Request to use “your art” image on Instagram

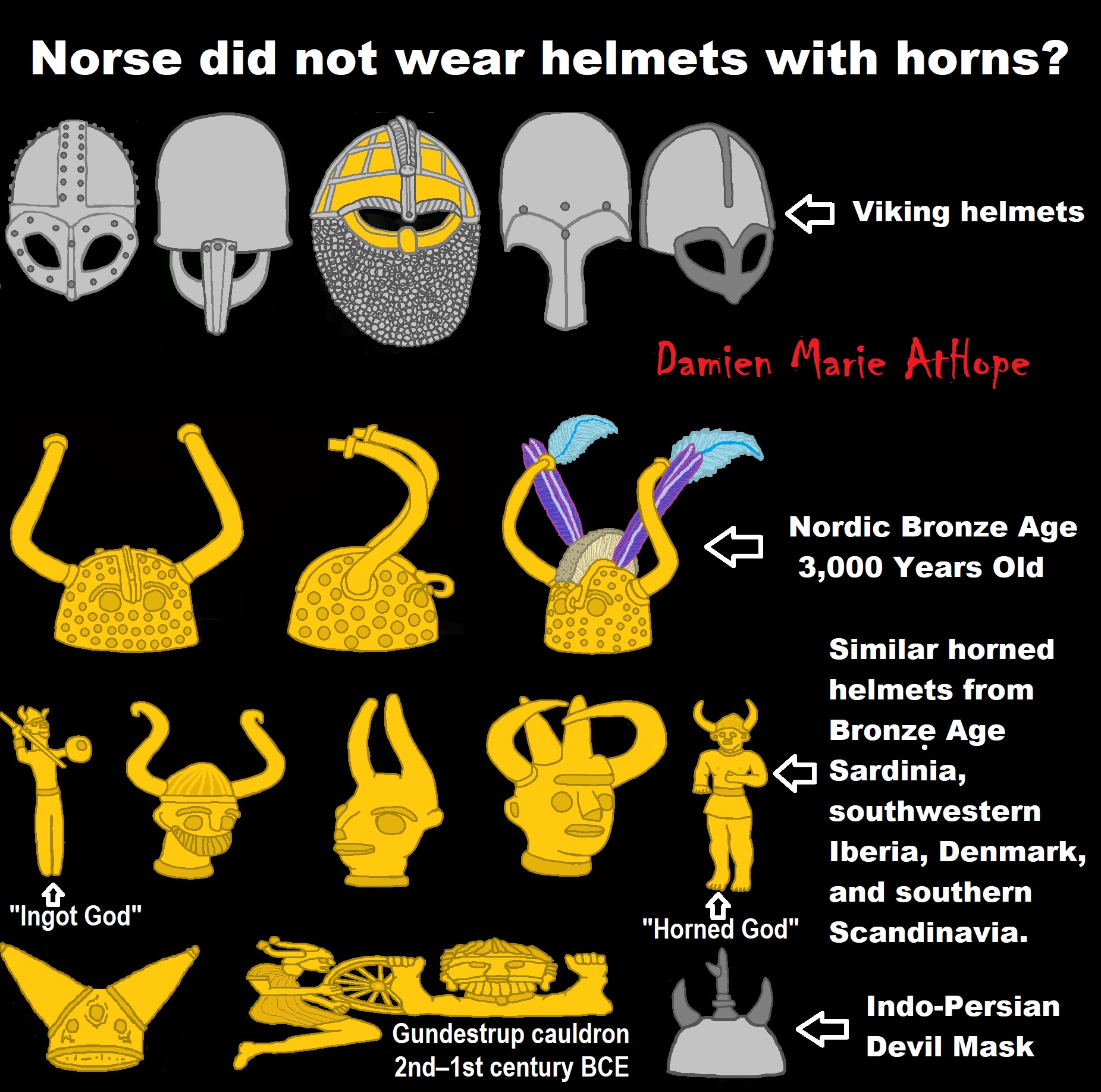

“Dear Demian Marie AtHope, We request permission to use the image “Norse did not wear helmets with norns?” on our Instagram account (@nucleo.neve). The image will be translated into Portuguese and your link and Instagram account will be published in the post description: @athopedamien. Our intention is to disseminate information about the history of Scandinavia from the Viking Age. All the best, Johnni Langer, Ph.D. Editor-in-chief: Scandia: Journal of Medieval Norse Studies” – (from an email)

“God/spirit revealed it to me or a person of God/spirit had it revealed to them” – theist thinking

“Misinformation, Delusion, or Wishful thinking revealed it to you or them, you mean” – atheist interpreting the theist’s thinking

By the way, my genetics are German, Hungarian, Swedish, Norwegian, Irish, and Italian (according to my family).

DNA wise: My mother’s side is related to mainly the Early European Farmers (EEF). And my father’s side is mainly the Yamnaya culture also known as the Pit Grave culture.

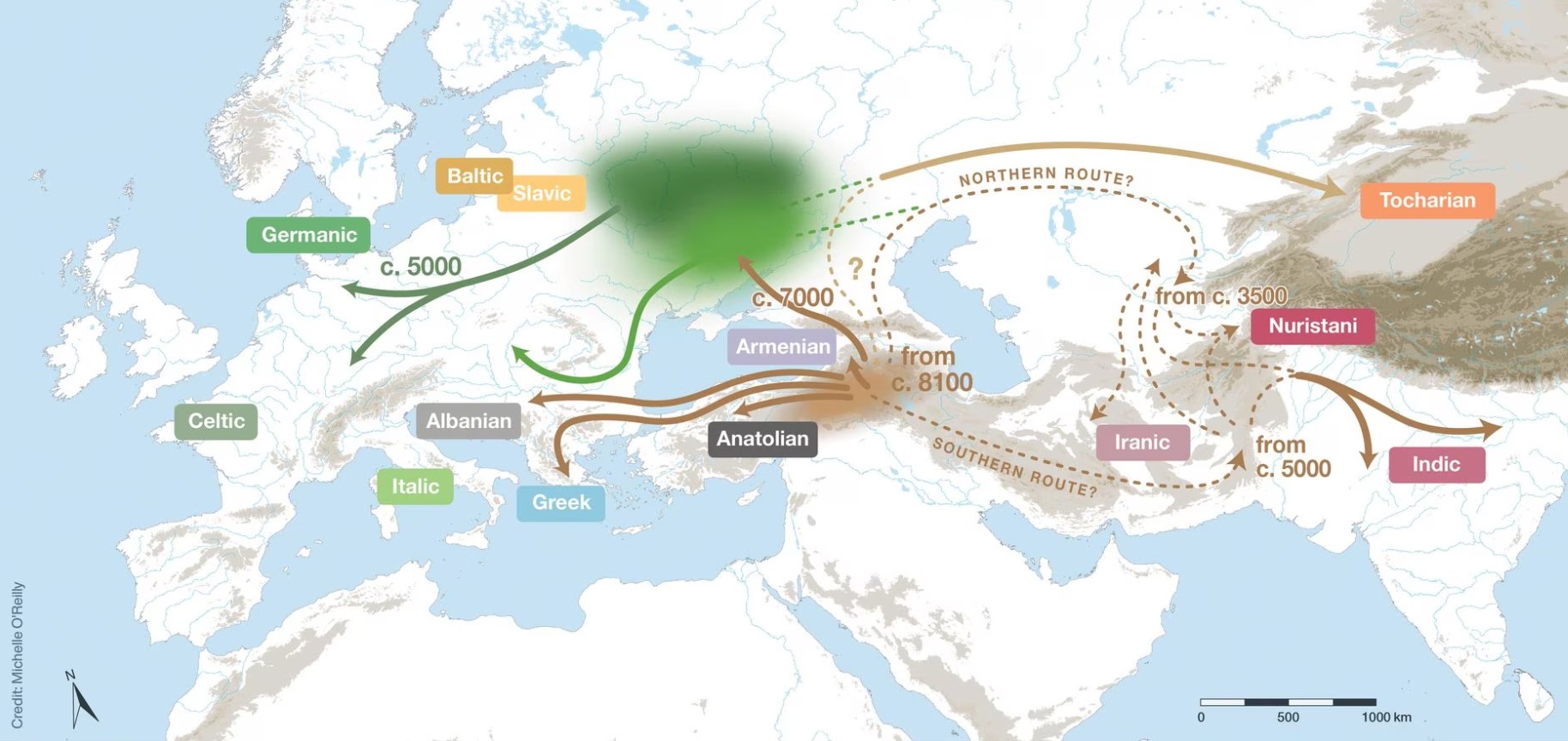

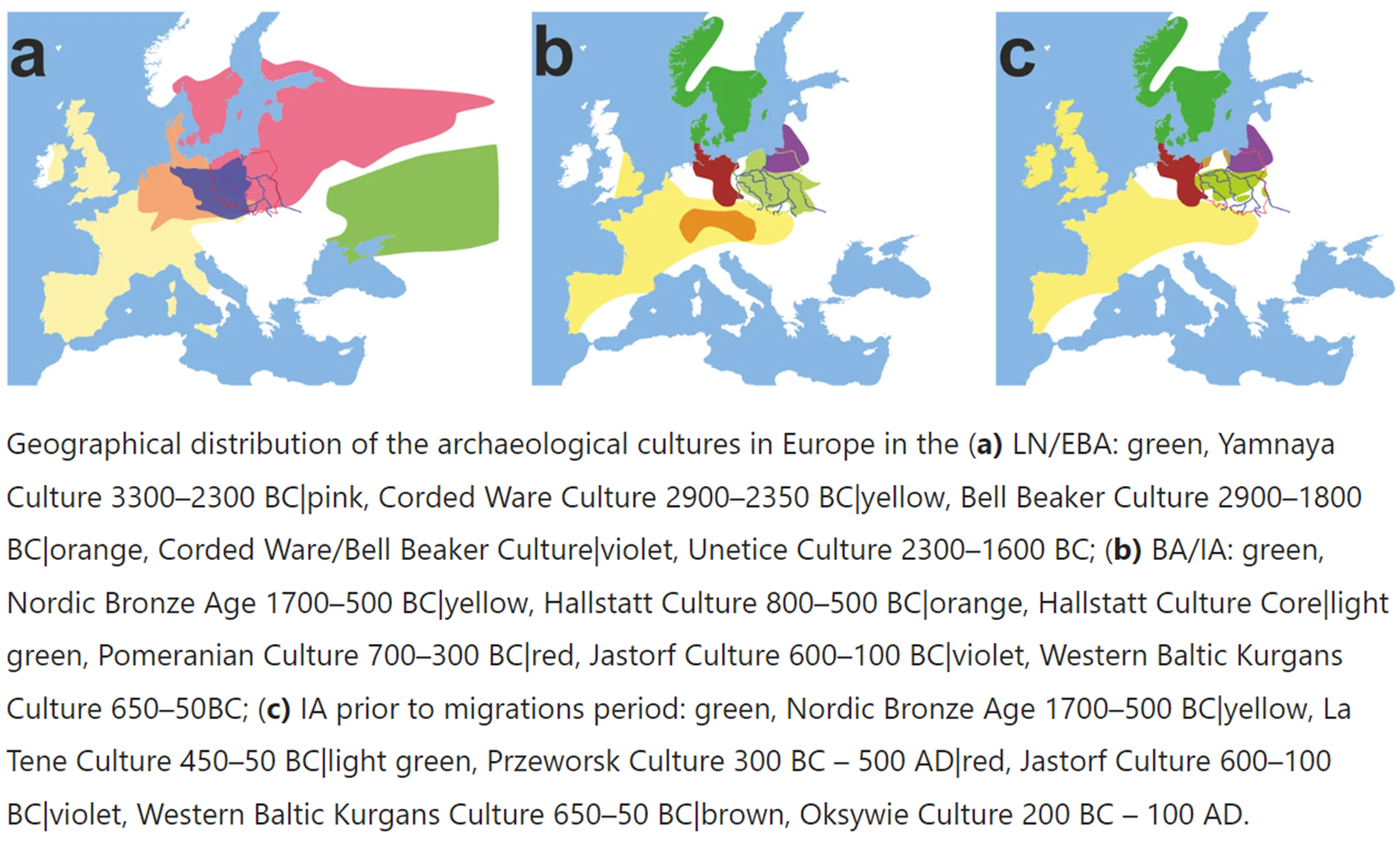

“Early European Farmers (EEF), First European Farmers (FEF), Neolithic European Farmers, Ancient Aegean Farmers, or Anatolian Neolithic Farmers (ANF) are names used to describe a distinct group of early Neolithic farmers who brought agriculture to Europe and Northwest Africa (Maghreb). Although the spread of agriculture from the Middle East to Europe has long been recognised through archaeology, it is only recent advances in archaeogenetics that have confirmed that this spread was strongly correlated with a migration of these farmers, and was not just a cultural exchange. The Early European Farmers moved into Europe from Asia Minor through Southeast Europe from around 7,000 BC, gradually spread north and westwards, and reached Northwest Africa via the Iberian Peninsula. Genetic studies have confirmed that Early European Farmers can be modelled as Anatolian Neolithic Farmers with a minor contribution from Western Hunter-Gatherers (WHGs), with significant regional variation. European farmer and hunter-gatherer populations coexisted and traded in some locales, although evidence suggests that the relationship was not always peaceful. Over the course of the next 4,000 years or so, Europe was transformed into agricultural communities, and WHGs were displaced to the margins. During the Chalcolithic and early Bronze Age, the Early European Farmer cultures were overwhelmed by new migrations from the Pontic steppe by a group related to people of the Yamnaya culture who carried Western Steppe Herder ancestry and probably spoke Indo-European languages. Once again the populations mixed, and EEF ancestry is common in modern European populations, with EEF ancestry highest in Southern Europeans, especially Sardinians and Basque people.” ref

