ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

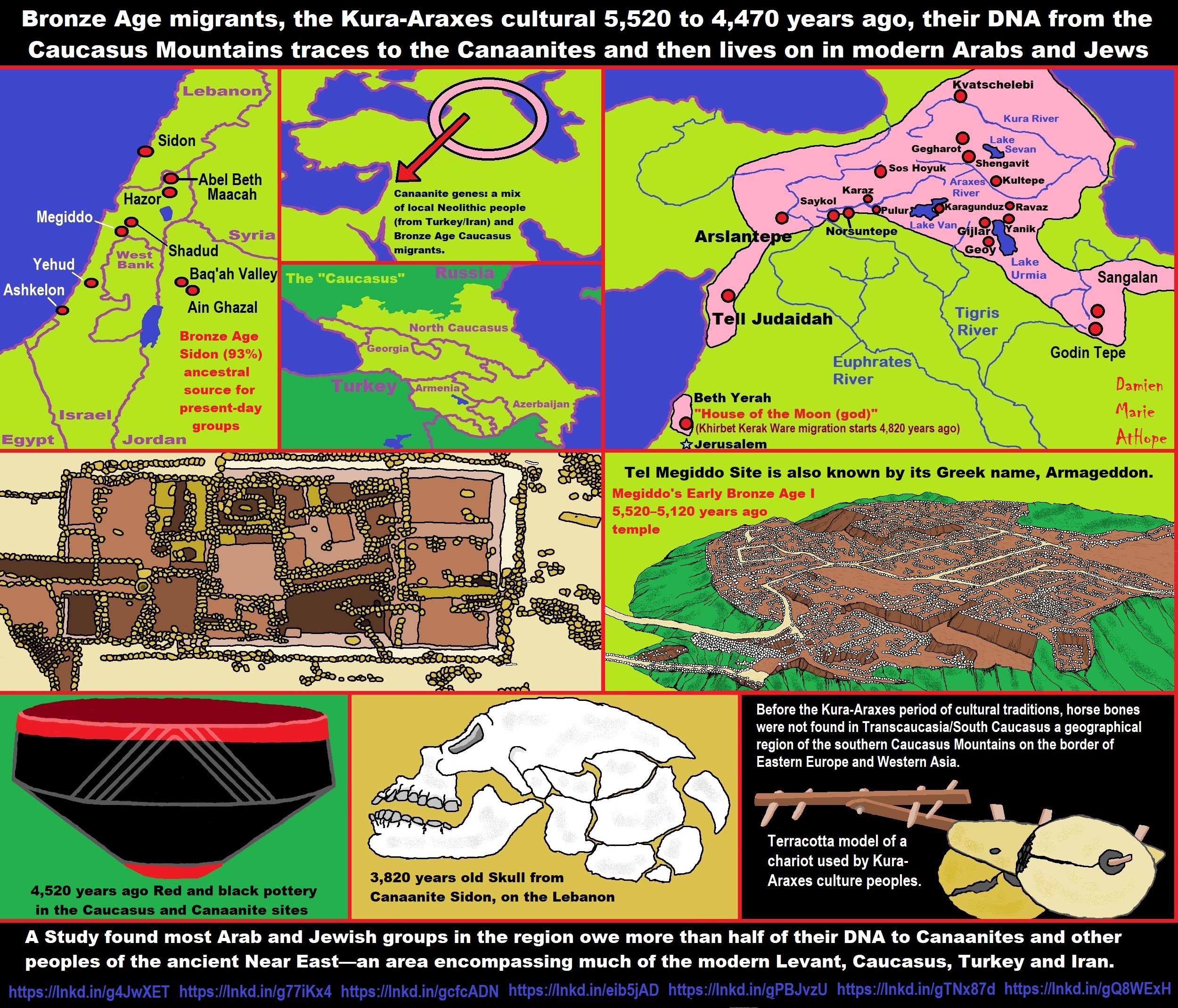

Bronze Age migrants, the Kura-Araxes cultural 5,520 to 4,470 years ago, their DNA from the Caucasus Mountains traces to the Canaanites and then lives on in modern Arabs and Jews. A Study found most Arab and Jewish groups in the region owe more than half of their DNA to Canaanites and other peoples of the ancient Near East—an area encompassing much of the modern Levant, Caucasus, Turkey, and Iran. Before the Kura-Araxes period of cultural traditions, horse bones were not found in Transcaucasia/South Caucasus a geographical region of the southern Caucasus Mountains on the border of Eastern Europe and Western Asia.

“The Kura–Araxes culture, also named Kur–Araz culture, or the Early Transcaucasian culture was a civilization that existed from about 4000 BCE until about 2000 BCE or around 6,020 to 4,020 years ago, which has traditionally been regarded as the date of its end; in some locations, it may have disappeared as early as 2600 or 2700 BCE or around 4,620 to 4,720 years ago. The earliest evidence for this culture is found on the Ararat plain; it spread northward in Caucasus by 3000 BCE or around 5,020 years ago). Altogether, the early Transcaucasian culture enveloped a vast area and mostly encompassed, on modern-day territories, the Southern Caucasus (except western Georgia), northwestern Iran, the northeastern Caucasus, eastern Turkey, and as far as Syria. The name of the culture is derived from the Kura and Araxes river valleys. Kura–Araxes culture is sometimes known as Shengavitian, Karaz (Erzurum), Pulur, and Yanik Tepe (Iranian Azerbaijan, near Lake Urmia) cultures. Furthermore, it gave rise to the later Khirbet Kerak-ware culture found in Syria and Canaan after the fall of the Akkadian Empire. While it is unknown what cultures and languages were present in Kura-Araxes, the two most widespread theories suggest a connection with Hurro-Urartian and/or Anatolian languages.” ref

“The Kura-Araxes cultural tradition existed in the highlands of the South Caucasus from 3500 to 2450 BCE or 5,520 to 4,470 years ago. This tradition represented an adaptive regime and a symbolically encoded common identity spread over a broad area of patchy mountain environments. By 3000 BCE or around 5,020 years ago, groups bearing this identity had migrated southwest across a wide area from the Taurus Mountains down into the southern Levant, southeast along the Zagros Mountains, and north across the Caucasus Mountains. In these new places, they became effectively ethnic groups amid already heterogeneous societies. This paper addresses the place of migrants among local populations as ethnicities and the reasons for their disappearance in the diaspora after 2450 BCE.” ref

“DNA from the Bible’s Canaanites lives on in modern Arabs and Jews: A new study of ancient DNA traces the surprising heritage of these mysterious Bronze Age people. Tel Megiddo was an important Canaanite city-state during the Bronze Age, approximately 3500 to 1200 B.CE or 5,520 to 3,220 years ago. DNA analysis reveals that the city’s population included migrants from the distant Caucasus Mountains. They are best known as the people who lived “in a land flowing with milk and honey” until they were vanquished by the ancient Israelites and disappeared from history. But a scientific report published today reveals that the genetic heritage of the Canaanites survives in many modern-day Jews and Arabs. The study in Cell also shows that migrants from the distant Caucasus Mountains combined with the indigenous population to forge the unique Canaanite culture that dominated the area between Egypt and Mesopotamia during the Bronze Age. The team extracted ancient DNA from the bones of 73 individuals buried over the course of 1,500 years at five Canaanite sites scattered across Israel and Jordan. They also factored in data from an additional 20 individuals from four sites previously reported. “Individuals from all sites are highly genetically similar,” says co-author and molecular evolutionist Liran Carmel of Jerusalem’s Hebrew University.” ref

“So while the Canaanites lived in far-flung city-states, and never coalesced into an empire, they shared genes as well as a common culture. The researchers also compared the ancient DNA with that of modern populations and found that most Arab and Jewish groups in the region owe more than half of their DNA to Canaanites and other peoples who inhabited the ancient Near East—an area encompassing much of the modern Levant, Caucasus, and Iran. The study—a collaborative effort between Carmel’s lab, the ancient DNA lab at Harvard University headed by geneticist David Reich, and other groups—was by far the largest of its type in the region. Its findings are the latest in a series of recent breakthroughs in our understanding of this mysterious people who left behind few written records. Marc Haber, a geneticist at the Wellcome Trust’s Sanger Institute in Hinxton, United Kingdom, co-led a 2017 study of five Canaanite individuals from the coastal town of Sidon. The results showed that modern Lebanese can trace more than 90 percent of their genetic ancestry to Canaanites.” ref

“As Egyptians built pyramids and Mesopotamians constructed ziggurats some 4,500 years ago, the Canaanites began to develop towns and cities between these great powers. They first appear in the historical record around 1800 B.C., when the king of the city-state of Mari in today’s eastern Syria complained about “thieves and Canaanites.” Diplomatic correspondence written five centuries later mentions several Canaanite kings, who often struggled to maintain independence from Egypt. “The land of Canaan is your land and its kings are your servants,” acknowledged one Babylonian monarch in a letter to the Egyptian pharaoh Akhenaten. Biblical texts, written many centuries later, insist that Yahweh promised the land of Canaan to the Israelites after their escape from Egypt. Jewish scripture says the newcomers eventually triumphed, but archaeological evidence doesn’t show widespread destruction of Canaanite populations. Instead, they appear to have been gradually overpowered by later invaders such as the Philistines, Greeks, and Romans.” ref

