There will be 6 shows on this blog in total:

- Show One: Paleolithic or Old Stone Age in China and Different Approaches to Defining Civilization

- Show Two: Early Neolithic China: Ritual, Religion, and Civilization

- Show Three: Middle Neolithic China: Ritual, Religion, Elites, and Language

- Show Four: Late Neolithic and Bronze Age China: Ritual, Religion, Elites, Language, and Empires

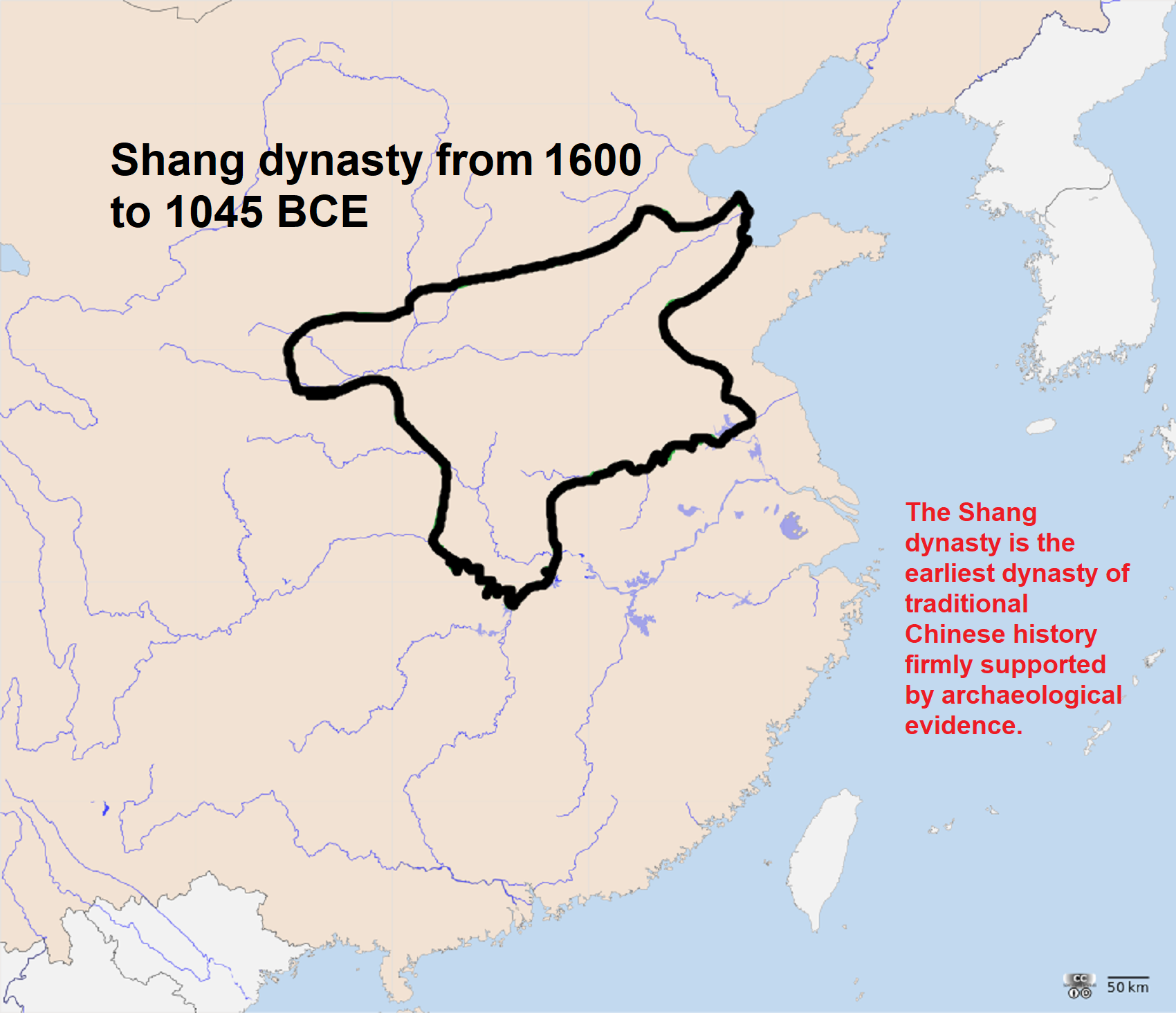

- Show Five: Bronze Age and Ancient China: Ritual, Religion, Elites, Language, and Empires

- Show Six: Ancient China: Ritual, Religion, Elites, Language, Slavery, Eunuchs, and Empires

Part one Paleolithic or Old Stone Age in China

First let’s address the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age (from 3 million years ago, to around 12,000 years ago when it becomes the Neolithic or New Stone Age: 12,000 years ago to around 6,500 years ago when it becomes the Chalcolithic or Copper Age) in China. I am adding this so there is an understanding of how China’s populations formed and led to more cultural development in the Neolithic and beyond.

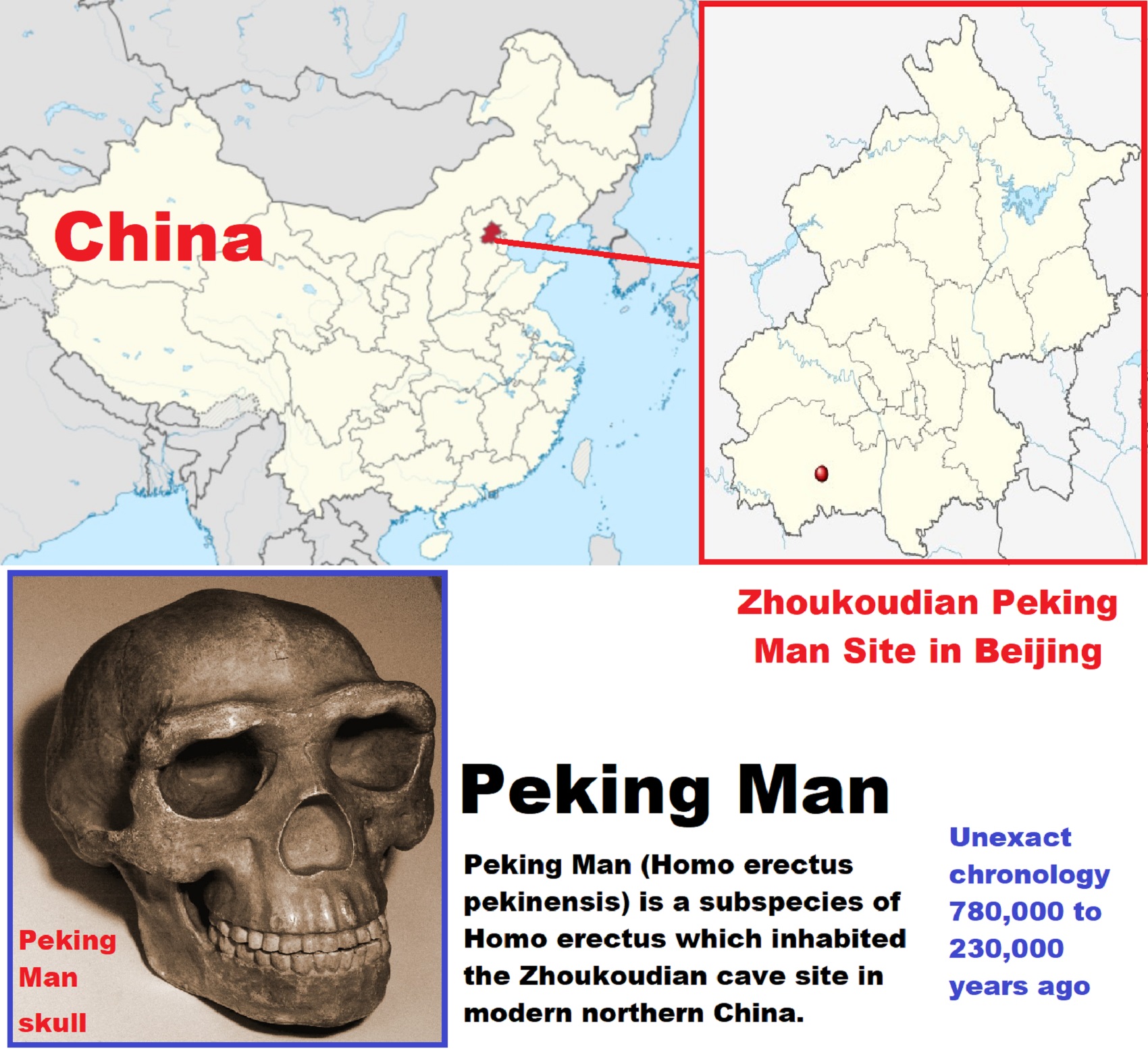

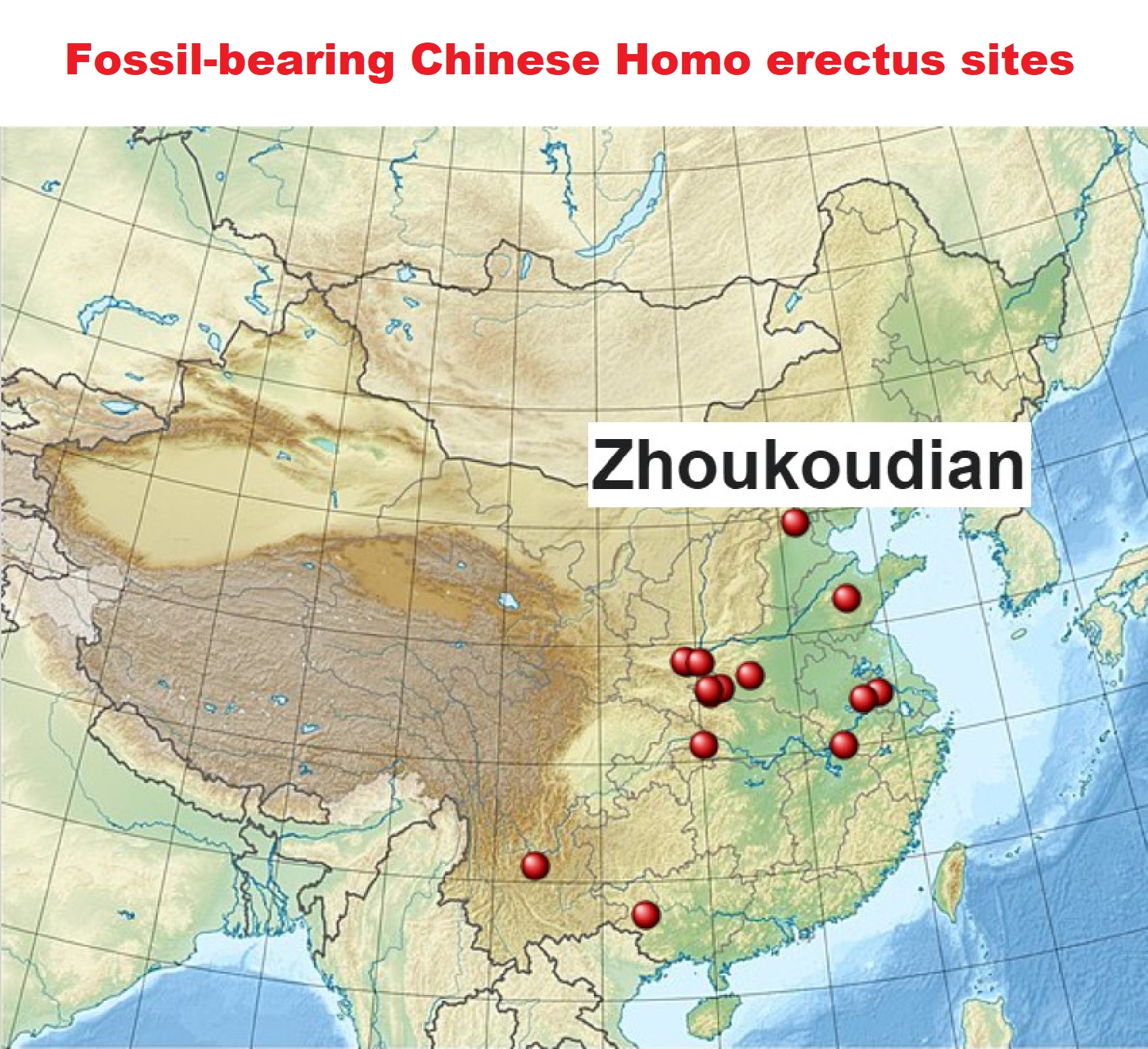

“Peking Man (Homo erectus pekinensis) is a subspecies of H. erectus which inhabited the Zhoukoudian cave site in modern northern China, discovered in the Zhoukoudian Cave has since then become the most productive Homo erectus site in the world. The fossils became the center of anthropological discussion and were classified as a direct human ancestor, propping up the Out of Asia hypothesis that humans evolved in Asia. Peking Man also played a vital role in the restructuring of the Chinese identity following the Chinese Communist Revolution, and was intensively communicated to working class and peasant communities to introduce them to Marxism and science (overturning deeply-rooted superstitions and creation myths).” ref

“Early models of Peking Man society strongly leaned towards communist or nationalist ideals, leading to discussions on primitive communism and polygenism. This produced a strong schism between Western and Eastern interpretations, especially as the West adopted the Out of Africa hypothesis by late 1967, and Peking Man’s role in human evolution diminished as merely an offshoot of the human line. Though Out of Africa is now the consensus, Peking Man interbreeding with human ancestors is frequently discussed especially in Chinese circles. Peking Man lived in a cool, predominantly steppe, partially forested environment, alongside deer, rhinos, elephants, bison, buffalo, bears, wolves, big cats, and a menagerie of other creatures. Peking Man intermittently inhabited the Zhoukoudian Cave, but the exact chronology is unclear, with estimates as far back as 780,000 years ago and as recent as 230,000 years ago.” ref

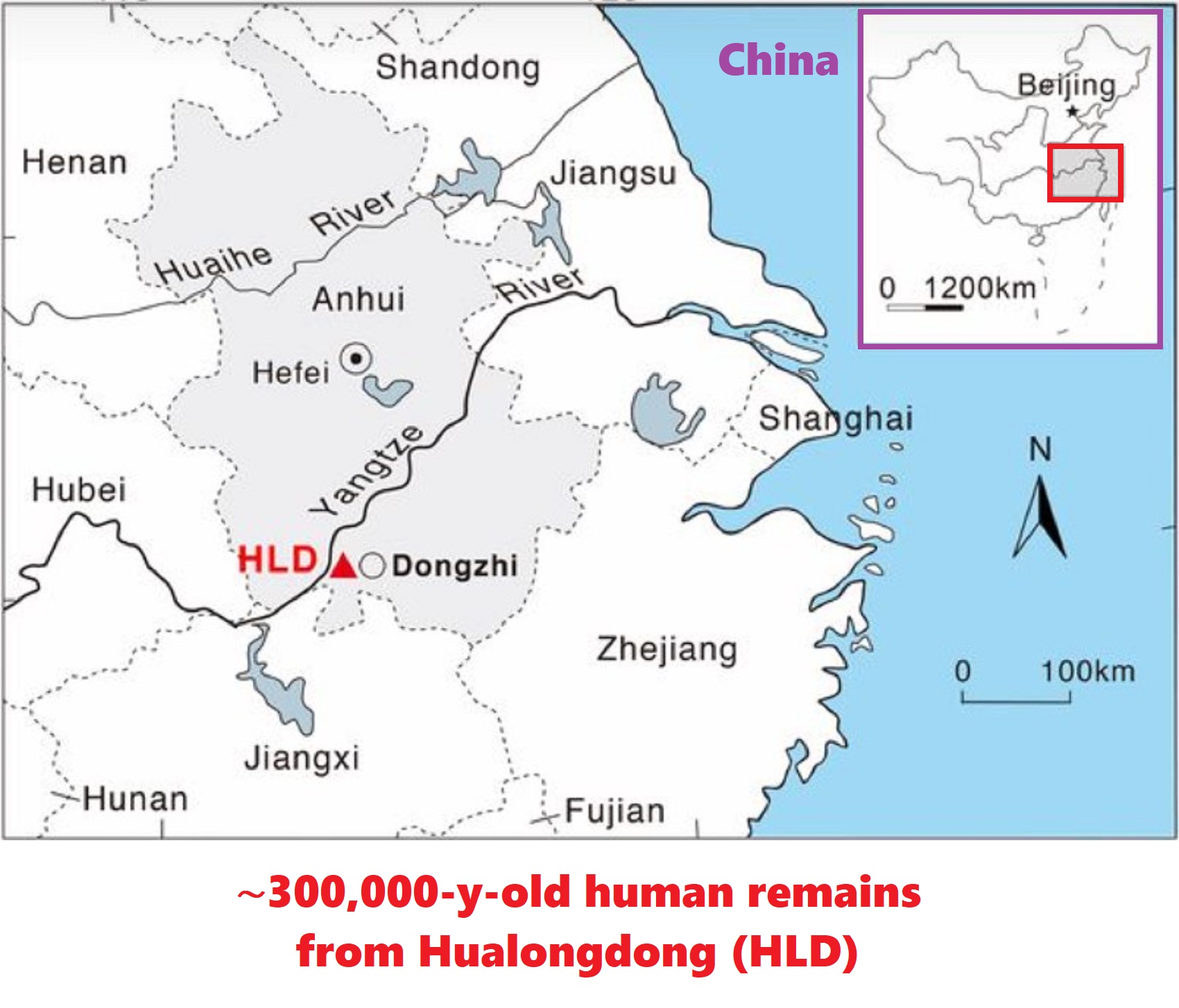

“Abstract: Late Middle Pleistocene hominins in Africa displaying key modern morphologies by 315,000 years ago are claimed as the earliest Homo sapiens. Evolutionary relationships among East Asian hominins appear complex due to a growing fossil record of late Middle Pleistocene hominins from the region, reflecting mosaic morphologies that contribute to a lack of consensus on when and how the transition to modern humans transpired. Newly discovered 300,000 years ago hominin fossils from Hualongdong, China, provide further evidence to clarify these relationships in the region. In this study, facial morphology of the juvenile partial cranium (HLD 6) is described and qualitatively and quantitatively compared with that of other key Early, Middle, and Late Pleistocene hominins from East Asia, Africa, West Asia, and Europe and with a sample of modern humans. Qualitatively, facial morphology of HLD 6 resembles that of Early and Middle Pleistocene hominins from Zhoukoudian, Nanjing, Dali, and Jinniushan in China, as well as others from Java, Africa, and Europe in some of these features (e.g., supraorbital and malar regions), and Late Pleistocene hominins and modern humans from East Asia, Africa, and Europe in other features (e.g., weak prognathism, flat face and features in nasal and hard plate regions). Comparisons of HLD 6 measurements to group means and multivariate analyses support close affinities of HLD 6 to Late Pleistocene hominins and modern humans. Expression of a mosaic morphological pattern in the HLD 6 facial skeleton further complicates evolutionary interpretations of regional morphological diversity in East Asia. The prevalence of modern features in HLD 6 suggests that the hominin population to which HLD 6 belonged may represent the earliest pre-modern humans in East Asia. Thus, the transition from archaic to modern morphology in East Asian hominins may have occurred at least by 300,000 years ago, which is 80,000 to 100,000 years earlier than previously recognized.” ref

Y Chromosome Study Suggests Asians, Too, Came from Africa

“Geneticist Li Jin of the University of Texas and his colleagues examined Y chromosomal DNA from more than 12,000 males belonging to 163 populations in Asia and Oceania. Multiregionalism posits that archaic humans such as Neandertals contributed to the modern human gene pool. Thus modern Southeast Asian populations, for example, should retain some ancient lineages inherited from the archaic populations that once inhabited that region, an argument that the multiregionalists have bolstered with fossil evidence. But Jin and his colleagues only found markers associated with a gene mutation known to have arisen in an African ancestor sometime between 35,000 and 89,000 years ago. This, the authors write, “indicates that modern humans of African origin completely replaced earlier populations in East Asia.” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

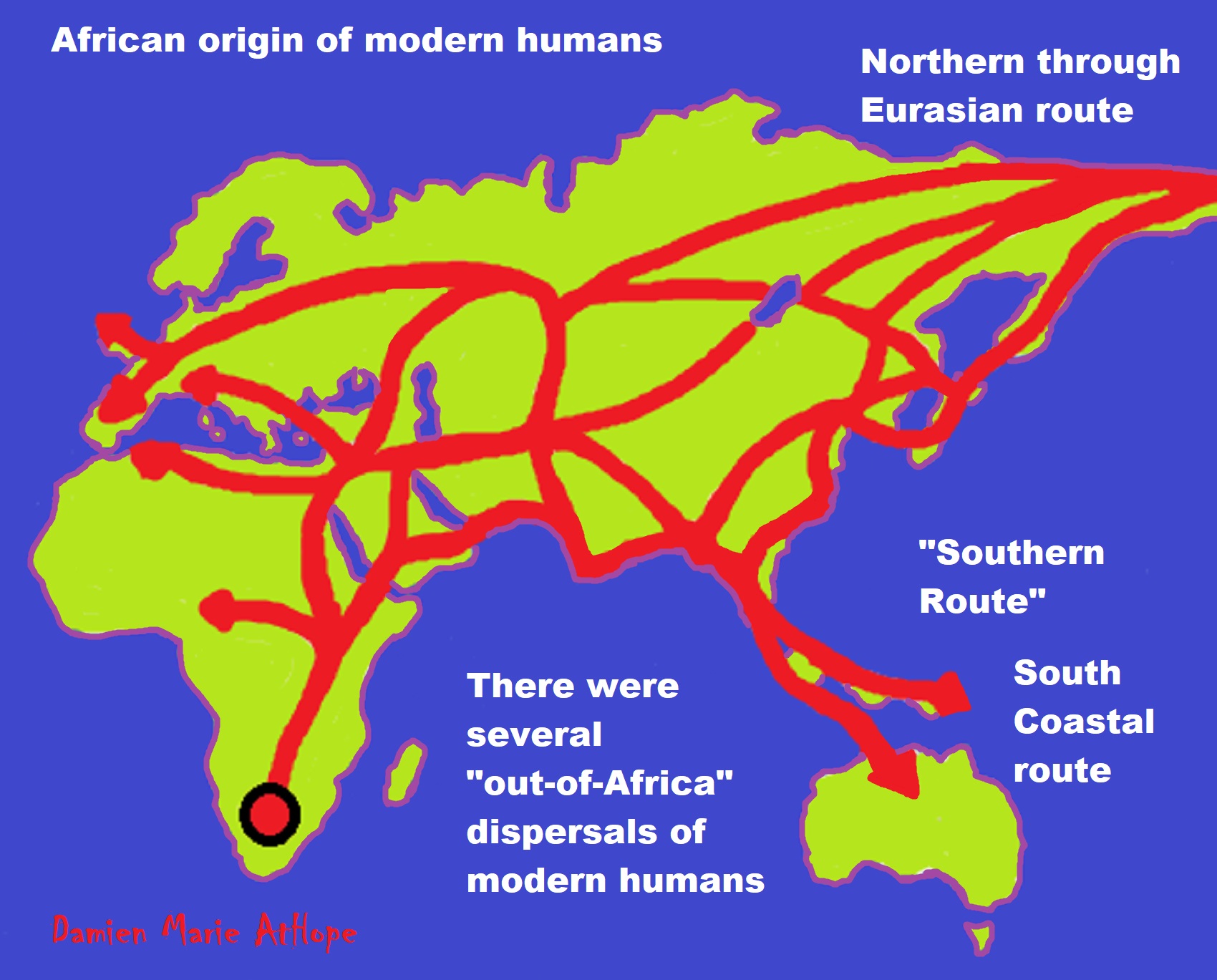

“There are two geographically plausible routes that have been proposed for humans to emerge from Africa: through the current Egypt and Sinai (Northern Route), or through Ethiopia, the Bab el Mandeb strait, and the Arabian Peninsula (Southern Route).” ref