“The Yamnaya culture or the Yamna culture, also known as the Pit Grave culture or Ochre Grave culture, was a late Copper Age to early Bronze Age archaeological culture of the region between the Southern Bug, Dniester, and Ural rivers (the Pontic–Caspian steppe), dating to 3300–2600 BCE. It was discovered by Vasily Gorodtsov following his archaeological excavations near the Donets River in 1901–1903. Its name derives from its characteristic burial tradition: Я́мная (romanization: yamnaya) is a Russian adjective that means ‘related to pits (yama)’, as these people used to bury their dead in tumuli (kurgans) containing simple pit chambers. The Yamnaya economy was based upon animal husbandry, fishing, and foraging, and the manufacture of ceramics, tools, and weapons. The people of the Yamnaya culture lived primarily as nomads, with a chiefdom system and wheeled carts and wagons that allowed them to manage large herds. They are also closely connected to Final Neolithic cultures, which later spread throughout Europe and Central Asia, especially the Corded Ware people and the Bell Beaker culture, as well as the peoples of the Sintashta, Andronovo, and Srubnaya cultures. Back migration from Corded Ware also contributed to Sintashta and Andronovo. In these groups, several aspects of the Yamnaya culture are present. Yamnaya material culture was very similar to the Afanasevo culture of South Siberia, and the populations of both cultures are genetically indistinguishable. This suggests that the Afanasevo culture may have originated from the migration of Yamnaya groups to the Altai region or, alternatively, that both cultures developed from an earlier shared cultural source. Genetic studies have suggested that the people of the Yamnaya culture can be modelled as a genetic admixture between a population related to Eastern European Hunter-Gatherers (EHG) and people related to hunter-gatherers from the Caucasus (CHG) in roughly equal proportions, an ancestral component which is often named “Steppe ancestry”, with additional admixture from Anatolian, Levantine, or Early European farmers. Genetic studies also indicate that populations associated with the Corded Ware, Bell Beaker, Sintashta, and Andronovo cultures derived large parts of their ancestry from the Yamnaya or a closely related population. There is now a rough scholarly consensus that the common ancestor of all Indo-European languages, with the possible exception of Anatolian, originated on the Pontic-Caspian steppe, and this language has been associated with the people of the Yamnaya culture. Additionally, the Pontic-Caspian steppe is currently seen as the most likely candidate for the original homeland (German, Urheimat) of the Proto-Indo-European language, including the ancestor of the Anatolian branch.” ref

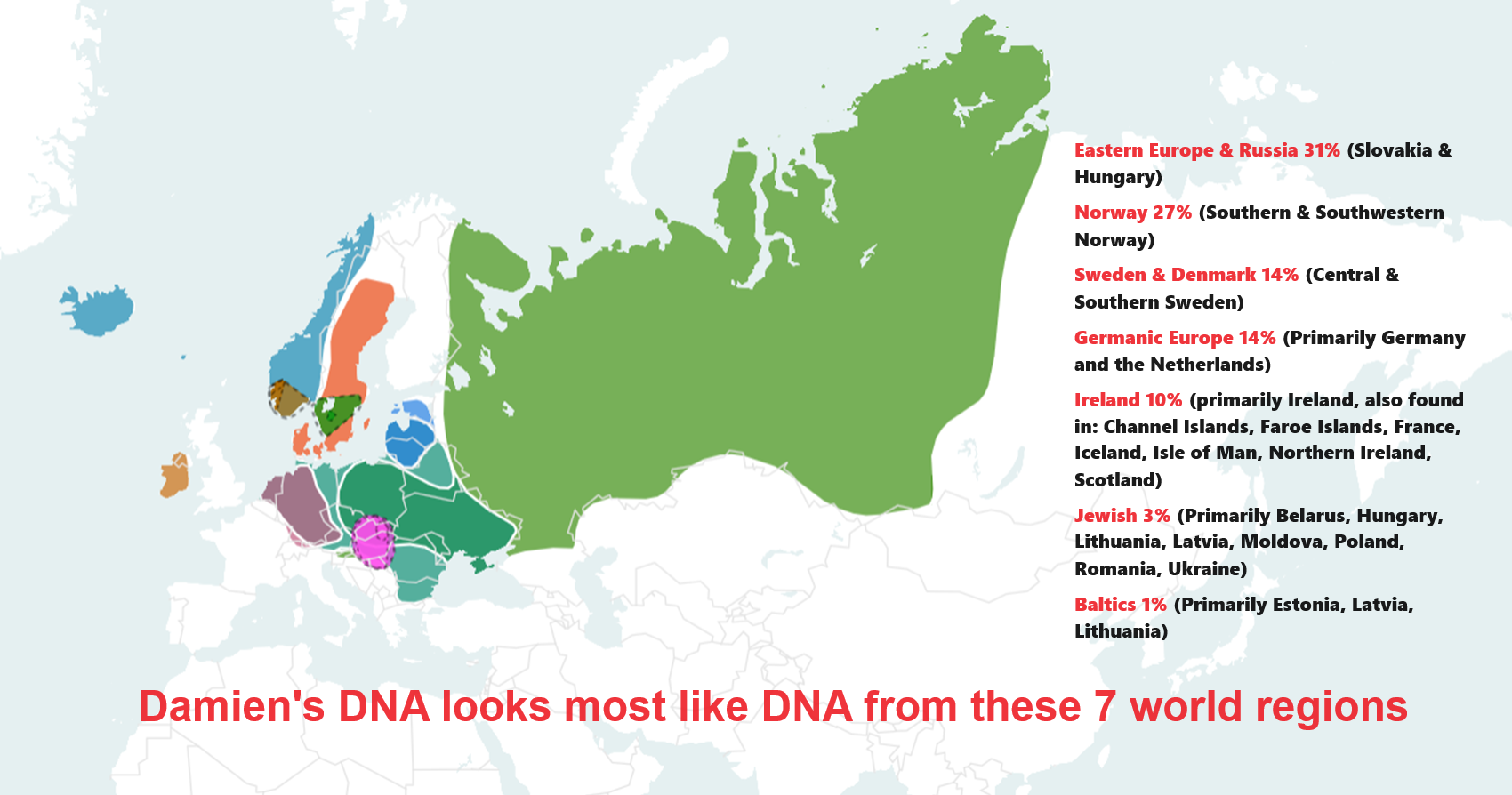

Damien’s DNA looks most like DNA from these 7 world regions

Ethnicity estimate: Damien’s DNA looks most like DNA from these 7 world regions

Eastern Europe & Russia 31% (Slovakia & Hungary)

Norway 27% (Southern & Southwestern Norway)

Sweden & Denmark 14% (Central & Southern Sweden)

Germanic Europe 14% (Primarily Germany and the Netherlands)

Ireland 10% (primarily Ireland, also found in: Channel Islands, Faroe Islands, France, Iceland, Isle of Man, Northern Ireland, Scotland)

Jewish 3% (Primarily Belarus, Hungary, Lithuania, Latvia, Moldova, Poland, Romania, Ukraine)

Baltics 1% (Primarily Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania)

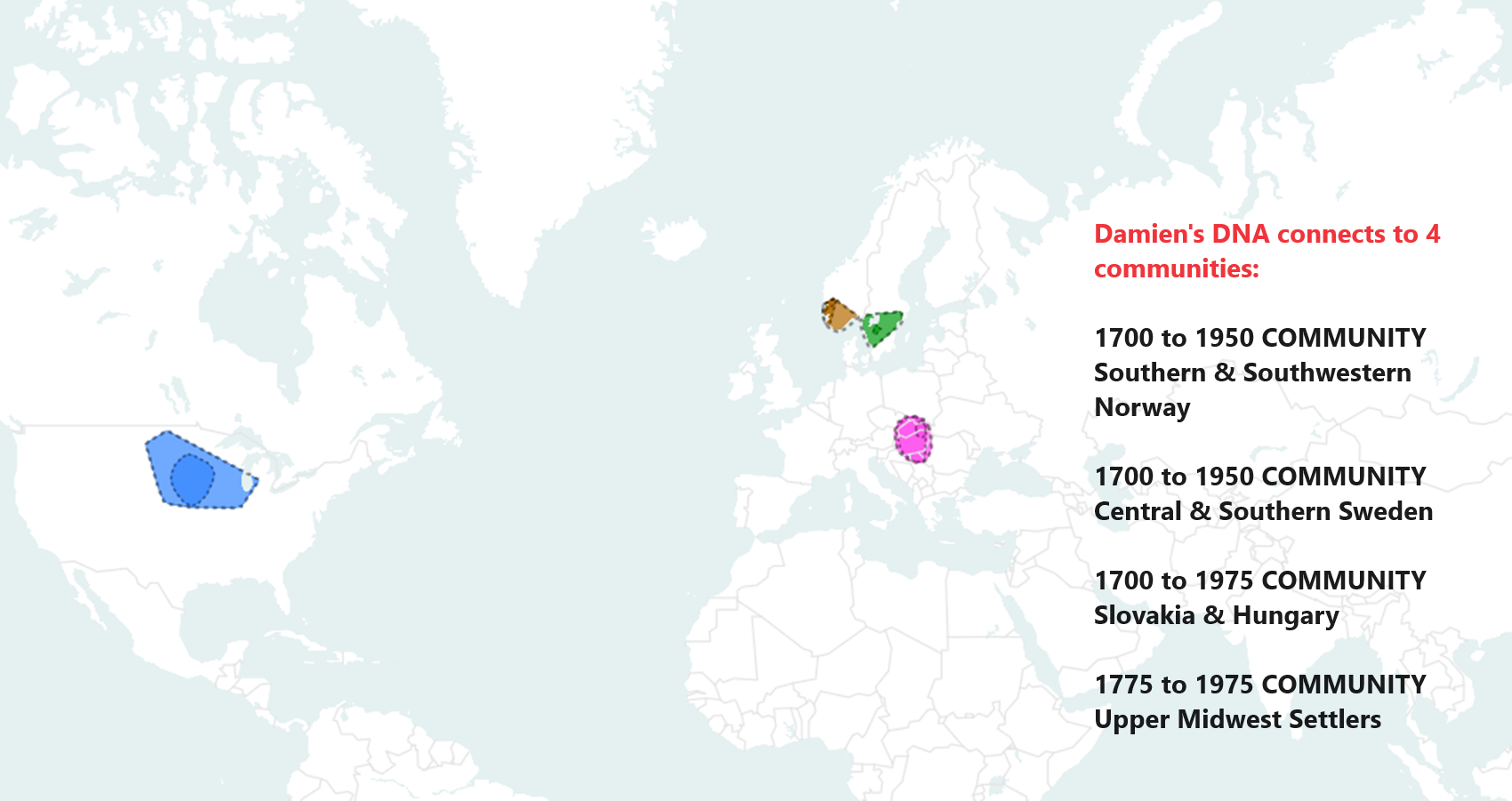

Damien’s DNA connects to 4 communities:

1700 to 1950 COMMUNITY Southern & Southwestern Norway

1700 to 1950 COMMUNITY Central & Southern Sweden

1700 to 1975 COMMUNITY Slovakia & Hungary

1775 to 1975 COMMUNITY Upper Midwest Settlers

Ancient North Eurasian (ANE)

Ancient Beringian/Ancestral Native American (AB/ANA)

Eastern Hunter-Gatherer (EHG)

Western Hunter-Gatherers (WHG)

Western Steppe Herders (WSH)

Scandinavian Hunter-Gatherer (SHG)

Early European Farmers (EEF)

Jōmon people (Ainu people OF Hokkaido Island)

Neolithic Iranian farmers (Iran_N) (Iran Neolithic)

