ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

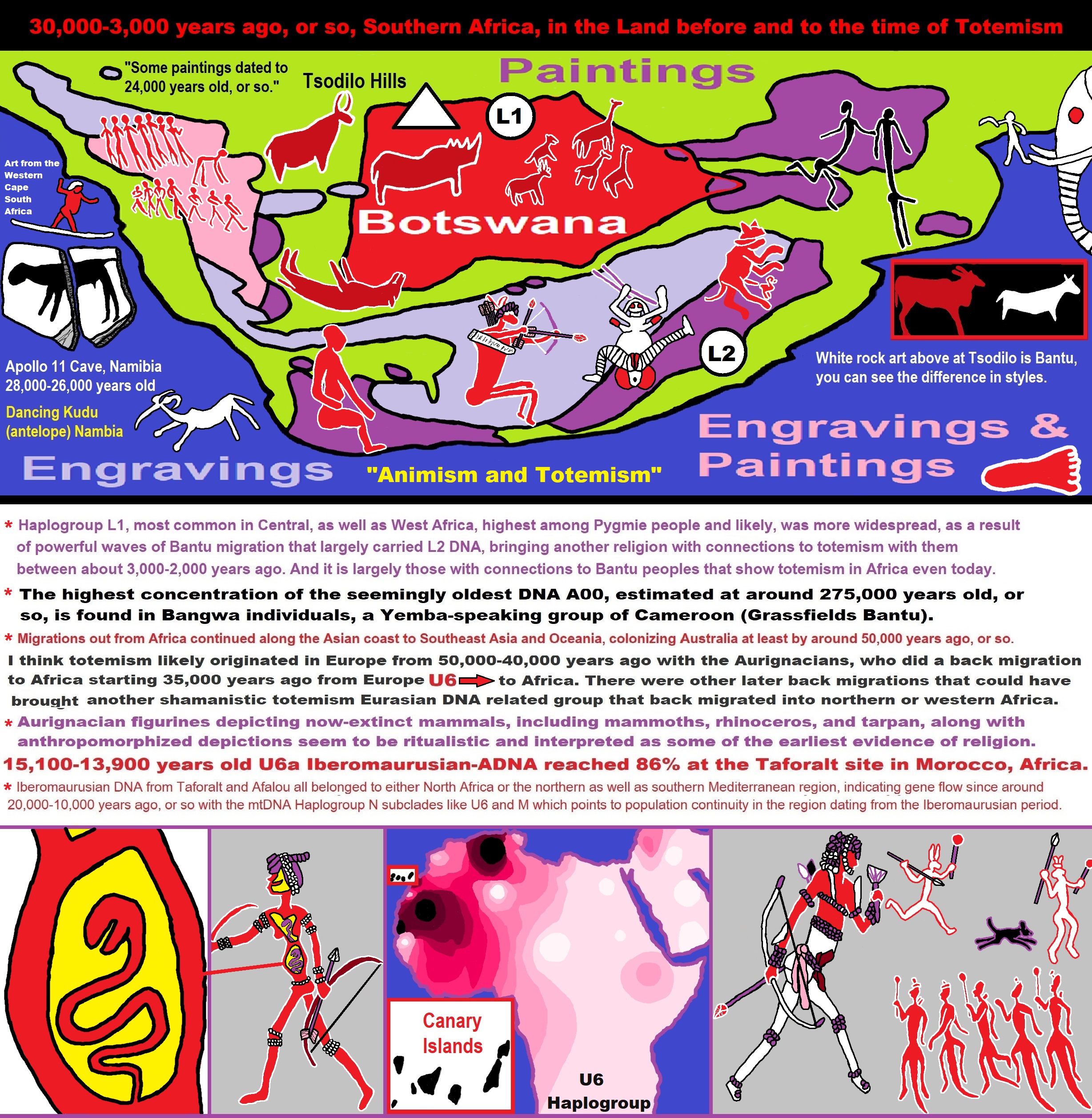

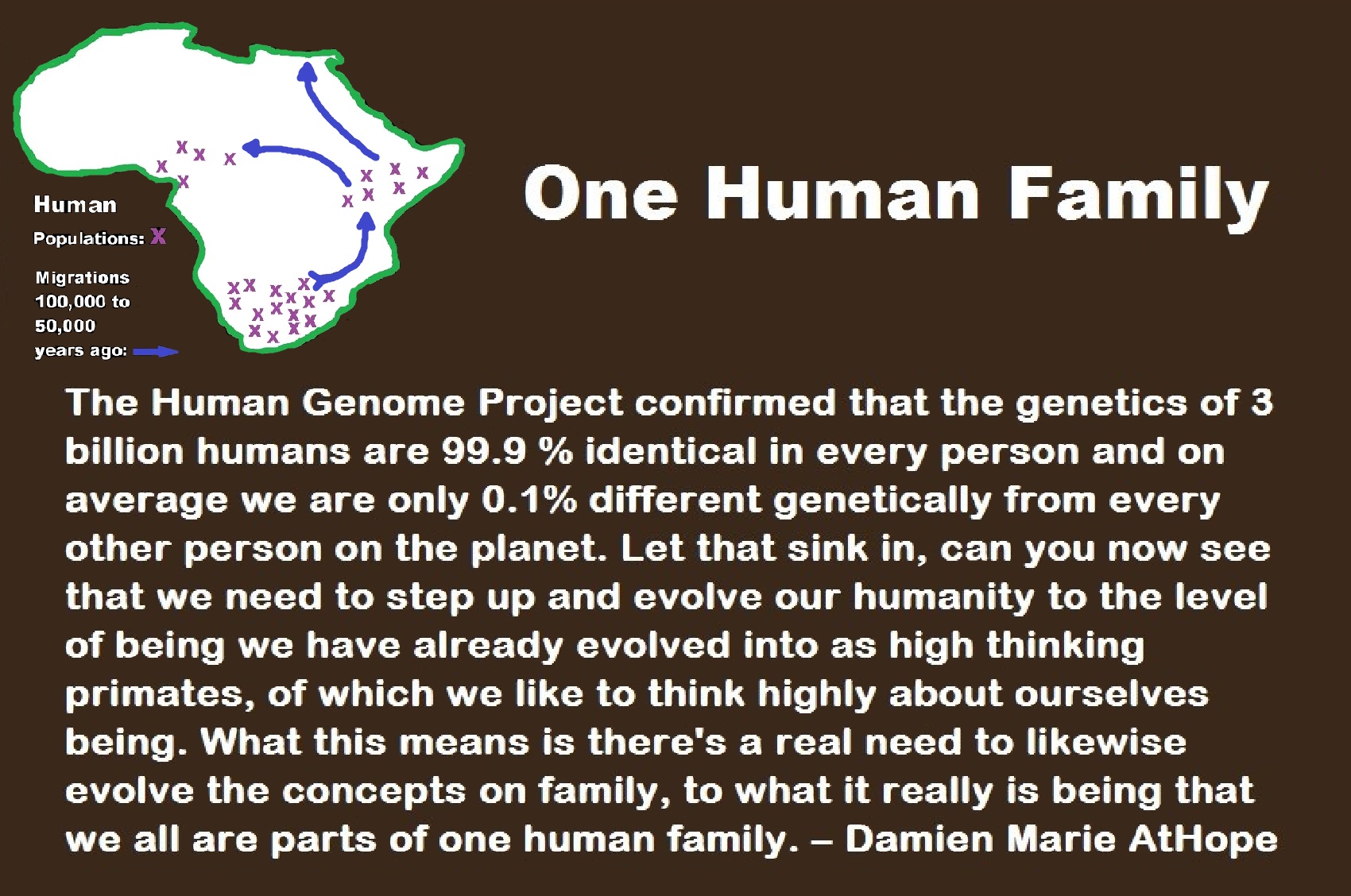

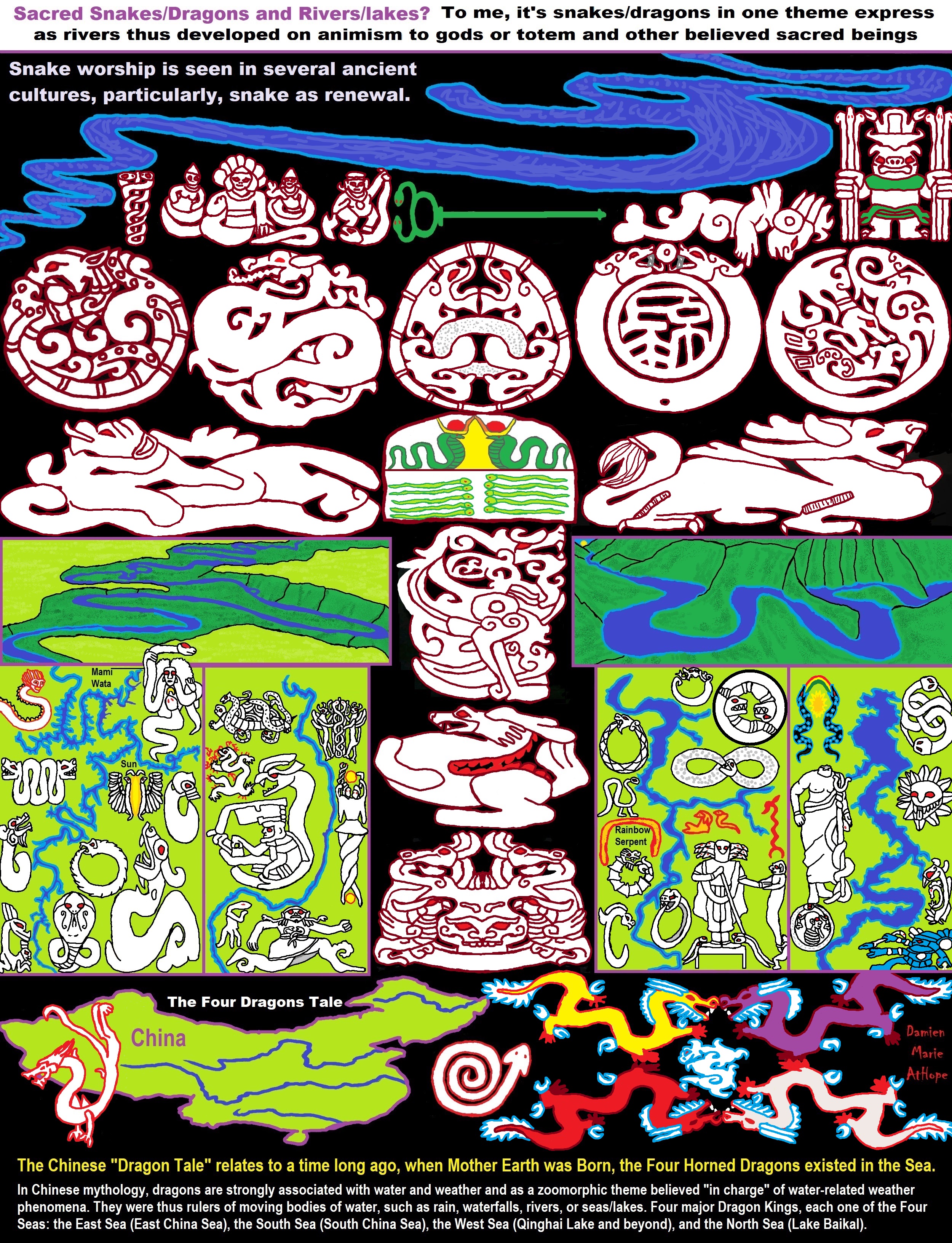

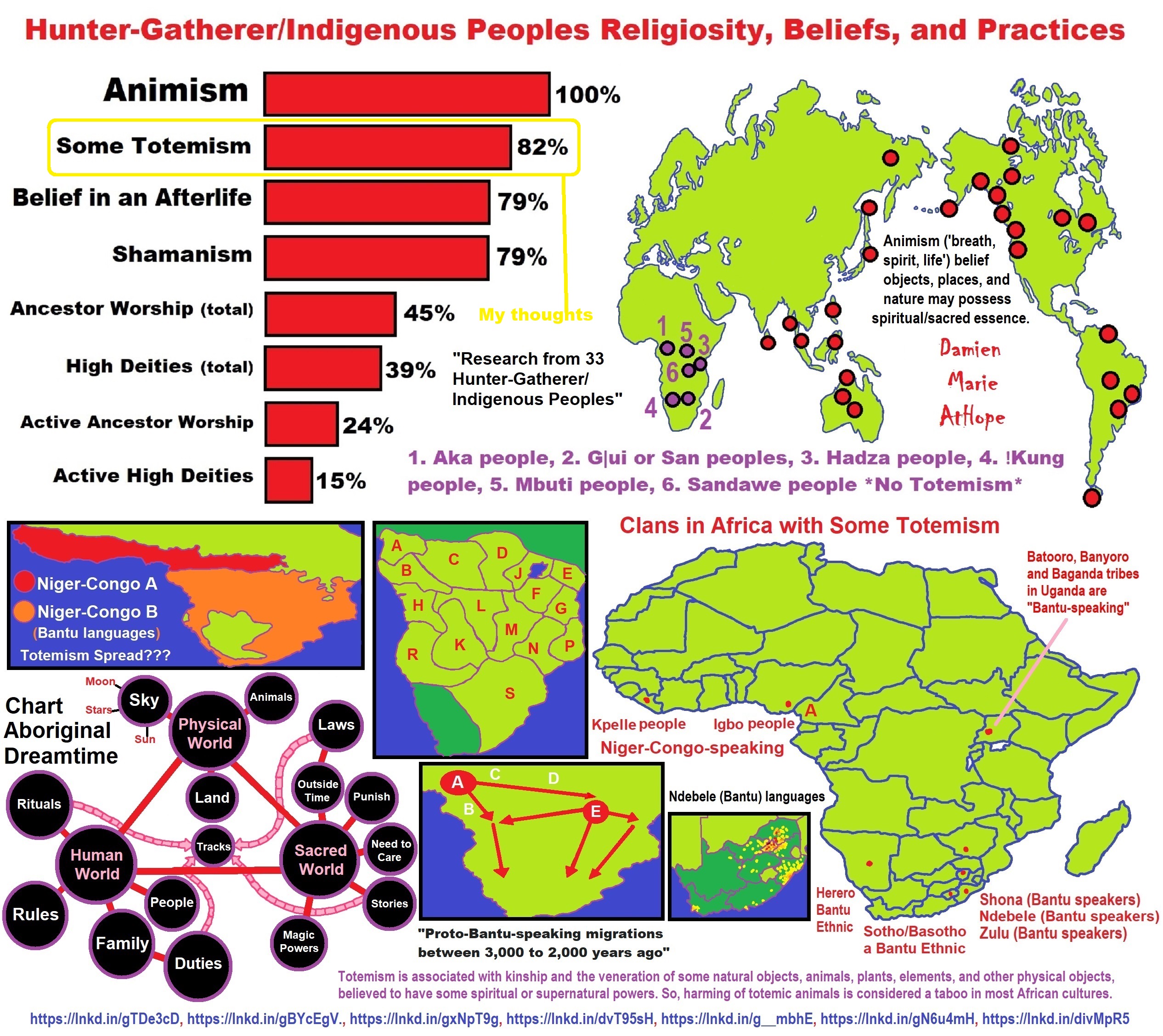

Explaining the Earliest Religious Expression of Animism (beginning 100,000 70,000 years ago?) to Totemism (beginning 30,000 to 3,000 years ago?) in Southern Africa

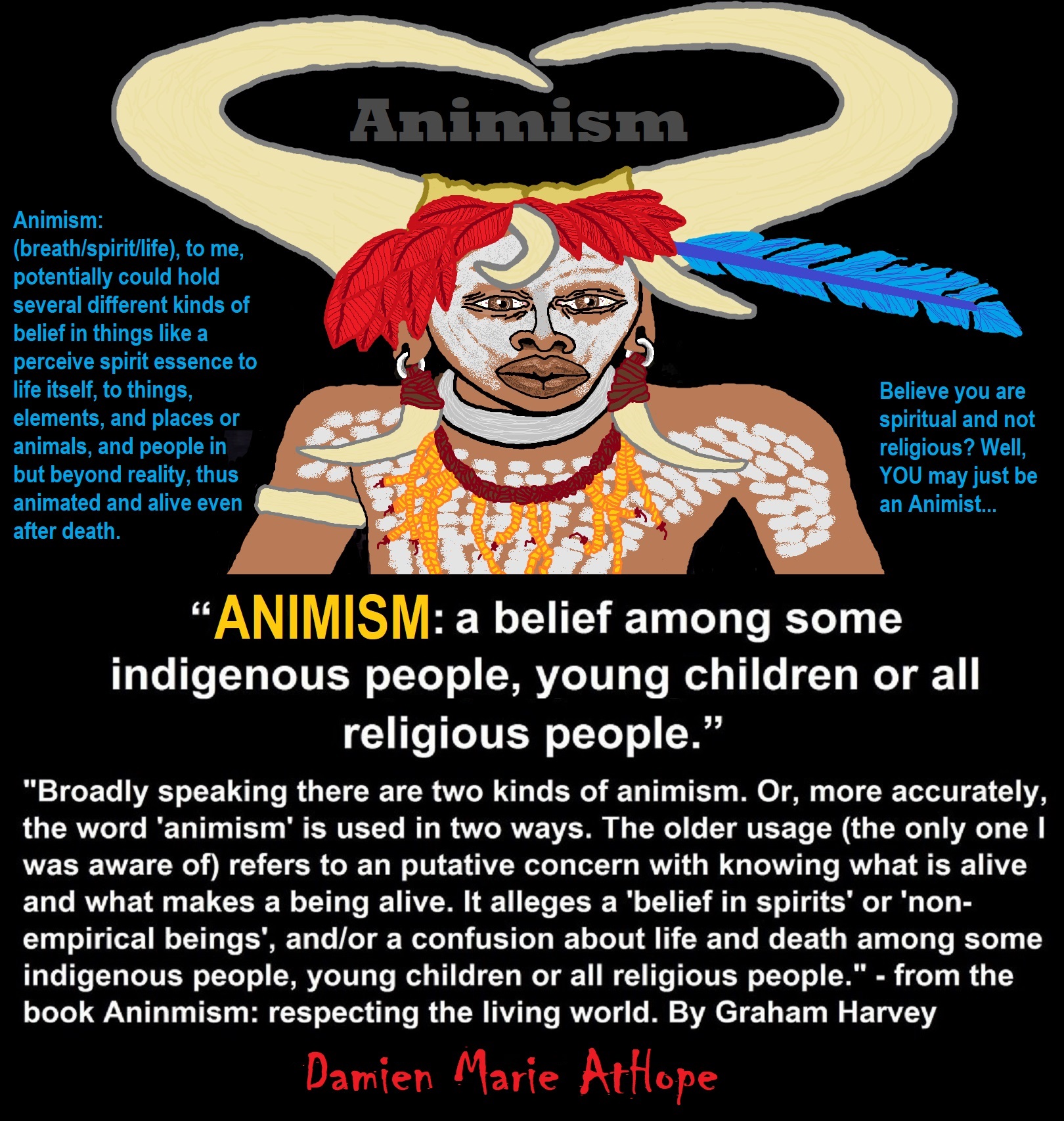

Animism: a belief among some indigenous people, young children, or all religious people!

Animism: an approximately 100,000-year-old belief system?

My Speculations are, Yes.

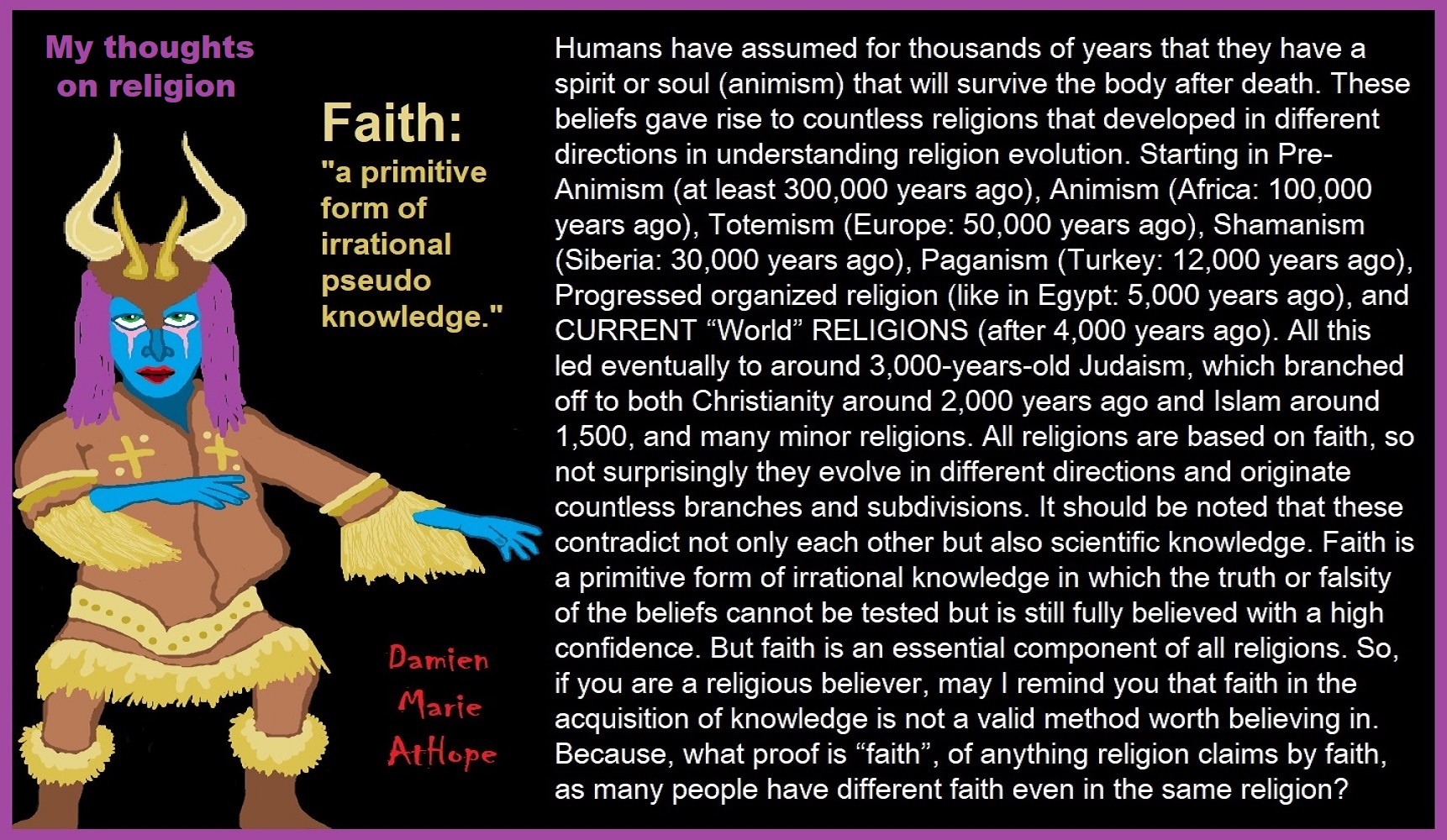

“Animism (from Latin anima, “breath, spirit, life”) is the religious belief that objects, places, and creatures all possess a distinct spiritual essence. Potentially, animism perceives all things—animals, plants, rocks, rivers, weather systems, human handiwork, and perhaps even words—as animated and alive. Animism is the oldest known type of belief system in the world that even predates paganism. It is still practiced in a variety of forms in many traditional societies. Animism is used in the anthropology of religion as a term for the belief system of many indigenous tribal peoples, especially in contrast to the relatively more recent development of organized religions. Although each culture has its own different mythologies and rituals, “animism” is said to describe the most common, foundational thread of indigenous peoples’ “spiritual” or “supernatural” perspectives. The animistic perspective is so widely held and inherent to most animistic indigenous peoples that they often do not even have a word in their languages that corresponds to “animism” (or even “religion”); the term is an anthropological construct.” ref

