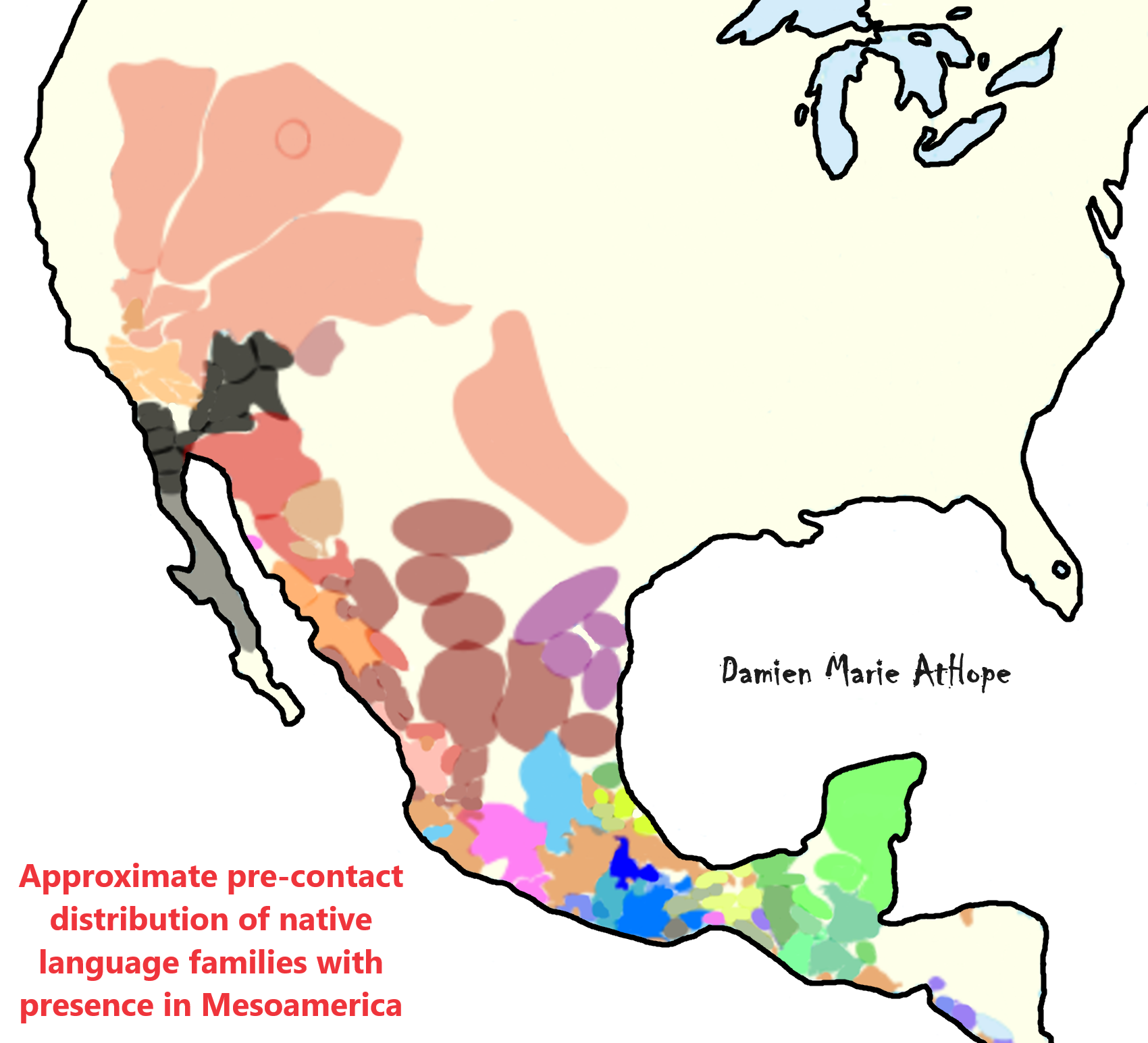

“We recognize that communities and constellations of practice entail activities that overlap, transcend, and defy categorization within conventional geographic or cultural boundaries. Indigenous peoples of the Americas include more than half a million speakers of indigenous languages. And while identity can sometimes to linked to indigenous languages, indigenous identities are further complicated for indigenous groups whose identities are not strictly tied to language.” – Info from: Pre-Columbian Central America, Colombia, and Ecuador: Toward an Integrated Approach (Dumbarton Oaks Other Titles in Pre-Columbian Studies) by Colin McEwan (Editor), John W. Hoopes (Editor)

“Shellfish was a major source of protein, and shells also became tools and artifacts. In Pre-Colombia art and oral traditions, many animals that were not utilized for food, still feature prominently: birds (Vultures and Eagles), felids (Jaguars, Ocelots, Margays, and others), crocodiles (Crocodiles and Caymans), saurian (Iguanas and basilisks), anurans (Frogs and Toads), rodents (Agoutis and Rabbits), snakes (Pit vipers and Rattlesnakes), and simians (Spider, Howler, Capuchin, and Squirrel monkeys) .” – Info from: Pre-Columbian Central America, Colombia, and Ecuador: Toward an Integrated Approach (Dumbarton Oaks Other Titles in Pre-Columbian Studies) by Colin McEwan (Editor), John W. Hoopes (Editor)

“The early Holocene period (“The Holocene: began approximately 9,700 BCE or 11,650 cal years ago, and corresponds with the rapid proliferation, growth, and impacts of the human species worldwide, including all of its written history, technological revolutions, development of major civilizations, and overall significant transition towards urban living in the present.” ref), saw the first documented use of wild food plants.” – Info from: Pre-Columbian Central America, Colombia, and Ecuador: Toward an Integrated Approach (Dumbarton Oaks Other Titles in Pre-Columbian Studies) by Colin McEwan (Editor), John W. Hoopes (Editor)

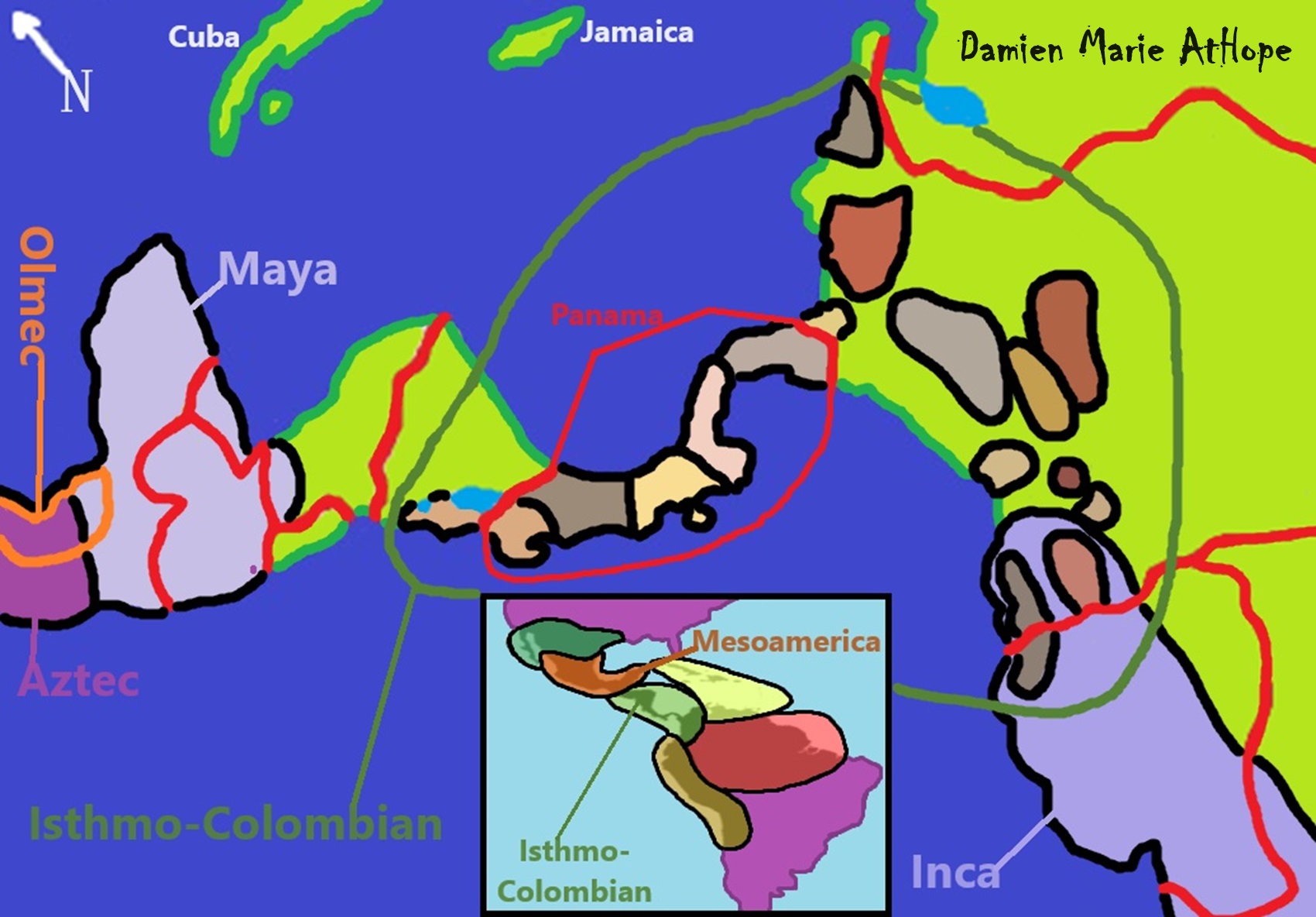

“Genetic diversity may have begun in the Late Pleistocene (“between 129,000 to 11,700 years ago” ref) as populations crossing the Isthmus (“Isthmus and land bridge are related terms, with isthmus having a broader meaning. A land bridge is an isthmus connecting Earth’s major land masses.” ref) dispersing both eastward and south. According to the linguistic and genetic evidence, the Chibchan-speaking populations separated into distinct groups in the Early Holocene and maintained a significant level of identity and cohesion thought the archaeological record.” – Info from: Pre-Columbian Central America, Colombia, and Ecuador: Toward an Integrated Approach (Dumbarton Oaks Other Titles in Pre-Columbian Studies) by Colin McEwan (Editor), John W. Hoopes (Editor)

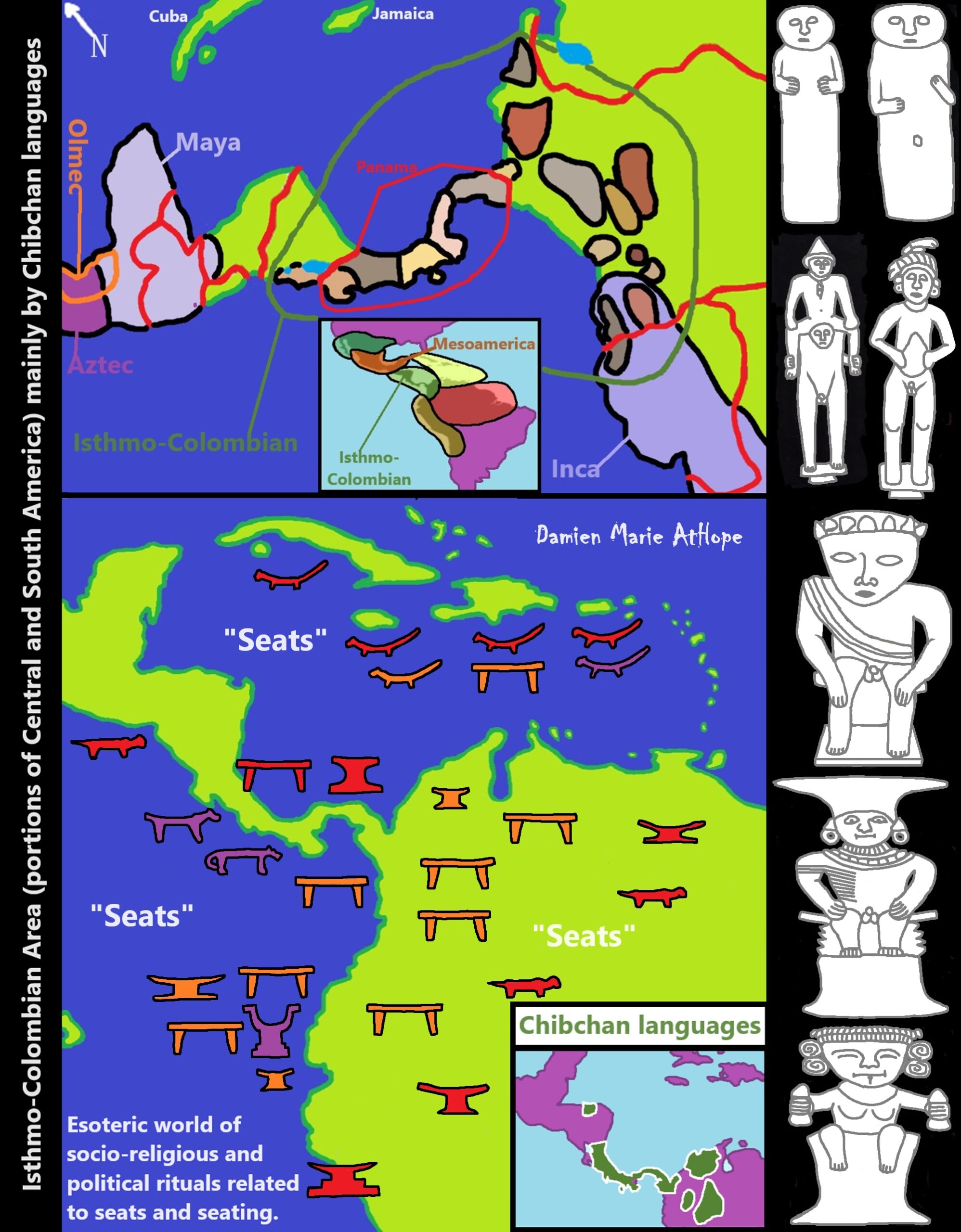

“People spoke Chibchan languages throughout the Isthmo-Colombian Area, from eastern Honduras to southern Colombia. There is no reason to characterize Chibchan languages as “South American” than there is to label them “Central American.” Furthermore, what some authors called “Mesoamerican influence” in Colombia may have come from southern Central America instead. New evidence confirms chthonous expansion beginning in the Late Pleistocene of populations, technologies, sociopolitical strategies, interregional interactions, and ideological systems.” – Info from: Pre-Columbian Central America, Colombia, and Ecuador: Toward an Integrated Approach (Dumbarton Oaks Other Titles in Pre-Columbian Studies) by Colin McEwan (Editor), John W. Hoopes (Editor)

