Arcane Capitalism: Primitive capital, Private ownership, Class discrimination and Petite bourgeoisie (Video)

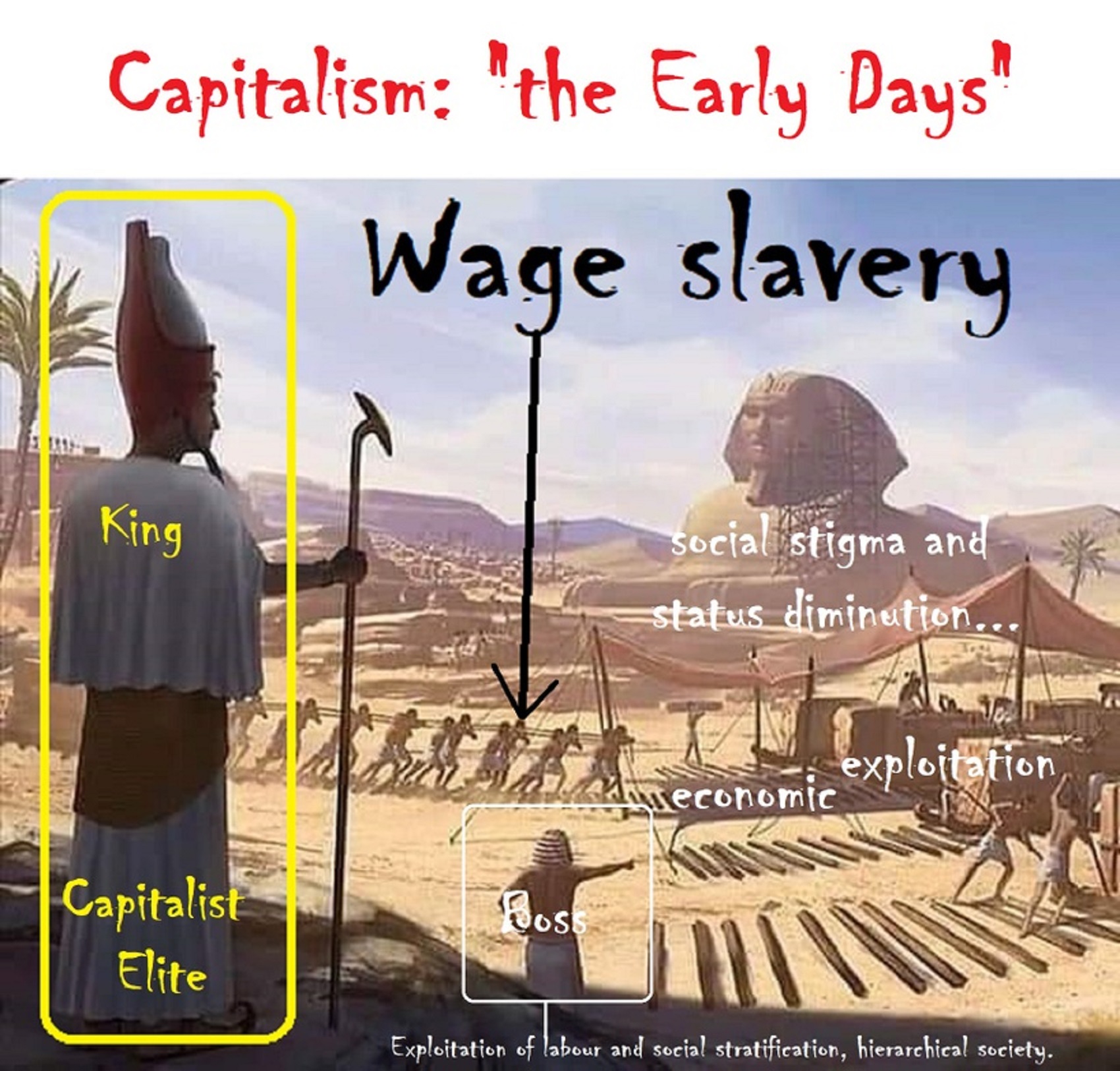

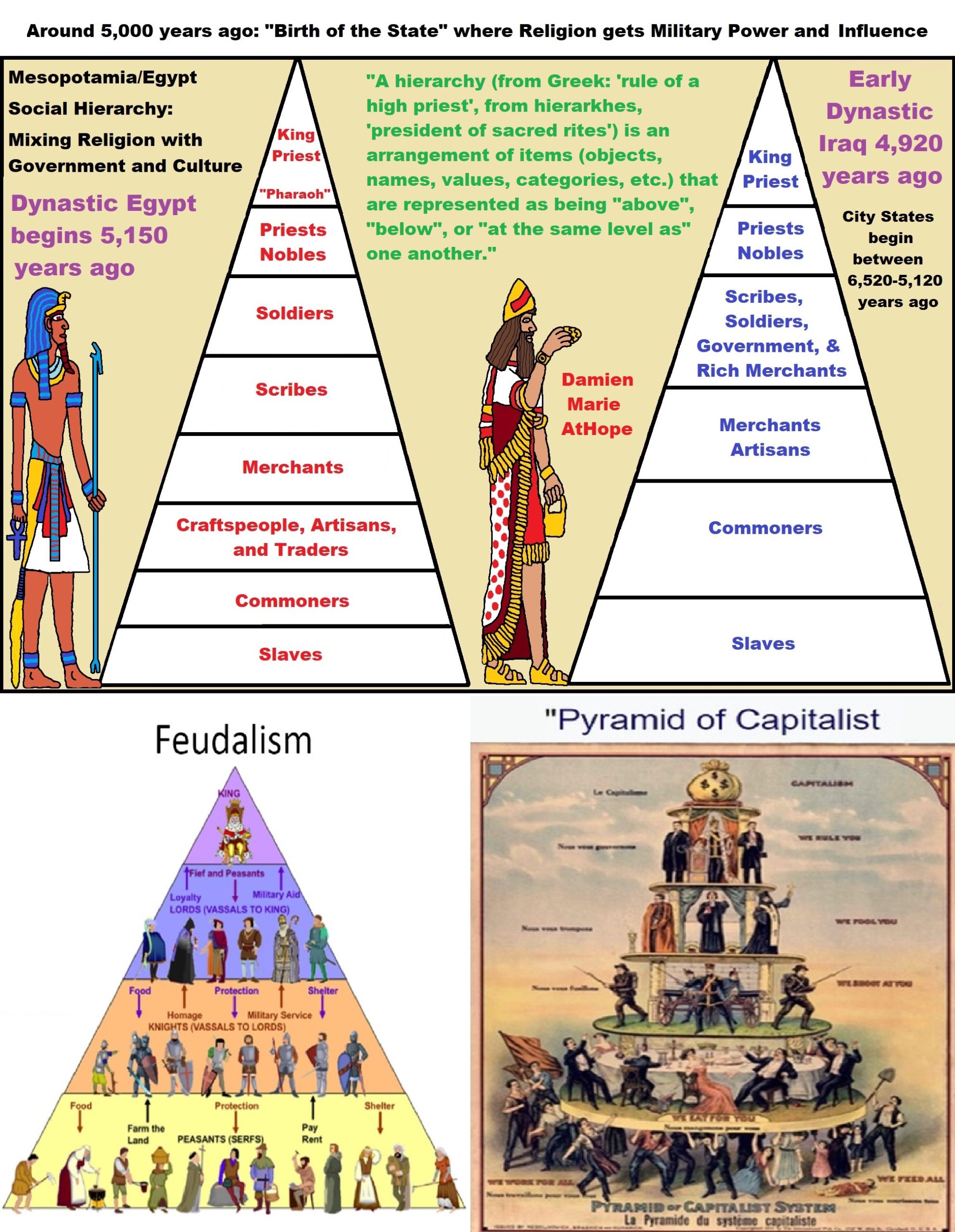

“The Pyramid of Capitalist System is a common name of a 1911 American cartoon caricature critical of capitalism, copied from a Russian flyer of c. 1901. The graphic focus is on stratification by social class and economic inequality. The work has been described as “famous”, “well-known and widely reproduced”. A number of derivative works exist. The picture shows a literal “social pyramid” or hierarchy, with the wealthy few on the top, and the impoverished masses at the bottom. Crowned with a money bag representing capitalism, the top layer, “we rule you”, is occupied by the royalty and state leaders. Underneath them are the clergy (“we fool you”), followed by the military (“we shoot at you”), and the bourgeoisie (“we eat for you”). The bottom of the pyramid is held up by the workers and the peasants (“we work for all… we feed all”). The basic message of the image is a critique of the capitalist system, depicting a hierarchy of power and wealth. It illustrates a working class supporting all others, and if it would withdraw their support from the system it could topple the existing social order. This type of criticism of capitalism is attributed to the French socialist Louis Blanc.” ref

