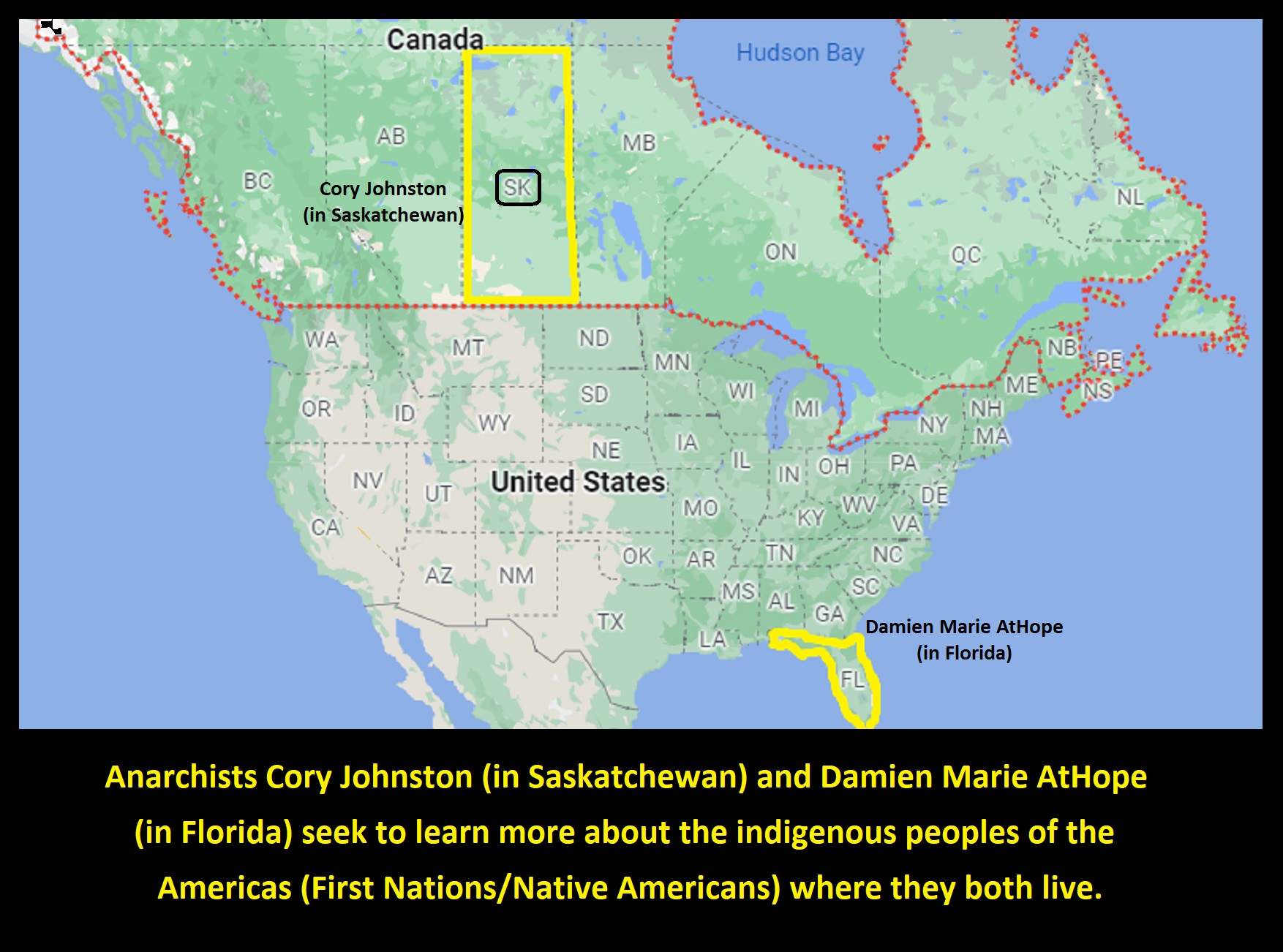

Genetics and archaeogenetics of South Asia

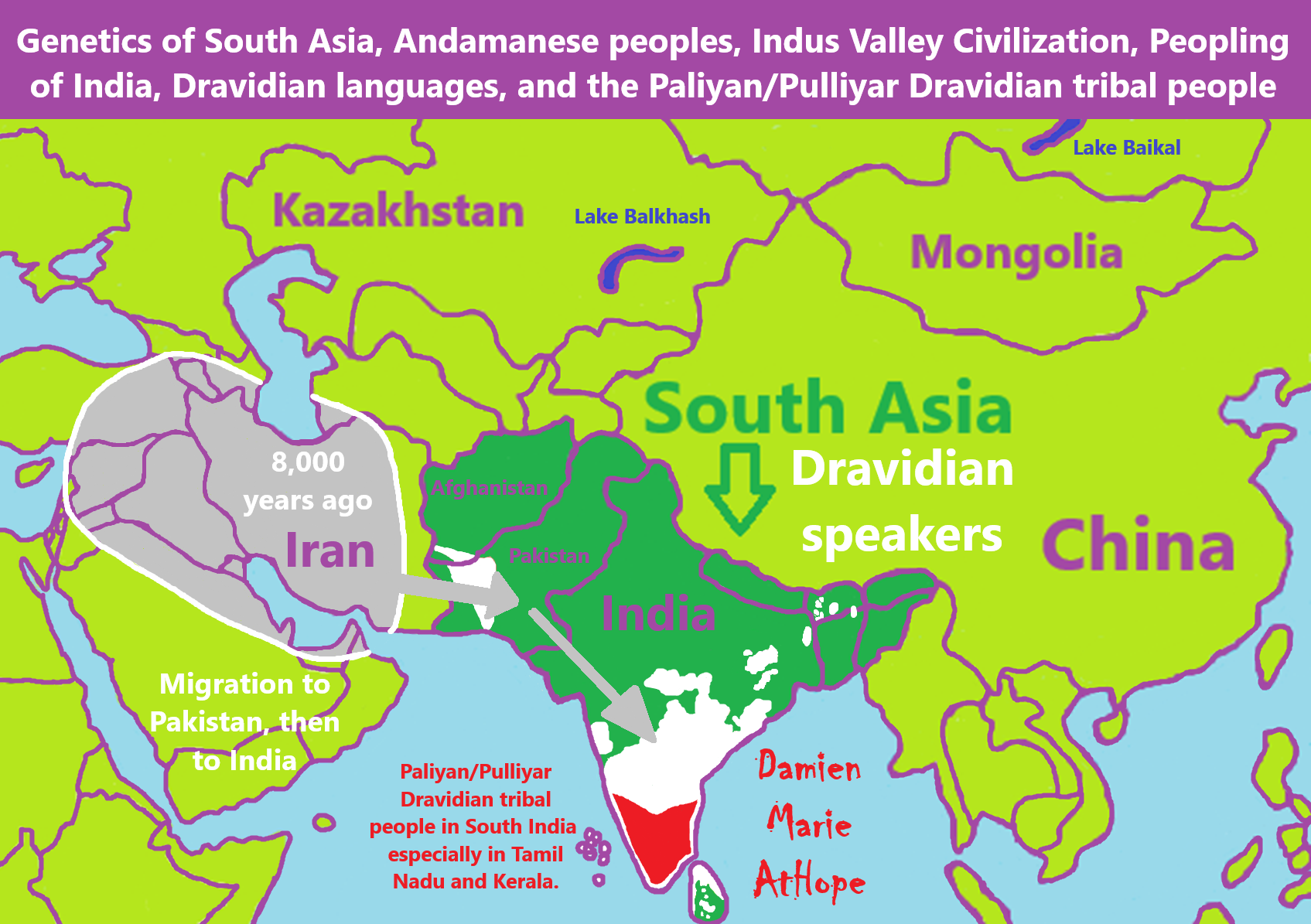

“The peopling of India refers to the migration of Homo sapiens into the Indian subcontinent. Anatomically modern humans settled India in multiple waves of early migrations, over tens of millennia. The first migrants came with the Coastal Migration/Southern Dispersal 65,000 years ago, whereafter complex migrations within South and Southeast Asia took place. West Asian (Iranian) hunter-gatherers migrated to South Asia after the Last Glacial Period but before the onset of farming. Together with ancient South Asian hunter-gatherers they formed the population of the Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC).” ref

