The transmission of pottery technology among prehistoric European hunter-gatherers

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41562-022-01491-8

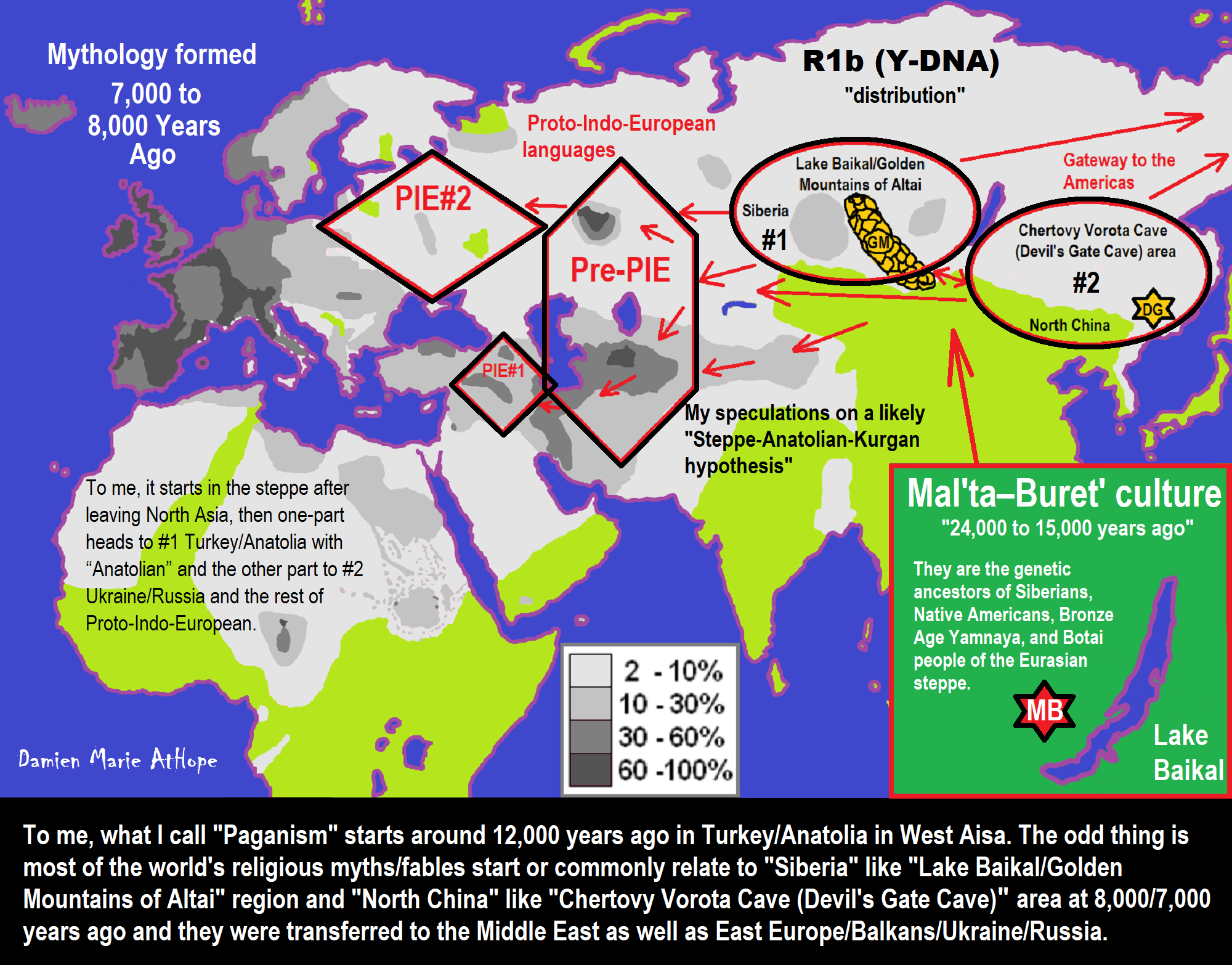

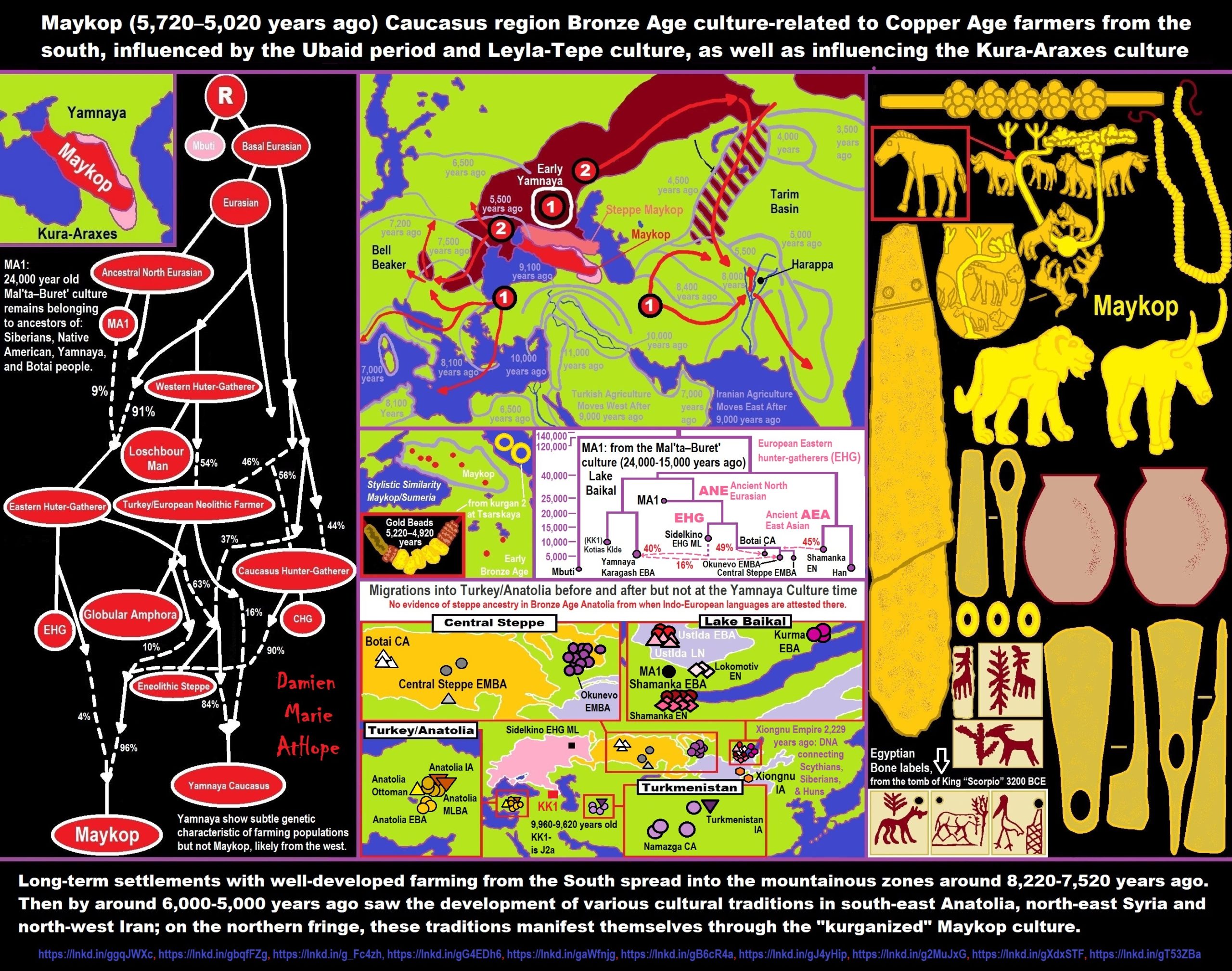

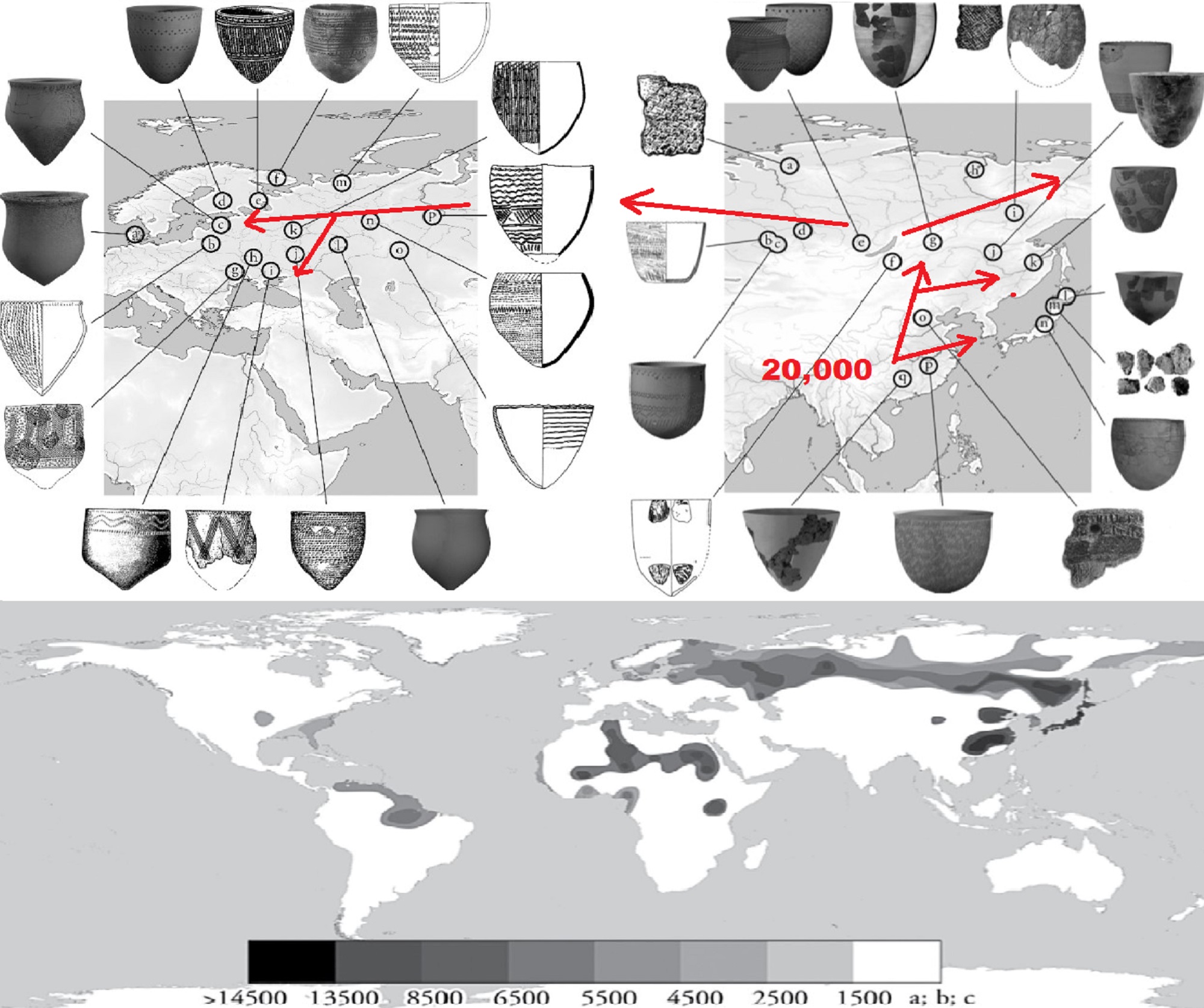

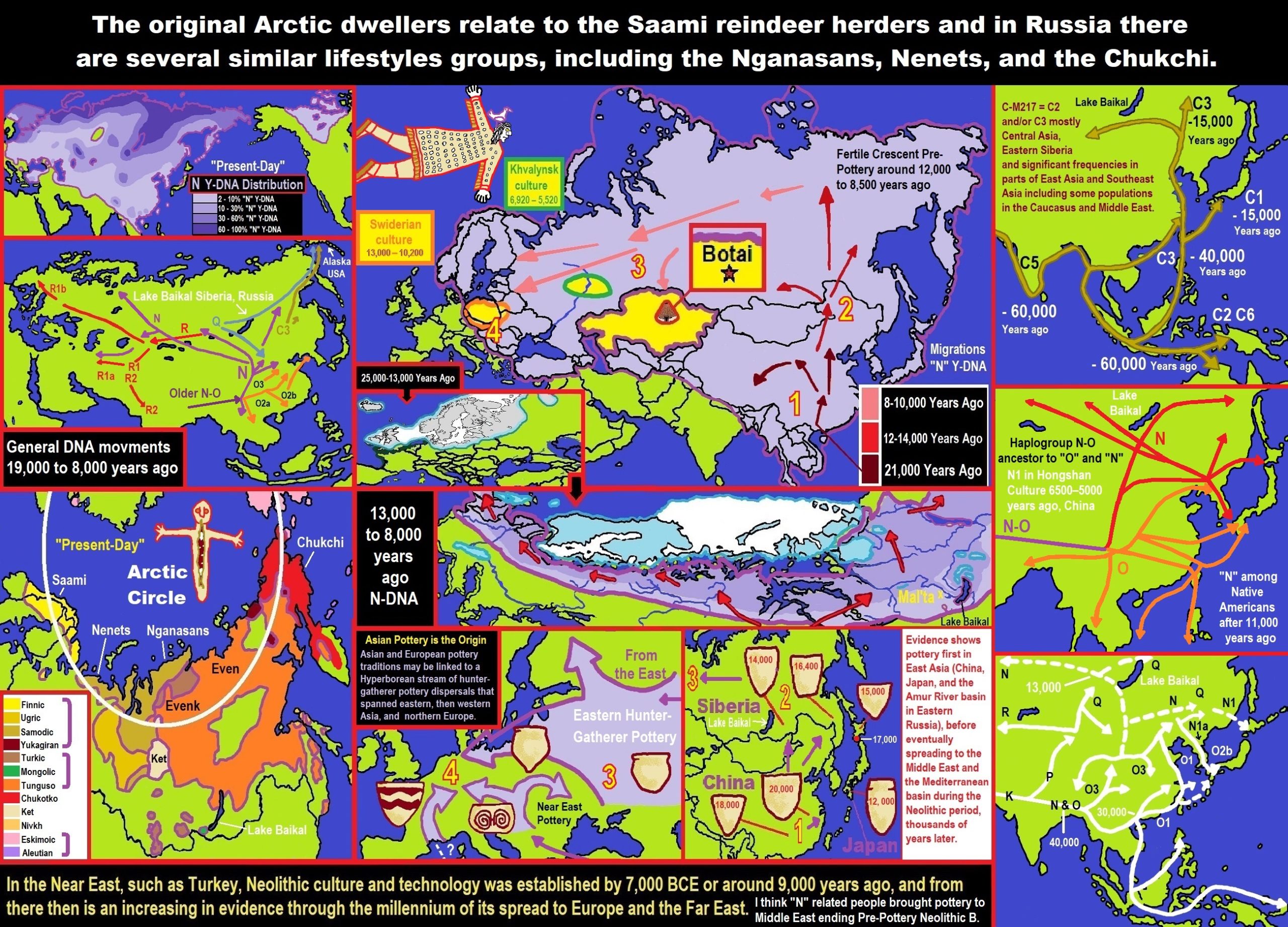

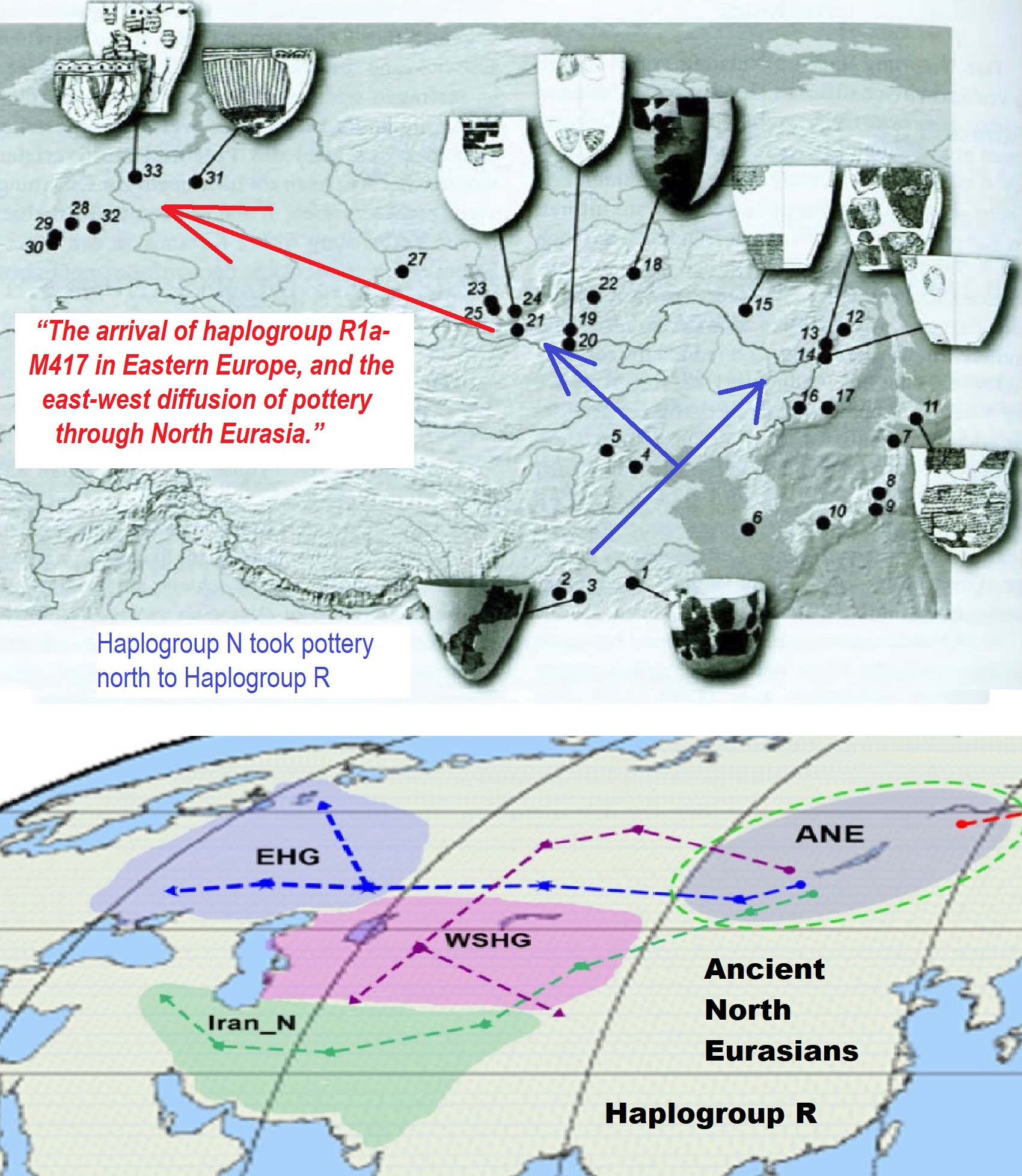

“Although isolated cases of innovation cannot be excluded, a continuous process of adoption with the earlier occurrence of an antecedent tradition in western Siberia or central Asia, Siberia fit better though both are consistent with an ultimate origin for these traditions in the Far East.” ref

Unearthing the Origins of Agriculture?

