ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

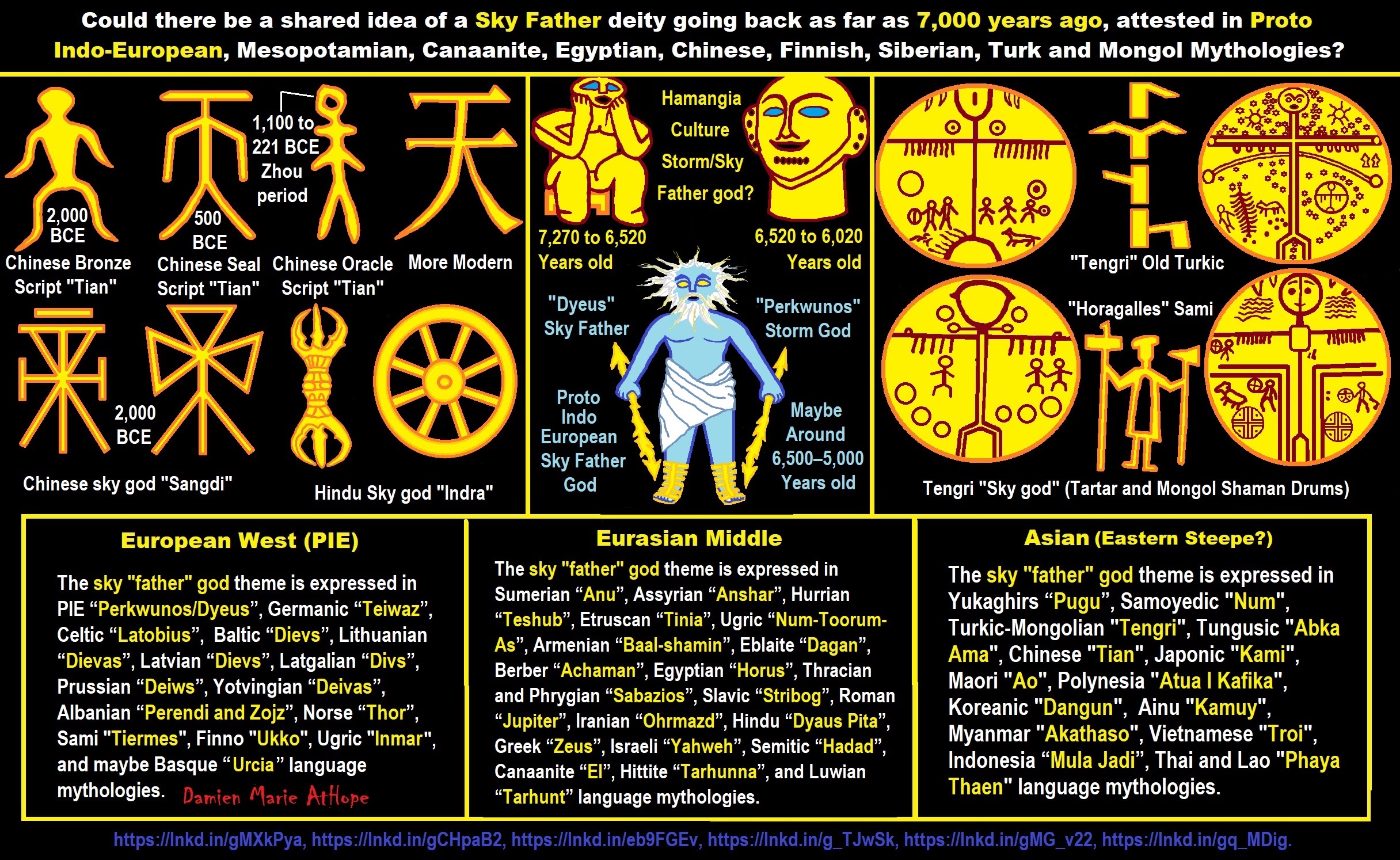

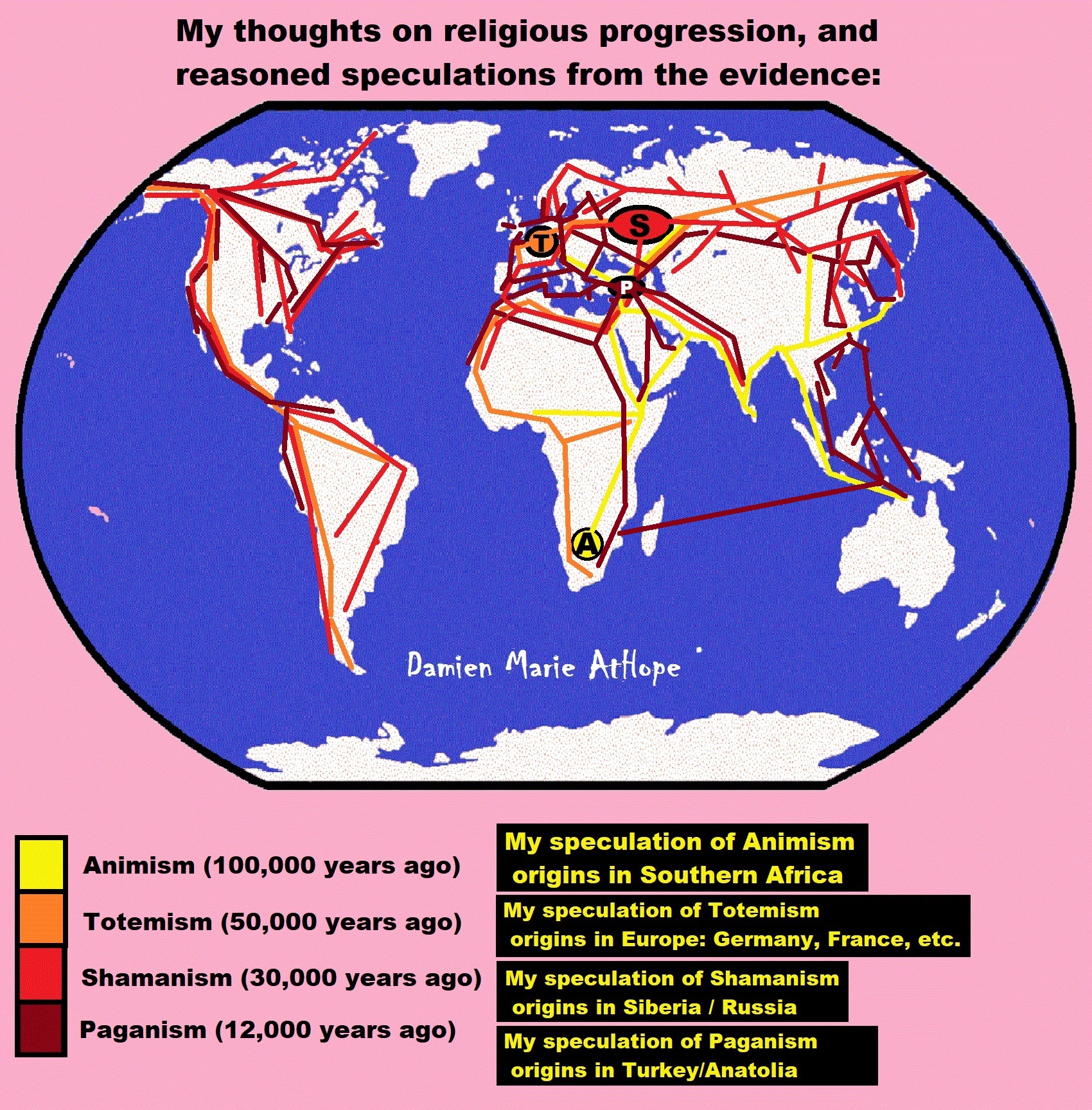

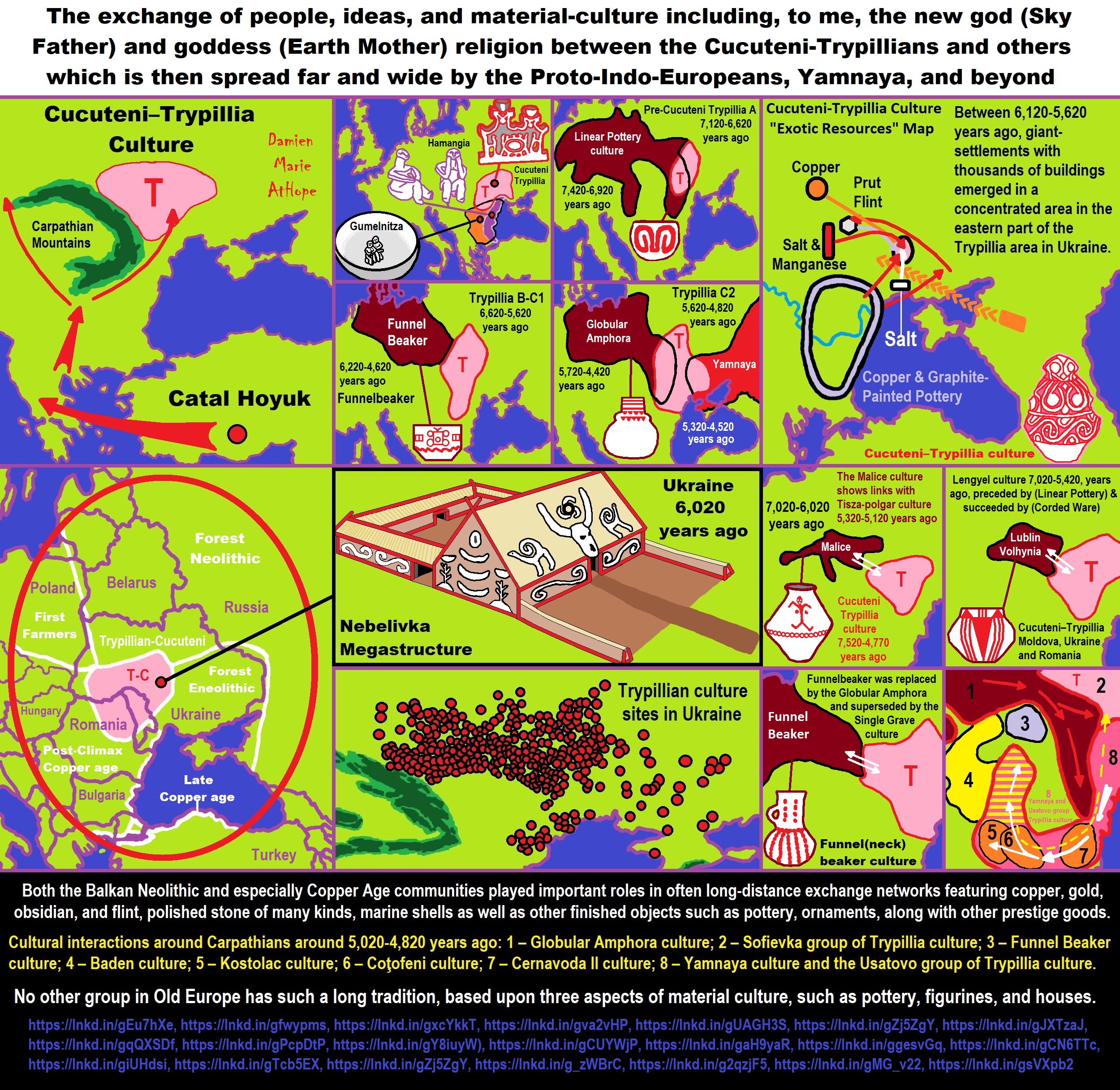

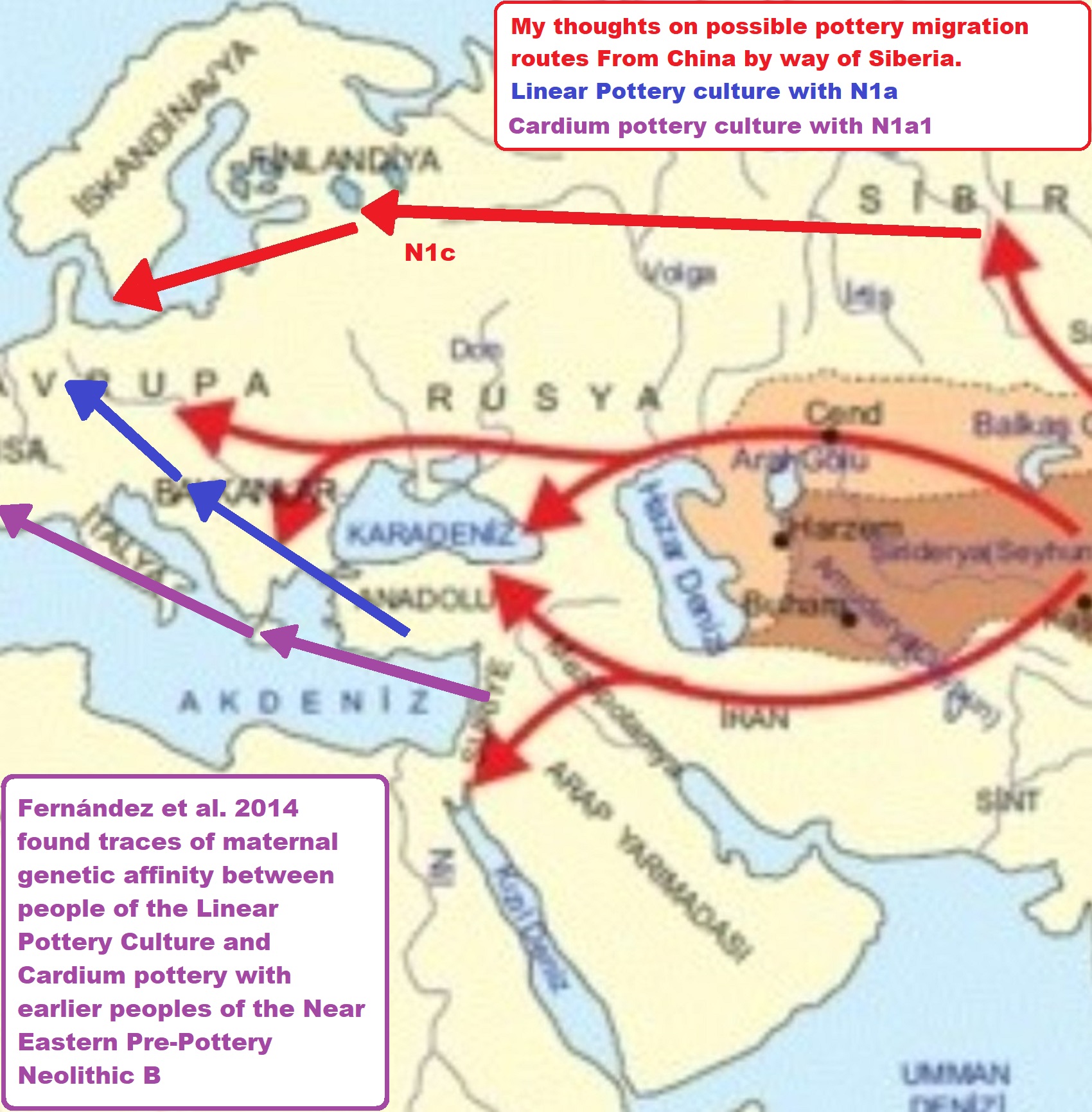

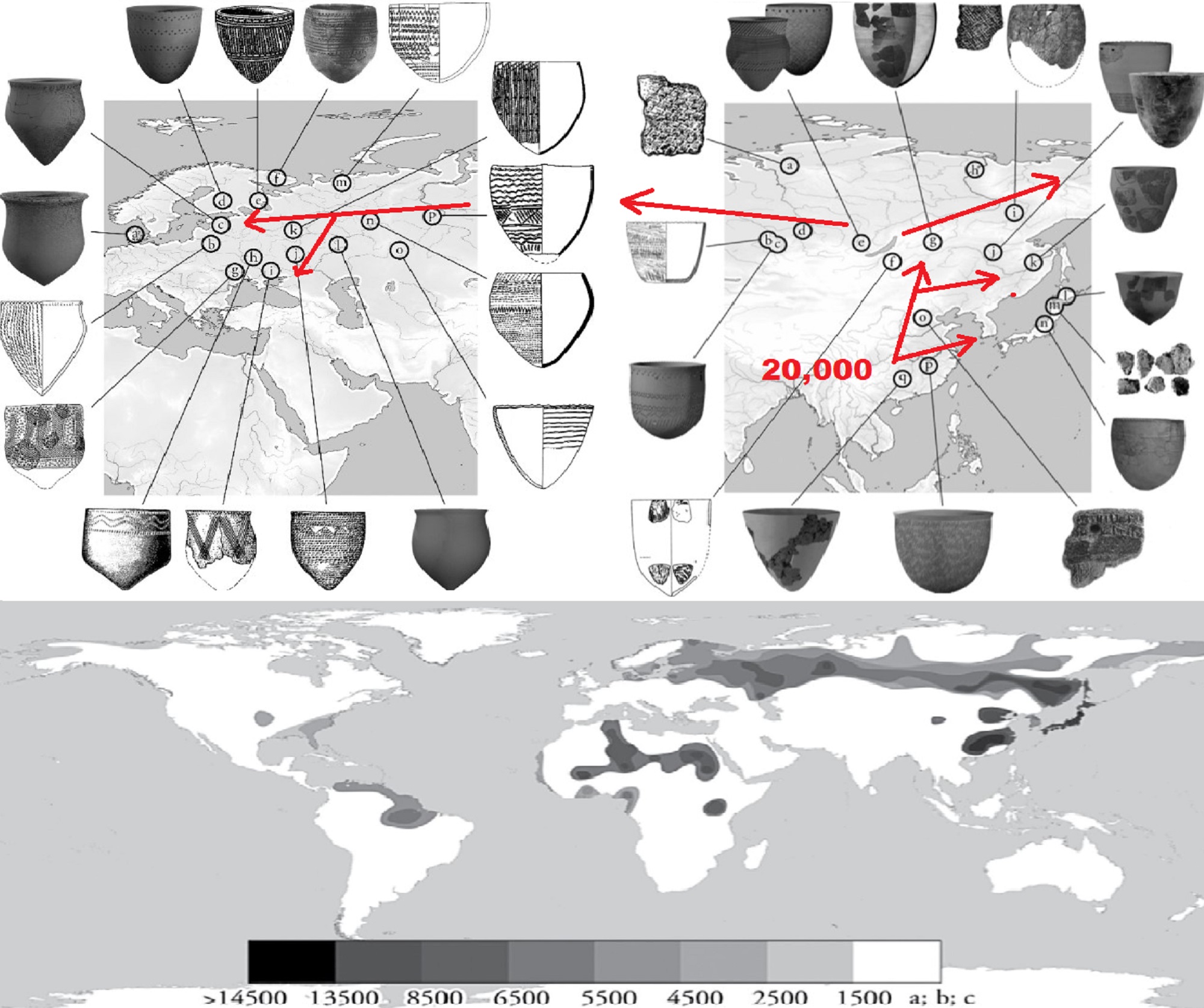

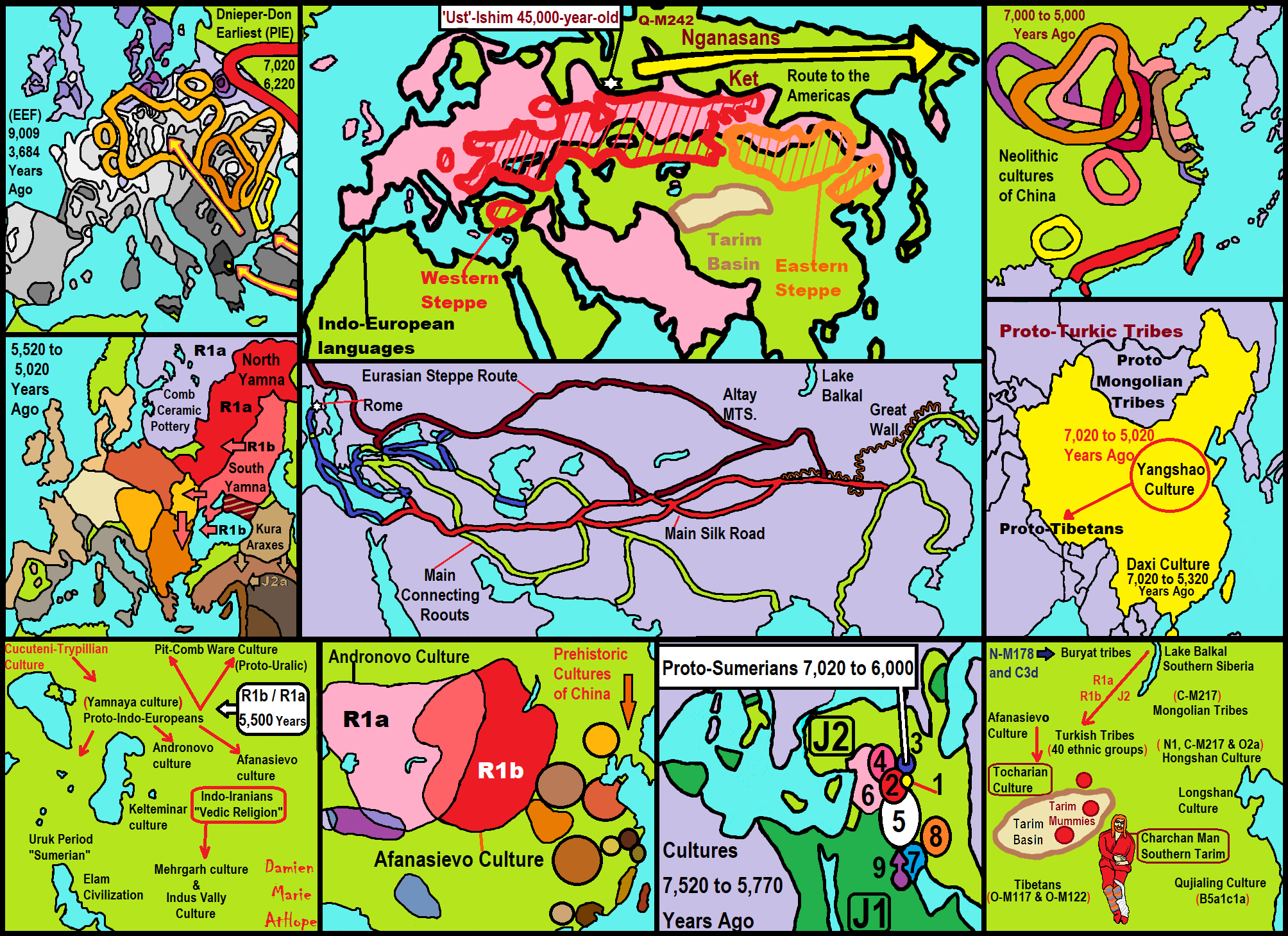

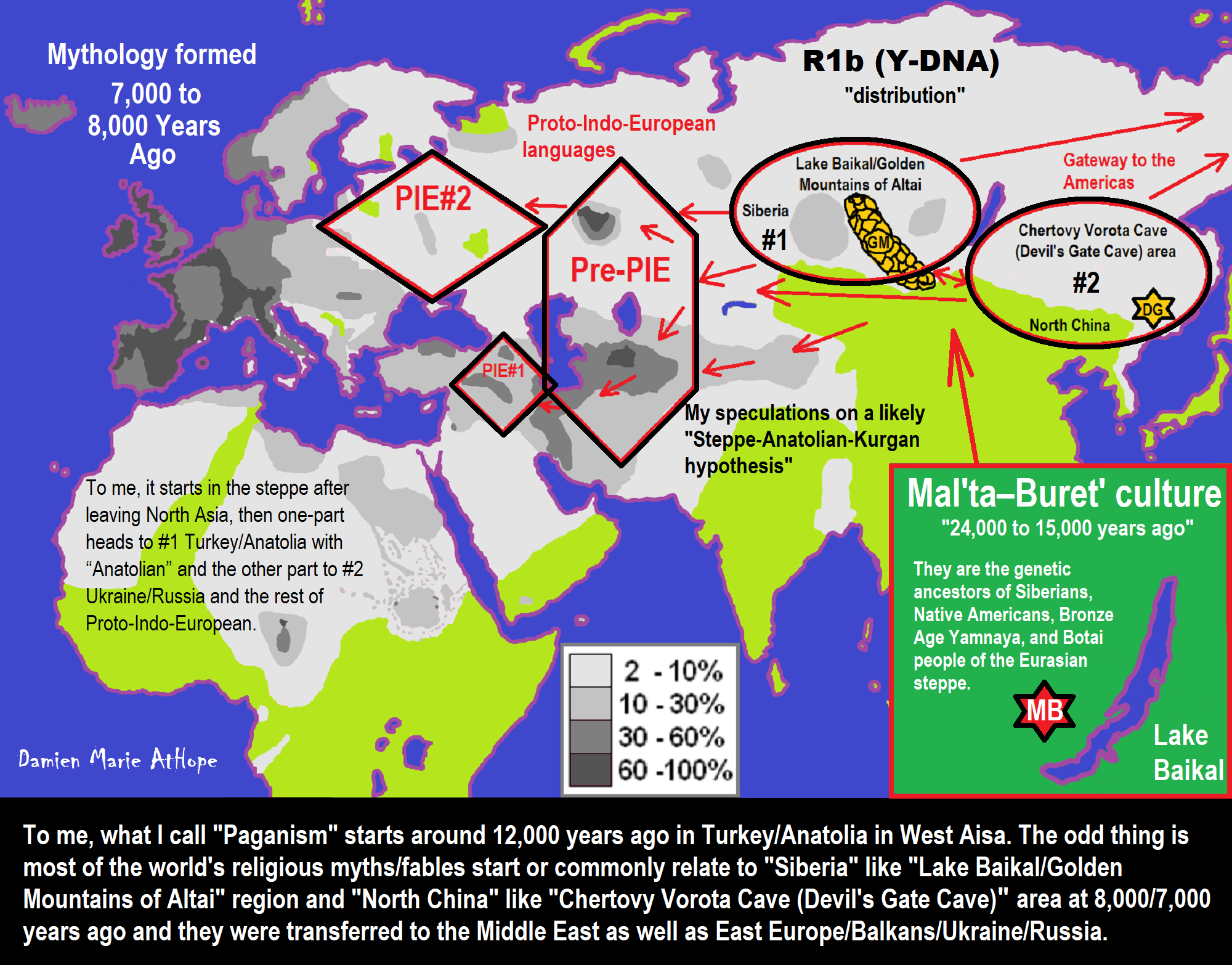

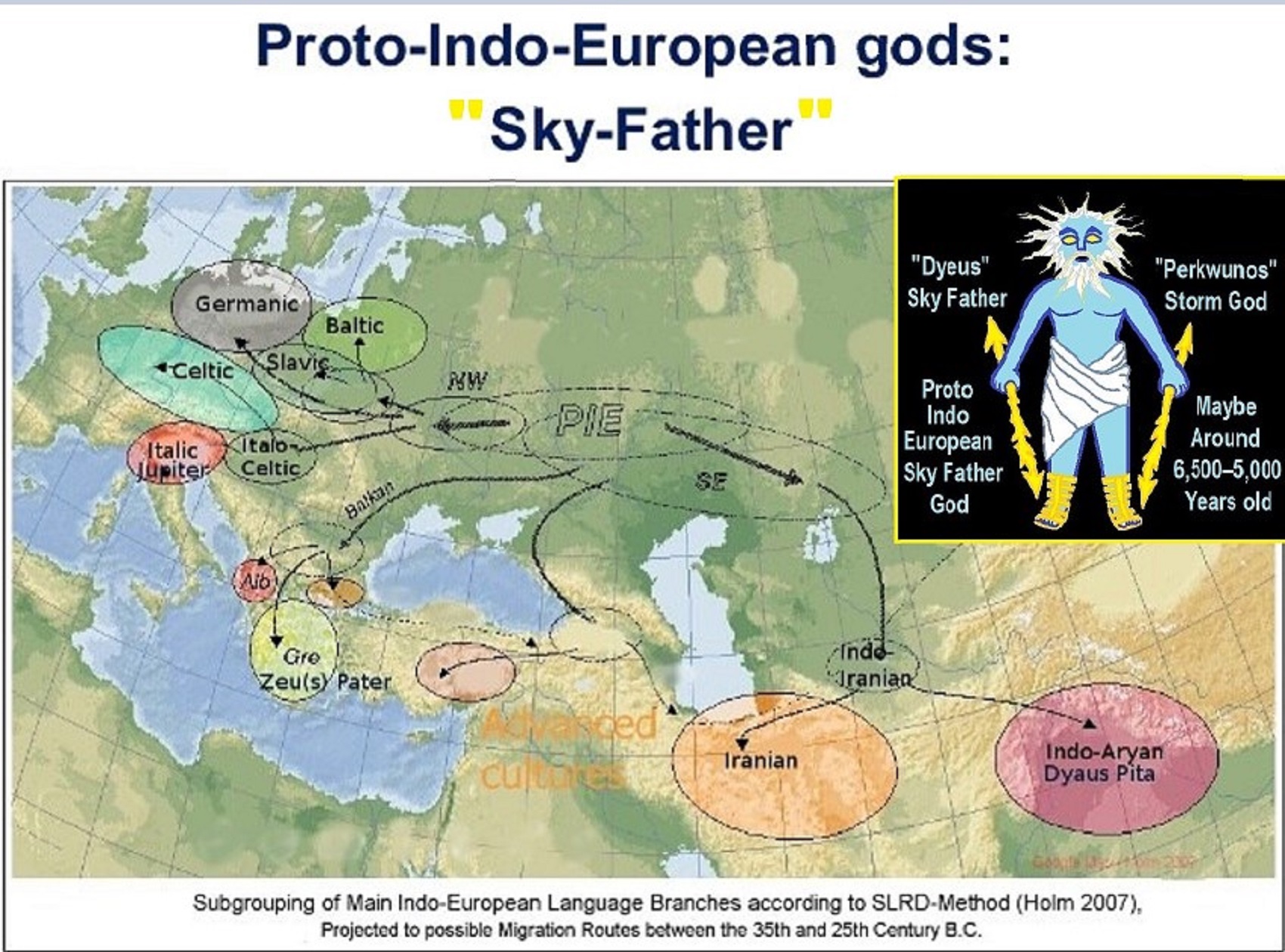

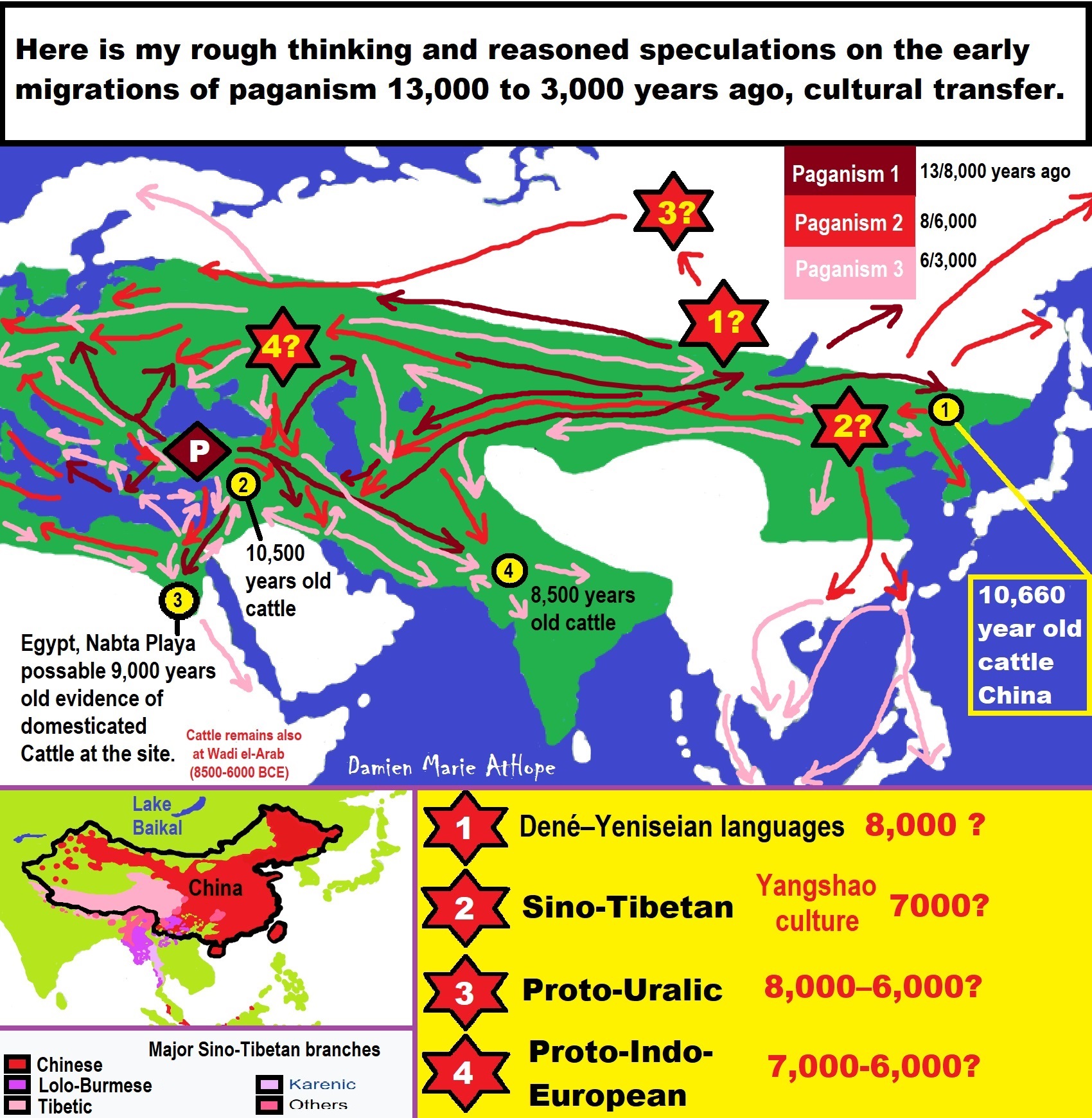

The exchange of people, ideas, and material-culture including, to me, the new god (Sky Father) and goddess (Earth Mother) religion between the Cucuteni-Trypillians and others which is then spread far and wide by the Proto-Indo-Europeans, Yamnaya, and beyond?

