ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

Raqefet Cave

13,000-year-old stone mortars offers the earliest known physical evidence

of an extensive ancient beer-brewing operation.

“The find comes on the heels of a July report that archaeologists working in northeastern Jordan discovered the charred remains of bread baked by Natufians some 11,600 to 14,600 years ago. According to the Stanford scientists, the ancient beer residue comes from 11,700 to 13,700 years old. Through laboratory analysis, other archaeological evidence found in the cave, and the wear of the stones, the team discovered that the ancient Natufians used species from seven plant families, “including wheat or barley, oat, legumes and bast fibers (including flax),” according to the article. “They packed plant-foods, including malted wheat/barley, in fiber-made containers and stored them in boulder mortars. They used bedrock mortars for pounding and cooking plant-foods, including brewing wheat/barley-based beer likely served in ritual feasts ca. 13,000 years ago,” the scientists write. “It has long been speculated that the thirst for beer may have been the stimulus behind cereal domestication, which led to a major social-technological change in human history; but this hypothesis has been highly controversial,” the Stanford authors say. “We report here of the earliest archaeological evidence for cereal-based beer brewing by a semi-sedentary, foraging people.” ref

“Beer making was an integral part of rituals and feasting, a social regulatory mechanism in hierarchical societies,” said Stanford’s Wang. The Raqefet Cave discovery of the first man-made alcohol production, the cave also provides one of the earliest pieces of evidence of the use of flower beds on gravesites, discovered under human skeletons. “The Natufian remains in Raqefet Cave never stop surprising us,” co-author Prof. Dani Nadel, of the University of Haifa’s Zinman Institute of Archaeology, said in a press release. “We exposed a Natufian burial area with about 30 individuals, a wealth of small finds such as flint tools, animal bones, and ground stone implements, and about 100 stone mortars and cupmarks. Some of the skeletons are well-preserved and provided direct dates and even human DNA, and we have evidence for flower burials and wakes by the graves.” ref

“And now, with the production of beer, the Raqefet Cave remains provide a very vivid and colorful picture of Natufian lifeways, their technological capabilities, and inventions,” he said. Stanford’s Liu posited that the beer production was of a religious nature because its production was found near a graveyard. “This discovery indicates that making alcohol was not necessarily a result of agricultural surplus production, but it was developed for ritual purposes and spiritual needs, at least to some extent, prior to agriculture,” she said. “Alcohol making and food storage were among the major technological innovations that eventually led to the development of civilizations in the world, and archaeological science is a powerful means to help reveal their origins and decode their contents,” said Liu. “We are excited to have the opportunity to present our findings, which shed new light on a deeper history of human society.” ref

Religion and Alcohol

“The world’s religions have had differing relationships with alcohol. Many religions forbid alcoholic consumption or see it as sinful or negative. Others have allocated a specific place for it, such as in the Christian practice of using wine during the Eucharist rite. Hinduism does not have a central authority which is followed by all Hindus, though religious texts forbid the use or consumption of alcohol. In Śruti texts such as Vedas and Upanishads which are the most authoritative texts in Hinduism and considered apauruṣeya, which means “not of a man, superhuman”, all alcoholic drinks or intoxication are considered as a recipe of sinfulness, weakness, failure, and destruction in several verses.” ref

“Judaism relates to the consumption of alcohol, particularly of wine, in a complex manner. Wine is viewed as a substance of import and it is incorporated in religious ceremonies, and the general consumption of alcoholic beverages is permitted, however, inebriation (drunkenness) is discouraged. This compound approach to wine can be viewed in the verse in Psalms 104:15, “Wine gladdens human hearts,” countered by the verses in Proverbs 20:1, “Wine is a mocker, strong drink is riotous; and whoever stumbles in it is not wise,” and Proverbs 23:20, “Be not among drunkards or among gluttonous eaters of meat.” Christian views on alcohol are varied. Throughout the first 1,800 years of Church history, Christians generally consumed alcoholic beverages as a common part of everyday life and used “the fruit of the vine” in their central rite—the Eucharist or Lord’s Supper. They held that both the Bible and Christian tradition taught that alcohol is a gift from God that makes life more joyous, but that over-indulgence leading to drunkenness is sinful or at least a vice.” ref

“Observant Buddhists typically avoid consuming alcohol (surāmerayamajja, referring to types of intoxicating fermented beverages), as it violates the 5th of the Five Precepts, the basic Buddhist code of ethics, and can disrupt mindfulness and impede one’s progress in the Noble Eightfold Path. In Jainism alcohol consumption of any kind is not allowed, neither are there any exceptions like occasional or social drinking. The most important reason against alcohol consumption is the effect of alcohol on the mind and soul. In Jainism, any action or reaction that alter or impacts the mind is violence (himsa) towards own self, which is a five-sense human being. Violence to other five sense beings or to own self is violence. Jains do not consume fermented foods (beer, wine, and other alcohols) to avoid killing of a large number of microorganisms associated with the fermenting process. An initiated Sikh cannot use or consume intoxicants, of which wine is one.” ref

“In the Quran, khamr, meaning “wine”, is variably referenced as an incentive from Satan, as well as a cautionary note against its adverse effect on human attitude in several verses: such as, O you who have believed, indeed, intoxicants, gambling, [sacrificing on] stone altars [to other than Allah], and divining arrows are but defilement from the work of Satan, so avoid it that you may be successful. — Surat 5:90 AND Satan only wants to cause between you animosity and hatred through intoxicants and gambling and to avert you from the remembrance of Allah and from prayer. So will you not desist? — Surat 5:91 Whereas Sake is often consumed as part of Shinto purification rituals in Japan. Sakes served to gods as offerings prior to drinking are called Omiki. People drink Omiki with gods to communicate with them and to solicit rich harvests the following year.” ref

Older Historical Religions and Alcohol

“In Ancient Egyptian religion, beer and wine were drunk and offered to the gods in rituals and festivals. Beer and wine were also stored with the mummified dead in Egyptian burials. Other ancient religious practices like Chinese ancestor worship, Sumerian and Babylonian religion used alcohol as offerings to gods and to the deceased. The Mesopotamian cultures had various wine gods and a Chinese imperial edict (c. 1,116 BCE) states that drinking alcohol in moderation is prescribed by Heaven.” ref

“IN MESOPOTAMIA, evidence of winemaking from the fourth millennium BCE (the late Uruk period) has been found in the city-states of Uruk and Tello in southern Iraq and the Elamite capital of Susa in Iran. The Babylonian and Egyptian found that if they crushed grapes or warmed and moisten grain, the covered mush would bubble and produce drink with a kick. Ancient beer was thick and nutritious. The fermentation process added essential B vitamins and amino acids converted from yeast. Mesopotamians drank beer and wine but seemed to have preferred beer. By some estimates forty percent of the wheat from Sumerian harvest went to make beer. Thus lends credence to the beer theory, that man switched to agriculture so that people could to settle down and grow grain so they sit around and drink beer together on small villages.” ref

“It has been argued that beer was preferred over wine because beer-producing barley grows better in the hot, dry climate of southern Iraq than wine-producing grapes. Cylinder seals from the Early Dynastic period (2900-2350 BCE) show monarchs and the courtiers drinking beer from large jars with straws. Another beverage, possibly wine, was consumed from hand-held cups and goblets. Cuneiform tablets show allocations of beer and wine for royal occasions. One tablet from northeastern Syria allocates 80 liters of the “best quality beer” to honor “the man from Babylon.” By 700 BCE, the Phrgyians in present-day Turkey were drinking an alcoholic beverage made from wine, barley beer, and honey mead. For hangovers, the Assyrians consumed a mixture of ground bird’s beaks and myrrh.” ref

“In the ancient Mediterranean world, the Cult of Dionysus and the Orphic mysteries used wine as part of their religious practices. During Dionysian festivals and rituals, wine was drunk as way to reach ecstatic states along with music and dance. Intoxication from alcohol was seen as a state of possession by spirit of the god of wine Dionysus. Religious drinking festivals called Bacchanalia were popular in Italy and associated with the gods Bacchus and Liber. These Dionysian rites were frequently outlawed by the Roman Senate. In the Norse religion the drinking of ales and meads was important in several seasonal religious festivals such as Yule and Midsummer as well as more common festivities like wakes, christenings, and ritual sacrifices called Blóts. Neopagan and Wiccan religions also allow for the use of alcohol for ritual purposes as well as for recreation.” ref

Nectar of the Gods: Alcoholic Mythology

“Here are a handful of stories from around the globe that illustrate the long-time love of alcohol that connects the world. Norse mythology tells of Aegir, the ale brewer of the gods, who held a big party for honored guests every winter. The party was held inside a great hall whose floor was littered with glittering gold, providing enough light that no fires were necessary for illumination. The special beer for the event was brewed in a giant cauldron given to him by Thor and served in magical cups that refilled as soon as they were empty. He even had a couple of loyal servants who distributed food and otherwise cared for the guests’ needs. The shindig was the highlight of the social season and all the gods attended. However, like so many off-campus college parties, alcohol and animosity could sometimes spoil a perfectly good evening.” ref

“According to the Poetic Edda, a collection of mythological poems, the party started off great, with everyone drinking and eating and telling stories. As they sat down for the big feast, the inebriated guests offered praise to the two lowly servants, Fimafeng and Eldir. The snobby rich kid of the gods, Loki, in his drunken arrogance, took offense to the gesture, feeling the servants were not worth such accolades, and killed Fimafeng. The others kicked him out of the party for being a jerk, but he returned shortly after, demanding to be shown some respect and allowed back at the table. Loki didn’t get away unharmed, though. Skaoi, one of the goddesses he insulted that night, caught up with the god and tied him to a rock. Above his naked body, she hung a poisonous snake, whose fangs dripped acidic venom into a small dish, held up by Loki’s wife, Sigyn. Whenever the dish filled, she had to pull it away and pour the venom on the ground. This meant the venom would occasionally drip onto her husband, causing him immense pain. According to legend, Loki’s violent writhing is what causes earthquakes. Of course, this could have all been avoided if Loki had simply known when to say when.” ref

“The Aztec drink of choice was pulque, a syrupy, pulpy alcohol made from the fermented sap of the agave plant. Pulque was available to almost everyone, but most people were cut off after four cups. The elderly, on the other hand, had earned as many cups as they could handle. The priests were also able to drink as much as they wanted in order to commune with the gods – and work up the nerve to commit human sacrifices. A believer’s drunkenness was measured on a scale of rabbits, with two or three rabbits being a petty good buzz, all the way up to 400, which we can only imagine meant, “poke him with a stick and see if he’s dead.” So the next time you’re doing tequila shots with friends, instead of saying “three sheets to the wind,” perhaps you could say you’re “at least 10 rabbits in” and pay a little honor to Mayahuel, Patecatl, and their 400 kids.” ref

List of Deities of Wine and Beer

“Deities of wine and beer include a number of agricultural deities associated with the fruits and grains used to produce alcoholic beverages, as well as the processes of fermentation and distillation.

