Adapted from (Living Religions: A Brief Introduction by Mary Pat Fisher) http://books.google.com/books/about/Living_Religions.html?id=ITnlAAAAMAAJ

Religious and nonreligious terms, labels, or definitions have been used and may still be used as or related to all kinds of bigotry from religious bigotry, ethnocentrism, classism, colonialism, racism, sexism, etc.

Religious Intolerance/Bigotry

“Religious intolerance is intolerance of another’s religious beliefs, practices, or lack thereof. Statements which are contrary to one’s religious beliefs do not constitute intolerance. Religious intolerance, rather, occurs when a person or group (e.g., a society, a religious group, a non-religious group) specifically refuses to tolerate the religious convictions and practices of a religious group or individual.” ref

“Monotheistic religion is the oldest and most encompassing framework for bigotry in the West. Its Manichean binaries of good and evil, pure and impure, superior and inferior, us and them have been leveraged over centuries to justify bigotry. That ideology of stark division and uncompromising difference has survived in spite of the powerful prophetic traditions of those same Abrahamic religions urging social justice, compassion, and peace. Bigotry has been installed in religious institutions in the West for millennia, but at the same time, those institutions have authorized power to undermine bigotry.” ref

“They have contributed crucially to the fashioning of counter-ideologies aimed at liberation from narrow views of human subjectivity and social life that engendered suffering. The problem of religious bigotry then, is a complex one, tied to spatial and temporal contexts, and frequently admitting a measure of ambiguity. In other words, it is like bigotry in some other areas of American life, including race, gender, sexuality, and disability, but it differs from those because of its exceptional

deep-rootedness in institutions. In addition to interreligious bigotry, there also are examples of intrareligious bigotry among various denominations, sects, and branches of religions.” ref

“The appearance of permanence and impeccable authority cultivated by religious institutions, and the leveraging of those seeming assets in violent litigations of factional differences, has served in turn as a template for other kinds of structural bigotry. Structural bigotry denotes a broad range of acts and policies of social injustice/domination typically grounded in transgenerational claims of entitlement; legitimated by institutions, ideologies, policies, media, and custom; and driven by expressions of animus, including shared symbolism and hateful vocabulary, verbal and physical assaults including hate crimes, and exclusion which serves to entrench power in privileged insiders, in which all members of a society can be implicated subjects/beneficiaries.” ref

“Religious bigotry, like all structural bigotry, is exercised in order to hold power. Groups perceived as competitors for the resources claimed by religion are assessed as impure, dangerous, and an imminent threat to the very existence of the religious community. Religious intolerance is perhaps the earliest example of structural bigotry. Many early societies were

configured around religious identity and religious group membership. Religious identity or lack thereof provided a ready proxy for exclusion, discrimination, persecution, oppression, and violence. Religious intolerance remains a strong driver of structural bigotry in the modern United States. Targets of religious intolerance are often those who practice or are perceived to practice faiths other than mainstream Christianity and those who are secular or otherwise reject religious practice or affiliation.” ref

“Inflammatory religious rhetoric and the violence marshaled to its cause have been present throughout national histories, including the earliest colonial settlements of North America. The American history of religious intolerance as a record of violence between religious groups is replete with generations of conflict among every religious group, large and small. Protestants of all stripes, Catholics, Jews, Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists, Mormons, Jehovah’s Witness, Quakers, Shakers, Amish, indigenous religions, Afro-Caribbean religions – all of these and more have experienced religious intolerance and

many have perpetrated it.” ref

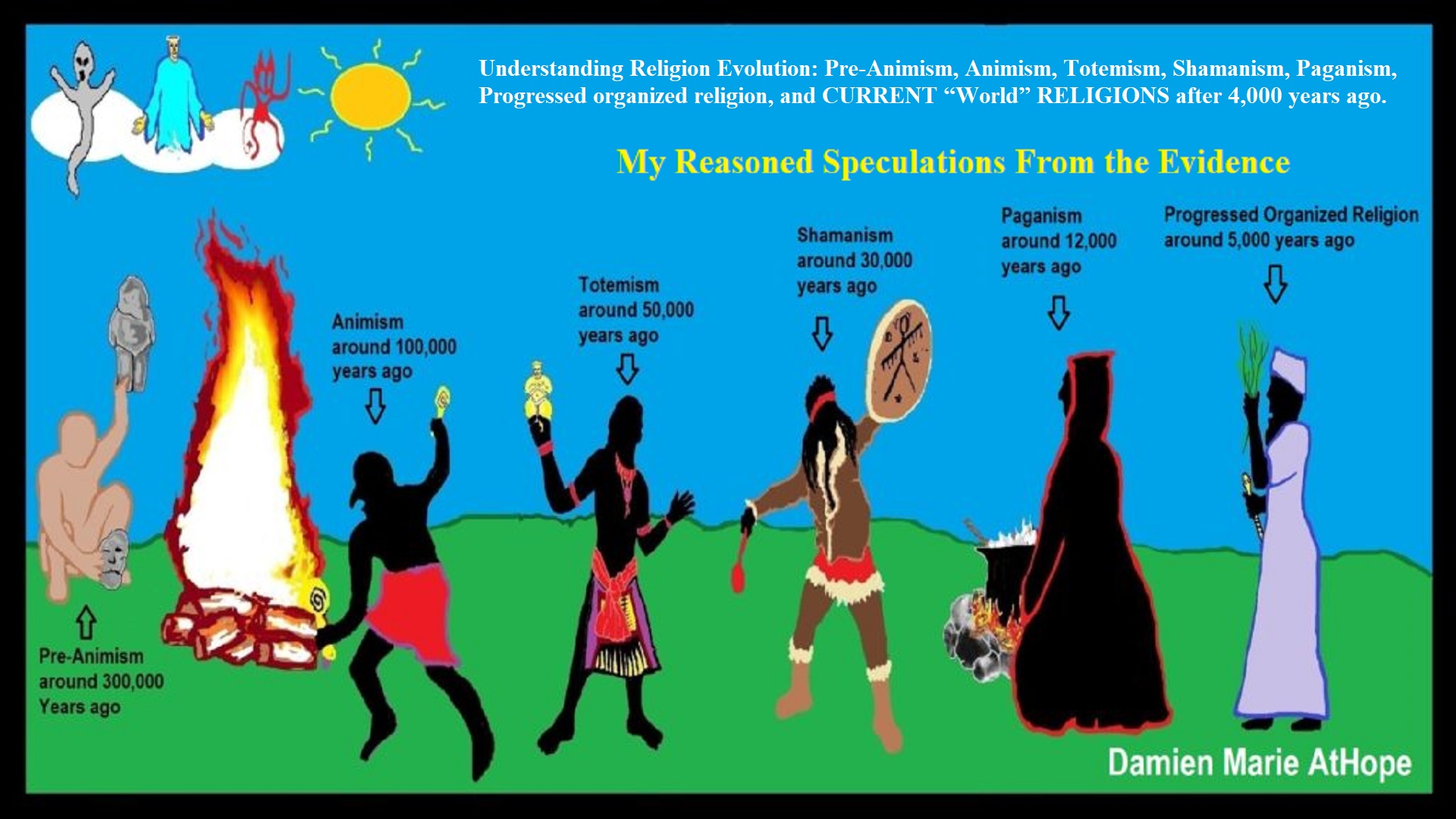

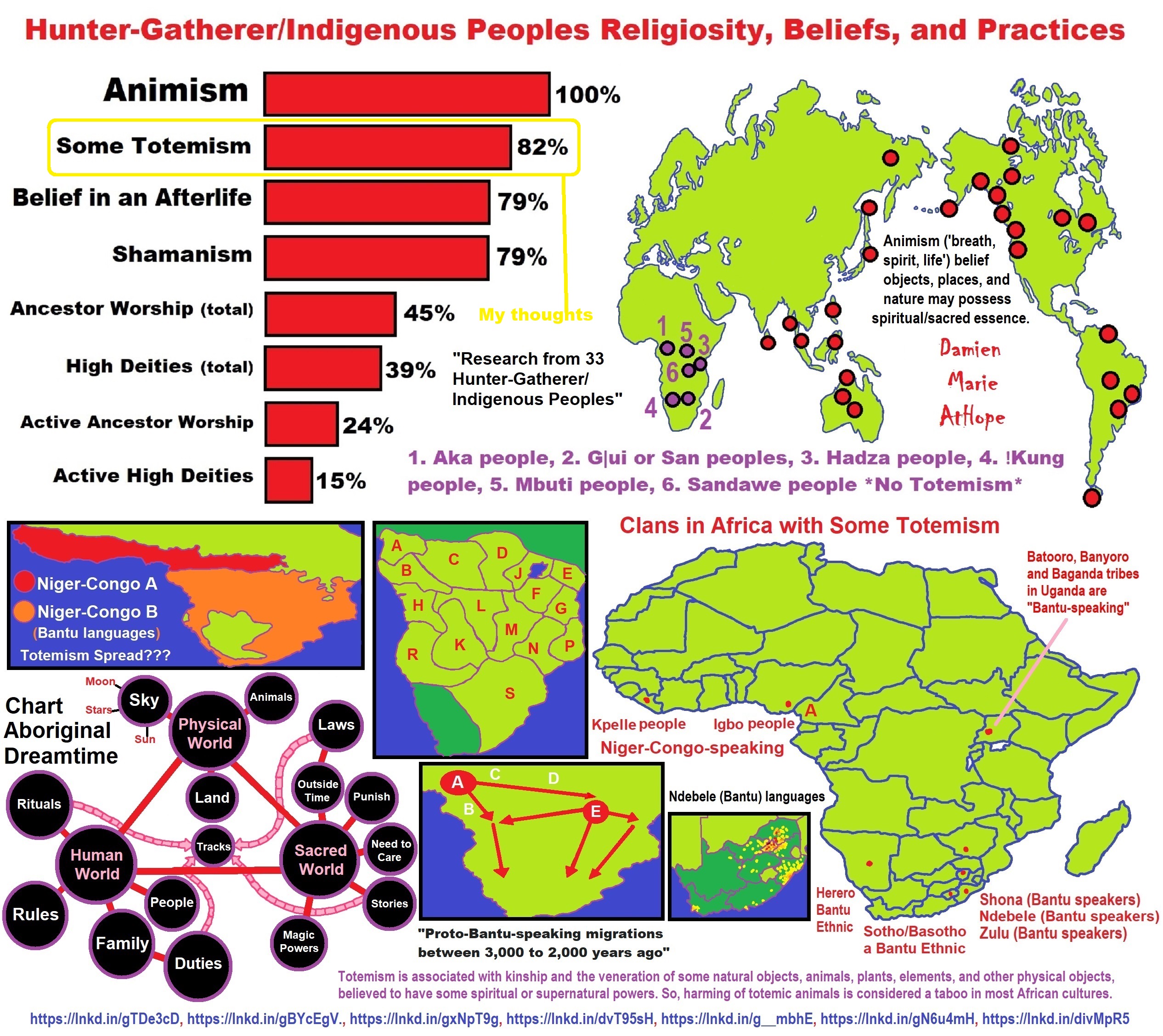

“Animism (from Latin: anima meaning ‘breath, spirit, life‘) is the belief that objects, places, and creatures all possess a distinct spiritual essence. Animism perceives all things—animals, plants, rocks, rivers, weather systems, human handiwork, and in some cases words—as animated and alive. Animism is used in anthropology of religion as a term for the belief system of many Indigenous peoples, in contrast to the relatively more recent development of organized religions. Animism focuses on the metaphysical universe, with a specific focus on the concept of the immaterial soul.” ref

“Although each culture has its own mythologies and rituals, animism is said to describe the most common, foundational thread of indigenous peoples’ “spiritual” or “supernatural” perspectives. The animistic perspective is so widely held and inherent to most indigenous peoples that they often do not even have a word in their languages that corresponds to “animism” (or even “religion”). The term “animism” is an anthropological construct.” ref

“Largely due to such ethnolinguistic and cultural discrepancies, opinions differ on whether animism refers to an ancestral mode of experience common to indigenous peoples around the world or to a full-fledged religion in its own right. The currently accepted definition of animism was only developed in the late 19th century (1871) by Edward Tylor. It is “one of anthropology‘s earliest concepts, if not the first.” ref

“Animism encompasses beliefs that all material phenomena have agency, that there exists no categorical distinction between the spiritual and physical world, and that soul, spirit, or sentience exists not only in humans but also in other animals, plants, rocks, geographic features (such as mountains and rivers), and other entities of the natural environment. Examples include water sprites, vegetation deities, and tree spirits, among others. Animism may further attribute a life force to abstract concepts such as words, true names, or metaphors in mythology. Some members of the non-tribal world also consider themselves animists, such as author Daniel Quinn, sculptor Lawson Oyekan, and many contemporary Pagans.” ref

Alice Beck Kehoe (Anthropologist and Archaeologist) stated:

