“Many Amerindian minority languages are spoken throughout Brazil, mostly in Northern Brazil. Indigenous languages with about 10,000 speakers or more are Ticuna (language isolate), Kaingang (Gean family), Kaiwá Guarani, Nheengatu (Tupian), Guajajára (Tupian), Macushi (Cariban), Terena (Arawakan), Xavante (Gean) and Mawé (Tupian). Tucano (Tucanoan) has half that number, but is widely used as a second language in the Amazon.” ref

“Indigenous peoples once comprised an estimated 2,000 tribes and nations inhabiting what is now the country of Brazil, before European contact around 1500 CE. At the time of European contact, some of the indigenous peoples were traditionally semi-nomadic tribes who subsisted on hunting, fishing, gathering and migrant agriculture. Many tribes suffered extinction as a consequence of the European settlement and many were assimilated into the Brazilian population.” ref

“The Indigenous population was decimated by European diseases, declining from a pre-Columbian high of 2 to 3 million to some 300,000 as of 1997, distributed among 200 tribes. By the 2022 IBGE census, 1,693,535 Brazilians classified themselves as Indigenous, and the same census registered 274 indigenous languages of 304 different indigenous ethnic groups. On 18 January 2007, FUNAI reported 67 remaining uncontacted tribes in Brazil, up from 40 known in 2005. With this addition Brazil passed New Guinea, becoming the country with the largest number of uncontacted peoples in the world.” ref

“Anthropological and genetic evidence indicates that most Amerindian people descended from migrant peoples from Siberia and Mongolia who entered the Americas across the Bering Strait and along the western coast of North America in at least three separate waves. According to an autosomal DNA genetic study from 2012, Native Americans descend from at least three main migrant waves from Siberia. The third migratory waves from Siberia, which are thought to have generated the Aleut, Inuit, and Yupik people, apparently did not reach farther than the southern United States and Canada, respectively.)” ref

“Several branches of haplogroup Q-M242 have been predominant pre-Columbian male lineages in indigenous peoples of the Americas. Most of them are descendants of the major founding groups who migrated from Asia into the Americas by crossing the Bering Strait. These small groups of founders must have included men from the Q-M346, Q-L54, Q-Z780, and Q-M3 lineages. Haplogroup Q-M242 has been found in approximately 94% of Indigenous peoples of Mesoamerica and South America. The second migratory wave from Siberia is thought to have generated the Athabaskan speakers, or Na-Dene languages. The indigenous people of North America, Q-M242 is found in Na-Dené speakers at an average rate of 68%. The highest frequency is 92.3% in Navajo, followed by 78.1% in Apache, and 87% in SC Apache.” ref

“The haplogroup C-M217 is now found at high frequencies among Central Asian peoples, indigenous Siberians, and some Native peoples of North America. C2a1a1-F3918 subsumes C2a1a1a-P39, which has been found at high frequency in samples of some indigenous North American populations, and C2a1a1b-FGC28881, which is now found with varying (but generally quite low) frequency all over the Eurasian steppe. The subclade C-P39 is common among males of the indigenous North American peoples whose languages belong to the Na-Dené phylum. C2b1a1a P39 Canada, USA (Found in several Indigenous peoples of North America, including some Na-Dené-, Algonquian-, or Siouan-speaking).” ref

“Males carrying C-M130 are believed to have migrated to the Americas some 6,000-8,000 years ago, and was carried by Na-Dené-speaking peoples into the northwest Pacific coast of North America. Haplogroup C-M130 being found at high frequency amongst modern Kazakhs and Mongolians as well as in some Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Manchurians. C-M217 stretches longitudinally from Central Europe and Turkey, to the Wayuu people of Colombia and Venezuela, and latitudinally from the Athabaskan peoples of Alaska to Vietnam to the Malay Archipelago.” ref

“The initial settling of the Americas was followed by a rapid expansion south down the coast, with little gene flow later, especially in South America. One exception to this is the Chibcha speakers, whose ancestry comes from both North and South America. The Muisca (also called Chibcha) are an indigenous people and culture of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, Colombia, that formed the Muisca Confederation before the Spanish conquest. The people spoke Muysccubun, a language of the Chibchan language family, also called Muysca and Mosca. They were encountered by conquistadors dispatched by the Spanish Empire in 1537 at the time of the conquest.” ref, ref

“Another study, focused on mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), inherited only through the maternal line, revealed that the maternal ancestry of the Indigenous people of the Americas traces back to a few founding lineages from Siberia, which would have arrived via the Bering Strait. According to this study, the ancestors of Native Americans likely remained for a time near the Bering Strait, after which there would have been a rapid movement of settling of the Americas, taking the founding lineages to South America. According to a 2016 study, focused on mtDNA lineages, “a small population entered the Americas via a coastal route around 16,000 years ago, following previous isolation in eastern Beringia for ~2,400 to 9,000 years after separating from eastern Siberian populations. After rapidly spreading throughout the Americas, limited gene flow in South America resulted in a marked phylogeographic structure of populations, which persisted through time. All of the ancient mitochondrial lineages detected in this study were absent from modern data sets, suggesting a high extinction rate. To investigate this further, we applied a novel principal components multiple logistic regression test to Bayesian serial coalescent simulations. The analysis supported a scenario in which European colonization caused a substantial loss of pre-Columbian lineages.” ref

“Linguistic studies have backed up genetic studies, with ancient patterns having been found between the languages spoken in Siberia and those spoken in the Americas. Two 2015 autosomal DNA genetic studies confirmed the Siberian origins of the Natives of the Americas. However an ancient signal of shared ancestry with the Natives of Australia and Melanesia was detected among the Natives of the Amazon region. The migration coming out of Siberia would have happened 23,000 years ago.” ref

“Brazilian native people, unlike those in Mesoamerica and the Andean civilizations, did not keep written records or erect stone monuments, and the humid climate and acidic soil have destroyed almost all traces of their material culture, including wood and bones. Therefore, what is known about the region’s history before 1500 has been inferred and reconstructed from small-scale archaeological evidence, such as ceramics and stone arrowheads.” ref

