Certainty and Probability

No God: No evidence, No intelligence, and No goodness = Valid Atheism Conclusion

Theological Noncognitivist & Ignosticism

- No evidence, to move past the Atheistic Null Hypothesis: There is no God/Gods (in inferential statistics, a Null Hypothesis generally assumed to be true until evidence indicates otherwise. Thus, a Null Hypothesis is a statistical hypothesis that there is no significant difference reached between the claim and the non-claim, as it is relatively provable/demonstratable in reality some way. “The god question” Null Hypothesis is set at as always at the negative standard: Thus, holding that there is no God/Gods, and as god faith is an assumption of the non-evidentiary wishful thinking non-reality of “mystery thing” found in all god talk, until it is demonstratable otherwise to change. Alternative hypothesis: There is a God (offered with no proof: what is a god and how can anyone say they know), therefore, results: Insufficient evidence to overturn the null hypothesis of no God/Gods.

- No intelligence, taking into account the reality of the world we do know with 99 Percent Of The Earth’s Species Are Extinct an intelligent design is ridiculous. Five Mass Extinctions Wiped out 99 Percent of Species that have ever existed on earth. Therefore like a child’s report card having an f they need to retake the class thus, profoundly unintelligent design.

- No goodness, assessed through ethically challenging the good god assumptions as seen in the reality of pain and other harm of which there are many to demonstrates either a god is not sufficiently good, not real or as I would assert, god if responsible for this world, would make it a moral monster ripe for the problem of evil and suffering (Argument from Evil). God would be responsible for all pain as life could easily be less painful and yet there is mass suffering. In fact, to me, every child born with diseases from birth scream out against a caring or loving god with the power to do otherwise. It could be different as there is Congenital insensitivity to pain (CIP), also known as congenital analgesia, in which a person cannot feel (and has never felt) physical pain.[1]

Disproof by logical contradiction

‘A Logical Impossibility’

My Methodological Rationalism: investigate (ontology), expose (epistemology) and judge (axiology)

Folk Logic: YOU CAN’T PROVE A NEGATIVE because you can PROVE A NEGATIVE

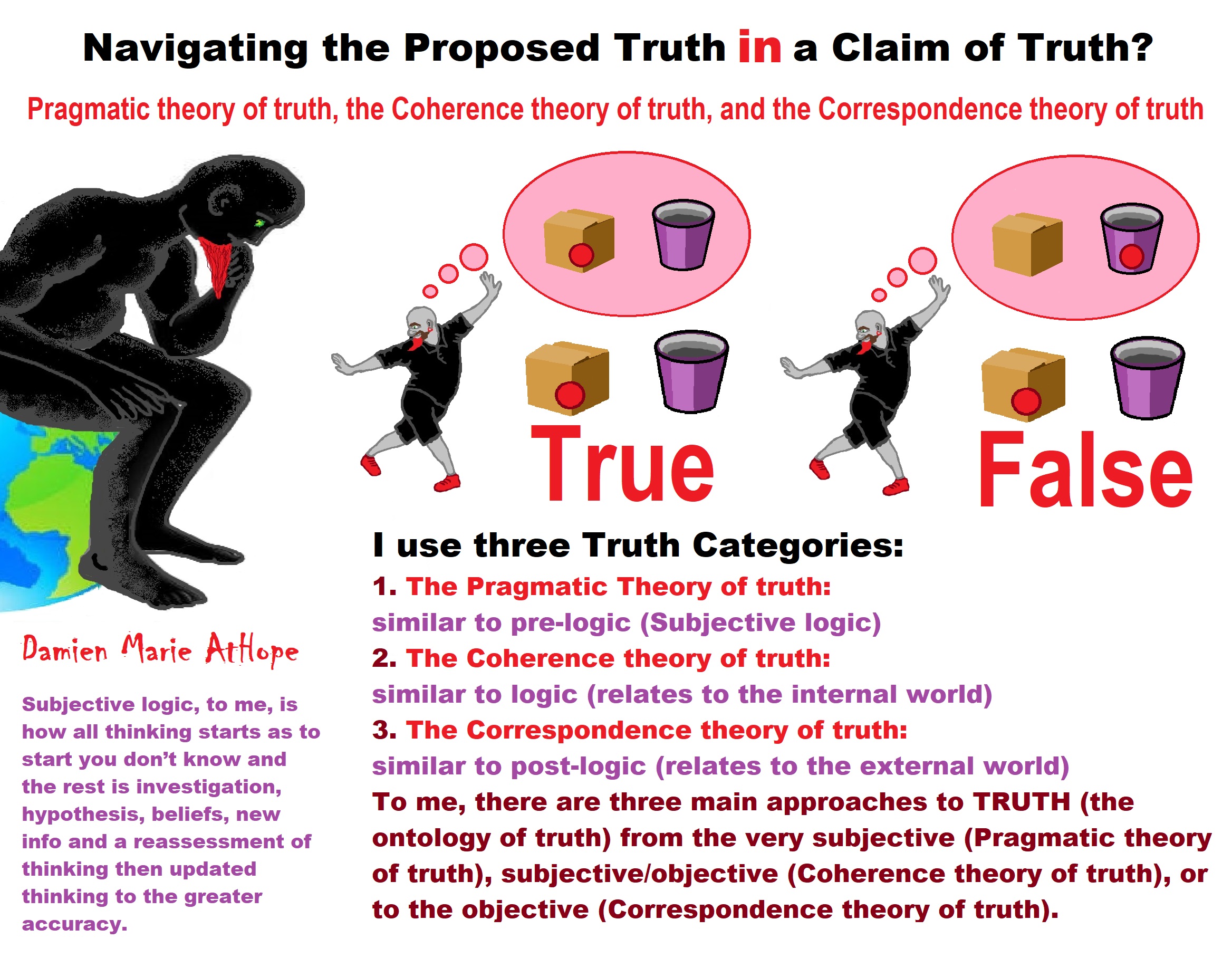

- The objective measure is a measure of the rational degree of belief in a proposition given a set of evidential propositions.

- The subjective measure is the measure of a particular subject’s dispositions to decide between options. In both measures, certainty is a degree of belief, however, there can be cases where one belief is stronger than another yet both beliefs are plausibly measurable as objectively and subjectively certain.

A second kind of certainty is epistemic. Roughly characterized, a belief is certain in this sense when it has the highest possible epistemic status. Epistemic certainty is often accompanied by psychological certainty, but it need not be. It is possible that a subject may have a belief that enjoys the highest possible epistemic status and yet be unaware that it does. In such a case, the subject may feel less than the full confidence that her epistemic position warrants. I will say more below about the analysis of epistemic certainty and its relation to psychological certainty.

Archaeological, Scientific, & Philosophic evidence shows the god myth is man-made nonsense.