“Although there is a general consensus on the African origin of early modern humans, there is disagreement about how and when they dispersed to Eurasia. This paper reviews genetic and Middle Stone Age/Middle Paleolithic archaeological literature from northeast Africa, Arabia, and the Levant to assess the timing and geographic backgrounds of Upper Pleistocene human colonization of Eurasia. At the center of the discussion lies the question of whether eastern Africa alone was the source of Upper Pleistocene human dispersals into Eurasia or were there other loci of human expansions outside of Africa? The reviewed literature hints at two modes of early modern human colonization of Eurasia in the Upper Pleistocene: (i) from multiple Homo sapiens source populations that had entered Arabia, South Asia, and the Levant prior to and soon after the onset of the Last Interglacial (MIS-5), (ii) from a rapid dispersal out of East Africa via the Southern Route (across the Red Sea basin), dating to ~74,000-60,000 years ago.” ref

“Within Africa, Homo sapiens dispersed around the time of its speciation, roughly 300,000 years ago. The so-called “recent dispersal” of modern humans took place about 70–50,000 years ago. It is this migration wave that led to the lasting spread of modern humans throughout the world. The coastal migration between roughly 70,000 and 50,000 years ago is associated with mitochondrial haplogroups M and N, both derivative of L3. Europe was populated by an early offshoot that settled the Near East and Europe less than 55,000 years ago. Modern humans spread across Europe about 40,000 years ago, possibly as early as 43,000 years ago, rapidly replacing the Neanderthal population.” ref, ref

- Lower Paleolithic (around 3.3 million to 300,000 years ago)

- Middle Paleolithic (around 300,000 to 50,000 years ago)

- Upper Paleolithic (around 50,000 to 12,000 years ago)

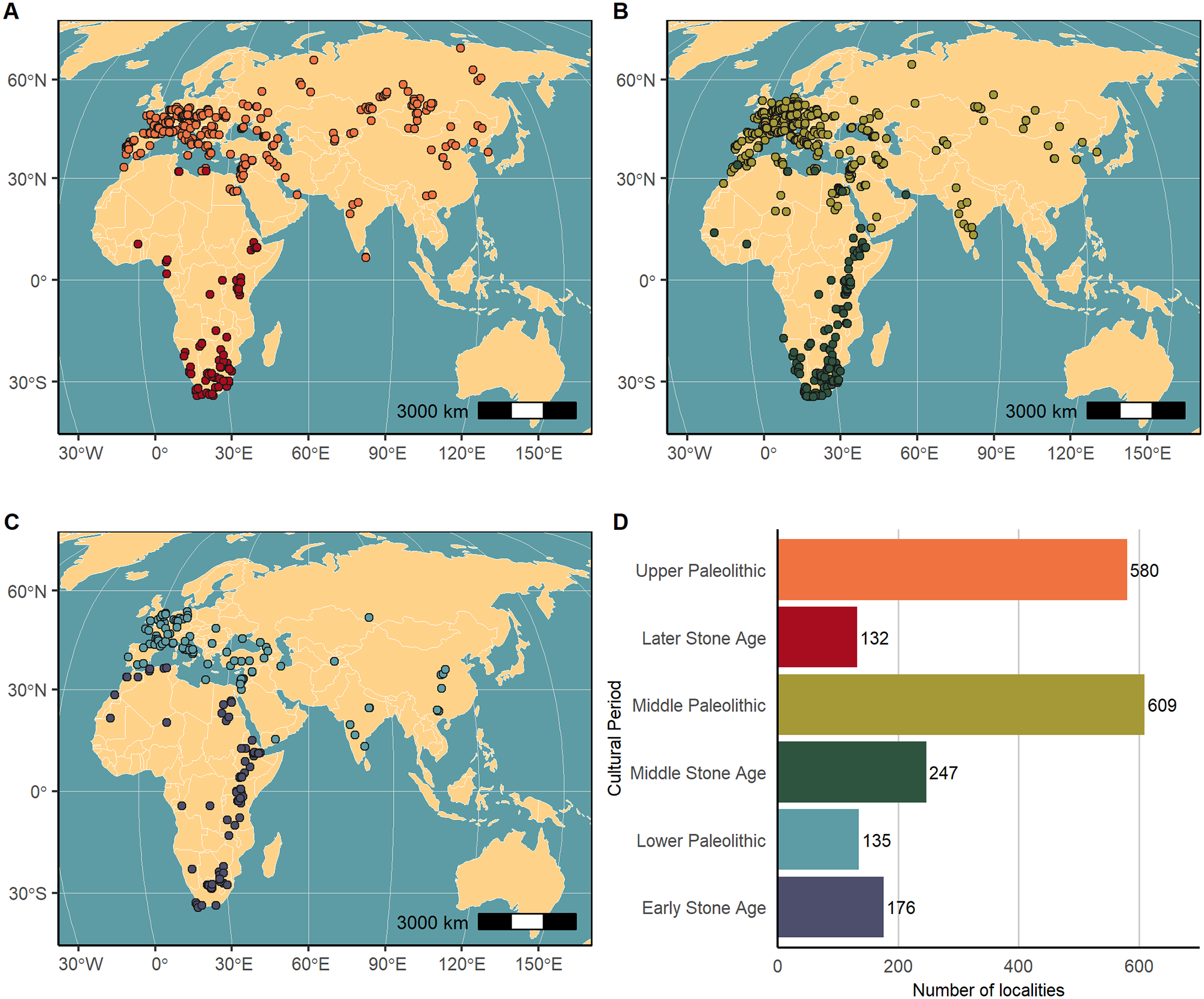

The ROCEEH Out of Africa Database (ROAD): A large-scale research database serves as an indispensable tool for human evolutionary studies

“Abstract: Large-scale databases are critical for helping scientists decipher long-term patterns in human evolution. This paper describes the conception and development of such a research database and illustrates how big data can be harnessed to formulate new ideas about the past. The Role of Culture in Early Expansions of Humans (ROCEEH) is a transdisciplinary research center whose aim is to study the origins of culture and the multifaceted aspects of human expansions across Africa and Eurasia over the last three million years. To support its research, the ROCEEH team developed an online tool named the ROCEEH Out of Africa Database (ROAD) and implemented its web-based applications. ROAD integrates geographical data as well as archaeological, paleoanthropological, paleontological, and paleobotanical content within a robust chronological framework. In fact, a unique feature of ROAD is its ability to dynamically link scientific data both spatially and temporally, thereby allowing its reuse in ways that were not originally conceived. The data stem from published sources spanning the last 150 years, including those generated by the research team. Descriptions of these data rely on the development of a standardized vocabulary and profit from online explanations of each table and attribute. By synthesizing legacy data, ROAD facilitates the reuse of heritage data in novel ways. Database queries yield structured information in a variety of interoperable formats. By visualizing data on maps, users can explore this vast dataset and develop their own theories. By downloading data, users can conduct further quantitative analyses, for example with Geographic Information Systems, modeling programs, and artificial intelligence. In this paper, we demonstrate the innovative nature of ROAD and show how it helps scientists studying human evolution to access datasets from different fields, thereby connecting the social and natural sciences. Because it permits the reuse of “old” data in new ways, ROAD is now an indispensable tool for researchers of human evolution and paleogeography.”

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0289513

“Abstract: The evolutionarily recent dispersal of anatomically modern humans (AMH) out of Africa (OoA) and across Eurasia provides a unique opportunity to examine the impacts of genetic selection as humans adapted to multiple new environments. Analysis of ancient Eurasian genomic datasets (~1,000 to 45,000 y old) reveals signatures of strong selection, including at least 57 hard sweeps after the initial AMH movement OoA, which have been obscured in modern populations by extensive admixture during the Holocene. The spatiotemporal patterns of these hard sweeps provide a means to reconstruct early AMH population dispersals OoA. We identify a previously unsuspected extended period of genetic adaptation lasting ~30,000 y, potentially in the Arabian Peninsula area, prior to a major Neandertal genetic introgression and subsequent rapid dispersal across Eurasia as far as Australia. Consistent functional targets of selection initiated during this period, which we term the Arabian Standstill, include loci involved in the regulation of fat storage, neural development, skin physiology, and cilia function. Similar adaptive signatures are also evident in introgressed archaic hominin loci and modern Arctic human groups, and we suggest that this signal represents selection for cold adaptation. Surprisingly, many of the candidate selected loci across these groups appear to directly interact and coordinately regulate biological processes, with a number associated with major modern diseases including the ciliopathies, metabolic syndrome, and neurodegenerative disorders. This expands the potential for ancestral human adaptation to directly impact modern diseases, providing a platform for evolutionary medicine.” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

“There were at least several “out-of-Africa” dispersals of modern humans, possibly beginning as early as 270,000 years ago, including 215,000 years ago to at least Greece, and certainly via northern Africa and the Arabian Peninsula about 130,000 to 115,000 years ago. These early waves appear to have mostly died out or retreated by 80,000 years ago.” ref

“The most significant “recent” wave out of Africa took place about 70,000–50,000 years ago, via the so-called “Southern Route“, spreading rapidly along the coast of Asia and reaching Australia by around 65,000–50,000 years ago, (though some researchers question the earlier Australian dates and place the arrival of humans there at 50,000 years ago at earliest, while others have suggested that these first settlers of Australia may represent an older wave before the more significant out of Africa migration and thus not necessarily be ancestral to the region’s later inhabitants) while Europe was populated by an early offshoot which settled the Near East and Europe less than 55,000 years ago.” ref

- “An Eastward Dispersal from Northeast Africa to Arabia 150,000–130,000 years ago based on the finds at Jebel Faya dated to 127,000 years ago (discovered in 2011). Possibly related to this wave are the finds from Zhirendong cave, Southern China, dated to more than 100,000 years ago. Other evidence of modern human presence in China has been dated to 80,000 years ago.” ref

- “The most significant out of Africa dispersal took place around 50–70,000 years ago via the so-called Southern Route, either before or after the Toba event, which happened between 69,000 and 77,000 years ago. This dispersal followed the southern coastline of Asia, and reached Australia around 65,000-50,000 years ago, or according to some research, by 50,000 years ago at earliest. Western Asia was “re-occupied” by a different derivation from this wave around 50,000 years ago, and Europe was populated from Western Asia beginning around 43,000 years ago.” ref

- “Wells (2003) describes an additional wave of migration after the southern coastal route, namely a northern migration into Europe at circa 45,000 years ago. However, this possibility is ruled out by Macaulay et al. (2005) and Posth et al. (2016), who argue for a single coastal dispersal, with an early offshoot into Europe.” ref

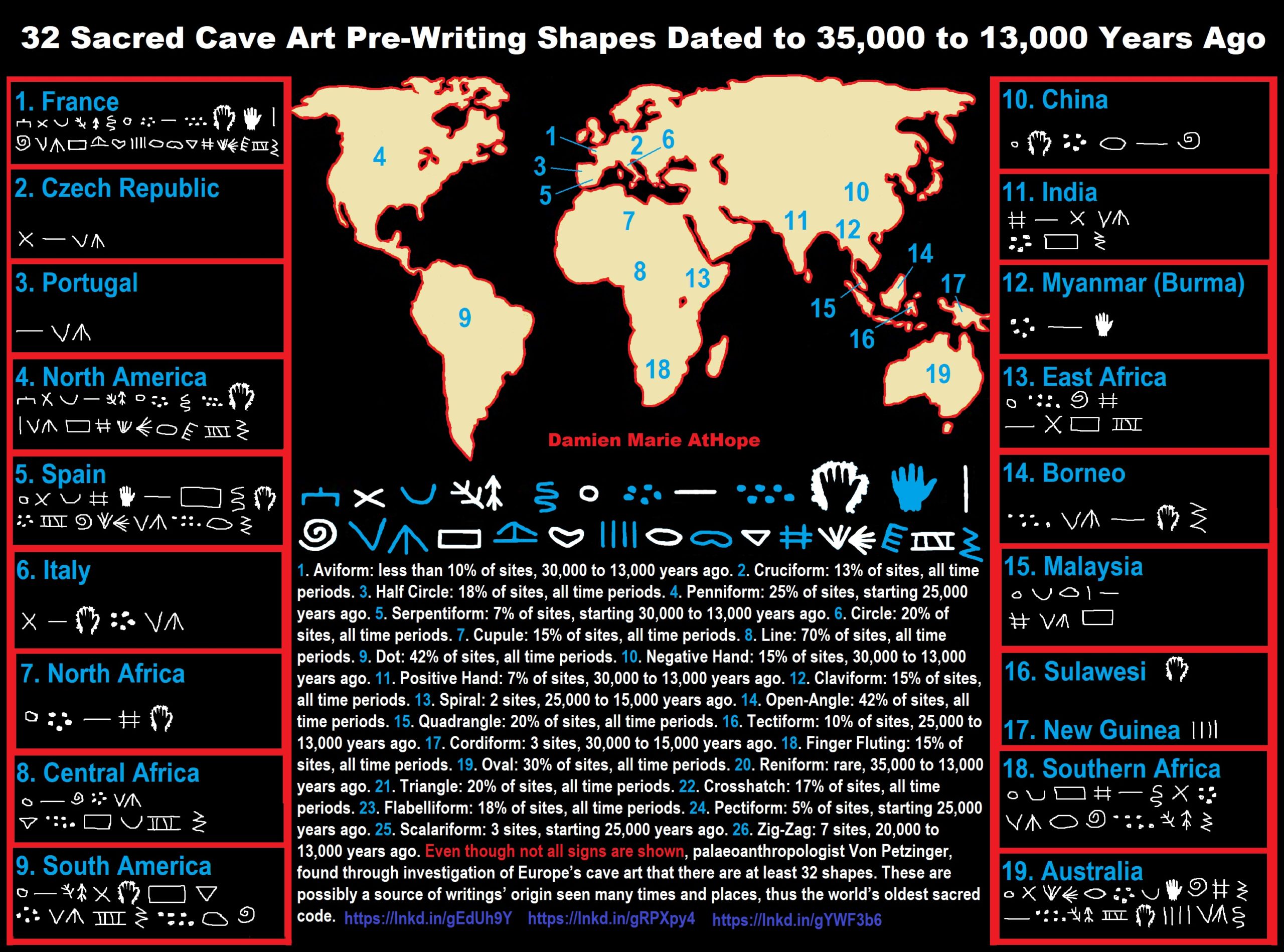

Why are these 32 symbols found in caves all over Europe

32 Sacred Cave Art Pre-Writing Shapes Dated to 35,000 to 13,000 Years Ago

- 1. Aviform: less than 10% of sites, 30,000 to 13,000 years ago.

- 2. Cruciform: 13% of sites, all time periods.

- 3. Half Circle: 18% of sites, all time periods.

- 4. Penniform: 25% of sites, starting 25,000 years ago.

- 5. Serpentiform: 7% of sites, starting 30,000 to 13,000 years ago.

- 6. Circle: 20% of sites, all time periods.

- 7. Cupule: 15% of sites, all time periods.

- 8. Line: 70% of sites, all time periods.

- 9. Dot: 42% of sites, all time periods.

- 10. Negative Hand: 15% of sites, 30,000 to 13,000 years ago.

- 11. Positive Hand: 7% of sites, 30,000 to 13,000 years ago.

- 12. Claviform: 15% of sites, all time periods.

- 13. Spiral: 2 sites, 25,000 to 15,000 years ago.

- 14. Open-Angle: 42% of sites, all time periods.

- 15. Quadrangle: 20% of sites, all time periods.

- 16. Tectiform: 10% of sites, 25,000 to 13,000 years ago.

- 17. Cordiform: 3 sites, 30,000 to 15,000 years ago.

- 18. Finger Fluting: 15% of sites, all time periods.

- 19. Oval: 30% of sites, all time periods.

- 20. Reniform: rare, 35,000 to 13,000 years ago.

- 21. Triangle: 20% of sites, all time periods.

- 22. Crosshatch: 17% of sites, all time periods.

- 23. Flabelliform: 18% of sites, all time periods.

- 24. Pectiform: 5% of sites, starting 25,000 years ago.

- 25. Scalariform: 3 sites, starting 25,000 years ago.

- 26. Zig-Zag: 7 sites, 20,000 to 13,000 years ago.

Even though not all signs are shown, palaeoanthropologist Von Petzinger, found through investigation of Europe’s cave art that there are at least 32 shapes. These are possibly a source of writings’ origin seen many times and places, thus the world’s oldest sacred code. A paleoanthropologist and rock art researcher explains that even though to many written language is the hallmark of human civilization, this construct in behavior didn’t just suddenly appear one day. Thousands of years before the first fully developed writing systems, our ancestors scrawled geometric signs across the walls of the caves they sheltered in. She has studied and codified these ancient markings in caves across Europe, suggesting that graphic communication, and the ability to preserve and transmit messages beyond a single moment in time, may be much older than we think. ref, ref, ref, ref