“Animism” is not a religion, it’s a 19th-century label, as is “Totemism”, these labels are armchair gentlemens’ labels for what they read in travelers’ books. You should get a copy of the new book, paperback available, Pilgrimage to Broken Mountain, by Alan and Pamela Sandstrom. An amazing magnum opus from decades of superb ethnography by a family (parents, both Ph.D.s, and their son) who spent a great deal of time with a Nahua community in NE Mexico mountains, going on five pilgrimages with them to holy mountains. On page 4, left-hand column near bottom, the Sandstroms explain why “animism” is a bad label, and instead say “ontological monism”. “Damien, listen carefully: all 3 words as used in the past AND STILL TODAY, are LABELS imposed by armchair gentlemen creating a newer (19th century) version of the Great Chain of Being. See The Great Chain of Being — Arthur O. Lovejoy. Harvard University https://www.hup.harvard.edu › catalog “In this volume, which embodies the William James lectures for 1933”. . . ” – Alice Beck Kehoe, From an email message

“Also, of course, Lovejoy and G. Boas (NOT Franz, no relation), on Primitivism. The classically educated gentlemen were following the Enlightenment practice of IMPOSING classificatory labels on everything, to put everything inside classificatory boxes that would construct research paradigms and ultimately lead to universal laws about all organisms including humans. The labels were created to put the Primitives into classificatory structures, which demarcated them from Us the Civilized Christians. Yes, they have no sexist connotations now, nor did they originally. They are, however, blatantly RACIST in that they separate non-Western peoples from (White) Christians. Thus, you should not use these labels. As for the term shamanism, we don’t have data for its earlier form or forms other than maybe the wu of early Chinese writing (c 2000 years ago). Shamanic religions are a historical cultural tradition in Asia, that spread from the ferment of religious revelations and movements around 2000 years ago (Hinduism becoming written down, Buddhism in opposition to it, Chinese educated class interested in these). Animism and totemism are purely academic impositions of Western imperialist culture. Look at it this way: would you lump the cuisines of India along with the work of the Sioux Chef in one category because both are Indians? And put that category opposed to fine French cuisine, with the common implication that the French cuisine is Civilized but the other two not because their nations were conquered by the Europeans who ate French cuisine?” – Alice Beck Kehoe, From an email message

My response, I appreciate Alice Beck Kehoe’s thoughts and think it important to explain and expose past bigotry, sexism, racism, homophobia, transphobia, etc. I think I will, in the future, do a blog and video addressing bigotry in terms used in religious explanations past and present as this is also an important subject. This blog post is part of this. I also need to restate to people that I am a revolutionary who uses prehistory and history as a path to greater intellectualism and enlightenment. I am not making my blogs for archaeologists or anthropologists, but for the general public, to inform and inspire new learning and a desire to learn more thus becoming more culturally aware. Words that are now descriptive of religious thinking and behavior are not the same as racist or sexist words with clear racist or sexist meanings.

The Shaman’s Secrets from Archaeology Magazine, a Publication of the Archaeological Institute of America

I post these articles on shaman burials to show not all anthropologists or archaeologists disagree with me. The 12,000-year-old Shaman’s burial is from an anthropology-related article and the other is an archaeology-related article on a 9,000-year-old shaman’s burial.

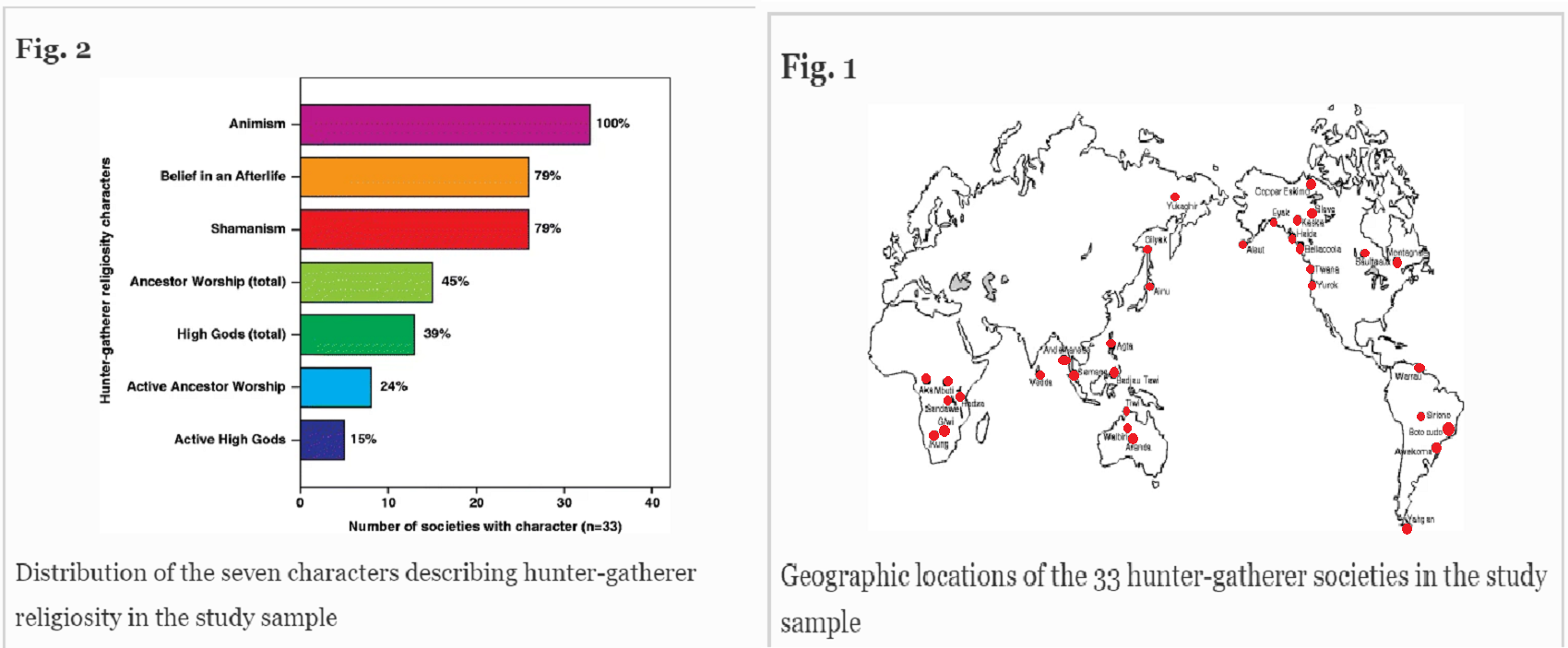

Hunter-Gatherers and the Origins of Religion (2016)

“The universality of religion across human society points to a deep evolutionary past.”

“Old animism” definitions?

“Earlier anthropological perspectives, which have since been termed the old animism, were concerned with knowledge on what is alive and what factors make something alive. The old animism assumed that animists were individuals who were unable to understand the difference between persons and things. Critics of the old animism have accused it of preserving “colonialist and dualistic worldviews and rhetoric.” ref

“The idea of animism was developed by anthropologist Sir Edward Tylor through his 1871 book Primitive Culture, in which he defined it as “the general doctrine of souls and other spiritual beings in general.” According to Tylor, animism often includes “an idea of pervading life and will in nature;” a belief that natural objects other than humans have souls. This formulation was little different from that proposed by Auguste Comte as “fetishism“, but the terms now have distinct meanings.” ref

“For Tylor, animism represented the earliest form of religion, being situated within an evolutionary framework of religion that has developed in stages and which will ultimately lead to humanity rejecting religion altogether in favor of scientific rationality. Thus, for Tylor, animism was fundamentally seen as a mistake, a basic error from which all religions grew. He did not believe that animism was inherently illogical, but he suggested that it arose from early humans’ dreams and visions and thus was a rational system. However, it was based on erroneous, unscientific observations about the nature of reality.” ref

“Stringer notes that his reading of Primitive Culture led him to believe that Tylor was far more sympathetic in regard to “primitive” populations than many of his contemporaries and that Tylor expressed no belief that there was any difference between the intellectual capabilities of “savage” people and Westerners. The idea that there had once been “one universal form of primitive religion” (whether labelled animism, totemism, or shamanism) has been dismissed as “unsophisticated” and “erroneous” by archaeologist Timothy Insoll, who stated that “it removes complexity, a precondition of religion now, in all its variants.” ref

“Tylor’s definition of animism was part of a growing international debate on the nature of “primitive society” by lawyers, theologians, and philologists. The debate defined the field of research of a new science: anthropology. By the end of the 19th century, an orthodoxy on “primitive society” had emerged, but few anthropologists still would accept that definition. The “19th-century armchair anthropologists” argued, that “primitive society” (an evolutionary category) was ordered by kinship and divided into exogamous descent groups related by a series of marriage exchanges. Their religion was animism, the belief that natural species and objects had souls.” ref

“With the development of private property, the descent groups were displaced by the emergence of the territorial state. These rituals and beliefs eventually evolved over time into the vast array of “developed” religions. According to Tylor, as society became more scientifically advanced, fewer members of that society would believe in animism. However, any remnant ideologies of souls or spirits, to Tylor, represented “survivals” of the original animism of early humanity.” ref

“New animism” non-archaic definitions

“Many anthropologists ceased using the term animism, deeming it to be too close to early anthropological theory and religious polemic. However, the term had also been claimed by religious groups—namely, Indigenous communities and nature worshippers—who felt that it aptly described their own beliefs, and who in some cases actively identified as “animists”. It was thus readopted by various scholars, who began using the term in a different way, placing the focus on knowing how to behave toward other beings, some of whom are not human. As religious studies scholar Graham Harvey stated, while the “old animist” definition had been problematic, the term animism was nevertheless “of considerable value as a critical, academic term for a style of religious and cultural relating to the world.” ref

‘‘Animism’’ Revisited (Current Anthropology Volume 40, Supplement, February 1999)

‘‘Animism’’ is projected in the literature as simple religion and a failed epistemology, to a large extent because it has hitherto been viewed from modernist perspectives. Previous theories, from classical to recent, are critiqued. An ethnographic example of a hunter-gatherer people is given to explore how animistic ideas operate within the context of social practices, with attention to local constructions of a relational personhood and to its relationship with ecological perceptions of the environment. A reformulation of their animism as a relational epistemology is offered. The concept of animism, which E. B. Tylor developed in his 1871 masterwork Primitive Culture, is one of anthropology’s earliest concepts, if not the first. The intellectual genealogy of central debates in the field goes back to it. Anthropology textbooks continue to introduce it as a basic notion, for example, as ‘‘the belief that inside ordinary visible, tangible bodies there is normally invisible, normally intangible being: the soul . . . each culture [having] its own distinctive animistic beings and its own specific elaboration of the soul concept’’ (Harris 1983:186).” ref

“Encyclopedias of anthropology commonly present it, for instance, as ‘‘religious beliefs involving the attribution of life or divinity to such natural phenomena as trees, thunder, or celestial bodies’’ (Hunter and Whitten 1976:12). The notion is widely employed within the general language of ethnology (e.g., Sahlins 1972:166, 180; Gudeman 1986:44; Descola 1996:88) and has become important in other academic disciplines as well, especially in studies of religion (as belief in spirit-beings) and in developmental psychology referring to children’s tendency to consider things as living and conscious). Moreover, the word has become a part of the general English vocabulary and is used in everyday conversations and in the popular media. It appears in many dictionaries, including such elementary ones as the compact school and office edition of Webster’s New World Dictionary (1989), which defines it as ‘‘the belief that all life is produced by a spiritual force or that all natural phenomena have souls.’’ It is found in mainstream compendia such as the Dictionary of the Social Sciences (Gould and Kolb 1965), which sums it up as ‘‘the belief in the existence of a separable soul-entity, potentially distinct and apart from any concrete embodiment in a living individual or material organism.” ref

“The term is presented in dictionaries of the occult: the Encyclopedia of Ghosts and Spirits (Guilei 1992), for example, defines it as ‘‘the system of beliefs about souls and spirits typically found in tribal societies,’’ and the Dictionary of Mysticism and the Occult (Drury 1985) defines it as ‘‘the belief, common among many pre-literate societies, that trees, mountains, rivers and other natural formations possess an animating power or spirit.’’ Amazingly, the century-old Tylorian concept appears in all these diverse sources (popular and academic, general and specific) revised little if at all. Animism, a 19th-century representation of an ethnographically researchable practice particularly conspicuous among indigenous peoples but by no means limited to them, is depicted by them all as an ‘‘object’’ in-the-world. The survival of the Tylorian representation is enigmatic because the logic underlying it is today questionable. Tylor was not as rigid a positivist as he is often made out to be (see Ingold 1986:94–96; Leopold 1980). However, he developed this representation within a positivistic spiritual/materialist dichotomy of 19th-century design in direct opposition to materialist science, in the belief and as part of an effort to prove this belief) that only science yielded ‘‘true’’ knowledge of the world. Furthermore, the moral implications of this representation are unacceptable now. Tylor posited that ‘‘animists’’ understood the world childishly and erroneously, and under the influence of 19th-century evolutionism he read into this cognitive underdevelopment.” ref

