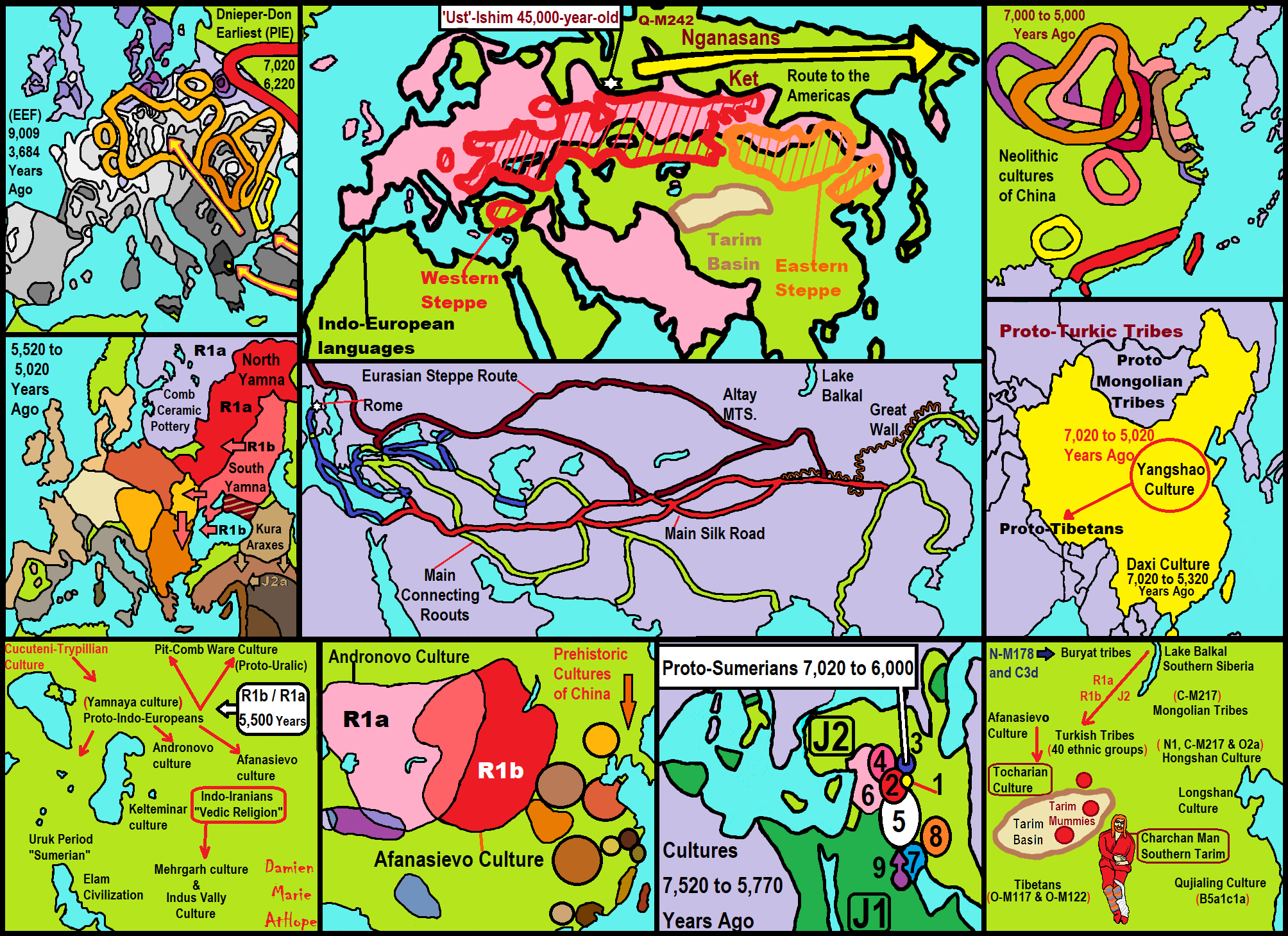

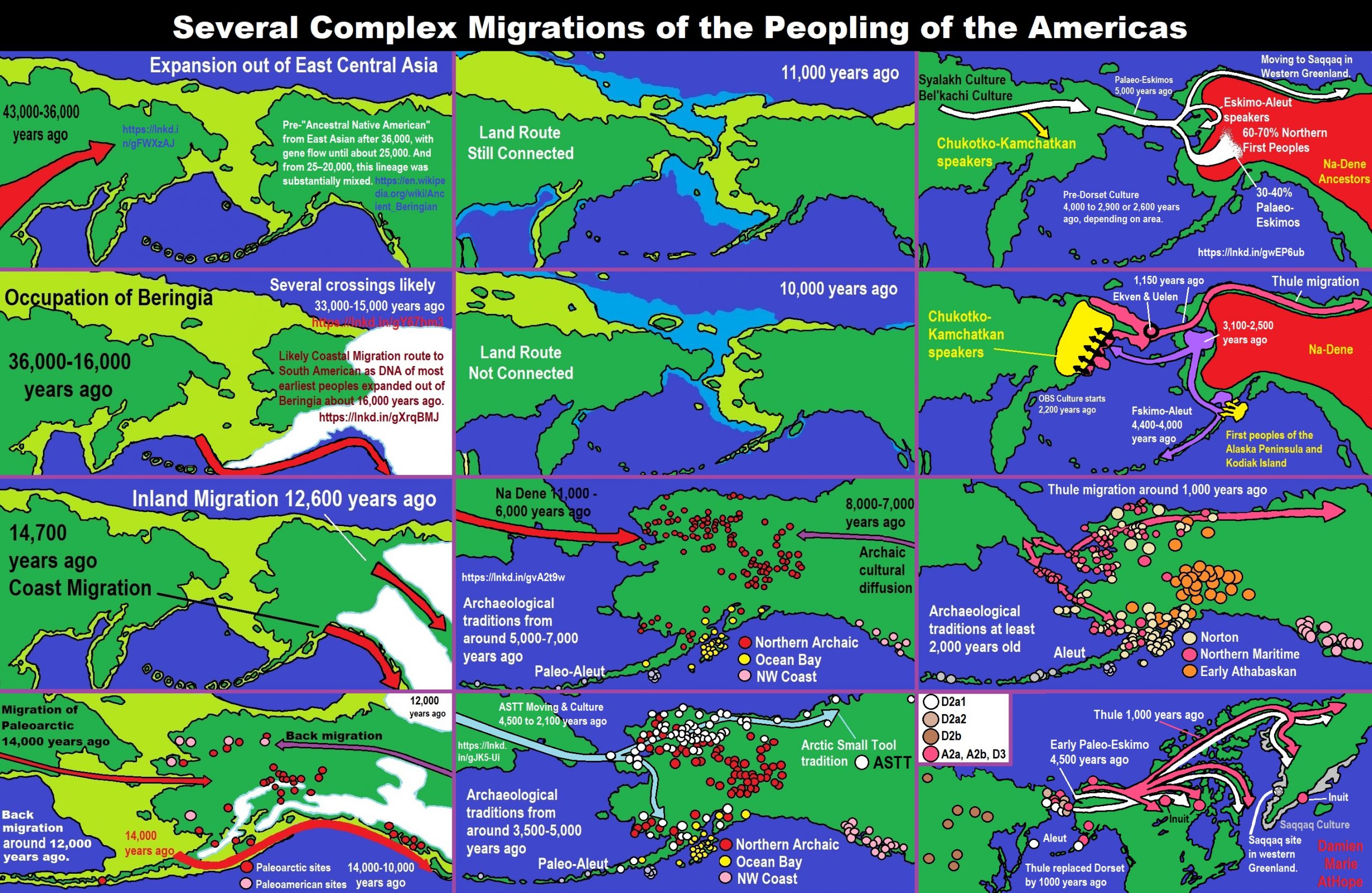

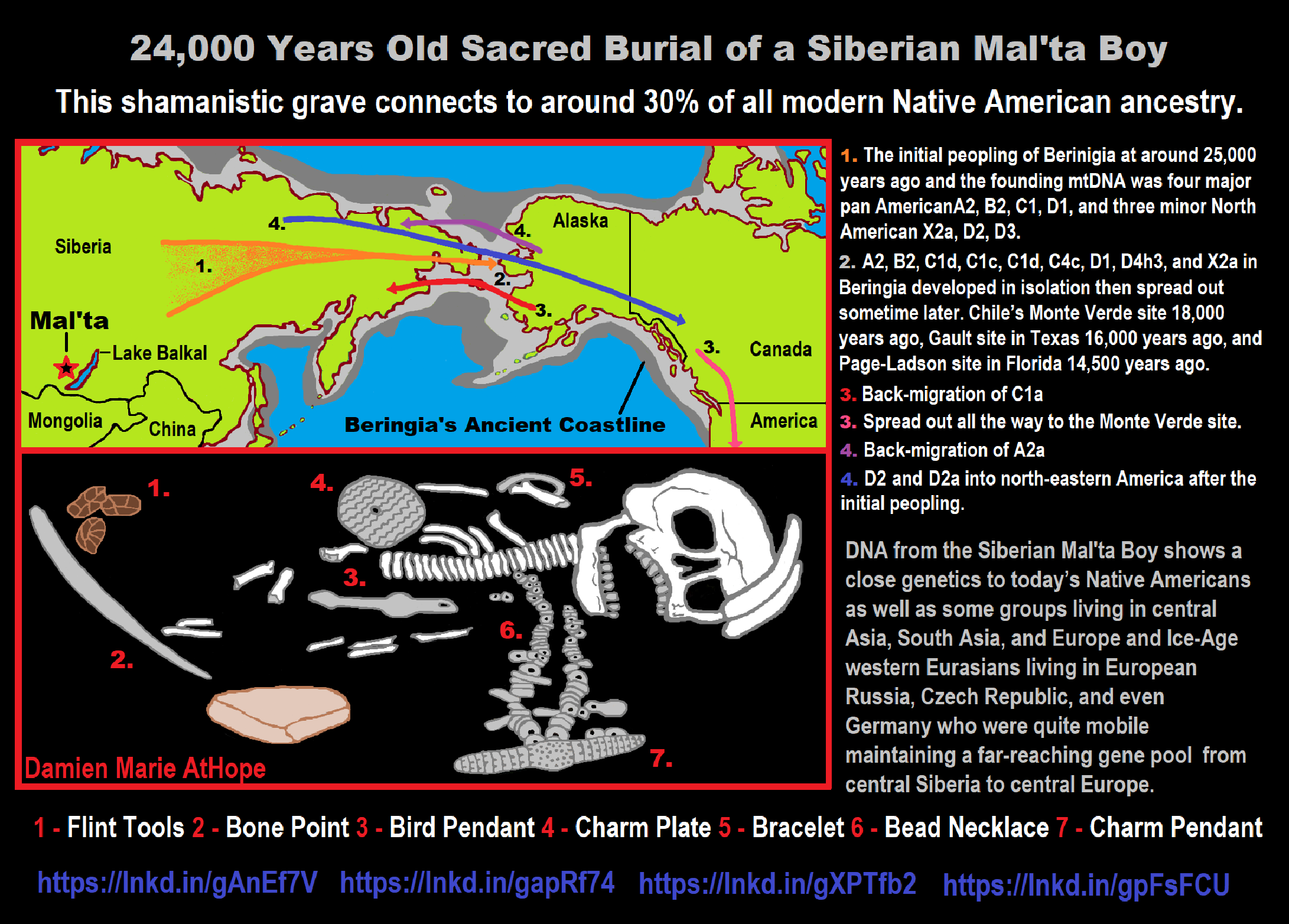

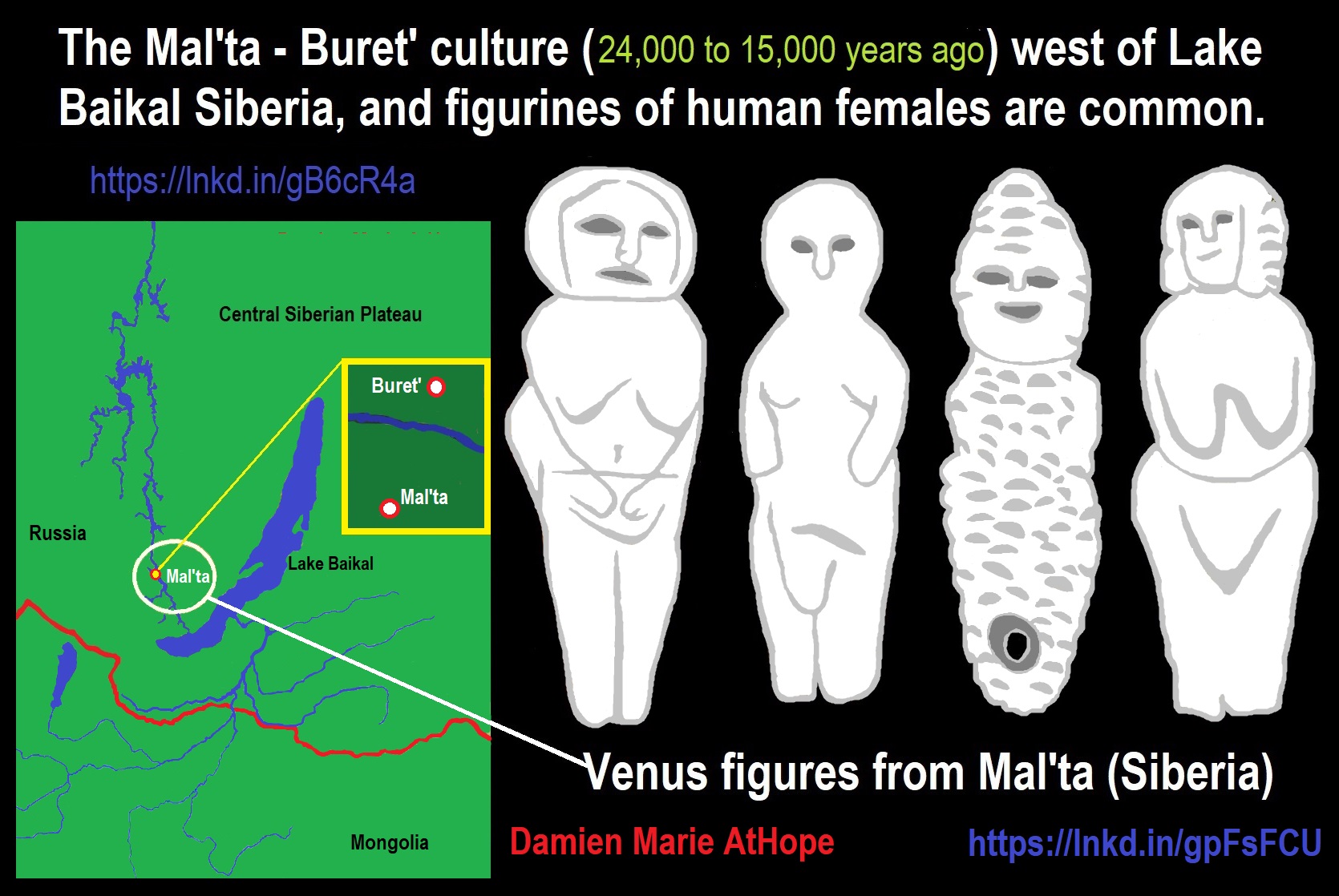

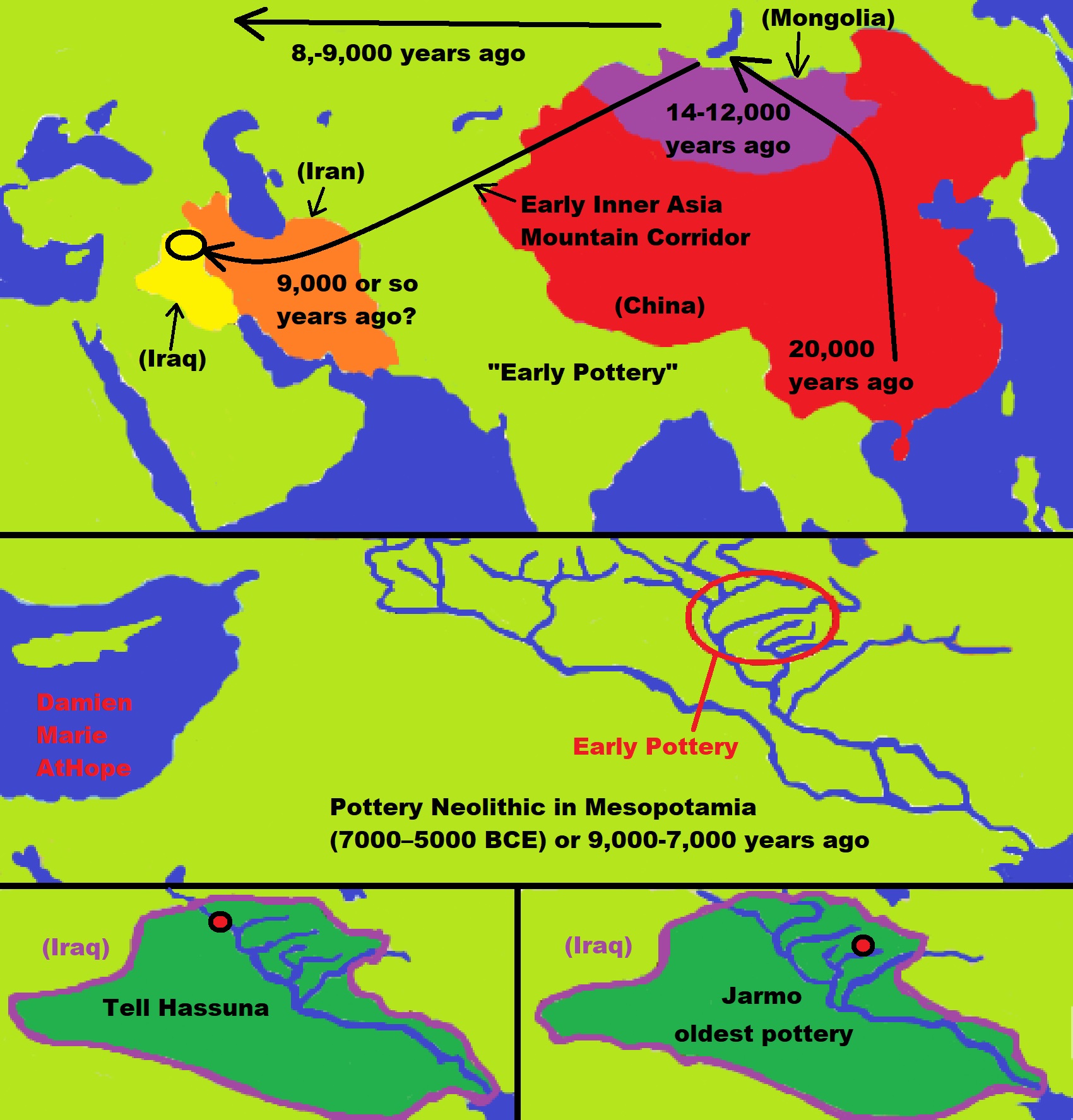

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

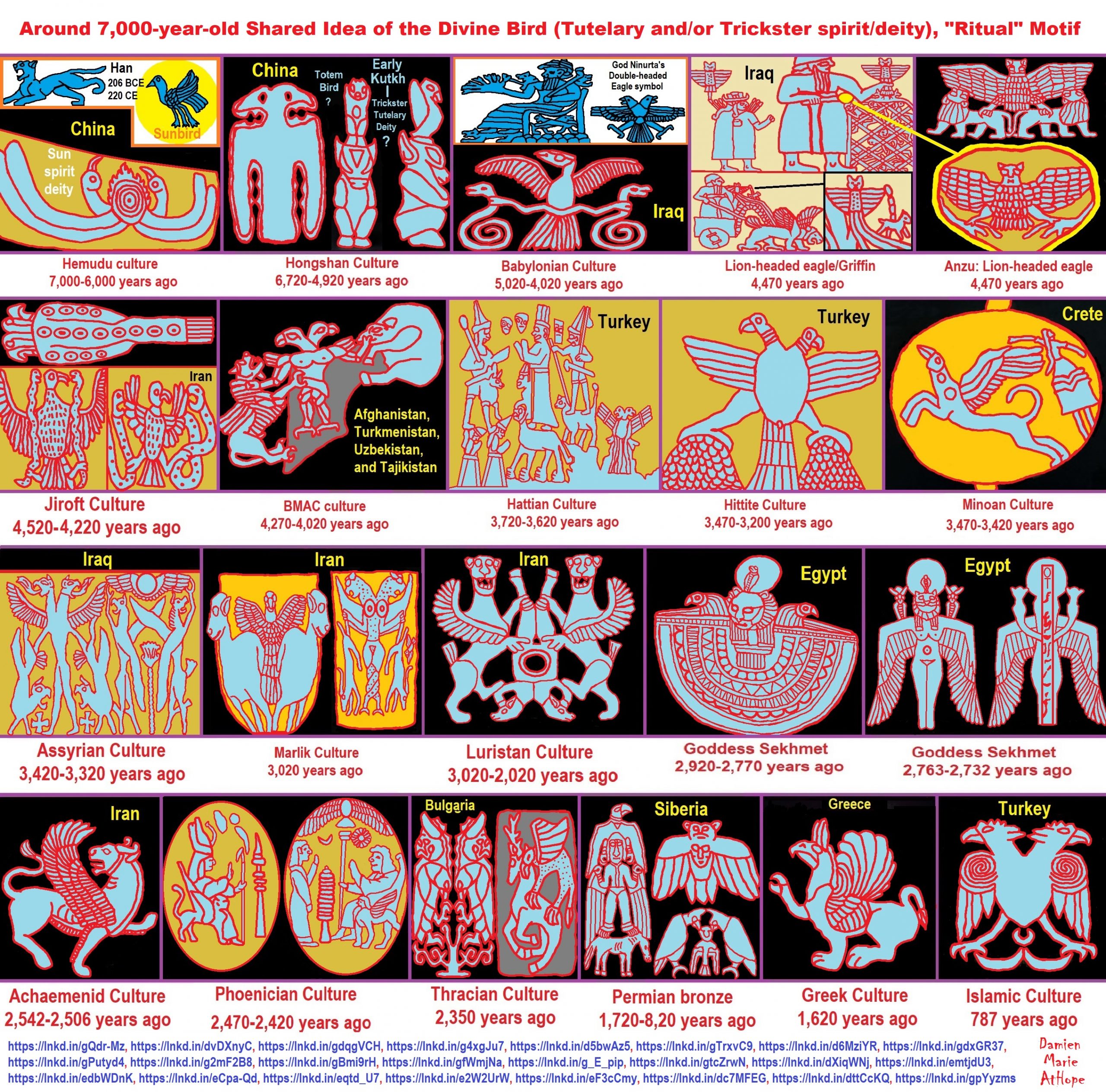

Divine Birds?

“The logic is pretty simple: the gods, as everyone knows, live somewhere up in the sky. Birds also inhabit the sky, or at least spend more time there than any other creature in common experience. Therefore, birds have a special connection with the divine. Many cultures see birds as bearers of omens, whether good or bad depending on the type of bird, and some go even farther, with myths and tales depicting them as messengers proffering instructions and advice to mortals, or even providing services of some sort. Angels, additionally, are often depicted as winged and are seen mainly as messengers of God in scripture. Specific species of bird can be associated with certain gods. Eagles are particular favorites and often serve the Top God of a particular pantheon; however, note that eagles are also used to represent mundane values and so are not always part of this trope. If the writer is feeling more fantastically-inclined, mythical birds such as phoenixes might get used. Gods of death or the underworld have their own preferred representatives which would best be avoided: see Creepy Crows and Owl Be Damned. Vultures are another popular choice. Other flighted creatures are sometimes seen in the same way: see Butterfly of Death and Rebirth and Macabre Moth Motif. Birds being seen as sinister in general are Feathered Fiends.” ref

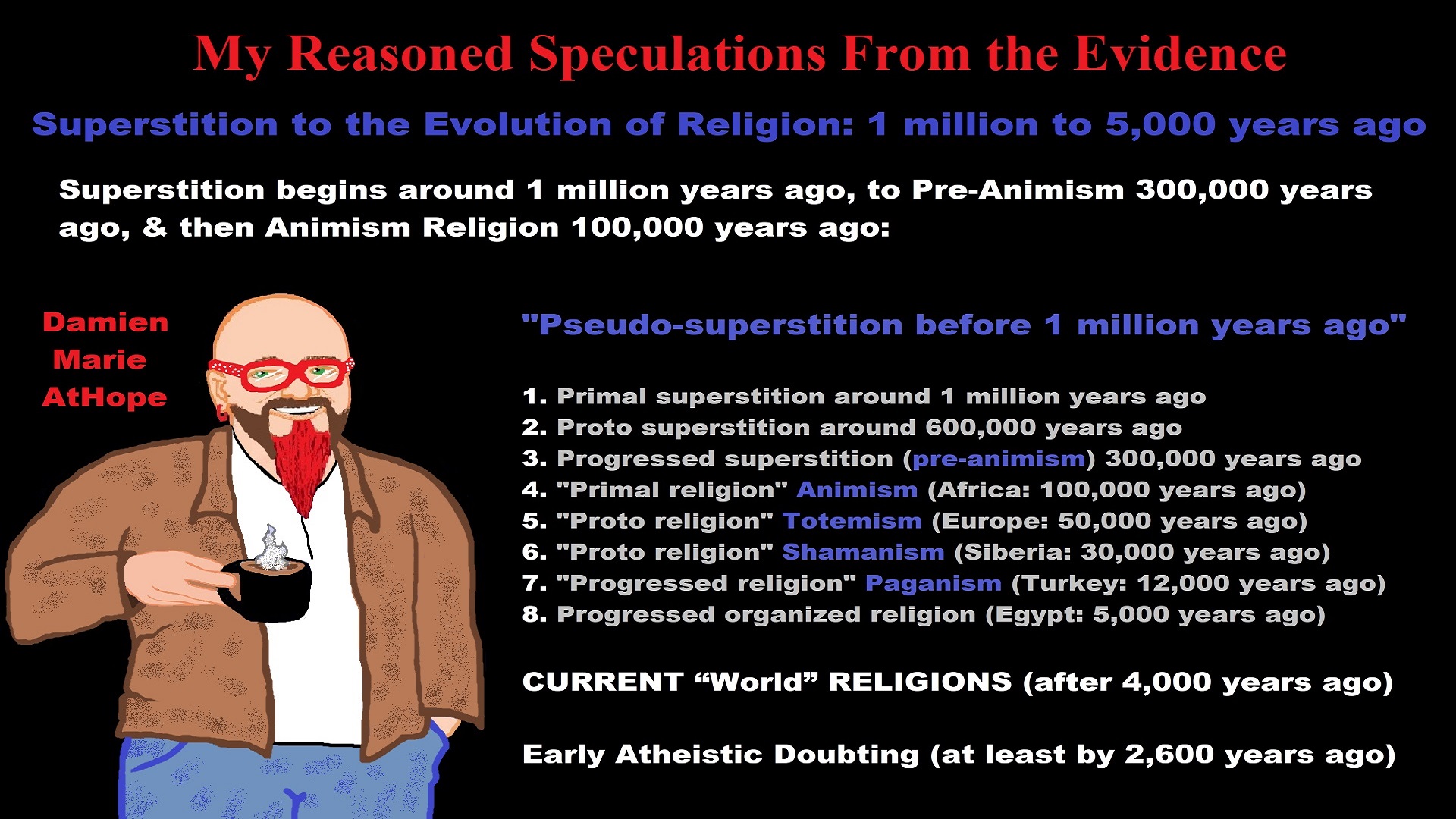

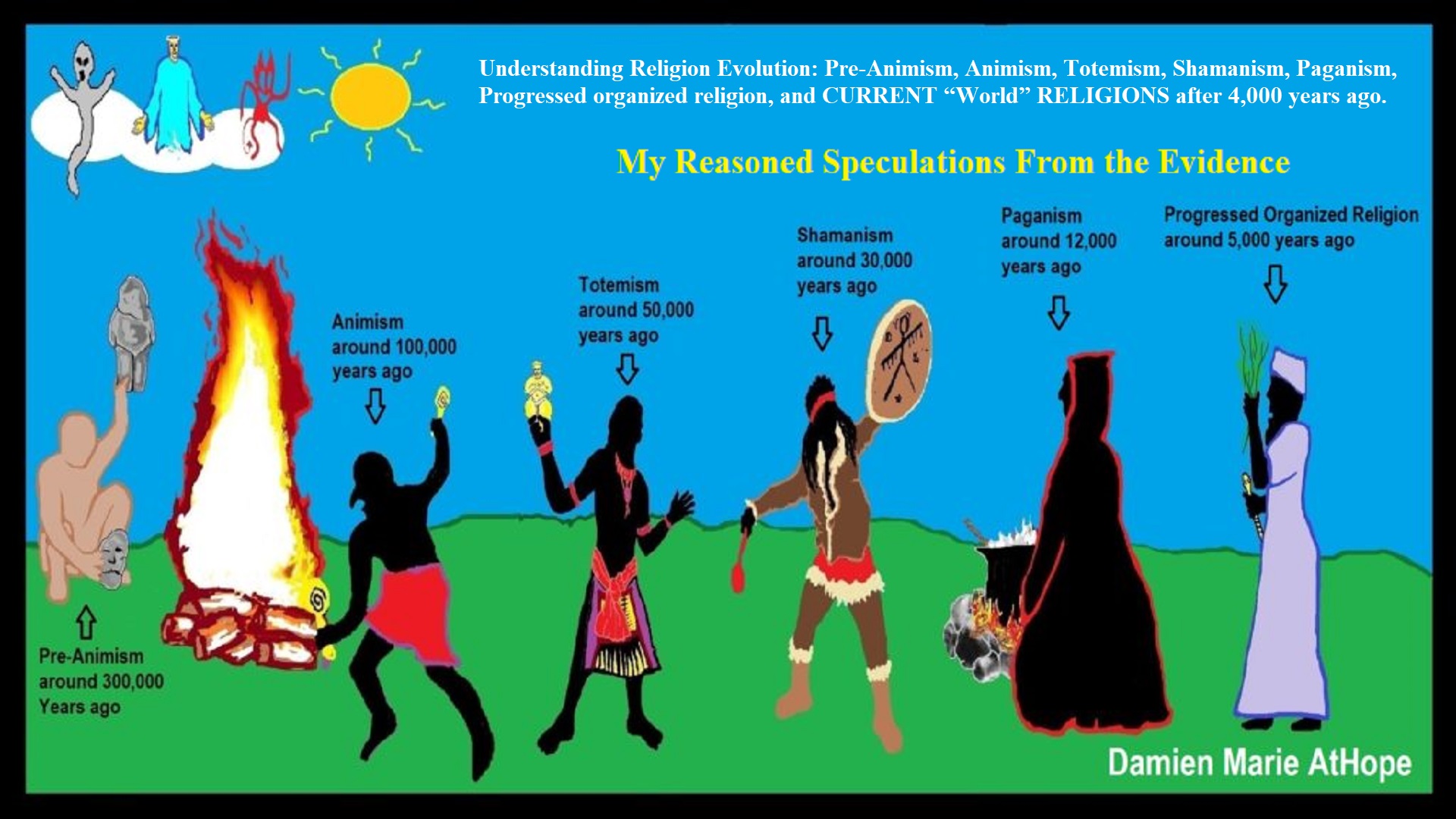

Double-headed eagle

“In heraldry and vexillology, the double-headed eagle (or double-eagle) is a charge associated with the concept of Empire. Most modern uses of the symbol are directly or indirectly associated with its use by the Byzantine Empire, whose use of it represented the Empire’s dominion over the Near East and the West. The symbol is much older, and its original meaning is debated among scholars. The eagle has long been a symbol of power and dominion. The double-headed eagle or double-eagle is a motif that appears in Mycenaean Greece and in the Ancient Near East, especially in Hittite iconography. It re-appeared during the High Middle Ages, from around the 10th or 11th centuries, and was notably used by the Byzantine Empire, but 11th or 12th century representations have also been found originating from Islamic Spain, France, and the Serbian principality of Raška. From the 13th century onward, it became even more widespread, and was used by the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum and the Mamluk Sultanate within the Islamic world, and within the Christian world by the Holy Roman Empire, Serbia, several medieval Albanian noble families, and Russia. Used in the Byzantine Empire as a dynastic emblem of the Palaiologoi, it was adopted during the Late Medieval to Early Modern period in the Holy Roman Empire on the one hand, and in Orthodox principalities (Serbia and Russia) on the other, representing an augmentation of the (single-headed) eagle or Aquila associated with the Roman Empire. In a few places, among them the Holy Roman Empire and Russia, the motif was further augmented to create the less prominent triple-headed eagle.” ref