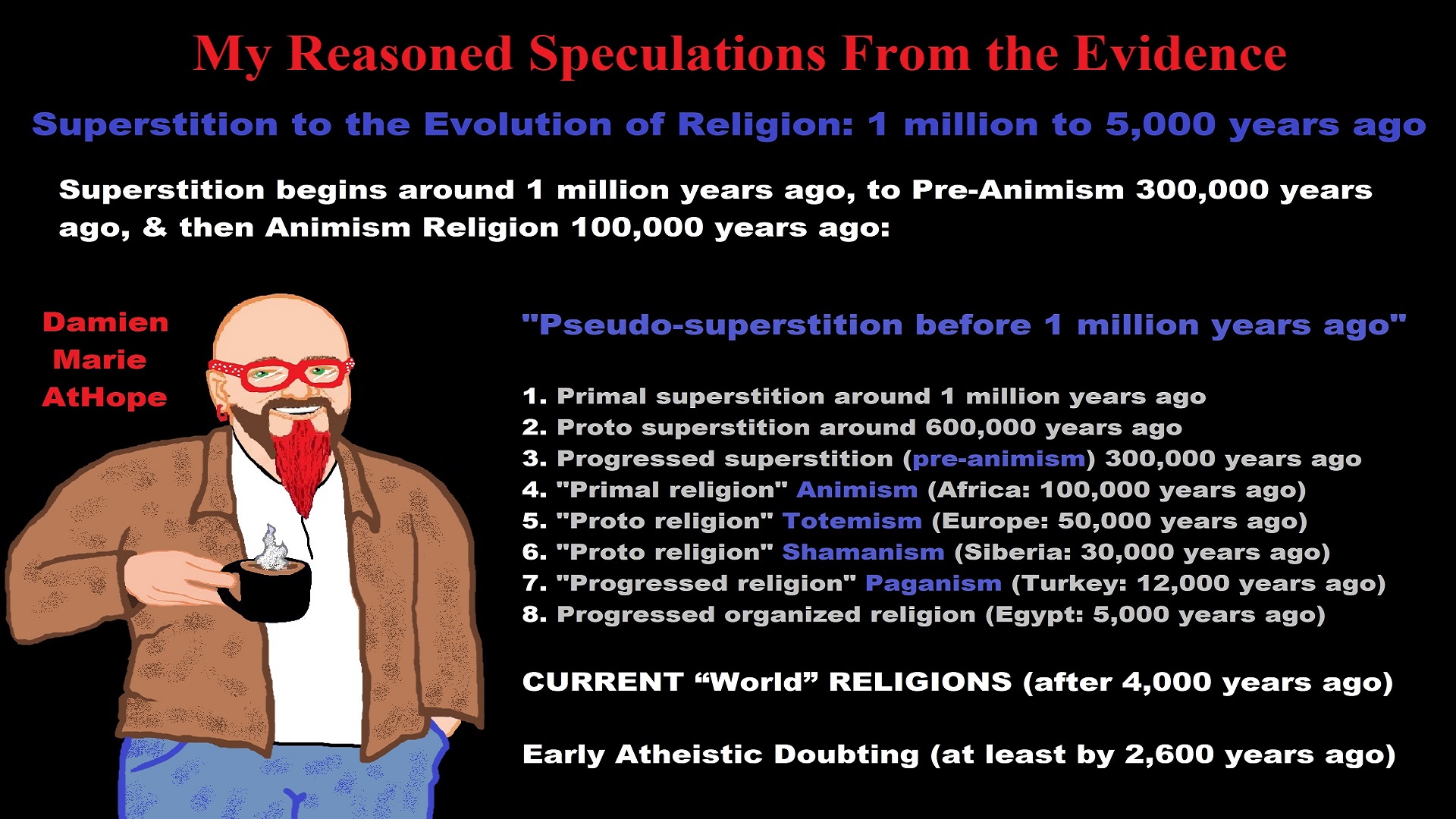

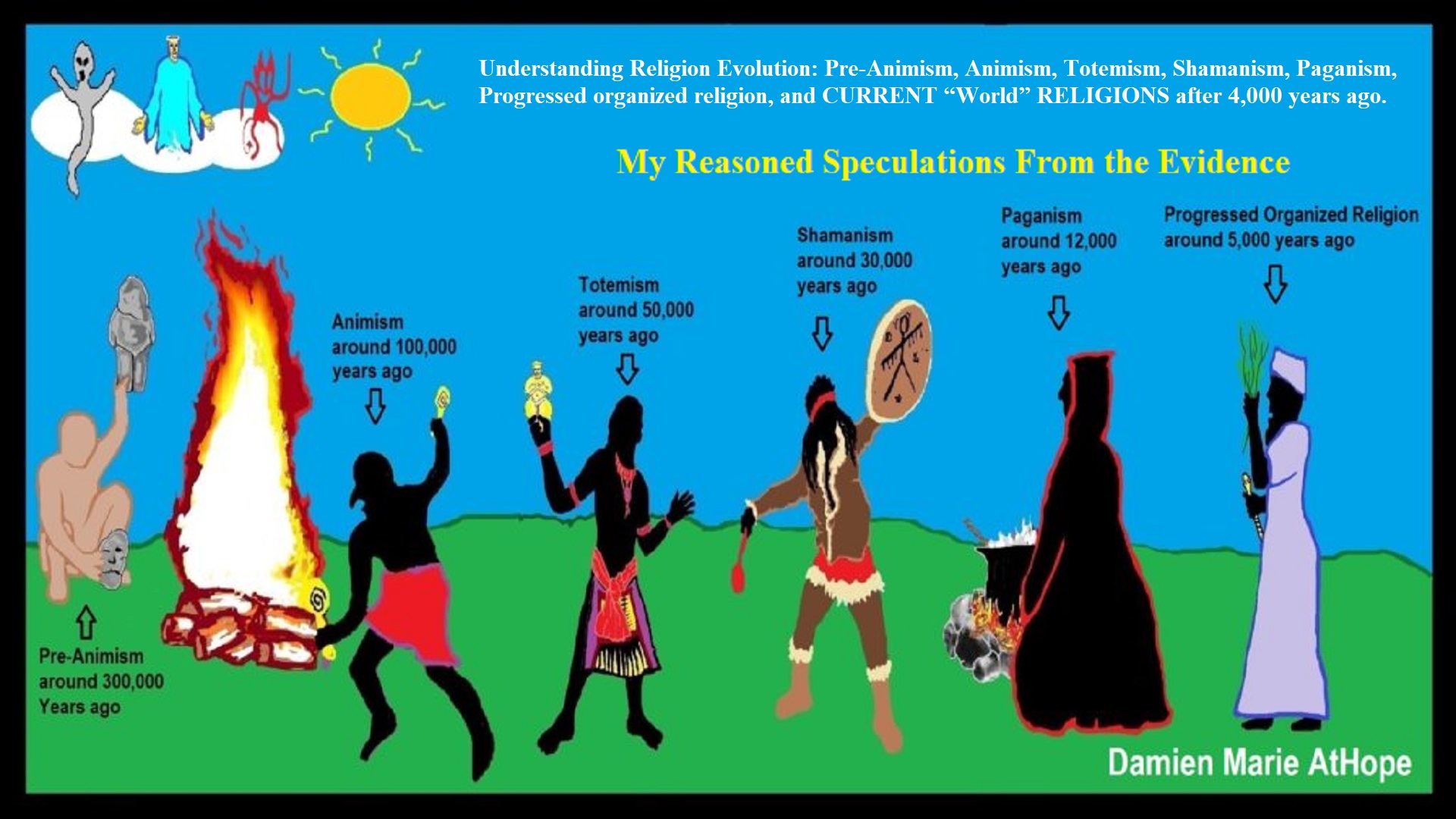

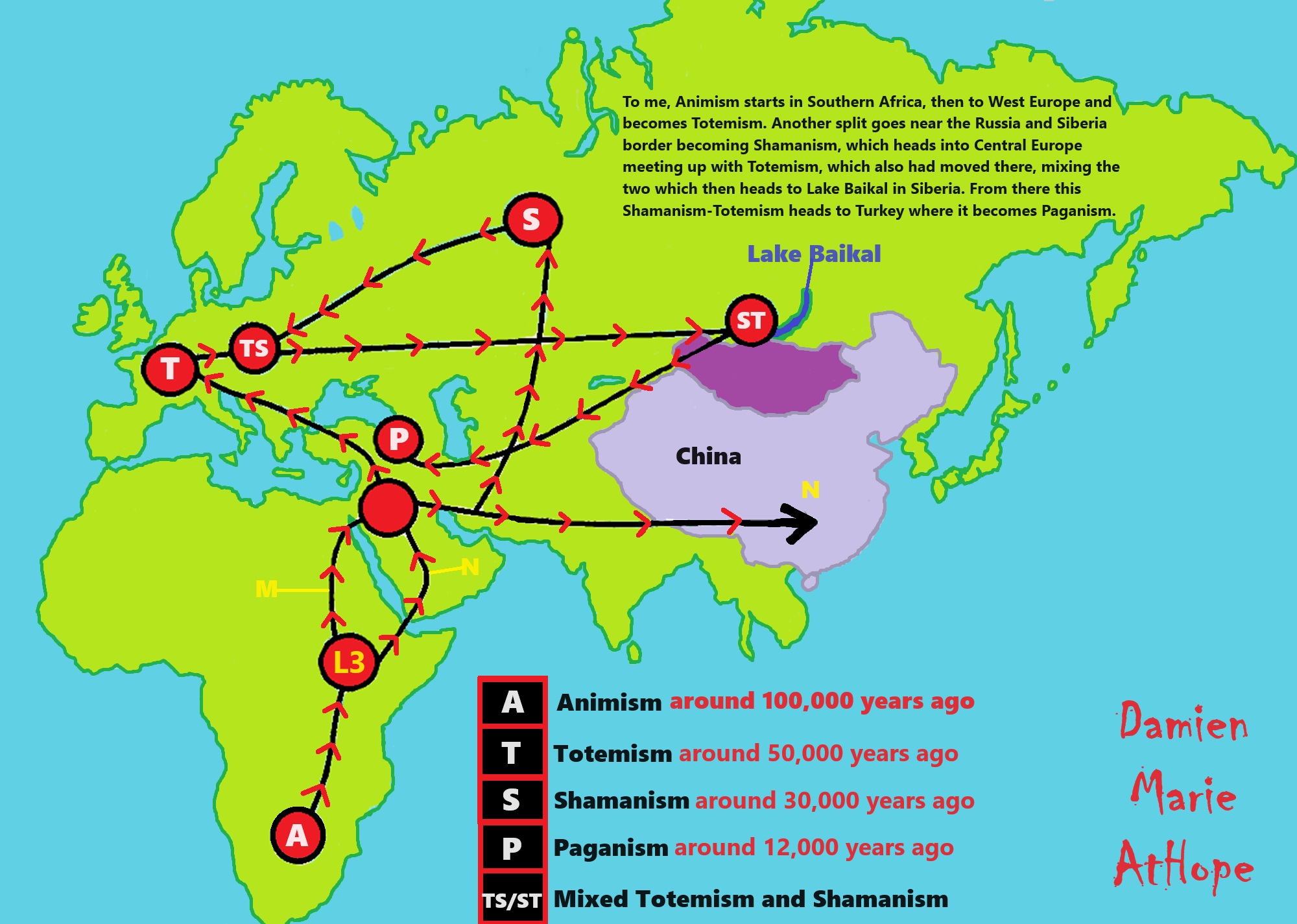

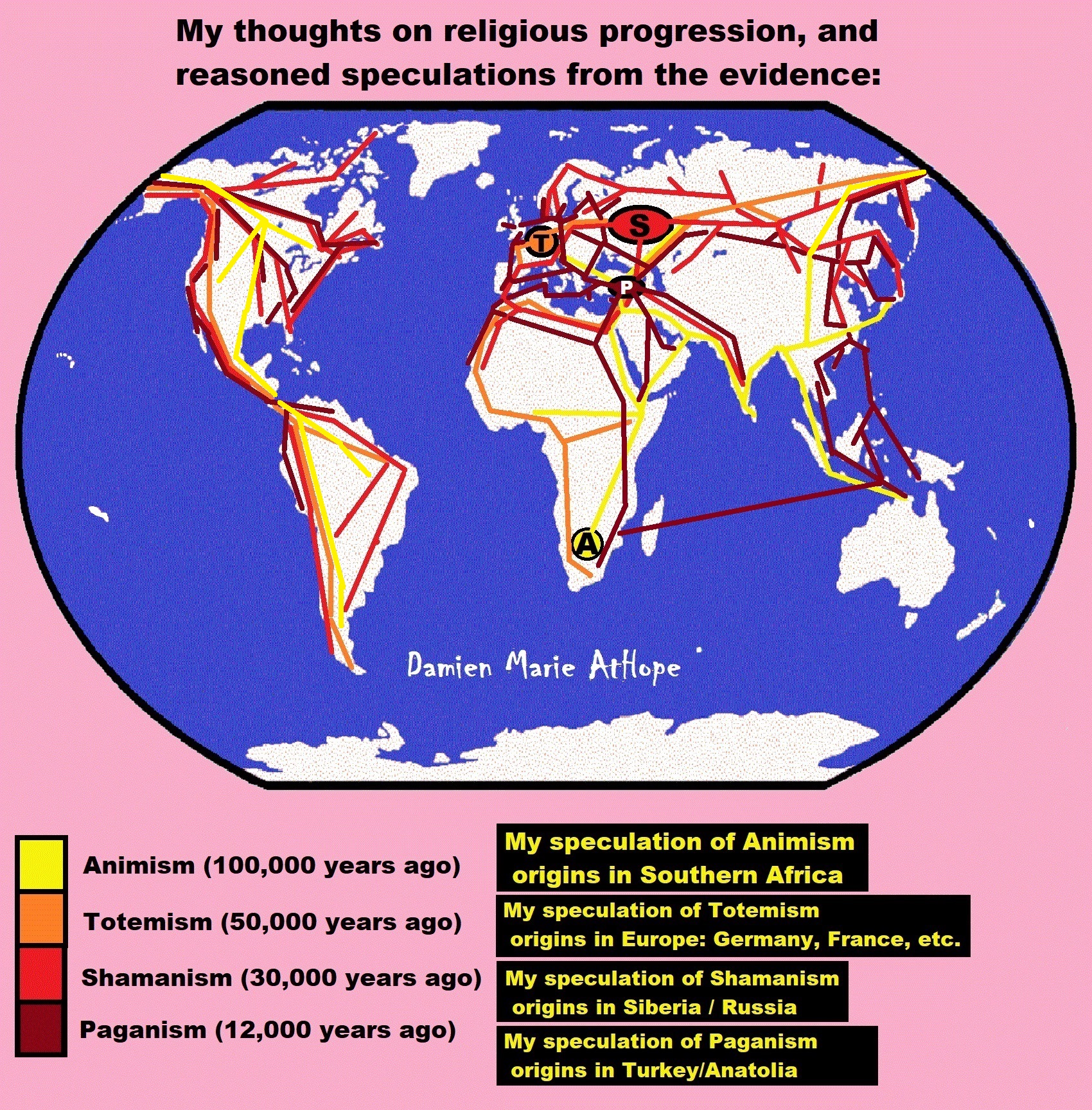

I am not an academic though I work hard for accuracy and facts, I do this hard work of addressing prehistory and religion as activism (Pro-science and Atheist). I know quite a lot as I started researching the “Evolution of Religion” starting in 2006.

I tabbed the pages from: by I want to get a quote from. There are a few. lol

Chibchan Genetics

“Genetic differences between Chibcha and Non-Chibcha speaking tribes based on mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplogroups from 21 Amerindian tribes from Colombia: Our results showed a high degree of mtDNA diversity and genetic heterogeneity. Frequencies of mtDNA haplogroups A and C were high in the majority of populations studied. The distribution of these four mtDNA haplogroups from Amerindian populations was different in the northern region of the country compared to those in the south. Haplogroup A was more frequently found among Amerindian tribes in northern Colombia, while haplogroup D was more frequent among tribes in the south. Haplogroups A, C and D have clinal tendencies in Colombia and South America in general. Populations belonging to the Chibcha linguistic family of Colombia and other countries nearby showed a strong genetic differentiation from the other populations tested, thus corroborating previous findings. Genetically, the Ingano, Paez and Guambiano populations are more closely related to other groups of south eastern Colombia, as also inferred from other genetic markers and from archeological data. Strong evidence for a correspondence between geographical and linguistic classification was found, and this is consistent with evidence that gene flow and the exchange of customs and knowledge and language elements between groups is facilitated by close proximity.” ref

Genetic Variation of the Y Chromosome (Q-M3 haplogroup) in Chibcha-Speaking Amerindians of Costa Rica and Panama

“Genetic variation of the Y chromosome in five Chibchan tribes (Bribri, Cabecar, Guaymi, Huetar, and Teribe) of Costa Rica and Panama was analyzed using six microsatellite loci (DYS19, DYS389A, DYS389B, DYS390, DYS391, and DYS393), the Y-chromosome-specific alphoid system (αh), the Y-chromosome Alu polymorphism (YAP), and a specific pre-Columbian transition (C → T) (M3 marker) in the DYS199 locus that defines the Q-M3 haplogroup. Thirty-nine haplotypes were found, resulting in a haplotype diversity of 0.937. The Huetar were the most diverse tribe, probably because of their high levels of interethnic admixture. A candidate founder Y-chromosome haplotype was identified (15.1% of Chibchan chromosomes), with the following constitution: YAP-, DYS199*T, αh-II, DYS19*13, DYS389A*17, DYS389B*10 y DYS390*24, DYS391*10, and DYS393*13. This haplotype is the same as the one described previously as one of the most frequent founder paternal lineages in native American populations. Analysis of molecular variance indicated that the between-population variation was smaller than the within-population variation, and the comparison with mtDNA restriction data showed no evidence of differential structuring between maternally and paternally inherited genes in the Chibchan populations. The mismatch-distribution approach indicated estimated coalescence times of the Y chromosomes of the Q-M3 haplogroup of 3,113 and 13,243 years before present; for the mtDNA-restriction haplotypes the estimated coalescence time was between 7,452 and 9,834 years before present. These results are compatible with the suggested time for the origin of the Chibchan group based on archeological, linguistic, and genetic evidence.” ref

Q-M3 haplogroup

“Possible time of origin: 10,000-15,000 years ago, Possible place of origin, Beringia: Either East Asia or North America. Q-M3 is present in some Siberian populations in Asia. It is unclear whether these are remnants of the founding lineage or evidence of back-migrations from Beringia to East Asia. Haplogroup Q-M3 is one of the Y-Chromosome haplogroups linked to the indigenous peoples of the Americas (over 90% of indigenous people in Meso & South America). Today, such lineages also include other Q-M242 branches (Q-M346, Q-L54, Q-P89.1, Q-NWT01, and Q-Z780), haplogroup C-M130 branches (C-M217 and C-P39), and R-M207, which are almost exclusively found in the North America. Haplogroup Q-M3 is defined by the presence of the (M3) single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP). Q-M3 occurred on the Q-L54 lineage roughly 10-15 thousand years ago as the migration into the Americas was underway. There is some debate as to on which side of the Bering Strait this mutation occurred, but it definitely happened in the ancestors of the indigenous peoples of the Americas.” ref

“Populations carrying Q-M3 are widespread throughout the Americas. Since the discovery of Q-M3, several subclades of Q-M3 bearing populations have been discovered in the Americas as well. An example is in South America where some populations have a high prevalence of SNP M19 which defines subclade Q-M19. M19 has been detected in 59% of Amazonian Ticuna men and in 10% of Wayuu men. Subclades Q-M19 and Q-M199 appear to be unique to South American populations and suggests that population isolation and perhaps even the establishment of tribes began soon after migration into the Americas. The Kennewick Man has a Y chromosome that belongs to the most common sub-clade Q1b1a1a-M3 while the Anzick’s Y chromosome belongs to the minor Q1b1a2-M971 lineage.” ref

“The current status of the polygentic tree for Q-M3 is published by pinotti et al. in the article Y Chromosome Sequences Reveal a Short Beringian Standstill, Rapid Expansion, and early Population structure of Native American Founders (2018). Calibrated phylogeny of Y haplogroup for Q-M3 and its relation to the branches within Q-L54.

