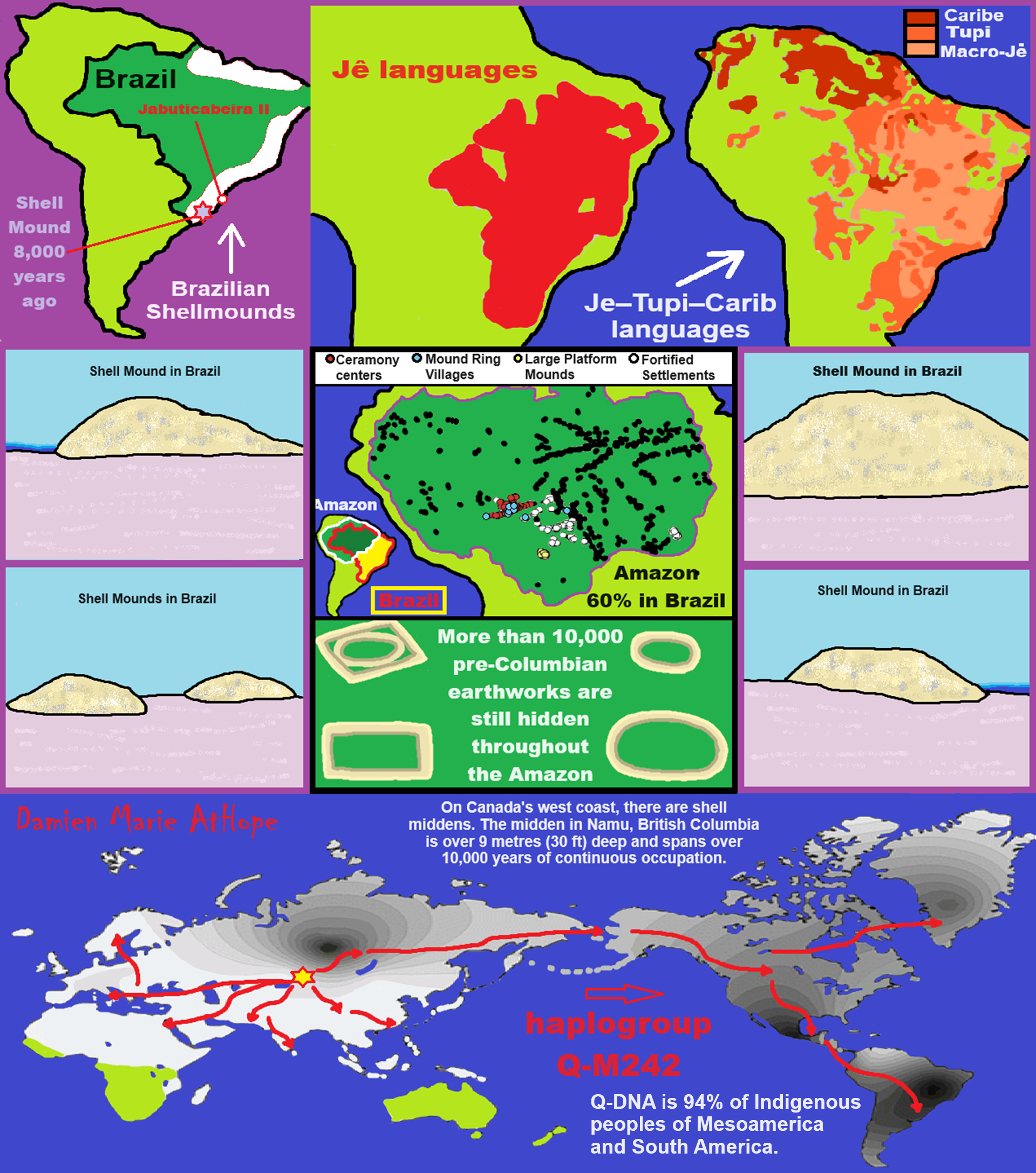

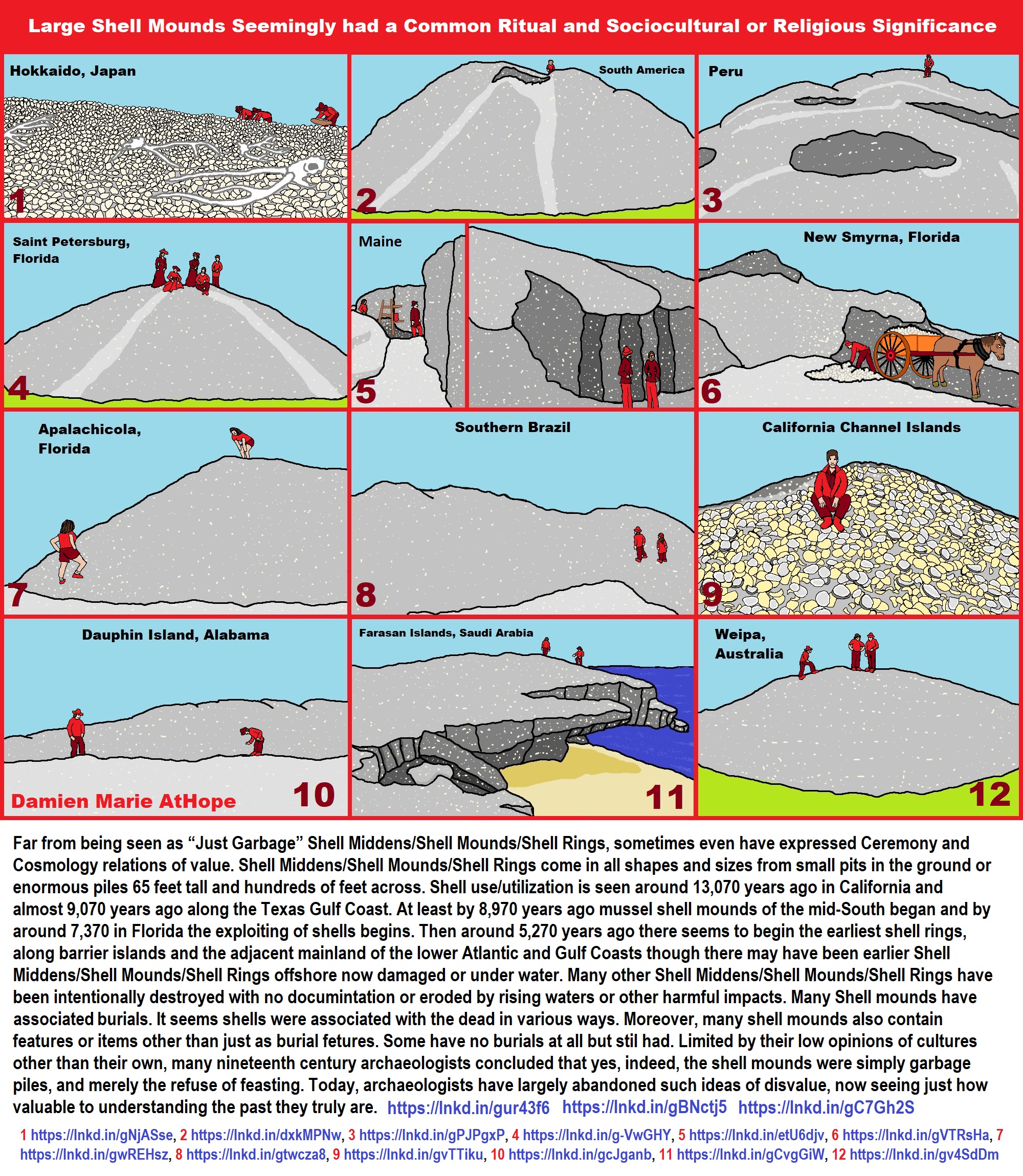

“At the site in the coastal city of Sao Luis had uncovered thousands of artifacts left by ancient peoples up to 9,000 years ago, 43 human skeletons and more than 100,000 artifacts, stone tools, ceramic shards, decorated shells and bones. The top layer was left by the Tupinamba people, who inhabited the region when European colonizers founded Sao Luis in 1612. Then comes a layer of artifacts typical of Amazon rainforest peoples, followed by a “sambaqui” (Shell Mound): a mound of pottery, shells and bones used by some Indigenous groups to build their homes or bury their dead. Beneath that, about 6.5 feet below the surface, lies another layer, left by a group that made rudimentary ceramics and lived around 8,000 to 9,000 years ago, based on the depth of the find. That is far older than the oldest documented “pre-sambaqui” settlement found so far in the region, which dates to 6,600 years ago, Lage said. Lage’s find suggests they settled this region of modern-day Brazil at least 1,400 years earlier than previously thought. The announcement of the discovery came just as archeologists said they uncovered a cluster of lost cities in the Amazon rainforest that was home to at least 10,000 farmers about 2,000 years ago in Ecuador.” ref

“The sambaquis (Shell Mounds), also known as “shell mounds,” were established about 8,000 to 1,000 years ago along a stretch of more than 3,000 kilometers on the eastern coast of South America. According to archaeological records, the sambaqui builders shared clear cultural similarities. However, contrary to what was expected, these groups of people showed significant genetic differences. In their study, published today in the journal “Nature Ecology and Evolution,” the scientists attribute this to different demographic trajectories, possibly due to regional contacts with inland groups.” ref

The people of Jabuticabeira II: Reconstruction of the way of life in a Brazilian shellmound

“Sambaquis (Shell Mounds) are huge shellmounds built along almost the entire Brazilian coast between 8000 and 600 years ago. In the present article, 14 osteological markers from 89 individuals excavated at the Sambaqui Jabuticabeira II (around 2,890 years ago) are analyzed in order to reconstruct the population’s health status and way of life. The present palaeopathological findings (such as lower frequency of degenerative joint diseases in legs, as compared to arms, and the rarity of traumas) together with archaeological findings support the idea of nearby resource abundance and infrequent interpersonal competition. The presence of auditory exostoses mainly in males corroborates previous findings indicating the importance of marine resources. The low caries frequency and the high degrees of dental wear point to a diet poor in cariogenic food, and rich in abrasives such as sand, shell fragments and phytoliths. This suggests a broader diet, based on marine protein as well as plants, than previously thought. The etiology of cribra orbitalia could be explained by gastrointestinal parasites or other sources of physiological stress. These parasites, in turn, could have led to higher frequencies of infectious diseases, either by the debilitation of the immune system or by the direct contact with infectious agents. Despite the periods of illness various individuals experienced, the daily life among the builders of the Sambaqui Jabuticabeira II seems to have been relatively easy due to the abundance and predictability of resources and the paucity of violent traumas.” ref