Ancient Near East and Anatolia

“Polycephalous mythological beasts are very frequent in the Bronze Age and Iron Age pictorial legacy of the Ancient Near East, especially in the Assyrian sphere. These latter were adopted by the Hittites. Use of the double-headed eagle in Hittite imagery has been interpreted as “royal insignia”. A monumental Hittite relief of a double-headed eagle grasping two hares is found at the eastern pier of the Sphinx Gate at Alaca Hüyük. For more examples of double-headed eagles in the Hittite context see Jesse David Chariton, “The Function of the Double-Headed Eagle at Yazılıkaya.” ref

Mycenaean Greece

“In Mycenaean Greece, evidence of the double-eagle motif was discovered in Grave Circle A, an elite Mycenaean cemetery; the motif was part of a series of gold jewelry, possibly a necklace with a repeating design.” ref

Middle Ages

“After the Bronze Age collapse, there is a gap of more than two millennia before the re-appearance of the double-headed eagle motif. The earliest occurrence in the context of the Byzantine Empire appears to be on a silk brocade dated to the 10th century, which was, however, likely manufactured in Islamic Spain; similarly, early examples, from the 10th or 11th century, are from Bulgaria and from France.” ref

Byzantine Empire

“The early Byzantine Empire continued to use the (single-headed) imperial eagle motif. The double-headed eagle appears only in the medieval period, by about the 10th century in Byzantine art, but as an imperial emblem only much later, during the final century of the Palaiologos dynasty. In Western European sources, it appears as a Byzantine state emblem since at least the 15th century. A modern theory, forwarded by Zapheiriou (1947), connected the introduction of the motif to Byzantine Emperor Isaac I Komnenos (1057–1059), whose family originated in Paphlagonia. Zapheiriou supposed that the Hittite motif of the double-headed bird, associated with the Paphlagonian city of Gangra (where it was known as Haga, Χάγκα) might have been brought to the Byzantine Empire by the Komnenoi.” ref

Adoption in the Muslim world

“The double-headed eagle motif was adopted in the Seljuk Sultanate of Rûm and the Turkic beyliks of medieval Anatolia in the early 13th century. A royal association of the motif is suggested by its appearance on the keystone of an arch of the citadel built at Konya (former Ikonion) under Kayqubad I (r. 1220–1237). The motif appears on Turkomen coins of this era, notably on coins minted under Artuqid ruler Nasir al-Din Mahmud of Hasankeyf (r. 1200–1222). It is also found on some stone reliefs on the towers of Diyarbakır Fortress. Later in the 13th century, the motif was also adopted in Mamluk Egypt; it is notably found on the pierced-globe handwarmer made for Mamluk amir Badr al-Din Baysari (c. 1270), and in a stone relief on the walls of the Cairo Citadel.” ref