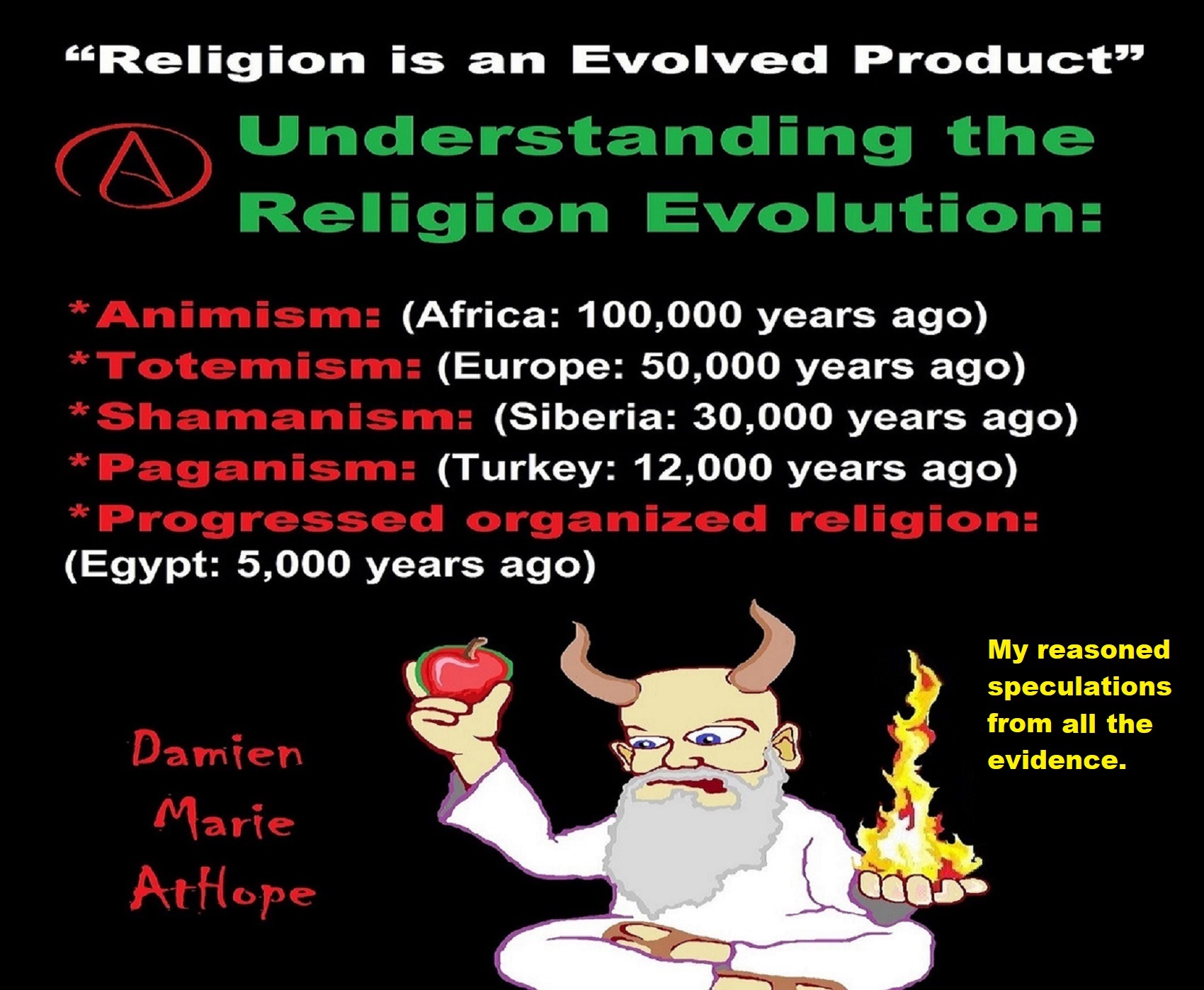

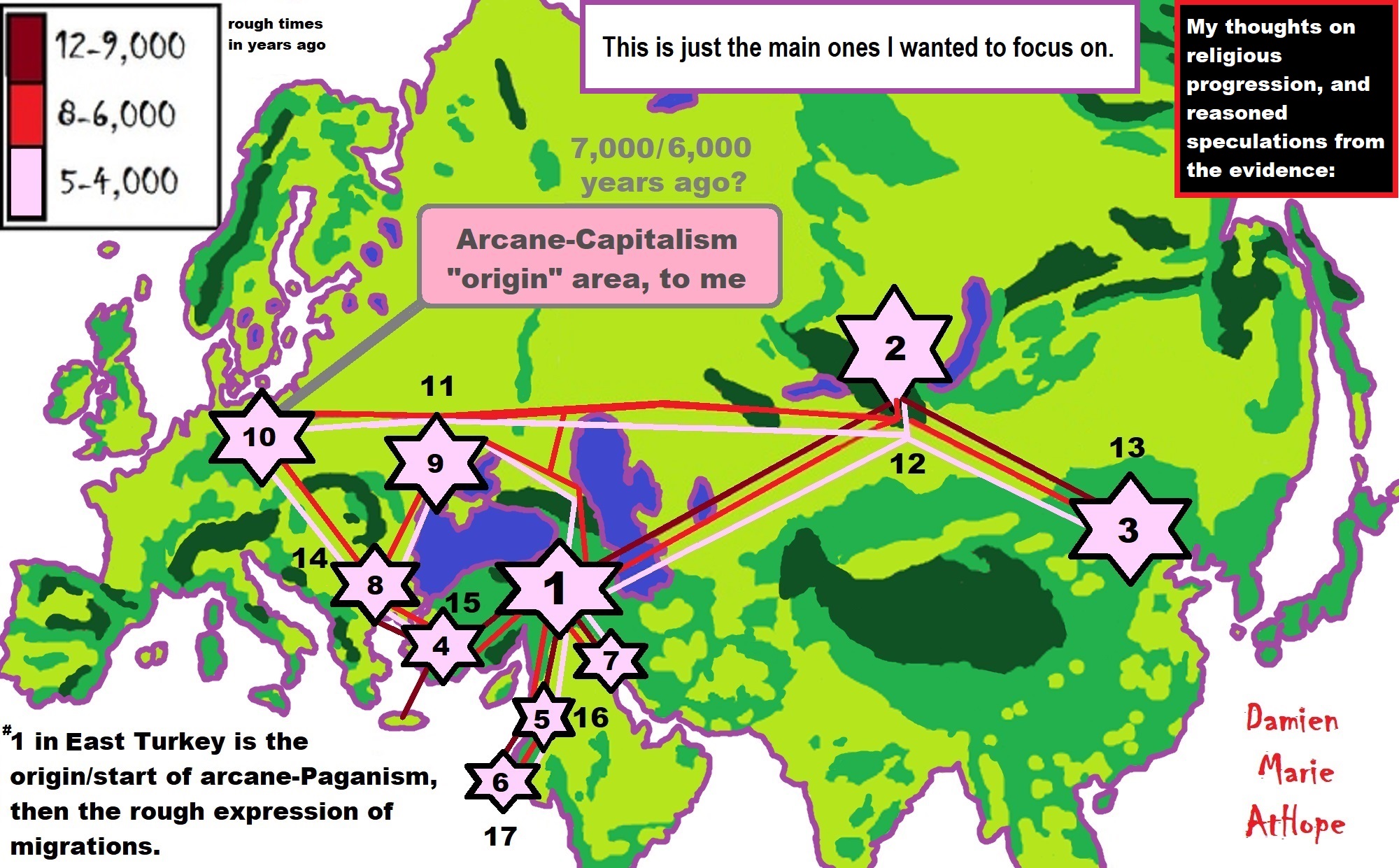

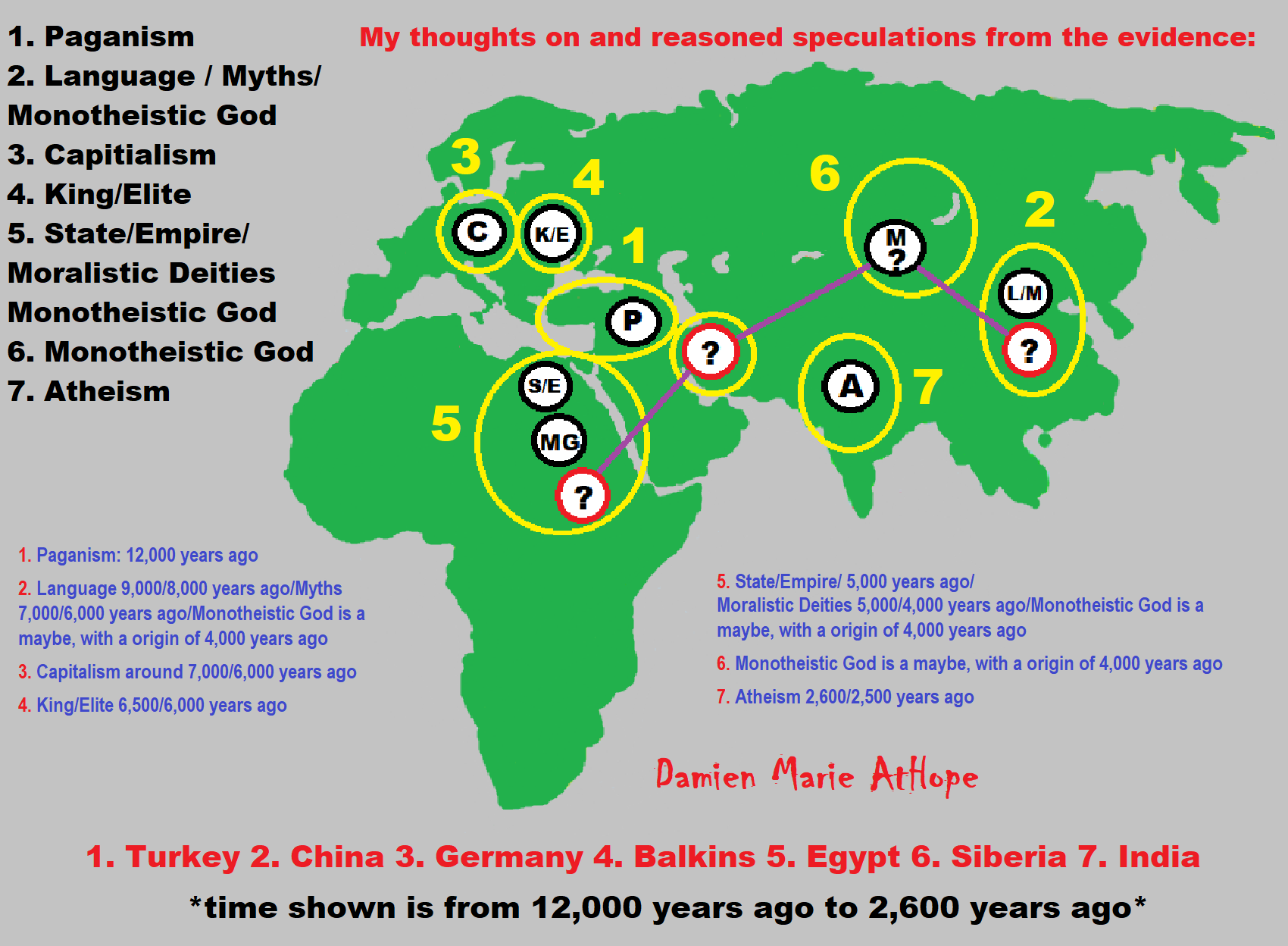

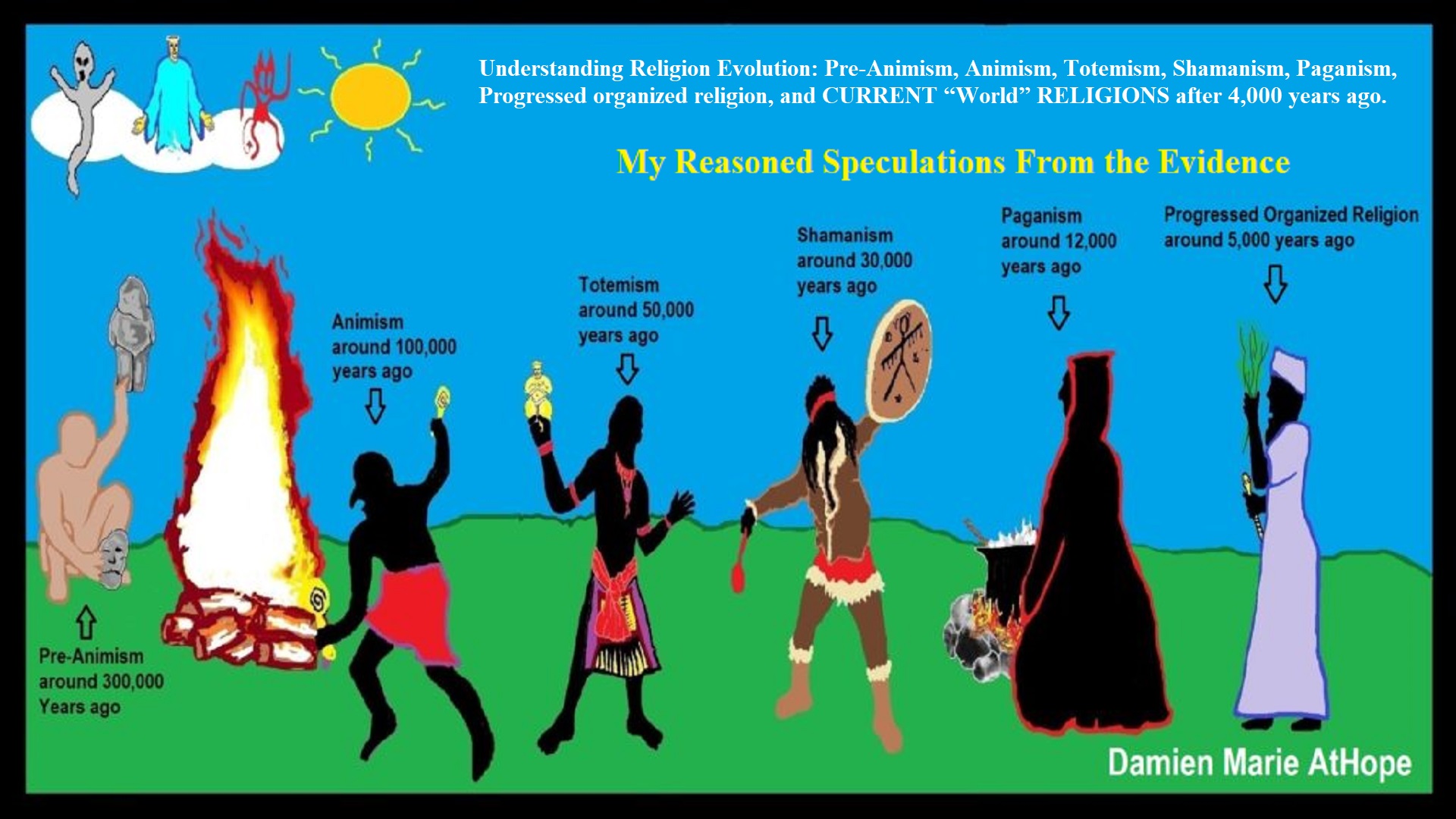

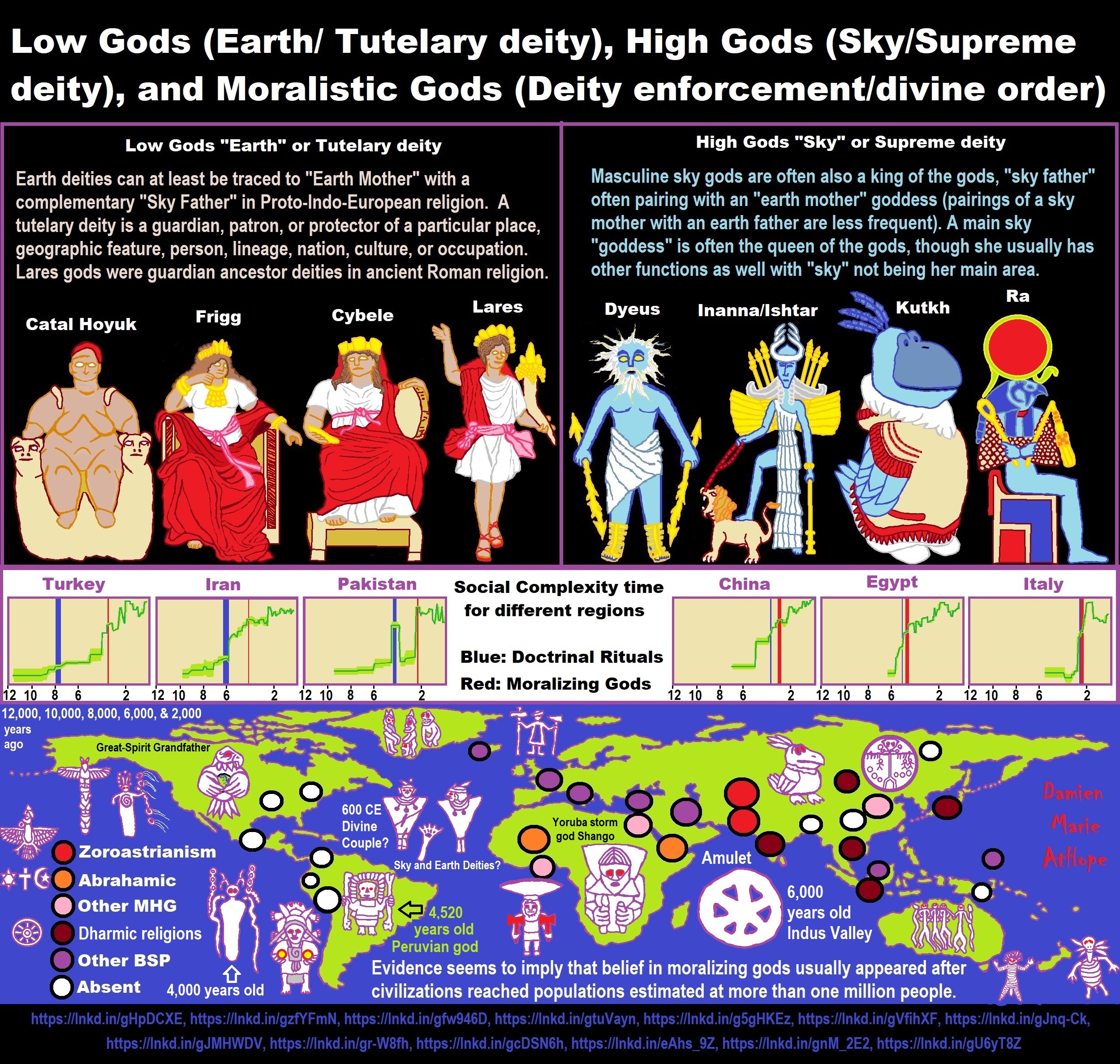

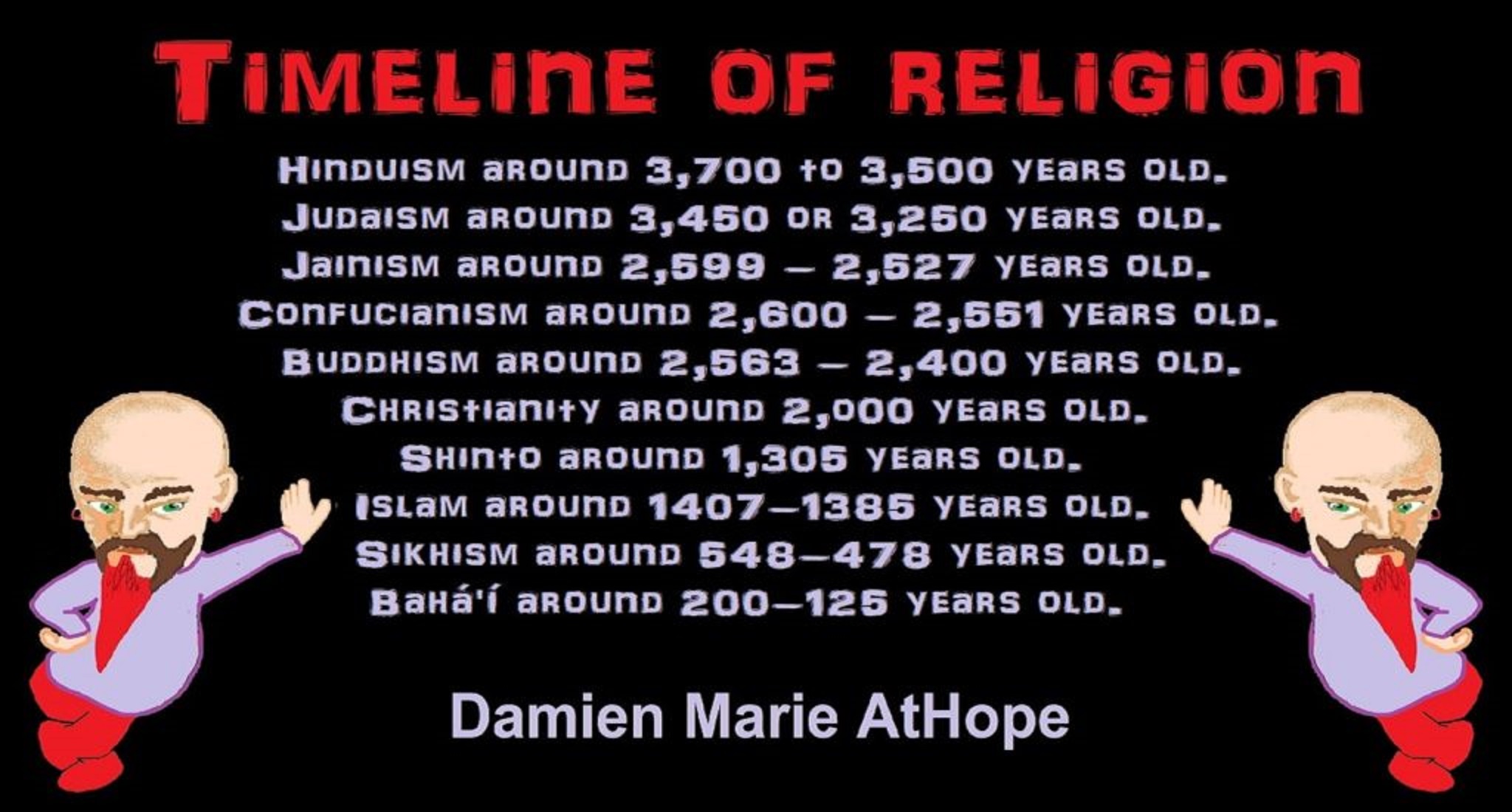

“These ideas are my speculations from the evidence.”

European Culture Links:

Groups partially derived from the Ancient North Eurasians

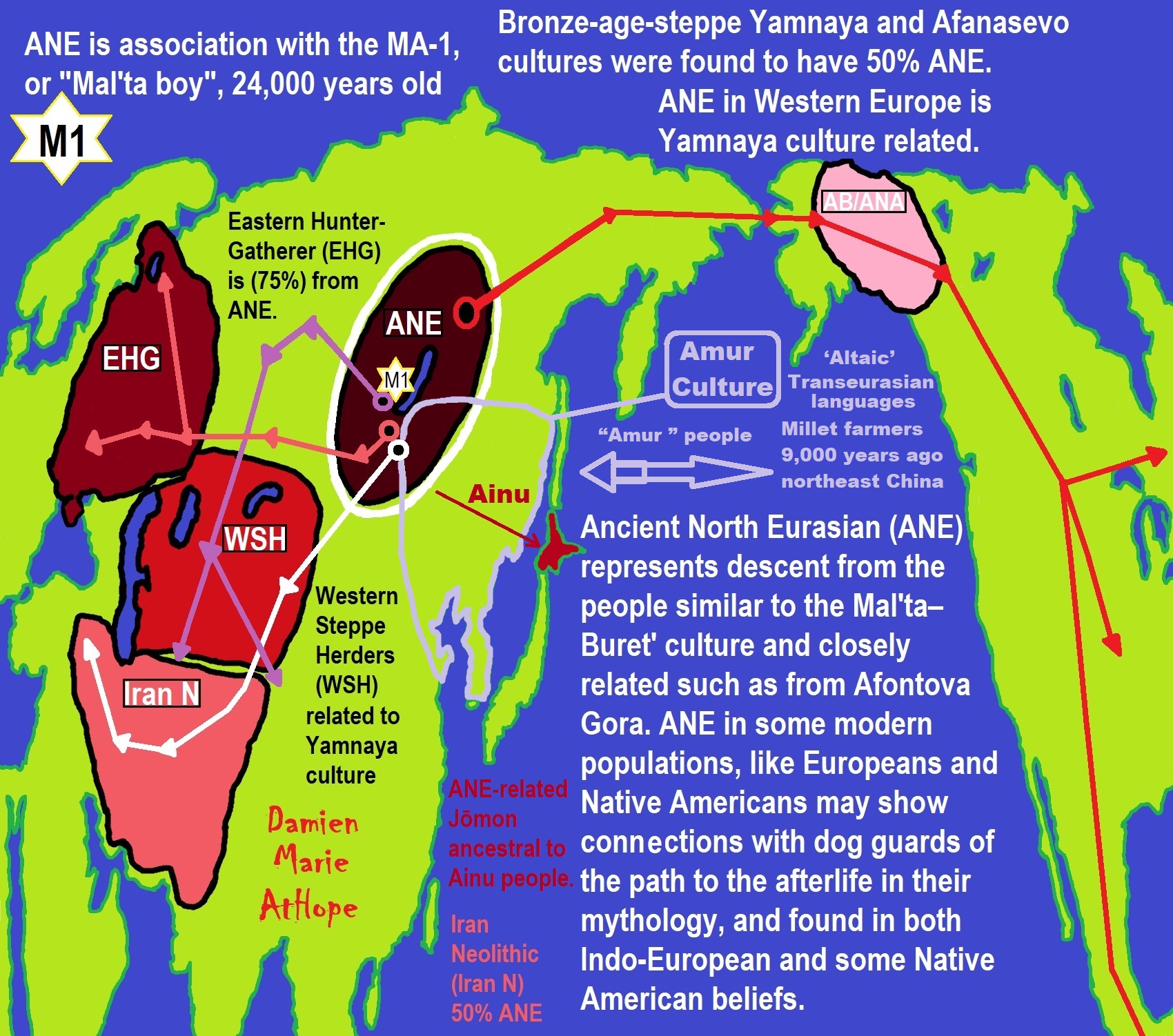

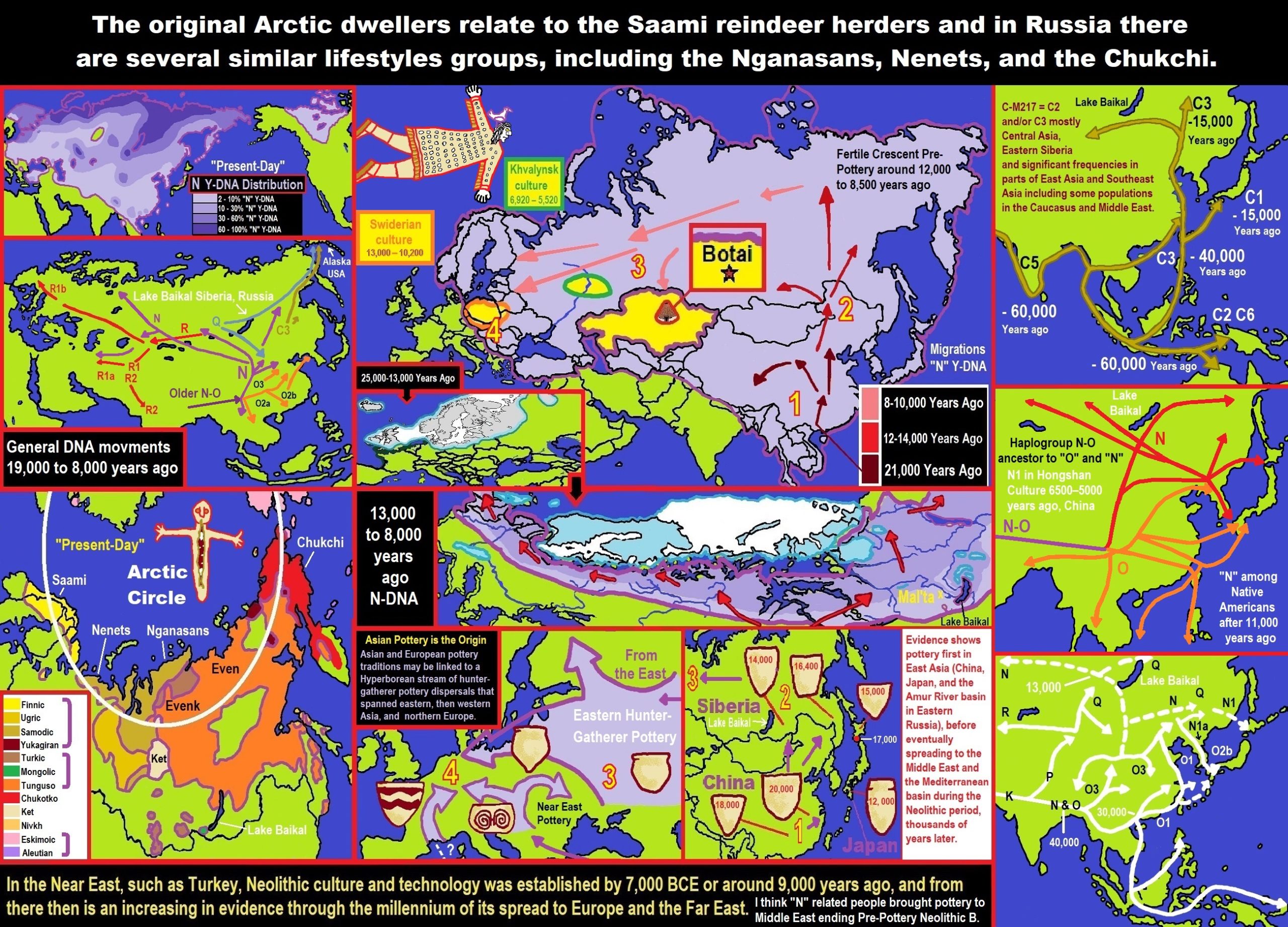

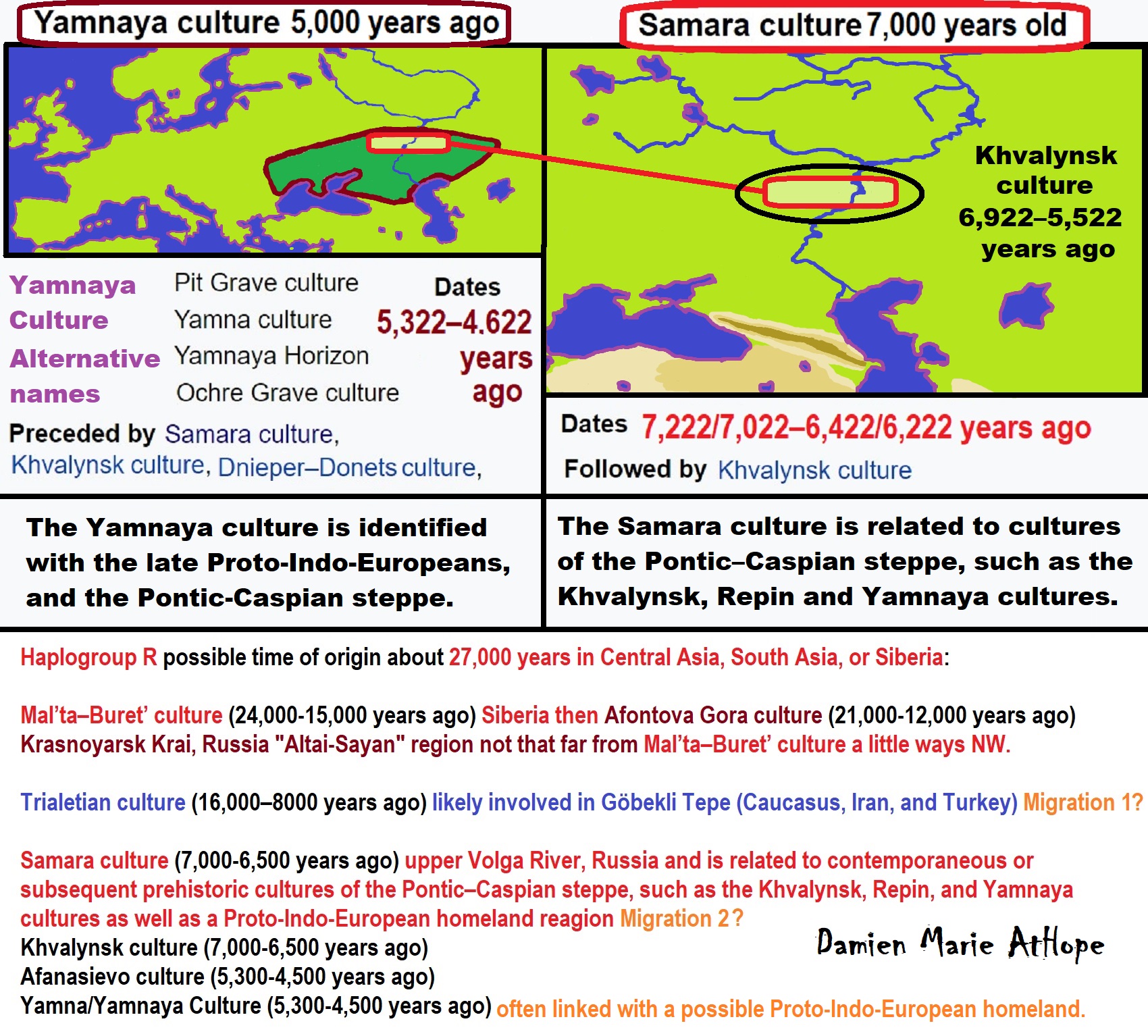

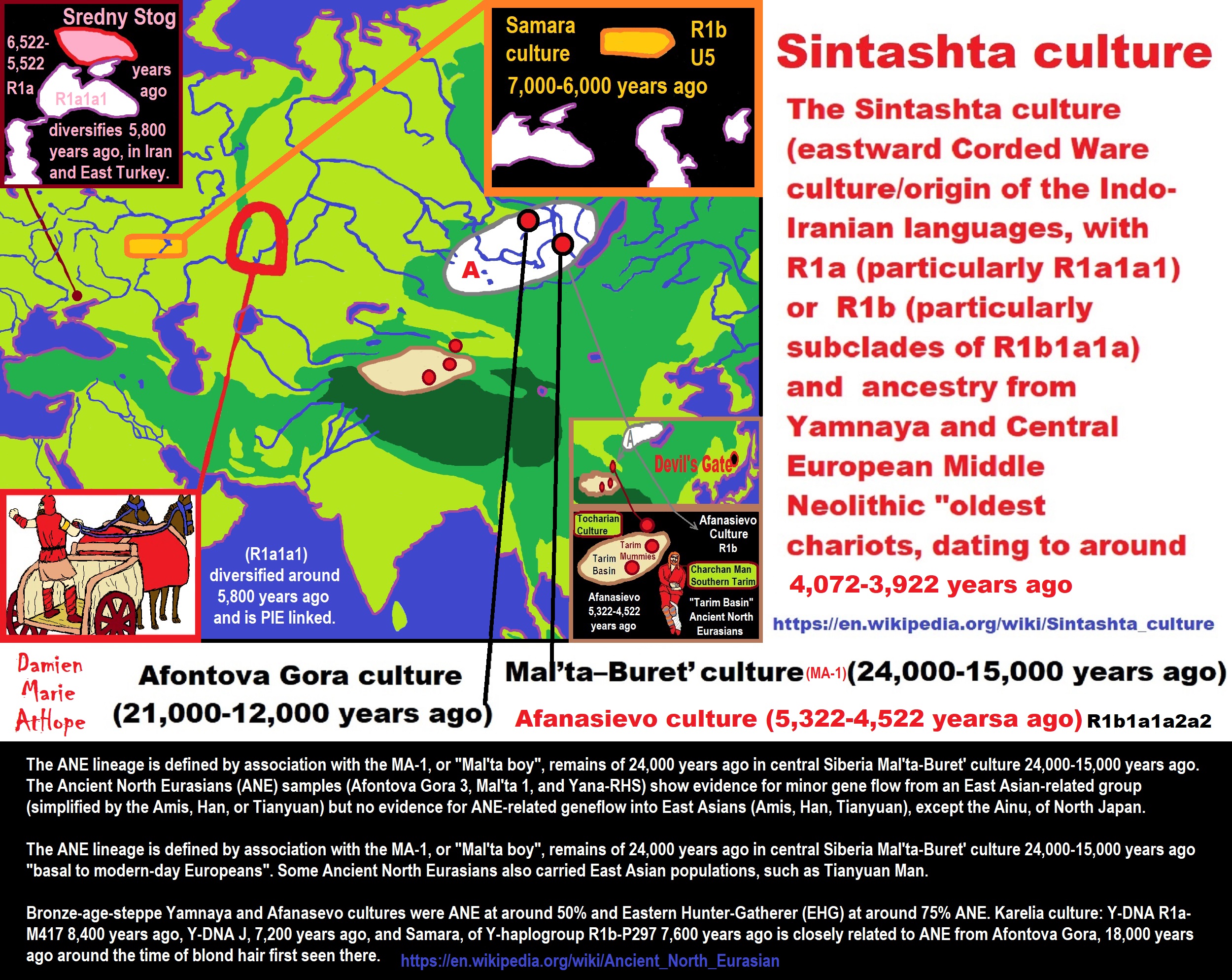

“The ANE lineage is defined by association with the MA-1, or “Mal’ta boy”, remains of 24,000 years ago in central Siberia Mal’ta-Buret’ culture 24,000-15,000 years ago. The Ancient North Eurasians (ANE) samples (Afontova Gora 3, Mal’ta 1, and Yana-RHS) show evidence for minor gene flow from an East Asian-related group (simplified by the Amis, Han, or Tianyuan) but no evidence for ANE-related geneflow into East Asians (Amis, Han, Tianyuan), except the Ainu, of North Japan.” ref

“The ANE lineage is defined by association with the MA-1, or “Mal’ta boy”, remains of 24,000 years ago in central Siberia Mal’ta-Buret’ culture 24,000-15,000 years ago “basal to modern-day Europeans”. Some Ancient North Eurasians also carried East Asian populations, such as Tianyuan Man.” ref

“Bronze-age-steppe Yamnaya and Afanasevo cultures were ANE at around 50% and Eastern Hunter-Gatherer (EHG) at around 75% ANE. Karelia culture: Y-DNA R1a-M417 8,400 years ago, Y-DNA J, 7,200 years ago, and Samara, of Y-haplogroup R1b-P297 7,600 years ago is closely related to ANE from Afontova Gora, 18,000 years ago around the time of blond hair first seen there.” ref

Ancient North Eurasian

“In archaeogenetics, the term Ancient North Eurasian (often abbreviated as ANE) is the name given to an ancestral West Eurasian component that represents descent from the people similar to the Mal’ta–Buret’ culture and populations closely related to them, such as from Afontova Gora and the Yana Rhinoceros Horn Site. Significant ANE ancestry are found in some modern populations, including Europeans and Native Americans.” ref

“The ANE lineage is defined by association with the MA-1, or “Mal’ta boy“, the remains of an individual who lived during the Last Glacial Maximum, 24,000 years ago in central Siberia, Ancient North Eurasians are described as a lineage “which is deeply related to Paleolithic/Mesolithic hunter-gatherers in Europe,” meaning that they diverged from Paleolithic Europeans a long time ago.” ref

“The ANE population has also been described as having been “basal to modern-day Europeans” but not especially related to East Asians, and is suggested to have perhaps originated in Europe or Western Asia or the Eurasian Steppe of Central Asia. However, some samples associated with Ancient North Eurasians also carried ancestry from an ancient East Asian population, such as Tianyuan Man. Sikora et al. (2019) found that the Yana RHS sample (31,600 BP) in Northern Siberia “can be modeled as early West Eurasian with an approximately 22% contribution from early East Asians.” ref

“Populations genetically similar to MA-1 were an important genetic contributor to Native Americans, Europeans, Central Asians, South Asians, and some East Asian groups, in order of significance. Lazaridis et al. (2016:10) note “a cline of ANE ancestry across the east-west extent of Eurasia.” The ancient Bronze-age-steppe Yamnaya and Afanasevo cultures were found to have a noteworthy ANE component at ~50%.” ref

“According to Moreno-Mayar et al. 2018 between 14% and 38% of Native American ancestry may originate from gene flow from the Mal’ta–Buret’ people (ANE). This difference is caused by the penetration of posterior Siberian migrations into the Americas, with the lowest percentages of ANE ancestry found in Eskimos and Alaskan Natives, as these groups are the result of migrations into the Americas roughly 5,000 years ago.” ref

“Estimates for ANE ancestry among first wave Native Americans show higher percentages, such as 42% for those belonging to the Andean region in South America. The other gene flow in Native Americans (the remainder of their ancestry) was of East Asian origin. Gene sequencing of another south-central Siberian people (Afontova Gora-2) dating to approximately 17,000 years ago, revealed similar autosomal genetic signatures to that of Mal’ta boy-1, suggesting that the region was continuously occupied by humans throughout the Last Glacial Maximum.” ref

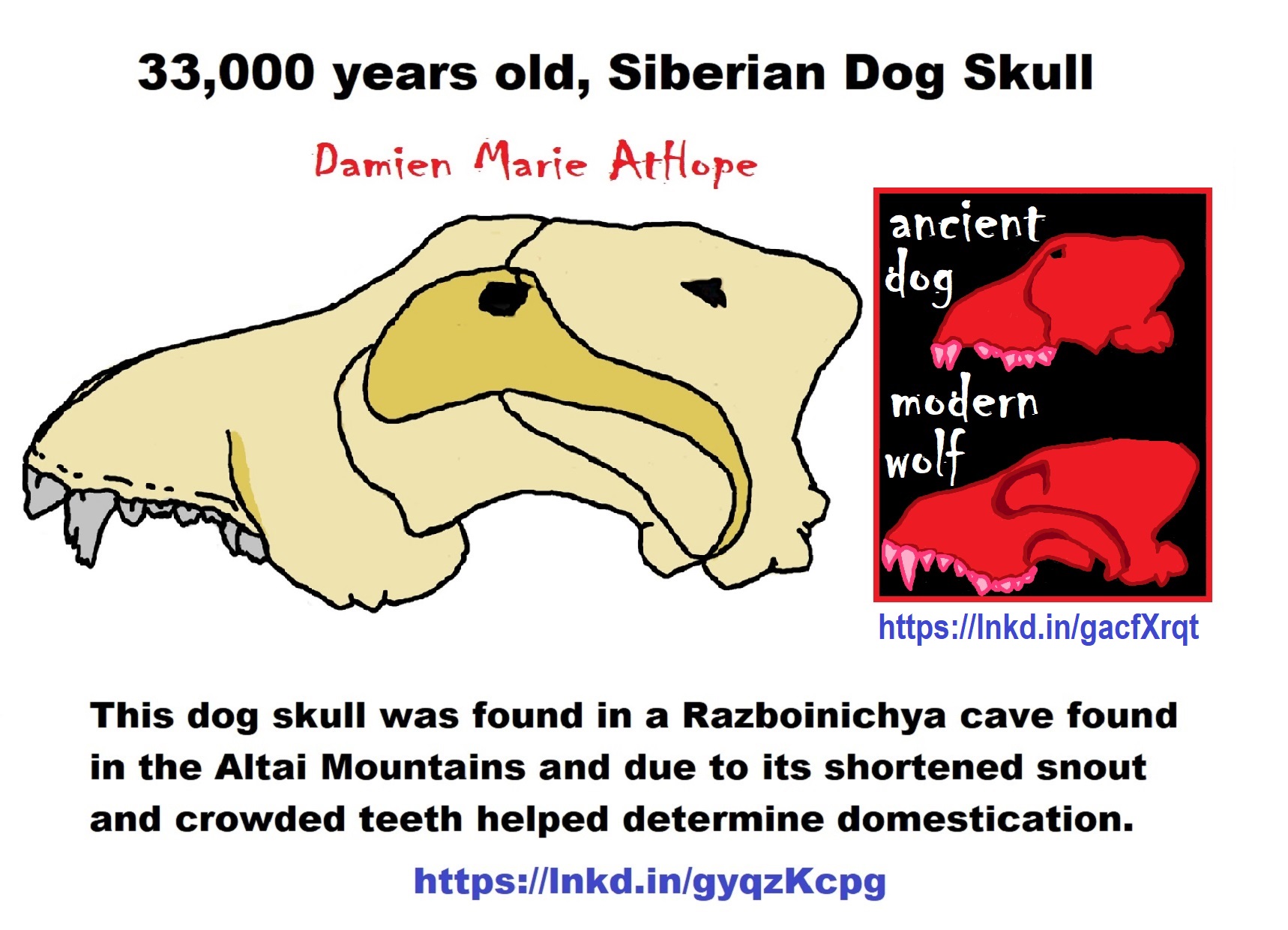

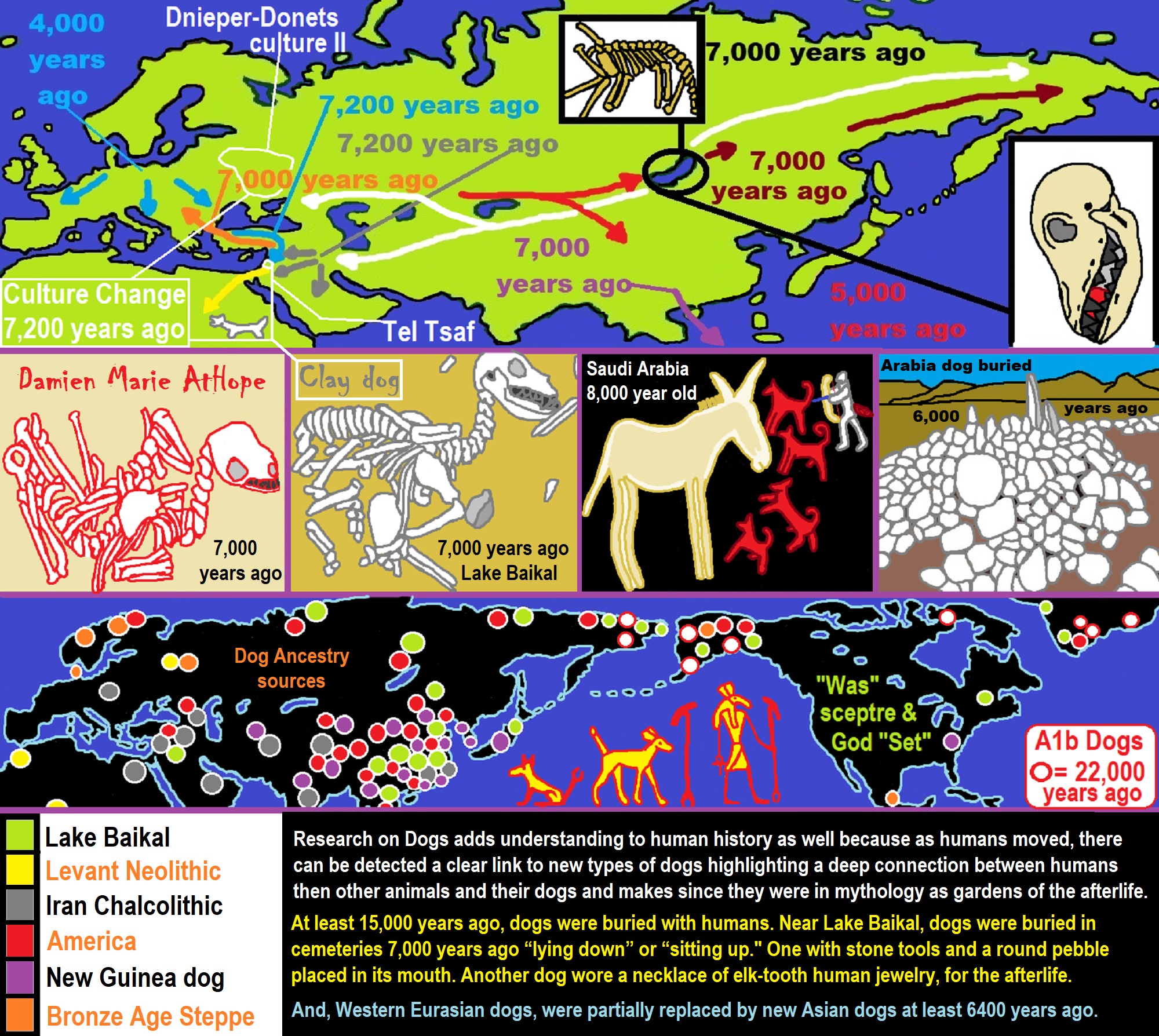

“The earliest known individual with a genetic mutation associated with blonde hair in modern Europeans is an Ancient North Eurasian female dating to around 16000 BCE from the Afontova Gora 3 site in Siberia. It has been suggested that their mythology may have included a narrative, found in both Indo-European and some Native American fables, in which a dog guards the path to the afterlife.” ref

“Genomic studies also indicate that the ANE component was introduced to Western Europe by people related to the Yamnaya culture, long after the Paleolithic. It is reported in modern-day Europeans (7%–25%), but not of Europeans before the Bronze Age. Additional ANE ancestry is found in European populations through paleolithic interactions with Eastern Hunter-Gatherers, which resulted in populations such as Scandinavian Hunter-Gatherers.” ref

“The Ancient North Eurasians (ANE) split from the ancestors of European peoples somewhere in the Middle East or South-central Asia, and used a northern dispersal route through Central Asia into Northern Asia and Siberia. Genetic analyses show that all ANE samples (Afontova Gora 3, Mal’ta 1, and Yana-RHS) show evidence for minor gene flow from an East Asian-related group (simplified by the Amis, Han, or Tianyuan). In contrast, no evidence for ANE-related geneflow into East Asians (Amis, Han, Tianyuan), except the Ainu, was found.” ref

“Genetic data suggests that the ANE formed during the Terminal Upper-Paleolithic (36+-1,5ka) period from a deeply European-related population, which was once widespread in Northern Eurasia, and from an early East Asian-related group, which migrated northwards into Central Asia and Siberia, merging with this deeply European-related population. These population dynamics and constant northwards geneflow of East Asian-related ancestry would later gave rise to the “Ancestral Native Americans” and Paleosiberians, which replaced the ANE as dominant population of Siberia.” ref

Groups partially derived from the Ancient North Eurasians

“Eastern Hunter-Gatherer (EHG) is a lineage derived predominantly (75%) from ANE. It is represented by two individuals from Karelia, one of Y-haplogroup R1a-M417, dated c. 8.4 kya, the other of Y-haplogroup J, dated c. 7.2 kya; and one individual from Samara, of Y-haplogroup R1b-P297, dated c. 7.6 kya. This lineage is closely related to the ANE sample from Afontova Gora, dated c. 18 kya. After the end of the Last Glacial Maximum, the Western Hunter-Gatherers (WHG) and EHG lineages merged in Eastern Europe, accounting for early presence of ANE-derived ancestry in Mesolithic Europe. Evidence suggests that as Ancient North Eurasians migrated West from Eastern Siberia, they absorbed Western Hunter-Gatherers and other West Eurasian populations as well.” ref

“Caucasian Hunter-Gatherer (CHG) is represented by the Satsurblia individual dated ~13 kya (from the Satsurblia cave in Georgia), and carried 36% ANE-derived admixture. While the rest of their ancestry is derived from the Dzudzuana cave individual dated ~26 kya, which lacked ANE-admixture, Dzudzuana affinity in the Caucasus decreased with the arrival of ANE at ~13 kya Satsurblia.” ref

“Scandinavian Hunter-Gatherer (SHG) is represented by several individuals buried at Motala, Sweden ca. 6000 BC. They were descended from Western Hunter-Gatherers who initially settled Scandinavia from the south, and later populations of EHG who entered Scandinavia from the north through the coast of Norway.” ref

“Iran Neolithic (Iran_N) individuals dated ~8.5 kya carried 50% ANE-derived admixture and 50% Dzudzuana-related admixture, marking them as different from other Near-Eastern and Anatolian Neolithics who didn’t have ANE admixture. Iran Neolithics were later replaced by Iran Chalcolithics, who were a mixture of Iran Neolithic and Near Eastern Levant Neolithic.” ref

“Ancient Beringian/Ancestral Native American are specific archaeogenetic lineages, based on the genome of an infant found at the Upward Sun River site (dubbed USR1), dated to 11,500 years ago. The AB lineage diverged from the Ancestral Native American (ANA) lineage about 20,000 years ago.” ref

“West Siberian Hunter-Gatherer (WSHG) are a specific archaeogenetic lineage, first reported in a genetic study published in Science in September 2019. WSGs were found to be of about 30% EHG ancestry, 50% ANE ancestry, and 20% to 38% East Asian ancestry.” ref

“Western Steppe Herders (WSH) is the name given to a distinct ancestral component that represents descent closely related to the Yamnaya culture of the Pontic–Caspian steppe. This ancestry is often referred to as Yamnaya ancestry or Steppe ancestry.” ref

“Late Upper Paeolithic Lake Baikal – Ust’Kyakhta-3 (UKY) 14,050-13,770 BP were mixture of 30% ANE ancestry and 70% East Asian ancestry.” ref

“Lake Baikal Holocene – Baikal Eneolithic (Baikal_EN) and Baikal Early Bronze Age (Baikal_EBA) derived 6.4% to 20.1% ancestry from ANE, while rest of their ancestry was derived from East Asians. Fofonovo_EN near by Lake Baikal were mixture of 12-17% ANE ancestry and 83-87% East Asian ancestry.” ref

“Hokkaido Jōmon people specifically refers to the Jōmon period population of Hokkaido in northernmost Japan. Though the Jōmon people themselves descended mainly from East Asian lineages, one study found an affinity between Hokkaido Jōmon with the Northern Eurasian Yana sample (an ANE-related group, related to Mal’ta), and suggest as an explanation the possibility of minor Yana gene flow into the Hokkaido Jōmon population (as well as other possibilities). A more recent study by Cooke et al. 2021, confirmed ANE-related geneflow among the Jōmon people, partially ancestral to the Ainu people. ANE ancestry among Jōmon people is estimated at 21%, however, there is a North to South cline within the Japanese archipelago, with the highest amount of ANE ancestry in Hokkaido and Tohoku.” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

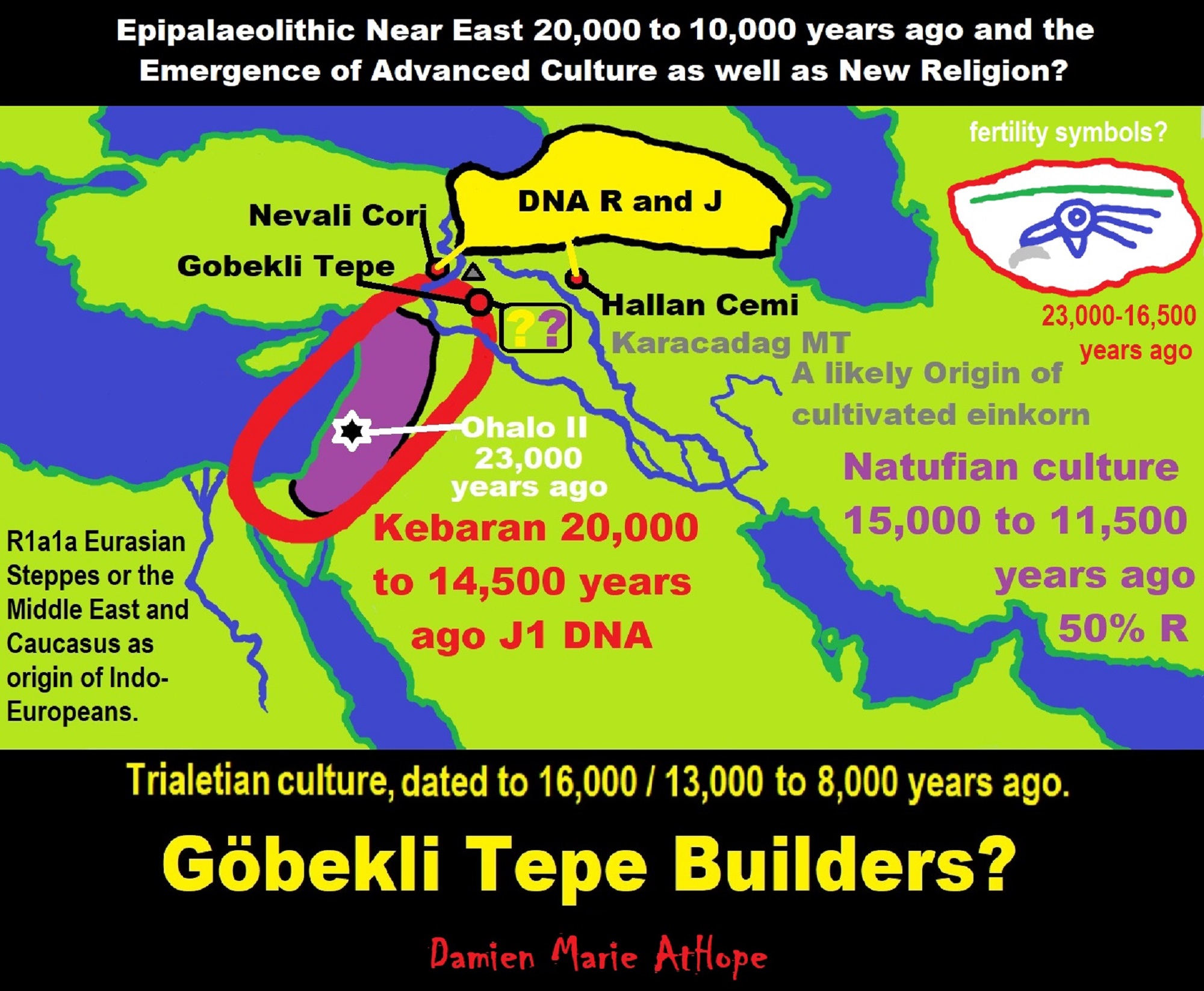

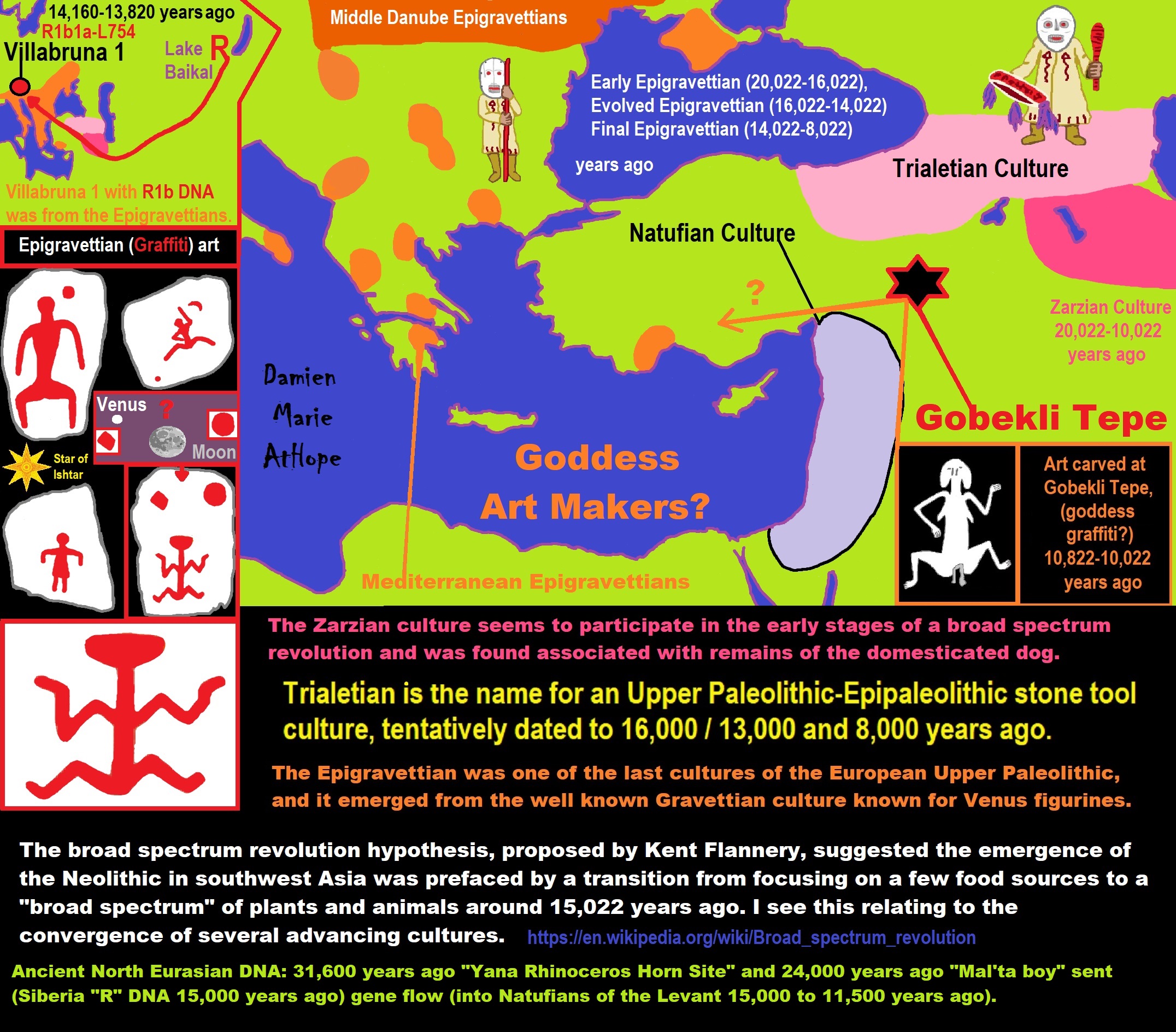

Trialetian culture (16,000–8000 years ago) the Caucasus, Iran, and Turkey, likely involved in Göbekli Tepe. Migration 1?