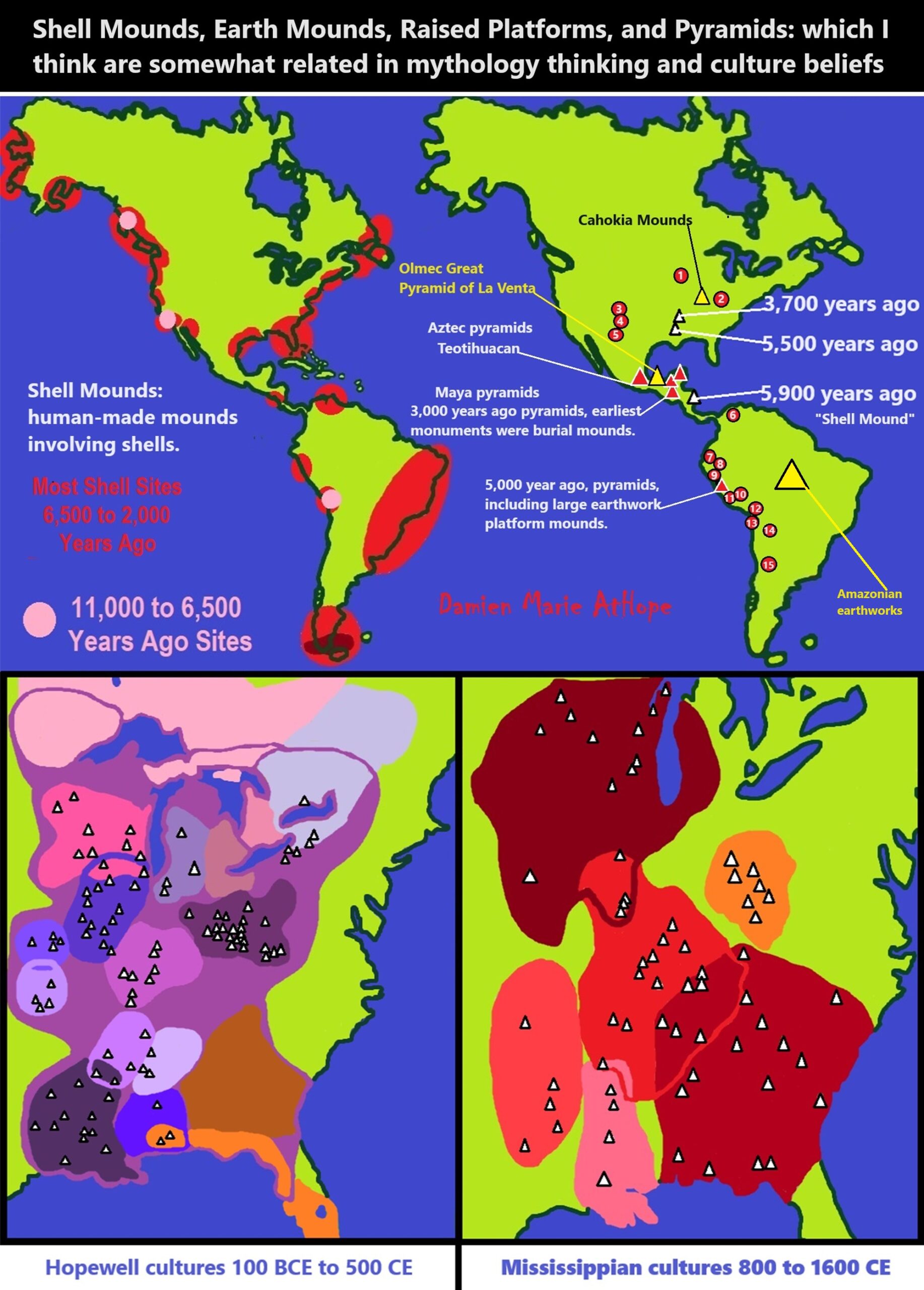

“The most conspicuous remains of these societies are very large mounds of discarded shellfish (sambaquis) found in some coastal sites which were continuously inhabited for over 5,000 years; and the substantial “black earth” (terra preta) deposits in several places along the Amazon, which are believed to be ancient garbage dumps (middens). Recent excavations of such deposits in the middle and upper course of the Amazon have uncovered remains of some very large settlements, containing tens of thousands of homes, indicating a complex social and economic structure.” ref

“Studies of the wear patterns of the prehistoric inhabitants of coastal Brazil found that the surfaces of anterior teeth facing the tongue were more worn than surfaces facing the lips, which researchers believe was caused by using teeth to peel and shred abrasive plants.” ref

“Marajoara culture flourished on Marajó island at the mouth of the Amazon River. Archeologists have found sophisticated pottery in their excavations on the island. These pieces are large, and elaborately painted and incised with representations of plants and animals. These provided the first evidence that a complex society had existed on Marajó. Evidence of mound building further suggests that well-populated, complex, and sophisticated settlements developed on this island, as only such settlements were believed capable of such extended projects as major earthworks.” ref

“The extent, level of complexity, and resource interactions of the Marajoara culture have been disputed. Working in the 1950s in some of her earliest research, American Betty Meggers suggested that the society migrated from the Andes and settled on the island. Many researchers believed that the Andes were populated by Paleoindian migrants from North America who gradually moved south after being hunters on the plains.” ref

“In the 1980s, another American archeologist, Anna Curtenius Roosevelt, led excavations and geophysical surveys of the mound Teso dos Bichos. She concluded that the society that constructed the mounds originated on the island itself.” ref

“The pre-Columbian culture of Marajó may have developed social stratification and supported a population as large as 100,000 people. The Native Americans of the Amazon rain forest may have used their method of developing and working in Terra preta to make the land suitable for the large-scale agriculture needed to support large populations and complex social formations such as chiefdoms.” ref

Xinguano Civilisation

“The Xingu peoples built large settlements connected by roads and bridges, often bearing moats. The apex of their development was between 1200 CE and 1600 CE, with their population inflating to the tens of thousands. The Xingu are an indigenous people of Brazil living near the Xingu River. They have many cultural similarities despite their different ethnicity. Xingu people represent fifteen tribes and all four of Brazil’s indigenous language groups, but they share similar belief systems, rituals, and ceremonies.” ref, ref

“The Upper Xingu region was heavily populated prior to European and African contact. Densely populated settlements developed from 1200 to 1600 CE. Ancient roads and bridges linked communities that were often surrounded by ditches or moats. The villages were pre-planned and featured circular plazas. Archaeologists have unearthed 19 villages so far. The different tribes comprising the Xingu have not been reported to battle each other in war. The only violence seen between the groups are murdering for witchcraft and wrestling matches that take place either between people of the same tribe or between people of different tribes as a means of letting people release the anger they have towards one another, and defending themselves from invasions from other tribes.” ref

“The Xingu classify people into three different categories that they believe exist because the Sun gave people different personal traits; these categories are the Xingu people, the other indigenous people, and the white people. In a Wauja myth, the Xingu are seen as peaceful, whereas these other two groups are seen as violent. The Xingu people maintain peace within their own tribes through trade, intermarriage, and ceremonies.” ref

“One religious practice that the Xingu engage in involves fishing, as many people within the Xingu communities depend on eating fish to provide them with protein. Specifically, shamans expel smoke from herbs in an attempt to prevent the fishermen from being harmed by alligators. The community participates in the preparation of the fish, in which many fish are cooked on an open fire. Women prepare beiju, which are pancakes that are made of cassava. All of the Xingu tribes attend ceremonies to inaugurate new tribal chiefs and honor deceased chiefs.” ref

“Xingu people have historically used fire as a landscaping tool. For centuries, they have understood and utilized the environment based on oral traditions. Xingu tribes from the twenty-first century are noticing changes in the level of fire in the rainforest as well as hotter temperatures, changing rain patterns, and higher river levels. For generations, the Xingu and other tribes in the South American lowlands have been using the emergence of the Pleiades to predict the start of the rainy season, but now this method is not able to be used as consistently. Evidence of the rising river is seen in a meeting of Waurá elders about the year 2005, when turtles failed to hatch because the river rose at an earlier point in the year than what was observed in previous years.” ref

“With the exception of the hunter-gatherer Goitacases, the coastal Tupi and Tapuia tribes were primarily agriculturalists. The subtropical Guarani cultivated maize, tropical Tupi cultivated manioc (cassava), and highland Jês cultivated peanut, as the staple of their diet. Supplementary crops included beans, sweet potatoes, cará (yam), jerimum (pumpkin), and cumari (capsicum pepper).” ref

“Behind these coasts, the interior of Brazil was dominated primarily by Tapuia (Jê) people, although significant sections of the interior (notably the upper reaches of the Xingu, Teles Pires, and Juruena Rivers – the area now covered roughly by modern Mato Grosso state) were the original pre-migration Tupi-Guarani homelands. Besides the Tupi and Tapuia, it is common to identify two other indigenous mega-groups in the interior: the Caribs, who inhabited much of what is now northwestern Brazil, including both shores of the Amazon River up to the delta and the Nuaraque group, whose constituent tribes inhabited several areas, including most of the upper Amazon (west of what is now Manaus) and also significant pockets in modern Amapá and Roraima states.” ref

“The names by which the different Tupi tribes were recorded by Portuguese and French authors of the 16th century are poorly understood. Most do not seem to be proper names, but descriptions of relationship, usually familial – e.g. tupi means “first father”, tupinambá means “relatives of the ancestors”, tupiniquim means “side-neighbors”, tamoio means “grandfather”, temiminó means “grandson”, tabajara means “in-laws” and so on.” ref

“Some etymologists believe these names reflect the ordering of the migration waves of Tupi people from the interior to the coasts, e.g. first Tupi wave to reach the coast being the “grandfathers” (Tamoio), soon joined by the “relatives of the ancients” (Tupinamba), by which it could mean relatives of the Tamoio, or a Tamoio term to refer to relatives of the old Tupi back in the upper Amazon basin. The “grandsons” (Temiminó) might be a splinter. The “side-neighbors” (Tupiniquim) meant perhaps recent arrivals, still trying to jostle their way in. However, by 1870 the Tupi tribes’ population had declined to 250,000 indigenous people and by 1890 had diminished to an approximate 100,000.” ref

Environmental and territorial rights movement

“Many of the indigenous tribes’ rights and rights claims parallel the environmental and territorial rights movement. Although indigenous people have gained 21% of the Brazilian Amazon as part of indigenous land, many issues still affect the sustainability of Indigenous territories today. Climate change is one issue that indigenous tribes attribute as a reason to keep their territory.” ref

“Some indigenous peoples and conservation organizations in the Brazilian Amazon have formed alliances, such as the alliance of the A’ukre Kayapo village and the Instituto SocioAmbiental (ISA) environmental organization. They focus on environmental, education, and developmental rights. For example, Amazon Watch collaborates with various indigenous organizations in Brazil to fight for both territorial and environmental rights. “Access to natural resources by indigenous and peasant communities in Brazil has been considerably less and much more insecure,” so activists focus on more traditional conservation efforts, and expanding territorial rights for indigenous people.” ref

