ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

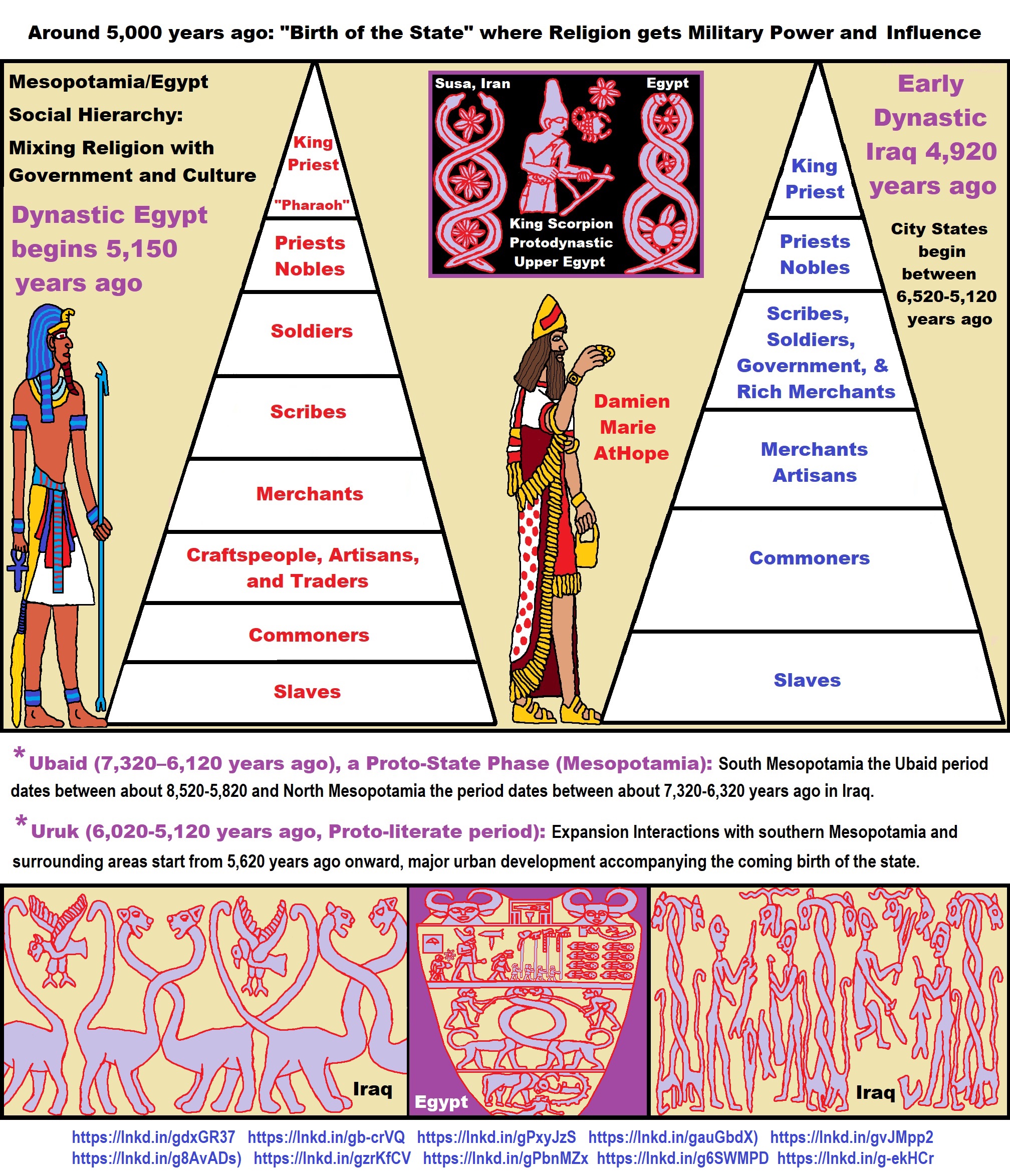

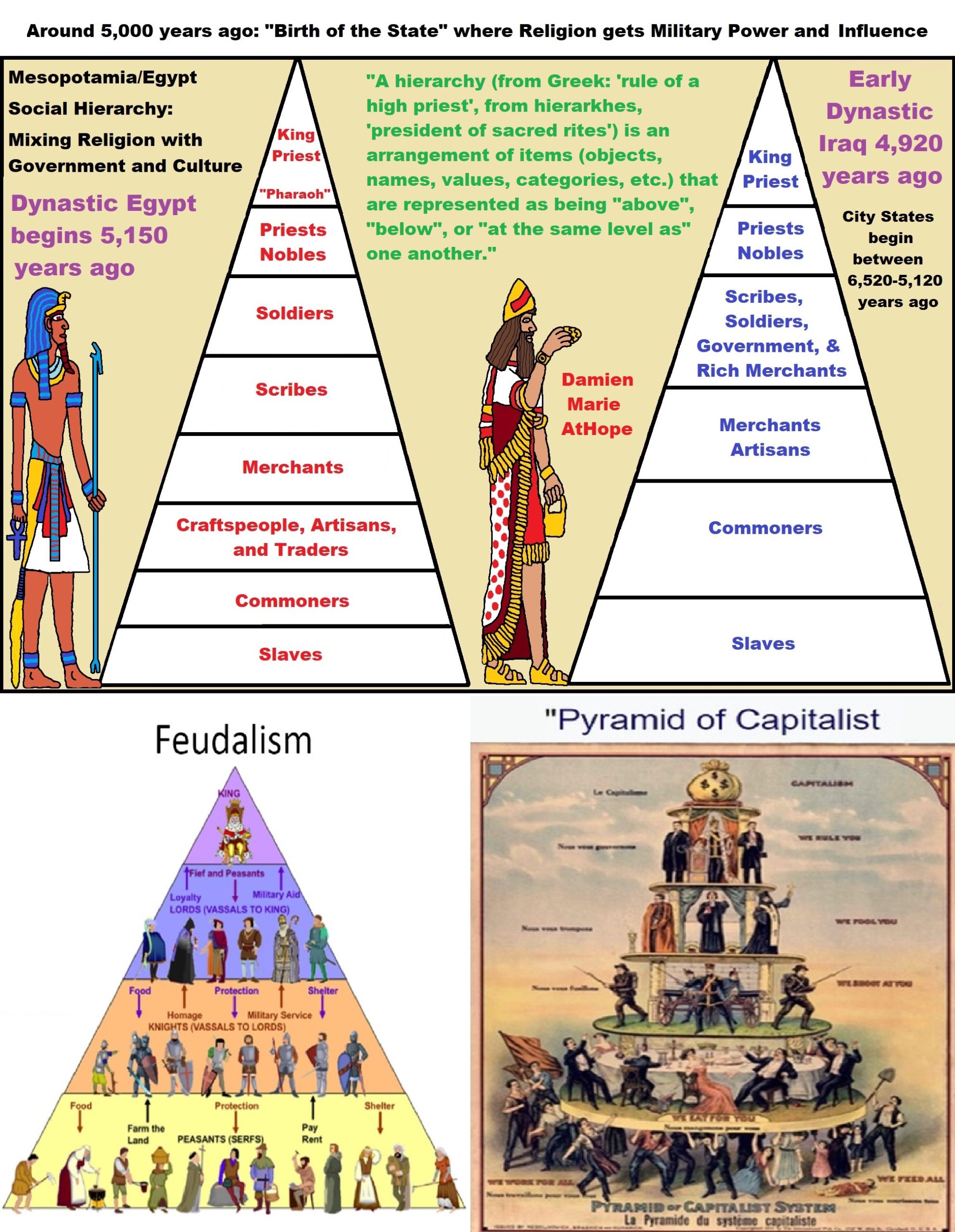

Mesopotamia/Egypt Social Hierarchy: Mixing Religion with Government and Culture

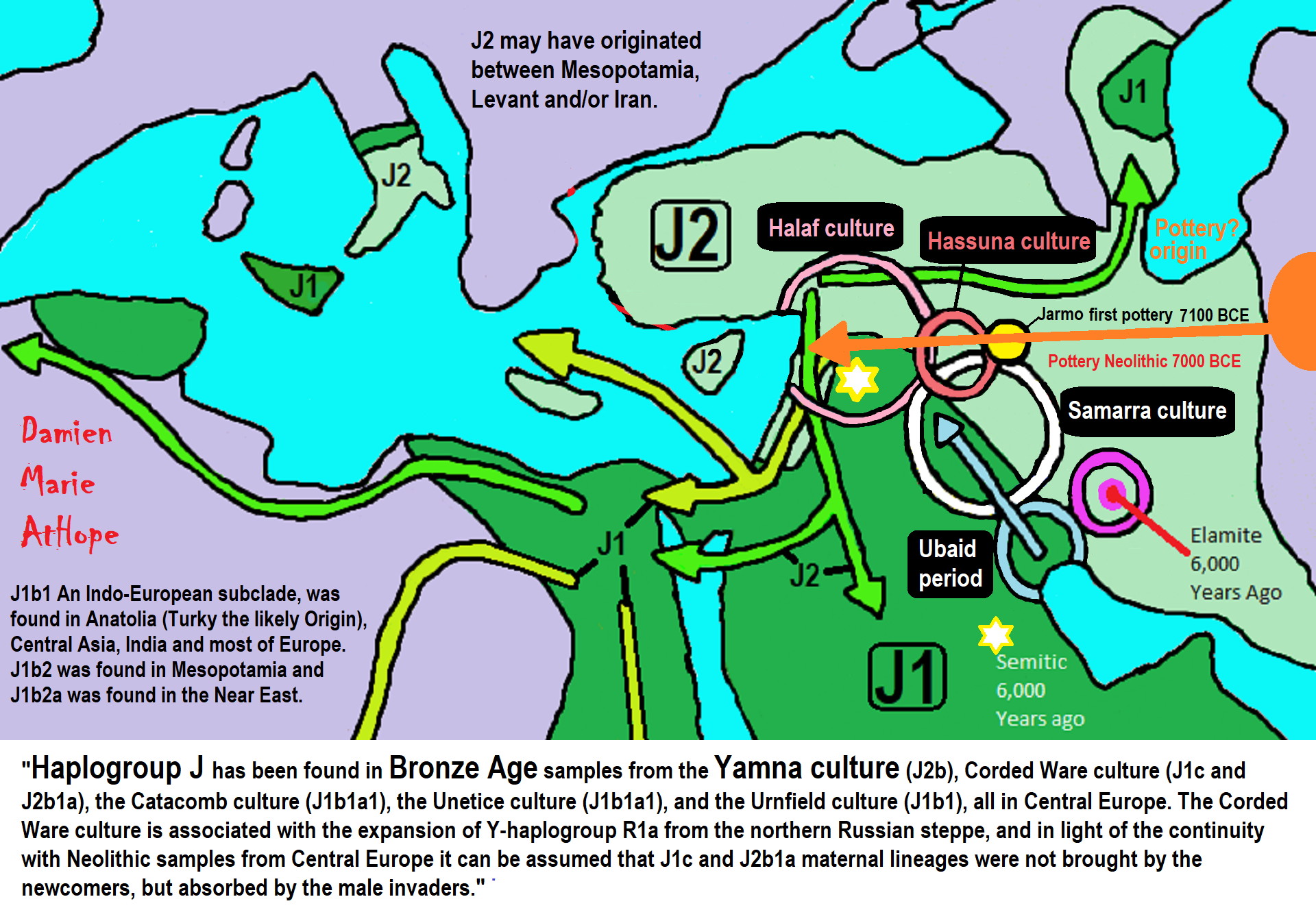

*Ubaid (7,320–6,120 years ago): a Proto-State Phase (Mesopotamia): South Mesopotamia the Ubaid period dates between about 8,520-5,820 and North Mesopotamia the period dates between about 7,320-6,320 years ago in Iraq. ref

“The Ubaid period (c. 6500–3800 BCE or around 8,520-5,820 years ago) is a prehistoric period of Mesopotamia. The name derives from Tell al-‘Ubaid where the earliest large excavation of Ubaid period material was conducted initially by Henry Hall and later by Leonard Woolley. In South Mesopotamia, the period is the earliest known period on the alluvial plain although it is likely earlier periods exist obscured under the alluvium. In the south, it has a very long duration between about 6500 – 3800 BCE when it is replaced by the Uruk period. In North Mesopotamia, the period runs only between about 5300 – 4300 BCE or 7,320-6,320 years ago. It is preceded by the Halaf period and the Halaf-Ubaid Transitional period and succeeded by the Late Chalcolithic period.” ref

*Uruk (6,020-5,120 years ago, Proto-literate period): Expansion Interactions with southern Mesopotamia and surrounding areas start from 5,620 years ago onward, with major urban development accompanying the coming birth of the state. ref

“The Uruk period (ca. 4000 to 3100 BCE) existed from the protohistoric Chalcolithic to Early Bronze Age period in the history of Mesopotamia, after the Ubaid period and before the Jemdet Nasr period. Named after the Sumerian city of Uruk, this period saw the emergence of urban life in Mesopotamia and the Sumerian civilization. The late Uruk period (34th to 32nd centuries BCE) saw the gradual emergence of the cuneiform script and corresponds to the Early Bronze Age; it has also been described as the “Protoliterate period”. It was during this period that pottery painting declined as copper started to become popular, along with cylinder seals.” ref