“Red and black pottery circa 2500 BCE or around 4,520 years old was found in the Caucasus Mountains, as well as at Canaanite sites far to the southwest. The Canaanites spoke a Semitic language and were long thought to derive from earlier populations that settled in the region thousands of years before. But archaeologists have puzzled over red-and-black pottery discovered at Canaanite sites that closely resembles ceramics found in the Caucasus Mountains, some 750 miles to the northwest. Historians also have noted that many Canaanite names derive from Hurrian, a non-Semitic language originating in the Caucasus. Whether this resulted from long-distance trade or migration was uncertain. The new study demonstrates that significant numbers of people, and not just goods, were moving around during humanity’s first era of cities and empires. The genes of Canaanite individuals proved to be a mix of local Neolithic people and the Caucasus migrants, who began showing up in the region around the start of the Bronze Age. Carmel adds that the migration appears to have been more than a one-time event, and “could have involved multiple waves throughout the Bronze Age.” One brother and sister who lived around 1500 B.C. in Megiddo, in what is now northern Israel, were from a family that had migrated relatively recently from the northeast. The team also noted that individuals at two coastal sites—Ashkelon in Israel and Sidon in Lebanon—show slightly more genetic diversity. That may be the result of broader trade links in Mediterranean port towns than inland settlements.” ref

“Glenn Schwartz, an archaeologist at Johns Hopkins University who was not involved in the study, said that the biological data provides important insight into how Canaanites shared a notable number of genes as well as cultural traits. And Haber from the Wellcome Trust noted that the quantity of DNA results is particularly impressive, given the difficulty of extracting samples from old bones buried in such a warm climate that can quickly degrade genetic material. Both Israeli and Palestinian politicians claim the region of Israel and the Palestinian territories is the ancestral home of their people, and maintain that the other group was a late arrival. “We are the Canaanites,” asserted Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas last year. “This land is for its people…who were here 5,000 years ago.” Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, meanwhile, said recently that the ancestors of modern Palestinians “came from the Arabian peninsula to the Land of Israel thousands of years” after the Israelites. The new study suggests that despite tumultuous changes in the area since the Bronze Age, “the present-day inhabitants of the region are, to a large extent, descended from its ancient residents,” concludes Schwartz—although Carmel adds that there are hints of later demographic shifts. Carmel hopes to soon expand the findings by collecting DNA from the remains of those who can be identified as Judean, Moabite, Ammonite, and other groups mentioned in the Bible and other texts. “One could analyze ‘Canaanite’ as opposed to ‘Israelite’ individuals,” adds archaeologist Mary Ellen Buck, who wrote a book on the Canaanites. “The Bible claims that these are distinct and mutually antagonistic groups, yet there’s reason to believe that they were very closely related.” ref

“As reported from genome-wide DNA data for 73 individuals from five archaeological sites across the Bronze and Iron Ages Southern Levant. These individuals, who share the “Canaanite” material culture, can be modeled as descending from two sources: (1) earlier local Neolithic populations and (2) populations related to the Chalcolithic Zagros or the Bronze Age Caucasus. The non-local contribution increased over time, as evinced by three outliers who can be modeled as descendants of recent migrants. We show evidence that different “Canaanite” groups genetically resemble each other more than other populations. We find that Levant-related modern populations typically have substantial ancestry coming from populations related to the Chalcolithic Zagros and the Bronze Age Southern Levant. These groups also harbor ancestry from sources we cannot fully model with the available data, highlighting the critical role of post-Bronze-Age migrations into the region over the past 3,000 years.” ref