“Archaeobiology is offering new insights into the long-debated roots and evolution of the practice that made large human settlements and our modern complex society possible—even if at a cost.” ref

“For hundreds of thousands of years, our ancestors had survived by hunting animals and gathering edible wild plants. But starting about 11,700 years ago, people began to use wild plants in ways that changed the plants themselves, a process called domestication. People also began to alter their environments as they cultivated those plants. The result was the profound landscape and cultural transformation we know as agriculture.” ref

“The precise drivers of agriculture remain a matter of fierce debate. Were people pushed into relying on plants for food because of stresses such as growing populations or climate change? Or did plants lure people in by being so abundant and useful that it made sense to turn them into dietary staples? And did religious or cultural practices, such as a tradition of providing bountiful feasts, drive the emergence of agriculture? Or perhaps plant cultivation itself made those religious or cultural ideas possible?” ref

Pic ref

Abstract

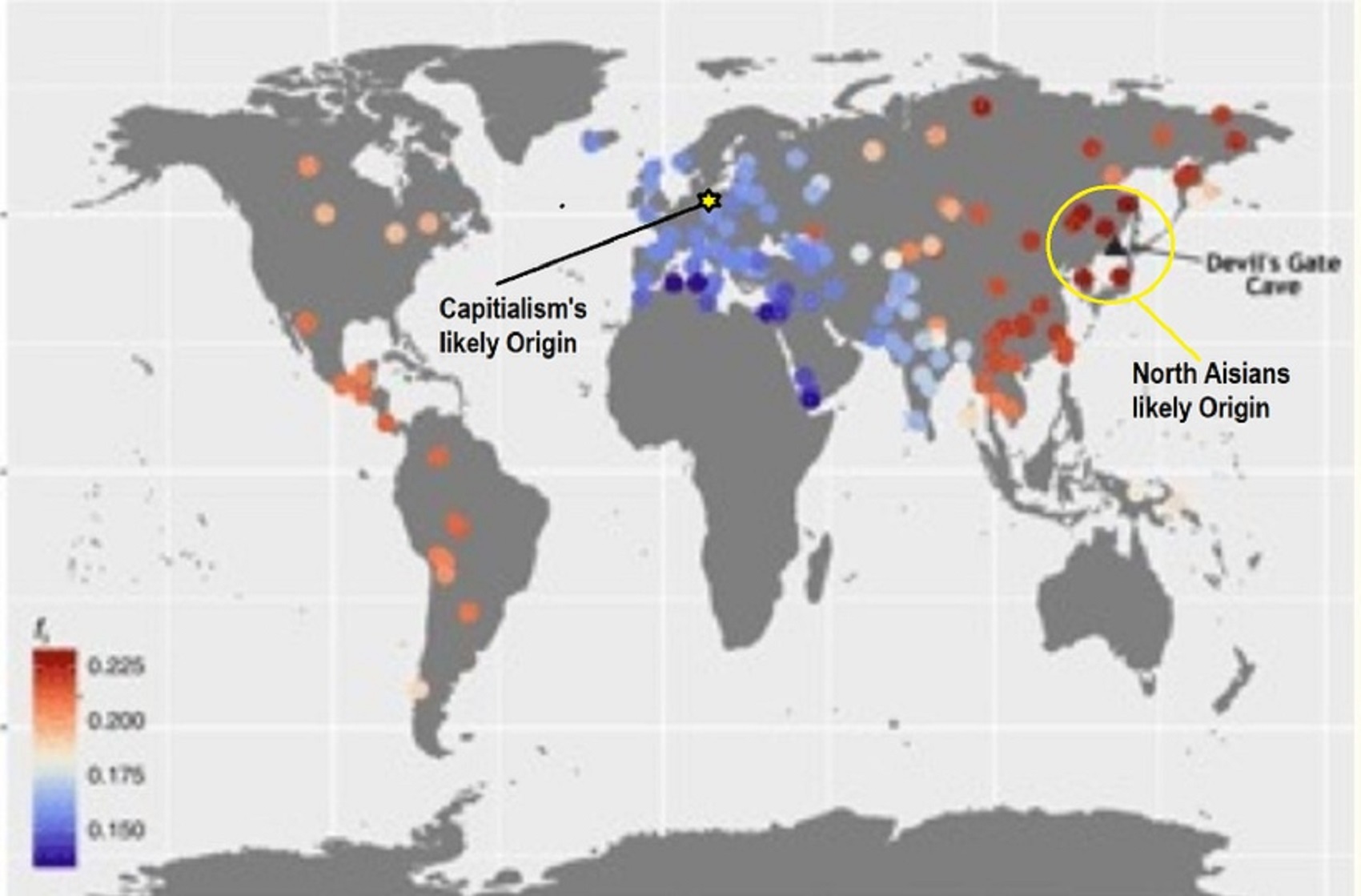

“Ancient genomes have revolutionized our understanding of Holocene prehistory and, particularly, the Neolithic transition in western Eurasia. In contrast, East Asia has so far received little attention, despite representing a core region at which the Neolithic transition took place independently ~3 millennia after its onset in the Near East. We report genome-wide data from two hunter-gatherers from Devil’s Gate, an early Neolithic cave site (dated to ~7.7 thousand years ago) located in East Asia, on the border between Russia and Korea. Both of these individuals are genetically most similar to geographically close modern populations from the Amur Basin, all speaking Tungusic languages, and, in particular, to the Ulchi. The similarity to nearby modern populations and the low levels of additional genetic material in the Ulchi imply a high level of genetic continuity in this region during the Holocene, a pattern that markedly contrasts with that reported for Europe.” ref

About witchcraft and the birth of the world in rock paintings?

“I dare to test the soundscape by drumming. The rock wakes up to the drumming with a tremendous reverberation, and we drum together for a moment. The rock of painting closes me to its own world, where the rest is forgotten. Jacob Fellman tells of the Sámi ceremonies with the seids that “They held feasts in honor of the gods by singing and drumming, and the brighter the drum played, the better it pleased the gods”. At least on this basis, Hahlavuori is the most favorable place for the gods.” – Tarja Soiniola, Senior Archivist, MA, Helsinki, Southern Finland, Finland

Writings on culture, research, and cultural heritage: About witchcraft and the birth of the world in rock paintings

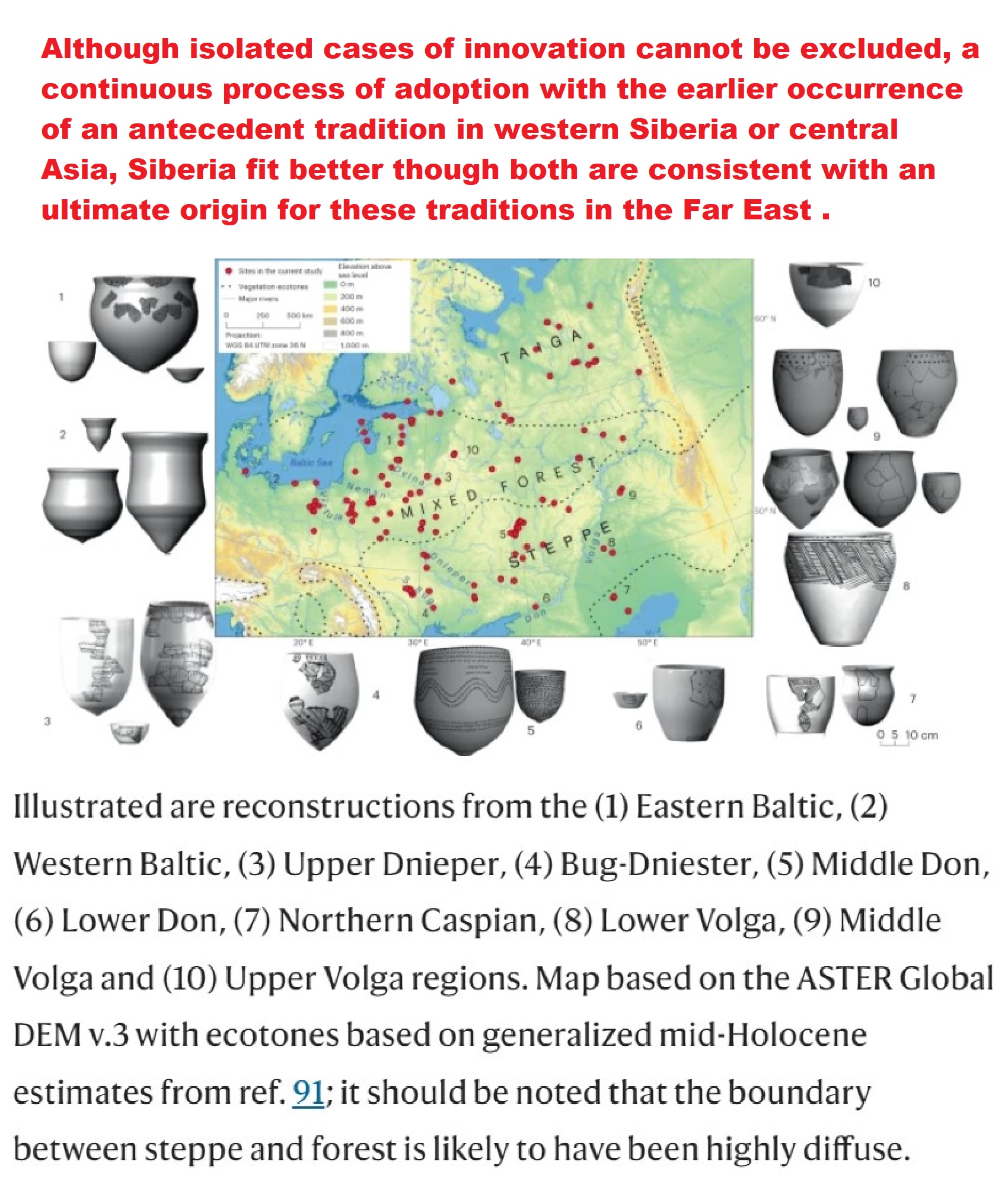

Bridging the Boreal Forest: Siberian Archaeology and the Emergence of Pottery among Prehistoric Hunter-Gatherers of Northern Eurasia

Abstract

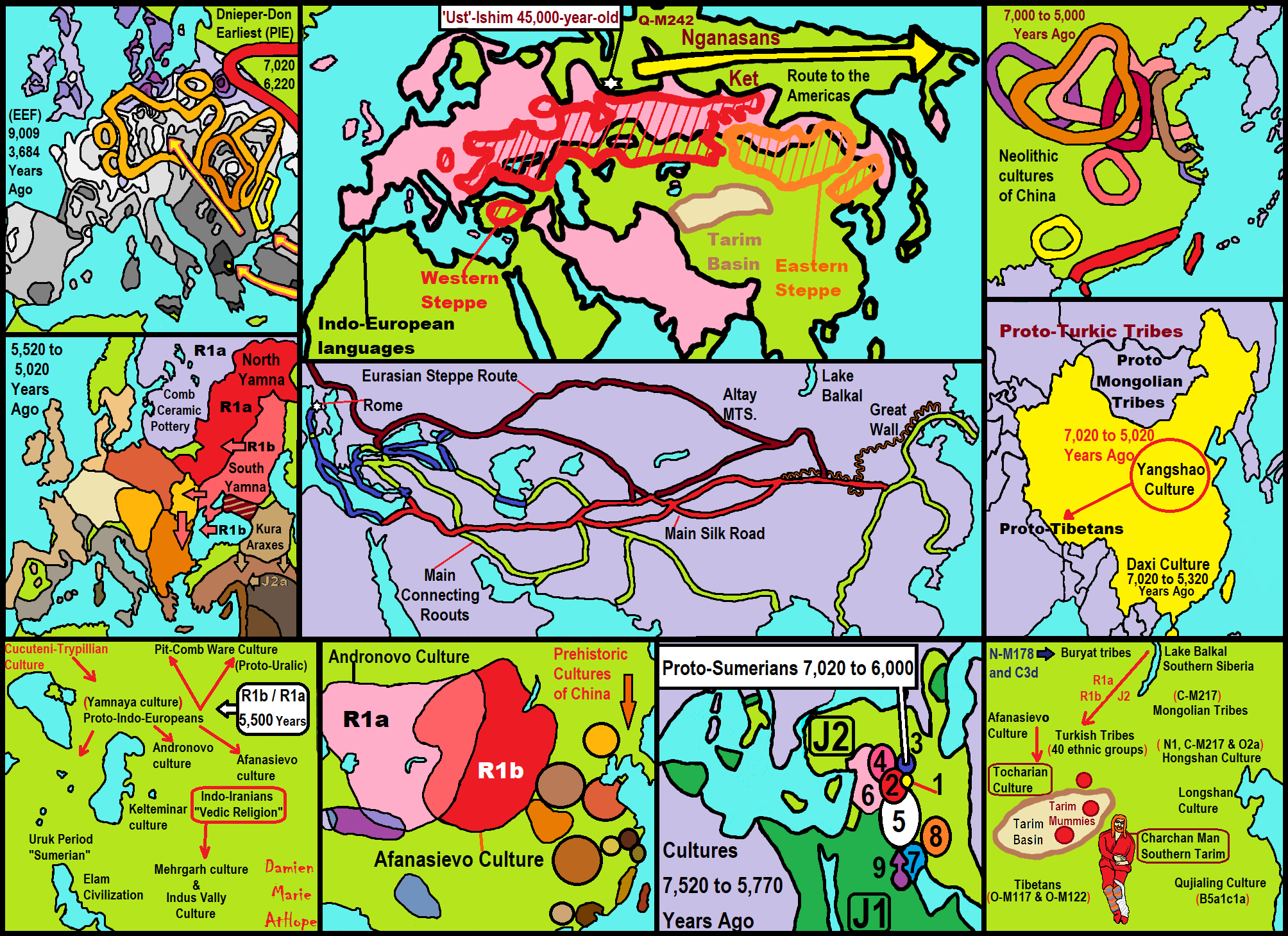

“This article examines Siberia’s increasingly important role in the study of the emergence of pottery across northern Eurasia. The world’s earliest pottery comes from Late Pleistocene hunter-gatherer sites in East Asia. This material is typically seen as disconnected from later pottery traditions in Europe, which are generally associated with sedentary farmers. However, new evidence suggests that Asian and European pottery traditions may be linked to a Hyperborean stream of hunter-gatherer pottery dispersals that spanned eastern and western Asia, and introduced pottery into the prehistoric societies of northern Europe. As a potential bridge between the eastern and western early pottery traditions, Siberia’s prehistory is therefore set to play an increasingly central role in one of world archaeology’s most important debates.” ref

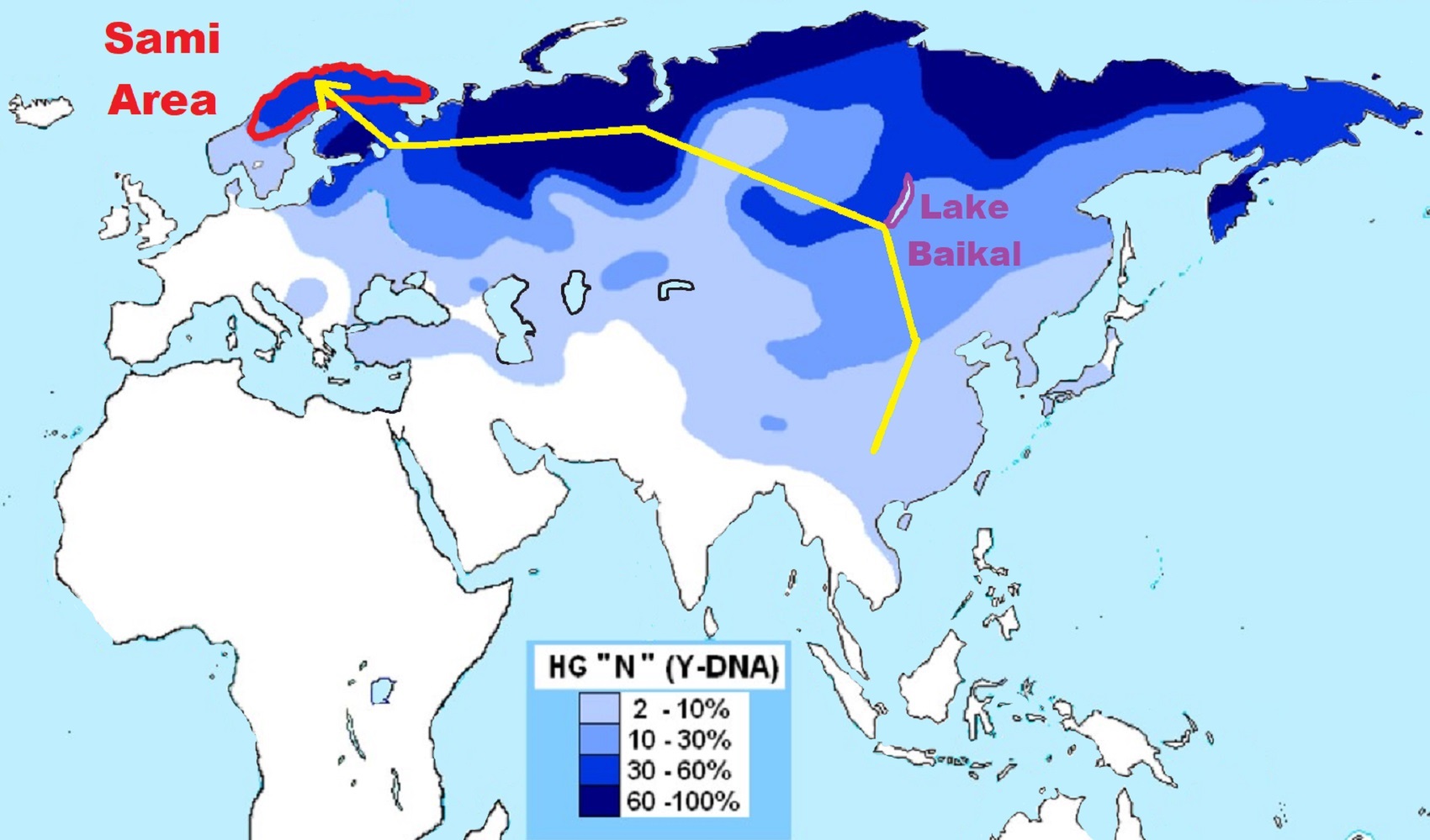

Haplogroup N-M231

“Haplogroup N (M231) is a Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup and it is most commonly found in males originating from northern Eurasia. It also has been observed at lower frequencies in populations native to other regions, including the Balkans, Central Asia, East Asia, and Southeast Asia. Haplogroup NO-M214 – its most recent common ancestor with its sibling, haplogroup O-M175 – is estimated to have existed about 36,800–44,700 years ago. It is generally considered that N-M231 arose in East Asia approximately 19,400 (±4,800) years ago and populated northern Eurasia after the Last Glacial Maximum. Males carrying the marker apparently moved northwards as the climate warmed in the Holocene, migrating in a counter-clockwise path, to eventually become concentrated in areas as far away as Fennoscandia and the Baltic (Rootsi et al. 2006). The apparent dearth of haplogroup N-M231 amongst Native American peoples indicates that it spread after Beringia was submerged (Chiaroni, Underhill & Cavalli-Sforza 2009), about 11,000 years ago.” ref

Distribution

“Projected distributions of haplogroup N sub-haplogroups. (A) N*-M231, (B) N1*-LLY22g, (C) N1a-M128, (D) N1b-P43, (E) N1c-M46. Haplogroup N has a wide geographic distribution throughout northern Eurasia, and it also has been observed occasionally in other areas, including Central Asia and the Balkans.” ref

“It has been found with the greatest frequency among indigenous peoples of Russia, including Finnic peoples, Mari, Udmurt, Komi, Khanty, Mansi, Nenets, Nganasans, Turkic peoples (Yakuts, Dolgans, Khakasses, Tuvans, Tatars, Chuvashes, etc.), Buryats, Tungusic peoples (Evenks, Evens, Negidals, Nanais, etc.), Yukaghirs, Luoravetlans (Chukchis, Koryaks), and Siberian Eskimos, but certain subclades are very common in Finland, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, and other subclades are found at low frequency in China (Yi, Naxi, Lhoba, Han Chinese, etc.). Especially in ethnic Finnic peoples and Baltic-speaking peoples of northern Europe, the Ob-Ugric-speaking and Northern Samoyed peoples of western Siberia, and Turkic-speaking peoples of Russia (especially Yakuts (McDonald 2005), but also Altaians, Shors, Khakas, Chuvashes, Tatars, and Bashkirs). Nearly all members of haplogroup N among these populations of northern Eurasia belong to subclades of either haplogroup N-Tat or haplogroup N-P43.” ref

‘Y-chromosomes belonging to N1b-F2930/M1881/V3743, or N1*-CTS11499/L735/M2291(xN1a-F1206/M2013/S11466), have been found in China and sporadically throughout other parts of Eurasia. N1a-F1206/M2013/S11466 is found in high numbers in Northern Eurasia.” ref

‘N2-Y6503, the other primary subclade of haplogroup N, is extremely rare and is mainly represented among extant humans by a recently formed subclade that is virtually restricted to the countries making up the former Yugoslavia (Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, and Montenegro), Hungary, and Austria. Other members of N2-Y6503 include a Hungarian with recent ancestry from Suceava in Bukovina, a Slovakian, a few British individuals, and an Altaian.” ref

N* (M231)

“Y-chromosomes that display the M231 mutation that defines Haplogroup N-M231, but do not display the CTS11499, L735, M2291 mutations that define Haplogroup N1 are said to belong to paragroup N-M231*. N-M231* has been found at low levels in China. Out of a sample of 165 Han males from China, two individuals (1.2%) were found to belong to N*. (Karafet et al. 2010). One originated from Guangzhou and one from Xi’an. Among the ancient samples from the Baikal Early Neolithic Kitoi culture, one of the Shamanka II samples (DA250), dated to c. 6500 BP, was analyzed as NO1-M214.” ref

N1 (CTS11499, Z4762, CTS3750)

“In 2014, there was a major change in the definition of subclade N1, when LLY22g was retired as the main defining SNP for N1 because of reports of LLY22g’s unreliability. According to ISOGG, LLY22g is problematic because it is a “palindromic marker and can easily be misinterpreted.” Since then, the name N1 has been applied to a clade marked by a great number of SNPs, including CTS11499, Z4762, and CTS3750. N1 is the most recent common ancestor of all extant members of Haplogroup N-M231 except members of the rare N2-Y6503 (N2-B482) subclade. The TMRCA of N1 is estimated to be 18,000 years before present (16,300–19,700 BP; 95% CI).” ref

“Since the revision of 2014, the position of many examples of “N1-LLY22g” within haplogroup N have become unclear. Therefore, it is better to check yfull and ISOGG 2019 in order to understand the updated structure of N-M231. However, in older studies, N-LLY22g has been reported to reach a frequency of up to 30% (13/43) among the Yi people of Butuo County, Sichuan in Southwest China (Hammer et al. 2005, Karafet et al. 2001, and Wen2004b). It is also found in 34.6% of Lhoba people (Wen 2004, Bo Wen 2004).” ref

N1-LLY22g* has been found in samples of Han Chinese, but with widely varying frequency:

- 15.0% (6/40) Han from Guangzhou (Hammer et al. 2005 and Karafet et al. 2001)

- 6.8% (3/44) Han from Xi’an (Hammer et al. 2005 and Karafet et al. 2001)

- 6.7% (2/30) Han from Lanzhou (Xue et al. 2006)

- 3.6% (3/84) Taiwanese Han (Hammer et al. 2005)

- 2.9% (1/34) Han from Chengdu (Xue et al. 2006)

- 2.9% (1/35) Han from Harbin (Xue et al. 2006)

- 2.9% (1/35) Han from Meixian District (Xue et al. 2006)

- 0% (0/32) Han from Yining City (Xue et al. 2006) ref

Other populations in which representatives of N1*-LLY22g have been found include:

- Hani people (4/34 = 11.8%) (Xue et al. 2006)

- Sibe people (4/41 = 9.8%) (Xue et al. 2006)

- Tujia people (2/49 = 4.1%) (Hammer et al. 2005)

- Manchu people (2/52 = 3.8% (Hammer et al. 2005) to 2/35 = 5.7% (Xue et al. 2006)

- Bit people (1/28 = 3.6%) (Cai 2011)

- Uyghurs (2/70 = 2.9% (Xue et al. 2006) to 2/67 = 3.0%) (Hammer et al. 2005)

- Tibetan people (3/105 = 2.9% (Hammer et al. 2005) to 3/35 = 8.6% (Xue et al. 2006))

- Koreans (0/106 = 0.0% – 2/25 = 8% (Rootsi et al. 2006, Xue et al. 2006, and Kim 2007)

- Vietnamese people (2/70 = 2.9%) (Hammer et al. 2005)

- Japanese people (0/70 Tokushima – 2/26 = 7.7% Aomori) (Hammer et al. 2005)

- Manchurian Evenks (0/26 = 0.0% (Xue et al. 2006) to 1/41 = 2.4%(Hammer et al. 2005))

- Altai people (0/50 Northern to 5/96 = 5.2% Southern, or 0/43 Beshpeltir to 5/46 = 10.9% Kulada),(Hammer et al. 2005)(Kharkov 2007)

- Shors (2/23 = 8.7%) (Rootsi et al. 2006)

- Khakas people (5/181 = 2.8%) (Rootsi et al. 2006)

- Tuvans (5/311 = 1.6%) (Rootsi et al. 2006)

- Southern Borneo (1/40 = 2.5%) (Rootsi et al. 2006)

- Forest Nenets (1/89 = 1.1%) (Rootsi et al. 2006)

- Yakuts (0/215 – 1/121 = 0.8%) (Rootsi et al. 2006)

- Turkish people (1/523 = 0.2%) (Rootsi et al. 2006) In Turkey, the total of subclades of haplogroup N-M231 amounts to 4% of the male population.