Haplogroup R possible time of origin about 27,000 years in Central Asia, South Asia, or Siberia:

- Mal’ta–Buret’ culture (24,000-15,000 years ago)

- Afontova Gora culture (21,000-12,000 years ago)

- Trialetian culture (16,000–8000 years ago)

- Samara culture (7,000-6,500 years ago)

- Khvalynsk culture (7,000-6,500 years ago)

- Afanasievo culture (5,300-4,500 years ago)

- Yamna/Yamnaya Culture (5,300-4,500 years ago)

- Andronovo culture (4,000–2,900 years ago) ref

Trialetian sites

Caucasus and Transcaucasia:

- Edzani (Georgia)

- Chokh (Azerbaijan), layers E-C200

- Kotias Klde, layer B” ref

Eastern Anatolia:

- Hallan Çemi (from ca. 8.6-8.5k BC to 7.6-7.5k BCE)

- Nevali Çori shows some Trialetian admixture in a PPNB context” ref

Trialetian influences can also be found in:

- Cafer Höyük

- Boy Tepe” ref

Southeast of the Caspian Sea:

- Hotu (Iran)

- Ali Tepe (Iran) (from cal. 10,500 to 8,870 BCE)

- Belt Cave (Iran), layers 28-11 (the last remains date from ca. 6,000 BCE)

- Dam-Dam-Cheshme II (Turkmenistan), layers7,000-3,000 BCE)” ref

“Migration from Siberia behind the formation of Göbeklitepe: Expert states. People who migrated from Siberia formed the Göbeklitepe, and those in Göbeklitepe migrated in five other ways to spread to the world, said experts about the 12,000-year-old Neolithic archaeological site in the southwestern province of Şanlıurfa.“ The upper paleolithic migrations between Siberia and the Near East is a process that has been confirmed by material culture documents,” he said.” ref

“Semih Güneri, a retired professor from Caucasia and Central Asia Archaeology Research Center of Dokuz Eylül University, and his colleague, Professor Ekaterine Lipnina, presented the Siberia-Göbeklitepe hypothesis they have developed in recent years at the congress held in Istanbul between June 11 and 13. There was a migration that started from Siberia 30,000 years ago and spread to all of Asia and then to Eastern and Northern Europe, Güneri said at the international congress.” ref

“The relationship of Göbeklitepe high culture with the carriers of Siberian microblade stone tool technology is no longer a secret,” he said while emphasizing that the most important branch of the migrations extended to the Near East. “The results of the genetic analyzes of Iraq’s Zagros region confirm the traces of the Siberian/North Asian indigenous people, who arrived at Zagros via the Central Asian mountainous corridor and met with the Göbeklitepe culture via Northern Iraq,” he added.” ref

“Emphasizing that the stone tool technology was transported approximately 7,000 kilometers from east to west, he said, “It is not clear whether this technology is transmitted directly to long distances by people speaking the Turkish language at the earliest, or it travels this long-distance through using way stations.” According to the archaeological documents, it is known that the Siberian people had reached the Zagros region, he said. “There seems to be a relationship between Siberian hunter-gatherers and native Zagros hunter-gatherers,” Güneri said, adding that the results of genetic studies show that Siberian people reached as far as the Zagros.” ref

“There were three waves of migration of Turkish tribes from the Southern Siberia to Europe,” said Osman Karatay, a professor from Ege University. He added that most of the groups in the third wave, which took place between 2600-2400 BCE, assimilated and entered the Germanic tribes and that there was a genetic kinship between their tribes and the Turks. The professor also pointed out that there are indications that there is a technology and tool transfer from Siberia to the Göbeklitepe region and that it is not known whether people came, and if any, whether they were Turkish.” ref

“Around 12,000 years ago, there would be no ‘Turks’ as we know it today. However, there may have been tribes that we could call our ‘common ancestors,’” he added. “Talking about 30,000 years ago, it is impossible to identify and classify nations in today’s terms,” said Murat Öztürk, associate professor from İnönü University. He also said that it is not possible to determine who came to where during the migrations that were accepted to have been made thousands of years ago from Siberia. On the other hand, Mehmet Özdoğan, an academic from Istanbul University, has an idea of where “the people of Göbeklitepe migrated to.” ref

“According to Özdoğan, “the people of Göbeklitepe turned into farmers, and they could not stand the pressure of the overwhelming clergy and started to migrate to five ways.” “Migrations take place primarily in groups. One of the five routes extends to the Caucasus, another from Iran to Central Asia, the Mediterranean coast to Spain, Thrace and [the northwestern province of] Kırklareli to Europe and England, and one route is to Istanbul via [Istanbul’s neighboring province of] Sakarya and stops,” Özdoğan said. In a very short time after the migration of farmers in Göbeklitepe, 300 settlements were established only around northern Greece, Bulgaria, and Thrace. “Those who remained in Göbeklitepe pulled the trigger of Mesopotamian civilization in the following periods, and those who migrated to Mesopotamia started irrigated agriculture before the Sumerians,” he said.” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

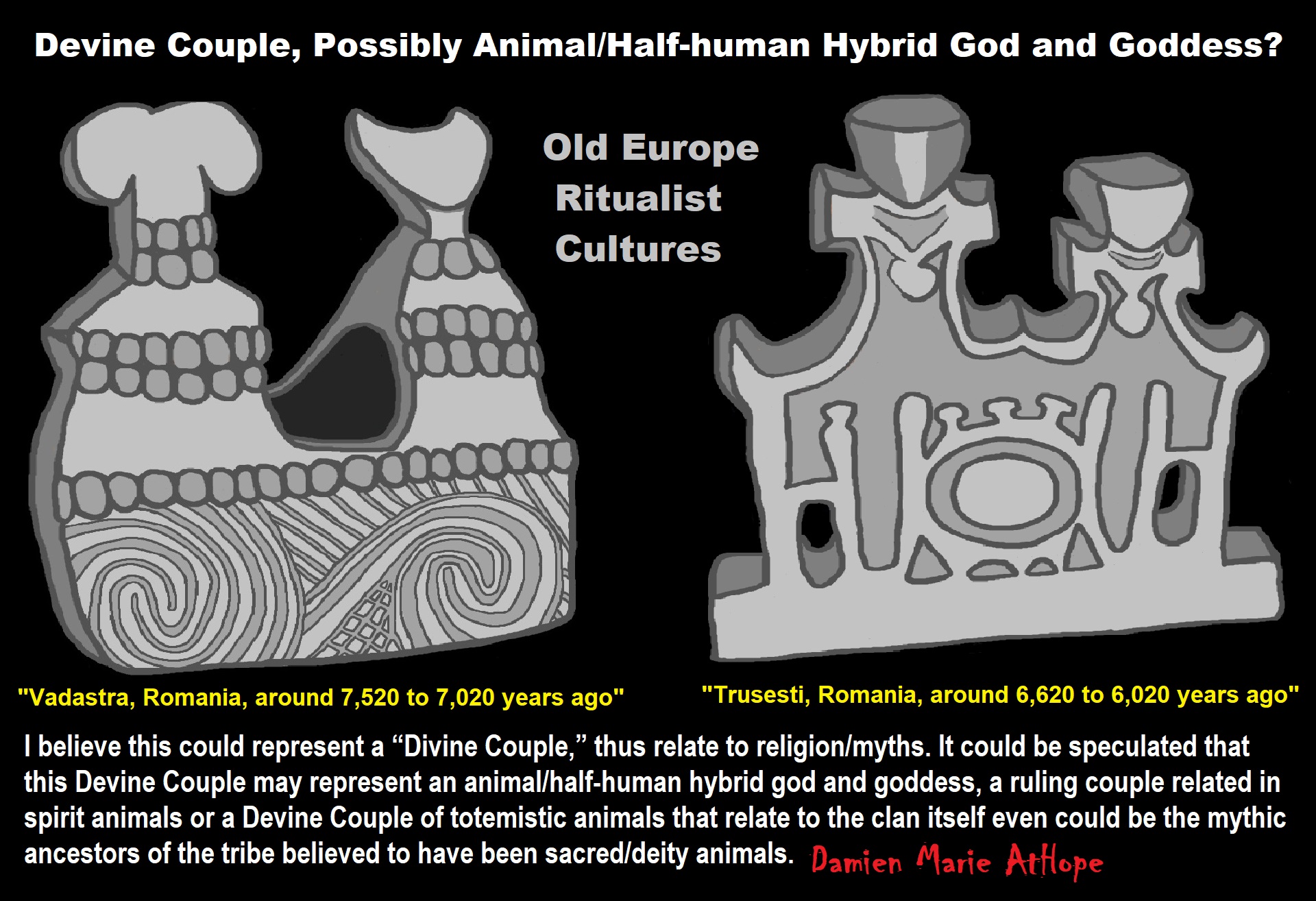

Trialetian peoples which I think we’re more male-centric and involved in the creation of Göbekli Tepe, from its start around Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (12,000 – 10,800 years ago) began with their influence and this is seen in animal deities many clearly male and the figures also being expressively male themed as well at first, and only around Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (10,800 – 8,500 years ago) or so it seems with what I am guessing is new Epigravettian peoples with a more female-centric style (reminiscent but less than the Gravettians known for Venus figurines) influence from migration into the region, to gain new themes that add a female element both with A totem pole seeming to express birth or something similar and graffiti of a woman either ready for sex or giving birth or both. and Other bare figures seem to show a similar body position reminiscent of the graffiti of a woman.

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

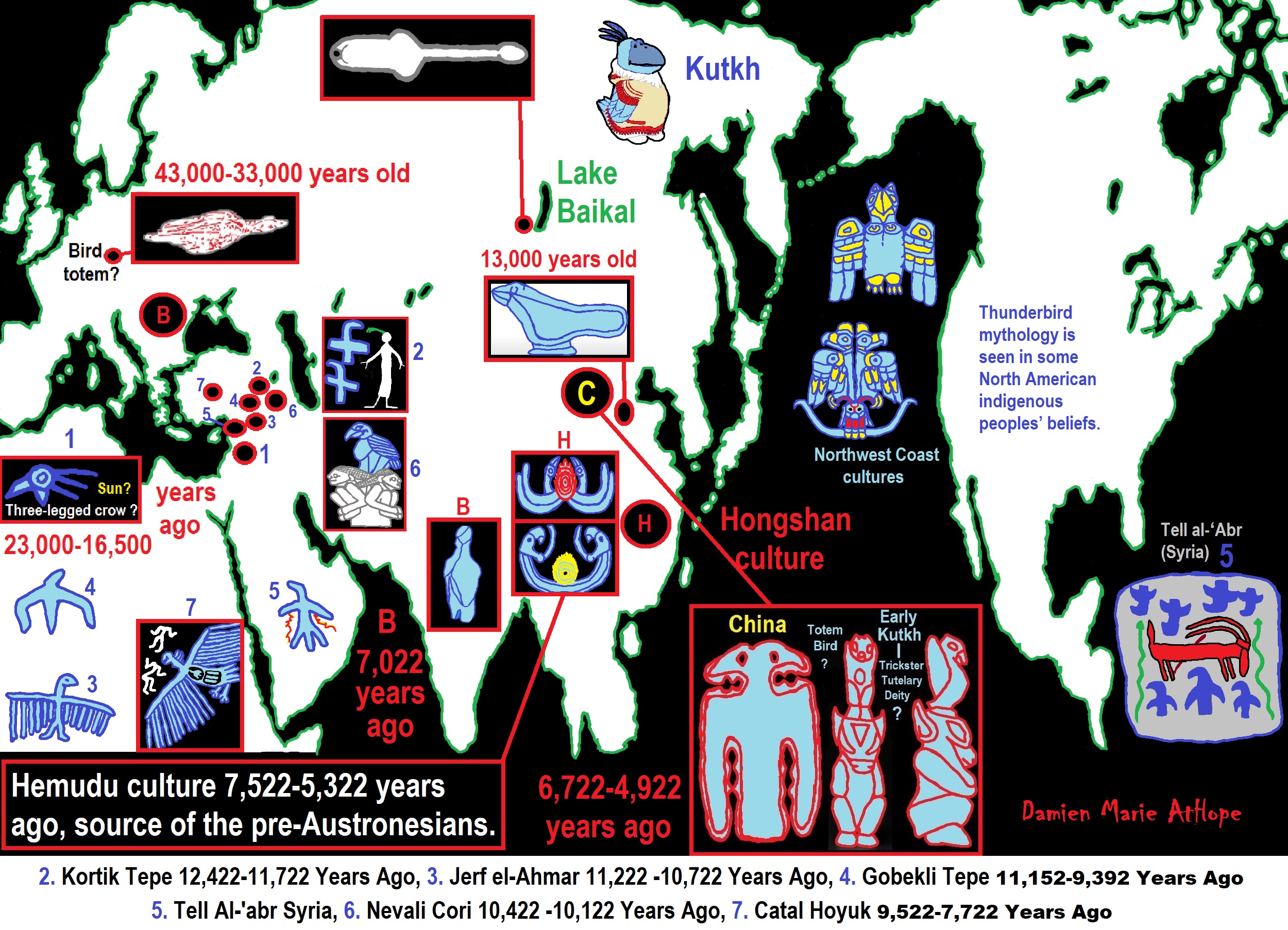

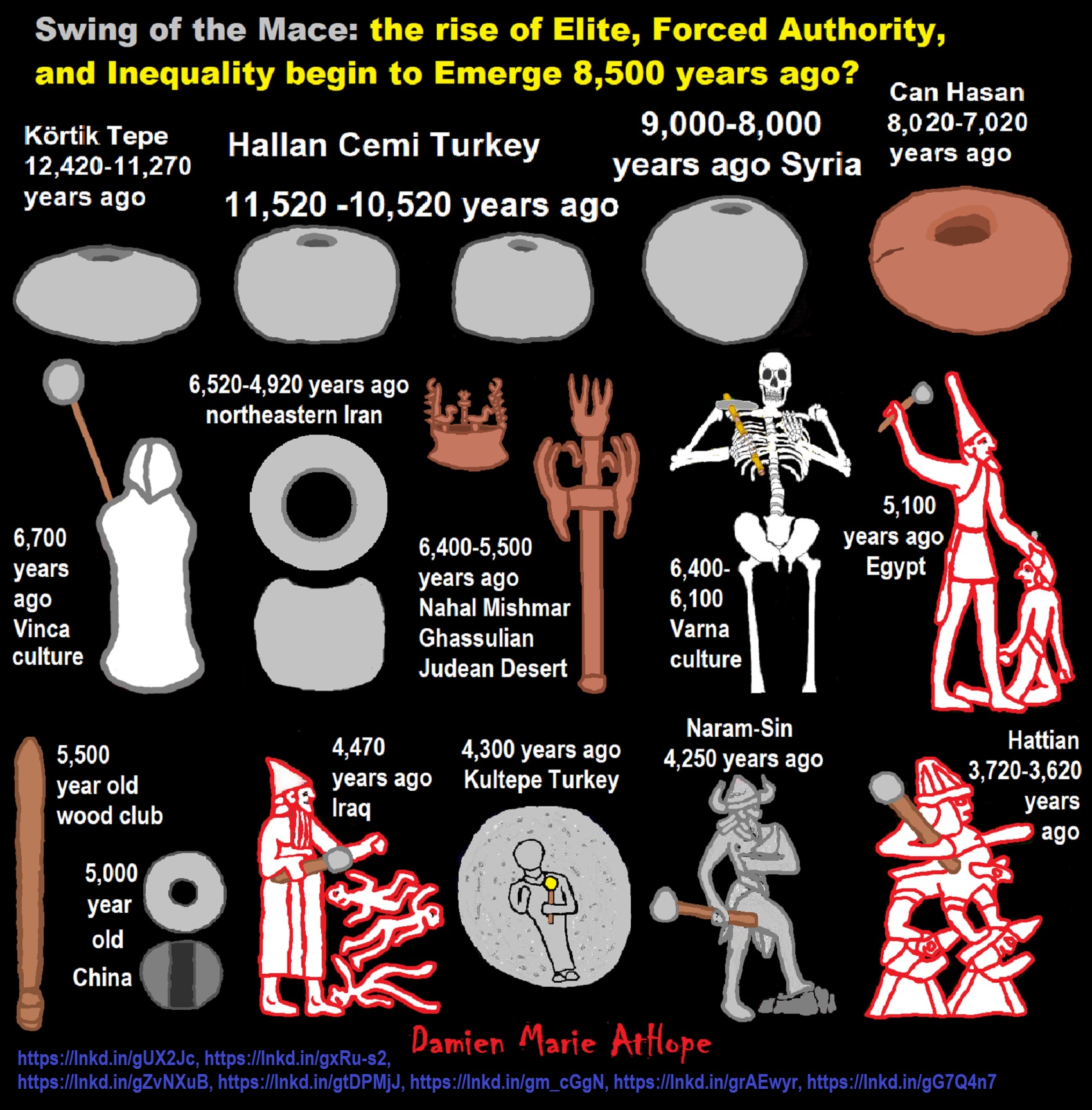

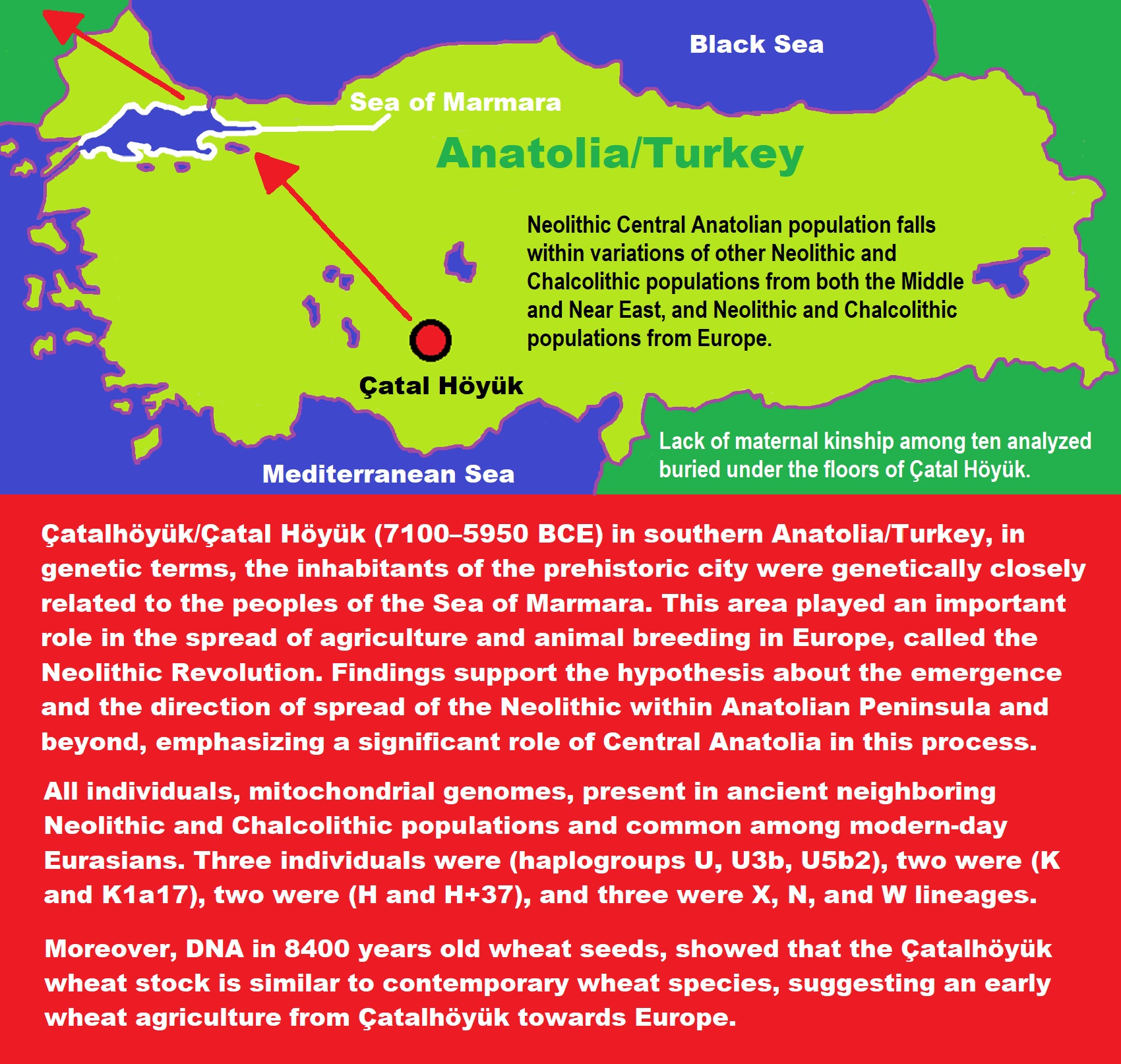

1. Kebaran culture 23,022-16,522 Years Ago, 2. Kortik Tepe 12,422-11,722 Years Ago, 3. Jerf el-Ahmar 11,222 -10,722 Years Ago, 4. Gobekli Tepe 11,152-9,392 Years Ago, 5. Tell Al-‘abrUbaid and Uruk Periods, 6. Nevali Cori 10,422 -10,122 Years Ago, 7. Catal Hoyuk 9,522-7,722 Years Ago

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

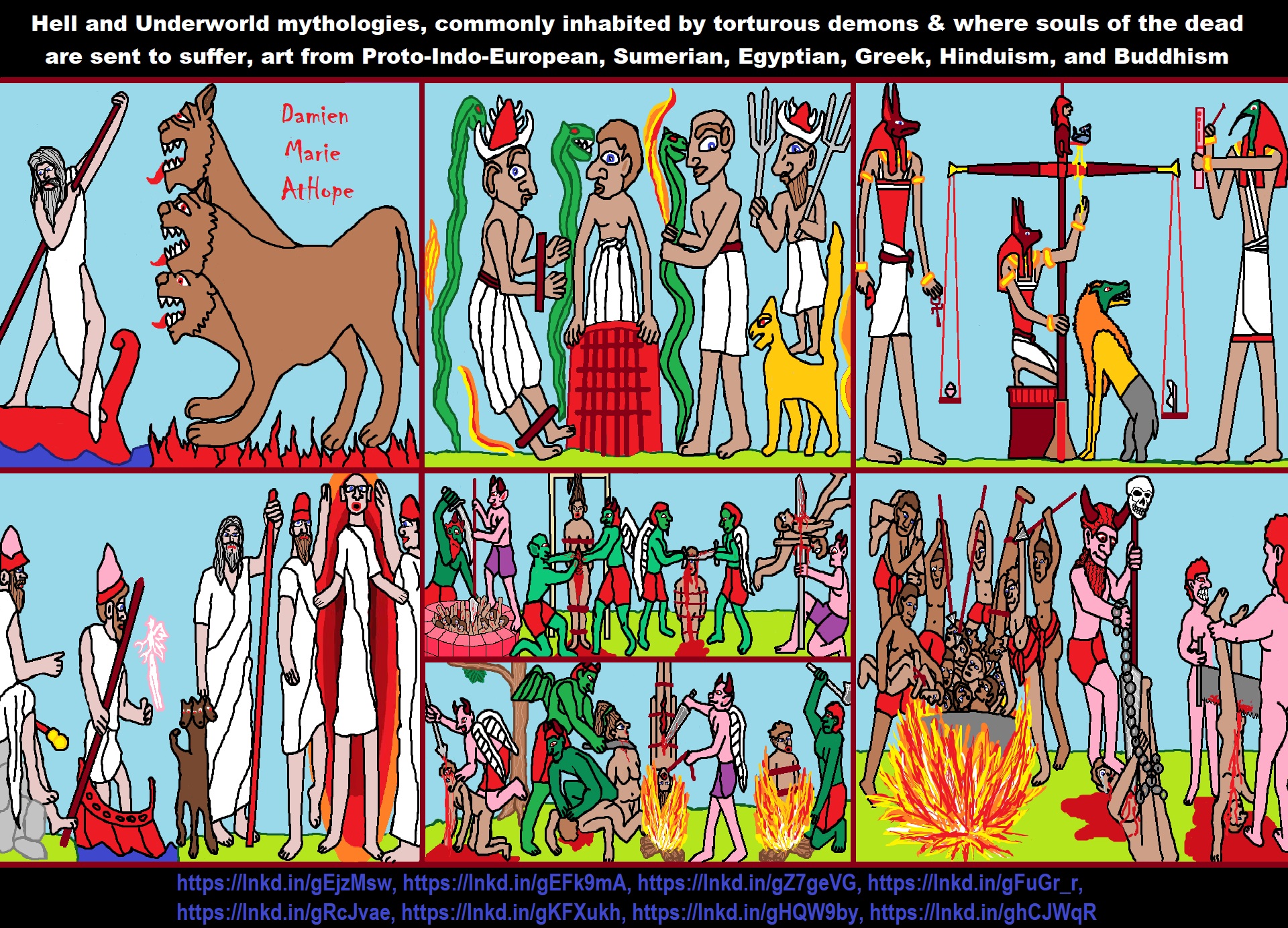

“The shaman is, above all, a connecting figure, bridging several worlds for his people, traveling between this world, the underworld, and the heavens. He transforms himself into an animal and talks with ghosts, the dead, the deities, and the ancestors. He dies and revives. He brings back knowledge from the shadow realm, thus linking his people to the spirits and places which were once mythically accessible to all.–anthropologist Barbara Meyerhoff” ref