“Q-M19 M19 This lineage is found among Indigenous South Americans, such as the Ticuna and the Wayuu. Origin: South America approximately 5,000 to 10,000 years ago.” ref

“Q-M194 It has only been found in South American populations.” ref

“Q-M199 This lineage has only been found in South American populations.” ref

“Q-L663 This lineage was discovered by citizen scientists. It is linked to indigenous populations in Central Mexico and has been associated with the Otomies (Hñähñús, as they self-identify) from Hidalgo, Mexico (Gómez et al, 2021). Q-L663’s paternal line was formed around 550 BCE. The man who is the most recent common ancestor of this line is estimated to have been born around 1250 CE. Extensive research on this haplogroup is being conducted by members of the New Mexico Genealogical Society, with at least 16 NGS Y-DNA tests as of 2023. The earliest known genealogical records for a Q-L663 descendant were for a man named Nicolás de Espinosa, a native of the Villa de los Lagos, Nueva Galicia, Mexico, who was born circa 1673.” ref

Haplogroup C

“Haplogroup C is found in ancient populations on every continent except Africa and is the predominant Y-DNA haplogroup among males belonging to many peoples indigenous to East Asia, Central Asia, Siberia, North America and Australia as well as a some populations in Europe, the Levant, and later Japan. Males carrying C-M130 are believed to have migrated to the Americas some 6,000-8,000 years ago, and was carried by Na-Dené-speaking peoples into the northwest Pacific coast of North America. According to Sakitani et al., haplogroup C-M130 originated in Central Asia. The haplogroup C-M217 is now found at high frequencies among Central Asian peoples, indigenous Siberians, and some Native peoples of North America. Haplogroup C-M217 is believed to have begun spreading approximately 34,000 [95% CI 31,500 <-> 36,700] years before present in eastern or central Asia. More precisely, haplogroup C2-M217 is now divided into two primary subclades: C2a-L1373 (sometimes called the “northern branch” of C2-M217) and C2b-F1067 (sometimes called the “southern branch” of C2-M217). The oldest sample with C2-M217 is AR19K in the Amur River basin (19,587-19,175 cal BP). C2a-L1373 (estimated TMRCA 16,000 [95% CI 14,300 <-> 17,800] ybp) has been found often in populations from Central Asia through North Asia to the Americas, and rarely in individuals from some neighboring regions, such as Europe or East Asia.” ref, ref

“Haplogroup C2 (M217) – the most numerous and widely dispersed C lineage – was once believed to have originated in Central Asia, spread from there into Northern Asia and the Americas while other theory it originated from East Asia. C-M217 stretches longitudinally from Central Europe and Turkey, to the Wayuu people of Colombia and Venezuela, and latitudinally from the Athabaskan peoples of Alaska to Vietnam to the Malay Archipelago. Haplogroup C-M217 is the only variety of Haplogroup C-M130 to be found among Native Americans, among whom it reaches its highest frequency in Na-Dené populations. C-P39 (C2b1a1a) is found among several indigenous peoples of North America, including some Na-Dené-, Algonquian– and Siouan-speaking populations.” ref

“C2a-L1373 subsumes two subclades: C2a1-F3447 and C2a2-BY63635/MPB374. C2a1-F3447 includes all extant Eurasian members of C2a-L1373, whereas C2a2-BY63635/MPB374 contains extant South American members of C2a-L1373 as well as ancient archaeological specimens from South America and Chertovy Vorota Cave in Primorsky Krai. C2a1-F3447 (estimated TMRCA 16,000 [95% CI 14,700 <-> 17,400] ybp) includes the Y-DNA of an approximately 14,000-year-old specimen from the Ust’-Kyakhta 3 site (located on the right bank of the Selenga River in Buryatia, near the present-day international border with Mongolia) and C2a1b-BY101096/ACT1942 (found in individuals from present-day Liaoning Province of China, South Korea, Japan, and a Nivkh from Russia) in addition to the expansive C2a1a-F1699 clade. C2a1a-F1699 (estimated TMRCA 14,000 [95% CI 12,700 <-> 15,300] ybp) subsumes four subclades: C2a1a1-F3918, C2a1a2-M48, C2a1a3-M504, and C2a1a4-M8574. C2a1a1-F3918 subsumes C2a1a1a-P39, which has been found at high frequency in samples of some indigenous North American populations, and C2a1a1b-FGC28881, which is now found with varying (but generally quite low) frequency all over the Eurasian steppe, from Heilongjiang and Jiangsu in the east to Jihočeský kraj, Podlaskie Voivodeship, and Giresun in the west.” ref

“Haplogroup C2a1a2-M48 is especially frequent and diverse among present-day Tungusic peoples, but branches of it also constitute the most frequently observed Y-DNA haplogroup among present-day Mongols in Mongolia, Alshyns in western Kazakhstan, and Kalmyks in Kalmykia. Extant members of C2a1a3-M504 all share a relatively recent common ancestor (estimated TMRCA 3,900 [95% CI 3,000 <-> 4,800] ybp), and they are found often among Mongols, Manchus (e.g. Aisin Gioro), Kazakhs (most tribes of the Senior Zhuz as well as the Kerei tribe of the Middle Zhuz), Kyrgyz, and Hazaras. C2a1a4-M8574 is sparsely attested and deeply bifurcated into C-Y176542, which has been observed in an individual from Ulsan and an individual from Japan, and C-Y11990. C-Y11990 is likewise quite ancient (estimated TMRCA 9,300 [95% CI 7,900 <-> 10,700] ybp according to YFull or 8,946 [99% CI 11,792 – 6,625] ybp according to FTDNA) but rare, with one branch (C-Z22425) having been found sporadically in Jammu and Kashmir, Germany, and the United States and another branch (C-ZQ354/C-F8513) having been found sporadically in Slovakia (Prešov Region), China, Turkey, and Kipchak of the central steppe (Lisakovsk 23 Kipchak in Kazakhstan, medieval nomad from 920 +- 25 BP uncal or 1036 – 1206 CE).” ref

“Haplogroup C-M217 is the modal haplogroup among Mongolians and most indigenous populations of the Russian Far East, such as the Buryats, Northern Tungusic peoples, Nivkhs, Koryaks, and Itelmens. The subclade C-P39 is common among males of the indigenous North American peoples whose languages belong to the Na-Dené phylum. The frequency of Haplogroup C-M217 tends to be negatively correlated with distance from Mongolia and the Russian Far East, but it still comprises more than ten percent of the total Y-chromosome diversity among the Manchus, Koreans, Ainu, and some Turkic peoples of Central Asia. Beyond this range of high-to-moderate frequency, which contains mainly the northeast quadrant of Eurasia and the northwest quadrant of North America, Haplogroup C-M217 continues to be found at low frequencies, and it has even been found as far afield as Northwest Europe, Turkey, Pakistan, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Nepal and adjacent regions of India, Vietnam, Maritime Southeast Asia, and the Wayuu people of South America.” ref

C2b L1373, F1396

- C2b L1373* Ecuador (Bolívar Province), USA

- C2b F3447, F3914

- C2b Y163913, ACT1932, BY75034

- C2b1 F4032

- C2b1a F1699, F6301

- C2b1a* Japanese, Germany

- C2b1a1 F3918, Y10418/FGC28813/F8894

- C2b1a1* Yugurs

- C2b1a1a P39 Canada, USA (Found in several indigenous peoples of North America, including some Na-Dené-, Algonquian-, or Siouan-speaking populations)” ref

- C2b1a F1699, F6301

Biological relationship between Central and South American Chibchan speaking populations: evidence from mtDNA

“Abstract: We examined mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplogroup and haplotype diversity in 188 individuals from three Chibchan (Kogi, Arsario, and Ijka) populations and one Arawak (Wayuú) group from northeast Colombia to determine the biological relationship between lower Central American and northern South American Chibchan speakers. mtDNA haplogroups were obtained for all individuals and mtDNA HVS-I sequence data were obtained for 110 samples. Resulting sequence data were compared to 16 other Caribbean, South, and Central American populations using diversity measures, neutrality test statistics, sudden and spatial mismatch models, intermatch distributions, phylogenetic networks, and a multidimensional scaling plot. Our results demonstrate the existence of a shared maternal genetic structure between Central American Chibchan, Mayan populations and northern South American Chibchan-speakers. Additionally, these results suggest an expansion of Chibchan-speakers into South America associated with a shift in subsistence strategies because of changing ecological conditions that occurred in the region between 10,000-14,000 years before present.” ref

Mitochondrial DNA analysis suggests a Chibchan migration into Colombia

“Haplogroups were determined by analysis of RFLPs. Most frequent was haplogroup A, with 338 individuals (48.3%). Haplogroup A is also one of the most frequent haplogroups in Mesoamerica, and we interpret our finding as supporting models that propose Chibchan-speaking groups migrated to northern Colombia from Mesoamerica in prehistoric times. Haplogroup C was found in 199 individuals (28.4%), while less frequent were B and D, with 113 and 41 (16% and 6%) individuals, respectively. The haplogroups of nine (9) individuals (1.3%) could not be determined due to the low quality of the samples of DNA. Although all the sampled populations had genetic structures that fit broadly into the patterns that might be expected for contemporary Central and South American indigenous groups, it was found that haplogroups A and B were more frequent in northern Colombia, while haplogroups C and D were more frequent in southern and south-western Colombia.” ref

South-to-north migration preceded the advent of intensive farming in the Maya region

“The genetic prehistory of human populations in Central America is largely unexplored leaving an important gap in our knowledge of the global expansion of humans. We report genome-wide ancient DNA data for a transect of twenty individuals from two Belize rock-shelters dating between 9,600-3,700 calibrated radiocarbon years before present (cal. BP). The oldest individuals (around 9,600-7,300 years ago) descend from an Early Holocene Native American lineage with only distant relatedness to present-day Mesoamericans, including Mayan-speaking populations. After ~5,600 years ago a previously unknown human dispersal from the south made a major demographic impact on the region, contributing more than 50% of the ancestry of all later individuals. This new ancestry derived from a source related to present-day Chibchan speakers living from Costa Rica to Colombia. Its arrival corresponds to the first clear evidence for forest clearing and maize horticulture in what later became the Maya region.” ref

“Previous ancient DNA analyses have indicated that the earliest Central and South Americans, as well as present-day groups from the same regions, descend primarily from the more southerly of two founding Native American genetic lineages. Published early Holocene (9400–7300 years ago) individuals from Belize (N = 3) are consistent in deriving their ancestry from this same large-scale north-to-south movement of people, but they display only distant relatedness to present-day groups in Mexico and Central America, including local Maya-speaking populations. Instead, Maya people today show the greatest affinities to both South Americans and Indigenous Mexicans, suggesting the potential for further episodes of population movement and admixture in this region during the past 7300 years. The genetic history of the region is essential to understand the evolution of cultures, languages, and technologies, including domesticated plant crops that transformed the neotropics.” ref

CHIBCHA RELIGION

“The Chibcha, a group of South American natives, occupied the high valleys surrounding the modern cities of Bogotá and Tunja in Colombia before the Spanish conquest. The Chibcha religion was of both state and individual concern. Each political division had its own set of priests. Apparently some kind of hierarchy was recognized and the priests were a professional hereditary class. Priests, who were clearly distinguished from shamans, had as their functions the intercession at public ceremonies for the public good, the dispensing of oracles, and consultation with private individuals. Shamans served the individual more than the state and cured illnesses, interpreted dreams, and foretold the future. The Chibchas had an elaborate pantheon of gods headed by Chiminigagua, the supreme god and creator. In addition to the state temples and idols, many natural habitats were considered to be holy places. Ceremonial practices included offerings, public rites, pilgrimages, and human sacrifice. Human sacrifice was said to be fairly common and was made primarily to the sun.” ref

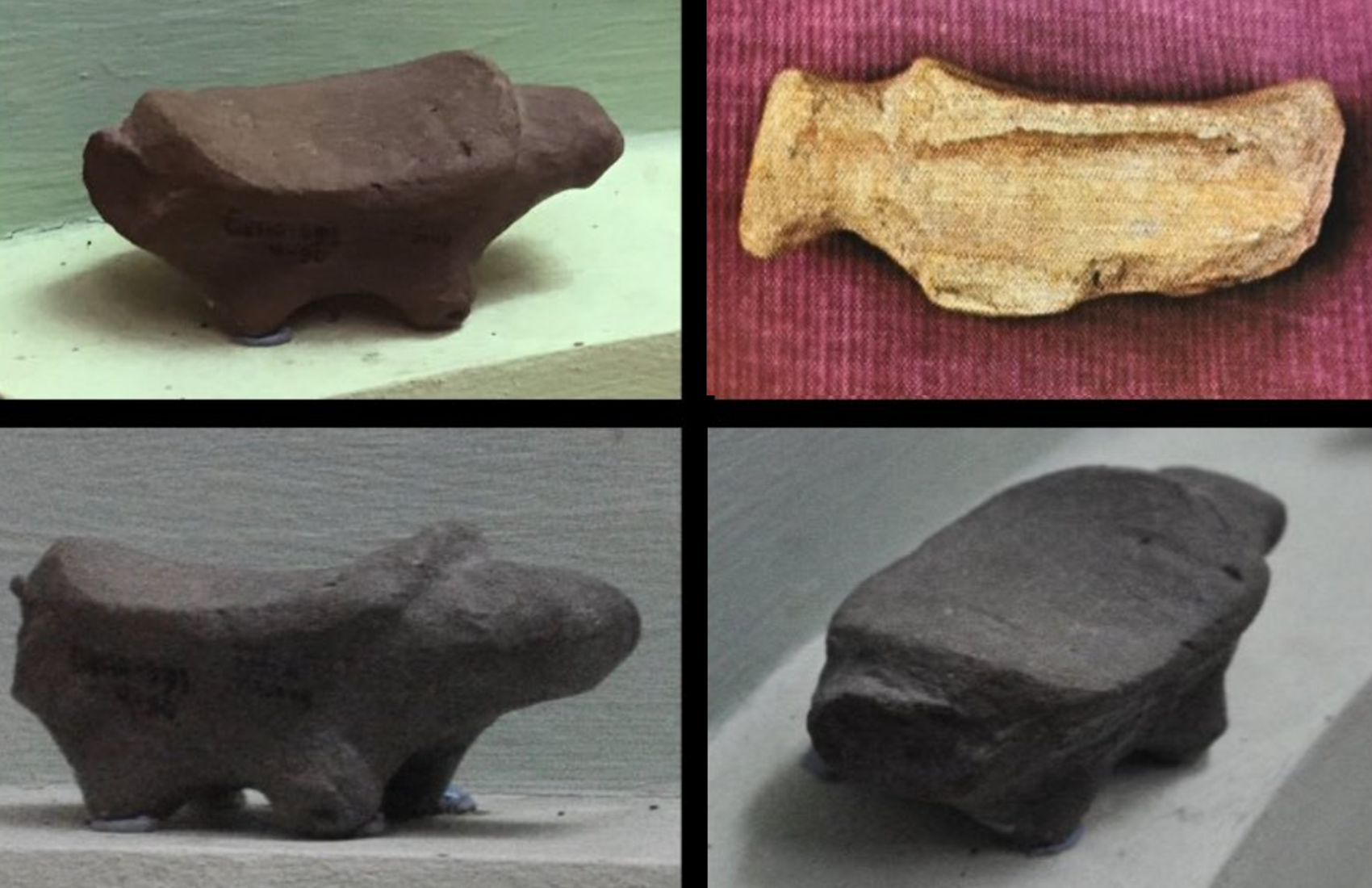

The esoteric world of socio-religious and political rituals related to seats and seating.

“Shaman Seats”

Photo credits for the first Pic is John Hoopes. The objects are in the Real Alto site museum.