* “animist” Believe in spirit-filled life and/or afterlife (you are a hidden animist/Animism : an approximately 100,000-year-old belief system Qafzeh: Oldest Intentional Burial of 15 individuals with red ocher and Border Cave: intentional burial of an infant with red ochre and a shell ornament (possibly extending to or from Did Neanderthals teach us “Primal Religion (Animism?)” 120,000 Years Ago, as they too used red ocher? well it seems to me it may be Neanderthals who may have transmitted a “Primal Religion (Animism?)” or at least burial and thoughts of an afterlife they seem to express what could be perceived as a Primal “type of” Religion, which could have come first is supported in how 250,000 years ago Neanderthals used red ochre and 230,000 years ago shows evidence of Neanderthal burial with grave goods and possibly a belief in the afterlife. Think the idea that Neanderthals who may have transmitted a “Primal Religion” as crazy then consider this, it appears that Neanderthals built mystery underground circles 175,000 years ago. Evidence suggests that the Neanderthals were the first humans to intentionally bury the dead, doing so in shallow graves along with stone tools and animal bones. Exemplary sites include Shanidar in Iraq, Kebara Cave in Israel and Krapina in Croatia. Or maybe Neanderthals had it transmitted to them Evidence of earliest burial: a 350,000-year-old pink stone axe with 27 Homo heidelbergensis. As well as the fact that the oldest Stone Age Art dates to around 500,000 to 233,000 Years Old and it could be of a female possibly with magical believed qualities or representing something that was believed to)

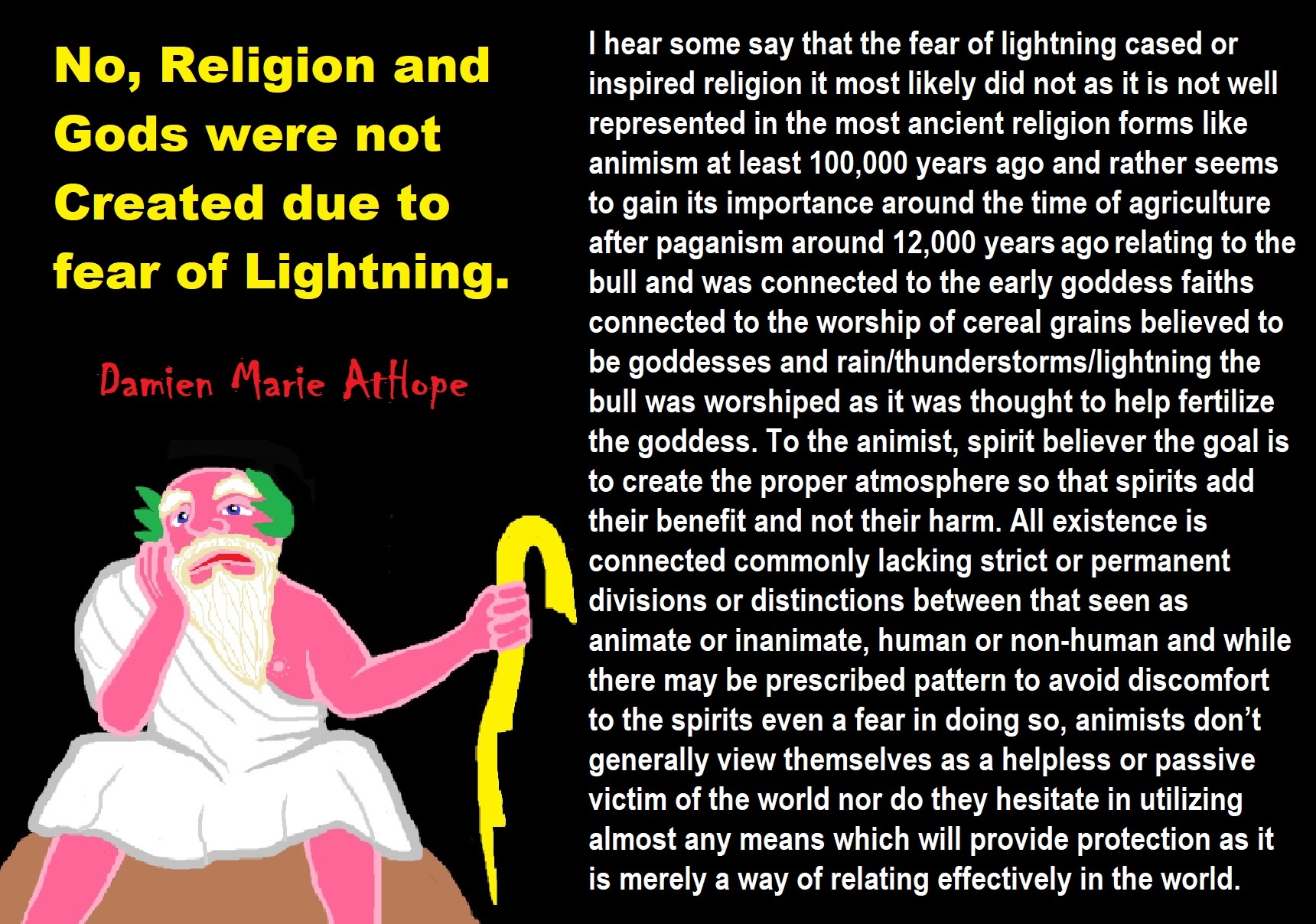

No, Religion and Gods were not Created due to fear of Lightning.

I hear some say that the fear of lightning, caused or inspired religion it most likely did not as it is not well represented in the most ancient religious forms like animism at least 100,000 years ago and rather seems to gain its importance around the time of agriculture after paganism around 12,000 years ago relating to the bull and was connected to the early goddess faiths connected to the worship of cereal grains believed to be goddesses and rain/thunderstorms/lightning the bull was worshiped as it was thought to help fertilize the goddess. To the animist, spirit believer the goal is to create the proper atmosphere so that spirits add their benefit and not their harm. All existence is connected commonly lacking strict or permanent divisions or distinctions between that seen as animate or inanimate, human or non-human and while there may be prescribed patterns to avoid discomfort to the spirits even a fear in doing so, animists don’t generally view themselves as a helpless or passive victim of the world nor do they hesitate in utilizing almost any means which will provide protection as it is merely a way of relating effectively in the world. ref

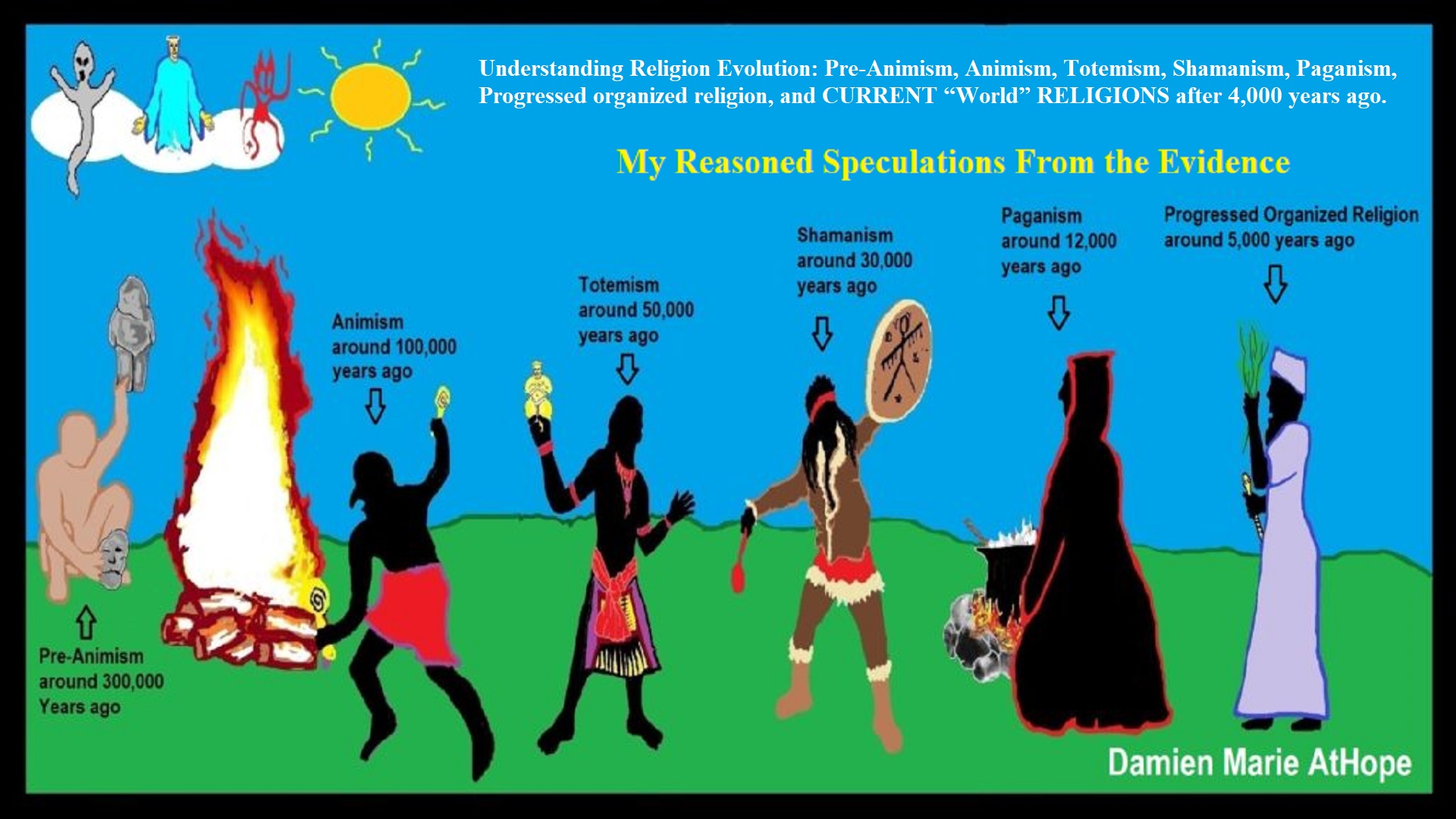

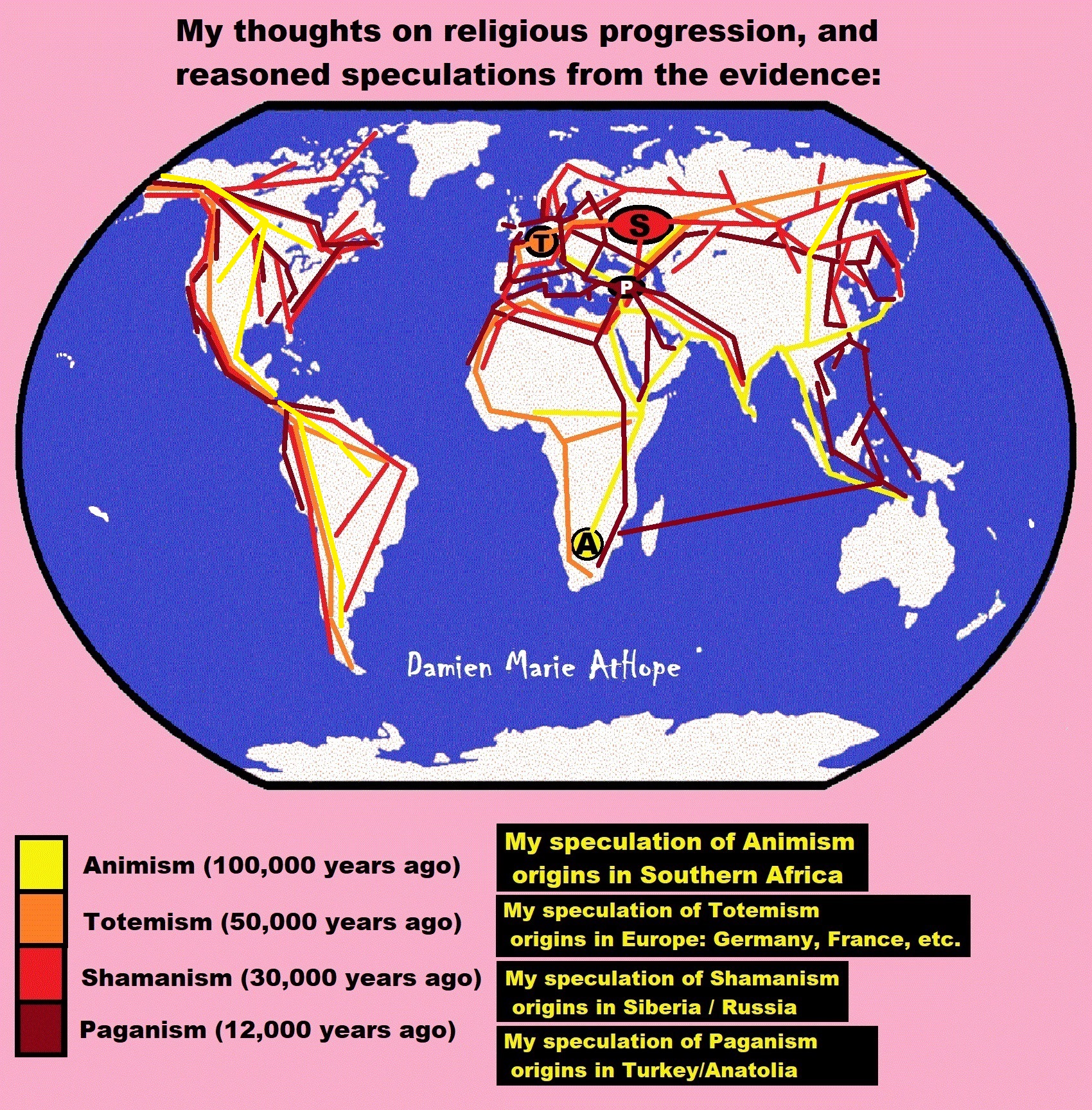

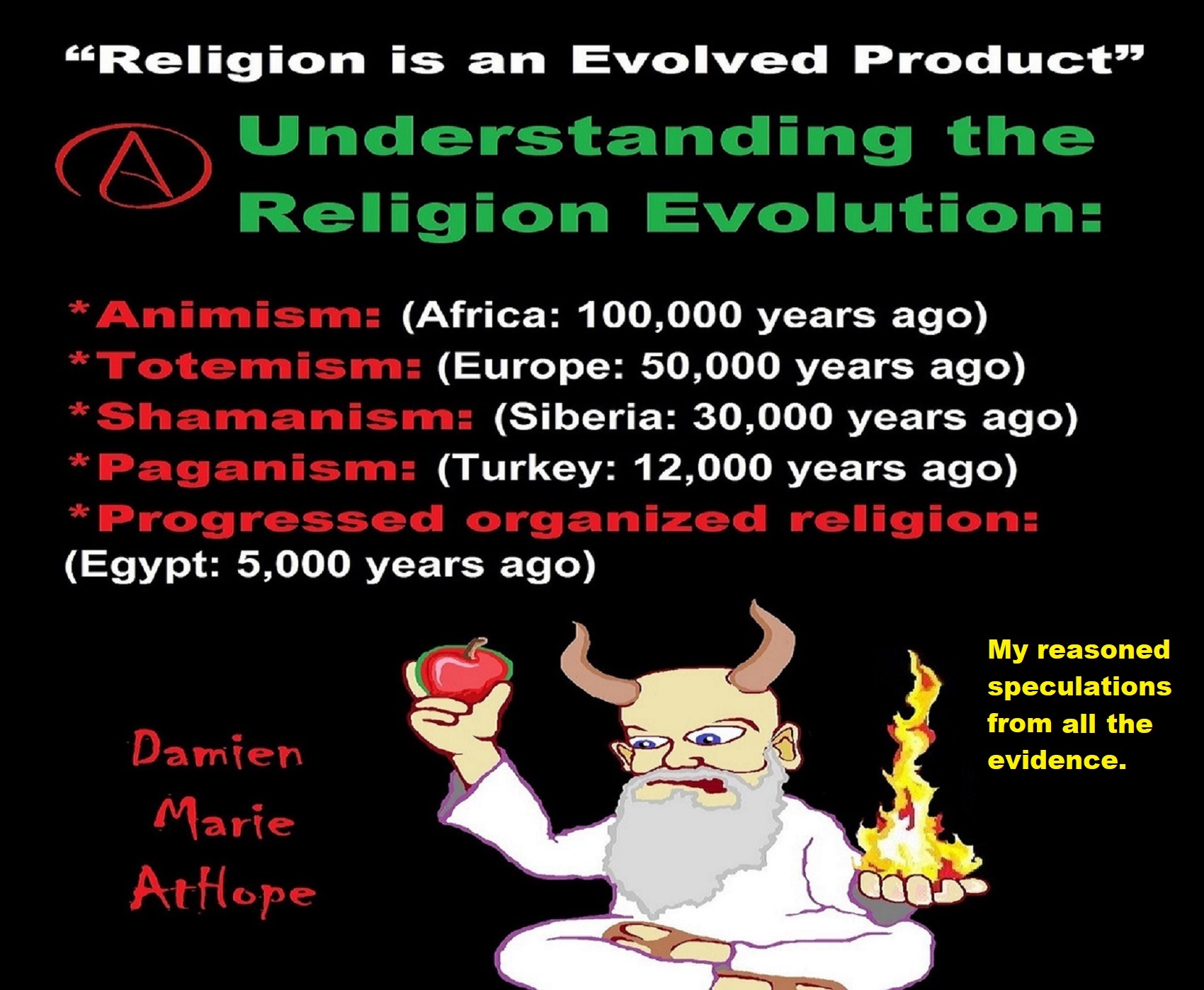

Understanding Religion Evolution

My thoughts on Religion Progression

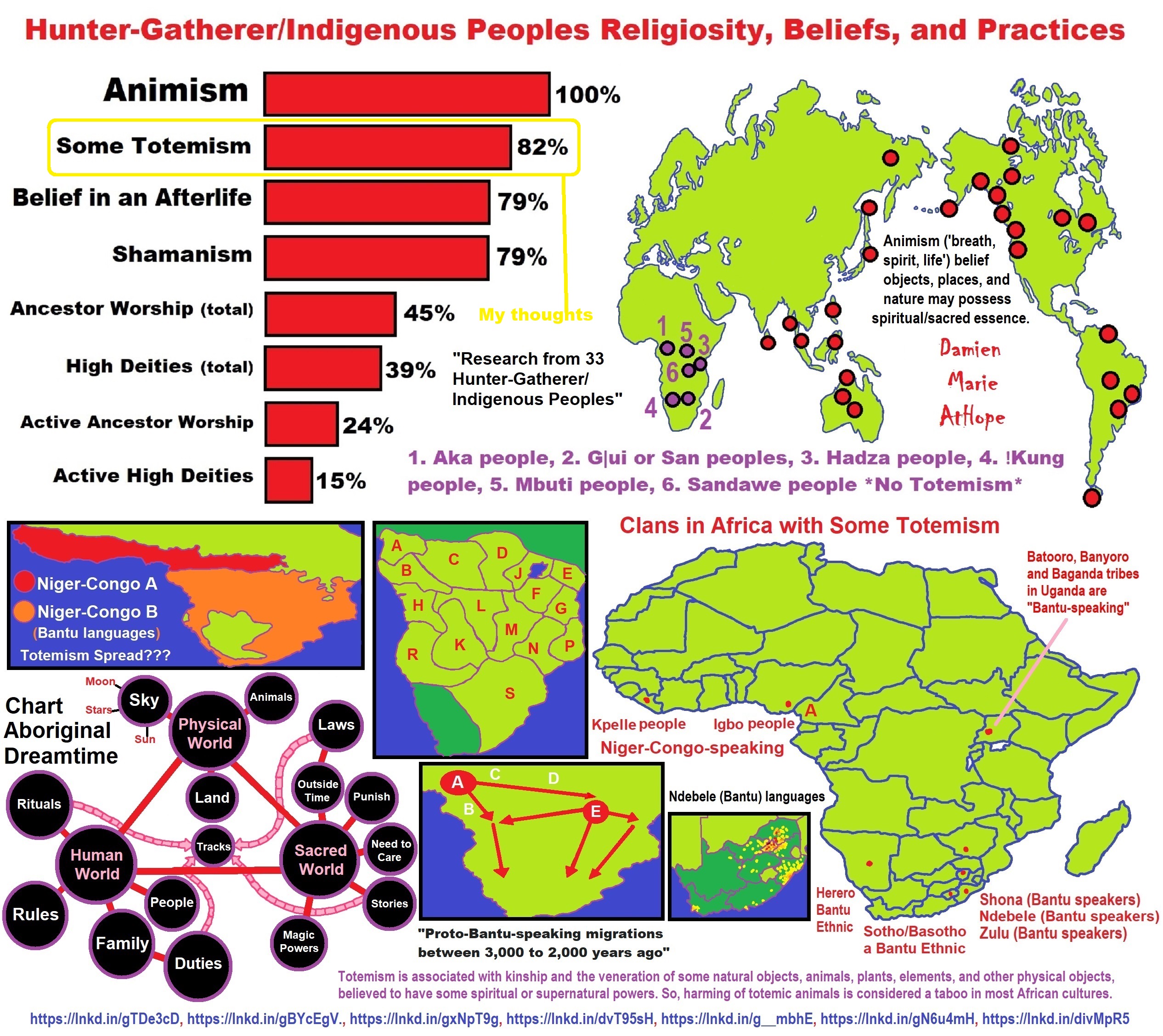

- Animism (a belief in a perceived spirit world) passably by at least 100,000 years ago “the primal stage of early religion”

- Totemism (a belief that these perceived spirits could be managed with created physical expressions) passably by at least 50,000 years ago “progressed stage of early religion”

- Shamanism (a belief that some special person can commune with these perceived spirits on the behalf of others by way of rituals) passably by at least 30,000 years ago

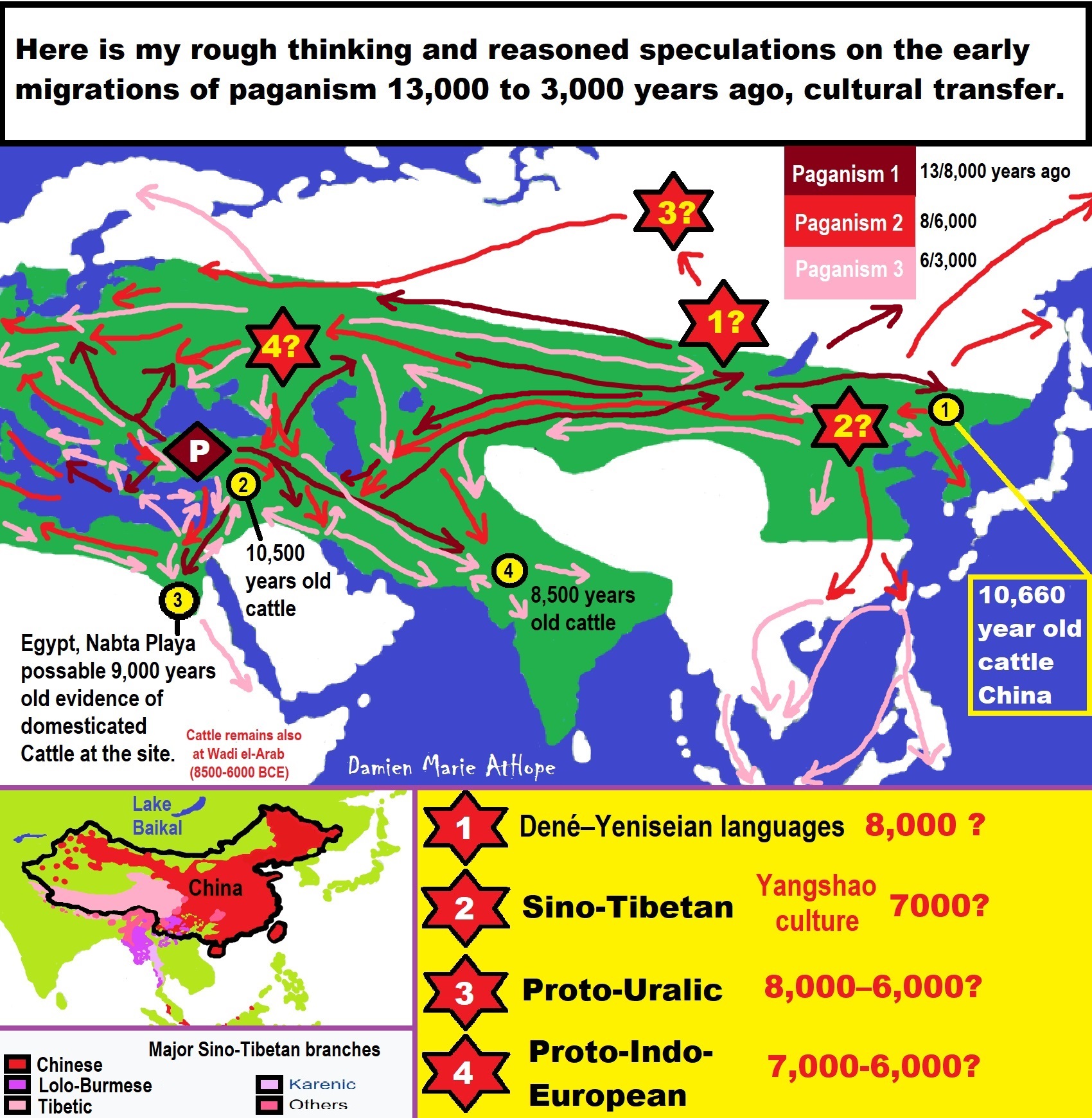

- Paganism “Early organized nature-based religion” mainly like an evolved shamanism with gods (passably by at least 12,000 years ago).

