Dogs in Religion

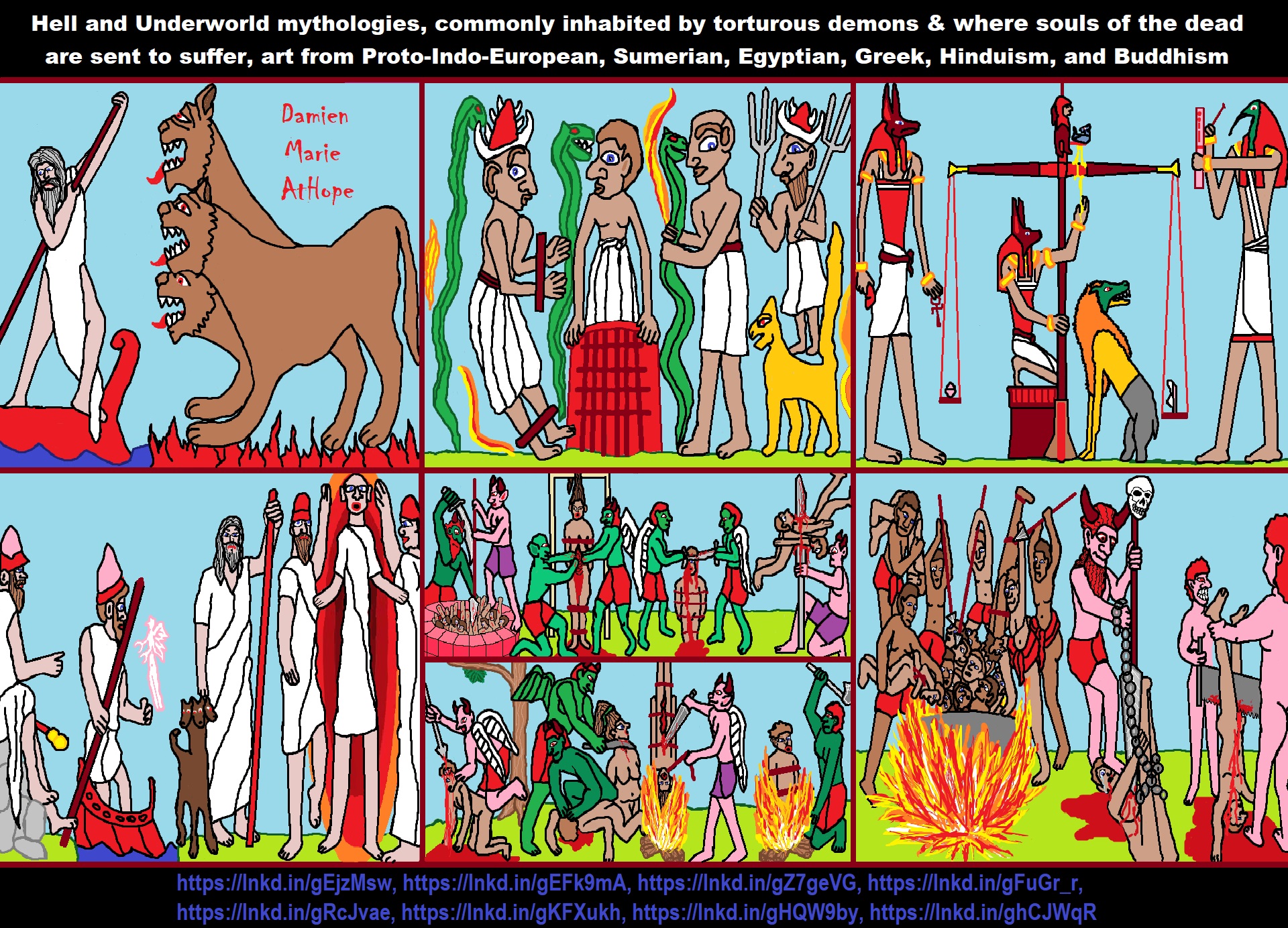

“Dogs have played a role in the religion, myths, tales, and legends of many cultures. In mythology, dogs often serve as pets or as watchdogs. Stories of dogs guarding the gates of the underworld recur throughout Indo-European mythologies and may originate from Proto-Indo-European religion. Historian Julien d’Huy has suggested three narrative lines related to dogs in mythology. One echoes the gatekeeping noted above in Indo-European mythologies—a linkage with the afterlife; a second “related to the union of humans and dogs”; a third relates to the association of dogs with the star Sirius. Evidence presented by d’Huy suggests a correlation between the mythological record from cultures and the genetic and fossil record related to dog domestication.” ref

“The Ancient Egyptians are often more associated with cats in the form of Bastet, yet here too, dogs are found to have a sacred role and figure as an important symbol in religious iconography. Dogs were associated with Anubis, the jackal headed god of the underworld. At times throughout its period of being in use the Anubieion catacombs at Saqqara saw the burial of dogs. Anput was the female counterpart of her husband, Anubis, she was often depicted as a pregnant or nursing jackal, or as a jackal wielding knives. Other dogs can be found in Egyptian mythology. Am-heh was a minor god from the underworld.” ref

“He was depicted as a man with the head of a hunting dog who lived in a lake of fire. Duamutef was originally represented as a man wrapped in mummy bandages. From the New Kingdom onwards, he is shown with the head of a jackal. Wepwawet was depicted as a wolf or a jackal, or as a man with the head of a wolf or a jackal. Even when considered a jackal, Wepwawet usually was shown with grey, or white fur, reflecting his lupine origins. Khenti-Amentiu was depicted as a jackal-headed deity at Abydos in Upper Egypt, who stood guard over the city of the dead.” ref

God “Set” Animal

“In art, Set is usually depicted as an enigmatic creature referred to by Egyptologists as the Set animal, a beast not identified with any known animal, although it could be seen as a resembling an aardvark, an African wild dog, a donkey, a hyena, a jackal, a pig, an antelope, a giraffe, an okapi, a saluki, or a fennec fox. The animal has a downward curving snout; long ears with squared-off ends; a thin, forked tail with sprouted fur tufts in an inverted arrow shape; and a slender canine body. Sometimes, Set is depicted as a human with the distinctive head.” ref

“Some early Egyptologists proposed that it was a stylized representation of the giraffe, owing to the large flat-topped “horns” which correspond to a giraffe’s ossicones. The Egyptians themselves, however, used distinct depictions for the giraffe and the Set animal. During the Late Period, Set is depicted as a donkey or as a man wearing a donkey’s-head mask.” ref

“The earliest representations of what might be the Set animal comes from a tomb dating to the Amratian culture (“Naqada I”) of prehistoric Egypt (3790–3500 BCE or 5,812-5,522 years ago), though this identification is uncertain. If these are ruled out, then the earliest Set animal appears on a ceremonial macehead of Scorpion II, a ruler of the Naqada III phase. The head and the forked tail of the Set animal are clearly present on the mace. In the Book of the Faiyum, he is depicted with a flamingo head.” ref

“Set (or Greek: Seth) is a god of deserts, storms, disorder, violence, and foreigners in ancient Egyptian religion. In Ancient Greek, the god’s name is given as Sēth (Σήθ). Set had a positive role where he accompanies Ra on his barque to repel Apep, the serpent of Chaos. Set had a vital role as a reconciled combatant. He was lord of the Red Land, where he was the balance to Horus‘ role as lord of the Black Land.” ref

“In ancient Egyptian astronomy, Set was commonly associated with the planet Mercury. Since he is related to the west of Nile which is the desert, he is sometimes associated with a lesser deity, Ha, god of the desert, which is a deity depicted as a man with a desert determinative on his head. Set is the son of Geb, the Earth, and Nut, the Sky; his siblings are Osiris, Isis, and Nephthys. He married Nephthys and fathered Anubis and in some accounts, he had relationships with the foreign goddesses Anat and Astarte. From these relationships is said to be born a crocodile deity called Maga.” ref

Was-sceptre

“The was (Egyptian wꜣs “power, dominion”) sceptre is a symbol that appeared often in relics, art, and hieroglyphs associated with the ancient Egyptian religion. It appears as a stylized animal head at the top of a long, straight staff with a forked end. Was sceptres were used as symbols of power or dominion, and were associated with ancient Egyptian deities such as Set or Anubis as well as with the pharaoh. Was sceptres also represent the Set animal. In later use, it was a symbol of control over the force of chaos that Set represented.” ref

“In a funerary context the was sceptre was responsible for the well-being of the deceased, and was thus sometimes included in the tomb-equipment or in the decoration of the tomb or coffin. The sceptre is also considered an amulet. The Egyptians perceived the sky as being supported on four pillars, which could have the shape of the was. This sceptre was also the symbol of the fourth Upper Egyptian nome, the nome of Thebes (called wꜣst in Egyptian).” ref

“Was sceptres were depicted as being carried by gods, pharaohs, and priests. They commonly occur in paintings, drawings, and carvings of gods, and often parallel with emblems such as the ankh and the djed-pillar. Remnants of real was sceptres have been found. They are constructed of faience or wood, where the head and forked tail of the Set animal are visible. The earliest examples date to the First Dynasty. The Was (wꜣs) is the Egyptian hieroglyph character representing power.” ref

“A sceptre (British English) or scepter (American English) is a staff or wand held in the hand by a ruling monarch as an item of royal or imperial insignia. Figuratively, it means a royal or imperial authority or sovereignty. The Was and other types of staves were signs of authority in Ancient Egypt. For this reason they are often described as “sceptres”, even if they are full-length staffs. One of the earliest royal sceptres was discovered in the 2nd Dynasty tomb of Khasekhemwy in Abydos. Kings were also known to carry a staff, and Pharaoh Anedjib is shown on stone vessels carrying a so-called mks-staff. The staff with the longest history seems to be the heqa-sceptre (the “shepherd’s crook”).” ref

“The sceptre also assumed a central role in the Mesopotamian world, and was in most cases part of the royal insignia of sovereigns and gods. This is valid throughout the whole Mesopotamian history, as illustrated by both literary and administrative texts and iconography. The Mesopotamian sceptre was mostly called ĝidru in Sumerian and ḫaṭṭum in Akkadian. The ancient Tamil work of Tirukkural dedicates one chapter each to the ethics of the sceptre. According to Valluvar, “it was not his spear but the sceptre which bound a king to his people.” Among the early Greeks, the sceptre (Ancient Greek: σκῆπτρον, skeptron, “staff, stick, baton”) was a long staff, such as Agamemnon wielded (Iliad, i) or was used by respected elders (Iliad, xviii. 46; Herodotus 1. 196), and came to be used by judges, military leaders, priests, and others in authority.” ref

“It is represented on painted vases as a long staff tipped with a metal ornament. When the sceptre is borne by Zeus or Hades, it is headed by a bird. It was this symbol of Zeus, the king of the gods and ruler of Olympus, that gave their inviolable status to the kerykes, the heralds, who were thus protected by the precursor of modern diplomatic immunity. When, in the Iliad, Agamemnon sends Odysseus to the leaders of the Achaeans, he lends him his sceptre.Among the Etruscans, sceptres of great magnificence were used by kings and upper orders of the priesthood. Many representations of such sceptres occur on the walls of the painted tombs of Etruria. The British Museum, the Vatican, and the Louvre possess Etruscan sceptres of gold, most elaborately and minutely ornamented.” ref

“The Roman sceptre probably derived from the Etruscan. Under the Republic, an ivory sceptre (sceptrum eburneum) was a mark of consular rank. It was also used by victorious generals who received the title of imperator, and its use as a symbol of delegated authority to legates apparently was revived in the marshal’s baton. In the First Persian Empire, the Biblical Book of Esther mentions the sceptre of the King of Persia. Esther 5:2 “When the king saw Esther the queen standing in the court, she obtained favor in his sight; and the king held out to Esther the golden scepter that was in his hand.” ref

“So Esther came near, and touched the top of the scepter.”Under the Roman Empire, the sceptrum Augusti was specially used by the emperors, and was often of ivory tipped with a golden eagle. It is frequently shown on medallions of the later empire, which have on the obverse a half-length figure of the emperor, holding in one hand the sceptrum Augusti, and in the other the orb surmounted by a small figure of Victory.” ref

“The baton can most likely be traced back to the mace, with ancient Kings and Pharaohs often being buried with ceremonial maces. The ceremonial baton is a short, thick stick-like object, typically in wood or metal, that is traditionally the sign of a field marshal or a similar high-ranking military officer, and carried as a piece of their uniform. The baton is distinguished from the swagger stick in being thicker and effectively without any practical function. A staff of office is rested on the ground; a baton is not. Unlike a royal sceptre that is crowned on one end with an eagle or globe, a baton is typically flat-ended.” ref

Humans and Dogs

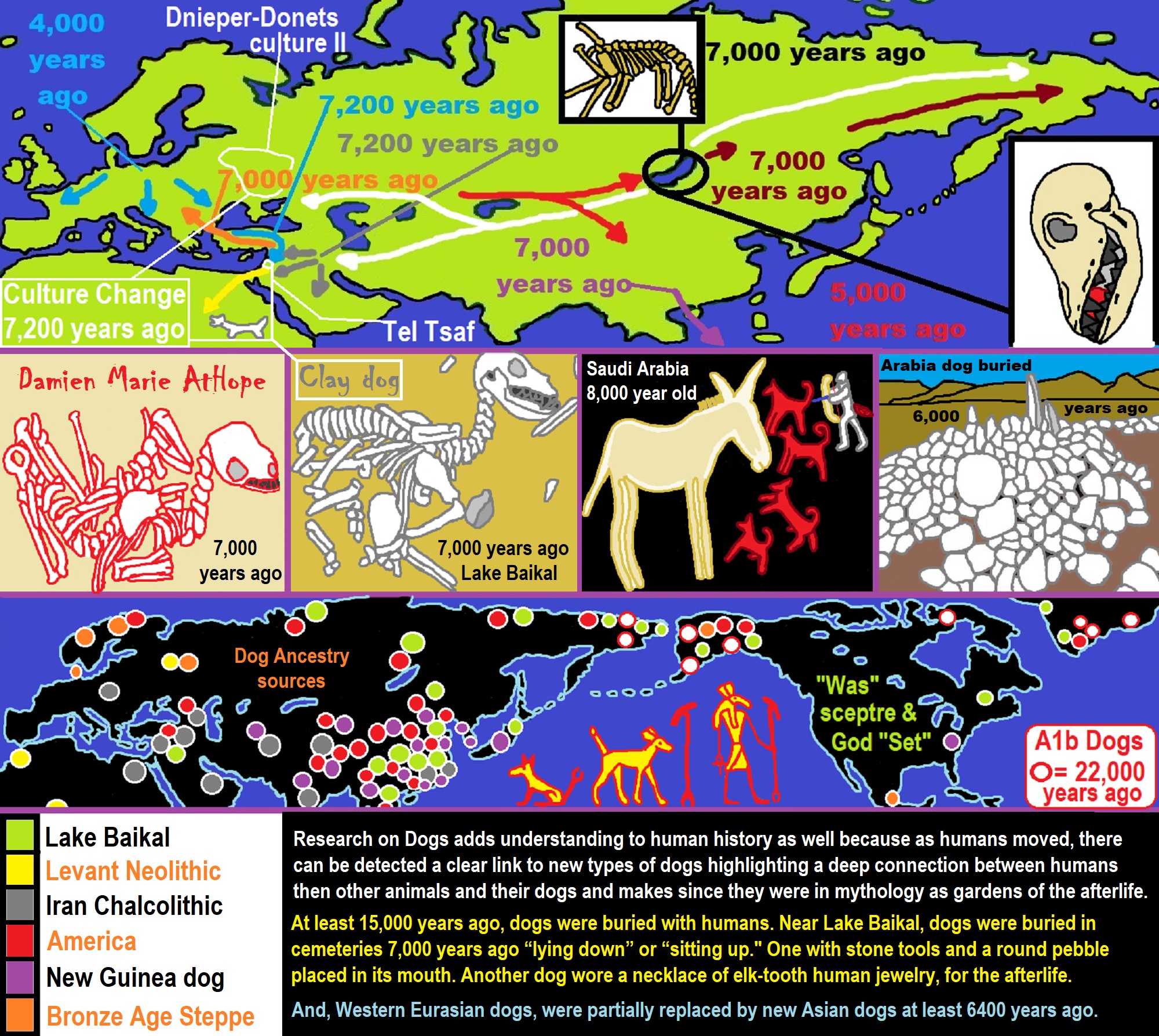

“The Western Eurasian dog population (European) was then partially replaced by a human-mediated translocation of Asian dogs at least 6400 years ago, a process that took place gradually after the arrival of the eastern dog population.” ref

Study: At Least Five Dog Lineages Existed 11,000 Years Ago: http://www.sci-news.com/archaeology/five-dog-lineages-paleolithic-09012.html

“A recent study of dozens of ancient dog genomes suggests that these lineages were all established by at least 11,000 years ago. Based on their morphology and context, additional potential dogs may be present at Pleistocene Siberian sites such as Afontova Gora, Diuktai Cave, and Verkholenskaia Gora, although their status has yet to be established. In the Americas, the earliest confirmed archaeological dog remains, based on combined morphological, genetic, isotopic, and contextual evidence, are from the Koster and Stilwell II sites, which have been dated to ∼10,000 years ago.” https://www.pnas.org/content/pnas/118/6/e2010083118.full.pdf

“Swedish farmers and their dogs are both descended from canines of the Near East, suggesting that man and dog followed the development of agriculture together through Europe. On the other hand, German farmers 7,000 years ago came from the Near East, but their dogs didn’t.” https://bigthink.com/the-past/ancient-dogs/

Research on Dogs adds understanding to human history as well because as humans moved, there can be detected a clear link to new types of dogs highlighting a deep connection between humans then other animals and their dogs and makes since they were in mythology as gardens of the afterlife. http://www.sci-news.com/archaeology/five-dog-lineages-paleolithic-09012.html

Tell-tail signs of dual dog domestication: https://www.scienceintheclassroom.org/research-papers/tell-tail-signs-dual-dog-domestication

Dog domestication and the dual dispersal of people and dogs into the Americas: https://www.pnas.org/content/118/6/e2010083118

Diet adaptation in dog reflects spread of prehistoric agriculture: https://www.nature.com/articles/hdy201648

A refined proposal for the origin of dogs: the case study of Gnirshöhle, a Magdalenian cave site: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-83719-7

Dogs ‘first domesticated in China’ https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2016-04/27/content_24875302.htm

The Origins of Dogs, Our best friends’ earliest lineage is shrouded in mystery. New genetic research may finally reveal their roots. https://www.discovermagazine.com/planet-earth/the-origins-of-dogs

Rethinking dog domestication by integrating genetics, archeology, and biogeography https://www.pnas.org/content/109/23/8878

“Burial remains of a dog that lived over 7,000 years ago in Siberia suggest the male Husky-like animal probably lived and died similar to how humans did at that time and place, eating the same food, sustaining work injuries, and getting a human-like burial.” https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna41830341

“Pet dog buried 6,000 years ago is earliest evidence of its domestication in Arabia. The ancient tomb where the remains were found is one of the oldest in the region, dating back to about 4300 B.C. The tomb had been used by many generations over a period of around 600 years during the Neolithic-Chalcolithic era. It was also built above ground, which was unusual for the time because it would be easily seen by grave robbers, according to the researchers.” https://www.livescience.com/earliest-evidence-dog-domestication-arabian-peninsula.html

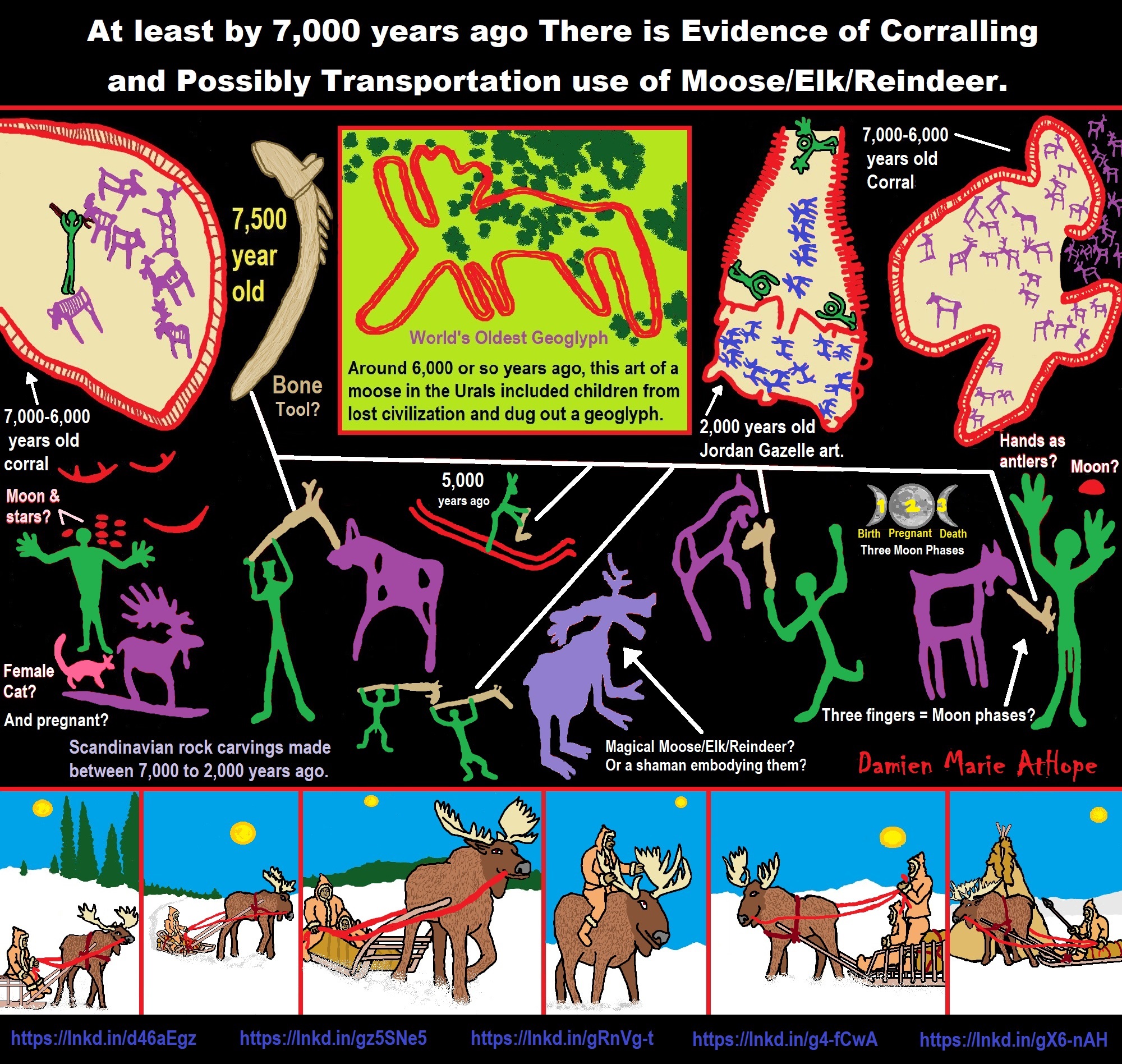

“At least 15,000 years ago, dogs were buried with humans. Near Lake Baikal, dogs were buried in cemeteries 7,000 years ago “lying down” or “sitting up.” One with stone tools and a round pebble placed in its mouth. Another dog wore a necklace of elk-tooth human jewelry, for the afterlife. This dog was buried about 7,000 years ago near Lake Baikal in southern Siberia with stone tools and a round pebble placed in its mouth. At least 15,000 years ago, dogs were getting buried with humans. When dogs died near Lake Baikal, the human hunter-gatherers treated them as family. The dogs buried in cemeteries 7,000 years ago near Lake Baikal in southern Siberia, one with stone tools and a round pebble placed in its mouth. The dogs were in “sleeping” or “sitting up” positions. Another dog wore a necklace of elk-tooth jewelry that humans wore obvious gifts, presumably offerings into the dog graves meant for the afterlife. Like people when they died, they’d transport the dog long distances to these cemeteries,” Losey said in a phone interview from his office at the University of Alberta. “They’d put items on its body in the grave – spoons, necklaces, arrowheads, antlers from roe deer – the same grave goods they’d leave in the graves of humans. “People had long lives with those dogs – the dogs we found were mostly older dogs, so they’d been with these people for years.” They ate the same food. Chemical tests on dog and human bones showed both were eating a lot of fish. “Given that the dogs weren’t fishing, it means they were fed.” Losey could tell from DNA and from dog skeletons that the Lake Baikal dogs were medium-sized, with yellow and white thick fur and heads shaped like modern Siberian huskies. “If you saw them walking down the street, you’d recognize them immediately as dogs and not wolves.” They worked for their living, likely hauling sleds and guarding camps full of children and grandmothers from predators and rival bands of hunters. “But there was clearly also an emotional bond,” Losey said.” https://www.kansas.com/news/local/article142279974.html