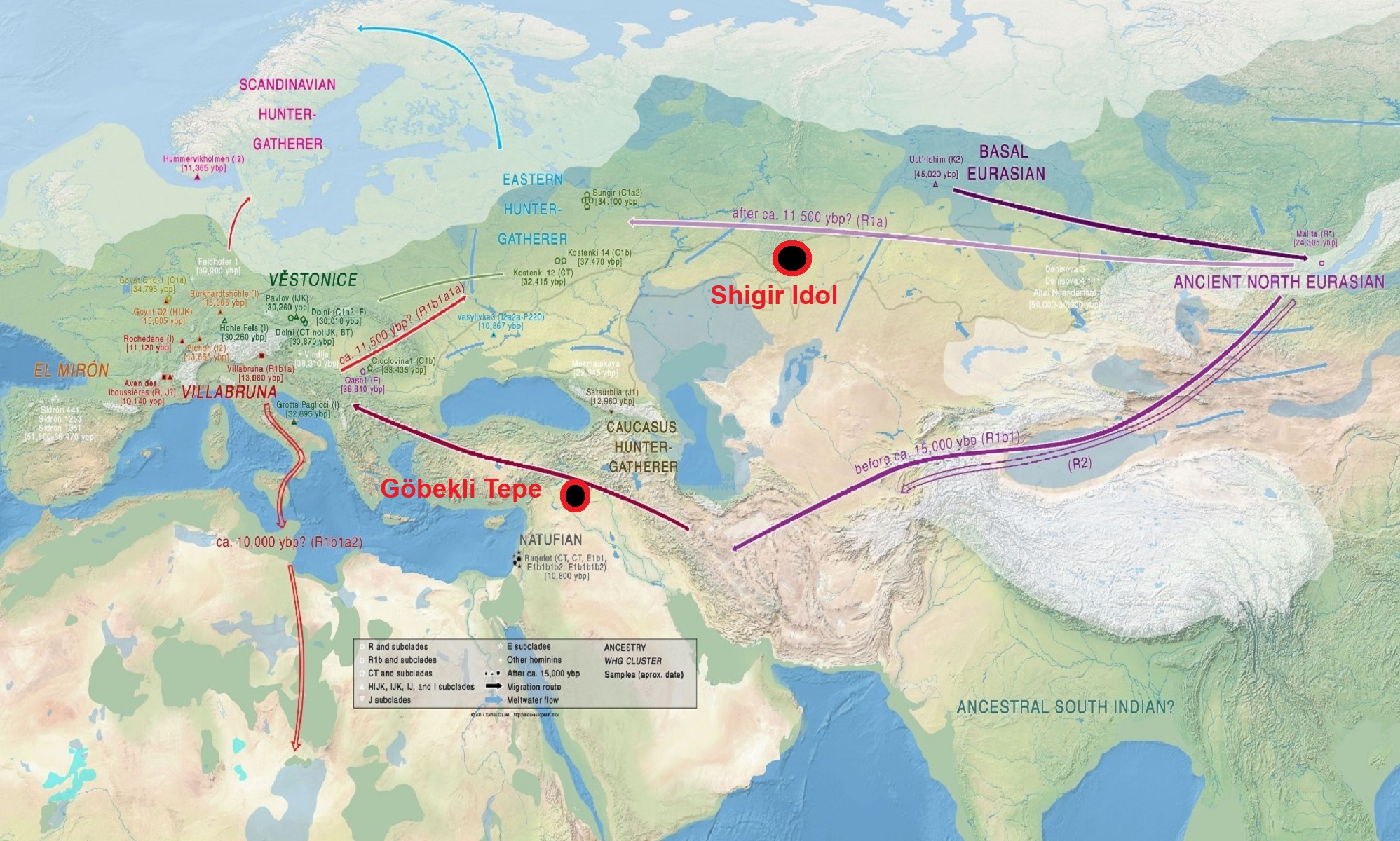

Haplogroup R possible time of origin about 27,000 years in Central Asia, South Asia, or Siberia:

- Mal’ta–Buret’ culture (24,000-15,000 years ago)

- Afontova Gora culture (21,000-12,000 years ago)

- Trialetian culture (16,000–8000 years ago)

- Samara culture (7,000-6,500 years ago)

- Khvalynsk culture (7,000-6,500 years ago)

- Afanasievo culture (5,300-4,500 years ago)

- Yamna/Yamnaya Culture (5,300-4,500 years ago)