“Yet the concept still pervasively persists. Equally surprisingly, the ethnographic referent—the researchable cultural practices which Tylor denoted by the signifier/signified of ‘‘animism’’—has remained a puzzle despite the great interest which the subject has attracted. Ethnographers continue to cast fresh ethnographic material far richer than Tylor had (or could have imagined possible) into one or more of the Tylorian categories ‘‘religion,’’ ‘‘spirits,’’ and ‘‘supernatural beings’’ (e.g., Endicott 1979, Howell 1984, Morris 1981, Bird-David 1990, Gardner 1991, Feit 1994, Povinelli 1993, Riches 1994). At the same time, they have commonly avoided the issue of animism and even the term itself rather than revisit this prevalent notion in light of their new and rich ethnographies. A twofold vicious cycle has ensued. The more the term is used in its old Tylorian sense, without benefit of critical revision, the more Tylor’s historically situated perspective is taken as ‘‘real,’’ as the phenomenon which it only glosses, and as a ‘‘symbol that stands for itself’’ (Wagner 1981). In turn, anthropology’s success in universalizing the use of the term itself reinforces derogatory images of indigenous people whose rehabilitation from them is one of its popular roles.” ref

“As a hypothesis, furthermore, I am willing to agree with Tylor, not least because Guthrie goes some way towards substantiating the point, that the tendency to animate things is shared by humans. However, this common tendency, I suggest, is engendered by human socially biased cognitive skills, not by ‘‘survival’’ of mental confusion (Tylor) or by wrong perceptual guesses (Guthrie). Recent work relates the evolution of human cognition to social interaction with fellow humans. Its underlying argument is that interpersonal dealings, requiring strategic planning and anticipation of action-response-reaction, are more demanding and challenging than problems of physical survival (Humphrey 1976). Cognitive skills have accordingly evolved within and for a social kind of engagement and are ‘‘socially biased’’ (Goody 1995). We spontaneously employ these skills in situations when we cannot control or totally predict our interlocutor’s behavior, when its behavior is not predetermined but in ‘‘conversation’’ with our own.” ref

“We employ these skills in these situations, irrespective of whether they involve humans or other beings (the respective classification of which is sometimes part of reflective knowing, following rather than preceding the engagement situation). We do not first personify other entities and then socialize with them but personify them as, when, and because we socialize with them. Recognizing a ‘‘conversation’’ with a counter-being—which amounts to accepting it into fellowship rather than recognizing a common essence—makes that being a self in relation with ourselves. Finally, the common human disposition to frame things relationally in these situations is culturally mediated and contextualized in historically specific ways not least in relation with cultural concepts of the person). A diversity of animisms exists, each animistic project with its local status, history, and structure (in Sahlins’s [1985] sense).” ref

“There follow intriguing questions deserving study, for example: How does hunter-gatherer animism compare with the current radical environmental discourses (e.g., Kovel 1988, Leahy 1991, Regan 1983, Tester 1991) that some scholars have described as the ‘‘new animism’’ (Bouissac 1989; see also Kennedy’s ‘‘new anthropomorphism’’ [1992])? What other forms of animism are there? How do they articulate in each case with other cosmologies and epistemologies? How do animistic projects relate to fetish practices? Surely, however, the most intriguing question is why and how the modernist project estranged itself from the tendency to animate things, if it is indeed universal. How and why did it stigmatize ‘‘animistic language’’ as a child’s practice, against massive evidence see Guthrie 1993) to the contrary?” ref

“How did it succeed in delegitimating animism as a valid means to knowledge, constantly fending off the impulse to deploy it and regarding it as an ‘‘incurable disease’’ (see Kennedy 1992 and Masson and McCarthy 1995)? The answers are bound to be complex. Ernest Gellner (1988) argued that nothing less than ‘‘a near-miraculous concatenation of circumstances’’ can explain the cognitive shift that occurred in Western Europe around the 17th century. Ironically, history has it that Descartes—a reclusive man—was once accidentally locked in a steam room, where under hallucination he had the dualist vision on which the modern project is founded (see Morris 1991: 6). Can it be that a Tylorian kind of ‘‘dream thesis’’ helps explain not the emergence of primitive animism but, to the contrary, the modernist break from it?” ref

Animism: Respecting the Living World by Graham Harvey

“How have human cultures engaged with and thought about animals, plants, rocks, clouds, and other elements in their natural surroundings? Do animals and other natural objects have a spirit or soul? What is their relationship to humans? In this new study, Graham Harvey explores current and past animistic beliefs and practices of Native Americans, Maori, Aboriginal Australians, and eco-pagans. He considers the varieties of animism found in these cultures as well as their shared desire to live respectfully within larger natural communities. Drawing on his extensive casework, Harvey also considers the linguistic, performative, ecological, and activist implications of these different animisms.” ref

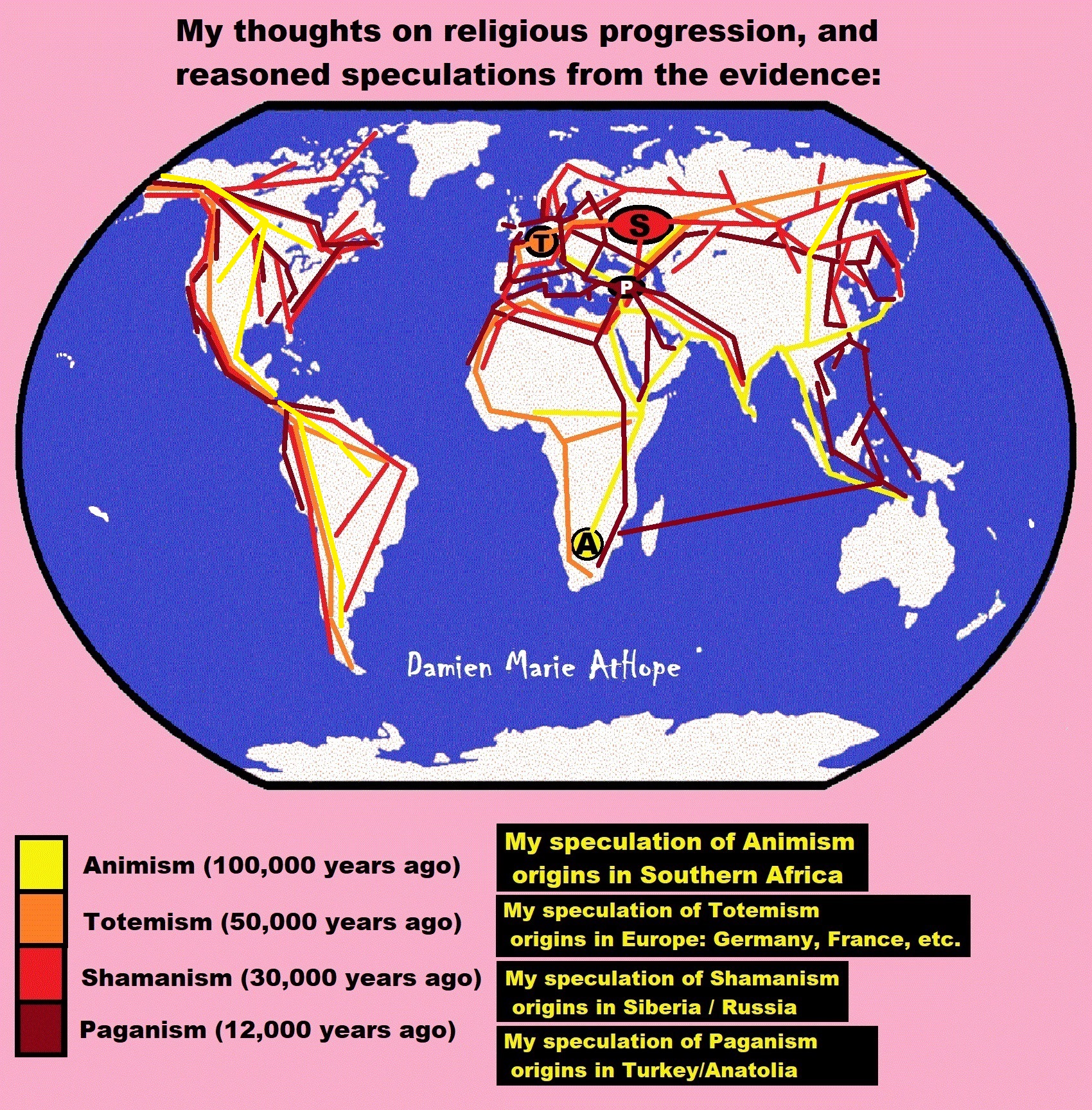

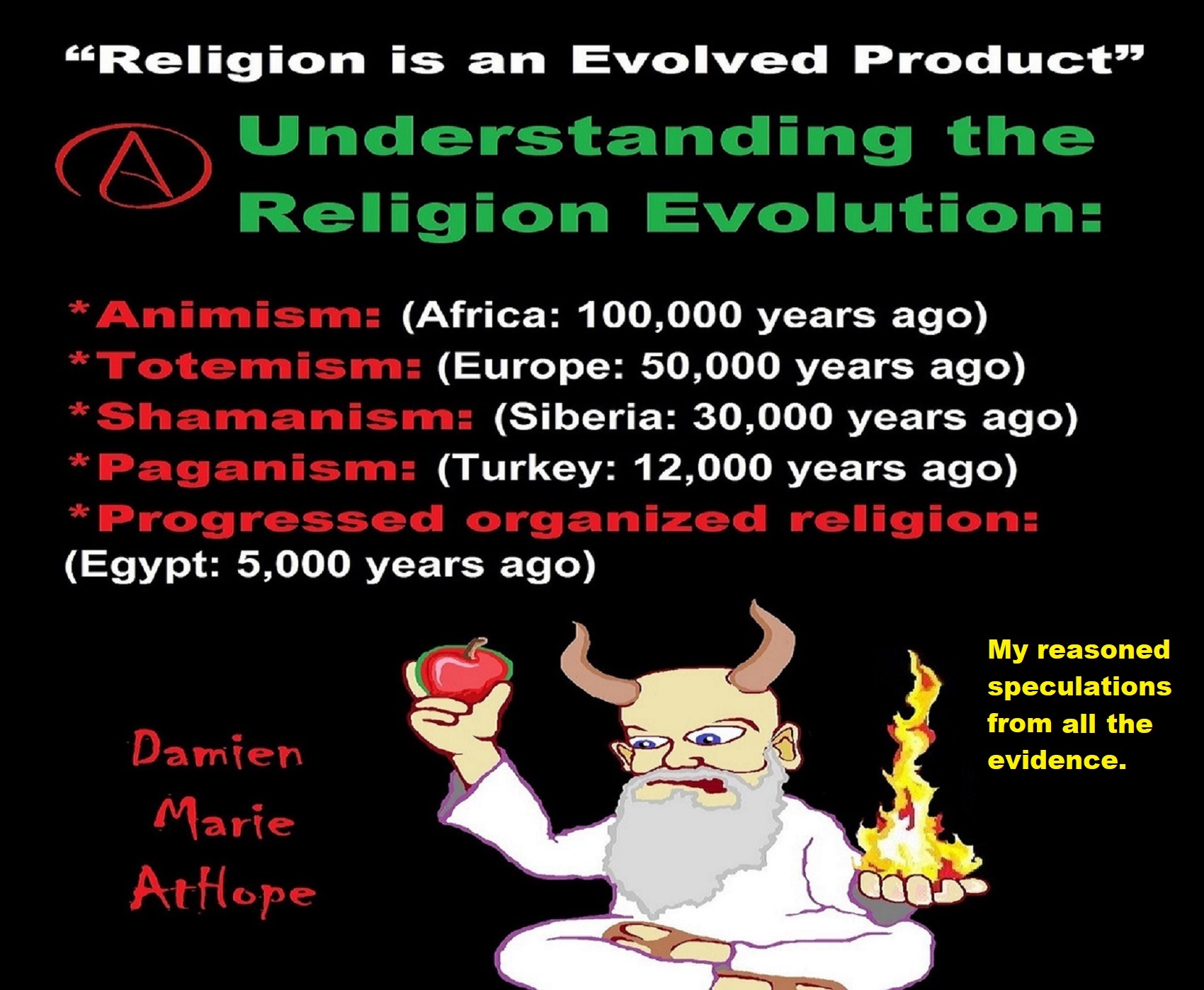

My Thoughts on Animism

I use the Animism term as a definition of spirit-beliefs or a kind of Supernatural-Spiritism thinking, that to me, are in all spiritual or religious type beliefs, not primitive but core. I see Animism as the original religion (religious non-naturalism/supernatural persuasion or spiritual/magical thinking) of all humanity and is still in all the religions of the world.

