Gender inequality in Papua New Guinea

“Examples of Gender inequality Papua New Guinea includes poverty, violence, limited access to education and health care, and witch hunts. Cases of violence against women in Papua New Guinea are under reported. There is also a lack of services for women who experience violence. There are reports of sexual abuse by police officers, on arrest and whilst in police custody. These incidents lack documentation or investigation, consequently, perpetrators are rarely prosecuted or punished. The government of Papua New Guinea (PNG) has introduced legislation to combat these issues, though with limited success. Many traditional cultural practices are followed in Papua New Guinea. These include polygamy, bride price, and the stereotypical roles assigned to both men and women. These cultural practices reflect deep-rooted patriarchal attitudes which reinforce the unequal status of women in many areas. These practices continue due to a lack of sustained, systematic action by the government.” ref

Papua New Guineans are murdered or tortured after being accused of “Sanguma” — meaning “Black magic or Sorcery/Witchcraft”

“Sanguma is a local word referring to black magic or sorcery, Belief in sanguma is widespread in Papua New Guinea’s highlands region, and Sanguma accusations are often made following a sudden death or illness. A growing number of Papua New Guineans are being murdered or tortured by their communities after being accused of “sanguma” — a local word that refers to black magic or sorcery.” ref

“Margaret Peter is one victim. The mother of four said she was making breakfast in her hut in the country’s remote Enga Province when a group of men forced her out of her home. “I was still in the house when my 10-year-old daughter ran to me and said, ‘Mother they are calling you sanguma woman’,” Ms Peter said. A huge mob was waiting for her outside.” ref

“The men accused her of using magic to remove the heart of a young boy, who had collapsed near a river far from the village. “I went outside and went with the mob to the boy’s house,” Ms Peter said. “They said he fainted … and I said, ‘So, what do I have to do with it?'” The men tortured Ms Peter with hot knives after stripping her naked. “They tore a blouse I was wearing. They covered my eyes with it and brought me to a place where they had a fire going on,” Ms Peter said.” ref

“They heated bush knives and started to burn my toes. That’s when I began to scream. “They kept on burning me, while asking me where I put the boy’s heart. I kept on telling them, ‘I don’t know anything about this thing’, but they kept on burning me.” The men later released her when the boy woke up. He explained that he fainted because he had not eaten all day.” ref

“Lutheran missionary Anton Lutz went to see Ms Peter the morning after her ordeal. Mr Lutz, who has been involved in efforts against sorcery violence in Enga province for years, said the men would have killed her. “[The attackers] believe that the woman has eaten the heart of another person or has caused sickness or death,” he said. In November, Mr Lutz helped rescue a six-year-old girl who was being tortured over false sanguma allegations. The men accused her of inheriting witchcraft from her mother, who had been burnt to death by a mob four years earlier.” ref

“Professor Phil Gibbs from Papua New Guinea‘s Divine Word University said belief in sanguma, and subsequent violence against people falsely accused of sorcery, has become a nation-wide problem. “When you are talking about sorcery-related killings, most of that seems to be occurring in the highlands these days. There are also some happening on the coast,” he said. “You’ve got what I call a pre-scientific worldview — which some would call a magical worldview — that things can happen magically, people can cause deaths magically.” ref

“‘We protect rapists, we protect murderers’ Police in Papua New Guinea rarely arrest the perpetrators of such violence. Officers working in the country’s vast highlands region say they lack the necessary manpower, and that communities simply refuse to cooperate with police. The Government itself took some action, repealing a decades-old law that allowed sorcery to be used as a defense to murder.” ref

“However, the number of victims has continued to increase over the last six years. In what is believed to be the first conviction for a sorcery-related attack, Papua New Guinea’s National Court earlier this month found a group of 97 men guilty over the brutal murder of seven people in Madang province. But many other allegations are never investigated, and the perpetrators go unpunished. Papua New Guineans are now wondering how to stop this wave of violence before it gets even worse.” ref

“It is estimated that 67% of women in Papua New Guinea have suffered domestic abuse, and over 50% of women have been raped. This reportedly increases to 100% in the Highlands. Further studies have found that 86% of women had been beaten during pregnancy. Studies estimate that 60% of men have participated in a gang rape. A 2014 study by UN Women found that when accessing public transport more than 90% of women and girls had experienced some kind of violence. Cultural practices and traditional attitudes often act as a barrier for women and girls trying to access education. There is a high level of harassment and sexual abuse experienced by girls in education facilities. Papua New Guinea also has low rates of contraceptive use, causing high rates of teenage pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections.” ref

“Cases of violence against women in Papua New Guinea are under reported. This is due in part to gender-based violence being socially legitimized and the accompanying culture of silence. Additionally, there is a lack of services for women who experience violence. These services include shelters, counselling and safe houses. Papua New Guinea has also faced reports of sexual abuse of women by police officers. These abuses have occurred on arrest and whilst in police custody. These assaults are reportedly carried out by both police officers and male detainees. There are also reports of collective rape. These incidents lack documentation or investigation. Consequently, perpetrators are not prosecuted or punished.” ref

“Amnesty International highlights the issue of gendered violence in the Papua New Guinea 2016-2017 human rights report. This report highlights widespread violence which is experienced by women and children. The prosecution of incidents of violence is rare. This report also highlights key cultural practices which are seen as continually undermining the rights of women. These cultural practices include bride price and polygamy. Accessibility to affordable and appropriate health care is an issue faced by women in Papua New Guinea, particularly for women located in the outer islands. This is linked to the high rate of maternal mortality. Papua New Guinea has the second-highest rate of maternal death in the Asia Pacific region. It is estimated that just over 50% of women give birth with the aid of a health facility or skilled attendant.” ref

“Many traditional customary practices are followed in Papua New Guinea. These include polygamy, bride price (dava), the stereotypical roles assigned to both men and women, and the continuing custom that compensation payments can include women. These cultural practices reflect deep-rooted stereotypes and patriarchal attitudes. Witch killings are an ongoing phenomenon in PNG, especially in the Highlands. The UN has estimated that 200 witch killings occur annually. The government recognises both “white magic”, which involves healing and fertility, and sorcery. Sorcery or “black magic” carries a jail sentence of up to 2 years imprisonment. Witch killings tend to be carried out by groups of men and often the whole community is involved. Women and girls tend to be accused of performing witchcraft. Often the individuals targeted are vulnerable young women, or widows without sons. In 2014, 122 people were charged following the deaths of more than seven people accused of sorcery.” ref

“Witch-Hunts in Papua New Guinea are still occurring in the twenty-first century. They are attacks launched against predominantly female victims accused of using sorcery, commonly known as ‘sanguma’, with malevolent intent. In 2012 the Law Reform Commission concluded that since the 1980s sorcery-related attacks had been on the rise. For example, in the province of Simbu alone more than 150 cases of witch-hunting occur each year. Local activists also estimate that in total over fifty-thousand people have been chased from their homes as a result of witchcraft accusations. The women’s advocacy group, the Leniata Legacy, was founded following the murder of Kepari Leniata in 2013. Leniata was publicly tortured and burned to death after being accused of sorcery.” ref

“Although the nature of witch-hunting varies across Papua New Guinea, a very ethnically diverse country, in most cases, witchcraft accusations are triggered by the illness or death of a family member or friend, leading to relatives and other villagers seeking vengeance against the suspected ‘witch’ who they believe to have caused their misfortune. Attacks on those branded as witches are usually very violent, with victims often being subjected to prolonged physical, emotional, and sexual torture. In serious cases, accused witches are killed by large mobs using brutal methods, for instance, burning alive is a still common form of execution.” ref

“There are many underlying causes as to why witch hunts occur in Papua New Guinea. High rates of HIV/AIDS and increasing rates of diseases caused by drug and alcohol abuse, alongside a general lack of quality healthcare provision, have led to a rise in untimely deaths in many Papua New Guinean communities, which usually form the basis of sanguma accusations. Migration and social dislocation caused by the use of land for extracting natural resources as well as new development and rapid modernisation have also led to disruption and the spread of sanguma beliefs, helping to make the country fertile ground for witch-hunting.” ref

“A witch hunt is started after a victim is singled out by neighbors, relatives, or other community members as a scapegoat for illness, death, and other misfortune. Sometimes communities seek the help of a ‘witch doctor‘, a person who practices sorcery but openly declares not to use it for malevolent purposes, to identify a witch. Being a witch doctor is a recognized occupation in many villages, and practitioners are often paid well for their services. Although men have been known to be accused of witchcraft, women and girls are six times more likely to be branded as a witch than men according to Amnesty International.” ref

“More vulnerable women are particularly at risk, such as single mothers, widows, the infirm, the mentally ill, and women who have fewer male relatives who could advocate for and protect them if they were to be labeled a witch. One reason for this is the belief that the female body is more suited to host a ‘witch spirit’ than a man’s as these evil spirits prefer to reside in a woman’s womb. The likelihood of being branded as a witch also tends to increase if a family member has been accused of the same crime in the past as it is believed that the ability to perform black magic is passed down through generations.” ref

“Once someone is suspected of witchcraft they can be tortured in order to extract a confession to ‘prove’ their crime. Methods of torture include beating (sometimes with barbed wire), hanging over the fire, burning with hot irons, cutting, flaying, and amputation of body parts, and raping. For example, in November 2017 a young girl was blamed for the illness of a cousin, diagnosed as kaikai lewa (to eat the heart), where a witch uses black magic to remove and eat a person’s heart. Shortly after, the girl was abducted and tortured for five days, being strung up by the ankles and flayed with hot machetes in order to force an admission of witchcraft and get her to ‘return’ her cousin’s heart.” ref

