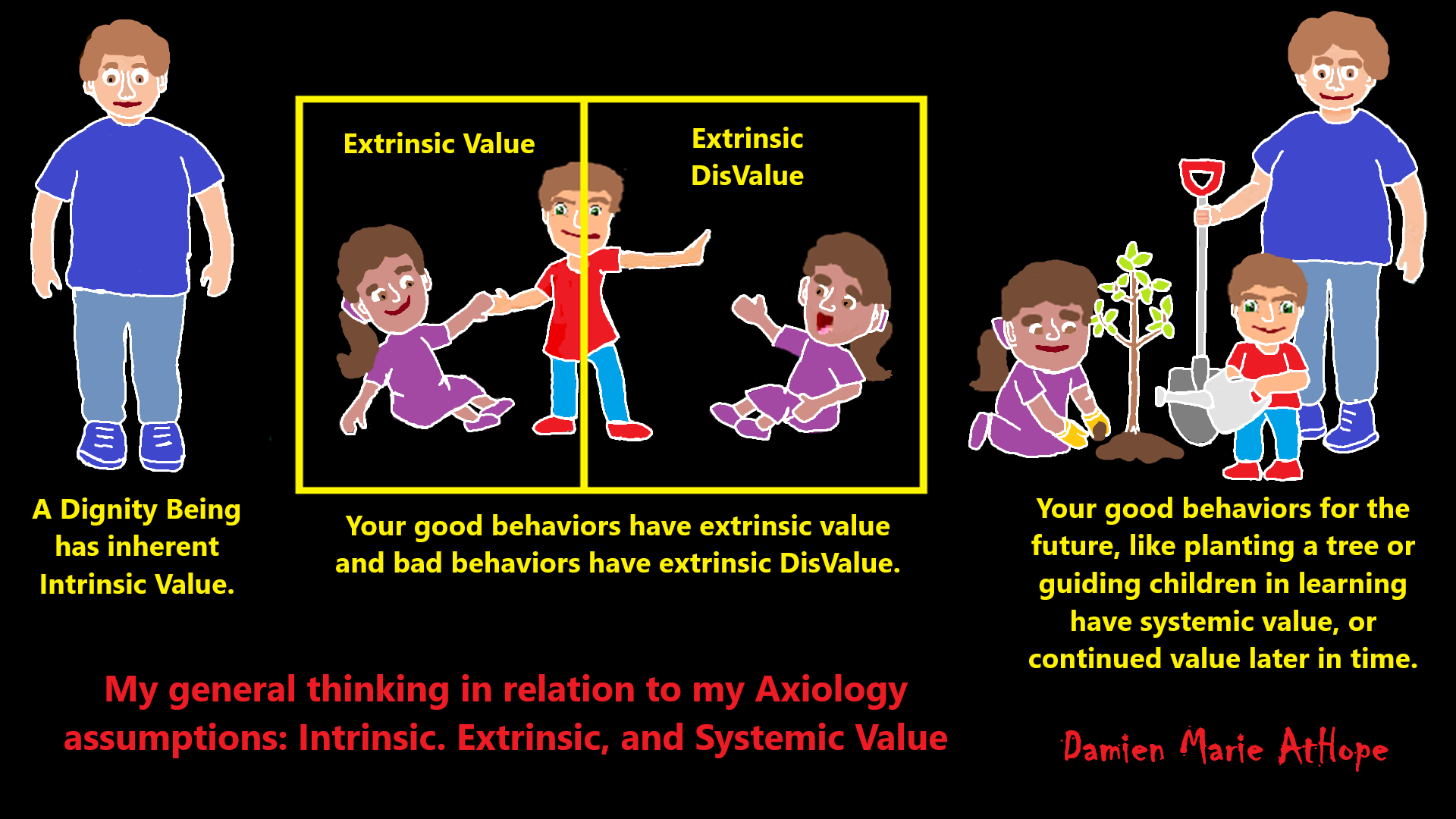

- Intrinsic Value: (such as human rights)

- Extrinsic Value: (such as relating to its accuracy, truth, quality, what value that is produced, Its use-value, or an added level of its agreeableness or desirability to it)

- Systemic Value: (such as how things may improve or worsen in relation to time. Things like rape rightly motivate our outrage, not simply for the harm of the moment of the violation. No, most thinkers mildly inclined towards ethics could see. Such an awareness or expanded effort to understand it could realize the tragic harm or strain it can have throughout a lifespan. It is this and even more, like how it puts more fear or stress on others who hear of this, see this, or are personally/emotionally connected to them. Too many people under such assault to one’s dignity that rape is. And for those victims of such oppression, too often, it brings all kinds of potential body shame or self-hatred. Yet it doesn’t end there, and others just seem to stop caring altogether. I feel for them all. Not to mention, I am sure I would miss some that others could add. Etc., Etc., Etc.)

My general thinking in relation to my Axiology assumptions: Intrinsic. Extrinsic, and Systemic Value

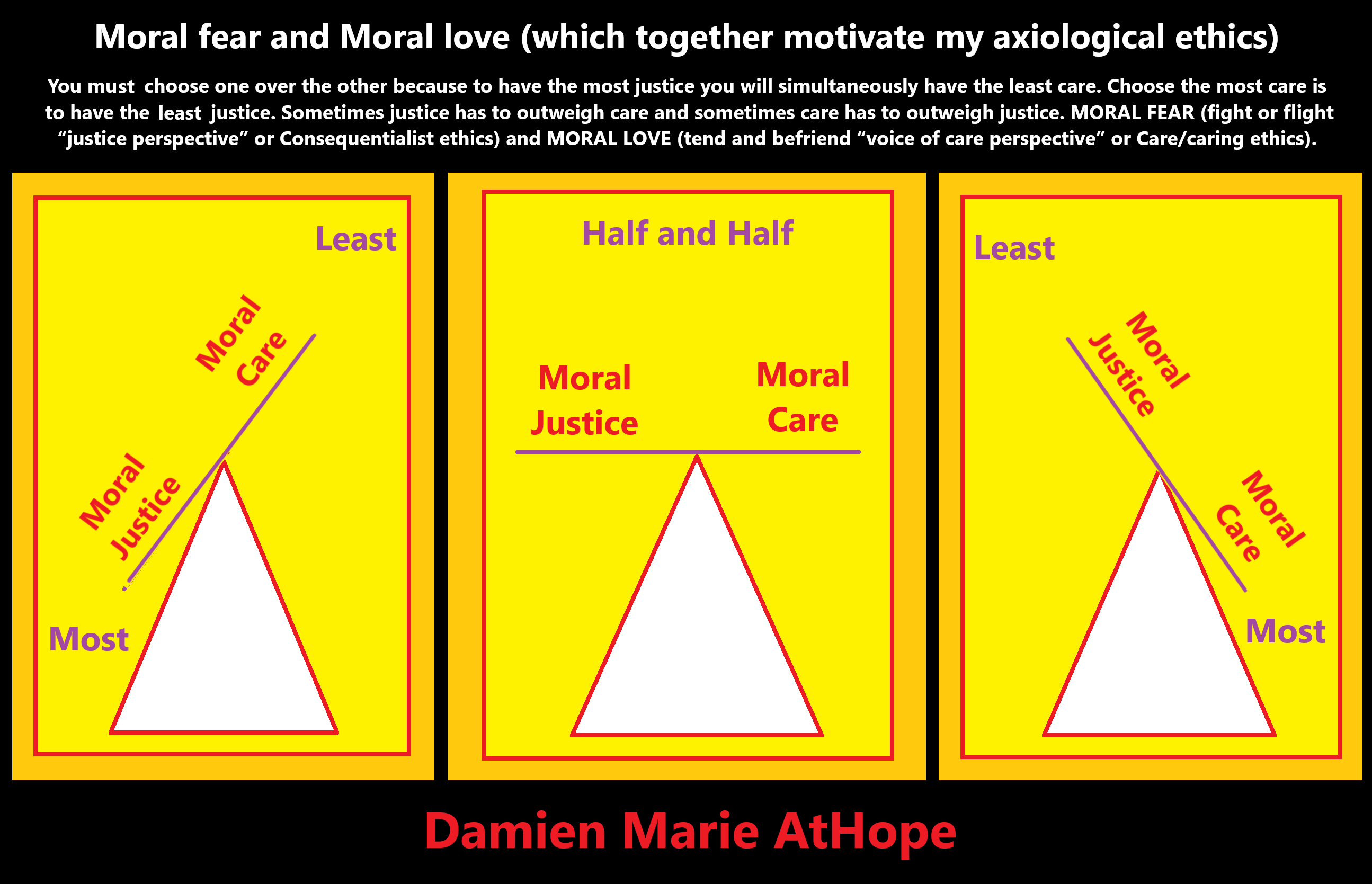

Moral fear and Moral love (which together motivate my Axiological ethics)

“In philosophy, axiological ethics is concerned with the values by which people uphold ethical standards, and the investigation and development of theories of ethical behavior. Axiological ethics investigates and questions what the intellectual bases for a system of values. Axiologic ethics explore the justifications for value systems, and examine if there exists an objective justification, beyond arbitrary personal preference, for the existence and practise of a given value system. Moreover, although axiological ethics are a subfield of Ethical philosophy, axiological investigation usually includes epistemology and the value theory.” ref