“Near Lake Baikal on the Siberian steppes, archeologists were opening 7,000-year-old graves. The bodies had been carefully interred. One was buried with a long, carved spoon. Another had been honored with a necklace of elk teeth.” When the first farmers came to Europe from what is now eastern Turkey, they didn’t adopt the dogs already living there. They brought their own.” https://lethbridgenewsnow.com/2020/10/29/they-came-with-dogs-genomes-show-canines-humans-share-long-history/

“The site at Lake Baikal points to some of the earliest evidence of dog domestication but also suggests dogs were held in the same high esteem as humans. ‘The dogs were being treated just like people when they died. An ancient cemetery where dogs were buried like humans (remains shown) between 5,000 and 8,000 years ago is shedding light on our close relationship with man’s best friend. Prized canines were buried wearing decorative collars, or with objects such as spoons, suggesting people believed they had souls in the afterlife. Some of the graves contain artifacts such as spoons and collars, suggesting people thought the dogs had souls and access to an afterlife.” https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-3485496/Ancient-burials-reveal-dogs-man-s-best-friend-Canines-treated-like-humans-8-000-years-ago.html

“Canids as persons: Early Neolithic dog and wolf burials, Cis-Baikal, Siberia” https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S027841651100002X

“This 8,000-Year-Old Rock Art Is The Earliest Depiction of Domesticated Dogs” https://www.sciencealert.com/1000-year-old-rock-art-saudi-arabia-earliest-depiction-domestic-dogs-hunting

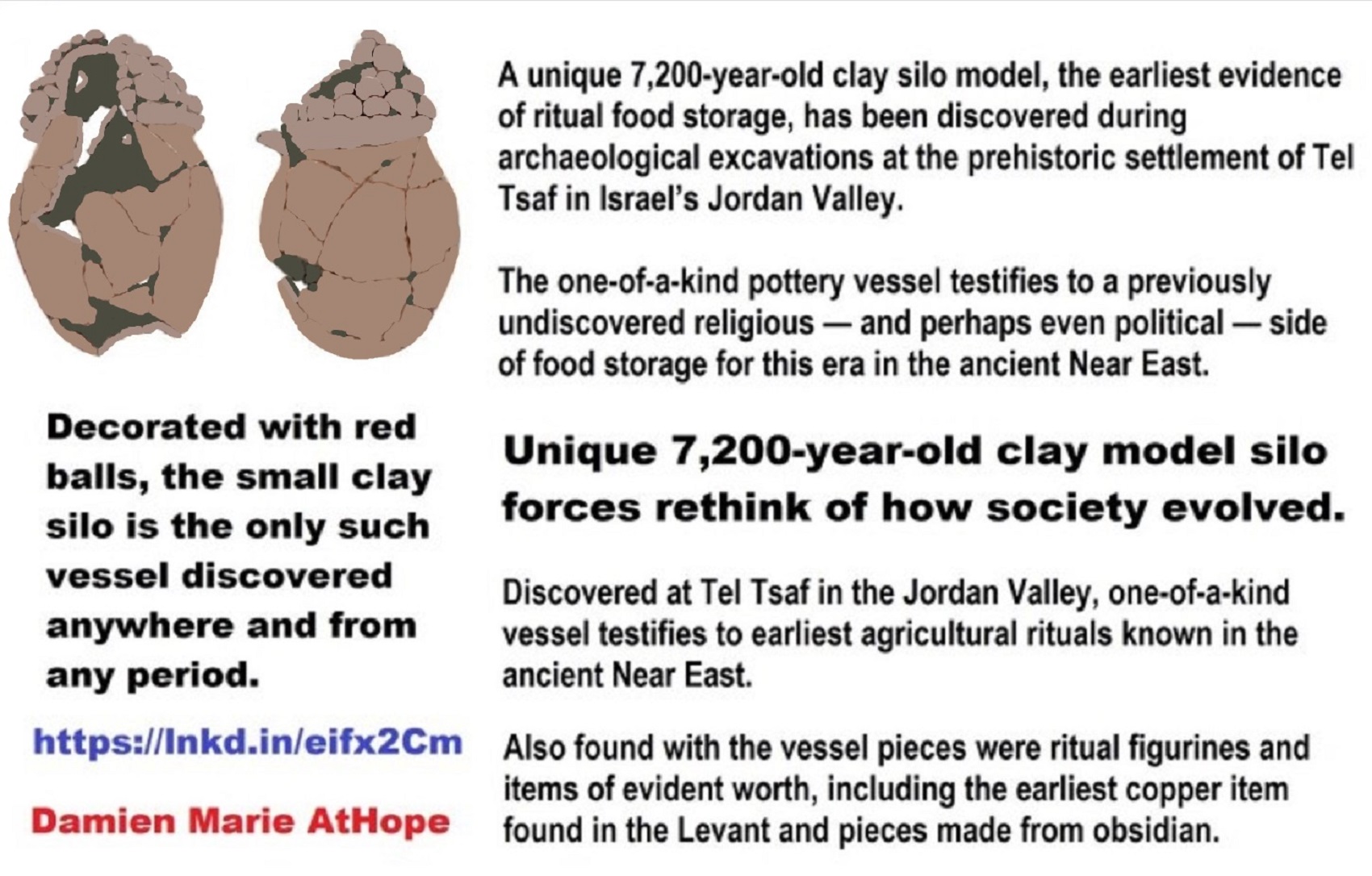

Tel Tsaf

“is an archaeological site located in the central Jordan Valley, south-east of Beit She’an. Tel Tsaf is dated to ca. 5200–4700 BCE or 7,222-6,722 years ago, sometimes called the Middle Chalcolithic, a little-known period in the archaeology of the Levant, post-dating the Wadi Rabah phase and pre-dating the Ghassulian Chalcolithic phase.” ref

“The excavations unearthed four architectural complexes. Each consists of a closed courtyard with rounded or rectangular rooms and numerous rounded silos. Four burials were found within or adjacent to silos. Outside the settlement a well was cut into the water table, approximately 6.5 m in depth. Common finds included numerous flints, pottery, and animal bones.” ref

“The terms “Tel Tsaf Decoration” or “Tsafian” were derived from an assemblage of painted pottery, consisting mainly of relatively elaborate vessels bearing geometric decoration using red and black paint on a white slip background. The decoration was executed in two steps: first, white wash was applied to the upper part of the vessel, while the lower part was covered with red wash. Second, the patterns were painted in continuous horizontal bands on the upper part of the vessel. The painting was executed with a fine brush, in some cases 0.5 mm.” ref

“Other finds included about 150 clay sealings (bullae) and a rich assemblage of imported exotic items including artifacts of basalt and obsidian, beads, sea shells, Nilotic shell, and a few pottery sherds of the Ubaid culture of north Syria. This is the first reported occurrence of Ubaid sherds in an excavation in the southern Levant.” ref

Tel Tsaf Silos

“The silos are cylindrical, barrel-shaped structures with an outer diameter between 2 and 4 m. The base is a podium, probably built to protect the cereals from rodents. It consists of several courses of bricks sealed inside with lime plaster. The silos demonstrate several universal principles guiding the construction of silos worldwide, past and present:

1. Rounded sides, giving the structure a cylindrical shape. This form better withstands the pressure exerted by the contents, which is distributed evenly onto the sides of the silo and does not create excessive stress at the base or the corners as is the case with a rectilinear shape.

2. Building of a number of silos near one another allows for greater ease of handling than one big installation. This facilitates separation of grain from different years or different crops. In the event of fire, humidity, rodent or insect infestation, some of the stored grain may be spared.

3. Organization of silos in adjacent rows facilitates their arrangement within a confined space. The stability of silo shape over considerable periods of time and large geographical regions provide an outstanding case in human architecture.” ref

Tel Tsaf and the Oldest metal artifact found in the Southern Levant

“An awl made of cast-metal copper and dated to the late sixth millennium or early fifth millennium BCE was found in 2007 during excavations. It was part of the grave goods accompanying the burial of a woman wearing a belt decorated with 1,668 ostrich eggshell beads. This is the most elaborate burial of its period in the entire Levant, the presence of the awl being an indication of the high prestige enjoyed by metal objects in that time and region. The fact that the grave was dug inside an abandoned silo is an indication for both the high status of the woman, and the importance ascribed to the silo. The chemical composition of the copper let the researchers believe that the awl originated in the Caucasus, from a distance of ca. 1,000 kilometers.” ref

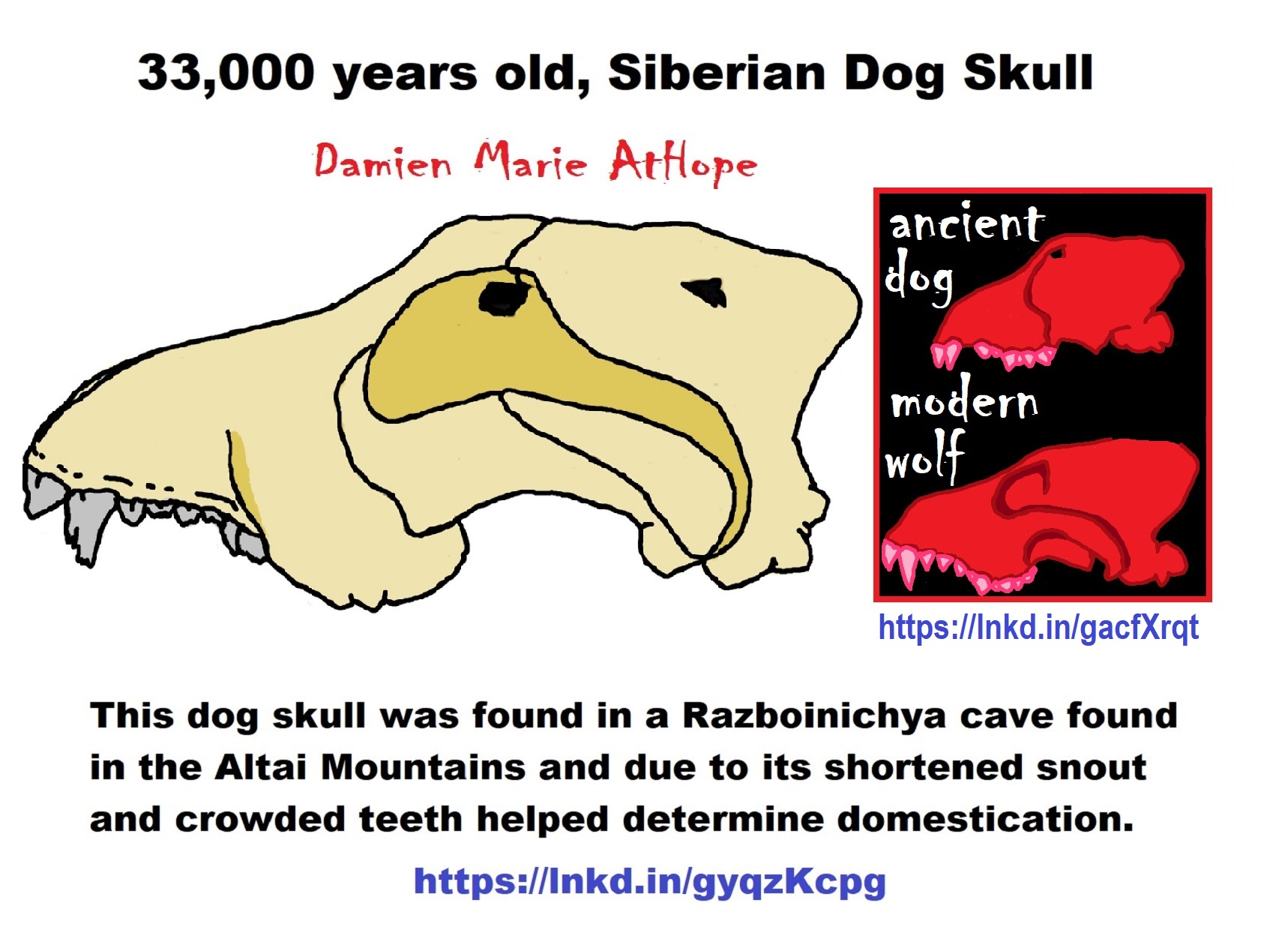

“The Paleolithic dog was a Late Pleistocene canine. They were directly associated with human hunting camps in Europe over 30,000 years ago and it is proposed that these were domesticated. They are further proposed to be either a proto-dog and the ancestor of the domestic dog or an extinct, morphologically and genetically divergent wolf population. There are a number of recently discovered specimens which are proposed as being Paleolithic dogs, however, their taxonomy is debated. These have been found in either Europe or Siberia and date 40,000–17,000 years ago. They include Hohle Fels in Germany, Goyet Caves in Belgium, Predmosti in the Czech Republic, and four sites in Russia: Razboinichya Cave in the Altai Republic, Kostyonki-8, Ulakhan Sular in the Sakha Republic, and Eliseevichi 1 on the Russian plain.” ref

1. 40,000–35,500 years ago Hohle Fels, Schelklingen, Germany

2. 36,500 years ago Goyet Caves, Samson River Valley, Belgium

3. 33,500 years ago Razboinichya Cave, Altai Mountains, (Russia/Siberia)

4. 33,500–26,500 years ago Kostyonki-Borshchyovo archaeological complex, (Kostenki site) Voronezh, Russia

5. 31,000 years ago Predmostí, Moravia, Czech Republic

6. 26,000 years ago Chauvet Cave, Vallon-Pont-d’Arc, Ardèche region, France

7. 17,300–14,100 years ago Dyuktai Cave, northern Yakutia, Siberia

8. 17,000–16,000 years ago Eliseevichi-I site, Bryansk Region, Russian Plain, Russia

9. 16,900 years ago Afontova Gora-1, Yenisei River, southern Siberia

10. 14,223 years ago Bonn–Oberkassel, Germany

11. 13,500 years ago Mezine, Chernigov region, Ukraine

12. 13,000 years ago Palegawra, (Zarzian culture) Iraq

13. 12,800 years ago Ushki I, Kamchatka, eastern Siberia

14. 12,790 years ago Nanzhuangtou, China

15. 12,300 years ago Ust’-Khaita site, Baikal region, Siberia

16. 12,000 years ago Ain Mallaha (Eynan) and HaYonim terrace, Israel

17. 10,150 years ago Lawyer’s Cave, Alaska, USA

18. 9,000 years ago Jiahu site, China

19. 8,000 years ago Svaerdborg site, Denmark

20. 7,425 years ago Lake Baikal region, Siberia

21. 7,000 years ago Tianluoshan archaeological site, Zhejiang province, China ref

1. 40,000–35,500 years ago Hohle Fels, Schelklingen, Germany

“Canid maxillary fragment. The size of the molars matches those of a wolf, the morphology matches a dog. Proposed as a Paleolithic dog. The figurine Venus of Hohle Fels was discovered in this cave and dated to this time.” ref

2. 36,500 years ago Goyet Caves, Samson River Valley, Belgium

“The “Goyet dog” is proposed as being a Paleolithic dog. The Goyet skull is very similar in shape to that of the Eliseevichi-I dog skulls (16,900 years ago) and to the Epigravettian Mezin 5490 and Mezhirich dog skulls (13,500 years ago), which are about 18,000 years younger. The dog-like skull was found in a side gallery of the cave, and Palaeolithic artifacts in this system of caves date from the Mousterian, Aurignacian, Gravettian, and Magdalenian, which indicates recurrent occupations of the cave from the Pleniglacial until the Late Glacial. The Goyet dog left no descendants, and its genetic classification is inconclusive because its mitochondrial DNA (mDNA) does not match any living wolf nor dog. It may represent an aborted domestication event or phenotypically and genetically distinct wolves. A genome-wide study of a 35,000-year-old Pleistocene wolf fossil from northern Siberia indicates that the dog and the modern grey wolf genetically diverged from a common ancestor between 27,000 and 40,000 years ago.” ref

3. 33,500 years ago Razboinichya Cave, Altai Mountains, (Russia/Siberia)

“The “Altai dog” is proposed as being a Paleolithic dog. The specimens discovered were a dog-like skull, mandibles (both sides), and teeth. The morphological classification, and an initial mDNA analysis, found it to be a dog. A later study of its mDNA was inconclusive, with 2 analyses indicating dog and another 2 indicating wolf. In 2017, two prominent evolutionary biologists reviewed the evidence and supported the Altai dog as being a dog from a lineage that is now extinct and that was derived from a population of small wolves that are also now extinct.” ref

4. 33,500–26,500 years ago Kostyonki-Borshchyovo archaeological complex, (Kostenki site) Voronezh, Russia

“One left mandible paired with the right maxilla, proposed as a Paleolithic dog.” ref

5. 31,000 years ago Predmostí, Moravia, Czech Republic

“Three dog-like skulls proposed as being Paleolithic dogs. Predmostí is a Gravettian site. The skulls were found in the human burial zone and identified as Palaeolithic dogs, characterized by – compared to wolves – short skulls, short snouts, wide palates and braincases, and even-sized carnassials. Wolf skulls were also found at the site. One dog had been buried with a bone placed carefully in its mouth. The presence of dogs buried with humans at this Gravettian site corroborates the hypothesis that domestication began long before the Late Glacial. Further analysis of bone collagen and dental microwear on tooth enamel indicates that these canines had a different diet when compared with wolves (refer under diet).” ref

6. 26,000 years ago Chauvet Cave, Vallon-Pont-d’Arc, Ardèche region, France

“50-metre trail of footprints made by a boy of about ten years of age alongside those of a large canid. The size and position of the canid’s shortened middle toe in relation to its pads indicate a dog rather than a wolf. The footprints have been dated by soot deposited from the torch the child was carrying. The cave is famous for its cave paintings. A later study using geometric morphometric analysis to compare modern wolves with modern dog tracks proposes that these are wolf tracks.” ref

7. 17,300–14,100 years ago Dyuktai Cave, northern Yakutia, Siberia

“Large canid remains along with human artifacts. And from a nearby site dating to around 17,200–16,800 Ulakhan Sular, northern Yakutia, Siberia held a fossil dog-like skull similar in size to the “Altai dog”, proposed as a Paleolithic dog.” ref

8. 17,000–16,000 years ago Eliseevichi-I site, Bryansk Region, Russian Plain, Russia

“Two fossil canine skulls proposed as being Paleolithic dogs. In 2002, a study looked at the fossil skulls of two large canids that had been found buried 2 meters and 7 meters from what was once a mammoth-bone hut at this Upper Paleolithic site, and using an accepted morphologically based definition of domestication declared them to be “Ice Age dogs”. The carbon dating gave a calendar-year age estimate that ranged between 16,945 and 13,905 years ago. The Eliseevichi-1 skull is very similar in shape to the Goyet skull (36,000 years ago), the Mezine dog skull (13,500 years ago) and Mezhirich dog skull (13,500 years ago). In 2013, a study looked at the mDNA sequence for one of these skulls and identified it as Canis lupus familiaris i.e. dog. However, in 2015 a study using three-dimensional geometric morphometric analyses indicated the skull is more likely from a wolf. These animals were larger in size than most grey wolves and approached the size of a Great Dane.” ref

9. 16,900 years ago Afontova Gora-1, Yenisei River, southern Siberia

“Fossil dog-like tibia, proposed as a Paleolithic dog. The site is on the western bank of the Yenisei River about 2,500 km southwest of Ulakhan Sular, and shares a similar timeframe to that canid. A skull from this site described as dog-like has been lost in the past, but there exists a written description of it possessing a wide snout and a clear stop, with a skull length of 23 cm that falls outside of those of wolves.” ref

10. 14,223 years ago Bonn–Oberkassel, Germany

“The “Bonn-Oberkassel dog“. Undisputed dog skeleton buried with a man and woman. All three skeletal remains were found sprayed with red hematite powder. The consensus is that a dog was buried along with two humans. Analysis of mDNA indicates that this dog was a direct ancestor of modern dogs. Domestic dog.” ref

11. 13,500 years ago Mezine, Chernigov region, Ukraine

“Ancient dog-like skull proposed as being a Paleolithic dog. Additionally, ancient wolf specimens were found at the site. Dated to the Epigravettian period (17,000–10,000 years ago). The Mezine skull is very similar in shape to the Goyet skull (36,000 years ago), the Eliseevichi-1 dog skulls (16,900 years ago), and the Mezhirich dog skull (13,500 years ago). The Epigravettian Mezine site is well known for its round mammoth bone dwelling. Taxonomy uncertain.” ref

12. 13,000 years ago Palegawra, (Zarzian culture) Iraq

“The fossil jaw and teeth of a domesticated dog, recovered from a cave in Iraq, have been found to be about 14,000 years old. The bone was found in a shallow cave with a number of stone tools suggesting that its keepers were hunters. The scientists who found and studied the bone speculated that the animal served either as a hunting dog in the field or as a watchdog back at the cave or perhaps as both.” ref, ref

13. 12,800 years ago Ushki I, Kamchatka, eastern Siberia

“Complete skeleton buried in a buried dwelling. Located 1,800 km to the southeast from Ulakhan Sular. Domestic dog.” ref

14. 12,790 years ago Nanzhuangtou, China

“31 fragments including a complete dog mandible.” ref

15. 12,300 years ago Ust’-Khaita site, Baikal region, Siberia

“Sub-adult skull located 2,400 km southwest of Ulakhan Sular and proposed as a Paleolithic dog. Also a somewhat close find at 12,450 years old mummified dog carcass. The “Black Dog of Tumat” was found frozen into the ice core of an oxbow lake steep ravine at the middle course of the Syalaah River in the Ust-Yana region. DNA analysis confirmed it as an early dog.” ref The Archaeology of Ushki Lake, Kamchatka, and the Pleistocene Peopling of the Americas: The Ushki Paleolithic sites of Kamchatka, Russia, have long been thought to contain information critical to the peopling of the Americas, especially the origins of Clovis. New radiocarbon dates indicate that human occupation of Ushki began only 13,000 calendar years ago-nearly 4000 years later than previously thought. Although biface industries were widespread across Beringia contemporaneous to the time of Clovis in western North America, these data suggest that late-glacial Siberians did not spread into Beringia until the end of the Pleistocene, perhaps too recently to have been ancestral to proposed pre-Clovis populations in the Americas.” ref

16. 12,000 years ago Ain Mallaha (Eynan) and HaYonim terrace, Israel

“Three canid finds. A diminutive carnassial and a mandible, and a wolf or dog puppy skeleton buried with a human during the Natufian culture. These Natufian dogs did not exhibit tooth-crowding. The Natufian culture occupied the Levant, and had earlier interred a fox together with a human in the Uyun al-Hammam burial site, Jordan dated 17,700–14,750 years ago.” ref

17. 10,150 years ago Lawyer’s Cave, Alaska, USA

“Bone of a dog, oldest find in North America. DNA indicates a split from Siberian relatives 16,500 years ago, indicating that dogs may have been in Beringia earlier. Lawyer’s Cave is on the Alaskan mainland east of Wrangell Island in the Alexander Archipelago of southeast Alaska.” ref

18. 9,000 years ago Jiahu site, China

“Eleven dog interments. Jaihu is a Neolithic site 22 kilometers north of Wuyang in Henan Province.” ref Most archaeologists consider the Jaihu site to be one of the earliest examples of the Peiligang culture. Settled around 7000 BCE or around 9,000 years ago, the site was later flooded and abandoned around 5700 BCE or around 7,700 years ago. At one time, it was “a complex, highly organized Chinese Neolithic society”, home to at least 250 people and perhaps as many as 800. The important discoveries of the Jiahu archaeological site include the Jiahu symbols, possibly an early example of proto-writing, carved into tortoise shells and bones; the thirty-three Jiahu flutes carved from the wing bones of cranes, believed to be among the oldest playable musical instruments in the world; and evidence of alcohol fermented from rice, honey and hawthorn leaves.” ref

19. 8,000 years ago Svaerdborg site, Denmark

“Three different sized dog types recorded at this Maglemosian culture site. Maglemosian (c. 9000 – c. 6000 BCE or around 11,000 to 8,000 years ago) is the name given to a culture of the early Mesolithic period in Northern Europe. In Scandinavia, the culture was succeeded by the Kongemose culture. It appears that they had domesticated the dog. Similar settlements were excavated from England to Poland and from Skåne in Sweden to northern France.” ref, ref

20. 7,425 years ago Lake Baikal region, Siberia

“Dog buried in a human burial ground. Additionally, a human skull was found buried between the legs of a “tundra wolf” dated 8,320 years ago (but it does not match any known wolf DNA). The evidence indicates that as soon as formal cemeteries developed in Baikal, some canids began to receive mortuary treatments that closely paralleled those of humans. One dog was found buried with four red deer canine pendants around its neck dated 5,770 years ago. Many burials of dogs continued in this region with the latest finding at 3,760 years ago, and they were buried lying on their right side and facing towards the east as did their humans. Some were buried with artifacts, e.g., stone blades, birch bark, and antler bone.” ref