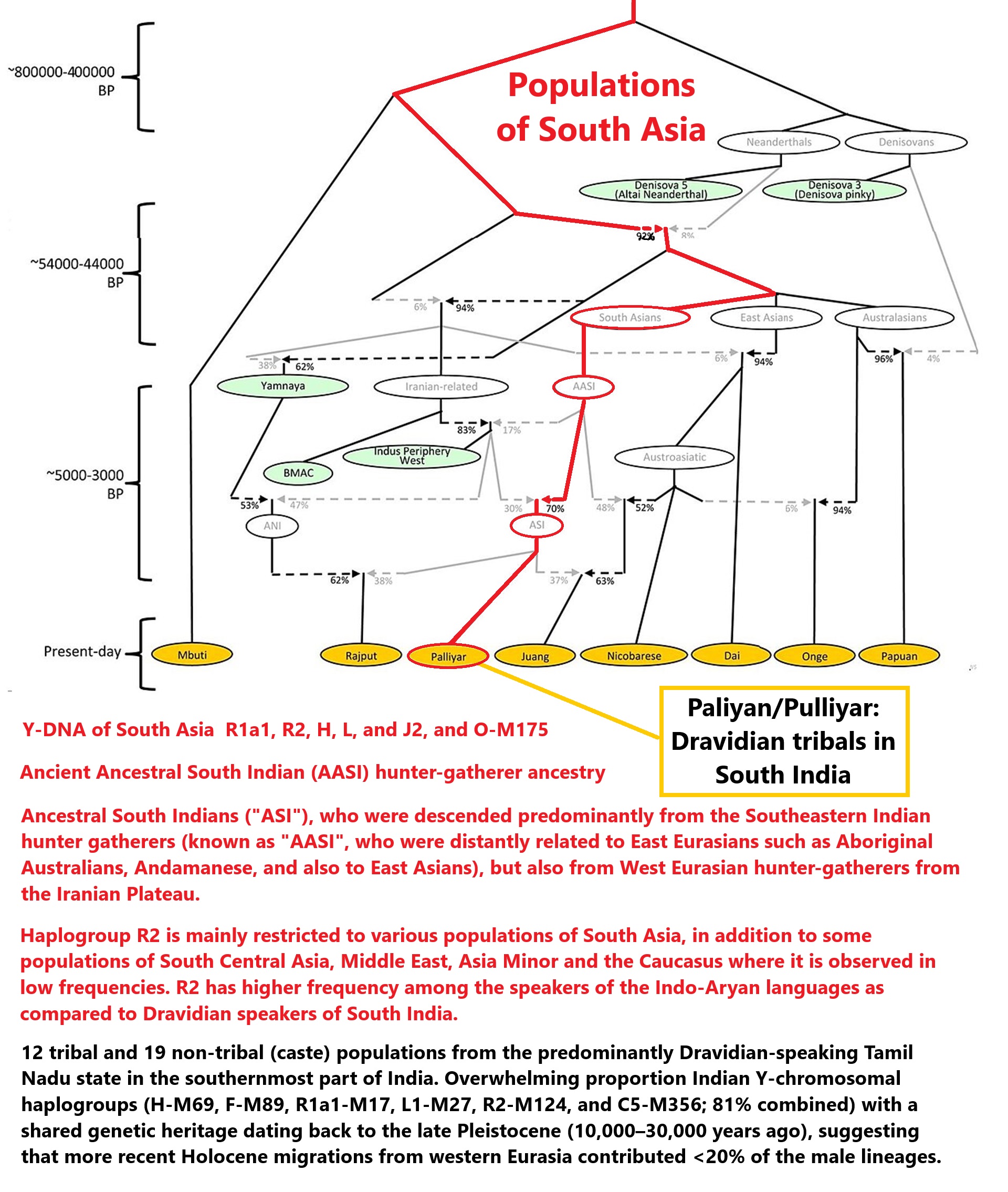

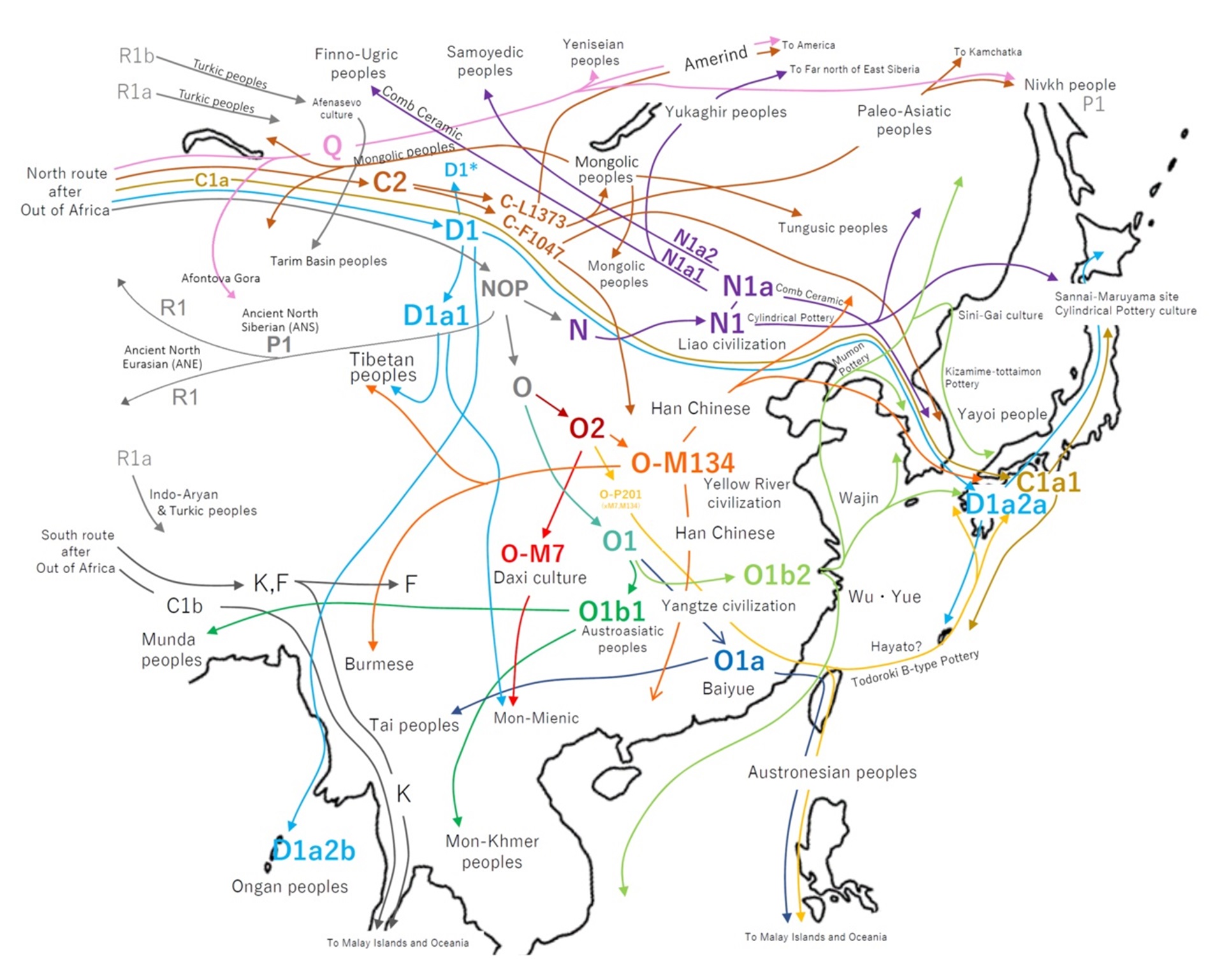

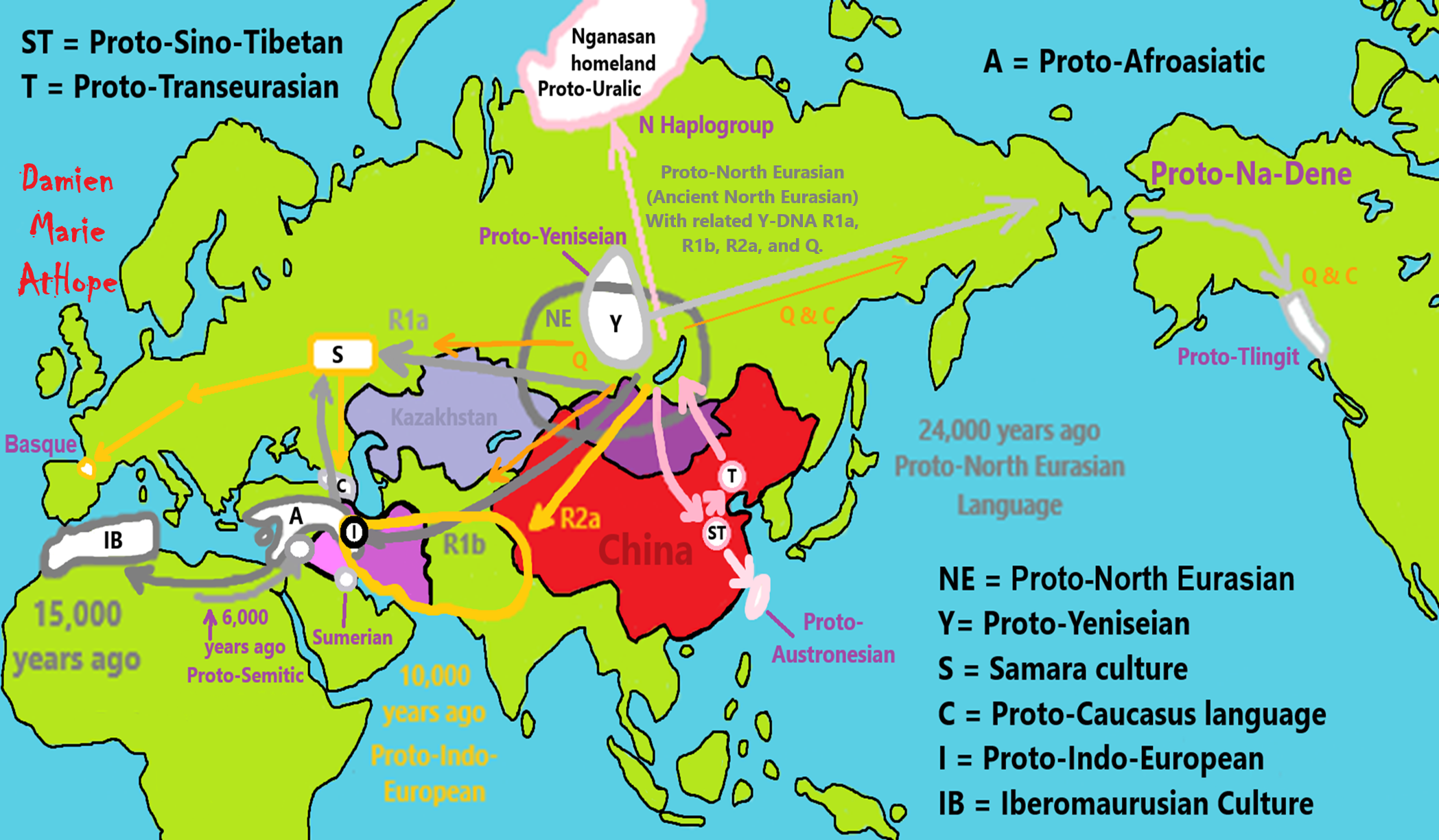

“With the decline of the IVC, and the migration of Indo-Europeans, the IVC-people contributed to the formation of both the Ancestral North Indians (“ANI”), who were closer to contemporary West Eurasians, and the Ancestral South Indians (“ASI”), who were descended predominantly from the Southeastern Indian hunter gatherers (known as “AASI”, who were distantly related to East Eurasians such as Aboriginal Australians, Andamanese, and also to East Asians), but also from West Eurasian hunter-gatherers from the Iranian Plateau. These two ancestral populations (ASI and ANI) mixed extensively between 1,900-4,200 years ago, after the fall of the IVC and their respective southward migration, and affected both modern Indo-European populations as well as the Dravidian populations in the subcontinent, while the migrations of the Munda people and the Sino-Tibetan-speaking people from East Asia also added new elements.” ref

“Genetics and archaeogenetics of South Asia is the study of the genetics and archaeogenetics of the ethnic groups of South Asia. It aims at uncovering these groups’ genetic histories. The geographic position of the Indian subcontinent makes its biodiversity important for the study of the early dispersal of anatomically modern humans across Asia. The people of South Asia are broadly of a mixture of Western Steppe Herder (WSH) and native South Asian heritage, the latter of which combines IVC-related ancestry with Ancient Ancestral South Indian (AASI) hunter-gatherer ancestry.” ref

“Based on mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) variations, genetic unity across various South Asian subpopulations have shown that most of the ancestral nodes of the phylogenetic tree of all the mtDNA types originated in the subcontinent. Conclusions of studies based on Y chromosome variation and autosomal DNA variation have been varied.” ref

“The genetic makeup of modern South Asians can be described at the deepest level as a combination of West Eurasian (related to ancient and modern people in Europe and West Asia) ancestries with divergent East Eurasian ancestries. The latter primarily include a proposed indigenous South Asian component (termed Ancient Ancestral South Indians, short “AASI”) that is distantly related to the Andamanese peoples, as well as to East Asians and Aboriginal Australians, and further include additional, regionally variable East/Southeast Asians components.” ref

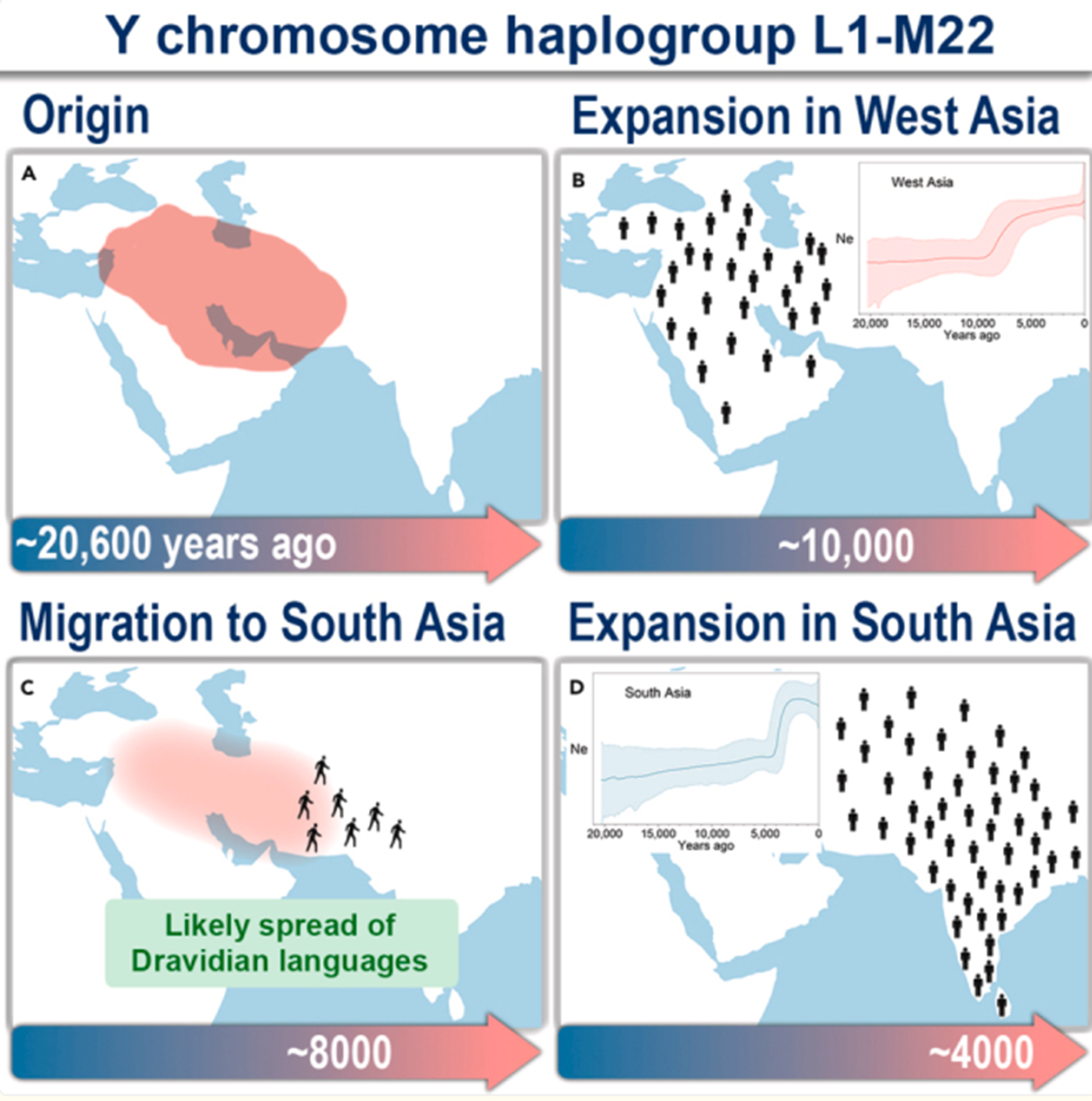

“Previous studies that pooled Indian populations from a wide variety of geographical locations, have obtained contradictory conclusions about the processes of the establishment of the Varna caste system and its genetic impact on the origins and demographic histories of Indian populations. To further investigate these questions we took advantage that both Y chromosome and caste designation are paternally inherited, and genotyped 1,680 Y chromosomes representing 12 tribal and 19 non-tribal (caste) endogamous populations from the predominantly Dravidian-speaking Tamil Nadu state in the southernmost part of India. Tribes and castes were both characterized by an overwhelming proportion of putatively Indian autochthonous Y-chromosomal haplogroups (H-M69, F-M89, R1a1-M17, L1-M27, R2-M124, and C5-M356; 81% combined) with a shared genetic heritage dating back to the late Pleistocene (10,000–30,000 years ago), suggesting that more recent Holocene migrations from western Eurasia contributed <20% of the male lineages.” ref

“Reserchers found strong evidence for genetic structure, associated primarily with the current mode of subsistence. Coalescence analysis suggested that the social stratification was established 4,000–6,000 years ago and there was little admixture during the last 3,000 years ago, implying a minimal genetic impact of the Varna (caste) system from the historically-documented Brahmin migrations into the area. In contrast, the overall Y-chromosomal patterns, the time depth of population diversifications and the period of differentiation were best explained by the emergence of agricultural technology in South Asia. These results highlight the utility of detailed local genetic studies within India, without prior assumptions about the importance of Varna rank status for population grouping, to obtain new insights into the relative influences of past demographic events for the population structure of the whole of modern India.” ref

“The proposed AASI type ancestry is closest to the non-West Eurasian part, termed S-component, extracted from South Asian samples, especially those from the Irula tribe, and is generally found throughout all South Asian ethnic groups in varying degrees. The West Eurasian ancestry, which is closely related to Mesolithic hunter-gatherers and Neolithic farmers who lived on the Iranian Plateau (who are also closely related to Caucasus hunter-gatherers), forms the major source of the South Asian genetic makeup, and combined with varying degrees of AASI ancestry, formed the Indus Periphery Cline around ~5400–3700 BCE or around 7,400 to 5,700 years ago, which constitutes the main ancestral heritage of most modern South Asian groups.” ref

“The Indus Periphery ancestry, around the 2nd millennium BCE or around 4,000 years ago, mixed with another West Eurasian wave, the incoming mostly male-mediated Yamnaya-Steppe component (archaeogenetically dubbed the Western Steppe Herders) to form the Ancestral North Indians (ANI), while at the same time it contributed to the formation of Ancestral South Indians (ASI) by admixture with hunter-gatherers having higher proportions of AASI-related ancestry.” ref

“The ANI-ASI gradient, as demonstrated by the higher proportion of ANI in traditionally upper caste and Indo-European speakers, that resulted because of the admixture between the ANI and the ASI after 2000 BCE at various proportions is termed as the Indian Cline. The East Asian ancestry component forms the major ancestry among Tibeto-Burmese and Khasian speakers, and is generally restricted to the Himalayan foothills and Northeast India, with substantial presence also in Munda-speaking groups, as well as in some populations of northern, central and eastern South Asia.” ref

“Contemporary Indian populations exhibit a high cultural, morphological, and linguistic diversity, as well as some of the highest genetic diversities among continental populations after Africa. Indian populations are broadly classified into two categories: ‘tribal’ and ‘non-tribal’ groups. Tribal groups, constituting 8% of the Indian population, are characterized by traditional modes of subsistence such as hunting and gathering, foraging and seasonal agriculture of various kinds. In contrast, most other Indians fall into non-tribal categories, many of them classified as castes under the Hindu Varna (Color caste) system which groups caste populations, primarily on occupation, into Brahmin (priestly class), Kshatriya (warrior and artisan), Vyasa (merchant), Shudra (unskilled labor) and the most recently added fifth class, Panchama, the scheduled castes of India. Generally, both non-tribal and tribal populations employ a patrilineal caste endogamy. This practice, together with the male-specific genetic transmission of the non-recombining portion of the Y-chromosome (NRY), provides a unique opportunity to study the impact of historical demographic processes and the social structure on the gene pool of India.” ref

“The distribution of deep-rooted Indian-specific Y-chromosomal and mitochondrial lineages suggests an initial settlement of modern humans in the subcontinent from the early out-of-Africa migration. The greater genetic isolation of many tribal groups and their differences in Y-chromosomal haplogroup (HG) lineages compared to non-tribal groups, have generally been interpreted as evidence of tribes being direct descendants of the earliest Indian settlers. Moreover, these tribe-caste genetic differences have been attributed to the establishment of the Hindu Varna system that has been maintained for millennia since both Y chromosome and caste designation are paternally inherited. However, the origin of caste system in India is still a controversial subject, and there are two main schools of thought about it.” ref

“First, demic diffusion models propose an expansion of Indo-European (IE) speakers 3,000 years ago from Central Asia . Alternatively, other models propose the origin of caste as the result of cultural diffusion and/or autochthonous demographic processes without any major genetic influx from outside India. Overall, the genetic impact and mode of establishment of the caste system, the extent of a common indigenous Pleistocene (10,000 to 30,000 years ago) genetic heritage and the degree of admixture from West Eurasian Holocene (10,000 years ago) migrations and their level of impact on the tribal and non-tribal groups from India, remain unresolved. The lack of consensus among previous studies may reflect difficulties associated with the conflicting relationships between genetics and the socio-cultural factors used to pool truly endogamous groups into broader categories, sometimes grouping Indian populations sampled from a wide variety of geographical locations together, such as a tribe-caste dichotomy or caste-rank hierarchy.” ref

“One goal of pooling data from multiple populations has been to smooth individual drift effects in an effort to reconstruct putative ancestry and thereby potentially infer the past demographic processes shaping genetic diversity. However, the success of this approach relies on whether the classification employed indeed reflects the true historical relationships among these endogamous groups. Methods seeking to identify the best grouping from an exploration of alternative possible classifications, based on seeking maximal between-population differences and minimal within-population variation, would be of special relevance for studies on Indian populations classified based on Varna status. This is the case because several castes have suffered from historically fluid definitions of their rank status, and both the origins and the scope of the genetic impact of the Varna system on these populations are still unclear.” ref

“Further, since the implementation of the Varna system throughout India was not a uniform process, broad classifications of multiple Indian samples from all over the subcontinent based on Varna status, or tribe-caste dichotomy, may not reflect true endogamous populations and could also obscure genetic signals and the finer details of Indian demographic histories. For this reason, a genetic study using a careful and extensive sampling of well-defined non-tribal and tribal endogamous populations from a restricted area designed to reduce the confounding relationships among socio-cultural factors, without presuming Varna rank status, to find empirically the best approach of population grouping, could be a successful model to obtain new insights of past Indian demographic processes.