Arcane = complicated and therefore understood or known by only a few people

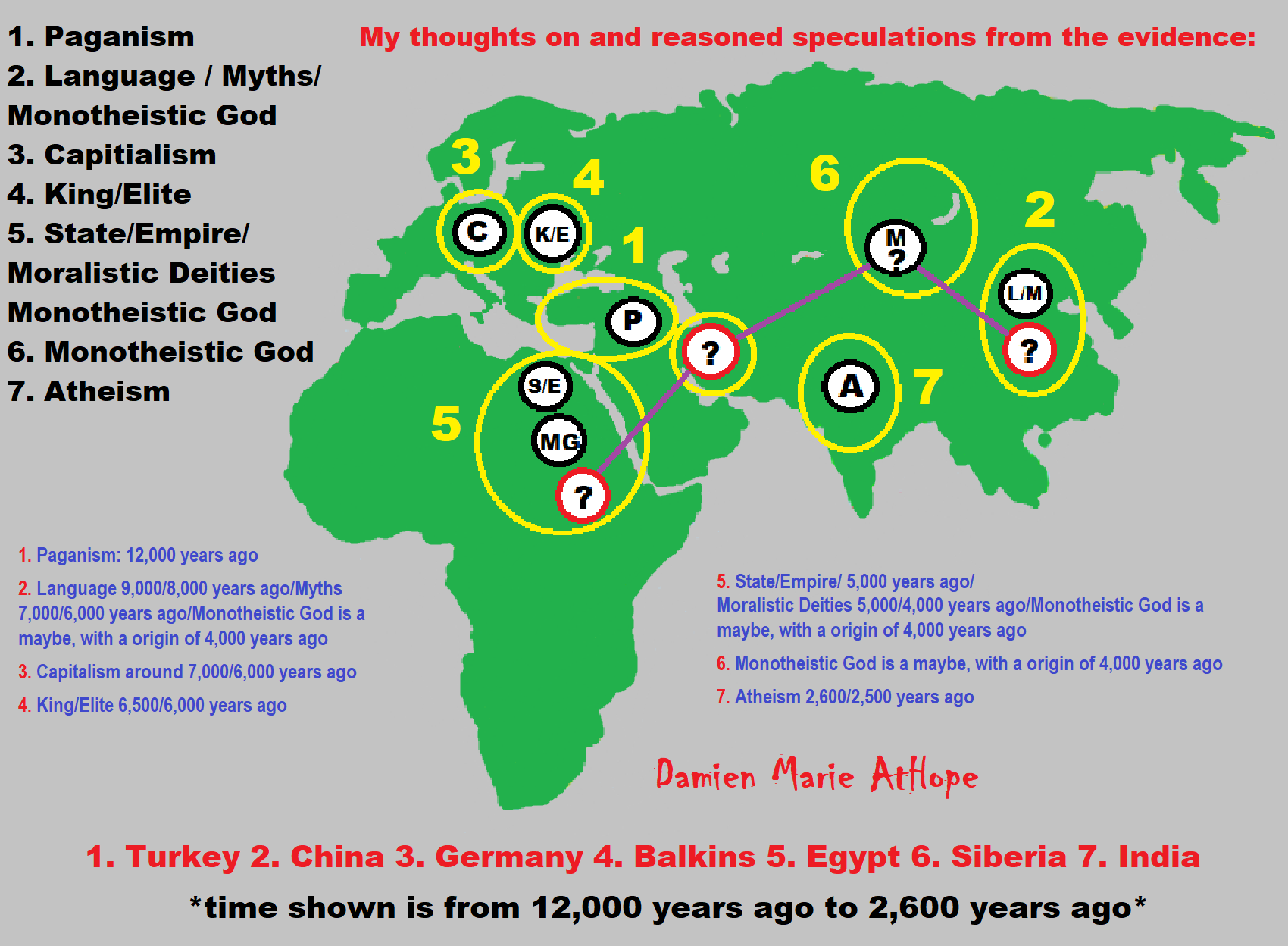

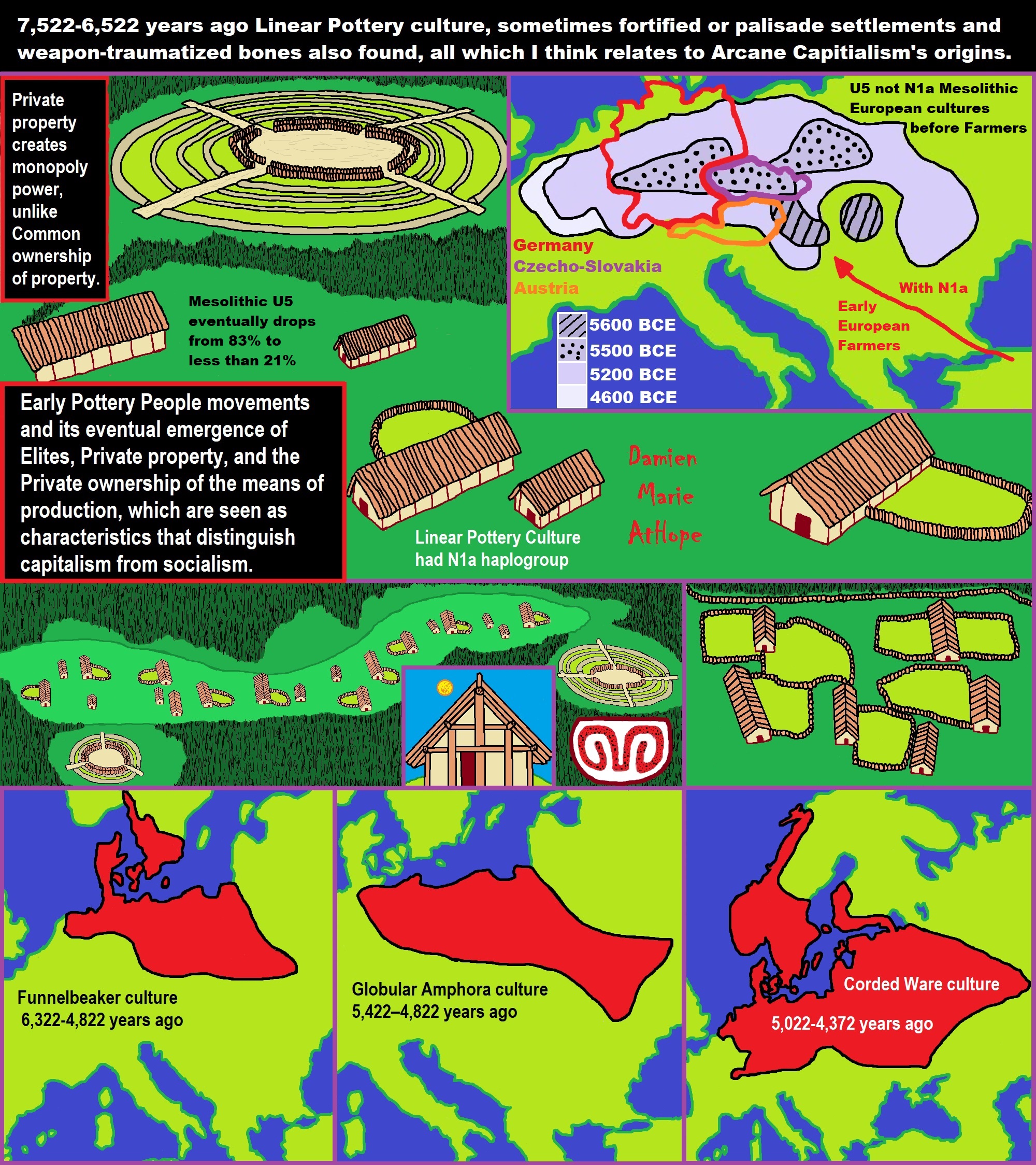

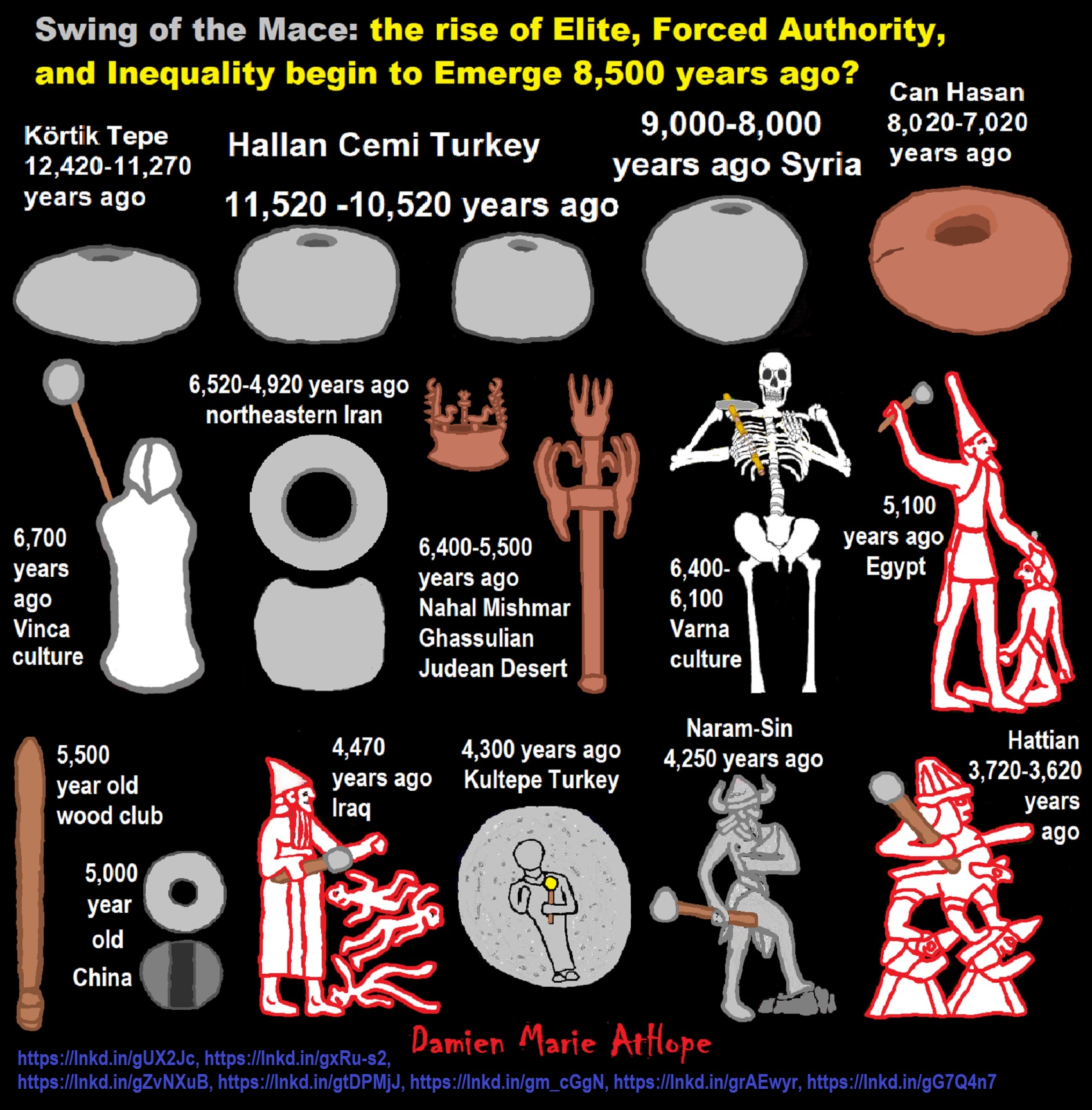

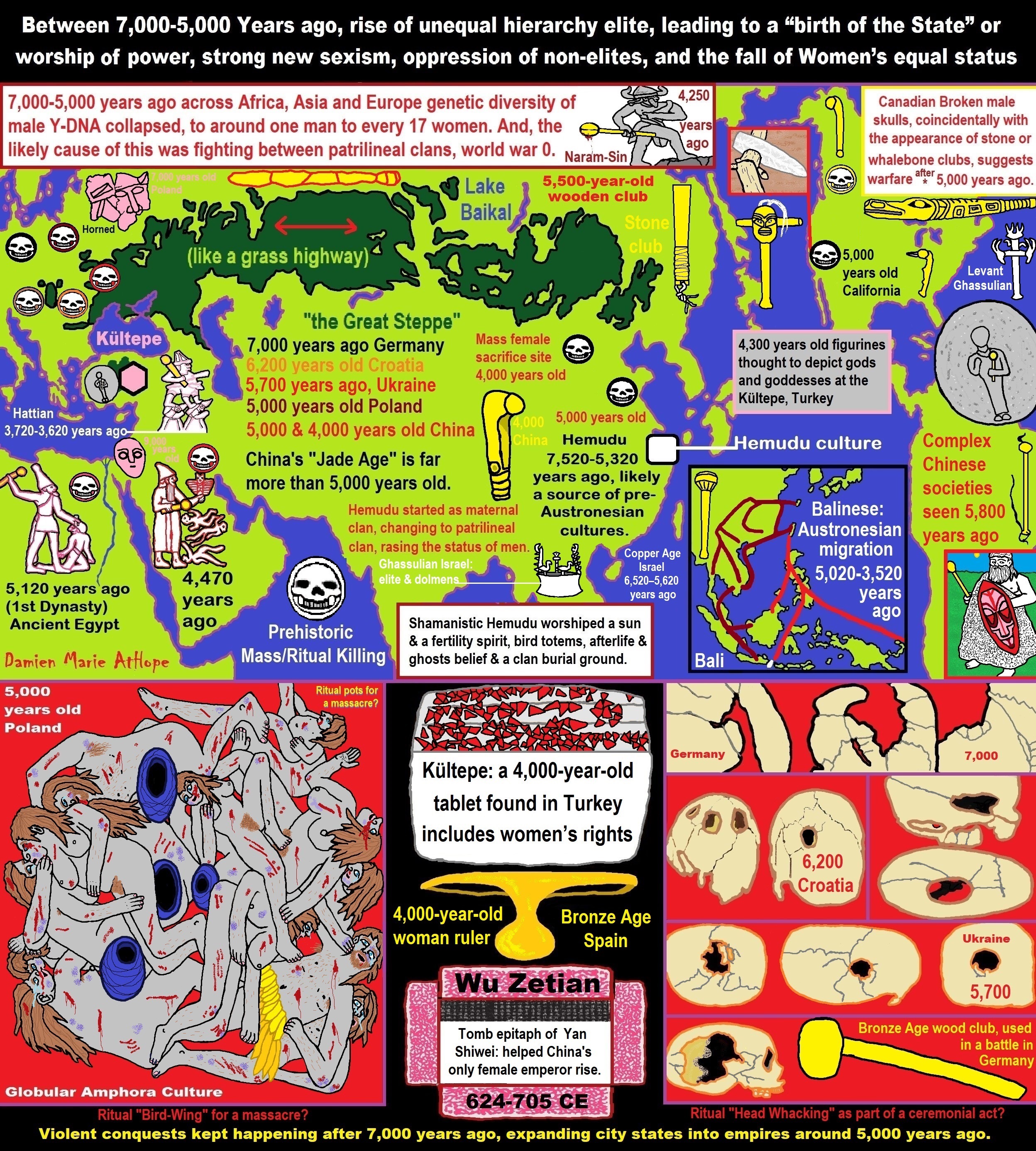

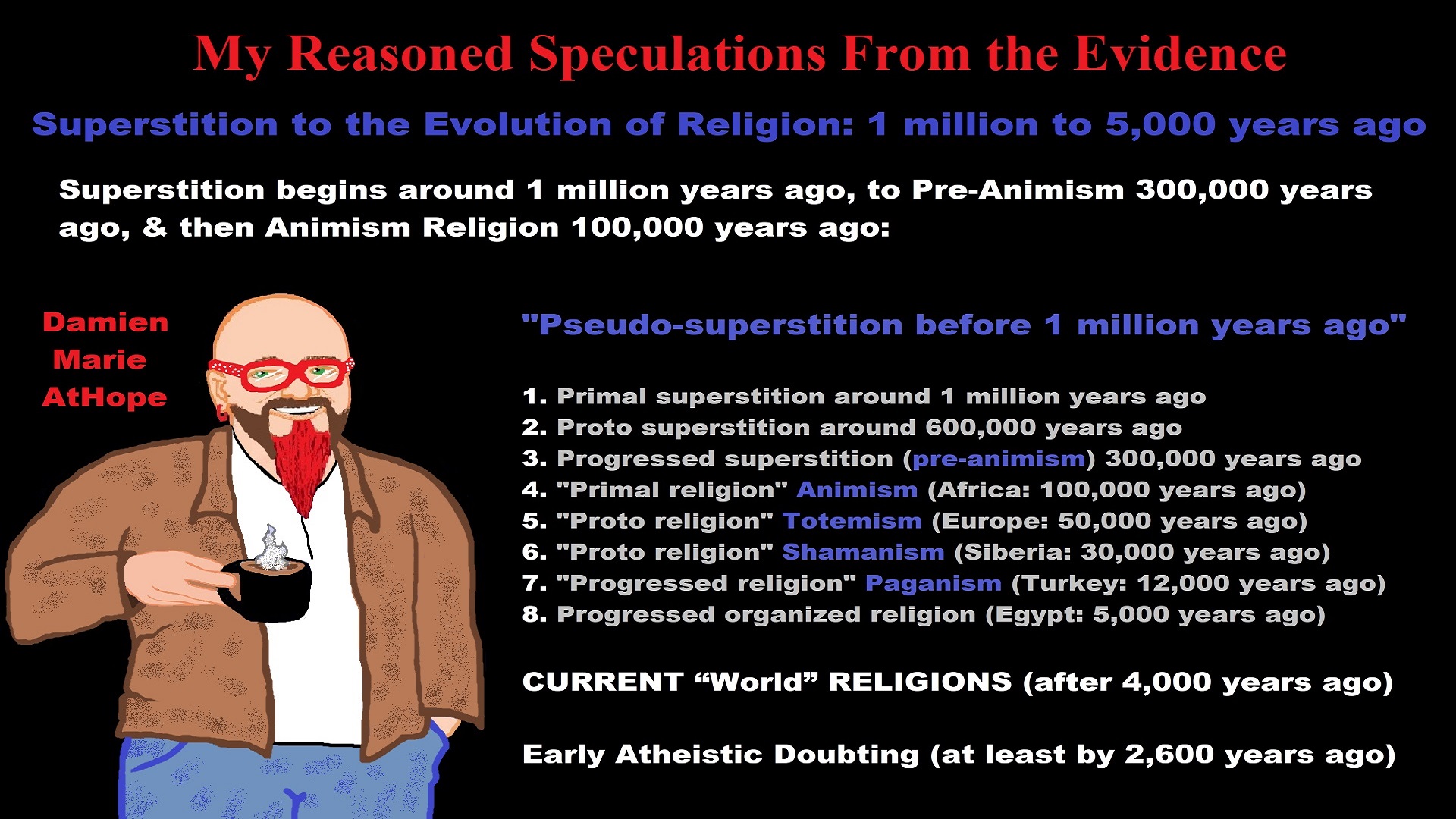

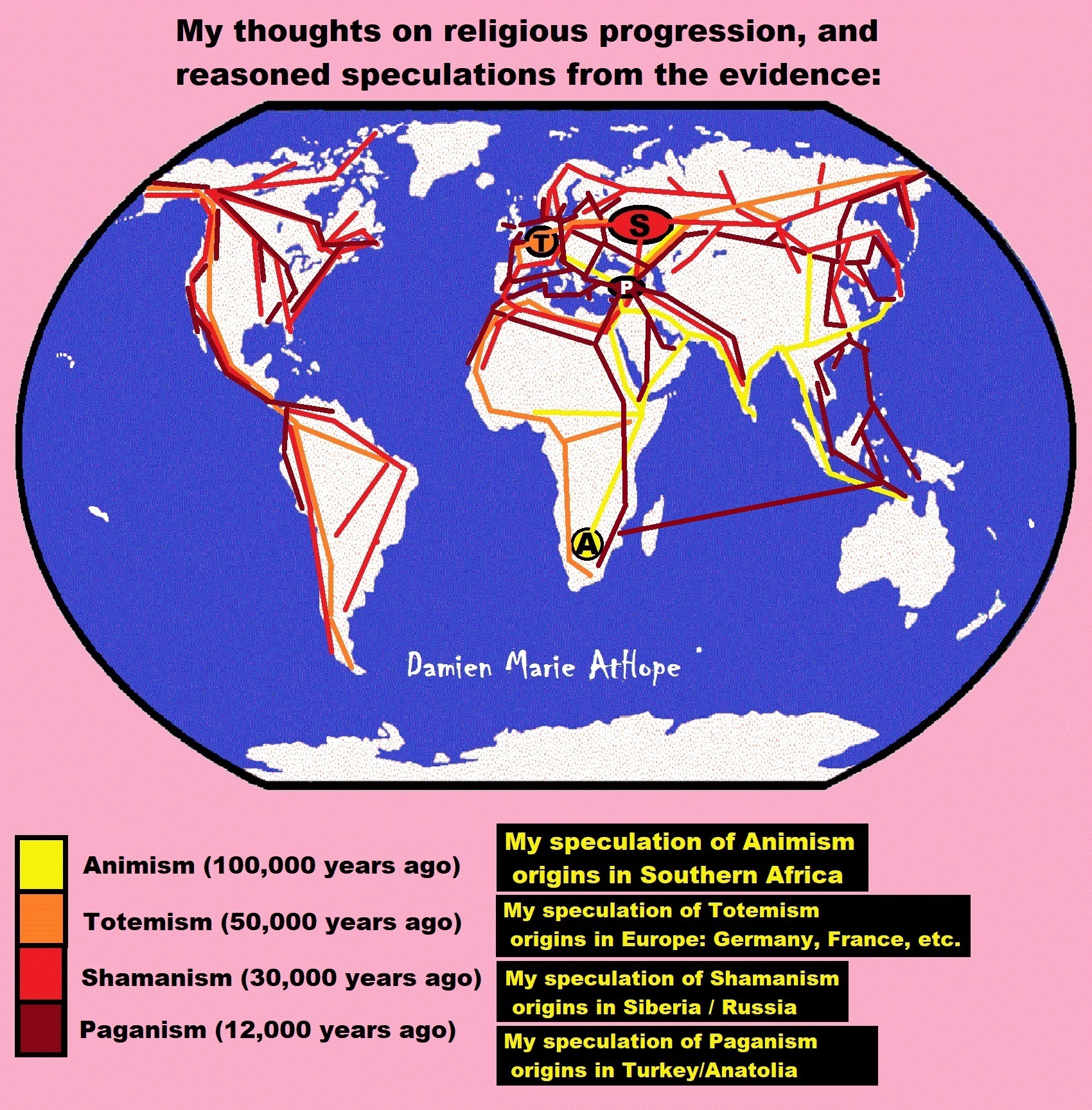

To me, societies start with primitive anarchism and socialism at least 100,000 years ago and are seen in animist-only thinking that is now largely limited to southern Africa today. Then they lose systematic anarchism possibly by 50,000 to 40,000 years ago but keeps socialism/primitive communism with the emergence of totemism largely limited to Europe and then spreading out from there. And to me, arcane/primitive capitalism emerges at or around 7,000 to 5,000 years ago in central Europe especially southern Germany or surrounding areas (Czecho-Slovakia and Austria), and then spread out from there.

7,522-6,522 years ago Linear Pottery culture which I think relates to Arcane Capitalism’s origins

7,522-6,522 years ago Linear Pottery culture, sometimes fortified or palisade settlements and weapon-traumatized bones also found, all which I think relates to Arcane Capitalism’s origins.

Early Pottery People movements and its eventual emergence of Elites, Private property, and the Private ownership of the means of production, (private accumulation of capital) which are seen as characteristics that distinguish capitalism from socialism.

