Most gods can be explained or linked to mythology, not fully reality; it was people giving human or animal attributes to the nature around them. I think this was motivated by animistic beliefs and their way of explaining natural phenomena as having a supernatural/spirit nature. Thinking that to the scientifically minded would at best be seen as wishful thinking, beliefs to gain a sense of control in a world they are powerless in.

Dragons and Serpents?

“Usually large to gigantic, serpent-like legendary creatures that appear in the folklore of many cultures around the world. Beliefs about dragons vary drastically by region, but dragons in Western cultures since the High Middle Ages have often been depicted as winged, horned, four-legged, and capable of breathing fire, whereas dragons in Eastern cultures are usually depicted as wingless, four-legged, serpentine creatures with above-average intelligence. One-on-one epic battles between these beasts are noted throughout many cultures. Typically, they consist of a hero or god battling a single to polycephalic dragon. The motif of Chaoskampf (German: [

“A few notable examples include: Zeus vs. Typhon and H

Parallels: Order Vanquishing Chaos in Dragon Slaying Mythology

“In many myths, dragons play an integral role in creation. Sometimes, like with the Rainbow Serpent, they are the creator. Other times, such as with Vrtra, they are the tool of the creator. I want to take a look at some of the different roles dragons have played in creation: Hatuibwari, Rainbow Serpent, Vrtra, Tiamat, Leviathan, and Jormungandr; Slaying the Dragon to Bring Order. Each of the dragons/serpents had some role in creation, creativity, or global change. In most of the stories, gods, demi-gods, or even special humans slay the dragon to end this tumultuous period, bringing about a time of order.” ref

“The further west you go, the more chaotic and evil the dragon’s creation cycle becomes. In the Hatuibwari example, the dragon was benevolent until challenged by humans. This, to me, represents humans attempting to fight nature and learning they should not; it is a cautionary tale to respect nature. Similarly, with the Rainbow Serpent, the creation was mostly peaceful until humans challenged the creator. It was then that the creation process grew violent. Although the Rainbow Serpent serves to caution people to respect nature, it also acknowledges the natural dark forces within nature.” ref

“As we go west, we get Vrtra, who was evil and chaotic for the sake of chaos, and slain by the god of thunder to give the natural lifecycle back to earth. Day and night, dry and rain, should not be chaotic but cyclical. However, we know that sometimes the order of nature is broken. There ARE droughts; there are eclipses. This story explains humanity’s will to defeat those chaotic parts of nature. Next, we get Tiamat and the Leviathan, which I believe to be very similar. Cosmic creators that are slain by gods in order to create the order of the earth.” ref

“Finally, we have Jormungandr, whose chaos is tamed by Thor, ushering in the next era. Jaz had a theory that the cultures that have creation dragons that were not slain, tend to be those cultures who live in harmony with nature, who do not see nature as something chaotic that needs to be tamed. In essence, those who do not see nature as evil.” ref

Dragon-Serpent Slayers?

“A dragonslayer is a person or being that slays dragons. Dragonslayers and the creatures they hunt have been popular in traditional stories from around the world: they are a type of story classified as type 300 in the Aarne–Thompson classification system. They continue to be popular in modern books, films, video games, and other forms of entertainment. Dragonslayer-themed stories are also sometimes seen as having a chaoskampf theme—in which a heroic figure struggles against a monster that epitomises chaos.” ref

“A dragonslayer is often the hero in a “Princess and dragon” tale. In this type of story, the dragonslayer kills the dragon in order to rescue a high-class female character, often a princess, from being devoured by it. This female character often then becomes the love interest of the account. One notable example of this kind of legend is the story of Ragnar Loðbrók, who slays a giant serpent, thereby rescuing the maiden, Þóra borgarhjörtr, whom he later marries.” ref

“There are, however, several notable exceptions to this common motif. In the legend of Saint George and the Dragon, for example, Saint George overcomes the dragon as part of a plot that ends with the conversion of the dragon’s grateful victims to Christianity, rather than Saint George being married to the rescued princess character.” ref

“In a Norse legend from the Völsunga saga, the dragonslayer, Sigurd, kills Fáfnir—a dwarf who has been turned into a dragon as a result of guarding the cursed ring that had once belonged to the dwarf, Andvari. After slaying the dragon, Sigurd drinks some of the dragon’s blood and thereby gains the ability to understand the speech of birds. He also bathes in the dragon’s blood, causing his skin to become invulnerable. Sigurd overhears two nearby birds discussing the heinous treachery being planned by his companion, Regin. In response to the plot, Sigurd kills Regin, thereby averting the treachery.” ref

“A dragon is a magical legendary creature that appears in the folklore of multiple cultures worldwide. Beliefs about dragons vary considerably through regions, but dragons in Western cultures since the High Middle Ages have often been depicted as winged, horned, and capable of breathing fire. Dragons in eastern cultures are usually depicted as wingless, four-legged, serpentine creatures with above-average intelligence. Commonalities between dragons’ traits are often a hybridization of reptilian, mammalian, and avian features. The word dragon entered the English language in the early 13th century from Old French dragon, which, in turn, comes from Latin draco (genitive draconis), meaning “huge serpent, dragon”, from Ancient Greek δράκων, drákōn (genitive δράκοντος, drákontos) “serpent”. The Greek and Latin term referred to any great serpent, not necessarily mythological. The Greek word δράκων is most likely derived from the Greek verb δέρκομαι (dérkomai), meaning “I see,” the aorist form of which is ἔδρακον (édrakon). This is thought to have referred to something with a “deadly glance” or unusually bright or “sharp” eyes, or because a snake’s eyes appear to be always open; each eye actually sees through a big transparent scale in its eyelids, which are permanently shut. The Greek word probably derives from an Indo-European base *derḱ- meaning “to see”; the Sanskrit root दृश् (dr̥ś-) also means “to see.” ref

“The serpent, or snake, is one of the oldest and most widespread mythological symbols. The word is derived from Latin serpens, a crawling animal or snake. Snakes have been associated with some of the oldest rituals known to humankind and represent dual expression[3] of good and evil. In some cultures, snakes were fertility symbols. For example, the Hopi people of North America performed an annual snake dance to celebrate the union of Snake Youth (a Sky spirit) and Snake Girl (an Underworld spirit) and to renew the fertility of Nature. During the dance, live snakes were handled, and at the end of the dance, the snakes were released into the fields to guarantee good crops. “The snake dance is a prayer to the spirits of the clouds, the thunder, and the lightning, that the rain may fall on the growing crops.” To the Hopi, snakes symbolized the umbilical cord, joining all humans to Mother Earth. The Great Goddess often had snakes as her familiars—sometimes twining around her sacred staff, as in ancient Crete—and they were worshiped as guardians of her mysteries of birth and regeneration.” ref

“The anthropologist Lynne Isbell has argued that, as primates, the serpent as a symbol of death is built into our unconscious minds because of our evolutionary history. Isbell argues that for millions of years snakes were the only significant predators of primates, and that this explains why fear of snakes is one of the most common phobias worldwide and why the symbol of the serpent is so prevalent in world mythology; the serpent is an innate image of danger and death. Furthermore, the psychoanalyst Joseph Lewis Henderson and the ethnologist Maude Oakes have argued that the serpent is a symbol of initiation and rebirth precisely because it is a symbol of death. Using phylogenetical and statistical methods on related motifs from folklore and myth, French comparativist Julien d’Huy managed to reconstruct a possible archaic narrative about the serpent. In this Paleolithic “ophidian” myth, snakes are connected to rains and storms, and even to water sources. In regards to the latter, it blocks rivers and other water sources in exchange for human sacrifices and/or material good offerings.” ref

“Mythologists such as Joseph Campbell have argued that dragonslayer myths can be seen as a psychological metaphor:

“But as Siegfried [Sigurd] learned, he must then taste the dragon blood, in order to take to himself something of that dragon power. When Siegfried has killed the dragon and tasted the blood, he hears the song of nature. he has transcended his humanity and re-associated himself with the powers of nature, which are powers of our life, and from which our minds remove us. …Psychologically, the dragon is one’s own binding of oneself to one’s own ego.” ref

“Draconic creatures appear in virtually all cultures around the globe and the earliest attested reports of draconic creatures resemble giant snakes. Draconic creatures are first described in the mythologies of the ancient Near East and appear in ancient Mesopotamian art and literature. Stories about storm-gods slaying giant serpents occur throughout nearly all Near Eastern and Indo-European mythologies. Famous prototypical draconic creatures include the mušḫuššu of ancient Mesopotamia; Apep in Egyptian mythology; Vṛtra in the Rigveda; the Leviathan in the Hebrew Bible; Grand’Goule in the Poitou region in France; Python, Ladon, Wyvern and the Lernaean Hydra in Greek mythology; Kulshedra in Albanian Mythology; Unhcegila in Lakota mythology; Quetzalcoatl in Aztec Culture; Jörmungandr, Níðhöggr, and Fafnir in Norse mythology; the dragon from Beowulf; and aži and az in ancient Persian mythology, closely related to another mythological figure, called Aži Dahaka or Zahhak.” ref

“Nonetheless, scholars dispute where the idea of a dragon originates from, and a wide variety of hypotheses have been proposed. In his book An Instinct for Dragons (2000), anthropologist David E. Jones suggests a hypothesis that humans, like monkeys, have inherited instinctive reactions to snakes, large cats, and birds of prey. He cites a study that found that approximately 39 people in a hundred are afraid of snakes and notes that fear of snakes is especially prominent in children, even in areas where snakes are rare. The earliest attested dragons all resemble snakes or have snakelike attributes. Jones therefore concludes that dragons appear in nearly all cultures because humans have an innate fear of snakes and other animals that were major predators of humans’ primate ancestors. Dragons are usually said to reside in “dark caves, deep pools, wild mountain reaches, sea bottoms, haunted forests,” all places which would have been fraught with danger for early human ancestors.” ref

“In her book The First Fossil Hunters: Dinosaurs, Mammoths, and Myth in Greek and Roman Times (2000), Adrienne Mayor argues that some stories of dragons may have been inspired by ancient discoveries of fossils belonging to dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals. She argues that the dragon lore of northern India may have been inspired by “observations of oversized, extraordinary bones in the fossilbeds of the Siwalik Hills below the Himalayas“ and that ancient Greek artistic depictions of the Monster of Troy may have been influenced by fossils of Samotherium, an extinct species of giraffe whose fossils are common in the Mediterranean region. In China, a region where fossils of large prehistoric animals are common, these remains are frequently identified as “dragon bones” and are commonly used in traditional Chinese medicine. Mayor, however, is careful to point out that not all stories of dragons and giants are inspired by fossils and notes that Scandinavia has many stories of dragons and sea monsters, but has long “been considered barren of large fossils.” ref

“In one of her later books, she states that, “Many dragon images around the world were based on folk knowledge or exaggerations of living reptiles, such as Komodo dragons, Gila monsters, iguanas, alligators, or, in California, alligator lizards, though this still fails to account for the Scandinavian legends, as no such animals (historical or otherwise) have ever been found in this region. Robert Blust in The Origin of Dragons (2000) argues that, like many other creations of traditional cultures, dragons are largely explicable as products of a convergence of rational pre-scientific speculation about the world of real events. In this case, the event is the natural mechanism governing rainfall and drought, with particular attention paid to the phenomenon of the rainbow.” ref