- One individual who belongs either to N* or N1* has been found in a sample of 77 males from Kathmandu, Nepal (1/77 = 1.3% N-M231(xM128,P43, Tat)) (Gayden 2007) ref

N1(xN1a, N1c) was found in ancient bones of Liao civilization:

- Niuheliang (Hongshan Culture, 6500–5000 BP) 66.7%(=4/6)

- Halahaigou (Xiaoheyan Culture, 5000–4200 BP) 100.0%(=12/12)

- Dadianzi (Lower Xiajiadian culture, 4200–3600 BP) 60.0%(=3/5) ref

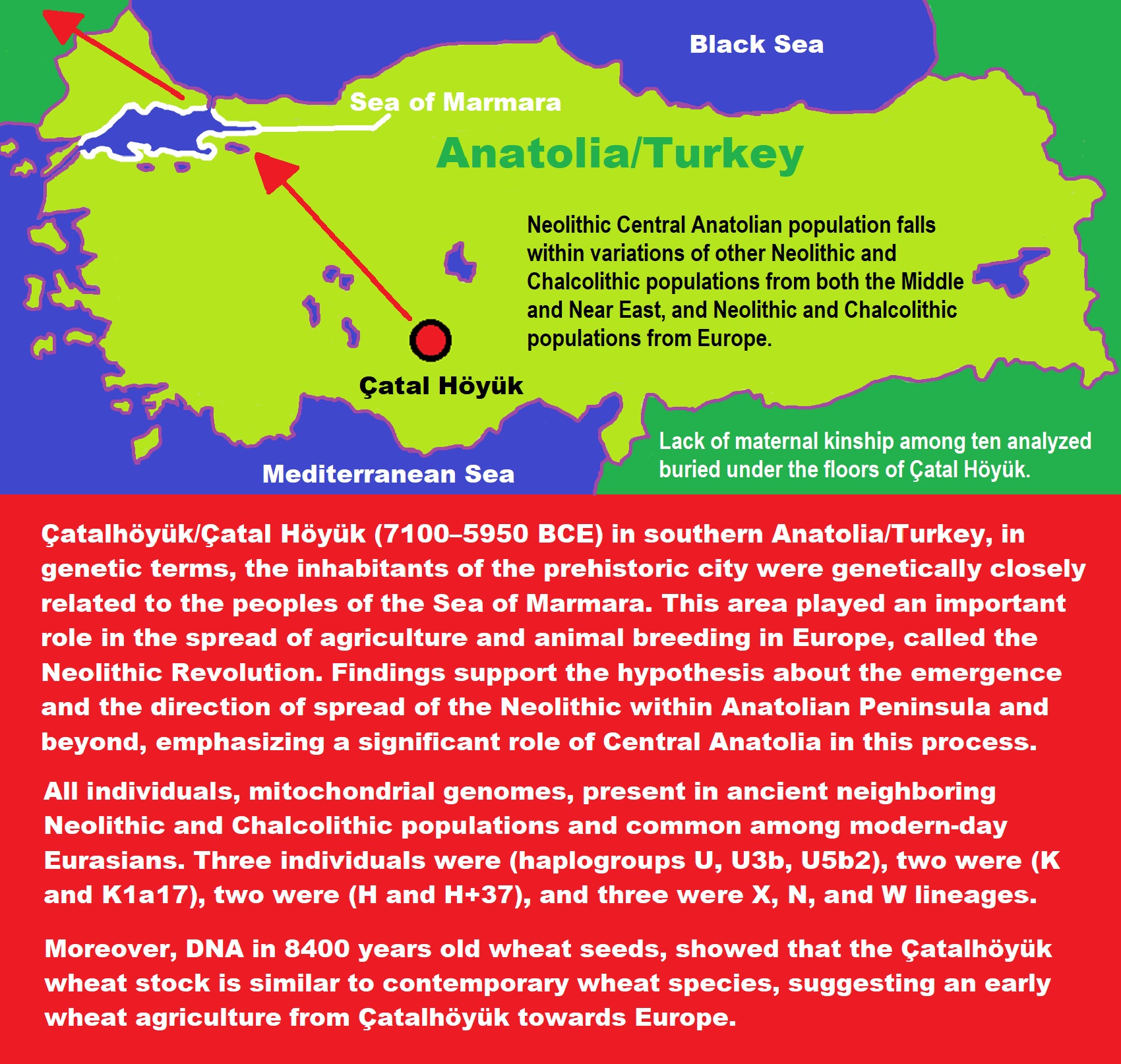

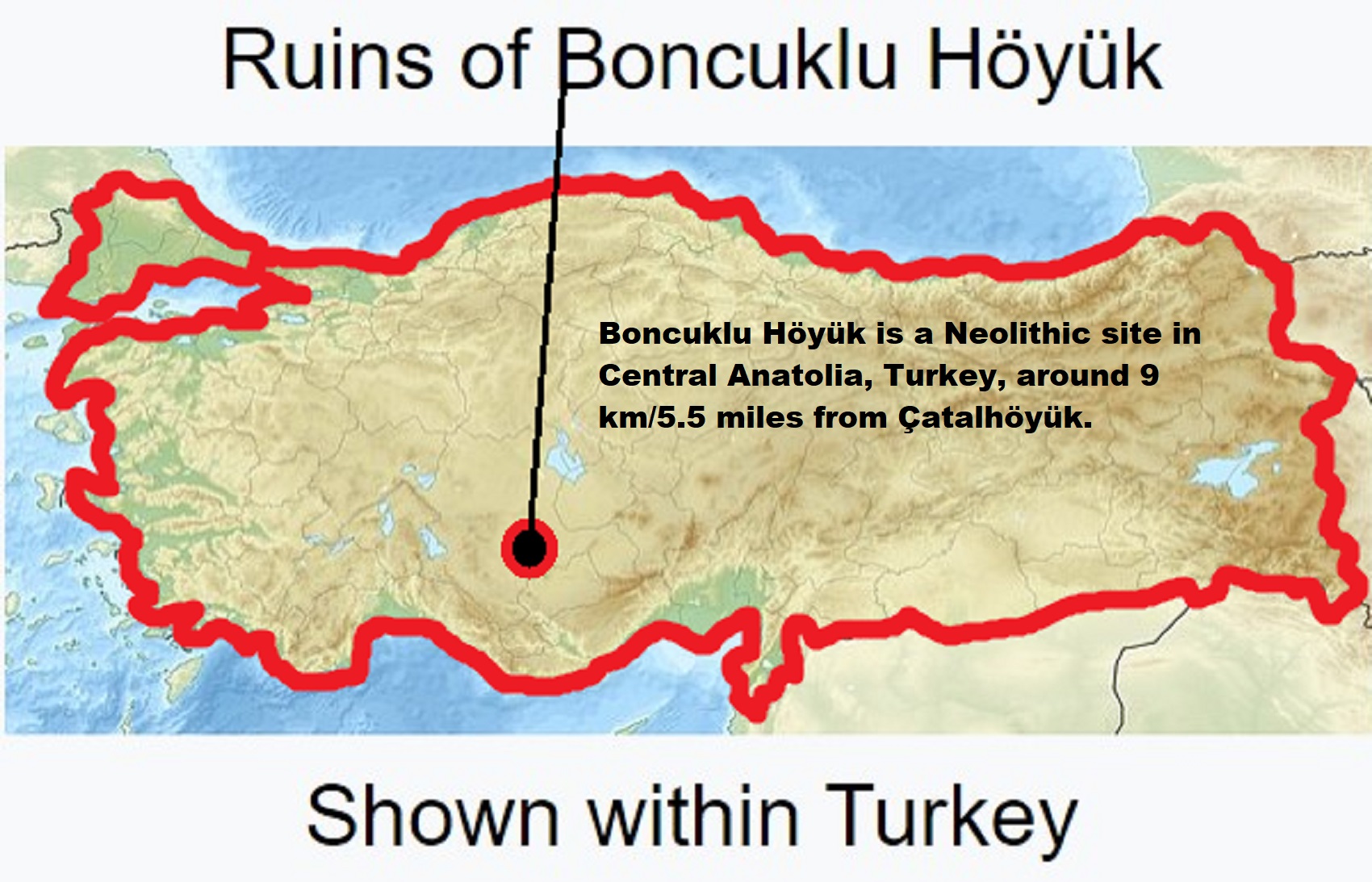

Boncuklu Höyük: The earliest ceramics on the Anatolian plateau?

“Boncuklu Höyük is a Neolithic site in Central Anatolia, Turkey, around 9 km/5.5 miles from Çatalhöyük.” ref

Ancient mDNA “N1a1a1” and Pottery?

Bon005 – Boncuklu Höyük mtDNA N1a1a1 around 10,220 years ago Turkey – Central Anatolia ref

Bon004 – Boncuklu Höyük mtDNA N1a1a1 around 10,076 years ago Turkey – Central Anatolia ref

ZHAG – Boncuklu Höyük mtDNA N1a1a1 around 9,900 years ago Turkey – Central Anatolia ref

People who lived in ancient settlement in central Turkey migrated to Europe: archaeologists

“10,300-year-old Boncuklu Höyük settlement in Turkey revealed that the people who lived in the settlement migrated to Europe. And the Boncuklu Höyük settlement was established a thousand years before Çatalhöyük, so is the ancestor of later Çatalhöyük.” ref

Ash040 – Aşıklı Höyük mtDNA N1a1a1 around 9,875 years ago Turkey – Central Anatolia ref

CCH144 – Çatalhöyük mtDNA N1a1a1 around 8,808 years ago Turkey – Central Anatolia ref

I1096 – Barcın Höyük mtDNA N1a1a1 around 8,300 years ago Turkey – Northwest Anatolia ref

Bar25 – Barcın Höyük mtDNA N1a1a1 around 8,295 years ago Turkey – Northwest Anatolia ref

Tep004 – Tepecik-Çiftlik Höyük mtDNA N1a1a1 around 8,237 years ago Turkey – Northwest Anatolia ref

Tep006 – Tepecik-Çiftlik Höyük mtDNA N1a1a1 around 8,099 years ago Turkey – Northwest Anatolia ref

I0725 – Mentese mtDNA N1a1a1 around 7,950 years ago Turkey – South-Western corner, on the Aegean Sea ref

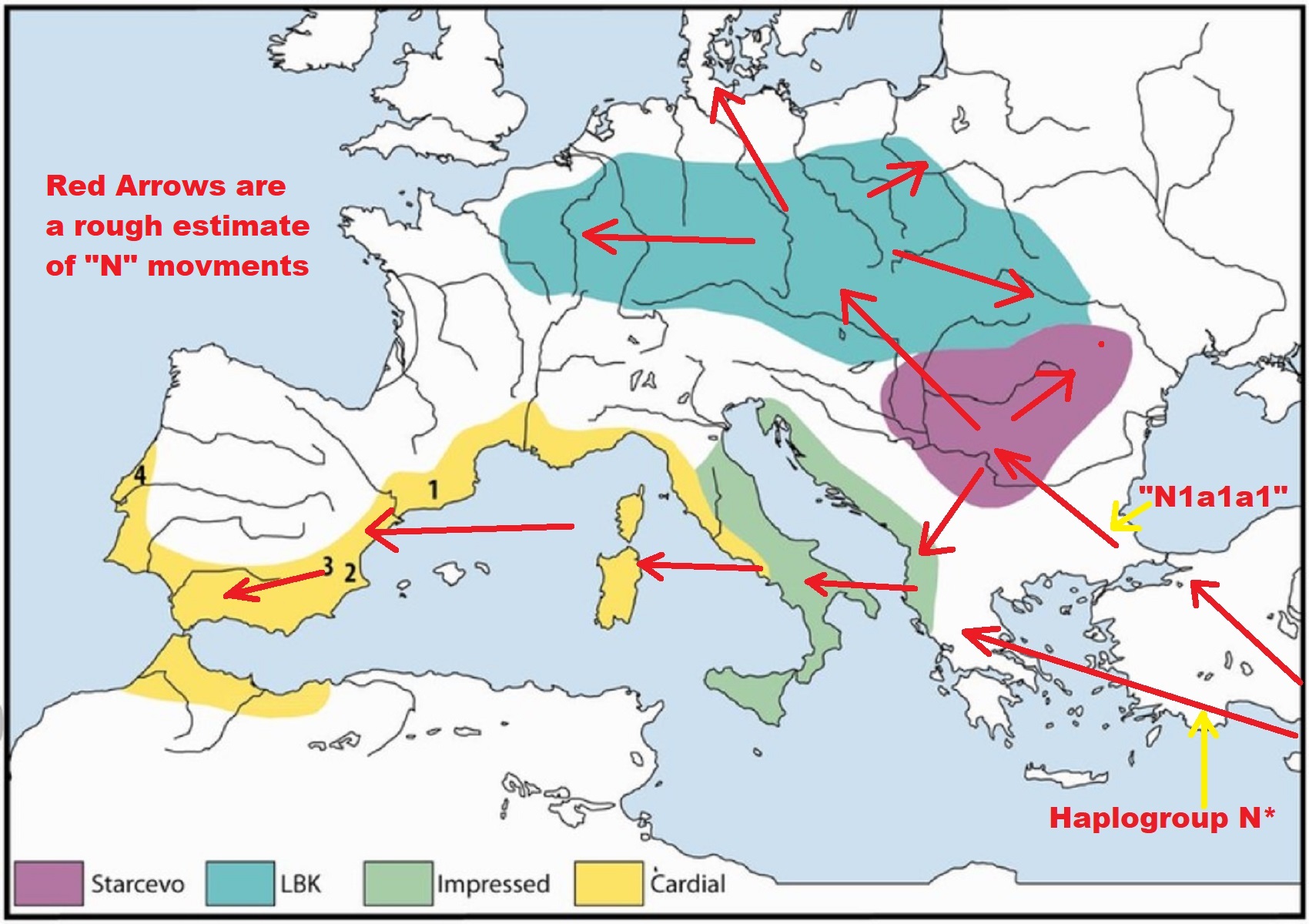

I0174 – Alsonyek-Bataszek mtDNA N1a1a1 around 7,558 years ago Hungary – Starcevo ref (Starčevo–Körös–Criș culture: 6,200 – 4,500 BCE or around 8,223-6,523 years ago)

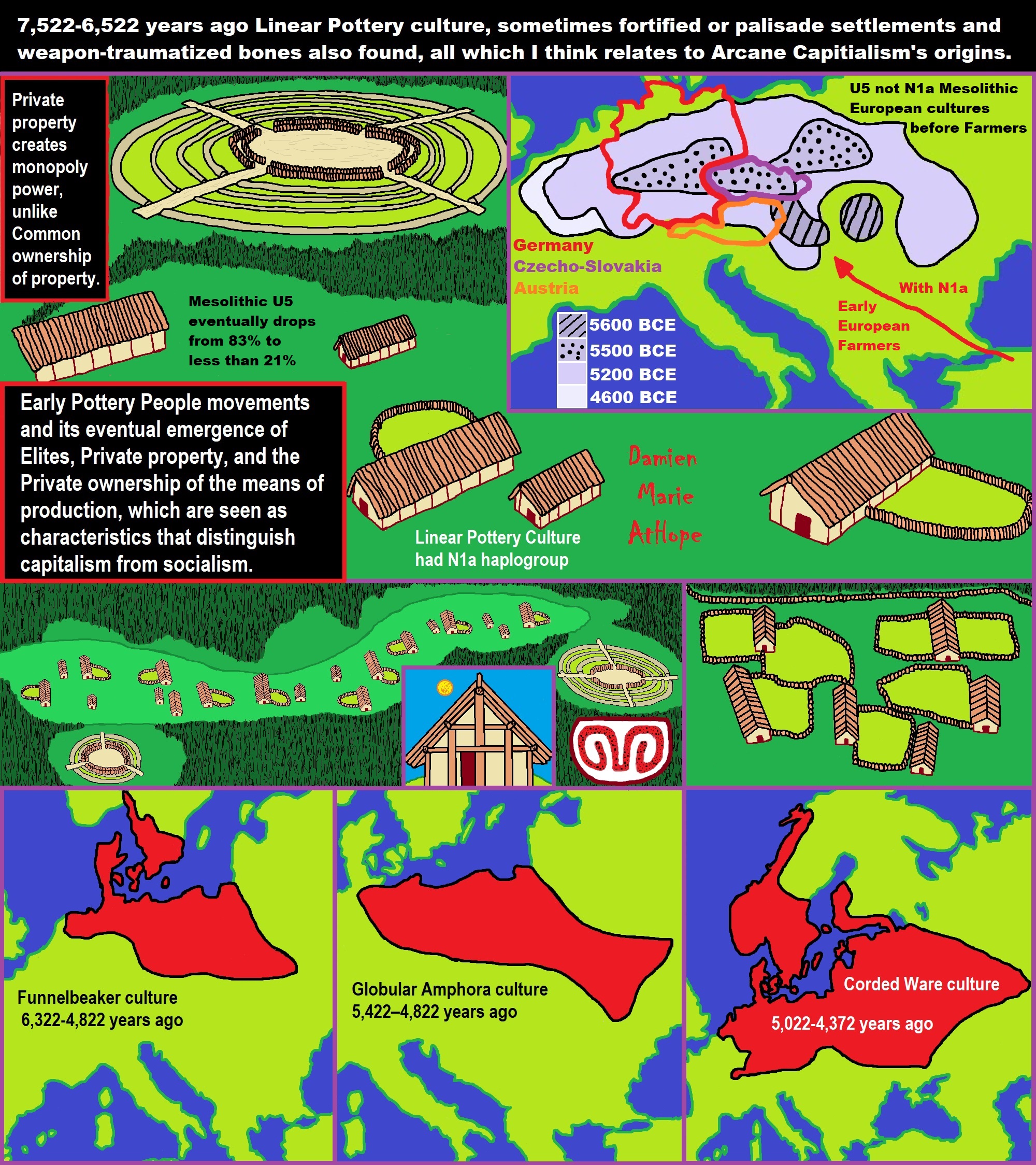

“Starčevo culture of Southeastern Europe originates in the spread of the Neolithic package of peoples and technological innovations including farming and ceramics from Anatolia to the area of Sesklo. The Starčevo culture marks its spread to the inland Balkan peninsula as the Cardial ware culture did along the Adriatic coastline. It forms part of the wider Starčevo–Körös–Criş culture which gave rise to the central European Linear Pottery culture c. 700 years after the initial spread of Neolithic farmers towards the northern Balkans.” ref

Klein1 – Kleinhadersd mtDNA N1a1a1 around 7,500 years ago Austria – LBK/AVK ref (Linear Pottery culture *LBK*: 5,500–4,500 BCE or around 7,523-6,523 years ago)

UZZ74 – Grotta dell’Uzzo, Sicily mtDNA N1a1a1 around 7,223 years ago Italy – Stentinello I ref (Stentinello culture: dated to the 5th millennium BCE: 5000 to 4000 BCE or around 7,023-6,023 years ago)