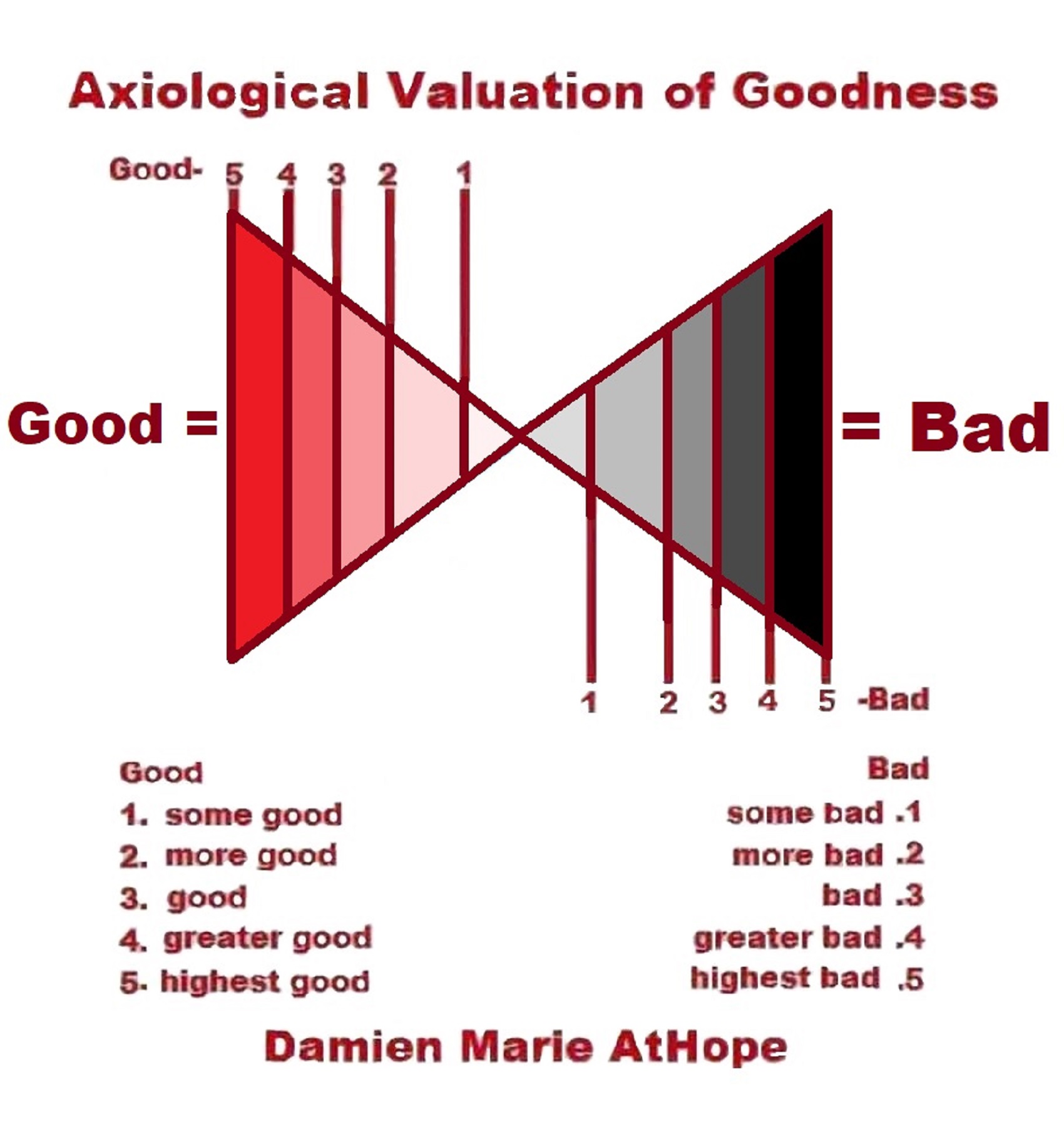

To understand axiological ethics, an understanding of axiology and ethics is necessary. Axiology is the philosophical study of goodness (value) and is concerned with two questions. The first question regards defining and exploring understandings of ‘the good’ or value. This includes, for example, the distinction between intrinsic and instrumental values—or intrinsic, extrinsic, and systemic value/disvalue. The second area is the application of such understandings of value to a variety of fields within the social sciences and humanities. Ethics is a philosophical field that is concerned with morality, and in particular, the conduction of the right action. The defining of what the ‘right’ action is influenced by axiological thought in itself, much like the defining of ‘beauty’ within the philosophical branch of aesthetics.” ref

“Axiological ethics can be understood as the application of axiology onto the study of ethics. It is concerned with questioning the moral grounds which we base ethical judgements on. This is done through questioning the values in which ethical principles are grounded on. Once there is recognition and understanding of the underlying values hidden within ethical claims, they can be assessed and critiqued. Through breaking ethics down to an examination of values, rather than the good, morality can be reconstructed based on redefined values or confirmed on already set values.” ref

Learning Axiology Value and Disvalue: Intrinsic Value, Extrinsic value, and Systemic Value

*Intrinsic Value: The value of things in themselves, independent of their usefulness or consequences. Humans have dignity or intrinsic value. Things are not dignity beings, and thus do not/can not have intrinsic value. Things can have extrinsic and Systemic Value, but this is Value is for others, like humans, not intrinsic to itself. A rock can only have extrinsic or systemic value, but never intrinsic value. Is cutting down a tree murder? No, it is not a dignity being. A tree is a large plant. It is not the same to cut off a tree limb as to cut off a human’s arm. Once a person is born, they have 100% intrinsic value. They as all of us have the same 100% intrinsic value until we die. Not even becoming a mass murderer will change this intrinsic value that is related to the dignity beings we are. The disvalue extrinsically or disvalue systemically are in one being a mass murderer.

*Extrinsic value: (thing/idea is valued for their consequences or usefulness). Humans have intrinsic value as who they are, this only ends when they die. While they are alive, their thoughts and actions have extrinsic value if good and extrinsic disvalue if bad.

*Systemic Value: the value of things in relation to their contribution to a larger system or context and relates to the role or function of something within a broader framework or structure. We look down on rape not simply due to the violation but the lifelong harm. So, the lifelong psychological harm of rape relates to Systemic disvalue.

I used part of the definitions I offer above from the Framework of Formal Axiology; There are three primary value dimensions in Axiology: Systemic Value, Extrinsic Value, and Intrinsic Value

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Intrinsic Value?

“Intrinsic value has traditionally been thought to lie at the heart of ethics. Philosophers use a number of terms to refer to such value. The intrinsic value of something is said to be the value that that thing has “in itself,” or “for its own sake,” or “as such,” or “in its own right.” Extrinsic value is value that is not intrinsic.” ref

“Many philosophers take intrinsic value to be crucial to a variety of moral judgments. For example, according to a fundamental form of consequentialism, whether an action is morally right or wrong has exclusively to do with whether its consequences are intrinsically better than those of any other action one can perform under the circumstances. Many other theories also hold that what it is right or wrong to do has at least in part to do with the intrinsic value of the consequences of the actions one can perform. Moreover, if, as is commonly believed, what one is morally responsible for doing is some function of the rightness or wrongness of what one does, then intrinsic value would seem relevant to judgments about responsibility, too. Intrinsic value is also often taken to be pertinent to judgments about moral justice (whether having to do with moral rights or moral desert), insofar as it is good that justice is done and bad that justice is denied, in ways that appear intimately tied to intrinsic value. Finally, it is typically thought that judgments about moral virtue and vice also turn on questions of intrinsic value, inasmuch as virtues are good, and vices bad, again in ways that appear closely connected to such value.” ref

“All four types of moral judgments have been the subject of discussion since the dawn of western philosophy in ancient Greece. The Greeks themselves were especially concerned with questions about virtue and vice, and the concept of intrinsic value may be found at work in their writings and in the writings of moral philosophers ever since. Despite this fact, and rather surprisingly, it is only within the last one hundred years or so that this concept has itself been the subject of sustained scrutiny, and even within this relatively brief period the scrutiny has waxed and waned.” ref

“The question “What is intrinsic value?” is more fundamental than the question “What has intrinsic value?,” but historically these have been treated in reverse order. For a long time, philosophers appear to have thought that the notion of intrinsic value is itself sufficiently clear to allow them to go straight to the question of what should be said to have intrinsic value. Not even a potted history of what has been said on this matter can be attempted here, since the record is so rich. Rather, a few representative illustrations must suffice.” ref

“In his dialogue Protagoras, Plato [428–347 B.C.E.] maintains (through the character of Socrates, modeled after the real Socrates [470–399 B.C.E.], who was Plato’s teacher) that, when people condemn pleasure, they do so, not because they take pleasure to be bad as such, but because of the bad consequences they find pleasure often to have. For example, at one point Socrates says that the only reason why the pleasures of food and drink and sex seem to be evil is that they result in pain and deprive us of future pleasures (Plato, Protagoras, 353e). He concludes that pleasure is in fact good as such and pain bad, regardless of what their consequences may on occasion be. In the Timaeus, Plato seems quite pessimistic about these consequences, for he has Timaeus declare pleasure to be “the greatest incitement to evil” and pain to be something that “deters from good” (Plato, Timaeus, 69d). Plato does not think of pleasure as the “highest” good, however. In the Republic, Socrates states that there can be no “communion” between “extravagant” pleasure and virtue (Plato, Republic, 402e) and in the Philebus, where Philebus argues that pleasure is the highest good, Socrates argues against this, claiming that pleasure is better when accompanied by intelligence (Plato, Philebus, 60e).” ref

“Many philosophers have followed Plato’s lead in declaring pleasure intrinsically good and pain intrinsically bad. Aristotle [384–322 B.C.E.], for example, himself a student of Plato’s, says at one point that all are agreed that pain is bad and to be avoided, either because it is bad “without qualification” or because it is in some way an “impediment” to us; he adds that pleasure, being the “contrary” of that which is to be avoided, is therefore necessarily a good (Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, 1153b). Over the course of the more than two thousand years since this was written, this view has been frequently endorsed. Like Plato, Aristotle does not take pleasure and pain to be the only things that are intrinsically good and bad, although some have maintained that this is indeed the case. This more restrictive view, often called hedonism, has had proponents since the time of Epicurus [341–271 B.C.E.]. Perhaps the most thorough renditions of it are to be found in the works of Jeremy Bentham [1748–1832] and Henry Sidgwick [1838–1900] (see Bentham 1789, Sidgwick 1907); perhaps its most famous proponent is John Stuart Mill [1806–1873] (see Mill 1863).” ref

“Most philosophers who have written on the question of what has intrinsic value have not been hedonists; like Plato and Aristotle, they have thought that something besides pleasure and pain has intrinsic value. One of the most comprehensive lists of intrinsic goods that anyone has suggested is that given by William Frankena (Frankena 1973, pp. 87–88): life, consciousness, and activity; health and strength; pleasures and satisfactions of all or certain kinds; happiness, beatitude, contentment, etc.; truth; knowledge and true opinions of various kinds, understanding, wisdom; beauty, harmony, proportion in objects contemplated; aesthetic experience; morally good dispositions or virtues; mutual affection, love, friendship, cooperation; just distribution of goods and evils; harmony and proportion in one’s own life; power and experiences of achievement; self-expression; freedom; peace, security; adventure and novelty; and good reputation, honor, esteem, etc. (Presumably a corresponding list of intrinsic evils could be provided.) Almost any philosopher who has ever addressed the question of what has intrinsic value will find his or her answer represented in some way by one or more items on Frankena’s list. (Frankena himself notes that he does not explicitly include in his list the communion with and love and knowledge of God that certain philosophers believe to be the highest good, since he takes them to fall under the headings of “knowledge” and “love.”) One conspicuous omission from the list, however, is the increasingly popular view that certain environmental entities or qualities have intrinsic value (although Frankena may again assert that these are implicitly represented by one or more items already on the list). Some find intrinsic value, for example, in certain “natural” environments (wildernesses untouched by human hand); some find it in certain animal species; and so on.” ref

