- My Thoughts on Possible Migrations of “R” DNA and Proto-Indo-European?

- Migrations and Changing Europeans Beginning around 8,000 Years Ago

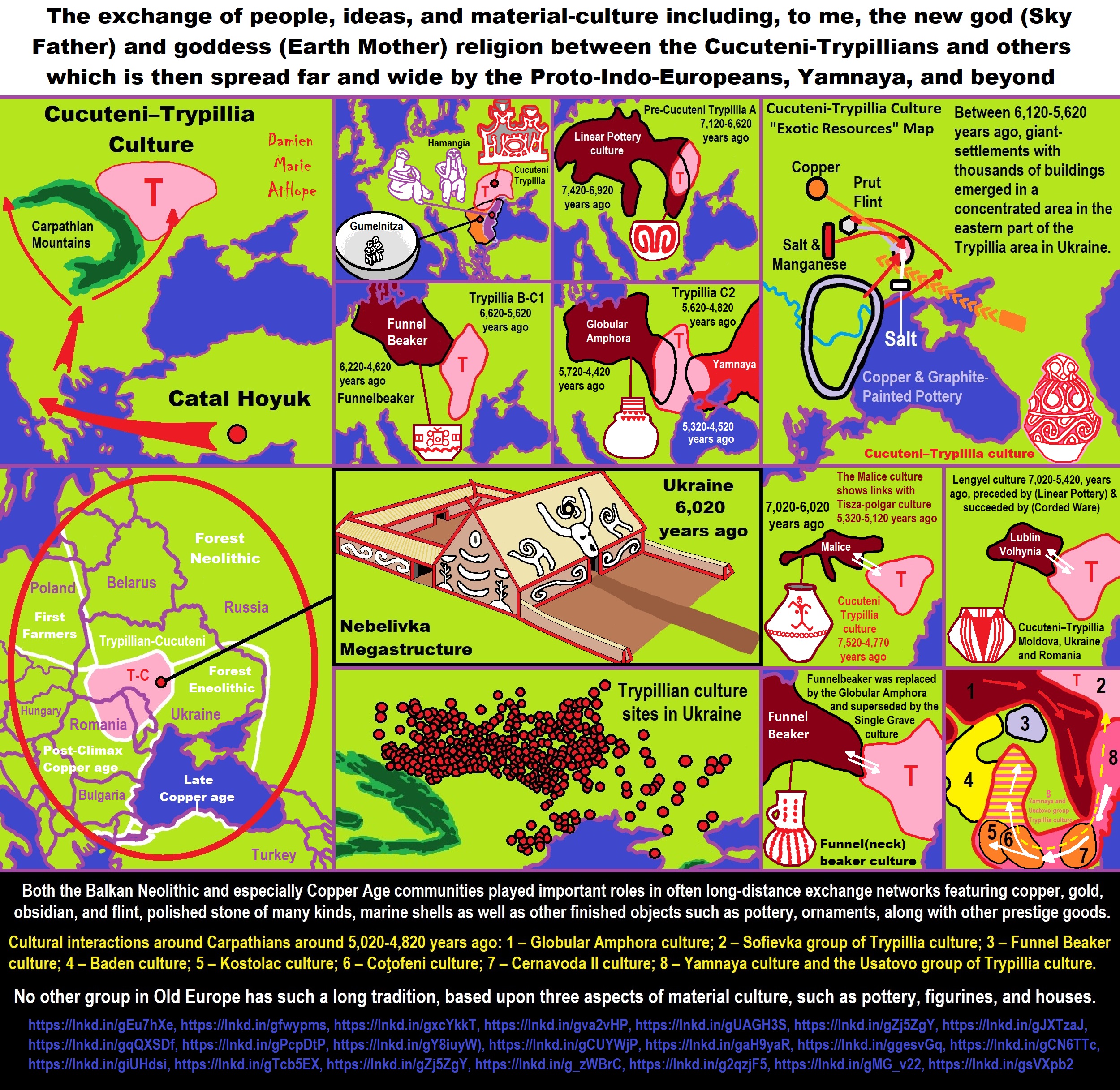

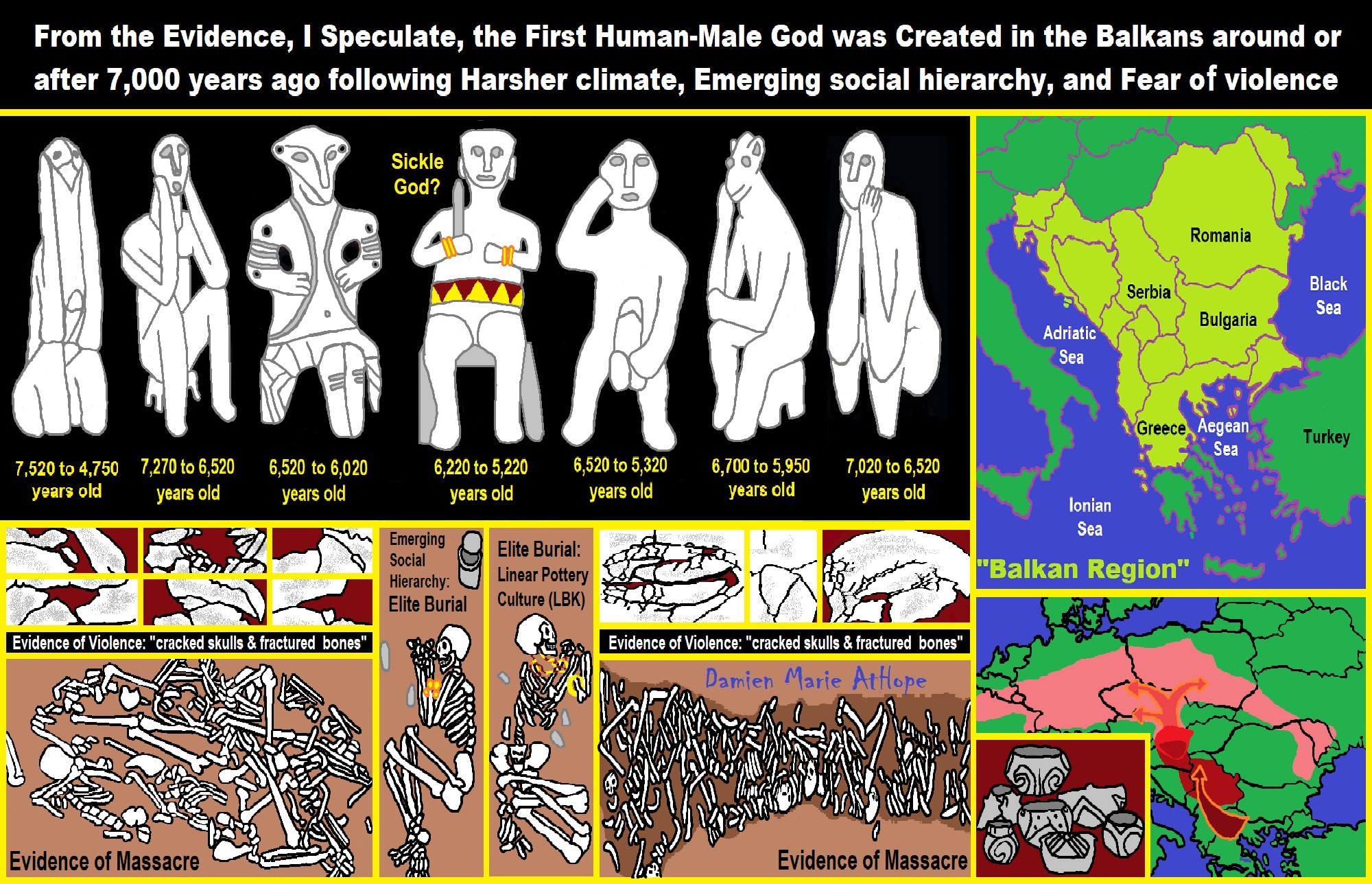

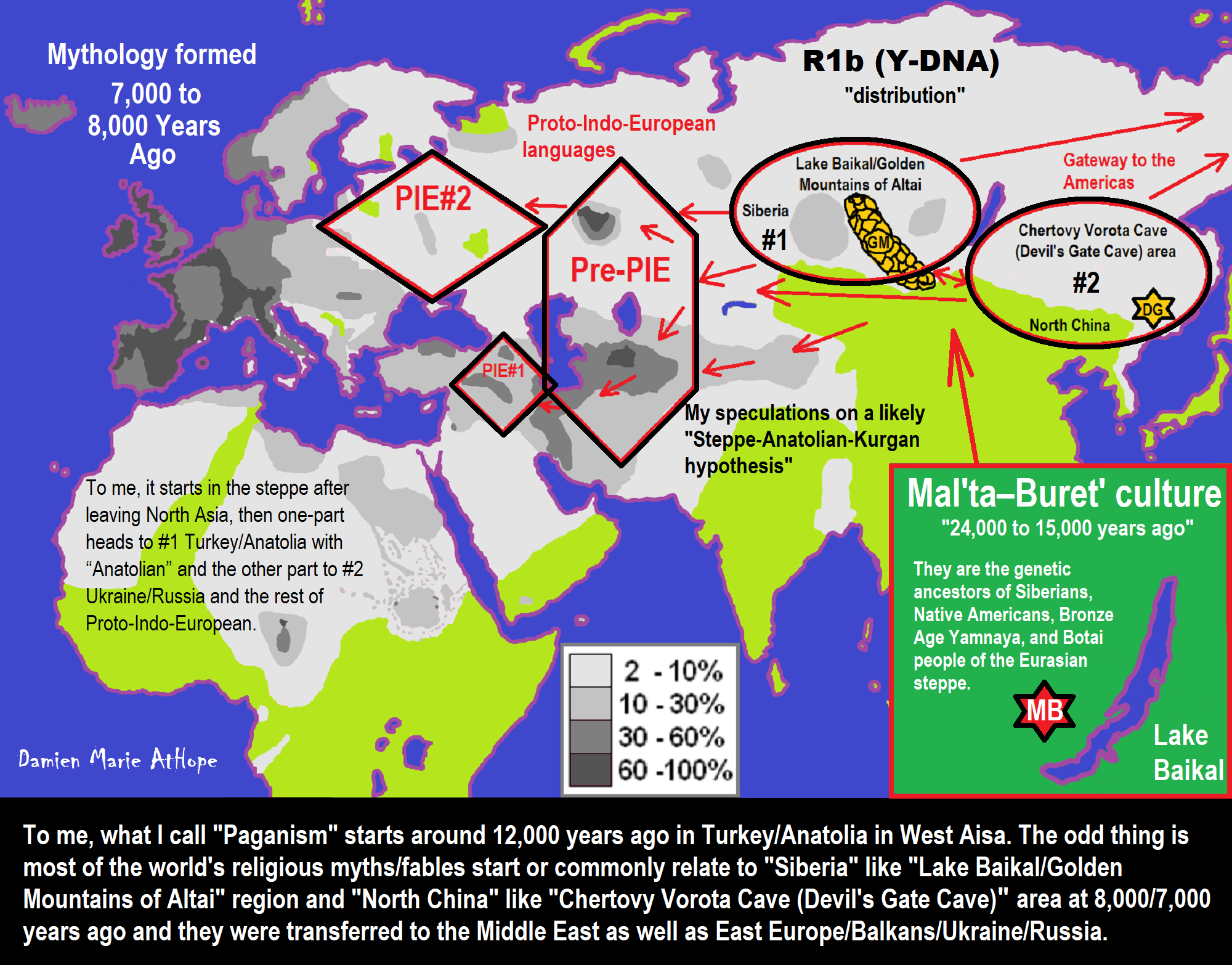

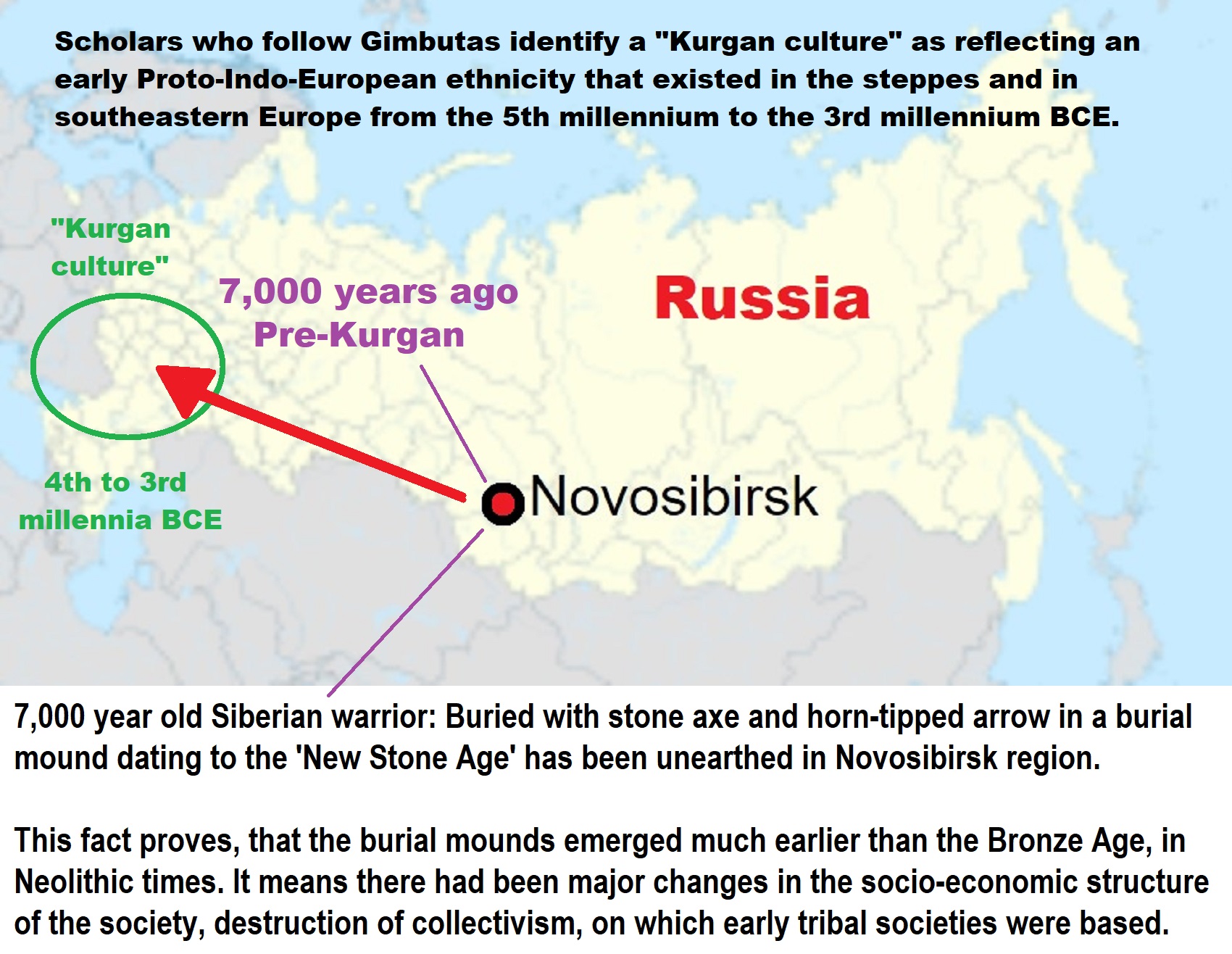

- My “Steppe-Anatolian-Kurgan hypothesis” 8,000/7,000 years ago

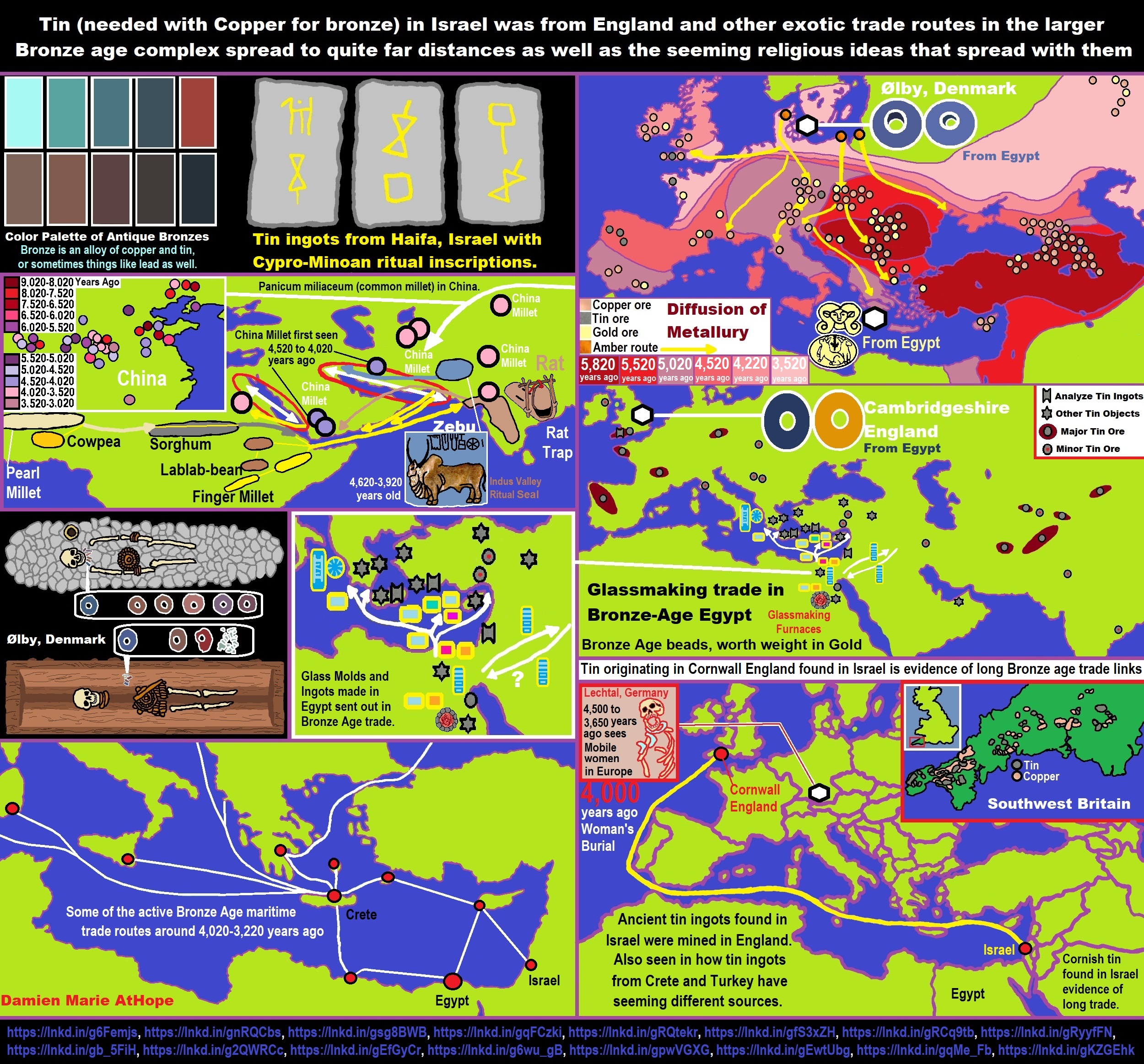

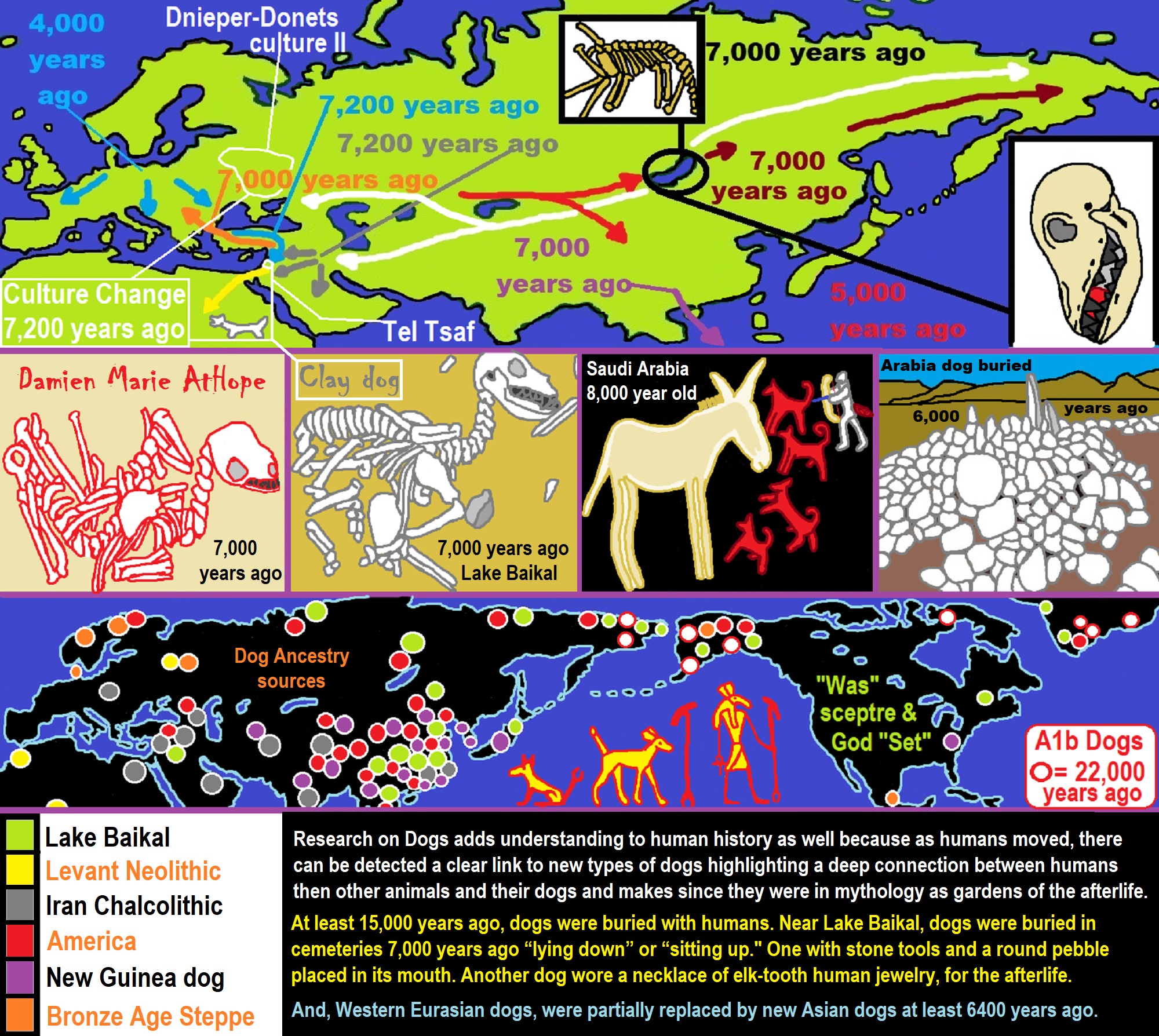

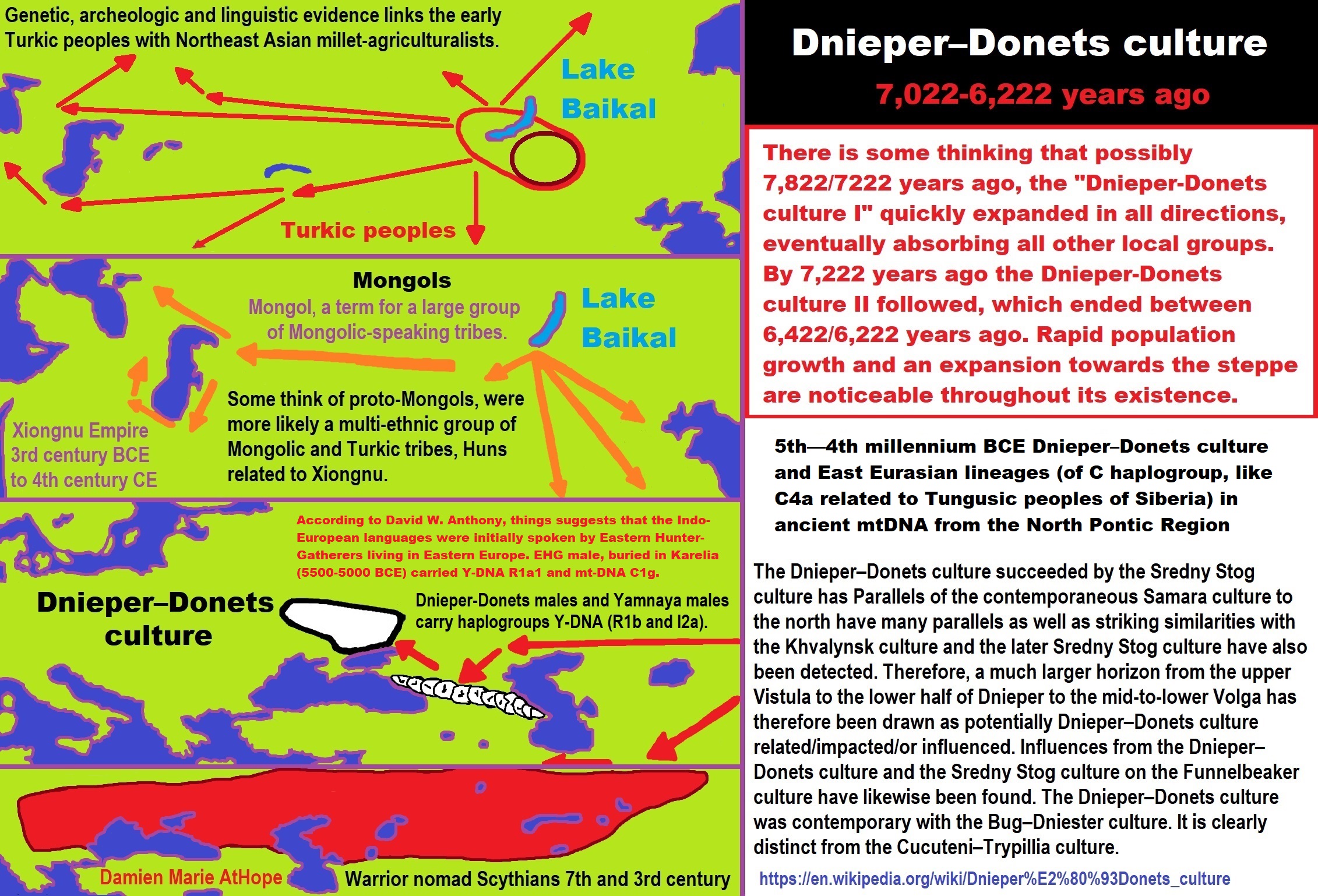

- The Dnieper–Donets culture and Asian varieties of Millet from China to the Black Sea region of Europe by 7,022 years ago

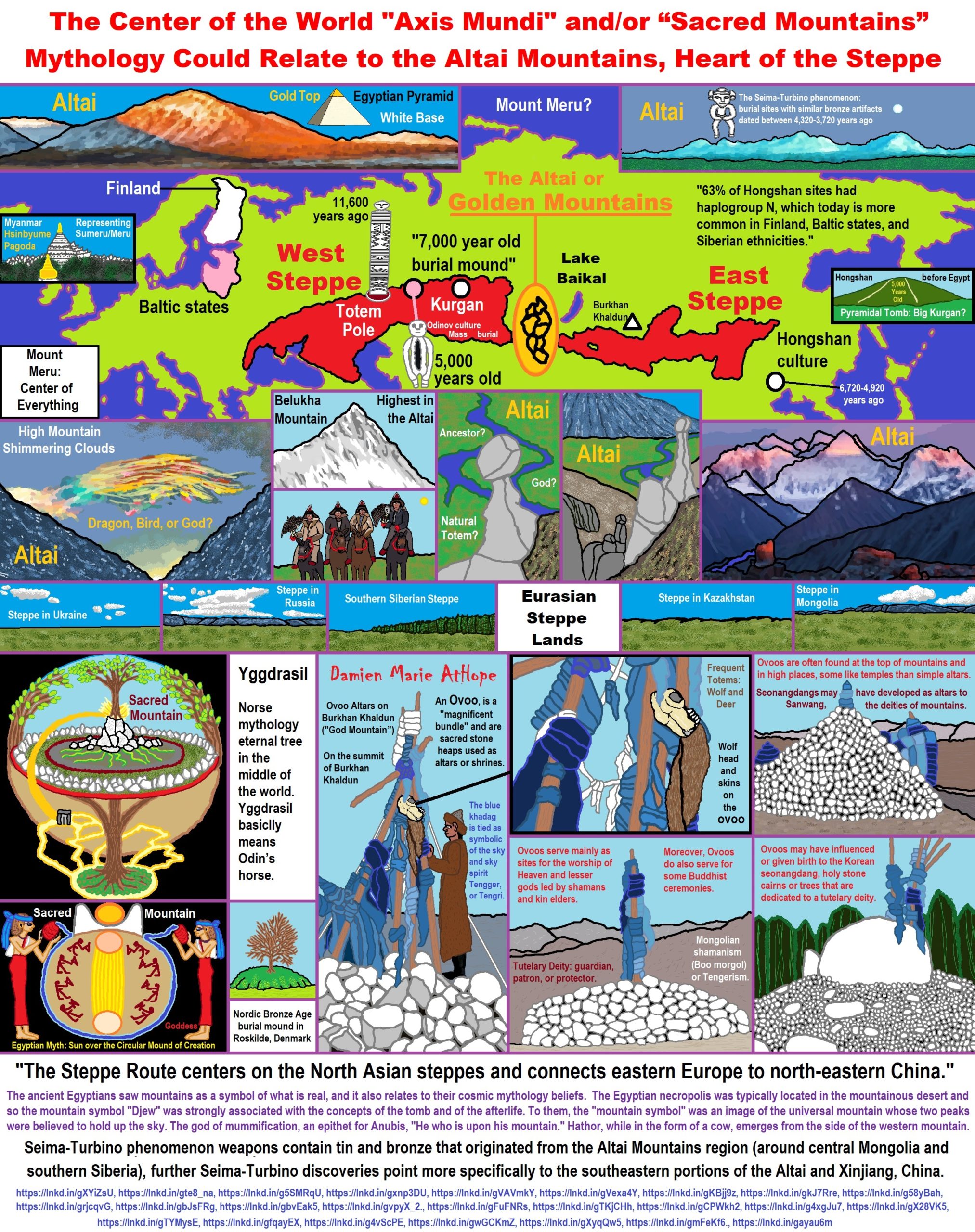

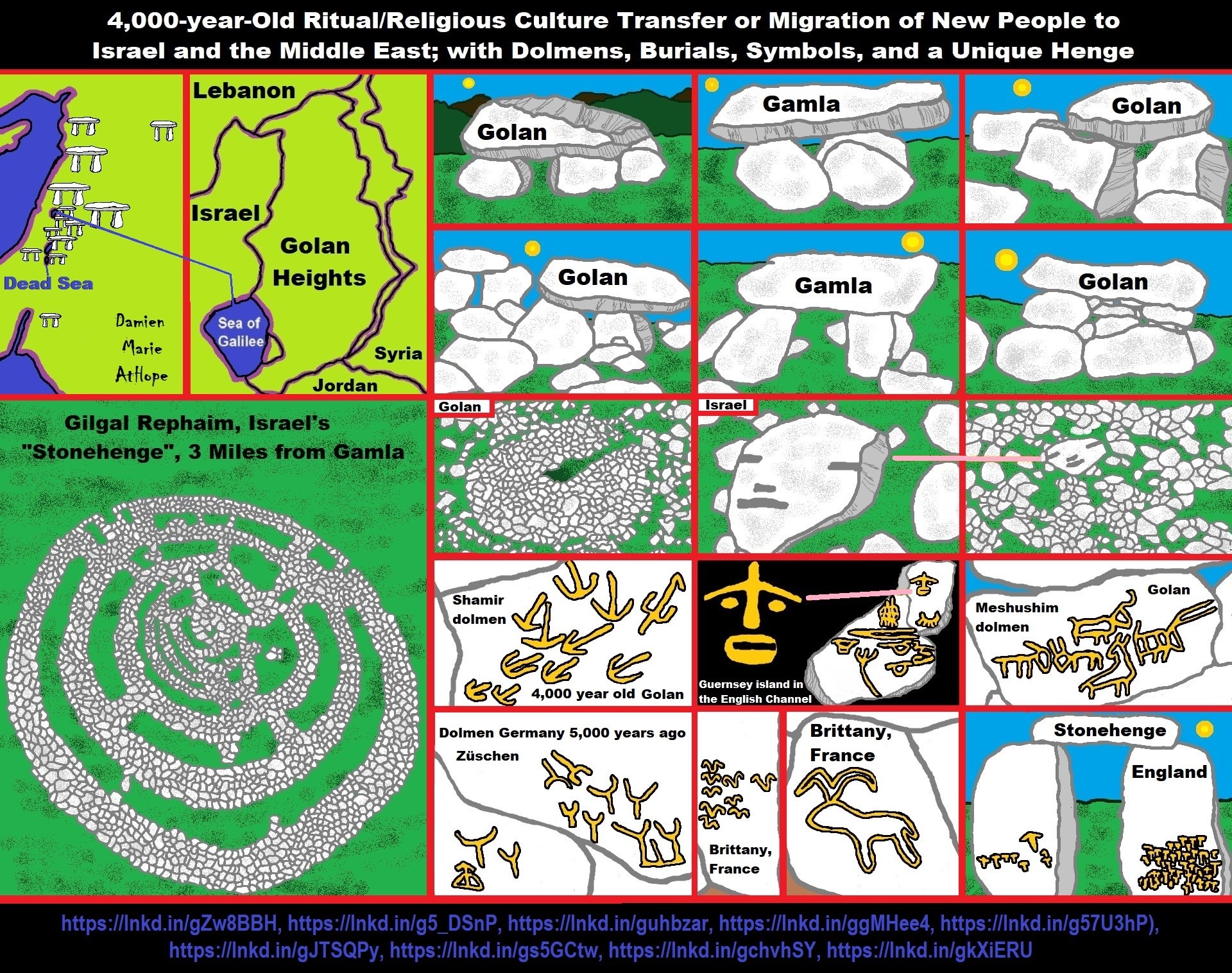

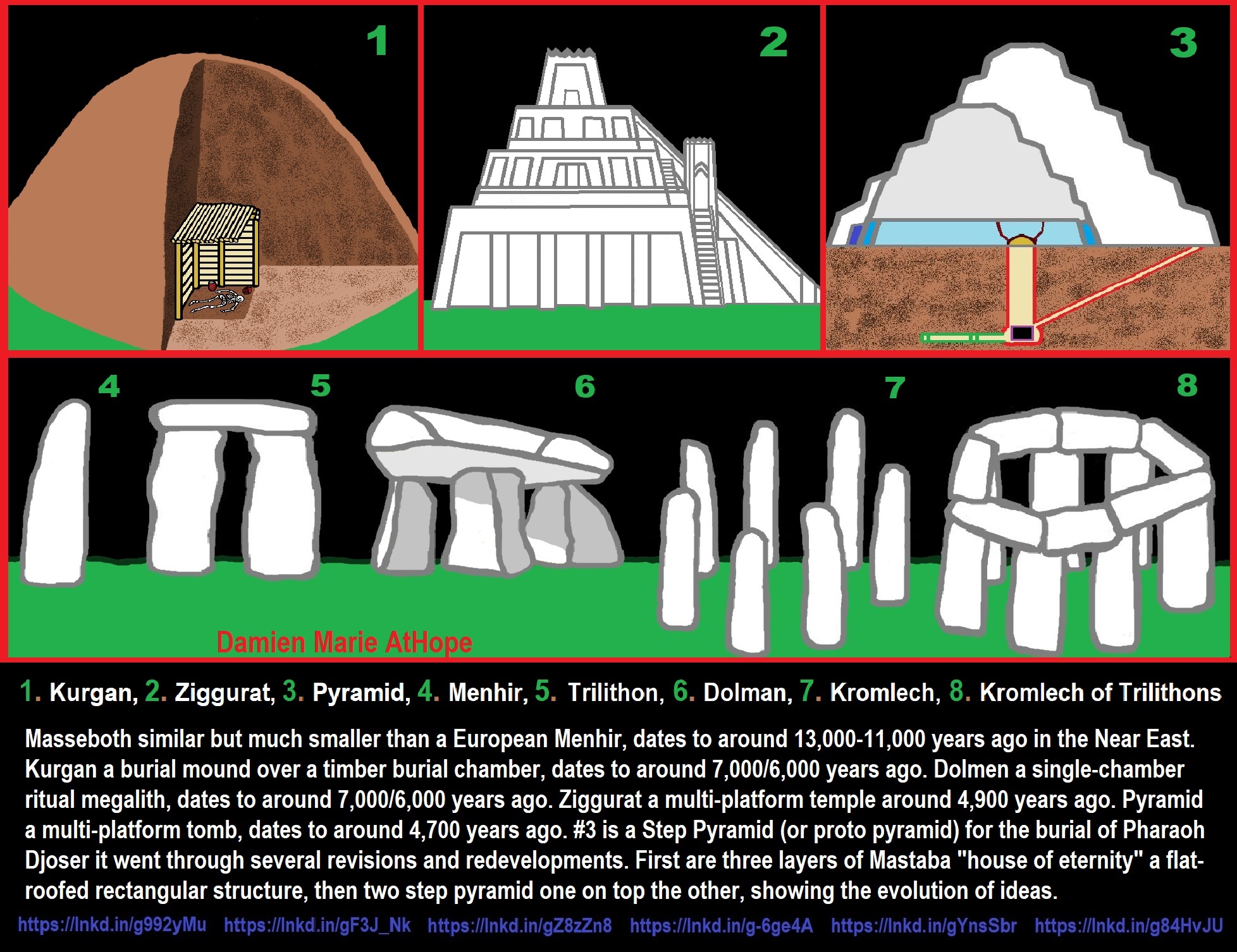

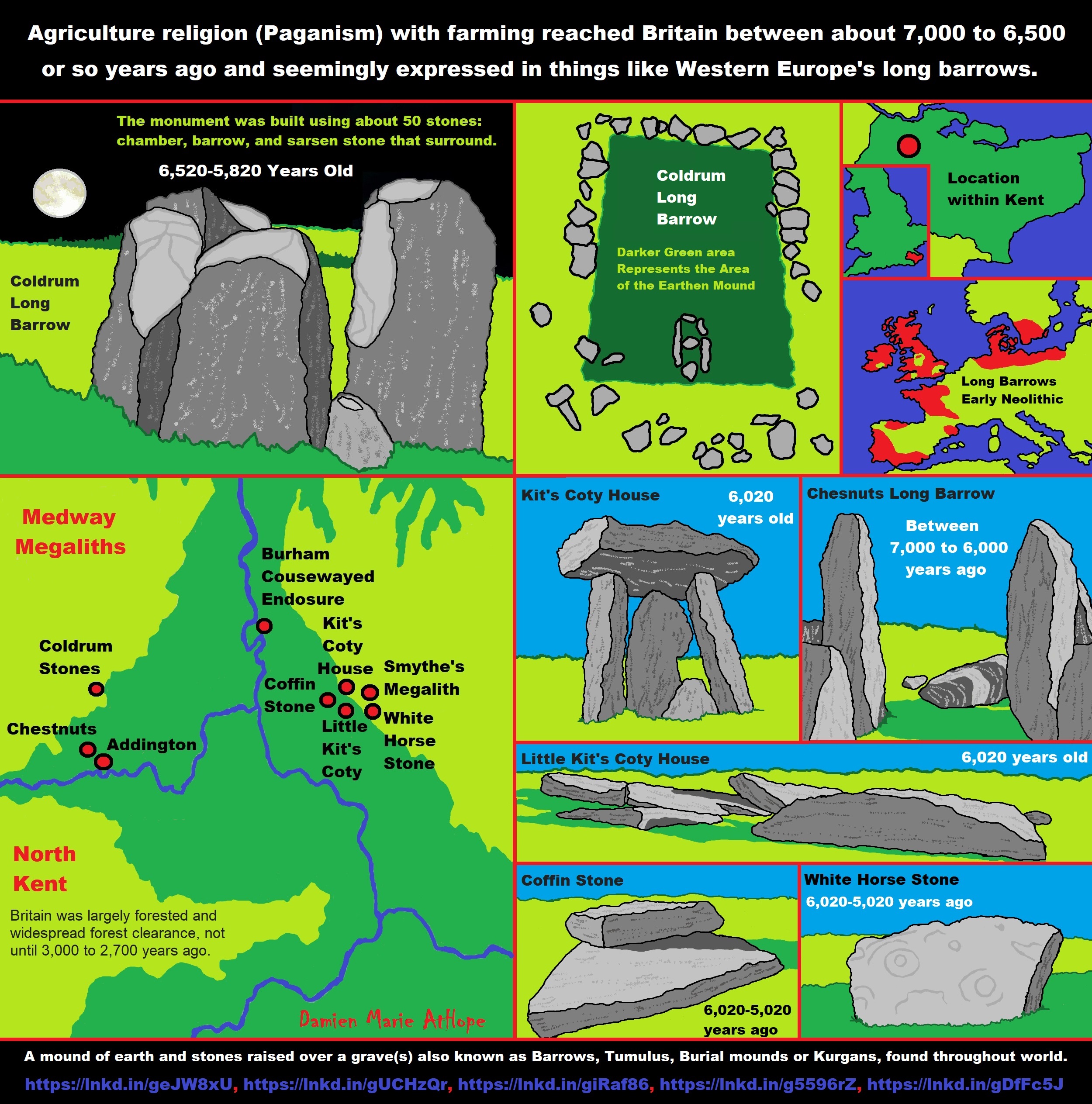

- Kurgan 6,000 years ago/dolmens 7,000 years ago: funeral, ritual, and other?