“In cases where an alleged victim of sanguma does not recover, accused witches can be killed by large mobs as a way of seeking revenge. Those branded as a witch can be executed in a number of brutal ways. For example, there are cases where victims have been hung, burned alive, hacked to death with machetes, stoned, and buried alive in witch hunts across the country. Even if the accused survives, in most instances, the effects of physical, sexual, and emotional torture caused by sorcery-related attacks lead to long-lasting trauma for survivors.” ref

“One reason behind the violence is that perpetrators rarely face conviction and prosecution for witch-hunting. A 20-year-long study by the Australian National University found less than one percent of perpetrators were successfully prosecuted in 1,440 cases of torture and 600 killings. The main reasons for this are first that witnesses and survivors of witch-hunts fear that speaking out could provoke an attack on them or their property. Moreover, police in Papua New Guinea are understaffed and paid poorly, and some are just as likely to believe that victims are real witches as perpetrators; overcrowded prisons also deter them from investigating these crimes.” ref

“Additionally, until 2013, the country also had a law which allowed murderers to use an allegation of witchcraft as a legitimate defence in court and acknowledged “widespread belief throughout the country that there is such a thing as sorcery, and sorcerers have extra-ordinary powers that can be used sometimes for good purposes but more often bad ones” in the 1971 Sorcery Act.” ref

“Legal efforts to prevent the practice of witch-hunting and branding have been made by the government of Papua New Guinea. One of the most notable examples of this was the repeal of the 1971 Sorcery Act in 2013. This controversial act acknowledged the existence of witchcraft and criminalised it, punishing accused witches with up to two years in prison. Under the act, murderers could also use a witchcraft allegation as a legitimate defence in court and reduce their prison sentences if sorcery was involved in their case. Furthermore, in the same year, the death penalty was reintroduced for murder, in an attempt to reduce sorcery-related lynching and murders. Many believe this legal crackdown on witch hunts was prompted by the high-profile media case of Kepari Leniata, a 20-year-old woman who was burned alive by a mob after being accused of using witchcraft to kill a young boy.” ref

“The effectiveness of these legislative changes has been questioned as sorcery accusation related violence is still on the rise in the country. One of the key problems halting progress are low rates of conviction of witch-hunters, evidenced in a 20-year-long study by the Australian National University, which showed that less than one per cent of perpetrators from over 2,000 cases of witchcraft-related torture and killings were prosecuted.” ref

“National and international non-governmental organisations (NGOs) play an important role in the drive to end witch-hunts in Papua New Guinea. Many focus on educating communities on the negative impacts of witch-hunts, for instance, through holding discussions and workshops and reaching out to community leaders and local influencers. NGOs also combat witch-hunting and branding by taking steps to alleviate poverty in communities vulnerable to harmful superstitions. Oxfam, for example, has advocated providing access to clean water, hygiene education, and improved agricultural practices to reduce the likelihood of sickness and premature deaths, common triggers of witch-branding.” ref

“Anti-witch hunting activists have also aided the fight against the practice. For example, Ruth Kissam is a community organizer and human rights activist who, in 2013, advocated for the repeal of the 1971 Sorcery Act, playing a critical role in the success of its removal. Today, Kissam works with the Papua New Guinea Tribal Foundation, an organization that works in areas of maternal and child health, education, and gender-based violence. Here, she led the Senisim Pasin (Change Behaviour) film campaign, a national campaign aimed at changing cultural attitudes about how women are valued in Papua New Guinea. Additionally, the foundation has been responsible for the rescue and repatriation of over 150 women since its creation in 2013. Kissam herself rescued and, in 2018, adopted Kerpari Leniata’s six-year-old daughter who, like her mother, also suffered abuse and torture at the hands of witch-hunters.” ref

“Papua New Guinea (PNG) is often labeled as potentially the worst place in the world for gender-based violence.” ref

“According to a 1992 survey by the PNG Law Reform Commission, an estimated 67% of wives have been beaten by their husbands with close to 100% in the Highlands Region. In urban areas, one in six women interviewed needed treatment for injuries caused by their husbands. The most common forms of violence include kicking, punching, burning, and cutting with knives, accounting for 80–90% of the injuries treated by health workers. According to a 1993 Survey by the PNG Medical Research Institute, an estimated 55% of women have experienced forced sex, in most cases by men known to them. Abortion in Papua New Guinea is illegal unless it is necessary to save the woman’s life, so those who experience pregnancy from rape have no legal way of terminating forced pregnancies.” ref

“UNICEF describes the children in Papua New Guinea as some of the most vulnerable in the world. According to UNICEF, nearly half of reported rape victims are under 15 years of age, and 13% are under seven, while a report by ChildFund Australia citing former Parliamentarian Dame Carol Kidu claimed 50% of those seeking medical help after rape are under 16, 25% are under 12 and 10% are under eight. Up to 50 percent of girls are at risk of becoming involved in sex work, or being internally trafficked. Many are forced into marriage from 12 years of age under customary law. One in three sex workers are under 20 years of age.” ref

“Initiation rites of prepubescent boys as young as seven among groups in the highlands of New Guinea involved sexual acts with older males. Fellatio and semen ingestion were found among the Sambia, the Baruya, and Etoro. Among the Kaluli people, this involved anal sex to deliver semen to the boy. These rites often revolve around beliefs that women represent a cosmic disorder. A 2013 study found that 7.7% of men have sexually assaulted another male.” ref

“A 2013 study by Rachel Jewkes and colleagues, on behalf of the United Nations Multi-country Cross-sectional Study on Men and Violence research team, found that 41% of men on Bougainville Island admit to coercing a non-partner into sex, and 59% admit to having sex with their partner when she was unwilling. According to this study, about 14.1% of men have committed multiple perpetrator rape. In a survey in 1994 by the Papua New Guinea Institute of Medical Research, approximately 60% of men interviewed reported to have participated in gang rape (known as lainap) at least once.” ref

“In urban areas, particularly slum areas, Raskol gangs often require raping women for initiation reasons. Peter Moses, one of the leaders of the “Dirty Dons 585” Raskol gang, stated that raping women was a “must” for the young members of the gang. In rural areas, when a boy wants to become a man, he may go to an enemy village and kill a pig to be accepted as an adult, while in the cities “women have replaced pigs”. Moses, who claimed to have raped more than 30 women himself, said, “And it is better if a boy kills her afterwards, there will be less problems with the police.” ref

Addressing Gendered Violence in Papua New Guinea

“In 2015, Papua New Guinea (PNG) celebrated 40 years of independence. Despite Papua New Guinea’s current extractives-led boom, an estimated 40 percent of the country lives in poverty. Pressing issues include gender inequality, violence, corruption, and excessive use of force by police, including against children. Rates of family and sexual violence are among the highest in the world, and perpetrators are rarely prosecuted. PNG is one of the most dangerous places in the world to be a woman or girl, with an estimated 70 percent of women experiencing rape or assault in their lifetime.” ref

“Police and prosecutors are very rarely prepared to pursue investigations or criminal charges against people who commit family violence—even in cases of attempted murder, serious injury, or repeated rape—and instead prefer to resolve them through mediation and/or the payment of compensation. Police also often demand money (“for fuel”) from victims before taking action, or simply ignore cases that occur in rural areas. There is also a severe lack of services for people requiring assistance after having suffered family violence, such as safe houses, qualified counselors, case management, financial support, or legal aid.” ref

“Reports continue of violent mobs attacking individuals accused of “sorcery” or “witchcraft,” the victims mostly being women and girls. In May, a group of men in a remote part of Enga province killed a woman after she was accused of “sorcery.” In August, three women and a man were also attacked in Mendi in the Southern Highlands province following sorcery accusations. Sorcery accusations are often accompanied by brutal attacks, including burning of homes, assault, and sometimes murder. The risks to people accused of sorcery are so severe that the main approach used by nongovernmental organizations seeking to help them is to permanently resettle them in another community.” ref

“Each year, more than 1.5 million women and girls in Papua New Guinea experience gender-based violence tied to inter-communal conflict, political intimidation, domestic abuse, and other causes. It is, according to a 2023 Human Rights Watch report, “one of the most dangerous places to be a woman or girl.” ref

- “Extremely high rates of gendered violence in Papua New Guinea (PNG) are a critical concern for peace and security because the political and economic stability of a country are linked to the status and security of its women.

- Rising economic inequality and lack of investment in basic services in recent years have fueled increasingly lethal intercommunal, intimate partner, and sorcery accusation–related violence in PNG.

- Violence is worse in Hela Province, home to the extractive oil industry, but is also unfolding in Morobe Province and across PNG, particularly as the number of internally displaced persons increases.

- State-centric and rule-of-law approaches to addressing gender-based violence have been ineffective in PNG, where state institutions have little reach beyond urban areas; local norms and customary law do not neatly align with other legal frameworks; and society is organized around informal, dynamic political and social networks.