The First City

“The first cities which fit both Chandler’s and Wirth’s definitions of a “city” and especially the City State developed in the region known as Mesopotamia between 4500 and 3100 BCE or 6,520-5,120 years ago. The city of Uruk, today considered the oldest in the world, was first settled in c. 4500 BCE or 6,520 years ago and walled cities, for defense, were common by 2900 BCE throughout the region. The city of Eridu, close to Uruk, was considered the first city in the world by the Sumerians while other cities that lay claim to the title of “first city” are Byblos, Jericho, Damascus, Aleppo, Jerusalem, Sidon, Luoyang, Athens, Argos, and Varasani. All of these cities are certainly ancient and are located in regions that have been populated from a very early date. Uruk, however, is the only contender for the title of `oldest city’ which has physical evidence and written documentation, in the form of cuneiform texts, dating the activities of the community from the earliest period. Sites such as Jericho, Sidon, and even Eridu, which were no doubt settled before Uruk, lack the same sort of documentation. Their age and continuity of habitation has been gauged based upon the foundations of buildings unearthed in archaeological excavations rather than primary documents found on site.” ref

“Historical city-states included Sumerian cities such as Uruk and Ur; Ancient Egyptian city-states, such as Thebes and Memphis; the Phoenician cities (such as Tyre and Sidon); the five Philistine city-states; the Berber city-states of the Guarantees; the city-states of ancient Greece (the poleis such as Athens, Sparta, Thebes, and Corinth); the Roman Republic (which grew from a city-state into a great power); the Mayan and other cultures of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica (including cities such as Chichen Itza, Tikal, Copán and Monte Albán); the central Asian cities along the Silk Road; the city-states of the Swahili coast; the Italian city-states, such as Florence, Siena, Genoa, Venice and Ferrara; Ragusa; states of the medieval Russian lands such as Novgorod and Pskov; and many others. Danish historian Poul Holm has classed the Viking colonial cities in medieval Ireland, most importantly Dublin, as city-states.” ref

What is a City-state?

“A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world since the dawn of history, including cities such as Rome, Athens, Carthage, and the Italian city-states during the Middle Ages and Renaissance, such as Florence, Venice, Genoa, and Milan. With the rise of nation-states worldwide, only a few modern sovereign city-states exist, with some disagreement as to which qualify; Monaco, Singapore, and Vatican City are most commonly accepted as such. Singapore is the clearest example: with full self-governance, its own currency, a robust military, and a population of 5.6 million.” ref

Population in Ancient Cities

“The population of ancient cities, depending upon which definition of `city’ one uses, differed sharply from what one might consider proper for a city in the modern-day. Professor Smith claims, “Many ancient cities had only modest populations, often under 5,000 persons” while other scholars, such as Modelski, cite higher population possibilities in the range of 10,000 to 80,000 depending upon the period under consideration. Modelski, for example, cites the population of Uruk at 14,000 in the year 3700 BCE or 5,720 years ago, but 80,000 by the year 2800 BCE or 4,820 years ago. Historian Lewis Mumford, however, notes that “Probably no city in antiquity had a population of much more than a million inhabitants, not even Rome; and, except for China, there were no later “Romes” until the nineteenth century”. Mumford’s point highlights the problem of using population as a means of defining an ancient city as it has been proven that urban centers designated `settlements’ (such as Tell Brak) had larger populations than many modern cities in the present day. The gathering of the populace of a region into an urban center became more and more common following the rise of the cities in Mesopotamia and, once enclosed within the walls of a city, the population increased or, at least, such an increase became more measurable.” ref

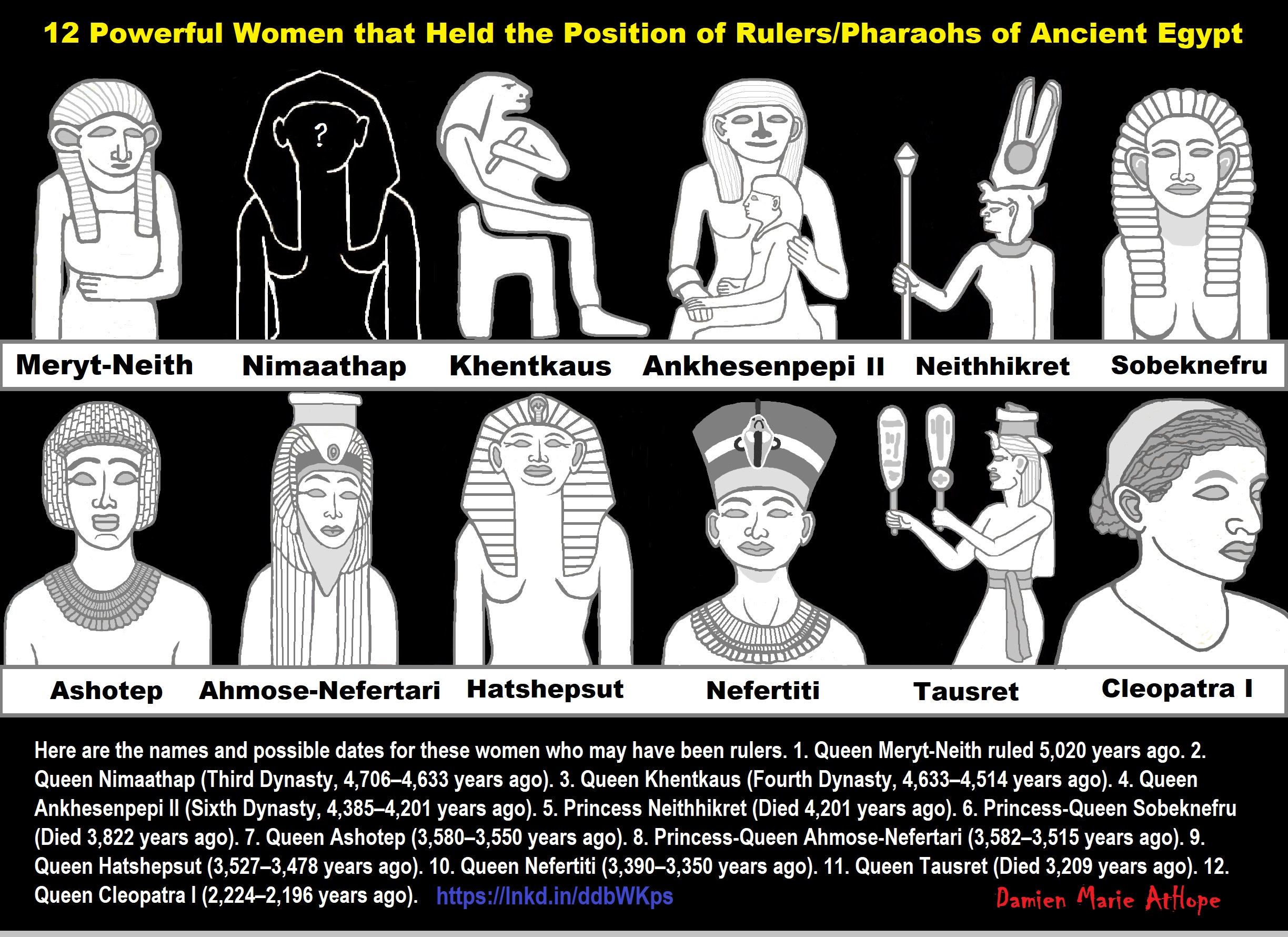

Early Dynastic Period (Egypt) 5,170 – 4,706 years ago

“The Archaic or Early Dynastic Period of Egypt (also known as Thinite Period, from Thinis, the supposed hometown of its rulers) is the era immediately following the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt around 3100 BCE or 5,120 years ago. It is generally taken to include the First and Second Dynasties, lasting from the end of the Naqada III archaeological period until about 2686 BC, or the beginning of the Old Kingdom. With the First Dynasty, the capital moved from Thinis to Memphis with a unified Egypt ruled by an Egyptian god-king. Abydos remained the major holy land in the south. The hallmarks of ancient Egyptian civilization, such as art, architecture, and many aspects of religion, took shape during the Early Dynastic Period. Before the unification of Egypt, the land was settled with autonomous villages. With the early dynasties, and for much of Egypt’s history thereafter, the country came to be known as the Two Lands. The pharaohs established a national administration and appointed royal governors. The buildings of the central government were typically open-air temples constructed of wood or sandstone. The earliest Egyptian hieroglyphs appear just before this period, though little is known of the spoken language they represent.” ref

Early Dynastic Period (Mesopotamia: Mainly “Iraq”)

“The Early Dynastic period is an archaeological culture in Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) that is generally dated to c. 2900–2350 BC and was preceded by the Uruk and Jemdet Nasr periods. It saw the development of writing and the formation of the first cities and states. The Early Dynastic period itself was characterized by the existence of multiple city-states: small states with a relatively simple structure that developed and solidified over time. This development ultimately led to the unification of much of Mesopotamia under the rule of Sargon, the first monarch of the Akkadian Empire. Despite this political fragmentation, the Early Dynastic period city-states shared a relatively homogeneous material culture. Sumerian cities such as Uruk, Ur, Lagash, Umma, and Nippur located in Lower Mesopotamia were very powerful and influential. To the north and west stretched states centered on cities such as Kish, Mari, Nagar, and Ebla. The study of Central and Lower Mesopotamia has long been given priority over neighboring regions. Archaeological sites in Central and Lower Mesopotamia—notably Girsu but also Eshnunna, Khafajah, Ur, and many others—have been excavated since the 19th century. These excavations have yielded cuneiform texts and many other important artifacts. As a result, this area was better known than neighboring regions, but the excavation and publication of the archives of Ebla have changed this perspective by shedding more light on surrounding areas, such as Upper Mesopotamia, western Syria, and southwestern Iran. These new findings revealed that Lower Mesopotamia shared many socio-cultural developments with neighboring areas and that the entirety of the ancient Near East participated in an exchange network in which material goods and ideas were being circulated.” ref

“The First Dynasty of Ur was a 26th century-25th century BCE or 4,620-4,520 years ago, the dynasty of rulers of the city of Ur in ancient Sumer. It is part of the Early Dynastic period III of the History of Mesopotamia. It was preceded by the earlier First dynasty of Kish and the First Dynasty of Uruk. Like other Sumerians, the people of Ur were a non-Semitic people who may have come from the east circa 3300 BCE or 5,320 years ago, and spoke a language isolate. But during the 3rd millennium BC, a close cultural symbiosis developed between the Sumerians and the East-Semitic Akkadians, which gave rise to widespread bilingualism. The reciprocal influence of the Sumerian language and the Akkadian language is evident in all areas, from lexical borrowing on a massive scale, to syntactic, morphological, and phonological convergence. This has prompted scholars to refer to Sumerian and Akkadian in the 3rd millennium BCE or 5,020-3,020 years ago as a Sprachbund. Sumer was conquered by the Semitic-speaking kings of the Akkadian Empire around 2270 BCE or 4,290 years ago (short chronology), but Sumerian continued as a sacred language. Native Sumerian rule re-emerged for about a century in the Third Dynasty of Ur at approximately 2100–2000 BCE or 4,120-4,020 years ago, but the Akkadian language also remained in use.” ref

Before the First Mesopotamian Dynasty

“The more eminent time period preceding the First Dynasty, but taking place after the reign of Sargon the Great (the first ruler of the Akkadian Empire, around 2334–2284 BCE or 4,354-4,304 years ago), is referred to as the Third Dynasty of Ur or the Ur III period. This time period took place during the end of the third millennium BCE or 5,020-4,020 years ago and early second millennium BCE or 4,020-3,020 years ago. Common behaviors of the kings during this time period, especially Ur-Namma and Shulgi, included reunifying Mesopotamia and developing rules for the kingdom to abide by. Most notably, these rulers of Ur contributed to the development of ziggurats, which were religious monumental stepped towers that would in turn bring religious peoples together. In order to gain and retain power, it was not unfamiliar for Ur princesses to marry the kings of Elam; Elaminites were a commonly known enemy of Mesopotamians. Ur rulers would also, along with arranged marriage, send gifts and letters to other rulers as a peace offering. This is known because of the hefty amount of administrative records dating to the Ur III period.” ref

“The First Babylonian Empire, or Old Babylonian Empire, is dated to around 1894 – 1595 BCE or 3,914-3,615 years ago, and comes after the end of Sumerian power with the destruction of the 3rd dynasty of Ur, and the subsequent Isin-Larsa period. The chronology of the first dynasty of Babylonia is debated as there is a Babylonian King List A and a Babylonian King List B. In this chronology, the regnal years of List A are used due to their wide usage. The reigns in List B are longer, in general.” ref

Ancient Egyptian Religion: Forced Similarity of Beliefs

Ancient Egyptian religion, mixed with state control changed it all. So, to me, ancient Egyptian religion can, in a way, be thought of as the youngest of the oldest in religions before Organized religions really embodied power. World religions, that had been advancemening to ever-greater complexity and organization/standardization of myth/beliefs in all the religions before Egypt. But it is also the oldest of the new theme of very organized religions embodied the power of forced similarity of beliefs would take over the world.