“Suppose that you were confronted with some proposed list of intrinsic goods. It would be natural to ask how you might assess the accuracy of the list. How can you tell whether something has intrinsic value or not? On one level, this is an epistemological question about which this article will not be concerned. (See the entry in this encyclopedia on moral epistemology.) On another level, however, this is a conceptual question, for we cannot be sure that something has intrinsic value unless we understand what it is for something to have intrinsic value.” ref

“The concept of intrinsic value has been characterized above in terms of the value that something has “in itself,” or “for its own sake,” or “as such,” or “in its own right.” The custom has been not to distinguish between the meanings of these terms, but we will see that there is reason to think that there may, in fact, be more than one concept at issue here. For the moment, though, let us ignore this complication and focus on what it means to say that something is valuable for its own sake as opposed to being valuable for the sake of something else to which it is related in some way. Perhaps it is easiest to grasp this distinction by way of illustration.” ref

“Suppose that someone were to ask you whether it is good to help others in time of need. Unless you suspected some sort of trick, you would answer, “Yes, of course.” If this person were to go on to ask you why acting in this way is good, you might say that it is good to help others in time of need simply because it is good that their needs be satisfied. If you were then asked why it is good that people’s needs be satisfied, you might be puzzled. You might be inclined to say, “It just is.” Or you might accept the legitimacy of the question and say that it is good that people’s needs be satisfied because this brings them pleasure. But then, of course, your interlocutor could ask once again, “What’s good about that?” Perhaps at this point you would answer, “It just is good that people be pleased,” and thus put an end to this line of questioning. Or perhaps you would again seek to explain the fact that it is good that people be pleased in terms of something else that you take to be good. At some point, though, you would have to put an end to the questions, not because you would have grown tired of them (though that is a distinct possibility), but because you would be forced to recognize that, if one thing derives its goodness from some other thing, which derives its goodness from yet a third thing, and so on, there must come a point at which you reach something whose goodness is not derivative in this way, something that “just is” good in its own right, something whose goodness is the source of, and thus explains, the goodness to be found in all the other things that precede it on the list. It is at this point that you will have arrived at intrinsic goodness (cf. Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, 1094a). That which is intrinsically good is nonderivatively good; it is good for its own sake. That which is not intrinsically good but extrinsically good is derivatively good; it is good, not (insofar as its extrinsic value is concerned) for its own sake, but for the sake of something else that is good and to which it is related in some way. Intrinsic value thus has a certain priority over extrinsic value. The latter is derivative from or reflective of the former and is to be explained in terms of the former. It is for this reason that philosophers have tended to focus on intrinsic value in particular.” ref

“The account just given of the distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic value is rough, but it should do as a start. Certain complications must be immediately acknowledged, though. First, there is the possibility, mentioned above, that the terms traditionally used to refer to intrinsic value, in fact, refer to more than one concept; again, this will be addressed later (in this section and the next). Another complication is that it may not, in fact, be accurate to say that whatever is intrinsically good is nonderivatively good; some intrinsic value may be derivative. This issue will be taken up (in Section 5) when the computation of intrinsic value is discussed; it may be safely ignored for now. Still another complication is this. It is almost universally acknowledged among philosophers that all value is “supervenient” or “grounded in” on certain nonevaluative features of the thing that has value. Roughly, what this means is that, if something has value, it will have this value in virtue of certain nonevaluative features that it has; its value can be attributed to these features. For example, the value of helping others in time of need might be attributed to the fact that such behavior has the feature of being causally related to certain pleasant experiences induced in those who receive the help. Suppose we accept this and accept also that the experiences in question are intrinsically good. In saying this, we are (barring the complication to be discussed in Section 5) taking the value of the experiences to be nonderivative. Nonetheless, we may well take this value, like all value, to be supervenient on, or grounded in, something. In this case, we would probably simply attribute the value of the experiences to their having the feature of being pleasant. This brings out the subtle but important point that the question whether some value is derivative is distinct from the question whether it is supervenient. Even nonderivative value (value that something has in its own right; value that is, in some way, not attributable to the value of anything else) is usually understood to be supervenient on certain nonevaluative features of the thing that has value (and thus to be attributable, in a different way, to these features).” ref

“To repeat: whatever is intrinsically good is (barring the complication to be discussed in Section 5) nonderivatively good. It would be a mistake, however, to affirm the converse of this and say that whatever is nonderivatively good is intrinsically good. As “intrinsic value” is traditionally understood, it refers to a particular way of being nonderivatively good; there are other ways in which something might be nonderivatively good. For example, suppose that your interlocutor were to ask you whether it is good to eat and drink in moderation and to exercise regularly. Again, you would say, “Yes, of course.” If asked why, you would say that this is because such behavior promotes health. If asked what is good about being healthy, you might cite something else whose goodness would explain the value of health, or you might simply say, “Being healthy just is a good way to be.” If the latter were your response, you would be indicating that you took health to be nonderivatively good in some way. In what way, though? Well, perhaps you would be thinking of health as intrinsically good. But perhaps not. Suppose that what you meant was that being healthy just is “good for” the person who is healthy (in the sense that it is in each person’s interest to be healthy), so that John’s being healthy is good for John, Jane’s being healthy is good for Jane, and so on. You would thereby be attributing a type of nonderivative interest-value to John’s being healthy, and yet it would be perfectly consistent for you to deny that John’s being healthy is intrinsically good. If John were a villain, you might well deny this. Indeed, you might want to insist that, in light of his villainy, his being healthy is intrinsically bad, even though you recognize that his being healthy is good for him. If you did say this, you would be indicating that you subscribe to the common view that intrinsic value is nonderivative value of some peculiarly moral sort.” ref

“Let us now see whether this still rough account of intrinsic value can be made more precise. One of the first writers to concern himself with the question of what exactly is at issue when we ascribe intrinsic value to something was G. E. Moore [1873–1958]. In his book Principia Ethica, Moore asks whether the concept of intrinsic value (or, more particularly, the concept of intrinsic goodness, upon which he tended to focus) is analyzable. In raising this question, he has a particular type of analysis in mind, one which consists in “breaking down” a concept into simpler component concepts. (One example of an analysis of this sort is the analysis of the concept of being a vixen in terms of the concepts of being a fox and being female.) His own answer to the question is that the concept of intrinsic goodness is not amenable to such analysis (Moore 1903, ch. 1). In place of analysis, Moore proposes a certain kind of thought-experiment in order both to come to understand the concept better and to reach a decision about what is intrinsically good. He advises us to consider what things are such that, if they existed by themselves “in absolute isolation,” we would judge their existence to be good; in this way, we will be better able to see what really accounts for the value that there is in our world. For example, if such a thought-experiment led you to conclude that all and only pleasure would be good in isolation, and all and only pain bad, you would be a hedonist. Moore himself deems it incredible that anyone, thinking clearly, would reach this conclusion. He says that it involves our saying that a world in which only pleasure existed—a world without any knowledge, love, enjoyment of beauty, or moral qualities—is better than a world that contained all these things but in which there existed slightly less pleasure (Moore 1912, p. 102). Such a view he finds absurd.” ref

“Regardless of the merits of this isolation test, it remains unclear exactly why Moore finds the concept of intrinsic goodness to be unanalyzable. At one point, he attacks the view that it can be analyzed wholly in terms of “natural” concepts—the view, that is, that we can break down the concept of being intrinsically good into the simpler concepts of being A, being B, being C…, where these component concepts are all purely descriptive rather than evaluative. (One candidate that Moore discusses is this: for something to be intrinsically good is for it to be something that we desire to desire.) He argues that any such analysis is to be rejected, since it will always be intelligible to ask whether (and, presumably, to deny that) it is good that something be A, B, C,…, which would not be the case if the analysis were accurate (Moore 1903, pp. 15–16). Even if this argument is successful (a complicated matter about which there is considerable disagreement), it, of course, does not establish the more general claim that the concept of intrinsic goodness is not analyzable at all, since it leaves open the possibility that this concept is analyzable in terms of other concepts, some or all of which are not “natural” but evaluative. Moore apparently thinks that his objection works just as well where one or more of the component concepts A, B, C,…, is evaluative; but, again, many dispute the cogency of his argument. Indeed, several philosophers have proposed analyses of just this sort. For example, Roderick Chisholm [1916–1999] has argued that Moore’s own isolation test, in fact, provides the basis for an analysis of the concept of intrinsic value. He formulates a view according to which (to put matters roughly) to say that a state of affairs is intrinsically good or bad is to say that it is possible that its goodness or badness constitutes all the goodness or badness that there is in the world (Chisholm 1978).” ref

“Eva Bodanszky and Earl Conee have attacked Chisholm’s proposal, showing that it is, in its details, unacceptable (Bodanszky and Conee 1981). However, the general idea that an intrinsically valuable state is one that could somehow account for all the value in the world is suggestive and promising; if it could be adequately formulated, it would reveal an important feature of intrinsic value that would help us better understand the concept. We will return to this point in Section 5. Rather than pursue such a line of thought, Chisholm himself responded (Chisholm 1981) in a different way to Bodanszky and Conee. He shifted from what may be called an ontological version of Moore’s isolation test—the attempt to understand the intrinsic value of a state in terms of the value that there would be if it were the only valuable state in existence—to an intentional version of that test—the attempt to understand the intrinsic value of a state in terms of the kind of attitude it would be fitting to have if one were to contemplate the valuable state as such, without reference to circumstances or consequences.” ref

“This new analysis, in fact, reflects a general idea that has a rich history. Franz Brentano [1838–1917], C. D. Broad [1887–1971], W. D. Ross [1877–1971], and A. C. Ewing [1899–1973], among others, have claimed, in a more or less qualified way, that the concept of intrinsic goodness is analyzable in terms of the fittingness of some “pro” (i.e., positive) attitude (Brentano 1969, p. 18; Broad 1930, p. 283; Ross 1939, pp. 275–76; Ewing 1948, p. 152). Such an analysis, which has come to be called “the fitting attitude analysis” of value, is supported by the mundane observation that, instead of saying that something is good, we often say that it is valuable, which itself just means that it is fitting to value the thing in question. It would thus seem very natural to suppose that for something to be intrinsically good is simply for it to be such that it is fitting to value it for its own sake. (“Fitting” here is often understood to signify a particular kind of moral fittingness, in keeping with the idea that intrinsic value is a particular kind of moral value. The underlying point is that those who value for its own sake that which is intrinsically good thereby evince a kind of moral sensitivity.)” ref

