ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

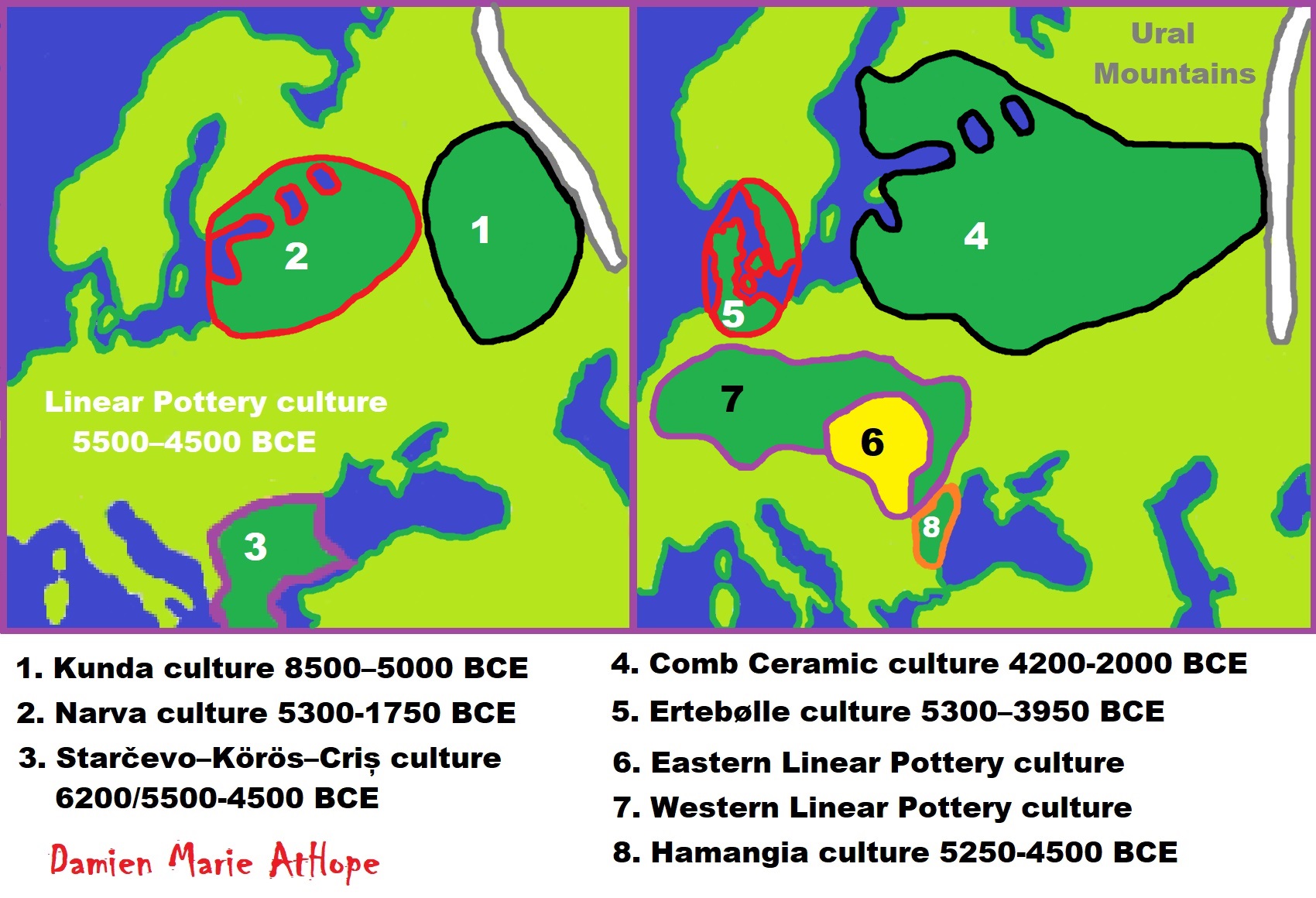

1. Kama culture

3. Starčevo–Körös–Criș culture

6. Eastern Linear Pottery culture

7. Western Linear Pottery culture

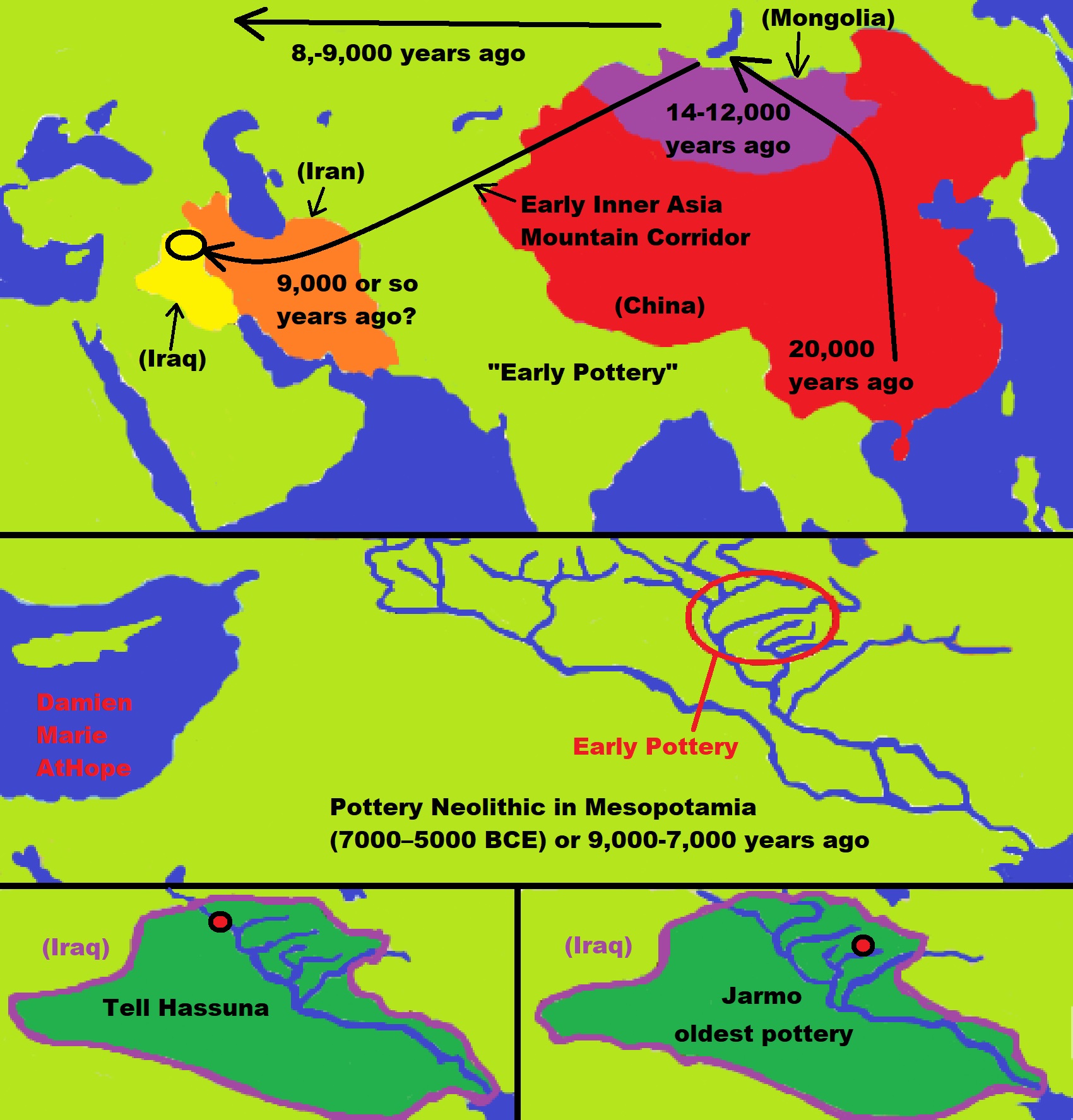

Pre-Pottery Neolithic (10000 – 6500 BCE) and Pottery Neolithic (7000–5000 BCE)

Ancient DNA Reveals Prehistoric Gene-Flow from Siberia in the Complex Human Population History of North-East Europe

“North East Europe harbors a high diversity of cultures and languages, suggesting a complex genetic history. Archaeological, anthropological, and genetic research has revealed a series of influences from Western and Eastern Eurasia in the past. While genetic data from modern-day populations is commonly used to make inferences about their origins and past migrations, ancient DNA provides a powerful test of such hypotheses by giving a snapshot of the past genetic diversity. In order to better understand the dynamics that have shaped the gene pool of North East Europeans, we generated and analyzed 34 mitochondrial genotypes from the skeletal remains of three archaeological sites in northwest Russia. These sites were dated to the Mesolithic and the Early Metal Age (7,500 and 3,500 uncalibrated years Before Present).” ref

“Comparisons of genetic data from ancient and modern-day populations revealed significant changes in the mitochondrial makeup of North East Europeans through time. Mesolithic foragers showed high frequencies and diversity of haplogroups U (U2e, U4, U5a), a pattern observed previously in European hunter-gatherers from Iberia to Scandinavia. In contrast, the presence of mitochondrial DNA haplogroups C, D, and Z in Early Metal Age individuals suggested discontinuity with Mesolithic hunter-gatherers and genetic influx from central/eastern Siberia. We identified remarkable genetic dissimilarities between prehistoric and modern-day North East Europeans/Saami, which suggests an important role of post-Mesolithic migrations from Western Europe and subsequent population replacement/extinctions.” ref

“The history of human populations can be retraced by studying the archaeological and anthropological record, but also by examining the current distribution of genetic markers, such as the maternally inherited mitochondrial DNA. Ancient DNA research allows the retrieval of DNA from ancient skeletal remains and contributes to the reconstruction of the human population history through the comparison of ancient and present-day genetic data. Analyzed the mitochondrial DNA of prehistoric remains from archaeological sites dated to 7,500 and 3,500 years Before Present. These sites are located in North-East Europe, a region that displays a significant cultural and linguistic diversity today but for which no ancient human DNA was available before. We show that prehistoric hunter-gatherers of North East Europe were genetically similar to other European foragers. We also detected a prehistoric genetic input from Siberia, followed by migrations from Western Europe into North-East Europe.” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

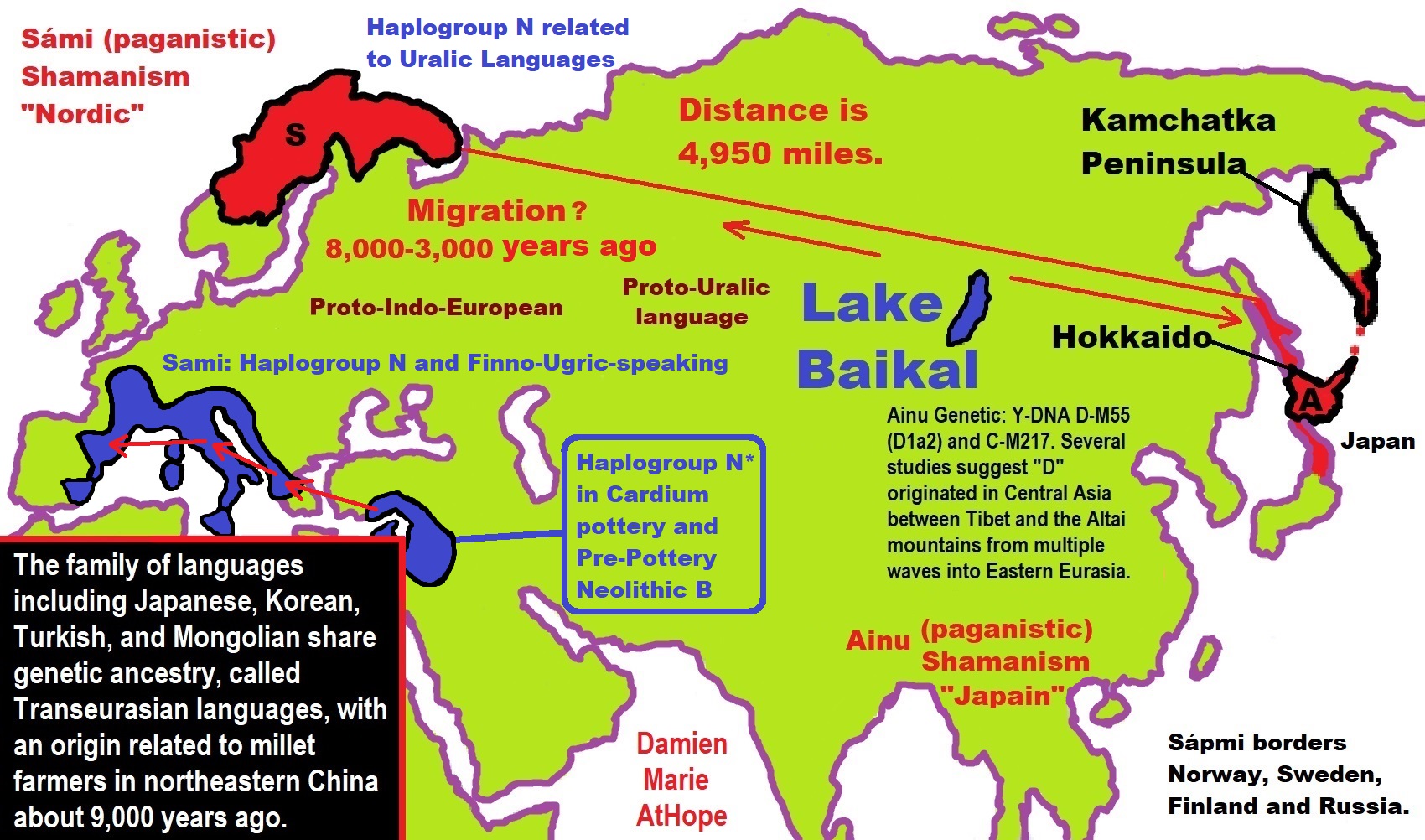

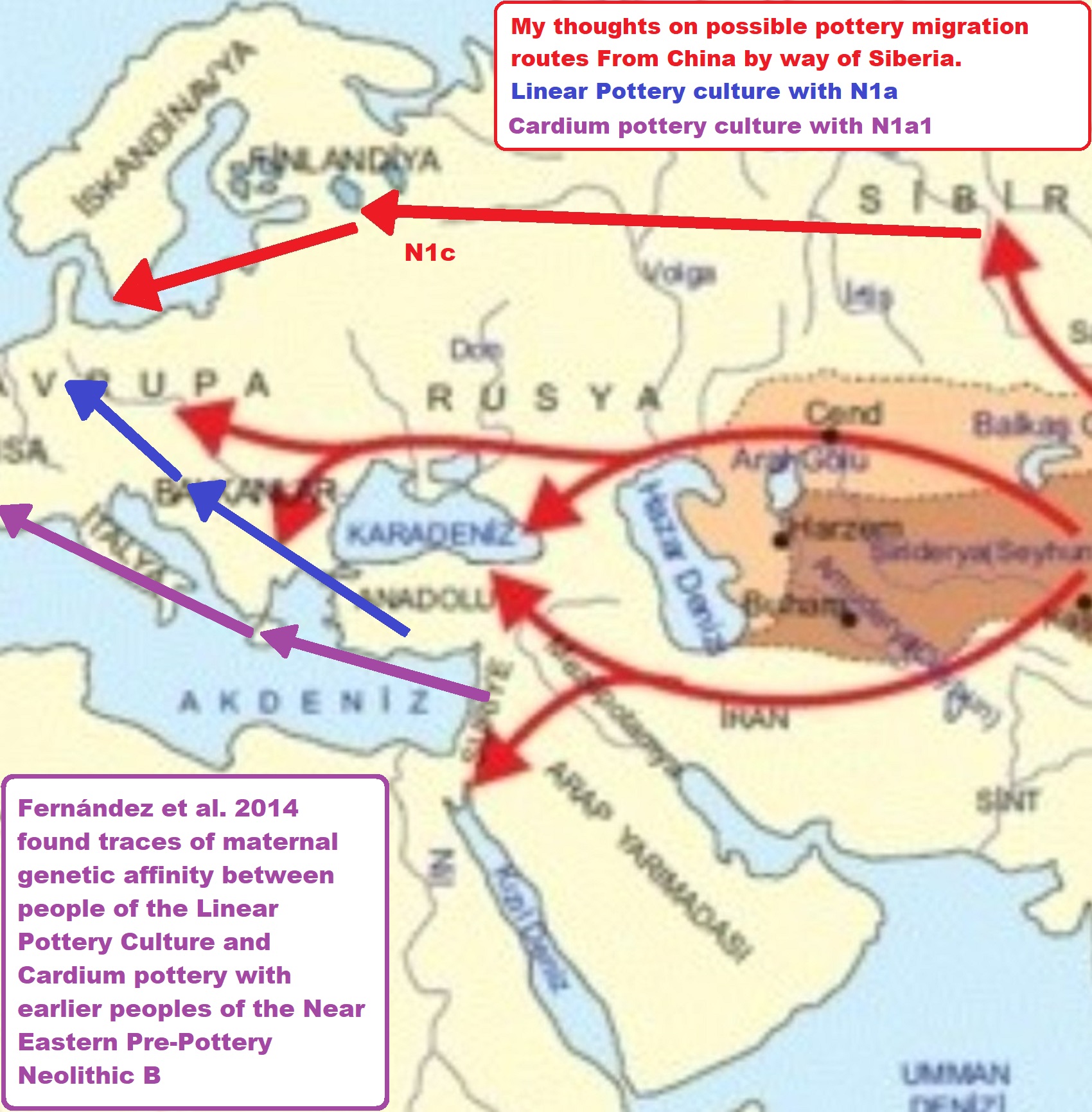

“Rare unclassified haplogroup N* has been found among fossils belonging to the Cardial and Epicardial culture (Cardium pottery) and the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B. Haplogroup N1a – Arabian Peninsula and Northeast Africa. Found also in Central Asia and Southern Siberia. This branch is well attested in ancient people from various cultures of Neolithic Europe, from Hungary to Spain, and among the earliest farmers of Anatolia.” ref