Adoption in Christian Europe

“Adoption of the double-headed eagle in Albania, Serbia, Russia, and in the Holy Roman Empire begins still in the medieval period, possibly as early as the 12th century, but widespread use begins after the fall of Constantinople, in the late 15th century. The oldest preserved depiction of a double-headed eagle in Serbia is the one found in the donor portrait of Miroslav of Hum in the Church of St. Peter and Paul in Bijelo Polje, dating to 1190. The double-headed eagle in the Serbian royal coat of arms is well attested in the 13th and 14th centuries. An exceptional medieval depiction of a double-headed eagle in the West, attributed to Otto IV, is found in a copy of the Chronica Majora of Matthew of Paris (Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, Parker MS 16 fol. 18, 13th century).” ref

Early Modern use

“In Serbia, the Nemanjić dynasty adopted a double-headed eagle by the 14th century (recorded by Angelino Dulcert 1339). The double-headed eagle was used in several coats of arms found in the Illyrian Armorials, compiled in the early modern period. The white double-headed eagle on a red shield was used for the Nemanjić dynasty, and the Despot Stefan Lazarević. A “Nemanjić eagle” was used at the crest of the Hrebeljanović (Lazarević dynasty), while a half-white half-red eagle was used at the crest of the Mrnjavčević. The use of the white eagle was continued by the modern Karađorđević, Obrenović, and Petrović-Njegoš ruling houses.” ref

Russia

“After the fall of Constantinople, the use of two-headed eagle symbols spread to Grand Duchy of Moscow after Ivan III‘s second marriage (1472) to Zoe Palaiologina (a niece of the last Byzantine emperor Constantine XI Palaiologos, who reigned 1449–1453),[17] The last prince of Tver, Mikhail III of Tver (1453–1505), was stamping his coins with two-headed eagle symbol. The double-headed eagle remained an important motif in the heraldry of the imperial families of Russia (the House of Romanov (1613-1762)). The double-headed eagle was a main element of the coat of arms of the Russian Empire (1721–1917), modified in various ways from the reign of Ivan III (1462–1505) onwards, with the shape of the eagle getting its definite Russian form during the reign of Peter the Great (1682–1725). It continued in Russian use until abolished (being identified with Tsarist rule) with the Russian Revolution in 1917; it was restored in 1993 after that year’s constitutional crisis and remains in use up to the present, although the eagle charge on the present coat of arms is golden rather than the traditional, imperial black.” ref

Holy Roman Empire

“The use of a double-headed Imperial Eagle, improved from the single-headed Imperial Eagle used in the high medieval period, became current in the 15th to 16th centuries. The double-headed Reichsadler was in the coats of arms of many German cities and aristocratic families in the early modern period. A distinguishing feature of the Holy Roman eagle was that it was often depicted with haloes. After the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, the double-headed eagle was retained by the Austrian Empire, and served also as the coat of arms of the German Confederation. The German states of Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt and Schwarzburg-Sondershausen continued to use the double-headed eagle as well until they were abolished shortly after the First World War, and so did the Free City of Lübeck until it was abolished by the Nazi government in 1937. Austria, which switched to a single-headed eagle after the end of the monarchy, briefly used a double-headed eagle – with haloes – once again when it was a one-party state 1934–1938; this, too, was ended by the Nazi government. Since then, Germany and Austria, and their respective states, have not used double-headed eagles.” ref

Mysore

“The Gandabherunda is a bicephalous bird, not necessarily an eagle but very similar in design to the double-headed eagle used in Western heraldry, used as a symbol by the Wadiyar dynasty of the Kingdom of Mysore from the 16th century. Coins (gold pagoda or gadyana) from the rule of Achyuta Deva Raya (reigned 1529–1542) are thought[by whom?] to be the first to use the Gandabherunda on currency. An early instance of the design is found on a sculpture on the roof of the Rameshwara temple in the temple town of Keladi in Shivamogga. The symbol was in continued use by the Maharaja of Mysore into the modern period, and was adopted as the state symbol of the State of Mysore (now Karnataka) after Indian independence.” ref

Albania

“The Kastrioti family in Albania had a double-headed eagle as their emblem in the 14th and 15th centuries. Some members of the Dukagjini family and the Arianiti family also used double-headed eagles, and a coalition of Albanian states in the 15th century, later called the League of Lezhë, also used the Kastrioti eagle as its flag. The current flag of Albania features a black two-headed eagle with a crimson background. During John Hunyadi’s campaign in Niš in 1443, Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg and a few hundred Albanians defected from the Turkish ranks and used the double-headed eagle flag. The eagle was used for heraldic purposes in the Middle Ages by a number of Albanian noble families in Albania and became the symbol of the Albanians. The Kastrioti‘s coat of arms, depicting a black double-headed eagle on a red field, became famous when he led a revolt against the Ottoman Empire resulting in the independence of Albania from 1443 to 1479. This was the flag of the League of Lezhë, which was the first unified Albanian state in the Middle Ages and the oldest Parliament with extant records.” ref

Modern use

“Albania, Serbia, Montenegro, and Russia have a double-headed eagle in their coat of arms. In 1912, Ismail Qemali raised a similar version of that flag. The flag has gone through many alterations, until 1992 when the current flag of Albania was introduced. The double-headed eagle is now used as an emblem by a number of Orthodox Christian churches, including the Greek Orthodox Church and the Orthodox Autocephalous Church of Albania. In modern Greece, it appears in official use in the Hellenic Army (Coat of Arms of Hellenic Army General Staff) and the Hellenic Army XVI Infantry Division, The two-headed eagle appears, often as a supporter, on the modern and historical arms and flags of Austria-Hungary, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, Austria (1934–1938), Albania, Armenia, Montenegro, the Russian Federation, Serbia. It was also used as a charge on the Greek coat of arms for a brief period in 1925–1926. It is also used in the municipal arms of a number of cities in Germany, Netherlands, and Serbia, the arms and flag of the city and Province of Toledo, Spain, and the arms of the town of Velletri, Italy. An English heraldic tradition, apparently going back to the 17th century, attributes coats of arms with double-headed eagles to the Anglo-Saxon earls of Mercia, Leofwine, and Leofric. The design was introduced in a number of British municipal coats of arms in the 20th century, such as the Municipal Borough of Wimbledon in London, the supporters in the coat of arms of the city and burgh of Perth, and hence in that of the district of Perth and Kinross (1975). The motif is also found in a number of British family coats of arms. In Turkey, General Directorate of Security and the municipality of Diyarbakır have a double-headed eagle in their coat of arms. The Double-Headed Eagle is used as an emblem by the Scottish Rite of Freemasonry. It was introduced in France in the early 1760s as the emblem of the Kadosh degree. In 2021, Alexei Navalny revealed in a documentary that many double-headed eagles appear in the gigantic palace secretly built for Vladimir Putin on the Russian coast of the Black Sea, especially on the front portal, using the same design as used in the Winter Palace.” ref

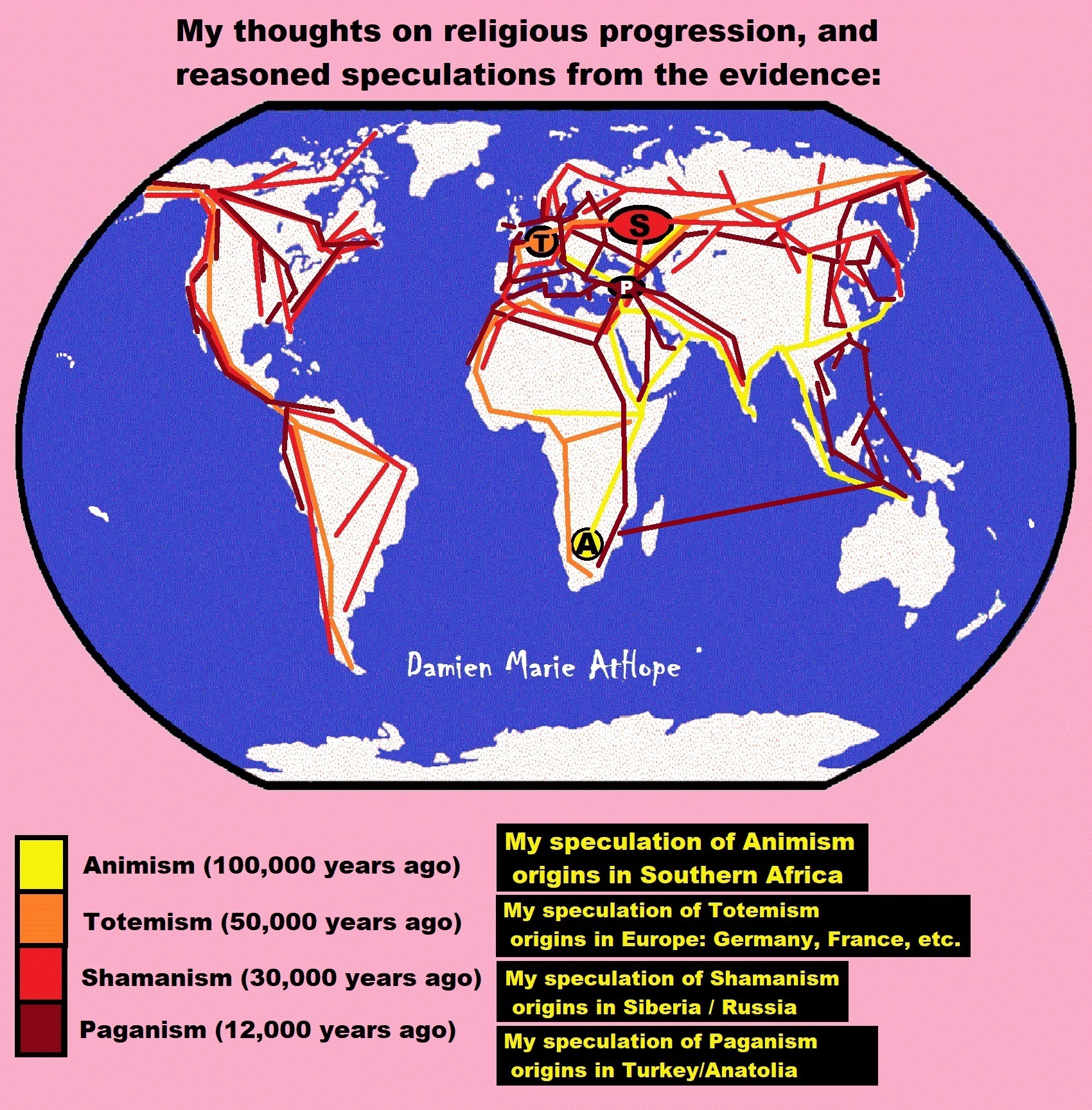

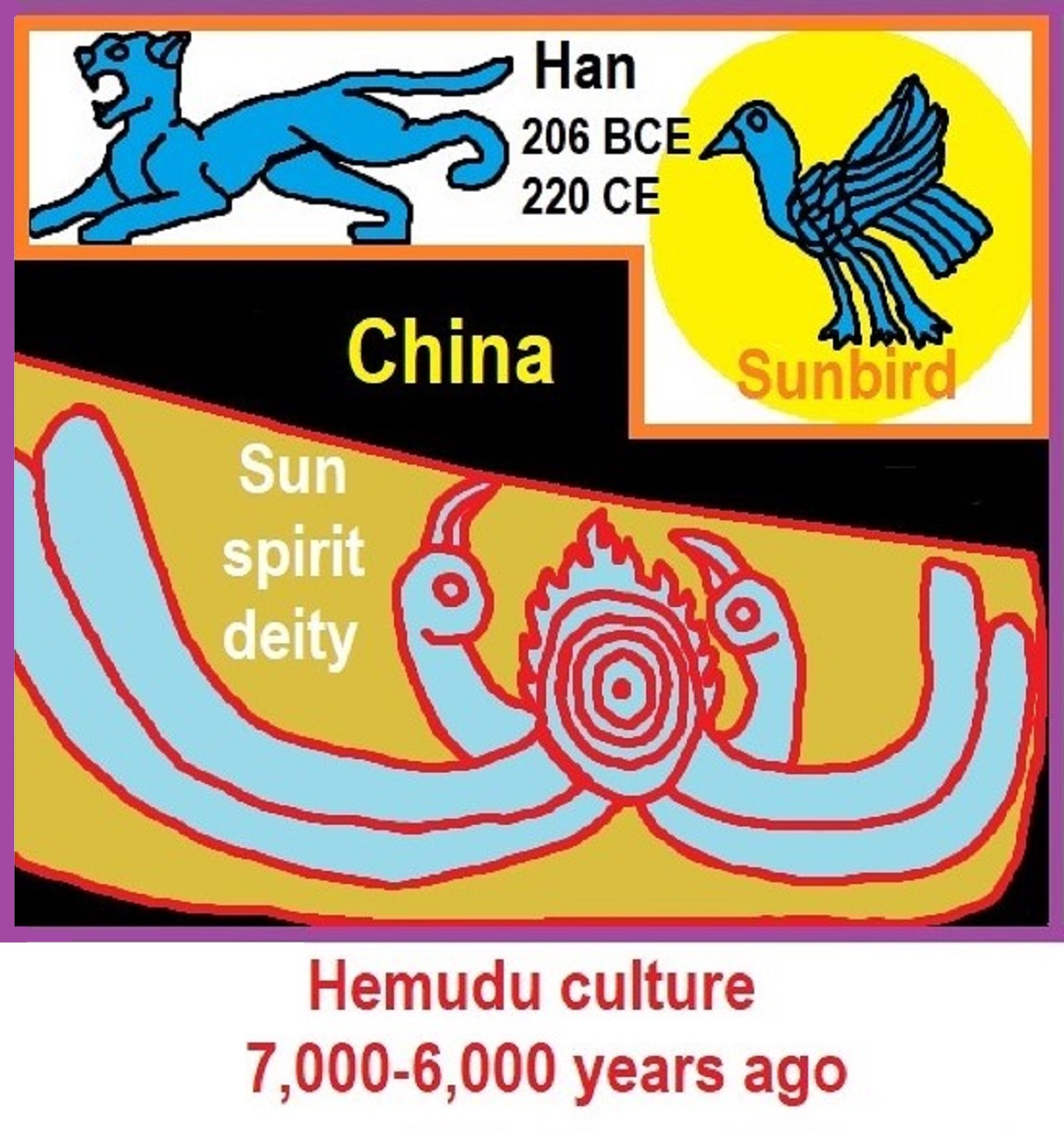

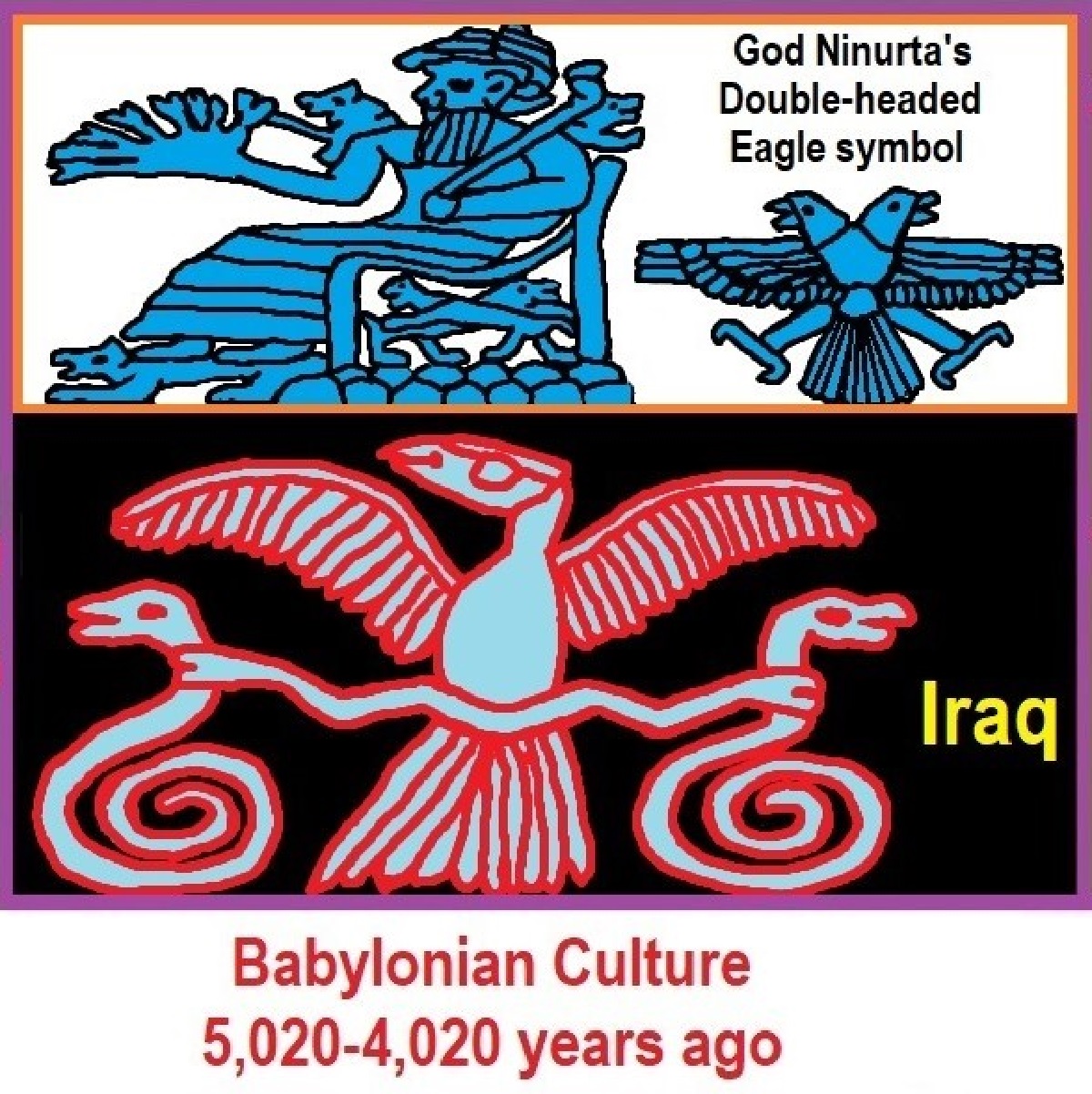

Hemudu culture *Pic 1

“The Hemudu culture (5500 BC to 3300 BCE or around 7,520-5,320 years ago) was a Neolithic culture that flourished just south of the Hangzhou Bay in Jiangnan in modern Yuyao, Zhejiang, China. The culture may be divided into early and late phases, before and after 4000 BCE or around 6,020 years ago respectively. Hemudu sites were also discovered at Tianluoshan in Yuyao city, and on the islands of Zhoushan. Hemudu is said to have differed physically from inhabitants of the Yellow River sites to the north. Some authors propose that the Hemudu Culture was a source of the pre-Austronesian cultures. Some scholars assert that the Hemudu culture co-existed with the Majiabang culture as two separate and distinct cultures, with cultural transmissions between the two. Other scholars group Hemudu in with Majiabang subtraditions. Two major floods caused the nearby Yaojiang River to change its course and inundated the soil with salt, forcing the people of Hemudu to abandon its settlements. The Hemudu people lived in long, stilt houses. Communal longhouses were also common in Hemudu sites, much like the ones found in modern-day Borneo.” ref