References

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Probability

- http://www.thegreatideas.org/apd-cert.html

- https://www.ma.utexas.edu/users/mks/statmistakes/uncertainty.html

- http://www.castela.net/praxis/vol1issue1/PROBABILITY%20AND%20CERTAINTY.pdf

- http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/certainty/

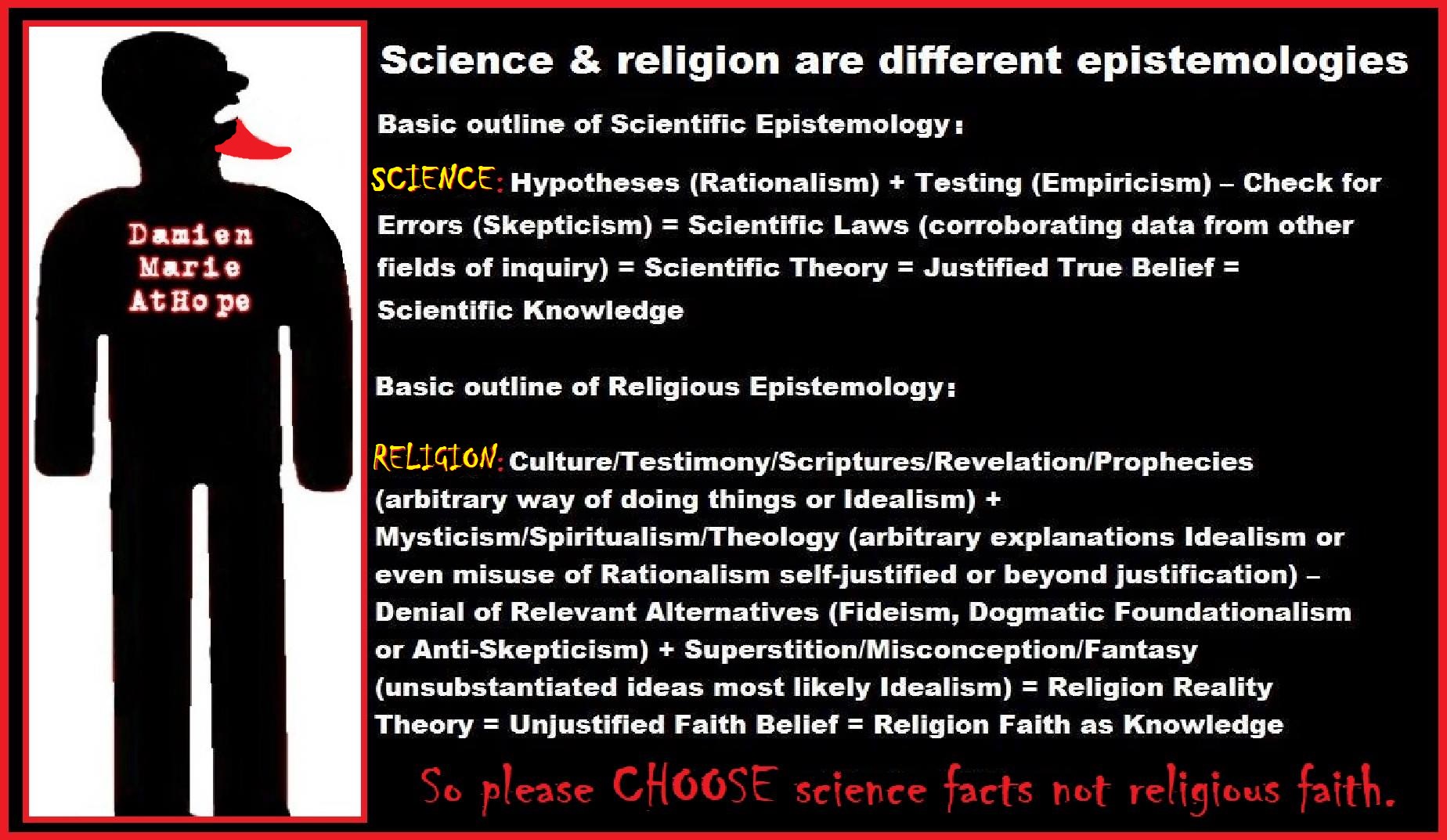

Epistemological atheism: highlights a branch of philosophy that deals with determining what is and what is not true, and why we believe or disbelieve what we or others do. On one hand, this is begging the question of having the ability to measure “truth” – as though there is an “external” something that one measures against. Epistemology is the analysis of the nature of knowledge, how we know, what we can and cannot know, and how we can know that there are things we know we cannot know. In Greek episteme, meaning “knowledge, understanding”, and logos, meaning “discourse, study, ratio, calculation, reason. Epistemology is the investigation of what distinguishes justified belief from opinion. In other words, it is the academic term associated with the study of how we conclude that certain things are true. Epistemology: the theory of knowledge, especially with regard to its methods, validity, and scope. From this atheist orientation, there is no, nor has there ever been, nor will there ever be, any “external” something so there can be no god-concept. Many debates between atheist and theists revolve around fundamental issues which people don’t recognize or never get around to discussing. Many of these are epistemological in nature: in disagreeing about whether it’s reasonable to believe in the existence of a god something, to believe in miracles, to accept revelation and scriptures as authoritative, and so forth, atheists and theists are ultimately disagreeing about basic epistemological principles. Without understanding this and understanding the various epistemological positions, people will just end up talking past each other. it’s common for Epistemological atheism to differ in what they consider to be appropriate criteria for truth and, therefore, the proper criteria for a reasonable disbelief. Atheists demand proof and evidence for other worldviews, yet there is no proof and evidence that atheism is true. Also, despite the abundant evidence for Christianity and the lack of proof and evidence for atheism, atheists reject the truth of Christianity. *Epistemology (knowledge of things) questions to explode or establish and confirm knowledge. Epistemology “Truth” questions/assertion: Lawyer searches for warrant or justification for the claim. Epistemology, (understanding what you know or can know; as in you do have anything in this reality to know anything about this term you call god, and no way of knowing if there is anything non-naturalism beyond this universe and no way to state any about it if there were). -How do know your claim? -How reliable or valid must aspects be for your claim? -How does the source of your claim make it different than other similar claims? I may respond, “how do you know that what is your sources and how reliable they are” (asking to find the truth or as usual expose the lack of a good Epistemology) Atheists refuse to go where the evidence clearly leads. In addition, when atheist make claims related to naturalism, make personal claims or make accusations against theists, they often employ lax evidential standards instead of employing rigorous evidential standards. For the most part, atheists have presumed that the most reasonable conclusions are the ones that have the best evidential support. And they have argued that the evidence in favor of a god something’s existence is too weak, or the arguments in favor of concluding there is no a god something are more compelling. Traditionally the arguments for a god something’s existence have fallen into several families: ontological, teleological, and cosmological arguments, miracles, and prudential justifications. For a detailed discussion of those arguments and the major challenges to them that have motivated the atheist conclusion, the reader is encouraged to consult the other relevant sections of the encyclopedia. Arguments for the non-existence of a god something are deductive or inductive. Deductive arguments for the non-existence of a god something are either single or multiple property disproofs that allege that there are logical or conceptual problems with one or several properties that are essential to any being worthy of the title “GOD.” Inductive arguments typically present empirical evidence that is employed to argue that a god something’s existence is improbable or unreasonable. Briefly stated, the main arguments are: a god something’s non-existence is analogous to the non-existence of Santa Claus. The existence of widespread human and non-human suffering is incompatible with an all powerful, all knowing, all good being. Discoveries about the origins and nature of the universe, and about the evolution of life on Earth make a god something hypothesis an unlikely explanation. Widespread non-belief and the lack of compelling evidence showing that a god something who seeks belief in humans does not exist. Broad considerations from science that support naturalism, or the view that all and only physical entities and causes exist, have also led many to the atheism conclusion. 1 2 3 4

by Matt McCormick

We can divide the justifications for atheism into several categories. For the most part, atheists have taken an evidentialist approach to the question of a god something’s existence. That is, atheists have taken the view that whether or not a person is justified in having an attitude of belief towards the proposition, “a god something exists,” is a function of that person’s evidence. “Evidence” here is understood broadly to include a priori arguments, arguments to the best explanation, inductive and empirical reasons, as well as deductive and conceptual premises. An asymmetry exists between theism and atheism in that atheists have not offered faith as a justification for non-belief. That is, atheists have not presented non-evidentialist defenses for believing that there is no god something. Not all theists appeal only to faith, however. Evidentialists theist and evidentialist atheists may have a number of general epistemological principles concerning evidence, arguments, and implication in common, but then disagree about what the evidence is, how it should be understood, and what it implies.

They may disagree, for instance, about whether the values of the physical constants and laws in nature constitute evidence for intentional fine tuning, but agree at least that whether a god something exists is a matter that can be explored empirically or with reason. Many non-evidentialist theists may deny that the acceptability of particular religious claim depends upon evidence, reasons, or arguments as they have been classically understood. Faith or prudential based beliefs in a god something, for example, will fall into this category. The evidentialist atheist and the non-evidentialist theist, therefore, may have a number of more fundamental disagreements about the acceptability of believing, despite the inadequate or contrary evidence, the epistemological status of prudential grounds for believing, or the nature of a god something belief.

Their disagreement may not be so much about the evidence, or even about a god something, but about the legitimate roles that evidence, reason, and faith should play in human belief structures. It is not clear that arguments against atheism that appeal to faith have any prescriptive force the way appeals to evidence do. The general evidentialist view is that when a person grasps that an argument is Sound that imposes an epistemic obligation on her to accept the conclusion. Insofar as having faith that a claim is true amounts to believing contrary to or despite a lack of evidence, one person’s faith that a god something exists does not have this sort of inter-subjective, epistemological implication. Failing to believe what is clearly supported by the evidence is ordinarily irrational. Failure to have faith that some claim is true is not similarly culpable. Justifying atheism, then, can entail several different projects. There are the evidential disputes over what information we have available to us, how it should be interpreted, and what it implies.

