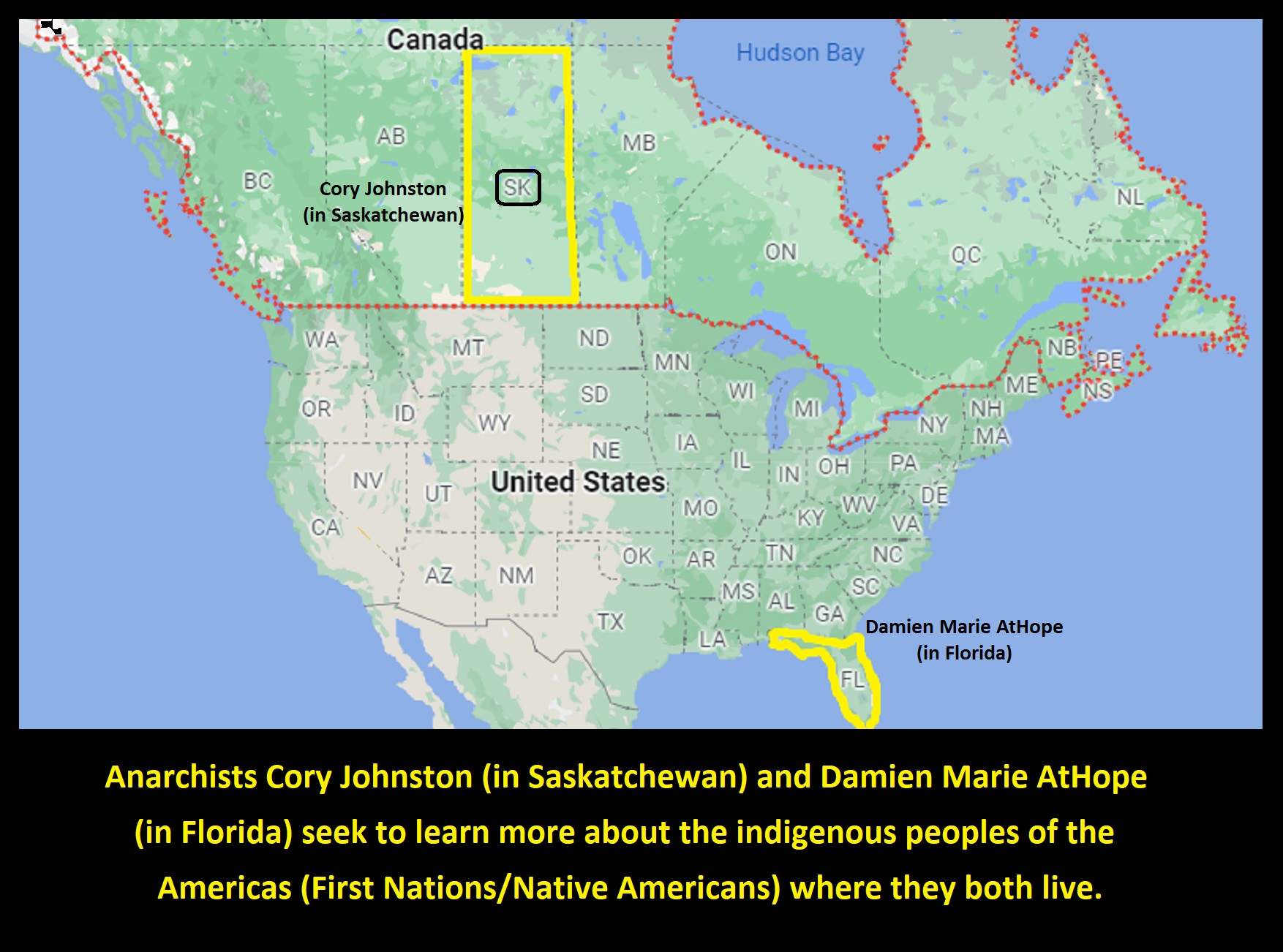

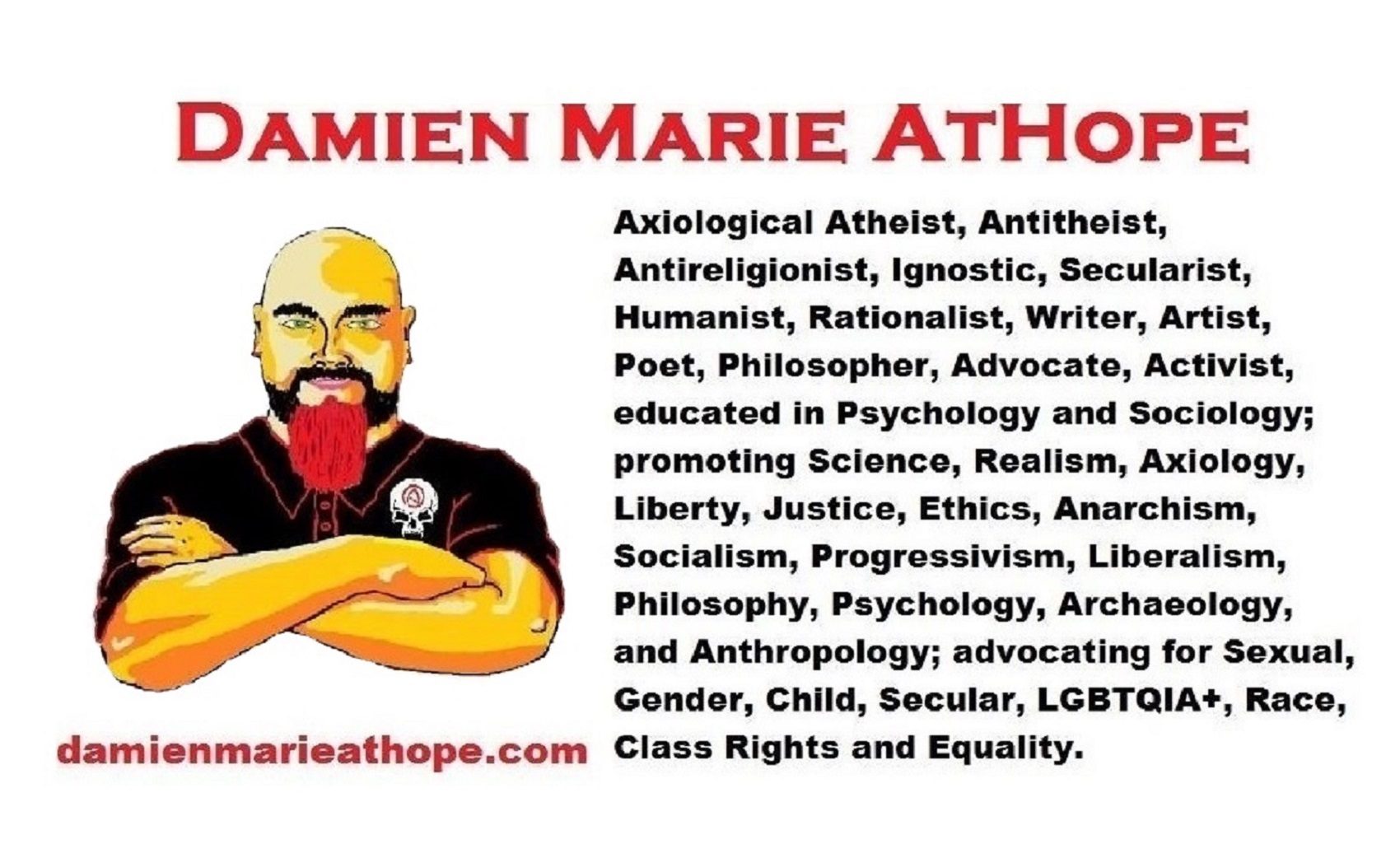

Anarchists Cory Johnston (in Saskatchewan) and Damien Marie AtHope (in Florida) seek to learn more about the indigenous peoples of the Americas (First Nations/Native Americans) where they both live.

“The First Nations of Saskatchewan are: Nêhiyawak (Plains Cree), Nahkawininiwak (Saulteaux), Nakota (Assiniboine), Dakota and Lakota (Sioux), and Denesuline (Dene/Chipewyan).” ref

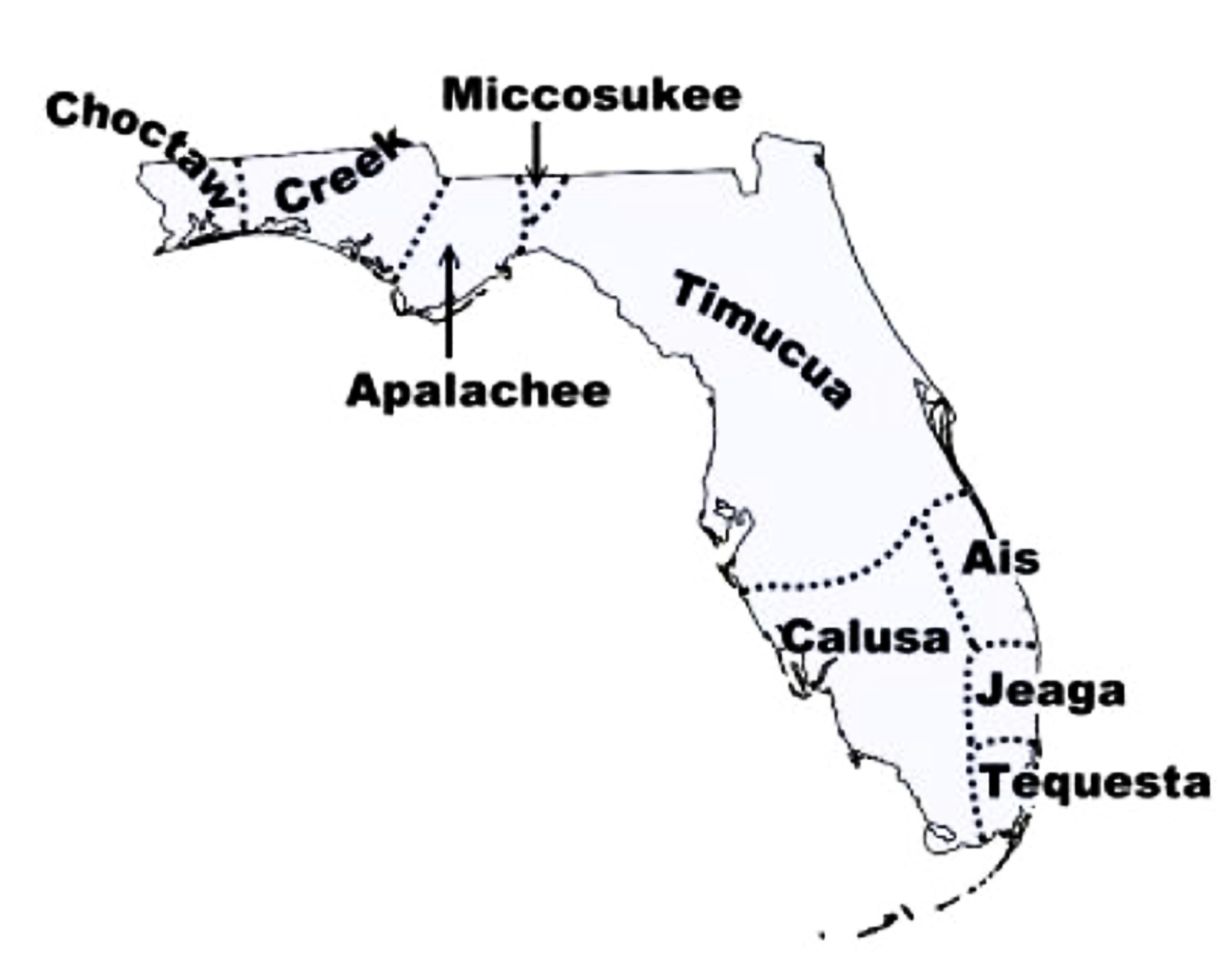

“Native Americans in Florida are: Ais, Apalachee, Calusa, Creek, Miccosukee, Seminole, Timucua, and Yemassee.” ref

Damien and Cory live around a 40 hr. drive apart.

Damien is an Anarchist-Socialist

Anarchist relates to being against hierarchy and Socialist is about economic equity to put it simply. No rulers and no masters. No one really owns the earth and all humanity is one family. No borders and no nations, just people supporting others in solidarity as an equal humanity. Not the full explanation just my own highlight explanation, for a quick reference. We rise by helping each other and Damien welcomes all good humans.

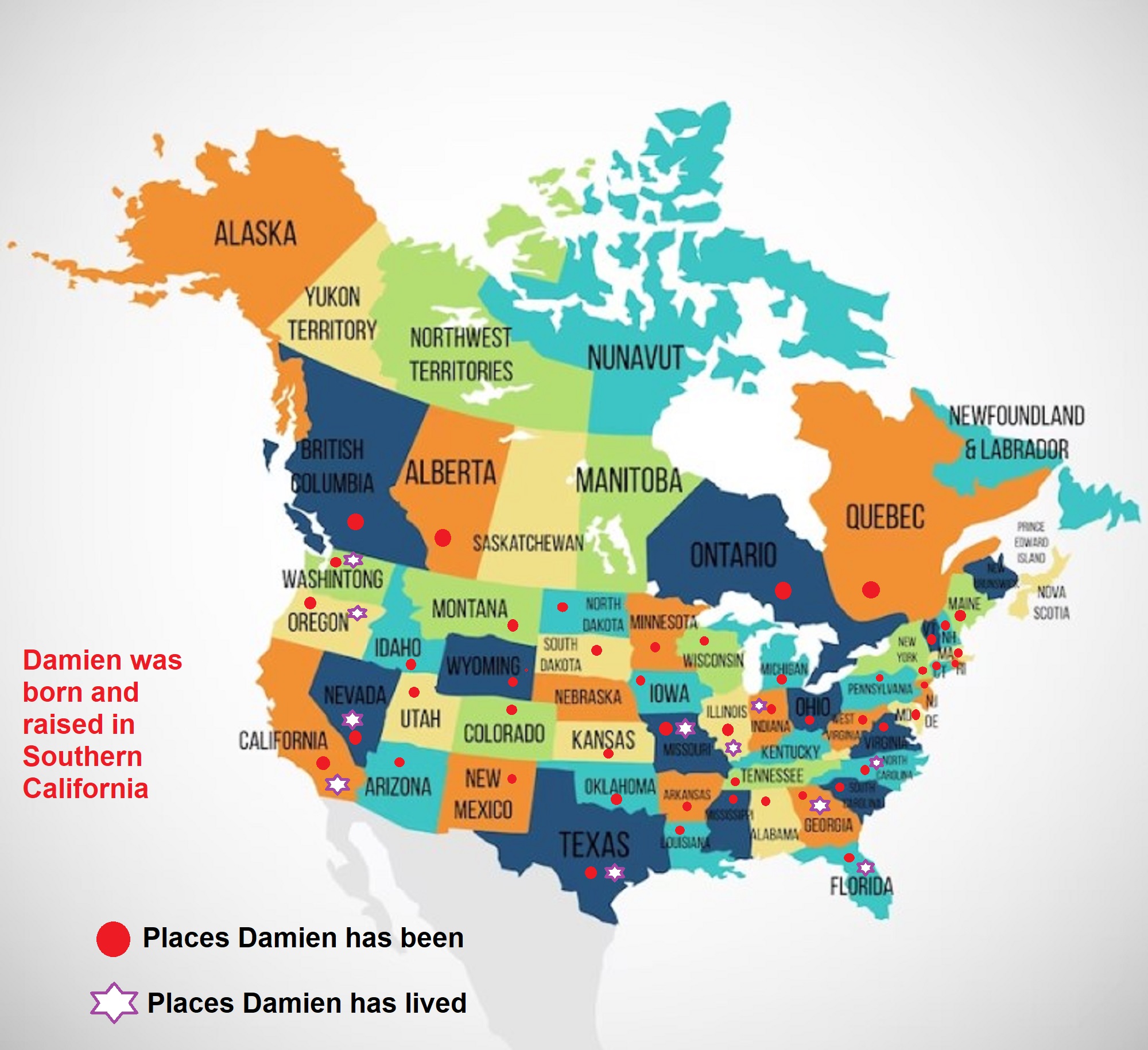

Damien was born and raised in Southern California but traveled to 48 states in America and 4 provinces of Canada. He also lived in several states in America, including Hawaii not listed.