“Territorial rights for the indigenous populations of Brazil largely fall under socio-economic issues. There have been violent conflicts regarding rights to land between the government and the indigenous population, and political rights have done little to stop them. There have been movements of the landless (MST) that help keep land away from the elite living in Brazil.” ref

“Indigenous languages with about 10,000 speakers or more are Ticuna (language isolate), Kaingang (Gean family), Kaiwá Guarani, Nheengatu (Tupian), Guajajára (Tupian), Macushi (Cariban), Terena (Arawakan), Xavante (Gean) and Mawé (Tupian). Tucano (Tucanoan) has half that number, but is widely used as a second language in the Amazon.” ref

* Ticuna (language isolate)

“Ticuna, Tikuna, Tucuna or Tukuna is a language spoken by approximately 50,000 people in the Amazon Basin, including the countries of Brazil, Peru, and Colombia. It is the native language of the Ticuna people and is considered “stable” by ethnologue. Ticuna is generally classified as a language isolate, but may be related to the extinct Yuri language (see Tïcuna-Yuri) and there has been some research indicating similarities between Ticuna and Carabayo.” ref

* Kaingang (Southern Jê language)

“The Kaingang language (also spelled Kaingáng) is a Southern Jê language (Jê, Macro-Jê) spoken by the Kaingang people of southern Brazil. The Kaingang language is a member of the Jê family, the largest language family in the Macro-Jê stock.” ref

“Macro-Jê (also spelled Macro-Gê) is a medium-sized language family in South America, mostly in Brazil but also in the Chiquitanía region in Santa Cruz, Bolivia, as well as (formerly) in small parts of Argentina and Paraguay. It is centered on the Jê language family, with most other branches currently being single languages due to recent extinctions.” ref

* Kaiwá Guarani, Nheengatu (Tupian)

“Kaiwá is a Guarani language spoken by about 18,000 Kaiwá people in Brazil in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul and 510 people in northeastern Argentina. Guarani languages make up about half a dozen or so languages in the Tupi–Guarani language family.” ref, ref

“The Nenhengatu language is native to Brazil, Colombia, Venezuela and is a Tupi–Guarani language.” ref

Tupi-Guarani or Tupian language family

“The Tupi or Tupian language family comprises some 70 languages spoken in South America, of which the best known are Tupi proper and Guarani.” ref

“The Tupi people, a subdivision of the Tupi-Guarani linguistic families, were one of the largest groups of indigenous peoples in Brazil before its colonization. Scholars believe that while they first settled in the Amazon rainforest, from about 2,900 years ago the Tupi started to migrate southward and gradually occupied the Atlantic coast of Southeast Brazil.” ref

* Guajajára/Tenetehára (Tupian)

“Tenetehára is a Tupi–Guarani language spoken in the state of Maranhão in Brazil. Sociolinguistically, it is two languages, each spoken by the Guajajara and the Tembé people, though these are mutually intelligible.” ref

* Macushi (Cariban)

“Macushi is an indigenous language of the Carib family spoken in Brazil, Guyana and Venezuela. It is also referred to as Makushi, Makusi, Macuxi, Macusi, Macussi, Teweya or Teueia. It is the most populous of the Cariban languages.” ref

“The Cariban languages are a family of languages indigenous to north-eastern South America. They are widespread across northernmost South America, from the mouth of the Amazon River to the Colombian Andes, and they are also spoken in small pockets of central Brazil. Mostly within north-central South America, with extensions in the southern Caribbean and in Central America. The Cariban languages share irregular morphology with the Jê and Tupian families. Ribeiro connects them all in a Je–Tupi–Carib family. Meira, Gildea, & Hoff (2010) note that likely morphemes in proto-Tupian and proto-Cariban are good candidates for being cognates, but that work so far is insufficient to make definitive statements. Extensive lexical similarities between Cariban and various Macro-Jê languages suggest that Cariban languages had originated in the Lower Amazon region (rather than in the Guiana Highlands). There they were in contact with early forms of Macro-Jê languages, which were likely spoken in an area between the Parecis Plateau and upper Araguaia River.” ref

* Terena (Arawakan)

“Terêna language is native to Brazil and is part of the Arawakan language family. There are also many Tupi-Guarani loanwords in Terena and other southern Arawakan languages. The Terena people are a Brazilian indigenous people. The Terena are largely an agriculturally focused society, with occupational dominance focusing on agroforestry. The language of the Terena people belongs to the Arawak family, and is reported to have incorporated elements of the Mbayá-Guaikuru family as well. Linguistic studies focusing on the Bolivia-Parana subsector found the highest degree of linguistic similarity between Terena, Mojeño, and Paunaka Language than others in their subgroup. Scholars describe the Awarakan family as a language “matrix” indigenous to South American regions spanning the Terena territory within Brazil.” ref, ref

“Arawakan (Arahuacan, Maipuran Arawakan, “mainstream” Arawakan, Arawakan proper), also known as Maipurean (also Maipuran, Maipureano, Maipúre), is a language family that developed among ancient indigenous peoples in South America. Branches migrated to Central America and the Greater Antilles in the Caribbean and the Atlantic, including what is now the Bahamas. Almost all present-day South American countries are known to have been home to speakers of Arawakan languages, the exceptions being Ecuador, Uruguay, and Chile. Maipurean may be related to other language families in a hypothetical Macro-Arawakan stock. As one of the most geographically widespread language families in all of the Americas, Arawakan linguistic influence can be found in many language families of South America. Jolkesky (2016) notes that there are lexical similarities with the Arawa, Bora-Muinane, Guahibo, Harakmbet-Katukina, Harakmbet, Katukina-Katawixi, Irantxe, Jaqi, Karib, Kawapana, Kayuvava, Kechua, Kwaza, Leko, Macro-Jê, Macro-Mataguayo-Guaykuru, Mapudungun, Mochika, Mura-Matanawi, Nambikwara, Omurano, Pano-Takana, Pano, Takana, Puinave-Nadahup, Taruma, Tupi, Urarina, Witoto-Okaina, Yaruro, Zaparo, Saliba-Hodi, and Tikuna-Yuri language families due to contact. However, these similarities could be due to inheritance, contact, or chance.” ref

* Xavante (Gean)

“The Xavante language is an Akuwẽ (Central Jê) language (Jê, Macro-Jê) spoken by the Xavante people in the area surrounding Eastern Mato Grosso, Brazil.” ref

* Mawé (Tupian)

“The Mawé language of Brazil, also known as Sateré (Mabue, Maragua, Andira, Arapium), is one of the Tupian languages. The Mawé, also known as the Sateré or Sateré-Mawé, are an indigenous people of Brazil living in the state of Amazonas. The Mawé speak the Sateré-Mawé language, which belongs to the Tupian family.” ref, ref

* Tucano (Tucanoan)

“Tucano, also Tukano or Tucana, endonym Dahseyé (Dasea), is a Tucanoan language spoken in Amazonas, Brazil, and Colombia.” ref

Tucano people

“The Tucano people (sometimes spelt Tukano) are a group of Indigenous South Americans in the northwestern Amazon, along the Vaupés River and the surrounding area. They are mostly in Colombia, but some are in Brazil. They are usually described as being made up of many separate tribes, but that oversimplifies the social and linguistic structure of the region. The Tucano are multilingual because men must marry outside their language group: no man may have a wife who speaks his language, which would be viewed as a kind of incest.” ref

“Men choose women from various neighboring tribes who speak other languages. Furthermore, on marriage, women move into the men’s households or longhouses. Consequently, in any village several languages are used: the language of the men; the various languages spoken by women who originate from different neighboring tribes; and a widespread regional ‘trade’ language. Children are born into the multilingual environment: the child’s father speaks one language (considered the Tucano language), the child’s mother another, other women with whom the child has daily contact, and perhaps still others.” ref

“However, everyone in the community is interested in language-learning so most people can speak most of the languages. Multilingualism is taken for granted, and moving from one language to another in the course of a single conversation is very common. In fact, multilingualism is so usual that the Tucano are hardly conscious that they do speak different languages as they shift easily from one to another. They cannot readily tell an outsider how many languages they speak, and they must be suitably prompted to enumerate the languages that they speak and to describe how well they speak each one.” ref

“As mentioned above, the Tucano practice linguistic exogamy. Members of a linguistic descent group marry outside their own linguistic descent group. As a result, it is normal for Tucano people to speak two, three, or more Tucanoan languages, and any Tucano household (longhouse) is likely to be host to numerous languages. The descent groups (sometimes referred to as tribes) all have their accompanying language. The Tucano are swidden horticulturalists and grow manioc and other staples in forest clearings. They also hunt, trap, fish, and forage wild plants and animals.” ref