Seats of Power

“It was common for ancient furniture to have religious or symbolic purposes. The Incans had chacmools which were dedicated to sacrifice. Similarly, in Dilmun they had sacrificial altars. In many civilizations, the furniture depended on wealth. Sometimes certain types of furniture could only be used by the upper class citizens. For example, in Egypt, thrones could only be used by the rich. Sometimes the way the furniture was decorated depended on wealth. For example, in Mesopotamia tables would be decorated with expensive metals, chairs would be padded with felt, rushes, and upholstery. Some chairs had metal inlays.” ref

“As some of the earliest forms of seat, stools are sometimes called backless chairs despite how some modern stools have backrests. The origins of stools are obscure, but they are known to be one of the earliest forms of wooden furniture. Several kingdoms and chiefdoms in Africa had and still have traditions of using stools in the place of chairs as thrones. One of the most famous of them, the Golden Stool of the Asantehene in Ghana, was the cause of one of the most famous events in the history of colonized Africa, the so-called War of the Golden Stool between the British and the Ashanti.” ref

“Some of the first people that Christopher Columbus met in the American continent were the Taino people. Duhos are carved seats found in the houses of Taino caciques or chiefs throughout the Caribbean region. Duhos “figured prominently in the maintenance of Taino political and ideological systems . . . [and were] . . . literally seats of power, prestige, and ritual.” The Taíno ritual seat is a Pre-Columbian wooden seat made in the form of a man on all fours. It was made by the Taino people and found in a cave near the city of Santo Domingo in the Dominican Republic. The seat was made before Christopher Columbus landed in the Caribbean and is an important remnant of the Taino culture and civilisation that existed before the arrival of Europeans.” ref

“In Akkad, Chairs would also have brightly colored wooden and ivory finials depicting arms and bull’s heads. Oftentimes the chairs would have bronze panels that had images of griffins and winged deities carved into them. The Royal Standard of Ur showcases the king of Ur on a low-back chair with animal legs. The seats depicted on the Royal Standard were likely made of Rush and Cane. During this period of Sumerian history chairs were not used by the majority of people. Most people simply sat on the floor. Low-backed chairs with curved or flat seats and turned legs were incredibly common in the Akkadian Empire.” ref

“From the Assyrian records we learn that Mesopotamian furniture was similar to Egyptian furniture. There was a wide variety of Assyrian chairs. Some chairs had backs and arms, some resembled a footstool. Tombs dating back to the First Dynasty have wooden furniture. The chair developed from the stool in the second dynasty. A stele found in a tomb from this time period depicts Prince Nisuheqet sitting on a chair. The chair has a high back made of plain sawn boards. Suggesting that the earliest chairs were used by the wealthy. Egyptian chairs likely continued to be status symbols. In another tomb, this time from the third dynasty, more depictions of chairs are found.” ref

“Animal legs were usually supported on a small cone-shaped pedestal. In the Middle Kingdom of Egypt chairs were still straight legged with cushioned backs and upholstered vertical backs. During this period, chairs became more stylized. The legs of these chairs were animal shaped, however instead of bovine shaped, they were slender and gazelle shaped or lion shaped. Much of the old Egyptian furniture which still survives to this day has only survived due to the ancient Egyptians beliefs about the afterlife. Furniture would be placed in tombs, and a result would survive to the modern day.” ref

“The chairs from Tutankhamen’s tomb were highly decorated with imported ebony and ivory inlay. They were also made for ceremonial purposes. Funerary paraphernalia was common amongst these chairs. Stools did not come into being in Egypt until the 18th Dynasty. Still, the majority of people did not have chairs, so stools were most people’s only option for comfortable seating. Ceremonial stools would be blocks of stone or wood. If the stool was made out of wood it would have a flint seat. Footstools were made of wood. The Royal Footstool had enemies of Egypt painted on the footstool, so that way the pharaoh could symbolically crush them. Stools used by the upper-class would have upward sweeping corners and woven leather seats, with a padded cushion on top.” ref

“The modern word “throne” is derived from the ancient Greek thronos (Greek singular: θρόνος), which was a seat designated for deities or individuals of high status or honor. The colossal chryselephantine statue of Zeus at Olympia, constructed by Phidias and lost in antiquity, featured the god Zeus seated on an elaborate throne, which was decorated with gold, precious stones, ebony, and ivory, according to Pausanias. Less extravagant though more influential in later periods is the klismos (Greek singular: κλισμός), an elegant Greek chair with a curved backrest and legs whose form was copied by the Romans and is now part of the vocabulary of furniture design. A fine example is shown on the grave stele of Hegeso, dating to the late fifth century BCE. As with earlier furniture from the east, the klismos and thronos could be accompanied by footstools.” ref

“The most common form of Greek seat was the backless stool. These were known as diphroi (Greek singular: δίφρος) and they were easily portable. The Parthenon frieze displays numerous examples, upon which the gods are seated. Several fragments of a stool were discovered in the forth-century BCE. tomb in Thessaloniki, including two of the legs and four transverse stretchers. The Greek folding stool survives in numerous depictions, indicating its popularity in the Archaic and Classical periods; the type may have been derived from earlier Minoan and Mycenaean examples, which in turn were likely based on Egyptian models. Greek folding stools might have plain straight legs or curved legs that typically ended in animal feet. The sella curulis, or folding stool, was an important indicator of power in the Roman period.” ref

“In one Mayan ceramic, a god who is possibly the God L is shown seated on a throne-like stool covered in cloth placed on a raised platform. Most likely, the only big furniture in a home would be wooden stools or benches. A quantity of furniture in an Aztec home would have been uncommon sight. Usually instead of beds or chairs, mats made of reeds or dirt platforms were used to sit or sleep on.” ref

“Chair comes from the early 13th-century English word chaere, from Old French chaiere (“chair, seat, throne”), from Latin cathedra (“seat”). Chairs were in existence since at least the Early Dynastic Period of Egypt (c. 3100 BCE or around 5,100 years ago). In ancient Egypt, chairs appear to have been of great richness and splendor. Generally speaking, the higher ranked an individual was, the taller and more sumptuous was the chair he sat on and the greater the honor. On state occasions, the pharaoh sat on a throne, often with a little footstool in front of it. The average Egyptian family seldom had chairs, and if they did, it was usually only the master of the household who sat on a chair.” ref

“According to the Hebrew Bible, the kaporet (Hebrew: כַּפֹּרֶת kapōreṯ) or mercy seat was the gold lid placed on the Ark of the Covenant, with two cherubim beaten out of the ends to cover and create the space in which Yahweh appeared and dwelled. This was connected with the rituals of the Day of Atonement. The term also appears in later Jewish sources, and twice in the New Testament, from where it has significance in Christian theology. Two golden cherubim were placed at each end of the cover facing one another and the mercy seat, with their wings spread to enclose the mercy seat (Exodus 25:18–21). The cherubim formed a seat for Yahweh (1 Samuel 4:4). The Holy of Holies could be entered only by the high priest on the Day of Atonement. The high priest sprinkled the blood of a sacrificial bull onto the mercy seat as an atonement for the sins of the people of Israel.” ref

“Although the Holy See is sometimes metonymically referred to as the “Vatican“, the Vatican City State was distinctively established with the Lateran Treaty of 1929, the word “see” comes from the Latin word sedes, meaning ‘seat’, which refers to the episcopal throne (cathedra). The Holy See is one of the last remaining seven absolute monarchies in the world, along with Saudi Arabia, Eswatini, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Brunei and Oman.” ref

“A sacrificial tripod, whose name comes from the Greek meaning “three-footed”, is a three-legged piece of religious furniture used in offerings and other ritual procedures. Tripods had two types and several functions. Firstly, some oracles sat on large tripods to pronounce. Far more common were the tripods and bowls in which smaller sacrifices were burnt. These are particularly associated with Apollo and the Delphic oracle in ancient Greece. These were also given to temples as votive offerings, awarded as prizes in contests associated with religious festivals, and just given as gifts between individuals. The most famous tripod of ancient Greece was the Delphic Tripod on which the Pythian priestess took her seat to deliver the oracles of the deity.” ref

“Sacrificial tripods also were used as dedicatory offerings to the deities, and in the dramatic contests at the Dionysia the victorious choregus (a wealthy citizen who bore the expense of equipping and training the chorus) received a crown and a tripod. He would either dedicate the tripod to some deity or set it upon the top of a marble structure erected in the form of a small circular temple in a street in Athens, called the street of tripods, from the large number of memorials of this kind. According to Herodotus (The Histories, I.144), the victory tripods were not to be taken from the temple sanctuary precinct, but left there as dedications.” ref

Thrones: Seating of Power

Isaiah 40:22: 22 “God sits on his throne above the circle of the earth, and compared to him, people are like grasshoppers.”

Matthew 23:22: “And whoever swears by heaven, swears both by the throne of God and by Him who sits upon it.”

Revelation 4:9: “When the living creatures give glory and honor to Him who sits on the throne, to Him who lives forever and ever.”

“A throne is the seat of state of a potentate or dignitary, especially the seat occupied by a sovereign (or viceroy) on state occasions; or the seat occupied by a pope or bishop on ceremonial occasions. “Throne” in an abstract sense can also refer to the monarchy or the Crown itself, an instance of metonymy, and is also used in many expressions such as “the power behind the throne“. A throne is a symbol of divine and secular rule and the establishment of a throne as a defining sign of the claim to power and authority. It can be with a high backrest and feature heraldic animals or other decorations as adornment and as a sign of power and strength.” ref

“The throne of God is the reigning centre of God in the Abrahamic religions: primarily Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. The throne is said by various holy books to reside beyond the Seventh Heaven which is called Araboth (Hebrew: עֲרָבוֹת ‘ărāḇōṯ) in Judaism. The heavenly throne room or throne room of God is a more detailed presentation of the throne, into the representation of throne room or divine court. Micaiah‘s extended prophecy (1 Kings 22:19) is the first detailed depiction of a heavenly throne room in Judaism. Zechariah 3 depicts a vision of the heavenly throne room where Satan and the Angel of the Lord contend over Joshua the High Priest in the time of his grandson Eliashib the High Priest. “The concept of a heavenly throne occurs in three Dead Sea Scroll texts.” ref

“Abu Mansur al-Baghdadi (d. 429/1037) in his al-Farq bayn al-Firaq (The Difference between the Sects) reports that ‘Ali ibn Abi Talib, said: “God created the Throne as an indication of His power, not for taking it as a place for Himself.” The vast majority of Islamic scholars, including Sunnis (Ash’aris, Maturidis and Sufis), Mu’tazilis, and Shi’is (Twelvers and Isma’ilis) believe the Throne (Arabic: العرش al-‘Arsh) as a symbol of God’s power and authority and not as a dwelling place for Himself, while some Islamic sects, such as the Karramis and the Salafis/Wahhabis believe that God has created it as a place of dwelling. The Quran depicts the angels as carrying the throne of God and praising his glory, similar to Old Testament images. Prophetic hadith also establish that The Throne is above the roof of Al-Firdaus Al-‘Ala, the highest level of Paradise where God’s closest and most beloved servants in the hereafter shall dwell.” ref

“The Quran mentions the throne some 25 times (33 times as Al-‘Arsh), such as in verse Q10:3 and Q23:116:

Indeed, your Lord is Allah, who created the heavens and the earth in six days and then established Himself above the Throne (Arsh), arranging the matter [of His creation]. There is no intercessor except after His permission. That is Allah, your Lord, so worship Him. Then will you not remember? – Yunus 10:3

And it is He who created the heavens and the earth in six days – and His Throne had been upon water – that He might test you as to which of you is best in deed. But if you say, “Indeed, you are resurrected after death,” those who disbelieve will surely say, “This is not but obvious magic.” – Hud 11:7

So Exalted be Allah, the True King – None has the right to be worshipped but He – Lord of the Supreme Throne! – al-Mu’minoon 23:116” ref

“A throne can be placed underneath a canopy or baldachin. The throne can stand on steps or a dais and is thus always elevated. The expression “ascend (mount) the throne” takes its meaning from the steps leading up to the dais or platform, on which the throne is placed, being formerly comprised in the word’s significance. Coats of arms or insignia can feature on throne or canopy and represent the dynasty. Even in the physical absence of the ruler an empty throne can symbolise the everlasting presence of the monarchical authority.” ref

“When used in a political or governmental sense, a throne typically exists in a civilization, nation, tribe, or other politically designated group that is organized or governed under a monarchical system. Throughout much of human history societies have been governed under monarchical systems, in the beginning as autocratic systems and later evolved in most cases as constitutional monarchies within liberal democratic systems, resulting in a wide variety of thrones that have been used by given heads of state. These have ranged from stools in places such as in Africa to ornate chairs and bench-like designs in Europe and Asia, respectively.” ref

“Often, but not always, a throne is tied to a philosophical or religious ideology held by the nation or people in question, which serves a dual role in unifying the people under the reigning monarch and connecting the monarch upon the throne to his or her predecessors, who sat upon the throne previously. Accordingly, many thrones are typically held to have been constructed or fabricated out of rare or hard to find materials that may be valuable or important to the land in question. Depending on the size of the throne in question it may be large and ornately designed as an emplaced instrument of a nation’s power, or it may be a symbolic chair with little or no precious materials incorporated into the design. When used in a religious sense, throne can refer to one of two distinct uses. Many of these thrones—such as China’s Dragon Throne—survive today as historic examples of nation’s previous government.” ref

“The first use derives from the practice in churches of having a bishop or higher-ranking religious official (archbishop, pope, etc.) sit on a special chair which in church referred to by written sources as a “throne”, or “cathedra” (Latin for ‘chair’) and is intended to allow such high-ranking religious officials a place to sit in their place of worship. The other use for throne refers to a belief among many of the world’s monotheistic and polytheistic religions that the deity or deities that they worship are seated on a throne. Such beliefs go back to ancient times, and can be seen in surviving artwork and texts which discuss the idea of ancient gods (such as the Twelve Olympians) seated on thrones. In the major Abrahamic religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, the Throne of God is attested to in religious scriptures and teachings, although the origin, nature, and idea of the Throne of God in these religions differs according to the given religious ideology practiced.” ref

“Thrones were found throughout the canon of ancient furniture. The depiction of monarchs and deities as seated on chairs is a common topos in the iconography of the Ancient Near East. The word throne itself is from Greek θρόνος (thronos), “seat, chair”, in origin a derivation from the PIE root *dher- “to support” (also in dharma “post, sacrificial pole”). Early Greek Διὸς θρόνους (Dios thronous) was a term for the “support of the heavens”, i.e. the axis mundi, which term when Zeus became an anthropomorphic god was imagined as the “seat of Zeus”. In Ancient Greek, a “thronos” was a specific but ordinary type of chair with a footstool, a high status object but not necessarily with any connotations of power. The Achaeans (according to Homer) were known to place additional, empty thrones in the royal palaces and temples so that the gods could be seated when they wished to be. The most famous of these thrones was the throne of Apollo in Amyclae.” ref

“The word “throne” in English translations of the Bible renders Hebrew כסא kissē’. The pharaoh of the Exodus is described as sitting on a throne (Exodus 11:5, 12:29), but mostly the term refers to the throne of the kingdom of Israel, often called the “throne of David” or “throne of Solomon“. The literal throne of Solomon is described in 1 Kings 10:18–20: “Moreover the king made a great throne of ivory, and overlaid it with the best gold.. The throne had six steps, and the top of the throne was round behind: and there were stays on either side on the place of the seat, and two lions stood beside the stays. And twelve lions stood there on the one side and on the other upon the six steps: there was not the like made in any kingdom.” In the Book of Esther (5:3), the same word refers to the throne of the king of Persia.” ref

“The God of Israel himself is frequently described as sitting on a throne, referred to outside of the Bible as the Throne of God, in the Psalms, and in a vision Isaiah (6:1), and notably in Isaiah 66:1, YHWH says of himself “The heaven is my throne, and the earth is my footstool” (this verse is alluded to by Matthew 5:34-35). In the Old Testament, Book of Kings I explicits the throne of Solomon: “Then the king made a great throne covered with ivory and overlaid with fine gold. The throne had six steps, and its back had a rounded top. On both sides of the seat were armrests, with a lion standing beside each of them. Twelve lions stood on the six steps, one at either end of each step” in Chapter 10 18-20. Jesus promised his apostles that they would sit upon “twelve thrones”, judging the twelve tribes of Israel (Matthew 19:28). John‘s Revelation states: “And I saw a great white throne, and him that sat on it, from whose face the earth and the heaven fled away” (Revelation 20:11).” ref

“In the Indian subcontinent, the traditional Sanskrit name for the throne was siṃhāsana (lit., seat of a lion). In the Mughal times the throne was called Shāhī takht ([ˈʃaːhiː ˈtəxt]). The term gadi or gaddi (Hindustani pronunciation: [ˈɡəd̪ːi], also called rājgaddī) referred to a seat with a cushion used as a throne by Indian princes. That term was usually used for the throne of a Hindu princely state‘s ruler, while among Muslim princes or Nawabs, save exceptions such as the Travancore State royal family, the term musnad ([ˈməsnəd]), also spelt as musnud, was more common, even though both seats were similar.” ref

“The Dragon Throne is the term used to identify the throne of the emperor of China. As the dragon was the emblem of divine imperial power, the throne of the emperor, who was considered a living god, was known as the Dragon Throne. The throne of the emperors of Vietnam are often referred to as ngai vàng (“golden throne”) or ngôi báu (大寳/寶座) literally “great precious” (seat/position). The throne is always adorned with the pattern and motif of the Vietnamese dragon, which is the exclusive and privileged symbol of the Vietnamese emperors. In Vietnamese folk religion, the gods, deities and ancestral spirits are believed to seat figuratively on thrones at places of worship. Therefore, on Vietnamese altars, there are various types of liturgical “throne” often decorated with red paint and golden gilding.” ref