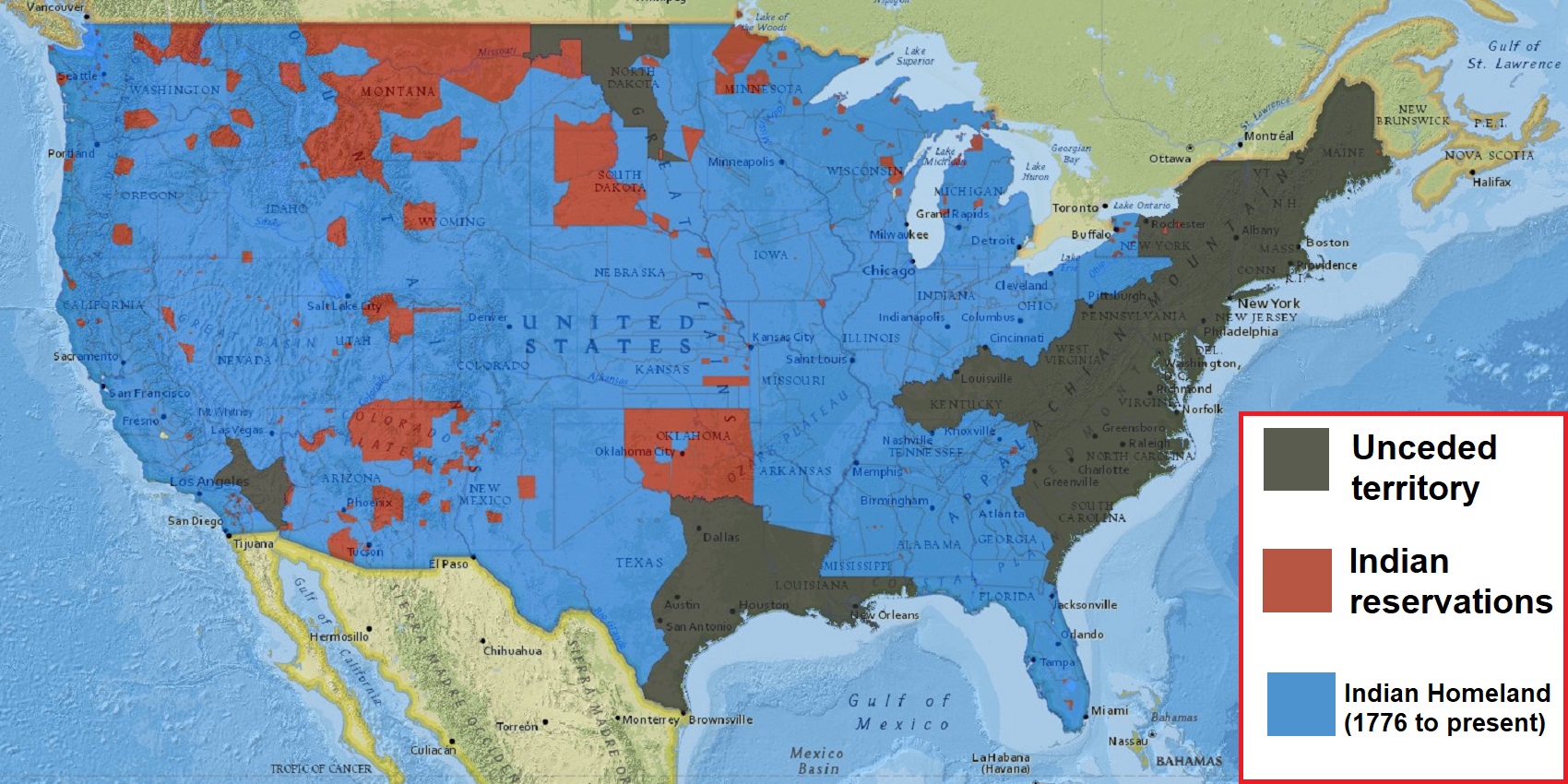

And what areas are native american or first nations peoples’ land? Link: pic.twitter.com/pbe0MIjYHT

“Land Back (or #LandBack) is a decentralised campaign by Native Americans in the United States and Indigenous peoples in Canada that seeks to reestablish Indigenous sovereignty, with political and economic control of their unceded traditional lands. Activists have also used the Land Back framework in Mexico, and scholars have applied it in New Zealand and Fiji. Land Back is part of a broader Indigenous struggle for decolonisation. Land Back aims to reestablish Indigenous political authority over territories that Indigenous tribes claim by treaty. Scholars from the Indigenous-run Yellowhead Institute at Toronto Metropolitan University describe it as a process of reclaiming Indigenous jurisdiction. The NDN collective describes it as synonymous with decolonisation and dismantling white supremacy. Land Back advocates for Indigenous rights, preserves languages and traditions, and works toward food sovereignty, decent housing, and a clean environment. They say that the campaign enables decentralised Indigenous leadership and addresses structural racism faced by Indigenous people that is rooted in theft of their land.” ref

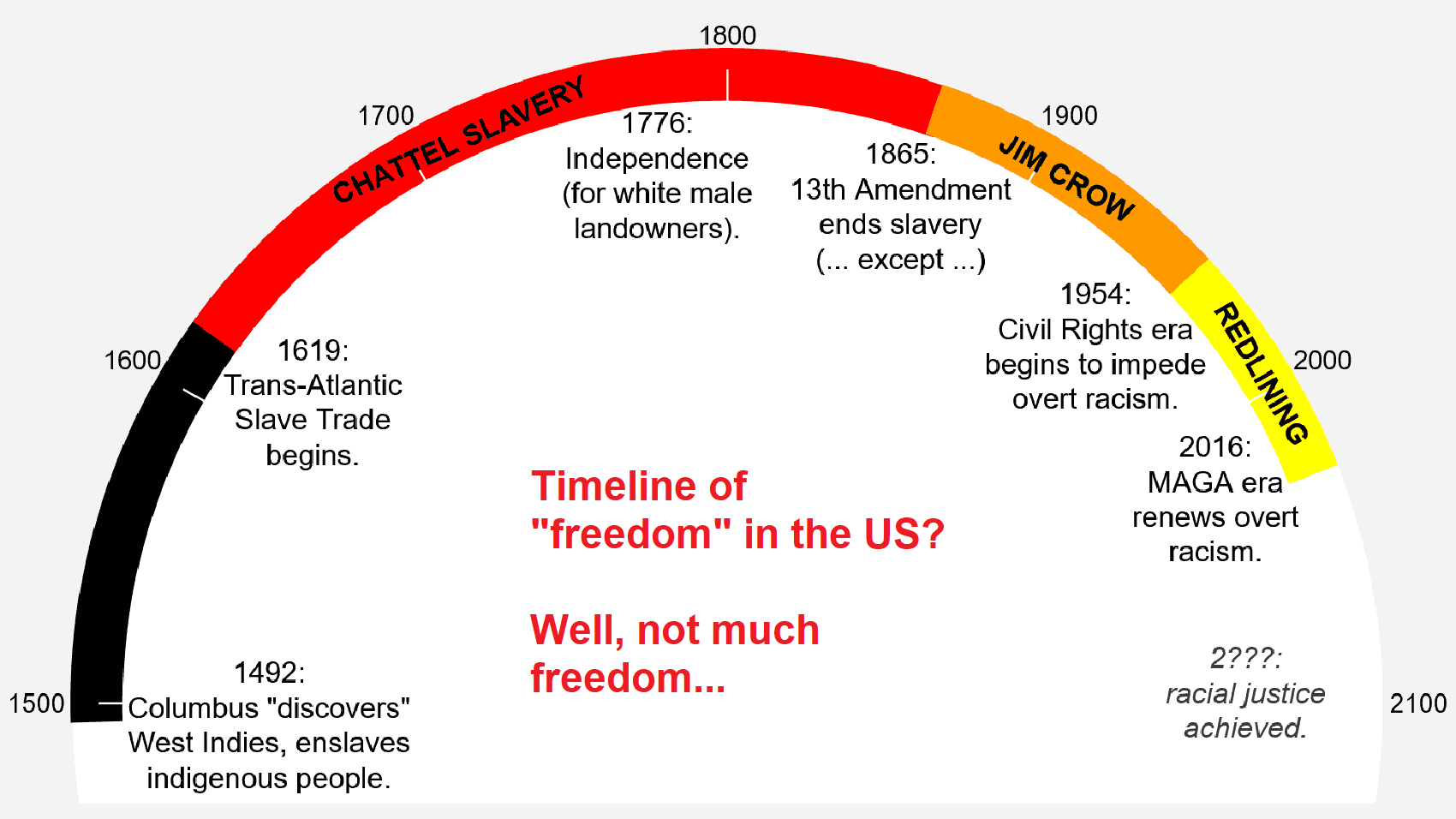

Native American Slavery?

“Native American slavery “is a piece of the history of slavery that has been glossed over,” Fisher said. “Between 1492 and 1880, between 2 and 5.5 million Native Americans were enslaved in the Americas in addition to 12.5 million African slaves.” ref

“The untold history of Native American enslavement. Long before the trans-Atlantic African slave trade was established in North America, Europeans were conducting a trade of enslaved Indigenous peoples, beginning with Christopher Columbus on Haiti in 1492.” ref

Colonization vs Colonialism

“When attempting to understand controversial issues, whether historical or contemporary, one must not get tripped up by the lingo. In this age of political correctness and sensitivity, the terminology will keep changing but that does not detract from what has already transpired or is currently ongoing. The purpose of defining terminology is so that everyone is starting from the same foundational base. Although the words colonization and colonialism are similar, their definitions show slight differences in meaning.” ref

“According to the Oxford Dictionary:

Colonization: is the action or process of settling among and establishing control over the indigenous people of an area.

Colonialism: is the policy or practice of acquiring full or partial political control over another country, occupying it with settlers, and exploiting it economically.” ref

“Colonialism is broader in that it refers to entire countries rather than an area and adding the economic exploitation factor. Whether the term being used is colonization or colonialism, the long-standing effects on Indigenous Peoples in Canada and other colonized countries remains the same.” ref

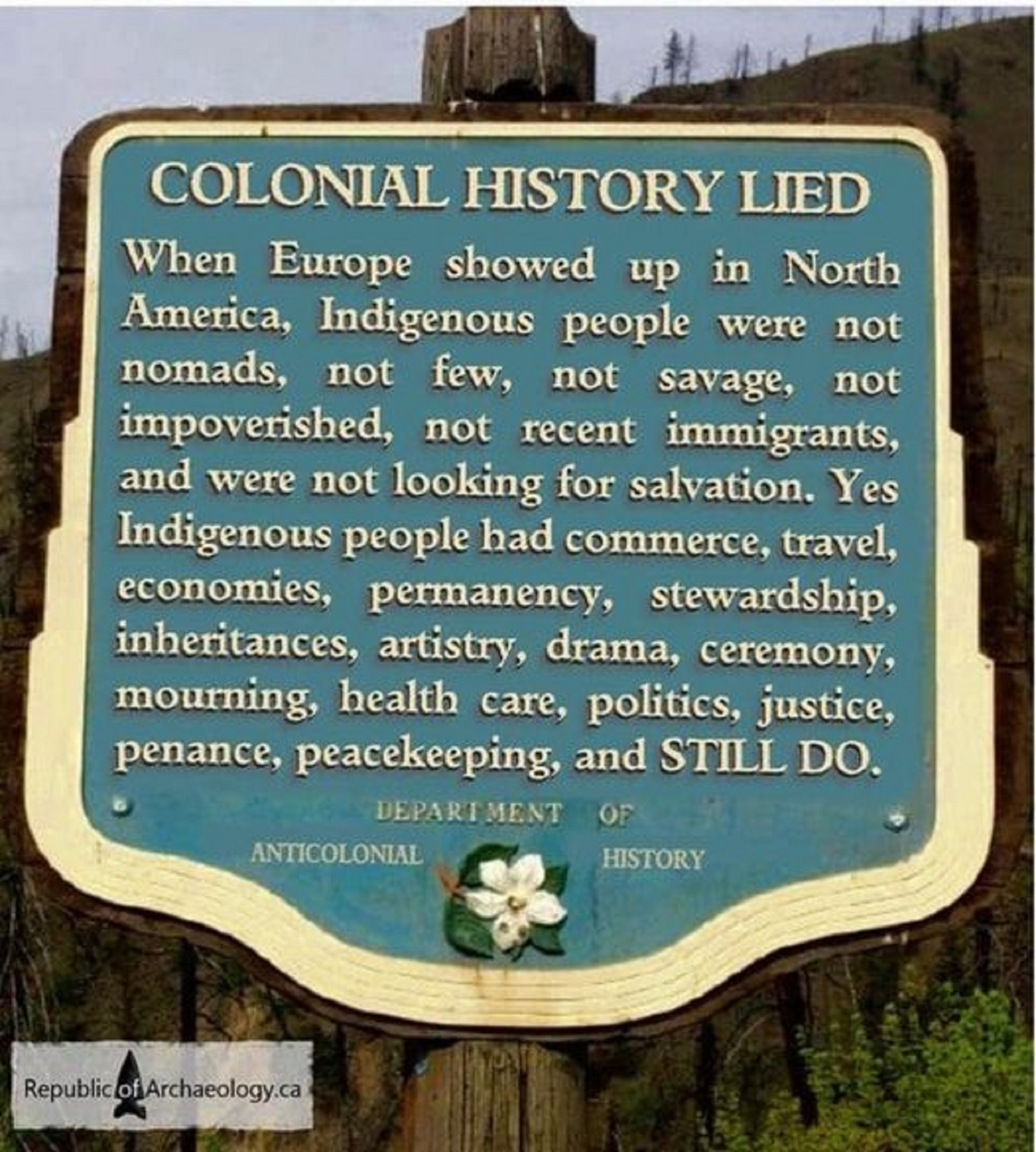

COLONIAL HISTORY LIED

“When Europe showed up in North America, Indigenous people were not nomads, not few, not savages, not impoverished, not recent immigrants, and were not looking for salvation. Yes, Indigenous people had commerce, travel, economies, permanency, stewardship, inheritances, artistry, drama, ceremony, mourning, health care, politics, justice, penance, peacekeeping, and STILL DO.” – Department of Anticolonial History

“Hate of others” is a disgusting display of foolishness.

