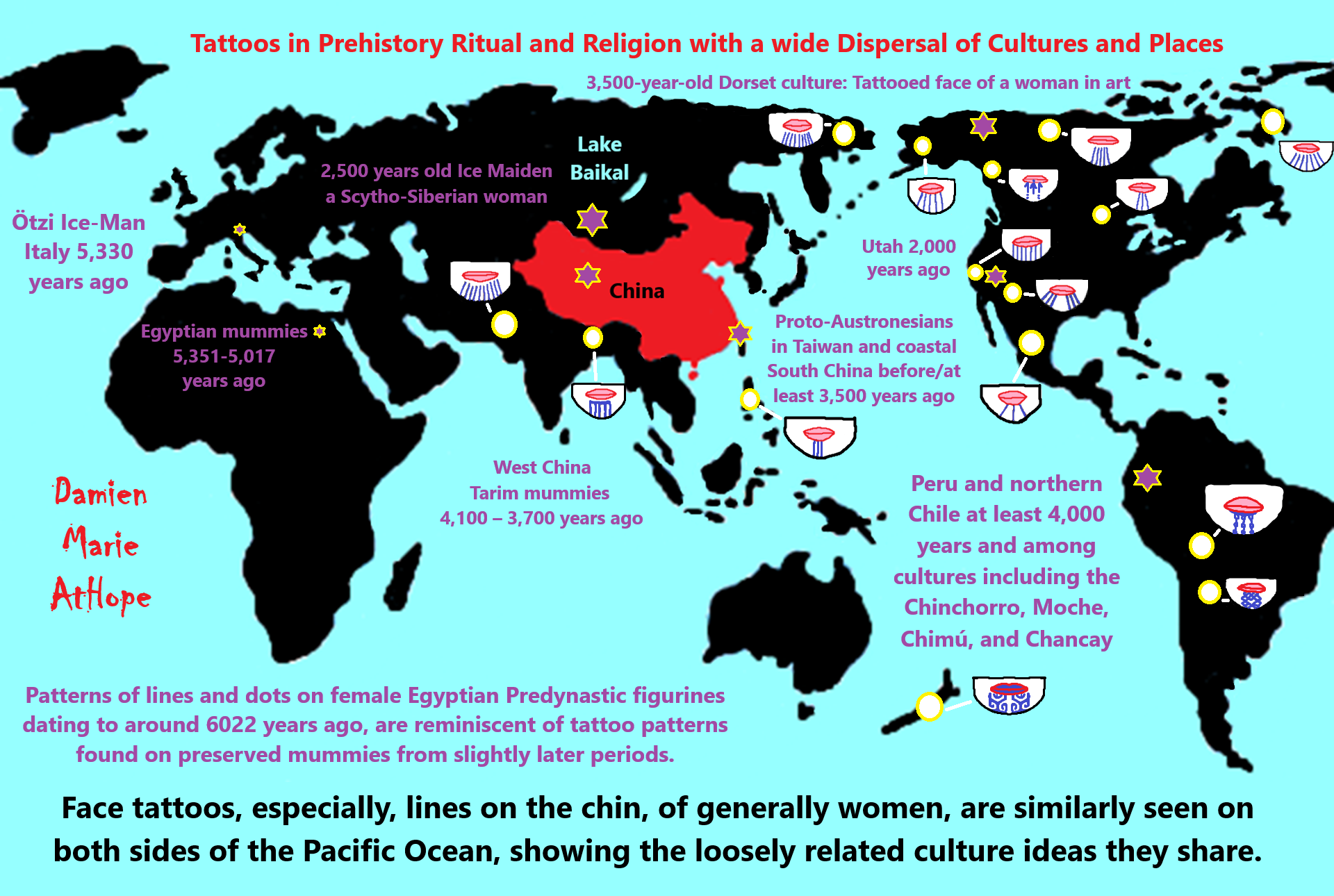

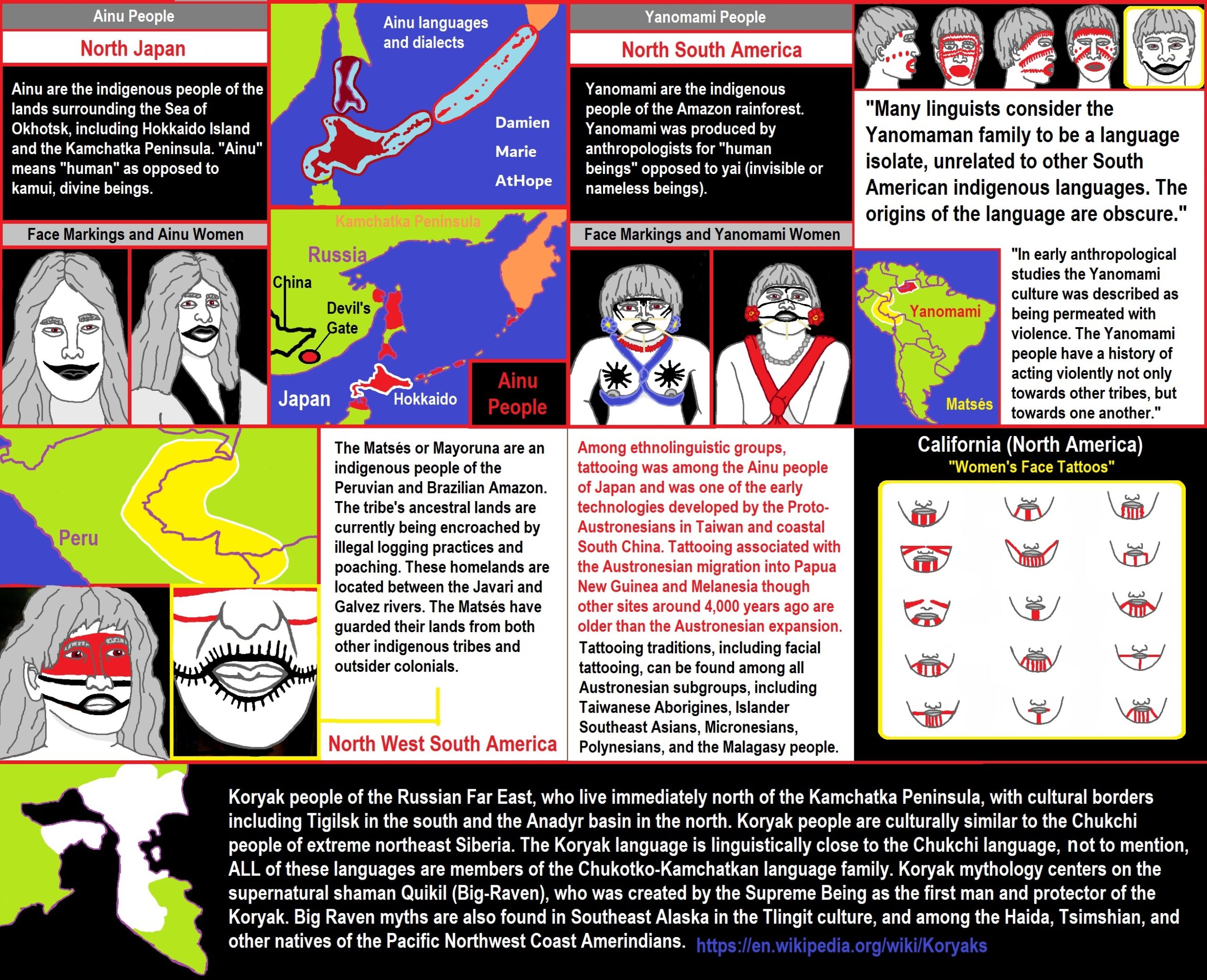

Face tattoos, especially, lines on the chin, of generally women, are similarly seen on both sides of the Pacific Ocean, showing the loosely related culture ideas they share.

Ancient Tattoos

Ancient Siberians (Time???) 2,500 years old Ice Maiden, a Scytho-Siberian woman ref

“In Siberian nomadic society, such as the Scythians and Pazyryks, both likely used tattoos. In such cultures of Siberia tattoos were the ultimate status symbol. For these culturs had tattoos that let everyone know just how tough and important they were. Warriors would get inked to show off their battle victories or their loyalty to a particular tribe/clan. It was like wearing your resume on your skin, but with way more flair. These tattoos weren’t just for art. They were like walking talismans—meant to guide and protect the nomads through both life and the afterlife. Some might even say these tattoos were the original multi-purpose accessory: part fashion statement, part spiritual armor.” ref

Ancient Egypt Patterns of lines and dots on female Egyptian Predynastic figurines dating to around 6022 years ago are reminiscent of tattoo patterns found on preserved mummies from slightly later periods.

Mesopotamia 5522-4362 years ago Cuneiform list tattooed slaves

Ancient Italy Ötzi Ice-Man 5,250 years ago

Nubians

North Africa

West Africa

Central Africa

Ancient Inuit Arctic and subarctic regions of North America, USA and Canada, including Greenland

North Americas

Alaska Arctic Alaskan Yupiit (“real people”) and Inupiat (“real people”) replace an old term “Eskimo” peoples. 3,500-year-old ivory marketed art from the Dorset culture representing the oldest known human portrait from the Arctic of tattooed linres that cover the face of the woman.

Utah 2000-year-old artifact at Turkey Pen site a well-known Anasazi ruin in Grand Gulch ref

Washington

Oregon

California

South Americans

Peru and northern Chile at least 4,000 years and among cultures including the Chinchorro, Moche, Chimú, and Chancay

Peru not used by Incas but the Chimu people who preceded them did. Chimú culture succeeding the Moche culture, and later conquered by the Inca ref, ref

Brazil

Ancient Greeks

Ancient-Balkan peoples and later limited to the western Balkans

Ancient India

China Tarim mummies 4,100 – 3,700 years ago

Proto-Austronesians in Taiwan and coastal South China before/at least 3,500 years ago

Japan

Philippines

Borneo

Polynesians

Rapa Nui/Easter Island

Australia

Tasmania

Melanesia

New Zealand

Face tattoos, especially, lines on the chin, of generally women, are similarly seen on both sides of the Pacific Ocean, showing the loosely related culture ideas they share.

