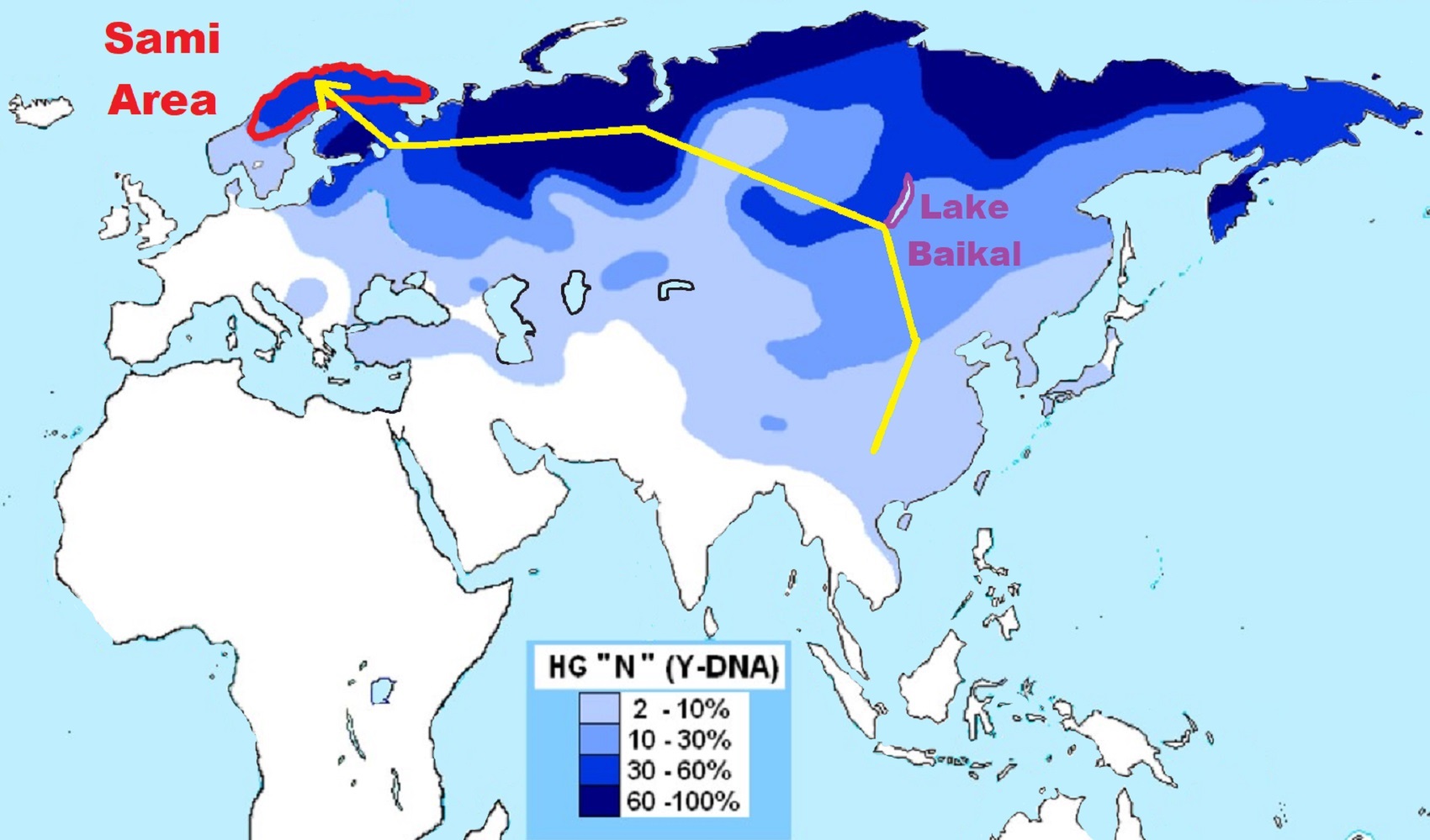

“Aurignacian (43,000 to 26,000 years ago), Gravettian (33,000 to 21,000 years ago), Magdalenian (17,000 to 12,000 years ago), and Sami (Haplogroup N Y-DNA) at least by 3,500 years ago until the fifteenth century) were all nomadic peoples of Ancient Europe. N1c correlates closely with the distribution of the Finno-Ugrian languages. The Sami languages are thought to have split from their common ancestor about 3300 years ago.” ref, ref

“Mitochondrial DNA studies of Sami people, haplogroup U5 are consistent with multiple migrations to Scandinavia from Volga-Ural region, starting 6,000 to 7,000 years before present.” ref