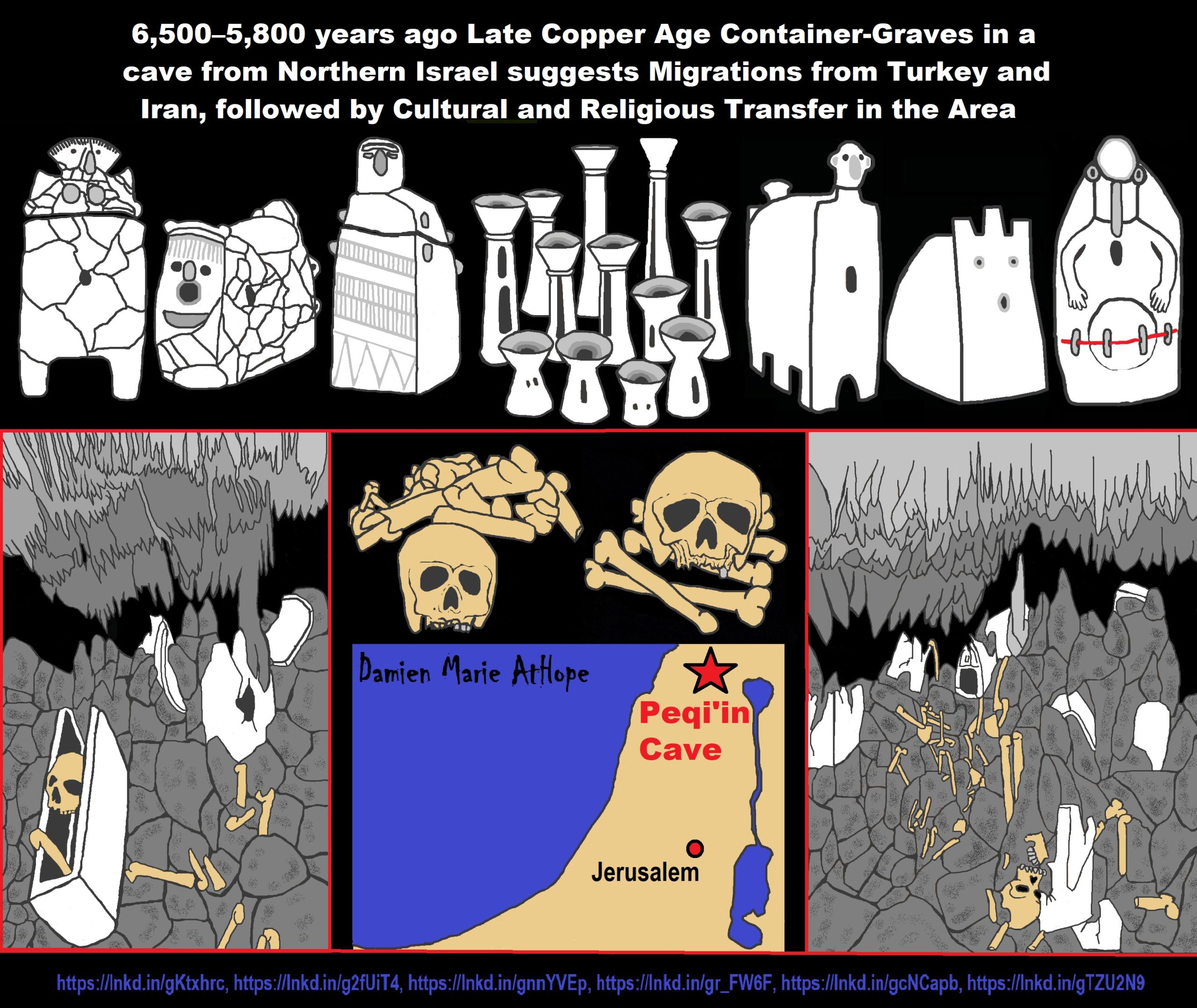

“The Bronze Age (ca. 3500–1150 BCE) was a formative period in the Southern Levant, a region that includes present-day Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, the Palestinian Authority, and southwest Syria. This era, which ended in a large-scale civilization collapse across this region (Cline, 2014), shaped later periods both demographically and culturally. The following Iron Age (ca. 1150–586 BCE) saw the rise of territorial kingdoms such as biblical Israel, Judah, Ammon, Moab, and Aram-Damascus, as well as the Phoenician city-states. In much of the Late Bronze Age, the region was ruled by imperial Egypt, although in later phases of the Iron Age it was controlled by the Mesopotamian-centered empires of Assyria and Babylonia. Archaeological and historical research has documented major changes during the Bronze and Iron Ages, such as the cultural influence of the northern (Caucasian) populations related to the Kura-Araxes tradition during the Early Bronze Age (Greenberg and Goren, 2009) and effects from the “Sea Peoples” (such as Philistines) from the west in the beginning of the Iron Age (Yasur-Landau, 2010). The inhabitants of the Southern Levant in the Bronze Age are commonly described as “Canaanites,” that is, residents of the Land of Canaan. The term appears in several 2nd millennium BCE sources (e.g., Amarna, Alalakh, and Ugarit tablets) and in biblical texts dating from the 8th–7th centuries BCE and later (Bienkowski, 1999, Lemche, 1991, Na’aman, 1994a). In the latter, the Canaanites are referred to as the pre-Israelite inhabitants of the land (Na’aman, 1994a). Canaan of the 2nd millennium BCE was organized in a system of city-states (Goren et al., 2004), where elites ruled from urban hubs over rural (and in some places pastoral) countryside. The material culture of these city-states was relatively uniform (Mazar, 1992), but whether this uniformity extends to their genetic ancestry is unknown. Although genetic ancestry and material culture are unlikely to ever match perfectly, past ancient DNA analyses show that they might sometimes be strongly associated. In other cases, a direct correspondence between genetics and culture cannot be established. We discuss several examples in the Discussion. Previous ancient DNA studies published genome-scale data for thirteen individuals from four Bronze Age sites in the Southern Levant: three individuals from ‘Ain Ghazal in present-day Jordan, dated to ∼2300 BCE (Intermediate Bronze Age) (Lazaridis et al., 2016); five from Sidon in present-day Lebanon, dated to ∼1750 BCE (Middle Bronze Age) (Haber et al., 2017); two from Tel Shadud in present-day Israel, dated to ∼1250 BCE (Late Bronze Age) (van den Brink et al., 2017); and three from Ashkelon in present-day Israel, dated to ∼1650–1200 BCE (Middle and Late Bronze Age) (Feldman et al., 2019). The ancestry of these individuals could be modeled as a mixture of earlier local groups and groups related to the Chalcolithic people of the Zagros Mountains, located in present-day Iran and designated in previous studies as Iran_ChL (Haber et al., 2017, Lazaridis et al., 2016). The Bronze Age Sidon group could be modeled as a major (93% ± 2%) ancestral source for present-day groups in the region (Haber et al., 2017). A study of Chalcolithic individuals from Peqi’in cave in the Galilee (present-day Israel) showed that the ancestry of this earlier group included an additional component related to earlier Anatolian farmers, which was excluded as a substantial source for later Bronze Age groups from the Southern Levant, with the exception of the coastal groups from Sidon and Ashkelon (Feldman et al., 2019, Harney et al., 2018). These observations point to a degree of population turnover in the Chalcolithic-Bronze Age transition, consistent with archaeological evidence for a disruption between local Chalcolithic and Early Bronze cultures (de Miroschedji, 2014). Addressing three issues: First, we sought to determine the extent of genetic homogeneity among the sites associated with Canaanite material culture. Second, we analyzed the data to gain insights into the timing, extent, and origin of gene flow that brought Zagros- and Caucasus-related ancestry to the Bronze Age Southern Levant. Third, we assessed the extent to which additional gene flow events have affected the region since that time. To address these questions, we generated genome-wide ancient DNA data for 71 Bronze Age and 2 Iron Age individuals, spanning roughly 1,500 years, from the Intermediate Bronze Age to the Early Iron Age. Combined with previously published data on the Bronze and Iron Ages in the Southern Levant, we assembled a dataset of 93 individuals from 9 sites across present-day Israel, Jordan, and Lebanon, all demonstrating Canaanite material culture. We show that the sampled individuals from the different sites are usually genetically similar, albeit with subtle but in some cases significant differences, especially in residents of the coastal regions of Sidon and Ashkelon. Almost all individuals can be modeled as a mixture of local earlier Neolithic populations and populations from the northeastern part of the Near East. However, the mixture proportions change over time, revealing the demographic dynamics of the Southern Levant during the Bronze Age. Finally, we show that the genomes of present-day groups geographically and historically linked to the Bronze Age Levant, including the great majority of present-day Jewish groups and Levantine Arabic-speaking groups, are consistent with having 50% or more of their ancestry from people related to groups who lived in the Bronze Age Levant and the Chalcolithic Zagros. These present-day groups also show ancestries that cannot be modeled by the available ancient DNA data, highlighting the importance of additional major genetic effects on the region since the Bronze Age.” ref

Their Results

DNA from the bones of 73 individuals from 5 archaeological sites in the Southern Levant (Table S1; STAR Methods; Figure 1A):

- Thirty-five individuals from Tel Megiddo (northern Israel), most of whom date to the Middle-to-Late Bronze Age, except for one dating to the Intermediate Bronze Age and one dating to the Early Iron Age

- Twenty-one individuals from the Baq‛ah in central Jordan (northeast of Amman), mostly from the Late Bronze Age

- Thirteen individuals from Yehud (central Israel), dating to the Intermediate Bronze Age

- Three individuals from Tel Hazor (northern Israel) dating to the Middle-to-Late Bronze Age

- One individual from Tel Abel Beth Maacah (northern Israel), dating to the Iron Age ref

“For all analyzed samples but one, DNA was extracted from petrous bones. The DNA was converted to double-indexed half Uracil-DNA glycosylase (UDG)-treated libraries that we enriched for about 1.2 million single nucleotide polymorphism (SNPs) before sequencing (see STAR Methods). The median number of autosomal SNPs covered was 288,863 (range 4,883–945,269). In addition to genetic data, we measured values of strontium isotopes for 12 individuals (and for 8 additional individuals that did not produce DNA) (STAR Methods; Methods S1A), and generated accelerator mass spectrometry radiocarbon dates for 20 individuals (Table S1). We combined our newly generated data with published data for 13 Bronze Age Southern Levant individuals from ‘Ain-Ghazal, Sidon, Tel Shadud, and Ashkelon (van den Brink et al., 2017, Feldman et al., 2019, Haber et al., 2017, Lazaridis et al., 2016), and 7 Iron Age Southern Levant Individuals from Ashkelon (Feldman et al., 2019). The projected the autosomal genetic data onto the plane spanned by the first two principal components of 777 present-day West Eurasian individuals genotyped for roughly 600,000 SNPs on the Affymetrix Human Origins SNP array (Lazaridis et al., 2014). The reserchers restricted the plot to 68 individuals represented by at least 30,000 autosomal SNPs (Figure 1B), a coverage threshold where the ability to infer ancestry was robust to sampling noise (Methods S1B). All Bronze and Iron Age Levant individuals (blue and green shapes) form a tight cluster, except for three outliers from Megiddo, and previously identified outliers from the Ashkelon population known as Iron Age I (IA1) (Feldman et al., 2019). We also ran ADMIXTURE on a set of 1,663 present-day and ancient individuals (see STAR Methods; Figure S1). The ADMIXTURE results are qualitatively consistent with the principal component analysis (PCA), suggesting that all individuals but the outliers from Megiddo and the Ashkelon IA1 population have similar ancestry (Figure 1C). The method described in (Olalde et al., 2019) to identify 17 individuals as being first-, second-, or third-degree relatives of other individuals in the dataset. They fall within seven families: five in Tel Megiddo and two in the Baq‛ah. In most families, we used only the member with the highest SNP coverage in subsequent analyses (Table S1). Two of the three Megiddo outliers are a brother and a sister (Family 4, I2189 and I2200), leaving in the final dataset two individuals marked as outliers. After removing low-coverage individuals and closely related family members, 62 individuals were left for further analysis (Table S1). High Degree of Genetic Affinities between Multiple Sites: The reserch divided the 26 high-coverage individuals from Tel Megiddo into the following groups, on the basis of geographic location, archaeological period, and genetic clustering in PCA (Table S1): Intermediate Bronze Age (Megiddo_IBA, a single individual), Middle-to-Late Bronze Age (Megiddo_MLBA, 22 individuals), Iron Age (Megiddo_IA, a single individual), as well as the two outliers, Megiddo_I2200 and Megiddo_I10100, which were each treated as a separate group. We compared these groups and the other populations in our dataset to previously published data from other sites in the broader region and from earlier periods, including the Early Bronze Age Caucasus (Armenia_EBA), the Middle-to-Late Bronze Age Caucasus (Armenia_MLBA), the Chalcolithic Zagros Mountains (Iran_ChL), the Chalcolithic Caucasus (Armenia_ChL), the Neolithic of the Southern Levant (Levant_N), the Neolithic of the Zagros Mountains (Iran_N), and the Neolithic of Anatolia (Anatolia_N) (Lazaridis et al., 2016).” ref

“To test for variation in ancestry proportions among the Levant Bronze and Iron Age groups, we used qpWave. qpWave tests whether each possible pair of groups (Testi, Testj) is consistent with descending from a common ancestral population—that is, consistent with being a clade—since separation from the ancestors of a set of outgroup populations. qpWave works by computing symmetry test statistics of the form f4(Testi, Testj; Outgroupk, Outgroupl), which have an expected value of zero if (Testi, Testj) form a clade with respect to the outgroups. qpWave then generates a single p value corrected for the empirically measured correlation among the statistics (Reich et al., 2012). Using a distantly related set of outgroups, we found that with the exception of the outliers from Megiddo, Ashkelon IA1, and Sidon, all Bronze and Iron Age Levant groups are consistent with being pairwise clades with respect to the outgroups (Figure 2). We discuss each of qpWave’s findings of significant population substructure in turn. The Megiddo outliers not only fail to form a clade with the other populations, but also with each other. Ashkelon IA1 has previously been reported to harbor European ancestry, and so our finding that it is genetically differentiated from contemporary groups is unsurprising (Feldman et al., 2019). The significant differentiation of the Sidon individuals in qpWave—despite the fact that they roughly cluster with the other Southern Levant Bronze Age groups in PCA and ADMIXTURE—is notable, especially because we find that they are consistent with forming a clade with the two groups from coastal Ashkelon that do not have European-related admixture (the Bronze Age and later Iron Age groups ASH_LBA and ASH_IA2). Speculatively, this observation could be related to the fact that both Sidon and Ashkelon were port towns with connections to other Mediterranean coastal groups outside the Southern Levant, which could have introduced ancestry components that are absent from inland Levantine Bronze Age groups, although it is difficult to test this hypothesis in the absence of high resolution ancient DNA sampling from the eastern Mediterranean rim. The genetic distinctiveness of the Sidon individuals is also compatible with previous findings that Chalcolithic Levantine individuals from Peqi’in Cave are consistent with contributing some ancestry to the Sidon individuals, but not to the ‘Ain Ghazal ones (Harney et al., 2018). We considered the possibility that the significantly different genetic patterns we detect in the Sidon individuals could reflect their different experimental treatment compared with that of the other individuals in this study (shotgun sequencing of non-UDG-treated libraries compared with enrichment of UDG-treated libraries). To test this, we repeated the analyses by using only transversion SNPs, which are less prone to characteristic ancient DNA errors, but found no indication of systematic bias (Wang et al., 2015). However, we did find evidence of substructure within the Sidon individuals, and some but not all were consistent with forming a clade with inland Southern Levant populations, a finding that could reflect substantial cosmopolitan nature of this coastal site (Methods S1C, see Discussion).” ref