“The Hemudu culture was one of the earliest cultures to cultivate rice. Recent excavations at the Hemudu period site of Tianluoshan has demonstrated rice was undergoing evolutionary changes recognized as domestication. Most of the artifacts discovered at Hemudu consist of animal bones, exemplified by hoes made of shoulder bones used for cultivating rice. The culture also produced lacquer wood. A red lacquer wood bowl at the Zhejiang Museum is dated to 4000-5000 BCE or around 6,020-7,020 years ago. It is believed to be the earliest such object in the world. The remains of various plants, including water caltrop, Nelumbo nucifera, acorns, melon, wild kiwifruit, blackberries, peach, the foxnut or Gorgon euryale, and bottle gourd, were found at Hemudu and Tianluoshan. The Hemudu people likely domesticated pigs but practiced extensive hunting of deer and some wild water buffalo. Fishing was also carried out on a large scale, with a particular focus on crucian carp. The practices of fishing and hunting are evidenced by the remains of bone harpoons and bows and arrowheads. Music instruments, such as bone whistles and wooden drums, were also found at Hemudu. Artifact design by Hemudu inhabitants bears many resemblances to those of Insular Southeast Asia.” ref

Hemudu Religion

Hemudu’s inhabitants worshiped a sun spirit as well as a fertility spirit. They also enacted shamanistic rituals to the sun and believed in bird totems. A belief in an afterlife and ghosts is thought to have been widespread as well. People were buried with their heads facing east or northeast and most had no burial objects. Infants were buried in urn-casket style burials, while children and adults received earth level burials. They did not have a definite communal burial ground, for the most part, but a clan communal burial ground has been found from the later period. Two groups in separate parts of this burial ground are thought to be two intermarrying clans. There were noticeably more burial goods in this communal burial ground.” ref

“The culture produced a thick, porous pottery. This distinctive pottery was typically black and made with charcoal powder. Plant and geometric designs were commonly painted onto the pottery; the pottery was sometimes also cord-marked. The culture also produced carved jade ornaments, carved ivory artifacts, and small clay figurines. The early Hemudu period is considered the maternal clan phase. The descent is thought to have been matrilineal and the social status of children and women comparatively high. In the later periods, they gradually transitioned into patrilineal clans. During this period, the social status of men rose and the descent was passed through the male line.” ref

HEMUDU, LIANGZHU, AND MAJIABANG: CHINA’S LOWER YANGTZE NEOLITHIC CULTURES

“Archaeologists now believe that the Yangtze River region was just as much of a birthplace of Chinese culture and civilization as the Yellow River basin. Various cultures flourished in the regions surrounding the mouth of the Yangze River, where later the states of Wu and Yue would thrive. These cultures progressed through a number of stages. The latest phase, called the Liangzhu culture, and is dated to 3500-2000 BCE or around 5,520-4,020 years ago. Along the Yangtze archeologists have discovered thousands of items of pottery, porcelain, polished stone tools, and axes, elaborately carved jade rings, bracelets, and necklaces that date back to at least 6000 B.C. Neolthic residents of the Lower Yangtze are said to have differed physically from inhabitants of the Yellow River sites to the north. Scholars view the Hemudu Culture as a source of the proto-Austronesian cultures.” ref

“The main Lower Kuahuqiao sites: 1# Shangshan (Upper Qiantang valley 9050–6550 BCE or 11,070-8,570 years ago), 2# Kuahuqiao (Upper to lower Qiantang valley, More than 6050–5050 B.CE or 8,070-7,070 years ago), 3# Hemudu and Majiabang (Hemudu sites concentrate in the Ningshao Plain; Majiabang sites distributed around Lake Tai. 5050–3850 B.CE or 7,070-5,870 years ago), 4# Songze (Mostly on the Hangjiahu Plain, 3750–3350 BCE or 5,770-5,370 years ago), 5# Liangzhu (Mostly on the Hangjiahu Plain, 3250–2350 BCE or around 5,270-4,370 years ago. Human activity has been verified in the Three Gorges area of the Yangtze River as far back as 27,000 years ago, and by the 5th millennium BCE or 7,020-6,020 years ago, the lower Yangtze was a major population center occupied by the Hemudu and Majiabang cultures, both among the earliest cultivators of rice. By the 3rd millennium BCE or 5,020-4,020 years ago, the successor Liangzhu culture showed evidence of influence from the Longshan peoples of the North China Plain. A study of Liangzhu remains found a high prevalence of haplogroup O1, linking it to Austronesian and Daic populations.” ref

The climate in the Lower Yangtze 5000 to 4000 years ago was warm and humid, typical of a mid subtropical zone climate, with the temperature was two to three degrees higher than today. The land was covered by lush growth of evergreen chinquapin and big leave trees. Along with the expanding of the Yangtze River delta towards the sea, the area became farther from the seaside with many lakes and ponds. There many water plants and fruits on the trees all year around. Many big and medium mammals including tigers, elephants, alligators, and rhinoceros, in the forests and swamps. Small animals, birds, and fishes provided plentiful sources of food.” ref

“The Hemudu Archaeological Site in Hemudu Town, Yuyao county — 22 kilometers northwest of Ningbo — has items dating back to more than 7,500 years ago. They were found in June 1973 by local villagers during construction work. The discovery is one of the most important archeological events in China in the 20th century. The findings there called into question the conventional view that the Yellow River region, to the north, was more advanced than the rest of China and showed that Chinese civilization originated in both the Yellow and Yangtze river areas. The evidence included rice seeds and wooden oars from a flourishing Neolithic culture on the river delta, as well as those archaeologists, have dug out at various sites around Cihu Lake, Fujia, Tianluo, Zishan, Xiangjia, and Xiangshan mountains and the Mingshanhou village. They date from 5,000 to 3,000 BCE or 7,020-5,020 years ago. The Hemudu Site in Ningbo holds one of the earliest records of China’s Neolithic Age in the southeastern area.” ref

Over 7,000 items have been unearthed at Hemdud sites, including production tools, tools for daily life, and construction components. Among the most significant finds are some of the earliest human-grown rice, the earliest wood-structured well, and some of the earliest for examples of weaving and oar-powered boats. The site offers strong evidence that both the Yangtze River valley and Yellow River valley are the cradles of the Chinese civilization. The Hemudu Site covers forty thousand square meters and has a cultural layer that is a total of 3.7 meters in depth. Four separate cultural layers can be distinguished that, after calibrated carbon fourteen testing, date to between 7,000 and 3,500 years ago. In 1982, this site was declared a National Key Cultural Protected Unit. Fossilized amoeboids and pollen suggests Hemudu culture emerged and developed in the middle of the Holocene Climatic Optimum. A study of a sea-level highstand in the Ningshao Plain from 7000 – 5000 BP shows that there may have been stabilized lower sea levels at this time followed by, from 5000 to 3900 BP, frequent flooding. The climate was said to be tropical to subtropical with high temperatures and much precipitation throughout the year. Two major floods caused the nearby Yaojiang River to change its course and inundated the soil with salt, forcing the people of Hemudu to abandon its settlements.” ref

“The Hemudu Site Museum was divided into two parts: the actual site of excavation and an exhibition of objects. It covers a total of 26,000 square meters and the building area covers a space of 3,163 square meters. The building area is composed of six separate buildings that are joined to one another by corridors. The general layout of the buildings conforms to the unique Hemudu style of architecture, which in Chinese is called ganlan-style, or trunk and railing. This includes a long ridgepole, short eaves, and a high foundation. The building rests on 456 pillars on which lie groups of cross beams, symbolizing the tenon and mortise technology already used some 7000 years ago. The foyer is in the shape of a legendary ‘roc’ spreading its wings, expressing the worship of birds that was practiced by the early Hemudu people. The museum exhibits around 3,000 objects that were retrieved in two main excavation periods at the site. Among the objects are remains of rice kernels planted by man, ceramic fragments that have traces of carbonized rice grains, rice-husk-patterned pottery fragments, bone items, wooden joint pieces, ivory bird-shaped artifacts, ivory carved plate-shaped containers with sun motifs, jade items, and so on. These are all worthy of being described as gems of neolithic culture.” ref

The second hall of the museum covers 300 square meters, and reflects the hunting and gathering life as well as the rice-agriculture of the time. It exhibits actual items such as man-cultivated grain, agricultural implements made of bone, a husker made of wood, and stone grinders, ceramic axes, etc., as well as containers for holding food, appropriate for an exhibition of rice-producing culture. The third hall covers 400 square meters and includes two parts, one on the life of the settlement and one on its spiritual or intellectual culture. Exhibited here are pillars, beams, boards, and other wooden architectural elements, wooden tools, stone ax, stone awl, bone awl, a reconstructed trunk and railing style building (portion), and a model of a well. Parts of a primitive loom are also displayed, including many things that no longer have contemporary names. The Hemudu people lived in long, stilt houses, which make sense in a region with a lot of water. Communal longhouses — much like the ones found in modern-day Borneo and found among some Southeast Asian ethnic groups — were also common in Hemudu sites.” ref

“The culture also produced lacquer wood. The remains of various plants, including water caltrop, Nelumbo nucifera, acorns, melon, wild kiwifruit, blackberries, peach, the foxnut or Gorgon euryale, and bottle gourd, were found at Hemudu and Tianluoshan.”9] The Hemudu people likely domesticated pigs, and dogs but practiced extensive hunting of deer and some wild water buffalo. Fishing was also carried out on a large scale, with a particular focus on crucian carp. The practices of fishing and hunting are evidenced by the remains of bone harpoons and bows and arrowheads. Music instruments, such as bone whistles and wooden drums, were also found at Hemudu. Artifact design by Hemudu inhabitants bears many resemblances to those of Insular Southeast Asia. The culture produced a thick, porous pottery. The distinct pottery was typically black and made with charcoal powder. Plant and geometric designs were commonly painted onto the pottery; the pottery was sometimes also cord-marked. The culture also produced carved jade ornaments, carved ivory artifacts, and small, clay figurines.” ref

“In the early Hemudu period is the maternal clan phase. The descent is said to be matrilineal and the social status of children and women is comparatively high. In the later periods, they gradually transitioned into patrilineal clans. During this period, the social status of men rose and descent is passed through the male line. Hemudu’s inhabitants worshiped a sun spirit as well as a fertility spirit. They also enacted shamanistic rituals to the sun and believed in bird totems. A belief in an afterlife and ghosts is believed to have taken place as well. People were buried with theirs heads facing east or northeast and most had no burial objects. Infants were buried in urn-casket style burials, while children and adults received earth level burials. They did not have a definite communal burial ground, for the most part, but a clan communal burial ground has been found in the later period. Two groups in separate parts of this burial ground are thought to be two intermarrying clans. There were noticeably more burial goods in this communal burial ground.” ref

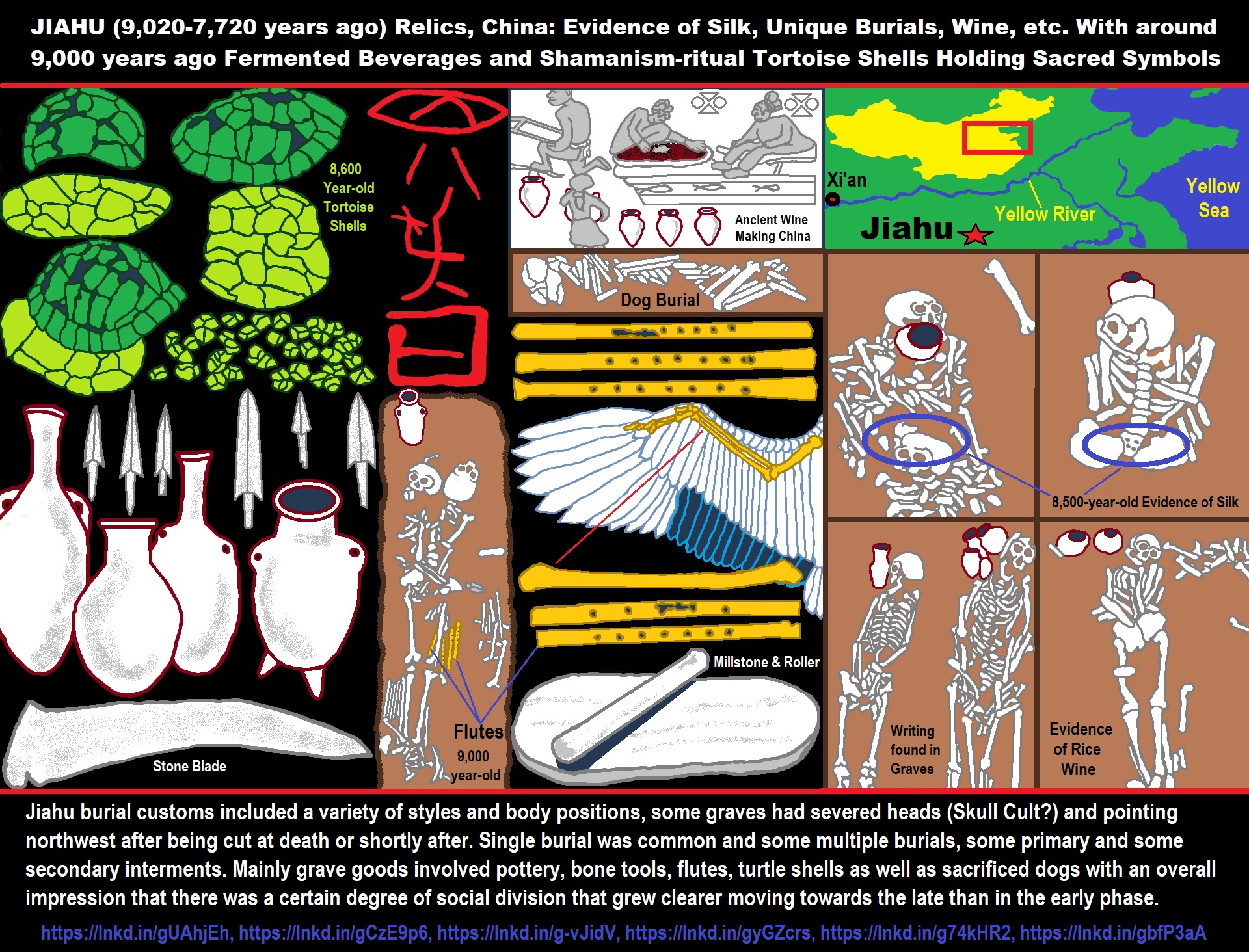

List of Neolithic cultures of China

China Neolithic

Peiligang culture Pengtoushan culture Beixin culture Cishan culture Dadiwan culture Houli culture Xinglongwa culture Xinle culture Zhaobaogou culture Hemudu culture Daxi culture Majiabang culture Yangshao culture Hongshan culture Dawenkou culture Songze culture Liangzhu culture Majiayao culture Qujialing culture Longshan culture Baodun culture Shijiahe culture Yueshi culture Neolithic Tibet

South Asia Neolithic

Lahuradewa Mehrgarh Rakhigarhi Kalibangan Chopani Mando Jhukar Daimabad Chirand Koldihwa Burzahom Mundigak Brahmagiri

Other Asian Neolithic

Pic ref

Ancient Women Found in a Russian Cave Turn Out to Be Closely Related to The Modern Population https://www.sciencealert.com/ancient-women-found-in-a-russian-cave-turn-out-to-be-closely-related-to-the-modern-population