Private property creates monopoly power, harming allocative efficiency, unlike the Common ownership of property helping allocative efficiency. ref

“An earlier view saw the Linear Pottery Culture as living a “peaceful, unfortified lifestyle”. Since then, settlements with palisades and weapon-traumatized bones have been discovered, such as at Herxheim, which, whether the site of a massacre or of a martial ritual, demonstrates, “…systematic violence between groups”. Most of the known settlements, however, left no trace of violence.” ref

Linear Pottery Culture (Linearbandkeramik) and Violence

“There seems to be considerable evidence that relationships between the Mesolithic hunter-gatherers in Europe and the LBK migrants were not entirely peaceful. Evidence for violence exists at many LBK village sites. Massacres of whole villages and portions of villages appear to be in evidence at sites such as Talheim, Schletz-Asparn, Herxheim, and Vaihingen. Mutilated remains suggesting cannibalism have been noted at Eilsleben and Ober-Hogern. The westernmost area appears to have the most evidence for violence, with about one-third of the burials showing evidence of traumatic injuries.” ref

“Further, there is a fairly high number of LBK villages that evidence some kind of fortification efforts: an enclosing wall, a variety of ditch forms, complex gates. Whether this resulted from direct competition between local hunter-gatherers and competing LBK groups is under investigation; this kind of evidence can only be partly helpful. However, the presence of violence on Neolithic sites in Europe is under some amount of debate. Some scholars have dismissed the notions of violence, arguing that the burials and the traumatic injuries are evidence of ritual behaviors, not inter-group warfare. Some stable isotope studies have noted that some mass burials are of non-local people; some evidence of enslavement has also been noted.” ref

“Although no significant population transfers were associated with the start of the Linear Pottery Culture, population diffusion along the wetlands of the mature civilization (about 5200 BCE) had leveled the high percentage of the rare gene sequence mentioned above by the late Linear Pottery Culture. The population was much greater by then, a phenomenon termed the Neolithic demographic transition (NDT). According to Bocquet-Appel beginning from a stable population of “small connected groups exchanging migrants” among the “hunter-gatherers and horticulturalists,” the Linear Pottery Culture experienced an increase in birth rate caused by a “reduction in the length of the birth interval.” ref

“The author hypothesizes a decrease in the weaning period made possible by the division of labor. At the end of the Linear Pottery Culture, the NDT was over and the population growth disappeared due to an increase in the mortality rate, caused, the author speculates, by new pathogens passed along by increased social contact. Investigation of the Neolithic skeletons found in the Talheim Death Pit suggests that prehistoric men from neighboring tribes were prepared to fight and kill each other in order to capture and secure women. The mass grave at Talheim in southern Germany is one of the earliest known sites in the archaeological record that shows evidence of organized violence in Early Neolithic Europe, among various Linear Pottery Culture tribes.” ref

Primitive socialism

“Primitive socialist accumulation, sometimes referred to as the socialist accumulation, was a concept put forth in the early Soviet Union during the period of the New Economic Policy. It was developed as a counterpart to the process of the primitive accumulation of capital that took place during the early stages and development of capitalist economies. Because the Soviet economy was underdeveloped and largely agrarian in nature, the Soviet Union would have to be the agent of primitive capital accumulation to rapidly develop the economy. The concept was proposed originally as a means to industrialize the Russian economy through extracting surplus from the peasantry to finance the industrial sector.

“The major proponent of the concept was Yevgeni Preobrazhensky in his 1926 work The New Economics which was based on his 1924 lecture in the Communist Academy, titled The Fundamental Law of Socialist Accumulation. The concept was proposed during the period of the New Economic Policy. Its main principle is that the state sector of the economy of the transitional period has to appropriate the peasant‘s surplus product to accumulate resources necessary for the growth of the industry. To this end, the major mechanisms were the foreign trade monopoly held by the state and price control in favor of industry which in effect caused price scissors.” ref

“This theory was criticized politically and associated with Leon Trotsky and the Left Opposition, but it was in fact put into practice by Joseph Stalin in the 1930s as when Stalin said in his speech to The Captains of Industry that the Soviet Union had to accomplish in a decade what England had taken centuries to do in terms of economic development in order to be prepared for an invasion from the West.” ref

“Beyond publications and policy debates, the application of this theory affected the working class as well, as more surplus was extracted from them for industrial capital investment. Real wages for both regular workers and managers plummeted despite the growing wage differential. Piece work production relations were introduced wholesale. The Soviet penal policy also tightened, causing a significant growth of inmates in the Gulag. It was not until after Stalin’s death that a minimum wage was introduced, reductions to piece work production relations were made and mass rehabilitations resulted in the dissolution of most of the Gulag.” ref

“Pre-Marxist communism, While Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels defined communism as a political movement, there were already similar ideas in the past which one could call communist experiments. Marx himself saw primitive communism as the original hunter-gatherer state of humankind. Marx theorized that only after humanity was capable of producing surplus did private property develop.” ref

“Karl Marx and other early communist theorists believed that hunter-gatherer societies as were found in the Paleolithic through to horticultural societies as found in the Chalcolithic were essentially egalitarian and he, therefore, termed their ideology to be primitive communism. Since Marx, sociologists and archaeologists have developed the idea of and research on primitive communism. According to Harry W. Laidler, one of the first writers to espouse a belief in the primitive communism of the past was the Roman Stoic philosopher Seneca who stated, “How happy was the primitive age when the bounties of nature lay in common…They held all nature in common which gave them secure possession of the public wealth.” ref

“Because of this he believed that such primitive societies were the richest as there was no poverty. Due to the strong evidence of an egalitarian society, lack of hierarchy, and lack of economic inequality, historian Murray Bookchin has argued that Çatalhöyük was an early example of anarcho-communism, and so an example of primitive communism in a proto-city. It has been argued that the Indus Valley Civilisation is an example of a primitive communist society, due to its perceived lack of conflict and social hierarchies. Others argue that such an assessment of the Indus Valley civilization is not correct.” ref

“The idea of a classless and stateless society based on communal ownership of property and wealth also stretches far back in Western thought long before The Communist Manifesto. There are scholars who have traced communist ideas back to ancient times, particularly in the work of Pythagoras and Plato. Followers of Pythagoras, for instance, lived in one building and held their property in common because the philosopher taught the absolute equality of property with all worldly possessions being brought into a common store.” ref

“It is argued that Plato’s Republic described in great detail a communist-dominated society wherein power is delegated in the hands of intelligent philosophers or military guardian class and rejected the concept of family and private property. In a social order divided into warrior-kings and the Homeric demos of craftsmen and peasants, Plato conceived an ideal Greek city-state without any form of capitalism and commercialism with business enterprise, political plurality, and working-class unrest considered as evils that must be abolished.” ref

“While it is a matter of debate as to the extent Plato was a precursor of communist thinking, his utopian speculations are shared by other utopian thinkers later on. An important feature that distinguishes Plato’s ideal society in the Republic is that the ban on private property applies only to the superior classes (rulers and warriors), not to the general public.” ref

“Peter Kropotkin argued that the elements of mutual aid and mutual defense expressed in the medieval commune of the middle ages and its guild system were the same sentiments of collective self-defense apparent in modern anarchism, communism, and socialism. From the High Middle Ages in Europe, various groups supporting Christian and religious communism were occasionally adopted by reformist Christian sects. An early 12th century proto-Protestant group originating in Lyon known as the Waldensians held their property in common in accordance with the Book of Acts, but were persecuted by the Catholic Church and retreated to Piedmont.” ref

“Around 1300 the Apostolic Brethren in northern Italy were taken over by Fra Dolcino who formed a sect known as the Dulcinians which advocated ending feudalism, dissolving hierarchies in the church, and holding all property in common. The Peasants’ Revolt in England has been an inspiration for “the medieval ideal of primitive communism”, with the priest John Ball of the revolt being an inspirational figure to later revolutionaries and having allegedly declared, “things cannot go well in England, nor ever will, until all goods are held in common.” ref

“Biblical scholars have argued that the mode of production seen in early Hebrew society was a communitarian domestic one that was akin to primitive communism. The early Church Fathers, like their non-Abrahamic predecessors, maintained that human society had declined to its current state from a now lost egalitarian social order. There are those who view that the early Christian Church, such as that one described in the Acts of the Apostles (specifically Acts 2:44-45 and Acts 4:32-45) was an early form of communism. The view is that communism was just Christianity in practice and Jesus Christ was himself a communist.” ref

“This link was highlighted in one of Marx’s early writings which stated: “As Christ is the intermediary unto whom man unburdens all his divinity, all his religious bonds, so the state is the mediator unto which he transfers all his Godlessness, all his human liberty”. Furthermore, the Marxist ethos that aims for unity reflects the Christian universalist teaching that humankind is one and that there is only one god who does not discriminate among people. Later historians have supported the reading of early church communities as communistic in structure. Pre-Marxist communism was also present in the attempts to establish communistic societies such as those made by the ancient Jewish sects the Essenes and by the Judean Desert sect.” ref

“Thomas Müntzer led a large Anabaptist communist movement during the German Peasants’ War. Engels’ analysis of Thomas Müntzer work in and the wider German Peasants’ War lead Marx and Engels to conclude that the communist revolution, when it occurred, would be led not by a peasant army but by an urban proletariat. In the 16th century, English writer Sir Thomas More portrayed a society based on common ownership of property in his treatise Utopia, whose leaders administered it through the application of reason.” ref

“Several groupings in the English Civil War supported this idea, but especially the Diggers who espoused communistic and agrarian ideals. Oliver Cromwell and the Grandees’ attitude to these groups was at best ambivalent and often hostile. Engels considered the Levellers of the English Civil War as a group representing the proletariat fighting for a utopian socialist society. Though later commentators have viewed the Levellers as a bourgeois group that did not seek a socialist society. During the Age of Enlightenment in 18th century France, some liberal writers increasingly began to criticize the institution of private property even to the extent they demanded its abolition. Such writings came from thinkers such as the deeply religious philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau.” ref

“In his hugely influential The Social Contract (1762) Rousseau outlined the basis for a political order based on popular sovereignty rather than the rule of monarchs, and in his Discourse on Inequality (1755) inveighed against the corrupting effects of private property claiming that the invention of private property had led to the,” crimes, wars, murders, and suffering” that plagued civilization. Raised a Calvinist, Rousseau was influenced by the Jansenist movement within the Roman Catholic Church. The Jansenist movement originated from the most orthodox Roman Catholic bishops who tried to reform the Roman Catholic Church in the 17th century to stop secularization and Protestantism. One of the main Jansenist aims was democratizing to stop the aristocratic corruption at the top of the Church hierarchy.” ref

“Victor d’Hupay’s 1779 work Project for a Philosophical Community described a plan for a communal experiment in Marseille where all private property was banned. d’Hupay referred to himself as a communiste, the French form of the word “communist”, in a 1782 letter, the first recorded instance of that term. The Shakers of the 18th century under Joseph Meacham developed and practiced their own form of communalism, as a sort of religious communism, where property had been made a “consecrated whole” in each Shaker community. Many Pre-Marx socialists lived, developed, and published their works and theories during this period from the late 18th century to the mid 19th century, including: Charles Fourier, Louis Blanqui, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Pierre Leroux, Thomas Hodgskin, Claude Henri de Saint-Simon, Wilhelm Weitling, and Étienne Cabet. Utopian socialist writers such as Robert Owen are also sometimes regarded as communists.” ref

“The currents of thought in French philosophy from the Enlightenment from Rousseau and d’Hupay proved influential during the French Revolution of 1789 in which various anti-monarchists, particularly the Jacobins, supported the idea of redistributing wealth equally among the people, including Jean-Paul Marat and Francois Babeuf. The latter was involved in the Conspiracy of the Equals of 1796 intending to establish a revolutionary regime based on communal ownership, egalitarianism, and the redistribution of property. Babeuf was directly influenced by Morelly’s anti-property utopian novel The Code of Nature and quoted it extensively, although he was under the erroneous impression it was written by Diderot.” ref

“Also during the revolution the publisher Nicholas Bonneville, the founder of the Parisian revolutionary Social Club used his printing press to spread the communist treatises of Restif and Sylvain Maréchal. Maréchal, who later joined Babeuf’s conspiracy, would state it his Manifesto of the Equals (1796), “we aim at something more sublime and more just, the COMMON GOOD or the COMMUNITY OF GOODS” and “The French Revolution is just a precursor of another revolution, far greater, far more solemn, which will be the last.” Restif also continued to write and publish books on the topic of communism throughout the Revolution. Accordingly, through their egalitarian programs and agitation Restif, Maréchal, and Babeuf became the progenitors of modern communism.” ref