“To reveal subtler population structure, we repeated the qpWave analysis adding outgroups that are genetically closer to the test groups, such as Armenia_MLBA and Natufian (Figure 3). With this more powerful set of outgroups, Baq‛ah and Megiddo_IBA also provide evidence of not being pairwise clades with the remaining groups. Thus, beyond the broad observation of genetic affinities between sites, we also observe subtle ancestry heterogeneity across the region during the Bronze Age (see Discussion). Gene Flow into the Southern Levant During the Bronze Age: Two previous studies of Bronze Age individuals from ‘Ain Ghazal and Sidon modeled them as derived from a mixture of earlier local groups (Levant_N) and groups related to peoples of the Chalcolithic Zagros mountains (Iran_ChL) (Haber et al., 2017, Lazaridis et al., 2016). These groups were estimated to harbor around 56%±±3% and 48%±±4% Neolithic Levant-related ancestry for ‘Ain Ghazal (Lazaridis et al., 2016) and Sidon (Haber et al., 2017), respectively. We used qpAdm to estimate that Bronze and Iron Age Ashkelon (ASH_LBA and ASH_IA2) carry 54%±±5% and 42%±±5% Neolithic Levant-related ancestry, respectively. Next, we used qpAdm to test the same model for the data reported here and found that most Middle-to-Late Bronze Age groups fit the model, with point estimates of 48%–57% Levant_N ancestry. These ancestry proportions are statistically indistinguishable (Bonferroni-corrected z test), which corroborates the fact that they are consistent with forming pairwise clades in qpWave (Table S2; Methods S1D). The only group that failed to fit this model was Baq‛ah (p = 0.0003), even when using a wide range of outgroup populations (Table S2). This might be a result of ancestry heterogeneity across the Baq‛ah individuals. To obtain insight into the Zagros-related ancestry component, we focused on two questions: what is the likely origin of this ancestry component and what is its likely timing? Although people of the Chalcolithic Zagros are so far the best proxy population for this ancestry component, there is no archaeological evidence for cultural spread directly from the Zagros into the Southern Levant during the Bronze Age. In contrast, there is archaeological support for connections between Bronze Age Southern Levant groups and the Caucasus (Greenberg and Goren, 2009), a term we use to represent both present-day Caucasus, as well as neighboring regions such as eastern Anatolia (see Discussion). With regard to the timing of these events, archaeology points to cultural affinities between the Kura-Araxes (Caucasus) and Khirbet Kerak (Southern Levant) archaeological cultures in the first half of the 3rd millennium BCE (Greenberg and Goren, 2009), and textual evidence documents a number of non-Semitic, Hurrian (from the northeast of the ancient Near East) personal names in the 2nd millennium BCE, for example in the Amarna archive of the 14th century BCE (Na’aman, 1994b). The reserchers, therefore, reasoned that the Chalcolithic Zagros component might have arrived into the Southern Levant through the Caucasus (and even more proximately the northeastern areas of the ancient Near East, although we have no ancient DNA sampling from this region). This movement might not have been limited to a short pulse, and instead could have involved multiple waves throughout the Bronze Age. To test whether the origin of the gene flow was from the Caucasus, rather than directly from the Zagros region, we ran qpAdm, replacing Iran_ChL with Early Bronze Age Caucasus (Armenia_EBA). We found that the Caucasus model received similar support to that of the Zagros model (Table S2; Methods S1E). Next, we modeled Armenia_EBA as a mixture of an earlier Caucasus population (Chalcolithic Armenia, Armenia_ChL) and Iran_ChL and found that indeed Armenia_EBA is compatible with this model (Table S2). Altogether, we conclude that our data are also compatible with a model in which Zagros-related ancestry in the Southern Levant arrived through the Caucasus, either directly or via intermediates.” ref

“To study the timing of the admixture of Zagros-related ancestry in the Southern Levant, we leveraged the large time span of individuals in our dataset, extending across roughly 1,500 years, from the Intermediate Bronze Age to the Early Iron Age. Using qpAdm-based ancestry estimates for each of the individuals, we found that almost all are compatible with being an admixture of groups related to the Neolithic Levant and Chalcolithic Zagros. One exception to this is an individual in Megiddo_MLBA that is weakly compatible with the model. Another exception is three individuals in the Baq’ah (Table S2), which suggests that the difficulty in modeling individuals from this site as a mixture of Neolithic Levant and Chalcolithic Zagros might reflect ancestry heterogeneity (Figure 3). These results do not change qualitatively when we used a larger set of outgroup populations (Table S2). We observed that the oldest individuals in our collection, from the Intermediate Bronze Age, already carried significant Zagros-related ancestry, suggesting that gene flow into the region started before ca. 2400 BCE. This is consistent with the hypothesis that people of Kura-Araxes archaeological complex of the 3rd millennium BCE might have affected the Southern Levant not only culturally, but also through some degree of movement of people. Our data also imply an increase in the proportion of Zagros-related ancestry after the Intermediate Bronze Age, as reflected in a significantly positive slope in a linear regression of the Chalcolithic-Zagros-related ancestry over the calendar year (β=1.4⋅104±0.4⋅104β=1.4⋅104±0.4⋅104, Jackknife), amounting to an increase of ∼14% per thousand years (Figures 4 and S2A). However, we caution that the number of individuals and their time span are insufficient to determine whether the increase in the Zagros-related ancestry happened continuously during the Middle and Late Bronze Ages, or whether there were multiple distinct migration events. The two outliers from Megiddo (three including the sibling pair) provide additional evidence for the timing and origin of gene flow into the region. The three were found in close proximity to each other at Level K-10, which is radiocarbon dated to 1581–1545 BCE (domestic occupation) and 1578–1421 BCE (burials; both ± 1 s) (Martin et al., 2020, Toffolo et al., 2014), whereas the bone of one of the three (I10100) was directly dated (1688–1535 BCE, ± 2Σ). The reason these individuals are distinct from the rest is that their Caucasus- or Zagros-related genetic component is much higher, reflecting ongoing gene flow into the region from the northeast (Table S2; Figure S2B). The Neolithic Levant component is 22%–27% in I2200, and 9%–26% in I10100. These individuals are unlikely to be first generation migrants, as strontium isotope analysis on the two outlier siblings (I2189 and I2200) (Methods S1A) suggests that they were raised locally. This implies that the Megiddo outliers might be descendants of people who arrived in recent generations. Direct support for this hypothesis comes from the fact that in sensitive qpAdm modeling (including closely related sets of outgroups), the only working northeast source population for these two individuals is the contemporaneous Armenia_MLBA, whereas the earlier Iran_ChL and Armenia_EBA do not fit (Table S2). The addition of Iran_ChL to the set of outgroups does not change this result or cause model failure. Finally, no other Levantine group shows a similar admixture pattern (Table S2). This shows that some level of gene flow into the Levant took place during the later phases of the Bronze Age and suggests that the source of this gene flow was the Caucasus. Altogether, our analyses show that gene flow into the Levant from people related to those in the Caucasus or Zagros was already occurring by the Intermediate Bronze Age, and that it lingered, episodically or continuously, at least in inland sites, during the Middle-to-Late Bronze Age.” ref

