Endogamy

“Endogamy is the cultural practice of mating within a specific social group, religious denomination, caste, or ethnic group, rejecting any from outside of the group or belief structure as unsuitable for marriage or other close personal relationships. Its opposite, exogamy, describes the social norm of marriage outside of the group. Endogamy is common in many cultures and ethnic groups. Several religious and ethnic religious groups are traditionally more endogamous, although sometimes mating outside of the group occurs with the added dimension of requiring marital religious conversion. This permits an exogamous marriage, as the convert, by accepting the partner’s religion, becomes accepted within the endogamous group. Endogamy, as distinct from consanguinity, may result in transmission of genetic disorders, the so-called founder effect, within the relatively closed community.” ref

“Endogamy can encourage sectarianism and serves as a form of self-segregation. For instance, a community resists integration or completely merging with the surrounding population. Minorities can use it to stay ethnically homogeneous over a long time as distinct communities within societies that have other practices and beliefs. Endogamic marriage patterns may increase the frequency of various levels of cousin marriage in a population, and may cause high probability of children of first, second, third cousins, etcetera. If a cousin marriage has accrued in a known ancestral tree of a person, in historical time, it is referred to as pedigree collapse. A long term pattern of endogamy in a region may increase the risk of repeated cousin marriage during a long period of time, referred to as inbreeding. It may cause additional noise in the DNA autosomal data, giving the impressions that DNA matches with roots in that region are more closely related than they are.” ref

“High rates of ethnic endogamy may not be driven by ethnic preferences per se, but by preferences for other characteristics that are correlated with ethnicity. For example, given the large role played by family in the rituals and practices of many religions, it may not be surprising that religious homogamy rates are quite high. Preferences for a spouse with the same religion can ultimately result in high rates of ethnic endogamy given the strong relationship between ethnicity and religion. It may be challenging, for example, for a Hindu spouse-searcher to find a non-Indian Hindu.” ref

“It is difficult to analyze the role of religion in interethnic marriage decisions because of the lack of information on religion in most nationally representative surveys in the US. However, the percentage of the country of origin that is, Christian has been found to decrease endogamy among childhood arriving immigrants and the native-born children of immigrants in the US. Using data from Sweden, Dribe and Lundh provide evidence that several cultural factors, including religion, play a role in explaining endogamy rates.” ref

“While religious homogamy is generally decreasing, assortative matching on education has increased since the 1960s. Given the importance of matching on education and the variation in average schooling levels across ethnic groups, individuals with education levels that are typical within their ethnic group may end up marrying endogamously simply because it is relatively easy to meet a coethnic with a similar level education. On the other hand, ethnics with education levels that deviate from the norm within their ethnicity are likely to find it more difficult to find a same-ethnicity and same-education spouse and so compromises must be made.” ref

“Several studies have found that the closer a person’s own education is to his ethnic group’s average, the more likely he is to marry endogamously. Furtado and Furtado and Theodoropoulos show that an increase in schooling leads to a decrease in the probability of marriage within ethnicity for people in low-education groups but an increase for those in education ethnicities. Consistent with this evidence, Kalmijn shows that education increases out-marriage most in low-education groups and least in high-education groups. Interestingly, he never finds that education increases endogamy, not even in the most highly educated groups. He hypothesizes that, as discussed above, education tends to decrease in-group preferences so that while the highly educated members of high-education groups have access to same-education, same-ethnicity spouses, they may not value ethnic endogamy to the same degree as those with less education.” ref

“Schooling may also affect marriage patterns via the preferences of marriage-market participants who do not identify with any particular ethnic background. For example, it may be that, as predicted by exchange theory, people are only willing to marry ethnic minorities, especially those with strong ethnic attachments, if they are compensated in the form of a spouse’s higher education. It may also be that ultimate marriage patterns are driven by the majority population’s perceptions of ethnic minorities, perceptions that are likely to be influenced by average schooling levels of the ethnic group. Kalmijn finds that, conditional on a person’s own education, belonging to a group with a higher average education is associated with an increase in the likelihood of out-marriage. He interprets this result as evidence of the importance of natives’ perceptions of a person’s ethnic group.” ref

Bands, Tribes, Chiefdoms

“Another means of identifying the boundaries between modern and traditional societies was the categorization of the differences between the manner of their social organization and their driving mechanism. Based on the multi-criteria approach the American Elman Service was the first anthropologist to define the division of society into four groups, while his typology also reflected its evolutionary aspect. The division into bands, tribes, chieftain units, and states is still in current use today, though not without certain reservations. Critics point in particular to the problems that are associated with attempts to apply a typology that was created in relation to recent pre-industrial populations to societies that are identified only in historical or archaeological sources.” ref

“Smaller groups of hunter-gatherers are referred to as bands. In general, their members were related either by blood or by marriage. The bands lacked any formal chieftains, nor were there any striking differences in regard to the ownership of property or of social status between the members. The fact that the bands were both quite small and mobile was also reflected in the size and structure of their settlements. Modern examples of bands of this nature are the Bushmen of southern Africa and the Hadza in Tanzania.” ref

“According to Elman Service, generally the tribes were more significant than the bands, but only rarely did the number of their members attain several thousand people. Their diet usually comprised domestic resources. They were both sedentarised farmers and migrant herders. The tribe comprised a collection of individual communities (families, villages, etc.) that were mutually linked by family ties, either real or declared (i.e. claimed). Tribes usually lacked both official representatives and a “Capital City” because there was no need for an economic base in order to create power structures. The settlements took the form of homesteads or of villages. According to Service, this grouping was supposed to represent some sort of transitional form, somewhere between a band and a chiefdom.” ref

“As social organizations, chiefdoms were made up of several branches of various kinship groups or conical clans. Their members were internally differentiated in them on the basis of their kinship with a real or a mythological ancestor who was viewed as being the founder. The political representative of a society of this nature was a chieftain who inherited his position from within a specific defined circle of relatives. Prestige and status in the society were derived from how close the relationship between the individual and the chieftain was. This was also reflected in the funeral rites. The centralization of power was manifested primarily in the area of spiritual ceremonies and rituals. The authority of the chieftain largely coincided with his priestly functions. Another feature, therefore, was also the existence of a permanent sacred place. It must be admitted that there could be a large number of chieftain systems with different mechanisms of functioning that could co-exist. Historical traces of this can be found on the northwest coast of North America, for example.” ref