There are also broader meta-epistemological concerns about the roles of argument, reasoning, belief, and religiousness in human life. The atheist can find herself not just arguing that the evidence indicates that there is no god something, but defending science, the role of reason, and the necessity of basing beliefs on evidence more generally. If someone has arrived at what they take to be a reasonable and well-justified conclusion that there is no god something, then what attitude should she take about another person’s persistence in believing in a god something, particularly when that other person appears to be thoughtful and at least prima facie reasonable? It seems that the atheist could take one of several views. The theist’s belief, as the atheist sees it, could be rational or irrational, justified or unjustified. Must the atheist who believes that the evidence indicates that there is no god something conclude that the theist’s believing in a god something is irrational or unjustified? No. Most modern epistemologists have said that whether a conclusion C is justified for a person S will be a function of the information (correct or incorrect) that S possesses and the principles of inference that S employs in arriving at C. But whether or not C is justified is not directly tied to its truth, or even to the truth of the evidence concerning C. That is, a person can have a justified, but false belief. One could arrive at a conclusion through an epistemically inculpable process and yet get it wrong.

Ptolemy, for example, the greatest astronomer of his day, who had mastered all of the available information and conducted exhaustive research into the question, was justified in concluding that the Sun orbits the Earth. A medieval physician in the 1200s who guesses (correctly) that the bubonic plague was caused by the bacterium yersinia pestis would not have been reasonable or justified given his background information and given that the bacterium would not even be discovered for 600 years. We can call the view that rational, justified beliefs can be false, as it applies to atheism, friendly or fallibilist atheism. See the article on Fallibilism.The friendly atheist can grant that a theist may be justified or reasonable in believing in a god something, even though the atheist takes the theist’s conclusion to be false. What could explain their divergence to the atheist? The believer may not be in possession of all of the relevant information. The believer may be basing her conclusion on a false premise or premises. The believer may be implicitly or explicitly employing inference rules that themselves are not reliable or truth-preserving, but the background information she has leads her, reasonably, to trust the inference rule. The same points can be made for the friendly theist and the view that he may take about the reasonableness of the atheist’s conclusion. It is also possible, of course, for both sides to be unfriendly and conclude that anyone who disagrees with what they take to be justified is being irrational. Given developments in modern epistemology and Rowe’s argument, however, the unfriendly view is neither correct nor conducive to a constructive and informed analysis of the question of a god something. Atheists have offered a wide range of justifications and accounts for non-belief.

A notable modern view is Antony Flew’s Presumption of Atheism. Flew argues that the default position for any rational believer should be neutral with regard to the existence of a god something and to be neutral is to not have a belief regarding its existence. And not having a belief with regard to a god something is to be a negative atheist on Flew’s account. “The onus of proof lies on the man who affirms, not on the man who denies. . . on the proposition, not on the opposition,” Flew argues. Beyond that, coming to believe that such a thing does or does not exist will require justification, much as a jury presumes innocence concerning the accused and requires evidence in order to conclude that he is guilty. Flew’s negative atheist will presume nothing at the outset, not even the logical coherence of the notion of a god something, but one’s presumption will be defeasible, or revisable in the light of evidence. We shall call this view atheism by default. The atheism by default position contrasts with a more permissive attitude that is sometimes taken regarding religious belief.

The notions of religious tolerance and freedom are sometimes understood to indicate the epistemic permissibility of believing despite a lack of evidence in favor or even despite evidence to the contrary. One is in violation of no epistemic duty by believing, even if one lacks conclusive evidence in favor or even if one has evidence that is on the whole against. In contrast to Flew’s jury model, we can think of this view as treating religious beliefs as permissible until proven incorrect. Some aspects of fideistic accounts or Plantinga’s reformed epistemology can be understood in this light. This sort of epistemic policy about a god something or any other matter has been controversial, and a major point of contention between atheists and theists. Atheists have argued that we typically do not take it to be epistemically inculpable or reasonable for a person to believe in Santa Claus, the Tooth Fairy, or some other supernatural being merely because they do not possess evidence to the contrary. Nor would we consider it reasonable for a person to begin believing that they have cancer because they do not have proof to the contrary. The atheist by default argues that it would be appropriate to not believe in such circumstances.

The epistemic policy here takes its inspiration from an influential piece by W.K. Clifford in which he argues that it is wrong, always, everywhere, and for anyone, to believe anything for which there is an insufficient reason. There are several other approaches to the justification of atheism that we will consider below. There is a family of arguments, sometimes known as exercises in deductive atheology, for the conclusion that the existence of a god something is impossible. Another large group of important and influential arguments can be gathered under the heading inductive atheology. These probabilistic arguments invoke considerations about the natural world such as widespread suffering, nonbelief, or findings from biology or cosmology. Another approach, atheistic noncognitivism, denies that a god something talk is even meaningful or has any propositional content that can be evaluated in terms of truth or falsity.

Rather, religious speech acts are better viewed as a complicated sort of emoting or expression of spiritual passion. Inductive and deductive approaches are cognitivistic in that they accept that claims about a god something has meaningful content and can be determined to be true or false. Many discussions about the nature and existence of a god something has either implicitly or explicitly accepted that the concept of a god something is logically coherent. That is, for many believers and non-believers the assumption has been that such a being as a god something could possibly exist but they have disagreed about whether there actually is one. Atheists within the deductive atheology tradition, however, have not even granted that a god something, as he is typically described, is possible. The first question we should ask, argues the deductive atheist, is whether the description or the concept is logically consistent. If it is not, then no such being could possibly exist.

The deductive atheist argues that some, one, or all of a god-something’s essential properties are logically contradictory. Since logical impossibilities are not and cannot be real, a god something does not and cannot exist. Consider a putative description of an object as a four-sided triangle, a married bachelor, or prime number with more than 2 factors. We can be certain that no such thing fitting that description exists because what they describe is demonstrably impossible. If deductive atheological proofs are successful, the results will be epistemically significant. Many people have doubts that the view that there is no god something that can be rationally justified. But if deductive disproofs show that there can exist no being with a certain property or properties and those properties figure essentially in the characterization of a god something, then we will have the strongest possible justification for concluding that there is no being fitting any of those characterizations.

If a god something is impossible, then a god something does not exist. It may be possible at this point to re-engineer the description of a god something so that it avoids the difficulties, but now the theist faces several challenges according to the deductive atheologist. First, if the traditional description of a god something is logically incoherent, then what is the relationship between a theist’s belief and some revised, more sophisticated account that allegedly does not suffer from those problems? Is that a god something that one believed in all along? Before the account of a god-something was improved by consideration of the atheological arguments, what were the reasons that led her to believe in that conception of a god something? Secondly, if the classical characterizations of a god something are shown to be logically impossible, then there is a legitimate question as to whether any new description that avoids those problems describes a being that is worthy of the label. It will not do, in the eyes of many theists and atheists, to retreat to the view that a god something is merely a somewhat powerful, partially-knowing, and partly-good being, for example. Thirdly, the atheist will still want to know on the basis of what evidence or arguments should we conclude that a being as described by this modified account exists? Fourthly, there is no question that there exists less than Omni-beings in the world. We possess less than infinite power, knowledge, and goodness, as do many other creatures and objects in our experience.

What is the philosophical importance or metaphysical significance of arguing for the existence of those sorts of beings and advocating belief in them? Fifthly, and most importantly, if it has been argued that a god something’s essential properties are impossible, then any move to another description seems to be a concession that positive atheism about a god something is justified. Another possible response that the theist may take in response to deductive atheological arguments is to assert that a god something is something beyond proper description with any of the concepts or properties that we can or do employ as suggested in Kierkegaard or Tillich. So complications from incompatibilities among properties of a god something indicate problems for our descriptions, not the impossibility of a divine being worthy of the label.