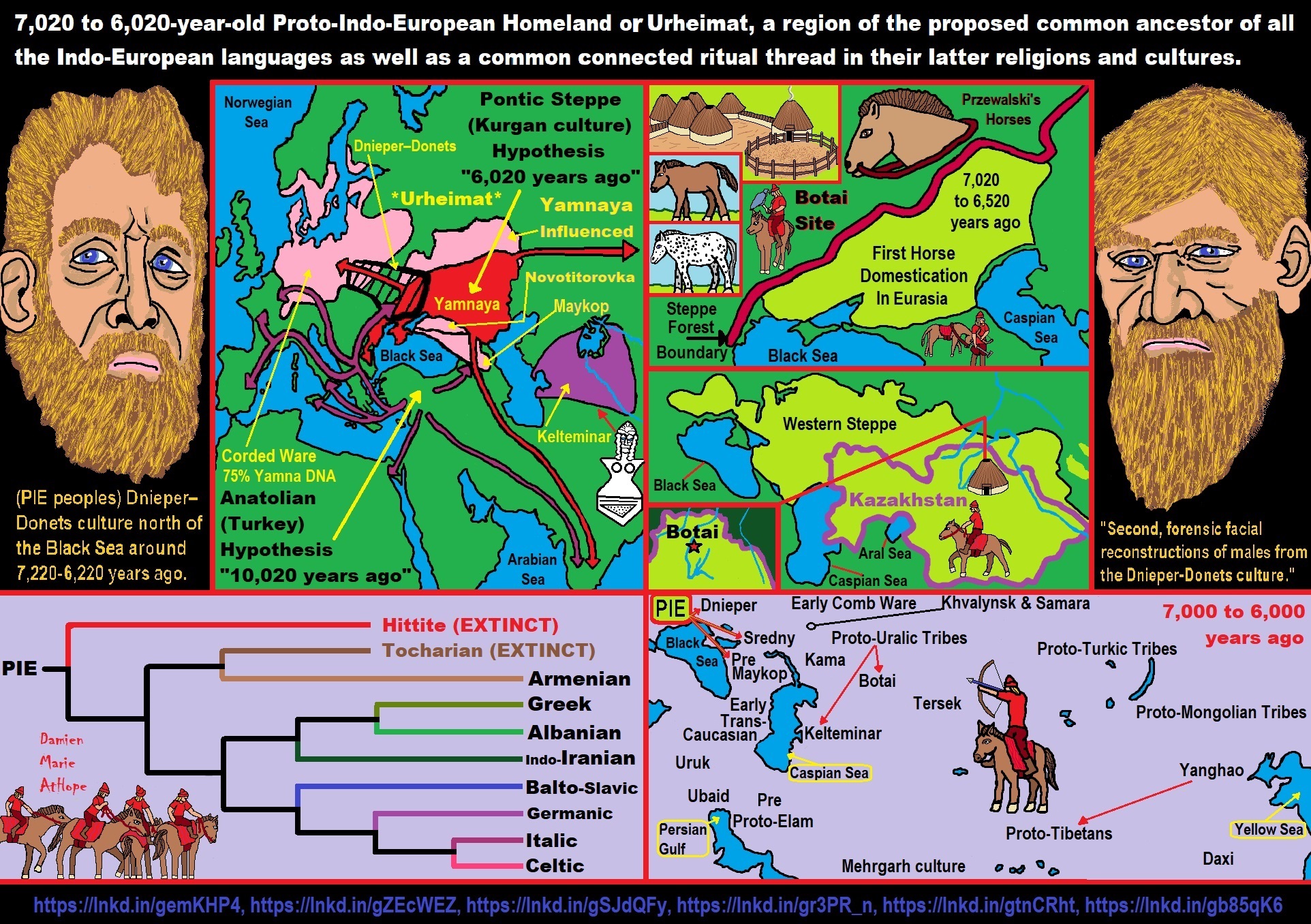

- 7,020 to 6,020-year-old Proto-Indo-European Homeland of Urheimat or proposed home of their Language and Religion

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

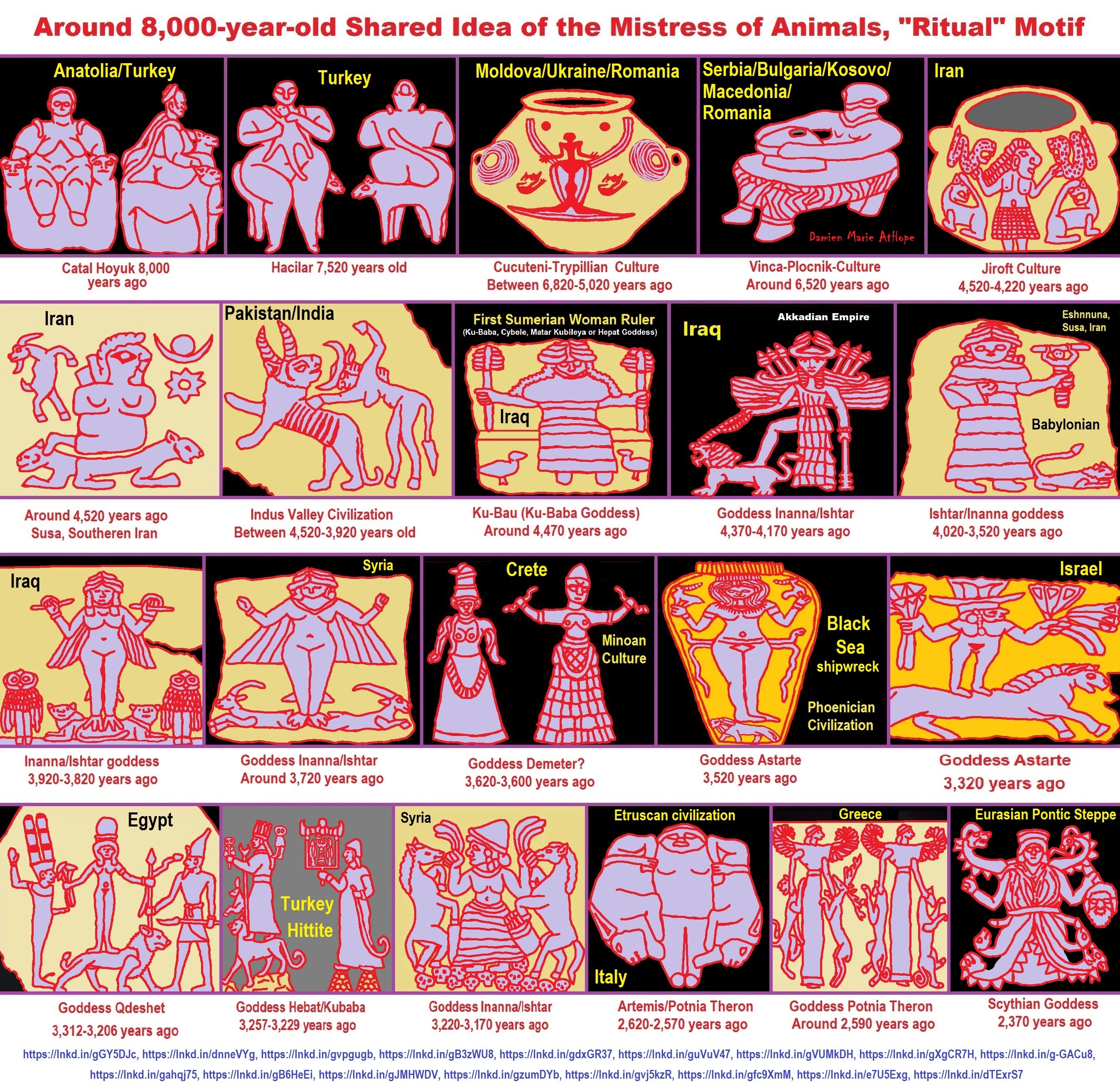

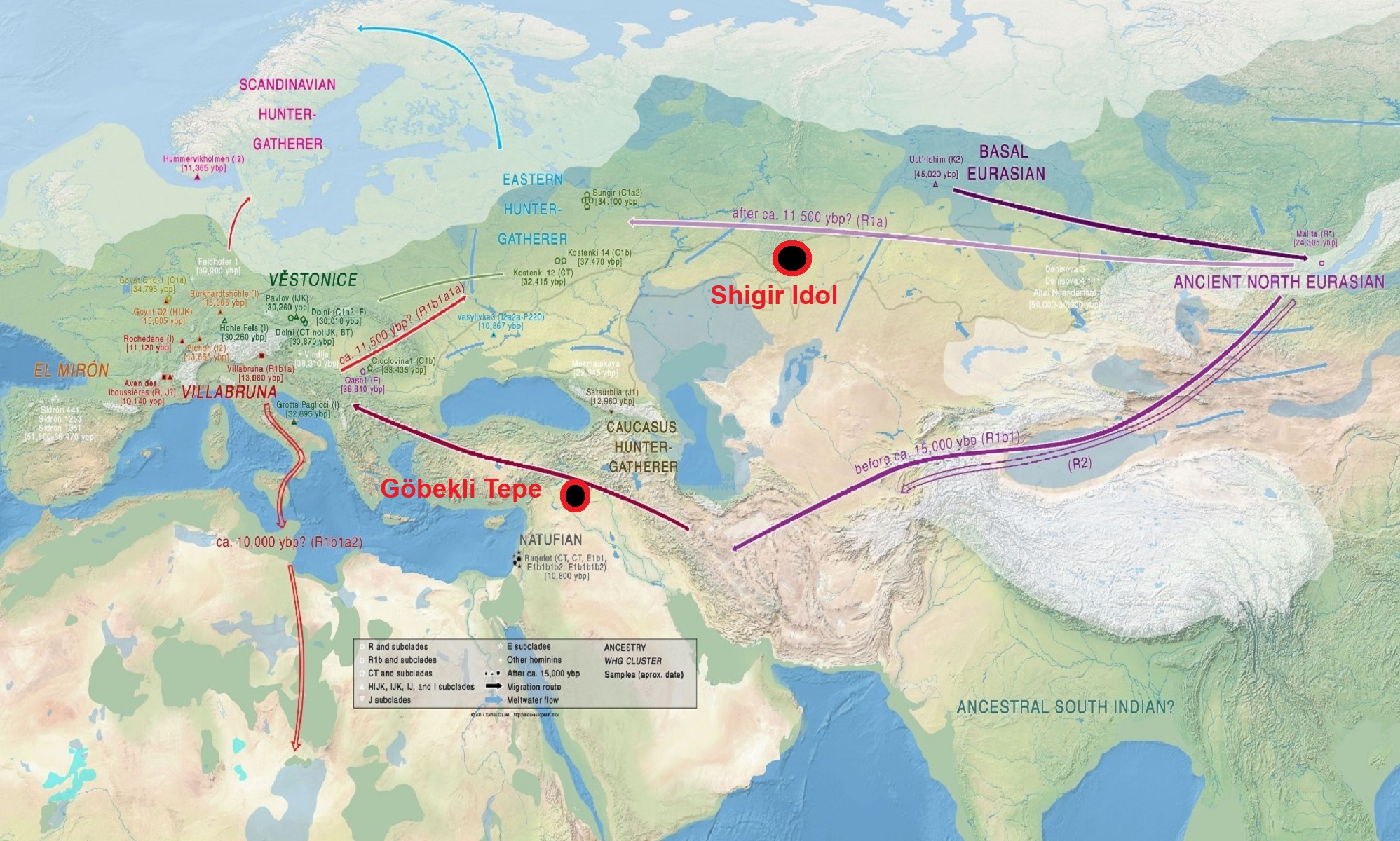

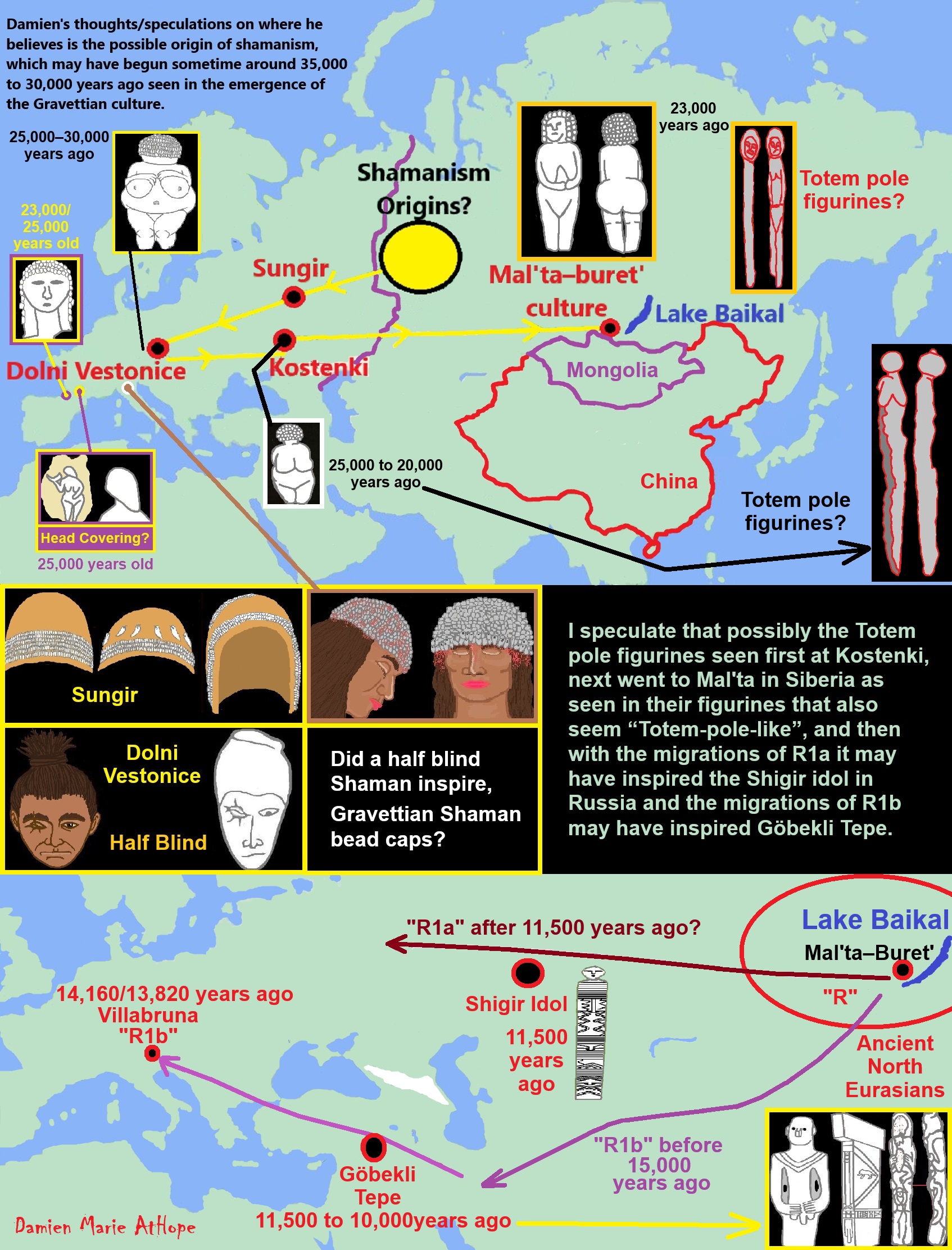

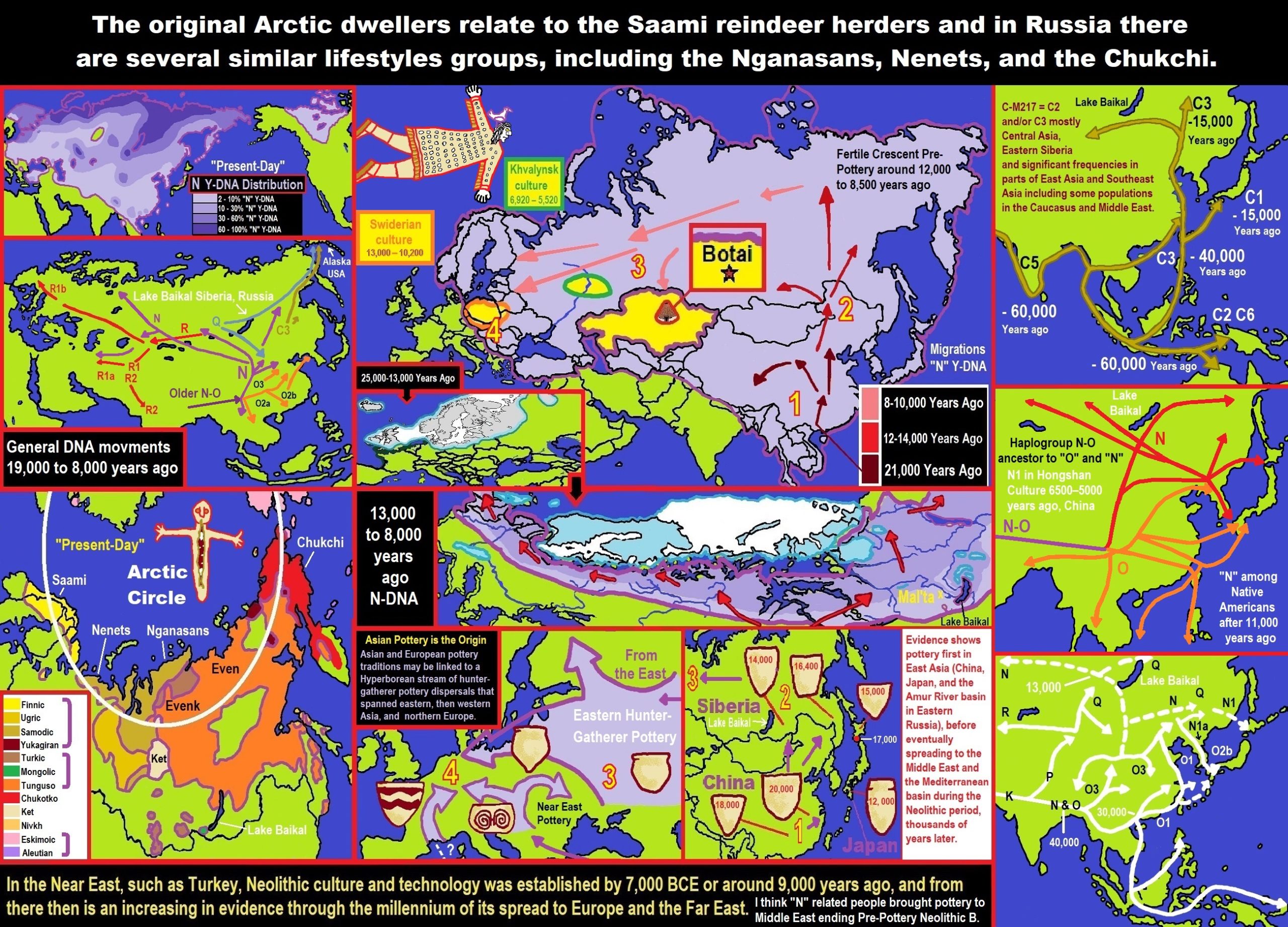

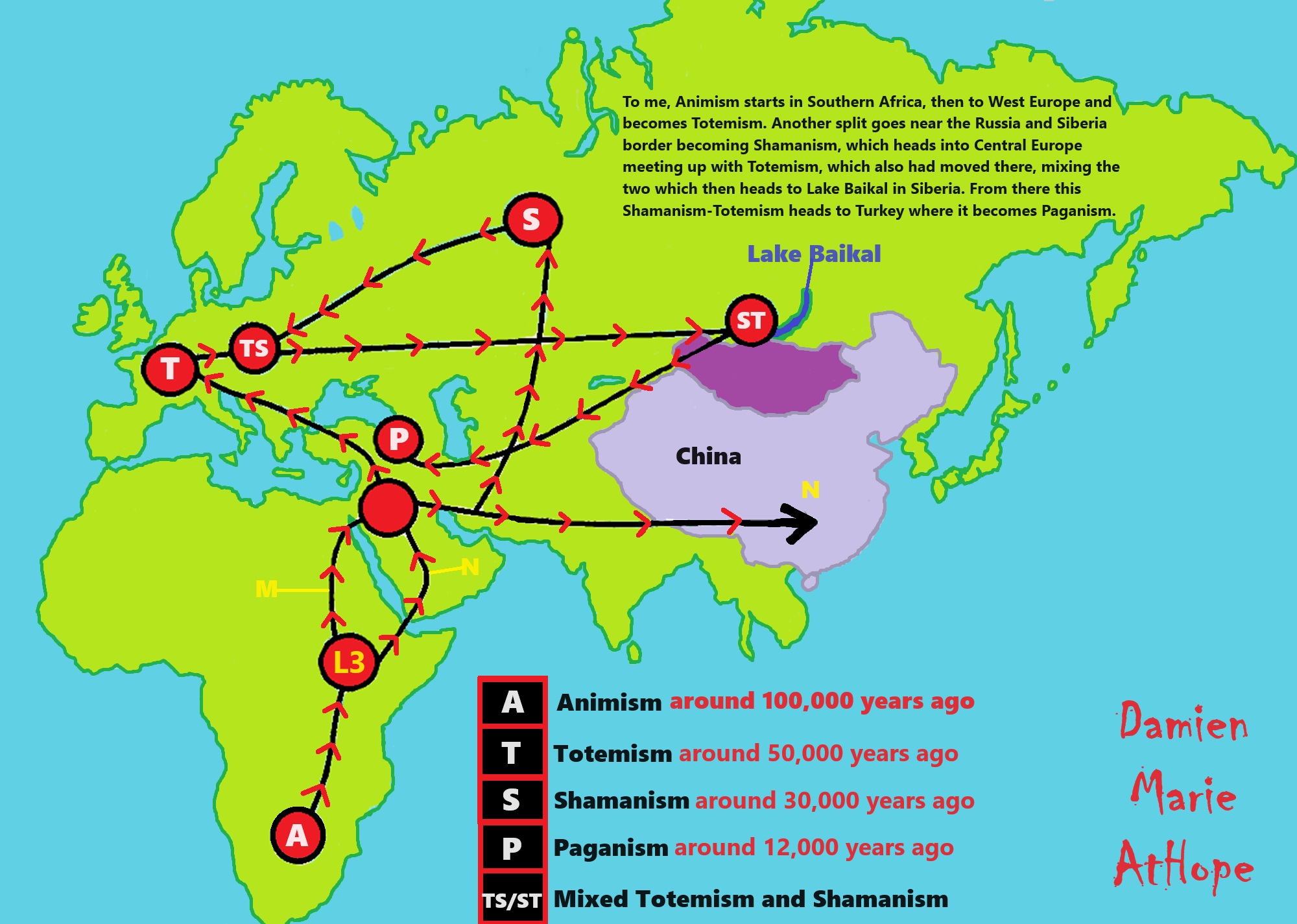

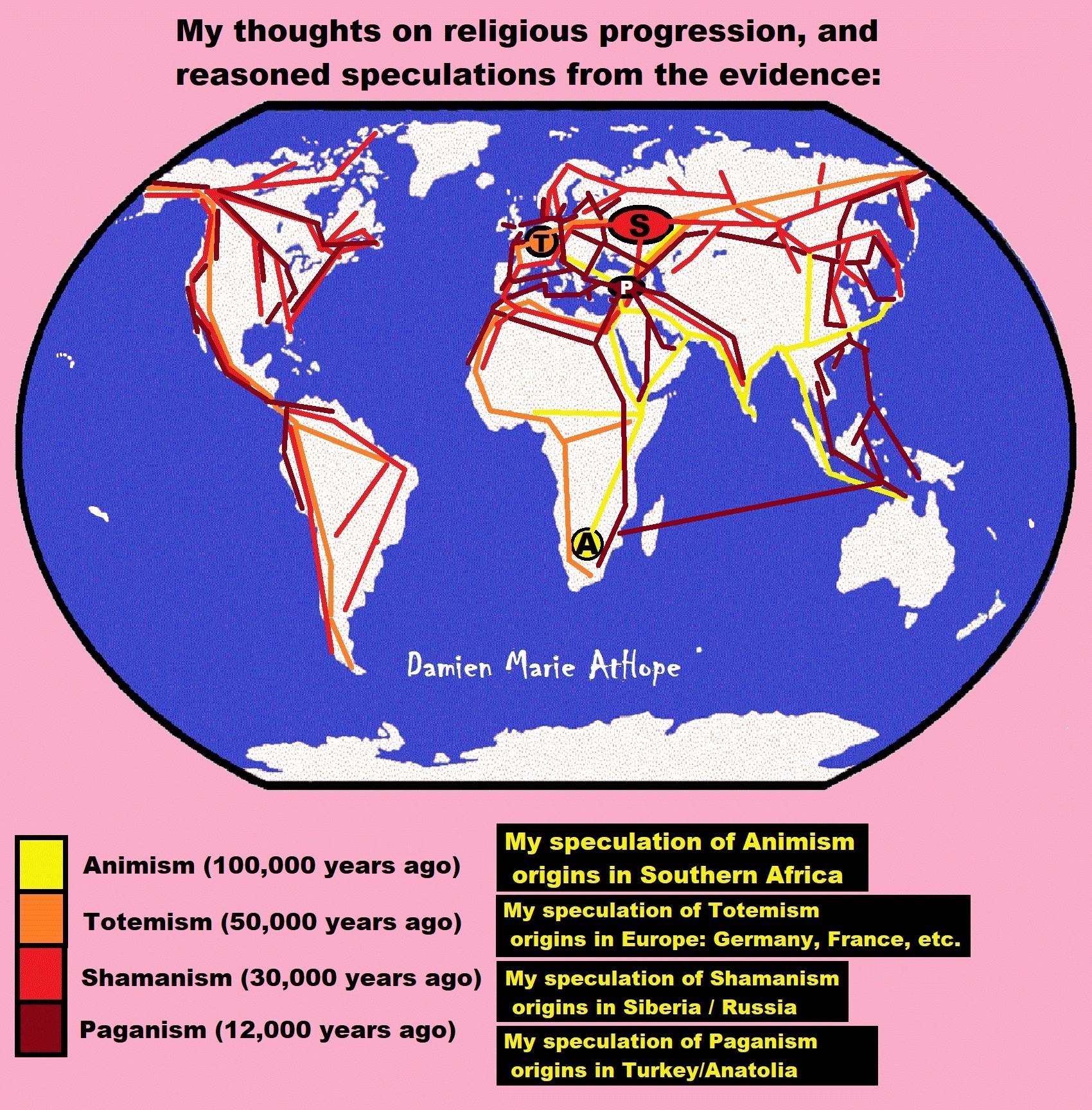

Here are my thoughts/speculations on where I believe is the possible origin of shamanism, which may have begun sometime around 35,000 to 30,000 years ago seen in the emergence of the Gravettian culture, just to outline his thinking, on what thousands of years later led to evolved Asian shamanism, in general, and thus WU shamanism as well. In both Europe-related “shamanism-possible burials” and in Gravettian mitochondrial DNA is a seeming connection to Haplogroup U. And the first believed Shaman proposed burial belonged to Eastern Gravettians/Pavlovian culture at Dolní Věstonice in southern Moravia in the Czech Republic, which is the oldest permanent human settlement that has ever been found. It is at Dolní Věstonice where approximately 27,000-25,000 years ago a seeming female shaman was buried and also there was an ivory totem portrait figure, seemingly of her.

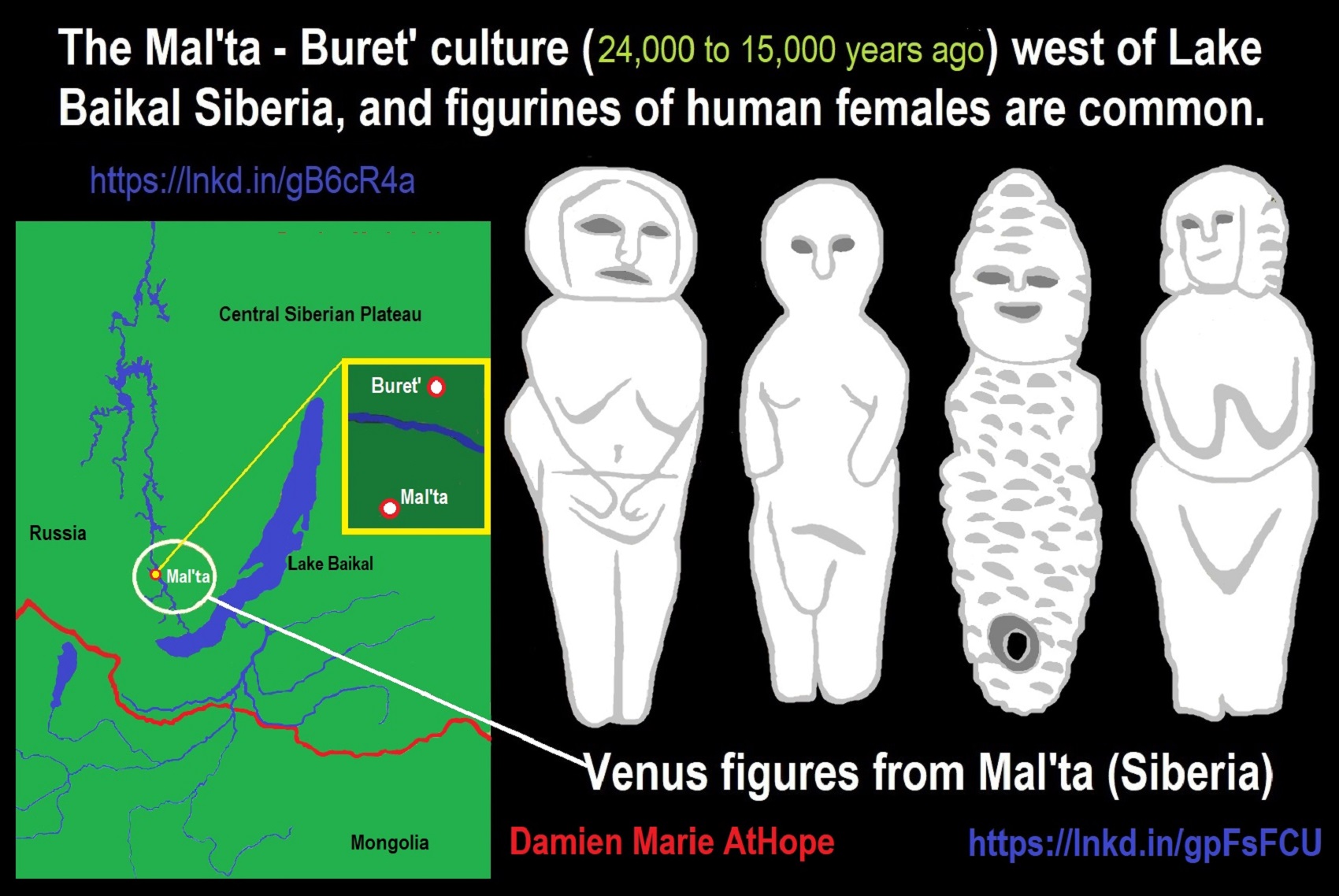

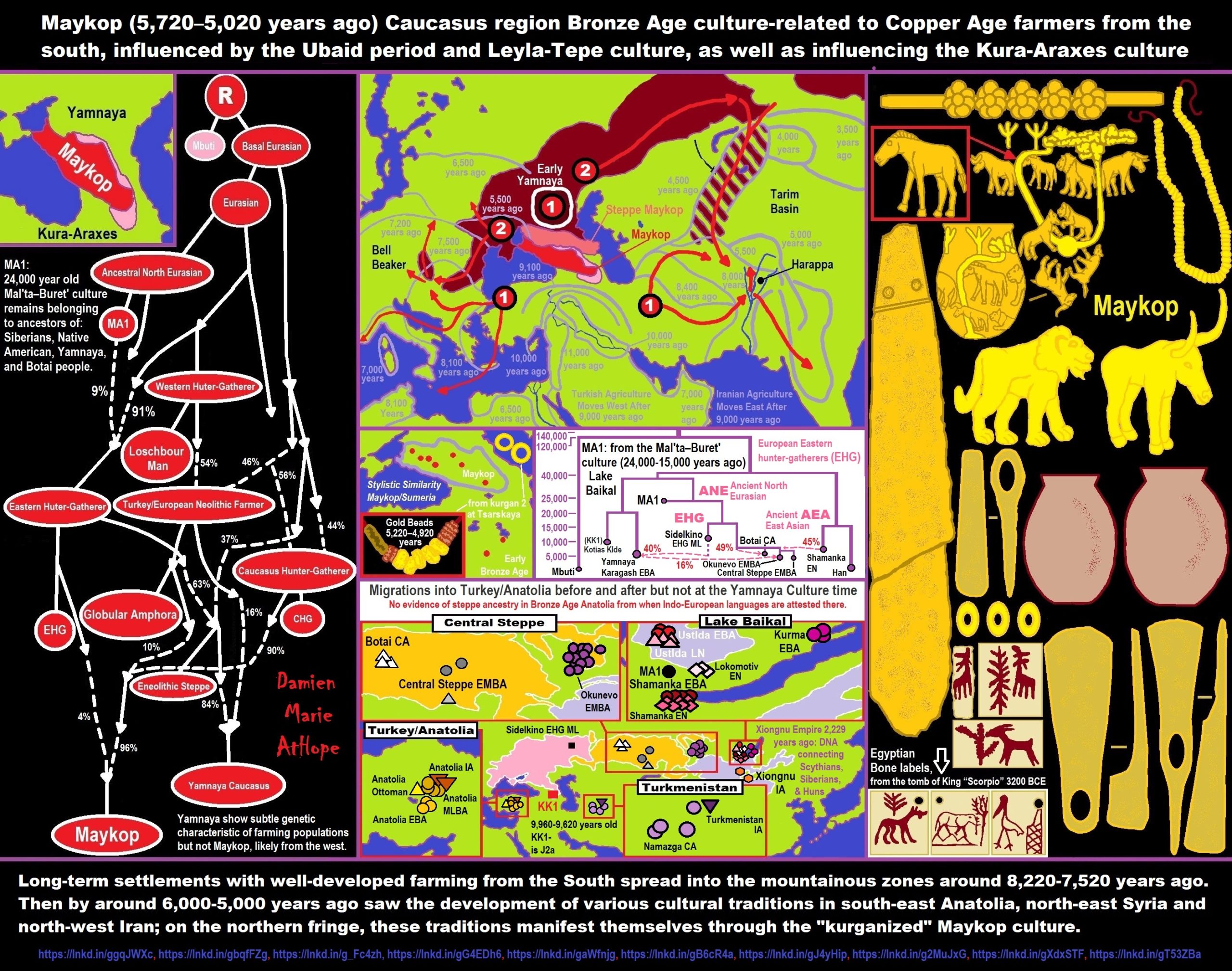

And my thoughts on how cultural/ritual aspects were influenced in the area of Göbekli Tepe. I think it relates to a few different cultures starting in the area before the Neolithic. Two different groups of Siberians first from northwest Siberia with U6 haplogroup 40,000 to 30,000 or so. Then R Haplogroup (mainly haplogroup R1b but also some possible R1a both related to the Ancient North Eurasians). This second group added its “R1b” DNA of around 50% to the two cultures Natufian and Trialetian. To me, it is likely both of these cultures helped create Göbekli Tepe. Then I think the female art or graffiti seen at Göbekli Tepe to me possibly relates to the Epigravettians that made it into Turkey and have similar art in North Italy. I speculate that possibly the Totem pole figurines seen first at Kostenki, next went to Mal’ta in Siberia as seen in their figurines that also seem “Totem-pole-like”, and then with the migrations of R1a it may have inspired the Shigir idol in Russia and the migrations of R1b may have inspired Göbekli Tepe.