“Sambaquis (shellmounds) are archaeological sites associated with populations that intensely colonized the entire Brazilian coast, specially the Southern regions. The name given to these sites originates from the tupi words ‘‘tamba’’ (mollusk) and ‘‘ki’’ (accumulation), thus meaning ‘‘shellmound.” These coastal populations lived from 8000 to 600 years ago. This long period of time and large area of occupation, associated with the huge size of many of these sites, suggests that these populations were very well adapted to the coastal environment. Because of their use for the extraction of lime, the Portuguese colonists knew the Sambaquis already in the 16th century. But these sites have only been scientifically studied since the 19th century. Although about 1000 of these sites have been catalogued and partially analyzed until the present, there are only a few reports published in international journals.” ref

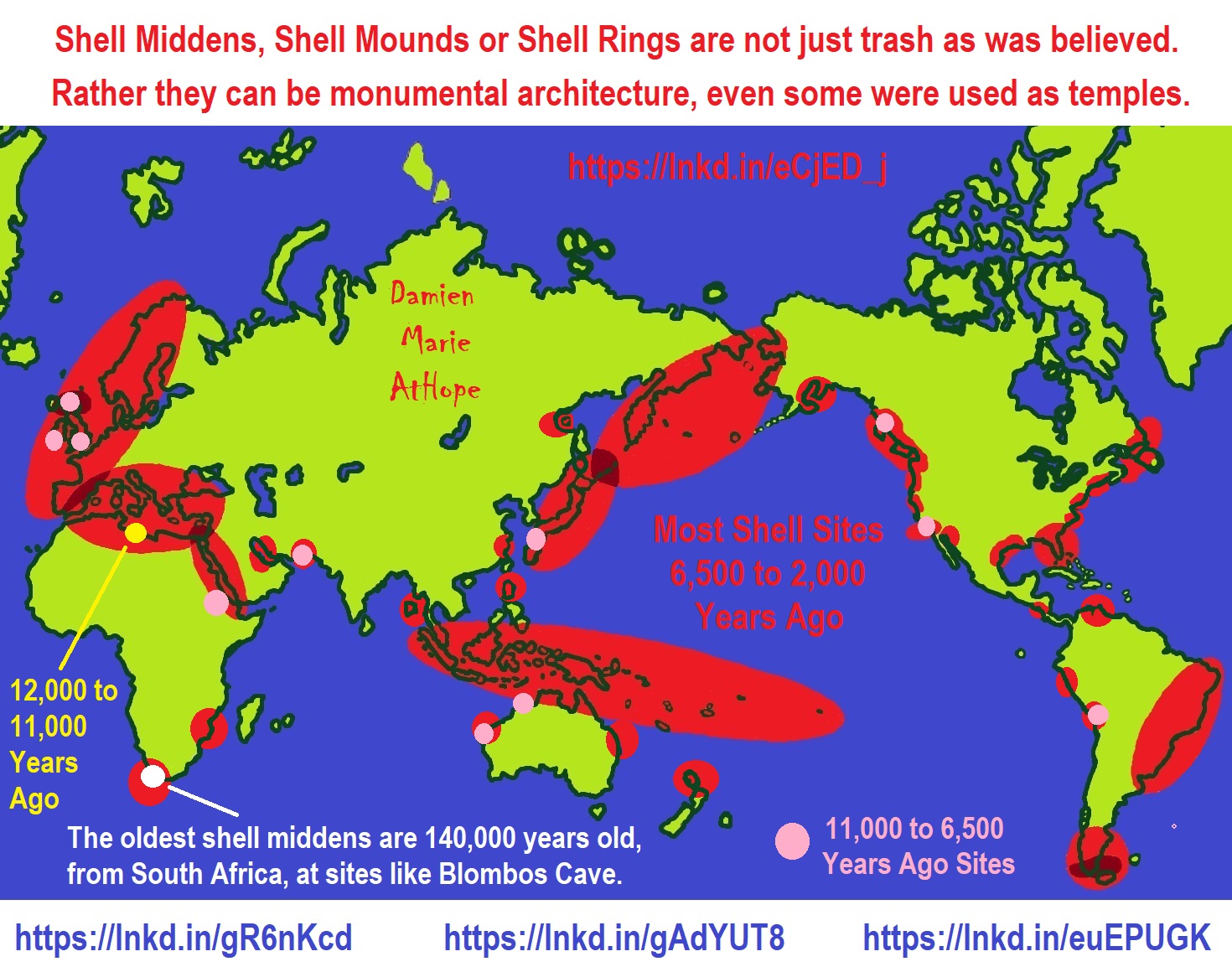

“In early Sambaqui (shellmound) studies, two main ideas about their origin predominated. One of these interpreted Sambaquis as natural structures formed by sea level decline. The other one stated that they were artificially formed by the accumulation of food remains left over by prehistoric populations. However, the fact that some of the Brazilian Sambaquis are so huge (some sites measure 30 m in height and several hundred meters in diameter) suggests that they were not incidental structures, but rather the result of the intention to form a well-visible construction. The presence of beautiful bone and lithic artifacts in the Sambaquis, along with findings of recent zooarchaeological and stable isotope studies indicate that the subsistence of these peoples was mainly based on fishing and gathering of molluscs. This latter process would have been the activity that led to the construction of the Sambaquis.” ref

“The occurrence of pottery in Sambaquis (shellmounds), although used to define pre-ceramic and ceramic periods, is limited to a few pieces usually scattered around the surface of the site, without any other cultural change and no burial associations. These ceramic fragments might represent occasional trade with surrounding groups, and appear to indicate that pottery did not play a significant role in their cooking technology, nor that pottery can be safely associated with high caries indices. Although there are hypotheses that propose the existence of two or three morphologically distinct populations within the Sambaqui culture some authors favor the occurrence of a morphological unity of these groups. However, more detailed comparative morphological studies are necessary to test these hypotheses. Apart from craniometrical studies, most of the research carried out on skeletal remains is concentrated on the description of oral pathologies, as well as cribra orbitalia and porotic hyperostosis in single Sambaquis.” ref

“Recently, archaeological excavations in the Sambaquis (shellmounds) have been more systematic, and permit the meaningful analysis of population history at specific Sambaquis sites. The present article focuses on the description of the health status of 89 individuals buried in the shellmound Jabuticabeira II based on an assessment of 14 osteological markers. Archaeological context of Sambaqui Jabuticabeira II The material reported in this article was excavated from a Sambaqui called Jabuticabeira II. The excavation of this site is part of a multidisciplinary project called ‘‘Settlement patterns and formation of Sambaquis from the Santa Catarina state’’. Its main objective is the systematic approach of a whole series of Sambaquis, localized around the lake Camacho, at the southern coast of Brazil, in order to obtain understand their construction processes.” ref

“Besides Jabuticabeira II, there are 22 Sambaquis built between 2,000 and 4,000 years ago that are scattered around this lake. In the past this group of Sambaquis was significantly closer to the coast, due to the decrease in sea level that began 5,100 years ago. Thirty-nine radiocarbon dates for Jabuticabeira II indicate that it was constructed between around 2,890 and 2,186 years ago or over a period of about 700 years. What remained of this site after mining activities measures approximately 400 m (NW–SE) by 250 m by 6 m height. The osteological material from Jabuticabeira II derives from profiles as well as traditional horizontal excavations, which reveal a long and continuous depositional history involving recurrent burial and mortuary activities and the lack of habitation structures. The high number and great density of burials, each of which is often covered over by a layer of sand and shells, suggest that the utilization of this Sambaqui as cemetery was linked to its construction process.” ref

“The burials are distributed over most of the locations excavated, and are accompanied, in the majority of cases, by hearths, post-holes, as well as lithic artifacts, beads, some evidence of food (mainly fish), red pigment and different ways of interment indicating elaborate funeral rituals (Edwards et al 2001). Based on the ratio of burials per cubic meter, Fish et al (2000) estimated an astonishing number of approximately 40 000 persons that must have been buried during the construction of Jabuticabeira II. Even if this is an overestimate, it suggests a large number of people living nearby the Sambaqui, sharing a common social identity and getting together for the construction of this mortuary monument.” ref

Sex and age at death

“The estimation of the MNI yielded a total of 89 persons. The distribution of the age at death is shown in Table 1. Due to their incompleteness (76.4% of all individuals had less than 50% of all bones) many of the adult skeletons lack a more precise age determination. That is why the sample of adults was not divided into age categories when analyzed. The same problem of incompleteness prevented sex determination in 63% of the adults. An interesting palaeopathological finding refers to a double burial of a six-month old infant and a three-year-old child. Both were buried together in an undoubtedly secondary burial, with many beads and a carved shell positioned near their heads. The data obtained from Jabuticabeira II revealed that approximately one-third of the buried individuals were juveniles. This high proportion of juveniles has been observed in most prehistoric cemeteries, this indicates that burial rituals were not altering the natural demographic composition. This statement was corroborated by the fact that the sexes were evenly distributed and that the age at death of adults ranged from 21 to more than 50 years.” ref

“Out of 14 adults (six males and eight females) only two of the females presented trauma, against three of the males. Moreover, two out of seven adults (28.6%) of undetermined sex presented traumas. They were localized on one femur, two vertebrae, one ulna, one elbow and also on one skull. Most of them were not severe and presented no evidence of interpersonal violence. Furthermore, they were in the process of healing at the time of death. Skeletal markers are among the most powerful tools used to reconstruct the biological features of ancient populations. A more complete reconstruction of their way of life can be made if there is an integration of the study of these markers with data obtained from other sources such as zooarchaeology, palaeobotany, material culture and settlement patterns. According to more recent studies, Sambaqui populations were fisher-gatherers who used a wide variety of plants for food, fuel, artifact production and construction and engaged in elaborate mortuary rituals. They possibly shared a common identity with neighboring Sambaqui peoples and used their often huge mounds for purposes as diverse as habitation, cemetery and as a place for tool production.” ref