- Abundantia, Roman goddess of abundance (see also: Habonde).

- Acan, Mayan God of alcohol.

- Acratopotes, one of Dionysus’ companions and a drinker of unmixed wine.

- Aegir, a Norse divinity associated with ale, beer, and mead.

- Aizen Myō-ō, Shinto god of tavern keepers.

- Amphictyonis/Amphictyonis, Greek goddess of wine and friendship.

- Bacchus, Roman god of wine, usually identified with the Greek Dionysus.

- Ba-Maguje, Hausa spirit of drunkenness.

- Bes, Egyptian god, protector of the home, and patron of beer brewers.

- Biersal/Bierasal/Bieresal, Germanic kobold of the beer cellar.

- Ceraon, who watched over the mixing of wine with water.

- Brigid of Kildare, patron saint of brewing.

- Dionysus, Greek god of wine, usually identified with the Roman Bacchus.

- Du Kang, Chinese Sage of wine. Inventor of wine and patron to the alcohol industry.

- Inari, Shinto god(dess) of sake.

- Li Bai, Chinese god of wine and sage of poetry.

- Liber Pater, a Roman god of wine.

- Liu Ling, Chinese god of wine. One of the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove

- Mayahuel, Mexican goddess of pulque.

- Methe, Greek personification of drinking and drunkenness.

- Nephthys, Egyptian goddess of beer.

- Ninkasi, Sumerian goddess of beer.

- Nokhubulwane, Zulu goddess of the rainbow, agriculture, rain, and beer.

- Oenotropae, Greek goddesses, “the women who change (anything into) wine”.

- Ogoun, Yoruba/West African/Voodoo god of rum.

- Ometochtli, Aztec gods of excess.

- Siduri, wise Mesopotamian female divinity of beer and wine in the Epic of Gilgamesh.

- Silenus, Greek god of wine, wine pressing, and drunkenness.

- Siris, Mesopotamian goddess of beer.

- Sucellus, Celtic god of agriculture, forests, and of the alcoholic drinks of the Gauls.

- Tao Yuanming, Chinese spirit of wine.

- Tenenet, Egyptian goddess of childbirth and beer.

- Varuni, Hindu goddess of wine.” ref

“Beer goddess:

- Dea Latis, Celtic goddess of beer.

- Mbaba Mwana Waresa, Zulu goddess of the rainbow, agriculture, rain and beer.

- Nephthys, Egyptian goddess of beer.

- Ninkasi, Sumerian goddess of beer.

- Nokhubulwane, see Mbaba Mwana Waresa.

- Siduri, wise female divinity of beer in the Epic of Gilgamesh.

- Siris (goddess), Mesopotamian goddess of beer.

- Tenenet, Egyptian goddess of childbirth and beer.” ref

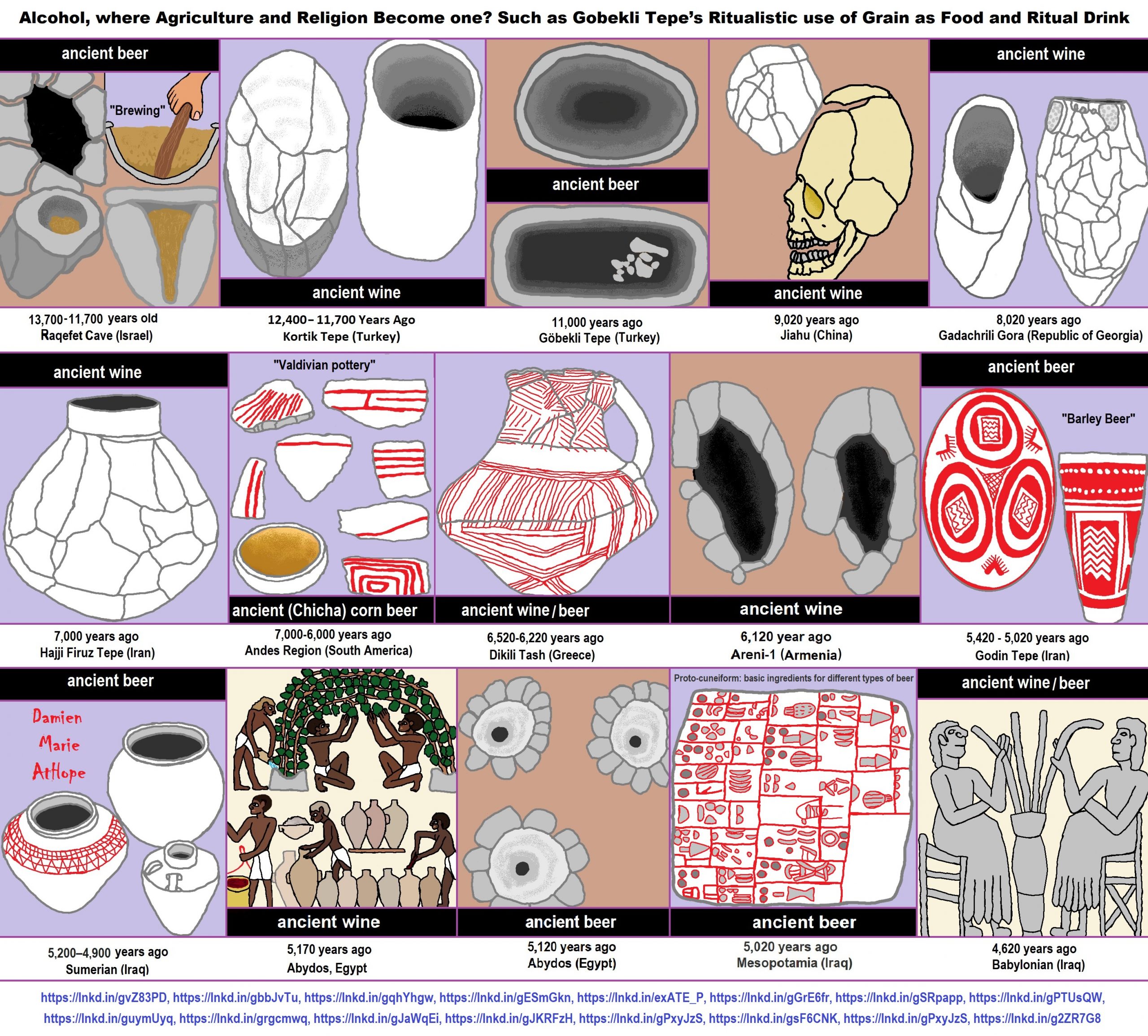

Alcohol, where Agriculture and Religion Become one?

Such as Gobekli Tepe’s ritualistic use of grain as food and ritual drink.

Alcohol use in an Archaeology/Anthropology context theorized:

(My thoughts on alcohol in prehistoric religious rituals could have a dual nature. One of Euphoria and thus altered states religions tend to seek. Second is its association with the grave and death, such as how one can get so intoxicated on alcohol, they blackout or pass out (pseudo-death early peoples may have believe killed you, then miraculously in time the drinker would arise again from an alcohol stupor and it would have seemed like magic, thus they may have associated alcohol with reincarnation thinking.)

History of alcoholic drinks

“Purposeful production of alcoholic drinks is common and often reflects cultural and religious peculiarities as much as geographical and sociological conditions. The Discovery of late Stone Age jugs suggests that intentionally fermented beverages existed at least as early as the Neolithic period (c. 10000 BCE). The ability to metabolize alcohol likely predates humanity with primates eating fermenting fruit. The oldest verifiable brewery has been found in a prehistoric burial site in a cave near Haifa in modern-day Israel. Researchers have found residue of 13,000-year-old beer that they think might have been used for ritual feasts to honor the dead. The traces of a wheat-and-barley-based alcohol were found in stone mortars carved into the cave floor.” ref

“As early as 7000 BCE, chemical analysis of jars from the neolithic village Jiahu in the Henan province of northern China revealed traces of a mixed fermented beverage. According to a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2004, chemical analysis of the residue confirmed that a fermented drink made of grapes, hawthorn berries, honey, and rice was being produced in 7000–6650 BCE. This is approximately the time when barley beer and grape wine were beginning to be made in the Middle East.” ref

“Evidence of alcoholic beverages has also been found dating from 5400-5000 BC in Hajji Firuz Tepe in Iran, 3150 BCE in ancient Egypt, 3000 BCE in Babylon, 2000 BCE in pre-Hispanic Mexico, and 1500 BCE in Sudan. According to Guinness, the earliest firm evidence of wine production dates back to 6000 BCE in Georgia. The medicinal use of alcohol was mentioned in Sumerian and Egyptian texts dating from about 2100 BCE. The Hebrew Bible recommends giving alcoholic drinks to those who are dying or depressed, so that they can forget their misery (Proverbs 31:6-7).” ref

“Wine was consumed in Classical Greece at breakfast or at symposia, and in the 1st century BCE, it was part of the diet of most Roman citizens. Both the Greeks and the Romans generally drank diluted wine (the strength varying from 1 part wine and 1 part water, to 1 part wine and 4 parts water). In Europe during the Middle Ages, beer, often of very low strength, was an everyday drink for all classes and ages of people. A document from that time mentions nuns having an allowance of six pints of ale each day. Cider and pomace wine were also widely available; grape wine was the prerogative of the higher classes.” ref