Tattoos in Prehistory Ritual and Religion with a wide Dispersal of Cultures and Places

“The Worldwide History of Tattoos: Ancient ink exhibited religious faith, relieved pain, protected wearers and indicated class. Humans have been marking their skin for thousands of years. Around the world, across cultures, tattoos have held countless different significances. Ancient Siberian nomads, Indigenous Polynesians, Nubians, Native South Americans and Greeks all used tattoos—and for a variety of reasons: such as to protect from evil; signify status or religious beliefs.” ref

“A tattoo is a form of body modification made by inserting tattoo ink, dyes, and/or pigments, either indelible or temporary, into the dermis layer of the skin to form a design. The history of tattooing goes back to at least Neolithic times, practiced across the globe by many cultures, and the symbolism and impact of tattoos varies in different places and cultures. Many tattoos serve as rites of passage, marks of status and rank, symbols of religious and spiritual devotion, decorations for bravery, marks of fertility, pledges of love, amulets and talismans, protection, and as punishment, like the marks of outcasts, slaves and convicts.” ref

“Modifying the natural body, whether temporarily or permanently, is a universal behavior among human societies of the past and present, and archaeological evidence shows that tattooing has existed in societies all across the globe for at least the past 5,000 years. the greatest concentration of preserved ancient tattoos identified to date is found in the Pacific coastal deserts of Peru and northern Chile. In that region, tattooing took place over at least 4,000 years among cultures including the Chinchorro, Moche, Chimú, and Chancay.” ref

Tattooing Antiquity, Symbolism, and Practice in Early Cultures

“As one of the most permanent markings of culture etched into human skin, tattooing provides a unique view into the beliefs and practices of the human species. Tattooing has existed throughout human history, but it can be difficult to establish its true purpose and antiquity within early cultures. This is due in part to biological degradation and misclassification of the material implements of tattooing, as well as the scarcity of tattooed physical human remains. Archeological context and the identification of possible material artifacts associated with tattooing, along with the examination (or re-examination) of physical human remains for evidence of tattooing, will help place tattooing’s presence and purpose within a historical context. For this paper, I reviewed ten scientific journal articles on the subject of tattooing within early cultures. Current investigations into the proposed purposes of early tattoos focus on iconographic and symbolic use, as well as cross-cultural therapeutic application. Tattoos, as instruments that transmit culture, can provide new insights into ancient societies and thereby reveal new avenues for exploring the visual language of Paleolithic times.” ref

“Preserved tattoos on ancient mummified human remains reveal that tattooing has been practiced throughout the world for thousands of years. In 2015, scientific re-assessment of the age of the two oldest known tattooed mummies identified Ötzi as the oldest example then known. This body, with 61 tattoos, was found embedded in glacial ice in the Alps, and was dated to 3250 BCE. In 2018, the oldest figurative tattoos in the world were discovered on two mummies from Egypt which are dated between 3351 and 3017 BCE. Although tattoo art has existed at least since the first known tattooed person, Ötzi, lived around the year 3330 BCE or around 5,330 years ago, the way society perceives tattoos has varied immensely throughout history. Even in the 21st century, people choose to be tattooed for sentimental/memorial, religious, and spiritual reasons, or to symbolize their belonging to or identification with particular groups or a particular ethnic group or subculture.” ref

“Ancient Egyptians used tattoos to show dedication to a deity, and the tattoos were believed to convey divine protection. In Hinduism, Buddhism, and Neopaganism, tattoos are accepted. Southeast Asia has a tradition of protective tattoos variously known as sak yant or yantra tattoos that include Buddhist images, prayers, and symbols. Images of the Buddha or other religious figures have caused controversy in some Buddhist countries when incorporated into tattoos by Westerners who do not follow traditional customs regarding respectful display of images of Buddhas or deities. Judaism generally prohibits tattoos among its adherents based on the commandments in Leviticus 19. Jews tend to believe this commandment only applies to Jews and not to gentiles. However, an increasing number of young Jews are getting tattoos either for fashion, or an expression of their faith. Tattoos are considered to be haram for many Sunni Muslims, based on rulings from scholars and passages in the Sunni Hadith. Shia Islam does not prohibit tattooing, and many Shia Muslims (Lebanese, Iraqis, Iranians) have tattoos, specifically with religious themes.” ref

“The word tattoo, or tattow in the 18th century, is a loanword from the Samoan word tatau, meaning “to strike”, from Proto-Oceanic *sau₃ referring to a wingbone from a flying fox used as an instrument for the tattooing process. British anthropologist Ling Roth in 1900 described four methods of skin marking and suggested they be differentiated under the names “tatu”, “moko“, “cicatrix” and “keloid. The first is by pricking that leaves the skin smooth as found in places including the Pacific Islands. The second is a tattoo combined with chiseling to leave furrows in the skin as found in places including New Zealand. The third is scarification using a knife or chisel as found in places including West Africa. The fourth and the last is scarification by irritating and re-opening a preexisting wound, and re-scarification to form a raised scar as found in places including Tasmania, Australia, Melanesia, and Central Africa. Owing to the Biblical strictures against the practice, Emperor Constantine I banned tattooing the face around CE 330, and the Second Council of Nicaea banned all body markings as a pagan practice in CE 787.” ref

“Ancient tattooing was most widely practiced among the Austronesian people. It was one of the early technologies developed by the Proto-Austronesians in Taiwan and coastal South China prior to at least 1500 BCE or around 3,500 years ago, before the Austronesian expansion into the islands of the Indo-Pacific. It may have originally been associated with headhunting. Tattooing traditions, including facial tattooing, can be found among all Austronesian subgroups, including Taiwanese indigenous peoples, Islander Southeast Asians, Micronesians, Polynesians, and the Malagasy people. Austronesians used the characteristic hafted skin-puncturing technique, using a small mallet and a piercing implement made from Citrus thorns, fish bone, bone, and oyster shells. Ancient tattooing traditions have also been documented among Papuans and Melanesians, with their use of distinctive obsidian skin piercers. Some archeological sites with these implements are associated with the Austronesian migration into Papua New Guinea and Melanesia.” ref

“But other sites are older than the Austronesian expansion, being dated to around 1650 to 2000 BCE, suggesting that there was a preexisting tattooing tradition in the region. Among other ethnolinguistic groups, tattooing was also practiced among the Ainu people of Japan; some Austroasians of Indochina; Berber women of Tamazgha (North Africa); the Yoruba, Fulani and Hausa people of Nigeria; Native Americans of the Pre-Columbian Americas; people of Rapa Nui; Picts of Iron Age Britain; and Paleo-Balkan peoples (Illyrians and Thracians, as well as Daunians in Apulia), a tradition that has been preserved in the western Balkans by Albanians (Albanian traditional tattooing), Catholics in Bosnia and Herzegovina (Sicanje), and women of some Vlach communities.” ref

“Evidence for tattooing exists as iconographic depictions and identifiable tattoo implements, with the most easily identifiable and defensible being preserved tattooed human remains. There is evidence of tattooing in ancient and pre-literate societies in the form of figurative art displaying tattoo-like markings and what could be tattoo tools ranging as far back as the Upper Paleolithic. The most irrefutable evidence of tattooing is undoubtedly preserved human skin. Tattooing in these early cultures remains a question for anthropologists and archeologists. Artistic depictions of possible tattoos have been found throughout the ancient world in the form of incised or painted ornamentation on human shaped figurines, rock art, ceramic vessels and bone.” ref

“While not definitive evidence of tattooing, isolated decorative patterns on figurines are the most suggestive examples of real-life tattooing. Patterns of lines and dots on female Egyptian Predynastic figurines dating to around 6022 years ago are reminiscent of tattoo patterns found on preserved mummies from slightly later periods. An Ipiutak Pendant from Deering Alaska is a good example of iconographic tattooing being an incised male face carved from antler. A rare example of Inuit realistic portraiture dated to 2361 years ago, it depicts facial carvings strikingly similar to what is seen in modern Inuit facial tattooing. These iconographic representations provide a possible framework for understanding the cultural significance of body decoration and tattooing, but a better marker for tattooing is the actual implements required to create tattoos.” ref

“Human Remains Direct evidence of tattooing remains naturally and deliberately preserved human skin. The oldest archeological proof of the antiquity of tattooing has long been thought to be the Tyrolean Iceman Ötzi and seen as the world’s oldest preserved tattooed human remains. Discovered in the Tyrolean Alps, Ötzi has 61 tattoo marks on his body consisting of groupings of various length lines ranging from one to three mmm in thickness and seven to forty mm in length. Most of these tattoos are located on his lower legs, lower back, and torso and don’t appear to represent any identifiable form. Long thought to be the oldest, he is not the only ancient tattooed mummified human remains to have been discovered. There have been mummified tattooed human remains found throughout much of the world.” ref

“While figurative and iconographic evidence of tattooing exists from approximately 6,022 years ago no physical proof from that early era had been discovered until just recently. Seven naturally occurring mummies from the British Museum’s Egyptian mummy catalog were re-examined forsigns of body modification as part of a newly implemented conservation program. Tattoos were found on one female and one male from the Gebelein site in Upper Egypt dating to approximately 6,000 years ago, putting them right around the same age as Ötzi. The other five mummies did not show evidence of tattoos but it must be acknowledged that their tightly constricted body positioning and physical state were not conducive to exhaustive examination and the possibility of tattooing remains. The newly discovered tattooed remains from Gebelein show distinctive figurative tattoos that mirror motifs found in Predynastic (5,351 and 5,017 years ago) art.” ref, ref

“Although not noticeable under normal conditions, infrared imaging shows that the male has what appears to be two horned animals on his upper right arm. Infrared examination of the female body provides evidence of four small ‘S’ shaped motifs running vertically over her right shoulder, below which is a linear motif. There is also evidence of an irregular dark line that runs horizontally across her lower abdomen but due to the contracted positioning of the body it is not possible to investigate further without causing damage. Upon examination many of these tattoos have been associated with symbolic meaning. Symbolic Meaning Associated with Tattoos Horned animals are a popular motif in Predynastic art and play an important role in ancient Egyptian imagery as a symbol of male power and virility, often appearing on carved ivories, incised potmarks, and rock art.” ref

“The female’s tattoos are more difficult to interpret but may be a depiction of the crooked staves that symbolize power and status, and which are always presented in multiples on decorated Predynastic pottery. CT scans of these mummies do not reveal any underlying conditions near or below the tattoos, suggesting that unlike the possible therapeutic motivation of some of Ötzi’s 61 tattoos, these have a more symbolic/mystical meaning. The Gebelein mummies not only provides evidence of earlier tattooing in Egypt than previous finds, but also challenge conventional thought and circumstantial evidence that Egyptian tattooing was almost exclusively female related. Previously documented physical evidence of tattooing consisted of specific groupings of dots found only on female remains. Egyptians, both ancient and modern, ascribe special symbolic meaning to certain numbers.” ref

“Due to the placement of many of these early tattoos being on female lower abdomens, combined with number symbolism still practiced today, a prevailing theory has been that these tattoos were primarily related to protection during childbirth as well as being associated with eroticism/prostitution and the goddess Hathor. While the Gebelein mummies also show evidence of number symbolism in their repetitive patterning, they are most definitely figurative in design and easily identifiable with other figurative art mediums employed by Egyptians throughout an extended time period. Around roughly the same period in Ancient Mesopotamia evidence of tattooing is found almost exclusively in text form.” ref

“Unlike in Egypt were tattooing appears to be symbolic and protective in practice, textual evidence of tattooing in Ancient Mesopotamia is almost universally punitive in nature. Early examples of cuneiform writing are principally economic. Cuneiform tablets from the fourth millennium c. 5522-4362 years ago in Mesopotamia list tattooed slaves and animals owned by temple households. Specifically, tattooing was used to mark slaves and temple dependents and to punitively identify runaway or insubordinate slaves. This practice of ownership marking appeared to be so widespread that a recurring theme is the tendency to note when an owned person was not marked. Although there is less documented evidence of textual tattooing from Mesopotamia’s second millennium (c.4022-3023 years ago), the Babylonian lexical text ana ittisu describes the punishment of a runaway slave in such a way that it has received attention due to the parallels it draws in neighboring cultures at a much later date.” ref

“The slave’s owner shackled him in chains and “Runaway! Seize!” was engraved on his face. The practice of ownership identification spread as the ancient world became more economically diverse and the slave trade proliferated with the Greeks and Romans adopting the convention of marking slaves and prisoners of war many centuries later. Textual evidence from pre-modern China also references the stigma and social ostracism related to tattooed individuals. By the Eighth Century BCE tattooing within the Near East became an internationally recognized sign of servitude that could be written in many languages, often resulting in slaves who were marked in multiple languages thus denoting far-reaching trade. It has been proposed that the Greek word stigmata actually indicates tattooing and that the word was then transmitted to the Romans which raises interesting biblical implications.” ref