Cardium pottery

“Cardium pottery or Cardial ware is a Neolithic decorative style that gets its name from the imprinting of the clay with the heart-shaped shell of the Corculum cardissa , a member of the cockle family Cardiidae. These forms of pottery are in turn used to define the Neolithic culture which produced and spread them, commonly called the “Cardial culture”. The alternative name, impressed ware, is given by some archaeologists to define this culture, because impressions can be made with sharp objects other than cockle shells, such as a nail or comb.” ref

“Impressed pottery is much more widespread than the Cardial. Impressed ware is found in the zone “covering Italy to the Ligurian coast” as distinct from the more western Cardial extending from Provence to western Portugal. The sequence in prehistoric Europe has traditionally been supposed to start with widespread Cardial ware, and then to develop other methods of impression locally, termed “epi-Cardial”. However the widespread Cardial and Impressed pattern types overlap and are now considered more likely to be contemporary.” ref

“This pottery style gives its name to the main culture of the Mediterranean Neolithic: Cardium pottery culture or Cardial culture, or impressed ware culture, which eventually extended from the Adriatic sea to the Atlantic coasts of Portugal and south to Morocco. The earliest impressed ware sites, dating to 6400–6200 BCE, are in Epirus and Corfu. Settlements then appear in Albania and Dalmatia on the eastern Adriatic coast dating to between 6100 and 5900 BCE. The earliest date in Italy comes from Coppa Nevigata on the Adriatic coast of southern Italy, perhaps as early as 6000 cal BCE.” ref

“Also during Su Carroppu culture in Sardinia, already in its early stages (low strata into Su Coloru cave, c. 6000 BCE) early examples of cardial pottery appear. Northward and westward all secure radiocarbon dates are identical to those for Iberia c. 5500 cal BCE, which indicates a rapid spread of Cardial and related cultures: 2,000 km from the gulf of Genoa to the estuary of the Mondego in probably no more than 100–200 years. This suggests a seafaring expansion by planting colonies along the coast. Older Neolithic cultures existed already at this time in eastern Greece and Crete, apparently having arrived from the Levant, but they appear distinct from the Cardial or impressed ware culture.” ref

“The ceramic tradition in the central Balkans also remained distinct from that along the Adriatic coastline in both style and manufacturing techniques for almost 1,000 years from the 6th millennium BCE. Early Neolithic impressed pottery is found in the Levant, and certain parts of Anatolia, including Mezraa-Teleilat, and in North Africa at Tunus-Redeyef, Tunisia. So the first Cardial settlers in the Adriatic may have come directly from the Levant.” ref

“Of course, it might equally well have come directly from North Africa, and impressed pottery also appears in Egypt. Along the East Mediterranean coast impressed ware has been found in North Syria, Palestine, and Lebanon. Cardial and Epicardial fossils that were analyzed for ancient DNA were found to carry the rare mtDNA (maternal) basal haplogroup N*, supporting an early Neolithic maritime colonization of Mainland Europe through Cyprus and the Aegean Islands by Near-Eastern farmers.” ref

“Fernández et al. 2014 found traces of maternal genetic affinity between people of the Linear Pottery Culture and Cardium pottery with earlier peoples of the Near Eastern Pre-Pottery Neolithic B, and suggested that Neolithic period was initiated by seafaring colonists from the Near East. Olalde et al. 2015 examined the remains of 6 Cardials buried in Spain c. 5470-5220 BCE. The 6 samples of mtDNA extracted belonged to the maternal haplogroups K1a2a, X2c, H4a1a (2 samples), H3, and K1a4a1.” ref

“The authors of the study suggested that the Cardials and peoples of the Linear Pottery Culture were descended from a common farming population in the Balkans, which had subsequently migrated further westwards into Europe along the Mediterranean coast and Danube river respectively. Among modern populations, the Cardials were found to be most closely related to Sardinians and Basque people. The Iberian Cardials carried a noticeable amount of hunter-gatherer ancestry. This hunter-gatherer ancestry was more similar to that of Eastern Hunter-Gatherers (EHGs) than Iberian hunter-gatherers, and appeared to have been acquired before the Cardial expansion into Iberia.” ref

“Mathieson et al. 2018 examined three Cardials buried at the Zemunica Cave in modern-day Croatia c. 5800 BCE. The two samples of Y-DNA extracted belonged to the paternal haplogroups C1a2 and E1b1b1a1b1, while the three samples of mtDNA extracted belonged to the maternal haplogroups H1, K1b1a, and N1a1. The team further examined two Cardials buried at Kargadur in modern-day Croatia c. 5600 BCE. The one male carried the paternal haplogroup G2a2a1, and the maternal haplogroup H7c, and the female carried H5a.” ref

“All three belonged to the Early European Farmer (EEF) cluster, thus being closely related to earlier Neolithic populations of north-west Anatolia, of the Balkan Neolithic, contemporary peoples of the Central European Linear Pottery culture, and later peoples of the Cardial Ware culture in Iberia. This would suggest that the Cardial Ware people and the Linear Pottery people were derived from a single migration from Anatolia into the Balkans, which then split into two and expanded northward and westward further into Europe.” ref

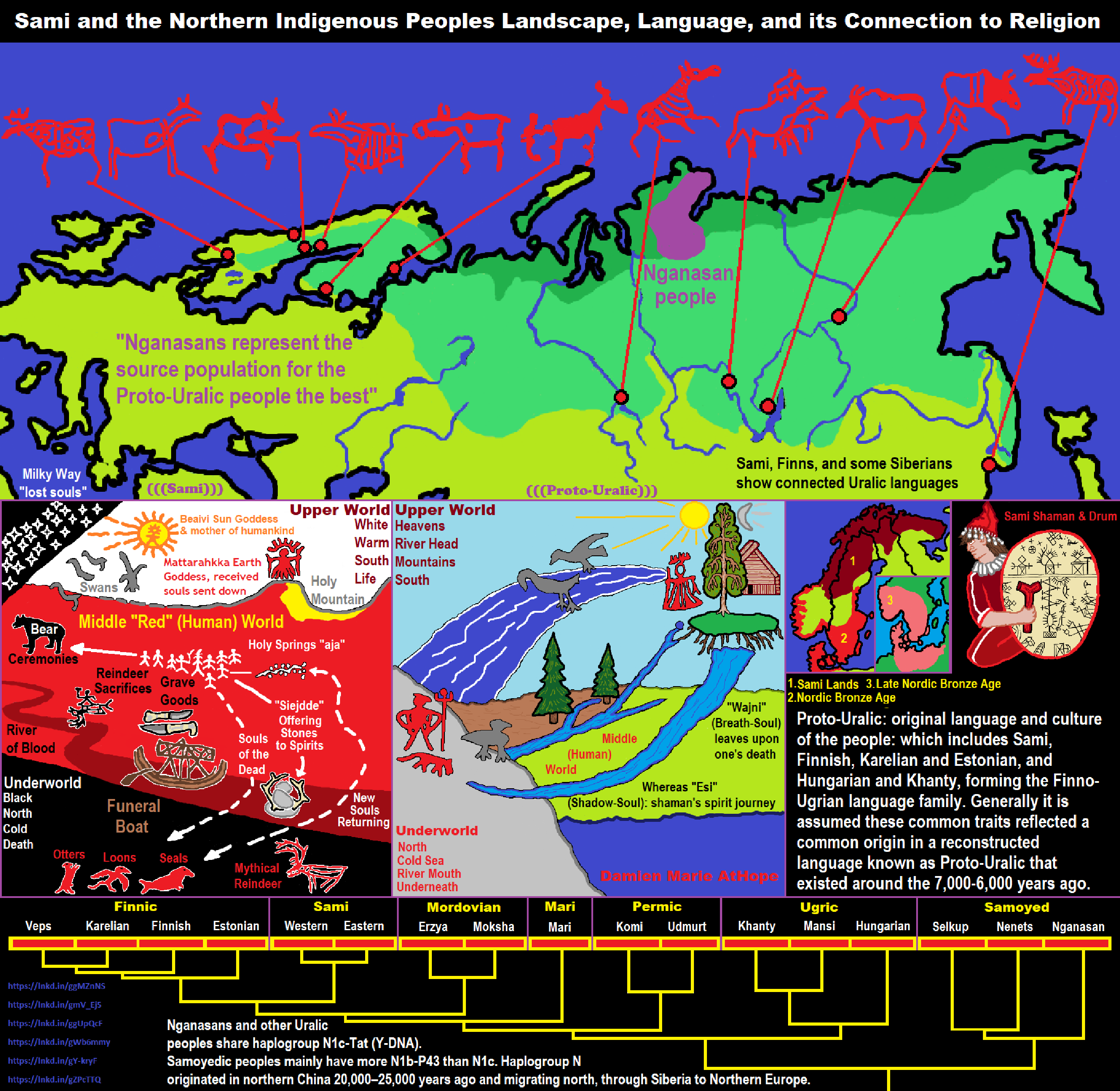

Haplogroup N1c (Y-DNA)

“Haplogroup N1c is found chiefly in north-eastern Europe, particularly in Finland (61%), Lapland (53%), Estonia (34%), Latvia (38%), Lithuania (42%), and northern Russia (30%), and to a lower extent also in central Russia (15%), Belarus (10%), eastern Ukraine (9%), Sweden (7%), Poland (4%) and Turkey (4%). N1c is also prominent among the Uralic-speaking ethnicities of the Volga-Ural region, including the Udmurts (67%), Komi (51%), Mari (50%), and Mordvins (20%), but also among their Turkic neighbors like the Chuvashs (28%), Volga Tatars (21%) and Bashkirs (17%), as well as the Nogais (9%) of southern Russia.” ref

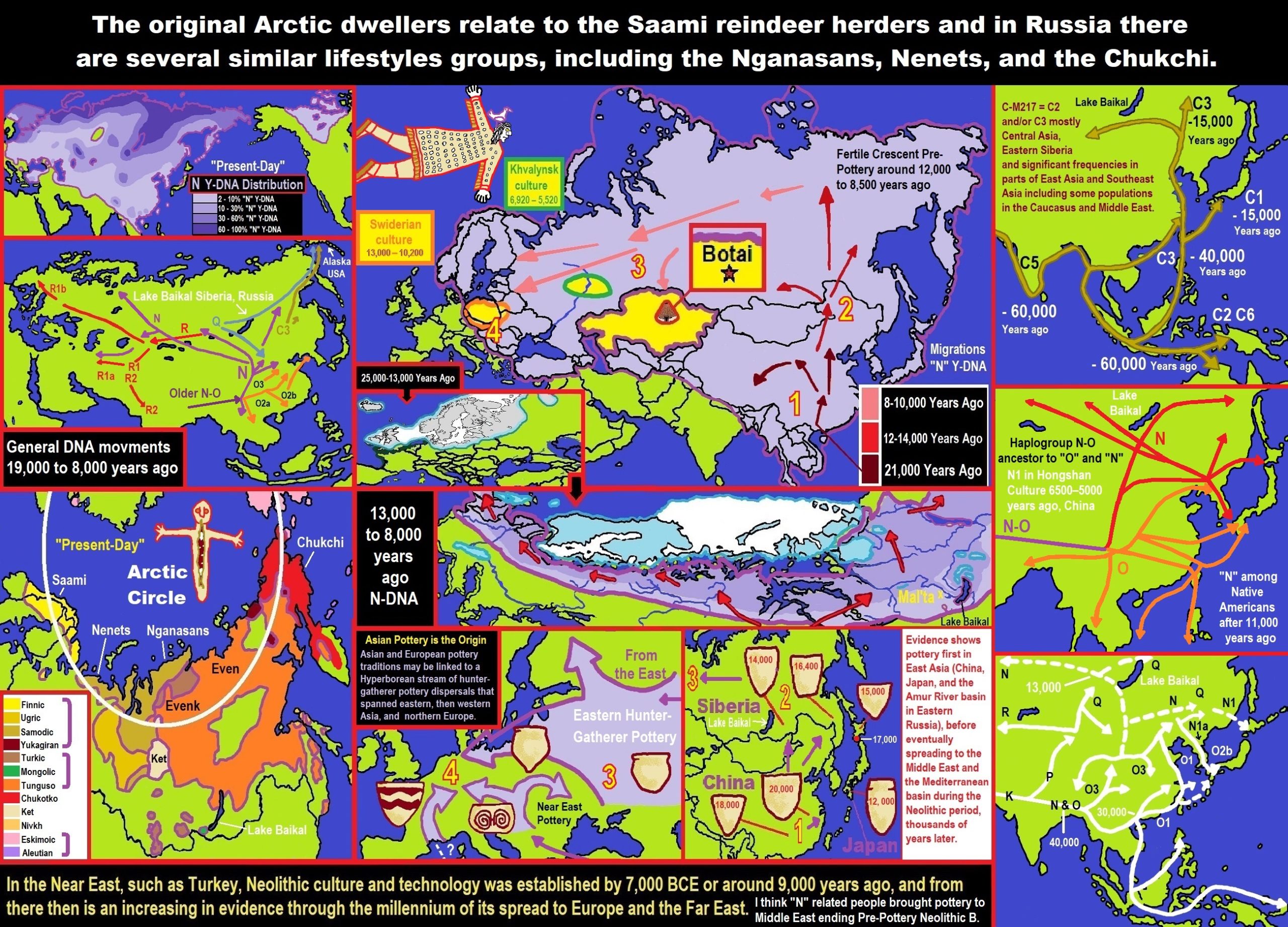

“N1c represents the western extent of haplogroup N, which is found all over the Far East (China, Korea, Japan), Mongolia, and Siberia, especially among Uralic speakers of northern Siberia. Haplogroup N1 reaches a maximum frequency of approximately 95% in the Nenets (40% N1c and 57% N1b) and Nganassans (all N1b), two Uralic tribes of central-northern Siberia, and 90% among the Yakuts (all N1c), a Turkic people who live mainly in the Sakha (Yakutia) Republic in central-eastern Siberia.” ref

“Haplogroup N is a descendant of East Asian macro-haplogroup NO. It is believed to have originated in Indochina or southern China approximately 15,000 to 20,000 years ago. Haplogroup N1* and N1c were both found at high frequency (26 out of 70 samples, or 37%) in Neolithic and Bronze Age remains (4500-700 BCE) from the West Liao River valley in Northeast China (Manchuria) by Yinqiu Cui et al. (2013). Among the Neolithic samples, haplogroup N1 made up two thirds of the samples from the Hongshan culture (4700-2900 BCE) and all the samples from the Xiaoheyan culture (3000-2200 BCE), hinting that N1 people played a major role in the diffusion of the Neolithic lifestyle around Northeast China, and probably also to Mongolia and Siberia.” ref