I0412 – Els Trocs, Bisaurri, Huesca, Aragón mtDNA N1a1a1 around 7,177 years ago Spain – Epicardial ref (Cardium/Cardial–Epicardial pottery culture: 6400 – 5500 BCE or around 8,423-7,023 years ago)

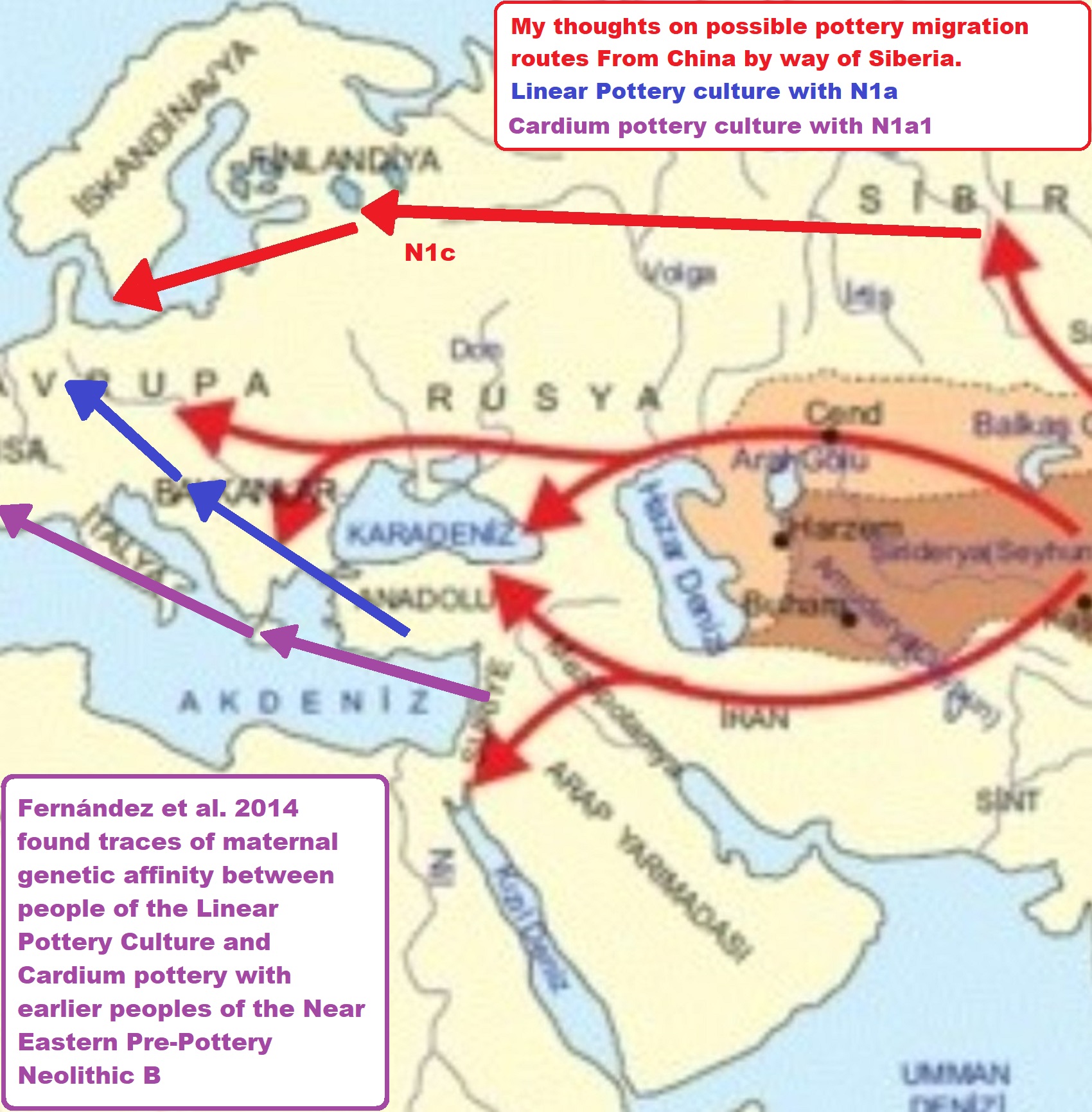

“Fernández et al. 2014 found traces of maternal genetic affinity between people of the Linear Pottery Culture and Cardium pottery with earlier peoples of the Near Eastern Pre-Pottery Neolithic B, including the rare mtDNA (maternal) basal haplogroup N*, and suggested that Neolithic period was initiated by seafaring colonists from the Near East. Mathieson et al. 2018 examined three Cardials buried at the Zemunica Cave near Bisko in modern-day Croatia c. 5800 BCE the three samples of mtDNA extracted belonged to the maternal haplogroups H1, K1b1a, and N1a1.” ref

“Main cultures of the earliest Neolithic of Central and Western Europe around 6,000–5,500 cal BCE.” ref

“Research suggested Cardial and Linear Pottery Cultures were descended from a common farming population in the Balkans.” ref

SMH011 – Baden-Württemberg mtDNA N1a1a1 around 7,127 years ago Germany – Linear Pottery Culture/LBK_SMH ref

XN205 – Baden-Württemberg mtDNA N1a1a1 around 7,100 years ago Germany – Linear Pottery Culture/LBK_SMH ref

XN165 – Baden-Württemberg mtDNA N1a1a1 around 7,099 years ago Germany – Linear Pottery Culture/LBK_SMH ref

I0057 – Halberstadt-Sonntagsfeld mtDNA N1a1a1 around 7,070 years ago Germany – Linear Pottery Culture ref

SCH004 – Baden-Württemberg mtDNA N1a1a1 around 7,050 years ago Germany – Linear Pottery Culture ref

I2008 – Halberstadt-Sonntagsfeld mtDNA N1a1a1 around 7,041 years ago Germany – Linear Pottery Culture ref

OBN006 – Bas-Rhin mtDNA N1a1a1 around 7,026 years ago France (Northeastern France near the border of Germany) – France_MN_OBN_C ref

XN215 – Baden-Württemberg mtDNA N1a1a1 around 7,010 years ago Germany – Linear Pottery Culture/LBK_SMH ref

I2379 – Hejőkürt-Lidl logisztikai központ mtDNA N1a1a1 around 6,984 years ago Hungary – ALPc_Tiszadob_MN ref

I10942 – Europa 1, Gibraltar mtDNA N1a1a1 around 6,950 years ago Gibraltar (southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula/bordered to the north by Spain) – SW_Iberia_EN ref

ALE 16 – Alsónyék-Elkerülő 2. Site mtDNA N1a1a1 around 6,889 years ago Hungary – Sopot_LN ref

SZEH2 – Szemely-Hegye mtDNA N1a1a1 around 6,855 years ago Hungary – Sopot_LN ref

ALE16 – Alsónyék-elkerülő 2. lh. mtDNA N1a1a1 around 6,850 years ago Hungary – Sopot_MN ref

I0175 – Bátaszék-Lajvérpuszta mtDNA N1a1a1 around 6,650 years ago Hungary – Lengyel_Neolithic ref

BAM27 – Alsónyék-Bátaszék, Mérnöki telep mtDNA N1a1a1 around 6,580 years ago Hungary – Lengyel_LN ref

BAL16 – Bátaszék-Lajvér mtDNA N1a1a1 around 6,525 years ago Hungary – Lengyel_LN ref

BAL26 – Bátaszék-Lajvér mtDNA N1a1a1 around 6,525 years ago Hungary – Lengyel_LN ref

CSAT1 – Csabdi-Télizöldes mtDNA N1a1a1 around 6,525 years ago Hungary – Lengyel_LN ref

CSAT20 – Csabdi-Télizöldes mtDNA N1a1a1 around 6,525 years ago Hungary – Lengyel_LN ref

CSAT29 – Csabdi-Télizöldes mtDNA N1a1a1 around 6,525 years ago Hungary – Lengyel_LN ref

MORT12 – Mórágy-Tűzkődomb, B1 mtDNA N1a1a1 around 6,525 years ago Hungary – Lengyel_LN ref

N18 – Pikutkowo mtDNA N1a1a1 around 5,459 years ago Poland – Funnel Beaker ref (Funnel Beaker culture: 4300 – 2800 BCE or around 6,323-4,823 years ago north-central Europe)

“Genetic finds in the Funnelbeaker (TrB) culture, Malmström et al. 2015 examined 9 skeletons from Resmo, Sweden, and Gökhem, Sweden c. 3300-2600 BCE. The 8 samples of mtDNA extracted belonged to various subtypes of maternal haplogroup J, H/R, N, K, and T. The examined Funnelbeakers were closely related to Central European farmers, and different from people of the contemporary Pitted Ware culture. The striking diversity of the maternal lineages suggested that maternal kinship was of little importance in Funnelbeaker society. The evidence suggested that the Neolithization of Scandinavia was accompanied by significant human migration.” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

“The shaman is, above all, a connecting figure, bridging several worlds for his people, traveling between this world, the underworld, and the heavens. He transforms himself into an animal and talks with ghosts, the dead, the deities, and the ancestors. He dies and revives. He brings back knowledge from the shadow realm, thus linking his people to the spirits and places which were once mythically accessible to all.–anthropologist Barbara Meyerhoff” ref

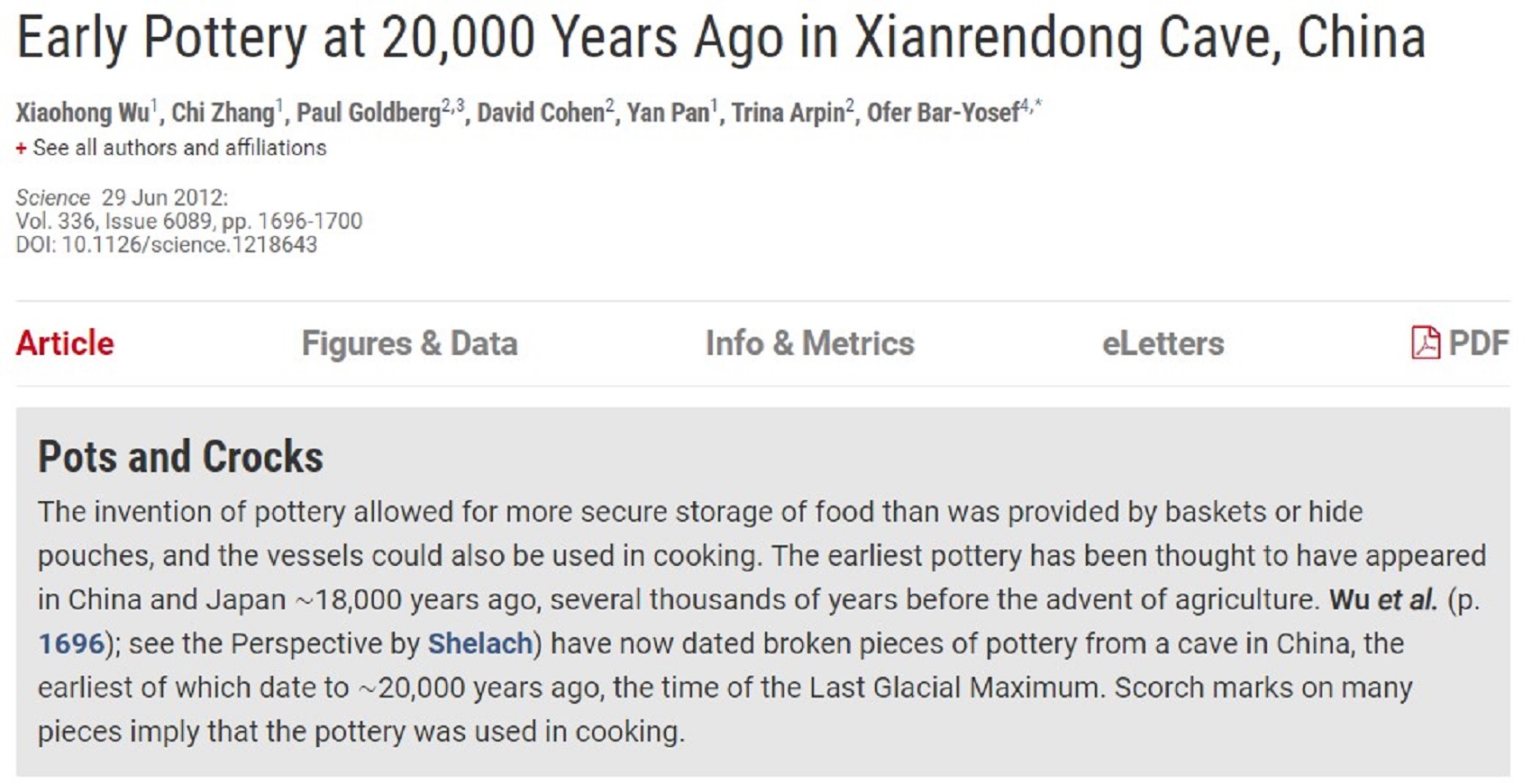

Early Pottery at 20,000 Years Ago in Xianrendong Cave, China

https://science.sciencemag.org/content/336/6089/1696

The oldest pottery, in China, remains of crude pots and bowls, hints at cooking’s ice-age origins

https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn21985-oldest-pottery-hints-at-cookings-ice-age-origins

The Advent and Spread of Early Pottery in East Asia: New Dates and New Considerations for the World’s Earliest Ceramic Vessels

Abstract and Figures

“This paper discusses recent data from North and South China, Japan, and the Russian Far East and eastern Siberia on the dating and function of early pottery during the Late Pleistocene period and shows how reconsiderations are needed for the patterns and reasons for its emergence and spread. Early pottery typically appears in contexts that, except for containing small amounts of pottery, are otherwise similar to Late Paleolithic sites. There is also no evidence of plant cultivation, so clearly, in eastern Asia, the old view of pottery’s emergence or dispersal as only coming within agricultural societies is no longer viable. Greater consideration needs to be given to the invention and spread of pottery in hunter-gatherer societies.” ref

“This paper first reviews recent finds of early pottery sites in South China and North China that now clearly show that the pottery first appears in otherwise Late Paleolithic contexts. Excavations and re-dating at Xianrendong Cave (Jiangxi) in South China show that pottery appears there in securely dated stratigraphic contexts dating to ca. 20,000 cal BP, during the Last Glacial Maximum, some ten millennia before sedentary, Early Neolithic villages first appear in China. Yuchanyan Cave (Hunan) has pottery dating to 18,300 cal BP, evidence for processing deer bones to extract marrow and grease, and perhaps evidence of seasonal visits to the site in annual rounds by mobile hunter-gatherer groups. Sites with early pottery in North China, such as Yujiagou, Zhuannian, Donghulin, Lijiagou, and Nanzhuangtou, appear relatively late, from the climatic downturn of the Younger Dryas, some eight millennia after sites in South China and four millennia after early pottery in Japan and the Russian Far East.” ref

“North China sites variously feature such adaptations as microblades and/or grinding stones, as well as evidence for the exploitation of wild grasses (including millets), acorns, and tubers. These sites might represent hunter-gatherers retreating to more favorable habitats during the Younger Dryas and indicate reduced mobility and semisedentary practices with more intensified exploitation of closer resources. Early pottery finds beginning from ca. 16,800 cal BP in Japan (Incipient Jōmon) and the Russian Far East (“Initial Neolithic”) are also reviewed. Incipient Jōmon sites occur contemporaneously with Final Upper Paleolithic sites, and are found from southern Kyūshū to Hokkaidō (Taishō 3 site). With over 80 known sites, Japan has a better evidence for changes in pottery distribution patterns and diverse adaptations to climatic changes from the time period of the earliest site, Ōdai Yamamoto I, to the Holocene. Molecular and stable isotope analyses of pottery adhesions provide valuable data on the use of early pottery in Japan lacking for all other regions: these indicate the widespread use of pottery for processing marine and freshwater animals.” ref

“Like Final Upper Paleolithic sites, Incipient Jōmon sites also may have microblades, edge polished stone axes, arrowheads, and bifacial spear points. Undecorated pottery with Mikoshiba-type lithics are found in the initial phase of pottery making (Ōdai Yamamoto I, Kitahara, and Maeda Kōji sites, dating ca. 16,500-13,500 BP). Decorated pottery (Phase 2) begins ca.15,700 cal BP during the Bølling-Allerød warming period and rapidly disperses across the archipelago at a time when there may have been significant changes in subsistence and mobility patterns. Phase 1 pottery might occur during a time of intensive information flow and fluidity of social networks, while diversification of pottery in Phase 2 occurs when social networks were becoming more embedded in place. Russian “Initial Neolithic” early pottery sites, such as Khummy, Gasya, and Goncharka 1 in the Lower Amur River basin, are transitional between Paleolithic traditions and typical Neolithic sites of the Holocene, with pottery and ground stone tools gradually appearing amongst Upper Paleolithic toolkits.” ref

“As in China and Japan, early pottery production is at a very low scale, with only limited quantities of sherds being found at a few sites. Eastern Siberia early pottery is first present at the Ust’-Karenga 12 site ca. 13,000 cal BP. Pottery may have dispersed westerly across Siberia as forested areas expanded, perhaps resulting in the introduction of pottery into Europe by hunter-gatherer groups. Across East Asia, early pottery appears only in small amounts and at a few sites, and it persists in this episodic, low scale usage from the Last Glacial Maximum until the Early Holocene. We still need to better understand why this is the case. Early pottery may have been invented and used for special purposes, such as in feasting that was carried out to achieve various socio-political goals.” ref

“While pottery also offered utilitarian or economic value, its long-lasting, low-scale use, but widespread dispersal despite this, cannot be fully accounted for only in terms of it being an adaptation tied to subsistence and increasing energy yields. Questions still remain over whether pottery was the result of a single or multiple inventions in East Asia. South China sites are clearly earlier, and the contemporaneity of Japan and Russia does not rule out singular invention and spread, as sites of the same radiocarbon date in the Late Pleistocene actually fall within a real calendrical range on a centuries-long scale. We need to better understand the scale and patterns of hunter-gatherer mobility and the extent of information exchange networks through which knowledge of pottery making could have spread widely in Late Pleistocene East Asia.” ref

“The arrival of haplogroup R1a-M417 in Eastern Europe, and the east-west diffusion of pottery through North Eurasia.” https://indo-european.eu/2018/02/the-arrival-of-haplogroup-r1a-m417-in-eastern-europe-and-the-east-west-diffusion-of-pottery-through-north-eurasia/

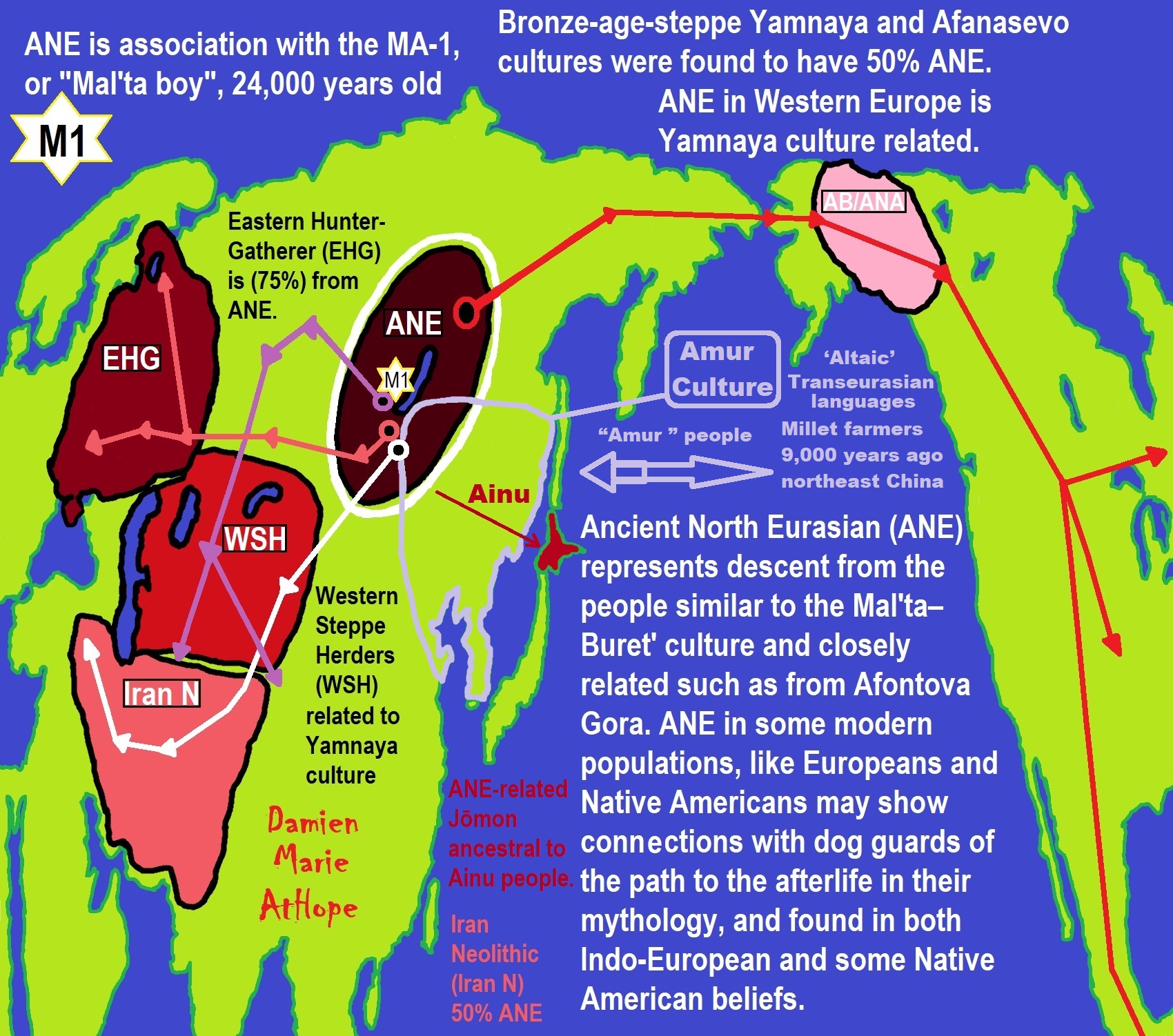

Ancient North Eurasian https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_North_Eurasian

Ancient North Eurasian/Mal’ta–Buret’ culture haplogroup R* https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mal%27ta%E2%80%93Buret%27_culture

“The arrival of haplogroup R1a-M417 in Eastern Europe, and the east-west diffusion of pottery through North Eurasia.” ref

R-M417 (R1a1a1)

“R1a1a1 (R-M417) is the most widely found subclade, in two variations which are found respectively in Europe (R1a1a1b1 (R-Z282) ([R1a1a1a*] (R-Z282) and Central and South Asia (R1a1a1b2 (R-Z93) ([R1a1a2*] (R-Z93).” ref

R-Z282 (R1a1a1b1a) (Eastern Europe)

“This large subclade appears to encompass most of the R1a1a found in Europe.