This was especially evident first in the joining of upper and lower Egypt through war also established a never before shared-set of religious beliefs, ones that lasted a few thousand years.

The beginning of the First Dynasty (Sometime between 3218–3035, with 95% confidence, commonly held as 5,170 years ago or so). ref

Pic ref

The Birth of the State by Cambridge.org

Abstract

“Western Asia was the first primary center of domestication of plants and animals, followed closely by China. The presence in the Fertile Crescent of vegetal and animal species that could be domesticated, along with the Crescent’s situation as hub, were factors favoring the emergence of what has been called the “Neolithic Revolution.” During the ninth millennium BCE, cereals (emmer wheat, einkorn wheat, barley), pulses (pea, lentil, bitter vetch, chickpea), and a fiber crop (flax) were grown and then domesticated.” ref

The Neolithic Center of the Fertile Crescent

“Western Asia was the first primary center of domestication of plants and animals, followed closely by China. The presence in the Fertile Crescent of vegetal and animal species that could be domesticated, along with the Crescent’s situation as hub, were factors favoring the emergence of what has been called the “Neolithic Revolution.” During the ninth millennium BCE, cereals (emmer wheat, einkorn wheat, barley), pulses (pea, lentil, bitter vetch, chickpea), and a fiber crop (flax) were grown and then domesticated. Animals (goats, sheep, cattle, and pigs) were domesticated at the same time or slightly later. Agriculture and livestock farming encouraged a process of sedentarization of communities, rendering them able to harvest and to store food that could feed larger populations, and enabling them also to produce textiles and work leather. A change in social organization and a transformation in belief systems accompanied this revolution. Cohabiting with domesticated animals brought in new diseases that would prove to be efficient weapons for the Neolithic centers in their relations with foreign countries. From western Asia, cultivated plants and animals arrived in Turkmenistan and in the Indus valley (Mehrgarh) during the seventh millennium; these arrivals reveal terrestrial and perhaps maritime contacts.” ref

“The diffusion of Asian species occurred as early as the eighth or seventh millennium in Egypt, Greece, and Crete. Even before the expansion of highly stratified societies, long-distance trade was noticeable; obsidian from Anatolia arrived in the Levant and in Mesopotamia, and shells were carried from the Persian Gulf to Mesopotamia, or from coastal Sind to Mehrgarh, during the fifth millennium. Lapis lazuli (originating in northern Afghanistan [Badakshan]), turquoise, and copper have been discovered at Mehrgarh and can be dated to the same period. Lapis lazuli may have been traded as early as the sixth millennium. When did the first maritime journeys in the Persian Gulf and along the coasts of South Asia occur? Probably very early on, if we consider the prehistory of the Mediterranean Sea (on Cyprus, the site of Aetokremnos, inhabited by hunter-gatherers, is dated to the tenth millennium BCE or 12,020 years ago). There is no reason to suppose that the (pre-)Neolithic Arab and Asian societies did not develop the same skills in navigation.” ref

‘Ubaid, a Proto-State Phase

“Favored by progress in irrigation, visible at Eridu, Larsa, and Choga Mami (marks left by the use of the ard have been discovered, dated to 4500 BCE or 6,520 years ago), demographic and economic growth, and increasing long-distance trade in Mesopotamia: all fueled a first expansionary process from the sixth millennium onward, in the ‘Ubaid period (c. 5300–4100 BCE or 7,320-6,120 years ago), at least during its phases 3 and 4. This expansion was also based on organizational innovations and a shared ideology, as shown in architecture, and in “seals with near-identical motifs at widely separated sites”. These changes led to competition between “households” as well as to hierarchies and growing social complexity, which in turn encouraged the populations to invest in new techniques. A monumental architecture developed with the first proto-urban centers. As Stein expresses it, sites such as Eridu, Uqair (Iraq), and Zeidan (Syria) were “ancient towns on the threshold of urban civilization”.” ref

“The Late ‘Ubaid phases clearly “provide the prototype for the Mesopotamian city”. The successive “temples” at Eridu in particular – public buildings probably serving various functions – marked the emergence of a new type of social organization, overtaking kinship-based structures. Exhibiting niches and buttresses, erected on terraces (prefiguring the later ziggurat),4 temples became larger during the ‘Ubaid 4 period, toward the end of the fifth millennium. It is likely that a private sector already coexisted with a public sector, with interactions and structuring of power relations among the rulers of family households (extended families and their dependants), temples, and councils representing territorial communities. Within the concurrent process of political centralization, control over the temples may have already been a crucial issue. The presence of fine ceramics and of stamp seals as well as evidence for a weaving industry in the “temples” of the urban center of Eridu reveal an economic role that goes well beyond that of “food banks” redistributing agricultural resources. “A Late ‘Ubaid cemetery at Eridu, however, reveals little evidence of the social differentiation attested to in the architecture of either Eridu or sites like Zeidan and Uqair”.” ref

“Agriculture and livestock farming progressed during this period. The culture of the date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) probably began during the sixth millennium (see below). The fifth millennium saw the development of the olive tree in the Levant, and of grapevine culture in Georgia, southern Turkey, Iran, and the Levant. The rise of tree fruit production went along with exchanges. This would become more apparent during the period of urbanization. Moreover, sheep farming developed in Iran and neighboring regions for the production of wool, thus laying the foundation for a textile industry. The ‘Ubaid culture expanded in different directions during the ‘Ubaid 3 phase. The Mesopotamians acquired prestige goods and the raw materials they needed by building maritime and terrestrial networks, probably by exporting textiles, leather, and agricultural products. In the Persian Gulf, the Ubaidians practiced fishing and exchanged goods with coastal Arab communities. They brought in domesticated animals and plants, and allowed for the spread of shipbuilding techniques. ‘Ubaid pottery has been discovered at over sixty sites in eastern Saudi Arabia and Oman; it is mainly dated to the ‘Ubaid 2/3, ‘Ubaid 3 periods and to a lesser extent ‘Ubaid 4.” ref

“Contacts stopped during the ‘Ubaid 5 period. Arab communities played an active role in exchanges, along the coasts and in the Arabian interior, where trade networks carried myrrh and incense from the Dhofar and the Hadramawt. Large quantities of ‘Ubaid (3–4, c. 4500–4100 BCE or 6,520-6,120 years ago) pottery have been found at Ain Qannas (al-Hufūf oasis), located inland, as well as some remains of cattle and goats. Also traded were obsidian (from Yemen or Ethiopia?), shells, shell beads, dried fish, and stone vessels, through the oasis of Yabrin and al-Hasa. Shells of the Cypraea type have been discovered in fifth-millennium levels at Chaga Bazar in northern Syria, imported from the Gulf. An interesting result of the excavation on Dalma Island is the discovery of charred date pits (probably from cultivated date palms); these dates may have been brought there via trade exchanges, or perhaps they were cultivated on the island (they are dated to the end of the sixth/beginning of the fifth millennium). Remains of fruit have also been unearthed at as-Ṣabīya (Kuwait) dated to the second half of the sixth millennium (dates would have great importance in food and trade from the third millennium onward). Recent genetic research tends to support a Mesopotamian origin for date-palm domestication. The presence of carnelian beads (a stone originating in Iran or the Indus) is noteworthy at Qatari sites, along with Mesopotamian pottery. Carnelian beads have also been discovered in Mesopotamia dating from the ‘Ubaid period. At that time, Arabia was undergoing a subpluvial phase (7000–4000 BCE or 9,20-6,020 years ago) marked by a strong summer monsoon; the Intertropical Convergence Zone was located 10° north of its modern position. Weaker monsoons and a southward shift of the Intertropical Convergence Zone were accompanied by growing aridization; this put an end to the use of the inland routes at the start of the third millennium or around 5,020 years ago.” ref

“The first Mesopotamian explorations in what was known as the “Lower Sea” favored the diffusion of shipbuilding techniques. Excavations at as-Ṣabīya (Kuwait, ‘Ubaid 2/3 period) have unearthed bitumen which was used to caulk reed ships. The site yielded a terracotta model of these boats, which were of Mesopotamian design. Probably carried on the inland routes of Arabia, obsidian which may have come from Yemen was discovered along with the remains of these boats. As-Ṣabīya yielded a painted disc featuring a boat with a sail supported by a bipod mast. Clay boat models from the cemetery of Eridu also show the use of a sail at the end of the ‘Ubaid period; these models appear to represent wooden ships, as does the model found in Syria at Tell Mashnaqa. The role of the ‘Ubaidians should not obscure the existence of other networks, operated by Arab communities, along the coasts, and in the interior of the Arabian peninsula. The location of the sites in the Gulf suggests that the ‘Ubaid pottery found beyond Bahrain was probably carried by local communities, who used seagoing ships, as revealed by tuna fishing – tuna was eaten and prepared for export by Omani communities during the fourth millennium. This pottery was considered a luxury item: sites in outlying areas produced imitations of the ‘Ubaid pottery.” ref

“The ‘Ubaid culture also extended eastward into Khuzistan, where Susa constituted a proto-urban center. It also extended north of Mesopotamia (especially during the Late ‘Ubaid phase), toward routes already linking Central Asia, Afghanistan, and the upper valleys of the Tigris and the Euphrates: one finds Ubaid pottery as far as the Transcaucasus region, and lapis lazuli from Afghanistan is present at Tell Arpachiyah and Nineveh, in northeast Iraq; Tepe Gawra yielded lapis lazuli, as well as carnelian from Iran, but the blue stone could be more recent at this site. Pottery from Susa, dated to the late fifth millennium, has been found further east in Iran, in a region rich in copper. The quest for copper obviously played a crucial role in ‘Ubaid and ‘Ubaid-related expansion, as shown by the ‘Ubaid “colony” of Deǧirmentepe, which was located near substantial copper, lead, and silver sources.” ref

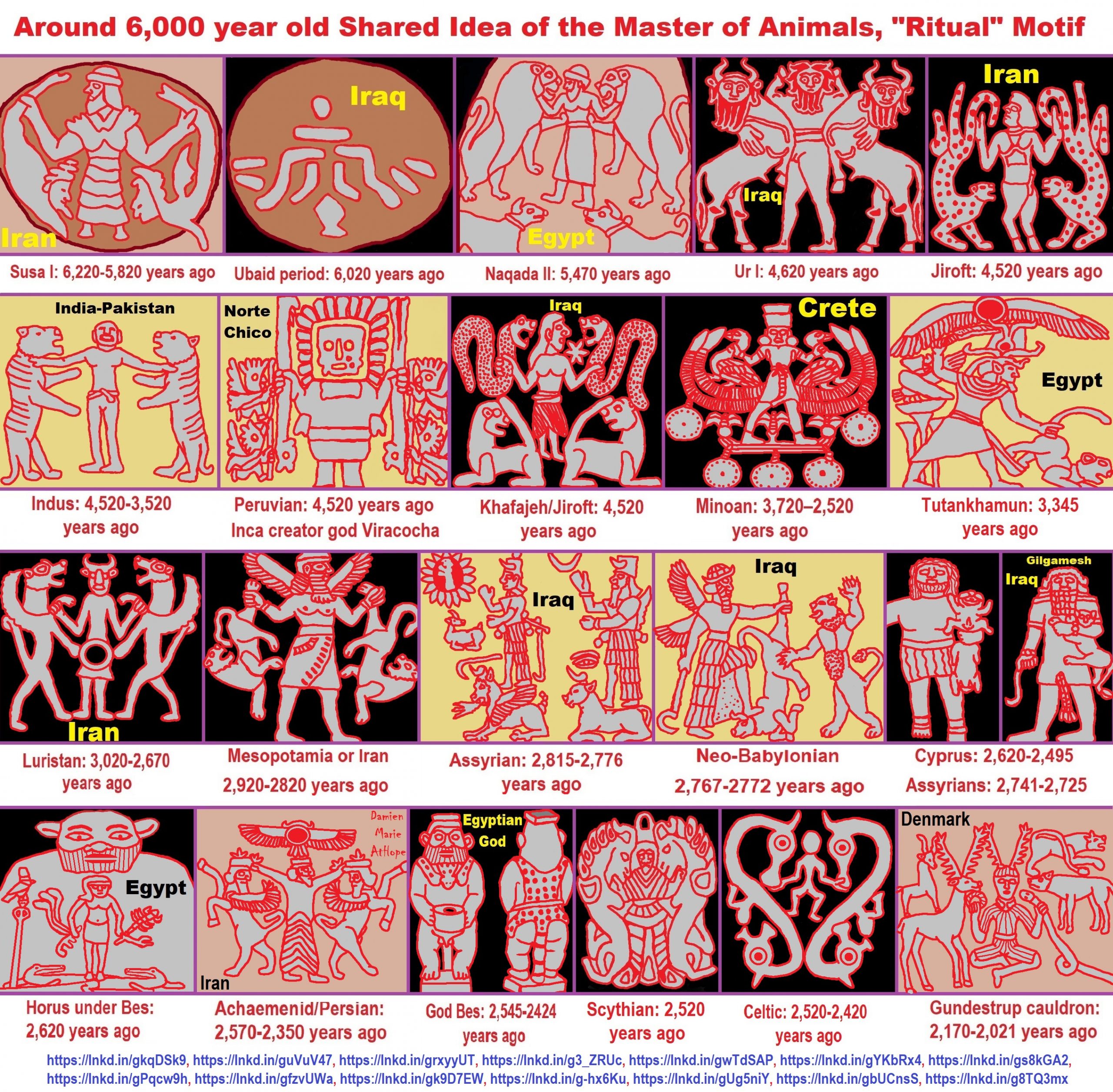

“Trade in copper and exotic goods favored a process of social differentiation, not only at Gawra, which Oates considers as “a northern Ubaid settlement,” but also at Zeidan (12.5 ha), in northern Syria (Euphrates River valley), a site revealing monumental architecture. Zeidan yielded evidence for copper metallurgy and administrative activity (a stamp seal has been found, dated to c. 4100 BCE or 6,120 years ago). At Susa, a settlement founded around the end of the ‘Ubaid period rapidly grew to cover 10 ha. It included a high platform bearing a building (residence, warehouse). Seals and imprints have been discovered, with geometric and sometimes figurative designs (the motif of the “master of animals” is already present). During this period, Mesopotamia formed itself into a “central civilization”. This expansion was accompanied by new social complexity in different regions, with the probable emergence of servile labor regulated by family chiefs. One notes the use of stamp seals in Khuzistan, Luristan, and Fars, as well as in areas north of Mesopotamia.” ref

