Khoi-san and Hadza peoples of southern Africa: The Khoekhoen people have an “Indigenous nomadic pastoralist culture,” and the San people have an “Indigenous hunter-gatherer culture,” which is one of the oldest surviving cultures of the region. The Hadza people, who have an “indigenous hunter-gatherer culture,” were a pre-Bantu expansion culture not closely related to Khoisan speakers.

Khoisan

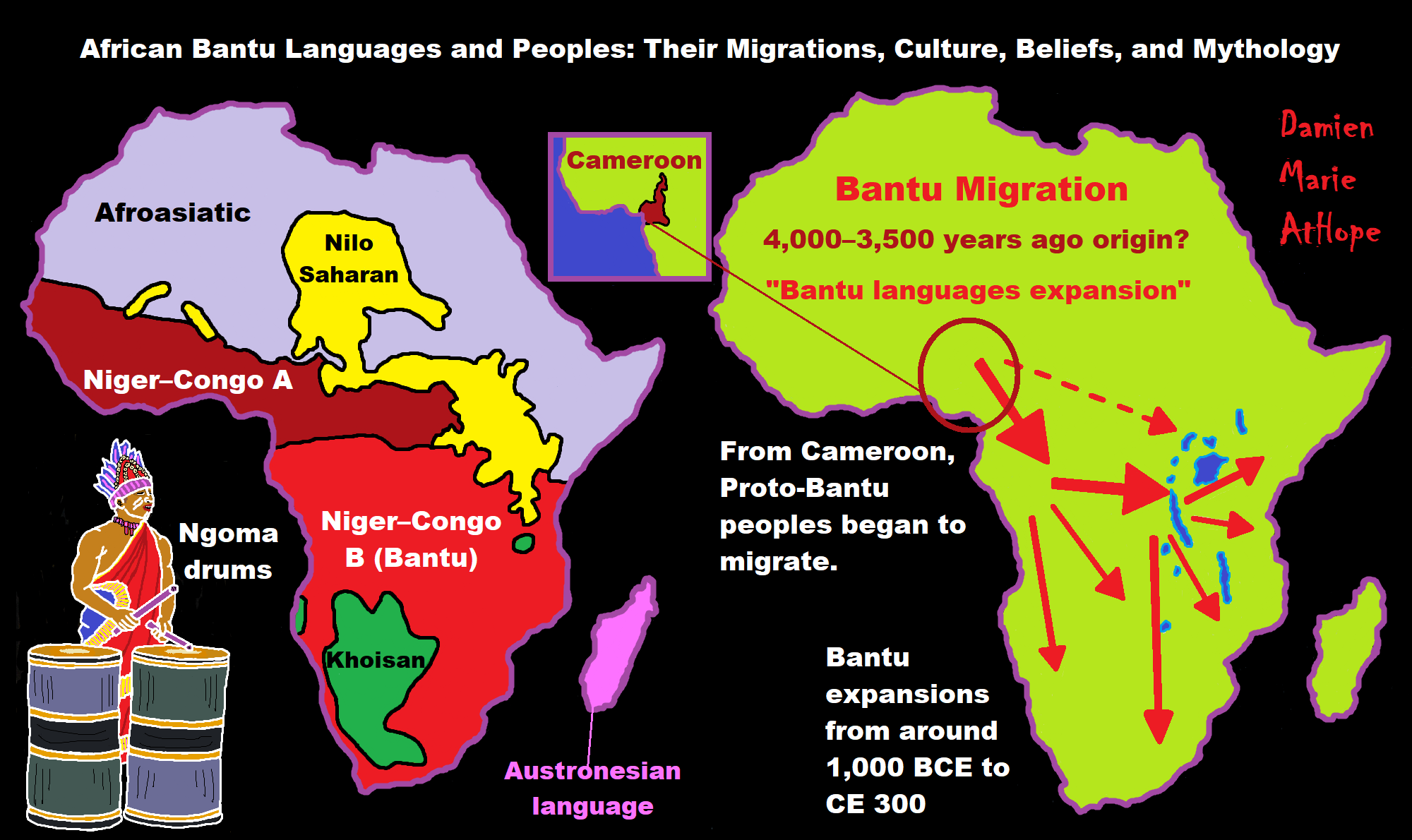

“Khoisan /ˈkɔɪsɑːn/ KOY-sahn, or Khoe-Sān (pronounced [kxʰoesaːn]), is a catch-all term for the indigenous peoples of Southern Africa who traditionally speak non-Bantu languages, combining the Khoekhoen (formerly “Hottentots“) and the Sān peoples (also called “Bushmen”). Khoisan populations traditionally speak click languages and are considered to be the historical communities throughout Southern Africa, remaining predominant until European colonisation in areas climatically unfavorable to Bantu (sorghum-based) agriculture, such as the Cape region, through to Namibia, where Khoekhoe populations of Nama and Damara people are prevalent groups, and Botswana. Considerable mingling with Bantu-speaking groups is evidenced by prevalence of click phonemes in many especially Xhosa Southern African Bantu languages.

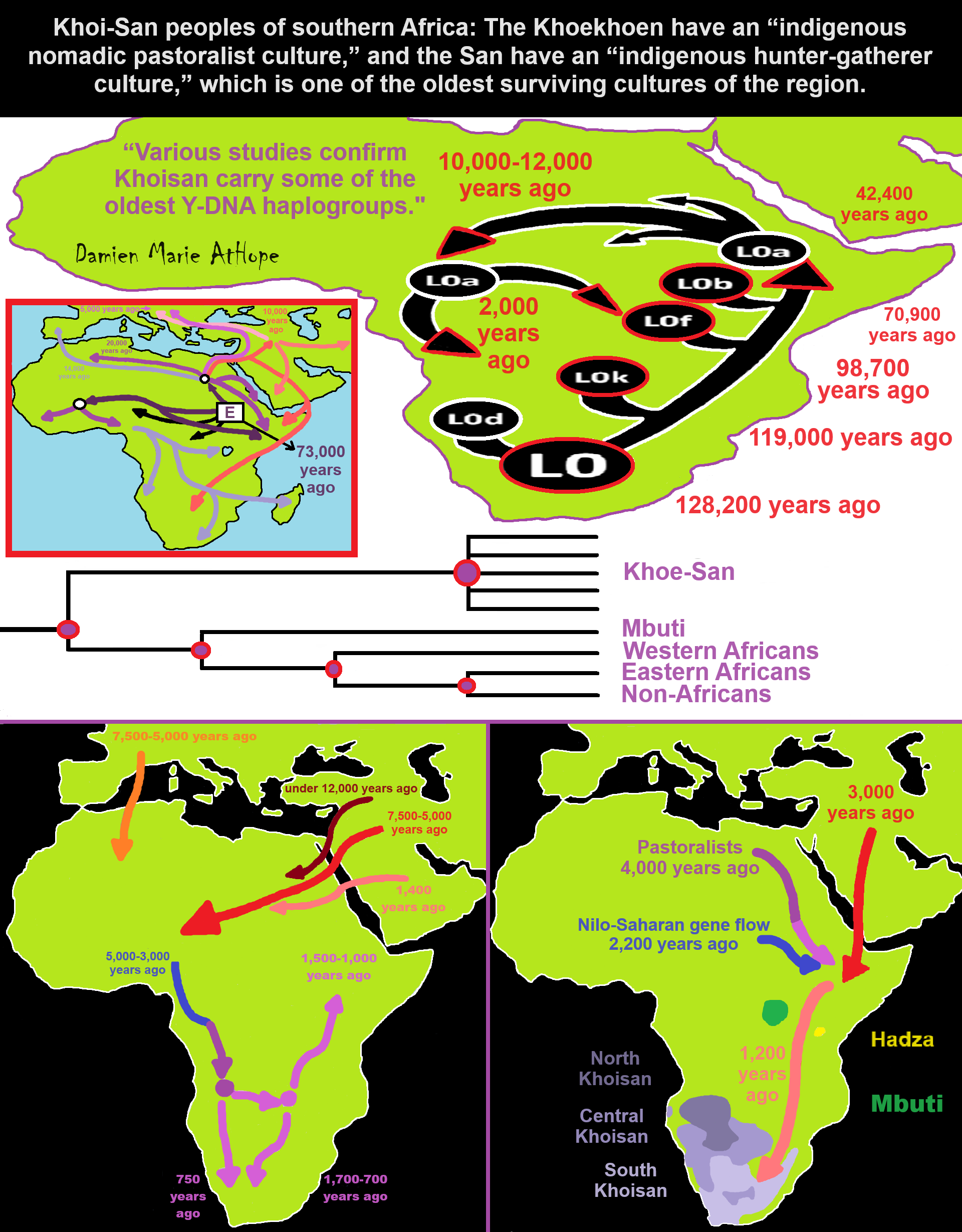

“Many Khoesān peoples are the descendants of a very early dispersal of anatomically modern humans to Southern Africa before 150,000 years ago. (However, see below for recent work supporting a multi-regional hypothesis that suggests the Khoisan may be a source population for anatomically modern humans.) Their languages show a vague typological similarity, largely confined to the prevalence of click consonants. They are not verifiably derived from a common proto-language, but are today split into at least three separate and unrelated language families (Khoe-Kwadi, Tuu and Kxʼa). It has been suggested that the Khoekhoe may represent Late Stone Age arrivals to Southern Africa, possibly displaced by Bantu expansion reaching the area roughly between 1,500 and 2,000 years ago.” ref

“Sān are popularly thought of as foragers in the Kalahari Desert and regions of Botswana, Namibia, Angola, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Lesotho and Northern South Africa. The word sān is from the Khoekhoe language and refers to foragers (“those who pick things up from the ground”) who do not own livestock. As such, it was used in reference to all hunter-gatherer populations who came into contact with Khoekhoe-speaking communities, and was largely referring to the lifestyle, distinct from a pastoralist or agriculturalist one, and not to any particular ethnicity. While there are attendant cosmologies and languages associated with this way of life, the term is an economic designator rather than a cultural or ethnic one.” ref