21. 7,000 years ago Tianluoshan archaeological site, Zhejiang province, China

“In 2020, an mDNA study of ancient dog fossils from the Yellow River and Yangtze River basins of southern China showed that most of the ancient dogs fell within haplogroup A1b, as do the Australian dingoes and the pre-colonial dogs of the Pacific, but in low frequency in China today. The specimen from the Tianluoshan archaeological site is basal to the entire lineage. The dogs belonging to this haplogroup were once widely distributed in southern China, then dispersed through Southeast Asia into New Guinea and Oceania, but were replaced in China 2,000 years ago by dogs of other lineages.” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

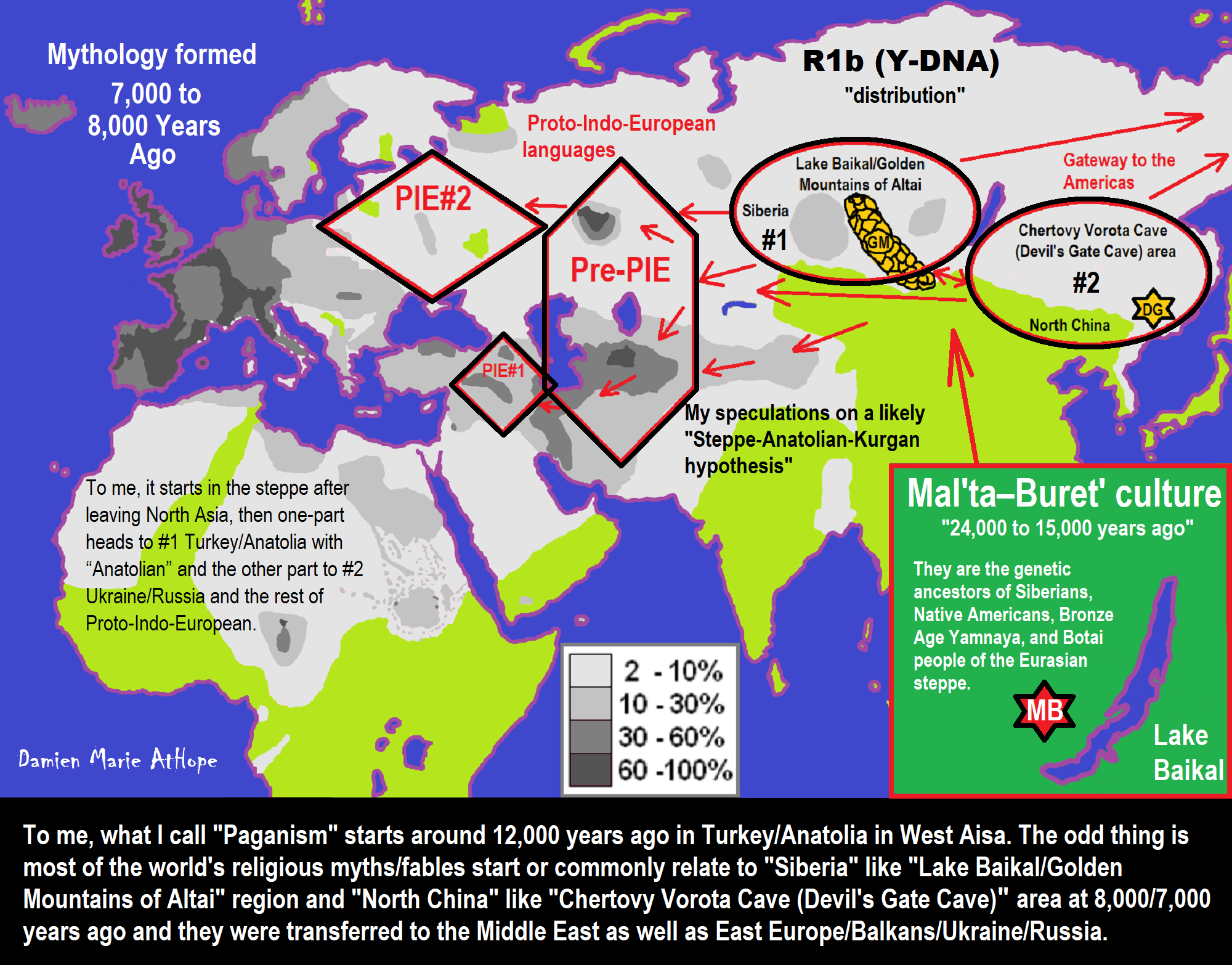

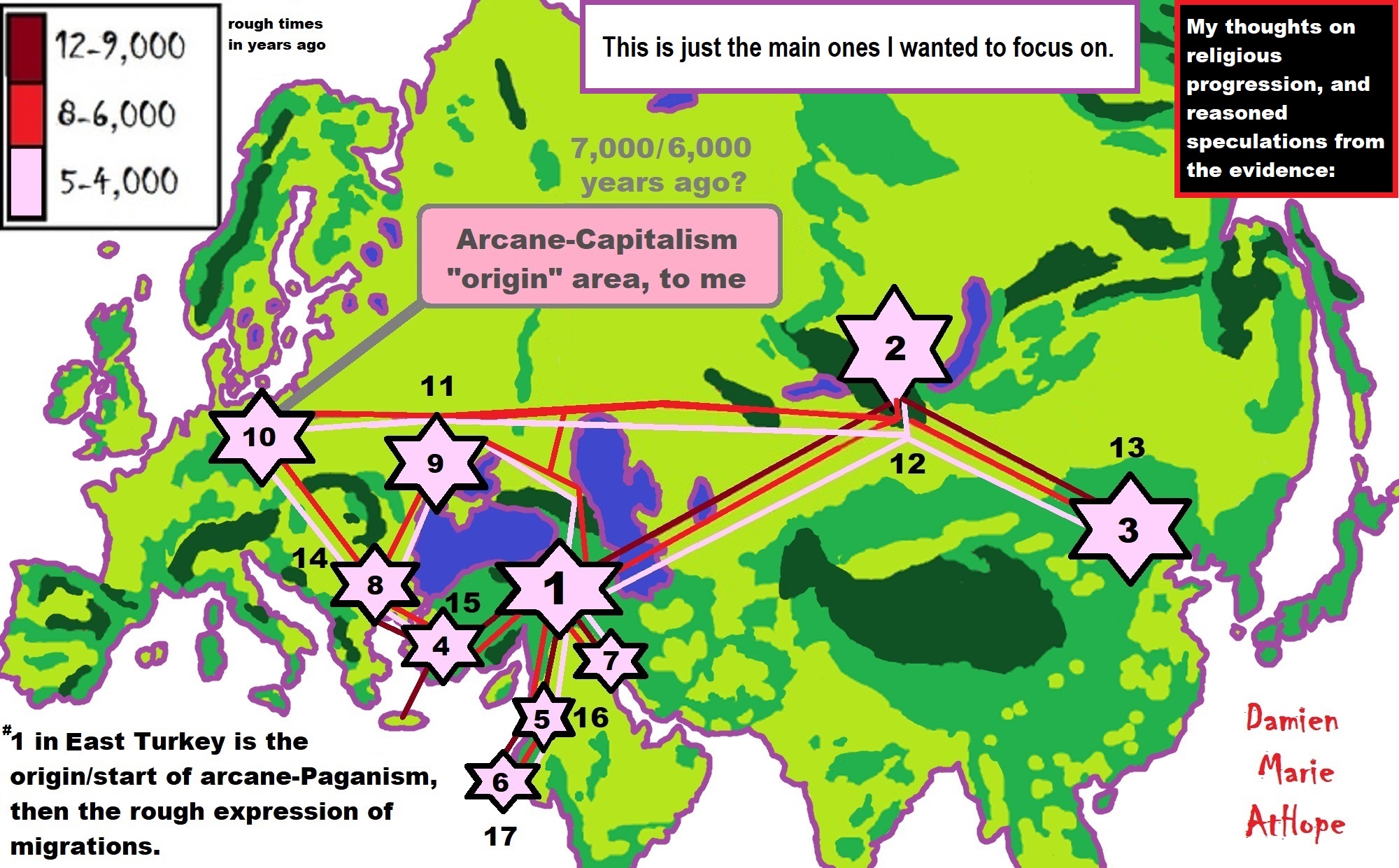

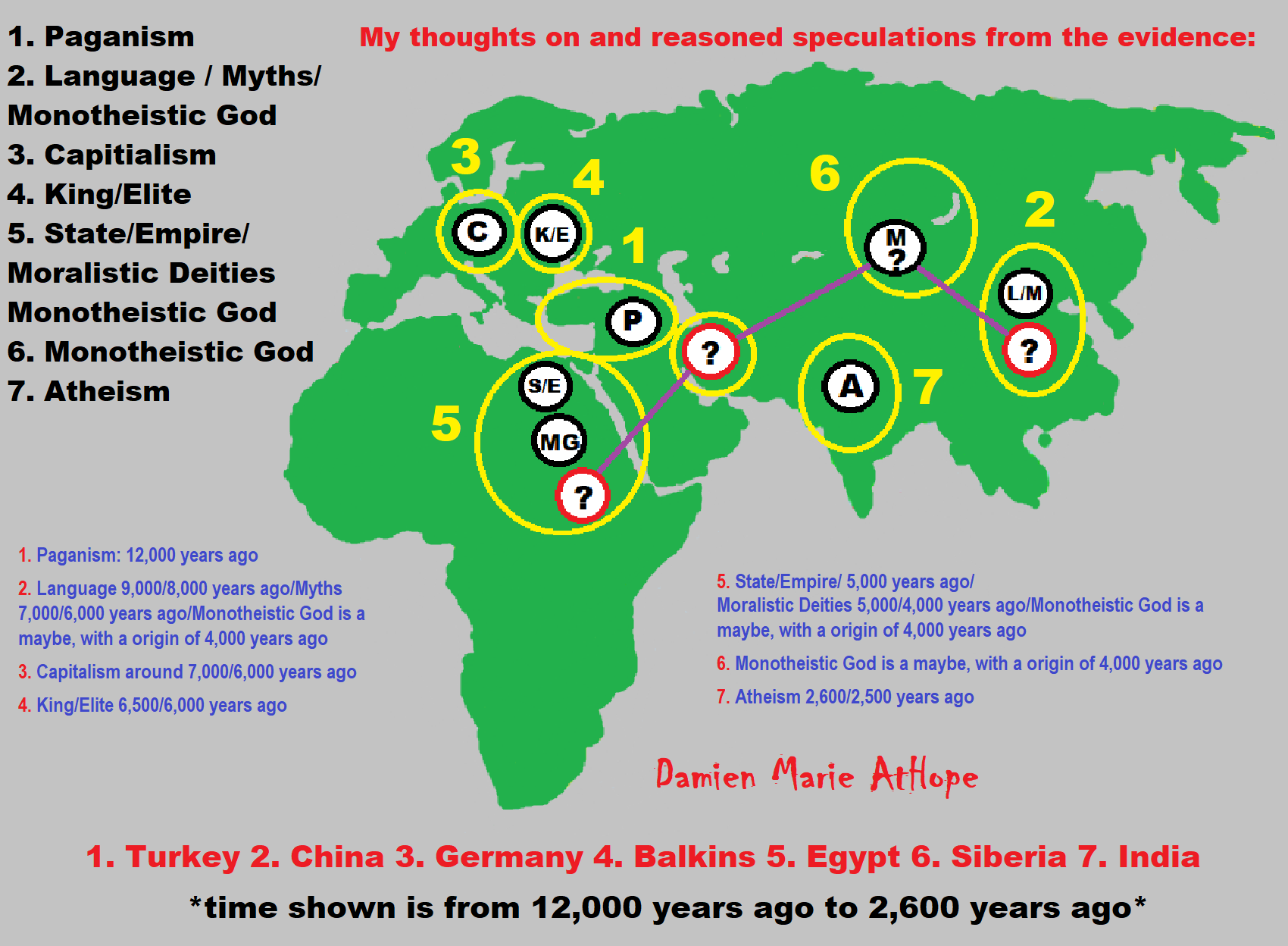

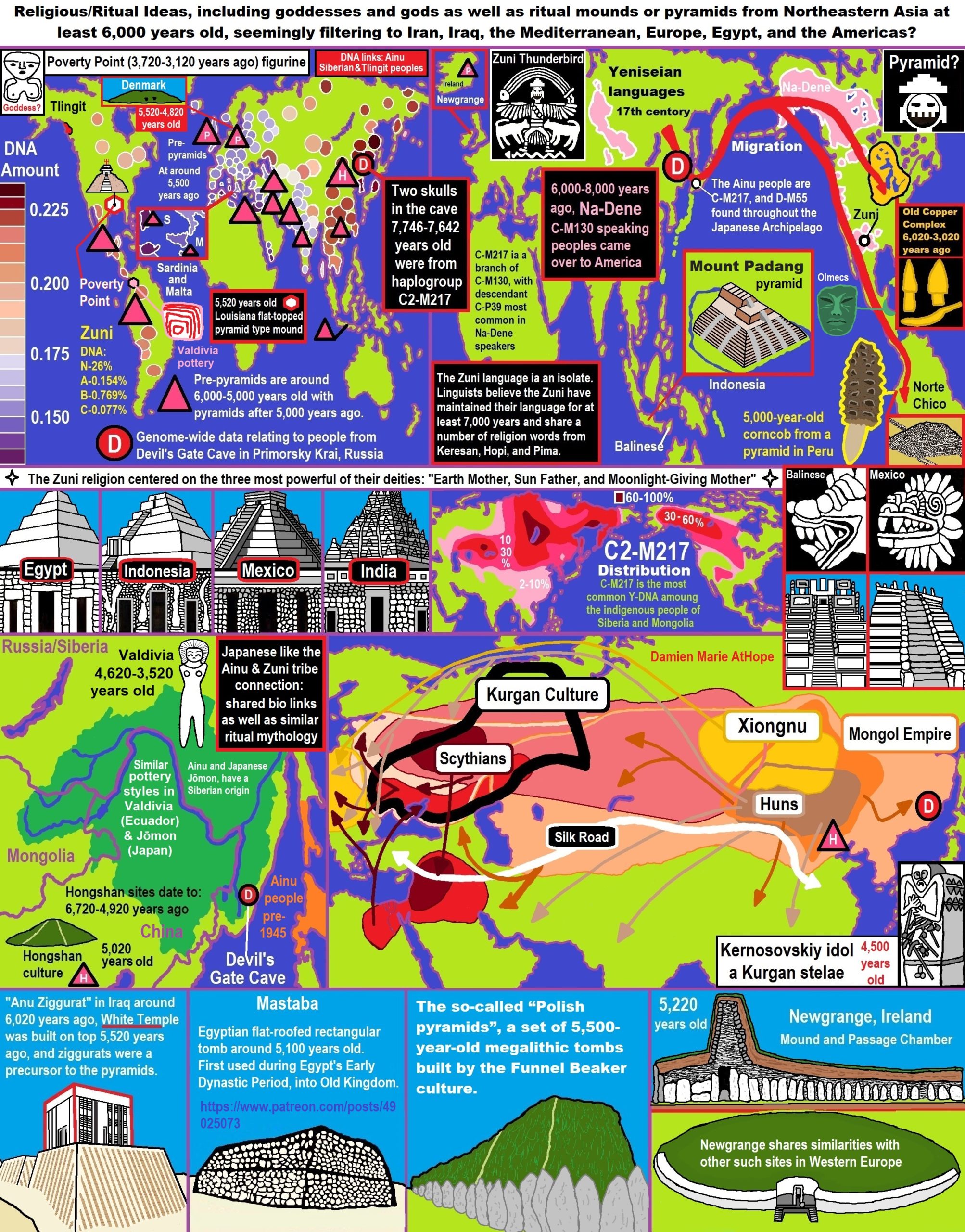

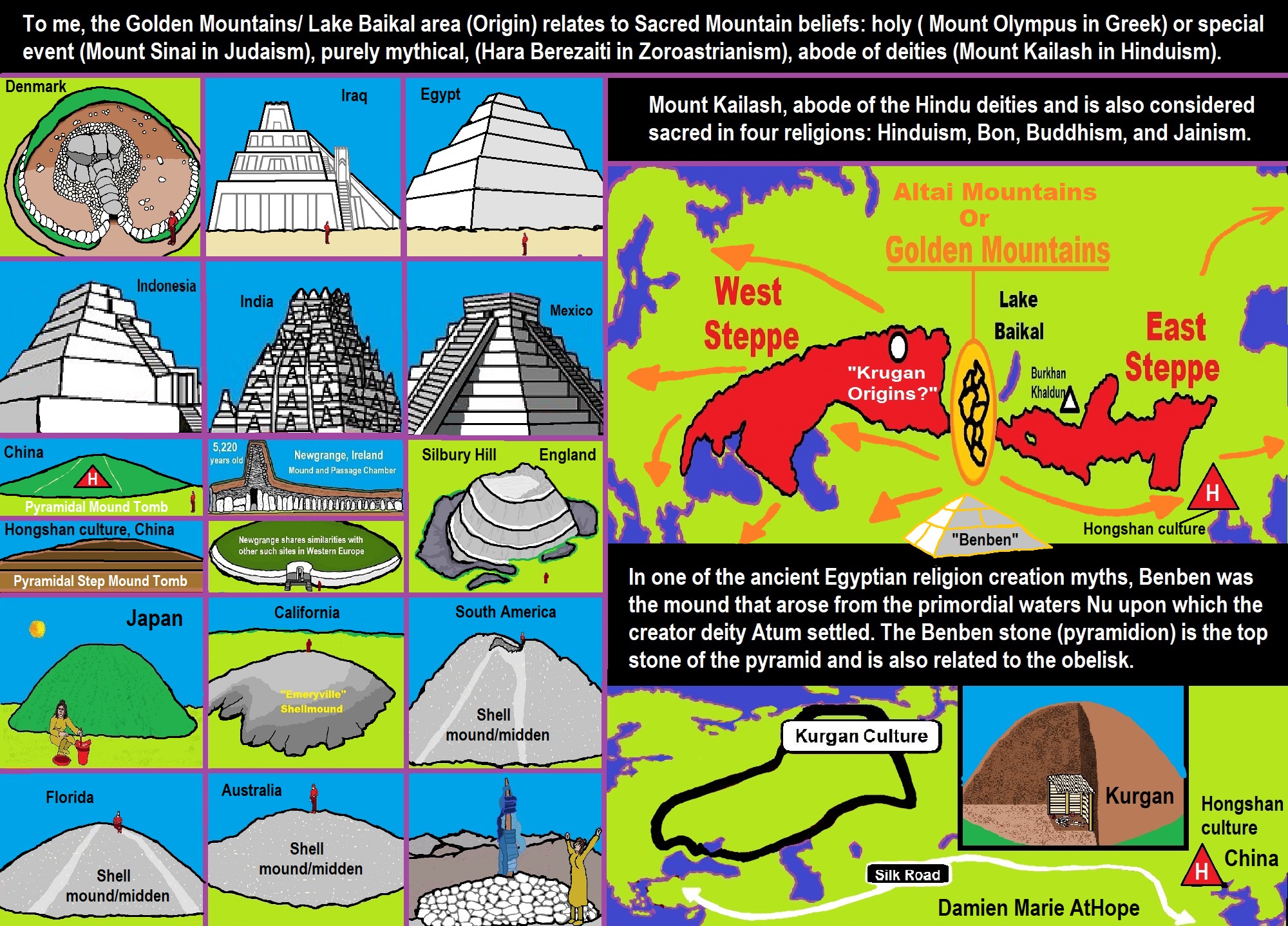

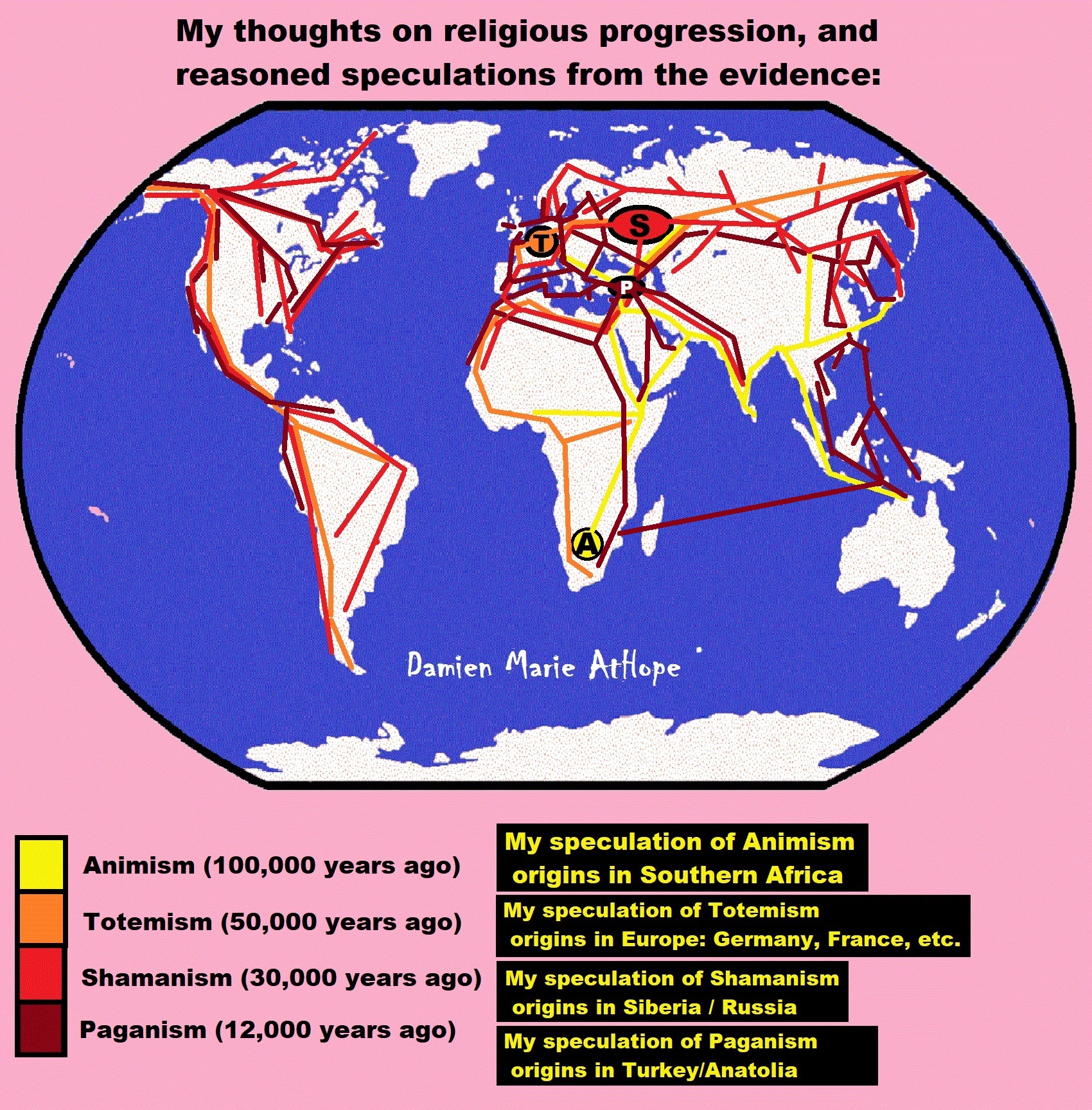

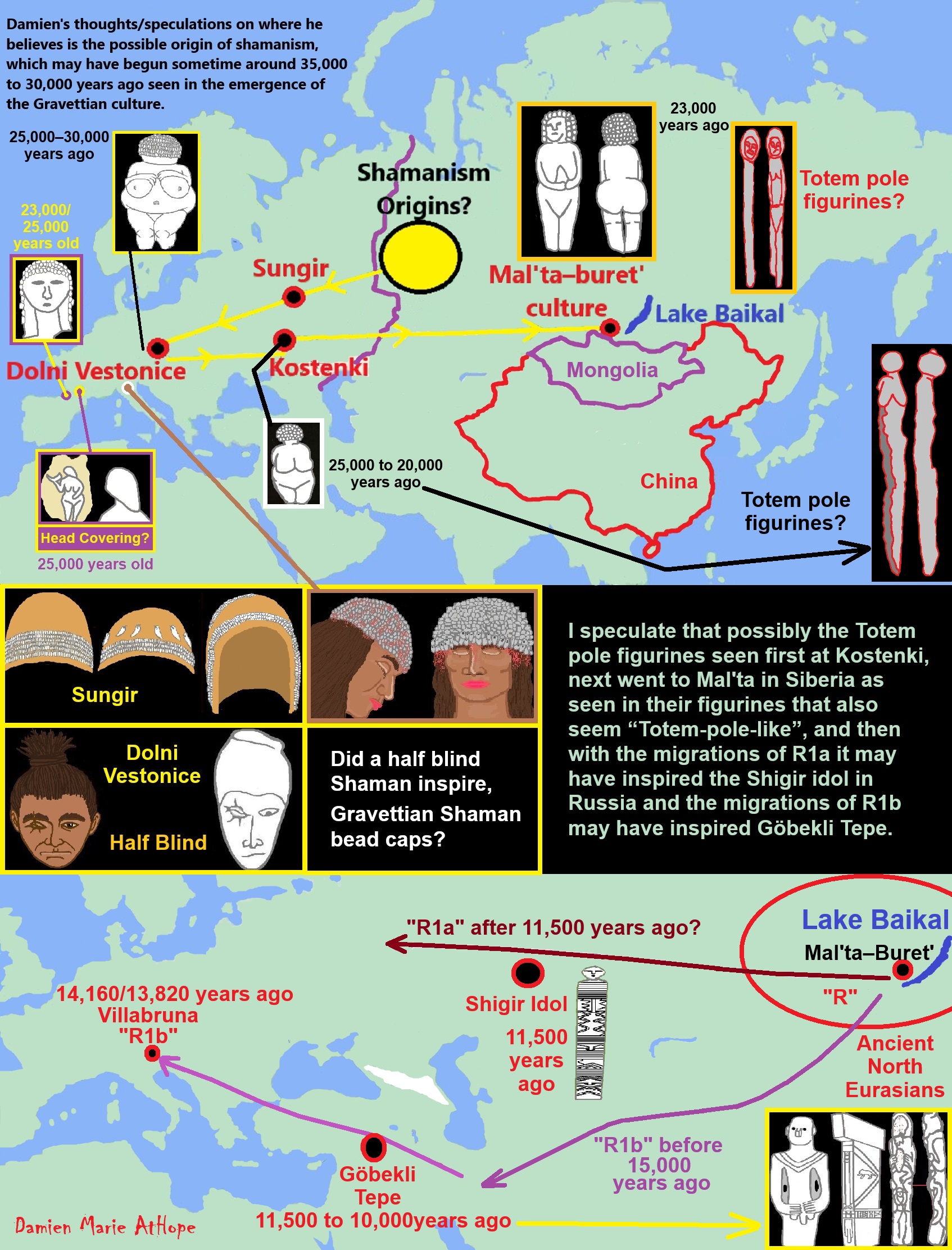

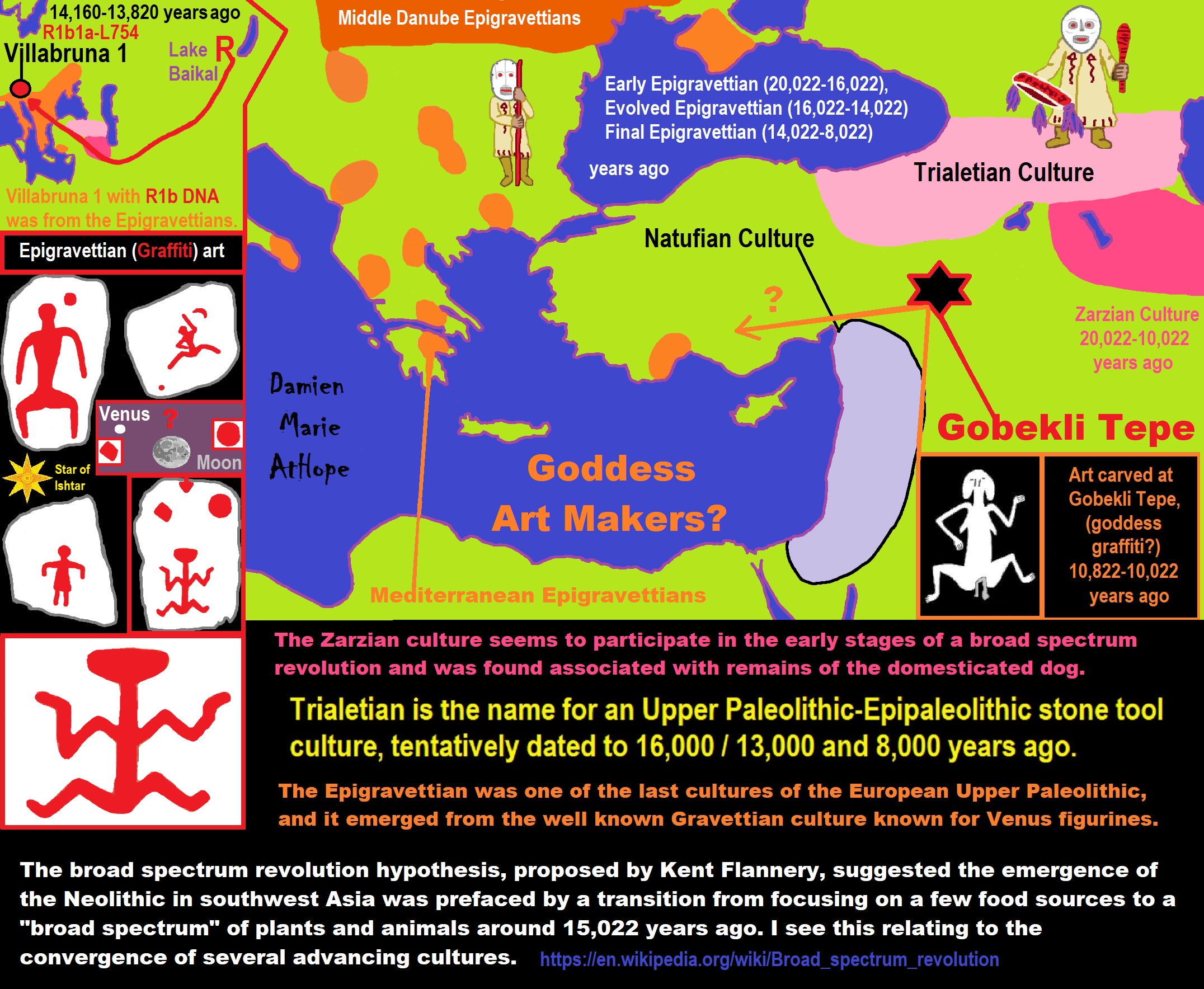

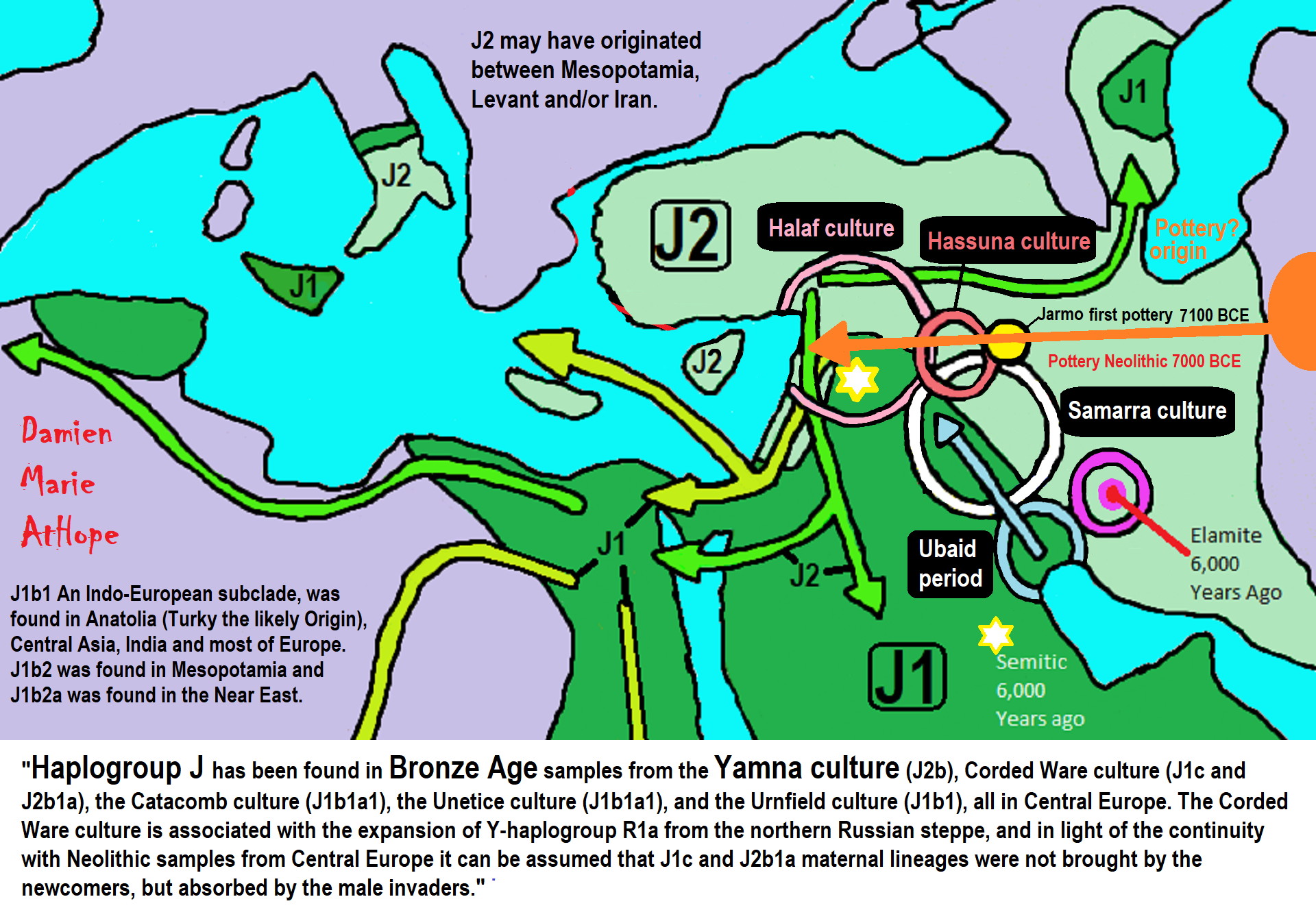

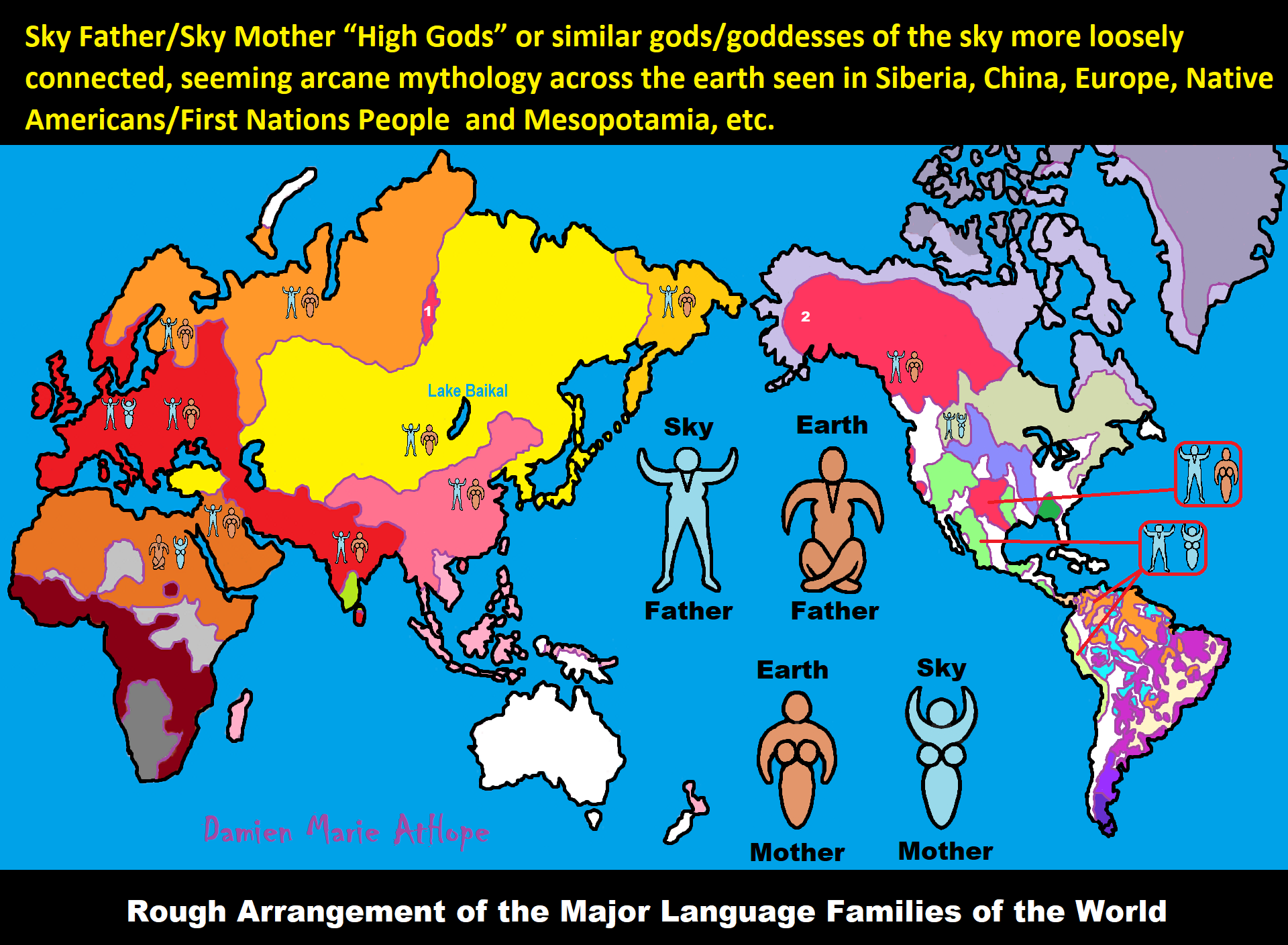

Here are my thoughts/speculations on where I believe is the possible origin of shamanism, which may have begun sometime around 35,000 to 30,000 years ago seen in the emergence of the Gravettian culture, just to outline his thinking, on what thousands of years later led to evolved Asian shamanism, in general, and thus WU shamanism as well. In both Europe-related “shamanism-possible burials” and in Gravettian mitochondrial DNA is a seeming connection to Haplogroup U. And the first believed Shaman proposed burial belonged to Eastern Gravettians/Pavlovian culture at Dolní Věstonice in southern Moravia in the Czech Republic, which is the oldest permanent human settlement that has ever been found. It is at Dolní Věstonice where approximately 27,000-25,000 years ago a seeming female shaman was buried and also there was an ivory totem portrait figure, seemingly of her.