“By the time the Europeans reached the Americas in the 15th century, several native civilizations had developed alcoholic beverages. According to a post-conquest Aztec document, consumption of the local “wine” (pulque) was generally restricted to religious ceremonies but was freely allowed to those who were older than 70 years. The natives of South America produced a beer-like beverage from cassava or maize, which had to be chewed before fermentation in order to turn the starch into sugar. (Beverages of this kind are known today as cauim or chicha.) This chewing technique was also used in ancient Japan to make sake from rice and other starchy crops.” ref

Ancient China

“The earliest evidence of wine was found in what is now China, where jars from Jiahu which date to about 7000 BCE were discovered. This early rice wine was produced by fermenting rice, honey, and fruit. What later developed into Chinese civilization grew up along the more northerly Yellow River and fermented a kind of huangjiu from millet. The Zhou attached great importance to alcohol and ascribed the loss of the mandate of Heaven by the earlier Xia and Shang as largely due to their dissolute and alcoholic emperors. An edict ascribed to c. 1116 BCE makes it clear that the use of alcohol in moderation was believed to be prescribed by heaven.” ref

“Unlike the traditions in Europe and the Middle East, China abandoned the production of grape wine before the advent of writing and, under the Han, abandoned beer in favor of huangjiu and other forms of rice wine. These naturally fermented to a strength of about 20% ABV; they were usually consumed warmed and frequently flavored with additives as part of traditional Chinese medicine. They considered it spiritual food and extensive documentary evidence attests to the important role it played in religious life. “In ancient times people always drank when holding a memorial ceremony, offering sacrifices to gods or their ancestors, pledging resolution before going into battle, celebrating victory, before feuding and official executions, for taking an oath of allegiance, while attending the ceremonies of birth, marriage, reunions, departures, death, and festival banquets.” Marco Polo‘s 14th-century record indicates grain and rice wine were drunk daily and were one of the treasury’s biggest sources of income.” ref

“Alcoholic beverages were widely used in all segments of Chinese society, were used as a source of inspiration, were important for hospitality, were considered an antidote for fatigue, and were sometimes misused. Laws against making wine were enacted and repealed forty-one times between 1100 BC and AD 1400. However, a commentator writing around 650 BCE asserted that people “will not do without beer. To prohibit it and secure total abstinence from it is beyond the power even of sages. Hence, therefore, we have warnings on the abuse of it.” The Chinese may have independently developed the process of distillation in the early centuries of the Common Era, during the Eastern Han dynasty.” ref

Ancient Persia (or Ancient Iran)

“A major step forward in our understanding of Neolithic winemaking came from the analysis of a yellowish residue excavated by Mary M. Voigt at the site of Hajji Firuz Tepe in the northern Zagros Mountains of Iran. The jar that once contained wine, with a volume of about 9 liters (2.5 gallons) was found together with five similar jars embedded in the earthen floor along one wall of a “kitchen” of a Neolithic mudbrick building, dated to c. 5400-5000 BCE. In such communities, winemaking was the best technology they had for storing highly perishable grapes, although whether the resulting beverage was intended for intoxication as well as nourishment is not known.” ref

Ancient Egypt

“Brewing dates from the beginning of civilization in ancient Egypt, and alcoholic beverages were very important at that time. Egyptian brewing began in the city of Hierakonpolis around 3400 BCE; its ruins contain the remains of the world’s oldest brewery, which was capable of producing up to three hundred gallons (1,136 liters) per day of beer. Symbolic of this is the fact that while many gods were local or familial, Osiris was worshiped throughout the entire country. Osiris was believed to be the god of the dead, of life, of vegetable regeneration, and of wine. Both beer and wine were deified and offered to gods. Cellars and wine presses even had a god whose hieroglyph was a winepress. The ancient Egyptians made at least 17 types of beer and at least 24 varieties of wine. The most common type of beer was known as hqt. Beer was the drink of common laborers; financial accounts report that the Giza pyramid builders were allotted a daily beer ration of one and one-third gallons. Alcoholic beverages were used for pleasure, nutrition, medicine, ritual, remuneration, and funerary purposes. The latter involved storing the beverages in tombs of the deceased for their use in the after-life.” ref

“Numerous accounts of the period stressed the importance of moderation, and these norms were both secular and religious. While Egyptians did not generally appear to define drunkenness as a problem, they warned against taverns (which were often houses of prostitution) and excessive drinking. After reviewing extensive evidence regarding the widespread but generally moderate use of alcoholic beverages, the nutritional biochemist and historian William J. Darby makes a most important observation: all these accounts are warped by the fact that moderate users “were overshadowed by their more boisterous counterparts who added ‘color’ to history.” Thus, the intemperate use of alcohol throughout history receives a disproportionate amount of attention. Those who abuse alcohol cause problems, draw attention to themselves, are highly visible, and cause legislation to be enacted. The vast majority of drinkers, who neither experience nor cause difficulties, are not noteworthy. Consequently, observers and writers largely ignore moderation. Evidence of distillation comes from alchemists working in Alexandria, Roman Egypt, in the 1st century CE. Distilled water has been known since at least c. 200 CE, when Alexander of Aphrodisias described the process.” ref

Ancient Babylon

“Beer was the major beverage among the Babylonians, and as early as 2700 BCE they worshiped a wine goddess and other wine deities. Babylonians regularly used both beer and wine as offerings to their gods. Around 1750 BCE, the famous Code of Hammurabi devoted attention to alcohol. However, there were no penalties for drunkenness; in fact, it was not even mentioned. The concern was fair commerce in alcohol. Although it was not a crime, the Babylonians were critical of drunkenness.” ref

Ancient India

“Alcohol distillation likely originated in India. Alcoholic beverages in the Indus Valley Civilization appeared in the Chalcolithic Era. These beverages were in use between 3000 to 2000 BCE. Sura, a beverage brewed from rice meal, wheat, sugar cane, grapes, and other fruits, was popular among the Kshatriya warriors and the peasant population. Sura is considered to be a favorite drink of Indra.” ref

“The Hindu Ayurvedic texts describe both the beneficent uses of alcoholic beverages and the consequences of intoxication and alcoholic diseases. Ayurvedic texts concluded that alcohol was a medicine if consumed in moderation, but a poison if consumed in excess. Most of the people in India and China, have continued, throughout, to ferment a portion of their crops and nourish themselves with the alcoholic product. In ancient India, alcohol was also used by the orthodox population. Early Vedic literature suggests the use of alcohol by priestly classes.” ref

“The two great Hindu epics, Ramayana and Mahabharata, mention the use of alcohol. In Ramayana, alcohol consumption is depicted in a good/bad dichotomy. The bad faction members consumed meat and alcohol while the good faction members were abstinent vegetarians. However, in Mahabharata, the characters are not portrayed in such a black-white contrast. Alcohol abstinence was promoted as a moral value in India by Mahavira, the founder of Jainism, and Adi Shankaracharya. Distillation was known in the ancient Indian subcontinent, evident from baked clay retorts and receivers found at Taxila and Charsadda in modern Pakistan, dating back to the early centuries of the Common Era. These “Gandhara stills” were only capable of producing very weak liquor, as there was no efficient means of collecting the vapors at low heat.” ref

Ancient Greece

“While the art of wine making reached the Hellenic peninsula by about 2000 BCE, the first alcoholic beverage to obtain widespread popularity in what is now Greece was mead, a fermented beverage made from honey and water. However, by 1700 BCE, wine making was commonplace. During the next thousand years wine drinking assumed the same function so commonly found around the world: It was incorporated into religious rituals. It became important in hospitality, used for medicinal purposes, and became an integral part of daily meals. As a beverage, it was drunk in many ways: warm and chilled, pure and mixed with water, plain and spiced. Alcohol, specifically wine, was considered so important to the Greeks that consumption was considered a defining characteristic of the Hellenic culture between their society and the rest of the world; those who did not drink were considered barbarians.” ref

“While habitual drunkenness was rare, intoxication at banquets and festivals was not unusual. In fact, the symposium, a gathering of men for an evening of conversation, entertainment, and drinking typically ended in intoxication. However, while there are no references in ancient Greek literature to mass drunkenness among the Greeks, there are references to it among foreign peoples. By 425 BCE, warnings against intemperance, especially at symposia, appear to become more frequent.” ref

“Xenophon (431-351 BCE) and Plato (429-347 BCE) both praised the moderate use of wine as beneficial to health and happiness, but both were critical of drunkenness, which appears to have become a problem. Plato also believed that no one under the age of eighteen should be allowed to touch wine. Hippocrates (cir. 460-370 BCE) identified numerous medicinal properties of wine, which had long been used for its therapeutic value. Later, both Aristotle (384-322 BCE) and Zeno (cir. 336-264 BCE) were very critical of drunkenness. Among Greeks, the Macedonians viewed intemperance as a sign of masculinity and were well known for their drunkenness. Their king, Alexander the Great (356-323 BCE), whose mother adhered to the Dionysian cult, developed a reputation for inebriety.” ref

Pre-Columbian America

“Several Native American civilizations developed alcoholic beverages. Many versions of these beverages are still produced today. The making of pulque, as illustrated in the Florentine Codex (Book 1 Appendix, fo.40). Pulque, or octli is an alcoholic beverage made from the fermented juice of the maguey, and is a traditional native beverage of Mesoamerica. Though commonly believed to be a beer, the main carbohydrate is a complex form of fructose rather than starch. Pulque is depicted in Native American stone carvings from as early as CE 200. The origin of pulque is unknown, but because it has a major position in religion, many folk tales explain its origins.” ref

“Balché is the name of a honey wine brewed by the Maya, associated with the Mayan deity Acan. The drink shares its name with the balché tree (Lonchocarpus violaceus), the bark of which is fermented in water together with honey from the indigenous stingless bee. Tepache is a mildly alcoholic beverage indigenous to Mexico that is created by fermenting pineapple, including the rind, for a short period of three days. Tejuino, traditional to the Mexican state of Jalisco, is a maize-based beverage that involves fermenting masa dough.” ref