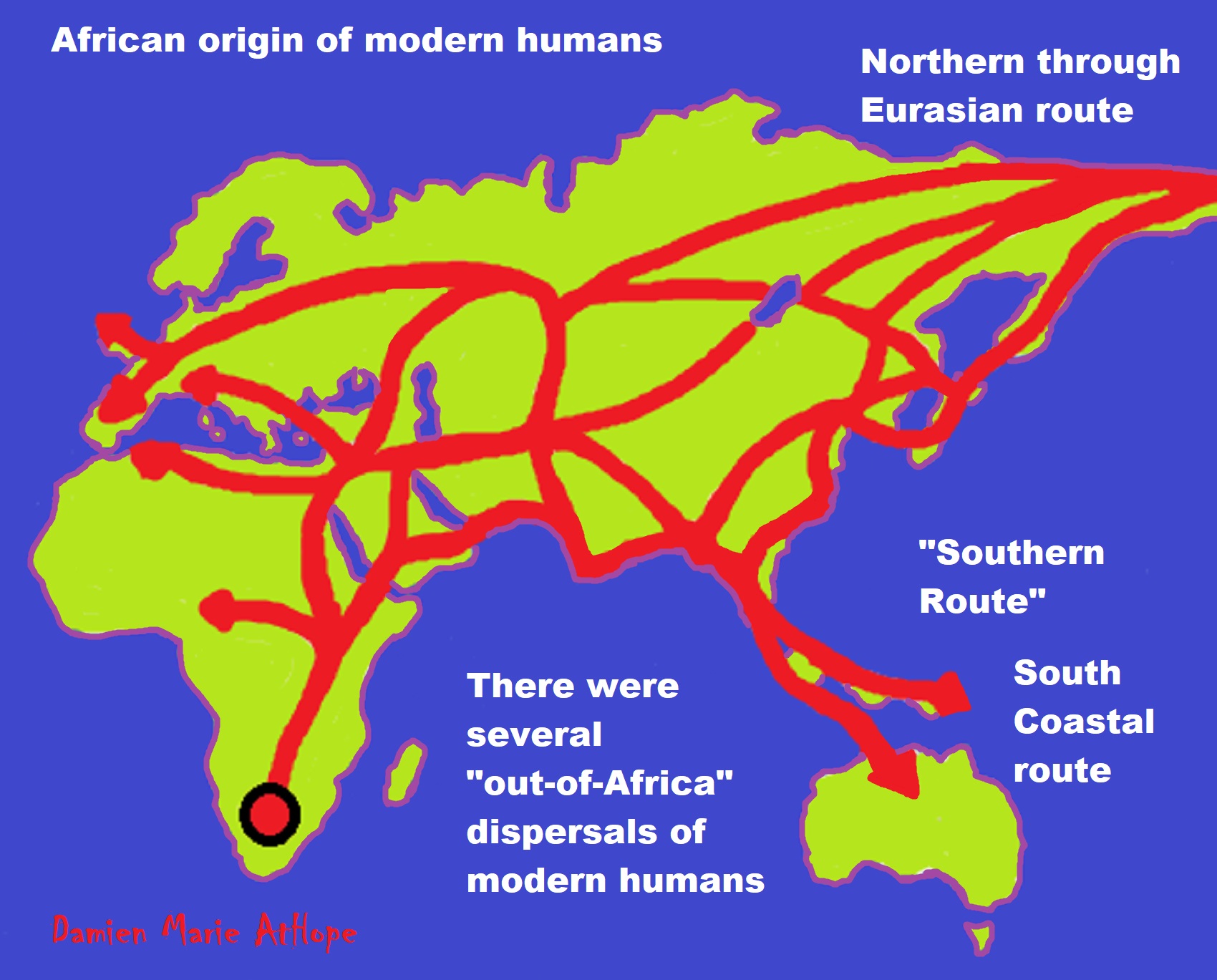

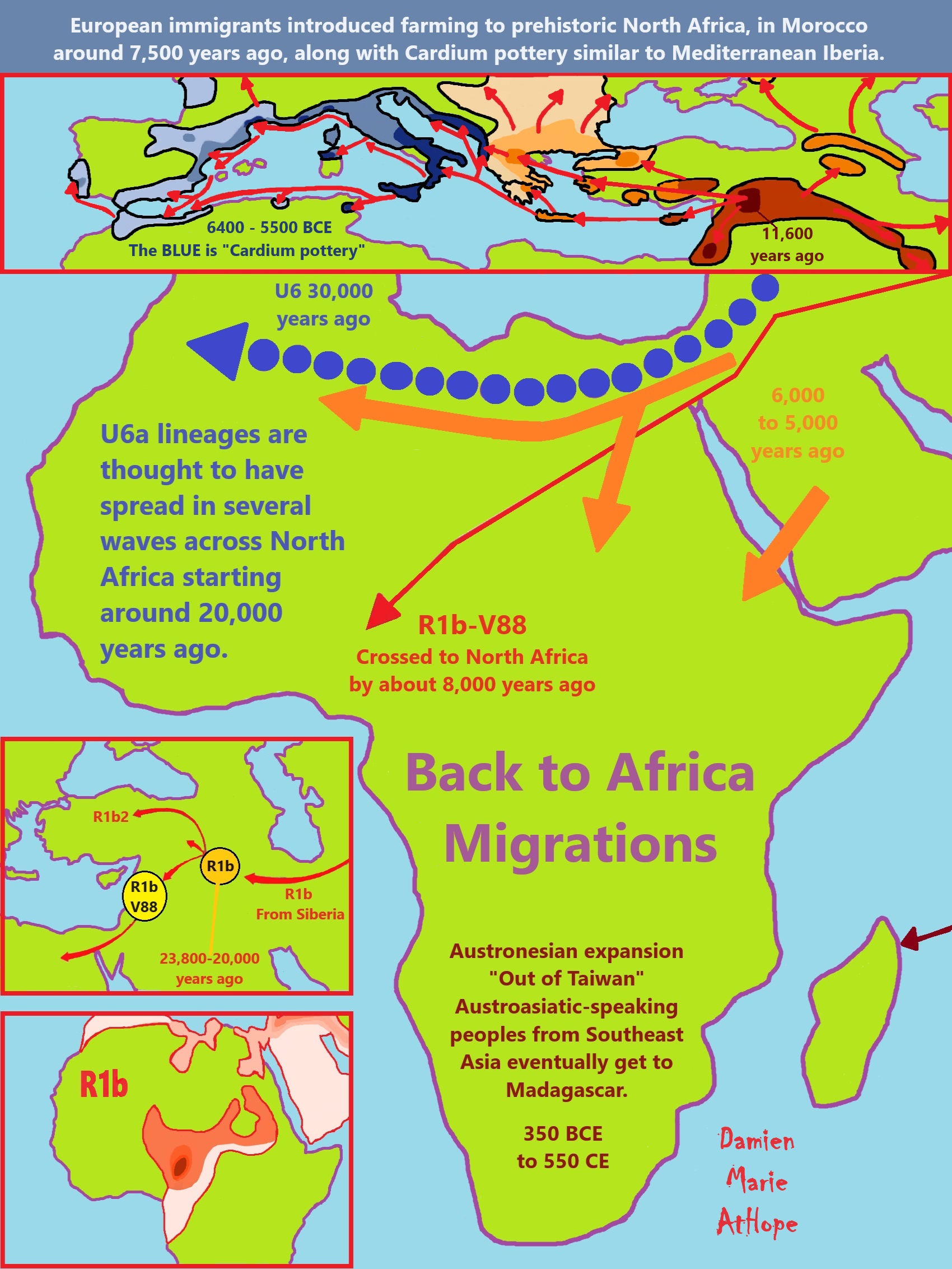

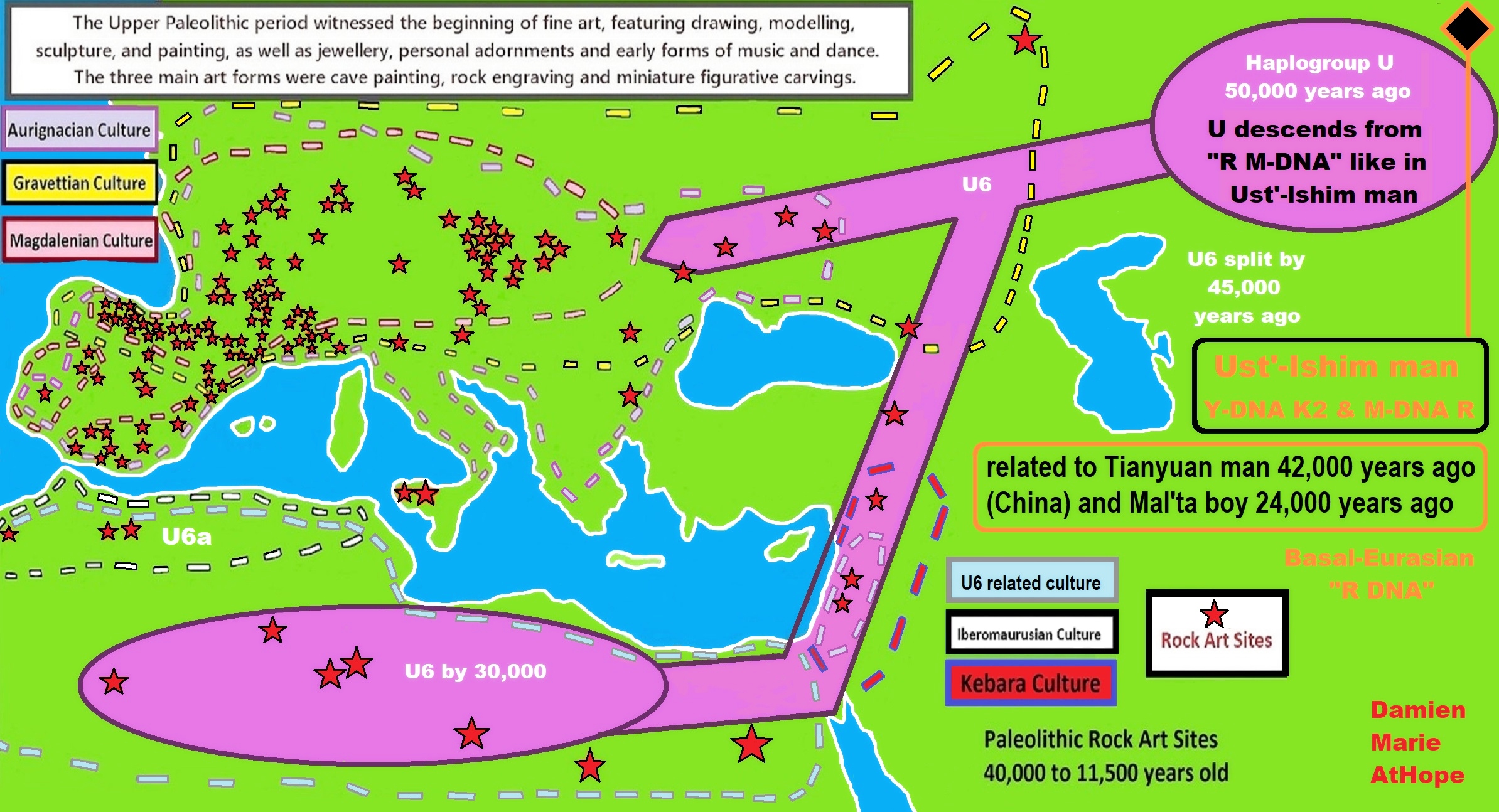

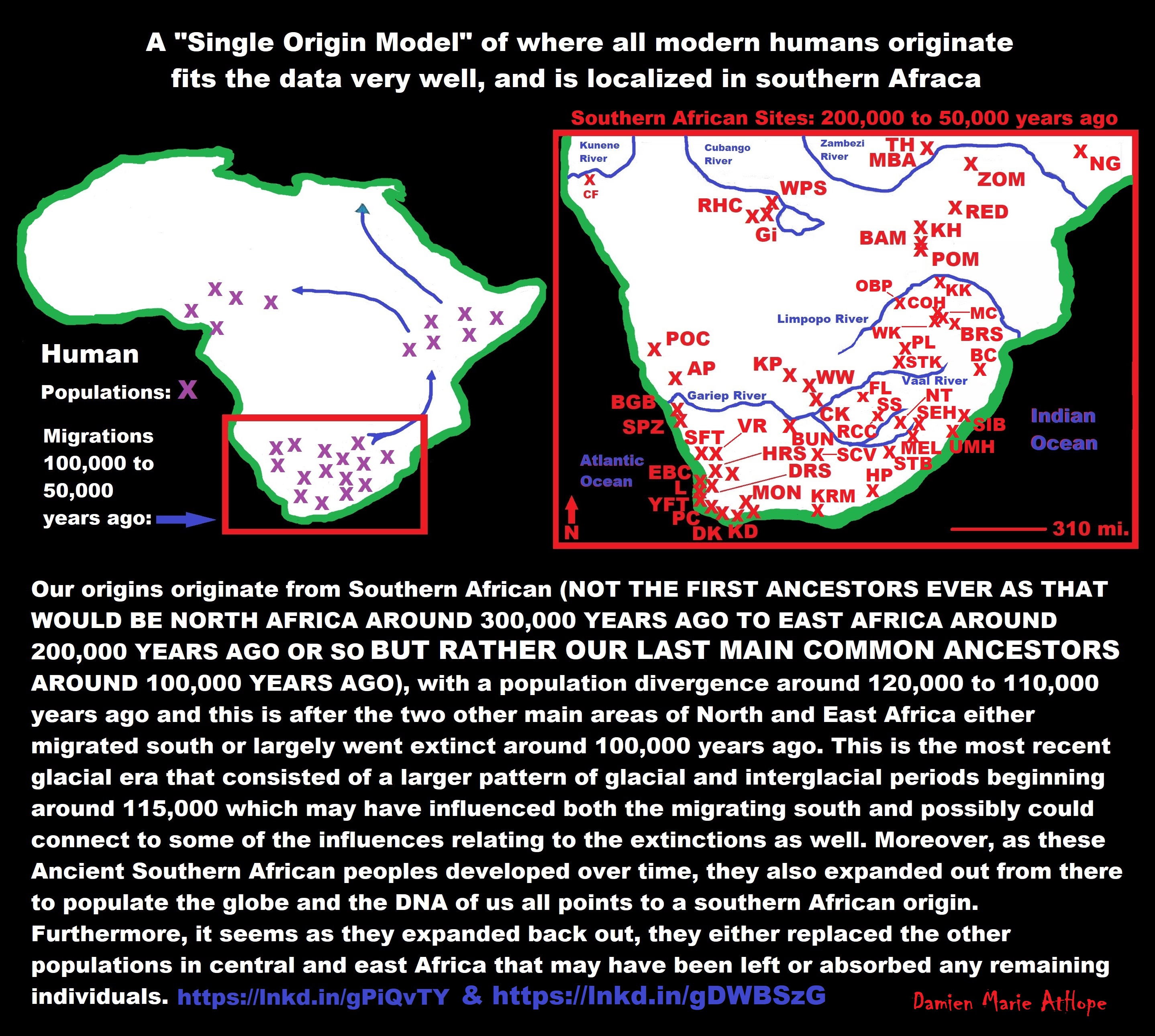

“It is suggested that the ancestors of the modern Khoisan expanded to southern Africa (from East or Central Africa) before 150,000 years ago, possibly as early as before 260,000 years ago, so that by the beginning of the MIS 5 “megadrought” 130,000 years ago, there were two ancestral population clusters in Africa, bearers of mt-DNA haplogroup L0 in southern Africa ancestral to the Khoi-San, and bearers of haplogroup L1-6 in central/eastern Africa ancestral to everyone else. This group gave rise to the San population of hunter gatherers. A much later wave of migration, around or before the beginning of the Common Era, gave rise to the Khoe people, who were pastoralists. This group carried DNA from Eurasian as well as some Neanderthal groups.” ref

“Due to their early expansion and separation, the populations ancestral to the Khoisan have been estimated as having represented the “largest human population” during the majority of the anatomically modern human timeline, from their early separation before 150 kya until the recent peopling of Eurasia some 70,000 years ago. They were much more widespread than today, their modern distribution being due to their decimation in the course of the Bantu expansion. They were dispersed throughout much of southern and southeastern Africa. There was also a significant back-migration of bearers of L0 towards eastern Africa between 120,000 and 75,000 years ago.” ref

“Rito et al. (2013) speculate that pressure from such back-migration may even have contributed to the dispersal of East African populations out of Africa at about 70,000 years ago. Recent work has suggested that the multi-regional hypothesis may be supported by current human population genetic data. A 2023 study published in the journal Nature suggests that current genetic data may be best understood as reflecting internal admixtures of multiple population sources across Africa, including ancestral populations of the Khoisan.” ref

“The San populations ancestral to the Khoisan were spread throughout much of southern and eastern Africa throughout the Late Stone Age after about 75,000 years ago. A further expansion dated to about 20,000 years ago has been proposed based on the distribution of the L0d haplogroup. Rosti et al. suggest a connection of this recent expansion with the spread of click consonants to eastern African languages (Hadza language).” ref

“The Late Stone Age Sangoan industry occupied southern Africa in areas where annual rainfall is less than a metre (1000 mm; 39.4 in). The contemporary San and Khoi peoples resemble those represented by the ancient Sangoan skeletal remains. Against the traditional interpretation that finds a common origin for the Khoi and San, other evidence has suggested that the ancestors of the Khoi peoples are relatively recent pre-Bantu agricultural immigrants to southern Africa who abandoned agriculture as the climate dried and either joined the San as hunter-gatherers or retained pastoralism.” ref

“With the hypothesized arrival of pastoralists & bantoid agro-pastoralists in southern Africa starting around 2,300 years ago, linguistic development is later seen in the click consonants and loan words from ancient Khoe-san languages into the evolution of blended agro-pastoralist & hunter-gatherer communities that would eventually evolve into the now extant, amalgamated modern native linguistic communities found in South Africa, Botswana & Namibia (e.g. in South African Xhosa, Sotho, Tswana, Zulu people.) The Khoikhoi enter the historical record with their first contact with Portuguese explorers, about 1,000 years after their displacement by the Bantu.” ref