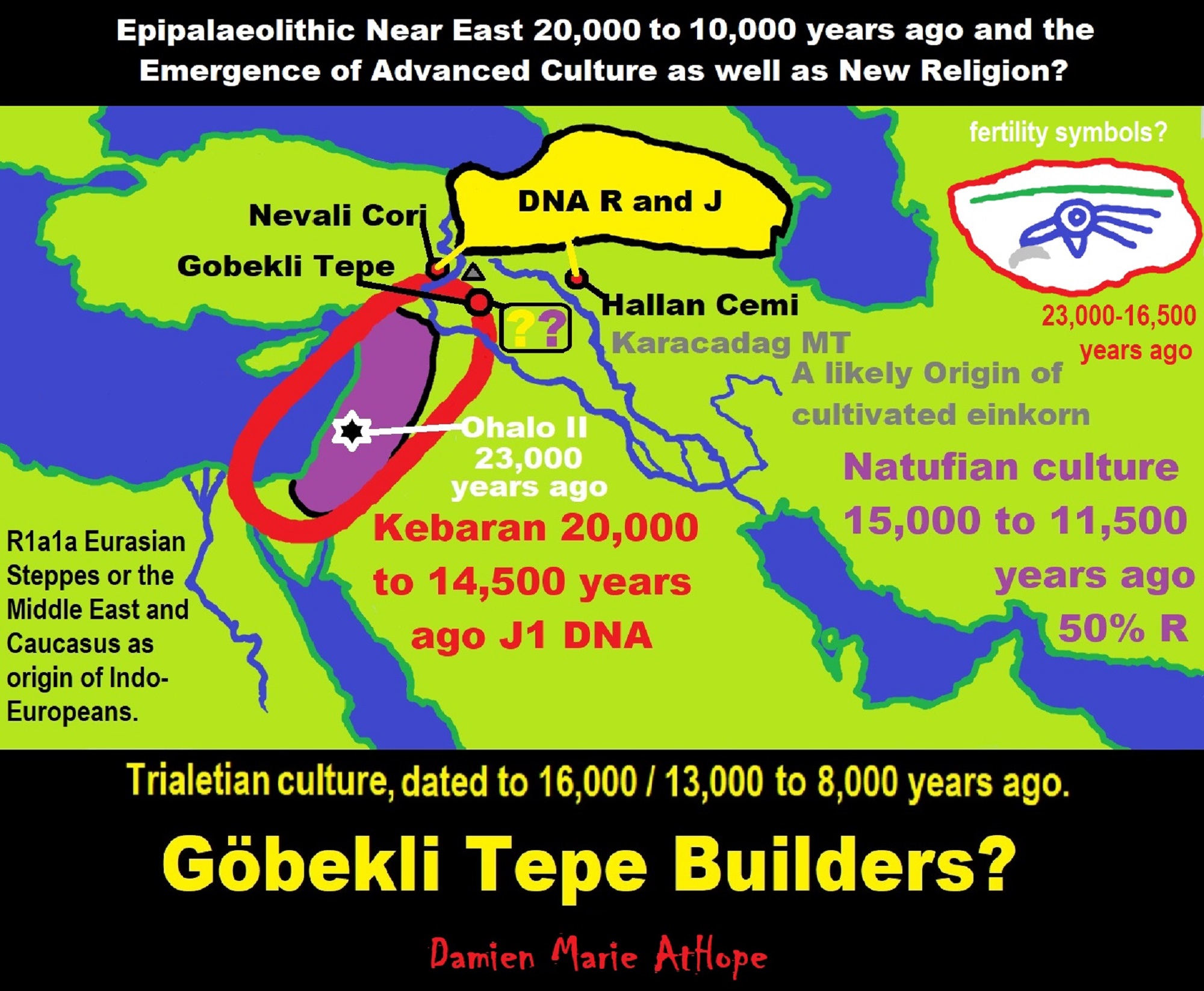

And my thoughts on how cultural/ritual aspects were influenced in the area of Göbekli Tepe. I think it relates to a few different cultures starting in the area before the Neolithic. Two different groups of Siberians first from northwest Siberia with U6 haplogroup 40,000 to 30,000 or so. Then R Haplogroup (mainly haplogroup R1b but also some possible R1a both related to the Ancient North Eurasians). This second group added its “R1b” DNA of around 50% to the two cultures Natufian and Trialetian. To me, it is likely both of these cultures helped create Göbekli Tepe. Then I think the female art or graffiti seen at Göbekli Tepe to me possibly relates to the Epigravettians that made it into Turkey and have similar art in North Italy. I speculate that possibly the Totem pole figurines seen first at Kostenki, next went to Mal’ta in Siberia as seen in their figurines that also seem “Totem-pole-like”, and then with the migrations of R1a it may have inspired the Shigir idol in Russia and the migrations of R1b may have inspired Göbekli Tepe.

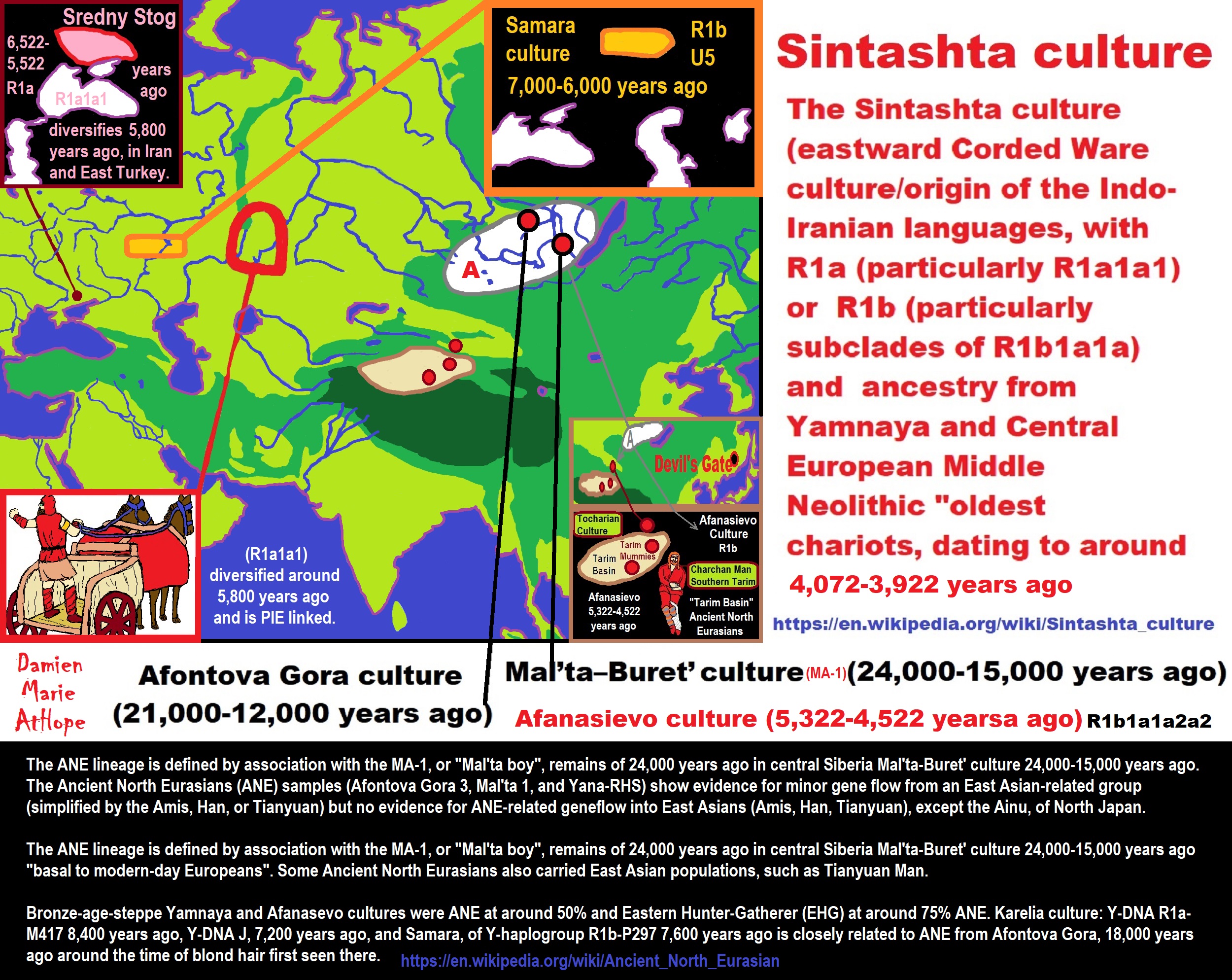

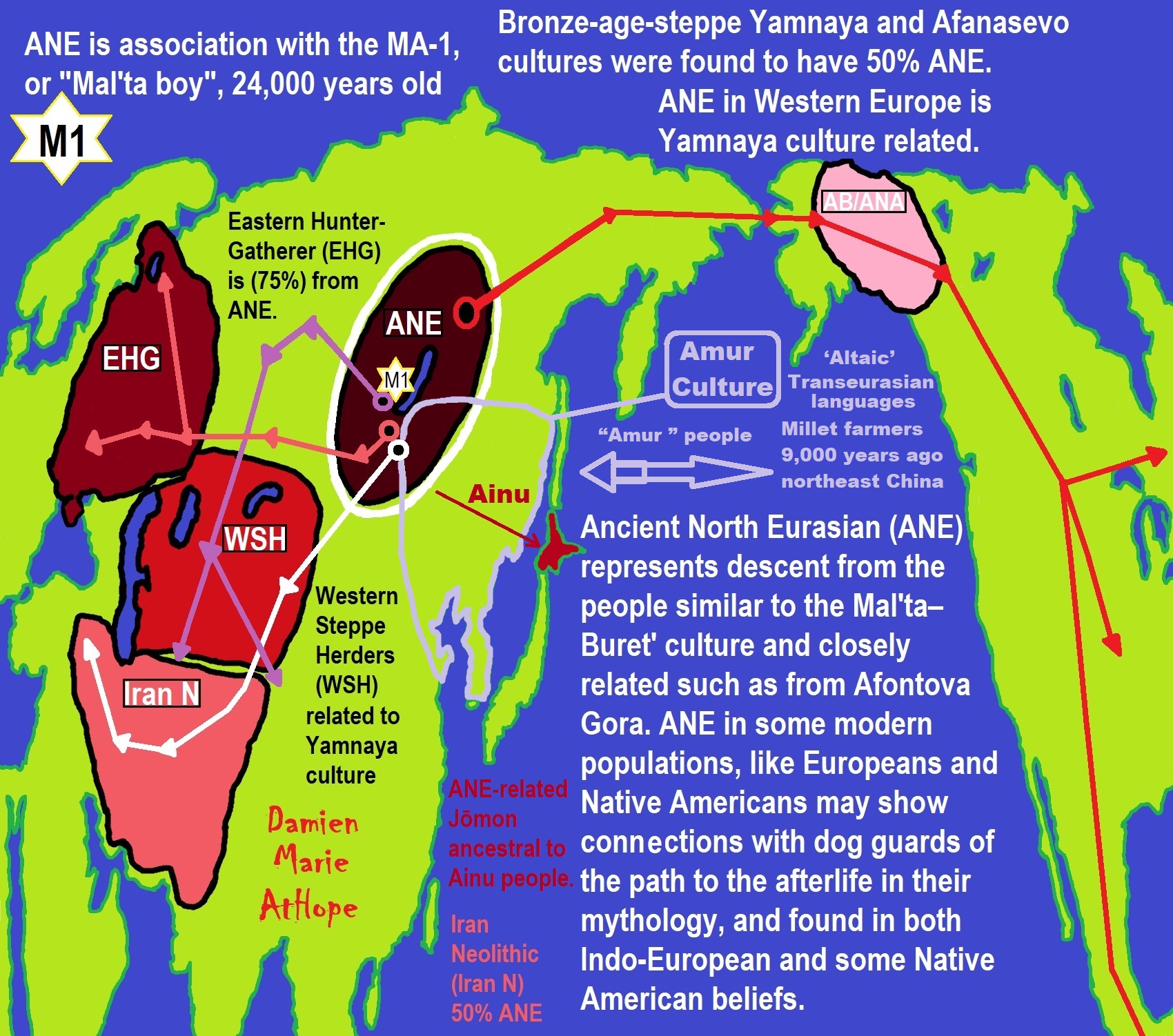

“The ANE lineage is defined by association with the MA-1, or “Mal’ta boy“, the remains of an individual who lived during the Last Glacial Maximum, 24,000 years ago in central Siberia. Populations genetically similar to MA-1 were an important genetic contributor to Native Americans, Europeans, Ancient Central Asians, South Asians, and some East Asian groups (such as the Ainu people), in order of significance.” ref