Abstract

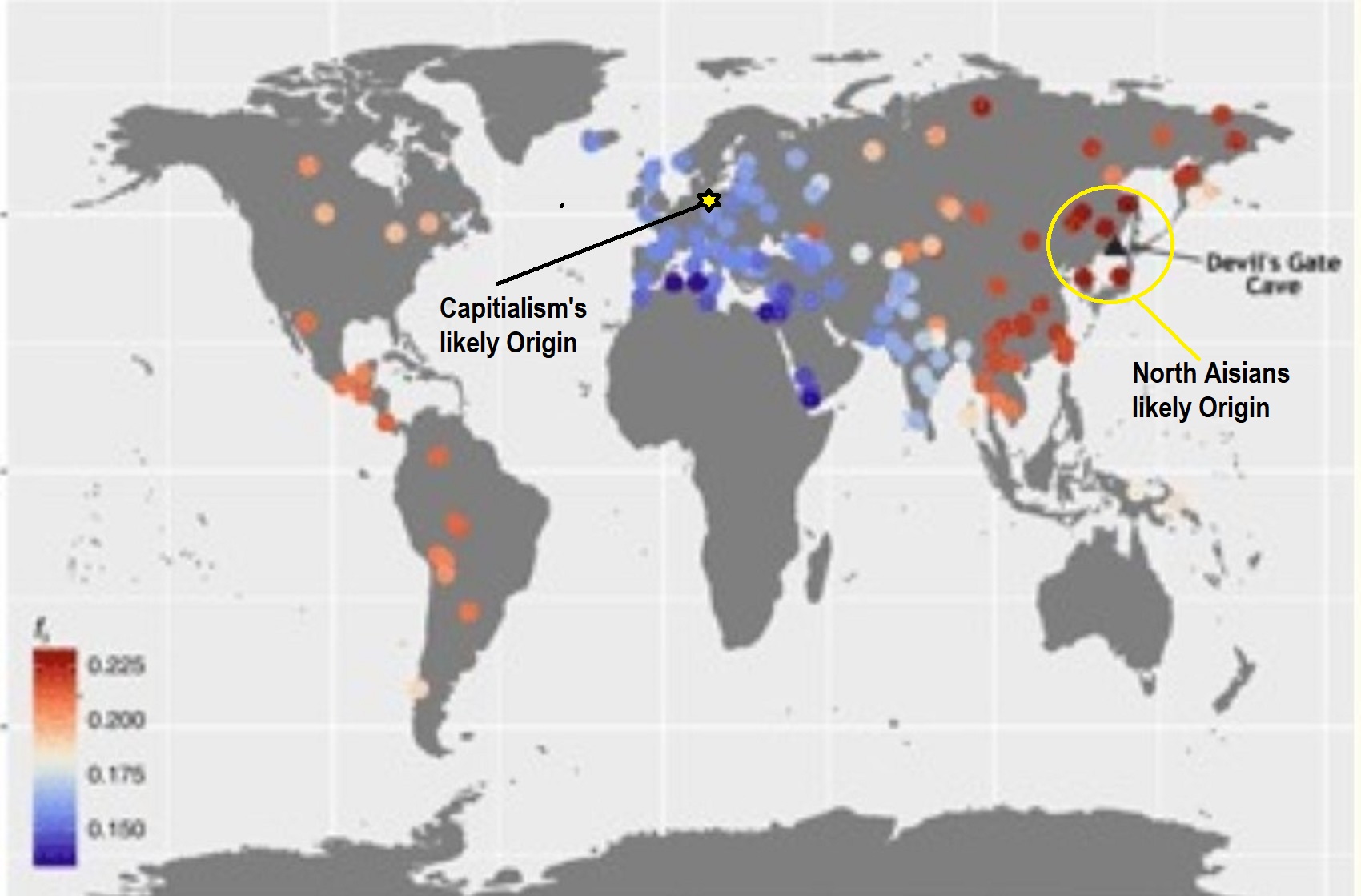

“Ancient genomes have revolutionized our understanding of Holocene prehistory and, particularly, the Neolithic transition in western Eurasia. In contrast, East Asia has so far received little attention, despite representing a core region at which the Neolithic transition took place independently ~3 millennia after its onset in the Near East. We report genome-wide data from two hunter-gatherers from Devil’s Gate, an early Neolithic cave site (dated to ~7.7 thousand years ago) located in East Asia, on the border between Russia and Korea. Both of these individuals are genetically most similar to geographically close modern populations from the Amur Basin, all speaking Tungusic languages, and, in particular, to the Ulchi. The similarity to nearby modern populations and the low levels of additional genetic material in the Ulchi imply a high level of genetic continuity in this region during the Holocene, a pattern that markedly contrasts with that reported for Europe.” ref

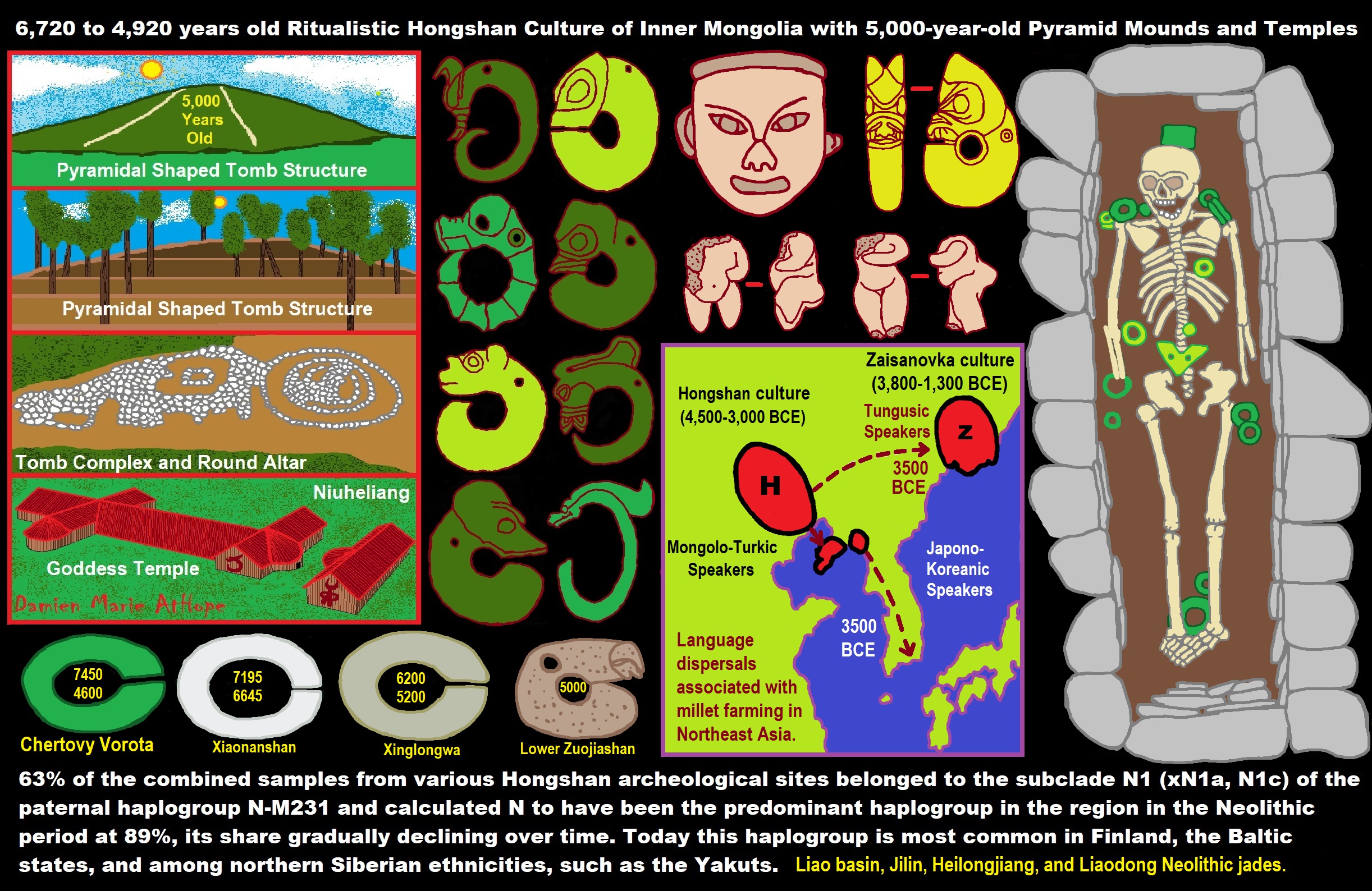

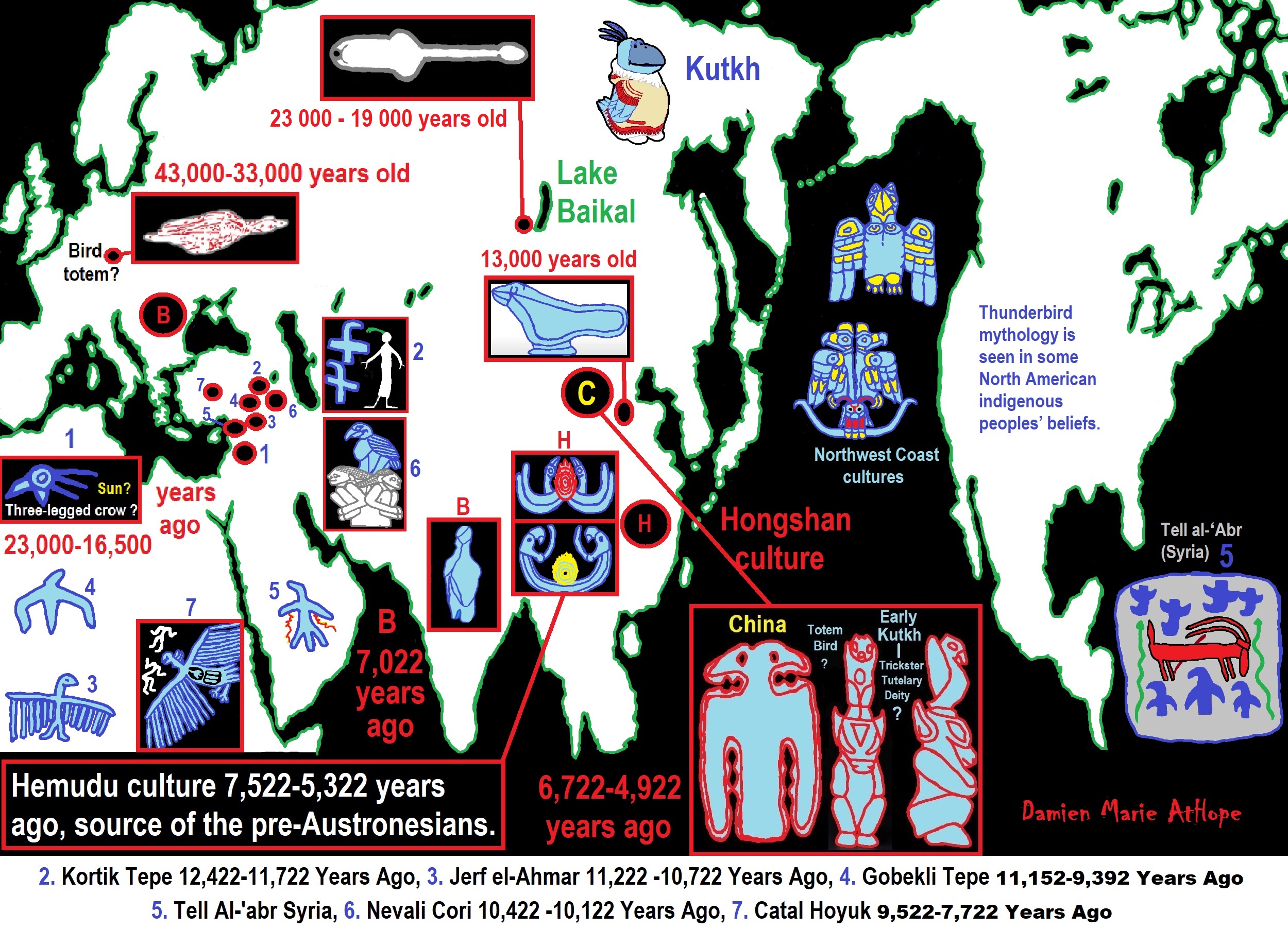

Hongshan culture *Pic 2

“The Hongshan culture was a Neolithic culture in the Liao river basin in northeast China. Hongshan sites have been found in an area stretching from Inner Mongolia to Liaoning, and dated from about 4700 to 2900 BCE or 6,720-4,920 years ago. In northeast China, Hongshan culture was preceded by Xinglongwa culture (6200–5400 BC), Xinle culture (5300–4800 BC), and Zhaobaogou culture, which may be contemporary with Xinle and a little later. Yangshao culture was in the larger area and contemporary with Hongshan culture (see map). These two cultures interacted with each other. A study by Yinqiu Cui et al. from 2013 found that 63% of the combined samples from various Hongshan archeological sites belonged to the subclade N1 (xN1a, N1c) of the paternal haplogroup N-M231 and calculated N to have been the predominant haplogroup in the region in the Neolithic period at 89%, its share gradually declining over time. Today this haplogroup is most common in Finland, the Baltic states, and among northern Siberian ethnicities, such as the Yakuts. Other paternal haplogroups identified in the study were C and O2a (O2a2), both of which predominate among the present-day inhabitants. Nelson et al. 2020 attempts to link the Hongshan culture to a “Transeurasian” linguistic context (see Altaic).” ref

“Hongshan burial artifacts include some of the earliest known examples of jade working. The Hongshan culture is known for its jade pig dragons and embryo dragons. Clay figurines, including figurines of pregnant women, are also found throughout Hongshan sites. Small copper rings were also excavated. The archaeological site at Niuheliang is a unique ritual complex associated with the Hongshan culture. Excavators have discovered an underground temple complex—which included an altar—and also cairns in Niuheliang. The temple was constructed of stone platforms, with painted walls. Archaeologists have given it the name Goddess Temple due to the discovery of a clay female head with jade inlaid eyes. It was an underground structure, 1m deep. Included on its walls are mural paintings.” ref

“Housed inside the Goddess Temple are clay figurines as large as three times the size of real-life humans. The exceedingly large figurines are possibly deities, but for a religion not reflective in any other Chinese culture. The existence of complex trading networks and monumental architecture (such as pyramids and the Goddess Temple) point to the existence of a “chiefdom” in these prehistoric communities. Painted pottery was also discovered within the temple. Over 60 nearby tombs have been unearthed, all constructed of stone and covered by stone mounds, frequently including jade artifacts. Cairns were discovered atop two nearby two hills, with either round or square stepped tombs, made of piled limestone. Entombed inside were sculptures of dragons and tortoises. It has been suggested that religious sacrifice might have been performed within the Hongshan culture.” ref

Feng shui

“Just as suggested by evidence found at early Yangshao culture sites, Hongshan culture sites also provide the earliest evidence for feng shui. The presence of both round and square shapes at Hongshan culture ceremonial centers suggests an early presence of the gaitian cosmography (“round heaven, square earth”). Early feng shui relied on astronomy to find correlations between humans and the universe. Some Chinese archaeologists such as Guo Da-shun see the Hongshan culture as an important stage of early Chinese civilization. Whatever the linguistic affinity of the ancient denizens, Hongshan culture is believed to have exerted an influence on the development of early Chinese civilization. The culture also have contributed to the development of settlements in ancient Korea.” ref

Yangshao culture

“The Yangshao culture was a Neolithic culture that existed extensively along the Yellow River in China. It is dated from around 5000 BC to 3000 BCE or 7,020-5,020 years ago. Recent research indicates a common origin of the Sino-Tibetan languages with the Cishan, Yangshao, and/or the Majiayao cultures. The Yangshao culture crafted pottery. Yangshao artisans created fine white, red, and black painted pottery with human facial, animal, and geometric designs. Unlike the later Longshan culture, the Yangshao culture did not use pottery wheels in pottery-making. Excavations found that children were buried in painted pottery jars. The Yangshao culture produced silk to a small degree and wove hemp. Men wore loin clothes and tied their hair in a top knot. Women wrapped a length of cloth around themselves and tied their hair in a bun. Although early reports suggested a matriarchal culture, others argue that it was a society in transition from matriarchy to patriarchy, while still others believe it to have been patriarchal. The debate hinges on differing interpretations of burial practices. The discovery of a dragon statue dating back to the fifth millennium BC in the Yangshao culture makes it the world’s oldest known dragon depiction, and the Han Chinese continue to worship dragons to this day.” ref