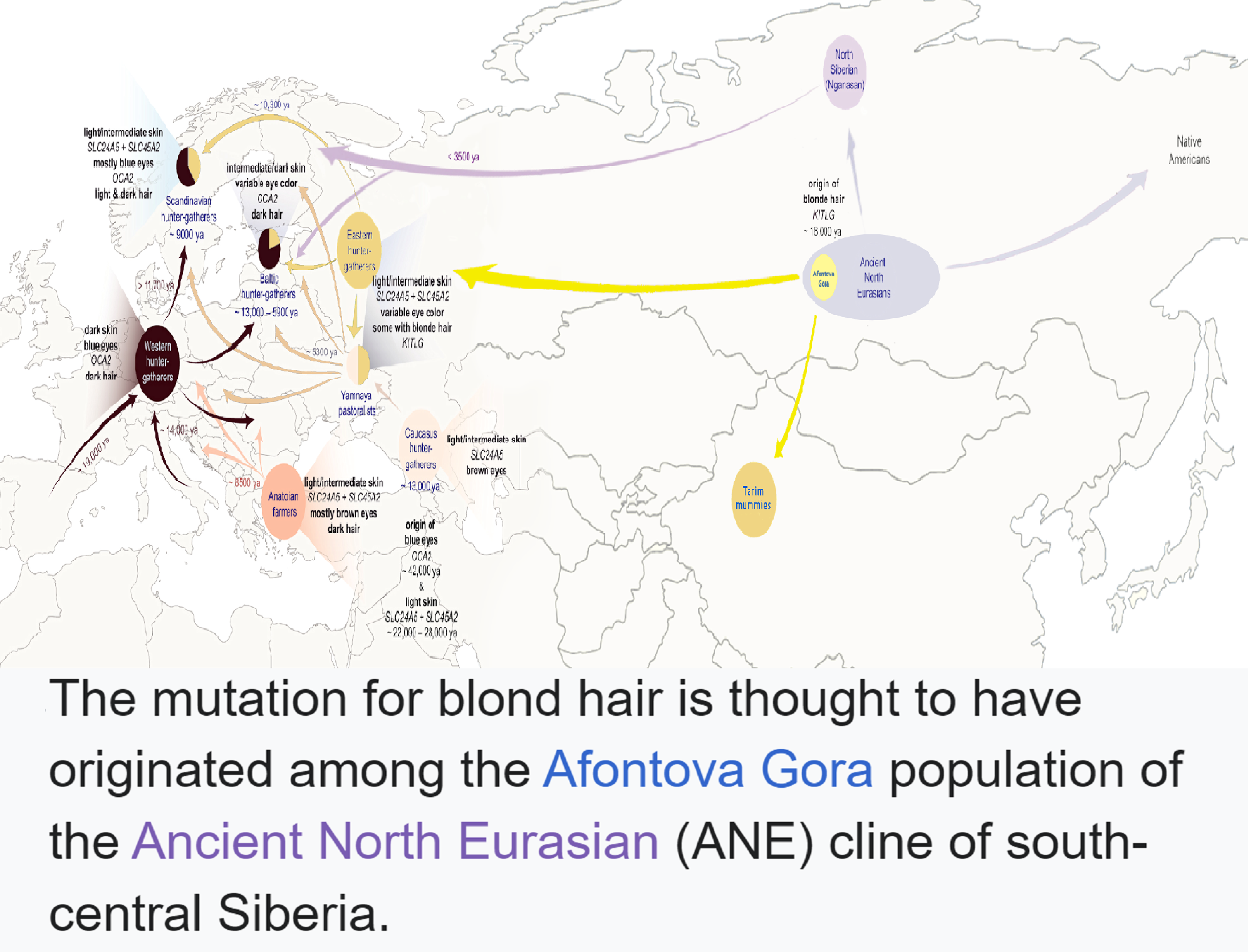

“Nearly half of all Sami and one-fifth of Finnish maternal lineages belong to U5. U5 arrived in Europe with the Gravettian and appears to have been a major maternal lineage among the Paleolithic European hunter-gatherers and even the dominant lineage during the European Mesolithic at more than 80%. Among 16 Gravettian samples, six belonged to U5.” ref

“U5b1b1 arose approximately 10,000 years ago, over two millennia after the end of the Last Glaciation, when the Neolithic Revolution was already underway in the Near East. Despite this relatively young age, U5b1b1 is found scattered across all of Europe and well beyond its boundaries. The Saami, who live in the far European North and have 48% of U5 and 42% of V lineages, belong exclusively to the U5b1b1 subclade. Amazingly, the Berbers of Northwest Africa also possess that U5b1b1 subclade and haplogroup V. How could two peoples separated by some 6,000 km (3,700 mi) share such close maternal ancestry? The Berbers also have other typically Western European lineages such as H1 and H3, as well as African haplogroups like M1, L1, L2, and L3. The Saami and the Berbers presumably descend from nomadic hunter-gatherers from the Franco-Cantabrian refugium who recolonized Europe and North Africa after the LGM.” ref

“The journey of U5b1b1 didn’t stop there. The Fulbe of Senegal were also found to share U5b1b1b with the Berbers, surely through intermarriages. More impressively, the Yakuts of eastern Siberia, who have a bit under 10% of European mtDNA (including haplogroups H, HV1, J, K, T, U4, U5, and W), also share the exact same deep subclade (U5b1b1a) as the Saami and the Berbers.” ref