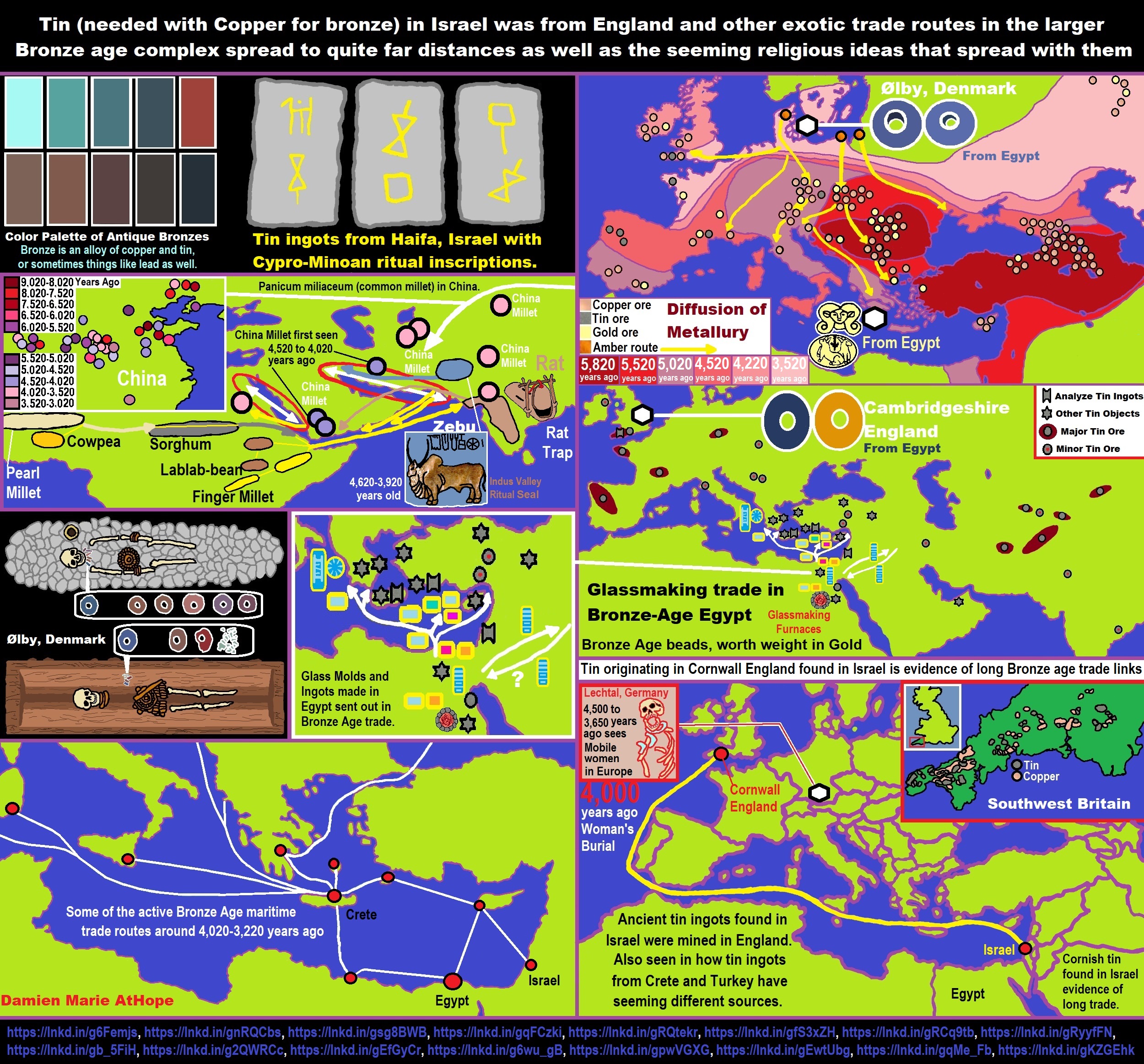

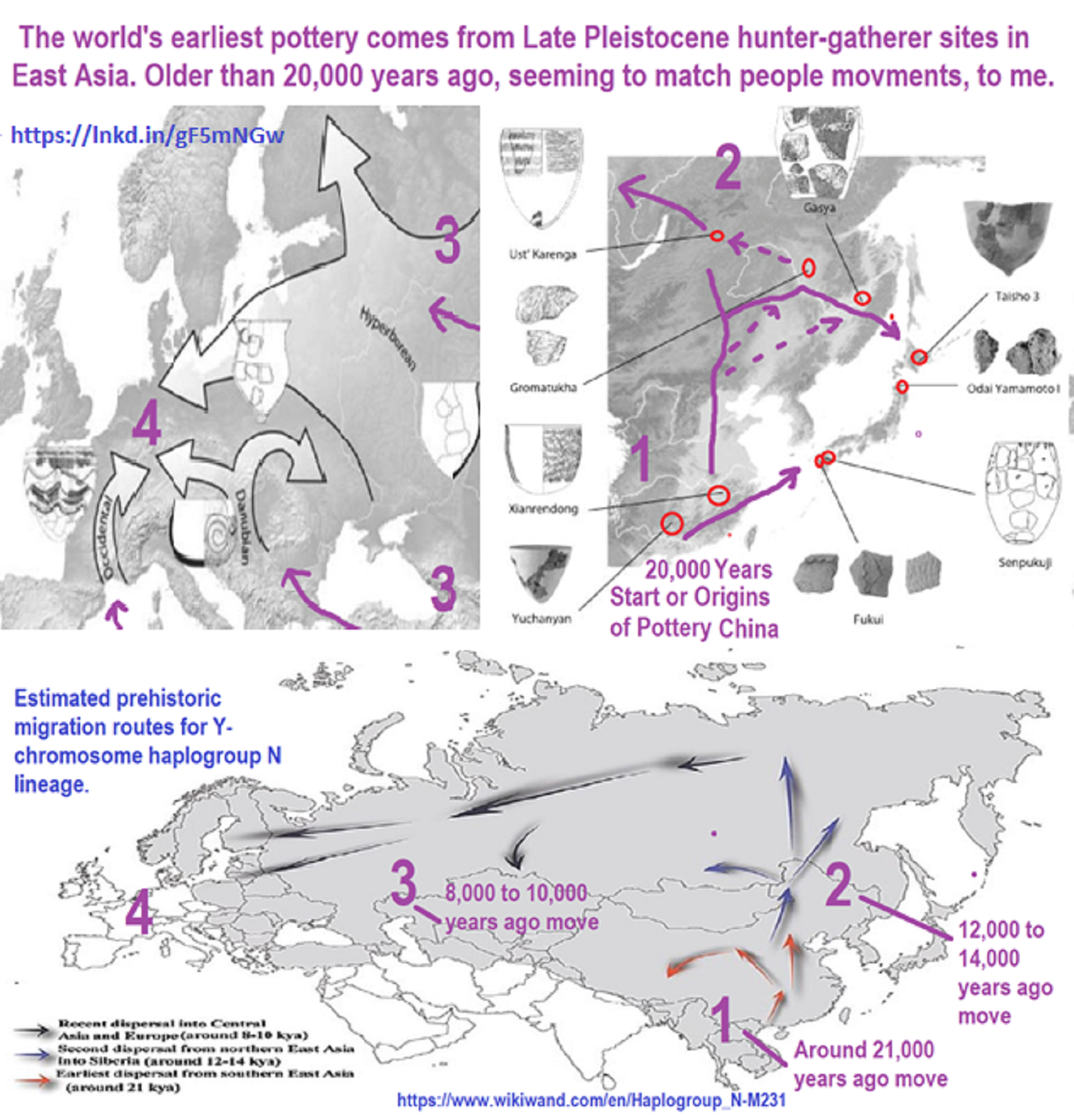

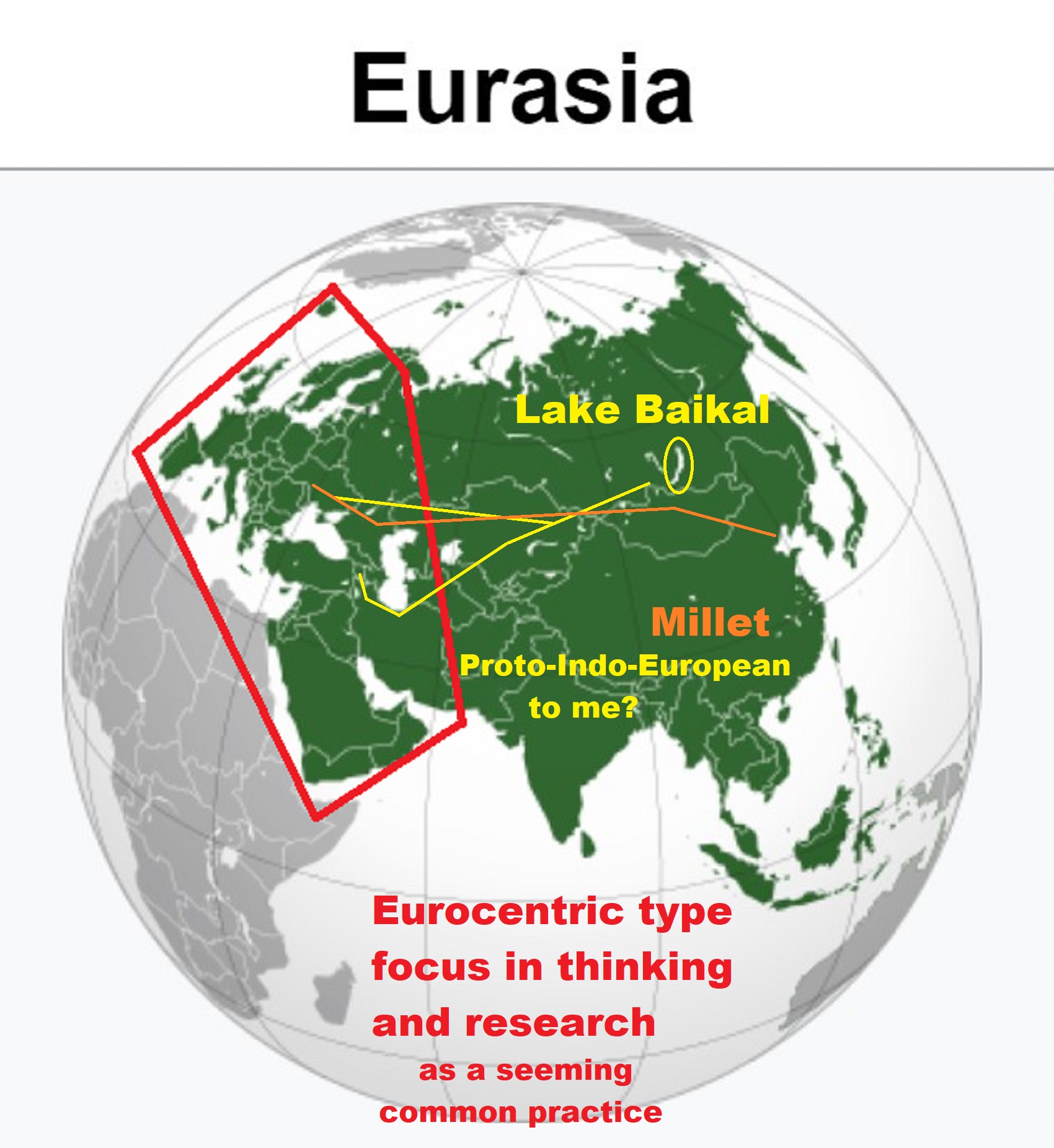

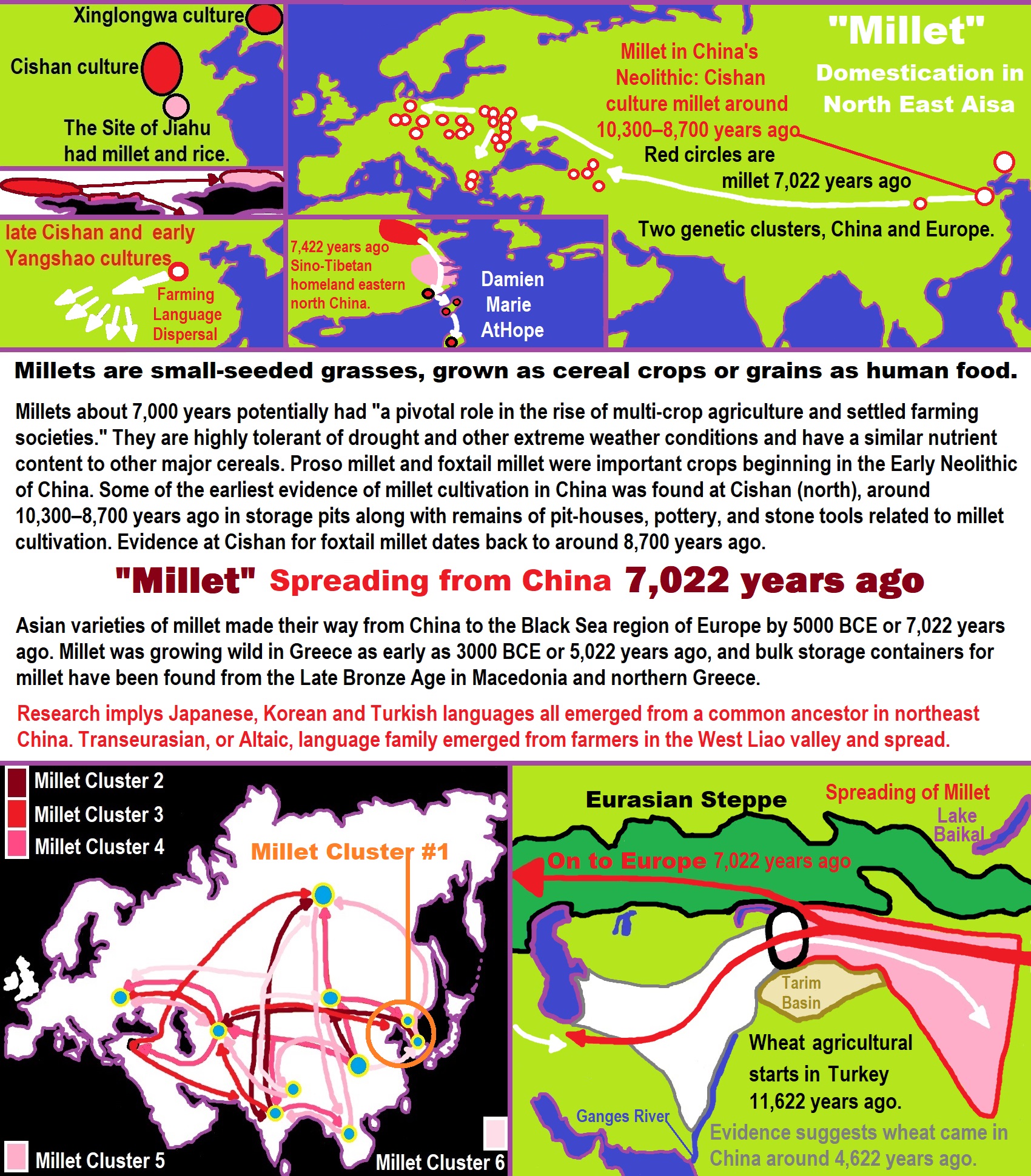

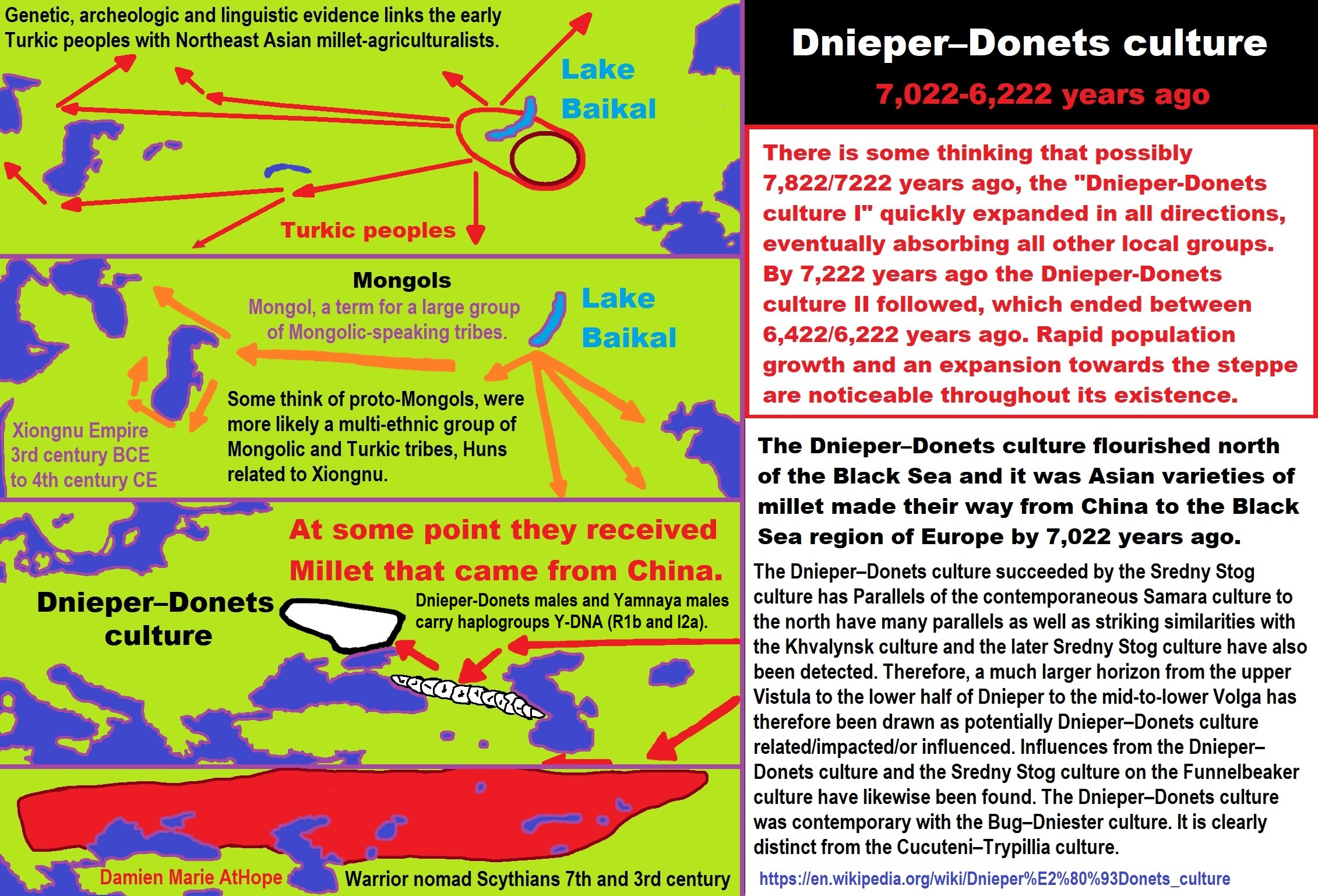

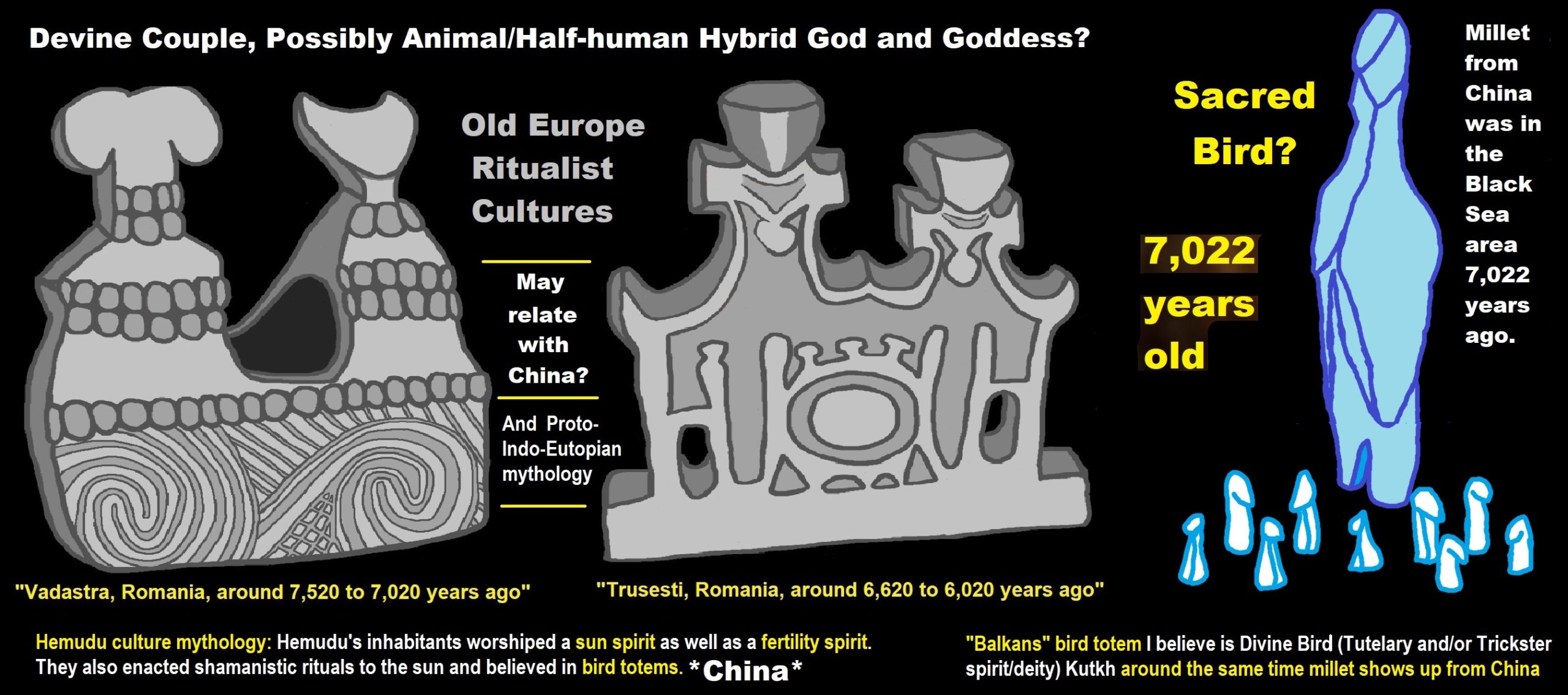

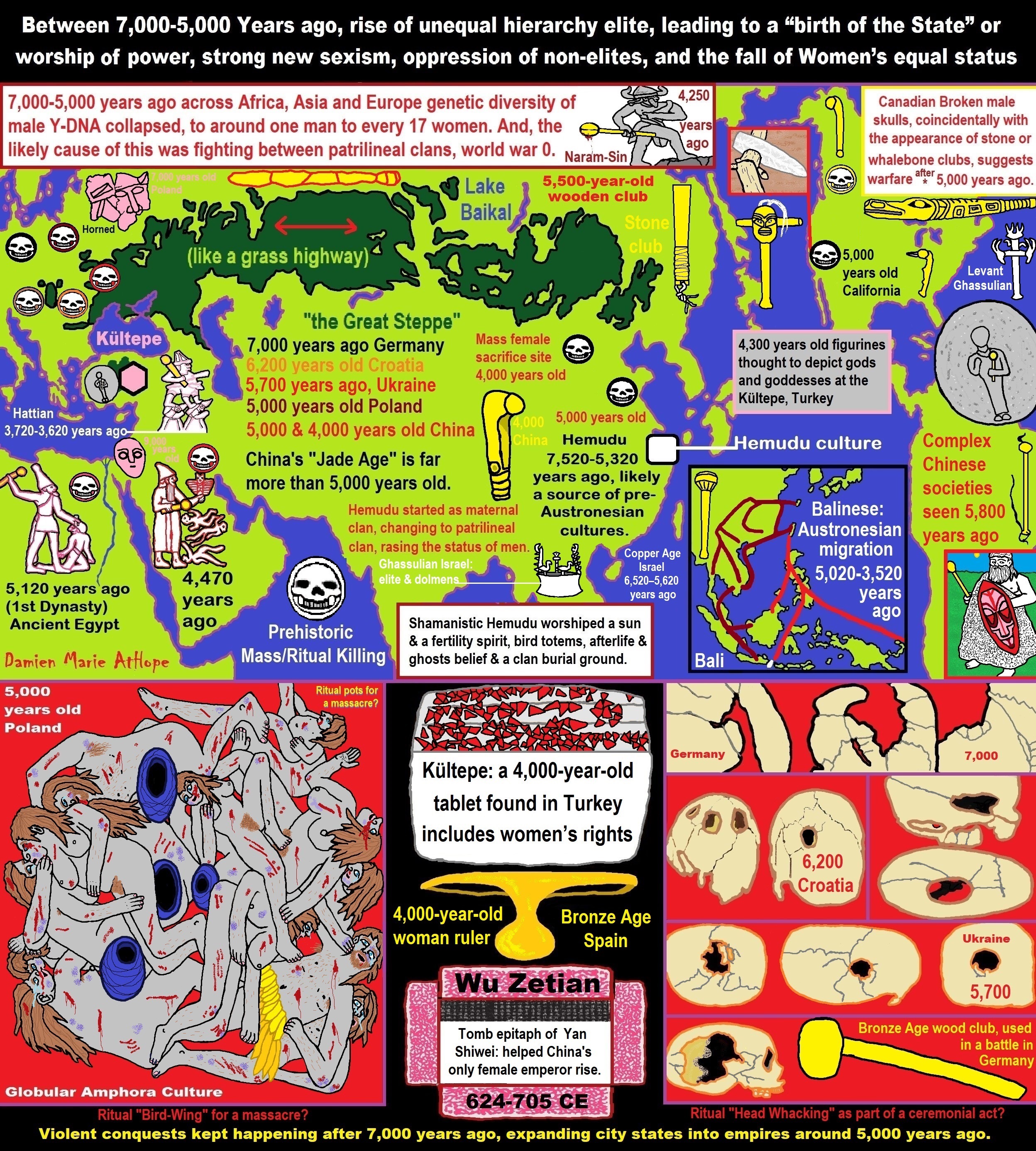

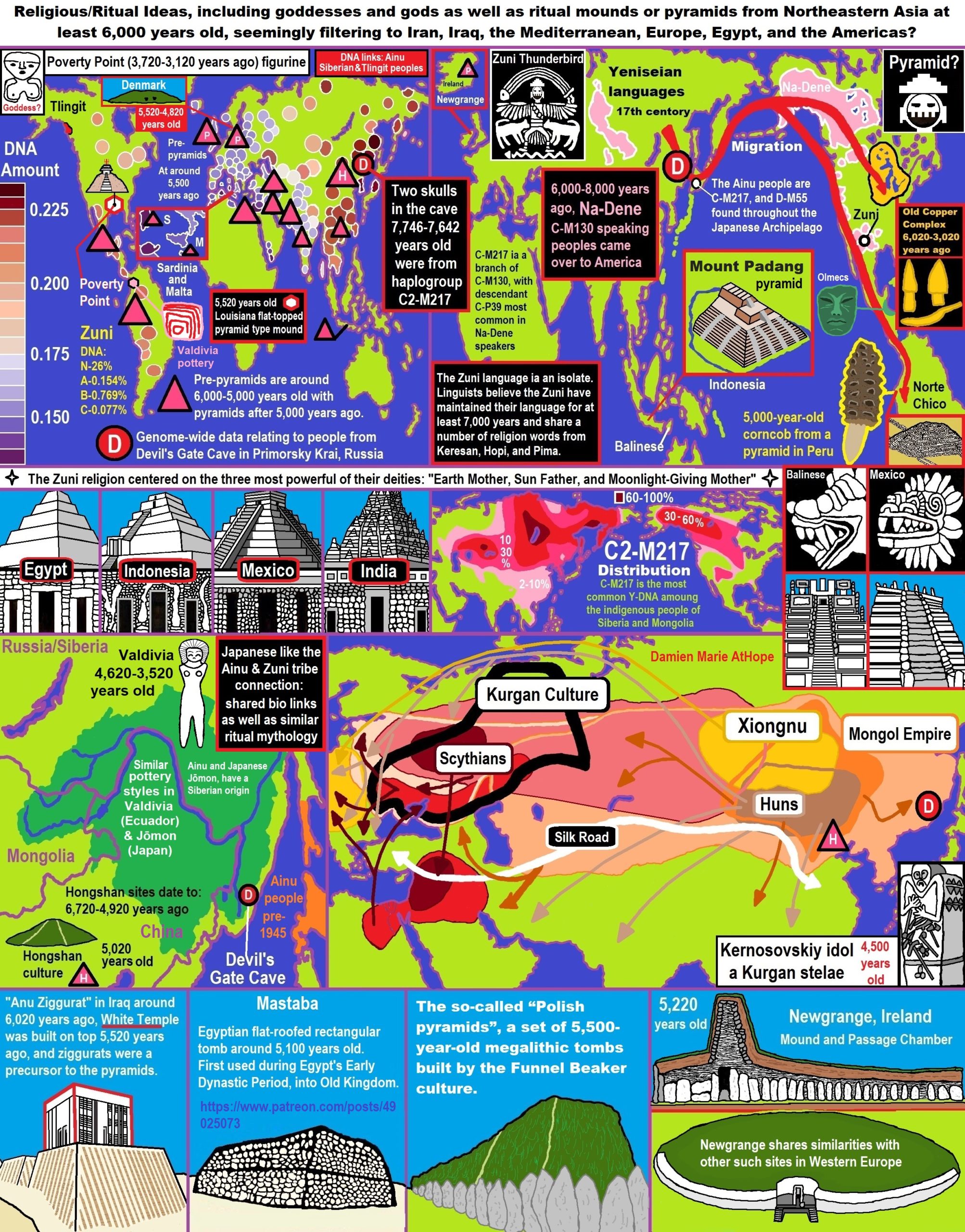

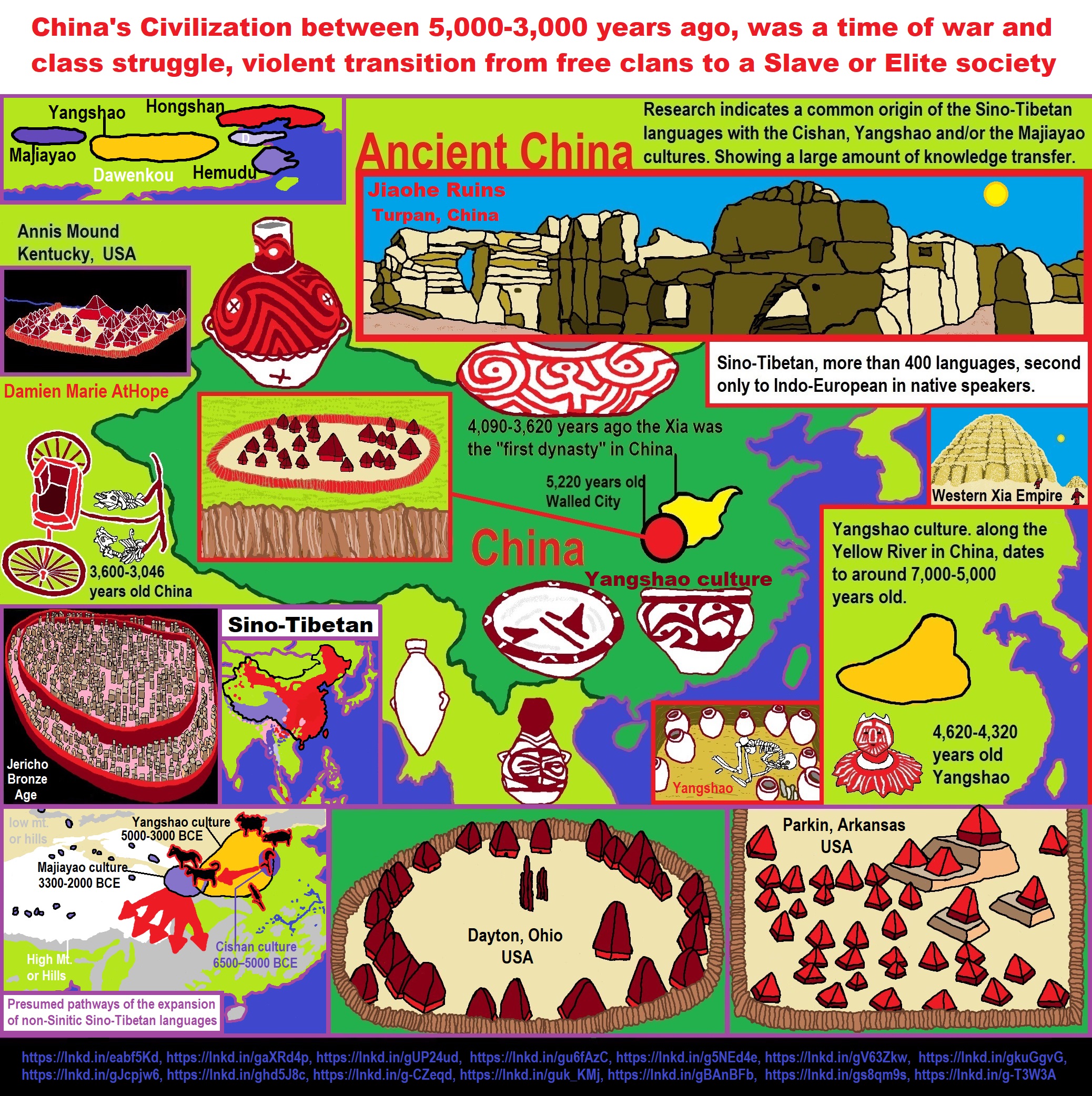

“Asian varieties of millet made their way from China to the Black Sea region of Europe by 5000 BCE or 7,000 years ago.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Millet

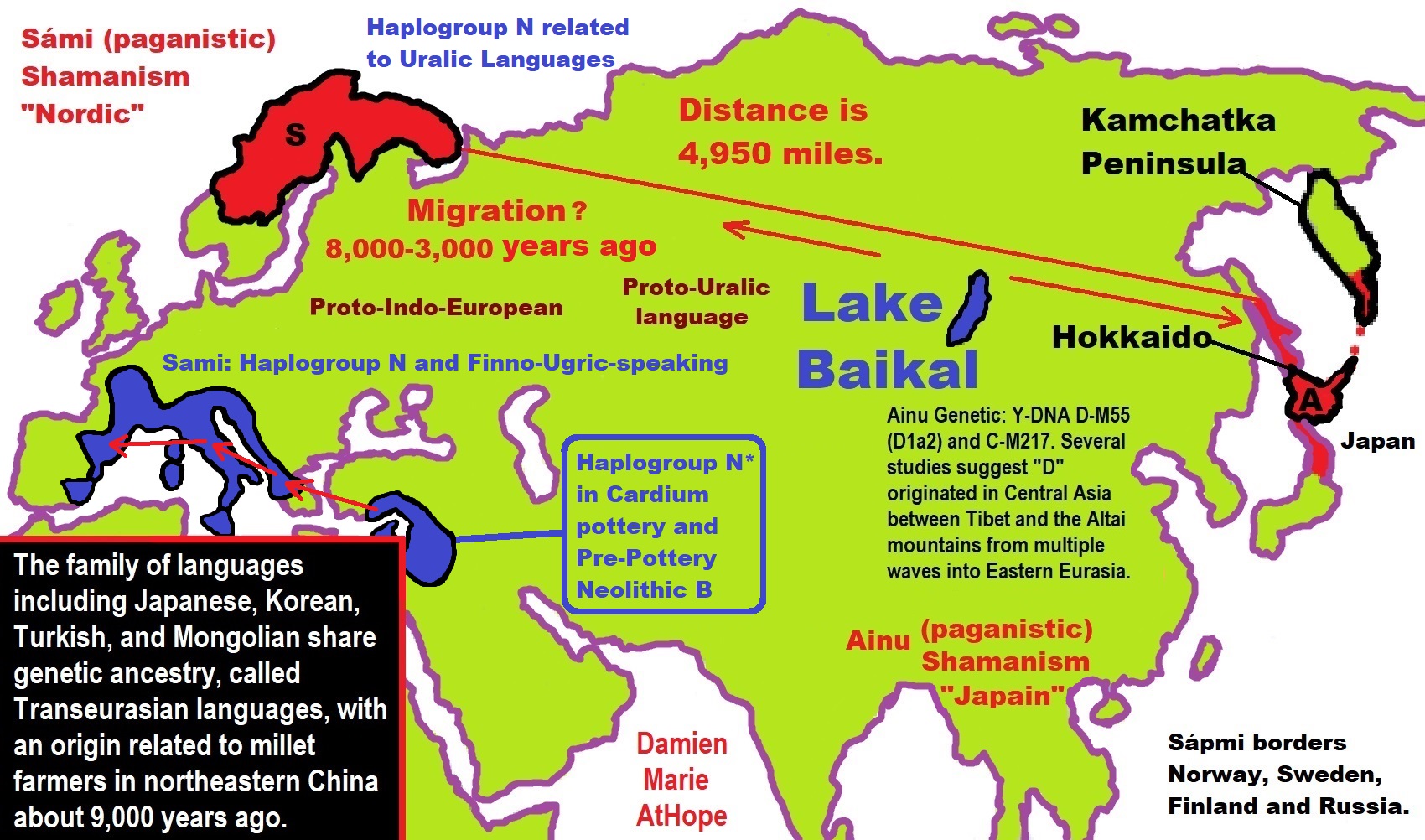

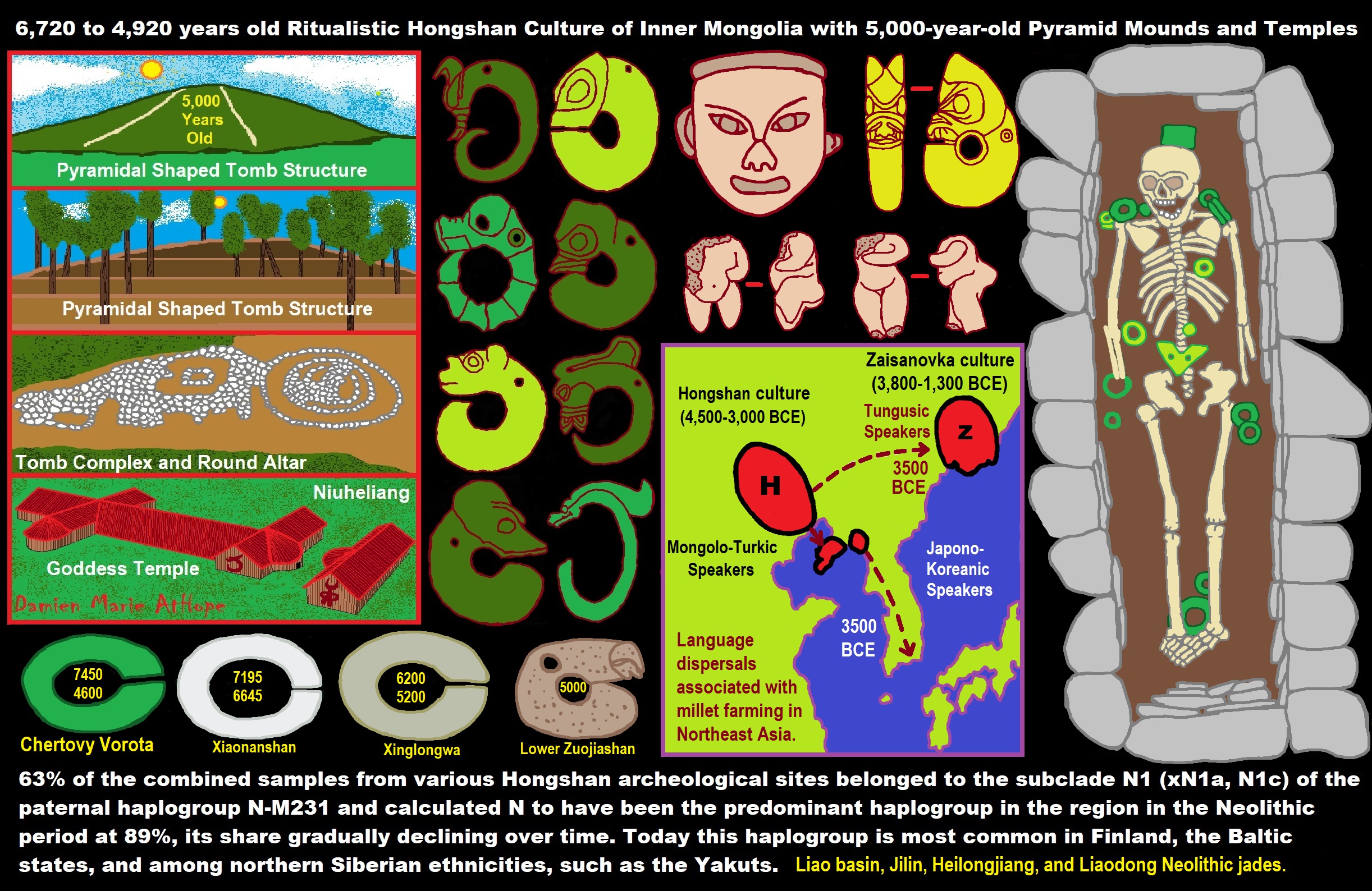

Origins of ‘Transeurasian’ languages traced to Neolithic millet farmers in north-eastern China about 9,000 years ago