- The application of USIP’s Gender Inclusive Framework and Theory points to promising opportunities for programming, such as providing innovative support to micro-level initiatives led by efficacious actors, promoting nonviolent masculinities, and addressing youth disenfranchisement and intergenerational trauma.” ref

“Bleak as this may seem, it is not hopeless. USIP’s new report identifies several promising approaches for peacebuilding programming to reduce gender-based violence and effect meaningful and lasting change in Papua New Guinea. This report examines the challenges that peace programs face in addressing gendered violence in Papua New Guinea. It also presents programmatic opportunities and options based on a conflict-sensitive gender analysis of Hela and Morobe Provinces. The review utilized the Gender Inclusive Framework and Theory developed by the Women, Peace and Security Program at the United States Institute of Peace (USIP). Desk research was funded in part by the United States Agency for International Development.” ref

Papua New Guinea is the Most Dangerous Country for Women

“In fact, the Australian region has the worst record of gender-based violence in the world, according to the United Nation’s report, Eliminating Violence Against Women in the Asia-Pacific Region. Two out of every three women in the region experience violence in their lifetime — a scale that cannot be underestimated, according to the report. “Gender-based violence prevents women from exercising their rights, compromises their health, restricts them from becoming fully productive and realizing their full social and economic potential,” Steven Groff, Asian Development Bank Vice-President, said in the report. Australia’s closest neighbours in the Pacific face some of the highest rates of incidence of violence against women in the world with over 60% of women and girls having experienced violence at the hand of a partner, spouse, or family member. In many of these countries, laws and law enforcement fail to protect them, with some forms of violence, such as marital rape, not being a criminal offense.” ref

“Papua New Guinea (PNG) is one of Australia’s closest neighbors. It is also considered to be the most dangerous country in the world for women, according to Human Rights Watch World Report 2017. PNG still has some of the highest rates of domestic and sexual violence in the world. The prevalence of sexual violence alone is estimated to be 55%. Domestic violence was criminalized in PNG in 2013 when the Family Protection Act (FPA) was passed in parliament. The law created new penalties for family violence and put in place systems for specialized police units to assist victims. However, four years later and the law is still not being enforced. As the World Report states, ‘since the FPA was passed, it has not been implemented’. According to the International Women’s development Agency (IWDA), without access to safe housing and legal aid, ‘many of these women have no alternative but to return home, to the place where the abuse occurred, to face further and often worse violence’. A woman named Janella, age 39, told The Human Rights Watch that she went to the police 17 times asking them to arrest her husband, and they refused.” ref

“As well as poor law reform and enforcement in the region, there are also many cultural customs, practices, beliefs and strong gender stereotypes that lead to discrimination against women. In many Asian Pacific countries, violence against women is often normalized, and perpetrators go unpunished. For example, in Vanuatu, a country where three in five women have experienced violence from their spouse or intimate partner, UN Women have found that “50% of women believe that a good wife must obey her husband even if she disagrees with him, and 40% believe that the man should be the boss in the marriage. The custom of ‘bride price’ is also harmful to women, with 53% believing that a wife becomes the husband’s property after the bride price is paid.” As the organization Pacific Women points out, when it comes to eliminating violence against women, addressing gender inequality and tackling these deeply entrenched beliefs that justify men’s violence against women is essential to eliminating family violence.” ref

“A press release from UN Women also discusses barriers that prevent female victims from getting justice. “Many women shrink away from reporting crimes due to social stigma and weak justice systems,” it says. “The costs and practical difficulties of seeking justice can be prohibitive — from travel to a distant court, to paying for expensive legal advice. The result is high drop-out rates in cases where women seek redress, especially on gender-based violence.” If we look at PNG as an example we can see that introducing fair legislation is just the beginning when it comes to leveling the law and protecting women’s rights. More needs to be done to enforce the laws, assist victims in reporting the crime, achieving justice, and convicting the perpetrators as well as providing support services to survivors. IWDA also points out that increased political representation of women and having them included in all levels of decision making is crucial to addressing inequalities and preventing violence.” ref

“The report cites reasons for the lack of justice for women to include:

1. Police corruption – police often demanding money before they look into reports of violence

2. Prosecutors failing to investigate crimes – even cases of rape and murder – and preferring to resolve matters through mediation and/or monetary compensation.

3. Lack of services for victims of family violence, such as safe houses, counselors, or legal aid.” ref

“We chose death over being raped’ PNG kidnapping survivor speaks out.” ref

“A woman who was part of a group kidnapped in Papua New Guinea in February 2024 has spoken out after the kidnapping and reported rape of 17 schoolgirls in the same area of Southern Highlands earlier this month. Cathy Alex, the New Zealand-born Australian academic Bryce Barker, and two female researchers, were taken in the Bosavi region and held for ransom. They were all released when the Papua New Guinea government paid the ransom of US$28,000 to the kidnappers to secure their release. Alex, who heads the Advancing Women’s Leaders’ Network, said what the 17 abducted girls had gone through prompted her to speak out, after the country, she believed, had done nothing. A local said family members of the girls negotiated with the captors and were eventually able to secure their release. The villagers reportedly paid an undisclosed amount of cash and a few pigs as the ransom. Alex said she and the other women in her group had feared they would be raped when they were kidnapped.” ref

“My life was preserved even though there was a time where the three of us were pushed to go into the jungle so they could do this to us. “We chose death over being raped. Maybe the men will not understand, but for a woman or a girl, rape is far worse than death.” Alex said they had received a commitment that they would not be touched, so the revelations about what happened to the teenage girls were horrifying. She said her experience gave her some insight into the age and temperament of the kidnappers. “Young boys, 16 and up, a few others. No Tok Pisin, no English. It’s a generation that’s been out there that has had no opportunities. What is happening in Bosavi is a glimpse, a dark glimpse of where our country is heading to.” The teenage girls from the most recent kidnapping are now safe and being cared for but they cannot return to their village because it is too dangerous. Cathy Alex said there is a need for a focus on providing services to the rural areas as soon as possible. She said people are resilient and can change, as long as the right leadership is provided.” ref

“The PNG gang that kidnapped an Australian professor is allegedly unleashing new horrors on girls and women.” ref

“A few hours after nightfall in the remote Southern Highlands village of Walagu in Papua New Guinea, a gang of armed men moved in and began knocking on doors. A young woman, who the ABC is choosing to call Jane, said she opened the door assuming a loved one had come to visit. “We thought they were our relatives,” Jane told the ABC. “Three of them came into the house, one of them took me.” Jane said she was led to the church, where about a dozen women and girls from the village were being held. One was a young mother who had her newborn with her. Five of those taken were teenagers attending the local school — some were as young as 12. From there, an unimaginable nightmare unfolded for the women and girls. “They took us into the jungle, they gave us their bags to carry,” Jane said. “They hit us with bush knives and sticks and raped us and did so many things.” Jane said when the village elders caught up with the group the following morning, the gang took her and the hostages back to Walagu, but they continued to hold them for days while a ransom was being negotiated.” ref

“After payment in cash and pigs, the women were let go, and the gang moved on. The survivors have since been medically examined at a health center in the province. Multiple sources, including PNG officials, have told the ABC they believe the sexual assaults were carried out by the same bandits who held an Australian professor and three Papua New Guinean women hostage in February. It is believed the gang targeted the women partly as a reprisal, given police and defense based their operations in response to the February kidnapping in the villages around Mount Bosavi. The gang has now been labeled “domestic terrorists” by PNG’s police commissioner, who wants to beef up the country’s criminal code in response.” ref

“Gangs in the area are known to travel large distances through the dense jungle between the remote western province near the Indonesian border, through the villages around Mount Bosavi in Southern Highlands province, and then on to Hela province. In February, police believe the kidnappers stumbled upon Professor Bryce Barker and three female Papua New Guineans by chance in Fogoma’iu as they were trekking some 150 kilometers from Kamusi to their home in Komo. Many of them have been identified from that incident, but tracking them down to prosecute them has been the challenge. This time, an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) will be used to aid the search in the dense jungle for the gang. Police acknowledge the limited phone reception, a lack of roads and the difficult terrain will be a challenge in their search.” ref

“The latest incident involving the women from Walagu is likely a response to the kidnapping of Professor Barker, according to Hela Governor Philip Undialu, who was interviewed by The National newspaper. “Police at that time should have gone in and arrested the culprits, enforced the law,” he said. “It’s because nothing was done that these incidents are continuing to happen. ” Jane told ABC the kidnappers claimed she and the others were being taken because she cooked for police and defense during the operation in February. “They said things like that and belted me very badly,” she said. Although kidnapping is not a new development in the Southern Highlands, Western, and Hela provinces, women in the region say the rape of underage girls is increasingly being used to terrorize their communities.” ref

“Professor Barker was kidnapped along with three female researchers while doing field work on an archaeological site. One of the three women has spoken about her experience for the first time. The ABC is choosing not to identify her to protect her identity. “There was a time where the three of us were pushed to go into the jungles so they could do this to us,” she said. “We chose death over being raped.” She said she was not sexually assaulted but was not ready to talk about the details of her ordeal. She said some in the gang were teenagers. “Young boys, 16 and up, a few others,” she said. “What is happening in Bosavi is a dark glimpse of where our country is heading to.” ref

“Papua New Guinea fails to end ‘evil’ of sorcery-related violence.” ref

“Brutal torture and assault of women accused of witchcraft go unpunished while initiatives to end crime make little progress. Papua New Guinea continues to see cases of women accused of sorcery and subjected to brutal torture.” ref

“Reports of machete-wielding men slashing innocent bystanders, arson attacks, sexual violence against girls, and the displacement of thousands of people during last month’s election in Papua New Guinea have drawn international condemnation. But an even more insidious form of violence continues to plague the country: sorcery-accusation-related violence (SARV), the public torture and murder of women accused of witchcraft.” ref

Why Is Papua New Guinea Still Hunting Witches?