Genetic Studies on Sami

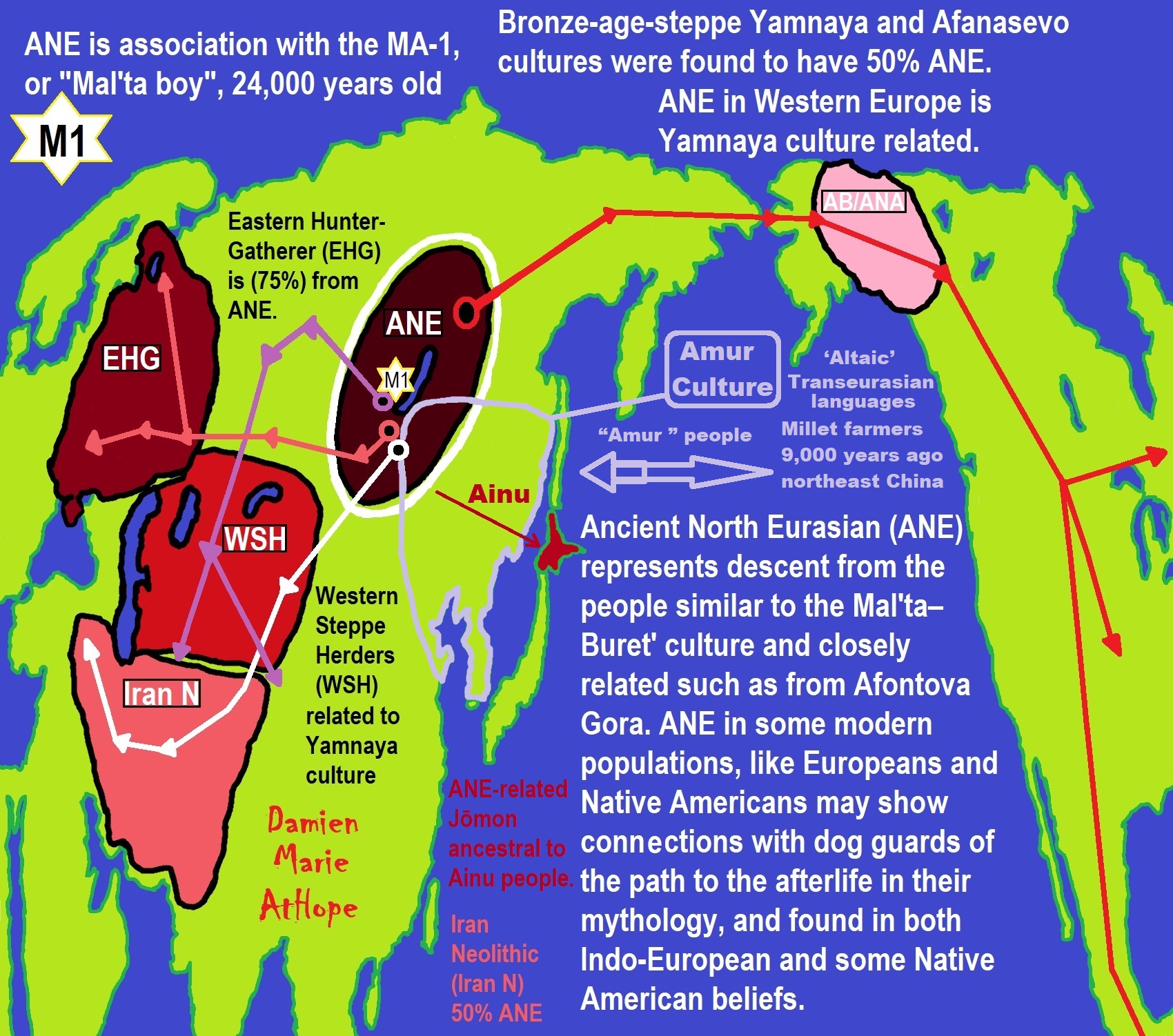

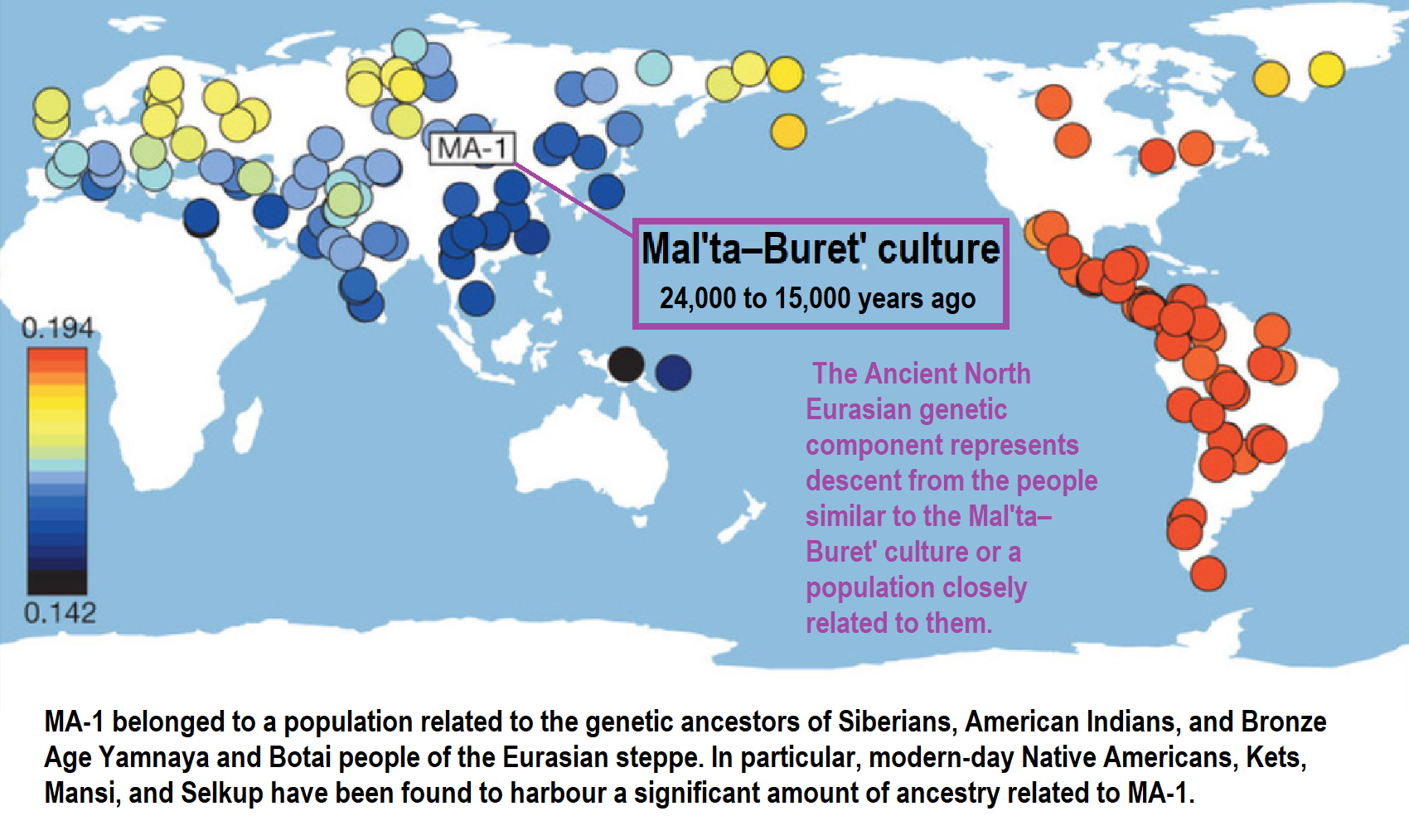

“Genetic studies on Sami are the genetic research that has been carried out on the Sami people. The Sami languages belong to the Uralic languages family of Eurasia. Siberian origins are still visible in the Sámi, Finns, and other populations of the Finno-Ugric language family. An abundance of genes has journeyed all the way from Siberia to Finland, a recent study indicates. As late as the Iron Age, people with a genome similar to that of the Sámi people lived much further south in Finland compared to today. The first study on the DNA of the ancient inhabitants of Finland has been published, with results indicating that a copious number of Siberian genetic variants are present in modern Sami populations.” ref

“Genetic material from remains associated with Western Siberian hunter-gatherers has been found in the inhabitants of the Kola Peninsula from as far back as approximately 4,000 years ago, later spreading also to Finland. The study also corroborates the assumption that people genetically similar to the Sámi lived much further south than currently. The Western Siberian hunter-gatherers (WSHG) themselves harbored about 30% EHG (Eastern European Hunter-Gatherers) ancestry, 50% ANE (Ancient North Eurasian) ancestry, and 20% East Asian ancestry, therefore mostly European-related ancestry, and also resembled the earlier Botai samples of northern Central Asia. The genetic samples compared in the study were collected from human bones found in a 3,500-year-old burial place in the Kola Peninsula and the 1,500-year-old lake burial site at Levänluhta in South Ostrobothnia, Finland. All of the samples contained identical Siberian genes.” ref