I don’t see religious terms Animism, Totemism, Shamanism, or Paganism as primitive but original or core elements that are different parts of world views and their supernatural/non-natural beliefs or thinking.

In the past or even lingering today, are beliefs often ripe with religious bigotry, seen in how religious/spiritual thinking not Abrahamic (Judaism, Christianity, or Islam) religious thinking are often believed to be primitive, unequal, or less than monotheism (preserved as the only real or not the correct religious beliefs if not monotheism).

I see all religions as having shared or similar features or core elements that relate to religious terms Animism, Totemism, Shamanism, or Paganism including Abrahamic (Judaism, Christianity, or Islam) religious thinking.

I don’t class any religious thinking as primitive but in error to what I see as a natural-only world, that religious thinking then makes up a myriad of non-natural/non-empirical themes/beings, stories, and myths about which group together are called religions.

I don’t believe there is a one and only one shamanism expression, any more than there is only one paganism, or almost any other religious thinking perspective or worldview. There is no one Christianity nor one Islam, neither is there only one Buddhism or one type of Hinduism.

Do I as an atheist, think there may be any chance I would ever go back to religion or become religious of any type?

My response, No, I don’t see myself believing in non-reality beliefs supported by faith. I don’t value faith. Atheism is a lack of belief in gods, so it doesn’t mean one can’t have other beliefs even religious or spiritual (whatever this loose term spiritual means). I am an atheist, antitheist, and antireligionist. So, I don’t enjoy attending any religious services nor follow any religious-themed teaching but understand others who are atheists may. People should do as they feel works for them.

Atheism

“Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there are no deities. Atheism is contrasted with theism, which in its most general form is the belief that at least one deity exists. The first individuals to identify themselves as atheists lived in the 18th century during the Age of Enlightenment. The French Revolution, noted for its “unprecedented atheism”, witnessed the first significant political movement in history to advocate for the supremacy of human reason. In 1967, Albania declared itself the first official atheist country according to its policy of state Marxism.” ref

“Writers disagree on how best to define and classify atheism, contesting what supernatural entities are considered gods, whether atheism is a philosophical position in its own right or merely the absence of one, and whether it requires a conscious, explicit rejection. However, the norm is to define atheism in terms of an explicit stance against theism. Before the 18th century, the existence of God was so accepted in the Western world that even the possibility of true atheism was questioned. This is called theistic innatism—the notion that all people believe in God from birth; within this view was the connotation that atheists are in denial. There is also a position claiming that atheists are quick to believe in God in times of crisis, that atheists make deathbed conversions, or that “there are no atheists in foxholes.” ref

“There have, however, been examples to the contrary, among them examples of literal “atheists in foxholes”. Some atheists have challenged the need for the term “atheism”. In his book Letter to a Christian Nation, Sam Harris wrote:

In fact, “atheism” is a term that should not even exist. No one ever needs to identify himself as a “non-astrologer” or a “non-alchemist“. We do not have words for people who doubt that Elvis is still alive or that aliens have traversed the galaxy only to molest ranchers and their cattle. Atheism is nothing more than the noises reasonable people make in the presence of unjustified religious beliefs.” ref

“In early ancient Greek, the adjective átheos (ἄθεος, from the privative ἀ- + θεός “god”) meant “godless”. It was first used as a term of censure roughly meaning “ungodly” or “impious”. In the 5th century BCE, the word began to indicate more deliberate and active godlessness in the sense of “severing relations with the gods” or “denying the gods”. The term ἀσεβής (asebēs) then came to be applied against those who impiously denied or disrespected the local gods, even if they believed in other gods. Modern translations of classical texts sometimes render átheos as “atheistic”. As an abstract noun, there was also ἀθεότης (atheotēs), “atheism”. Cicero transliterated the Greek word into the Latin átheos. The term found frequent use in the debate between early Christians and Hellenists, with each side attributing it, in the pejorative sense, to the other.” ref

“The term atheist (from the French athée), in the sense of “one who … denies the existence of God or gods”, predates atheism in English, being first found as early as 1566, and again in 1571. Atheist as a label of practical godlessness was used at least as early as 1577. The term atheism was derived from the French athéisme, and appears in English about 1587. An earlier work, from about 1534, used the term atheonism. Karen Armstrong writes that “During the 16th and 17th centuries, the word ‘atheist’ was still reserved exclusively for polemic … The term ‘atheist’ was an insult. Nobody would have dreamed of calling himself an atheist.” Atheism was first used to describe a self-avowed belief in late 18th-century Europe, specifically denoting disbelief in the monotheistic Abrahamic god. In the 20th century, globalization contributed to the expansion of the term to refer to disbelief in all deities, though it remains common in Western society to describe atheism as “disbelief in God.” ref

Discrimination Against Atheists

“Discrimination against atheists, sometimes called atheophobia, atheistophobia, or anti-atheism, both at present and historically, includes persecution of and discrimination against people who are identified as atheists. Discrimination against atheists may be manifested by negative attitudes, prejudice, hostility, hatred, fear, or intolerance towards atheists and atheism and is often based in distrust regardless of its manifestation. Perceived Atheist prevalence seems to be correlated with reduction in prejudice.” ref

“Because atheism can be defined in various ways, those discriminated against or persecuted on the grounds of being atheists might not have been considered atheists in a different time or place. Thirteen Muslim countries officially punish atheism or apostasy by death and Humanists International asserts that “the overwhelming majority” of the 193 member states of the United Nations “at best discriminate against citizens who have no belief in a god and at worst can jail them for offences dubbed blasphemy”. In some Muslim-majority countries, atheists face persecution and severe penalties such as the withdrawal of legal status or, in the case of apostasy, capital punishment.” ref

“Tim Whitmarsh argues atheism existed in the ancient world, though it remains difficult to assess its extent given that atheists are referenced (usually disparagingly) rather than having surviving writings. Given monotheism at the time was a minority view, atheism generally attacked polytheistic beliefs and associated practices in references found. The word “atheos” (godless) also was used for religious dissent generally (including the monotheists) which complicates study further. Despite these difficulties, Whitmarsh believes that otherwise atheism then was much the same. While atheists (or people perceived as such) were occasionally persecuted, this was rare (perhaps due to being a small group, plus a relative tolerance toward different religious views). Other scholars believe it arose later in the modern era. Lucien Febvre has referred to the “unthinkability” of atheism in its strongest sense before the sixteenth century, because of the “deep religiosity” of that era. Karen Armstrong has concurred, writing “from birth and baptism to death and burial in the churchyard, religion dominated the life of every single man and woman.” ref

“Every activity of the day, which was punctuated by church bells summoning the faithful to prayer, was saturated with religious beliefs and institutions: they dominated professional and public life—even the guilds and the universities were religious organizations. … Even if an exceptional man could have achieved the objectivity necessary to question the nature of religion and the existence of God, he would have found no support in either the philosophy or the science of his time.” As governmental authority rested on the notion of divine right, it was threatened by those who denied the existence of the local god. Those labeled as atheist, including early Christians and Muslims, were as a result targeted for legal persecution.” ref

“During the early modern period, the term “atheist” was used as an insult and applied to a broad range of people, including those who held opposing theological beliefs, as well as those who had committed suicide, immoral or self-indulgent people, and even opponents of the belief in witchcraft. Atheistic beliefs were seen as threatening to order and society by philosophers such as Thomas Aquinas. Lawyer and scholar Thomas More said that religious tolerance should be extended to all except those who did not believe in a deity or the immortality of the soul. John Locke, a founder of modern notions of religious liberty, argued that atheists (as well as Catholics and Muslims) should not be granted full citizenship rights.” ref

“During the Inquisition, several of those who were accused of atheism or blasphemy, or both, were tortured or executed. These included the priest Giulio Cesare Vanini who was strangled and burned in 1619 and the Polish nobleman Kazimierz Łyszczyński who was executed in Warsaw, as well as Etienne Dolet, a Frenchman executed in 1546. Though heralded as atheist martyrs during the nineteenth century, recent scholars hold that the beliefs espoused by Dolet and Vanini are not atheistic in modern terms. Baruch Spinoza was effectively excommunicated from the Sephardic Jewish community of Amsterdam for atheism, though he did not claim to be an atheist.” ref