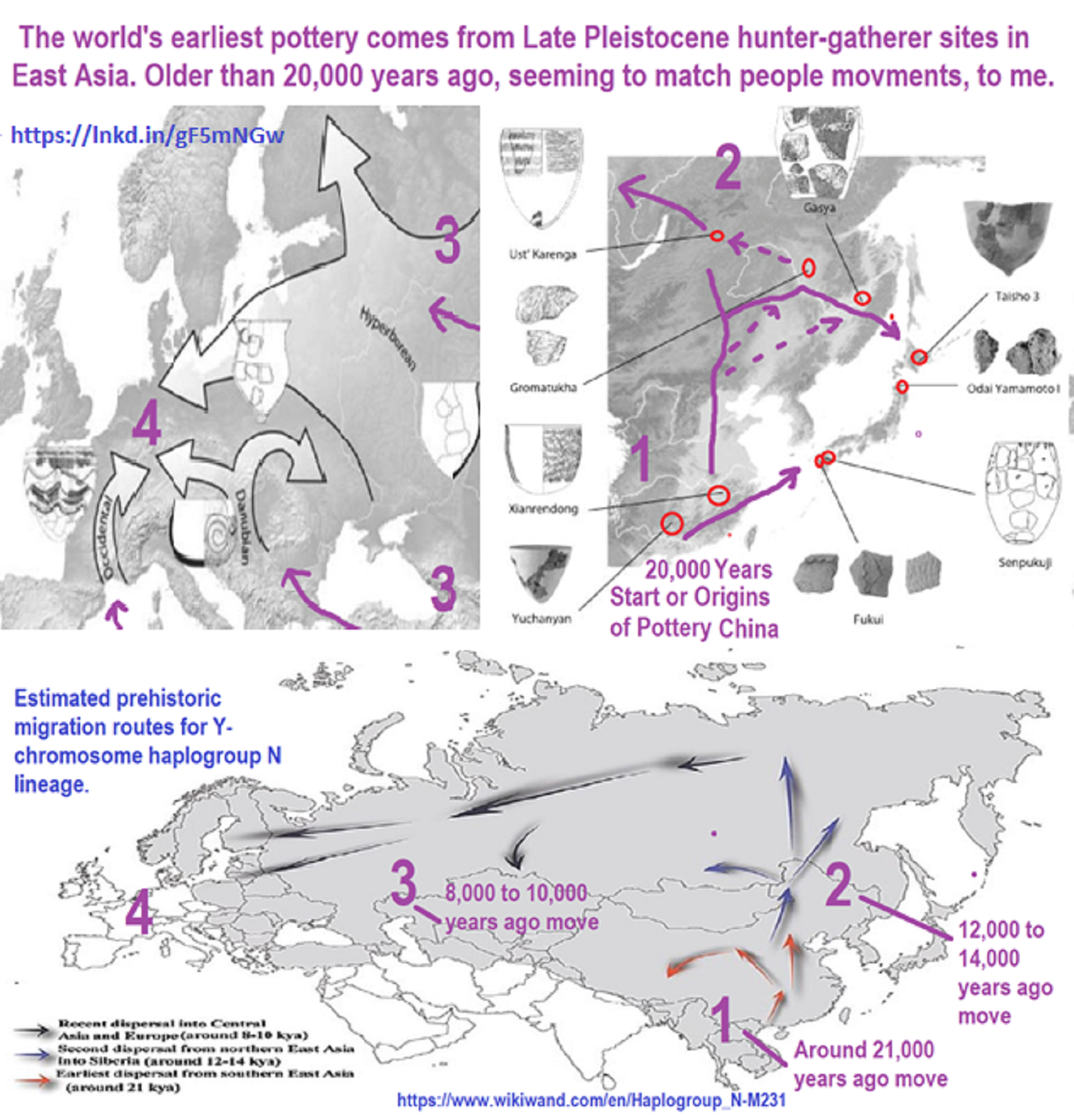

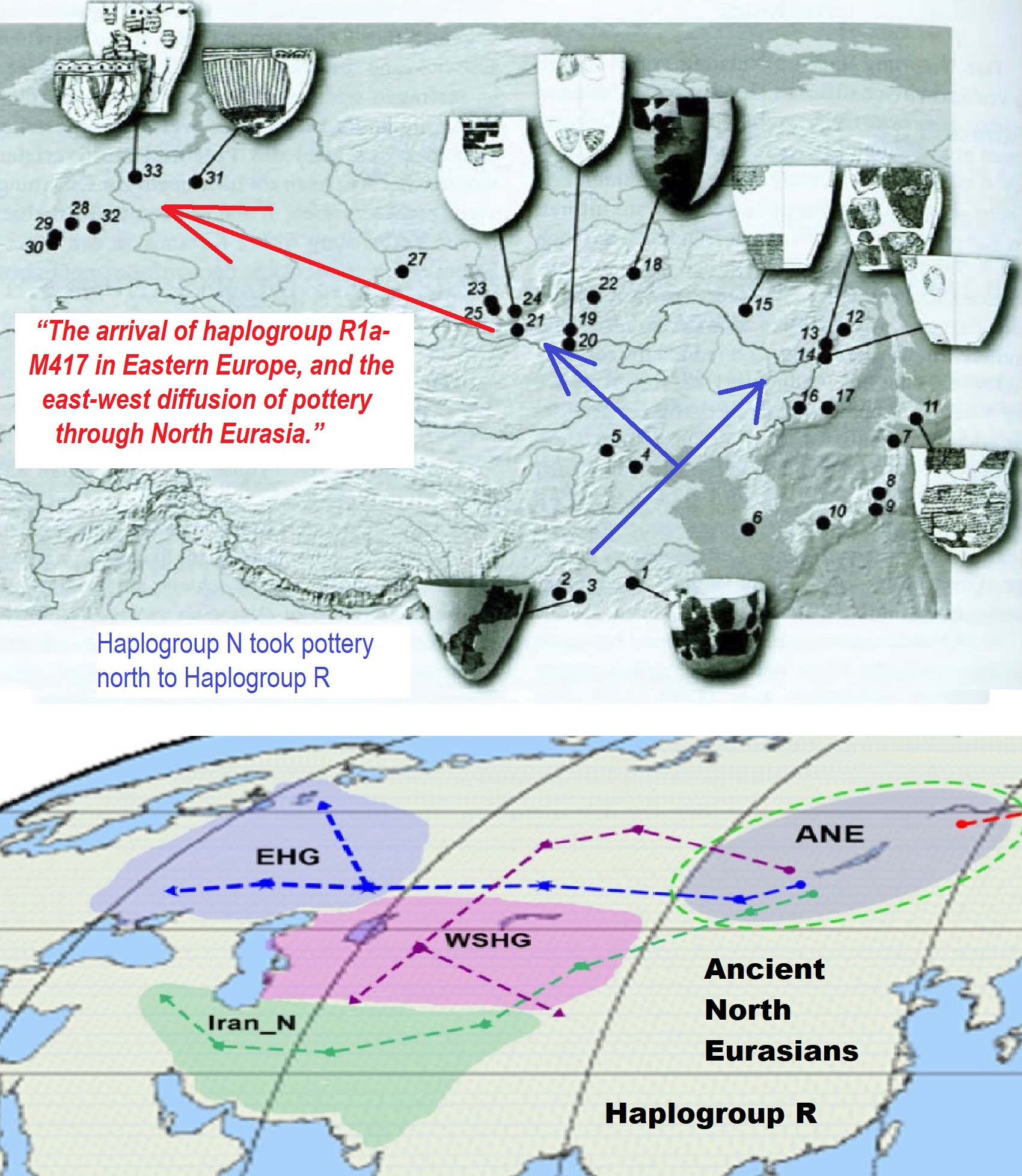

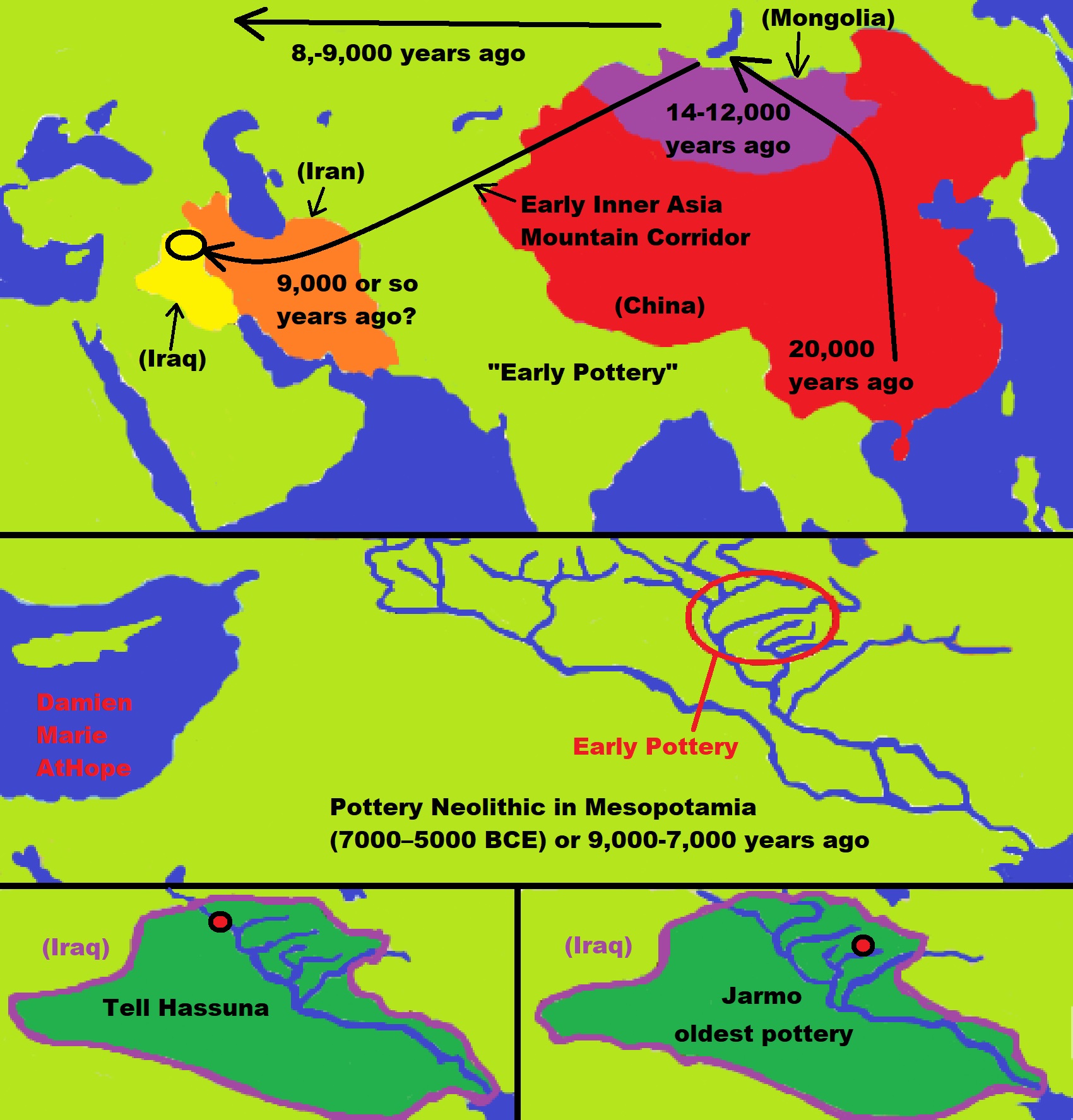

“The arrival of haplogroup R1a-M417 in Eastern Europe, and the east-west diffusion of pottery through North Eurasia.” https://indo-european.eu/2018/02/the-arrival-of-haplogroup-r1a-m417-in-eastern-europe-and-the-east-west-diffusion-of-pottery-through-north-eurasia/

Ancient North Eurasian https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_North_Eurasian

Ancient North Eurasian/Mal’ta–Buret’ culture haplogroup R* https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mal%27ta%E2%80%93Buret%27_culture

“The arrival of haplogroup R1a-M417 in Eastern Europe, and the east-west diffusion of pottery through North Eurasia.” ref

R-M417 (R1a1a1)

“R1a1a1 (R-M417) is the most widely found subclade, in two variations which are found respectively in Europe (R1a1a1b1 (R-Z282) ([R1a1a1a*] (R-Z282) and Central and South Asia (R1a1a1b2 (R-Z93) ([R1a1a2*] (R-Z93).” ref

R-Z282 (R1a1a1b1a) (Eastern Europe)

“This large subclade appears to encompass most of the R1a1a found in Europe.

- R1a1a1b1a [R1a1a1a*] (R-Z282*) occurs in northern Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia at a frequency of c. 20%.

- R1a1a1b1a3 [R1a1a1a1] (R-Z284) occurs in Northwest Europe and peaks at c. 20% in Norway.

- R1a1a1c (M64.2, M87, M204) is apparently rare: it was found in 1 of 117 males typed in southern Iran.” ref

R1a1a1b2 (R-Z93) (Asia)

“This large subclade appears to encompass most of the R1a1a found in Asia, being related to Indo-European migrations (including Scythians, Indo-Aryan migrations, and so on).

- R-Z93* or R1a1a1b2* (R1a1a2* in Underhill (2014)) is most common (>30%) in the South Siberian Altai region of Russia, cropping up in Kyrgyzstan (6%) and in all Iranian populations (1-8%).

- R-Z2125 occurs at highest frequencies in Kyrgyzstan and in Afghan Pashtuns (>40%). At a frequency of >10%, it is also observed in other Afghan ethnic groups and in some populations in the Caucasus and Iran.

- R-M434 is a subclade of Z2125. It was detected in 14 people (out of 3667 people tested), all in a restricted geographical range from Pakistan to Oman. This likely reflects a recent mutation event in Pakistan.

- R-M560 is very rare and was only observed in four samples: two Burushaski speakers (north Pakistan), one Hazara (Afghanistan), and one Iranian Azerbaijani.

- R-M780 occurs at high frequency in South Asia: India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and the Himalayas. The group also occurs at >3% in some Iranian populations and is present at >30% in Roma from Croatia and Hungary.” ref

R-M458 (R1a1a1b1a1)

“R-M458 is a mainly Slavic SNP, characterized by its own mutation, and was first called cluster N. Underhill et al. (2009) found it to be present in modern European populations roughly between the Rhine catchment and the Ural Mountains and traced it to “a founder effect that … falls into the early Holocene period, 7.9±2.6 KYA.” M458 was found in one skeleton from a 14th-century grave field in Usedom, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany. The paper by Underhill et al. (2009) also reports a surprisingly high frequency of M458 in some Northern Caucasian populations (for example 27.5% among Karachays and 23.5% among Balkars, 7.8% among Karanogays and 3.4% among Abazas).” ref

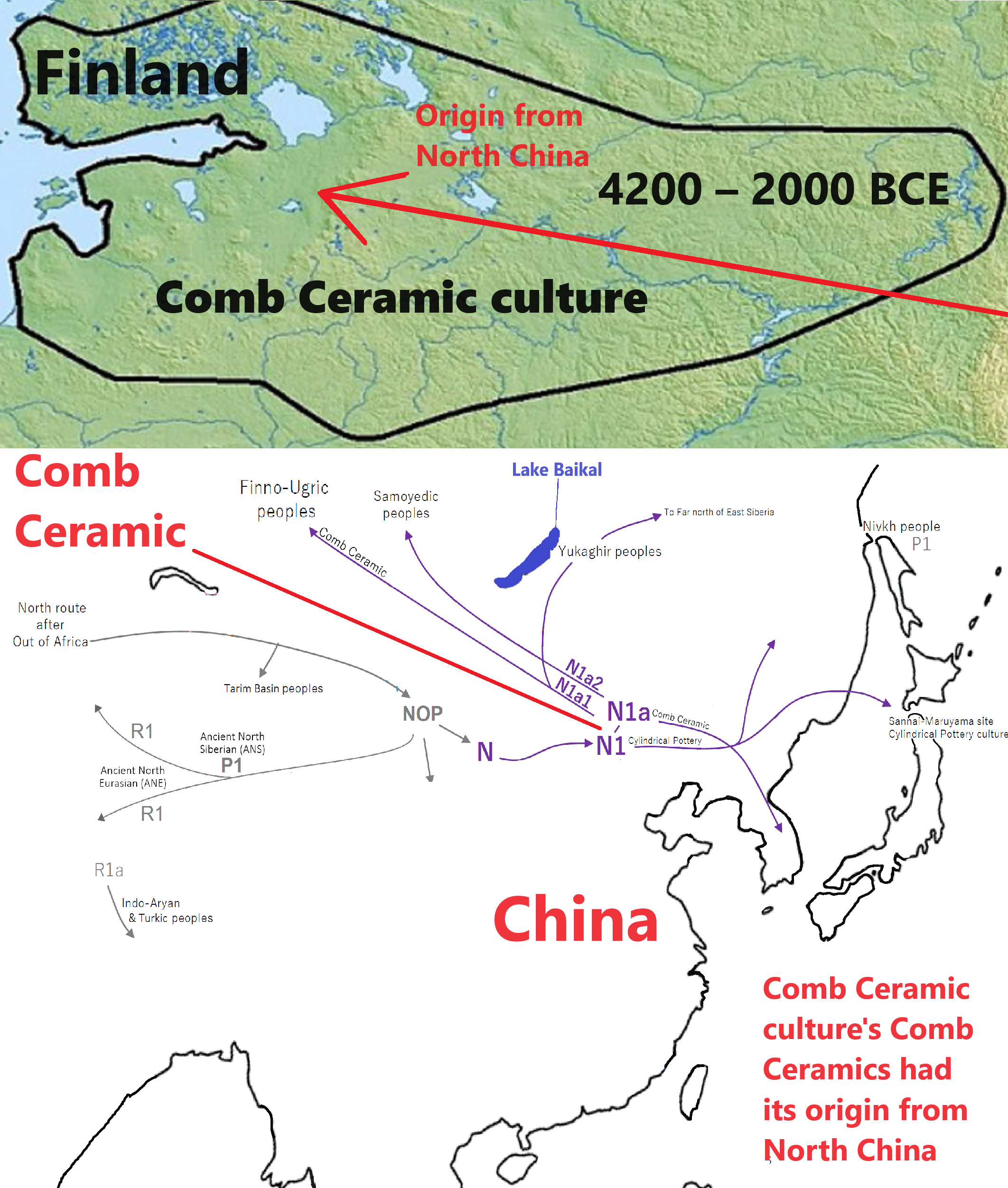

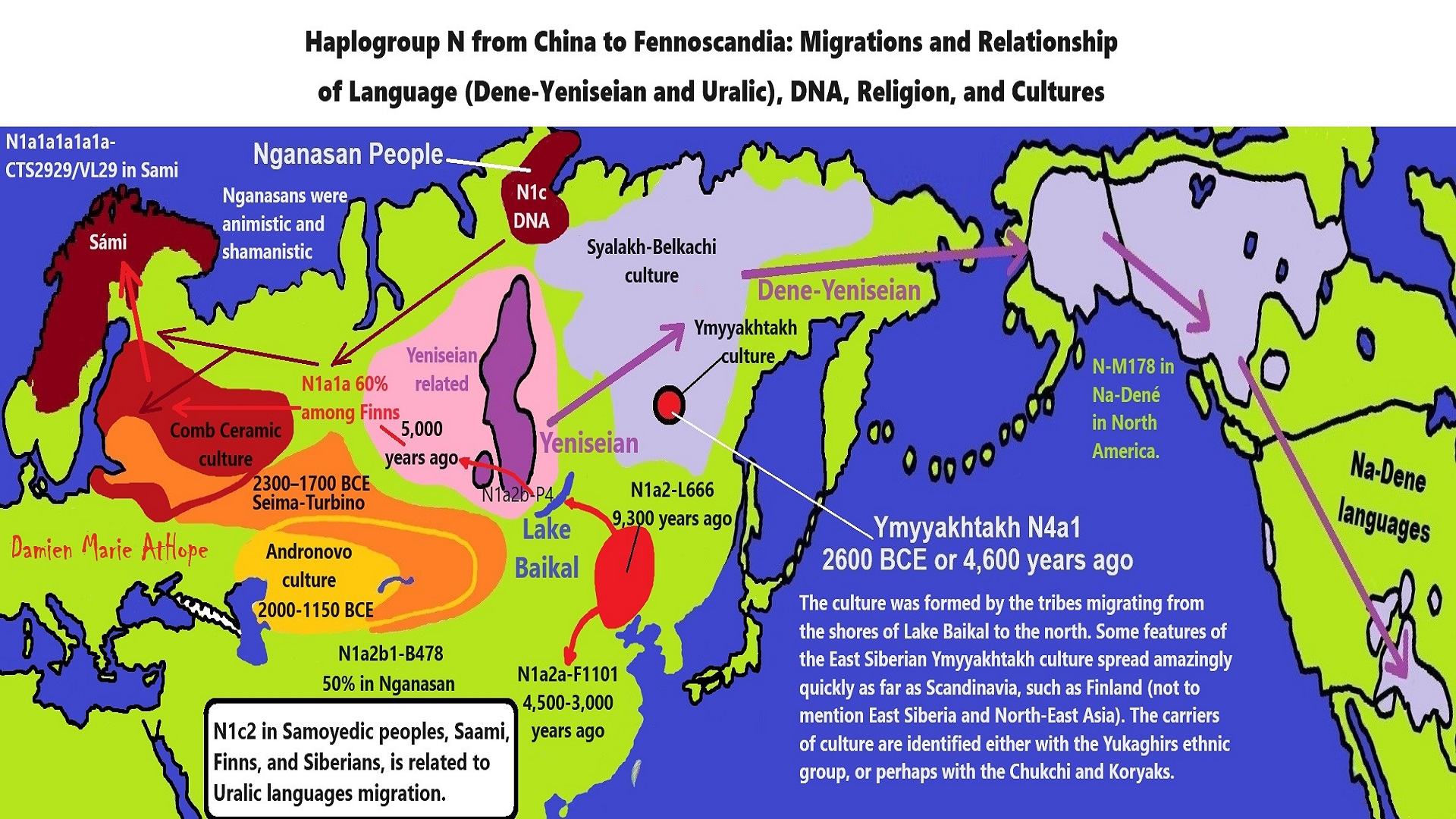

Comb Ceramic culture

“The Comb Ceramic culture or Pit-Comb Ware culture, often abbreviated as CCC or PCW, was a northeast European culture characterised by its Pit–Comb Ware. It existed from around 4200 BCE to around 2000 BCE. The bearers of the Comb Ceramic culture are thought to have still mostly followed the Mesolithic hunter-gatherer (Eastern Hunter-Gatherer) lifestyle, with traces of early agriculture. The distribution of the artifacts found includes Finnmark (Norway) in the north, the Kalix River (Sweden) and the Gulf of Bothnia (Finland) in the west and the Vistula River (Poland) in the south. It would include the Narva culture of Estonia and the Sperrings culture in Finland, among others. They are thought to have been essentially hunter-gatherers, though e.g. the Narva culture in Estonia shows some evidence of agriculture. Some of this region was absorbed by the later Corded Ware horizon. The Pit–Comb Ware culture is one of the few exceptions to the rule that pottery and farming coexist in Europe. In the Near East farming appeared before pottery, then when farming spread into Europe from the Near East, pottery-making came with it. However, in Asia, where the oldest pottery has been found, pottery was made long before farming. It appears that the Comb Ceramic Culture reflects influences from Siberia and distant China.” ref

“By dating according to the elevation of land, the ceramics have traditionally (Äyräpää 1930) been divided into the following periods: early (Ka I, c. 4200 BC – 3300 BC), typical (Ka II, c. 3300 BC – 2700 BC) and late Comb Ceramic (Ka III, c. 2800 BC – 2000 BC). However, calibrated radiocarbon dates for the comb-ware fragments found (e.g., in the Karelian isthmus), give a total interval of 5600 BC – 2300 BC (Geochronometria Vol. 23, pp 93–99, 2004). The settlements were located at sea shores or beside lakes and the economy was based on hunting, fishing, and the gathering of plants. In Finland, it was a maritime culture that became more and more specialized in hunting seals. The dominant dwelling was probably a teepee of about 30 square meters where some 15 people could live. Also, rectangular houses made of timber became popular in Finland from 4000 BC cal. Graves were dug at the settlements and the dead were covered with red ochre. The typical Comb Ceramic age shows an extensive use of objects made of flint and amber as grave offerings.” ref

“The stone tools changed very little over time. They were made of local materials such as slate and quartz. Finds suggest a fairly extensive exchange network: red slate originating from northern Scandinavia, asbestos from Lake Saimaa, green slate from Lake Onega, amber from the southern shores of the Baltic Sea, and flint from the Valdai area in northwestern Russia. The culture was characterized by small figurines of burnt clay and animal heads made of stone. The animal heads usually depict moose and bears and were derived from the art of the Mesolithic. There were also many rock paintings. There are sources noting that the typical comb ceramic pottery had a sense of luxury and that its makers knew how to wear precious amber pendants. The great westward dispersal of the Uralic languages is suggested to have happened long after the demise of the Comb Ceramic culture, perhaps in the 1st millennium BC.” ref

“Saag et al. (2017) analyzed three CCC individuals buried at Kudruküla as belonging to Y-hg R1a5-YP1272 (R1a1b~ after ISOGG 2020), along with three mtDNA samples of mt-hg U5b1d1, U4a and U2e1. Mittnik (2018) analyzed two CCC individuals. The male carried R1 (2021: R1b-M343) and U4d2, while the female carried U5a1d2b. Generally, the CCC individuals were mostly of Eastern Hunter-Gatherer (EHG) descent, with even more EHG than people of the Narva culture. Lamnidis et al. (2018) found 15% Western Hunter-Gatherer (WHG) ancestry, 65% Eastern Hunter-Gatherer (EHG) – higher than among earlier cultures of the eastern Baltic, and 20% Western Steppe Herder (WSH).” ref

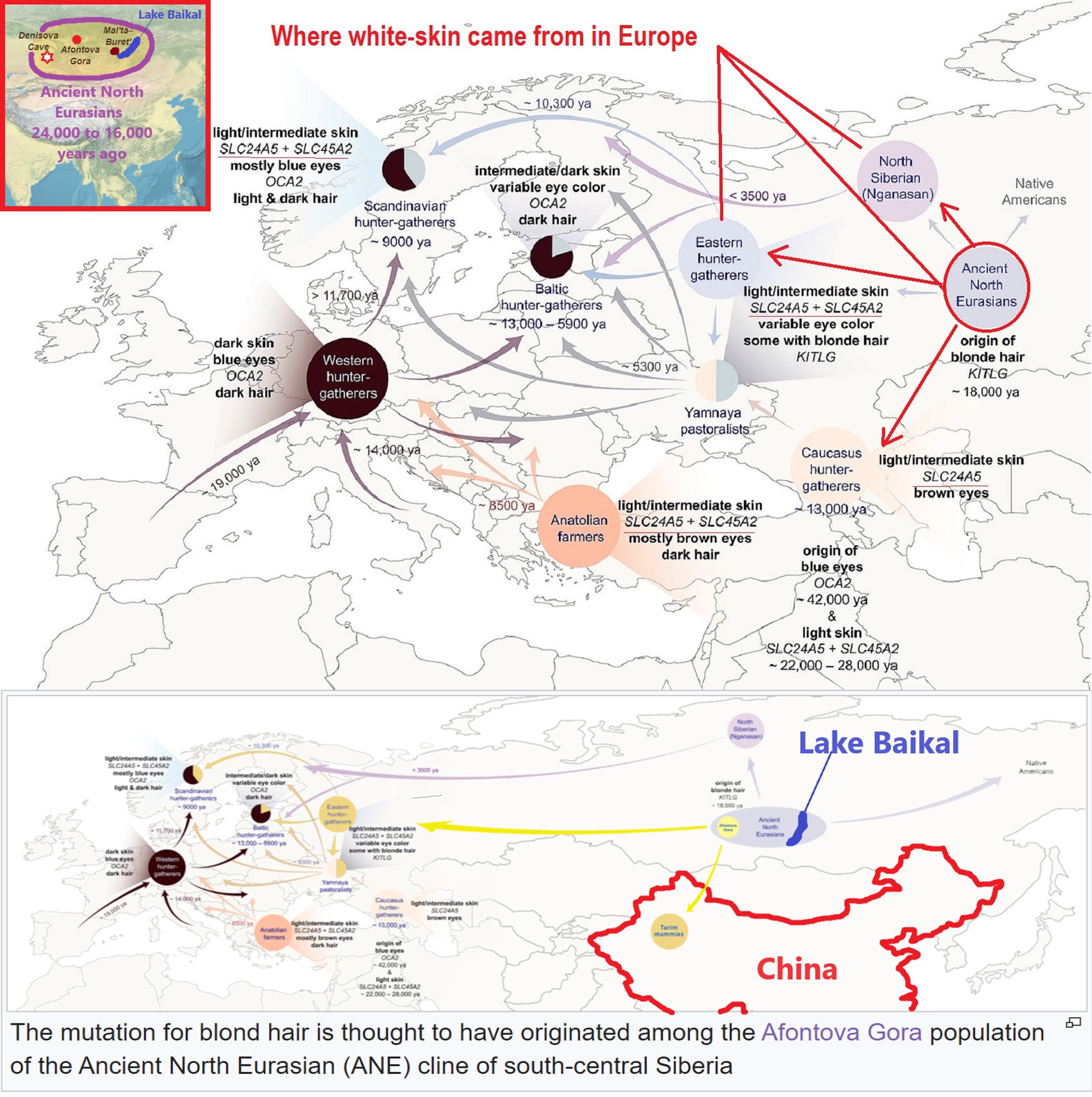

“Lighter skin and blond hair evolved in the Ancient North Eurasian (ANE) population. The SLC24A5 gene’s derived threonine or Ala111Thr allele (rs1426654) has been shown to be a major factor in the light skin tone of Europeans. Possibly originating as long as 19,000 years ago, it has been the subject of selection in the ancestors of Europeans as recently as within the last 5,000 years, and is fixed in modern European populations.” ref, ref

DNA-researcher: It’s not ‘woke’ to portray prehistoric Europeans with dark skin.

“It’s evolution. Ancient DNA analyses suggest that prehistoric Europeans looked different from modern Europeans today, but some people find that hard to accept. There was an artistic picture of an almost 6,000-year-old, girl who was walking along Lolland’s south coast and spits a piece of birch tar into the reeds. It didn’t taste great, but it helped to soothe her toothache. Fast forward 6,000 years, Danish archaeologists working on the Fehmarnbelt project stumble across the piece and recognize it for what it is: an almost 6,000-year-old piece of chewing gum. This ancient piece of gum is now on display at the Museum Lolland-Falster in southern Denmark among an amazing collection of Stone Age artifacts uncovered during the excavations. If you have not been, it is well worth a visit. In 2019, my research team at the University of Copenhagen managed something quite remarkable: We succeeded in extracting DNA from the gum and used it to reconstruct the girl’s entire genome — the first time anyone had sequenced an ancient human genome from anything other than skeletal remains. As the gum had been found on Lolland, we affectionately nicknamed her ‘Lola’.” ref

Stone-age girl in social media ‘shitstorm’

“The story of Lola and her chewing gum made headlines around the world when we published the genome in 2019 and then, suddenly, in the summer of 2023, Lola was back in the news, caught up in a media ‘shitstorm’. The ‘shitstorm’ first gathered pace on X, the platform formerly known as Twitter, and escalated to the point where the museum had to defend itself on national TV. Even the Danish newspaper ‘Ekstrabladet’ felt they had to comment and gave their opinion in a passionate editorial. So, what happened? These things are difficult to reconstruct, but evidently some people who had seen the image of Lola thought that she looked “way too dark” and accused us—and the museum—of ‘blackwashing’ the past. I suppose this episode says more about our own biases than anything else, and I would like to take this opportunity to explain why we portrayed Lola the way we did and what this tells us about the evolution of skin color in this part of the world.” ref

What we know about Lola

“First a disclaimer, we do not know exactly how old Lola was when she spat that chewing gum into the water. But based on her genome and other DNA trapped in the gum, we learned a lot of other things about her and her world. For example, we learned that she was a hunter-gatherer who lived off wild resources like fish, nuts, and wild game. At the time, small farming communities started to appear in other parts of Europe, but from what we can tell Lola and her kin still lived — as her ancestors had done for thousands of years before her — as hunter-gatherers. We also learned that she likely had dark skin, dark hair, and blue eyes. But how do we know that?” ref

The genetics of human skin pigmentation

“Skin color is a highly heritable and polygenic trait, meaning that it is influenced by multiple genes and their interactions with one another. One of the most well-known genes associated with skin pigmentation is the melanocortin 1 receptor gene (MC1R), but there are dozens more that have been reported to be involved in the pigmentation process. Most of these genes influence skin color by regulating the production of melanin, a dark pigment that protects from the deleterious effects of UV radiation. Basically, the more melanin you have in your skin, the darker it will be, and the more sun your skin can tolerate before you get sunburn. Eye and hair color are determined in a similar way, but the mechanisms that control the production of melanin in the eyes and hair are quite complex and independent processes. That is why it is possible to end up with different combinations of traits, such as the dark hair and blue eyes that are often seen in Europeans today, or the light hair and brown eyes that are common for Solomon Islanders, for example.” ref

How do we know what Lola looked like?