- Institutional religion “organized religion” as a social institution with official dogma usually set in a hierarchical/bureaucratic structure that contains strict rules and practices dominating the believer’s life.

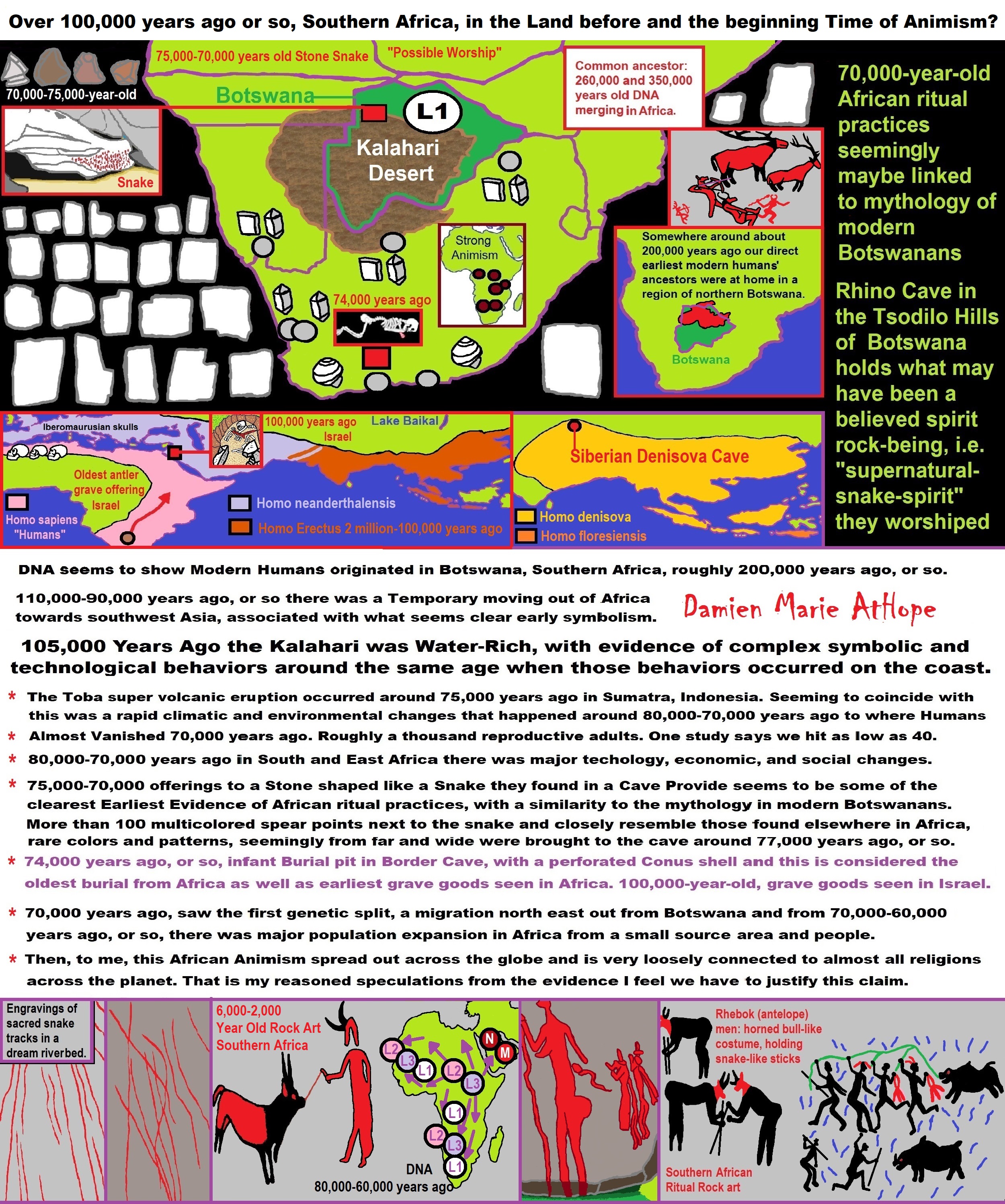

Over 100,000 years ago or so, Southern Africa, in the Land before and the beginning Time of Animism?

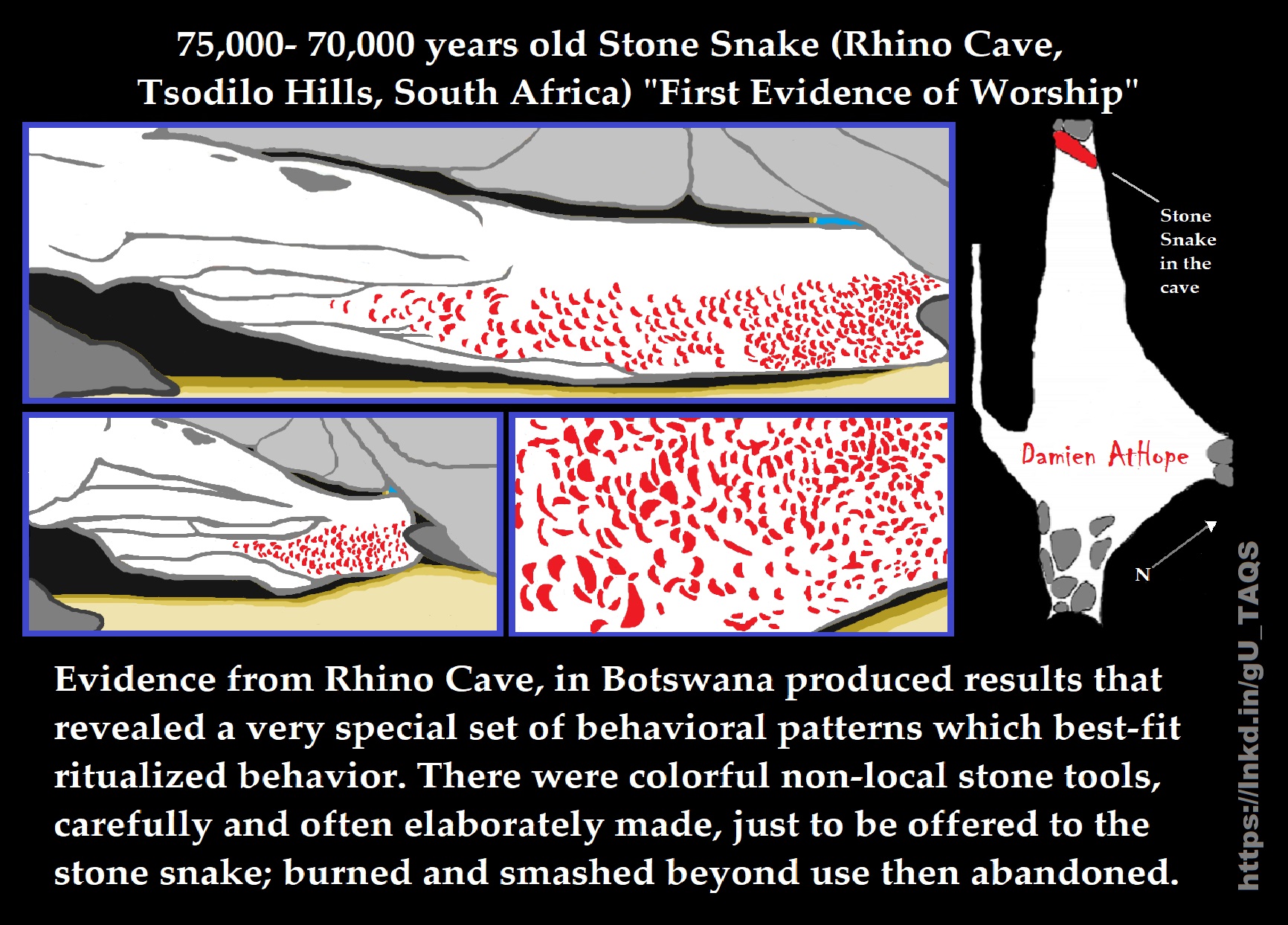

75,000-70,000 years old Stone Snake Possible Worship

Then, to me, this African Animism spread out across the globe and is very loosely connected to almost all religions across the planet. That is my reasoned speculations from the evidence I feel we have to justify this claim.

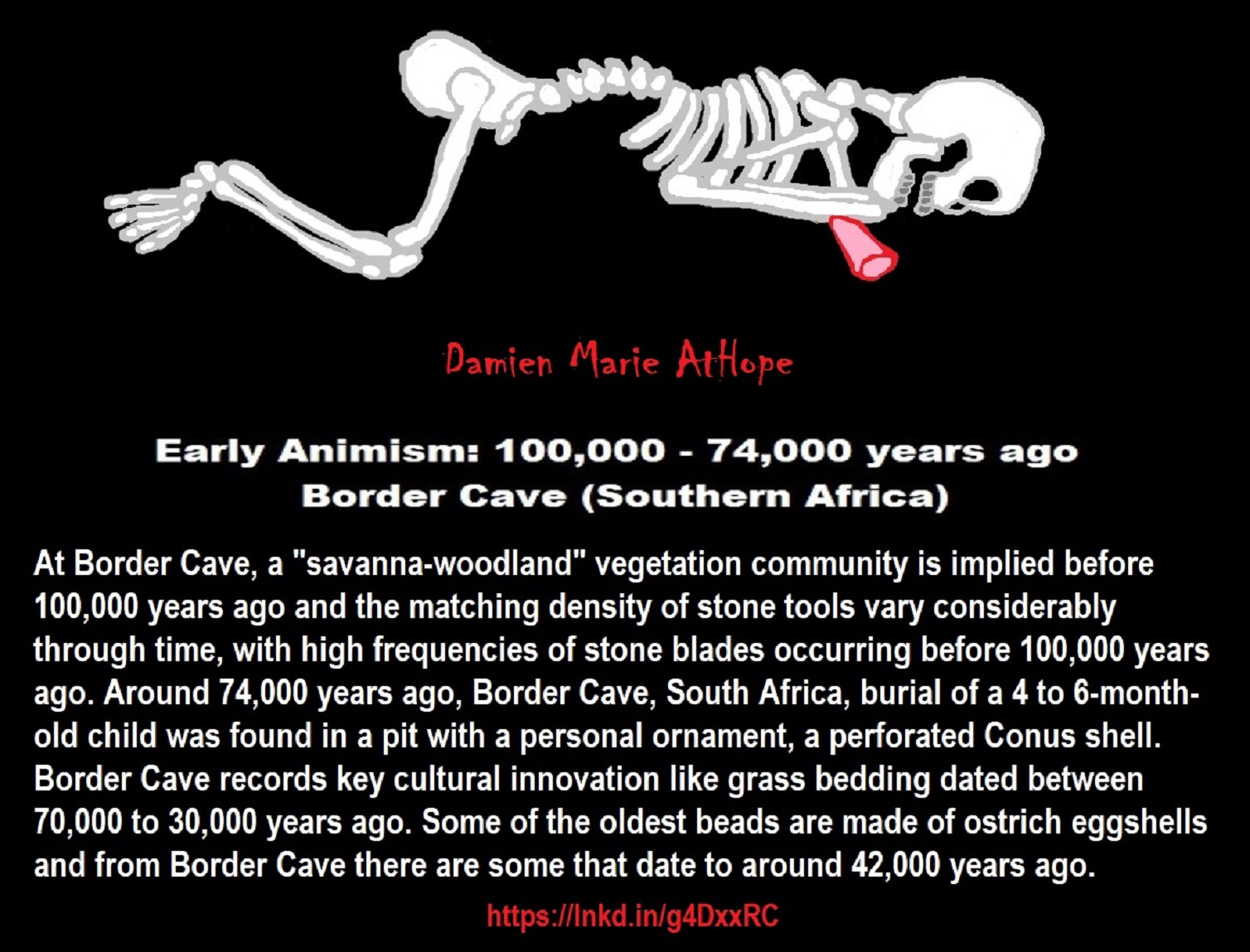

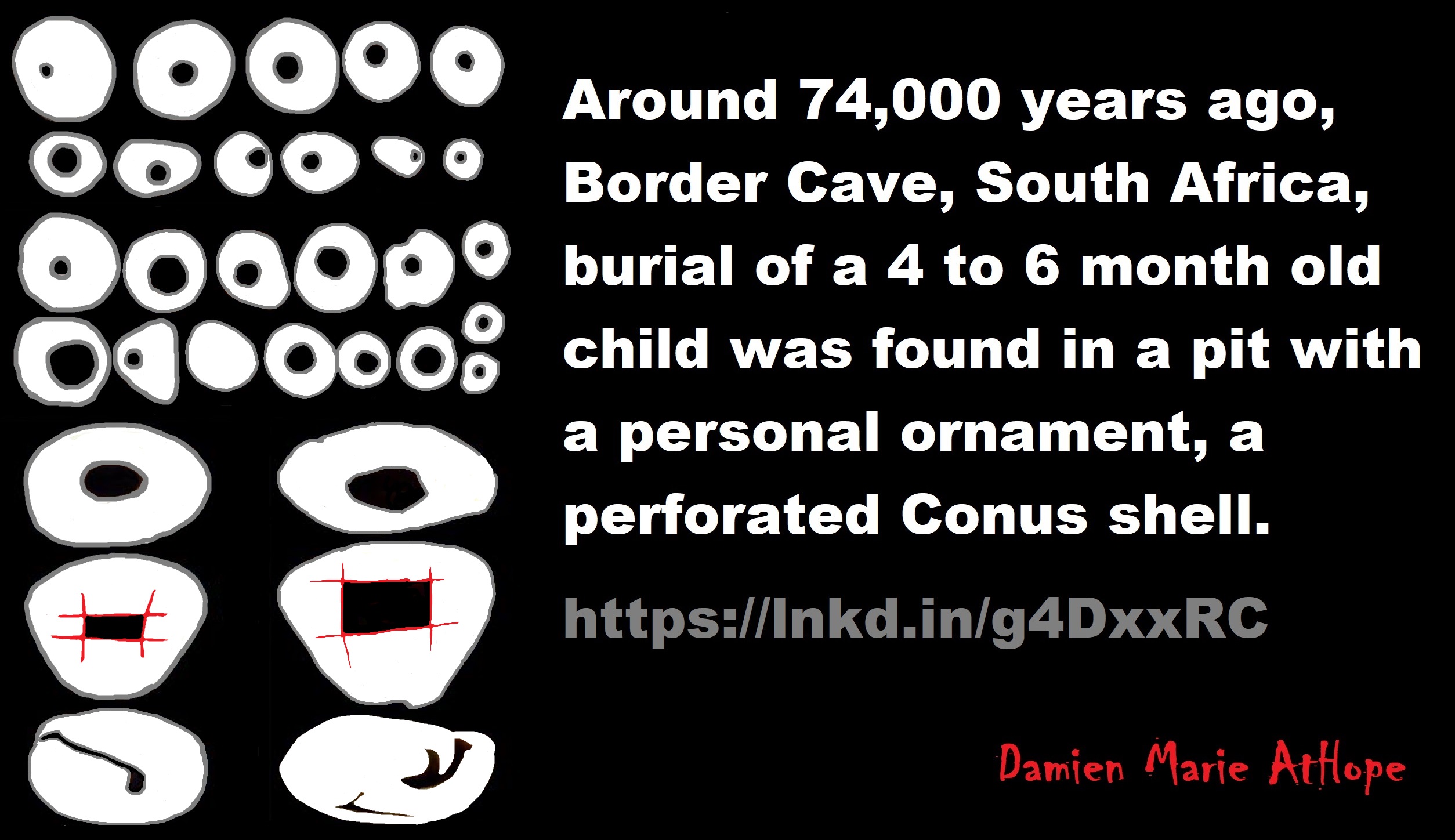

74,000 years ago, or so, infant Burial pit in Border Cave, with a perforated Conus shell, and this is considered the oldest burial from Africa as well as earliest grave goods are seen in Africa. 100,000-year-old, grave goods are seen in Israel.

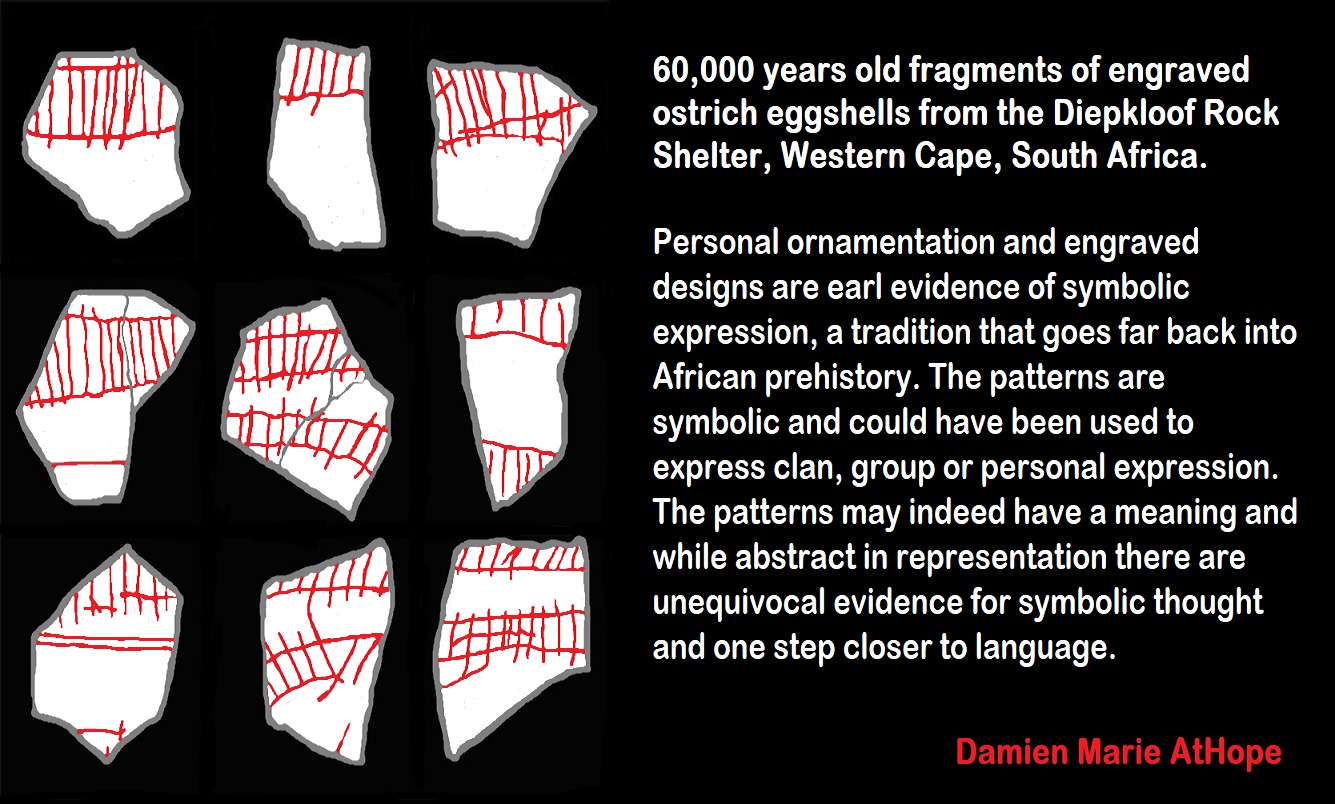

In Africa, it is interpreted that after around 500,000 years ago as some of the earliest evidence for collective ritual. The ubiquitous use of red ochre by 170,000 years ago.

In Africa, symbolic culture was in place by around 100 years ago seen in evidence such as red ochre use, geometric engravings, beads. In Israel around this time, burials even with animals and ochre. In southern Africa around 70,000 to 75,000 years ago sees the first worship of a monolithic stone snake stone in a cave before humanity’s common ancestry separated out of Africa.

Rhino Cave in the Tsodilo Hills of Botswana holds what may have been a believed spirit rock-being, i.e. “supernatural- snake-spirit” they worshiped.

Offerings to a Stone Snake provide the Earliest clear Evidence of Religion in 70,000-year-old African ritual practices linked to the mythology of modern Botswanans.

Is there a seeming gradual evolution of collective ritual, out of which was forged a template of symbolic culture, or at least elements which might be inferred by the time of “Modern Human” dispersal beyond Africa? So, one can reason red and glittery pigment use in Rain Serpents in Northern Australia and Southern Africa: a Common Ancestry?

Animism: Respecting the Living World by Graham Harvey

“How have human cultures engaged with and thought about animals, plants, rocks, clouds, and other elements in their natural surroundings? Do animals and other natural objects have a spirit or soul? What is their relationship to humans? In this new study, Graham Harvey explores current and past animistic beliefs and practices of Native Americans, Maori, Aboriginal Australians, and eco-pagans. He considers the varieties of animism found in these cultures as well as their shared desire to live respectfully within larger natural communities. Drawing on his extensive casework, Harvey also considers the linguistic, performative, ecological, and activist implications of these different animisms.” ref

“Religion is an Evolved Product”

What we don’t understand we can come to fear. That which we fear we often learn to hate. Things we hate we usually seek to destroy. It is thus upon us to try and understand the unknown or unfamiliar not letting fear drive us into the unreasonable arms of hate and harm.