“Besides its benign nature, the low frequency of traumas observed in Jabuticabeira II is not unexpected, since this has also been observed at other Sambaqui sites. The broad temporal and geographic distribution of Sambaquis and especially the use of multiple concomitant neighboring sites sharing the same territory, suggest that the Sambaqui populations. The daily life among the Sambaqui dwellers from Jabuticabeira II seems to have been relatively easy due to the abundance and predictability of marine and plant resources and the rarity of traumas, be they violent or not.” ref

“Research at Jabuticabeira II was essential for reformulating the meaning of the largest sambaquis of the southern coast of Santa Catarina. Its construction continued uninterrupted for hundreds of years and its function was strictly oriented to funeral activities points out that faunal remains, especially fish, played an integral role in feasts performed to honor the dead. An important feature of Jabuticabeira II is the presence of a dark sediment layer covering the conchiferous layers across the whole site. This dark layer, also described as fishmound, is composed primarily of fish bones and sediments rich in charcoal and organic materials. Both Jabuticabeira II and Cabeçuda are cemeteries, and systematic archaeological excavations observed variability in relation to burial practices that could indicate different moments of occupation. In Jabuticabeira II, there are visible changes in the site construction layers (shellmound vs. fishmound), with the presence of pottery in the latest one. During excavations of Cabeçuda during the 1950’s, were identified two distinct contexts with higher burial density and different funerary characteristics: one group of burials located between 2 and 3 meters deep and another group between 6 and 8 meters deep, which could indicate different moments of occupation with potentially different morbidity and mortality realities.” ref

“Human skeletal remains were exhumed in an area of the site with older dates (between around 3,235 and 2,925 years ago) that could also be related to another moment of occupation. Changes related to funerary rituals occurred throughout the construction of Cabeçuda. Archaeologists usualy argued for the continuity and stability in the lifestyles of the sambaqui builders, as reflected in the homogeneity of various aspects of material culture. According to these studies, these groups could have an egalitarian political organization, sharing the same environment and resources, and recognizing themselves as belonging to the same identitary group. This paper aims to discuss this hypothesis for the study area through the analysis of physical stress markers (Porotic Hyperostosis, Cribra orbitalia, and Linear Enamel Hypoplasia) in individuals buried in the Cabeçuda and Jabuticabeira II sambaquis. Sambaquis are shellmounds situated along the Brazilian coast, intentionally constructed by fisher-hunter-gatherer groups through the long-term accumulation of shells, fish bones and sediments, interspersed in a complex stratigraphy, with a material culture that includes burials, lithic and bone artifacts, hearths, and food waste. They are one of the most numerous and well-documented Brazilian sites, with a great density of archaeological datas that allow important inferences about the lifestyle of their builders.” ref

“Most coastal sambaquis are located in bays, estuaries, lagoons, and mangroves, that constitute a range of environments or ecological zones with high and diverse biotic productivity. The southern coast of the state of Santa Catarina is an ecotonal zone characterized by the meeting of Atlantic Forest, restinga vegetation, mangroves, lagoons, and Atlantic Ocean marine environments. It is thus a region with a vast and varied availability of resources that perhaps facilitated human settlement. Currently, it is known that sambaqui people had a broad dietary spectrum, based on marine protein, but which also incorporated terrestrial protein and a diversity of plants. The high concentration of sambaquis on the southern coast of Santa Catarina state, active for thousands of years, with large dimensions, high burial density, similar building patterns, and similar bone and lithic industries, suggest that these people would constitute a complex and long-lasting social system, with an economic, social, and political stability over these years of permanence in the coast. Taking as a case study this region of interest, the present research studied the human remains from two large and important sambaquis in the region: Cabeçuda and Jabuticabeira II.” ref

Ancient Sambaqui Societies Were Genetically Diverse

“The investigation that covered four different parts of Brazil carried out analysis of genomic data from 34 fossils, including larger skeletons and the famous mounds of shells and fishbones built on the coast. DNA analysis of ancient remains, obtained across four different parts of Brazil, reveal new insights into the ancient communities that occupied eastern South America thousands of years ago. In pre-colonial South America, populations of Sambaqui societies inhabited large regions across the Atlantic coast from approximately 8,000–1,000 years ago. Sambaqui is a Brazilian term that describes large mounds of fishbones and shells that were built by these ancient communities and often used as cemeteries, homes and markers of territorial boundaries. They are considered an iconic feature of Brazilian archeology, with over 1,000 sambaqui locations recorded in the country’s national register of archeological sites.” ref

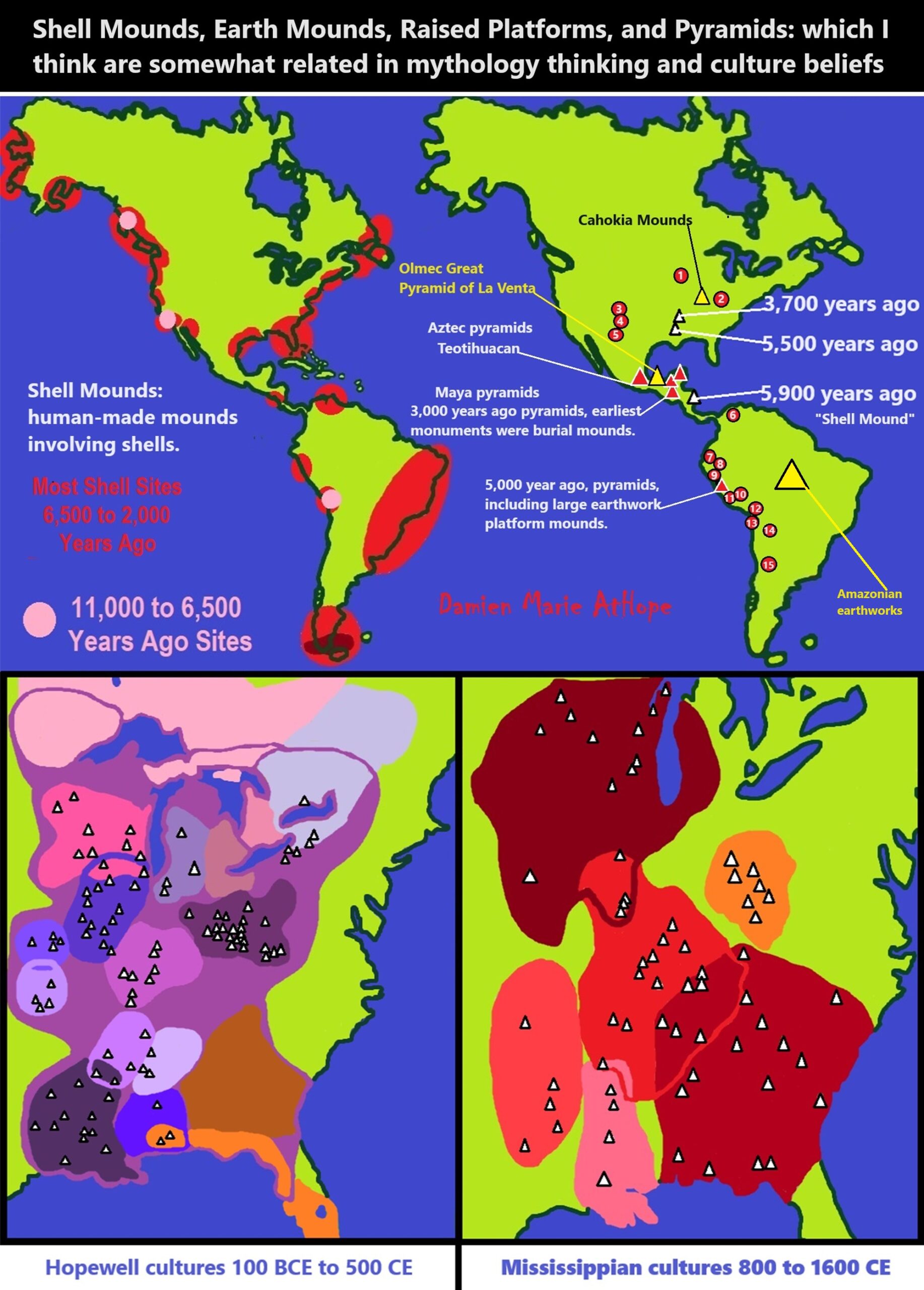

“According to Strauss and colleagues, Sambaqui societies are “among the most intriguing archaeological phenomena in pre-colonial South America.” However, our understanding of how these populations might have been connected to early Holocene hunter-gatherers – and whether this contributed to the processes that saw the late Holocene ceramists “rule the coast” – is limited. The earliest evidence of human activity and settlement on the Atlantic coast dates back ~8,700 years ago, with an intensification of sambaqui construction approximately 5,500 years ago. We know that there were both coastal and riverine Sambaqui societies, but there are a number of outstanding questions surrounding their genetic similarities, and their relationship to present-day Indigenous populations. Further questions stem from the seemingly mysterious disappearance of the dominant Atlantic coast sambaqui builders: “After the Andean civilizations, the Atlantic coast sambaqui builders were the human phenomenon with the highest demographic density in pre-colonial South America. They were the ‘kings of the coast’ for thousands and thousands of years. They vanished suddenly about 2,000 years ago,” Strauss says.” ref