“Though undoubtedly attractive, this analysis can be and has been challenged. Brand Blanshard [1892–1987], for example, argues that the analysis is to be rejected because, if we ask why something is such that it is fitting to value it for its own sake, the answer is that this is the case precisely because the thing in question is intrinsically good; this answer indicates that the concept of intrinsic goodness is more fundamental than that of the fittingness of some pro attitude, which is inconsistent with analyzing the former in terms of the latter (Blanshard 1961, pp. 284–86). Ewing and others have resisted Blanshard’s argument, maintaining that what grounds and explains something’s being valuable is not its being good but rather its having whatever non-value property it is upon which its goodness supervenes; they claim that it is because of this underlying property that the thing in question is “both” good and valuable (Ewing 1948, pp. 157 and 172. Cf. Lemos 1994, p. 19). Thomas Scanlon calls such an account of the relation between valuableness, goodness, and underlying properties a buck-passing account, since it “passes the buck” of explaining why something is such that it is fitting to value it from its goodness to some property that underlies its goodness (Scanlon 1998, pp. 95 ff.). Whether such an account is acceptable has recently been the subject of intense debate. Many, like Scanlon, endorse passing the buck; some, like Blanshard, object to doing so. If such an account is acceptable, then Ewing’s analysis survives Blanshard’s challenge; but otherwise not. (Note that one might endorse passing the buck and yet reject Ewing’s analysis for some other reason. Hence a buck-passer may, but need not, accept the analysis. Indeed, there is reason to think that Moore himself is a buck-passer, even though he takes the concept of intrinsic goodness to be unanalyzable; cf. Olson 2006).” ref

“Even if Blanshard’s argument succeeds and intrinsic goodness is not to be analyzed in terms of the fittingness of some pro attitude, it could still be that there is a strict correlation between something’s being intrinsically good and its being such that it is fitting to value it for its own sake; that is, it could still be both that (a) it is necessarily true that whatever is intrinsically good is such that it is fitting to value it for its own sake, and that (b) it is necessarily true that whatever it is fitting to value for its own sake is intrinsically good. If this were the case, it would reveal an important feature of intrinsic value, recognition of which would help us to improve our understanding of the concept. However, this thesis has also been challenged.” ref

“Krister Bykvist has argued that what he calls solitary goods may constitute a counterexample to part (a) of the thesis (Bykvist 2009, pp. 4 ff.). Such (alleged) goods consist in states of affairs that entail that there is no one in a position to value them. Suppose, for example, that happiness is intrinsically good, and good in such a way that it is fitting to welcome it. Then, more particularly, the state of affairs of there being happy egrets is intrinsically good; so too, presumably, is the more complex state of affairs of there being happy egrets but no welcomers. The simpler state of affairs would appear to pose no problem for part (a) of the thesis, but the more complex state of affairs, which is an example of a solitary good, may pose a problem. For if to welcome a state of affairs entails that that state of affairs obtains, then welcoming the more complex state of affairs is logically impossible. Furthermore, if to welcome a state of affairs entails that one believes that that state of affairs obtains, then the pertinent belief regarding the more complex state of affairs would be necessarily false. In neither case would it seem plausible to say that welcoming the state of affairs is nonetheless fitting. Thus, unless this challenge can somehow be met, a proponent of the thesis must restrict the thesis to pro attitudes that are neither truth- nor belief-entailing, a restriction that might itself prove unwelcome, since it excludes a number of favorable responses to what is good (such as promoting what is good, or taking pleasure in what is good) to which proponents of the thesis have often appealed.” ref

“As to part (b) of the thesis: some philosophers have argued that it can be fitting to value something for its own sake even if that thing is not intrinsically good. A relatively early version of this argument was again provided by Blanshard (1961, pp. 287 ff. Cf. Lemos 1994, p. 18). Recently the issue has been brought into stark relief by the following sort of thought-experiment. Imagine that an evil demon wants you to value him for his own sake and threatens to cause you severe suffering unless you do. It seems that you have good reason to do what he wants—it is appropriate or fitting to comply with his demand and value him for his own sake—even though he is clearly not intrinsically good (Rabinowicz and Rønnow-Rasmussen 2004, pp. 402 ff.). This issue, which has come to be known as “the wrong kind of reason problem,” has attracted a great deal of attention. Some have been persuaded that the challenge succeeds, while others have sought to undermine it.” ref

“One final cautionary note. It is apparent that some philosophers use the term “intrinsic value” and similar terms to express some concept other than the one just discussed. In particular, Immanuel Kant [1724–1804] is famous for saying that the only thing that is “good without qualification” is a good will, which is good not because of what it effects or accomplishes but “in itself” (Kant 1785, Ak. 1–3). This may seem to suggest that Kant ascribes (positive) intrinsic value only to a good will, declaring the value that anything else may possess merely extrinsic, in the senses of “intrinsic value” and “extrinsic value” discussed above. This suggestion is, if anything, reinforced when Kant immediately adds that a good will “is to be esteemed beyond comparison as far higher than anything it could ever bring about,” that it “shine[s] like a jewel for its own sake,” and that its “usefulness…can neither add to, nor subtract from, [its] value.” ref

“For here Kant may seem not only to be invoking the distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic value but also to be in agreement with Brentano et al. regarding the characterization of the former in terms of the fittingness of some attitude, namely, esteem. (The term “respect” is often used in place of “esteem” in such contexts.) Nonetheless, it becomes clear on further inspection that Kant is in fact discussing a concept quite different from that with which this article is concerned. A little later on he says that all rational beings, even those that lack a good will, have “absolute value”; such beings are “ends in themselves” that have a “dignity” or “intrinsic value” that is “above all price” (Kant 1785, Ak. 64 and 77). Such talk indicates that Kant believes that the sort of value that he ascribes to rational beings is one that they possess to an infinite degree. But then, if this were understood as a thesis about intrinsic value as we have been understanding this concept, the implication would seem to be that, since it contains rational beings, ours is the best of all possible worlds. Yet this is a thesis that Kant, along with many others, explicitly rejects elsewhere (Kant, Lectures in Ethics). It seems best to understand Kant, and other philosophers who have since written in the same vein (cf. Anderson 1993), as being concerned not with the question of what intrinsic value rational beings have—in the sense of “intrinsic value” discussed above—but with the quite different question of how we ought to behave toward such creatures (cf. Bradley 2006).” ref

“In the history of philosophy, relatively few seem to have entertained doubts about the concept of intrinsic value. Much of the debate about intrinsic value has tended to be about what things actually do have such value. However, once questions about the concept itself were raised, doubts about its metaphysical implications, its moral significance, and even its very coherence began to appear. Among those who do not doubt the coherence of the concept of intrinsic value there is considerable difference of opinion about what sort or sorts of entity can have such value. Moore does not explicitly address this issue, but his writings show him to have a liberal view on the matter. There are times when he talks of individual objects (e.g., books) as having intrinsic value, others when he talks of the consciousness of individual objects (or of their qualities) as having intrinsic value, others when he talks of the existence of individual objects as having intrinsic value, others when he talks of types of individual objects as having intrinsic value, and still others when he talks of states of individual objects as having intrinsic value.” ref

“Consider, first, the metaphysics underlying ascriptions of intrinsic value. It seems safe to say that, before the twentieth century, most moral philosophers presupposed that the intrinsic goodness of something is a genuine property of that thing, one that is no less real than the properties (of being pleasant, of satisfying a need, or whatever) in virtue of which the thing in question is good. (Several dissented from this view, however. Especially well known for their dissent are Thomas Hobbes [1588–1679], who believed the goodness or badness of something to be constituted by the desire or aversion that one may have regarding it, and David Hume [1711–1776], who similarly took all ascriptions of value to involve projections of one’s own sentiments onto whatever is said to have value. See Hobbes 1651, Hume 1739.) It was not until Moore argued that this view implies that intrinsic goodness, as a supervening property, is a very different sort of property (one that he called “nonnatural”) from those (which he called “natural”) upon which it supervenes, that doubts about the view proliferated.” ref

“One of the first to raise such doubts and to press for a view quite different from the prevailing view was Axel Hägerström [1868–1939], who developed an account according to which ascriptions of value are neither true nor false (Hägerström 1953). This view has come to be called “noncognitivism.” The particular brand of noncognitivism proposed by Hägerström is usually called “emotivism,” since it holds (in a manner reminiscent of Hume) that ascriptions of value are in essence expressions of emotion. (For example, an emotivist of a particularly simple kind might claim that to say “A is good” is not to make a statement about A but to say something like “Hooray for A!”) This view was taken up by several philosophers, including most notably A. J. Ayer [1910–1989] and Charles L. Stevenson [1908–1979] (see Ayer 1946, Stevenson 1944). Other philosophers have since embraced other forms of noncognitivism. R. M. Hare [1919–2002], for example, advocated the theory of “prescriptivism” (according to which moral judgments, including judgments about goodness and badness, are not descriptive statements about the world but rather constitute a kind of command as to how we are to act; see Hare 1952) and Simon Blackburn and Allan Gibbard have since proposed yet other versions of noncognitivism (Blackburn 1984, Gibbard 1990).” ref

“Hägerström characterized his own view as a type of “value-nihilism,” and many have followed suit in taking noncognitivism of all kinds to constitute a rejection of the very idea of intrinsic value. But this seems to be a mistake. We should distinguish questions about value from questions about evaluation. Questions about value fall into two main groups, conceptual (of the sort discussed in the last section) and substantive (of the sort discussed in the first section). Questions about evaluation have to do with what precisely is going on when we ascribe value to something. Cognitivists claim that our ascriptions of value constitute statements that are either true or false; noncognitivists deny this. But even noncognitivists must recognize that our ascriptions of value fall into two fundamental classes—ascriptions of intrinsic value and ascriptions of extrinsic value—and so they too must concern themselves with the very same conceptual and substantive questions about value as cognitivists address. It may be that noncognitivism dictates or rules out certain answers to these questions that cognitivism does not, but that is of course quite a different matter from rejecting the very idea of intrinsic value on metaphysical grounds.” ref