Further Change in Levantine Populations Since the Bronze Age

“To develop a sense of population changes in the Levant since the Bronze Age, we attempted to model groups that have a tradition of descent from ancient people in the region (Jews) as well as Levantine Arabic-speakers as mixtures of various ancient source populations. qpAdm assumes no admixture between groups related to the outgroups and the source populations, but almost all present-day Levantine and Mediterranean populations have significant sub-Saharan-African-related admixture that the ancient groups did not. This eliminates many key outgroups for qpAdm and reduces the utility of the method in this context. In particular, we were not able to apply qpAdm to get a single working model for the majority of present-day West Eurasian populations. As an alternative, we developed a methodology we call LINADMIX, which relies on the output of ADMIXTURE (Alexander et al., 2009) and uses constrained least-squares to estimate the contribution of given source populations to a target population (see STAR Methods). As a complementary approach, we developed a tool we call pseudo-haplotype ChromoPainter (PHCP), which is an adaptation of the haplotype-based method ChromoPainter (Lawson et al., 2012) to ancient genomes (see STAR Methods; Methods S1F). We first established that these methods provide meaningful estimates of ancestry in the context of this study by using them to re-compute the ancestry proportions that we were able to model with qpAdm. Both LINADMIX and PHCP (Table S3; Figure S3; Methods S1F) produce qualitatively similar estimates as qpAdm (Table S2). To further establish the methods, we performed simulations that were designed to test the methods’ abilities to infer ancestry proportions in present-day populations in a setup similar to the current study (Methods S1H). For this, we generated present-day populations as a mixture of two closely related ancient populations with and without a third, more distant, population. Both methods estimated the ancestry proportion of the distant source population with errors of up to 4% and the proportions of the closely related source populations with errors of up to 10%. Thus, although ADMIXTURE, the basis of LINADMIX, is known to have certain pitfalls as a tool for quantifying ancestry proportions (Lawson et al., 2018), in the case of individuals with ancestry sources similar to those we have analyzed here, our results suggest that both LINADMIX and PHCP are highly informative. For the LINADMIX analysis of present-day populations, we used a background dataset of 1,663 present-day and ancient individuals from 239 populations genotyped by using SNP arrays and focused our analysis on 14 Jewish and Levantine present-day populations, along with modern English, Tuscan, and Moroccan populations that were used as controls. We used LINADMIX to model each of the 17 present-day populations as an admixture of four sources: (1) Megiddo_MLBA (the largest group) as a representative of the Middle-to-Late Bronze Age component; (2) Iran_ChL as a representative of the Zagros and the Caucasus; (3) Present-day Somalis as representatives of an Eastern African source (in the absence of genetic data on ancient populations from the region); and (4) Europe_LNBA as a representative of ancient Europeans from the Late Neolithic and Bronze Age (Methods S1I; Table S4; Figure S4). We also applied PHCP to these 17 present-day populations (Methods S1G; Table S4; Figure S4). Comparison of PHCP and LINADMIX shows that they agree well with respect to the Somali and Europe_LNBA component, and therefore also for the combined contribution of Iran_ChL and Megiddo_MLBA (Methods S1G; Figure S4). However, they deviate regarding the respective contributions of Iran_ChL and Megiddo_MLBA (Figure S4), likely because of the fact that the Megiddo_MLBA and Iran_ChL are already very similar populations (Table S3). To only consider results that are robust and shared by LINADMIX and PHCP, we have combined Megiddo_MLBA and Iran_ChL to a single source population representing the Middle East for our main results (Figure 5). We further verified these conclusions, as well as the robustness of the estimations, by using a different representative for the Bronze Age Levantine groups as a source (Tables S4 and S5; Methods S1J) and using perturbations to the ADMIXTURE parameters (Table S4; Methods S1K). Combined, these results suggest that modern populations related to the Levant are consistent with having a substantial ancestry component from the Bronze Age Southern Levant and the Chalcolithic Zagros. Nonetheless, other potential ancestry sources are possible, and more ancient samples might enable a refined picture (Table S4).” ref

The results show that since the Bronze Age, an additional East-African-related component was added to the region (on average ∼10.6%, excluding Ethiopian Jews who harbor ∼80% East African component), as well as a European-related component (on average ∼8.7%, excluding Ashkenazi Jews who harbor a ∼41% European-related component). The East-African-related component is highest in Ethiopian Jews and North Africans (Moroccans and Egyptians). It exists in all Arabic-speaking populations (apart from the Druze). The European-related component is highest in the European control populations (English and Tuscan), as well as in Ashkenazi and Moroccan Jews, both having a history in Europe (Atzmon et al., 2010, Carmi et al., 2014, Schroeter, 2008). This component is present, although in smaller amount, in all other populations except for Bedouin B and Ethiopian Jews. As expected, the English and Tuscan populations have a very low Middle-Eastern-related component. Whereas LINADMIX and PHCP have high uncertainty in estimating the relative contributions of Megiddo_MLBA and Iran_ChL, the results and simulations nevertheless suggest that additional Zagros-related ancestry has penetrated the region since the Bronze Age (Methods S1I). Except for the populations with the highest Zagros-related component, PHCP estimates lower magnitudes of this component (Figure S4A), and therefore detection by PHCP of a Zagros-related ancestry is likely an indication for the presence of this component. Indeed, examining the results of LINADMIX and PHCP on all four source populations (Figure S4), we observe a relatively large Zagros-related component in many Arabic-speaking groups, suggesting that gene flow from populations related to those of the Zagros and Caucasus (although not necessarily from these specific regions) continued even after the Iron Age (Methods S1I). Altogether, the patterns of the present-day populations reflect demographic processes that occurred after the Bronze Age and are plausibly related to processes known from the historical literature (Methods S1I). These include an Eastern-African-related component that is present in Arabic-speaking groups but is lower in non-Ethiopian Jewish groups, as well as Zagros-related contribution to Levantine populations, which is highest in the northernmost population examined, suggesting a contribution of populations related to the Zagros even after the Bronze and Iron Ages. The results provide a comprehensive genetic picture of the primary inhabitants of the Southern Levant during the 2nd millennium BCE, known in the historical record and based on shared material culture as “Canaanites.” We carried out a detailed analysis aimed at answering three basic questions: how genetically homogeneous were these people, what were their plausible origins with respect to earlier peoples, and how much change in ancestry has there been in the region since the Bronze Age? Earlier genetic analyses modeled the genomes of Middle-to-Late Bronze Age people of the Southern Levant as having almost equal shares of earlier local populations (Levant_N) and populations that are related to the Chalcolithic Zagros (Feldman et al., 2019, Haber et al., 2017, Lazaridis et al., 2016), suggesting a movement from the northeast into the Southern Levant. Here, we provide more details on this process, taking into account evidence from both archaeology and our temporally and geographically diverse genetic data. Because there is little archaeological evidence of a direct cultural connection between the Southern Levant and the Zagros region in this period, the Caucasus is a more likely source for this ancestry. We used our data to compare these two scenarios and concluded that the genetic data are compatible with both.” ref

“The Megiddo outliers, which we inferred to be relative newcomers to the region, are particularly important in demonstrating that the gene flow continued throughout the Bronze Age and that at least some of the gene flow likely came from the Caucasus rather than the Zagros. These two individuals have the highest proportions of Zagros- or Caucasian-related ancestry in our dataset. Analysis of these outliers gave significantly stronger evidence of a Caucasus source compared with a Zagros one, although this conclusion might be revised once ancient DNA data from the Middle-to-Late Bronze Age in the Zagros region become available. The two Megiddo individuals with the next lowest Neolithic Levant component (I10769 and I10770, brothers) were found near the monumental tomb that was likely related to the palace at Megiddo, raising the possibility that they might be associated with the ruling caste. Indeed, a ruler of Taanach (a town located immediately to the south of Megiddo) mentioned in a 15th century BCE cuneiform tablet found at the site and the rulers of Megiddo and Taanach mentioned in the 14th century BCE Amarna letters (found in Egypt) carry Hurrian names (a language spoken in the northeast of the ancient Near East, possibly including the Caucasus) (Na’aman, 1994b). This provides some evidence—albeit so far only suggestive—that at least some of the ruling groups in these (and other) cities might have originated from the northeast of the ancient Near East. The Caucasus is represented in this study by ancient groups from the present-day country of Armenia, but the region known to have had cultural ties with the Southern Levant is much broader. Evidence of cultural effects on the Southern Levant is mainly focused on the Kura-Araxes culture during the Early Bronze Age (archaeology) and on the Hurrians during the Middle-to-Late Bronze Age (linguistic testimony). These two complexes were spread over the Caucasus, Eastern Anatolia, and neighboring regions. The Armenian sites we analyzed are the best representatives to date of these cultures. The Early Bronze Age individuals from Armenia (Armenia_EBA) come from an Early Bronze Age Kura-Araxes burial ground, and the later Middle-to-Late Bronze Age individuals (Armenia_MLBA) come from the Aragatsotn Province in northwestern Armenia. It is important to note that the Neolithic and Chalcolithic Anatolian individuals analyzed in this study come from the northwestern part of Anatolia, which is not part of the Caucasus. The Chalcolithic Zagros individuals come from the Kangavar Valley in Iran, which is located on the border of the Kura-Araxes influence.” ref

“The term “Canaanites” is loosely defined, referring to a collection of groups (which in the Bronze Age were organized in a city-state system) and thus in principle could lack genetic coherence. The individuals examined here cover a wide geographic span—coming from nine sites in present-day Lebanon, Israel, and Jordan. Our analyses revealed that, with the exception of Sidon (and to a smaller extent the individuals of the Baq‛ah), they are homogeneous in the sense of being closer to each other than to other contemporary and neighboring populations. This suggests that the archaeological and historical category of “Canaanites” correlates with shared ancestry (Eisenmann et al., 2018). This resembles the pattern observed in the Aegean basin during the 2nd millennium BCE, where the cultural categories of “Minoan” and “Mycenaean” show evidence of genetic homogeneity across multiple sites albeit with potentially subtle ancestry differences within these groupings (Lazaridis et al., 2017). Another example is the “Yamnaya” pastoralists of late 3rd and early 2nd millennium BCE in the western Eurasian Steppe (Allentoft et al., 2015, Haak et al., 2015). This contrasts with the pattern seen in other places, such as for the Bell Beaker cultural complex of the 2nd millennium BCE (Olalde et al., 2018), where people sharing similar cultural practices had widely varying ancestry. In any case, the detection of such associations—as we do here—cannot by itself prove that group identities in the past were related to genetics. From the groups we have examined, the only one that is somewhat diverged from the rest is Sidon. We provide evidence against the possibility that this observation is a batch effect (Methods S1C). Rather, we suggest that the relative remoteness of Sidon stems from the fact that this population is genetically heterogeneous and has different individuals showing resemblance to different Southern Levantine groups (Methods S1C). During the 2nd millennium BCE, Sidon was a major port city and was connected in trading relations with the eastern Mediterranean basin, which could have led to a significant genetic inflow, making its population more heterogeneous than that of inland cities. This might also be the reason that the site that most resembles Sidon is Ashkelon, which is another coastal site. The only inland population that resembles Sidon is Abel Beth Maacah, perhaps because of its geographic proximity (Figures 1A and 2). Apart from Sidon, Baq‛ah also shows some minor deviations from the rest when taking a richer set of outgroup populations (Figure 3). The Baq‛ah is located on the fringe of the Syrian desert, therefore this population might be admixed with more eastern groups, which are not yet genetically sampled. This might be reflected by the fact that the individuals of the Baq‛ah also show some degree of variability in their ancestry patterns (Table S2).” ref