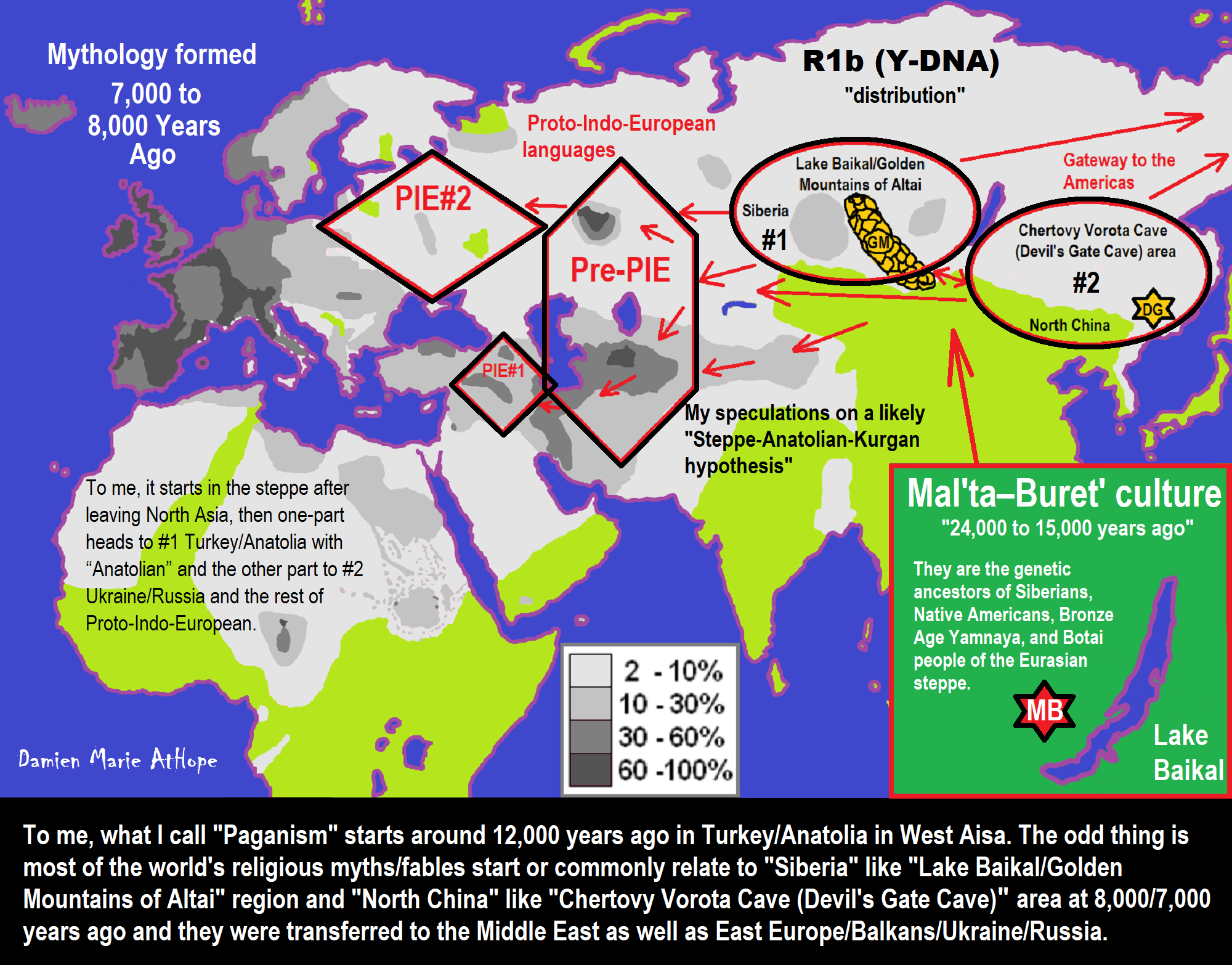

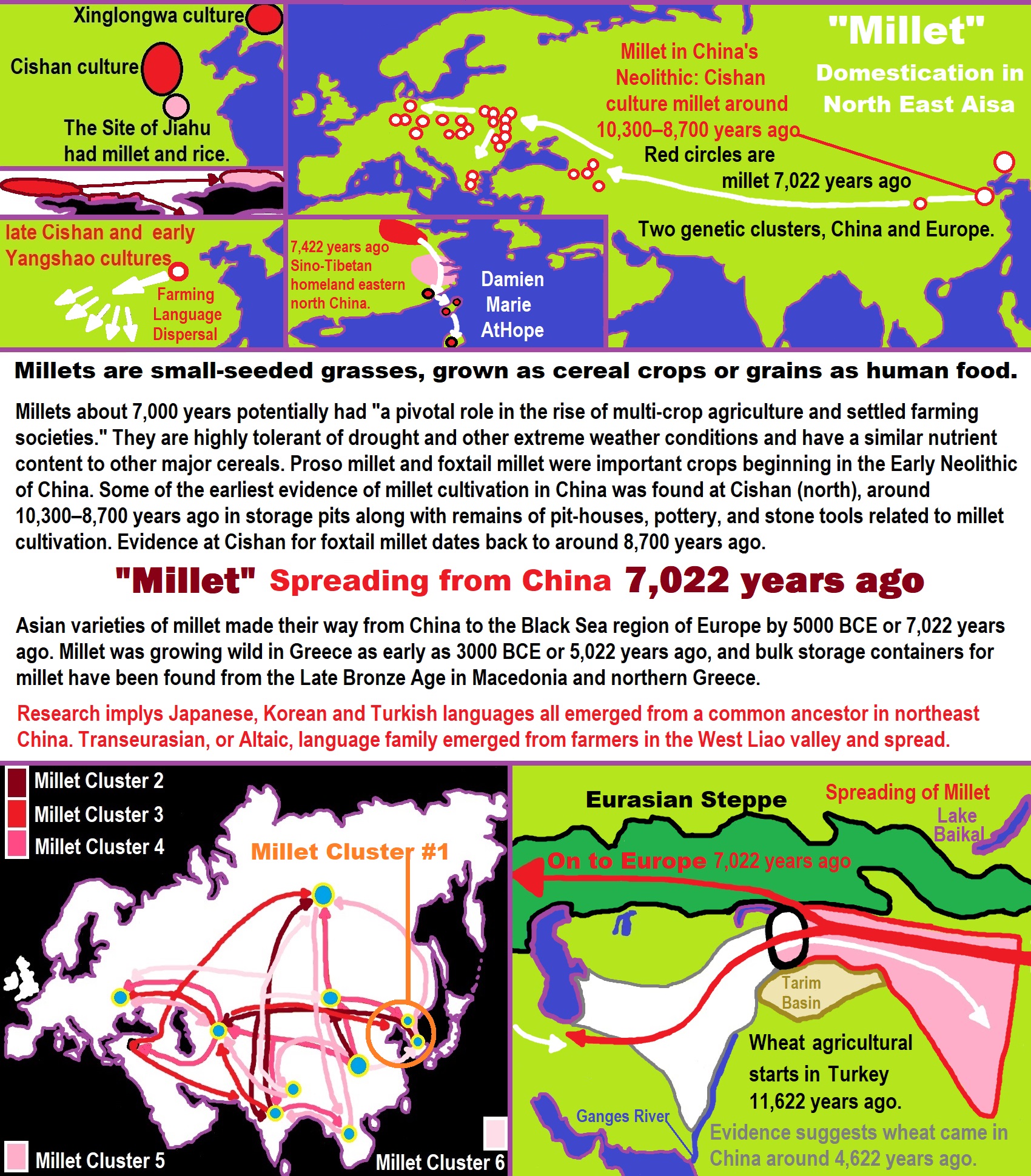

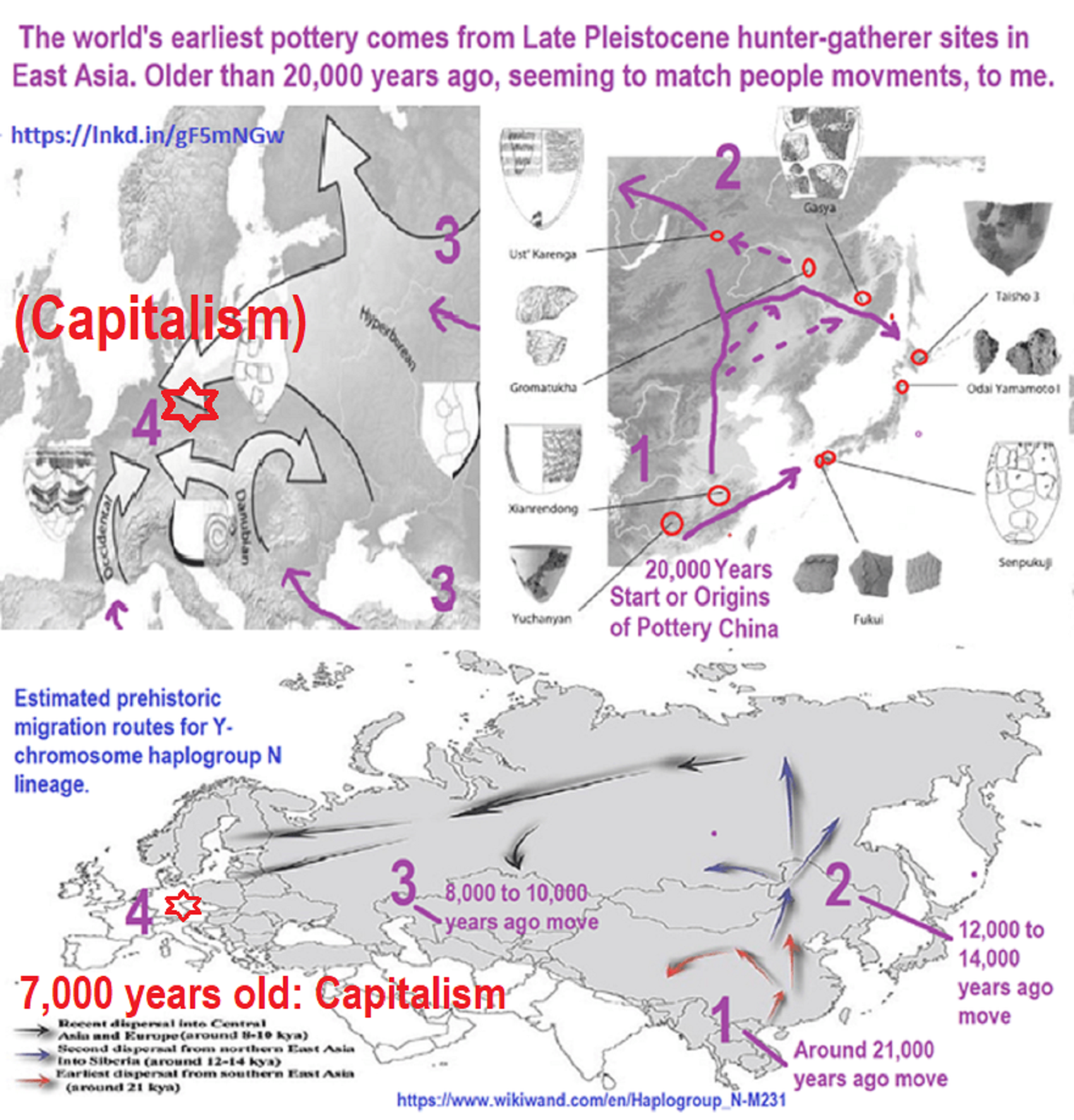

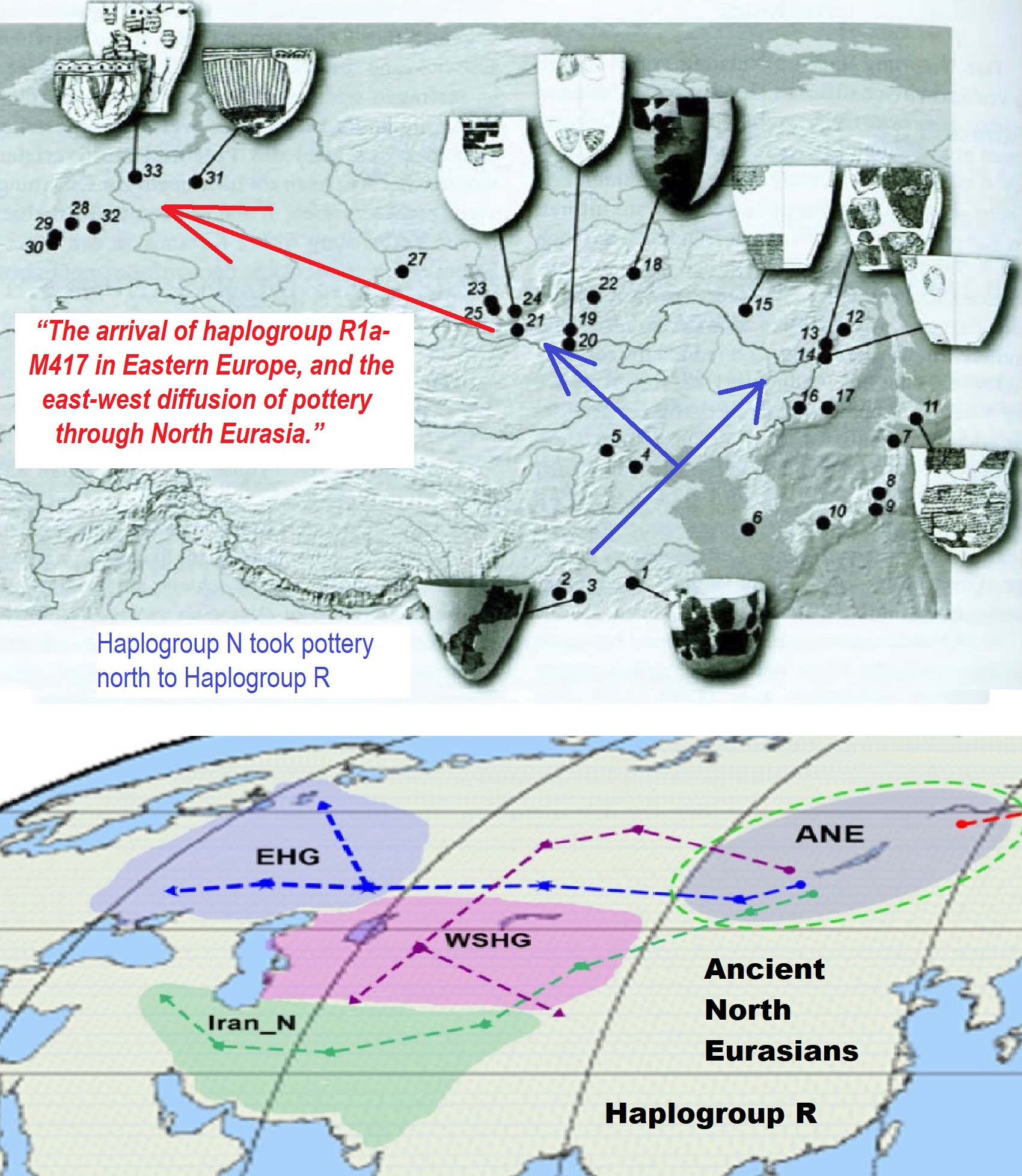

“Ye Zhang et al. 2016 found 100% of Y-DNA N out of 17 samples from the Xueshan culture (Jiangjialiang site) dating from 3600–2900 BCE, and among those 41% belonged to N1c1-Tat. It is therefore extremely likely that the N1c1 subclade found in Europe today has its roots in the Chinese Neolithic. It would have progressively spread across Siberia until north-eastern Europe, possibly reaching the Volga-Ural region around 5500 to 4500 BCE with the Kama culture (5300-3300 BCE), and the eastern Baltic with the Comb Ceramic culture (4200-2000 BCE), the presumed ancestral culture of Proto-Finnic and pre-Baltic people. There is little evidence of agriculture or domesticated animals in Siberia during the Neolithic, but pottery was widely used. In that regard it was the opposite development from the Near East, which first developed agriculture then only pottery from circa 5500 BCE, perhaps through contact with East Asians via Siberia or Central Asia.” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

Kama culture

“The Kama culture (also known as Volga-Kama or Khutorskoye from finds near the Khutorskoye settlement) is an Eastern European Subneolithic archaeological culture from the 6th-4th millennium BCE. The area covers the Kama, Vyatka, and the Ik–Belaya watershed (Perm and Kirov regions, Udmurtia, Tatarstan, and Bashkortostan).” ref

“The definition of the Kama culture remains a subject of debate. Initially, it was determined by O.H. Bader on the territory of the Middle Kama, where he distinguished two phases: Borovoye (Borovoy Lake I) and Khutorskoye. A.Kh. Khalikov united the finds with Pitted and Combed Ware of the Lower and Middle Kama into one Volga-Kama culture. I.V. Kalinina, based on the study of ceramics came to the conclusion that there are two distinct cultures: Volga-Kama pitted pottery and Kama combed pottery. A.A.” ref

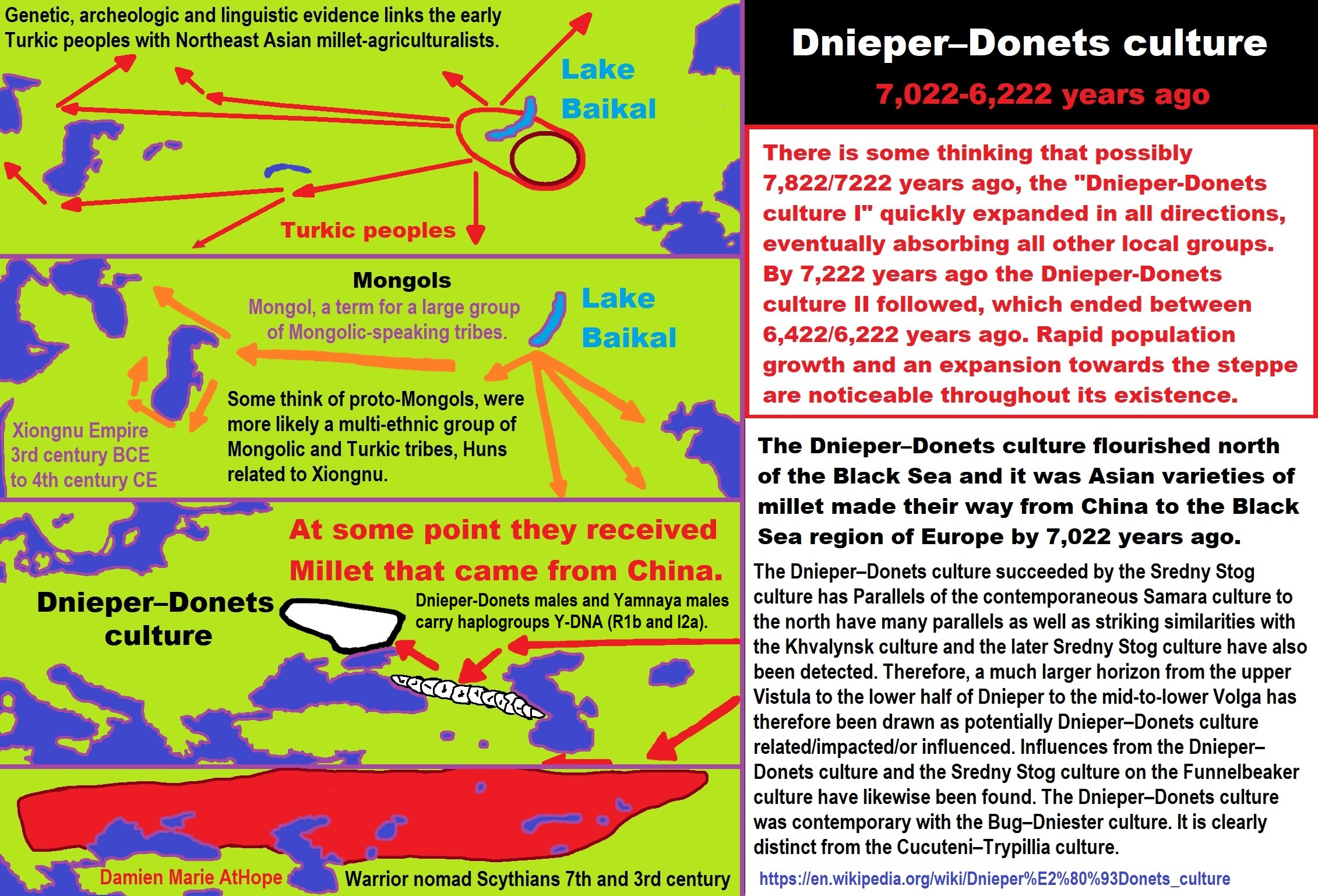

“Vibornov identified three stages of development in the Kama culture, and V.P. Denisov and L.A. Nagovitchin joined the Kama Neolithic finds with combed ceramics into a single Khutorskoye culture, synchronous with the Poluden culture in the Ural Mountains. Its comb-decorated pottery is similar to that of the Upper Volga culture. The Kama culture is also culturally close and genetically related to the Volosovo culture. There are scholars who also believe that the culture is related to the Dnieper-Donetsk. There are no signs of agriculture. The economy was based on hunting and fishing. Burials are unknown.” ref