“A six-year-old girl tortured for ‘witchcraft’ sparks international outrage. n most parts of the world, stories about witch-hunts are confined to documentaries and mini-series. But in the Southeast Asian nation of Papua New Guinea, real-life witch-hunts that end in torture or murder are so commonplace they rarely make the evening news. Most also go uninvestigated by police. This comes despite the introduction of the death penalty for witch-hunting in 2013, after Kepari Leniata, a 20-year-old woman accused of using witchcraft to kill a neighbor’s boy, was burnt alive on a busy street corner as hundreds of people looked on.” ref

“But when news broke that a six-year-old girl accused of sorcery had been tortured by a group of men and only narrowly escaped with her life following a daring rescue mission by lay-missionary Anton Lutz from Iowa, the story made headlines not only in Papua New Guinea but across the world. The drama began when a man fell ill at a remote village in Enga Province in the highlands of Papua New Guinea. It could have been HIV/AIDS or just an upset stomach. But his sickness was diagnosed as kaikai lewa (to eat the heart), where a witch uses black magic to secretly remove and eat the victim’s heart to gain their virility. As the daughter of a woman who’d been accused of the same crime, the six-year-old girl was fingered as the prime suspect. So a group of villagers took her, stripped her naked, and tortured her for days, using hot knives to remove the skin from her back and buttocks.” ref

“To understand why belief in something as ridiculous as sorcery remains a quotidian fact of life across all geographic and socio-economic divides in Papua New Guinea, one must first understand the nation’s contemporary history. In the late 1800s, the conglomeration of more than 800 perpetually warring and cannibalistic tribes was thrust unprepared by German colonialists into the modern age, while highland regions like Enga remained undiscovered well into the late 1930s. Constructs like animism, ancestor worship, and sorcery, which have been used to make sense of the world since time immemorial, have not been easy to cast aside – even among Papua New Guinea’s most educated people.” ref

Escaping Papua New Guinea’s Crucible of Sorcery/Witchcraft

“Justice is 7 years old. She’s besotted with Frozen’s Princess Elsa and knows all the words to the film’s hit song “Let It Go.” Every morning, she collects the frangipani flowers that have fallen into her guardian’s yard in the Papua New Guinea capital Port Moresby and turns them into floral brooches, poking the central stem through each snowy petal. When Justice laughs, which is often, her smile beams so wide it seems to stretch her face to breaking point.” ref

“It’s hard to imagine how anyone would consider this little girl the encapsulation of pure evil. Yet in November 2017, the population of her village convinced themselves Justice was a witch. That’s why a mob imprisoned and tortured Justice for five days. It’s why they strung her up by her wrists and ankles and began flaying her with heated machetes. It’s why they screamed at her to recant the black magic they accused her of using to strike down another youngster. “They came to my house and wanted to kill me,” Justice tells TIME matter-of-factly. “They got a big knife and put it in the fire and then hurt my feet.” ref

“Justice, whose real name TIME agreed not to use for fear of reprisals, was eventually rescued by the Papua New Guinea Tribal Foundation, an NGO based in Port Moresby that provides education, health care and humanitarian assistance in Papa New Guinea’s remotest communities. Justice has since been cared for by the organization’s director of operations, Ruth J. Kissam, who is now her legal guardian. TIME met Justice and Kissam for a playdate in Port Moresby, where she has lived since her flight from Papa New Guinea’s arcane Highlands.” ref

“No child should have to describe such heinous cruelty. But Kissam, who became a community activist after being forced to drop out of law school to care for her ailing mother and three younger siblings, has spent her life battling the sorcery-related violence that increasingly blights this southwest Pacific country of 8 million. Kissam allowed TIME to meet with Justice because she says the child will only reconcile her ordeal by talking about it. But there is also a far grimmer reason. “We are talking now to raise awareness because we are seeing a lot more kids just like her coming into our system,” says Kissam, whose work earned her the Westpac Outstanding Woman of 2018 Award, which celebrates Papua New Guinea’s most dedicated female talent.” ref

“Belief in sorcery, known locally as sanguma, exists across the Pacific and especially in Papua New Guinea or PNG, a country just off the northern coast of Australia incorporating half the island of Guinea, plus some 600 other islands. Eighty percent of the population live in far-flung villages without access to electricity, running water or health care. Its clans speak over 800 distinct languages. Many aspects of sanguma are entirely benign, part of a folk religion that stretches back millennia. Hunters may collect a tendon from a dead relative’s body to rub on their bows while hunting, believing the spirit helps guide the arrow home. Colds and other ailments are ascribed to the meddling of capricious spirits. Surprisingly, sanguma and Christianity — introduced mainly by Western missionaries — are often revered side-by-side.” ref

“But Papua New Guinea is experiencing a spike in lynching of suspected witches, as uneven development means ever more people leave their villages looking for work. Without established village chiefs or time-honored tribal justice systems in place for addressing sanguma accusations, these swelling communities of economic migrants become more vulnerable to hotheads instigating violence. And because most people who live in Papua New Guinea lack education and proper healthcare, when a sudden death or illness strikes — a growing scourge as junk food and drugs make previously unknown conditions like diabetes and HIV/Aids more prevalent — angry mobs often go looking for a scapegoat. “There are people who go to different communities and say, ‘If you pay me 1,000 kina [$300], I’ll tell you who is a sorcerer,” says Gary Bustin, director of the Tribal Foundation.” ref

“Victims are almost exclusively vulnerable women: single mothers, widows, the infirm or mentally ill. The U.N. has estimated that there are 200 killings of “witches” in Papua New Guinea annually, while local activists estimate up to 50,000 people have been chased from their homes due to sorcery accusations. But sanguma is so secretive, and communities so remote, that experts say the vast majority of incidences slip under the radar. “It’s a really big problem,” says Geejay Milli, a political science lecturer at the University of Papua New Guinea and former crime reporter. “The media is not reporting on it enough.” ref

‘They just slaughter them’: how sorcery violence spreads fear across Papua New Guinea

“Five alleged sorcery-related deaths – including the hanging of a 13-year-old boy – in a single week in one Papua New Guinea province, has revived a nationwide angst over the persistent crime of alleged witchcraft killings. In the highland villages and the lowland towns of Papua New Guinea, it is the crime that everybody knows about, that many see, but that few can, or do, anything to stop. Those who survive it are left disfigured: limbs shattered and missing, faces scarred and swollen, souls forever damaged. Those are the lucky ones, the survivors, the few who live. Most do not.” ref

“Five alleged sorcery-related deaths – including the hanging of a 13-year-old boy – in a single week in one Papua New Guinea province, has revived a nationwide angst over the persistent crime of alleged witchcraft killings. In PNG’s remote East Sepik region, in the north of New Guinea island, a woman and a teenaged school student were allegedly murdered in the village of Gavien. A 13-year-old boy from the same village was allegedly kidnapped before his body was found hanged.” ref

“A man died from an illness [in February in Angoram],” Beli told the National newspaper. “After that, people started accusing and killing each other.” Unrelated, a man and his son were killed at Suanum outside the provincial capital Wewak the same week. Police have alleged their deaths were also linked to sorcery allegations. Sorcery deaths are murders where the victims are accused of practicing some sort of witchcraft, often on a neighboring family or village, resulting in death, illness, or bad luck.” ref

“The events before and after someone is accused of practicing sorcery are often described as unfolding like a bushfire. In many villages and communities in Papua New Guinea, the dry tinder is often the widespread belief that misfortune or bad events can be caused by the supernatural. Several years ago, in the remote village of Wanikipa in Hela Province, the drowning of a young boy in the river served as the spark. The boy’s father fanned the flames by accusing Elli Mark, a distant relative, of killing the boy through sorcery, or sanguma. Elli can still clearly recall the day the bushfire came for her.” ref

“Four men walked past our flower garden and entered my yard,” she said. “I called out to God, and I said they will destroy my life.” The men accused the young mother of being a sanguma, and she was led away to a nearby tree, pushed up against it, and attacked. “They cut me on my head and the cut was deep, blood came rushing out,” she said. “I tried to block a bush knife and two of my fingers were chopped off in the process.” Eventually, the men walked away, leaving her to die. But though she had lost a lot of blood, she clung on to life and was flown to Tari hospital days later. Elli now lives in Tari — the provincial capital of Hela, which is 100 kilometres away from her former home — with a hooded jumper concealing her dismembered hand.” ref

“While she survived her ordeal and found a safe haven, others accused of sorcery have struggled to escape. In an effort to improve the lives of those impacted by sorcery accusation-related violence (SARV), locals are banding together to offer victims emergency accommodation and an economic lifeline. In PNG, some communities believe humans can be possessed by a spirit, transforming them into sangumas that feed off the hearts of others, academics say. Accusations of sorcery usually follow a sudden or unexplained death, with a grieving family member or relative looking for someone to blame, particularly if their loved one died from an illness or disease that hasn’t been understood by the community. Those accused of being a sanguma are sometimes brutally murdered, tortured, burned, or suffer other horrific consequences.” ref

The gruesome fate of “witches” in Papua New Guinea

“The law criminalizing sorcery was only repealed in 2013. IT BEGAN, as it usually does, with an unexpected death: in this case, of Jenny’s husband, an esteemed village leader in the province of Eastern Highlands, in Papua New Guinea (PNG). Some local boys accused Jenny of having cast a spell to kill him. She says they began beating her over the head with large branches. Her family supported her accusers. She fled into the surrounding fields, eventually making her way to the provincial capital of Goroka, where she has lived for the past three years. “I can never go back to my village,” she says, “and I never want to see my family again.” ref

“Jenny was lucky: she escaped. Every year, hundreds of suspected witches and sorcerers are killed in PNG. Accusers often enlist the aid of a “glass man” (or “glass Mary”): a diviner whom they pay to confirm their accusations. Most of the victims are poor, vulnerable women, including widows like Jenny. “If you have a lot of strong sons,” says Charlotte Kakebeeke of Oxfam, a charity, “you won’t be accused.” ref