Amazon Rainforest

“The Amazon rainforest, also called Amazon jungle or Amazonia, is a moist broadleaf tropical rainforest in the Amazon biome that covers most of the Amazon basin of South America. This basin encompasses 7,000,000 km2 (2,700,000 sq mi), of which 6,000,000 km2 (2,300,000 sq mi) are covered by the rainforest. This region includes territory belonging to nine nations and 3,344 formally acknowledged indigenous territories.” ref

“The majority of the forest, 60%, is in Brazil, followed by Peru with 13%, Colombia with 10%, and with minor amounts in Bolivia, Ecuador, French Guiana, Guyana, Suriname, and Venezuela. Four nations have “Amazonas” as the name of one of their first-level administrative regions, and France uses the name “Guiana Amazonian Park” for French Guiana’s protected rainforest area. The Amazon represents over half of Earth‘s remaining rainforests, and comprises the largest and most biodiverse tract of tropical rainforest in the world, with an estimated 390 billion individual trees in about 16,000 species.” ref

“More than 30 million people of 350 different ethnic groups live in the Amazon, which are subdivided into 9 different national political systems and 3,344 formally acknowledged indigenous territories. Indigenous peoples make up 9% of the total population, and 60 of the groups remain largely isolated. Based on archaeological evidence from an excavation at Caverna da Pedra Pintada, human inhabitants first settled in the Amazon region at least 11,200 years ago.” ref

“For a long time, it was thought that the Amazon rainforest was never more than sparsely populated, as it was impossible to sustain a large population through agriculture given the poor soil. Archeologist Betty Meggers was a prominent proponent of this idea, as described in her book Amazonia: Man and Culture in a Counterfeit Paradise. She claimed that a population density of 0.2 inhabitants per square kilometre (0.52/sq mi) is the maximum that can be sustained in the rainforest through hunting, with agriculture needed to host a larger population. However, recent anthropological findings have suggested that the region was actually densely populated. The Upano Valley sites in present-day eastern Ecuador predate all known complex Amazonian societies.” ref

Some 5 million people may have lived in the Amazon region in CE 1500, divided between dense coastal settlements, such as that at Marajó, and inland dwellers. Based on projections of food production, one estimate suggests over 8 million people living in the Amazon in 1492. By 1900, the native indigenous population had fallen to 1 million and by the early 1980s it was less than 200,000.” ref

“The first European to travel the length of the Amazon River was Francisco de Orellana in 1542. The BBC’s Unnatural Histories presents evidence that Orellana, rather than exaggerating his claims as previously thought, was correct in his observations that a complex civilization was flourishing along the Amazon in the 1540s. The Pre-Columbian agriculture in the Amazon Basin was sufficiently advanced to support prosperous and populous societies.” ref

“The BBC’s Unnatural Histories presented evidence that the Amazon rainforest, rather than being a pristine wilderness, has been shaped by man for at least 11,000 years through practices such as forest gardening and terra preta. Terra preta is found over large areas in the Amazon forest; and is now widely accepted as a product of indigenous soil management. The development of this fertile soil allowed agriculture and silviculture in the previously hostile environment; meaning that large portions of the Amazon rainforest are probably the result of centuries of human management, rather than naturally occurring as has previously been supposed. In the region of the Xingu tribe, remains of some of these large settlements in the middle of the Amazon forest were found in 2003 by Michael Heckenberger and colleagues of the University of Florida. Among those were evidence of roads, bridges, and large plazas.” ref

“In the Amazonas, there has been fighting and wars between the neighboring tribes of the Jivaro. Several tribes of the Jivaroan group, including the Shuar, practiced headhunting for trophies and headshrinking. The accounts of missionaries to the area in the borderlands between Brazil and Venezuela have recounted constant infighting in the Yanomami tribes. More than a third of the Yanomamo males, on average, died from warfare. The Munduruku were a warlike tribe that expanded along the Tapajós River and its tributaries and were feared by neighboring tribes. In the early 19th century, the Munduruku were pacified and subjugated by the Brazilians.” ref

The myth of the pristine Amazon rainforest

“Indigenous inhabitants shaped the rainforest by domesticating tree species in pre-Columbian times. Trees that were domesticated by pre-Columbian peoples still dominate the forests of the Amazon Basin. The findings put a dent in the notion that the vast rainforests were untouched by human hands before the arrival of the Spanish explorers in South America. In an article published in Science, an international team, including Florian Wittmann from the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry, the scientists reported their findings.” ref

“As far back as 8,000 years ago, the peoples of Amazonia began to domesticate plants such as the Brazil nut, the cacao tree and the acai palm tree. For a long time, it was not clear to what extent the indigenous inhabitants of the forest really transformed the forest by specifically tending to or cultivating certain trees or carrying their seeds over large distances. The international team headed by Carolina Levis from the Brazilian national institute for Amazon research (INPA) therefore investigated the occurrence of 85 tree species used for food or as a construction material by the pre-Columbian inhabitants. The database contains an inventory of tree species found at approximately one thousand study sites in the Amazon Basin.” ref

More domesticated species than expected are widely distributed

“The team found that 20 out of 85 domesticated species are abundant in the entire Amazon Basin and dominate large swathes of the rainforest. A study published in 2013 and co-authored by Florian Wittmann identified 4,962 different tree species in total at the ATDN study sites. Only 227 of these were widely distributed. While only five percent of all tree species are abundant in the Amazon Basin, 24 percent of the domesticated species occur frequently there. The proportion of abundant domesticated species was thus five times greater than would have been expected if humans had not interfered.” ref

“Florian Wittmann comments on the result: “The study sheds considerable light on how many tree species were propagated by humans; for example, Bertholletia, the Brazil nut.” A researcher in Manaus (Brazil) for the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry until 2016, Wittmann is now working at Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT). Genetic studies have demonstrated that there are only very slight genetic differences between Brazil nut trees found in different areas of the Amazon region. Since the differences are much greater among species that have spread through the rainforest by chance, it is very probable that the species’ propagation was helped along by humans. Further investigation is required to confirm such findings concerning other trees, such as the cacao tree.” ref

Humans made their mark on the Amazon rainforest long before the arrival of the Spanish

“The study produced another finding: Around archaeological sites, the abundance and richness of domesticated trees increased. Carolina Levis and her colleagues concluded that the American indigenous populations conferred an advantage on useful trees through their activities, thereby changing the ecosystems. The scientists believe that the finding confirms that human activities shaped the Amazon rainforest before the arrival of the Spanish. Florian Wittmann agrees: “Hardly any corner of Amazonia has been left untouched by humans,” the expert on floodplains ecology says. “According to estimates, about ten million people lived there prior to European colonisation.” ref

“For years, Wittmann has been working with Brazilian scientists and oversees several of the Amazon Tree Diversity Network study sites. Nine of them, which are located approx. 150 kilometres northeast of the megacity of Manaus, deep in the jungle, were included in the study in question. The study areas each span a hectare and are situated near the Amazon Tall Tower Observatory (ATTO). The primary purpose of the 325-metre tall tower is to help German and Brazilian scientists study climate issues. “We are looking at the extent to which the rainforest affects the climate and vice versa – how the atmosphere affects the rainforest,” Wittmann explains.” ref

Indigenous tree knowledges in Amazonia

“Indigenous understandings of rainforests and the plants within them reveal a way to live perennially. In Shuar culture, as in others in Amazonia, the architect or leading builder of the jea (collective extended family house) is not only the eldest member of the clan – he who has acquired the knowhow from his forebears – but also he who can select a tree with hands, eyes, nose and tongue; he who develops a relationship with the chosen tree whose permission is needed before toppling and symbolically replanting it as a column or support in a home.” ref

“The act of toppling a tree lies at the core of many syncretic (animistic, Catholic, and African) versions of stories that exist of the Tree of Abundance: a dominant origin myth in western Amazonia. In one of the Kichwa Napo Runa narratives, a formidable cedar, bearer of all seeds and fruits, grows beyond reach. In some hyperbolic versions, its vast crown covers the world. In other versions, the tree of the original seed, seed of seeds, was born from a woman. When the tree reached the skies, making its fruit inaccessible, wise elders or mythological beings had to decide whether to topple the colossal bearer of life or not. After much deliberation, they decided it was imperative to cut down the mighty tree. Eventually, severed, it tumbled down, with a thunder, and its branches cascaded into the muddy waters of Amazonian tributaries descending from the Andes.” ref