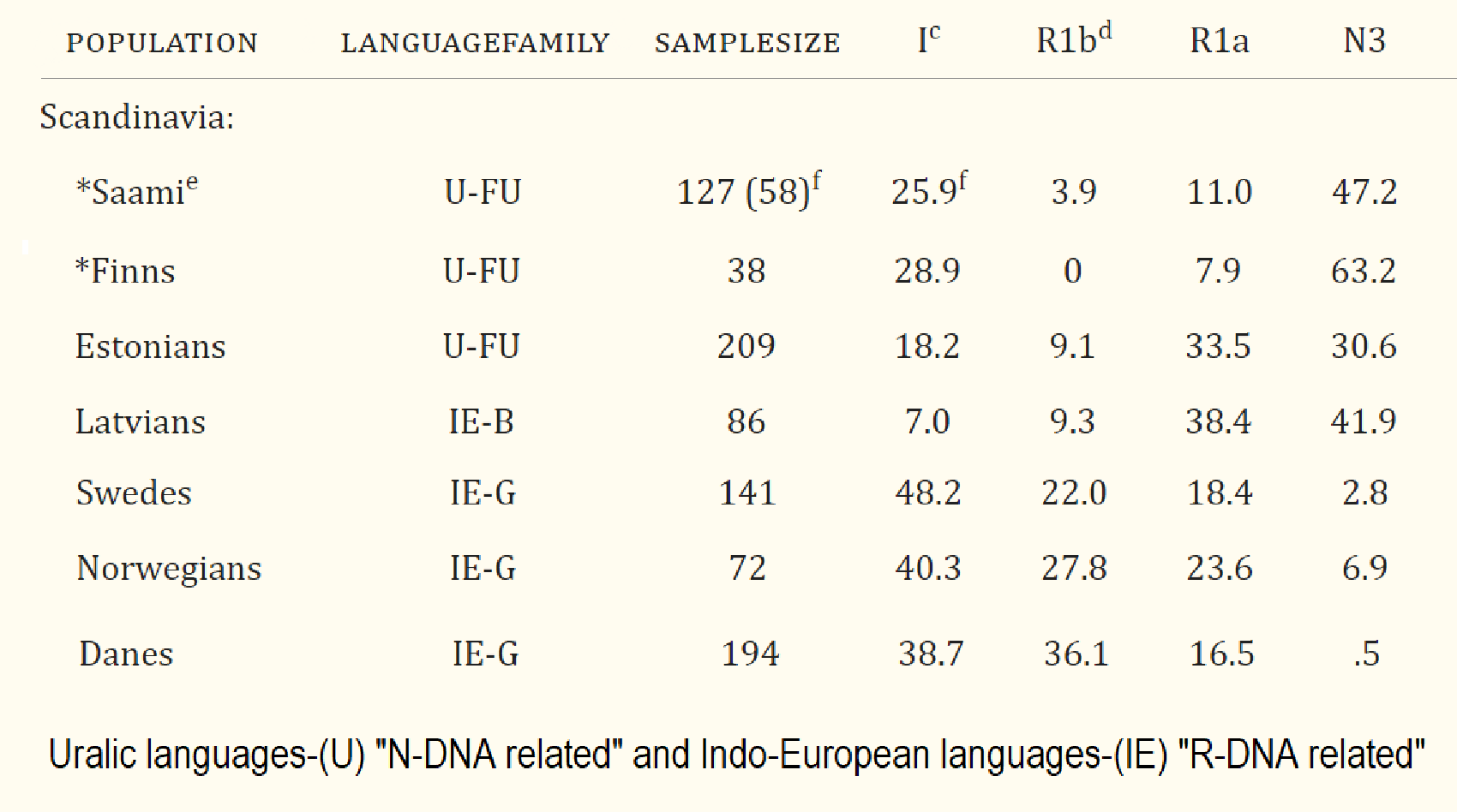

Sami Y-DNA

“Three Y chromosome haplogroups dominate the distribution among the Sami: N1c (formerly N3a), I1 – today is more commonly known as I-M253 – and R1a, at least in the study carried out by K. Tambets et al. in 2004. The most common haplogroup among the Sami is N1c, with I1 as a close second according to that study. Haplogroup R1a in Sami is mostly seen in the Swedish Sami and Kola Sami populations, with a low level among the Finnish Sami according to Tambets and colleagues, a finding that suggests that N1c and R1a probably reached Fennoscandia from eastern Europe, where these haplogroups can be found in high frequencies. In Finland, there is also a general difference within the Finnish population between eastern and western Finland, where the eastern show a dominance of N-haplogroup and the west a dominance of I-haplogroup, where the latter is explained by a migration from southern parts of today’s Norway and Sweden over to Finland as we know it today.” ref

“But the spread of R1a-haplogroup amongst Sami in Sweden shows a big span from 10.1% to 36.0%, with an average of 20%, to be compared with Sami in Finland with a span from 9% to 9.9% Because Sami groups in Sweden show differences between haplogroups – such as U5b and V even thought that are mtDNA-groups – in the south of Sweden and in the north of the country (see below), the spread of Y-haplogroups such as R1a amongst groups of Sami in Sweden might be significant as well. No such study has yet been done though.” ref

“However the two haplogroups R1a and N1c have a distinctly distribution when it comes to linguistics. R1a is common among Eastern Europeans speaking Indo-European languages, while N1c correlates closely with the distribution of the Finno-Ugrian languages. For example, N1c is common among the Finns, while haplogroup R1a is common among all the neighbours of the Sami.” ref

“Haplogroup I1 is the most common haplogroup in Sweden, and the Jokkmokk Sami in Sweden have a similar structure to Swedes and Finns for haplogroup I1 and N1c. Haplogroup I-M253 in Sami is explained by immigration (of men) during the 14th century. That is quite late in Sami history bearing in mind that an distinctive Sami culture can be traced and first observed back to 1000 BCE. The Sami languages are thought to have split from their common ancestor about 3300 years ago.” ref

Sami mtDNA

“Classification of the Sami mtDNA lineages revealed that the majority are clustered in a subset of the European mtDNA pool. The two haplogroups V and U5b dominate, between them accounting for about 89% of the total. This gives the Sami regions the highest level of Haplogroups V and U5b thus far found. Both haplogroups V and U5b are spread at moderate frequencies across Europe, from Iberia to the Ural Mountains. Haplogroups H, D5, and Z represent most of the remaining averaged total. Overall 98% of the Sami mtDNA pool is encompassed within haplogroups V, U5b, H, Z, and D5. Local frequencies among the Sami vary.” ref