“Among the archeological material analyzed by Strauss and team was “Luzio”, São Paulo’s oldest male human skeleton that is estimated to be ~10,400 years old. “This individual was named ‘Luzio’, as a reference to ‘Luzia’, a final Pleistocene female skeleton found in the Lagoa Santa region in east-central Brazil. Both individuals are at the center of long-lasting debates for exhibiting the so-called paleoamerican cranial morphology that differs from that of present-day indigenous peoples. Genome analysis revealed Luzio was, in fact, an Amerindian “like the Tupi, Quechua or Cherokee,” says Strauss. The term Amerindian is used to refer to American Indians, also referred to as Native Americans, Indigenous Americans and Aboriginal Americans. “That doesn’t mean they’re all the same, but from a global perspective, they all derive from a single migratory wave that arrived in the Americas not more than 16,000 years ago. If there was another population here 30,000 years ago, it didn’t leave descendants among these groups.” Luzio is not considered to be a direct ancestor of the huge classical Sambaqui population that appeared later in time, as his remains were discovered in a river midden.” ref

“A subtle difference between these communities, and the genetic analysis confirmed it,” Strauss says. “We discovered that one of the reasons was that these coastal populations weren’t isolated but ‘swapped genes’ with inland communities. Over thousands of years, this process must have contributed to the regional differences between Sambaquis.” Why did the coastal sambaqui builders vanish? The researchers say that when coastal and inland contact increased – approximately 2,200 years ago – there was a decline in the construction of shell mounds and the introduction of pottery, which led to changes in practices such as cooking. “This information is compatible with a study that analyzed pottery shards from sambaquis and found that the pots in question were used to cook not domesticated vegetables, but fish. They [the coastal Sambaqui] appropriated technology from the hinterland to process food that was already traditional there,” Strauss explains.” ref

“The complex history of intercultural contact between inland horticulturists and coastal populations becomes genetically evident during the final horizon of sambaqui societies, from around 2,200 years ago, corroborating evidence of cultural change,” the authors say. They emphasize that their data challenges descriptions of ancient populations in archeological records, and “highlights the need to perform more regional and micro-scale studies to improve our understanding of the genomic history of eastern South America.” ref

Sambaquis (shellmounds) from the Southern Brazilian Coast: Landscape Building and Enduring Heterarchical Societies throughout the Holocene

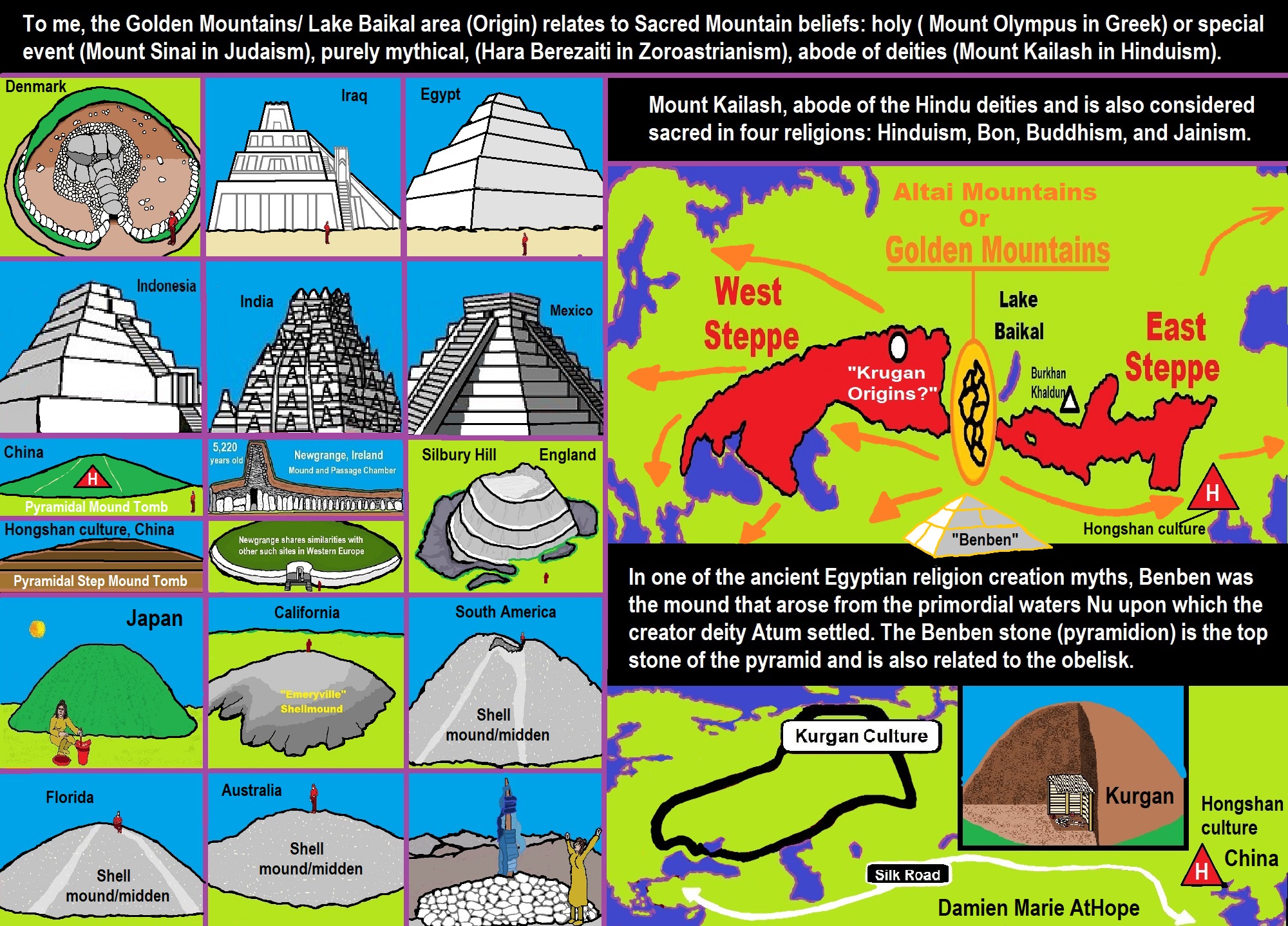

“Abstract: This paper presents a heterarchical model for the regional occupation of the sambaqui (shellmound) societies settled in the southern coast of Santa Catarina, Brazil. Interdisciplinary approaches articulate the geographical scope and environmental dynamics of the Quaternary with human occupation patterns that took place therein between the middle and late Holocene (approximately 7,500 to 1,500 years ago). The longue durée perspective on natural and social processes, as well as landscape construction, evince stable, integrated, and territorially organized communities around the lagoon setting. Funerary patterns, as well as mound distribution in the landscape, indicate a rather equalitarian society, sharing the economic use of coastal resources in cooperative ways. This interpretation is reinforced by a common ideological background involving the cult of the ancestors, which seems widespread all over the southern Brazilian shores along that period of time. Such a long-lived cultural tradition has endured until the arrival of fully agricultural Je and Tupi speaking societies in the southern shores.” ref

“These sites achieve impressive dimensions especially in the southern Atlantic shores, where they may reach up to 70 m high and 500 m wide. It is also towards the southern shores that they reach larger aggregates, with hundreds of mounds clustered into the bay and estuarine and coastal island areas, ecologically diverse and very productive coastal niches. Sambaquis, especially the bigger ones, typically exhibit heterogeneous stratigraphic sequences, with packs of light-colored shell interspersed with darker strata rich of organic materials. These last ones are composed mostly of charcoal, burnt fishbone, and smashed soft shell into a sandy substrate, and into them a variety of stone and bone tools can be found, and a great deal of fire-cracked rocks. These dark layers frequently include as well abundant burial structures, configuring a sequence of specially prepared funerary areas located on former mound platform surfaces. Eventually, from time to time, these funerary areas are closed and covered by packs of clean shell, setting the place for new burials, at a higher platform ground.” ref

“In fact, several burials, usually tightly flexed and disposed in shallow pits, are reported in most sambaqui descriptions. The dead are carefully, ceremonially lain down into these prepared places, accompanied by adornments and artifacts, food offerings, and hearths. Remains of wooden tumular structures and palisades (postholes) have also been described. In sum, most of the sambaquis, especially the large ones, are collective funerary structures. In some excavated larger mounds, dozens of burials have been documented, such as Cabeçuda (337 individuals), Congonhas (22 individuals), Armação do Sul (86 burials), Jaboticabeira II (204 burials), and Morro do Ouro (some 100 burials). Several other mounds are reported as having a large number of burials, such as Carniça and Jaboticabeira I, but they have never been studied or accounted properly. Small interventions (such as test-pits and small-scale profiling) at some mounds have disclosed a few burials, suggesting a much bigger number of them, among many others).” ref

“Habitation areas of the sambaqui people have never been acknowledged. Smaller mounds and other discreet features, without burials, often surround larger funerary mounds, but there is no undisputable evidence of habitational debris on them. It might be that the bulk of debris from living areas located at the sandy terraces, not far from the mounds, has been remobilized into them, perhaps on a regular basis (funerary occasions, for instance). This behavior would generate low visibility for habitational contexts in such a plastic, unconsolidated environment, such as the discreet activity traces described by Attorre surrounding larger mounds.” ref

“Moreover, there is very scanty evidence that moundbuilders might have lived on palafittes (stilt-houses), wooden constructions located in the shifting fringes of the ever-changing lake borders. Such structures have been reported towards northern coastal lacustrine contexts, in the southeastern border of the Amazon area. However, if such structures really existed along the southern shores, they have long disappeared due to Holocene dynamic coastal landscape reshaping by sea level fluctuations. The chance of finding them seems very elusive, but some might have survived at low-energy filling-in patches of the old lagoon borders.” ref

“Though recognition and analysis of the relationship between sambaquis and the dynamic quaternary coastal environment appear in early studies, ecological approaches remain rare. The connection of older mounds to former coastal lines, as well as paleo beach strands which, sometimes, are located well back from the coast today. Mound distribution as related to former regional landscapes, noting the significant difference between past and present coastline and island configurations along Holocene sea-level fluctuations and associated sedimentary processes.” ref