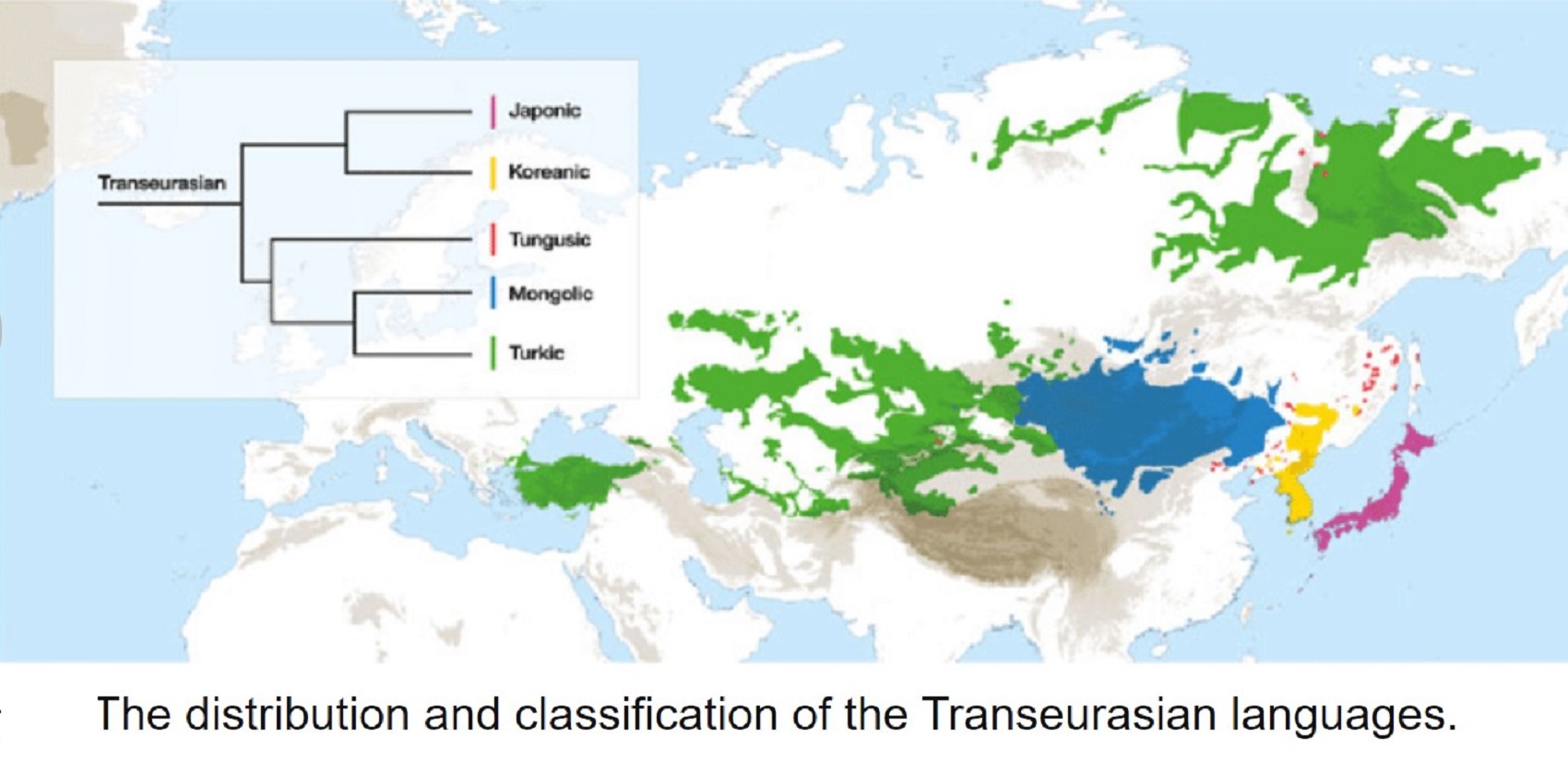

“A study combining linguistic, genetic, and archaeological evidence has traced the origins of a family of languages including modern Japanese, Korean, Turkish and Mongolian and the people who speak them to millet farmers who inhabited a region in north-eastern China about 9,000 years ago. The findings outlined on Wednesday document a shared genetic ancestry for the hundreds of millions of people who speak what the researchers call Transeurasian languages across an area stretching more than 5,000 miles (8,000km).” ref

“Millet was an important early crop as hunter-gatherers transitioned to an agricultural lifestyle. There are 98 Transeurasian languages, including Korean, Japanese, and various Turkic languages in parts of Europe, Anatolia, Central Asia, and Siberia, various Mongolic languages, and various Tungusic languages in Manchuria and Siberia. This language family’s beginnings were traced to Neolithic millet farmers in the Liao River valley, an area encompassing parts of the Chinese provinces of Liaoning and Jilin and the region of Inner Mongolia. As these farmers moved across north-eastern Asia over thousands of years, the descendant languages spread north and west into Siberia and the steppes and east into the Korean peninsula and over the sea to the Japanese archipelago.” ref

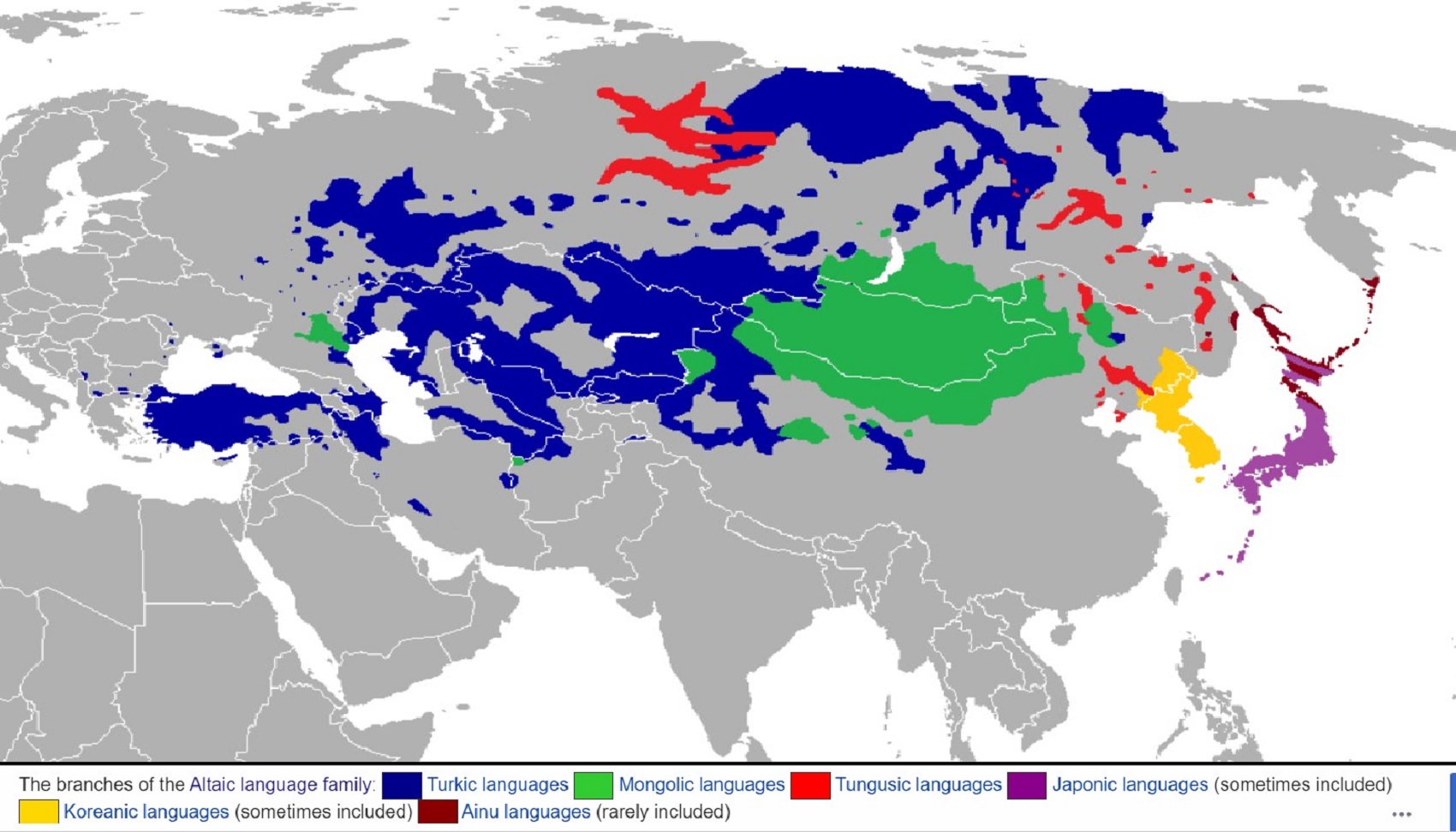

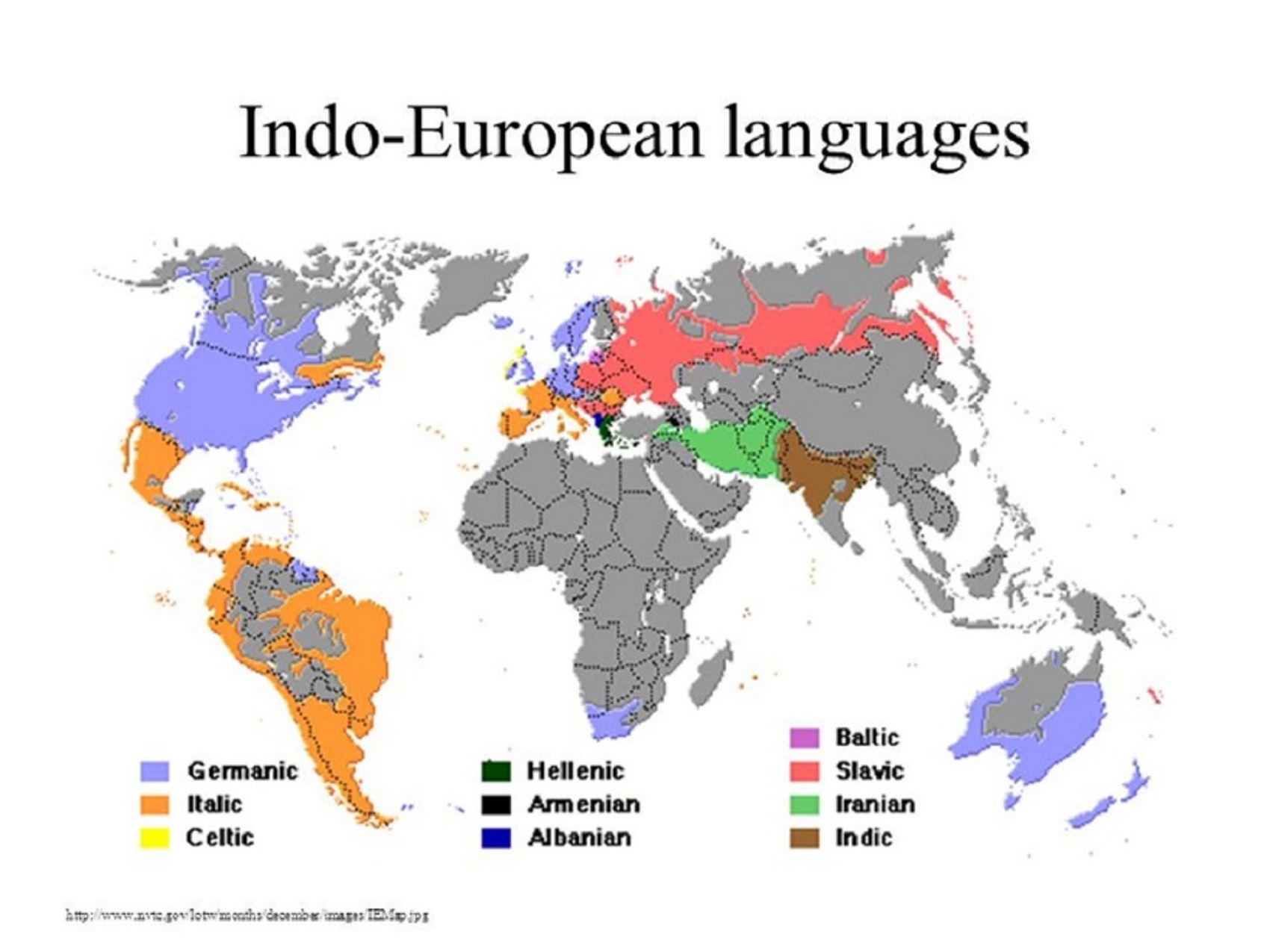

“Eurasiatic is a proposed language with many language families historically spoken in northern, western, and southern Eurasia; which typically include Altaic (Mongolic, Tungusic, and Turkic), Chukchi-Kamchatkan, Eskimo–Aleut, Indo-European, and Uralic.” ref

“Voiced stops such as /d/ occur in the Indo-European, Yeniseian, Turkic, Mongolian, Tungusic, Japonic and Sino-Tibetan languages. They have also later arisen in several branches of Uralic.” ref

“Uralo-Siberian is a hypothetical language family of Uralic, Yukaghir, Eskimo–Aleut and besides linguistic evidence, several genetic studies, support a common origin in Northeast Asia.” ref

“Altaic (also called Transeurasian) is a proposed language family that would include the Turkic, Mongolic, and Tungusic language families and possibly also the Japonic and Koreanic languages. Speakers of these languages are currently scattered over most of Asia north of 35 °N and in some eastern parts of Europe, extending in longitude from Turkey to Japan. The group is named after the Altai mountain range in the center of Asia.” ref

Tracing population movements in ancient East Asia through the linguistics and archaeology of textile production – 2020

Abstract

“Archaeolinguistics, a field which combines language reconstruction and archaeology as a source of information on human prehistory, has much to offer to deepen our understanding of the Neolithic and Bronze Age in Northeast Asia. So far, integrated comparative analyses of words and tools for textile production are completely lacking for the Northeast Asian Neolithic and Bronze Age. To remedy this situation, here we integrate linguistic and archaeological evidence of textile production, with the aim of shedding light on ancient population movements in Northeast China, the Russian Far East, Korea, and Japan. We show that the transition to more sophisticated textile technology in these regions can be associated not only with the adoption of millet agriculture but also with the spread of the languages of the so-called ‘Transeurasian’ family. In this way, our research provides indirect support for the Language/Farming Dispersal Hypothesis, which posits that language expansion from the Neolithic onwards was often associated with agricultural colonization.” ref

Pic ref

Ancient Human Genomes…Present-Day Europeans – Johannes Krause (Video)

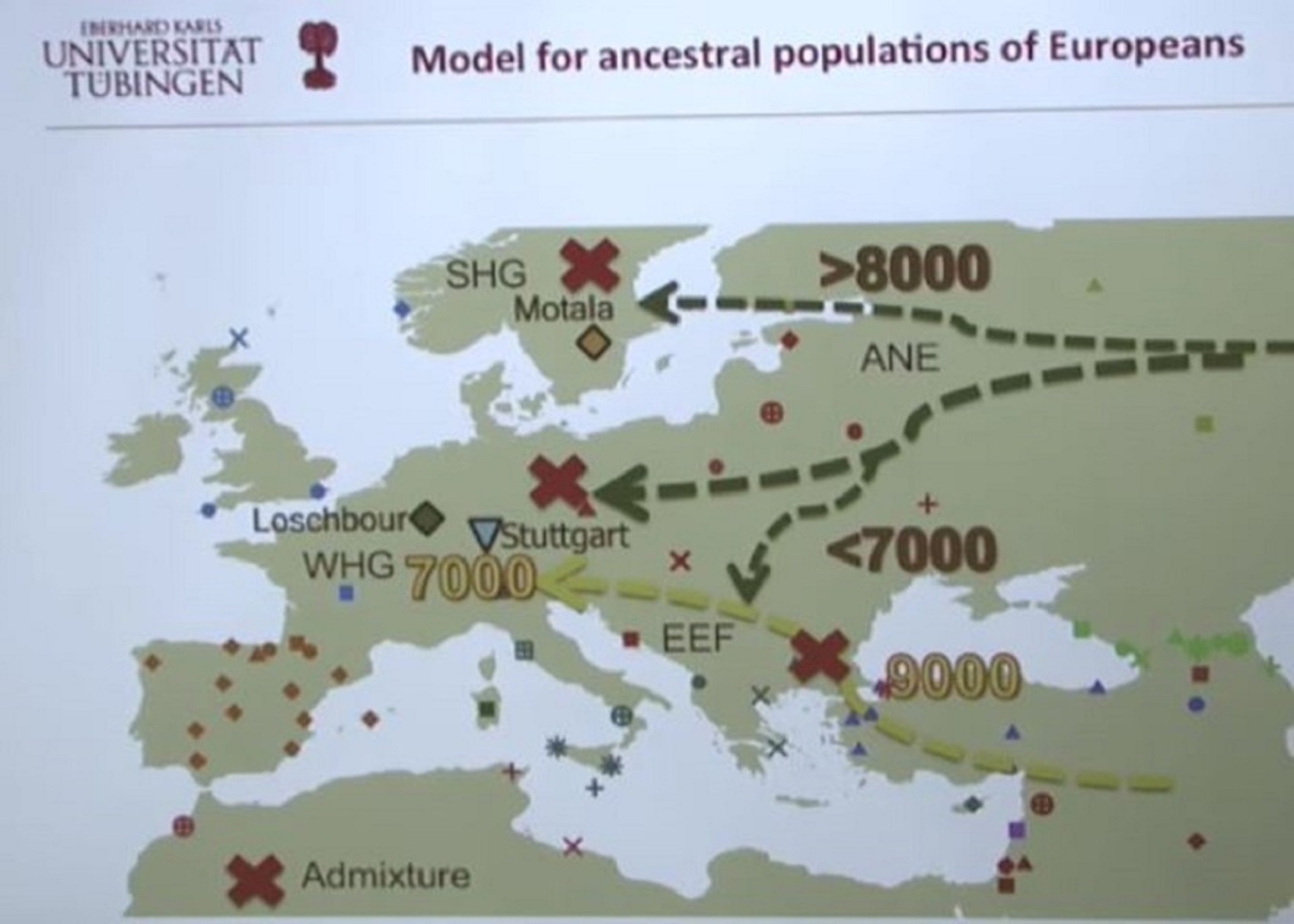

Ancient North Eurasian (ANE)

Eastern Hunter-Gatherer (EHG)

Western Hunter-Gatherers (WHG)

Scandinavian Hunter-Gatherer (SHG)

Early European Farmers (EEF)

A quick look at the Genetic history of Europe

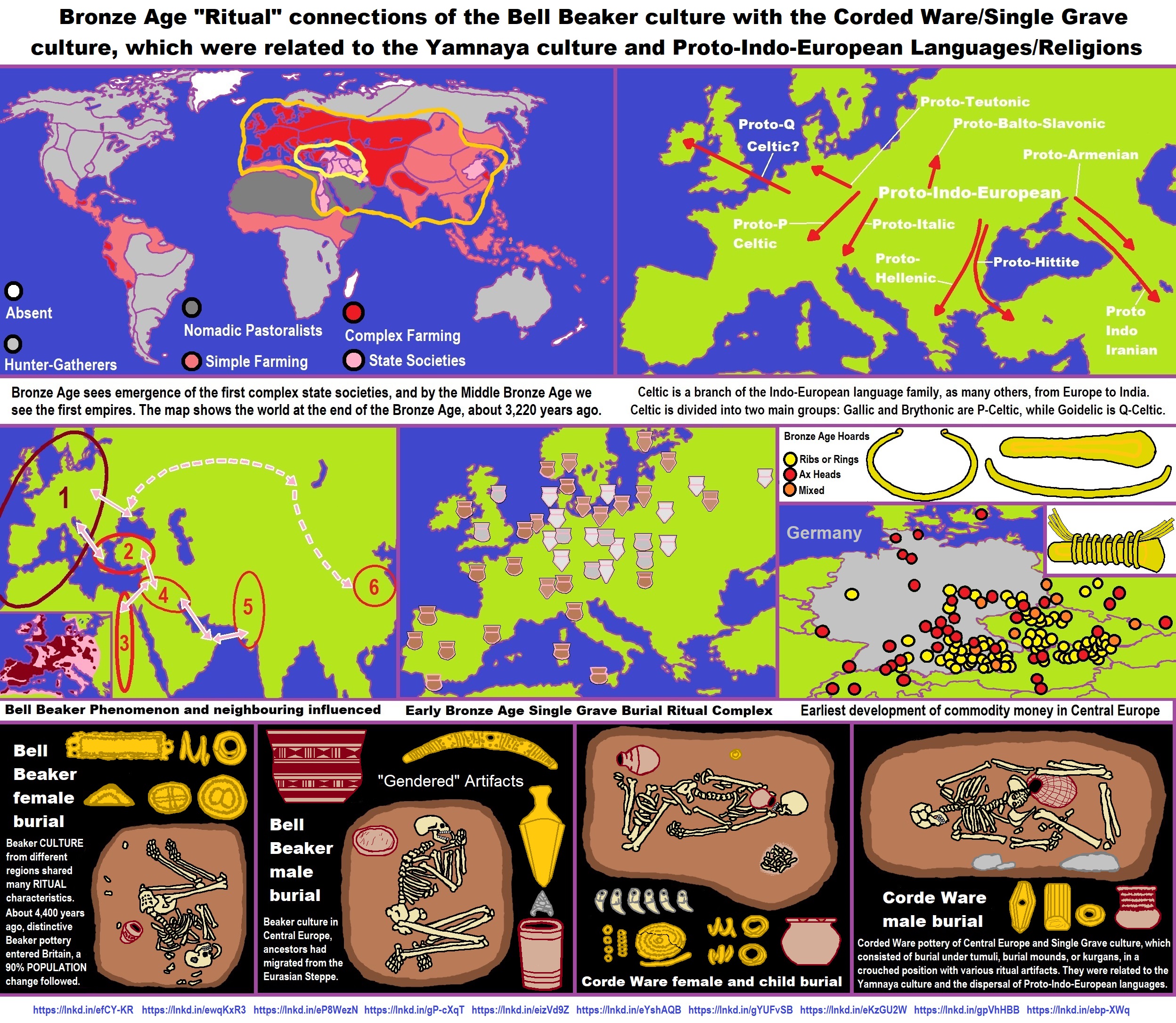

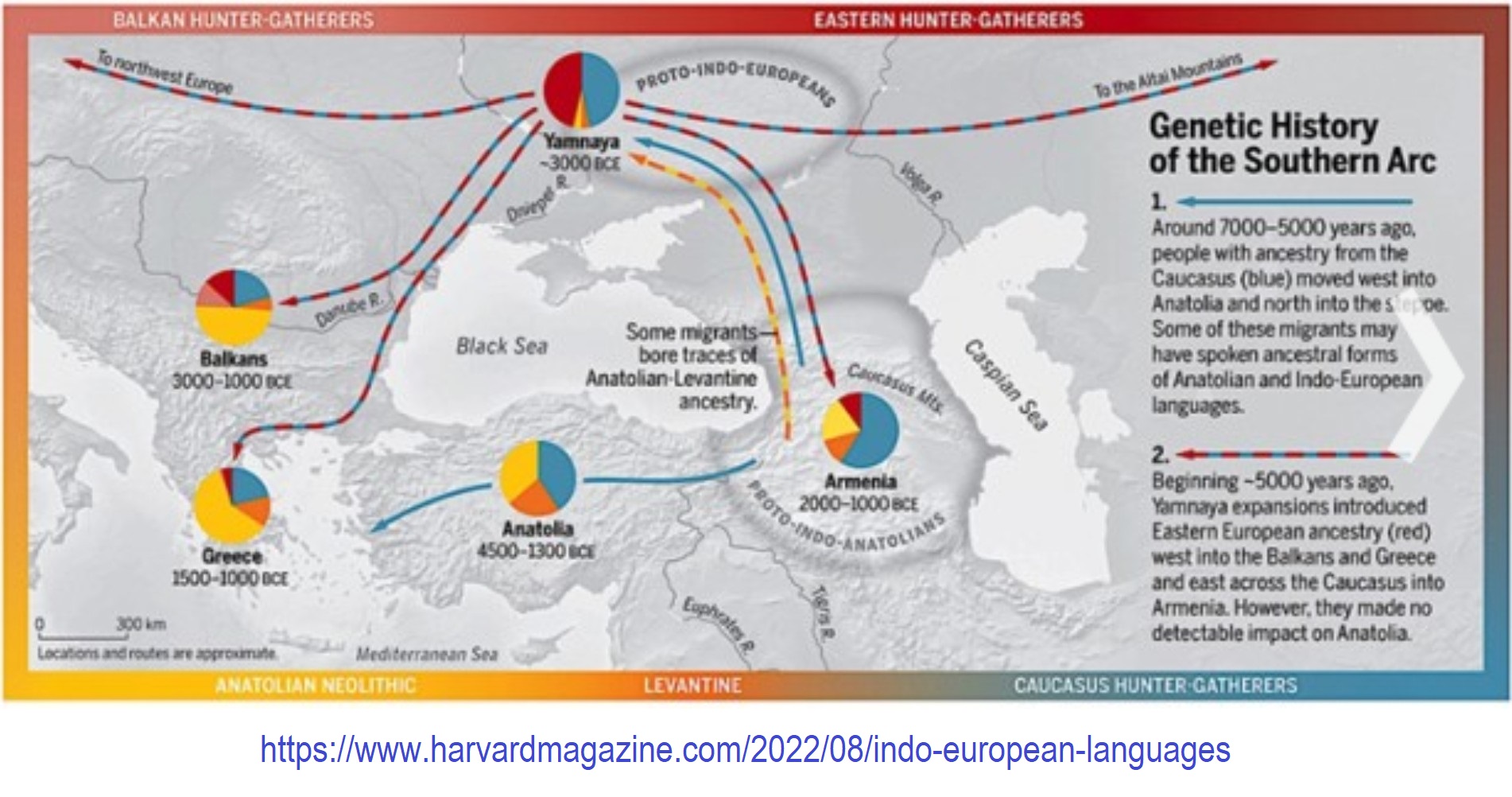

“The most significant recent dispersal of modern humans from Africa gave rise to an undifferentiated “non-African” lineage by some 70,000-50,000 years ago. By about 50–40 ka a basal West Eurasian lineage had emerged, as had a separate East Asian lineage. Both basal East and West Eurasians acquired Neanderthal admixture in Europe and Asia. European early modern humans (EEMH) lineages between 40,000-26,000 years ago (Aurignacian) were still part of a large Western Eurasian “meta-population”, related to Central and Western Asian populations. Divergence into genetically distinct sub-populations within Western Eurasia is a result of increased selection pressure and founder effects during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM, Gravettian). By the end of the LGM, after 20,000 years ago, A Western European lineage, dubbed West European Hunter-Gatherer (WHG) emerges from the Solutrean refugium during the European Mesolithic. These Mesolithic hunter-gatherer cultures are substantially replaced in the Neolithic Revolution by the arrival of Early European Farmers (EEF) lineages derived from Mesolithic populations of West Asia (Anatolia and the Caucasus). In the European Bronze Age, there were again substantial population replacements in parts of Europe by the intrusion of Ancient North Eurasian (ANE) lineages from the Pontic–Caspian steppes. These Bronze Age population replacements are associated with the Beaker culture archaeologically and with the Indo-European expansion linguistically.” ref

“As a result of the population movements during the Mesolithic to Bronze Age, modern European populations are distinguished by differences in WHG, EEF, and ANE ancestry. Admixture rates varied geographically; in the late Neolithic, WHG ancestry in farmers in Hungary was at around 10%, in Germany around 25%, and in Iberia as high as 50%. The contribution of EEF is more significant in Mediterranean Europe, and declines towards northern and northeastern Europe, where WHG ancestry is stronger; the Sardinians are considered to be the closest European group to the population of the EEF. ANE ancestry is found throughout Europe, with a maximum of about 20% found in Baltic people and Finns. Ethnogenesis of the modern ethnic groups of Europe in the historical period is associated with numerous admixture events, primarily those associated with the Roman, Germanic, Norse, Slavic, Berber, Arab and Turkish expansions. Research into the genetic history of Europe became possible in the second half of the 20th century, but did not yield results with a high resolution before the 1990s. In the 1990s, preliminary results became possible, but they remained mostly limited to studies of mitochondrial and Y-chromosomal lineages. Autosomal DNA became more easily accessible in the 2000s, and since the mid-2010s, results of previously unattainable resolution, many of them based on full-genome analysis of ancient DNA, have been published at an accelerated pace.” ref