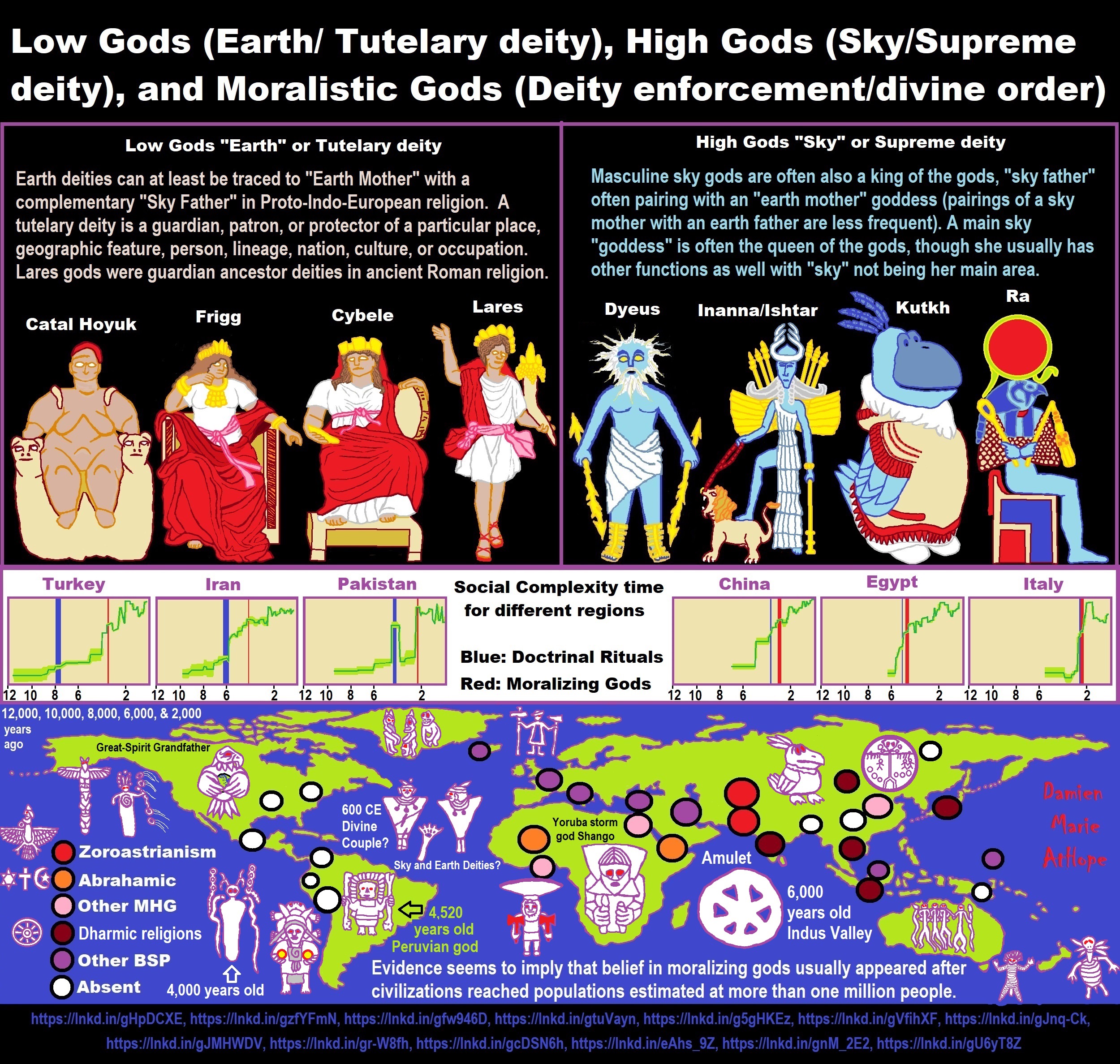

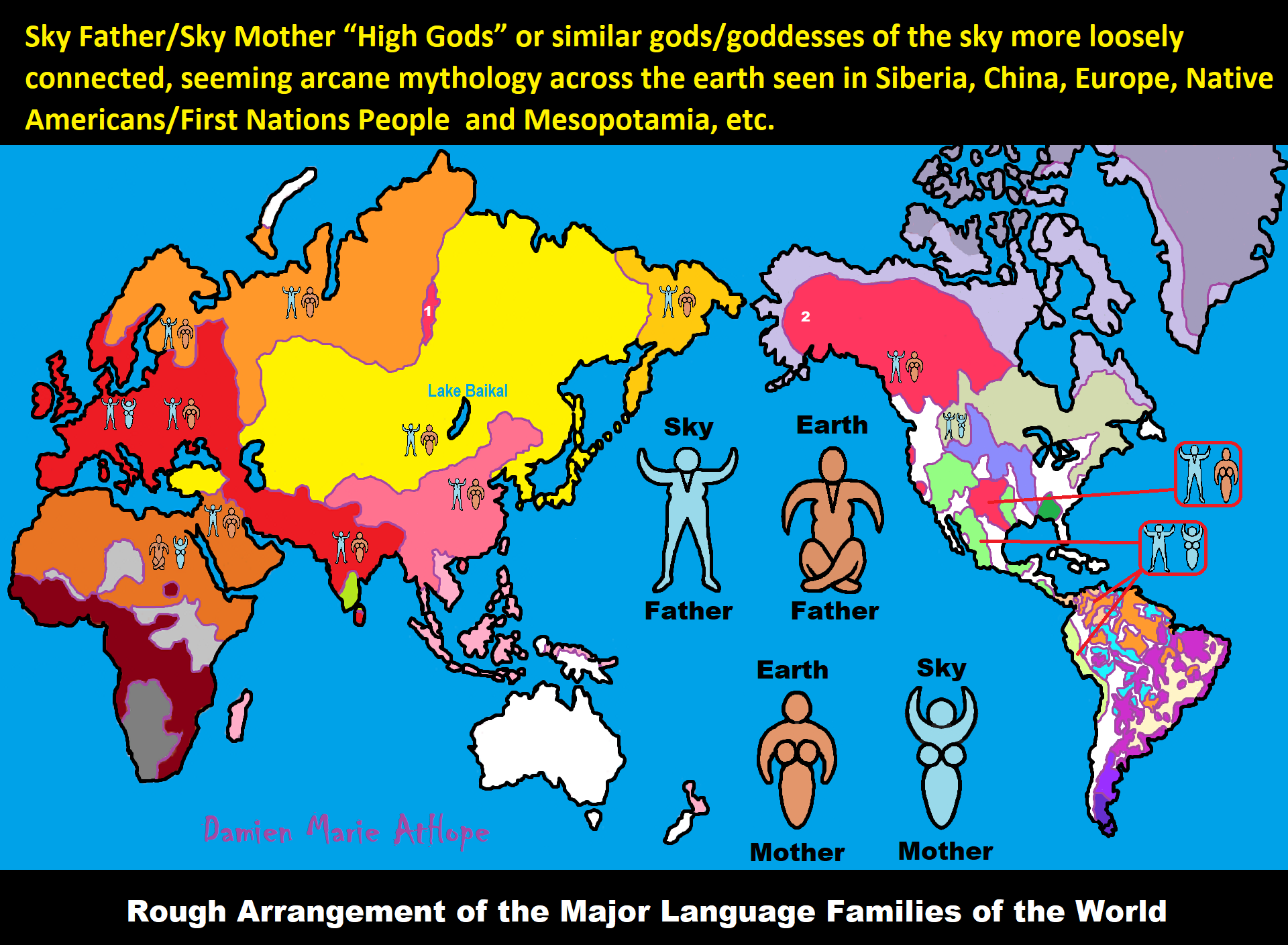

Totemism

“Confounding animism with totemism? In 1869 (three years after Tylor proposed his definition of animism), Edinburgh lawyer John Ferguson McLennan, argued that the animistic thinking evident in fetishism gave rise to a religion he named totemism. Primitive people believed, he argued, that they were descended from the same species as their totemic animal. Subsequent debate by the “armchair anthropologists” (including J. J. Bachofen, Émile Durkheim, and Sigmund Freud) remained focused on totemism rather than animism, with few directly challenging Tylor’s definition. Anthropologists “have commonly avoided the issue of animism and even the term itself, rather than revisit this prevalent notion in light of their new and rich ethnographies.” ref

“According to anthropologist Tim Ingold, animism shares similarities with totemism but differs in its focus on individual spirit beings which help to perpetuate life, whereas totemism more typically holds that there is a primary source, such as the land itself or the ancestors, who provide the basis to life. Certain indigenous religious groups such as the Australian Aboriginals are more typically totemic in their worldview, whereas others like the Inuit are more typically animistic.” ref

“From his studies into child development, Jean Piaget suggested that children were born with an innate animist worldview in which they anthropomorphized inanimate objects and that it was only later that they grew out of this belief. Conversely, from her ethnographic research, Margaret Mead argued the opposite, believing that children were not born with an animist worldview but that they became acculturated to such beliefs as they were educated by their society.” ref

“Stewart Guthrie saw animism—or “attribution” as he preferred it—as an evolutionary strategy to aid survival. He argued that both humans and other animal species view inanimate objects as potentially alive as a means of being constantly on guard against potential threats. His suggested explanation, however, did not deal with the question of why such a belief became central to the religion. In 2000, Guthrie suggested that the “most widespread” concept of animism was that it was the “attribution of spirits to natural phenomena such as stones and trees.” ref

“Totemism, system of belief in which humans are said to have kinship or a mystical relationship with a spirit-being, such as an animal or plant. The entity, or totem, is thought to interact with a given kin group or an individual and to serve as their emblem or symbol. The term totemism has been used to characterize a cluster of traits in the religion and in the social organization of many peoples. Totemism is manifested in various forms and types in different contexts and is most often found among populations whose traditional economies relied on hunting and gathering, mixed farming with hunting and gathering, or emphasized the raising of cattle. Totemism is a complex of varied ideas and ways of behavior based on a worldview drawn from nature. There are ideological, mystical, emotional, reverential, and genealogical relationships of social groups or specific persons with animals or natural objects, the so-called totems.” ref

“The term totem is derived from the Ojibwa word ototeman, meaning “one’s brother-sister kin.” The grammatical root, ote, signifies a blood relationship between brothers and sisters who have the same mother and who may not marry each other. In English, the word totem was introduced in 1791 by a British merchant and translator who gave it a false meaning in the belief that it designated the guardian spirit of an individual, who appeared in the form of an animal—an idea that the Ojibwa clans did indeed portray by their wearing of animal skins. It was reported at the end of the 18th century that the Ojibwa named their clans after those animals that live in the area in which they live and appear to be either friendly or fearful. The first accurate report about totemism in North America was written by a Methodist missionary, Peter Jones, himself an Ojibwa, who died in 1856 and whose report was published posthumously. According to Jones, the Great Spirit had given toodaims (“totems”) to the Ojibwa clans, and because of this act, it should never be forgotten that members of the group are related to one another and on this account may not marry among themselves.” ref

“A totem (from Ojibwe: ᑑᑌᒼ or ᑑᑌᒻ doodem) is a spirit being, sacred object, or symbol that serves as an emblem of a group of people, such as a family, clan, lineage, or tribe, such as in the Anishinaabe clan system. While the word totem itself is an anglicisation of the Ojibwe term (and both the word and beliefs associated with it are part of the Ojibwe language and culture), belief in tutelary spirits and deities is not limited to the Ojibwe people.” ref

“Similar concepts, under differing names and with variations in beliefs and practices, may be found in a number of cultures worldwide. The term has also been adopted, and at times redefined, by anthropologists and philosophers of different cultures. Contemporary neoshamanic, New Age, and mythopoetic men’s movements not otherwise involved in the practice of a traditional, tribal religion have been known to use “totem” terminology for the personal identification with a tutelary spirit or spirit guide. However, this can be seen as cultural misappropriation.” ref

“The totem poles of the Pacific Northwestern Indigenous peoples of North America are carved, monumental poles featuring many different designs (bears, birds, frogs, people, and various supernatural beings and aquatic creatures). They serve multiple purposes in the communities that make them. Similar to other forms of heraldry, they may function as crests of families or chiefs, recount stories owned by those families or chiefs, or commemorate special occasions. These stories are known to be read from the bottom of the pole to the top.” ref

“The spiritual, mutual relationships between Aboriginal Australians, Torres Strait Islanders, and the natural world are often described as totems. Many Indigenous groups object to using the imported Ojibwe term “totem” to describe a pre-existing and independent practice, although others use the term. The term “token” has replaced “totem” in some areas. In some cases, such as the Yuin of coastal New South Wales, a person may have multiple totems of different types (personal, family or clan, gender, tribal and ceremonial). The lakinyeri or clans of the Ngarrindjeri were each associated with one or two plant or animal totems, called ngaitji. Totems are sometimes attached to moiety relations (such as in the case of Wangarr relationships for the Yolngu). Torres Strait Islanders have auguds, typically translated as totems. An augud could be a kai augud (“chief totem”) or mugina augud (“little totem”).” ref

“Early anthropologists sometimes attributed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander totemism to ignorance about procreation, with the entrance of an ancestral spirit individual (the “totem”) into the woman believed to be the cause of pregnancy (rather than insemination). James George Frazer in Totemism and Exogamy wrote that Aboriginal people “have no idea of procreation as being directly associated with sexual intercourse, and firmly believe that children can be born without this taking place”. Frazer’s thesis has been criticised by other anthropologists, including Alfred Radcliffe-Brown in Nature in 1938.” ref

“Early anthropologists and ethnologists like James George Frazer, Alfred Cort Haddon, John Ferguson McLennan and W. H. R. Rivers identified totemism as a shared practice across indigenous groups in unconnected parts of the world, typically reflecting a stage of human development. Scottish ethnologist John Ferguson McLennan, following the vogue of 19th-century research, addressed totemism in a broad perspective in his study The Worship of Animals and Plants (1869, 1870). McLennan did not seek to explain the specific origin of the totemistic phenomenon but sought to indicate that all of the human race had, in ancient times, gone through a totemistic stage.” ref

“Another Scottish scholar, Andrew Lang, early in the 20th century, advocated a nominalistic explanation of totemism, namely, that local groups or clans, in selecting a totemistic name from the realm of nature, were reacting to a need to be differentiated. If the origin of the name was forgotten, Lang argued, there followed a mystical relationship between the object—from which the name was once derived—and the groups that bore these names. Through nature myths, animals and natural objects were considered as the relatives, patrons, or ancestors of the respective social units. British anthropologist Sir James George Frazer published Totemism and Exogamy in 1910, a four-volume work based largely on his research among Indigenous Australians and Melanesians, along with a compilation of the work of other writers in the field.” ref

“By 1910, the idea of totemism as having common properties across cultures was being challenged, with Russian American ethnologist Alexander Goldenweiser subjecting totemistic phenomena to sharp criticism. Goldenweiser compared Indigenous Australians and First Nations in British Columbia to show that the supposedly shared qualities of totemism—exogamy, naming, descent from the totem, taboo, ceremony, reincarnation, guardian spirits and secret societies and art—were actually expressed very differently between Australia and British Columbia, and between different peoples in Australia and between different peoples in British Columbia. He then expands his analysis to other groups to show that they share some of the customs associated with totemism, without having totems. He concludes by offering two general definitions of totemism, one of which is: “Totemism is the tendency of definite social units to become associated with objects and symbols of emotional value.” ref

“The founder of a French school of sociology, Émile Durkheim, examined totemism from a sociological and theological point of view, attempting to discover a pure religion in very ancient forms and claimed to see the origin of religion in totemism. In addition, he argued that totemism also served as a form of collective worship, reinforcing social cohesion and solidarity. The leading representative of British social anthropology, A. R. Radcliffe-Brown, took a totally different view of totemism. Like Franz Boas, he was skeptical that totemism could be described in any unified way. In this, he opposed the other pioneer of social anthropology in England, Bronisław Malinowski, who wanted to confirm the unity of totemism in some way and approached the matter more from a biological and psychological point of view than from an ethnological one.” ref

“According to Malinowski, totemism was not a cultural phenomenon, but rather the result of trying to satisfy basic human needs within the natural world. As far as Radcliffe-Brown was concerned, totemism was composed of elements that were taken from different areas and institutions, and what they have in common is a general tendency to characterize segments of the community through a connection with a portion of nature. In opposition to Durkheim’s theory of sacralization, Radcliffe-Brown took the point of view that nature is introduced into the social order rather than secondary to it. At first, he shared with Malinowski the opinion that an animal becomes totemistic when it is “good to eat.” He later came to oppose the usefulness of this viewpoint, since many totems—such as crocodiles and flies—are dangerous and unpleasant. In 1938, the structural functionalist anthropologist A. P. Elkin wrote The Australian Aborigines: How to understand them. His typologies of totemism included eight “forms” and six “functions.” ref

“The forms identified totemism were:

- individual (a personal totem),

- sex (one totem for each gender),

- moiety(the “tribe” consists of two groups, each with a totem),

- section (the “tribe” consists of four groups, each with a totem),

- subsection (the “tribe” consists of eight groups, each with a totem),

- clan (a group with common descent share a totem or totems),

- local (people living or born in a particular area share a totem) and

- “multiple” (people across groups share a totem).” ref

“The functions identified were:

- social (totems regulate marriage, and often a person cannot eat the flesh of their totem),