“In Egyptian mythology, Apep or Apophis is a giant serpentine creature who resides in the Duat, the Egyptian Underworld. The Bremner-Rhind papyrus, written around 310 BCE, preserves an account of a much older Egyptian tradition that the setting of the sun is caused by Ra descending to the Duat to battle Apep. In some accounts, Apep is as long as the height of eight men with a head made of flint. Thunderstorms and earthquakes were thought to be caused by Apep’s roar, and solar eclipses were thought to be the result of Apep attacking Ra during the daytime. In some myths, Apep is slain by the god Set. Nehebkau is another giant serpent who guards the Duat and aided Ra in his battle against Apep. Nehebkau was so massive in some stories that the entire earth was believed to rest atop his coils. Denwen is a giant serpent mentioned in the Pyramid Texts whose body was made of fire and who ignited a conflagration that nearly destroyed all the gods of the Egyptian pantheon. He was ultimately defeated by the Pharaoh, a victory which affirmed the Pharaoh’s divine right to rule.” ref

“The ouroboros was a well-known Egyptian symbol of a serpent swallowing its own tail. The precursor to the ouroboros was the “Many-Faced,” a serpent with five heads, who, according to the Amduat, the oldest surviving Book of the Afterlife, was said to coil around the corpse of the sun god Ra protectively. The earliest surviving depiction of a “true” ouroboros comes from the gilded shrines in the tomb of Tutankhamun. In the early centuries AD, the ouroboros was adopted as a symbol by Gnostic Christians, and chapter 136 of the Pistis Sophia, an early Gnostic text, describes “a great dragon whose tail is in its mouth.” In medieval alchemy, the ouroboros became a typical western dragon with wings, legs, and a tail. A famous image of the dragon gnawing on its tail from the eleventh-century Codex Marcianus was copied in numerous works on alchemy.” ref

“Ancient people across the Near East believed in creatures similar to what modern people call “dragons.” These ancient people were unaware of the existence of dinosaurs or similar creatures in the distant past. References to dragons of both benevolent and malevolent characters occur throughout ancient Mesopotamian literature. In Sumerian poetry, great kings are often compared to the ušumgal, a gigantic, serpentine monster. A draconic creature with the foreparts of a lion and the hind-legs, tail, and wings of a bird appears in Mesopotamian artwork from the Akkadian Period (c. 2334 – 2154 BCE) until the Neo-Babylonian Period (626–539 BCE). The dragon is usually shown with its mouth open. It may have been known as the (ūmu) nā’iru, which means “roaring weather beast,” and may have been associated with the god Ishkur (Hadad). A slightly different lion-dragon with two horns and the tail of a scorpion appears in art from the Neo-Assyrian Period (911–609 BCE). A relief, probably commissioned by Sennacherib shows the gods Ashur, Sin, and Adad standing on its back.” ref

“Another draconic creature with horns, the body and neck of a snake, the forelegs of a lion, and the hind-legs of a bird appears in Mesopotamian art from the Akkadian Period until the Hellenistic Period (323–31 BCE). This creature, known in Akkadian as the mušḫuššu, meaning “furious serpent,” was used as a symbol for particular deities and also as a general protective emblem. It seems to have originally been the attendant of the Underworld god Ninazu, but later became the attendant to the Hurrian storm-god Tishpak, as well as, later, Ninazu’s son Ningishzida, the Babylonian national god Marduk, the scribal god Nabu, and the Assyrian national god Ashur.” ref

“Scholars disagree regarding the appearance of Tiamat, the Babylonian goddess personifying primeval chaos, slain by Marduk in the Babylonian creation epic Enûma Eliš. She was traditionally regarded by scholars as having had the form of a giant serpent, but several scholars have pointed out that this shape “cannot be imputed to Tiamat with certainty” and she seems to have at least sometimes been regarded as anthropomorphic. Nonetheless, in some texts, she seems to be described with horns, a tail, and a hide that no weapon can penetrate, all features which suggest she was conceived as some form of dragoness.” ref

“In the mythologies of the Ugarit region, specifically the Baal Cycle from the Ugaritic texts, the sea-dragon Lōtanu is described as “the twisting serpent / the powerful one with seven heads.” In KTU 1.5 I 2–3, Lōtanu is slain by the storm-god Baal, but, in KTU 1.3 III 41–42, he is instead slain by the virgin warrior goddess Anat. In the Hebrew Bible, in the Book of Psalms, Psalm 74, Psalm 74:13–14, the sea-dragon Leviathan, is slain by Yahweh, god of the kingdoms of Israel and Judah, as part of the creation of the world. Isaiah describes Leviathan as a tannin (תנין), which is translated as “sea monster,” “serpent,” or “dragon.” ref

In Isaiah 27:1, Yahweh’s destruction of Leviathan is foretold as part of his impending overhaul of the universal order:

|

“In that day the LORD will take His sharp, great, and mighty sword, and bring judgment on Leviathan the fleeing serpent — Leviathan the coiling serpent — and He will slay the dragon of the sea.” —Isaiah 27:1 |

“Leviathan, in Jewish mythology, a primordial sea serpent. Its source is in prebiblical Mesopotamian myth, especially that of the sea monster in the Ugaritic myth of Baal (see Yamm). In the Old Testament, Leviathan appears in Psalms 74:14 as a multiheaded sea serpent that is killed by God and given as food to the Hebrews in the wilderness. In Isaiah 27:1, Leviathan is a serpent and a symbol of Israel’s enemies, who will be slain by God. In Job 41, it is a sea monster and a symbol of God’s power of creation.” ref

“Job 41:1–34 contains a detailed description of the Leviathan, who is described as being so powerful that only Yahweh can overcome it. Job 41:19–21 states that the Leviathan exhales fire and smoke, making its identification as a mythical dragon clearly apparent. In some parts of the Old Testament, the Leviathan is historicized as a symbol for the nations that stand against Yahweh. Rahab, a synonym for “Leviathan,” is used in several Biblical passages in reference to Egypt. Isaiah 30:7 declares: “For Egypt’s help is worthless and empty, therefore I have called her ‘the silenced Rahab‘.” Similarly, Psalm 87:3 reads: “I reckon Rahab and Babylon as those that know me…” In Ezekiel 29:3–5 and Ezekiel 32:2–8, the pharaoh of Egypt is described as a “dragon” (tannîn). In the deuterocanonical story of Bel and the Dragon from the Book of Daniel, the prophet Daniel sees a dragon being worshipped by the Babylonians. Daniel makes “cakes of pitch, fat, and hair”; the dragon eats them and bursts open.” ref

“Azhi Dahaka (Avestan Great Snake) is a dragon or demonic figure in the texts and mythology of Zoroastrian Persia, where he is one of the subordinates of Angra Mainyu. Alternate names include Azi Dahak, Dahaka, and Dahak. Aži (nominative ažiš) is the Avestan word for “serpent” or “dragon. The Avestan term Aži Dahāka and the Middle Persian azdahāg are the sources of the Middle Persian Manichaean demon of greed “Az,” Old Armenian mythological figure Aždahak, Modern Persian ‘aždehâ/aždahâ,’ Tajik Persian ‘azhdahâ,’ Urdu ‘azhdahā’ (اژدها). The name also migrated to Eastern Europe, assumed the form “azhdaja” and the meaning “dragon,” “dragoness” or “water snake” in the Balkanic and Slavic languages. Despite the negative aspect of Aži Dahāka in mythology, dragons have been used on some banners of war throughout the history of Iranian peoples. The Azhdarchid group of pterosaurs are named from a Persian word for “dragon” that ultimately comes from Aži Dahāka. In Persian Sufi literature, Rumi writes in his Masnavi that the dragon symbolizes the sensual soul (nafs), greed, and lust, that need to be mortified in a spiritual battle.” ref

“In Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh, the Iranian hero Rostam must slay an 80-meter-long dragon (which renders itself invisible to human sight) with the aid of his legendary horse, Rakhsh. As Rostam is sleeping, the dragon approaches; Rakhsh attempts to wake Rostam, but fails to alert him to the danger until Rostam sees the dragon. Rakhsh bites the dragon, while Rostam decapitates it. This is the third trial of Rostam’s Seven Labors. Rostam is also credited with the slaughter of other dragons in the Shahnameh and in other Iranian oral traditions, notably in the myth of Babr-e-Bayan.” ref

“In the Rigveda, the oldest of the four Vedas, Indra, the Vedic god of storms, battles Vṛtra, a giant serpent who represents drought. Indra kills Vṛtra using his vajra (thunderbolt) and clears the path for rain, which is described in the form of cattle: “You won the cows, hero, you won the Soma,/You freed the seven streams to flow” (Rigveda 1.32.12). In another Rigvedic legend, the three-headed serpent Viśvarūpa, the son of Tvaṣṭṛ, guards a wealth of cows and horses. Indra delivers Viśvarūpa to a god named Trita Āptya, who fights and kills him and sets his cattle free. Indra cuts off Viśvarūpa’s heads and drives the cattle home for Trita. This same story is alluded to in the Younger Avesta, in which the hero Thraētaona, the son of Āthbya, slays the three-headed dragon Aži Dahāka and takes his two beautiful wives as spoils. Thraētaona’s name (meaning “third grandson of the waters”) indicates that Aži Dahāka, like Vṛtra, was seen as a blocker of waters and cause of drought.” ref

“In this tale, Rostam is still an adolescent and kills a dragon in the “Orient” (either India or China, depending on the source) by forcing it to swallow either ox hides filled with quicklime and stones or poisoned blades. The dragon swallows these foreign objects, and its stomach bursts, after which Rostam flays the dragon and fashions a coat from its hide called the babr-e bayān. In some variants of the story, Rostam then remains unconscious for two days and nights, but is guarded by his steed Rakhsh. On reviving, he washes himself in a spring. In the Mandean tradition of the story, Rostam hides in a box, is swallowed by the dragon, and kills it from inside its belly. The king of China then gives Rostam his daughter in marriage as a reward.” ref

“The word “dragon” has come to be applied to the legendary creature in Chinese mythology, loong (traditional 龍, simplified 龙, Japanese simplified 竜, Pinyin lóng), which is associated with good fortune, and many East Asian deities and demigods have dragons as their personal mounts or companions. Dragons were also identified with the Emperor of China, who, during later Chinese imperial history, was the only one permitted to have dragons on his house, clothing, or personal articles. Archaeologist Zhōu Chong-Fa believes that the Chinese word for dragon is an onomatopoeia of the sound of thunder or lùhng in Cantonese. The Chinese dragon (simplified Chinese: 龙; traditional Chinese: 龍; pinyin: lóng) is the highest-ranking creature in the Chinese animal hierarchy. Its origins are vague, but its “ancestors can be found on Neolithic pottery as well as Bronze Age ritual vessels.” A number of popular stories deal with the rearing of dragons.” ref