“Because the genes involved in pigmentation have been well studied, it is possible to predict the skin, eye, and hair color of an individual based on their genotype with a certain probability, something that is routinely done in forensic investigations. In practice, this works by checking which variants of a gene are present and what phenotype they are associated with. The more genes we can include in this analysis, the more confident we can be that our prediction is correct. In Lola’s case, we studied 41 gene variants across her genome that have been associated with skin, hair, and eye color in humans, and concluded that she likely had this unusual (at least for today) combination of dark skin, dark hair, and blue eyes.” ref

A common look in prehistoric Europe

“It is difficult to know exactly what people looked like 10,000 years ago. But based on ancient DNA studies, it appears that Lola’s ‘look’ was much more common in prehistoric Europe than it is today. Thanks to advances in ancient DNA sequencing, we now have the genomes of dozens of Upper Palaeolithic and Mesolithic (i.e. the period between around 50,000 and 5,000 years before present in Europe) individuals from Western Europe. And interestingly they all seem to lack the skin-lightening variants that are so common in Europeans today, indicating that they had dark skin. This is true for ‘Cheddar Man’ who lived around 10,000 years ago in southern England, as well as dozens of other Upper Palaeolithic and Mesolithic hunter-gatherer individuals from France, northern Italy, Spain, the Baltic, and other parts of Europe. Like skin color, eye color is also a fairly complex trait, involving the interaction of many different genes. Therefore, eye color is fairly difficult to predict, but it looks like Upper Palaeolithic and Mesolithic hunter-gatherers from Western Europe often had blue eyes, just like Lola. Overall, it looks like Lola’s phenotype—the combination of dark skin, dark hair, and blue eyes—was much more common in prehistoric Europe than it is today.” ref

How Europeans got their lighter skin

“So, why did people in prehistoric Europe look so different from northern Europeans today? The answer to this question lies in a complex interplay between our genes, our changing diets, population movements, and the environment. It has been theorized for some time that lighter skin emerged as an adaptive trait to light poor environments as it allows you to absorb sunlight more effectively, which is essential for the production of vitamin D. However, it was unclear when this happened. Early studies suggested that we first may have evolved lighter skin as our ancestors moved out of Africa and into Europe c. 50,000 years ago, but we now believe that this happened much later in European prehistory. In fact, there is evidence that lighter skin only evolved within the last 5,000 years or so, as a result of genetic admixture from Neolithic farming populations (who carried the skin-lightening variant) and strong selection favoring lighter skin.” ref

Our changing diet also played a part

“In addition, it looks like our changing diets also played a part. During most of European prehistory people relied on wild resources like nuts, game, and fish that are all rich in vitamin D, which is essential to our health. That changed dramatically during the Neolithic when people started to rely on a farmer’s diet that was rich in carbohydrates, but poor in vitamin D. Interestingly, this is exactly the period when we see lighter skin tones evolve in Western Europe and we think that the lack of vitamin D in the diet may have increased the selection pressures favouring lighter skin. All in all, there is solid evidence to suggest that lighter skin tones only evolved in Europe within the last 5,000 years or so, and that people who lived in Europe before then typically had darker skin. It is not that surprising, then, that Lola had darker skin. It simply reflects the fact that she lived at a time when Europeans had not yet evolved their lighter skin.” ref

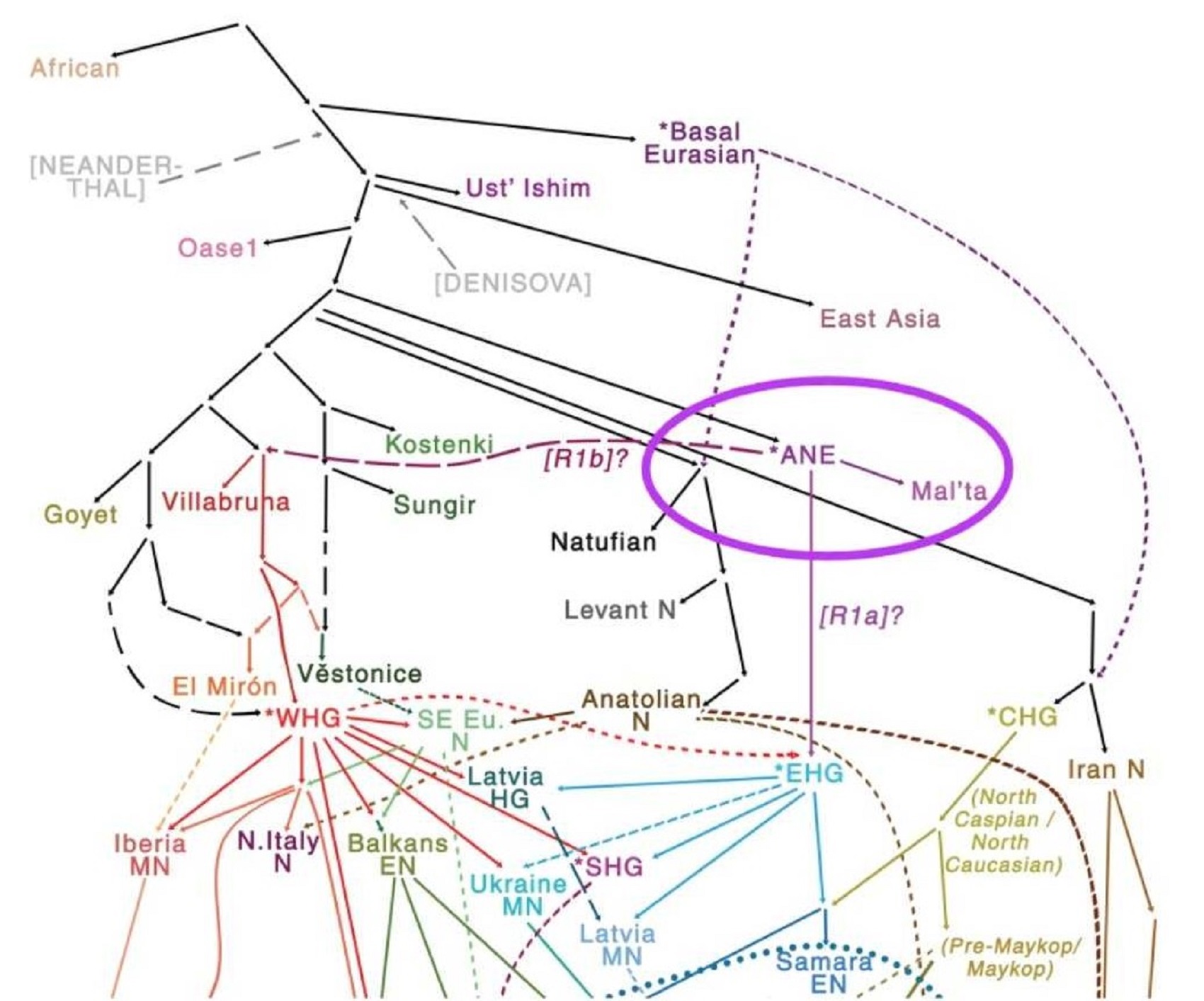

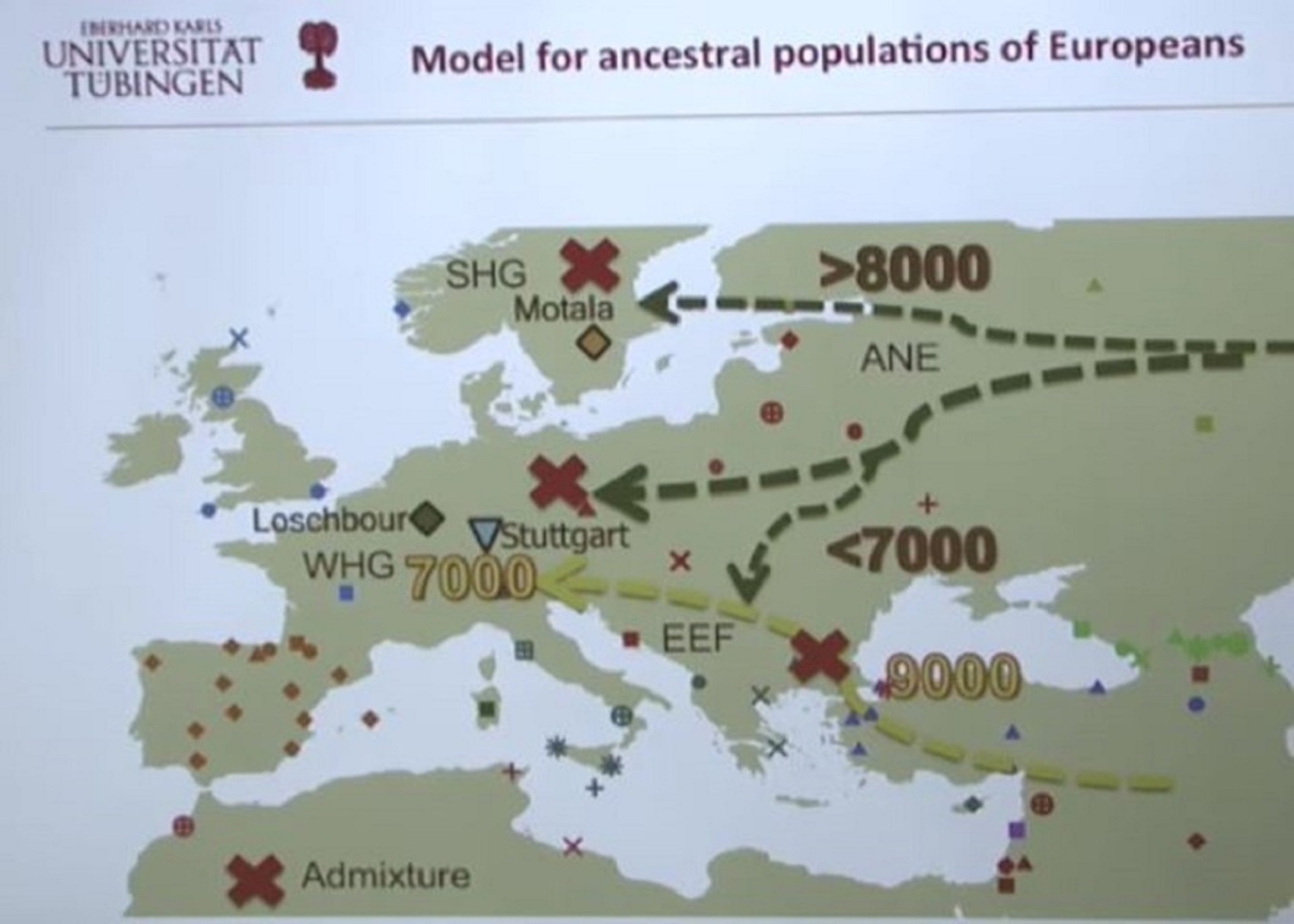

Ancient North Eurasian (ANE)

Ancient Beringian/Ancestral Native American (AB/ANA)

Eastern Hunter-Gatherer (EHG)

Western Hunter-Gatherers (WHG)

Western Steppe Herders (WSH)

Scandinavian Hunter-Gatherer (SHG)

Early European Farmers (EEF)

Jōmon people (Ainu people OF Hokkaido Island)

Neolithic Iranian farmers (Iran_N) (Iran Neolithic)

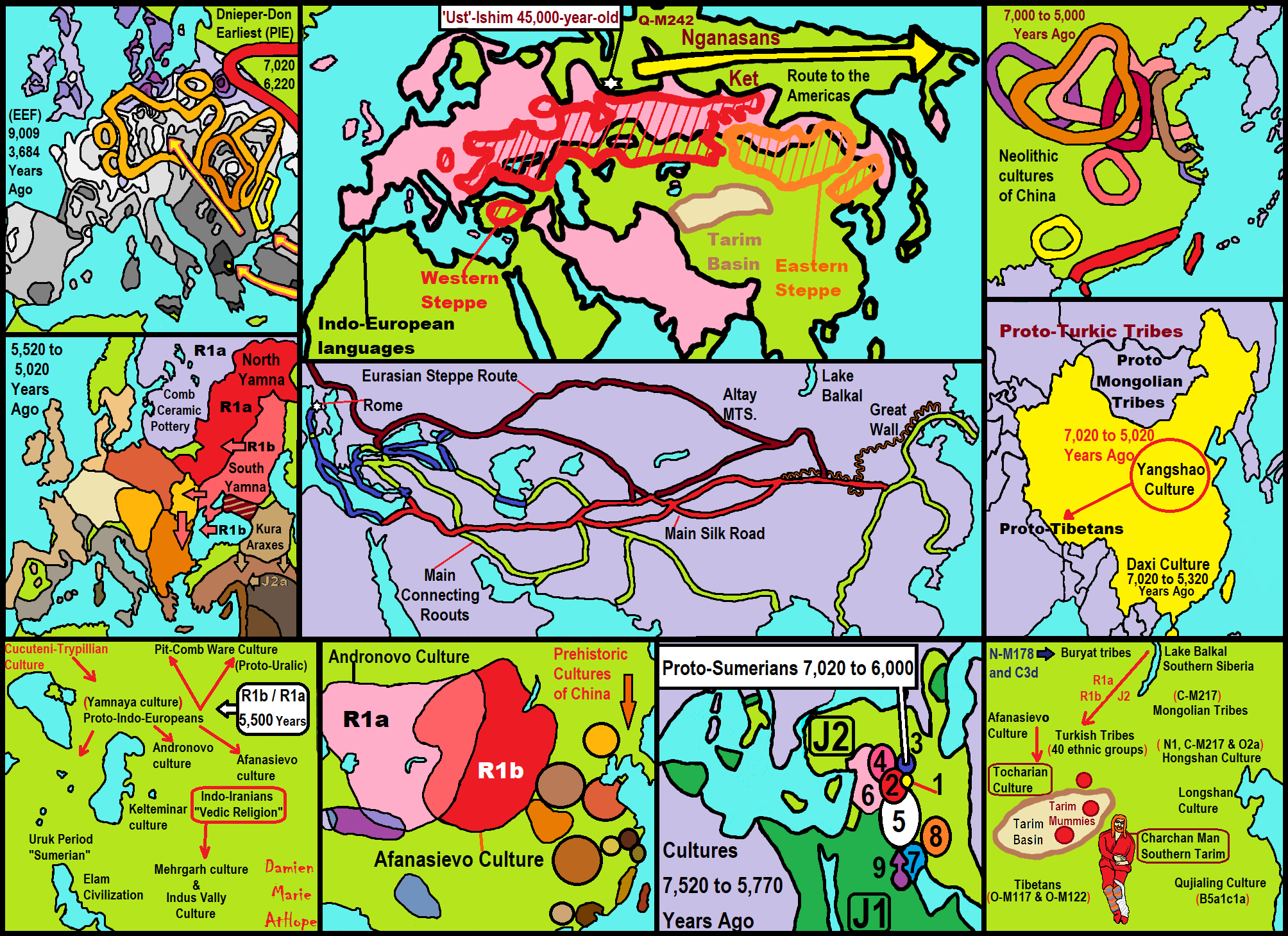

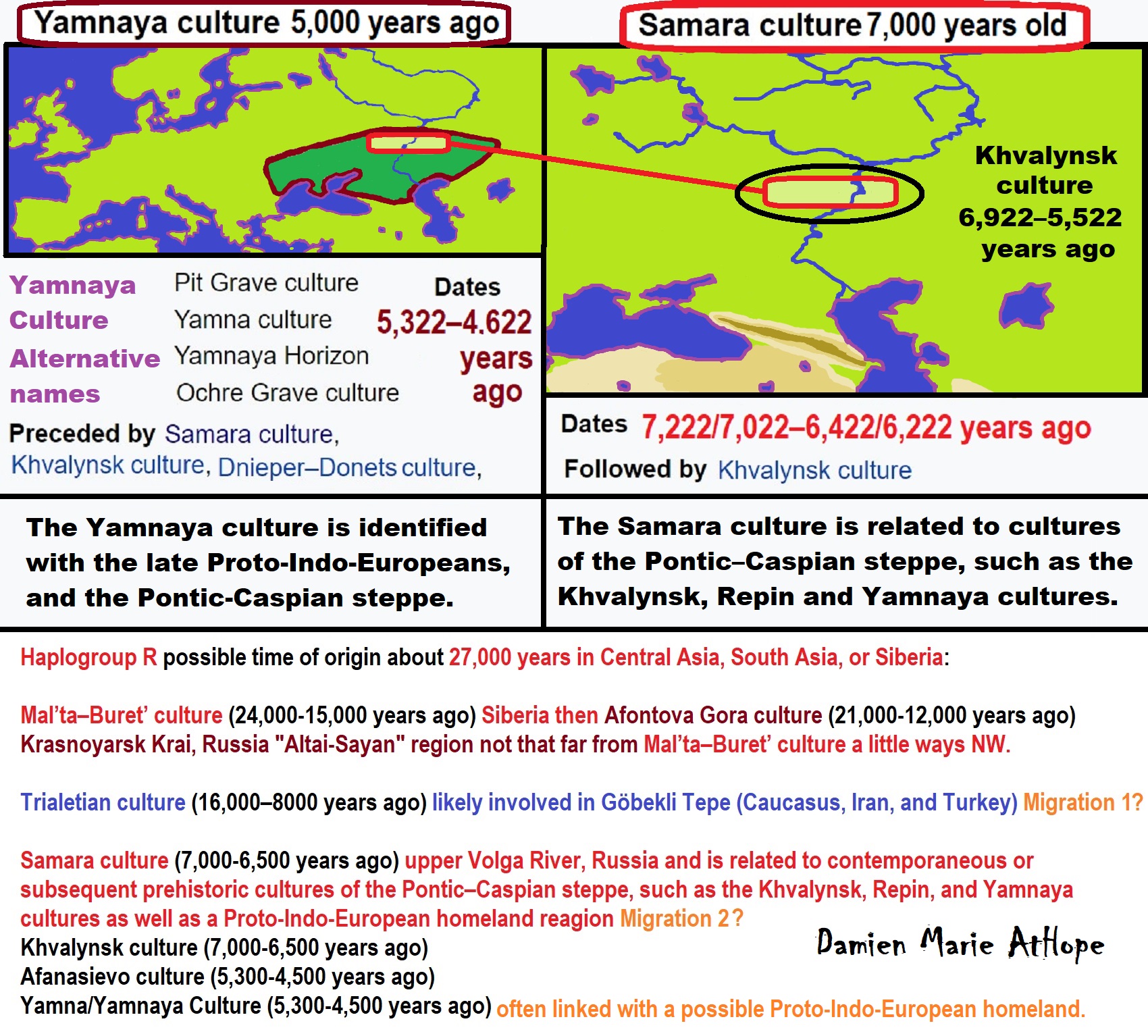

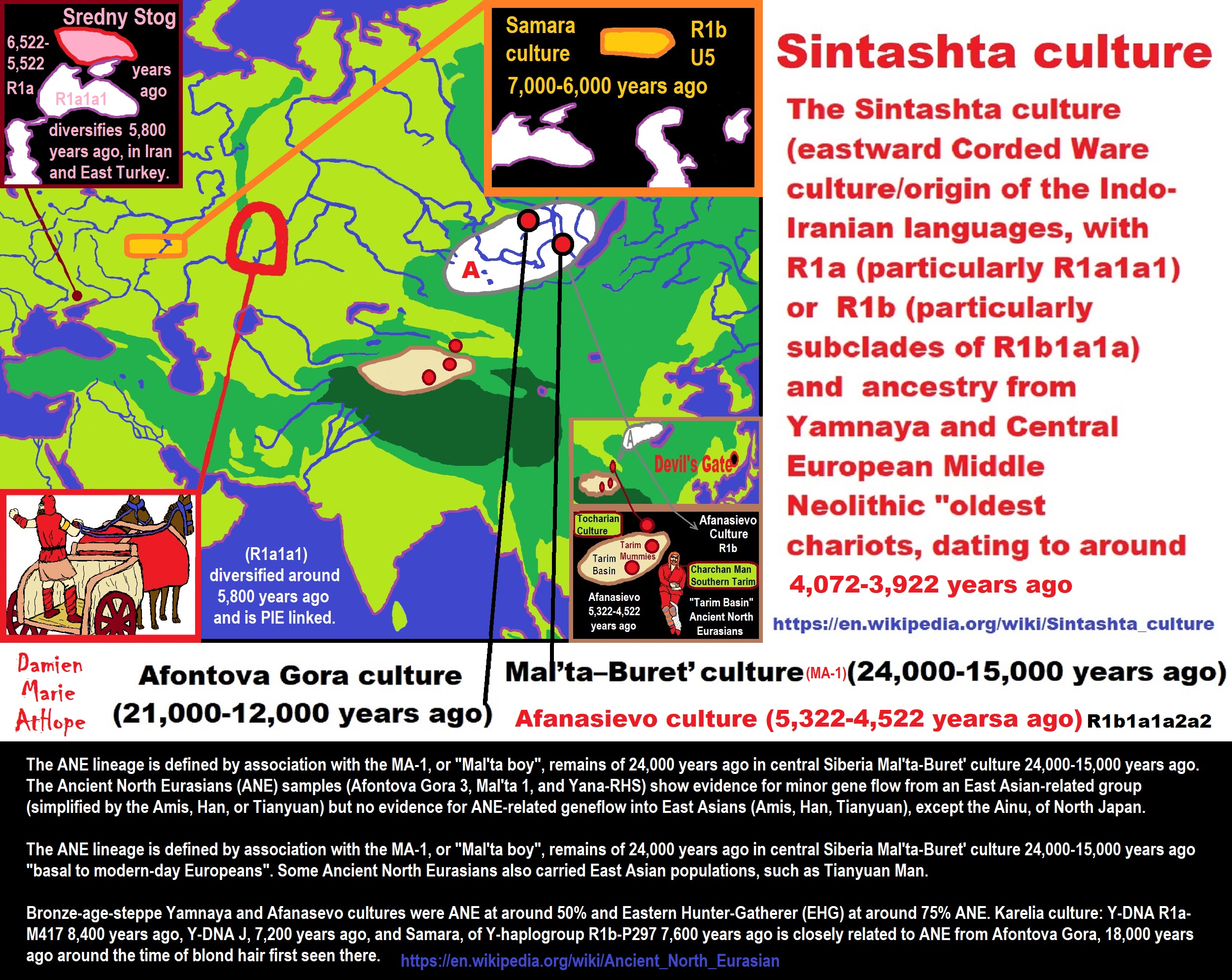

Haplogroup R possible time of origin about 27,000 years in Central Asia, South Asia, or Siberia:

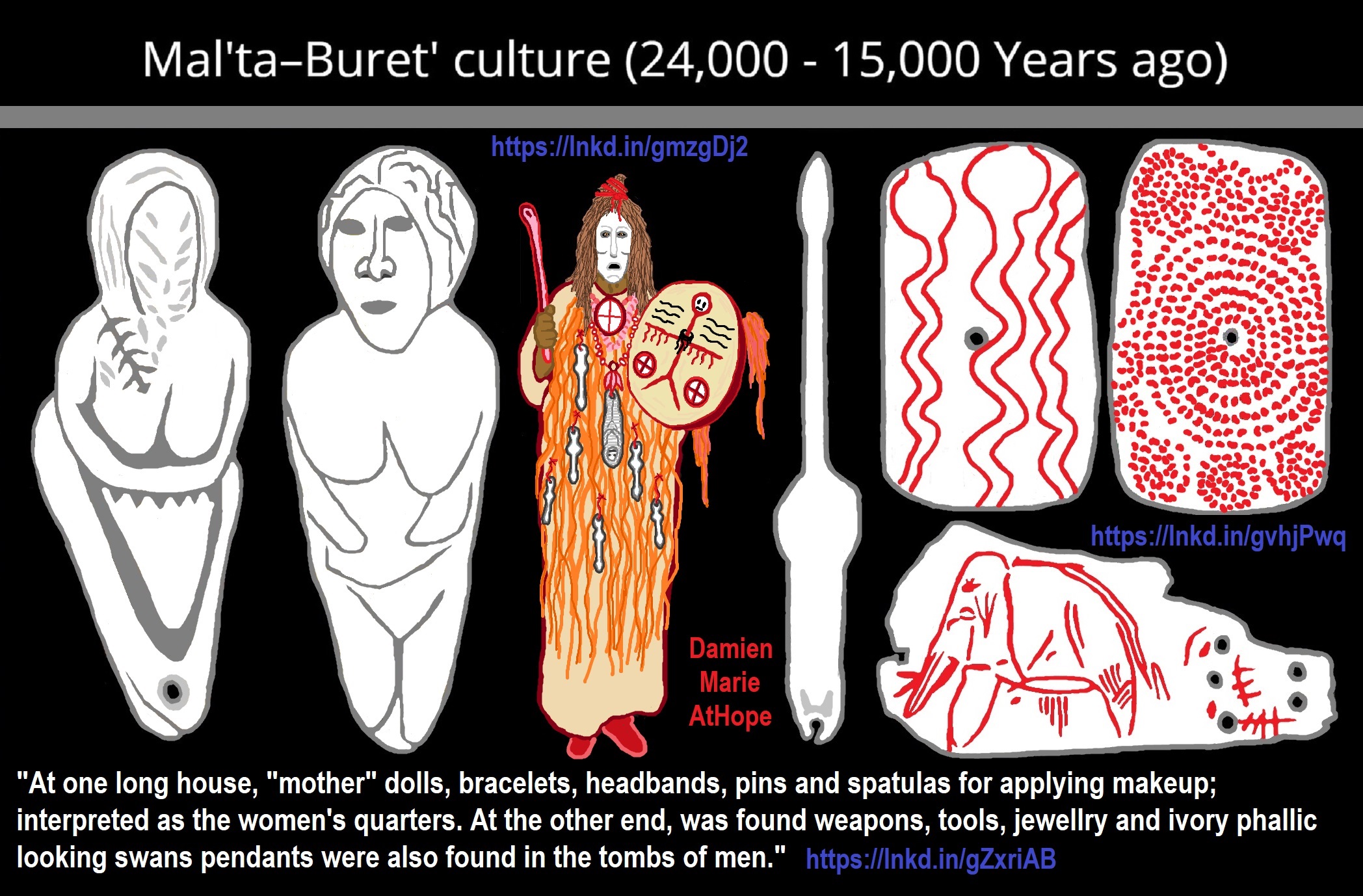

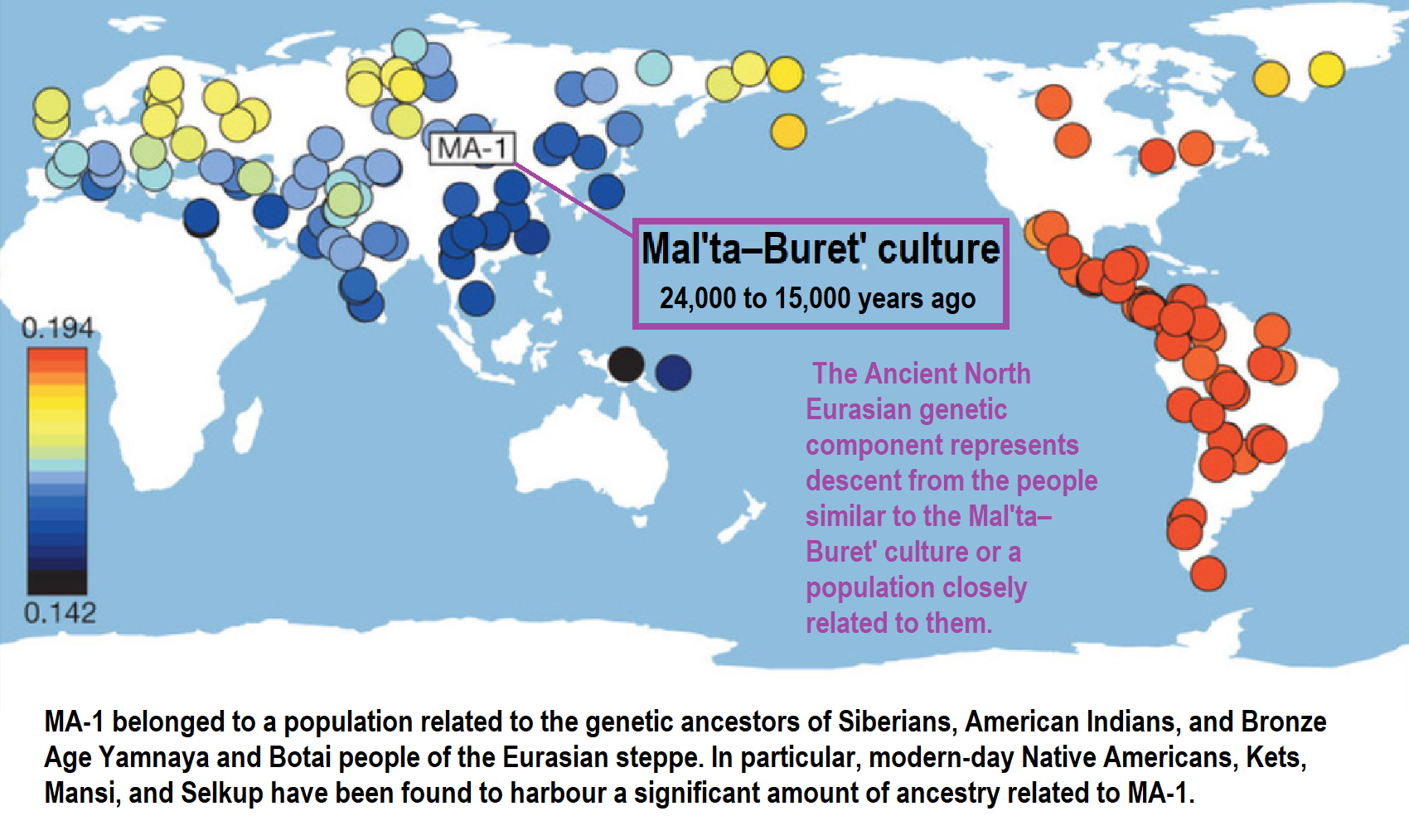

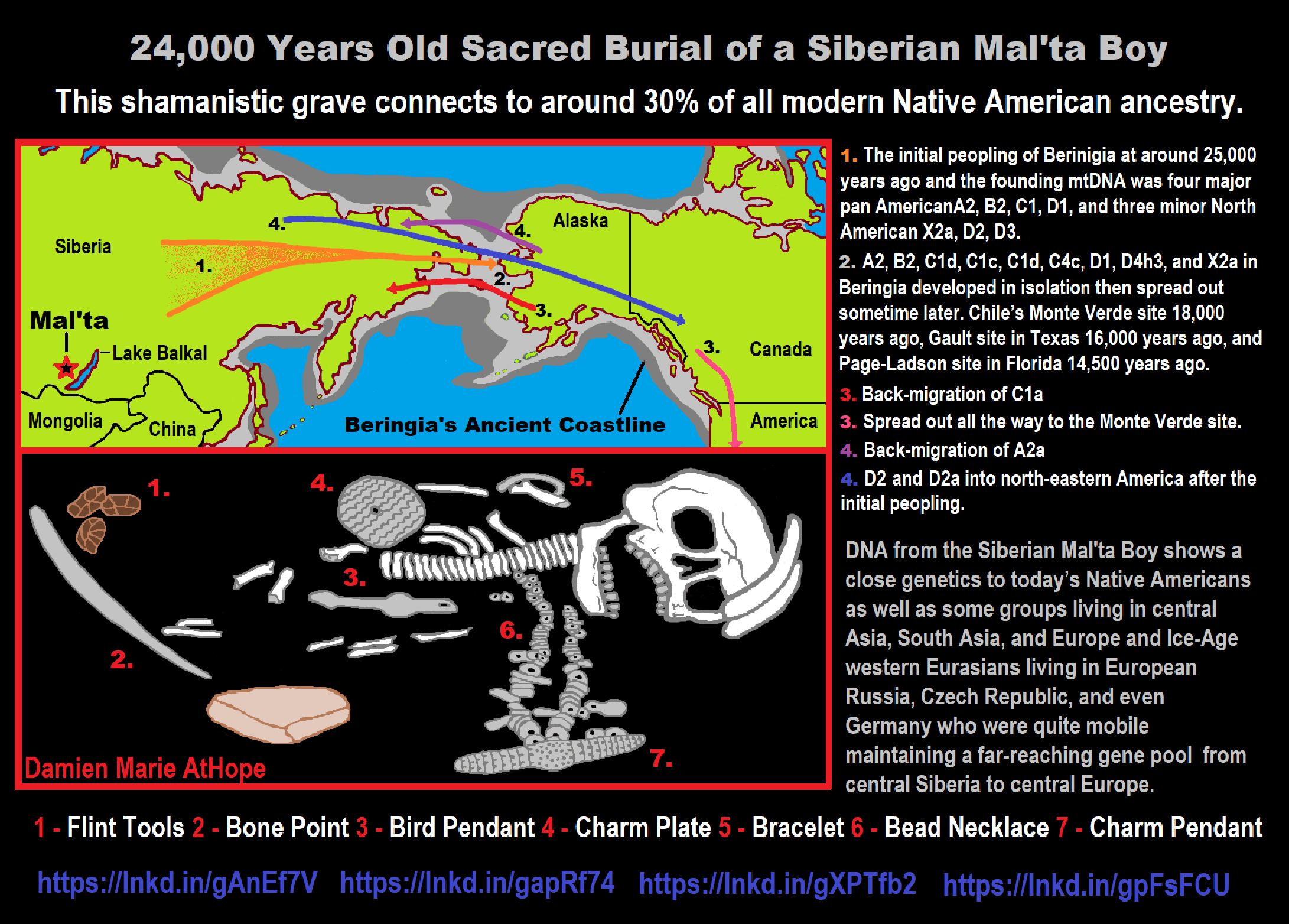

- Mal’ta–Buret’ culture (24,000-15,000 years ago)

- Afontova Gora culture (21,000-12,000 years ago)

- Trialetian culture (16,000–8000 years ago)

- Samara culture (7,000-6,500 years ago)

- Khvalynsk culture (7,000-6,500 years ago)

- Afanasievo culture (5,300-4,500 years ago)

- Yamna/Yamnaya Culture (5,300-4,500 years ago)

- Andronovo culture (4,000–2,900 years ago) ref

Groups partially derived from the Ancient North Eurasians

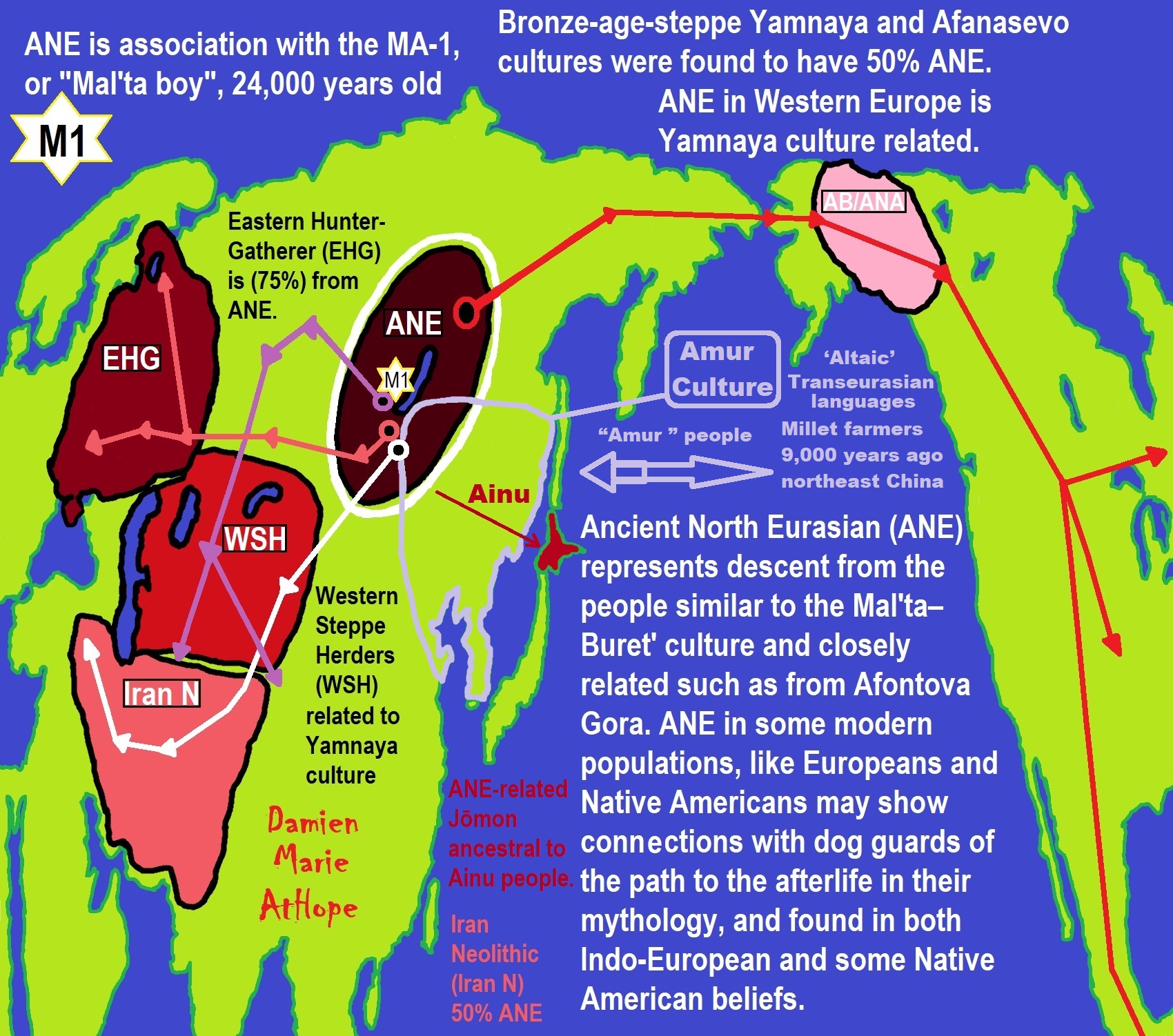

“The ANE lineage is defined by association with the MA-1, or “Mal’ta boy”, remains of 24,000 years ago in central Siberia Mal’ta-Buret’ culture 24,000-15,000 years ago. The Ancient North Eurasians (ANE) samples (Afontova Gora 3, Mal’ta 1, and Yana-RHS) show evidence for minor gene flow from an East Asian-related group (simplified by the Amis, Han, or Tianyuan) but no evidence for ANE-related geneflow into East Asians (Amis, Han, Tianyuan), except the Ainu, of North Japan.” ref