Bigotry is the shame people smear all over themselves trying to look better than others.

“In Canada up until 1975, most of British Columbia, Québec, Yukon, and Nunavut were unceded territory. Since then, there have been some new treaties seeking to fill in these gaps, such as the 1975 James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement and the 1993 Nunavut Land Claims Agreement. Below is where things stood before 1975. The white areas of the map were those not covered by any treaty.” ref

What we mean when we say Indigenous land is ‘unceded’

“To be more precise: the Maritimes, nearly all of British Columbia, and a large swath of eastern Ontario and Quebec, which includes Ottawa, sit on territories that were never signed away by the Indigenous people who inhabited them before Europeans settled in North America. In other words, this land was stolen. (It’s worth noting that territories covered by treaties also weren’t necessarily ceded — in many cases, the intent of the agreements was the sharing of territory, not the relinquishing of rights.)” ref

The Environmental Context of (Settler) Colonialism in Canada

“In the wake of the Idle No More movement, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Indigenous-led critiques of Canada 150 and, most recently, efforts by multiple First Nations to locate burial sites at former residential schools (to name just four catalysts), historians have increasingly sought to situate and interrogate Canada as a settler colonial nation. Environmental historians have much to contribute to this work. In Canada as elsewhere, settler colonizers sought, in part, to dispossess Indigenous peoples of their traditional territories through slow and fast forms of violence and to remake these lands in the image of those they had left behind. As Shiri Pasternak and Hayden King note, the theft of Indigenous lands and waters and their development by governments and corporations are foundational components of Canada’s political and economic landscapes, in the past and present.” ref

“Yet settler colonialism sensu stricto has not always been the dominant form of colonialism in what is presently Canada, as measured either in terms of space or time. Liza Piper and John Sandlos observe that the successful creation of what Alfred Crosby called Neo-Europes was very much the exception rather than the rule. These agricultural Arcadias were “limited to relatively discrete temperate areas such as the southern Prairies, southern Ontario, the St. Lawrence Valley, and Prince Edward Island.” Likewise, scholars have dated the rise and consolidation of settler colonial forms of occupation and rule to roughly the late eighteenth century in the eastern parts of Canada, roughly the late nineteenth century in its western portions, and (though this is certainly debatable) roughly the late twentieth century in the North. Allan Greer has argued that two alternate forms of colonialism—imperial/commercial penetration, and extractivism—better capture the presence of Europeans, and the spiralling consequences of their presence, in arctic and subarctic Canada.” ref

Colonialism Is Alive and Well in Canada

“When I hear about the arrest of peaceful land protectors, I think about all the times I’ve heard that colonialism happened “a long time ago.” It never ended. When I see colonial violence in action I grieve not only for those brave people who stand peacefully as they are overwhelmed on their own lands, but also for future generations who will be forced to pay for our hubris. The ongoing “colonial violence” that Hayalthkin’geme speaks to is not only manifest in Wet’suwet’en territory as hereditary leaders, community members, and supporters are arrested for defending those territories. Colonialism remains embedded in the legal, political, and economic context of Canada today.” ref

A Brief and Brutal History of Canadian Colonialism

“Despite the painful history, there’s always been Indigenous resistance. Is settler society finally waking up (from 2021)? In the weeks since the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation announced it had found the remains of 215 children at what was once Canada’s largest residential school in Kamloops, an opportunity to reconcile a painful past, a troubling present and a hopeful future might be emerging.” ref

“The Truth and Reconciliation Commission had previously confirmed 51 deaths at the Kamloops Indian Residential School, but the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc community had long believed there were many more former students buried in unmarked graves. The discovery of 215 children’s remains using ground-penetrating radar confirmed the horrific truth, and the ensuing grief among Indigenous peoples was public and palpable.” ref

“In addition to the shock and outrage, and in spite of this deep sorrow, First Nations have courageously responded with compassion and solidarity. Since the grim revelation on May 27, people have travelled from hundreds of kilometres away to Kamloops to support one another and pay homage to the lost children. Honour songs have been sung, prayers said, burnings and smudges offered, tears shed and community connections reaffirmed.” ref

Experiences of Indigenous Women under Settler Colonialism

“If the meta-narrative of Canadian history excluded Indigenous peoples’ stories, it rendered Indigenous women doubly invisible. Indigenous women show up at the peripheries of older settler histories, often exoticized by European observers whose understanding of sexual relationships were peculiarly rigid. Individual women slip in and out of the fur trade records if and when they married and then were deserted by European and Canadian men; they might reappear if they married a successor trader from Montréal or Scotland. A small number loom large. There’s Kateri Tekakwitha, the first Indigenous person in North America to be canonized by the Pope. The campaign to recognize Kateri began in 1680, shortly after her death at about twenty-four years of age, and culminated in sainthood in 2012. Her story—or versions of it—is familiar to the Catholic Indigenous communities and beyond. Another widely-known character is Thanadelthur (ca. 1697 to 1717), held out as a heroic figure in bringing peace to the Dënesųlįné (Chipewyan) and Cree of western Hudson’s Bay. But for all of that, she was dead by the time she was about twenty years old. Konwatsi’tsiaienni (a.k.a. Molly Brant) had a longer career as a diplomat and leader of her people, the Kanien’kehá:ka, and a life that ran from ca. 1736 to 1796.” ref

“There are other female figures who stand out in the meta-narratives, but not many, and none are so prominent as these three. By the time the Dominion of Canada had taken over responsibility for colonial relations with Indigenous people, Victorian society had ceased to see women as participants in political life: Indigenous women were treated by the Canadians as outsiders in treaty negotiations, and they were excluded from federally-recognized leadership positions within their communities. “Colonial values,” as Carmen Watson points out:

. . . thus began to relegate Indigenous women to apolitical environments, effectively restructuring the socio-political dynamics that had existed pre-contact. Colonizers viewed Indigenous men as the gateway to establishing political, or seemingly political relationships. Women, however, were seen as an impediment to the process, taking up spots that could be occupied by men.

Given this erasure over the course of hundreds of years of colonial history-making, how do we go about recovering and making sense of the histories of Indigenous women?” ref

“The Canadian Indian residential school system was a network of boarding schools for Indigenous peoples. The network was funded by the Canadian government‘s Department of Indian Affairs and administered by Christian churches. The school system was created to isolate Indigenous children from the influence of their own culture and religion in order to assimilate them into the dominant Canadian culture. Over the course of the system’s more than hundred-year existence, around 150,000 children were placed in residential schools nationally. By the 1930s, about 30 percent of Indigenous children were attending residential schools. The number of school-related deaths remains unknown due to incomplete records. Estimates range from 3,200 to over 30,000, mostly from disease.” ref

“The system had its origins in laws enacted before Confederation, but it was primarily active from the passage of the Indian Act in 1876, under Prime Minister Alexander MacKenzie. Under Prime Minister John A. Macdonald, the government adopted the residential industrial school system of the United States, a partnership between the government and various church organizations. An amendment to the Indian Act in 1894, under Prime Minister Mackenzie Bowell, made attendance at day schools, industrial schools, or residential schools compulsory for First Nations children. Due to the remote nature of many communities, school locations meant that for some families, residential schools were the only way to comply. The schools were intentionally located at substantial distances from Indigenous communities to minimize contact between families and their children. Indian Commissioner Hayter Reed argued for schools at greater distances to reduce family visits, which he thought counteracted efforts to assimilate Indigenous children. Parental visits were further restricted by the use of a pass system designed to confine Indigenous peoples to reserves. The last federally-funded residential school, Kivalliq Hall in Rankin Inlet, closed in 1997. Schools operated in every province and territory with the exception of New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island.” ref

“The residential school system harmed Indigenous children significantly by removing them from their families, depriving them of their ancestral languages, and exposing many of them to physical and sexual abuse. Conditions in the schools led to student malnutrition, starvation, and disease. Students were also subjected to forced enfranchisement as “assimilated” citizens that removed their legal identity as Indians. Disconnected from their families and culture and forced to speak English or French, students often graduated being unable to fit into their communities but remaining subject to racist attitudes in mainstream Canadian society. The system ultimately proved successful in disrupting the transmission of Indigenous practices and beliefs across generations. The legacy of the system has been linked to an increased prevalence of post-traumatic stress, alcoholism, substance abuse, suicide, and intergenerational trauma which persist within Indigenous communities today.” ref

“Starting in the late 2000s, Canadian politicians and religious communities have begun to recognize, and issue apologies for, their respective roles in the residential school system. Prime Minister Stephen Harper offered a public apology on his behalf and that of the other federal political party leaders. On June 1, 2008, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) was established to uncover the truth about the schools. The commission gathered about 7,000 statements from residential school survivors through various local, regional, and national events across Canada. In 2015, the TRC concluded with the establishment of the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation and released a report that concluded that the school system amounted to cultural genocide. Ongoing efforts since 2021 have identified thousands of probable unmarked graves on the grounds of former residential schools, though no human remains have been exhumed. During a penitential pilgrimage to Canada in July 2022, Pope Francis reiterated the apologies of the Catholic Church for its role, also acknowledging the system as genocide. In October 2022, the House of Commons unanimously passed a motion calling on the federal Canadian government to recognize the residential school system as genocide.” ref

RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL … THE SHAMAN

by Acco-Carrière, Anne

| Description: | “This short story chronicles four Cree-Métis brothers and their times during the Second World War and a shaman`s prophesy regarding their return to northern Saskatchewan following the war’s conclusion. This document is copyrighted to the author and can only be used for reading purposes only. Any further use shall require the permission of the author.” ref |

Saskatchewan

“Saskatchewan is a province in Western Canada, bordered on the west by Alberta, on the north by the Northwest Territories, on the east by Manitoba, to the northeast by Nunavut, and on the south by the U.S. states of Montana and North Dakota. Saskatchewan and Alberta are the only landlocked provinces of Canada. Saskatchewan has been inhabited for thousands of years by indigenous groups. Europeans first explored the area in 1690 and first settled in the area in 1774. It became a province in 1905, carved out from the vast North-West Territories, which had until then included most of the Canadian Prairies. Saskatchewan is the only province without a natural border. As its borders largely follow the geographic coordinates of longitude and latitude, the province is roughly a quadrilateral, or a shape with four sides.” ref

“In 1992, the federal and provincial governments signed a historic land claim agreement with First Nations in Saskatchewan. The First Nations received compensation which they could use to buy land on the open market for the bands. They have acquired about 3,079 square kilometres (761,000 acres; 1,189 sq mi), new reserve lands under this process. Some First Nations have used their settlement to invest in urban areas, including Regina and Saskatoon. The name of the province is derived from the Saskatchewan River. The river is known as ᑭᓯᐢᑳᒋᐘᓂ ᓰᐱᐩ kisiskāciwani-sīpiy (“swift flowing river”) in the Cree language. Henday’s spelling was Keiskatchewan, with the modern rendering, Saskatchewan, being officially adopted in 1882 when a portion of the present-day province was designated a provisional district of the North-West Territories.” ref

“Saskatchewan is part of the western provinces and is bounded on the west by Alberta, on the north by the Northwest Territories, on the north-east by Nunavut, on the east by Manitoba, and on the south by the U.S. states of Montana and North Dakota. Saskatchewan has the distinction of being the only Canadian province for which no borders correspond to physical geographic features (i.e. they are all parallels and meridians). Along with Alberta, Saskatchewan is one of only two land-locked provinces.” ref

“Saskatchewan has been populated by various indigenous peoples of North America, including members of the Sarcee, Niitsitapi, Atsina, Cree, Saulteaux, Assiniboine (Nakoda), Lakota and Sioux. The first known European to enter Saskatchewan was Henry Kelsey from England in 1690, who travelled up the Saskatchewan River in hopes of trading fur with the region’s indigenous peoples. Fort La Jonquière and Fort de la Corne were first established in 1751 and 1753 by early French explorers and traders. The first permanent European settlement was a Hudson’s Bay Company post at Cumberland House, founded in 1774 by Samuel Hearne. The southern part of the province was part of Spanish Louisiana from 1762 until 1802.” ref

“In 1803, the Louisiana Purchase transferred from France to the United States part of what is now Alberta and Saskatchewan. In 1818, the U.S. ceded the area to Britain. Most of what is now Saskatchewan was part of Rupert’s Land and controlled by the Hudson’s Bay Company, which claimed rights to all watersheds flowing into Hudson Bay, including the Saskatchewan River, Churchill, Assiniboine, Souris, and Qu’Appelle River systems. In the late 1850s and early 1860s, scientific expeditions led by John Palliser and Henry Youle Hind explored the prairie region of the province.” ref

“In 1870, Canada acquired the Hudson’s Bay Company’s territories and formed the North-West Territories to administer the vast territory between British Columbia and Manitoba. The Crown also entered into a series of numbered treaties with the indigenous peoples of the area, which serve as the basis of the relationship between First Nations, as they are called today, and the Crown. Since the late twentieth century, land losses and inequities as a result of those treaties have been subject to negotiation for settlement between the First Nations in Saskatchewan and the federal government, in collaboration with provincial governments.” ref

“In 1876, following their defeat of United States Army forces at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in Montana Territory in the United States, the Lakota Chief Sitting Bull led several thousand of his people to Wood Mountain. Survivors and descendants founded Wood Mountain Reserve in 1914. The North-West Mounted Police set up several posts and forts across Saskatchewan, including Fort Walsh in the Cypress Hills, and Wood Mountain Post in south-central Saskatchewan near the United States border.” ref

“Many Métis people, who had not been signatories to a treaty, had moved to the Southbranch Settlement and Prince Albert district north of present-day Saskatoon following the Red River Rebellion in Manitoba in 1870. In the early 1880s, the Canadian government refused to hear the Métis’ grievances, which stemmed from land-use issues. Finally, in 1885, the Métis, led by Louis Riel, staged the North-West Rebellion and declared a provisional government. They were defeated by a Canadian militia brought to the Canadian prairies by the new Canadian Pacific Railway. Riel, who surrendered and was convicted of treason in a packed Regina courtroom, was hanged on November 16, 1885. Since then, the government has recognized the Métis as an aboriginal people with status rights and provided them with various benefits.” ref