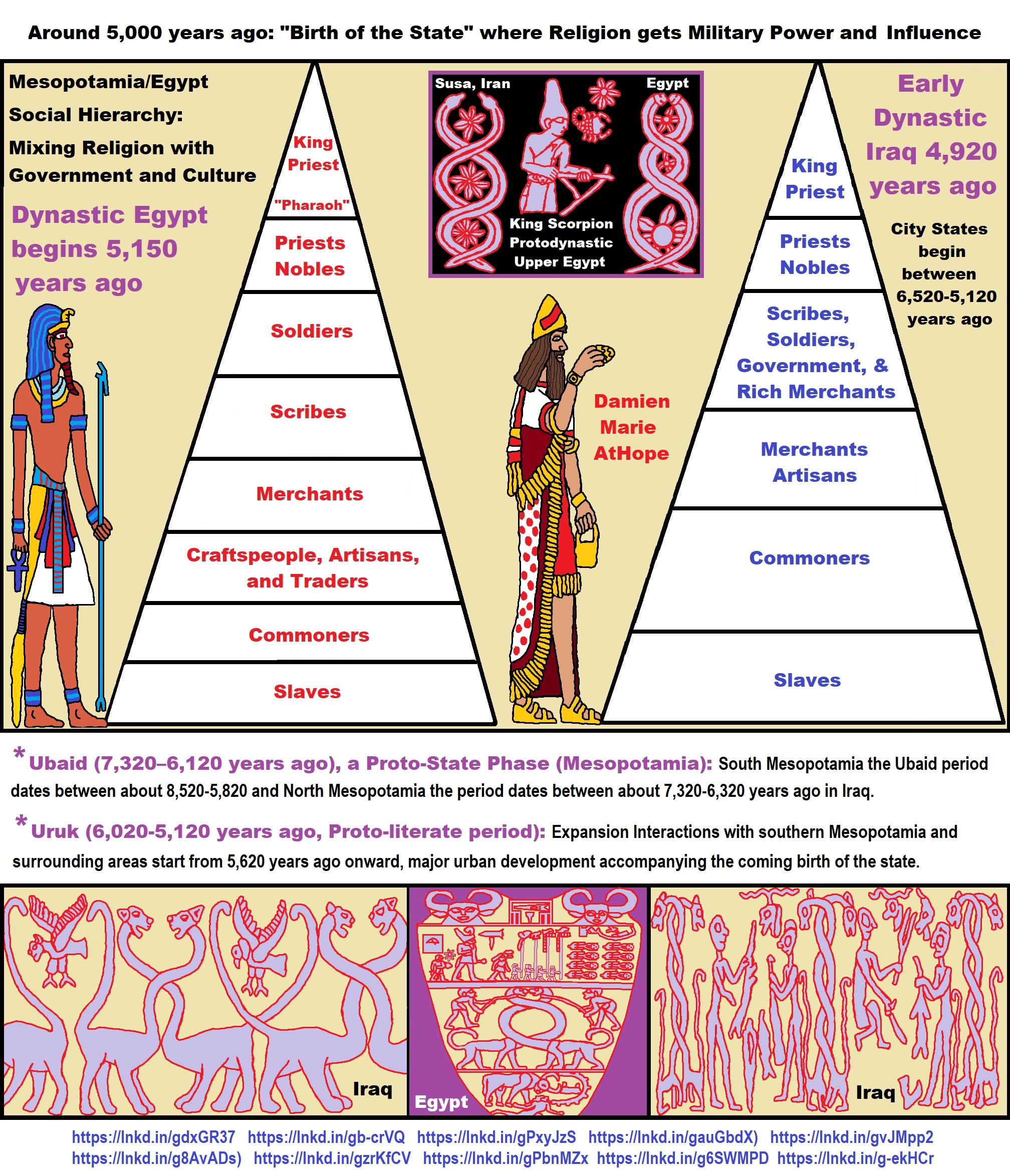

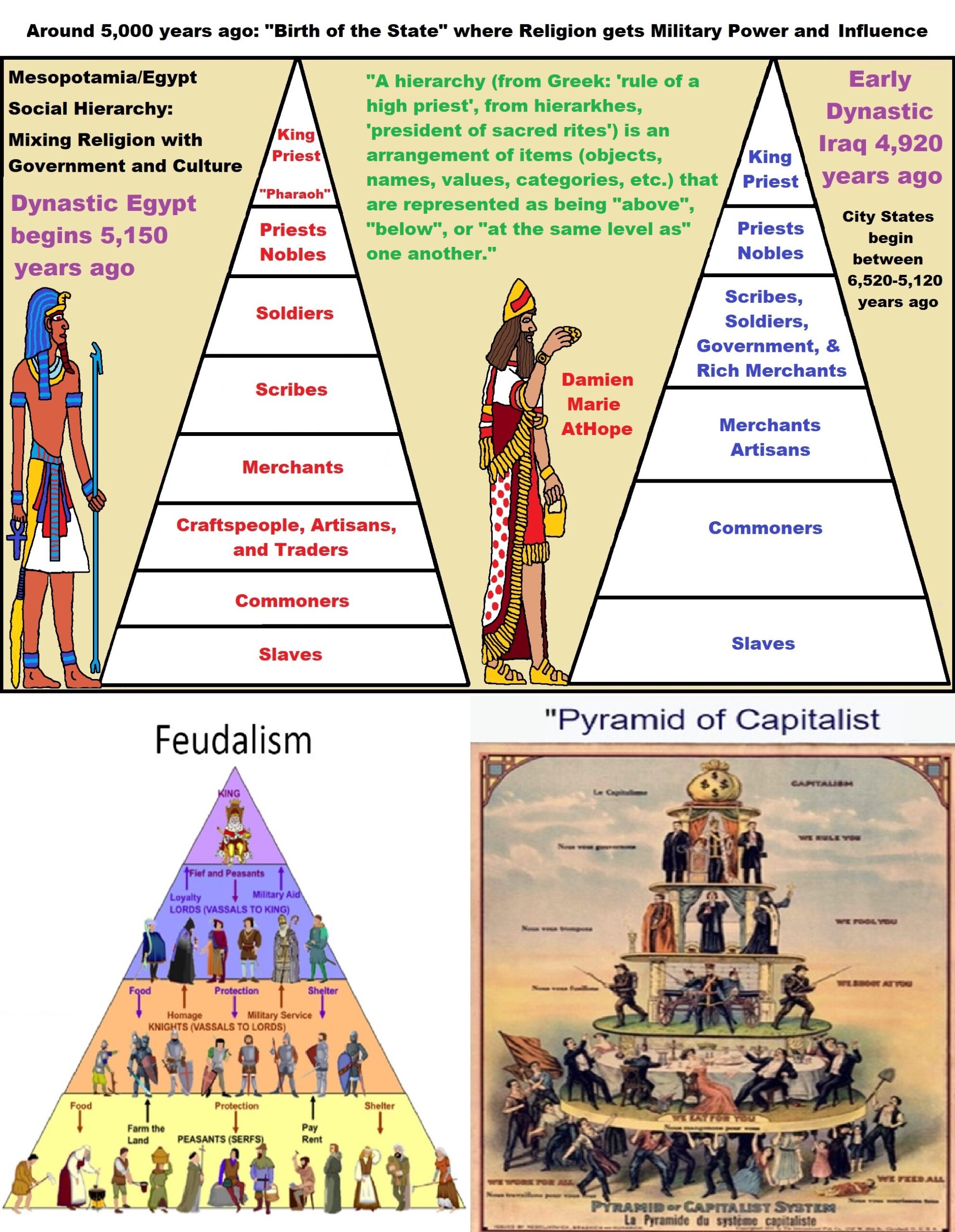

“The last category is that of the early states. They gave rise to a complexity that characterizes the more intricate social formations. Though the early states retained a number of the features of the chieftain groups, unlike them, these were societies of a non-relational type (i.e., status was acquired based on qualities, not on origin) stratified into different social classes. This gave rise to an elite that included officials, soldiers, and priests. The top level of this imaginary pyramid was occupied by the King. He had explicitly been given the power to implement laws and to enforce them, even by violent means. The institution of donation also ended in the early stages and was replaced by the levying of taxes.” ref

“Usually, the early states were small in terms of the size of their territory, often consisting of a single dominant city together with its economic hinterland. Because the state-building process was also regionally contagious, so to speak, several states coexisted in the area more or less on a regular basis. Inevitably, together, they formed an interactive network that dynamically transformed its goals from peacekeeping to war. The King had become the King of Kings by conquering the neighboring rulers, and inevitably, his empires ceased to meet the requisite criteria for being an early stage.” ref

“All cultures have one element in common: they somehow exercise social control over their own members. Like the “invisible hand” of the market to which Adam Smith refers in analyzing the workings of capitalism, two forces govern the workings of politics: power—the ability to induce behavior of others in specified ways by means of coercion or use or threat of physical force—and authority—the ability to induce behavior of others by persuasion. Extreme examples of the exercise of power are the gulags (prison camps) in Stalinist Russia, the death camps in Nazi-ruled Germany and Eastern Europe, and so-called Supermax prisons such as Pelican Bay in California and the prison for “enemy combatants” in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, by the United States. In all of these settings, prisoners comply or are punished or executed. At the other extreme are most forager societies, which typically exercise authority more often than power. Groups in those societies comply with the wishes of their most persuasive members.” ref

“In actuality, power and authority are points on a continuum, and both are present in every society to some degree. Even Hitler, who exercised absolute power in many ways, had to hold the Nuremberg rallies to generate popular support for his regime and persuade the German population that his leadership was the way to national salvation. In the Soviet Union, leaders had a great deal of coercive and physical power but still felt the need to hold parades and mass rallies on May Day every year to persuade people to remain attached to their vision of a communal society. At the other end of the political spectrum, societies that tend to use persuasion through authority also have some forms of coercive power. Among the Inuit, for example, individuals who flagrantly violated group norms could be punished, including by homicide.” ref

“A related concept in both politics and law is legitimacy: the perception that an individual has a valid right to leadership. Legitimacy is particularly applicable to complex societies that require centralized decision-making. Historically, the right to rule has been based on various principles. In agricultural states such as ancient Mesopotamia, the Aztec, and the Inca, justification for the rule of particular individuals was based on hereditary succession and typically granted to the eldest son of the ruler. Even this principle could be uncertain at times, as was the case when the Inca emperor Atahualpa had just defeated his rival and brother Huascar when the Spaniards arrived in Peru in 1533.” ref

“In many cases, supernatural beliefs were invoked to establish legitimacy and justify rule by an elite. Incan emperors derived their right to rule from the Sun God and Aztec rulers from Huitzilopochtli (Hummingbird-to-the-Left). European monarchs invoked a divine right to rule that was reinforced by the Church of England in Britain and by the Roman Catholic Church in other countries prior to the Reformation. In India, the dominance of the Brahmin elite over the other castes is justified by karma, cumulative forces created by good and evil deeds in past lives. Secular equivalents also serve to justify rule by elites; examples include the promise of a worker’s paradise in the former Soviet Union and racial purity of Aryans in Nazi Germany. In the United States and other democratic forms of government, legitimacy rests on the consent of the governed in periodic elections (though in the United States, the incoming president is sworn in using a Christian Bible despite the alleged separation of church and state).” ref

“In some societies, dominance by an individual or group is viewed as unacceptable. Christopher Boehm (1999) developed the concept of reverse dominance to describe societies in which people rejected attempts by any individual to exercise power. They achieved this aim using ridicule, criticism, disobedience, and strong disapproval and could banish extreme offenders. Richard Lee encountered this phenomenon when he presented the !Kung with whom he had worked over the preceding year with a fattened ox. Rather than praising or thanking him, his hosts ridiculed the beast as scrawny, ill fed, and probably sick. This behavior is consistent with reverse dominance.” ref

“Even in societies that emphasize equality between people, decisions still have to be made. Sometimes, particularly persuasive figures such as headmen make them, but persuasive figures who lack formal power are not free to make decisions without coming to a consensus with their fellows. To reach such a consensus, there must be general agreement. Essentially, then, even if in a backhanded way, legitimacy characterizes societies that lack institutionalized leadership. Another set of concepts refers to the reinforcements or consequences for compliance with the directives and laws of a society. Positive reinforcements are the rewards for compliance; examples include medals, financial incentives, and other forms of public recognition. Negative reinforcements punish noncompliance through fines, imprisonment, and death sentences. These reinforcements can be identified in every human society, even among foragers or others who have no written system of law. Reverse dominance is one form of negative reinforcement.” ref