“Groups partially derived from the Ancient North Eurasians: Eastern Hunter-Gatherer (R1a-M417, around 8,400 years ago), Scandinavian Hunter-Gatherer (around 8,000 years ago), Ancient Beringian/Ancestral Native American (around 11,500 years ago), West Siberian Hunter-Gatherer, Western Steppe Herders (closely related to the Yamnaya culture), Late Upper Paeolithic Lake Baikal (14,050-13,770 years ago), Lake Baikal Holocene (around 11,650 years ago to the present), Jōmon people, pre-Neolithic population of Japan (and present-day Ainu people).” ref

“Since the term ‘Ancient North Eurasian’ refers to a genetic bridge of connected mating networks, scholars of comparative mythology have argued that they probably shared myths and beliefs that could be reconstructed via the comparison of stories attested within cultures that were not in contact for millennia and stretched from the Pontic–Caspian steppe to the American continent.” ref

“For instance, the mytheme of the dog guarding the Otherworld possibly stems from an older Ancient North Eurasian belief, as suggested by similar motifs found in Indo-European, Native American, and Siberian mythology. In Siouan, Algonquian, Iroquoian, and in Central and South American beliefs, a fierce guard dog was located in the Milky Way, perceived as the path of souls in the afterlife, and getting past it was a test. The Siberian Chukchi and Tungus believed in a guardian-of-the-afterlife dog and a spirit dog that would absorb the dead man’s soul and act as a guide in the afterlife. In Indo-European myths, the figure of the dog is embodied by Cerberus, Sarvarā, and Garmr. Anthony and Brown note that it might be one of the oldest mythemes recoverable through comparative mythology.” ref

“A second canid-related series of beliefs, myths, and rituals connected dogs with healing rather than death. For instance, Ancient Near Eastern and Turkic–Kipchaq myths are prone to associate dogs with healing and generally categorized dogs as impure. A similar myth-pattern is assumed for the Eneolithic site of Botai in Kazakhstan, dated to 3500 BC, which might represent the dog as absorber of illness and guardian of the household against disease and evil. In Mesopotamia, the goddess Nintinugga, associated with healing, was accompanied or symbolized by dogs. Similar absorbent-puppy healing and sacrifice rituals were practiced in Greece and Italy, among the Hittites, again possibly influenced by Near Eastern traditions.” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

Trialetian culture (16,000–8000 years ago) the Caucasus, Iran, and Turkey, likely involved in Göbekli Tepe. Migration 1?

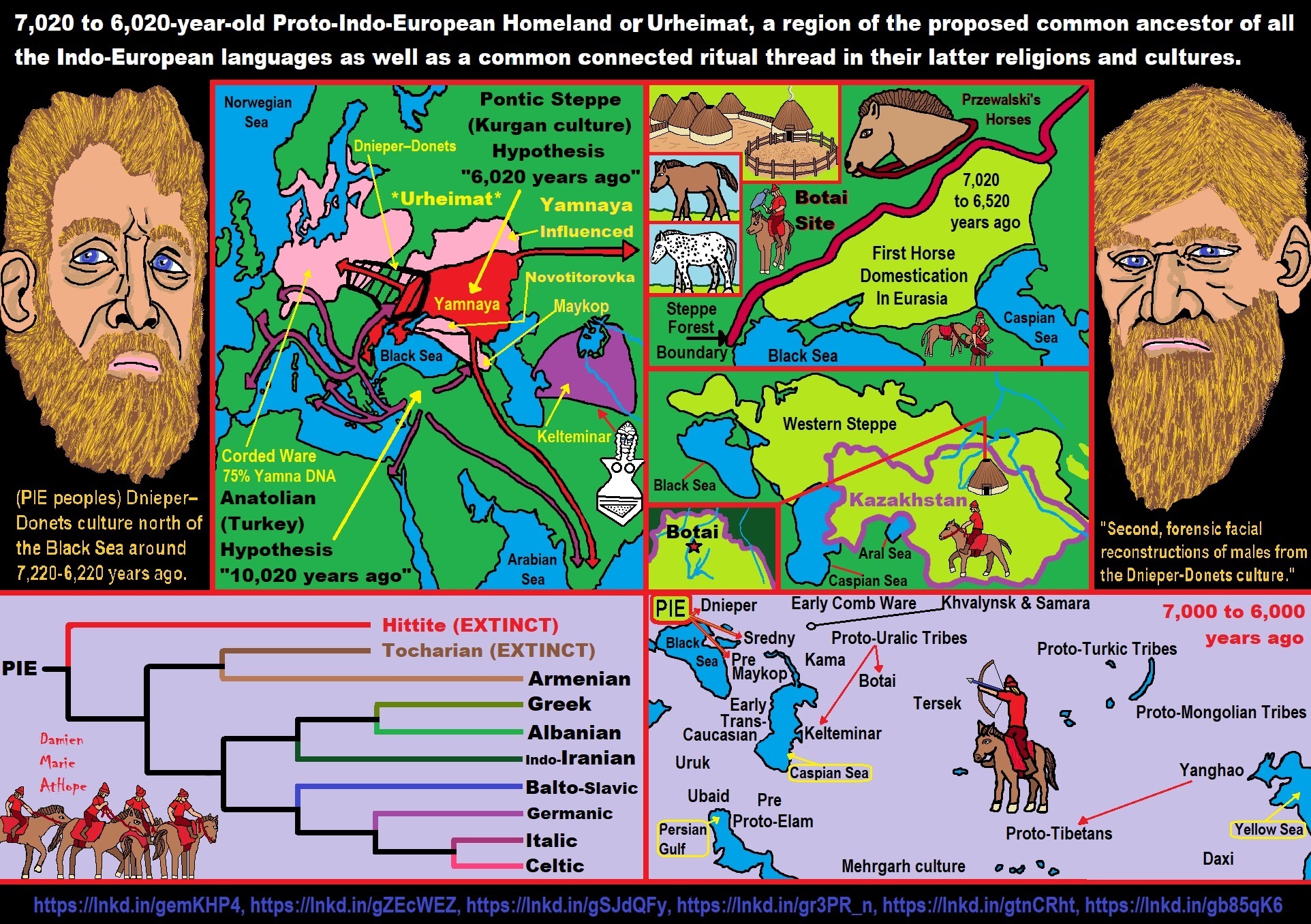

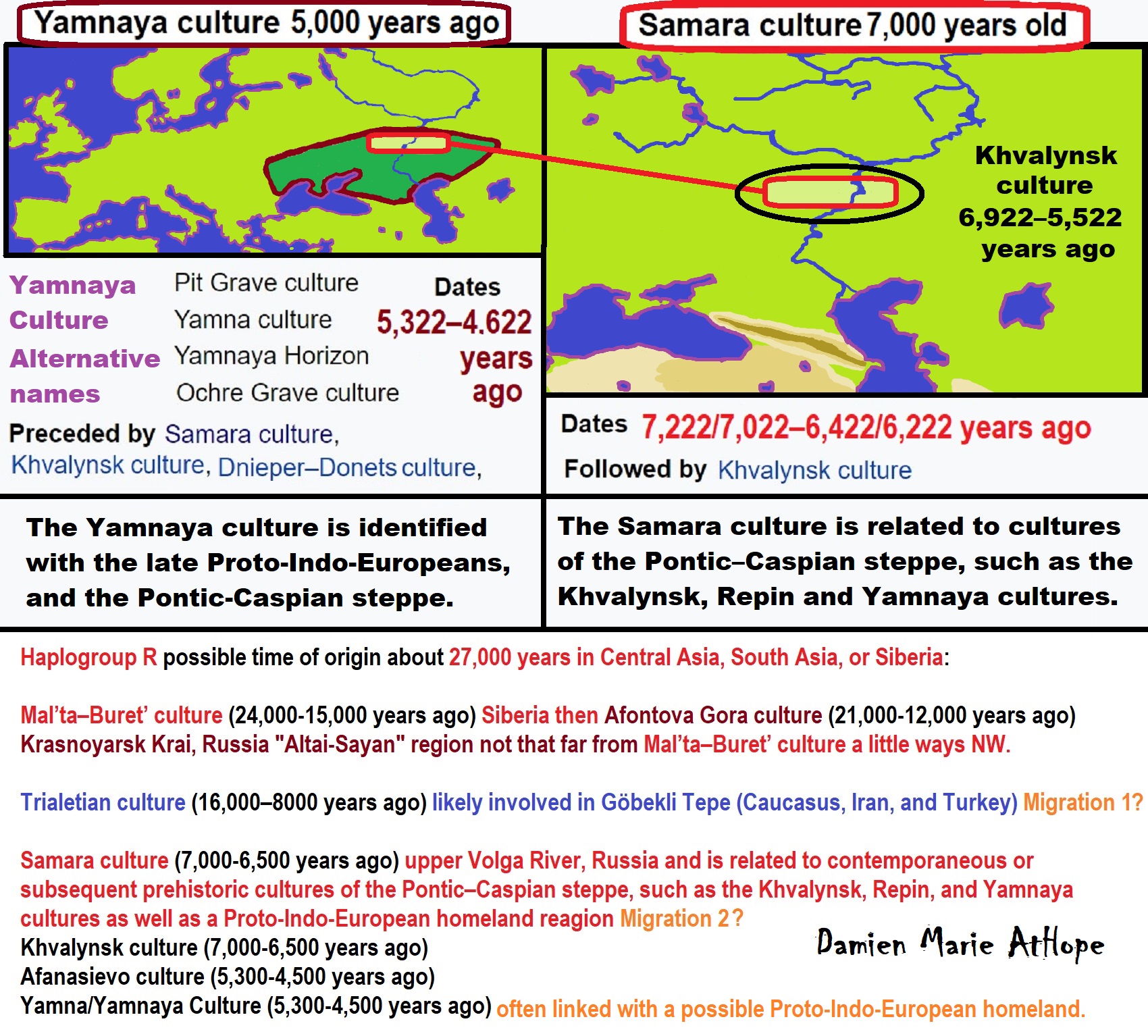

Haplogroup R possible time of origin about 27,000 years in Central Asia, South Asia, or Siberia:

- Mal’ta–Buret’ culture (24,000-15,000 years ago)

- Afontova Gora culture (21,000-12,000 years ago)

- Trialetian culture (16,000–8000 years ago)

- Samara culture (7,000-6,500 years ago)

- Khvalynsk culture (7,000-6,500 years ago)

- Afanasievo culture (5,300-4,500 years ago)

- Yamna/Yamnaya Culture (5,300-4,500 years ago)

- Andronovo culture (4,000–2,900 years ago) ref

Trialetian sites

Caucasus and Transcaucasia:

- Edzani (Georgia)

- Chokh (Azerbaijan), layers E-C200

- Kotias Klde, layer B” ref

Eastern Anatolia:

- Hallan Çemi (from ca. 8.6-8.5k BC to 7.6-7.5k BCE)

- Nevali Çori shows some Trialetian admixture in a PPNB context” ref

Trialetian influences can also be found in:

- Cafer Höyük

- Boy Tepe” ref

Southeast of the Caspian Sea:

- Hotu (Iran)

- Ali Tepe (Iran) (from cal. 10,500 to 8,870 BCE)

- Belt Cave (Iran), layers 28-11 (the last remains date from ca. 6,000 BCE)

- Dam-Dam-Cheshme II (Turkmenistan), layers7,000-3,000 BCE)” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

Trialetian peoples which I think we’re more male-centric and involved in the creation of Göbekli Tepe, from its start around Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (12,000 – 10,800 years ago) began with their influence and this is seen in animal deities many clearly male and the figures also being expressively male themed as well at first, and only around Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (10,800 – 8,500 years ago) or so it seems with what I am guessing is new Epigravettian peoples with a more female-centric style (reminiscent but less than the Gravettians known for Venus figurines) influence from migration into the region, to gain new themes that add a female element both with A totem pole seeming to express birth or something similar and graffiti of a woman either ready for sex or giving birth or both. and Other bare figures seem to show a similar body position reminiscent of the graffiti of a woman.

Pic ref

Ancient Women Found in a Russian Cave Turn Out to Be Closely Related to The Modern Population https://www.sciencealert.com/ancient-women-found-in-a-russian-cave-turn-out-to-be-closely-related-to-the-modern-population

Abstract

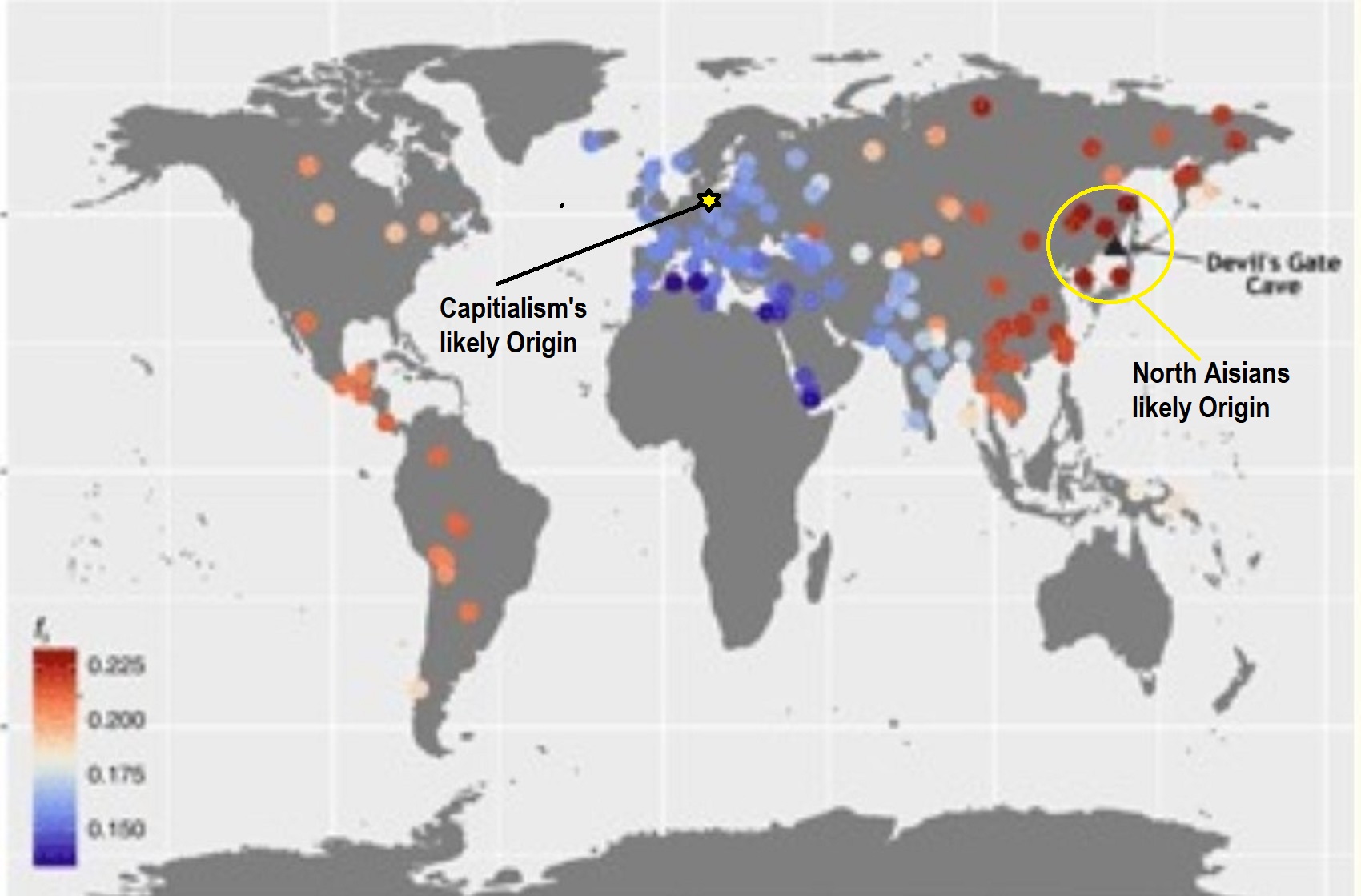

“Ancient genomes have revolutionized our understanding of Holocene prehistory and, particularly, the Neolithic transition in western Eurasia. In contrast, East Asia has so far received little attention, despite representing a core region at which the Neolithic transition took place independently ~3 millennia after its onset in the Near East. We report genome-wide data from two hunter-gatherers from Devil’s Gate, an early Neolithic cave site (dated to ~7.7 thousand years ago) located in East Asia, on the border between Russia and Korea. Both of these individuals are genetically most similar to geographically close modern populations from the Amur Basin, all speaking Tungusic languages, and, in particular, to the Ulchi. The similarity to nearby modern populations and the low levels of additional genetic material in the Ulchi imply a high level of genetic continuity in this region during the Holocene, a pattern that markedly contrasts with that reported for Europe.” ref

“The ANE lineage is defined by association with the MA-1, or “Mal’ta boy“, the remains of an individual who lived during the Last Glacial Maximum, 24,000 years ago in central Siberia. Populations genetically similar to MA-1 were an important genetic contributor to Native Americans, Europeans, Ancient Central Asians, South Asians, and some East Asian groups (such as the Ainu people), in order of significance.” ref

“Groups partially derived from the Ancient North Eurasians: Eastern Hunter-Gatherer (R1a-M417, around 8,400 years ago), Scandinavian Hunter-Gatherer (around 8,000 years ago), Ancient Beringian/Ancestral Native American (around 11,500 years ago), West Siberian Hunter-Gatherer, Western Steppe Herders (closely related to the Yamnaya culture), Late Upper Paeolithic Lake Baikal (14,050-13,770 years ago), Lake Baikal Holocene (around 11,650 years ago to the present), Jōmon people, pre-Neolithic population of Japan (and present-day Ainu people).” ref

“Since the term ‘Ancient North Eurasian’ refers to a genetic bridge of connected mating networks, scholars of comparative mythology have argued that they probably shared myths and beliefs that could be reconstructed via the comparison of stories attested within cultures that were not in contact for millennia and stretched from the Pontic–Caspian steppe to the American continent.” ref

“For instance, the mytheme of the dog guarding the Otherworld possibly stems from an older Ancient North Eurasian belief, as suggested by similar motifs found in Indo-European, Native American, and Siberian mythology. In Siouan, Algonquian, Iroquoian, and in Central and South American beliefs, a fierce guard dog was located in the Milky Way, perceived as the path of souls in the afterlife, and getting past it was a test. The Siberian Chukchi and Tungus believed in a guardian-of-the-afterlife dog and a spirit dog that would absorb the dead man’s soul and act as a guide in the afterlife. In Indo-European myths, the figure of the dog is embodied by Cerberus, Sarvarā, and Garmr. Anthony and Brown note that it might be one of the oldest mythemes recoverable through comparative mythology.” ref

“A second canid-related series of beliefs, myths, and rituals connected dogs with healing rather than death. For instance, Ancient Near Eastern and Turkic–Kipchaq myths are prone to associate dogs with healing and generally categorized dogs as impure. A similar myth-pattern is assumed for the Eneolithic site of Botai in Kazakhstan, dated to 3500 BC, which might represent the dog as absorber of illness and guardian of the household against disease and evil. In Mesopotamia, the goddess Nintinugga, associated with healing, was accompanied or symbolized by dogs. Similar absorbent-puppy healing and sacrifice rituals were practiced in Greece and Italy, among the Hittites, again possibly influenced by Near Eastern traditions.” ref