“Chicha is a Spanish word for any of variety of traditional fermented beverages from the Andes region of South America. It can be made of maize, manioc root (also called yuca or cassava) or fruits among other things. During the Inca Empire women were taught the techniques of brewing chicha in Acllahuasis (feminine schools). Chicha de jora is prepared by germinating maize, extracting the malt sugars, boiling the wort, and fermenting it in large vessels, traditionally huge earthenware vats, for several days. In some cultures, in lieu of germinating the maize to release the starches, the maize is ground, moistened in the chicha maker’s mouth and formed into small balls which are then flattened and laid out to dry. Naturally occurring diastase enzymes in the maker’s saliva catalyze the breakdown of starch in the maize into maltose. Chicha de jora has been prepared and consumed in communities throughout in the Andes for millennia. The Inca used chicha for ritual purposes and consumed it in vast quantities during religious festivals. In recent years, however, the traditionally prepared chicha is becoming increasingly rare. Only in a small number of towns and villages in southern Peru and Bolivia is it still prepared. Other traditional drinks made from fermented maize or maize flour include pozol and pox.” ref

“Manioc root being prepared by Indian women to produce an alcoholic drink for ritual consumption, by Theodor de Bry, Frankfurt, 1593. Women in the lower left can be seen spitting into the manioc mash. Salivary enzymes break down complex starches, and saliva introduces bacteria and yeast that hasten the fermentation process. Cauim is a traditional alcoholic beverage of the Native American populations of Brazil since pre-Columbian times. It is still made today in remote areas throughout Panama and South America. Cauim is very similar to chicha and it is also made by fermenting manioc or maize, sometimes flavored with fruit juices. The Kuna Indians of Panama use plantains. A characteristic feature of the beverage is that the starting material is cooked, chewed, and re-cooked prior to fermentation. As in the making of chicha, enzymes from the saliva of the cauim maker break down the starches into fermentable sugars.” ref

“Tiswin, or niwai is a mild, fermented, ceremonial beverage produced by various cultures living in the region encompassing the southwestern United States and northern Mexico. Among the Apache, tiswin was made from maize, while the Tohono O’odham brewed tiswin using saguaro sap. The Tarahumara variety, called tesgüino, can be made from a variety of different ingredients. Recent archaeological evidence has also revealed the production of a similar maize-based intoxicant among the ancestors of the Pueblo peoples. Okolehao is produced by Native Hawaiians from juice extracted from the roots of the ti plant. Cacao wine was produced during the formative stage of the Olmec Culture (1100-900 BCE). Evidence from Puerto Escondido indicates that a weak alcoholic beverage (up to 5% alcohol by volume) was made from fermented cacao pulp and stored in pottery containers.” ref

In addition:

· The Iroquois fermented sap from the sugar maple tree to produce a mildly alcoholic beverage.

· The Chiricahua prepared a kind of corn beer called tula-pah using sprouted corn kernels, dried and ground, flavored with locoweed or lignum vitae roots, placed in water and allowed to ferment.[42]

· The Coahuiltecan in Texas combined mountain laurel with agave sap to create an alcoholic drink similar to pulque.

· The Zunis made fermented beverages from aloe, maguey, corn, prickly pear, pitaya, and grapes.

· The Creek of Georgia and Cherokee of the Carolinas used berries and other fruits to make alcoholic beverages.

· The Huron made a mild beer by soaking corn in water to produce a fermented gruel to be consumed at tribal feasts.

· The Kwakiutl of Vancouver Island produced a mildly alcoholic drink using elderberry juice, black chitons, and tobacco.

· Both the Aleuts and Yuit of Kodiak Island in Alaska were observed making alcoholic drinks from fermented raspberries.” ref

Ancient Rome

“Bacchus, the god of wine – for the Greeks, Dionysus – is the patron deity of agriculture and the theater. He was also known as the Liberator (Eleutherios), freeing one from one’s normal self, by madness, ecstasy, or wine. The divine mission of Dionysus was to mingle the music of the aulos and to bring an end to care and worry. The Romans would hold dinner parties where wine was served to the guest all day along with a three-course feast. Scholars have discussed Dionysus’ relationship to the “cult of the souls” and his ability to preside over communication between the living and the dead. The Roman belief that wine was a daily necessity made the drink “democratic” and ubiquitous: wine was available to slaves, peasants, women, and aristocrats alike. To ensure the steady supply of wine to Roman soldiers and colonists, viticulture and wine production spread to every part of the empire. The Romans diluted their wine before drinking it. The wine was also used for religious purposes, in the pouring of libations to deities.” ref

“Though beer was drunk in Ancient Rome, it was replaced in popularity by wine. Tacitus wrote disparagingly of the beer brewed by the Germanic peoples of his day. Thracians were also known to consume beer made from rye, even since the 5th century BC, as the ancient Greek logographer Hellanicus of Lesbos says. Their name for beer was brutos, or brytos. The Romans called their brew cerevisia, from the Celtic word for it. Beer was apparently enjoyed by some Roman legionaries. For instance, among the Vindolanda tablets (from Vindolanda in Roman Britain, dated c. 97-103 AD), the cavalry decurion Masculus wrote a letter to prefect Flavius Cerialis inquiring about the exact instructions for his men for the following day. This included a polite request for beer to be sent to the garrison (which had entirely consumed its previous stock of beer).” ref

Ancient Sub-Saharan Africa

“Palm wine played an important social role in many African societies. Thin, gruel-like, alcoholic beverages have existed in traditional societies all across the African continent, created through the fermentation of sorghum, millet, bananas, or in modern times, maize or cassava.” ref

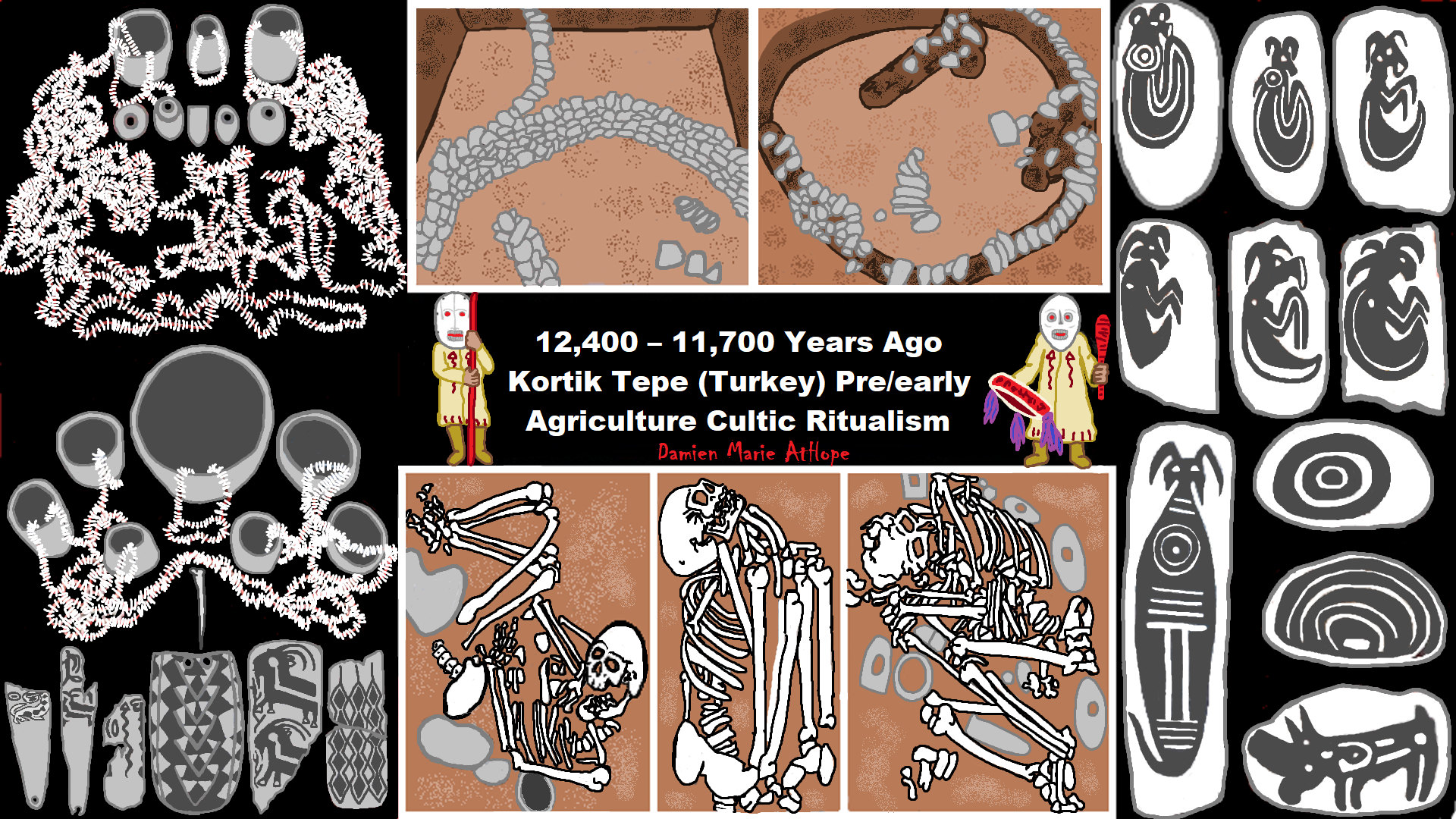

Kortik Tepe

“McGovern (2009) presented preliminary results from chemical studies made on two stone vessels from the PPN necropolis at Körtik Tepe which yielded traces of tartaric acid that accrues during the wine production process. The consensus is that early grain crops would have been far better suited to the production of gruel or beer than bread, especially considering that the glumes of primitive domesticated plants would have adhered to the grain. Even though this idea (fermentation) was raised frequently in subsequent years, particularly in the context of the previously noted advantages (higher nutritional value) afforded by this process, it was considered improbable that beer was actually produced. Ever since the so-called Braidwood Symposium in 1953, there has been a debate as to whether beer – and not bread – was the first product made from domesticated crops. Based on the discovery of grain at the site of Qalat Jarmo, and at the suggestion of the archaeo-botanist Sauer, Braidwood inquired whether or not the discovery of fermentation could have been the spark that triggered the targeted selection, and ultimately domestication, of certain crops. Fermented grain, which sees its starch transformed into sugars, is well known for its beneficial properties, including an increase in nutritional value, also making it easier to digest.” ref