“If cultures of various sizes and configurations are to be compared, there must be some common basis for defining political organization. In many small communities, the family functions as a political unit. As Julian Steward wrote about the Shoshone, a Native American group in the Nevada basin, “all features of the relatively simple culture were integrated and functioned on a family level. The family was the reproductive, economic, educational, political, and religious unit.” In larger more complex societies, however, the functions of the family are taken over by larger social institutions. The resources of the economy, for example, are managed by authority figures outside the family who demand taxes or other tribute. The educational function of the family may be taken over by schools constituted under the authority of a government, and the authority structure in the family is likely to be subsumed under the greater power of the state. Therefore, anthropologists need methods for assessing political organizations that can be applied to many different kinds of communities. This concept is called levels of socio-cultural integration.” ref

“Elman Service developed an influential scheme for categorizing the political character of societies that recognized four levels of socio-cultural integration: band, tribe, chiefdom, and state. A band is the smallest unit of political organization, consisting of only a few families and no formal leadership positions. Tribes have larger populations but are organized around family ties and have fluid or shifting systems of temporary leadership. Chiefdoms are large political units in which the chief, who usually is determined by heredity, holds a formal position of power. States are the most complex form of political organization and are characterized by a central government that has a monopoly over legitimate uses of physical force, a sizeable bureaucracy, a system of formal laws, and a standing military force.” ref

“Each type of political integration can be further categorized as egalitarian, ranked, or stratified. Band societies and tribal societies generally are considered egalitarian—there is no great difference in status or power between individuals and there are as many valued status positions in the societies as there are persons able to fill them. Chiefdoms are ranked societies; there are substantial differences in the wealth and social status of individuals based on how closely related they are to the chief. In ranked societies, there are a limited number of positions of power or status, and only a few can occupy them. State societies are stratified. There are large differences in the wealth, status, and power of individuals based on unequal access to resources and positions of power. Socio-economic classes, for instance, are forms of stratification in many state societies.” ref

“In a complex society, it may seem that social classes—differences in wealth and status—are, like death and taxes, inevitable: that one is born into wealth, poverty, or somewhere in between and has no say in the matter, at least at the start of life, and that social class is an involuntary position in society. However, is social class universal? As they say, let’s look at the record, in this case, ethnographies. We find that among foragers, there is no advantage to hoarding food; in most climates, it will rot before one’s eyes. Nor is there much personal property, and leadership, where it exists, is informal. In forager societies, the basic ingredients for social class do not exist. Foragers such as the !Kung, Inuit, and aboriginal Australians, are egalitarian societies in which there are few differences between members in wealth, status, and power. Highly skilled and less skilled hunters do not belong to different strata in the way that the captains of industry do from you and me. The less skilled hunters in egalitarian societies receive a share of the meat and have the right to be heard on important decisions. Egalitarian societies also lack a government or centralized leadership. Their leaders, known as headmen or big men, emerge by consensus of the group. Foraging societies are always egalitarian, but so are many societies that practice horticulture or pastoralism. In terms of political organization, egalitarian societies can be either bands or tribes.” ref

BAND-LEVEL POLITICAL ORGANIZATION

“Societies organized as a band typically comprise foragers who rely on hunting and gathering and are therefore nomadic, are few in number (rarely exceeding 100 persons), and form small groups consisting of a few families and a shifting population. Bands lack formal leadership. Richard Lee went so far as to say that the Dobe! Kung had no leaders. To quote one of his informants, “Of course, we have headmen. Each one of us is headman over himself.” At most, a band’s leader is primus inter pares or “first among equals” assuming anyone is first at all. Modesty is a valued trait; arrogance and competitiveness are not acceptable in societies characterized by reverse dominance. What leadership there is in band societies tends to be transient and subject to shifting circumstances. For example, among the Paiute in North America, “rabbit bosses” coordinated rabbit drives during the hunting season but played no leadership role otherwise. Some “leaders” are excellent mediators who are called on when individuals are involved in disputes, while others are perceived as skilled shamans or future-seers who are consulted periodically. There are no formal offices or rules of succession.” ref

“Bands were probably the first political unit to come into existence outside the family itself. There is some debate in anthropology about how the earliest bands were organized. Elman Service argued that patrilocal bands organized around groups of related men served as the prototype, reasoning that groups centered on male family relationships made sense because male cooperation was essential to hunting. M. Kay Martin and Barbara Voorhies pointed out in rebuttal that gathering vegetable foods, which typically was viewed as women’s work, actually contributed a greater number of calories in most cultures and thus that matrilocal bands organized around groups of related women would be closer to the norm..Indeed, in societies in which hunting is the primary source of food, such as the Inuit, women tend to be subordinate to men while men and women tend to have roughly equal status in societies that mainly gather plants for food.” ref

Law in Band Societies

“Within bands of people, disputes are typically resolved informally. There are no formal mediators or any organizational equivalent of a court of law. A good mediator may emerge—or may not. In some cultures, duels are employed. Among the Inuit, for example, disputants engage in a duel using songs in which, drum in hand, they chant insults at each other before an audience. The audience selects the better chanter and thereby the winner in the dispute. The Mbuti of the African Congo use ridicule; even children berate adults for laziness, quarreling, or selfishness. If ridicule fails, the Mbuti elders evaluate the dispute carefully, determine the cause, and, in extreme cases, walk to the center of the camp and criticize the individuals by name, using humor to soften their criticism—the group, after all, must get along.” ref

Warfare in Band Societies

“Nevertheless, conflict does sometimes break out into war between bands and, sometimes, within them. Such warfare is usually sporadic and short-lived since bands do not have formal leadership structures or enough warriors to sustain conflict for long. Most of the conflict arises from interpersonal arguments. Among the Tiwi of Australia, for example, failure of one band to reciprocate another band’s wife-giving with one of its own female relative led to abduction of women by the aggrieved band, precipitating a “war” that involved some spear-throwing (many did not shoot straight and even some of the onlookers were wounded) but mostly violent talk and verbal abuse. For the Dobe !Kung, Lee found 22 cases of homicide by males and other periodic episodes of violence, mostly in disputes over women—not quite the gentle souls Elizabeth Marshall Thomas depicted in her Harmless People.” ref

TRIBAL POLITICAL ORGANIZATION

“Whereas bands involve small populations without structure, tribal societies involve at least two well-defined groups linked together in some way and range in population from about 100 to as many as 5,000 people. Though their social institutions can be fairly complex, there are no centralized political structures or offices in the strict sense of those terms. There may be headmen, but there are no rules of succession, and sons do not necessarily succeed their fathers as is the case with chiefdoms. Tribal leadership roles are open to anyone—in practice, usually men, especially elder men who acquire leadership positions because of their personal abilities and qualities. Leaders in tribes do not have a means of coercing others or formal powers associated with their positions. Instead, they must persuade others to take actions they feel are needed. A Yanomami headsman, for instance, said that he would never issue an order unless he knew it would be obeyed. The headman Kaobawä exercised influence by example and by making suggestions and warning of consequences of taking or not taking an action.” ref

“Like bands, tribes are egalitarian societies. Some individuals in a tribe do sometimes accumulate personal property but not to the extent that other tribe members are deprived. And every (almost always male) person has the opportunity to become a headman or leader and, like bands, one’s leadership position can be situational. One man may be a good mediator, another an exemplary warrior, and a third capable of leading a hunt or finding a more ideal area for cultivation or grazing herds. An example illustrating this kind of leadership is the big man of New Guinea; the term is derived from the languages of New Guinean tribes (literally meaning “man of influence”). The big man is one who has acquired followers by doing favors they cannot possibly repay, such as settling their debts or providing bride-wealth. He might also acquire as many wives as possible to create alliances with his wives’ families. His wives could work to care for as many pigs as possible, for example, and in due course, he could sponsor a pig feast that would serve to put more tribe members in his debt and shame his rivals. It is worth noting that the followers, incapable of repaying the Big Man’s gifts, stand metaphorically as beggars to him.” ref

“Still, a big man does not have the power of a monarch. His role is not hereditary. His son must demonstrate his worth and acquire his own following—he must become a big man in his own right. Furthermore, there usually are other big men in the village who are his potential rivals. Another man who proves himself capable of acquiring a following can displace the existing big man. The big man also has no power to coerce—no army or police force. He cannot prevent a follower from joining another big man, nor can he force the follower to pay any debt owed. There is no New Guinean equivalent of a U.S. marshal. Therefore, he can have his way only by diplomacy and persuasion—which do not always work.” ref

Tribal Systems of Social Integration

Tribal societies have much larger populations than bands and thus must have mechanisms for creating and maintaining connections between tribe members. The family ties that unite members of a band are not sufficient to maintain solidarity and cohesion in the larger population of a tribe. Some of the systems that knit tribes together are based on family (kin) relationships, including various kinds of marriage and family lineage systems, but there are also ways to foster tribal solidarity outside of family arrangements through systems that unite members of a tribe by age or gender.” ref