- Andronovo culture (4,000–2,900 years ago) ref

Groups partially derived from the Ancient North Eurasians

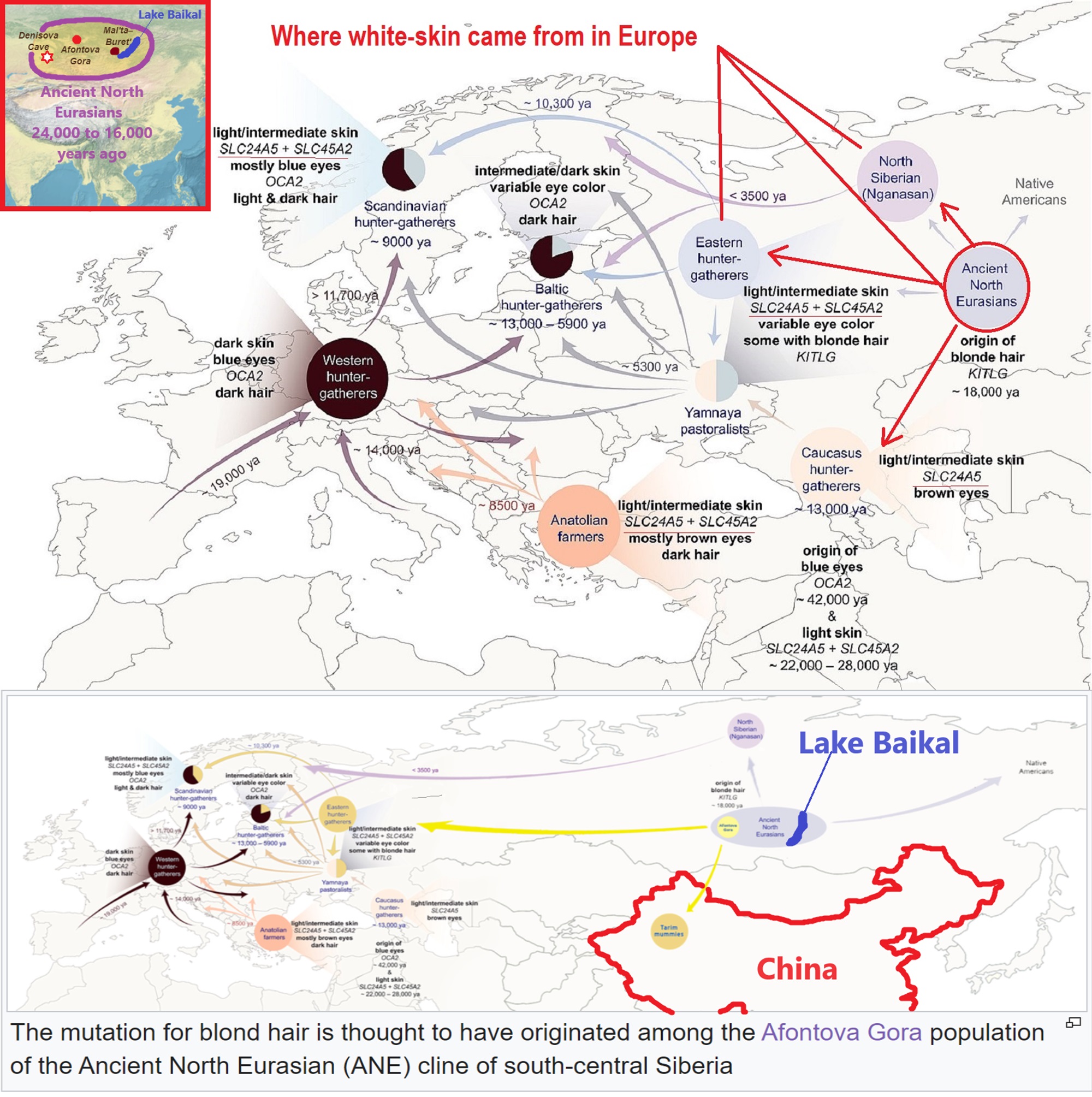

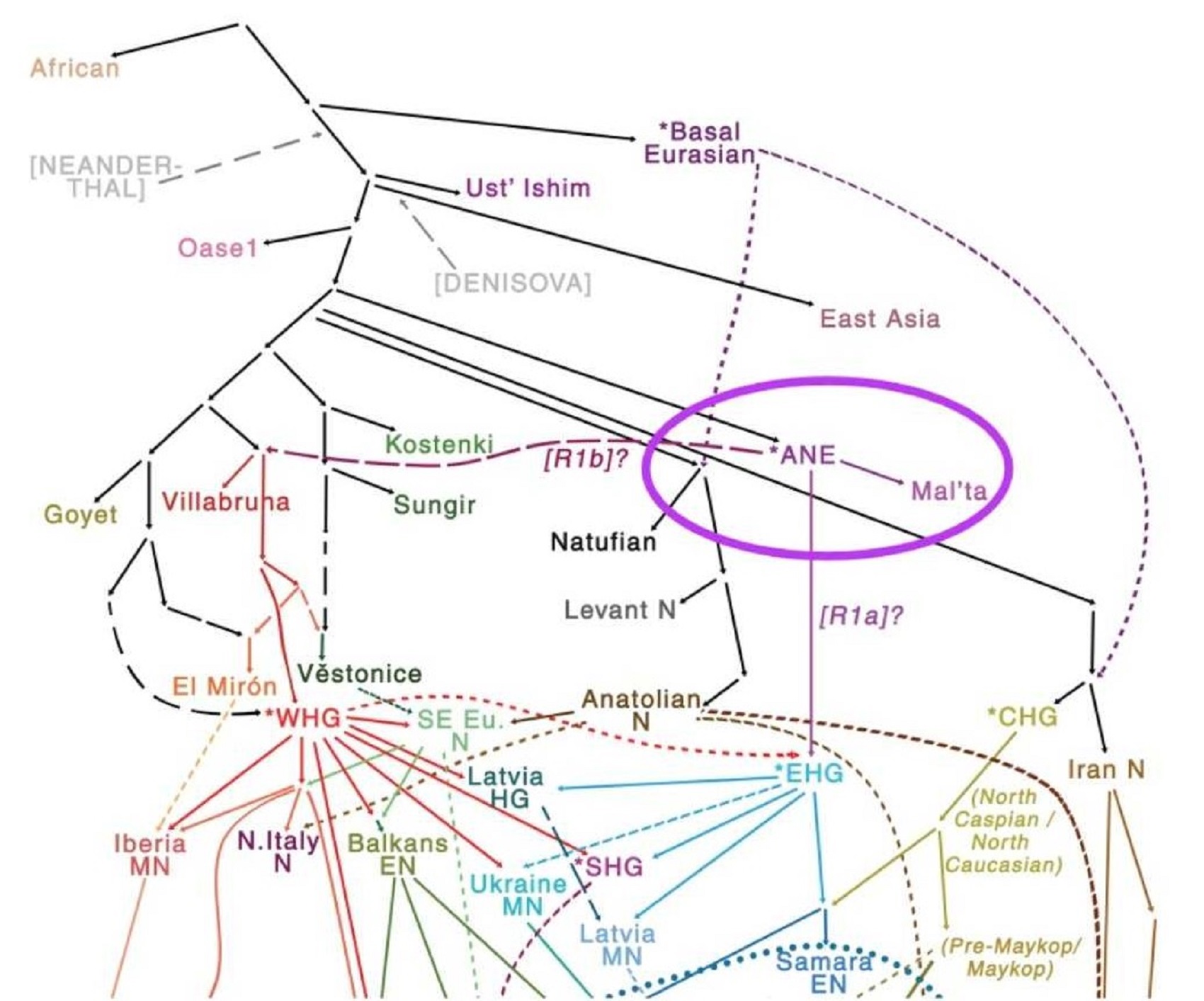

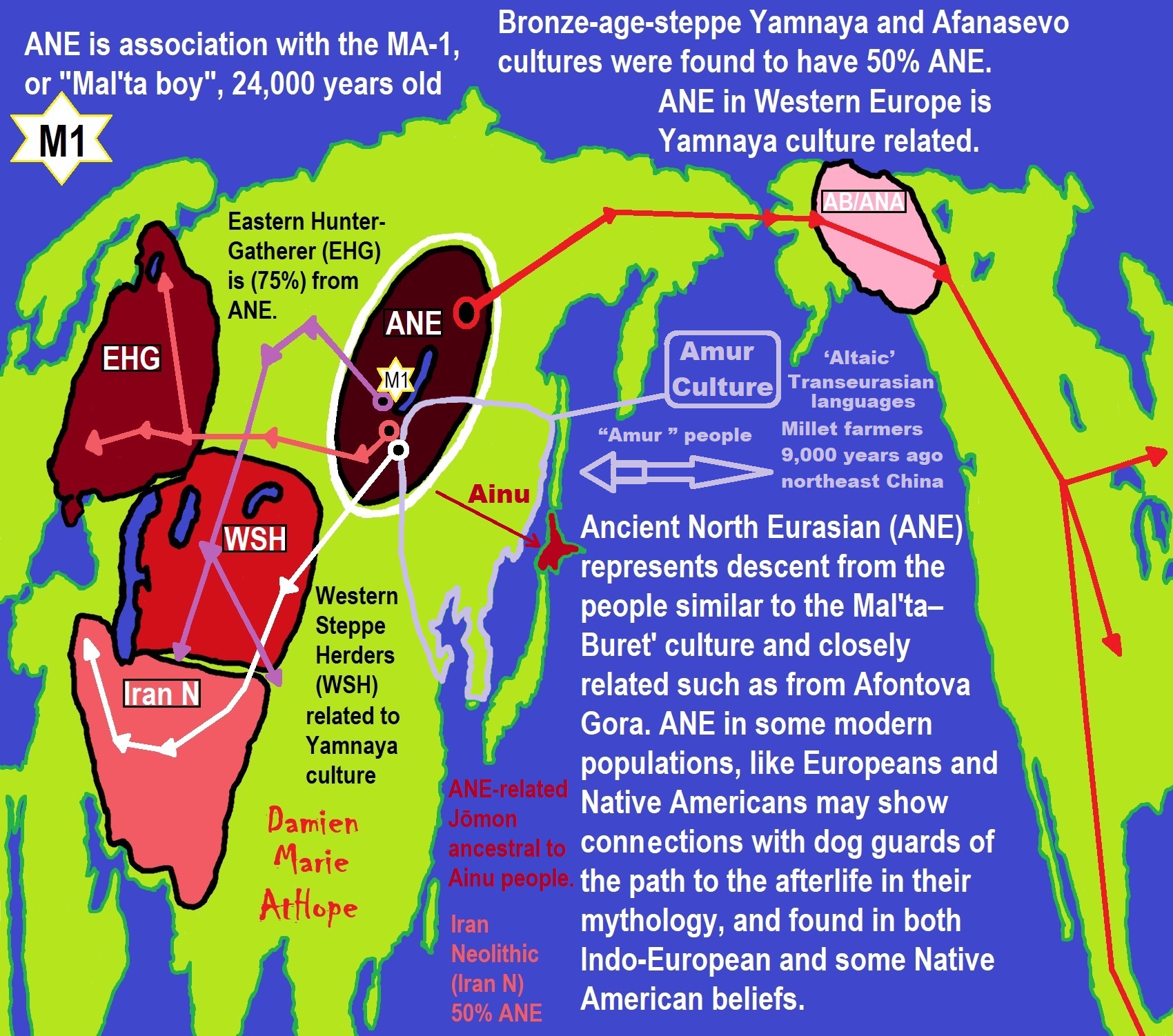

“The ANE lineage is defined by association with the MA-1, or “Mal’ta boy”, remains of 24,000 years ago in central Siberia Mal’ta-Buret’ culture 24,000-15,000 years ago. The Ancient North Eurasians (ANE) samples (Afontova Gora 3, Mal’ta 1, and Yana-RHS) show evidence for minor gene flow from an East Asian-related group (simplified by the Amis, Han, or Tianyuan) but no evidence for ANE-related geneflow into East Asians (Amis, Han, Tianyuan), except the Ainu, of North Japan.” ref

“The ANE lineage is defined by association with the MA-1, or “Mal’ta boy”, remains of 24,000 years ago in central Siberia Mal’ta-Buret’ culture 24,000-15,000 years ago “basal to modern-day Europeans”. Some Ancient North Eurasians also carried East Asian populations, such as Tianyuan Man.” ref

“Bronze-age-steppe Yamnaya and Afanasevo cultures were ANE at around 50% and Eastern Hunter-Gatherer (EHG) at around 75% ANE. Karelia culture: Y-DNA R1a-M417 8,400 years ago, Y-DNA J, 7,200 years ago, and Samara, of Y-haplogroup R1b-P297 7,600 years ago is closely related to ANE from Afontova Gora, 18,000 years ago around the time of blond hair first seen there.” ref

Ancient North Eurasian

“In archaeogenetics, the term Ancient North Eurasian (often abbreviated as ANE) is the name given to an ancestral West Eurasian component that represents descent from the people similar to the Mal’ta–Buret’ culture and populations closely related to them, such as from Afontova Gora and the Yana Rhinoceros Horn Site. Significant ANE ancestry are found in some modern populations, including Europeans and Native Americans.” ref

“The ANE lineage is defined by association with the MA-1, or “Mal’ta boy“, the remains of an individual who lived during the Last Glacial Maximum, 24,000 years ago in central Siberia, Ancient North Eurasians are described as a lineage “which is deeply related to Paleolithic/Mesolithic hunter-gatherers in Europe,” meaning that they diverged from Paleolithic Europeans a long time ago.” ref

“The ANE population has also been described as having been “basal to modern-day Europeans” but not especially related to East Asians, and is suggested to have perhaps originated in Europe or Western Asia or the Eurasian Steppe of Central Asia. However, some samples associated with Ancient North Eurasians also carried ancestry from an ancient East Asian population, such as Tianyuan Man. Sikora et al. (2019) found that the Yana RHS sample (31,600 BP) in Northern Siberia “can be modeled as early West Eurasian with an approximately 22% contribution from early East Asians.” ref

“Populations genetically similar to MA-1 were an important genetic contributor to Native Americans, Europeans, Central Asians, South Asians, and some East Asian groups, in order of significance. Lazaridis et al. (2016:10) note “a cline of ANE ancestry across the east-west extent of Eurasia.” The ancient Bronze-age-steppe Yamnaya and Afanasevo cultures were found to have a noteworthy ANE component at ~50%.” ref

“According to Moreno-Mayar et al. 2018 between 14% and 38% of Native American ancestry may originate from gene flow from the Mal’ta–Buret’ people (ANE). This difference is caused by the penetration of posterior Siberian migrations into the Americas, with the lowest percentages of ANE ancestry found in Eskimos and Alaskan Natives, as these groups are the result of migrations into the Americas roughly 5,000 years ago.” ref

“Estimates for ANE ancestry among first wave Native Americans show higher percentages, such as 42% for those belonging to the Andean region in South America. The other gene flow in Native Americans (the remainder of their ancestry) was of East Asian origin. Gene sequencing of another south-central Siberian people (Afontova Gora-2) dating to approximately 17,000 years ago, revealed similar autosomal genetic signatures to that of Mal’ta boy-1, suggesting that the region was continuously occupied by humans throughout the Last Glacial Maximum.” ref

“The earliest known individual with a genetic mutation associated with blonde hair in modern Europeans is an Ancient North Eurasian female dating to around 16000 BCE from the Afontova Gora 3 site in Siberia. It has been suggested that their mythology may have included a narrative, found in both Indo-European and some Native American fables, in which a dog guards the path to the afterlife.” ref

“Genomic studies also indicate that the ANE component was introduced to Western Europe by people related to the Yamnaya culture, long after the Paleolithic. It is reported in modern-day Europeans (7%–25%), but not of Europeans before the Bronze Age. Additional ANE ancestry is found in European populations through paleolithic interactions with Eastern Hunter-Gatherers, which resulted in populations such as Scandinavian Hunter-Gatherers.” ref

“The Ancient North Eurasians (ANE) split from the ancestors of European peoples somewhere in the Middle East or South-central Asia, and used a northern dispersal route through Central Asia into Northern Asia and Siberia. Genetic analyses show that all ANE samples (Afontova Gora 3, Mal’ta 1, and Yana-RHS) show evidence for minor gene flow from an East Asian-related group (simplified by the Amis, Han, or Tianyuan). In contrast, no evidence for ANE-related geneflow into East Asians (Amis, Han, Tianyuan), except the Ainu, was found.” ref

“Genetic data suggests that the ANE formed during the Terminal Upper-Paleolithic (36+-1,5ka) period from a deeply European-related population, which was once widespread in Northern Eurasia, and from an early East Asian-related group, which migrated northwards into Central Asia and Siberia, merging with this deeply European-related population. These population dynamics and constant northwards geneflow of East Asian-related ancestry would later gave rise to the “Ancestral Native Americans” and Paleosiberians, which replaced the ANE as dominant population of Siberia.” ref

Groups partially derived from the Ancient North Eurasians

“Eastern Hunter-Gatherer (EHG) is a lineage derived predominantly (75%) from ANE. It is represented by two individuals from Karelia, one of Y-haplogroup R1a-M417, dated c. 8.4 kya, the other of Y-haplogroup J, dated c. 7.2 kya; and one individual from Samara, of Y-haplogroup R1b-P297, dated c. 7.6 kya. This lineage is closely related to the ANE sample from Afontova Gora, dated c. 18 kya. After the end of the Last Glacial Maximum, the Western Hunter-Gatherers (WHG) and EHG lineages merged in Eastern Europe, accounting for early presence of ANE-derived ancestry in Mesolithic Europe. Evidence suggests that as Ancient North Eurasians migrated West from Eastern Siberia, they absorbed Western Hunter-Gatherers and other West Eurasian populations as well.” ref

“Caucasian Hunter-Gatherer (CHG) is represented by the Satsurblia individual dated ~13 kya (from the Satsurblia cave in Georgia), and carried 36% ANE-derived admixture. While the rest of their ancestry is derived from the Dzudzuana cave individual dated ~26 kya, which lacked ANE-admixture, Dzudzuana affinity in the Caucasus decreased with the arrival of ANE at ~13 kya Satsurblia.” ref

“Scandinavian Hunter-Gatherer (SHG) is represented by several individuals buried at Motala, Sweden ca. 6000 BC. They were descended from Western Hunter-Gatherers who initially settled Scandinavia from the south, and later populations of EHG who entered Scandinavia from the north through the coast of Norway.” ref

“Iran Neolithic (Iran_N) individuals dated ~8.5 kya carried 50% ANE-derived admixture and 50% Dzudzuana-related admixture, marking them as different from other Near-Eastern and Anatolian Neolithics who didn’t have ANE admixture. Iran Neolithics were later replaced by Iran Chalcolithics, who were a mixture of Iran Neolithic and Near Eastern Levant Neolithic.” ref

“Ancient Beringian/Ancestral Native American are specific archaeogenetic lineages, based on the genome of an infant found at the Upward Sun River site (dubbed USR1), dated to 11,500 years ago. The AB lineage diverged from the Ancestral Native American (ANA) lineage about 20,000 years ago.” ref

“West Siberian Hunter-Gatherer (WSHG) are a specific archaeogenetic lineage, first reported in a genetic study published in Science in September 2019. WSGs were found to be of about 30% EHG ancestry, 50% ANE ancestry, and 20% to 38% East Asian ancestry.” ref

“Western Steppe Herders (WSH) is the name given to a distinct ancestral component that represents descent closely related to the Yamnaya culture of the Pontic–Caspian steppe. This ancestry is often referred to as Yamnaya ancestry or Steppe ancestry.” ref

“Late Upper Paeolithic Lake Baikal – Ust’Kyakhta-3 (UKY) 14,050-13,770 BP were mixture of 30% ANE ancestry and 70% East Asian ancestry.” ref

“Lake Baikal Holocene – Baikal Eneolithic (Baikal_EN) and Baikal Early Bronze Age (Baikal_EBA) derived 6.4% to 20.1% ancestry from ANE, while rest of their ancestry was derived from East Asians. Fofonovo_EN near by Lake Baikal were mixture of 12-17% ANE ancestry and 83-87% East Asian ancestry.” ref

“Hokkaido Jōmon people specifically refers to the Jōmon period population of Hokkaido in northernmost Japan. Though the Jōmon people themselves descended mainly from East Asian lineages, one study found an affinity between Hokkaido Jōmon with the Northern Eurasian Yana sample (an ANE-related group, related to Mal’ta), and suggest as an explanation the possibility of minor Yana gene flow into the Hokkaido Jōmon population (as well as other possibilities). A more recent study by Cooke et al. 2021, confirmed ANE-related geneflow among the Jōmon people, partially ancestral to the Ainu people. ANE ancestry among Jōmon people is estimated at 21%, however, there is a North to South cline within the Japanese archipelago, with the highest amount of ANE ancestry in Hokkaido and Tohoku.” ref