The First Nations of Saskatchewan are:

Nêhiyawak (Plains Cree):

“The Cree (Cree: néhinaw, néhiyaw, nihithaw, etc.; French: Cri) are a North American Indigenous people. They live primarily in Canada, where they form one of the country’s largest First Nations. In Canada, over 350,000 people are Cree or have Cree ancestry. The major proportion of Cree in Canada live north and west of Lake Superior, in Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and the Northwest Territories. About 27,000 live in Quebec. In the United States, Cree people historically lived from Lake Superior westward. Today, they live mostly in Montana, where they share the Rocky Boy Indian Reservation with Ojibwe (Chippewa) people. The documented westward migration over time has been strongly associated with their roles as traders and hunters in the North American fur trade.” ref

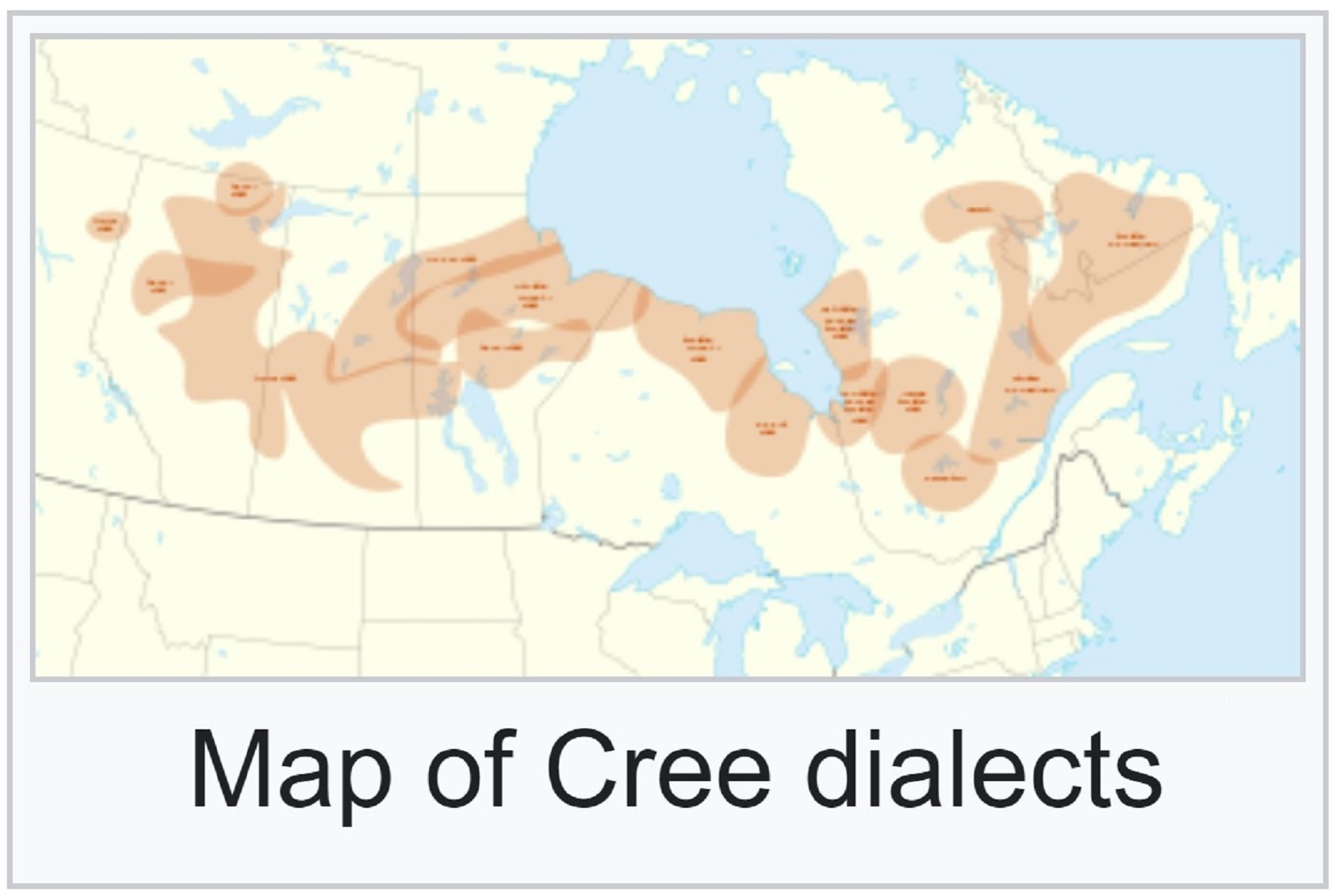

“Cree language (also known as Cree–Montagnais–Naskapi) is a dialect continuum of Algonquian languages spoken by approximately 117,000 people across Canada, from the Northwest Territories to Alberta to Labrador. If considered one language, it is the aboriginal language with the highest number of speakers in Canada.” ref

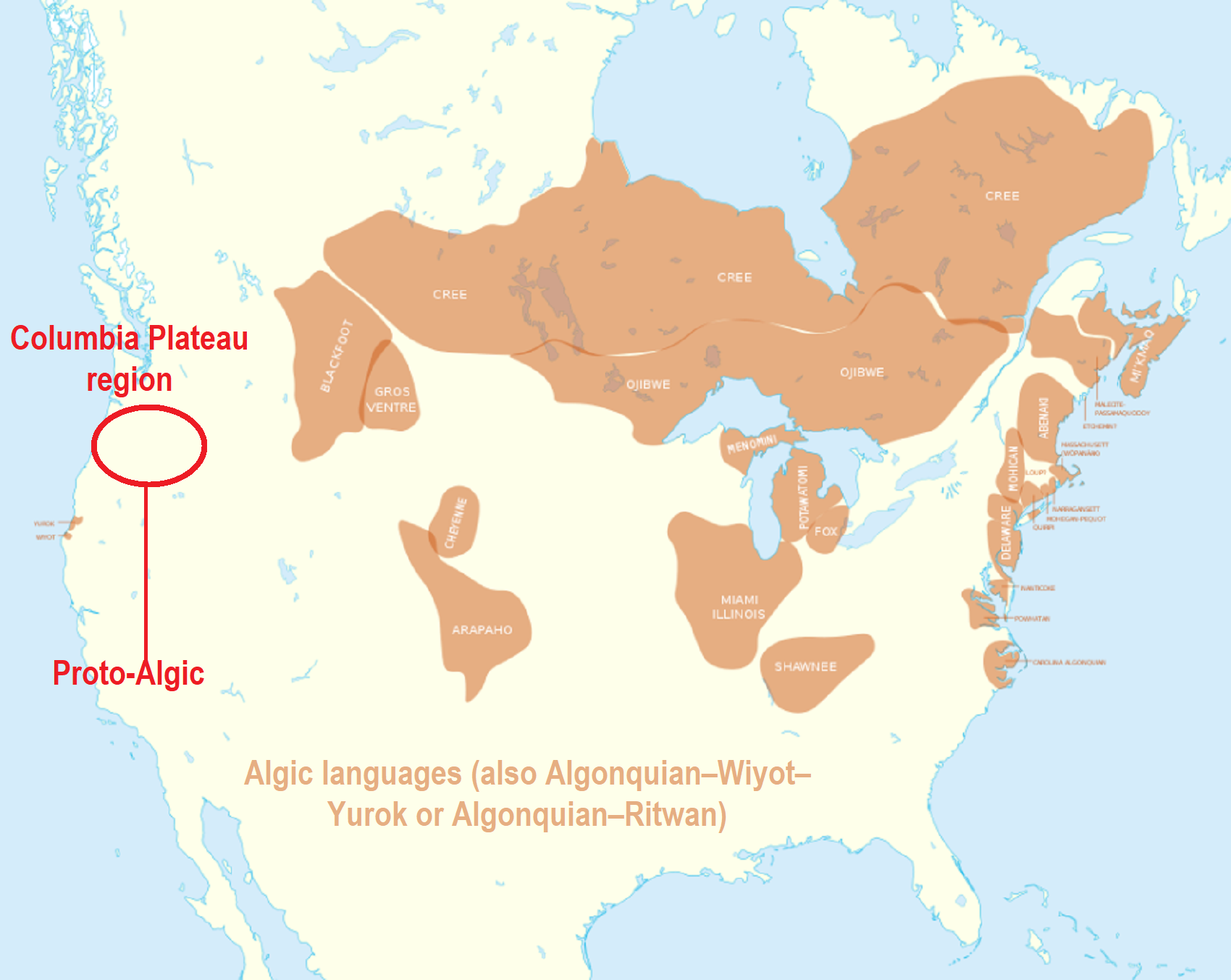

“Speakers of Algonquian languages stretch from the east coast of North America to the Rocky Mountains. The proto-language from which all of the languages of the family descend, Proto-Algonquian, was spoken around 2,500 to 3,000 years ago. The Algonquian family, which is a branch of the larger Algic language family, is usually divided into three subgroups: Eastern Algonquian, which is a genetic subgroup, and Central Algonquian and Plains Algonquian, both of which are areal groupings. In the historical linguistics of North America, Proto-Algonquian is one of the best-studied, most thoroughly reconstructed proto-languages. It is descended from Proto-Algic. Proto-Algic is the proto-language from which the Algic languages (Wiyot language, Yurok language, and Proto-Algonquian) are descended. It is estimated to have been spoken about 7,000 years ago somewhere in the American Northwest, possibly around the Columbia Plateau.” ref, ref, ref

“The Cree are generally divided into eight groups based on dialect and region. These divisions do not necessarily represent ethnic sub-divisions within the larger ethnic group:

- Naskapiand Montagnais (together known as the Innu) are inhabitants of an area they refer to as Nitassinan. Their territories comprise most of the present-day political jurisdictions of eastern Quebec and Labrador. Their cultures are differentiated, as some of the Naskapi are still caribou hunters and more nomadic than many of the Montagnais. The Montagnais have more settlements. The total population of the two groups in 2003 was about 18,000 people, of which 15,000 lived in Quebec. Their dialects and languages are the most distinct from the Cree spoken by the groups west of Lake Superior.

- Atikamekware inhabitants of the area they refer to as Nitaskinan (Our Land), in the upper St. Maurice River valley of Quebec (about 300 km or 190 mi north of Montreal). Their population is around 8,000.

- East Cree– Grand Council of the Crees; approximately 18,000 Cree (Iyyu in Coastal Dialect / Iynu in Inland Dialect) of Eeyou Istchee and Nunavik regions of Northern Quebec.

- Moose Cree– Moose Factory in the Northeastern Ontario; this group lives on Moose Factory Island, near the mouth of the Moose River, at the southern end of James Bay. (“Factory” used to refer to a trading post.)

- Swampy Cree– this group lives in northern Manitoba along the Hudson Bay coast and adjacent inland areas to the south and west, and in Ontario along the coast of Hudson Bay and James Bay. Some also live in eastern Saskatchewan around Cumberland House. Their dialect has 4,500 speakers.

- Woodland Creeand Rocky Cree – a group in northern Alberta, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan.

- Plains Cree– a total of 34,000 people in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and Montana.” ref

“Due to the many dialects of the Cree language, the people have no modern collective autonym. The Plains Cree and Attikamekw refer to themselves using modern forms of the historical nêhiraw, namely nêhiyaw and nêhirawisiw, respectively. Moose Cree, East Cree, Naskapi, and Montagnais all refer to themselves using modern dialectal forms of the historical iriniw, meaning ‘man.’ Moose Cree use the form ililiw, coastal East Cree and Naskapi use iyiyiw (variously spelled iiyiyiu, iiyiyuu, and eeyou), inland East Cree use iyiniw (variously spelled iinuu and eenou), and Montagnais use ilnu and innu, depending on dialect. The Cree use “Cree,” “cri,” “Naskapi, or “montagnais” to refer to their people only when speaking French or English. As hunter-gatherers, the basic unit of organization for Cree peoples was the lodge, a group of perhaps eight or a dozen people, usually the families of two separate but related married couples, who lived together in the same wigwam (domed tent) or tipi (conical tent), and the band, a group of lodges who moved and hunted together.” ref

“In the case of disagreement, lodges could leave bands and bands could be formed and dissolved with relative ease. However, as there is safety in numbers, all families would want to be part of some band, and banishment was considered a very serious punishment. Bands would usually have strong ties to their neighbours through intermarriage and would assemble together at different parts of the year to hunt and socialize together. Besides these regional gatherings, there was no higher-level formal structure, and decisions of war and peace were made by consensus with allied bands meeting together in council. People could be identified by their clan, which is a group of people claiming descent from the same common ancestor; each clan would have a representative and a vote in all important councils held by the band (compare: Anishinaabe clan system).” ref

“Each band remained independent of each other. However, Cree-speaking bands tended to work together and with their neighbors against outside enemies. Those Cree who moved onto the Great Plains and adopted bison hunting, called the Plains Cree, were allied with the Assiniboine, the Metis Nation, and the Saulteaux in what was known as the “Iron Confederacy“, which was a major force in the North American fur trade from the 1730s to the 1870s. The Cree and the Assiniboine were important intermediaries in the Indian trading networks on the northern plains.” ref

“When a band went to war, they would nominate a temporary military commander, called a okimahkan. loosely translated as “war chief”. This office was different from that of the “peace chief”, a leader who had a role more like that of diplomat. In the run-up to the 1885 North-West Rebellion, Big Bear was the leader of his band, but once the fighting started Wandering Spirit became war leader. The name “Cree” is derived from the Algonkian-language exonym Kirištino˙, which the Ojibwa used for tribes around Hudson Bay. The French colonists and explorers, who spelled the term Kilistinon, Kiristinon, Knisteneaux, Cristenaux, and Cristinaux, used the term for numerous tribes which they encountered north of Lake Superior, in Manitoba, and west of there. The French used these terms to refer to various groups of peoples in Canada, some of which are now better distinguished as Severn Anishinaabe (Ojibwa), who speak dialects different from the Algonquin.” ref

“Depending on the community, the Cree may call themselves by the following names: the nēhiyawak, nīhithaw, nēhilaw, and nēhinaw; or ininiw, ililiw, iynu (innu), or iyyu. These names are derived from the historical autonym nēhiraw (of uncertain meaning) or from the historical autonym iriniw (meaning “person”). Cree using the latter autonym tend to be those living in the territories of Quebec and Labrador.” ref

“The Cree language (also known in the most broad classification as Cree-Montagnais, Cree-Montagnais-Naskapi, to show the groups included within it) is the name for a group of closely related Algonquian languages, the mother tongue (i.e. language first learned and still understood) of approximately 96,000 people, and the language most often spoken at home of about 65,000 people across Canada, from the Northwest Territories to Labrador. It is the most widely spoken aboriginal language in Canada. The only region where Cree has official status is in the Northwest Territories, together with eight other aboriginal languages.” ref