Integration through Age Grades and Age Sets

Tribes use various systems to encourage solidarity or feelings of connectedness between people who are not related by family ties. These systems, sometimes known as sodalities, unite people across family groups. In one sense, all societies are divided into age categories. In the U.S. educational system, for instance, children are matched to grades in school according to their age—six-year-olds in first grade and thirteen-year-olds in eighth grade. Other cultures, however, have established complex age-based social structures. Many pastoralists in East Africa, for example, have age grades and age sets. Age sets are named categories to which men of a certain age are assigned at birth. Age grades are groups of men who are close to one another in age and share similar duties or responsibilities. All men cycle through each age grade over the course of their lifetimes. As the age sets advance, the men assume the duties associated with each age grade.” ref

“An example of this kind of tribal society is the Tiriki of Kenya. From birth to about fifteen years of age, boys become members of one of seven named age sets. When the last boy is recruited, that age set closes, and a new one opens. For example, young and adult males who belonged to the “Juma” age set in 1939 became warriors by 1954. The “Mayima” were already warriors in 1939 and became elder warriors during that period. In precolonial times, men of the warrior age grade defended the herds of the Tiriki and conducted raids on other tribes while the elder warriors acquired cattle and houses and took on wives. There were recurring reports of husbands who were much older than their wives, who had married early in life, often as young as fifteen or sixteen. As solid citizens of the Tiriki, the elder warriors also handled decision-making functions of the tribe as a whole; their legislation affected the entire village while also representing their own kin groups. The other age sets also moved up through age grades in the fifteen-year period.” ref

“The elder warriors in 1939, “Nyonje,” became the judicial elders by 1954. Their function was to resolve disputes that arose between individuals, families, and kin groups, of which some elders were a part. The “Jiminigayi,” judicial elders in 1939, became ritual elders in 1954, handling supernatural functions that involved the entire Tiriki community. During this period, the open age set was “Kabalach.” Its prior members had all grown old or died by 1939 and new boys joined it between 1939 and 1954. Thus, the Tiriki age sets moved in continuous 105-year cycles. This age grade and age set system encourages bonds between men of similar ages. Their loyalty to their families is tempered by their responsibilities to their fellows of the same age.” ref

“Among most, if not all, tribes of New Guinea, the existence of men’s houses serves to cut across family lineage groups in a village. Perhaps the most fastidious case of male association in New Guinea is the bachelor association of the Mae-Enga, who live in the northern highlands. In their culture, a boy becomes conscious of the distance between males and females before he leaves home at age five to live in the men’s house. Women are regarded as potentially unclean, and strict codes that minimize male-female relations are enforced. Sanggai festivals reinforce this division. During the festival, every youth of age 15 or 16 goes into seclusion in the forest and observes additional restrictions, such as avoiding pigs (which are cared for by women) and avoiding gazing at the ground lest he see female footprints or pig feces. One can see, therefore, that every boy commits his loyalty to the men’s house early in life even though he remains a member of his birth family. Men’s houses are the center of male activities. There, they draw up strategies for warfare, conduct ritual activities involving magic and honoring of ancestral spirits, and plan and rehearse periodic pig feasts.” ref

“Exchanges and the informal obligations associated with them are primary devices by which bands and tribes maintain a degree of order and forestall armed conflict, which was viewed as the “state of nature” for tribal societies by Locke and Hobbes, in the absence of exercises of force by police or an army. Marcel Mauss, nephew and student of eminent French sociologist Emile Durkheim, attempted in 1925 to explain gift giving and its attendant obligations cross-culturally in his book, The Gift: Forms and Functions of Exchange in Archaic Societies. He started with the assumption that two groups have an imperative to establish a relationship of some kind. There are three options when they meet for the first time. They could pass each other by and never see each other again. They may resort to arms with an uncertain outcome. One could wipe the other out or, more likely, win at great cost of men and property or fight to a draw. The third option is to “come to terms” with each other by establishing a more or less permanent relationship. Exchanging gifts is one way for groups to establish this relationship.” ref

“These gift exchanges are quite different from Western ideas about gifts. In societies that lack a central government, formal law enforcement powers, and collection agents, the gift exchanges are obligatory and have the force of law in the absence of law. Mauss referred to them as “total prestations.” Though no Dun and Bradstreet agents would come to collect, the potential for conflict that could break out at any time reinforced the obligations. According to Mauss, the first obligation is to give; it must be met if a group is to extend social ties to others. The second obligation is to receive; refusal of a gift constitutes rejection of the offer of friendship as well. Conflicts can arise from the perceived insult of a rejected offer. The third obligation is to repay. One who fails to make a gift in return will be seen as in debt—in essence, a beggar. Mauss offered several ethnographic cases that illustrated these obligations. Every gift conferred power to the giver, expressed by the Polynesian terms mana (an intangible supernatural force) and hau (among the Maori, the “spirit of the gift,” which must be returned to its owner). Marriage and its associated obligations also can be viewed as a form of gift-giving as one family “gives” a bride or groom to the other.” ref

“Understanding social solidarity in tribal societies requires knowledge of family structures, which are also known as kinship systems. The romantic view of marriage in today’s mass media is largely a product of Hollywood movies and romance novels from mass-market publishers such as Harlequin. In most cultures around the world, marriage is largely a device that links two families together; this is why arranged marriage is so common from a cross-cultural perspective. And, as Voltaire admonished, if we are to discuss anything, we need to define our terms. Marriage is defined in numerous ways, usually (but not always) involving a tie between a woman and a man. Same-sex marriage is also common in many cultures. Nuclear families consist of parents and their children. Extended families consist of three generations or more of relatives connected by marriage and descent.” ref

“Bilateral descent (commonly used in the United States) recognizes both the mother’s and the father’s “sides” of the family while unilineal descent recognizes only one sex-based “side” of the family. Unilineal descent can be patrilineal, recognizing only relatives through a line of male ancestors, or matrilineal, recognizing only relatives through a line of female ancestors. Groups made up of two or more extended families can be connected as larger groups linked by kinship ties. A lineage consists of individuals who can trace or demonstrate their descent through a line of males or females to the founding ancestor. Most tribal societies’ political organizations involve marriage, which is a logical vehicle for creating alliances between groups. One of the most well-documented types of marriage alliance is bilateral cross-cousin marriage in which a man marries his cross-cousin—one he is related to through two links, his father’s sister and his mother’s brother.” ref

“These marriages have been documented among the Yanomami, an indigenous group living in Venezuela and Brazil. Yanomami villages are typically populated by two or more extended family groups also known as lineages. Disputes and disagreements are bound to occur, and these tensions can potentially escalate to open conflict or even physical violence. Bilateral cross-cousin marriage provides a means of linking lineage groups together over time through the exchange of brides. Because cross-cousin marriage links people together by both marriage and blood ties (kinship), these unions can reduce tension between the groups or at least provide an incentive for members of rival lineages to work together.” ref

“Another type of kin-based integrative mechanism is a segmentary lineage. As previously noted, a lineage is a group of people who can trace or demonstrate their descent from a founding ancestor through a line of males or a line of females. A segmentary lineage is a hierarchy of lineages that contains both close and relatively distant family members. At the base are several minimal lineages whose members trace their descent from their founder back two or three generations. At the top is the founder of all of the lineages, and two or more maximal lineages can derive from the founder’s lineage. Between the maximal and the minimal lineages are several intermediate lineages.” ref

“The classic examples of segmentary lineages were described by E. E. Evans-Pritchard (1940) in his discussion of the Nuer, pastoralists who lived in southern Sudan. Paul Bohannan also described this system among the Tiv, who were West African pastoralists, and Robert Murphy and Leonard Kasdan analyzed the importance of these lineages among the Bedouin of the Middle East. Segmentary lineages often develop in environments in which a tribal society is surrounded by several other tribal societies. Hostility between the tribes induces their members to retain ties with their kin and to mobilize them when external conflicts arise. An example of this is ties maintained between the Nuer and the Dinka. Once a conflict is over, segmentary lineages typically dissolve into their constituent units. Another attribute of segmentary lineages is local genealogical segmentation, meaning close lineages dwell near each other, providing a physical reminder of their genealogy.” ref

Law in Tribal Societies

“Tribal societies generally lack systems of codified law whereby damages, crimes, remedies, and punishments are specified. Only state-level political systems can determine, usually by writing formal laws, which behaviors are permissible and which are not (discussed later in this chapter). In tribes, there are no systems of law enforcement whereby an agency such as the police, the sheriff, or an army can enforce laws enacted by an appropriate authority. And, as already noted, headman and big men cannot force their will on others.” ref

In tribal societies, as in all societies, conflicts arise between individuals. Sometimes the issues are equivalent to crimes—taking of property or commitment of violence—that are not considered legitimate in a given society. Other issues are civil disagreements—questions of ownership, damage to property, an accidental death. In tribal societies, the aim is not so much to determine guilt or innocence or to assign criminal or civil responsibility as it is to resolve conflict, which can be accomplished in various ways. The parties might choose to avoid each other. Bands, tribes, and kin groups often move away from each other geographically, which is much easier for them to do than for people living in complex societies.” ref

One issue in tribal societies, as in all societies, is guilt or innocence. When no one witnesses an offense or an account is deemed unreliable, tribal societies sometimes rely on the supernatural. Oaths, for example, involve calling on a deity to bear witness to the truth of what one says; the oath given in court is a holdover from this practice. An ordeal is used to determine guilt or innocence by submitting the accused to dangerous, painful, or risky tests believed to be controlled by supernatural forces. The poison oracle used by the Azande of the Sudan and the Congo is an ordeal based on their belief that most misfortunes are induced by witchcraft (in this case, witchcraft refers to ill feeling of one person toward another). A chicken is force fed a strychnine concoction known as benge just as the name of the suspect is called out. If the chicken dies, the suspect is deemed guilty and is punished or goes through reconciliation.” ref