“The homogeneity of the material ‘Ubaid culture implies active exchange networks, at the local level and between regions. Parallels established between the northern temple at Tepe Gawra XIII and buildings at Uruk (tripartite floor plan, orientation, elaboration) reflect some cultural community and shared beliefs. Religion must have played an important role in controlling communities and exchange networks. In 1936, 1952, and 1954, A. Hocart had already pointed out the possible religious origin of trade, and of social and state institutions. Moreover, ceramics made on the turnette (slow wheel) and the use of stamp seals can be observed throughout the ‘Ubaid area: the diffusion of these technologies contributed to the homogenization of this space. A marked increase in the use of seals and mass-produced pottery (suggesting the distribution of rations) signal new social complexity. Seals and other devices reveal administrative activity. At Tell Abada, in east-central Iraq, in ‘Ubaid buildings, tokens have been found in pottery vessels, probably reflecting the keeping of records.” ref

“The expansion of the ‘Ubaid culture during the fifth millennium clearly shows the new dimension of the exchange networks, brought about principally by the rise of copper metallurgy. This technology appeared during the sixth millennium in Anatolia, and during the fifth millennium in Mesopotamia, Iran, Pakistan, and southeastern Europe. It then spread to the north of the Black Sea (4400 BCE or 6,420 years ago), and on to the Middle Danube valley (4000 BCE or 6,020 years ago), to Sicily and the southern Iberian peninsula (3800 BCE or 5,820 years ago). This progression provides clear evidence for the expansion of exchange networks. Metalworking reached the Asian steppes from southern Russia during the fourth millennium. It would later spread to northwestern Europe around 2500 BCE or 4,520 years ago. Copper and then bronze metallurgy required a supply of metal ore and an ability to transport it; thus new trade networks were set up on a larger scale, within social contexts that implied profound ideological and organizational changes. The ‘Ubaid civilization acted as a catalyst for societies further north and east of Mesopotamia, with long-distance trade now involving a large area. “The end of the ‘Ubaid phase c. 4100 BCE or 6,120 years ago seems to have coincided with a period of global cooling and aridization in the eastern Mediterranean region and the Levant. In Susiana, “even the Acropole of Susa was abandoned ca. 4000”. The ‘Ubaid period prefigures the flowering of the Sumerian civilization during the Urukian period.” ref

The Urban Revolution and the Development of the State in Mesopotamia

The First Half of the Fourth Millennium BCE

“New progress in metallurgy was noteworthy during the fourth millennium. Anatolian sites operated mines (mainly in the region of Ergani) and practiced ore smelting (Çatal Hüyük, Tepeçik, Deǧirmentepe, Norşuntepe …). There are clues indicating copper metallurgy at Mehrgarh (Pakistan) before 4000 BCE or 6,020 years ago. A wheel-shaped amulet from Mehrgarh has recently been identified as the oldest known artifact made by lost-wax casting (it is dated to between 4500 and 3600 BCE or 5,620 years ago). It had been thought that tin bronze was produced at Mundigak (Afghanistan) during the second half of the fourth millennium, but recent reanalyses show no evidence of tin bronze. Feinan (Jordan) has been dated to between 3600 – 3100 BCE or 5,620-5,120 years ago for copper ore mining. This progress in metallurgy and the transportation of various goods (not only raw materials but also manufactured products) probably explains why active trade routes were established during this period. These routes would remain of importance throughout the ensuing two millennia. The first bronze tools appear at Beycesultan around 4000 BCE or 6,020 years ago, and at Aphrodisias around 4300 BCE or 6,320 years ago (southwestern Turkey). Beycesultan also yields silver items very early on.” ref

“After the ‘Ubaid period, eastern Anatolia took advantage of improved climate conditions and a fresh increase in exchanges. This region, along with northern Mesopotamia, saw the formation of proto-urban centers (Arslantepe, Hacınebi, Tepe Gawra, and most importantly, Khirbat al-Fakhar and Tell Brak). Societies in Syria and Anatolia were already showing complex organizational characteristics during the first half of the fourth millennium, before “the documentation of regular contacts with the southern Uruk world”. Public buildings were erected at Arslantepe during phase VII, before the period of contact with the Urukian world. Godin (VI) was also expanding during the first half of the fourth millennium. Hacınebi shows some social complexity during a phase dated 4100–3700 BCE or 6,120-5,720 years ago, with stone architecture, administrative activity (stamp seals, also found at Gawra, Tell Brak, Arslantepe, Deǧirmentepe), and metallurgy.” ref

“Hacınebi was involved in exchanges between the Mediterranean, the Euphrates and Tigris valleys, and regions further east; it yielded artifacts made from chlorite, a stone imported from a region located 300 km to the east, shells termed “cowries” (Mediterranean shells?), some bitumen (from Mesopotamia), copper items (the metal probably came from the region of Ergani and/or from the Caucasus), and even silver earrings. In northeastern Iraq, Khirbat al-Fakhar was a much larger proto-urban settlement – of low density – covering 300 ha, whereas the total area of the Late Chalcolithic 2 (LC2) (4100–3800 BCE or 6,120-5,820 years ago) settlement at Brak reached at least 55. At this time, Rothman has reported the existence of specialized “temple” institutions at Tepe Gawra, Tell Hammam et-Turkman, and Tell Brak. “At Tell Brak, adjacent to a monumental building was a structure with abundant evidence for the manufacture of various craft items. The structure itself contained obsidian, spindle whorls, mother-of-pearl inlays, … ”. Mass-produced ceramics have been found, along with “a unique, obsidian and white marble ‘chalice’ ”, showing the existence of social differentiation and organized labor.” ref

“These (proto-)urban centers constituted nodes along east–west networks that extended further into Iran and Afghanistan, in one direction, and to the Syrian coast in the other. Lapis lazuli has been found at Iranian sites such as Tepe Sialk, Tepe Giyan (first half of the fourth-millennium BCE or around 6,020 years ago), Tepe Yahya (3750–3650 BCE 5,770-5,670 years ago), and in northern Mesopotamia, at Tepe Gawra (3200 BCE? or 5,220 years ago), Nineveh, Arpachiyah (4500–3900 BCE or 6,520-5920 years ago). “There was extensive evidence for exploitation of lapis lazuli at Tepe Hissar during the 4th millennium BCE”. The presence of lapis lazuli reveals the existence of routes linking Central Asia, Iran, and northern Mesopotamia; it is rare, however, during the ‘Ubaid period and the first half of the fourth millennium. Moreover, trade networks formed with northern regions: obsidian came from central or eastern Anatolia, and “ceramics [from northern Mesopotamia] have been found in eastern Anatolia and in Azerbaijan”. Interactions between the spheres of Anatolia–Levant, and Mesopotamia took place during the flourishing of the ‘Ubaid culture; they continued after its demise. On the basis of glyptic art, H. Pittman notes “a shared symbolic ideology” during the Late ‘Ubaid–Early Uruk in Syria, northern Mesopotamia, and Khuzistan.” ref

“During the LC2 period, the first proto-urban centers seem to have lacked internal political centralization. But from the LC3 period (3800–3600 BCE or 5,820-5,620 years ago), Tell Brak grew into a large urban center, becoming a dense settlement of 130 ha, “prior to the Uruk expansion”. Another major site was located at al-Hawa, 40 km east of Hamoukar; it may have been as large as 33–50 ha. Hamoukar (near Khirbat al-Fakhar) and Leilan were smaller settlements. According to Algaze, however, Hawa and Samsat – a city now submerged as a result of the construction of the Ataturk dam – truly developed “after the onset of contacts with the Uruk world”. Domestic structures in Tell Brak “show evidence of high-value items and exotic materials,” and of property-control mechanisms. “A cache from a pit included two stamp seals and 350 beads, mostly of carnelian but also silver, gold, lapis lazuli, and rock crystal”. Seals and sealings have also been discovered at Hamoukar. “Brak’s urban significance has been downplayed because, unlike the cities of southern Mesopotamia, it was a primate center without intermediate centers in a proper urban hierarchy”.” ref

“The process of urbanization was accompanied by violence: traces of massacres have been discovered in Tell Brak, and structures were destroyed by fire at Hamoukar and Brak. Whether due to internal disorder or attacks by southerners, the origin of this violence is still debated. Also debated is the dating of the Eye Temple at Tell Brak. For Oates et al., it was built prior to the Uruk expansion, in the LC3 period (3800–3600 BCE or 5,820-5,620 years ago), but other archaeologists date the construction of the temple to 3500–3300 BCE or 5,620-5,320 years ago. The temple was decorated with clay cones, copper panels, and goldwork, in a style similar to contemporary temples of southern Mesopotamia. “Eye idols have also been found at Tell Hamoukar.” ref

The Urukian Expansion during the Second Half of the Fourth Millennium BCE (6,020-5,020 years ago)

“Interactions with southern Mesopotamia can be seen from 3600 BCE or 5,620 years ago onward, when the latter region experienced major urban development accompanying the birth of the state. As Algaze makes clear, “polities in the north hardly equaled their southern counterparts”. This southern urban development was based on agricultural progress generating demographic growth. Increased irrigation, the use of the ard drawn by oxen, and the creation of date-palm plantations led to the creation of large estates; only estates of significant size were able to invest on a scale ensuring surpluses that supported urbanization. It has been shown convincingly that the ard was developed along with the urbanization process; it may have been first employed to make furrows for irrigation; it required a major investment, which in turn explains its symbolic link with political power. The use of sledges on rollers to remove seed husks heralded the invention of the wheel.” ref

“Urbanization was also based on the progress of various crafts, such as ceramics (the invention of the potter’s wheel made mass production possible, and this was linked to new social practices [the use of fermented beverages] and organization [distribution of rations]), metal artifacts, and textiles made of flax or wool (see below). Growth in sheep populations is seen at several Urukian sites at the end of the fourth millennium (such as Tell Rubeidheh); this may have been spurred by the state leadership. Sheep production certainly represented one driver of the Uruk expansion. Selected in Iran, wool-bearing sheep breeds spread rapidly westward: some of the first-known wool remains, dating to the late fourth millennium, come from El Omari, in Egypt.” ref