“The Zuo zhuan, which was probably written during the Warring States period, describes a man named Dongfu, a descendant of Yangshu’an, who loved dragons and, because he could understand a dragon’s will, he was able to tame them and raise them well. He served Emperor Shun, who gave him the family name Huanlong, meaning “dragon-raiser”. In another story, Kong Jia, the fourteenth emperor of the Xia dynasty, was given a male and a female dragon as a reward for his obedience to the god of heaven, but could not train them, so he hired a dragon-trainer named Liulei, who had learned how to train dragons from Huanlong. One day, the female dragon died unexpectedly, so Liulei secretly chopped her up, cooked her meat, and served it to the king, who loved it so much that he demanded Liulei to serve him the same meal again. Since Liulei had no means of procuring more dragon meat, he fled the palace.” ref

“One of the most famous dragon stories is about the Lord Ye Gao, who loved dragons obsessively, even though he had never seen one. He decorated his whole house with dragon motifs and, seeing this display of admiration, a real dragon came and visited Ye Gao, but the lord was so terrified at the sight of the creature that he ran away. In Chinese legend, the culture hero Fu Hsi is said to have been crossing the Lo River, when he saw the lung ma, a Chinese horse-dragon with seven dots on its face, six on its back, eight on its left flank, and nine on its right flank. He was so moved by this apparition that, when he arrived home, he drew a picture of it, including the dots. He later used these dots as letters and invented Chinese writing, which he used to write his book I Ching. In another Chinese legend, the physician Ma Shih Huang is said to have healed a sick dragon. Another legend reports that a man once came to the healer Lo Chên-jen, telling him that he was a dragon and that he needed to be healed. After Lo Chên-jen healed the man, a dragon appeared to him and carried him to heaven.” ref

“In the Shanhaijing, a classic mythography probably compiled mostly during the Han dynasty, various deities and demigods are associated with dragons. One of the most famous Chinese dragons is Ying Long (“responding dragon”), who helped the Huangdi, the Yellow Emperor, defeat the tyrant Chiyou. The dragon Zhulong (“torch dragon”) is a god “who composed the universe with his body.” In the Shanhaijing, many mythic heroes are said to have been conceived after their mothers copulated with divine dragons, including Huangdi, Shennong, Emperor Yao, and Emperor Shun. The god Zhurong and the emperor Qi are both described as being carried by two dragons, as are Huangdi, Zhuanxu, Yuqiang, and Roshou in various other texts. According to the Huainanzi, an evil black dragon once caused a destructive deluge, which was ended by the mother goddess Nüwa by slaying the dragon.” ref

“A large number of ethnic myths about dragons are told throughout China. The Houhanshu, compiled in the fifth century BCE by Fan Ye, reports a story belonging to the Ailaoyi people, which holds that a woman named Shayi who lived in the region around Mount Lao became pregnant with ten sons after being touched by a tree trunk floating in the water while fishing. She gave birth to the sons and the tree trunk turned into a dragon, who asked to see his sons. The woman showed them to him, but all of them ran away except for the youngest, who the dragon licked on the back and named Jiu Long, meaning “sitting back.” The sons later elected him king and the descendants of the ten sons became the Ailaoyi people, who tattooed dragons on their backs in honor of their ancestor. The Miao people of southwest China have a story that a divine dragon created the first humans by breathing on monkeys that came to play in his cave. The Han people have many stories about Short-Tailed Old Li, a black dragon who was born to a poor family in Shandong. When his mother saw him for the first time, she fainted, and when his father came home from the field and saw him, he hit him with a spade and cut off part of his tail. Li burst through the ceiling and flew away to the Black Dragon River in northeast China, where he became the god of that river. On the anniversary of his mother’s death on the Chinese lunar calendar, Old Li returns home, causing it to rain. He is still worshipped as a rain god.” ref

“In China, a dragon is thought to have power over rain. Dragons and their associations with rain are the source of the Chinese customs of dragon dancing and dragon boat racing. Dragons are closely associated with rain and drought is thought to be caused by a dragon’s laziness. Prayers invoking dragons to bring rain are common in Chinese texts. The Luxuriant Dew of the Spring and Autumn Annals, attributed to the Han dynasty scholar Dong Zhongshu, prescribes making clay figurines of dragons during a time of drought and having young men and boys pace and dance among the figurines in order to encourage the dragons to bring rain. Texts from the Qing dynasty advise hurling the bone of a tiger or dirty objects into the pool where the dragon lives; since dragons cannot stand tigers or dirt, the dragon of the pool will cause heavy rain to drive the object out. Rainmaking rituals invoking dragons are still very common in many Chinese villages, where each village has its own god said to bring rain, and many of these gods are dragons. The Chinese dragon kings are thought of as the inspiration for the Hindu myth of the naga. According to these stories, every body of water is ruled by a dragon king, each with a different power, rank, and ability, so people began establishing temples across the countryside dedicated to these figures.” ref

“Li Ji Slays the Giant Serpent” (traditional Chinese: 李寄斬蛇; simplified Chinese: 李寄斩蛇; pinyin: Lǐ Jì Zhǎn Shé) is a Chinese tale first published in the 4th-century compilation Soushen Ji attributed to the Jin-dynasty official Gan Bao (or Kan Pao). The story concerns a young heroine named Li Ji (or Li Chi) who bravely rids her village of a terrible snake. Alternate English names for the tale are: “The Girl-Eating Serpent”; “Li Chi Slays the Serpent”; “Li Ji Slays the Great Serpent”; “Li Ji Hacks Down the Snake”; “Li Chi Slays the Great Serpent”; “Li Chi, the Serpent Slayer”; “Li Ji, the Serpent Slayer”; and “The Serpent Sacrifice.” ref

“The story is set in Jiangle County (Chiang-lo), Minzhong Commandery, Eastern Yue (or Dongyue) Kingdom, when southeastern China was still fragmented into small kingdoms and territories. In the Yong (Yung) mountains there lived a serpent that “demanded” (through people’s dreams and wu shamans) the sacrifice of maidens from the village below. The town officials, afraid of the creature, give in to its horrible requests and send the daughters of slaves and criminals to the cave’s opening. These sacrifices repeat eight more times, always during “the first week of the eighth lunar month.” ref

“One day, Li Ji (or Li Chi), the youngest daughter of Li Dan (or Li Tan), offers herself to be the sacrifice, since her mother and father have five other daughters and no son. She goes to the mountains to face the serpent, armed with a sword and accompanied by a snake-biting dog. Li Ji puts a basket of sweet-smelling rice cakes to draw the serpent out of its hideout, and while it is distracted by the food, unleashes the dog on the animal. The serpent retreats to the cave, but the girl follows after it, always hitting and striking its body with the sword, until it dies. Li Ji sees the skeletons of the nine sacrificed maidens and either laments they were devoured or that they let themselves be devoured by the beast. The King of Dongyue learns of Li Ji’s bravery and marries her. Her father also becomes the Magistrate of Jiangle.” ref

“Chinese folklorist and scholar Ting Nai-tung established a second typological classification of Chinese folktales (the first was by Wolfram Eberhard in the 1930s). In his new system, he indexed the story of Li Ji as the Chinese type 300, “The Dragon-Slayer.” Ting’s type corresponds, in the international Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index, to tale type ATU 300, “The Dragon-Slayer”: the hero fights against a dragon with the help of his dogs in order to rescue a maiden offered as a sacrifice. The tale shares similarities with tales about dragonslaying around the globe. However, in this tale, a serpent takes the place of the dragon. Some scholars interpret the tale as a contrast of Li Ji’s bravery against the ineffectualness of the male village officers, who preferred to obey the serpent instead of trying to fight it.” ref

“The tale has also been interpreted under an anthropological lens: the snake would be linked to female sexuality and fertility. It has also been suggested that the snake foe (a python with supernatural powers, in some accounts) may represent an old local deity with serpentine form, and the sacrifice of virginal maidens merits comparison to fertility rites. As a new belief system was being diffused through the country, the old animal-shaped divinities were subject to a process of religious reformation that demoted them to adversarial roles of the newcomer human-like deities. In the same vein, the tale could be related to a phenomenon researcher Wu Chunming named “suppression of the snake,” brought about by “Sinnitic immigrants to the region.” ref

“Hugh R. Clark also identifies the tale as belonging to traditions from “the Min River valley” and, by extension, reflective of the Yue culture. Similarly, ancient Chinese scholars once associated the culture of Min with snakes, which is further reinforced by the fact that folktales collected in Fujian show snakes as vicious enemies to be vanquished. Professor Biwu Shang also cites another tale about serpent-slaying, “The Great Serpent.” According to him, in this tale of the zhiguai genre, a similarly named heroine Li Ji slays a human-killing serpent.” ref

Princess and Dragon

“Princess and dragon is an archetypical premise common to many legends, fairy tales, and chivalric romances. Northrop Frye identified it as a central form of the quest romance. The story involves an upper-class woman, generally a princess or similar high-ranking nobility, saved from a dragon, either a literal dragon or a similar danger, by the virtuous hero (see damsel in distress). She may be the first woman endangered by the peril, or may be the end of a long succession of women who were not of as high birth as she is, nor as fortunate. Normally, the princess ends up married to the dragonslayer. The motifs of the hero who finds the princess about to be sacrificed to the dragon and saves her, the false hero who takes his place, and the final revelation of the true hero, are the identifying marks of the Aarne–Thompson folktale type 300, the Dragon-Slayer. They also appear in type 303, the Two Brothers. These two tales have been found, in different variants, in countries all over the world. The “princess and dragon” scenario is given even more weight in popular imagination than it is in the original tales; the stereotypical hero is envisioned as slaying dragons even though, for instance, the Brothers Grimm had only a few tales of dragon and giant slayers among hundreds of tales.” ref

“One of the earliest examples of the motif comes from the Ancient Greek tale of Perseus, who rescued the princess Andromeda from Cetus, a sea monster often described as resembling a serpent or dragon. This was taken up into other Greek myths, such as Heracles, who rescued the princess Hesione of Troy from a similar sea monster. Most ancient versions depicted the dragon as the expression of a god’s wrath: in Andromeda’s case, because her mother Queen Cassiopeia had compared her beauty to that of the sea nymphs, and in Hesione’s, because her father had reneged on a bargain with Poseidon. This is less common in fairy tales and other, later versions, where the dragon is frequently acting out of malice. The homosexual variety of the tale is also found in Greek mythology; similar myths existed in Crissa and Thespiae of a terrifying beast that ravaged the place unless a young man was sacrificed, Alcyoneus in Crisa and Cleostratus in Thespiae to them. In both cases a man who is in love with the youth (Eurybarus and Menestratus respectively) and steps in to take the youth’s place and slay the monster.” ref

“The Japanese legend of Yamata no Orochi also invokes this motif. The god Susanoo encounters two “Earthly Deities” who have been forced to sacrifice their seven daughters to the many-headed monster, and their daughter Kushinadahime is the next victim. Susanoo is able to kill the dragon after getting it drunk on sake (rice wine). Another variation is from the tale of Saint George and the Dragon. The tale begins with a dragon making its nest at the spring which provides a city-state with water. Consequently, the citizens had to temporarily remove the dragon from its nest in order to collect water. To do so, they offered the dragon a daily human sacrifice. The victim of the day was chosen by drawing lots. Eventually in this lottery, the lot happened to fall to the local princess. The local monarch is occasionally depicted begging for her life with no result. She is offered to the dragon but at this point a traveling Saint George arrives. He faces and defeats the dragon and saves the princess; some versions claim that the dragon is not killed in the fight, but pacified once George ties the princess’ sash around its neck. The grateful citizens then abandon their ancestral paganism and convert to Christianity.” ref