“A more commonly exercised option is to find ways to resolve the dispute. In small groups, an unresolved question can quickly escalate to violence and disrupt the group. The first step is often negotiation; the parties attempt to resolve the conflict by direct discussion in hope of arriving at an agreement. Offenders sometimes make a ritual apology, particularly if they are sensitive to community opinion. In Fiji, for example, offenders make ceremonial apologies called i soro, one of the meanings of which is “I surrender.” An intermediary speaks, offers a token gift to the offended party, and asks for forgiveness, and the request is rarely rejected.” ref

“When negotiation or a ritual apology fails, often the next step is to recruit a third party to mediate a settlement as there is no official who has the power to enforce a settlement. A classic example in the anthropological literature is the Leopard Skin Chief among the Nuer, who is identified by a leopard skin wrap around his shoulders. He is not a chief but is a mediator. The position is hereditary, has religious overtones, and is responsible for the social well-being of the tribal segment. He typically is called on for serious matters such as murder. The culprit immediately goes to the residence of the Leopard Skin Chief, who cuts the culprit’s arm until blood flows. If the culprit fears vengeance by the dead man’s family, he remains at the residence, which is considered a sanctuary, and the Leopard Skin Chief then acts as a go-between for the families of the perpetrator and the dead man.” ref

“The Leopard Skin Chief cannot force the parties to settle and cannot enforce any settlement they reach. The source of his influence is the desire for the parties to avoid a feud that could escalate into an ever-widening conflict involving kin descended from different ancestors. He urges the aggrieved family to accept compensation, usually in the form of cattle. When such an agreement is reached, the chief collects the 40 to 50 head of cattle and takes them to the dead man’s home, where he performs various sacrifices of cleansing and atonement. This discussion demonstrates the preference most tribal societies have for mediation given the potentially serious consequences of a long-term feud. Even in societies organized as states, mediation is often preferred. In the agrarian town of Talea, Mexico, for example, even serious crimes are mediated in the interest of preserving a degree of local harmony. The national authorities often tolerate local settlements if they maintain the peace.” ref

Warfare in Tribal Societies

“What happens if mediation fails and the Leopard Skin Chief cannot convince the aggrieved clan to accept cattle in place of their loved one? War. In tribal societies, wars vary in cause, intensity, and duration, but they tend to be less deadly than those run by states because of tribes’ relatively small populations and limited technologies. Tribes engage in warfare more often than bands, both internally and externally. Among pastoralists, both successful and attempted thefts of cattle frequently spark conflict. Among pre-state societies, pastoralists have a reputation for being the most prone to warfare.” ref

“However, horticulturalists also engage in warfare, as the film Dead Birds, which describes warfare among the highland Dani of west New Guinea (Irian Jaya), attests. Among anthropologists, there is a “protein debate” regarding causes of warfare. Marvin Harris in a 1974 study of the Yanomami claimed that warfare arose there because of a protein deficiency associated with a scarcity of game, and Kenneth Good supported that thesis in finding that the game a Yanomami villager brought in barely supported the village. He could not link this variable to warfare, however. In rebuttal, Napoleon Chagnon linked warfare among the Yanomami with abduction of women rather than disagreements over hunting territory, and findings from other cultures have tended to agree with Chagnon’s theory.” ref

“Tribal wars vary in duration. Raids are short-term uses of physical force that are organized and planned to achieve a limited objective such as acquisition of cattle (pastoralists) or other forms of wealth and, often, abduction of women, usually from neighboring communities. Feuds are longer in duration and represent a state of recurring hostilities between families, lineages, or other kin groups. In a feud, the responsibility to avenge rests with the entire group, and the murder of any kin member is considered appropriate because the kin group as a whole is considered responsible for the transgression. Among the Dani, for example, vengeance is an obligation; spirits are said to dog the victim’s clan until its members murder someone from the perpetrator’s clan.” ref

RANKED SOCIETIES AND CHIEFDOMS

“Unlike egalitarian societies, ranked societies (sometimes called “rank societies”) involve greater differentiation between individuals and the kin groups to which they belong. These differences can be, and often are, inherited, but there are no significant restrictions in these societies on access to basic resources. All individuals can meet their basic needs. The most important differences between people of different ranks are based on sumptuary rules—norms that permit persons of higher rank to enjoy greater social status by wearing distinctive clothing, jewelry, and/or decorations denied those of lower rank. Every family group or lineage in the community is ranked in a hierarchy of prestige and power. Furthermore, within families, siblings are ranked by birth order, and villages can also be ranked.” ref

“The concept of a ranked society leads us directly to the characteristics of chiefdoms. Unlike the position of headman in a band, the position of chief is an office—a permanent political status that demands a successor when the current chief dies. There are, therefore, two concepts of chief: the man (women rarely, if ever, occupy these posts) and the office. Thus the expression “The king is dead, long live the king.” With the New Guinean big man, there is no formal succession. Other big men will be recognized and eventually take the place of one who dies, but there is no rule stipulating that his eldest son or any son must succeed him. For chiefs, there must be a successor, and there are rules of succession.” ref

“Political chiefdoms usually are accompanied by an economic exchange system known as redistribution in which goods and services flow from the population at large to the central authority represented by the chief. It then becomes the task of the chief to return the flow of goods in another form. The chapter on economics provides additional information about redistribution economies. These political and economic principles are exemplified by the potlatch custom of the Kwakwaka’wakw and other indigenous groups who lived in chiefdom societies along the northwest coast of North America from the extreme northwest tip of California through the coasts of Oregon, Washington, British Columbia, and southern Alaska. Potlatch ceremonies observed major events such as births, deaths, marriages of important persons, and installment of a new chief.” ref

“Families prepared for the event by collecting food and other valuables such as fish, berries, blankets, animal skins, carved boxes, and copper. At the potlatch, several ceremonies were held, dances were performed by their “owners,” and speeches delivered. The new chief was watched very carefully. Members of the society noted the eloquence of his speech, the grace of his presence, and any mistakes he made, however egregious or trivial. Next came the distribution of gifts, and again the chief was observed. Was he generous with his gifts? Was the value of his gifts appropriate to the rank of the recipient or did he give valuable presents to individuals of relatively low rank? Did his wealth allow him to offer valuable objects?” ref

“The next phase of the potlatch was critical to the chief’s validation of his position. Visitor after visitor would arise and give long speeches evaluating the worthiness of this successor to the chieftainship of his father. If his performance had so far met their expectations, if his gifts were appropriate, the guests’ speeches praised him accordingly. They were less than adulatory if the chief had not performed to their expectations and they deemed the formal eligibility of the successor insufficient. He had to perform. If he did, then the guests’ praise not only legitimized the new chief in his role, but also it ensured some measure of peace between villages. Thus, in addition to being a festive event, the potlatch determined the successor’s legitimacy and served as a form of diplomacy between groups.” ref

“Much has been made among anthropologists of rivalry potlatches in which competitive gifts were given by rival pretenders to the chieftainship. Philip Drucker argued that competitive potlatches were a product of sudden demographic changes among the indigenous groups on the northwest coast. When smallpox and other diseases decimated hundreds, many potential successors to the chieftainship died, leading to situations in which several potential successors might be eligible for the chieftainship. Thus, competition in potlatch ceremonies became extreme with blankets or copper repaid with ever-larger piles and competitors who destroyed their own valuables to demonstrate their wealth. The events became so raucous that the Canadian government outlawed the displays in the early part of the twentieth century. Prior to that time, it had been sufficient for a successor who was chosen beforehand to present appropriate gifts.” ref

Kin-Based Integrative Mechanisms: Conical Clans

“With the centralization of society, kinship is most likely to continue playing a role, albeit a new one. Among Northwest Coast Indians, for example, the ranking model has every lineage ranked, one above the other, siblings ranked in order of birth, and even villages in a ranking scale. Drucker points out that the further north one goes, the more rigid the ranking scheme is. The most northerly of these coastal peoples trace their descent matrilineally; indeed, the Haida consist of four clans. Those further south tend to be patrilineal, and some show characteristics of an ambilineal descent group. It is still unclear, for example, whether the Kwakiutl numaym are patrilineal clans or ambilineal descent groups.” ref

“Because chiefdoms cannot enforce their power by controlling resources or by having a monopoly on the use of force, they rely on integrative mechanisms that cut across kinship groups. As with tribal societies, marriage provides chiefdoms with a framework for encouraging social cohesion. However, since chiefdoms have more-elaborate status hierarchies than tribes, marriages tend to reinforce ranks. The patrilineal cross-cousin marriage system also operates in a complex society in highland Burma known as the Kachin. In that system, the wife-giving lineage is known as mayu and the wife-receiving lineage as dama to the lineage that gave it a wife. Thus, in addition to other mechanisms of dominance, higher-ranked lineages maintain their superiority by giving daughters to lower-ranked lineages and reinforce the relations between social classes through the mayu-dama relationship.” ref