“The divergence time for the Sami haplogroup V sequences was estimated by Max Ingman and Ulf Gyllensten at 7600 YBP (years before present), and for U5b1b1 as 5500 YBP amongst Sami and 6600 YBP amongst Sami and Finns. This suggests to them an arrival in the region soon after the retreat of the glacial ice. Other research on Sami shows that most of them do not belong to the mtDNA Haplogroup I (not to be confused for the aforementioned paternal Haplogroup I-M170) that is shared by many Finnic peoples.” ref

Sami U5b

“The great majority of Sami belong to U5b Haplogroup U (mtDNA) even though a small proportion falls into U4. The percentage of total Sami mtDNA samples tested by K. Tambets and her colleagues (published in 2004) which were U5b ranged from 56.8% in Norwegian Sami to 26.5% in Swedish Sami. In research made by M. Ingman and U. Gyllensten in 2006 is a slightly different setting shown: Norwegian Sami belongs to U5b as well as U5b1b1 to 56.8%, Finnish Sami with 40.6%, Northern Sami in Sweden to 35.5% and Southern Sami in Sweden within reindeer herding to 23.9% while Southern Sami in Sweden outside of reindeer herding/other occupation belong to U5b to 16.3% and to U5b1b1 to 12%.” ref

“Sami U5b falls into subclade U5b1b1. The Sami U5b1b1 sub-clade is present in many different populations, e.g. 3% or higher frequencies in Karelia, Finland, and Northern-Russia. The Sami U5b1 motif is additionally found in very low frequencies for instance in the Caucasus region, however this is explained as recent migration from Europe. However, 38% of the Sami U5b1b1 mtDNAs have haplotype so far exclusive to the Sami, containing a transition at np 16148. Alessandro Achilli and colleagues noted that the Sami and the Berbers share U5b1b, which they estimated at 9,000 years old, and argued that this provides evidence for a radiation of the haplogroup from the Franco-Cantabrian refuge area of southwestern Europe.” ref

“M. Engman’s and U. Gyllensten’s studie on mtDNA amongst Sami in Scandinavia also reveals that haplogroup H is 15.2% within the Sami traditional group in the south of Sweden, and 34.8% amongst Southern Sami in Sweden, and as high as 44.6% amongst Southern non-traditional Sami in Sweden, but just 2.6% amongst Northern Sami in Sweden, and 2.9 within the Sami group in Finland and amongst Sami in Norway to 4.7%. That result points in the direction that South Sami in Sweden have been more exposed to and/or intermarried the continental European haplogroup H earlier, and much more frequent, than Sami in the north of Sweden, in Finland and in Norway, which can be explained by Scandinavian/Swedish settlers that migrated into Southern Sami areas in Sweden from areas like Mälardalen.” ref