“Another type of metaphysical challenge to intrinsic value stems from the theory of “pragmatism,” especially in the form advanced by John Dewey [1859–1952] (see Dewey 1922). According to the pragmatist, the world is constantly changing in such a way that the solution to one problem becomes the source of another, what is an end in one context is a means in another, and thus it is a mistake to seek or offer a timeless list of intrinsic goods and evils, of ends to be achieved or avoided for their own sakes. This theme has been elaborated by Monroe Beardsley, who attacks the very notion of intrinsic value (Beardsley 1965; cf. Conee 1982). Denying that the existence of something with extrinsic value presupposes the existence of something else with intrinsic value, Beardsley argues that all value is extrinsic. (In the course of his argument, Beardsley rejects the sort of “dialectical demonstration” of intrinsic value that was attempted in the last section, when an explanation of the derivative value of helping others was given in terms of some nonderivative value.) A quick response to Beardsley’s misgivings about intrinsic value would be to admit that it may well be that, the world being as complex as it is, nothing is such that its value is wholly intrinsic; perhaps whatever has intrinsic value also has extrinsic value, and of course many things that have extrinsic value will have no (or, at least, neutral) intrinsic value. Far from repudiating the notion of intrinsic value, though, this admission would confirm its legitimacy. But Beardsley would insist that this quick response misses the point of his attack, and that it really is the case, not just that whatever has value has extrinsic value, but also that nothing has intrinsic value. His argument for this view is based on the claim that the concept of intrinsic value is “inapplicable,” in that, even if something had such value, we could not know this and hence its having such value could play no role in our reasoning about value. But here Beardsley seems to be overreaching. Even if it were the case that we cannot know whether something has intrinsic value, this of course leaves open the question whether anything does have such value. And even if it could somehow be shown that nothing does have such value, this would still leave open the question whether something could have such value. If the answer to this last question is “yes,” then the legitimacy of the concept of intrinsic value is in fact confirmed rather than refuted.” ref

“As has been noted, some philosophers do indeed doubt the legitimacy, the very coherence, of the concept of intrinsic value. Before we turn to a discussion of this issue, however, let us for the moment presume that the concept is coherent and address a different sort of doubt: the doubt that the concept has any great moral significance. Recall the suggestion, mentioned in the last section, that discussions of intrinsic value may have been compromised by a failure to distinguish certain concepts. This suggestion is at the heart of Christine Korsgaard’s “Two Distinctions in Goodness” (Korsgaard 1983). Korsgaard notes that “intrinsic value” has traditionally been contrasted with “instrumental value” (the value that something has in virtue of being a means to an end) and claims that this approach is misleading. She contends that “instrumental value” is to be contrasted with “final value,” that is, the value that something has as an end or for its own sake; however, “intrinsic value” (the value that something has in itself, that is, in virtue of its intrinsic, nonrelational properties) is to be contrasted with “extrinsic value” (the value that something has in virtue of its extrinsic, relational properties). (An example of a nonrelational property is the property of being round; an example of a relational property is the property of being loved.) As an illustration of final value, Korsgaard suggests that gorgeously enameled frying pans are, in virtue of the role they play in our lives, good for their own sakes. In like fashion, Beardsley wonders whether a rare stamp may be good for its own sake (Beardsley 1965); Shelly Kagan says that the pen that Abraham Lincoln used to sign the Emancipation Proclamation may well be good for its own sake (Kagan 1998); and others have offered similar examples (cf. Rabinowicz and Rønnow-Rasmussen 1999 and 2003). Notice that in each case the value being attributed to the object in question is (allegedly) had in virtue of some extrinsic property of the object. This puts the moral significance of intrinsic value into question, since (as is apparent from our discussion so far) it is with the notion of something’s being valuable for its own sake that philosophers have traditionally been, and continue to be, primarily concerned.” ref

“There is an important corollary to drawing a distinction between intrinsic value and final value (and between extrinsic value and nonfinal value), and that is that, contrary to what Korsgaard herself initially says, it may be a mistake to contrast final value with instrumental value. If it is possible, as Korsgaard claims, that final value sometimes supervenes on extrinsic properties, then it might be possible that it sometimes supervenes in particular on the property of being a means to some other end. Indeed, Korsgaard herself suggests this when she says that “certain kinds of things, such as luxurious instruments, … are valued for their own sakes under the condition of their usefulness” (Korsgaard 1983, p. 185). Kagan also tentatively endorses this idea. If the idea is coherent, then we should in principle distinguish two kinds of instrumental value, one final and the other nonfinal. If something A is a means to something else B and has instrumental value in virtue of this fact, such value will be nonfinal if it is merely derivative from or reflective of B’s value, whereas it will be final if it is nonderivative, that is, if it is a value that A has in its own right (due to the fact that it is a means to B), irrespective of any value that B may or may not have in its own right.” ref

“Even if it is agreed that it is final value that is central to the concerns of moral philosophers, we should be careful in drawing the conclusion that intrinsic value is not central to their concerns. First, there is no necessity that the term “intrinsic value” be reserved for the value that something has in virtue of its intrinsic properties; presumably it has been used by many writers simply to refer to what Korsgaard calls final value, in which case the moral significance of (what is thus called) intrinsic value has of course not been thrown into doubt. Nonetheless, it should probably be conceded that “final value” is a more suitable term than “intrinsic value” to refer to the sort of value in question, since the latter term certainly does suggest value that supervenes on intrinsic properties. But here a second point can be made, and that is that, even if use of the term “intrinsic value” is restricted accordingly, it is arguable that, contrary to Korsgaard’s contention, all final value does after all supervene on intrinsic properties alone; if that were the case, there would seem to be no reason not to continue to use the term “intrinsic value” to refer to final value. Whether this is, in fact, the case depends in part on just what sort of thing can be valuable for its own sake—an issue to be taken up in the next section.” ref

“In light of the matter just discussed, we must now decide what terminology to adopt. It is clear that moral philosophers since ancient times have been concerned with the distinction between the value that something has for its own sake (the sort of nonderivative value that Korsgaard calls “final value”) and the value that something has for the sake of something else to which it is related in some way. However, given the weight of tradition, it seems justifiable, perhaps even advisable, to continue, despite Korsgaard’s misgivings, to use the terms “intrinsic value” and “extrinsic value” to refer to these two types of value; if we do so, however, we should explicitly note that this practice is not itself intended to endorse, or reject, the view that intrinsic value supervenes on intrinsic properties alone.” ref

“Let us now turn to doubts about the very coherence of the concept of intrinsic value, so understood. In Principia Ethica and elsewhere, Moore embraces the consequentialist view, mentioned above, that whether an action is morally right or wrong turns exclusively on whether its consequences are intrinsically better than those of its alternatives. Some philosophers have recently argued that ascribing intrinsic value to consequences in this way is fundamentally misconceived. Peter Geach, for example, argues that Moore makes a serious mistake when comparing “good” with “yellow.” Moore says that both terms express unanalyzable concepts but are to be distinguished in that, whereas the latter refers to a natural property, the former refers to a nonnatural one. Geach contends that there is a mistaken assimilation underlying Moore’s remarks, since “good” in fact operates in a way quite unlike that of “yellow”—something that Moore wholly overlooks. This contention would appear to be confirmed by the observation that the phrase “x is a yellow bird” splits up logically (as Geach puts it) into the phrase “x is a bird and x is yellow,” whereas the phrase “x is a good singer” does not split up in the same way. Also, from “x is a yellow bird” and “a bird is an animal” we do not hesitate to infer “x is a yellow animal,” whereas no similar inference seems warranted in the case of “x is a good singer” and “a singer is a person.” On the basis of these observations Geach concludes that nothing can be good in the free-standing way that Moore alleges; rather, whatever is good is good relative to a certain kind.” ref

“Judith Thomson has recently elaborated on Geach’s thesis (Thomson 1997). Although she does not unqualifiedly agree that whatever is good is good relative to a certain kind, she does claim that whatever is good is good in some way; nothing can be “just plain good,” as she believes Moore would have it. Philippa Foot, among others, has made a similar charge (Foot 1985). It is a charge that has been rebutted by Michael Zimmerman, who argues that Geach’s tests are less straightforward than they may seem and fail after all to reveal a significant distinction between the ways in which “good” and “yellow” operate (Zimmerman 2001, ch. 2). He argues further that Thomson mischaracterizes Moore’s conception of intrinsic value. According to Moore, he claims, what is intrinsically good is not “just plain good”; rather, it is good in a particular way, in keeping with Thomson’s thesis that all goodness is goodness in a way. He maintains that, for Moore and other proponents of intrinsic value, such value is a particular kind of moral value. Mahrad Almotahari and Adam Hosein have revived Geach’s challenge (Almotahari and Hosein 2015). They argue that if, contrary to Geach, “good” could be used predicatively, we would be able to use the term predicatively in sentences of the form ‘a is a good K’ but, they argue, the linguistic evidence indicates that we cannot do so (Almotahari and Hosein 2015, 1493–4).” ref