“The Kachin are not alone in using interclass marriage to reinforce dominance. The Natchez peoples, a matrilineal society of the Mississippi region of North America, were divided into four classes: Great Sun chiefs, noble lineages, honored lineages, and inferior “stinkards.” Unlike the Kachin, however, their marriage system was a way to upward mobility. The child of a woman who married a man of lower status assumed his/her mother’s status. Thus, if a Great Sun woman married a stinkard, the child would become a Great Sun. If a stinkard man were to marry a Great Sun woman, the child would become a stinkard. The same relationship obtained between women of noble lineage and honored lineage and men of lower status. Only two stinkard partners would maintain that stratum, which was continuously replenished with people in warfare.” ref

“Other societies maintained status in different ways. Brother-sister marriages, for example, were common in the royal lineages of the Inca, the Ancient Egyptians, and the Hawaiians, which sought to keep their lineages “pure.” Another, more-common type was patrilateral parallel-cousin marriage in which men married their fathers’ brothers’ daughters. This marriage system, which operated among many Middle Eastern nomadic societies, including the Rwala Bedouin chiefdoms, consolidated their herds, an important consideration for lineages wishing to maintain their wealth.” ref

“Poro and sande secret societies for men and women, respectively, are found in the Mande-speaking peoples of West Africa, particularly in Liberia, Sierra Leone, the Ivory Coast, and Guinea. The societies are illegal under Guinea’s national laws. Elsewhere, they are legal and membership is universally mandatory under local laws. They function in both political and religious sectors of society. So how can such societies be secret if all men and women must join? According to Beryl Bellman, who is a member of a poro association, the standard among the Kpelle of Liberia is an ability to keep secrets. Members of the community are entrusted with the political and religious responsibilities associated with the society only after they learn to keep secrets. There are two political structures in poros and sandes: the “secular” and the “sacred.” ref

“The secular structure consists of the town chief, neighborhood and kin group headmen, and elders. The sacred structure (the zo) is composed of a hierarchy of “priests” of the poro and the sande in the neighborhood, and among the Kpelle the poro and sande zo take turns dealing with in-town fighting, rapes, homicides, incest, and land disputes. They, like leopard skin chiefs, play an important role in mediation. The zo of both the poro and sande are held in great respect and even feared. Some authors have suggested that sacred structure strengthens the secular political authority because chiefs and landowners occupy the most powerful positions in the zo. Consequently, these chiefdoms seem to have developed formative elements of a stratified society and a state, as we see in the next section.” ref

STRATIFIED SOCIETIES

“Opposite from egalitarian societies in the spectrum of social classes is the stratified society, which is defined as one in which elites who are a numerical minority control the strategic resources that sustain life. Strategic resources include water for states that depend on irrigation agriculture, land in agricultural societies, and oil in industrial societies. Capital and products and resources used for further production are modes of production that rely on oil and other fossil fuels such as natural gas in industrial societies. (Current political movements call for the substitution of solar and wind power for fossil fuels.)” ref

“Operationally, stratification is, as the term implies, a social structure that involves two or more largely mutually exclusive populations. An extreme example is the caste system of traditional Indian society, which draws its legitimacy from Hinduism. In caste systems, membership is determined by birth and remains fixed for life, and social mobility—moving from one social class to another—is not an option. Nor can persons of different castes marry; that is, they are endogamous. Although efforts have been made to abolish castes since India achieved independence in 1947, they still predominate in rural areas.” ref

“India’s caste system consists of four varna, pure castes, and one collectively known as Dalit and sometimes as Harijan—in English, “untouchables,” reflecting the notion that for any varna caste member to touch or even see a Dalit pollutes them. The topmost varna caste is the Brahmin or priestly caste. It is composed of priests, governmental officials and bureaucrats at all levels, and other professionals. The next highest is the Kshatriya, the warrior caste, which includes soldiers and other military personnel and the police and their equivalents. Next are the Vaishyas, who are craftsmen and merchants, followed by the Sudras (pronounced “shudra”), who are peasants and menial workers. Metaphorically, they represent the parts of Manu, who is said to have given rise to the human race through dismemberment. The head corresponds to Brahmin, the arms to Kshatriya, the thighs to Vaishya, and the feet to the Sudra.” ref

“There are also a variety of subcastes in India. The most important are the hundreds, if not thousands, of occupational subcastes known as jatis. Wheelwrights, ironworkers, landed peasants, landless farmworkers, tailors of various types, and barbers all belong to different jatis. Like the broader castes, jatis are endogamous, and one is born into them. They form the basis of the jajmani relationship, which involves the provider of a particular service, the jajman, and the recipient of the service, the kamin. Training is involved in these occupations but one cannot change vocations. Furthermore, the relationship between the jajman and the kamin is determined by previous generations. If I were to provide you, my kamin, with haircutting services, it would be because my father cut your father’s hair. In other words, you would be stuck with me regardless of how poor a barber I might be. This system represents another example of an economy as an instituted process, an economy embedded in society.” ref

“Similar restrictions apply to those excluded from the varna castes, the “untouchables” or Dalit. Under the worst restrictions, Dalits were thought to pollute other castes. If the shadow of a Dalit fell on a Brahmin, the Brahmin immediately went home to bathe. Thus, at various times and locations, the untouchables were also unseeable, able to come out only at night. Dalits were born into jobs considered polluting to other castes, particularly work involving dead animals, such as butchering (Hinduism discourages consumption of meat so the clients were Muslims, Christians, and believers of other religions), skinning, tanning, and shoemaking with leather. Contact between an upper caste person and a person of any lower caste, even if “pure,” was also considered polluting and was strictly forbidden.” ref

“The theological basis of caste relations is karma—the belief that one’s caste in this life is the cumulative product of one’s acts in past lives, which extends to all beings, from minerals to animals to gods. Therefore, though soul class mobility is nonexistent during a lifetime, it is possible between lifetimes. Brahmins justified their station by claiming that they must have done good in their past lives. However, there are indications that the untouchable Dalits and other lower castes are not convinced of their legitimation.” ref

“Although India’s system is the most extreme, it not the only caste system. In Japan, a caste known as Burakumin is similar in status to Dalits. Though they are no different in physical appearance from other Japanese people, the Burakumin people have been forced to live in ghettos for centuries. They descend from people who worked in the leather tanning industry, a low-status occupation, and still work in leather industries such as shoemaking. Marriage between Burakumin and other Japanese people is restricted, and their children are excluded from public schools.” ref

“Some degree of social mobility characterizes all societies, but even so-called open-class societies are not as mobile as one might think. In the United States, for example, actual movement up the social latter is rare despite Horatio Alger and rags-to-riches myths. Stories of individuals “making it” through hard work ignore the majority of individuals whose hard work does not pay off or who actually experience downward mobility. Indeed, the Occupy Movement, which began in 2011, recognizes a dichotomy in American society of the 1 percent (millionaires and billionaires) versus the 99 percent (everyone else), and self-styled socialist Bernie Sanders made this the catch phrase of his campaign for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination. In India (a closed-class society), on the other hand, there are exceptions to the caste system. In Rajasthan, for example, those who own or control most of the land are not of the warrior caste as one might expect; they are of the lowest caste and their tenants and laborers are Brahmins.” ref

STATE LEVEL OF POLITICAL ORGANIZATION

“The state is the most formal of the four levels of political organization under study here. In states, political power is centralized in a government that exercises a monopoly over the legitimate use of force. It is important to understand that the exercise of force constitutes a last resort; one hallmark of a weak state is frequent use of physical force to maintain order. States develop in societies with large, often ethnically diverse populations—hundreds of thousands or more—and are characterized by complex economies that can be driven by command or by the market, social stratification, and an intensive agricultural or industrial base.” ref

“Several characteristics accompany a monopoly over use of legitimate force in a state. First, like tribes and chiefdoms, states occupy a more or less clearly defined territory or land defined by boundaries that separate it from other political entities that may or not be states (exceptions are associated with the Islamic State and are addressed later). Ancient Egypt was a state bounded on the west by desert and possibly forager or tribal nomadic peoples. Mesopotamia was a series of city-states competing for territory with other city-states.” ref

“Heads of state can be individuals designated as kings, emperors, or monarchs under other names or can be democratically elected, in fact or in name—military dictators, for example, are often called presidents. Usually, states establish some board or group of councilors (e.g., the cabinet in the United States and the politburo in the former Soviet Union.) Often, such councils are supplemented with one or two legislative assemblies. The Roman Empire had a senate (which originated as a body of councilors) and as many as four assemblies that combined patrician (elite) and plebian (general population) influences. Today, nearly all of the world’s countries have some sort of an assembly, but many rubber-stamp the executive’s decisions (or play an obstructionist role, as in the U.S. Congress during the Obama administration).” ref

“States also have an administrative bureaucracy that handles public functions provided for by executive orders and/or legislation. Formally, the administrative offices are typically arranged in a hierarchy, and the top offices delegate specific functions to lower ones. Similar hierarchies are established for the personnel in a branch. In general, agricultural societies tend to rely on inter-personal relations in the administrative structure while industrial states rely on rational hierarchical structures. An additional state power is taxation—a system of redistribution in which all citizens are required to participate. This power is exercised in various ways. Examples include the mitá or labor tax of the Inca, the tributary systems of Mesopotamia, and monetary taxes familiar to us today and to numerous subjects throughout the history of the state. Control over others’ resources is an influential mechanism undergirding the power of the state.” ref