“An Archaeological/Anthropological Understanding of Religion Evolution”

If you are a religious believer, may I remind you that faith in the acquisition of knowledge is not a valid method worth believing in. Because, what proof is “faith”, of anything religion claims by faith, as many people have different faith even in the same religion?

Did Neanderthals teach us

“Primal Religion (Pre-Animism/Animism?)”

120,000 Years Ago?

Evidence suggests that the Neanderthals were the first humans to intentionally bury the dead, doing so in shallow graves along with stone tools and animal bones. 130,000 years ago – Earliest undisputed evidence for intentional burial. Neanderthals bury their dead at sites such as Krapina in Croatia. ref

Homo sapiens – is known to have reached the Levant between 120,000 and 90,000 years ago, but that exit from Africa evidently went extinct. ref

Homo sapiens – is known to have reached the Levant between 120,000 and 90,000 years ago, but that exit from Africa evidently went extinct. ref

A population that diverged early from other modern humans in Africa contributed genetically to the ancestors of Neanderthals from the Altai Mountains roughly 100,000 years ago. By contrast, we do not detect such a genetic contribution in the Denisovan or the two European Neanderthals. In addition to later interbreeding events, the ancestors of Neanderthals from the Altai Mountains and early modern humans met and interbred, possibly in the Near East, many thousands of years earlier than previously thought. ref

In 2005, a set of 7 teeth from Tabun Cave in Israel were studied and found to most likely belong to a Neandertal that may have lived around 90,000 years ago ref

and another Neandertal (C1) from Tabun Cave was estimated to be in northern Israel. The limb bones are characteristic of Neanderthals, whereas the lower jaw has a combination of Neanderthal and earlier features. These fossils date from more than 150,000 years ago ref

A fossilized human jawbone in a collapsed cave in Israel that they said is between 177,000 and 194,000 years old. ref

The Tabun Cave contains a Neanderthal-type female, dated to about 120,000 years ago. It is one of the most ancient human skeletal remains found in Israel. ref

Objects at Tabun suggests that ancestral humans used fire at the site on a regular basis since about 350,000 years ago. ref

The remains of seven adults and three children were found, some of which (Skhul;1,4, and 5) are claimed to have been burials. ref

Assemblages of perforated Nassarius shells (a marine genus) significantly different from local fauna have also been recovered from the area, suggesting that these people may have collected and employed the shells as a bead as they are unlikely to have been used as food. ref

Skhul Layer B has been dated to an average of 81,000-101,000 years ago with the electron spin resonance method, and to an average of 119,000 years ago with the thermoluminescence method. ref

Skhul 5 had the mandible of a wild boar on its chest. The skull displays prominent supraorbital ridges and jutting jaw, but the rounded braincase of modern humans. When found, it was assumed to be an advanced Neanderthal, but is today generally assumed to be a modern human, if a very robust one. ref, ref

It is possible that Neandertals and early moderns did make contact in the region and it may be possible that the Skhul and Qafzeh hominids are partially of Neandertal descent. Non-African modern humans contain 1-4% Neandertal genetic material, with hybridization possibly having taken place in the Middle East. ref

It has been suggested, however, that the Skhul/Qafzeh hominids represent an extinct lineage. If this is the case, modern humans would have re-exited Africa around 70,000 years ago, crossing the narrow Bab-el-Mandeb strait between Eritrea and the Arabian Peninsula. ref

Modern humans were present in Arabia and South Asia earlier than currently believed, and probably coincident with the presence of Homo sapiens in the Levant between ca 130 and 70,000 years ago. ref

This is the same route proposed to have been taken by the people who made the modern tools at Jebel Faya. ref

This Neandertal girl’s toe bone had ancient DNA her ancestors picked up by mating with modern humans more than 100,000 years ago. ref

If the Skhul burials took place within a relatively short time span, then the best age estimate lies between 100,000 and 135,000 years ago. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that the material associated with the Skhul IX burial is older than those of Skhul II and Skhul V. These and other recent age estimates suggest that the three burial sites, Skhul, Qafzeh, and Tabun are broadly contemporaneous, falling within the time range of 100,000 to 130,000 years ago. The presence of early representatives of both early modern humans and Neanderthals in the Levant during Marine Isotope Stage 5 inevitably complicates attempts at segregating these populations by date or archaeological association. Nevertheless, it does appear that the oldest known symbolic burials are those of early modern humans at Skhul and Qafzeh. This supports the view that, despite the associated Middle Palaeolithic technology, elements of modern human behavior were represented at Skhul and Qafzeh prior to 100,000 years ago. ref

As some of the first bands of modern humans moved out of Africa, they met and mated with Neandertals about 100,000 years ago—perhaps in the fertile Nile Valley, along the coastal hills of the Middle East, or in the once-verdant Arabian Peninsula. These early modern humans’ own lineages died out, and they are not among the ancestors of living people. But a small bit of their DNA survived in the toe bone of a Neandertal woman who lived more than 50,000 years ago in Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains of Siberia, Russia. ref

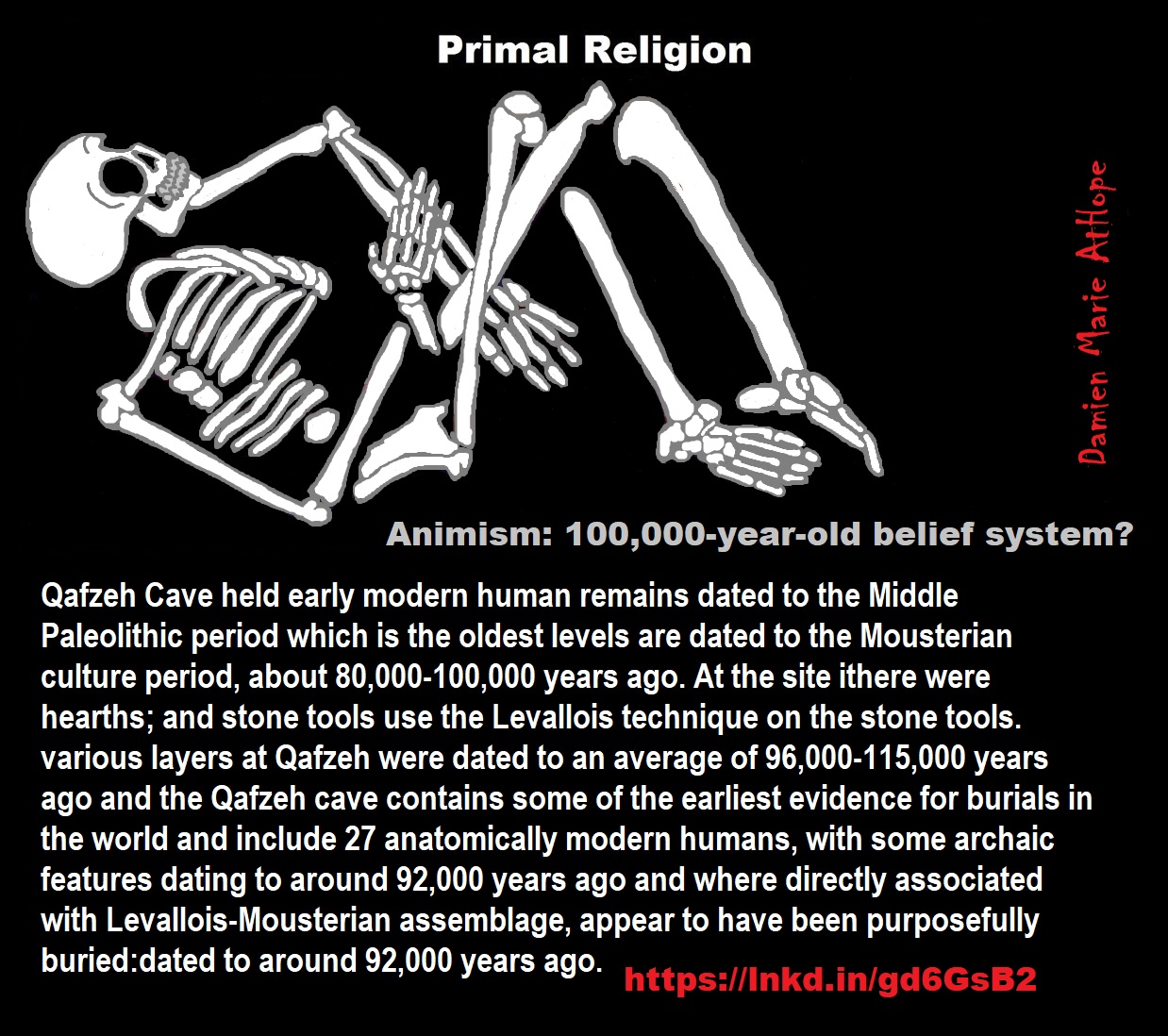

100,000 years ago – The oldest known ritual burial of modern humans at Qafzeh in Israel: a double burial of what is thought to be a mother and child. The bones have been stained with red ochre. By 100,000 years ago anatomically modern humans migrated to the middle east from Africa. However, the fossil record of these humans ends after 100,000 years ago, leading scholars to believe that the population either died out or returned to Africa. 100,000 to 50,000 years ago – Increased use of red ochre at several Middle Stone Age sites in Africa. Red Ochre is thought to have played an important role in ritual. The human skeletons were associated with red ochre which was found only alongside the bones, suggesting that the burials were symbolic in nature. ref

Within Israel’s Qafzeh Cave, researchers found evidence of a sophisticated culture and remains of modern humans that are up to 100,000 years old. About 100,000 years ago, tall, long-limbed humans lived in the caves of Qafzeh, east of Nazareth, and Skhul, on Israel’s Mount Carmel. The Skhul-Qafzeh people gathered shells from a shoreline more than 20 miles away, decorated them, and strung them as jewelry. They buried their dead, most likely with grave goods, and cared for their living: A child born with hydrocephalus, sometimes called water on the brain, lived with a profound disability until the age of 3 or so, a feat only possible with patient, loving care. The Qafzeh humans were around 92,000 years old, and the Skhul people were even older, averaging about 115,000 years ago. Around 75,000 years ago, close to the time, the Homo sapiens of Skhul and Qafzeh disappear from the fossil record, the climate in the Levant shifted in Neanderthals’ favor. Rapid glaciation left the region both cooler and drier. Steppe-deserts advanced, and forests retreated. Neanderthal bodies were adapted for colder conditions. Their stocky, barrel-chested build lost less heat and offered plenty of insulating muscle, and their systems were streamlined to extract calories from food and turn them into body heat. The Skhul-Qafzeh people’s slender physiques were better at getting rid of heat than making it. Or, as Shea says, “Neanderthals liked cold and dry. Our ancestors liked warm and wet. It got cold, and humans retreated.” ref, ref

Neanderthals may have transmitted:

“Primal Religion (Pre-Animism/Animism?)” or at least burial and thoughts of an afterlife may have been transferred from Neanderthals to arcane humans when they bread with them.

Neanderthals, also interbred with Homo erectus, the “upright walking man,” Homo habilis, the “tool-using man,” and possibly others which means they could have possibly learned some pre-animism ideas from one of them like that expressed in portable anthropomorphic art that could have related to so kind of ancestor veneration as well. ref

Pre-Animism (at least 300,000 years ago)

- Around 500,000 – 233,000 years ago, Oldest Anthropomorphic art (Pre-animism) is Related to Female

- 400,000 Years Old Sociocultural Evolution

- Pre-Animism: Portable Rock Art at least 300,000-year-old

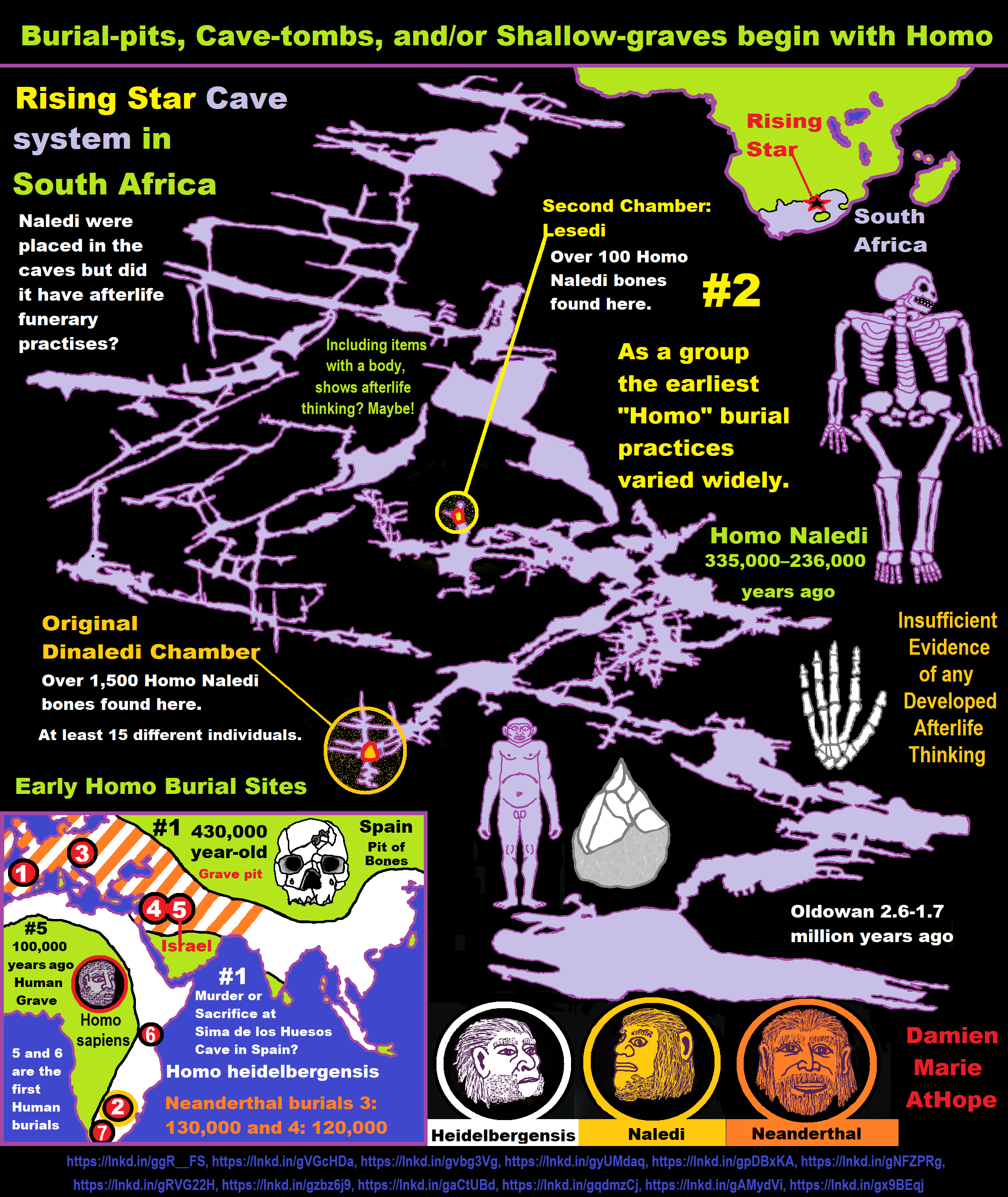

- Homo Naledi and an Intentional Cemetery “Pre-Animism” dating to around 250,000 years ago?

First, there was Pre-Animism: Portable Rock Art

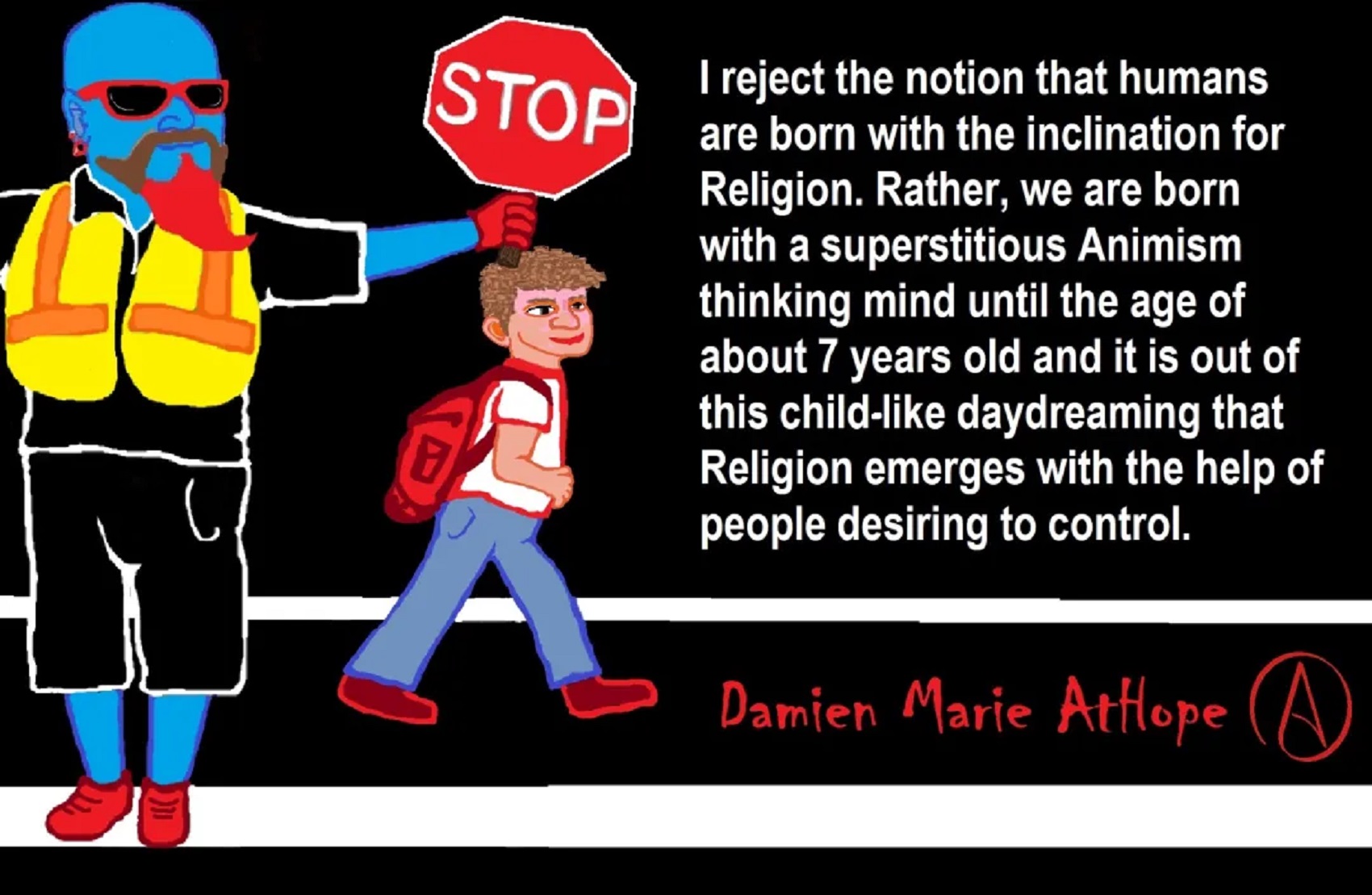

Around a million years ago, I surmise that Pre-Animism, “animistic superstitionism”, began and led to the animistic somethingism or animistic supernaturalism, which is at least 300,000 years old and about 100,00 years ago, it evolves to a representation of general Animism, which is present in today’s religions.

Anthropology states that Pre-animism is “A stage of religious development supposed to have preceded animism, in which material objects were believed to contain spiritual energy.” ref

To me, it is a kind of “Primal Pre-Religion (Pre-Animism/Proto-Animism” or at least burial and thoughts of an afterlife, may have been transferred from the Neanderthals to arcane humans when they bred with them. Neanderthals, also interbred with Homo erectus, the ‘upright walking man,’ Homo habilis, the ‘tool-using man” and possibly others, which means they could have possibly learned some pre-animism ideas from one of the other hominids thas is expressed in portable anthropomorphic art, which could have been related to some kind of ancestor veneration as well. ref

Around 500,000 to 400,000 years ago, the earliest European hominin crania associated with Acheulean handaxes are at the sites of Arago, Atapuerca Sima de los Huesos, and Swanscombe. The Atapuerca fossils and the Swanscombe cranium belong to the Neandertals whereas the Arago hominins have been attributed to Homo heidelbergensis or to a subspecies of Homo erectus, which is an incipient stage of Neandertal evolution. A cranium (Aroeira 3) from the Gruta da Aroeira (Almonda karst system, Portugal) dating to 436,000 to 390,000 years ago provides important evidence on the earliest European Acheulean-bearing hominins as well as could show a transfer of ideas. ref

Homo erectus, the “upright walking man,” lived between 1.89 million and 143,000 years ago, whereas early African Homo erectus and sometimes called Homo ergaster are the oldest known early humans to have possessed modern human-like attributes. The earliest evidence of campfires occurred during the time of Homo erectus. While there is evidence that campfires were used for cooking, and probably sharing food, they are likely to have been placed for social interaction, used for warmth, to keep away large predators, and possibly even relating to Primal Religion, “Pre-Animism,” which may have included Fire Sacralizing and/or Worship. ref

Neanderthals used fire 400,000 years ago and there is evidence of a 300,000-year-old ‘campfire’ from Israel, which is not that surprising since our human ancestors have controlled fire from 1.5 million to 300,000 years ago and beyond. The benefits of fire are not only to cook food and fend off predators, but also extended their day and added to the community by how a fire in the middle of the darkness mellows and also excite people, which possibly inspire pre-animism’s “animistic superstitionism.” ref

Sun-worshipping baboons rise early to catch the African sunrise and race each other to the top for the best spots. Thus, we may rightly ponder how much did fireside tales aid to the socio-cultural-religious transformations or evolution. In the dark under flickering lights from the stars above and the fire below was the scene of wonder, fear, and mystery. Was superstition expanded and religion further imagined? It would seem that superstition was expanded and religion further imagined because both heavenly lights and flickering fire have been sacralized. This does seem to be somewhat supported by a researcher who spent 40 years studying African Bushmen who gathered evidence of the importance of gathering around a nighttime campfire as a time for bonding, social information, and shared emotions with fireside tales. This may provide a correlation that our prehistoric ancestors likely lived in a similar way to how the Bushmen currently do. Although, we cannot directly peer into the past or fully know the past from the indigenous Bushmen, these people do live in a way that our ancient ancestors lived for around 99% of our evolution.

Fire, as sacred or magic, can be seen in:

- Consuming fire as volcanos/lightning as gods and gods’power/vengeance.

- Holy fire as a means of transformation or magical purification.

- A magical being as used in worshipping the sun or punishment such as hell/lake of fire, which could be seen as mixing fire and water, if only symbolically.

- Ceremonies such as bonfires, eternal flames, or sacred candles/incense/lights/lamps are in one form or another incorporated in many faiths such as judaism, christianity, islam, hinduism, buddhism, sikhism, bahaism, shintoism, taoism, etc. ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

All this worship of fire/sun is hardly special to humans since many other primates worship thunderstorms, others fire, or sunrises. We have forgotten how nature worship, animistic superstitionism, animistic somethingism, or animistic supernatralism is presented in today’s religion. The mega religions now think they are removed from animistic superstitionism, which they are not. Their rituals, beliefs, and prayers have a connection to animism nature worship but are more hidden or stylized such as burning candles, which is worshipping fire.