“Recently, further chemical analyses were conducted by M. Zarnkow (Technical University of Munich, Weihenstephan) on six large limestone vessels from Göbekli Tepe. These (barrel/trough-shaped) vessels, with capacities of up to 160 litres, were found in-situ in PPNB contexts at the site. Already during excavations, it was noted that some vessels carried grey-black adhesions. A first set of analyses made on these substances returned partly positive for calcium oxalate, which develops in the course of the soaking, mashing, and fermenting of grain. Although these intriguing results are only preliminary, they provide initial indications for the brewing of beer at Göbekli Tepe, thus provoking renewed discussions relating to the production and consumption of alcoholic beverages at this early time. Further, they are particularly significant in light of results from genetic analyses, undertaken by a team from the Norwegian University of Life Sciences in Oslo, which have suggested that the earliest domestication of grain occurred in the vicinity of the Karacadağ (Karaca Dağ is a shield volcano located in eastern Turkey). It was also known as Mount Masia i.e. very near to Göbekli Tepe. Once again, we must ask whether the production of alcohol and the domestication of grain are interrelated. Finally, the aforementioned insights also provoke new questions relating to the use and consumption of alcohol at Göbekli Tepe, which may have been in the context of religiously motivated feasts and celebrations. Not surprisingly, such events are well attested in the ethnographic literature as a means of attracting and motivating large groups of people to undertake communal work and projects.” ref

“Studying encoded ideas the site of Körtik Tepe may serve as a starting point. Körtik Tepe is one of the earliest permanent settlements in Southeastern Turkey. Possible local adaptations of the Körtik Tepe belly-shaped vessel type/decoration 1- Göbekli Tepe 2- Tell ‘Abr 3. Examples of possibly kept and reused chlorite sherds with decoration similar to the belly-shaped standardized vessel from Körtik Tepe: 1- Tell Qaramel; 2- Tell ‘Abr 3, both in northern Syria. Import or copy? Chlorite vessels from 1- Jerf el Ahmar and 2- Tell ‘Abr 3. A very similar item was found at Körtik Tepe.” ref

“Körtik Tepe is a low mound on the Tigris in Southeastern Turkey, rich lithic industries, hundreds of zoomorphic and anthropomorphic decorated stone vessels, undecorated stone vessels, decorated ritual bone objects, thousands of shell beads, and several kinds of stone beads, animal decorated stone plaques, bone tools & fishing hooks, perforated stones large and small in size, and many mortars and pestles.” ref

Living by the water – Boon, and Bane for the People of Körtik Tepe

“Despite a long and on-going discussion on the development of early sedentism and the broad spectrum revolution as a precondition for sedentary farming communities, many studies have been biased by focusing on the study of wild cereal remains. However, recent botanical and archaeozoological studies have shown clearly a wide spectrum of plants and small game that were used by hunter-gatherers opportunistically. Many ethnographic examples and pioneering studies on prehistoric coastal fishing and even trade of marine fishes into the hinterland during the early Holocene demonstrate the importance of fish for sedentary communities. Nevertheless, fish remains have rarely been studied systematically. A recent overview on data of Near Eastern Early Neolithic sites could list only a handful of Epipalaeolithic and Early Neolithic sites for which a systematic collection of fish bones had been practiced. The missing systematic collection of microfauna and fish remains sieving has hampered quantitative as well as qualitative analyses of fish remains and microfauna on many sites. Although a systematic collection of fish remains at Körtik Tepe only in future seasons, we argue that the archaeological materials and archaeozoological remains in the sediments and graves clearly illustrate that freshwater resources such as fish and waterfowl, besides other small game such as tortoise, played an important role for the fourishing of the Körtik Tepe community during the PPNA1 and contributed much to its richness and identity.” ref

The Site and Environmental Conditions

“The extraordinary findings and the lavishly endowed burials of the early Holocene site of Körtik Tepe (37°48’51.90” N, 40°59’02.02”E) have been presented recently in this journal and in many other publications. The site is located near the confluence of the Batman Creek and Tigris River. An old channel of the Batman Creek visible on the aerial photo passes directly by the site. Preliminary analyses of charcoal remains suggest that Körtik Tepe lay in the oak park-woodland at the beginnings of the Holocene, with the dominance of oak and some Amygdalus sp., Maloideae, Pistacia sp., Celtis sp. and Rhamnus sp. Furthermore, Tamarix sp., Populus sp. /Salix sp., Vitis sp., Alnus sp., and Fraxinus sp. hint at the proximity of gallery forests indicative of water. The seed remains underline the proximity to water reservoirs.3 They comprise a wide spectrum of wild plants including hygrophilous species such as sea club rush (Scirpus maritimus) (12 %). The abundance of taxa such as tragant (Astragalus sp.) and medusahead (Taeniatherum caput-medusea/crinitium), however, indicate the presence of open vegetation. Large-seeded grasses (Poaceae) contribute the main portion (37 %) and occur in every sample, whereas progenitors of modern cereals account for less than 6 %. A specialization on one or the other plant does not show up in the botanical remains, and domestication of plants could not been proven so far (Riehl et al. n.d.). The people of Körtik Tepe thus had access to at least three different environmental milieus, of which they used the plant and animal resources opportunistically.” ref

Excavations at Körtik Tepe. A New Pre-Pottery Neolithic A Site in Southeastern Anatolia

“With its location near the point where Batman Çayı and the Tigris River meet, approximately 30 km west of Batman in southeastern Anatolia, Körtik Tepe is situated on the west bank the Tigris near a Pınarbaşı field of the Ağıl Village (Ancolini) within the administrative borders of Bismil district, Diyarbakır. In the form of a low hill, the mound extends across an area of 100 x 150 m and a height 5.50 m above its surroundings. The mound, also known by its traditional names Kotuk or Kotik, was first detected in surveys carried out in 1989 and evaluated as a late site (Algaze and Rosenberg 1990). Archaeological excavations that began in 2000 continued until 2009. Excavations exposed an area of approximately 2600 m² in 89 trenches of 5.00 x 5.00 m, reaching variable depths between 1.00- 5.50 m (Fig. 2). Together with Hallan Çemi, Körtik Tepe is one of the earliest sites in which the transition from hunter-gatherer communities following a nomadic way of life to settled village life is represented.” ref

“The PPN cultural structure of the mound generally reflects important differences, especially in terms of small finds, from other well-known contemporary settlements in the region. All data indicate that Körtik Tepe is a permanent settlement. Excavations during 2005-2009 showed that there are at least six separate architectural layers. It is possible to gather Körtik Tepe structures in three main groups. The first group is composed of 77 round buildings. All houses are round in plan with dirt floors surrounded by single-leaf walls of unworked stones. Walls were badly damaged by the construction activity of the medieval phase occupations. Among these, there are many structures that are not walled at all. These structures, varying in size between 2.30-3.00 m, are constructed directly on the ground.” ref

“The floors of stones pressed into the compact earth. Based on a preliminary judgment, these round buildings from Körtik Tepe, whether with flat or concave floors, are single-family dwellings characteristic of the earliest Pre-Pottery Neolithic period and similar in nature to Hallan Çemi, Göbekli Tepe, Tell Abr, Jerf el-Ahmar, Sheikh Hassan, Mureybet, Qermez Dere and Nemrik. The second group is composed of 34 buildings that are too small for residences. The sizes of these buildings, which are found in almost all levels in the excavated areas and are also round in plan, vary between 1.10–2.10 m in diameter. Floors of this group are also paved with pebbles. These structures must have served as storage units similar to those at Hallan Çemi, confirmed by the dense vegetable remains in them.” ref

“The last group of structures in our sample (Y3, Y11, Y44, Y35) is completely different in terms of their sizes and floors as well as in their rare numbers. Data are not sufficient to explain the functions of these, but we suspect they may have played some special roles, similar in some ways to the public structures at Hallan Çemi. However, despite the architectural similarities with Hallan Çemi, Körtik Tepe stands apart in terms of its small finds. Although there are no direct similarities with Çayönü or Nevalı Çori, similar structures to the third group are found in other Neolithic settlements of Anatolia. In the Levant region there are comparable structures in such early settlements such as ‘Ain Mallaha, Jericho, and the lower layers of Beidha. Though they include specific differences in terms of features, structure types, finds, and some functions, it is not surprising that the rarity of these buildings are generally considered to be public structures. Therefore, the site of Körtik Tepe shows parallels not only with Anatolia but also with the Levant.” ref

“Burials Graves play an important role in terms of characterizing the social and cultural structure of Körtik Tepe. The majority of skeletons were buried with grave goods, and a large proportion of the burials on the mound were found beneath house floors (Figs. 4-5). The context of a few graves is uncertain as they are near the surface and badly disturbed. Burials inside houses show that the places where people were living were sanctified as well as profane. Instead of being buried haphazardly, rules of treating the dead included practices before burial as well as internment itself. One specific practice was the partial smearing of skeletons with gypsum plaster. For many of the plastered skeletons, including skulls, colored parallel bands occur in the upper parts of the bones. In two different samples red and black lines are parallel to each other. Such color traces are also seen on grave goods.” ref

“All these data show that the dead were defleshed, subsequently partly covered with plaster, and then pigmented. Similar practices in the later PPN period have been noted, but Körtik Tepe holds a special place in terms of the specific kinds of plastering treatment. Traditions of burying the dead and the accompanying grave goods help to demonstrate the sociocultural system of the era. It is possible to gain an understanding in such related features as production, technology, labor, and decoration of grave gifts, most of which were of worked stone. Jewelry was made of different stones; decorated and undecorated bone objects and stone figurines were numerous. Other grave goods include stone vessels, axes, pestles, mortars, perforated stones, and cutting-piercing tools (Figs. 6-9). Similarities to tools used in daily life indicate fundamental beliefs among the Körtik Tepe settlers, particularly the concept of a continuation of life after the death.” ref

Chipped and Ground Stone Artifacts Chipped stone artifacts from Körtik Tepe are chiefly composed of flint.