“In Canada, Cree are the largest group of First Nations in Canada, with 220,000 members and 135 registered bands. Together, their reserve lands are the largest of any First Nations group in the country. The largest Cree band and the second largest First Nations Band in Canada after the Six Nations Iroquois is the Lac La Ronge Band in northern Saskatchewan.” ref

“Given the traditional Cree acceptance of mixed marriages, it is acknowledged by academics that all bands are ultimately of mixed heritage and multilingualism and multiculturalism was the norm. In the West, mixed bands of Cree, Saulteaux and Assiniboine, all partners in the Iron Confederacy, are the norm. However, in recent years, as indigenous languages have declined across western Canada where there were once three languages spoken on a given reserve, there may now only be one. This has led to a simplification of identity, and it has become “fashionable” for bands in many parts of Saskatchewan to identify as “Plains Cree” at the expense of a mixed Cree-Salteaux history. There is also a tendency for bands to recategorize themselves as “Plains Cree” instead of Woods Cree or Swampy Cree. Neal McLeod argues this is partly due to the dominant culture’s fascination with Plains Indian culture as well as the greater degree of written standardization and prestige Plains Cree enjoys over other Cree dialects.” ref

“The Métis (from the French, Métis – of mixed ancestry) are people of mixed ancestry, such as Cree (or Anishinaabe) and French, English, or Scottish heritage. According to Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada, the Métis were historically the children of French fur traders and Cree women or, from unions of English or Scottish traders and northern Dene women (Anglo-Métis). The Métis National Council defines a Métis as “a person who self-identifies as Métis, is distinct from other Aboriginal peoples, is of historic Métis Nation Ancestry and who is accepted by the Métis Nation.” ref

“Cree are the most populous and widely distributed Indigenous peoples in Canada. Other words the Cree use to describe themselves include nehiyawak, nihithaw, nehinaw and ininiw. Cree First Nations occupy territory in the Subarctic region from Alberta to Quebec, as well as portions of the Plains region in Alberta and Saskatchewan. According to 2016 census data, 356,655 people identified as having Cree ancestry and 96,575 people speak the Cree language. In the 2016 census, 356,655 people identified as having Cree ancestry. Cree live in areas from Alberta to Quebec in the Subarctic and Plains regions, a geographic distribution larger than that of any other Indigenous group in Canada.” ref

“Moving from west to east, the main divisions of Cree, based on environment, language and dialect are Plains Cree (paskwâwiyiniwak or nehiyawak) in Alberta and Saskatchewan, Woods Cree (sakâwiyiniwak) in Saskatchewan and Manitoba, Swampy Cree (maskêkowiyiniwak) in Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Ontario, and James Bay/Eastern Cree (Eeyouch) in Québec; Moose Cree (in Ontario) is considered a sub-group/dialect of Swampy Cree. The suffix –iyiniwak, meaning people, is used to distinguish people of particular sub-groups. For example, the kâ-têpwêwisîpîwiyiniwak are the Calling River People, while the amiskowacîwiyiniwak are the Beaver Hills People.” ref

“The Eastern Cree are closely related, in both culture and language, to the Innu (Montagnais-Naskapi) and Atikamekw. Many Cree First Nations in western provinces have blended populations of Ojibwa, Saulteaux, Assiniboine, Denesuline and others. In addition, the Oji-Cree of Manitoba and Ontario are a distinct people of mixed Cree and Ojibwa culture and heritage. Many Métis people also descend from Cree women and French Canadian fur traders and voyageurs. (See also Fur Trade.)” ref

“For thousands of years, the ancestors of the Cree were thinly spread over much of the woodland area that they still occupy. Known as the Ndooheenou (“nation of hunters”), the Cree followed seasonal animal migrations to obtain meat for food and animal hides and bones for the making of tools and clothing. They traveled by canoe in summer, and by snowshoes and toboggan in winter, living in cone- or dome-shaped lodges, covered in animal skins. (See also Architectural History of Indigenous Peoples in Canada.) Many Cree still consider hunting an important part of their culture and way of life; the hunting and trapping of moose, caribou, rabbit and other animals is fairly common in Cree communities.” ref

“After the arrival of Europeans, participation in the fur trade pushed Swampy Cree west into the Plains. During this time, many Cree remained in the boreal forest and the tundra area to the north, where a stable culture persisted. They continued to rely on hunting moose, caribou, smaller game, geese, ducks and fish, which they preserved by drying over fire. The Cree also traded meat, furs and other goods in exchange for metal tools, twine and European goods. Plains Cree exchanged the canoe for horses, and subsisted primarily through the buffalo hunt.” ref

“Cree lived in small bands or hunting groups for most of the year, and gathered into larger groups in the summer for socializing, exchanges and ceremonies. They historically had cultural, trade and social relations with other Algonquian-speaking nations, most directly with the Innu (Montagnais-Naskapi), Algonquin and Ojibwa.” ref

“Although the Cree strived to maintain a communal and egalitarian society, some individuals were regarded as more powerful, both in the practical activities of hunting and in the spiritual activities that influenced other persons. (See also Shaman.) Leaders in group hunts, raids and trading were granted authority in directing such tasks, but otherwise the ideal was to lead by means of exemplary action. Some of the most well-known Cree chiefs and leaders include Mistahimaskwa (Big Bear), Pitikwahanapiwiyin (Poundmaker) and Piapot — all of whom strove to maintain traditional ways of life in the face of change after the arrival of Europeans.” ref

“The Cree participated in a variety of cultural ceremonies and rituals, including the Sun Dance (also known as the Thirst Dance, and particularly celebrated by the Plains Cree), powwows, vision quests, feasts, pipe ceremonies, sweat lodges and more. Many of such rituals were banned by the Indian Act until 1951; however, the traditions survive to this day.” ref

“One of such ceremonies is the “walking out ceremony” — a ritual in which children are officially welcomed into the community. Cree tradition dictates that children’s feet are not to touch the ground outside of a tent until the ceremony takes place. Therefore, the ritual is usually held as soon as a child is able to stand or walk on their own. The morning of the ceremony, the child — dressed in traditional clothing — awaits the arrival of the Elders. Once they arrive, the Elders send the child outside of the tent. Accompanied by an adult, the children walk around a designated area outside the tent. Usually, they are told to mimic hunting or other traditional roles of adults. Once they have done this, the children re-enter the tent and give the Elders gifts. The community gathered inside the tent embraces the children as new members of their society. A feast usually follows.” ref

“Art and music are important elements of Cree culture. Well-known for their beadwork, Cree women created beautiful and functional clothing, bags, and furniture. Plains Cree peoples also decorated the outsides of their tipis with paint. A well-known modern Cree artist is George Littlechild. Drumming is significant to the Cree as well as to most other Indigenous nations. Drums are sacred, and the music that comes from them is likened to the heartbeat of the nation. Drum music can be heard at festivals and religious ceremonies.” ref

Religion and Spirituality

“The Cree worldview describes the interconnectivity between people and nature; health and happiness was achieved by living a life in balance with nature. Religious life was based on relations with animal and other spirits which often revealed themselves in dreams. People tried to show respect for each other by an ideal ethic of non-interference, in which each individual was responsible for his or her actions and the consequences of those actions. Food was always the first priority, and would be shared in times of hardship or in times of plenty when people gathered to celebrate by feasting.” ref

“The Cree worldview also incorporates Trickster (wîsahkêcâhk) mythology. A trickster is a cultural and spiritual figure that exhibits great intellect, but uses it to cause mischief and get into trouble. The Cree believe one can learn important lessons about how to live — and not to live — good lives from the examples set by the tricksters. One common trickster figure in Cree spirituality is Wisakedjak — a demigod and cultural hero that is featured in some versions of the Cree creation story. (See also Religion and Spirituality of Indigenous Peoples in Canada.)” ref

Nahkawininiwak (Saulteaux):

“The Saulteaux otherwise known as the Plains Ojibwe, are a First Nations band government in Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia, Canada. They are a branch of the Ojibwe who pushed west. They formed a mixed culture of woodlands and plains Indigenous customs and traditions. The Saulteaux are a branch of the Ojibwe Nations within Canada. They are sometimes called the Anihšināpē (Anishinaabe). Saulteaux is a French term meaning “people of the rapids,” referring to their former location in the area of Sault Ste. Marie. They are primarily hunters and fishers, and when still the primary dwellers of their sovereign land, they had extensive trading relations with the French, British and later Americans at that post.” ref

“The Saulteaux historically were settled around Lake Superior and Lake Winnipeg, principally in the areas of present-day Sault Ste. Marie and northern Michigan. Pressure from European Canadians and Americans gradually pushed the tribe westward to Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta, with one community in British Columbia. Today most of the Saulteaux live in the Interlake District; Swan River, Duck Bay, Camperville, the southern part of Manitoba, and in Saskatchewan (Kamsack and surrounding areas). Because they were forced to move to land ill-suited for European crops, they were lucky to escape European-Canadian competition for their lands and have kept much of that assigned territory in reserves. Generally, the Saulteaux have three major divisions.” ref

“Western Ojibwa (also known as Nakawēmowin, Saulteaux, and Plains Ojibwa) is a dialect of the Ojibwe language, a member of the Algonquian language family. It is spoken by the Saulteaux, a subnation of the Ojibwe people, in southern Manitoba and southern Saskatchewan, Canada, west of Lake Winnipeg. Saulteaux is generally used by its speakers, and Nakawēmowin is the general term in the language itself.” ref

“The Saulteaux or Plains Ojibway (Nahkawininiwak in their language) speak a language belonging to the Algonquian language family; Algonquian people can be found from Newfoundland to the Rocky Mountains, and from Hudson Bay to the southeastern United States. Algonquian languages comprise Algonkin, Blackfoot, Cheyenne, Cree, Delaware, Menominee, Ojibwa, Ottawa, Potawatomi, Sauk/Fox, and Nahkawiwin (Saulteaux). The name Saulteaux is said to come from the French word saulteurs, meaning People of the Rapids; this name refers to the location around the St. Mary’s River (Sault Ste. Marie), where French fur traders and the Ojibwa met to trade in the late 17th century. Amongst some storytellers there is a migration story that predates contact with the people of France and England. It relates the movement of the people to the west, where they began to settle and set up with their neighbors, the Lakota and Dakota, alliances which allowed for peaceful coexistence. It was during the fur-trade rivalry between the French and English that these alliances were broken.” ref

“With the fur trade in decline, the disappearance of the bison, and the increase of settlers of European origin, the Nahkawininiwak, along with other plains First Nations, began the treaty-making process with the newly developed government of Canada. Nahkawininiwak leaders signed, on behalf of their various bands, Treaties 1 and 2. Later, in 1874 and 1876, Nahkawininiwak were signatories to Treaties 4 and 6. These four treaties ceded to the government of Canada much of the land of southern Manitoba and southern Saskatchewan, as well as portions of Alberta. In return, the First Nations were promised annuities ($3-$5 per person per year), reserves, education, as well as hunting, fishing and trapping rights.” ref

“In Saskatchewan, the following First Nations communities have Nahkawininiwak speakers: Cote, Cowessess, Fishing Lake, Gordons, Keeseekoose, Key, Muskowpetung, Nut Lake, Pasqua, Poorman, Sakimay, Saulteaux, and Yellowquill. In addition, the following communities have a mixture of Nahkawininiwak, Nêhiyawêwin and other languages: Cowessess, Gordons, White Bear, and Keeseekoose. There is some movement to adopt the original name of Anishinabe, which is the name that the Ojibway people used in earlier times to identify themselves. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many of the ceremonies and traditional beliefs of the Nahkawininiwak were banned by law. In the 21st century some of these ceremonies are being revived, belief systems such as the Midewiwiwin are being reintroduced, and some Nahkawininiwak have adopted Plains ceremonies such as the Sun Dance.” ref

Nakota (Assiniboine):

“Nakota (or Nakoda or Nakona) is the endonym used by those Assiniboine Indigenous people in the US, and by the Stoney People, in Canada. The Assiniboine branched off from the Great Sioux Nation (aka the Oceti Sakowin) long ago and moved further west from the original territory in the woodlands of what is now Minnesota into the northern and northwestern regions of Montana and North Dakota in the United States, and Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta in Canada. In each of the Western Siouan language dialects, nakota, dakota and lakota all mean “friend.” ref

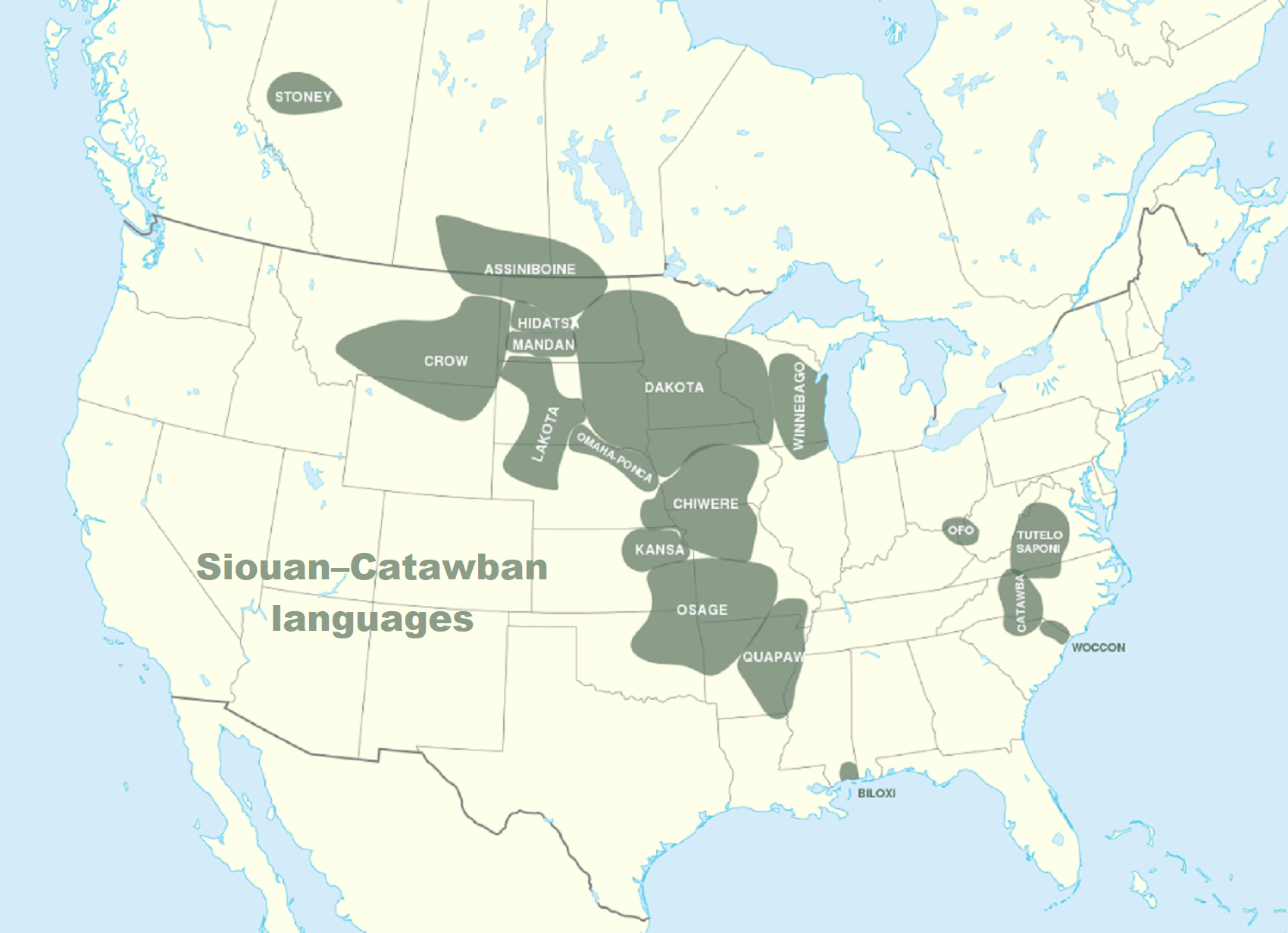

“The Western Siouan languages, also called Siouan proper or simply Siouan, are a large language family native to North America. They are closely related to the Catawban languages, sometimes called Eastern Siouan, and together with them constitute the Siouan (Siouan–Catawban) language family. Linguistic and historical records indicate a possible southern origin of the Siouan people, with migrations over a thousand years ago from North Carolina and Virginia to Ohio. Some continued down the Ohio River, to the Mississippi and up to the Missouri. Others went down the Mississippi, settling in what is now Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana. Others traveled across Ohio to what is now Illinois, Wisconsin, and Minnesota, home of the Dakota.” ref

“Siouan or Siouan–Catawban is a language family of North America that is located primarily in the Great Plains, Ohio, and Mississippi valleys and southeastern North America with a few other languages in the east.” ref

“Historically, the tribes belonging to the Sioux nation have generally been classified into three large language groups:

- Lakota(Thítȟuŋwaŋ; anglicized as Teton), who form the westernmost group.