“Its splinters became myriad fish. Its trunk became the mother of all rivers, estuaries, and canals. Its fruits and seeds dispersed through the waters into the tropical rainforests of South America, to feed all. This river of fruits flows downwards and drains its countless branches to the east. From the mighty Tree of Abundance stemmed the water tree that irrigates all life. It is a symbol of the intricate system of interdependencies that sustains us. No being is insignificant in this Amazonian socio‑natural web of reciprocal relations. The Tree of Abundance is not the Tree of Life nor the Tree of Knowledge, yet, in its branches, humanity can peacefully gather and rest.” ref

South American Forest Indian

“South American forest Indian, indigenous inhabitants of the tropical forests of South America. The tribal cultures of South America are so various that they cannot be adequately summarized in a brief space. The mosaic is baffling in its complexity: the cultures have interpenetrated one another as a result of constant migratory movements and through intertribal relations, leading to the obliteration of formerly significant differences, and to new cultural systems made up of elements of heterogeneous origin. Hundreds of languages, in very irregular geographic distribution, with innumerable dialects, are or have been spoken in the tropical area of South America. Thus, only the broadest generalizations can be made; one can mention certain cultural manifestations that are present in a great number of groups, even though varying in their actual expression, and illustrate them with specific examples—but always with the qualification that in a neighboring tribe or group a distinctly contrasting idea or institution may exist.” ref

“The innumerable native peoples differ in their patterns of adaptation to their natural environment. Whether they live in the rainforest, in the gallery forests lining the rivers, in the arid savannas, or in the swamps, however, they share a common cultural background; they often combine hunting, fishing, and gathering wild plant foods with rudimentary farming. Most are relatively sedentary, but some are nomadic or semi-nomadic. Greater differences are sometimes found among neighboring groups living in the same forest than between some forest and savanna peoples. And some tribes, when migrating to open areas, maintain to a great extent the forest characteristics of their culture. On the banks of the great rivers and in zones between the forest and the savanna live tribes who gain their subsistence from farming and fishing. Hunters and gatherers, almost all of whom also practice some farming, have settled near the heads of rivers, in open land, or in gallery forests.” ref

“Tribes speaking related languages are scattered over a large part of the continent. The tribes of the Arawak and the Carib linguistic families are most numerous in the Guianas (French Guiana, Guyana, Suriname, and the adjacent regions of Venezuela and Brazil) as well as in other parts of the northern Amazon, but the former have representatives as far south as the Chaco and the latter as far south as the upper Xingu. The Tupí tribes extend to the south of the Amazon valley. The Ge family includes groups most of which are located in the semi-arid lands of central Brazil. In the extreme northwest of Brazil and in the jungles of eastern Peru and Bolivia live the Pano tribes. The Jívaro of Ecuador are famous headhunters. They cut off the enemy’s head, separate the soft part from the skull, and, with the help of hot sand, reduce it to the size of a fist without altering the physiognomy. They attribute great magical power to these trophies, or tsantsa.” ref

“A characteristic feature of the tropical forest cultures is their combination of farming with hunting, fishing, and gathering. Before the arrival of Europeans, the Indians of the tropical forest had no domestic animals except the dog. As is typical of most farmer-foragers, these people did not write or erect stone buildings as did the Indians of Middle America, form states with centralized political organizations, or have castes of warriors or priests. Their utensils and instruments were almost all of vegetable or animal origin, since in large sections of the area stones for making axes, arrowheads, and other objects were quite scarce. One finds evidence of metalwork only in the regions near the Andean civilizations, although objects of copper and other metals occasionally found their way across the continent, through channels of trade.” ref

“In almost all of the tropical forest area the population density was low, probably averaging less than one person per square mile. Populous centres existed only along the coast and the main rivers, particularly the Amazon; the latter, according to reports by early European explorers, was fringed with Indian villages. For the most part, however, the Indians were dispersed throughout the vast territory in innumerable tribes and tribelets. This is why a classification by languages and cultures gives only a vague idea of the complex picture of the forest populations. Peoples having the same dialect and culture might exist as separate groups, even as enemies. While some Indians considered themselves primarily members of their local group, others, like the Xerente (Sherenté), gave greater value to a common language and culture than to village divisions. But differences in dialect and culture often imposed obstacles to the recognition of tribal solidarity.” ref

“There were no permanent political associations or confederations encompassing tribes of different languages and cultures. From time to time tribes might form ephemeral confederations for warfare against a common enemy. Certain close relations sometimes existed between groups of diverse origin, especially through tribal intermarriage. The best known examples are along the Río Negro in northwest Brazil, where numerous populations, mostly Arawak and Tucano, are united in a vast network of interethnic relations. At the headwaters of the Xingu, a complex system of intertribal institutions also exists among formerly autonomous groups. Few tropical forest tribes are strictly monogamous. Polygyny with two or more women is usually restricted, however, to chiefs and other men of prestige. It is perhaps most accentuated among the Jívaro, where headhunting once killed off many of the men; it frequently takes the form of marriage with two or more sisters. Examples of polyandry are rare.” ref

“The choice of a partner is sometimes limited by the division of the tribe into clans and segments to which an individual belongs by heredity and within which marriage is prohibited. In some cases, for example in the Guianas and in the Río Negro region, the individual must find a mate outside his village or even outside his tribe (exogamy). The Terena of the southern Mato Grosso divide themselves into endogamous groups: the man and wife must come from the same group, called by ethnologists a moiety. Marriage between cross cousins, that is, between children of siblings of different sex, is considered ideal in many tribes; that of parallel cousins, children of siblings of the same sex, is frequently prohibited.” ref

“Kinship groups and household communities are based predominantly on the principle of lineage, that is, on relation through either the male or female line. Communities of extended patrilineal families were typical of the Tupí-Guaraní. In many Amazon tribes and in others farther north, the lineages or groups of lineages are patrilineal exogamous clans. Tribes with matrilineal clans, although less numerous, can be found throughout South America. In some tribes the clans number 40 or more, as among the Mundurukú; they are generally organized into two groups so that the whole tribe comprises two exogamous moieties. The dual divisions of the Ge Indians, often not related to kinship and marriage, are mainly ceremonial.” ref

“In general, the tropical forest cultures do not exhibit much social stratification. When there is inequality, it is normally made up of ethnic outsiders who do not constitute a class as such. War captives may be reduced to slavery, as among the northern Carib and Arawak, the Huitoto, and the Mundurukú. Among the extinct Tupí of the Brazilian coast, slavery was the fate of those destined for ritual sacrifice. In many cases, chiefly among the northern Carib, slavery had primarily an economic function: the captives form a servile group known as peito—the same term applied to a fiancé during the period in which he is obliged to work for his future father-in-law. The Rucuyen, a Carib tribe of French Guiana, for some time maintained in servitude a great number of the Oyampī, their Tupí neighbors. In the northwest Amazon, Arawak and Tucano tribes hunt and enslave Makú men, who are forced to work in their gardens; the Makú women and children are used as domestic servants.” ref

“A tendency to form a class of nobility has been found in many Arawak groups, who not uncommonly impose themselves over other tribes by means of intermarriage, especially among families of chiefs. In some regions, relatives of chiefs constitute a kind of nobility. In tribes divided into clans, it is common to attribute superior status to a certain clan or even to scale them in hierarchic order. Nevertheless, the local or tribal community is essentially egalitarian. The children learn through play and imitation. Boys acquire skill in the use of weapons by practicing with small bows or blowguns made by their fathers. Girls learn to cook in little clay pots and to weave on small looms; they help their mothers in the preparation of manioc flour. The young also participate in the general religious life. The transmission of moral standards is rarely of a formal nature, and there is little punishment or repression.” ref

“The institution of the couvade is found throughout the forest culture. The father of a newborn infant must observe a rigorous diet for a week or so after the infant’s birth. It is based on the idea of a mystical relation between the father and the child. Puberty rites are often quite elaborate. In many tribes, such as the Guaraní, the symbol of masculine maturity is the labret, an ornament worn in a perforation of the lip; the ritual is preceded by an instruction period during which the boys, isolated from the community, learn the religious chants and dances, and it culminates with the perforation of their lower lips. Initiation rites may be limited to boys or to girls or may be for both sexes. The initiation of the boys is generally done collectively for those who have reached the eve of sexual maturity, while that of the girls is normally held individually on the occasion of the first menstruation.” ref

“In many of the Indian cultures these rites take a central position among other important ceremonies such as funerals and fertility rites. In the Guianas and the northwest Amazon region, the initiation of the boys is very complex. The Yurupary celebration inducts the boys into the secret society of mature men. Special rites are revealed to them; they are shown the sacred trumpets or the masks representing ancestral spirits. They are subjected to violent whippings, which they must tolerate without the least expression of pain. In the Guianas, the ritual torture consists of the stings of hornets or the bites of poisonous ants. The girls’ initiation, generally more developed in the Amazon area near the Andes, is also frequently accompanied by difficult tests. Among the Tikuna (Tucuna) and other Amazonian groups, all the hair of the girl is pulled out; its regrowth symbolizes the emergence of a new adult personality.” ref