“In 2019, scientists from the University of the Free State discovered 8,000-year-old carvings made by the Khoisan people. The carvings depicted a hippopotamus, horse, and antelope in the ‘Rain Snake’ Dyke of the Vredefort impact structure, which may have spiritual significance regarding the rain-making mythology of the Khoisan. In the 1990s, genomic studies of the world’s peoples found that the Y chromosome of San men share certain patterns of polymorphisms that are distinct from those of all other populations. Because the Y chromosome is highly conserved between generations, this type of DNA test is used to determine when different subgroups separated from one another, and hence their last common ancestry. The authors of these studies suggested that the San may have been one of the first populations to differentiate from the most recent common paternal ancestor of all extant humans.” ref

“Various Y-chromosome studies since confirmed that the Khoisan carry some of the most divergent (oldest) Y-chromosome haplogroups. These haplogroups are specific sub-groups of haplogroups A and B, the two earliest branches on the human Y-chromosome tree. Similar to findings from Y-chromosome studies, mitochondrial DNA studies also showed evidence that the Khoisan people carry high frequencies of the earliest haplogroup branches in the human mitochondrial DNA tree. The most divergent (oldest) mitochondrial haplogroup, L0d, has been identified at its highest frequencies in the southern African Khoi and San groups. The distinctiveness of the Khoisan in both matrilineal and patrilineal groupings is a further indicator that they represent a population historically distinct from other Africans.” ref

“Some genomic studies have further revealed that Khoisan groups have been influenced by 9 to 30% genetic admixture in the last few thousand years from an East African population who carried a Eurasian admixture component. Furthermore, they place an East African origin for the paternal haplogroup E1b1b found in these Southern African populations, as well as the introduction of pastoralism into the region. The paper also noted that the Bantu expansion had a notable genetic impact in a number of Khoisan groups. On the basis of PCA projections, the East African ancestry identified in the genomes of Khoe-Kwadi speakers and other southern Africans is related to an individual from the Tanzanian Luxmanda.” ref

Khoekhoe

“Khoekhoe (or Khoikhoi in former orthography) are the traditionally nomadic pastoralist indigenous population of South Africa. They are often grouped with the hunter-gatherer San (literally “Foragers”) peoples. The designation “Khoekhoe” is actually a kare or praise address, not an ethnic endonym, but it has been used in the literature as an ethnic term for Khoe-speaking peoples of Southern Africa, particularly pastoralist groups, such as the Griqua, Gona, Nama, Khoemana and Damara nations. The Khoekhoe were once known as Hottentots, a term now considered offensive.” ref

“While the presence of Khoekhoe in Southern Africa predates the Bantu expansion, according to a scientific theory based mainly on linguistic evidence, it is not clear when, possibly in the Late Stone Age, the Khoekhoe began inhabiting the areas where the first contact with Europeans occurred. At that time, in the 17th century, the Khoekhoe maintained large herds of Nguni cattle in the Cape region. Their Khoekhoe language is related to certain dialects spoken by foraging San peoples of the Kalahari, such as the Khwe and Tshwa, forming the Khoe language family. Khoekhoe subdivisions today are the Nama people of Namibia, Botswana and South Africa (with numerous clans), the Damara of Namibia, the Orana clans of South Africa (such as Nama or Ngqosini), the Khoemana or Griqua nation of South Africa, and the Gqunukhwebe or Gona clans which fall under the Xhosa-speaking polities.” ref

“The broad ethnic designation of “Khoekhoen”, meaning the peoples originally part of a pastoral culture and language group to be found across Southern Africa, is thought to refer to a population originating in the northern area of modern Botswana. This culture steadily spread southward, eventually reaching the Cape approximately 2,000 years ago. “Khoekhoe” groups include ǀAwakhoen to the west, and ǀKx’abakhoena of South and mid-South Africa, and the Eastern Cape. Both of these terms mean “Red People”, and are equivalent to the IsiXhosa term “amaqaba”. Husbandry of sheep, goats and cattle grazing in fertile valleys across the region provided a stable, balanced diet, and allowed these lifestyles to spread, with larger groups forming in a region previously occupied by the subsistence foragers.” ref