“A similar tale to St. George’s, attributed to Russian sources, is that of St. Yegóry, the Brave: after the kingdoms of Sodom and Komor fall, the kingdom of “Arabia” is menaced by a sea-monster that demanded a sacrifice of a human victim every day. The queenly stepmother sent the Princess Elizabeth, the Fair, as the sacrifice. Yegóry, the Brave rescues Elizabeth and uses her sash to bind the beast. To mark her deliverance, he demands the building of three churches. In a tale from Tibet, a kingdom suffers from drought due to two “serpent-gods” blocking the streams of water at the source. Both dragons also demand the sacrifices of citizens from the kingdom, men and women, to appease them, until prince Schalu and his faithful companion Saran decide to put an end to their existence.” ref

“When the tale is not about a dragon but a troll, giant, or ogre, the princess is often a captive rather than about to be eaten, as in The Three Princesses of Whiteland. These princesses are often a vital source of information to their rescuers, telling them how to perform tasks that the captor sets to them, or how to kill the monster, and when she does not know, as in The Giant Who Had No Heart in His Body, she frequently can pry the information from the giant. Despite the hero’s helplessness without this information, the princess is incapable of using the knowledge herself.” ref

“Again, if a false claimant intimidates her into silence about who actually killed the monster as in the fairy tale The Two Brothers, when the hero appears, she will endorse his story, but she will not tell the truth prior to them; she often agrees to marry the false claimant in the hero’s absence. The hero has often cut out the tongue of the dragon, so when the false hero cuts off its head, his claim to have killed it is refuted by its lack of a tongue; the hero produces the tongue and so proves his claim to marry the princess. In some tales, however, the princess herself takes steps to ensure that she can identify the hero—cutting off a piece of his cloak as in Georgic and Merlin, giving him tokens as in The Sea-Maiden—and so separate him from the false hero.” ref

“This dragon-slaying hero appears in medieval romances about knights-errant, such as the Russian Dobrynya Nikitich. In some variants of Tristan and Iseult, Tristan wins Iseult for his uncle, King Mark of Cornwall, by killing a dragon that was devastating her father’s kingdom; he has to prove his claim when the king’s steward claims to be the dragon-slayer. Ludovico Ariosto took the concept up into Orlando Furioso using it not once but twice: the rescue of Angelica by Ruggiero, and Orlando rescuing Olimpia. The monster that menaced Olimpia reconnected to the Greek myths; although Ariosto described it as a legend to the characters, the story was that the monster sprung from an offense against Proteus. In neither case did he marry the rescued woman to the rescuer. Edmund Spenser depicts St. George in The Faerie Queene, but while Una is a princess who seeks aid against a dragon, and her depiction in the opening with a lamb fits the iconography of St. George pageants, the dragon imperils her parents’ kingdom, and not her alone.” ref

“Many tales of dragons, ending with the dragon-slayer marrying a princess, do not precisely fit this cliché because the princess is in no more danger than the rest of the threatened kingdom. An unusual variant occurs in Child ballad 34, Kemp Owyne, where the dragon is the maiden; the hero, based on Ywain from Arthurian legend, rescues her from the transformation with three kisses. Mythological comparativist Julien d’Huy ran an analytical study of the antiquity and diffusion of the snake- or dragon-battling mytheme in different cultural traditions. Scholarship suggests a connection between the episode of the dragon-slaying by the hero and the journey on an eagle’s back, akin to the Mesopotamian myth of Etana.” ref

Proto-Indo-European

“The tale of a hero slaying a giant serpent occurs in almost all Indo-European mythology. In most stories, the hero is some kind of thunder-god. In nearly every iteration of the story, the serpent is either multi-headed or “multiple” in some other way. Furthermore, in nearly every story, the serpent is always somehow associated with water. Bruce Lincoln has proposed that a Proto-Indo-European dragon-slaying myth can be reconstructed as follows: First, the sky gods give cattle to a man named *Tritos (“the third”), who is so named because he is the third man on earth, but a three-headed serpent named *Ngwhi steals them. *Tritos pursues the serpent and is accompanied by *Hanér, whose name means “man.” Together, the two heroes slay the serpent and rescue the cattle.” ref

“The ancient Greek word usually translated as “dragon” (δράκων drákōn, genitive δράκοντοϛ drákontos) could also mean “snake,” but it usually refers to a kind of giant serpent that either possesses supernatural characteristics or is otherwise controlled by some supernatural power. The first mention of a “dragon” in ancient Greek literature occurs in the Iliad, in which Agamemnon is described as having a blue dragon motif on his sword belt and an emblem of a three-headed dragon on his breast plate. In lines 820–880 of the Theogony, a Greek poem written in the seventh century BCE by the Boeotian poet Hesiod, the Greek god Zeus battles the monster Typhon, who has one hundred serpent heads that breathe fire and make many frightening animal noises. Zeus scorches all of Typhon’s heads with his lightning bolts and then hurls Typhon into Tartarus. In other Greek sources, Typhon is often depicted as a winged, fire-breathing serpent-like dragon. In the Homeric Hymn to Apollo, the god Apollo uses his poisoned arrows to slay the serpent Python, who has been causing death and pestilence in the area around Delphi. Apollo then sets up his shrine there. The Roman poet Virgil in his poem Culex, lines 163–201 Appendix Vergiliana: Culex, describing a shepherd having a fight with a big constricting snake, calls it “serpens” and also “draco“, showing that in his time the two words were probably interchangeable.” ref

“Hesiod also mentions that the hero Heracles slew the Lernaean Hydra, a multiple-headed serpent which dwelt in the swamps of Lerna. The name “Hydra” means “water snake” in Greek. According to the Bibliotheka of Pseudo-Apollodorus, the slaying of the Hydra was the second of the Twelve Labors of Heracles. Accounts disagree on which weapon Heracles used to slay the Hydra, but, by the end of the sixth century BCE, it was agreed that the clubbed or severed heads needed to be cauterized to prevent them from growing back. Heracles was aided in this task by his nephew Iolaus. During the battle, a giant crab crawled out of the marsh and pinched Heracles’s foot, but he crushed it under his heel. Hera placed the crab in the sky as the constellation Cancer. One of the Hydra’s heads was immortal, so Heracles buried it under a heavy rock after cutting it off. For his Eleventh Labor, Heracles must procure a golden apple from the tree in the Garden of the Hesperides, which is guarded by an enormous serpent that never sleeps, which Pseudo-Apollodorus calls “Ladon.” ref

“In earlier depictions, Ladon is often shown with many heads. In Pseudo-Apollodorus’s account, Ladon is immortal, but Sophocles and Euripides both describe Heracles as killing him, although neither of them specifies how. Some suggest that the golden apple was not claimed through battle with Ladon at all but through Heracles charming the Hesperides. The mythographer Herodorus is the first to state that Heracles slew him using his famous club. Apollonius of Rhodes, in his epic poem, the Argonautica, describes Ladon as having been shot full of poisoned arrows dipped in the blood of the Hydra.” ref

“In Pindar‘s Fourth Pythian Ode, Aeëtes of Colchis tells the hero Jason that the Golden Fleece he is seeking is in a copse guarded by a dragon, “which surpassed in breadth and length a fifty-oared ship.” Jason slays the dragon and makes off with the Golden Fleece together with his co-conspirator, Aeëtes’s daughter, Medea. The earliest artistic representation of this story is an Attic red-figure kylix dated to c. 480–470 BCE, showing a bedraggled Jason being disgorged from the dragon’s open mouth as the Golden Fleece hangs in a tree behind him and Athena, the goddess of wisdom, stands watching. A fragment from Pherecydes of Athens states that Jason killed the dragon, but fragments from the Naupactica and from Herodorus state that he merely stole the Fleece and escaped. In Euripides’s Medea, Medea boasts that she killed the Colchian dragon herself. In the final scene of the play, Medea also flies away on a chariot pulled by two dragons. In the most famous retelling of the story from Apollonius of Rhodes’s Argonautica, Medea drugs the dragon to sleep, allowing Jason to steal the Fleece. Greek vase paintings show her feeding the dragon the sleeping drug in a liquid form from a phialē, or shallow cup.” ref

“In the founding myth of Thebes, Cadmus, a Phoenician prince, was instructed by Apollo to follow a heifer and found a city wherever it laid down. Cadmus and his men followed the heifer and, when it laid down, Cadmus ordered his men to find a spring so he could sacrifice the heifer to Athena. His men found a spring, but it was guarded by a dragon, which had been placed there by the god Ares, and the dragon killed them. Cadmus killed the dragon in revenge, either by smashing its head with a rock or using his sword. Following the advice of Athena, Cadmus tore out the dragon’s teeth and planted them in the earth. An army of giant warriors (known as spartoi, which means “sown men”) grew from the teeth like plants. Cadmus hurled stones into their midst, causing them to kill each other until only five were left. To make restitution for having killed Ares’s dragon, Cadmus was forced to serve Ares as a slave for eight years. At the end of this period, Cadmus married Harmonia, the daughter of Ares and Aphrodite. Cadmus and Harmonia moved to Illyria, where they ruled as king and queen, before eventually being transformed into dragons themselves.” ref

“In the fifth century BCE, the Greek historian Herodotus reported in Book IV of his Histories that western Libya was inhabited by monstrous serpents and, in Book III, he states that Arabia was home to many small, winged serpents, which came in a variety of colors and enjoyed the trees that produced frankincense. Herodotus remarks that the serpent’s wings were like those of bats and that, unlike vipers, which are found in every land, winged serpents are only found in Arabia. The second-century BCE Greek astronomer Hipparchus (c. 190 – c. 120 BCE) listed the constellation Draco (“the dragon”) as one of forty-six constellations. Hipparchus described the constellation as containing fifteen stars, but the later astronomer Ptolemy (c. 100 – c. 170 CE) increased this number to thirty-one in his Almagest.” ref

“In the New Testament, Revelation 12:3, written by John of Patmos, describes a vision of a Great Red Dragon with seven heads, ten horns, seven crowns, and a massive tail, an image which is clearly inspired by the vision of the four beasts from the sea in the Book of Daniel and the Leviathan described in various Old Testament passages. The Great Red Dragon knocks “a third of the sun … a third of the moon, and a third of the stars” out of the sky and pursues the Woman of the Apocalypse. Revelation 12:7–9 declares: “And war broke out in Heaven. Michael and his angels fought against Dragon. Dragon and his angels fought back, but they were defeated, and there was no longer any place for them in Heaven. Dragon the Great was thrown down, that ancient serpent who is called Devil and Satan, the one deceiving the whole inhabited World – he was thrown down to earth, and his angels were thrown down with him.” Then a voice booms down from Heaven heralding the defeat of “the Accuser” (ho Kantegor).” ref