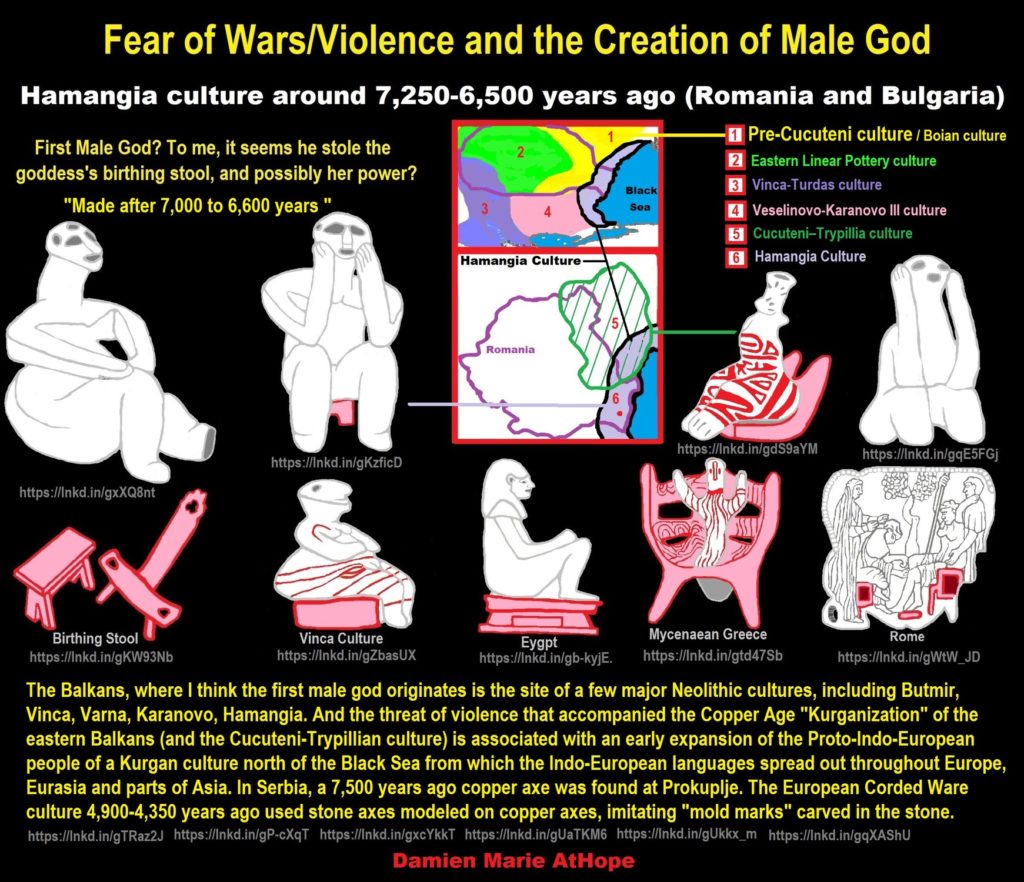

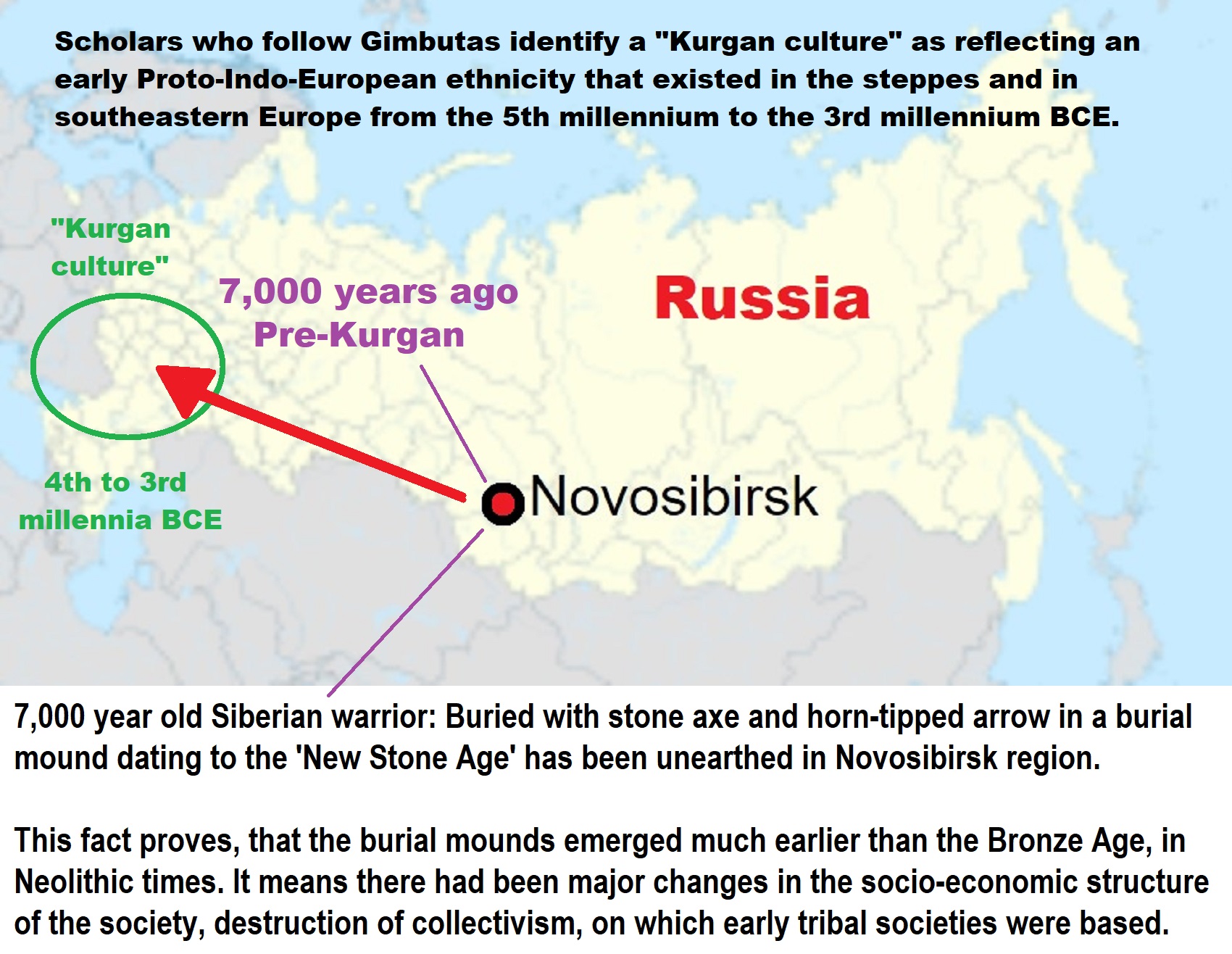

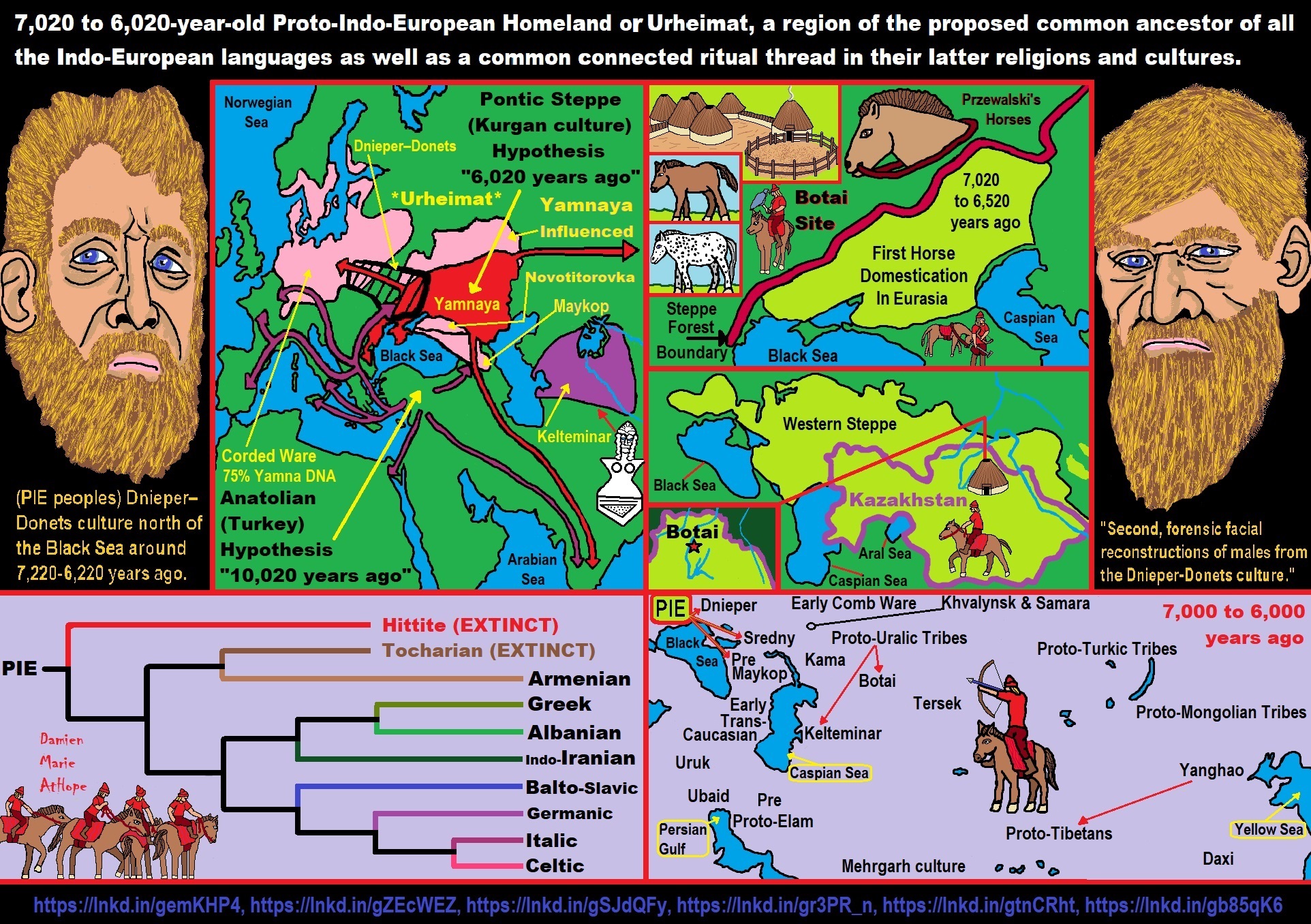

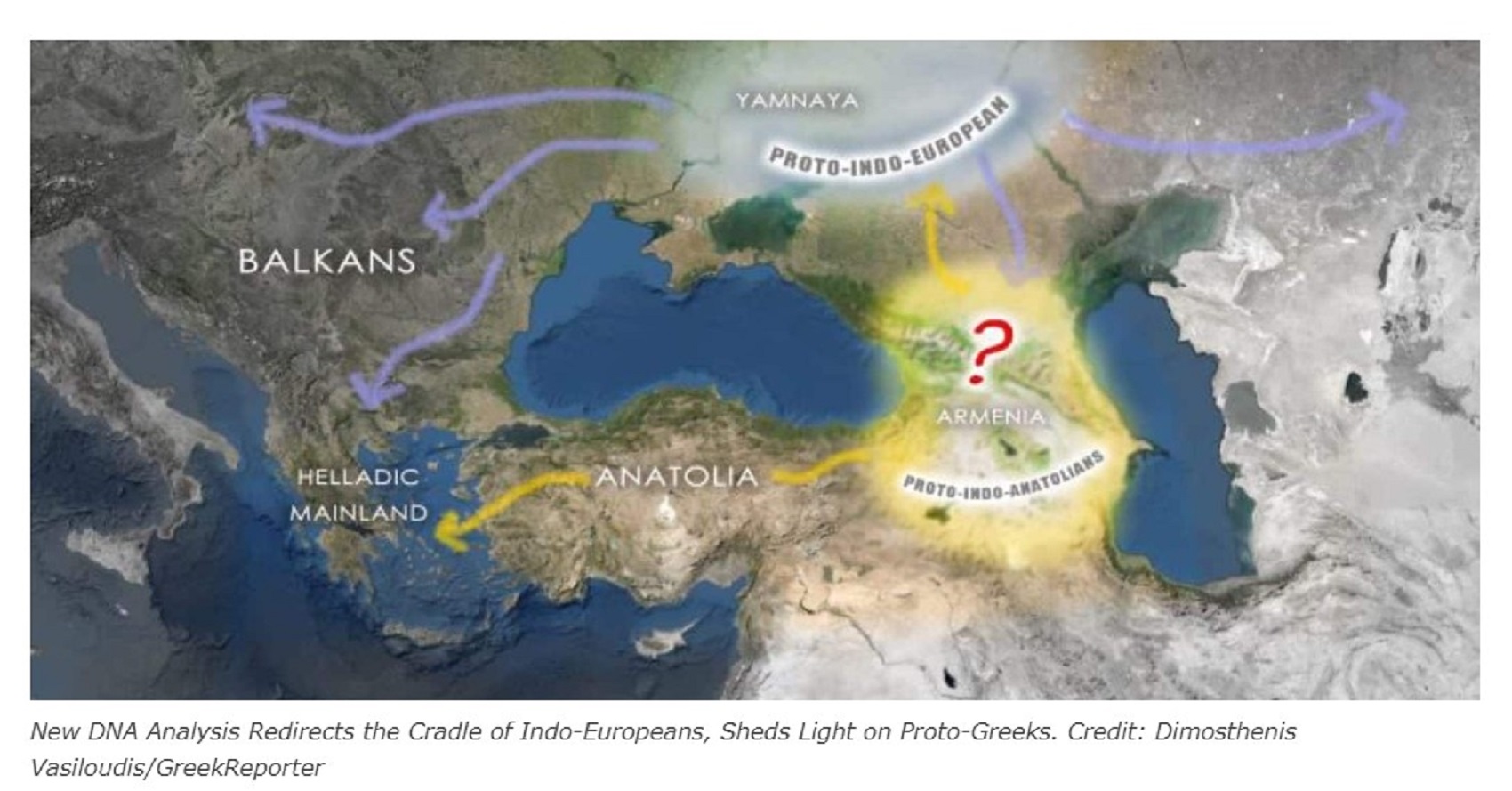

Kurgan Hypothesis

“The Kurgan hypothesis (also known as the Kurgan theory or Kurgan model) or Steppe theory is the most widely accepted proposal to identify the Proto-Indo-European homeland from which the Indo-European languages spread out throughout Europe and parts of Asia. It postulates that the people of a Kurgan culture in the Pontic steppe north of the Black Sea were the most likely speakers of the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE). The term is derived from the Russian kurgan (курга́н), meaning tumulus or burial mound. The Steppe theory was first formulated by Otto Schrader (1883) and V. Gordon Childe (1926), then systematized in the 1950s by Marija Gimbutas, who used the term to group various prehistoric cultures, including the Yamnaya (or Pit Grave) culture and its predecessors. In the 2000s, David Anthony instead used the core Yamnaya culture and its relationship with other cultures as a point of reference.” ref

“Gimbutas defined the Kurgan culture as composed of four successive periods, with the earliest (Kurgan I) including the Samara and Seroglazovo cultures of the Dnieper–Volga region in the Copper Age (early 4th millennium BCE). The people of these cultures were nomadic pastoralists, who, according to the model, by the early 3rd millennium BCE had expanded throughout the Pontic–Caspian steppe and into Eastern Europe. Recent genetics studies have demonstrated that populations bearing specific Y-DNA haplogroups and a distinct genetic signature expanded into Europe and South Asia from the Pontic-Caspian steppe during the third and second millennia BCE. These migrations provide a plausible explanation for the spread of at least some of the Indo-European languages, and suggest that the alternative Anatolian hypothesis, which places the Proto-Indo-European homeland in Neolithic Anatolia, is less likely to be correct.” ref

“Cultures that Gimbutas considered as part of the “Kurgan culture”:

- Bug–Dniester (6th millennium)

- Samara (5th millennium)

- Khvalynsk (5th millennium)

- Dnieper–Donets (5th to 4th millennia)

- Sredny Stog (mid-5th to mid-4th millennia)

- Maikop–Dereivka (mid-4th to mid-3rd millennia)

- Yamnaya (Pit Grave): This is itself a varied cultural horizon, spanning the entire Pontic–Caspian steppe from the mid-4th to the 3rd millennium.

- Usatovo culture (late 4th millennium)” ref

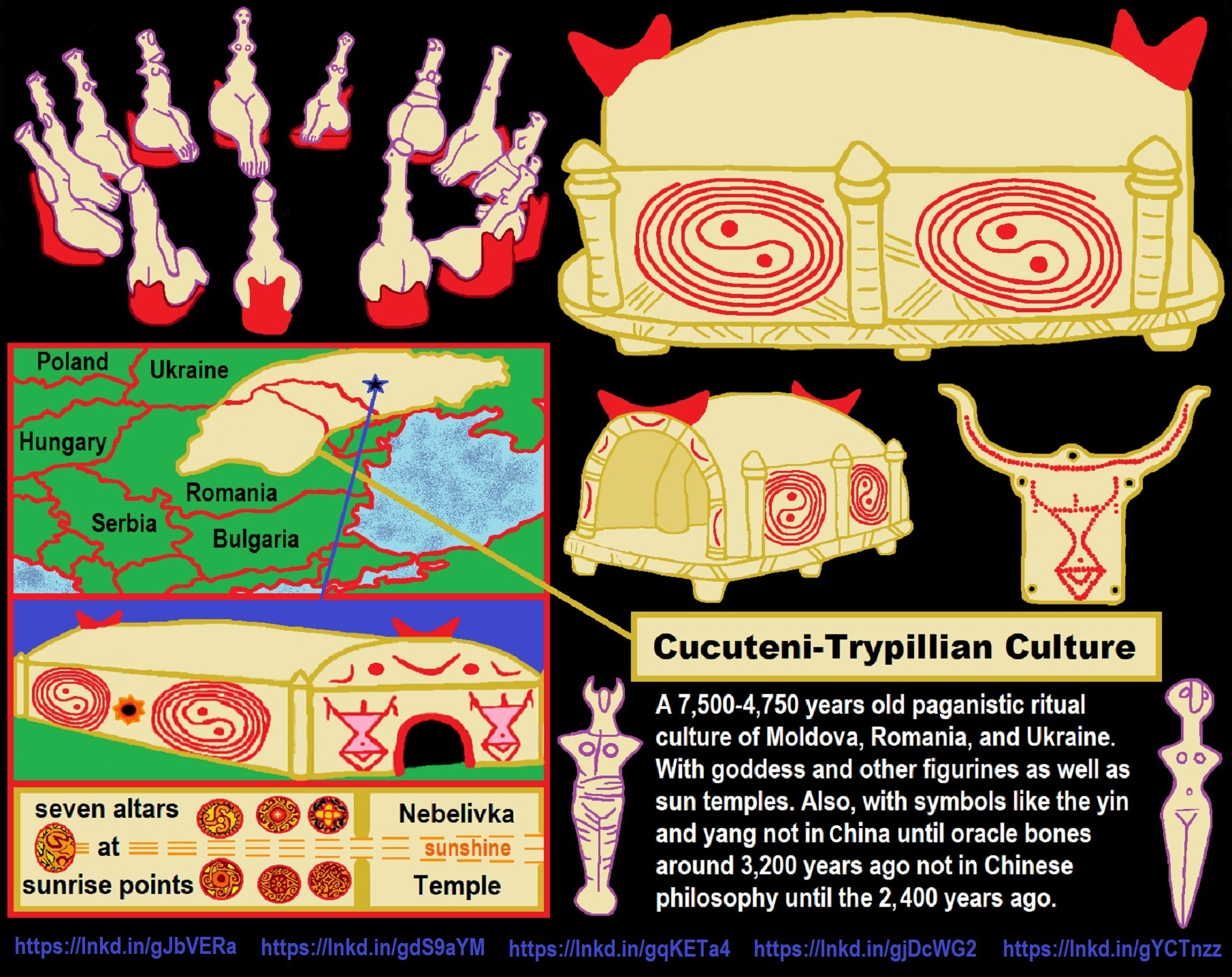

Cucuteni–Trypillia Culture

“The Cucuteni–Trypillia culture (Romanian: Cultura Cucuteni and Ukrainian: Трипільська культура), also known as the Tripolye culture (Russian: Трипольская культура), is a Neolithic–Eneolithic archaeological culture (c. 5500 to 2750 BCE) of Eastern Europe. It extended from the Carpathian Mountains to the Dniester and Dnieper regions, centered on modern-day Moldova and covering substantial parts of western Ukraine and northeastern Romania, encompassing an area of 350,000 km2 (140,000 sq mi), with a diameter of 500 km (300 mi; roughly from Kyiv in the northeast to Brașov in the southwest).” ref

“The majority of Cucuteni–Trypillia settlements consisted of high-density, small settlements (spaced 3 to 4 kilometers apart), concentrated mainly in the Siret, Prut, and Dniester river valleys. During the Middle Trypillia phase (c. 4000 to 3500 BCE), populations belonging to the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture built the largest settlements in Neolithic Europe, some of which contained as many as three thousand structures and were possibly inhabited by 20,000 to 46,000 people.” ref

“One of the most notable aspects of this culture was the periodic destruction of settlements, with each single-habitation site having a lifetime of roughly 60 to 80 years.[7] The purpose of burning these settlements is a subject of debate among scholars; some of the settlements were reconstructed several times on top of earlier habitational levels, preserving the shape and the orientation of the older buildings. One particular location; the Poduri site in Romania, revealed thirteen habitation levels that were constructed on top of each other over many years.” ref

“The Cucuteni–Trypillia culture flourished in the territory of what is now Moldova, northeastern Romania, and parts of Western, Central, and Southern Ukraine. The culture thus extended northeast from the Danube river basin around the Iron Gates to the Black Sea and the Dnieper. It encompassed the central Carpathian Mountains as well as the plains, steppe, and forest steppe on either side of the range. Its historical core lay around the middle to upper Dniester (the Podolian Upland). During the Atlantic and Subboreal climatic periods in which the culture flourished, Europe was at its warmest and moistest since the end of the last Ice Age, creating favorable conditions for agriculture in this region. As of 2003, about 3,000 cultural sites have been identified, ranging from small villages to “vast settlements consisting of hundreds of dwellings surrounded by multiple ditches”.” ref

Periodization

“Traditionally separate schemes of periodization have been used for the Ukrainian Trypillia and Romanian Cucuteni variants of the culture. The Cucuteni scheme, proposed by the German archaeologist Hubert Schmidt in 1932, distinguished three cultures: Pre-Cucuteni, Cucuteni, and Horodiştea–Folteşti; which were further divided into phases (Pre-Cucuteni I–III and Cucuteni A and B). The Ukrainian scheme was first developed by Tatiana Sergeyevna Passek in 1949 and divided the Trypillia culture into three main phases (A, B, and C) with further sub-phases (BI–II and CI–II). Initially based on informal ceramic seriation, both schemes have been extended and revised since first proposed, incorporating new data and formalized mathematical techniques for artifact seriation.” ref

“The Cucuteni–Trypillia culture is commonly divided into an Early, Middle, Late period, with varying smaller sub-divisions marked by changes in settlement and material culture. A key point of contention lies in how these phases correspond to radiocarbon data. The following chart represents this most current interpretation: • Early (Pre-Cucuteni I–III to Cucuteni A–B, Trypillia A to Trypillia BI–II):5800 to 5000 BCE• Middle (Cucuteni B, Trypillia BII to CI–II): 5000 to 3500 BCE• Late (Horodiştea–Folteşti, Trypillia CII): 3500 to 3000 BCE.” ref

Exchange of People, Ideas and Things between Cucuteni-Trypillian Complex and Areas of South-Eastern Poland

Abstract and Figures

“Influences of Cucuteni-Tripolye culture complex on the cultures in Lesser Poland were not intensive. At the turn of 5th and 4th millennia BCE, communities of Lublin-Volhynia culture adopted the laminar oblique retouch to form the long blades made of flint. Later, i.e. in the mid of the 4th millennium BCE, communities of Funnel Beaker culture imitated the production of Tripolyan big rectangular flint axes and the way of ornamentation of ceramic cups using figurines of rams’ heads. At the end of 4th and at the turn of 4th and 3rd millennia BCE Funnel Beaker culture communities in Lesser Poland (Gródek Nadbużny, Zimne, Kamień Łukawski) used to import some painted pottery from Cucuteni-Tripolyan partners.” ref

“A little later ornamentation of some pottery wares with cord imprints was recorded on some settlements of Funnel Beaker culture (Zimne, Majdan Nowy, Tominy) in the way characteristic for Kasperivtsy and Gorodsk groups of the late Tripolye culture. Transfer of Cucuteni-Tripolye ideas into Lesser Poland, what is confirmed by the presence of mentioned above elements of material culture: Tripolyan retouched blades and axes made of flint, imports of painted pottery and ornamentation of pottery with cord imprints, slightly imposed on mentioned cultures in the south-eastern part of Poland, but did not changed their character. Lublin-Volhynia culture communities remained still as a Polgarlike one, and Funnel Beaker culture communities did not change their megalithic face. In the reacher’s opinion, the modern theory of the network society (of Maffesoli and Castells) better explains the presence of Cucuteni-Tripolyan imitations and artifacts in the south-eastern part of Poland in the 4th millennium BCE than some traditional models like diffusion, ethnic migrations, or simply so-called „influences”.” ref

Introduction

“In the forming period of the Trypillia culture, the most important cultural influences came from the area on the lower Danube, the eastern Balkans, and the western coast of the Black Sea. From the BII phase, however, the culture increasingly influenced the Pontic steppe, especially the area between the mouth of the Danube and the Dnieper. Trypillian contacts with the Polgár cultures of the Carpathian Basin and the younger Danubian cultures from Małopolska have frequently been discussed. Polish and Ukrainian archaeology takes much interest in Trypillian relationships with the Funnel Beaker and the Globular Amphorae cultures in the CII phase. Researchers also point out the oldest transmission of cord impressions as a decorative motif on ceramics and of elements of funeral rites, as well as the borrowing of the Thuringian amphora form, crucial for the genesis of the Corded Ware culture, from the environment of late Trypillian groups.” ref

“Contacts between Cucuteni-Trypillian complex and areas of South-Eastern Poland one can consider in frames of five chronological horizons:

1. Malice culture, phase IIa – Trypillia culture, phase BI-BII – 4400/4200-4000 BCE.

2. Malice culture, phase IIb, and Lublin-Volhynia culture, phase II – Trypillia culture, phase BII – 4000-3800 BCE.

3. Lublin-Volhynia culture, phase III and Funnel Beaker culture, phase Gródek I,

Bronocice II – Trypillia culture, phase CI – 3800-3550 BCE (Bilcze Złote, phase Werteba I).

4. Funnel Beaker culture, phase Gródek I, Bronocice III – Trypillia culture, phase CII (early) – 3550-3100 BC (Bilcze Złote, phase Werteba II).

5. Funnel Beaker culture, phase Gródek II, Bronocice IV-V, Baden and Globular Amphorae culture – Trypillia culture, phase CII (late) – 3100-2700 BC (Bilcze Złote, phase Werteba III).” ref

Horizon 1

“The earliest pottery imports from South-Eastern Poland are concentrated in the area of the upper and northern part of the middle Dniester basin, at sites belonging to the Zaleshchiki group of Trypillia culture (Bilshivtsy 1, Viktoriv, Korzhova, Bilcze Złote -Ogród site. They originated in the Malice culture and can be dated mainly to its phase IIa, probably also to the very beginnings of the Lublin-Volhynia culture. The „cooking” ceramics from Bilcze Złote (some of them show Malice culture influences) are predominantly made of well-mixed mass of clay tempered with a large or quite large admixture of crushed mollusk shells. This type of admixture points to a continuation of Eastern European traditions. The ceramics tempered with crushed mollusk.” ref

“Introduction In the forming period of the Trypillia culture, the most important cultural influences came from the area on the lower Danube, the eastern Balkans, and the western coast of the Black Sea. From the BII phase, however, the culture increasingly influenced the Pontic steppe, especially the area between the mouth of the Danube and the Dnieper. Trypillian contacts with the Polgár cultures of the Carpathian Basin and the younger Danubian cultures from Małopolska have frequently been discussed. Polish and Ukrainian archaeology takes much interest and the Globular Amphorae cultures in the CII phase. Researchers also point out the oldest transmission of cord impressions as a decorative motif on ceramics and of elements of funeral rites, as well as the borrowing of the Thuringian amphora form, crucial for the genesis of the Corded Ware culture, from the environment of late Trypillian groups.” ref

“Contacts between Cucuteni-Trypillian complex and areas of South-Eastern Poland one can consider in frames of five chronological horizons. 1. Malice culture, phase IIa – Trypillia culture, phase BI-BII – 4400/4200-4000 BCE. 2. Malice culture, phase IIb, and Lublin-Volhynia culture, phase II – Trypillia culture, phase BII – 4000-3800 BCE. 3. Lublin-Volhynia culture, phase III and Funnel Beaker culture, phase Gródek I, Bronocice II – Trypillia culture, phase CI – 3800-3550 BCE (Bilcze Złote, phase Werteba I). 4. Funnel Beaker culture, phase Gródek I, Bronocice III – Trypillia culture, phase CII (early) – 3550-3100 BCE (Bilcze Złote, phase Werteba II) . 5. Funnel Beaker culture, phase Gródek II, Bronocice IV-V, Baden and Globular Amphorae culture – Trypillia culture, phase CII (late) – 3100-2700 BCE (Bilcze Złote, phase Werteba III). Horizon 1: The earliest pottery imports from South-Eastern Poland are concentrated in the area of the upper and northern part of the middle Dniester basin, at sites belonging to the Zaleshchiki group of Trypillia culture (Bilshivtsy 1, Viktoriv, Korzhova, Bilcze Złote – Ogród site.” ref

“They originated in the Malice culture and can be dated mainly to its phase IIa, probably also to the very beginnings of the Lublin-Volhynia culture. The „cooking” ceramics from Bilcze Złote (some of them show Malice culture influences) are predominantly made of well-mixed mass of clay tempered with a large or quite large admixture of crushed mollusk shells. This type of admixture points to a continuation of Eastern European traditions. The ceramics tempered with crushed mollusk shells make up over 70% of the entire assemblage of the „cooking” ceramics. Interestingly, the „cooking” ceramics tempered with an admixture of crushed pottery and fine sand, but without crushed mollusk shells, predominate distinctly in the modest material recovered from the Ogród site at Bilcze Złote, linked with three oldest settlement horizons (from the BI / BII phases to the early CI phase of Trypillia culture). Afterwards, the ceramics with crushed shells become prevalent. Relationships between formal traits, ornamentation, chronology, and local or – more broadly – Eastern European traditions of preparing the mass of clay at Bilcze Złote are very interesting.” ref

“Among 119 bowls, as many as 63 items (almost 53% of the group) do not contain any admixture of crushed mollusk shells. This refers particularly to three- or two-part bowls, sometimes having a slightly sharper profile. These forms, dated to the oldest horizon of settlement at the Ogród site, are linked with the Ogród I ceramic assemblage at Bilcze Złote, attributed to the Zaleshchiki group from the turn of the BI and BII phases of the Trypillia culture. In earlier interpretations, this group of vessels had its models in assemblages attributed to the II phase of the Malice culture). At present, it seems that the inspiration came from the environment of the Kodžadermen-Gumelniţa-Karanovo VI cultural complex and from cultures around the Danube Delta. Influences from the Malice culture, however, cannot be ruled out completely. In its late (II) phase, the culture spread also to Volhynia; its single sites have been found in the upper Dniester basin, as well. Perhaps some of these vessels, difficult to point out, should be treated as western „imports” in the Trypillian environment.” ref

“The presence of similar bowls in successive horizons of settlement at the Ogród and the Werteba sites in Bilcze Złote, thus at an increasing temporal distance from the Malice culture, may mean that the period of „imports” and imitations was followed by the period of adaptations and creative development of that group of ceramics in the Trypillian environment. This seems to be confirmed by the wealth of bowl forms and by the accepted mode of their production based on technology typical of the Trypillia culture, i.e. with shells tempering the mass of clay. This local development should undoubtedly be linked with the horizon defined by the chronology of the Ogród III assemblage, i.e. the early CI phase of the Trypillia culture at the latest.

Horizon 2

Later Danubian imports from South-Eastern Poland (within stages BI-BII of the Trypillia culture) are connected with some influences of phase II of the Lublin-Volhynia-culture. They are present both at the settlements of the Western basin of the Boh river (Sokiltsy-Polizhok V, Klishchiv), as well as on the territory between the Boh and the Dnieper rivers (Krasnostavka, Veseliy Kut). M. Videiko recorded a lot of Polgár elements on many areas of Trypillia culture, including the Dniester, Southern Bug, Middle Dnieper regions.” ref

“Some of these influences penetrated into mentioned territories through the Lublin-Volhynia culture. To real imports from the Lublin-Volhynia culture at Bilcze Złote belongs a cup ornamented with white paint. It should probably be linked with the Ogród II ceramic assemblage (Mereshovka group of Trypillia culture). Among „serving vessels” in the Werteba I ceramic assemblage at Bilcze Złote, one may distinguish a group of thin-walled vessels made of adobe clay, often tempered with crushed pottery (nearly a hundred items, i.e. almost 4% of the whole assemblage). The vessels are usually undecorated, sometimes with small handles pierced horizontally. Most fragments of large and medium forms have the proportions of half-barrel-shaped vessels or vases. Since there are few handles preserved in this class, most of the vessels probably had no handles. Semispherical bowls come second as regards their number in the group; fragments of vessels with high, smooth cylindrical necks are even less frequent. Fragments of egg-shaped vessels have handles below the rim. Bowls shaped like three-fourths of a sphere and semispherical bowls also belong to the group of handled forms. On two items, handles are arranged in a chequered pattern: on a semispherical bowl, in two zones; on a half-barrel-shaped vessel, in three zones. Fragments of other vessels with handles below the rim are ornamented with monochromatic or bicolored diagonal stripes and a bicolored arc.” ref

“These forms may be viewed as „imports” or rather, as imitations of vessels produced in the late phase of the Lublin-Volhynia culture (numerous half-barrel-shaped vessels) and the Bodrogkeresztúr culture (handled vessels). „Imports” and influences of the Bodrogkeresztúr culture and other cultural centers point to the development of contacts with the Carpathian Basin and loess uplands of Małopolska and Volhynia in the late phase of the Shipentsy group of the Trypillia culture. The great number of those „imports” and influences shows that the contacts were intensive and multidirectional. The half-barrel-shaped vessel at Bilcze Złote is definitely a form of Central European origin. Each of the six preserved items of that type was made without the shell admixture in the mass of clay. Those vessels were mainly related to the Lublin-Volhynia culture as its most important group of ceramics, with variants produced in all its phases. In the Lublin-Volhynia culture flint industry was exclusively oriented towards the production of blade blanks (including microlithic ones).” ref

“In this culture, an interregional role of Volhynian raw materials is evident, particularly for fulfilling non-utilitarian functions arising from developing social relations. One of the basic techniques of tool production was oblique covering parallel retouching. It was used to shape basically all retouched blades and triangular points, but also a large part of truncated pieces, scrapers, and even some perforators. This kind of retouch was borrowed from the North-Western groups of the Trypillia culture. Probably the tendency to produce the longest possible flint blades was also influenced by this culture.” ref

Horizon 3

The interaction between the Lublin-Volhynia in its late (III) phase of and Trypillia cultures in its CI phase was continued. Late Danubian pottery features were absorbed by Trypillian communities. On the other hand, some Trypillian flint industry features were adopted by Lublin-Volhynia culture groups. At the same time, contacts between the oldest (pre-classic) phase of the Funnel Beaker and Trypillia culture are confirmed. Groups of the Funnel Beaker population colonized for the first time a borderland between two cultures (Korytyny, Grodzisko III site on the upper Dniester river). On the other hand, pottery features of the Funnel Beaker culture are recorded in assemblages of Chapaevka, Kolomishchina, and Lukashi groups in the Middle Dnieper Region of Trypillia culture.