Here, we attempted to apply this strategy to unravel the population structure and genetic history of the southernmost state of India, Tamil Nadu (TN), which is well known for its rigid caste system, and to relate the resulting genetic data to the paleoclimatic, archaeological, and historical evidence from this region. The paleoclimatic and archaeological records show post-LGM (Last Glacial Maximum) wet period expansions of foragers into the region, whose interactions with later aridification-driven migrations of agriculturists have been traced. Archaeology also reveals the establishment of metallurgy and river settlements, just several centuries prior to the creation of the earliest written records of the Sangam literature (300 BCE “2,300 years ago” to 300 CE). These historical records named several populations including some in the present study (e.g., Paliyan, Pulayar, Valayar) reflecting the existence of these now endogamous groups at that time.” ref

“More recent reports dated to the 6th century CE, under the reign of the Sarabhapuriyas, illustrate the local implementation of the Varna system around 1,000 years ago, following the arrival of Brahmins into the region. The Tamil epics of this period, such as the Purananuru anthology and Silapathikaram, describe a society with a well-defined occupational class structure based on subsistence practices. Earlier genetic studies of TN populations identified clear differentiations of endogamous ethnic groups classified into Major Population Groups (MPG) based on socio-cultural characteristics reflecting subsistence, traditional occupation, and native language (mother tongue). Although some studies have identified hill tribes as the earliest settlers, and others suggested a common genetic signature among distantly ranked-caste populations, the main evolutionary and demographic processes shaping the observed genetic differences among populations from TN are still unresolved in the literature.” ref

“In the present study, we examined the Y-chromosomal lineages of 1,680 individuals sampled from 12 tribal and 19 non-tribal well-defined endogamous populations. We first investigated whether tribal and non-tribal groups shared a common genetic heritage and characterized the proportion of putatively autochthonous and non-autochthonous Indian Y-chromosomal haplogroups. It is important to note that the total sample size used here is higher than those in other studies covering the entire Indian subcontinent. Further, the detailed anthropological annotation of endogamous populations sampled from a restricted region within India, together with the paleoclimatic, archeological and historical regional-background were all important aspects needed to reduce the confounding relationships among socio-cultural factors. This general approach allowed us to infer important genetic signals and the finer details of the population demographic histories.” ref

“Therefore, we sought to determine which of the classifications based either on the Varna system (rank status, tribe-caste dichotomy), or social-cultural factors (reflecting subsistence, traditional customs and native language), or geography better indicated true endogamous groups by exhibiting higher between-population differences and lower within-population variation. Since both Y chromosome and caste designation are paternally inherited, we further explored whether any of these genetic differences could be attributed to the historical evidences of the establishment of the Hindu Varna system. In contrast, we found the overall Y-chromosomal patterns, the time depth of population diversifications and the period of differentiation correlated better with archeological evidences and the demographic processes of Neolithic agricultural expansions into the region.” ref

Paliyan/Pulliyar People

“The Paliyan, or Pulliyar, Palaiyar or Pazhaiyarare are a group of around 9,500 formerly nomadic Dravidian tribals living in the South Western Ghats montane rain forests in South India, especially in Tamil Nadu and Kerala. They are traditional nomadic hunter-gatherers, honey hunters and foragers. Yams are their major food source. In the early part of the 20th century the Paliyans dressed scantily and lived in rock crevices and caves. Most have now transformed to traders of forest products, food cultivators and beekeepers. Some work intermittently as wage laborers, mostly on plantations. They are a Scheduled Tribe. They speak a Dravidian language, Paliyan, closely related to Tamil.” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

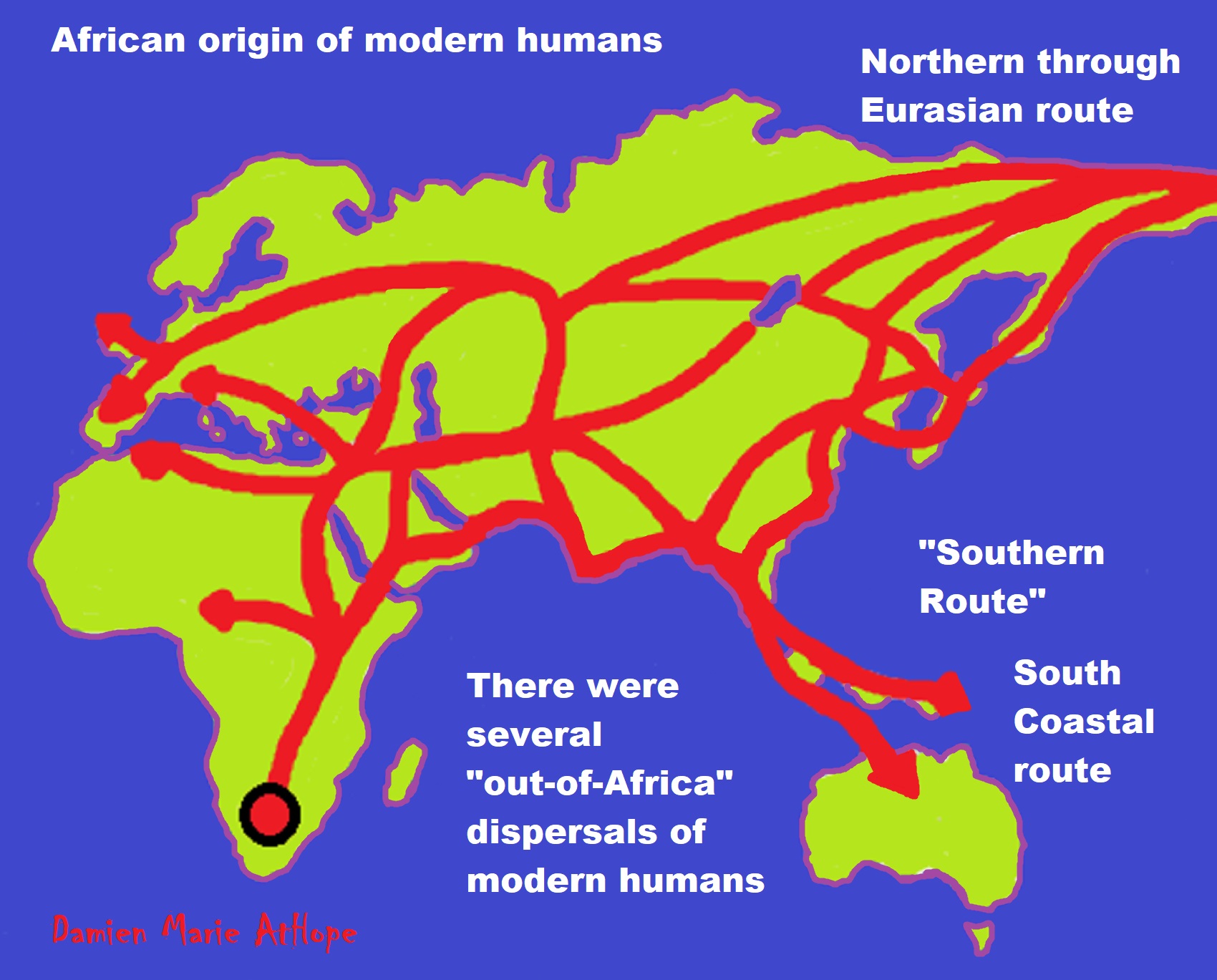

“There are two geographically plausible routes that have been proposed for humans to emerge from Africa: through the current Egypt and Sinai (Northern Route), or through Ethiopia, the Bab el Mandeb strait, and the Arabian Peninsula (Southern Route).” ref

“Although there is a general consensus on the African origin of early modern humans, there is disagreement about how and when they dispersed to Eurasia. This paper reviews genetic and Middle Stone Age/Middle Paleolithic archaeological literature from northeast Africa, Arabia, and the Levant to assess the timing and geographic backgrounds of Upper Pleistocene human colonization of Eurasia. At the center of the discussion lies the question of whether eastern Africa alone was the source of Upper Pleistocene human dispersals into Eurasia or were there other loci of human expansions outside of Africa? The reviewed literature hints at two modes of early modern human colonization of Eurasia in the Upper Pleistocene: (i) from multiple Homo sapiens source populations that had entered Arabia, South Asia, and the Levant prior to and soon after the onset of the Last Interglacial (MIS-5), (ii) from a rapid dispersal out of East Africa via the Southern Route (across the Red Sea basin), dating to ~74,000-60,000 years ago.” ref

“Within Africa, Homo sapiens dispersed around the time of its speciation, roughly 300,000 years ago. The so-called “recent dispersal” of modern humans took place about 70–50,000 years ago. It is this migration wave that led to the lasting spread of modern humans throughout the world. The coastal migration between roughly 70,000 and 50,000 years ago is associated with mitochondrial haplogroups M and N, both derivative of L3. Europe was populated by an early offshoot that settled the Near East and Europe less than 55,000 years ago. Modern humans spread across Europe about 40,000 years ago, possibly as early as 43,000 years ago, rapidly replacing the Neanderthal population.” ref, ref

Out of Africa: “the evolution of religion seems tied to the movement of people”

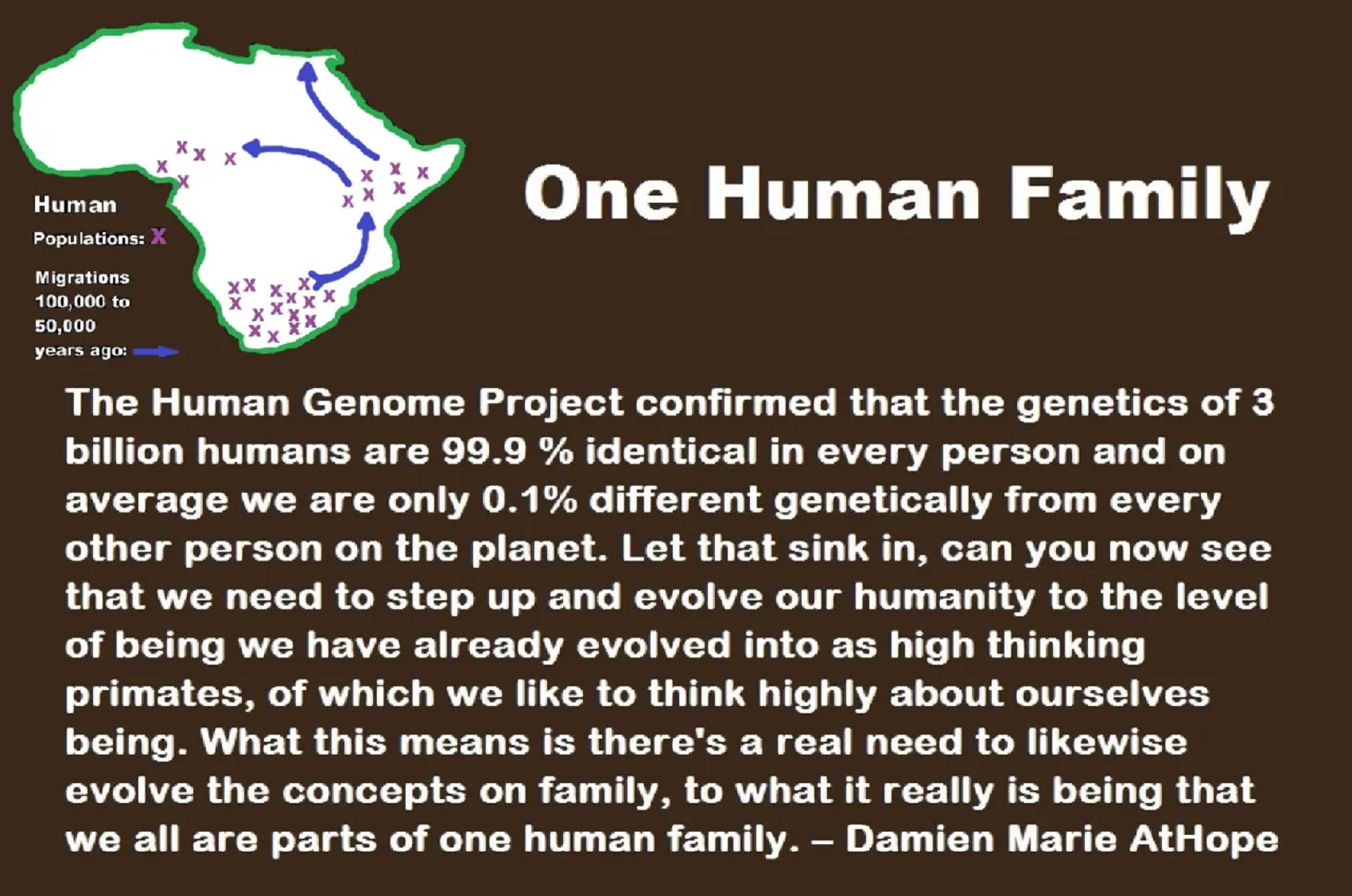

“When researchers completed the final analysis of the Human Genome Project in April 2003, they confirmed that the 3 billion base pairs of genetic letters in humans were 99.9 percent identical in every person. It also meant that individuals are, on average, 0.1 percent different genetically from every other person on the planet. And in that 0.1 percent lies the mystery of why some people are more susceptible to a particular illness or more likely to be healthy than their neighbor – or even another family member.” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