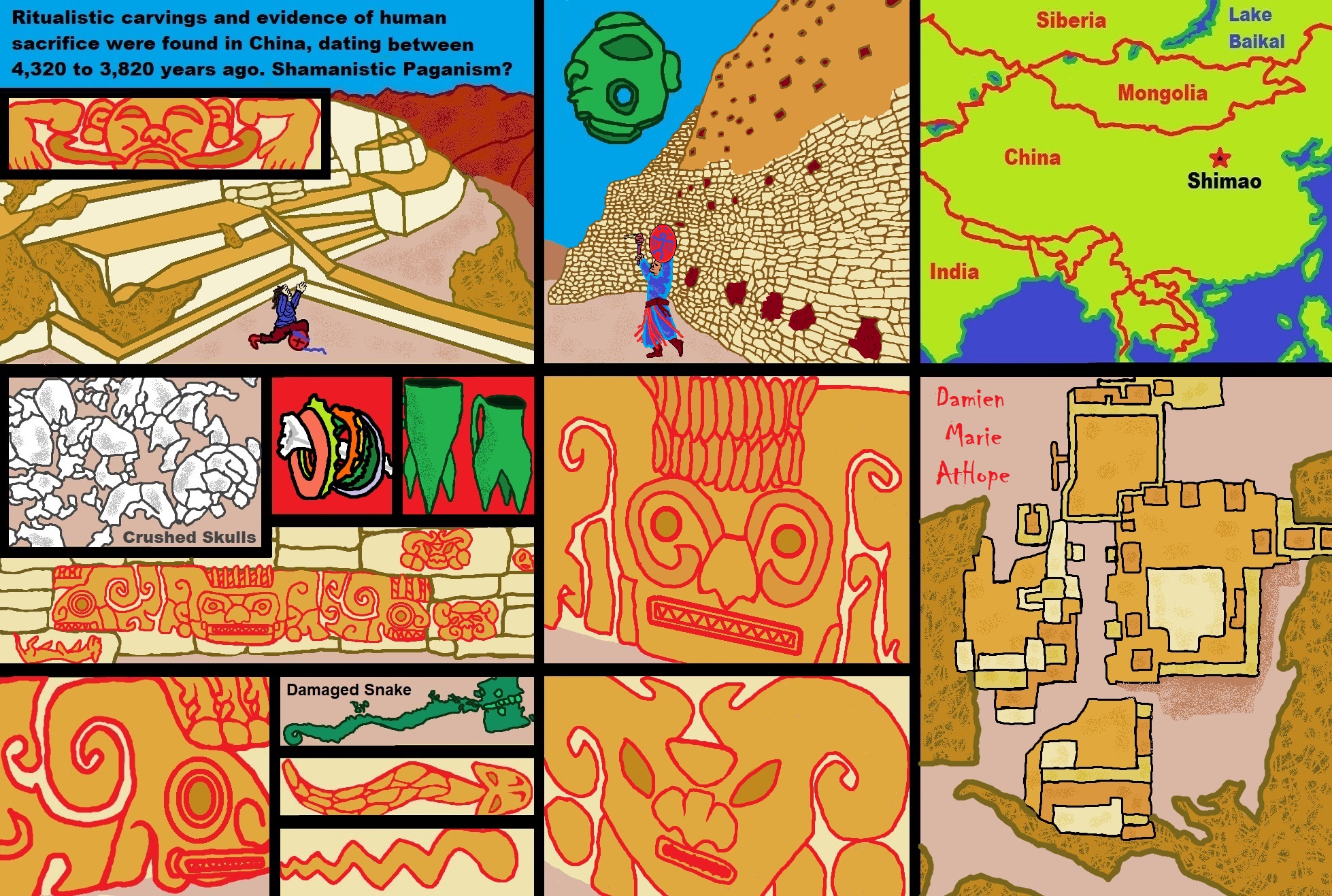

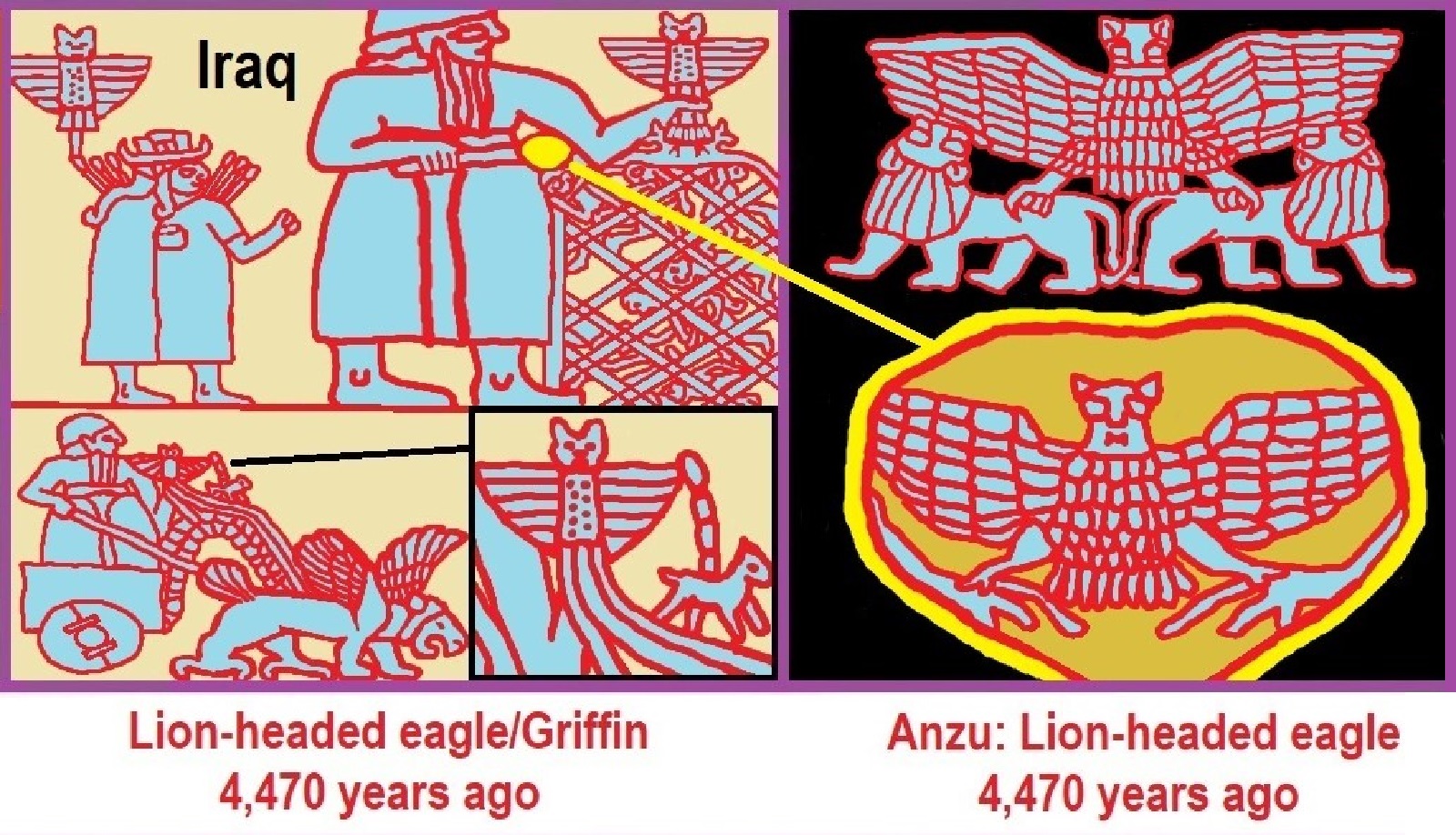

Mesopotamian god: Ninurta Top of Pic #3

“Ninurta (Sumerian: ????????????????: DNIN.URTA, meaning of this name not known), also known as Ninĝirsu (Sumerian: ????????????????????: DNIN.ĜIR2.SU, meaning “Lord of Girsu”),is an ancient Mesopotamian god associated with farming, healing, hunting, law, scribes, and war who was first worshipped in early Sumer. In the earliest records, he is a god of agriculture and healing, who releases humans from sickness and the power of demons. In later times, as Mesopotamia grew more militarized, he became a warrior deity, though he retained many of his earlier agricultural attributes. He was regarded as the son of the chief god Enlil and his main cult center in Sumer was the Eshumesha temple in Nippur. Ninĝirsu was honored by King Gudea of Lagash (ruled 2144–2124 BC), who rebuilt Ninĝirsu’s temple in Lagash. Later, Ninurta became beloved by the Assyrians as a formidable warrior. The Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II (ruled 883–859 BC) built a massive temple for him at Kalhu, which became his most important cult center from then on. After the fall of the Assyrian Empire, Ninurta’s statues were torn down and his temples abandoned because he had become too closely associated with the Assyrian regime, which many conquered peoples saw as tyrannical and oppressive.” ref

“In the epic poem Lugal-e, Ninurta slays the demon Asag using his talking mace Sharur and uses stones to build the Tigris and Euphrates rivers to make them useful for irrigation. In a poem sometimes referred to as the “Sumerian Georgica“, Ninurta provides agricultural advice to farmers. In an Akkadian myth, he was the champion of the gods against the Anzû bird after it stole the Tablet of Destinies from his father Enlil and, in a myth that is alluded to in many works but never fully preserved, he killed a group of warriors known as the “Slain Heroes”. His major symbols were a perched bird and a plow. Ninurta may have been the inspiration for the figure of Nimrod, a “mighty hunter” who is mentioned in association with Kalhu in the Book of Genesis. Conversely, and more conventionally, the mythological Ninurta may have been inspired by a historical person, such as the biblical Nimrod purports to be. He may also be mentioned in the Second Book of Kings under the name Nisroch. In the nineteenth century, Assyrian stone reliefs of winged, eagle-headed figures from the temple of Ninurta at Kalhu were commonly, but erroneously, identified as “Nisrochs” and they appear in works of fantasy literature from the time period.” ref

“Ninurta was worshipped in Mesopotamia as early as the middle of the third millennium BC by the ancient Sumerians, and is one of the earliest attested deities in the region. His main cult center was the Eshumesha temple in the Sumerian city-state of Nippur, where he was worshipped as the god of agriculture and the son of the chief-god Enlil. Though they may have originally been separate deities, in historical times, the god Ninĝirsu, who was worshipped in the Sumerian city-state of Girsu, was always identified as a local form of Ninurta. According to the Assyriologists Jeremy Black and Anthony Green, the two gods’ personalities are “closely intertwined”. King Gudea of Lagash (ruled 2144–2124 BC) dedicated himself to Ninĝirsu and the Gudea cylinders, dating to c. 2125 BC, record how he rebuilt the temple of Ninĝirsu in Lagash as the result of a dream in which he was instructed to do so. The Gudea cylinders record the longest surviving account written in the Sumerian language known to date. Gudea’s son Ur-Ninĝirsu incorporated Ninĝirsu’s name as part of his own in order to honor him. As the city-state of Girsu declined in importance, Ninĝirsu became increasingly known as “Ninurta”. Though Ninurta was originally worshipped solely as a god of agriculture, in later times, as Mesopotamia became more urban and militarized, he began to be increasingly seen as a warrior deity instead. He became primarily characterized by the aggressive, warlike aspect of his nature. In spite of this, however, he continued to be seen as a healer and protector, and he was commonly invoked in spells to protect against demons, disease, and other dangers.” ref

In later times, Ninurta’s reputation as a fierce warrior made him immensely popular among the Assyrians. In the late second millennium BC, Assyrian kings frequently held names which included the name of Ninurta, such as Tukulti-Ninurta (“the trusted one of Ninurta”), Ninurta-apal-Ekur (“Ninurta is the heir of [Ellil’s temple] Ekur”), and Ninurta-tukulti-Ashur (“Ninurta is the god Aššur’s trusted one”). Tukulti-Ninurta I (ruled 1243–1207 BC) declares in one inscription that he hunts “at the command of the god Ninurta, who loves me.” Similarly, Adad-nirari II (ruled 911–891 BC) claimed Ninurta and Aššur as supporters of his reign, declaring his destruction of their enemies as moral justification for his right to rule. In the ninth century BC, when Ashurnasirpal II (ruled 883–859 BC) moved the capital of the Assyrian Empire to Kalhu, the first temple he built there was one dedicated to Ninurta. The walls of the temple were decorated with stone relief carvings, including one of Ninurta slaying the Anzû bird. Ashurnasirpal II’s son Shalmaneser III (ruled 859–824 BC) completed Ninurta’s ziggurat at Kalhu and dedicated a stone relief of himself to the god. On the carving, Shalmaneser III’s boasts of his military exploits and credits all his victories to Ninurta, declaring that, without Ninurta’s aid, none of them would have been possible. When Adad-nirari III (ruled 811–783 BC) dedicated a new endowment to the temple of Aššur in Assur, they were sealed with both the seal of Aššur and the seal of Ninurta. Assyrian stone reliefs from the Kalhu period show Aššur as a winged disc, with Ninurta’s name written beneath it, indicating the two were seen as near-equals.” ref

“After the capital of Assyria was moved away from Kalhu, Ninurta’s importance in the pantheon began to decline. Sargon II favored Nabu, the god of scribes, over Ninurta. Nonetheless, Ninurta still remained an important deity. Even after the kings of Assyria left Kalhu, the inhabitants of the former capital continued to venerate Ninurta, who they called “Ninurta residing in Kalhu”. Legal documents from the city record that those who violated their oaths were required to “place two minas of silver and one mina of gold in the lap of Ninurta residing in Kalhu.” The last attested example of this clause dates to 669 BC, the last year of the reign of King Esarhaddon (ruled 681 – 669 BC). The temple of Ninurta at Kalhu flourished until the end of the Assyrian Empire, hiring the poor and destitute as employees. The main cultic personnel were a šangû-priest and a chief singer, who were supported by a cook, a steward, and a porter. In the late seventh century BC, the temple staff witnessed legal documents, along with the staff of the temple of Nabu at Ezida. The two temples shared a qēpu-official. Ninurta was believed to be the son of Enlil. In Lugal-e, his mother is identified as the goddess Ninmah, whom he renames Ninhursag, but, in Angim dimma, his mother is instead the goddess Ninlil. Under the name Ninurta, his wife is usually the goddess Gula, but, as Ninĝirsu, his wife is the goddess Bau. Gula was the goddess of healing and medicine and she was sometimes alternately said to be the wife of the god Pabilsaĝ or the minor vegetation god Abu. Bau was worshipped “almost exclusively in Lagash” and was sometimes alternately identified as the wife of the god Zababa. She and Ninĝirsu were believed to have two sons: the gods Ig-alima and Šul-šagana. Bau also had seven daughters, but Ninĝirsu was not claimed to be their father. As the son of Enlil, Ninurta’s siblings include: Nanna, Nergal, Ninazu, Enbilulu, and sometimes Inanna.” ref

Ninurta’s Iconography

“In artistic representations, Ninurta is shown as a warrior, carrying a bow and arrow and clutching Sharur, his magic talking mace. He sometimes has a set of wings, raised upright, ready to attack. In Babylonian art, he is often shown standing on the back of or riding a beast with the body of a lion and the tail of a scorpion. Ninurta remained closely associated with agricultural symbolism as late as the middle of the second millennium BC. On kudurrus from the Kassite Period (c. 1600 — c. 1155 BC), a plough is captioned as a symbol of Ninĝirsu. The plough also appears in Neo-Assyrian art, possibly as a symbol of Ninurta. A perched bird is also used as a symbol of Ninurta during the Neo-Assyrian Period. One speculative hypothesis holds that the winged disc originally symbolized Ninurta during the ninth century BC, but was later transferred to Aššur and the sun-god Shamash. This idea is based on some early representations in which the god on the winged disc appears to have the tail of a bird. Most scholars have rejected this suggestion as unfounded. Astronomers of the eighth and seventh centuries BC identified Ninurta (or Pabilsaĝ) with the constellation Sagittarius. Alternatively, others identified him with the star Sirius, which was known in Akkadian as šukūdu, meaning “arrow”. The constellation of Canis Major, of which Sirius is the most visible star, was known as qaštu, meaning “bow”, after the bow and arrow Ninurta was believed to carry. In Babylonian times, Ninurta was associated with the planet Saturn.” ref

Ninurta’s Mythology

Lugal-e

“Second only to the goddess Inanna, Ninurta probably appears in more myths than any other Mesopotamian deity. In the Sumerian poem Lugal-e, also known as Ninurta’s Exploits, a demon known as Asag has been causing sickness and poisoning the rivers. Ninurta’s talking mace Sharur urges him to battle Asag. Ninurta confronts Asag, who is protected by an army of stone warriors. Ninurta initially “flees like a bird”, but Sharur urges him to fight, Ninurta slays Asag and his armies. Then Ninurta organizes the world, using the stones from the warriors he has defeated to build the mountains, which he designs so that the streams, lakes, and rivers all flow into the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, making them useful for irrigation and agriculture. Ninurta’s mother Ninmah descends from Heaven to congratulate her son on his victory. Ninurta dedicates the mountain of stone to her and renames her Ninhursag, meaning “Lady of the Mountain”. Nisaba, the goddess of scribes, appears and writes down Ninurta’s victory, as well as Ninhursag’s new name. Finally, Ninurta returns home to Nippur, where he is celebrated as a hero. This myth combines Ninurta’s role as a warrior deity with his role as an agricultural deity. The title Lugal-e means “O king!” and comes from the poem opening phrase in the original Sumerian. Ninurta’s Exploits is a modern title assigned to it by scholars. The poem was eventually translated into Akkadian after Sumerian became regarded as too difficult to understand. A companion work to the Lugal-e is Angim dimma, or Ninurta’s Return to Nippur, which describes Ninurta’s return to Nippur after slaying Asag. It contains little narrative and is mostly a praise piece, describing Ninurta in larger-than-life terms and comparing him to the god An. Angim dimma is believed to have originally been written in Sumerian during the Third Dynasty of Ur (c. 2112 – c. 2004 BC) or the early Old Babylonian Period (c. 1830 – c. 1531 BC), but the oldest surviving texts of it date to Old Babylonian Period. Numerous later versions of the text have also survived. It was translated into Akkadian during the Middle Babylonian Period (c. 1600 — c. 1155 BC).” ref

Anzû myth

“In the Old, Middle, and Late Babylonian myth of Anzû and the Tablet of Destinies, the Anzû is a giant, monstrous bird. Enlil gives Anzû a position as the guardian of his sanctuary, but Anzû betrays Enlil and steals the Tablet of Destinies, a sacred clay tablet belonging to Enlil that grants him his authority, while Enlil is preparing for his bath. The rivers dry up and the gods are stripped of their powers. The gods send Adad, Gerra, and Shara to defeat the Anzû, but all of them fail. Finally, the god Ea proposes that the gods should send Ninurta, Enlil’s son. Ninurta confronts the Anzû and shoots it with his arrows, but the Tablet of Destinies has the power to reverse time and the Anzû uses this power to make Ninurta’s arrows fall apart in midair and revert to their original components: the shafts turn back into canebrake, the feathers into live birds, and the arrowheads return to the quarry. Even Ninurta’s bow returns to the forest and the wool bowstring turns into a live sheep.” ref