“The ANE lineage is defined by association with the MA-1, or “Mal’ta boy”, remains of 24,000 years ago in central Siberia Mal’ta-Buret’ culture 24,000-15,000 years ago “basal to modern-day Europeans”. Some Ancient North Eurasians also carried East Asian populations, such as Tianyuan Man.” ref

“Bronze-age-steppe Yamnaya and Afanasevo cultures were ANE at around 50% and Eastern Hunter-Gatherer (EHG) at around 75% ANE. Karelia culture: Y-DNA R1a-M417 8,400 years ago, Y-DNA J, 7,200 years ago, and Samara, of Y-haplogroup R1b-P297 7,600 years ago is closely related to ANE from Afontova Gora, 18,000 years ago around the time of blond hair first seen there.” ref

Ancient North Eurasian

“In archaeogenetics, the term Ancient North Eurasian (often abbreviated as ANE) is the name given to an ancestral West Eurasian component that represents descent from the people similar to the Mal’ta–Buret’ culture and populations closely related to them, such as from Afontova Gora and the Yana Rhinoceros Horn Site. Significant ANE ancestry are found in some modern populations, including Europeans and Native Americans.” ref

“The ANE lineage is defined by association with the MA-1, or “Mal’ta boy“, the remains of an individual who lived during the Last Glacial Maximum, 24,000 years ago in central Siberia, Ancient North Eurasians are described as a lineage “which is deeply related to Paleolithic/Mesolithic hunter-gatherers in Europe,” meaning that they diverged from Paleolithic Europeans a long time ago.” ref

“The ANE population has also been described as having been “basal to modern-day Europeans” but not especially related to East Asians, and is suggested to have perhaps originated in Europe or Western Asia or the Eurasian Steppe of Central Asia. However, some samples associated with Ancient North Eurasians also carried ancestry from an ancient East Asian population, such as Tianyuan Man. Sikora et al. (2019) found that the Yana RHS sample (31,600 BP) in Northern Siberia “can be modeled as early West Eurasian with an approximately 22% contribution from early East Asians.” ref

“Populations genetically similar to MA-1 were an important genetic contributor to Native Americans, Europeans, Central Asians, South Asians, and some East Asian groups, in order of significance. Lazaridis et al. (2016:10) note “a cline of ANE ancestry across the east-west extent of Eurasia.” The ancient Bronze-age-steppe Yamnaya and Afanasevo cultures were found to have a noteworthy ANE component at ~50%.” ref

“According to Moreno-Mayar et al. 2018 between 14% and 38% of Native American ancestry may originate from gene flow from the Mal’ta–Buret’ people (ANE). This difference is caused by the penetration of posterior Siberian migrations into the Americas, with the lowest percentages of ANE ancestry found in Eskimos and Alaskan Natives, as these groups are the result of migrations into the Americas roughly 5,000 years ago.” ref

“Estimates for ANE ancestry among first wave Native Americans show higher percentages, such as 42% for those belonging to the Andean region in South America. The other gene flow in Native Americans (the remainder of their ancestry) was of East Asian origin. Gene sequencing of another south-central Siberian people (Afontova Gora-2) dating to approximately 17,000 years ago, revealed similar autosomal genetic signatures to that of Mal’ta boy-1, suggesting that the region was continuously occupied by humans throughout the Last Glacial Maximum.” ref

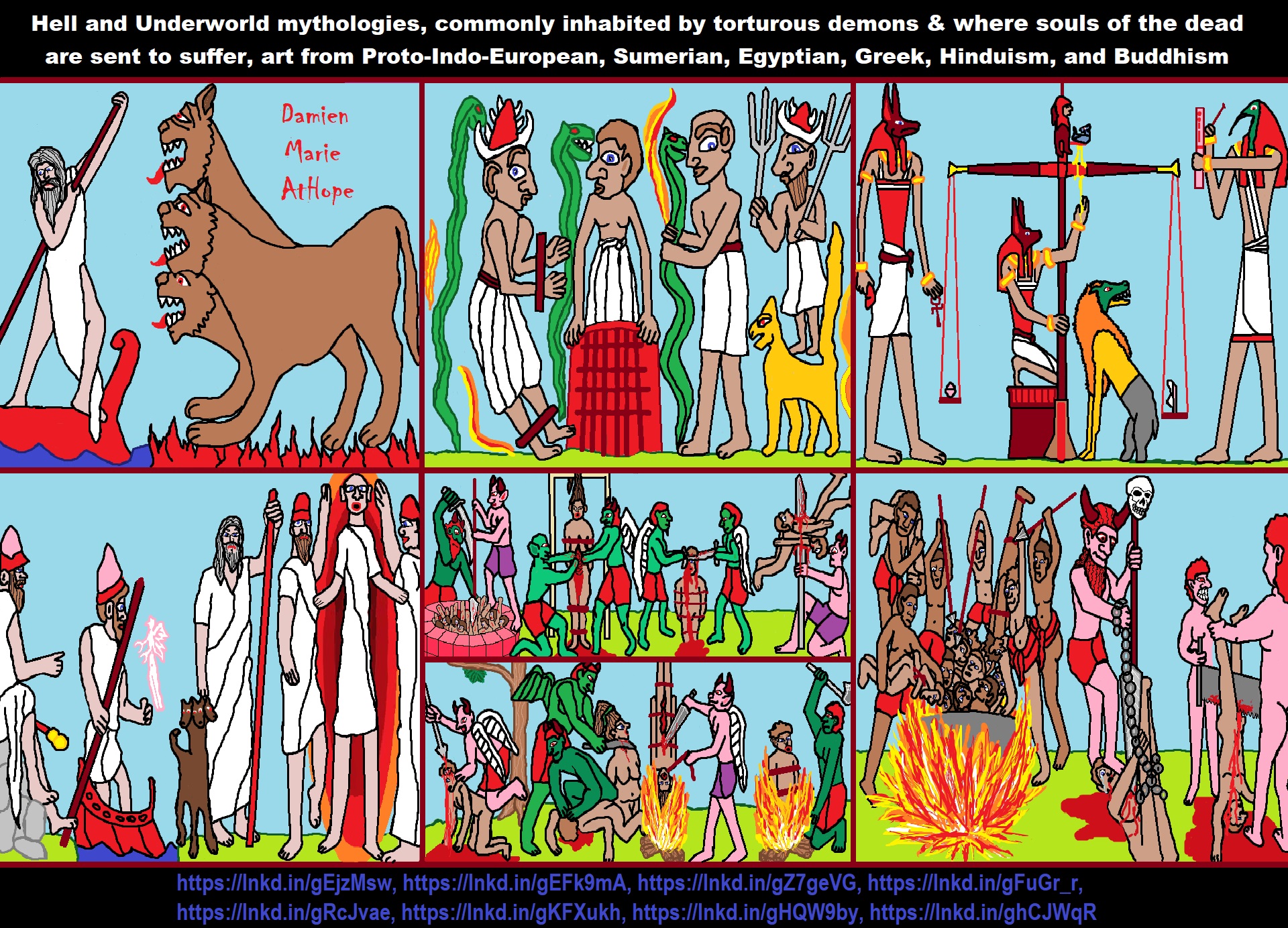

“The earliest known individual with a genetic mutation associated with blonde hair in modern Europeans is an Ancient North Eurasian female dating to around 16000 BCE from the Afontova Gora 3 site in Siberia. It has been suggested that their mythology may have included a narrative, found in both Indo-European and some Native American fables, in which a dog guards the path to the afterlife.” ref

“Genomic studies also indicate that the ANE component was introduced to Western Europe by people related to the Yamnaya culture, long after the Paleolithic. It is reported in modern-day Europeans (7%–25%), but not of Europeans before the Bronze Age. Additional ANE ancestry is found in European populations through paleolithic interactions with Eastern Hunter-Gatherers, which resulted in populations such as Scandinavian Hunter-Gatherers.” ref

“The Ancient North Eurasians (ANE) split from the ancestors of European peoples somewhere in the Middle East or South-central Asia, and used a northern dispersal route through Central Asia into Northern Asia and Siberia. Genetic analyses show that all ANE samples (Afontova Gora 3, Mal’ta 1, and Yana-RHS) show evidence for minor gene flow from an East Asian-related group (simplified by the Amis, Han, or Tianyuan). In contrast, no evidence for ANE-related geneflow into East Asians (Amis, Han, Tianyuan), except the Ainu, was found.” ref

“Genetic data suggests that the ANE formed during the Terminal Upper-Paleolithic (36+-1,5ka) period from a deeply European-related population, which was once widespread in Northern Eurasia, and from an early East Asian-related group, which migrated northwards into Central Asia and Siberia, merging with this deeply European-related population. These population dynamics and constant northwards geneflow of East Asian-related ancestry would later gave rise to the “Ancestral Native Americans” and Paleosiberians, which replaced the ANE as dominant population of Siberia.” ref

Groups partially derived from the Ancient North Eurasians

“Eastern Hunter-Gatherer (EHG) is a lineage derived predominantly (75%) from ANE. It is represented by two individuals from Karelia, one of Y-haplogroup R1a-M417, dated c. 8.4 kya, the other of Y-haplogroup J, dated c. 7.2 kya; and one individual from Samara, of Y-haplogroup R1b-P297, dated c. 7.6 kya. This lineage is closely related to the ANE sample from Afontova Gora, dated c. 18 kya. After the end of the Last Glacial Maximum, the Western Hunter-Gatherers (WHG) and EHG lineages merged in Eastern Europe, accounting for early presence of ANE-derived ancestry in Mesolithic Europe. Evidence suggests that as Ancient North Eurasians migrated West from Eastern Siberia, they absorbed Western Hunter-Gatherers and other West Eurasian populations as well.” ref

“Caucasian Hunter-Gatherer (CHG) is represented by the Satsurblia individual dated ~13 kya (from the Satsurblia cave in Georgia), and carried 36% ANE-derived admixture. While the rest of their ancestry is derived from the Dzudzuana cave individual dated ~26 kya, which lacked ANE-admixture, Dzudzuana affinity in the Caucasus decreased with the arrival of ANE at ~13 kya Satsurblia.” ref

“Scandinavian Hunter-Gatherer (SHG) is represented by several individuals buried at Motala, Sweden ca. 6000 BC. They were descended from Western Hunter-Gatherers who initially settled Scandinavia from the south, and later populations of EHG who entered Scandinavia from the north through the coast of Norway.” ref

“Iran Neolithic (Iran_N) individuals dated ~8.5 kya carried 50% ANE-derived admixture and 50% Dzudzuana-related admixture, marking them as different from other Near-Eastern and Anatolian Neolithics who didn’t have ANE admixture. Iran Neolithics were later replaced by Iran Chalcolithics, who were a mixture of Iran Neolithic and Near Eastern Levant Neolithic.” ref

“Ancient Beringian/Ancestral Native American are specific archaeogenetic lineages, based on the genome of an infant found at the Upward Sun River site (dubbed USR1), dated to 11,500 years ago. The AB lineage diverged from the Ancestral Native American (ANA) lineage about 20,000 years ago.” ref

“West Siberian Hunter-Gatherer (WSHG) are a specific archaeogenetic lineage, first reported in a genetic study published in Science in September 2019. WSGs were found to be of about 30% EHG ancestry, 50% ANE ancestry, and 20% to 38% East Asian ancestry.” ref

“Western Steppe Herders (WSH) is the name given to a distinct ancestral component that represents descent closely related to the Yamnaya culture of the Pontic–Caspian steppe. This ancestry is often referred to as Yamnaya ancestry or Steppe ancestry.” ref

“Late Upper Paeolithic Lake Baikal – Ust’Kyakhta-3 (UKY) 14,050-13,770 BP were mixture of 30% ANE ancestry and 70% East Asian ancestry.” ref

“Lake Baikal Holocene – Baikal Eneolithic (Baikal_EN) and Baikal Early Bronze Age (Baikal_EBA) derived 6.4% to 20.1% ancestry from ANE, while rest of their ancestry was derived from East Asians. Fofonovo_EN near by Lake Baikal were mixture of 12-17% ANE ancestry and 83-87% East Asian ancestry.” ref

“Hokkaido Jōmon people specifically refers to the Jōmon period population of Hokkaido in northernmost Japan. Though the Jōmon people themselves descended mainly from East Asian lineages, one study found an affinity between Hokkaido Jōmon with the Northern Eurasian Yana sample (an ANE-related group, related to Mal’ta), and suggest as an explanation the possibility of minor Yana gene flow into the Hokkaido Jōmon population (as well as other possibilities). A more recent study by Cooke et al. 2021, confirmed ANE-related geneflow among the Jōmon people, partially ancestral to the Ainu people. ANE ancestry among Jōmon people is estimated at 21%, however, there is a North to South cline within the Japanese archipelago, with the highest amount of ANE ancestry in Hokkaido and Tohoku.” ref

“Migration from Siberia behind the formation of Göbeklitepe: Expert states. People who migrated from Siberia formed the Göbeklitepe, and those in Göbeklitepe migrated in five other ways to spread to the world, said experts about the 12,000-year-old Neolithic archaeological site in the southwestern province of Şanlıurfa.“ The upper paleolithic migrations between Siberia and the Near East is a process that has been confirmed by material culture documents,” he said.” ref

“Semih Güneri, a retired professor from Caucasia and Central Asia Archaeology Research Center of Dokuz Eylül University, and his colleague, Professor Ekaterine Lipnina, presented the Siberia-Göbeklitepe hypothesis they have developed in recent years at the congress held in Istanbul between June 11 and 13. There was a migration that started from Siberia 30,000 years ago and spread to all of Asia and then to Eastern and Northern Europe, Güneri said at the international congress.” ref

“The relationship of Göbeklitepe high culture with the carriers of Siberian microblade stone tool technology is no longer a secret,” he said while emphasizing that the most important branch of the migrations extended to the Near East. “The results of the genetic analyzes of Iraq’s Zagros region confirm the traces of the Siberian/North Asian indigenous people, who arrived at Zagros via the Central Asian mountainous corridor and met with the Göbeklitepe culture via Northern Iraq,” he added.” ref

“Emphasizing that the stone tool technology was transported approximately 7,000 kilometers from east to west, he said, “It is not clear whether this technology is transmitted directly to long distances by people speaking the Turkish language at the earliest, or it travels this long-distance through using way stations.” According to the archaeological documents, it is known that the Siberian people had reached the Zagros region, he said. “There seems to be a relationship between Siberian hunter-gatherers and native Zagros hunter-gatherers,” Güneri said, adding that the results of genetic studies show that Siberian people reached as far as the Zagros.” ref

“There were three waves of migration of Turkish tribes from the Southern Siberia to Europe,” said Osman Karatay, a professor from Ege University. He added that most of the groups in the third wave, which took place between 2600-2400 BCE, assimilated and entered the Germanic tribes and that there was a genetic kinship between their tribes and the Turks. The professor also pointed out that there are indications that there is a technology and tool transfer from Siberia to the Göbeklitepe region and that it is not known whether people came, and if any, whether they were Turkish.” ref

“Around 12,000 years ago, there would be no ‘Turks’ as we know it today. However, there may have been tribes that we could call our ‘common ancestors,’” he added. “Talking about 30,000 years ago, it is impossible to identify and classify nations in today’s terms,” said Murat Öztürk, associate professor from İnönü University. He also said that it is not possible to determine who came to where during the migrations that were accepted to have been made thousands of years ago from Siberia. On the other hand, Mehmet Özdoğan, an academic from Istanbul University, has an idea of where “the people of Göbeklitepe migrated to.” ref

“According to Özdoğan, “the people of Göbeklitepe turned into farmers, and they could not stand the pressure of the overwhelming clergy and started to migrate to five ways.” “Migrations take place primarily in groups. One of the five routes extends to the Caucasus, another from Iran to Central Asia, the Mediterranean coast to Spain, Thrace and [the northwestern province of] Kırklareli to Europe and England, and one route is to Istanbul via [Istanbul’s neighboring province of] Sakarya and stops,” Özdoğan said. In a very short time after the migration of farmers in Göbeklitepe, 300 settlements were established only around northern Greece, Bulgaria, and Thrace. “Those who remained in Göbeklitepe pulled the trigger of Mesopotamian civilization in the following periods, and those who migrated to Mesopotamia started irrigated agriculture before the Sumerians,” he said.” ref

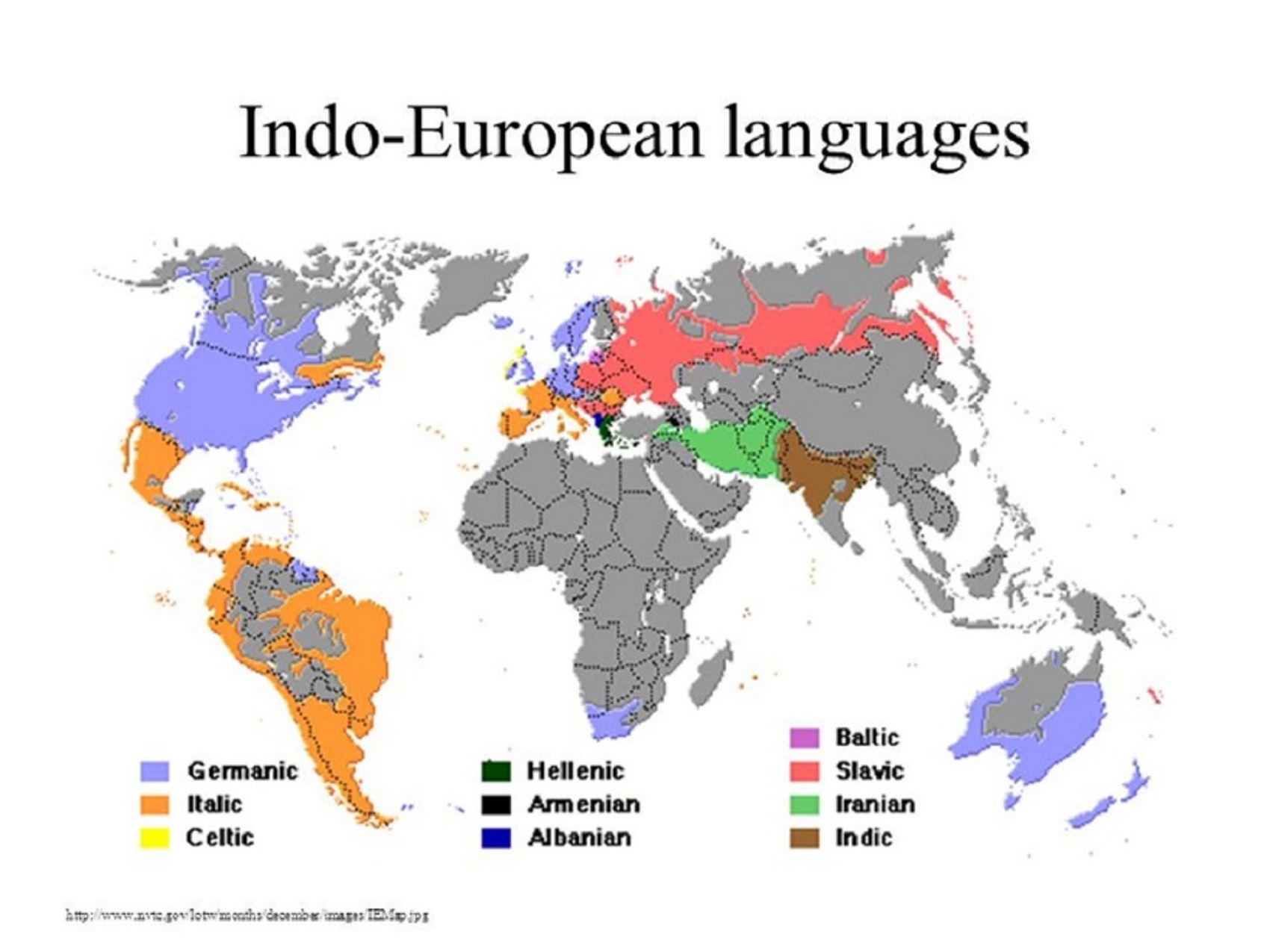

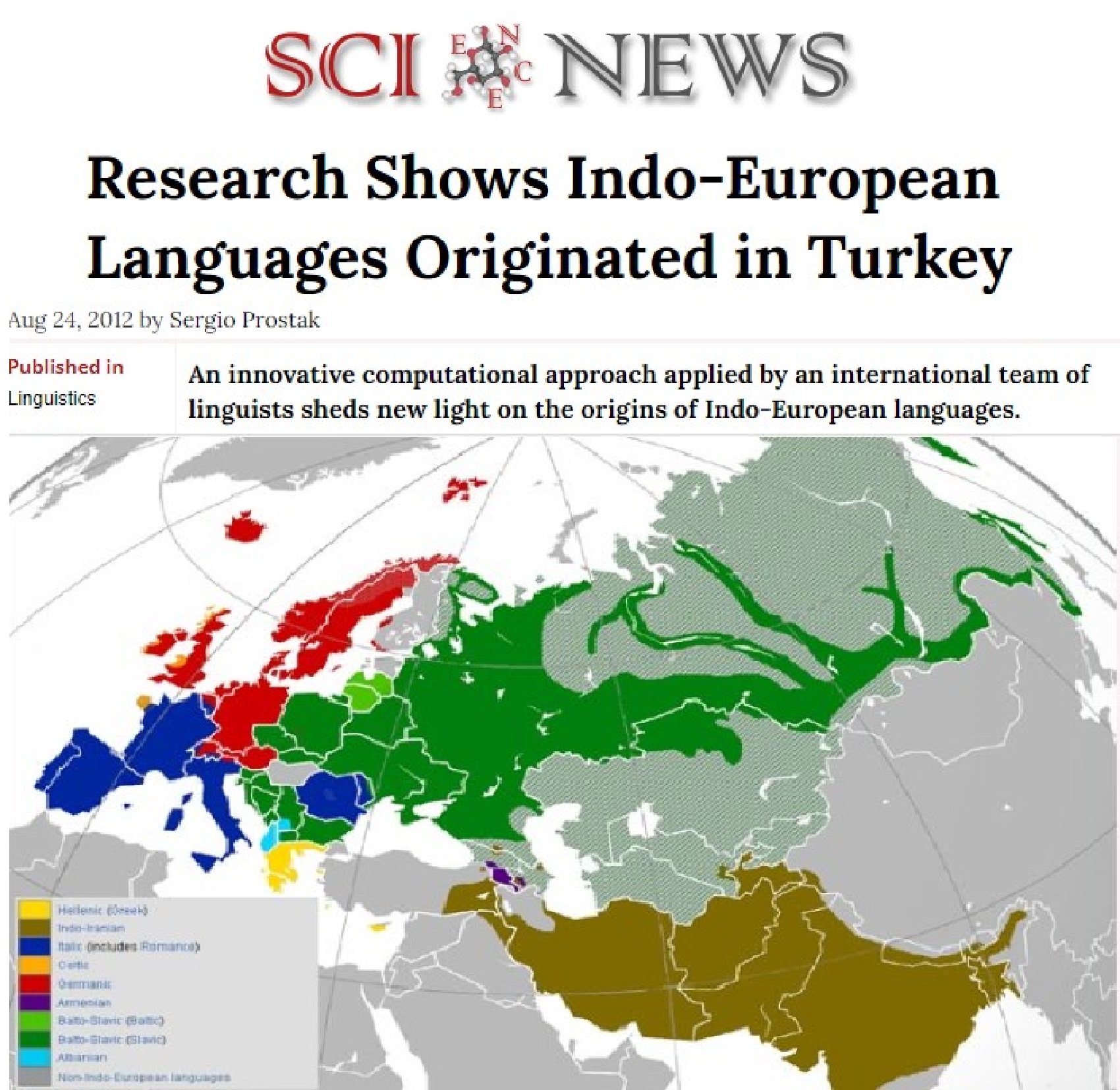

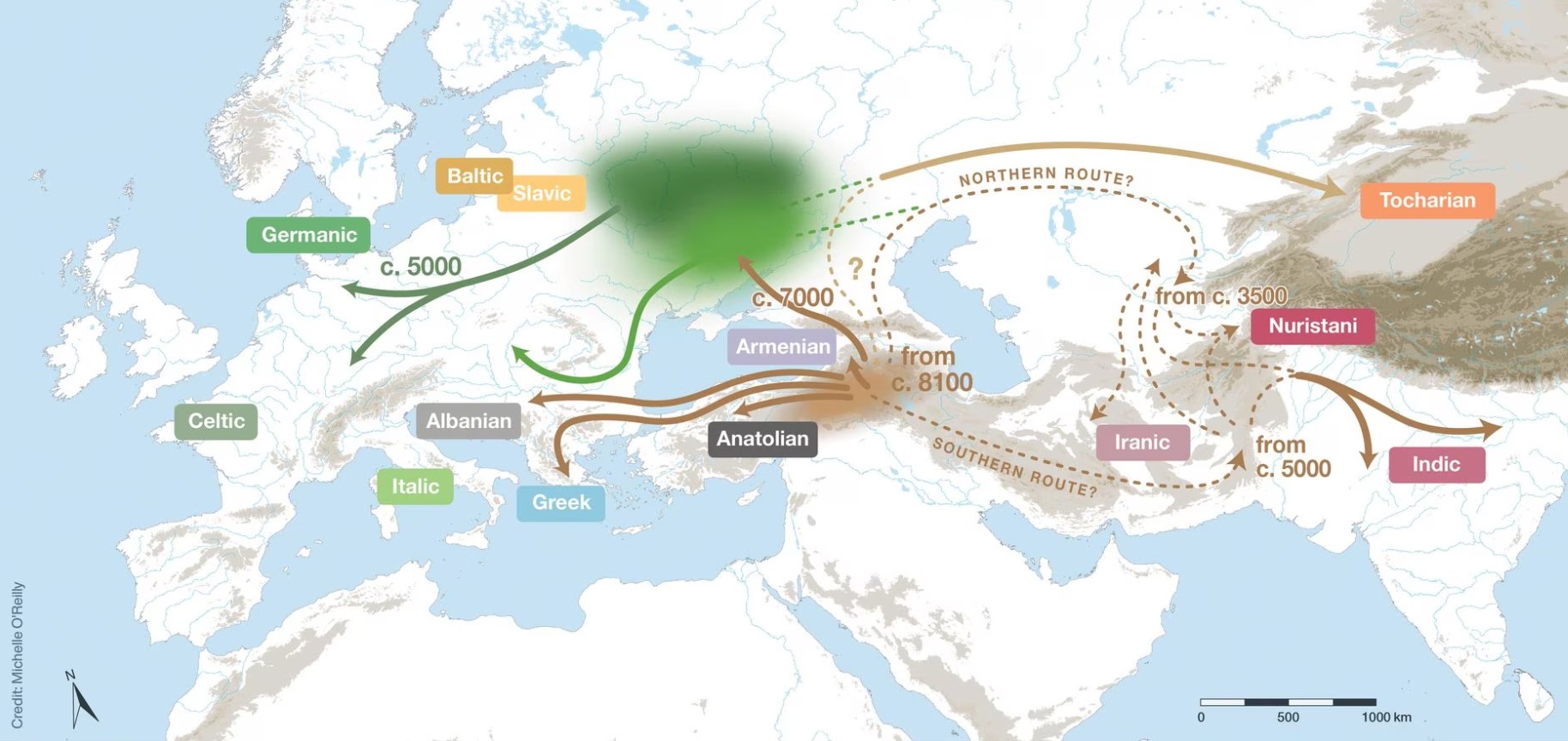

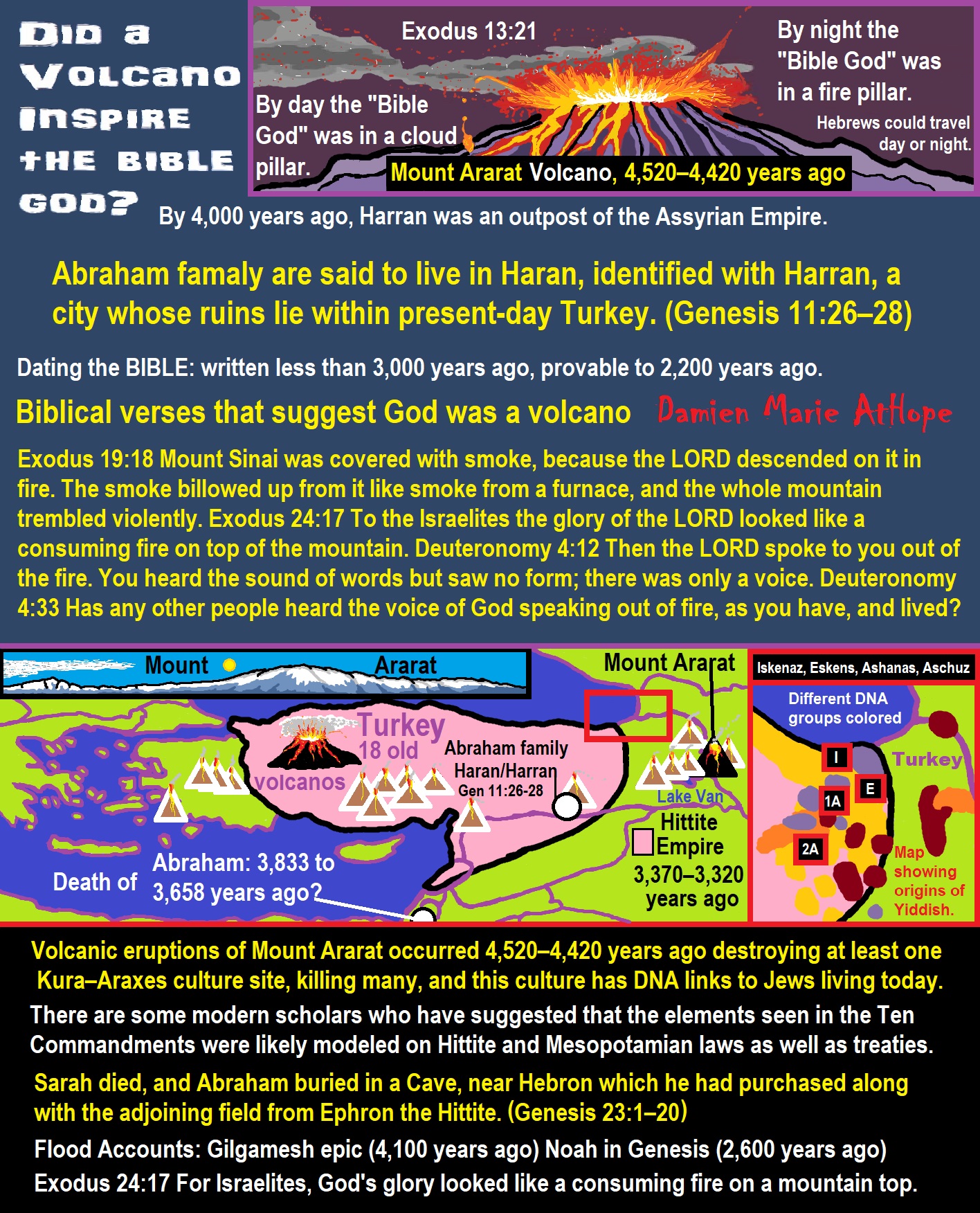

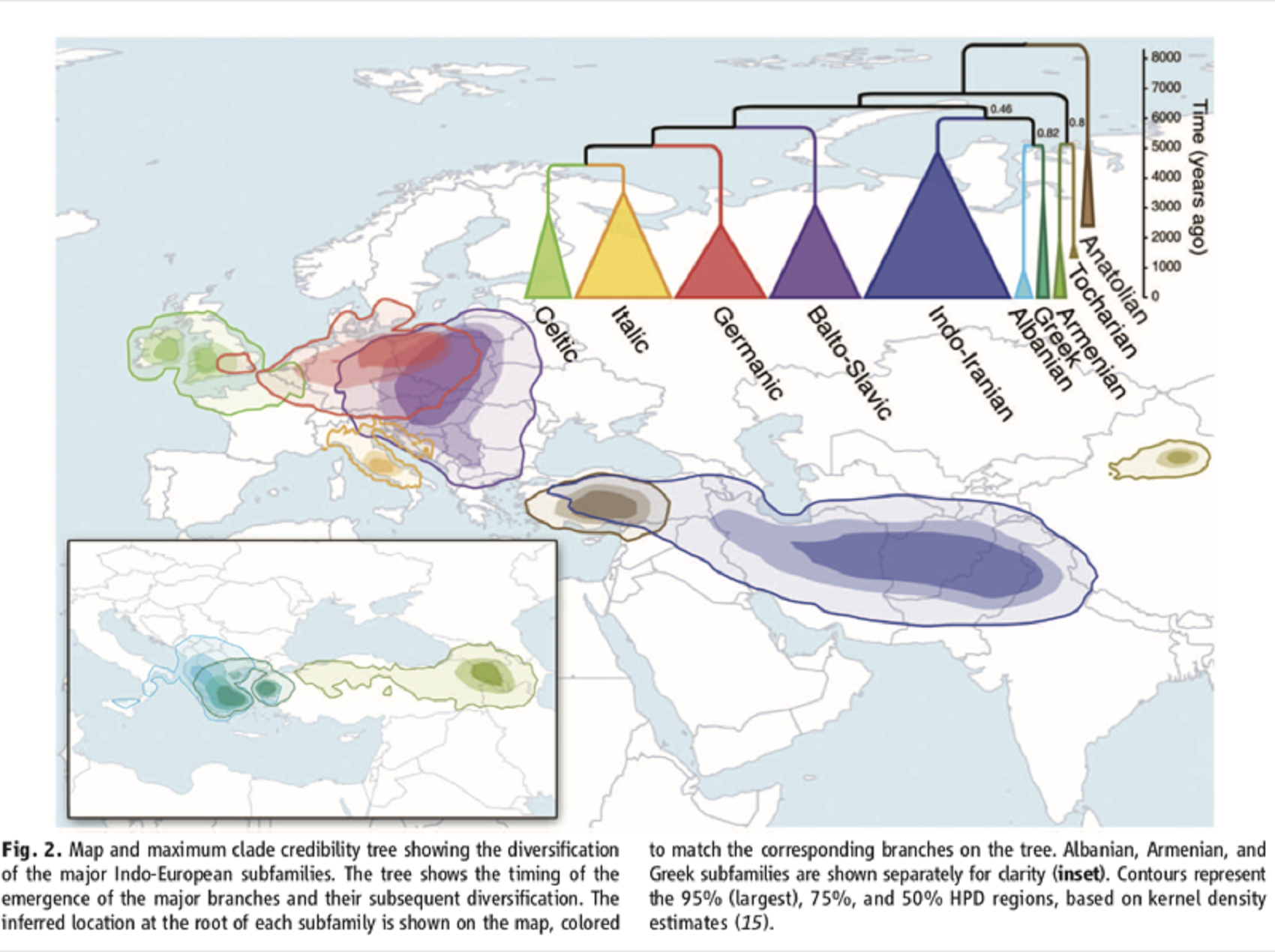

Research Shows Indo-European Languages Originated in Turkey (2012)

“The Indo-European languages belong to one of the widest spread language families of the world. For the last two millennia, many of these languages have been written, and their history is relatively clear. But controversy remains about the time and place of the origins of the family. The majority view in historical linguistics is that the homeland of Indo-European is located in the Pontic steppes – present-day Ukraine – around 6,000 years ago. The evidence for this comes from linguistic paleontology: in particular, certain words to do with the technology of wheeled vehicles are arguably present across all the branches of the Indo-European family; and archaeology tells us that wheeled vehicles arose no earlier than this date. The minority view links the origins of Indo-European with the spread of farming from Anatolia 8,000-9,500 years ago. The team’s innovative Bayesian phylogeographic analysis of Indo-European linguistic and spatial data, including basic vocabulary data from 103 ancient and contemporary Indo-European languages, decisively supports this theory. The linguists report their results in a paper in the journal Science.” ref

Indo-European dialects dispersed across Eurasia in successive waves over the course of 8,000 years.