“The initiation of the boys assumes great importance in the social structure of some Ge groups of central Brazil, whose complex of rites begins at ten years of age and continues in cycles until 20. In one such tribe, the Xerente, candidates spend three years isolated from community life preparing themselves for manhood. In these Ge groups, those who have been initiated together form a distinct set of persons who feel united the rest of their lives. While the bands of gatherers rarely exceed a few dozen individuals, the farmers’ villages have been known to include as many as 2,000. As a rule they are much smaller, dividing whenever the population becomes too large. A characteristic arrangement is the circular village of houses placed around a central plaza. This is found, for example, in the upper Xingu, in various Ge tribes, and among the Bororo of the Mato Grosso. The plan of the Bororo village, like that of the Ge, is a real map of the social structure. Each household represents a particular segment of the local group, such as an extended family or a patrilineal or matrilineal clan. The centre of the plaza is often occupied by the men’s house, where the men spend the night and the greater part of the day, and which is at times the locus of ceremonial activities.” ref

“A great variety of economic systems is found in the tropical forest. The tribes cannot accurately be classified as hunters and gatherers on the one hand or as farmers on the other. The differences lie in the emphasis given to agriculture rather than in the presence or lack of it. The Guayakí of the forests of eastern Paraguay are one of the few tribes without any agriculture; they feed on wild honey and larvae, catch fish with arrows, and hunt jaguars and armadillos. The Sirionó of Bolivia and most of the Makú (a denomination that comprises rather heterogeneous Amazonian groups) are nomads who hunt, fish, and gather. A few Makú groups, however, influenced by their neighbors, have become more or less sedentary farmers. The same holds for the Shirianá and Waica of the Orinoco–Amazon headwaters.” ref

“The crops are chiefly bitter manioc as well as other tubers and roots, and, in the western regions, maize (corn). Some Ge tribes grow mainly sweet potatoes and yams. The forest is cleared by felling the trees (the stone axe has now been everywhere replaced by the iron axe) and, when the underbrush is dry, setting fire to it. The same plot is used for several (but never more than six) consecutive crops and then left fallow for several years until it is covered by new vegetation. The group must therefore move periodically. The slash-and-burn system does not, except in the more fertile lowlands, permit the growth of dense populations. It does, however, provide a seasonal food surplus that might in many cases, considering the available techniques, be increased. But the Indian has no incentive to store up goods in a generally egalitarian society, since goods are not a source of prestige.” ref

“The tropical forest Indians are highly inventive. They have developed many types of harpoons, arrows, traps, snares, and blowguns. In fishing they employ a variety of drugs that stun or kill the fish without making them inedible. The bow and arrow are today known everywhere; in some Amazon regions they have replaced the spear thrower, a device still in use in certain western tribes. The bow and arrow are the principal weapons of warfare, although some groups fight with clubs and lances. The techniques of basketry have a wealth of variations, mainly in the Guianas, the northwest Amazon region, and among the Ge peoples. Along with many kinds of baskets and hampers, these folk plait sifters, traps, fans, mats, and other household articles out of palm leaves and shafts of taquara, or bamboo.” ref

“The potter’s wheel was traditionally unknown, but coiled ceramics reached a high degree of development, particularly among the Arawak and Pano tribes. Among nomadic groups pottery is either nonexistent or very rudimentary; instead, the nomads use gourds, calabashes, baskets, and fibre pouches. Spinning and weaving, though well-known, remain at an elementary level since most tropical forest Indians, instead of dressing, prefer to paint the body and to embellish it with all sorts of adornments. From cotton, growing wild or planted, they make tunics, as well as belts of various types, skirts, and particularly hammocks. They use simple spindles, which they whirl like tops. The most common loom is the heddle loom: the threads of the weft, separated by heddles, are wound around a vertical frame. In regions close to the Andes, especially in eastern Bolivia, the Indians make cloth of beaten bark.” ref

“Land is generally owned by the group occupying or exploiting it—a band, a village, or a clan—and parcelled out to families or other small units for hunting, fishing, or planting. Collective tribal land or territory exists only in rare cases, when the solidarity between the various groups of a people is particularly strong. There are rigorous norms for the distribution of game among the hunter’s family and among other families to which he is associated by certain ties; the hunter himself may receive a rather small share. Cleared land almost always belongs to the family using it, but when necessary others may have access to its products. Generosity is greatly valued. This also holds for intertribal relations, when gifts are exchanged on the occasion of visits or celebrations.” ref

“Weapons and household utensils are the property of individual men and women, but canoes and other objects used collectively are not. Body adornments generally belong to the wearer. Intangible property may belong to the clan or other social unit, but it may also be individually owned, as in the case of the name or ritual functions among Ge tribes, and magical–religious chants among the Guaraní. Brisk trade among tribes is carried on in parts of the Guianas, in northwest Amazonia, and in upper Xingu. Indians of the upper Orinoco export urucu, a red dye, to groups living downriver. The Arawak frequently trade ceramic wares produced by their women; they also supply blowguns in exchange for poisonous curare and barter manioc graters. Carib tribes often trade cotton products. Some groups specialize in the manufacture of canoes, which are much in demand by neighboring groups.” ref

“The most complex trading system is that of the upper Xingu; it includes a dozen tribes, each with its own products. Commerce contributes significantly toward reducing cultural differences among the tribes, the more so because it is accompanied at times by ceremonial activities through which religious ideas and practices, as well as elements of social organization, are transmitted. The tropical forest Indians believe that their well-being depends on being able to control innumerable supernatural powers, which in personal or impersonal form permeate or inhabit objects, living beings, and nature in general. Through shamanistic rites or collective ceremonies, humans must encourage and maintain their harmonious integration in the universe, controlling the forces that govern it; their beneficial or harmful effects are largely determined by human action.” ref

“In most of the cultures, magical measures and precautions are more important than the religious cult as such. The strength and health of the body, the normal growth of children, the capacity to procreate, and even psychic qualities are obtained by magical means. For the individual these means may include the perforation of the lips, nasal septum, or ear lobes, the painting of the body, and the use of various adornments. A little stick passed through the nasal septum, such as that used by the Pawumwa of the Guaporé River, prevents sickness. The hunter or fisherman, in order to be successful and not to be panema (unlucky), as they say in many Amazonian regions, takes precautions such as scarring his arms or abstaining from certain foods. The magical devices of the hunter, the fisherman, and the warrior are considered much more important than their ability. Arrows must be treated by rubbing with a certain drug, since their magical attributes are believed to be more effective than their technical properties.” ref

“Stimulants and narcotics are of great importance in the magic and religious practices of most tropical forest Indians. Secular use of drugs is much rarer. Tobacco is known by almost all tribes. The Tupinamba shaman fumigates his rattle with tobacco, which he believes contains an animating principle that confers on the rattle the faculty of “speaking,” that is, of revealing the future. Alcoholic beverages, consumed mainly in religious festivals, are obtained by fermentation of manioc, corn, and other plants. They are unknown among the Ge, in the upper Xingu, and in some regions of Bolivia and Ecuador. Coca leaves are chewed, especially in the sub-Andean regions. Infusion of maté is taken in the Paraguay area, as well as by the Jívaro and other groups of Ecuador. Hallucinogens are used mainly in the Amazon–Orinoco area; they include species of Banisteriopsis (a tropical liana), from which is made a potion that produces visions.” ref

“In certain tribes, the use of this drug is restricted to shamanistic practices; in others, as in the Uaupés River area, it is an essential element in religious festivals in which the community revives its mythic tradition. Other narcotics in ritual use, among them the yopo, or paricá (Piptadenia), known among many northern groups, are often breathed in the form of snuff, which partners blow into one another’s nostrils; the Omagua of the upper Amazon used it as an enema. Some magical practices are reserved for the shaman, who acquires status by natural endowment, by inspiration, by apprenticeship, or by painful initiation.” ref

“The shaman may practice medicine, perform magic rites, and lead religious ceremonies. Rarely, however, is he a priest in the usual sense of the term. In many groups his influence is superior to that of the political chief; in some, as among the Guaraní, the two roles may coincide. Not uncommonly, his influence continues even after his death: in the Guianas and elsewhere, his soul becomes an auxiliary spirit of his living colleagues, helping them in their curing practices and in the control of harmful spirits; among the Rucuyen, the bodies of common individuals were cremated, while that of the shaman was kept in a special place so that his soul might live on.” ref