Archaeology reveals that the world’s oldest sculpture was enhanced by hominid hand. To date, the oldest known human three-dimensional representation is the Tan-Tan sculpture, which is an anthropomorific human form from Morocco was found in ancient river deposits of the Draa river. It is Acheulian and has been dated between 500,000 to 300,000 years old. 500,000 to 233,000 years ago, in Israel, another sculpture, which may be the oldest Stone Age Art was found at the Berekhat Ram site on the Golan Heights that consist of a small quartzite pebble, which resembles a human female figure with magical believed qualities or representing something that was believed to be magical. ref

Is this just art or a form of ancestor veneration?

Pre-animism ideas can be seen in rock art such as that expressed in portable anthropomorphic art, which may be related to some kind of ancestor veneration. This magical thinking may stem from a social or non-religious function of ancestor veneration, which cultivates kinship values such as filial piety, family loyalty, and continuity of the family lineage. Ancestor veneration occurs in societies with every degree of social, political, and technological complexity and it remains an important component of various religious practices in modern times.

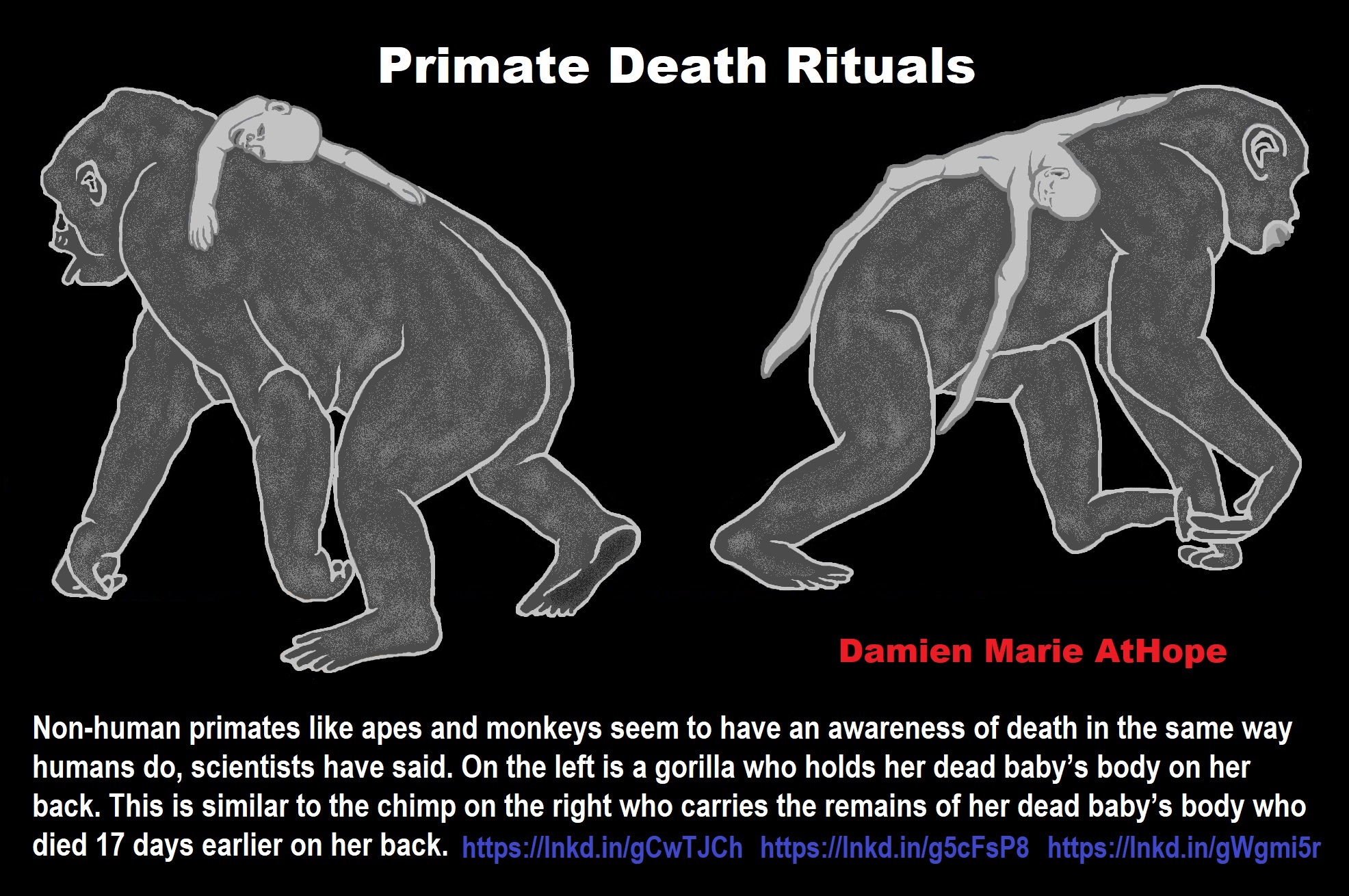

Humans are not the only species, which bury their dead. The practice has been observed in chimpanzees, elephants, and possibly dogs. Intentional burial, particularly with grave goods, signify a “concern for the dead” and Neanderthals were the first human species to practice burial behavior and intentionally bury their dead, doing so in shallow graves along with stone tools and animal bones. Exemplary sites include Shanidar in Iraq, Kebara Cave in Israel and Krapina in Croatia. The earliest undisputed human burial dates back 100,000 years ago with remains stained with red ochre, which show ritual intentionality similar to the Neanderthals before them. ref, ref

- “300,000 years ago: the first possible appearance of Homo sapiens, in Jebel Irhoud, Morocco.

- 270,000 years ago: age of Y-DNA haplogroup A00(“Y-chromosomal Adam“).

- 250,000 years ago: the first appearance of Homo neanderthalensis (Saccopastore skulls)

- 250,000-200,000 years ago: modern human presence in West Asia (Misliya cave)

- 230,000–150,000 years ago: age of mt-DNA haplogroup L (“Mitochondrial Eve“)

- 195,000 years ago: Omo remains (Ethiopia), the emergence of anatomically modern humans.

- 160,000 years ago: Homo sapiens idaltu

- 170,000 years ago: humans are wearing clothing by this date.

- 150,000 years ago: Peopling of Africa: Khoisanid separation, an age of mtDNA haplogroup L0

- 125,000 years ago: the peak of the Eemian interglacial period.

- 120,000–90,000 years ago: Abbassia Pluvial in North Africa—the Sahara desert region is wet and fertile.” ref

Pre-Animism: Portable Rock Art

Pre-animism ideas seen in rock art, such as that expressed in portable anthropomorphic art that could have related to so kind of ancestor veneration, which may be a magical thinking but stem from the social or non-religious function of ancestor veneration is to cultivate kinship values, such as filial piety, family loyalty, and continuity of the family lineage. Ancestor veneration occurs in societies with every degree of social, political, and technological complexity, and it remains an important component of various religious practices in modern times. Ancestor reverence is not the same as the worship of a deity or deities. In some Afro-diasporic cultures, ancestors are seen as being able to intercede on behalf of the living, often as messengers between humans and the gods. As spirits who were once human themselves, they are seen as being better able to understand human needs than would a divine being. In other cultures, the purpose of ancestor veneration is not to ask for favors but to do one’s filial duty. Some cultures believe that their ancestors actually need to be provided for by their descendants, and their practices include offerings of food and other provisions. Others do not believe that the ancestors are even aware of what their descendants do for them, but that the expression of filial piety is what is important. Although there is no generally accepted theory concerning the origins of ancestor veneration, this social phenomenon appears in some form in all human cultures documented so far. David-Barrett and Carney claim that ancestor veneration might have served a group coordination role during human evolution, and thus it was the mechanism that led to religious representation fostering group cohesion. Humans are not the only species that bury their dead; the practice has been observed in chimpanzees, elephants, and possibly dogs. Intentional burial, particularly with grave goods, signifies a “concern for the dead” and Neanderthals were the first human species to practice burial behavior and intentionally bury their dead, doing so in shallow graves along with stone tools and animal bones. Exemplary sites include Shanidar in Iraq, Kebara Cave in Israel, and Krapina in Croatia. The earliest undisputed human burial dates back 100,000 years with remains stained with red ochre showing ritual intentionality similar to the Neanderthals before them. ref, ref

Pre-animism: Anthropology; “A stage of religious development supposed to have preceded animism, in which material objects were believed to contain spiritual energy.” ref

Animism (from Latin anima, “breath, spirit, life”) is the religious belief that objects, places, and creatures all possess a distinct spiritual essence. Potentially, animism perceives all things—animals, plants, rocks, rivers, weather systems, human handiwork, and perhaps even words—as animated and alive. Animism is the oldest known type of belief system in the world that even predates paganism. It is still practiced in a variety of forms in many traditional societies. Animism is used in the anthropology of religion as a term for the belief system of many indigenous tribal peoples, especially in contrast to the relatively more recent development of organized religions. Although each culture has its own different mythologies and rituals, “animism” is said to describe the most common, foundational thread of indigenous peoples’ “spiritual” or “supernatural” perspectives. The animistic perspective is so widely held and inherent to most animistic indigenous peoples that they often do not even have a word in their languages that corresponds to “animism” (or even “religion”); the term is an anthropological construct. ref

Animism (beginning around 100,000 years ago)

Animism (such as that seen in Africa: 100,000 years ago)

- Aterian Culture (North African 145,000–20,000 years ago)

- Sangoan Culture (sub-Saharan African 130,000-10,000 years ago)

- Animism: an approximately 100,000-year-old belief system?

- Rock crystal stone tools 75,000 Years Ago – (Spain) made by Neanderthals

- Stone Snake of South Africa: “first human worship” 70,000 years ago

- Similarities and differences in Animism and Totemism

- Did Neanderthals Help Inspire Totemism? Because there is Art Dating to Around 65,000 Years Ago in Spain?

- History of Drug Use with Religion or Sacred Rituals possibly 58,000 years ago?

Animism is approximately a 100,000-year-old belief system and believe in spirit-filled life and/or afterlife. If you believe like this, regardless of your faith, you are a hidden animist.

The following is evidence of Animism: 100,000 years ago, in Qafzeh, Israel, the oldest intentional burial had 15 African individuals covered in red ocher was from a group who visited and returned back to Africa. 100,000 to 74,000 years ago, at Border Cave in Africa, an intentional burial of an infant with red ochre and a shell ornament, which may have possible connections to the Africans buried in Qafzeh, Israel. 120,000 years ago, did Neanderthals teach us Primal Religion (Pre-Animism/Animism) as they too used red ocher and burials? ref, ref

It seems to me, it may be the Neanderthals who may have transmitted a “Primal Religion (Animism)” or at least burial and thoughts of an afterlife. The Neanderthals seem to express what could be perceived as a Primal “type of” Religion, which could have come first and is supported in how 250,000 years ago, the Neanderthals used red ochre and 230,000 years ago shows evidence of Neanderthal burial with grave goods and possibly a belief in the afterlife. ref

Do you think it is crazy that the Neanderthals may have transmitted a “Primal Religion”? Consider this, it appears that 175,000 years ago, the Neanderthals built mysterious underground circles with broken-off stalactites. This evidence suggests that the Neanderthals were the first humans to intentionally bury the dead, doing so in shallow graves along with stone tools and animal bones. Exemplary sites include Shanidar in Iraq, Kebara Cave in Israel, and Krapina in Croatia. Other evidence may suggest the Neanderthals had it transmitted to them by Homo heidelbergensis, 350,000 years ago, by their earliest burial in a shaft pit grave in a cave that had a pink stone ax on the top of 27 Homo heidelbergensis individuals and 250,000 years ago, Homo Naledi had an intentional cemetery in South Africa cave. ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

- “120,000–90,000 years ago: Abbassia Pluvial in North Africa—the Sahara desert region is wet and fertile.

- 120,000 to 75,000 years ago: Khoisanid back-migration from Southern Africa to East Africa.

- 82,000 years ago: small perforated seashell beads from Taforalt in Morocco are the earliest evidence of personal adornment found anywhere in the world.

- 75,000 years ago: Toba Volcano supereruption that almost made humanity extinct. Populations could have been lowered to about 3000-1000 people on the Earth.

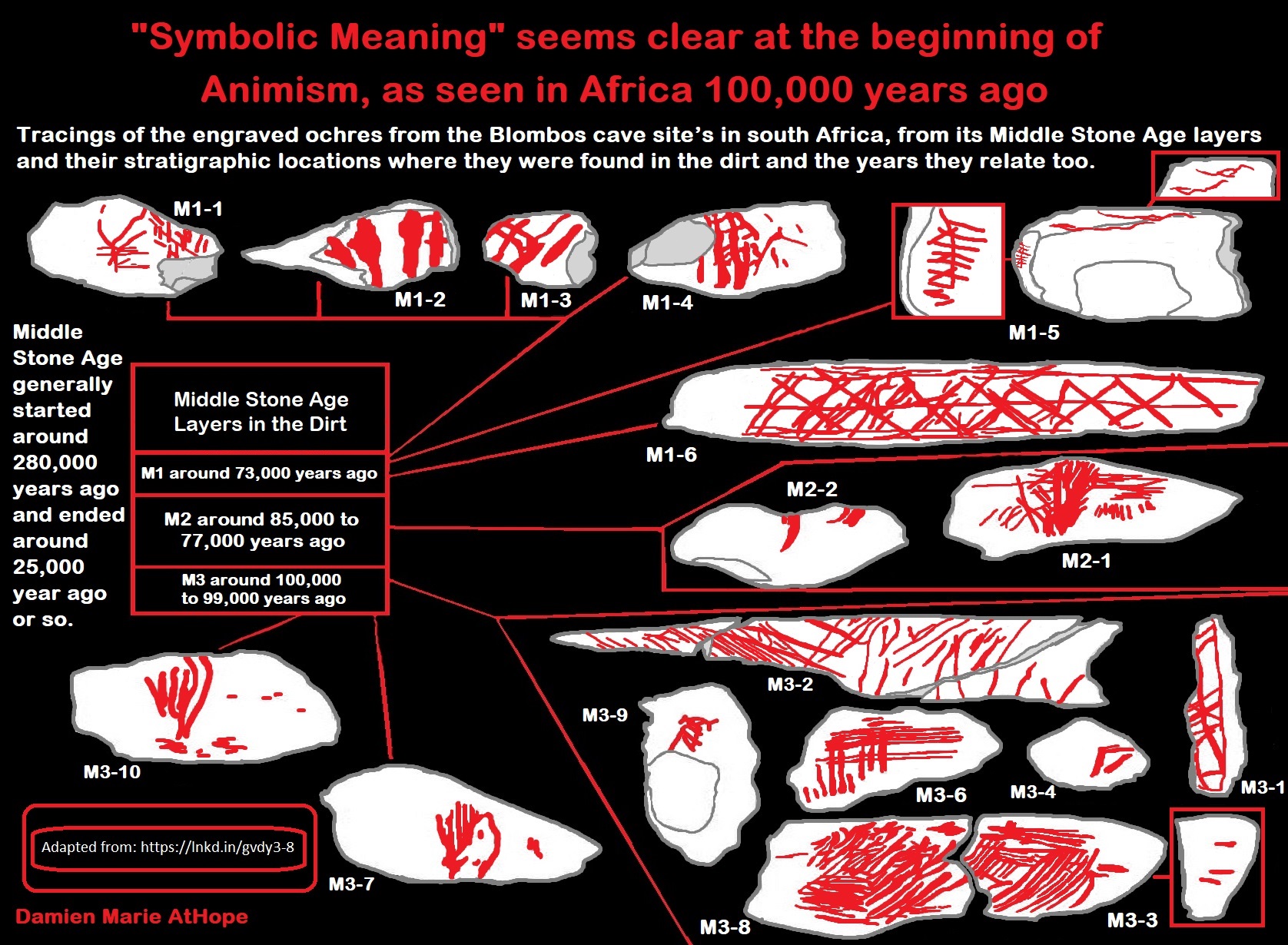

- 70,000 years ago: earliest example of abstract art or symbolic art from Blombos Cave, South Africa—stones engraved with grid or cross-hatch patterns.

- 70,000 years ago: Recent African origin: separation of sub-Saharan Africans and non-Africans.” ref

143,000 – 120,000 Years Ago – Tabun Cave (Israel), found evidence of a Neanderthal-type burial of an archaic type of human female. There is some evidence of burial in Skhul Cave 130,000 – 100,000 which may be Neanderthal humans hybrids, thought early modern humans started engaging in burial around 100,000 years ago. So one should wonder did Neanderthals teach humans religion or at least ritual burial around 120,000 – 100,000 years ago? I think maybe it seems to possibly be the case by 100,000 years ago, but this is just my speculation of somewhat loose but interesting evidence. Burial seems to have been and is now certainly evidence of some concern about what happened when someone died perhaps even proof of a belief that would be one of the key tenets of most religions of the world today, which is life after this one.

100,000 Years Ago – Qafzeh cave (Israel), found a burial site of 15 early modern humans stained with red ochre and grave goods, 71 pieces of red ocher, and red ocher-stained stone tools near the bones suggest ritual or symbolic use, as well as seashells with traces of being strung, and a few also had ochre stains which may also suggest ritual or symbolic use. Likewise, a wild boar jaw found placed in the arms of one of the skeletons.

Only after 100,000 years ago modern human burials become more frequent. Could this seemingly new practice of barrel among early modern humans with the use of red ochre be in some way connected or influenced by the meeting, interbreeding, and possible idea sharing with the Neanderthal ancestors of the Neanderthals from the Altai Mountains of Central Asia around 100,000 years ago possibly in the Near East, maybe even in Israel or some other part of the with the levant? Well to me it sounds like a real possibility that Neanderthals may have directly taught or indirectly been observed thus in a way are responsible candidates for possibly teaching humans the beginnings of religion, or at least superstitionism/supernaturalism seen in the act of doing burial and the ritual and seemingly sacralized use of red ocher around 100,000 years ago. This thinking Neanderthals Primal Religion could have come first is supported in how 250,000 years ago Neanderthals used red ochre and 230,000 years ago shows evidence of Neanderthal burial with grave goods and possibly a belief in the afterlife.

*Believe in spirit-filled life and/or afterlife (you are a hidden animist/Animism: an approximately 100,000-year-old belief system) Animism: the (often hidden) religion thinking all religionists (as well as most who say they are the so-called spiritual and not religious which to me are often just reverting back to have to Animism (even though this religious stance is often hidden to their realization so they are still very religious whether they know it or not) some extent or another. Ref

References: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9

Ancient human burials, By Sally McBrearty

Whereas with modern people, anatomically modern Homo sapiens from somewhat later in time, you find artifacts that are definitely grave offerings. You find quantities of red ochre, which have been sprinkled over the skeleton, beads, and other kinds of objects, bone tools, and things like that, which appear to have been placed in the grave with the person when they were interred. And there’s really no doubt that they’re deliberate burials. The evidence for the burial of the dead in Africa is very very spotty. There’s one site in South Africa that’s called Border Cave, where there are a number of burials, including the burial of an infant, with a little shell ornament, it’s a pierced sea shell ornament, and the argument has been about whether that is in good stratographic context or whether it is an intrusive burial into earlier deposits. And so the age of that is not particularly well established. If it is in good context, then it’s about 100,000 years old, and it is the earliest in Africa. There are early burials of anatomically modern Homo sapiens in Israel, from the site of Qafzeh. There is a modern human that probably dates to about the same time, about maybe 90,000 to 100,000 years ago. ref

Neandertal burials, By Sally McBrearty

The Neandertals have always been thought to bury their dead, because there’s so many complete skeletons of Neandertals that have been found. And I think from the number of skeletons that have been found, it’s probably a good guess that they were deliberately burying the dead. However, there are a lot of skeletons of other cave-dwelling animals that are found in caves: cave bears or hyenas, that because they live in caves they often die in caves. And there, people have argued about whether rock falls, or simply accidental death, or natural death, occurring in a cave could preserve whole skeletons better than in the open air. But the argument has also been about the objects that you find associated with the Neandertal burials, because what you find together with Neandertal skeletons are really mundane objects, like stone tools, or animal bones that would be food remains. ref