“Settlements involve, rectangular partially sunken dwellings, ranging in size from 6×8 to 16×5m, are grouped in unfortified permanent and temporary settlements, located on the banks of lakes, floodplains, and on river terraces. The pottery is thick-walled, egg-shaped, both round- and pointed-bottomed. The stone and bone inventory of the pottery culture demonstrated a Mesolithic character. It is heavily ornamented with comb stamp designs, vertical and horizontal zigzags, sloping rows, braids, triangles, and banded comb meshes. Kama culture is noted for its metal work and handicrafts. The instruments for work include scrapers, sharpeners, knives, leaf-shaped, and semi-rhombic arrowheads, chisels, adzes, and weights.” ref

“In its development, the Kama culture passed through three stages: early (sites: Mokino, Ust-Bukorok, Ziarat, Ust-Shizhma), middle (sites: Khutorskaya Kryazhskaya, Lebedynska), and late (sites: Lyovshino, Chernashka). The culture was formed in the early Neolithic on a local Mesolithic substrate under the influence of southern steppe populations. The prehistoric phase according to archaeologists emerged around 2,000 BCE. During this stage, the culture existed in the area that began in the Ufa River (in modern Bashkortostan) through the entire Kama drainage area to the upper Pechora River (Komimu).” ref

“In the southern regions, the influence of the nearby forest-steppe cultures of the Middle Volga can be observed during the whole period of existence. In the developed Neolithic a population of Trans-Ural origin penetrates in the upper and middle Kama. In this period there are formed local variants: Verkhnekamsk, Ikska-Belsky and Nizhnekamsk. At the end of the Neolithic the lower Kama falls under the influence of the Early Eneolithic Samara culture.” ref

Narva culture

“Narva culture or eastern Baltic was a European Neolithic archaeological culture found in present-day Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Kaliningrad Oblast (former East Prussia), and adjacent portions of Poland, Belarus, and Russia. A successor of the Mesolithic Kunda culture, Narva culture continued up to the start of the Bronze Age. The culture spanned from c. 5300 to 1750 BCE. The technology was that of hunter-gatherers. The culture was named after the Narva River in Estonia.” ref

“The people of the Narva culture had little access to flint; therefore, they were forced to trade and conserve their flint resources. For example, there were very few flint arrowheads and flint was often reused. The Narva culture relied on local materials (bone, horn, schist). As evidence of trade, researchers found pieces of pink flint from Valdai Hills and plenty of typical Narva pottery in the territory of the Neman culture while no objects from the Neman culture were found in Narva. Heavy use of bones and horns is one of the main characteristics of the Narva culture.” ref

“The bone tools, continued from the predecessor Kunda culture, provide the best evidence of continuity of the Narva culture throughout the Neolithic period. The people were buried on their backs with few grave goods. The Narva culture also used and traded amber; a few hundred items were found in Juodkrantė. One of the most famous artifacts is a ceremonial cane carved of horn as a head of female elk found in Šventoji. The people were primarily fishers, hunters, and gatherers. They slowly began adopting husbandry in the middle Neolithic. They were not nomadic and lived in the same settlements for long periods as evidenced by abundant pottery, middens, and structures built in lakes and rivers to help fishing.” ref

“The pottery shared similarities with the Comb Ceramic culture, but had specific characteristics. One of the most persistent features was mixing clay with other organic matter, most often crushed snail shells. The pottery was made of 6-to-9 cm (2.4-to-3.5 in) wide clay strips with minimal decorations around the rim. The vessels were wide and large; the height and the width were often the same. The bottoms were pointed or rounded, and only the latest examples have narrow flat bottoms. From mid-Neolithic, Narva pottery was influenced and eventually disappeared into the Corded Ware culture.” ref

“For a long time, archaeologists believed that the first inhabitants of the region were Finnic, who were pushed north by people of the Corded Ware culture. At first, it was believed that Narva culture ended with the appearance of the Corded Ware culture. However, newer research extended it up to the Bronze Age. As Narva culture spanned several millennia and encompassed a large territory, archaeologists attempted to subdivide the culture into regions or periods. For example, in Lithuania two regions are distinguished: southern (under influence of the Neman culture) and western (with major settlements found in Šventoji). There is an academic debate what ethnicity the Narva culture represented: speakers of Finno-Ugric languages or other Europids, preceding the arrival of the Indo-Europeans.” ref

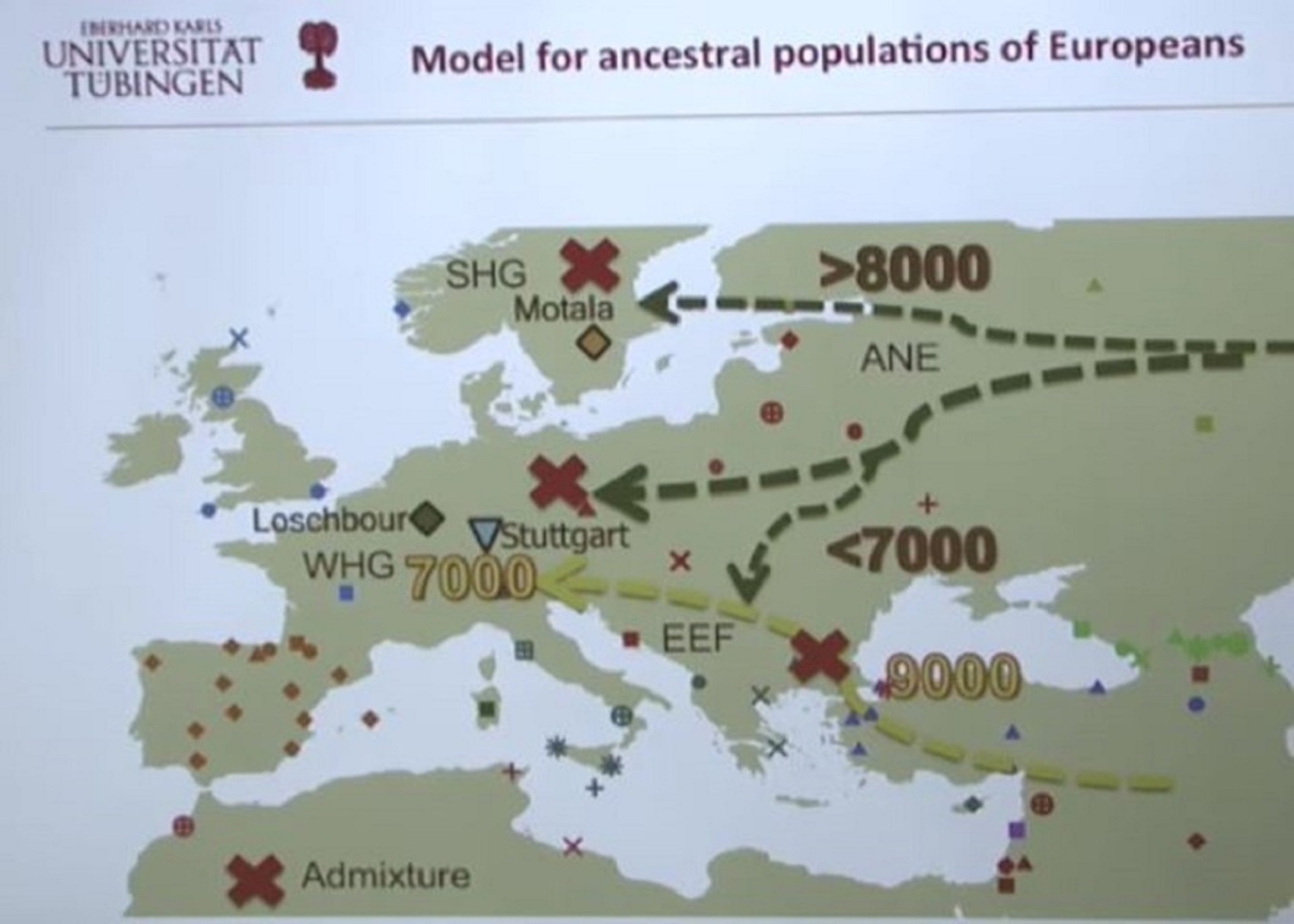

“It is also unclear how the Narva culture fits with the arrival of the Indo-Europeans (Corded Ware and Globular Amphora cultures) and the formation of the Baltic tribes. Mathieson (2015) analyzed a large number of individuals buried at the Zvejnieki burial ground, most of whom were affiliated with the Kunda culture and the succeeding Narva culture. The mtDNA extracted belonged exclusively to haplotypes of U5, U4, and U2. With regards to Y-DNA, the vast majority of samples belonged to R1b1a1a haplotypes and I2a1 haplotypes. The results affirmed that the Kunda and Narva cultures were about 70% WHG and 30% EHG. The nearby contemporary Pit–Comb Ware culture was on the contrary found to be about 65% EHG.” ref

“An individual from the Corded Ware culture, which would eventually succeed the Narva culture, was found to have genetic relations with the Yamnaya culture. Jones et al. (2017) examined the remains of a male of the Narva culture buried c. 5780-5690 BCE. He was found to be a carrier of the paternal haplogroup R1b1b and the maternal haplogroup U2e1. People of the Narva culture and preceding Kunda culture were determined to have closer genetic affinity with Western Hunter-Gatherers (WHGs) than Eastern Hunter-Gatherers (EHGs).” ref

“Saag et al. (2017) determined haplogroup U5a2d in a Narva male. Mittnik et al. (2018) analyzed 24 Narva individuals. Of the four samples of Y-DNA extracted, one belonged to I2a1a2a1a, one belonged to I2a1b, one belonged to I, and one belonged to R1. Of the ten samples of mtDNA extracted, eight belonged to U5 haplotypes, one belonged to U4a1, and one belonged to H11. U5 haplotypes were common among Western Hunter-Gatherers (WHGs) and Scandinavian Hunter-Gatherers (SHGs). Genetic influence from Eastern Hunter-Gatherers (EHGs) was also detected.” ref

Starčevo–Körös–Criș culture

“The Starčevo–Karanovo I-II–Körös culture or Starčevo–Körös–Criș culture is a grouping of two related Neolithic archaeological cultures in Southeastern Europe: the Starčevo culture and the Körös or Criș culture. Some of the earliest settlements of the Starčevo–Körös–Criș culture were discovered in the Banat Plain and southwest “Transylvania,” a historical region in central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the Apuseni Mountains. Cultural sites were also discovered in the north-west Balkans, which yielded painted pottery noted for its “barbotine” vessel surfaces. Specifically, the Starčevo settlements were located in Serbia, Körös in Hungary, and Criș in Romania.” ref

“The Starčevo culture is an archaeological culture of Southeastern Europe, in what is now Serbia, dating to the Neolithic period between c. 5500 and 4500 BCE (according to another source, between 6200 and 5200 BCE). The Starčevo culture is sometimes grouped together and sometimes not. The Körös culture is another Neolithic archaeological culture, but in Central Europe. It was named after the river Körös in eastern Hungary and western Romania, where it is named Criș. It survived from about 5800 to 5300 BCE.” ref

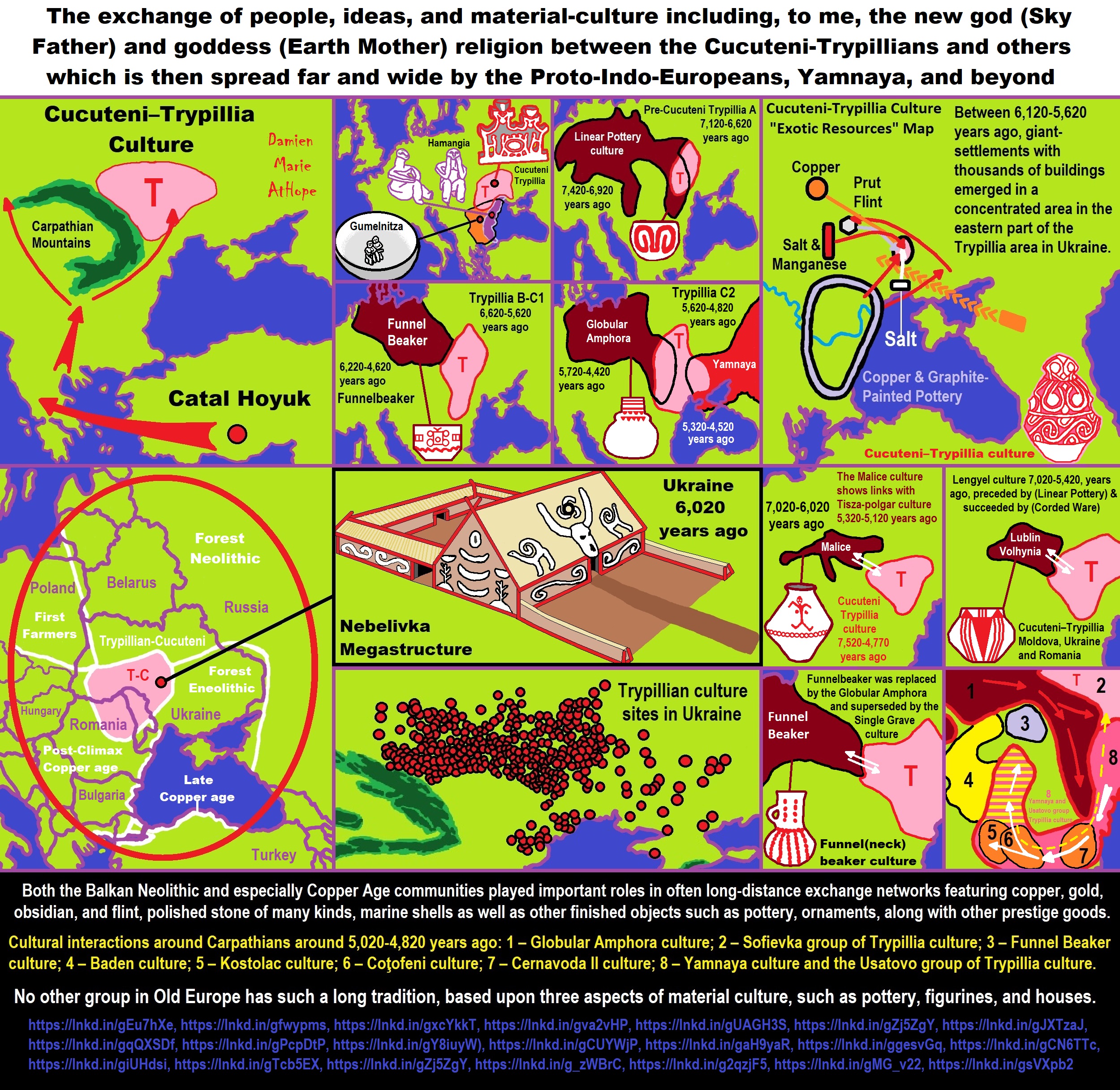

“The Starčevo–Kőrös–Criș culture encompasses various Early Neolithic archeological cultures from the Balkans, including those of Anzabegovo, Chavdar, Conevo, Criș, Dudești-Cernica, Karanovo, Kőrös, Kremikovci, Ovtcharovo, Porodin, Starčevo, and Tsonevo. It is commonly known simply under the appellation of Starčevo culture. Represents the advance of Early Neolithic farmers from Anatolia to south-east Europe, including present-day Bulgaria, Macedonia, Kosovo, Montenegro, Serbia, Bosnia, northern Croatia, south-west Hungary, and Romania. The Starčevo–Kőrös–Criș culture is the precursor of the Alföld Linear Pottery, the LBK culture, and the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture – in other words all the Early Neolithic cultures from northern France to western Ukraine.” ref

“The Starčevo–Kőrös–Criș culture’s neolithic agricultural economy was based primarily on the cultivation of crops from the Fertile Crescent, such as Emmer wheat, Einkorn wheat, barley, spelt millet, pulses (peas and bitter vetch), and buckwheat. Some fruit trees were also cultivated, including plums and apricots. Starčevo farmers bred livestock, especially goats and sheep, but to a lower extent also cattle and pigs. They also supplemented their diets by fishing in rivers and hunting deer and wild boar in forests. Starčevo farmers lived in dug-out rectangular dwellings with a timber frame, wattle-and-daub walls, and clay-plastered foors. Most houses were small, measuring approximately 7–10 m in length and 4–6 m in width (i.e. 30 to 60 m²). They were built on a single storey, which consisted of a single room, without any internal divisions. Some structures may have contained a loft on the second floor, probably used as a granary.” ref

“Pottery types varied between regional groups, and could be painted in white-on-red and dark-on-red as in the Starčevo culture around Serbia, or be unpainted as in the Körös culture in Hungary. Ceramic vessels were typically decorated with net patterns, spirals, garlands, floral motives, ridges, and finger imprints. Anthropomorphic and zoomorphic representations of goats and deer were common. Like in other Neolithic cultures, most tools were made of stone, bones, or antlers. Flints, obsidian, and quartzes were used to make blades, cutters, scrapers, and drills. Axes, hatchets, and grinding stones were made of sandstone, limestone, granite, quartz, and other rocks.” ref

“Very few graves were found in the Starčevo culture, and those were generally single graves. Most burials identified belonged to women or children, who were placed in the graves in a crouched position, lying on the right or the left side. They were inhumed under the floors of personal residences, a practice that continued until 4000 BCE. Graves rarely contained goods. When they did, it was pottery, grinding stones, flint tools, or jewelry. The sequencing of ancient DNA samples of Early Neolithic cultures conducted since the early 2010’s confirmed that the Neolithic lifestyle was brought to Europe by Anatolian farmers – represented by Y-haplogroup G2a.” ref

“For the first 1,700 years of agriculture in the Balkans, those Near Eastern farmers did not intermingle much with Mesolithic European hunter-gatherers in the Balkans. The few Mesolithic Balkanic lineages that may have been assimilated by farmers would have belonged to Y-haplogroup I2 and mt-haplogroups HV0 and V, and possibly J1c, J2a1, K1c, and T2. Since the Balkans were relatively depopulated in the Mesolithic, it is likely that these assimilations took place in north-west Anatolia, where European hunter-gatherers had migrated. Ancient DNA tests have shown that Starčevo people had fair skin, brown eyes, and dark hair, in contrast to Mesolithic Europeans who had darker skin, and dark hair, but blue eyes. Both groups were lactose intolerant.” ref