“In 217 CE, Flavius Philostratus discussed dragons (δράκων, drákōn) in India in The Life of Apollonius of Tyana (II,17 and III,6–8). The Loeb Classical Library translation (by F.C. Conybeare) mentions (III,7) that, “In most respects the tusks resemble the largest swine’s, but they are slighter in build and twisted, and have a point as unabraded as sharks’ teeth.” According to a collection of books by Claudius Aelianus called On Animals, Ethiopia was inhabited by a species of dragon that hunted elephants and could grow to a length of 180 feet (55 m) with a lifespan rivaling that of the most enduring of animals. In the 4th century, Basil of Caesarea, on chapter IX of his Address to Young Men on Greek Literature, mentions mythological dragons as guarding treasures and riches.” ref

“In the Old Norse poem Grímnismál in the Poetic Edda, the dragon Níðhöggr is described as gnawing on the roots of Yggdrasil, the world tree. In Norse mythology, Jörmungandr is a giant serpent that encircles the entire realm of Miðgarð in the sea around it. According to the Gylfaginning from the Prose Edda, written by the thirteenth-century Icelandic mythographer Snorri Sturluson, Thor, the Norse god of thunder, once went out on a boat with the giant Hymnir to the outer sea and fished for Jörmungandr using an ox-head as bait. Thor caught the serpent and, after pulling its head out of the water, smashed it with his hammer, Mjölnir. Snorri states that the blow was not fatal: “and men say that he struck its head off on the sea bed. But I think the truth to tell you is that the Miðgarð Serpent still lives and lies in the surrounding sea.” ref

“Towards the end of the Old English epic poem Beowulf, a slave steals a cup from the hoard of a sleeping dragon, causing the dragon to wake up and go on a rampage of destruction across the countryside. The eponymous hero of the poem insists on confronting the dragon alone, even though he is of advanced age, but Wiglaf, the youngest of the twelve warriors Beowulf has brought with him, insists on accompanying his king into the battle. Beowulf’s sword shatters during the fight and he is mortally wounded, but Wiglaf comes to his rescue and helps him slay the dragon. Beowulf dies and tells Wiglaf that the dragon’s treasure must be buried rather than shared with the cowardly warriors who did not come to the aid of their king.” ref

“In the Old Norse Völsunga saga, the hero Sigurd catches the dragon Fafnir by digging a pit between the cave where he lives and the spring where he drinks his water and kills him by stabbing him in the underside. At the advice of Odin, Sigurd drains Fafnir’s blood and drinks it, which gives him the ability to understand the language of the birds, who he hears talking about how his mentor Regin is plotting to betray him so that he can keep all of Fafnir’s treasure for himself. The motif of a hero trying to sneak past a sleeping dragon and steal some of its treasure is common throughout many Old Norse sagas. The fourteenth-century Flóres saga konungs ok sona hans describes a hero who is actively concerned not to wake a sleeping dragon while sneaking past it. In the Yngvars saga víðförla, the protagonist attempts to steal treasure from several sleeping dragons, but accidentally wakes them up.” ref

Dragonslayer Characters in Antiquity:

- Enki

- Ninurta

- Inanna

- Marduk

- Ra

- Teshub

- Indra

- Garuda

- Janamejaya

- Uttanka

- Baal

- El (deity)

- Yahweh

- Michael

- Daniel

- Apollo

- Perun

- Zeus

- Jupiter

- Perseus

- Heracles

- Menestratus

- Heros

- Saint George

- Vahagn

- Tarḫunz

- Cadmus

- Rostam

- Fereydun

- Garshasp

- Yu the Great

- Erlang Shen

- Li Ji

- Eurybarus

- Mwindo

Dragonslayer Characters in Medieval and early Modern legend:

- Guy of Warwick

- Baldr

- Beowulf

- Sigurd or Siegfried

- Dietrich von Bern

- Tristan

- Margaret the Virgin

- Heinrich von Winkelried

- Gawain

- Dobrynya Nikitich

- Skuba Dratewka/Krakus

- Drangue

- Zjermi

- E Bija e Hënës dhe e Diellit

- Susanoo

- Nezha

- Lancelot

- Făt-Frumos

- Fráech

- Bayajidda

- Bahrām Gūr

- Iovan Iorgovan

- Prâslea the Brave

- Greuceanu

- Haymon

- Wada Heita Tanenaga

- John Lambton

- Mamadi Sefe Dekote (Africa)

- Benzaiten aka Saraswati

- Teodosio de Goñi

- Piers Shonks

- Dieudonné de Gozon

Serpents and Sacred Trees

“In many myths, the chthonic serpent (sometimes a pair) lives in or is coiled around a Tree of Life situated in a divine garden. In the Genesis story of the Torah and biblical Old Testament, the tree of the knowledge of good and evil is situated in the Garden of Eden together with the tree of life and the serpent. In Greek mythology, Ladon coiled around the tree in the garden of the Hesperides protecting the golden apples. Similarly Níðhöggr (Nidhogg Nagar), the dragon of Norse mythology, eats from the roots of the Yggdrasil, the World Tree. Under yet another tree (the Bodhi Tree of Enlightenment), the Buddha sat in ecstatic meditation. When a storm arose, the mighty serpent king Mucalinda rose up from his place beneath the earth and enveloped the Buddha in seven coils for seven days, so as not to break his ecstatic state.” ref

“The Vision Serpent was a symbol of rebirth in Maya mythology, with origins going back to earlier Maya conceptions, lying at the center of the world as the Mayans conceived it. “It is in the center axis atop the World Tree. Essentially the World Tree and the Vision Serpent, representing the king, created the center axis which communicates between the spiritual and the earthly worlds or planes. It is through ritual that the king could bring the center axis into existence in the temples and create a doorway to the spiritual world, and with it power.” ref

“Sometimes the Tree of Life is represented (in a combination with similar concepts such as the World Tree and Axis mundi or “World Axis”) by a staff such as those used by shamans. Examples of such staffs featuring coiled snakes in mythology are the caduceus of Hermes, the Rod of Asclepius, the Staff of Moses, and the papyrus reeds and deity poles entwined by a single serpent Wadjet, dating to earlier than 3000 BCE. The oldest known representation of two snakes entwined around a rod is that of the Sumerian fertility god Ningizzida, who was sometimes depicted as a serpent with a human head, eventually becoming a god of healing and magic. It is the companion of Dumuzi (Tammuz), with whom it stood at the gate of heaven. In the Louvre, there is a famous green steatite vase carved for King Gudea of Lagash (dated variously 2200–2025 BCE) with an inscription dedicated to Ningizzida. Ningizzida was the ancestor of Gilgamesh, who, according to the epic, dived to the bottom of the waters to retrieve the plant of life. But while he rested from his labor, a serpent came and ate the plant. The snake became immortal, and Gilgamesh was destined to die.” ref

“Ningizzida has been popularized in the 20th century by Raku Kei (Reiki, a.k.a. “The Way of the Fire Dragon”), where “Nin Giz Zida” is believed to be a fire serpent of Tibetan rather than Sumerian origin. “Nin Giz Zida” is another name for the ancient Hindu concept Kundalini, a Sanskrit word meaning either “coiled up” or “coiling like a snake”. “Kundalini” refers to the mothering intelligence behind yogic awakening and spiritual maturation leading to altered states of consciousness. There are a number of other translations of the term, usually emphasizing a more serpentine nature to the word—e.g. “serpent power”. It has been suggested by Joseph Campbell that the symbol of snakes coiled around a staff is an ancient representation of Kundalini physiology. The staff represents the spinal column, with the snake(s) being energy channels. In the case of two coiled snakes, they usually cross each other seven times, a possible reference to the seven energy centers called chakras.” ref

“In Ancient Egypt, where the earliest written cultural records exist, the serpent appears from the beginning to the end of their mythology. Ra and Atum (“he who completes or perfects”) became the same god, Atum, the “counter-Ra”, associated with earth animals, including the serpent: Nehebkau (“he who harnesses the souls”) was the two-headed serpent deity who guarded the entrance to the underworld. He is often seen as the son of the snake goddess Renenutet. She often was confused with (and later was absorbed by) their primal snake goddess Wadjet, the Egyptian cobra, who from the earliest of records was the patron and protector of the country, all other deities, and the pharaohs. Hers is the first known oracle. She was depicted as the crown of Egypt, entwined around the staff of papyrus and the pole that indicated the status of all other deities, as well as having the all-seeing eye of wisdom and vengeance. She never lost her position in the Egyptian pantheon.” ref

“The image of the serpent as the embodiment of the wisdom transmitted by Sophia was an emblem used by gnosticism, especially those sects that the more orthodox characterized as “Ophites” (“Serpent People”). The chthonic serpent was one of the earth-animals associated with the cult of Mithras. The basilisk, the venomous “king of serpents” with the glance that kills, was hatched by a serpent, Pliny the Elder and others thought, from the egg of a cock. Outside Eurasia, in Yoruba mythology, Oshunmare was another mythic regenerating serpent. The Rainbow Serpent (also known as the Rainbow Snake) is a major mythological being for Aboriginal people across Australia, although the creation myths associated with it are best known from northern Australia. In Fiji, Ratumaibulu was a serpent god who ruled the underworld and made fruit trees bloom. In the Northern Flinders Ranges reigns the Arkaroo, a serpent who drank Lake Frome empty, refuges into the mountains, carving valleys and waterholes, earthquakes through snoring.” ref

“World Serpent or World Snake may refer to:

- Antaboga, the world serpent of traditional Javanese mythology

- Jörmungandr, also known as the Midgard Serpent, in Norse mythology

- Ouroboros, a world serpent or dragon swallowing its own tail

- Shesha, the serpent containing the universe in Hindu mythology.” ref

Cosmic Serpents

“The serpent, when forming a ring with its tail in its mouth, is a clear and widespread symbol of the “All-in-All”, the totality of existence, infinity and the cyclic nature of the cosmos. The most well known version of this is the Aegypto-Greek ourobouros. It is believed to have been inspired by the Milky Way, as some ancient texts refer to a serpent of light residing in the heavens. The Ancient Egyptians associated it with Wadjet, one of their oldest deities, as well as another aspect, Hathor. In Norse mythology the World Serpent (or Midgard serpent) known as Jörmungandr encircled the world in the ocean’s abyss biting its own tail.” ref

“In Hindu mythology Lord Vishnu is said to sleep while floating on the cosmic waters on the serpent Shesha. In the Puranas Shesha holds all the planets of the universe on his hoods and constantly sings the glories of Vishnu from all his mouths. He is sometimes referred to as “Ananta-Shesha,” which means “Endless Shesha”. In the Samudra manthan chapter of the Puranas, Shesha loosens Mount Mandara for it to be used as a churning rod by the Asuras and Devas to churn the ocean of milk in the heavens in order to make Soma (or Amrita), the divine elixir of immortality. As a churning rope another giant serpent called Vasuki is used.” ref

“In pre-Columbian Central America Quetzalcoatl was sometimes depicted as biting its own tail. The mother of Quetzalcoatl was the Aztec goddess Coatlicue (“the one with the skirt of serpents”), also known as Cihuacoatl (“The Lady of the serpent”). Quetzalcoatl’s father was Mixcoatl (“Cloud Serpent”). He was identified with the Milky Way, the stars, and the heavens in several Mesoamerican cultures.” ref