Horizon 4

“In the 2nd part of IV millennium BCE populations of Funnel Beaker culture expanded into the East and settled areas to the Gniła Lipa and Bystrzyca Sołotwińska rivers, tributaries of the Upper Dniester. The Funnel Beaker culture settlers meet East of these rivers groups of Trypillia culture inhabitants (Koshilivtsy group) from the older stage of its CII phase. As a result of it, a mixed settlement zone was created in the Upper Dniester basin. In Volhynia compact settlement zone of Funnel Beaker culture reached Styr river. However, single settlement points of this culture were found also more to the East, i.e. in the neighborhood of Ostrog town. On Novomalin-Podobanka site materials of classic Funnel Beaker culture together with Trypillian ones (from the beginnings of phase CII) were recorded. Close contacts with Trypillian world was mirrored in numerous Funnel Beaker-like pottery elements on the vast territories between the upper Dniester, Volhynia ad Dnieper. At the same time, communities of Trypillia culture settled more intensely middle and eastern part of Volhynia.” ref

“Imports of painted Trypillian (Koshilivtsy and Bryndzeny groups) pottery were discovered on the Polish-Ukrainian borderland in Gródek Nadbużny, Zimno and Male Gribovichi and even more to the West of Vistula river at Kamień Łukawski, Bronocice, and even in Kuyavia. The appearance of ram’s heads, so characteristic ornament of some pottery vessels in the South-Eastern group of the Funnel Beaker culture, might be an effect of Trypillian culture influences. However the most dominant were Trypillian influences on the Funnel Beaker culture flint industry. Long blades and large axes were produced due to their symbolic meanings rather than functional requirements. Probably they served as prestige objects.” ref

“This production involved a multi-level system of specialization, apparent on various levels (of regions, settlements, and individual homes). A leading supra-regional role was played by Świeciechów and striped raw materials, which deposits are located in the Holy Cross Mountains. Different tools were made of these flints. Large tetrahedral axes from Świeciechów flint were produced imitating Trypillian patterns. There were also differences in access to their deposits and processing organization. The same one can say about their distribution systems. In Volhynia, imported assemblages of Świeciechów and striped tools differ in quantities of imported artifacts and regards to the kinds of implements and raw materials used to make them. Only finished tools were being distributed from the Holy Cross Mountains production centers. They circulated as a part of an exchange system of prestige goods.” ref

“The flint industry of the Funnel Beaker culture communities in Małopolska (fig. 9, 10), especially production of blades, axes and triangular arrowheads was more related to the Trypillia culture than to the other Funnel Beaker culture groups. The key to understanding the evolution of flint processing in Małopolska leading up to the emergence of the industry of south-eastern Funnel Beaker culture group is the evolution of the flint industry of the Trypillia culture. Strong Trypillian influences on Funnel Beaker culture flint industry are also visible on Polish Lowlands.” ref

Horizon 5

“The turn of 4th and 3rd and beginnings of 3rd millennium BCE was the scene of a particular intensification of contacts between different cultures in Europe. This period was defined as the crisis of Neolithic societies. There are several indications of possible direct contacts of Baden communities from Slovakia with the area between the Prut and Dnieper rivers, which was inhabited by local groups of the Tripolye culture of phase CII. Many traditions and imports of the Baden Culture can be observed at Horodiștea-Erbiceni sites. This culture group transmitted directly Baden traditions to the East of the Carpathians.” ref

“Gordinești (closely connected with Horodiștea-Erbiceni group) and Kasperivtsy groups display features of the Baden Culture in its pottery stylistics too. Elements of Gordinești group are present on many sites of Troyaniv-Gorodsk group. The Sofievka group evolved under the direct influence of the Gordinești and Troyaniv-Gorodsk groups and indirectly of the Baden-Kostolac-Coţofeni and Cernavoda II culture. The lower and middle Danube was one of the most important axes of intense contacts, transfer of things and ideas, and human migration. From the West to the East moved cultural elements of the Baden culture and its related cultural units. In the opposite direction moved groups of Yamna culture. Baden elements, especially in form of Funnel Beaker-badenized assemblages, reached at the same time the central part of Volhynia. They moved to the East directly from Małopolska Uplands. The whole settlement agglomeration of such assemblages was lately discovered in the upper Styr river basin in the neighborhood of Ostrog town.” ref

“Similar pottery materials were discovered also at Korytyny, Grodzisko III site, located on the bank of the upper Dniester river. In addition to migrations from the East to the West and from the West to the East it took place the transmission of people, things, and ideas from the South to the North and vice versa. In addition to the late Funnel Beaker culture assemblages with Baden elements in South-Eastern Poland there are also sites of this culture with cord decorated pottery. On two sites: Majdan Nowy and Tominy, site 12 cord ornamentation was accompanied by vessls with their rims obliquely cut off inwards. Similar elements are recorded in the Kasperivtsy and Gorodsk group of the Trypillia culture. They can be dated to the first centuries of the 3rd millennium BCE. As regards direct sources of inspiration for the use of ‘cord’ ornamentation, they are to be found in the late groups of the Trypillia culture, chiefly Kasperivtsy and Gorodsk groups. Jointly occurring in them, specifically, in the former, lips with their rims obliquely cut off inwards and cord ornamentation are recorded in Majdan Nowy and Tominy, site 12.” ref

“The origin of the former trait have their roots in Anatolia and the eastern Balkans (culture complexes Sitagroi Va – Radomir I-II – Yunacite XIII-IX traditions), while the latter trait – cord ornaments – comes from Pontic steppes. The two traits may have merged in the late groups of the Trypillia culture at the mouth of the Danube. The best example of the move from the north (eastern part of Poland) to the south (the Danube Delta) was great migration of Globular Amphorae culture communities. There are numerous Globular Amphorae culture traits in the assemblages of the late Trypillia culture pottery. Groups of people of Globular Amaphorae culture, returning from the south on Sandomierz Upland in south-eastern Poland, brought with them a new form of pottery, so-called Thuringian amphora, borrowed from the Usatovo group. The time of it could be dated to the period between 2900-2700 BCE. This resulted in the origins of the Złota culture. Złota Culture can be interpreted as a stylistically distinct, intermediate stage between the Globular Amphorae culture and Corded Ware culture, which was not occurring on the other territories.” ref

“This local phenomenon was a part of the broader processes which took place mainly in south-eastern Europe (the eastern Balkans, Ukraine and Moldova), resulting in a profound civilizational change, i.e. the creation of the great cultural complex of Corded Ware culture. Conclusions In the second half of the 5th millennium BCE (horizon 1), communities of the Tripolye culture, phases BI-BII, had contacts with the population of the late (IIa) phase of the Malice culture. The areas settled by both cultural complexes were located at a great distance from each other. The communities of the Tripolye culture adopted selected features of Malice ceramic production. This seems to have resulted from marital exchange: on a moderate scale, Tripolye men sought out their wives in the area of the Malice culture and, according to patrilocal marriage customs, the women then moved to the Tripolye settlements, sporadically transferring ready-made ceramic products, so-called imports, to the Tripolye culture. Thus, the wives were responsible for the considerably more numerous imitations of the Malice ceramics and the long-lasting, though selective, traditions of Malice pottery passed down in their new environment.” ref

“The patrilocal marriage customs involving the Malice women and the Tripolye men (never the other way round), and the fact that pottery was women’s domain, led to the unidirectional transfer of vessels, technology, and norms of ceramic production from the Malice culture to the Tripolye culture. The turn of the 5th and the 4th millennia and the early 4th millennium BC (horizon 2) witnessed the deepening interaction between the populations of the youngest (IIb) phase of the Malice culture and the classic (II) phase of the Lublin-Volhynia culture on the one hand and the communities of phase BII of the Tripolye culture on the other. The Danube and the Tripolye settlement complexes came into contact on the upper Dniester and between the Styr and the Horyn rivers in Volhynia. This helped to continue the previous forms of marital exchange, which resulted in the further popularisation of the ceramics and the traditions of ceramic production typical of the Danube cultures, i.e. the Malice and the Lublin-Volhynia cultures, and also the Polgár culture, in the areas settled by the Tripolye cultural complex. As the civilizational norms of the Eneolithic (Copper) Age became widespread in that period, the forms of interaction described above acquired new elements.” ref

“The deepening internal diversification of the early Eneolithic communities of the Lublin-Volhynia culture led to a growing demand for prestige objects, which was met with import or imitation of copper artifacts, mainly those from the Carpathian Basin, and with flint tools produced from long blades. That type of flint production depended largely on new technologies derived from the Tripolye culture, as proven by such borrowings as trough-like retouch or the very idea and technology for the production of long flint blades in the Lublin-Volhynia culture. It seems that the influx of Tripolye settlers into flint-bearing areas in Volhynia and on the upper Dniester, adjacent to the settlement centers of the late phase of the Malice culture and the Lublin-Volhynia culture, created sufficient conditions for the expanding influence of the Tripolye flint working on the communities of the Eneolithic Lublin-Volhynia culture. In the mid-4th millennium BCE (horizon 3), those forms of interaction between the Danube communities (the late phase of the Lublin-Volhynian culture) and the Tripolye communities (phase CI) (fig. 3) were continued.” ref

“Elements of the Danube pottery still grew in popularity in the Tripolye population, while selected features of the Tripolye flint working were adopted by the Lublin-Volhynia culture. In that period, the population of the Funnel Beaker culture of the pre-classic and early classic phases (the beginnings of Gródek 1 and Bronocice III), until then absent from those areas, quite quickly drove out and replaced the Danube population in western Volhynia and the upper Dniester basin. This caused significant changes in the forms and intensity of the intercultural interaction, which became fully apparent already in the 2nd half of the 4th millennium BC. In the following period (horizon 4), the population of the classic phase of the Funnel Beaker culture (Gródek 1, Bronocice III) settled more and more intensively the upper Dniester basin, up to the Hnyla Lypa river, and western Volhynia, up to the Styr river.” ref

“East of those rivers, the Funnel Beaker settlers created considerable areas where they mixed with settlers from early phase CII of the Tripolye culture. Their coexistence, lasting there for many generations, resulted in deepening the interactions between members of both cultural complexes and in developing entirely new forms of relationships. This is shown by imports and imitations of the Tripolye painted ceramics at Funnel Beaker sites located not only at the eastern edge of that culture (e.g. Gródek Nadbużny, Zimno), but also in the Sandomierz-Opatów Upland (e.g. Kamień Łukawski), the Western Małopolska Upland (e.g. Bronocice) and Kuyavia, and by contemporaneous imitations of the Funnel Beaker ceramics documented in large areas of the Tripolye culture. The higher level of the interaction resulted e.g. in specialized workshops near Sandomierz which produced prestige flint axes modeled on the Tripolye tools, meeting the demand of communities inhabiting vast areas of present-day Poland.” ref

“It seems that the production was possible only with the participation of specialists from the Tripolye culture, and that complying with the high technological standards needed in that work required long apprenticeship with a master; mere observation of the technological process or attempted imitation based only on the analysis of ready-made axes would not have been sufficient. The strong influence of the Tripolye culture on the flint working in the Funnel Beaker culture in Małopolska and western Ukraine, together with the maximization of the length of the produced blades, indicate that the flint working had more in common with the Tripolye traditions than with the standards of production of flint tools in the other areas of the Funnel Beaker culture. The intensifying interaction between the communities of the Funnel Beaker culture and the Tripolye culture, early phase CII, in the 2nd half of the 4th millennium BC (horizon 4) was an introduction to, and perhaps a condition for, even more frequent contacts in the next period, the first centuries of the 3rd millennium BC (horizon 5).” ref

“In that case, the interaction was mainly triggered by multidirectional migrations of larger human groups, involving a significant part of the population of all cultures from the areas discussed here. The Tripolye communities of younger phase CII settled Volhynia, its eastern areas in particular, from the south and the south-east, while groups representing the younger phases of the Funnel Beaker culture (Gródek 2), often with Baden features (Bronocice IV and V), moved increasingly into the western part of that region. The Yamna communities expanded along the lower and central Danube to the west, whereas the populations of the late phase of the Baden culture took the opposite direction, reaching as far as Kiev in the north-east, and contributed to the cultural character of the Sofievka group.” ref

“The communities of the Globular Amphora culture migrated from the north-west, from eastern Poland, towards the Danube Delta and as far as the Dnieper in the east, while the multicultural population from the areas around the mouth of the Danube moved in the opposite direction, carrying with them cultural elements from Thrace, or even from Anatolia. Some of them returned to the starting point (to south-eastern Poland), bringing with them a new form of pottery, so-called Thuringian amphora, borrowed from the late Trypillian Usatovo group. This resulted in origins of the Złota culture, a cultural phenomenon that gave beginnings to the oldest Corded Ware culture. Inventories of both cultures contained the already mentioned Thuringian amphorae.” ref

“The events described above-formed part of the broader processes which took place mainly in south-eastern Europe (the eastern Balkans, Ukraine and Moldova), resulting in the so-called crisis of the early farming communities and in a profound civilizational change. The cultures that had developed there until then were superseded by the mobile communities of three large cultural complexes: the Yamnaya, the Corded Ware, and the Bell Beaker cultures.” ref

Comprehensive Site Chronology and Ancient Mitochondrial DNAAnalysis from Verteba Cave – a Trypillian Culture Site of Eneolithic Ukraine

ABSTRACT

“This manuscript presents a study of a ritual site of the Trypillian culture complex (TC) in western Ukraine where material artifacts are found side-by-side with human and animal remains. The organic content in pottery sherds made it possible to carbon date the ceramics found with bone remains, thus allowing a reference point for carbon dating bone collagen. This allowed us to develop a comprehensive chronology of the usage of the cave. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) extracted from human remains shed additional light on the history of the site’s occupation by early agrarians on the territory of Ukraine.” ref

Introduction

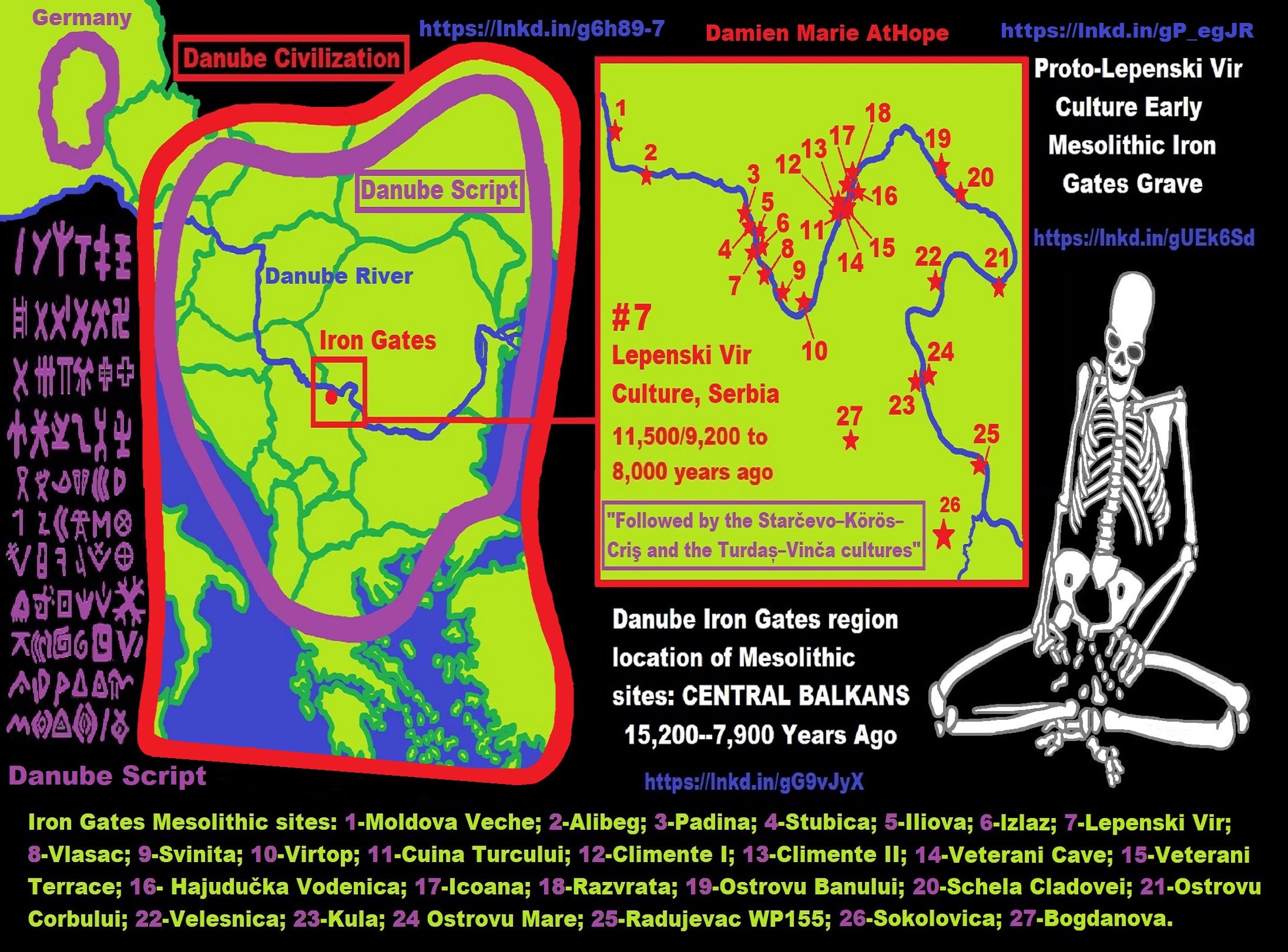

“Farming in Europe spread from western Anatolia after 7000 BCE. The European Neolithic initially developed in Greece, from where it expanded northward into the Balkans, and westward along the Mediterranean coast. After 6000 BCE Neolithic cultures of the Danube basin, such as Starčevo-Körös-Kriş and the Linear Pottery culture (Linearbandkeramik or LBK) began to appear east of the Carpathian Mountains. On the foundations laid by these and other Neolithic groups, a new archaeological culture began to form in the pre-Carpathian region around 5400 BCE. This culture became known as Precucuteni, and later as Cucuteni in Romania and Moldova, and Trypillia A (formally spelled “Trypolie” or “Tripolye”) followed by Trypillia B and C, in Ukraine. The Trypillian cultural complex (TC) existed from 5400 to 2700 BCE on a vast area extending from the Carpathian piedmont, east to the Dnipro River, and south to the shores of the Black Sea.” ref

“As an archaeological culture, TC was discovered in 1896 by V. Khvoika near the village Trypillia, Ukraine. TC is characterized by advanced agriculture, developed metallurgy, pottery-making, sophisticated architecture, and social organization, including the first proto-cities on European soil. TC occupies a prominent place in Eastern European archaeology but still remains largely unknown to the Western science. The new TC chronology identifies the following brackets for each TC phase: AII-III-3 from 5400–4300 BCE, BI from 4300–4100 BCE, BII from 4100–3600 BCE, CI from 3600–3200 BCE, and CII from 3400–2750 BCE. More than 40 local archaeological groups are recognized within the TC complex, with the region- and group-specific variations in the styles of pottery and plastics, in many cases infuenced by contemporaneous neighboring cultures. At the material culture level, TC is known for a variety of painted pottery as well as anthropomorphic and zoomorphic clay figurines. While the material culture of TC has been well studied and documented, human remains are scarce. In fact, they are virtually non-existent until the CII phase, when burials of TC begin to appear on a regular basis. This creates a gap in our understanding of the biological origins of TC and in their cultural traditions, such as rituals for the dead.” ref

Trypillia Megasites in Context: Independent Urban Development in Chalcolithic Eastern Europe

Abstract

“The Trypillia megasites of the Ukrainian forest steppe formed the largest fourth-millennium bc sites in Eurasia and possibly the world. Discovered in the 1960s, the megasites have so far resisted all attempts at an understanding of their social structure and dynamics. Multi-disciplinary investigations of the Nebelivka megasite by an Anglo-Ukrainian research project brought a focus on three research questions: (1) what was the essence of megasite lifeways? (2) can we call the megasites early cities? and (3) what were their origins? The first question is approached through a summary of Project findings on Nebelivka and the subsequent modelling of three different scenarios for what transpired to be a different kind of site from our expectations. The second question uses a relational approach to urbanism to show that megasites were so different from other coeval settlements that they could justifiably be termed ‘cities’. The third question turns to the origins of sites that were indeed larger and earlier than the supposed first cities of Mesopotamia and whose development indicates that there were at least two pathways to early urbanism in Eurasia.” ref

Introduction

‘The concept of “city” is notoriously hard to define.‘ This is the opening statement of Childe’s seminal article ‘The urban revolution’. Almost 70 years later, this task has become even harder, with urbanism attested in a far wider range of environments, cultural trajectories, and material forms than were known to Childe. Yet in western Asia and Europe, the traditional supremacy of Uruk urbanism—earlier than the first European city by two millennia—has remained intact and untroubled by global difference. While Minoan statehood may be dated to 2400 BCE, the Late Minoan city of Knossos—at 100 ha the largest settlement on Crete—dates to the mid-second millennium bc, showing that states may have developed without cities. Later still, classic examples of European cities co-emerged with states in the first millennium BCE in Greece, Etruria, and Rome, while large, low-density, temperate European Iron Age oppida have an ambiguous relationship to urbanism. This narrative enshrines the powerful tradition of equating urbanism with political and economic centralization, which this reacher disputes.” ref

“The second, empirical problem with this narrative is its exclusion of the largest sites in fourth-millennium bc Eurasia, if not the world—the Trypillia Chalcolithic megasites of the Ukrainian forest-steppe—and this despite a vigorous discussion of urban and non-urban status conducted largely in Russian and Ukrainian since the 1970s (Korvin-Piotrovskiy 2003; Masson 1990; Shmaglij 2001; summarized in Supplementary Materials 1, online). Ignoring Fletcher’s (1995) recognition of megasites as the only exception to his global rule of settlement constraints, most authors even today consider megasites as ‘large villages’ (see chapters in Müller et al. 2016b), with none of the core traits of Childean urbanism and no urban legacy (for an exception, see Wengrow 2015). However, advancing a relational approach rather than a Childean check-list compilation provides a new perspective on the urban debate.” ref

“In this article, we use the results of an AHRC-funded research project to investigate the question of European urbanism on the North Pontic forest-steppe through the multi-disciplinary study of a single Trypillia megasite—Nebelivka (Novoarhangelsk region, Kirovograd County)—in its wider landscape and cultural context. The Trypillia–Cucuteni network (Russian Tripolye; hereafter ‘CT’) covers over two millennia and three modern states—Romania, Moldova, and Ukraine. Unlike the Cucuteni part of the CT network, found in eastern Romania and Moldova, and which displayed a strong tendency to settlement dispersion in the late fifth millennium BCE, the Trypillia part contained megasites defined as settlements of 100 ha or larger from 4100 to 3400 BCE.” ref

“There are three research questions which are of primary concern: origins, megasite lifeways, and urban status. We address these questions in a different order,2 since consideration of both urban status and megasite origins must be grounded in an interpretation of megasite lifeways that is radically different from the standard view of megasites as long-term permanently occupied settlements with tens of thousands of residents living in thousands of coevally used houses at the same time.” ref

“The first question focuses on megasite lifeways—the essence of what a megasite was and how it came to function in a large-scale landscape. It is here that the most dramatic changes in interpretation have emerged in the last decade. The traditional narrative has relied on the planned layout of megasites and the large number of solid, permanent houses, which in most accounts were coevally occupied, as proxies for long-term all-year-round occupation for thousands of people. Our research has managed to deconstruct this approach, leading to the modeling of three different scenarios for Nebelivka. While the social underpinning of two of the models rests on the seasonal patterning of social life, the third model relies on a broadly heterarchical social pact supporting permanent dwelling.” ref

“The second question confronts the urban status of Trypillia megasites, using a relational approach in which lifeways on a typical, small Trypillia site are compared and contrasted with what would have happened on a megasite. The results show that there is a strong case for calling Trypillia megasites ‘cities’ in their forest steppe context. The origins of the Trypillia megasites have been regularly discussed over the last 30 years, with the military/strategic response to internal and/or external threat generally being considered adequate to explain this settlement hyper-nucleation. Our approach takes a different starting-point of how Trypillia communities used to living in settlements of 20–40 ha could have imagined the possibility of creating a site 10 to 20 times as large. But before we turn to the research questions, it is important to gain some perspectives on how we conceptualized megasites and developed a feel for the contexts in which megasite archaeology has developed.” ref

Conceptualizing/contextualizing megasites

“Studying megasites and Balkan Neolithic tells may be mapped onto the difference between the Orient Express and a commuter train from Bushey to Euston: it is hard to comprehend the vastness of the former, while not denying the intrinsic interest of the latter. It is not only the megasites that are vast—it is also their landscapes and the time-space dimensions of the CT network. The rolling forest steppe-covered loess landscapes carry on for thousands of kilometers, while, at a local level, a single Soviet-era field in central Ukraine can be larger than an entire English parish. Moreover, the CT network lasted longer and covered a wider area than any other central and eastern European network—from 5000 to 2800 BCE and more than 250,000 sq. km. By comparison, the Vădastra network in modern Romania lasted 200 years and covered 6000 sq. km, while the Veselinovo network in Bulgaria lasted 300 years and covered 60,000 sq. km. Ukrainian specialists have claimed the existence of more than 60 local ‘groups’ within the Trypillia network alone. The scale of these phenomena is not only theoretically challenging but also poses many methodological problems of how to investigate such sites/landscapes/cultural groups (Table 1).” ref

“The first question of scale concerns the way that clearly similar though the varying material culture was replicated over such distances and reproduced over 80+ generations. Reachers found the concept of the ‘Big Other’ stimulating in this respect. Alongside and ‘above’ the daily household practices which characterized the habitus—what Bloch has termed ‘transactional social practice’— the Big Other played an overarching, integrative role as a virtual symbolic order (in Bloch’s terms, a ‘transcendental entity’) that existed only through its subjects believing in it—something which was sufficiently general and significant to attract the support of most members of society but, at the same time, sufficiently ambiguous to allow the kinds of localized alternative interpretations (‘transactional practices’, according to Bloch) that avoid constant schismatic behavior.” ref

“These localized interpretations became materialized in three principal forms which were all central to CT cultural identity: different types of painted pottery, different kinds of figurines and houses of different shapes and sizes. All three forms were concentrated in the domestic domain, where the mortuary domain and hoarding practices were virtually invisible.4 While for typological ‘splitters’, the variability in these three forms permitted the etic differentiation of over 60 local groups, a CT person would have emically recognized a vessel as ‘theirs’ in a pottery assemblage from a settlement 800 km away from their home. Diachronic studies of CT figurine usage shows continuity in discard practices over the entire CT timespan. The Big Other was fundamental in the growth and expansion of the CT network, transcending face-to-face contact and local social networks to enable continuities of practice and identities across vast distances. But the Big Other leads us to an important question concerning the role of imagination in the CT network.” ref

“In Imagined Communities, Anderson’s influential study of the anomaly of modern nationalism, the author reminds us that all communities larger than a single village were ‘imagined communities’, because separate communities have, by definition, never lived together with a second group. Bloch has recently expanded the use of the term ‘imagined communities’ to beyond the political framework, suggesting that the transcendental social consists of essentialized groups that exist because they are ‘imagined’, whether as descent groups or religious groupings. There are therefore three different levels at which imagined communities have taken root in the CT network: at the level of the megasite, at the level of the descent group whose members spanned two or more settlements, and at the far larger scale of the ‘Big Other’ itself. The Big Other can be conceived in Bloch’s terms as ‘a totalising transcendental representation without its political foundation’.” ref

“For the imagined community of megasites, we suggest that the first step of the integration of people beyond their normal, face-to-face groups had been taken through the evolution of the Big Other as much as the development of transcendent local and regional descent groups. But local Trypillia settlement groups still required a vision of how diverse communities could live together to derive benefits from the new settlement form that were considered greater than the difficulties this linkage may have brought. After all, there is a long tradition, supported by Childe, of actualizing the advantages of autarky—living in independent, face-to-face communities—which put a long-term brake on the scale of settlement nucleation in prehistoric Europe.” ref

“It is easy to forget the unprecedented nature of Trypillia megasites, which have created immense problems of explanation and understanding, but first of all, problems of imagination. On the Eurasian continent of the fifth–fourth millennia bc, the Trypillia megasites were unique in size and scale. There was nothing anywhere else on the planet, at 4200 BCE, to compare with the Phase BI megasite of Vesely Kut, covering an area of 150 ha—no analogies from which to derive this extraordinary place. In our discussion of how the earliest megasites were imagined, we shall return to the issues of their cultural background, the changes which stimulated their growth and their advantages and disadvantages.” ref

“In the theoretically divided terrain of the last three decades, one of the areas in which post-processualists, interpretative archaeologists, and those of the ontological turn have made least impact has been urbanism. With a handful of exceptions, research into urban developments has been the domain of the processualists, who have focused on wide-ranging processes of change and often grand narratives to account for what was clearly a critical step in the human past. One of the problems that interpretative archaeologists have faced is the scale of the processes, which tend to be beyond their comfort zone. As previously discussed, the similarities of the scale of CT settlement and those of early urban networks make the interpretation of CT just as problematic as other early cities. This means that conceptualizing CT in terms of the Big Other and ‘imagined communities’ does not make for ready linkages to urban origins. The route that we have taken remains, however, true to post-1980s contextual and relational approaches.” ref

“The term ‘urban’ is a modern analytical construct, largely used as an essentialist concept, but more recently used to encompass very different phenomena worldwide. This contradictory usage stems from the tension between the desirability of a single definition and the diversity of cases that make this impossible. Historical, anthropological, and epigraphic sources informing us about the emic views of cities reveal not only linguistic differences but, more significantly, very different understandings of the phenomenon. Thus, the introduction of an etic category such as ‘urban’ seems reasonable to reconcile these cross-cultural differences, allowing comparisons of human development. It is easy to overlook this feature of the term ‘urban’ due to its Latin origin, its implied Eurocentrism, and the unfortunate interchangeability of the terms ‘urban’ and ‘city’.” ref

“Defining ‘urban’ might be helpful in distinguishing between ‘urban’ and ‘non-urban’ lifeways, were it not for the static and descriptive aspects of any definition, especially in a constantly expanding field. By contrast, analytical constructs are more flexible and can be regularly updated. In this paper, we have chosen not to produce a definition of ‘urban’ since we believe that such an operation has, in the past, done more harm than good through the essentialization of selected criteria. Instead, we rely on ‘urban’ as an analytical construct whose constitutive points are relational rather than fixed. In this sense, the term ‘megasite’ resembles the Chinese character for ‘city’ or the Greek word ‘polis’.” ref