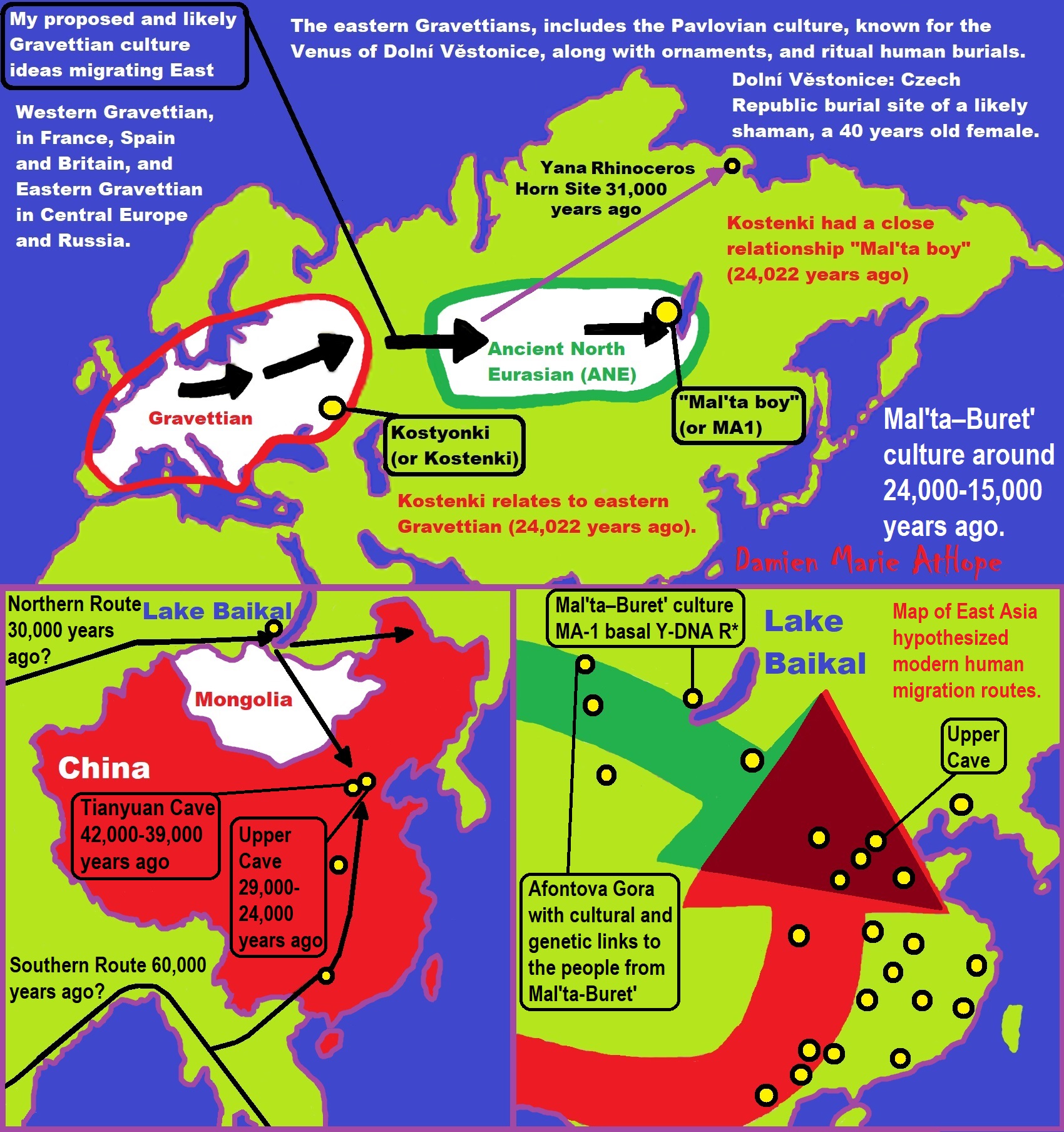

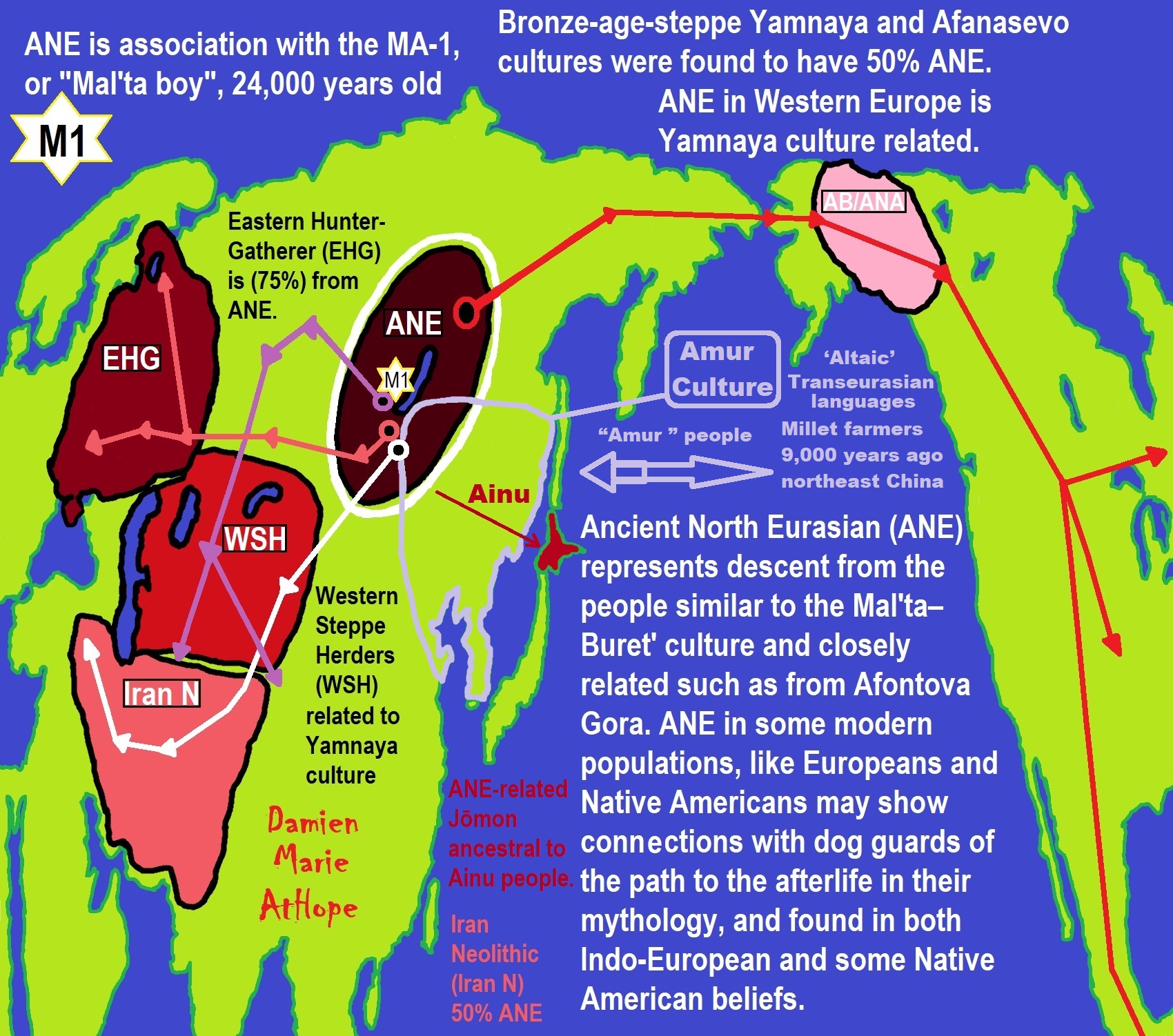

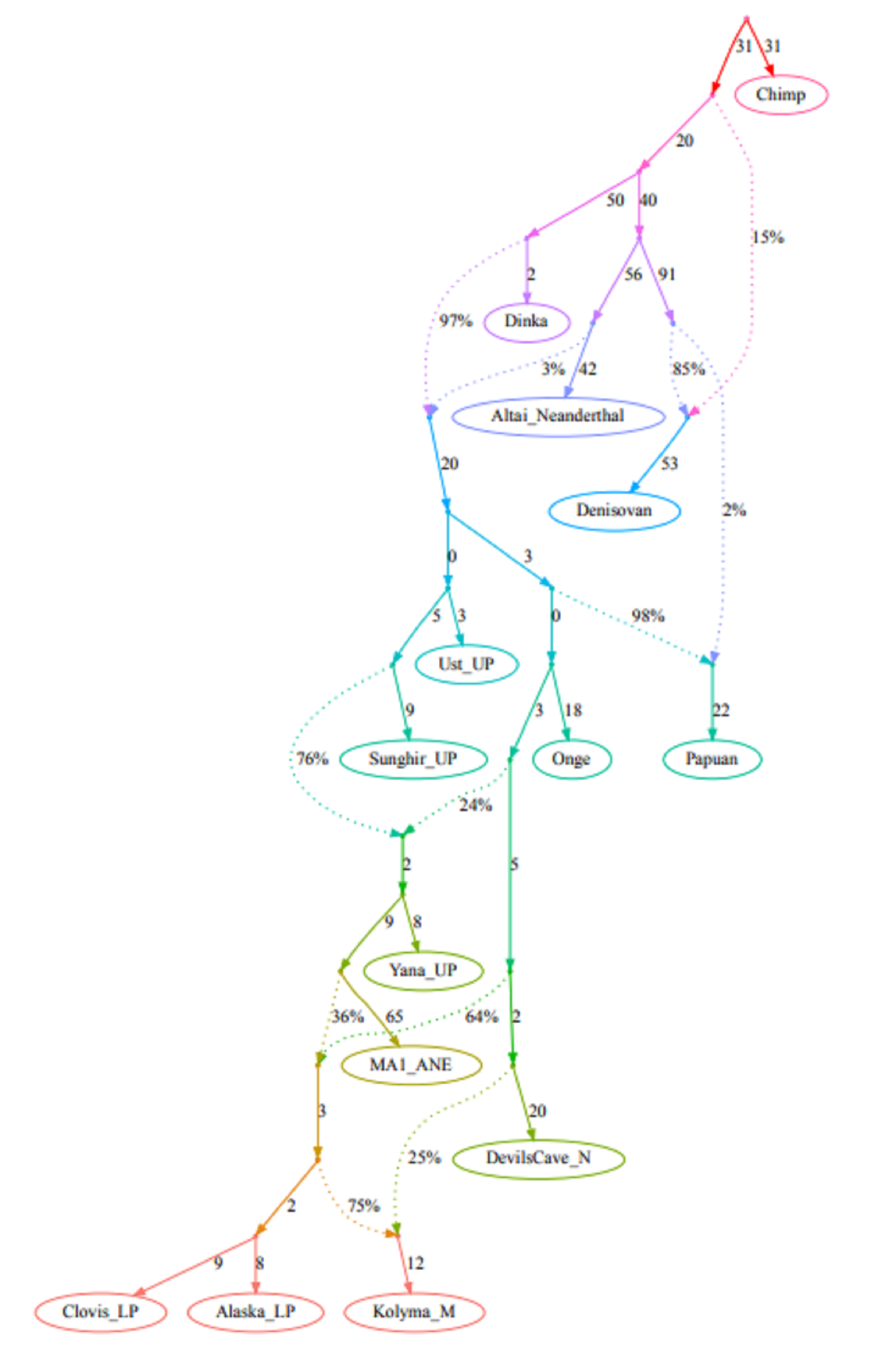

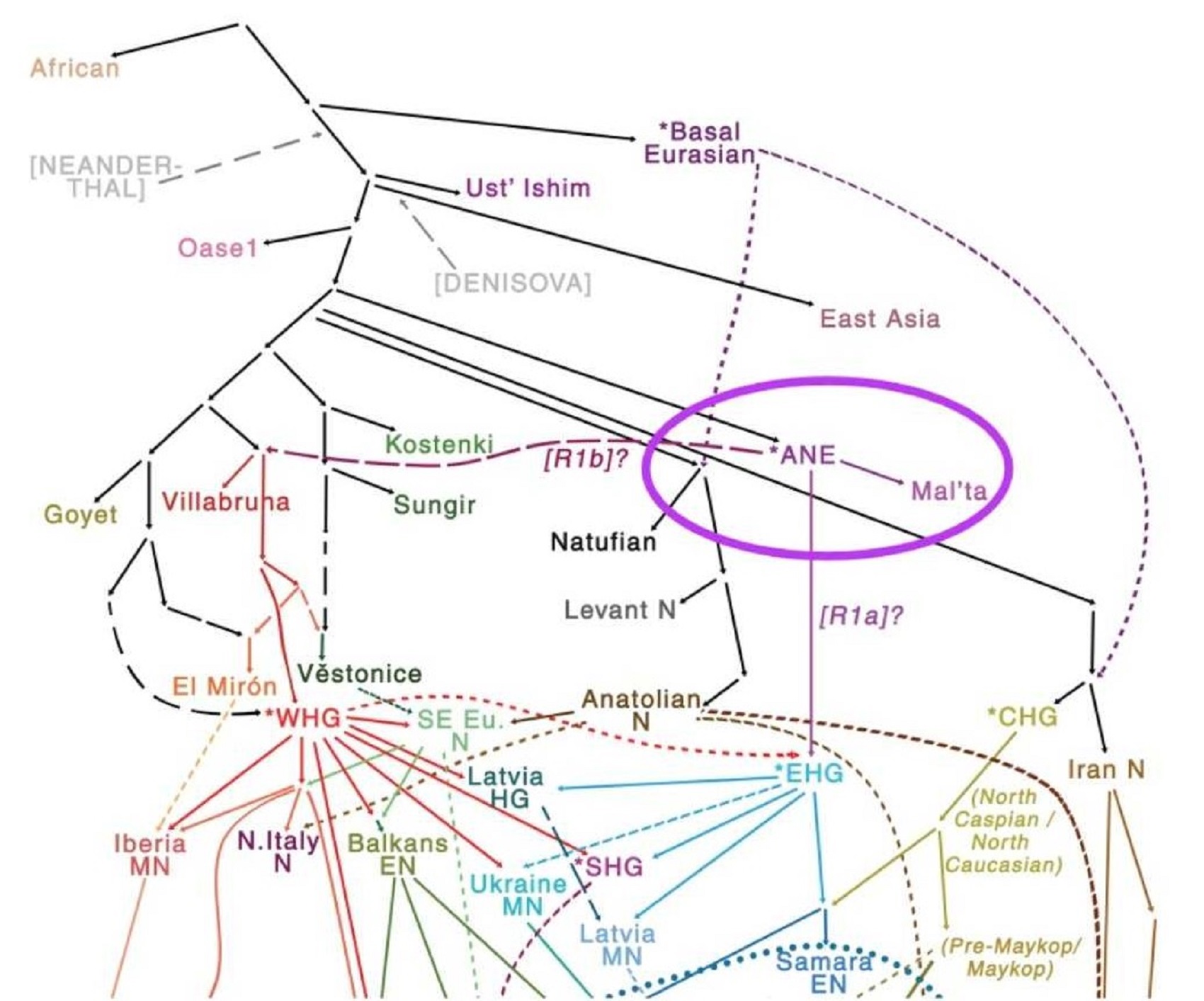

Groups partially derived from the Ancient North Eurasians

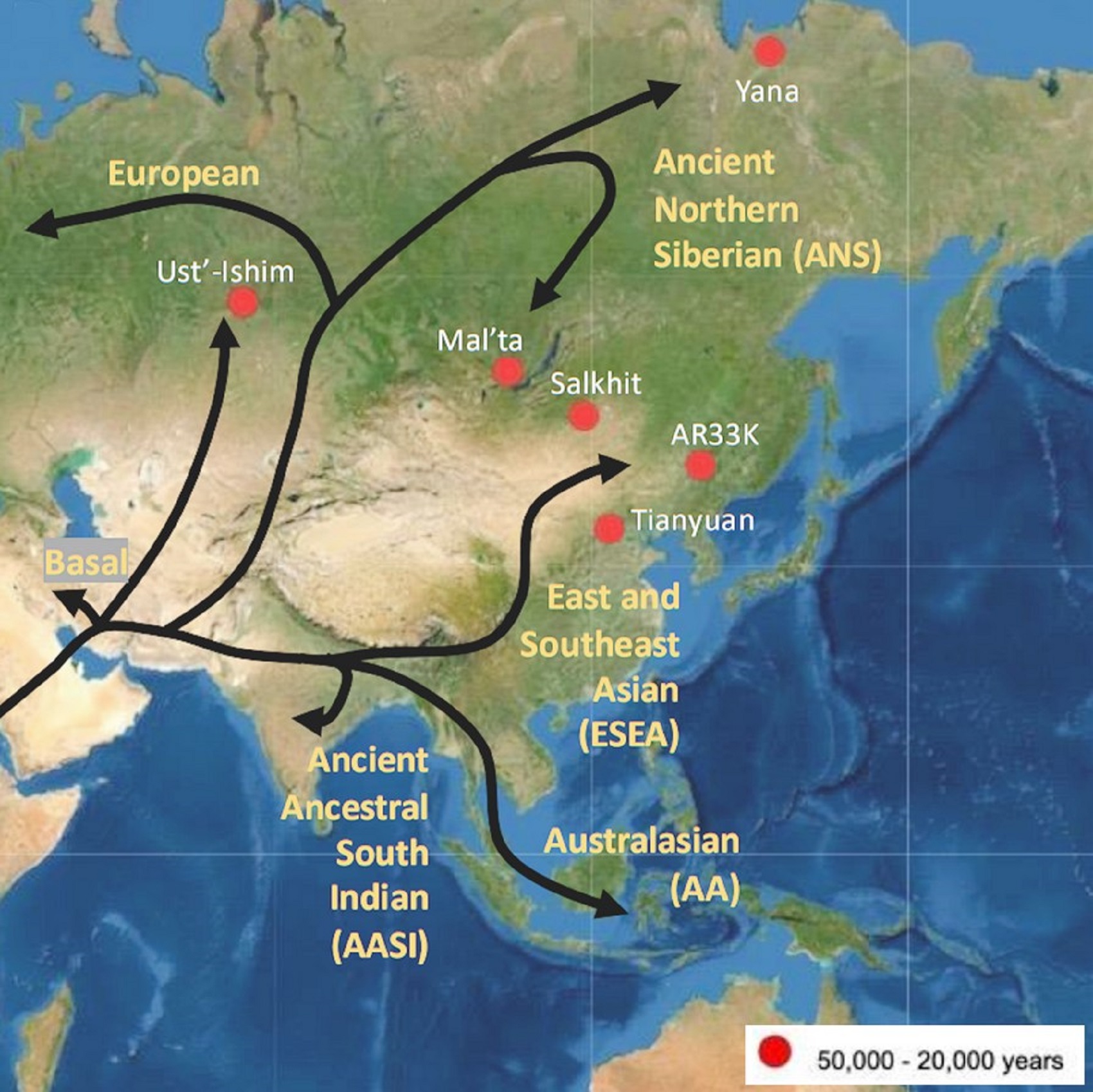

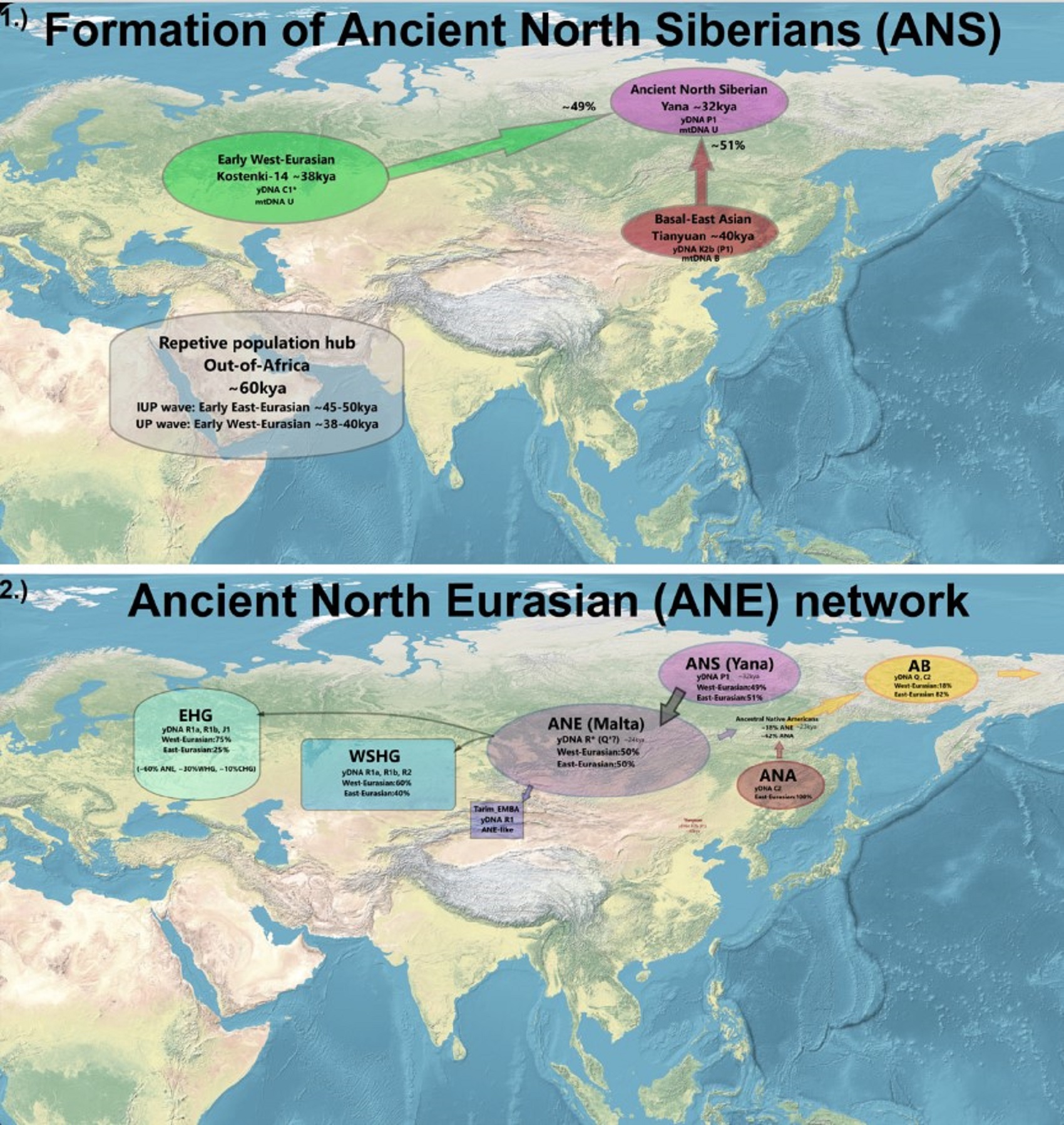

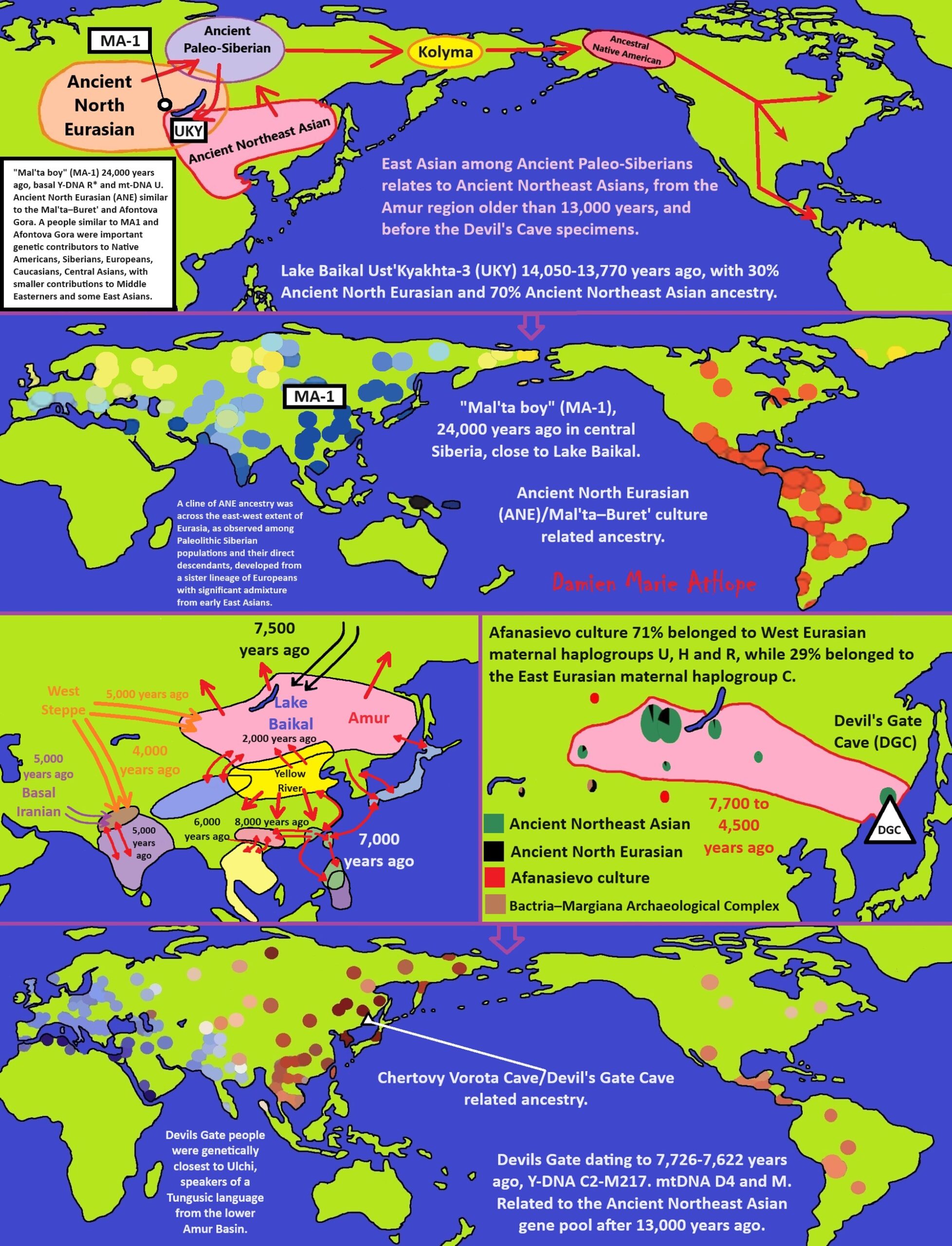

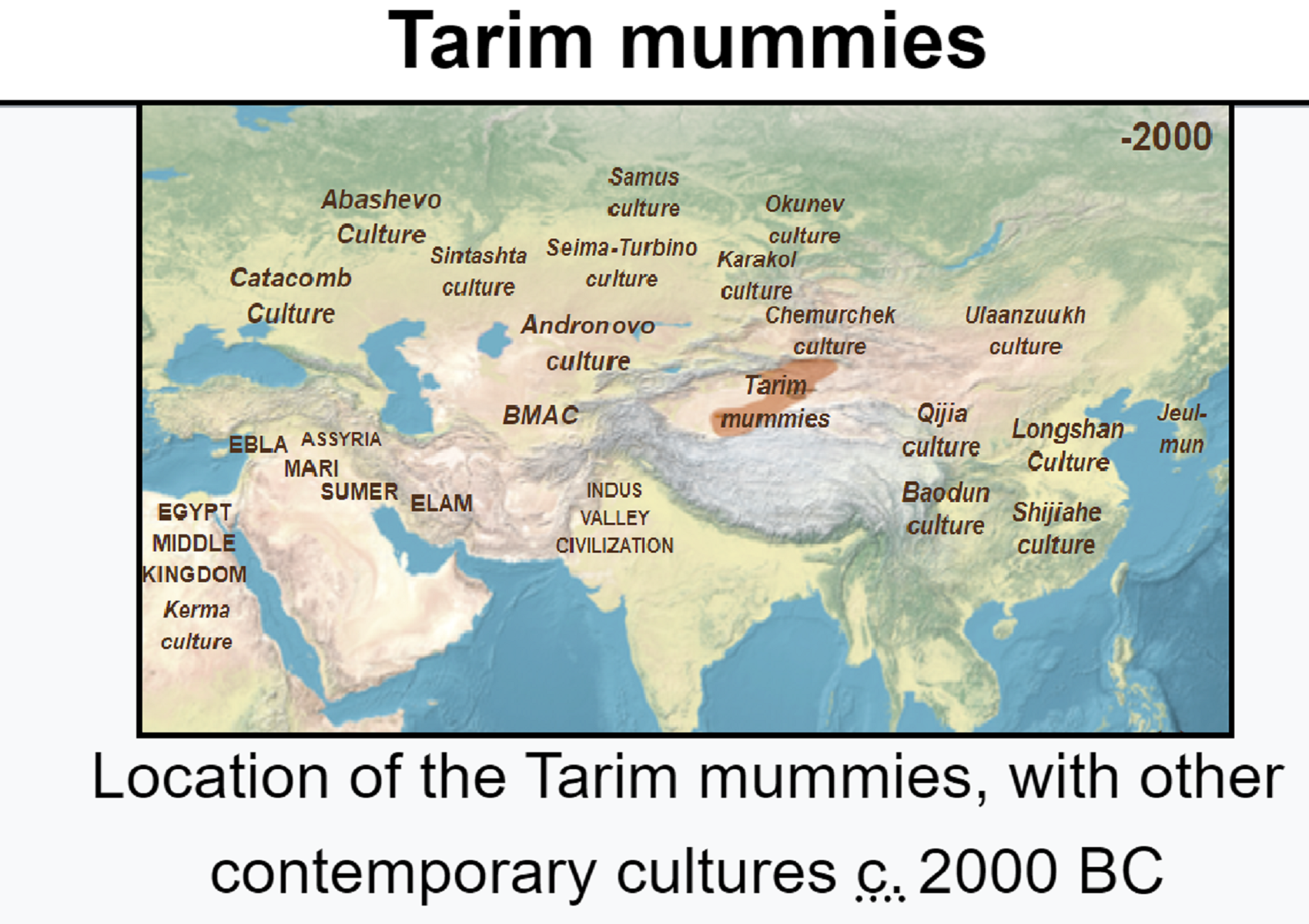

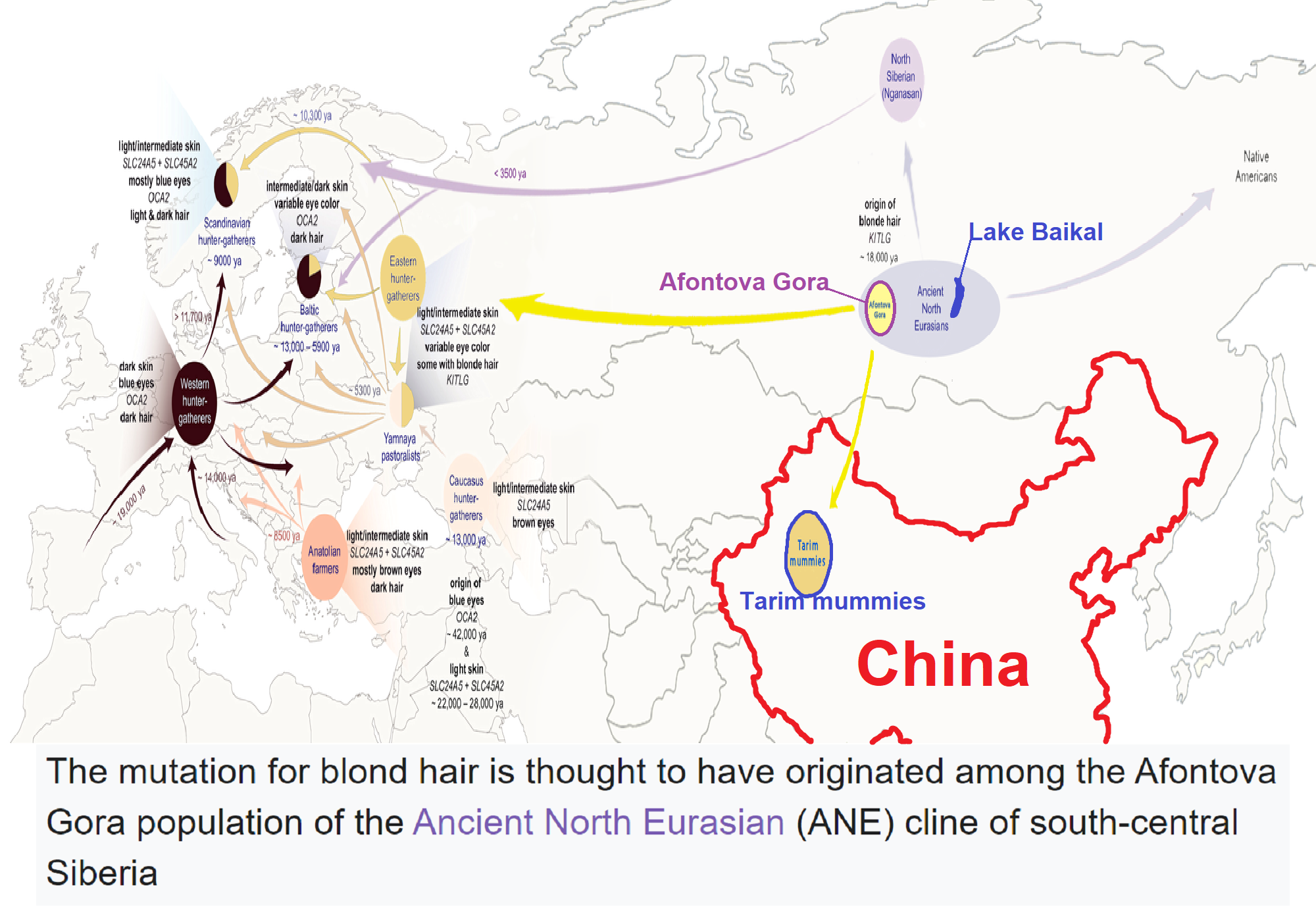

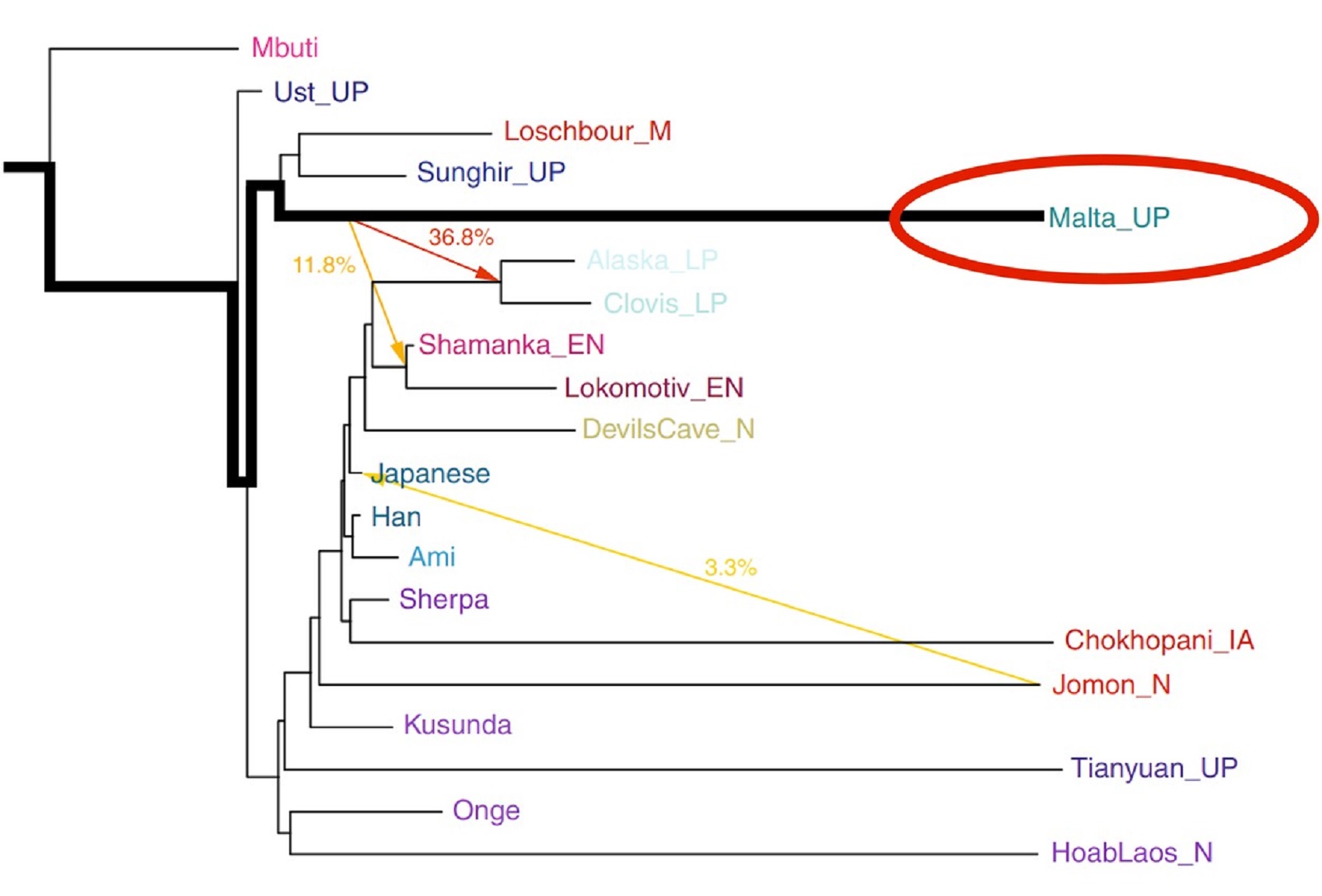

“The ANE lineage is defined by association with the MA-1, or “Mal’ta boy”, remains of 24,000 years ago in central Siberia Mal’ta-Buret’ culture 24,000-15,000 years ago. The Ancient North Eurasians (ANE) samples (Afontova Gora 3, Mal’ta 1, and Yana-RHS) show evidence for minor gene flow from an East Asian-related group (simplified by the Amis, Han, or Tianyuan) but no evidence for ANE-related geneflow into East Asians (Amis, Han, Tianyuan), except the Ainu, of North Japan.” ref

“The ANE lineage is defined by association with the MA-1, or “Mal’ta boy”, remains of 24,000 years ago in central Siberia Mal’ta-Buret’ culture 24,000-15,000 years ago “basal to modern-day Europeans”. Some Ancient North Eurasians also carried East Asian populations, such as Tianyuan Man.” ref

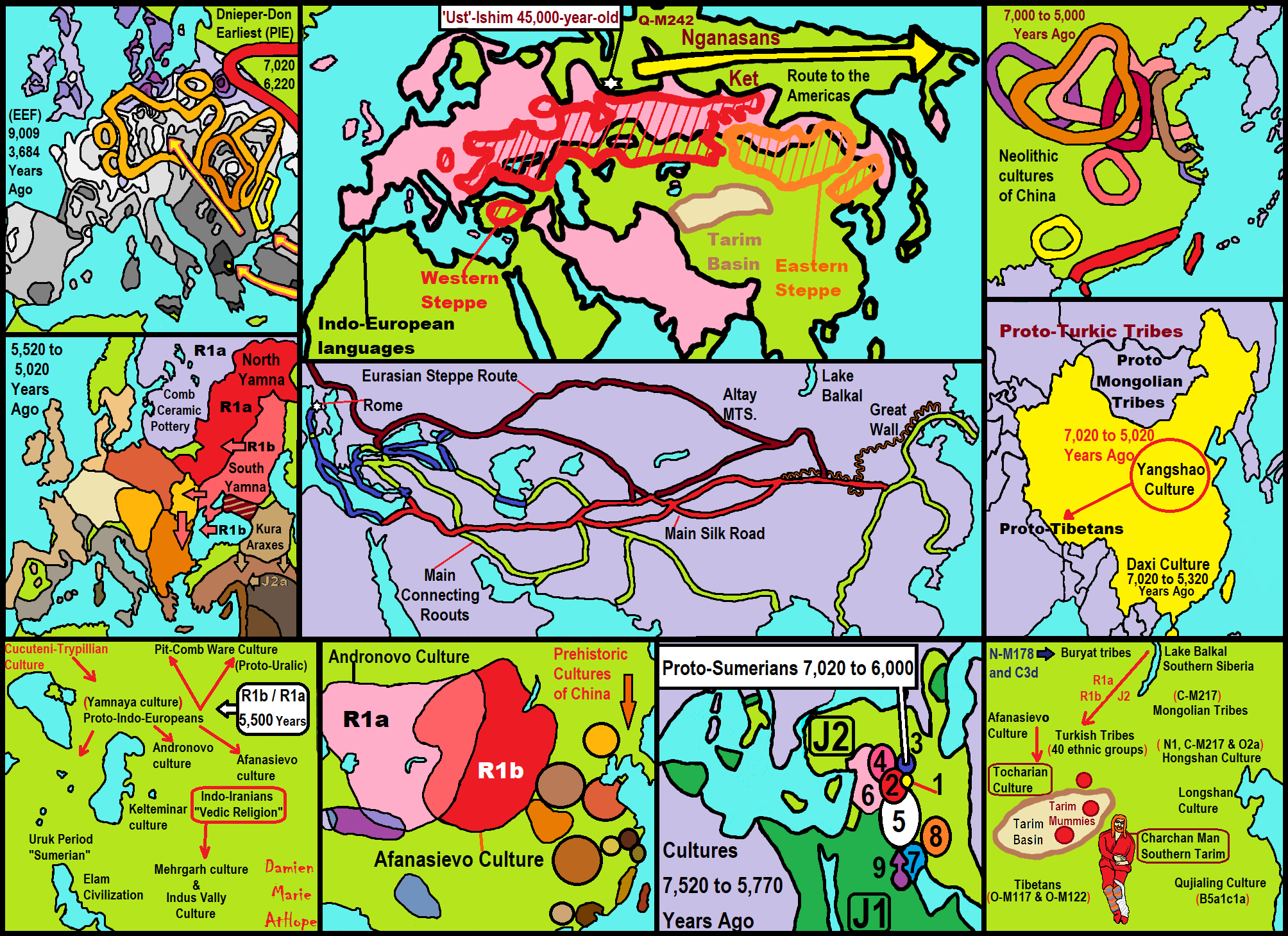

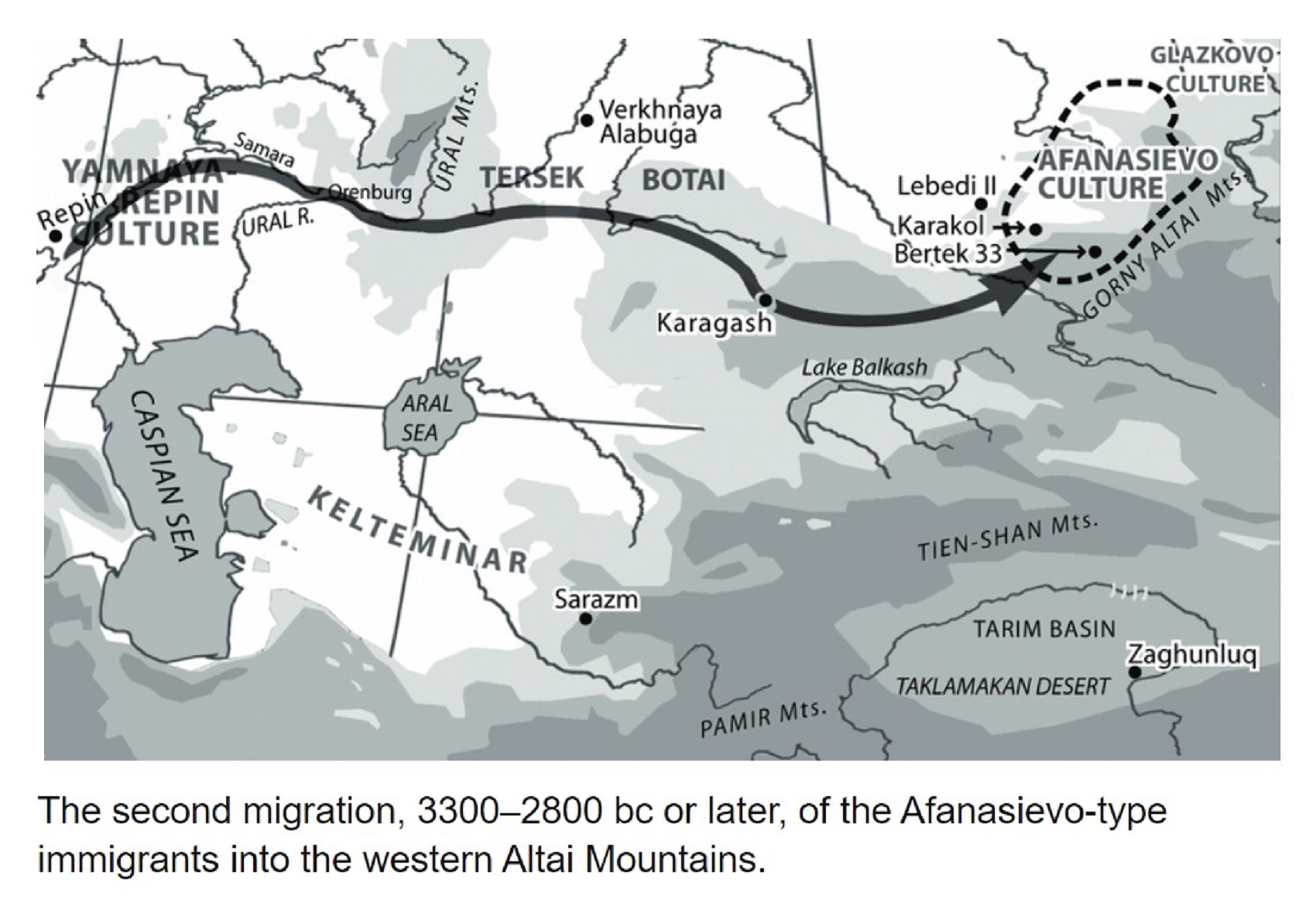

“Bronze-age-steppe Yamnaya and Afanasevo cultures were ANE at around 50% and Eastern Hunter-Gatherer (EHG) at around 75% ANE. Karelia culture: Y-DNA R1a-M417 8,400 years ago, Y-DNA J, 7,200 years ago, and Samara, of Y-haplogroup R1b-P297 7,600 years ago is closely related to ANE from Afontova Gora, 18,000 years ago around the time of blond hair first seen there.” ref