“Obsidian tools and debitage are secondary. Furthermore, although rare numerically, quartz raw material was also used. Among tool groups Çayönü tools show up although in small quantities. Notably, although projectile points are numerous, no arrowheads of Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) or Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) types common to the classic Levant or Zagros traditions were found. Instead, tool types are more typical of the Epipaleolithic, characterized by microliths and arch-backed blades, generally similar to the inventory from Hallan Çemi. There is nothing among the tool types to contradict our interpretation that wild plant collecting was the principal means of acquiring plant foods. Some tools still reflect Paleolithic origins, with large scrapers being very important. It is observed that more formal tools were produced from obsidian, and these mostly consist of lunates and other geometric forms. The obsidian at Körtik Tepe was only obtainable from a great distance, whether through exchange or direct acquisition. As was the case for Hallan Çemi, the green transparent obsidian is likely East Anatolian in origin.” ref

“Most of the material from the mound consists of ground stone artifacts, and the majority of these came from burials; a small proportion came from domestic contexts. Except for a few examples that were preserved as complete objects, most finds included as grave goods were broken, including many stone vessels, utilitarian and ceremonial axes in different shapes and sizes, mortars, pestles, and grinding stones, all of which reflect the rich cultural collection in Körtik Tepe. Foremost among the types, stone vessels constitute a special group with their broad formal repertoire and their geometric and natural decoration. All parts of the stone vessels are covered by engraved animal figures, mostly snakes, wild goats, scorpions, birds, and mixed creatures that likely represent elements of their belief system. Despite their rarity throughout the region, it is clear that such stone vessels are seen in Pre-Pottery Neolithic period communities in Near East. One type of ground stone object brings relationships among Körtik Tepe and contemporary sites into sharp relief. This is the pestle produced for utilitarian and ceremonial use. Samples worked from coarse stone include abrasion traces as a result of use, and they generally display rough formal features. Ones that have shiny surfaces are made of more workable chlorite that is also used for stone vessels.” ref

“Most of the pestles of this type have upper ends finished with stylized wild bird and goat heads and are found as grave goods. Nearly identical pestles also came from Hallan Çemi and Çayönü in Anatolia and from Nemrik 9 in Iraq. Among the Körtik Tepe finds, stone axes comprise another important group. In addition to some with rough formal features, there are others that were shaped carefully. Axes differ in terms of size based on different stone types; however, they all share similar morphologies. Axes among the grave goods have holes carefully bored in the center. The majority of axes from non-burial contexts are abraded from rough usage. In addition to axes included as grave goods, there are also small, carefully fashioned mace heads with compressed circular forms. Chlorite stone figurines included as grave goods made by abrasion and incision are often of undefinable animals, although there is one that is clearly a goat.” ref

“Such figurines are not known from contemporary sites in the Near East, and they appear to be expressions of a local belief system. The concentric circles on the shoulders of the figures are also commonly found on decorated stone vessels among the grave goods, adding to the uniqueness of these objects. Another exotic piece that is of unknown use is a stone decorated with patterned incisions. Another type of shaped stone object from Körtik Tepe includes small-sized pointed cylinders that reflect close cultural ties with other early and late Pre-Pottery Neolithic period sites in Anatolia/Turkey. Shaped by means of abrasion, these chlorite objects have simple incised lines; one of them, with deep corrugations, has counterparts at Hallan Çemi and Demirköy. Bone Artifacts Bone artifacts make up another basic group at Körtik Tepe. The majority of them were found in burials, although a few were found in other contexts. Considering their formal features and decoration, it is possible to classify bone artifacts in two groups as either decorative or utilitarian. Utilitarian tools consist of awls, hooks, and points.” ref

“Most of them are fragmentary, but definable awls reflect morphological differences with Çayönü samples. Awls with their bigger size and stubby heads differ from points. Close equivalents of small-sized bone points that are used as pins are known from Çayönü. Once again, the bone material from Körtik Tepe shows similarities with bone finds from Hallan Çemi (Rosenberg 1999) and is related to the Zarzian tradition, connected to some degree with traditions known from other sites of the region in form and function. Personal Ornaments Different jewelry groups produced from different materials reveal the richness of the collection of grave goods from the mound. Beads are one group placed in burials as gifts next to skeletons or in stone vessels. Most of the beads were produced from burgundy-colored stone, which is easily worked. This kind of ornament is the largest group, but another includes vertebrae of animals such as birds, fish, and shell.” ref

“As in other kinds of grave goods, the quantity and quality of beads vary from burial to burial; some graves lack ornaments altogether. Although they are represented by only a few samples, some beads are made of chlorite, the same material the stone vessels are fashioned from. Ornaments were competently made involving decoration of parallel incised lines and carefully drilled holes. Although generally oval in shape, serpentine beads also occur in different forms, similar to those from Hallan Çemi. Although there are some specific differences, the jewelry from Körtik Tepe is similar to that from Çayönü as well. The disparity of grave good distributions suggests that those burials with large quantities of beads and other jewelry are of a different social class than those people buried in graves with none or only a few objects. This, in turn, indicates that social complexity had already appeared among the residents of Körtik Tepe by the PPNA period.” ref

“Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) denotes the first stage of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic, in early Levantine and Anatolian Neolithic culture, dating to around 12,020 – 10,820 years ago, that is, 10,000–8,800 BCE. Archaeological remains are located in the Levantine and Upper Mesopotamian region of the Fertile Crescent. The time period is characterized by tiny circular mud-brick dwellings, the cultivation of crops, the hunting of wild game, and unique burial customs in which bodies were buried below the floors of dwellings. The Pre-Pottery Neolithic A and the following Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) were originally defined by Kathleen Kenyon in the type site of Jericho (Palestine). During this time, pottery was not yet in use. They precede the ceramic Neolithic (Yarmukian). PPNA succeeds the Natufian culture of the Epipaleolithic (Mesolithic).” ref

“Sedentism of this time allowed for the cultivation of local grains, such as barley and wild oats, and for storage in granaries. Sites such as Dhra′ and Jericho retained a hunting lifestyle until the PPNB period, but granaries allowed for year-round occupation. This period of cultivation is considered “pre-domestication“, but may have begun to develop plant species into the domesticated forms they are today. Deliberate, extended-period storage was made possible by the use of “suspended floors for air circulation and protection from rodents”. This practice “precedes the emergence of domestication and large-scale sedentary communities by at least 1,000 years”. Granaries are positioned in places between other buildings early on c. 11,500 BP, however, beginning around 10,500 BP, they were moved inside houses, and by 9,500 BP storage occurred in special rooms. This change might reflect changing systems of ownership and property as granaries shifted from a communal use and ownership to become under the control of households or individuals. It has been observed of these granaries that their “sophisticated storage systems with subfloor ventilation are a precocious development that precedes the emergence of almost all of the other elements of the Near Eastern Neolithic package—domestication, large scale sedentary communities, and the entrenchment of some degree of social differentiation”. Moreover, “[b]uilding granaries may […] have been the most important feature in increasing sedentism that required active community participation in new life-ways”.” ref

With more sites becoming known, archaeologists have defined a number of regional variants of Pre-Pottery Neolithic A:

- Sultanian in the Jordan River valley and the southern Levant, with the type site of Jericho. Other sites include Netiv HaGdud, El-Khiam, Hatoula, and Nahal Oren.

- Mureybetian in the Northern Levant, defined by the finds from Mureybet IIIA, IIIB, typical: Helwan points, sickle-blades with base amenagée or short stem and terminal retouch. Other sites include Sheyk Hasan and Jerf el-Ahmar.

- (Aswadian) in the Damascus Basin, defined by finds from Tell Aswad IA; typical: bipolar cores, big sickle blades, Aswad points. The ‘Aswadian’ variant recently was abolished by the work of Danielle Stordeur in her initial report from further investigations in 2001–2006. The PPNB horizon was moved back at this site, to around 10,700 BP.

- Sites in “Upper Mesopotamia” include Çayönü and Göbekli Tepe, with the latter possibly being the oldest ritual complex yet discovered.

- Sites in central Anatolia that include the ‘mother city’ Çatalhöyük and the smaller, but older site, rivaling even Jericho in age, Aşıklı Höyük. ref

“Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) is part of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic, a Neolithic culture centered in upper Mesopotamia and the Levant, dating to c. 10,800 – c. 8,500 years ago, that is, 8,800–6,500 BCE. It was typed by Kathleen Kenyon during her archaeological excavations at Jericho in the West Bank. Like the earlier PPNA people, the PPNB culture developed from the Mesolithic Natufian culture. However, it shows evidence of a northerly origin, possibly indicating an influx from the region of northeastern Anatolia. Cultural tendencies of this period differ from that of the earlier Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) period in that people living during this period began to depend more heavily upon domesticated animals to supplement their earlier mixed agrarian and hunter-gatherer diet.” ref

“In addition, the flint tool kit of the period is new and quite disparate from that of the earlier period. One of its major elements is the naviform core. This is the first period in which architectural styles of the southern Levant became primarily rectilinear; earlier typical dwellings were circular, elliptical, and occasionally even octagonal. Pyrotechnology, the expanding capability to control fire, was highly developed in this period. During this period, one of the main features of houses is a thick layer of white clay plaster flooring, highly polished and made of lime produced from limestone. It is believed that the use of clay plaster for floor and wall coverings during PPNB led to the discovery of pottery. The earliest proto-pottery was White Ware vessels, made from lime and gray ash, built up around baskets before firing, for several centuries around 7000 BCE at sites such as Tell Neba’a Faour (Beqaa Valley).” ref

“Sites from this period found in the Levant utilizing rectangular floor plans and plastered floor techniques were found at Ain Ghazal, Yiftahel (western Galilee), and Abu Hureyra (Upper Euphrates). The period is dated to between c. 10,700 and c. 8,000 BP or 7000–6000 BCE. Plastered human skulls were reconstructed human skulls that were made in the ancient Levant between 9000 and 6000 BCE in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B period. They represent some of the oldest forms of art in the Middle East and demonstrate that the prehistoric population took great care in burying their ancestors below their homes. The skulls denote some of the earliest sculptural examples of portraiture in the history of art.” ref