Word origins and ancient DNA reveal the evolutionary path traveled by the languages spoken by half the world.

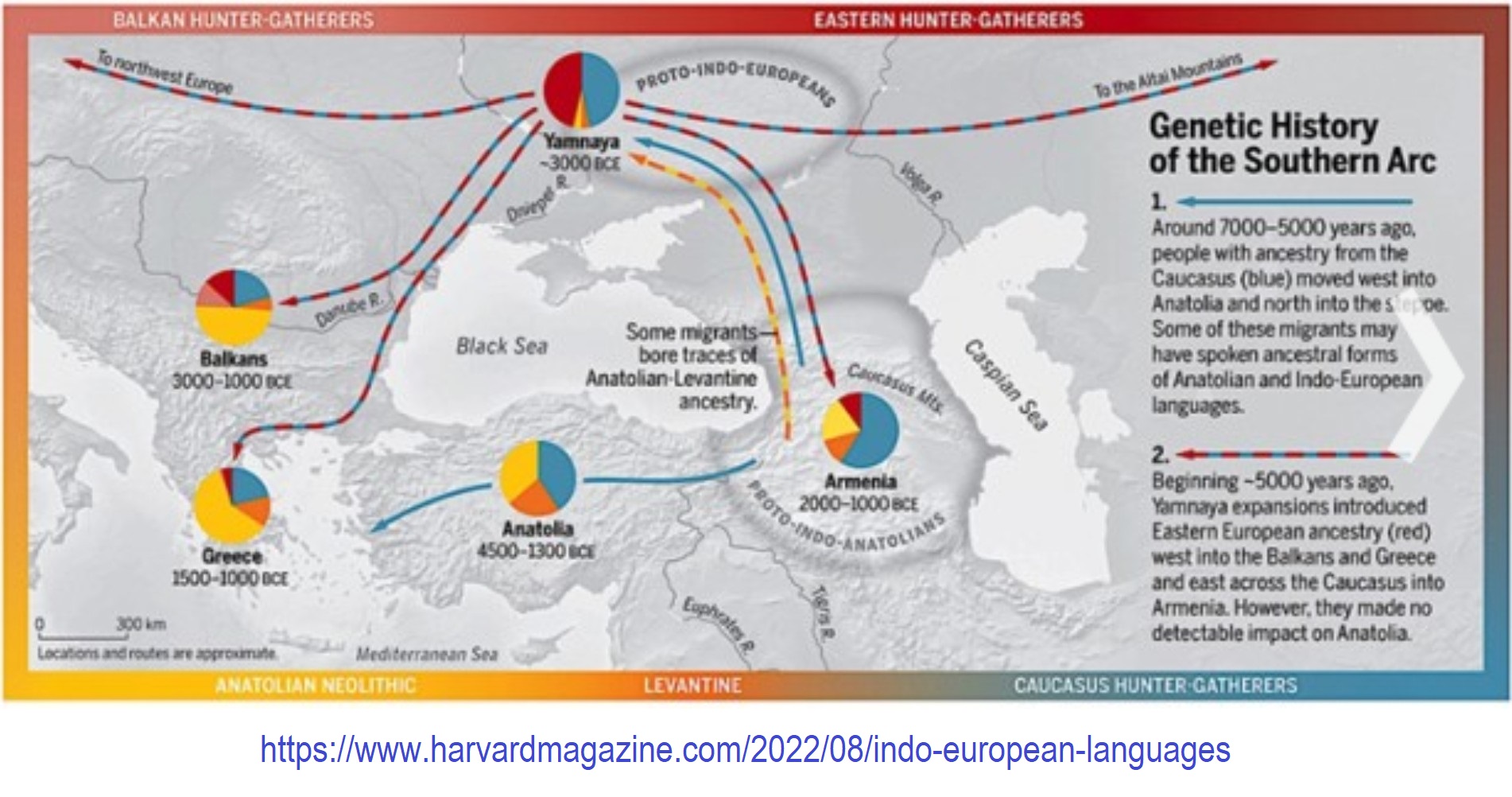

“Approximately 7,000 years ago, the Indo-European linguistic lineage had already split into numerous distinct branches, according to the study published in Science. “This would rule out the steppe hypothesis,” said Heggarty. Around 8,120 years ago, the Proto-Indo-European language likely experienced its initial diversification event, give or take a few centuries. Recent studies of ancient DNA suggest that farmers from the Caucasus region — between the Black Sea and Caspian Sea — migrated towards Anatolia, which supports the Anatolian theory. Hittite, an extinct language spoken by the Anatolian civilization, is another significant branch of the Indo-European family. For decades, a large group of linguists argued that Hittite was the common ancestor of the other Indo-European languages, with some even considering it to be the direct heir of Proto-Indo-European.” ref

“Ancient DNA, on the other hand, has provided compelling evidence in support of the steppe hypothesis. Since 2015, it has become clear that individuals originating from the Pontic steppe, situated to the south and northeast of present-day Russia, Ukraine, and Kazakhstan, migrated to Central Europe approximately 6,000 to 4,500 years ago. Their genetic legacy is evident in both modern Europeans and the indigenous populations of that era. Notably, studies conducted in 2018 and 2019 revealed how these migrant eastern populations replaced a significant proportion of males on the Iberian Peninsula. Furthermore, they brought with them Italic, Germanic, and Celtic languages. It is important to note that when they departed from their original homeland, they likely spoke a common or closely related language descended from Proto-Indo-European. However, as their very slow journey progressed (the Celts took centuries to reach present-day Ireland) and they settled in new territories, language diversification began to emerge.” ref

“The Albanians, Greek-speaking Mycenaeans, and Hittites do not have a dominant genetic signal from the steppe.” ref

Paul Heggarty, researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany.

“Heggarty’s team made a significant contribution by shedding light on this question. By combining phylogenetic analysis of cognates with insights from ancient DNA, they found potentially two distinct origins. Expansion initially originated from the southern Caucasus region, resulting in the separation of five major language families approximately 7,000 years ago. “The Albanians, Greek-speaking Mycenaeans, and Hittites do not have a dominant genetic signal from the steppe,” said Heggarty. Several millennia later, another wave emerged, led by nomadic steppe herders from the north. This wave not only influenced the development of western branches of the language tree, but it also possibly played a role in the evolution of Slavic and Baltic languages. It even extended its influence to the Indian subcontinent, while giving rise to the now-extinct Tocharian languages in what is present-day Tibet.” ref

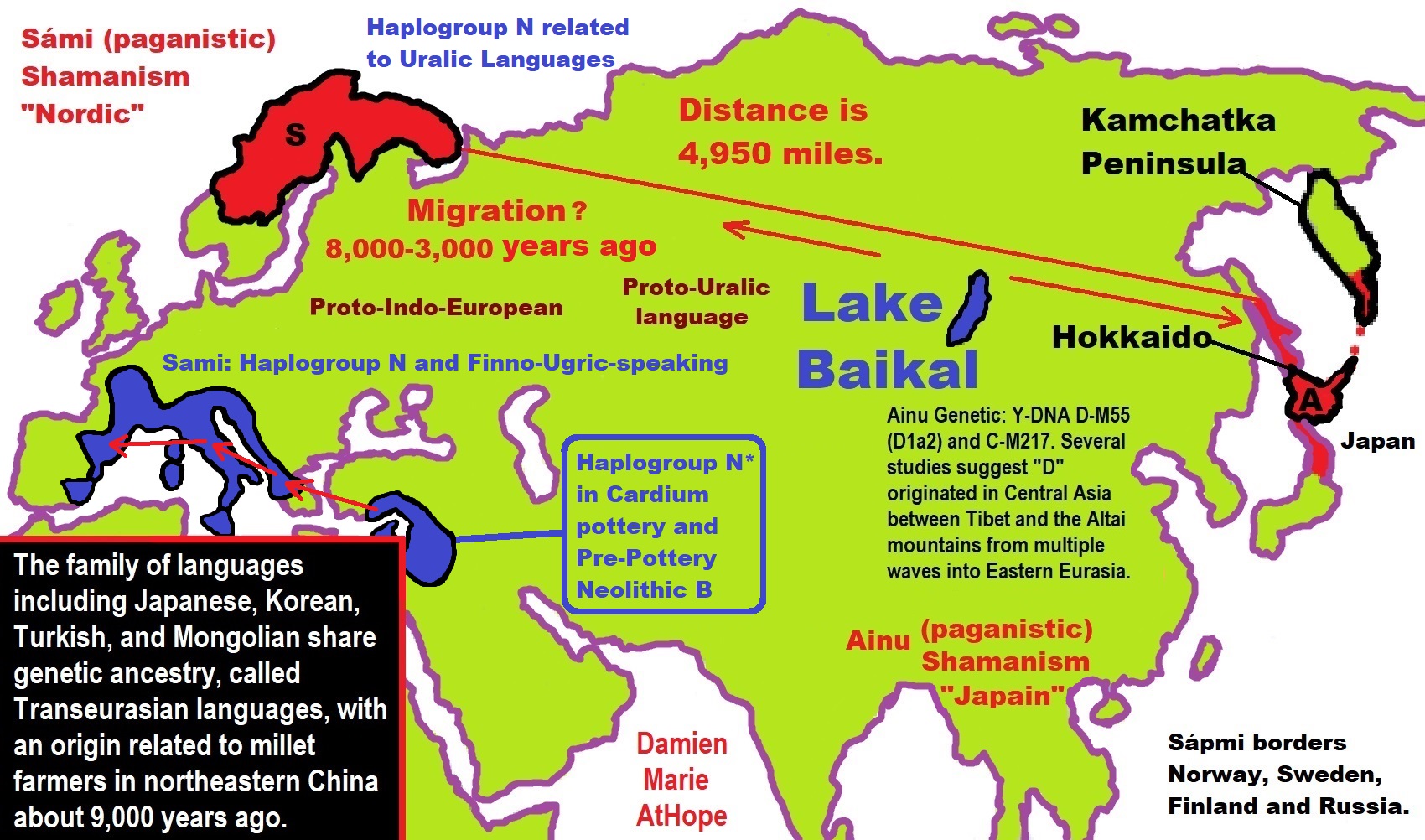

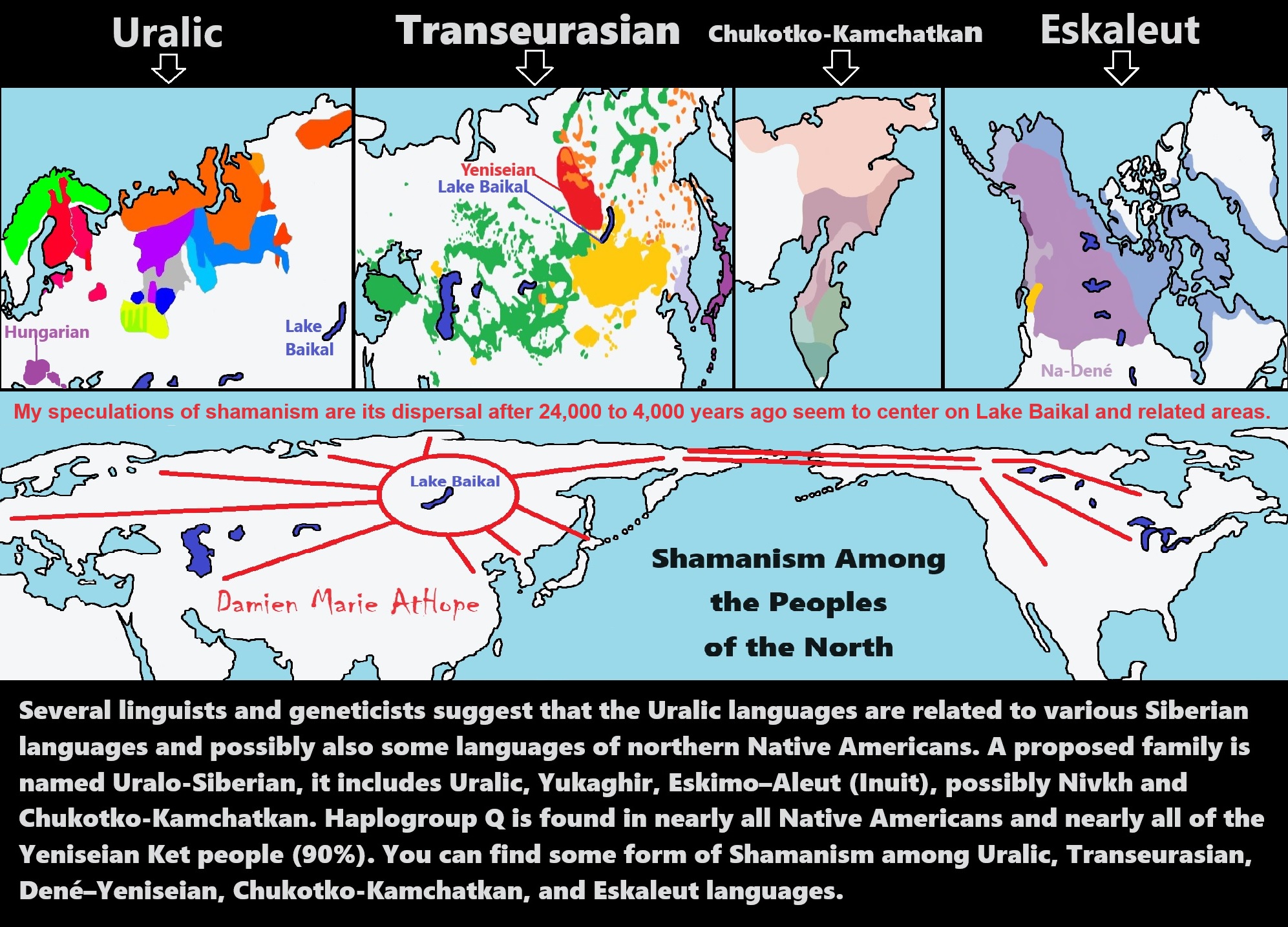

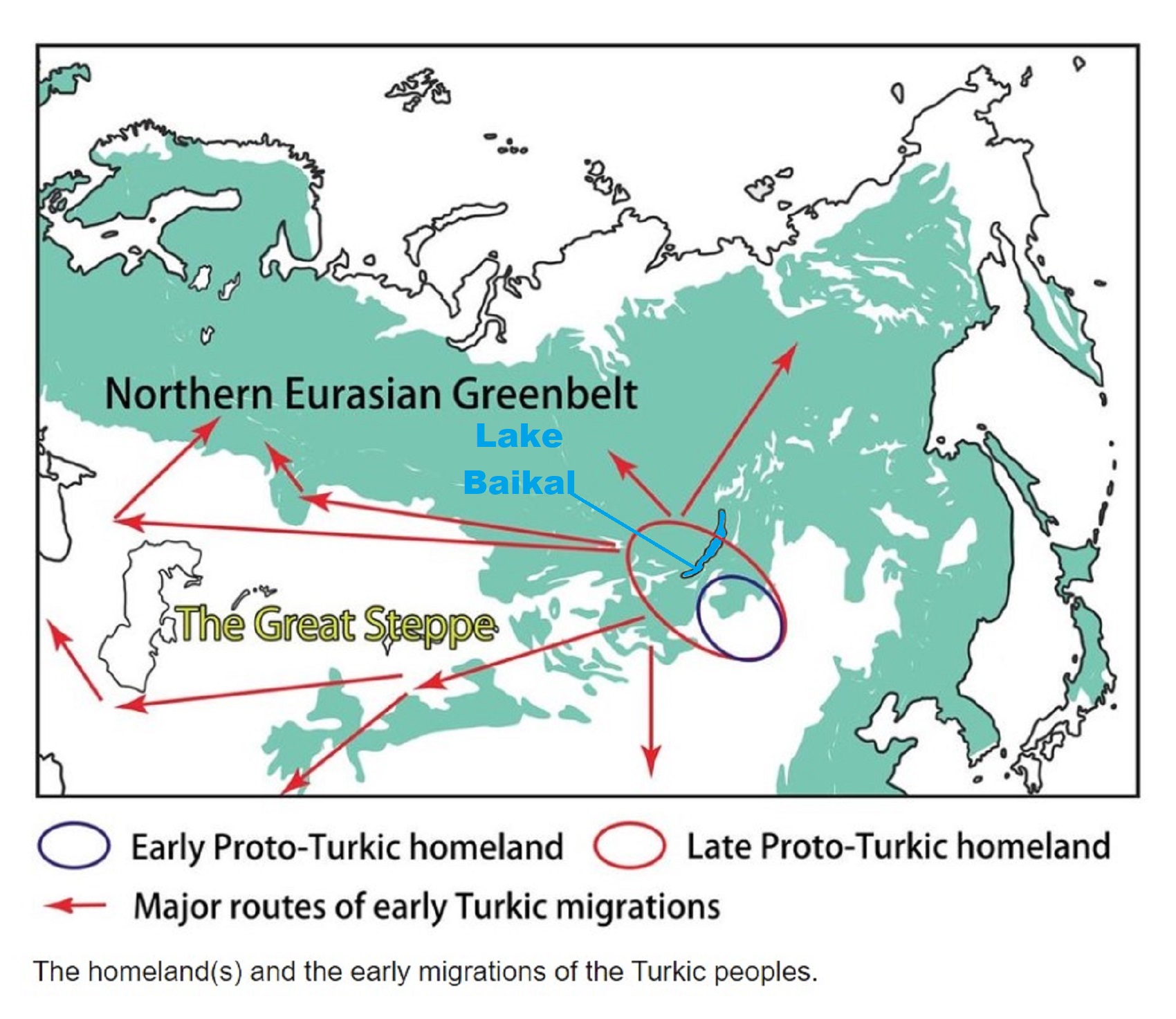

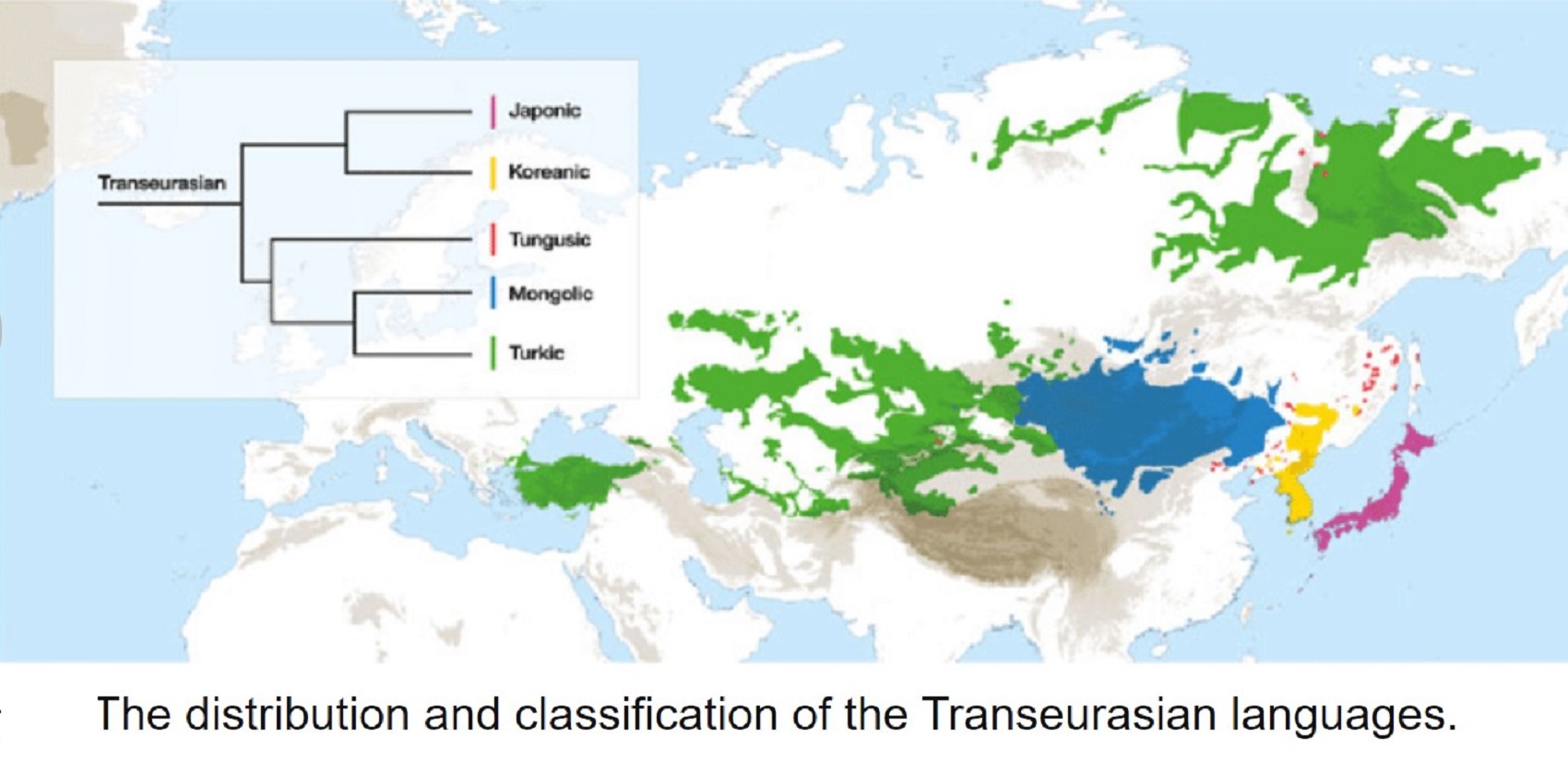

Origins of ‘Transeurasian’ languages traced to Neolithic millet farmers in north-eastern China about 9,000 years ago

“A study combining linguistic, genetic, and archaeological evidence has traced the origins of a family of languages including modern Japanese, Korean, Turkish and Mongolian and the people who speak them to millet farmers who inhabited a region in north-eastern China about 9,000 years ago. The findings outlined on Wednesday document a shared genetic ancestry for the hundreds of millions of people who speak what the researchers call Transeurasian languages across an area stretching more than 5,000 miles (8,000km).” ref

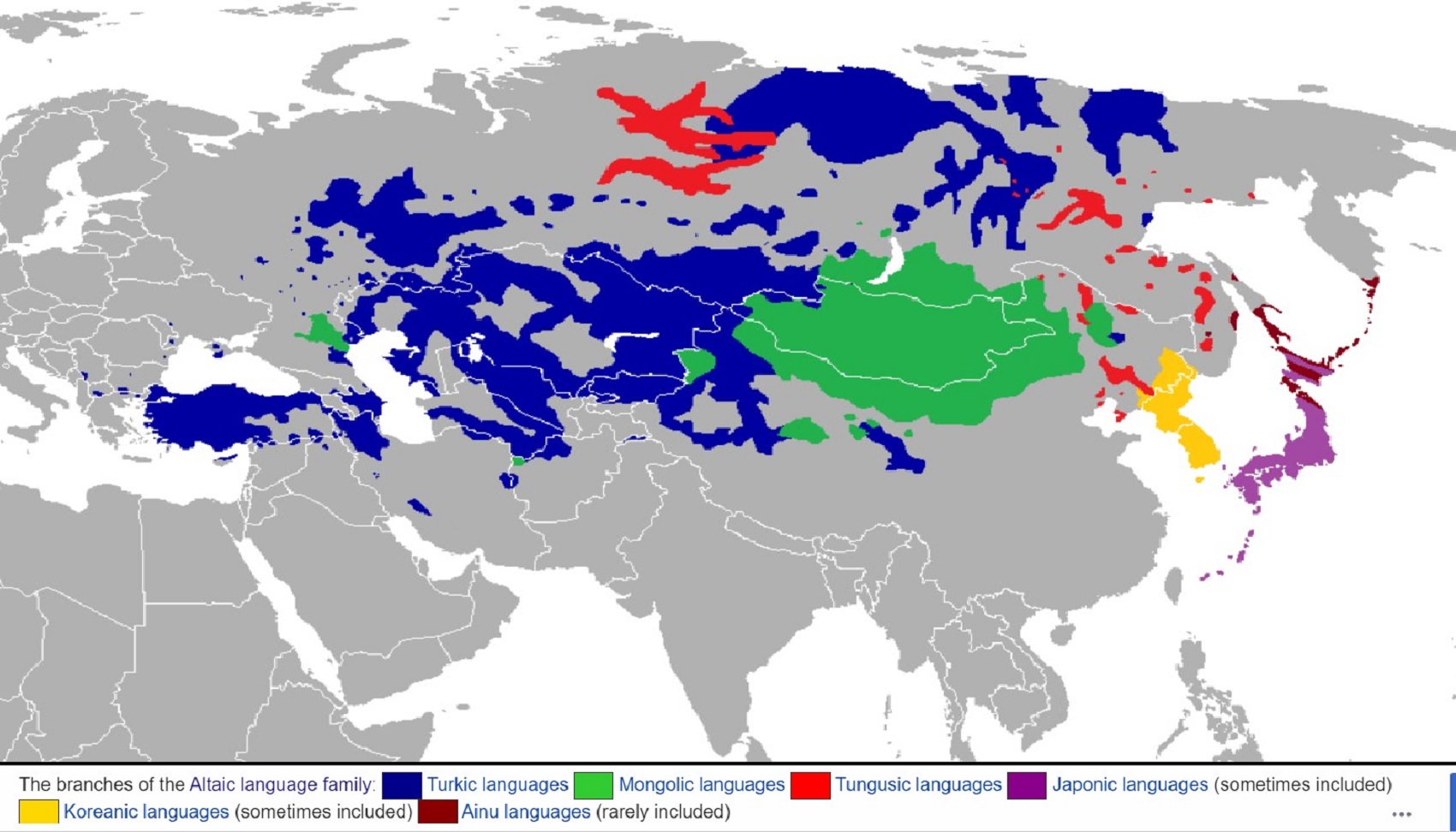

“Millet was an important early crop as hunter-gatherers transitioned to an agricultural lifestyle. There are 98 Transeurasian languages, including Korean, Japanese, and various Turkic languages in parts of Europe, Anatolia, Central Asia, and Siberia, various Mongolic languages, and various Tungusic languages in Manchuria and Siberia. This language family’s beginnings were traced to Neolithic millet farmers in the Liao River valley, an area encompassing parts of the Chinese provinces of Liaoning and Jilin and the region of Inner Mongolia. As these farmers moved across north-eastern Asia over thousands of years, the descendant languages spread north and west into Siberia and the steppes and east into the Korean peninsula and over the sea to the Japanese archipelago.” ref

“Eurasiatic is a proposed language with many language families historically spoken in northern, western, and southern Eurasia; which typically include Altaic (Mongolic, Tungusic, and Turkic), Chukchi-Kamchatkan, Eskimo–Aleut, Indo-European, and Uralic.” ref

“Voiced stops such as /d/ occur in the Indo-European, Yeniseian, Turkic, Mongolian, Tungusic, Japonic and Sino-Tibetan languages. They have also later arisen in several branches of Uralic.” ref

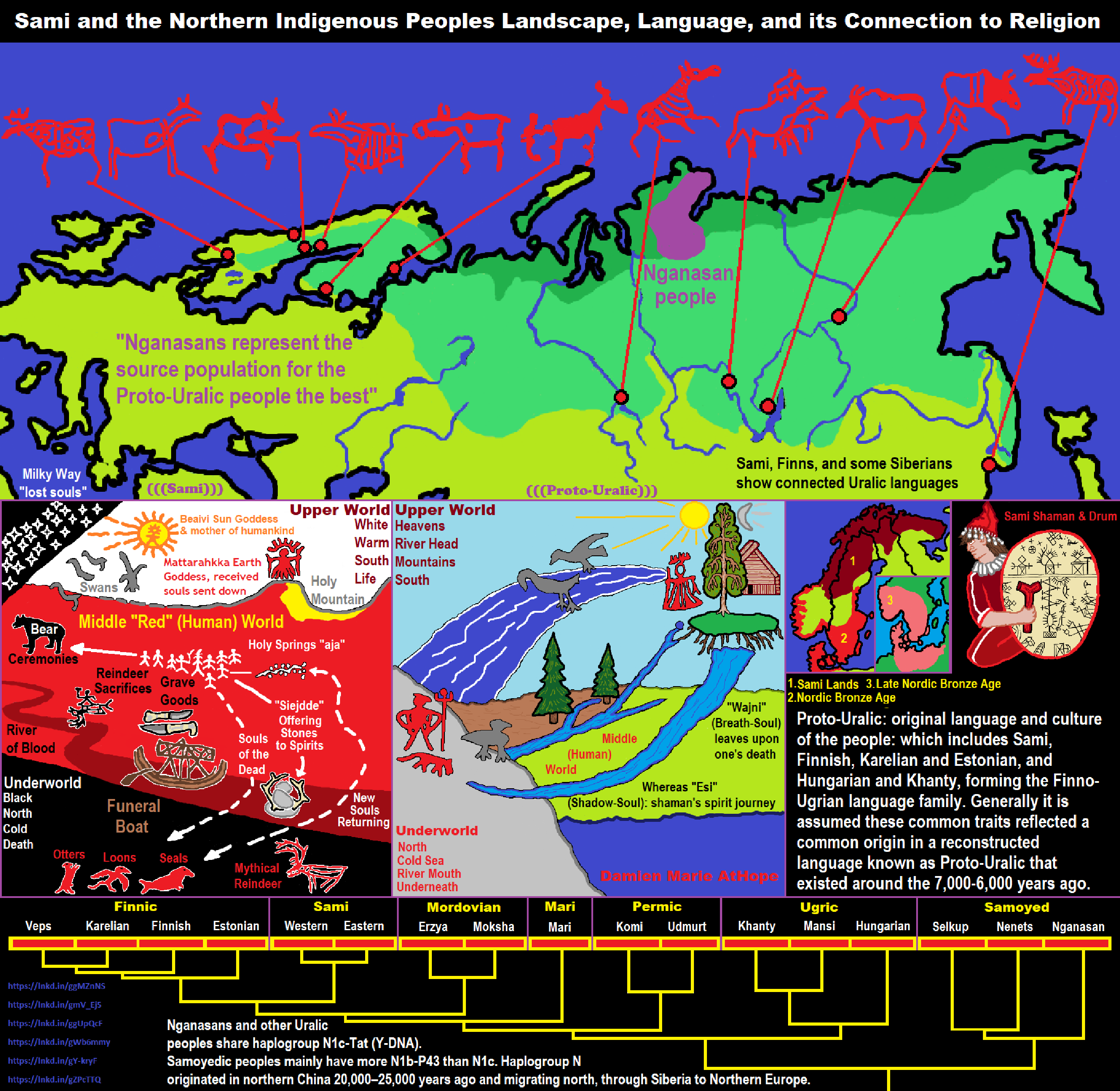

“Uralo-Siberian is a hypothetical language family of Uralic, Yukaghir, Eskimo–Aleut and besides linguistic evidence, several genetic studies, support a common origin in Northeast Asia.” ref

Postglacial genomes from foragers across Northern Eurasia reveal prehistoric

mobility associated with the spread of the Uralic and Yeniseian languages

Abstract

“The North Eurasian forest and forest-steppe zones have sustained millennia of sociocultural connections among northern peoples. We present genome-wide ancient DNA data for 181 individuals from this region spanning the Mesolithic, Neolithic, and Bronze Age. We find that Early to Mid-Holocene hunter-gatherer populations from across the southern forest and forest-steppes of Northern Eurasia can be characterized by a continuous gradient of ancestry that remained stable for millennia, ranging from fully West Eurasian in the Baltic region to fully East Asian in the Transbaikal region. In contrast, cotemporaneous groups in far Northeast Siberia were genetically distinct, retaining high levels of continuity from a population that was the primary source of ancestry for Native Americans. By the mid-Holocene, admixture between this early Northeastern Siberian population and groups from Inland East Asia and the Amur River Basin produced two distinctive populations in eastern Siberia that played an important role in the genetic formation of later people. Ancestry from the first population, Cis-Baikal Late Neolithic-Bronze Age (Cisbaikal_LNBA), is found substantially only among Yeniseian-speaking groups and those known to have admixed with them. Ancestry from the second, Yakutian Late Neolithic-Bronze Age (Yakutia_LNBA), is strongly associated with present-day Uralic speakers. We show how Yakutia_LNBA ancestry spread from an east Siberian origin ~4.5kya, along with subclades of Y-chromosome haplogroup N occurring at high frequencies among present-day Uralic speakers, into Western and Central Siberia in communities associated with Seima-Turbino metallurgy: a suite of advanced bronze casting techniques that spread explosively across an enormous region of Northern Eurasia ~4.0kya. However, the ancestry of the 16 Seima-Turbino-period individuals–the first reported from sites with this metallurgy–was otherwise extraordinarily diverse, with partial descent from Indo-Iranian-speaking pastoralists and multiple hunter-gatherer populations from widely separated regions of Eurasia. Our results provide support for theories suggesting that early Uralic speakers at the beginning of their westward dispersal where involved in the expansion of Seima-Turbino metallurgical traditions, and suggests that both cultural transmission and migration were important in the spread of Seima-Turbino material culture.” ref

Ancient mDNA “N1a1a1” and Pottery?

Bon005 – Boncuklu Höyük mtDNA N1a1a1 around 10,220 years ago Turkey – Central Anatolia ref

Bon004 – Boncuklu Höyük mtDNA N1a1a1 around 10,076 years ago Turkey – Central Anatolia ref

ZHAG – Boncuklu Höyük mtDNA N1a1a1 around 9,900 years ago Turkey – Central Anatolia ref

People who lived in ancient settlement in central Turkey migrated to Europe: archaeologists

“10,300-year-old Boncuklu Höyük settlement in Turkey revealed that the people who lived in the settlement migrated to Europe. And the Boncuklu Höyük settlement was established a thousand years before Çatalhöyük, so is the ancestor of later Çatalhöyük.” ref

Ash040 – Aşıklı Höyük mtDNA N1a1a1 around 9,875 years ago Turkey – Central Anatolia ref

CCH144 – Çatalhöyük mtDNA N1a1a1 around 8,808 years ago Turkey – Central Anatolia ref

I1096 – Barcın Höyük mtDNA N1a1a1 around 8,300 years ago Turkey – Northwest Anatolia ref

Bar25 – Barcın Höyük mtDNA N1a1a1 around 8,295 years ago Turkey – Northwest Anatolia ref

Tep004 – Tepecik-Çiftlik Höyük mtDNA N1a1a1 around 8,237 years ago Turkey – Northwest Anatolia ref

Tep006 – Tepecik-Çiftlik Höyük mtDNA N1a1a1 around 8,099 years ago Turkey – Northwest Anatolia ref

I0725 – Mentese mtDNA N1a1a1 around 7,950 years ago Turkey – South-Western corner, on the Aegean Sea ref

I0174 – Alsonyek-Bataszek mtDNA N1a1a1 around 7,558 years ago Hungary – Starcevo ref (Starčevo–Körös–Criș culture: 6,200 – 4,500 BCE or around 8,223-6,523 years ago)

“Starčevo culture of Southeastern Europe originates in the spread of the Neolithic package of peoples and technological innovations including farming and ceramics from Anatolia to the area of Sesklo. The Starčevo culture marks its spread to the inland Balkan peninsula as the Cardial ware culture did along the Adriatic coastline. It forms part of the wider Starčevo–Körös–Criş culture which gave rise to the central European Linear Pottery culture c. 700 years after the initial spread of Neolithic farmers towards the northern Balkans.” ref

Klein1 – Kleinhadersd mtDNA N1a1a1 around 7,500 years ago Austria – LBK/AVK ref (Linear Pottery culture *LBK*: 5,500–4,500 BCE or around 7,523-6,523 years ago)

UZZ74 – Grotta dell’Uzzo, Sicily mtDNA N1a1a1 around 7,223 years ago Italy – Stentinello I ref (Stentinello culture: dated to the 5th millennium BCE: 5000 to 4000 BCE or around 7,023-6,023 years ago)

I0412 – Els Trocs, Bisaurri, Huesca, Aragón mtDNA N1a1a1 around 7,177 years ago Spain – Epicardial ref (Cardium/Cardial–Epicardial pottery culture: 6400 – 5500 BCE or around 8,423-7,023 years ago)

“Fernández et al. 2014 found traces of maternal genetic affinity between people of the Linear Pottery Culture and Cardium pottery with earlier peoples of the Near Eastern Pre-Pottery Neolithic B, including the rare mtDNA (maternal) basal haplogroup N*, and suggested that Neolithic period was initiated by seafaring colonists from the Near East. Mathieson et al. 2018 examined three Cardials buried at the Zemunica Cave near Bisko in modern-day Croatia c. 5800 BCE the three samples of mtDNA extracted belonged to the maternal haplogroups H1, K1b1a, and N1a1.” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

“Several linguists and geneticists suggest that the Uralic languages are related to various Siberian languages and possibly also some languages of northern Native Americans. A proposed family is named Uralo-Siberian, it includes Uralic, Yukaghir, Eskimo–Aleut (Inuit), possibly Nivkh, and Chukotko-Kamchatkan. Haplogroup Q is found in nearly all Native Americans and nearly all of the Yeniseian Ket people (90%).” ref, ref

You can find some form of Shamanism, among Uralic, Transeurasian, Dené–Yeniseian, Chukotko-Kamchatkan, and Eskaleut languages.