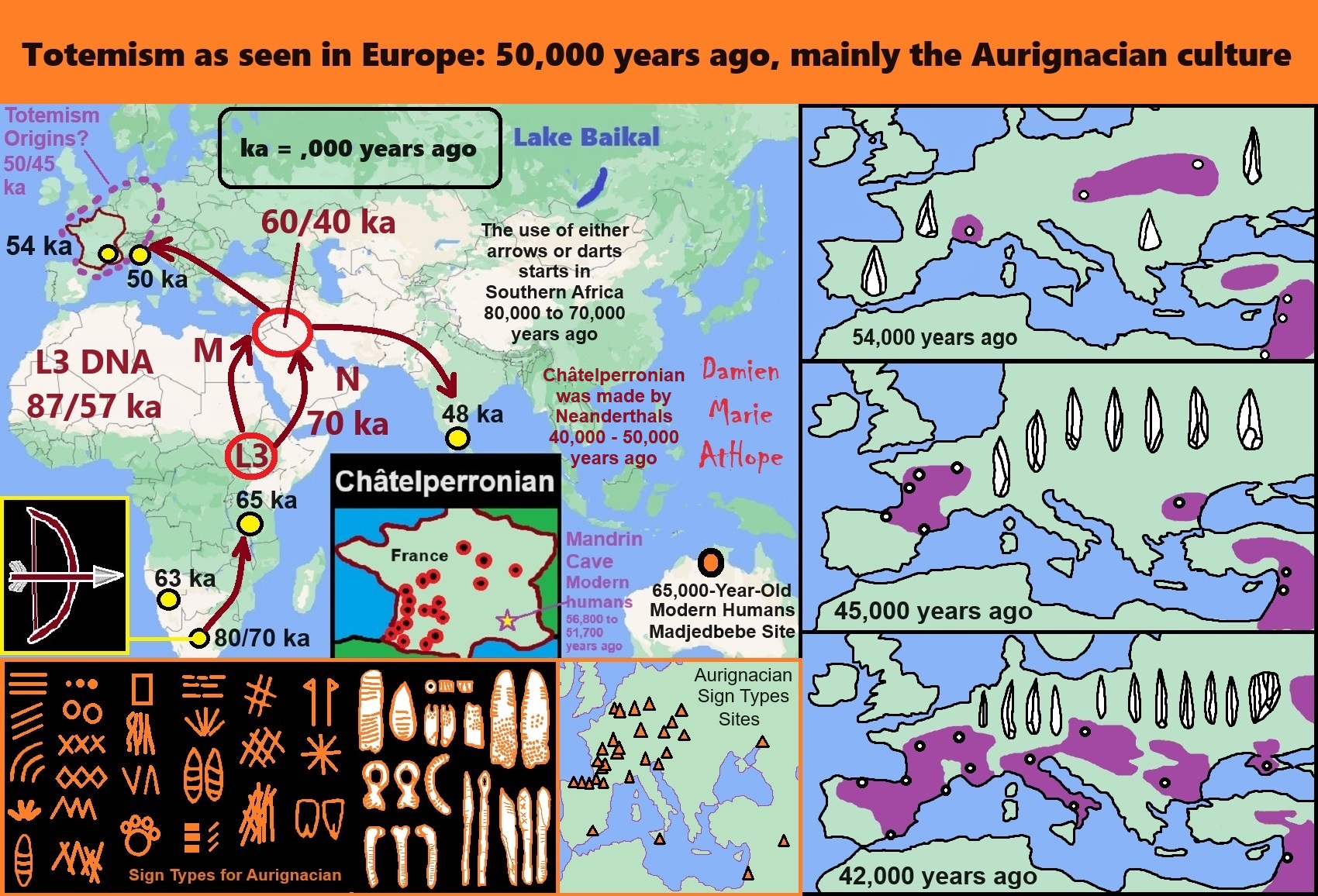

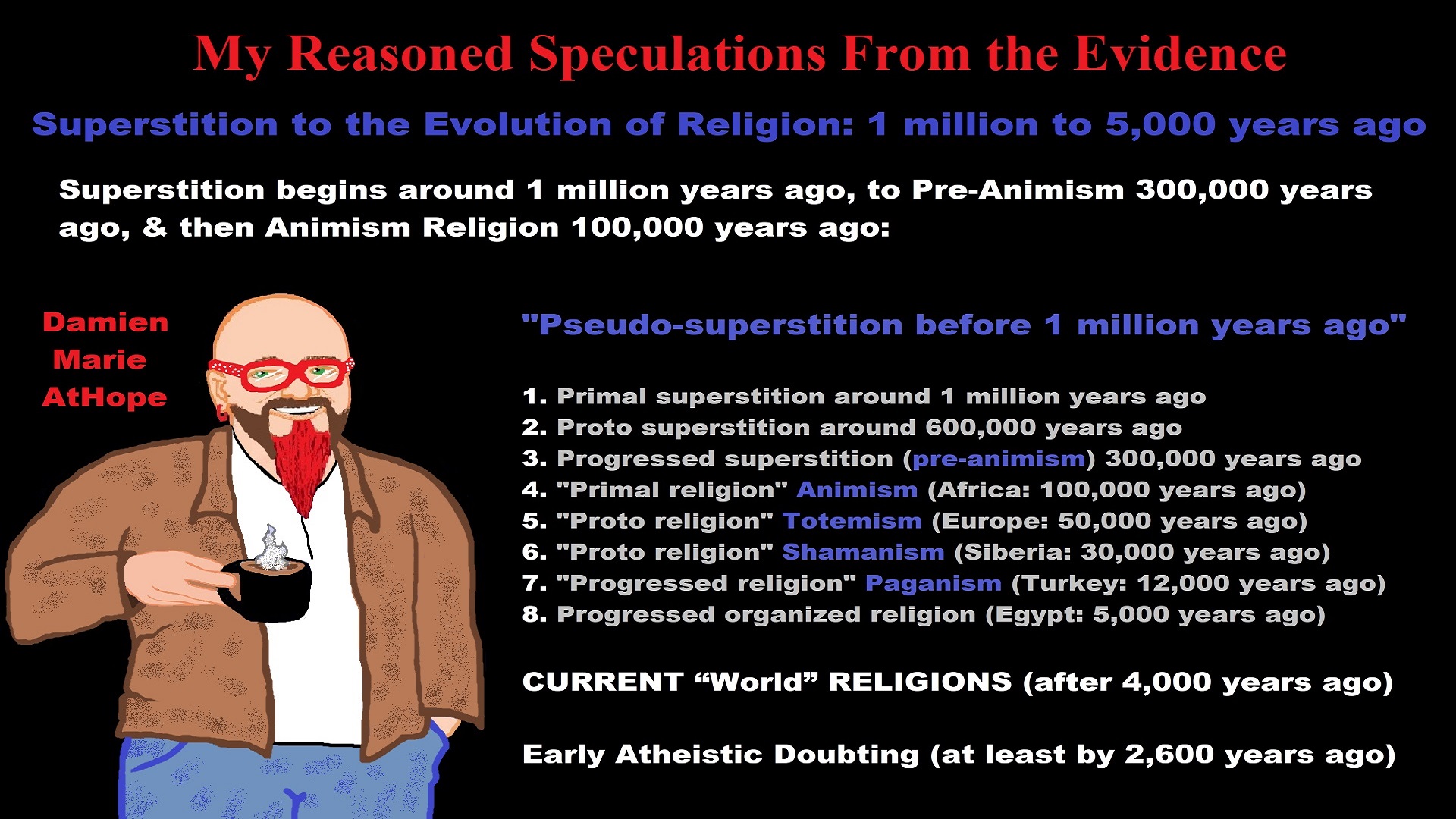

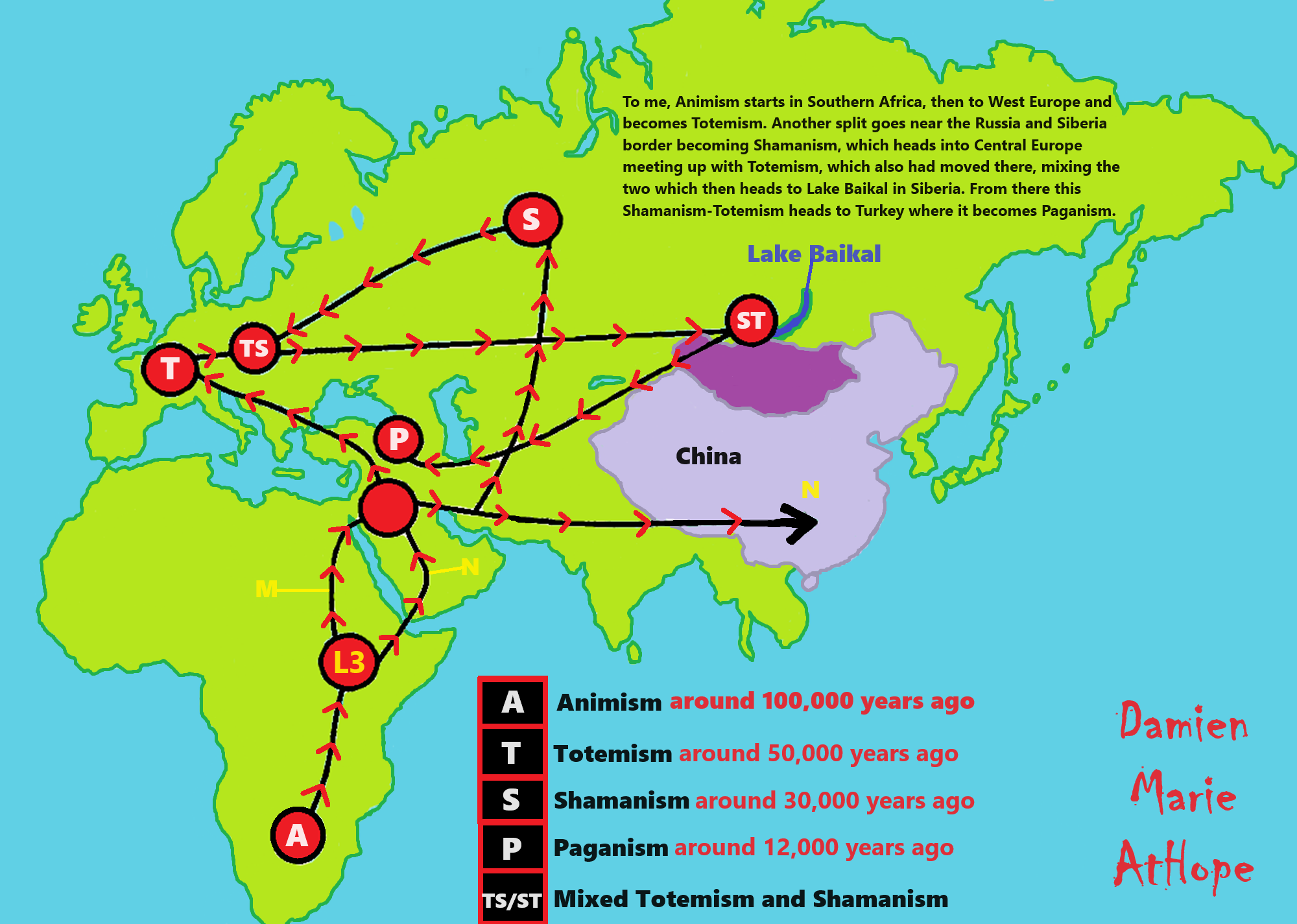

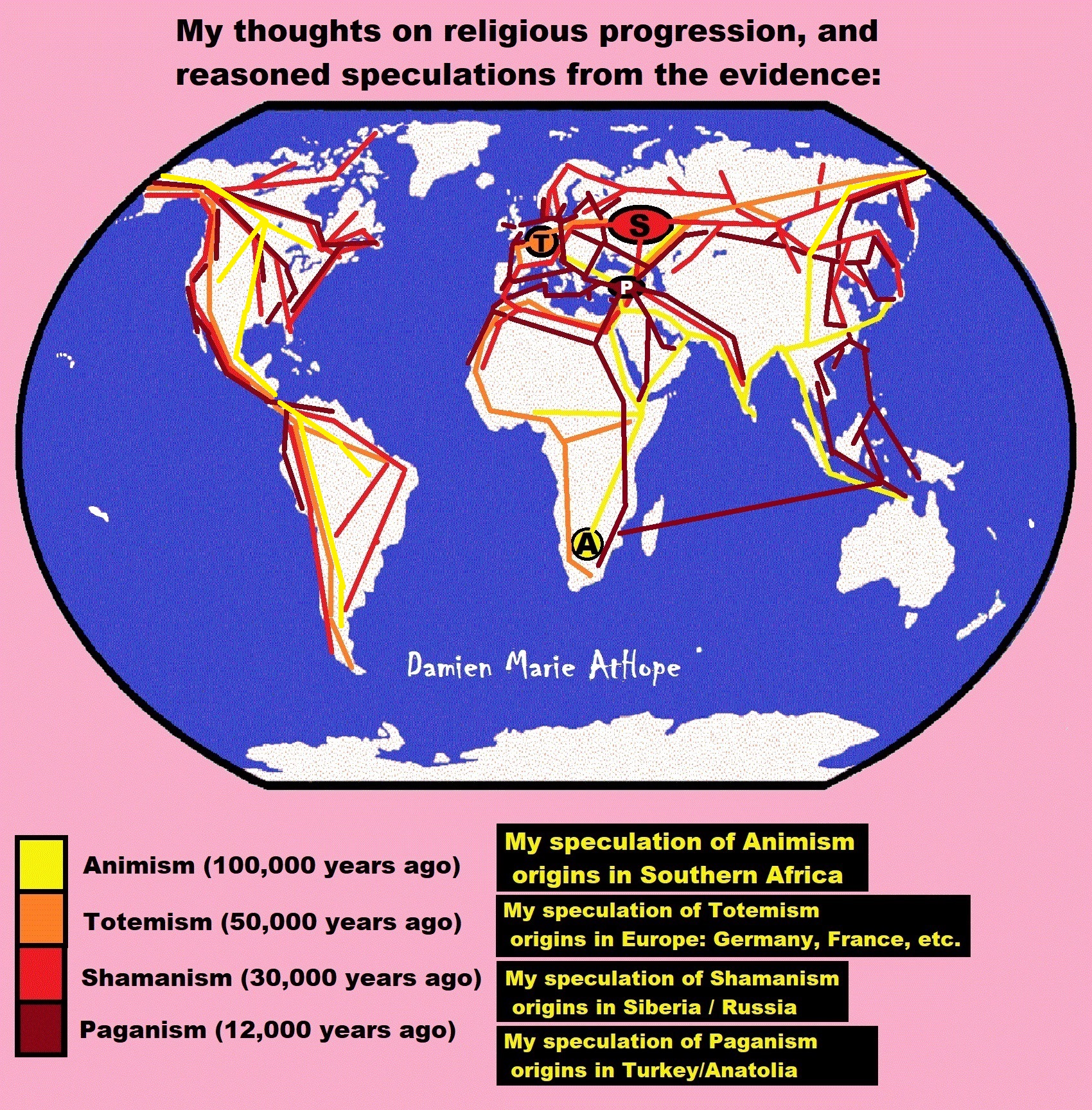

This is my thoughts/speculations on the origins of Totemism

Totemism as seen in Europe: 50,000 years ago, mainly the Aurignacian culture

- Pre-Aurignacian “Châtelperronian” (Western Europe, mainly Spain and France, possible transitional/cultural diffusion between Neanderthals and humans around 50,000-40,000 years ago)

- Archaic–Aurignacian/Proto-Aurignacian (Europe around 46,000-35,000)

- Aurignacian “classical/early to late” (Europe and other areas around 38,000 – 26,000 years ago)

“In the realm of culture, the archeological evidence also supports a Neandertal contribution to Europe’s earliest modern human societies, which feature personal ornaments completely unknown before immigration and are characteristic of such Neandertal-associated archeological entities as the Chatelperronian and the Uluzzian.” – (PDF) Neandertals and Moderns Mixed, and It Matters: Link