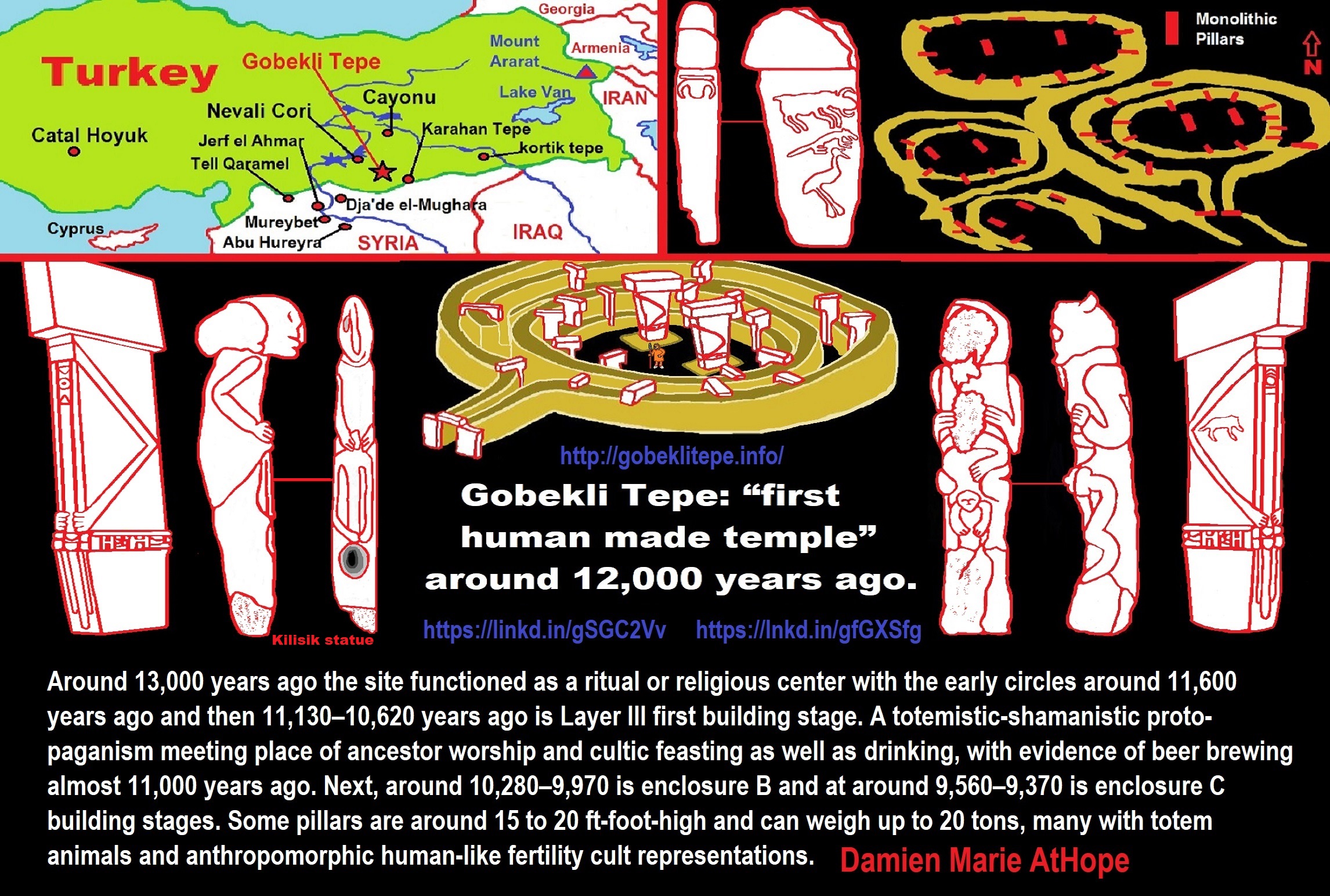

The role of cult and feasting in the emergence of Neolithic communities. New evidence from Göbekli Tepe, south-eastern Turkey: Changing Medialities – Symbols of Neolithic Corporate Identities

“Sedentism not only challenged the economic system of hunter-gatherers, but above all the social and ideological framework of their lives. Larger groups, increasing social differentiation and the potential for accumulating material possessions may have led to a decrease in trust and an increase in alienation, fear, and of aggression. Both processes can be counteracted by adjusting ideological and ethical concepts. One option of a society adapting to such stress is to strengthen corporate identities by an increased demonstration and standardization of symbolic praxis, including (communal) architecture as symbols in space, rituals as symbols in action, and systems of recurring signs, with an implied shared symbolic meaning. This introduction to the ideological and intangible ideas of corporate identities surrounds discussing if and how we can track shifts in ideological frameworks from the Epipaleolithic to the Early Neolithic in the Near East. It is suggested that an integrative approach combining anthropological, archaeological, and neurobiological research with studies of mediality may be capable of reconstructing the social impact of symbolic systems. Instead of creating a uniform picture of a monolithic symbolic system, we focus on tensions and contradictions of symbolic actions and representations with daily praxis. The observed shift in mediality probably aimed at creating strong social networks with present and bygone generations to counteract tendencies in ever larger communities. However, the increased display of corporate identities seems to be a transitional phenomenon. When living in permanent settlements had become customary, monumental and ubiquitous symbolic representations almost vanished.” ref

Göbekli Tepe

“Investigating the function of Pre-Pottery Neolithic stone troughs from Göbekli Tepe – An integrated approach Abstract: An integrated approach using contextual, use-wear, scientific, and experimental methods was used to analyze the role of stone troughs of up to 165 l capacity at the Early Neolithic site Göbekli Tepe in the context of other stone containers found there. Around 600 (mostly fragmentary) vessels from the site constitute the largest known assemblage from the Pre-Pottery Neolithic of the Near East. Besides the large limestone troughs, it encompasses middle-sized, coarsely made limestone vessels, finely executed platters, and ‘greenstone’ vessels. All lines of evidence taken together indicate the use of limestone troughs for the cooking of cereals.” ref

“Is there any evidence for any production activities in Göbekli Tepe (for instance agriculture, or beer-brewing as was mentioned by Dietrich et al.)? Traces of typical domestic activities are missing so far at Göbekli Tepe, as are any traces of Prehistoric agriculture or husbandry – any remains of plants and animals discovered as of yet hint at the respective wild forms only. However, numerous flint tools and flint flakes clearly hint at flint knapping on a grand scale taking place at and around Göbekli Tepe. The possible production of beer in the frame of large scale feasting is indeed a point worthy of discussion in the frame of these already mentioned large feasts – since preliminary chemical analysis hints at oxalate residues in large stone vessels at the site.” ref

Around 13,000 years ago the site functioned as a ritual or religious center with the early circles around 11,600 years ago and then 11,130–10,620 years ago is Layer III first building stage. A totemistic-shamanistic proto-paganism meeting place of ancestor worship and cultic feasting as well as drinking, with evidence of beer brewing almost 11,000 years ago. Next, around 10,280–9,970 is enclosure B, and at around 9,560–9,370 is enclosure C building stages. Some pillars are around 15 to 20 ft-foot-high and can weigh up to 20 tons, many with totem animals and anthropomorphic human-like fertility cult representations. ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

Consequences of Agriculture in Mesopotamia, Anatolia, and the Levant

“The ancient Near East was one of the earliest centers of agriculture in the world, giving rise to domesticated herd animals, cereals, and legumes that today have become primary agricultural staples worldwide. Although much attention has been paid to the origins of agriculture, identifying when, where, and how plants and animals were domesticated, equally important are the social and environmental consequences of agriculture. Shortly after the advent of domestication, agricultural economies quickly replaced hunting and gathering across Mesopotamia, the Levant, and Anatolia. The social and environmental context of this transition has profound implications for understanding the rise of social complexity and incipient urbanism in the Near East.” ref

“Economic transformation accompanied the expansion of agriculture throughout small-scale societies of the Near East. These farmsteads and villages, as well as mobile pastoral groups, formed the backbone of agricultural production, which enabled tradable surpluses necessary for more expansive, community-scale economic networks. The role of such economies in the development of social complexity remains debated, but they did play an essential role in the rise of urbanism. Cities depended on agricultural specialists, including farmers and herders, to feed urban populations and to enable craft and ritual specializations that became manifest in the first cities of southern Mesopotamia. The environmental implications of these agricultural systems in the Mesopotamian lowlands, especially soil salinization, were equally substantial. The environmental implications of Mesopotamian agriculture are distinct from those accompanying the spread of agriculture to the Levant and Anatolia, where deforestation, erosion, and loss of biodiversity can be identified as the hallmarks of agricultural expansion.” ref

“Agriculture is intimately connected with the rise of territorial empires across the Near East. Such empires often controlled agricultural production closely, for both economic and strategic ends, but the methods by which they encouraged the production of specific agricultural products and the adoption of particular agricultural strategies, especially irrigation, varied considerably between empires. By combining written records, archaeological data from surveys and excavation, and paleoenvironmental reconstruction, together with the study of plant and animal remains from archaeological sites occupied during multiple imperial periods, it is possible to reconstruct the environmental consequences of imperial agricultural systems across the Near East. Divergent environmental histories across space and time allow us to assess the sustainability of the agricultural policies of each empire and to consider how resulting environmental change contributed to the success or failure of those polities.” ref

On Scorpions, Birds, and Snakes—Evidence for Shamanism in Northern Mesopotamia during the Early Holocene

“Based on a systematic ethno-archaeological approach and comparison of figurative decorations in northern Mesopotamia, we suggest new interpretations of the figurative art of early Holocene sites in that region. Recently discovered decorated objects from different early Holocene sites hint at shamanistic practices and at close cultural-ideological ties in northern Mesopotamia from the upper Tigris to the middle Euphrates during the early Holocene. The data indicate a highly standardized symbolic repertoire. We argue that the monumental buildings at Göbekli Tepe and the emergence of standardized associations of motives indicate a society in a liminal state, with adherents still closely tied to their traditions; but some aspects of the applied mediality distinguish them from the highly flexible and situational ideologies of hunter-gatherers and point to the development of institutionalized religious authorities and dogma before farming.” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