Many atheists have not been satisfied with this response. The theist has now asserted the existence of an attempted to argue in favor of believing in a being that we cannot form a proper idea of, one that does not have properties that we can acknowledge; it is a being that defies comprehension. It is not clear how we could have reasons or justifications for believing in the existence of such a thing. It is not clear how it could be an existing thing in any familiar sense of the term in that it lacks comprehensible properties. Or put another way, as Patrick Grim notes, “If a believer’s notion of a god something remains so vague as to escape all impossibility arguments, it can be argued, it cannot be clear to even one what one believes—or whether what he takes for pious belief one’s any content at all,”. It is not clear how it could be reasonable to believe in such a thing, and it is even more doubtful that it is epistemically unjustified or irresponsible to deny that such a thing exists.

It is clear, however, that the deductive atheologist must acknowledge the growth and development of our concepts and descriptions of reality over time, and she must take a reasonable view about the relationship of those attempts and revisions in our ideas about what may turn out to be real. Deductive disproofs have typically focused on logical inconsistencies to be found either within a single property or between multiple properties. Philosophers have struggled to work out the details of what it would be to be omnipotent, for instance. It has come to be widely accepted that a being cannot be omnipotent where omnipotence simply means to power to do anything including the logically impossible. This definition of the term suffers from the stone paradox.

An omnipotent being would either be capable of creating a rock that one cannot lift, or he is incapable. If one is incapable, then there is something one cannot do, and therefore one does not have the power to do anything. If one can create such a rock, then again there is something that one cannot do, namely, lift the rock he just created. So paradoxically, having the ability to do anything would appear to entail being unable to do some things. As a result, many theists and atheists have agreed that a being could not have that property. A number of attempts to work out an account of omnipotence have ensued. It has also been argued that omniscience is impossible and that the most knowledge that can possibly be had is not enough to be fitting of a god something.

One of the central problems has been that a god something cannot have knowledge of indexical claims such as, “I am here now.” It has also been argued that a god something can’t know future free choices or a god something cannot know future contingent propositions, or that Cantor’s and Gödel proofs imply that the notion of a set of all truths cannot be made coherent. See the article on Omniscience and Divine Foreknowledge for more details.

The logical coherence of eternality, personhood, moral perfection, causal agency, and many others have been challenged in the deductive atheology literature. Another form of deductive atheological argument attempts to show the logical incompatibility between two or more properties that a god something is thought to possess. A long list of properties have been the subject of multiple property disproofs, transcendence, and personhood, justice, and mercy, immutability, and omniscience, immutability and omnibenevolence, omnipresence and agency, perfection and love, eternality and omniscience, eternality and creator of the universe, omnipresence, and consciousness. The combination of omnipotence and omniscience have received a great deal of attention.

To possess all knowledge, for instance, would include knowing all of the particular ways in which one will exercise one’s power, or all of the decisions that one will make, or all of the decisions that one has made in the past. But knowing any of those entails that the known proposition is true. So does a god something have the power to act in some fashion that he has not foreseen, or differently than he already has without compromising his omniscience? It has also been argued that a god something cannot be both unsurpassably good and free. When attempts to provide evidence or arguments in favor of the existence of something fail, a legitimate and important question is whether anything except the failure of those arguments can be inferred. That is, does positive atheism follow from the failure of arguments for theism? A number of authors have concluded that it does. They have taken the view that unless some case for the existence of a god something succeeds, we should believe that there is no god something.

Many have taken an argument J.M. Findlay to be pivotal. Findlay, like many others, argues that in order to be worthy of the label “GOD,” and in order to be worthy of a worshipful attitude of reverence, emulation, and abandoned admiration, the being that is the object of that attitude must be inescapable, necessary, and unsurpassably supreme. If a being like a god something was to exist, his existence would be necessary. And his existence would be manifest as an a priori, conceptual truth. That is to say that of all the approaches to a god something’s existence, the ontological argument is the strategy that we would expect to be successful were there a god something, and if they do not succeed, then we can conclude that there is no god something, Findlay argues. As most see it these attempts to prove a god something have not met with success, Findlay says, “The general philosophical verdict is that none of these ‘proofs’ is truly compelling.” The view that there is no god something or god somethings has been criticized on the grounds that it is not possible to prove a negative.

No matter how exhaustive and careful our analysis, there could always be some proof, some piece of evidence, or some consideration that we have not considered. A god-something could be something that we have not conceived, or a god something exists in some form or fashion that has escaped our investigation. Positive atheism draws a stronger conclusion than any of the problems with arguments for a god something’s existence alone could justify. The absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. Findlay and the deductive atheological arguments attempt to address these concerns, but a central question put to atheists has been about the possibility of giving inductive or probabilistic justifications for negative existential claims The response to them, “You cannot prove a negative” criticism has been that it invokes an artificially high epistemological standard of justification that creates a much broader set of problems not confined to atheism. The general principle seems to be that one is not epistemically entitled to believe a proposition unless you have exhausted all of the possibilities and proven beyond any doubt that a claim is true. Or put negatively, one is not justified in disbelieving unless you have proven with absolute certainty that the thing in question does not exist.

The problem is that we do not have a priori disproof that many things do not exist, yet it is reasonable and justified to believe that they do not: the Dodo bird is extinct, unicorns are not real, there is no teapot orbiting the Earth on the opposite side of the Sun, there is no Santa Claus, ghosts are not real, a defendant is not guilty, a patient does not have a particular disease, and so on. There are a wide range of other circumstances under which we take it that believing that X does not exist is reasonable even though no logical impossibility is manifest. None of these achieve the level of deductive, a priori or conceptual proof. The objection to inductive atheism undermines itself in that it generates a broad, pernicious skepticism against far more than religious or irreligious beliefs. “It will not be sufficient to criticize each argument on its own by saying that it does not prove the intended conclusion, that is, does not put it beyond all doubt. That follows at once from the admission that the argument is non-deductive, and it is absurd to try to confine our knowledge and belief to matters which are conclusively established by sound deductive arguments. The demand for certainty will inevitably be disappointed, leaving skepticism in command of almost every issue.” If the atheist is unjustified for lacking deductive proof, then it is argued, it would appear that so are the beliefs that planes fly, fish swim, or that there exists a mind-independent world. The atheist can also wonder what the point of the objection is. When we lack deductive disproof that X exists, should we be agnostic about it? Is it permissible to believe that it does exist? Clearly, that would not be appropriate.

Gravity may be the work of invisible, undetectable elves with sticky shoes. We don’t have any certain disproof of the elves—physicists are still struggling with an explanation of gravity. But surely someone who accepts the sticky-shoed elves view until they have deductive disproof is being unreasonable. It is also clear that if you are a positive atheist about the gravity elves, you would not be unreasonable. You would not be overstepping your epistemic entitlement by believing that no such things exist. On the contrary, believing that they exist or even being agnostic about their existence on the basis of their mere possibility would not be justified. So there appear to be a number of precedents and epistemic principles at work in our belief structures that provide room for inductive atheism. However, these issues in the epistemology of atheism and recent work by Graham Oppy suggest that more attention must be paid to the principles that describe epistemic permissibility, culpability, reasonableness, and justification with regard to the theist, atheist, and agnostic categories.

The Santa Claus Argument

Martin offers this general principle to describe the criteria that render the belief, “X does not exist” justified:

A person is justified in believing that X does not exist if

(1) all the available evidence used to support the view that X exists is shown to be inadequate; and

(2) X is the sort of entity that, if X exists, then there is a presumption that would be evidence adequate to support the view that X exists; and

(3) this presumption has not been defeated although serious efforts have been made to do so; and

(4) the area where evidence would appear, if there were any, has been comprehensively examined; and

(5) there are no acceptable beneficial reasons to believe that X exists.