Totemism as seen in Europe: 50,000 years ago, mainly the Aurignacian culture

Totemism as seen in Europe: 50,000 years ago, mainly the Aurignacian culture

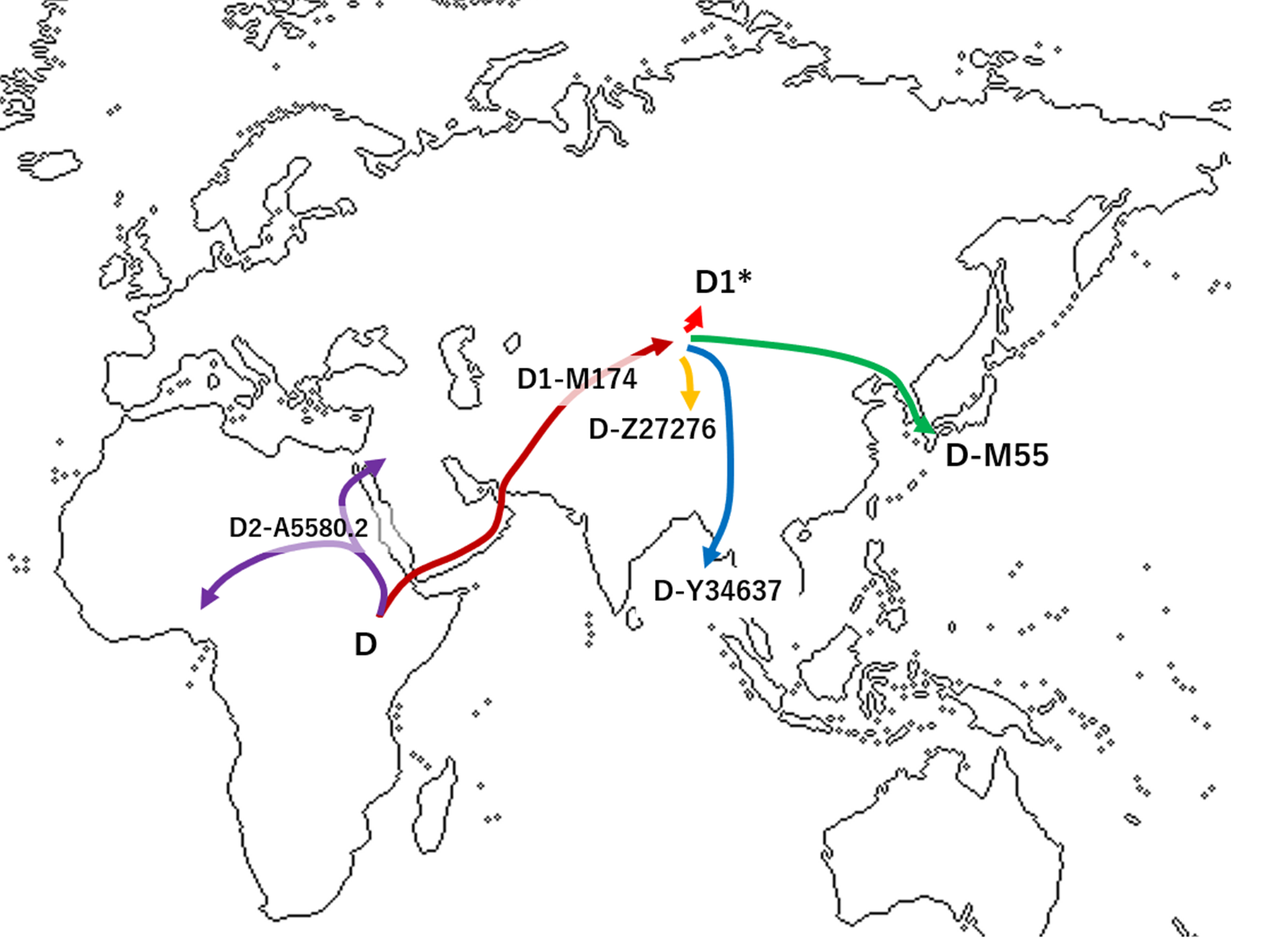

Haplogroup D

“D1 and D2 are found primarily in East Asia, at low frequency in Central Asia and Southeast Asia, and at very low frequency in Western Africa and Western Asia.” ref

Andamanese People

“The Great Andamanese are an indigenous people of the Great Andaman archipelago in the Andaman Islands. Historically, the Great Andamanese lived throughout the archipelago, and were divided into ten major tribes. Their distinct but closely related languages comprised the Great Andamanese languages, one of the two identified Andamanese language families. The Great Andamanese were clearly related to the other Andamanese peoples, but were well separated from them by culture, language, and geography. The languages of those other four groups were only distantly related to those of the Great Andamanese and mutually unintelligible; they are classified in a separate family, the Ongan languages.” ref

“They were once the most numerous of the five major groups in the Andaman Islands, with an estimated population between 2,000 and 6,600, before they were killed or died out due to diseases, alcohol, colonial warfare, and loss of hunting territory. Only 52 remained as of February 2010; by August 2020, there were 59. The tribal and linguistic distinctions have largely disappeared, so they may now be considered a single Great Andamanese ethnic group with mixed Burmese, Hindi, and aboriginal descent. The Great Andamanese are classified by anthropologists as one of the Negrito peoples, which also include the other four aboriginal groups of the Andaman islands (Onge, Jarawa, Jangil, and Sentinelese) and five other isolated populations of Southeast Asia. The Andaman Negritos are thought to be the first inhabitants of the islands, having emigrated from the mainland tens of thousands of years ago.” ref

“The Andamanese are the various indigenous peoples of the Andaman Islands, part of India‘s Andaman and Nicobar Islands, the union territory in the southeastern part of the Bay of Bengal. The Andamanese are a designated Scheduled Tribe in India’s constitution. The Andamanese peoples are among the various groups considered Negrito, owing to their dark skin and diminutive stature. All Andamanese traditionally lived a hunter-gatherer lifestyle, and appear to have lived in substantial isolation for thousands of years. It is suggested that the Andamanese settled in the Andaman Islands around the latest glacial maximum, around 26,000 years ago.” ref

“The Andamanese peoples included the Great Andamanese and Jarawas of the Great Andaman archipelago, the Jangil of Rutland Island, the Onge of Little Andaman, and the Sentinelese of North Sentinel Island. Among the Andamanese, a division of two groups can be made. One is more open to contact with civilization, and the other is hostile and resistant to communicating with the outer world. At the end of the 18th century, when they first came into sustained contact with outsiders, an estimated 7,000 Andamanese remained. In the next century, they experienced a massive population decline due to epidemics of outside diseases and loss of territory. Today, only roughly over 500 Andamanese remain, with the Jangil being extinct. Only the Jarawa and the Sentinelese maintain a steadfast independence, refusing most attempts at contact by outsiders.” ref

“The oldest archaeological evidence for the habitation of the islands dates to the 1st millennium BCE. Genetic evidence suggests that the indigenous Andamanese peoples share a common origin, and that the islands were settled sometime after 26,000 years ago, possibly at the end of the Last Glacial Period, when sea levels were much lower reducing the distance between the Andaman Islands and the Asian mainland, with genetic estimates suggesting that the two main linguistic groups (Great Andamanese and Onge/Jarawa) diverged around 16,000 years ago. It was previously assumed that the Andaman ancestors were part of the initial Great Coastal Migration (South-Eurasians or Australasians) that was the first expansion of humanity out of Africa, via the Arabian peninsula, along the coastal regions of the South Asia towards Insular Southeast Asia, and Oceania.” ref

“The Andamanese were considered to be a pristine example of a hypothesized Negrito population, which showed similar physical characteristics, and was supposed to have existed throughout southeast Asia. The existence of a specific Negrito-population is nowadays doubted. Their commonalities could be the result of evolutionary convergence and/or a shared history. Recent genetic studies conclusively demonstrate Negrito groups do not share a common origin to the exclusion of other Asians. The four major groups of Andamanese. By the end of the eighteenth century, there were an estimated 5,000 Great Andamanese living on Great Andaman. Altogether they comprised ten distinct tribes with different languages. The population quickly dwindled to 600 in 1901 and to 19 by 1961. It has increased slowly after that, following their move to a reservation on Strait Island. As of 2010, the population was 52, representing a mix of the former tribes.” ref

“The Jarawa originally inhabited southeastern Jarawa Island and have migrated to the west coast of Great Andaman in the wake of the Great Andamanese. The Onge once lived throughout Little Andaman and now are confined to two reservations on the island. The Jangil, who originally inhabited Rutland Island, were extinct by 1931: the last individual was sighted in 1907. Only the Sentinelese are still living in their original homeland on North Sentinel Island, largely undisturbed, and have fiercely resisted all attempts at contact. The Andamanese languages are considered to be the fifth language family of India, following the Indo-European, Dravidian, Austroasiatic, and Sino-Tibetan. While some connections have been tentatively proposed with other language families, such as Austronesian, or the controversial Indo-Pacific family, the consensus view is currently that Andamanese languages form a separate language family – or rather, two unrelated linguistic families: Greater Andamanese and Ongan.” ref

Until contact, the Andamanese were strict hunter-gatherers. They did not practice cultivation, and lived off hunting indigenous pigs, fishing, and gathering. Their only weapons were the bow, adzes, and wooden harpoons. The Andamanese knew of no method for making fire in the nineteenth century. They instead carefully preserved embers in hollowed-out trees from fires caused by lightning strikes. The men wore girdles made of hibiscus fiber which carried useful tools and weapons for when they went hunting. The women on the other hand wore a tribal dress containing leaves that were held by a belt. A majority of them had painted bodies as well. They usually slept on leaves or mats and had either permanent or temporary habitation among the tribes. All habitations were man made.” ref

“Some of the tribe members were credited with having supernatural powers. They were called oko-pai-ad, which meant dreamer. They were thought to have an influence on the members of the tribe and would bring misfortune to those who did not believe in their abilities. Traditional knowledge practitioners were the ones who helped with healthcare. The medicine that was used to cure illnesses were herbal most of the time. Various types of medicinal plants were used by the islanders. 77 total traditional knowledge practitioners were identified and 132 medicinal plants were used. The members of the tribes found various ways to use leaves in their everyday lives including clothing, medicine, and to sleep on.” ref

“Anthropologist A.R. Radcliffe Brown argued that the Andamanese had no government and made decisions by group consensus. The native Andamanese religion and belief system is a form of animism. Ancestor worship is an important element in the religious traditions of the Andaman islands. Andamanese Mythology held that humans emerged from split bamboo, whereas the women were fashioned from clay. One version found by Alfred Reginald Radcliffe-Brown held that the first man died and went to heaven, a pleasurable world, but this blissful period ended due to breaking a food taboo, specifically eating the forbidden vegetables in the Puluga‘s garden. Thus Catastrophe ensued, and eventually the people grew overpopulated and didn’t follow Puluga‘s laws, and hence there was a Great Flood that left four survivors, who lost their fire.” ref

“Negritos, specifically Andamanese, are grouped together by phenotype and anthropological features. Three physical features that distinguish the Andaman islanders include: skin color, hair, and stature. Those of the Andaman islands have dark skin, are short in stature, and have “frizzy” hair, while displaying “Asiatic facial features”.Dental characteristics also group the Andamanese between Negrito and East-Asian samples. When comparing dental morphology the focus is on overall size and tooth shape. To measure the size and shape, Penrose’s size and shape statistic is used. To calculate tooth size, the sum of the tooth area is taken. Factor analysis is applied to tooth size to achieve tooth shape. Results have shown that the dental morphology of Andaman Islanders resembles that of tribal populations of South Asia (Adivasi) the most, followed by Philippine Negrito groups, contemporary Southeast Asians, and East Asians. The tooth size of the Andamanese was found to be most similar to that of Han Chinese and Japanese.” ref

“Genetic analysis, both of nuclear DNA and mitochondrial DNA provide information about the origins of the Andamanese. Genetic studies agree that Great Andamanese as well as Onge and Jawara, share a common origin to the exclusion of other Asians, and that they are highly genetically divergent from other Asian populations. The Andamanese show a very small genetic variation, which is indicative of populations that have experienced a population bottleneck and then developed in isolation for a long period.” ref

“An allele has been discovered among the Jarawas that is found nowhere else in the world. Blood samples of 116 Jarawas were collected and tested for Duffy blood group and malarial parasite infectivity. Results showed a total absence of both Fya and Fyb antigens in two areas (Kadamtala and R.K Nallah) and low prevalence of both Fya antigen in another two areas (Jirkatang and Tirur). There was an absence of malarial parasite Plasmodium vivax infection though Plasmodium falciparum infection was present in 27·59% of cases. A very high frequency of Fy (a–b–) in the Jarawa tribe from all the four jungle areas of Andaman Islands along with total absence of P. vivax infections suggests the selective advantage offered to Fy (a–b–) individuals against P. vivax infection.” ref

“Genetic studies have revealed that the Andamanese people display affinity to the indigenous South Asian hunter-gatherers, often termed “Ancient Ancestral South Indians” (AASI), as well as to Australasian populations (AA), such as Melanesians, and contemporary East/Southeast Asian peoples (ESEA). While the Andamanese are occasionally used as an imperfect proxy for the AASI component, they are genetically closer to the ‘Basal East Asian’ Tianyuan man.” ref

“Phylogenetic data suggests that an early initial eastern lineage trifurcated, and gave rise to Australasians (Oceanians), the AASI, Andamanese, as well as East/Southeast Asians, although Papuans may have also received some geneflow from an earlier group (xOoA), around 2%, next to additional archaic admixture in the Sahul region. Concerning the use of Andamanese as proxy for AASI ancestry, Yelmen et al. (2019) deduced that the non West Eurasian component, termed S-component, extracted from South Asian samples would serve as a much better proxy for AASI ancestry, especially those extracted from Irula samples, than the Andamanese. Overall, the Malaysian Negritos (Semang), such as the Maniq people, Jahai people, and Batek people, are the closest modern living relatives of the Andamanese people.” ref

When compared with ancient DNA samples, Andamanese peoples are closest to the pre-Neolithic Hoabinhians in Mainland Southeast Asia (covered by two samples from Malaysia and Laos), and display high genetic affinity to the Tianyuan man in Northern China, with both being basal to contemporary East Asians, forming a “deep Asian” ancestral lineage. Deep Asian ancestry (Tianyuan/Onge) contributed to the Peopling of Southeast Asia. The male Y-chromosome in humans is inherited exclusively through paternal descent. All sampled males of Onges (23/23) and Jarawas (4/4) belong to a sublineage of D-M174(D1a3). However, male Great Andamanese do not appear to carry these clades. A low resolution study suggests that they belong to haplogroups K, L, O, and P1 (P-M45).” ref

“A 2017 study by Mondal et al. finds that the Y-chromosome of the Riang people (a Tibeto-Burmese population), sublineage D1a3 (D-M174*) and the Andamanese D1a3 (*D-Y34637) have their nearest related lineages in East Asia, splitting about 23,000 years ago from an East Asian-related population. The Jarawa and Onge shared this D1a3 lineage with each other within the last ~7,000 years, suggesting a bottleneck event. They further suggest that: “This strongly suggests that haplogroup D does not indicate a separate ancestry for Andamanese populations. Rather, haplogroup D was part of the standing variation carried by the OOA expansion, and later lost from most of the populations except in Andaman and partially in Japan and Tibet”. Other haplogroups found among Andamanese include haplogroup P, and L-M20.” ref

“Several studies (Hammer et al. 2006, Shinoda 2008, Matsumoto 2009, Cabrera et al. 2018) suggest that the paternal haplogroup D-M174 originated somewhere in Central Asia. According to Hammer et al., haplogroup D-M174 originated between Tibet and the Altai mountains. He suggests that there were multiple waves into Eastern Eurasia. In a 2019 study by Haber et al. showed that Haplogroup D-M174 originated in Central Asia and evolved as it migrated to different directions of the continent. One group of population migrated to Siberia, others to Japan and Tibet, and another group migrated to the Andaman islands.” ref