“Ntu-speaking agriculturalist culture is thought to have entered the region in the 3rd century AD, pushing pastoralists into the Western areas. The example of the close relation between the ǃUriǁ’aes (High clan), a cattle-keeping population, and the !Uriǁ’aeǀ’ona (High clan children), a more-or-less sedentary forager population (also known as “Strandlopers”), both occupying the area of ǁHuiǃgaeb, shows that the strict distinction between these two lifestyles is unwarranted, as well as the ethnic categories that are derived. Foraging peoples who ideologically value non-accumulation as a social value system would be distinct, however, but the distinctions among “Khoekhoe pastoralists”, “San hunter-gatherers” and “Bantu agriculturalists” do not hold up to scrutiny, and appear to be historical reductionism.” ref

The religious mythology of the Khoe-speaking cultures gives special significance to the Moon, which may have been viewed as the physical manifestation of a supreme being associated with heaven. Thiǁoab (Tsui’goab) is also believed to be the creator and the guardian of health, while ǁGaunab is primarily an evil being, who causes sickness or death. Many Khoe-speakers have converted to Christianity and Nama Muslims make up a large percentage of Namibia’s Muslims.” ref

Nomadic pastoralism

“Nomadic pastoralism is a form of pastoralism in which livestock are herded in order to seek for fresh pastures on which to graze. True nomads follow an irregular pattern of movement, in contrast with transhumance, where seasonal pastures are fixed. However, this distinction is often not observed and the term ‘nomad’ used for both—and in historical cases the regularity of movements is often unknown in any case. The herded livestock include cattle, water buffalo, yaks, llamas, sheep, goats, reindeer, horses, donkeys or camels, or mixtures of species. Nomadic pastoralism is commonly practised in regions with little arable land, typically in the developing world, especially in the steppe lands north of the agricultural zone of Eurasia. Pastoralists often trade with sedentary agrarians, exchanging meat for grains, however have been known to raid.” ref

“Nomadic pastoralism was a result of the Neolithic Revolution and the rise of agriculture. During that revolution, humans began domesticating animals and plants for food and started forming cities. Nomadism generally has existed in symbiosis with such settled cultures trading animal products (meat, hides, wool, cheese and other animal products) for manufactured items not produced by the nomadic herders. Henri Fleisch tentatively suggested the Shepherd Neolithic industry of Lebanon may date to the Epipaleolithic and that it may have been used by one of the first cultures of nomadic shepherds in the Beqaa valley. Andrew Sherratt demonstrates that “early farming populations used livestock mainly for meat, and that other applications were explored as agriculturalists adapted to new conditions, especially in the semi‐arid zone.” ref

“In the past it was asserted that pastoral nomads left no presence archaeologically or were impoverished, but this has now been challenged, and was clearly not so for many ancient Eurasian nomads, who have left very rich kurgan burial sites. Pastoral nomadic sites are identified based on their location outside the zone of agriculture, the absence of grains or grain-processing equipment, limited and characteristic architecture, a predominance of sheep and goat bones, and by ethnographic analogy to modern pastoral nomadic peoples Juris Zarins has proposed that pastoral nomadism began as a cultural lifestyle in the wake of the 6200 BCE or around 8,200 years ago climatic crisis when Harifian pottery making hunter-gatherers in the Sinai fused with Pre-Pottery Neolithic B agriculturalists to produce the Munhata culture, a nomadic lifestyle based on animal domestication, developing into the Yarmoukian and thence into a circum-Arabian nomadic pastoral complex, and spreading Proto-Semitic languages.” ref

“In Bronze Age Central Asia, nomadic populations are associated with the earliest transmissions of millet and wheat grains through the region that eventually became central for the Silk Road. Early Indo-European migrations from the Pontic–Caspian steppe spread Yamnaya Steppe pastoralist ancestry and Indo-European languages across large parts of Eurasia. By the medieval period in Central Asia, nomadic communities exhibited isotopically diverse diets, suggesting a multitude of subsistence strategies. David Christian made the following observations about pastoralism. The agriculturist lives from domesticated plants and the pastoralist lives from domesticated animals.” ref

“Since animals are higher on the food chain, pastoralism supports a thinner population than agriculture. Pastoralism predominates where low rainfall makes farming impractical. Full pastoralism required the Secondary products revolution when animals began to be used for wool, milk, riding and traction as well as meat. Where grass is poor herds must be moved, which leads to nomadism. Some peoples are fully nomadic while others live in sheltered winter camps and lead their herds into the steppe in summer. Some nomads travel long distances, usually north in summer and south in winter. Near mountains, herds are led uphill in summer and downhill in winter (transhumance). Pastoralists often trade with or raid their agrarian neighbors.” ref

“David Christian distinguished ‘Inner Eurasia’, which was pastoral with a few hunter-gatherers in the far north, from ‘Outer Eurasia’, a crescent of agrarian civilizations from Europe through India to China. High civilization is based on agriculture where tax-paying peasants support landed aristocrats, kings, cities, literacy and scholars. Pastoral societies are less developed and as a result, according to Christian, more egalitarian. One tribe would often dominate its neighbors, but these ’empires’ usually broke up after a hundred years or so. The heartland of pastoralism is the Eurasian steppe. In the center of Eurasia pastoralism extended south to Iran and surrounded agrarian oasis cities. When pastoral and agrarian societies went to war, horse-borne mobility counterbalanced greater numbers.” ref

“Attempts by agrarian civilizations to conquer the steppe usually failed until the last few centuries. Pastoralists frequently raided and sometimes collected regular tribute from their farming neighbors. Especially in north China and Iran, they would sometimes conquer agricultural societies, but these dynasties were usually short-lived and broke up when the nomads became ‘civilized’ and lost their warlike virtues. Nomadic pastoralism was historically widespread throughout less fertile regions of Earth. It is found in areas of low rainfall such as the Arabian Peninsula inhabited by Bedouins, as well as Northeast Africa inhabited, among other ethnic groups, by Somalis (where camel, cattle, sheep and goat nomadic pastoralism is especially common).” ref

“Nomadic transhumance is also common in areas of harsh climate, such as Northern Europe and Russia inhabited by the indigenous Sami people, Nenets people and Chukchis. There are an estimated 30–40 million nomads in the world. Pastoral nomads and semi-nomadic pastoralists form a significant but declining minority in such countries as Saudi Arabia (probably less than 3%), Iran (4%), and Afghanistan (at most 10%). They comprise less than 2% of the population in the countries of North Africa except Libya and Mauritania.” ref

“The Eurasian steppe has been largely populated by pastoralist nomads since the late prehistoric times, with a succession of peoples known by the names given to them by surrounding literate sedentary societies, including the Bronze Age Proto-Indo-Europeans, and later Proto-Indo-Iranians, Scythians, Sarmatians, Cimmerians, Massagetae, Alans, Pechenegs, Cumans, Kipchaks, Karluks, Saka, Yuezhi, Wusun, Jie, Xiongnu, Xianbei, Khitan, Pannonian Avars, Huns, Mongols, Dzungars and various Turkics.” ref

“The Mongols in what is now Mongolia, Russia and China, and the Tatars or Turkic people of Eastern Europe and Central Asia were nomadic people who practiced nomadic transhumance on harsh Asian steppes. Some remnants of these populations are nomadic to this day. In Mongolia, about 40% of the population continues to live a traditional nomadic lifestyle. In China, it is estimated that a little over five million herders are dispersed over the pastoral counties, and more than 11 million over the semi-pastoral counties. This brings the total of the (semi)nomadic herder population to over 16 million, in general living in remote, scattered and resource-poor communities.” ref

“In Chad, nomadic pastoralists include the Zaghawa, Kreda, and Mimi. Farther north in Egypt and western Libya, the Bedouins also practice pastoralism. Sometimes nomadic pastoralists move their herds across international borders in search of new grazing terrain or for trade. This cross-border activity can occasionally lead to tensions with national governments as this activity is often informal and beyond their control and regulation. In East Africa, for example, over 95% of cross-border trade is through unofficial channels and the unofficial trade of live cattle, camels, sheep and goats from Ethiopia sold to Somalia, Kenya and Djibouti generates an estimated total value of between US$250 and US$300 million annually (100 times more than the official figure). This trade helps lower food prices, increase food security, relieve border tensions and promote regional integration. However, there are also risks as the unregulated and undocumented nature of this trade runs risks, such as allowing disease to spread more easily across national borders. Furthermore, governments are unhappy with lost tax revenue and foreign exchange revenues.” ref

Pastoralism

“Pastoralism is a form of animal husbandry where domesticated animals (known as “livestock“) are released onto large vegetated outdoor lands (pastures) for grazing, historically by nomadic people who moved around with their herds. The animal species involved include cattle, camels, goats, yaks, llamas, reindeer, horses, and sheep. Pastoralism occurs in many variations throughout the world, generally where environmental characteristics such as aridity, poor soils, cold or hot temperatures, and lack of water make crop-growing difficult or impossible. Operating in more extreme environments with more marginal lands means that pastoral communities are very vulnerable to the effects of global warming.” ref

“Pastoralism remains a way of life in many geographic areas, including Africa, the Tibetan plateau, the Eurasian steppes, the Andes, Patagonia, the Pampas, Australia and many other places. As of 2019, between 200 million and 500 million people globally practiced pastoralism, and 75% of all countries had pastoral communities. Pastoral communities have different levels of mobility. Sedentary pastoralism has become more common as the hardening of political borders, land tenures, expansion of crop farming, and construction of fences and dedicated agricultural buildings all reduce the ability to move livestock around freely, leading to the rise of pastoral farming on established grazing-zones (sometimes called “ranches“).” ref

“Sedentary pastoralists may also raise crops and livestock together in the form of mixed farming, for the purpose of diversifying productivity, obtaining manure for organic farming, and improving pasture conditions for their livestock. Mobile pastoralism includes moving herds locally across short distances in search of fresh forage and water (something that can occur daily or even within a few hours); as well as transhumance, where herders routinely move animals between different seasonal pastures across regions; and nomadism, where nomadic pastoralists and their families move with the animals in search for any available grazing-grounds—without much long-term planning. Grazing in woodlands and forests may be referred to as silvopastoralism. Those who practice pastoralism are called “pastoralists.” ref

“Pastoralist herds interact with their environment, and mediate human relations with the environment as a way of turning uncultivated plants (like wild grass) into food. In many places, grazing herds on savannas and in woodlands can help maintain the biodiversity of such landscapes and prevent them from evolving into dense shrublands or forests. Grazing and browsing at the appropriate levels often can increase biodiversity in Mediterranean climate regions. Pastoralists shape ecosystems in different ways: some communities use fire to make ecosystems more suitable for grazing and browsing animals. One theory suggests that pastoralism developed from mixed farming. Bates and Lees proposed that the incorporation of irrigation into farming resulted in specialization.” ref