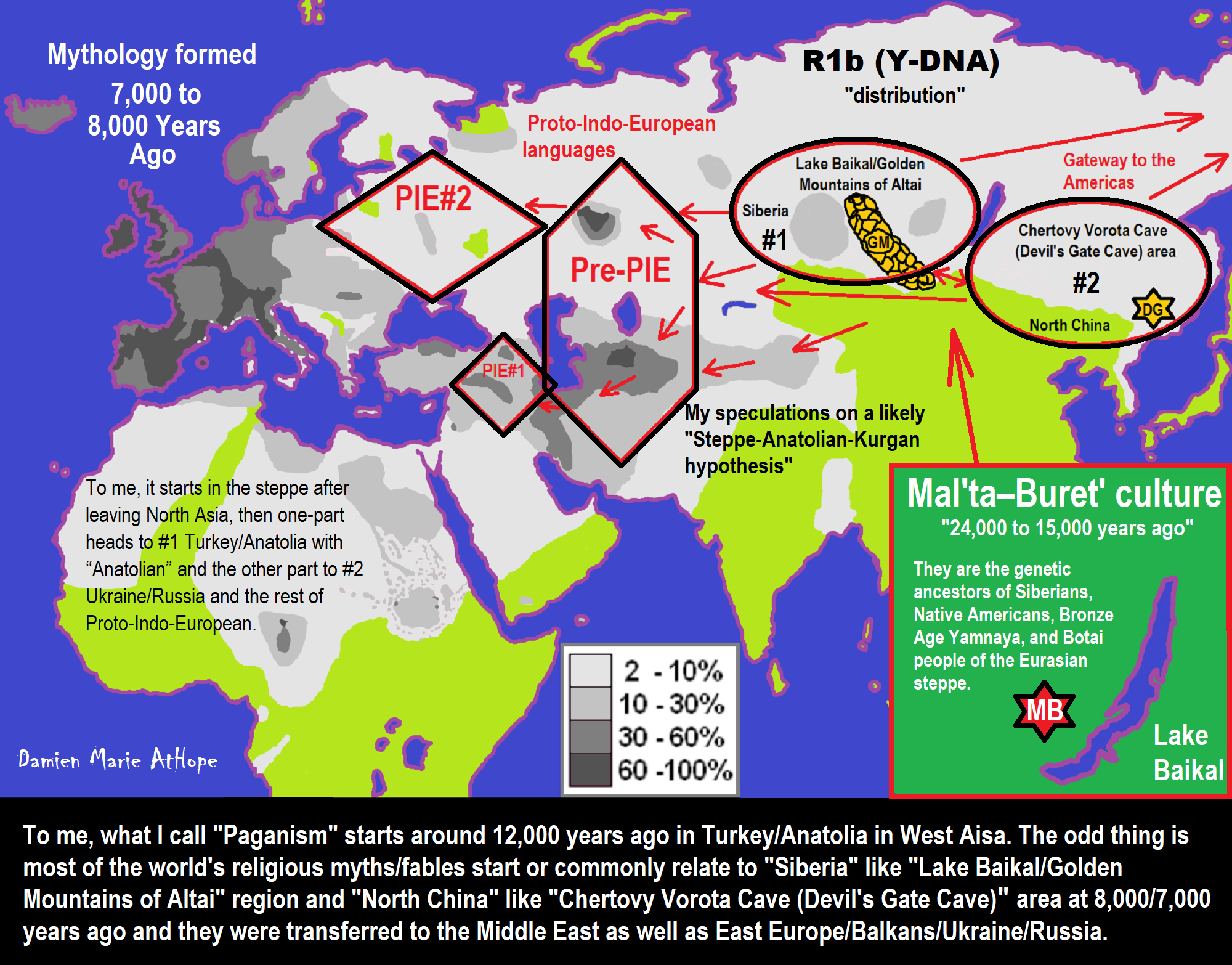

- My Thoughts on the Mal’ta–Buret’ culture‘s Ancient North Eurasian “R” (Y-DNA) Migrations and its Possible relations/influence on Afroasiatic and Proto-Indo-European languages

- My Thoughts on Possible Migrations of “R” DNA and Proto-Indo-European?

- Proto-Indo-European (PIE), ancestor of Indo-European languages: DNA, Society, Language, and Mythology

- Yamnaya culture or at least Proto-Indo-European Languages/Religions may actually relate back to North Asia?

- My Thoughts on Possible Migrations of “R” DNA and Proto-Indo-European?

- Proto-Indo-European (PIE), ancestor of Indo-European languages: DNA, Society, Language, and Mythology

- Indo-European language Trees fit an Agricultural expansion from Anatolia beginning 8,000 – 9,500 years ago?

- 7,020 to 6,020-year-old Proto-Indo-European Homeland of Urheimat or proposed home of their Language and Religion

- Understanding Proto-Indo-Europeans and Paganism Religions

- Hell and Underworld mythologies starting maybe as far back as 7,000 to 5,000 years ago with the Proto-Indo-Europeans?

“Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is the reconstructed common ancestor of the Indo-European language family. No direct record of Proto-Indo-European exists; its proposed features have been derived by linguistic reconstruction from documented Indo-European languages. As speakers of Proto-Indo-European became isolated from each other through the Indo-European migrations, the regional dialects of Proto-Indo-European spoken by the various groups diverged, as each dialect underwent shifts in pronunciation (the Indo-European sound laws), morphology, and vocabulary. Commonly proposed subgroups of Indo-European languages include Italo-Celtic, Graeco-Aryan, Graeco-Armenian, Graeco-Phrygian, Daco-Thracian, and Thraco-Illyrian.” ref

“Scholars have proposed multiple hypotheses about when, where, and by whom PIE was spoken. The Kurgan hypothesis, first put forward in 1956 by Marija Gimbutas, has become the most popular. It proposes that the original speakers of PIE were the Yamnaya culture associated with the kurgans (burial mounds) on the Pontic–Caspian steppe north of the Black Sea. Other theories include the Anatolian hypothesis, which posits that PIE spread out from Anatolia with agriculture beginning c. 7500–6000 BCE or around 9,500 to 8,000 years ago, the Armenian hypothesis, the Paleolithic continuity paradigm, and the indigenous Aryans theory. The latter two of these theories are not regarded as credible within academia. Out of all the theories for a PIE homeland, the Kurgan and Anatolian hypotheses are the ones most widely accepted, and also the ones most debated against each other.” ref

“The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family—English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Dutch, and Spanish—have expanded through colonialism in the modern period and are now spoken across several continents. The Indo-European family is divided into several branches or sub-families, of which there are eight groups with languages still alive today: Albanian, Armenian, Balto-Slavic, Celtic, Germanic, Hellenic, Indo-Iranian, and Italic/Romance; and another nine subdivisions that are now extinct. Today, the individual Indo-European languages with the most native speakers are Spanish, English, Hindi–Urdu, Bengali, Portuguese, Russian, Punjabi, French, and German each with over 100 million native speakers; many others are small and in danger of extinction.” ref

“Proto-Indo-European mythology is the body of myths and deities associated with the Proto-Indo-Europeans, speakers of the hypothesized Proto-Indo-European language. Although the mythological motifs are not directly attested – since Proto-Indo-European speakers lived in preliterate societies – scholars of comparative mythology have reconstructed details from inherited similarities found among Indo-European languages, based on the assumption that parts of the Proto-Indo-Europeans’ original belief systems survived in the daughter traditions. Various schools of thought exist regarding possible interpretations of the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European mythology. The main mythologies used in comparative reconstruction are Indo-Iranian, Baltic, Roman, and Norse, often supported with evidence from the Celtic, Greek, Slavic, Hittite, Armenian, Illyrian, and Albanian traditions as well.” ref

“The Proto-Indo-European pantheon includes a number of securely reconstructed deities, since they are both cognates – linguistic siblings from a common origin – and associated with similar attributes and body of myths: such as *Dyḗws Ph₂tḗr, the daylight-sky god; his consort *Dʰéǵʰōm, the earth mother; his daughter *H₂éwsōs, the dawn goddess; his sons the Divine Twins; and *Seh₂ul and *Meh₁not, a solar goddess and moon god, respectively. Some deities, like the weather god *Perkʷunos or the herding-god *Péh₂usōn, are only attested in a limited number of traditions – Western (i.e. European) and Graeco-Aryan, respectively – and could therefore represent late additions that did not spread throughout the various Indo-European dialects. The Meteorological or Naturist School holds that Proto-Indo-European myths initially emerged as explanations for natural phenomena, such as the Sky, the Sun, the Moon, and the Dawn.” ref

“Some myths are also securely dated to Proto-Indo-European times, since they feature both linguistic and thematic evidence of an inherited motif: a story portraying a mythical figure associated with thunder and slaying a multi-headed serpent to release torrents of water that had previously been pent up; a creation myth involving two brothers, one of whom sacrifices the other in order to create the world; and probably the belief that the Otherworld was guarded by a watchdog and could only be reached by crossing a river. The mythology of the Proto-Indo-Europeans is not directly attested and it is difficult to match their language to archaeological findings related to any specific culture from the Chalcolithic. Nonetheless, scholars of comparative mythology have attempted to reconstruct aspects of Proto-Indo-European mythology based on the existence of linguistic and thematic similarities among the deities, religious practices, and myths of various Indo-European peoples. This method is known as the comparative method.” ref

“One of the earliest attested and thus one of the most important of all Indo-European mythologies is Vedic mythology, especially the mythology of the Rigveda, the oldest of the Vedas. Early scholars of comparative mythology such as Friedrich Max Müller stressed the importance of Vedic mythology to such an extent that they practically equated it with Proto-Indo-European myths. Modern researchers have been much more cautious, recognizing that, although Vedic mythology is still central, other mythologies must also be taken into account. Another of the most important source mythologies for comparative research is Roman mythology. The Romans possessed a very complex mythological system, parts of which have been preserved through the characteristic Roman tendency to rationalize their myths into historical accounts. Despite its relatively late attestation, Norse mythology is still considered one of the three most important of the Indo-European mythologies for comparative research, due to the vast bulk of surviving Icelandic material.” ref

“Norse, Nordic, or Scandinavian mythology, is the body of myths belonging to the North Germanic peoples, stemming from Old Norse religion and continuing after the Christianization of Scandinavia, and into the Nordic folklore of the modern period. The northernmost extension of Germanic mythology and stemming from Proto-Germanic folklore, Norse mythology consists of tales of various deities, beings, and heroes derived from numerous sources from both before and after the pagan period, including medieval manuscripts, archaeological representations, and folk tradition. The source texts mention numerous gods such as the thunder-god Thor, the raven-flanked god Odin, the goddess Freyja, and numerous other deities.” ref

“Most of the surviving mythology centers on the plights of the gods and their interaction with several other beings, such as humanity and the jötnar, beings who may be friends, lovers, foes, or family members of the gods. The cosmos in Norse mythology consists of Nine Worlds that flank a central sacred tree, Yggdrasil. Units of time and elements of the cosmology are personified as deities or beings. Various forms of a creation myth are recounted, where the world is created from the flesh of the primordial being Ymir, and the first two humans are Ask and Embla. These worlds are foretold to be reborn after the events of Ragnarök when an immense battle occurs between the gods and their enemies, and the world is enveloped in flames, only to be reborn anew. There the surviving gods will meet, and the land will be fertile and green, and two humans will repopulate the world.” ref

“Norse mythology has been the subject of scholarly discourse since the 17th century when key texts attracted the attention of the intellectual circles of Europe. By way of comparative mythology and historical linguistics, scholars have identified elements of Germanic mythology reaching as far back as Proto-Indo-European mythology. During the modern period, the Romanticist Viking revival re-awoke an interest in the subject matter, and references to Norse mythology may now be found throughout modern popular culture. The myths have further been revived in a religious context among adherents of Germanic Neopaganism.” ref

“Approximately 7,000 years ago, the Indo-European linguistic lineage had already split into numerous distinct branches, according to the study published in Science. “This would rule out the steppe hypothesis,” said Heggarty. Around 8,120 years ago, the Proto-Indo-European language likely experienced its initial diversification event, give or take a few centuries. Recent studies of ancient DNA suggest that farmers from the Caucasus region — between the Black Sea and Caspian Sea — migrated towards Anatolia, which supports the Anatolian theory. Hittite, an extinct language spoken by the Anatolian civilization, is another significant branch of the Indo-European family. For decades, a large group of linguists argued that Hittite was the common ancestor of the other Indo-European languages, with some even considering it to be the direct heir of Proto-Indo-European.” ref

“Ancient DNA, on the other hand, has provided compelling evidence in support of the steppe hypothesis. Since 2015, it has become clear that individuals originating from the Pontic steppe, situated to the south and northeast of present-day Russia, Ukraine, and Kazakhstan, migrated to Central Europe approximately 6,000 to 4,500 years ago. Their genetic legacy is evident in both modern Europeans and the indigenous populations of that era. Notably, studies conducted in 2018 and 2019 revealed how these migrant eastern populations replaced a significant proportion of males on the Iberian Peninsula. Furthermore, they brought with them Italic, Germanic, and Celtic languages. It is important to note that when they departed from their original homeland, they likely spoke a common or closely related language descended from Proto-Indo-European. However, as their very slow journey progressed (the Celts took centuries to reach present-day Ireland) and they settled in new territories, language diversification began to emerge.” ref

“The Albanians, Greek-speaking Mycenaeans, and Hittites do not have a dominant genetic signal from the steppe.” ref

Paul Heggarty, researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany.