“This stigma persists in modern culture and scholars help explain why archaeological bias contributed to theories that ancient Egyptian tattooing was associated with female eroticism and prostitution. Egyptian females of high rank continued to voluntarily tattoo themselves for centuries. Regardless, during Ramses III’s reign (approximately 3208-3177 years ago) Egyptian depictions of prisoners of war tattooed with Ramses’ name appear on a relief in the temple at Medinet Habu. Not all tattoos found on human remains have clear symbolic meaning, some are thought to have a more therapeutic value.” ref

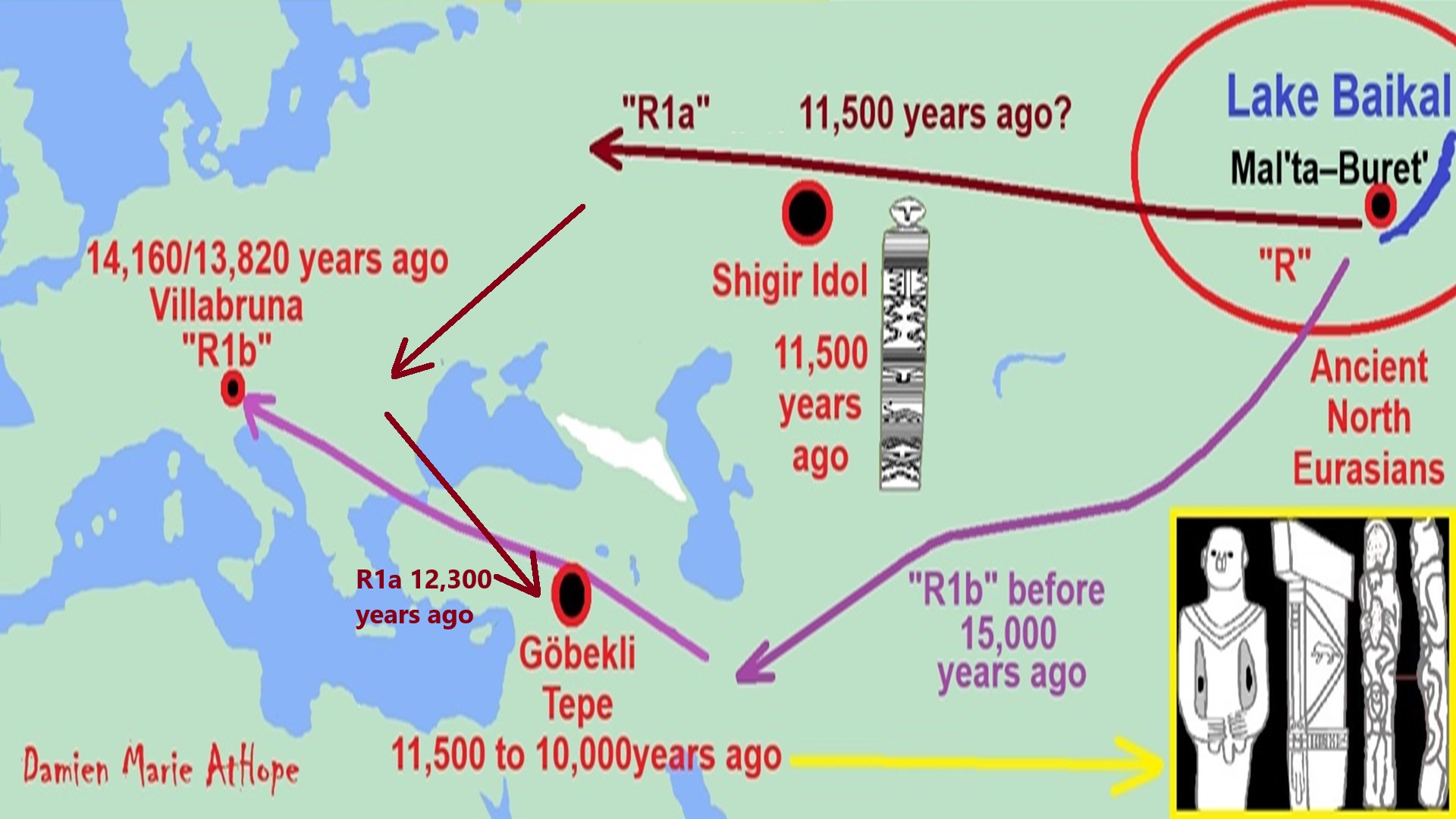

Tattoos in Ancient China

“Cemeteries throughout the Tarim Basin (Xinjiang of western China) including the sites of Qäwrighul, Yanghai, Shengjindian, Zaghunluq, and Qizilchoqa have revealed several tattooed mummies with Western Asian/Indo-European physical traits and cultural materials. These date from between 2100 and 550 BCE. The Tarim mummies are a series of mummies discovered in the Tarim Basin in present-day Xinjiang, China, which date from 1800 BCE to the first centuries BCE, with a new group of individuals recently dated to between c. 2100 and 1700 BCE. A genomic study published in 2021 found that these early mummies (dating from 2,135 to 1,623 BCE) had high levels of Ancient North Eurasian ancestry (ANE, about 72%), with smaller admixture from Ancient Northeast Asians (ANA, about 28%), but no detectable Western Steppe-related ancestry.” ref, ref

“They formed a genetically isolated local population that “adopted neighbouring pastoralist and agriculturalist practices, which allowed them to settle and thrive along the shifting riverine oases of the Taklamakan Desert.” These mummified individuals were long suspected to have been “Proto-Tocharian-speaking pastoralists”, ancestors of the Tocharians, but this has now been largely discredited by their absence of a genetic connection with Indo-European-speaking migrants, particularly the Afanasievo or BMAC cultures. Later Tarim Mummies dated to the Iron Age (1st millennium BCE), such as those of the Subeshi culture, have characteristics closely resembling those of the Saka (Scythian) Pazyryk culture of the Altai Mountains, in particular in the areas of weaponry, horse gear and garments. They are candidates as the Iron Age predecessors of the Tocharians. The rather recent easternmost mummies at Qumul (Yanbulaq culture, 1100–500 BCE), provide the earliest Asian mummies found in the Tarim Basin, and have a mix of “Europoid” and “Mongoloid” mummies.” ref

“The Tarim mummies were found to have formed their own cluster, distinct from the European-related Steppe pastoralists of the Andronovo and Afanasievo cultures, or the inhabitants of the Western Asian BMAC culture. Later Tarim mummies displayed varying affinities with Andronovo-like, BMAC-like or Han-like populations, suggesting different waves of migration into the Tarim basin. The mummies share many typical Caucasian body features, and many of them have their hair physically intact, ranging in color from blond to red to deep brown, and generally long, curly and braided. Their costumes, and especially textiles, may indicate a common origin with Indo-European neolithic clothing techniques or a common low-level textile technology. Chärchän man wore a red twill tunic and tartan leggings. Textile expert Elizabeth Wayland Barber, who examined the tartan-style cloth, discusses similarities between it and fragments recovered from salt mines associated with the Hallstatt culture.” ref

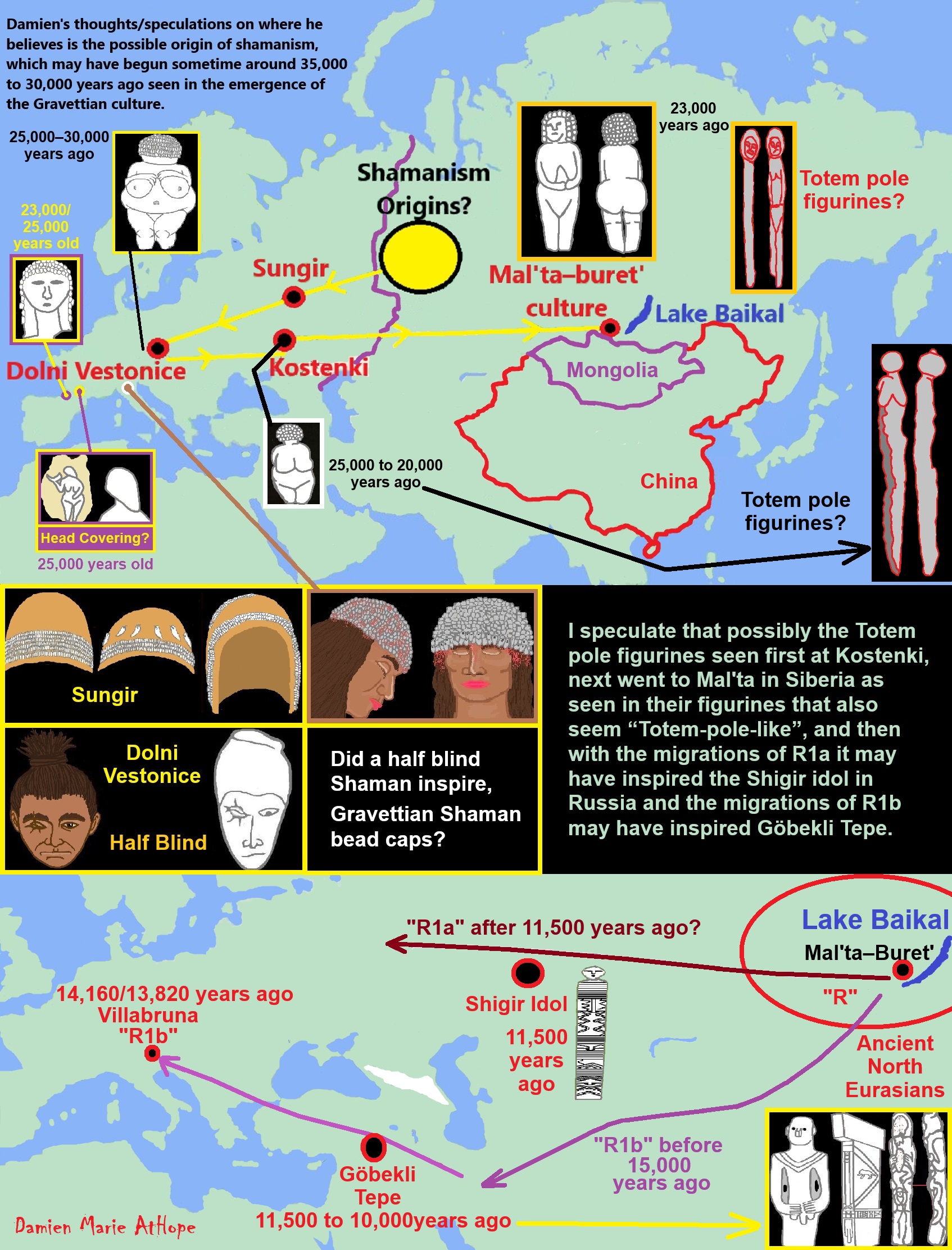

“A 2021 genetic study on the Tarim mummies (13 mummies, including 11 from Xiaohe Cemetery, ranging from 2,135 to 1,623 BCE) found that they were most closely related to an earlier identified group called the Ancient North Eurasians, particularly the population represented by the Afontova Gora 3 specimen (AG3), genetically displaying “high affinity” with it. The genetic profile of the Afontova Gora 3 individual represented about 72% of the ancestry of the Tarim mummies from Xiaohe, while the remaining 28% of their ancestry was derived from Ancient Northeast Asians (ANA, Early Bronze Age Baikal populations). Tarim mummies from Beifang have a slightly higher amount of ANA ancestry and can be modelled as having 89% Xiaohe-like ancestry and about 11% ANA ancestry. The Tarim mummies are thus one of the rare Holocene populations who derive most of their ancestry from the Ancient North Eurasians (ANE, specifically the Mal’ta and Afontova Gora populations), despite their distance in time (around 14,000 years). More than any other ancient population, the Tarim mummies can be considered as “the best representatives” of the Ancient North Eurasians.” ref