“Advantages of mixed farming include reducing risk of failure, spreading labor, and re-utilizing resources. The importance of these advantages and disadvantages to different farmers or farming societies differs according to the sociocultural preferences of the farmers and the biophysical conditions as determined by rainfall, radiation, soil type, and disease. The increased productivity of irrigation agriculture led to an increase in population and an added impact on resources. Bordering areas of land remained in use for animal breeding. This meant that large distances had to be covered by herds to collect sufficient forage. Specialization occurred as a result of the increasing importance of both intensive agriculture and pastoralism. Both agriculture and pastoralism developed alongside each other, with continuous interactions.” ref

“A different theory suggests that pastoralism evolved from the hunting and gathering. Hunters of wild goats and sheep were knowledgeable about herd mobility and the needs of the animals. Such hunters were mobile and followed the herds on their seasonal rounds. Undomesticated herds were chosen to become more controllable for the proto-pastoralist nomadic hunter and gatherer groups by taming and domesticating them. Hunter-gatherers’ strategies in the past have been very diverse and contingent upon the local environmental conditions, like those of mixed farmers. Foraging strategies have included hunting or trapping big game and smaller animals, fishing, collecting shellfish or insects, and gathering wild-plant foods such as fruits, seeds, and nuts.” ref

“These diverse strategies for survival amongst the migratory herds could also provide an evolutionary route towards nomadic pastoralism. Pastoralism occurs in uncultivated areas. Wild animals eat the forage from the marginal lands and humans survive from milk, blood, and often meat of the herds and often trade by-products like wool and milk for money and food. Pastoralists do not exist at basic subsistence. Some pastoralists supplement herding with hunting and gathering, fishing and/or small-scale farming or pastoral farming.” ref

“Pastoralists often compile wealth and participate in international trade. Pastoralists have trade relations with agriculturalists, horticulturalists, and other groups. Pastoralists are not extensively dependent on milk, blood, and meat of their herd. McCabe noted that when common property institutions are created, in long-lived communities, resource sustainability is much higher, which is evident in the East African grasslands of pastoralist populations. However, the property rights structure is only one of the many different parameters that affect the sustainability of resources, and common or private property per se, does not necessarily lead to sustainability.” ref

“Mobility allows pastoralists to adapt to the environment, which opens up the possibility for both fertile and infertile regions to support human existence. Important components of pastoralism include low population density, mobility, vitality, and intricate information systems. The system is transformed to fit the environment rather than adjusting the environment to support the “food production system.” Mobile pastoralists can often cover a radius of a hundred to five hundred kilometers. The violent herder–farmer conflicts in Nigeria, Mali, Sudan, Ethiopia and other countries in the Sahel and Horn of Africa regions have been exacerbated by climate change, land degradation, and population growth.” ref

“Pastoralists and their livestock have impacted the environment. Lands long used for pastoralism have transformed under the forces of grazing livestock and anthropogenic fire. Fire was a method of revitalizing pastureland and preventing forest regrowth. The collective environmental weights of fire and livestock browsing have transformed landscapes in many parts of the world. Fire has permitted pastoralists to tend the land for their livestock. Political boundaries are based on environmental boundaries. The Maquis shrublands of the Mediterranean region are dominated by pyrophytic plants that thrive under conditions of anthropogenic fire and livestock grazing.” ref

“Nomadic pastoralists have a global food-producing strategy depending on the management of herd animals for meat, skin, wool, milk, blood, manure, and transport. Nomadic pastoralism is practiced in different climates and environments with daily movement and seasonal migration. Pastoralists are among the most flexible populations. Pastoralist societies have had field armed men protect their livestock and their people and then to return into a disorganized pattern of foraging. The products of the herd animals are the most important resources, although the use of other resources, including domesticated and wild plants, hunted animals, and goods accessible in a market economy are not excluded. The boundaries between states impact the viability of subsistence and trade relations with cultivators.” ref

“Some pastoralists are constantly moving, which may put them at odds with sedentary people of towns and cities. The resulting conflicts can result in war for disputed lands. These disputes are recorded in ancient times in the Middle East, as well as for East Asia. Other pastoralists are able to remain in the same location which results in longer-standing housing. Different mobility patterns can be observed: Somali pastoralists keep their animals in one of the harshest environments but they have evolved of the centuries. Somalis have well developed pastoral culture where complete system of life and governance has been refined. Somali poetry depicts humans interactions, pastoral animals, beasts on the prowl, and other natural things such the rain, celestial events and historic events of significance.” ref

“The basis of pastoral organization almost everywhere in the world is the clan, a set of patrilineally related households traced (in theory) to an apical ancestor. The great majority of pastoral societies are patrilineal and male-dominated.” ref

“The basis of pastoral organization almost everywhere in the world is the clan, a set of patrilineally related households traced (in theory) to an apical ancestor. Such groupings can be very small, and the ancestry stretch back for only a short time span, or so great that the ancestral figure is semi-mythical, in which case the working kin group is a lineage. The preservation of these genealogies is very important – especially to the aristocratic strata of nomad society, because it makes their position legitimate.” ref

“Well-known exceptions to the rule are the Tuareg, who had matrilineal descent groups in some areas, and subarctic peoples such as the Saami, the Chukchi and the Koryak, who had neither unilineal descent groups nor elaborate genealogies. One of the most distinctive features of pastoralism in East Africa and the Horn of Africa is the system of age-sets. Among the Boran of southern Ethiopia, for example, men born within a seven-year cohort fall into a named age-set, which has rights and privileges within society as well as acting as a powerful force for cohesion and a calendrical system.” ref

“A key aspect of pastoral systems is the strong relationship between wealth in livestock and labor. Herds that grow beyond a certain size cannot be managed with household labor alone, and outside herders must be sought. In the twentieth century, this is generally through hired labor, but formerly it was often through slavery or vassal castes. The great herds of cattle owned today by Fuel herders in the Niger were managed by slave labor in the nineteenth century, and many pastoral societies in Africa and the Near East developed elaborate caste systems based on slaves and non-slaves. In the case of the Tuareg, for example, society was divided into:

- Imajer.en: nobles;

- Iklan: (former) slaves;

- Izeggar.en: agricultural laborers;

- Ineden: blacksmiths.” ref

“Marriages between these groups were formerly forbidden, and even today remain uncommon. When slaves were freed in the colonial era, they stayed with their original camps for some time, but have gradually broken away and now form independent households, often remote from their original site so that traditional authority cannot be brought to bear. Similar systems were found throughout much of the Bedouin areas and in the Horn of Africa.” ref

ROLE OF WOMEN IN PASTORAL SOCIETY

“The role of women among pastoralists has been much discussed, in part because pastoral societies are more male-dominated than most other subsistence systems. Despite the well-known exception of the Saharan Tuareg, the great majority of pastoral societies are patrilineal and male-dominated. The reasons for this are much debated, but the root cause appears to be related to the importance of not dispersing viable herds. In an exogamous system, if women can own significant herds of their own, they will take these away on marriage to a new camp and potentially deplete the herd of an individual household. Many pastoral societies practice pre-inheritance, the father dispersing the herd among his sons prior to his death, since the principle of patrilocality means that the animals will anyway remain in the same physical herd.” ref

“In pastoral societies, particularly those affected by Islamic inheritance rules, some animals go to daughters on the death of the household head, but these are then “managed” by the women’s brothers. In most pastoral societies gender roles are strongly marked, and patterns seem to be extremely similar across the world. Women are typically responsible for milking and dairy processing; they may or may not sell the milk, and they usually have control over the proceeds in order to feed the family. Men are responsible for herding and selling meat animals. In systems in which herds are split, women usually stay at fixed homesteads while men go away with the animals.” ref

“Pastoral societies typically tend towards monogamy because of the importance of the division of labor. In other words, for a pastoral household to be viable, there must be a wife to carry out key tasks. If there are too many polygynous households, the system will become unviable. There are exceptions to this rule, the Maasai being one well-known example. The Maasai system of age-sets, in which young men are assigned to a social category, makes it possible for older men to have several wives because moran warriors are not allowed to marry. Only after a young man has graduated from being a moran is he able to marry.” ref

PASTORAL IDENTITIES

“Throughout much of Eurasia, pastoralism is interwoven with the culture of itinerants; groups who move around supplying services to fixed communities. The most well-known of these are the gypsies, who are spread from Wales to India under a variety of names and associated with a variety of occupations. Rao (1982, 1987) calls these groups “peripatetics” and describes some of their activities, notably those concerned with crafts. As with gypsies and horse-coping, some peripatetics play an important role in livestock trade, although they generally do not produce food. Such groups are particularly numerous in the area between Afghanistan and India. They fall into casted, endogamous groups and are often stereotyped as ethnically distinct, as are pastoralists, whom national governments often put into the same category as these other. In Afghanistan, both pastoral nomads and peripatetics live in tents; those of livestock producers are made out of black goat-hair, while peripatetic tents are white.” ref

LAND TENURE AND THE COMMON PROPERTY RESOURCES DEBATE

“Pastoral systems have been at the heart of many debates on the nature of common property resources. While settled farmers usually develop relatively explicit systems of tenure, many pastoral peoples have fluid systems that are hard to pin down. This is in keeping with their opportunistic grazing strategies. When pasture is extremely patchy and likely to appear at different sites each year, investing heavily in ownership of a specific piece of land is hardly worthwhile. The negative side of this is that farmers can come and cultivate the land that herders regularly use for grazing their stock, without having to ask for permission. Because they are generally operating in remote areas without access to schools, pastoralists rarely have the literacy necessary to register land claims and so are outcompeted by both farmers and urban-based ranchers. In Jordan, the Badia rangelands were the preserve of sheep-herders because agriculture was considered to be impossible.” ref

“However, a combination of more boreholes and new irrigation techniques is pushing farms ever further into traditional grazing land, and the government is unwilling to halt this process because of its own political constituency. Tenure is thus divided by both ecology and the potential for agriculture. In much of the snowy steppe, agriculture is not practical, so pastoralists compete with one another for prime sites. The same is true in the subarctic regions, where reindeer herders do not interact with farmers. In much of Central Asia, the command economies overrode traditional access rights and created mapped and demarcated territories for collectivized units. These are in the process of being dismantled, and more traditional access rights are being reasserted. However, legal frameworks for this new situation are only now being developed.” ref

“The tenure of pastoralists in all parts of the world is not deemed sufficiently strong to prevent it from being overridden by the State in its search for minerals. Land can be appropriated for building and transport infrastructure, generally without compensation. There is no doubt that, if pastoralism is to survive, effective tenure must be developed in many parts of the world. This is proving difficult, because few governments have the political will to protect pastoralists against the vested interests of urban groups. The usual indicator of tenure in the ranching areas is the fence, a high-investment strategy that is only effective in countries where specific legal frameworks are in place.” ref

Double Marginalized Livelihoods: Invisible Gender Inequality in Pastoral Societies