“A less tangible but no less powerful characteristic of states is their ideologies, which are designed to reinforce the right of powerholders to rule. Ideologies can manifest in philosophical forms, such as the divine right of kings in pre-industrial Europe, karma and the caste system in India, consent of the governed in the United States, and the metaphorical family in Imperial China. More often, ideologies are less indirect and less perceptible as propaganda. We might watch the Super Bowl or follow the latest antics of the Kardashians, oblivious to the notion that both are diversions from the reality of power in this society. Young Americans, for example, may be drawn to military service to fight in Iraq by patriotic ideologies just as their parents or grandparents were drawn to service during the Vietnam War. In a multitude of ways across many cultures, Plato’s parable of the shadows in the cave—that watchers misperceive shadows as reality—has served to reinforce political ideologies.” ref

“Finally, there is delegation of the state’s coercive power. The state’s need to use coercive power betrays an important weakness—subjects and citizens often refuse to recognize the powerholders’ right to rule. Even when the legitimacy of power is not questioned, the use and/or threat of force serves to maintain the state, and that function is delegated to agencies such as the police to maintain internal order and to the military to defend the state against real and perceived enemies and, in many cases, to expand the state’s territory. Current examples include a lack of accountability for the killing of black men and women by police officers; the killing of Michael Brown by Darren Wilson in Ferguson, Missouri, is a defining example.” ref

State and Nation

“Though state and nation are often used interchangeably, they are not the same thing. A state is a coercive political institution; a nation is an ethnic population. There currently are about 200 states in the world, and many of them did not exist before World War II. Meanwhile, there are around 5,000 nations identified by their language, territorial base, history, and political organization. Few states are conterminous with a nation (a nation that wholly comprises the state). Even in Japan, where millions of the country’s people are of a single ethnicity, there is a significant indigenous minority known as the Ainu who at one time were a distinct biological population as well as an ethnic group. Only recently has Japanese society opened its doors to immigrants, mostly from Korea and Taiwan. The vast majority of states in the world, including the United States, are multi-national.” ref

Some ethnicities/nations have no state of their own. The Kurds, who reside in adjacent areas of Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and Iran, are one such nation. In the colonial era, the Mande-speaking peoples ranged across at least four West African countries, and borders between the countries were drawn without respect to the tribal identities of the people living there. Diasporas, the scattering of a people of one ethnicity across the globe, are another classic example. The diaspora of Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews is well-known. Many others, such as the Chinese, have more recently been forced to flee their homelands. The current ongoing mass migration of Syrians induced by formation of the Islamic State and the war in Syria is but the most recent example.” ref

Formation of States

“How do states form? One precondition is the presence of a stratified society in which an elite minority controls life-sustaining strategic resources. Another is increased agricultural productivity that provides support for a larger population. Neither, however, is a sufficient cause for development of a state. A group of people who are dissatisfied with conditions in their home region has a motive to move elsewhere—unless there is nowhere else to go and they are circumscribed. Circumscription can arise when a region is hemmed in by a geographic feature such as mountain ranges or desert and when migrants would have to change their subsistence strategies, perhaps having to move from agriculture back to foraging, herding, or horticulture or to adapt to an urban industrialized environment. The Inca Empire did not colonize on a massive scale beyond northern Chile to the south or into the Amazon because indigenous people there could simply pick up and move elsewhere. Still, the majority of the Inca population did not have that option. Circumscription also results when a desirable adjacent region is taken by other states or chiefdoms.” ref

“Who, then, were the original subjects of these states? One short answer is peasants, a term derived from the French paysan, which means “countryman.” Peasantry entered the anthropological literature relatively late. In his 800-page tome Anthropology published in 1948, Alfred L. Kroeber defined peasantry in less than a sentence: “part societies with part cultures.” Robert Redfield defined peasantry as a “little tradition” set against a “great tradition” of national state society. Louis Fallers argued in 1961 against calling African cultivators “peasants” because they had not lived in the context of a state-based civilization long enough.” ref

“Thus, peasants had been defined in reference to some larger society, usually an empire, a state, or a civilization. In light of this, Wolf sought to place the definition of peasant on a structural footing. Using a funding metaphor, he compared peasants with what he called “primitive cultivators.” Both primitive cultivators and peasants have to provide for a “caloric fund” by growing food and, by extension, provide for clothing, shelter, and all other necessities of life. Second, both must provide for a “replacement fund”—not only reserving seeds for next year’s crop but also repairing their houses, replacing broken pots, and rebuilding fences. And both primitive cultivators and peasants must provide a “ceremonial fund” for rites of passage and fiestas. They differ in that peasants live in states, and primitive cultivators do not. The state exercises domain over peasants’ resources, requiring peasants to provide a “fund of rent.” That fund appears in many guises, including tribute in kind, monetary taxes, and forced labor to an empire or lord. In Wolf’s conception, primitive cultivators are free of these obligations to the state.” ref