Comb Ceramic culture

“The Comb Ceramic culture or Pit-Comb Ware culture, often abbreviated as CCC or PCW, was a northeast European culture characterized by its Pit–Comb Ware. It existed from around 4200 BCE to around 2000 BCE. The bearers of the Comb Ceramic culture are thought to have still mostly followed the Mesolithic hunter-gatherer lifestyle, with traces of early agriculture.” ref

“The distribution of the artifacts found includes Finnmark (Norway) in the north, the Kalix River (Sweden) and the Gulf of Bothnia (Finland) in the west and the Vistula River (Poland) in the south. It would include the Narva culture of Estonia and the Sperrings culture in Finland, among others. They are thought to have been essentially hunter-gatherers, though e.g. the Narva culture in Estonia shows some evidence of agriculture. Some of this region was absorbed by the later Corded Ware horizon. The ceramics consist of large pots that are rounded or pointed below, with a capacity from 40 to 60 litres. The forms of the vessels remained unchanged but the decoration varied.” ref

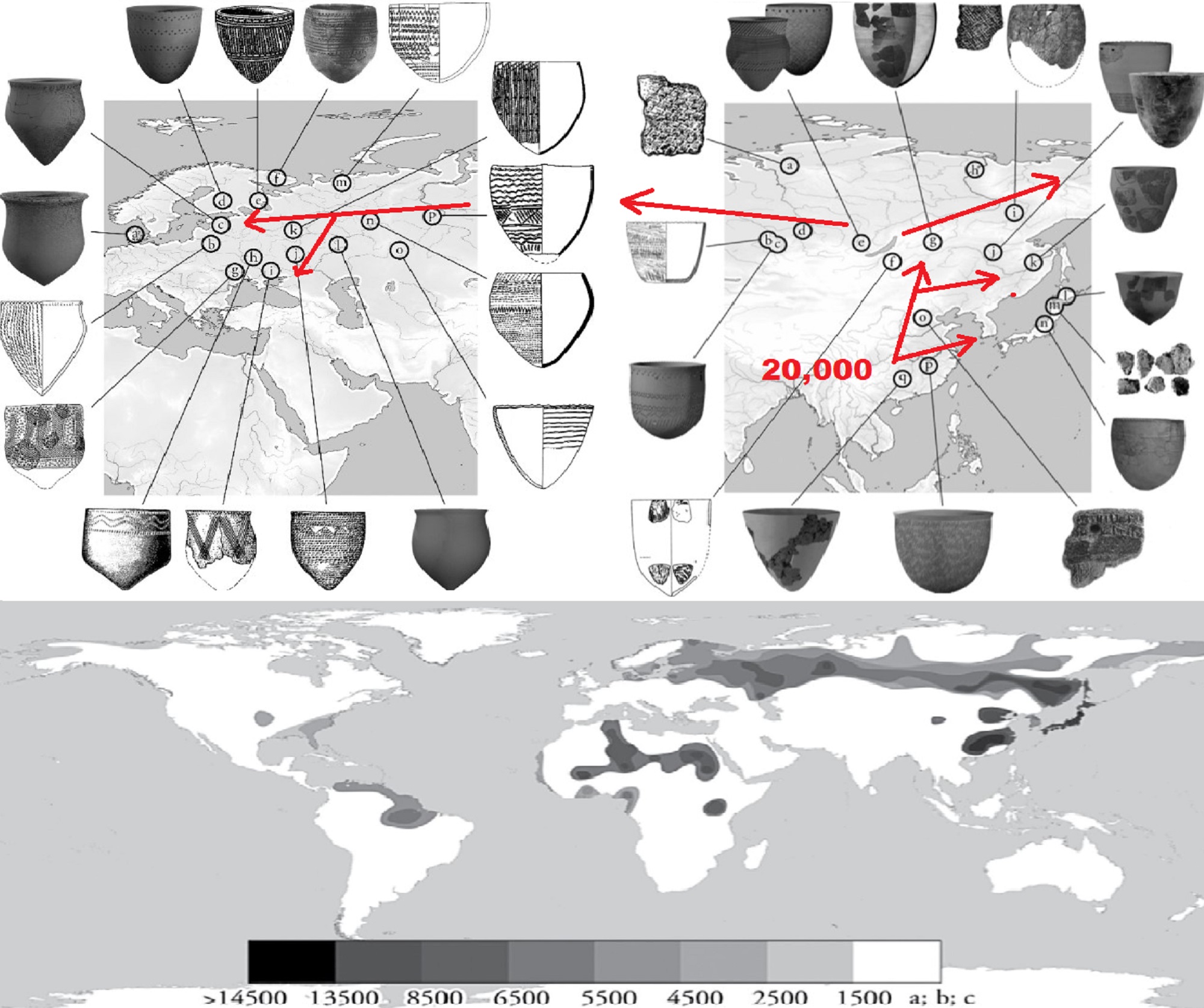

“The Pit–Comb Ware culture is one of the few exceptions to the rule that pottery and farming coexist in Europe. In the Near East farming appeared before pottery, then when farming spread into Europe from the Near East, pottery-making came with it. However, in Asia, where the oldest pottery has been found, pottery was made long before farming. It appears that the Comb Ceramic Culture reflects influences from Siberia and distant China. By dating according to the elevation of land, the ceramics have traditionally (Äyräpää 1930) been divided into the following periods: early (Ka I, c. 4200 – 3300 BCE), typical (Ka II, c. 3300 – 2700 BCE), and late Comb Ceramic (Ka III, c. 2800 – 2000 BCE).” ref

“However, calibrated radiocarbon dates for the comb-ware fragments found (e.g., in the Karelian isthmus), give a total interval of 5600 – 2300 BCE (Geochronometria Vol. 23, pp 93–99, 2004). Among the many styles of comb ware, there is one that makes use of the characteristics of asbestos: Asbestos ware. In this tradition, which persisted through different cultures into the Iron Age, asbestos was used to temper the ceramic clay. Other styles are Pyheensilta, Jäkärlä, Kierikki, Pöljä and Säräisniemi pottery with their respective subdivisions. Sperrings ceramics is the original name given for the younger early Comb ware (Ka I:2) found in Finland.” ref

“The settlements were located at sea shores or beside lakes and the economy was based on hunting, fishing, and the gathering of plants. In Finland, it was a maritime culture which became more and more specialized in hunting seals. The dominant dwelling was probably a teepee of about 30 square meters where some 15 people could live. Also, rectangular houses made of timber become popular in Finland from 4000 BCE cal. Graves were dug at the settlements and the dead were covered with red ochre. The typical Comb Ceramic age shows an extensive use of objects made of flint and amber as grave offerings.” ref

“The stone tools changed very little over time. They were made of local materials such as slate and quartz. Finds suggest a fairly extensive exchange network: red slate originating from northern Scandinavia, asbestos from Lake Saimaa, green slate from Lake Onega, amber from the southern shores of the Baltic Sea, and flint from the Valdai area in northwestern Russia. The culture was characterized by small figurines of burnt clay and animal heads made of stone. The animal heads usually depict moose and bears and were derived from the art of the Mesolithic. There were also many rock paintings. There are sources noting that the typical comb ceramic pottery had a sense of luxury and that its makers knew how to wear precious amber pendants.” ref

“In earlier times, it was often suggested that the spread of the Comb Ware people was correlated with the diffusion of the Uralic languages, and thus an early Uralic language would have been spoken throughout this culture. It was also suggested that bearers of this culture likely spoke Finno-Ugric languages. Another view is that the Comb Ware people may have spoken Palaeo-European languages, as some toponyms and hydronyms also indicate a non-Uralic, non-Indo-European language at work in some areas. In addition, modern scholars have located the Proto-Uralic homeland east of the Volga, if not even beyond the Urals. The great westward dispersal of the Uralic languages is suggested to have happened long after the demise of the Comb Ceramic culture, perhaps in the 1st millennium BCE.” ref

“Saag et al. (2017) analyzed three CCC individuals buried at Kudruküla as belonging to Y-hg R1a5-YP1272 (R1a1b~ after ISOGG 2020), along with three mtDNA samples of mt-hg U5b1d1, U4a, and U2e1. Mittnik (2018) analyzed two CCC individuals. The male carried R1 (2021: R1b-M343) and U4d2, while the female carried U5a1d2b. Generally, the CCC individuals were mostly of Eastern Hunter-Gatherer (EHG) descent, with even more EHG than people of the Narva culture. Lamnidis et al. (2018) confirmed and specified this to 65% Eastern Hunter-Gatherer (EHG), 20% Western Steppe Herder (WSH), and 15% Western Hunter-Gatherer (WHG) ancestry. This amount of EHG ancestry was higher than among earlier cultures of the eastern Baltic, while WSH ancestry had previously not even been attested among such an early culture in the region.” ref

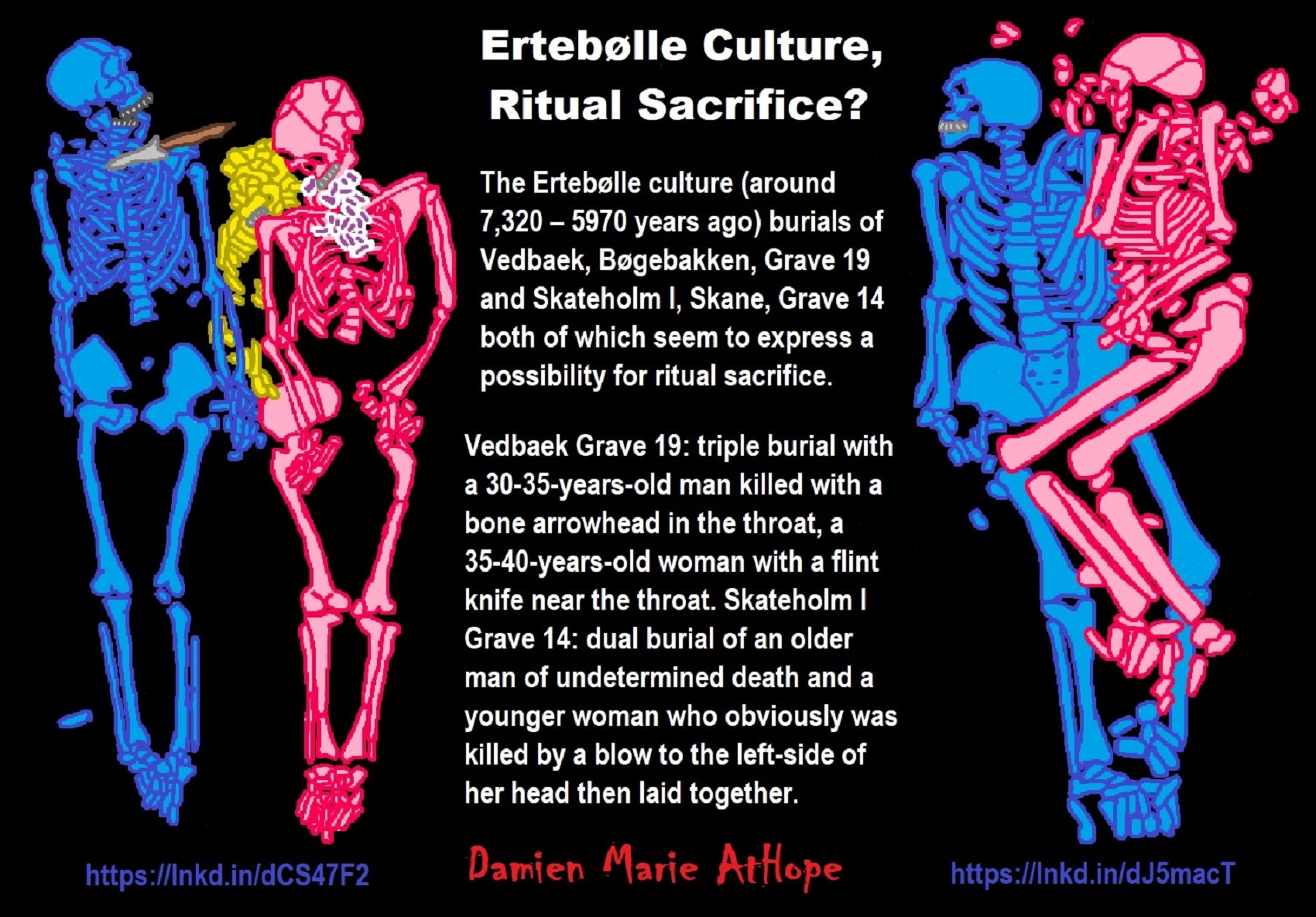

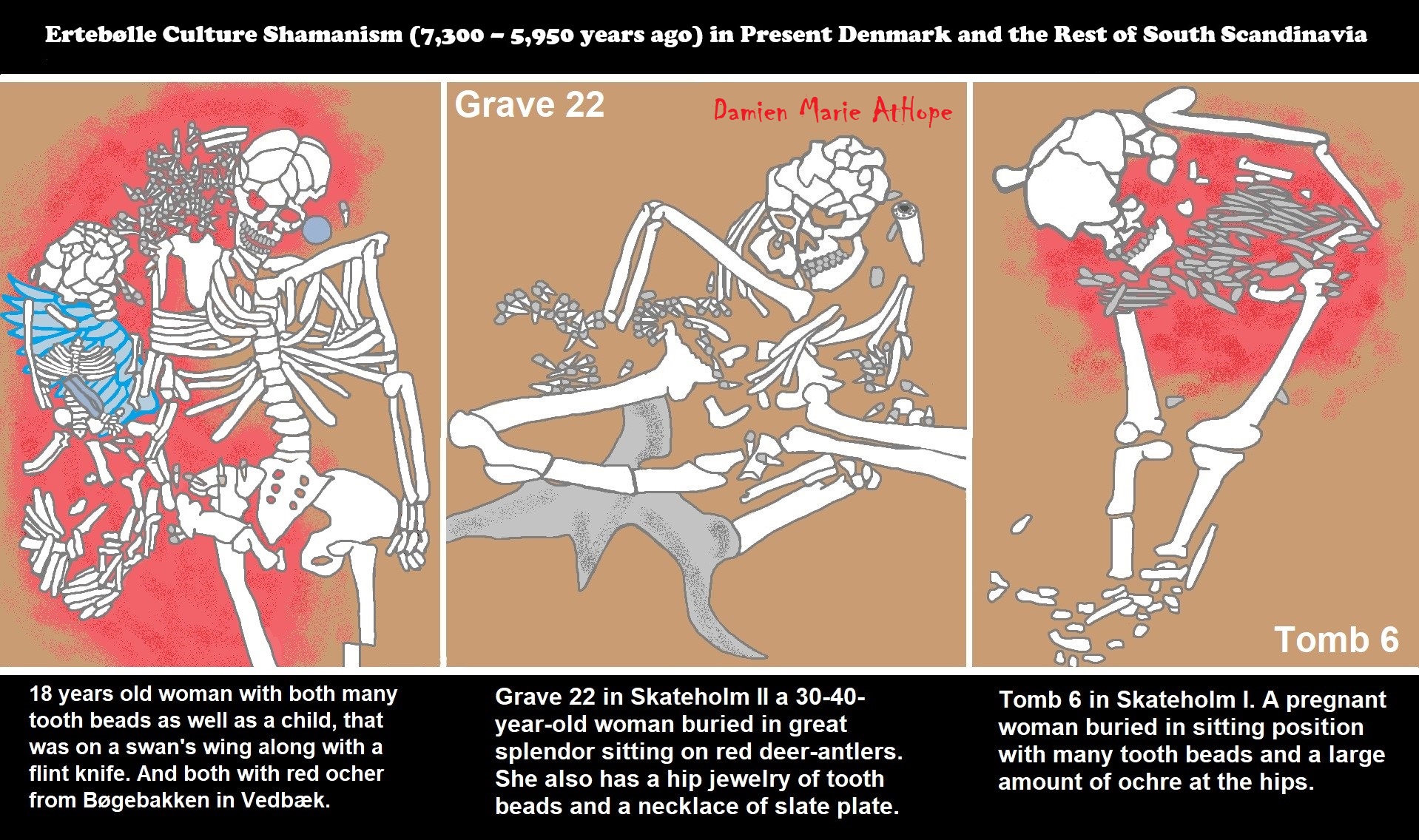

Ertebølle culture

“The Ertebølle culture (ca 5300 – 3950 BCE) is the name of a hunter-gatherer and fisher, pottery-making culture dating to the end of the Mesolithic period. The culture was concentrated in Southern Scandinavia. It is named after the type site, a location in the small village of Ertebølle on Limfjorden in Danish Jutland. In the 1890s, the National Museum of Denmark excavated heaps of oyster shells there, mixed with mussels, snails, bones and bone, antler, and flint artifacts, which were evaluated as kitchen middens, or refuse dumps. Accordingly, the culture is less commonly named the Kitchen Midden. As it is approximately identical to the Ellerbek culture of Schleswig-Holstein, the combined name, Ertebølle-Ellerbek is often used. The Ellerbek culture (German Ellerbek Kultur) is named after a type site in Ellerbek, a community on the edge of Kiel, Germany.” ref

“In the 1960s and 1970s another closely related culture was found in the (now dry) Noordoostpolder in the Netherlands, near the village Swifterbant and the former island of Urk. Named the Swifterbant culture (5300 – 3400 BCE) they show a transition from hunter-gatherer to both animal husbandry, primarily cows and pigs, and cultivation of barley and emmer wheat. During the formative stages contact with nearby Linear Pottery culture settlements in Limburg has been detected. Like the Ertebølle culture, they lived near open water, in this case, creeks, river dunes, and bogs along post-glacial banks of the Overijsselse Vecht. Recent excavations show a local continuity going back to (at least) 5600 BCE, when burial practices resembled the contemporary gravefields in Denmark and South Sweden “in all details”, suggesting only part of a diverse ancestral “Ertebølle”-like heritage was locally continued into the later (Middle Neolithic) Swifterbant tradition (4200 – 3400 BCE).” ref