“In curing the sick, the shaman must remove the object causing the sickness: a small stone, a leaf, an insect, any substance that has been sent through the black magic of an evildoer. The cure consists of massages, suction, blowing, and fumigation. If the illness comes from loss of the soul, the shaman must search for and recover it. If it comes from a bad spirit, he tries to overcome the evil influence with the help of one or more auxiliary spirits. The soul has its seat in the bones, the heart, the wrist, or in other parts of the body. Some Indians believe that two or more souls are responsible for various vital functions. One finds also the idea of a purely spiritual soul. The Guaraní believe that man has an animal soul governing his temperament and his instinctive reactions but that he also has a second, spiritual one, sent by a divinity at the moment of conception. Thanks to his second soul, man thinks, speaks, and is capable of noble sentiments. After death this second soul returns to live among the gods, while the other soul wanders the Earth as a ghost menacing the living.” ref

“Nature is believed to be peopled by demons and spirits that are beneficial or malevolent, depending on man’s behavior. Besides the soul that gives life to every living thing, many plants and animals have a “mother” or “master,” as do manioc, maize, and game animals. The mythology of almost all tribes includes a creator of the universe and of people. This creator seldom sustains interest in his handiwork, and thus, there is usually no cult attached to him. Social institutions, customs, knowledge, techniques, and cultivated plants are deeds or gifts of a culture hero or a pair of them, sometimes twin brothers who may represent the Sun and Moon. A number of myths are told about these figures; sometimes the pair consists of a hero and a trickster who opposes him.” ref

“Ceremonial practices vary, depending on the tribe and its way of life. Some great collective ceremonies have been associated with war, as among the northern Carib and the coastal Tupí, both famous for cannibalism, and the headhunting Mundurukú and Jívaro. Ceremonies are often believed to be indispensable for regulating the course of the Sun and the Moon, the sequence of the seasons, the fertility of plants, the procreation of animals, and the very continuity of human life. Their objective may also be to commune with the dead or with mythical ancestors; when they are connected with the disposal of the dead, they are at the same time passage rites, by means of which the spirits of the dead are made harmless. Among the Guaraní, most religious ceremonies mean profound spiritual communion with the gods.” ref

“Corpses are commonly disposed of by ground burial within or without the house. Urn burial has also been known, especially among Tupí groups; some groups have been known to unearth bones, clean them, and then rebury them. The Tarariu (Tarairiu) of northeastern Brazil and some Pano broiled the flesh of their dead and mixed the pulverized bones and hair with water or with a manioc-base beverage that they drank. Tribes of the Caribbean coast, after drying the body by fire, allowed it to decompose and later added the powder to a drink. In other northern regions, one still finds the custom of cremating the cadaver and consuming the charred and crushed bones in a banana mush.” ref

“Artistic efforts are most commonly applied to decoration, whether of the human body, objects of practical or ritual use, or even houses. The most common body adornments are paint and feather ornaments. Tattooing has also been practiced, especially among the Mundurukú and many Arawak tribes. Magical and religious ideas are usually expressed in these adornments. The Carib tribes of the Guianas and some Tupí were outstanding in featherwork. The plumed mantles of the Tupinamba, the delicate and elaborate adornments of the Caapor of Maranhão state, and the rich and varied ones of the Mundurukú are much celebrated.” ref

“The design of ornaments is almost always geometrical, with characteristic patterns for particular tribes; the styles vary with the cultural areas. Masks, generally used in ceremonial dances, are restricted to the tribes of certain areas: the Guartegaya and Amniapé (Amniepe) of the upper Madeira, the tribes of the upper Xingu, the Karajá and the Tapirapé of the Araguáia River area, some Ge of central Brazil, and the Guaraní of southern Bolivia. The masks represent the spirits of plants, fish, and other animals, as well as mythical heroes and divinities. They are highly stylized in form but, on occasion, naturalistic in expression. The Waurá women of the upper Xingu are famous for their pots and animal-shaped bowls. Of the historic tribes, the Tapajó of the Amazon had the richest style in ceramics, excelled only by the archaeological remains of the Ilha de Marajó. Among some groups in the Guianas and western Amazonia, artistic activity includes wood carving.” ref

The Ancient Shihuahuaco: the Amazon’s tree of life

“No story is as old and universal as the tree of life. In Nordic mythology, a huge tree connects the nine worlds of the universe. In Iroquois legend, a pregnant woman creates the world by planting a tree on a turtle’s back. In his theory of evolution, Darwin shows that all organisms are interconnected in a single tree of life. While shihuahuaco fruits are not industrially commercialized, many Indigenous groups prize the seeds, and some use the bark as an antimicrobial medicine. Others, like the Boras people, make the shell-like pods into necklaces and other decorative objects.” ref

“If one species embodies the tree of life in the modern day, it might be the Dipteryx micrantha, known as the shihuahuaco in Peru. Among roughly 390 billion trees growing in the Amazon, shihuahuacos are among the tallest and most ancient. They take about one millennium to grow to full height of up to 60 m or almost 200 feet. Forest giants like the shihuahuaco are called “emergent trees” because they reach the emergent layer or overstory of the forest. The emergent layer endures heavy winds, rain and sun exposure. Despite these harsh conditions, bold animals like eagles, bats and monkeys all venture to the emergent layer.” ref

“Identified as a keystone species, the shihuahuaco sustains a staggering amount of life. During the wet season, lilac flowers blossom in its upper canopy. By the dry season, these flower clusters have morphed into heavy fruit pods or legumes (the shihuahuaco is a member of the bean family). Bats, spider monkeys, agoutis, possums, squirrels, and spiny rats all rely on these fruits. After eating them, these critters store the seeds in a special hiding place for future use. Sometimes, the animals forget where they stored the seeds, allowing the seeds to germinate and the parent tree to reproduce. A towering tree like the shihuahuaco may owe its life to the forgetfulness of a tiny squirrel 1,000 years ago!” ref

“Slow-growth species like the shihuahuaco also play a crucial role in carbon dioxide absorption. By itself, a mature shihuahuaco sequesters almost one third of an average hectare of rainforest. As a whole, the Amazon rainforest absorbs about 2 billion tons of CO2 per year, about 5% of global annual emissions. While more shihuahuacos are being cut down than ever before, more are also being planted. Which way the scale tips will decide not only the fate of the shihuahuaco but all organisms that depend on it, including us.” ref

Tree of Life

“The tree of life is a fundamental archetype in many of the world’s mythological, religious, and philosophical traditions. It is closely related to the concept of the sacred tree. The tree of knowledge connecting to heaven and the underworld such as Yggdrasil and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil in Genesis, and the tree of life, connecting all forms of creation, are forms of the world tree or cosmic tree, and are portrayed in various religions and philosophies as the same tree. The concept of world trees is a prevalent motif in the Mesoamerican cosmovision and iconography, appearing in the pre-Columbian era. World trees embody the four cardinal directions, which represented also the fourfold nature of a central world tree, a symbolic axis mundi connecting the planes of the Underworld and the sky with that of the terrestrial world.” ref

“Depictions of world trees, both in their directional and central aspects, are found in the art and mythological traditions of cultures such as the Maya, Aztec, Izapan, Mixtec, Olmec, and others, dating to at least the Mid/Late Formative periods of the Mesoamerican chronology. The tomb of Kʼinich Janaabʼ Pakal of the Maya city-state of Palenque, who became its ajaw or leader when he was twelve years old, has tree of life inscriptions within the walls of his burial place, showing just how important it was. Among the Maya, the central world tree was conceived as or represented by a Ceiba pentandra and is known variously as a wacah chan or yax imix che in different Mayan languages.” ref

“The trunk of the tree could also be represented by an upright caiman, whose skin evokes the tree’s spiny trunk. Directional world trees are also associated with the four Year Bearers in Mesoamerican calendars and associated with the directional colors and deities. Mesoamerican codices which have this association outlined include the Dresden, Borgia, and Fejérváry-Mayer codices. It is supposed that Mesoamerican sites and ceremonial centers frequently had actual trees planted at each of the four cardinal directions, representing the quadripartite concept. World trees are frequently depicted with birds in their branches, and their roots extending into earth or water, sometimes atop a “water-monster,” symbolic of the underworld. The central world tree has also been interpreted as a representation of the band of the Milky Way.” ref

“In a myth passed down among the Iroquois, The World on the Turtle’s Back, explains the origin of the land in which a tree of life is described. According to the myth, it is found in the heavens, where the first humans lived, until a pregnant woman fell and landed in an endless sea. Saved by a giant turtle from drowning, she formed the world on its back by planting bark taken from the tree. The tree of life motif is present in the traditional Ojibway cosmology and traditions. It is sometimes described as Grandmother Cedar, or Nookomis Giizhig in Anishinaabemowin.” ref