“In ancient China, tattoos were considered a barbaric practice associated with the Yue peoples of southeastern and southern China. Tattoos were often referred to in literature depicting bandits and folk heroes. As late as the Qing dynasty, it was common practice to tattoo characters such as 囚 (“Prisoner”) on convicted criminals’ faces. Although relatively rare during most periods of Chinese history, slaves were also sometimes marked to display ownership. However, tattoos seem to have remained a part of southern culture. Marco Polo wrote of Quanzhou, “Many come hither from Upper India to have their bodies painted with the needle in the way we have elsewhere described, there being many adepts at this craft in the city”. At least three of the main characters – Lu Zhishen, Shi Jin (史進), and Yan Ching (燕青) – in the classic novel Water Margin are described as having tattoos covering nearly all of their bodies. Wu Song was sentenced to a facial tattoo describing his crime after killing Xi Menqing (西門慶) to avenge his brother. In addition, Chinese legend claimed the mother of Yue Fei (a famous Song general) tattooed the words “Repay the Country with Pure Loyalty” (精忠報國, jing zhong bao guo) down her son’s back before he left to join the army.” ref

“Tattoos were part of the ancient Wu culture of the Yangtze River Delta but had negative connotations in traditional Han culture in China. The Zhou refugees Wu Taibo and his brother Zhongyong were recorded cutting their hair and tattooing themselves to gain acceptance before founding the state of Wu, but Zhou and imperial Chinese culture tended to restrict tattooing as a punishment for marking criminals. The association of tattoos with criminals was transmitted from China to influence Japan. Tattooing of criminals and slaves was commonplace in the Roman Empire.] Catholic Croats of Bosnia, especially children and women, used Sicanje for protection against conversion to Islam during the Ottoman rule in the Balkans.” ref

Tattoos in Ancient Americas

“Many Indigenous peoples of North America practice tattooing. Native Americans also used tattoos to represent their tribe. European explorers and traders who met Native Americans noticed these tattoos and wrote about them, and a few Europeans chose to be tattooed by Native Americans. See history of tattooing in North America. Of the three best-known Pre-Columbian civilizations in the Americas, the Mayas and the Aztecs of Central America were known to wear tattoos while the Incas of South America were not. However, there is evidence that the Chimu people who preceded the Incas did wear tattoos for magic and medical purposes. The diverse tribes of the Amazon have also worn tattoos for millennia and continue to do so to this day, including facial tattoos and notably, the people of the Xingu River in the North of Brazil and the Putumayo River between Peru, Brazil, and Colombia São Paulo, Brazil is largely regarded as one of the most tattooed cities in the world.” ref

Tattoos in Ancient Australia

“Scarring was practiced widely amongst the Indigenous peoples of Australia, now only really found in parts of Arnhem Land.” ref

Tattoos in Ancient New Zealand

“The Māori people of New Zealand have historically practiced tattooing. Amongst these are facial designs worn to indicate lineage, social position, and status within the tribe called tā moko. The tattoo art was a sacred marker of identity among the Māori and also referred to as a vehicle for storing one’s tapu, or spiritual being, in the afterlife. One practice was after death to preserve the skin-covered skull known as Toi moko or mokomokai. In the period of early contact between Māori and Europeans these heads were traded especially for firearms. Many of these are now being repatriated back to New Zealand led by the national museum Te Papa.” ref

“Among Austronesian societies, tattoos had various functions. Among men, they were strongly linked to the widespread practice of head-hunting raids. In head-hunting societies, like the Ifugao and Dayak people, tattoos were records of how many heads the warriors had taken in battle, and were part of the initiation rites into adulthood. The number, design, and location of tattoos, therefore, were indicative of a warrior’s status and prowess. They were also regarded as magical wards against various dangers like evil spirits and illnesses. Among the Visayans of the pre-colonial Philippines, tattoos were worn by the tumao nobility and the timawa warrior class as permanent records of their participation and conduct in maritime raids known as mangayaw. In Austronesian women, like the facial tattoos among the women of the Tayal and Māori people, they were indicators of status, skill, and beauty.” ref

Tattoo Styles

- Albanian traditional tattooing

- Borneo traditional tattooing

- Deq (tattoo) – Traditional Kurdish tattoos

- Irezumi – Several forms of traditional Japanese tattooing

- Peʻa – Traditional male tatau of Samoa

- Indian Yantra tattooing or Sak Yant tattooing

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

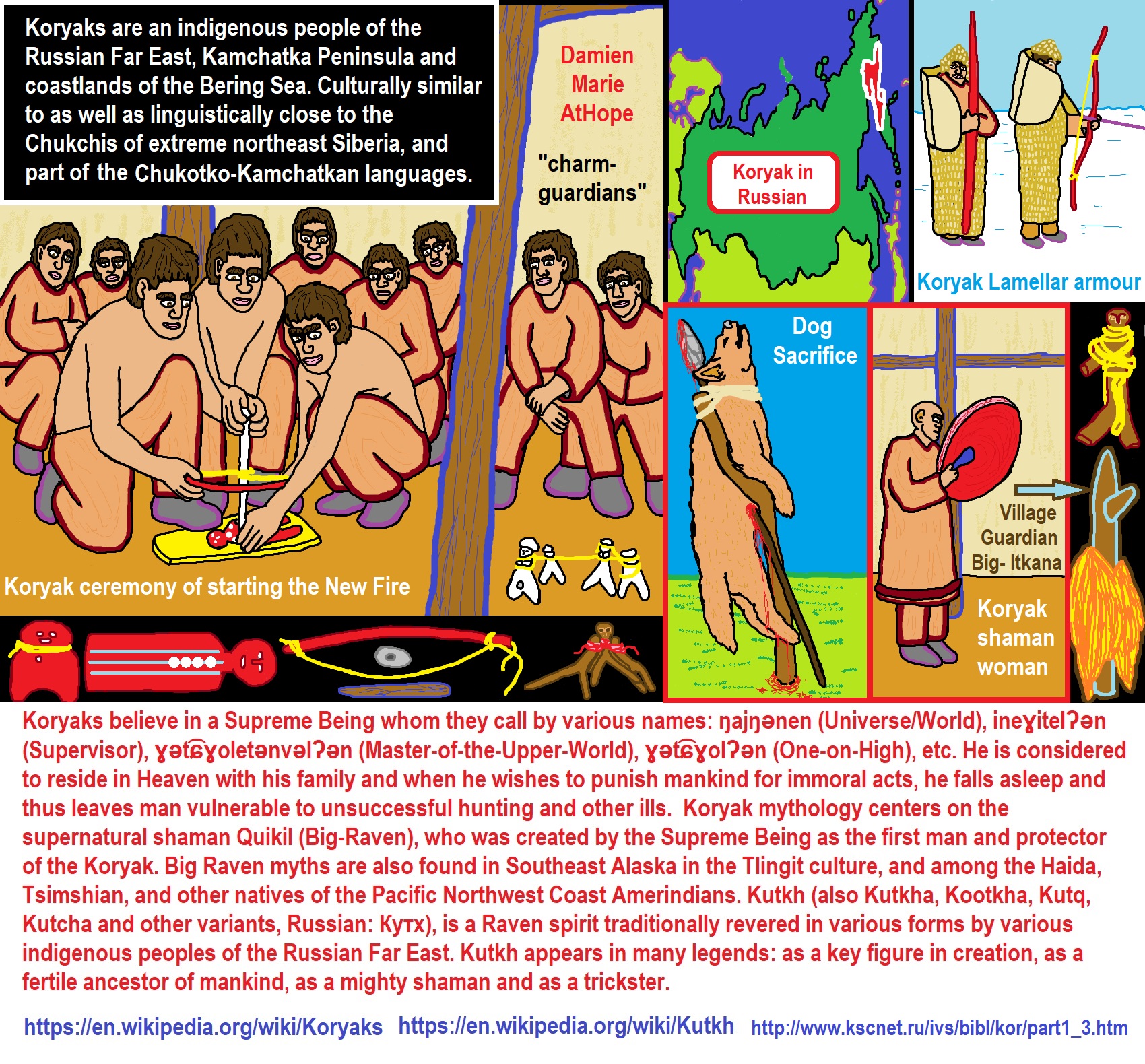

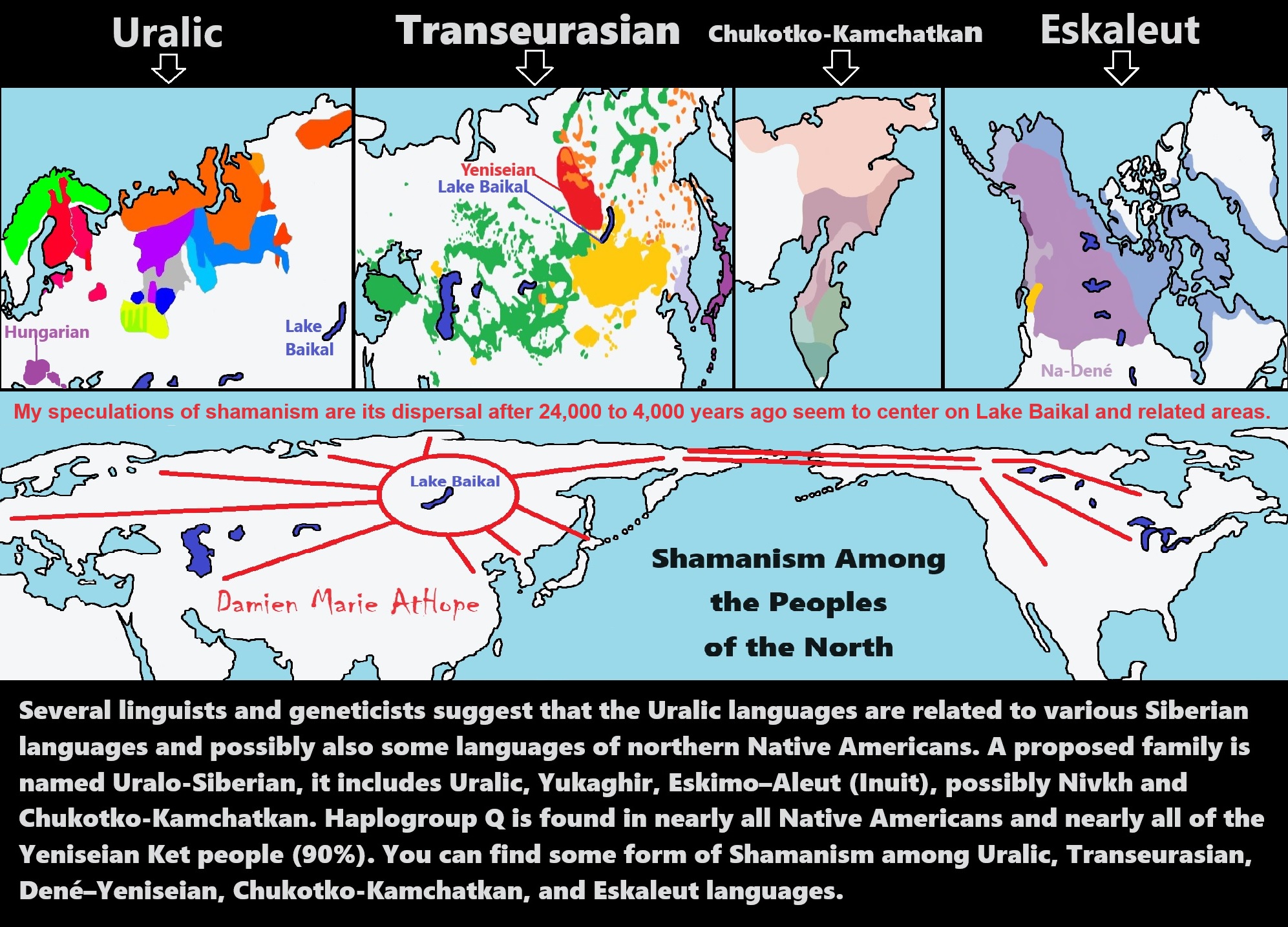

“Koryak people of the Russian Far East, who live immediately north of the Kamchatka Peninsula, with cultural borders including Tigilsk in the south and the Anadyr basin in the north. Koryak people are culturally similar to the Chukchi people of extreme northeast Siberia. The Koryak language is linguistically close to the Chukchi language, not to mention, ALL of these languages are members of the Chukotko-Kamchatkan language family. Koryak mythology centers on the supernatural shaman Quikil (Big-Raven), who was created by the Supreme Being as the first man and protector of the Koryak. Big Raven myths are also found in Southeast Alaska in the Tlingit culture, and among the Haida, Tsimshian, and other natives of the Pacific Northwest Coast Amerindians.” ref