Many of the major works in philosophical atheism that address the full range of recent arguments for a god something’s existence can be seen as providing evidence to satisfy the first, fourth and fifth conditions. A substantial body of articles with a narrower scope can also be understood to play this role in justifying atheism. A large group of discussions of Pascal’s Wager and related prudential justifications in the literature can also be seen as relevant to the satisfaction of the fifth condition. One of the interesting and important questions in the epistemology of philosophy of religion has been whether the second and third conditions are satisfied concerning a god something. If there were a god something, how and in what ways would we expect him to show in the world? Empirically? Conceptually? Would he be hidden? Martin argues, and many others have accepted implicitly or explicitly, that a god something is the sort of thing that would manifest in some discernible fashion to our inquiries. Martin concludes, therefore, that a god something satisfied all of the conditions, so, positive narrow atheism is justified. 1

Axiological “Presumptive-Value”

Your god myth is an Axiological “Presumptive-Value” Failure

I am an Axiological (value theorist) Atheist, and Claims of god are a Presumptive-Value failure. Simply, if you presume a thing is of value that you can’t justify, then you have committed an axiological presumptive value failure.

Axiological “presumptive-value” Success: Sound Thinker: uses disciplined rationality (sound axiological judgment the evaluation of evidence to make a decision) supporting a valid and reliable justification.

Axiological “presumptive-value” Failure: Shallow Thinker: undisciplined, situational, sporadic, or limited thinking (unsound axiological judgment, lacking required evidence to make a “presumptive-value” success decision) lacking the support of a needed valid and reliable justification.

“Ok, So basically, the difference between reasoning with evidence and without?” – Questioner

My response, Well with or without valid justification because of evidence. As in you can’t claim to know the value of something you can’t demonstrate as having good qualities to attach the value claim too so if you lack evidence of the thing in question then you cannot validate its value. So it’s addressing justificationism (uncountable) Theory of justification, An (philosophy standard) approach that regards the justification of a claim as primary, while the claim itself is secondary; thus, criticism consists of trying to show that a claim cannot be reduced to the authority or criteria that it appeals to. Think of is as a use-matrix. If I say this is of great use for that, can you validate its use or value, and can I use this as a valid method to state a valid justification for my claims without evidence to value judge from? No, thus an axiological presumptive-value failure as a valid anything. Theory of justification is a part of epistemology that attempts to understand the justification of propositions and beliefs. Epistemologists are concerned with various epistemic features of belief, which include the ideas of justification, warrant, rationality, and probability. Loosely speaking, justification is the reason that someone (properly) holds a belief. When a claim is in doubt, justification can be used to support the claim and reduce or remove the doubt. Justification can use empiricism (the evidence of the senses), authoritative testimony (the appeal to criteria and authority), or reason. – Wikipedia

“Presumptions are things that are credited as being true until evidence of their falsity is presented. Presumptions have many forms and value (Axiology) is just one. In ethics, value denotes the degree of importance of something or action, with the aim of determining what actions are best to do or what way is best to live (normative ethics), or to describe the significance of different actions. It may be described as treating actions as abstract objects, putting VALUE to them. It deals with right conduct and living a good life, in the sense that a highly, or at least relatively high valuable action may be regarded as ethically “good” (adjective sense), and that an action of low value, or relatively low in value, may be regarded as “bad”. What makes an action valuable may, in turn, depend on the ethic values of the objects it increases, decreases or alters. An object with “ethic value” may be termed an “ethic or philosophic good” (noun sense). Values can be defined as broad preferences concerning appropriate courses of actions or outcomes. As such, values reflect a person’s sense of right and wrong or what “ought” to be. “Equal rights for all”, “Excellence deserves admiration”, and “People should be treated with respect and dignity” are representatives of values. Values tend to influence attitudes and behavior and these types include ethical/moral values, doctrinal/ideological(religious, political) values, social values, and aesthetic values. It is debated whether some values that are not clearly physiologically determined, such as altruism, are intrinsic, and whether some, such as acquisitiveness, should be classified as vices or virtues.” ref, ref

“Sound thinking to me, in a general way, is thinking, reasoning, or belief that tends to make foresight a desire to be as accurate as one can with valid and reliable reason and evidence.”

Sound axiological judgment, to me, a “presumptive-value” success, is value judged opinions expressed as facts with a valid and reliable justification. In an informal and psychological sense, it is used in reference to the quality of cognitive faculties and adjudicational (relating to adjudication) capabilities of particular individuals, typically called wisdom or discernment. In a legal sense, – used in the context of a legal trial, to refer to a final finding, statement, or ruling, based on a considered weighing of evidence, called, “adjudication“.

Sound Thinkers don’t value FAITH

Sound thinking to me, in a general way, is thinking, reasoning, or belief

that tends to make foresight a desire to be as accurate as one can

with valid and reliable reason and evidence.

Dogmatic–Propaganda vs. Disciplined-Rationality

Religionists and fideists, promote Dogmatic-Propaganda whereas atheists and antireligionists mostly promote Disciplined-Rationality. Dogmatic–Propaganda commonly is a common motivator of flawed or irrational thinking but with over seventy belief biases identified in people, this is hardly limited to just the religious or faith inclined. Let me illustrate what I am saying, to me all theists are believing lies or irrationally in that aspect of their lives relating to god belief. So the fact of any other common intellectual indexers where there may be right reason in beliefs cannot remove the flawed god belief corruption being committed. What I am saying is like this if you kill one person you are a killer. If you believe in one “god” I know you are a follower of Dogmatic-Propaganda and can not completely be a follower of Disciplined-Rationality. However, I am not proclaiming all atheists are always rational as irrationally is revolving door many people believe or otherwise seem to stumble through. It’s just that god belief does this with intentionally.

Disciplined-Rationality is motivated by principles of correct reasoning with emphasis on valid and reliable methods or theories leading to a range of rational standpoints or conclusions understanding that concepts and beliefs often have consequences thus hold an imperative for truth or at least as close to truth as can be acquired rejecting untruth. Disciplined-Rationality can be seen as an aid in understanding the fundamentals for knowledge, sound evidence, justified true belief and involves things like decision theory and the concern with identifying the value(s), reasonableness, verification, certainties, uncertainties and other relevant issues resulting in the most clear optimal decision/conclusion and/or belief/disbelief. Disciplined-Rationality attempts to understand the justification or lack thereof in propositions and beliefs concerning its self with various epistemic features of belief, truth, and/or knowledge, which include the ideas of justification, warrant, rationality, reliability, validity, and probability.

ps. “Sound Thinker”, “Shallow Thinker”, “Dogmatic–Propaganda” & “Disciplined-Rationality” are concepts/terms I created*

If you are a religious believer, may I remind you that faith in the acquisition of knowledge is not a valid method worth believing in. Because, what proof is “faith”, of anything religion claims by faith, as many people have different faith even in the same religion?

- To Find Truth You Must First Look

- Archaeology Knowledge Challenge?

- The Evolution of Fire Sacralizing and/or Worship 1.5 million to 300,000 years ago and beyond?

- Stone Age Art: 500,000 – 233,000 Years Old

- Around 500,000 – 233,000 years ago, Oldest Anthropomorphic art (Pre-animism) is Related to Female

- 400,000 Years Old Sociocultural Evolution

- Pre-Animism: Portable Rock Art at least 300,000-year-old

- Homo Naledi and an Intentional Cemetery “Pre-Animism” dating to around 250,000 years ago?

- Did Neanderthals teach us “Primal Religion (Pre-Animism/Animism?)” 120,000 Years Ago?

- Animism: an approximately 100,000-year-old belief system?

- Stone Snake of South Africa: “first human worship” 70,000 years ago

- Similarities and differences in Animism and Totemism

- History of Drug Use with Religion or Sacred Rituals possibly 58,000 years ago?

- Totemism: an approximately 50,000-year-old belief system?

- Australia & Aboriginal Religion at least around 50,000 years old

- Modern Humans start around 50,000 years ago Helped by Feminisation

- Out of Africa: “the evolution of religion seems tied to the movement of people”

- Totemism and Shamanism Dispersal Theory Expressed around 50,000 to 30,000 years ago

- Possible Religion Motivations in the First Cave Art at around 43,000 years ago?

- 40,000 years old Aurignacian Lion Figurine Early Totemism?

- 40,000-35,000 years ago “first seeming use of a Totem” ancestor, animal, and possible pre-goddess worship?

- Prehistoric Egypt 40,000 years ago to The First Dynasty 5,150 years ago

- Prehistoric Child Burials Begin Around 34,000 Years Ago

- Early Shamanism around 34,000 to 20,000 years ago: Sungar (Russia) and Dolni Vestonice (Czech Republic)

- 31,000 – 20,000 years ago Oldest Shaman was Female, Buried with the Oldest Portrait Carving

- Shamanism: an approximately 30,000-year-old belief system

- ‘Sky Burial’ theory and its possible origins at least 12,000 years ago to likely 30,000 years ago or older.