“Babeuf’s plot was detected, however, and he and several others involved were arrested and executed. Because of his views and methods, Babeuf has been described as an anarchist, communist, and a socialist by later scholars. The word “communism” was first used in English by Goodwyn Barmby in a conversation with those he described as the “disciples of Babeuf”. Despite the setback of the loss of Babeuf, the example of the French Revolutionary regime and Babeuf’s doomed insurrection was an inspiration for French socialist thinkers such as Henri de Saint-Simon, Louis Blanc, Charles Fourier, and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. Proudhon, the founder of modern anarchism and libertarian socialism would later famously declare “property is theft!” a phrase first invented by the French revolutionary Brissot de Warville.” ref

“Maximilien Robespierre and his Reign of Terror, aimed at exterminating the monarchy, nobility, clergy, and conservatives, was admired among some anarchists, communists, and socialists. In his turn, Robespierre was a great admirer of Voltaire and Rousseau. By the 1830s and 1840s in France, the egalitarian concepts of communism and the related ideas of socialism had become widely popular in revolutionary circles thanks to the writings of social critics and philosophers such as Pierre Leroux and Théodore Dézamy, whose critiques of bourgeoisie liberalism and individualism led to a widespread intellectual rejection of laissez-faire capitalism on economic, philosophical and moral grounds.” ref

“According to Leroux writing in 1832, “To recognize no other aim than individualism is to deliver the lower classes to brutal exploitation. The proletariat is no more than a revival of antique slavery.” He also asserted that private ownership of the means of production allowed for the exploitation of the lower classes and that private property was a concept divorced from human dignity. It was only in the year 1840 that proponents of common ownership in France, including the socialists Théodore Dézamy, Étienne Cabet, and Jean-Jacques Pillot began to widely adopt the word “communism” as a term for their belief system. Those inspired by Étienne Cabet created the Icarian movement setting up communities based on non-religious communal ownership in various states across the US, the last of these communities located a few miles outside Corning, Iowa, disbanded voluntarily in 1898.” ref

“The participants of the Taiping Rebellion, who founded the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, are viewed by the Chinese Communist Party as proto-communists. Marx referred to the communist tendencies in the Taiping Rebellion as “Chinese socialism”. The Communards and the Paris Commune are often seen as proto-communists, and had a significant influence on the ideas of Karl Marx, who described it as an example of the “dictatorship of the proletariat“. Marx saw communism as the original state of mankind from which it rose through classical society and then feudalism to its current state of capitalism. He proposed that the next step in social evolution would be a return to communism. In its contemporary form, communism grew out of the workers’ movement of 19th-century Europe. As the Industrial Revolution advanced, socialist critics, blamed capitalism for creating a class of poor, urban factory workers who toiled under harsh conditions and for widening the gulf between rich and poor.” ref

Primitive communism

“Primitive communism is a way of describing the gift economies of hunter-gatherers throughout history, where resources and property hunted or gathered are shared with all members of a group in accordance with individual needs. In political sociology and anthropology, it is also a concept (often credited to Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels) that describes hunter-gatherer societies as traditionally being based on egalitarian social relations and common ownership. A primary inspiration for both Marx and Engels were Lewis H. Morgan‘s descriptions of “communism in living” as practiced by the Haudenosaunee of North America. In Marx’s model of socioeconomic structures, societies with primitive communism had no hierarchical social class structures or capital accumulation.” ref

Americas Pre-Columbian era Primitive Socialism/Communism

“Lewis Henry Morgan‘s descriptions of “communism in living” as practiced by the Haudenosaunee of North America, through research enabled by and coauthored with Ely S. Parker, were viewed as a form of pre-marxist communism. Morgan’s works were a primary inspiration for Marx and Engel’s description of primitive communism, and has led to some believing that early communist-like societies also existed outside of Europe, in Native American society and other pre-Colonized societies in the Western hemisphere. Though the belief of primitive communism as based on Morgan’s work is flawed due to Morgan’s misunderstandings of Haudenosaunee society and his, since proven wrong, theory of social evolution. This, and subsequent more accurate research, has led to the society of the Haudenosaunee to be of interest in communist and anarchist analysis. Particularly aspects where land was not treated as a commodity, communal ownership, and near non-existent rates of crime.” ref

“Primitive communism, meaning societies that practiced economic cooperation among the members of their community, where almost every member of a community had their own contribution to society, and land and natural resources would often be shared peacefully among the community. Some such communities in North America and South America still existed well into the 20th century. Historian Barry Pritzker lists the Acoma, Cochiti, and Isleta Puebloans as living in socialist-like societies. It is assumed modern egalitarianism seen in Pueblo communities stems from this historic socio-economic structure. David Graeber has also commented that the Inuit have practiced communism and fended off unjust hierarchy for “thousands of years”. The Chachapoya culture indicated an egalitarian non-hierarchical society through a lack of archaeological evidence and a lack of power expressing architecture that would be expected for societal leaders such as royalty or aristocracy.” ref

“The original idea of primitive communism is rooted in the idea of the noble savage present in the works of Jean-Jacques Rousseau and the early anthropology work of Morgan and Ely S. Parker. Engels was the first to write about primitive communism in detail, with the 1884 publication of The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State. Engels categorized primitive communist societies into two phases: the “wild” (hunter-gatherer) phase which lacked a permanent superstructure and had close relationships with the natural world, and the “barbarian” phase which held a superstructure like that of the ancient Germanic populations beyond the borders of the Roman Empire and the Indigenous peoples of North America before colonization by Europeans, being intra-communally egalitarian and matrilineal within the community. Marx and Engels used the term more broadly than Marxists did later, and applied it not only to hunter-gatherers but also to some communities that engaged in subsistence agriculture.” ref

“There is also no agreement among later scholars, including Marxists, on the historical extent, or longevity, of primitive communism. Marx and Engels also noted how capitalist accumulation latched itself onto social organizations of primitive communism. For instance, in private correspondence the same year that The Origin of the Family was published, Engels attacked European colonialism, describing the Dutch regime in Java directly organizing agricultural production and profiting from it, “on the basis of the old communistic village communities”. He added that cases like the Dutch East Indies, British India, and the Russian Empire showed “how today primitive communism furnishes … the finest and broadest basis of exploitation.” ref

“Anarchists, including Peter Kropotkin and Élisée Reclus, believed that societies that exemplified primitive communism were also examples of anarchist society before industrialisation. An example of this is Kropotkin’s anthropological work on anarchism and gift economies, Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution, which uses a study of the San people of southern Africa for its thesis. There was little development in the research of “primitive communism” among Marxist scholars beyond Engels’ study until the 20th and 21st centuries when Ernest Mandel, Rosa Luxemburg, Ian Hodder, Marija Gimbutas, and others took up and developed upon the original theses.” ref

“Non-Marxist scholars of prehistory and early history did not take the term seriously, although it was occasionally engaged with and often dismissed. The term primitive communism first appeared in Russian scholarship in the late 19th century, with references to primitive communism existing in ancient Crete. However, it was not researched in any depth until the 20th century, with work such as that of the ethnographer Dmitry Konstantinovich Zelenin, who looked at non-hunter-gatherer societies within the Soviet Union to identify remnants of primitive communism within their societies.” ref

“The belief of primitive communism as based on Morgan’s work is flawed due to Morgan’s misunderstandings of Haudenosaunee society and his since-proven-wrong theory of social evolution. Subsequent and more accurate research has focused on hunter-gatherer societies and aspects of such societies in relation to land ownership, communal ownership, and criminality and justice. A newer definition of primitive communism could be summarized as societies that practice economic cooperation among the members of their community, where almost every member of a community has their own contribution to society and land and natural resources are often shared peacefully among the community.” ref

“From the 20th century onward, sociologists and archaeologists have looked at the application of the term of primitive communism to hunter-gatherer societies of the paleolithic through to horticultural societies of the Chalcolithic, including Paleo-American societies from the lithic stage through the archaic period. Soviet archaeologists, influenced by Morgan’s and Engels’ works, interpreted the various paleolithic cultures that created Venus figures, many of which were found in the Soviet Union in the 1920s and 1930s, as evidence of the societies being primitive communist and matriarchal in nature. The psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich concluded in 1931 the existence of an early communism from the information in Bronisław Malinowski‘s work. However, Malinowski and the philosopher Erich Fromm did not consider this conclusion to be compelling. Ernest Borneman supported Reich’s ideas in his 1975 work Das Patriarchat.” ref

Primitive Communist Societies

“In a primitive communist society, the productive forces would have consisted of all able-bodied persons engaged in obtaining food and resources from the land, and everyone would share in what was produced by hunting and gathering. There would be no private property, which is distinguished from personal property such as articles of clothing and similar personal items, because primitive society produced no surplus; what was produced was quickly consumed and this was because there existed no division of labor, hence people were forced to work together. The few things that existed for any length of time – the means of production (tools and land), housing – were held communally. In Engels’ view, in association with matrilocal residence and matrilineal descent, reproductive labor was shared. There would have also been a lack of state.” ref

“Domestication of animals and plants following the Neolithic Revolution through herding and agriculture, and the subsequent urban revolution, were seen as the turning point from primitive communism to class society, as this transition was followed by the appearance of private ownership and slavery, with the inequality that those entail. In addition, parts of the population began to specialize in different activities, such as manufacturing, culture, philosophy, and science which lead in part to social stratification and the development of social classes. Egalitarian and communist-like hunter-gatherer societies have been studied and described by many well-known social anthropologists including James Woodburn, Richard Borshay Lee, Alan Barnard, and Jerome Lewis.” ref

“Anthropologists such as Christopher Boehm, Chris Knight, and Lewis offer theoretical accounts to explain how communistic, assertively egalitarian social arrangements might have emerged in the prehistoric past. Despite differences in emphasis, these and other anthropologists follow Engels in arguing that evolutionary change—resistance to primate-style sexual and political dominance—culminated eventually in a revolutionary transition. Lee criticizes the mainstream and dominant culture‘s long-time bias against the idea of primitive communism, deriding “Bourgeois ideology [that] would have us believe that primitive communism doesn’t exist. In popular consciousness, it is lumped with romanticism, exoticism: the noble savage.” ref

“Papers have argued that the depiction of hunter-gatherers as egalitarian is misleading. According to one paper published in Current Anthropology, while levels of inequality were low, they were still present, with the average hunter-gatherer group having a Gini coefficient of 0.25 (for comparison, this was attained by the nation of Denmark in 2007). This argument is in part supported by Alain Testart and others, who have said that a society without property is not free from problems of exploitation, domination, or wars. Marx and Engels, however, did not argue that communism brought about equality, as according to them equality was a concept without connection in physical reality. Testart does support Engels’ observations that societies without surplus are economically egalitarian and conversely that societies with a surplus are unequal.” ref

“Arnold Petersen has used the existence of primitive communism to argue against the idea that communism goes against human nature. Hikmet Kıvılcımlı in his The Thesis of History argued that in pre-capitalist societies, the main dynamic of historical change “was not class struggle within society but rather the strong collective action” of egalitarian and collectivist values of “primitive socialist society”. Biblical scholars have also argued that the mode of production seen in early Hebrew society was a communitarian domestic one that was akin to primitive communism. Claude Meillassoux has commented on how the mode of production seen in many primitive societies is a communistic domestic one.” ref