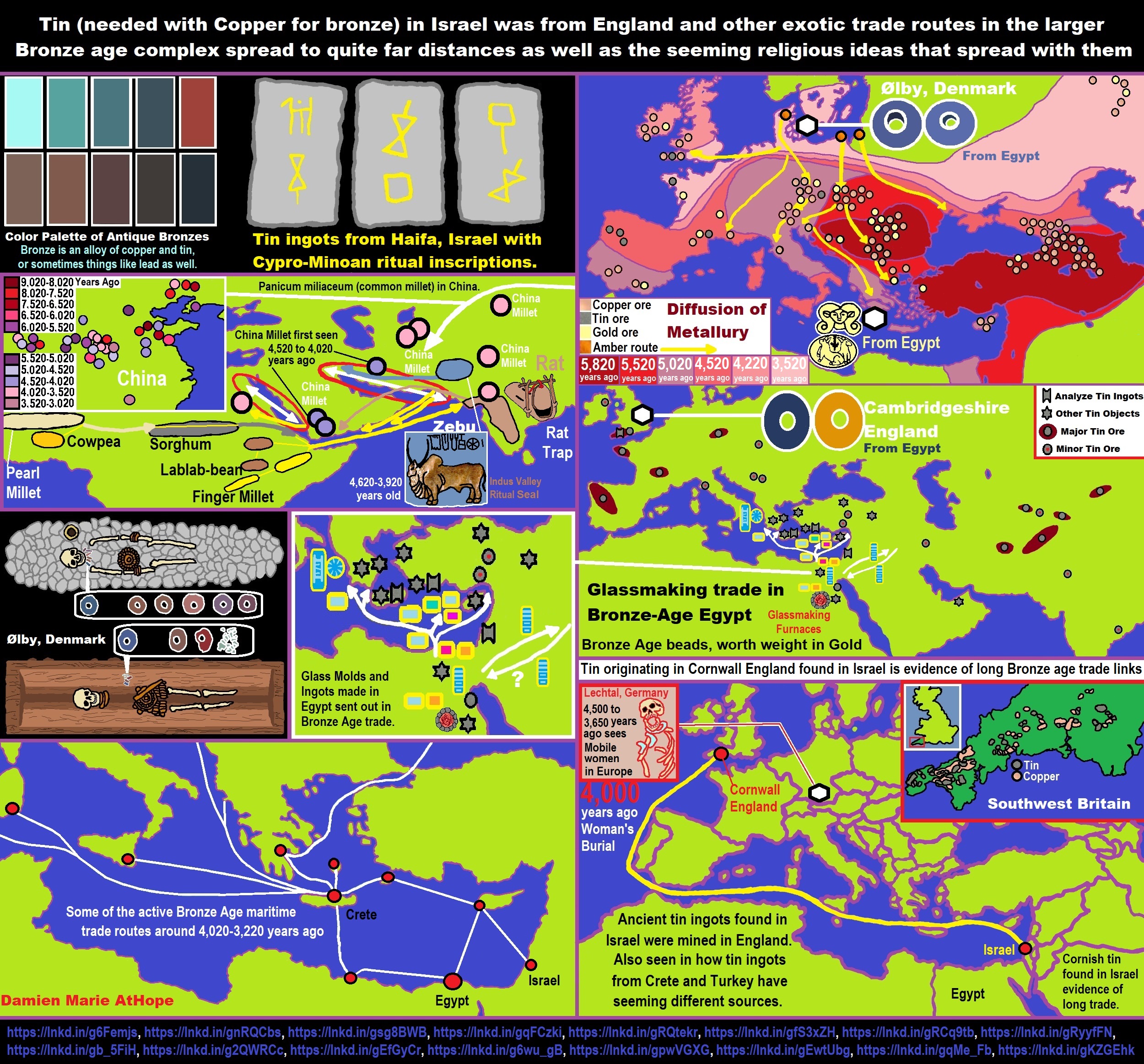

“The production of new goods was connected to the building of hierarchized urban societies; not only did export manufactured goods lay the groundwork for an asymmetric exchange with peripheral regions; they also fostered local developments (the social role of fermented beverages in Mesopotamia, for example, may have led to an expansion in grapevine culture on the Mediterranean shores, as Sherratt has suggested). The Urban Revolution benefited from increased long-distance trade, and helped further its development; commerce first involved textiles, slaves, and copper, which was used to produce weapons and tools. The development of copper and later, bronze metallurgy underlay the emergence of political power: “only elites could organize the long-distance procurements of costly copper and tin, as both were scarce,” and both proved necessary to social reproduction. Bronze was initially an alloy of copper and arsenic, then of copper and tin (the latter alloy being harder than the arsenical bronze). Bronze metallurgy spread from the fourth millennium onward, through the trade routes, with a possible diffusion to China between 3000 – 2000 BCE or 5,020-4,020 years ago. The production of bronze artifacts increased not only agricultural productivity, but also military power: competition between cities was not always peaceful, and the extension of conflicts certainly played an important role in the building of the state. The rise in exchanges was partly linked to the birth of a new ideology of political control as well as to institutional innovations. The state played a crucial role, organizing production and exchanges, as well as redistributing wealth.” ref

“In conjunction with the rise in exchanges and processes of internal development, southern Mesopotamia experienced a radical new flourishing. Already inhabited c. 4600 BCE or 6,620 years ago, the site of Uruk (Warka) grew from 3600 BCE or 5,620 years ago (Middle Uruk) and covered 250 ha c. 3100 BCE 5,120 years ago – which may have represented a population of 20,000 to 40,000 – and 600 ha c. 2900 BCE or 4,920 years ago at the end of the Jemdet Nasr period (Uruk had 45,000–50,000 inhabitants by the late fourth millennium). During the Early Uruk period, the city of Warka grew “at the expense of the Nippur-Adab and Eridu-Ur areas” and of Upper Mesopotamia: the population of the northern Jazirah decreased, especially from 3500 to 3300 BCE or 5,620-5,320 years ago; the same held true for the Fars Plain; northern cities (Tell Brak, Hamoukar) grew smaller, leading Algaze to speak here of an “aborted urbanism”. Other southern cities probably expanded during the late fourth millennium, absorbing rural populations: Nippur, Adab, Kish, Girsu, Ur, Umma, Tell al-Hayyad. None of these cities, however, are comparable to Uruk. Algaze rightly emphasizes that “large settlement agglomerations were almost certainly unable to demographically reproduce themselves without a constant stream of new population”. (It has been “pointed out intensified mortality as a result of crowding, with the appearance of a variety of diseases.”)” ref

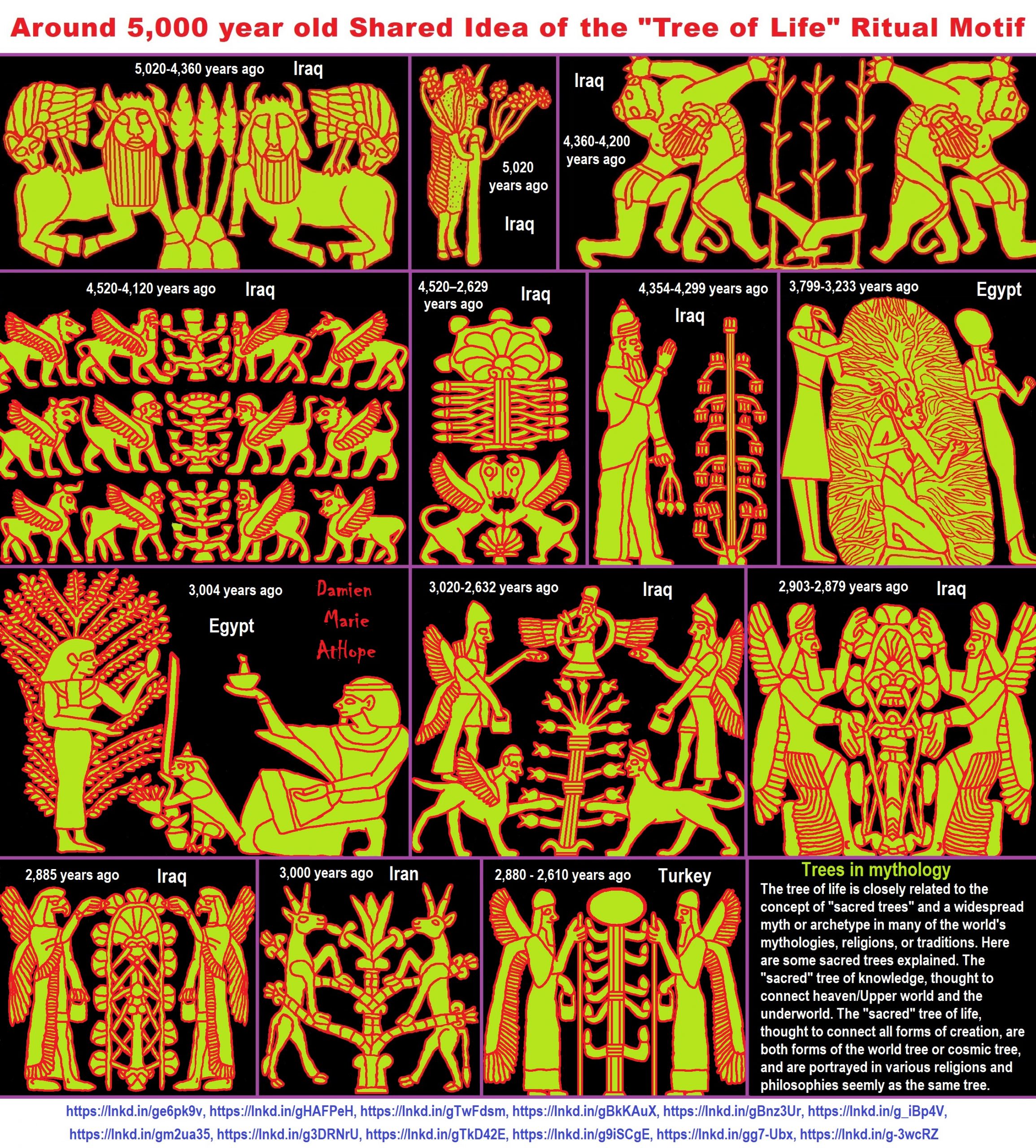

“Various authors have stressed the importance of the ideological and organizational changes occurring during the birth of the state. The Mesopotamian agglomerations probably meet the criteria proposed by Wengrow for defining a city: “the existence of a class or classes of individuals not directly involved in agrarian production, a high density of permanent residents, access to ports and trade routes, centralized bureaucracy, a concentration of knowledge and specialised crafts, political and/or economic control over a rural hinterland, the existence of institutions that embody civic identity,” and the monumentality of some of its buildings. These towns or cities constituted – at one and the same time – political, economic, and religious centers. It is possible that chiefs were primarily religious chiefs. Political power may have emerged as the result of the internal dynamics of the royal system: “It was only when the [various] ritual functions of the [chief] were separated from one another that political power and state organization emerged and developed”. L. de Heusch also writes: “It is the symbolic construction elaborated on the figure of a magician-chief that allows the genesis of the state, wherever a hierarchy of status or social classes develops”.” ref

“Not only was there intensification of labor through biological, technological, and organizational innovations; there was also a more efficient mobilization of the labor force itself. Southern Mesopotamian cities proved better able “to amass and control information, labor, and surpluses vis-à-vis those of their immediate neighbors”. This efficiency was seen in both economic and political-religious organization. Community lands held by extended families came under the management of “institutional households.” The temples, which owned land, craft workshops, and herds, were organized as “profit centers”. The growing importance of the temple complex paralleled the emergence of a ruling class that was organized as an assembly of community leaders, who managed most of the production and long-distance trade. According to Pollock, the Uruk rulers probably extracted tribute to feed the city. Uruk was the religious capital of Sumer, and may also have been the political capital of a Sumerian state. Various elements, however, do suggest the existence of a league of Sumerian cities around 3100 BCE or 5,120 years ago (rather than a single state), a league perhaps headed – as later in the third millennium – by a LUGAL (“great man”), “ceremonial head of the assembly [UNKEN] of city rulers.” For Glassner, there was no king yet at the head of the state: an assembly of community leaders was “managing the affairs of the city.” Twenty cities are thus mentioned on a seal, from Urum (Tell Uqair) in the north to Ur in the south. Remains of temples and “palaces” have been discovered; they show decorations of niches and pilasters as well as characteristic facade ornamentation using colored “nails” forming geometrical patterns. Algaze, however, believes that kingship was already instituted. The “Titles and professions list” during the Jemdet Nast period starts with a man called NAM2+ESDA, a term translated as “king” during the second half of the 3rd millennium. Moreover, Algaze emphasizes an “iconographic continuity between the 4th and the 3rd millennia for the ‘priest-king/city ruler’”. The true nature of the Urukian institutions, in fact, remains unknown.” ref

“Some ceramic objects – beveled-rim bowls – were mass-produced and standardized, probably reflecting the distribution of “rations,” in “a system of mass labor” clearly made visible through the size of public buildings; these rations may also have been linked to workshops producing goods for the state such as textiles. “Many of the Archaic texts record disbursement of textiles and grain to individuals. [They may represent] rations given to some sort of fully or partly dependent workers”. In S. Pollock’s view, during the third millennium, the economy moved from a tributary system (tributes were extracted from the rural sector) to a system of “households” employing their own labor forces, servile or not; these “houses” were not only temples and palaces, but also estates belonging to high-level officials or the rulers of extended families. As early as the Urukian period, the archives of the institutional estates evoke the management of land, of herds, and of the labor force, probably with economic viability in mind: here we are outside the context of a simple tributary system.” ref

“The emergence of the state and the rise of exchanges brought about the use of new techniques that spread widely, allowing for growing control over the movement of goods, information, and individuals. Calculi and seals on clay bullae containing these calculi represent systems noting quantities that reveal accounting management. They can be found in a vast zone going from Iran to Mesopotamia and Syria: all of western Asia was involved. At Uruk, then at Susa, around 3500 BCE (or slightly later?) or around 5,520 years ago, cylinder seals appeared (only stamp seals had been used in earlier times) to seal merchandise (bales or jars) and doors. Numerical tablets, each one sealed by the imprint of a cylinder seal, have been unearthed in levels belonging to this period. With the development of cylinder seals, a new iconography flourished that legitimated the power of the elite: it often figures a hero – perhaps already a “priest-king” or deity? (see above) – who is a master of wild beasts, a war leader, a feeder of domestic animals and “a fountain of agricultural wealth” (the hero holds a vase with flowing streams, a symbol of abundance and a possible reference to the role of the state in irrigation systems); he is alternately portrayed as an officiator in religious ceremonies (according to Glassner, however, versus Algaze, the seals and cultic objects feature different characters, not just one). We can observe this iconography from early periods in Iran and Egypt. For Pittman, in fact, “the characteristic Uruk imagery was first developed and found its richest expression in Susiana”. At Susa and Choga Mish, east of Susa, cylinder seal impressions show temples on high platforms.” ref