- The Peopling of the Americas Pre-Paleoindians/Paleoamericans around 30,000 to 12,000 years ago

- Similarity in Shamanism?

- Black, White, and Yellow Shamanism?

- Shamanistic rock art from central Aboriginal Siberians and Aboriginal drums in the Americas

- Horned female shamans and Pre-satanism Devil/horned-god Worship?

- Possible Clan Leader/Special “MALE” Ancestor Totem Poles At Least 13,500 years ago?

- Fertile Crescent 12,500 – 9,500 Years Ago: fertility and death cult belief system?

- 12,400 – 11,700 Years Ago – Kortik Tepe (Turkey) Pre/early-Agriculture Cultic Ritualism

- 12,000 – 10,000 years old Shamanistic Art in a Remote Cave in Egypt

- Gobekli Tepe: “first human-made temple” around 12,000 years ago.

- Sedentism and the Creation of goddesses around 12,000 years ago as well as male gods after 7,000 years ago.

- First Patriarchy: Split of Women’s Status around 12,000 years ago & First Hierarchy: fall of Women’s Status around 5,000 years ago.

- Natufians: an Ancient People at the Origins of Agriculture and Sedentary Life

- J DNA and the Spread of Agricultural Religion (paganism)

- Paganism: an approximately 12,000-year-old belief system

- Need to Mythicized: gods and goddesses

- “36cu0190” a Historic and Prehistoric site in Pennsylvania

- 12,000 – 10,000 years old Shamanistic Art in a Remote Cave in Egypt

- 12,000 – 7,000 Years Ago – Paleo-Indian Culture (The Americas)

- 12,000 – 2,000 Years Ago – Indigenous-Scandinavians (Nordic)

- Norse did not wear helmets with horns?

- Pre-Pottery Neolithic Skull Cult around 11,500 to 8,400 Years Ago?

- 9,000-8500 year old Female shaman Bad Dürrenberg Germany

- Kurgan 6,000 years ago/dolmens 7,000 years ago: funeral, ritual, and other?

- Connected “dolmen phenomenon” of above-ground stone burial structures?

- Stars: Ancestors, Spirit Animals, and Deities (at least back to around 6,000 years ago)

- Evolution Of Science at least by 5,500 years ago

- 5,500 Years old birth of the State, the rise of Hierarchy, and the fall of Women’s status

- “Jiroft culture” 5,100 – 4,200 years ago and the History of Iran

- Progressed organized religion starts, an approximately 5,000-year-old belief system

- Origin of Logics is Naturalistic Observation at least by around 5,000 years ago.

- Ziggurats (multi-platform temples: 4,900 years old) to Pyramids (multi-platform tombs: 4,700 years old)

- “Happy Easter” Well Happy Eostre/Ishter

- 4,250 to 3,400 Year old Stonehenge from Russia: Arkaim?

- When was the beginning: TIMELINE OF CURRENT RELIGIONS, which start around 4,000 years ago.

- Kultepe? An archaeological site with a 4,000 years old women’s rights document.

- Single God Religions (Monotheism) = Man-o-theism started around 4,000 years ago?

- Confucianism’s Tiān (Shangdi god 4,000 years old): Supernaturalism, Pantheism or Theism?

- Yes, Your Male God is Ridiculous

- The Weakening of Ancient Trade and the Strengthening of Religions around 3000 years ago?

- Are you aware that there are religions that worship women gods, explain now religion tears women down?

- Animistic, Totemistic, and Paganistic Superstition Origins of bible god and the bible’s Religion.

- Jews, Judaism, and the Origins of Some of its Ideas

- An Old Branch of Religion Still Giving Fruit: Sacred Trees

- Dating the BIBLE: naming names and telling times (written less than 3,000 years ago, provable to 2,200 years ago)

- Did a Volcano Inspire the bible god?

- No “dinosaurs and humans didn’t exist together just because some think they are in the bible itself”

- Everyone Killed in the Bible Flood? “Nephilim” (giants)?

- Hey, Damien dude, I have a question for you regarding “the bible” Exodus.

- Archaeology Disproves the Bible

- Bible Battle, Just More, Bible Babble

- The Jericho Conquest lie?

- Canaanites and Israelites?

- Archaeology Knowledge Challenge?

- Accurate Account on how did Christianity Began?

- Let’s talk about Christianity.

- So the 10 commandments isn’t anything to go by either right?

- Misinformed christian

- Debunking Jesus?

- Paulism vs Jesus

- Ok, you seem confused so let’s talk about Buddhism.

- Unacknowledged Buddhism: Gods, Savior, Demons, Rebirth, Heavens, Hells, and Terrorism

- His Foolishness The Dalai Lama

- Yin and Yang is sexist with an ORIGIN around 2,300 years ago?

- I Believe Archaeology, not Myths & Why Not, as the Religious Myths Already Violate Reason!

- Archaeological, Scientific, & Philosophic evidence shows the god myth is man-made nonsense.

- Aquatic Ape Theory/Hypothesis? As Always, Just Pseudoscience.

- Ancient Aliens Conspiracy Theorists are Pseudohistorians

- The Pseudohistoric and Pseudoscientific claims about “Bakoni Ruins” of South Africa

- Why do people think Religion is much more than supernaturalism and superstitionism?

- Religion is an Evolved Product

- Was the Value of Ancient Women Different?

- 1000 to 1100 CE, human sacrifice Cahokia Mounds a pre-Columbian Native American site

- Feminist atheists as far back as the 1800s?

- Promoting Religion as Real is Mentally Harmful to a Flourishing Humanity

- Screw All Religions and Their Toxic lies, they are all fraud

- Forget Religions’ Unfounded Myths, I Have Substantiated “Archaeology Facts.”

- Religion Dispersal throughout the World

- I Hate Religion Just as I Hate all Pseudoscience

- Exposing Scientology, Eckankar, Wicca and Other Nonsense?

- Main deity or religious belief systems

- Quit Trying to Invent Your God From the Scraps of Science.

- Archaeological, Scientific, & Philosophic evidence shows the god myth is man-made nonsense.

- Empiricism-Denier?

I Don’t Have to Respect Ideas

People get confused ideas are not alive nor do they have beingness, Ideas don’t have rights nor the right to even exist only people have such a right. Ideas don’t have dignity nor can they feel violation only people if you attack them personally. Ideas don’t deserve any special anything they have no feelings and cannot be shamed they are open to the most brutal merciless attack and challenge without any protection and deserve none nor will I give them any if they are found wanting in evidence or reason. I will never respect Ideas if they are devoid of merit I only respect people. When I was young it was all about me, I wanted to be liked. Then I got older and it was even more about me, I wanted power. Now I am beyond a toxic ego and it is not just about me, I want to make a difference. Sexism is that evil weed that can sadly grow even in the well-tended garden of the individual with an otherwise developed mind. Which is why it particularly needs to be attacked and exposed; and is why I support feminism. Here are four blogs on that: Activism Labels Matter, thus Feminism is Needed, Feminist atheists as far back as the 1800s?, Sexism in the Major World Religions and Rape, Sexism and Religion?

Having privilege in race, gender, sexuality, ability, class, nationality, etc. does not mean one did not have it hard in life, it just was not hard due to race, gender, sexuality, ability, class, nationality, etc. if one has privilege in that area.

Empathy: think in another’s thinking, try to feel their feeling, and care about their experience.

Theism is presented as adding love to your life… But to me, more often it peddles in ignorance (pseudo-science, pseudo-history, and pseudo-morality), tribalism (strong in-group loyalty if you believe like them and aversion to difference; like shunning: social rejection, emotional distance, or ostracism), and psychological terrorism; primarily targeting well being both safety and comfort (you are born a sinner, you are evil by nature, you are guilty of thought crimes, threats of misfortune, suffering, and torture “hell”).

Hell yes, I am against the fraud that is the world religions.