“Due to the strong evidence of an egalitarian society, lack of hierarchy, and lack of economic inequality, historian Murray Bookchin has argued that Çatalhöyük was an early example of anarcho-communism, and so an example of primitive communism in a proto-city. However, still, others use Çatalhöyük a very large Neolithic and Chalcolithic proto-city settlement in southern Anatolia/Turkey, which existed from approximately 7500 to 6400 BCE or 9,522-8,400 years ago, as an example that refutes the concept of primitive communism. Similarly, it has been argued that the Indus Valley Civilisation is an example of a primitive communist society due to its perceived lack of conflict and social hierarchies. Daniel Miller and others argue that such an assessment of the Indus Valley civilization is not correct.” ref

“The Marxist archaeologist V. Gordon Childe carried out excavations in Scotland from the 1920s and concluded that there was a neolithic classless society that reached as far as the Orkney Islands. This has been supported by Perry Anderson, who argued that primitive communism was prevalent in pre-Roman western Europe. Descriptions of such societies are also present in the works of classical authors. The Indian communist politician Shripad Amrit Dange considered ancient Indian society to be of a primitive communist nature. Other communists within India have also labeled the societies of current indigenous groups, such as the Adivasi, as examples of primitive communism. In Alfred Radcliffe-Brown‘s study of the Andamanese at the beginning of the 20th century, he comments that they have “customs which result in an approach to communism” and “their domestic policy may be described as communism.” ref

“Alexander Mikhailovich Zolotarev, in his 1960 work on the development of religious cult communities from tribal communities in the Balkans, spoke of the primitive communism of the “archaic form of the tribal system”. Rolf Jensen in the 1980s conducted a historical study of Wolof society in west Africa looking at the development of class antagonisms from a primitive communist society. Also in the 1980s, Bourgeault looked at the forceful transition of indigenous societies in Canada from their traditional structures, which were anarchist and communistic in nature, into capitalist exploitation due to encroaching imperialism and colonialism. Such an area of interest has been a common topic of research for many fields beyond just Marxist scholars.” ref

“Some anthropologists, such as John H. Moore, have continued to argue that societies such as those of Native Americans constitute primitive communist societies, whilst acknowledging and incorporating the research showing the complexity and diversity in native American societies. James Connolly believed that “Gaelic primitive communism” existed in remnants in Irish society after it “had almost entirely disappeared” from much of western Europe. The agrarian communes of the rundale system in Ireland have subsequently been assessed using a framework of primitive communism, where the system fits Marx and Engels’ definition. Soviet theorists and anthropologists, such as Lev Sternberg, considered some of the indigenous groups of Siberia and the Russian far east (such as the Nivkh) to be primitive communists in nature.” ref

Primitive Communism Criticism

“Criticism of the idea of primitive communism relates to definitions of property, where anthropologists such as Margaret Mead argue that private property exists in hunter-gatherer and other “primitive societies” but provide examples that Marx and subsequent theorists label as personal property, not private property. The idea has also been critiqued by other anthropologists for being based on Morgan’s evolutionary model of society and for romanticising non‐Western societies. Western and non-Western Scholars have criticized applying models that are too ethnocentrically European to non-European societies.” ref

“Western scholars, including Leacock, have also criticized the ethnocentric point of view and biases in previous ethnographic research into hunter-gatherer societies. This is similar to criticism of adhering to stadialism in analyzing cultures. Feminist scholars have criticized the idea of the lack of subjugation of women as suggested from the works of Engels, while Marxist feminists have been critical of and have reassessed Engels’ ideas and suggestions in The Origin of the Family related to the development of women’s subjugation in the transition from primitive communism to class society. The Marxian economist Ernest Mandel criticized the research of Soviet scholars on primitive communism due to the influence of “Soviet-Marxist ideology” in their social sciences work.” ref

“David Graeber and David Wengrow‘s The Dawn of Everything challenges the notion that humans ever lived in precarious, small-scale societies with little or no surplus. While they provide examples of sharing egalitarian societies in pre-history they claim that a huge variety of complex societies (some with large cities) existed long before the supposed agricultural and then urban revolutions proposed by V. Gordon Childe. Graeber and Wengrow’s understanding of hunter-gatherer societies has, however, been questioned by other anthropologists. The use of the term “communism” to describe these societies has been questioned when put in comparison with a future post-industrial communism, particularly in relation to the difference in scale from small communal groups to the size of modern nation-states.” ref

The use of the term “primitive” can be taken wrong…

“Primitive” in recent anthropological and social studies has begun to fall out of use due to racial stereotypes surrounding the ideas of what is primitive. Such a move has been supported by indigenous peoples who have faced racial stereotyping and violence due to being viewed as “primitive”. Due to this, the term “primitive communism” may be replaced by terms such as Pre-Marxist communism. Alain Testart and others have said that anthropologists should be careful when using research on current hunter-gatherer societies to determine the structure of societies in the paleolithic, where viewing current hunter-gatherer communities as “the most ancient of so-called primitive societies” is likely due to appearances and perceptions and does not reflect the progress and development that such societies have undergone in the past 10,000 years. There have been Marxist historians criticized for their comments on the “primitivism” and “barbarism” of societies prior to their contact with European empires, such as the comments of Endre Sík. Such views on “primitivism” and “barbarism” are also prevalent in the works of their non-Marxist contemporaries. Marxist anthropologists have criticized and denounced Soviet anthropologists and historians for declaring indigenous communities they were studying for primitive communism as “degenerate.” ref

Primitive Accumulation of Capital

“In Marxian economics and preceding theories, the problem of primitive accumulation (also called previous accumulation, original accumulation) of capital concerns the origin of capital, and therefore of how class distinctions between possessors and non-possessors came to be. Adam Smith‘s account of primitive-original accumulation depicted a peaceful process, in which some workers labored more diligently than others and gradually built up wealth, eventually leaving the less diligent workers to accept living wages for their labor. Karl Marx rejected this account as “childish” for its omission of violence, war, enslavement, and colonialism in the historical accumulation of land and wealth. Marxist Scholar David Harvey explains Marx’s primitive accumulation as a process that principally “entailed taking land, say, enclosing it, and expelling a resident population to create a landless proletariat, and then releasing the land into the privatized mainstream of capital accumulation.” ref

“The concept was initially referred to in various different ways, and the expression of an “accumulation” at the origin of capitalism began to appear with Adam Smith. Smith, writing The Wealth of Nations in his native English, spoke of a “previous” accumulation; Karl Marx, writing Das Kapital in German, reprised Smith’s expression, by translating it to German as ursprünglich (“original, initial”); Marx’s translators, in turn, rendered it into English as primitive. James Steuart, with his 1767 work, is considered by some scholars as the greatest classical theorist of primitive accumulation.” ref

The myths of political economy

“In disinterring the origins of capital, Marx felt the need to dispel what he felt were religious myths and fairy-tales about the origins of capitalism. Marx wrote:

This primitive accumulation plays in political economy about the same part as original sin in theology. Adam bit the apple, and thereupon sin fell on the human race. Its origin is supposed to be explained when it is told as an anecdote of the past. In times long gone-by there were two sorts of people; one, the diligent, intelligent, and, above all, frugal elite; the other, lazy rascals, spending their substance, and more, in riotous living. (…) Thus it came to pass that the former sort accumulated wealth, and the latter sort had at last nothing to sell except their own skins. And from this original sin dates the poverty of the great majority that, despite all its labor, has up to now nothing to sell but itself, and the wealth of the few that increases constantly although they have long ceased to work. Such childishness is every day preached to us in the defense of property.— Capital, Volume I, chapter 26″ ref

“What has to be explained is how the capitalist relations of production are historically established. In other words, how it comes about that means of production get to be privately owned and traded in, and how the capitalists can find workers on the labor market ready and willing to work for them, because they have no other means of livelihood; also referred to as the “Reserve Army of Labor.” ref

The link between primitive accumulation and colonialism

“At the same time as local obstacles to investment in manufactures are being overcome, and a unified national market is developing with a nationalist ideology, Marx sees a strong impulse to business development coming from world trade: The discovery of gold and silver in America, the extirpation, enslavement, and entombment in mines of the aboriginal population, the beginning of the conquest and looting of the East Indies, the turning of Africa into a warren for the commercial hunting of black-skins, signaled the rosy dawn of the era of capitalist production. These idyllic proceedings are the chief moments of primitive accumulation. On their heels treads the commercial war of the European nations, with the globe for a theatre. It begins with the revolt of the Netherlands from Spain, assumes giant dimensions in England’s Anti-Jacobin War, and is still going on in the opium wars against China, &c.” ref

“The different moments of primitive accumulation distribute themselves now, more or less in chronological order, particularly over Spain, Portugal, Holland, France, and England. In England at the end of the 17th century, they arrive at a systematical combination, embracing the colonies, the national debt, the modern mode of taxation, and the protectionist system. These methods depend in part on brute force, e.g., the colonial system. But, they all employ the power of the state, the concentrated and organized force of society, to hasten, hot-house fashion, the process of transformation of the feudal mode of production into the capitalist mode, and to shorten the transition. Force is the midwife of every old society pregnant with a new one. It is itself an economic power.— Capital, Volume I, chapter 31, emphasis added.” ref

Primitive Accumulation and Privatization

“According to Marx, the whole purpose of primitive accumulation is to privatize the means of production, so that the exploiting owners can make money from the surplus labor of those who, lacking other means, must work for them. Marx says that primitive accumulation means the expropriation of the direct producers, and more specifically “the dissolution of private property based on the labor of its owner… Self-earned private property, that is based, so to say, on the fusing together of the isolated, independent laboring individual with the conditions of his labor, is supplanted by capitalistic private property, which rests on exploitation of the nominally free labor of others, i.e., on wage-labor” (emphasis added).” ref

The social relations of capitalism

“In the last chapter of Capital, Volume I, Marx described the social conditions he thought necessary for capitalism with a comment about Edward Gibbon Wakefield‘s theory of colonization:

Wakefield discovered that in the Colonies, property in money, means of subsistence, machines, and other means of production, does not as yet stamp a man as a capitalist if there be wanting the correlative – the wage-worker, the other man who is compelled to sell himself of his own free-will. He discovered that capital is not a thing, but a social relation between persons, established by the instrumentality of things. Mr. Peel, he moans, took with him from England to Swan River, West Australia, means of subsistence and of production to the amount of £50,000. Mr. Peel had the foresight to bring with him, besides, 3,000 persons of the working-class, men, women, and children. Once arrived at his destination, ‘Mr. Peel was left without a servant to make his bed or fetch him water from the river.’ Unhappy Mr. Peel, who provided for everything except the export of English modes of production to Swan River!” ref

“This is indicative of Marx’s more general fascination with settler colonialism, and his interest in how “free” lands—or, more accurately, lands seized from indigenous people—could disrupt capitalist social relations.” ref