“The Susiana Plain was “part of the Uruk world between 3800 – 3150 BCE or 5,820-5,170 years ago”; it is likely, however, that during the Early and Middle Uruk periods, “an independent state-based at Susa developed in Susiana”. For her part, Pittman “queries the primacy of southern Mesopotamia in the development of the administrative innovations that took place in the 4th millennium”, Susa was the source of many of the “Mesopotamian” innovations. One notes the appearance “of bevel-rim bowls and other Uruk forms at Ghabristan, Sialk, Tal-e Kureh and possibly Tal-e Iblis”: the question remains to know whether we observe a process of colonization, trade, or emulation/coevolution (at Susa for example, and from Susa).” ref

“Copper metallurgy developed in Iran during the fourth millennium bce, using crucible-based smelting technology, for example at Tal-e Iblis (periods III and IV), Tepe Sialk (III and IV), Tepe Hissar (II), Tepe Ghabristan (II), Arisman, Godin Tepe (VI.1), and Susa. We do not have evidence of ancient mining at Anarak, but local mineral sources must have been used. Iran exported copper and copper artifacts. The juridical power of the state was constituted at this time. We know from Nissen that “group size and amount and level of conflicts are systematically and inseparably interconnected”; the dimension of Uruk implies the setting up of a system of laws and sanctions, as well as an organization that is able to implement them.” ref

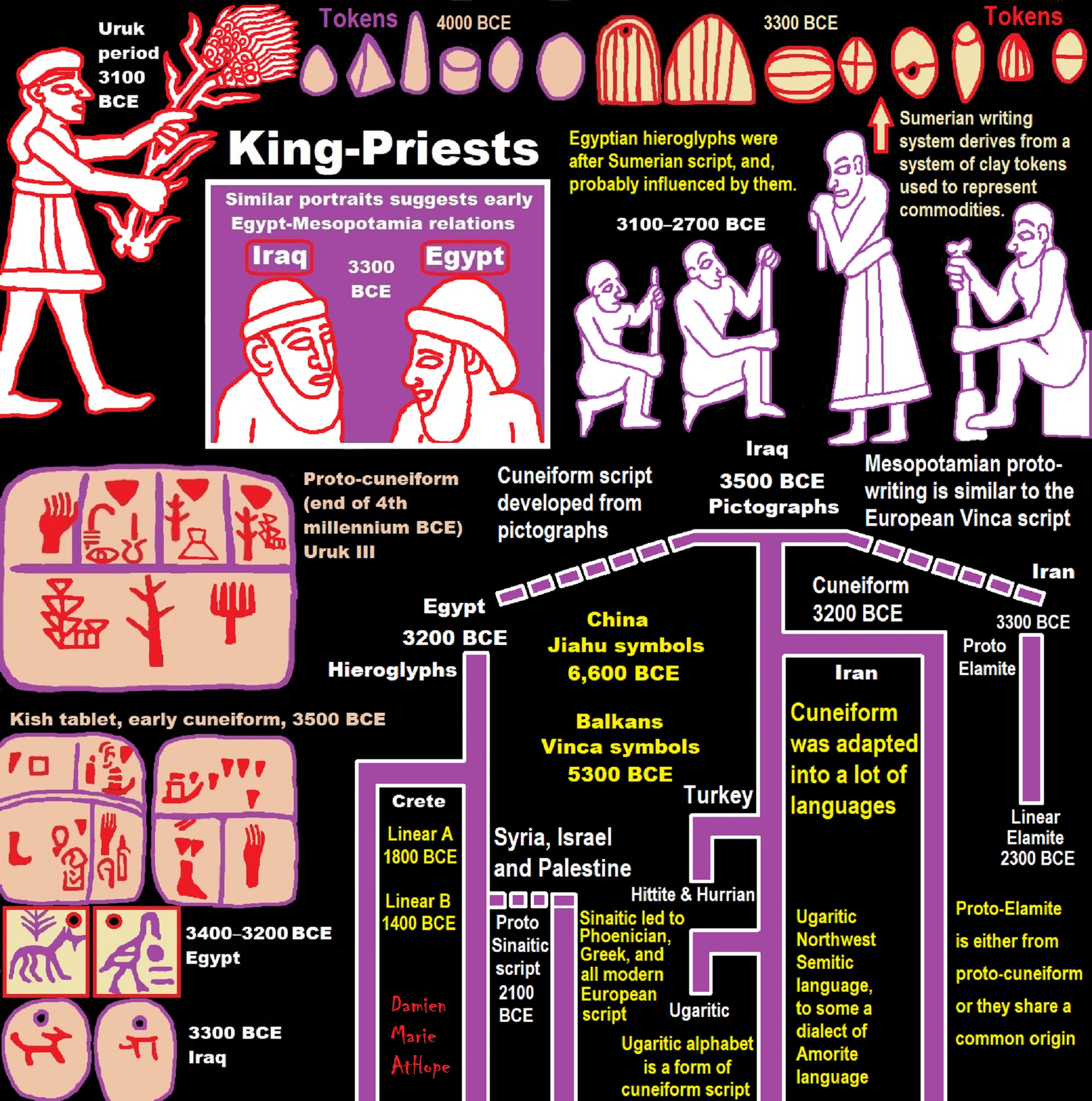

“Among the crucial innovations of the Urban Revolution figure techniques of power and new forms of organization. Bullae, calculi, and cylinder seals have already been mentioned. The first signs of writing appeared around 3300 BCE or 5,320 years ago at Uruk (the exact period is not known), in response to the growing complexity of commercial transactions and social organization, and to the building of a system of relations between the Sumerian city-states, interacting with a periphery of pastoralist or sedentary populations. The development of writing laid the groundwork for the state’s ideology, with the creation of a body of scribes whose apprenticeship must have also been an “indoctrination”. Writing quickly acquired a sacred dimension: along with iconography, it brought about contact with the world of the gods. In the economic field, most of the ancient documents contain lists of goods that were received, sent, or stored, such as grains, milk products, wool, textiles, metals … Some of these documents show attempts at economic planning. They have usually been found in the vicinity of public buildings. A vast majority of tablets thus reflect the existence of a centralized and hierarchized administration. Archaic texts from Uruk refer to social differentiation and the organization of various professions. They reveal the existence of slaves of local or foreign origin. “A larger pool of dependent labor available gave a comparative advantage” to southern Mesopotamia. Slaves probably worked on irrigation systems and constructions. As Algaze rightly points out, “innovations in communication [writing, accounting systems], [transportation] and labor control were fundamental for the Sumerian takeoff.” The city of Uruk was crisscrossed by canals used for transport and irrigation.” ref

“Slaves also worked in workshops. “The second most frequently mentioned commodity in Archaic texts [after barley] is female slaves”. A tablet from Uruk refers to 211 women slaves, who produced textiles for the temple. Many Uruk texts deal with wool and textiles (woven woolen cloth), which probably represented the first exports of the Mesopotamian cities, in addition to leather, agricultural products, perfumed oils, and metal artifacts. During the third millennium, “iconography from cylinder seals and sealings depict various stages of textile production”. Archaic texts “attest to the existence of temple/state-controlled sheep herds”. It is likely, also, that raw wool imports contributed to the growth of the textile industry in the southern Mesopotamian cities. Wool, notes Algaze, was more easily dyed than linen, and “economies of scale were achievable by using wool as opposed to flax.” “The mass production of textiles” financed by elites was clearly “an urban phenomenon”. “The earliest economic records and lexical lists also include numerous references to metals”. In sum, the flourishing of different crafts linked to institutions can be observed. Southern Mesopotamia had at least two other crucial advantages over the north: a higher density of population and efficient water transport, facilitating trade. The Mesopotamian elites ensured the supply of necessary raw materials: metals, stone, and wood. There is little doubt that the state was involved in long-distance trade. During the second half of the fourth millennium, exchanges benefited from innovations in transportation: waterway development, clearly visible at Uruk; improvements in shipbuilding; domestication of the donkey (both in Egypt and in western Asia), and the use of the wheel. A written sign reflects the presence of donkeys during the Uruk period. Recent genetic research shows that donkey domestication first took place in Egypt, from a Nubian subspecies, Equus asinus africanus (the first remains of domesticated donkeys were discovered in a Predynastic tomb, at Ma’adi, dated c. 4500 BCE or 6,520 years ago). A second domestication occurred from another subspecies related to Equus asinus somaliense, but another breed – today extinct – may have lived between Yemen and the Levant; it may have been the ancestor of this second domesticated set. Wild donkeys may have been domesticated in Mesopotamia, where remains are dated to the Middle Uruk period at Tell Rubeidheh, in the Diyala valley. As already mentioned, the wheel was probably developed in northern Mesopotamia, Syria, or eastern Anatolia at the time of the Urukian expansion. From Anatolia, use of the wheel and the wagon spread along the Danube and the Black Sea. Their arrival went along with the dislocation of the large villages of the Cucuteni-Tripol’ye culture (located between the Dnieper and the Danube) around 3600/3500 BCE or 5,620/5,520 years ago, during an ecological crisis brought about by a climatic aridification and a degradation of the environment linked to anthropogenic activities.” ref

“We cannot exclude a diffusion of wheel and cart through the Caucasus. The remains of a wagon found in a kurgan at Starokorsunskaja (Maykop culture) have been dated to c. 3500 BCE or 5,520 years ago. Clay models of wheels have also been excavated from the earliest levels at the site of Velikent (same period) (northeastern Caucasus). The ard and the wheel spread together and rapidly across Europe along pre-existing trade routes, following the Danube valley and other large rivers, such as the Oder, around the middle of the fourth millennium, probably at the same time as innovations such as wool sheep breeding, the preparation of fermented beverages and the use of bivalve molds for casting metal objects. The adoption of more intensive agricultural practices provided a means of facing the crisis linked to the combination of population surge and climatic deterioration during this period. These diffusions were accompanied by major social transformations. “The use of draught power appears to have been linked to an élite able to mobilize resources; it implied concentration of power and control on herds and therefore on men”.” ref

“The crucial aspect of the invention of bronze has already been emphasized. It allowed for the growing production of weapons: besides trade, war played a major role in forming a dominant political elite and in building the state. Texts from Ur, dated to the end of the Urukian period / beginning of the Early Dynastic, refer to hierarchized military organization. Interestingly, “male slaves [in Archaic texts] are often qualified as being of foreign origin”. The need to maintain an adequate flow of imports to ensure the stability and growth of a type of production destined both for the southern Mesopotamian social space and for export partially explains the Uruk expansion to the north and east: it was a complex phenomenon, variable in both space and time. Not only did the city of Uruk take part in this expansion, but so did Nippur, Kish, Ur, and probably other cities, as suggested by the presence of the gods Enlil and Ninhursag at Mari, and of Ningal at Ugarit during the third millennium. Mesopotamia needed to import metals, wood, stone, and luxury goods – as these were indispensable for affirming the power of its elites.” ref

“Whereas the city had no copper, arsenic, or tin, it managed to develop an elaborate copper and later a bronze industry. The earliest economic tablets already contain a pictogram for a smith, and the remains of a foundry showing division of labor have been unearthed at Uruk. Two types of bronze were used in western Asia: arsenical bronze, found mainly along a north–south axis: the Caucasus; eastern Anatolia; Palestine; southern Mesopotamia; and a type of tin bronze appearing in the early third millennium, along an east–west axis: Afghanistan; Anatolia; northern Syria; Cilicia. Imported into southern Mesopotamia prior to the middle of the fourth millennium, copper came from the Iranian plateau, northern Iraq (Tiyari mountains), or eastern Anatolia. Already known in Palestine, the lost-wax casting technique developed both in Mesopotamia and at Susa. The cupellation process used to separate lead and silver – from galena, a lead ore containing silver – was attested c. 3300 BCE or 5,320 years ago at Habuba Kabira, and mid-fourth millennium at Arisman, in the vicinity of the Anarak copper source.” ref

“In addition to needs and economic opportunities, ideology probably underpinned both the Urukian expansion and the emergence of ruling elites. Here, as is still the case, religion played several roles: it had an integrative function within a multiethnic population; it represented a kind of sanctification through which leaders could claim legitimacy, and it allowed for the regulation of economic activities when both cooperation and forced labor became necessary. We must take into account not only religion itself, but a system of thought and practices, along with changes in clothing and food consumption accompanying social hierarchization in Urukian society. The role of religious networks in the Urukian world may explain why cultural signs were maintained, differentiating the southern Mesopotamians and their hosts for several centuries, at sites such as Hacınebi (Anatolia), but the “ideological Sumerian capital” also influenced many societies: the spread of “Urukian” potteries may have been linked to the consumption of fermented beverages embedded in new social relations.” ref