- R1a1a1b1a [R1a1a1a*] (R-Z282*) occurs in northern Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia at a frequency of c. 20%.

- R1a1a1b1a3 [R1a1a1a1] (R-Z284) occurs in Northwest Europe and peaks at c. 20% in Norway.

- R1a1a1c (M64.2, M87, M204) is apparently rare: it was found in 1 of 117 males typed in southern Iran.” ref

R1a1a1b2 (R-Z93) (Asia)

“This large subclade appears to encompass most of the R1a1a found in Asia, being related to Indo-European migrations (including Scythians, Indo-Aryan migrations, and so on).

- R-Z93* or R1a1a1b2* (R1a1a2* in Underhill (2014)) is most common (>30%) in the South Siberian Altai region of Russia, cropping up in Kyrgyzstan (6%) and in all Iranian populations (1-8%).

- R-Z2125 occurs at highest frequencies in Kyrgyzstan and in Afghan Pashtuns (>40%). At a frequency of >10%, it is also observed in other Afghan ethnic groups and in some populations in the Caucasus and Iran.

- R-M434 is a subclade of Z2125. It was detected in 14 people (out of 3667 people tested), all in a restricted geographical range from Pakistan to Oman. This likely reflects a recent mutation event in Pakistan.

- R-M560 is very rare and was only observed in four samples: two Burushaski speakers (north Pakistan), one Hazara (Afghanistan), and one Iranian Azerbaijani.

- R-M780 occurs at high frequency in South Asia: India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and the Himalayas. The group also occurs at >3% in some Iranian populations and is present at >30% in Roma from Croatia and Hungary.” ref

R-M458 (R1a1a1b1a1)

“R-M458 is a mainly Slavic SNP, characterized by its own mutation, and was first called cluster N. Underhill et al. (2009) found it to be present in modern European populations roughly between the Rhine catchment and the Ural Mountains and traced it to “a founder effect that … falls into the early Holocene period, 7.9±2.6 KYA.” M458 was found in one skeleton from a 14th-century grave field in Usedom, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany. The paper by Underhill et al. (2009) also reports a surprisingly high frequency of M458 in some Northern Caucasian populations (for example 27.5% among Karachays and 23.5% among Balkars, 7.8% among Karanogays and 3.4% among Abazas).” ref

Pic ref

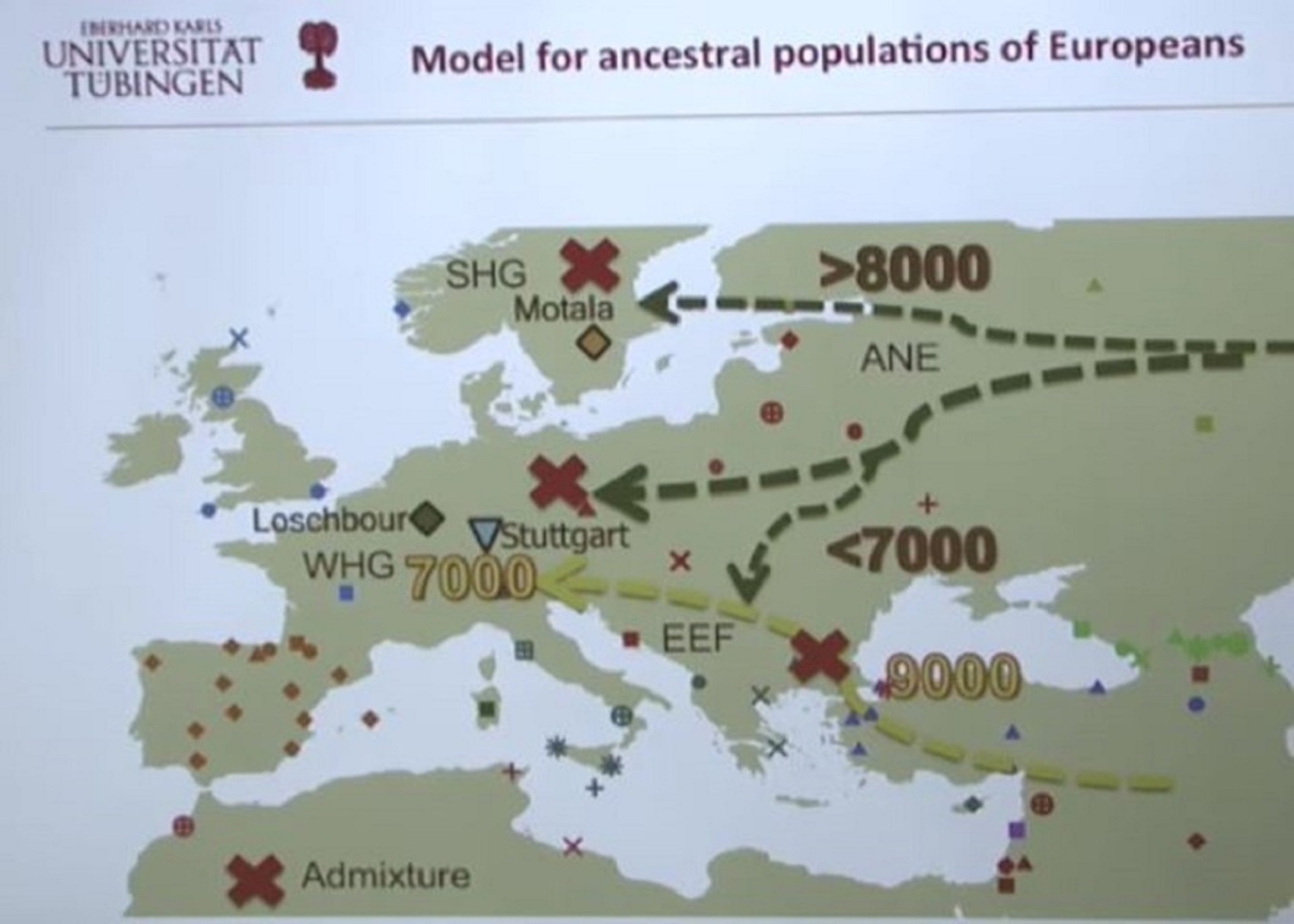

Ancient Human Genomes…Present-Day Europeans – Johannes Krause (Video)

Ancient North Eurasian (ANE)

Eastern Hunter-Gatherer (EHG)

Western Hunter-Gatherers (WHG)

Scandinavian Hunter-Gatherer (SHG)

Early European Farmers (EEF)

A quick look at the Genetic history of Europe

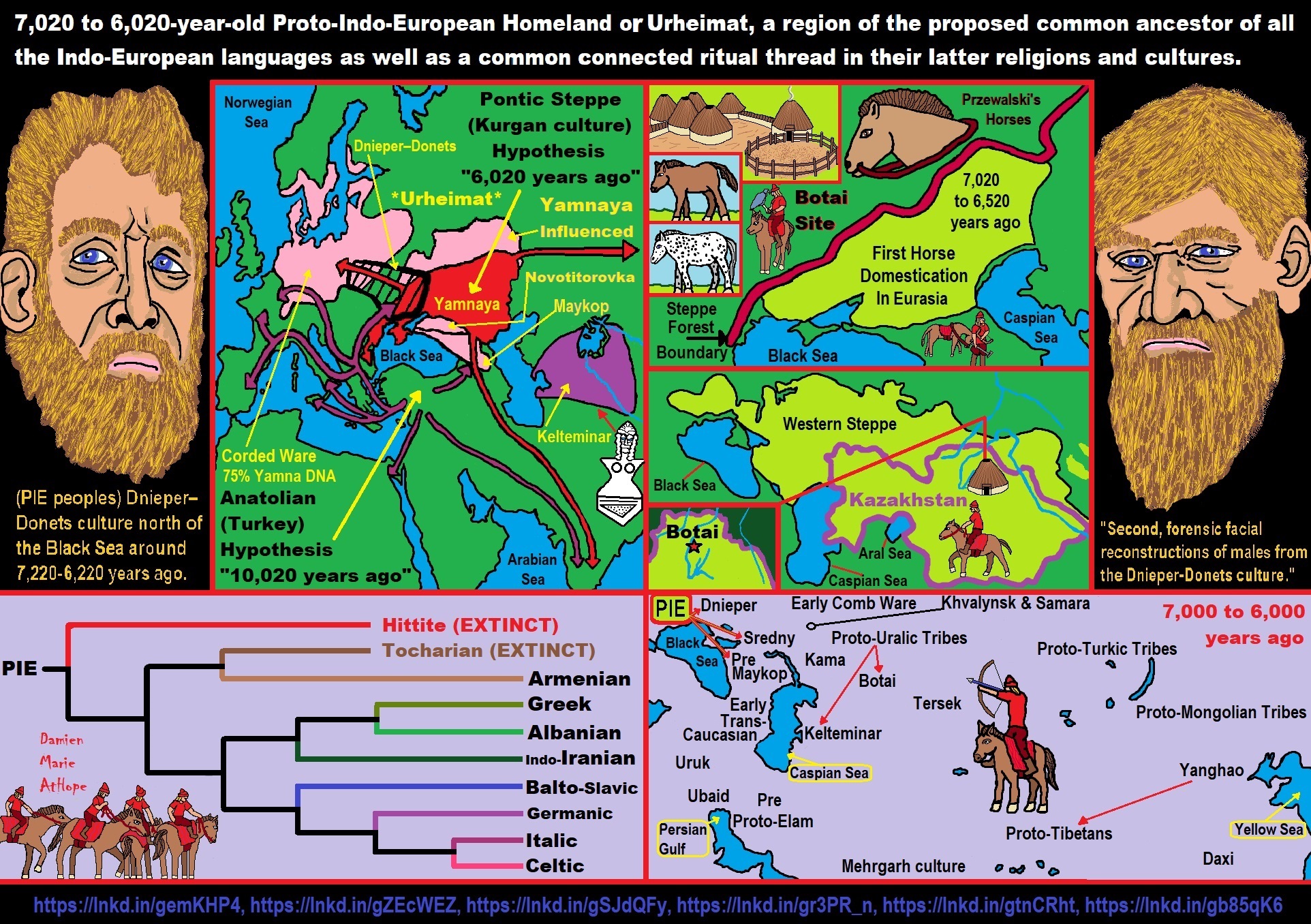

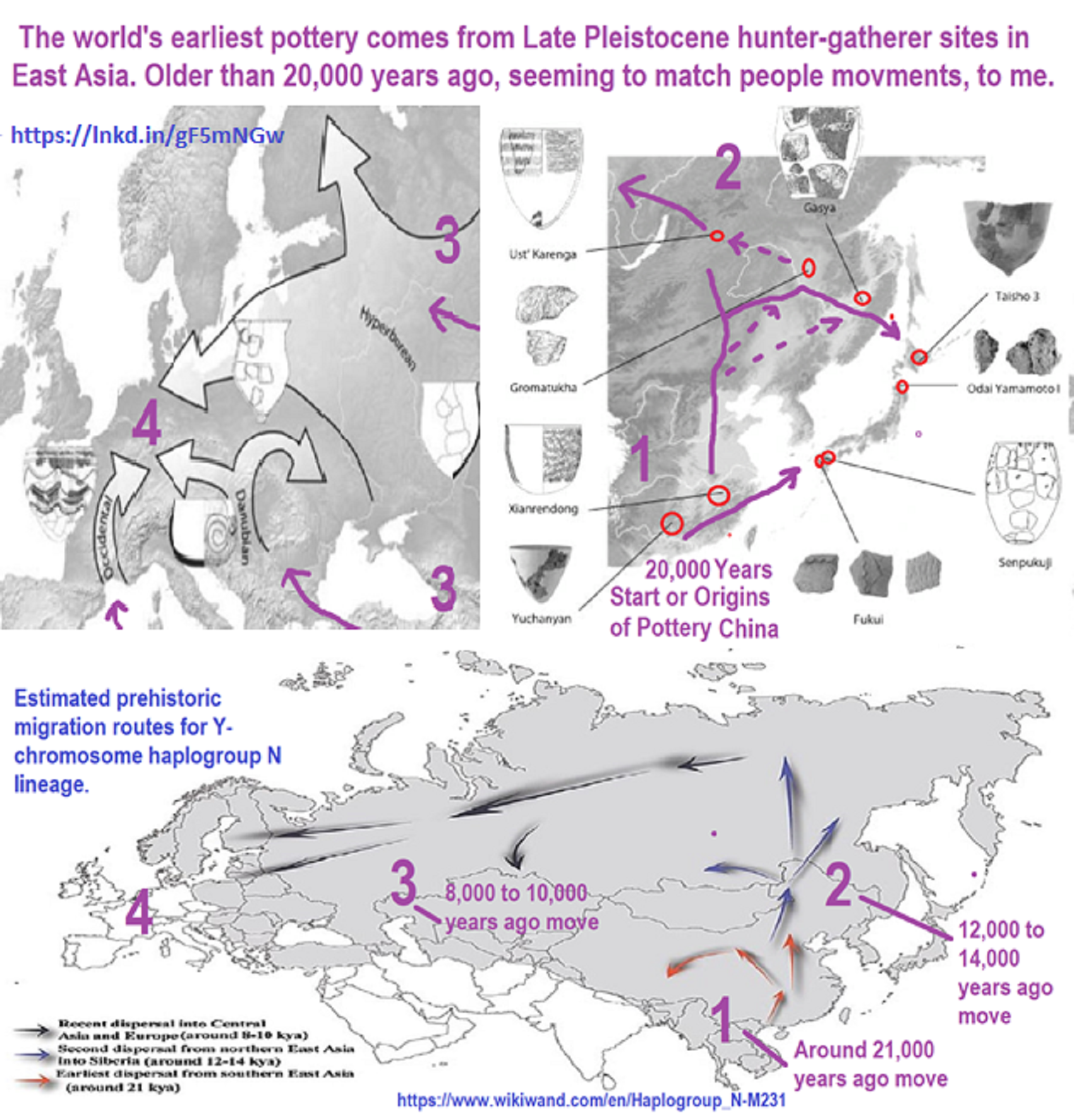

“The most significant recent dispersal of modern humans from Africa gave rise to an undifferentiated “non-African” lineage by some 70,000-50,000 years ago. By about 50–40 ka a basal West Eurasian lineage had emerged, as had a separate East Asian lineage. Both basal East and West Eurasians acquired Neanderthal admixture in Europe and Asia. European early modern humans (EEMH) lineages between 40,000-26,000 years ago (Aurignacian) were still part of a large Western Eurasian “meta-population”, related to Central and Western Asian populations. Divergence into genetically distinct sub-populations within Western Eurasia is a result of increased selection pressure and founder effects during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM, Gravettian). By the end of the LGM, after 20,000 years ago, A Western European lineage, dubbed West European Hunter-Gatherer (WHG) emerges from the Solutrean refugium during the European Mesolithic. These Mesolithic hunter-gatherer cultures are substantially replaced in the Neolithic Revolution by the arrival of Early European Farmers (EEF) lineages derived from Mesolithic populations of West Asia (Anatolia and the Caucasus). In the European Bronze Age, there were again substantial population replacements in parts of Europe by the intrusion of Ancient North Eurasian (ANE) lineages from the Pontic–Caspian steppes. These Bronze Age population replacements are associated with the Beaker culture archaeologically and with the Indo-European expansion linguistically.” ref

“As a result of the population movements during the Mesolithic to Bronze Age, modern European populations are distinguished by differences in WHG, EEF, and ANE ancestry. Admixture rates varied geographically; in the late Neolithic, WHG ancestry in farmers in Hungary was at around 10%, in Germany around 25%, and in Iberia as high as 50%. The contribution of EEF is more significant in Mediterranean Europe, and declines towards northern and northeastern Europe, where WHG ancestry is stronger; the Sardinians are considered to be the closest European group to the population of the EEF. ANE ancestry is found throughout Europe, with a maximum of about 20% found in Baltic people and Finns. Ethnogenesis of the modern ethnic groups of Europe in the historical period is associated with numerous admixture events, primarily those associated with the Roman, Germanic, Norse, Slavic, Berber, Arab and Turkish expansions. Research into the genetic history of Europe became possible in the second half of the 20th century, but did not yield results with a high resolution before the 1990s. In the 1990s, preliminary results became possible, but they remained mostly limited to studies of mitochondrial and Y-chromosomal lineages. Autosomal DNA became more easily accessible in the 2000s, and since the mid-2010s, results of previously unattainable resolution, many of them based on full-genome analysis of ancient DNA, have been published at an accelerated pace.” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