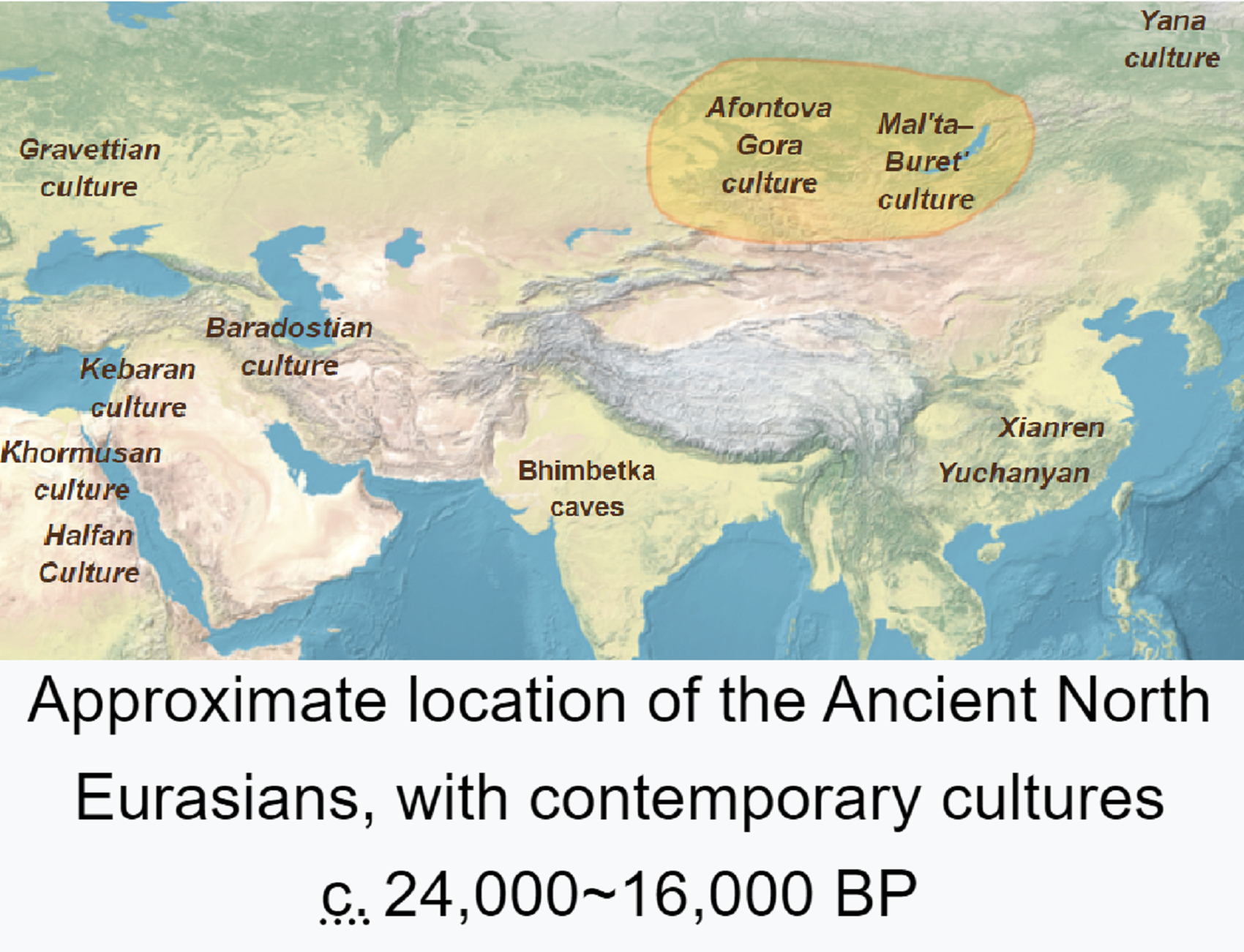

Ancient North Eurasian

“In archaeogenetics, the term Ancient North Eurasian (often abbreviated as ANE) is the name given to an ancestral West Eurasian component that represents descent from the people similar to the Mal’ta–Buret’ culture and populations closely related to them, such as from Afontova Gora and the Yana Rhinoceros Horn Site. Significant ANE ancestry are found in some modern populations, including Europeans and Native Americans.” ref

“The ANE lineage is defined by association with the MA-1, or “Mal’ta boy“, the remains of an individual who lived during the Last Glacial Maximum, 24,000 years ago in central Siberia, Ancient North Eurasians are described as a lineage “which is deeply related to Paleolithic/Mesolithic hunter-gatherers in Europe,” meaning that they diverged from Paleolithic Europeans a long time ago.” ref

“The ANE population has also been described as having been “basal to modern-day Europeans” but not especially related to East Asians, and is suggested to have perhaps originated in Europe or Western Asia or the Eurasian Steppe of Central Asia. However, some samples associated with Ancient North Eurasians also carried ancestry from an ancient East Asian population, such as Tianyuan Man. Sikora et al. (2019) found that the Yana RHS sample (31,600 BP) in Northern Siberia “can be modeled as early West Eurasian with an approximately 22% contribution from early East Asians.” ref