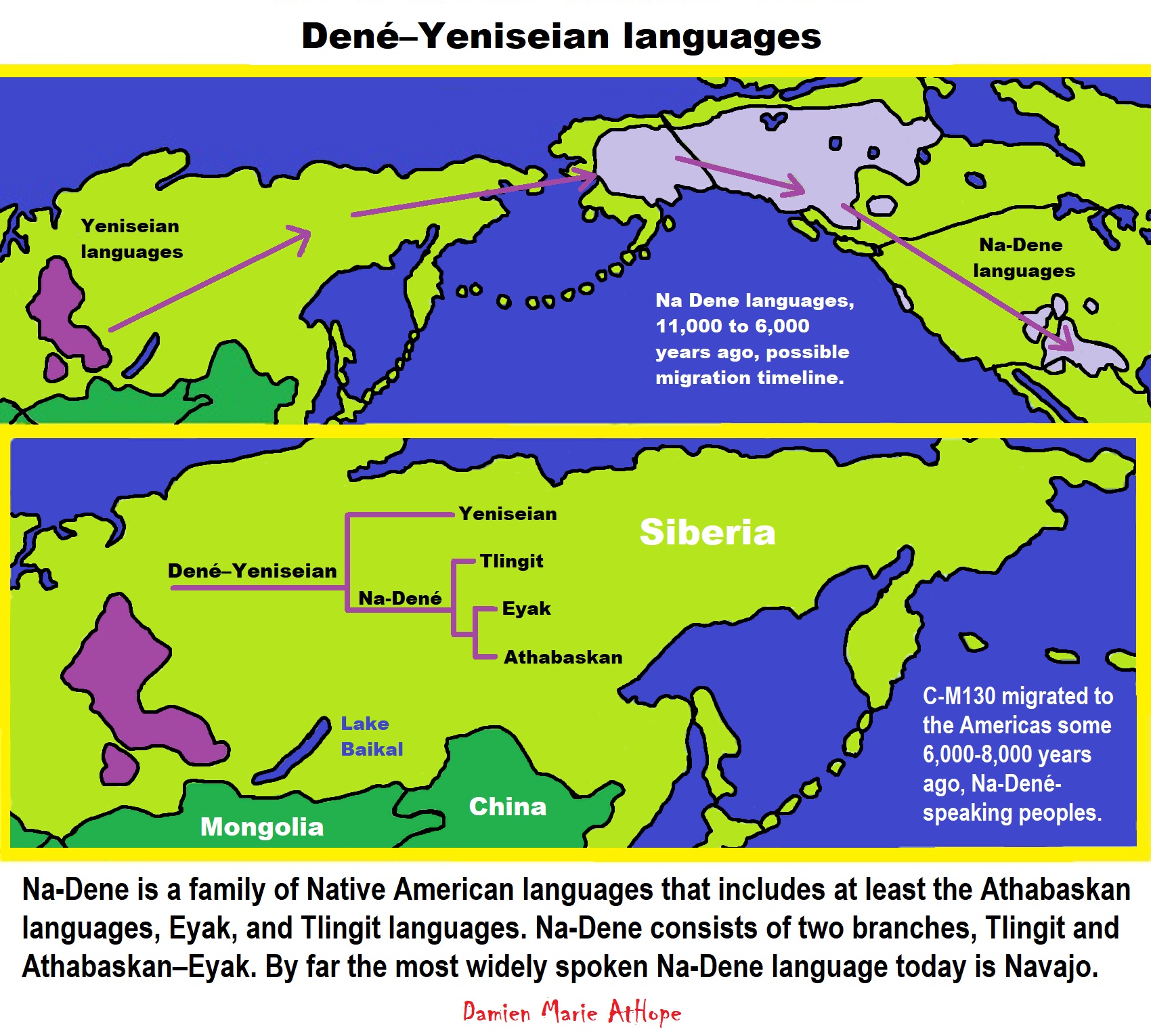

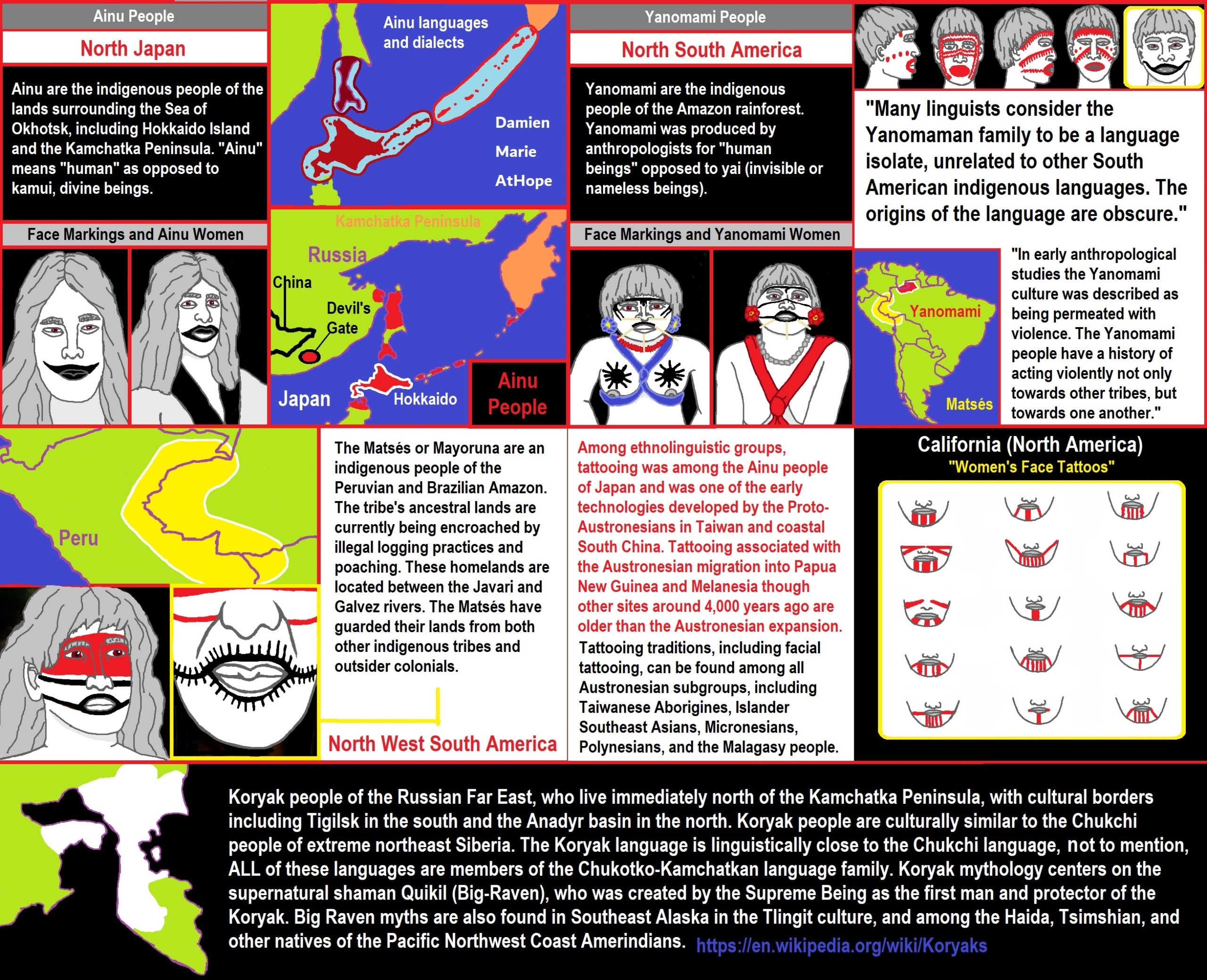

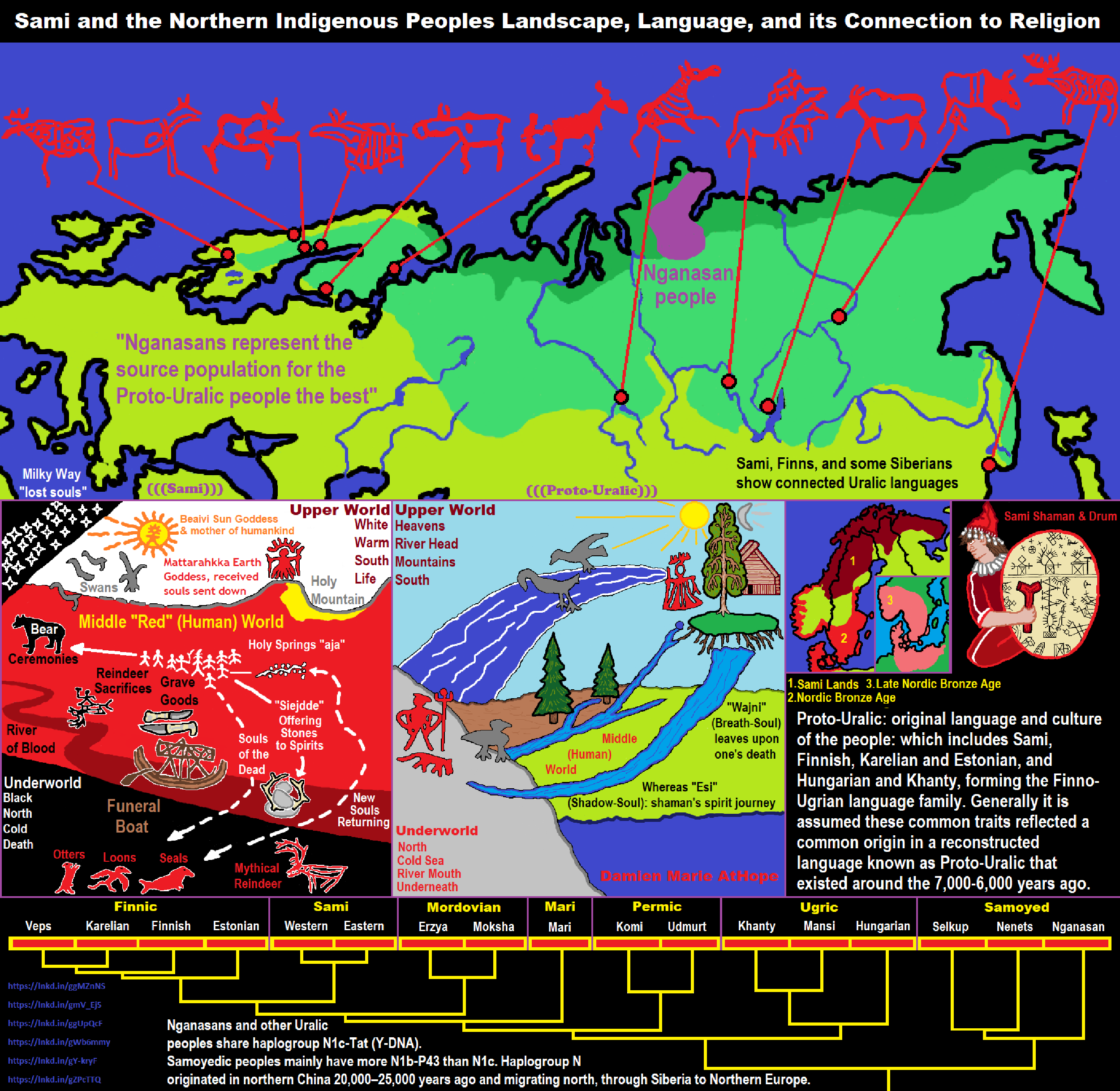

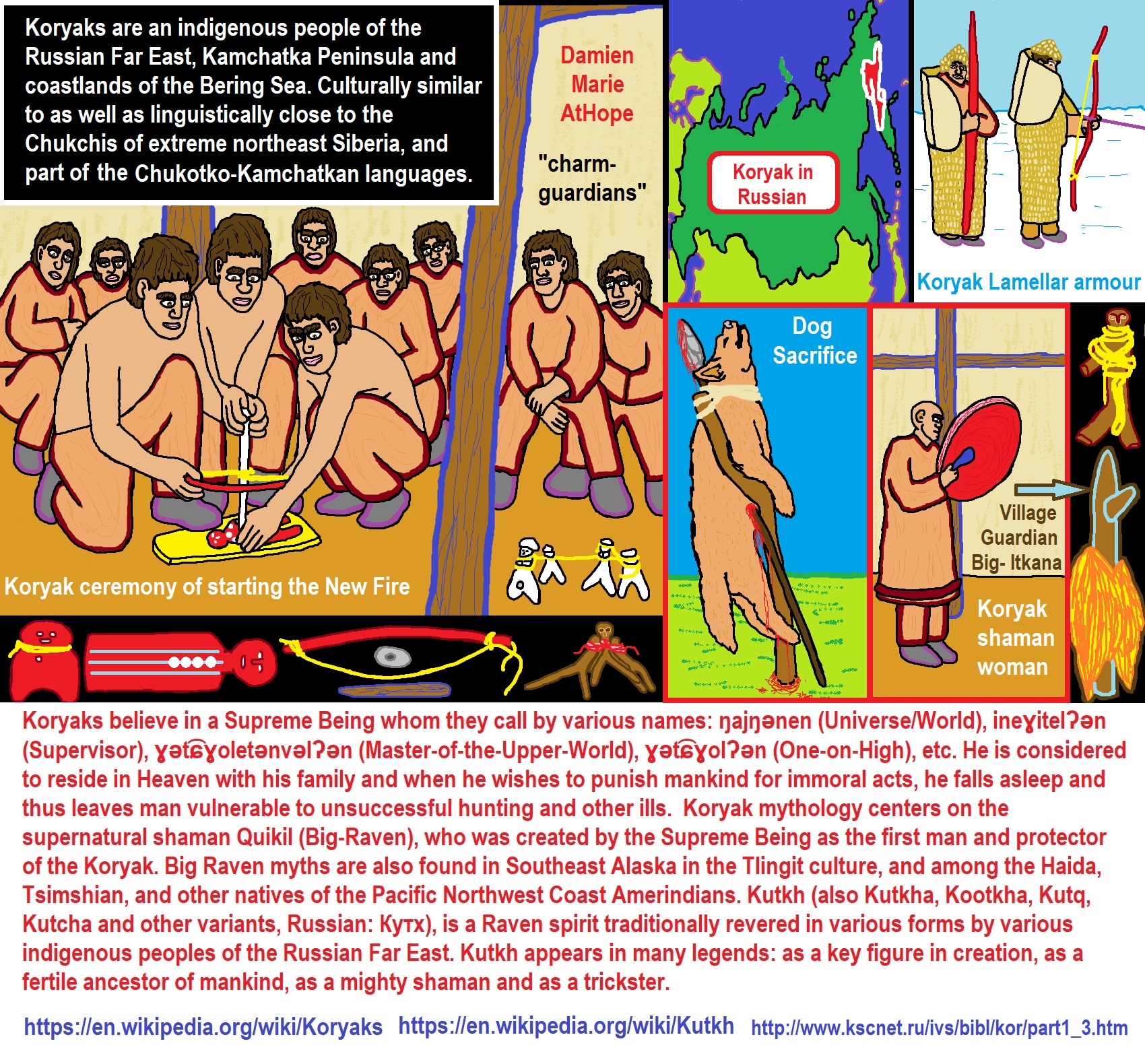

“Koryaks (Russian: коряки) are an Indigenous people of the Russian Far East, who live immediately north of the Kamchatka Peninsula in Kamchatka Krai and inhabit the coastlands of the Bering Sea. The cultural borders of the Koryaks include Tigilsk in the south and the Anadyr basin in the north. The Koryaks are culturally similar to the Chukchis of extreme northeast Siberia. The Koryak language and Alutor (which is often regarded as a dialect of Koryak), are linguistically close to the Chukchi language. All of these languages are members of the Chukotko-Kamchatkan language family. They are more distantly related to the Itelmens on the Kamchatka Peninsula. All of these peoples and other, unrelated minorities in and around Kamchatka are known collectively as Kamchadals.” ref

“The origin of the Koryak is unknown. Anthropologists have speculated that a land bridge connected the Eurasian and North American continent during Late Pleistocene. It is possible that migratory peoples crossed the modern-day Koryak land en route to North America. Scientists have suggested that people traveled back and forth between this area and Haida Gwaii before the ice age receded. They theorize that the ancestors of the Koryak had returned to Siberian Asia from North America during this time. Cultural and some linguistic similarity exist between the Nivkh and the Koryak. Families usually gathered into groups of six or seven, forming bands. The nominal chief had no predominating authority, and the groups relied on consensus to make decisions, resembling common small group egalitarianism.” ref

“The inland Koryak rode reindeer to get around, cutting off their antlers to prevent injuries. They also fitted a team of reindeer with harnesses and attached them to sleds to transport goods and people when moving camp. Koryaks believe in a Supreme Being whom they call by various names: ŋajŋənen (Universe/World), ineɣitelʔən (Supervisor), ɣət͡ɕɣoletənvəlʔən (Master-of-the-Upper-World), ɣət͡ɕɣolʔən (One-on-High), etc. He is considered to reside in Heaven with his family and when he wishes to punish mankind for immoral acts, he falls asleep and thus leaves man vulnerable to unsuccessful hunting and other ills. Koryak mythology centers on the supernatural shaman Quikil (Big-Raven), who was created by the Supreme Being as the first man and protector of the Koryak. Big Raven myths are also found in Southeast Alaska in the Tlingit culture, and among the Haida, Tsimshian, and other natives of the Pacific Northwest Coast Amerindians.” ref

“Archeologists have uncovered evidence of sled dogs during thousand year old excavations in the Kamchatka Peninsula. Early 18th century writers report the abundance of sled dogs in the region and local dependence on sled dogs for transportation. However, the Kamchatka sled dog was also used for clothing and spiritual purposes by the native Koryak people. Koryaks believe that the door to the afterlife was guarded by dogs which had to be bribed to allow the newly deceased to pass through. Prior to the introduction of reindeer, Kamchatka sled dogs were allowed to roam freely during the summer to find their own food. With the introduction of reindeer, the dogs needed to be tied up during the summers, creating a dependency on humans for feeding. While generally the Chukotka sled dog is considered the progenitor of the Siberian huskies, it is theorized that the Kamchatka sled dog may also have been intermingled, contributing the characteristic blue eyes seen in Siberian huskies but which are not standard in Chukotka sled dogs.” ref

Koryak Dog Sacrifices

“The Koryak people impaled dogs on a post as an offering to local spirits. Spiritual forces in traditional Koryak religion are associated with a particular geography, like a region, a hill, or even a house. Spirits from one place had to be kept separate from spirits associated with other places, therefore visitors would be “cleansed” by a brief ritual involving smoke and a few words. A spiritually “charged” drum used for shamanic healing was not carried from house to house by an individual shaman, but rather each household had a drum associated with the spirits of that place, which a shaman would use to talk to the spirits and heal a sick person. Scholars often refer to this kind of shamanic activity as “familial shamanism.” Each family had a person who was skilled in drumming and had some influence with spirits, and he or she would heal family and friends. Professional shamans, like those known among the Evenk (Tungus) or Sakha (Yakut) were unknown among Koryaks.” ref

“The sacrifice of nearly a whole team of dogs by coastal Koryaks (indigenous people of Siberia), was made in early spring to ensure the success of the new hunting season. The dogs are hung from poles stuck in the snow in front of a Koryak semi–dugout house.” ref

“Laikas are aboriginal spitz from Northern Russia, especially Siberia but also sometimes expanded to include Nordic hunting breeds. Laika breeds are primitive dogs who flourish with minimal care even in hostile weather. Generally, laika breeds are expected to be versatile hunting dogs, capable of hunting game of a variety of sizes by treeing small game, pointing and baying larger game, and working as teams to corner bear and boar. However, a few laikas have specialized as herding or sled dogs. Indeed the word laika is often used to refer not only to hunting dogs but also to the related sled dog breeds of the tundra belt, which the FCI classifies as “Nordic Sled Dogs” and even occasionally all spitz breeds.” ref

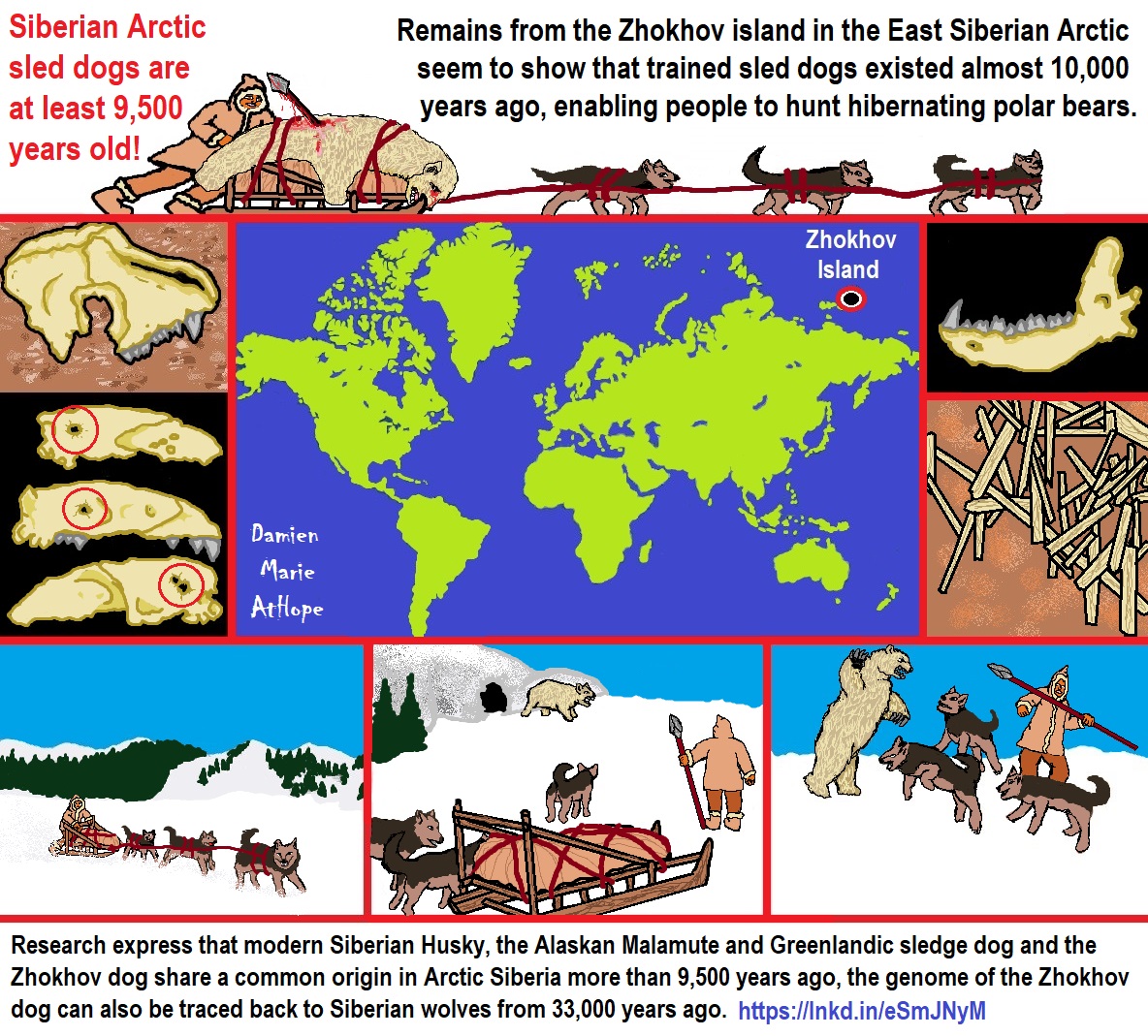

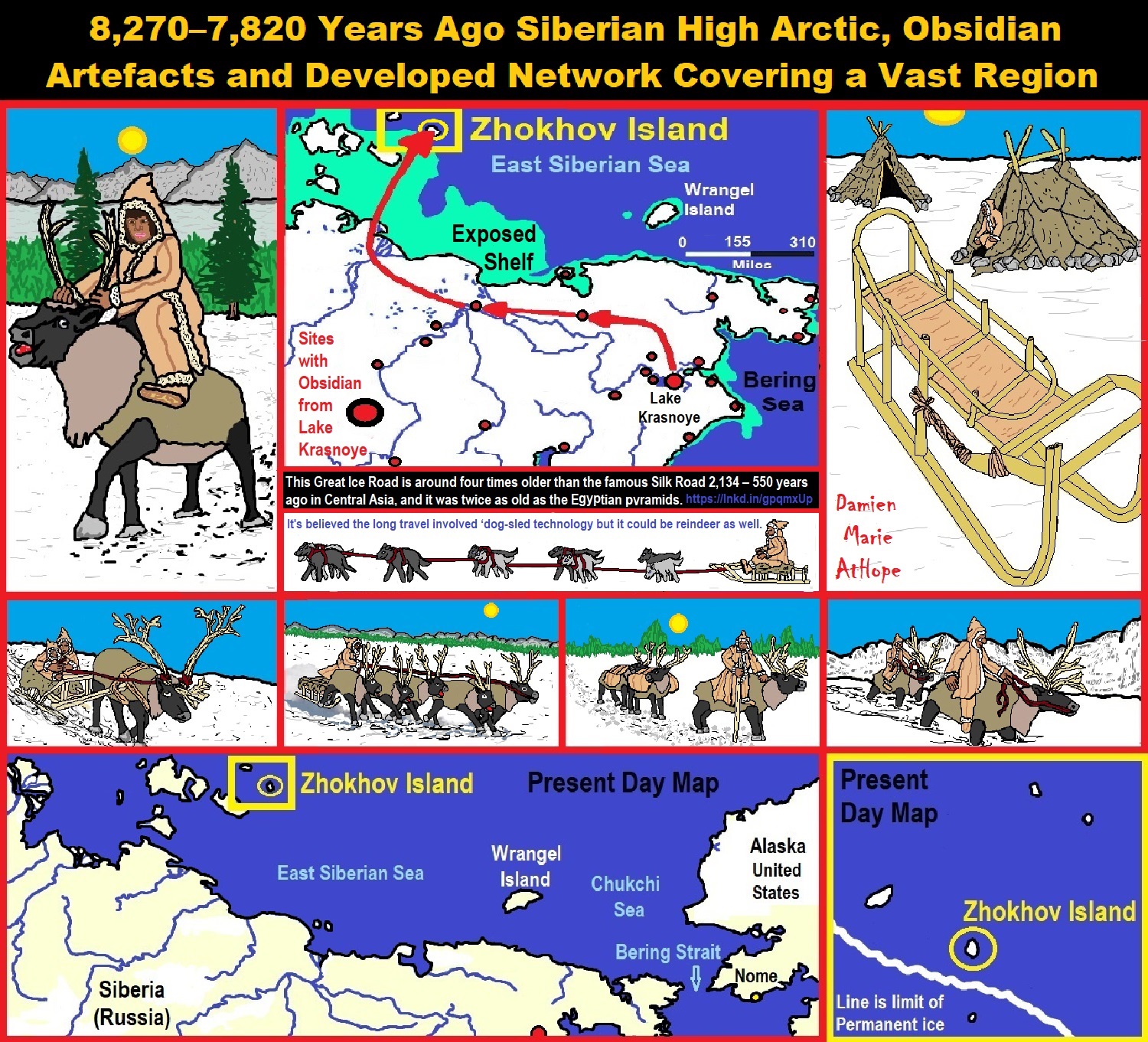

“Modern Siberian dog ancestry was shaped by several thousand years of Eurasian-wide trade and human dispersal. The Siberian Arctic has witnessed numerous societal changes since the first known appearance of dogs in the region ∼10,000 years ago. Dogs have been essential to life in the Siberian Arctic for over 9,500 years ago, and this tight link between people and dogs continues in Siberian communities. Although Arctic Siberian groups such as the Nenets received limited gene flow from neighboring groups, archaeological evidence suggests that metallurgy and new subsistence strategies emerged in Northwest Siberia around 2,000 years ago. It is unclear if the Siberian Arctic dog population was as continuous as the people of the region or if instead admixture occurred, possibly in relation to the influx of material culture from other parts of Eurasia. To address this question, we sequenced and analyzed the genomes of 20 ancient and historical Siberian and Eurasian Steppe dogs. Our analyses indicate that while Siberian dogs were genetically homogenous between 9,500 to 7,000 years ago, the later introduction of dogs from the Eurasian Steppe and Europe led to substantial admixture. This is clearly the case in the Iamal-Nenets region (Northwestern Siberia) where dogs from the Iron Age period (∼2,000 years ago) possess substantially less ancestry related to European and Steppe dogs than dogs from the medieval period (∼1,000 years ago). These changes include the introduction of ironworking ∼2,000 years ago and the emergence of reindeer pastoralism ∼800 years ago. The analysis of 49 ancient dog genomes reveals that the ancestry of Arctic Siberia dogs shifted over the last 2,000 years due to an influx of dogs from the Eurasian Steppe and Europe. Combined with genomic data from humans and archaeological evidence, our results suggest that though the ancestry of human populations in Arctic Siberia did not change over this period, people there participated in trade with distant communities that involved both dogs and material culture.” ref