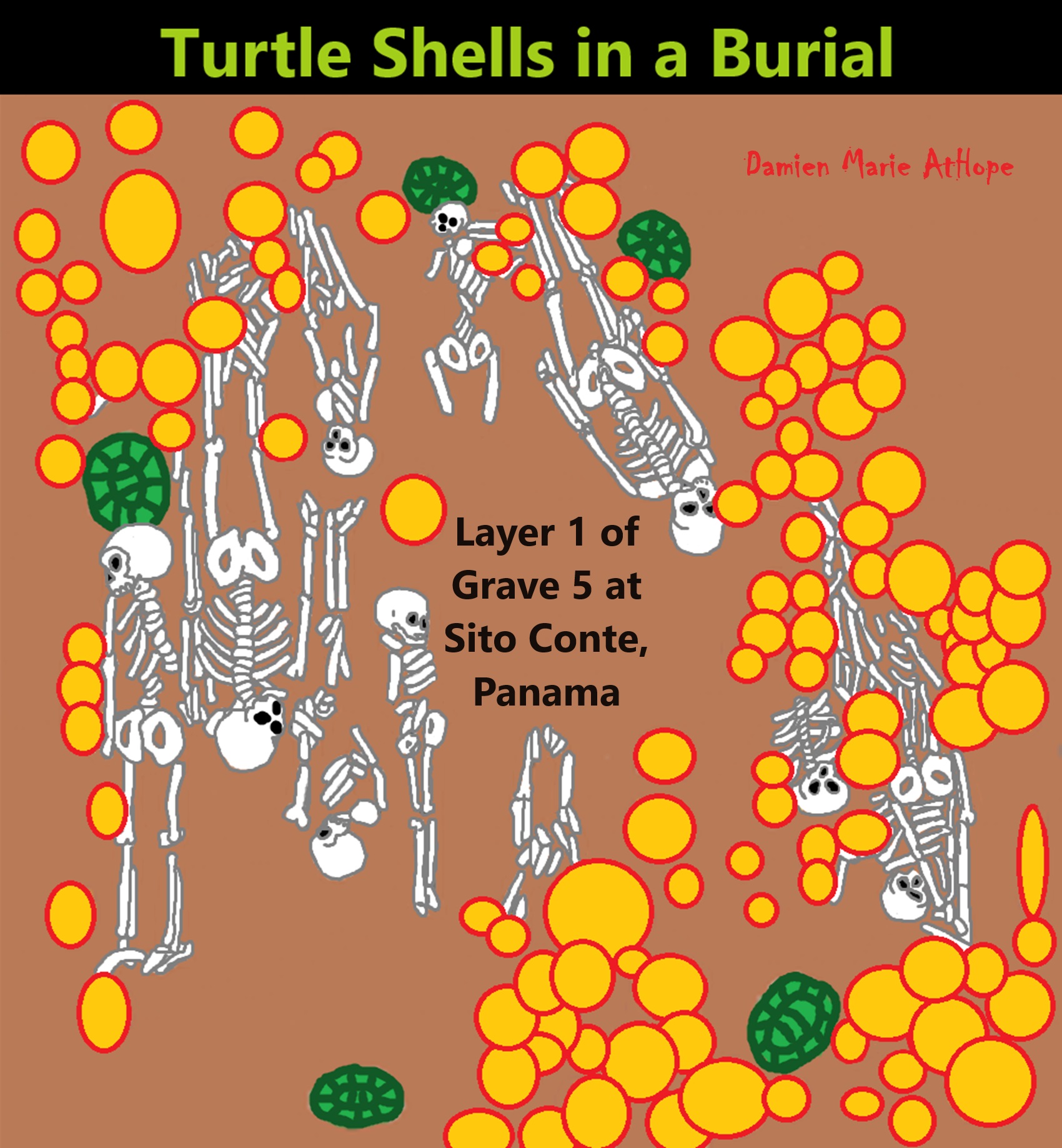

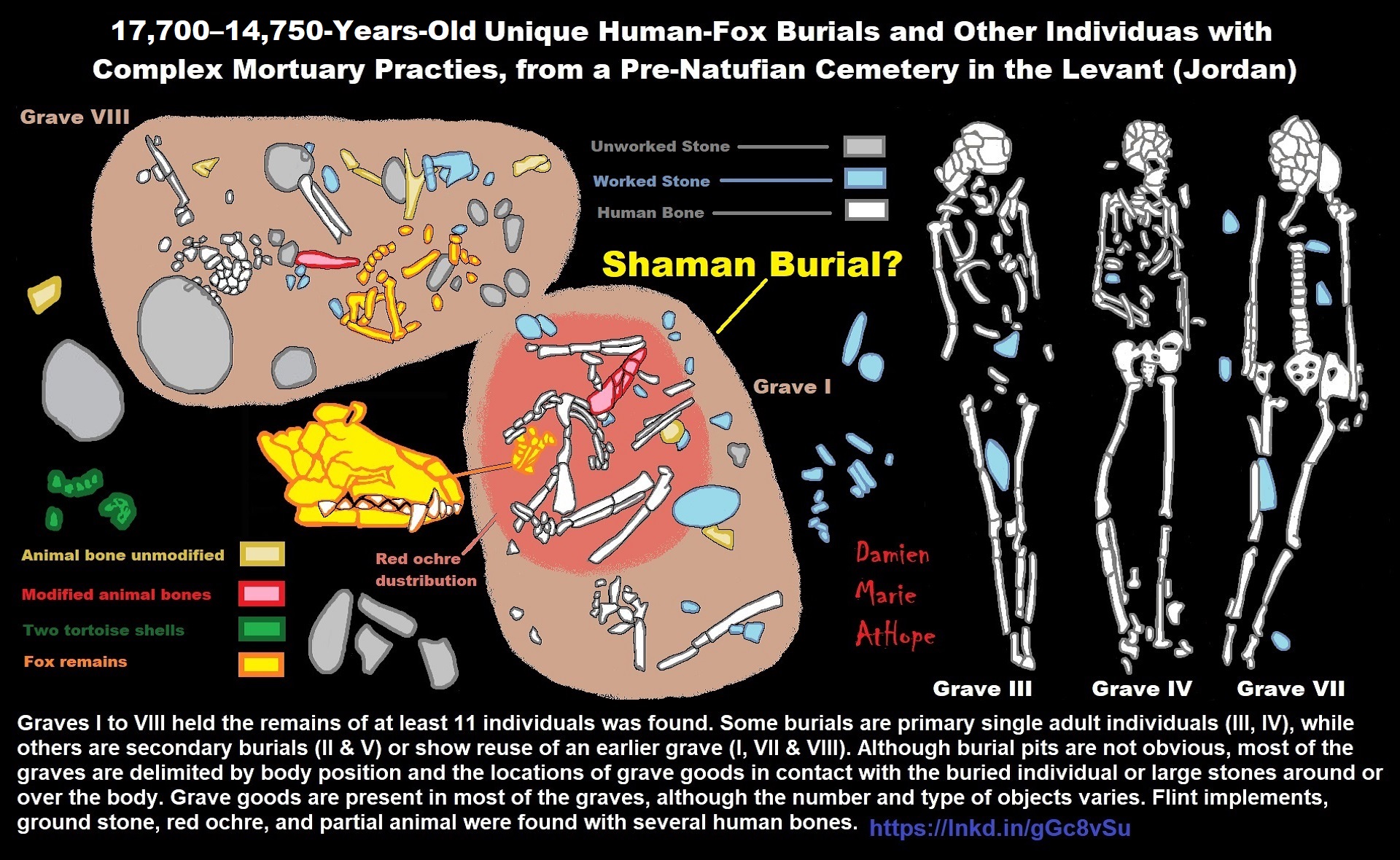

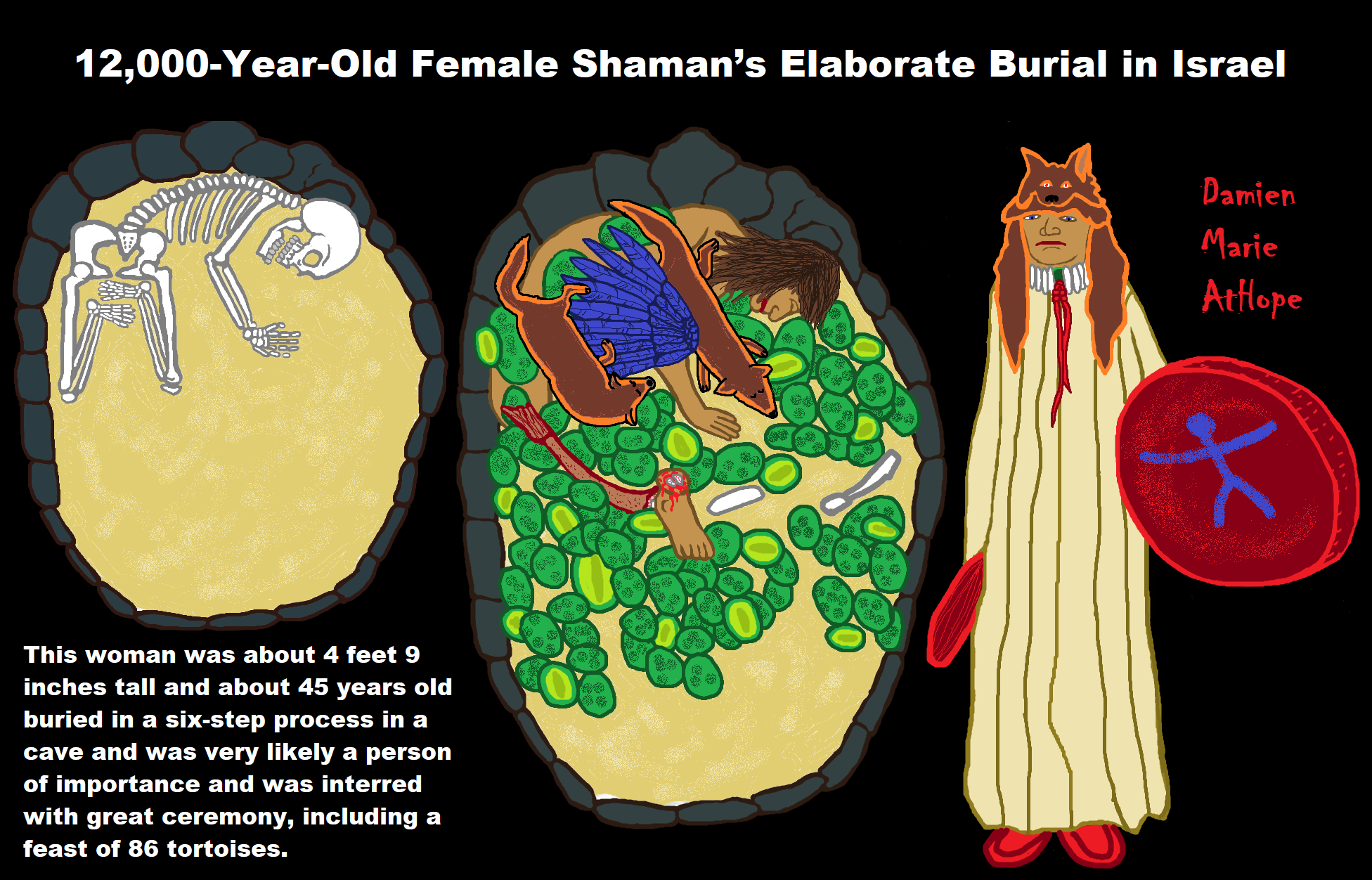

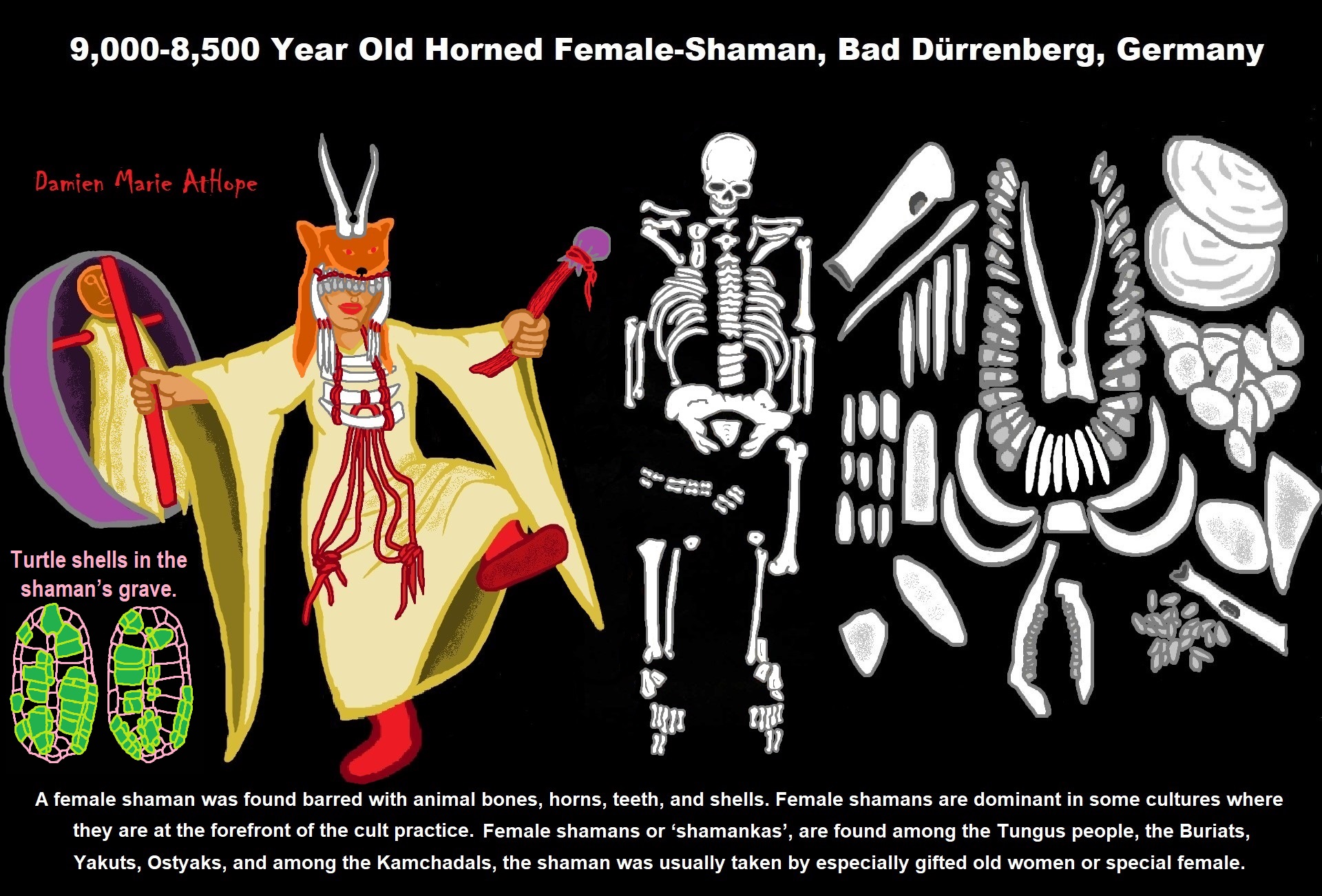

Chatting with John Hoopes

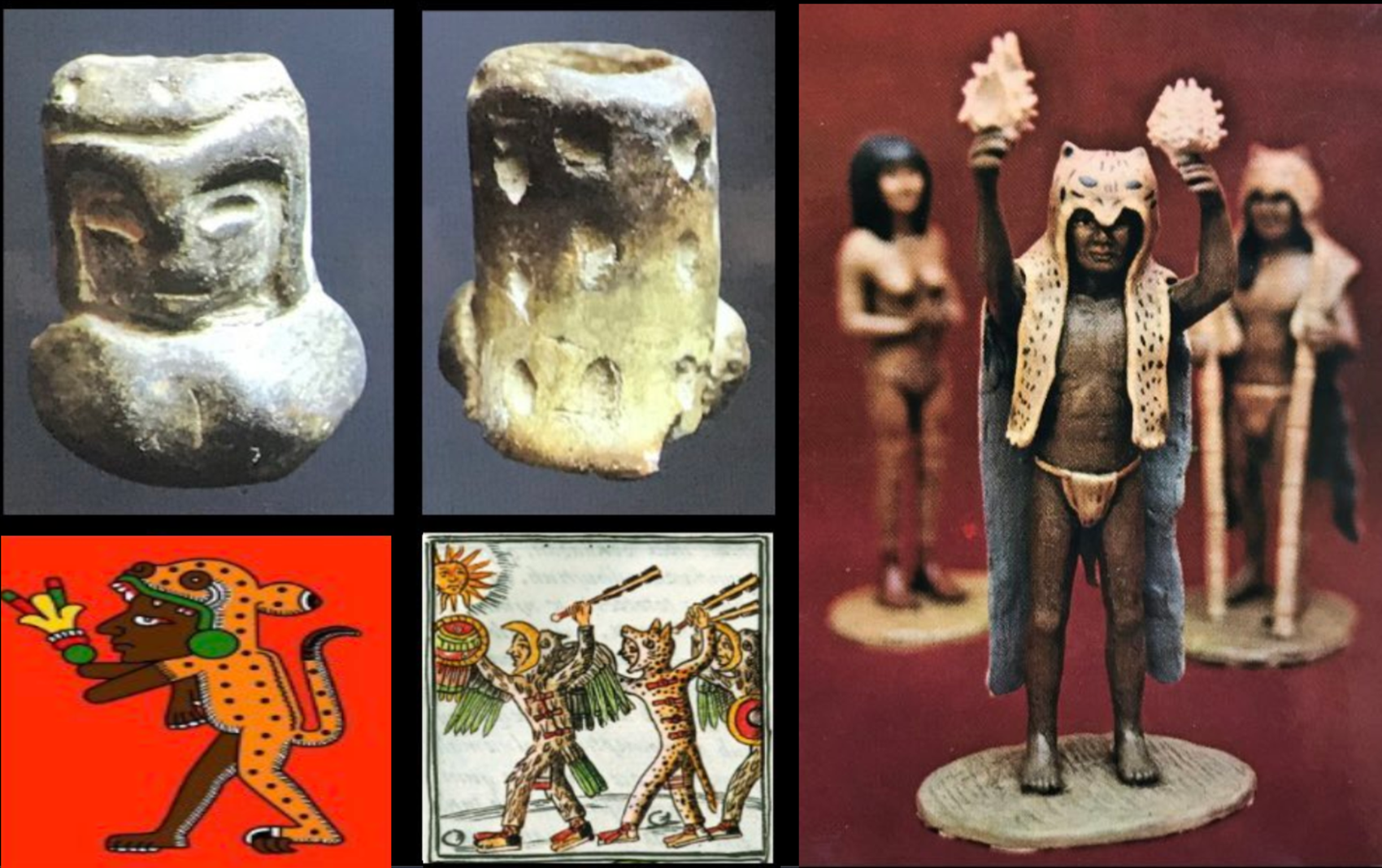

“The oldest known “shaman seats” are small ceramic models from the Valdivia culture in Ecuador that date to about 2500 BCE. Seats and their relations are such a rich source of information. I could do a whole book on just seats, stools, duhos, and thrones. Donald Lathrap thought this modeled spout was an early representation (ca. 2500 BCE) of a shaman wearing a jaguar pelt. You’ll be interested to know that I’m returning to more scholarship on shamanism.” – John Hoopes @KUHoopes (Anthropologist with broad training in the archaeology of pre-Hispanic indigenous cultures in Latin America)