“Abstract: Achieving gender equality is the Third Millennium Development Goal, and the major challenge to poverty reduction is the inability of governments to address this at grass root levels. This study is therefore aimed at assessing gender inequality as it pertains to socio-economic factors in (agro-) pastoral societies. It tries to explain how “invisible” forces perpetuate gender inequality, based on data collected from male and female household heads and community representatives. The findings indicate that in comparison with men, women lack access to control rights over livestock, land, and income, which are critical to securing a sustainable livelihood. However, this inequality remains invisible to women who appear to readily submit to local customs, and to the community at large due to a lack of public awareness and gender based interventions. In addition, violence against women is perpetuated through traditional beliefs and sustained by tourists to the area. As a result, (agro-) pastoral woman face double marginalization, for being pastoralist, and for being a woman.” ref

Nomads

“Nomads are communities without fixed habitation who regularly move to and from areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), tinkers and trader nomads. Nomadic hunting and gathering—following seasonally available wild plants and game—is by far the oldest human subsistence method. Pastoralists raise herds of domesticated livestock, driving or accompanying them in patterns that normally avoid depleting pastures beyond their ability to recover. Nomadism is also a lifestyle adapted to infertile regions such as steppe, tundra, or ice and sand, where mobility is the most efficient strategy for exploiting scarce resources. For example, many groups living in the tundra are reindeer herders and are semi-nomadic, following forage for their animals. Sometimes also described as “nomadic” are various itinerant populations who move among densely populated areas to offer specialized services (crafts or trades) to their residents—external consultants, for example. These groups are known as “peripatetic nomads.” ref

“Nomadic pastoralism seems to have developed first as a part of the secondary-products revolution proposed by Andrew Sherratt, in which early pre-pottery Neolithic cultures that had used animals as live meat (“on the hoof”) also began using animals for their secondary products, for example: milk and its associated dairy products, wool and other animal hair, hides (and consequently leather), manure (for fuel and fertilizer), and traction.” ref

“The first nomadic pastoral society developed in the period from 8,500 to 6,500 BCE or around 10,500 to 8,500 years ago in the area of the southern Levant. There, during a period of increasing aridity, Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) cultures in the Sinai were replaced by a nomadic, pastoral pottery-using culture, which seems to have been a cultural fusion between them and a newly-arrived Mesolithic people from Egypt (the Harifian culture), adopting their nomadic hunting lifestyle to the raising of stock.” ref

“Harifian is a specialized regional cultural development of the Epipalaeolithic of the Negev Desert. It corresponds to the latest stages of the Natufian culture. Like the Natufian, Harifian is characterized by semi-subterranean houses. These are often more elaborate than those found at Natufian sites. For the first time arrowheads are found among the stone tool kit. The Harifian dates to between approximately 10,800/10,500 and 10,000/10,200 years ago. It is restricted to the Sinai and Negev, and is probably broadly contemporary with the Late Natufian or Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA). Microlithic points are a characteristic feature of the industry, with the Harif point being both new and particularly diagnostic – Bar-Yosef (1998) suggests that it is an indication of improved hunting techniques. Lunates, isosceles and other triangular forms were backed with retouch, and some Helwan lunates are found. This industry contrasts with the Desert Natufian which did not have the roughly triangular points in its assemblage. There are two main groups within the Harifian. One group consists of ephemeral base camps in the north of Sinai and western Negev, where stone points comprise up to 88% of all microliths, accompanied by only a few lunates and triangles. The other group consists of base camps and smaller campsites in the Negev and features a greater number of lunates and triangles than points. These sites probably represent functional rather than chronological differences. The presence of Khiam points in some sites indicates that there was communication with other areas in the Levant at this time.” ref

“This lifestyle quickly developed into what Jaris Yurins has called the circum-Arabian nomadic pastoral techno-complex and is possibly associated with the appearance of Semitic languages in the region of the Ancient Near East. The rapid spread of such nomadic pastoralism was typical of such later developments as of the Yamnaya culture of the horse and cattle nomads of the Eurasian steppe (c. 3300–2600 BCE), and of the Mongol spread in the later Middle Ages. Yamnaya steppe pastoralists from the Pontic–Caspian steppe, who were among the first to master horseback riding, played a key role in Indo-European migrations and in the spread of Indo-European languages across Eurasia.” ref

“Trekboers in southern Africa adopted nomadism from the 17th century. Some elements of gaucho culture in colonial South America also re-invented nomadic lifestyles. Hunter-gatherers (also known as foragers) move from campsite to campsite, following game and wild fruits and vegetables. Hunting and gathering describes early peoples’ subsistence living style. Following the development of agriculture, most hunter-gatherers were eventually either displaced or converted to farming or pastoralist groups. Only a few contemporary societies, such as the Pygmies, the Hadza people, and some uncontacted tribes in the Amazon rainforest, are classified as hunter-gatherers; some of these societies supplement, sometimes extensively, their foraging activity with farming or animal husbandry.” ref

“Pastoral nomads are nomads moving between pastures. Nomadic pastoralism is thought to have developed in three stages that accompanied population growth and an increase in the complexity of social organization. Karim Sadr has proposed the following stages:

- Pastoralism: This is a mixed economy with a symbiosis within the family.

- Agropastoralism: This is when symbiosis is between segments or clans within an ethnic group.

- True Nomadism: This is when symbiosis is at the regional level, generally between specialised nomadic and agricultural populations.” ref

“The pastoralists are sedentary to a certain area, as they move between the permanent spring, summer, autumn and winter (or dry and wet season) pastures for their livestock. The nomads moved depending on the availability of resources.” ref

Nguni cattle

“The Nguni is a cattle breed indigenous to Southern Africa. A hybrid of different Indian and later European cattle breeds, they were introduced by pastoralist tribes ancestral to modern Nguni people to Southern Africa during their migration from the North of the continent. Nguni cattle are dairy and beef cattle. Nguni cattle are known for their fertility and resistance to diseases, being the favourite and most beloved breed amongst the local Bantu-speaking people of southern Africa (South Africa, Eswatini, Namibia, Zimbabwe, Botswana, and Angola). They are a principal form of Sanga cattle (collective name for indigenous cattle of some regions in Africa), which originated as hybrids of Zebu (originating in South Aisa, first domesticated between 7,000 and 6,000 years ago, and In some regions, zebu have significant religious meaning) and humpless cattle in East Africa. DNA analyses have confirmed that they are a combination of Bos indicus and Bos taurus, that is a combination of different Zebu and European cattle breeds.” ref

Zebu cattle

“Zebu cattle were found to derive from the Indian form of aurochs and have first been domesticated between 7,000 and 6,000 years ago at Mehrgarh, present-day Pakistan, by people linked to or coming from Mesopotamia. Its wild ancestor, the Indian aurochs, became extinct during the Indus Valley civilisation likely due to habitat loss, caused by expanding pastoralism and interbreeding with domestic zebu. Its latest remains ever found were dated to 3,800 years ago, making it the first of the three aurochs subspecies to die out. Archaeological evidence including depictions on pottery and rocks suggests that humped cattle likely imported from the Near East was present in Egypt around 4,000 years ago. Its first appearance in the Subsahara is dated to after 700 CE and it was introduced to the Horn of Africa around 1000 CE. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that all the zebu Y chromosome haplotype groups are found in three different lineages: Y3A, the most predominant and cosmopolitan lineage; Y3B, only observed in West Africa; and Y3C, predominant in south and northeast India.” ref

Nguni languages

“The Nguni languages are a group of Bantu languages spoken in southern Africa (mainly South Africa, Zimbabwe and Eswatini) by the Nguni people. Nguni languages include Xhosa, Hlubi, Zulu, Ndebele, and Swati. The appellation “Nguni” derives from the Nguni cattle type. Ngoni (see below) is an older, or a shifted, variant. It is sometimes argued that the use of Nguni as a generic label suggests a historical monolithic unity of the people in question, where in fact the situation may have been more complex. The linguistic use of the label (referring to a subgrouping of Bantu) is relatively stable.” ref

“Within a subset of Southern Bantu, the label “Nguni” is used both genetically (in the linguistic sense) and typologically (quite apart from any historical significance). The Nguni languages are closely related, and in many instances different languages are mutually intelligible; in this way, Nguni languages might better be construed as a dialect continuum than as a cluster of separate languages. On more than one occasion, proposals have been put forward to create a unified Nguni language.” ref

“In scholarly literature on southern African languages, the linguistic classificatory category “Nguni” is traditionally considered to subsume two subgroups: “Zunda Nguni” and “Tekela Nguni”. This division is based principally on the salient phonological distinction between corresponding coronal consonants: Zunda /z/ and Tekela /t/ (thus the native form of the name Swati and the better-known Zulu form Swazi), but there is a host of additional linguistic variables that enables a relatively straightforward division into these two substreams of Nguni.” ref

Nguni people

“The Nguni people are a linguistic cultural group of Bantu cattle herders who migrated from central Africa into Southern Africa, made up of ethnic groups formed from hunter-gatherer pygmy and proto-agrarians, with offshoots in neighboring colonially-created countries in Southern Africa. Swazi (or Swati) people live in both South Africa and Eswatini, while Ndebele people live in both South Africa and Zimbabwe.” ref

“The Xhosa were formed out of pastoralist blended from pygmies and proto-Bantu agro-pastoralists and established federations (AbaThembu, AmaMpondo, AmaXhosa, and AmaMpondomise) in the 5th century AD. The Xhosa trace their name back to the Khoikhoi, as the Khoi named them Xhosa, signifying “violent angry” people. The recent homeland of the Xhosa people is marked by lands in the Eastern Cape from the Gamtoos River up to Umzimkhulu near Natal, which confined and restricted their pastoral ancestors from the rest of the Cape by an expanding and setting of the VOC Cape Colony frontier. This closed frontier was set in the late 1700s. The Xhosa often called the “Red Blanket People,” are speakers of Bantu languages living in south-east South Africa and in the last two centuries throughout the southern and central-southern parts of the country.” ref

“Most of what is believed about ancient Nguni history comes from oral history and legends. Traditionally, their partial ancestors are said to have migrated to Africa’s Great Lakes region from the north. According to linguistic evidence and historians (including John H. Robertson, Rebecca Bradley, T. Russell, Fabio Silva, and James Steele), some of the ancestors of the Nguni people migrated from west of the geographic centre of Africa towards modern-day South Africa 7000 years ago (5000 BCE or around 7,000 years ago). Nguni ancestors had migrated within South Africa to KwaZulu-Natal by the 1st century CE and were also present in the Transvaal region at the same time. These partially nomadic ancestors of the modern Nguni people brought with them sheep, cattle, goats, and horticultural crops, many of which had never been used in South Africa at that time.” ref

“Other provinces in present-day South Africa, such as the Cape, saw the emergence of Nguni speakers around the same time. Some groups split off and settled along the way, while others kept going. Thus, the following settlement pattern formed: the southern Ndebele in the north, the Swazi in the northeast, the Xhosa in the south, and the Zulu towards the east. Because these peoples had a common origin, their languages and cultures show marked similarities. Partial ancestors of the Nguni eventually met and merged with San hunters, which accounts for the use of click consonants in the languages of the Nguni.” ref