“Bulbeck (2013) shows the Andamanese maternal mtDNA is entirely mitochondrial Haplogroup M. Haplogroup M (mtDNA) is a descendant of haplogroup L3, typically found in Eurasia and parts of Africa. The mtDNA M is found in all Onge and most of the Great Andamanese samples. Analysis of mtDNA, which is inherited exclusively by maternal descent, confirms the above results. Haplogroup M is, however, also the single most common mtDNA haplogroup in Asia, where it represents 60% of all maternal lineages. Haplogroup M is also relatively common in Northeast Africa of Somalis, Oromo at over 20%. Also in the Tuareg in Mali and Burkina Faso at 18.42%.” ref

“Unlike some Negrito populations of Southeast Asia, Andaman Islanders have not been found to have Denisovan ancestry. However, they are estimated, like all other non-African populations, to possess approximately 1-2% Neanderthal ancestry. A 2019 study concluded that all Asian and Australo-Papuan populations, including Andaman Islanders, also share between 2.6 and 3.4% of the genetic profile of a previously unknown hominin that was genetically roughly equidistant to Denisovans and Neanderthals.” ref

Y-DNA haplogroups in populations of South Asia

“South Asia, located on the crossroads of Western Eurasia and Eastern Eurasia, accounts for about 39.49% of Asia‘s population, and over 24% of the world’s population. It is home to a vast array of people who belong to diverse ethnic groups, who migrated to the region during different periods of time. The presence of Himalayas in northern and eastern borders of South Asia have limited migrations from Eastern Eurasia into Indian subcontinent in the past. Hence most of the male-mediated migrations into South Asia occurred from Western Eurasia into the region, as seen in the Y-chromosome DNA Haplogroup variations of populations in the region.” ref

“The major paternal lineages of South Asian populations, represented by Y chromosomes, are haplogroups R1a1, R2, H, L, and J2, as well as O-M175 in some parts (northeastern region) of the Indian subcontinent. Haplogroup R is the most observed Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup among the populations of South Asia, followed by H, L, and J, in the listed order. These four haplogroups together constitute nearly 80% of all male Y-chromosome DNA haplogroups found in various populations of the region. The Y-chromosome DNA Haplogroups R1a1, R2, L, and J2, which are found in higher frequencies among various populations of the Indian subcontinent, are also observed among various populations of Europe, Central Asia, and Middle East.” ref

“Some researchers have argued that Y-DNA Haplogroup R1a1 (M17) is of autochthonous South Asian origin. However, proposals for a Eurasian Steppe origin for R1a1 are also quite common and supported by several more recent studies. The spread of R1a1 in Indian subcontinent is associated with Indo-Aryan migrations into the region from South Central Asia that occurred around 3,500-4,000 years before present. The R1a-Z93 paternal genetic in Romani people was also discovered. Indian-Brahmin origin of paternal haplogroup R1a1*. The Haplogroup R2 is mainly restricted to various populations of South Asia, in addition to some populations of South Central Asia, Middle East, Asia Minor and the Caucasus where it is observed in low frequencies. R2 has higher frequency among the speakers of the Indo-Aryan languages as compared to Dravidian speakers of South India.” ref

“The Haplogroup H (also known as the “Indian marker”), which is a direct descendant of the Upper Paleolithic Eurasian Haplogroup HIJK, is mostly restricted to South Asian populations of the Indian subcontinent, in addition to some populations of South Central Asia and eastern Iranian Plateau, where it is found in low frequencies. It originated somewhere in the Middle East or South Central Asia and traveled to South Asia and adjoining areas of the eastern Iranian Plateau around 40,000-50,000 years before present.” ref

“The Haplogroup L, which is thought to have originated near Pamir Mountains of present-day Tajikistan in South Central Asia, traveled throughout Indian subcontinent during the Neolithic period, and it is associated with the spread of the Bronze Age Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC) in South Asia, which existed around 3,300-5,300 years before present. It is also observed among many populations of the Iranian Plateau. The spread of the Haplogroup J2 from Iranian Plateau into Indian subcontinent also occurred during the Neolithic period, alongside L.” ref

“The Haplogroup O-M175, which is a major haplogroup observed among the populations of East and Southeast Asia, is found largely restricted among the Tibeto-Burman and Austroasiatic speakers of the Himalayan and northeastern regions of South Asia. Listed below are some notable groups and populations from South Asia by human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroups based on various relevant studies. The samples are taken from individuals identified with specific linguistic designations (IE=Indo-European, Dr=Dravidian, AA=Austro-Asiatic, ST=Sino-Tibetan) and individual linguistic groups, the third column (n) gives the sample size studied, and the other columns give the percentage of the respective haplogroups.” ref

“Majority of the Indo-European (IE) speakers of South Asia speak Indo-Aryan languages, followed by Iranian languages, both of which belong to Indo-Iranian branch of the Indo-European language family. They form around 75% of the South Asian populations. The Dravidian (Dr) speakers of South Asia are mostly clustered in South India and Balochistan, as well as parts of Central India. They form around 20% of the South Asian populations. The Sino-Tibetan (ST) speakers in the Himalayas and northeastern parts of the South Asia speak various languages belonging to Tibeto-Burman branch of the Sino-Tibetan language family. The Austroasiatic (AA) speakers of South Asia are scattered in parts of Central, Eastern and Northeastern India as well in parts of Nepal and Bangladesh.” ref

“Genetics and archaeogenetics of South Asia is the study of the genetics and archaeogenetics of the ethnic groups of South Asia. It aims at uncovering these groups’ genetic histories. The geographic position of the Indian subcontinent makes its biodiversity important for the study of the early dispersal of anatomically modern humans across Asia. Based on mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) variations, genetic unity across various South Asian subpopulations have shown that most of the ancestral nodes of the phylogenetic tree of all the mtDNA types originated in the subcontinent. Conclusions of studies based on Y chromosome variation and autosomal DNA variation have been varied.” ref

“The genetic makeup of modern South Asians can be described at the deepest level as a combination of West Eurasian (related to ancient and modern people in Europe and West Asia) ancestries with divergent East Eurasian ancestries. The latter primarily include a proposed indigenous South Asian component (termed Ancient Ancestral South Indians, short “AASI”) that is distantly related to the Andamanese peoples, as well as to East Asians and Aboriginal Australians, and further include additional, regionally variable East/Southeast Asians components. The proposed AASI type ancestry is closest to the non-West Eurasian part, termed S-component, extracted from South Asian samples, especially those from the Irula tribe, and is generally found throughout all South Asian ethnic groups in varying degrees.” ref

“The West Eurasian ancestry, which is closely related to Mesolithic hunter-gatherers and Neolithic farmers who lived on the Iranian Plateau (who are also closely related to Caucasus hunter-gatherers), forms the major source of the South Asian genetic makeup, and combined with varying degrees of AASI ancestry, formed the Indus Periphery Cline around ~5400–3700 BCE, which constitutes the main ancestral heritage of most modern South Asian groups. The Indus Periphery ancestry, around the 2nd millennium BCE, mixed with another West Eurasian wave, the incoming mostly male-mediated Yamnaya-Steppe component (archaeogenetically dubbed the Western Steppe Herders) to form the Ancestral North Indians (ANI), while at the same time it contributed to the formation of Ancestral South Indians (ASI) by admixture with hunter-gatherers having higher proportions of AASI-related ancestry.” ref

“The ANI-ASI gradient, as demonstrated by the higher proportion of ANI in traditionally upper caste and Indo-European speakers, that resulted because of the admixture between the ANI and the ASI after 2000 BCE at various proportions is termed as the Indian Cline. The East Asian ancestry component forms the major ancestry among Tibeto-Burmese and Khasian speakers, and is generally restricted to the Himalayan foothills and Northeast India, with substantial presence also in Munda-speaking groups, as well as in some populations of northern, central and eastern South Asia. Modern South Asians are descendants of a combination of Western Eurasian ancestries (notably “Iran Neolithic Farmers” and “Western Steppe Herder” components) with an indigenous South Asian component (termed Ancient Ancestral South Indians, short “AASI”) closest to the non–West Eurasian part extracted from South Asian samples; distantly related to the Andamanese peoples, as well as to East Asians and Aboriginal Australians, as well as regional variable additional East/Southeast Asian components respectively.” ref

“The proposed AASI lineage, which is hypothesized to represent the ancestry of the very first hunter-gatherers and peoples of the Indian subcontinent, formed around ~40,000 years BCE. It was found that the AASI are distinct from Western Eurasian groups and have a closer genetic affinity with Ancient East Eurasians (such as Andamanese Onge or East Asian peoples). Based on this, it has been inferred that the AASI lineage diverged from other Eastern Eurasian lineages, such as ‘Australasians’ and ‘East/Southeast Asian people‘, during their dispersal using a Southern route. The Andamanese people are among the relatively most closely related modern populations to the AASI component and henceforth used as an (imperfect) proxy for it, but others (Yelmen et al. 2019) note that both are deeply diverged from each other, and propose the Southern Indian tribal groups, such as Paniya and Irula as better proxies for indigenous South Asian (AASI) ancestry, although noting that these tribal groups also carry varying degrees of Ancient Iranian admixture. Shinde et al. 2019 noted that both Andamanese Onge or East Siberian groups can be used as proxy for the non-West Eurasian-related component in the “qpAdm” admixture-modelling of an IVC-related individual (labelled “I6113”) because both populations “have the same phylogenetic relationship to the non-West Eurasian-related of I6113 likely due to shared ancestry deeply in time.” ref

“According to Yang (2022):

This distinct South Asian ancestry, denoted as the Ancient Ancestral South Indian (AASI) lineage, was only found in a small percentage of ancient and present-day South Asians. Present-day Onge from the Andamanese Islands are the best reference population to date, but Narasimhan et al. used qpGraph to show that the divergence between the AASI lineage and the ancestry found in present-day Onge was very deep. Ancestry associated with the AASI lineage was found at low levels in almost all present-day Indian populations.” ref

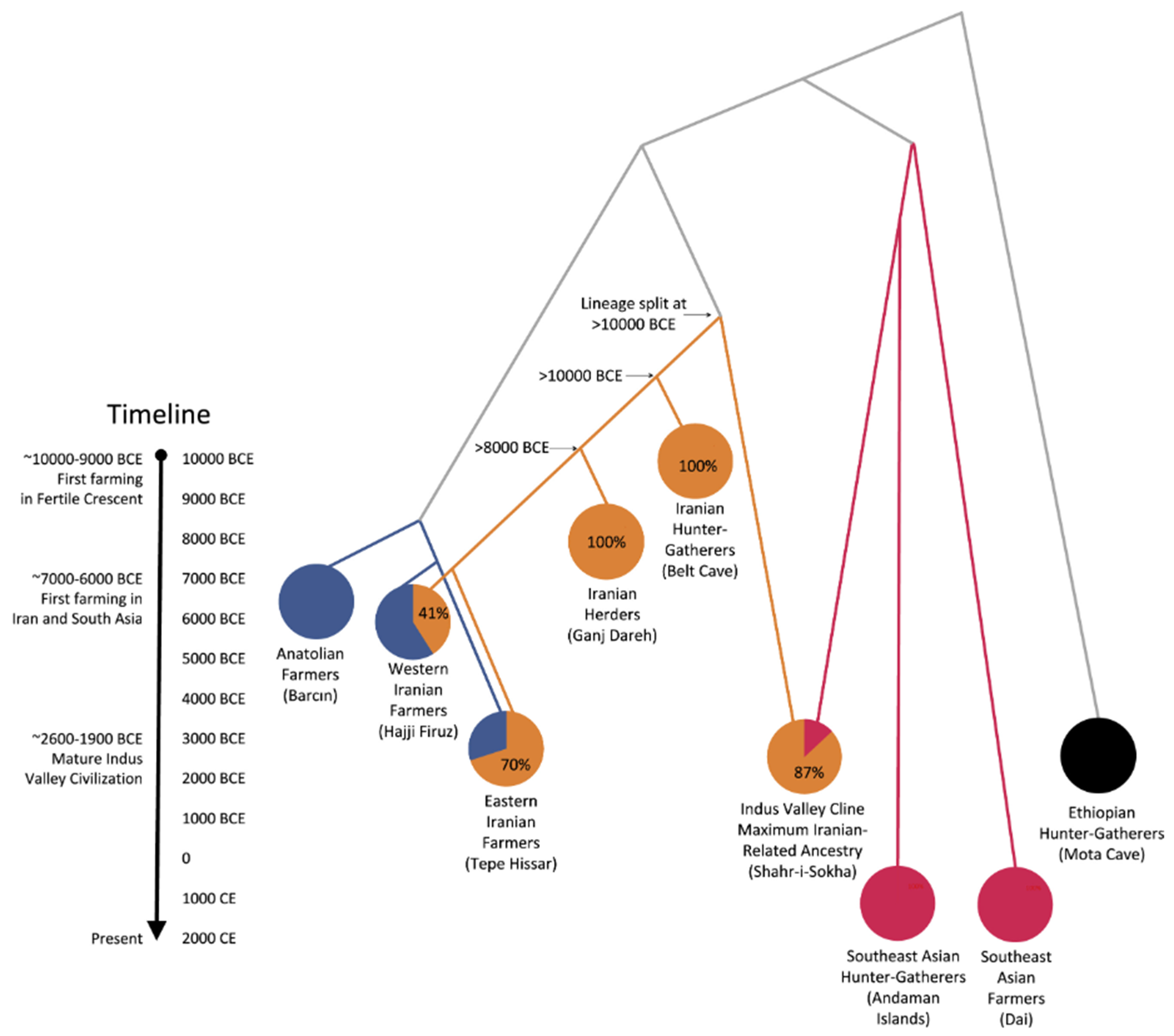

“Genetic data shows that the main West Eurasian geneflow event happened during the Neolithic period, or already during the Holocene (pre-Neolithic period). There is also evidence that some West Eurasian like ancestry reached South Asia earlier, during the Upper Paleolithic (around 40,000–30,000 years BCe).” The Neolithic or Pre-Neolithic Iranian lineage, which may be associated with the spread of Dravidian languages, forms the major source of the South Asian gene pool, and contributed foundational to all modern South Asians. Paired with varying degrees of AASI admixture, the Ancient Iranian lineage gave rise to the Indus Periphery Cline, which is characteristic for modern South Asians and central in the South Asian genetic heritage. Genetic data suggests that the specific Ancient Iranian-related lineage, diverged from Neolithic Iranian plateau lineages more than 10,000 years ago. According to an international research team led by palaeogeneticists of the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU), the main ancestry component of South Asians is derived from a population related to Neolithic farmers from the eastern Fertile Crescent and Iran.” ref

“In the 2nd millennium BCE, the Indus Periphery-related ancestry mixed with the arriving Yamnaya-Steppe component forming the Ancestral North Indians (ANI), while at the same time it contributed to the formation of Ancestral South Indians (ASI) by admixture with hunter-gatherers further South having higher proportions of AASI-related ancestry. The proximity to West Eurasian populations is based on the ANI-ASI gradient, also termed the Indian Cline, with the groups harboring higher ANI-ancestry being closer to West Eurasians as compared to populations harboring higher ASI-ancestry. Tribal groups from southern India harbor mostly ASI ancestry and sits farthest from West Eurasian groups on the PCA compared to other South Asians. The Yamnaya or Western Steppe pastoralist component is found in higher frequency among Indo-Aryan speakers, and is distributed throughout the Indian subcontinent at lower frequency. Certain communities and caste groups from the northern Indian subcontinent display a peak of Western Steppe Herders ancestry at similar amounts as Northern Europeans.” ref