“The demigod Aidophedo of the West African Ashanti people is also a serpent biting its own tail. In Dahomey mythology of Benin in West Africa, the serpent that supports everything on its many coils was named Dan. In the Vodou of Benin and Haiti, Ayida-Weddo (a.k.a. Aida-Wedo, Aido Quedo, “Rainbow-Serpent”) is a spirit of fertility, rainbows and snakes, and a companion or wife to Dan, the father of all spirits. As Vodou was exported to Haiti through the slave trade, Dan became Danballah, Damballah or Damballah-Wedo. Because of his association with snakes, he is sometimes disguised as Moses, who carried a snake on his staff. He is also thought by many to be the same entity of Saint Patrick, known as a snake banisher.” ref

“The serpent Hydra is a star constellation representing either the serpent thrown angrily into the sky by Apollo or the Lernaean Hydra as defeated by Heracles for one of his Twelve Labors. The constellation Serpens represents a snake being tamed by Ophiuchus the snake-handler, another constellation. The most probable interpretation is that Ophiuchus represents the healer Asclepius.” ref

“Occasionally, serpents and dragons are used interchangeably, having similar symbolic functions. The venom of the serpent is thought to have a fiery quality similar to a fire-breathing dragon. The Greek Ladon and the Norse Níðhöggr (Nidhogg Nagar) are sometimes described as serpents and sometimes as dragons. In Germanic mythology, “serpent” (Old English: wyrm, Old High German: wurm, Old Norse: ormr) is used interchangeably with the Greek borrowing “dragon” (OE: draca, OHG: trahho, ON: dreki). In China and especially in Indochina, the Indian serpent nāga was equated with the lóng or Chinese dragon. The Aztec and Toltec serpent god Quetzalcoatl also has dragon-like wings, like its equivalent in K’iche’ Maya mythology Q’uq’umatz (“feathered serpent”), which had previously existed since Classic Maya times as the deity named Kukulkan.” ref

“In Africa the chief centre of serpent worship was Dahomey, but the cult of the python seems to have been of exotic origin, dating back to the first quarter of the 17th century. By the conquest of Whydah the Dahomeyans were brought in contact with a people of serpent worshipers, and ended by adopting from them the beliefs which they at first despised. At Whydah, the chief centre, there is a serpent temple, tenanted by some fifty snakes. Every python of the danh-gbi kind must be treated with respect, and death is the penalty for killing one, even by accident. Danh-gbi has numerous wives, who until 1857 took part in a public procession from which the profane crowd was excluded; a python was carried round the town in a hammock, perhaps as a ceremony for the expulsion of evils.” ref

“The rainbow-god of the Ashanti was also conceived to have the form of a snake. His messenger was said to be a small variety of boa, but only certain individuals, not the whole species, were sacred. In many parts of Africa the serpent is looked upon as the incarnation of deceased relatives. Among the amaZulu, as among the Betsileo of Madagascar, certain species are assigned as the abode of certain classes. The Maasai, on the other hand, regard each species as the habitat of a particular family of the tribe.” ref

“In ancient Mesopotamia, Nirah, the messenger god of Ištaran, was represented as a serpent on kudurrus, or boundary stones. Representations of two intertwined serpents are common in Sumerian art and Neo-Sumerian artwork and still appear sporadically on cylinder seals and amulets until as late as the thirteenth century BCE. The horned viper (Cerastes cerastes) appears in Kassite and Neo-Assyrian kudurrus and is invoked in Assyrian texts as a magical protective entity. A dragon-like creature with horns, the body and neck of a snake, the forelegs of a lion, and the hind-legs of a bird appears in Mesopotamian art from the Akkadian period until the Hellenistic period (323 BCE–31 BCE). This creature, known in Akkadian as the mušḫuššu, meaning “furious serpent”, was used as a symbol for particular deities and also as a general protective emblem. It seems to have originally been the attendant of the underworld god Ninazu, but later became the attendant to the Hurrian storm-god Tishpak, as well as, later, Ninazu’s son Ningishzida, the Babylonian national god Marduk, the scribal god Nabu, and the Assyrian national god Ashur.” ref

“Snake cults were well established in Canaanite religion in the Bronze Age, for archaeologists have uncovered serpent cult objects in Bronze Age strata at several pre-Israelite cities in Canaan: two at Megiddo, one at Gezer, one in the sanctum sanctorum of the Area H temple at Hazor, and two at Shechem. In the surrounding region, serpent cult objects figured in other cultures. A late Bronze Age Hittite shrine in northern Syria contained a bronze statue of a god holding a serpent in one hand and a staff in the other. In 6th-century Babylon, a pair of bronze serpents flanked each of the four doorways of the temple of Esagila. At the Babylonian New Year’s festival, the priest was to commission from a woodworker, a metalworker, and a goldsmith two images, one of which “shall hold in its left hand a snake of cedar, raising its right [hand] to the god Nabu.” At the tell of Tepe Gawra, at least seventeen Early Bronze Age Assyrian bronze serpents were recovered.” ref

“Python, in Greek mythology, a huge serpent that was killed by the god Apollo at Delphi either because it would not let him found his oracle, being accustomed itself to giving oracles, or because it had persecuted Apollo’s mother, Leto, during her pregnancy. In the earliest account, the Homeric Hymn to Apollo, the serpent is nameless and female, but later it is male, as in Euripides’ Iphigenia Among the Taurians, and named Python (found first in the account of the 4th-century-bc historian Ephorus; Pytho was the old name for Delphi). Python was traditionally the child of Gaea (Earth) who had an oracle at Delphi before Apollo came. The Pythian Games held at Delphi were supposed to have been instituted by Apollo to celebrate his victory over Python.” ref

Serpent-Slaying Myth

“One common myth found in nearly all Indo-European mythologies is a battle ending with a hero or god slaying a serpent or dragon of some sort. Although the details of the story often vary widely, several features remain remarkably the same in all iterations. The protagonist of the story is usually a thunder-god, or a hero somehow associated with thunder. His enemy the serpent is generally associated with water and depicted as multi-headed, or else “multiple” in some other way. Indo-European myths often describe the creature as a “blocker of waters”, and his many heads get eventually smashed up by the thunder-god in an epic battle, releasing torrents of water that had previously been pent up. The original legend may have symbolized the Chaoskampf, a clash between forces of order and chaos. The dragon or serpent loses in every version of the story, although in some mythologies, such as the Norse Ragnarök myth, the hero or the god dies with his enemy during the confrontation.” ref

“Historian Bruce Lincoln has proposed that the dragon-slaying tale and the creation myth of *Trito killing the serpent *H₂n̥gʷʰis may actually belong to the same original story. Reflexes of the Proto-Indo-European dragon-slaying myth appear in most Indo-European poetic traditions, where the myth has left traces of the formulaic sentence *(h₁e) gʷʰent h₁ógʷʰim, meaning “[he] slew the serpent”. In Hittite mythology, the storm god Tarhunt slays the giant serpent Illuyanka, as does the Vedic god Indra the multi-headed serpent Vritra, which has been causing a drought by trapping the waters in his mountain lair. Several variations of the story are also found in Greek mythology. The original motif appears inherited in the legend of Zeus slaying the hundred-headed Typhon, as related by Hesiod in the Theogony, and possibly in the myth of Heracles slaying the nine-headed Lernaean Hydra and in the legend of Apollo slaying the earth-dragon Python.” ref

“The story of Heracles‘s theft of the cattle of Geryon is probably also related. Although he is not usually thought of as a storm deity in the conventional sense, Heracles bears many attributes held by other Indo-European storm deities, including physical strength and a knack for violence and gluttony. The original motif is also reflected in Germanic mythology. The Norse god of thunder Thor slays the giant serpent Jörmungandr, which lived in the waters surrounding the realm of Midgard. In the Völsunga saga, Sigurd slays the dragon Fafnir and, in Beowulf, the eponymous hero slays a different dragon. The depiction of dragons hoarding a treasure (symbolizing the wealth of the community) in Germanic legends may also be a reflex of the original myth of the serpent holding waters.” ref

“In Zoroastrianism and in Persian mythology, Fereydun (and later Garshasp) slays the serpent Zahhak. In Albanian mythology, the drangue, semi-human divine figures associated with thunders, slay the kulshedra, huge multi-headed fire-spitting serpents associated with water and storms. The Slavic god of storms Perun slays his enemy the dragon-god Veles, as does the bogatyr hero Dobrynya Nikitich to the three-headed dragon Zmey. A similar execution is performed by the Armenian god of thunders Vahagn to the dragon Vishap, by the Romanian knight hero Făt-Frumos to the fire-spitting monster Zmeu, and by the Celtic god of healing Dian Cecht to the serpent Meichi.” ref

“In Shinto, where Indo-European influences through Vedic religion can be seen in mythology, the storm god Susanoo slays the eight-headed serpent Yamata no Orochi. The Genesis narrative of Judaism and Christianity, as well as the dragon appearing in Revelation 12 can be interpreted as a retelling of the serpent-slaying myth. The Deep or Abyss from or on top of which God is said to make the world is translated from the Biblical Hebrew Tehom (Hebrew: תְּהוֹם). Tehom is a cognate of the Akkadian word tamtu and Ugaritic t-h-m which have similar meaning. As such it was equated with the earlier Babylonian serpent Tiamat. Folklorist Andrew Lang suggests that the serpent-slaying myth morphed into a folktale motif of a frog or toad blocking the flow of waters.” ref

Amaru (mythology )

“In mythology of Andean civilizations of South America, the amaru or katari (aymara) is a mythical serpent or dragon. In Inca mythology, Amaru is a huge double-headed serpent that dwells underground, at the bottom of lakes and rivers. Illustrated with the heads of a bird and a puma, Amaru can be seen emerging from a central element in the center of a stepped mountain or pyramid motif in the Gateway of the Sun at Tiwanaku, Bolivia. When illustrated on religious vessels, amaru is often seen with bird-like feet and wings, so that it resembles a dragon. Amaru is believed to be capable of transcending boundaries to and from the spiritual realm of the subterranean world.” ref

On Inca mythology it is described: “Dragon or rather a Chimera of Inca Mythology. It had multiple heads consisting of either a puma’s, a condor’s, or a llama’s head with a fox’s muzzle, condor wings, snake’s body, fish’s tail, and coated in crocodilian or lizard scales. It was found frequently throughout Andean iconography and naming within the empire, and likely predates the rise of the Inca”. Another author stated: “(Sacred serpent) was a serpent or dragon deity often represented as a giant winged serpent, with crystalline eyes, a reddish snout, a llama head, taruka horns, and a fish tail. Depending on the variations of the Amaru, whether in the various animal features, names or tonality of its skin according to the legend told, the ophidic form of the Amaru was always present. Its symbolism is very broad: water, storms, hail, wisdom, rainbow, the Milky Way, etc.” ref

“In Inca mythology, it was a symbol of wisdom, which is why the image of said totemic being was placed in the children of the Houses of Knowledge “Yachay Wasikuna.” Amaru is associated with the economy of water, that irrigate the agricultural lands, symbolizing the vitality of the water that allows the existence of the Aymara people. Thus, the deity Amaru symbolizes the water that runs through the irrigation canals, rivers, and springs, and that makes it possible for the seeds of the crop to be transformed into vegetables. Amaru is a mythical being that is also related to the underworld, the earth, and earthquakes. According to the myths, the Amarus have protective or destructive behavior. There’s a myth called “Amaru Aranway” that is about two powerful Amarus fighting against each other, causing destruction and death as the fight still goes on. Then, Viracocha send the god Illapa (Lightning) and Wayra (Wind) to defeat them. The two Amarus tried to fight the gods but then they tried to escape flying to the skies, but Wayra drag them back to earth with the power of wind, and Illapa fought and put the final blow to them. When the two Amarus died, they turned into the chain of mountains that are located in valle del Mantaro, Peru.” ref