“In 2019, lack of accountability for police violence persisted in Papua New Guinea (PNG), and weak enforcement of laws criminalizing corruption and violence against women and children continued to foster a culture of impunity and lawlessness. Although a resource-rich country, almost 40 percent of its population lives in poverty, which, together with poor health care, barriers to education, corruption, and economic mismanagement, stunts PNG’s progress. PNG imposes the death penalty for serious crimes such as murder, treason, and rape, amongst others, although authorities have not carried out any executions since 1954.” ref

“Domestic violence affects more than two-thirds of women in Papua New Guinea. In March 2019, more than 200 domestic violence and sexual violence cases were reported in Lae and Port Moresby, where over 23 murders alone were attributed to domestic violence. In July, six people were killed in an ambush in Menima village, and in retaliation for their deaths, days later gunmen killed eight women and five children in a brutal massacre in the Hela Province. Newly appointed Prime Minister James Marape condemned the killings, calling for the death penalty against perpetrators, although no one had been arrested at time of writing.” ref

“Sorcery-related violence continued to endanger the lives of women and girls, although there were no new reported incidents during 2019 at time of writing. In June, six men in New Ireland were sentenced to eight years in jail for torturing three women in 2015, claiming they had practiced sorcery. This followed a 2018 sentence, where eight men were sentenced to death, and 88 were imprisoned for life for sorcery-related killings. According to a report by international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) released in July, 75 percent of children surveyed across 30 communities in Bougainville, an autonomous island region, and Morobe province had experienced violence at home.” ref

“Papua New Guinea has an underfunded health system, and children are particularly vulnerable to disease. An estimated one in thirteen children die each year from preventable diseases, and large numbers of children experienced malnutrition resulting in stunted growth. School attendance rates for children have improved, however the United Nations Children’s Fund, UNICEF, estimates that a quarter of primary and secondary school-aged children do not attend school, especially girls. Only 50 percent of girls enrolled in primary school make the transition to secondary school.” ref

“Despite the establishment of a police task force in 2018 to investigate unlawful conduct by police officers in Port Moresby, police violence continues, especially targeting those suspected of crimes. In November, a video emerged on social media of police viciously beating three men in Port Moresby. Two police officers were charged and suspended following the release of the video. Media reports state that between September 2018 and January 2019, 133 police have been investigated and 42 arrested, yet convictions remain rare outside Port Moresby. In the same time period, Papua New Guinea courts convicted and imprisoned 15 police officers in the country’s capital for a range of offences including brutality, aiding prison escapees, and domestic violence.” ref

“At time of writing in 2020, no police officers had been prosecuted for killing 17 prison escapees in 2017 and four prison escapees from Buimo prison in Lae in 2018. Police officers who shot and injured eight student protesters in Port Moresby in 2016 have also not been held accountable. In March, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) reported 50 complaints by the community of Alotau in the Milne Bay Province against police for brutality. In July, the National Court in Kimbe sentenced three officers to 20 years in prison for killing a person while they were drunk on duty.” ref

“At time of writing in 2020, about 262 refugees and asylum seekers remain in Papua New Guinea, transferred there by the Australian government since 2013. In 2019, the government shut down refugee and asylum seeker facilities on Manus Island and transferred refugees to other facilities in Port Moresby. About 50 “failed” asylum seekers, mostly from Iran, are detained in the Bomana Immigration Center, held virtually incommunicado, and denied access to lawyers and their families. Refugee advocates reported that detainees at the Bomana Immigration Centre have no access to phones or the internet, unless they have agreed to assisted “voluntary” return.” ref

The dangers of defending women accused of sorcery in Papua New Guinea

“In Papua New Guinea, defending women accused of sorcery, has become a life-threatening occupation. The UN and European Union run Spotlight Initiative, is promoting legislation that will protect threatened human rights defenders in the country, who risk violence, torture, and death. “When we are trying to help others, or when we go to court to take up someone’s case, we face threats and intimidation,” says Mary Kini, of the Highlands Human Rights Defenders Networks.” ref

“For more than 14 years, she has been working to assist victims of sorcery-related violence, and gender-based violence, in Papua New Guinea (PNG), despite the high personal cost that often comes with it. Ms. Kini recently joined fellow human rights defenders Eriko Fuferefa, of the Kafe Urban Settlers Women’s Association, and Angela Apa, of the Kup Women for Peace in Mount Hagen, for a three-day consultation on the development of a Human Rights Defenders’ Protection bill.” ref

“For so many years we have not been protected and some human rights defenders have been killed along the way,” said Ms. Fuferefa. “Some of them are abused, or tortured. We have so many bruises.” Following advocacy from the Spotlight Initiative, there is now greater political ownership of issues of violence against women and children, demonstrated by the country’s first Special Parliamentary Inquiry on gender-based violence, which delivered recommendations to parliament and has made notable legislative advances in the area of sorcery accusation-related violence.” ref

“Practices to identify those accused of sorcery vary between districts, but generally, when someone has died unexpectedly, the family of the deceased will consult a Glasman (male) or Glasmeri (female) to identify who in the community is responsible. Accusations of sorcery by a glasman or glasmeri have led to the torture and murder of dozens of women across PNG. While accusations can be levelled at both men and women, most of the victims of violence are women.” ref

“When my husband died, we took him to his village and there, his family began to suspect that I killed him, so they planned to cut off my head and bury me with my late husband,” explains one survivor. “It wasn’t true, they just wanted to kill me.” “People have these norms, these beliefs,” said Ms. Kini. “When a Glasman or Glasmeri comes along and says something, people automatically react to what they are saying.” ref

“Human rights defenders are often targeted when they assist a survivor of sorcery accusation-related violence because they are seen as interfering in a customary practice, or when they help survivors of gender-based violence to move provinces, because they are considered to be meddling in a family matter. According to media reports, an average of 388 cases of sorcery accusation-related violence are reported across four Highlands provinces every year, but fear of retaliation means the true number of victims is likely far higher.” ref

Papua New Guinea: Asia’s Fastest Growing Economy Burns Witches Alive.

“The men pack the witch’s mouth with rags. The time for confessions has come and gone. Neighbors crowd into a circle around her, here on this hill of rubbish next to their settlement, Warakum. They watch as the men blindfold her before tying her arms, legs and stomach to a log. They watch as wood is stacked and gasoline poured. They watch as their witch is pushed facedown onto the pyre. Camera phones are held up and aimed. The match is struck and thrown.” ref

“This is the consequence of rending the social fabric, of exercising divisive power, the men say to the thing in their midst. This creature at the center of the settlement dwellers is not a friend or a relative, as the crowd might have once thought. It is a poisonous weed, a snek-no-gut underfoot. Adulterers, the AIDS-marked unclean, and witches such as this one—these evils must be uprooted from the community. It has been so for as long as any can remember.” ref

“The crowd can feel the shush of the flames against the skin of their faces. Then—a low, wet, chewing sound, a sound like a hive of insects eating and eating, as the fire feeds on the pile of refuse. The men roll truck tires over the witch’s trussed, prone figure. The crowd says nothing. This is self-defense. This is a body doing what a body does when a harmful foreign object is located. It marshals its strength, it pushes the object out, it becomes whole and healthy once again.” ref

“The witch was a 20-year-old mother of two who had been blamed for the death of a 6-year-old neighbor boy in her Papua New Guinean shantytown in 2013. Based on his symptoms, the cause of the boy’s death was most likely rheumatic fever. But in PNG, any death that cannot be chalked up to simple old age is believed to have a malevolent agent behind it. A group of 50 or so of the dead boy’s relatives apprehended the young mother, stripped her, tortured her, and burned her alive in the settlement’s landfill just outside the city of Mount Hagen. A number of bystanders were uniformed police officers who helped turn back a fire engine when it whined to the scene.” ref

This particular witch killing splashed across the homepages of international tabloids because members of the crowd had snapped photos and shared them proudly on social media. Journalists descended, ascertaining a few grisly details as well as the woman’s identity (which cannot be said for many victims of sorcery-related violence in PNG): Her name was Kepari Leniata. The context that their stories lacked, the thing these journalists neglected to mention, was this: In PNG (which was fully “opened” to the outside world only in the late 19th century), the tradition of witch hunting has not simply persisted in the face of Western intervention—it has become much worse. The ritual is warping, the violence is metastasizing.” ref

“Witch hunts, which had been a part of many if not all traditional Papua New Guinean cultures, are now commonplace throughout the villages, townships, and small cities dotting the country. Mobs are publicly humiliating and brutally torturing neighbors, family members, friends—often but not always women—and then murdering them, or else forcing them out of their communities, which in a deeply tribal society like Papua New Guinea amounts to much the same thing.” ref

“No one is sure how many supposed witches have been killed—are being killed—in Papua New Guinea. The country’s Constitutional and Law Reform Commission recently estimated 150 killings per year throughout the developing island nation, which lies just off the northernmost cape of Australia. Religious organizations, the people most involved on the ground, dispute this number. The United Nations reported that more than 200 killings take place every year in just one of Papua New Guinea’s 20 provinces alone.” ref

“Kepari Leniata’s public execution was at least the third committed at the Warakum settlement’s trash dump between 2009 and 2013. Two more have occurred there since. A third was set to take place in December 2014, near the end of a trip I took to the area in hopes of understanding how and why. How anyone with a camera phone could still believe in witches, and why this violence was now going from endemic to epidemic.” ref

How Science Can Defeat Witchcraft Fears in Papua New Guinea

“Belief in witchcraft and sorcery is deeply rooted in Papua New Guinea’s culture and history, but it can lead to violence, particularly against women. Local public health experts are working to end this violence through education.” ref

Sanguma and scepticism: questioning witchcraft in the Highlands of Papua New Guinea

“Some anthropologists prefer clear-cut depictions of the societies they study, preferring to ignore differences of opinion, failures of belief, and expressions of scepticism and doubt. This tendency is increasingly being challenged, and an emerging literature now explores scepticism. Contributing to this literature, I discuss the scepticism towards witchcraft expressed by my interlocutors in the Papua New Guinea highlands province of Chimbu. I do not juxtapose witchcraft to science, for witchcraft must be taken seriously – especially since accusations often have severe consequences. Expressions of scepticism bring into doubt the absolute certainty of witchcraft as the explanation for misfortunes such as illness and death, and its study provides a more nuanced picture of a society, showing how cultural norms can be transformed and the foundations of violence can be disrupted. This applies to the scepticism I heard expressed, because the challenge it poses to witchcraft accusations may help prevent further violence. An anthropology of scepticism could usefully be applied more broadly to many aspects of culture, since study of scepticism is one way of reaching an understanding of how social change occurs.” ref

People don’t commonly teach religious history, even that of their own claimed religion. No, rather they teach a limited “pro their religion” history of their religion from a religious perspective favorable to the religion of choice.