Pic ref

Pic ref

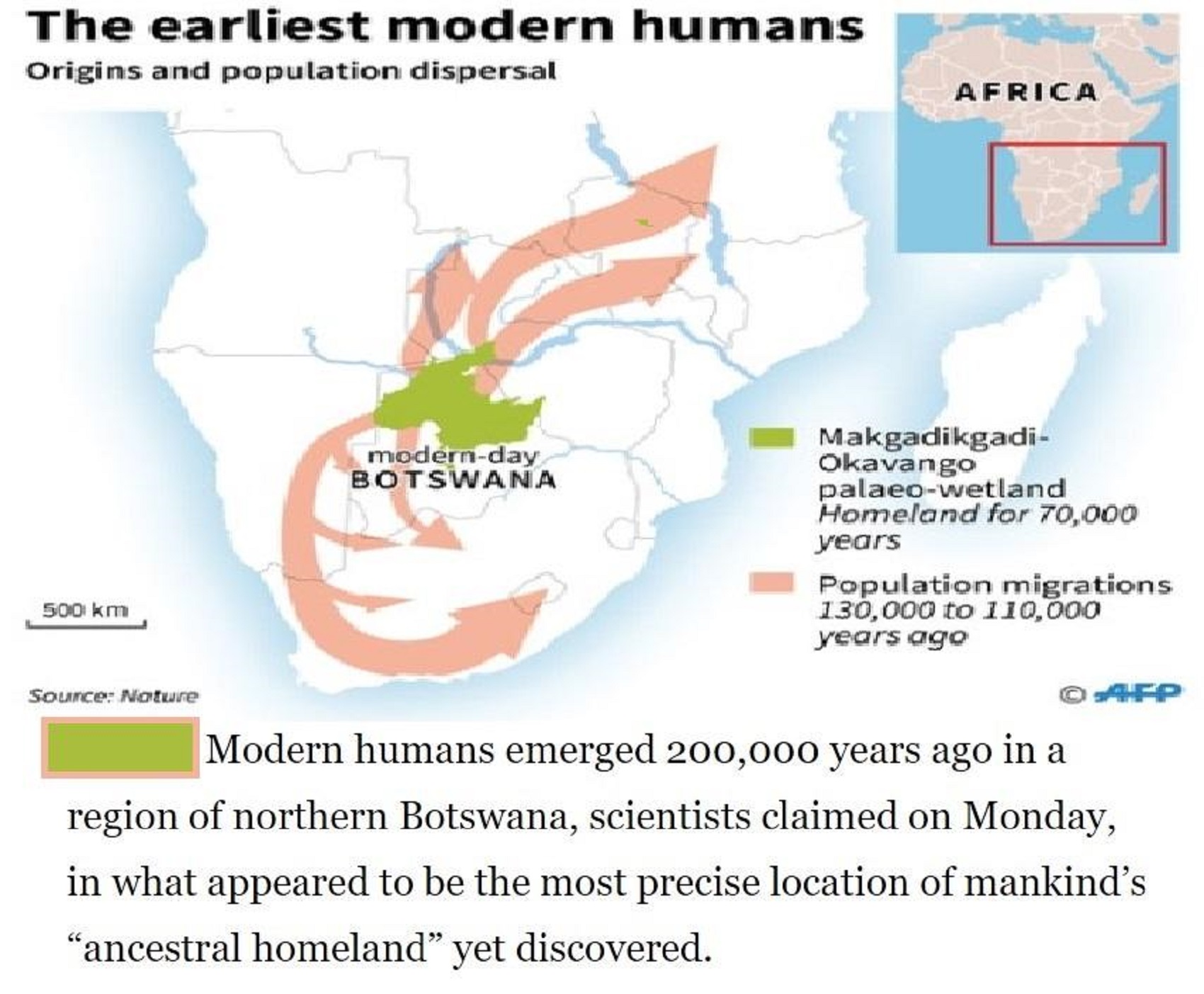

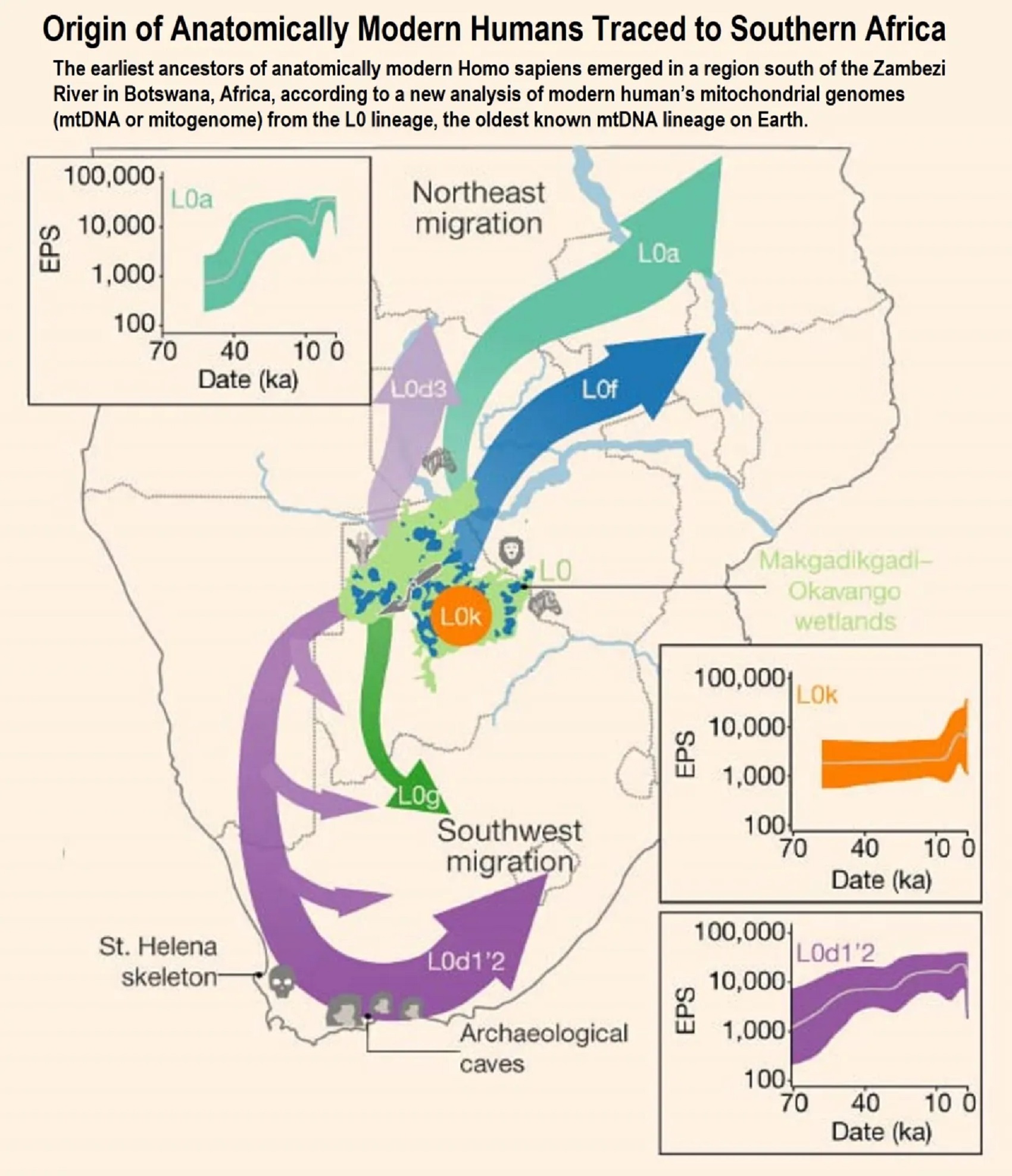

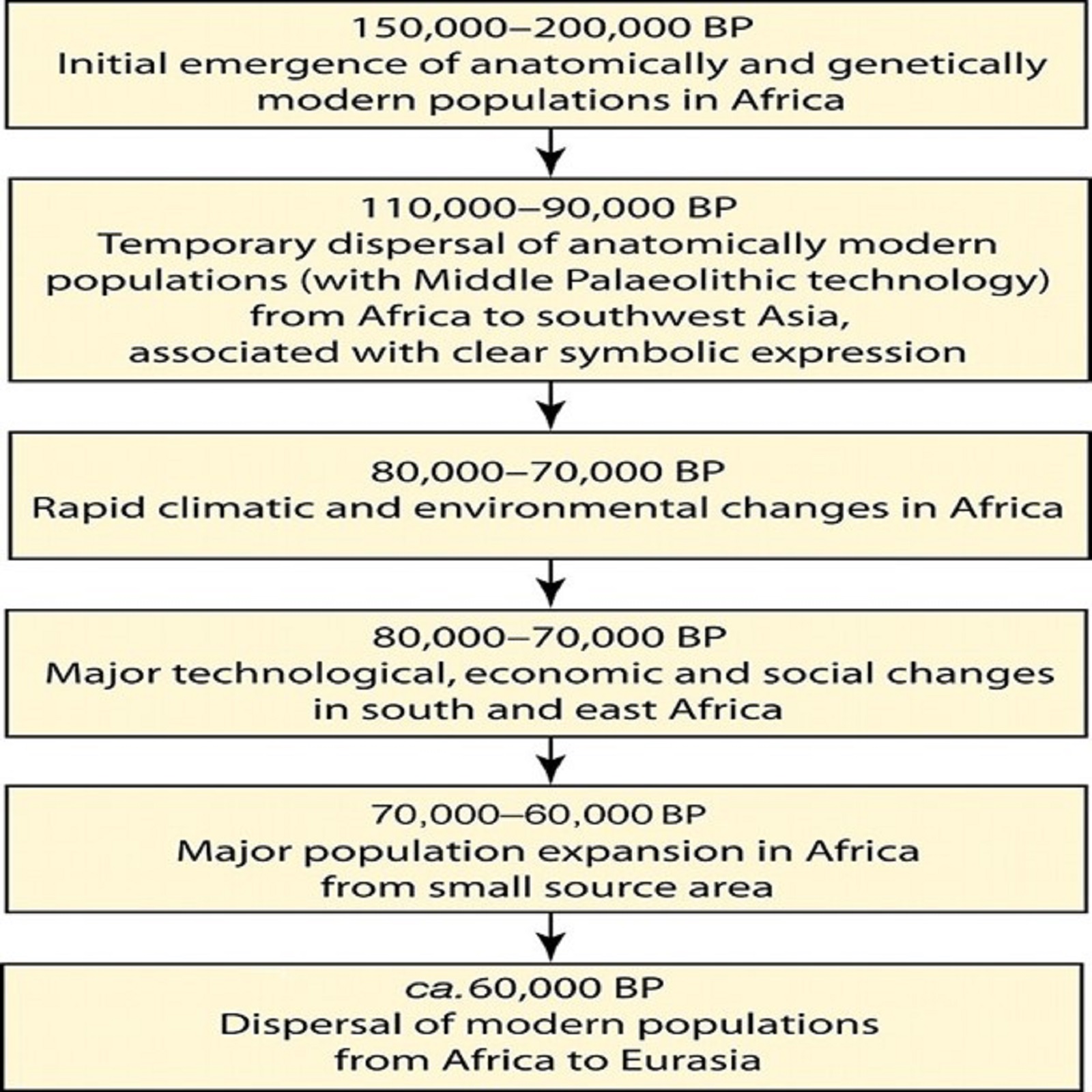

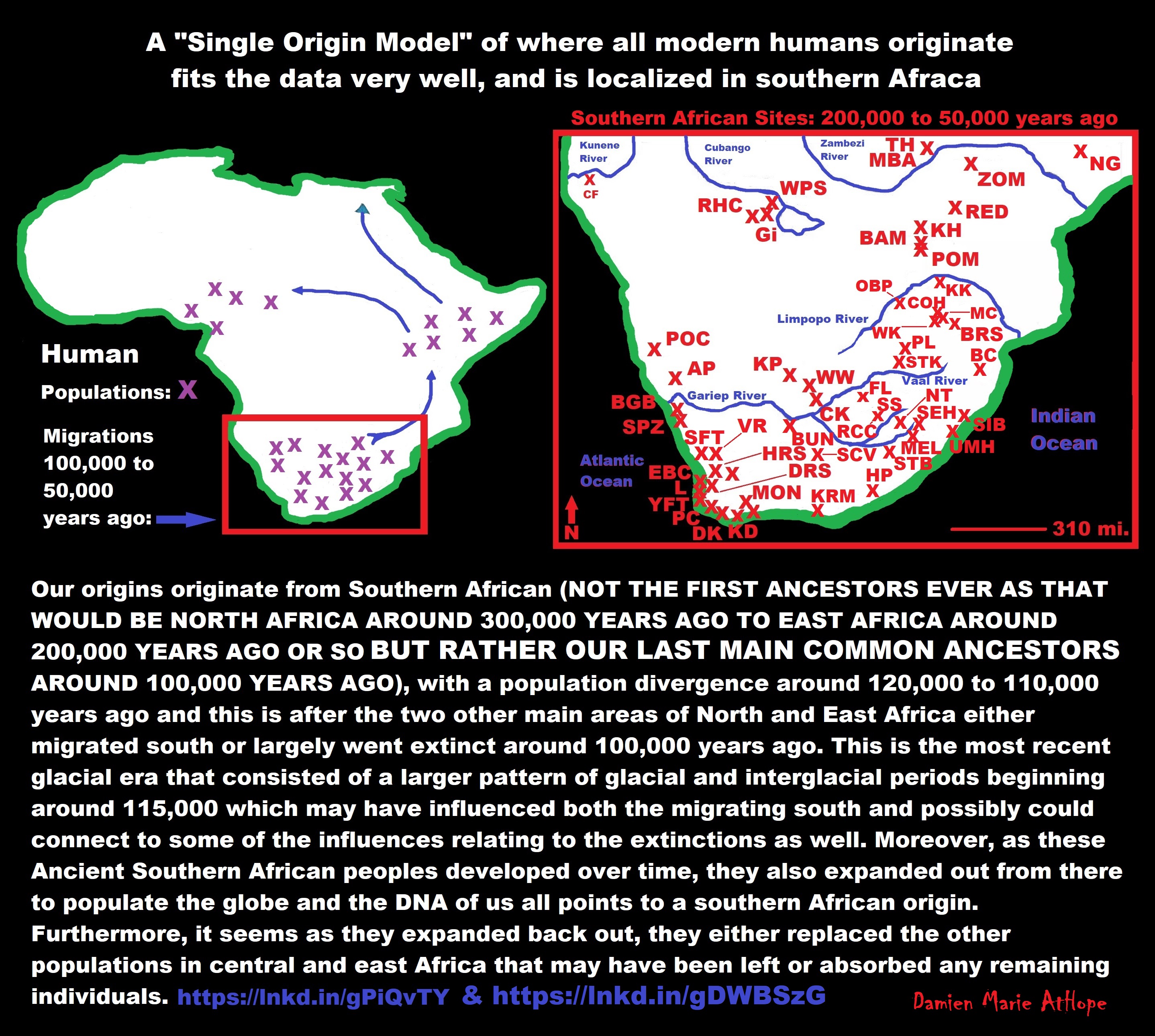

“The earliest ancestors of anatomically modern Homo sapiens emerged in a region south of the Zambezi River in Botswana, Africa, according to a new analysis of modern human’s mitochondrial genomes (mtDNA or mitogenome) from the L0 lineage, the oldest known mtDNA lineage on Earth.” ref

“In terms of mitochondrial haplogroups, the mt-MRCA is situated at the divergence of macro-haplogroup L into L0 and L1–6. As of 2013, estimates on the age of this split ranged at around 155,000 years ago, consistent with a date later than the speciation of Homo sapiens but earlier than the recent out-of-Africa dispersal.” ref

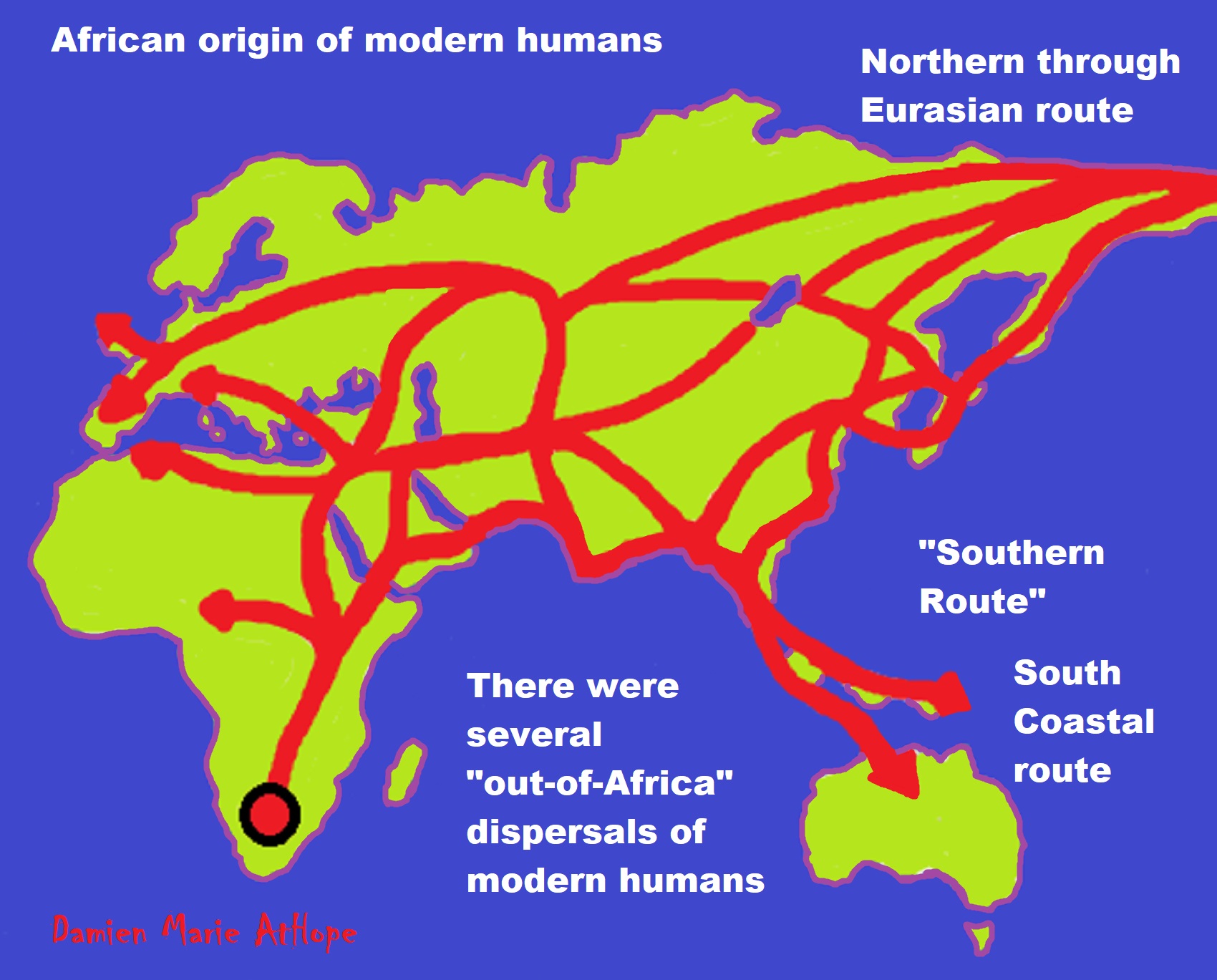

“There were at least several “out-of-Africa” dispersals of modern humans, possibly beginning as early as 270,000 years ago, including 215,000 years ago to at least Greece, and certainly via northern Africa and the Arabian Peninsula about 130,000 to 115,000 years ago. There is evidence that modern humans had reached China around 80,000 years ago. Practically all of these early waves seem to have gone extinct or retreated back, and present-day humans outside Africa descend mainly from a single expansion out 70,000–50,000 years ago. The most significant “recent” wave out of Africa took place about 70,000–50,000 years ago, via the so-called “Southern Route“, spreading rapidly along the coast of Asia and reaching Australia by around 65,000–50,000 years ago, (though some researchers question the earlier Australian dates and place the arrival of humans there at 50,000 years ago at earliest, while others have suggested that these first settlers of Australia may represent an older wave before the more significant out of Africa migration and thus not necessarily be ancestral to the region’s later inhabitants) while Europe was populated by an early offshoot which settled the Near East and Europe less than 55,000 years ago.” ref

“Haplogroup L3 is a human mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplogroup. The clade has played a pivotal role in the early dispersal of anatomically modern humans. It is strongly associated with the out-of-Africa migration of modern humans of about 70–50,000 years ago. It is inherited by all modern non-African populations, as well as by some populations in Africa. Haplogroup L3 arose close to 70,000 years ago, near the time of the recent out-of-Africa event. This dispersal originated in East Africa and expanded to West Asia, and further to South and Southeast Asia in the course of a few millennia, and some research suggests that L3 participated in this migration out of Africa. L3 is also common amongst African Americans and Afro-Brazilians. A 2007 estimate for the age of L3 suggested a range of 104–84,000 years ago. More recent analyses, including Soares et al. (2012) arrive at a more recent date, of roughly 70–60,000 years ago. Soares et al. also suggest that L3 most likely expanded from East Africa into Eurasia sometime around 65–55,000 years ago years ago as part of the recent out-of-Africa event, as well as from East Africa into Central Africa from 60 to 35,000 years ago. In 2016, Soares et al. again suggested that haplogroup L3 emerged in East Africa, leading to the Out-of-Africa migration, around 70–60,000 years ago.” ref

“Haplogroups L6 and L4 form sister clades of L3 which arose in East Africa at roughly the same time but which did not participate in the out-of-Africa migration. The ancestral clade L3’4’6 has been estimated at 110 kya, and the L3’4 clade at 95 kya. The possibility of an origin of L3 in Asia was also proposed by Cabrera et al. (2018) based on the similar coalescence dates of L3 and its Eurasian-distributed M and N derivative clades (ca. 70 kya), the distant location in Southeast Asia of the oldest known subclades of M and N, and the comparable age of the paternal haplogroup DE. According to this hypothesis, after an initial out-of-Africa migration of bearers of pre-L3 (L3’4*) around 125 kya, there would have been a back-migration of females carrying L3 from Eurasia to East Africa sometime after 70 kya. The hypothesis suggests that this back-migration is aligned with bearers of paternal haplogroup E, which it also proposes to have originated in Eurasia. These new Eurasian lineages are then suggested to have largely replaced the old autochthonous male and female North-East African lineages.” ref

“According to other research, though earlier migrations out of Africa of anatomically modern humans occurred, current Eurasian populations descend instead from a later migration from Africa dated between about 65,000 and 50,000 years ago (associated with the migration out of L3). Vai et al. (2019) suggest, from a newly discovered old and deeply-rooted branch of maternal haplogroup N found in early Neolithic North African remains, that haplogroup L3 originated in East Africa between 70,000 and 60,000 years ago, and both spread within Africa and left Africa as part of the Out-of-Africa migration, with haplogroup N diverging from it soon after (between 65,000 and 50,000 years ago) either in Arabia or possibly North Africa, and haplogroup M originating in the Middle East around the same time as “N.” A study by Lipson et al. (2019) analyzing remains from the Cameroonian site of Shum Laka found them to be more similar to modern-day Pygmy peoples than to West Africans, and suggests that several other groups (including the ancestors of West Africans, East Africans, and the ancestors of non-Africans) commonly derived from a human population originating in East Africa between about 80,000-60,000 years ago, which they suggest was also the source and origin zone of haplogroup L3 around 70,000 years ago.” ref

Did Pleistocene Africans use the spearthrower‐and‐dart?

“Well, evidence grows apace for ever-more ancient bow-and-arrow use. List of age estimates, locations, and current evidence bundles for the use of either arrows or darts by/before 30,000 years ago, the list may not be exhaustive, but we suggest that it broadly summarizes current knowledge (MSA = middle stone age).” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref ,ref, ref, ref

Homo Naledi

“Homo Naledi is a species of archaic human discovered in the Rising Star Cave, Cradle of Humankind, South Africa dating to the Middle Pleistocene 335,000–236,000 years ago. The initial discovery comprises 1,550 specimens, representing 737 different elements, and at least 15 different individuals. Despite this exceptionally high number of specimens, their classification with other Homo remains unclear.” ref

“Along with similarities to contemporary Homo, they share several characteristics with the ancestral Australopithecus and early Homo as well (mosaic anatomy), most notably a small cranial capacity of 465–610 cm3 (28.4–37.2 cu in), compared to 1,270–1,330 cm3 (78–81 cu in) in modern humans. They are estimated to have averaged 143.6 cm (4 ft 9 in) in height and 39.7 kg (88 lb) in weight, yielding a small encephalization quotient of 4.5. Nonetheless, Homo Naledi’s brain anatomy seems to have been similar to contemporary Homo, which could indicate equatable cognitive complexity. The persistence of small-brained humans for so long in the midst of bigger-brained contemporaries revises the previous conception that a larger brain would necessarily lead to an evolutionary advantage, and their mosaic anatomy greatly expands the known range of variation for the genus.” ref

“Homo Naledi anatomy indicates that, though they were capable of long-distance travel with a humanlike stride and gait, they were more arboreal than other Homo, better adapted to climbing and suspensory behavior in trees than endurance running. Tooth anatomy suggests consumption of gritty foods covered in particulates such as dust or dirt. Though they have not been associated with stone tools or any indication of material culture, they appear to have been dextrous enough to produce and handle tools, and likely manufactured Early or Middle Stone Age industries. It has also been controversially postulated that these individuals were given funerary rites, and were carried into and placed in the chamber.” ref

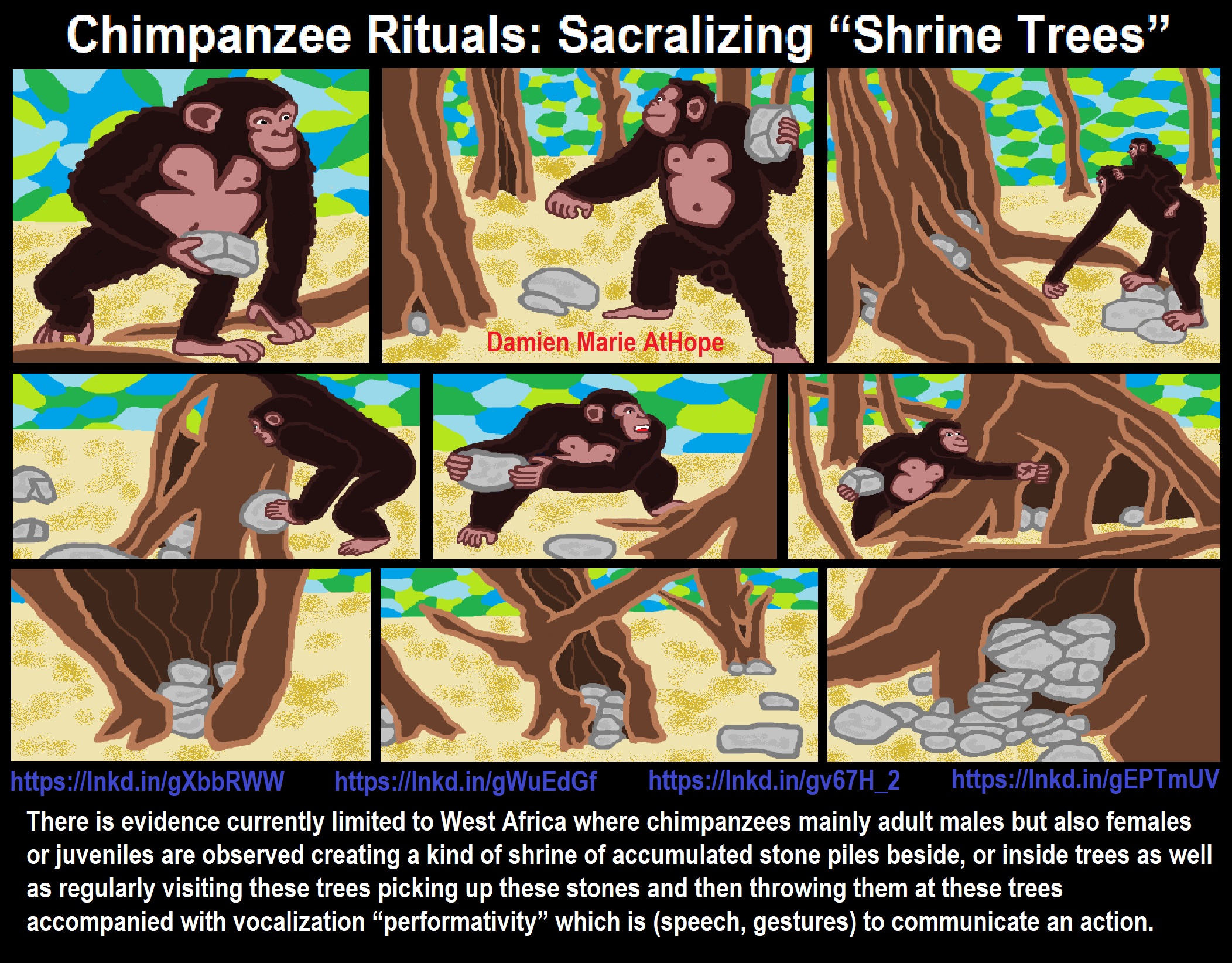

Chimpanzees Sacralizing Trees?