Why not be against the promotion of woo-woo pseudo-truth, when I am very against all pseudo-science, pseudo-history, and pseudo-morality and the harm they can produce. Along with the hate, such as sexism and homophobia are too often seen or the forced indoctrination of children. And this coercive indoctrination of the world religions, with their pseudo-science, pseudo-history, and pseudo-morality mainly furthered by forced Hereditary Religion (family or cultural, religious beliefs forced on children because the parent or caregiver believes that way). This is sadly done, even before a child can be expected to successfully navigate reason; it’s almost as if religious parents believe their “woo-woo pseudo-truth” lies will not be so easily accepted if they wait on a mind that can make its own choice. Because we do see how hard it is for the ones forced into Hereditary Religion. It seems difficult for them to successfully navigate reason in relation to their woo-woo pseudo-truth, found in a religion they were indoctrinationally taught to prefer, because after being instructed on how to discern pseudo-truth as truth than just wishing that their blind servitude belief in a brand of religious pseudo-truth devoid of justified, valid or reliable reason and evidence. I care because I am a rationalist, as well as an atheist.

Thus, this religious set of “woo-woo pseudo-truth” pushed on the simple-minded as truth bothers me greatly. So, here it is as simple as I can make it you first need a good thinking standard to address beliefs one may approach as a possible belief warranted to be believed. I wish to smash that lying pig of religion with the Hammer of Truth: Ontology, Epistemology, and Axiology Questions (a methodological use of philosophy). Overall, I wish to promote in my self and for others; to value a worthy belief etiquette, one that desires a sound accuracy and correspondence to the truth: Reasoned belief acquisitions, good belief maintenance, and honest belief relinquishment. May we all be authenticly truthful rationalists that put facts over faith.

I have made many mistakes in my life but the most common one of all is my being resistant to change. However, now I wish to be more, to be better, as I desire my openness to change if needed, not letting uncomfortable change hold me back. May I be a rationalist, holding fast to a valued belief etiquette: demanding reasoned belief acquisitions, good belief maintenance, and honest belief relinquishment.

Truth Navigation: Techniques for Discussions or Debates

I do truth navigation, both inquiry questions as well as

strategic facts in a tag team of debate and motivational teaching.

Truth Navigation and the fallacy of Fideism “faith-ism”

Compare ideas not people, attack thinking and not people. In this way, we have a higher chance to promote change because it’s the thinking we can help change if we address the thinking and don’t attack them.

My eclectic set of tools for my style I call “Truth Navigation” (Techniques for Discussions or Debates) which involves:

- *REMS: reason (rationalism), evidence (empiricism), and methodological “truth-seeking” skepticism (Methodic doubt) (the basic or general approach)

- *The Hammer of Truth: ontology, epistemology, and axiology (methodological use of philosophy)

- *Dialectical Rhetoric = truth persuasion: use of facts and reasoning (motivational teaching)

- *Utilizing Dignity: strategic dignity attacks or dignity enrichments (only used if confusion happens or resistance is present)

Asking the right questions at the right time with the right info can also change minds, you can’t just use facts all on their own. Denial likes consistency, the pattern of thinking cannot vary from a fixed standard of thinking, or the risk of truth could slip in. Helping people alter skewed thinking is indeed a large task but most definitely a worthy endeavor. Some of my ideas are because I am educated both some in college (BA in Psychology with addiction treatment, sociology, and a little teaching and criminology) and also as an autodidact I have become somewhat educated in philosophy, science, archeology, anthropology, and history but this is not the only reason for all my ideas. It is also because I am a deep thinker, just striving for truth. Moreover, I am a seeker of truth and a lover of that which is true.

Ok, I am a kind of “Militant” Atheist

“Damien, what I find interesting is how an atheist like you

spends so much time and energy on God and religion.” – Challenger

My response, Well, let’s see, maybe because we atheists and anti-religionists care to inform our fellow humans who have been lied to and are lying to others and often forcing religion on children indoctrinating them with lies over truth and it’s harming us all. You know, all the religious hate groups and religious violence stuff and the like. What I find interesting is how could a responsible caring ethical person stay silent against religions, that my friend is a much better question.

“Theists, there has to be a god, as something can not come from nothing.”

Well, thus something (unknown) happened and then there was something. This does not tell us what the something that may have been involved with something coming from nothing. A supposed first cause, thus something (unknown) happened and then there was something is not an open invitation to claim it as known, neither is it justified to call or label such an unknown as anything, especially an unsubstantiated magical thinking belief born of mythology and religious storytelling.

While hallucinogens are associated with shamanism, it is alcohol that is associated with paganism.

The Atheist-Humanist-Leftist Revolutionaries Shows in the prehistory series:

Show two: Pre-animism 300,000 years old and animism 100,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism”

Show tree: Totemism 50,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism”

Show four: Shamanism 30,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism”

Show five: Paganism 12,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism”

Show six: Emergence of hierarchy, sexism, slavery, and the new male god dominance: Paganism 7,000-5,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism” (Capitalism) (World War 0) Elite and their slaves!

Prehistory: related to “Anarchism and Socialism” the division of labor, power, rights, and recourses: VIDEO

Pre-animism 300,000 years old and animism 100,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism”: VIDEO

Totemism 50,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism”: VIDEO

Shamanism 30,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism”: VIDEO

Paganism 12,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism” (Pre-Capitalism): VIDEO

Paganism 7,000-5,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism” (Capitalism) (World War 0) Elite and their slaves: VIEDO

Paganism 5,000 years old: progressed organized religion and the state: related to “Anarchism and Socialism” (Kings and the Rise of the State): VIEDO

Paganism 4,000 years old: related to “Anarchism and Socialism” (First Moralistic gods, then the Origin time of Monotheism): VIEDO

I do not hate simply because I challenge and expose myths or lies any more than others being thought of as loving simply because of the protection and hiding from challenge their favored myths or lies.

The truth is best championed in the sunlight of challenge.

An archaeologist once said to me “Damien religion and culture are very different”

My response, So are you saying that was always that way, such as would you say Native Americans’ cultures are separate from their religions? And do you think it always was the way you believe?

I had said that religion was a cultural product. That is still how I see it and there are other archaeologists that think close to me as well. Gods too are the myths of cultures that did not understand science or the world around them, seeing magic/supernatural everywhere.

I personally think there is a goddess and not enough evidence to support a male god at Çatalhöyük but if there was both a male and female god and goddess then I know the kind of gods they were like Proto-Indo-European mythology.

This series idea was addressed in, Anarchist Teaching as Free Public Education or Free Education in the Public: VIDEO

Our 12 video series: Organized Oppression: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of power (9,000-4,000 years ago), is adapted from: The Complete and Concise History of the Sumerians and Early Bronze Age Mesopotamia (7000-2000 BC): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=szFjxmY7jQA by “History with Cy“

Show #1: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power (Samarra, Halaf, Ubaid)

Show #2: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power

Show #3: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power (Uruk and the First Cities)

Show #4: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power (First Kings)

Show #5: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power (Early Dynastic Period)

Show #6: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power

Show #7: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power (Sargon and Akkadian Rule)

Show #9: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power (Gudea of Lagash and Utu-hegal)

Show #12: Mesopotamian State Force and the Politics of Power (Aftermath and Legacy of Sumer)

The “Atheist-Humanist-Leftist Revolutionaries”

Cory Johnston ☭ Ⓐ Atheist Leftist @Skepticallefty & I (Damien Marie AtHope) @AthopeMarie (my YouTube & related blog) are working jointly in atheist, antitheist, antireligionist, antifascist, anarchist, socialist, and humanist endeavors in our videos together, generally, every other Saturday.

Why Does Power Bring Responsibility?

Think, how often is it the powerless that start wars, oppress others, or commit genocide? So, I guess the question is to us all, to ask, how can power not carry responsibility in a humanity concept? I know I see the deep ethical responsibility that if there is power their must be a humanistic responsibility of ethical and empathic stewardship of that power. Will I be brave enough to be kind? Will I possess enough courage to be compassionate? Will my valor reach its height of empathy? I as everyone, earns our justified respect by our actions, that are good, ethical, just, protecting, and kind. Do I have enough self-respect to put my love for humanity’s flushing, over being brought down by some of its bad actors? May we all be the ones doing good actions in the world, to help human flourishing.