Do you truly think “Religious Belief” is only a matter of some personal choice?

Do you not see how coercive one’s world of choice is limited to the obvious hereditary belief, in most religious choices available to the child of religious parents or caregivers? Religion is more commonly like a family, culture, society, etc. available belief that limits the belief choices of the child and that is when “Religious Belief” is not only a matter of some personal choice and when it becomes hereditary faith, not because of the quality of its alleged facts or proposed truths but because everyone else important to the child believes similarly so they do as well simply mimicking authority beliefs handed to them. Because children are raised in religion rather than being presented all possible choices but rather one limited dogmatic brand of “Religious Belief” where children only have a choice of following the belief as instructed, and then personally claim the faith hereditary belief seen in the confirming to the belief they have held themselves all their lives. This is obvious in statements asked and answered by children claiming a faith they barely understand but they do understand that their family believes “this or that” faith, so they feel obligated to believe it too. While I do agree that “Religious Belief” should only be a matter of some personal choice, it rarely is… End Hereditary Religion!

Animism: Respecting the Living World by Graham Harvey

“How have human cultures engaged with and thought about animals, plants, rocks, clouds, and other elements in their natural surroundings? Do animals and other natural objects have a spirit or soul? What is their relationship to humans? In this new study, Graham Harvey explores current and past animistic beliefs and practices of Native Americans, Maori, Aboriginal Australians, and eco-pagans. He considers the varieties of animism found in these cultures as well as their shared desire to live respectfully within larger natural communities. Drawing on his extensive casework, Harvey also considers the linguistic, performative, ecological, and activist implications of these different animisms.” ref

We are like believing machines we vacuum up ideas, like Velcro sticks to almost everything. We accumulate beliefs that we allow to negatively influence our lives, often without realizing it. Our willingness must be to alter skewed beliefs that impend our balance or reason, which allows us to achieve new positive thinking and accurate outcomes.

My thoughts on Religion Evolution with external links for more info:

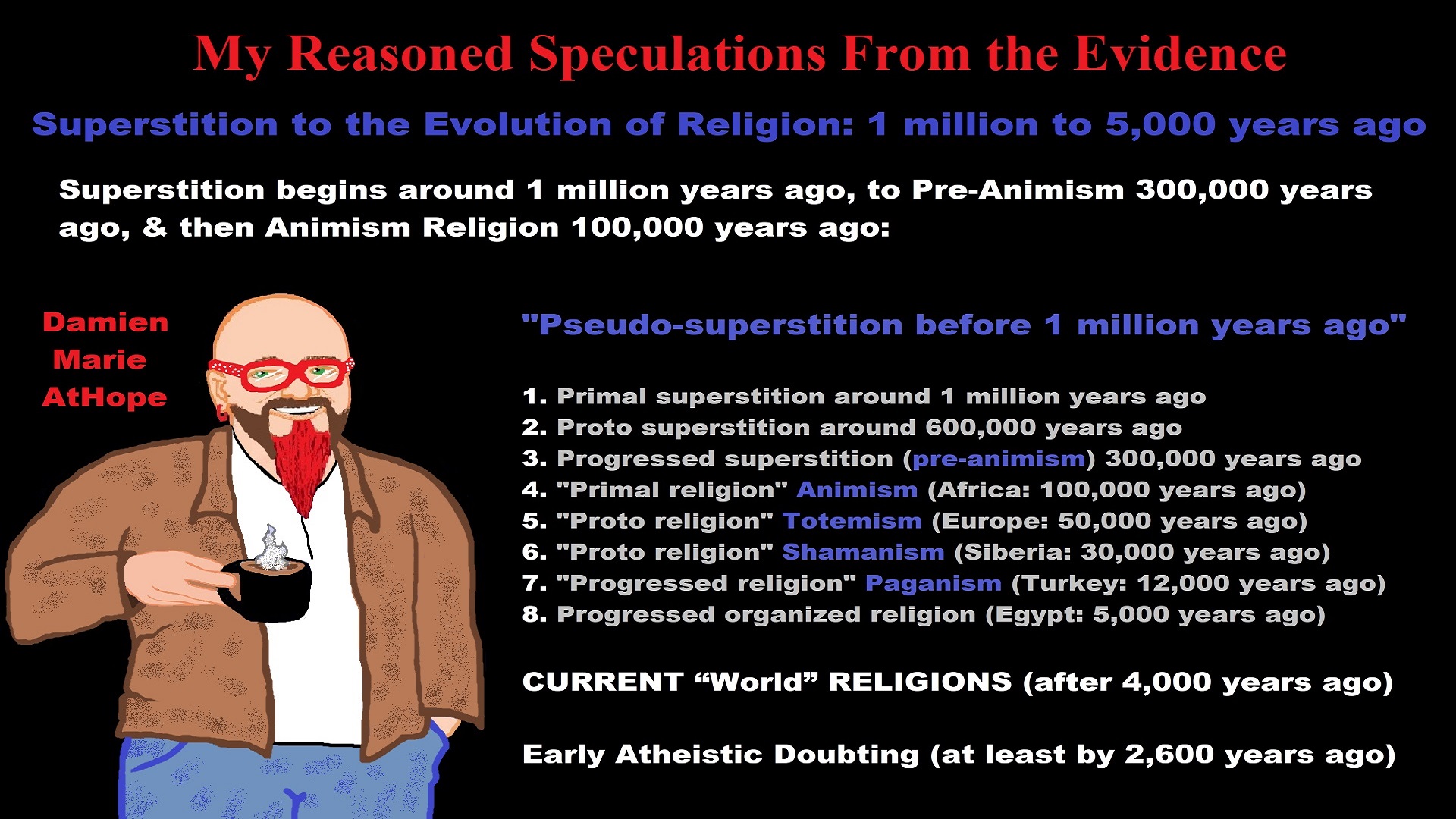

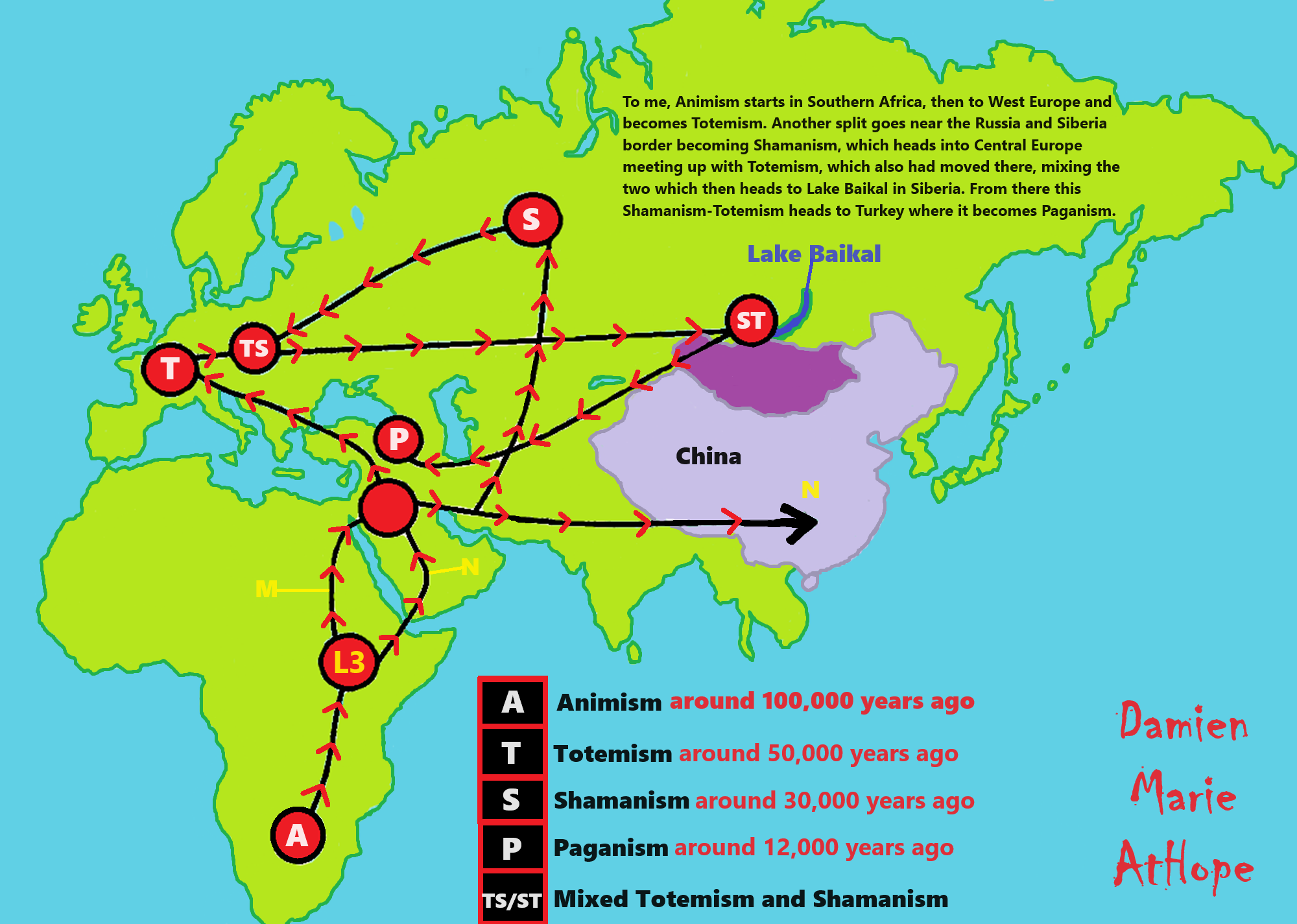

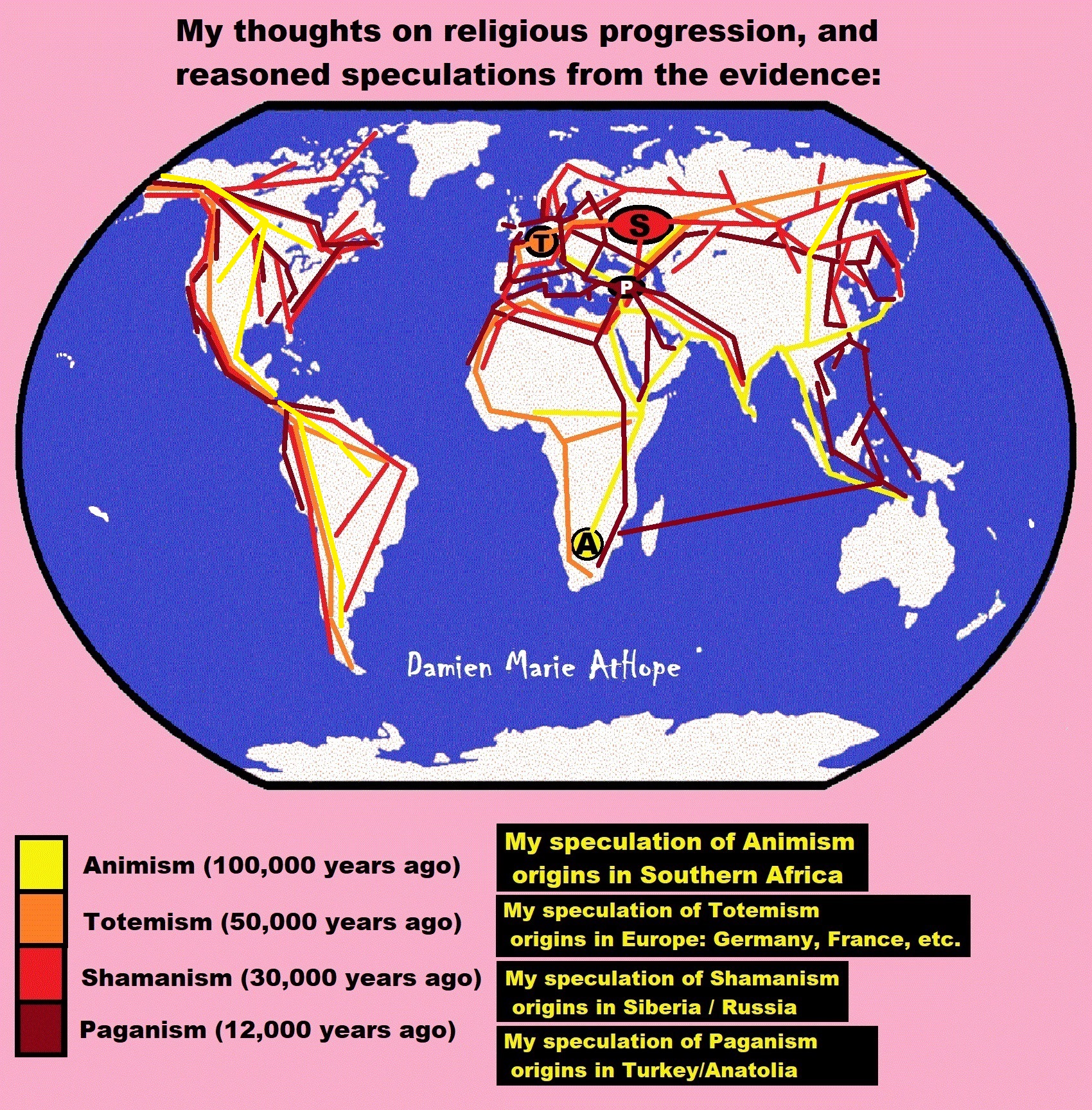

- (Pre-Animism Africa mainly, but also Europe, and Asia at least 300,000 years ago), (Pre-Animism – Oxford Dictionaries)

- (Animism Africa around 100,000 years ago), (Animism – Britannica.com)

- (Totemism Europe around 50,000 years ago), (Totemism – Anthropology)

- (Shamanism Siberia around 30,000 years ago), (Shamanism – Britannica.com)

- (Paganism Turkey around 12,000 years ago), (Paganism – BBC Religion)

- (Progressed Organized Religion “Institutional Religion” Egypt around 5,000 years ago), (Ancient Egyptian Religion – Britannica.com)

- (CURRENT “World” RELIGIONS after 4,000 years ago) (Origin of Major Religions – Sacred Texts)

- (Early Atheistic Doubting at least by 2,600 years ago) (History of Atheism – Wikipedia)

“Religion is an Evolved Product” and Yes, Religion is Like Fear Given Wings…

Atheists talk about gods and religions for the same reason doctors talk about cancer, they are looking for a cure, or a firefighter talks about fires because they burn people and they care to stop them. We atheists too often feel a need to help the victims of mental slavery, held in the bondage that is the false beliefs of gods and the conspiracy theories of reality found in religions.

Understanding Religion Evolution:

- Pre-Animism (at least 300,000 years ago)

- Animism (Africa: 100,000 years ago)

- Totemism (Europe: 50,000 years ago)

- Shamanism (Siberia: 30,000 years ago)

- Paganism (Turkey: 12,000 years ago)

- Progressed organized religion (Egypt: 5,000 years ago), (Egypt, the First Dynasty 5,150 years ago)

- CURRENT “World” RELIGIONS (after 4,000 years ago)

- Early Atheistic Doubting (at least by 2,600 years ago)

“An Archaeological/Anthropological Understanding of Religion Evolution”

It seems ancient peoples had to survived amazing threats in a “dangerous universe (by superstition perceived as good and evil),” and human “immorality or imperfection of the soul” which was thought to affect the still living, leading to ancestor worship. This ancestor worship presumably led to the belief in supernatural beings, and then some of these were turned into the belief in gods. This feeble myth called gods were just a human conceived “made from nothing into something over and over, changing, again and again, taking on more as they evolve, all the while they are thought to be special,” but it is just supernatural animistic spirit-belief perceived as sacred.

Quick Evolution of Religion?

Pre-Animism (at least 300,000 years ago) pre-religion is a beginning that evolves into later Animism. So, Religion as we think of it, to me, all starts in a general way with Animism (Africa: 100,000 years ago) (theoretical belief in supernatural powers/spirits), then this is physically expressed in or with Totemism (Europe: 50,000 years ago) (theoretical belief in mythical relationship with powers/spirits through a totem item), which then enlists a full-time specific person to do this worship and believed interacting Shamanism (Siberia/Russia: 30,000 years ago) (theoretical belief in access and influence with spirits through ritual), and then there is the further employment of myths and gods added to all the above giving you Paganism (Turkey: 12,000 years ago) (often a lot more nature-based than most current top world religions, thus hinting to their close link to more ancient religious thinking it stems from). My hypothesis is expressed with an explanation of the building of a theatrical house (modern religions development). Progressed organized religion (Egypt: 5,000 years ago) with CURRENT “World” RELIGIONS (after 4,000 years ago).

Historically, in large city-state societies (such as Egypt or Iraq) starting around 5,000 years ago culminated to make religion something kind of new, a sociocultural-governmental-religious monarchy, where all or at least many of the people of such large city-state societies seem familiar with and committed to the existence of “religion” as the integrated life identity package of control dynamics with a fixed closed magical doctrine, but this juggernaut integrated religion identity package of Dogmatic-Propaganda certainly did not exist or if developed to an extent it was highly limited in most smaller prehistoric societies as they seem to lack most of the strong control dynamics with a fixed closed magical doctrine (magical beliefs could be at times be added or removed). Many people just want to see developed religious dynamics everywhere even if it is not. Instead, all that is found is largely fragments until the domestication of religion.

Religions, as we think of them today, are a new fad, even if they go back to around 6,000 years in the timeline of human existence, this amounts to almost nothing when seen in the long slow evolution of religion at least around 70,000 years ago with one of the oldest ritual worship. Stone Snake of South Africa: “first human worship” 70,000 years ago. This message of how religion and gods among them are clearly a man-made thing that was developed slowly as it was invented and then implemented peace by peace discrediting them all. Which seems to be a simple point some are just not grasping how devastating to any claims of truth when we can see the lie clearly in the archeological sites.

I wish people fought as hard for the actual values as they fight for the group/clan names political or otherwise they think support values. Every amount spent on war is theft to children in need of food or the homeless kept from shelter.