My response, Wonderful, I look forward to learning more from you. I support you and all you do. I want to understand what is actually true. And I think it is an interesting topic as what seems like the emergence of male god/elite: socio-political or religious all are sitting around 7,000 years ago in the Balkins.

“Archaeology is all about getting as close as we can to the best possible approximation of the truth without actually declaring that we know it. We are always tinkering and fine-tuning as well as trying to answer more questions. As technical as those books from Dumbarton Oaks are, they do have art as the central focus. I’ve always felt that art is a more successful path to truth than science. It’s nice to combine the two. On the jadeite and gold objects: for the people who made and used them, they were tools for creating both magic and power. And together, the books help tell the story of peoples who have been largely forgotten but deserve to be remembered.” – John Hoopes @KUHoopes (Anthropologist with broad training in the archaeology of pre-Hispanic indigenous cultures in Latin America)

“The Isthmo-Colombian Area was the first part of the mainland to be colonized by the Spanish. As a consequence, its peoples were the first—after the Taíno of the Antilles—to suffer genocide and see their ancient cultures destroyed. However, because they did not build pyramids, they tend to be overlooked, even by archaeologists. The first Spanish colony on the mainland was in Panama in 1500. Cortes didn’t arrive in Mexico until 1519 and Pizarro didn’t reach Peru until 1532. The first place Columbus’s men set foot on the mainland was in southern Costa Rica.” – John Hoopes @KUHoopes (Anthropologist with broad training in the archaeology of pre-Hispanic indigenous cultures in Latin America)

“Conquest, Imagination, and the Dawn of the Modern Age: The Gold of Panama In Its Historical Context, this article helps put things in context. A lot of what shapes our world right now has roots in what happened back then. The anticipation of vast quantities of stolen gold from the Americas is the story that Charles V took to his bankers in order to get massive loans to underwrite the Spanish conquest. Ultimately, much less loot was found than was expected. Charles V ultimately stepped down because of his massive debts.” – John Hoopes @KUHoopes (Anthropologist with broad training in the archaeology of pre-Hispanic indigenous cultures in Latin America)

“However, in the meantime, these loans allowed Charles V to equip armies that successfully prevented Muslim armies from invading Central Europe. Ironically, the promise of gold from the Americas is what kept Europe Christian. And, of course, allowed the spread of Christianity in the Americas. It was the beginning of massive international debt and its consequences. The engine of capitalism. The beginning of the Modern Age. The notion of progress is highly overrated. For me, progress is discovering, recovering, and learning from what was destroyed long ago.” – John Hoopes @KUHoopes (Anthropologist with broad training in the archaeology of pre-Hispanic indigenous cultures in Latin America)

“The intimate relationship between European conquests of the Americas and the Protestant Reformation is worth exploring. Martin Luther was doing his thing as Cortes and his men were dismantling the Aztec empire. Jean Cauvin (John Calvin) was doing his thing as the Pizarros and their thugs were destroying the Inca empire. These big events of long ago shaped the world we have now.” – John Hoopes @KUHoopes (Anthropologist with broad training in the archaeology of pre-Hispanic indigenous cultures in Latin America)

My response, You have a lot to teach. I think you are great.

“Yes, and teachers gonna teach. Thanks. I do what I can but without getting all commercial about it. I get zero royalties from those books and don’t have anything to sell. In our capitalist society, that confuses people about the issue of value.” – John Hoopes @KUHoopes (Anthropologist with broad training in the archaeology of pre-Hispanic indigenous cultures in Latin America)

My response, I like how open you are to teaching for free. I do the same. I do plan on finishing writing my book, “The Tree of Lies and its Hidden Roots: exposing the evolution of religion and removing the rationale of faith.” I have been working on it for years. I will make something on it but will not try that hard to push it all the time. Rather, I will do a little promoting, and then I plan on transitioning to making my own Jewelry and doing that commercially. But still will do most things for free as I want to make my stuff available for anyone and money is not stopping them.

“The compensation that academic archaeologists get comes in the form of our salaries. In my case, that’s from a state university. So, public funds pay for my labor. I’m grateful for that and try to give back what I can.” – John Hoopes @KUHoopes (Anthropologist with broad training in the archaeology of pre-Hispanic indigenous cultures in Latin America)

My response, I am happy John, that public funds, pay for your labor as you are working on understanding humanity, from the past.

“Shaman Wearing a Jaguar Pelt”

Photo credits for the second Pic come from an Ecuadorian book about Valdivia.

shape-shift·er: one that seems able to change form or identity at will. especially: a mythical figure that can assume different forms (as of animals) ref

Shapeshifting

I am going eventually to do a blog post on shape-shifting beliefs, and how I see them likely emerging out of shamanism and then was often adopted when deity beliefs emerged.

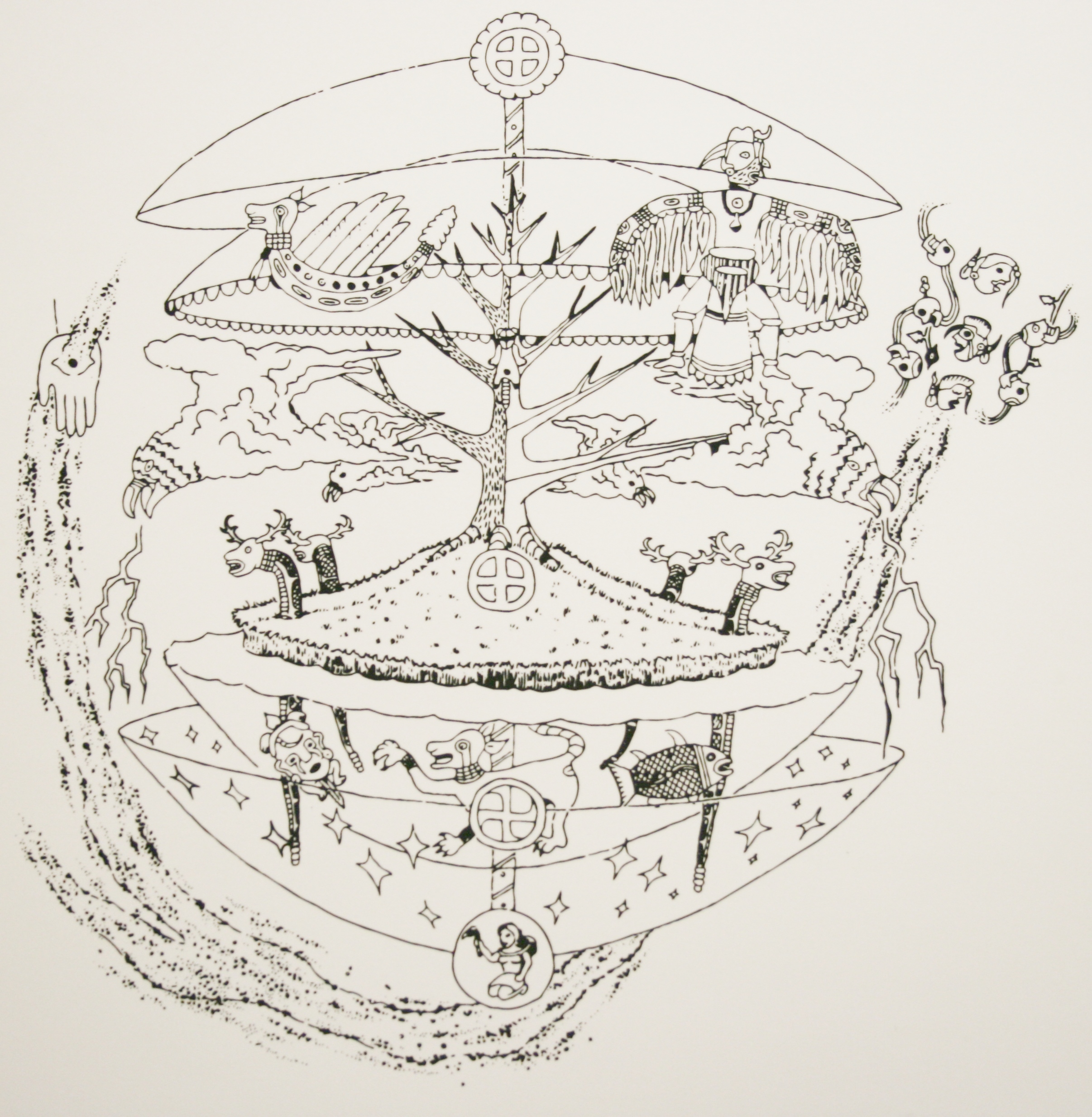

“In mythology, folklore, and speculative fiction, shapeshifting is the ability to physically transform oneself through unnatural means. The idea of shapeshifting is in the oldest forms of totemism and shamanism, as well as the oldest existent literature and epic poems such as the Epic of Gilgamesh and the Iliad.” ref

“Popular shapeshifting creatures in folklore are werewolves and vampires (mostly of European, Canadian, and Native American/early American origin), ichchadhari naag and ichchadhari naagin (shapeshifting cobras) of India, the huli jing of East Asia (including the Japanese kitsune and Korean kumiho), and the gods, goddesses, and demons and demonesses like succubus and incubus and other numerous mythologies, such as the Norse Loki or the Greek Proteus. Shapeshifting to the form of a gray wolf is specifically known as lycanthropy, and such creatures who undergo such change are called lycanthropes. Therianthropy is the more general term for human-animal shifts, but it is rarely used in that capacity. It was also common for deities to transform mortals into animals and plants.” ref

“Other terms for shapeshifters include metamorph, the Navajo skin-walker, mimic, and therianthrope. The prefix “were-“, coming from the Old English word for “man” (masculine rather than generic), is also used to designate shapeshifters; despite its root, it is used to indicate female shapeshifters as well. While the popular idea of a shapeshifter is of a human being who turns into something else, there are numerous stories about animals that can transform themselves as well.” ref

“Examples of shapeshifting in classical literature include many examples in Ovid‘s Metamorphoses, Circe‘s transforming of Odysseus‘ men to pigs in Homer‘s The Odyssey, and Apuleius‘s Lucius becoming a donkey in The Golden Ass. Proteus was noted among the gods for his shapeshifting; both Menelaus and Aristaeus seized him to win information from him, and succeeded only because they held on during his various changes. Nereus told Heracles where to find the Apples of the Hesperides for the same reason.” ref

“The Oceanid Metis, the first wife of Zeus and the mother of the goddess Athena was believed to be able to change her appearance into anything she wanted. In one story, she was so proud, that her husband, Zeus, tricked her into changing into a fly. He then swallowed her because he feared that he and Metis would have a son who would be more powerful than Zeus himself. Metis, however, was already pregnant. She stayed alive inside his head and built armor for her daughter. The banging of her metalworking made Zeus have a headache, so Hephaestus clove his head with an axe. Athena sprang from her father’s head, fully grown, and in battle armor.” ref

“In Greek mythology, the transformation is often a punishment from the gods to humans who crossed them.

- Zeus transformed King Lycaon and his children into wolves (hence lycanthropy) as a punishment for either killing Zeus’ children or serving him the flesh of Lycaon’s own murdered son Nyctimus, depending on the exact version of the myth.

- Ares assigned Alectryon to keep watch for Helios the sun god during his affair with Aphrodite, but Alectryon fell asleep, leading to their discovery and humiliation that morning. Ares turned Alectryon into a rooster, which always crows to signal the morning and the arrival of the sun.

- Demeter transformed Ascalabus into a lizard for mocking her sorrow and thirst during her search for her daughter Persephone. She also turned King Lyncus into a lynx for trying to murder her prophet Triptolemus.

- Athena transformed Arachne into a spider for challenging her as a weaver and/or weaving a tapestry that insulted the gods. She also turned Nyctimene into an owl, though in this case it was an act of mercy, as the girl wished to hide from the daylight out of shame of being raped by her father.

- Artemis transformed Actaeon into a stag for spying on her bathing, and he was later devoured by his hunting dogs.

- Galanthis was transformed into a weasel or cat after interfering in Hera‘s plans to hinder the birth of Heracles.

- Atalanta and Hippomenes were turned into lions after making love in a temple dedicated to Zeus or Cybele.

- Io was a priestess of Hera in Argos, a nymph who was raped by Zeus, who changed her into a heifer to escape detection.

- Hera punished young Tiresias by transforming him into a woman and, seven years later, back into a man.

- King Tereus, his wife Procne, and her sister Philomela were all turned into birds (a hoopoe, a swallow and a nightingale respectively), after Tereus raped Philomela and cut out her tongue, and in revenge she and Procne served him the flesh of his murdered son Itys (who in some variants is resurrected as a goldfinch).

- Callisto was turned into a bear by either Artemis or Hera for being impregnated by Zeus.