Sami V

“The divergence time for the Sami haplogroup V sequences is estimated by M. Ingman and U. Gyllensten at 7,600 years ago. But there is a difference within the Sami group in Sweden according to their study. North Sami (Sami in the North of Swedish Lapland) belong to haplogroup V with 58.6% and South Sami (Sami in the South of Swedish Lapland) within reindeer herding to 37.0% and South Sami outside reindeer herding/other occupation to 8.7%. That can be compared with Sami in Norway that has a 33.1% belonging to haplogroup V and Sami in Finland to 37.7%. Sami in Finland and South Sami within reeinder herding in Sweden have the same percentage belonging to haplogroup V.” ref

“But according to K. Tambets’ et al. study is haplogroup V the most frequent haplogroup in the Swedish Sami and is present at significantly lower frequencies in Norwegian and Finnish subpopulations. Note though, that in the study made by K. Tambet’s et al. has no differentiation between Sami in the north and the south of Sweden been made, which otherwise probably would change the outcome of their study. Torroni and colleagues have suggested that the spread of haplogroup V in Scandinavia and in eastern Europe is due to its late Pleistocene/early Holocene expansion from a Franco-Cantabrian glacial refugium.” ref

“However subsequent studies found that haplogroup V is also significantly present in eastern Europeans. Furthermore, haplogroup V lineages with HVS-I transitions 16153 and 16298 that are frequent in the Sami population are much more widespread in eastern than in western Europe. So haplogroup V might have reached Fennoscandia via central/eastern Europe. Such a scenario is indirectly supported by the absence, among the Sami, of the pre-V mtDNAs that are characteristic of southwestern Europeans and northwestern Africans.” ref

Sami Z

“Haplogroup Z is found at low frequency in the Sami and Northern Asian populations but is virtually absent in Europe. Several conserved substitutions group the Sami Z lineages with those from Finland and the Volga-Ural region of Russia. The estimated dating of the lineage at 2700 years suggests a small, relatively recent contribution of people from the Volga-Ural region to the Sami population.” ref

“Haplogroup Z is most frequent in Northeastern Asia. It is also present in Siberian populations as well as in the region of Volga-Ural, as just mentioned. Subhaplogroup Z1 is present in lineages in Western Asia and Northern Europe as well as in the Koryak and Itel’men populations. Interestingly enough is haplogroup Z most frequent amongst maritim Koryaks with just a bit over 10%, but is not at all present in reindeer-herding Koryaks. The Itel’men and Koryak populations live on the Kamchatka peninsula, the former in the south and the latter in the very north.” ref

“In Sámi shamanism, the noaidi used the drum to get into a trance, or to obtain information from the future, or other realms. The drum was held in one hand, and beaten with the other. While the noaidi was in trance, his “free spirit” was said to leave his body to visit the spirit-world. When used for divination, the drum was beaten with a drum hammer; a vuorbi (‘index’ or ‘pointer’), a kind of die made of brass or horn, would move around on the drumhead when the drum was struck. Future events would be predicted according to the symbols upon which the vuorbi stopped on the membrane.

The patterns on the drum membrane reflect the worldview of the owner and his family, both in religious and worldly matters, such as reindeer herding, hunting, householding, and relations with their neighbors and the non-Sámi community.” ref

Sami Y-DNA: “three haplogroups N1c, I1, and R1a dominate”

N1c (formerly N3a ), I1 (I-M253), R1a, and R1b.

Sami – mtDNA: “two haplogroups V and U5b dominate”

V, U5b, H, Z, and D5. ref

DNA Explained

DNA haplogroups I1 and U5b are related to Magdalenians predominantly Y-DNA haplogroup I and HIJK with all samples of mtDNA belonging to U, including five samples of U8b and one sample of U5b. (Western Hunter-Gatherer – WHG) were predominantly Y-DNA haplogroup I and mtDNA haplogroup U5. ref, ref

Y-DNA haplogroup R1a and R1b and mt-DNA U5 and C1 were found in Eastern Hunter-Gatherers (EHG). The EHG male of Samara (5650-5550 BCE) carried Y-haplogroup R1b1a1a* and mt-haplogroup U5a1d. The other EHG male, buried in Karelia (5500-5000 BCE) carried Y-haplogroup R1a1 and mt-haplogoup C1g. ref

“Haplogroup N1 (N1a, N1c) was found in ancient bones of Liao civilization (at least by 6,200 BCE or around 8,200 years ago):