Here are several of my blog posts on history:

- To Find Truth You Must First Look

- (Magdalenian/Iberomaurusian) Connections to the First Paganists of the early Neolithic Near East Dating from around 17,000 to 12,000 Years Ago

- Natufians: an Ancient People at the Origins of Agriculture and Sedentary Life

- Possible Clan Leader/Special “MALE” Ancestor Totem Poles At Least 13,500 years ago?

- Jewish People with DNA at least 13,200 years old, Judaism, and the Origins of Some of its Ideas

- Baltic Reindeer Hunters: Swiderian, Lyngby, Ahrensburgian, and Krasnosillya cultures 12,020 to 11,020 years ago are evidence of powerful migratory waves during the last 13,000 years and a genetic link to Saami and the Finno-Ugric peoples.

- The Rise of Inequality: patriarchy and state hierarchy inequality

- Fertile Crescent 12,500 – 9,500 Years Ago: fertility and death cult belief system?

- 12,400 – 11,700 Years Ago – Kortik Tepe (Turkey) Pre/early-Agriculture Cultic Ritualism

- Ritualistic Bird Symbolism at Gobekli Tepe and its “Ancestor Cult”

- Male-Homosexual (female-like) / Trans-woman (female) Seated Figurine from Gobekli Tepe

- Could a 12,000-year-old Bull Geoglyph at Göbekli Tepe relate to older Bull and Female Art 25,000 years ago and Later Goddess and the Bull cults like Catal Huyuk?

- Sedentism and the Creation of goddesses around 12,000 years ago as well as male gods after 7,000 years ago.

- Alcohol, where Agriculture and Religion Become one? Such as Gobekli Tepe’s Ritualistic use of Grain as Food and Ritual Drink

- Neolithic Ritual Sites with T-Pillars and other Cultic Pillars

- Paganism: Goddesses around 12,000 years ago then Male Gods after 7,000 years ago

- First Patriarchy: Split of Women’s Status around 12,000 years ago & First Hierarchy: fall of Women’s Status around 5,000 years ago.

- Natufians: an Ancient People at the Origins of Agriculture and Sedentary Life

- J DNA and the Spread of Agricultural Religion (paganism)

- Paganism: an approximately 12,000-year-old belief system

- Paganism 12,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism” (Pre-Capitalism)

- Shaman burial in Israel 12,000 years ago and the Shamanism Phenomena

- Need to Mythicized: gods and goddesses

- 12,000 – 7,000 Years Ago – Paleo-Indian Culture (The Americas)

- 12,000 – 2,000 Years Ago – Indigenous-Scandinavians (Nordic)

- Norse did not wear helmets with horns?

- Pre-Pottery Neolithic Skull Cult around 11,500 to 8,400 Years Ago?

- 10,400 – 10,100 Years Ago, in Turkey the Nevail Cori Religious Settlement

- 9,000-6,500 Years Old Submerged Pre-Pottery/Pottery Neolithic Ritual Settlements off Israel’s Coast

- Catal Huyuk “first religious designed city” around 9,500 to 7,700 years ago (Turkey)

- Cultic Hunting at Catal Huyuk “first religious designed city”

- Special Items and Art as well as Special Elite Burials at Catal Huyuk

- New Rituals and Violence with the appearance of Pottery and People?

- Haplogroup N and its related Uralic Languages and Cultures

- Ainu people, Sámi people, Native Americans, the Ancient North Eurasians, and Paganistic-Shamanism with Totemism

- Ideas, Technology and People from Turkey, Europe, to China and Back again 9,000 to 5,000 years ago?

- First Pottery of Europe and the Related Cultures

- 9,000 years old Neolithic Artifacts Judean Desert and Hills Israel

- 9,000-7,000 years-old Sex and Death Rituals: Cult Sites in Israel, Jordan, and the Sinai

- 9,000-8500 year old Horned Female shaman Bad Dürrenberg Germany

- Neolithic Jewelry and the Spread of Farming in Europe Emerging out of West Turkey

- 8,600-year-old Tortoise Shells in Neolithic graves in central China have Early Writing and Shamanism

- Swing of the Mace: the rise of Elite, Forced Authority, and Inequality begin to Emerge 8,500 years ago?

- Migrations and Changing Europeans Beginning around 8,000 Years Ago

- My “Steppe-Anatolian-Kurgan hypothesis” 8,000/7,000 years ago

- Around 8,000-year-old Shared Idea of the Mistress of Animals, “Ritual” Motif

- Pre-Columbian Red-Paint (red ochre) Maritime Archaic Culture 8,000-3,000 years ago

- 7,522-6,522 years ago Linear Pottery culture which I think relates to Arcane Capitalism’s origins

- Arcane Capitalism: Primitive socialism, Primitive capital, Private ownership, Means of production, Market capitalism, Class discrimination, and Petite bourgeoisie (smaller capitalists)

- 7,500-4,750 years old Ritualistic Cucuteni-Trypillian culture of Moldova, Romania, and Ukraine

- Roots of a changing early society 7,200-6,700 years ago Jordan and Israel

- Agriculture religion (Paganism) with farming reached Britain between about 7,000 to 6,500 or so years ago and seemingly expressed in things like Western Europe’s Long Barrows

- My Thoughts on Possible Migrations of “R” DNA and Proto-Indo-European?

- “Millet” Spreading from China 7,022 years ago to Europe and related Language may have Spread with it leading to Proto-Indo-European

- Proto-Indo-European (PIE), ancestor of Indo-European languages: DNA, Society, Language, and Mythology

- The Dnieper–Donets culture and Asian varieties of Millet from China to the Black Sea region of Europe by 7,022 years ago

- Kurgan 6,000 years ago/dolmens 7,000 years ago: funeral, ritual, and other?

- 7,020 to 6,020-year-old Proto-Indo-European Homeland of Urheimat or proposed home of their Language and Religion

- Ancient Megaliths: Kurgan, Ziggurat, Pyramid, Menhir, Trilithon, Dolman, Kromlech, and Kromlech of Trilithons

- The Mytheme of Ancient North Eurasian Sacred-Dog belief and similar motifs are found in Indo-European, Native American, and Siberian comparative mythology

- Elite Power Accumulation: Ancient Trade, Tokens, Writing, Wealth, Merchants, and Priest-Kings

- Sacred Mounds, Mountains, Kurgans, and Pyramids may hold deep connections?

- Between 7,000-5,000 Years ago, rise of unequal hierarchy elite, leading to a “birth of the State” or worship of power, strong new sexism, oppression of non-elites, and the fall of Women’s equal status

- Paganism 7,000-5,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism” (Capitalism) (World War 0) Elite & their slaves

- Hell and Underworld mythologies starting maybe as far back as 7,000 to 5,000 years ago with the Proto-Indo-Europeans?

- The First Expression of the Male God around 7,000 years ago?

- White (light complexion skin) Bigotry and Sexism started 7,000 years ago?

- Around 7,000-year-old Shared Idea of the Divine Bird (Tutelary and/or Trickster spirit/deity), “Ritual” Motif

- Nekhbet an Ancient Egyptian Vulture Goddess and Tutelary Deity

- 6,720 to 4,920 years old Ritualistic Hongshan Culture of Inner Mongolia with 5,000-year-old Pyramid Mounds and Temples

- First proto-king in the Balkans, Varna culture around 6,500 years ago?

- 6,500–5,800 years ago in Israel Late Chalcolithic (Copper Age) Period in the Southern Levant Seems to Express Northern Levant Migrations, Cultural and Religious Transfer

- KING OF BEASTS: Master of Animals “Ritual” Motif, around 6,000 years old or older…

- Around 6000-year-old Shared Idea of the Solid Wheel & the Spoked Wheel-Shaped Ritual Motif

- “The Ghassulian Star,” a mysterious 6,000-year-old mural from Jordan; a Proto-Star of Ishtar, Star of Inanna or Star of Venus?

- Religious/Ritual Ideas, including goddesses and gods as well as ritual mounds or pyramids from Northeastern Asia at least 6,000 years old, seemingly filtering to Iran, Iraq, the Mediterranean, Europe, Egypt, and the Americas?

- Maykop (5,720–5,020 years ago) Caucasus region Bronze Age culture-related to Copper Age farmers from the south, influenced by the Ubaid period and Leyla-Tepe culture, as well as influencing the Kura-Araxes culture

- 5-600-year-old Tomb, Mummy, and First Bearded Male Figurine in a Grave

- Kura-Araxes Cultural 5,520 to 4,470 years old DNA traces to the Canaanites, Arabs, and Jews

- Minoan/Cretan (Keftiu) Civilization and Religion around 5,520 to 3,120 years ago

- Evolution Of Science at least by 5,500 years ago

- 5,500 Years old birth of the State, the rise of Hierarchy, and the fall of Women’s status

- “Jiroft culture” 5,100 – 4,200 years ago and the History of Iran

- Stonehenge: Paganistic Burial and Astrological Ritual Complex, England (5,100-3,600 years ago)

- Around 5,000-year-old Shared Idea of the “Tree of Life” Ritual Motif

- Complex rituals for elite, seen from China to Egypt, at least by 5,000 years ago

- Around 5,000 years ago: “Birth of the State” where Religion gets Military Power and Influence

- The Center of the World “Axis Mundi” and/or “Sacred Mountains” Mythology Could Relate to the Altai Mountains, Heart of the Steppe

- Progressed organized religion starts, an approximately 5,000-year-old belief system

- China’s Civilization between 5,000-3,000 years ago, was a time of war and class struggle, violent transition from free clans to a Slave or Elite society

- Origin of Logics is Naturalistic Observation at least by around 5,000 years ago.