- Selene transformed Myia into a fly when she became a rival for the love of Endymion.” ref

“While the Greek gods could use transformation punitively – such as Medusa, who turned to a monster for having sexual intercourse (raped in Ovid’s version) with Poseidon in Athena‘s temple – even more frequently, the tales using it are of amorous adventure. Zeus repeatedly transformed himself to approach mortals as a means of gaining access:

- Danaë as a shower of gold

- Europa as a bull

- Leda as a swan

- Ganymede, as an eagle

- Alcmene as her husband Amphitryon

- Hera as a cuckoo

- Aegina as an eagle or a flame

- Persephone as a serpent

- Io, as a cloud

- Callisto as either Artemis or Apollo

- Nemesis (Goddess of retribution) transformed into a goose to escape Zeus‘ advances, but he turned into a swan. She later bore the egg in which Helen of Troy was found.” ref

“Vertumnus transformed himself into an old woman to gain entry to Pomona‘s orchard; there, he persuaded her to marry him. In other tales, the woman appealed to other gods to protect her from rape, and was transformed (Daphne into laurel, Corone into a crow). Unlike Zeus and other gods’ shapeshifting, these women were permanently metamorphosed. In one tale, Demeter transformed herself into a mare to escape Poseidon, but Poseidon counter-transformed himself into a stallion to pursue her, and succeeded in the rape. Caenis, having been raped by Poseidon, demanded of him that she be changed to a man. He agreed, and she became Caeneus, a form he never lost, except, in some versions, upon death.” ref

“Clytie was a nymph who loved Helios, but he did not love her back. Desperate, she sat on a rock with no food or water for nine days looking at him as he crossed the skies, until she was transformed into a purple, sun-gazing flower, the heliotropium. As a final reward from the gods for their hospitality, Baucis and Philemon were transformed, at their deaths, into a pair of trees. Eos, the goddess of the dawn, secured immortality for her lover the Trojan prince Tithonus, but not eternal youth, so he aged without dying as he shriveled and grew more and more helpless. In the end, Eos transformed him into a cicada. In some variants of the tale of Narcissus, he is turned into a narcissus flower.” ref

“Sometimes metamorphoses transform objects into humans. In the myths of both Jason and Cadmus, one task set to the hero was to sow dragon’s teeth; on being sown, they would metamorphose into belligerent warriors, and both heroes had to throw a rock to trick them into fighting each other to survive. Deucalion and Pyrrha repopulated the world after a flood by throwing stones behind them; they were transformed into people. Cadmus is also often known to have transformed into a dragon or serpent towards the end of his life. Pygmalion fell in love with Galatea, a statue he had made. Aphrodite had pity on him and transformed the stone into a living woman.” ref

“Fairies, witches, and wizards were all noted for their shapeshifting ability. Not all fairies could shapeshift, some having only the appearance of shapeshifting, through their power, called “glamour”, to create illusions, and some were limited to changing their size, as with the spriggans, and others to a few forms. But others, such as the Hedley Kow, could change to many forms, and both human and supernatural wizards were capable of both such changes, and inflicting them on others.” ref

“In Celtic mythology, Pwyll was transformed by Arawn into Arawn’s shape, and Arawn transformed himself into Pwyll’s so that they could trade places for a year and a day. Llwyd ap Cil Coed transformed his wife and attendants into mice to attack a crop in revenge; when his wife is captured, he turns himself into three clergymen in succession to try to pay a ransom.” ref

“Math fab Mathonwy and Gwydion transform flowers into a woman named Blodeuwedd, and when she betrays her husband Lleu Llaw Gyffes, who is transformed into an eagle, they transform her again, into an owl. Gilfaethwy committed rape on Goewin, Math fab Mathonwy’s virgin foothold, with help from his brother Gwydion. Both were transformed into animals, for one year each. Gwydion was transformed into a stag, sow, and wolf, and Gilfaethwy into a hind, boar, and she-wolf. Each year, they had a child. Math turned the three young animals into boys.” ref

“Gwion, having accidentally taken some of the wisdom potions that Ceridwen was brewing for her son, fled from her through a succession of changes that she answered with changes of her own, ending with his being eaten, a grain of corn, by her as a hen. She became pregnant, and he was reborn in a new form, as Taliesin.” ref

“Tales abound about the selkie, a seal that can remove its skin to make contact with humans for only a short amount of time before it must return to the sea. Clan MacColdrum of Uist‘s foundation myths include a union between the founder of the clan and a shape-shifting selkie. Another such creature is the Scottish selkie, which needs its sealskin to regain its form. In The Great Silkie of Sule Skerry the (male) selkie seduces a human woman. Such stories surrounding these creatures are usually romantic tragedies.” ref

“Scottish mythology features shapeshifters, which allows the various creatures to trick, deceive, hunt, and kill humans. Water spirits such as the each-uisge, which inhabit lochs and waterways in Scotland, were said to appear as a horse or a young man. Other tales include kelpies who emerge from lochs and rivers in the disguise of a horse or woman to ensnare and kill weary travelers. Tam Lin, a man captured by the Queen of the Fairies is changed into all manner of beasts before being rescued. He finally turned into a burning coal and was thrown into a well, whereupon he reappeared in his human form. The motif of capturing a person by holding him through all forms of transformation is a common thread in folktales.” ref

“Perhaps the best-known Irish myth is that of Aoife who turned her stepchildren, the Children of Lir, into swans to be rid of them. Likewise, in the Tochmarc Étaíne, Fuamnach jealously turns Étaín into a butterfly. The most dramatic example of shapeshifting in Irish myth is that of Tuan mac Cairill, the only survivor of Partholón‘s settlement of Ireland. In his centuries-long life, he became successively a stag, a wild boar, a hawk, and finally a salmon before being eaten and (as in the Wooing of Étaín) reborn as a human.” ref

The Púca is a Celtic faery, and also a deft shapeshifter. He can transform into many different, terrifying forms. Sadhbh, the wife of the famous hero Fionn mac Cumhaill, was changed into a deer by the druid Fer Doirich when she spurned his amorous interests. There is a significant amount of literature about shapeshifters that appear in a variety of Norse tales. In the Lokasenna, Odin and Loki taunt each other with having taken the form of females and nursing offspring to which they had given birth. A 13th-century Edda relates Loki taking the form of a mare to bear Odin’s steed Sleipnir which was the fastest horse ever to exist, and also the form of a she-wolf to bear Fenrir.” ref

“Svipdagr angered Odin, who turned him into a dragon. Despite his monstrous appearance, his lover, the goddess Freyja, refused to leave his side. When the warrior Hadding found and slew Svipdagr, Freyja cursed him to be tormented by a tempest and shunned like the plague wherever he went. In the Hyndluljóð, Freyja transformed her protégé Óttar into a boar to conceal him. She also possessed a cloak of falcon feathers that allowed her to transform into a falcon, which Loki borrowed on occasion.” ref

“The Volsunga saga contains many shapeshifting characters. Siggeir‘s mother changed into a wolf to help torture his defeated brothers-in-law with slow and ignominious deaths. When one, Sigmund, survived, he and his nephew and son Sinfjötli killed men wearing wolfskins; when they donned the skins themselves, they were cursed to become werewolves. The dwarf Andvari is described as being able to magically turn into a pike. Alberich, his counterpart in Richard Wagner‘s Der Ring des Nibelungen, using the Tarnhelm, takes on many forms, including a giant serpent and a toad, in a failed attempt to impress or intimidate Loki and Odin/Wotan.” ref

“Fafnir was originally a dwarf, a giant, or even a human, depending on the exact myth, but in all variants, he transformed into a dragon—a symbol of greed—while guarding his ill-gotten hoard. His brother, Ótr, enjoyed spending time as an otter, which led to his accidental slaying by Loki. In Scandinavia, there existed, for example, the famous race of she-werewolves known by the name of Maras, women who took on the appearance of huge half-human and half-wolf monsters that stalked the night in search of human or animal prey. If a woman gives birth at midnight and stretches the membrane that envelopes the child when it is brought forth, between four sticks and creeps through it, naked, she will bear children without pain; but all the boys will be shamans, and all the girls Maras.” ref

“The Nisse is sometimes said to be a shapeshifter. This trait also is attributed to Hulder. Gunnhild, Mother of Kings (Gunnhild konungamóðir) (c. 910 – c. 980), a quasi-historical figure who appears in the Icelandic Sagas, according to which she was the wife of Eric Bloodaxe, was credited with magic powers – including the power of shapeshifting and turning at will into a bird. She is the central character of the novel Mother of Kings by Poul Anderson, which considerably elaborates on her shapeshifting abilities.” ref

“In Armenian mythology, shapeshifters include the Nhang, a serpentine river monster that can transform itself into a woman or seal, and will drown humans and then drink their blood; or the beneficial Shahapet, a guardian spirit that can appear either as a man or a snake. Tatar folklore includes Yuxa, a hundred-year-old snake that can transform itself into a beautiful young woman, and seeks to marry men to have children.” ref

Indian

- Shapeshifting cobra: A common male cobra will become an ichchadhari naag (male shapeshifting cobra) and a common female cobra will become an ichchadhari naagin (female shapeshifting cobra) after 100 years of tapasya (penance). After being blessed by Lord Shiva, they attain a human form of their own, can shapeshift into any living creature, and can live for more than a hundred years without getting old.

- Yoginis were associated with the power of shapeshifting into female animals.

- In the Indian fable The Dog Bride from Folklore of the Santal Parganas by Cecil Henry Bompas, a buffalo herder falls in love with a dog that has the power to turn into a woman when she bathes.

- In Kerala, there was a legend about the Odiyan clan, who in Kerala folklore are men believed to possess shapeshifting abilities and can assume animal forms. Odiyans are said to have inhabited the Malabar region of Kerala before the widespread use of electricity.” ref

“Chinese mythology contains many tales of animal shapeshifters, capable of taking on human form. The most common such shapeshifter is the huli jing, a fox spirit that usually appears as a beautiful young woman; most are dangerous, but some feature as the heroines of love stories. Madame White Snake is one such legend; a snake falls in love with a man, and the story recounts the trials she and her husband faced.” ref

“In Japanese folklore obake are a type of yōkai with the ability to shapeshifting. The fox, or kitsune is among the most commonly known, but other such creatures include the bakeneko, the mujina, and the tanuki. Korean mythology also contains a fox with the ability to shapeshift. Unlike its Chinese and Japanese counterparts, the kumiho is always malevolent. Usually its form is of a beautiful young woman; one tale recounts a man, a would-be seducer, revealed as a kumiho. The kumiho has nine tails and as she desires to be a full human, she uses her beauty to seduce men and eat their hearts (or in some cases livers where the belief is that 100 livers would turn her into a real human).” ref

“Philippine mythology includes the Aswang, a vampiric monster capable of transforming into a bat, a large black dog, a black cat, a black boar, or some other form to stalk humans at night. The folklore also mentions other beings such as the Kapre, the Tikbalang, and the Engkanto, which change their appearances to woo beautiful maidens. Also, talismans (called “anting-anting” or “birtud” in the local dialect), can give their owners the ability to shapeshift. In one tale, Chonguita the Monkey Wife, a woman is turned into a monkey, only becoming human again if she can marry a handsome man.” ref

“In Somali mythology Qori ismaris (“One who rubs himself with a stick”) was a man who could transform himself into a “Hyena-man” by rubbing himself with a magic stick at nightfall and by repeating this process could return to his human state before dawn. ǀKaggen is a demi-urge and folk hero of the ǀXam people of southern Africa. He is a trickster god who can shape shift, usually taking the form of a praying mantis but also a bull eland, a louse, a snake, and a caterpillar. The Ligahoo or loup-garou is the shapeshifter of Trinidad and Tobago’s folklore. This unique ability is believed to be handed down in some old creole families, and is usually associated with witch-doctors and practitioners of African magic.” ref

“Mapuche (Argentina and Chile), The name of the Nahuel Huapi Lake in Argentina derives from the toponym of its major island in Mapudungun (Mapuche language): “Island of the Jaguar (or Puma)”, from nahuel, “puma (or jaguar)”, and huapí, “island”. There is, however, more to the word “Nahuel” – it can also signify “a man who by sorcery has been transformed into a puma” (or jaguar). In Slavic mythology, one of the main gods Veles was a shapeshifting god of animals, magic and the underworld. He was often represented as a bear, wolf, snake or owl. He also became a dragon while fighting Perun, the Slavic storm god.” ref

Therianthropy

“Therianthropy is the mythological ability or affliction of individuals to metamorphose into animals or hybrids by means of shapeshifting. It is possible that cave drawings found at Cave of the Trois-Frères, in France, depict ancient beliefs in the concept. The best-known form of therianthropy, called lycanthropy, is found in stories of werewolves. Therianthropy was used to describe spiritual beliefs in animal transformation in a 1915 Japanese publication, A History of the Japanese People from the Earliest Times to the End of the Meiji Era.” ref

“Therianthropy refers to the fantastical, or mythological, ability of some humans to change into animals. Therianthropes are said to change forms via shapeshifting. Therianthropy has long existed in mythology, and seems to be depicted in ancient cave drawings such as The Sorcerer, a pictograph executed at the Palaeolithic cave drawings found in the Pyrenees at the Cave of the Trois-Frères, France, archeological site. Theriocephaly (Greek “animal headedness”) refers to beings that have an animal head attached to an anthropomorphic, or human, body; for example, the animal-headed forms of gods depicted in ancient Egyptian religion (such as Ra, Sobek, Anubis).” ref

Skin-walkers and naguals

“Some Native American and First Nation legends talk about skin-walkers—people with the supernatural ability to turn into any animal they desire. To do so, however, they first must be wearing a pelt of the specific animal. In the folk religion of Mesoamerica, a nagual (or nahual) is a human being who has the power to magically turn themselves into animal forms—most commonly donkeys, turkeys, and dogs—but can also transform into more powerful jaguars and pumas.” ref

Animal Ancestors

“Stories of humans descending from animals are found in the oral traditions of many tribal and clan origins. Sometimes the original animals had assumed human form in order to ensure their descendants retained their human shapes; other times the origin story is of a human marrying a normal animal. North American indigenous traditions mingle the ideas of bear ancestors and ursine shapeshifters, with bears often being able to shed their skins to assume human form, marrying human women in this guise. The offspring may be creatures with combined anatomy, they may be very beautiful children with uncanny strength, or they may be shapeshifters themselves.” ref

“P’an Hu is represented in various Chinese legends as a supernatural dog, a dog-headed man, or a canine shapeshifter that married an emperor’s daughter and founded at least one race. When he is depicted as a shapeshifter, all of him can become human except for his head. The race(s) descended from P’an Hu were often characterized by Chinese writers as monsters who combined human and dog anatomy. In Turkic mythology, the wolf is a revered animal. The Turkic legends say the people were descendants of wolves. The legend of Asena is an old Turkic myth that tells of how the Turkic people were created. In the legend, a small Turkic village in northern China is raided by Chinese soldiers, with one baby left behind. An old she-wolf with a sky-blue mane named Asena finds the baby and nurses him. She later gives birth to half-wolf, half-human cubs who are the ancestors of the Turkic people.” ref

“In Melanesian cultures there exists the belief in the tamaniu or atai, which describes the animal counterpart to a person. Specifically among the Solomon Islands in Melanesia, the term atai means “soul” in the Mota language and is closely related to the term ata, meaning a “reflected image” in Maori and “shadow” in Samoan. Terms relating to the “spirit” in these islands such as figona and vigona convey a being that has not been in human form The animal counterpart depicted may take the form of an eel, shark, lizard, or some other creature. This creature is considered to be corporeal and can understand human speech. It shares the same soul as its master. This concept is found in similar legends which have many characteristics typical of shapeshifter tales. Among these characteristics is the theory that death or injury would affect both the human and animal form at once.” ref

“Among a sampled set of psychiatric patients, the belief of being part animal, or clinical lycanthropy, is generally associated with severe psychosis but not always with any specific psychiatric diagnosis or neurological findings. Others regard clinical lycanthropy as a delusion in the sense of the self-disorder found in affective and schizophrenic disorders, or as a symptom of other psychiatric disorders.” ref