“Indeed, sambaqui chronology throughout the Brazilian coast coincides with the maximum sea level oscillation and the following regressive processes, along the middle and lower Holocene (approx. 7,000 to 1,500 years ago). Nevertheless, the principal characteristics of the sambaqui culture (moundbuilding related to funerary activities, technological and stylistic patterns of lithic and bone industries, the close connection to large bodies of water, among others) are already tied together in the oldest known sites (around 8,000 to 6,000 years ago), strongly suggesting that it is a much older culture, probably deriving from coastal migrations by the end of the Pleistocene. Mounded sites even older than that have survived into inland riverine locations, but ancient coastal ones seem to have been mostly wiped out by coastline remodeling along the early and middle Holocene.” ref

“Bone and lithic technology is similar across the southern and southeastern coast, where cutting, carving, drilling, and polishing techniques have been used for manufacturing a variety of tools such as points, spatulas, and even sculpted effigies. The presence of spindle disks strongly suggests the practice of some kind of weaving among sambaqui societies. Several authors point out that most burials of the southern shores have been tightly disposed, probably enveloped by some kind of tissue or straw mat for evidence in another interesting Pacific coast context). This artefactual similarity reinforces the hypothesis of a common origin for these sambaqui societies from the southern and southwestern coast, and maybe also from the northern shores.” ref

“Since the beginning, our investigations in the sambaquis from the southern shores have developed an adequate balance between understanding ecological and environmental factors, on one side, and sociocultural adaptation on the other. This perspective eventually evolved towards the understanding of demographic and economic intensification on coastal resources and the emergence of a long-lived integrative, heterarchical social organization around the lagoon and its ecological patches along the Holocene. Indeed, gradually, the idea of “adapting to nature” has given place to the perception of the influence of cultural behavior as regards landscape constitution and shaping—that is, “adapting the nature” to human purposes. Ultimately, we have been committed to understanding the evolution of the landscape and social environment as a whole, integrated phenomena.” ref

“Most studies of Archaic and Formative societies link the development of social and economic complexity to the emergence of hierarchical social differentiation. This sort of evolutive thinking has been a kind of rule of thumb since the XIX century, becoming common sense after the influential models from the 1960s. Alternative perspectives on social evolution argue that many past societies maintained and even expanded social organization without the emergence of structured or formal social stratification or any kind of statutory political leadership. Proposed models where politically equivalent communities share specific territories into a network structure are starting to appear (see 68 and 9 for examples in very different contexts). As we shall see in this paper, sambaqui societies from Brazilian southern Atlantic shores seem to provide a pretty good case for such an interpretive perspective.” ref

This approach is not a new one. Indeed, the conception of “primitive communism”, first elaborated by Engels, has gained wide influence on social sciences since the late 19th century. Throughout the 20th century, both European and American archaeologies have drawn deep into materialistic and techno-economical perspectives of investigation. In Latin America, a strong line of research in Social Archaeology has appeared and acquired wide influence, especially across Spanish-speaking research groups.” ref

“Some 20th century ethnographies of South American indigenous peoples argue that several societies from different environments developed mechanisms inhibiting aggrandizement and social differentiation based on the accumulation of material goods. In such societies, social prestige achieved by non-material means corresponds with individuals’ social status, but do not imply in rigid hierarchical structuring (see, particularly). Viveiros de Castro has noted a deep-rooted ecological worldview, characteristic of Amerindian societies, connecting culture and nature, including transfiguring, interchangeable perspectives across these worlds. Complementary, Vilaça, among others, has pointed out the deep connection of the living with the dead. Her study among the Wari people from southwestern Amazonia evinces how funerary events have this powerful capability of creating strong bounds among people from villages across a wide territory.” ref

“Following these lines, the model delineated further on in this paper can be summarized by this: Initial communities spread all over the area, always keeping close contact among themselves. Working in cooperative ways, they expand demographically and intensify the management of the landscape. Local community identities, probably based on familiar bonds (tribes or tribelets) remain strong, expressed as they are in the architecture of the mounds. This thriving expansion, in due time, develops new systems of social organization at a regional scope, with the development of an overall religious ideology regulating and mediating relationships among communities. Apparently, this religious apparel has never acquired a structured political dimension; sambaqui communities remain integrated in a rather equalitarian, heterarchical way.” ref

“Thus, the researchers makes a case for the sambaqui societies of the southern Brazilian coast, focusing on moundbuilders’ heterarchical behavioral patterns. Available economical, ideological, and organizational evidence for it is summarized below, in order to contextualize the sambaqui society’s endurance in living into these affluent coastal settings throughout several millennia. As most of the information herein discussed comes from the southern Santa Catarina coast, natural characteristics and ecological changes of the shoreline environment of this area throughout the Holocene.” ref

“The Santa Marta lagoon area, in the southern shores of Brazil, Santa Catarina State, encompasses an expansive, mostly flat, and open lagoonal system infilled with recent (quaternary) sedimentary deposits. Interspersed rocky promontories and small isolated outcrops, that once formed a string of islands at the mouth of an open bay, today anchor elongated sand strips and dune fields enclosing several lakes of brackish water. Canals connect these remnant lakes throughout this complex and dynamic mosaic of inter-related marine, lagoon, and aeolian deposits, where the Tubarão river, running from the scarped mountains at the hinterland, configures one of the largest inner deltas of the world.” ref

“Early Holocene sea-level rise drowned older marine terraces and dune formations before stabilizing around 5,700 years ago. The slow and regular lowering of the sea level since the middle Holocene has allowed the development of sandy barriers that gradually isolated the former bay area into the almost closed lagoon system we see today. Open dune fields frequently intersperse with archaeological deposits, creating intricate depositional contexts. This area displays a large aggregate of sambaquis, reinforcing the perception that great and productive bodies of brackish water are fundamental environmental references for the adaptive patterns of sambaqui communities. Indeed, this open and mostly flat landscape congregates nearby environments including shallow aquatic settings, mangrove, and rain forest patches on the fringe of surrounding hills, making it truly an ecological (sub) tropical paradise, with abundant and diversified resources from sea and ground.” ref

“Minor climatic oscillations along the middle and recent Holocene, particularly as regards humidity, temperature, and water salinity, have made of it an ever-changing scenario, especially in terms of the small-scale distribution of vegetation patches (such as mangrove) and spots of fish and shellfish concentration. In spite of these variations, landscape structural and environmental characteristics have changed at a rather moderate pace and scale, providing stable and reliable conditions for human adaptation. Into such a very productive landscape, as well as at several others along the Atlantic Brazilian coast, sambaqui-making people clustered and built mounds over many millennia. This southern area has been chosen as strategical for archaeological research due to its optimal combination of environmental diversity and the presence of a large number of mounds still preserved, including some of the biggest ever recorded anywhere in the world.” ref

“Since the middle 1990s, our research group has systematically explored this portion of the southern shores of Santa Catarina, with an international team of interdisciplinary investigators from different institutions. Such a setting provided for an approach focusing on regional understanding of territorial patterns and settlement evolution, as well as mound formation processes and architectural design, with special attention to the interrelationship of natural and cultural phenomena into site and off-site formation processes. This research project, generically named Sambaquis and Paisagem, has produced a considerable amount of literature, especially as academic works such as theses and dissertations. For the investigation of moundbuilding processes, the strategy has been systematically profiling into some large mounds, taking advantage of extensive walls left on them by intensive mining for shell materials in the past. This approach has allowed us to explore stratigraphic sequences across the whole mound, mapping the distribution of burials and other structures therein, as well as sampling for dating and zooarchaeological and sedimentological analyses. Some mounds, especially Jaboticabeira II (JabII), have been studied in greater detail, including trenching and small-scale excavations.” ref

“More than 120 sambaquis have been recorded so far in the Santa Marta study area, and, surely, other mounds have succumbed facing intensive mining and recent urban development. Almost three hundred radiocarbon dates provide a fairly well distributed sample for a regional chronology. Intra mound dating into large sambaquis shows coherent and uniform sequences, usually without important interruptions for centuries—indeed, some larger funerary mounds have been continuously built throughout more than two thousand years. On a regional perspective, dating indicates that sambaqui occupation in this area has no important interruption throughout at least five thousand years ago. It starts around 7,500 years ago, showing an expansion of active funerary sites up to approximately 3000 years ago, decaying after that, but with sites still active until 1000 years ago approximately.” ref

“During the “classic” sambaqui period (between 5,000 and 3,000 years ago approximately), small mounds and other discreet peri-sambaqui structures appear, frequently with a single stratigraphic horizon. Although the compositional and functional variability of these smaller sites/events are still poorly explored, most of them seem to gravitate around the bigger mounds, being functionally related to them. Moreover, several sambaquis constituted by twin-mounds, frequently sharing the same basal platform, appear around this period. Similar concomitant funerary moundbuilding processes at different locales across the area, and along several generations, point to stable and enduring cultural patterns towards the dead, shared by all communities around the lagoon. Such a homogeneous architectural design (and its endurance) finds resonance into the long permanence of lithic and bone technological and stylistic patterns all through this area, and well beyond.” ref

“Sites located up to 10 km away from the actual seashore indicate that the sambaqui occupation of this paleo bay/lagoonal system was already flourishing on its inner and most sheltered portion by at least 7,500 years ago —that is, well before the medium sea level reached its maximum, about 2.3 m above actual sea level. These small older mounds are rare and rather difficult to find—and, usually, very disturbed by modern land use. Nevertheless, they already display a well-defined trace association pattern, featuring typical characteristics of the later (“classic”) sambaqui culture. It includes settling at the border of large water bodies (lakes, bays, estuaries), shell-mounding formation processes involving funerary use, and the presence of peculiar votive sculptures (see ahead). These deep-lagoonal mounds, once located at the very bottom of the paleo bay area, reveal that sambaqui adaptive patterns to coastal environments, already present and active by the early/middle Holocene, are even older, probably of Pleistocene origins. Deep inland shell-mounded funerary sites found further to the north (at the São Paulo state), settled at lowland riverine environments and dated from the end of Pleistocene, make a strong case for this argument.” ref