Ainu people

“The Ainu are the indigenous people of the lands surrounding the Sea of Okhotsk, including Hokkaido Island, Northeast Honshu Island, Sakhalin Island, the Kuril Islands, the Kamchatka Peninsula, and Khabarovsk Krai, before the arrival of the Yamato Japanese and Russians. These regions are referred to as Ezo (蝦夷) in historical Japanese texts. In 1966 there were about 300 native Ainu speakers, while in 2008, there were about 100 native Ainu speakers.” ref

Official estimates place the total Ainu population of Japan at 25,000. Unofficial estimates place the total population at 200,000 or higher, as the near-total assimilation of the Ainu into Japanese society has resulted in many individuals of Ainu descent having no knowledge of their ancestry. As of 2000, the number of “pure” Ainu was estimated at about 300 people.” ref

“This people’s most widely known ethnonym, “Ainu” (Ainu: アィヌ; Japanese: アイヌ; Russian: Айны) means “human” in the Ainu language, particularly as opposed to kamui, divine beings. Ainu also identify themselves as “Utari” (“comrade” or “people”). Official documents use both names.” ref

“The Ainu are the native people of Hokkaido, Sakhalin and the Kurils. Early Ainu-speaking groups (mostly hunters and fishermen) migrated also into the Kamchatka Peninsula and into Honshu, where their descendants are today known as the Matagi hunters, who still use a large amount of Ainu vocabulary in their dialect. Other evidence for Ainu-speaking hunters and fishermen migrating down from Northern Hokkaido into Honshu is through the Ainu toponyms which are found in several places of northern Honshu, mostly among the western coast and the Tōhoku region. Evidence for Ainu speakers in the Amur region is found through Ainu loanwords in the Uilta and Ulch people.” ref

“Research suggests that Ainu culture originated from a merger of the Okhotsk and Satsumon cultures. According to Lee and Hasegawa, the Ainu-speakers descend from the Okhotsk people which rapidly expanded from northern Hokkaido into the Kurils and Honshu. These early inhabitants did not speak the Japanese language; some were conquered by the Japanese early in the 9th century. In 1264, the Ainu invaded the land of the Nivkh people. The Ainu also started an expedition into the Amur region, which was then controlled by the Yuan Dynasty, resulting in reprisals by the Mongols who invaded Sakhalin. Active contact between the Wa-jin (the ethnically Japanese, also known as Yamato-jin) and the Ainu of Ezogashima (now known as Hokkaidō) began in the 13th century. The Ainu formed a society of hunter-gatherers, surviving mainly by hunting and fishing. They followed a religion which was based on natural phenomena.” ref

“The Ainu have often been considered to descend from the diverse Jōmon people, who lived in northern Japan from the Jōmon period (c. 14,000 to 300 BCE). One of their Yukar Upopo, or legends, tells that “[t]he Ainu lived in this place a hundred thousand years before the Children of the Sun came”. Recent research suggests that the historical Ainu culture originated from a merger of the Okhotsk culture with the Satsumon culture, cultures thought to have derived from the diverse Jōmon-period cultures of the Japanese archipelago. The Ainu economy was based on farming, as well as on hunting, fishing, and gathering.” ref

“According to Lee and Hasegawa of the Waseda University, the direct ancestors of the later Ainu people formed during the late Jōmon period from the combination of the local but diverse population of Hokkaido, long before the arrival of contemporary Japanese people. Lee and Hasegawa suggest that the Ainu language expanded from northern Hokkaido and may have originated from a relative more recent Northeast Asian/Okhotsk population, which established themselves in northern Hokkaido and had significant impact on the formation of Hokkaido’s Jōmon culture.” ref

“The linguist and historian Joran Smale similarly found that the Ainu language likely originated from the ancient Okhotsk people, which had strong cultural influence on the “Epi-Jōmon” of southern Hokkaido and northern Honshu, but that the Ainu people themselves formed from the combination of both ancient groups. Additionally, he notes that the historical distribution of Ainu dialects and its specific vocabulary corresponds to the distribution of the maritime Okhotsk culture.” ref

“Recently in 2021, it was confirmed that the Hokkaido Jōmon people formed from “Jōmon tribes of Honshu” and from “Terminal Upper-Paleolithic people” (TUP people) indigenous to Hokkaido and Paleolithic Northern Eurasia. The Honshu Jōmon groups arrived about 15,000 BC and merged with the indigenous “TUP people” to form the Hokkaido Jōmon. The Ainu in turn formed from the Hokkaido Jōmon and from the Okhotsk people.” ref

“Another study in 2021 (Sato et al.) analyzed the indigenous populations of northern Japan and the Russian Far East. They concluded that Siberia and northern Japan was populated by two distinct waves: “the southern migration wave seems to have diversified into the local populations in East Asia (defined in this paper as a region including China, Japan, Korea, Mongol, and Taiwan) and Southeast Asia, and the northern wave, which probably runs through the Siberian and Eurasian steppe regions and mixed with the southern wave, probably in Siberia. Archaeologists have considered that bear worship, which is a religious practice widely observed among the northern Eurasian ethnic groups, including the Ainu, Finns, Nivkh, and Sami, was also shared by the Okhotsk people. On the other hand, no traces of such a religious practice have ever been discovered from archaeological sites of the Jomon and Epi-Jomon periods, which were anterior to the Ainu cultural period. This implies that the Okhotsk culture contributed to the forming of the Ainu culture.” ref

Genetics: Genetic history of East Asians and Jōmon people

Paternal lineages

“Genetic testing has shown that the Ainu belong mainly to Y-DNA haplogroup D-M55 (D1a2) and C-M217. Y DNA haplogroup D M55 is found throughout the Japanese Archipelago, but with very high frequencies among the Ainu of Hokkaidō in the far north, and to a lesser extent among the Ryukyuans in the Ryukyu Islands of the far south. Recently it was confirmed that the Japanese branch of haplogroup D M55 is distinct and isolated from other D branches for more than 53,000 years.” ref

“Several studies (Hammer et al. 2006, Shinoda 2008, Matsumoto 2009, Cabrera et al. 2018) suggest that haplogroup D originated somewhere in Central Asia. According to Hammer et al., the ancestral haplogroup D originated between Tibet and the Altai mountains. He suggests that there were multiple waves into Eastern Eurasia.” ref

“A study by Tajima et al. (2004) found two out of a sample of sixteen Ainu men (or 12.5%) belong to Haplogroup C M217, which is the most common Y chromosome haplogroup among the indigenous populations of Siberia and Mongolia. Hammer et al. (2006) found that one in a sample of four Ainu men belonged to haplogroup C M217.” ref

Maternal lineages

“Based on analysis of one sample of 51 modern Ainu, their mtDNA lineages consist mainly of haplogroup Y [11⁄51 = 21.6% according to Tanaka et al. 2004, or 10⁄51 = 19.6% according to Adachi et al. 2009, who have cited Tajima et al. 2004], haplogroup D [9⁄51 = 17.6%, particularly D4 (xD1)], haplogroup M7a (8⁄51 = 15.7%), and haplogroup G1 (8⁄51 = 15.7%). Other mtDNA haplogroups detected in this sample include A (2⁄51), M7b2 (2⁄51), N9b (1⁄51), B4f (1⁄51), F1b (1⁄51), and M9a (1⁄51). Most of the remaining individuals in this sample have been classified definitively only as belonging to macro-haplogroup M.” ref

“According to Sato et al. (2009), who have studied the mtDNA of the same sample of modern Ainus (N=51), the major haplogroups of the Ainu are N9 [14⁄51 = 27.5%, including 10⁄51 Y and 4⁄51 N9 (xY)], D [12⁄51 = 23.5%, including 8⁄51 D (xD5) and 4⁄51 D5], M7 (10⁄51 = 19.6%), and G (10⁄51 = 19.6%, including 8⁄51 G1 and 2⁄51 G2); the minor haplogroups are A (2⁄51), B (1⁄51), F (1⁄51), and M (xM7, M8, CZ, D, G) (1⁄51).” ref

“Studies published in 2004 and 2007 show the combined frequency of M7a and N9b were observed in Jōmons and which are believed by some to be Jōmon maternal contribution at 28% in Okinawans [7⁄50 M7a1, 6⁄50 M7a (xM7a1), 1⁄50 N9b], 17.6% in Ainus [8⁄51 M7a (xM7a1), 1⁄51 N9b], and from 10% [97⁄1312 M7a (xM7a1), 1⁄1312 M7a1, 28⁄1312 N9b] to 17% [15⁄100 M7a1, 2⁄100 M7a (xM7a1)] in mainstream Japanese. In addition, haplogroups D4, D5, M7b, M9a, M10, G, A, B, and F have been found in Jōmon people as well. These mtDNA haplogroups were found in various Jōmon samples and in some modern Japanese people.” ref

“A study by Kanazawa-Kiriyama in 2013 about mitochondrial haplogroups, found that the Ainu people (including samples from Hokkaido and Tōhoku) have a high frequency of N9b, which is also found among Udege people of eastern Siberia, and more common among Europeans than Eastern Asians, but absent from the geographically close Kantō Jōmon period samples, which have a higher frequency of M7a7, which is commonly found among East and Southeast Asians. According to the authors, these results add to the internal-diversity observed among the Jōmon period population and that a significant percentage of the Jōmon period people had ancestry from a Northeast Asian source population, suggested to be the source of the proto-Ainu language and culture, which is not detected in samples from Kantō.” ref

Autosomal DNA

“A 2004 reevaluation of cranial traits suggests that the Ainu resemble the Okhotsk more than they do the Jōmon but there are large variations. This agrees with the references to the Ainu as a merger of Okhotsk and Satsumon referenced above. Similarly, more recent studies link the Ainu to the local Hokkaido Jōmon period samples, such as the 3,800-year-old Rebun sample.” ref