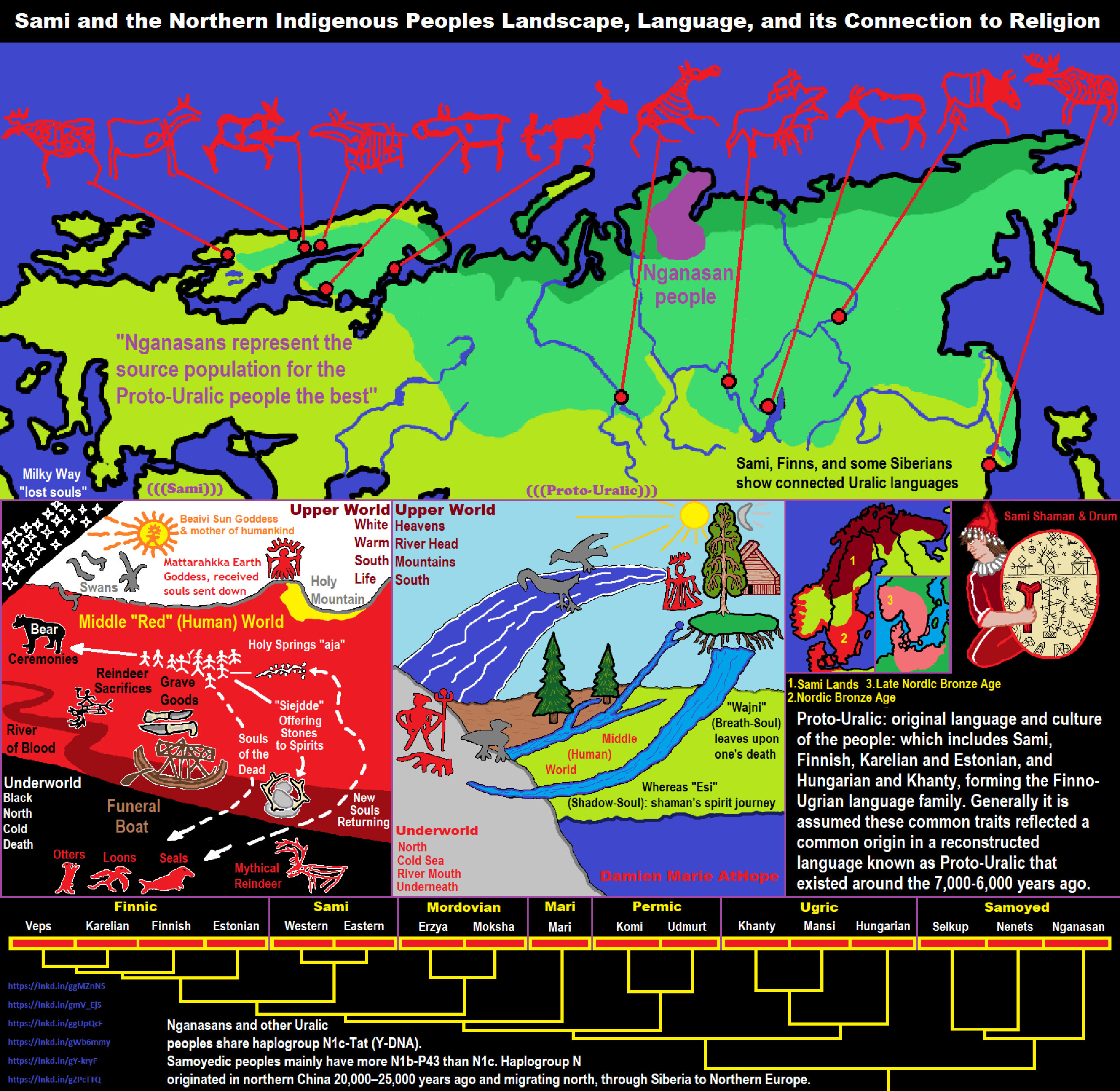

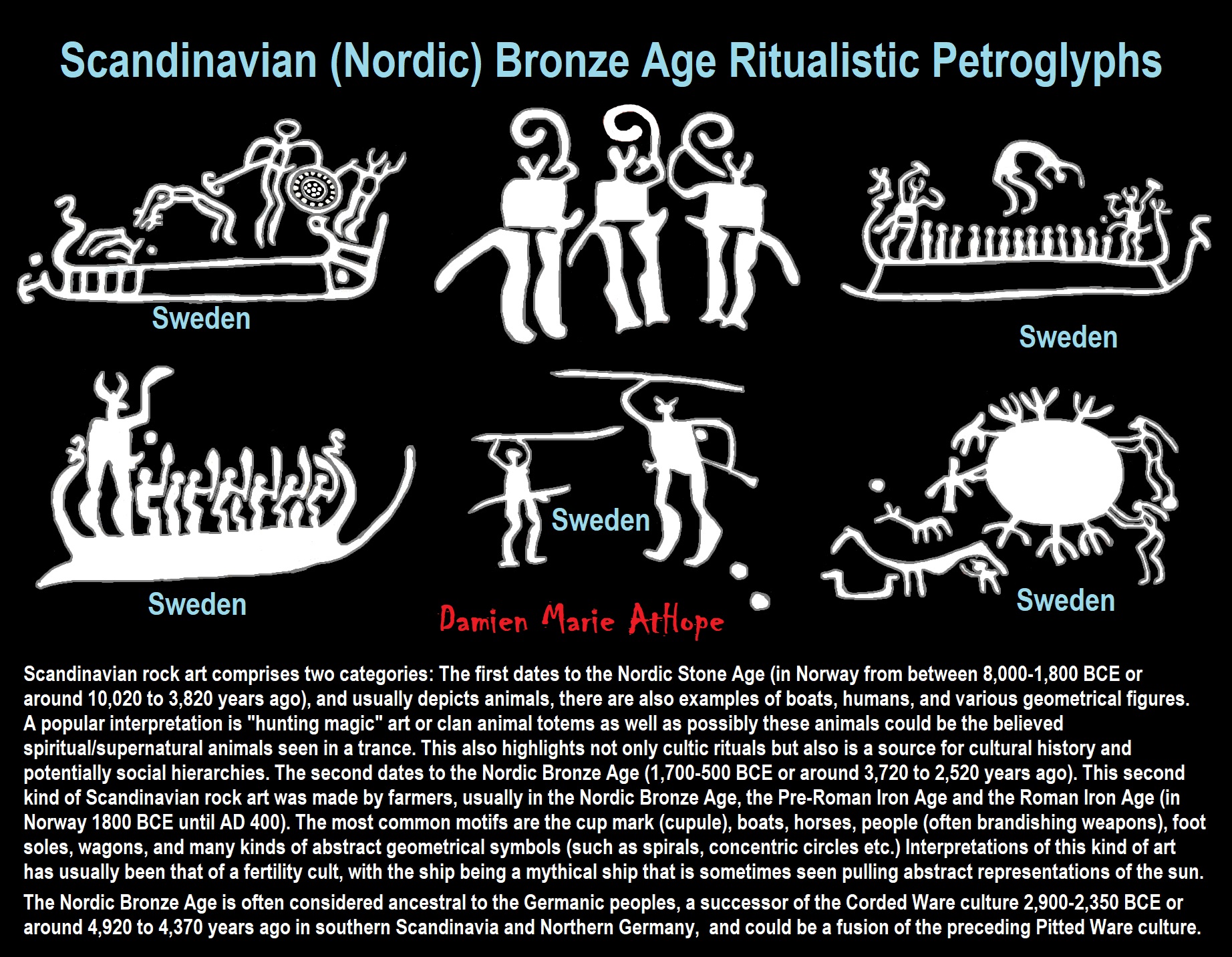

Archaeology shows both the common culture and genetics of the earliest Indo-Europeans in Europe were forming from the 8,000-6,020 years ago, due to migration of the Western Baltic Mesolithic population linked with Poland. Scandinavian Hunter-Gatherers: mix of Western and Eastern Hunter-Gatherers beginning around 13,000 years ago.

Baltic Reindeer Hunters: Swiderian, Lyngby, Ahrensburgian, and Krasnosillya cultures 12,020 to 11,020 years ago are evidence of powerful migratory waves during the last 13,000 years and a genetic link to Saami and the Finno-Ugric peoples. Two Different Bone Point Phases: fine-barbed 11,200–10,100 years ago and larger-barbed 9,658–8,413 years ago.

Pre-Pottery Neolithic B

“Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) is part of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic, a Neolithic culture centered in upper Mesopotamia and the Levant, dating to c. 10,820 – c. 8,520 years ago, that is, 8,800–6,500 BCE. It was typed by Kathleen Kenyon during her archaeological excavations at Jericho in the West Bank. Like the earlier PPNA people, the PPNB culture developed from the Mesolithic Natufian culture. However, it shows evidence of a northerly origin, possibly indicating an influx from the region of northeastern Anatolia. Area of the fertile crescent main Pre-Pottery Neolithic sites, Mesopotamia proper was not yet settled by humans.” ref

“The earliest proto-pottery in the fertile crescent was White Ware vessels, made from lime and gray ash, built up around baskets before firing, for several centuries around 7000 BCE or 9,020 years ago at sites such as Tell Neba’a Faour (Beqaa Valley). Sites from this period found in the Levant utilizing rectangular floor plans and plastered floor techniques were found at Ain Ghazal, Yiftahel (western Galilee), and Abu Hureyra (Upper Euphrates). The period is dated to between c. 9,020 and c. 8,020 years ago or 7000–6000 BCE. Though, the site of ‘Ain Ghazal in Jordan has indicated a later Pre-Pottery Neolithic C period, which existed between 8,220 and 7,920 years ago.” ref

“The culture disappeared during the 8.2 kiloyear event, a term that climatologists have adopted for a sudden decrease in global temperatures that occurred approximately 8,220 years before the present, or c. 6200 BCE, and which lasted for the next two to four centuries. In the following Munhatta and Yarmukian post-pottery Neolithic cultures that succeeded it, rapid cultural development continues, although PPNB culture continued in the Amuq valley, where it influenced the later development of the Ghassulian culture.” ref

“Around 8000 BCE or 10,020 years ago, before the invention of pottery, several early settlements became experts in crafting beautiful and highly sophisticated containers from stone, using materials such as alabaster or granite, and employing sand to shape and polish. Artisans used the veins in the material to the maximum visual effect. Such objects have been found in abundance on the upper Euphrates river, in what is today eastern Syria, especially at the site of Bouqras. These form the early stages of the development of the Art of Mesopotamia.” ref

Haplogroup N* found among the fertile crescent Pre-Pottery Neolithic B

“Pre-Pottery Neolithic B fossils that were analysed for ancient DNA were found to carry the Y-DNA (paternal) haplogroups E1b1b (2/7; ~29%), CT (2/7; ~29%), E(xE2,E1a,E1b1a1a1c2c3b1,E1b1b1b1a1,E1b1b1b2b) (1/7; ~14%), T(xT1a1,T1a2a) (1/7; ~14%), and H2 (1/7; ~14%). The CT clade was also observed in a Pre-Pottery Neolithic C specimen (1/1; 100%). Maternally, the rare basal haplogroup N* has been found among skeletal remains belonging to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B, as have the mtDNA clades L3 and K.” ref

“DNA analysis has also confirmed ancestral ties between the Pre-Pottery Neolithic culture bearers and the makers of the Epipaleolithic Iberomaurusian culture of North Africa, the Mesolithic Natufian culture of the Levant, the Savanna Pastoral Neolithic culture of East Africa, the Early Neolithic Cardium culture of Morocco, and the Ancient Egyptian culture of the Nile Valley, with fossils associated with these early cultures all sharing a common genomic component.” ref

Pottery Neolithic the fertile crescent

“The Neolithic period is traditionally divided into the Pre-Pottery (A and B) and Pottery phases. PPNA developed from the earlier Natufian cultures of the area. This is the time of the agricultural transition and development of farming economies in the Near East, and the region’s first known megaliths (and Earth’s oldest known megalith, other than Gobekli Tepe, which is in the Northern Levant and from an unknown culture) with a burial chamber and tracking of the sun or other stars. In addition, the Levant in the Neolithic (and later, in the Chalcolithic) was involved in large-scale, far-reaching trade.” ref

“Trade on an impressive scale and covering large distances continued during the Chalcolithic (c. 4500–3300 BCE). Obsidian found in the Chalcolithic levels at Gilat, Israel have had their origins traced via elemental analysis to three sources in Southern Anatolia: Hotamis Dağ, Göllü Dağ, and as far east as Nemrut Dağ, 500 km (310 mi) east of the other two sources. This is indicative of a very large trade circle reaching as far as the Northern Fertile Crescent at these three Anatolian sites.” ref

“The Ghassulian period created the basis of the Mediterranean economy which has characterized the area ever since. A Chalcolithic culture, the Ghassulian economy was a mixed agricultural system consisting of extensive cultivation of grains (wheat and barley), intensive horticulture of vegetable crops, commercial production of vines and olives, and a combination of transhumance and nomadic pastoralism. The Ghassulian culture, according to Juris Zarins, developed out of the earlier Munhata phase of what he calls the “circum Arabian nomadic pastoral complex”, probably associated with the first appearance of Semites in this area.” ref

“The urban development of Canaan lagged considerably behind that of Egypt and Mesopotamia and even that of Syria, where from 3,500 BCE or 5,520 years ago a sizable city developed at Hamoukar. This city, which was conquered, probably by people coming from the Southern Iraqi city of Uruk, saw the first connections between Syria and Southern Iraq that some have suggested lie behind the patriarchal traditions. Urban development again began culminating in Early Bronze Age sites like Ebla, which by 2,300 BCE or 4,320 years ago, was incorporated once again into the Empire of Sargon, and then Naram-Sin of Akkad (Biblical Accad). The archives of Ebla show reference to a number of Biblical sites, including Hazor, Jerusalem, and a number of people have claimed, also to Sodom and Gomorrah, mentioned in the patriarchal records. The collapse of the Akkadian Empire, saw the arrival of peoples using Khirbet Kerak Ware pottery, coming originally from the Zagros Mountains, east of the Tigris. It is suspected by some that this event marks the arrival in Syria and Palestine of the Hurrians, people later known in the Biblical tradition possibly as Horites.” ref

“The following Middle Bronze Age period was initiated by the arrival of “Amorites” from Syria in Southern Iraq, an event which people like Albright (above) associated with the arrival of Abraham’s family in Ur. This period saw the pinnacle of urban development in the area of Syria and Palestine. Archaeologists show that the chief state at this time was the city of Hazor, which may have been the capital of the region of Israel. This is also the period in which Semites began to appear in larger numbers in the Nile delta region of Egypt.” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

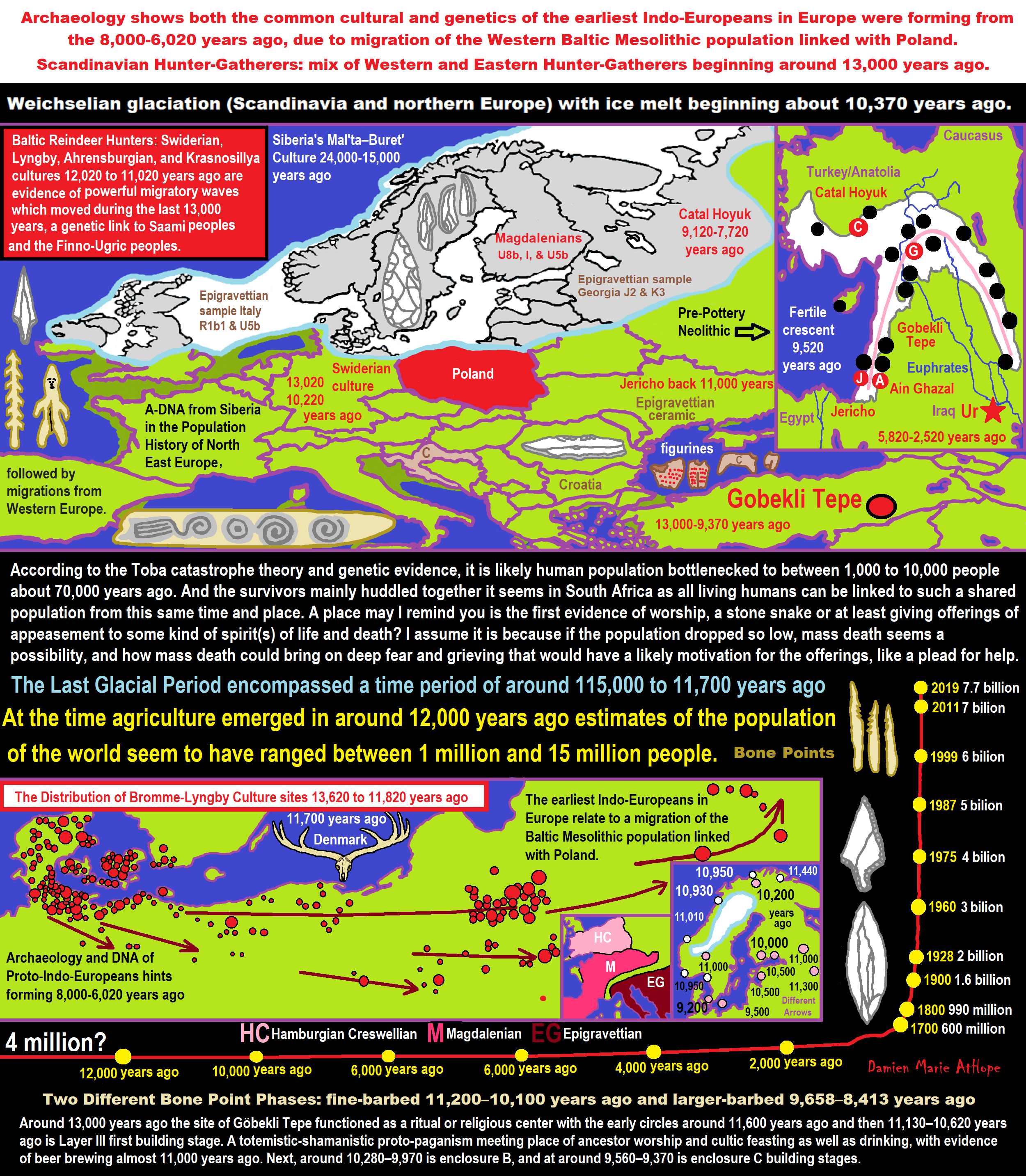

Raqefet Cave

13,000-year-old stone mortars offers the earliest known physical evidence of an extensive ancient beer-brewing operation.

“The find comes on the heels of a July report that archaeologists working in northeastern Jordan discovered the charred remains of bread baked by Natufians some 11,600 to 14,600 years ago. According to the Stanford scientists, the ancient beer residue comes from 11,700 to 13,700 years old. Through laboratory analysis, other archaeological evidence found in the cave, and the wear of the stones, the team discovered that the ancient Natufians used species from seven plant families, “including wheat or barley, oat, legumes and bast fibers (including flax),” according to the article. “They packed plant-foods, including malted wheat/barley, in fiber-made containers and stored them in boulder mortars. They used bedrock mortars for pounding and cooking plant-foods, including brewing wheat/barley-based beer likely served in ritual feasts ca. 13,000 years ago,” the scientists write. “It has long been speculated that the thirst for beer may have been the stimulus behind cereal domestication, which led to a major social-technological change in human history; but this hypothesis has been highly controversial,” the Stanford authors say. “We report here of the earliest archaeological evidence for cereal-based beer brewing by a semi-sedentary, foraging people.” ref

“Beer making was an integral part of rituals and feasting, a social regulatory mechanism in hierarchical societies,” said Stanford’s Wang. The Raqefet Cave discovery of the first man-made alcohol production, the cave also provides one of the earliest pieces of evidence of the use of flower beds on gravesites, discovered under human skeletons. “The Natufian remains in Raqefet Cave never stop surprising us,” co-author Prof. Dani Nadel, of the University of Haifa’s Zinman Institute of Archaeology, said in a press release. “We exposed a Natufian burial area with about 30 individuals, a wealth of small finds such as flint tools, animal bones and ground stone implements, and about 100 stone mortars and cupmarks. Some of the skeletons are well-preserved and provided direct dates and even human DNA, and we have evidence for flower burials and wakes by the graves.” ref

“And now, with the production of beer, the Raqefet Cave remains provide a very vivid and colorful picture of Natufian lifeways, their technological capabilities, and inventions,” he said. Stanford’s Liu posited that the beer production was of a religious nature because its production was found near a graveyard. “This discovery indicates that making alcohol was not necessarily a result of agricultural surplus production, but it was developed for ritual purposes and spiritual needs, at least to some extent, prior to agriculture,” she said. “Alcohol making and food storage were among the major technological innovations that eventually led to the development of civilizations in the world, and archaeological science is a powerful means to help reveal their origins and decode their contents,” said Liu. “We are excited to have the opportunity to present our findings, which shed new light on a deeper history of human society.” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

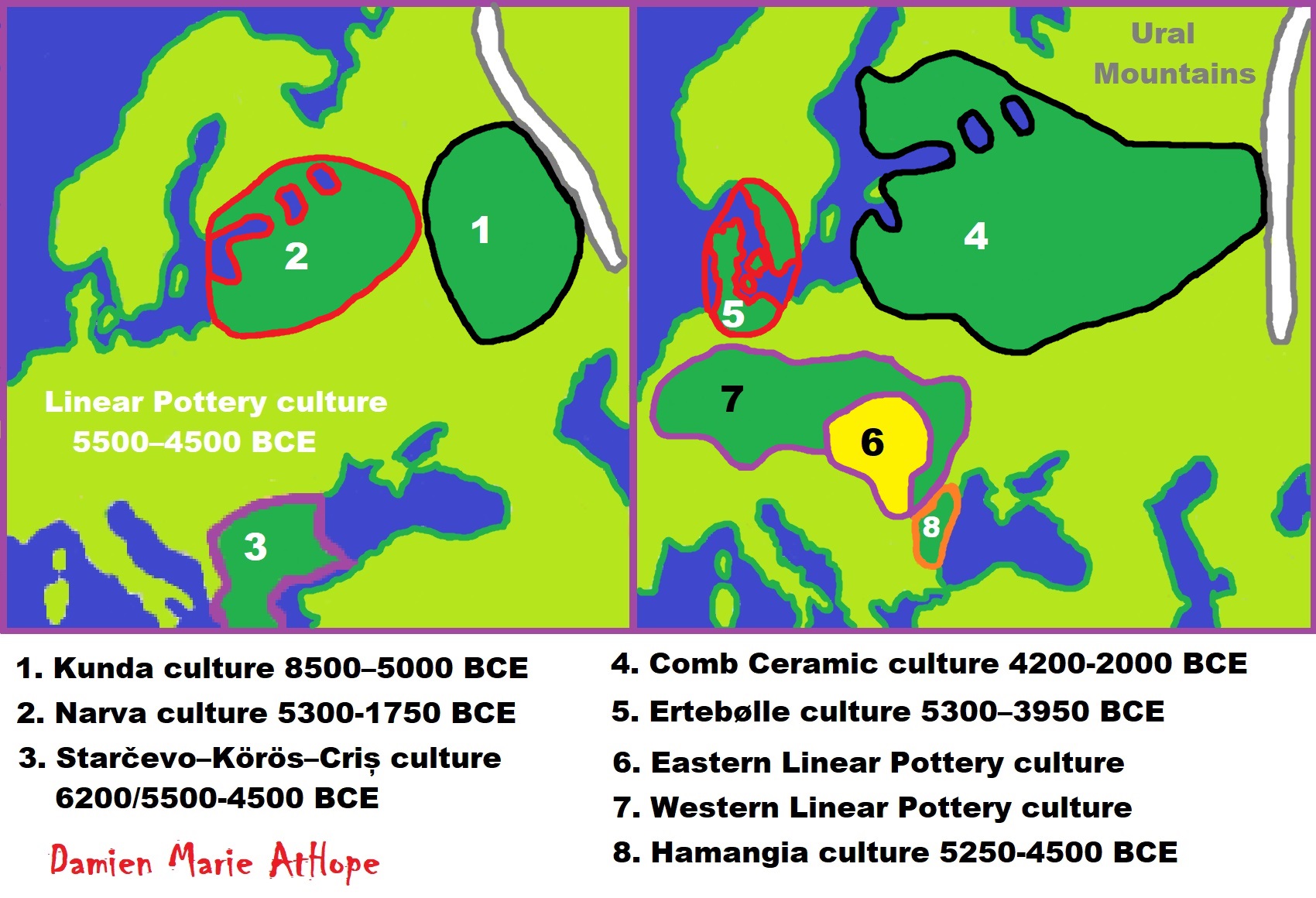

Swiderian culture c. 11,000 – c. 8,200 BCE centered on the area of modern Poland.