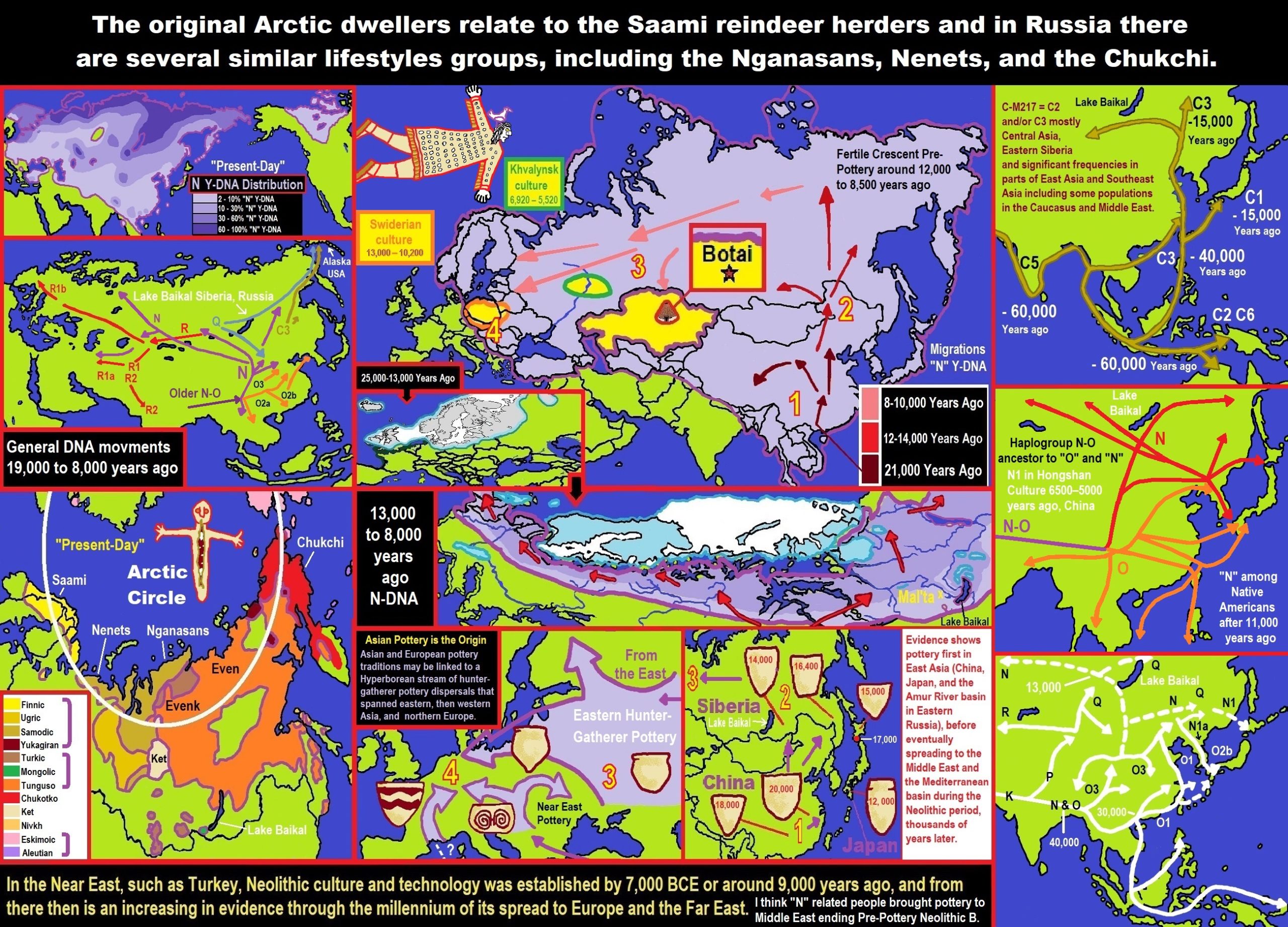

“Populations genetically similar to MA-1 were an important genetic contributor to Native Americans, Europeans, Central Asians, South Asians, and some East Asian groups, in order of significance. Lazaridis et al. (2016:10) note “a cline of ANE ancestry across the east-west extent of Eurasia.” The ancient Bronze-age-steppe Yamnaya and Afanasevo cultures were found to have a noteworthy ANE component at ~50%.” ref

“According to Moreno-Mayar et al. 2018 between 14% and 38% of Native American ancestry may originate from gene flow from the Mal’ta–Buret’ people (ANE). This difference is caused by the penetration of posterior Siberian migrations into the Americas, with the lowest percentages of ANE ancestry found in Eskimos and Alaskan Natives, as these groups are the result of migrations into the Americas roughly 5,000 years ago.” ref

“Estimates for ANE ancestry among first wave Native Americans show higher percentages, such as 42% for those belonging to the Andean region in South America. The other gene flow in Native Americans (the remainder of their ancestry) was of East Asian origin. Gene sequencing of another south-central Siberian people (Afontova Gora-2) dating to approximately 17,000 years ago, revealed similar autosomal genetic signatures to that of Mal’ta boy-1, suggesting that the region was continuously occupied by humans throughout the Last Glacial Maximum.” ref

“The earliest known individual with a genetic mutation associated with blonde hair in modern Europeans is an Ancient North Eurasian female dating to around 16000 BCE from the Afontova Gora 3 site in Siberia. It has been suggested that their mythology may have included a narrative, found in both Indo-European and some Native American fables, in which a dog guards the path to the afterlife.” ref

“Genomic studies also indicate that the ANE component was introduced to Western Europe by people related to the Yamnaya culture, long after the Paleolithic. It is reported in modern-day Europeans (7%–25%), but not of Europeans before the Bronze Age. Additional ANE ancestry is found in European populations through paleolithic interactions with Eastern Hunter-Gatherers, which resulted in populations such as Scandinavian Hunter-Gatherers.” ref

“The Ancient North Eurasians (ANE) split from the ancestors of European peoples somewhere in the Middle East or South-central Asia, and used a northern dispersal route through Central Asia into Northern Asia and Siberia. Genetic analyses show that all ANE samples (Afontova Gora 3, Mal’ta 1, and Yana-RHS) show evidence for minor gene flow from an East Asian-related group (simplified by the Amis, Han, or Tianyuan). In contrast, no evidence for ANE-related geneflow into East Asians (Amis, Han, Tianyuan), except the Ainu, was found.” ref

“Genetic data suggests that the ANE formed during the Terminal Upper-Paleolithic (36+-1,5ka) period from a deeply European-related population, which was once widespread in Northern Eurasia, and from an early East Asian-related group, which migrated northwards into Central Asia and Siberia, merging with this deeply European-related population. These population dynamics and constant northwards geneflow of East Asian-related ancestry would later gave rise to the “Ancestral Native Americans” and Paleosiberians, which replaced the ANE as dominant population of Siberia.” ref

Groups partially derived from the Ancient North Eurasians

“Eastern Hunter-Gatherer (EHG) is a lineage derived predominantly (75%) from ANE. It is represented by two individuals from Karelia, one of Y-haplogroup R1a-M417, dated c. 8.4 kya, the other of Y-haplogroup J, dated c. 7.2 kya; and one individual from Samara, of Y-haplogroup R1b-P297, dated c. 7.6 kya. This lineage is closely related to the ANE sample from Afontova Gora, dated c. 18 kya. After the end of the Last Glacial Maximum, the Western Hunter-Gatherers (WHG) and EHG lineages merged in Eastern Europe, accounting for early presence of ANE-derived ancestry in Mesolithic Europe. Evidence suggests that as Ancient North Eurasians migrated West from Eastern Siberia, they absorbed Western Hunter-Gatherers and other West Eurasian populations as well.” ref

“Caucasian Hunter-Gatherer (CHG) is represented by the Satsurblia individual dated ~13 kya (from the Satsurblia cave in Georgia), and carried 36% ANE-derived admixture. While the rest of their ancestry is derived from the Dzudzuana cave individual dated ~26 kya, which lacked ANE-admixture, Dzudzuana affinity in the Caucasus decreased with the arrival of ANE at ~13 kya Satsurblia.” ref

“Scandinavian Hunter-Gatherer (SHG) is represented by several individuals buried at Motala, Sweden ca. 6000 BC. They were descended from Western Hunter-Gatherers who initially settled Scandinavia from the south, and later populations of EHG who entered Scandinavia from the north through the coast of Norway.” ref

“Iran Neolithic (Iran_N) individuals dated ~8.5 kya carried 50% ANE-derived admixture and 50% Dzudzuana-related admixture, marking them as different from other Near-Eastern and Anatolian Neolithics who didn’t have ANE admixture. Iran Neolithics were later replaced by Iran Chalcolithics, who were a mixture of Iran Neolithic and Near Eastern Levant Neolithic.” ref

“Ancient Beringian/Ancestral Native American are specific archaeogenetic lineages, based on the genome of an infant found at the Upward Sun River site (dubbed USR1), dated to 11,500 years ago. The AB lineage diverged from the Ancestral Native American (ANA) lineage about 20,000 years ago.” ref

“West Siberian Hunter-Gatherer (WSHG) are a specific archaeogenetic lineage, first reported in a genetic study published in Science in September 2019. WSGs were found to be of about 30% EHG ancestry, 50% ANE ancestry, and 20% to 38% East Asian ancestry.” ref

“Western Steppe Herders (WSH) is the name given to a distinct ancestral component that represents descent closely related to the Yamnaya culture of the Pontic–Caspian steppe. This ancestry is often referred to as Yamnaya ancestry or Steppe ancestry.” ref

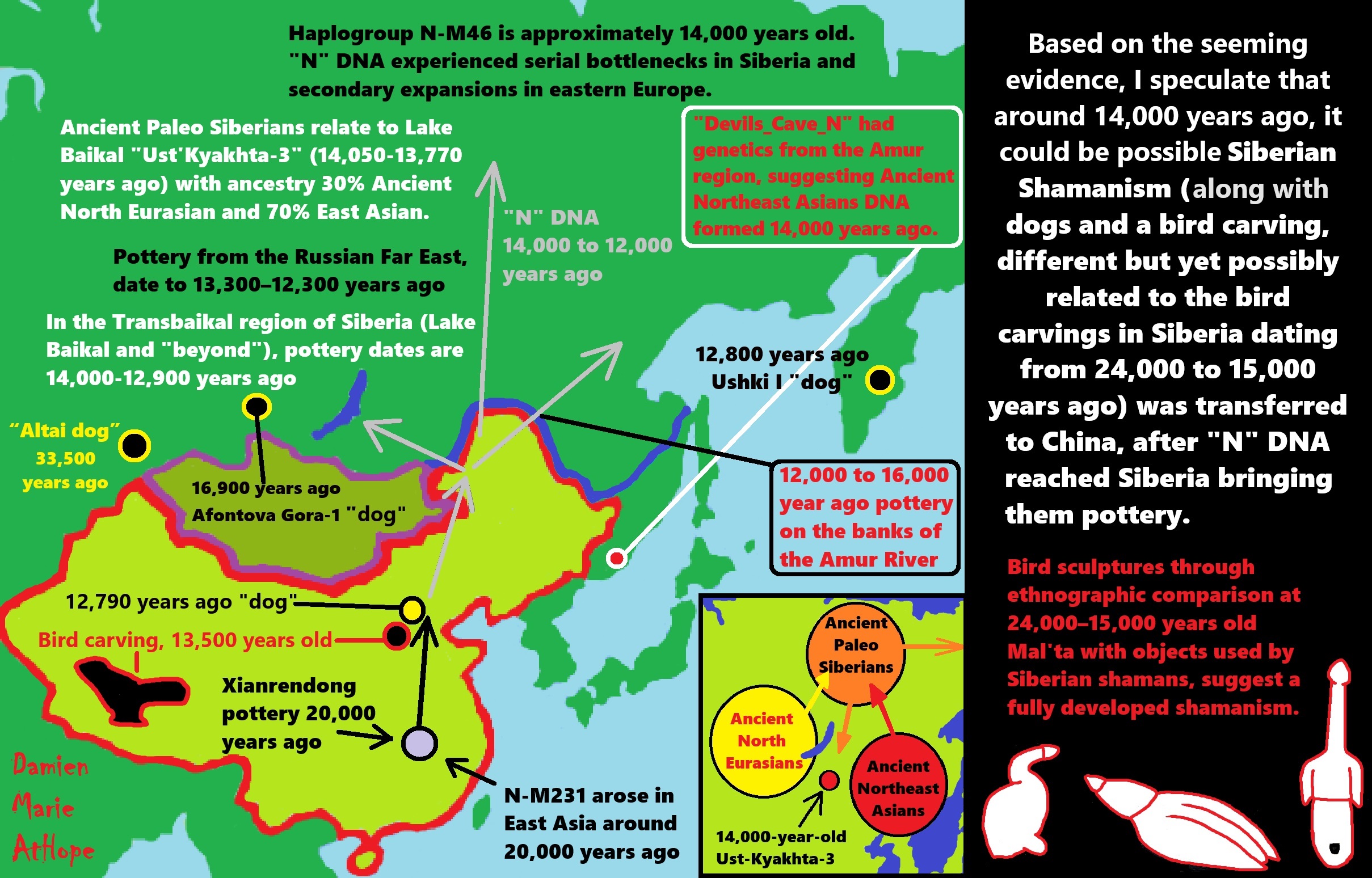

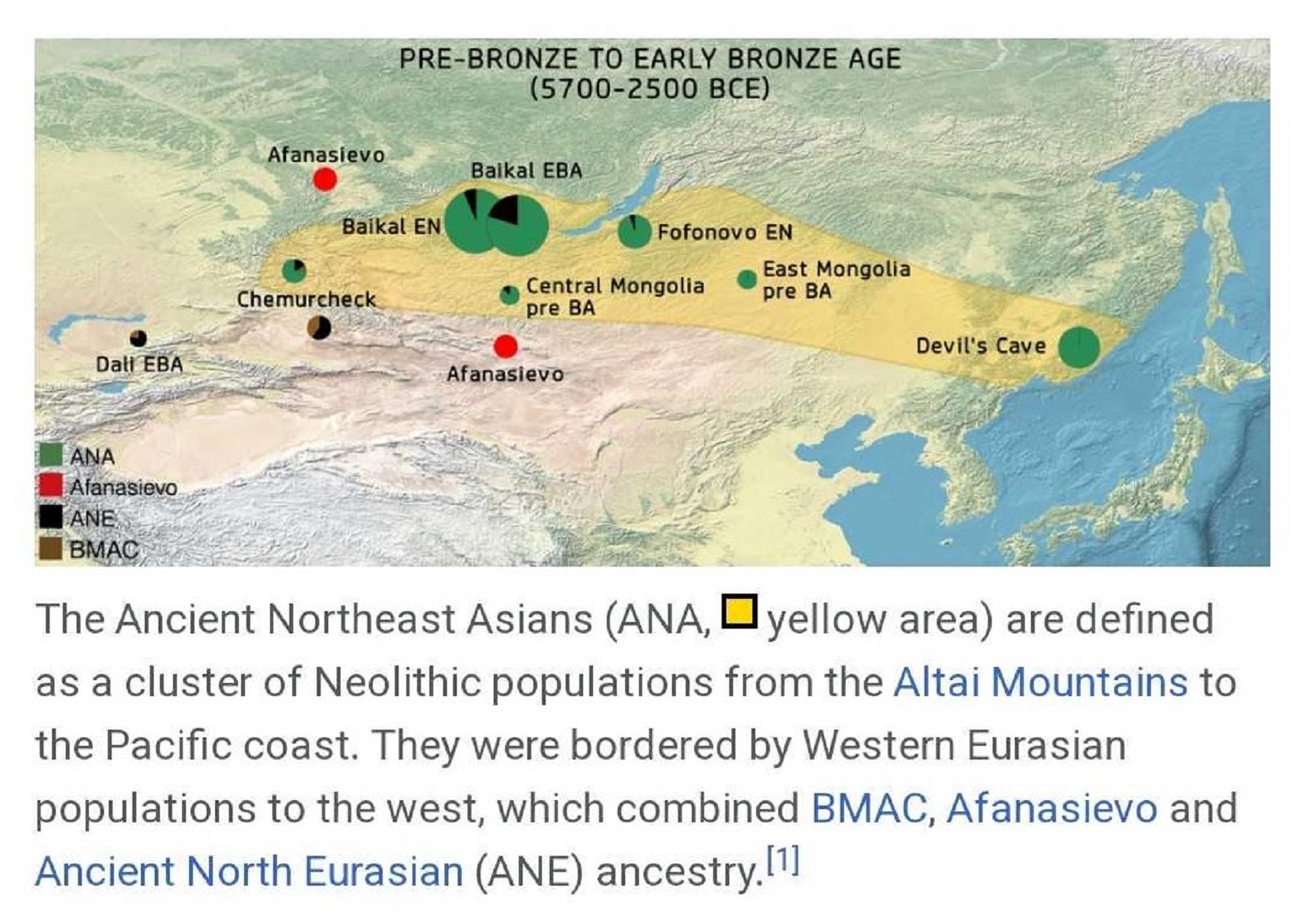

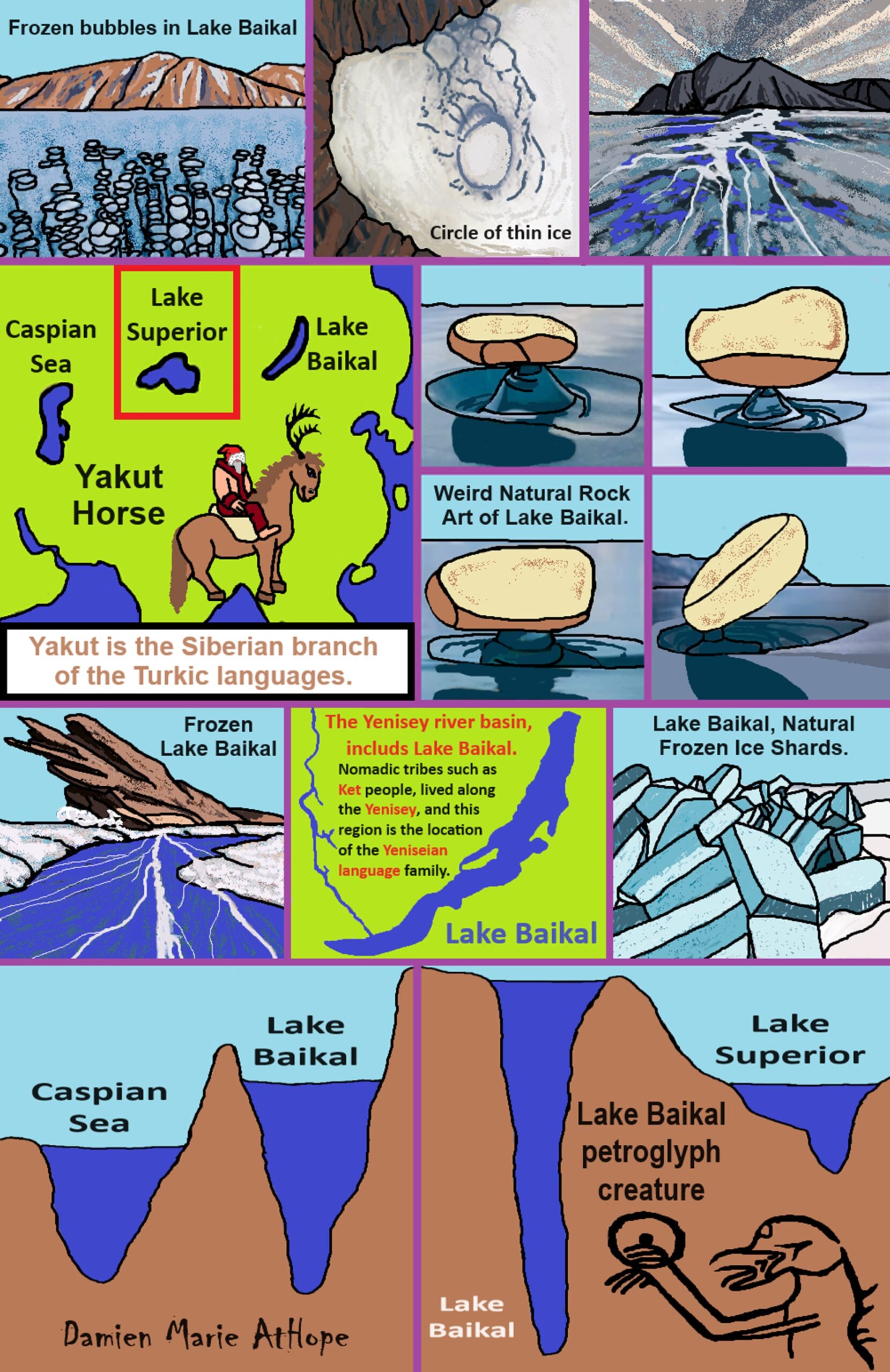

“Late Upper Paeolithic Lake Baikal – Ust’Kyakhta-3 (UKY) 14,050-13,770 BP were mixture of 30% ANE ancestry and 70% East Asian ancestry.” ref

“Lake Baikal Holocene – Baikal Eneolithic (Baikal_EN) and Baikal Early Bronze Age (Baikal_EBA) derived 6.4% to 20.1% ancestry from ANE, while rest of their ancestry was derived from East Asians. Fofonovo_EN near by Lake Baikal were mixture of 12-17% ANE ancestry and 83-87% East Asian ancestry.” ref

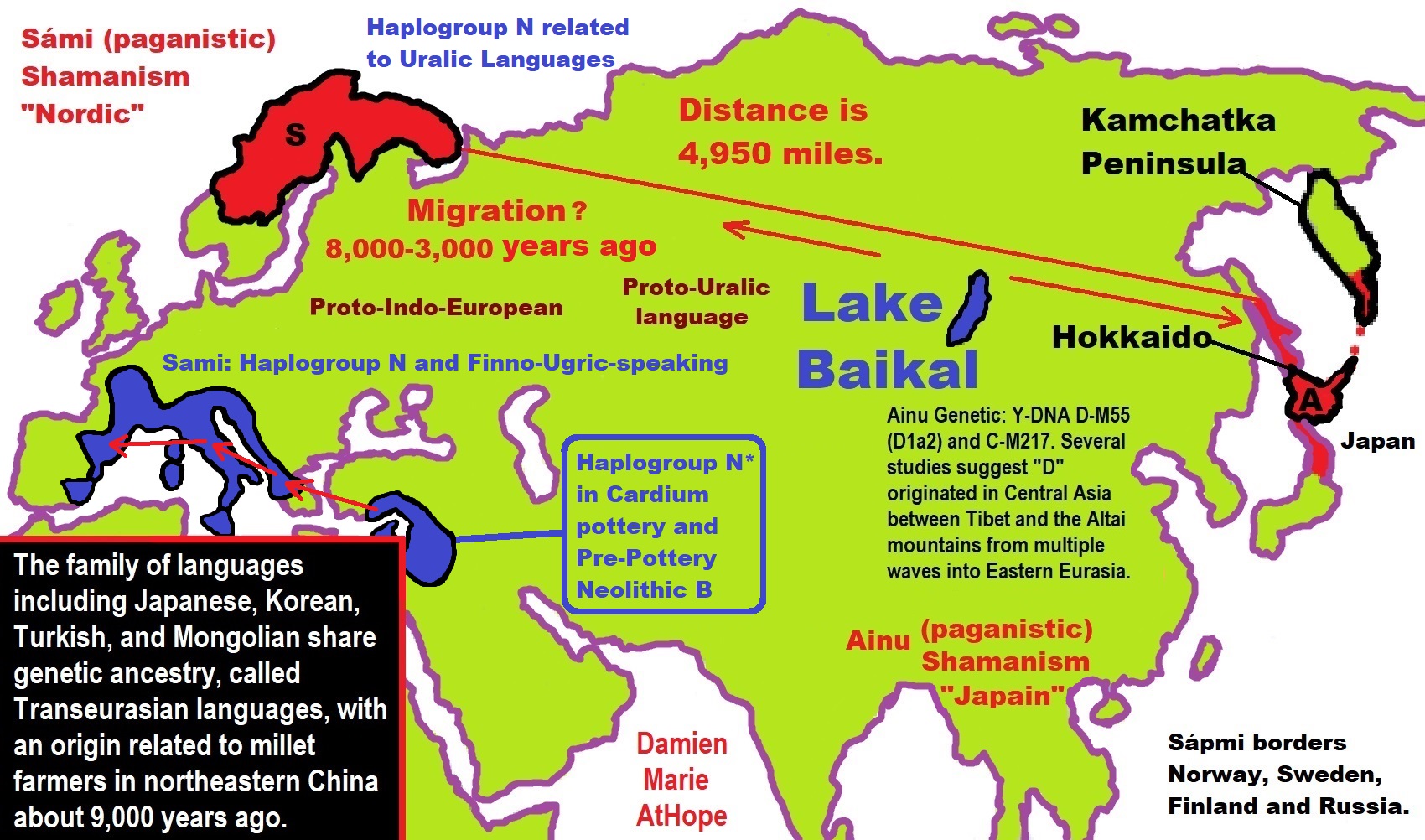

“Hokkaido Jōmon people specifically refers to the Jōmon period population of Hokkaido in northernmost Japan. Though the Jōmon people themselves descended mainly from East Asian lineages, one study found an affinity between Hokkaido Jōmon with the Northern Eurasian Yana sample (an ANE-related group, related to Mal’ta), and suggest as an explanation the possibility of minor Yana gene flow into the Hokkaido Jōmon population (as well as other possibilities). A more recent study by Cooke et al. 2021, confirmed ANE-related geneflow among the Jōmon people, partially ancestral to the Ainu people. ANE ancestry among Jōmon people is estimated at 21%, however, there is a North to South cline within the Japanese archipelago, with the highest amount of ANE ancestry in Hokkaido and Tohoku.” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