“Ninurta calls upon the south wind for aid, which rips the Anzû’s wings off. Ninurta slits the Anzû’s throat and takes the Tablet of Destinies. The god Dagan announces Ninurta’s victory in the assembly of the gods and, as a reward, Ninurta is granted a prominent seat on the council. Enlil sends the messenger god Birdu to request Ninurta to return the Tablet of Destinies. Ninurta’s reply to Birdu is fragmentary, but it is possible he may initially refuse to return the Tablet. In the end, however, Ninurta does return the Tablet of Destinies to his father. This story was particularly popular among scholars of the Assyrian royal court. The myth of Ninurta and the Turtle, recorded in UET 6/1 2, is a fragment of what was originally a much longer literary composition. In it, after defeating the Anzû, Ninurta is honored by Enki in Eridu. Ninurta has brought back a chicklet from the Anzû, for which Enki praises him. Ninurta, however, hungry for power and even greater accolades, “set[s] his sights on the whole world. Enki senses his thoughts and creates a giant turtle, which he releases behind Ninurta and which bites the hero’s ankle. As they struggle, the turtle digs a pit with its claws, which both of them fall into. Enki gloats over Ninurta’s defeat. The end of the story is missing; the last legible portion of the account is a lamentation from Ninurta’s mother Ninmah, who seems to be considering finding a substitute for her son. According to Charles Penglase, in this account, Enki is clearly intended as the hero and his successful foiling of Ninurta’s plot to seize power for himself is intended as a demonstration of Enki’s supreme wisdom and cunning.” ref

Divine Bird (Tutelary and/or Trickster spirit/deity) Anzu *Pic 4/5

“Anzû, also known as dZû and Imdugud (Sumerian: ???????????? AN.IM.DUGUDMUŠEN), is a lesser divinity or monster in several Mesopotamian religions. He was conceived by the pure waters of the Apsu and the wide Earth, or as the son of Siris. Anzû was depicted as a massive bird who can breathe fire and water, although Anzû is alternately depicted as a lion-headed eagle. Stephanie Dalley, in Myths from Mesopotamia, writes that “the Epic of Anzu is principally known in two versions: an Old Babylonian version of the early second millennium BCE, giving the hero as Ningirsu; and ‘The Standard Babylonian’ version, dating to the first millennium BC, which appears to be the most quoted version, with the hero as Ninurta”. However, the Anzu character does not appear as often in some other writings, as noted below. The name of the mythological being usually called Anzû was actually written in the oldest Sumerian cuneiform texts as ???????????????? (AN.IM.MIMUŠEN; the cuneiform sign ????, or MUŠEN, in context, is an ideogram for “bird”). In texts of the Old Babylonian period, the name is more often found as ???????????????? AN.IM.DUGUDMUŠEN. Landsberger argued that this name should be read as “Anzu”, and most researchers have followed suit. In 1989, Thorkild Jacobsen noted that the original reading of the cuneiform signs as written (giving the name “dIM.dugud”) is also valid, and was probably the original pronunciation of the name, with Anzu derived from an early phonetic variant. Similar phonetic changes happened to parallel terms, such as imdugud (meaning “heavy wind”) becoming ansuk. Changes like these occurred by the evolution of the im to an (a common phonetic change) and the blending of the new n with the following d, which was aspirated as dh, a sound which was borrowed into Akkadian as z or s.” ref

“It has also been argued based on contextual evidence and transliterations on cuneiform learning tablets, that the earliest, Sumerian form of the name was at least sometimes also pronounced Zu, and that Anzu is primarily the Akkadian form of the name. However, there is evidence for both readings of the name in both languages, and the issue is confused further by the fact that the prefix ???? (AN) was often used to distinguish deities or even simply high places. AN.ZU could therefore mean simply “heavenly eagle”. Thorkild Jacobsen proposed that Anzu was an early form of the god Abu, who was also syncretized by the ancients with Ninurta/Ningirsu, a god associated with thunderstorms. Abu was referred to as “Father Pasture”, illustrating the connection between rainstorms and the fields growing in Spring. According to Jacobsen, this god was originally envisioned as a huge black thundercloud in the shape of an eagle, and was later depicted with a lion’s head to connect it to the roar of thunder. Some depictions of Anzu, therefore, depict the god alongside goats (which, like thunderclouds, were associated with mountains in the ancient Near East) and leafy boughs. The connection between Anzu and Abu is further reinforced by a statue found in the Tell Asmar Hoard depicting a human figure with large eyes, with an Anzu bird carved on the base. It is likely that this depicts Anzu in his symbolic or earthly form as the Anzu-bird, and in his higher, human-like divine form as Abu. Though some scholars have proposed that the statue actually represents a human worshiper of Anzu, others have pointed out that it does not fit the usual depiction of Sumerian worshipers, but instead matches similar statues of gods in human form with their more abstract form or their symbols carved onto the base.” ref

“In Sumerian and Akkadian mythology, Anzû is a divine storm-bird and the personification of the southern wind and the thunder clouds. This demon—half man and half bird—stole the “Tablet of Destinies” from Enlil and hid them on a mountaintop. Anu ordered the other gods to retrieve the tablet, even though they all feared the demon. According to one text, Marduk killed the bird; in another, it died through the arrows of the god Ninurta. Anzu also appears in the story of “Inanna and the Huluppu Tree”, which is recorded in the preamble to the Sumerian epic poem Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld. Anzu appears in the Sumerian Lugalbanda and the Anzud Bird (also called: The Return of Lugalbanda). The shorter Old Babylonian version was found at Susa. Full version in Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, The Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others by Stephanie Dalley, page 222 and at The Epic of Anzû, Old Babylonian version from Susa, Tablet II, lines 1-83, read by Claus Wilcke. The longer Late Assyrian version from Nineveh is most commonly called The Myth of Anzu. (Full version in Dalley, page 205). An edited version is at Myth of Anzu. Also in Babylonian myth, Anzû is a deity associated with cosmogeny. Anzû is represented as stripping the father of the gods of umsimi (which is usually translated “crown” but in this case, as it was on the seat of Bel, it refers to the “ideal creative organ”). Regarding this, Charles Penglase writes that “Ham is the Chaldean Anzû, and both are cursed for the same allegorically described crime,” which parallels the mutilation of Uranus by Cronus and of Osiris by Set.” ref

- Anzu wyliei, a theropod dinosaur named for Anzû

- Asakku, similar Mesopotamian deity

- Griffin or griffon, lion-bird hybrid

- Lamassu, Assyrian deity, bull/lion-eagle-human hybrid

- Ziz, giant griffin-like bird in Jewish mythology

- Zuism, Icelander protest against tax for religion

- Hybrid creatures in mythology

- List of hybrid creatures in mythology

- Tiamat

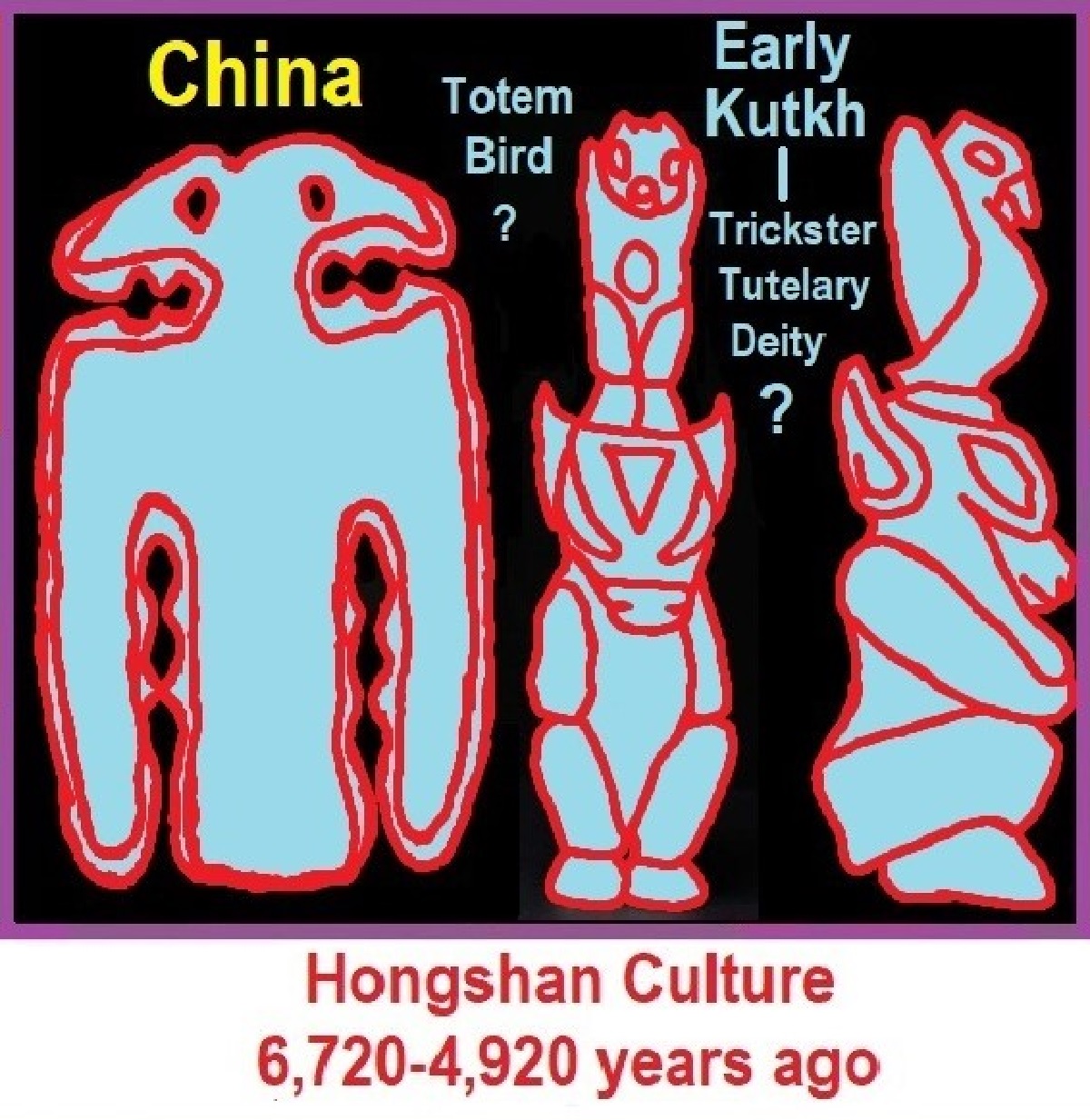

Divine Bird (Tutelary and/or Trickster spirit/deity) Kutkh

“Kutkh (also Kutkha, Kootkha, Kutq Kutcha and other variants, Russian: Кутх), is a Raven spirit traditionally revered in various forms by various indigenous peoples of the Russian Far East. Kutkh appears in many legends: as a key figure in creation, as a fertile ancestor of mankind, as a mighty shaman, and as a trickster. He is a popular subject of the animist stories of the Chukchi people and plays a central role in the mythology of the Koryaks and Itelmens of Kamchatka. Many of the stories regarding Kutkh are similar to those of the Raven among the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast, suggesting a long history of indirect cultural contact between Asian and North American peoples. Kutkh is known widely among the people that share a common Chukotko-Kamchatkan language family. Regionally, he is known as Kúrkil among the Chukchi; as Kutq among the Itelmens; and as KútqI, KútqIy, or KúsqIy among the southeastern Koryaks and KúykIy or QúykIy among the northwestern Koryaks. In Koryak, the name is employed commonly in its augmentative form, (KutqÍnnaku, KusqÍnnaku, KuyÍnnaku) all meaning “Big Kutkh” and often translated simply as “God”.” ref

Kutkh Myths

“The tales of Kutkh come in many, often contradictory versions. In some tales, he is explicitly created by a Creator and lets the dawn onto the earth by chipping away at the stones surrounding her. In others, he creates himself (sometimes out of an old fur coat) and takes pride in his independence from the Creator. In some, Kamchatka is created as he drops a feather while flying over the earth. In others, islands and continents are created by his defecation, rivers, and lakes out of his waters. The difficult volcanic terrain and swift rivers of Kamchatka are thought to reflect Kutkh’s capricious and willful nature. The bringing of light in the form of the sun and the moon is a common theme. Sometimes, he tricks an evil spirit which has captured the celestial bodies much in the style of analogous legends about the Tlingit and Haida in the Pacific Northwest. In others, it is he who must be tricked into releasing the sun and the moon from his bill. Kutkh’s virility is emphasized in many legends. Many myths concern his children copulating with other animal spirits and creating the peoples that populate the world.” ref

“In the animistic tradition of north-Eurasian peoples, Kutkh has a variety of interactions and altercations with Wolf, Fox, Bear, Wolverine, Mouse, Owl, Dog, Seal, Walrus, and a host of other spirits. Many of these interactions involve some sort of trickery in which Kutkh comes out on top about as often as he is made a fool of. An example of these contradictions is given to the Chukchi legend of Kutkh and the Mice. The great and mighty raven Kutkh was flying through the cosmos. Tired from constant flight, he regurgitated the Earth from his gut, transformed into an old man, and alighted on the empty land to rest. Out of his first footsteps emerged the first Mice. Curious, playful, and fearless, they entered the sleeping Kutkh’s nose. The fury of the subsequent sneeze buckled the earth and created the mountains and the valleys. Attempts to stamp them out led to the formation of the ocean. Further harassments led to a great battle between the forces of snow and fire which created the seasons. Thus, the variable world recognizable to people emerged from the dynamic interaction between the mighty Kutkh and the small but numerous Mice.” ref

“Although Kutkh is supposed to have given mankind variously light, fire, language, fresh water, and skills such as net-weaving and copulation, he is also often portrayed as a laughing-stock, hungry, thieving, and selfish. In its contradictions, his character is similar that of other trickster gods, such as Coyote. The early Russian explorer and ethnographer of Kamchatka Stepan Krasheninnikov (1711–1755) summarize the Itelmen’s relationship to Kutkh as follows:

They pay no homage to him and never ask any favor of him; they speak of him only in derision. They tell such indecent stories about him that I would be embarrassed to repeat them. They upbraid him for having made too many mountains, precipices, reefs, sand banks and swift rivers, for causing rainstorms and tempests which frequently inconvenience them. In winter when they climb up or down the mountains, they heap abuses on him and curse him with imprecations. They behave the same way when they are in other difficult or dangerous situations.” ref

“The image of Kutkh remains popular and iconic in Kamchatka, used often in advertising and promotional materials. Stylized carvings of Kutkh by Koryak artisans, often adorned with beads and lined with fur, are sold widely as souvenirs. The Chukchi creator-deity, roughly analogous to Bai-Ulgan of the Turkic pantheon. The Koryaks refer to him as Quikinna’qu (“Big Raven”) and in Kamchadal (Itelmens) mythology he is called Kutkhu.” ref

Three-legged crow Top of Pic #1

“The three-legged (or tripedal) crow is a creature found in various mythologies and arts of East Asia. It is believed by East Asian cultures to inhabit and represent the Sun. It has also been found figured on ancient coins from Lycia and Pamphylia. The earliest forms of the tripedal crow have been found in China. Evidence of the earliest bird-Sun motif or totemic articles excavated around 5000 BCE or 7,020 years ago from the lower Yangtze River delta area. This bird-Sun totem heritage was observed in later Yangshao and Longshan cultures. The Chinese have several versions of crow and crow-Sun tales. But the most popular depiction and myth of the Sun crow is that of the Yangwu or Jinwu, the “golden crow“. In Chinese mythology and culture, the three-legged crow is called the sanzuwu and is present in many myths. It is also mentioned in the Shanhaijing. The earliest known depiction of a three-legged crow appears in Neolithic pottery of the Yangshao culture. The sanzuwu is also of the Twelve Medallions that is used in the decoration of formal imperial garments in ancient China.” ref

Sun crow in Chinese mythology

The most popular depiction and myth of a sanzuwu is that of a sun crow called the Yangwu (陽烏; yángwū) or more commonly referred to as the Jīnwū (金烏; jīnwū) or “golden crow“. Even though it is described as a crow or raven, it is usually colored red instead of black. A silk painting from the Western Han excavated at the Mawangdui archaeological site also depicts a “golden crow” in the sun. According to folklore, there were originally ten sun crows which settled in 10 separate suns. They perched on a red mulberry tree called the Fusang (扶桑; fúsāng), literally meaning “the leaning mulberry tree”, in the East at the foot of the Valley of the Sun. This mulberry tree was said to have many mouths opening from its branches. Each day one of the sun crows would be rostered to travel around the world on a carriage, driven by Xihe, the ‘mother’ of the suns. As soon as one sun crow returned, another one would set forth in its journey crossing the sky. According to Shanhaijing, the sun crows loved eating two grasses of immortality, one called the Diri (地日; dìrì), or “ground sun”, and the other the Chunsheng (春生; chūnshēng), or “spring grow”. The sun crows would often descend from heaven on to the earth and feast on these grasses, but Xihe did not like this; thus, she covered their eyes to prevent them from doing so. Folklore also held that, at around 2170 BC, all ten sun crows came out on the same day, causing the world to burn; Houyi, the celestial archer saved the day by shooting down all but one of the sun crows. (See Mid-Autumn Festival for variants of this legend.)” ref