- cult (totems associated with a secret organization),

- conception (multiple meanings),

- dream (the person appears as this totem in others’ dreams),

- classificatory (the totem sorts people) and

- assistant (the totem assists a healer or clever person).” ref

“The terms in Elkin’s typologies see some use today, but Aboriginal customs are seen as more diverse than his typologies suggest. As a chief representative of modern structuralism, French ethnologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, and his Le Totémisme aujourd’hui (“Totemism Today” [1958]) are often cited in the field. In the 21st century, Australian anthropologists question the extent to which “totemism” can be generalized even across different Aboriginal Australian peoples, let alone to other cultures like the Ojibwe from whom the term was originally derived. Rose, James, and Watson write that: The term ‘totem’ has proved to be a blunt instrument. Far more subtlety is required, and again, there is regional variation on this issue.” ref

“Instances of the naming of clans for natural species among North American peoples were known long before the practice came to be called totemism. By the time the origin, significance, and definition of totemism became a major topic of controversy among theorists of tribal religion, the area of ethnographic exemplification had shifted from the Americas to central Australia. This shift was in part a consequence of the splendid ethnography of Baldwin Spencer and Francis James Gillen, but it also coincided with the widespread adoption of the evolutionist notion of the “psychic unity of mankind.” According to this idea, human culture was essentially unitary and universal, having arisen everywhere through the same stages, so that if we could identify a people who were “frozen” into an earlier stage, we would observe modes of thought and action that were directly ancestral to our own. Australia, a continent populated originally by hunting and gathering peoples alone, seemed to furnish examples of the most primitive stages available.” ref

“Together with the concept of taboo, and perhaps also that of mana, totemism became, for the later cultural evolutionists, the emblem (or perhaps the “totem”) of primitive thought or religion—its hallmark, and therefore also the key to its suspected irrationality. The origin and significance of totemism became the subject of widespread theoretical speculation during the first two decades of the twentieth century. Much of the early theorization developed along the lines of E. B. Tylor’s conception of the evolution of the soul (for example, totemic species as representations or repositories of the soul), or as literalizations of names (as in Herbert Spencer‘s hypothesis that totems arose from an aberration in nicknaming).” ref

“The controversy over totemism reached its peak after the publication of Frazer’s Totemism and Exogamy (1910). In that work, Frazer distinguished totemism, as implying a relationship of equality or kinship with the totem, from religion, as a relationship with higher powers. He emphasized the solidarity function of totemism, which knits people into social groups, as a contribution to the “cause of civilization.” Frazer’s speculation concerning the origin of totemism, however, came more and more to reflect the particulars of his Australian exemplars. From an initial theory identifying the totem as a repository for a soul entrusted to it for safekeeping, Frazer turned to an explanation based on the Intichiuma rites of central desert Aborigines, in which each subgroup is responsible for the ritual replenishment of some (economically significant) natural species. The idea of the economic basis of totemism was later revived, in simplified form, by Bronislaw Malinowski. Finally, Frazer developed the “conception theory” of totemism, on the model of the Aranda people of central Australia, according to which a personal totem is identified for a child by its mother on the basis of experiences or encounters at the moment she becomes aware that she is pregnant. A creature or feature of the land thus “signified” becomes the child’s totem.” ref

“In 1910, Goldenweiser, who had studied under Boas, published “Totemism: An Analytical Study,” an essay that became the definitive critique of “evolutionary” totemism. Goldenweiser called into question the unitary nature of the phenomenon, pointing out that there was no necessary connection between the existence of clans, the use of totemic designations for them, and the ideology of a relationship between human beings and totemic beings. Each of these phenomena, he argued, could in many cases be shown to exist independently of the others, so that totemism appeared less an institution or religion than an adventitious combination of simpler and more widespread usages.” ref

“Despite the acuity and ultimate persuasiveness of Goldenweiser’s arguments, the more creative “evolutionary” theories appeared in the years after the publication of his critique. Like Frazer’s theory, Durkheim’s conception of totemism is exemplified primarily through Australian ethnography. Durkheim viewed totemism as dominated by what he called a quasi-divine principle (Durkheim, 1915, p. 235), one that turned out to be none other than the representation of the social group or clan itself, presented to the collective imagination in the symbolic form of the creature that serves as the totem. Totemism, then, was a special case of the argument of Elementary Forms of the Religious Life, a work stating that religion is the form in which society takes account of (reveres, worships, fears) its own collective force.” ref

“Sigmund Freud included the concept of totemism, as an exemplar (like the notion of taboo) of contemporary ideas of primitive thought, in his psychodynamic reassessment of cultural and religious forms. Freud’s Totem and Taboo (1918) projected human culture as the creative result of a primal oedipal guilt. The totem was selected and revered as a substitute for the murdered father, and totemic exogamy functioned as an expiatory resignation on the part of the sons of claims to the women freed by the murder of the father.” ref

“In the last major theoretical treatment of “evolutionary” totemism, Arnold van Gennep argued, against Goldenweiser, that its status as a particular combination of three elements did not disqualify totemism’s integrity as a phenomenon. Yet Gennep rejected the views of Durkheim and other social determinists to the effect that totemic categorization was based on social interests. Anticipating Lévi-Strauss, who based his later views on this position (Lévi-Strauss, 1966, p. 162), Gennep saw totemism as a special case of the more general cultural phenomenon of classification, although he did not pursue the implications of this position to the degree that Lévi-Strauss did.” ref

“Claude Lévi-Strauss’s modern critique effectively concludes the attack on evolutionary totemism begun by Goldenweiser, although it aims at the term totemism itself. In Totemism (1963), Lévi-Strauss critically reviews the history of the subject and reaches the conclusion that totemism is the illusory construct of an earlier period in anthropological theory. Reviewing the more recent ethnographic findings of writers like Meyer Fortes and Raymond Firth, he arrives at the proposition that it is the differences alone, among a series of totemic creatures, that serve to distinguish the corresponding human social units. He disavows, in other words, any sort of analogic relationship (of substance, origin, identity, or interest) between a totem and its human counterpart, and he thus reduces totemism to a special case of denomination or designation. This leaves unexplained (or reduces to mere detail) perhaps the bulk of the ethnographic material to totemism, concerned as it is with special ties and relationships between totem and human unit. In order to deal with this question, Lévi-Strauss developed, in The Savage Mind (1966), his notion of the “science of the concrete,” in which totemic “classifications” are but a special instance of a more widespread tradition of qualitative logic. Thus Lévi-Strauss is able to substitute the systematic tendencies of an abstract classifying schema for the specific relations between a totem and its social counterpart.” ref

“What is the place of totemism in the life of an ongoing community? Consider the Walbiri, an Aboriginal people of the central Australian desert. Walbiri men are divided into about forty lines of paternal descent, each associated with a totemic lodge devoted to the lore and ritual communication with an ancestral Dreaming totem (kangaroo, wallaby, rain, etc.). When they enact the Dreaming rituals, the men are believed to enter the “noumenal” phase of existence (Meggitt, 1972, p. 72) and to merge with the totemic ancestors themselves. Here the analogies between human beings and totemic creatures are sacramentally transformed into identities, made ritually into real relationships of mutual origin and creation, so that men of the different lodges actually belong to different totemic species. When the ritual is concluded, however, they return to everyday “phenomenal” existence and reassume their human character, so that the totemic designations revert to mere names, linked to respective moieties, linked subsections, and other constituents of the complex Walbiri social structure.” ref

“Thus the “noumenal phase” of Walbiri life, the ritual state, is constituted by the analogies drawn between human beings and their totems, whereas in the “phenomenal phase” these analogies collapse into arbitrary labels. Only in the latter phase does Lévi-Strauss’s proposition about the “differences alone” being the basis for coding human groups apply, for, as human beings, the members of these subsections and moieties can marry one another’s sisters and daughters, something that different species cannot do. Within the same culture, in other words, totemic distinctions can serve either as “labels,” to code the differences or distinctions among human groups, or, by expanding into metaphoric analogues, accomplish the religious differentiation of men into different “species.” ref

“The totemic symbolization of social units is, in many cultures, integrated into a larger or more comprehensive categorial or cosmological scheme, so that the totemic creatures themselves may be organized into broader categories. Among the Ojibwa of North America, totems are grouped according to habitat (earth, air, or water). Aboriginal Australia is distinctive in carrying this tendency to the extreme of “totem affiliation,” in which all the phenomena of experience, including colors, human implements, traits, weather conditions, as well as plants and animals, are assigned and grouped as totems (Brandenstein, 1982, p. 87). These universalized systems, in turn, are generally organized in terms of an overarching duality of principles. Brandenstein identifies three of these—quick/slow, warm/cold, and round/flat (large/small)—as generating, in their various permutations and combinations, the totemic-classificatory systems of aboriginal Australia (ibid., pp. 148–149). A similarly comprehensive system is found among the Zuni of the American Southwest, for whom totemic clans are grouped in respective association with seven directional orientations (the four directions, plus zenith, nadir, and center), which are also linked to corresponding colors, social functions, and, in some cases, seasons.” ref

“At the other extreme is individuating, or particularizing totemism, for the individual is also a social unit. Among the Sauk and Osage of North America, traits, qualities, or attributes of a clan totem will be assigned to clan members, as personal names, so that members of the Black Bear clan will be known for its tracks, its eyes, the female of the species, and so on (Lévi-Strauss, 1966, p. 173). Among the Kujamaat Diola of Senegal, on the other hand, individuals are totemized secretly through relationships with personalized animal doubles, which are produced by defecation from their own bodies, and which live in the bush near their dwellings (Sapir, 1977). Among the Usen Barok of New Ireland, individual names are taken from plant or animal manifestations of the essentially formless masalai, or tutelary clan spirit. Wherever personal names are conceived of as a relation between the bearer of the name and some phenomenal entity, we can consider naming itself to be a form of individual totemism.” ref

“Totemic individuation of this sort, in which the character of the name itself bears a specific relational significance, occurs frequently in the naming of modern sports teams, and in formal or informal national symbols, such as the eagle or the bear. Totemism has been proposed as the antecedent of the syncretistic religion of ancient Egypt, with possible indirect connections to the Greco-Roman pantheon. Predynastic Egypt was subdivided into a large number of local territorial units called nomes, each identified through the worship of a particular theriomorphic deity. As the unification of Egypt involved the political joining of these nomes, so the evolution of Egyptian religion led to the combining of the totemic creatures into compound deities such as Amun-Re (“ram-sun”), or Re-Harakhte (“sun-hawk”). There are possible archaic connections of these theriomorphic deities, with Homeric Greek divinities: for example, the cow Hathor with the “ox-eyed Hera.” Alternatively, of course, these divinities may have acquired such characterizations as the heritage of an indigenous totemism.” ref

“Totemism may not be the key to “primitive thought” that Frazer, Durkheim, and Freud imagined it to be, but the use of concrete phenomenal images as a means of differentiation is not easily explained away as merely another mode of designation, or naming. Wherever social units of any kind—individuals, groups, clans, families, corporations, sports teams, or military units—are arrayed on an equal footing and in “symmetrical” opposition to one another, the possibility arises of transforming a mere quantitative diversity into qualitative meaning through the use of concrete imagery. Diversity is then not merely encoded but instead enters the dimension of meaning, of identity as a concrete, positive quality.” ref

“Whenever we speak of a sports team as the Braves, Indians, Cubs, or Vikings, or speak of the Roman, American, German, or Polish eagle, or consider Raven, Eagle, and Killer Whale clans, we make the differences among the respective units something more than differences, and we give each unit a center and a significance of its own. Whenever this occurs, the possibility arises of developing this significance, to a greater or lesser degree, into a profound relationship of rapport, communion, power, or mythic origin. Viewed in this light, the “totems” of a social entity become markers and carriers of its identity and meaning; to harm or consume the totem may well, under certain cultural circumstances, become a powerful metaphor for the denial of qualitative meaning. When theorists of totemism sought to explain the phenomenon solely in terms of the food quest, marriage restrictions, coding, or classification, they subverted the force of cultural meaning to considerations that would find an easier credibility in a materialistically and pragmatically oriented society, “consuming,” as it were, meaning through its markers and carriers.” ref

“The ostensibly “primitive” character of totemism is an illusion, based on a tendency of literate traditions to overvalue abstraction and to reduce the rich and varied spectrum of meaning to the barest requirements of information coding. In fact abstract reference and concrete image are inextricably interrelated; they imply each other, and neither can exist without the other. Certainly, peoples whose social organizations lack hierarchy and organic diversity (e.g., social class or the division of labor) tend to develop and dramatize a qualitative differentiation through the imagery of natural species, whereas those whose social units show an organic diversity need not resort to a symbolic differentiation. The choice, however, is not a matter of primitiveness or sophistication but rather of the complementarity between social form and one of two equally sophisticated, and mutually interdependent, symbolic alternatives.” ref

Can Totemism Save The World?