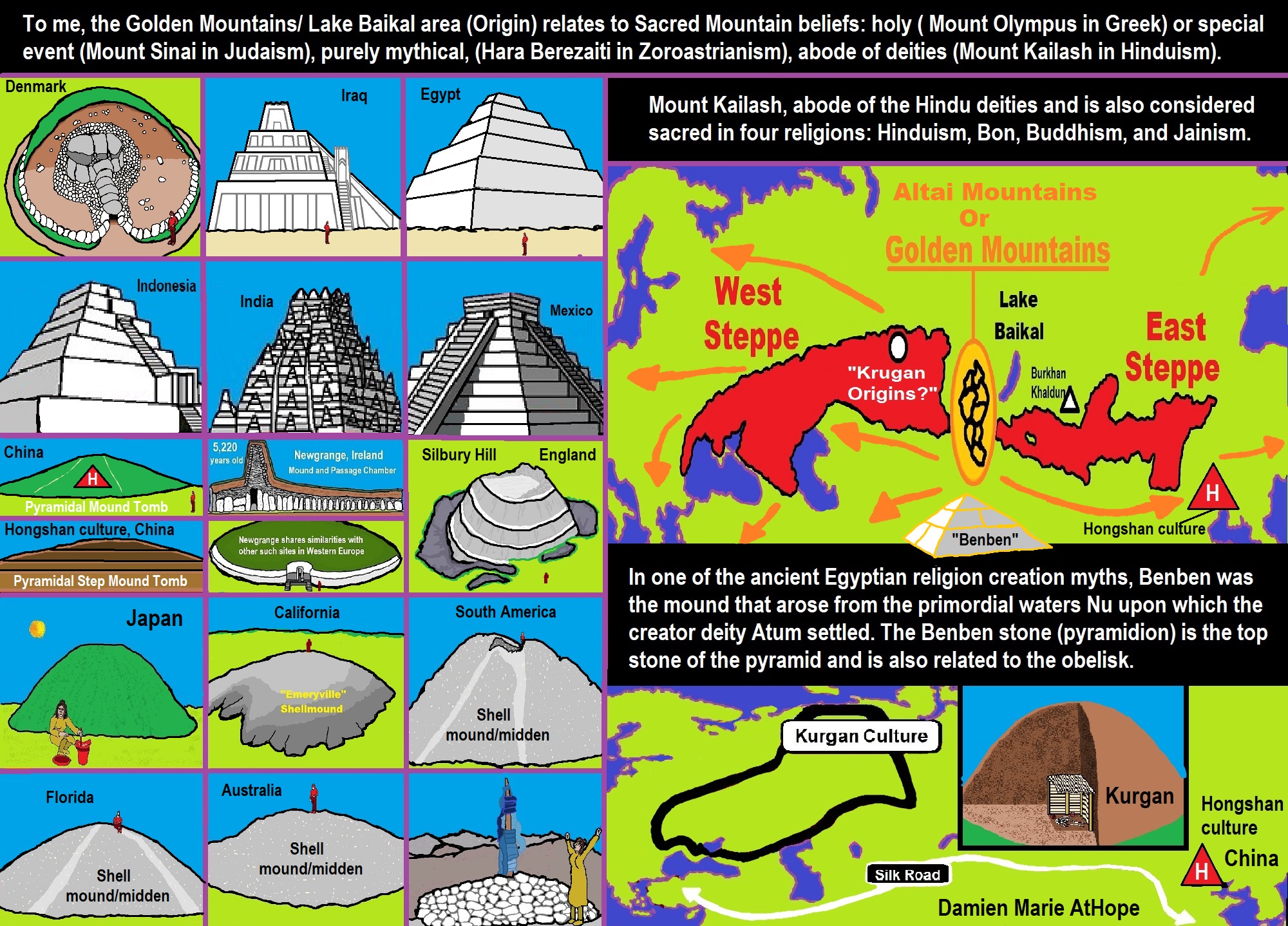

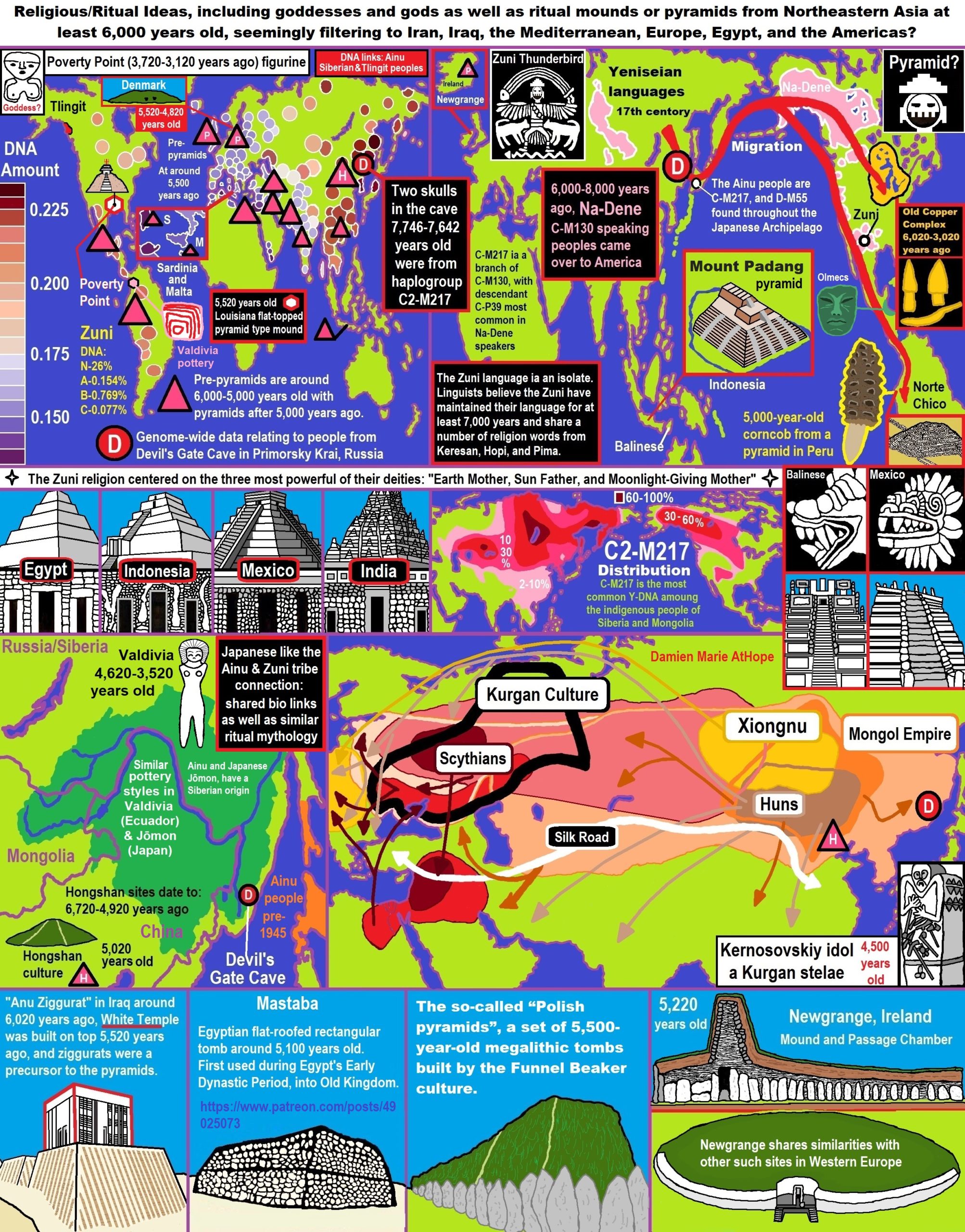

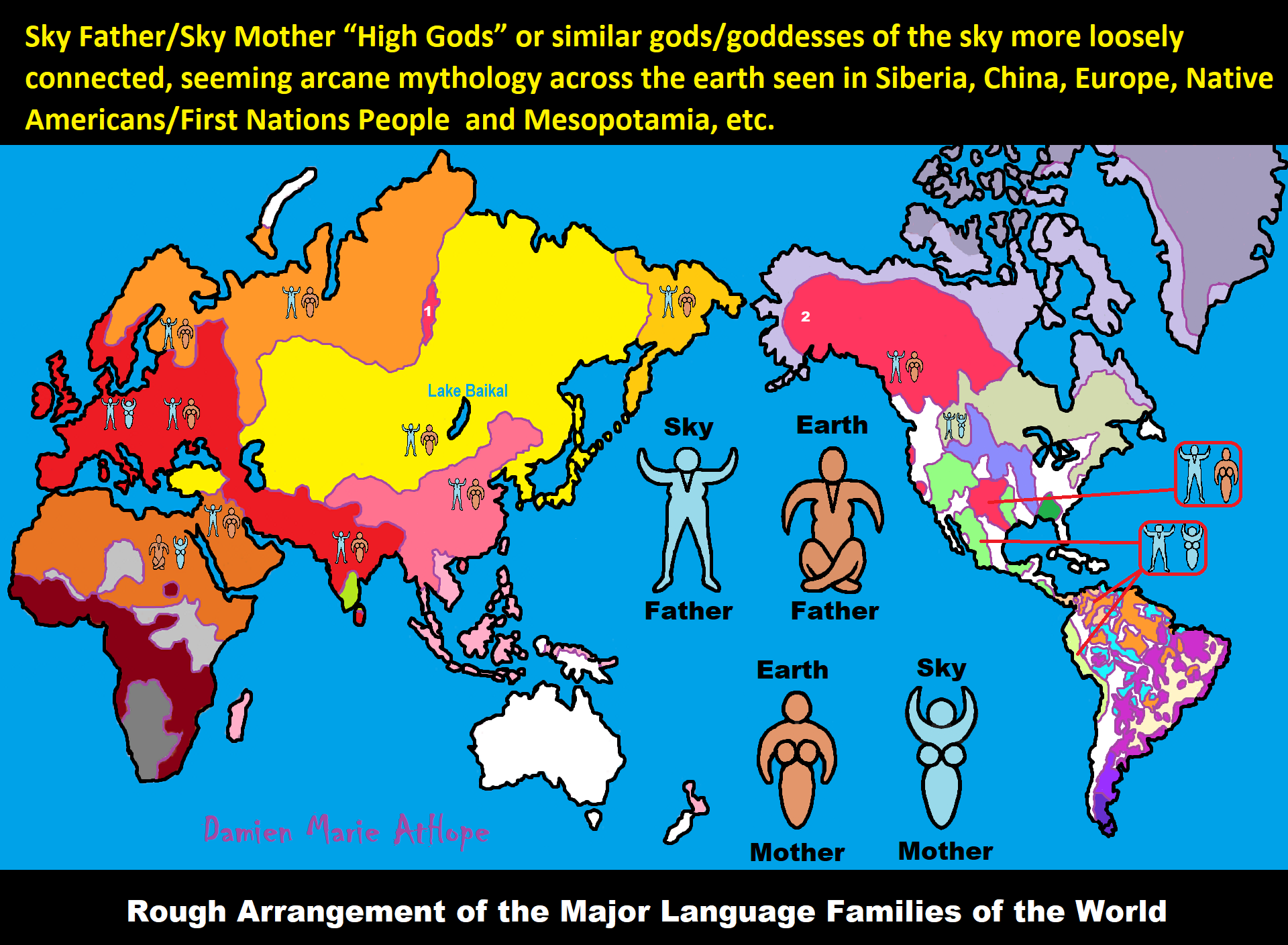

My speculations of shamanism are its dispersals, after 24,000 to 4,000 years ago, seem to center on Lake Baikal and related areas. To me, the hotspot of Shamanism goes from west of Lake Baikal in the “Altai Mountains” also encompassing “Lake Baikal” and includes the “Amur Region/Watershed” east of Lake Baikal as the main location Shamanism seems to have radiated out from.

“Altaic (also called Transeurasian) is a proposed language family that would include the Turkic, Mongolic, and Tungusic language families and possibly also the Japonic and Koreanic languages. Speakers of these languages are currently scattered over most of Asia north of 35 °N and in some eastern parts of Europe, extending in longitude from Turkey to Japan. The group is named after the Altai mountain range in the center of Asia.” ref

Tracing population movements in ancient East Asia through the linguistics and archaeology of textile production – 2020

Abstract

“Archaeolinguistics, a field which combines language reconstruction and archaeology as a source of information on human prehistory, has much to offer to deepen our understanding of the Neolithic and Bronze Age in Northeast Asia. So far, integrated comparative analyses of words and tools for textile production are completely lacking for the Northeast Asian Neolithic and Bronze Age. To remedy this situation, here we integrate linguistic and archaeological evidence of textile production, with the aim of shedding light on ancient population movements in Northeast China, the Russian Far East, Korea, and Japan. We show that the transition to more sophisticated textile technology in these regions can be associated not only with the adoption of millet agriculture but also with the spread of the languages of the so-called ‘Transeurasian’ family. In this way, our research provides indirect support for the Language/Farming Dispersal Hypothesis, which posits that language expansion from the Neolithic onwards was often associated with agricultural colonization.” ref

Pic ref

Ancient Human Genomes…Present-Day Europeans – Johannes Krause (Video)

Ancient North Eurasian (ANE)

Eastern Hunter-Gatherer (EHG)

Western Hunter-Gatherers (WHG)

Scandinavian Hunter-Gatherer (SHG)

Early European Farmers (EEF)

A quick look at the Genetic history of Europe

“The most significant recent dispersal of modern humans from Africa gave rise to an undifferentiated “non-African” lineage by some 70,000-50,000 years ago. By about 50–40 ka a basal West Eurasian lineage had emerged, as had a separate East Asian lineage. Both basal East and West Eurasians acquired Neanderthal admixture in Europe and Asia. European early modern humans (EEMH) lineages between 40,000-26,000 years ago (Aurignacian) were still part of a large Western Eurasian “meta-population”, related to Central and Western Asian populations. Divergence into genetically distinct sub-populations within Western Eurasia is a result of increased selection pressure and founder effects during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM, Gravettian). By the end of the LGM, after 20,000 years ago, A Western European lineage, dubbed West European Hunter-Gatherer (WHG) emerges from the Solutrean refugium during the European Mesolithic. These Mesolithic hunter-gatherer cultures are substantially replaced in the Neolithic Revolution by the arrival of Early European Farmers (EEF) lineages derived from Mesolithic populations of West Asia (Anatolia and the Caucasus). In the European Bronze Age, there were again substantial population replacements in parts of Europe by the intrusion of Ancient North Eurasian (ANE) lineages from the Pontic–Caspian steppes. These Bronze Age population replacements are associated with the Beaker culture archaeologically and with the Indo-European expansion linguistically.” ref

“As a result of the population movements during the Mesolithic to Bronze Age, modern European populations are distinguished by differences in WHG, EEF, and ANE ancestry. Admixture rates varied geographically; in the late Neolithic, WHG ancestry in farmers in Hungary was at around 10%, in Germany around 25%, and in Iberia as high as 50%. The contribution of EEF is more significant in Mediterranean Europe, and declines towards northern and northeastern Europe, where WHG ancestry is stronger; the Sardinians are considered to be the closest European group to the population of the EEF. ANE ancestry is found throughout Europe, with a maximum of about 20% found in Baltic people and Finns. Ethnogenesis of the modern ethnic groups of Europe in the historical period is associated with numerous admixture events, primarily those associated with the Roman, Germanic, Norse, Slavic, Berber, Arab and Turkish expansions. Research into the genetic history of Europe became possible in the second half of the 20th century, but did not yield results with a high resolution before the 1990s. In the 1990s, preliminary results became possible, but they remained mostly limited to studies of mitochondrial and Y-chromosomal lineages. Autosomal DNA became more easily accessible in the 2000s, and since the mid-2010s, results of previously unattainable resolution, many of them based on full-genome analysis of ancient DNA, have been published at an accelerated pace.” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

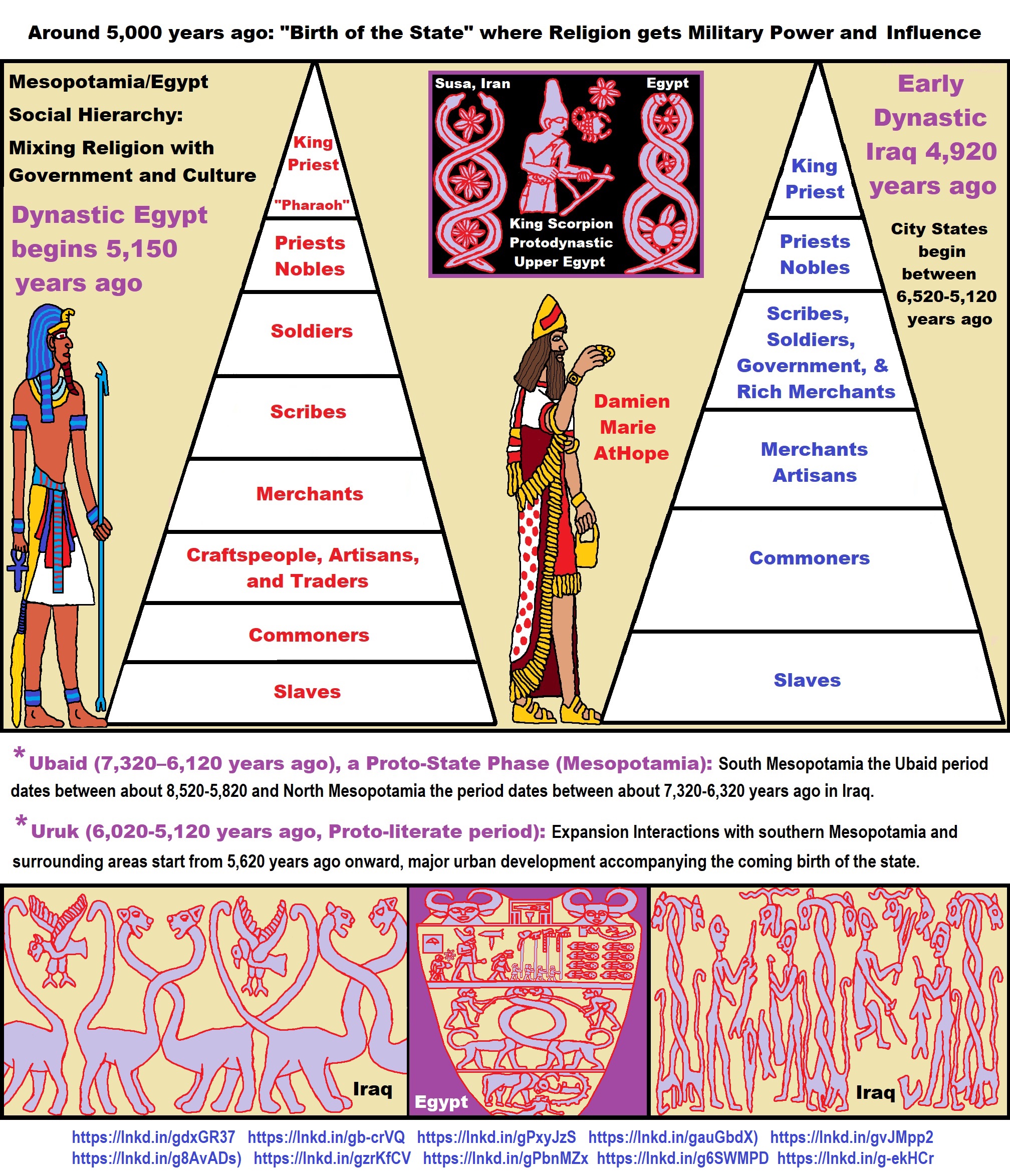

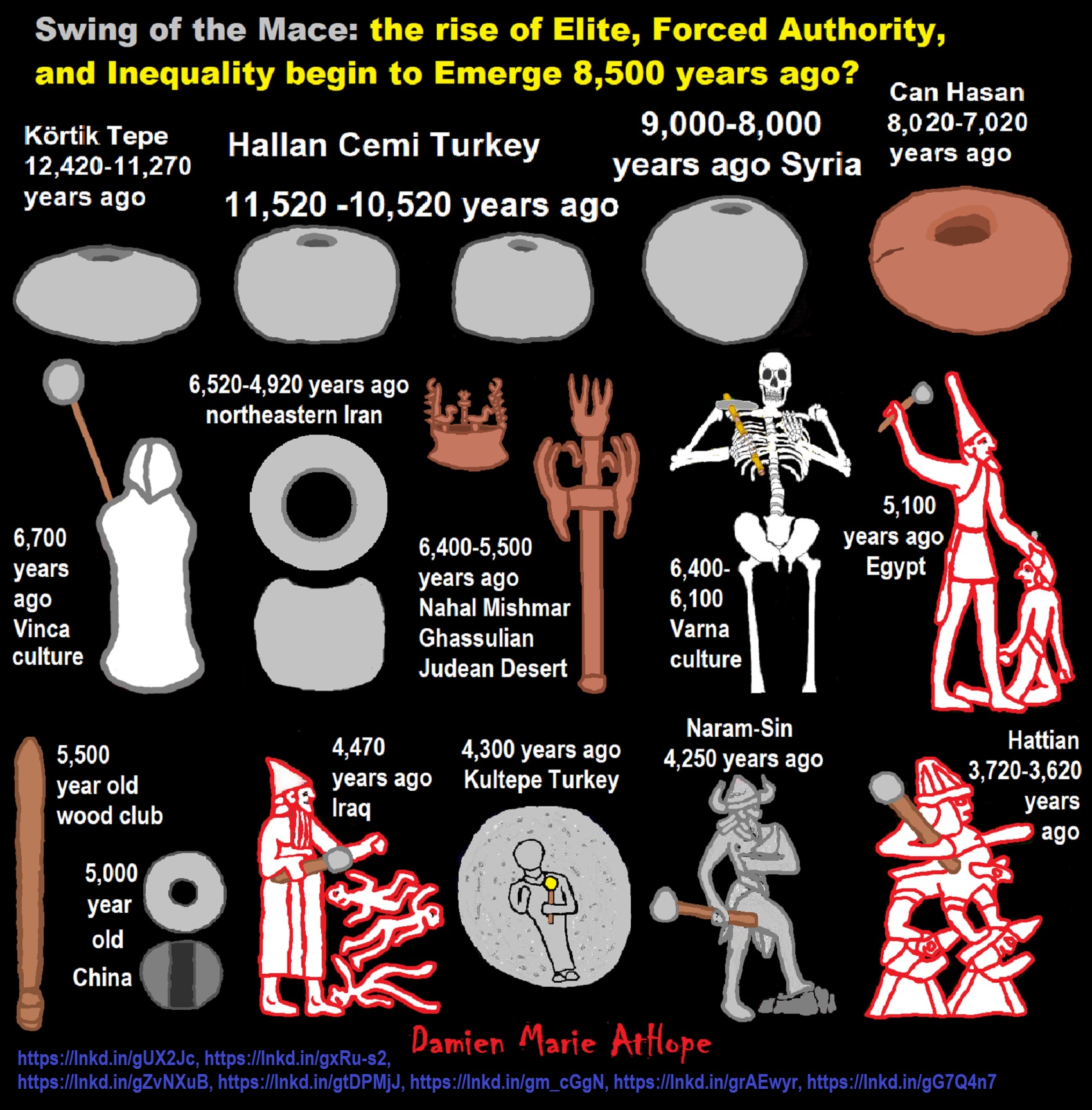

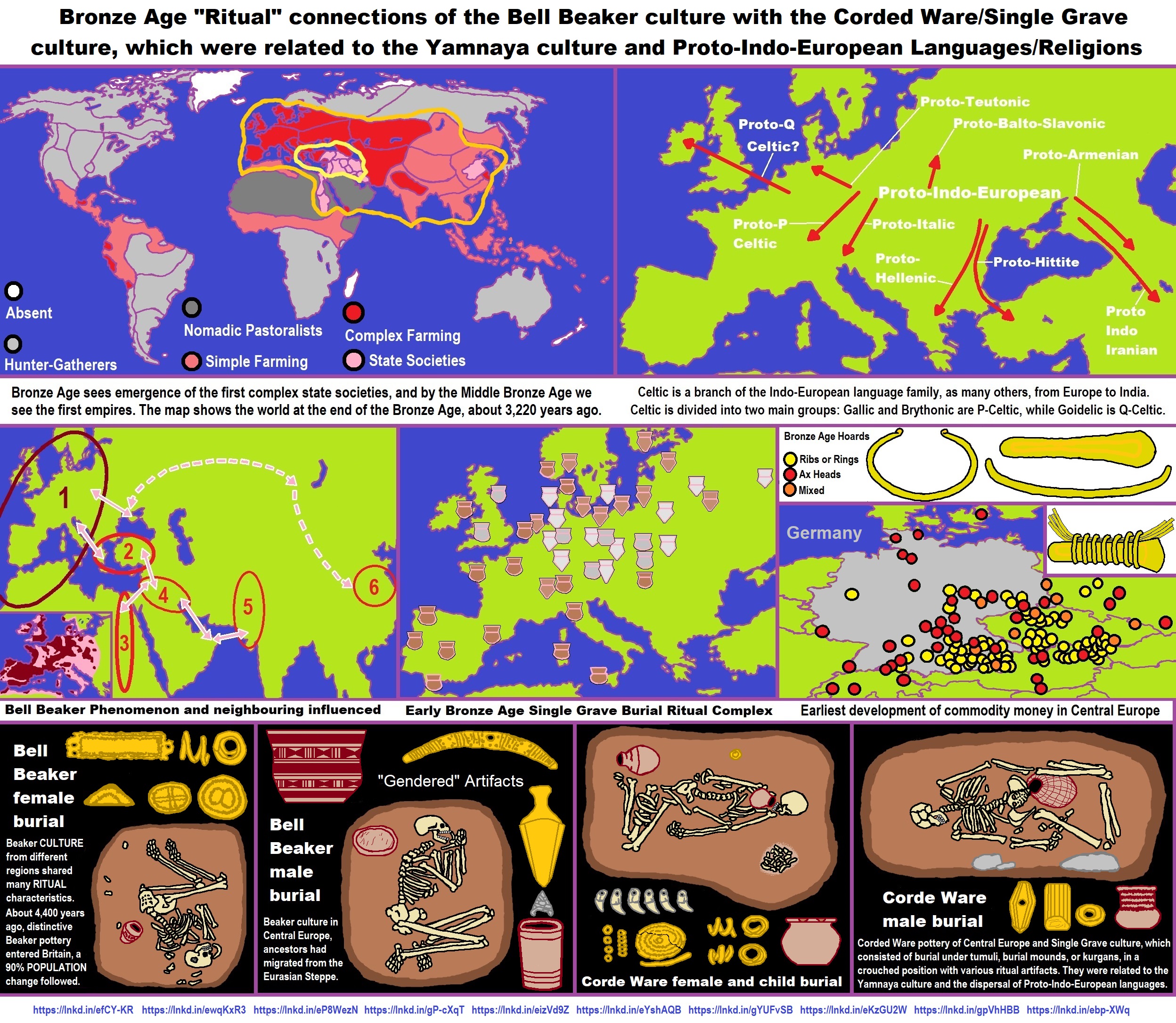

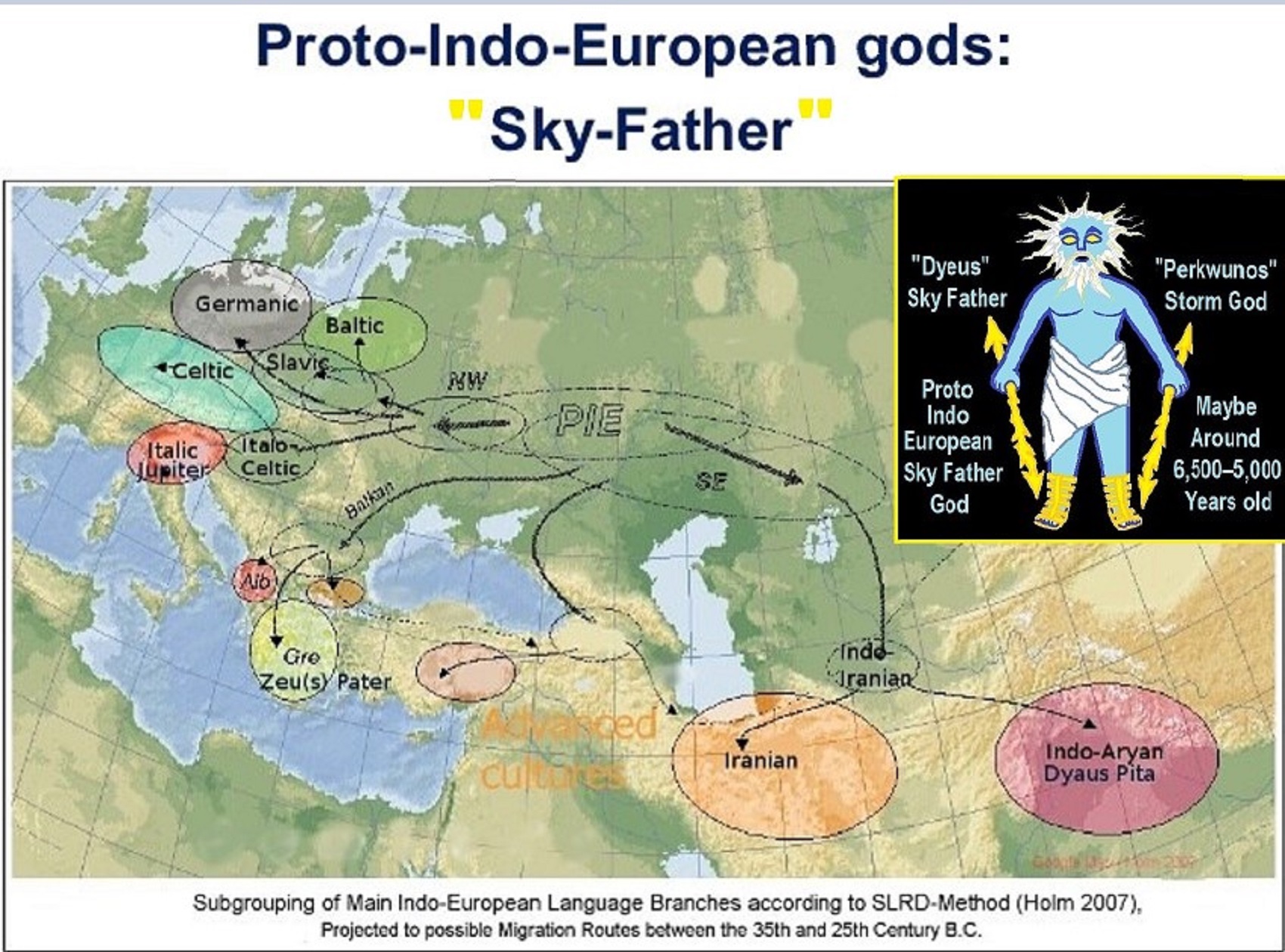

Proto-Indo-Europeans: Western Steppe Herders

“The Proto-Indo-Europeans are a hypothetical prehistoric population of Eurasia who spoke Proto-Indo-European (PIE), the ancestor of the Indo-European languages according to linguistic reconstruction. Knowledge of them comes chiefly from that linguistic reconstruction, along with material evidence from archaeology and archaeogenetics. The Proto-Indo-Europeans likely lived during the late Neolithic, or roughly the 4th millennium BCE. Mainstream scholarship places them in the Pontic–Caspian steppe zone in Eastern Europe (present-day Ukraine and southern Russia).” ref

“Some archaeologists would extend the time depth of PIE to the middle Neolithic (5500 to 4500 BCE or 7,522-6,522 years ago) or even the early Neolithic (7500 to 5500 BCE or 9,522-7,522 years ago), and suggest alternative location hypotheses. By the early second millennium BCE, descendants of the Proto-Indo-Europeans had reached far and wide across Eurasia, including Anatolia (Hittites), the Aegean (the linguistic ancestors of Mycenaean Greece), the north of Europe (Corded Ware culture), the edges of Central Asia (Yamnaya culture), and southern Siberia (Afanasievo culture).” ref

“While ‘Proto-Indo-Europeans’ is used in scholarship to designate the group of speakers associated with the reconstructed proto-language and culture, the term ‘Indo-Europeans’ may refer to any historical people that speak an Indo-European language. In the words of philologist Martin L. West, “If there was an Indo-European language, it follows that there was a people who spoke it: not a people in the sense of a nation, for they may never have formed a political unity, and not a people in any racial sense, for they may have been as genetically mixed as any modern population defined by language.” ref

“Using linguistic reconstruction from old Indo-European languages such as Latin and Sanskrit, hypothetical features of the Proto-Indo-European language are deduced. Assuming that these linguistic features reflect the culture and environment of the Proto-Indo-Europeans, the following cultural and environmental traits are widely proposed:

- pastoralism, including domesticated cattle, horses, and dogs

- agriculture and cereal cultivation, including technology commonly ascribed to late-Neolithic farming communities, e.g., the plow