“Heggarty’s team made a significant contribution by shedding light on this question. By combining phylogenetic analysis of cognates with insights from ancient DNA, they found potentially two distinct origins. Expansion initially originated from the southern Caucasus region, resulting in the separation of five major language families approximately 7,000 years ago. “The Albanians, Greek-speaking Mycenaeans and Hittites do not have a dominant genetic signal from the steppe,” said Heggarty. Several millennia later, another wave emerged, led by nomadic steppe herders from the north. This wave not only influenced the development of western branches of the language tree, but it also possibly played a role in the evolution of Slavic and Baltic languages. It even extended its influence to the Indian subcontinent, while giving rise to the now-extinct Tocharian languages in what is present-day Tibet.” ref

Nordic Paganism/Shamanism, Vikings, White Supremacists Imaginary Viking Past,

Neo-paganism/Neo-Shamanism, and Far-right Religio-Nationalism Bigotry

Religious Nationalism

“Religious nationalism can be understood in a number of ways, such as nationalism as a religion itself, a position articulated by Carlton Hayes in his text Nationalism: A Religion, or as the relationship of nationalism to a particular religious belief, dogma, ideology, or affiliation. In the former aspect, a shared religion can be seen to contribute to a sense of national unity, a common bond among the citizens of the nation. Another political aspect of religion is the support of a national identity, similar to a shared ethnicity, language, or culture. The danger is that when the state derives political legitimacy from adherence to religious doctrines, this may leave an opening to overtly religious elements, institutions, and leaders, making the appeals to religion more ‘authentic’ by bringing more explicitly theological interpretations to political life. Thus, appeals to religion as a marker of ethnicity create an opening for more strident and ideological interpretations of religious nationalism. Many ethnic and cultural nationalisms include religious aspects, but as a marker of group identity, rather than the intrinsic motivation for nationalist claims. Such thinking is related to Buddhist Nationalism, Christian nationalism, Hindu nationalism, Muslim nationalism, Nationalism in modern paganism, Jewish nationalism, Shinto nationalism, and Sikh nationalism, etc.” ref

The Worldwide Rise of Religious Nationalism

“The rise of new forms of religious nationalism at the end of the 20th and beginning of the 21st centuries is to a large extent a by-product of globalization. As nation-states are permeated by transnational economics and trends and secular nationalism is challenged by the global diaspora of peoples and cultures, new ethno-religious movements have arisen to shore up a sense of national community and purpose. One can project at least three different futures for religious and ethnic nationalism in a global world: one where religious and ethnic politics ignore globalization, where they rail against it, and where they envision their own transnational futures. Religious nationalism is not a new phenomenon, however. Beginning in the 1970s, new forms of nationalism based on religion began to appear around the world, defying the legacy of secular nationalism based on the ideas of the European Enlightenment. Initially, the independent nation-states that emerged earlier in the 20th century at the end of the colonial era followed the pattern of secularism set during colonial rule, but at the end of the century, this began to change. Assertions of religious politics began to arise in the Middle East, South Asia, and elsewhere. Prominent among them was the Islamic revolution in Iran in 1978, in a country that had not been part of a colonial Empire; it created the first modern religious nation-state and set a standard for religious politics that other countries would follow. Religious nationalism was on the rise.” ref

“History seems poised on the brink of an era of globalization, hardly the time for new national aspirations to emerge. In fact, some observers have cited the appearance of ethnic and religious nationalism in such areas as the former Yugoslavia and the former Soviet Union, Algeria and the Middle East, South Asia, Japan, and among right-wing movements in Europe and the United States as evidence that globalization has not reached all quarters of the globe. It should not be surprising that new sociopolitical forms are emerging at this moment of history since globalization is redefining virtually everything on the planet. This includes especially those social and political conventions associated with the nation-state. Among other things, global forces are undermining many of the traditional pillars on which the secular nation-state have been based, such as national sovereignty, economic autonomy, and social identity. As it turns out, however, these aspects of the nation-state have been vulnerable to change for some time.” ref

“Born as a stepchild of the European Enlightenment, the idea of the modern nation-state is profound and simple: the state is created by the people within a given national territory. Secular nationalism—the ideology that originally gave the nation-state its legitimacy—contends that a nation’s authority is based on the secular idea of a social compact of equals rather than on ethnic ties or sacred mandates. It is a compelling idea, one with pretensions of universal applicability. It reached its widest extent of worldwide acceptance in the mid-twentieth century. But the latter half of the century was a different story. The secular nation-state proved to be a fragile artifice, especially in those areas of the world where nations had been created by retreating colonial powers—in Africa by Britain, Portugal, Belgium, and France; in Latin America by Spain and Portugal; in South and Southeast Asia by Britain, France, the Netherlands, and the United States; and in Eurasia by the Soviet Union.” ref

“In some cases, boundary disputes led to squabbles among neighboring nations. In others, the very idea of the nation was a cause for suspicion. Many of these imagined nations—some with invented names such as Yugoslavia, Pakistan, Indonesia, and Iraq—were not accepted by everyone within their territories. In yet other cases, the tasks of administration became too difficult to perform in honest and efficient ways. The newly created nations had only brief histories of prior colonial control to unite them, and after independence they had only the most modest of economic, administrative, and cultural infrastructures to hold their disparate regions together.” ref

Religious Nationalism Around the World

“In order to understand the role of religion in modern nationalism, it’s important to first recognize that nationalism is, at its most fundamental level, a form of identity.” ref

“Religion’s powerful impact on modern politics may seem obvious, but for much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, there was an assumption among social scientists that religion was destined to wither away. So, as nationalism exploded in the nineteenth century, religion often played a smaller role in society as it gave way to newer and more secular notions of society. For example, in addition to replacing the monarchy with a republic, the humanist revolutionaries of the French Revolution also transformed Catholic churches into “Temples of Reason.” Both the monarchy and the Church became anachronisms. After all, who needs the Church when you have reason?” ref

“And yet, religion refused to go away. By the late-twentieth century, clear reminders of the importance of religion in the modern world were abundant. In Europe alone, the Troubles in Northern Ireland between Protestants and Catholics, the genocide in Srebrenica carried out by Orthodox Serbs against Muslim Bosniaks, and the Catholic-fueled Solidarity movement in Poland all showed the importance of religion in modern politics and modern nations. Scholars now recognize that modernity can in fact undermine religion, as was predicted for many years, but the very same modernization is also destabilizing. And as the pace of change accelerates in the world around us, that instability is disconcerting, and it can lead us to seek out those forces that provide us with a greater context and help us to feel more grounded. In that way, the chaos of the modern world can actually strengthen religion.” ref

“In order to understand the role of religion in modern nationalism, it’s important to first recognize that nationalism is, at its most fundamental level, a form of identity. It tells us who we are, and that in turn can impact our values, our purpose, and our sense of where we belong. And like all forms of identity, nationalism is inherently tied to the concept of “the other.” If you pause and think about your core identities—whether that be your national identity, ethnicity, gender, occupation, religion, or role in your family—each identity is shaped in response to what you are not. The identity of fathers is shaped in response to what sets them apart from both mothers and children. The identity of Protestants is shaped in response to what distinguishes them from Catholics. Similarly, American national identity is tied to those values and characteristics that distinguish it from other nations. Universal characteristics aren’t useful in-group identification. As a result, national groups are always informed and shaped by the traits that distinguish them from other groups.” ref

Professor: White Supremacists Used Civil Rights Script To Create ‘Unite The Right’ Rally

“Aniko Bodroghkozy is a professor who studies history, so she isn’t keen to make it. That changed Aug. 11, 2017, as white supremacists clutching tiki torches marched through the University of Virginia and then, a day later, headed towards the pedestal of the Robert E. Lee statue in downtown Charlottesville. Bodroghkozy took to the streets as a counterprotester, but steered clear of the violent clashes that were the top national story that night. By the end of the two days of violence, counterprotester Heather Heyer was dead after a car attack that hurt scores of others. And two state police troopers perished when their helicopter that had been monitoring the rioting crashed. In the days and weeks that followed, Bodroghkozy reflected on how the media tactics employed by “Unite the Right” organizers seemed familiar. Their playbook, she says, looked a lot like what she studies: how 1960s civil rights leaders gained attention for the cause. Those initial thoughts led to a new book, “Making #Charlottesville,” which she recently discussed on the radio show “With Good Reason.” ref

“I had no distance from what I was attempting to make sense of. As a media historian who mostly stays in the 1960s, I don’t tend to write about current or near-current events. But coming out of Charlottesville’s “Summer of Hate,” I had no choice. I felt compelled as someone who had been on the streets, as well as a scholar at this University, to understand what happened using the analytical tools I have. I’ve written and taught about the Civil Rights Movement and media coverage. So I brought a comparative historical framework to the task. It became clear to me that what happened in Charlottesville was linked to civil rights-era struggles against white supremacy, but in mirror-image reverse. “Charlottesville” became a worldwide media event, as did key campaigns of the Civil Rights Movement, in particular the Birmingham campaign of 1963 and the Selma voting rights campaign of 1965.” ref

“In examining how the media covered the Aug. 11 and 12 events in Charlottesville, particularly the most heavily circulated visual imagery, I found surprising similarities and resonances with the most iconic imagery from the Civil Rights Movement: white racists as active and empowered (such as the images of tiki torch marchers in front of the Rotunda chanting their racist, antisemitic slogans); African American victims, prone, helpless and brutalized by racists (such as viral video and images of the beating of DeAndre Harris by pole-wielding alt-right marchers), nonviolent counterprotesters as heroic but imperiled by swarms of white supremacists (like the small group of students at the Jefferson statue surrounded by menacing tiki torch marchers). All of these images have remarkable similarity to the most well-known photos of the civil rights era, telling very similar stories.” ref

Norse SHAMANISM

“What is shamanism, and to what extent was it present among the pre-Christian Norse and other Germanic peoples? “Shamanism,” like “love,” is a notoriously hard word to define. Any meaningful discussion of an idea, however, depends on the idea first being clearly defined so that everyone understands exactly what is being discussed. For our purposes here, shamanism can be considered to be the practice of entering an ecstatic trance state in order to contact spirits and/or travel through spiritual worlds with the intention of accomplishing some specific purpose. It is a feature of countless magical and religious traditions from all over the world, especially those that are tied to a particular people and/or place.” ref

“The pre-Christian religion of the Germanic peoples teems with shamanic elements – so much so that it would be impossible to discuss them all here. Our discussion will have to be confined to those that are the most significant. We’ll start with Odin, the father of the gods, who possesses numerous shamanic traits. From there, we’ll examine shamanism in Norse magical traditions that were part of the female sphere of traditional northern European social life, and then move on to the male sphere of the berserkers and other “warrior-shamans” before concluding.” ref

Odin and Shamanism

“Odin, the chief of the gods, is often portrayed as a consummate shamanic figure in the oldest primary sources that contain information about the pre-Christian ways of the Germanic peoples. His very name suggests this: “Odin” (Old Norse Óðinn) is a compound word comprised of óðr, “ecstasy, fury, inspiration,” and the suffix -inn, the masculine definite article, which, when added to the end of another word like this, means something like “the master of” or “a perfect example of.” The name “Odin” can therefore be most aptly translated as “The Master of Ecstasy.” The eleventh-century historian Adam of Bremen confirms this when he translates “Odin” as “The Furious.” This establishes a link between Odin and the ecstatic trance states that comprise one of the defining characteristics of shamanism.” ref

“Odin’s shamanic spirit-journeys are well-documented. The Ynglinga Saga records that he would “travel to distant lands on his own errands or those of others” while he appeared to others to be asleep or dead. Another instance is recorded in the Eddic poem “Baldur’s Dreams,” where Odin rides Sleipnir, an eight-legged horse typical of northern Eurasian shamanism, to the underworld to consult a dead seeress on behalf of his son. Odin, like shamans all over the world, is accompanied by many familiar spirits, most notably the two ravens Hugin and Munin. The shaman must typically undergo a ritual death and rebirth in order to acquire his or her powers, and Odin underwent exactly such an ordeal when he discovered the runes. Having done so, he became one of the cosmos’s wisest, most knowledgeable, and most magically powerful beings. He is a renowned practitioner of seidr, which he seems to have learned from the goddess Freya.” ref

Shamanism in Seidr

“Freya is the divine archetype of the völva, a professional or semi-professional practitioner of the Germanic magical tradition known as seidr. Seidr (Old Norse seiðr) was a form of magic concerned with discerning the fated course of events and symbolically weaving new events into being in accordance with fate’s framework. To do this, the practitioner, with ritual distaff in hand, would enter a trance and travel in spirit throughout the Nine Worlds accomplishing her intended task. This generally took the form of a prophecy, a blessing, or a curse. The völva wandered from town to town and farm to farm prophesying and performing other acts of magic in exchange for room, board, and often other forms of compensation as well. The most detailed account of such a woman and her doings comes from The Saga of Erik the Red, but numerous sagas, as well as some of the mythic poems (most notably the Völuspá, “The Insight of the Völva“) contain sparse accounts of seidr-workers and their practices.” ref

“Like other northern Eurasian shamans, the völva was “set apart” from her wider society, both in a positive and a negative sense – she was simultaneously exalted, sought-after, feared, and, in some instances, reviled. However, the völva is very reminiscent of the veleda, a seeress or prophetess who held a more clearly-defined and highly respected position amongst the Germanic tribes of the first several centuries CE. In either of these roles, the woman practitioner of these arts held a more or less dignified role among her people, even as the degree of her dignity varied considerably over time. Such was not usually the case for male practitioners of seidr. According to traditional Germanic gender constructs, it was extremely shameful and dishonorable for a man to adopt a female social or sexual role. A man who practiced seidr could expect to be labeled argr (Old Norse for “unmanly;” the noun form is ergi) by his peers – one of the gravest insults that could be hurled at a Germanic man.” ref