“Available estimates for demography are in the order of a few thousands of people living together around the lakes around 3,500 to 2.500 years ago. Sedentary life and population increase are also reinforced by available paleopathological data on the skeletal population of the sambaquis Cabeçuda and Jaboticabeira II. This demographic expansion, however, apparently does not bring perceptible changes or disruption on the homogeneous cultural and economic patterns of the sambaqui society along its enduring existence. There is almost no evidence of violent death among the buried population, and, as far as we can see, economic and organizational solutions for conflicting situations were “socially orchestrated”, in order to support population growth and the intensification of social interaction in the area. This orchestration, as already pointed out, involves free-flow and cooperation at a regional scale among several communities, and an ideological/religious “superstructure” promoting (or stimulating) integration and social isonomy.” ref

“Mound distribution into long-lasting clusters evinces that, throughout the middle and late Holocene, the large body of brackish water was the epicenter of the sambaqui social sphere. It became a shared and communal territory, vital space for economic and social interaction. Eventually, this has led to an increase in territorial circumscription in the lagoon area, and intensification upon available resources, drawing on the abundance, stability, and reliability of environmental conditions. Social flexibility and interaction among sambaqui communities around the lagoon are indicated by their similarity (that is, cultural homogeneity), concomitance, and the evenness of their spatial distribution.” ref

“This evidence points to an articulated social network and territorial sharing as fundamental aspects of the systemic integration among these communities. It suggests that each of these clusters represent, in both social and economic perspectives, a nuclear focus of occupation with its own social—and, to some degree, also territorial—identity, as represented by each unique (and long-lived) funerary locale. However, as regional chronology clearly shows, they are never alone, living among other analogous communities distributed around the lagoon, involved in a “face-to-face” (frequent, quotidian) network interaction.” ref

“An apparently abrupt change in depositional patterns occurs around 2100 to 1800 years ago. By this time, darker organic sediments rich in fish remains and charcoal replace the fore predominant shell accumulation. This “upper black horizon”—that, in some mounds, may reach more than two meters thick—is related to carefully disposed burials and assorted structures. Associated lithic and bone industries, also similar to previous phases, exhibit consistent functional, technological, and locational persistence. Depositional patterns involve remobilization of faunal (mostly fishbone) materials, charcoal, and burnt stone fragments within and above the burial ground. Despite the low frequencies of shell, the funerary ritual is still the principal mounding up driving process, and the large amounts of food remains, remobilized and frequently burnt, have been interpreted as resulting from well-attended, community-bound feasting upon the dead.” ref

“Shortly after (around 1,700 years ago), discreet dark-earthen mounded sites start to appear along the coast and nearby areas. Some of them are clearly funerary, while others look to be fishing shoreline campsites or aggregation places. The features and structures appearing in these sites, particularly as regards faunal composition, burial inception (including cremation, never present in the mounds before this period), and accompaniments, are rather distinct from earlier sambaquis. Differences also include the introduction of ceramics, around twelve hundred years ago. These events indicate significant cultural changes taking place around the lagoon, leading to the end of a long period of stability and cultural continuity of the sambaqui culture.” ref

“The characteristic ceramic styles occasionally found in these smaller “late sambaquis” are related to the ethnographically known Je speaking societies that have occupied most of the southern Brazilian coast since around seven hundred years before the arrival of European settlers. These later sites display higher evidence of violence among buried people, and also some evidence of changes in post-marital residence patterns. No archaeological settlement typically related to the coastal sambaqui culture has ever been found deeper into the mainland, outside the lagoon area and its surroundings—except for some scanty evidence of artifact circulation in a few large open valleys located to the northern shores, in Santa Catarina and São Paulo. Settlement distribution and sambaqui life center in the lagoon area; large bodies of water constitute the focal interaction sphere as regards social and economic relations among these circum-lacunar communities.” ref

“Although only a small number (around three hundred pieces) of these sculptures has ever been found, based on its distribution, it might be inferred that such a religious ideology has an ample regional dispersion and endurance, widespread among sambaqui societies from the southern and southeastern Brazilian shores. In fact, although shellmounds are conspicuous throughout the Atlantic coast of Brazil, these lithic sculptures have never been found to the north of the Tropic of Capricorn. Thus, this is a typically southern sambaqui cultural trace.” ref

“Such technical refinement and aesthetic taste are also evident in bone and teeth artifact production. A variety of items have been described, including fine tools such as needles and spinning implements, small-scale sculpted effigies and a variety of spatulas and adornments. Bone, teeth, and vertebrae from sea, land, and bird species have been used to manufacture exquisite, sophisticated collars and other adornments, frequently incorporated into the burials. Wooden tools did not preserve, but the typology of lithic implements, such as a variety of axes and wedges, although not yet specifically accessed in functional terms, leaves no doubt of intense wood use as raw material. It is important to call attention to the fact that the sambaqui culture is very much related to large bodies of water, living on the fringe of bay, lagoon, and estuarine environments among coastal islands and promontories. Aquatic environments and canoeing were essential to their way of life and subsistence. Marks on large bones and the auricular structure of human skeletal remains indicate that rowing and underwater activities were practiced regularly.” ref

“Most of the knowledge on mound formation processes comes from the Santa Marta area in the southern shores, where these funerary locales are enduring occupation places, actively used along several centuries. At Jaboticabeira II (3,300 to 1,200 years ago approximately) and Cabeçuda (circa 4800 to 1500 years ago), for instance, stratigraphically controlled radiocarbon dating shows an uninterrupted activity for more than two thousand years. These sites display an impressive volume (estimated 32,000 and 53,000 m3, respectively), reflecting this continuous and intensive building-up occupation for a long period of time. Ultimately, the succession of funerary areas, continuously reenacted throughout many generations (indeed, bigger mounds are millenarian), contributes to the incremental architecture and massive proportions of these sambaquis. This social phenomenon demonstrates a deep-rooted and enduring worldview based on the cult of the ancestors, where ritualized funerary ceremonies play a very important role. The impressive amounts of food consumption on such occasions, as well as the progressive monumentality achieved through continuous reenactment of feasting parties, indicate that funerary ceremonies were important occasions, socially meaningful events incorporating and integrating local people as well as from surrounding communities.” ref

“As already stated, exceptional, rare burials with distinctive and peculiar accompaniments such as lithic finely carved effigies and burial decor, seem to be related to some kind of religious leadership, given the association with votive effigies and some other occasional signs of prestige. In rare documented cases, these finely appareled burials are located at the base of the mounds, suggesting that a few socially influential personas might be the founding reference for brand new funerary areas—that is, the very starting up of new sambaquis, or new funerary locales at higher ground, accreting volume to the mounds. The presence of iron oxide (ochre) in mortuary contexts is recurrent (although not imperative) in sambaqui burial descriptions, usually dyeing, more or less intensely, bone, shell, and lithics associated with mortuary contexts. It is unclear if it was sprinkled over the body during burial inception, or eventually placed directly over the defleshed bones. On several sambaquis, a large amount of ochre, rendering the soil red, appears in some funerary features. In a dramatically suggestive way, Rohr describes some burials as drenched “in blood-red mud”. It does not seem to be related to any specific social category, though; its occurrence contemplates indistinctly both sexes and aged burials alike.” ref

“Shell and bone adornments are common accompaniments in sambaqui burials. Collars made of modified shark and monkey teeth, shell, and carp beads are not rare, although these items are not featured in most of the burials. As said, zoomorphic sculptures appear as rare and peculiar funerary accompaniments, and large bone pieces, such as whale ribs and big tortoise casks, have been described as funerary accompaniments in several sites, among others). Occasionally, sophisticated burial paraphernalia have been found, such as whale ribs arranged as a “coffin”, encircled by large amounts of ochre and hearths. Painted terracotta coverings and carved bone vessels have also been described. There are several records of child burials with rich accompaniments, such as ochre, collars, special rare shells, and large animal bones. Upon and surrounding these funerary structures, thin deposits of charcoal, burnt shellfish, and fishbone form small heaps, interpreted as residues of feasting on the deceased, carefully disposed over and around the burials. Evidence of burial revisiting has also been reported, as well as manipulation of former burials, with bone parts of older ancestors incorporated into new burials.” ref

“The initial evolution of the sambaqui occupation in the southern shores of Santa Catarina seems to follow what has been described as a “ideal free distribution” pattern, that is, “the movement of individuals and families from places where conditions were worse to places where they were better, in a way that equalizes fitness”. It has developed among early focal and well-located communities evenly distributed around former bay/lagoon borders and nearby coastal islands, exploring its rich resources in cooperative ways, mainly as organized fishing and sea hunting parties. Cooperation in these tasks must have been of adaptive significance, enhancing productivity and sharing of staple marine and also dryland resources.” ref

“The connection between these communities, possibly organized in sibs (or tribelets), seems to derive from common ancestors—real and/or mythical (totemic) ones. The archaeological perception of it is given by the regular and systematic construction, across several centuries, of funerary spaces at the same, permanent places, where all deceased group members are ritually disposed. Flexible marriage rules probably provide mobility and integration among social compounds, stimulating fitness and social isonomy, while funerary rituals (and probably others) tighten their social bonds. Indeed, the impressive amount of food (mostly fish and shellfish) incorporated into funerary features strongly indicates that the scale of these events is well beyond the local level, enhancing the perception of a territorially wide ideological and cultural background, certainly also linguistic.” ref

“Gradually, such a pattern increases economic (and demographic) intensification at specific patches of the landscape, including the management of animal and vegetal species. Intensification and management of resources in the lagoon and surrounding areas suggest the taking advantage of cooperation, maintaining a large regional network—that is, above the community level—of social integration. This tendency is favored by linguistic, parental, and ideological connections between these communities which, after all, have never been isolated. Their connectivity and interdependence persist towards later periods, expressed as they are on ceremonial occasions (funerary ritual is the most visible archaeologically), where common ancestors connected to an eschatology related to natural entities (as indicated by the votive effigies) seem to be of paramount, foundational importance.” ref

“It is suggested that for California hunter-gathering societies, this pattern promotes some degree of territorial compartment, always maintaining “mutually beneficial relations in trade, marriage, and ceremony”. Spatial proximity allows for high levels of interaction between community members; daily interaction reinforces social relationships and a common worldview. Shared practices and communal landscapes lead to what has been called “practices of affiliation”, conducting to the emergence, and maintenance, of community identity on a local/regional scope. Eventually, sustained demographic growth has favored the establishment of moieties among these communities, as a way to minimize conflict and organize relationships inside and among them. These moieties would be expressed archaeologically as twin-mounds, which became common sometime after four thousand years ago.” ref