- transportation by or across water

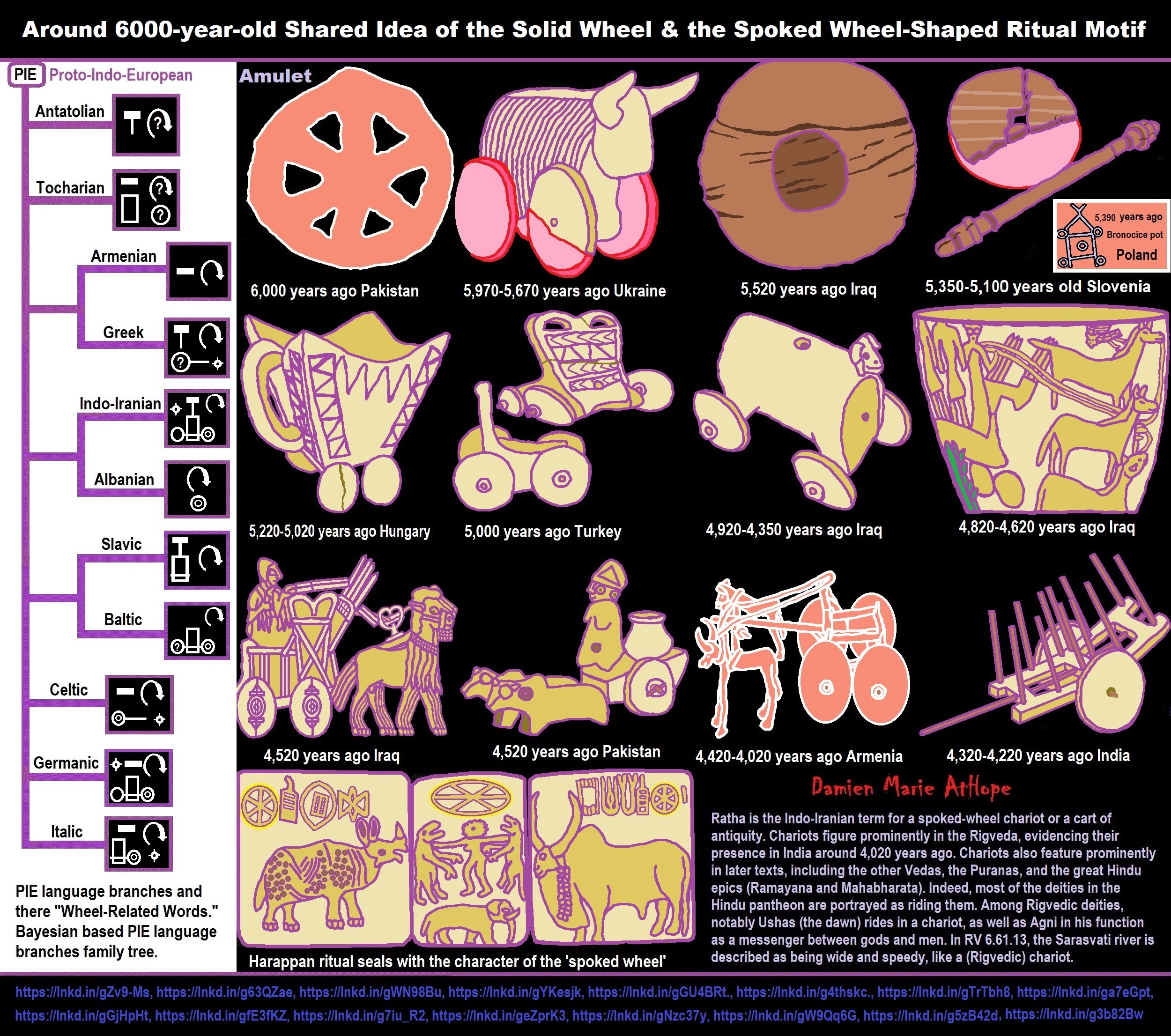

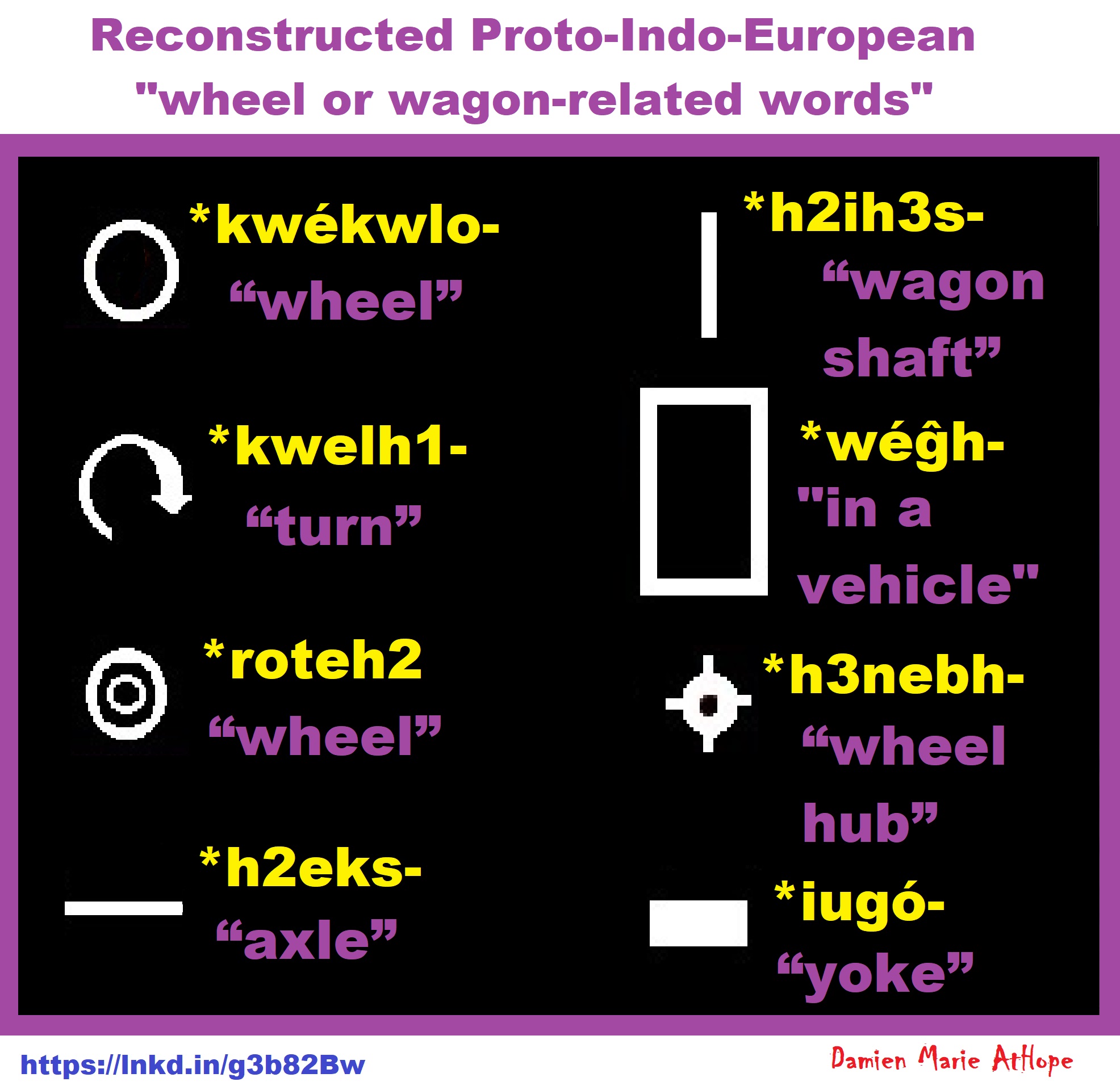

- the solid wheel, used for wagons, but not yet chariots with spoked wheels

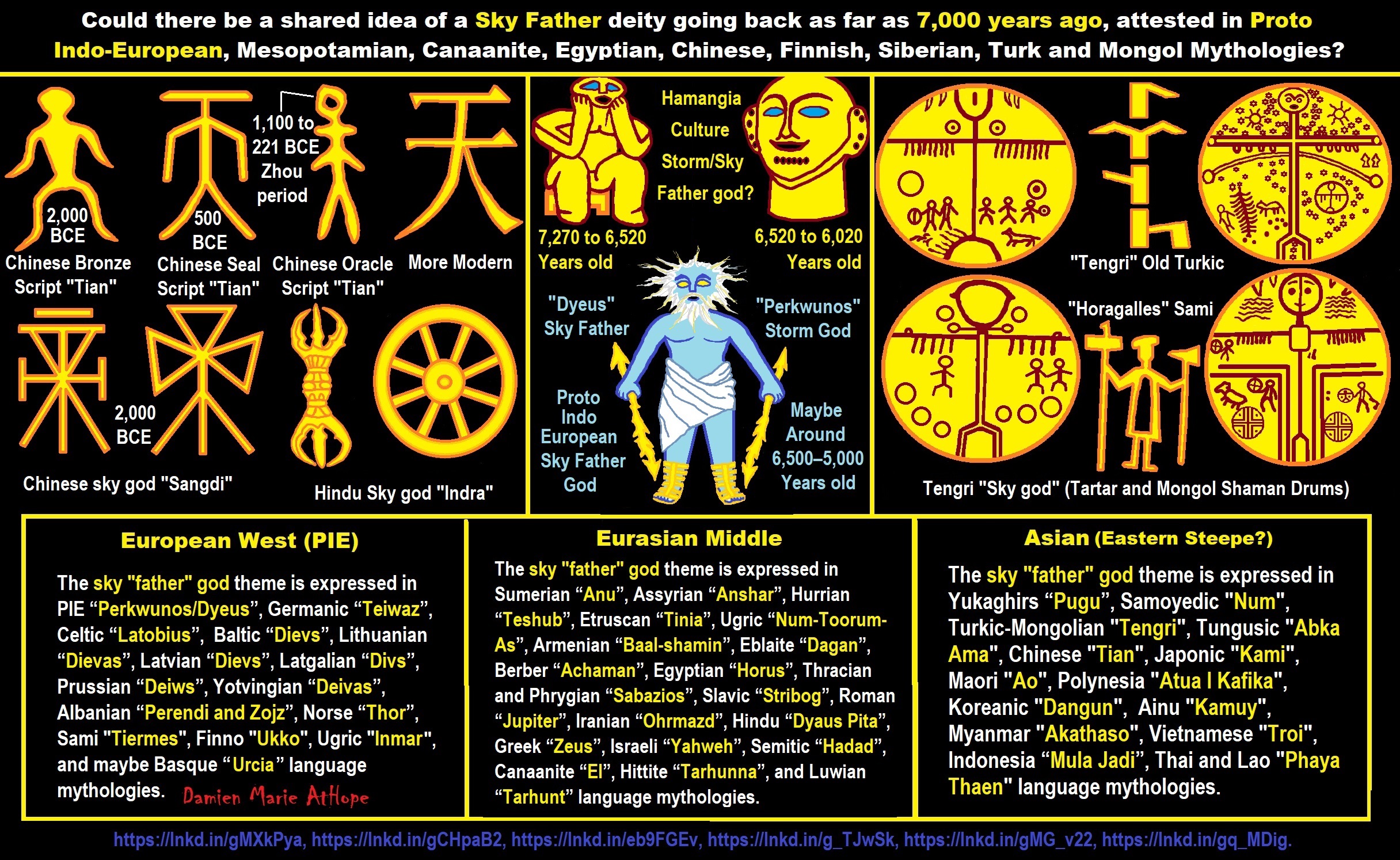

- worship of a sky god, *Dyḗus Ph2tḗr (lit. “sky father”; > Vedic Sanskrit Dyáuṣ Pitṛ́, Ancient Greek Ζεύς (πατήρ) / Zeus (dyeus)), vocative *dyeu ph2ter (> Latin Iūpiter, Illyrian Deipaturos)

- oral heroic poetry or song lyrics that used stock phrases such as imperishable fame (*ḱléwos ń̥dʰgʷʰitom) and the wheel of the sun (*sh₂uens kʷekʷlos).

- a patrilineal kinship-system based on relationships between men” ref

“A 2016 phylogenetic analysis of Indo-European folktales found that one tale, The Smith and the Devil, could be confidently reconstructed to the Proto-Indo-European period. This story, found in contemporary Indo-European folktales from Scandinavia to India, describes a blacksmith who offers his soul to a malevolent being (commonly a devil in modern versions of the tale) in exchange for the ability to weld any kind of materials together. The blacksmith then uses his new ability to stick the devil to an immovable object (often a tree), thus avoiding his end of the bargain. According to the authors, the reconstruction of this folktale to PIE implies that the Proto-Indo-Europeans had metallurgy, which in turn “suggests a plausible context for the cultural evolution of a tale about a cunning smith who attains a superhuman level of mastery over his craft.” ref

“Researchers have made many attempts to identify particular prehistoric cultures with the Proto-Indo-European-speaking peoples, but all such theories remain speculative. The scholars of the 19th century who first tackled the question of the Indo-Europeans’ original homeland (also called Urheimat, from German), had essentially only linguistic evidence. They attempted a rough localization by reconstructing the names of plants and animals (importantly the beech and the salmon) as well as the culture and technology (a Bronze Age culture centered on animal husbandry and having domesticated the horse).” ref

“The scholarly opinions became basically divided between a European hypothesis, positing migration from Europe to Asia, and an Asian hypothesis, holding that the migration took place in the opposite direction. In the early 20th century, the question became associated with the expansion of a supposed “Aryan race“, a now-discredited theory promoted during the expansion of European empires and the rise of “scientific racism“. The question remains contentious within some flavors of ethnic nationalism (see also Indigenous Aryans).” ref

“A series of major advances occurred in the 1970s due to the convergence of several factors. First, the radiocarbon dating method (invented in 1949) had become sufficiently inexpensive to be applied on a mass scale. Through dendrochronology (tree-ring dating), pre-historians could calibrate radiocarbon dates to a much higher degree of accuracy. And finally, before the 1970s, parts of Eastern Europe and Central Asia had been off-limits to Western scholars, while non-Western archaeologists did not have access to publications in Western peer-reviewed journals.” ref

“The pioneering work of Marija Gimbutas, assisted by Colin Renfrew, at least partly addressed this problem by organizing expeditions and arranging for more academic collaboration between Western and non-Western scholars. The Kurgan hypothesis, as of 2017 the most widely held theory, depends on linguistic and archaeological evidence, but is not universally accepted. It suggests PIE origin in the Pontic–Caspian steppe during the Chalcolithic. A minority of scholars prefer the Anatolian hypothesis, suggesting an origin in Anatolia during the Neolithic. Other theories (Armenian hypothesis, Out of India theory, Paleolithic Continuity Theory, Balkan hypothesis) have only marginal scholarly support.” ref

“In regard to terminology, in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the term Aryan was used to refer to the Proto-Indo-Europeans and their descendants. However, Aryan more properly applies to the Indo-Iranians, the Indo-European branch that settled parts of the Middle East and South Asia, as only Indic and Iranian languages explicitly affirm the term as a self-designation referring to the entirety of their people, whereas the same Proto-Indo-European root (*aryo-) is the basis for Greek and Germanic word forms which seem only to denote the ruling elite of Proto-Indo-European (PIE) society.” ref

“In fact, the most accessible evidence available confirms only the existence of a common, but vague, socio-cultural designation of “nobility” associated with PIE society, such that Greek socio-cultural lexicon and Germanic proper names derived from this root remain insufficient to determine whether the concept was limited to the designation of an exclusive, socio-political elite, or whether it could possibly have been applied in the most inclusive sense to an inherent and ancestral “noble” quality which allegedly characterized all ethnic members of PIE society. Only the latter could have served as a true and universal self-designation for the Proto-Indo-European people.” ref

“By the early twentieth century, this term had come to be widely used in a racist context referring to a hypothesized white, blonde, and blue-eyed “master race” (Herrenrasse), culminating with the pogroms of the Nazis in Europe. Subsequently, the term Aryan as a general term for Indo-Europeans has been largely abandoned by scholars (though the term Indo-Aryan is still used to refer to the branch that settled in Southern Asia).” ref

Proto-Indo-European Urheimat hypotheses and Indo-European migrations

“According to some archaeologists, PIE speakers cannot be assumed to have been a single, identifiable people or tribe, but were a group of loosely related populations ancestral to the later, still partially prehistoric, Bronze Age Indo-Europeans. This view is held especially by those archaeologists who posit an original homeland of vast extent and immense time depth. However, this view is not shared by linguists, as proto-languages, like all languages before modern transport and communication, occupied small geographical areas over a limited time span, and were spoken by a set of close-knit communities—a tribe in the broad sense. Researchers have put forward a great variety of proposed locations for the first speakers of Proto-Indo-European. Few of these hypotheses have survived scrutiny by academic specialists in Indo-European studies sufficiently well to be included in modern academic debate.” ref

- Medicine Wheel

- Serpent Mound

- Mesa Verde

- Chaco Canyon

- Casas Grandes/Paquime

- Ciudad Perdida “lost city”; Teyuna

- Ingapirca “Inca”

- Chavín de Huántar “pre-Inca”

- Sacred City of Caral-Supe *Caral culture developed between 3000 – 1800 BCE*

- Machu Picchu

- Nazca Lines

- Sacsayhuamán

- Tiwanaku/Tiahuanaco

- Atacama Giant/Lines

- Pucará de Tilcara “pre-Inca”

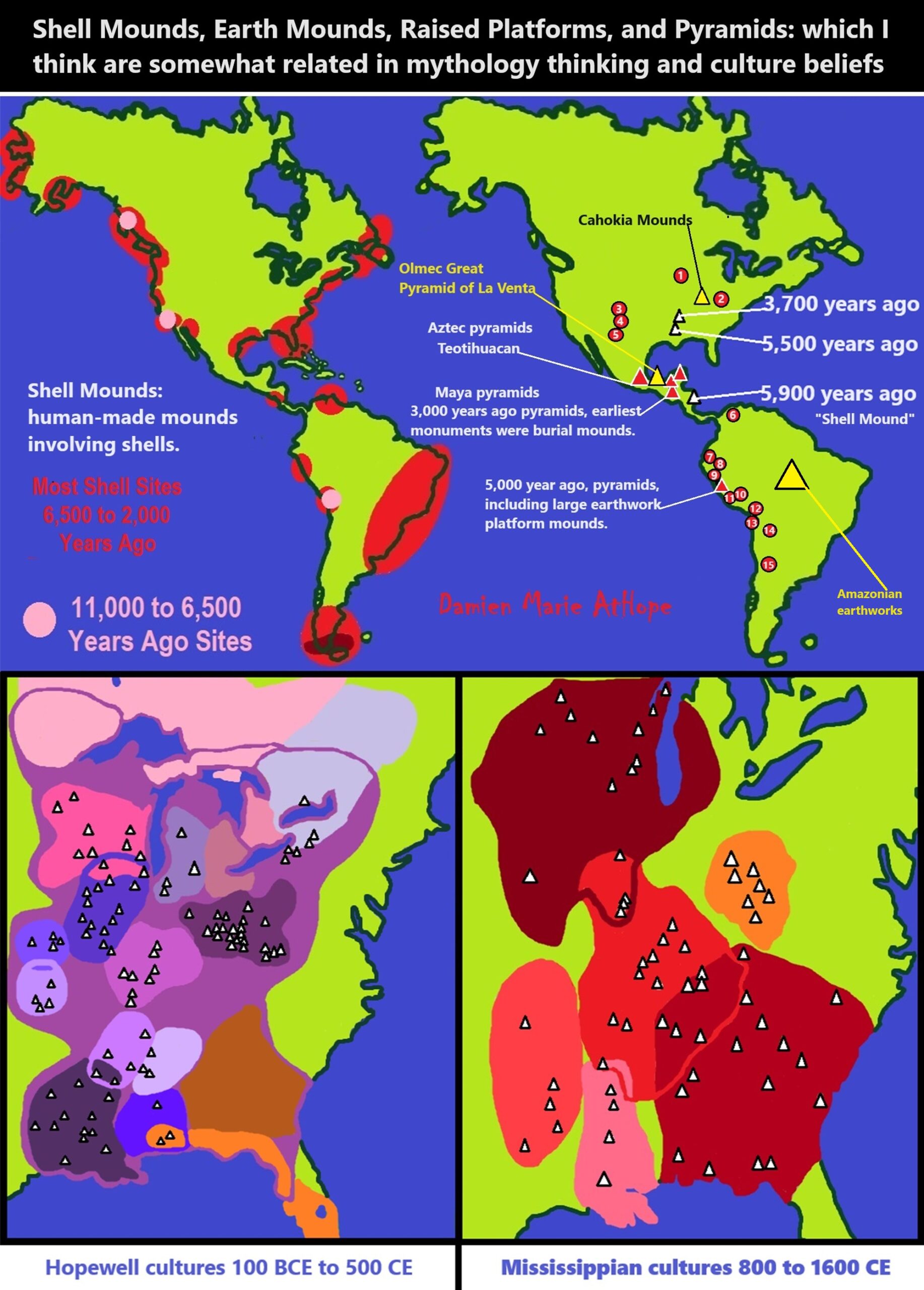

Eighth Millennium Pottery from a Prehistoric Shell Midden in the Brazilian Amazon

“The top layer was left by the Tupinamba people, who inhabited the region when European colonizers founded Sao Luis in 1612. Then comes a layer of artifacts typical of Amazon rainforest peoples, followed by a “sambaqui”: a mound of pottery, shells and bones used by some Indigenous groups to build their homes or bury their dead. Beneath that, about 6.5 feet below the surface, lies another layer, left by a group that made rudimentary ceramics and lived around 8,000 to 9,000 years ago, based on the depth of the find. Far older than the oldest documented “pre-sambaqui” settlement found so far in the region, which dates to 6,600 years ago.” ref

Sambaqui (Shell Mound) Societies of Coastal Brazil

“Sambaquis (the Brazilian term for shell mounds, derived from the Tupi language) are widely distributed along the shoreline of Brazil and were noted in European accounts as early as the sixteenth century. They typically occur in highly productive bay and lagoon ecotones where the mingling of salt and fresh waters supports mangrove vegetation and abundant shellfish, fish, and aquatic birds. More than one thousand sambaqui locations are recorded in Brazil’s national register of archaeological sites, but represent a fraction of the original number because colonial through modern settlements coincide with these favorable environments. Although sambaquis are of variable scale overall, massive shell mounds are characteristic of Brazil’s southern coast.” ref

“The term “sambaqui” is applied to cultural deposits of varying size and stratigraphy in which shell is a major constituent, undoubtedly encompassing accumulations with a range of functions and origins. Proportions of soil, sand, shell, and the kinds of cultural inclusions and features in sambaquis also are variable. Small sambaquis often consist of shell layers over sandy substrates or sequences of shell and sand layers, with or without signs of burning or significant numbers of artifacts. Larger shell mounds typically have horizontally and vertically complex stratigraphy, including alternating sequences of shell deposits, narrower and darker layers of charcoal and burned bone that mark occupation surfaces, and clusters of burials, hearths, and postholes descending from these surfaces.” ref

Mound cultures are some of the most amazing things in North America and so-called “Americans” don’t care, think it’s Aliens, or believe some mythical white people from the minds of bigots. All Americans should have to learn about Indigenous American history.

“Many pre-Columbian cultures in North America were collectively termed “Mound Builders” ref

Bleera Kaanu-Shell Mound Nicaragua 5,900 years ago human-made shell mound

Watson Brake Louisiana 5,500 years ago human-made mounds

Caral culture 5,000 years ago pyramids, large earthwork platform mounds, and sunken circular plazas

“Archaeological evidence suggests use of textile technology and, possibly, the worship of common deity symbols, both of which recur in pre-Columbian Andean cultures. A sophisticated government is presumed to have been required to manage the ancient Caral.” ref, ref

“The alternative name, Caral–Supe, is derived from the city of Caral in the Supe Valley, a large and well-studied Caral–Supe civilization site. Complex society in the Caral–Supe arose a millennium after Sumer in Mesopotamia, was contemporaneous with the Egyptian pyramids, and predated the Mesoamerican Olmec by nearly two millennia. In archaeological nomenclature, Caral–Supe is a pre-ceramic culture of the pre-Columbian Late Archaic; it completely lacked ceramics and no evidence of visual art has survived. The most impressive achievement of the civilization was its monumental architecture, including large earthwork platform mounds and sunken circular plazas.” ref

Poverty Point Louisiana 3,700 years ago human-made mounds

Olmec La Venta Great pyramid 2,394 years ago human-made earth and clay mound

“Olmecs can be divided into the Early Formative (1800-900 BCE), Middle Formative (900-400 BCE), and Late Formative (400 BCE-200 CE). Olmecs are known as the “mother culture” of Mesoamerica, meaning that the Olmec civilization was the first culture that spread and influenced Mesoamerica. The spread of Olmec culture eventually led to cultural features found throughout all Mesoamerican societies. Rising from the sedentary agriculturalists of the Gulf Lowlands as early as 1600 BCE in the Early Formative period, the Olmecs held sway in the Olmec heartland, an area on the southern Gulf of Mexico coastal plain, in Veracruz and Tabasco. Prior to the site of La Venta, the first Olmec site of San Lorenzo dominated the modern day state of Veracruz (1200-900 BCE).” ref

“Unlike later Maya or Aztec cities, La Venta was built from earth and clay—there was little locally abundant stone for the construction. Large basalt stones were brought in from the Tuxtla Mountains, but these were used nearly exclusively for monuments including the colossal heads, the “altars” (actually thrones), and various stelae. For example, the basalt columns that surround Complex A were quarried from Punta Roca Partida, on the Gulf coast north of the San Andres Tuxtla volcano. “Little more than half of the ancient city survived modern disturbances enough to map accurately.” Today, the entire southern end of the site is covered by a petroleum refinery and has been largely demolished, making excavations difficult or impossible. Many of the site’s monuments are now on display in the archaeological museum and park in the city of Villahermosa, Tabasco.” ref

“Complex C, “The Great Pyramid,” is the central building in the city layout, is constructed almost entirely out of clay, and is visible from a distance. The structure is built on top of a closed-in platform—this is where Blom and La Farge discovered Altars 2 and 3, thereby discovering La Venta and the Olmec civilization. A carbon sample from a burned area of the Structure C-1’s surface resulted in the date of 394 ± 30 BCE.” ref

“One of the earliest pyramids known in Mesoamerica, the Great Pyramid is 110 ft (34 m) high and contains an estimated 100,000 cubic meters of earth fill. The current conical shape of the pyramid was once thought to represent nearby volcanoes or mountains, but recent work by Rebecca Gonzalez Lauck has shown that the pyramid was in fact a rectangular pyramid with stepped sides and inset corners, and the current shape is most likely due to 2,500 years of erosion. The pyramid itself has never been excavated, but a magnetometer survey in 1967 found an anomaly high on the south side of the pyramid. Speculation ranges from a section of burned clay to a cache of buried offerings to a tomb.” ref

“Complex A is a mound and plaza group located just to the north of the Great Pyramid (Complex C). The centerline of Complex A originally oriented to Polaris (true north) which indicates the Olmec had some knowledge of astronomy. Surrounded by a series of basalt columns, which likely restricted access to the elite, it was erected in a period of four construction phases that span over four centuries (1000 – 600 BCE). Beneath the mounds and plazas were found a vast array of offerings and other buried objects, more than 50 separate caches by one count, including buried jade, polished mirrors made of iron-ores, and five large “Massive Offerings” of serpentine blocks. It is estimated that Massive Offering 3 contains 50 tons of carefully finished serpentine blocks, covered by 4,000 tons of clay fill.” ref

“Also unearthed in Complex A were three rectangular mosaics (also known as “Pavements”) each roughly 4.5 by 6 metres (15 by 20 feet) and each consisting of up to 485 blocks of serpentine. These blocks were arranged horizontally to form what has been variously interpreted as an ornate Olmec bar-and-four-dots motif, the Olmec Dragon, a very abstract jaguar mask, a cosmogram, or a symbolic map of La Venta and environs. Not intended for display, soon after completion these pavements were covered over with colored clay and then many feet of earth.” ref

“Five formal tombs were discovered within Complex A, one with a sandstone sarcophagus carved with what seemed to be an crocodilian earth monster. Diehl states that these tombs “are so elaborate and so integrated to the architecture that it seems clear that Complex A really was a mortuary complex dedicated to the spirits of deceased rulers.” ref

Maya 3,000 years ago mounds, raised platforms, pyramids

“The Maya are a people of southern Mexico and northern Central America (Guatemala, Belize, western Honduras, and El Salvador) (1000 BCE, approximately 3,000 years ago) they were building pyramidal-plaza ceremonial architecture. The earliest monuments consisted of simple burial mounds, the precursors to the spectacular stepped pyramids from the Terminal Pre-classic period and beyond. These pyramids relied on intricate carved stone in order to create a stair-stepped design. Many of these structures featured a top platform upon which a smaller dedicatory building was constructed, associated with a particular Maya deity. Maya pyramid-like structures were also erected to serve as a place of interment for powerful rulers. Maya pyramidal structures occur in a great variety of forms and functions, bounded by regional and periodical differences.” ref

“Hopewell mtDNA, showed clear links between Adena culture, and earlier Glacial Kame culture, confirming Hopewell culture as the descendants of Adena culture (circa 800 BCE to CE 1) who were, in turn, descended from Archaic cultures (circa 3000-500 BCE).” ref

“The Glacial Kame culture was a culture of Archaic people in North America that occupied southern Ontario, Michigan, Ohio, and Indiana from around 8000 to 1000 BCE. The name of this culture derives from its members’ practice of burying their dead atop glacier-deposited gravel hills. Among the most common types of artifacts found at Glacial Kame sites are shells of marine animals and goods manufactured from a copper ore, known as float copper. Other regional cultures include the Maple Creek Culture of southwestern Ohio, Red Ocher Culture and Old Copper Culture of Wisconsin.” ref

“Glacial Kame culture produced ceramics, as seen in the discovery of basic pottery at the Zimmerman site near Roundhead, Ohio. Excavation of Glacial Kame sites frequently yields few projectile points — some of the most important sites have yielded no projectile points at all — and their few points that have been found are of diverse styles. For this reason, it appears that different groups of Glacial Kame peoples independently developed different methods of manufacturing their projectile points. This diversity appears even in the culture’s heartland in Champaign, Hardin, and Logan counties in western Ohio; one large Logan County site yielded just three points, each of which was significantly different from the other two.” ref

“Glacial Kame Culture, Late Archaic cultural grouping found around Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, and southern Ontario in the period c.1500–1000 BCE. Characterized by mortuary rituals which involved interring the dead in natural hills of glacial gravel. Grave goods of copper ornaments and marine shells were sometimes included and attested to long‐distance trade links.” ref

“The Adena “mound-building” culture was a Pre-Columbian Native American culture that existed from 500 BCE to 100 CE, in a time known as the Early Woodland period. The Adena culture refers to what were probably a number of related Native American societies sharing a burial complex and ceremonial system. The Adena culture was centered on the location of the modern state of Ohio, but also extended into contiguous areas of northern Kentucky, eastern Indiana, West Virginia, and parts of extreme western Pennsylvania. The culture is the most prominently known of a number of similar cultures in eastern North America that began mound building ceremonialism at the end of the Archaic period.” ref

Amazonian Earthworks

“More than 1,100 ancient Amazonian earthworks, with over 1,050 geoglyphs and zanjas plus over 50 mound villages documented in both the Excel file and the KML placemarks file linked above. Almost all earthworks are outlined, along with highlighting of 1,000 lines, visible ancient roads and embankments. Hundreds of Geoglyphs Discovered in the Amazon.” ref

“Cahokia Mounds were involved in the largest and most influential urban settlement of the Mississippian culture, which developed advanced societies across much of what is now the Central and the Southeastern United States, beginning more than 1,000 years before European contact.” ref

In response to my art above John Hoopes @KUHoopes Archaeologist said, “Nice! Since you have the Ohio mound groups, you need to start adding the ones in Amazonia. Hundreds of Geoglyphs Discovered in the Amazon“

My response, I was not aware of the Amazonia mounds, thanks. The shell mound erected above the woman’s grave buried in what is now Nicaragua nearly 6,000 years ago. I thought this was cool.

John Hoopes @KUHoopes Archaeologist – “Yes, it is! The revelation of thousands of mounds and ditch-and-embankment structures (unfortunately named “geoglyphs”) is radically changing our understanding of ancient South America.”

My response, I totally agree, great stuff, made by the indigenous, and why I get upset when people like Graham Hancock or Ancient Aliens, say it was someone else.

John Hoopes @KUHoopes Archaeologist – “James Q. Jacobs’ work in Google Earth is amazing. If you don’t know it, you really should check it out.”

My response, I will check it out. Thanks for your help.

John Hoopes @KUHoopes Archaeologist – “Sure thing! Thanks for YOUR help in getting correct and accurate information out to a wide audience!”

My response, I appreciate your support.

Your Shell Mound blog post, “looks good, I did want to make one clarification. The Caddo people don’t see themselves (or their ancestors) as being a “Mississippian” culture. I see on the drawn map that a few sites (particularly Spiro) are shown for “Mississippian cultures”. I assume that is from the H. Roe’s map from 2010. That map was done before Caddo Nation worked with archaeologists to re-classify the social systems/traditions of their ancestors during that time and found that the “Mississippian” label didn’t align with the cultural systems of their ancestors. It is not a big deal but just something to be aware of in the future. I only know because I work with Caddo Nation now and rather knowledge about the latest research of the Caddo.” – Jeffrey (JT) Lewis @jtlewis_arch Southeastern archaeologist. MA, RPA. PhD Grad Student at OU.

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

“The shaman is, above all, a connecting figure, bridging several worlds for his people, traveling between this world, the underworld, and the heavens. He transforms himself into an animal and talks with ghosts, the dead, the deities, and the ancestors. He dies and revives. He brings back knowledge from the shadow realm, thus linking his people to the spirits and places which were once mythically accessible to all.–anthropologist Barbara Meyerhoff” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

Kurgan/Steppe hypothesis: Kurgan hypothesis

“The Kurgan hypothesis or steppe theory is the most widely accepted proposal to identify the Proto-Indo-European homeland from which the Indo-European languages spread out throughout Europe and parts of Asia. It postulates that the people of a Kurgan culture in the Pontic steppe north of the Black Sea were the most likely speakers of the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE). The term is derived from the Russian kurgan (курга́н), meaning tumulus or burial mound.” ref

Pontic-Caspian steppe hypothesis

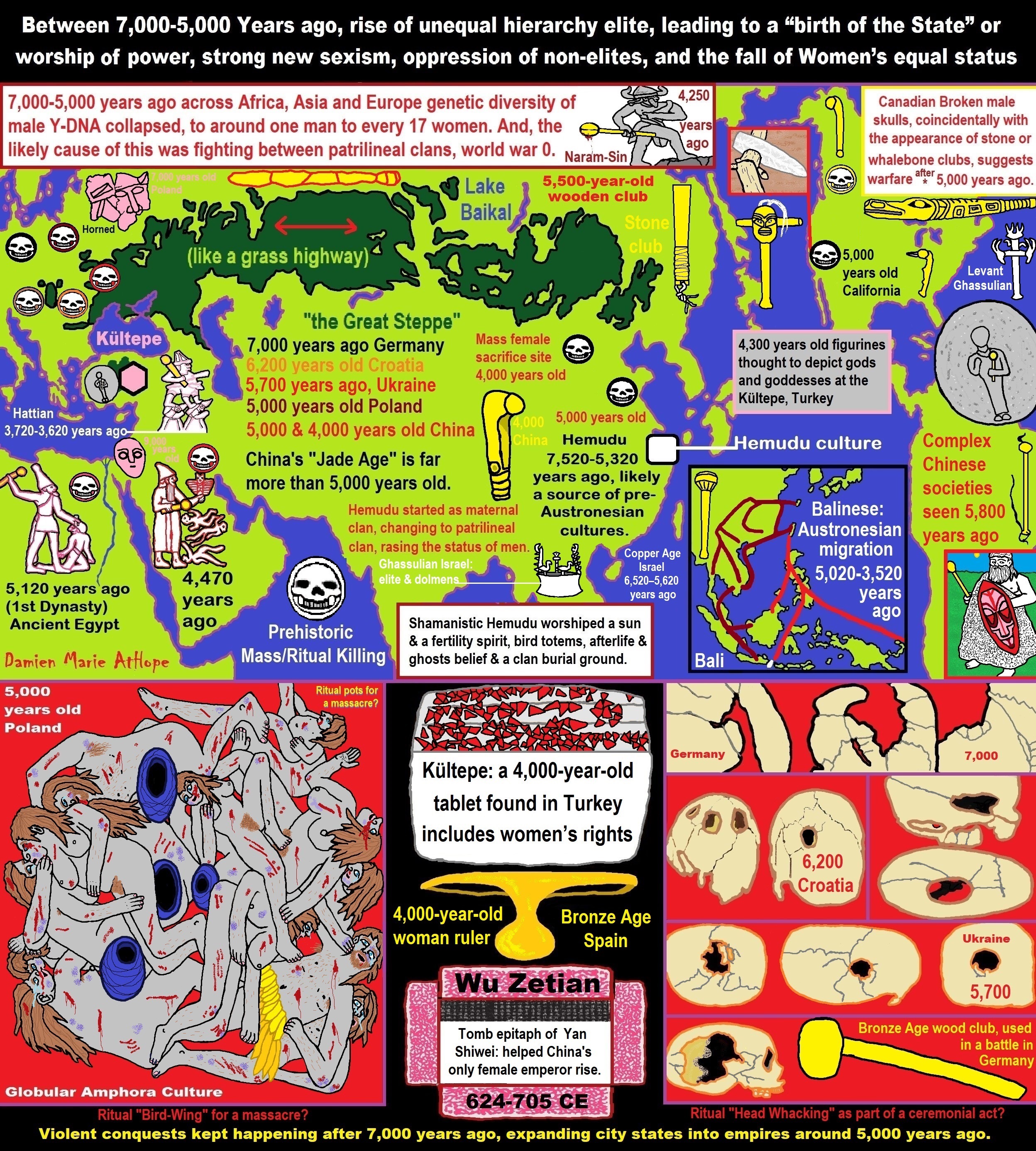

“The Kurgan (or Steppe) hypothesis was first formulated by Otto Schrader (1883) and V. Gordon Childe (1926), and was later systematized by Marija Gimbutas from 1956 onwards. The name originates from the kurgans (burial mounds) of the Eurasian steppes. The hypothesis suggests that the Indo-Europeans, a patriarchal, patrilinear, and nomadic culture of the Pontic–Caspian steppe (now part of Eastern Ukraine and Southern Russia), expanded in several waves during the 3rd millennium BCE, coinciding with the taming of the horse. Leaving archaeological signs of their presence (see Corded Ware culture), they subjugated the supposedly peaceful, egalitarian, and matrilinear European neolithic farmers of Gimbutas’ Old Europe. A modified form of this theory by J. P. Mallory, dating the migrations earlier (to around 3500 BCE or 5,522 years ago) and putting less insistence on their violent or quasi-military nature, remains the most widely accepted view of the Proto-Indo-European expansion.” ref

Armenian highland hypothesis or Iranian/Armenian hypothesis