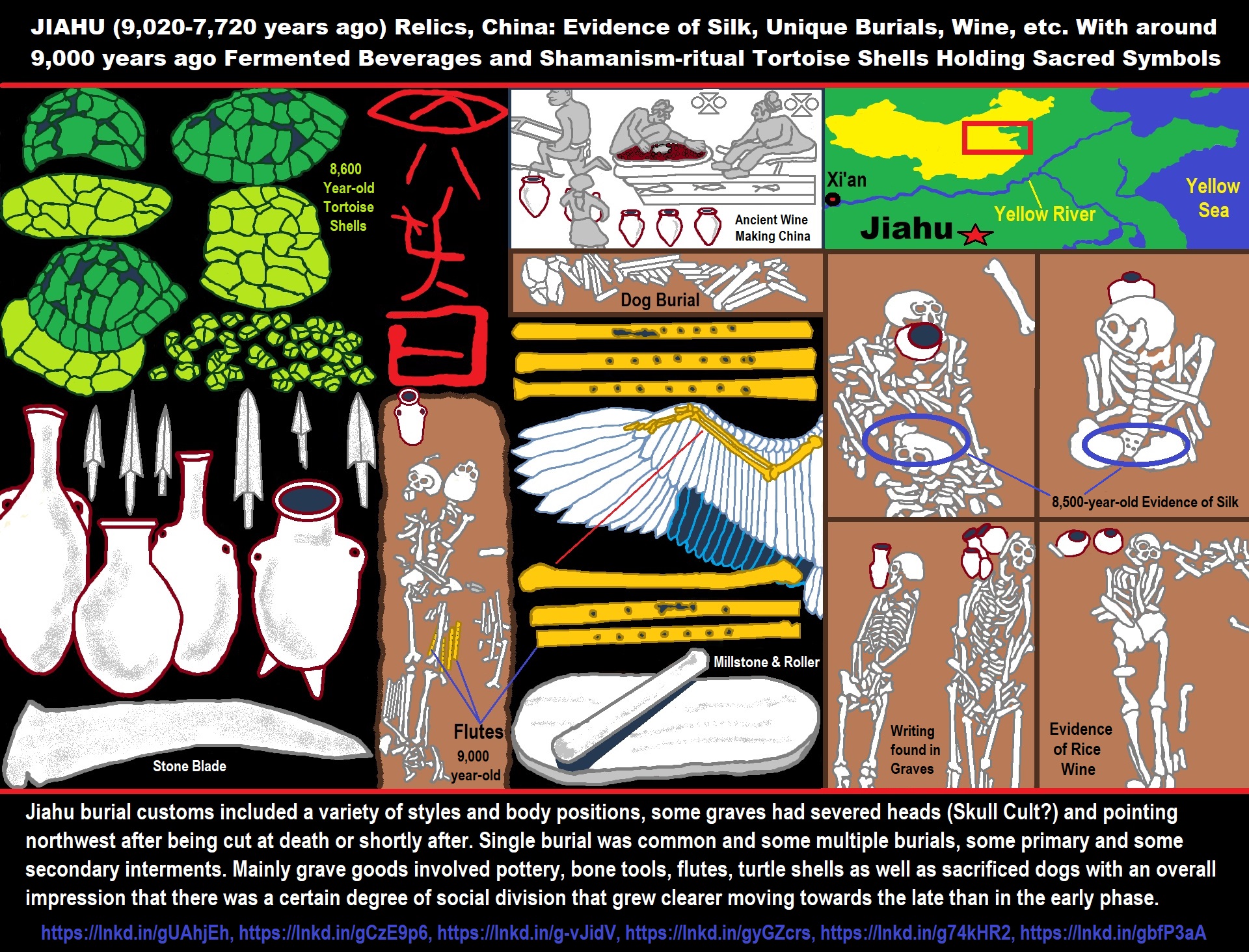

Jiahu

“9,020 years ago China (Evidence of Wine Making): “The grave of a shaman buried with a ceramic jug in Jiahu, Henan, China about 7000 BCE. Winemaking traces dating back to at least 9,000 years ago are found in central China. This “Neolithic cocktail” is discovered in the grave of a shaman, who is buried with a ceramic jug in Jiahu, Henan, about 7000 BC that contains traces of winemaking. It is currently thought to be the world’s oldest alcoholic drink, according to Peter Kupfer of Mainz University, who has been studying China for four decades and has investigated all aspects of the alcohol culture of the Middle Kingdom. Laboratory tests revealed the pottery jars discovered in the archaeological sites revealed traces of a mixed fermented drink made from a concoction of rice, honey, and either grapes or Hawthorne fruit.” ref

“Previously it is believed viticulture itself began only a little later, about 8,000 years ago in Georgia. Although still unproven, Kupfer believes that there were probably links between the most ancient winemaking sites – between Georgia 8,000 years ago and Jiahu in central China some 9,000 years ago. “Alcohol and, in particular, wine made using grapes has been a fundamentally important part of cultural life in Eurasia for thousands of years. And China has played a key role in its history,” said Kupfer. In his view, the emergence of China as one of the world’s leading wine-producing and wine-consuming countries is best seen against this background.” ref

“In his latest book on China’s wine history titled Amber Shine and Black Dragon Pearls: The History of Chinese Wine Culture, he says winemaking and drinking culture is ingrained in China’s history. “Without exception, the rise of all advanced Eurasian civilizations was intimately linked to the development of a wine and alcohol culture that was initially linked to magic and later played a role in social and religious rituals,” explains Kupfer. “The way the Chinese toast each other has remained unchanged for 3,000 years, as evidenced by ancient written precepts on the subject of hospitality,” adds Kupfer.” ref

“He says the country has been home to the world’s richest and most diverse range of species of the Vitis genus. During glacial periods, vines found a refuge in southern China, which is now home to over 40 Vitis species, 30 of which are indigenous. In the late 19th century, Chinese viticulture started to realign itself with its Western counterparts with imports of vines and technologies, largely thanks to Changyu Pioneers, today the country’s biggest winery.” ref

“Archaeologists in China have found what is believed to be the world’s oldest still-playable musical instrument — a 9,000-year-old flute carved from the wing bone of a crane. When scientists from the United States and China blew gently through the mottled brown instrument’s mouthpiece and fingered its holes, they produced tones that had not been heard for millennia, yet were familiar to the modern ear. “It’s a reedy, pleasant sound; a little thin, like a recorder,” said Garman Harbottle, a nuclear scientist who specializes in radiocarbon dating at Brookhaven National Laboratory on New York’s Long Island.” ref

“Harbottle and three Chinese archaeologists published their findings in the journal Nature. The flute was one of several instruments to be uncovered in Jiahu, an excavation site of Stone Age artifacts in China’s Yellow River Valley. Archaeologists have also found exquisitely wrought tools, weapons, and pottery there. Dated to 7,000 BCE, the flute is more than twice as old as instruments used in ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, and other early civilizations. In all, researchers have found some three dozen bone flutes at Jiahu. Five were riddled with cracks big and small; 30 others had fragmented. The flutes have as many as eight neatly hollowed tone holes and were held vertically to play.” ref

Aged 9,000 Years, Ancient Beer Finally Hits Stores

“Dogfish Head brewery is known for making exotic beer with ingredients like crystallized ginger or water from Antarctica, so it might not sound surprising that one of its recent creations is a brew flavored simply by grapes and flowers. It’s not the recipe that makes this beer so special; it’s where that recipe was found: a Neolithic burial site in China. Chateau Jiahu is a time capsule from 7,000 B.C., but to hear Dogfish Head owner Sam Calagione talk about what beer was actually like back then, it’s not the kind of thing that makes you say “Hey, pass me another ice-cold ancient ale!” ref

“Probably, all beer thousands of years ago — to our modern palates — would have tasted spoiled,” Calagione says. “In fact, in a lot of hieroglyphics, people are shown drinking beer using straws because they were trying to avoid the chunks of solids and wild yeast.” So how do you go from “chunks of wild yeast” to a beer that you can get at your local store? You don’t start with a brewery. You start with Dr. Patrick McGovern.” ref

Scraping The Bottom Of The Beer Barrel

“McGovern is a biomolecular archaeologist at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. He studies fermented beverages — otherwise known as booze — by analyzing the ancient pots that once held them. “We use techniques like infrared spectrometry, gas chromatography, and so forth,” he explains. McGovern helps Dogfish Head revive long-dead brews by figuring out what used to be inside the ancient pottery he comes across.” ref

“About 10 years ago, he set out to find some of this primordial crockery on a trip to China. In one town, he found pottery from an early Neolithic burial site. The pieces were about 9,000 years old — as were the skeletons they were found with. The Neolithic period, which began about 12,000 years ago, is thought to be about the time when humans started settling down, raising crops — and apparently getting a little tipsy. McGovern suspects that once humans stayed put, it didn’t take them long to discover the fermentation process that led to the world’s first alcohol.” ref

“The molecular evidence told McGovern the vessels from China once contained an alcoholic beverage made of rice, grapes, hawthorn berries, and honey. “What we found is something that was turning up all over the world from these early periods,” he says. “We don’t have just a wine or a beer or a mead, but we have like a combination of all three.” ref

Ancient Brews For Troubled Times

“That’s where Dogfish Head comes in. The Delaware-based brewery owns a tiny but respected sliver of the U.S. beer market, which Calagione says it earned by being a risk-taker. Dogfish and McGovern have produced other ancient beverages, including their Midas Touch brew, teased from pottery found in King Midas’ 2,700-year-old tomb. But, like Calagione says, Jiahu is different. It’s “the oldest-known fermented recipe in the history of mankind.” ref

“This year, Dogfish Head will brew about 3,000 cases of Jiahu — a small batch by commercial brewing standards. At $13 for a wine-size bottle, Jiahu is about six times the cost of Budweiser. Luckily, Calagione says, his sales of Jiahu and other specialty brews have actually increased during the recession. “What we do see in this economy is that people probably can’t afford a new SUV or a new vacation home, but they can surely afford to trade up to a world class beer,” he says. And while Jiahu may not be cheap, it’s a lot easier to get than a plane ticket to Neolithic China.” ref

WINE FROM JIAHU IN CHINA