“Most burial patterns, which exhibit some variability through time, are always ritualized and widespread throughout mounds on a regional scope. Nevertheless, some differentiated ones, more appareled than most, suggest that eventual “principals” might have a role in starting new lineages, as represented by new funerary areas, or even new mounds. Characteristic animal and geometric lithic zoomorphic sculpted representations (described above), found in connection with such atypical burials, suggest that social coordination might have been structured by religious leaders who, by means of collective rituals, promoted pacific articulation, economic cooperation, and political balance among communities. The small number of these sculptures ever found into these mounds seems to indicate that they result from very rigid stylistic rules on making and using them, across several generations, with symbolic meanings encompassing a large, all-inclusive social outreach.” ref

“Again, ritual occasions (of which, funerary rites surely are among principals) have a paramount and decisive function in accomplishing social and economic balance at a regional level, acting as a “glue” into a rather isonomic, heterarchical system. Such religious leadership, however, does not seem to have a consistent, or permanent, political presence at a regional, pan-lagoonal scale. As already pointed out, sambaqui clusters are evenly distributed around the bay/lagoon system of Santa Marta. They are not only concomitant, but also exhibit a high degree of cultural homogeneity. These characteristics indicate a social system in which the lagoon territory and its surroundings are shared by several communities, a regionally articulated pattern integrated within the scope of a greater pan-lagoonal organizational structure.” ref

“Heterarchy is expressed, particularly, by the even territorial distribution of the mounds and assorted sites, as well as their chronological, formal, volumetric, and stylistic similarity (both in an architectural as well as a technological sense). Especially among larger mounds, despite some variability in stratigraphic composition and internal distribution, structural characteristics of the formative processes are very similar. Mounds are equivalent; there is no evidence of central places, principal mounds, or the like. The lake is the center of the system, indicating that it is regularly used by the communities around it, a common “territory” that is shared by them all, in a network of social and economic relationships. As one researcher once said, they are “the people of the lake.” ref

“A heterarchy is a system of organization where the elements of the organization are unranked (non-hierarchical) or where they possess the potential to be ranked a number of different ways. Definitions of the term vary among the disciplines: in social and information sciences, heterarchies are networks of elements in which each element shares the same “horizontal” position of power and authority, each playing a theoretically equal role. In biological taxonomy, however, the requisite features of heterarchy involve, for example, a species sharing, with a species in a different family, a common ancestor which it does not share with members of its own family. This is theoretically possible under principles of “horizontal gene transfer“. A heterarchy may be orthogonal to a hierarchy, subsumed to a hierarchy, or it may contain hierarchies; the two kinds of structure are not mutually exclusive. In fact, each level in a hierarchical system is composed of a potentially heterarchical group which contains its constituent elements.” ref

“Into the mounds, some variability among burials occurs, but, in general, nothing seems to indicate noticeable structured social differentiation. For instance, distribution of bone and lithic artifacts among burials, even in the same mound or funerary area, is much diversified, with no clear distributive pattern. That is, although some differentiation among burials is evident (in terms of presence/absence and quantity of items), it does not appear to be particularly related to gender, age, or even some clear-cut, or well-defined, kind of social ranking. Differentiated and exuberant treatment for children, as well as other rare outstanding and “out of the curve” cases, does not seem to mean the emergence of any formal, institutionalized, or structured socio-political hierarchy. More likely, these distinctions are related to specific circumstances and/or beliefs as regards death—newborn or child, aged, in the sea or at the forest, by disease or while hunting, and so on. South American ethnographic analogies are abundant but not immediately applicable to the sambaqui context. In a careful examination, a small degree of sexual distinction as regards funerary accompaniments in the Saquarema Lake district, northern coast of Rio de Janeiro. They suggest the absence of well-defined gender roles among moundbuilders in that area, thus reinforcing the perception of a rather plastic society.” ref

“Occasional and exceptional, outstanding burials are found scattered in different mounds all over the southern and southeastern shores. In some situations, as already mentioned, it might well be related to prestigious personalities or lineage leaders, or religious paramount individuals related to deep-rooted beliefs regarding ancestors and mythic heroes. The occurrence of rare animal sculptures (zooliths, described above) within a number of these special burials reinforces this perspective. Perhaps the relationship with the ancestors was intermediated by important shamanic authorities, who would usufruct of considerable social distinction, reflected in these exquisite burials. Definitely, this is not yet clear enough, and should be an object of future research. Both intra-site as well as regional distributions of these richly appareled burials, and their apparently foundational inception among several other burials, seem to indicate that they symptom local prestige, expressed in a widespread cultural pattern. They do not seem to represent the emergence of a higher-ranking political instance, related to a more stable political establishment at a regional level.” ref

“From a socio-economic point of view, some useful contemporary ethnographic analogies might help to understand the sambaquis society and their socio-economic characteristics. Today, among vanishing traditional fishing communities from the southern shores, net fishing in canoes or small boats is always performed by parties, whether in the lagoon or nearshore open sea. This social articulation around subsistence production is based on kinship as well as acquaintanceship (neighborhood relations). Besides, traditional communities around the lagoon are socially equivalent; they not only share mutual recognition but also intense social relations involving kinship, work parties, and festivities (patron saints, weddings, etc.). These relations imply great regional mobility, with people frequently moving from one locality to another. In an analogous way, the sambaqui settlement distribution indicates the lagoon as a privileged area for social interaction and an economic emphasis among concomitant and culturally homogeneous moundbuilding communities.” ref

“The understanding of the lagoon as the social-economic sphere that structured sambaqui subsistence and life leads to the perception of it as a highly socialized landscape. It is characterized by intense production, circulation, and interaction, a communal space sharing different management areas for fishing, shell fishing, hunting, and other activities. This organization is reflected in the circular, that is, “face-to-face” configuration of the settlements around a “territory” that, after all, is centered and focused on water, a water land.” ref

“As far as we can see at this point, sambaqui clusters seem to constitute heterarchical social nuclear entities of a larger territorial organization with loose political ties, but configuring a network of intense social and economic connections. Mounds appear as landmarks associated with specific social groups (perhaps extensive family clans, or lineages), with enough demographic and political expressiveness, or identity, justifying the incremental construction of the same sambaquis along many generations. The construction of twin-mounds is reminiscent of the dual social organization of the historically known Je speaking societies from central and southern Brazil, but the existence of dual (clan) organization among moundbuilders is still to be adequately demonstrated.” ref

“The model hereby delineated—still too broad and filled with gaps, but consistently exploring available data—speaks of sedentary moundbuilding communities of fishers-hunters-gatherers and small-scale cultivators, socially articulated on a regional level and very well-adapted to the coastal environment. In such a water land, they have created a social landscape on their own. Their social organization patterns go far beyond the idea of small nomadic family bands that have guided archaeological interpretations about sambaquis in Brazil until recently. The persistence of ideological/religious traditions embodied in the mortuary program over several millennia is a hallmark of the sambaqui era. The scanty occurrence of the lithic zoomorphic sculptures and its association with specific burials evoke the emergence of early religious leadership; it strongly suggests that the cult of the ancestors has been the “glue” of the sambaqui society’s cohesiveness.” ref

“Funerary events would promote social integration of the communities across the lagoon by means of communal feasting, and recursive visiting afterwards. The ritualized funerary character of these mounds makes them sacred ground, where the memory of the ancestors is ever-present in social life, and common to all its members. These bonds are recurrently reinforced by intentional, standardized ways of moundbuilding at the same (persistent) places for many generations. Indeed, evidence shows that moundbuilding and recurrent visiting involve manipulation of former burials, reenacting the presence of the ancestors and the bonds they represent to the living. Therefore, there are essential structural (in Levi-Strauss’ sense) meanings linking the sambaqui society, their ancestors, and their (mostly aquatic) territory.” ref

“From that perspective, the highly visible shellmounds placed all around the lagoon create a rather culturally domesticated landscape, still visible to this day. The ever-present ancestors and their cosmological/ecological connections take part on the every-day life of the sambaqui builders’ society. These meanings grow stronger every time ritual funerary moundbuilding takes place, reenacting communal conceptions of world and life and perpetuating specific territorial rights upon these monumental landmarks easily and extensively recognizabl. Such events offered opportunities for social negotiation and balance, reinforcing the integration among communities and their ideological/cultural homogeneity. Monumental building, and rituals that create them by means of connection to the ancestors, assign ancestral (mythic) belonging in the landscape, and the entities that take part on it. In addition, as sambaqui distribution evokes a sharing and cooperative manner in the exploitation and management of the lagoon and its surroundings, it becomes a central reference for the perception of social heterarchy in their organization on a regional level.” ref

“In conclusion, regional chronology and settlement organization indicate permanent and long-lasting moundbuilding occupation in this ever-changing bay/lagoon environment for at least 6,000 years (about 7,500 to 1,500 years ago). The sambaquis emerge as monumental representations of a long, stable, and well-adapted coastal occupation, evincing as well the strong symbolic relationships established between the sambaqui people and their mostly aquatic habitat. Such a landscape has been incorporated into their culture as much as their culture has remained incorporated into the landscape until today.” ref

“We argue that it is a case for a heterarchical model of social organization, with several politically equivalent communities integrated into a pan-lacunar social network, which has indeed endured for most of the Holocene. Such a pattern strongly highlights this successful long-lasting tradition connected to a lagoon-adapted life style—which would only change significantly after the arrival of the Je speaking, pottery-making, and plant-cultivating societies, from around 1,500 years ago onwards. It is for no other reason that the sambaqui people from the southern shores have remained, for several millennia, rather introspected among themselves, with very scanty evidence of contacts with other, foreign cultures—the very “sovereigns of the coast.” ref