- Dakota, (Dakhótiyapi– Isáŋyathi anglicized as Santee) originally the easternmost group

- Nakota, originally the two central tribes of the Yankton and the Yanktonai” ref

“The Assiniboine separated from the Yankton-Yanktonai grouping at an early time. For a long time, very few scholars criticized this classification. In 1978, Douglas R. Parks, A. Wesley Jones, David S. Rood, and Raymond J. DeMallie engaged in systematic linguistic research at the Sioux and Assiniboine reservations to establish the precise dialectology of the Sioux language. They ascertained that both the Santee and the Yankton/Yanktonai referred (and refer) to themselves by the autonym “Dakota.” The name of Nakota (or Nakoda) was (and is) exclusive usage of the Assiniboine and of their Canadian relatives, the Stoney. The subsequent academic literature, however, especially if it is not produced by linguistic specialists, has seldom reflected Parks and DeMallie’s work. The change cannot be regarded as a subsequent terminological regression caused by the fact that Yankton-Yanktonai people lived together with the Santee in the same reserves.” ref

“Currently, the groups refer to themselves as follows in their mother tongues:

- Dakota people– Dakota, Santee, Yankton, and Yanktonai

- Lakota people– Lakota or Teton Sioux

- Nakota – the Nakoda people, the Assiniboine, and the Stoney” ref

“The Assiniboine are a Siouan-speaking people closely related linguistically to the Sioux and Stoney. Folk tradition suggesting a separation from the Yanktonai Sioux is not supported linguistically or historically. Linguistically, Nakota is on a continuum with the other Sioux dialects, no closer to one than the other, suggesting that the Assiniboine diverged from the Sioux at the same time the other Sioux dialects were differentiating from one another. The name Assiniboine derives from Ojibwa assini?- pwa? n, “stone enemy,” meaning “stone Sioux”—often with the –ak plural suffix, later a final –t, and by the 19th century the final –n or –ne. Nakota is their name for themselves and the language that they speak.” ref

“Assiniboines were first encountered by Europeans in the woodlands and parklands, already adept canoe users in their role as trade middlemen. In 1737 La Vérendrye distinguished the Woodland Assiniboines, who knew how to take fur-bearing animals, from the Plains Assiniboines, who had to be taught. Communal buffalo hunting utilized dogs until horses were acquired. Assiniboines utilized the buffalo pound to entrap and process much larger quantities than could be taken by single hunters.” ref

“In the 17th century, Assiniboine territory extended westward from Lake Winnipeg and the Forks of the Red and Assiniboine rivers into much of central and southern Saskatchewan. From the earliest descriptions, the Assiniboines allied with Algonquian-speaking Crees, and later, in the early to mid-19th century, with Saulteaux or western Ojibwas. Historical sources suggest a westward expansion of Assiniboine territory during the 18th century through the parklands of the central Saskatchewan River and into eastern Alberta; but these farthest reaches represented interaction spheres, and not a migration of fully articulated social groups reflecting the fur traders’ knowledge of the western prairies.” ref

“Alexander Henry the Younger listed in 1808 only one of eight Assiniboine bands occupying territory within the boundaries of the United States, along the Souris River in North Dakota. Population movements during the early 19th century shifted Assiniboine territory southward, and by 1840 three-quarters of the nation lived along the Missouri in the area of northwestern North Dakota and northeastern Montana. By the mid-19th century, Assiniboine territory extended east from the Moose and Wood mountains to the Cypress Hills, and north to south from the North Saskatchewan River to the Milk and Missouri rivers. Assiniboines first learned of the jurisdiction of the United States with the visit of Lewis and Clark, which marked the beginning of their incorporation.” ref

“The population history of the Assiniboines remains incomplete until well into the 19th century. A number of major disease episodes proved to be quite intrusive. The population was estimated at 10,000 before one-half to two-thirds were wiped out in the smallpox epidemic of 1780–81; the 1819–20 epidemic of measles and whooping cough again reduced the population by one-half. After the steamboats brought smallpox to the upper Missouri in the late 1830s the population began to recover, but as much as 60% of the population had been lost. After a slow recovery, two more smallpox epidemics struck the Assiniboine in 1856–57 and in 1869 before the population began another recovery.” ref

“By the last decades of the 19th century, Assiniboine reservations and reserves were located in Montana and Saskatchewan within the larger region they had occupied during the previous century. In Montana, the Upper Assiniboines were located with the Atsina Gros Ventre on the Fort Belknap Reservation, and the Lower Assiniboines with Yanktonai, Sisseton/Wahpeton Dakota and a small number of Hunkpapa and other Teton stragglers of Sitting Bull’s followers on the Fort Peck Reservation. In Saskatchewan, Assiniboines within Treaty 4 were the reserve bands of Pheasant’s Rump, Ocean Man, Carry the Kettle and Long Lodge, and Piapot’s Cree-speaking Assiniboines; and Assiniboines within Treaty 6 were the bands of Grizzly Bear’s Head and Lean Man, which often were known as the Battleford Stoneys.” ref

“Assiniboine population figures in the initial reservation/reserve period were complicated by tribally undifferentiated figures for the shared reservations in Montana, and similarly for some of the reserves in Canada. Contemporary population figures reflect the mixed heritage of many intermarriages: Carry the Kettle 2,009; Ocean Man 346; Pheasant Rump Nakota 316; White Bear 1,898; Mosquito, Grizzley Bear’s Head 1,049; Fort Belknap 2,245; and Fort Peck 4,197. Reservations in Montana and reserves in Saskatchewan remain homes for these respective tribes and First Nations. In every case, a large proportion of their populations reside off-reserve, mostly in cities, encouraged to do so both by increased economic opportunities and by various government policy initiatives in the decades following World War II. Since the 1970s, Nakota reserves in Saskatchewan have been leaders in the successful pursuit of land claims known as “specific claims,” and this has resulted in resources for a wide range of economic development initiatives. A fluorescence of religious practice has occurred in the last three decades, as communities support one another in their search for health and well-being.” ref

Dakota and Lakota (Sioux):

“The Lakota (pronounced [laˈkˣota]; Lakota: Lakȟóta/Lakhóta) are a Native American people. Also known as the Teton Sioux (from Thítȟuŋwaŋ), they are one of the three prominent subcultures of the Sioux people. Their current lands are in North and South Dakota. They speak Lakȟótiyapi—the Lakota language, the westernmost of three closely related languages that belong to the Siouan language family.” ref

“The seven bands or “sub-tribes” of the Lakota are:

- Sičháŋǧu(Brulé, Burned Thighs)

- Oglála(“They Scatter Their Own”)

- Itázipčho(Sans Arc, Without Bows)

- Húŋkpapȟa(Hunkpapa, “End Village”, Camps at the End of the Camp Circle)

- Mnikȟówožu(Miniconjou, “Plant Near Water”, Planters by the Water)

- Sihásapa(“Blackfeet” or “Blackfoot”)

- Oóhenuŋpa(Two Kettles)” ref

“Notable Lakota persons include Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake (Sitting Bull) from the Húnkpapȟa, Maȟpíya Ičáȟtagya (Touch the Clouds) from the Miniconjou, Heȟáka Sápa (Black Elk) from the Oglála, Maȟpíya Lúta (Red Cloud) from the Oglála, Tamakhóčhe Theȟíla (Billy Mills) from the Oglála, Tȟašúŋke Witkó (Crazy Horse) from the Oglála and Miniconjou, and Siŋté Glešká (Spotted Tail) from the Brulé. More recent activists include Russell Means from the Oglála.” ref

“Siouan language speakers may have originated in the lower Mississippi River region and then migrated to or originated in the Ohio Valley. They were agriculturalists and may have been part of the Mound Builder civilization during the 9th–12th centuries CE. Lakota legend and other sources state they originally lived near the Great Lakes: “The tribes of the Dakota before European contact in the 1600s lived in the region around Lake Superior. In this forest environment, they lived by hunting, fishing, and gathering wild rice.” ref

“They also grew some corn, but their locale was near the limit of where corn could be grown.” This may be conflation with the Algonquian-speaking groups typically in that region, though Siouan peoples probably migrated there later. In the late 16th and early 17th centuries, Dakota-Lakota speakers lived in the upper Mississippi Region in what is now organized as the states of Minnesota, Wisconsin, Iowa, and the Dakotas. Conflicts with Anishnaabe and Cree peoples pushed the Lakota west onto the Great Plains in the mid- to late-17th century.” ref

“Early Lakota history is recorded in their winter counts (Lakota: waníyetu wówapi), pictorial calendars painted on hides, or later recorded on paper. The ‘Battiste Good winter count’ records Lakota history back to 900 CE when White Buffalo Calf Woman gave the Lakota people the White Buffalo Calf Pipe. After 1720, the Lakota branch of the Seven Council Fires split into two major sects, the Saône, who moved to the Lake Traverse area on the South Dakota–North Dakota–Minnesota border, and the Oglála-Sičháŋǧu, who occupied the James River valley. However, by about 1750 the Saône had moved to the east bank of the Missouri River, followed 10 years later by the Oglála and Brulé (Sičháŋǧu).” ref

“Around 1730 Cheyenne people introduced the Lakota to horses, which they called šuŋkawakaŋ (“dog [of] power/mystery/wonder”). After they adopted horse culture, Lakota society centered on the buffalo hunt on horseback. The total population of the Sioux (Lakota, Santee, Yankton, and Yanktonai) was estimated at 28,000 in 1660 by French explorers. The Lakota population was estimated at 8,500 in 1805; it grew steadily and reached 16,110 in 1881, one of the few Native American tribes to increase in population in the 19th century. The number of Lakota has increased to more than 170,000 in 2010, of whom about 2,000 still speak the Lakota language (Lakȟótiyapi).” ref

“The large and powerful Arikara, Mandan, and Hidatsa villages had long prevented the Lakota from crossing Missouri. However, the great smallpox epidemic of 1772–1780 destroyed three-quarters of these tribes. The Lakota crossed the river into the drier, short-grass prairies of the High Plains. These newcomers were the Saône, well-mounted and increasingly confident, who spread out quickly. In 1765, a Saône exploring and raiding party led by Chief Standing Bear discovered the Black Hills (the Paha Sapa), then the territory of the Cheyenne. Ten years later, the Oglála and Brulé also crossed the Missouri. Under pressure from the Lakota, the Cheyenne moved west to the Powder River country. The Lakota made the Black Hills their home.” ref

“Dakota peoples emerged from a long history linked to the demise of Hopewell and later Mississippian archaeological cultures, and arrived in Minnesota/Wisconsin taking advantage of the region’s mosaic of forests, lakes and prairies. The ancestral Dakota were associated with the specific mid-western Woodland archaeological complexes: the Initial (c. 200 BCE–CE 500) and the Terminal (c. AD 500–1680) traditions. Concentrated at the Mississippi River headwaters in the parkland transitions zones between forest and prairie, the Dakota exploited the plentiful resources of these ecotones. Linguistically part of the Siouan language family, dialects emerged to distinguish the Dakota proper (Mdewakanton, Wahpeton, Sisseton, and Wapakute) and middle division (Yanktonai and Yankton) from the western division Lakota (Teton).” ref

“Dakota expansions onto the eastern prairies in the mid-17th century were a response to the population increases that came with access to French trade goods, including firearms. In the early 18th century, as Ojibwa-Dakota conflict increased over control of hunting territories and access to traders in the Mississippi watershed, the Lakotas moved west onto the prairies, crossed the Missouri to the high plains, and continued their expansion westward to control the Black Hills. As horses came through the trade networks, Lakotas expanded in number and flourished because of the abundant game resources. Their expansions were composed of forays into neighboring regions that comprised the border regions and territories of their enemies: Lake of the Woods and Rainy Lake, Turtle Mountains/Pembina Hills, as well as the Souris, White Earth, and Missouri-Yellowstone Rivers regions.” ref

“The Dakota, once abandoned by the French in the early 18th century, became allies of the British and were increasingly bound to them by treaties and trade alliances, involving fighting as British allies in the War of 1812. From the arrival of the Americans with the Pike expedition to the upper Mississippi in 1805, uneasiness characterized relations for much of the next decades. While the French had been acculturated as kinsmen, the English replaced these roles imperfectly; and when the Americans arrived, they did not grasp the importance of reciprocity for the Dakota. Treaties of friendship and trade gave way to extorted land cessions; the American appetite for land and resources was never satiated.” ref

“By the 1850s the Dakota were left with reservations upon which they were allowed to reside only at the discretion of the President of the United States. This dependency left them vulnerable and periodically destitute. Minnesota became a territory in 1849 and a state in 1858, surrounding them and filling up their former lands. While less circumscribed, the Lakota and Yankton-Yanktonai participated in the 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty that began a process of fixing the boundaries of tribal territorial domains, with pledges of annuities for cessation of intertribal warfare. However, as the United States drifted toward civil war, promises to Indians were all but forgotten amidst the graft and corruption in the Indian service.” ref