“The Ertebølle culture was roughly contemporaneous with the Linear Pottery culture, food-producers whose northernmost border was located just to the south. The Ertebølle did not practice agriculture but it did utilize domestic grain in some capacity, which it must have obtained from the south. The Ertebølle culture replaced the earlier Kongemose culture of Denmark. It was limited to the north by the Scandinavian Nøstvet and Lihult cultures. It is divided into an early phase ca 5300-4500 BCE, and a later phase ca 4500-3950 BCE. Shortly after 4100 BCE the Ertebølle began to expand along the Baltic coast at least as far as Rügen. Shortly thereafter it was replaced by the Funnelbeaker culture. Ertebølle peoples lived primarily on seafood. The mainstay of Ertebølle economy was fish. Three main methods of fishing are supported by the evidence, such as the boats and other equipment found in fragmentary form at Tybrind Vig and elsewhere: trapping, angling, and spearing.” ref

“In recent years archaeologists have found the acronym EBK most convenient, parallel to LBK for German Linearbandkeramik (Linear Pottery culture) and TRB for German Trichterbecher, Danish Tragtbæger (Funnelbeaker culture) and Dutch trechterbekercultuur. Ostensibly for Ertebølle Kultur, EBK could be either German or Danish and has the added advantage that Ellerbek also begins with E. The Ertebølle population derived its living from a variety of means, but chiefly from the sea. They prospered, grew healthy, and multiplied on a diet of fish. They were masters of the inland waters, which they traversed in paddled dugouts. Like many peoples known in history, they were able to hunt whales and seals from their dugouts. Their materials were mainly wood, with bone, antler, and flint for functions requiring harder surfaces. Homes were constructed of brush or light wood. The materials encourage us to view them as transitory. They were, nevertheless, able to place the dead in longer-used cemeteries. Perhaps the dwelling-places were transitory, but the territories were not.” ref

“Evidence of conflict: There is some evidence of conflict between Ertebølle settlements: an arrowhead in a pelvis at Skateholm, Sweden; a bone point in a throat at Vedbæk, Zealand; a bone point in the chest at Stora Biers, Sweden. More significant is evidence of cannibalism at Dyrholmen, Jutland, and Møllegabet on Ærø. Their human bones were broken open to obtain the marrow. The evidence of marrow exploitation in the Ertebølle remains indicates dietary rather than ritual cannibalism; as marrow is never the subject of ritualistic cannibalism. The Ertebølle culture is of a general type called Late Mesolithic, of which other examples can be found in Swifterbant culture, Zedmar culture, Narva culture, and in Russia. Some would include the Nøstvet culture and Lihult culture to the north as well. The various locations seem fragmented and isolated, but that characteristic may be an accident of discovery. Perhaps if all the submarine sites were known, a continuous coastal culture would appear from the Netherlands to the lakes of Russia, but this has yet to be demonstrated.” ref

“Judging from the remains of animal bones at their sites, the Ertebølle people hunted mainly three types of land animals: large forest browsers, fur animals, and maritime birds. The forest mammals are the red deer and roe deer, which were dietary staples, and the wild boar, european elk, less frequently the aurochs, and a rare horse, believed to have been wild. Only a left foreleg from Østenkær remains. It offers definitive proof that horses lived in the forests of Europe. On the plains to the east they are only found in association with man. The boar were supplemented by swine with mixed European and Near Eastern ancestry, obtained through their Neolithic farming neighbors, as early as 4600 BCE.” ref

“The fur animals are fairly widespread: the beaver, squirrel, polecat, badger, fox, lynx. Furs might have served as a currency and may have been traded to some degree, but this is speculation. Maritime birds must have been easily taken in the marshes and ponds of the region: red-throated diver, black-throated diver, Dalmatian pelican, capercaille, grebe, cormorant, swan, and duck. In addition are a few others: the dog and the wolf, and two snakes, the common grass snake, and the Aesculapian snake. As snakes do not appear in the art, it is impossible to say what cultural impact they had, if any.” ref

“Plant use: The EBK gathered berries for consumption and also prepared a number of wild plants, judging from the seed remains of plants that could not be consumed without preparation. Of the berries that have been found are raspberry (Rubus idaeus), dewberry (Rubus caesius), wild strawberry, and the somewhat less palatable dogwood (Cornus sanguinea), hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna, and C. oxyacantha), rowanberry (Sorbus aucuparia), crab apple and rose hips. Some seeds usually made into gruel in historical times are acorn and manna grass (Glyceria fluitans). Roots of the sea beet, Beta maritima, were prepared as well. That species is ancestral to modern domestic beets. Greens could have been boiled from nettle (Urtica dioica), orache (Atriplex), and goosefoot (Chenopodium album).” ref

“Some of the pottery evidences grain impressions, which some interpret as the use of food imported from the south. Certainly, they did not need to import food and were probably better nourished than the southerners. Analysis of charred remains in one pot indicates that it at least was used for fermenting a mixture of blood and nuts. Some have therefore guessed that fermentation of grain was used to produce beer. Finally, fragments of textiles from Tybrind Vig were woven in the needle-netting technique from spun plant fibers.” ref

“Pottery was manufactured from native clays tempered with sand, crushed stone, and organic material. The EBK pot was made by coil technique, being fired on the open bed of hot coals. It was not like the neighboring Neolithic Linearbandkeramik and appears related instead to a pottery type that first appears in Europe in the Samara region of Russia c. 7000 cal BC, and spread up the Volga to the Eastern Baltic and then westward along the shore. Two main types are found, a beaker and a lamp. The beaker is a pot-bellied pot narrowing at the neck, with a flanged, outward turning rim. The bottom was typically formed into a point or bulb (the “funnel”) of some sort that supported the pot when it was placed in clay or sand. One can imagine a sort of mobile pantry consisting of rows of jars set now in the hut, now by the fire, now in the clay layer at the bottom of a dugout.” ref

“The beaker came in various sizes from 8 to 50 cm high and from 5 to 20 cm in diameter. Decoration filled the entire surface with horizontal bands of fingertip or fingernail impressions. It must have been in the decoration phase that grains of wheat and barley left their impression in the clay. Late in the period technique and decoration became slightly more varied and sophisticated: the walls were thinner and different motifs were used in the impressions: chevrons, cord marks, and punctures made with animal bones. Handles are sometimes added and the rims may turn in instead of out. The blubber lamp was molded from a single piece of clay. The use of such lamps suggests some household activity in the huts after dark.” ref

“Paddles from Tybrind Vig show traces of highly developed and artistic woodcarving. This is an example of the embellishment of functional pieces. The population also polished and engraved non-functional or not obviously functional pieces of bone or antler. Motifs were predominantly geometric with some anthropomorphic or zoomorphic forms. Also in evidence (for example, at Fanø) are polished amber representations of animals, such as birds, boars, and bears. Jewelry was made of animal teeth or decorative shells. To what extent any of these pieces were symbolic of wealth and status is not clear. Cemeteries, such as the ones at Vedbæk and Skateholm, give a “sedentary” character to the settlements. Red ochre and deer antlers were placed in some graves, but not others. Some social distinctions may therefore have been made.” ref

“There was some appreciation of sexual dimorphism: the women wore necklaces and belts of animal teeth and shells. No special body position was used. Both burial and cremation were practiced. At Møllegabet, an individual was buried in a dugout, which some see as the beginning of Scandinavian boat burials. Skateholm contained also a dog cemetery. Dog graves were prepared and gifted the same as human, with ochre, antler, and grave goods. In either history or prehistory, the dog is an invaluable animal and is often treated as a person.” ref

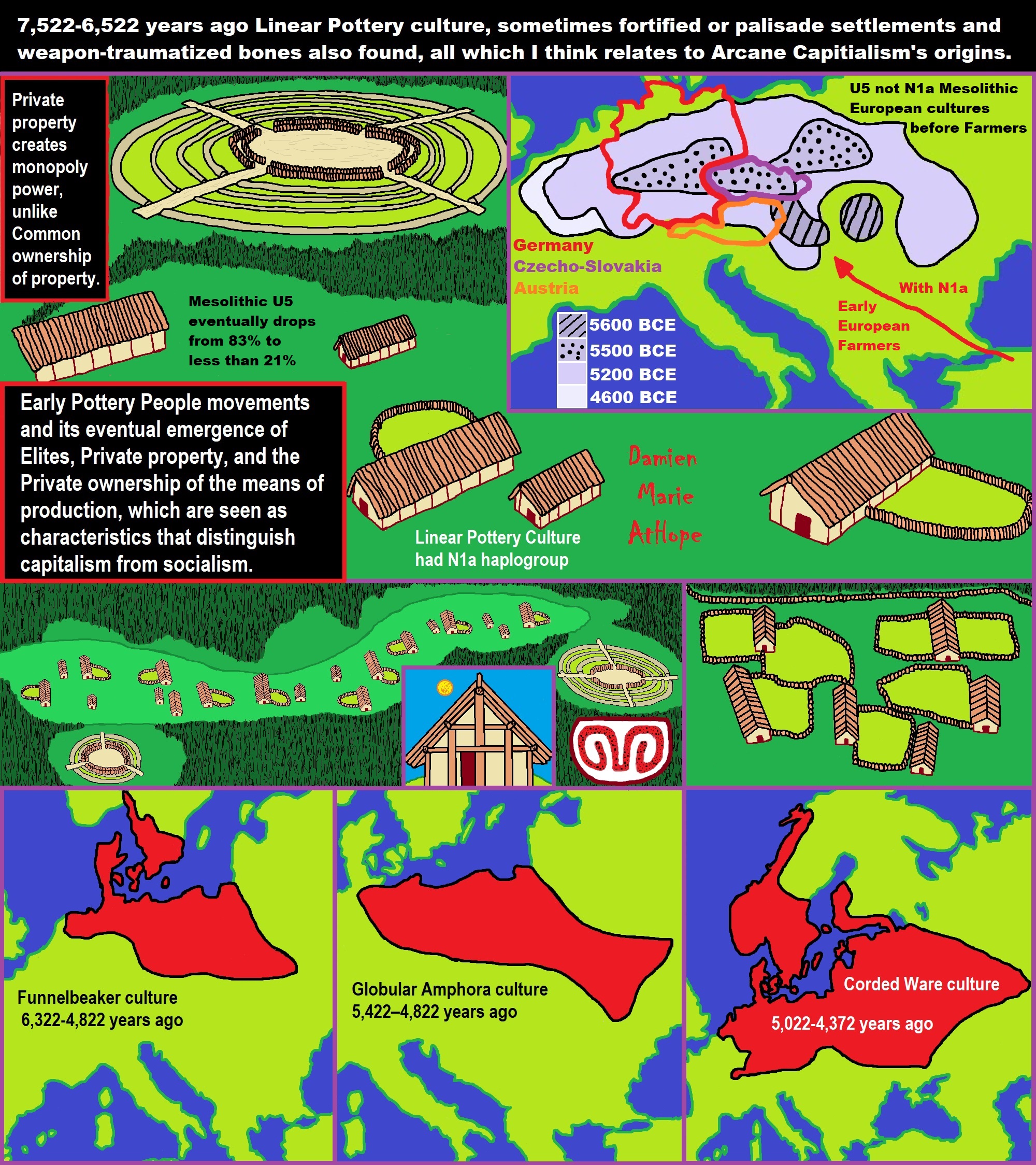

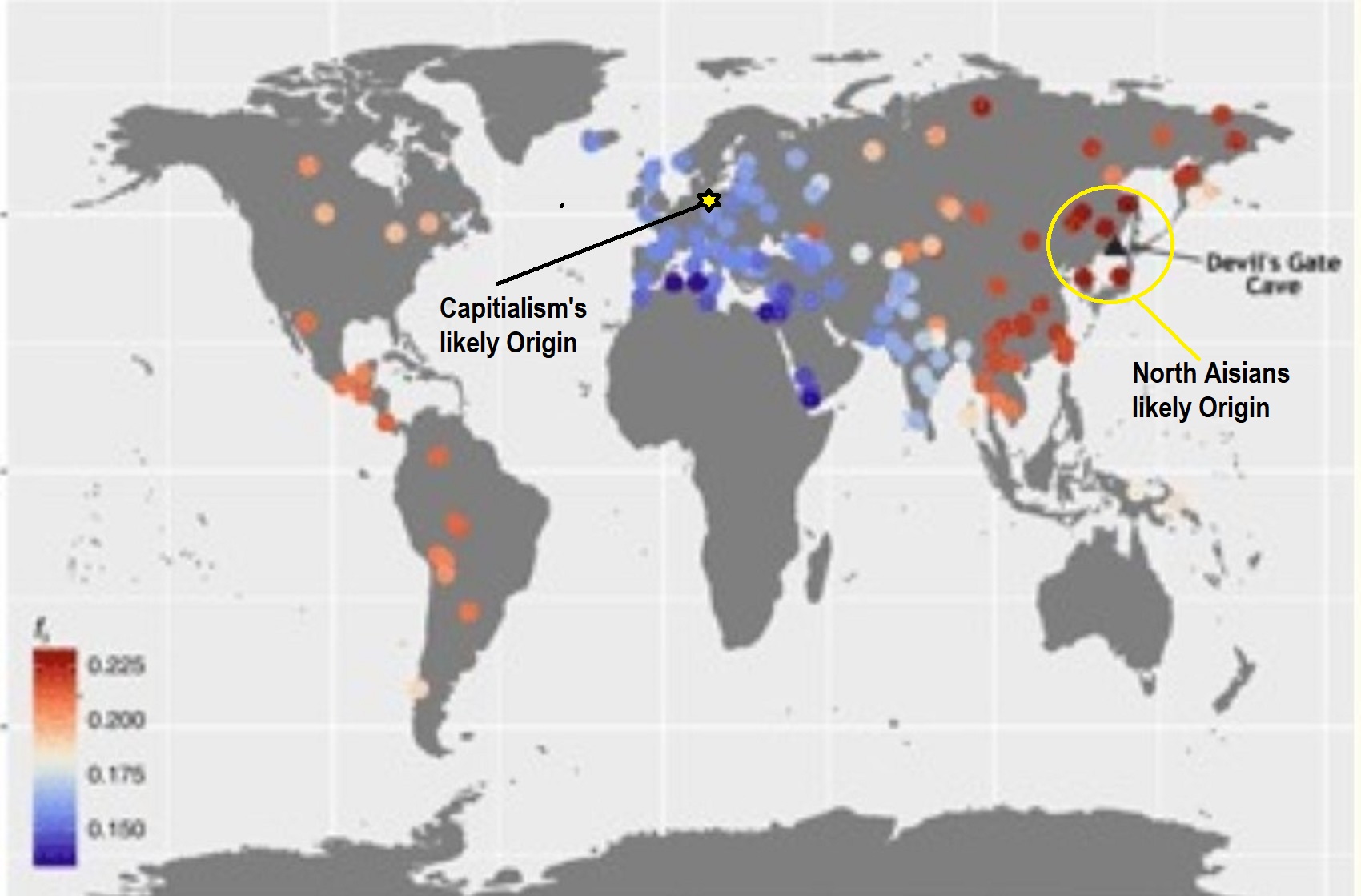

7,522-6,522 years ago Linear Pottery culture which I think relates to Arcane Capitalism’s origins

Eastern Linear Pottery Culture

“In contrast to the western Linear Pottery Culture, there is also an eastern or Alföld Linear Pottery Culture. The name is misleading since the western LPC can be found east of the eastern LPC. Since the term “Alföld LPC”, however, also covers only part of the distribution, we will use the name “eastern LPC” in this context. By means of vessel shapes and decoration and cultic remains, the eastern LPC can be well distinguished from the western LPC. House-building techniques of the eastern LPC which seemed to be characterized by so-called pit-houses for a long time include, however, also long-houses which are frequent in the western LPC.” ref

“The Eastern Linear Pottery culture developed in eastern Hungary and Transylvania roughly contemporaneously with, perhaps a few hundred years after, the Transdanubian. The great plain there (Hungarian Alföld) had been occupied by the Starčevo-Körös-Criş culture of “gracile Mediterraneans” from the Balkans as early as 6100 BCE. Hertelendi and others give a reevaluated date range of 5860–5330 BCE for the Early Neolithic, 5950–5400 BCE for the Körös. The Körös Culture went as far north as the edge of the upper Tisza and stopped. North of it the Alföld plain and the Bükk Mountains were intensively occupied by Mesolithics thriving on the flint tool trade.” ref

Western Linear Pottery Culture

“The early or earliest Western Linear Pottery culture began conventionally at 5500 BCE, possibly as early as 5700 BCE, in western Hungary, southern Germany, Austria, and the Czech Republic. It is sometimes called the Central European Linear Pottery (CELP) to distinguish it from the ALP phase of the Eastern Linear Pottery culture. In Hungarian it tends to be called DVK, Dunántúl Vonaldiszes Kerámia, translated as “Transdanubian Linear Pottery”. A number of local styles and phases of ware are defined.” ref

“The end of the early phase can be dated to its arrival in the Netherlands at about 5200 BCE. The population there was already food-producing to some extent. The early phase went on there, but meanwhile, the Music Note Pottery (Notenkopfkeramik) phase of the Middle Linear Band Pottery culture appeared in Austria at about 5200 BCE and moved eastward into Romania and Ukraine. The late phase, or Stroked Pottery culture (Stichbandkeramik or SBK, 5000–4500 BCE) evolved in central Europe and went eastward.” ref

Linear Pottery culture

“The Linear Pottery culture is a major archaeological horizon of the European Neolithic, flourishing c. 5500–4500 BCE. It is abbreviated as LBK (from German: Linearbandkeramik), and is also known as the Linear Band Ware, Linear Ware, Linear Ceramics, or Incised Ware culture, and falls within the Danubian I culture of V. Gordon Childe. The densest evidence for the culture is on the middle Danube, the upper and middle Elbe, and the upper and middle Rhine. It represents a major event in the initial spread of agriculture in Europe. The pottery after which it was named consists of simple cups, bowls, vases, and jugs, without handles, but in a later phase with lugs or pierced lugs, bases, and necks.” ref