“In the book Black Elk Speaks, Black Elk, an Oglala Lakota (Sioux) wičháša wakȟáŋ (medicine man and holy man), describes his vision in which after dancing around a dying tree that has never bloomed he is transported to the other world (spirit world) where he meets wise elders, 12 men and 12 women. The elders tell Black Elk that they will bring him to meet “Our Father, the two-legged chief” and bring him to the center of a hoop where he sees the tree in full leaf and bloom and the “chief” standing against the tree. Coming out of his trance he hopes to see that the earthly tree has bloomed, but it is dead.” ref

“The Oneidas tell that supernatural beings lived in the Skyworld above the waters which covered the earth. This tree was covered with fruits which gave them their light, and they were instructed that no one should cut into the tree otherwise a great punishment would be given. As the woman had pregnancy cravings, she sent her husband to get bark, but he accidentally dug a hole to the other world. After falling through, she came to rest on the turtle’s back, and four animals were sent out to find land, which the muskrat finally did.” ref

World Tree

“The world tree is a motif present in several religions and mythologies, particularly Indo-European, Siberian, and Native American religions. The world tree is represented as a colossal tree which supports the heavens, thereby connecting the heavens, the terrestrial world, and, through its roots, the underworld. It may also be strongly connected to the motif of the tree of life, but it is the source of wisdom of the ages. Scholarship states that many Eurasian mythologies share the motif of the “world tree”, “cosmic tree”, or “Eagle and Serpent Tree”. More specifically, it shows up in “Haitian, Finnish, Lithuanian, Hungarian, Indian, Chinese, Japanese, Norse, Siberian and northern Asian Shamanic folklore.” ref

“The World Tree is often identified with the Tree of Life, and also fulfills the role of an axis mundi, that is, a centre or axis of the world. It is also located at the center of the world and represents order and harmony of the cosmos. According to Loreta Senkute, each part of the tree corresponds to one of the three spheres of the world (treetops – heavens; trunk – middle world or earth; roots – underworld) and is also associated with a classical element (top part – fire; middle part – earth, soil, ground; bottom part – water).” ref

“Its branches are said to reach the skies and its roots to connect the human or earthly world with an underworld or subterranean realm. Because of this, the tree was worshipped as a mediator between Heavens and Earth. On the treetops are located the luminaries (stars) and heavenly bodies, along with an eagle’s nest; several species of birds perch among its branches; humans and animals of every kind live under its branches, and near the root is the dwelling place of snakes and every sort of reptiles.” ref

“A bird perches atop its foliage, “often …. a winged mythical creature” that represents a heavenly realm. The eagle seems to be the most frequent bird, fulfilling the role of a creator or weather deity. Its antipode is a snake or serpentine creature that crawls between the tree roots, being a “symbol of the underworld.” The imagery of the World Tree is sometimes associated with conferring immortality, either by a fruit that grows on it or by a springsource located nearby. As George Lechler also pointed out, in some descriptions this “water of life” may also flow from the roots of the tree.” ref

“The World Tree has also been compared to a World Pillar that appears in other traditions and functions as separator between the earth and the skies, upholding the latter. Another representation akin to the World Tree is a separate World Mountain. However, in some stories, the world tree is located atop the world mountain, in a combination of both motifs. A conflict between a serpentine creature and a giant bird (an eagle) occurs in Eurasian mythologies: a hero kills the serpent that menaces a nest of little birds, and their mother repays the favor – a motif comparativist Julien d’Huy dates to the Paleolithic. A parallel story is attested in the traditions of the indigenous peoples of the Americas, where the thunderbird is slotted into the role of the giant bird whose nest is menaced by a “snake-like water monster.” ref

- Among Indigenous Mesoamerican cultures, the concept of “world trees” is a prevalent motif in Mesoamerican cosmologies and iconography. The Temple of the Cross Complex at Palenque contains one of the most studied examples of the world tree in architectural motifs of all Mayan ruins. World trees embodied the four cardinal directions, which represented also the fourfold nature of a central world tree, a symbolic axis mundi connecting the planes of the Underworld and the sky with that of the terrestrial world.

- Depictions of world trees, both in their directional and central aspects, are found in the art and traditions of cultures such as the Maya, Aztec, Izapan, Mixtec, Olmec, and others, dating to at least the Mid/Late Formative periods of Mesoamerican chronology. Among the Maya, the central world tree was conceived as, or represented by, a ceiba tree, called yax imix che (‘blue-green tree of abundance’) by the Book of Chilam Balam of Chumayel. The trunk of the tree could also be represented by an upright caiman, whose skin evokes the tree’s spiny trunk. These depictions could also show birds perched atop the trees.

- A similarly named tree, yax cheel cab (‘first tree of the world’), was reported by 17th-century priest Andrés de Avendaño to have been worshipped by the Itzá Maya. However, scholarship suggests that this worship derives from some form of cultural interaction between “pre-Hispanic iconography and [millenary] practices” and European traditions brought by the Hispanic colonization.

- Directional world trees are also associated with the four Yearbearers in Mesoamerican calendars, and the directional colors and deities. Mesoamerican codices which have this association outlined include the Dresden, Borgia and Fejérváry-Mayer codices. It is supposed that Mesoamerican sites and ceremonial centers frequently had actual trees planted at each of the four cardinal directions, representing the quadripartite concept.

- World trees are frequently depicted with birds in their branches, and their roots extending into earth or water (sometimes atop a “water-monster”, symbolic of the underworld).

- The central world tree has also been interpreted as a representation of the band of the Milky Way.

- Izapa Stela 5 contains a possible representation of a world tree.” ref

“A common theme in most indigenous cultures of the Americas is a concept of directionality (the horizontal and vertical planes), with the vertical dimension often being represented by a world tree. Some scholars have argued that the religious importance of the horizontal and vertical dimensions in many animist cultures may derive from the human body and the position it occupies in the world as it perceives the surrounding living world. Many Indigenous cultures of the Americas have similar cosmologies regarding the directionality and the world tree, however the type of tree representing the world tree depends on the surrounding environment. For many Indigenous American peoples located in more temperate regions for example, it is the spruce rather than the ceiba that is the world tree; however the idea of cosmic directions combined with a concept of a tree uniting the directional planes is similar.” ref

World Tree/World Pillar/World Mountain relation to Shamanism?

“Romanian historian of religion, Mircea Eliade, in his monumental work Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy, suggested that the world tree was an important element in shamanistic worldview. Also, according to him, “the giant bird … hatches shamans in the branches of the World Tree”. Likewise, Roald Knutsen indicates the presence of the motif in Altaic shamanism. Representations of the world tree are reported to be portrayed in drums used in Siberian shamanistic practices. Some species of birds (eagle, raven, crane, loon, and lark) are revered as mediators between worlds and also connected to the imagery of the world tree. Another line of scholarship points to a “recurring theme” of the owl as the mediator to the upper realm, and its counterpart, the snake, as the mediator to the lower regions of the cosmos. Researcher Kristen Pearson mentions Northern Eurasian and Central Asian traditions wherein the World Tree is also associated with the horse and with deer antlers (which might resemble tree branches). Mircea Eliade proposed that the typical imagery of the world tree (bird at the top, snake at the root) “is presumably of Oriental origin.” Likewise, Roald Knutsen indicates a possible origin of the motif in Central Asia and later diffusion into other regions and cultures.” ref

“The world tree is also represented in the mythologies and folklore of North Asia and Siberia. According to Mihály Hoppál, Hungarian scholar Vilmos Diószegi located some motifs related to the world tree in Siberian shamanism and other North Asian peoples. As per Diószegi’s research, the “bird-peaked” tree holds the sun and the moon, and the underworld is “a land of snakes, lizards and frogs.” In the mythology of the Samoyeds, the world tree connects different realities (underworld, this world, upper world) together. In their mythology the world tree is also the symbol of Mother Earth who is said to give the Samoyed shaman his drum and also help him travel from one world to another. According to scholar Aado Lintrop, the larch is “often regarded” by Siberian peoples as the World Tree.” ref

INDIGENOUS MEDICINES + HERBS From Mexico to Brazil

“The root word of curanderismo is “curar”, which means “to heal”. Ismo is “the tradition/teaching or science of”. Combined, they offer us a linguistic bridge to the hundreds, if not thousands, of different tribal peoples throughout Central and South America who have each maintained their own beliefs, in the ways of accessing spirit energies.” ref