“Genetic analyses of HLA I and HLA II genes as well as HLA-A, -B, and -DRB1 gene frequencies links the Ainu to Indigenous peoples of the Americas. Genetic of variety Asian groups shows Ainu and of Native Americans are place relatively close can be traced back to Paleolithic groups in Siberia.” ref

“Hideo Matsumoto (2009) suggested, based on immunoglobulin analyses, that the Ainu (and Jōmon) have a Siberian origin. Compared with other East Asian populations, the Ainu have the highest amount of Siberian (immunoglobulin) components, higher than mainland Japanese people. A 2012 genetic study has revealed that the closest genetic relatives of the Ainu are the Ryukyuan people, followed by the Yamato people and Nivkh.” ref

“A genetic analysis in 2016 showed that although the Ainu have some genetic relations to the Japanese people and Eastern Siberians (especially Itelmens and Chukchis), they are not directly related to any modern ethnic group. Further, the study detected genetic contribution from the Ainu to populations around the Sea of Okhotsk but no genetic influence on the Ainu themselves. According to the study, the Ainu-like genetic contribution in the Ulch people is about 17.8% or 13.5% and about 27.2% in the Nivkhs. The study also disproved the idea about a relation to Andamanese or Tibetans; instead, it presented evidence of gene flow between the Ainu and “lowland East Asian farmer populations” (represented in the study by the Ami and Atayal in Taiwan, and the Dai and Lahu in Mainland East Asia).” ref

“A genetic study in 2016 about historical Ainu samples from southern Sakhalin (8) and northern Hokkaido (4), found that these samples were closely related to ancient Okhotsk people and various other Northeast Asians, such as indigenous populations in Kamchatka (Itelmens). The authors conclude that this points to heterogeneity among the historical Ainu, as other studies reported a rather isolated position of analyzed Ainu samples from southern Hokkaido.” ref

“Recent autosomal evidence suggests that the Ainu derive a majority of their ancestry from the local Jōmon period people of Hokkaido. A 2019 study by Gakuhari et al., analyzing ancient Jōmon remains, finds about 79.3% Hokkaido Jōmon ancestry in the Ainu. Another 2019 study (by Kanazawa-Kiriyama et al.) finds about 66% Hokkaido Jōmon ancestry. A genetic study in 2021 (Sato et al.) found that the Ainu probably derived about ~49% of their ancestry from the local Hokkaido Jōmon, ~22% from the Okhotsk (samplified by Chukotko-Kamchatkan peoples), and ~29% from the Yamato Japanese.” ref

“Population genomic data from various Jōmon period samples show that their main ancestry component split from other East Asian people at about 15,000 BCE. Following their migration into the Japanese archipelago, they became largely isolated from outside geneflow. However, geneflow from Ancient North Eurasians towards the Jōmon period population was detected along a North to South cline, with a peak among Hokkaido Jōmon.” ref

“A study by Adachi et al. 2018 concluded that: “Our results suggest that the Ainu were formed from the Hokkaido Jomon people, but subsequently underwent considerable admixture with adjacent populations. The present study strongly recommends revision of the widely accepted dual-structure model for the population history of the Japanese, in which the Ainu are assumed to be the direct descendants of the Jomon people.” ref

“The Ainu often resemble Native Americans, but exhibit a variation of phenotypes, ranging from “Caucasian” to East Asian, with many having an intermediate appearance. Physical differences could be observed between different Ainu subgroups and clans. The numerous large Kabata and Hidaka Ainu clans largely resembled Northeast Asians and Northeastern Siberians, rather than Europeans. The physical differences between Ainu and neighboring Japanese and Koreans, was found to be not as large as early historians suggested. Many Ainu men have abundant wavy hair and often have long beards. There was also a number of mixed Russian-Ainu individuals.” ref

“The book of Ainu Life and Legends by author Kyōsuke Kindaichi (published by the Japanese Tourist Board in 1942) contains a physical description of Ainu: “Many have wavy hair, but some straight black hair. Very few of them have wavy brownish hair. Their skins are generally reported to be light brown. But this is due to the fact that they labor on the sea and in briny winds all day. Old people who have long desisted from their outdoor work are often found to be as white as western men. The Ainu have broad faces, beetling eyebrows, and sometimes large sunken eyes, which are generally horizontal and of the so-called European type. Eyes of the Mongolian type are rare but occasionally found among them.” ref

“A comparative study by Brace et al. (2001) showed a closer morphological relation of the Ainu and their Hokkaido Jōmon ancestors with prehistoric and living European groups. The study concludes that part of their ancestors are descended from of a population (dubbed “Eurasians” by Brace et al.) that moved into northern Eurasia eastwards in the Late Pleistocene, which significantly predates the expansion of the modern core population of East Asia from Mainland Southeast Asia. According to the authors, these morphological similarities suggest distant genetic ties at one time, and provides some basis for the long-time claim that the Ainu have an Indo-European component among their ancestry.” ref

“A study by Kura et al. 2014 based on cranial and genetic characteristics suggests a mostly Northeastern Asian (“Arctic“) origin for Ainu people. Thus, despite Ainu sharing some morphological similarities to Caucasoid populations, the Ainu are essentially of North Asiatic origin. Genetic evidence supports a closer relation with Paleosiberian Arctic populations, such as the Chukchi people. A study by Omoto has shown that the Ainu are closer related to other East Asian groups (previously mentioned as ‘Mongoloid’) than to Western Eurasian groups (formerly termed as “Caucasian”), on the basis of fingerprints and dental morphology.” ref

“A study published in the scientific journal “Nature” by Jinam et al. 2015, using genome-wide SNP data comparison, found that a noteworthy amount of Ainu carry gene alleles associated with facial features which are commonly found among Europeans but absent from Japanese people and other East Asians, but these alleles are not found in all tested Ainu samples. These alleles are the reason for their pseudo-Caucasian appearance and likely arrived from Paleolithic Siberia.” ref

“In 2021, it was confirmed that the Hokkaido Jōmon population formed from “Terminal Upper-Paleolithic people” (TUP) indigenous to Hokkaido and Northern Eurasia and from migrants of Jōmon period Honshu. The Ainu themselves formed from these heterogeneous Hokkaido Jōmon and from a more recent Northeast Asian/Okhotsk population. Traditional Ainu culture was quite different from Japanese culture. According to Tanaka Sakurako from the University of British Columbia, the Ainu culture can be included into a wider “northern circumpacific region”, referring to various indigenous cultures of Northeast Asia and “beyond the Bering Strait” in North America.” ref

“Never shaving after a certain age, the men had full beards and moustaches. Men and women alike cut their hair level with the shoulders at the sides of the head, trimmed semicircularly behind. The women tattooed (anchi-piri) their mouths, and sometimes the forearms. The mouth tattoos were started at a young age with a small spot on the upper lip, gradually increasing with size.” ref

“The soot deposited on a pot hung over a fire of birch bark was used for colour. Their traditional dress was a robe spun from the inner bark of the elm tree, called attusi or attush. Various styles were made, and consisted generally of a simple short robe with straight sleeves, which was folded around the body, and tied with a band about the waist. The sleeves ended at the wrist or forearm and the length generally was to the calves. Women also wore an undergarment of Japanese cloth.” ref

“The Ainu hunted from late autumn to early summer. The reasons for this were, among others, that in late autumn, plant gathering, salmon fishing, and other activities of securing food came to an end, and hunters readily found game in fields and mountains in which plants had withered. A village possessed a hunting ground of its own or several villages used a joint hunting territory (iwor). Heavy penalties were imposed on any outsiders trespassing on such hunting grounds or joint hunting territory.” ref

“The Ainu hunted Ussuri brown bears, Asian black bears, Ezo deer (a subspecies of sika deer), hares, red foxes, Japanese raccoon dogs, and other animals. Ezo deer were a particularly important food resource for the Ainu, as were salmon. They also hunted sea eagles such as white-tailed sea eagles, raven, and other birds. The Ainu hunted eagles to obtain their tail feathers, which they used in trade with the Japanese.” ref

“The Ainu hunted with arrows and spears with poison-coated points. They obtained the poison, called surku, from the roots and stalks of aconites. The recipe for this poison was a household secret that differed from family to family. They enhanced the poison with mixtures of roots and stalks of dog’s bane, boiled juice of Mekuragumo (a type of harvestman), Matsumomushi (Notonecta triguttata, a species of backswimmer), tobacco, and other ingredients. They also used stingray stingers or skin covering stingers.” ref

“They hunted in groups with dogs. Before the Ainu went hunting, particularly for bear and similar animals, they prayed to the god of fire, the house guardian god, to convey their wishes for a large catch, and to the god of mountains for safe hunting.” ref

“The Ainu usually hunted bear during the spring thaw. At that time, bears were weak because they had not fed at all during their long hibernation. Ainu hunters caught hibernating bears or bears that had just left hibernation dens. When they hunted bear in summer, they used a spring trap loaded with an arrow, called an amappo. The Ainu usually used arrows to hunt deer. Also, they drove deer into a river or sea and shot them with arrows. For a large catch, a whole village would drive a herd of deer off a cliff and club them to death.” ref

“Fishing was important for the Ainu. They largely caught trout, primarily in summer, and salmon in autumn, as well as “ito” (Japanese huchen), dace, and other fish. Spears called “marek” were often used. Other methods were “tesh” fishing, “uray” fishing and “rawomap” fishing. Many villages were built near rivers or along the coast. Each village or individual had a definite river fishing territory. Outsiders could not freely fish there and needed to ask the owner.” ref

“Men wore a crown called sapanpe for important ceremonies. Sapanpe was made from wood fibre with bundles of partially shaved wood. This crown had wooden figures of animal gods and other ornaments on its center. Men carried an emush (ceremonial sword) secured by an emush at strap to their shoulders.” ref

“Women wore matanpushi, embroidered headbands, and ninkari, earrings. Ninkari was a metal ring with a ball. Matanpushi and ninkari were originally worn by men. Furthermore, aprons called maidari now are a part of women’s formal clothes. However, some old documents say that men wore maidari. Women sometimes wore a bracelet called tekunkani.” ref

“Women wore a necklace called rektunpe, a long, narrow strip of cloth with metal plaques. They wore a necklace that reached the breast called a tamasay or shitoki, usually made from glass balls. Some glass balls came from trade with the Asian continent. The Ainu also obtained glass balls secretly made by the Matsumae clan.” ref

“The Ainu people had various types of marriage. A child was promised in marriage by arrangement between his or her parents and the parents of his or her betrothed or by a go-between. When the betrothed reached a marriageable age, they were told who their spouse was to be. There were also marriages based on mutual consent of both sexes. In some areas, when a daughter reached a marriageable age, her parents let her live in a small room called tunpu annexed to the southern wall of her house. The parents chose her spouse from men who visited her. The age of marriage was 17 to 18 years of age for men and 15 to 16 years of age for women, who were tattooed. At these ages, both sexes were regarded as adults.” ref

“When a man proposed to a woman, he visited her house, ate half a full bowl of rice handed to him by her, and returned the rest to her. If the woman ate the rest, she accepted his proposal. If she did not and put it beside her, she rejected his proposal. When a man became engaged to a woman or they learned that their engagement had been arranged, they exchanged gifts. He sent her a small engraved knife, a workbox, a spool, and other gifts. She sent him embroidered clothes, coverings for the back of the hand, leggings, and other handmade clothes.” ref

“The worn-out fabric of old clothing was used for baby clothes because soft cloth was good for the skin of babies and worn-out material protected babies from gods of illness and demons due to these gods’ abhorrence of dirty things. Before a baby was breast-fed, they were given a decoction of the endodermis of alder and the roots of butterburs to discharge impurities. Children were raised almost naked until about the ages of four to five. Even when they wore clothes, they did not wear belts and left the front of their clothes open. Subsequently, they wore bark clothes without patterns, such as attush, until coming of age.” ref

“Newborn babies were named ayay (a baby’s crying), shipo, poyshi (small excrement), and shion (old excrement). Children were called by these “temporary” names until the ages of two to three. They were not given permanent names when they were born. Their tentative names had a portion meaning “excrement” or “old things” to ward off the demon of ill-health. Some children were named based on their behavior or habits. Other children were named after impressive events or after parents’ wishes for the future of the children. When children were named, they were never given the same names as others.” ref

“Men wore loincloths and had their hair dressed properly for the first time at age 15–16. Women were also considered adults at the age of 15–16. They wore underclothes called mour and had their hair dressed properly and wound waistcloths called raunkut and ponkut around their bodies. When women reached age 12–13, the lips, hands, and arms were tattooed. When they reached age 15–16, their tattoos were completed. Thus were they qualified for marriage.” ref

Face Tattoo

“A face tattoo or facial tattoo is a tattoo located on the bearer’s face or head. It is part of the traditional tattoos of many ethnic groups. In modern times, although it is considered taboo and socially unacceptable in many cultures, as well as considered extreme in body art, this style and placement of tattoo has emerged in certain subcultures. This is due to the continuing acceptance of tattoos and the emergence of hip-hop culture popularizing styles such as the teardrop tattoo. Face tattooing is traditionally practiced by many ethnic groups worldwide.