“Within the Nguni nations, the clan, based on male ancestry, formed the highest social unit. Each clan was led by a chieftain. Influential men tried to achieve independence by creating their own clan. The power of a chieftain often depended on how well he could hold his clan together. From about 1800, the rise of the Zulu clan of the Nguni, and the consequent Mfecane that accompanied the expansion of the Zulus under Shaka helped to drive a process of alliance and consolidation among many of the smaller clans.” ref

“For example, the kingdom of Eswatini was formed in the early nineteenth century by different Nguni groups allying with the Dlamini clan against the threat of external attack. Today, the kingdom encompasses many different clans that speak a Nguni language called Swati and are loyal to the king of Eswatini, who is also the head of the Dlamini clan. Ngunis may be Christians (Catholics or Protestants), practitioners of African traditional religions or members of forms of Christianity modified with traditional African values.They also follow a mix of these two religions, usually not separately.” ref

Khoe-San Genomes Reveal Unique Variation and Confirm the Deepest Population Divergence in Homo sapiens

“Abstract: The southern African indigenous Khoe-San populations harbor the most divergent lineages of all living peoples. Exploring their genomes is key to understanding deep human history. We sequenced 25 full genomes from five Khoe-San populations, revealing many novel variants, that 25% of variants are unique to the Khoe-San, and that the Khoe-San group harbors the greatest level of diversity across the globe. In line with previous studies, we found several gene regions with extreme values in genome-wide scans for selection, potentially caused by natural selection in the lineage leading to Homo sapiens and more recent in time. These gene regions included immunity-, sperm-, brain-, diet-, and muscle-related genes. When accounting for recent admixture, all Khoe-San groups display genetic diversity approaching the levels in other African groups and a reduction in effective population size starting around 100,000 years ago. Hence, all human groups show a reduction in effective population size commencing around the time of the Out-of-Africa migrations, which coincides with changes in the paleoclimate records, changes that potentially impacted all humans at the time.” ref

“Genetics has played an increasingly important role in revealing human evolutionary history, by demonstrating that Homo sapiens emerged from, with some groups outside Africa admixing with archaic humans. Our deepest roots include indigenous groups of current-day southern Africa, with modern-day Khoe-San representing one branch in the earliest population divergence in Homo sapiens, and all other Africans and non-Africans representing the other branch. Southern African hunter-gatherers (San) and herders (Khoekhoe) are collectively referred to as Khoe-San. Khoe-San people speak Khoisan languages, a group of languages that rely heavily on “click” sounds. Three out of the five major Khoisan language families are spoken in southern Africa, namely, Kx’a (formerly called Northern Khoisan), Tuu (formerly Southern Khoisan), and Khoe-Kwadi (formerly Central Khoisan). These three language families show no linguistic relatedness to each other. A few complete genomes from Khoe-San individuals have been investigated with poor representation among the different groups. As the Khoe-San represents one of two branches of the deepest population divergence within Homo sapiens, it is crucial to reveal their evolutionary history and their genetic diversity in order to understand the early evolutionary history of our species.” ref

“Researchers sequenced and analyzed 25 complete high-coverage genomes from five different Khoe-San groups, representing the three main Khoisan linguistic phyla, across an extensive geographic area. These genomes were placed into a global context by jointly investigating 11 previously published genomes from the HGDP panel, sequenced on the same platform and subjected to similar single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) calling procedures, and another 67 genomes sequenced on the Complete Genomics platform. Using these data sets, we characterized genome variation across the world and inferred past population history, where Khoe-San groups showed greater genetic diversity than any other group, but still revealed a reduction in effective population size coinciding with the Out-of-Africa migrations and bottleneck. We further discovered a number of selection targets in the Khoe-San and other groups, and within our common ancestors of >300,000 years ago. These results shed new light on Pleistocene human demographic history and evolution.” ref

“Researchers found a distinct signal of eastern African/non-African affinity and shared private variants among the Khoe-San, particularly for the Nama. This outcome is consistent with recent migration of mixed (eastern African-Eurasian) herding groups to southern Africa, and potentially long-term gene flow between eastern African hunter-gatherers (e.g., Hadza) and Khoe-San. This pattern can also be seen in mtDNA and Y chromosome data, with haplogroup sharing detected between the Ju|’hoansi and Hadza.” ref

“Researchers estimated population divergence between the Khoe-San and various other groups using different and complementary approaches. We applied a mutation rate of 1.25 × 10−8 per base pair per generation and a generation time of 30 years to convert estimates to years ago in the past. Consistent with previous studies, the deepest divergences included the Khoe-San populations; a result probably not caused by “archaic admixture” into the Khoe-San.” ref

“Modern-day Khoe-San have, however, >10% of their genetic material tracing to a recent admixture with external groups. By sequencing the genome of the Stone Age boy from Ballito Bay (BBA), South Africa, the deepest population divergence in Homo sapiens was estimated to 350,000–260,000 years ago. Consistent with the recent admixture into all modern-day Khoe-San groups, which reduces population divergence time estimates, we found the mean divergence time of all Khoe-San populations from all other groups to be within the 200,000–300,000 years ago range.” ref

“These dates correlate well with previous estimates that also fall within the 200,000–300,000 years ago range when applying the mutation rate used here. The Ju|’hoansi (with the lowest level of recent admixture) had a point estimate of ∼270,000 years ago (∼9,000 generations), SD 20,000 years ago (GphoCS method; TT method: ∼260,000 years ago, SD 12,000 years ago), whereas the Nama (with the greatest level of recent admixture) had a point estimate of ∼210,000 years ago, SD 30,000 years ago (TT method: ∼210,000 years ago, SD 30,000 years ago). The Mbuti then diverged around ∼220 ka, SD 10 ka (TT method: 215,000 years ago, SD 9,000 years ago), with the other population divergences occurring subsequently. We inferred a mean divergence time of ∼160,000 years ago, SD 20,000 years ago (TT method: ∼190,000 years ago, SD 20,000 years ago) among the different San groups, consistent with previous estimates.” ref

“If researchers jointly analyze two individuals (four haploid genomes) instead of one, it should provide more resolution on the timing of the bottleneck, because the mean time to first coalescence for four haploid genomes is 85,000 years ago (assuming an average ancestral Ne of 17,000 and a generation time of 30 years). For this analysis, we found that all Khoe-San groups showed a reduction to 1/3 of the previous Ne between 100,000 and 20,000 years ago. The same pattern was also observed with samples of five individuals (ten haploid genomes), though it could not be detected with samples of one single modern-day Khoe-San individual.” ref

“Researchers simulated data under a bottleneck model and ran MSMC on samples of one, two, four, and five individuals under a range of varying conditions of bottleneck strength, duration, and age. From this investigation, we observed a qualitatively similar pattern of reduced power to infer population-size changes around 80 ka when basing the inference on single genomes. Thus, all human groups appeared to have suffered reduced Ne, of varying degrees, between ∼100,000 and ∼20,000 years ago; declining to between 50% and 10% of an Ne of ∼30,000 at ∼300,000 years ago a.” ref

“The genetic diversity among the Khoe-San is the greatest among all human groups across the world, which, in part, is explained by relatively recent (pre-colonial) admixture. When the admixed DNA portion was excluded, the genetic diversity of the Khoe-San approached levels seen in other African populations. All human groups, including the Khoe-San, showed a reduction in Ne (between 1/3 and 1/10) between ∼100,000 and 20,000 years ago. The early phase of the reduction coincides with the Out-of-Africa bottleneck for non-Africans.” ref

“Sub-Saharan African populations would not have been impacted by this migration bottleneck, but they all (including the Khoe-San) show a reduction in Ne. This observation suggests that an additional factor—beyond the migration out of Africa—impacted all humans at this time, perhaps the change in climate. For example, work on the Lake Malawi core indicates severe drought and low-lake stage occurring between ∼109,000 and 92,000 years ago when the area is also shifting from leaf- to grass-dominated vegetation, which roughly aligns with a change from warm toward colder temperatures for Africa. These events may have caused a reduction in the number of humans; potentially also driving them out of arid African regions, such as the Sahara, and into western Asia.” ref

“By revealing substantial and previously unknown genetic variation, researchers demonstrate that a sizable portion of human genetic variation, including common variants, remains undiscovered among populations often overlooked in medical genetics. Researchers inferred adaptation signals in the genomes and found an overrepresentation of these signals overlapping immunity genes, irrespective of group or time period. This suggests that immunity genes have been under selection throughout human evolutionary history and across the globe.” ref

San people

“The compound Khoisan is used to refer to the pastoralist Khoi and the foraging San collectively. The San refer to themselves as their individual nations, such as ǃKung (also spelled ǃXuun, including the Juǀʼhoansi), ǀXam, Nǁnǂe (part of the ǂKhomani), Kxoe (Khwe and ǁAni), Haiǁom, Ncoakhoe, Tshuwau, Gǁana and Gǀui (ǀGwi), etc. Representatives of San peoples in 2003 stated their preference for the use of such individual group names, where possible, over the use of the collective term San.” ref

“The San peoples (also Saan), or Bushmen, are the members of any of the indigenous hunter-gatherer cultures of southern Africa, and the oldest surviving cultures of the region. Their recent ancestral territories span Botswana, Namibia, Angola, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Lesotho, and South Africa. The San speak, or their ancestors spoke, languages of the Khoe, Tuu, and Kxʼa language families, and can be defined as a people only in contrast to neighboring pastoralists such as the Khoekhoe and descendants of more recent waves of immigration such as the Bantu, Europeans, and Asians.” ref

“In Khoekhoegowab, the term “San” has a long vowel and is spelled Sān. It is an exonym meaning “foragers” and is used in a derogatory manner to describe people too poor to have cattle. Based on observation of lifestyle, this term has been applied to speakers of three distinct language families living between the Okavango River in Botswana and Etosha National Park in northwestern Namibia, extending up into southern Angola; central peoples of most of Namibia and Botswana, extending into Zambia and Zimbabwe; and the southern people in the central Kalahari towards the Molopo River, who are the last remnant of the previously extensive indigenous peoples of southern Africa.” ref

“The designations “Bushmen” and “San” are both exonyms. The San have no collective word for themselves in their own languages. “San” comes from a derogatory Khoekhoe word used to refer to foragers without cattle or other wealth, from a root saa “picking up from the ground” + plural -n in the Haiǁom dialect. “Bushmen” is the older cover term, but “San” was widely adopted in the West by the late 1990s. The term Bushmen, from 17th-century Dutch Bosjesmans, is still used by others and to self-identify, but is now considered pejorative or derogatory by many South Africans.” ref