There is evidence currently limited to West Africa where chimpanzees mainly adult males but also females or juveniles are observed creating a kind of shrine of accumulated stone piles beside, or inside trees as well as regularly visiting these trees picking up these stones, and then throwing them at these trees accompanied with vocalization “performativity” which is (speech, gestures) to communicate an action.

Chimpanzees have been observed engaging in “social learning,” both teaching and learning such as tool use as well as communication signals: vocal and gestures. Such social learning is seen as playing an important and unique role in the development of human language, culture, and mythologizing.

All together such things observed in these West Africa where chimpanzees could indicate some kind of what could be perceived as magical thinking or at least quasi-magical thinking in the sacralizing of trees as it does not seem connected to some utilitarian or food foraging practice of which rocks or tools would make since. This at first may sound too complex for a nonhuman animal but what needs to be understood is that chimpanzees have been known to exhibit “metacognition,” or think about thinking.

Also, chimpanzees have the greatest variation in tool-use behaviors of any animal, second only to humans, where humans seem to have magical thinking or irrational beliefs are hardwired in our brains at a very ancient level because they involve mentally-fabricated patterns of thinking. Moreover, such processing abilities are somewhat common among non-human primates if not lower mammals as well to some extent and can be seen as a part of evolutionary survival fitness and thus not uniquely human.

It can be thought that different emotions evolved at different times with fear being ancient care for offspring relatively next later followed likely by extended social emotions, such as guilt and pride, evolved among social primates. Why this could be important is it is believed that emotions evolved to reinforce memories of patterns adding to survival and reproduction as well as responses to internal or external events and in such remapping facilitated by emotions could involve mentally-fabricated patterns of thinking which could superstitionize things in the world that do not truly limit it to the way it is possibly adding a kind of animism or the like involving some amount of magical thinking such as sacralizing of trees.

Magical thinking such as beliefs that there are relationships between behaviors or sounds thought to have the ability to directly affect other events in the world. Whereas quasi-magical thinking is acting as if there is a false belief that action influences outcome, even though they may not really actualize or intentionally hold such a belief.

Now I doubt West African chimpanzees are fully mythologizing the trees to a human magical thinking extent but we can see some possibilities of what about them could be inspired by magical thinking. Magical thinking may lead to a type of causal reasoning or causal fallacy that looks for meaningful relationships of grouped phenomena (coincidence) between acts and events.

Moreover, magical thinking when applied to trees are significant as believed sacred totems and natural sacred representations in many of the world’s oldest myths possibly because of using magical thinking when observing the growth and annual death and then revival of their foliage, seen them as symbolic representations of growth, death, and rebirth.

As well as trees may be conceived as existing in three realms the underworld or death with the roots the world of the living the trunk existing in our world above the ground and its branches reaching to the heavens thus existing in the realm of the spirits, ancestors or gods.

An Old Branch of Religion Still Giving Fruit: Sacred Trees

References 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11

Animism, Totemism, Shamanism, and Paganism

The interconnectedness of religious thinking Animism, Totemism, Shamanism, and Paganism

So, it all starts in a general way with Animism (theoretical belief in supernatural powers/spirits), then this is physically expressed in or with Totemism (theoretical belief in mythical relationship with powers/spirits through a totem item), which then enlists a full-time specific person to do this worship and believed interacting Shamanism (theoretical belief in access and influence with spirits through ritual), and then there is the further employment of myths and gods added to all the above giving you Paganism (often a lot more nature-based than most current top world religions, thus hinting to their close link to more ancient religious thinking it stems from). My hypothesis is expressed with an explanation of the building of a theatrical house (modern religions development).

Religion and it’s fixation with holy land or places which is both an animism belief that areas or natural features have a sacredness and the totemistic clan thinking that a tribe of people own areas or natural features as some sacred right, often along with believing only they belong there, sometimes and n some places outsiders or those not deemed sacred enough are excluded or harmed even possibly killed. Similar to sectarianism, isolationism, extreme nationalism, ethnocentrism, racism, is one of the most decisive factors leading to harmful effects and death in the past, present, and likely into the future.

Yes, you need to know about Animism to understand Religion

Hidden Religious Expressions: “animist, totemist, shamanist & paganist”

- *Believe in spirit-filled life and/or afterlife (you are a hidden animist/Animism : an approximately 100,000-year-old belief system)

- *Believe in spirit-filled life and/or afterlife can be attached to or be expressed in things or objects (you are a hidden totemist/Totemism: an approximately 50,000-year-old belief system)

- *Believe in spirit-filled life and/or afterlife can be attached to or be expressed in things or objects and these objects can be used by special persons or in special rituals can connect to spirit-filled life and/or afterlife (you are a hidden shamanist/Shamanism: an approximately 30,000-year-old belief system)

- *Believe in spirit-filled life and/or afterlife can be attached to or be expressed in things or objects and these objects can be used by special persons or in special rituals can connect to spirit-filled life and/or afterlife who are guided/supported by a goddess/god or goddesses/gods (you are a hidden paganist/Paganism: an approximately 12,000-year-old belief system)

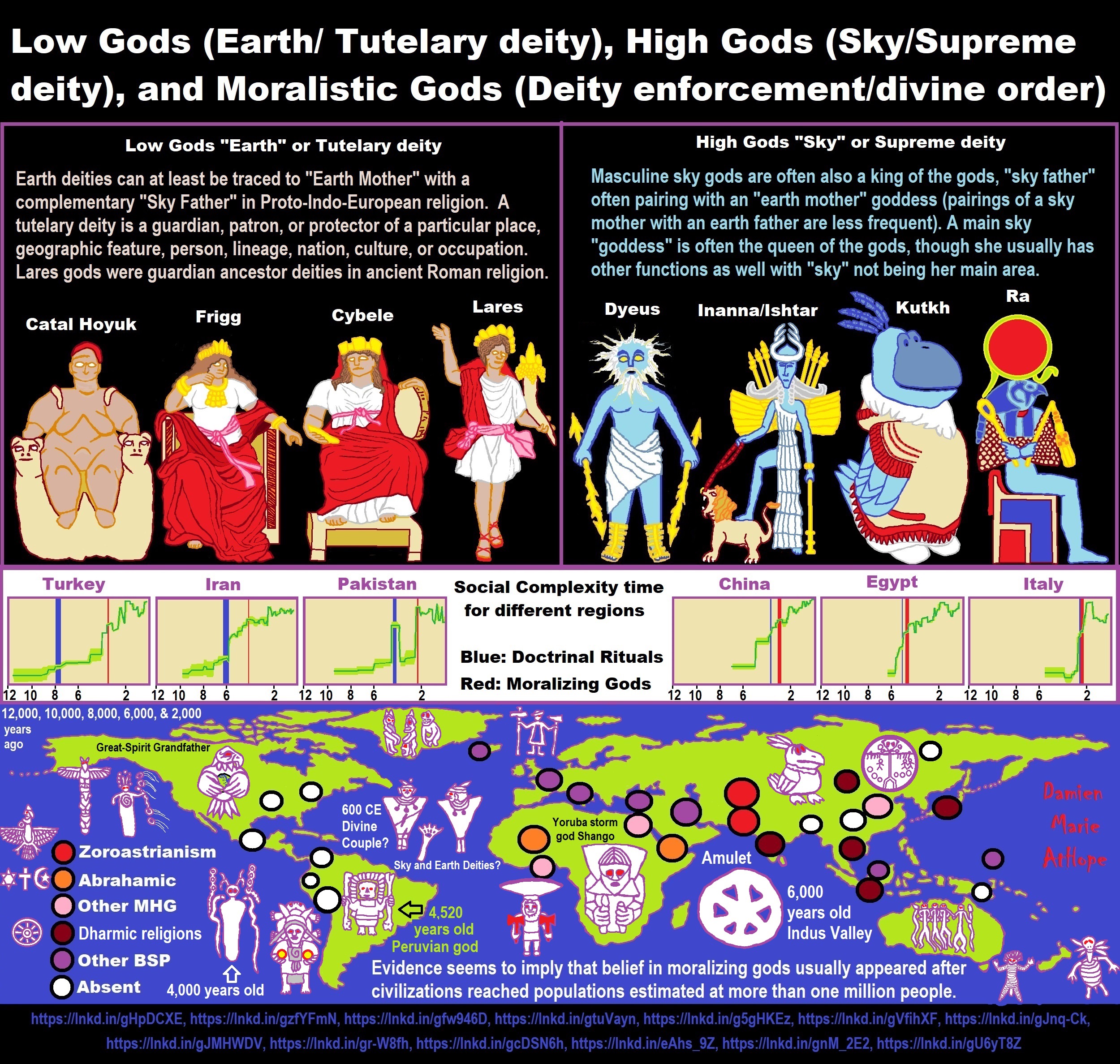

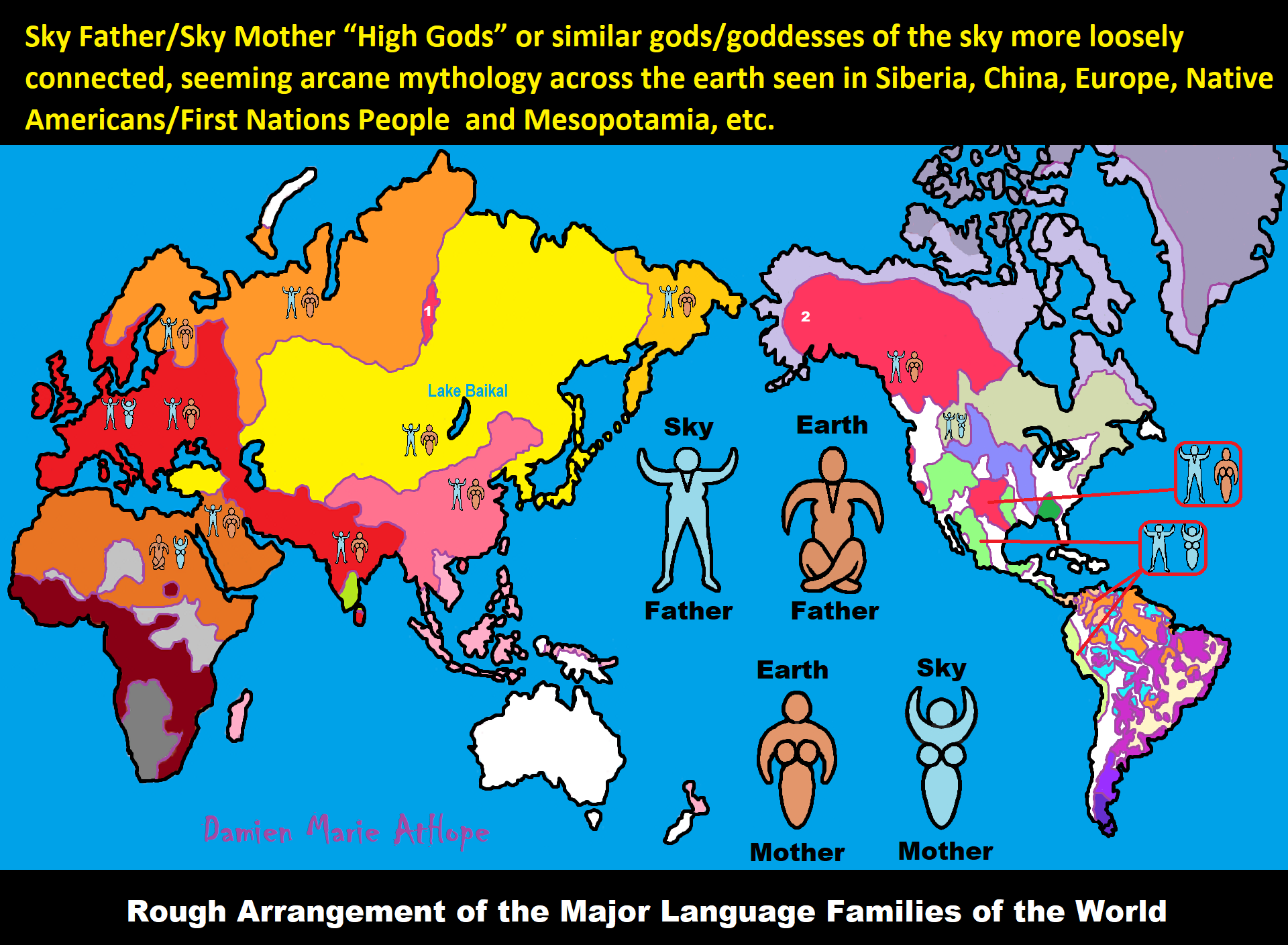

Religious Evolution?

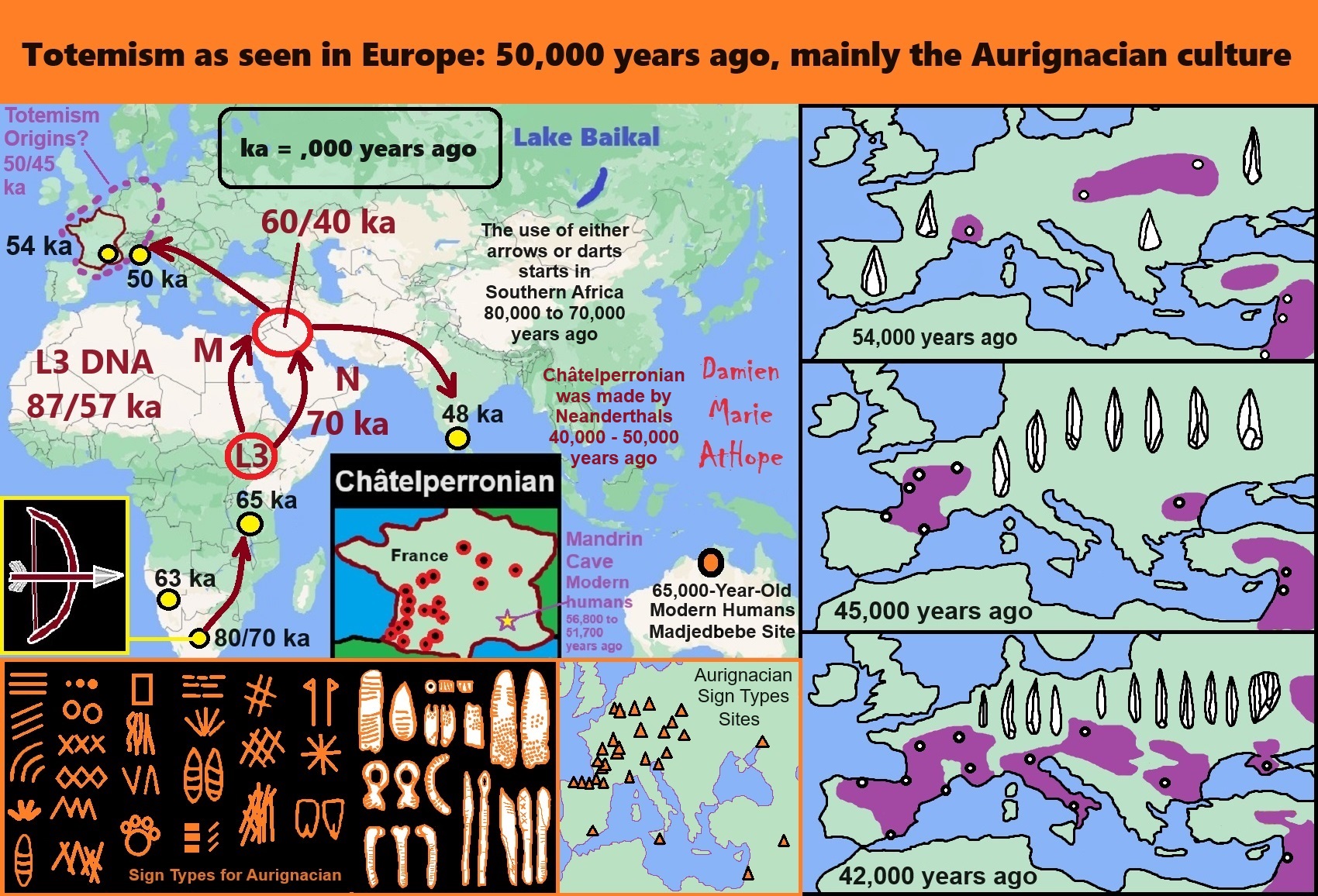

In my thinking on the evolution of religion, it seems a belief in animistic spirits” (a belief system dating back at least 100,000 years ago on the continent of Africa), that in totemism (dating back at least 50,000 years ago on the continent of Europe) with newly perceived needs where given artistic expression of animistic spirits both animal or human “seemingly focused on female humans to begin with and only much much later is there what look like could be added male focus”, but even this evolved into a believed stronger communion with more connections in shamanism (a belief system dating back at least 30,000 years ago on the continent of Siberia/Aisa) with newly perceived needs, then this also evolved into Paganism (a belief system dating back at least 13,000 years ago on the continent of eastern Europe/western Asia turkey mainly but eastern Mediterranean lavant as well to some extent or another) with newly perceived needs where you see the emergence of animal gods and female goddesses around into more formalized animal gods and female goddesses and only after 7,000 to 6,000 do male gods emerge one showing its link in the evolution of religion and the other more on it as a historical religion.

Ps. Progressed organized religion starts approximately 5,000-year-old belief system)

Promoting Religion as Real is Harmful?

Sometimes, when you look at things, things that seem hidden at first, only come clearer into view later upon reselection or additional information. So, in one’s earnest search for truth one’s support is expressed not as a one-time event and more akin to a life’s journey to know what is true. I am very anti-religious, opposing anything even like religion, including atheist church. but that’s just me. Others have the right to do atheism their way. I am Not just an Atheist, I am a proud antireligionist. I can sum up what I do not like about religion in one idea; as a group, religions are “Conspiracy Theories of Reality.”

These reality conspiracies are usually filled with Pseudo-science and Pseudo-history, often along with Pseudo-morality and other harmful aspects and not just ancient mythology to be marveled or laughed at. I regard all this as ridiculous. Promoting Religion as Real is Mentally Harmful to a Flourishing Humanity To me, promoting religion as real is too often promote a toxic mental substance that can divide a person from who they are shaming them for being human. In addition, religion is a toxic mental substance that can divide a person from real history, real science, or real morality to pseudohistory, pseudoscience, and pseudomorality.

Moreover, religion is a toxic mental substance that can divide a person from rational thought, critical thinking, or logic. Likewise, religion is a toxic mental substance that can divide a person from justice, universal ethics, equality, and liberty. Yes, religion is a toxic mental substance that can divide a person from loved ones, and religion is a toxic mental substance that can divide a person from humanity. Therefore, to me, promoting religion as real is too often promote a toxic mental substance that should be rejected as not only false but harmful as well even if you believe it has some redeeming quality. To me, promoting religion as real is mentally harmful to a flourishing humanity. Religion may have once seemed great when all you had or needed was to believe. Science now seems great when we have facts and need to actually know.

A Rational Mind Values Humanity and Rejects Religion and Gods

A truly rational mind sees the need for humanity, as they too live in the world and see themselves as they actually are an alone body in the world seeking comfort and safety. Thus, see the value of everyone around then as they too are the same and therefore rationally as well a humanistically we should work for this humanity we are part of and can either dwell in or help its flourishing as we are all in the hands of each other. You are “Free” to think as you like but REALITY is unchanged. While you personally may react, or think differently about our shared reality (the natural world devoid of magic anything), We can play with how we use it but there is still only one communal reality (a natural non-supernatural one), which we all share like it or not and you can’t justifiably claim there is a different reality. This is valid as the only one of warrant is the non-mystical natural world around us all, existing in or caused by nature; not made or caused by superstitions like gods or other monsters to many people sill fear irrationally.

Do beliefs need justification?

Yes, it all requires a justification, and if you think otherwise you should explain why but then you are still trying to employ a justification to challenge justification. So, I still say yes it all needs a justification and I know everything is reducible to feeling the substation of existence. I feel my body and thus I can start my justificationism standard right there and then build all logic inferences from that justified point and I don’t know a more core presupposition to start from. A presupposition is a core thinking stream like how a tree of beliefs always has a set of assumed sets of presuppositions or a presupposition is relatively a thing/thinking assumed beforehand at the beginning of a line of thinking point, belief projection, argument, or course of action. And that, as well as everything, needs justification to be concluded as reasonable. Sure, you can believe all kinds of things with no justification at all but we can’t claim them as true, nor wish others to actually agree unless something is somehow and or in some way justified. When is something true that has no justification? If you still think so then offer an example, you know a justification. Sure, there can be many things that may be true but actually receiving rational agreement that they are intact true needs justification.

Without Nonsense, Religion Dies

I am against ALL Pseudoscience, Pseudohistory, and Pseudomorality. And all of these should openly be debunked, when and where possible. Of course, not forgetting how they are all highly represented in religion. All three are often found in religion to the point that if they were removed, their loss would likely end religion as we know it. I don’t have to respect ideas. People get confused ideas are not alive nor do they have beingness, Ideas don’t have rights nor the right to even exist only people have such a right. Ideas don’t have dignity nor can they feel violation only people if you attack them personally. Ideas don’t deserve any special anything they have no feelings and cannot be shamed they are open to the most brutal merciless attack and challenge without any protection and deserve none nor will I give them any if they are found wanting in evidence or reason. I will never respect Ideas if they are devoid of merit I only respect people.