“An East Asian-related ancestry component forms the major ancestry among Tibeto-Burmese and Khasi an speakers in the Himalayan foothills and Northeast India, and is also found in substantial presence in Mundari-speaking groups. According to Zhang et al., Austroasiatic migrations from Southeast Asia into India took place after the last Glacial maximum, circa 10,000 years ago. Arunkumar et al. suggest Austroasiatic migrations from Southeast Asia occurred into Northeast India 5,200 years ago and into East India 4,300 years ago. Tätte et al. 2019 estimated that the Austroasiatic language speaking people admixed with Indian population about 2000–3800 years ago, which may suggest arrival of Southeast Asian genetic component in the area.” ref

“It has been found that the ancestral node of the phylogenetic tree of all the mtDNA types (mitochondrial DNA haplogroups) typically found in Central Asia, the West Asia and Europe are also to be found in South Asia at relatively high frequencies. The inferred divergence of this common ancestral node is estimated to have occurred slightly less than 50,000 years ago. In India, the major maternal lineages are various M subclades, followed by R and U sublineages. These mitochondrial haplogroups’ coalescence times have been approximated to date to 50,000 years ago.” ref

“The major paternal lineages of South Asians are represented by the West Eurasian-affiliated haplogroups R1a1, R2, H, L and J2. A minority belongs to the East Eurasian-affiliated Haplogroup O-M175. O-M175 is mainly restricted to Austroasiatic and Tibeto-Burmese speakers, and also common among East and Southeast Asians, while H is largely restricted to South Asians, and R1a1, J2, and L as well as a subclade of H (H2) are commonly found among European and Middle Eastern populations. Some researchers have argued that Y-DNA Haplogroup R1a1 (M17) is of autochthonous South Asian origin. However, proposals for a Central Asian/Eurasian steppe origin for R1a1 are also quite common and supported by several more recent studies. Other minor haplogroups include subclades of Q-M242, G-M201, R1b, as well as Haplogroup C-M130.” ref

“Genetic studies comparing eight X chromosome based STR markers using a multidimensional scaling plot (MDS plot), revealed that modern-day South Asians like Indians, Pakistanis, Bangladeshis, and Sinhalese people cluster close to each other, but also closer to Europeans. In contrast, Southeast Asians, East Asians, and Africans were placed at a distant positions, outside the main cluster.” ref

mtDNA

See also: Recent single origin hypothesis

“The most frequent mtDNA haplogroups in South Asia are M, R, and U (where U is a descendant of R). Arguing for the longer term “rival Y-Chromosome model”, Stephen Oppenheimer believes that it is highly suggestive that India is the origin of the Eurasian mtDNA haplogroups which he calls the “Eurasian Eves”. According to Oppenheimer it is highly probable that nearly all human maternal lineages in Central Asia, the Middle East, and Europe descended from only four mtDNA lines that originated in South Asia 50,000–100,000 years ago.” ref

“The Ancient Indus Valley Civilisation” ref

Mehrgarh 7000 BCE to 2600 BCE in Pakistan

Damb Sadat 3500 BCE in Pakistan

Harappa 3500 BCE to 1400 BCE in in Punjab (Pakistan)

Indus Valley Civilization: “Pre-Harappan era: Mehrgarh”

“Mehrgarh is a Neolithic (7000 BCE to c. 2500 BCE) mountain site in the Balochistan province of Pakistan, which gave new insights on the emergence of the Indus Valley Civilisation. Mehrgarh is one of the earliest sites with evidence of farming and herding in South Asia. Mehrgarh was influenced by the Near Eastern Neolithic, with similarities between “domesticated wheat varieties, early phases of farming, pottery, other archaeological artefacts, some domesticated plants and herd animals.” ref

“Jean-Francois Jarrige argues for an independent origin of Mehrgarh. Jarrige notes “the assumption that farming economy was introduced full-fledged from Near-East to South Asia,” and the similarities between Neolithic sites from eastern Mesopotamia and the western Indus valley, which are evidence of a “cultural continuum” between those sites. But given the originality of Mehrgarh, Jarrige concludes that Mehrgarh has an earlier local background, and is not a “‘backwater’ of the Neolithic culture of the Near East.” ref

“Lukacs and Hemphill suggest an initial local development of Mehrgarh, with a continuity in cultural development but a change in population. According to Lukacs and Hemphill, while there is a strong continuity between the neolithic and chalcolithic (Copper Age) cultures of Mehrgarh, dental evidence shows that the chalcolithic population did not descend from the neolithic population of Mehrgarh, which “suggests moderate levels of gene flow.” Mascarenhas et al. (2015) note that “new, possibly West Asian, body types are reported from the graves of Mehrgarh beginning in the Togau phase (3800 BCE).” ref

“Gallego Romero et al. (2011) state that their research on lactose tolerance in India suggests that “the west Eurasian genetic contribution identified by Reich et al. (2009) principally reflects gene flow from Iran and the Middle East.” They further note that “[t]he earliest evidence of cattle herding in South Asia comes from the Indus River Valley site of Mehrgarh and is dated to 7,000 years ago.” ref

Mehrgarh

“Mehrgarh is a Neolithic archaeological site (dated c. 7000 BCE – c. 2500/2000 BCE) situated on the Kacchi Plain of Balochistan in modern-day Pakistan. It is located near the Bolan Pass, to the west of the Indus River, and between the modern-day Pakistani cities of Quetta, Kalat, and Sibi. The site was discovered in 1974 by the French Archaeological Mission led by the French archaeologists Jean-François Jarrige and Catherine Jarrige. Mehrgarh was excavated continuously between 1974 and 1986, and again from 1997 to 2000. Archaeological material has been found in six mounds, and about 32,000 artifacts have been collected from the site. The earliest settlement at Mehrgarh, located in the northeast corner of the 495-acre (2.00 km2) site, was a small farming village dated between 7000 BCE and 5500 BCE.” ref

“Mehrgarh is one of the earliest known sites in South Asia showing evidence of farming and herding. It was influenced by the Neolithic culture of the Near East, with similarities between “domesticated wheat varieties, early phases of farming, pottery, other archaeological artefacts, some domesticated plants and herd animals.” According to Asko Parpola, the culture migrated into the Indus Valley and became the Indus Valley Civilisation of the Bronze Age. Jean-Francois Jarrige argues for an independent origin of Mehrgarh. Jarrige notes “the assumption that farming economy was introduced full-fledged from Near-East to South Asia,” and the similarities between Neolithic sites from eastern Mesopotamia and the western Indus Valley, which are evidence of a “cultural continuum” between those sites. However, given the originality of Mehrgarh, Jarrige concludes that Mehrgarh has an earlier local background,” and is not a “‘backwater’ of the Neolithic culture of the Near East.” ref

“Lukacs and Hemphill suggest an initial local development of Mehrgarh, with continuity in cultural development but a population change. According to Lukacs and Hemphill, while there is a strong continuity between the Neolithic and Chalcolithic cultures of Mehrgarh, dental evidence shows that the Chalcolithic population did not descend from the Neolithic population of Mehrgarh, which “suggests moderate levels of gene flow.” They wrote that “the direct lineal descendants of the Neolithic inhabitants of Mehrgarh are to be found to the south and the east of Mehrgarh, Pakistan in northwestern India and the western edge of the Deccan Plateau,” with Neolithic Mehrgarh showing greater affinity with Chalcolithic Inamgaon, south of Mehrgarh, than with Chalcolithic Mehrgarh.” ref

“Gallego Romero et al. (2011) state that their research on lactose tolerance in India suggests that “the west Eurasian genetic contribution identified by Reich et al. (2009) principally reflects gene flow from Pakistan, Iran, and the Middle East.” Gallego Romero notes that Indians who are lactose-tolerant show a genetic pattern regarding this tolerance which is “characteristic of the common European mutation.” According to Romero, this suggests that “the most common lactose tolerance mutation made a two-way migration out of the Middle East less than 10,000 years ago. While the mutation spread across Europe, another explorer must have brought the mutation eastward to India – likely traveling along the coast of the Persian Gulf where other pockets of the same mutation have been found.” They further note that “[t]he earliest evidence of cattle herding in south Asia comes from the Indus River Valley site of Mehrgarh and is dated to 7,000 years ago.” ref

Mehrgarh Period I (pre-7000–5500 BCE)

“The Mehrgarh Period I (pre-7000–5500 BCE) was Neolithic and aceramic (without the use of pottery). The earliest farming in the area was developed by semi-nomadic people using plants such as wheat and barley and animals such as sheep, goats, and cattle. The settlement was established with unbaked mud-brick buildings, and most of them had four internal subdivisions. Numerous burials have been found, many with elaborate goods such as baskets, stone and bone tools, beads, bangles, pendants, and occasionally animal sacrifices, with more goods left with burials of males. Ornaments of sea shell, limestone, turquoise, lapis lazuli, and sandstone have been found, along with simple figurines of women and animals. Seashells from far seashores, and lapis lazuli from as far away as present-day Badakshan, show good contact with those areas. One ground stone axe was discovered in a burial, and several more were obtained from the surface. These ground stone axes are the earliest to come from a stratified context in South Asia.” ref

“Periods I, II, and III are considered contemporaneous with another site called Kili Gul Mohammad. The aceramic Neolithic phase in the region had originally been called the Kili Gul Muhammad phase. While the Kili Gul Muhammad site itself probably started c. 5500 BCE, subsequent discoveries allowed the date range of 7000–5000 BCE to be defined for this aceramic Neolithic phase. In 2001, archaeologists studying the remains of nine men from Mehrgarh discovered that the people of this civilization knew proto-dentistry. In April 2006, it was announced in the scientific journal Nature that the oldest (and first early Neolithic) evidence for the drilling of human teeth in vivo (i.e. in a living person) was found in Mehrgarh. According to the authors, their discoveries point to a tradition of proto-dentistry in the early farming cultures of that region. “Here we describe eleven drilled molar crowns from nine adults discovered in a Neolithic graveyard in Pakistan that dates from 7,500 to 9,000 years ago. These findings provide evidence for a long tradition of a type of proto-dentistry in early farming culture.” ref

Mehrgarh Period II (5500–4800 BCE) and Period III (4800–3500 BCE)

“The Mehrgarh Period II (5500 BCE–4800 BCE) and Merhgarh Period III (4800 BCE–3500 BCE) were ceramic Neolithic, using pottery, and later chalcolithic. Period II is at site MR4 and Period III is at MR2. Much evidence of manufacturing activity has been found and more advanced techniques were used. Glazed faience beads were produced, and terracotta figurines became more detailed. Figurines of females were decorated with paint and had diverse hairstyles and ornaments. Two flexed burials were found in Period II with a red ochre cover on the body. The number of burial goods decreased over time, becoming limited to ornaments and with more goods left with burials of females. The first button seals were produced from terracotta and bone and had geometric designs. Technologies included stone and copper drills, updraft kilns, large pit kilns, and copper melting crucibles. There is further evidence of long-distance trade in Period II: important as an indication of this is the discovery of several beads of lapis lazuli, once again from Badakshan. Mehrgarh Periods II and III are also contemporaneous with an expansion of the settled populations of the borderlands at the western edge of South Asia, including the establishment of settlements like Rana Ghundai, Sheri Khan Tarakai, Sarai Kala, Jalilpur, and Ghaligai.” ref

“Period III was not much explored, but it was found that Togau phase (c. 4000–3500 BCE) was part of this level, covering around 100 hectares in the areas MR.2, MR.4, MR.5 and MR.6, encompassing ruins, burial and dumping grounds, but archaeologist Jean-François Jarrige concluded that “such wide extension was not due to contemporaneous occupation, but rather due to the shift and partial superimposition in time of several villages or settlement clusters across a span of several centuries.” ref

Togau Ceramics Phase appeared at Mehrgarh III

“At the beginning of Mehrgarh III, Togau ceramics appeared at the site. Togau ware was first defined by Beatrice de Cardi in 1948. Togau is a large mound in the Chhappar Valley of Sarawan, 12 kilometers northwest of Kalat in Balochistan. This type of pottery is found widely in Balochistan and eastern Afghanistan, at sites such as Mundigak, Sheri Khan Tarakai, and Periano Ghundai. According to Possehl it is attested at 84 sites up to date. Anjira is a contemporary ancient site near Togau. Togau ceramics are decorated with geometric designs and were already being made with a potter’s wheel. Mehrgarh Period III, during the second half of the 4th millennium BCE, is characterized by important new developments. There is a big increase in the number of settlements in the Quetta Valley, the Surab Region, the Kachhi Plain and elsewhere in the area. Kili Ghul Mohammad (II−III) pottery is similar to Togau Ware.” ref

Mehrgarh Periods IV, V and VI (3500–3000 BCE)

“Period IV was 3500–3250 BCE, Period V from 3250–3000 BCE, and Period VI was around 3000 BCE. The site containing Periods IV to VII is designated as MR1.” ref

Mehrgarh Period VII (2600–2000 BCE)

“Sometime between 2600 BCE and 2000 BCE, the city seems to have been largely abandoned in favor of the larger fortified town Nausharo five miles away, when the Indus Valley civilisation was in its middle stages of development. Historian Michael Wood suggests this took place around 2500 BCE. Archaeologist Massimo Vidale considers a series of semi-columns found in a structure at Mehrgarh, dated around 2500 BCE by the French mission there, to be very similar to semi-columns found in Period IV at Shahr-e Sukhteh.” ref

Mehrgarh Period VIII

“The last period is found at the Sibri cemetery, about 8 kilometers from Mehrgarh. Early Mehrgarh residents lived in mud brick houses, stored their grain in granaries, fashioned tools with local copper ore, and lined their large basket containers with bitumen. They cultivated six-row barley, einkorn and emmer wheat, jujubes, and dates, and herded sheep, goats and cattle. Residents of the later period (5500 BCE to 2600 BCE) put much effort into crafts, including flint knapping, tanning, bead production, and metal working. Mehrgarh is probably the earliest known center of agriculture in South Asia. The oldest known example of the lost-wax technique comes from a 6,000-year-old wheel-shaped copper amulet found at Mehrgarh. The amulet was made from unalloyed copper, an unusual innovation that was later abandoned.” ref

“The oldest ceramic figurines in South Asia were also found at Mehrgarh. They occur in all phases of the settlement and were prevalent even before pottery appears. The earliest figurines are quite simple and do not show intricate features. However, they grow in sophistication with time, and by 4000 BCE begins to show their characteristic hairstyles and typical prominent breasts. All the figurines up to this period were female. Male figurines appear only from period VII and gradually become more numerous. Many of the female figurines are holding babies, and were interpreted as depictions of a mother goddess. However, due to some difficulties in conclusively identifying these figurines with a mother goddess, some scholars prefer using the term “female figurines with likely cultic significance.” ref

“Evidence of pottery begins from Period II. In Period III, the finds become much more abundant as the potter’s wheel is introduced, and they show more intricate designs and also animal motifs. The characteristic female figurines appear beginning in Period IV and the finds show more intricate designs and sophistication. Pipal leaf designs are used in decoration from Period VI. Some sophisticated firing techniques were used from Periods VI and VII and an area reserved for the pottery industry has been found at mound MR1. However, by Period VIII, the quality and intricacy of designs seem to have suffered due to mass production, and a growing interest in bronze and copper vessels.” ref

Mehrgarh Burials

“There are two types of burials in the Mehrgarh site. There were individual burials where a single individual was enclosed in narrow mud walls and collective burials with thin mud-brick walls within which skeletons of six different individuals were discovered. The bodies in the collective burials were kept in a flexed position and were laid east to west. Child bones were found in large jars or urn burials (4000–3300 BCE).” ref