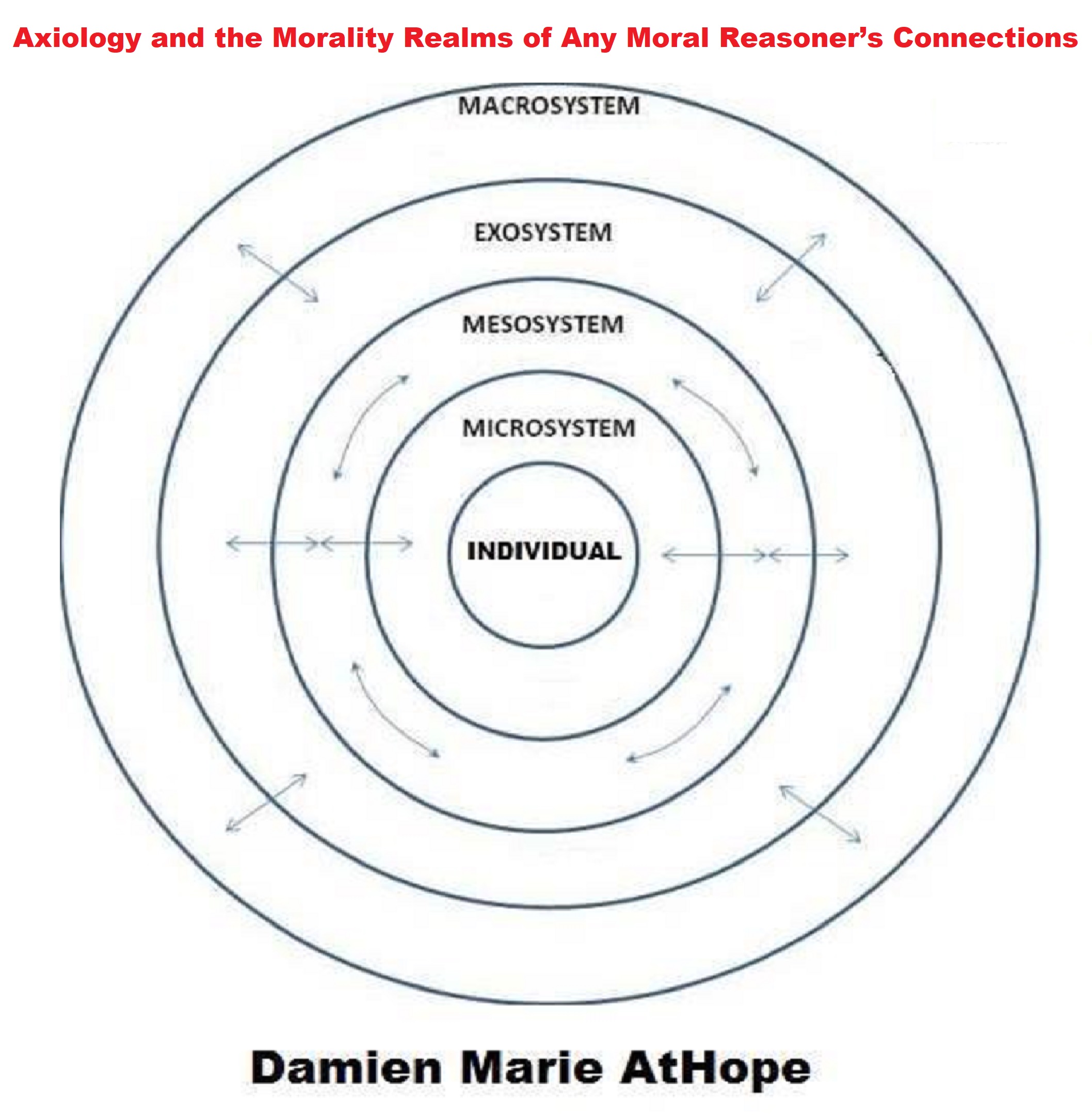

Axiology and the Morality Realms of Any Moral Reasoner’s Connections

Reasoned Axiological thinking on morality realms, of any moral reasoner’s connections, and the moral weight they could motivate or affect in any assessed or concluded valuation, they use in making an ultimate choice of behavior. The axiological Valuation approach to moral decision-making would likely use an Ecological Systems Theory modal. And in order to conceptualize “value” you need to understand the environmental contexts, five ecological systems:

- Individual: Usually highest value, though for some people, family members may have the same or higher value than themself.

- Microsystem: Usually the next highest value is placed with the closest relationships to an individual and encompasses interpersonal relationships and direct interactions with immediate surroundings, for example, family members or friends of friends.

- Mesosystem: Usually includes close to semi-close relationships, for example, family friends or friends of friends.

- Exosystem: Usually only involves things such as semi or not directly involved individuals, for example, people at one’s job, people at places you frequent, then moving out and lessening in assessed value as it goes to further removed or extended networks of connectedness or relatedness. Such as the likely value distinctions in the value of the people in one’s city, the people in one’s state, the people in one’s geographic location, region, and/or county, then their perceived home or chosen country.

- Macrosystem: Usually involving all other people outside their likely value distinctions in the value of the people in one’s city, the people in one’s state, the people in one’s geographic location, region, and/or county, then their perceived home or chosen country. Others not often even acknowledged or if assess generally not as favored as the known. As we seem to hold a tendency to overreact with fear at the different or unknown or even the unfamiliar. What we don’t understand, we come to fear. What we fear we learn to hate and often what we hate we seek to destroy. Thus, for clear thinking and ultimately good acting, we should fight such destructive fear. This area of connectedness relates to its farthest possible extent involving the entire world.

Ecological systems theory

“Ecological systems theory (also called development ‘ relationships within communities and the wider society. The theory is also commonly referred to as the ecological/systems framework. It identifies five environmental systems with which an individual interacts.” ref

- “Microsystem: Refers to the institutions and groups that most immediately and directly impact the child’s development including: family, school, religious institutions, neighborhood, and peers.” ref

- “Mesosystem: Consists of interconnections between the microsystems, for example between the family and teachers or between the child’s peers and the family.” ref

- “Exosystem: Involves links between social settings that do not involve the child. For example, a child’s experience at home may be influenced by their parent’s experiences at work. A parent might receive a promotion that requires more travel, which in turn increases conflict with the other parent resulting in changes in their patterns of interaction with the child.” ref

- “Macrosystem: Describes the overarching culture that influences the developing child, as well as the microsystems and mesosystems embedded in those cultures. Cultural contexts can differ based on geographic location, socioeconomic status, poverty, and ethnicity. Members of a cultural group often share a common identity, heritage, and values. Macrosystems evolve across time and from generation to generation.” ref

- “Chronosystem: Consists of the pattern of environmental events and transitions over the life course, as well as changing socio-historical circumstances. For example, researchers have found that the negative effects of divorce on children often peak in the first year after the divorce. By two years after the divorce, family interaction is less chaotic and more stable. An example of changing sociohistorical circumstances is the increase in opportunities for women to pursue a career during the last thirty years.” ref

“Later work by Bronfenbrenner considered the role of biology in this model as well; thus the theory has sometimes been called the Bioecological model. Per this theoretical construction, each system contains roles, norms, and rules which may shape psychological development. For example, an inner-city family faces many challenges which an affluent family in a gated community does not, and vice versa. The inner-city family is more likely to experience environmental hardships, like crime and squalor. On the other hand, the sheltered family is more likely to lack the nurturing support of extended family.” ref

“Since its publication in 1979, Bronfenbrenner’s major statement of this theory, The Ecology of Human Development has had widespread influence on the way psychologists and others approach the study of human beings and their environments. As a result of his groundbreaking work in human ecology, these environments — from the family to economic and political structures — have come to be viewed as part of the life course from childhood through adulthood.” ref

“Bronfenbrenner has identified Soviet developmental psychologist Lev Vygotsky and German-born psychologist Kurt Lewin as important influences on his theory. Bronfenbrenner’s work provides one of the foundational elements of the ecological counseling perspective, as espoused by Robert K. Conyne, Ellen Cook, and the University of Cincinnati Counseling Program. There are many different theories related to human development. Human ecology theory emphasizes environmental factors as central to development.” ref

Justice ethics vs. Care ethics

You must choose one over the other because to have the most justice, you will simultaneously have the least care. Choose the most care is to have the least justice. Sometimes, justice has to outweigh care, and sometimes, care has to outweigh justice.

MORAL FEAR (fight or flight “justice perspective” or similar to consequentialist ethics/utilitarian ethics)

MORAL LOVE (tend and befriend “voice of care perspective” or similar to “care ethics (ethics of care)/reciprocity (reciprocal altruism) ethics”)

Moral fear and Moral love (which together motivate my axiological ethics)?

Harm is often a violation of trust and a violation of expected trust makes bad things even worse like if I told you a child was killed, you would feel it was terrible but if I further told you it was the child’s doctor that murdered the child out of anger. You would be more angered as doctors are expected to care for people not harm them. And if you think that is bad what if I further told you the doctor who killed the child was her mother would you hold her even mone in contempt as mothers also are expected to care and not kill children, so a violation of trust is terrible and even makes things worse. Therefore, we can see why people that hold places of trust should never abuse them, and that we should hold them accountable if they do violate such trust by harming others. Morality first, that is morality should be at the forefront in all I do. I hope I am always strong enough to put my morality at the forefront in all I do, so much so, that it is obvious in the ways I think and behave. To better grasp, a naturalistic morality one should see the perspective of how there is a self-regulatory effect on the self-evaluative moral emotions, such as shame and guilt. Broadly conceived, self-regulation distinguishes between two types of motivation: approach/activation and avoidance/inhibition. one should conceptually understand the socialization dimensions (parental restrictiveness versus nurturance), associated emotions (anxiety versus empathy), and forms of morality (proscriptive versus prescriptive) that serve as precursors to each self-evaluative moral emotion.

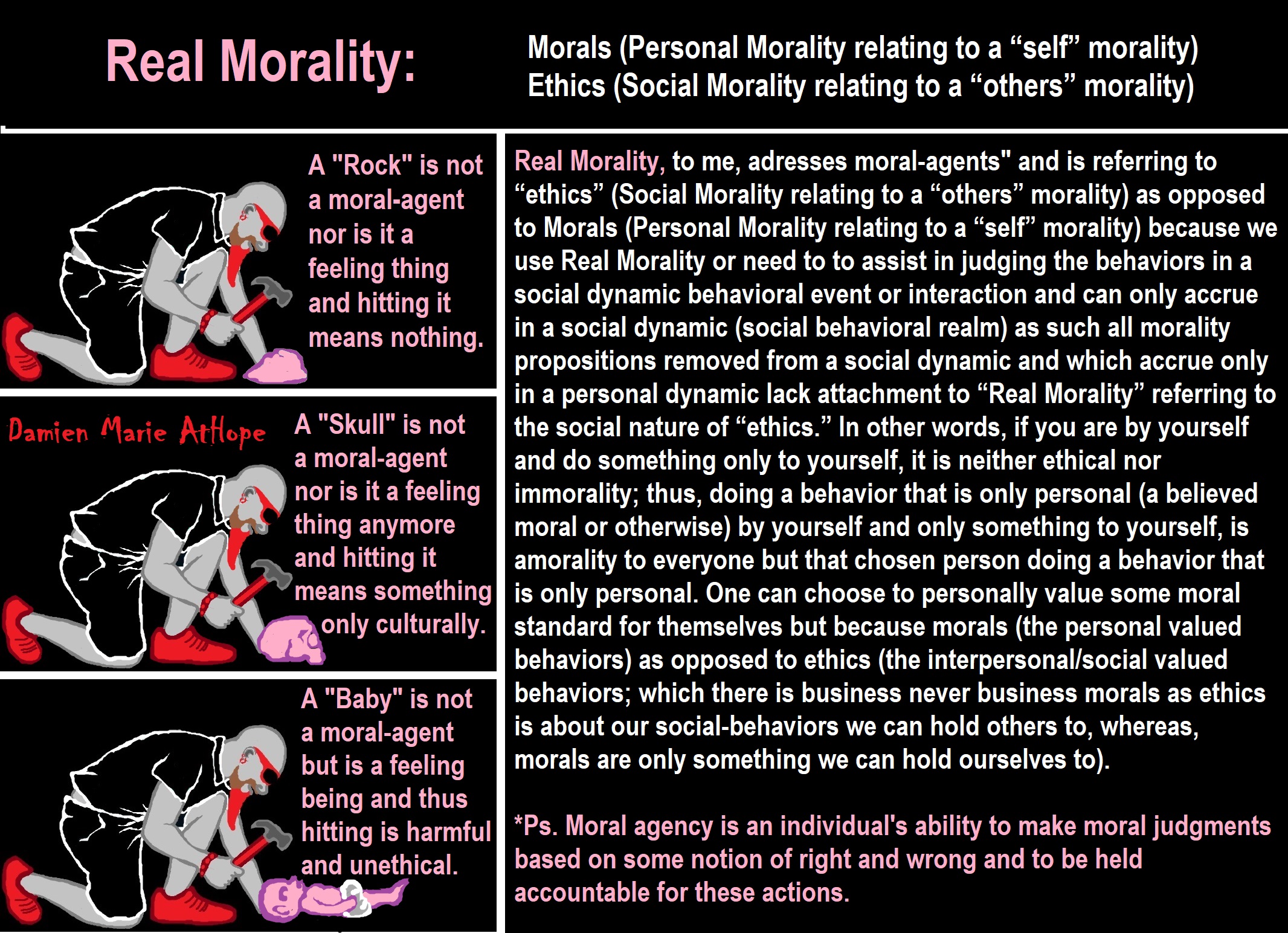

Real Morality vs. Pseudo Morality

Religions Promote Pseudo-Morality

Think there is no objective morality?