Ongoing primitive accumulation

“Orthodox” Marxists see primitive accumulation as something that happened in the late Middle Ages and finished long ago, when the capitalist industry started. They see primitive accumulation as a process happening in the transition from the feudal “stage” to the capitalist “stage”. However, this can be seen as a misrepresentation of both Marx’s ideas and historical reality, since feudal-type economies exist in various parts of the world, even in the 21st century. Marx’s story of primitive accumulation is best seen as a special case of the general principle of capitalist market expansion. In part, trade grows incrementally, but usually, the establishment of capitalist relations of production involves force and violence; transforming property relations means that assets previously owned by some people are no longer owned by them, but by other people, and making people part with their assets in this way involves coercion. This is an ongoing process of expropriation, Proletarianization, and Urbanization.” ref

“In his preface to Das Kapital Vol. 1, Marx compares the situation of England and Germany and points out that less developed countries also face a process of primitive accumulation. Marx comments that “if, however, the German reader shrugs his shoulders at the condition of the English industrial and agricultural laborers, or in optimist fashion comforts himself with the thought that in Germany things are not nearly so bad, I must plainly tell him, “De te fabula narratur! (the tale is told of you!)”.Marx was referring here to the expansion of the capitalist mode of production (not the expansion of world trade), through expropriation processes. He continues, “Intrinsically, it is not a question of the higher or lower degree of development of the social antagonism that results from the natural laws of capitalist production. It is a question of these laws themselves, of these tendencies working with iron necessity towards inevitable results. The country that is more developed industrially only shows, to the less developed, the image of its own future.” ref

David Harvey’s theory of accumulation by dispossession

“David Harvey expands the concept of “primitive accumulation” to create a new concept, “accumulation by dispossession“, in his 2003 book, The New Imperialism. Like Mandel, Harvey claims that the word “primitive” leads to a misunderstanding in the history of capitalism: that the original, “primitive” phase of capitalism is somehow a transitory phase that need not be repeated once commenced. Instead, Harvey maintains that primitive accumulation (“accumulation by dispossession”) is a continuing process within the process of capital accumulation on a world scale. Because the central Marxian notion of crisis via “over-accumulation” is assumed to be a constant factor in the process of capital accumulation, the process of “accumulation by dispossession” acts as a possible safety valve that may temporarily ease the crisis. This is achieved by simply lowering the prices of consumer commodities (thus pushing up the propensity for general consumption), which in turn is made possible by the considerable reduction in the price of production inputs. Should the magnitude of the reduction in the price of inputs outweigh the reduction in the price of consumer goods, it can be said that the rate of profit will, for the time being, increase.” ref

“Thus: Access to cheaper inputs is, therefore, just as important as access to widening markets in keeping profitable opportunities open. The implication is that non-capitalist territories should be forced open not only to trade (which could be helpful) but also to permit capital to invest in profitable ventures using cheaper labor power, raw materials, low-cost land, and the like. The general thrust of any capitalist logic of power is not that territories should be held back from capitalist development, but that they should be continuously opened up.— David Harvey, The New Imperialism, p. 139.” ref

“Harvey’s theoretical extension encompasses more recent economic dimensions such as intellectual property rights, privatization, and predation and exploitation of nature and folklore. Privatization of public services puts enormous profit into capitalists’ hands. If it belonged to the public sector, that profit would not have existed. In that sense, the profit is created by the dispossession of peoples or nations. Destructive industrial use of the environment is similar because the environment “naturally” belongs to everyone, or to no one: factually, it “belongs” to whoever lives there. Multinational pharmaceutical companies collect information about how herb or other natural medicine is used among natives in a less-developed country, do some R&D to find the material that make those natural medicines effective, and patent the findings.” ref

“By doing so, multinational pharmaceutical companies can now sell the medicine to the natives who are the original source of the knowledge that made the production of medicine possible. That is, dispossession of folklore (knowledge, wisdom, practice) through intellectual property rights. David Harvey also argues that accumulation by dispossession is a temporal or partial solution to over-accumulation. Because accumulation by dispossession makes raw materials cheaper, the profit rate can at least temporarily go up. Harvey’s interpretation has been criticized by Brass, who disputes the view that what is described as present-day primitive accumulation, or accumulation by dispossession, entails proletarianization.

“Because the latter is equated by Harvey with the separation of the direct producer (mostly smallholders) from the means of production (land), Harvey assumes this results in the formation of a workforce that is free. By contrast, Brass points out that in many instances the process of depeasantization leads to workers who are unfree, because they are unable personally to commodify or recommodify their labor-power, by selling it to the highest bidder.” ref

Schumpeter’s critique of Marx’s theory

“The economist Joseph Schumpeter disagreed with the Marxist explanation of the origin of capital, because Schumpeter did not believe in exploitation. In liberal economic theory, the market returns to each person the exact value she added into it; capitalists are just people who are very adept at saving and whose contributions are especially magnificent, and they do not take anything away from other people or the environment. Liberals believe that capitalism has no internal flaws or contradictions; only outside threats. To liberals, the idea of the necessity of violent primitive accumulation to capital is particularly incendiary. Schumpeter wrote rather testily:

[The problem of Original Accumulation] presented itself first to those authors, chiefly to Marx and the Marxists, who held an exploitation theory of interest and had, therefore, to face the question of how exploiters secured control of an initial stock of ‘capital’ (however defined) with which to exploit – a question which that theory per se is incapable of answering, and which may obviously be answered in a manner highly uncongenial to the idea of exploitation.— Joseph Schumpeter, Business Cycles, Vol. 1, New York; McGraw-Hill, 1939, p. 229.” ref

“Schumpeter argued that imperialism was not a necessary jump-start for capitalism, nor is it needed to bolster capitalism, because imperialism pre-existed capitalism. Schumpeter believed that, whatever the empirical evidence, capitalist world trade could in principle just expand peacefully. If imperialism occurred, Schumpeter asserted, it has nothing to do with the intrinsic nature of capitalism itself, or with capitalist market expansion. The distinction between Schumpeter and Marx here is subtle. Marx claimed that capitalism requires violence and imperialism—first, to kick-start capitalism with a pile of booty and to dispossess a population to induce them to enter into capitalist relations as workers, and then to surmount the otherwise-fatal contradictions generated within capitalist relations over time. Schumpeter’s view was that imperialism is an atavistic impulse pursued by a state independent of the interests of the economic ruling class.” ref

“Imperialism is the object-less disposition of a state to expansion by force without assigned limits… Modern Imperialism is one of the heirlooms of the absolute monarchical state. The “inner logic” of capitalism would have never evolved it. Its sources come from the policy of the princes and the customs of a pre-capitalist milieu. But even an export monopoly is not imperialism and it would never have developed to imperialism in the hands of the pacific bourgeoisie. This happened only because the war machine, its social atmosphere, and the martial will were inherited and because a martially oriented class (i.e., the nobility) maintained itself in a ruling position with which of all the varied interests of the bourgeoisie the martial ones could ally themselves. This alliance keeps alive fighting instincts and ideas of domination. It led to social relations that perhaps ultimately are to be explained by relations of production but not by the productive relations of capitalism alone.— Joseph A. Schumpeter, The Sociology of Imperialism (1918).” ref

Capital Accumulation

“Capital accumulation (also termed the accumulation of capital) is the dynamic that motivates the pursuit of profit, involving the investment of money or any financial asset with the goal of increasing the initial monetary value of said asset as a financial return whether in the form of profit, rent, interest, royalties or capital gains. The aim of capital accumulation is to create new fixed and working capitals, broaden and modernize the existing ones, grow the material basis of social-cultural activities, as well as constituting the necessary resource for reserve and insurance. The process of capital accumulation forms the basis of capitalism, and is one of the defining characteristics of a capitalist economic system.” ref

“The definition of capital accumulation is subject to controversy and ambiguities, because it could refer to:

“Most often, capital accumulation involves both a net addition and a redistribution of wealth, which may raise the question of who really benefits from it most. If more wealth is produced than there was before, a society becomes richer; the total stock of wealth increases. But if some accumulate capital only at the expense of others, wealth is merely shifted from A to B. It is also possible that some accumulate capital much faster than others. When one person is enriched at the expense of another in circumstances that the law sees as unjust it is called unjust enrichment. In principle, it is possible that a few people or organizations accumulate capital and grow richer, although the total stock of wealth of society decreases.” ref

“In economics and accounting, capital accumulation is often equated with an investment of profit income or savings, especially in real capital goods. The concentration and centralization of capital are two of the results of such accumulation.” ref

“Capital accumulation refers ordinarily to:

- real investment in tangible means of production, such as acquisitions, research, and development, etc. that can increase the capital flow.

- investment in financial assets represented on paper, yielding profit, interest, rent, royalties, fees, or capital gains.

- investment in non-productive physical assets such as residential real estate or works of art that appreciate in value.” ref

“And by extension to:

- human capital, i.e., new education and training increasing the skills of the (potential) labor force which can increase earnings from work.

- social capital, i.e. the wealth and productive capacity that the people in a society hold in common, rather than as individuals or corporations.

- etc.” ref

“Both non-financial and financial capital accumulation is usually needed for economic growth, since additional production usually requires additional funds to enlarge the scale of production. Smarter and more productive organization of production can also increase production without increased capital. Capital can be created without increased investment by inventions or improved organization that increase productivity, discoveries of new assets (oil, gold, minerals, etc.), the sale of property, etc. In modern macroeconomics and econometrics the term capital formation is often used in preference to “accumulation”, though the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) refers nowadays to “accumulation”. The term is occasionally used in national accounts.” ref

“Marx borrowed the idea of capital accumulation or the concentration of capital from early socialist writers such as Charles Fourier, Louis Blanc, Victor Considerant, and Constantin Pecqueur. In Karl Marx‘s economic theory, capital accumulation is the operation whereby profits are reinvested into the economy, increasing the total quantity of capital. Capital was understood by Marx to be expanding value, that is, in other terms, as a sum of capital, usually expressed in money, that is transformed through human labor into a larger value and extracted as profits. Here, capital is defined essentially as economic or commercial asset value that is used by capitalists to obtain additional value (surplus-value). This requires property relations that enable objects of value to be appropriated and owned, and trading rights to be established.” ref

Over-accumulation and crisis

“The Marxist analysis of capital accumulation and the development of capitalism identifies systemic issues with the process that arise with expansion of the productive forces. A crisis of overaccumulation of capital occurs when the rate of profit is greater than the rate of new profitable investment outlets in the economy, arising from increasing productivity from a rising organic composition of capital (higher capital input to labor input ratio). This depresses the wage bill, leading to stagnant wages and high rates of unemployment for the working class while excess profits search for new profitable investment opportunities. Marx believed that this cyclical process would be the fundamental cause for the dissolution of capitalism and its replacement by socialism, which would operate according to a different economic dynamic.” ref

“In Marxist thought, socialism would succeed capitalism as the dominant mode of production when the accumulation of capital can no longer sustain itself due to falling rates of profit in real production relative to increasing productivity. A socialist economy would not base production on the accumulation of capital, instead basing production on the criteria of satisfying human needs and directly producing use-values. This concept is encapsulated in the principle of production for use.” ref

Concentration and centralization

“According to Marx, capital has the tendency for concentration and centralization in the hands of richest capitalists. Marx explains:

It is the concentration of capitals already formed, destruction of their individual independence, expropriation of capitalist by capitalist, the transformation of many small into few large capitals…. Capital grows in one place to a huge mass in a single hand, because it has in another place been lost by many…. The battle of competition is fought by cheapening of commodities. The cheapness of commodities demands, caeteris paribus, on the productiveness of labor, and this again on the scale of production. Therefore, the larger capitals beat the smaller. It will further be remembered that, with the development of the capitalist mode of production, there is an increase in the minimum amount of individual capital necessary to carry on a business under its normal conditions. The smaller capitals, therefore, crowd into spheres of production that Modern Industry has only sporadically or incompletely got hold of. Here competition rages…. It always ends in the ruin of many small capitalists, whose capitals partly pass into the hands of their conquerors, partly vanish.” ref

Rate of accumulation

“In Marxian economics, the rate of accumulation is defined as (1) the value of the real net increase in the stock of capital in an accounting period, (2) the proportion of realized surplus-value or profit-income which is reinvested, rather than consumed. This rate can be expressed by means of various ratios between the original capital outlay, the realized turnover, surplus-value or profit, and reinvestment’s (see, e.g., the writings of the economist Michał Kalecki). Other things being equal, the greater the amount of profit-income that is disbursed as personal earnings and used for consumption purposes, the lower the savings rate and the lower the rate of accumulation is likely to be. However, earnings spent on consumption can also stimulate market demand and higher investment. This is the cause of endless controversies in economic theory about “how much to spend, and how much to save.” ref

“In a boom period of capitalism, the growth of investments is cumulative, i.e. one investment leads to another, leading to a constantly expanding market, an expanding labor force, and an increase in the standard of living for the majority of the people. In a stagnating, decadent capitalism, the accumulation process is increasingly oriented towards investment on military and security forces, real estate, financial speculation, and luxury consumption. In that case, income from value-adding production will decline in favor of interest, rent, and tax income, with as a corollary an increase in the level of permanent unemployment.” ref

“As a rule, the larger the total sum of capital invested, the higher the return on investment will be. The more capital one owns, the more capital one can also borrow and reinvest at a higher rate of profit or interest. The inverse is also true, and this is one factor in the widening gap between the rich and the poor. Ernest Mandel emphasized that the rhythm of capital accumulation and growth depended critically on (1) the division of a society’s social product between necessary product and surplus product, and (2) the division of the surplus product between investment and consumption. In turn, this allocation pattern reflected the outcome of competition among capitalists, competition between capitalists and workers, and competition between workers. The pattern of capital accumulation can therefore never be simply explained by commercial factors, it also involved social factors and power relationships.” ref

Circuit of capital accumulation from production

“Strictly speaking, capital has accumulated only when realized profit income has been reinvested in capital assets. But the process of capital accumulation in production has, as suggested in the first volume of Marx’s Das Kapital, at least seven distinct but linked moments:

- The initial investment of capital (which could be borrowed capital) in means of production and labor power.

- The command over surplus labor and its appropriation.

- The valorization (increase in value) of capital through production of new outputs.

- The appropriation of the new output produced by employees, containing the added value.

- The realization of surplus-value through output sales.

- The appropriation of realized surplus-value as (profit) income after deduction of costs.

- The reinvestment of profit income in production.” ref

“All of these moments do not refer simply to an economic or commercial process. Rather, they assume the existence of legal, social, cultural, and economic power conditions, without which creation, distribution, and circulation of the new wealth could not occur. This becomes especially clear when the attempt is made to create a market where none exists, or where people refuse to trade. In fact, Marx argues that the original or primitive accumulation of capital often occurs through violence, plunder, slavery, robbery, extortion, and theft. He argues that the capitalist mode of production requires that people be forced to work in value-adding production for someone else, and for this purpose, they must be cut off from sources of income other than selling their labor power.” ref

Simple and expanded reproduction

“In volume 2 of Das Kapital, Marx continues the story and shows that, with the aid of bank credit, capital in search of growth can more or less smoothly mutate from one form to another, alternately taking the form of money capital (liquid deposits, securities, etc.), commodity capital (tradeable products, real estate etc.), or production capital (means of production and labor power). His discussion of the simple and expanded reproduction of the conditions of production offers a more sophisticated model of the parameters of the accumulation process as a whole. At simple reproduction, a sufficient amount is produced to sustain society at the given living standard; the stock of capital stays constant.” ref

“At expanded reproduction, more product-value is produced than is necessary to sustain society at a given living standard (a surplus product); the additional product-value is available for investments which enlarge the scale and variety of production. The bourgeois claim there is no economic law according to which capital is necessarily re-invested in the expansion of production, that such depends on anticipated profitability, market expectations, and perceptions of investment risk. Such statements only explain the subjective experiences of investors and ignore the objective realities which would influence such opinions. As Marx states in Vol.2, simple reproduction only exists if the variable and surplus capital realized by Dept. 1—producers of means of production—exactly equals that of the constant capital of Dept. 2, producers of articles of consumption (pg 524).” ref

“Such equilibrium rests on various assumptions, such as a constant labor supply (no population growth). Accumulation does not imply a necessary change in total magnitude of value produced but can simply refer to a change in the composition of an industry (pg. 514). Ernest Mandel introduced the additional concept of contracted economic reproduction, i.e. reduced accumulation where business operating at a loss outnumbers growing business, or economic reproduction on a decreasing scale, for example, due to wars, natural disasters or devalorisation.” ref

“Balanced economic growth requires that different factors in the accumulation process expand in appropriate proportions. But markets themselves cannot spontaneously create that balance, in fact, what drives business activity is precisely the imbalances between supply and demand: inequality is the motor of growth. This partly explains why the worldwide pattern of economic growth is very uneven and unequal, even although markets have existed almost everywhere for a very long time. Some people argue that it also explains government regulation of market trade and protectionism.” ref

“According to Marx, capital accumulation has a double origin, namely in trade and in expropriation, both of a legal or illegal kind. The reason is that a stock of capital can be increased through a process of exchange or “trading up” but also through directly taking an asset or resource from someone else, without compensation. David Harvey calls this accumulation by dispossession. Marx does not discuss gifts and grants as a source of capital accumulation, nor does he analyze taxation in detail (he could not, as he died even before completing his major book, Das Kapital). Nowadays the tax take is often so large (i.e., 25-40% of GDP) that some authors refer to state capitalism. This gives rise to a proliferation of tax havens to evade tax liability.” ref

“The continuation and progress of capital accumulation depends on the removal of obstacles to the expansion of trade, and this has historically often been a violent process. As markets expand, more and more new opportunities develop for accumulating capital, because more and more types of goods and services can be traded in. But capital accumulation may also confront resistance, when people refuse to sell, or refuse to buy (for example a strike by investors or workers, or consumer resistance).” ref

Means of production

“The means of production is a term which can encompass anything (such as: land, labor, or capital) which can be used to produce products (such as: goods or services); however, it can also be used with narrower meanings, such as anything that is used to produce products. It can also be used as an abbreviation of the “means of production and distribution” which additionally includes the logistical distribution and delivery of products, generally through distributors, or as an abbreviation of the “means of production, distribution, and exchange” which further includes the exchange of distributed products, generally to consumers. The means of production can refer to both tangible aspects, such as physical raw materials, tools, or labor, and non-tangible aspects such as domestic labor or knowledge that contributes to production. This concept is used throughout fields of study including politics, economics, and sociology to discuss, broadly, the relationship between anything that can have productive use, its ownership, and the constituent social parts needed to produce it.” ref

“From the perspective of a firm, a firm uses its capital goods,[4] which are also known as tangible assets as they are physical in nature. Unfinished goods are transformed into products and services in the production process. Even if capital goods are not traded on the market as consumer goods, they can be valued as long as capital goods are produced commodities, which are required for production. The total values of capital goods constitute the capital value. The social means of production are capital goods and assets that require organized collective labor effort, as opposed to individual effort, to operate on. The ownership and organization of the social means of production is a key factor in categorizing and defining different types of economic systems.” ref

“The means of production includes two broad categories of objects: instruments of labor (tools, factories, infrastructure, etc.) and subjects of labor (natural resources and raw materials). People operate on the subjects of labor using the instruments of labor to create a product; or stated another way, labor acting on the means of production creates a good. In an agrarian society the principal means of production is the soil and the shovel. In an industrial society the means of production become social means of production and include factories and mines. In a knowledge economy, computers and networks are means of production. In a broad sense, the “means of production” also includes the “means of distribution” such as stores, the internet, and railroads (Infrastructural capital). The means of production of the firm may depreciate, which means there is a loss in the economic value of capital goods or tangible assets (e.g. machinery, factory equipment) due to wear and tear, and aging. This is known as the depreciation of capital goods.” ref

“The analysis of the technological sophistication of the means of production and how they are owned is a central component in the Marxist theoretical framework of historical materialism and in Marx critique of political economy, and later in Marxian economics. In Marx’s work and subsequent developments in Marxist theory, the process of socioeconomic evolution is based on the premise of technological improvements in the means of production. As the level of technology improves with respect to productive capabilities, existing forms of social relations become superfluous and unnecessary, creating contradictions between the level of technology in the means of production on the one hand and the organization of society and its economy on the other.” ref

“In relation to technological improvements in means of production, new technologies and scientific breakthroughs can rearrange the market structure, create massive economic impact and disrupt the profit pool in the economy. Further impact of disruptive technologies may lead to certain forms of labor power economically unnecessary and uncompetitive and even widening income inequality. These contradictions manifest themselves in the form of class conflicts, which develop to a point where the existing mode of production becomes unsustainable, either collapsing or being overthrown in a social revolution. The contradictions are resolved by the emergence of a new mode of production based on a different set of social relations including, most notably, different patterns of ownership for the means of production.” ref

“Ownership of the means of production and control over the surplus product generated by their operation is the fundamental factor in delineating different modes of production. Capitalism is defined as private ownership and control over the means of production, where the surplus product becomes a source of unearned income for its owners. Under this system, profit-seeking individuals or organizations undertake a majority of economic activities. However, capitalism does not indicate all material means of production are privately owned as partial economies are publicly owned. By contrast, socialism is defined as social ownership of the means of production so that the surplus product accrues to society at large.” ref

Determinant of class

“Marx’s theory of class defines classes in their relation to their ownership and control of the means of production. In a capitalist society, the bourgeoisie, or the capitalist class, is the class that owns the means of production and derives a passive income from their operation. Examples of the capitalist class include business owners, shareholders, and the minority of people who own factories, machinery, and lands. Countries considered as the capitalist countries include Australia, Canada, and other nations which hold a free market economy. In modern society, small business owners, minority shareholders, and other smaller capitalists are considered as Petite bourgeoisie according to Marx’s theory, which is distinct from bourgeoisie and proletariat as they can buy the labor of others but also work along with employees. In contrast, the proletariat, or working class, comprises the majority of the population that lacks access to the means of production and are therefore induced to sell their labor power for a wage or salary to gain access to necessities, goods, and services.” ref

“According to Marx, wages and salaries are considered as the price of labor power, related to working hours or outputs produced by the labor force. At the company level, an employee does not control and own the means of production in a capitalist mode of production. Instead, an employee is performing specific duties under a contract of employment, working for wages or salaries. As for firms and profit-seeking organizations, from a personnel economics perspective, to maximize efficiency and productivity there must be an equilibrium between labor markets and product markets. In human resource practices, compensation structure tend to shift towards pay-for-performance bonus or incentive pay rather than base salary to attract the right workers, even if conflicts of interest exist in an employer-worker relationship.” ref