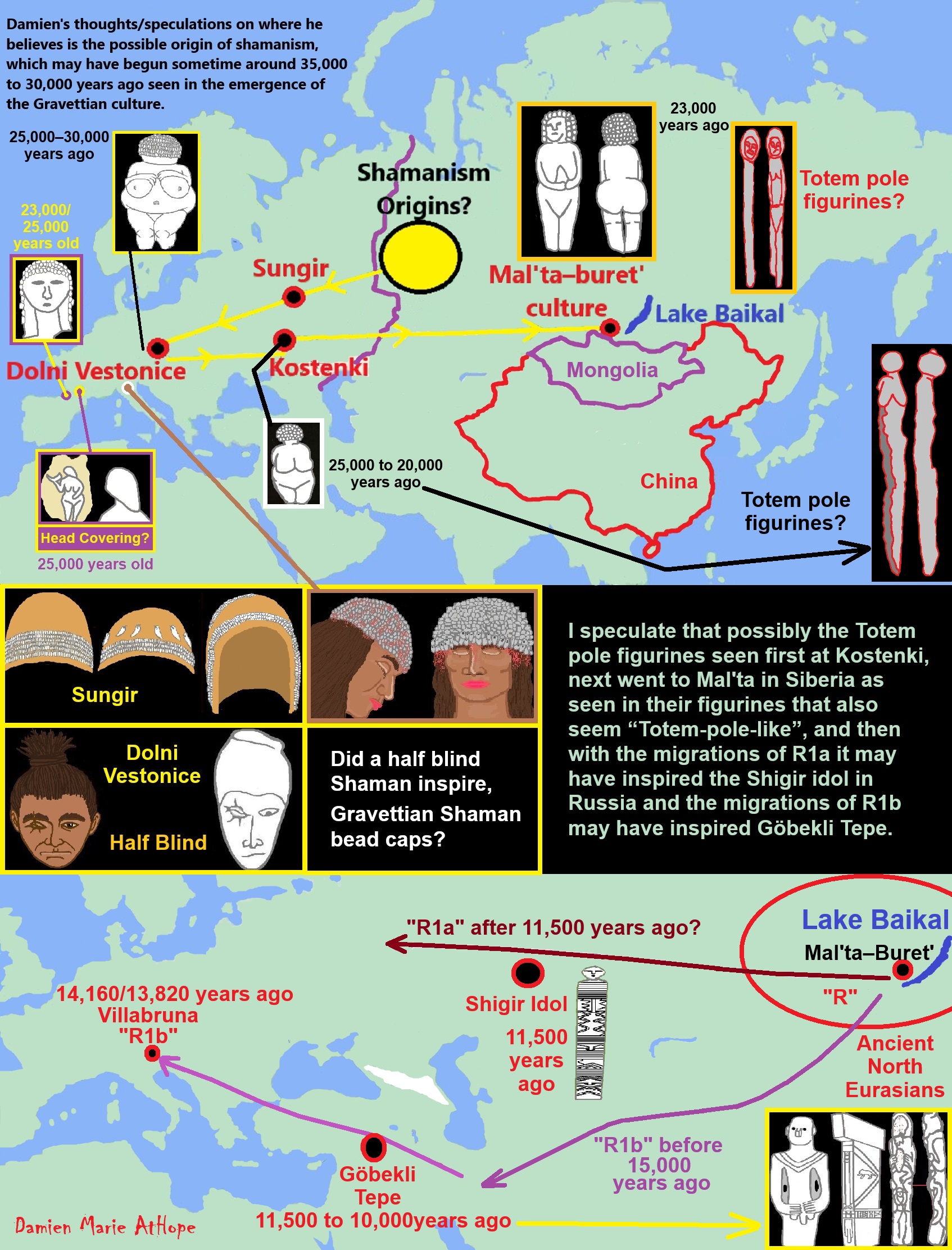

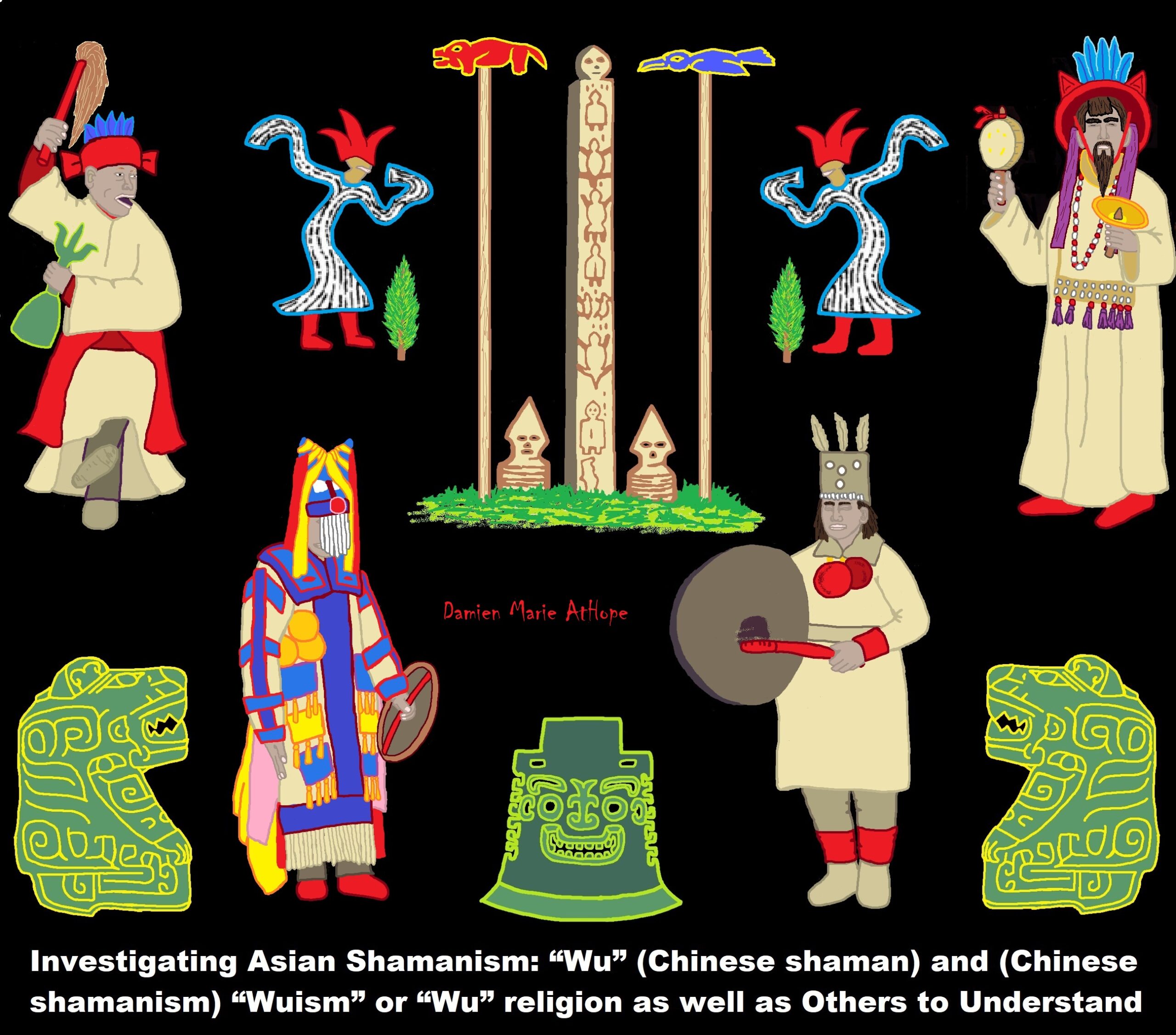

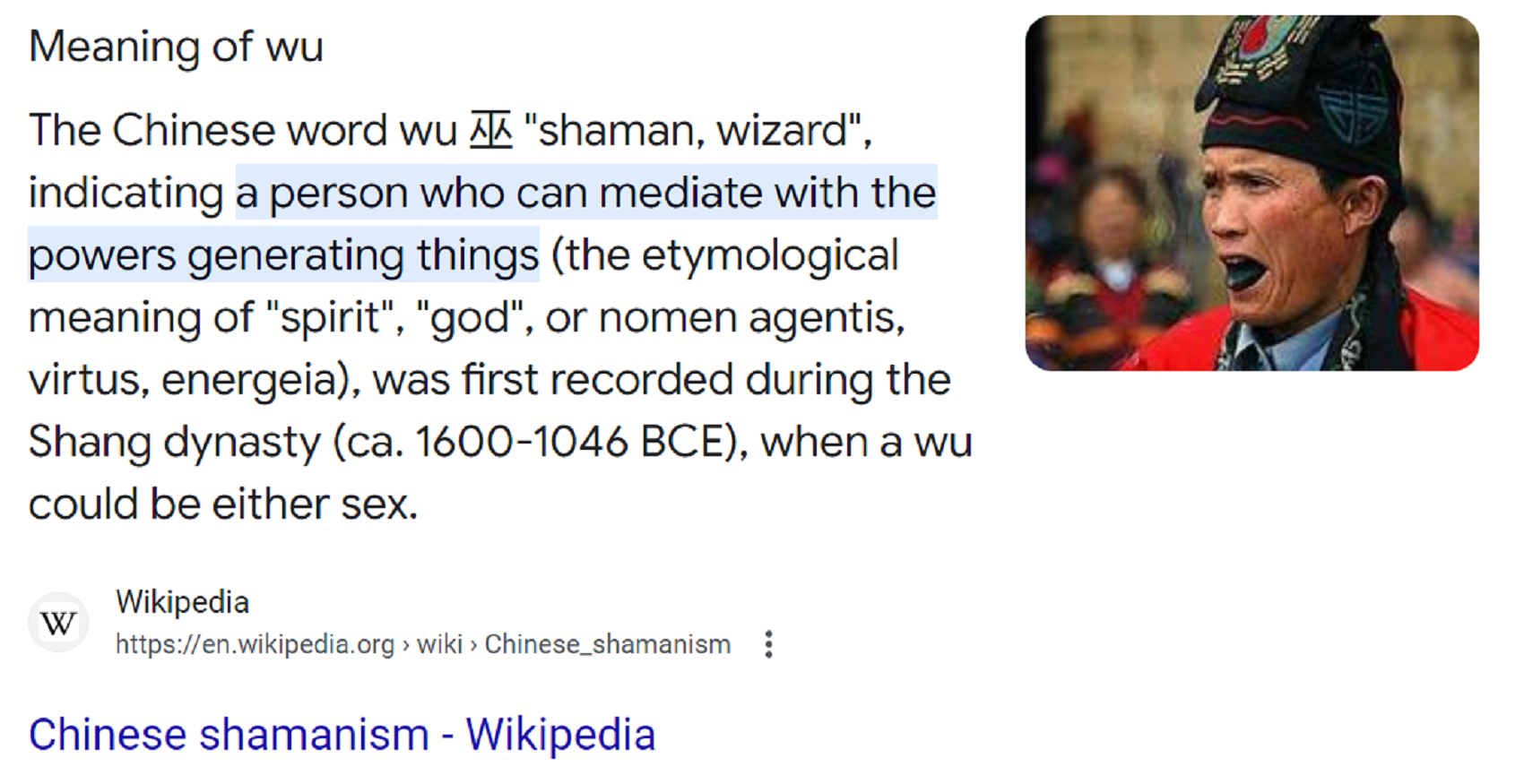

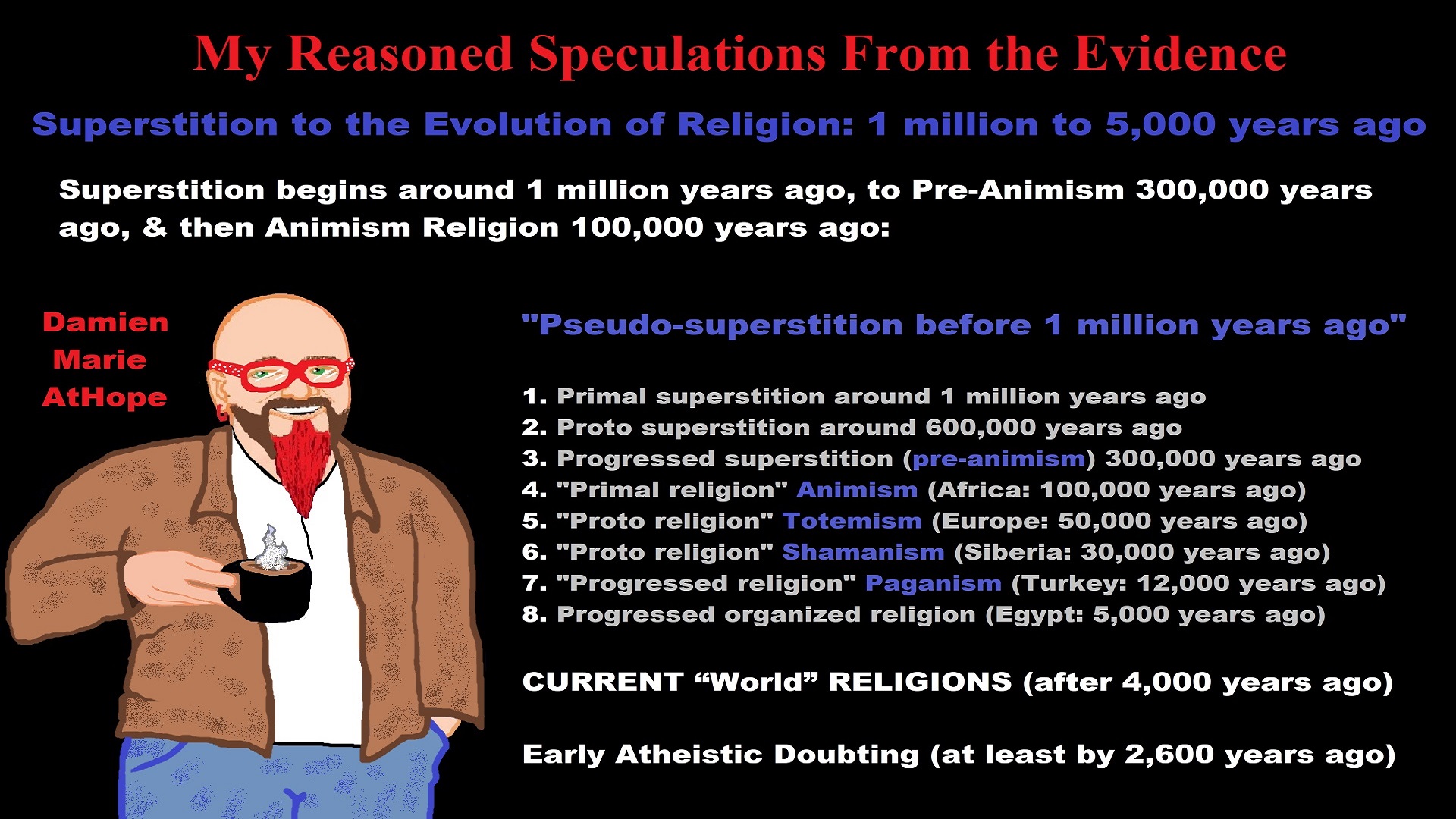

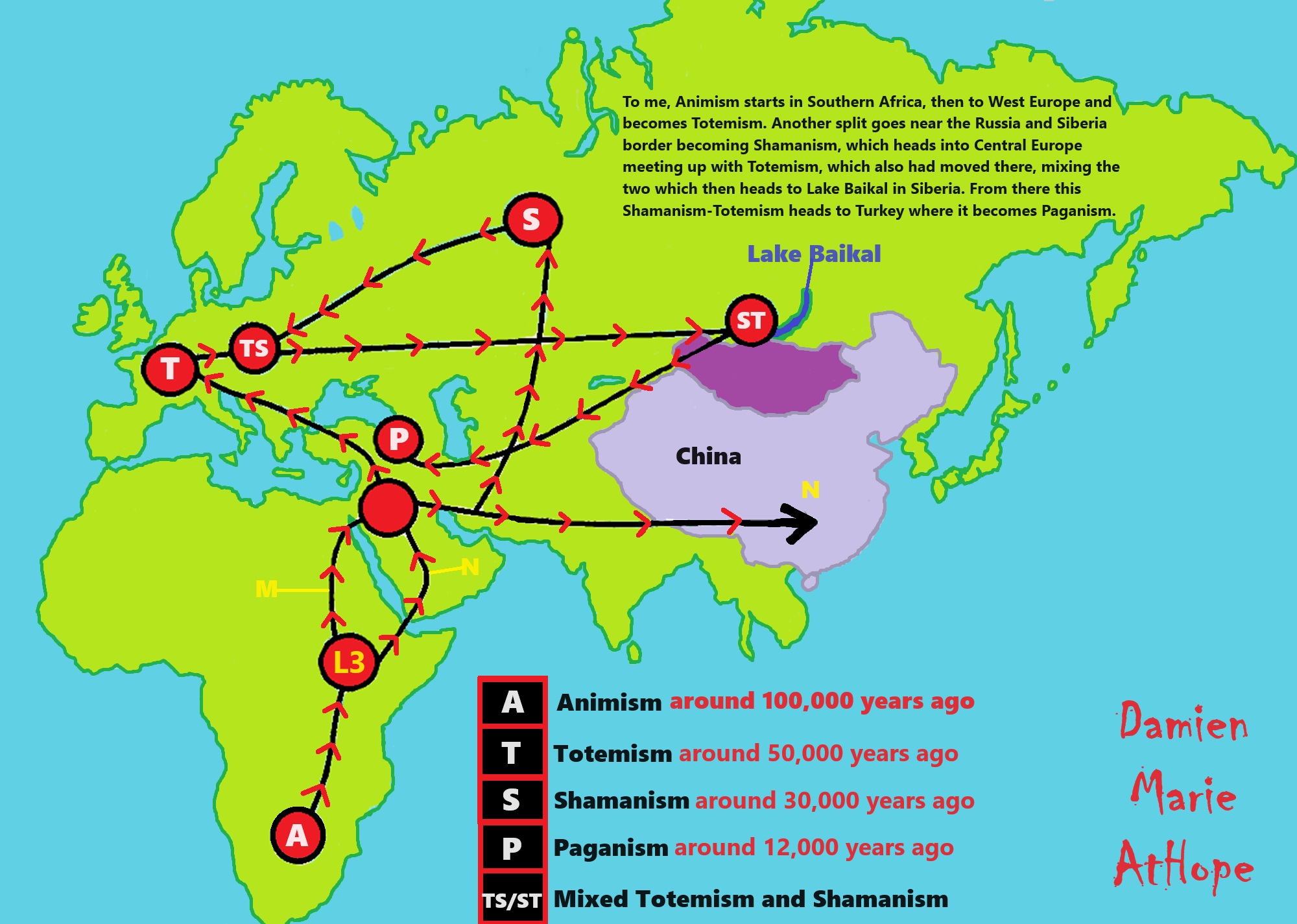

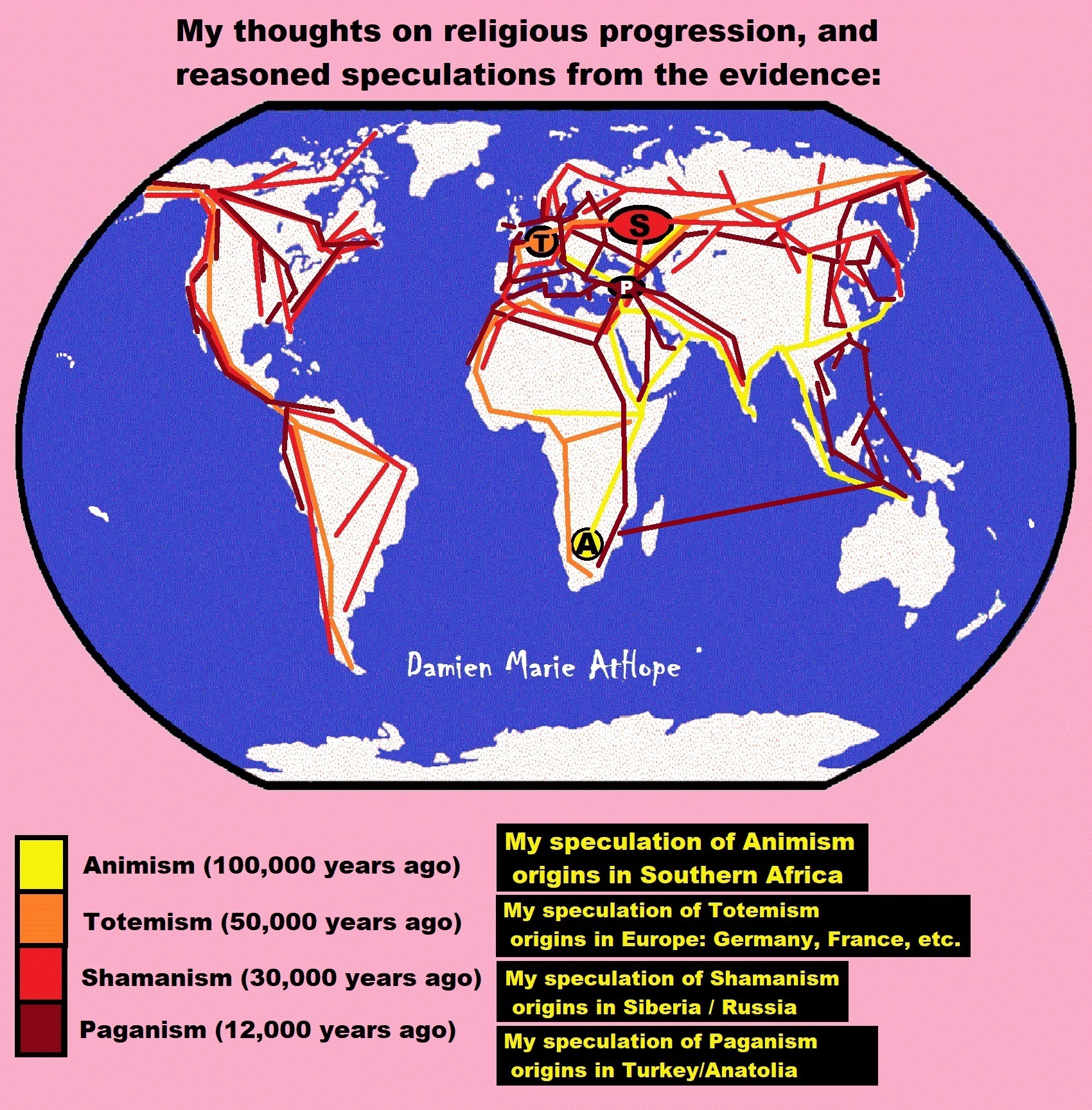

Here are my thoughts/speculations on where I believe is the possible origin of shamanism, which may have begun sometime around 35,000 to 30,000 years ago seen in the emergence of the Gravettian culture, just to outline his thinking, on what thousands of years later led to evolved Asian shamanism, in general, and thus WU shamanism as well. In both Europe-related “shamanism-possible burials” and in Gravettian mitochondrial DNA is a seeming connection to Haplogroup U. And the first believed Shaman proposed burial belonged to Eastern Gravettians/Pavlovian culture at Dolní Věstonice in southern Moravia in the Czech Republic, which is the oldest permanent human settlement that has ever been found. It is at Dolní Věstonice where approximately 27,000-25,000 years ago a seeming female shaman was buried and also there was an ivory totem portrait figure, seemingly of her.