True Morality Not the Golden Rule…

Axiological Atheism Morality Critique: of the bible god

Axiological Morality Critique of Pseudo-Morality/Pseudomorality?

True Morality summed up to me is largely the expression of axiological value judgments/assessments carried into an appropriate valueized action.

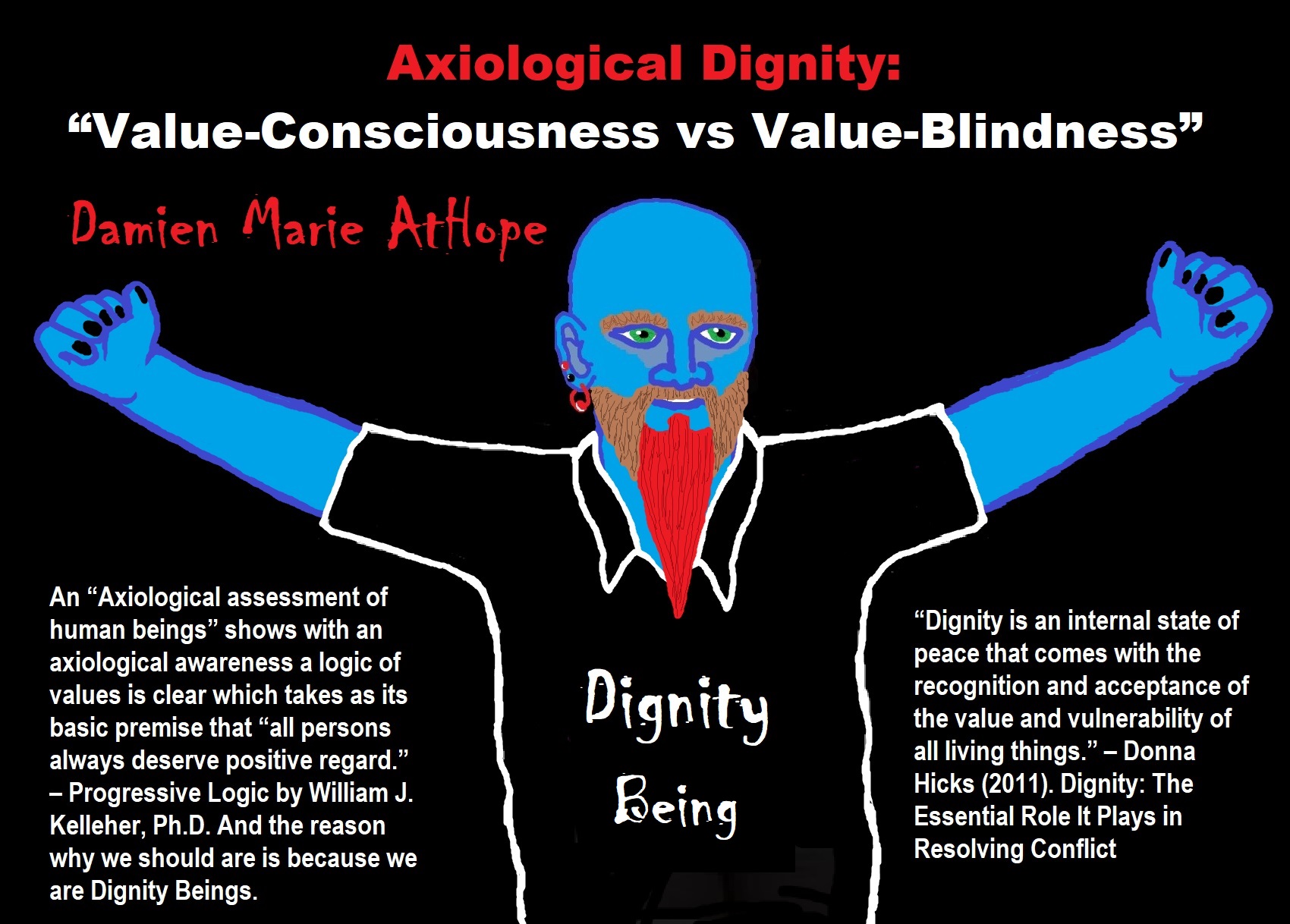

Why care? Because we are Dignity Beings.

*Axiological Dignity Being Theory*

I am inspired by philosophy, enlightened by archaeology and grounded by science that religious claims, on the whole, along with their magical gods, are but Dogmatic-Propaganda, myths and lies. Kindness beats prayers every time, even if you think prayer works, you know kindness works. Think otherwise, do both without telling people and see which one they notice. Aspire to master the heavens but don’t forget about the ones in need still here on earth. You can be kind and never love but you cannot love and never be kind. Therefore, it is this generosity of humanity, we need the most of. So, if you can be kind, as in the end some of the best we can be to others is to exchange kindness. For too long now we have allowed the dark shadow of hate to cloud our minds, while we wait in silence as if pondering if there is a need to commiserate. For too long little has been done and we too often have been part of this dark clouded shame of hate. Simply, so many humans now but sadly one is still left asking, where is the humanity?

Why Ought We Care?

Because kindness is like chicken soup to the essence of who we are, by validating the safety needs of our dignity. When the valuing of dignity is followed, a deep respect for one’s self and others as dignity beings has become one’s path. When we can see with the eyes of love and kindness, how well we finally see and understand what a demonstrates of a mature being of dignity when we value the human rights of others, as we now see others in the world as fellow beings of dignity. We need to understand what should be honored in others as fellow dignity beings and the realization of the value involved in that. As well as strive to understand how an attack to/on a person’s “human rights” is an attack to/on the value and worth of a dignity being.

Yes, I want to see “you” that previous being of dignity worthy of high value and an honored moral weight to any violation of their self-ownership. And this dignity being with self-ownership rights is here before you seeking connection. what will you do, here you are in the question ever present even if never said aloud, do you see me now or are you stuck in trying to evaluate my value and assess worth as a fellow being of dignity. A violation of one’s dignity (Which it the emotional, awareness or the emotional detection of the world) as a dignity being can be quite harmful, simply we must see how it can create some physiological disturbance in the dignity being its done to. I am a mutualistic thinker and to me, we all are in this life together as fellow dignity beings. Therefore, I want my life to be of a benefit to others in the world. We are natural evolutionary derived dignity beings not supernatural magic derived soul/spirit beings.

Stopping lying about who we are, as your made-up magic about reality which is forced causing a problem event (misunderstanding of axiological valuations) to the natural wonder of reality. What equals a dignity worth being, it is the being whose species has cognitive awareness and the expense of pain. To make another dignity being feel pain is to do an attack to their dignity as well as your own. What equals a dignity worth being, it is the being whose species has cognitive awareness and the expense of pain. When I was younger I felt proud when I harmed those I did not like now I find it deserving even if doing it was seen as the only choice as I now see us for who we are valuable beings of dignity. I am not as worried about how I break the box you believe I need to fit as I am worried about the possibility of your confining hopes of hindering me with your limits, these life traps you have decided about and for me are as owning character attacks to my dignity’s needs which can be generalized as acceptance, understanding, and support.

As I see it now, how odd I find it to have prejudice or bigotry against other humans who are intact previous fellow beings of dignity, we too often get blinded by the external packaging that holds a being of dignity internally. What I am saying don’t judge by the outside see the worth and human value they have as a dignity being. Why is it easier to see what is wrong then what is right? Why do I struggle in speaking what my heart loves as thorough and as passionate as what I dislike or hate? When you say “an act of mercy” the thing that is being appealed to or for is the proposal of or for the human quality of dignity. May my lips be sweetened with words of encouragement and compassion. May my Heart stay warm in the arms kindness. May my life be an expression of love to the world. Dignity arises in our emotional awareness depending on cognition. Our dignity is involved when you feel connected feelings with people, animals, plants, places, things, and ideas. Our dignity is involved when we feel an emotional bond “my family”, “my pet”, “my religion”, “my sport’s team” etc.

Because of the core sensitivity of our dignity, we feel that when we connect, then we are also acknowledging, understanding, and supporting a perceived sense of dignity. Even if it’s not actually a dignity being in the case of plants, places, things, and ideas; and is rightly interacting with a dignity being in people and animals. We are trying to project “dignity developing motivation” towards them somewhere near equally even though human and animals don’t have the same morality weight to them. I am anthropocentric (from Greek means “human being center”) as an Axiological Atheist. I see humans value as above all other life’s value. Some say well, we are animals so they disagree with my destination. But how do the facts play out? So, you don’t have any difference in value of life? Therefore, a bug is the same as a mouse, a mouse is the same as a dolphin, a dolphin is the same as a human, all to you have exactly the same value? You fight to protect the rights of each of them equally? And all killing of any of them is the same crime murder?

I know I am an animal but you also know that we do have the term humans which no other animal is classified. And we don’t take other animals to court as only humans and not any other animals are like us. We are also genetically connected to plants and stars and that still doesn’t remove the special class humans removed from all other animals. A society where you can kill a human as easily as a mosquito would simply just not work ethically to me and it should not to any reasonable person either. If you think humans and animals are of equal value, are you obviously for stronger punishment for all animals to the level of humans? If so we need tougher laws against all animals including divorce and spousal or child support and we will jail any animal parent (deadbeat animal) who does not adequately as we have been avoiding this for too long and thankfully now that in the future the ideas about animals being equal we had to create a new animal police force and animal court system, not to mention are new animal jails as we will not accept such open child abuse and disregard for responsibilities? As we don’t want to treat animals as that would be unjust to some humans, but how does this even make sense?