“The collision of events and circumstances that led to the Dakota outbreak were numerous. The breaking point was reached between August and December of 1862, when young men refused to watch their families starve any longer. With the onset of fighting, the diaspora of many Dakota began as vast numbers fled onto the prairies of eastern Dakota Territory, then north into Canada—first to the vicinity of the Red River settlement, then westward into present-day western Manitoba. Standing Buffalo led his followers back into Montana Territory, where he was killed in battle on June 5, 1871. His son, taking his father’s name, led part of this group back into Canada, eventually settling on the Standing Buffalo reserve in 1878.” ref

“White Cap had led followers into Manitoba and eventually into what became Saskatchewan, but when forced by the Métis to join in the fighting in 1885, White Cap’s group was punished; however, once rehabilitated they were given a reserve at Moose Woods. A group led by Hupa Yakta, previously affiliated with White Cap in 1890, asked for a reserve at Round Plain, which came to be called Wahpeton. Most of the followers of Sitting Bull went south and preceded his surrender to US authorities on July 19, 1881; however, a small group of Lakota remained and struggled for survival at the edges of Moose Jaw, and were finally granted a reserve at Wood Mountain in 1910. While reserves at Oak River, Birdtail, and Oak Lakes had been established for Dakota in the 1870s, and others for the Portage la Prairie bands in 1886 in Manitoba, the Dakota communities in Saskatchewan and Manitoba remained extremely isolated.” ref

“The contemporary Dakota/Lakota communities in Saskatchewan have remained outside of treaty, and have had differential relations with the various jurisdictions among which they must deal. A contemporary movement among the Sioux in Saskatchewan is pressing for treaty adhesions to bring them into full status and equal relations with Canada, as are the other First Nations within Saskatchewan.” ref

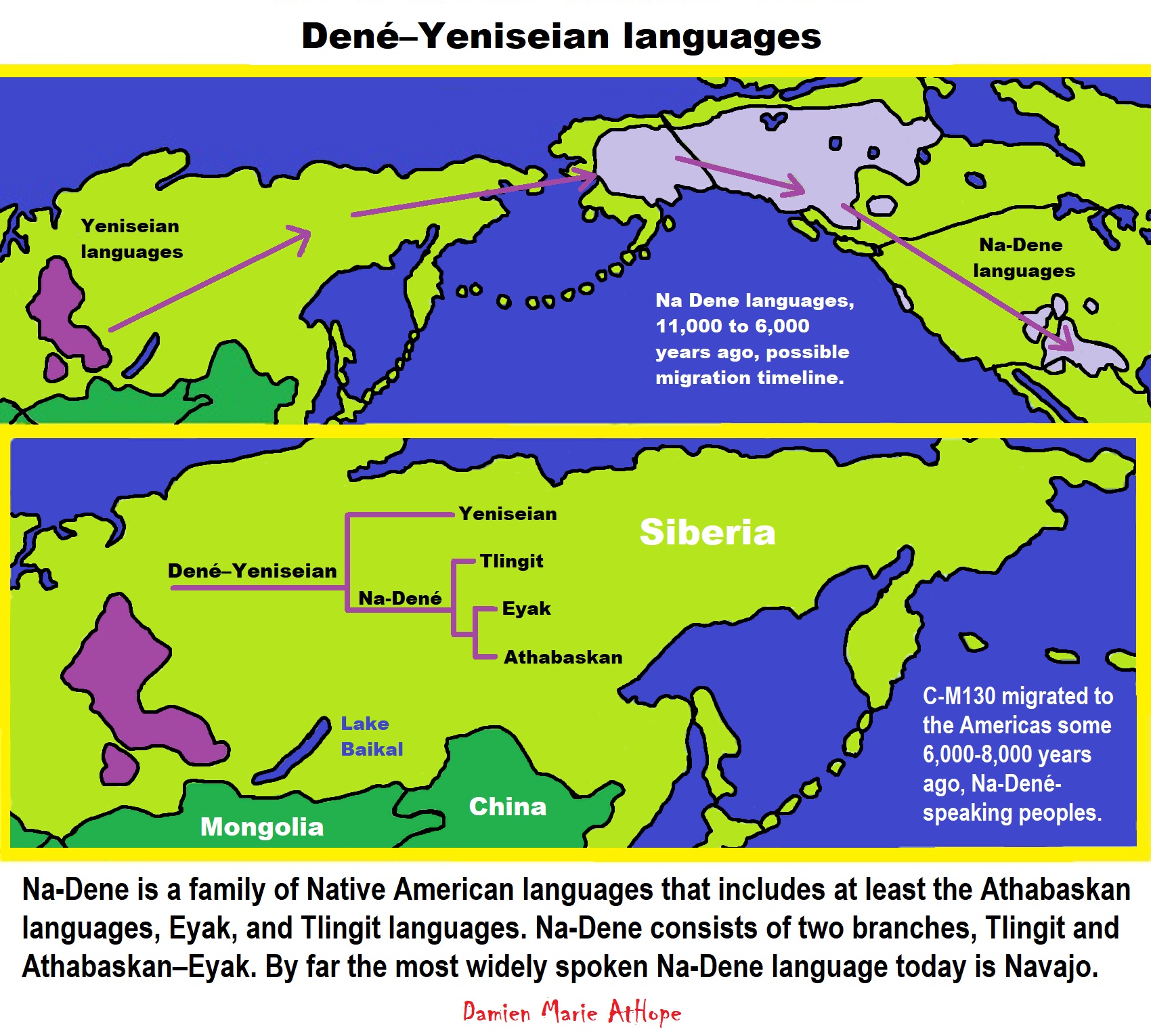

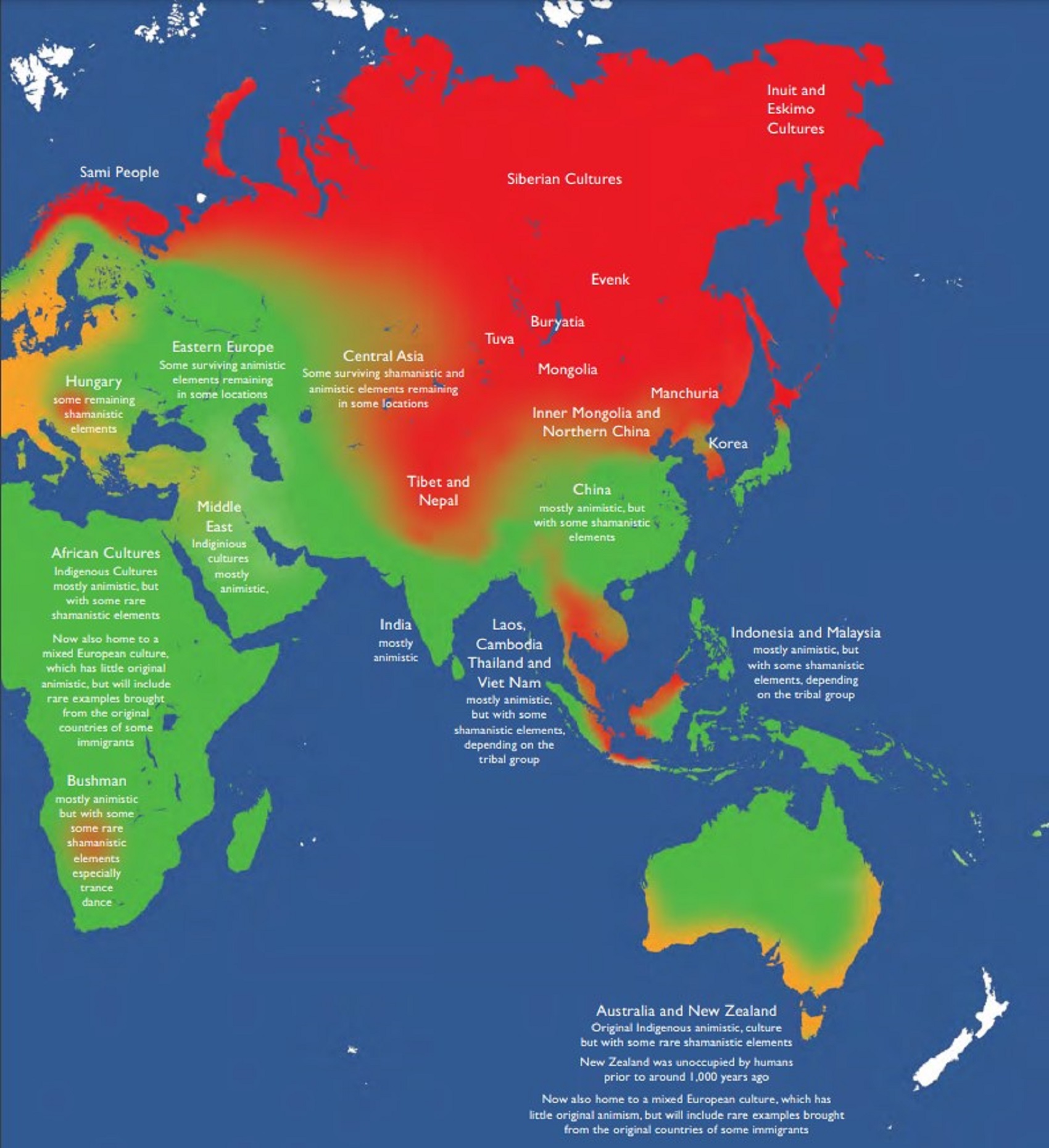

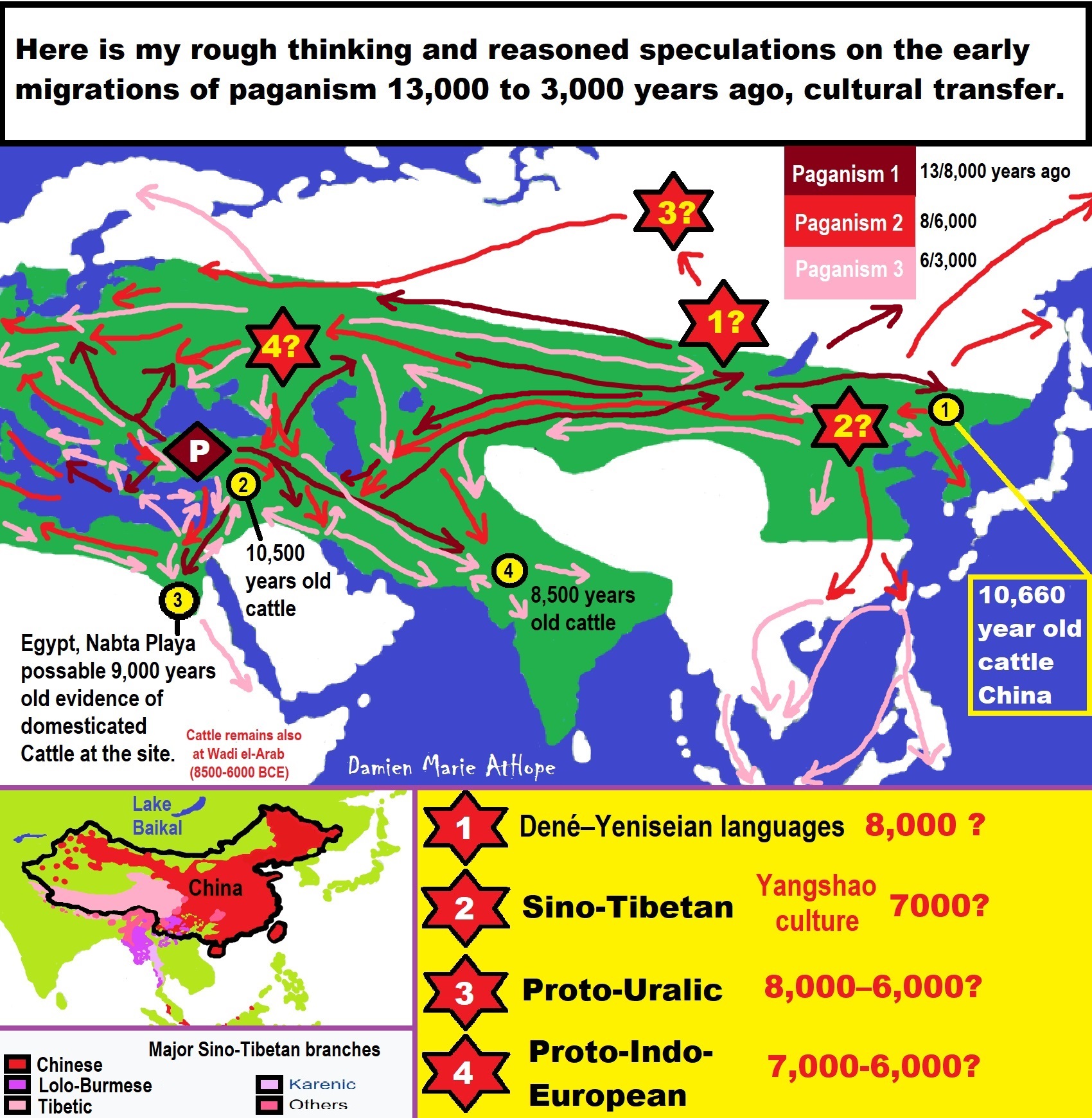

Dené–Yeniseian languages? (I think similar to the Sami or Ainu peoples, Dené–Yeniseian peoples who migrated related to beliefs that were likely “paganistic” Shamanism, with heavy totemism themes)