- Niuheliang (Hongshan Culture, 6500–5000 years ago) 66.7%

- Halahaigou (Xiaoheyan Culture, 5000–4200 years ago) 100.0%

- Dadianzi (Lower Xiajiadian culture, 4200–3600 years ago) 60.0%” ref

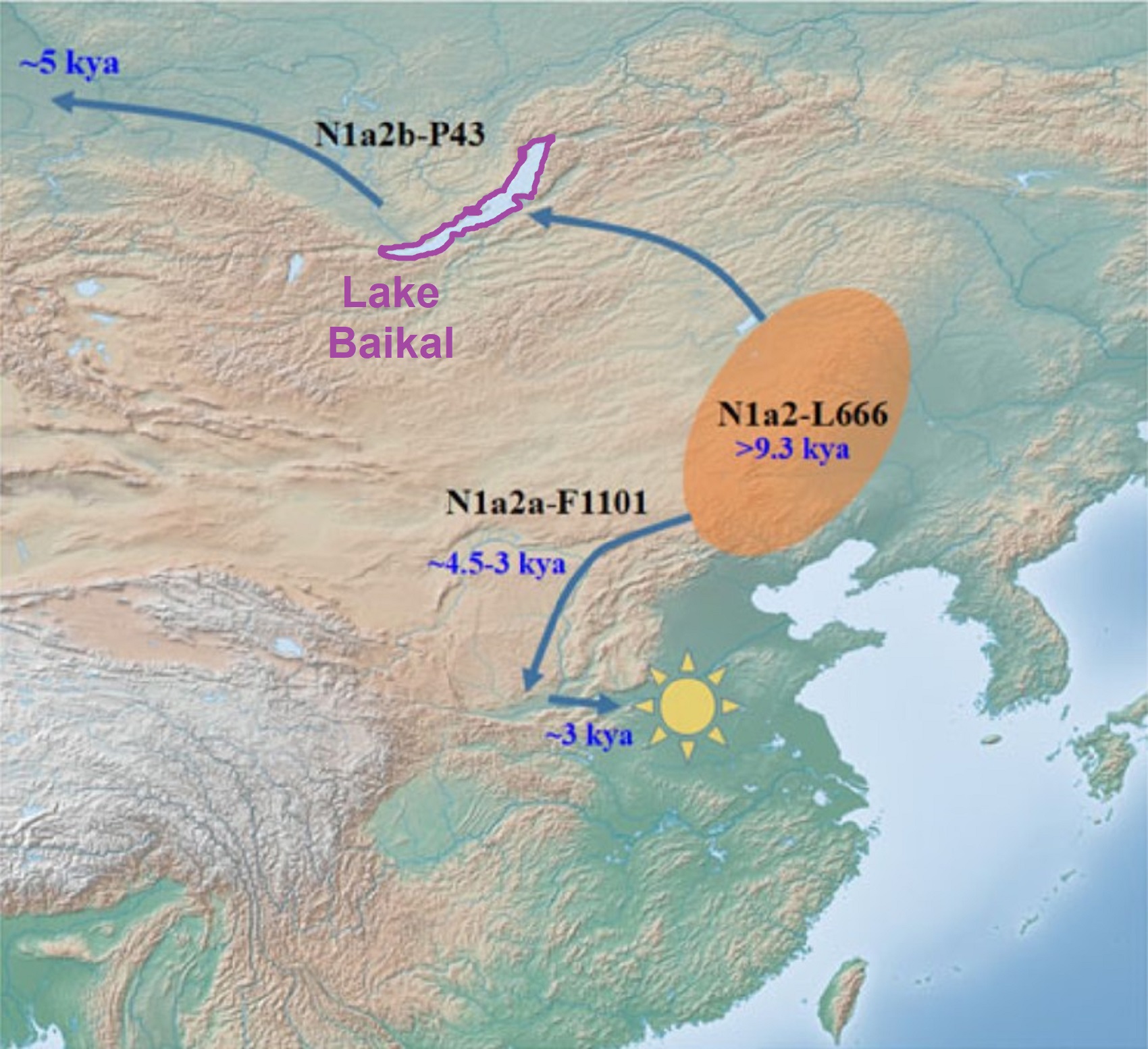

“N1a1a (M178) is seen at 60% among Finns and approximately 40% among Latvians, Lithuanians & 35% among Estonians. N1a2b (P43) estimated to be approximately 4,000 to 5,500 years old, is seen at low to moderate frequency among speakers of some other Uralic languages. Haplogroup N-P43 forms two distinctive subclusters of STR haplotypes, Asian and European, the latter mostly distributed among Finno-Ugric-speaking peoples and related populations. N has also been found in many samples of Neolithic human remains exhumed from Liao civilization in northeastern China, and in the circum-Baikal area of southern Siberia. It is suggested that yDNA N, reached southern Siberia from 12-14 kya. From there it reached southern Europe 8-10kya.” ref

“N1a1a1a1a1a-CTS2929/VL29 Found with high frequency among Lithuanians, Latvians, Estonians, northwestern Russians, Swedish Saami, Karelians, Nenetses, Finns, and Maris, moderate frequency among other Russians, Belarusians, Ukrainians, and Poles, and low frequency among Komis, Mordva, Tatars, Chuvashes, Dolgans, Vepsa, Selkups, Karanogays, and Bashkirs.” ref

“N1a1a1a1a1a1a1-L1025/B215 Highest frequency among Lithuanians, significant in Latvians and Estonians and lesser frequency in Belorussians, Ukrainians, South-West Russians, and Poles. With exception of Estonians, L1025 has highest share among N-M231 clades in previously mentioned populations. Also observed in Finland and Sweden, with sporadic instances in Norway, Germany, Netherlands, United Kingdom, the Azores, Czech Republic, and Slovakia.” ref

“N1a1a1a1a2-Z1936,CTS10082 Found with high frequency among Finns, Vepsa, Karelians, Swedish Saami, northwestern Russians, Bashkirs, and Volga Tatars, moderate frequency among other Russians, Komis, Nenetses, Ob-Ugrians, Dolgans, and Siberian Tatars, and low frequency among Mordva, Nganasans, Chuvashes, Estonians, Latvians, Ukrainians, and Karanogays.” ref

“Haplogroup N1c was known as N3. N1c represents the western extent of haplogroup N, which is found all over the Far East (China, Korea, Japan), Mongolia, and Siberia, especially among Uralic speakers of northern Siberia. Haplogroup N1 reaches a maximum frequency of approximately 95% in the Nenets (40% N1c and 57% N1b) and Nganassans (all N1b), two Uralic tribes of central-northern Siberia, and 90% among the Yakuts (all N1c), a Turkic people who live mainly in the Sakha (Yakutia) Republic in central-eastern Siberia. N1c is found chiefly in north-eastern Europe, particularly in Finland (61%), Lapland (53%), Estonia (34%), Latvia (38%), Lithuania (42%), and northern Russia (30%), and to a lower extent also in central Russia (15%), Belarus (10%), eastern Ukraine (9%), Sweden (7%), Poland (4%) and Turkey (4%). N1c is also prominent among the Uralic-speaking ethnicities of the Volga-Ural region, including the Udmurts (67%), Komi (51%), Mari (50%), and Mordvins (20%), but also among their Turkic neighbors like the Chuvashs (28%), Volga Tatars (21%) and Bashkirs (17%), as well as the Nogais (9%) of southern Russia.” ref