“The Urukian expansion favored an evolution that had begun earlier in Anatolia and Syria, and built upon it: interactions between the Anatolia–Levant and Mesopotamian spheres took place during the flowering of the ‘Ubaid culture, and continued after the end of the ‘Ubaid period. “Societies from Syria and Anatolia already exhibit complex organizational characteristics in the first part of the 4th millennium, prior to the rise of regular contacts with the Uruk world”. At the junction of various roads, Tell Brak exhibits links with southern Mesopotamia already during the Middle Uruk period or even earlier. Tepe Gawra and Arslantepe, though smaller settlements, were craft centers and nodes on exchange networks. Gawra produced textiles. The discovery of annular rimmed vessels which resemble primitive stills implies that perfumes were already being produced in the middle of the fourth millennium. As Algaze points out, however, the complexity of the northern settlements and their techniques of management and communication of information cannot be compared with those of Uruk and the cities of southern Mesopotamia. Lapis lazuli is present at sites in Iran such as Tepe Sialk (Middle Uruk/Late Uruk), Tepe Giyan (already in the first half of the fourth millennium BCE), Tepe Yahya (3750–3650 BCE or 5,770-5,670 years ago), and Tepe Hissar (phase 3600–3300, then 3300–3000 BCE), where it appears along with silver (perhaps originating in Anatolia, though this origin remains uncertain). Lapis has been found in northern Mesopotamia, at Arpachiyah, Nineveh (already during the ‘Ubaid period), Tell Brak, Tepe Gawra (Late Uruk?), and Jebel Aruda (before 3200 BCE), revealing the existence of trade routes linking Central Asia, Iran, and northern Mesopotamia. This blue stone was also present in the main southern Mesopotamian cities, during the second half of the fourth millennium: Uruk, Ur, Nippur, Khafajeh, and Telloh – but it remained a rarity prior to the Jemdet Nasr period c. 3100 BCE. Moreover, “the intrusion [in Pre-Maykop settlements] of northern Mesopotamian cultural elements or peoples (?) predating the subsequent southern Mesopotamian Uruk expansion” signals exchanges with regions beyond the Caucasus.” ref

“The Urukian expansion from 3600 BCE onward led to a growing connection of the southern Mesopotamian networks with those of northern Mesopotamia, Anatolia, and the Caucasus. Trading was active along the Euphrates, a river that played a crucial role in Urukian development. A Mesopotamian influence was felt in the plains of southwestern Iran (Susa II, 3500–3150 BCE) and in northern Mesopotamia (Brak, Hacınebi). From c. 3500 BCE, Uruk – and probably other rival Mesopotamian cities – created “colonies” (built by the state or by small groups independent of the state; this question remains debated): Qraya, Tiladir Tepe, Sheikh Hassan, and later Habuba Kabira and Jebel Aruda. The clear purpose of these colonies was to control access to regions of Anatolia and Iran that were rich in metal ores; to utilize pasture resources (for wool); and to interconnect the southern Mesopotamians with established trade centers and networks in Syria, between Anatolia and the Levant, and on routes crossing Iran. The importance of “outposts” such as Habuba Kabira implies active involvement by the public sector (palace, temple) in the process of creation. Urban planning and the building of its fortifications required a strong community, and therefore state-level organization.” ref

“The “Urukians” also settled in centers located either at network nodes or near coveted resources. Sites such as Hacınebi (as early as the Middle Uruk period) and Hassek HüyüK thus hosted Mesopotamian enclaves. In the sites where Urukians were present, they usually brought their own administrative techniques (bullae, seals, tablets, weights), ceramics, bitumen, and building techniques. When Hacınebi hosted an Urukian enclave, two administrative systems – Anatolian and Urukian – seem to have coexisted. In an attempt to refute the possible formation of a world-system centered on Uruk and other Mesopotamian cities, Stein alleges – while providing no evidence for it – that exchanges between the Anatolian and Urukian communities were symmetrical; in fact, we do not know what was really exchanged; textiles and slaves, for example, left no trace in the archaeological deposits. In any case, it seems that the Urukian demand stimulated copper production in Anatolia. Stein recognizes that we have little information to go on for understanding the context surrounding the Anatolian elite during Urukian phase B2. He also puts forward the unlikely idea that there were few interactions between the Anatolian and Urukian communities during their two or three hundred years of coexistence!” ref

“Moreover, contrary to Stein’s assertion, a core’s power over a region did not necessarily diminish with distance, nor did exchanges become increasingly “symmetric” when the distance increased – I will come back to this point. Chains of exchanges were formed, along which inequalities could be transmitted and strengthened. While distance and the existence of groups positioned as intermediaries could lead to lower profits for the agents of the core, they did not reduce exploitation of the system’s geographic or social peripheries. The fact that the Urukians sought alliances with the local elites does not imply equality in the situation of the two communities within the world-system. Moreover, the Urukians were settled on the highest part of the site, a fact Stein did not take into account. Lastly, Hacınebi was not a “periphery” as Stein terms it, but a semi-periphery: the level of social complexity, development of crafts, and density of its regional population show this clearly. The elites of northern semi-peripheries benefited from exchanges with the Urukians within a process of coevolution, but beneficial exchanges are not equivalent to symmetrical relations (Rothman commits the same error as Stein when he refutes Algaze’s model, arguing that “northern societies must have seen advantages to an exchange relation with Southerners”: these advantages recognized by the north did not imply the absence of dominance and exploitation by the southern Mesopotamians).” ref

“Other Anatolian sites, such as Tepecik, exhibit Mesopotamian influences without revealing an Urukian presence. This is also the case at Godin (level VI) (Iran) for the Middle Uruk period. The Euphrates River played a pivotal role because it offered access to the metal resources of the Ergani area, the Taurus forests, and the products of the Mediterranean region (the location of the colony of Habuba Kabira is enlightening in this respect). In Syria, the site of El-Kowm, which shows influences from Sheik Hassan from the thirty-fourth century BCE onward, forms the western boundary of the Urukian sphere. Algaze has defined the ensemble formed by the southern Mesopotamian core and the network of Urukian enclaves as an “informal empire” or a “world-system,” whose activity and survival depended primarily upon alliance networks with local chiefs. Moreover, Mesopotamian merchants and artisans may have been present at more isolated sites, located along trade routes (thus Godin Tepe [VI.1], Sialk [III], in Iran, close to copper resources of Anarak). For this “Urukian expansion,” we should probably consider the existence of merchant communities operating within indigenous societies. The regional configuration of established Urukian settlements shows dendritic forms that suggest the functioning of a monopolistic system or at least some kind of cooperation.” ref

“In Iran, tablets impressed by cylinder seals and bearing numerical notations have been found at Susa, Chogha Mish (Khuzistan), Tal-i Ghazir (between Khuzistan and Fars), and Godin Tepe (in Luristan). According to Potts, the numerical tablets from Godin are similar to tablets from northern Mesopotamia (Tell Brak, Mari, Jabal Aruda), “whereas those from Susiana are most like examples from Uruk”; for Dahl et al., however, “the Godin Tepe tablets are all Uruk-style tablets.” “A single tablet (T295) has been classed as numero-ideographic, it bears a pictographic Uruk IV sign”. Sialk (IV 1) yielded numerical tablets, prior to the appearance of Proto-Elamite documents. Proto-literate tablets have also been found in northeastern Iran, at Tepe Hissar. At Uruk, proto-cuneiform signs and numerical systems were present together on tablets, but at Susa, it was only at Level III that pictograms appeared, after Susa II and the numerical tablets. Only “three of the thirteen numerical systems attested at Uruk [Late Uruk and Jemdet Nasr periods] were introduced to Susa [Susa II]”. But the Proto-Elamite includes a “decimal counting system that is not attested at Uruk (Dahl et al.)”. Potts emphasizes that although Mesopotamian scribes probably settled at Susa, it is difficult to view Susa as an Urukian colony. In fact, it is possible that a state centered on Susa maintained its autonomy, and influenced the Iranian plateau.” ref

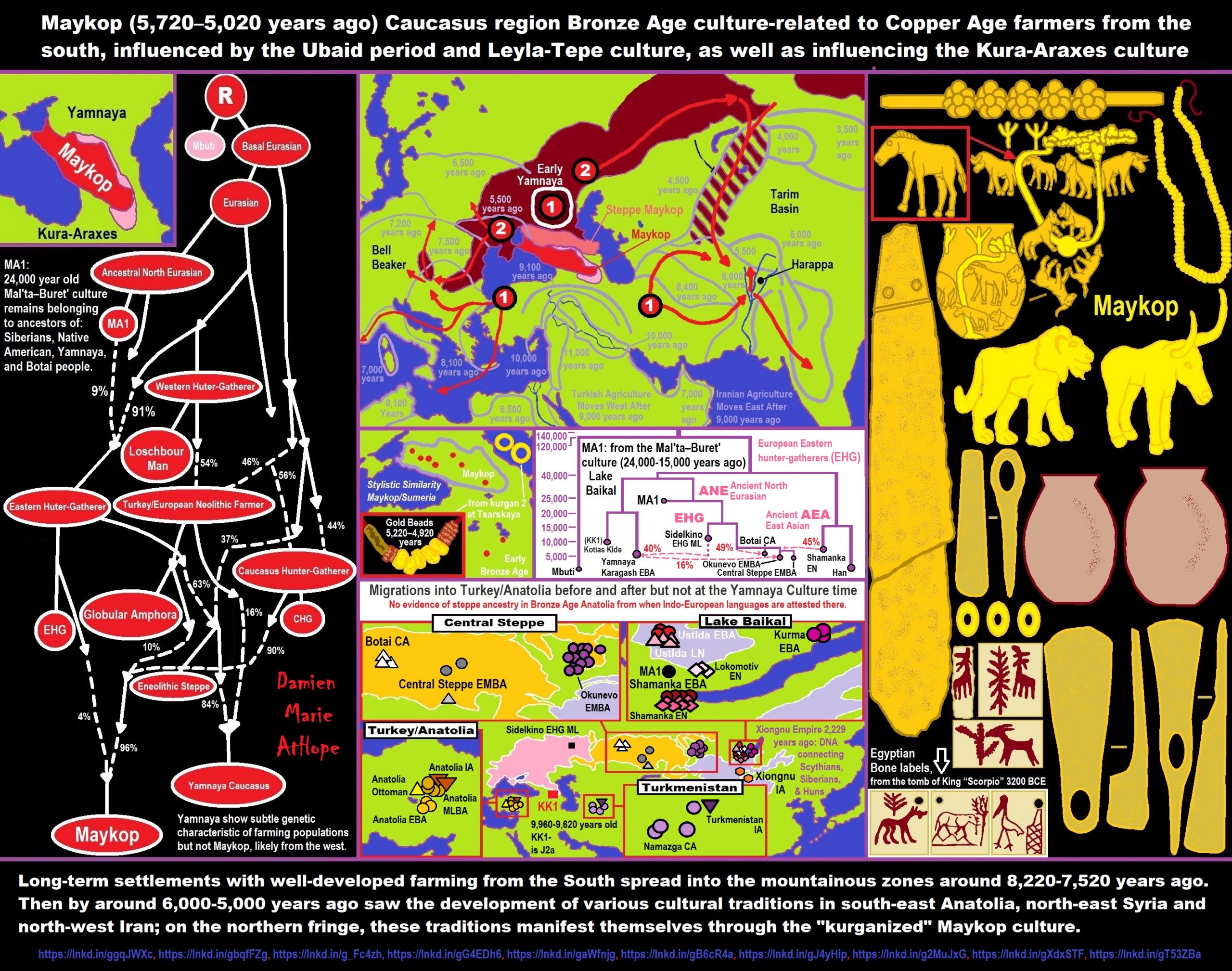

“The Urukian expansion fostered new development in Anatolia and Syria, where local elites took advantage of the exchanges and adopted some southern Mesopotamian practices such as the use of cylinder seals. They established themselves as intermediaries along the roads of coveted products and organized their own craft production. Arslantepe, where a vast public palace-like structure was built starting in 3500 BCE, appears to have been a minor power center, controlling local or regional production. Many seals have been excavated, that were used in accounting operations. The site shows connections with southern Mesopotamians, but also with Syria and the Maykop culture. As already pointed out, ideology – and ideational technologies – certainly played an important role in the southern Mesopotamian expansion; ideology clearly influenced the northern chiefdoms or proto-states and contributed to their configuration into semi-peripheries of the Urukian world-system. The culture of Maykop, in the northwestern Caucasus, clearly reflects Mesopotamian influences, first from northern Mesopotamia, with the borrowing of the slow wheel, and later from southern Mesopotamia, as revealed by the discovery of a cylinder seal and a toggle-pin with a triangular-shaped head known at Arslantepe during the Late Uruk period.” ref

“Brought through Iran and the region of Nineveh, lapis lazuli has been unearthed at no fewer than three sites (Maykop, Novosvobodnaya, Staromysatov). Carnelian and cotton from India have also been found, as well as turquoise from Tajikistan. The extension of exchange networks can also be seen in the northeastern Caucasus, where the site of Velikent, which appeared around 3500 bce, yielded arsenical bronze from its earliest levels. In the Urals, copper at the site of Kargaly was mined as early as the second half of the fourth millennium, and the “royal” kurgans exhibit extraordinary wealth in metals, including gold and silver objects. These interactions would lead to the emergence of new institutions in the Eurasian steppes. South of the Caucasus, in Transcaucasia, the Kura-Araxes formations expanded from 3500 BCE onward. Some tin-bronze ornaments have also been discovered in the tombs of Velikent; these bronzes would become more abundant during the first half of the third millennium in kurgans south of the Caucasus, and then further west, at Troy II and at Aegean sites and as far as the Adriatic (Velika Gruda). The tin may have come from Central Asia (Afghanistan, Samarkand, or regions further east?).” ref