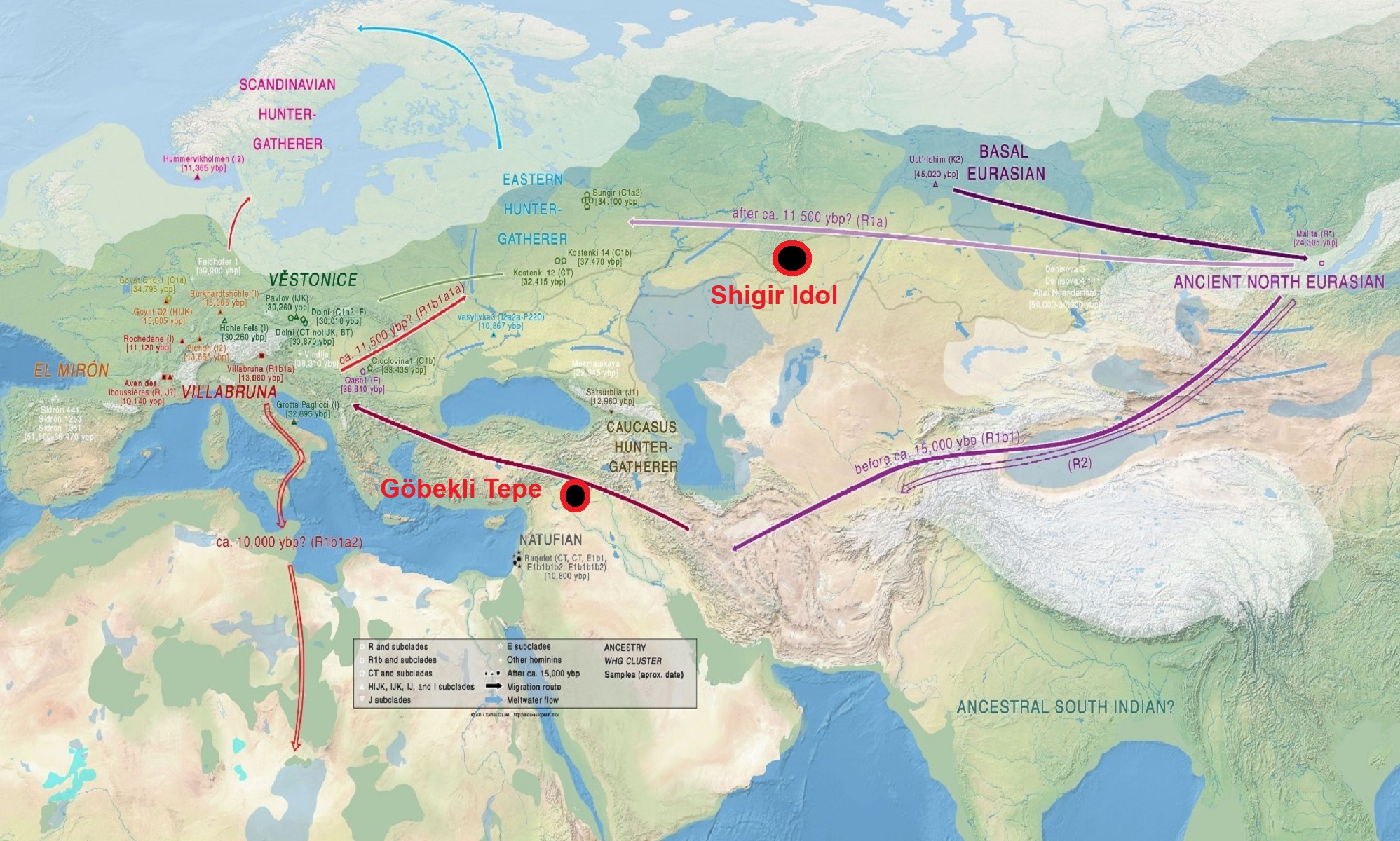

And my thoughts on how cultural/ritual aspects were influenced in the area of Göbekli Tepe. I think it relates to a few different cultures starting in the area before the Neolithic. Two different groups of Siberians first from northwest Siberia with U6 haplogroup 40,000 to 30,000 or so. Then R Haplogroup (mainly haplogroup R1b but also some possible R1a both related to the Ancient North Eurasians). This second group added its “R1b” DNA of around 50% to the two cultures Natufian and Trialetian. To me, it is likely both of these cultures helped create Göbekli Tepe. Then I think the female art or graffiti seen at Göbekli Tepe to me possibly relates to the Epigravettians that made it into Turkey and have similar art in North Italy. I speculate that possibly the Totem pole figurines seen first at Kostenki, next went to Mal’ta in Siberia as seen in their figurines that also seem “Totem-pole-like”, and then with the migrations of R1a it may have inspired the Shigir idol in Russia and the migrations of R1b may have inspired Göbekli Tepe.

The video used for this blog and our “Atheist-Humanist-Leftist Revolutionaries” YouTube show is:

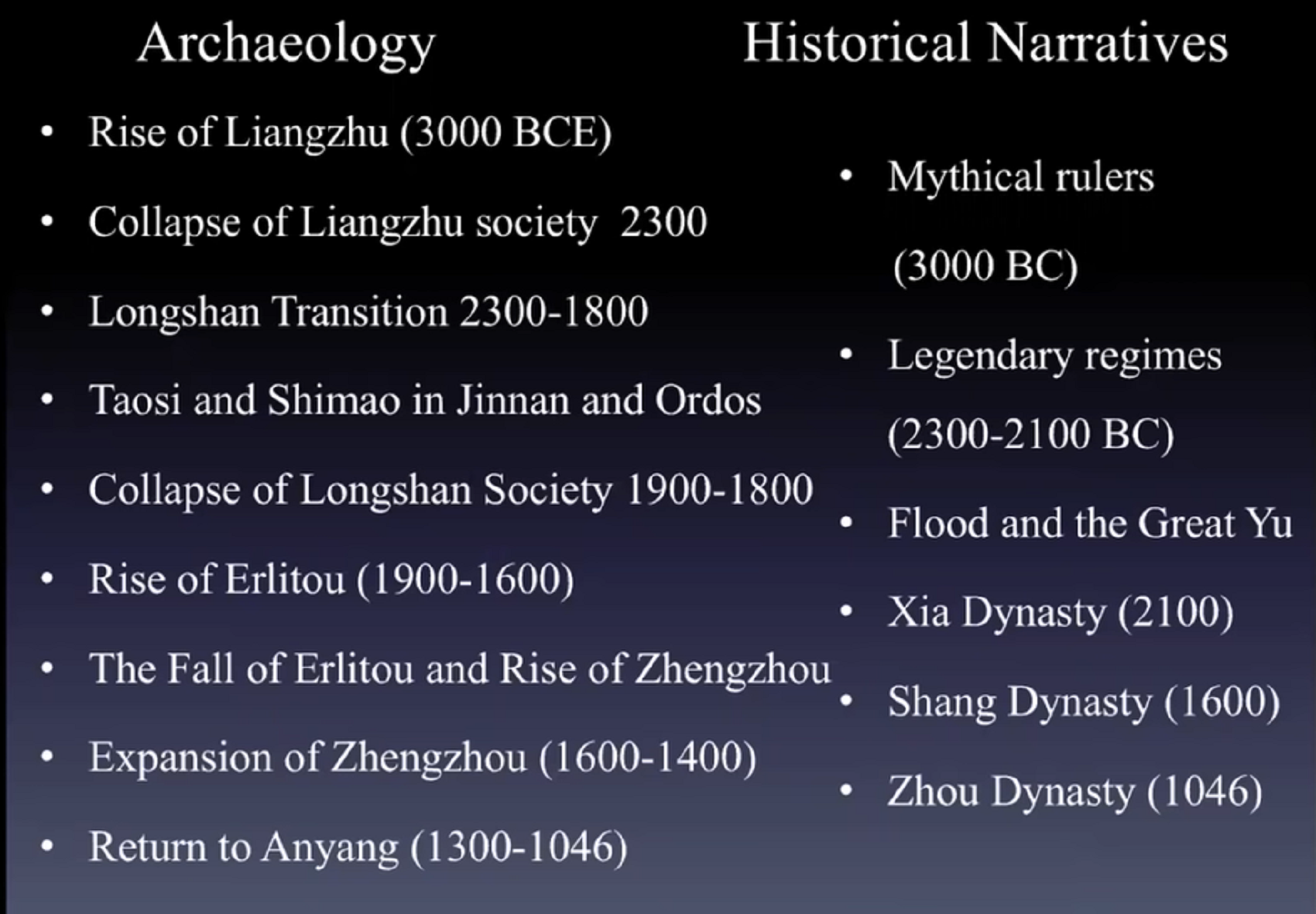

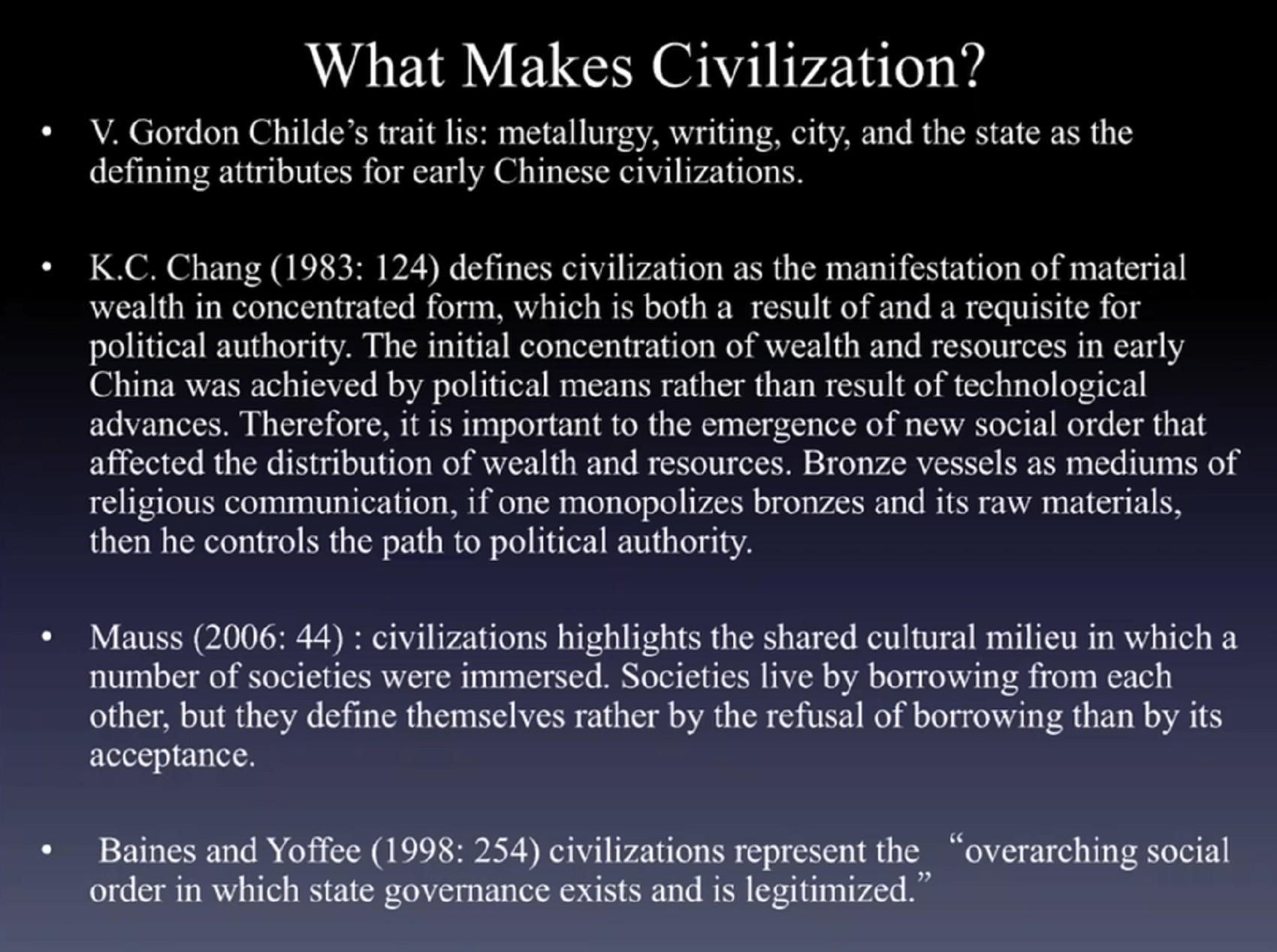

(The Rise of Early Chinese Civilization ~ Dr. Min Li): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lz4EQ0iYDI4&t=413s

“In this superb and intense crash course, Dr. Min Li defines the different approaches to defining Civilization and how these concepts are applied to Neolithic and Ancient China when tracing the early origins of Chinese Civilization.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lz4EQ0iYDI4&t=413s

“Li, Min (Ph.D, University of Michigan, 2008) is an associate professor of East Asian archaeology with a joint appointment at Department of Anthropology and Department of Asian Languages and Cultures at UCLA. His archaeological research spans from state formation in early China to early modern global trade network. He is also co-director of the landscape archaeology project in the Bronze Age city of Qufu, China. His first book Social Memory and State Formation in Early China with the Cambridge University Press.” https://www.academia.edu/83568661/Water_Management_at_the_Liangzhu_Prehistoric_Mound_Center_China

Show 1 “Palaeolithic” China and the Different Approaches to Defining Civilization

Use time 0:33 to 6:30 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lz4EQ0iYDI4&t=413s

|

18000–7000 |

Xianren Cave culture |

仙人洞、吊桶环遗址 |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Neolithic_cultures_of_China