“Important sites include Nitra in Slovakia; Bylany in the Czech Republic; Langweiler and Zwenkau in Germany; Brunn am Gebirge in Austria; Elsloo, Sittard, Köln-Lindenthal, Aldenhoven, Flomborn, and Rixheim on the Rhine; Lautereck and Hienheim on the upper Danube; and Rössen and Sonderhausen on the middle Elbe. In 2019, two large Rondel complexes were discovered east of the Vistula River near Toruń in Poland. Two variants of the early Linear Pottery culture are recognized: 1. The Early or Western Linear Pottery Culture developed on the middle Danube, including western Hungary, and was carried down the Rhine, Elbe, Oder, and Vistula. 2. The Eastern Linear Pottery Culture flourished in eastern Hungary.” ref

“Middle and late phases are also defined. In the middle phase, the Early Linear Pottery culture intruded upon the Bug-Dniester culture and began to manufacture musical note pottery. In the late phase, the Stroked Pottery culture moved down the Vistula and Elbe. A number of cultures ultimately replaced the Linear Pottery culture over its range, but without a one-to-one correspondence between its variants and the replacing cultures. The culture map, instead, is complex. Some of the successor cultures are the Hinkelstein, Großgartach, Rössen, Lengyel, Cucuteni-Trypillian, and Boian-Maritza cultures.” ref

“Since Starčevo-Körös pottery was earlier than the LBK and was located in a contiguous food-producing region, the early investigators looked for precedents there. Much of the Starčevo-Körös pottery features decorative patterns composed of convolute bands of paint: spirals, converging bands, vertical bands, and so on. The LBK appears to imitate and often improve these convolutions with incised lines; hence the term, linear, to distinguish incised band ware from painted band ware. The name depends on specialized meanings of “linear” and “band”, whether in English or in German. Unfortunately, these words without the qualifiers do not describe the decoration. There are few bands going around the pottery and the lines are mainly not straight.” ref

“The LBK did not begin with this range and only reached it toward the end of its time. It began in regions of densest occupation on the middle Danube (Bohemia, Moravia, Hungary) and spread over about 1,500 km (930 mi) along the rivers in 360 years. The rate of expansion was therefore about 4 km (2.5 mi) per year, which can hardly be called an invasion or a wave by the standard of current events, but over archaeological time seems especially rapid. The LBK was concentrated somewhat inland from the coastal areas; i.e., it is not evidenced in Denmark or the northern coastal strips of Germany and Poland, or the coast of the Black Sea in Romania. The northern coastal regions remained occupied by Mesolithic cultures exploiting the then rich Atlantic salmon runs. There are lighter concentrations of LBK in the Netherlands, such as at Elsloo, Netherlands, with the sites of Darion, Remicourt, Fexhe, or Waremme-Longchamps, and at the mouths of the Oder and Vistula. Evidently, the Neolithics and Mesolithics were not excluding each other.” ref

“The LBK at maximum extent ranged from about the line of the Seine–Oise (Paris Basin) eastward to the line of the Dnieper, and southward to the line of the upper Danube down to the big bend. An extension ran through the Southern Bug valley, leaped to the valley of the Dniester, and swerved southward from the middle Dniester to the lower Danube in eastern Romania, east of the Carpathians. A good many C-14 dates have been acquired on the LBK, making possible statistical analyses, which have been performed on different sample groups. One such analysis by Stadler and Lennais sets 68.2% confidence limits at about 5430–5040 BCE; that is, 68.2% of possible dates allowed by variation of the major factors that influence measurement, calculation, and calibration fall within that range. The 95.4% confidence interval is 5600–4750 BCE.” ref

Data continue to be acquired and therefore any one analysis should be taken as a rough guideline only. Overall, it is probably safe to say that the Linear Pottery culture spanned several hundred years of continental European prehistory in the late sixth and early fifth millennia BC, with local variations. Data from Belgium indicate a late survival of LBK there, as late as 4100 BCE. The Linear Pottery culture is not the only food-producing player on the stage of prehistoric Europe. It has been necessary, therefore, to distinguish between it and the Neolithic, which was most easily done by dividing the Neolithic of Europe into chronological phases. These have varied a great deal.” ref

“An approximation is:

- Early Neolithic, 6000–5500. The first appearance of food-producing cultures in the south of the future Linear Pottery culture range: the Körös of southern Hungary and the Dniester culture in Ukraine.

- Middle Neolithic, 5500–5000. Early and Middle Linear Pottery culture.

- Late Neolithic, 5000–4500. Late Linear Pottery and legacy cultures.” ref

“The last phase is no longer the end of the Neolithic. A “Final Neolithic” has been added to the transition between the Neolithic and the Bronze Age. All numbers depend to some extent on the geographic region. The pottery styles of the LBK allow some division of its window in time. Conceptual schemes have varied somewhat. One is:

- Early: The Eastern and Western LBK cultures, originating on the middle Danube

- Middle: Musical Note pottery – the incised lines of the decoration are broken or terminated by punctures, or “strokes”, giving the appearance of musical notes. The culture expanded to its maximum extent, and regional variants appeared. One variant is the late Bug-Dniester culture.

- Late: Stroked pottery – lines of punctures are substituted for the incised lines.” ref

“The earliest theory of Linear Pottery culture origin is that it came from the Starčevo-Körös culture of Serbia and Hungary. Supporting this view is the fact that the LBK appeared earliest about 5600–5400 BCE on the middle Danube in the Starčevo range. Presumably, the expansion northwards of early Starčevo-Körös produced a local variant reaching the upper Tisza that may have well been created by contact with native epi-Paleolithic people. This small group began a new tradition of pottery, substituting engravings for the paintings of the Balkanic cultures.” ref

“A site at Brunn am Gebirge just south of Vienna seems to document the transition to LBK. The site was densely settled in a long house pattern around 5550–5200 BCE. The lower layers feature Starčevo-type plain pottery, with large number of stone tools made of material from near Lake Balaton, Hungary. Over the time frame, LBK pottery and animal husbandry increased, while the use of stone tools decreased.” ref

“A second theory proposes an autochthonous development out of the local Mesolithic cultures. Although the Starčevo-Körös entered southern Hungary about 6000 BCE and the LBK spread very rapidly, there appears to be a hiatus of up to 500 years in which a barrier seems to have been in effect. Moreover, the cultivated species of the near and middle eastern Neolithic do not do well over the Linear Pottery culture range. And finally, the Mesolithics in the region prior to the LBK used some domestic species, such as wheat and flax. The La Hoguette culture on the northwest of the LBK range developed their own food production from native plants and animals.” ref

“A third theory attributes the start of Linear Pottery to an influence from the Mesolithic cultures of the east European plain. The pottery was used in intensive food gathering. The rate at which it spread was no faster than the spread of the Neolithic in general. Accordingly, Dolukhanov and others postulate that an impulse from the steppe to the southeast of the barrier stimulated the Mesolithics north of it to innovate their own pottery. This view only accounts for the pottery; presumably, the Mesolithics combined it de novo with local food production, which began to spread very rapidly throughout a range that was already producing some food.” ref

“The initial LBK population theory hypothesized that the culture was spread by farmers moving up the Danube practicing slash-and-burn methods. The presence of the Mediterranean sea shell, Spondylus gaederopus, and the similarity of the pottery to gourds, which did not grow in the north, seemed to be evidence of the immigration, as does the genetic evidence cited below. The lands into which they moved were believed untenanted or too sparsely populated by hunter-gatherers to be a significant factor. The barrier causing the hiatus mentioned above does not have an immediate geographical cause. The Körös culture ended in the middle of the Hungarian plain, and although the climate to the north is colder, the gradient is not so sharp as to form a barrier there.” ref

“In 2005, scientists successfully sequenced mtDNA coding region 15997–16409 derived from twenty-four 7,500- to 7,000-year-old human remains associated with the LBK culture. Of those remains, 22 were from locations in Germany near the Harz Mountains and the upper Rhine Valley, while one was from Austria and one from Hungary. The scientists did not reveal the detailed hypervariable segment I (HVSI) sequences for all the samples, but identified that seven of the samples belonged to H or V branch of the mtDNA phylogenetic tree, six belonged to the N1a branch, five belonged to the T branch, four belonged to the K(U8) branch, one belonged to the J branch, and one belonged to the U3 branch. All branches are extant in the current European population, although the K branch was present in roughly twice the percentages as would be found in Europe today (15% vs. 8% now).” ref

“A comparison of the N1a HVSI sequences with sequences of living individuals found three of them to correspond with those of individuals currently living in Europe. Two of the sequences corresponded to ancestral nodes predicted to exist or to have existed on the European branch of the phylogenetic tree. One of the sequences is related to European populations, but with no apparent descendants amongst the modern population. The N1a evidence supports the notion that the descendants of LBK culture have lived in Europe for more than 7,000 years and have become an integral part of the current European population. The lack of mtDNA haplogroup U5 supports the notion that U5 at this time is uniquely associated with mesolithic European cultures.” ref

“A 2010 study of ancient DNA suggested the LBK population had affinities to modern-day populations from the Near East and Anatolia, such as an overall prevalence of G2. The study also found some unique features, such as the prevalence of the now-rare Y-haplogroup H2 and mitochondrial haplogroup frequencies. Subsequent studies based on full-genome analysis have found that the LBK population was similar genetically to modern southern Europeans, and did not resemble modern Near Eastern or Anatolian populations. Neolithic Anatolian farmers have also been found to be more similar to modern southern Europeans that to modern Near Easterners or Anatolians.” ref

“Lipson et al. (2017) and Narasimhan et al. (2019) analyzed a large number of skeletons ascribed to the Linear Pottery Culture. Most of the Y-DNA belonged to G2a and subclades of it, some to I2 and subclades of it, beside few samples of T1a, CT, and C1a2. The samples of mtDNA extracted were various subclades of T, H, N, U, K, J, X, HV, and V. The LBK people settled on fluvial terraces and in the proximities of rivers. They were quick to identify regions of fertile loess. On it they raised a distinctive assemblage of crops and associated weeds in small plots, an economy that Gimbutas called a “garden type of civilization”. The difference between a crop and a weed in LBK contexts is the frequency.” ref

“The unit of residence was the long house, a rectangular structure, 5.5 to 7.0 m (18.0 to 23.0 ft) wide, of variable length; for example, a house at Bylany was 45 m (148 ft). Outer walls were wattle-and-daub, sometimes alternating with split logs, with slanted, thatched roofs, supported by rows of poles, three across. The exterior wall of the home was solid and massive, oak posts being preferred. Clay for the daub was dug from pits near the house, which were then used for storage. Extra posts at one end may indicate a partial second story. Some LBK houses were occupied for as long as 30 years.” ref

“It is thought that these houses had no windows and only one doorway. The door was located at one end of the house. Internally, the house had one or two partitions creating up to three areas. Interpretations of the use of these areas vary. Working activities might be carried out in the better lit door end, the middle used for sleeping and eating, and the end farthest from the door could have been used for grain storage. According to another view, the interior was divided in areas for sleeping, common life, and a fenced enclosure at the back end for keeping animals.” ref

When the First Farmers Arrived in Europe, Inequality Evolved

“Forests gave way to fields, pushing hunter-gatherers to the margins—geographically and socially. There is no clear genetic evidence of interbreeding along the central European route until the (Linear Pottery culture 5500–4500 BCE or 7,522-6,522 years ago) LBK farmers reached the Rhine. And yet the groups mixed in other ways—potentially right from the beginning. A tantalizing hint of such interactions came from Gamba’s discovery of a hunter-gatherer bone in a farming settlement at a place called Tiszaszőlős-Domaháza in Hungary. But there was nothing more to be said about that individual. Was he a member of that community? A hostage? Someone passing through?” ref

“With later evidence, the picture became clearer. At Bruchenbrücken, a site north of Frankfurt in Germany, farmers, and hunter-gatherers lived together roughly 7,300 years ago in what Gronenborn calls a “multicultural” settlement. It looks as if the hunters may have come there originally from farther west to trade with the farmers, who valued their predecessors’ toolmaking techniques—especially their finely chiseled stone arrowheads. Perhaps some hunter-gatherers settled, taking up the farming way of life. So fruitful were the exchanges at Bruchenbrücken and other sites, Gronenborn says, that they held up the westward advance of farming for a couple of centuries.” ref

“There may even have been rare exceptions to the rule that the two groups did not interbreed early on. The Austrian site of Brunn 2, in a wooded river valley not far from Vienna, dates from the earliest arrival of the LBK farmers in central Europe, around 7,600 years ago. Three burials at the site were roughly contemporaneous. Two were of individuals of pure farming ancestry, and the other was the first-generation offspring of a hunter and a farmer. All three lay curled up on their sides in the LBK way, but the “hunter” was buried with six arrowheads.” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

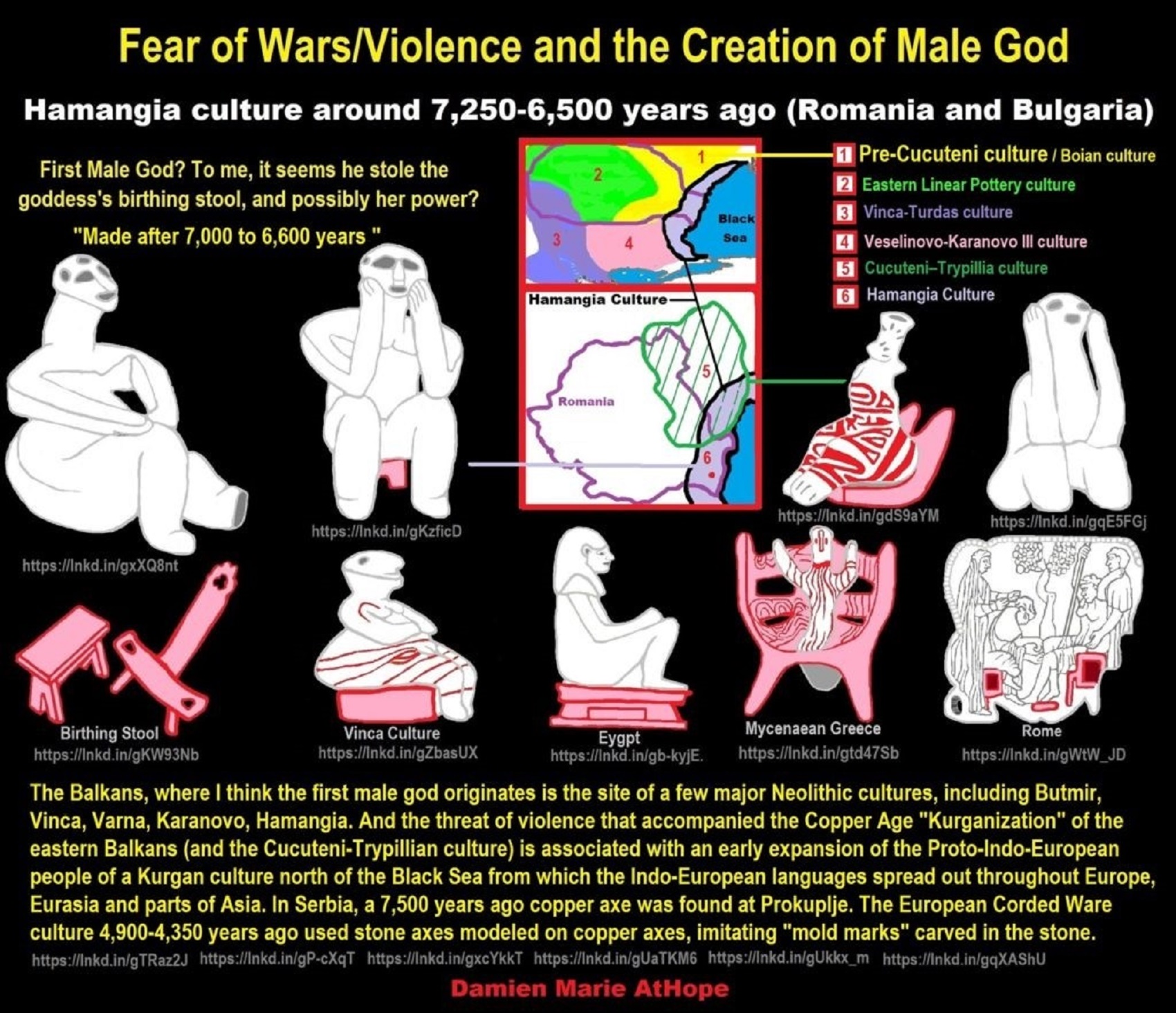

Hamangia culture

“The Hamangia culture is a Late Neolithic archaeological culture of Dobruja (Romania and Bulgaria) between the Danube and the Black Sea and Muntenia in the south. It is named after the site of Baia-Hamangia, discovered along Golovița Lake. The Hamangia culture began around 5250/5200 BCE and lasted until around 4550/4500 BCE. It was absorbed by the expanding Boian culture in its transition towards the Gumelniţa. Its cultural links with Anatolia suggest that it was the result of a recent settlement by people from Anatolia, unlike the neighboring cultures, which appear descended from earlier Neolithic settlements.” ref

“The Hamangia culture attracted and attracts the attention of many art historians because of its exceptional clay figures. Pottery figurines are normally extremely stylized and show standing naked faceless women with emphasized breasts and buttocks. Two figurines known as “The Thinker” and “The Sitting woman” are considered masterpieces of Neolithic art. Painted vessels with complex geometrical patterns based on spiral-motifs are typical. The shapes include: bowls and cylindric glasses (most of them with arched walls). They are decorated with dots, straight parallel lines, and zig-zags, which make Hamangia pottery very original.” ref