“It would be inaccurate to view the seven hundred years of the Middle and Late Uruk periods as a continuum of growth in space and time: several phases of growth and decline are apparent. A first phase of expansion occurred around 3600/3500 BCE, and another one a few centuries later (Habuba Kabira would come under this second phase). Rothman discerns three phases of expansion, the first at the start of the Middle Uruk period, the second later during the same period, and the third during the Late Uruk.” ref

“Moreover, as already mentioned, authors such as Ur tend to emphasize continuity with preceding centuries rather than “revolution.” Ur notes the presence of tripartite houses that were already known during the ‘Ubaid period: so-called “palaces” or “temples” retained the same structure. Ur rejects the idea that urbanism results from extending trade and growing tribute demands; he does not believe in the formation of social classes going along with the creation of true bureaucracies. “Urban society in the Uruk period was a dynamic network of nested households,” writes Ur. Here, however, he does not discuss the implications of the development of writing and of the impressive division of labor revealed by later lists of professions. For him, “broad social change is more likely to stem from the creative transformation of an existing structuring principle – in this case, the household – than from the revolutionary replacement of an existing structure with a completely new one.” He notes that “the term for ‘palace,’ e2-gal, literally meant ‘great house’.” However, this may be just a metaphor; and the fact that a city or a temple could remain under the rule of a particular household should not lead us to preclude the idea of new types of political or religious elites. Ur himself notes that some large tripartite houses built on high terraces must indeed be temples; their construction implies a large labor investment. Surely these “households” were not just common households. It is true, however, that when we consider ancient societies, “categories such as ‘urban’ and ‘state’ must be able to subsume a great deal of variability”, and the birth of the state does not imply the disappearance of kinship.” ref

“Most of the exchanges between southern Mesopotamians and northern populations are thought to have occurred within peaceful contexts. Military power must have played a role, however, especially when strong political entities emerged in the semi-peripheries of the Urukian area. During the Late Uruk period, settlements such as Habuba Kabira and Abu Salabikh were fortified: this appears to reflect growing conflicts. At Hamoukar, a conquest by southern Mesopotamians has been suggested. “Urukians” also took over Brak – after a period of interaction – and possibly Nineveh. Moreover, slaves may have been exchanged with the northern proto-states and then led to the cities of southern Mesopotamia. The Urukian expansion extended toward Egypt, via northern Syria. The existence of an Anatolia–Levant sphere of interaction is shown in the participation of Hama and sites of the Amuq in “a Syro-Anatolian glyptic tradition distinct from Mesopotamia,” the diffusion of the technology of the “Cananean blades,” the use of the pottery wheel, the presence of silver items at Byblos, in the southern Levant and in Egypt, and the relative abundance of copper at Byblos, with silver and copper coming from Anatolia. This sphere of interaction was already in place at the start of the fourth millennium.” ref

“In the Persian Gulf, in contrast to what can be observed in Upper Mesopotamia and Iran, the Urukian presence seems to have been limited, perhaps because the organizational level of Arab societies did not allow for an efficient utilization of resources. It is unlikely that the Mesopotamian influences observed in the Nile delta and in Upper Egypt resulted from the presence of Urukians who sailed around the Arab coasts. Exchanges did occur, however, during the fourth millennium, between Mesopotamia, Iran, and the eastern Arab coast. A clay bulla has been found at Dharan (end fourth millennium); Mesopotamian-type jars with tubular spouts discovered at Umm an-Nussi in the Yabrin oasis and at Umm ar-Ramadh in the al-Hufūf oasis may date to this period. Around 3400 BCE, at Ra’s al-Hamra (Masqat), grey ceramic from southeast Iran was used to heat bitumen imported from Mesopotamia. The name of Dilmun (which, during this period, refers to the Arabian coast in the region of Tarut-Dharan, and not yet to Bahrain) appears in a text from the Uruk IV phase: we hear of a “Dilmun tax-collector,” which means that Sumerians were involved in trade with Dilmun, and a text from Uruk III refers to a “Dilmun ax”.” ref

“Archaic texts from Uruk also mention copper from Dilmun, which may have originated in Oman. It could be that during the final years of the fourth millennium, barley and wheat were taken to Arabia. The term ŠIM, which seems to mean “aromatic essence, incense,” already appears in texts of the Uruk IV period. Archaic texts from Uruk mention “an aromatic product for the use of the priests”: aromatics certainly reached Dilmun at this time via a route linking Dhofar to Yabrin and al-Hasa (Zarins 1997, 2002). Moreover, the discovery of bowls of Urukian (or Proto-Elamite) type in Baluchistan renewed speculation on the possible role played by contacts with Susa and Mesopotamia in the emergence of the Harappan culture (Benseval 1994, Joffe 2000). Pottery of Urukian style unearthed at Tepe Yahya reflects southeastern Iranian links with Susa. The discovery of cotton fibers on fragments of plaster in a camp at Dhuweila (Jordan) (between 4450 and 3000 bce) reveals the importation of cotton fabrics, possibly from the Indus region.” ref

“Around 3200/3100 BCE, the Urukian “colonies” were suddenly abandoned; we observe a reorganization of the exchange networks as well as social transformations – not yet well understood – in southern Mesopotamia. Various reasons have been advanced. The decline observed in some “colonies” before their abandonment may have had its origin in the core of the system itself. A salinization of the lands – a consequence of faulty irrigation – may have led to weaker agricultural productivity and, therefore, to an increase in conflicts between city-states as well as to internal social problems: one notes “the abandonment of many of the public structures at the very core of Uruk itself.” Climate data for the end of the fourth millennium show a decline in oak woodland at Lakes Van and Zeribar, and low water volumes for the Tigris and the Euphrates, reflecting a drier climate. An aridization of southern Mesopotamia may have begun in the middle of the fourth millennium. In addition, one observes a weakening of the summer monsoon system of the Indian Ocean, especially around 3200 BCE. The pressure exerted by cities on their physical surroundings (deforestation …) and the human environment (tributes, corvées, urban migration) may also have been destabilizing factors. It is likely that the activity of the outposts depended in part on products such as textiles delivered from urban centers of the south. The profitability of these outposts could not be ensured within a climate of economic and political deterioration.” ref

“In addition, the destruction of the “palace” of Arslantepe by a fire c. 3000 BCE leads us to suspect other destabilizing factors that were not solely linked to climate change, but were also the indirect consequences of the Uruk expansion itself. Transcaucasian populations belonging to the Kura-Araxes formations entered the plain of Malatya; they had probably been displaced by the arrival of groups coming from the steppes and the northern Caucasus. These Transcaucasians occupied Arslantepe from 3000 to 2900 BCE. North of the Caucasus, the Maykop culture disappeared around the end of the fourth millennium. We observe a reduction in the number and size of the settlements in Anatolia following the collapse of the Urukian colonies, as well as a regional fragmentation. Pontic and Transcaucasian influences are also seen in northwestern Iran during the late fourth and the early third millennium, for example at Yaniktepe. At Godin, from 3100 to 2900, the Urukian/Susian influence diminished while at the same time, Transcaucasian pottery came into use (this pottery would become the most commonly used during phase IV). Godin shows evidence of a fire, as does Sialk III, which was destroyed c. 3000 BCE. The Kura-Araxes populations also migrated to the southwest, entering the Amuq plain (Syria) than northern Palestine, around 2800–2700 BCE. In northern Mesopotamia, the lower town at Brak was abandoned, trade networks faded away, and “the use of tokens and sealed bullae as administrative technology disappeared, and mass production of pottery, on a large scale in the mid- to late-fourth millennium, all but disappeared at the end of the Uruk period”. The Urukian networks obviously could not survive in a politically hostile environment. Trade relations between Egypt and Mesopotamia practically stopped around 3100/3000 BCE. Upheavals in the north of the Urukian sphere of interaction affected not only the north–south relations, but also east–west routes. The abandonment of the northern colonies corresponds to a shift in Mesopotamian trade southwards toward the Persian Gulf, where copper in Oman began to be utilized in a significant way, within a more fragmented political and cultural context.” ref

The City of Susa

“Susa was an ancient city in the lower Zagros Mountains about 250 km (160 mi) east of the Tigris River, between the Karkheh and Dez Rivers. One of the most important cities of the Ancient Near East, Susa served as the capital of Elam and the Achaemenid Empire, and remained a strategic center during the Parthian and Sasanian periods. The site currently consists of three archaeological mounds, covering an area of around one square kilometer. The modern Iranian town of Shush is located on the site of ancient Susa. Shush is identified as Shushan, mentioned in the Book of Esther and other Biblical books.” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

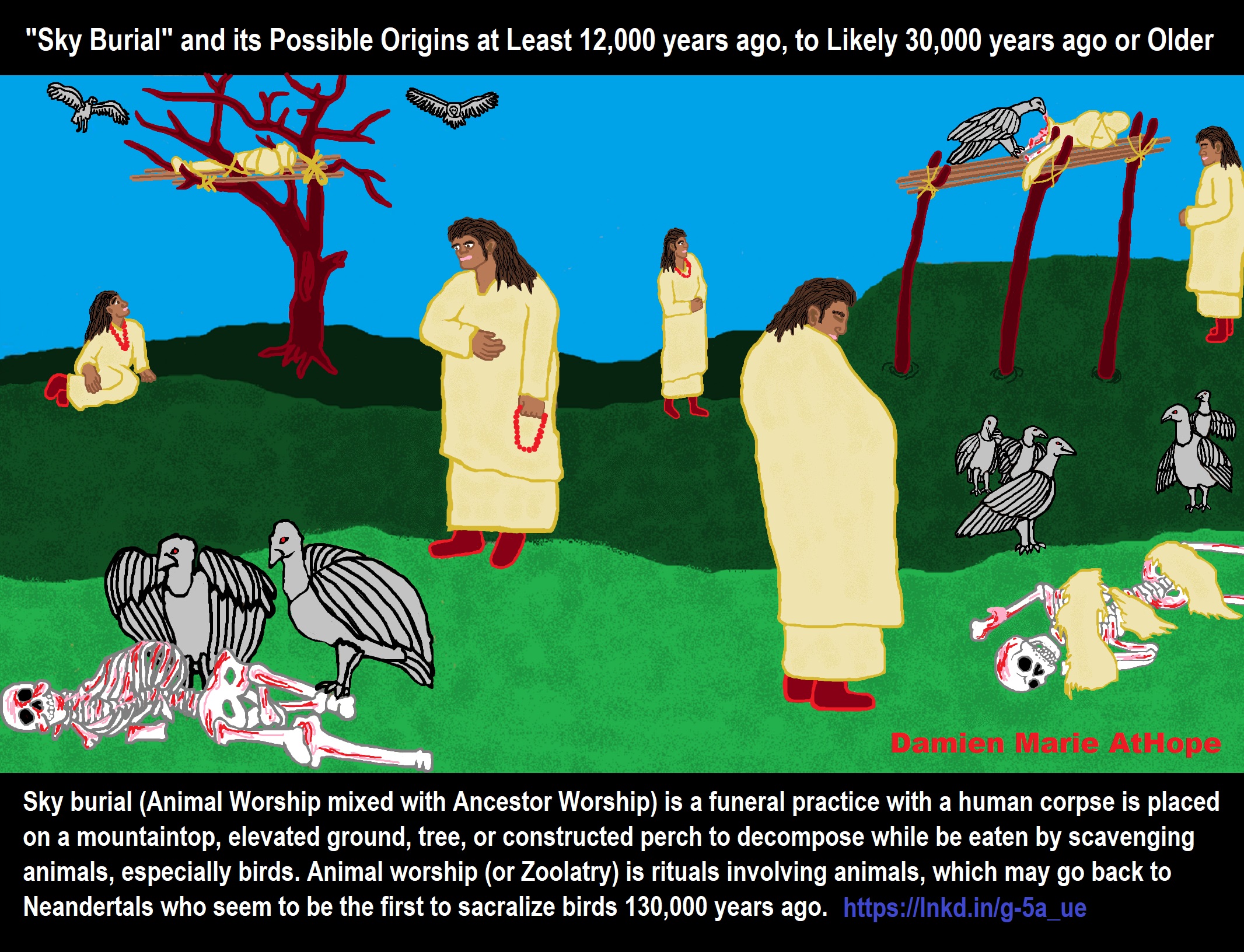

Sky Burials: Animism, Totemism, Shamanism, and Paganism

“In archaeology and anthropology, the term excarnation (also known as defleshing) refers to the practice of removing the flesh and organs of the dead before burial, leaving only the bones. Excarnation may be precipitated through natural means, involving leaving a body exposed for animals to scavenge, or it may be purposefully undertaken by butchering the corpse by hand. Practices making use of natural processes for excarnation are the Tibetan sky burial, Comanche platform burials, and traditional Zoroastrian funerals (see Tower of Silence). Some Native American groups in the southeastern portion of North America practiced deliberate excarnation in protohistoric times. Archaeologists believe that in this practice, people typically left the body exposed on a woven litter or altar.” ref

Ancient Headless Corpses Were Defleshed By Griffon Vultures