“In Chinese mythology, there are other three-legged creatures besides the crow, for instance, the yu 魊 “a three-legged tortoise that causes malaria”. The three-legged crow symbolizing the sun has a yin yang counterpart in the chánchú 蟾蜍 “three-legged toad” symbolizing the moon (along with the moon rabbit). According to an ancient tradition, this toad is the transformed Chang’e lunar deity who stole the elixir of life from her husband Houyi the archer, and fled to the moon where she was turned into a toad. The Fènghuáng is commonly depicted as being two-legged but there are some instances in art in which it has a three-legged appearance. Xi Wangmu (Queen Mother of the West) is also said to have three green birds (青鳥; qīngniǎo) that gathered food for her and in Han-period religious art they were depicted as having three legs. In the Yongtai Tomb dating to the Tang Dynasty Era, when the Cult of Xi Wangu flourished, the birds are also shown as being three-legged.” ref

Japan mythology

“In Japanese mythology, this flying creature is a raven or a jungle crow called Yatagarasu (八咫烏, “eight-span crow”) and the appearance of the great bird is construed as evidence of the will of Heaven or divine intervention in human affairs. Although Yatagarasu is mentioned in a number of places in Shintō, the depictions are primarily seen on Edo wood art, dating back to the early 1800s wood-art era. Although not as celebrated today, the crow is a mark of rebirth and rejuvenation; the animal that has historically cleaned up after great battles symbolized the renaissance after such tragedy. Yatagarasu as a crow-god is a symbol specifically of guidance. This great crow was sent from heaven as a guide for legendary Emperor Jimmu on his initial journey from the region which would become Kumano to what would become Yamato, (Yoshino and then Kashihara). It is generally accepted that Yatagarasu is an incarnation of Taketsunimi no mikoto, but none of the early surviving documentary records are quite so specific. In more than one instance, Yatagarasu appears as a three legged crow not in Kojiki but in Wamyō Ruijushō. Both the Japan Football Association and subsequently its administered teams such as the Japan national football team use the symbol of Yatagarasu in their emblems and badges respectively. The winner of the Emperor’s Cup is also given the honor of wearing the Yatagarasu emblem the following season. Although the Yatagarasu is commonly perceived as a three-legged crow, there is in fact no mention of it being such in the original Kojiki. Consequently, it is theorised that this is a result of a later possible misinterpretation during the Heian period that the Yatagarasu and the Chinese Yangwu refer to an identical entity.” ref

Korea mythology

“In Korean mythology, it is known as Samjogo (hangul: 삼족오; hanja: 三足烏). During the period of the Goguryo kingdom, the Samjok-o was considered a symbol of the sun. The ancient Goguryo people thought that a three-legged crow lived in the sun while a turtle lived in the moon. Samjok-o was a highly regarded symbol of power, thought superior to both the dragon and the Korean bonghwang. Although the Samjok-o is mainly considered the symbol of Goguryeo, it is also found in Goryeo and Joseon dynasties. Samjoko was appeared in the story Yeonorang Seonyeo. A couple, Yeono and Seo, lived on the beach of the East Sea in 157 (King Adalala 4), and rode to Japan on a moving rock. The Japanese took two people to Japan as kings and noblemen. At that time, the light of the sun and the moon disappeared in Silla. King Adalala sent an official to Japan to return the couple, but Yeono said to take the silk that made by his wife, Seo, and sacrifices it to the sky. As he said this, the sun and moon were brighter again. In modern Korea, Samjok-o is still found especially in dramas such as Jumong. The three-legged crow was one of several emblems under consideration to replace the bonghwang in the Korean seal of state when its revision was considered in 2008. The Samjok-o appears also in Jeonbuk Hyundai Motors FC‘s current emblem. There are some Korean companies using Samjok-o as their corporate logos.” ref

“Many references to ravens exist in world lore and literature. Most depictions allude to the appearance and behavior of the wide-ranging common raven (Corvus corax). Because of its black plumage, croaking call, and diet of carrion, the raven is often associated with loss and ill omen. Yet its symbolism is complex. As a talking bird, the raven also represents prophecy and insight. Ravens in stories often act as psychopomps, connecting the material world with the world of spirits. French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss proposed a structuralist theory that suggests the raven (like the coyote) obtained mythic status because it was a mediator animal between life and death. As a carrion bird, ravens became associated with the dead and with lost souls. In Swedish folklore, they are the ghosts of murdered people without Christian burials and, in German stories, damned souls. The Raven has appeared in the mythologies of many ancient peoples. Some of the more common stories are from those of Greek, Celtic, Norse, Pacific Northwest, and Roman mythology.” ref

Greco-Roman

“In Greek mythology, ravens are associated with Apollo, the god of prophecy. They are said to be a symbol of bad luck, and were the god’s messengers in the mortal world. According to the mythological narration, Apollo sent a white raven, or crow in some versions to spy on his lover, Coronis. When the raven brought back the news that Coronis had been unfaithful to him, Apollo scorched the raven in his fury, turning the animal’s feathers black. That’s why all ravens are black today. According to Livy, the Roman general Marcus Valerius Corvus (c. 370-270 BC) had a raven settle on his helmet during a combat with a gigantic Gaul, which distracted the enemy’s attention by flying in his face.” ref

Hebrew Bible and Judaism

“The raven (Hebrew: עורב; Koine Greek: κόραξ) is the first species of bird to be mentioned in the Hebrew Bible,[5] and ravens are mentioned on numerous occasions thereafter. In the Book of Genesis, Noah releases a raven from the ark after the great flood to test whether the waters have receded (Gen. 8:6-7). According to the Law of Moses, ravens are forbidden for food (Leviticus 11:15; Deuteronomy 14:14), a fact that may have colored the perception of ravens in later sources. In the Book of Judges, one of Kings of the Midianites defeated by Gideon is called “Orev” (עורב) which means “Raven”. In the Book of Kings 17:4-6, God commands the ravens to feed the prophet Elijah. King Solomon is described as having hair as black as a raven in the Song of Songs 5:11. Ravens are an example of God’s gracious provision for all his creatures in Psalm 147:9 and Job 38:41. (In the New Testament as well, ravens are used by Jesus as an illustration of God’s provision in Luke 12:24.) Philo of Alexandria (first century AD), who interpreted the Bible allegorically, stated that Noah’s raven was a symbol of vice, whereas the dove was a symbol of virtue (Questions and Answers on Genesis 2:38). In the Talmud, the raven is described as having been only one of three beings on Noah’s Ark that copulated during the flood and so was punished. The Rabbis believed that the male raven was forced to spit. According to the Icelandic Landnámabók—a story similar to Noah and the Ark — Hrafna-Flóki Vilgerðarson used ravens to guide his ship from the Faroe Islands to Iceland. Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer (chapter 25) explains that the reason the raven Noah released from the ark did not return to him was that the raven was feeding on the corpses of those who drowned in the flood.” ref

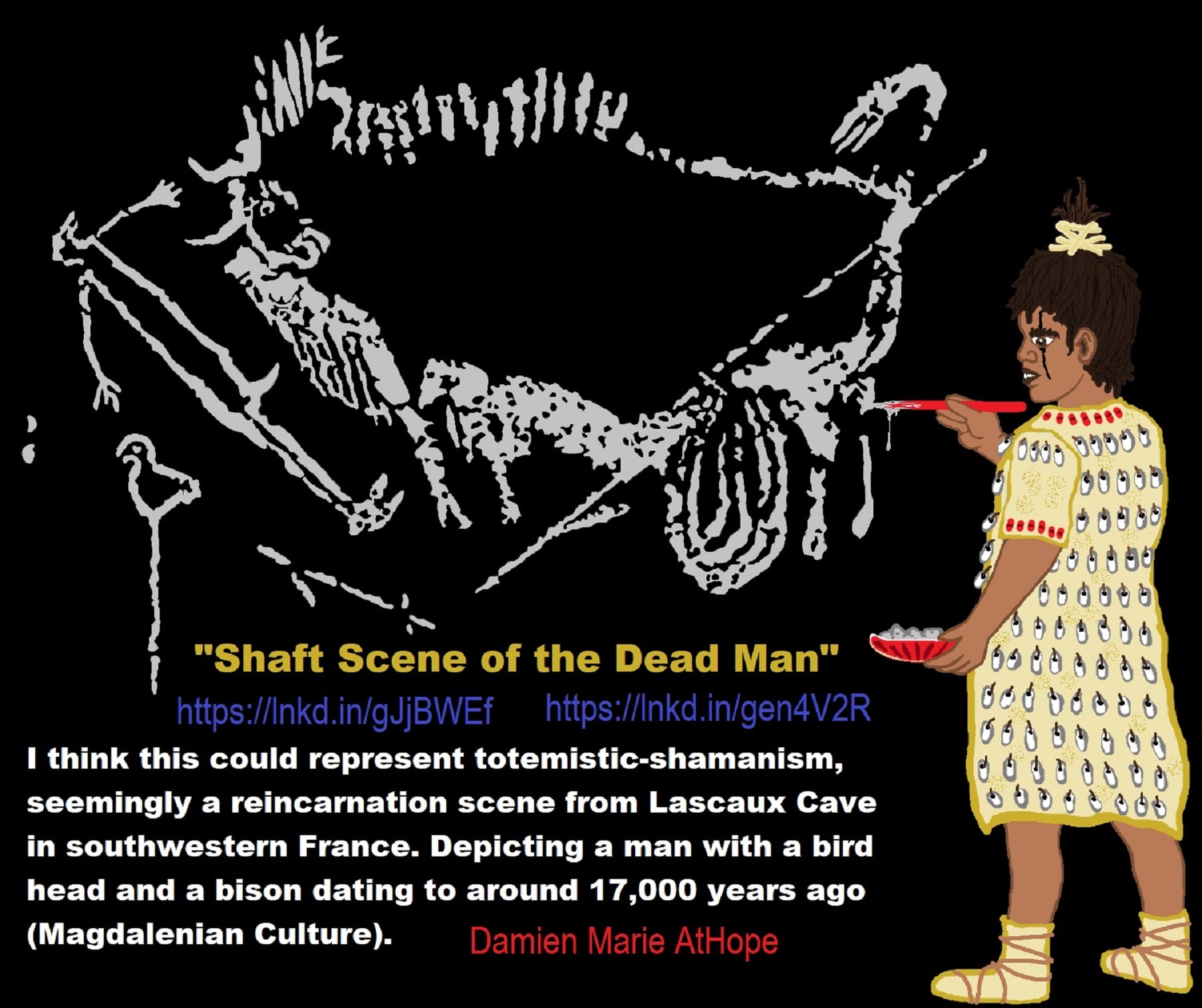

13,500 years ago Miniature bird sculpted

“A miniature bird sculpted out of burnt bone in China around 13,500 years ago is the oldest known figurine from East Asia, according to researchers who discovered it in a refuse heap near an archaeological site. The carefully crafted depiction of a songbird on a pedestal — smaller than an almond kernel — was found among burnt animal remains and fragments of ceramics at Lingjing in north-central Henan province, an area thought to have been home to some of China’s earliest civilizations. The figurine is the “oldest known carving from East Asia”, said Francesco D’Errico of the University of Bordeaux, who co-authored the research published in the journal PLOS One. In this way they estimated the age of the bird figurine to be 13,500 years, which they said predates previously known figurines from this region by almost 8,500 years.” ref

Birds in Chinese mythology

“Birds in Chinese mythology and legend are of numerous types and very important in this regard. Some of them are obviously based on real birds, other ones obviously not, and some in-between. The crane is an example of a real type of bird with mythological enhancements. Cranes are linked with immortality, and may be transformed xian immortals, or ferry an immortal upon their back. The Vermilion Bird is iconic of the south. Sometimes confused with the Fenghuang, the Vermilion Bird of the south is associated with fire. The Peng was a gigantic bird phase of the gigantic Kun fish. The Jingwei is a mythical bird which tries to fill up the ocean with twigs and pebbles symbolizing indefatigable determination. The Qingniao was the messenger or servant of Xi Wangmu. Written and spoken Chinese varieties have different character graphs and sounds representing mythological and legendary birds of China. The Chinese characters or graphs used have varied over time calligraphically or typologically. Historically main generic characters for bird are niǎo (old school, traditional character = 鳥 / simplified character, based on cursive form = 鸟) and the other main “bird” word / character graph zhuī (隹). Many specific characters are based on these two radicals; in other words, incorporating one or the other radical as constituent to a more complex character graph, for example in the case of the Peng bird (traditional character graph = 鵬 / simplified = 鹏): in both cases, a version of the niǎo character is radicalized on the right. Modern pronunciations vary and the ancient ones are not fully recoverable. Sometimes the Chinese terms for mythological or legendary birds include a generic term for “bird” appended to the pronounced name for “bird”; an example would be the Zhenniao, which is also known just as Zhen: the combination of Zhen plus niao means “Zhen bird”; thus, “Zhenniao” is the same as “Zhen bird”, or just “Zhen”.” ref

“Translation into English language of Chinese terms for legendary and mythological birds is difficult, especially considering that even in Chinese there is a certain amount of obscurity. In some cases, the classical Chinese term is obviously a descriptive term. In other cases, the classical Chinese term is clearly based on the alleged sound of said bird; that is, what is known as onomatopoeia. However, often, it’s not so simple (Strassberg 2002, xvii–xviii). Some birds in Chinese legend and mythology symbolize or represent various concepts of a more-or-less abstract nature. The Vermilion Bird of the South symbolically represents the cardinal direction south. It is red and associated with the wu xing “element” fire. The Jingwei bird represents determination and persistence, even in the face of seemingly over-whelming odds. A three-legged bird or birds are a solar motif. Sometimes depicted as a Three-legged crow. Totem birds: Some birds may function as totems or representative symbols of clans or other social groups. And some birds are associated with other mythological content. The Qingniao is associated with the Queen Mother of the West, bearing her messages or bringing her food. Some birds feature as part of visions of the mythological geography of China. According to the Shanhaijing and it’s commentaries, the Bifang can be found on Mount Zhang’e and/or east of the Feathered People (Youmin) and west of the Blue River. Certain birds in mythology transport deities, immortals, or others. One example is the Crane in Chinese mythology.” ref

“Other birds include the Bi Fang bird, a one-legged bird (Strassberg 2002, 110–111). Bi is also number nineteen of the Twenty-Eight Mansions of traditional Chinese astronomy, the Net (Bi). There are supposed to be the Jiān (鶼; jian1): the mythical one-eyed bird with one wing; Jianjian (鶼鶼): a pair of such birds dependent on each other, inseparable, hence representing husband and wife. There was a Shang-Yang rainbird. The Jiufeng is a nine-headed bird used to scare children. The Sù Shuāng (鷫鷞; su4shuang3) sometimes appears as a goose-like bird. The Zhen is a poisonous bird. There may be a Jiguang (吉光; jíguāng). The line between fantastic, mythological, or legendary birds and actually real exotic birds is sometimes blurred. Sometimes, the student of the real versus the unreal becomes challenged.” ref

Tutelary deity

“A tutelary is a deity or spirit who is a guardian, patron, or protector of a particular place, geographic feature, person, lineage, nation, culture, or occupation. The etymology of “tutelary” expresses the concept of safety and thus of guardianship. In late Greek and Roman religion, one type of tutelary deity, the genius, functions as the personal deity or daimon of an individual from birth to death. Another form of personal tutelary spirit is the familiar spirit of European folklore.” ref

America Tutelary deity

- Tonás, tutelary animal spirit among the Zapotec.

- Totem, familial or clan spirits among the Ojibwe, can be animals ref

Asia Tutelary deity

- Chinese folk religion, both past and present, includes a myriad of tutelary deities. Exceptional individuals, highly cultivated sages and prominent ancestors will be deified and honored after passing away. Lord Guan is the patron of military personnel and police, while Mazu is the patron of fishermen and sailors.Tu Di Gong (Earth Deity) is the tutelary deity of individual locality and each locality has its own Earth Deity.

Cheng Huang Gong (City God) is the guardian deity of individual city, and are worship by local officials and locals since imperial times. ref - In Hinduism, tutelary deities are known as ishta-devata and Kuldevi or Kuldevta. Gramadevata are guardian deities of villages. Devas can also be seen as tutelary. Shiva is patron of yogis and renunciants. City goddesses include:Mumbadevi (Mumbai)

Sachchika (Osian) ref

Kuladevis include:

- Ambika (Porwad)

- Mahalakshmi

- In Korean shamanism, jangseung and sotdae were placed at the edge of villages to frighten off demons. They were also worshiped as deities. Seonangshin is the patron deity of the village in Korean tradition and was believed to embody the Seonangdang.

- In Philippine animism, Diwata or Lambana are deities or spirits that inhabit sacred places like mountains and mounds and serve as guardians. ref

* Maria Makiling is the deity who guards Mt. Makiling.* Maria Cacao and Maria Sinukuan.

- In Shinto, the spirits, or kami, which give life to human bodies come from nature and return to it after death. Ancestors are therefore themselves tutelaries to be worshiped.

- Thai provincial capitals have tutelary city pillars and palladiums. The guardian spirit of a house is known as Chao Thi (เจ้าที่) or Phra Phum (พระภูมิ). Almost every traditional household in Thailand has a miniature shrine housing this tutelary deity, known as a spirit house.

- Tibetan Buddhism has Yidam as a tutelary deity. Dakini is the patron of those who seek knowledge. ref

Austronesian

Europe Tutelary deity

Ancient Greece

“The Greeks also thought deities guarded specific places: For instance, Athena was the patron goddess of the city of Athens. Socrates spoke of hearing the voice of his personal spirit or daimonion:

You have often heard me speak of an oracle or sign which comes to me … . This sign I have had ever since I was a child. The sign is a voice which comes to me and always forbids me to do something which I am going to do, but never commands me to do anything, and this is what stands in the way of my being a politician.” ref

Ancient Rome