“Although this study focuses on the Bronze Age, it also reports two new samples from the Iron Age—one from Megiddo and the other from Abel Beth Maacah. These two individuals show ancestry patterns that are very similar to those observed in the Middle and Late Bronze Age individuals (Figure 4), suggesting that the destruction at the end of the Bronze Age in the region did not necessarily lead to genetic discontinuity in each and every site. Notably, both Abel Beth Maacah and Megiddo are inland cities, and their genetic continuity throughout the transition from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age might not be representative of other sites in the region. For example, one of the two Iron Age populations in the Philistine coastal city of Ashkelon (ASH_IA1) showed evidence of mobility of populations related to southern Europe around the Bronze Age to Iron Age transition (Feldman et al., 2019). Estimating the ancestry proportions in present-day Middle Eastern populations with substantial sub-Saharan African admixture (as well as multiple sources of admixture from different parts of the Mediterranean), is difficult. We addressed the problem by developing two statistical techniques and then testing the robustness of our inference on the basis of a comparison between these methods, simulations, and perturbations of the input (see STAR Methods; Methods S1F–S1K). We examined 14 present-day populations that are historically or geographically linked to the Southern Levant and tested the contributions of East Africa, Europe, and the Middle East (combining Southern Levant Bronze Age populations and Zagros-related Chalcolithic ones) to their ancestry. We found that both Arabic-speaking and Jewish populations are compatible with having more than 50% Middle-Eastern-related ancestry. This does not mean that any these present-day groups bear direct ancestry from people who lived in the Middle-to-Late Bronze Age Levant or in Chalcolithic Zagros; rather, it indicates that they have ancestries from populations whose ancient proxy can be related to the Middle East. The Zagros- or Caucasian-related ancestry flow into the region apparently continued after the Bronze Age. We also see an Eastern-African-related ancestry entering the region after the Bronze Age with an approximate south-to-north gradient. In addition, we observe a European-related ancestry with the opposite gradient (north-to-south). Given the difficulties in separating the ancestry components arriving from the Southern Levant and the Zagros, an important direction for future work will be to reconstruct in high resolution the ancestry trajectories of each present-day group, and to understand how people from the Southern Levant Bronze Age mixed with other people in later periods in the context of processes known from the rich archaeological and historical records of the last three millennia.” ref

“The Kura-Araxes cultural tradition is reflected in the mountains north, east and west of Mesopotamia from the mid-fourth to mid-third millennia BC. Originating in the Armenian Highlands and its subset the South Caucasus, it developed over that period, and also spread across a wide area of the Taurus and Zagros mountains, down into the Southern Levant, and north beyond the Caucasus Mountains. Despite many decades of excavation of sites relating to this cultural tradition, we know surprisingly little about the societies of the homelands and their relationship to their migrant diaspora. This paper looks at one aspect of those cultures, ritual practice and ideology, to see if it is possibly better to define the nature of and changes in Kura-Araxes societies within the homelands, and their possible relationship to migrant communities.” ref

“Excavation of the early 3rd millennium levels at Arslantepe-Malatya, which reveal substantial changes following the collapse of the Late Chalcolithic centralized system in connection with the establishment of new groups linked to the Kura-Araxes culture . The new data show that these early 3rd millennium settlements, besides marking a break with respect to the earlier Chalcolithic period and a radically new organization, interestingly also show more elements of continuity than previously thought in the maintenance of a central role for Arslantepe in the Malatya region and in the continuation of some traditions such as those related to metallurgy. Rather than a momentary intrusion of pastoral communities of Transcaucasian origin, the new picture suggests the temporary appropriation of the site by mobile, probably transhumant groups moving in a wide area around the plain and already well-rooted in the region; after the destruction of the 4th millennium (4000 through 3000 BCE or around 6,020 to 5,020 years ago) palace, they used Arslantepe as their power center and landmark, probably competing with the local rural population for the control of the site and the region. This article presents the main results obtained during the recent excavation of levels from the beginning of the 3rd millennium in Arslantepe-Malatya, levels which revealed profound changes after the collapse of the centralized system of the Late Chalcolithic, in connection with the installation. on the site new population groups linked to the Kura-Araxe culture. Besides the fact that they mark a break with the Chalcolithic and testify to a radically new organization, recent data show that these occupations of the beginning of the 3rd millennium also present more elements of continuity than previously thought in the maintenance of the central role d’Arslantepe in the region of Malatya and in the pursuit of certain traditions such as those related to metallurgy. The image that is emerging now suggests the temporary appropriation of the site by mobile groups, probably transhumant, moving over a large area around the [Malatya] plain and already well established in this region, more than a temporary intrusion. pastoral communities from Transcaucasia. After the destruction of the 4th millennium palace.” ref

The formative processes of the Kura-Araxes cultural complex, and the date and circumstances of its rise, have been long debated. Shulaveri-Shomu culture preceded the Kura–Araxes culture in the area. There were many differences between these two cultures, so the connection was not clear. Later, it was suggested that the Sioni culture of eastern Georgia possibly represented a transition from the Shulaveri to the Kura-Arax cultural complex. At many sites, the Sioni culture layers can be seen as intermediary between Shulaver-Shomu-Tepe layers and the Kura-Araxes layers. This kind of stratigraphy warrants a chronological place of the Sioni culture at around 4000 BCE. Nowadays scholars consider the Kartli area, as well as the Kakheti area (in the river Sioni region) as key to forming the earliest phase of the Kura–Araxes culture. To a large extent, this appears as an indigenous culture of Caucasus that was formed over a long period, and at the same time incorporating foreign influences. There are some indications (such as at Arslantepe) of the overlapping in time of the Kura-Araxes and Uruk cultures; such contacts may go back even to the Middle Uruk period. Some scholars have suggested that the earliest manifestation of the Kura-Araxes phenomenon should be dated at least to the last quarter of the 5th millennium BC. This is based on the recent data from Ovçular Tepesi, a Late Chalcolithic settlement located in Nakhchivan by the Arpaçay river.” ref

Kura-Araxes Cultural Expansion

“They proceed westward to the Erzurum plain, southwest to Cilicia, and to the southeast into the area of Lake Van, and below the Urmia basin in Iran, such as to Godin Tepe. Finally, it proceeded into present-day Syria (Amuq valley), and as far as Palestine. Its territory corresponds to large parts of modern Armenia, Azerbaijan, Chechnya, Dagestan, Georgia, Ingushetia, North Ossetia, and parts of Iran and Turkey. At Sos Hoyuk, in Erzurum Province, Turkey, early forms of Kura-Araxes pottery were found in association with local ceramics as early as 3500-3300 BC. During the Early Bronze Age in 3000-2200 BC, this settlement was part of the Kura-Araxes phenomenon. At Arslantepe, Turkey, around 3000 BCE, there was widespread burning and destruction, after which Kura-Araxes pottery appeared in the area. According to Geoffrey Summers, the movement of Kura-Araxes peoples into Iran and the Van region, which he interprets as quite sudden, started shortly before 3000 BC, and may have been prompted by the ‘Late Uruk Collapse’ (end of the Uruk period), taking place at the end of Uruk IV phase c. 3100 BC.” ref

“Archaeological evidence of inhabitants of the Kura–Araxes culture showed that ancient settlements were found along the Hrazdan river, as shown by drawings at a mountainous area in a cave nearby. Structures in settlements have not revealed much differentiation, nor was there much difference in size or character between settlements, facts that suggest they probably had a poorly developed social hierarchy for a significant stretch of their history. Some, but not all, settlements were surrounded by stone walls. They built mud-brick houses, originally round, but later developing into subrectangular designs with structures of just one or two rooms, multiple rooms centered around an open space, or rectilinear designs. At some point, the culture’s settlements and burial grounds expanded out of lowland river valleys and into highland areas. Although some scholars have suggested that this expansion demonstrates a switch from agriculture to pastoralism and that it serves as possible proof of a large-scale arrival of Indo-Europeans, facts such as that settlement in the lowlands remained more or less continuous suggest merely that the people of this culture were diversifying their economy to encompass crop and livestock agriculture. Shengavit Settlement is a prominent Kura-Araxes site in present-day Yerevan area in Armenia. It was inhabited from approximately 3200 BC cal to 2500 BC cal. Later on, in the Middle Bronze Age, it was used irregularly until 2200 BC cal. The town occupied an area of six hectares, which is large for Kura-Araxes sites.” ref