To me, it doesn’t make sense as humans a different from all other animals even though some are similar in some ways. To further discuss my idea of *dignity developing motivation” can be seen in expressions like, I love you and I appreciate you. Or the behavior of living and appreciating. However, this is only true between higher cognitive aware beings as dignity and awareness of selfness is directly related to dignity awareness. The higher the dignity awareness the higher the moral weight of the dignity in the being’s dignity. What do you think are the best ways to cultivate dignity? Well, to me dignity is not a fixed thing and it feels honored or honoring others as well as help self-helping and other helping; like ones we love or those in need, just as our dignity is affected by the interactions with others. We can value our own dignity and we can and do grow this way, but as I see it because we are a social animals we can usually we cannot fully flourish with our dignity. Thus, dignity is emotionally needy for other dignity beings that is why I surmise at least a partially why we feel empathy and compassion or emotional bonds even with animals is a dignity awareness and response. Like when we say “my pet” cat one is acknowledging our increased personal and emotional connecting.

So, when we exchange in experience with a pet animal what we have done is we raze their dignity. Our dignity flourishes with acceptance, understanding and support. Our dignity withers with rejection, misunderstanding, and opposition. Dignity: is the emotional sensitivity of our sense of self or the emotional understanding about our sense of self. When you say, they have a right to what they believe, what I hear is you think I don’t have a right to comment on it. Dignity is the emotional sensitivity of our sense of self or the emotional understanding about our sense of self. To me when we say it’s wrong to kill a human, that person is appealing to our need to value the dignity of the person.’ The person with whom may possibly be killed has a life essence with an attached value and moral weight valuations. And moral weight,’ which is different depending on the value of the dignity being you are addressing understanding moral weight as a kind of liability, responsibility, or rights is actualized. So, it’s the dignity to which we are saying validates the right to life. But I believe all living things with cognitively aware have a dignity. As to me dignity is the name I home to the emotional experience, emotional expression, emotional intelligence or sensitivity at the very core of our sense of self the more aware the hire that dignity value and thus worth. Dignity is often shredded similar to my thinking: “Moral, ethical, legal, and political discussions use the concept of dignity to express the idea that a being has an innate right to be valued, respected, and to receive ethical treatment.

In the modern context dignity, can function as an extension of the Enlightenment-era concepts of inherent, inalienable rights. English-speakers often use the word “dignity” in prescriptive and cautionary ways: for example, in politics it can be used to critique the treatment of oppressed and vulnerable groups and peoples, but it has also been applied to cultures and sub-cultures, to religious beliefs and ideals, to animals used for food or research, and to plants. “Dignity” also has descriptive meanings pertaining to human worth. In general, the term has various functions and meanings depending on how the term is used and on the context.” Dignity, authenticity and integrity are of the highest value to our experience, yet ones that we must define for ourselves. People of hurt and harm, you are not as free to attack other beings of dignity without any effect on you as you may think. So, I am sorry not sorry that there is no such thing in general, as hurting or harming other beings of dignity without psychological destruction to the dignity being in us. This is an understanding that once done hunts and harm of other beings of dignity emotionally/psychologically hurts and harms your life as an acceptance needy dignity being, as we commonly experience moral discuss involuntary as on our deepest level as dignity beings. Disgust is deeply related to our sense of morality.

Babies & Morality?

“They believe babies are in fact born with an innate sense of morality, and while parents and society can help develop a belief system in babies, they don’t create one. A team of researchers at Yale University’s Infant Cognition Center, known as The Baby Lab, showed us just how they came to that conclusion.” Ref

Animals and Morality?

5 Animals With a Moral Compass Moreover, Animals can tell right from wrong: Scientists studying animal behavior believe they have growing evidence that species ranging from mice to primates are governed by moral codes of conduct in the same way as humans. Likewise, in the book: Wild Justice: The Moral Lives of Animals: Scientists have long counseled against interpreting animal behavior in terms of human emotions, warning that such anthropomorphizing limits our ability to understand animals as they really are. Yet what are we to make of a female gorilla in a German zoo who spent days mourning the death of her baby? Or a wild female elephant who cared for a younger one after she was injured by a rambunctious teenage male? Or a rat who refused to push a lever for food when he saw that doing so caused another rat to be shocked? Aren’t these clear signs that animals have recognizable emotions and moral intelligence? With Wild Justice Marc Bekoff and Jessica Pierce unequivocally answer yes. Marrying years of behavioral and cognitive research with compelling and moving anecdotes, Bekoff and Pierce reveal that animals exhibit a broad repertoire of moral behaviors, including fairness, empathy, trust, and reciprocity. Underlying these behaviors is a complex and nuanced range of emotions, backed by a high degree of intelligence and surprising behavioral flexibility. Animals, in short, are incredibly adept social beings, relying on rules of conduct to navigate intricate social networks that are essential to their survival. Ultimately, Bekoff and Pierce draw the astonishing conclusion that there is no moral gap between humans and other species: morality is an evolved trait that we unquestionably share with other social mammals.

Moral Naturalism (James Lenman)

While “moral naturalism” is sometimes used to refer to any approach to metaethics intended to cohere with naturalism in metaphysics more generally, the label is more usually reserved for naturalistic forms of moral realism according to which there are objective moral facts and properties and these moral facts and properties are natural facts and properties. Views of this kind appeal to many as combining the advantages of naturalism and realism. Ref

Moral fear and Moral love (which together motivate my axiological ethics)?

“Sometimes justice has to outweigh care and sometimes care has to outweigh justice.”

And one may ask or question how do you discern the appropriate morality course of action between what is ethically right? To me, it takes Axiology (i.e. value consciousness: value judgment analysis of ethical appropriateness do to assess value involved).

MORAL FEAR (fight or flight “justice perspective”):

To feel a kind of morality “anxiety” (ethical apprehension to potentially cause harm) about behaviors and their outcomes empathy (I feel you) or sympathy (I feel for you) about something moral that may be done, is being done, or that has been done, thus feeling of distress, apprehension or alarm caused by value driven emotional intelligence concern; moral/ethical anxiety to the possibility; chance (to do something as a moral thinker and an ethical actor) or dread; respect (to take the sensitivity of a personal moral choice that leads one to choose an ethical behavior(s) and grasping the moral weight of the actions involved and potential outcomes this engagement can or will likely create (using data from learning whether theoretical or practical to lessen the effect of an unpleasant choice as much as posable (morality development/awareness/goals/persuasion). “Moral Anxiety, improves us, while Social Anxiety kills. Some anxieties are indicators of healthy curiosity and strong moral fiber, while others are a source of severe stress. Knowing which is which can help you to navigate your personal, professional, and intellectual life more effectively.” Ref

Moral fear thus is a kind of morality “anxiety” that motivates a fascinating aspect of humanity, which is that we hold ourselves to high moral standards. With our values and emotional intelligence and moral development, we gain a developed prosocial persuasion thus “tend to self-impose rules on ourselves to protect society from the short-term temptations that might cause us to do things that would have a negative impact in the long-run. For example, we might be tempted to harm a person who bothers us, but a society in which everyone gave in to the temptation to hurt those who made us angry would quickly devolve into chaos. And once we accept that emotion plays some role in complex decisions, it is important to figure out which emotions are influencing different kinds of choices. Therefore, when we make these moral judgments to an extent we are somewhat driven by our ability to reason about the consequences of the actions or are influenced by their emotions to or about the outcomes of the consequences of the actions.” https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/ulterior-motives/201308/anxiety-and-moral-judgment

*ps. MORAL FEAR (fight or flight “consequentialist ethics/utilitarian ethics”) is roughly referring to the fight-or-flight response, also known as the acute stress response, refers to a physiological reaction that occurs in the presence of something that is terrifying, either mentally or physically. The fight-or-flight response (also called hyperarousal, or the acute stress response) is a physiological reaction that occurs in response to a perceived harmful event, attack, or threat to survival. An evolutionary psychology explanation is that early animals had to react to threatening stimuli quickly and did not have time to psychologically and physically prepare themselves. The fight or flight response provided them with the mechanisms to rapidly respond to threats against survival. This response is recognized as the first stage of the general adaptation syndrome that regulates stress responses among vertebrates and other organisms. The reaction begins in the amygdala, which triggers a neural response in the hypothalamus. The initial reaction is followed by activation of the pituitary gland and secretion of the hormone ACTH. The adrenal gland is activated almost simultaneously and releases the hormone epinephrine. The release of chemical messengers results in the production of the hormone cortisol, which increases blood pressure, blood sugar, and suppresses the immune system. The initial response and subsequent reactions are triggered in an effort to create a boost of energy. This boost of energy is activated by epinephrine binding to liver cells and the subsequent production of glucose. Additionally, the circulation of cortisol functions to turn fatty acids into available energy, which prepares muscles throughout the body for response. Catecholamine hormones, such as adrenaline (epinephrine) or noradrenaline (norepinephrine), facilitate immediate physical reactions associated with a preparation for violent muscular action and :

- Acceleration of heart and lung action

- Paling or flushing, or alternating between both

- Inhibition of stomach and upper-intestinal action to the point where digestion slows down or stops

- General effect on the sphincters of the body

- Constriction of blood vessels in many parts of the body

- Liberation of metabolic energy sources (particularly fat and glycogen) for muscular action

- Dilation of blood vessels for muscles

- Inhibition of the lacrimal gland (responsible for tear production) and salivation

- Dilation of pupil (mydriasis)

- Relaxation of bladder

- Inhibition of erection

- Auditory exclusion (loss of hearing)

- Tunnel vision (loss of peripheral vision)

- Disinhibition of spinal reflexes

- Shaking

The physiological changes that occur during the fight or flight response are activated in order to give the body increased strength and speed in anticipation of fighting or running. Some of the specific physiological changes and their functions include:

- Increased blood flow to the muscles activated by diverting blood flow from other parts of the body.

- Increased blood pressure, heart rate, blood sugars, and fats in order to supply the body with extra energy.

- The blood clotting function of the body speeds up in order to prevent excessive blood loss in the event of an injury sustained during the response.

- Increased muscle tension in order to provide the body with extra speed and strength. Ref, Ref

Here is a little on Consequentialist ethics and Utilitarian ethics