Genomic history of coastal societies from eastern South America

“Abstract: Sambaqui (shellmound) societies are among the most intriguing archaeological phenomena in pre-colonial South America, extending from approximately 8,000 to 1,000 years ago across 3,000 km on the Atlantic coast. However, little is known about their connection to early Holocene hunter-gatherers, how this may have contributed to different historical pathways and the processes through which late Holocene ceramists came to rule the coast shortly before European contact. To contribute to our understanding of the population history of indigenous societies on the eastern coast of South America, we produced genome-wide data from 34 ancient individuals as early as 10,000 years ago from four different regions in Brazil. Early Holocene hunter-gatherers were found to lack shared genetic drift among themselves and with later populations from eastern South America, suggesting that they derived from a common radiation and did not contribute substantially to later coastal groups. Our analyses show genetic heterogeneity among contemporaneous Sambaqui groups from the southeastern and southern Brazilian coast, contrary to the similarity expressed in the archaeological record. The complex history of intercultural contact between inland horticulturists and coastal populations becomes genetically evident during the final horizon of Sambaqui societies, from around 2,200 years ago, corroborating evidence of cultural change.” ref

“The settlement of the Atlantic coast by maritime societies is a central topic in South American archaeology. Across ~3,000 km of the coast of Brazil, semi-sedentary populations, with seemingly large demography, produced thousands of shellmounds and shell middens, locally known as sambaquis (heaps of shell, in the Tupi language), for over 7,000 years. Subsistence was based on a mixed economy, combining aquatic resources and plants, complemented by hunting of terrestrial mammals and horticulture. Sambaquis are the product of planned and long-term deposition of shells, fish remains, plants, artefacts, combustion debris and local sediments, and they were used as territorial markers, dwellings, cemeteries and/or ceremonial sites. On the southern Brazilian coast, funerary shellmounds can reach monumental heights (of up to 30 metres) and often contain hundreds of human burials, suggesting a high demographic density unparalleled in the South American lowlands. In a singular enclave south of São Paulo State, further inland from the coast (Vale do Ribeira de Iguape), sambaqui sites are within the Atlantic Forest.” ref

“Here there is evidence of early Holocene settlement in the riverine sambaqui of Capelinha, as revealed by a male individual directly dated to ~10,400 years ago. This individual was named ‘Luzio’, as a reference to ‘Luzia’, a final Pleistocene female skeleton found in the Lagoa Santa region in east-central Brazil. Both individuals are at the centre of long-lasting debates for exhibiting the so-called paleoamerican cranial morphology that differs from that of present-day indigenous peoples. The earliest evidence of human settlement on the Atlantic coast starts between ~8,700 and 7,000 years ago with an intensification of sambaqui construction between 5,500 years ago and 2,200 years ago. The relationship between riverine and coastal sambaquis is still a matter of debate, although bioarchaeological studies point towards a biological link, and some researchers suggest a late Pleistocene/early Holocene cultural connection that faded through time.” ref

“The disappearance of Sambaqui societies started 2,000 years ago, when funerary fishmounds replaced shellmounds in the territory where they previously thrived. This abrupt change in the archaeological record is concomitant with environmental and ecological changes related to coastal regression and climatic events that had an irreversible impact on the availability of key resources. Between 1,200 and 900 years ago, thin-walled non-decorated pottery (Taquara-Itararé tradition) appeared for the first time on the southern Brazilian coast. The makers of Taquara-Itararé ceramics were horticulturists that arrived in the southern Brazilian highlands about 3,000 years ago, lived in pit houses and cremated their dead in funerary mounds. They are considered to be the ancestors of present-day Jê-speaking indigenous peoples of southern Brazil (Kaingang, Xonkleng, Laklãnõ and the extinct Kimdá and Ingáin), a language family of the Macro-Jê stock.” ref

“The dispersal of Taquara-Itarare ceramics on the southern coast was first interpreted as resulting from the demographic expansion of inland horticulturists. However, evidence points to a complex scenario of social interaction between inland and coastal populations, with changes in funerary practices and post-marital residence patterns after the introduction of ceramics, biological continuity and maintenance of mobility patterns (with local variations), persistence in the exploitation of aquatic resources, and development of sophisticated fishing technologies. Ceramics appear in the southeast coast about 2,000 years ago but are associated with the Una tradition, also probably produced by speakers of the Macro-Jê language stock.” ref

“Shortly after the appearance of southern proto-Jê ceramics, another major transformation occurred on the Atlantic coast. This is documented by the arrival of speakers of the Tupi-Guarani language family (of the Tupi stock), a forest-farming culture who migrated from southern Amazonia more than 2,500 years ago in one of the largest expansion events in the indigenous history of South America. Although still a matter of debate, the Tupi-Guarani would have dispersed southwards from southwestern Amazonia (homeland of the Tupi stock) across the core of South America, reaching the La Plata basin, and almost simultaneously from southeastern Amazonia across the Atlantic coast of Brazil.” ref

“While on the southern coast of Brazil a late Tupi-Guarani chronology is well defined, on the southeast coast a much earlier arrival (~3,000 years ago) has been proposed on the basis of the archaeological record of the Araruama region (Rio de Janeiro State). European colonists encountered thousands of Tupi-Guarani peoples both on the Atlantic coast and along major rivers and their tributaries in southern Brazil and northeastern Argentina (Paraná, Paraguay and Uruguay river basins). The Tupi-Guarani produced painted ceramics (red and black on white painting), applied a diversity of plastic decorations and made pots with complex and composite contours that are archaeologically defined as Tupiguarani, Tupinambá and Guarani, depending on the geographical location.” ref

“Ancient DNA data from Brazil are still very sparse, with only 19 published individuals with analysable genomic coverage. Early Holocene individuals from Lapa do Santo in the Lagoa Santa region, dated between ~9,800 and 9,200 years ago, carried a distinct affinity to the oldest North American genome, which is associated with the Clovis cultural complex (Anzick-1, ~12,800 years ago). A genetic signal of 3–5% Australasian ancestry—known as the Population Y signal—was found in present-day indigenous individuals from southwestern Amazonia, Central Brazil and the northwestern South American coast and in one early Holocene individual from Lapa do Sumidouro (Sumidouro 5, dated to c. 10,400 years ago). However, this signal was not detected in the early Holocene burials from Lapa do Santo, located only four kilometres from Lapa do Sumidouro63. The complete absence of ancient DNA data for Amazonia and Northeast Brazil and the low-coverage data from the south/southeast Brazilian coast have prevented an assessment of whether the Population Y signal survived in those regions through time.” ref

Anzick-1

“Anzick-1 was a young (1–2 years old) Paleoindian child whose remains were found in south central Montana, United States, in 1968. He has been dated to 12,990–12,840 years ago. The child was found with more than 115 tools made of stone and antlers and dusted with red ocher, suggesting a deliberate burial. Anzick-1 is the only human whose remains are unambiguously associated with the Clovis culture, and is the first ancient Native American genome to be fully sequenced. Paleogenomic analysis of the remains revealed Siberian ancestry and a close genetic relationship to modern Native Americans, primarily those of Central and South America, rather than to contemporary Indigenous North Americans. These findings support the hypothesis that modern Native Americans are descended from Asian populations who crossed Beringia between 23,000 and 14,000 years ago.” ref

These analyses revealed that the Anzick-1 individual was closely related to Native Americans in Central and South America, instead of being closely related to the people of the Canadian Arctic, as had previously been thought likely. (The people of the Arctic are distinct from Native Americans to the south, including in lower North America and Central and South America.) The infant was also related to persons from Siberia and Central Asia, believed to be the ancestral population of indigenous peoples in the Americas. This finding supports the theory that the peopling of the Americas occurred from Asia across the Bering Strait. The Y-chromosome of Anzick-1 was sequenced, and researchers determined that his Y-chromosome haplogroup is Q-L54*(xM3), one of the major founding lineages of the Americas.” ref

“Morten Rasmussen and Sarah L. Anzick et al. sequenced the mitochondrial DNA of Anzick-1 and determined that the infant represents an ancient migration to North America from Siberia. They found that Anzick-1’s mtDNA belongs to the haplogroup D4h3a, a “founder” haplogroup that might represent people taking an early coastal migration route into the Americas. The D haplogroup is also found in modern Native American populations, which provides a link between Anzick-1 and modern Native Americans. Although it is rare in most of today’s Native Americans in the US and Canada, D4h3a genes are more common in native people of South America. This suggests a greater genetic complexity among Native Americans than previously thought, including an early divergence in the genetic lineage some 13,000 years ago. One theory suggested that after crossing into North America from Siberia, a group of the first Americans, with the lineage D4h3a, moved south along the Pacific coast and finally, through thousands of years, into Central and South America. Another line may have moved inland, east of the Rocky Mountains, ultimately populating most of what is now the United States and Canada.” ref

“Regarding Sambaqui societies, three previously published middle Holocene individuals from Laranjal and Moraes (both riverine shellmounds from the southeast coast of Brazil) and five individuals from the late Holocene site of Jabuticabeira II (one of the largest coastal shellmounds in southern Brazil) showed some level of genetic continuity with present-day indigenous populations. The analysed Jabuticabeira II individuals carried a significant affinity to present-day Kaingang (Jê speaking) from the southern Brazilian highlands. Although based on low-coverage genome-wide data, this supports a shared ancestry between the Sambaqui societies and the speakers of proto-Jê.” ref

“The long-term permanence, cultural similarity and rapid disappearance of Sambaqui societies, plus their archaeological and seemingly genetic disconnection from early Holocene hunter-gatherers, raise numerous questions about their origins and demographic history. First, were Sambaqui individuals genetically different from hunter-gatherers from the hinterland (for example, east-central and northeastern Brazil)? Second, were the riverine Sambaqui groups genetically related to the ones on coastal sites? Third, was there genetic homogeneity across Sambaqui groups from the south and southeast coast of Brazil? Fourth, was the demise of sambaqui construction after 2,000 years ago and the appearance of ceramics associated with an intensification of contacts with inland populations? Finally, are there genetic connections between Sambaqui groups and other archaeological and present-day indigenous populations from Amazonia and central and northeastern Brazil?” ref