“Swiderian culture, also published in English literature as Sviderian and Swederian, is the name of an Upper Palaeolithic/Mesolithic cultural complex, centered on the area of modern Poland. The type-site is Świdry Wielkie, in Otwock near the Swider River, a tributary to the Vistula River, in Masovia. The Swiderian is recognized as a distinctive culture that developed on the sand dunes left behind by the retreating glaciers. Rimantienė (1996) considered the relationship between Swiderian and Solutrean “outstanding, though also indirect”, in contrast with the Bromme-Ahrensburg complex (Lyngby culture), for which she introduced the term “Baltic Magdalenian” for generalizing all other North European Late Paleolithic culture groups that have a common origin in Aurignacian.” ref

“Three periods can be distinguished. The crude flint blades of Early Swiderian are found in the area of Nowy Mlyn in the Holy Cross Mountains region. The Developed Swiderian appeared with their migrations to the north and is characterized by tanged blades: this stage separates the northwestern European cultural province, embracing Belgium, Holland, northwest Germany, Denmark and Norway, and the Middle East European cultural province, embracing Silesia, Brandenburgia, Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, Central Russia, Ukraine, and the Crimea. Late Swiderian is characterized by blades with a blunted back.” ref

“The Swiderian culture plays a central role in the Palaeolithic-Mesolithic transition. It has been generally accepted that most of the Swiderian population emigrated at the very end of the Pleistocene (11,520 years ago or 9500 BCE calibrated) to the northeast following the retreating tundra, after the Younger Dryas. Recent radiocarbon dates prove that some groups of the Svidero-Ahrensburgian Complex persisted into the Preboreal. Unlike western Europe, the Mesolithic groups now inhabiting the Polish Plain were newcomers. This has been attested by a 300-year-long gap between the youngest Palaeolithic and the oldest Mesolithic occupation. The oldest Mesolithic site is Chwalim, located in western Silesia, Poland; it outdates the Mesolithic sites situated to the east in central and northeastern Poland by about 150 years. Thus, the Mesolithic population progressed from the west after a 300-year-long settlement break, and moved gradually towards the east. The lack of good flint raw materials in the Polish early Mesolithic has been interpreted thus that the new arriving people were not acquainted yet with the best local sources of flint, proving their external origin.” ref

“The Ukrainian archaeologist L. Zalizniak (1989, p. 83-84) believes Kunda culture of Central Russia and the Baltic zone, and other so-called post-Swiderian cultures, derive from the Swiderian culture. Sorokin (2004) rejects the “contact” hypothesis of the formation of Kunda culture and holds it originated from the seasonal migrations of Swiderian people at the turn of Pleistocene and Holocene when human subsistence was based on hunting reindeer. Many of the earliest Mesolithic sites in Finland are post-Swiderian; these include the Ristola site in Lahti and the Saarenoja 2 site in Joutseno with lithics in imported flint, as well as the Sujala site in Utsjoki in the province of Lapland.” ref

“The raw materials of the lithic assemblage at Sujala originate in the Varanger Peninsula in northern Norway. Concerning this region, the commonly held view today is that the earliest settlement of the North Norwegian coast originated in the Fosna culture of the western and southwestern coast of Norway and ultimately in the final Palaeolithic Ahrensburg culture of northwestern Europe. The combination of a coastal raw material and a lithic technique typical to Late Palaeolithic and very early Mesolithic industries of northern Europe, originally suggested that Sujala was contemporaneous to Phase 1 of the Norwegian Finnmark Mesolithic (Komsa proper), dating to between 9 000 and 10 000 years ago. Proposed parallels with the blade technology among the earliest Mesolithic finds in southern Norway would have placed the find closer or even before 10 000 years ago.” ref

“However, a preliminary connection to early North Norwegian settlements is contradicted by the shape of the tanged points and by the blade reduction technology from Sujala. The bifacially shaped tang and ventral retouch on the tip of the arrow points and the pressure technique used in blade manufacture are rare or absent in Ahrensburgian contexts, but very characteristic of the so-called Post-Swiderian cultures of northwestern Russia. There, counterparts of the Sujala cores can also be found. The Sujala assemblage is currently considered unquestionably post-Swiderian and is dated by radiocarbon to 9265-8930 BP, corresponding to 8300-8200 calBCE. Such an Early Mesolithic influence from Russia or the Baltic might imply an adjustment to previous thoughts on the colonization of the Barents Sea coast.” ref

Maglemosian culture c. 9000 – c. 6000 BCE or 11,020-8,020 years ago in Northern Europe.

“Maglemosian (c. 9000 – c. 6000 BC) is the name given to a culture of the early Mesolithic period in Northern Europe. In Scandinavia, the culture was succeeded by the Kongemose and Tardenoisian cultures. When the Maglemosian culture flourished, sea levels were much lower than now and what is now mainland Europe and Scandinavia were linked with Britain. The cultural period overlaps the end of the last ice age, when the ice retreated and the glaciers melted. It was a long process and sea levels in Northern Europe did not reach current levels until almost 6000 BC, by which time they had inundated large territories previously inhabited by Maglemosian people. Therefore, there is hope that the emerging discipline of underwater archaeology may reveal interesting finds related to the Maglemosian culture in the future. The Maglemosian people lived in forest and wetland environments, using fishing and hunting tools made from wood, bone, and flint microliths. It appears that they had domesticated the dog. Some may have lived settled lives, but most were nomadic.” ref

Kongemose culture c. 6,000 – 5,200 BCE or 8,020-7,220 years ago

The Kongemose culture (Kongemosekulturen) was a mesolithic hunter-gatherer culture in southern Scandinavia ca. 6000 BC–5200 BCE and the origin of the Ertebølle culture. It was preceded by the Maglemosian culture. In the north, it bordered on the Scandinavian Nøstvet and Lihult cultures. The Kongemose culture is named after a location in western Zealand and its typical form is known from Denmark and Skåne. The finds are characterized by long flintstone flakes, used for making characteristic rhombic arrowheads, scrapers, drills, awls, and toothed blades. Tiny micro blades constituted the edges of bone daggers that were often decorated with geometric patterns. Stone axes were made of a variety of stones, and other tools were made of horn and bone. The main economy was based on hunting red deer, roe deer, and wild boar, supplemented by fishing at the coastal settlements.” ref

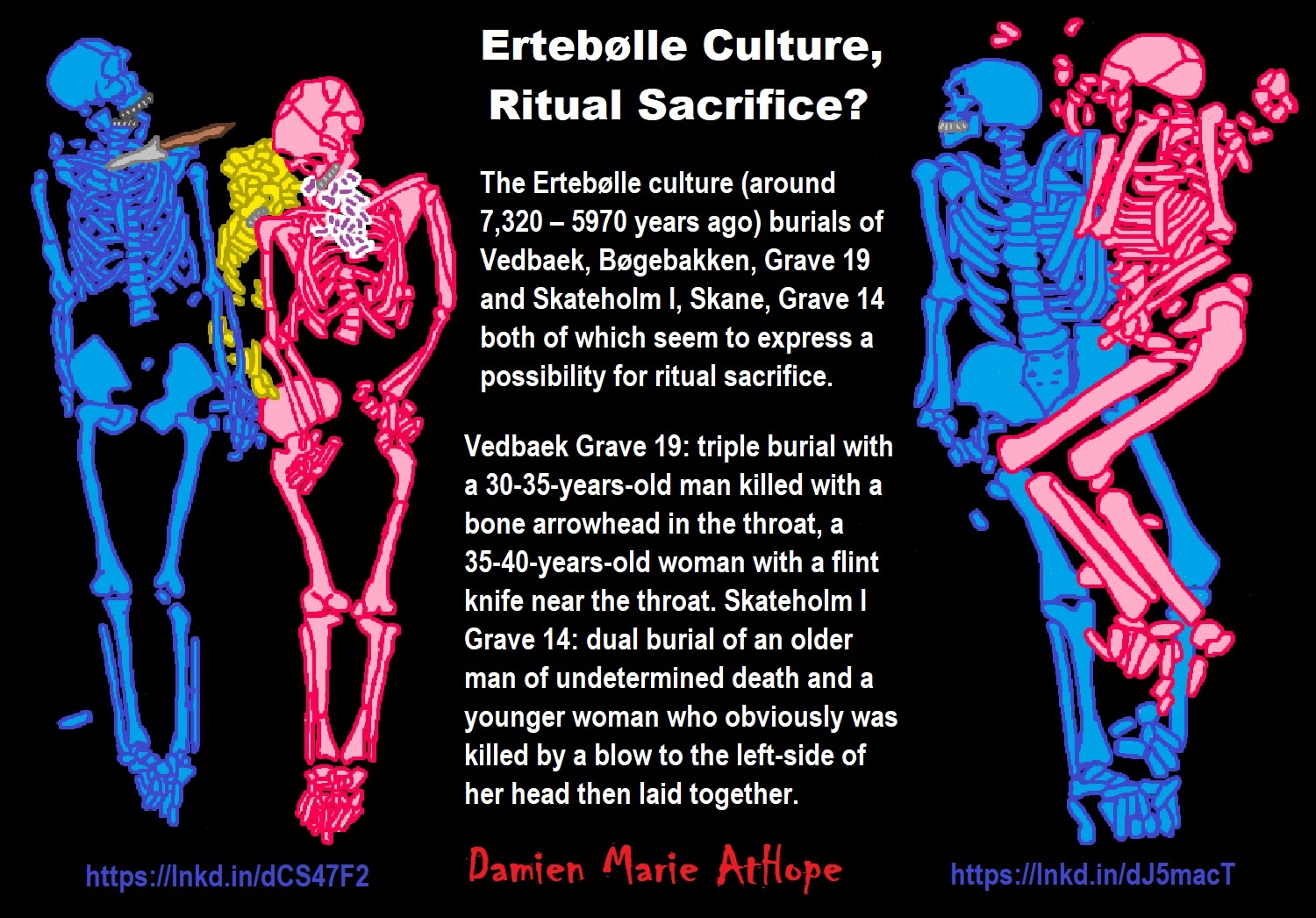

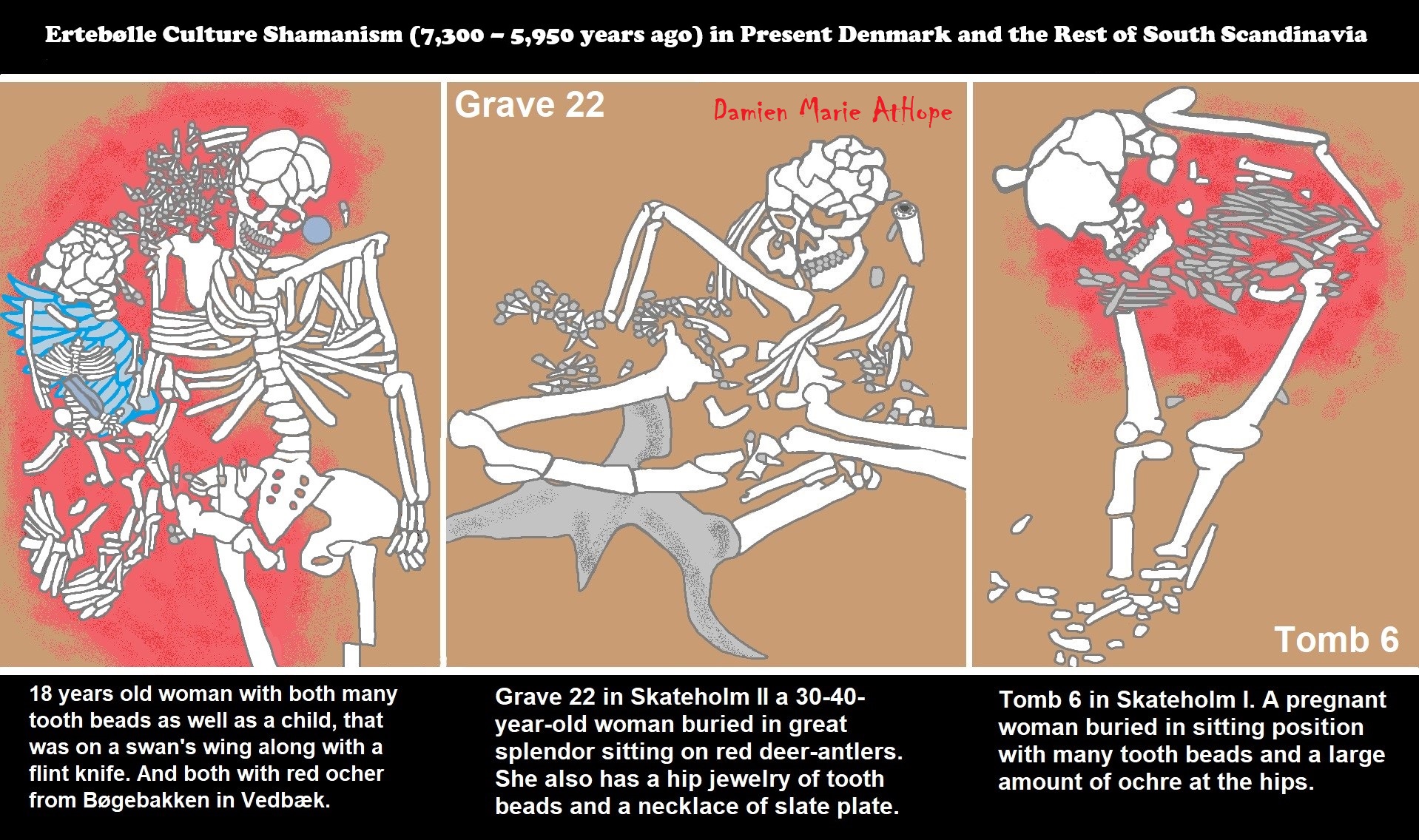

Ertebølle culture c. 5300 – 3400 BCE or 7,320-5,420 years ago

“The Ertebølle culture (ca 5300 – 3950 BCE or 7,320-5,420 years ago) (Danish pronunciation: [ˈɛɐ̯təˌpølə]) is the name of a hunter-gatherer and fisher, pottery-making culture dating to the end of the Mesolithic period. The culture was concentrated in Southern Scandinavia. It is named after the type site, a location in the small village of Ertebølle on Limfjorden in Danish Jutland. In the 1890s, the National Museum of Denmark excavated heaps of oyster shells there, mixed with mussels, snails, bones and bone, antler and flint artifacts, which were evaluated as kitchen middens (Danish køkkenmødding), or refuse dumps. Accordingly, the culture is less commonly named the Kitchen Midden. As it is approximately identical to the Ellerbek culture of Schleswig-Holstein, the combined name, Ertebølle-Ellerbek is often used. The Ellerbek culture (German Ellerbek Kultur) is named after a type site in Ellerbek, a community on the edge of Kiel, Germany.” ref

“In the 1960s and 1970s, another closely related culture was found in the (now dry) Noordoostpolder in the Netherlands, near the village Swifterbant and the former island of Urk. Named the Swifterbant culture (5300 – 3400 BCE or 7,320-5,420 years ago) they show a transition from hunter-gatherer to both animal husbandry, primarily cows and pigs, and cultivation of barley and emmer wheat. During the formative stages contact with nearby Linear Pottery culture settlements in Limburg has been detected. Like the Ertebølle culture, they lived near open water, in this case, creeks, river dunes, and bogs along post-glacial banks of the Overijsselse Vecht. Recent excavations show a local continuity going back to (at least) 5600 BCE or 7,620 years ago, when burial practices resembled the contemporary grave fields in Denmark and South Sweden “in all details”, suggesting only part of a diverse ancestral “Ertebølle”-like heritage was locally continued into the later (Middle Neolithic) Swifterbant tradition (4200 – 3400 BCE or 6,220-5,420 years ago).” ref

“The Ertebølle culture was roughly contemporaneous with the Linear Pottery culture, food-producers whose northernmost border was located just to the south. The Ertebølle did not practice agriculture but it did utilize domestic grain in some capacity, which it must have obtained from the south. The Ertebølle culture replaced the earlier Kongemose culture of Denmark. It was limited to the north by the Scandinavian Nøstvet and Lihult cultures. It is divided into an early phase ca 5300 – 4500 BCE or 7,320-6,520 years ago, and a later phase ca 4500 -3950 BCE or 6,520-5,970 years ago. Shortly after 4100 BCE or 6,120 years ago, the Ertebølle began to expand along the Baltic coast at least as far as Rügen. Shortly thereafter it was replaced by the Funnelbeaker culture.” ref

“In recent years archaeologists have found the acronym EBK most convenient, parallel to LBK for German Linearbandkeramik (Linear Pottery culture) and TRB for German Trichterbecher, Danish Tragtbæger (Funnelbeaker culture) and Dutch trechterbekercultuur. Ostensibly for Ertebølle Kultur, EBK could be either German or Danish and has the added advantage that Ellerbek also begins with E.” ref

Ertebølle culture Evidence of conflict

There is some evidence of conflict between Ertebølle settlements: an arrowhead in a pelvis at Skateholm, Sweden; a bone point in a throat at Vedbæk, Zealand; a bone point in the chest at Stora Biers, Sweden. More significant is evidence of cannibalism at Dyrholmen, Jutland, and Møllegabet on Ærø. There human bones were broken open to obtain the marrow. The evidence of marrow exploitation in the Ertebølle remains indicates dietary rather than ritual cannibalism; as marrow is never the subject of ritualistic cannibalism.” ref

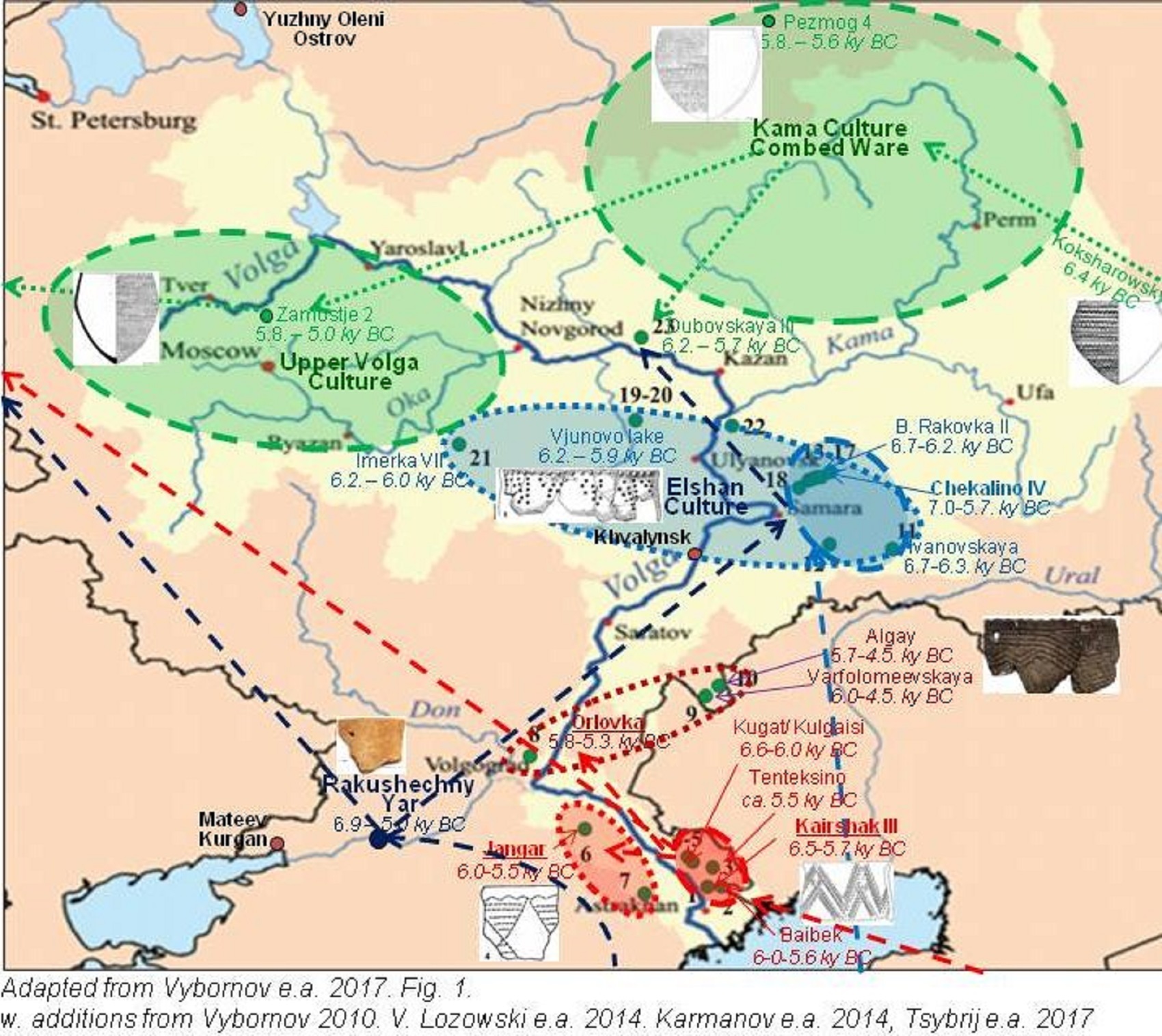

Ertebølle culture Pottery related to the Samara region of Russia c. 7000 cal BCE or 9,020 years ago

“Pottery was manufactured from native clays tempered with sand, crushed stone, and organic material. The EBK pot was made by coil technique, being fired on the open bed of hot coals. It was not like the neighboring Neolithic Linearbandkeramik and appears related instead to a pottery type that first appears in Europe in the Samara region of Russia c. 7000 cal BC, and spread up the Volga to the Eastern Baltic and then westward along the shore.” ref