“Settlements consist of rectangular houses with one or two rooms, built of wattle and daub, sometimes with stone foundations (in Durankulak). They are normally arranged on a rectangular grid and may form small tells. Settlements are located along the coast, on the coast of lakes, on lower or middle river terraces, and sometimes in caves. Crouched or extended inhumation in cemeteries. Grave-goods tend to be without pottery in Hamangia I. Grave-goods include flint, worked shells, bone tools, and shell-ornaments.” ref

“Important sites: The Durankulak lake settlement, now Archaeological Complex Durankulak, commenced on a small island, approximately 7000 BCE, and around 4700/4600 BCE the stone architecture was already in general use and became a characteristic phenomenon that was unique in Europe. Another site is Cernavodă, the necropolis where the famous statues “The Thinker” and “The Sitting Woman” were discovered. As well as the eponymous site of Baia-Hamangia, discovered along Lake Golovița, close to the Black Sea coast, in the Romanian province of Dobrogea.” ref

Neolithic Czech Republic farmers

“Insights into the cultural and biological lives of early farmers who lived in the Czech Republic around 7,500 years ago. The researchers conducted biochemical and DNA tests on the bones of a sample of 85 early Neolithic farmers found at the Linear Pottery culture cemetery in Vedrovice, Czech Republic. Their findings suggest that these early farmers were indigenous to Central Europe and not migrants from Anatolia and Levant in the Near East, as was previously thought. The Linear Pottery Ware culture was the major early Neolithic culture in continental Europe, stretching from northern France and Belgium across Germany all the way to southern Poland, Slovakia, and Hungary. This type of pottery has been seen as a signature of immigrant farming groups who came up from the south-east and colonized all these regions of Europe, pushing the local hunter-gatherers aside in the process. However, the new research indicates that it was the local hunter-gatherer communities, whose ancestry can be traced back to the local late Palaeolithic, who adopted farming for themselves – through contacts, trade, and partner exchange (e.g. marriage), with the first farmers of south-east Europe.” ref

Interactions between earliest Linearbandkeramik farmers and central European hunter-gatherers at the dawn of European Neolithization

“Archaeogenetic research over the last decade has demonstrated that European Neolithic farmers (ENFs) were descended primarily from Anatolian Neolithic farmers (ANFs). ENFs, including early Neolithic central European Linearbandkeramik (LBK) farming communities, also harbored ancestry from European Mesolithic hunter-gatherers (WHGs) to varying extents, reflecting admixture between ENFs and WHGs. The Linearbandkeramik or Linear Pottery culture (LBK) played a key role in the Neolithization of central Europe. Culturally, economically, and genetically, the LBK had its ultimate roots in western Anatolia, but it also displayed distinct features of autochthonous European Mesolithic hunter-gatherer societies. Several models for the origins of the LBK culture have been proposed over the years.” ref

“However, the timing and other details of this process are still imperfectly understood. In this report, we provide a bioarchaeological analysis of three individuals interred at the Brunn 2 site of the Brunn am Gebirge-Wolfholz archeological complex, one of the oldest LBK sites in central Europe. Two of the individuals had a mixture of WHG-related and ANF-related ancestry, one of them with approximately 50% of each, while the third individual had approximately all ANF-related ancestry. Stable carbon and nitrogen isotope ratios for all three individuals were within the range of variation reflecting the diets of other Neolithic agrarian populations. Strontium isotope analysis revealed that the ~50% WHG-ANF individual was non-local to the Brunn 2 area. Overall, our data indicate interbreeding between incoming farmers, whose ancestors ultimately came from western Anatolia, and local HGs, starting within the first few generations of the arrival of the former in central Europe, as well as highlighting the integrative nature and composition of the early LBK communities.” ref

“The Indigenist model suggests the LBK was founded through the adaptation of elements of the West Asian Neolithic Package by indigenous Mesolithic populations exclusively through frontier contact and cultural diffusion. The Integrationist model views the formation of LBK as the integration of Mesolithic hunter-gatherers into an agro-pastoral lifeway through mechanisms such as leapfrog colonization, frontier mobility, and contact. According to this model, small groups associated with the Starčevo-Körös-Criş (SKC) culture, the likely LBK predecessors in Europe, left their homelands in the Balkans (where most of their own ancestors had arrived earlier from Anatolia), and settled new areas to the northwest. Contacts with local Mesolithic groups and exchange of products would have resulted in the co-optation of hunter-gatherers into farming communities, where they would have adopted farming practices1. Evidence of such interactions exists at the Tiszaszőlős-Domaháza site in northeastern Hungary, containing interments of individuals of mostly hunter-gatherer genetic ancestry buried in a clearly SKC context.” ref

“The Migrationist model suggests that a sparsely populated territory of Mesolithic central Europe was taken over by pioneering agro-pastoral groups associated with the SKC culture, which gradually displaced indigenous hunting-gathering populations, who did not significantly influence the arriving Starčevo colonizers. According to this model, newcomers would have replicated their ancestral material culture in the newly settled territory without incorporating the material culture features of the local indigenous populations. Some variation, due to innovation and adaptation to the new environment and sources, would have involved changes in technology such as pottery and building material as well as lithic tool sources. At the same time, symbolic systems, such as decorative designs and cultural objects, would have remained unchanged. This model appeared at the end of the 1950s and gained wide support in the second half of the 20th century.” ref

“To date, ancient DNA (aDNA) studies have convincingly shown that Neolithic European farming populations were primarily genetic descendants of central and western Anatolian Neolithic farmers (ANFs). Their genetic signature is clearly distinct from autochthonous Mesolithic European hunter-gatherers (HGs) of central Europe (WHGs) at the level of uniparental markers such as mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and Y chromosome as well as genome-wide. Nevertheless, the extent to which the newcomers interacted both culturally and genetically with local hunter-gatherers remains unclear; that is, it remains unclear to what extent an Integrationist or Migrationist model is accurate. Genetically, Neolithic central European farmers carried a minor proportion of genetic ancestry characteristic to WHG populations, but the extent and the timing of the WHG admixture in the gene pool of the European Neolithic descendants of Anatolian farmers varies across central Europe. While the amount of WHG ancestry in European Neolithic farmers had been observed to increase throughout the Neolithic in the present-day territories of Hungary, Germany, and other regions of Europe, the initial degree of exchange remains unresolved, in part due to a scarcity of human remains contemporaneous with the earliest stages of the Neolithic farming migration.” ref

“The Brunn 2 archaeological site, part of the Brunn am Gebirge, Wolfholz archaeological complex south of Vienna, Austria (Fig. 1), is the oldest Neolithic site known in Austria and one of the oldest in all of central Europe. It belongs to the earliest stage of the development of LBK, called the Formative phase. Radiocarbon dates obtained for Brunn 2 time the site to about 5670–5350 cal BCE. The main characteristic of the settlements of the Formative phase is the absence of fine pottery and the use of coarse pottery with clear Starčevo features. The leading role of Anatolian migrants in the formation of cultural attributes of the earliest farmers of Europe is evident through the comparative typological analysis of material culture artifacts from the Brunn 2 site. In addition to a rich trove of cultural artifacts, Brunn 2 yielded four human burials. The initial radiocarbon dating of the remains confirmed these to be contemporaneous with the earliest phase of the Brunn am Gebirge complex and, thus, to represent some of the earliest central European Neolithic farmers. We set out to perform a bioarchaeological analysis of these individuals to examine genetic ancestry as well as diet and mobility at the dawn of the European Neolithization, in an effort to refine the model of the establishment of farming in Neolithic central Europe.” ref

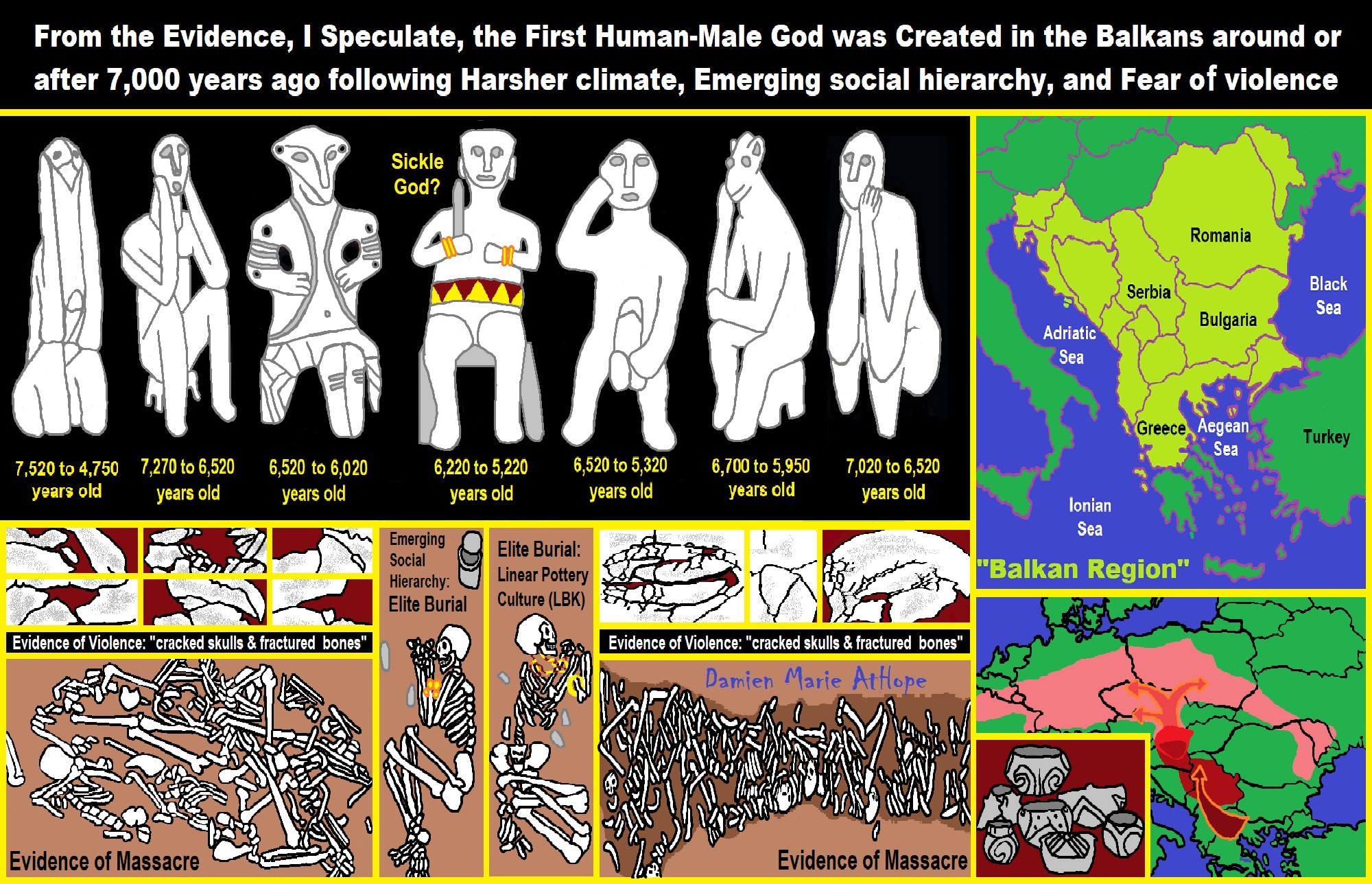

When the First Farmers Arrived in Europe, Inequality Evolved

“Forests gave way to fields, pushing hunter-gatherers to the margins—geographically and socially. Roughly 9,000 years ago farmers from the Middle East headed toward Europe, seeking new land to cultivate. The farmers traveled either along the Mediterranean coast or the Danube River, encountering hunter-gatherers who lived in dense forests. At first, the farmers and hunter-gatherers traded or mated. By 5,000 years ago, however, agriculture dominated the continent and hierarchical societies had evolved. Genetic studies suggest that individuals with high hunter-gatherer ancestry may have been treated as inferiors.” ref

“Eight thousand years ago small bands of seminomadic hunter-gatherers were the only human beings roaming Europe’s lush, green forests. Archaeological digs in caves and elsewhere have turned up evidence of their Mesolithic technology: flint-tipped tools with which they fished, hunted deer and aurochs (a now-extinct species of ox), and gathered wild plants. Many had dark hair and blue eyes, recent genetic studies suggest, and the few skeletons unearthed so far indicate that they were quite tall and muscular. Their languages remain mysterious to this day.” ref

“Three millennia later the forests they inhabited had given way to fields of wheat and lentils. Farmers ruled the continent. The transition was evident early on when excavations revealed bones of domesticated animals, pottery containing remnants of grain, and most intriguing of all, graveyards whose riddles are still being solved. Agriculture not only ushered in a new economic model but also brought about metal tools, new diets, and new patterns of land use, as well as novel human relationships with nature and with one another.” ref

“For 150 years scholars debated whether the farmers brought their Neolithic culture from the Middle East to Europe or whether it was only their ideas that traveled. Research on patterns of variation in modern genes provides irrefutable proof that the farmers came—streaming across the Aegean Sea and the Bosporus to reach Greece and the Balkan Peninsula, respectively. From there they spread north and west. This technological revolution enabled an unprecedented collaboration between archaeologists and geneticists, who rushed to characterize the DNA of individuals who had died in prehistoric hunter-gatherer or farmer settlements.” ref

“Researchers found a hunter-gatherer bone in an early farming community in Hungary, and a bewilderingly complex and multifaceted picture of the encounters between the residents and the immigrants has emerged. In some places, the two groups mingled from the time they met; in others, they kept their distance for centuries, if not millennia. Sometimes the farmers venerated their predecessors; at other times they dehumanized and subjugated them. Nevertheless, a clear trend is evident. As the decades passed and farmers increased in number, they assimilated and replaced the hunter-gatherers, pushing those who held out to the margins—both geographically and socially. Disturbingly, the progression toward greater inequality culminated, in at least a few places, in societies in which individuals with greater hunter-gatherer ancestry may have been enslaved—possibly even being sacrificed to accompany their masters to the afterlife.” ref

“Roughly 11,500 years ago Europe and the Middle East were emerging from an ice age. As the weather grew warmer and the land more bountiful, hunter-gatherers in the so-called Fertile Crescent—an envelope of land around the Euphrates, Tigris, and Nile Rivers and the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea—gradually became more sedentary. They spent less of their time hunting wild ibex and boar and gathering wild grasses, and they spent more of it tending their own domesticated animals and plants: sheep, goats, wheat, peas, and lentils. Archaeobotany—in particular the study of ancient pollen—and archaeozoology, the study of ancient animal bones, revealed this transition. These were the first farmers, people who spoke unknown languages (of which Basque could be a relic), used stone tools, and about 9,000 years ago, headed for Europe in search of new land to cultivate.” ref

“The farmers reached the new continent by two routes: in boats via the Mediterranean and on foot along the Danube River from the Balkans into central Europe. Radiocarbon dating of archaeological sites revealed that by about 7,500 years ago, Danubian farmers were building villages in the Carpathian Basin—modern-day Slovakia, Hungary, and Romania—and there they began creating a pottery culture. Archaeologists call it the Linear Pottery culture (LBK, by its German acronym, for Linearbandkeramik) because of the distinctive spiral motifs with which they decorated their ceramics.

Traveling rapidly westward across the fertile plains of what is now Germany, the LBK farmers reached the Rhine within just a few centuries, around 7,300 years ago. Fine-grained analysis of the evolution of pottery styles, along with radiocarbon dating, suggests that they practiced a form of leapfrog colonization. They took “stepwise movements with sometimes hundreds of kilometers covered, and then the landscape in between filled up,” says archaeologist Detlef Gronenborn of the Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum (Romano-Germanic Central Museum) in Mainz, Germany. At some point, they learned how to smelt copper, and a trade in precious copper objects sprang up between farming communities.” ref

“On the southern route, the farmers leapfrogged along the Mediterranean coast from Italy to France and on to the Iberian Peninsula. After reaching French shores, 7,800 or so years ago, they migrated northward toward the Paris Basin, the plain between the Rhine and the Atlantic Ocean that forms a kind of continental cul-de-sac. It was there that the two great streams of farmers met, around seven millennia ago. By then their cultures had diverged to some extent—they had been separated for more than 500 years—but they would still have recognized their own kind. They mingled both biologically and culturally.” ref

“A cemetery near Gurgy, in the southern part of the Paris Basin, dating from 7,000 years ago provides a snapshot of that mingling. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is typically inherited via the maternal line, and the mtDNA of about 50 individuals buried there has roughly equal contributions from LBK and southern farmers. From the Paris Basin, this mixed population spread out again—carrying its farming culture to every corner of the continent.” ref

“The first farmers to enter Europe probably came with their families, with those male and female farmers in roughly equal proportions. Other researchers have concluded that these societies were patrilocal, meaning wealth was passed down the male line and women married in from outside. Clues to the mobility of women come from the ratio of strontium isotopes in their teeth, which reflect their dietary history, and from the constant influx of outside artistic influences into farming communities, as evinced by their pottery. Women are thought to have decorated the pottery, as in agricultural societies of later eras.” ref

“As with all immigrants, the farmers might have taken a while to adapt to their new environment, but gradually they learned which plants and animals thrived in Europe’s temperate climes. They cleared the forest parcel by parcel and shaped its composition using ancient forest-management techniques such as coppicing and pollarding. (Coppicing involves cutting a tree back to its base and then allowing it to produce multiple new stems; pollarding is pruning of just the upper branches.) The farmers’ numbers began to increase. When there was no more room at a farm, the younger generation moved on, settling in what may have seemed to them a virgin forest. The newcomers might not have had the impression of encroaching on anybody else’s territory. But they were. Sooner or later the immigrant farmers must have met the resident hunter-gatherers—and when it happened, it must have been a shock.” ref

“Comparisons of their genes with those of modern Europeans indicate that the farmers were shorter than the Western hunter-gatherers who occupied most of the continent. They also had dark hair, dark eyes, and probably, lighter skin. There is no evidence of violence between the two groups in the earliest encounters—although the archaeological record is incomplete enough that violence cannot be ruled out. Yet in large parts of Europe, the hunter-gatherers and their Mesolithic culture simply vanished from both genetic and archaeological records the moment the farmers arrived.” ref