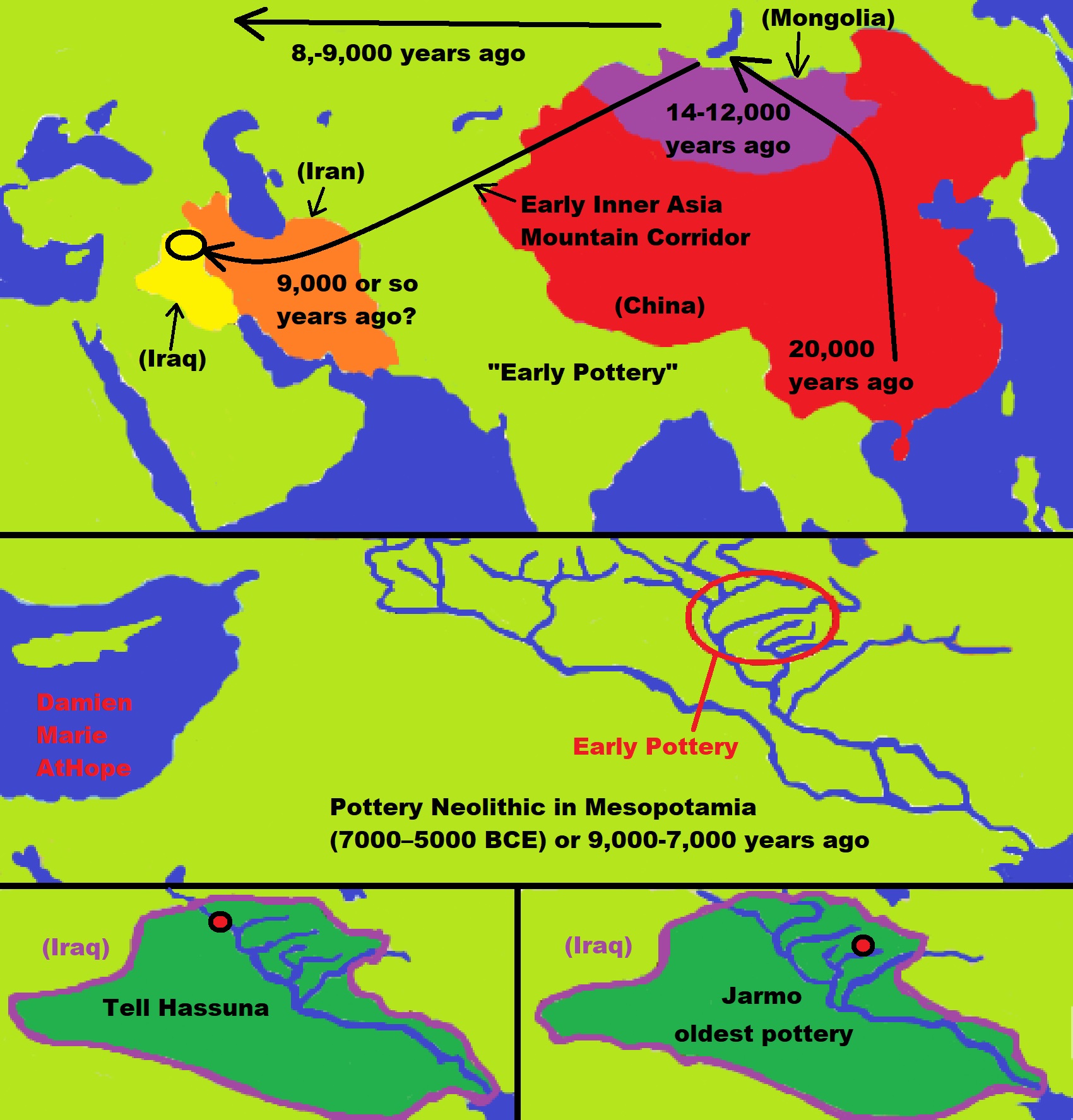

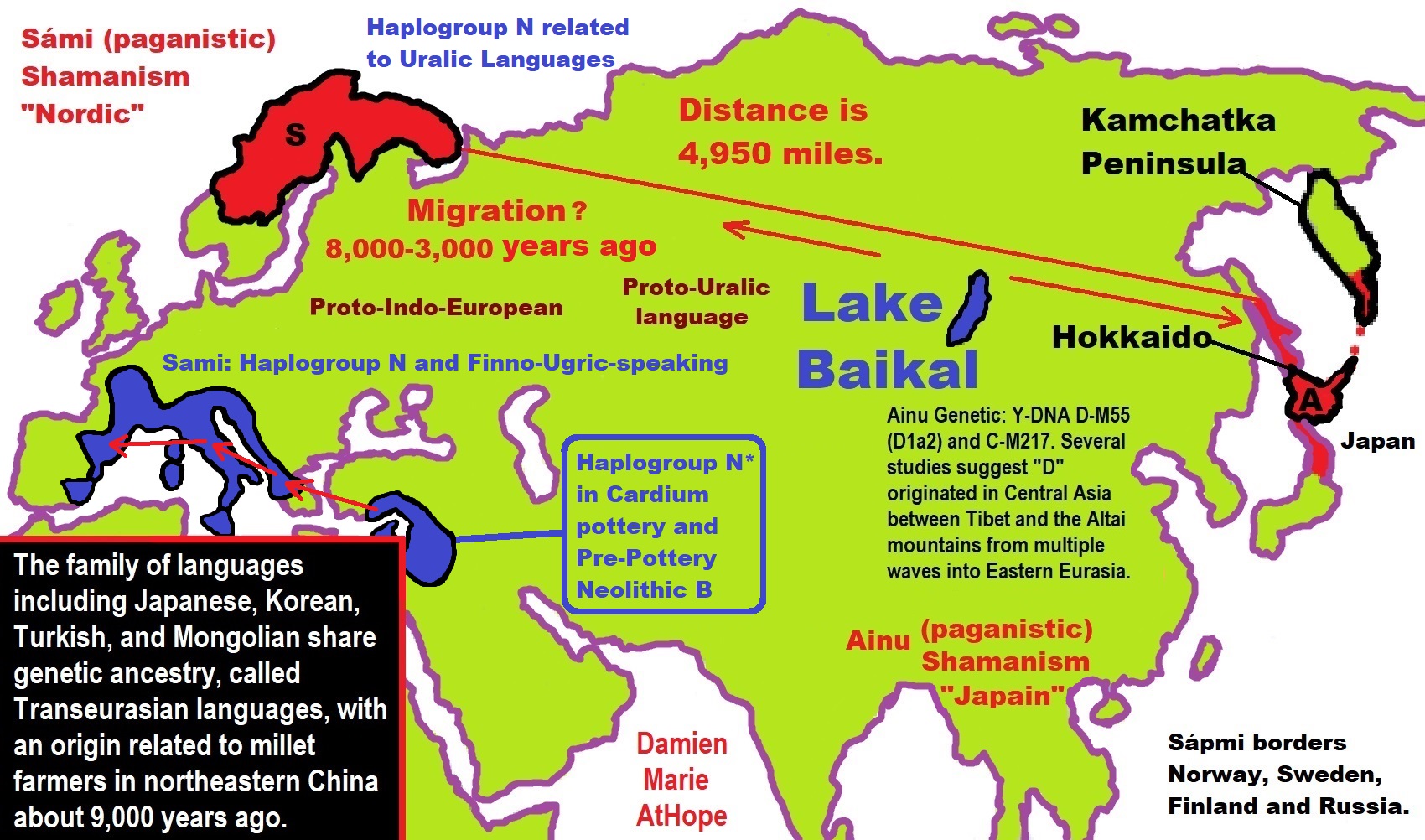

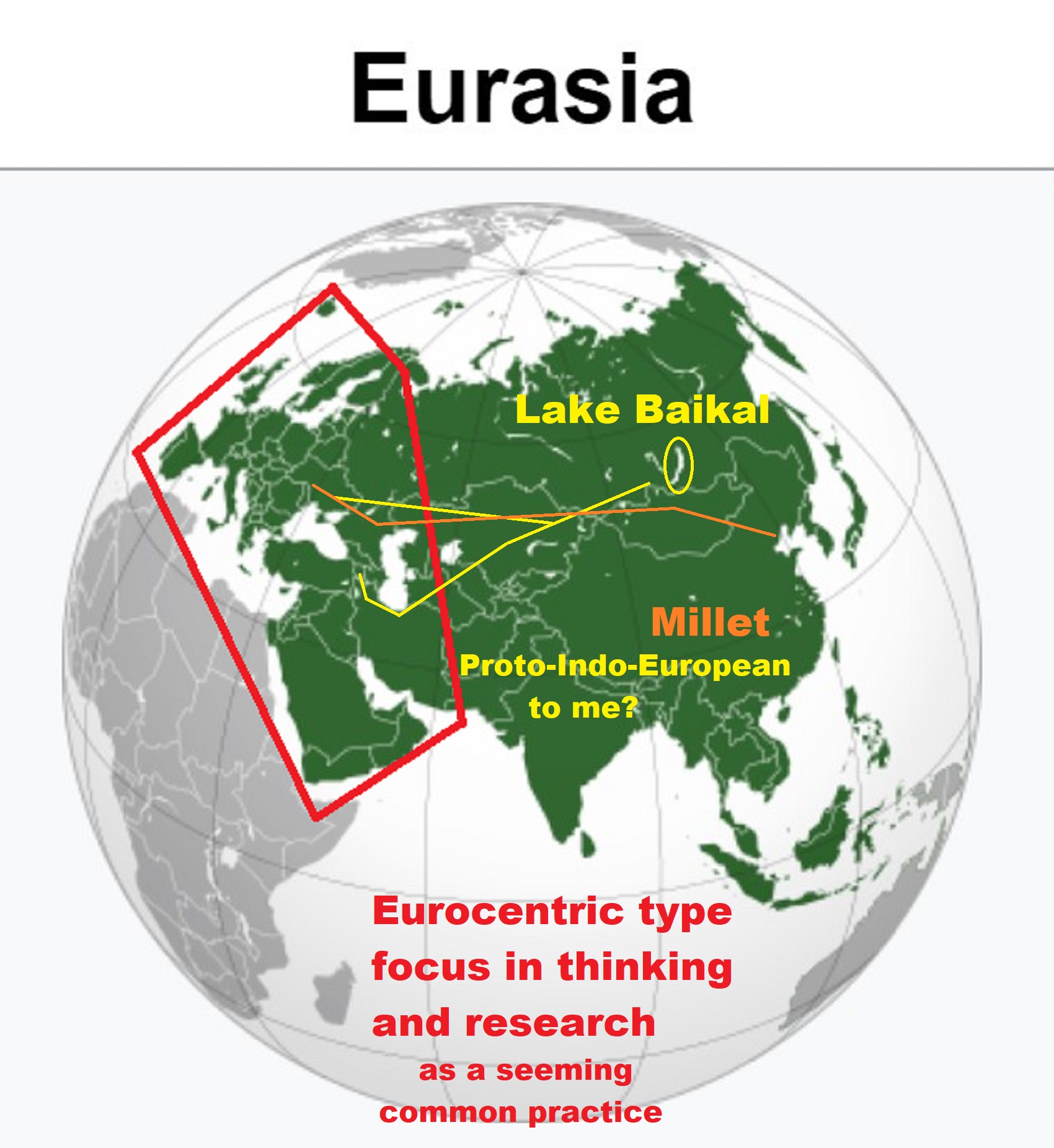

Origins of ‘Transeurasian’ languages traced to Neolithic millet farmers in north-eastern China about 9,000 years ago

“A study combining linguistic, genetic, and archaeological evidence has traced the origins of a family of languages including modern Japanese, Korean, Turkish and Mongolian and the people who speak them to millet farmers who inhabited a region in north-eastern China about 9,000 years ago. The findings outlined on Wednesday document a shared genetic ancestry for the hundreds of millions of people who speak what the researchers call Transeurasian languages across an area stretching more than 5,000 miles (8,000km).” ref

“Millet was an important early crop as hunter-gatherers transitioned to an agricultural lifestyle. There are 98 Transeurasian languages, including Korean, Japanese, and various Turkic languages in parts of Europe, Anatolia, Central Asia, and Siberia, various Mongolic languages, and various Tungusic languages in Manchuria and Siberia. This language family’s beginnings were traced to Neolithic millet farmers in the Liao River valley, an area encompassing parts of the Chinese provinces of Liaoning and Jilin and the region of Inner Mongolia. As these farmers moved across north-eastern Asia over thousands of years, the descendant languages spread north and west into Siberia and the steppes and east into the Korean peninsula and over the sea to the Japanese archipelago.” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

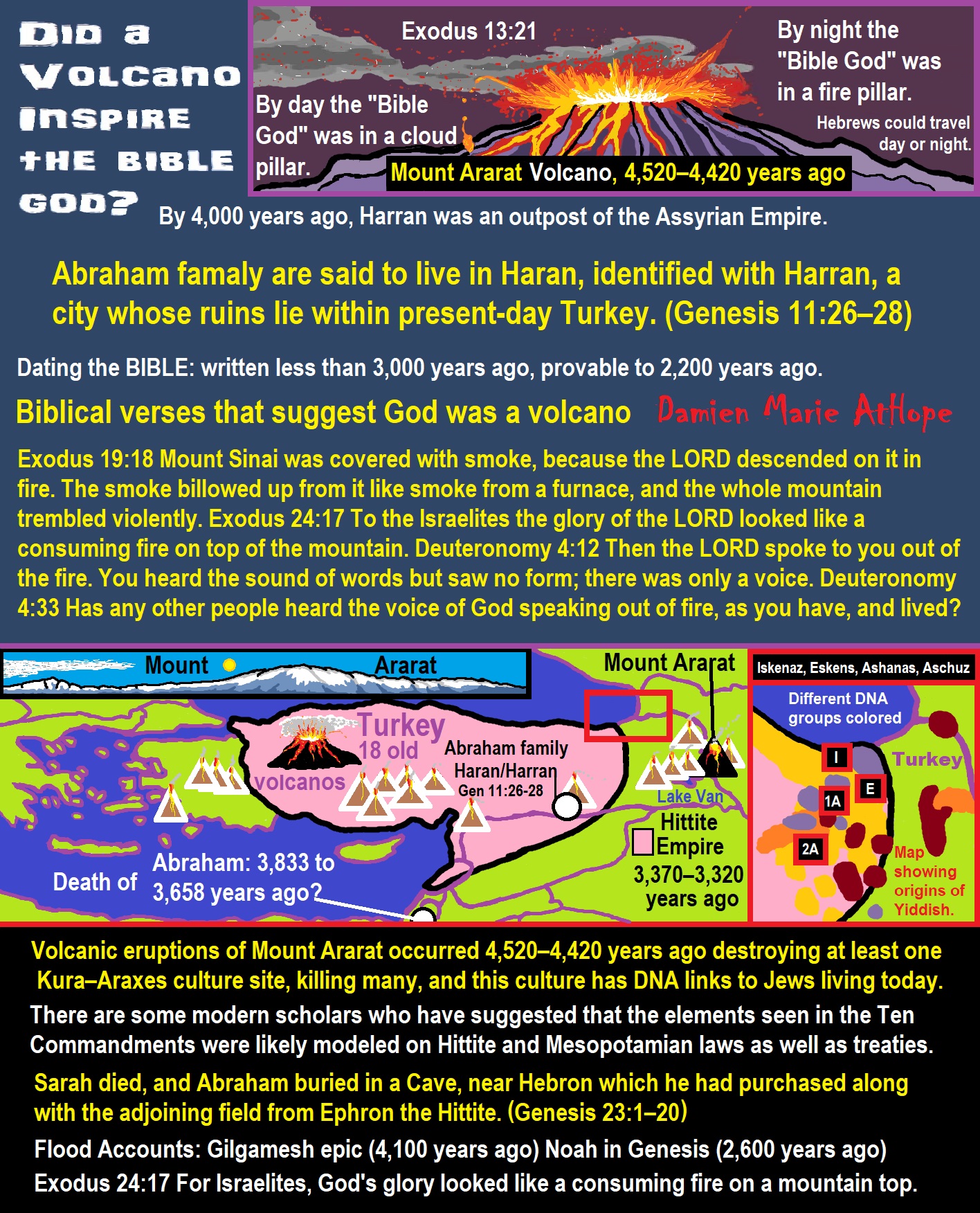

By day the LORD went ahead of them in a pillar of cloud to guide them on their way and by night in a pillar of fire to give them light, so that they could travel by day or night.

- By day the “Bible God” was in a cloud pillar.

- By night the “Bible God” was in a fire pillar.

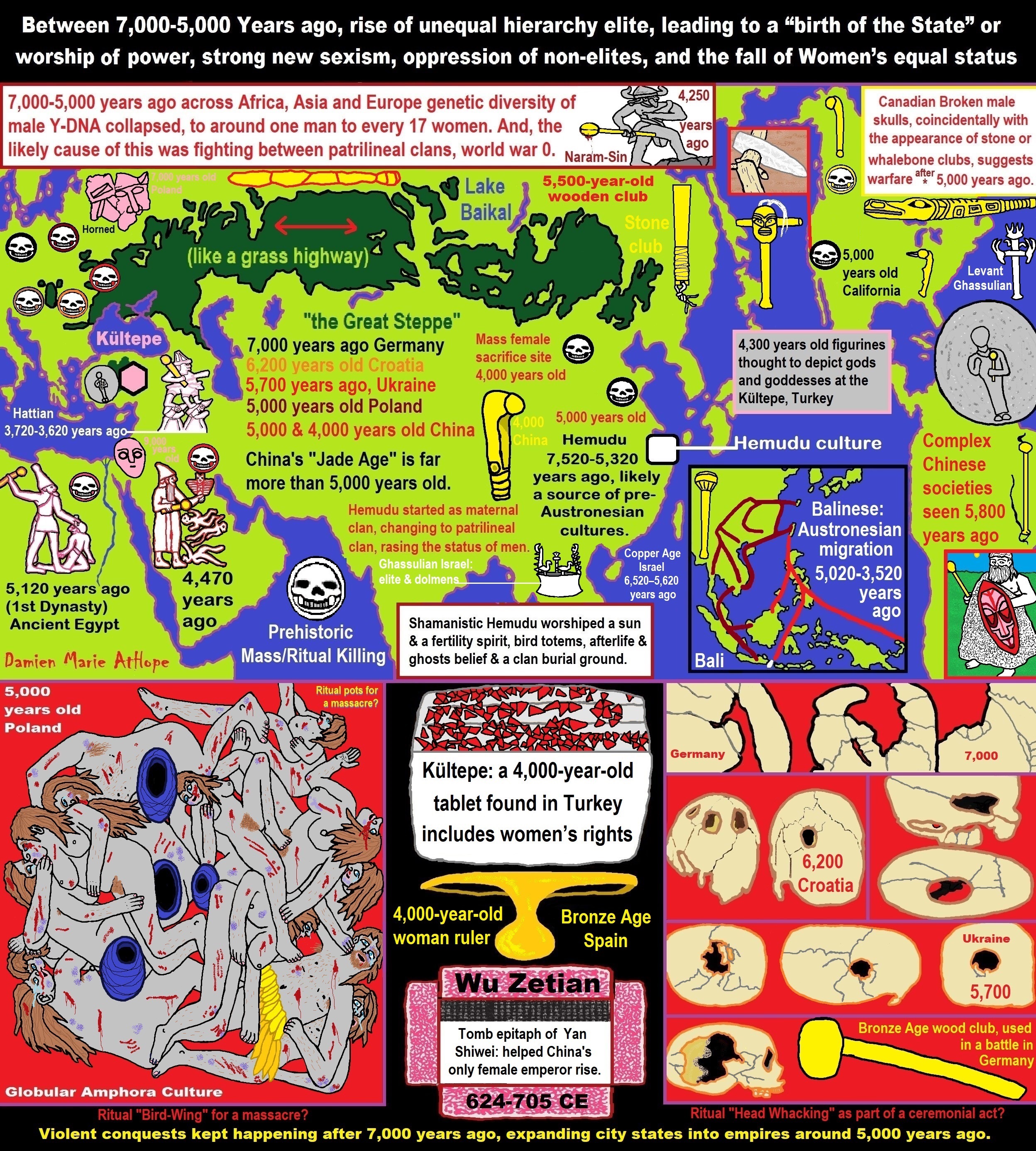

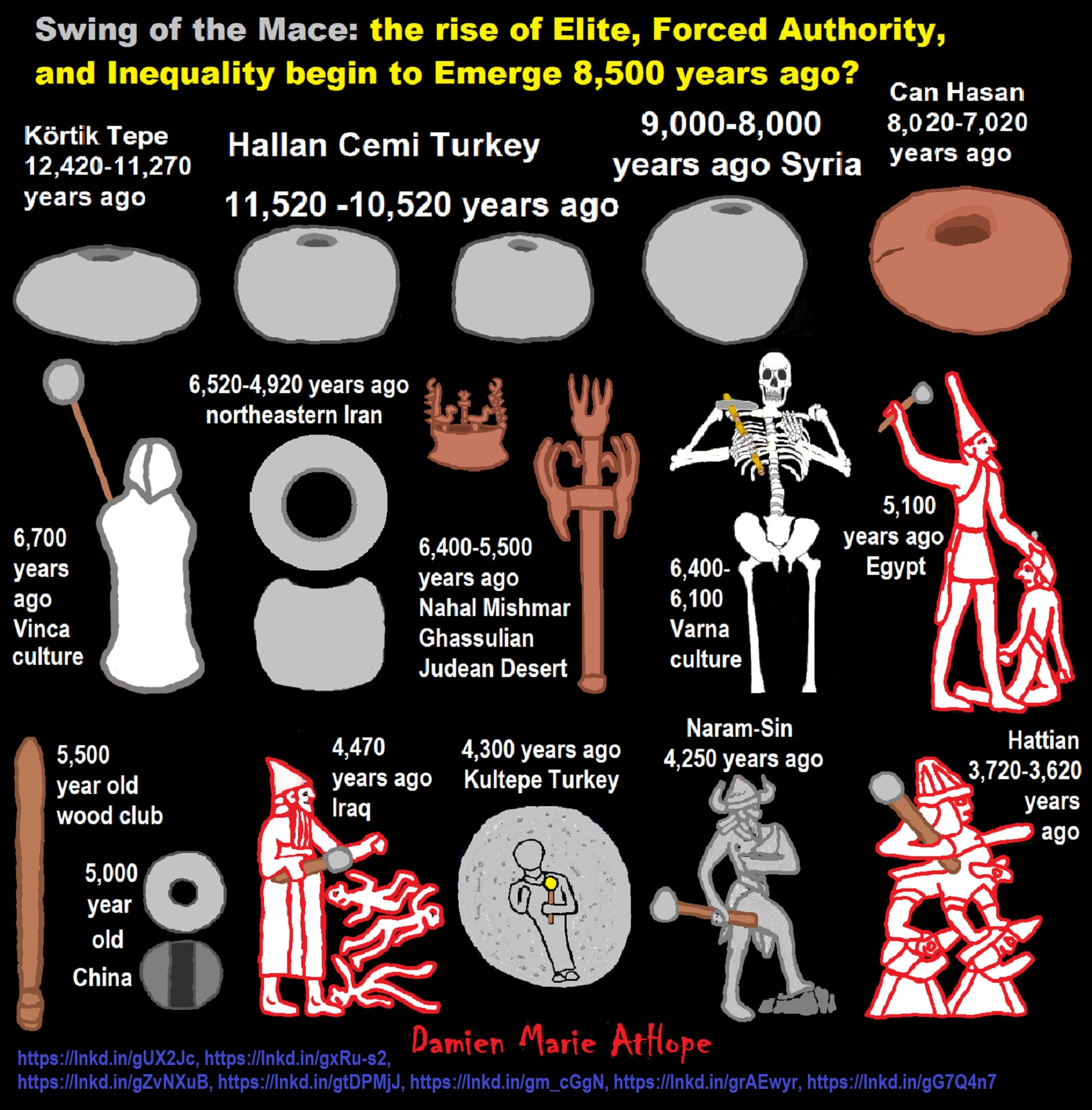

Mace (bludgeon)