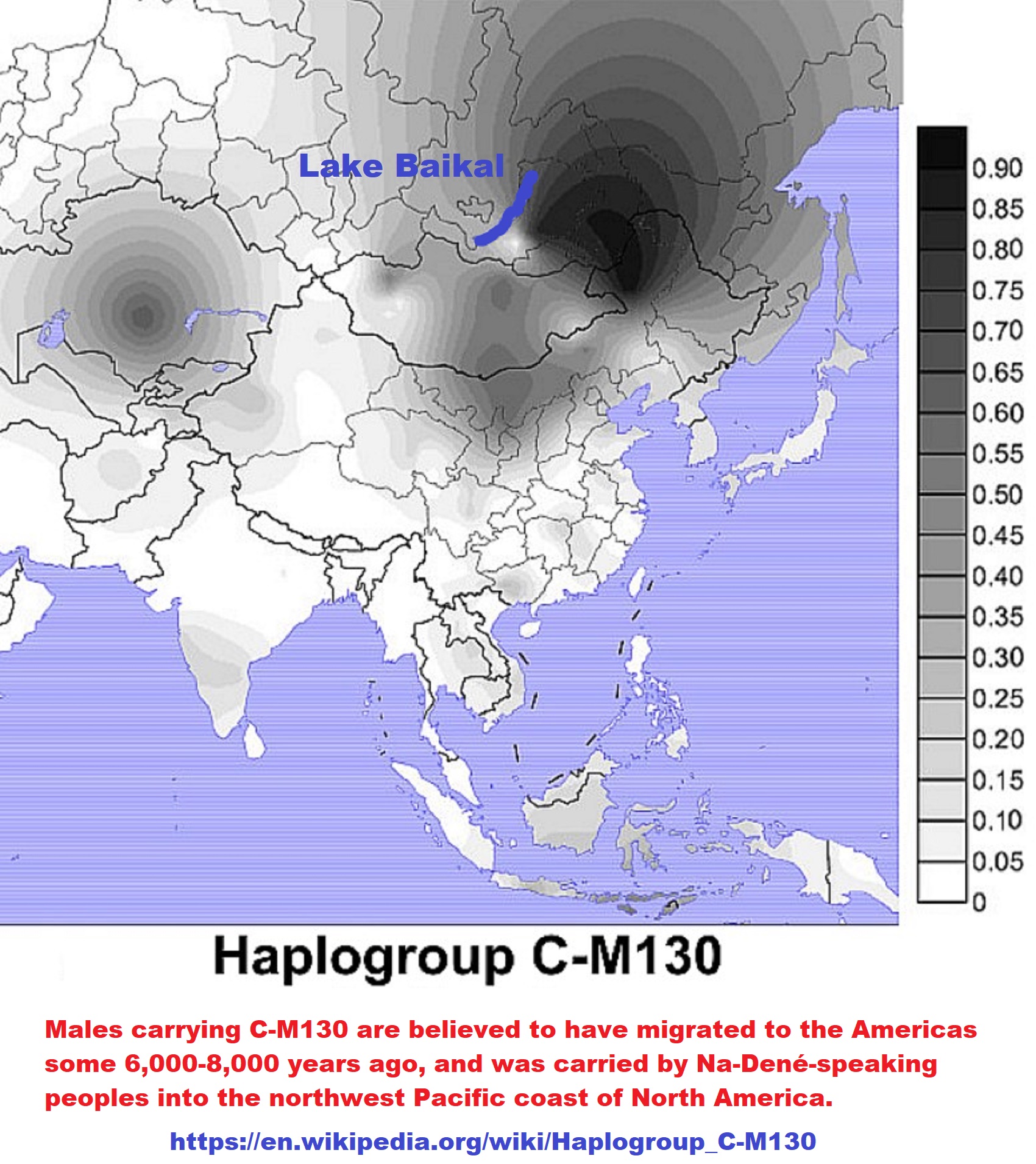

“Dené–Yeniseian is a proposed language family consisting of the Yeniseian languages of central Siberia and the Na-Dené languages of northwestern North America. Reception among experts has been somewhat favorable; thus, Dené–Yeniseian has been called “the first demonstration of a genealogical link between Old World and New World language families that meets the standards of traditional comparative–historical linguistics,” besides the Eskimo–Aleut languages spoken in far eastern Siberia and North America.” ref

“Na-Dene (/ˌnɑːdɪˈneɪ/; also Nadene, Na-Dené, Athabaskan–Eyak–Tlingit, Tlina–Dene) is a family of Native American languages that includes at least the Athabaskan languages, Eyak, and Tlingit languages. Haida was formerly included, but is now considered doubtful. By far the most widely spoken Na-Dene language today is Navajo. In February 2008, a proposal connecting Na-Dene (excluding Haida) to the Yeniseian languages of central Siberia into a Dené–Yeniseian family was published and well-received by a number of linguists. It was proposed in a 2014 paper that the Na-Dene languages of North America and the Yeniseian languages of Siberia had a common origin in a language spoken in Beringia, between the two continents.” ref

Denesuline (Dene/Chipewyan):

“The Dene people are an indigenous group of First Nations who inhabit the northern boreal and Arctic regions of Canada. The Dene speak Northern Athabaskan languages. Dene is the common Athabaskan word for “people”. The term “Dene” has two usages. More commonly, it is used narrowly to refer to the Athabaskan speakers of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut in Canada, especially including the Chipewyan (Denesuline), Tlicho (Dogrib), Yellowknives (T’atsaot’ine), Slavey (Deh Gah Got’ine or Deh Cho), and Sahtu (the Eastern group in Jeff Leer’s classification; part of the Northwestern Canada group in Keren Rice‘s classification). However, it is sometimes also used to refer to all Northern Athabaskan speakers, who are spread in a wide range all across Alaska and northern Canada. The Southern Athabaskan speakers, however, also refer to themselves by similar words: Diné (Navajo) and Indé (Apache).” ref

“Dene are spread through a wide region. They live in the Mackenzie Valley (south of the Inuvialuit), and can be found west of Nunavut. Their homeland reaches to western Yukon, and the northern part of British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Alaska and the southwestern United States. Dene were the first people to settle in what is now the Northwest Territories. In northern Canada, historically there were ethnic feuds between the Dene and the Inuit. In 1996, Dene and Inuit representatives participated in a healing ceremony to reconcile the centuries-old grievances. Behchoko, Northwest Territories is the largest Dene community in Canada.” ref

“The Dene include five main groups:

- Chipewyan(Denesuline), living east of Great Slave Lake, and including the Sayisi Dene living at Tadoule Lake, Manitoba

- Tlicho(Dogrib), living between Great Slave and Great Bear Lakes

- Yellowknives(T’atsaot’ine), living north of Great Slave Lake

- Slavey(Deh Gah Got’ine or Deh Cho), the North Slavey (Sahtu, (Sahtúot’ine), including the Locheux, Nahanni, and Bear Lake peoples) living along the Mackenzie River (Deh Cho) near Great Bear Lake, the South Slavey southwest of Great Slave Lake and into Alberta and British Columbia.

- Sahtu(Sahtúot’ine), including the Locheux, Nahanni, and Bear Lake peoples, in the central NWT.” ref

“Although the above-named groups are what the term “Dene” usually refers to in modern usage, other groups who consider themselves Dene include:

- Tsuu T’ina, aka the Sarcee, currently located near Calgary, Alberta.

- The Beaver people (Danezaa or Dunneza)of northeastern British Columbia and neighboring regions of northwestern Alberta.

- The Tahltan, Kaska, and Sekanipeople of the Northern Interior of British Columbia. Another group in this region, the Tsetsaut people, lived in the Portland Canal area of the northernmost BC Coast near the border with Alaska. They are now extinct.

- The Dakelh(Carrier) peoples of the Northern and Central Interior of British Columbia, and their subgroup the Wet’suwet’en

- The Tsilhqot’inpeople of the eponymous Chilcotin District of the Central Interior of British Columbia

- The extinct Nicola Athapaskans, aka the Stuwix (“strangers” in the Shuswap language), migrated south from northern BC into the Nicola Valley region in the late 18th century and were absorbed into the Nicola people, an alliance of Nlaka’pamux and Okanagan peoples.

- The Gwich’inand Tanana and other peoples of Yukon and Alaska are also considered to be Dene, which is to say part of the family of Athapaskan-speaking peoples.” ref

“The Denesuline (also known as Chipewyan) are Indigenous people in the Subarctic region of Canada, with communities in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and the Northwest Territories. Linguistically, the Denesuline are closely related to the Tlicho, Slavey, and Yellowknives, neighboring Dene who speak similar languages and whose territories share borders. Traditional Denesuline territory includes northern portions of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and the southern part of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut. With the exception of Nunavut, contemporary Denesuline communities exist in the same areas, generally between Lake Athabasca and Great Slave Lake.” ref

“The Denesuline (also known as Chipewyan) are Indigenous Peoples in the Subarctic region of Canada, with communities in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and the Northwest Territories. The Denesuline are Dene, and share many cultural and linguistic similarities with neighboring Dene communities. As of 2015, there were more than 23,000 registered members of Denesuline First Nations. The 2011 National Household Survey recorded 12,950 speakers of the Denesuline language. Denesuline are closely associated with other Dene groups as well as northern Cree and Métis, who may share their communities and also speak Denesuline. As such, population and language numbers are approximations.” ref

“The word “Dene” means “people” and serves many purposes. It is a collective term for people previously known as Athapaskans, and is often used as an equivalent to the Athapaskan language group. Dene may refer to the collective group (including Denesuline, Tlicho, Slavey, Yellowknives and others) as well as the specific Denesuline language. The 2011 National Household Survey recorded 12,950 speakers of the Denesuline language. There are two dialects of Denesuline — the “k” dialect is far less common than the “t” dialect — and many communities are attempting to revive the language through youth education programs.” ref

“Traditional Denesuline socio-territorial organization was based on hunting the migratory herds of barren-ground caribou. Hunting groups consisted of two or more related families that joined with other such groups to form larger local and regional bands, coalescing or dispersing with the herds. Leaders had limited, non-coercive authority which was based upon their ability, wisdom and generosity. Spiritual power was received in dream visions and exercised by shamans, and reflected a worldview intertwined with the natural world. Catholic missionaries were successful in converting the majority of Dene in the area, superseding traditional belief systems.” ref

“In Denesuline tradition, it was Thanadelthur, also known as the “Slave Woman,” who guided an employee of the Hudson’s Bay Company into Denesuline territory and introduced her people to Europeans. This successful meeting led the HBC in 1717 to establish Prince of Wales Fort, or Churchill, for the Denesuline fur trade. The fur trade aggravated relations between Denesuline and their southern neighbors, the Cree. Peaceful relations began to be established between Denesuline and Cree between 1716 and 1760, but in some places hostility continued much later. The fur trade also affected their relations in the late 18th century with their northern neighbors, Inuit, whom they termed hotel ena or “enemies of the flat area.” ref

“Hudson Bay to Great Slave Lake in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The Yellowknives took advantage of their strategic location and in the early 19th century, briefly occupied the Yellowknife River region, displacing its Tlicho inhabitants until they retaliated in 1823. Some Denesuline began to hunt and trap in the full boreal forest, where fur-bearing animals were more abundant, and they extended their territories to the south. Some even began to occupy the northern edge of the parkland, where they hunted bison. Others remained more independent from the trade, though some were willing to trade food provisions. By the late 19th century most contemporary Denesuline communities had settled in their current territories. Epidemics of European diseases decimated the population, with the first great smallpox epidemic occurring in 1781–82, and other epidemics continuing through the first half of the 20th century.” ref

“Settler colonialism in Canada is the continuation and the results of the colonization of the assets of the Indigenous peoples in Canada. As colonization progressed, the Indigenous peoples were subject to policies of forced assimilation and cultural genocide. The policies signed many of which were designed to both allowed stable houses. Governments in Canada in many cases ignored or chose to deny the aboriginal title of the First Nations. The traditional governance of many of the First Nations was replaced with government-imposed structures. Many of the Indigenous cultural practices were banned. First Nation’s people status and rights were less than that of settlers. The impact of colonization on Canada can be seen in its culture, history, politics, laws, and legislatures. The current relationship of Indigenous peoples in Canada and the Crown is one that has been heavily defined by the effects of settler colonialism and Indigenous resistance. Canadian Courts and recent governments have recognized and eliminated many discriminatory practices.” ref

The Reality of Saskatchewan’s Colonial Violence

“The recent attack on Colby Tootoosis is not an isolated incident, but rather part of the ongoing struggle between Indigenous people and settler colonialism in Saskatchewan. There are few places in Saskatchewan – both historically and in the present – that better exemplify the evolution of Indigenous-settler relations than the Battlefords region. The region once served as the Canadian government’s operations base during the North-West Resistance, and has been a flashpoint in the ongoing struggle between Indigenous Peoples and colonizers. Most recently, Battleford was where Colby Tootoosis, a Cree man from Poundmaker First Nation, was assaulted by white settlers in an unprovoked attack that happened in front of his six-year-old daughter.” ref

“Consisting of the city of North Battleford on the north side of the North Saskatchewan River and the town of Battleford to the south, the Battlefords have earned their name as a site of monumental struggle between Indigenous nations and the intrusion of settler colonialism. An ongoing struggle with a historical basis, from the earliest point in the history of European contact in the Plains, almost two centuries before Saskatchewan was called Saskatchewan, the area was home to fur trading outposts where Europeans traded with Indigenous nations – relationships that, if not friendly, were at least practical.” ref

“In 1875, six years after the Dominion of Canada purchased Rupert’s Land from the Hudson’s Bay Company in preparation for mass settlement in the region, Battleford was founded, and in 1876 became home to a North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) outpost. Here, the NWMP would maintain their offensive against the Indigenous communities whose knowledge and trade had long kept Europeans in the area alive. The Battlefords have earned their name as a site of monumental struggle between Indigenous nations and the intrusion of settler colonialism.” ref

“As Indigenous-European relations transitioned into an outright occupation of Indigenous land, Fort Battleford would play a role in the North-West Resistance. It was here that Cree bands sympathetic to the Métis cause would conduct raids to access weapons, horses, and food to prepare them to join the fight against colonization, while settlers took refuge in the NWMP’s palisade. Later, Chief Pitikwahanapiwiyin and others would surrender here. In November 1885, eight warriors of the resistance were publicly hanged at Battleford.” ref

“This is the largest mass execution in Canadian history and a symbolic turning point in Indigenous-settler relations that demonstrated the ferocity and brutality the Canadian state and its legal system were prepared to use in order to keep Indigenous resistance at bay. Like other places in the province with high proportions of Indigenous residents, North Battleford has been subjected to unflattering scrutiny from outside Saskatchewan. In 2017, Maclean’s magazine dubbed North Battleford “Canada’s most dangerous place.” ref

CCF Colonialism in Northern Saskatchewan – Battling Parish Priests, Bootleggers, and Fur Sharks, By David Quiring

“Saskatchewan’s Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), the forerunner of the NDP, is often remembered for its humanitarian platform and its pioneering social programs. But during the twenty years it governed, it wrought a much less scrutinized legacy in the northern regions of the province. Until the 1940s, churches, fur traders, and other influential newcomers held firm control over Saskatchewan’s northern region. Following its rise to power in 1944, the CCF made aggressive efforts to unseat these traditional powers and install a new socialist economy and society in largely Aboriginal communities.” ref

“The next two decades brought major changes to the region as well-meaning government planners grossly misjudged the challenges that confronted the north and failed to implement programs that would meet its needs. Northerners lacked the voice and political clout to determine policies for their half of the province, and the CCF effectively created a colonial apparatus, imposing its own ideas and plans in those communities without consulting residents. While it did ensure that parish priests, bootleggers, and “fur sharks” no longer dominated the north, it failed to establish a workable alternative.” ref

“In an elegantly written history that documents the colonial relationship between the CCF and northern Saskatchewan, David Quiring draws on extensive archival research and oral history to offer a fresh look at the CCF era. This examination will find a welcome audience among historians of the north, Aboriginal scholars, and general readers interested in Canadian history.” ref

Canada’s Colonial Genocide of Indigenous Peoples: A Review of the Psychosocial and Neurobiological Processes Linking Trauma and Intergenerational Outcomes