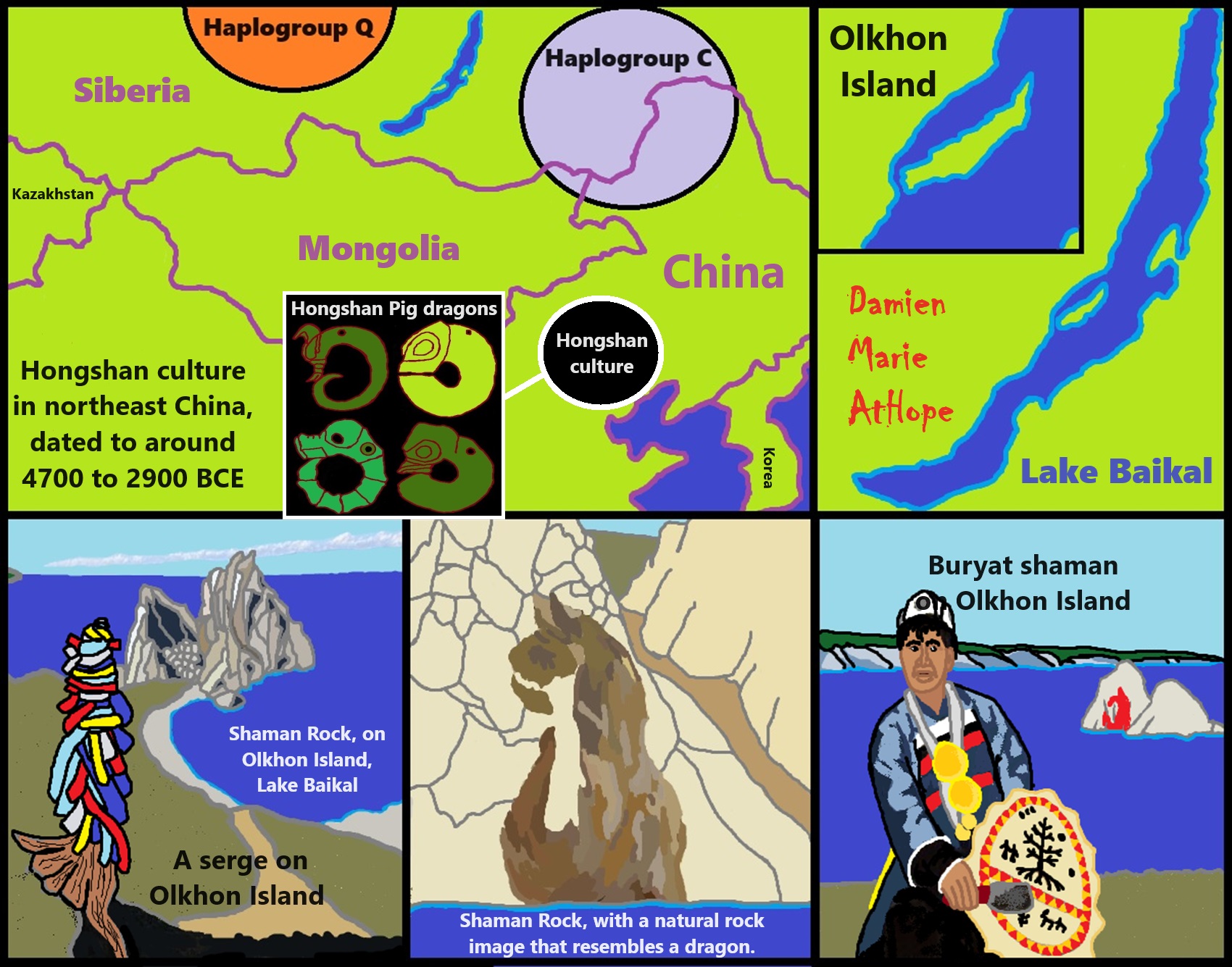

People may have first seen the Shaman Rock with the natural brown rock formation resembling a dragon between 30,000 to 25,000 years ago.

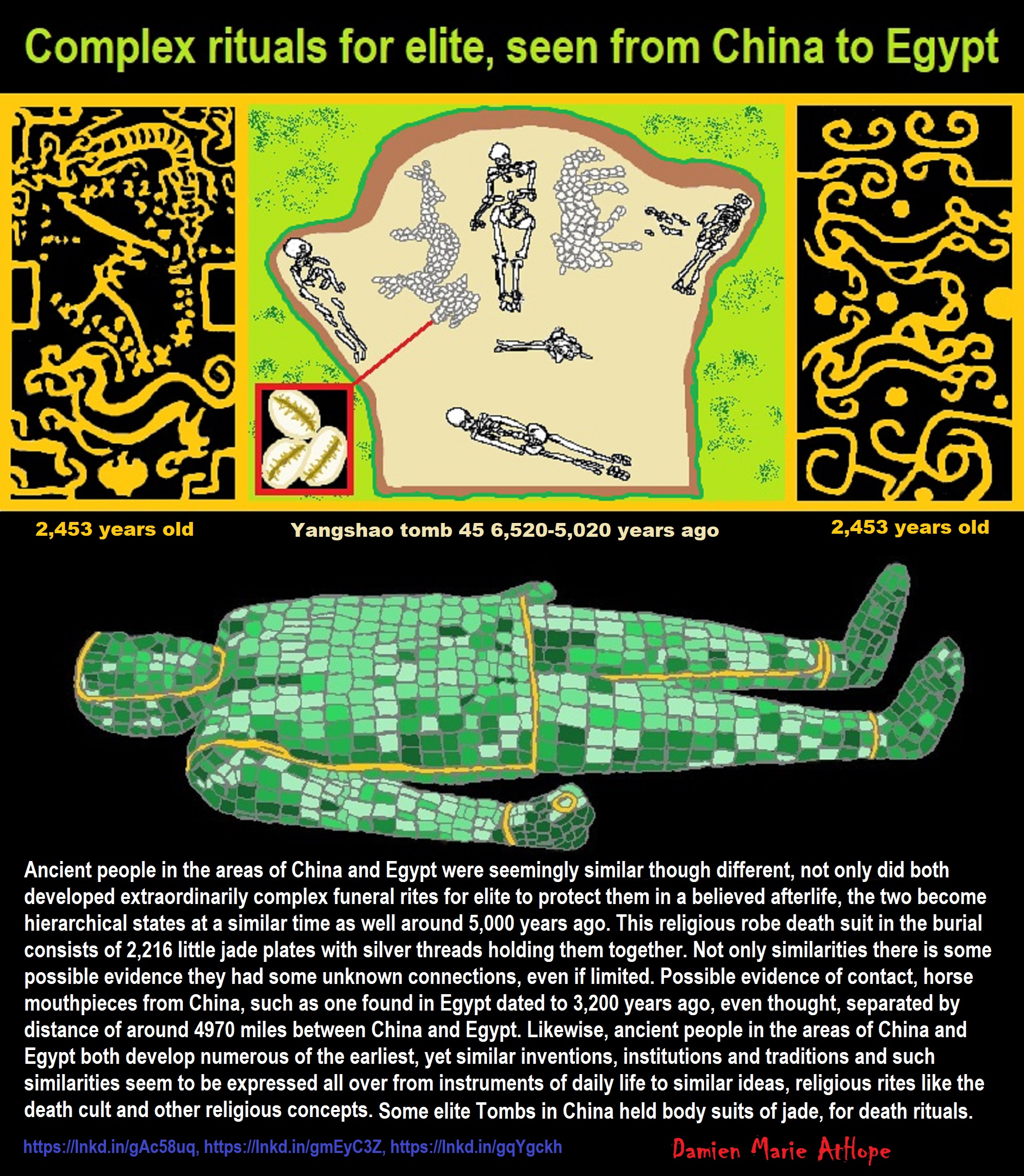

“Yangshao culture sites in Xi’an have produced clay pots with dragon motifs. A burial site Xishuipo in Puyang which is associated with the Yangshao culture shows a large dragon mosaic made out of clam shells. The Liangzhu culture also produced dragon-like patterns.” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

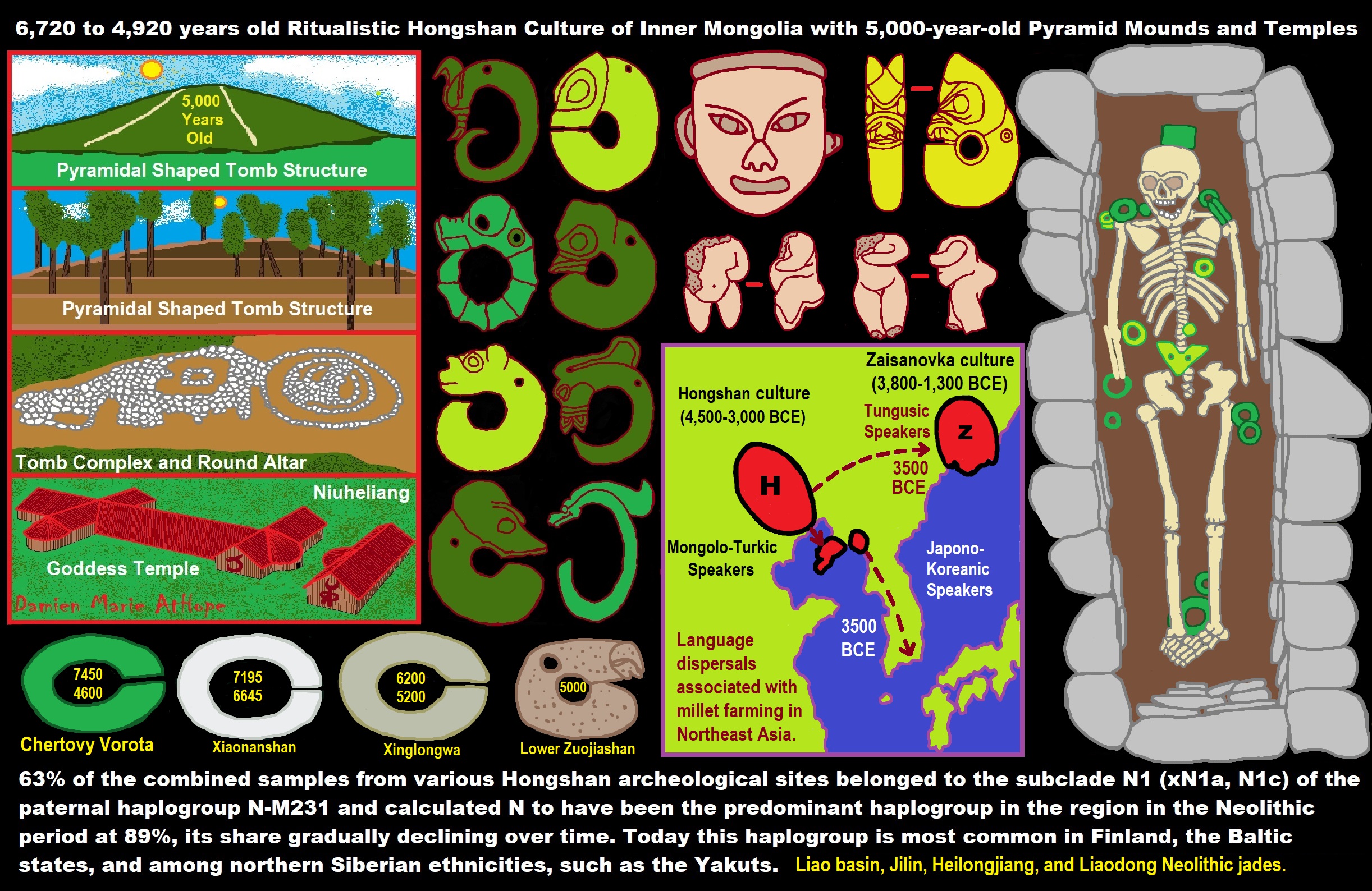

- Millet agriculture dispersed from Northeast China to the Russian Far East: Integrating archaeology, genetics, and linguistics