“While there were probably several reasons for seidr being considered to fall under the category of ergi, the greatest seems to have been the centrality of weaving, the paragon of the traditional female economic sphere, in seidr. Still, this didn’t stop numerous men from engaging in seidr, sometimes even as a profession. A few such men have had their deeds recorded in the sagas. The foremost among such seiðmenn was none other than Odin himself – and not even he escaped the charge of being argr. We can detect a high degree of ambivalence seething beneath the surface of this taunt; unmanly as seidr may have been seen as being, it was undeniably a source of incredible power – perhaps the greatest power in the cosmos, given that it could change the course of destiny itself. Perhaps the sacrifice of social prestige for these abilities wasn’t too bad of a bargain. After all, such men could look to the very ruler of Asgard as an example and a patron.” ref

Shamanism in Warrior Magic and Religion

“In any case, there were other forms of shamanism that were much more socially acceptable for men to practice. One of the central institutions of traditional Germanic society was the band of elite, ecstatic, totemistic warriors. Some of the warriors in these warbands were berserkers. These were no ordinary soldiers; the initiation rituals, fighting techniques, and other spiritual practices of these bands were such that their members could be aptly characterized as “warrior-shamans.” ref

“The divine guide and inspiration of such men was the same as for the seidr-workers: Odin. The Ynglinga Saga has this to say about them:

Odin’s men went armor-less into battle and were as crazed as dogs or wolves and as strong as bears or bulls. They bit their shields and slew men, while they themselves were harmed by neither fire nor iron. This is called “going berserk.” ref

“Or in the astute and evocative words of archaeologist Neil Price:

They run howling and foaming through the groups of fighting men. Some of them wear animal skins, some are naked, and some have thrown away shields and armour to rely on their consuming frenzy alone. Perhaps some of the greatest warriors do not take the field at all, but remain behind in their tents, their minds nevertheless focused on the combat. As huge animals their spirit forms wade through the battle, wreaking destruction.” ref

“This combat frenzy (“going berserk”) was one of the most common and most potent forms that Odin’s ecstasy (óðr) could take. In such a battle-trance, these hallowed warriors bit or cast away their shields, the symbolic indicators of their social persona, and became utterly possessed by the spirit of their totem animal, sometimes even shifting their shapes to become a bear or a wolf. By extension, they achieved a state of unification with the master of these beasts and the giver of this sublime furor: Odin. Given the prominence of shamanism in other traditional northern Eurasian societies, it would be shocking if it were absent from traditional Germanic society. So it’s hardly surprising to find, instead, that the established social customs of the pre-Christian Germanic peoples brimmed with shamanic elements.” ref

“It’s just as important, however, to stress the uniquely Germanic form of these elements. At the center of the Germanic shamanic complex is the “Allfather,” Odin, who inspires the female seidr-workers and the male “warrior-shamans” alike with his perilous gift of ecstasy, granting them an upper hand in life’s battles as well as communion with the divine world of consummate meaning. Looking for more great information on Norse mythology and religion? While this site provides the ultimate online introduction to the topic, my book The Viking Spirit provides the ultimate introduction to Norse mythology and religion period. I’ve also written a popular list of The 10 Best Norse Mythology Books, which you’ll probably find helpful in your pursuit.” ref

Neo-Shamanism

“Neoshamanism refers to new forms of shamanism. It usually means shamanism practiced by Western people as a type of New Age spirituality, without a connection to traditional shamanic societies. It is sometimes also used for modern shamanic rituals and practices which, although they have some connection to the traditional societies in which they originated, have been adapted somehow to modern circumstances. This can include “shamanic” rituals performed as an exhibition, either on stage or for shamanic tourism, as well as modern derivations of traditional systems that incorporate new technology and worldviews. Antiquarians such as John Dee may have practiced forerunner forms of neoshamanism. The origin of neoshamanic movements has been traced to the second half of the twentieth century, especially to counterculture movements and post-modernism. Three writers in particular are seen as promoting and spreading ideas related to shamanism and neoshamanism: Mircea Eliade, Carlos Castaneda, and Michael Harner.” ref

“In 1951, Mircea Eliade popularized the idea of the shaman with the publication of Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy. In it, he claimed that shamanism represented a kind of universal, primordial religion, with a journey to the spirit world as a defining characteristic. However, Eliade’s work was severely criticized in academic circles, with anthropologists such as Alice Beck Kehoe arguing that the term “shamanism” should not be used to refer to anything except the Siberian Tungus people who use the word to refer to themselves. Despite the academic criticism, Eliade’s work was nonetheless a critical part of the neoshamanism developed by Castaneda and Harner. In 1968, Carlos Castaneda published The Teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui Way of Knowledge, which he claimed was a research log describing his apprenticeship with a traditional “Man of Knowledge” identified as don Juan Matus, allegedly a Yaqui Indian from northern Mexico. Doubts existed about the veracity of Castaneda’s work from the time of their publication, and the Teaching of Don Juan, along with Castaneda’s subsequent works, are now widely regarded as works of fiction. Although Castaneda’s works have been extensively debunked, they nevertheless brought “…what he considered (nearly) universal traditional shamanic elements into an acultural package of practices for the modern shamanic seeker and participant.” ref

“The idea of an acultural shamanism was further developed by Michael Harner in his 1980 book The Way of the Shaman. Harner developed his own system of acultural shamanism that he called “Core Shamanism” (see below), which he wrote was based on his experiences with Conibo and Jívaro shamans in South America, including the consumption of hallucinogens. Harner broadly applied the term “shaman” to spiritual and ceremonial leaders in cultures that do not use this term, claiming that he also studied with “shamans” in North America; he wrote that these were Wintu, Pomo, Coast Salish, and Lakota people, but he did not name any individuals or specific communities. Harner claimed he was describing common elements of shamanic practice found among Indigenous people world-wide, having stripped those elements of specific cultural content so as to render them accessible to contemporary Western spiritual seekers. Influences cited by Harner also included Siberian shamanism, Mexican and Guatemalan culture, and Australian traditions, as well as the familiar spirits of European occultism, which aid the occultist in their metaphysical work. However, his practices do not resemble the religious practices or beliefs of any of these cultures.” ref

“Neoshamanism comprises an eclectic range of beliefs and practices that involve attempts to attain altered states and communicate with a spirit world through drumming, rattling, dancing, chanting, music, or the use of entheogens, although the last is controversial among some neoshamanic practitioners. One type of spirit that journeyers attempt to contact are animal tutelary spirits (called “power animals” in Core Shamanism). Core Shamanism, the neoshamanic system of practices synthesized, promoted, and invented by Michael Harner in the 1980s, are likely the most widely used in the West, and have had a profound impact on neoshamanism. While adherents of neoshamanism mention a number of different ancient and living cultures, and many do not consider themselves associated with Harner or Core Shamanism, Harner’s inventions, and similar approaches such as the decontextualized and appropriated structures of Amazonian Ayahuasca ceremonies, have all had a profound influence on the practices of most of these neoshamanic groups.” ref

“Neoshamans may also conduct “soul retrievals”, participate in rituals based on their interpretations of sweat lodge ceremonies, conduct healing ceremonies, and participate in drum circles. Wallis, an archaeologist who self-identifies as a “neo-Shaman” and participates in the neopagan and neoshamanism communities, has written that he believes the experiences of synesthesia reported by Core Shamanic journeyers are comparable with traditional shamanic practices. However, Aldred writes that the experiences non-Natives seek out at these workshops, “also incorporated into theme adult camps, wilderness training programs, and New Age travel packages” have “greatly angered” Native American activists who see these workshops as “the commercial exploitation of their spirituality.” Scholars have noted a number of differences between traditional shamanic practices and neoshamanism. In traditional contexts, shamans are typically chosen by a community or inherit the title (or both). With neoshamanism, however, anyone who chooses to can become a (neo)shaman, although there are still neoshamans who feel that they have been called to become shamans, and that it wasn’t a choice, similar to the situation in some traditional societies.” ref

“In traditional contexts, shamans serve an important culturally recognized social and ceremonial role, one which seeks the assistance of spirits to maintain cosmic order and balance. With neoshamanism, however, the focus is usually on personal exploration and development. While some neoshamanic practitioners profess to enact shamanic ceremonies in order to heal others and the environment, and claim a role in modern communities that they believe is analogous to the shaman’s role in traditional communities, the majority of adherents practice in isolation and the people they work on are paying clients. Another difference between neoshamanism and traditional shamanism is the role of negative emotions such as fear and aggression. Traditional shamanic initiations often involved pain and fear, while neoshamanic narratives tend to emphasize love over negative emotions. And while traditional shamanic healing was often tempered with ideas of malevolence or chaos, neoshamanism has a psychotherapeutic focus that leads to a “happy ending.” Harner, who created the neoshamanic practice of Core Shamanism, goes so far as to argue that those who engage in negative practices are sorcerers, not shamans, although this distinction is not present in traditional societies.” ref

“Although both traditional shamanism and neoshamanism posit the existence of both a spiritual and a material world, they differ in how they view them. In the traditional view, the spirit world is seen as primary reality, while in neoshamanism, materialist explanations “coexist with other theories of the cosmos,” some of which view the material and the “extra-material” world as equally real. Native American scholars have been critical of neoshamanic practitioners who misrepresent their teachings and practices as having been derived from Native American cultures, asserting that it represents an illegitimate form of cultural appropriation and that it is nothing more than a ruse by fraudulent spiritual leaders to disguise or lend legitimacy to fabricated, ignorant, and/or unsafe elements in their ceremonies in order to reap financial benefits. For example, Geary Hobson sees the New Age use of the term “shamanism” (which most neoshamans use to self-describe, rather than “neoshamanism”) as a cultural appropriation of Native American culture by white people who have distanced themselves from their own history. Additionally, Aldred notes that even those neoshamanic practitioners with “good intentions” who claim to support Native American causes are still commercially exploiting Indigenous cultures.” ref

“Members of Native American communities have also objected to neoshamanic workshops, highlighting that shamanism plays an important role in native cultures, and calling those offering such workshops charlatans who are engaged in cultural appropriation. Daniel C. Noel sees Core Shamanism as based on cultural appropriation and a misrepresentation of the various cultures by which Harner claims to have been inspired. Noel believes Harner’s work, in particular, laid the foundations for massive exploitation of Indigenous cultures by “plastic shamans” and other cultural appropriators. Note, however, that Noel does believe in “authentic western shamanism” as an alternative to neoshamanism, a sentiment echoed by Annette Høst who hopes to create a ‘Modern Western Shamanism’ apart from Core Shamanism in order “to practice with deeper authenticity”. Robert J. Wallis asserts that, because the practices of Core Shamanism have been divorced from their original cultures, the mention of traditional shamans by Harner is an attempt to legitimate his techniques while “remov[ing] indigenous people from the equation,” including not requiring that those practicing Core Shamanism to confront the “often harsh realities of modern indigenous life.” ref

Q SHAMAN’S NEW AGE-RADICAL RIGHT BLEND HINTS AT THE BLURRING OF SEEMINGLY DISPARATE CATEGORIES

“Q Shaman’s attire, the bricolage continues. The much-discussed furry hat with horns has been referred to as a Viking helmet as well as a Native American buffalo headdress. Perhaps the closest approximation is the ghost bison fur hat from the video game Red Dead Redemption. The torso tattooing also recalls another video game character, Kratos from God of War. There’s perhaps a strong element of cosplay or LARPing.” ref

“His own explanation, given to the Arizona Republic in a 2020 interview, is that it’s symbolic. The horns represent the buffalo, as in “you mess with the bull you get the horns,” while the skin is coyote, which he links to Native American mythology about the coyote as trickster. His face paint he also links to Native American traditions, calling it “war paint.” Such symbolism is necessary as he’s fighting on the side of the “angels” in a “spiritual war.” ref

“Fighting alongside Donald Trump and the angels in a spiritual war while sporting white supremacist-associated tattoos connects Q Shaman to evangelical Christian nationalism. At the same time, he identifies himself as a shaman. Now in federal custody, Q Shaman aka Jake Angeli aka Jacob Chansely [image below left] is a well-known figure at protests in Arizona in support of Trump’s false claims of election rigging, against Covid-19 lockdowns, as a counter-protestor at Black Lives Matter, and also at a climate protest.” ref

Norse TOTEMISM

“Totemism is a relationship of spiritual kinship between a human or group of humans and a particular species of animal or plant. The totem animal or plant is generally held to be an ancestor, guardian, and/or benefactor of the human or humans in question. The totem animal or plant is sometimes held to overlap with the human self in some way. In the pre-Christian worldview and practices of the Norse and other Germanic peoples, we find totemism manifested in two especially prominent and powerful areas: the animal helping spirits, most notably the fylgjur, and the patron animals of shamanic military societies.” ref

The Fylgjur

“Remember the cats, ravens, and other familiar spirits who are often the companions of witches in European folktales? These are fylgjur (pronounced “FILG-yur”) in the plural and fylgja (pronounced “FILG-ya”; Old Norse for “follower”) in the singular. The fylgja is generally an animal spirit, although, every now and then, a human helping spirit is also called a fylgja in Old Norse literature. The well-being of the fylgja is intimately tied to that of its owner – for example, if the fylgja dies, its owner dies, too. Its character and form are closely connected to the character of its owner; a person of noble birth might have a bear fylgja, a savage and violent person, a wolf, or a gluttonous person, a pig. This helping spirit can be seen as the totem of a single person rather than of a group. Many of the gods and goddesses have personal totem animals which may or may not be fylgjur. For example, Odin is particularly associated with wolves, ravens, and horses, Thor with goats, and Freya and Freyr with wild boars. It should come as no surprise, then, that their human devotees have personal totems of their own.” ref