I Hear Theists?

I hear what theists say and what I hear is that they make assertions with no justification discernable of or in reality just some book and your evidence lacking faith. I wish you were open to see but I know you have a wish to believe. I, however, wish to welcome reality as it is devoid of magic which all religions and gods thinkers believe. I want to be mentally free from misinformed ancient myths and free the minds of those confused in the realm of myths and the antihumanism views that they often attach to. So, I do have an agenda for human liberation from fears of the uninformed conception of reality. Saying that some features of reality are not fully known is not proof of god myth claims. II’s not like every time we lack knowledge, we can just claim magic and if we do we are not being intellectually honest to the appraisal of reality that is devoted of anything magic.

Theists seem to have very odd attempts as logic, as they most often start with some evidence devoid god myth they favor most often the hereditary favorite of the family or culture that they were born into so a continuous blind acceptance generation after generation of force indicated faith in that which on clear instinctually honest appraisal not only should inspire doubt but full disbelief until valid and reliable justification is offered.

Why are all gods unjustified? Well, anything you claim needs justification but no one has evidence of god claim attributes they are all unjustified. All god talk as if it is real acts as if one can claim magic is real by thinking it is so or by accepting someone’s claim of knowing the unjustifiably that they understand an unknowable, such as claims of gods being anything as no one has evidence to start such fact devoid things as all-knowing (there is no evidence of an all-knowing anything). Or an all-powerful (there is no evidence of an all-powerful anything).

Or the most ridiculous an all-loving (there is no evidence of an all-loving anything). But like all god claims, they are not just evidence lacking, the one claiming them has no justified reason to assume that they can even claim them as proof (it’s all the empty air of faith). Therefore, as the limit of all people, is to only be able to justify something from and that which corresponds to the real-world to be real, and the last time I checked there is no magic of any kind in our real-world experiences.

So, beyond the undefendable magical thinking not corresponding to the real-world how much more ridicules are some claimed supreme magical claimed being thus even more undefendable to the corresponding real-world, which the claimed god(s) thinking is a further and thus more extremely unjustified claim(s). What is this god you seem to think you have any justification to claim?

God: “antihumanism thinking”

God thinking is a superstitiously transmitted disease, that usually is accompanied with some kind of antihumanism thinking. Relatively all gods, in general, are said to have the will and power over humans. Likewise, such god claims often are attributed to be the ones who decide morality thus remove the true morality nature in humans that actually assist us in morality. So, adding a god is to welcome antihumanism burdens, because god concepts are often an expression. This is especially so when any so-called god somethingism are said to makes things like hells is an antihumanism thinking. A general humanism thinking to me is that everyone owns themselves, not some god, and everyone is equal. Such humanist thinking to me, requires a shunning of coercion force that removes a human’s rights or the subjugation of oppression and threats for things like requiring belief or demanding faith in some other unjustified abstraction from others. Therefore, humanism thinking is not open to being in such a beliefs, position, or situations that violate free expression of one’s human rights which are not just relinquished because some people believed right or their removal is at the whims of some claimed god (human rights removing/limiting/controlling = ANTIHUMANISM). Humanism to me, summed up as, humans solving human problems through human means. Thus, humanism thinking involves striving to do good without gods, and not welcoming the human rights removing/limiting/controlling, even if the myths could somehow come to be true.

But Why do I Hate Religion?

I was asked why I openly and publicly am so passionate in my hate of religion. further asking what specifically in your life contributed to this outcome.

I hate harm, oppression, bigotry, and love equality, self-ownership, self-empowerment, self-actualization, and self-mastery, as well as truth and not only does religion lie, it is a conspiracy theory of reality. Moreover, not only is religion a conspiracy theories of reality, it is a proud supporter of pseudohistory and or pseudoscience they also push pseudomorality. Religion on the whole to me deserves and earns hate, or at least disfavor when you really analyze it. Not to mention the corruption it has on politics or laws. As well as how destructive this unworthy political influence has and creates because of these false beliefs and the harm to the life of free adults but to the lives of innocent children as well (often robbed of the right to choose and must suffer indoctrination) as the disruption of educated even in public schools. Etc…

I as others do have the right to voice our beliefs, just as I or others then have the right to challenge voiced beliefs.

Long live mental freedom…

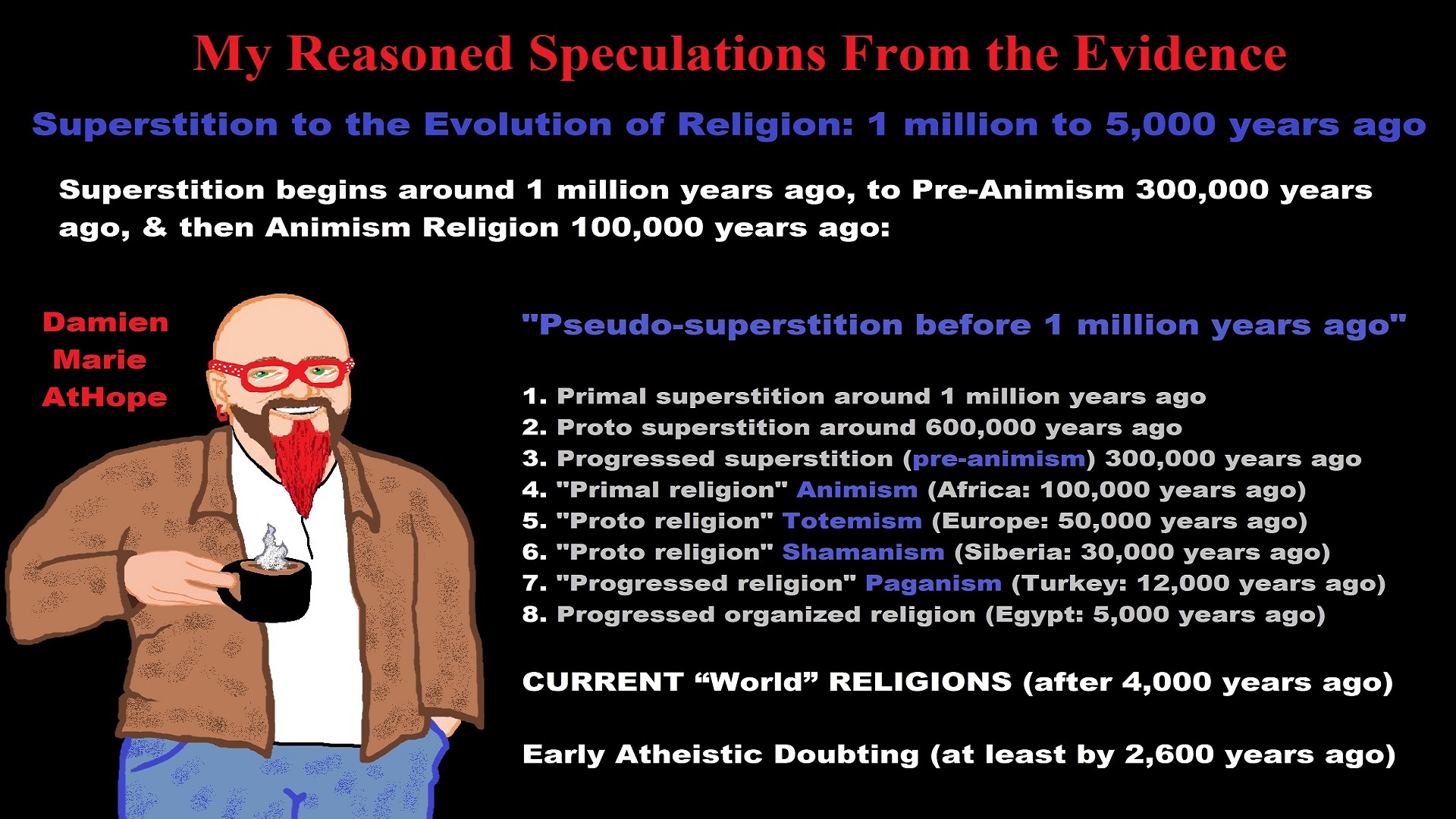

I would first like to point out that there seems to be some scant possible hinting of the earliest pseudo-superstition before 1 million years ago and possibly back to 2 million years ago.

Yet likely this is not truly full superstitionism and defiantly not religion, but there are still elements there that are forming that will further religions’ future evolution.

Superstition begins around 1 million years ago, to Pre-Animism 300,000 years ago, & then Animism Religion 100,000 years ago:

“Pseudo-superstition before 1 million years ago“

1. Primal superstition at around 1 million years ago

2. Proto superstition at around 600,000 years ago

3. Progressed superstition at around 300,000 years ago (pre-animism)

4. Primal religion Animism at around 100,000 years ago

5. Proto religion Early Animism at around 75,000 years ago

6. Progressed religion Totemism at around 50,000 years ago to 30,000 years ago with Shamanism

This pseudo-superstition starts with symbolic, superstition, or early sacralized behaviors seen mostly in tools that may have been possibly exhibited even if only in the most limited ways at the start to further standardize around 1 million years ago with primal superstition. Then the development of religion’s evolution increased around 600,000 years ago with proto superstition and then even to a greater extent around 300,000 years ago with progressed superstition. Religions’ evolution moves from the loose growing of superstitionism to a greater developed thought addiction that was used to manage fear and the desire to sway control over a dangerous world. This began to happen around 100,000 years ago with primal religion. next, the proto religion stage is around 75,000 years ago or less, the progressed religion stage is around 50,000 years ago to 30,000 years ago, and finally after around 13, 500 years ago, begins with the evolution of more organized religion.

The set of stages for the development of organized religion is subdivided into the following: the primal stage of organized religion is around 12,000 years ago with paganism with the emergence of goddesses. The proto organized religion stage of paganism is around 10,000 years ago spreading out to other areas and adapting and developing, and finally, the progressed organized religion stage of paganism is around 7,000 years ago involving the emergence of male gods with limited mythology to 5,000 years ago with the emergence of religious nation-states as well as the forming of full mythology and its connected set of Dogmatic-Propaganda strains of sacralized superstitionism.

Superstitionism is the Mother of Supernaturalism, thus Religion is its child.

Aron Ra interviewing me on my “Archaeological/Anthropological Understanding of Religion Evolution”

“Understanding Religion Evolution: Animism, Totemism, Shamanism, Paganism & Progressed organized religion”

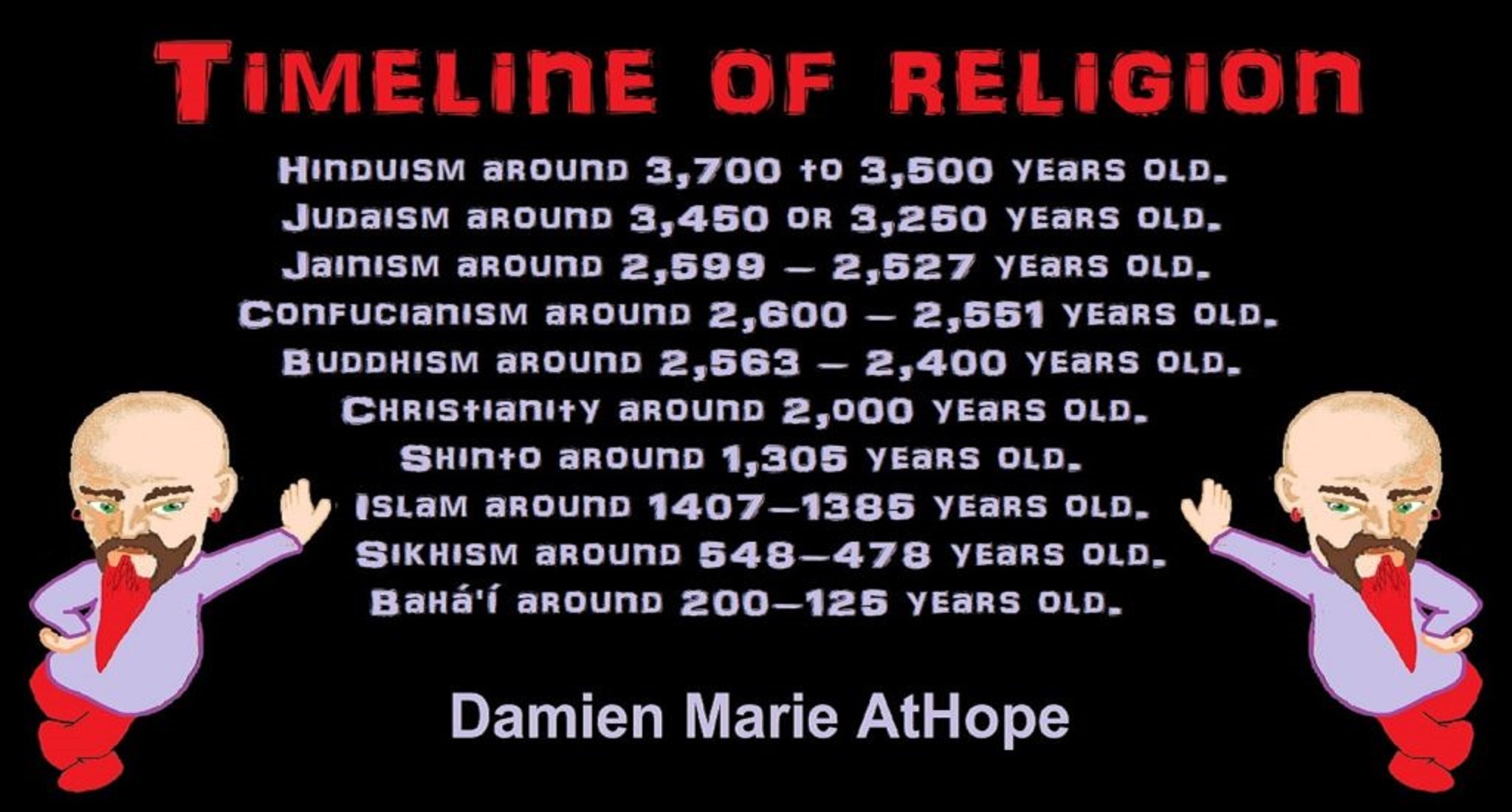

Understanding Religion Evolution:

- Pre-Animism (at least 300,000 years ago)

- Animism (Africa: 100,000 years ago)

- Totemism (Europe: 50,000 years ago)

- Shamanism (Siberia: 30,000 years ago)

- Paganism (Turkey: 12,000 years ago)

- Progressed organized religion (Egypt: 5,000 years ago), (Egypt, the First Dynasty 5,150 years ago)

- CURRENT “World” RELIGIONS (after 4,000 years ago)

- Early Atheistic Doubting (at least by 2,600 years ago)

“An Archaeological/Anthropological Understanding of Religion Evolution”

Animism (such as that seen in Africa: 100,000 years ago)

Did Neanderthals teach us “Primal Religion (Pre-Animism/Animism?)” 120,000 Years Ago? Homo sapiens – is known to have reached the Levant between 120,000 and 90,000 years ago, but that exit from Africa evidently went extinct. 100,000 years ago, in Qafzeh, Israel, the oldest intentional burial had 15 African individuals covered in red ocher was from a group who visited and returned back to Africa. 100,000 to 74,000 years ago, at Border Cave in Africa, an intentional burial of an infant with red ochre and a shell ornament, which may have possible connections to the Africans buried in Qafzeh.

Animism is approximately a 100,000-year-old belief system and believe in spirit-filled life and/or afterlife. If you believe like this, regardless of your faith, you are a hidden animist.

The following is evidence of Animism: 100,000 years ago, in Qafzeh, Israel, the oldest intentional burial had 15 African individuals covered in red ocher was from a group who visited and returned back to Africa. 100,000 to 74,000 years ago, at Border Cave in Africa, an intentional burial of an infant with red ochre and a shell ornament, which may have possible connections to the Africans buried in Qafzeh, Israel. 120,000 years ago, did Neanderthals teach us Primal Religion (Pre-Animism/Animism) as they too used red ocher and burials? ref, ref

It seems to me, it may be the Neanderthals who may have transmitted a “Primal Religion (Animism)” or at least burial and thoughts of an afterlife. The Neanderthals seem to express what could be perceived as a Primal “type of” Religion, which could have come first and is supported in how 250,000 years ago, the Neanderthals used red ochre and 230,000 years ago shows evidence of Neanderthal burial with grave goods and possibly a belief in the afterlife. ref

Do you think it is crazy that the Neanderthals may have transmitted a “Primal Religion”? Consider this, it appears that 175,000 years ago, the Neanderthals built mysterious underground circles with broken off stalactites. This evidence suggests that the Neanderthals were the first humans to intentionally bury the dead, doing so in shallow graves along with stone tools and animal bones. Exemplary sites include Shanidar in Iraq, Kebara Cave in Israel and Krapina in Croatia. Other evidence may suggest the Neanderthals had it transmitted to them by Homo heidelbergensis, 350,000 years ago, by their earliest burial in a shaft pit grave in a cave that had a pink stone axe on the top of 27 Homo heidelbergensis individuals and 250,000 years ago, Homo naledi had an intentional cemetery in South Africa cave. ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

Totemism (Europe: 50,000 years ago)

Did Neanderthals Help Inspire Totemism? Because there is Art Dating to Around 65,000 Years Ago in Spain? Totemism as seen in Europe: 50,000 years ago, mainly the Aurignacian culture. Pre-Aurignacian “Châtelperronian” (Western Europe, mainly Spain and France, possible transitional/cultural diffusion between Neanderthals and Humans around 50,000-40,000 years ago). Archaic–Aurignacian/Proto-Aurignacian Humans (Europe around 46,000-35,000). And Aurignacian “classical/early to late” Humans (Europe and other areas around 38,000 – 26,000 years ago).

Totemism is approximately a 50,000-year-old belief system and believe in spirit-filled life and/or afterlife that can be attached to or be expressed in things or objects. If you believe like this, regardless of your faith, you are a hidden totemist.

Toetmism may be older as there is evidence of what looks like a Stone Snake in South Africa, which may be the “first human worship” dating to around 70,000 years ago. Many archaeologists propose that societies from 70,000 to 50,000 years ago such as that of the Neanderthals may also have practiced the earliest form of totemism or animal worship in addition to their presumably religious burial of the dead. Did Neanderthals help inspire Totemism? There is Neanderthals art dating to around 65,000 years ago in Spain. ref, ref

Shamanism (beginning around 30,000 years ago)

Shamanism (such as that seen in Siberia Gravettian culture: 30,000 years ago). Gravettian culture (34,000–24,000 years ago; Western Gravettian, mainly France, Spain, and Britain, as well as Eastern Gravettian in Central Europe and Russia. The eastern Gravettians, which include the Pavlovian culture). And, the Pavlovian culture (31,000 – 25,000 years ago such as in Austria and Poland). 31,000 – 20,000 years ago Oldest Shaman was Female, Buried with the Oldest Portrait Carving.

Shamanism is approximately a 30,000-year-old belief system and believe in spirit-filled life and/or afterlife that can be attached to or be expressed in things or objects and these objects can be used by special persons or in special rituals that can connect to spirit-filled life and/or afterlife. If you believe like this, regardless of your faith, you are a hidden shamanist.

Around 29,000 to 25,000 years ago in Dolní Vestonice, Czech Republic, the oldest human face representation is a carved ivory female head that was found nearby a female burial and belong to the Pavlovian culture, a variant of the Gravettian culture. The left side of the figure’s face was a distorted image and is believed to be a portrait of an elder female, who was around 40 years old. She was ritualistically placed beneath a pair of mammoth scapulae, one leaning against the other. Surprisingly, the left side of the skull was disfigured in the same manner as the aforementioned carved ivory figure, indicating that the figure was an intentional depiction of this specific individual. The bones and the earth surrounding the body contained traces of red ocher, a flint spearhead had been placed near the skull, and one handheld the body of a fox. This evidence suggests that this was the burial site of a shaman. This is the oldest site not only of ceramic figurines and artistic portraiture but also of evidence of early female shamans. Before 5,500 years ago, women were much more prominent in religion.

Archaeologists usually describe two regional variants: the western Gravettian, known namely from cave sites in France, Spain, and Britain, and the eastern Gravettian in Central Europe and Russia. The eastern Gravettians include the Pavlovian culture, which were specialized mammoth hunters and whose remains are usually found not in caves but in open-air sites. The origins of the Gravettian people are not clear, they seem to appear simultaneously all over Europe. Though they carried distinct genetic signatures, the Gravettians and Aurignacians before them were descended from the same ancient founder population. According to genetic data, 37,000 years ago, all Europeans can be traced back to a single ‘founding population’ that made it through the last ice age. Furthermore, the so-called founding fathers were part of the Aurignacian culture, which was displaced by another group of early humans members of the Gravettian culture. Between 37,000 years ago and 14,000 years ago, different groups of Europeans were descended from a single founder population. To a greater extent than their Aurignacianpredecessors, they are known for their Venus figurines.

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, & ref

Paganism (beginning around 12,000 years ago)

Paganism (such as that seen in Turkey: 12,000 years ago). Gobekli Tepe: “first human-made temple” around 12,000 years ago. Sedentism and the Creation of goddesses around 12,000 years ago as well as male gods after 7,000 years ago. Pagan-Shaman burial in Israel 12,000 years ago and 12,000 – 10,000 years old Paganistic-Shamanistic Art in a Remote Cave in Egypt. Skull Cult around 11,500 to 8,400 Years Ago and Catal Huyuk “first religious designed city” around 10,000 years ago.

Paganism is approximately a 12,000-year-old belief system and believe in spirit-filled life and/or afterlife that can be attached to or be expressed in things or objects and these objects can be used by special persons or in special rituals that can connect to spirit-filled life and/or afterlife and who are guided/supported by a goddess/god, goddesses/gods, magical beings, or supreme spirits. If you believe like this, regardless of your faith, you are a hidden paganist.

Around 12,000 years ago, in Turkey, the first evidence of paganism is Gobekli Tepe: “first human-made temple” and around 9,500 years ago, in Turkey, the second evidence of paganism is Catal Huyuk “first religious designed city”. In addition, early paganism is connected to Proto-Indo-European language and religion. Proto-Indo-European religion can be reconstructed with confidence that the gods and goddesses, myths, festivals, and form of rituals with invocations, prayers, and songs of praise make up the spoken element of religion. Much of this activity is connected to the natural and agricultural year or at least those are the easiest elements to reconstruct because nature does not change and because farmers are the most conservative members of society and are best able to keep the old ways.

The reconstruction of goddesses/gods characteristics may be different than what we think of and only evolved later to the characteristics we know of today. One such characteristic is how a deity’s gender may not be fixed, since they are often deified forces of nature, which tend to not have genders. There are at least 40 deities and the Goddesses that have been reconstructed are: *Pria, *Pleto, *Devi, *Perkunos, *Aeusos, and *Yama.

The reconstruction of myths can be connected to Proto-Indo-European culture/language and by additional research, many of these myths have since been confirmed including some areas that were not accessible to the early writers such as Latvian folk songs and Hittite hieroglyphic tablets. There are at least 28 myths and one of the most widely recognized myths of the Indo-Europeans is the myth, “Yama is killed by his brother Manu” and “the world is made from his body”. Some of the forms of this myth in various Indo-European languages are about the Creation Myth of the Indo-Europeans.