Mehrgarh Metallurgy

“Metal findings have been dated as early as Period IIB, with a few copper items.” ref

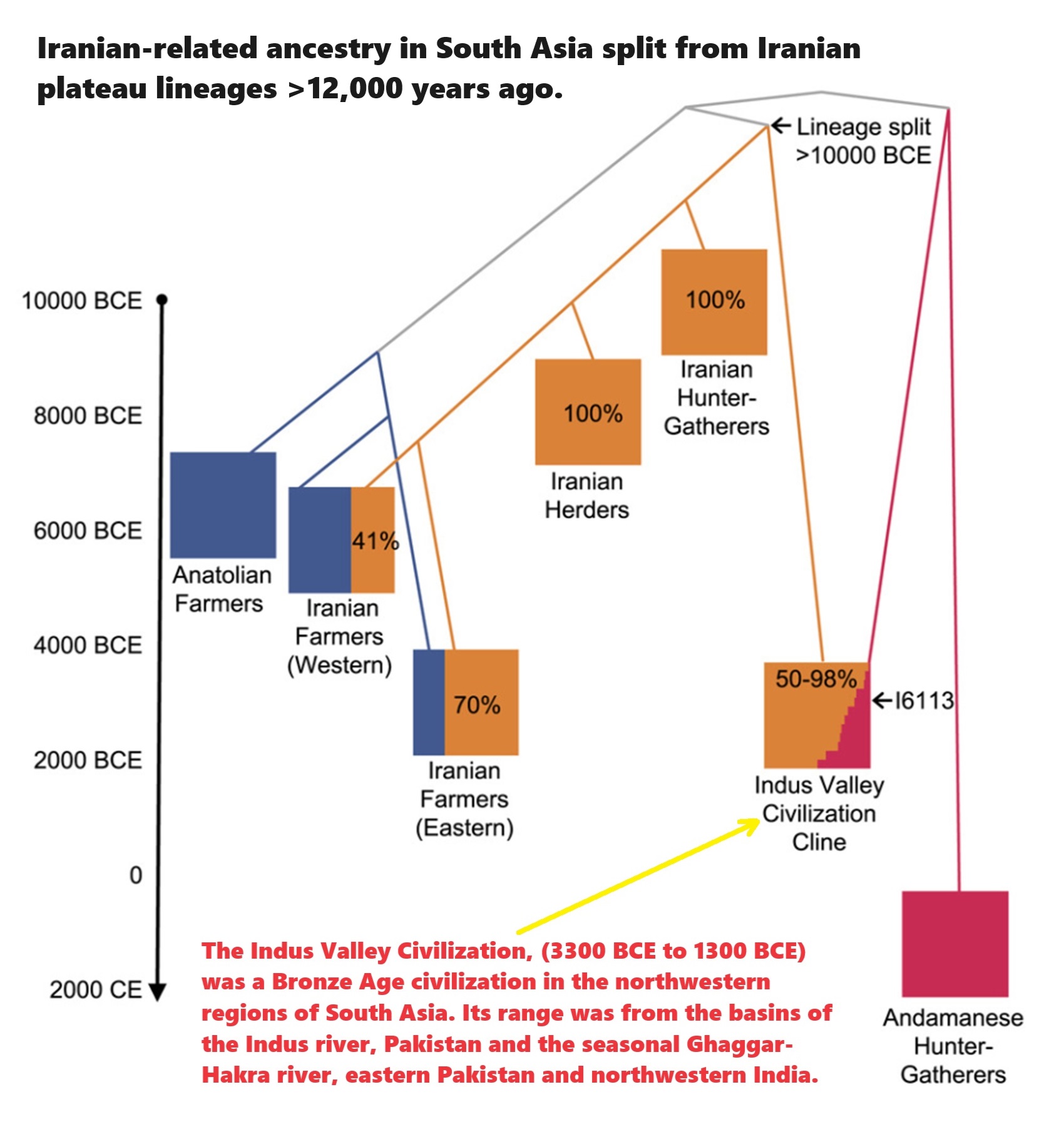

The Iranian-related ancestry in the IVC derives from a lineage leading to early Iranian farmers, herders, and hunter-gatherers before their ancestors separated, contradicting the hypothesis that the shared ancestry between early Iranians and South Asians reflects a large-scale spread of western Iranian farmers east. Instead, sampled ancient genomes from the Iranian plateau and IVC descend from different groups of hunter-gatherers who began farming without being connected by substantial movement of people.” ref

“The only fitting two-way models were mixtures of a group related to herders from the western Zagros mountains of Iran and also to either Andamanese hunter-gatherers (73% ± 6% Iranian-related ancestry; p = 0.103 for overall model fit) or East Siberian hunter-gatherers (63% ± 6% Iranian-related ancestry; p = 0.24) (the fact that the latter two populations both fit reflects that they have the same phylogenetic relationship to the non-West Eurasian-related component of I6113 likely due to shared ancestry deeply in time). This is the same class of models previously shown to fit the 11 outliers that form the Indus Periphery Cline (Narasimhan et al., 2019), and indeed, I6113 fits as a genetic clade with the pool of Indus Periphery Cline individuals in qpAdm (p = 0.42). Multiple lines of evidence suggest that the genetic similarity of I6113 to the Indus Periphery Cline individuals is due to gene flow from South Asia rather than in the reverse direction.” ref

“First, of the 44 individuals with good-quality data we have from Gonur and Shahr-i-Sokhta, only 11 (25%) have this ancestry profile; it would be surprising to see this ancestry profile in the one individual we analyzed from Rakhigarhi if it was a migrant from regions where this ancestry profile was rare. Second, of the three individuals at Shahr-i-Sokhta who have material culture linkages to Baluchistan in South Asia, all are IVC Cline outliers, specifically pointing to movement out of South Asia (Narasimhan et al., 2019).” ref

“Third, both the IVC Cline individuals and the Rakhigarhi individual have admixture from people related to present-day South Asians (ancestry deeply related to Andamanese hunter-gatherers) that is absent in the non-outlier Shahr-i-Sokhta samples and is also absent in Copper Age Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan (Narasimhan et al., 2019), implying gene flow from South Asia into Shahr-i-Sokhta and Gonur, whereas our modeling does not necessitate reverse gene flow. Based on these multiple lines of evidence, it is reasonable to conclude that individual I6113’s ancestry profile was widespread among people of the IVC at sites like Rakhigarhi, and it supports the conjecture (Narasimhan et al., 2019) that the 11 outlier individuals in the Indus Periphery Cline are migrants from the IVC living in non-IVC towns. We rename the genetic gradient represented in the combined set of 12 individuals the “IVC Cline” and then use higher-coverage individuals from this cline in lieu of I6113 to carry out fine-scale modeling of this ancestry profile.” ref

“Modeling the individuals on the IVC Cline using the two-way models previously fit for diverse present-day South Asians (Narasimhan et al., 2019), we find that, as expected from the PCA, it does not fit the two-way mixture that drives variation in modern South Asians as it is significantly depleted in Steppe pastoralist-related ancestry adjusting for its proportion of Iranian-related ancestry (p = 0.018 from a two-sided Z test). Modeling the IVC Cline using the simpler two-way admixture model without Steppe pastoralist-derived ancestry previously shown to fit the 11 outliers (Narasimhan et al., 2019), I6113 falls on the more Iranian-related end of the gradient, revealing that Iranian-related ancestry extended to the eastern geographic extreme of the IVC and was not restricted to individuals at its Iranian and Central Asian periphery.” ref

“The estimated proportion of ancestry related to tribal groups in southern India in I6113 is smaller than in present-day groups, suggesting that since the time of the IVC there has been gene flow into the part of South Asia where Rakhigarhi lies from both the northwest (bringing more Steppe ancestry) and southeast (bringing more ancestry related to tribal groups in southern India). The genetic profile that we document in this individual, with large proportions of Iranian-related ancestry but no evidence of Steppe pastoralist-related ancestry, is no longer found in modern populations of South Asia or Iran, providing further validation that the data we obtained from this individual reflects authentic ancient DNA.” ref

“To obtain insight into the origin of the Iranian-related ancestry in the IVC Cline, we co-modeled the highest-coverage individual from the IVC Cline, Indus_Periphery_West (who also happens to have one of the highest proportions of Iranian-related ancestry) with other ancient individuals from across the Iranian plateau representing early hunter-gatherer and food-producing groups: a ∼10,000 BCE individual from Belt Cave in the Alborsz Mountains, a pool of ∼8000 BCE early goat herders from Ganj Dareh in the Zagros Mountains, a pool of ∼6000 BCE farmers from Hajji Firuz in the Zagros Mountains, and a pool of ∼4000 BCE farmers from Tepe Hissar in Central Iran. Using qpGraph (Patterson et al., 2012), we tested all possible simple trees relating the Iranian-related ancestry component of these groups, accounting for known admixtures (Anatolian farmer-related admixture into Hajji Firuz and Tepe Hissar and Andamanese hunter-gatherer-related admixture in the IVC Cline) (Figure S3), using an acceptance criterion for the model fitting that the maximum |Z| scores between observed and expected f-statistics was <3 or that the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) was within 4 of the best-fit (Burnham and Anderson, 2004).” ref

“The only consistently fitting models specified that the Iranian-related lineage contributing to the IVC Cline split from the Iranian-related lineages sampled from ancient genomes of the Iranian plateau before the latter separated from each other (Figure 3 represents one such model consistent with our data). We confirmed this result by using symmetry tests that we applied first to stimulated data (Figure S4) and then evaluated the relationships among the Iranian-related lineages, correcting for the effects of Anatolian farmer-related, Andamanese hunter-gatherer-related, and West Siberian hunter-gatherer-related admixture (STAR Methods). We find that 94% of the resulting trees supported the Iranian-related lineage in the IVC Cline being the first to separate from the other lineages, consistent with our modeling results.” ref

“Our evidence that the Iranian-related ancestry in the IVC Cline diverged from lineages leading to ancient Iranian hunter-gatherers, herders, and farmers prior to their ancestors’ separation places constraints on the spread of Iranian-related ancestry across the combined region of the Iranian plateau and South Asia, where it is represented in all ancient and modern genomic data sampled to date. The Belt Cave individual dates to ∼10,000 BCE, definitively before the advent of farming anywhere in Iran, which implies that the split leading to the Iranian-related component in the IVC Cline predates the advent of farming there as well (Figure 3). Even if we do not consider the results from the low-coverage Belt Cave individual, our analysis shows that the Iranian-related lineage present in the IVC Cline individuals split before the date of the ∼8000 BCE Ganj Dareh individuals, who lived in the Zagros mountains of the Iranian plateau before crop farming began there around ∼7000–6000 BCE. Thus, the Iranian-related ancestry in the IVC Cline descends from a different group of hunter-gatherers from the ancestors of the earliest known farmers or herders in the western Iranian plateau.” ref

“Researchers also highlight a second line of evidence against the hypothesis that eastward migrations of descendants of western Iranian farmers or herders were the source of the Iranian-related ancestry in the IVC Cline. An independent study has shown that all ancient genomes from Neolithic and Copper Age crop farmers of the Iranian plateau harbored Anatolian farmer-related ancestry not present in the earlier herders of the western Zagros (Narasimhan et al., 2019). This includes western Zagros farmers (∼59% Anatolian farmer-related ancestry at ∼6000 BCE at Hajji Firuz) and eastern Alborsz farmers (∼30% Anatolian farmer-related ancestry at ∼4000 BCE at Tepe Hissar). That the 12 sampled individuals from the IVC Cline harbored negligible Anatolian farmer-related ancestry thus provides an independent line of evidence (in addition to their deep-splitting Iranian-related lineage that has not been found in any sampled ancient Iranian genomes to date) that they did not descend from groups with ancestry profiles characteristic of all sampled Iranian crop-farmers (Narasimhan et al., 2019). While there is a small proportion of Anatolian farmer-related ancestry in South Asians today, it is consistent with being entirely derived from Steppe pastoralists who carried it in mixed form and who spread into South Asia from ∼2000–1500 BCE (Narasimhan et al., 2019).” ref

“These findings suggest that in South Asia as in Europe, the advent of farming was not mediated directly by descendants of the world’s first farmers who lived in the fertile crescent. Instead, populations of hunter-gatherers—in Eastern Anatolia in the case of Europe (Feldman et al., 2019) and in a yet-unsampled location in the case of South Asia—began farming without large-scale movement of people into these regions. This does not mean that movements of people were unimportant in the introduction of farming economies at a later date; for example, ancient DNA studies have documented that the introduction of farming to Europe after ∼6500 BCE was mediated by a large-scale expansion of Western Anatolian farmers who descended largely from early hunter-gatherers of Western Anatolia (Feldman et al., 2019). It is possible that in an analogous way, an early farming population expanded dramatically within South Asia, causing large-scale population turnovers that helped to spread this economy within the region. Whether this occurred is still unverified and could be determined through ancient DNA studies from just before and after the farming transitions in South Asia.” ref

“Our results also have linguistic implications. One theory for the origins of the now-widespread Indo-European languages in South Asia is the “Anatolian hypothesis,” which posits that the spread of these languages was propelled by movements of people from Anatolia across the Iranian plateau and into South Asia associated with the spread of farming. However, we have shown that the ancient South Asian farmers represented in the IVC Cline had negligible ancestry related to ancient Anatolian farmers as well as an Iranian-related ancestry component distinct from sampled ancient farmers and herders in Iran. Since language proxy spreads in pre-state societies are often accompanied by large-scale movements of people (Bellwood, 2013), these results argue against the model (Heggarty, 2019) of a trans-Iranian-plateau route for Indo-European language spread into South Asia.” ref

“However, a natural route for Indo-European languages to have spread into South Asia is from Eastern Europe via Central Asia in the first half of the 2nd millennium BCE, a chain of transmission that did occur as has been documented in detail with ancient DNA. The fact that the Steppe pastoralist ancestry in South Asia matches that in Bronze Age Eastern Europe (but not Western Europe [de Barros Damgaard et al., 2018; Narasimhan et al., 2019]) provides additional evidence for this theory, as it elegantly explains the shared distinctive features of Balto-Slavic and Indo-Iranian languages (Ringe et al., 2002).” ref

“Our analysis of data from one individual from the IVC, in conjunction with 11 previously reported individuals from sites in cultural contact with the IVC, demonstrates the existence of an ancestry gradient that was widespread in farmers to the northwest of peninsular India at the height of the IVC, that had little if any genetic contribution from Steppe pastoralists or western Iranian farmers or herders, and that had a primary impact on the ancestry of later South Asians. While our study is sufficient to demonstrate that this ancestry profile was a common feature of the IVC, a single sample—or even the gradient of 12 likely IVC samples we have identified—cannot fully characterize a cosmopolitan ancient civilization. An important direction for future work will be to carry out ancient DNA analysis of additional individuals across the IVC range to obtain a quantitative understanding of how the ancestry of IVC people was distributed and to characterize other features of its population structure.” ref

“The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC), also known as the Indus Civilisation, was a Bronze Age civilisation in the northwestern regions of South Asia, lasting from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, and in its mature form from 2600 BCE to 1900 BCE. Together with ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, it was one of three early civilizations of North Africa, Southwest Asia, and South Asia, and of the three, the most widespread, its sites spanning an area including much of modern-day Pakistan, northwestern India, and northeast Afghanistan. The civilization flourished both in the alluvial plain of the Indus River, which flows through the length of Pakistan, and along a system of perennial monsoon-fed rivers that once coursed in the vicinity of the Ghaggar-Hakra, a seasonal river in northwest India and eastern Pakistan.” ref