“The hunter-gatherer San are among the oldest cultures on Earth, and are thought to be descended from the first inhabitants of what is now Botswana and South Africa. The historical presence of the San in Botswana is particularly evident in northern Botswana’s Tsodilo Hills region. San were traditionally semi-nomadic, moving seasonally within certain defined areas based on the availability of resources such as water, game animals, and edible plants. Peoples related to or similar to the San occupied the southern shores throughout the eastern shrubland and may have formed a Sangoan continuum from the Red Sea to the Cape of Good Hope.” ref

“The San kinship system reflects their history as traditionally small mobile foraging bands. San kinship is similar to Inuit kinship, which uses the same set of terms as in European cultures but adds a name rule and an age rule for determining what terms to use. The age rule resolves any confusion arising from kinship terms, as the older of two people always decides what to call the younger. Relatively few names circulate (approximately 35 names per sex), and each child is named after a grandparent or another relative, but never their parents.” ref

“Children have no social duties besides playing, and leisure is very important to San of all ages. Large amounts of time are spent in conversation, joking, music, and sacred dances. Women may be leaders of their own family groups. They may also make important family and group decisions and claim ownership of water holes and foraging areas. Women are mainly involved in the gathering of food, but sometimes also partake in hunting.” ref

“Water is important in San life. During long droughts, they make use of sip wells in order to collect water. To make a sip well, a San scrapes a deep hole where the sand is damp, and inserts a long hollow grass stem into the hole. An empty ostrich egg is used to collect the water. Water is sucked into the straw from the sand, into the mouth, and then travels down another straw into the ostrich egg.” ref

“Traditionally, the San were an egalitarian society. Although they had hereditary chiefs, their authority was limited. The San made decisions among themselves by consensus, with women treated as relative equals in decision making. San economy was a gift economy, based on giving each other gifts regularly rather than on trading or purchasing goods and services. Most San are monogamous, but if a hunter is able to obtain enough food, he can afford to have a second wife as well.” ref

“A set of tools almost identical to that used by the modern San and dating to 42,000 BCE was discovered at Border Cave in KwaZulu-Natal in 2012. Historical evidence shows that certain San communities have always lived in the desert regions of the Kalahari; however, eventually nearly all other San communities in southern Africa were forced into this region. The Kalahari San remained in poverty where their richer neighbours denied them rights to the land. Before long, in both Botswana and Namibia, they found their territory drastically reduced.” ref

“Various Y chromosome studies show that the San carry some of the most divergent (earliest branching) human Y-chromosome haplogroups. These haplogroups are specific sub-groups of haplogroups A and B, the two earliest branches on the human Y-chromosome tree. Mitochondrial DNA studies also provide evidence that the San carry high frequencies of the earliest haplogroup branches in the human mitochondrial DNA tree. This DNA is inherited only from one’s mother. The most divergent (earliest branching) mitochondrial haplogroup, L0d, has been identified at its highest frequencies in the southern African San groups.” ref

“In a study published in March 2011, Brenna Henn and colleagues found that the ǂKhomani San, as well as the Sandawe and Hadza peoples of Tanzania, were the most genetically diverse of any living humans studied. This high degree of genetic diversity hints at the origin of anatomically modern humans. A 2008 study suggested that the San may have been isolated from other original ancestral groups for as much as 50,000 to 100,000 years and later rejoined, re-integrating into the rest of the human gene pool. A DNA study of fully sequenced genomes, published in September 2016, showed that the ancestors of today’s San hunter-gatherers began to diverge from other human populations in Africa about 200,000 years ago and were fully isolated by 100,000 years ago.” ref

ǃKung people

“The ǃKung are one of the San peoples who live mostly on the western edge of the Kalahari desert, Ovamboland (northern Namibia and southern Angola), and Botswana. The names ǃKung (ǃXun) and Ju are variant words for ‘people’, preferred by different ǃKung groups. This band level society used traditional methods of hunting and gathering for subsistence up until the 1970s. Today, the great majority of ǃKung people live in the villages of Bantu pastoralists and European ranchers.” ref

“The ǃKung people of Southern Africa recognize a Supreme Being, ǃXu, who is the Creator and Upholder of life. Like other African High Gods, he also punishes man by means of the weather, and the Otjimpolo-ǃKung know him as Erob, who “knows everything”. They also have animistic and animatistic beliefs, which means they believe in both personifications and impersonal forces. For example, they recall a culture hero named Prishiboro, whose wife was an elephant. Prishiboro’s older brother tricked him into killing his wife and eating her flesh. Her herd tried to kill Prishiboro in revenge, but his brother defeated them.” ref

“Amongst the ǃKung there is a strong belief in the existence of spirits of the dead (llgauwasi) who live immortally in the sky. The llgauwasi can come to the earth and interact with humans. There is no particular connection to personal ancestors but the ǃKung fear the llgauwasi, pray to them for sympathy and mercy as well as call on them in anger.” ref

“The ǃKung practice shamanism to communicate with the spirit world, and to cure what they call “Star Sickness”. The communication with the spirit world is done by a natural healer entering a trance state and running through a fire, thereby chasing away bad spirits. Star Sickness is cured by laying hands on the diseased. Nisa, a ǃKung woman, reported through anthropologist Marjorie Shostak that a healer in training is given a root to help induce trance. Nisa said, “I drank it a number of times and threw up again and again. Finally, I started to tremble. People rubbed my body as I sat there feeling the effect getting stronger and stronger. … Trance-medicine really hurts! As you begin to trance, the nǀum [power to heal] slowly heats inside you and pulls at you. It rises until it grabs your insides and takes your thoughts away.” ref

“Healing rites are a primary part of the ǃKung culture. In the ǃKung state of mind, having health is equivalent to having social harmony, meaning that relationships within the group are stable and open between other people. Any ǃKung can become a healer because it “is a status accessible to all,” but it is a grand aspiration of many members because of its importance. Even though there is no restriction of the power, “nearly half the men and one-third of the women are acknowledged of having the power to heal,” but with the responsibility comes great pain and hardship. To become a healer, aspirants must become an apprentice and learn from older healers. Their training includes the older healer having to “go into a trance to teach the novices, rubbing their own sweat onto the pupils’ centers – their bellies, backs, foreheads, and spines.” “Most of the apprentices have the intentions of becoming a healer but then become frightened or have a lack of ambition and discontinue.” ref

“The ǃKung term for this powerful healing force is nǀum. This force resides in the bellies of men and women who have gone through the training and have become a healer. Healing can be transmitted through the ǃkia dance that begins at sundown and continues through the night. The ǃkia can be translated as “trance” which can give a physical image of a sleeping enchantment. While they dance, “in preparation for entering a trance state to effect a cure, the substance [the nǀum] heats up and, boiling, travels up the healer’s spine to explode with therapeutic power in the brain.” While the healers are in the trance they propel themselves in a journey to seek out the sickness and argue with the spirits. Women on the other hand have a special medicine called the gwah which starts in the stomachs and kidneys. During the Drum Dance, they enter the ǃkia state and the gwah travels up the spine and lodges in the neck.” ref

“In order to obtain the gwah power the women, “chop up the root of a short shrub, boil it into a tea and drink it.” They do not need to drink the tea every time because the power they obtain lasts a lifetime. The community of the ǃKung fully supports the healers and depends heavily on them. They have trust in the healers and the teachers to guide them psychologically and spiritually through life. The ǃKung have a saying: “Healing makes their hearts happy, and a happy heart is one that reflects a sense of community.” Because of their longing to keep the peace between people, their community is tranquil.” ref

“Traditionally, especially among Juǀʼhoansi ǃKung, women generally collect plant foods and water while men hunt. However, these gender roles are not strict and people do all jobs as needed with little or no stigma. Women generally take care of children and prepare food. However, this does restrict them to their homes, since these activities are generally done with, or close to, others, so women can socialize and help each other. Men are also engaged in these activities. Children are raised in village groups of other children of a wide age range. Sexual activities amongst children are seen as natural play for both sexes.” ref

“ǃKung women often share an intimate sociability and spend many hours together discussing their lives, enjoying each other’s company and children. In the short documentary film A Group of Women, ǃKung women rest, talk and nurse their babies while lying in the shade of a baobab tree. This illustrates “collective mothering”, where several women support each other and share the nurturing role. Marriage is the major focus of alliance formation between groups of ǃKung. When a woman starts to develop, she is considered ready for marriage. Every first marriage is arranged. The culture of the ǃKung is “being directed at marriage itself, rather than at a specific man.” ref

“Even though it does not matter who the man is, the woman’s family is looking for a specific type of man. On the marriage day, the tradition is the “marriage-by-capture” ceremony in which the bride is forcibly removed from her hut and presented to her groom. During the ceremony, the bride has her head covered and is carried and then laid down in the hut while the groom is led to the hut and sits beside the door. The couple stay respectfully apart from each other and do not join the wedding festivities. After the party is over, they spend the night together and the next morning they are ceremonially rubbed with oil by the husband’s mother.” ref

“Girls who are displeased with their parents’ selection may violently protest against the marriage by kicking and screaming and running away at the end of the ceremony. After she has run away, this may result in the dissolution of the arrangement. Half of all first-time marriages end in divorce, but because it is common, the divorce process is not long. Anthropologist Marjorie Shostak generalizes that, “Everyone in the village expresses a point of view” on the marriage and if the couple should be divorced or not. After the village weighs in, they are divorced and can live in their separate huts with their family. Relations between divorced individuals are usually quite amicable, with former partners living near one another and maintaining a cordial relationship. After a woman’s first divorce, she is free to marry a man of her choosing or stay single and live on her own.” ref

“Unlike other complex food-foraging groups, it is unusual for the ǃKung to have a chieftain or headman in a position of power over the other members. These San are not devoid of leadership, but neither are they dependent on it. San groups of the Southern Kalahari have had chieftains in the past; however, there is a somewhat complicated process to gain that position. Chieftainship within these San groups is not a position with the greatest power, as they have the same social status as those members of “aged years”. Becoming chieftain is mostly nominal, though there are some responsibilities the chieftain assumes, such as becoming the group’s “logical head”. This duty entails such roles as dividing up the meat from hunters’ kills; these leaders do not receive a larger portion than any other member of the village. The !Kung people have given name to the Theory of Regal and Kungic Societal Structures due to their peacefulness and egalitarian social structure.” ref

“Kinship is one of the central organizing principles for societies like the ǃKung. Richard Borshay Lee breaks ǃKung kinship principles down into three different sets (Kinship I, Kinship II, and Kinship III or wi). Kinship I follows conventional kin terms (father, mother, brother, sister) and is based on genealogical position. Kinship II applies to name relationships, meaning that people who share the same name (ǃkunǃa) are treated as though they are kin of the same family and are assigned the same kinship term. This is a common occurrence as there are a limited number of ǃKung names. Kung names are also strictly gendered meaning that men and women cannot share the same name. Names are passed down from ancestors according to a strict set of rules, though parents are never allowed to name their children after themselves. Every member of ǃKung society fits into one of these categories, there are no neutral people.” ref