Kura-Araxes Ritual Mounds

“In the 3rd millennium B.C., one particular group of mounds of the Kura–Araxes culture is remarkable for their wealth. This was the final stage of culture’s development. These burial mounds are known as the Martqopi (or Martkopi) period mounds. Those on the left bank of the river Alazani are often 20–25 meters high and 200–300 meters in diameter. They contain especially rich artefacts, such as gold and silver jewelry. Inhumation practices are mixed. Flat graves are found but so are substantial kurgan burials, the latter of which may be surrounded by cromlechs. This points to a heterogeneous ethno-linguistic population. Analyzing the situation in the Kura-Araxes period, T.A. Akhundov notes the lack of unity in funerary monuments, which he considers more than strange in the framework of a single culture; for the funeral rites reflect the deep culture-forming foundations and are weakly influenced by external customs. There are non-kurgan and kurgan burials, burials in-ground pits, in stone boxes and crypts, in the underlying ground strata, and on top of them; using both the round and rectangular burials; there are also substantial differences in the typical corpse position. Burial complexes of Kura–Araxes culture sometimes also include cremation. Here one can come to the conclusion that the Kura–Araxes culture developed gradually through a synthesis of several cultural traditions, including the ancient cultures of the Caucasus and nearby territories.” ref

‘Origin of Early Transcaucasian Culture (aka Kura-Araxes culture)

From the paper:

Akhundov (2007) recently uncovered pre-Kura-Araxes/Late Chalcolithic materials from the settlement of Boyuk Kesik and the kurgan necropolis of Soyuq Bulaq in northwestern Azerbaijan, and Makharadze (2007) has also excavated a pre-Kura-Araxes kurgan, Kavtiskhevi, in central Georgia. Materials recovered from both these recent excavations can be related to remains from the metal-working Late Chalcolithic site of Leilatepe on the Karabakh steppe near Agdam (Narimanov et al. 2007) and from the earliest level at the multi-period site of Berikldeebi in Kvemo Kartli (Glonti and Dzavakhishvili 1987). They reveal the presence of early 4th millennium raised burial mounds or kurgans in the southern Caucasus. Similarly, on the basis of her survey work in eastern Anatolia north of the Oriental Taurus mountains, C. Marro (2007)likens chafffaced wares collected at Hanago in the Sürmeli Plain and Astepe and Colpan in the eastern Lake Van district in northeastern Turkey with those found at the sites mentioned above and relates these to similar wares (Amuq E/F) found south of the Taurus Mountains in northern Mesopotamia

…

The new high dating of the Maikop culture essentially signifies that there is no

chronological hiatus separating the collapse of the Chalcolithic Balkan centre of

metallurgical production and the appearance of Maikop and the sudden explosion of Caucasian metallurgical production and use of arsenical copper/bronzes. More than forty calibrated radiocarbon dates on Maikop and related materials now support this high chronology; and the revised dating for the Maikop culture means that the earliest kurgans occur in the northwestern and southern Caucasus and precede by several centuries those of the Pit-Grave (Yamnaya) cultures of the western Eurasian steppes (cf. Chernykh and Orlovskaya 2004a and b). The calibrated radiocarbon dates suggest that the Maikop ‘culture’ seems to have had a formative influence on steppe kurgan burial rituals and what now appears to be the later development of the Pit-Grave (Yamnaya) culture on the Eurasian steppes (Chernykh and Orlovskaya 2004a: 97).

…

In other words, sometime around the middle of the 4th millennium BCE or slightly subsequent to the initial appearance of the Maikop culture of the NW Caucasus, settlements containing proto-Kura-Araxes or early Kura-Araxes materials first appear across a broad area that stretches from the Caspian littoral of the northeastern Caucasus in the north to the Erzurum region of the Anatolian Plateau in the west. For simplicity’s sake these roughly simultaneous developments across this broad area will be considered as representing the beginnings of the Early Bronze Age or the initial stages of development of the KuraAraxes/Early Transcaucasian culture.

…

The ‘homeland’ (itself a very problematic concept) of the Kura-Araxes culture-historical community is difficult to pinpoint precisely, a fact that may suggest that there is no single well-demarcated area of origin, but multiple interacting areas including northeastern Anatolia as far as the Erzurum area, the catchment area drained by the Upper Middle Kura and Araxes Rivers in Transcaucasia and the Caspian corridor and adjacent mountainous regions of northeastern Azerbaijan and southeastern Daghestan. While broadly (and somewhat imprecisely) defined, these regions constitute on present evidence the original core area out of which the Kura-Araxes ‘culture-historical community’ emerged.

Kura-Araxes materials found in other areas are primarily intrusive in the local sequences. Indeed, many, but not all, sites in the Malatya area along the Upper Euphrates drainage of eastern Anatolia (e.g., Norsun-tepe, Arslantepe) and western Iran (e.g., Yanik Tepe, Godin Tepe) exhibit— albeit with some overlap—a relatively sharp break in material remains, including new forms of architecture and domestic dwellings, and such changes support the interpretation of a subsequent spread or dispersal from this broadly defined core area in the north to the southwest and southeast. The archaeological record seems to document a movement of peoples north to south across a very extensive part of the Ancient Near East from the end of the 4th to the first half of the 3rd millennium BCE. Although migrations are notoriously difficult to document on archaeological evidence, these materials constitute one of the best examples of prehistoric movements of peoples available for the Early Bronze Age.” ref

Origins, Homelands and Migrations: Situating the Kura-Araxes Early Transcaucasian ‘Culture’ within the History of Bronze Age Eurasia

“This paper summarizes the current understanding of the emergence, nature and subsequent southwestern and southeastern spread of the early Transcaucasian (eTC) or Kura-Araxes ‘culture-historical community’ (Russian: obshchnost’) and then places this complex cultural phenomenon in the context of the larger early Bronze Age world of the Ancient Near East and the western Eurasian steppes.” ref

Early Bronze Age migrants and ethnicity in the Middle Eastern mountain zone

“This analysis shows the complex interaction of ethnic groups in antiquity, adapting to new locations and adopting and ultimately, assimilating into a majority culture. It occurs in a background of mountain valleys and highland plains, where ever-shifting populations carve out a living and an identity.” ref

Abstract

“The Kura-Araxes cultural tradition existed in the highlands of the South Caucasus from 3500 to 2450 BCE (before the Christian era). This tradition represented an adaptive regime and a symbolically encoded common identity spread over a broad area of patchy mountain environments. By 3000 BCE, groups bearing this identity had migrated southwest across a wide area from the Taurus Mountains down into the southern Levant, southeast along the Zagros Mountains, and north across the Caucasus Mountains. In these new places, they became effectively ethnic groups amid already heterogeneous societies. This paper addresses the place of migrants among local populations as ethnicities and the reasons for their disappearance in the diaspora after 2450 BCE.” ref

Kura-Araxes Case

“The societies of the so-called Kura-Araxes cultural tradition that emerged in the highlands during the fourth millennium and continued into the early third millennium BCE (before the Christian era)—Shengavitian, Karaz, Pulur, Yanik, Early Transcaucasian, and Khirbet Kerak are some of its other names—present scholars of the Greater Middle East and Eurasia with a laboratory for studying the evolution of human cultures and the societies that they spawned in highland zones, a topic much studied in ethnography and less so in archaeology.” ref

Kura-Araxes as a Cultural Tradition.

“How do we know that we are dealing with groups of ethnic migrants? The commonly cited answer is that the Kura-Araxes groups are marked by distinctive pottery styles (9⇓–11) (Fig. 2). This pottery corpus consists of very distinctive handmade, black burnished pottery, often with incised or raised designs. In the latter, a thick layer is added, and then, all but the design is removed, like a faux appliqué. The cultural importance of this pottery style is that it dominates the area of the earliest appearance of the Kura-Araxes cultural tradition for a millennium or more. In areas out of the homeland of the South Caucasus [the current nation-states of Georgia, Armenia, Azerbijan (specifically Nachiçevan), and northeastern Turkey], the same pottery begins to appear, most prominently in the late fourth and early third millennia BCE. Its contrast with the local buff, wheel-made pottery makes the Kura-Araxes black ware seem out of place. Based on this fact, archaeologists have argued that this pottery represents migrants, who became, in effect, ethnic groups within the areas of the Taurus Mountains (12), the Zagros Mountains (13), the Amuq, Galilee (14), and north of the Caucasus Mountains (15). Whereas the idea that pottery style alone can define social groups—pots equal peoples (4, 11, 16)—is suspect and was used by many 19th and early 20th century archaeologists to reach rather unsophisticated and frankly, wrong conclusions about social process, in this case, it may be valid (11, 17). More than simple style is evident. Based on studies of the inclusions in the fabric of pottery bodies—pure clay cannot be used to make stable pottery without the addition of tempering materials—petrographers who study the makeup of pottery fabric determined that the residents of Bet Yeraḥ (Khirbet Kerak) in the Southern Levantine Early Bronze III (2650 BCE) were using the same techniques as those of Kura-Araxes sites hundreds of years earlier and as many kilometers away in Armenia (18, 19). The Kura-Araxes/Khirbet Kerak people and the local Early Bronze III people did not even use the same clay sources, except for some cooking pot wares.” ref