“Haplogroup N is a descendant of East Asian macro-haplogroup NO. It is believed to have originated in Indochina or southern China approximately 15,000 to 20,000 years ago. Haplogroup N1* and N1c were both found at high frequency (26 out of 70 samples, or 37%) in Neolithic and Bronze Age remains (4500-700 BCE) from the West Liao River valley in Northeast China (Manchuria) by Yinqiu Cui et al. (2013). Among the Neolithic samples, haplogroup N1 made up two-thirds of the samples from the Hongshan culture (4700-2900 BCE) and all the samples from the Xiaoheyan culture (3000-2200 BCE), hinting that N1 people played a major role in the diffusion of the Neolithic lifestyle around Northeast China, and probably also to Mongolia and Siberia.” ref

“Ye Zhang et al. 2016 found 100% of Y-DNA N out of 17 samples from the Xueshan culture (Jiangjialiang site) dating from 3600–2900 BCE, and among those 41% belonged to N1c1-Tat. It is therefore extremely likely that the N1c1 subclade found in Europe today has its roots in the Chinese Neolithic. It would have progressively spread across Siberia until north-eastern Europe, possibly reaching the Volga-Ural region around 5500 to 4500 BCE with the Kama culture (5300-3300 BCE), and the eastern Baltic with the Comb Ceramic culture (4200-2000 BCE), the presumed ancestral culture of Proto-Finnic and pre-Baltic people. There is little evidence of agriculture or domesticated animals in Siberia during the Neolithic, but pottery was widely used. In that regard, it was the opposite development from the Near East, which first developed agriculture then only pottery from circa 5500 BCE, perhaps through contact with East Asians via Siberia or Central Asia.” ref

- “N1c1a (M178): found in Siberia (Khakass-Daurs)

- N1c1a1 (L708): found in Siberia (Anayins)

- N1c1a1a (P298): found in Siberia (Yakuts)

- N1c1a1a1 (L392, L1026): Finno-Ugric branch; found throughout north-east Europe

- N1c1a1a1a (CTS2929/VL29): Baltic-Finnic branch

- N1c1a1a1a1 (L550): West Finnic branch; found around the Baltic Sea and in places settled by the Vikings

- N1c1a1a1a1a (L1025)

- N1c1a1a1a1a1 (M2783): found especially in Balto-Slavic countries, with a peak in Lithuania and Latvia

- N1c1a1a1a1a2 (Y4706): found mostly in Finland and Scandinavia

- N1c1a1a1a2 (CTS9976): East Finnic branch; found among the Chudes (Karelia, Estonia)

- N1c1a1a1a2a (L1022)

- N1c1a1a1a2a1 (Z1936): Finno-Permic branch; found in the Volga-Ural region and among the Karelians and Savonians

- N1c1a1a1a2a1a (Z1925): found in Finland, Lapland, Scandinavia, the Volga-Ural and the Altai

- N1c1a1a1a2a1a1 (Z1933)

- N1c1a1a1a2a1a1a (Z1927): found among the Karelians

- N1c1a1a1a2a1a1b (CTS8565): found among the Savonians” ref

Haplogroup V (mtDNA)

“Haplogroup V is a human mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplogroup. The clade is believed to have originated over 14,000 years ago in Southern Europe. Haplogroup V derives from the HV0a subclade of haplogroup HV. In 1998 it was argued that V spread over Europe from an Ice Age refuge in Iberia. However, more recent estimates of the date of V would place it in the Neolithic. Haplogroup V is a relatively rare mtDNA haplogroup, occurring in around 4% of native Europeans. Its highest concentration is among the Saami people of northern Fennoscandia (~59%). It has been found at a frequency of approximately 10% among the Maris of the Volga-Ural region, leading to the suggestion that this region might be the source of the V among the Saami.” ref

“Haplogroup V has been observed at higher than average levels among Cantabrian people (15%) of northern Iberia, and among the adjacent Basque (10.4%). Haplogroup V is also found in parts of Northwest Africa. It is mainly concentrated among the Tuareg inhabiting the Gorom-Gorom area in Burkina Faso (21%), Sahrawi in the Western Sahara (17.9%), and Berbers of Matmata, Tunisia (16.3%). The rare V7a subclade occurs among Algerians in Oran (1.08%) and Reguibate Sahrawi (1.85%).” ref

“MtDNA haplogroup V has been reported in Neolithic remains of the Linear Pottery culture at Halberstadt, Germany c. 5000 BCE and Derenburg Meerenstieg, Germany c. 4910 BCE. Haplogroup V7 was found in representative Maykop culture samples in the excavations conducted by Alexei Rezepkin. Haplogroup V has been detected in representatives Trypil’ska and Unetice culture. Haplogroup V has also been found among Iberomaurusian specimens dating from the Epipaleolithic at the Taforalt prehistoric site 14,000 years ago.” ref

- V1a found mostly from central to northeast Europe

- V1a1 found in Scandinavia (including Lapland), Finland, and Baltic countries

- V1a2 found in Bronze Age Poland

- V7a found mostly in Slavic countries, but also in Scandinavia, Germany and France