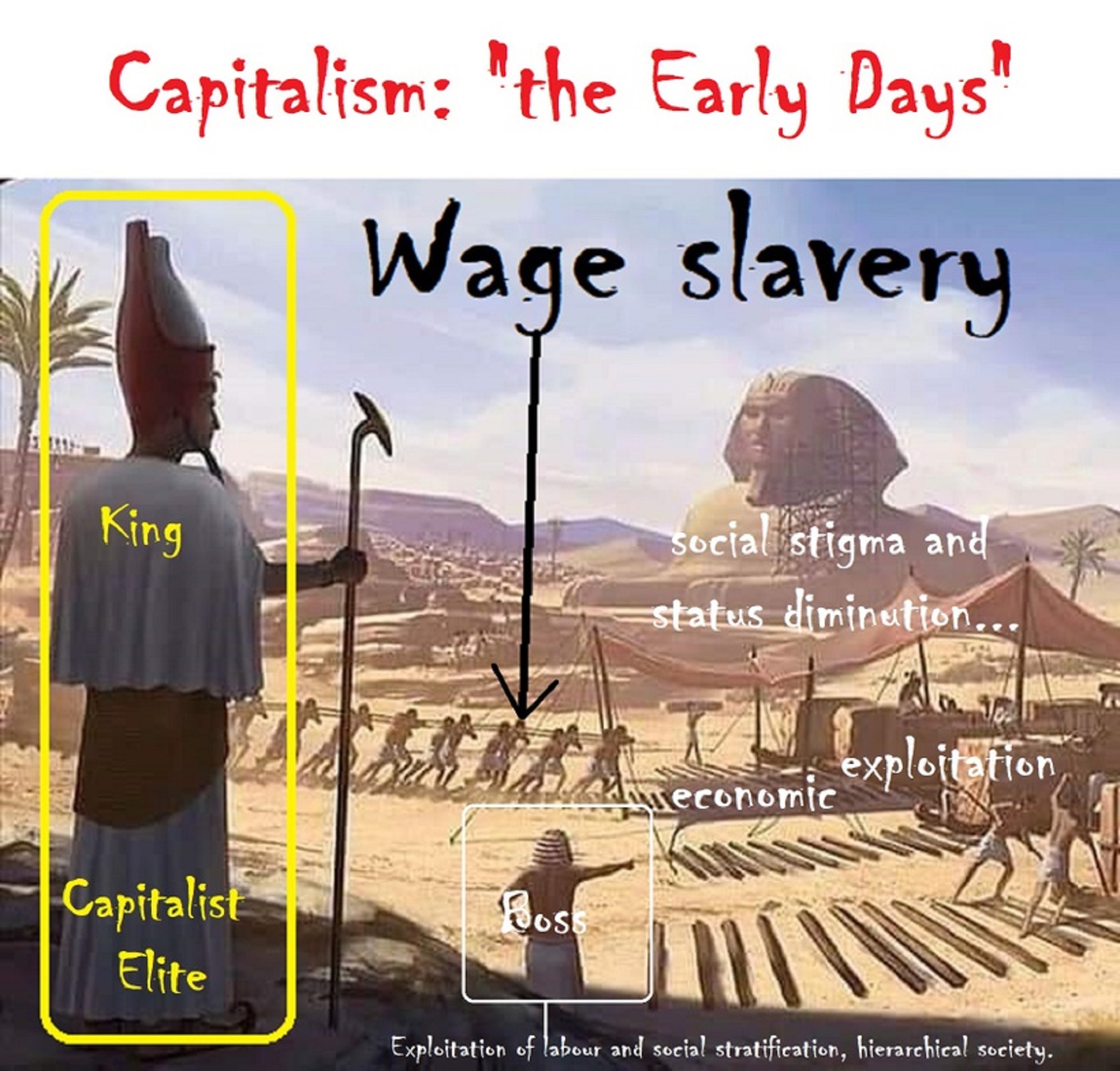

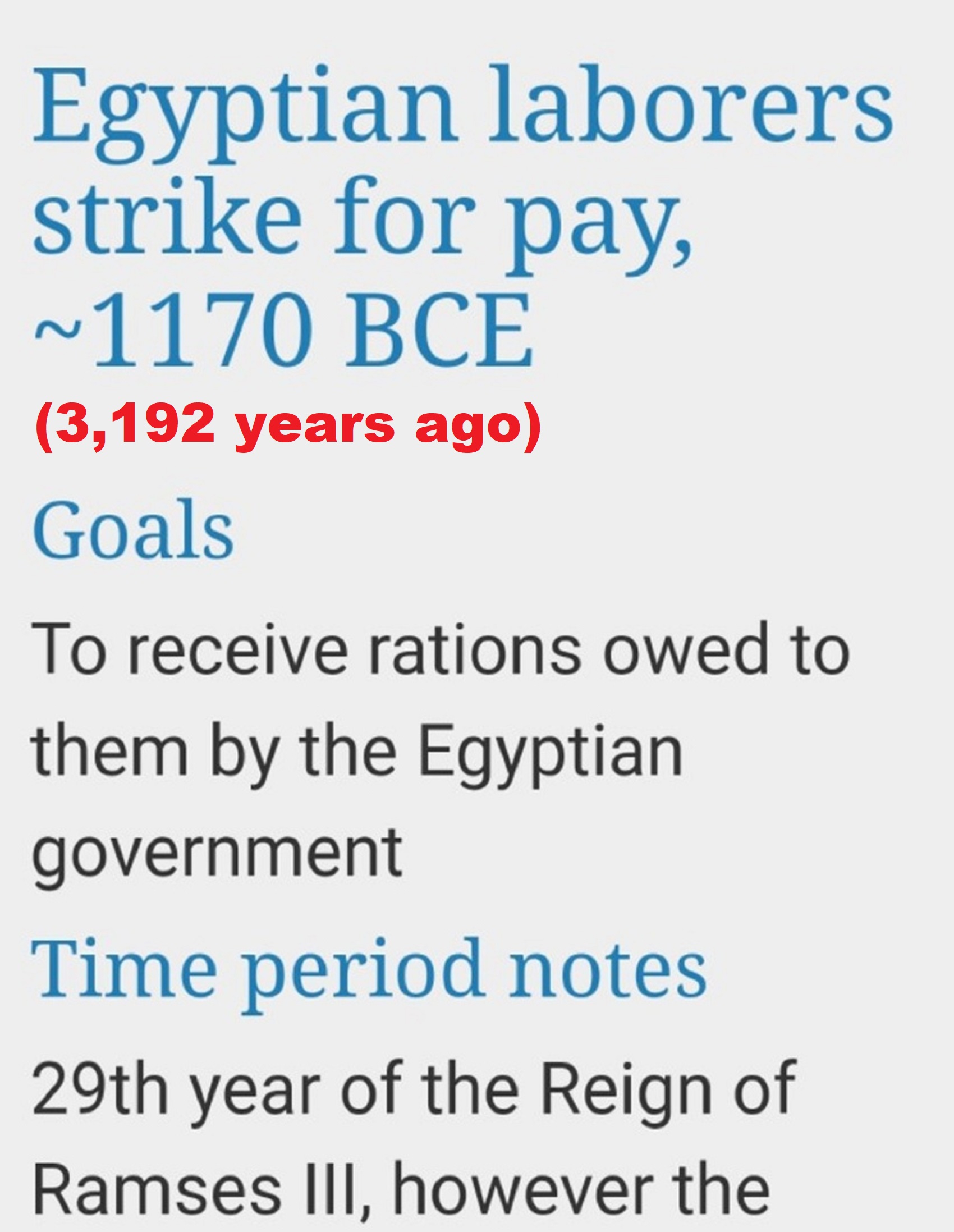

Subjects of states are not necessarily landed; there is a long history of landless populations. Slavery has long coexisted with the state, and forced labor without compensation goes back to chiefdoms such as Kwakwaka’wakw. Long before Portuguese, Spanish, and English seafarers began trading slaves from the west coast of Africa, Arab groups enslaved people from Africa and Europe. For peasants, proletarianization— loss of land—has been a continuous process. One example is landed gentry in eighteenth century England who found that sheepherding was more profitable than tribute from peasants and removed the peasants from the land. A similar process occurred when Guatemala’s liberal president privatized the land of Mayan peasants that, until 1877, had been held communally.” ref

Law and Order in States

“At the level of the state, the law becomes an increasingly formal process. Procedures are more and more regularly defined, and categories of breaches in civil and criminal law emerge, together with remedies for those breaches. Early agricultural states formalized legal rules and punishments through codes, formal courts, police forces, and legal specialists such as lawyers and judges. Mediation could still be practiced, but it often was supplanted by adjudication in which a judge’s decision was binding on all parties. Decisions could be appealed to a higher authority, but any final decision must be accepted by all concerned. The first known system of codified law was enacted under the warrior king Hammurabi in Babylon (present day Iraq). This law was based on standardized procedures for dealing with civil and criminal offenses, and subsequent decisions were based on precedents (previous decisions).” ref

“Crimes became offenses not only against other parties but also against the state. Other states developed similar codes of law, including China, Southeast Asia, and state-level Aztec and Inca societies. Two interpretations, which are not necessarily mutually exclusive, have arisen about the political function of codified systems of law. Fried (1978) argued, based on his analysis of the Hammurabi codes, that such laws reinforced a system of inequality by protecting the rights of an elite class and keeping peasants subordinates. This is consistent with the theory of a stratified society as already defined. Another interpretation is that maintenance of social and political order is crucial for agricultural states since any disruption in the state would lead to neglect of agricultural production that would be deleterious to all members of the state regardless of their social status. Civil laws ensure, at least in theory, that all disputing parties receive a hearing—so long as high legal expenses and bureaucratic logjams do not cancel out the process. Criminal laws, again in theory, ensure the protection of all citizens from offenses ranging from theft to homicide.” ref

“Inevitably, laws fail to achieve their aims. The United States, for example, has one of the highest crime rates in the industrial world despite having an extensive criminal legal system. The number of homicides in New York City in 1990 exceeded the number of deaths from colon and breast cancer and all accidents combined. Although the rate of violent crime in the United States declined during the mid-1990s, it occurred thanks more to the construction of more prisons per capita (in California) than of schools. Nationwide, there currently are more than one million prisoners in state and federal correctional institutions, one of the highest national rates in the industrial world. Since the 1990s, little has changed in terms of imprisonment in the United States. Funds continue to go to prisons rather than schools, affecting the education of minority communities and expanding “slave labor” in prisons, according to Michelle Alexander who, in 2012, called the current system the school-to-prison pipeline.” ref

Warfare in States

“Warfare occurs in all human societies but at no other level of political organization is it as widespread as in states. Indeed, warfare was integral to the formation of the agricultural state. As governing elites accumulated more resources, warfare became a major means of increasing their surpluses. And as the wealth of states became a target of nomadic pastoralists, the primary motivation for warfare shifted from control of resources to control of neighboring populations.” ref

“A further shift came with the advent of industrial society when industrial technologies driven by fossil fuels allowed states to invade distant countries. A primary motivation for these wars was to establish economic and political hegemony over foreign populations. World War I, World War II, and lesser wars of the past century have driven various countries to develop ever more sophisticated and deadly technologies, including wireless communication devices for remote warfare, tanks, stealth aircraft, nuclear weapons, and unmanned aircraft called drones, which have been used in conflicts in the Middle East and Afghanistan. Competition among nations has led to the emergence of the United States as the most militarily powerful nation in the world.” ref

“The expansion of warfare by societies organized as states has not come without cost. Every nation-state has involved civilians in its military adventures, and almost everyone has been involved in those wars in some way—if not as militarily, then as member of the civilian workforce in military industries. World War II created an unprecedented armament industry in the United States, Britain, Germany, and Japan, among others, and the aerospace industry underwent expansion in the so-called Cold War that followed. Today, one can scarcely overlook the role of the process of globalization to explain how the United States, for now an empire, has influenced the peoples of other countries in the world.” ref

Stability and Duration of States

“It should be noted that states have a clear tendency toward instability despite trappings designed to induce awe in the wider population. Few states have lasted a thousand years. The American state is more than 240 years old but increases in extreme wealth and poverty, escalating budget and trade deficits, a war initiated under false pretenses, escalating social problems, and a highly controversial presidential election suggest growing instability. Jared Diamond’s book Collapse compared the decline and fall of Easter Island, Chaco Canyon, and the Maya with contemporary societies such as the United States, and he found that overtaxing the environment caused the collapse of those three societies. Chalmers Johnson (2004) similarly argued that a state of perpetual war, loss of democratic institutions, systematic deception by the state, and financial overextension contributed to the decline of the Roman Empire and will likely contribute to the demise of the United States “with the speed of FedEx.” ref

“Why states decline is not difficult to fathom. Extreme disparities in wealth, use of force to keep populations in line, the stripping of people’s resources (such as the enclosures in England that removed peasants from their land), and the harshness of many laws all should create a general animosity toward the elite in a state. Yet, until recently (following the election of Donald Trump), no one in the United States was taking to the streets calling for the president to resign or decrying the government as illegitimate. In something of a paradox, widespread animosity does not necessarily lead to dissolution of a state or to an overthrow of the elite. Thomas Frank addressed this issue in What’s the Matter with Kansas? (2004). Despite the fact that jobs have been shipped abroad, that once-vibrant cities like Wichita are virtual ghost towns, and that both congress and the state legislature have voted against social programs time and again, Kansans continue to vote the Republicans whose policies are responsible for these conditions into office.” ref

“Nor is this confined to Kansas or the United States. That slaves tolerated slavery for hundreds of years (despite periodic revolts such as the one under Nat Turner in 1831), that workers tolerated extreme conditions in factories and mines long before unionization, that there was no peasant revolt strong enough to reverse the enclosures in England—all demand an explanation. Frank discusses reinforcing variables, such as propaganda by televangelists and Rush Limbaugh but offers little explanation beside them. However, recent works have provided new explanations. Days before Donald Trump won the presidential election on November 8, 2016, sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild released a book that partially explains how Trump appealed to the most marginalized populations of the United States, residents around Lake Charles in southwestern Louisiana.” ref