I create the world I want to live in, striving for flourishing. Which is not a place but a positive potential involvement and promotion; a life of humanist goal precision. To master oneself, also means mastering positive prosocial behaviors needed for human flourishing. I may have lost a god myth as an atheist, but I am happy to tell you, my friend, it is exactly because of that, leaving the mental terrorizer, god belief, that I truly regained my connected ethical as well as kind humanity.

Cory and I will talk about prehistory and theism, addressing the relevance to atheism, anarchism, and socialism.

At the same time as the rise of the male god, 7,000 years ago, there was also the very time there was the rise of violence, war, and clans to kingdoms, then empires, then states. It is all connected back to 7,000 years ago, and it moved across the world.

Cory Johnston: https://damienmarieathope.com/2021/04/cory-johnston-mind-of-a-skeptical-leftist/?v=32aec8db952d

The Mind of a Skeptical Leftist (YouTube)

Cory Johnston: Mind of a Skeptical Leftist @Skepticallefty

The Mind of a Skeptical Leftist By Cory Johnston: “Promoting critical thinking, social justice, and left-wing politics by covering current events and talking to a variety of people. Cory Johnston has been thoughtfully talking to people and attempting to promote critical thinking, social justice, and left-wing politics.” http://anchor.fm/skepticalleft

Cory needs our support. We rise by helping each other.

Cory Johnston ☭ Ⓐ @Skepticallefty Evidence-based atheist leftist (he/him) Producer, host, and co-host of 4 podcasts @skeptarchy @skpoliticspod and @AthopeMarie

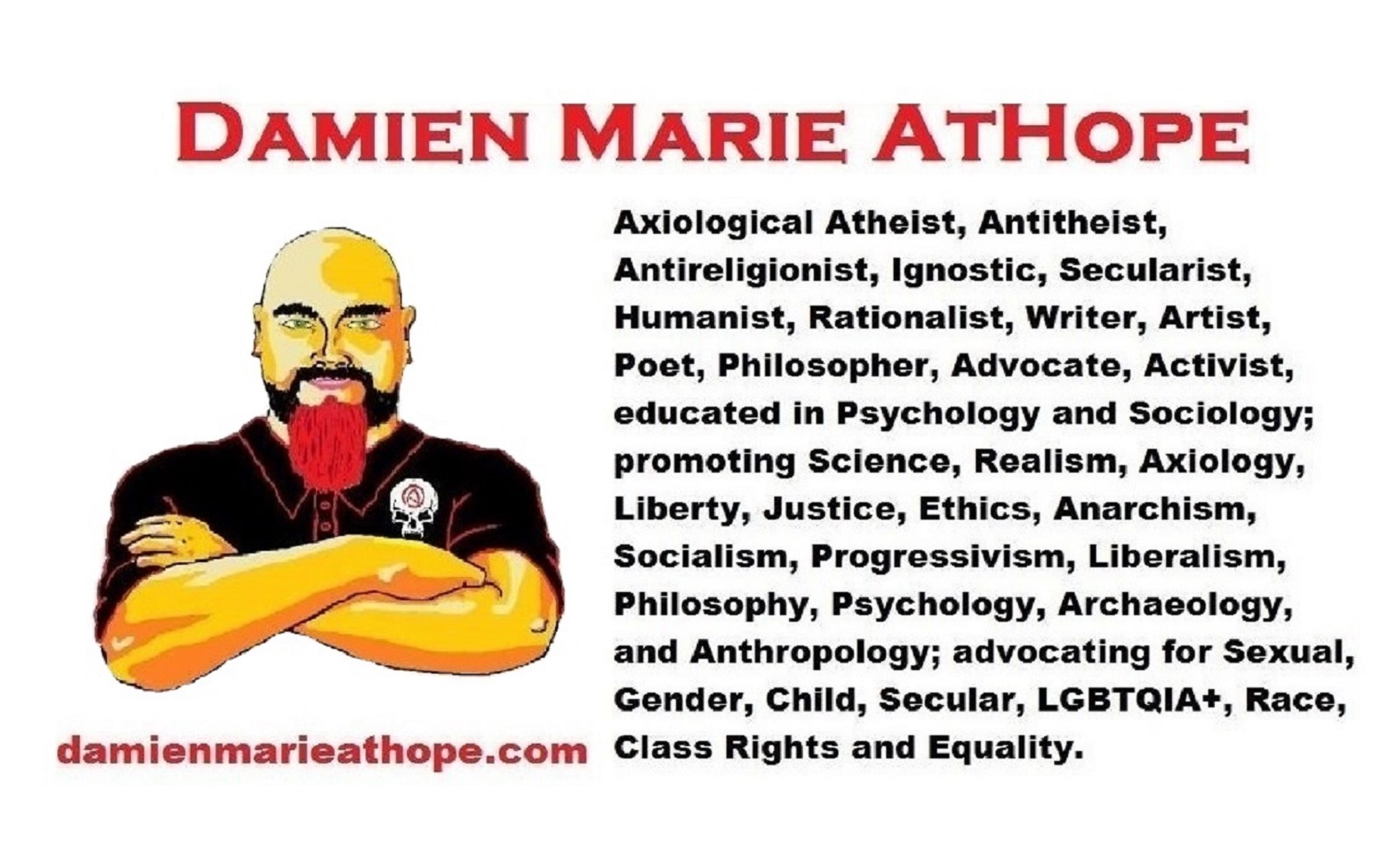

Damien Marie AtHope (“At Hope”) Axiological Atheist, Anti-theist, Anti-religionist, Secular Humanist. Rationalist, Writer, Artist, Poet, Philosopher, Advocate, Activist, Psychology, and Armchair Archaeology/Anthropology/Historian.

Damien is interested in: Freedom, Liberty, Justice, Equality, Ethics, Humanism, Science, Atheism, Antiteism, Antireligionism, Ignosticism, Left-Libertarianism, Anarchism, Socialism, Mutualism, Axiology, Metaphysics, LGBTQI, Philosophy, Advocacy, Activism, Mental Health, Psychology, Archaeology, Social Work, Sexual Rights, Marriage Rights, Woman’s Rights, Gender Rights, Child Rights, Secular Rights, Race Equality, Ageism/Disability Equality, Etc. And a far-leftist, “Anarcho-Humanist.”

I am not a good fit in the atheist movement that is mostly pro-capitalist, I am anti-capitalist. Mostly pro-skeptic, I am a rationalist not valuing skepticism. Mostly pro-agnostic, I am anti-agnostic. Mostly limited to anti-Abrahamic religions, I am an anti-religionist.

To me, the “male god” seems to have either emerged or become prominent around 7,000 years ago, whereas the now favored monotheism “male god” is more like 4,000 years ago or so. To me, the “female goddess” seems to have either emerged or become prominent around 11,000-10,000 years ago or so, losing the majority of its once prominence around 2,000 years ago due largely to the now favored monotheism “male god” that grow in prominence after 4,000 years ago or so.

My Thought on the Evolution of Gods?

Animal protector deities from old totems/spirit animal beliefs come first to me, 13,000/12,000 years ago, then women as deities 11,000/10,000 years ago, then male gods around 7,000/8,000 years ago. Moralistic gods around 5,000/4,000 years ago, and monotheistic gods around 4,000/3,000 years ago.

To me, animal gods were likely first related to totemism animals around 13,000 to 12,000 years ago or older. Female as goddesses was next to me, 11,000 to 10,000 years ago or so with the emergence of agriculture. Then male gods come about 8,000 to 7,000 years ago with clan wars. Many monotheism-themed religions started in henotheism, emerging out of polytheism/paganism.

Damien Marie AtHope (Said as “At” “Hope”)/(Autodidact Polymath but not good at math):

Axiological Atheist, Anti-theist, Anti-religionist, Secular Humanist, Rationalist, Writer, Artist, Jeweler, Poet, “autodidact” Philosopher, schooled in Psychology, and “autodidact” Armchair Archaeology/Anthropology/Pre-Historian (Knowledgeable in the range of: 1 million to 5,000/4,000 years ago). I am an anarchist socialist politically. Reasons for or Types of Atheism

My Website, My Blog, & Short-writing or Quotes, My YouTube, Twitter: @AthopeMarie, and My Email: damien.marie.athope@gmail.com