Here are a Few Traditions of Face Tattooing

“The Ainu are an indigenous ethnic group who reside in northern Japan and Southeastern Russia, including Hokkaido and the Tōhoku region of Honshu, as well as the land surrounding the Sea of Okhotsk, such as Sakhalin, the Kuril Islands, the Kamchatka Peninsula, and the Khabarovsk Krai.” ref

“The Ainu people of northern Japan and parts of Russia, including Sakhalin, the Kuril Islands, and Kamchatka Krai, have a practice of facial tattooing exclusive to women, in which a smile is inked around the mouth to prevent spirits from entering the body through the mouth. This form of tattooing also serves a secondary purpose of showing maturity.” ref

“In Taiwan, facial tattoos of the Atayal people are called ptasan; they are used to demonstrate that an adult man can protect his homeland, and that an adult woman is qualified to weave cloth and perform housekeeping.” ref

Indigenous tattoos of California

CALIFORNIA INDIGENOUS CHIN TATTOOING

“Lengua woman with facial tattoos, 1930.” ref

Marks of Transformation: Tribal Tattooing in California and the American Southwest

Tattoo “Doctors”

“Mohave warriors frequently had a large circle (or two smaller ones) tattooed on the chest with one or two lines radiating toward the shoulders. Other important men, like scalp-keepers, wore a T-shaped design on both sides of their face just below the cheek-bone. Like the Mohave, Nomlaki (Central Wintun) tattooists were specialists. Nomlaki informants interviewed about 1900 specifically stated that the ability was obtained through the Huta, a men’s secret society. The initiation was viewed as an experience through which youths acquired the ability to engage in a professional or special craft, and a prevailing attitude regarded that the ability was a special talent that presumably rested on a spiritual base.” ref

“Wintun. Trinity River Wintun women wore much heavier facial tattoos than their Chimariko and Hupa neighbors. The entire cheek up to the temples was tattooed as well as the chin, and burnt wormwood has been documented as the traditional pigment. The tattooing was restricted to the women alone, and was effected by the same method as among the Shasta and Hupa, namely by fine parallel cuts with obsidian or chert lancets rather than by puncture. The process was begun early in life, and the lines broadened by additions from time to time, until in some cases the chin became an almost solid area of blue. Certain women were considered experts in creating these marks, and were in much demand.” ref

“The Wintun, and presumably other groups, also practiced medicinal forms of tattooing that were employed for the relief of rheumatic and chronic pains. Both men and women utilized this therapy, and in such cases the tattooing was placed directly over the painful spot. Women were strictly excluded from all of the proceedings, and it is clear that there was no public announcement of what was to take place. Some elders stated that the rite took place in the spring and was typically held in conjunction with the construction of a new sweat house.” ref

“Members of the Huta called each other “brother,” and if a member was found to have divulged any of the esoteric knowledge associated with it to an outsider, he would be hunted down and killed. Informants stated that hired assassins among the Shasta were employed for this purpose. The practice of tattooing was called dopna or topa meaning “to cut.” A flint knife was used to make the necessary incisions, and soot from charred oak galls was rubbed into the cuts. The age for tattooing girls was between twelve and fourteen, but there is little indication that it was connected with their puberty ceremony.” ref

“The most frequent Nomlaki design was three serrated lines from the lower lip to the chin that was worn by both men and women. The northernmost Wintun tattooed a double line from the lip to the chin on women, and three double lines on the chin. Not every village had a tattooist, and frequently individuals had to travel to a distant settlement and pay for the operation. It is said that the Wintun considered their tattoos to be the best. “The Yuki and Wailaki have funny patterns – they just spoil their faces by making the whole face look black.” ref

Tolowa Indian with lines as chin tattoo, Edward Curtis, 1923

“The Tolowa people or Taa-laa-wa Dee-ni’ are a Native American people of the Athabaskan-speaking ethno-linguistic group, traditional territory in northwestern California. Tolowa people are members of several federally recognized tribes: Tolowa Dee-ni’ Nation (Tolowa, Chetco, Yurok), Elk Valley Rancheria (Tolowa and Yurok), Confederated Tribes of Siletz (more than 27 native tribes and bands, speaking 10 distinct languages, including Athapascans speaking groups of SW Oregon, like Upper Umpqua, Coquille, Tututni, Chetco, Tolowa, Galice and Applegate River people), Trinidad Rancheria (Chetco, Hupa, Karuk, Tolowa, Wiyot, and Yurok), Big Lagoon Rancheria (Yurok and Tolowa), Blue Lake Rancheria (Wiyot, Yurok, and Tolowa) as well as the unrecognized Tolowa Nation.” ref

“The Tolowa organized their subsistence around the plentiful riverine and marine resources and acorns (san-chvn). Their society was not formally stratified, but considerable emphasis was put on personal wealth. Tolowa villages were organized around a headman and usually consisted of related men, in a patrilineal kinship system, where inheritance and status passed through the male line. The men married women in neighboring tribes. The brides were usually related (sisters), in order for the wealth to remain in the paternal families.” ref

“Chukchi are a Siberian ethnic group native to the Chukchi Peninsula, the shores of the Chukchi Sea and the Bering Sea region of the Arctic Ocean all within modern Russia. They speak the Chukchi language, part of Chukotko-Kamchatkan: Kamchatkan, Itelmen, Chukchi, Koryak, Alyutor, and Kerek.” ref, ref

“Among the various Cordilleran (Igorot) peoples of the northern Philippines, facial tattoos indicated that a warrior belonged to the highest rank. Among the Kalinga people, pregnant women were also tattooed with small x-shaped marks on the forehead, cheeks, and the tip of the nose to protect them and the unborn child from the vengeful spirits of slain enemies.” ref

Inuit people, Indigenous Alaskans, and First Nations Indigenous peoples in Canada

“The Tlingit are Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America and constitute two of the 231 (As of 2022) federally recognized Tribes of Alaska. Most Tlingit are Alaska Natives; however, some are First Nations in Canada. Their language is the Tlingit language, spoken by the Tlingit people of Southeast Alaska and Western Canada, and is a branch of the Na-Dene language family, which includes at least the Athabaskan languages, Eyak, and Tlingit languages. In February 2008, a proposal connecting Na-Dene (excluding Haida) to the Yeniseian languages of central Siberia into a Dené–Yeniseian family was published and well received by a number of linguists. It was proposed in a 2014 paper that the Na-Dene languages of North America and the Yeniseian languages of Siberia had a common origin in a language spoken in Beringia, between the two continents.” ref, ref, ref

“Facial tattoos were practiced among Inuit women, but this practice was suppressed by missionaries. Yidįįłtoo are the traditional face tattoos of the Hän Gwich’in, who are indigenous to Alaska and Canada. Kakiniit and Tavlugun are other examples. In the 21st century, there was a revival of traditional facial tattooing among Indigenous Arctic women. Quannah Chasinghorse wears Yidįįłtoo.” ref

“Kakiniit (Inuktitut: ᑲᑭᓐᓃᑦ [kɐ.ki.niːt]; sing. kakiniq, ᑲᑭᓐᓂᖅ) are the traditional tattoos of the Inuit of the North American Arctic.” ref

“Kakiniit traditional tattoos of the Inuit of the North American Arctic. The practice is done almost exclusively among women, with women exclusively tattooing other women with the tattoos for various purposes. Men could also receive tattoos but these were often much less extensive than the tattoos a woman would receive. Facial tattoos are individually referred to as tunniit (ᑐᓃᑦ), and would mark an individual’s transition to womanhood. The individual tattoos bear unique meaning to Inuit women, with each individual tattoo carrying symbolic meaning.” ref

“However, in Inuinnaqtun, kakiniq refers to facial tattoos. Historically, the practice was done for aesthetic, medicinal purposes, part of the Inuit religion, and to ensure the individual access to the afterlife. Despite persecution by Christian missionaries during the 20th century, the practice has seen a modern revival by organizations such as the Inuit Tattoo Revitalization Project. Many Inuit women wear the tattoos as a source of pride in their Inuit culture.” ref

“The Proto-Inuit-Yupik root *kaki- means ‘pierce or prick’; this is etymon for the Iñupiaq (North Alaskan Inuit) kakinʸɨq* ‘tattoo’, Eastern Canadian Inuktitut kakiniq ‘tattoo’, West Greenlandic kakiuʀniʀit ‘tattoos’, and Tunumiit (East Greenlandic) ‘kaɣiniq ‘tattoo’. The root kaki- also means tattoo in Inuvialuktun (Western Canadian Inuktitut). The Proto-Inuit word *tupə(nəq) ‘tattoo’ is the etymology of Eastern Canadian Inuktitut tunniq ‘woman’s facial tattoo’. This might go back to Proto-Inuit-Yupik-Unangan *cumi-n ‘ornamental dots’.” ref

“Kakiniq (singular) or kakiniit (plural) is an Inuktitut term which refers to Inuit tattoos, while the term tunniit specifically refers to women’s facial tattoos. The terms are rendered in Inuktitut syllabics as ᑲᑭᓐᓃᑦ (Kakinniit), ᑲᑭᓐᓂᖅ (Kakinniq), and ᑐᓃᑦ (Tuniit). Kakiniit are tattoos done on the body, and tunniit are tattoos done on the face, they served a variety of symbolic purposes. Commonly, the tattooed portions would consist of the arms, hands, breasts, and thighs. In some extreme cases, some women would tattoo their entire bodies.” ref

“According to filmmaker Alethea Arnaquq-Baril, the stomach area was scarcely tattooed, with her remarking that she had never heard of the practice being done in that area of the body. The markings are done on women, and the practice of tattooing was done by women. Men would not receive the same tattoos as women; the tattoos men would receive would be much less extensive than female tattoos, and served the purpose as an amulet. However, there were reports of men who were raised female and received tunniit who later were wed as second wives. The patterns would consist of dots, zig-zags, shapes, and lines. The practice of facial tattooing is considered a part of coming into womanhood for Inuit women. Women were unable to marry until their faces were tattooed, and the tattoos meant that they had learned essential skills for later in life.” ref