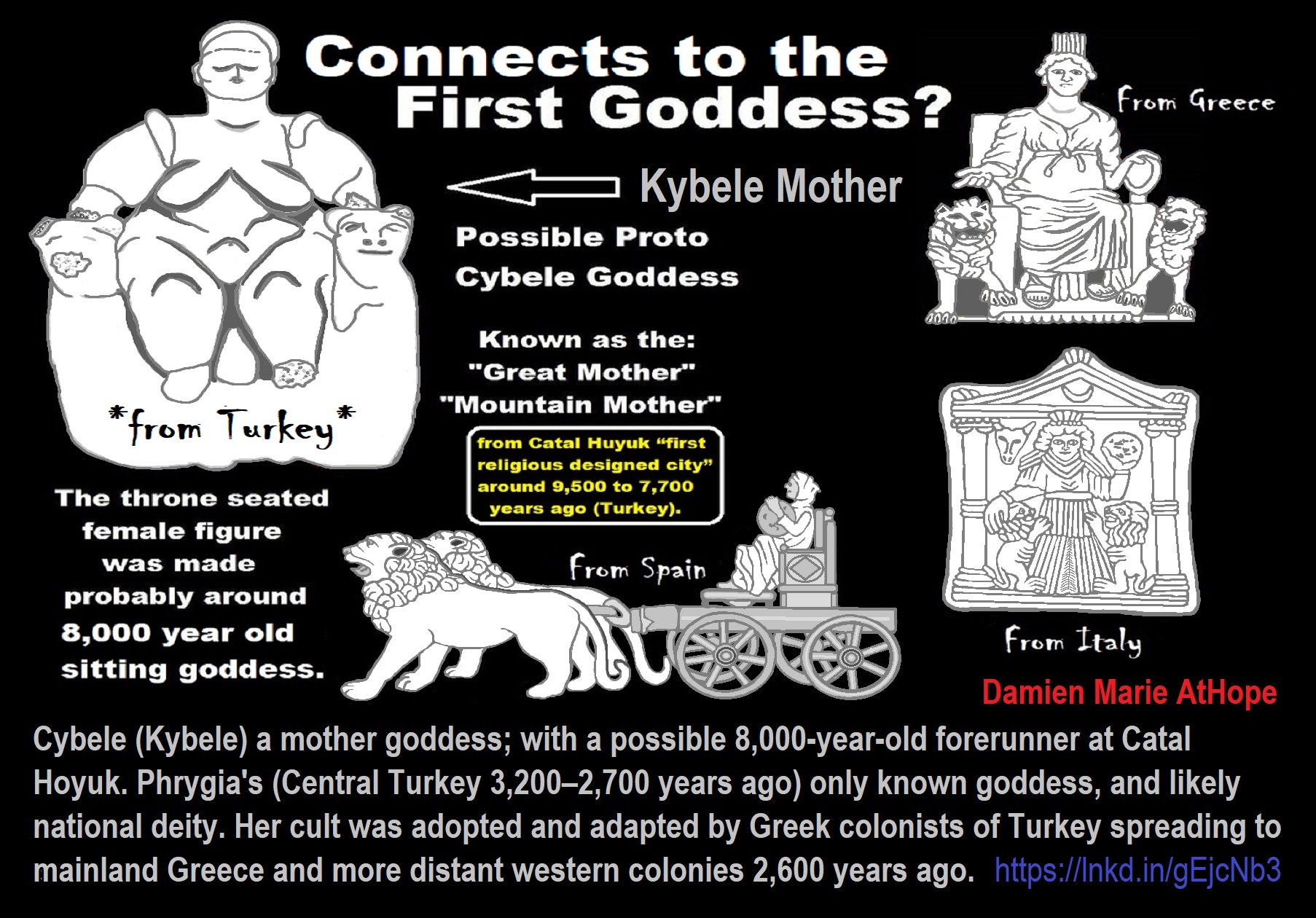

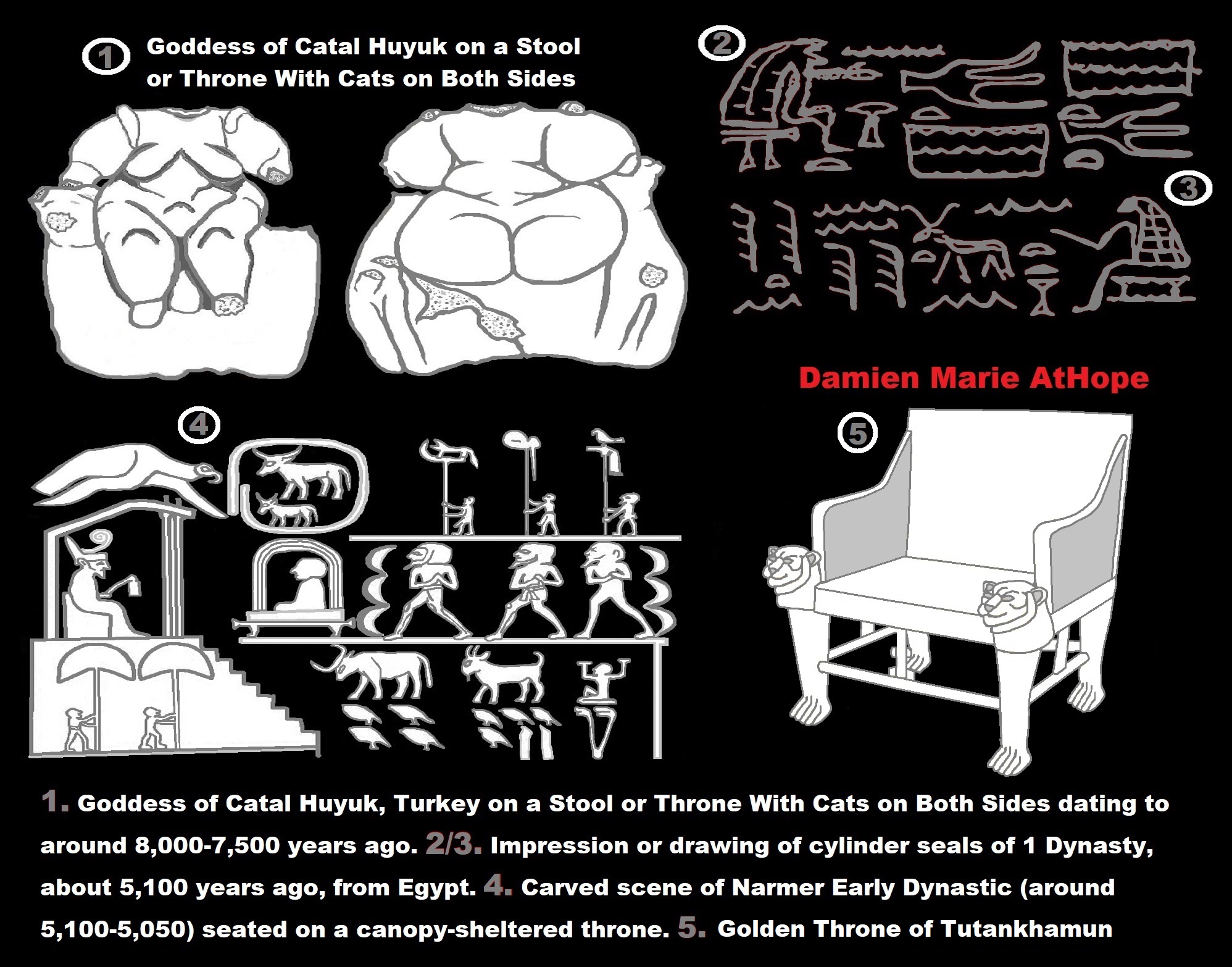

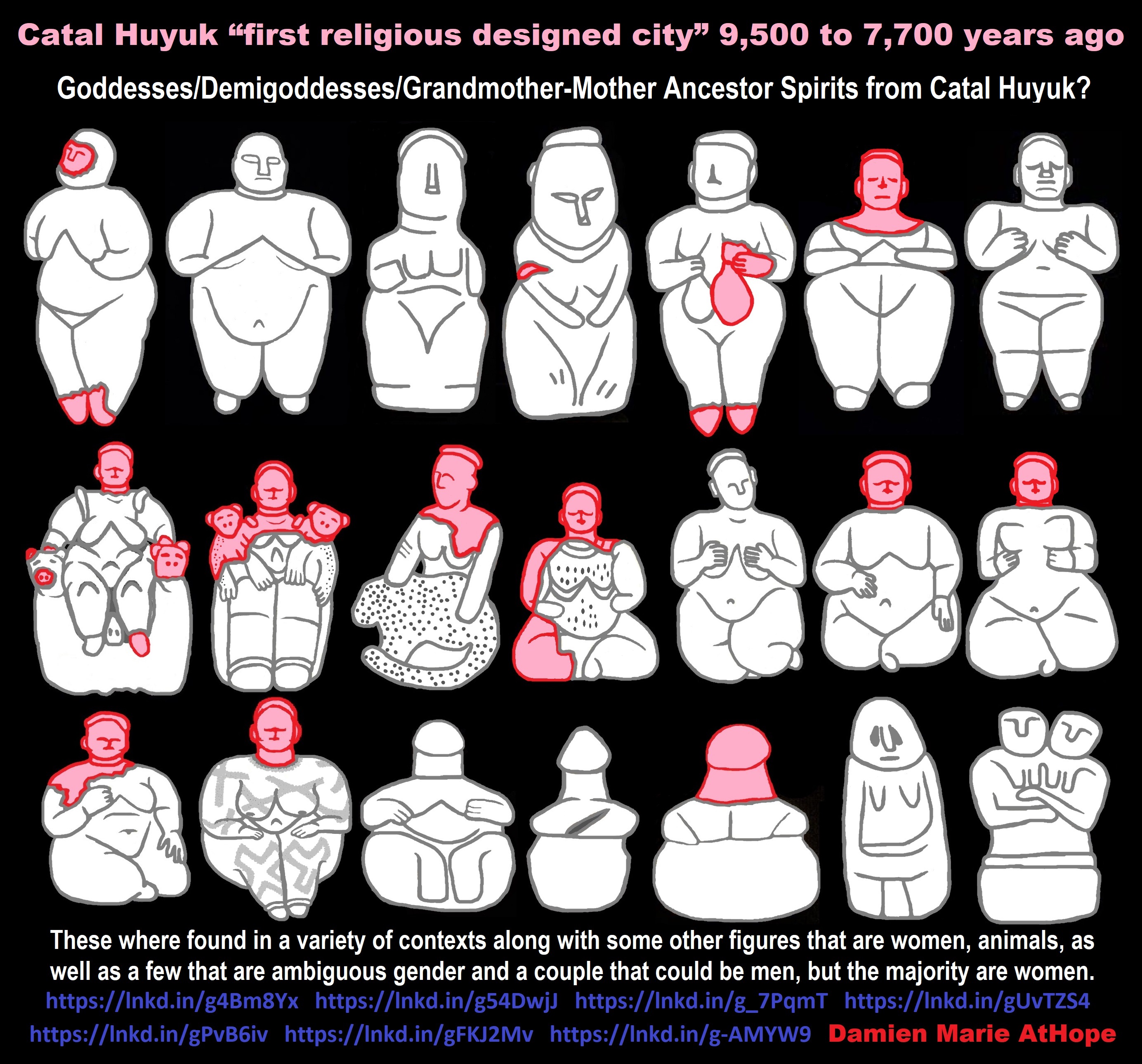

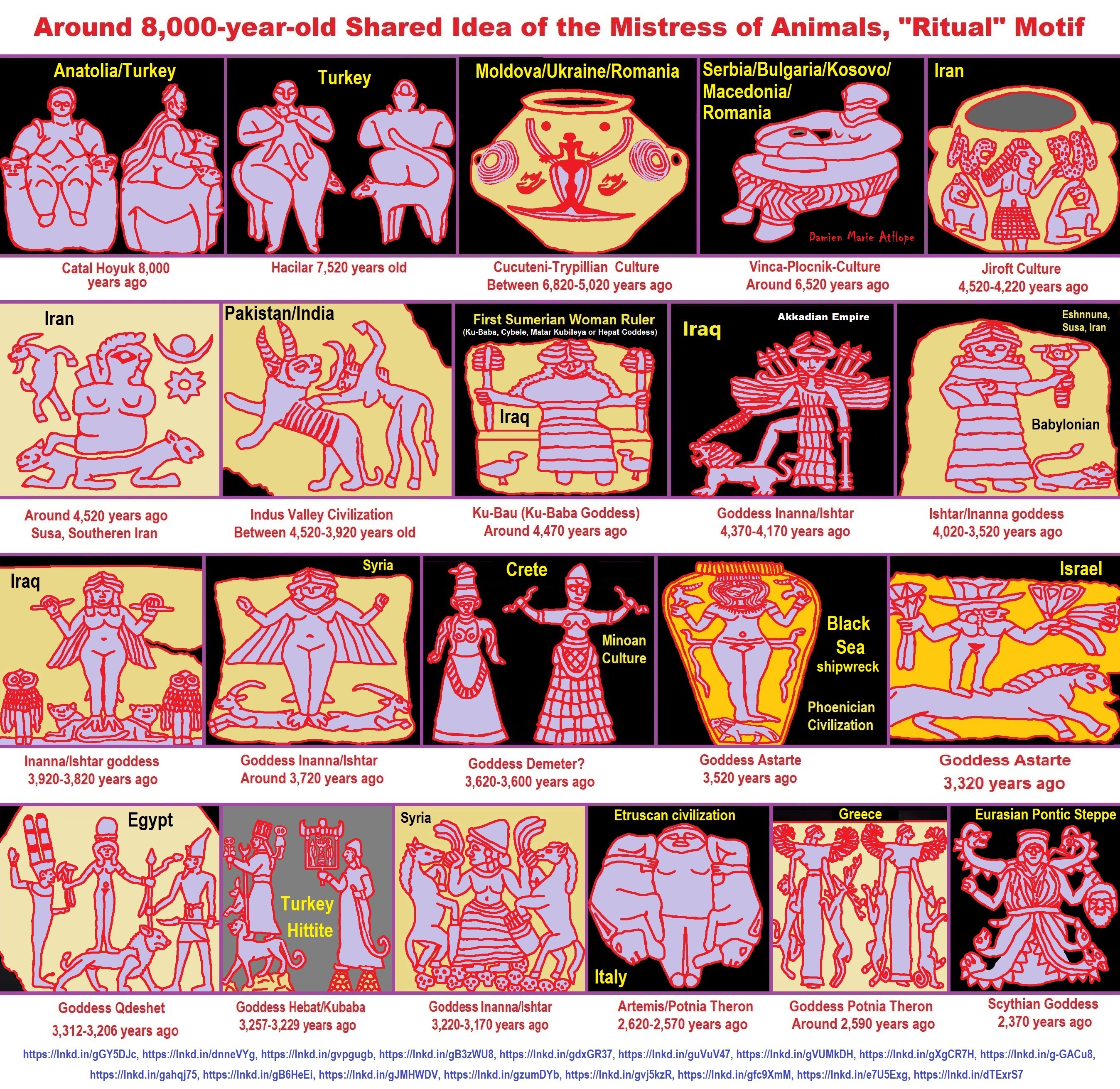

Seated Woman of Çatalhöyük

“The Seated Woman of Çatalhöyük (also Çatal Höyük) is a baked-clay, nude female form, seated between feline-headed arm-rests. It is generally thought to depict a corpulent and fertile Mother goddess in the process of giving birth while seated on her throne, which has two hand rests in the form of feline (lioness, leopard, or panther) heads in a Mistress of Animals motif. The statuette, one of several iconographically similar ones found at the site, is associated to other corpulent prehistoric goddess figures, of which the most famous is the Venus of Willendorf. It is a neolithic sculpture shaped by an unknown artist, and was completed in approximately 6000 BCE.” ref

Kubaba

“Kubaba is the only queen on the Sumerian King List, which states she reigned for 100 years – roughly in the Early Dynastic III period (ca. 2500–2330 BCE) of Sumerian history. A connection between her and a goddess known from Hurro–Hittite and later Luwian sources cannot be established on the account of spatial and temporal differences. Kubaba is one of very few women to have ever ruled in their own right in Mesopotamian history. Most versions of the king list place her alone in her own dynasty, the 3rd Dynasty of Kish, following the defeat of Sharrumiter of Mari, but other versions combine her with the 4th dynasty, that followed the primacy of the king of Akshak. Before becoming monarch, the king list says she was an alewife, brewess or brewster, terms for a woman who brewed alcohol.” ref

“Kubaba was a Syrian goddess associated particularly closely with Alalakh and Carchemish. She was adopted into the Hurrian and Hittite pantheons as well. After the fall of the Hittite empire, she continued to be venerated by Luwians. A connection between her and the similarly named legendary Sumerian queen Kubaba of Kish, while commonly proposed, cannot be established due to spatial and temporal differences. Emmanuel Laroche proposed in 1960 that Kubaba and Cybele were one and the same. This view is supported by Mark Munn, who argues that the Phrygian name Kybele developed from Lydian adjective kuvavli, first changed into kubabli and then simplified into kuballi, and finally kubelli. However, such an adjective is a purely speculative construction.” ref

Cybele

“Cybele (Phrygian: “Kubileya/Kubeleya Mother”, perhaps “Mountain Mother”) is an Anatolian mother goddess; she may have a possible forerunner in the earliest neolithic at Çatalhöyük, where statues of plump women, sometimes sitting, have been found in excavations. Phrygia‘s only known goddess, she was probably its national deity. Greek colonists in Asia Minor adopted and adapted her Phrygian cult and spread it to mainland Greece and to the more distant western Greek colonies around the 6th century BCE. In Greece, Cybele met with a mixed reception. She became partially assimilated to aspects of the Earth-goddess Gaia, of her possibly Minoan equivalent Rhea, and of the harvest–mother goddess Demeter. Some city-states, notably Athens, evoked her as a protector, but her most celebrated Greek rites and processions show her as an essentially foreign, exotic mystery-goddess who arrives in a lion-drawn chariot to the accompaniment of wild music, wine, and a disorderly, ecstatic following.” ref

“Uniquely in Greek religion, she had a eunuch mendicant priesthood. Many of her Greek cults included rites to a divine Phrygian castrate shepherd-consort Attis, who was probably a Greek invention. In Greece, Cybele became associated with mountains, town and city walls, fertile nature, and wild animals, especially lions. In Rome, Cybele became known as Magna Mater (“Great Mother”). The Roman State adopted and developed a particular form of her cult after the Sibylline oracle in 205 BCE recommended her conscription as a key religious ally in Rome’s second war against Carthage (218 to 201 BCE). Roman mythographers reinvented her as a Trojan goddess, and thus an ancestral goddess of the Roman people by way of the Trojan prince Aeneas. As Rome eventually established hegemony over the Mediterranean world, Romanized forms of Cybele’s cults spread throughout Rome’s empire. Greek and Roman writers debated and disputed the meaning and morality of her cults and priesthoods, which remain controversial subjects in modern scholarship.” ref

“Isis was a major goddess in ancient Egyptian religion believed to help the dead enter the afterlife. She was usually portrayed in art as a human woman wearing a throne-like hieroglyph on her head. During the New Kingdom (3,550–3,070 years ago), as she took on traits that originally belonged to Hathor, the preeminent goddess of earlier times, Isis came to be portrayed wearing Hathor’s headdress: a sun disk between the horns of a cow. Likewise, the expression of moon disks headdress: a moon disk between the horns of a cow. Her reputed magical power was greater than that of all other gods, and she was said to protect the kingdom from its enemies, govern the skies and the natural world, and have power over fate itself. Whereas some Egyptian deities appeared in the late Predynastic Period (before 5,100 years ago), neither Isis nor her husband Osiris were clearly mentioned before the Fifth Dynasty (4,494–4,345 years ago). The hieroglyphic writing of her name incorporates the sign for a throne, which Isis also wears on her head as a sign of her identity. Like other goddesses, such as Hathor, she also acted as a mother to the deceased, providing protection and nourishment. Thus, like Hathor, she sometimes took the form of Imentet, the goddess of the west, who welcomed the deceased soul into the afterlife as her child.” ref