Totemistic Warriors

“One of the most prominent examples of group totemism among the ancient Germanic peoples is that which occurs within the institutional framework of the initiatory military society. Many of these societies had a totem animal, usually the wolf or the bear, who would lend his ferocity and strength to the warriors. Initiation into one of these societies typically involved spending a period of time alone in the wilderness. The candidate’s food was obtained by hunting, gathering, and stealing provisions from nearby towns. In the words of archaeologist Dominique Briquel, “Rapto vivere, to live in the manner of wolves, is the beginning of this initiation. The bond with the savage world is indicated not only on the geographic plane – life beyond the limits of the civilized life of the towns… but also on what we would consider a moral plane: their existence is assured by the law of the jungle.” The candidate lived in imitation of the group’s totem beast.” ref

“As his training progressed, imitation gave way to identification. The warrior achieved a state of spiritual unification with the bear or the wolf, which would frequently erupt in bouts of ecstatic fury. This bond was displayed to others by the warrior’s dressing himself in a ritual costume made from the hide of the animal, an outward reminder of the man’s having gone beyond the confines of his humanity and become a divine predator. It’s hard to imagine a grislier or more frightening thing to encounter on the Viking Age battlefield.” ref

“This transformation was more than merely symbolic, and fell somewhere along the continuum that includes having the animal as one’s fylgja, possession, and, at the farthest extreme, shapeshifting. The sagas contain numerous accounts of elite warriors shapeshifting into a bear or a wolf; Egil’s Saga and The Saga of King Hrolf Kraki provide a few examples. The most telling example of this phenomenon, however, comes from The Saga of the Volsungs. As part of the hero Sigmund’s training of his protégé, Sinfjötli, the two don wolf pelts and become wolves, and in this form they rage through the forest killing their enemies. Sigmund and Sinfjötli are archetypal úlfheðnar (“wolf-hides”), Viking Age warriors who had wolves as their totem animals. Those who had bears as their totem animals were none other than the famous berserkers, “bear-shirts.” The names berserkir and úlfheðnar are both references to the ritual bear- or wolf-costumes worn by these warriors.” ref

What It Means To Be Human

“Totemism can be seen as a precursor to the modern idea of Darwinian evolution, and evolution, in turn, can be seen as a scientific restatement of some of totemism’s most fundamental assumptions. In the words of the contemporary philosopher David Abram,

Darwin had rediscovered the deep truth of totemism – the animistic assumption, common to countless indigenous cultures but long banished from polite society, that human beings are closely kindred to other creatures… In the wake of Darwin’s bold insights, we have learned to consider all humans as members of a common family. But the wild, animistic implication of Darwin’s insight has taken much longer to surface in our collective awareness, no doubt because it greatly threatens our cherished belief in human transcendence. Nonetheless, it is an inescapable implication of the evolutionary insight: we humans are corporeally related, by direct and indirect webs of evolutionary affiliation, to every other organism that we encounter.” ref

“In this perspective, while every species is unique in some way, humans aren’t uniquely unique compared to other species. There’s nothing that fundamentally separates mankind from the other animals or from the fleshly world we inhabit alongside them. The totemism of the Norse and other Germanic peoples is an instantiation of how they perceived much of the non-human world to be full of enchantment and spiritual qualities. Looking for more great information on Norse mythology and religion? While this site provides the ultimate online introduction to the topic, my book The Viking Spirit provides the ultimate introduction to Norse mythology and religion period. I’ve also written a popular list of The 10 Best Norse Mythology Books, which you’ll probably find helpful in your pursuit.” ref

Wolfs, Odin, Berserkers, and Norse Mythology

“The god Odin is also frequently mentioned in surviving texts. One-eyed, wolf– and raven-flanked, with a spear in hand, Odin pursues knowledge throughout the nine realms. In an act of self-sacrifice, Odin is described as having hanged himself upside-down for nine days and nights on the cosmological tree Yggdrasil to gain knowledge of the runic alphabet, which he passed on to humanity, and is associated closely with death, wisdom, and poetry.” ref

“Fenrir or Fenrisúlfr is an antagonistic being in Norse mythology under the shape of a monstrous wolf. Fenrir, along with Hel and the World Serpent, is a child of Loki and female jötunn Angrboða. He is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and the Prose Edda and Heimskringla, composed in the 13th century. In both the Poetic Edda and Prose Edda, Fenrir is the father of the wolves Sköll and Hati Hróðvitnisson, is a son of Loki and is foretold to kill the god Odin during the events of Ragnarök, but will in turn be killed by Odin’s son Víðarr. Old Norse Fenrir can roughly be translated as ‘fen-dweller’, with Fenrisúlfr (often translated as “Fenris-wolf”) meaning “Fenrir’s wolf”, possibly indicating the wolf as a hamr (magical shape) of Fenrir.” ref

“Other names for the beast includes Hróðvitnir and Vánagandr, the former roughly meaning ‘fame-wolf’, with vitnir being a noa-name for wolf, possibly cognate to Old Norse: víti, “penalty, punishment”, meaning something akin to criminal, alternatively the opposite based on other vitnir-compounds, such as punisher (“penalty giver”) and law-abiding (“penalty avoider”). Vánagandr on the other hand is a poetic title, meaning something akin to “the river Ván”, though, referencing the being of the river Ván. The word “gandr” can mean a variety of things in Old Norse, but mainly refers to elongated “living” entities and or supernatural beings, such as, among other things, fjord and river.” ref

“In the Old Norse written corpus, berserkers (Old Norse: berserkir) were those who were said to have fought in a trance-like fury, a characteristic which later gave rise to the modern English word berserk (meaning “furiously violent or out of control”). Berserkers are attested to in numerous Old Norse sources. It is proposed by some authors that the northern warrior tradition originated from hunting magic. Three main animal cults appeared: the cult of the bear, the wolf, and the wild boar. The Old Norse form of the word was berserk (plural berserkir). It likely means “bear-shirt” (compare the Middle English word ‘serk, meaning ‘shirt’), “someone who wears a coat made out of a bear’s skin“. Thirteenth-century historian Snorri Sturluson interpreted the meaning as “bare-shirt”, that is to say that the warriors went into battle without armor, but that view has largely been abandoned.” ref

“Wolf warriors appear among the legends of the Indo-Europeans, Turks, Mongols, and Native American cultures. The Germanic wolf-warriors have left their trace through shields and standards that were captured by the Romans and displayed in the armilustrium in Rome. Frenzy warriors wearing the skins of wolves called Ulfheðnar (“Wolf-Coats”; singular Ulfheðinn), are mentioned in the Vatnsdæla saga, the Haraldskvæði, and the Grettis saga and are consistently referred to in the sagas as a group of berserkers, always presented as the elite following of the first Norwegian king Harald Fairhair. They were said to wear the pelt of a wolf over their chainmail when they entered battle. Unlike berserkers, direct references to ulfheðnar are scant. Egil’s Saga features a man called Kveldulf (Evening-Wolf) who is said to have transformed into a wolf at night. This Kveldulf is described as a berserker, as opposed to an ulfheðinn. Ulfheðnar are sometimes described as Odin‘s special warriors: “[Odin’s] men went without their mailcoats and were mad as hounds or wolves, bit their shields…they slew men, but neither fire nor iron had an effect upon them. This is called ‘going berserk’.” In addition, the helm-plate press from Torslunda depicts a scene of a one-eyed warrior with bird-horned helm, assumed to be Odin, next to a wolf-headed warrior armed with a spear and sword as distinguishing features, assumed to be a berserker with a wolf pelt: “a wolf-skinned warrior with the apparently one-eyed dancer in the bird-horned helm, which is generally interpreted as showing a scene indicative of a relationship between berserkgang … and the god Odin.” ref

Boys Killed Pet Dogs to Become Warriors in Early Russia around 4,000 years ago

In Russia, dismembered dogs point to an ancient initiation rite.

“At the Bronze Age site of Krasnosamarkskoe in Russia’s Volga region, they unearthed the bones of at least 51 dogs and 7 wolves. All the animals had died during the winter months, judging from the telltale banding pattern on their teeth, and all were subsequently skinned, dismembered, burned, and chopped with an ax. Moreover, the butcher had worked in a precise, standardized way, chopping the dogs’ snouts into three pieces and their skulls into geometrically shaped fragments just an inch or so in size. “It was very strange,” says Anthony. Ancient Rite of Passage: In search of clues, Anthony and Brown combed the mythology, songs, and scriptures in Eurasia’s early and closely related Indo-European languages. Many ancient Indo-European speakers associated dogs with death and the underworld. Reading through prayers composed by tribes in India possibly as early as 1400 BCE or around 3,400 years ago, the researchers found a description of secret initiation rites for boys destined to become roving warriors. At the age of eight, the boys were sent to ritualists, who bathed them, shaved their heads, and gave them animal skins to wear. Eight years later, the initiates underwent a midwinter ceremony in which they ritually died and journeyed to the underworld. After this, the boys left their homes and families, painted their bodies black, donned a dog-skin cloak, and joined a band of warriors.” ref

“The dogs of war: A Bronze Age initiation ritual in the Russian steppes. At the Srubnaya-culture settlement of Krasnosamarskoe in the Russian steppes, dated 1900–1700 BCE or around 3,900 to 3,700 years ago, a ritual occurred in which the participants consumed sacrificed dogs, primarily, and a few wolves, violating normal food practices found at other sites, during the winter.” ref

Warrior Initiations, Midwinter Dog Sacrifices, and the Psychology of War

“Indo-European youthful initiatory war bands have not previously been documented archaeologically. Here we describe an archaeological site at Krasnosamarskoe, Russia, dated 1900–1700 BCE or around 3,900 to 3,700 years ago, that revealed the remains of a repeated series of winter-season sacrifices totaling at least 51 dogs, mostly older male dogs, and 7 wolves that were roasted, chopped and apparently eaten, an inversion of the local custom of avoidance of dogs and wolves as food. Krasnosamarskoe was a Late Bronze Age (LBA) settlement of the Srubnaya culture located in the middle Volga steppes near Samara, Russia. No other Srubnaya settlement in the region has produced so many canid bones, or canids chopped and segmented in this way.” ref

“Researchers used resources from comparative Indo-European linguistics and mythology to suggest that the canid-centered sacrificial rituals at Krasnosamarskoe were linked to the institution of initiatory Indo-European war-bands. Initiatory warrior bands associated with dogs and wolves can be found in mythological and epic traditions known in Germanic (Männerbünde), Celtic (fian), Italic (luperci or sodales), Greek (*koryos, ephebes), and in Indo-Iranian, particularly in Vedic sources (vrātyas). One largely unexplored aspect of this institution through which boys were prepared to become warriors was its psychological function. Behavioral studies of modern and ancient warfare permit us to evaluate the psychological efficacy of IE warrior bands as an institution to train young men to fight together while avoiding the psychological traumas that often affect warriors on their return home.” ref

“Archaeologists find mysterious, 4,000-year-old dog sacrifices in Russia and think it may relate to an ancient structure full of charred dog bones which to them points to a ritual related to werewolf myths. 4,000 years ago in the northern steppes of Eurasia, in the shadow of the Ural Mountains, a tiny settlement stood on a natural terrace overlooking the Samara River. The people who lived at Krasnosamarskoe were part of an Indo-European cultural group called Srubnaya, with Bronze Age technology. The Srubnaya lived in settlements year-round, but were not farmers. They kept animals, hunted for wild game, and gathered plants to eat opportunistically. Like many Indo-European peoples, they did not have what modern people would call an organized religion. But as Krasnosamarskoe demonstrates, they certainly had beliefs that were highly spiritual and symbolic. And they engaged in ritualistic practices over many generations. Perhaps the first unusual feature of Krasnosamarskoe is that the people who lived here chose to build on top of an abandoned settlement that was about 1,000 years gone when the Srubnaya moved in. That previous settlement left behind three large kurgans, or burial mounds.” ref

“Excavating one of these kurgans revealed a couple of 5,000-year-old skeletons from the first group, surrounded by 4,000-year-old remains from the Srubnaya. The people of Krasnosamarskoe obviously knew these were ancient grave mounds when they moved in, and chose to keep using them. After exhaustively cataloging dozens of burials in and around the kurgans, Anthony and his colleagues discovered a few patterns. First of all, most of the Srubnaya remains were of children. One showed signs of a degenerative disease, but the others appeared to have died of illnesses that didn’t leave clear marks on their skeletons. None showed any signs of violent death or abuse. It seems likely that people brought their sick children to this place, perhaps seeking ritual medicine. The archaeologists also found pollen from a medicinal plant, Seseli, in one of the structures. Seseli is a mild sedative and muscle relaxant that could have been used to calm the suffering children. Those who did not survive were laid to rest in the ancient cemetery.” ref