“In addition, a repeated pattern of migration is evident. In the Muş Province west of Lake Van, new sites appeared in the mountainous areas with early Kura-Araxes pottery followed by the appearance of greater population (determined by number of sites and total hectares) in the valley bottom. In the latest phases, residents were using pottery that was a fusion of Kura-Araxes and local Late Chalcolithic techniques (20). Farther west in the Taurus and the Levant, another pattern appeared. Archaeologists found small percentages of Kura-Araxes pottery first at central (or town) sites followed by the appearance of small sites dominated entirely by people using Kura-Araxes–styled pottery (12). At the same time, Frangipane and Palumbi (21) argue that, in the Upper Euphrates area near Arslantepe (Fig. 1), the fourth millennium BCE black burnished ware is not the same as the Kura-Araxes ware, deriving instead from central Anatolia to the west. In the Zagros, Kura-Araxes wares, often with design techniques different from those farther west, appear in newly founded and central sites, whereas neighboring areas lack any evidence of Kura-Araxes presence (pottery) (13).” ref

“This ethnic identity is not, however, limited to pottery style. Archaeologists found remains of a common religious ritual that spans large areas of the South Caucasian homeland and the immigrant diaspora. This common religious practice is represented by a type of ritual emplacement with decorated fireplaces (either ceramic or a free-standing andiron) (22, 23). House construction and layouts are also distinct. These practices indicate common structures of social groups (family) and activities (13). Metals items also share common design patterns, especially in decorative objects. Spiral earrings and pins with two spiral ends occur across the range of the Kura-Araxes (11, 24). Taken together, these different kinds of data suggest that there were Kura-Araxes ethnic groups within a large expanse of the upper Middle East, mostly in mountainous zones. To the west of the homeland, they were, in most cases, a minority within their new homelands and did not dominate or replace the local populations. In the Zagros to the east, they seem to be more dominant (see below). According to definitions of ethnicity by Barth (2) and Gross (3), they had the key elements of ethnic groups. They shared a symbolic identity, which was distinct and recognizable from their surrounding populations, and maintained a field of communication and interaction that extended all of the way back to their homeland. If the ritual practices are widespread—we have only a few excavated examples—their common religious ritual certainly represents a common set of values (23).” ref

“Furthermore, Anthony (25) relates these kinds of common ideological and ethnic identifiers through style (in this case, pottery, architecture, and metals) to language, one of the most prominent components of ethnographically and historically documented ethnic groups. Anthony (25) correlates distinctive regional languages and dialects to what he calls “Material-Culture Frontiers” (25). These frontiers are created by different sources of immigration and also, different ecological boundaries. The more self-sufficient that a group is in a particular environment, the more likely that they will tend toward a local language and a local, more homogeneous cultural style. This pattern may explain, in part, the many local variations in Kura-Araxes pottery designs and shapes, even in the homeland (26). However, in less certain environments or ones that require resources from a broad set of ecological niches, greater variability in language will exist. The latter describes, in part, the highland domain of the Kura-Araxes.” ref

Kura-Araxes in Broader Ecological Context.

“Issues of ecology and adaptation to local conditions within a broader geographical context are important in understanding ethnic identity and change. The Kura-Araxes homeland and the vast majority of its diaspora were mountainous environments. These environments go from the narrow valleys of the higher elevations in areas, like Shida Kartli (27), to the broader lower elevation plains, like Ararat (28, 29). All are in fairly marginal zones for agricultural, although rich in pastureland (30). One of the largest issues remaining to be resolved is the nature of the broader effect of intercultural interaction on reasons for migration (see below) and the comparison of the lowland and highland cultural structures. Archaeologists are still investigating direct relationships between the South Caucasian homeland and its adjoining regions. The raw materials for metal production north of the Caucasus (the Maikop) certainly were mined in the South Caucasus (15). Whether the Kura-Araxes societies were the source of metal technology—this possibility has long been a supposition of archaeologists—is now being questioned (31). Certainly, the Taurus and Zagros, where Kura-Araxes migrants went, are the key resources areas for the developing state societies of Mesopotamia (32⇓–34). The “supercities” of the Ukraine in the fourth millennium BCE, which are thought to be a result of exchange through the Mesopotamian Uruk expansion trading network (15, 35), had to pass through the South Caucasus. Archaeologists found fourth millennium BCE northern Mesopotamian pottery styles in the Kura-Araxes area of Georgia, and the precursors of the Kura-Araxes exhibit Mesopotamian-related styles (11, 31).” ref

“However, from what we know of the effects of the trading relationship with Mesopotamia on local societal development in other parts of the mountain zone (21, 36), such effects are not evident in the Kura-Araxes homeland. Societies and ethnic groups exhibiting the Kura-Araxes cultural tradition are a contrast to contemporary Mesopotamian societies. They were not urban societies, and as far as we can tell, they initially had subsistence economies. They had greater reliance on pastoral than agricultural products. Their productive technologies seem to have been tied to local resources, such as obsidian and flint; copper ores; semiprecious stones, like carnelian; and indigenous plants, such as wheat, barley, and grapes. Their social organization exhibited less centralization and less social differentiation than in Mesopotamia (23).” ref

Causes of Migration.

“To understand the role and the fate of ethnic groups in the diaspora, four questions need to be addressed. (i) Why did they emigrate in the first place? (ii) How does that reflect their place in the local societies? (iii) How did their new setting get reflected in their societies? (iv) In this case, why did they, in effect, disappear after 2500 B.C. as a distinct ethnic group? The first question, after evidence of a migration has been established, is to ask why it took place in enough numbers that we find their remains in mounded sites. However, “while it is often difficult to identify specific causes of particular migrations, even with the help of documentary data, it is somewhat easier to identify general structural conditions that favor the occurrence of migrations. Moreover, particular structural conditions favor migrations of particular types” (37). In other words, we need to understand the natural, cultural, and sociopolitical environments in their homeland and outside in areas of migration at the time that we are studying, and then, if there were significant movements of human groups, goods, or information, we can begin to understand how that changed the adaptations of all of the societies involved (38, 39).” ref

“The natural environments and presumably, the local conditions of émigré starting points varied. I have come to see roughly seven environmental zones with populations exhibiting the Kura-Araxes cultural tradition: (i) the higher mountain valleys of the South Caucasus, such as Shida Kartli; (ii) the lower broad areas of the South Caucasus comprising the Ararat Plains into Erzurum and the area north of Lake Van; (iii) Iran east and south of Lake Urmia; (iv) the Taurus zone from the western side of Urmia to the eastern part of Elaziğ; (v) the area of Malatya near the Euphrates, including Arslantepe; (vi) Daghestan into the northern Caucasus; and (vii) the Amuq and Khirbet Kerak of the Levant. These zones tend to elicit somewhat different symbolic languages and somewhat different adaptations. For example, styles in pottery within the overall Kura-Araxes corpus varied among these zones (9). Economically, the more northern, higher elevation societies within the Kura-Araxes cultural tradition tended to have a higher percentage of domesticated cattle than sheep compared with societies in the lower elevation environmental zones. Like dialects in language, these variations were based on the degree of interaction of people in each of these zones (26) and their particular local customs and institutions. On a continuum, they are much more similar to the styles of other peoples of the mountains than those of lowland Mesopotamia.” ref

“So, why did they leave as emigrants from their homeland? Following the suggestion by Anthony (25), what we know of the social and economic organization of these societies is that they were small scale, were nonurban, and had subsistence economies in the fourth millennium BCE but may have intensified production through irrigation in some places during the third millennium BCE (40). Areshian (29) posits a population growth in the Ararat Plain at that time. As I have argued (17, 26), the Kura-Araxes migrations did not take the form of a wave like what Ammerman and Cavalli-Sforza (41) proposed for the spread of agriculture and language into Europe from the Middle East during the Neolithic Period. I see it rather as a series of vectors of movements by small groups, perhaps clans, from place to place. Some have tried to match areas within the Kura-Araxes homeland with some variation in local pottery style within the environmental and style zones that I have listed above (9, 13, 42). As we gain more data, however, this proposed pattern does not seem to work all that well. Rather, a kind of crisscross pattern of groups moving and settling long enough to create mounded sites occurred (these people are not purely nomadic people, although they could be transhumant pastoralists). In northwestern Iran, for example, some small sites are dominated by pottery typical of that in the Shida Kartli highlands in Georgia, and others are dominated by pottery typical of that in the lower mountains of the Ararat Plain of Armenia (43).” ref

“So why did they move? Demographers speak of a push and a pull in all migrations (44⇓–46). There must be some reason to be pushed out of an earlier homeland, but there must also be something that pulls the mobile population in a particular direction. Burney and Lang (10) and Areshian (29) have proposed that there was a sharp rise in population in the homeland in the early third millennium BCE. Primogeniture or other customs favoring one family member, kinship segment, or class over another, for example, may cause the less economically fortunate to emigrate. However, was it enough of a rise in population to exceed the carrying capacity of the homeland? If it was not primarily a push, was it a pull? Moch (47) writes of modern migrations that “I argue that the primary determinants of migration patterns consist of fundamental structural elements of economic life: labor force demands in countryside and city, deployment of capital, population patterns (rates of birth, death, marriage), and landholding regimes. Shifts in those elements underlie changing migration itineraries” (47). At the same time, Moch (47) admits that configurations of political economy—this factor is what anthropologists would call social organization—underlie all of the different possible itineraries. As Anthony (46) points out, “[m]igration is a social strategy, not an automatic response to crowding” (46). In this case, environmental conditions were, in fact, propitious in the homeland, and therefore, a forced exit seems less necessary (30).” ref