- Language dispersals associated with millet farming in Neolithic Northeast Asia: “Hongshan Neolithic Culture”

- The Development of Complexity in Prehistoric Northern China: “Hongshan Neolithic Culture”

- Hongshan Neolithic Culture of China

- 5,000-year-old “Pyramid” Found in Inner Mongolia

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

Sacred Snakes or Dragons and Rivers? To me, it’s snakes/dragons in one theme express as rivers thus developed on animism to gods or totem and other believed sacred beings

Snake Worship?

“Snake worship is seen in several ancient cultures, particularly, snake as renewal. Snake worship is devotion to serpent deities. The tradition is present in several ancient cultures, particularly in religion and mythology, where snakes were seen as entities of strength and renewal.” ref

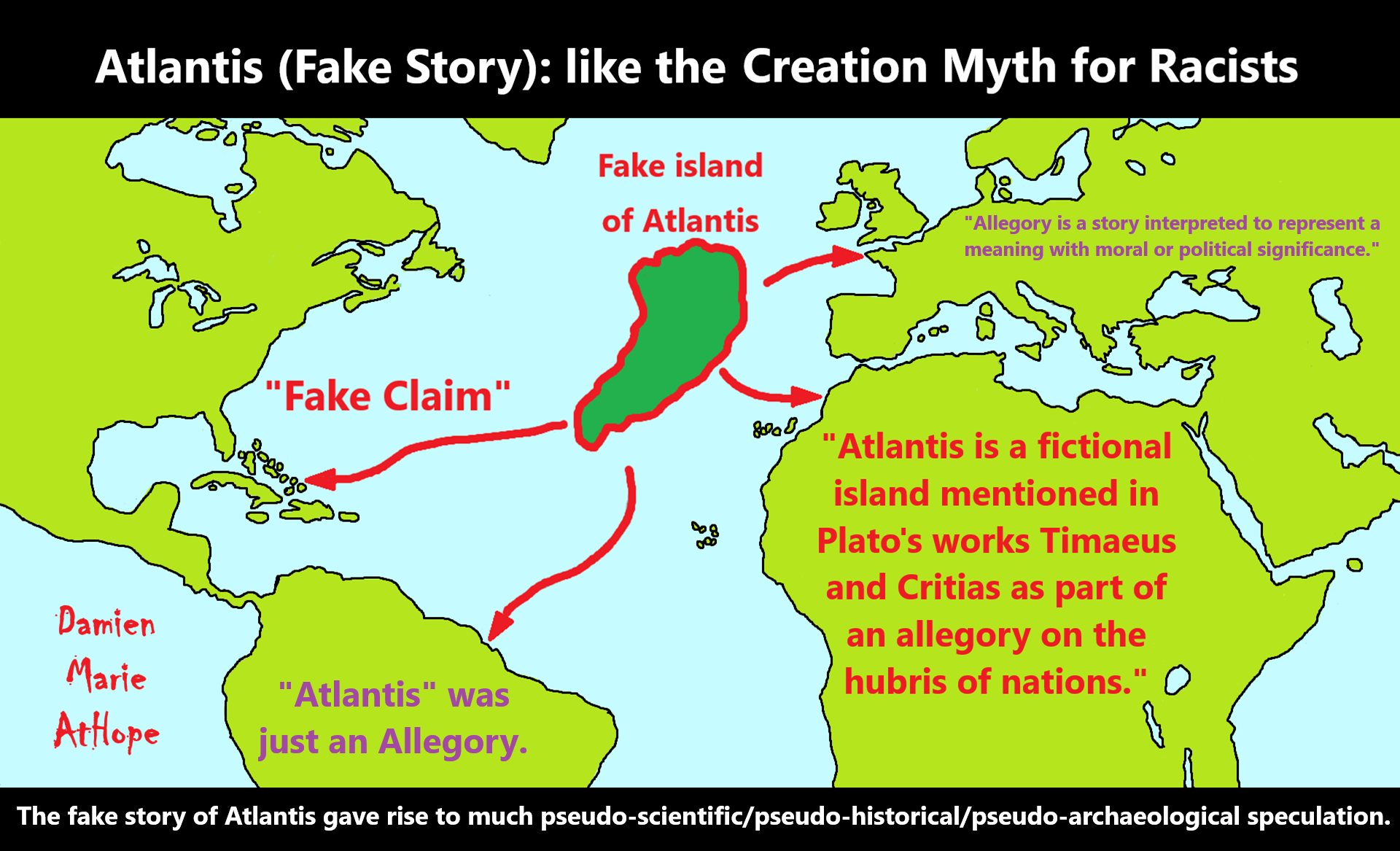

But is Atlantis real?

No. Atlantis (an allegory: “fake story” interpreted to reveal a hidden meaning) can’t be found any more than one can locate the Jolly Green Giant that is said to watch over frozen vegetables. Lol

May Reason Set You Free

There are a lot of truly great things said by anarchists in history, and also some deeply vile things, too, from not supporting Women’s rights to Anti-Semitism. There are those who also reject those supporting women’s rights as well as fight anti-Semitism. This is why I push reason as my only master, not anarchist thinking, though anarchism, to me, should see all humans everywhere as equal in dignity and rights.

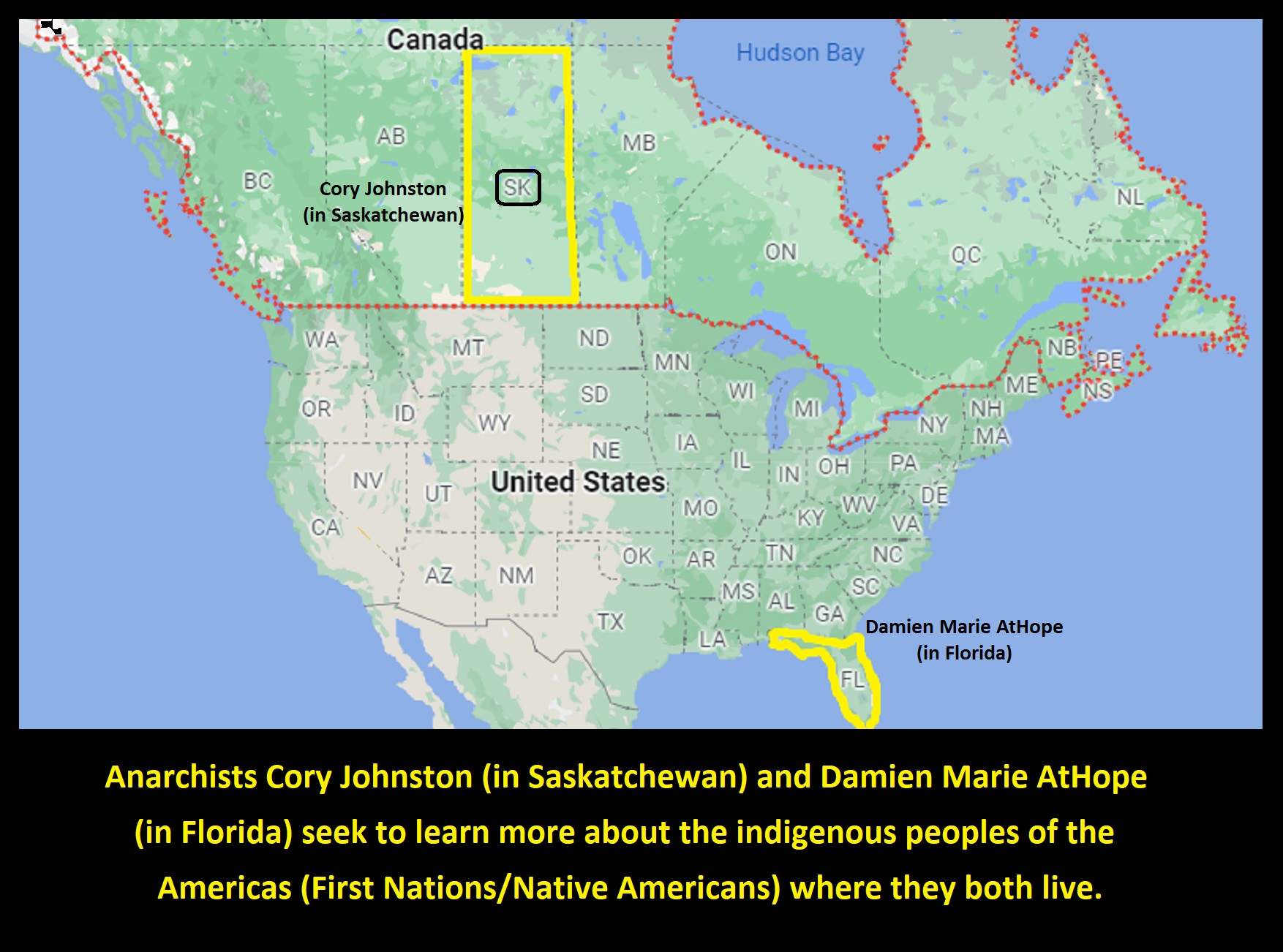

We—Cory and Damien—are following the greatness that can be found in anarchist thinking.

As an Anarchist Educator, Damien strives to teach the plain truth. Damien does not support violence as my method to change. Rather, I choose education that builds Enlightenment and Empowerment. I champion Dignity and Equality. We rise by helping each other. What is the price of a tear? What is the cost of a smile? How can we see clearly when others pay the cost of our indifference and fear? We should help people in need. Why is that so hard for some people? Rich Ghouls must End. Damien wants “billionaires” to stop being a thing. Tax then into equality. To Damien, there is no debate, Capitalism is unethical. Moreover, as an Anarchist Educator, Damien knows violence is not the way to inspire lasting positive change. But we are not limited to violence, we have education, one of the most lasting and powerful ways to improve the world. We empower the world by championing Truth and its supporters.

Anarchism and Education

“Various alternatives to education and their problems have been proposed by anarchists which have gone from alternative education systems and environments, self-education, advocacy of youth and children rights, and freethought activism.” ref