“Designs would vary depending on the region. Each individual pattern has symbolic meaning to its wearer, and served a ariety of purposes. Some are often given to commemorate a significant life event. Y-shaped markings represent essential tools used during the seal hunt, V-shaped markings on the forehead represent entering womanhood, stripes on the chin represent a woman’s first period, chest tattoos are given after childbirth and symbolize motherhood, and markings on the arms and fingers reference to the legend of Sedna. Due to persecution of the practice during the 20th century, and the subsequent loss of the meaning that some of the tattoos had embodied, modern wearers often invent new meanings for the tattoos as they reclaim the practice.” ref

“Tattooists were usually older women who had experience in embroidery. Traditionally, the practice was done through sinew from caribou that was spun into a thread and was soaked in a combination of qulliq lampblack and seal suet. The thread would then be poked under the skin through the use of a needle made of bone, wood, or steel. Other tools used historically were pokers, and knives, all these tools would be held in a seal-intestine skin bag. Once the tattoo had been completed, the tattooed area would be sterilized with a mixture of urine and soot. In modern times, the practice is primarily done through the use of a tattoo machine and its use of needles and ink. Both practices, the poking method, and the machine method, are used in modern times, with the traditional poking method employed by those who wish for the practice to be done traditionally.” ref

“Inuit legends regarding the meaning of the individual tattoos refer to the sea goddess Sedna who, while being thrown overboard by her angry father, had her fingers chopped off, the disembodied digits would become sea animals. Tattoos on the hands and arms refer to the story, representing where her hands were cut. Wearers of kakiniit in Inuit tradition would ensure that in the afterlife, the woman would be able to go to a place of happiness and good things. According to tradition, women who did not have hand tattoos would be denied access to the afterlife by Sedna, while women without facial tattoos were sent to the land of Noqurmiut, the “land of the crestfallen” where women would spend an eternity with smoke coming from their throat and their head hanging downwards.” ref

“According to anthropologist Lars Krutak, Inuit practices of tattooing remained unchanged for millennia. Evidence of prehistoric tattooing found on Alaska’s St. Lawrence Island resembled tattoos found on Greenlandic women in the 1880s. The practice was widespread and unchanged prior to colonization. On top of making individuals happy, the practice was done for a variety of reasons historically, some for acupuncture or as pain relief, beautification, and shamanistic reasons. With the introduction of Western medicine and fashion, the former reasons fell out of favor among Inuit, the third reason was extirpated through pressure from missionaries.” ref

“The practice of kakiniit was banned by the Catholic Church and missionaries during the early 20th century, who saw the practice as evil due to its non-Christian nature. Traditionally a source of pride and a rite of passage for Inuit women, the practice was considered shamanistic to the Catholic missionaries and the communities that they worked to convert. Biblical passages forbidding the practice of tattooing served as additional pressure to forbid the practice. The efforts of Anglican missionary Edmund Peck, who was fluent in Inuktitut, were particularly effective in extirpating Inuit cultural and religious practices, including kakiniit. However, the practice was not entirely extirpated during the time, and the practice went underground.” ref

Tattooed Inuit women from Baffin Island region. After Boas (1901-07: 108).

“Indigenous women from throughout Alaska share stories and photos of their traditional markings. Traditional markings may vary in placement and style. Some common markings include: tavluġun (chin tattoo); iri (tattoos in the corner of the eyes); siqñiq (forehead tattoo, also meaning “sun,”); and sassuma aana (tattoos on the fingers representing the sea mother).” ref

IDENTIFYING MARKS: Tattoos and Expression

“Alaska is home to diverse cultures and tattooing traditions. Inuit tattoo has been practiced in Alaska for millennia by Iñupiat and Yup’ik women. Colonization suppressed traditional tattooing, but a new generation of Indigenous women are revitalizing and restoring the practice. At the same time, tattoo traditions from Polynesia, Japan, and places throughout the US have made their way to Alaska and can be seen in the inventive styles of local tattoo artists working at shops throughout the state.” ref

“Traditional Inuit tattoos are signifiers of cultural belonging and are not intended for use or appropriation by those outside the culture. Inuit tattoos throughout the Circumpolar North region historically were made by women, for women. Receiving tattoos was a ceremonial rite of passage that marked important events in a woman’s life, such as the transition from girlhood to womanhood, or the birth of child. In the 19th and 20th centuries, Christian missionaries arrived in Alaska and forbade many important cultural practices, including Indigenous languages, dances, and tattoo. Generations of people experienced deep trauma resulting from the loss of culture and way of life under colonization. The revitalization of traditional tattooing practices is a powerful movement of Indigeneity and decolonization and an expression of cultural identity and sisterhood.” ref

“Yidiiltoo or Yidįįłtoo are the traditional face tattoos of Hän Gwich’in women, who are Indigenous to Alaska and Canada.” ref

“The Enxet, previously known as the Lengua people, an indigenous group of Paraguay. The Enxet are an indigenous people of about 17,000 living in the Gran Chaco region of western Paraguay.” ref, ref

“The Apatani people are an ethnic group and who live in the Ziro valley of Arunachal Pradesh’s Lower Subansiri region.” ref

“Tā moko or Māori tattooing, Among the Māori people, men traditionally received tattoos on the entire face, while in women it was mostly restricted to the lips (kauwae) and chins. These tattoos were traditionally part of the initiation into adulthood and signified rank and status, as well as being considered beautiful.” ref

Nanaia Mahuta is the first female MP in New Zealand to have a traditional Maori tattoo

Tā moko

“Tā moko is the permanent marking or tattooing as customarily practiced by Māori, the indigenous people of New Zealand. It is one of the five main Polynesian tattoo styles (the other four are Marquesan, Samoan, Tahitian, and Hawaiian). Tohunga-tā-moko (tattooists) were considered tapu, or inviolable and sacred. Tattoo arts are common in the Eastern Polynesian homeland of the Māori people, and the traditional implements and methods employed were similar to those used in other parts of Polynesia.” ref

“In pre-European Māori culture, many if not most high-ranking persons received moko. Moko were associated with mana and high social status; however, some very high-status individuals were considered too tapu to acquire moko, and it was also not considered suitable for some tohunga to do so. Receiving moko constituted an important milestone between childhood and adulthood, and was accompanied by many rites and rituals. Apart from signalling status and rank, another reason for the practice in traditional times was to make a person more attractive to the opposite sex. Men generally received moko on their faces, buttocks (raperape) and thighs (puhoro). Women usually wore moko on their lips (ngutu) and chins (kauae). Other parts of the body known to have moko include women’s foreheads, buttocks, thighs, necks, and backs and men’s backs, stomachs, and calves.” ref

“Historically, the skin was carved by uhi (chisels) rather than punctured as in common contemporary tattooing; this left the skin with grooves rather than a smooth surface. Later needle tattooing was used, but, in 2007, it was reported that the uhi was again being used by some artists. Originally tohunga-tā-moko (moko specialists) used a range of uhi (chisels) made from albatross bone, which were hafted onto a handle, and struck with a mallet. The pigments were made from the awheto for the body color, and ngarehu (burnt timbers) for the blacker face color. The soot from burnt kauri gum was also mixed with fat to make pigment. The pigment was stored in ornate vessels called oko, which were often buried when not in use. The oko were handed on to successive generations. A kōrere (feeding funnel) is believed to have been used to feed men whose mouths had become swollen from receiving tā moko. Men and a few women were tā moko specialists and would travel to perform their art.” ref

Middle East/North Africa

“Facial tattoos are widespread across various parts of the Middle East and parts of North Africa. In the Levant, facial tattoos are primarily adorned by the women of the Bedouin tribes living throughout Jordan to symbolize beauty and social status. In some instances tattoos are also used for their believed “magick” properties. Facial markings are also seen in Iraq among the Yezidi women. In North Africa, face tattoos can be found among the indigenous Berbers that populated the region before the arrival of Arab armies from the East. Egyptian women from different religious sub-sects of Islam and Christianity also sport face tattoos. In all cases, it is primarily the women that adorn facial markings and while men did have tattoos in some cases, they were primarily on the hands, arms, and feet. The tattoos throughout the Middle East and Africa share many similarities in the use and style of the geometric designs and glyphs that symbolize various animals, element signs, and physical attributes.” ref

“Batok Indigenous tattoos of the Philippines, among the heavily-tattooed Visayans of the central and southern Philippines, face tattoos were known as bangut or langi. They were often meant to resemble frightening masks, like crocodile jaws or raptorial beaks. These tattoos were reserved only for the most elite warriors (timawa), and possessing facial tattoos indicated high personal status.” ref

Batok

“Batok, batek, patik, batik, or buri, among other names, are general terms for indigenous tattoos of the Philippines. Tattooing on both sexes was practiced by almost all ethnic groups of the Philippine Islands during the pre-colonial era. Like other Austronesian groups, these tattoos were made traditionally with hafted tools tapped with a length of wood (called the “mallet”). Each ethnic group had specific terms and designs for tattoos, which are also often the same designs used in other art forms and decorations such as pottery and weaving. Tattoos range from being restricted only to certain parts of the body to covering the entire body. Tattoos were symbols of tribal identity and kinship, as well as bravery, beauty, and social or wealth status.” ref

“Tattooing traditions were mostly lost as Filipinos were converted to Christianity during the Spanish colonial era. Tattooing was also lost in some groups (like the Tagalog and the Moro people) shortly before the colonial period due to their (then recent) conversion to Islam. It survived until around the 19th to the mid-20th centuries in more remote areas of the Philippines, but also fell out of practice due to modernization and western influence. Today, it is a highly endangered tradition and only survives among some members of the Cordilleran peoples of the Luzon highlands, some Lumad people of the Mindanao highlands, and the Sulodnon people of the Panay highlands. Most names for tattoos in the different languages of the Philippines are derived from Proto-Austronesian *beCik (“tattoo”), *patik (“mottled pattern”), and *burik (“speckled”).” ref

“Tattoos are known as batok (or batuk) or patik among the Visayan people; batik, buri, or tatak among the Tagalog people; buri among the Pangasinan, Kapampangan, and Bicolano people; batek, butak, or burik among the Ilocano people; batek, batok, batak, fatek, whatok (also spelled fatok), or buri among the various Cordilleran peoples; and pangotoeb (also spelled pa-ngo-túb, pengeteb, or pengetev) among the various Manobo peoples. These terms were also applied to identical designs used in woven textiles, pottery, and decorations for shields, tool and weapon handles, musical instruments, and others. Affixed forms of these words were used to describe tattooed people, often as a synonym for “renowned/skilled person,” like Tagalog batikan, Visayan binatakan, and Ilocano burikan.” ref

“They were commonly repeating geometric designs (lines, zigzags, chevrons, checkered patterns, repeating shapes); stylized representations of animals (like snakes, lizards, eagles, dogs, deer, frogs, or giant centipedes), plants (like grass, ferns, or flowers), or humans; lightning, mountains, water, stars, or the sun. Each motif had a name, and usually a story or significance behind it, though most of them have been lost to time. They were the same patterns and motifs used in other artforms and decorations of the particular ethnic groups they belong to. Tattoos were, in fact, regarded as a type of clothing in itself, and men would commonly wear only loincloths (bahag) to show them off.