“Two main types are found, a beaker and a lamp. The beaker is a pot-bellied pot narrowing at the neck, with a flanged, outward turning rim. The bottom was typically formed into a point or bulb (the “funnel”) of some sort that supported the pot when it was placed in clay or sand. One can imagine a sort of mobile pantry consisting of rows of jars set now in the hut, now by the fire, now in the clay layer at the bottom of a dugout.” ref

“The beaker came in various sizes from 8 to 50 cm high and from 5 to 20 cm in diameter. Decoration filled the entire surface with horizontal bands of fingertip or fingernail impressions. It must have been in the decoration phase that grains of wheat and barley left their impression in the clay. Late in the period technique and decoration became slightly more varied and sophisticated: the walls were thinner and different motifs were used in the impressions: chevrons, cord marks, and punctures made with animal bones. Handles are sometimes added and the rims may turn in instead of out. The blubber lamp was molded from a single piece of clay. The use of such lamps suggests some household activity in the huts after dark.” ref

“The Ertebølle culture is of a general type called Late Mesolithic, of which other examples can be found in Swifterbant culture, Zedmar culture, Narva culture, and in Russia. Some would include the Nøstvet culture and Lihult culture to the north as well. The various locations seem fragmented and isolated, but that characteristic may be an accident of discovery. Perhaps if all the submarine sites were known, a continuous coastal culture would appear from the Netherlands to the lakes of Russia, but this has yet to be demonstrated. Some of the pottery shreds of evidence grain impressions, which some interpret as the use of food imported from the south. Certainly, they did not need to import food and were probably better nourished than the southerners. Analysis of charred remains in one pot indicates that it at least was used for fermenting a mixture of blood and nuts. Some have therefore guessed that fermentation of grain was used to produce beer.” ref

Swifterbant culture c. 5300 – 3400 BCE or 7,320-5,420 years ago

“The Swifterbant culture was a Subneolithic archaeological culture in the Netherlands, dated between 5300 – 3400 BCE. Like the Ertebølle culture, the settlements were concentrated near water, in this case, creeks, river dunes, and bogs along post-glacial banks of rivers like the Overijsselse Vecht. In the 1960s and 1970s, artifacts classified as “Swifterbant culture” were found in the (now dry) Flevopolder in the Netherlands, near the villages of Swifterbant and Dronten. Other well-known sites were uncovered in South Holland (Bergschenhoek) and the Betuwe (Hardinxveld-Giessendam).” ref

“The oldest finds related to this culture, dated to circa 5600 BCE, cannot be distinguished from the Ertebølle culture, normally associated with Northern Germany and Southern Scandinavia. The culture is ancestral to the Western group of the agricultural Funnelbeaker culture (4000–2700 BCE), which extended through Northern Netherlands and Northern Germany to the Elbe. The earliest dated sites are season settlements. A transition from hunter-gatherer culture to cattle farming, primarily cows and pigs, occurred around 4800–4500 BCE. Pottery has been attested from this period. In the region indications to the existence of pottery are present from before the arrival of the Linear Pottery culture in the neighborhood. The material culture reflects a local evolution from Mesolithic communities, with a pottery in a Nordic (Ertebølle) style and trade relationships with southern late Rössen culture communities, as testified by the presence of true Breitkeile pottery sherds.” ref

“The Rössen culture, being an offshoot of Linear Pottery, is older than the finds in Swifterbant, and contemporary to older stages of this culture as found in Hoge Vaart (Almere) and Hardinxveld. Contact between Swifterbant and Rössen expressed itself by some hybrid early Swifterbant pots in Anvers (Doel) and hybrid Rössen pottery Hamburg-Boberg. In general, Swifterbant pottery does not show the same variety as Rössen pottery and Swifterbant pottery with Rössen influences are rare. Possibly the idea of cooking could be derived from agricultural neighbors. However, the technical style for making pottery are too different to consider such external influences.” ref

“Wetland settlement, unlike previous opinions, was a deliberate choice by prehistoric communities, as this offered attractive ecological conditions and a high natural productivity or agricultural potential. The economy covered a broad spectrum of resources to gather food, ruled by a strategy to diversify rather than increasing volume. As such, the wetlands offered, next to hunting and fishing, optimized conditions for cattle and small-scale cultivation of different crops, each having conditions for growing of their own. The agrarian transformation of the prehistoric community was an exclusively indigenous process, that ultimately realized itself only at the end of the Neolithic. This view has been supported by the discovery of an agricultural field in Swifterbant dated 4300–4000 BCE. Animal sacrifices found in the bogs of Drenthe are attributed to Swifterbant and suggest a religious role for both wild and domesticated bovines.” ref

Narva culture c. 5300 – 1750 BCE or 7,320-3,770 years ago

“Narva culture or eastern Baltic was a European Neolithic archaeological culture found in present-day Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Kaliningrad Oblast (former East Prussia), and adjacent portions of Poland, Belarus, and Russia. A successor of the Mesolithic Kunda culture, Narva culture continued up to the start of the Bronze Age. The time span is debated. Zinkevičius and the Fin.wikipedia assign it from (c. 5300 to 1750 BCE) (indirectly cited), Saag (2020) from 4410 to 4286 BCE. The technology was that of hunter-gatherers. The culture was named after the Narva River in Estonia.” ref

“The people of the Narva culture had little access to flint; therefore, they were forced to trade and conserve their flint resources. For example, there were very few flint arrowheads and flint was often reused. The Narva culture relied on local materials (bone, horn, schist). As evidence of trade, researchers found pieces of pink flint from Valdai Hills and plenty of typical Narva pottery in the territory of the Neman culture while no objects from the Neman culture were found in Narva. Heavy use of bones and horns is one of the main characteristics of the Narva culture. The bone tools, continued from the predecessor Kunda culture, provide the best evidence of continuity of the Narva culture throughout the Neolithic period. The people were buried on their backs with few grave goods. The Narva culture also used and traded amber; a few hundred items were found in Juodkrantė. One of the most famous artifacts is a ceremonial cane carved of horn as a head of female elk found in Šventoji.” ref

“The people were primarily fishers, hunters, and gatherers. They slowly began adopting husbandry in the middle Neolithic. They were not nomadic and lived in same settlements for long periods as evidenced by abundant pottery, middens, and structures built in lakes and rivers to help fishing. The pottery shared similarities with the Comb Ceramic culture, but had specific characteristics. One of the most persistent features was mixing clay with other organic matter, most often crushed snail shells. The pottery was made of 6-to-9 cm (2.4-to-3.5 in) wide clay strips with minimal decorations around the rim. The vessels were wide and large; the height and the width were often the same. The bottoms were pointed or rounded, and only the latest examples have narrow flat bottoms. From mid-Neolithic, Narva pottery was influenced and eventually disappeared into the Corded Ware culture.” ref

“For a long time, archaeologists believed that the first inhabitants of the region were Finno-Ugric, who were pushed north by people of the Corded Ware culture. In 1931, Latvian archaeologist Eduards Šturms [lv] was the first to note that artifacts found near the Zebrus Lake in Latvia were different and possibly belonged to a separate archaeological culture. In the early 1950s settlements on the Narva River were excavated. Lembit Jaanits [et] and Nina Gurina [ru] grouped the findings with similar artifacts from the eastern Baltic region and described the Narva culture.” ref

“At first, it was believed that Narva culture ended with the appearance of the Corded Ware culture. However, newer research extended it up to the Bronze Age. As Narva culture spanned several millennia and encompassed a large territory, archaeologists attempted to subdivide the culture into regions or periods. For example, in Lithuania two regions are distinguished: southern (under influence of the Neman culture) and western (with major settlements found in Šventoji). There is an academic debate on what ethnicity the Narva culture represented: Finno-Ugrians or other Europids, preceding the arrival of the Indo-Europeans. It is also unclear how the Narva culture fits with the arrival of the Indo-Europeans (Corded Ware and Globular Amphora cultures) and the formation of the Baltic tribes.” ref

Narva culture Genetics

“Jones et al. (2017) examined the remains of a male of the Narva culture buried c. 5780-5690 BCE. He was found to be a carrier of the paternal haplogroup R1b1b and the maternal haplogroup U2e1. People of the Narva culture and preceding Kunda culture were determined to have a closer genetic affinity with Western Hunter-Gatherers (WHGs) than Eastern Hunter-Gatherers (EHGs). Saag et al. (2017) determined haplogroup U5a2d in a Narva male.” ref

“Mittnik et al. (2018) analyzed 24 Narva individuals. Of the four samples of Y-DNA extracted, one belonged to I2a1a2a1a, one belonged to I2a1b, one belonged to I, and one belonged to R1. Of the ten samples of mtDNA extracted, eight belonged to U5 haplotypes, one belonged to U4a1, and one belonged to H11. U5 haplotypes were common among Western Hunter-Gatherers (WHGs) and Scandinavian Hunter-Gatherers (SHGs). Genetic influence from Eastern Hunter-Gatherers (EHGs) was also detected.” ref

“Mathieson (2015) analyzed a large number of individuals buried at the Zvejnieki burial ground, most of whom were affiliated with the Kunda culture and the succeeding Narva culture. The mtDNA extracted belonged exclusively to haplotypes of U5, U4, and U2. With regards to Y-DNA, the vast majority of samples belonged to R1b1a1a haplotypes and I2a1 haplotypes. The results affirmed that the Kunda and Narva cultures were about 70% WHG and 30% EHG. The nearby contemporary Pit–Comb Ware culture was on the contrary found to be about 65% EHG. And an individual from the Corded Ware culture, which would eventually succeed the Narva culture, was found to have genetic relations with the Yamnaya culture.” ref

Michelsberg Culture c. 4400–3500 BCE of 6,420-5,520 years ago

“The Michelsberg culture (German: Michelsberger Kultur (MK)) is an important Neolithic culture in Central Europe. Its dates are c. 4400–3500 BCE. Its conventional name is derived from that of an important excavated site on Michelsberg (short for Michaelsberg) hill near Untergrombach, between Karlsruhe and Heidelberg (Baden-Württemberg). The Michelsberg culture belongs to the Central European Late Neolithic. Its distribution covered much of West Central Europe, along both sides of the Rhine.” ref

“The Michelsberg culture emerges in northeastern France c. 4400 BCE. Genetic evidence suggests that it originated through a migration of peoples from the Paris Basin. Its people appear to trace their origins to Mediterranean farmers expanding from the southwest. Shortly after its emergence in northeastern France, the Michelsberg culture expands rapidly throughout central Germany, northeastern France, eastern Belgium, and the southwestern Netherlands. These areas had previously been occupied by cultures derived from the Linear Pottery culture (LBK), with whom the Michelsberg culture shares surprisingly little cultural or genetic affinity. Archaeological evidence suggests that the Michelsberg expansion was accompanied by violence.” ref

“The Michelsberg culture has strong affinities to the Chasséen culture of central France. Archaeological evidence strongly suggests that colonists from the Michelsberg culture played an instrumental role in establishing the Funnelbeaker culture of Northern Europe, which brought agriculture to southern Scandinavia. The Michelsberg culture also displays close affinities to the cultures of the Neolithic British Isles. The spread of agriculture into the British Isles by colonists from the continent happens at almost exactly the same time as in Scandinavia, suggesting that the two events are connected. The Michelsberg culture ends about c. 3500 BCE. It is succeeded in its core area by the Wartberg culture, with which it displays strong signs of continuity.” ref

“Michelsberg pottery is characterized by undecorated pointy-based tulip beakers. Finds of barley and emmer indicate an agricultural economy. Animal husbandry is indicated by bones of domesticated cattle, pig, sheep, and goat. Domestic dogs have also been identified. Bones of deer and fox suggest that the MK diet was supplemented by hunting. Prehistoric settlement patterns in Central Europe are generally quite volatile. The abandonment of a settlement may be part of a broader economic and social system. Thus, the Bruchsal area appears to contain several earthworks from different phases within MK.” ref

“There was no indication of a destruction of the site; nor were there any finds suggesting humans meeting a violent end. Some pits contained the remains of food stores. Thus, the abandonment of the site may have had environmental reasons. A common suggestion is the drying up of the Rhine’s arms which used to flow by the bottom of the hill, due to an extensive dry period. As the result of such a change in climate, the area would not have easily supported agriculture anymore, forcing human communities (and their livestock) to relocate.” ref

Michelsberg Culture Burial habits

“Formal Michelsberg burials have only been recognized rarely. There is no indication of organized burial grounds, as known from the earlier Linear pottery (LBK) and Rössen cultures. Human skeletal remains, frequently disarticulated, have been found inside pits and ditches in many MK earthworks and have had considerable influence on the interpretation of such structures. Their discussion is closely connected with that of similar remains in the ditches of British Causewayed enclosures.” ref

“The MK settlement of Aue yielded eight pit graves, six containing a single individual and two containing several. The age profile of those buried is very striking, as it is limited to children under the age of seven and adults over 50 (a considerable age in Neolithic Europe). In other words, humans of the ages that must have dominated the active social and economic life of the settlement are absent. It has been suggested that their bodies may not have received formal burial, but were disposed of by excarnation, in which case the skeletal remains from rubbish pits may be the result of such activity.” ref

“The same may apply to human bones found in the fills of enclosure ditches around MK settlements. It has also been suggested (hypothetically) that partially articulated remains found in such ditches may indicate that graves were placed on the surfaces adjacent to them and later washed into the ditches due to erosion. Occasionally, earthwork ditches contain more structured deposits of human bone, e.g. adult skeletons surrounded by those of children. Such burials are probably connected to the realms of cult or ritual, as are specific depositions of offerings in some of the ditches, especially at the settlements of Aue and Scheelkopf. Here, ditches contained carefully placed complete vessels, well-preserved quern-stones, and the horns of aurochs. The latter had been neatly separated from the skulls, perhaps reflecting a special symbolic significance ascribed to that animal.” ref

“A hitherto unknown aspect to MK burial practice is suggested by the recent discovery of MK burials in the Blätterhof cave near Hagen, Westphalia. Here, a full age profile appears to be represented. An unusual burial was found at Rosheim (Bas-Rhin, France). Here, the fill of a pit contained the crouched remains of an adult woman, her legs leaning against a quernstone. She appeared to have been laid onto a carefully placed packing of clay lumps, mixed with pottery and bones. Her death had been caused by some blunt impact on her skull.” ref

“Beau et al. 2017 examined the remains 22 Michelsberg people buried at Gougenheim, France. The 21 samples of mtDNA extracted belonged to the maternal haplogroups H (7 samples), K (4 samples), J (2 samples), W (1 samples), N (1 sample), U (3 samples), and T (2 samples). The examined individuals displayed genetic links to earlier farming populations of the Paris Basin, and were genetically very different from previous post-LBK cultures of the region, suggesting that the Michelsberg culture emerged through a migration of people from west. They displayed genetic links to other farmers of Western Europe, and carried substantial amounts of hunter-gatherer ancestry. The authors of the study proposed that migrations of people associated with the Michelsberg culture may have been responsible for the resurgence of hunter-gatherer ancestry observed in Central Europe during the Middle Neolithic.” ref

“Lipson et al. 2017 examined the remains of 4 individuals buried c. 4000-3000 BCE at the Blätterhöhle site in modern-day Germany, ascribed to the Michelsberg culture and its successor, the Wartberg culture. The 3 samples of Y-DNA extracted belonged to the paternal haplogroups R1b1, R1, and I2a1, while the 4 samples of mtDNA extracted belonged to the maternal haplogroups U5b2a2, J1c1b1, H5, and U5b2b2. The individuals carried a very high amount of Western Hunter-Gatherer (WHG) ancestry, estimated at about 40–50%, with one individual displaying as much as c. 75% Brunel et al. 2020 examined the remains of 18 individuals ascribed to the Michelsberg culture. The 2 samples of Y-DNA belonged to the paternal haplogroup I, while the 16 samples of mtDNA extracted belonged to types of the maternal haplogroups H (3 samples), K (9 samples), X (1 sample), T (2 samples), and U (1 sample).” ref

Chasséen Culture c. 4500–3500 BCE of 6,520-5,520 years ago

“Chasséen culture is the name given to the archaeological culture of prehistoric France of the late Neolithic (Stone Age), which dates to roughly between 4500 – 3500 BCE. The name “Chasséen” derives from the type site near Chassey-le-Camp (Saône-et-Loire). Chasséen culture spread throughout the plains and plateaux of France, including the Seine basin and the upper Loire valleys, and extended to the present-day départments of Haute-Saône, Vaucluse, Alpes-de-Haute-Provence, Pas-de-Calais and Eure-et-Loir. Excavations at Bercy (in Paris) have revealed a Chasséen village (4000 – 3800 BCE) on the right bank of the Seine; artifacts include wood canoes, pottery, bows, and arrows, wood and stone tools.

“Chasséens were sedentary farmers (rye, panic grass, millet, apples, pears, prunes) and herders (sheep, goats, oxen, pigs). They lived in huts organized into small villages (100-400 people). Their pottery was little decorated. They had no metal technology (which appeared later), but mastered the use of flint. By roughly 3500 BCE, the Chasséen culture in France gave way to the late Neolithic transitional Seine-Oise-Marne culture (3100 – 2000 BCE) in Northern France and to a series of archaeological cultures in Southern France.

Chasséen Culture Time line

- “4000: Chasséen village of Bercy near Paris

- 4400: Chasséen village of Saint-Michel du Touch near Toulouse.

- 4400: Appearance of Rössen culture at Baume de Gonvillars in Haute-Saône.

- 3190: Chasséen culture in Calvados.

- 3530: Chasséen culture in Pas-de-Calais.

- 3450: End of Chasséen culture in Eure-et-Loir.

- 3400: End of Chasséen culture in Saint-Mitre (Alpes-de-Haute-Provence).” ref

Millet Domestication in East Asia

“Millets are important crops in the semiarid tropics of Asia and Africa, and Millets are indigenous to many parts of the world. The most widely grown millet is pearl millet, which is an important crop in India and parts of Africa. Finger millet, proso millet, and foxtail millet are also important crop species. Millets may have been consumed by humans for about 7,000 years and potentially had “a pivotal role in the rise of multi-crop agriculture and settled farming societies.” ref

“The various species called millet were initially domesticated in different parts of the world most notably East Asia, South Asia, West Africa, and East Africa. However, the domesticated varieties have often spread well beyond their initial area. Specialized archaeologists called palaeoethnobotanists, relying on data such as the relative abundance of charred grains found in archaeological sites, hypothesize that the cultivation of millets was of greater prevalence in prehistory than rice, especially in northern China and Korea. Millets also formed important parts of the prehistoric diet in Indian, Chinese Neolithic, and Korean Mumun societies.” ref

“Proso millet (Panicum miliaceum) and foxtail millet (Setaria italica) were important crops beginning in the Early Neolithic of China. Some of the earliest evidence of millet cultivation in China was found at Cishan (north), where proso millet husk phytoliths and biomolecular components have been identified around 10,300–8,700 years ago in storage pits along with remains of pit-houses, pottery, and stone tools related to millet cultivation. Evidence at Cishan for foxtail millet dates back to around 8,700 years ago. The oldest evidence of noodles in China were made from these two varieties of millet in a 4,000-year-old earthenware bowl containing well-preserved noodles found at the Lajia archaeological site in north China.” ref

“Palaeoethnobotanists have found evidence of the cultivation of millet in the Korean Peninsula dating to the Middle Jeulmun pottery period (around 3500–2000 BCE). Millet continued to be an important element in the intensive, multicropping agriculture of the Mumun pottery period (about 1500–300 BCE) in Korea. Millets and their wild ancestors, such as barnyard grass and panic grass, were also cultivated in Japan during the Jōmon period some time after 4000 BCE. Chinese myths attribute the domestication of millet to Shennong, a legendary Emperor of China, and Hou Ji, whose name means Lord Millet.” ref

“Little millet (Panicum sumatrense) is believed to have been domesticated around 5000 before present in India subcontinent and Kodo millet (Paspalum scrobiculatum) around 3700 before present, also in Indian subcontinent. Various millets have been mentioned in some of the Yajurveda texts, identifying foxtail millet (priyaṅgu), Barnyard millet (aṇu) and black finger millet (śyāmāka), indicating that millet cultivation was happening around 1200 BCE in India.” ref

“Pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum) was definitely domesticated in Africa by 3500 before present, though 8000 before present is thought likely. Early evidence includes finds at Birimi in West Africa with the earliest at Dhar Tichitt in Mauritania. Pearl millet was domesticated in the Sahel region of West Africa, where its wild ancestors are found. Evidence for the cultivation of pearl millet in Mali dates back to 2500 BCE, and pearl millet is found in the Indian subcontinent by 2300 BCE. Finger millet is originally native to the highlands of East Africa and was domesticated before the third millennium BCE. Its cultivation had spread to South India by 1800 BCE.” ref

Spreading of millet from China to the Black Sea region of Europe by 5000 BCE or 7,000 years ago

“The cultivation of common millet as the earliest dry crop in East Asia has been attributed to its resistance to drought, and this has been suggested to have aided its spread. Asian varieties of millet made their way from China to the Black Sea region of Europe by 5000 BCE. Millet was growing wild in Greece as early as 3000 BCE, and bulk storage containers for millet have been found from the Late Bronze Age in Macedonia and northern Greece. Hesiod describes that “the beards grow round the millet, which men sow in summer.” And millet is listed along with wheat in the third century BCE by Theophrastus in his “Enquiry into Plants”.” ref

Funnelbeaker culture c. 4300–2800 BCE of 6,320-4,820 years ago