“A mace is a blunt weapon, a type of club or virge that uses a heavy head on the end of a handle to deliver powerful strikes. A mace typically consists of a strong, heavy, wooden, or metal shaft, often reinforced with metal, featuring a head made of stone, bone, copper, bronze, iron, or steel. The head of a military mace can be shaped with flanges or knobs to allow greater penetration of plate armour.” ref

“The length of maces can vary considerably. The maces of foot soldiers were usually quite short (two or three feet, or sixty to ninety centimetres). The maces of cavalrymen were longer and thus better suited for blows delivered from horseback. Two-handed maces could be even larger.” ref

“Maces are rarely used today for actual combat, but many government bodies (for instance, the British House of Commons and the U.S. Congress), universities, and other institutions have ceremonial maces and continue to display them as symbols of authority. They are often paraded in academic, parliamentary, or civic rituals and processions. The Middle English word “mace” comes from the French “masse” (short for “Masse d’armes”) meaning ‘large hammer’, a hammer with a heavy mass at the end.” ref

“The mace was developed during the Upper Paleolithic from the simple club, by adding sharp spikes of flint or obsidian. In Europe, an elaborately carved ceremonial flint mace head was one of the artifacts discovered in excavations of the Neolithic mound of Knowth in Ireland, and Bronze Age archaeology cites numerous finds of perforated mace heads.” ref

“In ancient Ukraine, stone mace heads were first used nearly eight millennia ago. The others known were disc maces with oddly formed stones mounted perpendicularly to their handle. The Narmer Palette shows a king swinging a mace. See the articles on the Narmer Macehead and the Scorpion Macehead for examples of decorated maces inscribed with the names of kings.” ref

“Calcite mace head, 7-6th millennium BCE, Syria. The problem with early maces was that their stone heads shattered easily and it was difficult to fix the head to the wooden handle reliably. The Egyptians attempted to give them a disk shape in the predynastic period (about 3850–3650 BCE or 5,672 years ago) in order to increase their impact and even provide some cutting capabilities, but this seems to have been a short-lived improvement.” ref

“A rounded pear form of mace head known as a “piriform” replaced the disc mace in the Naqada II period of pre-dynastic Upper Egypt (3600–3250 BCE) and was used throughout the Naqada III period (3250–3100 BCE). Similar mace heads were also used in Mesopotamia around 2450–1900 BCE. On a Sumerian Clay tablet written by the scribe Gar.Ama, the title Lord of the Mace is listed in the year 3100 BCE. The Assyrians used maces probably about nineteenth century BCE and in their campaigns; the maces were usually made of stone or marble and furnished with gold or other metals, but were rarely used in battle unless fighting heavily armoured infantry.” ref

“An important, later development in mace heads was the use of metal for their composition. With the advent of copper mace heads, they no longer shattered and a better fit could be made to the wooden club by giving the eye of the mace head the shape of a cone and using a tapered handle. The Shardanas or warriors from Sardinia who fought for Ramses II against the Hittites were armed with maces consisting of wooden sticks with bronze heads. Many bronze statuettes of the times show Sardinian warriors carrying swords, bows, and original maces.” ref

“Persians used a variety of maces and fielded large numbers of heavily armoured and armed cavalry (see Cataphract). For a heavily armed Persian knight, a mace was as effective as a sword or battle axe. In fact, Shahnameh has many references to heavily armoured knights facing each other using maces, axes, and swords. The enchanted talking mace Sharur made its first appearance in Sumerian/Akkadian mythology during the epic of Ninurta.” ref

“The Indian epics Ramayana and Mahabharata describe the extensive use of the gada in ancient Indian warfare as gada-yuddha or ‘mace combat’. The ancient Romans did not make wide use of maces, probably because of the influence of armour, and due to the nature of the Roman infantry’s fighting style which involved the pilum (spear) and the gladius (short sword used in a stabbing fashion), though auxiliaries from Syria Palestina were armed with clubs and maces at the battles of Immae and Emesa in 272 CE. They proved highly effective against the heavily armoured horsemen of Palmyra.” ref

Comparative Mythology

“Since the term ‘Ancient North Eurasian’ refers to a genetic bridge of connected mating networks, scholars of comparative mythology have argued that they probably shared myths and beliefs that could be reconstructed via the comparison of stories attested within cultures that were not in contact for millennia and stretched from the Pontic–Caspian steppe to the American continent.” ref

“For instance, the mytheme of the dog guarding the Otherworld possibly stems from an older Ancient North Eurasian belief, as suggested by similar motifs found in Indo-European, Native American, and Siberian mythology. In Siouan, Algonquian, Iroquoian, and in Central and South American beliefs, a fierce guard dog was located in the Milky Way, perceived as the path of souls in the afterlife, and getting past it was a test. The Siberian Chukchi and Tungus believed in a guardian-of-the-afterlife dog and a spirit dog that would absorb the dead man’s soul and act as a guide in the afterlife. In Indo-European myths, the figure of the dog is embodied by Cerberus, Sarvarā, and Garmr. Anthony and Brown note that it might be one of the oldest mythemes recoverable through comparative mythology.” ref

“A second canid-related series of beliefs, myths, and rituals connected dogs with healing rather than death. For instance, Ancient Near Eastern and Turkic–Kipchaq myths are prone to associate dogs with healing and generally categorized dogs as impure. A similar myth-pattern is assumed for the Eneolithic site of Botai in Kazakhstan, dated to 3500 BCE or 5,522 years ago, which might represent the dog as absorber of illness and guardian of the household against disease and evil. In Mesopotamia, the goddess Nintinugga, associated with healing, was accompanied or symbolized by dogs. Similar absorbent-puppy healing and sacrifice rituals were practiced in Greece and Italy, among the Hittites, again possibly influenced by Near Eastern traditions.” ref

Proto-Indo-European mythology

“Proto-Indo-European mythology is the body of myths and deities associated with the Proto-Indo-Europeans, the hypothetical speakers of the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European language. Although the mythological motifs are not directly attested – since Proto-Indo-European speakers lived in preliterate societies – scholars of comparative mythology have reconstructed details from inherited similarities found among Indo-European languages, based on the assumption that parts of the Proto-Indo-Europeans’ original belief systems survived in the daughter traditions.” ref

“The Proto-Indo-European pantheon includes a number of securely reconstructed deities, since they are both cognates – linguistic siblings from a common origin –, and associated with similar attributes and body of myths: such as *Dyḗws Ph₂tḗr, the daylight-sky god; his consort *Dʰéǵʰōm, the earth mother; his daughter *H₂éwsōs, the dawn goddess; his sons the Divine Twins; and *Seh₂ul, a solar goddess. Some deities, like the weather god *Perkʷunos or the herding-god *Péh₂usōn, are only attested in a limited number of traditions – Western (European) and Graeco-Aryan, respectively – and could therefore represent late additions that did not spread throughout the various Indo-European dialects.” ref

“Some myths are also securely dated to Proto-Indo-European times, since they feature both linguistic and thematic evidence of an inherited motif: a story portraying a mythical figure associated with thunder and slaying a multi-headed serpent to release torrents of water that had previously been pent up; a creation myth involving two brothers, one of whom sacrifices the other in order to create the world; and probably the belief that the Otherworld was guarded by a watchdog and could only be reached by crossing a river.” ref

“Various schools of thought exist regarding possible interpretations of the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European mythology. The main mythologies used in comparative reconstruction are Indo-Iranian, Baltic, Roman, and Norse, often supported with evidence from the Celtic, Greek, Slavic, Hittite, Armenian, Illyrian, and Albanian traditions as well.” ref

The canine guardian

“In a recurrent motif, the Otherworld contains a gate, generally guarded by a multi-headed (sometimes multi-eyed) dog who could also serve as a guide and ensured that the ones who entered could not get out. The Greek Cerberus and the Hindu Śárvara most likely derive from the common noun *Ḱérberos (“spotted”). Bruce Lincoln has proposed a third cognate in the Norse Garmr, although this has been debated as linguistically untenable.” ref

“The motif of a canine guardian of the entrance to the Otherworld is also attested in Persian mythology, where two four-eyed dogs guard the Chinvat Bridge, a bridge that marks the threshold between the world of the living and the world of the dead. The Videvdat (Vendidad) 13,9 describes them as ‘spâna pəšu.pâna’ (“two bridge-guarding dogs”).” ref

“A parallel imagery is found in Historical Vedic religion: Yama, ruler of the underworld realm, is said to own two four-eyed dogs who also act as his messengers and fulfill the role of protectors of the soul in the path to heaven. These hounds, named Shyama (Śyāma) and Sabala, are described as the brood of Sarama, a divine female dog: one is black and the other spotted.” ref

“Slovene deity and hero Kresnik is also associated with a four-eyed dog, and a similar figure in folk belief (a canine with white or brown spots above its eyes – thus, “four-eyed”) is said to be able to sense the approach of death. In Nordic mythology, a dog stands on the road to Hel; it is often assumed to be identical with Garmr, the howling hound bound at the entrance to Gnipahellir.” ref

“In Albanian folklore, a never-sleeping three-headed dog is also said to live in the world of the dead. Another parallel may be found in the Cŵn Annwn (“Hounds of Annwn”), creatures of Welsh mythology said to live in Annwn, a name for the Welsh Otherworld. They are described as hell hounds or spectral dogs that take part in the Wild Hunt, chasing after the dead and pursuing the souls of men.” ref

“Remains of dogs found in grave sites of the Iron Age Wielbark culture, and dog burials of Early Medieval North-Western Slavs (in Pomerania) would suggest the longevity of the belief. Another dog-burial in Góra Chełmska and a Pomeranian legend about a canine figure associated with the otherworld seem to indicate the existence of the motif in Slavic tradition.” ref

“In a legend from Lokev, a male creature named Vilež (“fairy man”), who dwells in Vilenica Cave, is guarded by two wolves and is said to take men into the underworld. Belarusian scholar Siarhiej Sanko suggests that characters in a Belarusian ethnogenetic myth, Prince Bai and his two dogs, Staury and Gaury (Haury), are related to Vedic Yama and his two dogs. To him, Gaury is connected to Lithuanian gaurai ‘mane, shaggy (of hair)’.” ref

“An archeological find by Russian archeologist Alexei Rezepkin at Tsarskaya showed two dogs of different colors (one of bronze, the other of silver), each siding the porthole of a tomb. This imagery seemed to recall the Indo-Aryan myth of Yama and his dogs.” ref

“The mytheme possibly stems from an older Ancient North Eurasian belief, as evidenced by similar motifs in Native American and Siberian mythology, in which case it might be one of the oldest mythemes recoverable through comparative mythology. The King of the Otherworld may have been Yemo, the sacrificed twin of the creation myth, as suggested by the Indo-Iranian and, to a lesser extent, by the Germanic, Greek, and Celtic traditions.” ref

Proto-Indo-European Gods and goddesses

“The archaic Proto-Indo-European language (4500–4000) had a two-gender system which originally distinguished words between animate and inanimate, a system used to separate a common term from its deified synonym. For instance, fire as an active principle was *h₁n̥gʷnis (Latin ignis; Sanskrit Agní), while the inanimate, physical entity was *péh₂ur (Greek pyr; English fire). During this period, Proto-Indo-European beliefs were still animistic and their language did not yet make formal distinctions between masculine and feminine, although it is likely that each deity was already conceived as either male or female.” ref

“Most of the goddesses attested in later Indo-European mythologies come from pre-Indo-European deities eventually assimilated into the various pantheons following the migrations, like the Greek Athena, the Roman Juno, the Irish Medb, or the Iranian Anahita. Diversely personified, they were frequently seen as fulfilling multiple functions, while Proto-Indo-European goddesses shared a lack of personification and narrow functionalities as a general characteristic. The most well-attested female Indo-European deities include *H₂éwsōs, the Dawn, *Dʰéǵʰōm, the Earth, and *Seh₂ul, the Sun.” ref

“It is not probable that the Proto-Indo-Europeans had a fixed canon of deities or assigned a specific number to them. The term for “a god” was *deywós (“celestial”), derived from the root *dyew, which denoted the bright sky or the light of day. It has numerous reflexes in Latin deus, Old Norse Týr (< Germ. *tīwaz), Sanskrit devá, Avestan daeva, Irish día, or Lithuanian Dievas. In contrast, human beings were synonymous of “mortals” and associated with the “earthly” (*dʰéǵʰōm), likewise the source of words for “man, human being” in various languages.” ref

“Proto-Indo-Europeans believed the gods to be exempt from death and disease because they were nourished by special aliments, usually not available to mortals: in the Chāndogya Upaniṣad, “the gods, of course, neither eat nor drink. They become sated by just looking at this nectar”, while the Edda tells us that “on wine alone the weapon-lord Odin ever lives … he needs no food; wine is to him both drink and meat”. Sometimes concepts could also be deified, such as the Avestan mazdā (“wisdom”), worshipped as Ahura Mazdā (“Lord Wisdom”); the Greek god of war Ares (connected with ἀρή, “ruin, destruction”); or the Vedic protector of treaties Mitráh (from mitrám, “contract”).” ref

“Gods had several titles, typically “the celebrated”, “the highest”, “king”, or “shepherd”, with the notion that deities had their own idiom and true names which might be kept secret from mortals in some circumstances. In Indo-European traditions, gods were seen as the “dispensers” or the “givers of good things” (*déh₃tōr h₁uesuom). Compare the Irish god Dagda / Dagdae, “Good God” or “Shining God” from Proto-Celtic *Dago-deiwos, from Proto-Indo-European *dʰagʰo- (“shining”) (< *dʰegʷʰ- (“to burn”)) +*deywós (“divinity”), also Old Irish deg-, dag-, from Proto-Celtic *dagos (compare Welsh da ‘good’, Scottish Gaelic deagh ‘good’).” ref

“Although certain individual deities were charged with the supervision of justice or contracts, in general, the Indo-European gods did not have an ethical character. Their immense power, which they could exercise at their pleasure, necessitated rituals, sacrifices, and praise songs from worshipers to ensure they would in return bestow prosperity to the community. The idea that gods were in control of the nature was translated in the suffix *-nos (feminine -nā), which signified “lord of”. According to West, it is attested in Greek Ouranos (“lord of rain”) and Helena (“mistress of sunlight”), Germanic *Wōðanaz (“lord of frenzy”), Gaulish Epona (“goddess of horses”), Lithuanian Perkūnas (“lord of oaks”), and in Roman Neptunus (“lord of waters”), Volcanus (“lord of fire-glare”) and Silvanus (“lord of woods”).” ref

Pantheon

“Linguists have been able to reconstruct the names of some deities in the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) from many types of sources. Some of the proposed deity names are more readily accepted among scholars than others. According to philologist Martin L. West, “the clearest cases are the cosmic and elemental deities: the Sky-god, his partner Earth, and his twin sons; the Sun, the Sun Maiden, and the Dawn; gods of storm, wind, water, fire; and terrestrial presences such as the Rivers, spring and forest nymphs, and a god of the wild who guards roads and herds.” ref

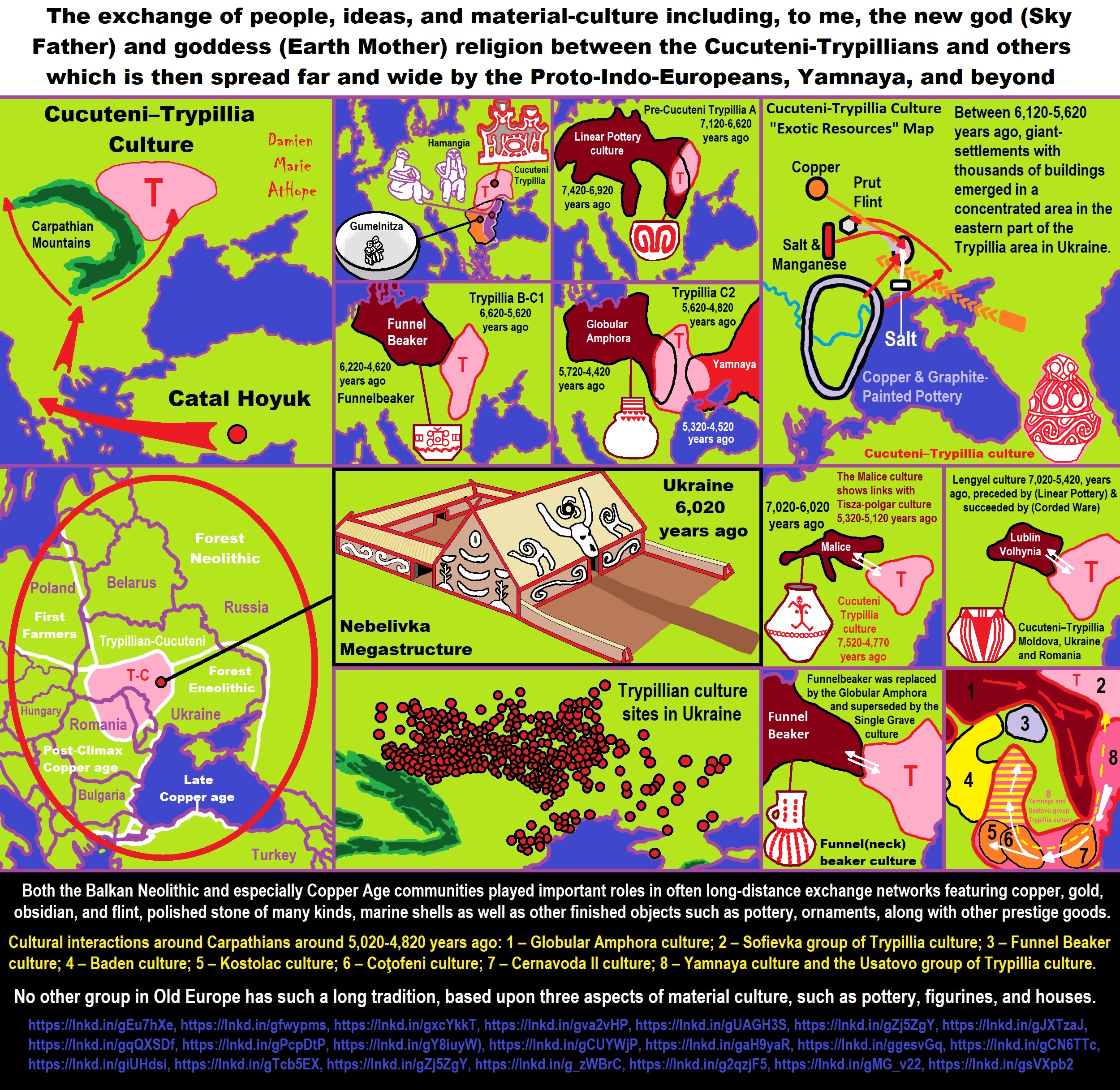

Cucuteni–Trypillia culture

“The Cucuteni–Trypillia culture (Romanian: Cultura Cucuteni and Ukrainian: Трипільська культура), also known as the Tripolye culture (Russian: Трипольская культура), is a Neolithic–Eneolithic archaeological culture (c. 5500 to 2750 BCE) of Eastern Europe. The majority of Cucuteni–Trypillia settlements consisted of high-density, small settlements (spaced 3 to 4 kilometers apart), concentrated mainly in the Siret, Prut, and Dniester river valleys.” ref

“It extended from the Carpathian Mountains to the Dniester and Dnieper regions, centered on modern-day Moldova and covering substantial parts of western Ukraine and northeastern Romania, encompassing an area of 350,000 km2 (140,000 sq mi), with a diameter of 500 km (300 mi; roughly from Kyiv in the northeast to Brașov in the southwest). During its middle phase (c. 4000 to 3500 BCE), populations belonging to the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture built the largest settlements in Neolithic Europe, some of which contained as many as three thousand structures and were possibly inhabited by 20,000 to 46,000 people.” ref

“One of the most notable aspects of this culture was the periodic destruction of settlements, with each single-habitation site having a lifetime of roughly 60 to 80 years. The purpose of burning these settlements is a subject of debate among scholars; some of the settlements were reconstructed several times on top of earlier habitational levels, preserving the shape and the orientation of the older buildings. One particular location; the Poduri site in Romania, revealed thirteen habitation levels that were constructed on top of each other over many years.” ref

“The Cucuteni–Trypillia culture is commonly divided into Early, Middle, and Late periods, with varying smaller sub-divisions marked by changes in settlement and material culture. A key point of contention lies in how these phases correspond to radiocarbon data. The following chart represents this most current interpretation:

• Early (Pre-Cucuteni I–III to Cucuteni A–B, Trypillia A to Trypillia BI–II):5800 to 5000 BCE• Middle (Cucuteni B, Trypillia BII to CI–II): 5000 to 3500 BCE• Late (Horodiştea–Folteşti, Trypillia CII): 3500 to 3000 BCE” ref

Early period (5800–5000 BCE)

“The roots of Cucuteni–Trypillia culture can be found in the Starčevo–Körös–Criș and Vinča cultures of the 6th to 5th millennia, with additional influence from the Bug–Dniester culture (6500–5000 BCE). During the early period of its existence (in the fifth millennium BCE), the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture was also influenced by the Linear Pottery culture from the north, and by the Boian culture from the south.” ref

“Through colonization and acculturation from these other cultures, the formative Pre-Cucuteni/Trypillia A culture was established. Over the course of the fifth millennium, the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture expanded from its ‘homeland’ in the Prut–Siret region along the eastern foothills of the Carpathian Mountains into the basins and plains of the Dnieper and Southern Bug rivers of central Ukraine.” ref

“Settlements also developed in the southeastern stretches of the Carpathian Mountains, with the materials known locally as the Ariuşd culture (see also: Prehistory of Transylvania). Most of the settlements were located close to rivers, with fewer settlements located on the plateaus. Most early dwellings took the form of pit-houses, though they were accompanied by an ever-increasing incidence of above-ground clay houses. The floors and hearths of these structures were made of clay, and the walls of clay-plastered wood or reeds. Roofing was made of thatched straw or reeds.” ref

“The inhabitants were involved with animal husbandry, agriculture, fishing, and gathering. Wheat, rye, and peas were grown. Tools included ploughs made of antler, stone, bone, and sharpened sticks. The harvest was collected with scythes made of flint-inlaid blades. The grain was milled into flour by quern-stones. Women were involved in pottery, textile– and garment-making, and played a leading role in community life. Men hunted, herded the livestock, made tools from flint, bone, and stone.” ref

“Of their livestock, cattle were the most important, with swine, sheep, and goats playing lesser roles. The question of whether or not the horse was domesticated during this time of the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture is disputed among historians; horse remains have been found in some of their settlements, but it is unclear whether these remains were from wild horses or domesticated ones.” ref

“Clay statues of females and amulets have been found dating to this period. Copper items, primarily bracelets, rings, and hooks, are occasionally found as well. A hoard of a large number of copper items was discovered in the village of Cărbuna, Moldova, consisting primarily of items of jewelry, which were dated back to the beginning of the fifth millennium BCE. Some historians have used this evidence to support the theory that a social stratification was present in early Cucuteni culture, but this is disputed by others.” ref

“Pottery remains from this early period are very rarely discovered; the remains that have been found indicate that the ceramics were used after being fired in a kiln. The outer colour of the pottery is a smoky grey, with raised and sunken relief decorations. Toward the end of this early Cucuteni–Trypillia period, the pottery begins to be painted before firing. The white-painting technique found on some of the pottery from this period was imported from the earlier and contemporary (5th millennium) Gumelnița–Karanovo culture.” ref

“Historians point to this transition to kiln-fired, white-painted pottery as the turning point for when the Pre-Cucuteni culture ended and Cucuteni Phase (or Cucuteni–Trypillia culture) began. Cucuteni and the neighbouring Gumelniţa–Karanovo cultures seem to be largely contemporary; the “Cucuteni A phase seems to be very long (4600–4050) and covers the entire evolution of the Gumelnița–Karanovo A1, A2, B2 phases (maybe 4650–4050).” ref

Middle period (5000–3500 BCE)