“The totemic religion is a blend of diverse concepts and ways of conduct established on a viewpoint that originates from the environment and is associated with a fundamental doctrine based on totems. Totems are a form of representation of the bonds humans have with the environment, including with animals, plants and natural inanimate objects. According to DW, totems serve as the symbol of a family, group or tribe that has ancestral connections. Monuments that portray totem animals can be seen throughout different cultures around the globe. Totemism is not only common across North America, but it is also seen in Africa and Oceania. Several groups around the world are linked with animals which are represented in various ways. Those that have a totem bestowed to them, being it personal or a group totem, connect emotionally and with profound respect with their totem.” ref

“The symbolic meanings of the totems are usually accompanied by the taboo of killing, hurting or disturbing your totem in any way as they are believed to have special spiritual and cultural associations. To harm or disrupt your totem is heavily looked down upon. Groups believe they are born from such totems, which has led some conservationists to question whether totemism might be an effective tool for conservation. Since these taboos exist, totems are protected by individuals or groups, which increases species and environmental conservation. Conservationists intend to use these taboos and beliefs to additionally help create higher protection rates for endangered species and habitats. If groups could reinvent the taboo of killing or harming these animals, it can be a useful form of conservation, such as the Urhobos tribal communities in the Niger Delta caring for the pythons. Species may be protected by community through traditional beliefs and taboos. Traditional belief systems may also play an important role in the conservation of natural resources.” ref

“Stephen Hopper is a professor at the University of Western Australia and a botanist who specializes in conservation biology. He believes totemism is a great environmental practice. For the last 10 years, Hopper has worked with elders of the Noongar aboriginal tribe in South Western Australia. He was bestowed totems by elders of the Noongar tribe while on a trip to the Outback, where he asked if “white blokes” could have them as well. Hopper’s totems include the black snake, pink eucalyptus tree, kangaroo puller plant, honeyeater birds, red-tailed black cockatoo and the honey possum. He has his fair share of totems, because as a botanist and conservationist, he is trying to protect as much of the flora and fauna as he can.” ref

“It became clearly apparent that western technological societies are struggling despite efforts,” says Hopper. He believes first nations have some cultural approaches that would be beneficial in terms of conservation. As stated by Hopper, Noongar people are deeply connected to the planet as most first nations are. Each of them are bestowed with an animal and plant totem at birth, and some additional totems can be acquired throughout life. When a person is bestowed with a totem, it is important to keep in mind that they become that organism, that organism becomes them, according to Hopper. “If your totem is in trouble, you are in trouble.” he says. “It’s on you to care for your totem, learn about it, and this is a lifelong commitment you make.” ref

“Sharing his own take on totemism, Hopper sees it to be a very simple cultural construct that shows a lot of promise for western societies to do a much better job at caring for land, plants and animals. Hopper firmly believes there are far too many species threatened on the planet for a single government, university or any organization to look out for them. However, he is confident that if every individual or organization, from small to large, decided to adopt just one animal and one plant from their local areas as a totem, the number of people caring for these threatened creatures would astronomically increase and give a much brighter prospect for their survival.” ref

“To create development in a sustainable manner means to accommodate present needs without affecting the resources and overall potential to meet needs in the future. According to a study in the Journal of Natural Sciences Research, biodiversity depletion is an ongoing problem around the world. Human activity is affecting the supplies of natural resources available on the planet. Environmental indigenous practices could promote environmental preservation. Advocating alternative indigenous methods of species conservation in the environment may be helpful. Indigenous peoples face environmental challenges with their ancient knowledge they have of the land.” ref

“To have indigenous peoples helping in conservation using their beliefs to benefit nature has shown positive results. The relationships between indigenous peoples and the environment is ingrained in the beliefs they hold. This connection started to be appreciated as the environmental concerns continue to rise. Scientists, such as Hopper, are trying to use the knowledge of indigenous peoples to help in conservation efforts. Indigenous cultural traditions contain key thoughts and processes that would help communities better care for diversity. A clear demand is upon humanity to do whatever it can to start developing sustainably, and a way to do so might be through appreciation of the indigenous cultural values that entail conservation.” ref

Totemism and Environmental Preservation among Nembe People in the South-South Zone, Nigeria

“Abstract (2014): This study explored environmental indigenous practices that could promote environmental preservation among the people of Nembe in Bayelsa State. In spite of much concerns of both local and international bodies in the quest to preserve species in the environment, their efforts have not been fully successful in achieving such goals. Yet, measures to control species extinctions prove to no avail. In the view of this, alternative indigenous methods of species conservation in the environment must be advocated. The descriptive design was adopted, while theoretical triangulation of functionalism, symbolic interactionism and biocentrism were used as theoretical frameworks of analysis. 382 respondents participated in the study using the instruments of questionnaire as well as 5 key informants’ interviewees (KII). Stratified random sample was employed for the selection of respondents as well as purposive sampling for the selection of key informants interviewees (KII) across the five communities (namely, Ogolomabiri, Basanbiri, Odeama, Okpoama and Brass) that constitutes the people of Nembe. Simple percentages and pie chart descriptive statistical tools were used for the analysis of the data collected for the study. Findings showed that totemism as an indigenous practice promotes species conservation which include python, eagle, shark, zimbaerema and snails with minimal threats or risks to the social environment. In the view of the findings of the study, policy instruments were provided in order to facilitate the design of environmental policies such as the establishment of zoos and game reserves, public enlightenment campaigns to encourage indigenous environmental practices across board as well as embarking on research in other indigenous practices that will promote environmental preservation and species conservatism.” ref

“In the mid 18th century Lindenau noted the Khorolors focused their religious devotion on the Raven, who was alternatively referred to as “Our ancestor”, “Our deity”, and “Our grandfather” by the Khorolors.” ref

“This article is based on new research which was undertaken by a Polish– Yakut team in the Sakha (Yakutia) Republic between 2001 and 2003. Accepting that shamanism is an archaic cultural practice of the Sakha people, and that it is also present in the wider territory of Siberia, it is assumed that some common topics of Siberian shamanism can provide a semantic context for elucidating the social or semantic meanings of rock art in the territory of the Sakha Republic. After a general characterization of rock art in Yakutia, the paper analyzes the possible shamanic overtones of some rock images from southern parts of the country, mainly along the middle Lena River basin, and in the northern territory, on the cliffs of the Olenek River. Attention is also paid to the contemporary veneration of sites with rock art, where ritual offerings are still practiced.” ref

I am an atheist, antitheist, and antireligionist. However, I am also a self-taught prehistorian, trying to explain the evolution of religion which requires me fully understand the connections of religious or spiritual beliefs to allow others to rethink the belief in them. To expose the evolution of religion and thus understand its humanness not just from reason but do to understanding all the facts of archaeology, anthropology, and religious mythology. It is to bring about awareness to inspire others to atheism or at least a new understanding of religion removing its believed special status when religion or spiritual beliefs are, to me, just “culture” or “sociocultural“ products, like language. I don’t believe in gods or ghosts, and nor souls either. I don’t believe in heavens or hells, nor any supernatural anything. I don’t believe in Aliens, Bigfoot, nor Atlantis. I strive to follow reason and be a rationalist. Reason is my only master and may we all master reason.

“Sociocultural factors characterize social and cultural forces that influence the feelings, attitudes, values, thoughts, beliefs, interactions, and behaviors of related individuals and groups.” ref

“Examples of sociocultural factors include:

- Income and wealth distribution

- Social classes

- Attitudes towards education and work,

- Language, customs, and taboos

- Business and health practices

- Housing

- Religious beliefs

- Population size and housing

- Social mobility

- Age distribution and social values” ref

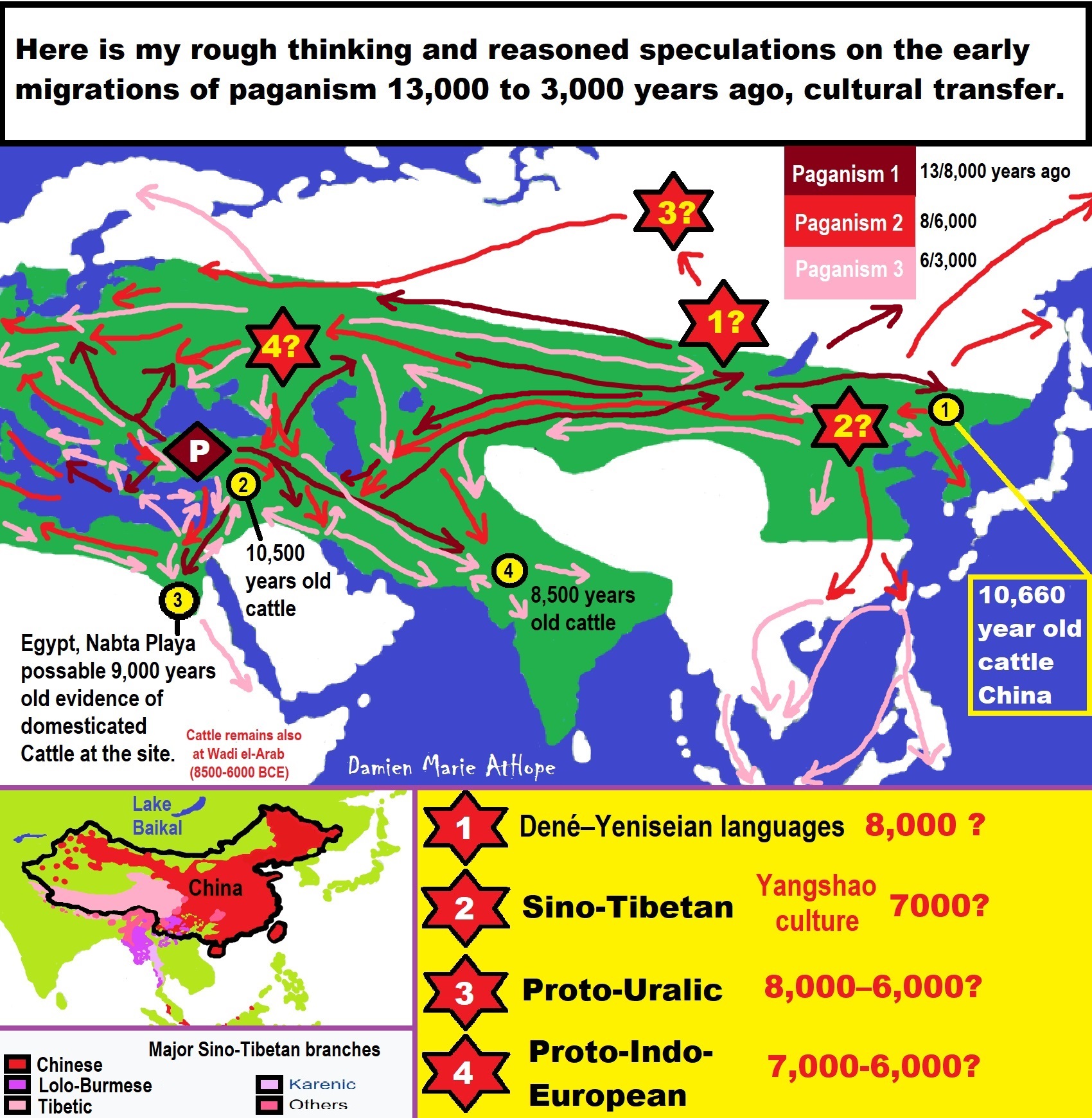

Shamanism

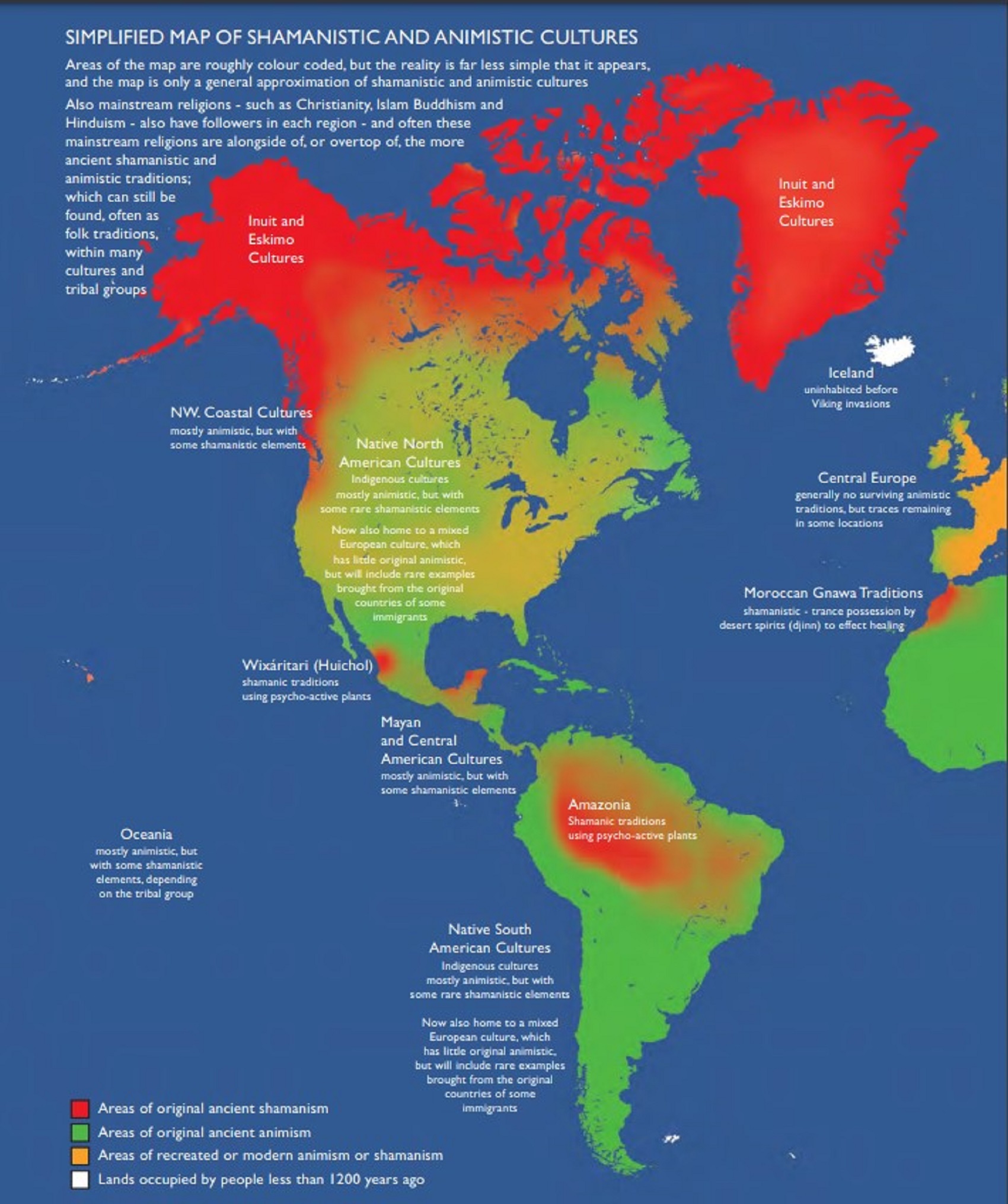

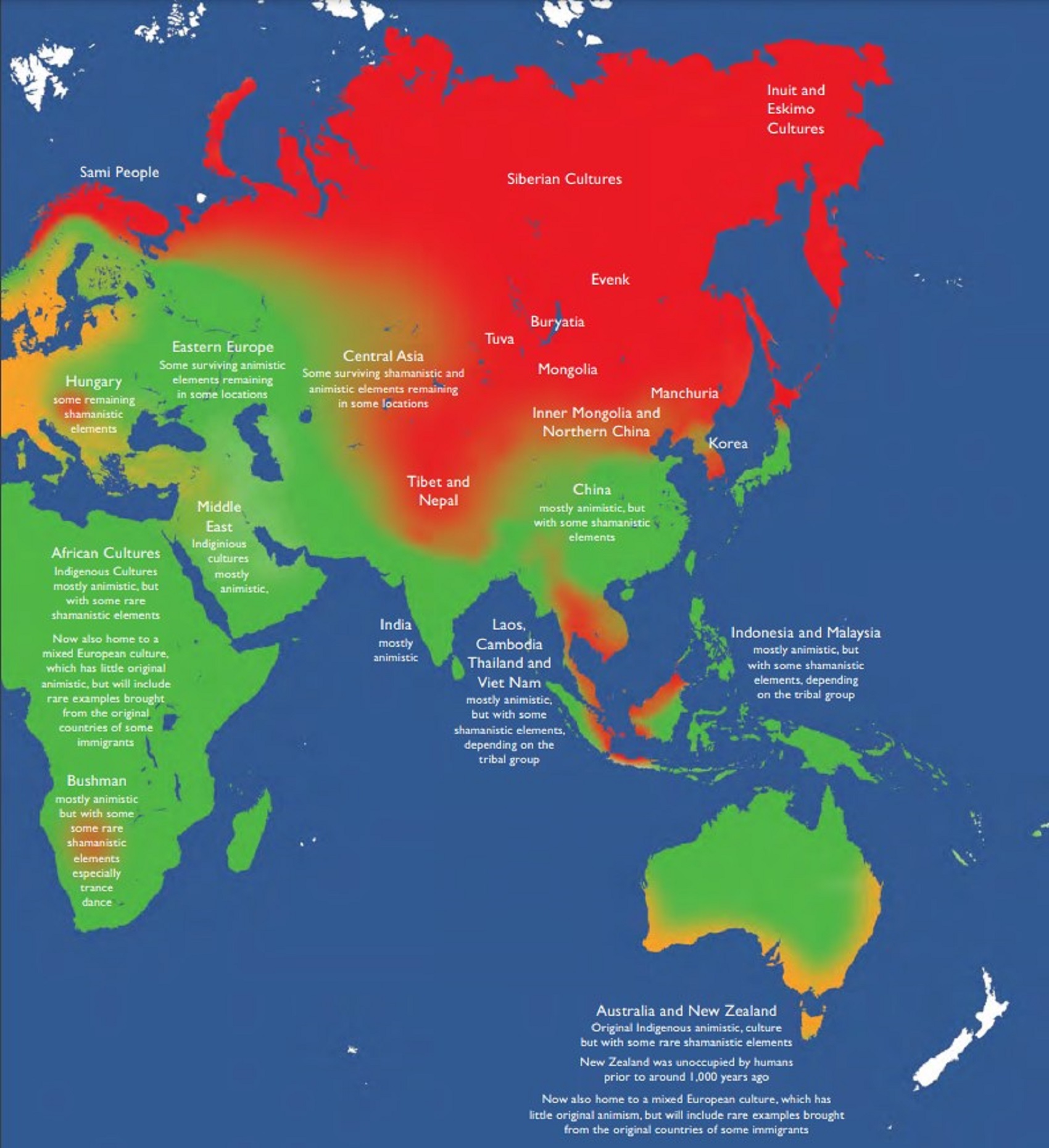

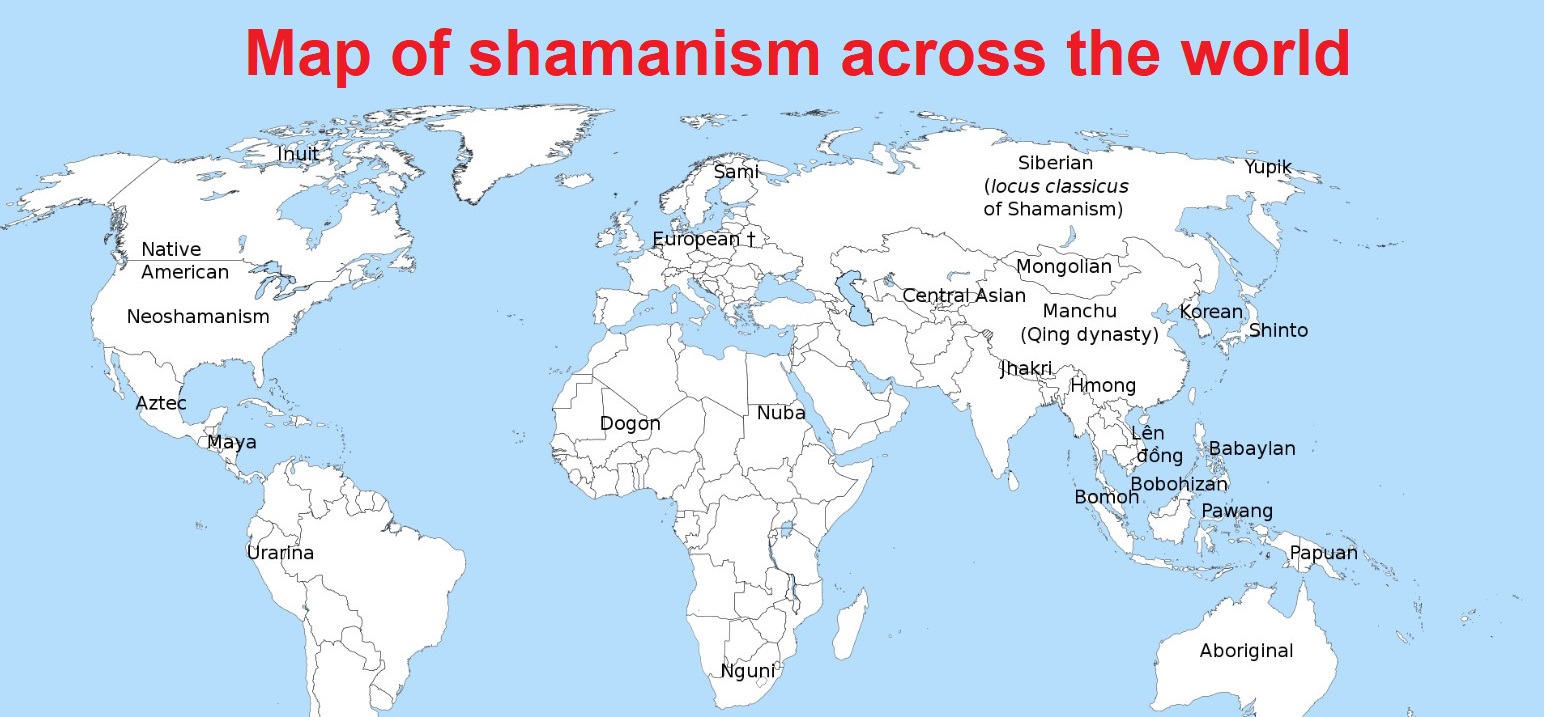

“shamanism, religious phenomenon centred on the shaman, a person believed to achieve various powers through trance or ecstatic religious experience. Although shamans’ repertoires vary from one culture to the next, they are typically thought to have the ability to heal the sick, to communicate with the otherworld, and often to escort the souls of the dead to that otherworld. The term shamanism comes from the Manchu-Tungus word šaman. The noun is formed from the verb ša- ‘to know’; thus, a shaman is literally “one who knows.” The shamans recorded in historical ethnographies have included women, men, and transgender individuals of every age from middle childhood onward.” ref

“As its etymology implies, the term applies in the strictest sense only to the religious systems and phenomena of the peoples of northern Asia and the Ural-Altaic, such as the Khanty and Mansi, Samoyed, Tungus, Yukaghir, Chukchi, and Koryak. However, shamanism is also used more generally to describe indigenous groups in which roles such as healer, religious leader, counselor, and councillor are combined. In this sense, shamans are particularly common among other Arctic peoples, American Indians, Australian Aborigines, and those African groups, such as the San, that retained their traditional cultures well into the 20th century. It is generally agreed that shamanism originated among hunting-and-gathering cultures, and that it persisted within some herding and farming societies after the origins of agriculture.” ref

“It is often found in conjunction with animism, a belief system in which the world is home to a plethora of spirit-beings that may help or hinder human endeavors. Opinions differ as to whether the term shamanism may be applied to all religious systems in which a central personage is believed to have direct intercourse with the transcendent world that permits him to act as healer, diviner, and the like. Since such interaction is generally reached through an ecstatic or trance state, and because these are psychosomatic phenomena that may be brought about at any time by persons with the ability to do so, the essence of shamanism lies not in the general phenomenon but in specific notions, actions, and objects connected with trance (see also hallucination).” ref

Journeys to the Sun: Heavenly Symbols in Shamanism and Rock Art of Siberia and Central Asia (for more info):

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318724562_Journeys_to_the_Sun_Heavenly_Symbols_in_Shamanism_and_Rock_Art_of_Siberia_and

“Shamanism or Samanism is a religious practice that involves a practitioner (shaman or saman) interacting with the spirit world through altered states of consciousness, such as trance. The goal of this is usually to direct spirits or spiritual energies into the physical world for the purpose of healing, divination, or to aid human beings in some other way. Beliefs and practices categorized as “shamanic” have attracted the interest of scholars from a variety of disciplines, including anthropologists, archeologists, historians, religious studies scholars, philosophers and psychologists. Hundreds of books and academic papers on the subject have been produced, with a peer-reviewed academic journal being devoted to the study of shamanism.” ref

“In the 20th century, non-Indigenous Westerners involved in countercultural movements, such as hippies and the New Age created modern magicoreligious practices influenced by their ideas of various Indigenous religions, creating what has been termed neoshamanism or the neoshamanic movement. It has affected the development of many neopagan practices, as well as faced a backlash and accusations of cultural appropriation, exploitation, and misrepresentation when outside observers have tried to practice the ceremonies of, or represent, centuries-old cultures to which they do not belong.” ref

“The Modern English word shamanism derives from the Russian word šamán, which itself comes from the word samān from a Tungusic language – possibly from the southwestern dialect of the Evenki spoken by the Sym Evenki peoples, or from the Manchu language. The etymology of the word is sometimes connected to the Tungus root sā-, meaning “To Know“. However, Finnish ethnolinguist Juha Janhunen questions this connection on linguistic grounds: “The possibility cannot be completely rejected, but neither should it be accepted without reservation since the assumed derivational relationship is phonologically irregular (note especially the vowel quantities).” ref