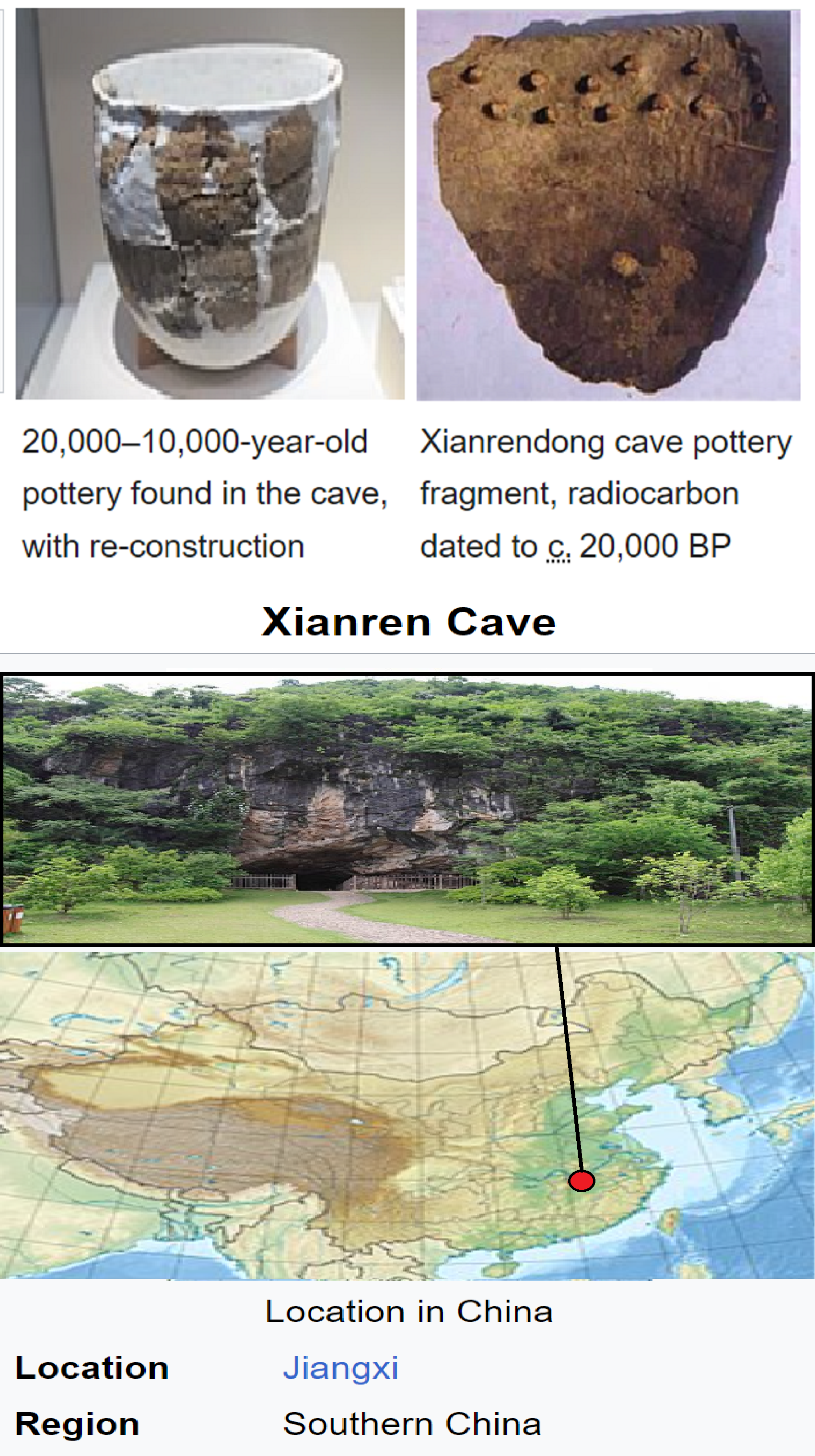

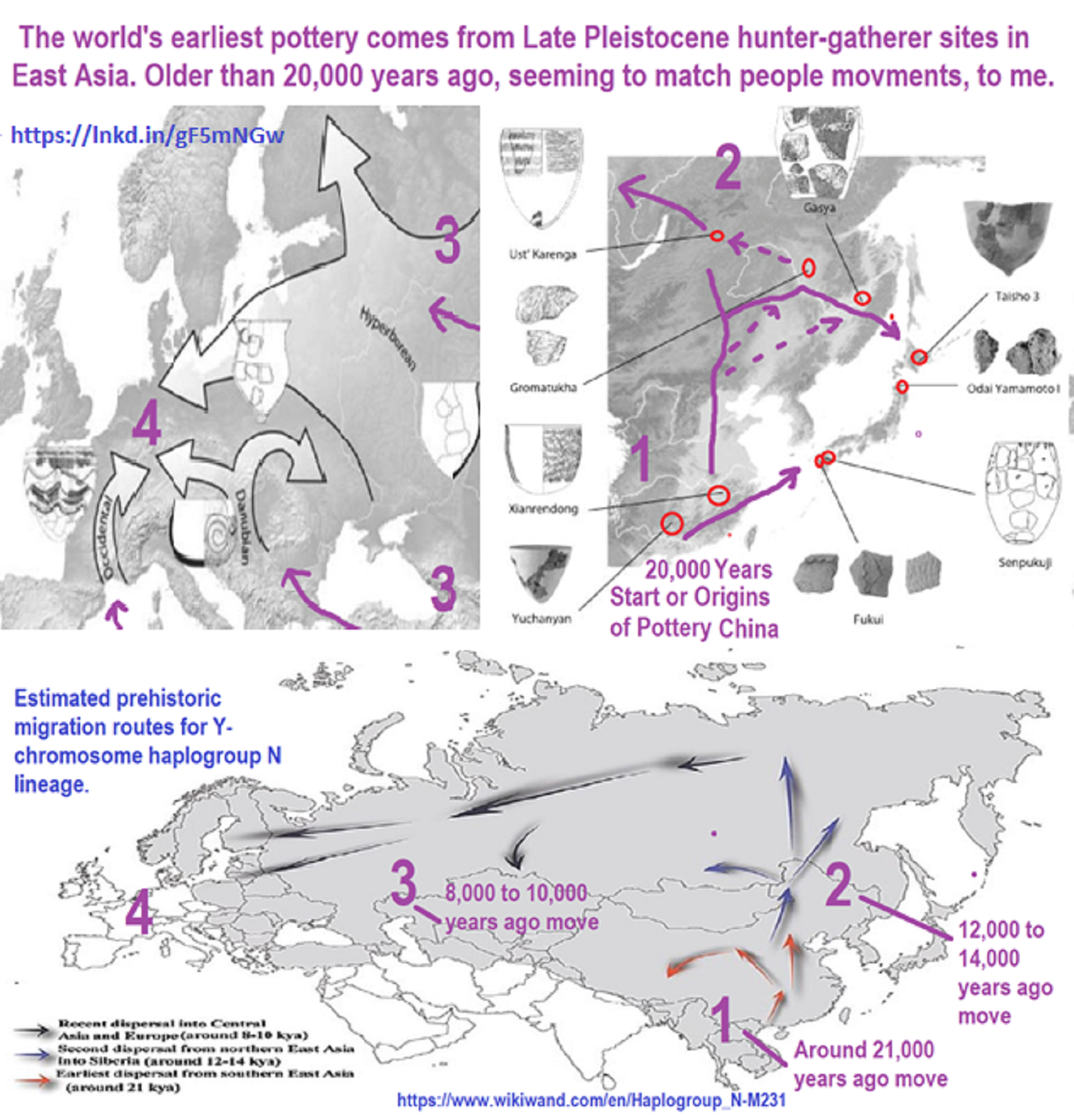

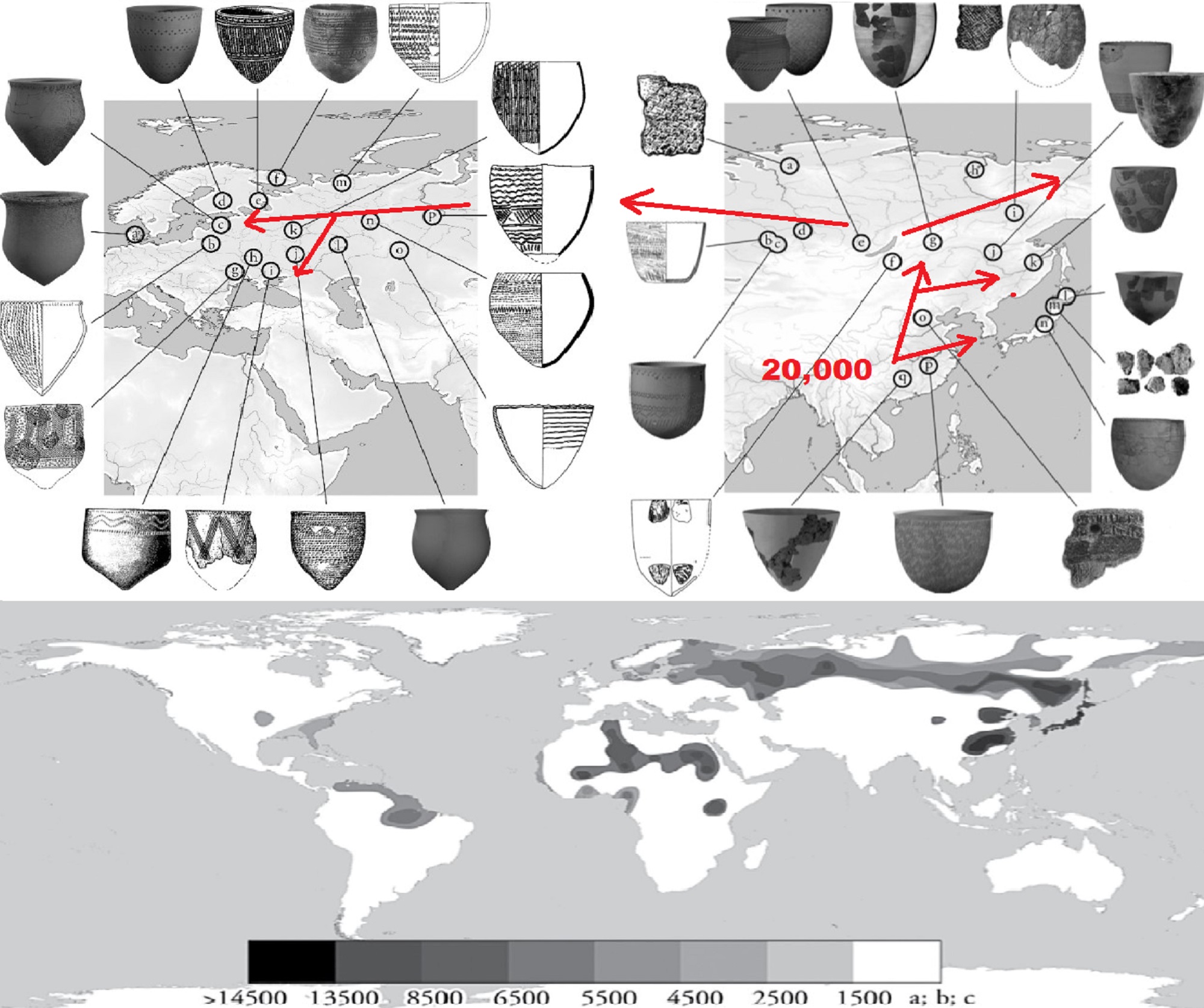

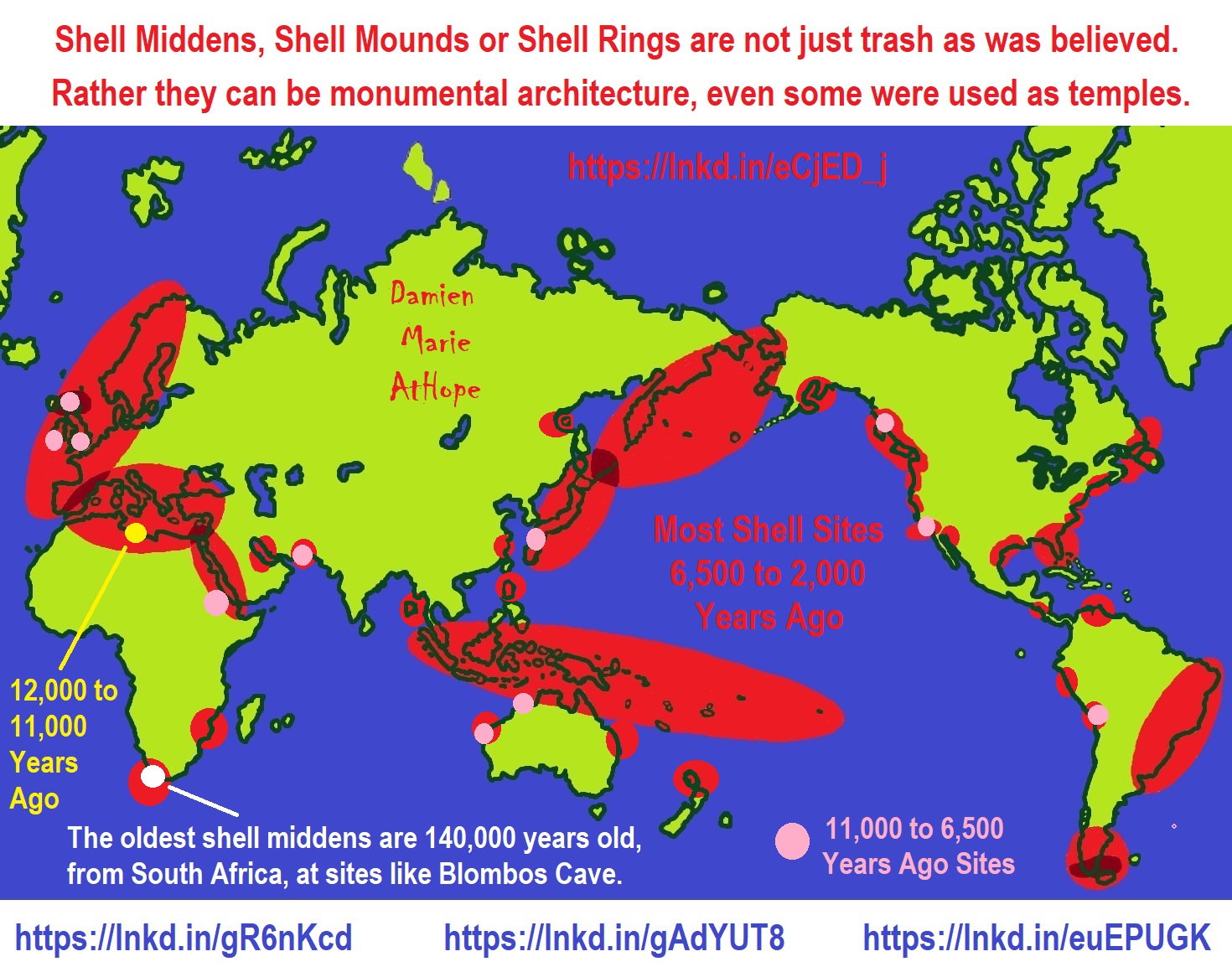

Chinese pottery dates to about 20,000 years BCE.

“China holds the earliest pottery yet known anywhere in the world was found at this site dating by radiocarbon to between 20,000 and 19,000 years ago. The carbon 14 datation was established by careful dating of surrounding sediments. Many of the pottery fragments had scorch marks, suggesting that the pottery was used for cooking. These early pottery containers were made well before the invention of agriculture (dated to 10,000 to 8,000 BC), by mobile foragers who hunted and gathered their food during the Late Glacial Maximum.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Xianren_Cave

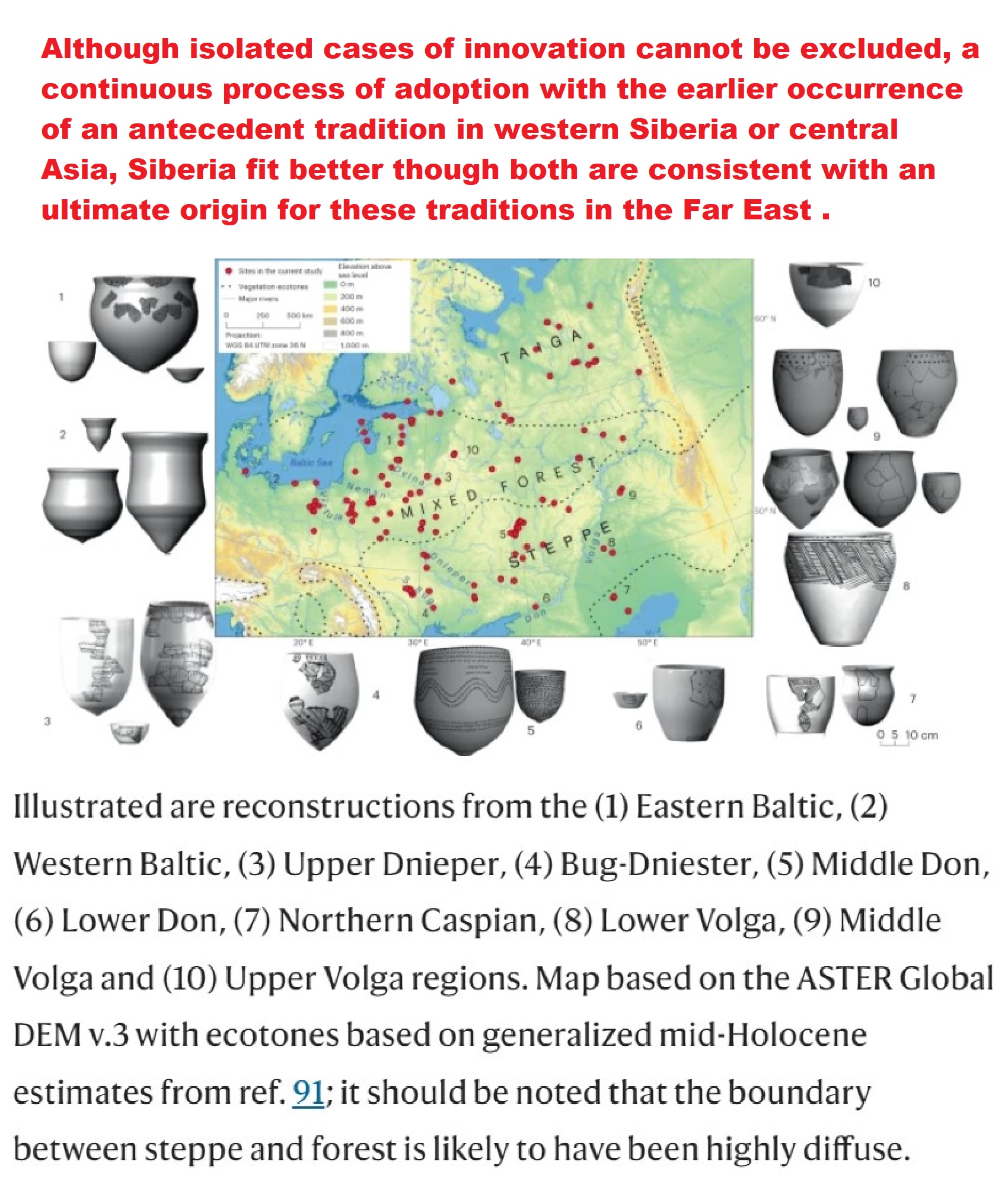

The transmission of pottery technology among prehistoric European hunter-gatherers

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41562-022-01491-8

“Although isolated cases of innovation cannot be excluded, a continuous process of adoption with the earlier occurrence of an antecedent tradition in western Siberia or central Asia, Siberia fit better though both are consistent with an ultimate origin for these traditions in the Far East.” ref

Show 2 “Early Neolithic” China: Ritual, Religion, and Civilization

Use time 6:30 to 8:24 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lz4EQ0iYDI4&t=413s

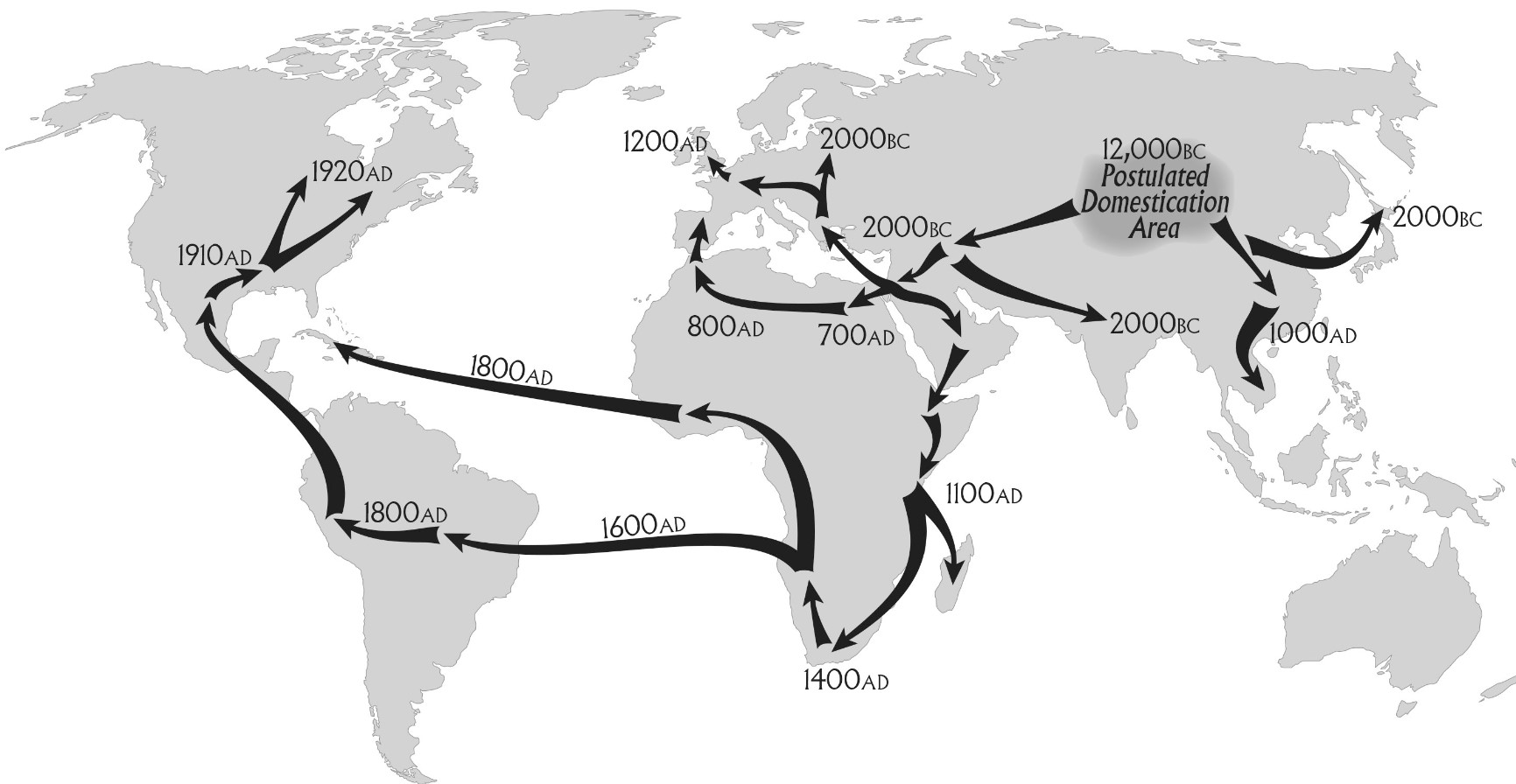

Starting in areas that included North China, the map shows the history of how cannabis traveled throughout the world.

“Hemp was also one of the first plants to be spun into usable fiber 50,000 years ago. It may also be one of the earliest plants to have been cultivated. The world-leading producer of hemp is China, which produces more than 70% of the world output.” ref

“Cannabis plants are believed to have evolved on the steppes of Central Asia, specifically in the regions that are now Mongolia and southern Siberia, according to Warf. The history of cannabis use goes back as far as 12,000 years, which places the plant among humanity’s oldest cultivated crops, according to information in the book “Marihuana: The First Twelve Thousand Years.” “It likely flourished in the nutrient-rich dump sites of prehistoric hunters and gatherers,” Warf wrote in his study.” ref

“Cannabis in China has been confirmed to have originated in Northwest China before the Ancient Chinese domesticated the plant to India and other parts of Asia, particularly the Central Asian steppe in 10,000 BCE or around 12,000 years ago.” ref

“Cannabis or marijuana, was first domesticated around 12,000 years ago in China, researchers found, after analyzing the genomes of plants from across the world. The study, published in the journal Science Advances on Friday, said the genomic history of cannabis domestication had been under-studied compared to other crop species, largely due to legal restrictions. The researchers compiled 110 whole genomes covering the full spectrum of wild-growing feral plants, landraces, historical cultivars, and modern hybrids of plants used for hemp and drug purposes.” ref

“Cannabis has a high nutritional content, which is why all parts of the plant, including the stem, seeds, roots, and flowers, have been used for food, feed, and therapeutic purposes for a long time.” ref

“The history of wheat from about 10,000 BCE or around 12,000 years ago and thought to have first been cultivated in the Fertile Crescent, an area in the Middle East spreading from Jordan, Palestine, and Lebanon to Syria, Turkey, Iraq, and Iran.” ref

“One of the first cultivated grains of the Fertile Crescent, barley was domesticated about 8000 BCE or around 10,000 years ago.” ref

“Earliest domestication of common millet (Panicum miliaceum) in East Asia extended to 10,000 years ago” ref

“Lentils were first cultivated in Southwest Asia 8000–10,000 years ago but archeological evidence is unclear as to how many times it may have been independently domesticated.” ref

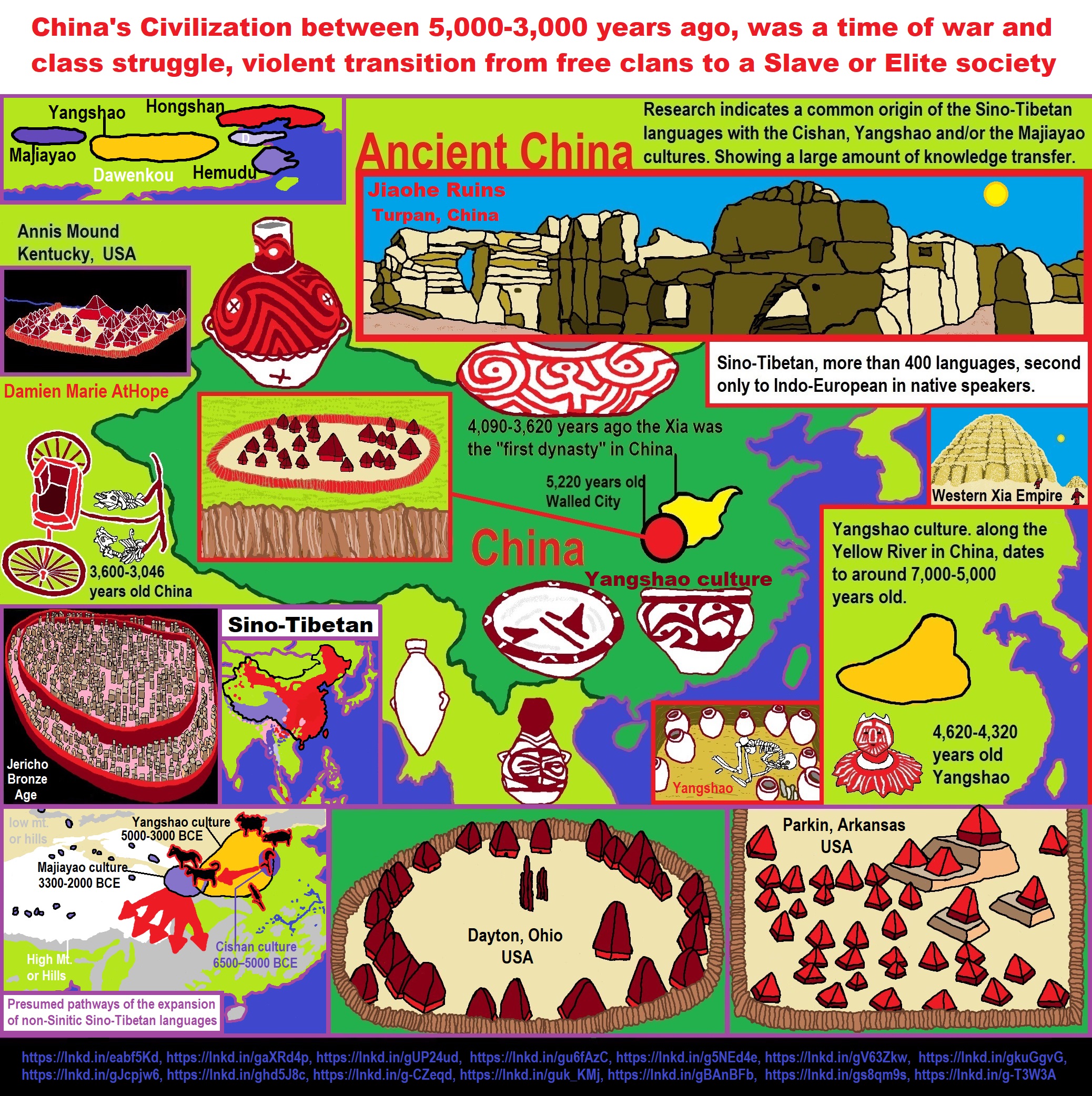

“The earliest archaeological evidence of Rice comes from central and eastern China and dates to 7000–5000 BCE or around 9,000 to 7,000 years ago.” ref

“The study said it identified “the time and origin of domestication, post-domestication divergence patterns, and present-day genetic diversity”. “Researchers show that cannabis sativa was first domesticated in early Neolithic times in East Asia and that all current hemp and drug cultivars diverged from an ancestral gene pool currently represented by feral plants and landraces in China”. Cannabis has been used for millennia for things like textiles/clothing, nets/etc. and for its medicinal and recreational properties, not to mention its likely ritual use. The evolution of the cannabis genome suggests the plant was cultivated for multipurpose use over several millennia.” ref

“Our genomic dating suggests that early domesticated ancestors of hemp and drug types diverged from Basal cannabis”, around 12,000 years ago, “indicating that the species had already been domesticated by early Neolithic times”, it said. “Contrary to a widely-accepted view, which associates cannabis with a Central Asian center of crop domestication, our results are consistent with a single domestication origin of cannabis sativa in East Asia, in line with early archaeological evidence.” It said that some of the wild plants currently found in China represent the closest descendants of the ancestral gene pool from which hemp and marijuana varieties have since derived.” ref

“East Asia has been shown to be an important ancient hot spot of domestication for several crop species… our results thus add another line of evidence,” the study said. The researchers said their study offered an “unprecedented” base of genomic resources for ongoing molecular breeding and functional research, both in medicine and in agriculture. The study, they said, also “provides new insights into the domestication and global spread of a plant with divergent structural and biochemical products at a time in which there is a resurgence of interest in its use, reflecting changing social attitudes and corresponding challenges to its legal status in many countries.” ref

“For the most part, it was widely used for medicine and spiritual purposes,” during pre-modern times, said Warf, a professor of geography at the University of Kansas in Lawrence. “The idea that this is an evil drug is a very recent construction,” and the fact that it is illegal is a “historical anomaly,” Warf said. Marijuana has been legal in many regions of the world for most of its history.” ref

“The use of hemp in Taiwan dates back at least 10,000 years.” An archeological site in the Oki Islands near Japan contained cannabis achenes from about 8000 BCE or 10,000 years ago, probably signifying use of the plant.” ref

“The Peiligang culture was a Neolithic culture in the Yi-Luo river basin (in modern Henan Province, China) that existed from about 7000 to 5000 BCE or around 9,000 to 7,000 years ago. The Peiligang culture used nets made from hemp fibers. The site at Jiahu also with nets made of hemp fibers, is the earliest site associated with Peiligang culture.” ref, ref

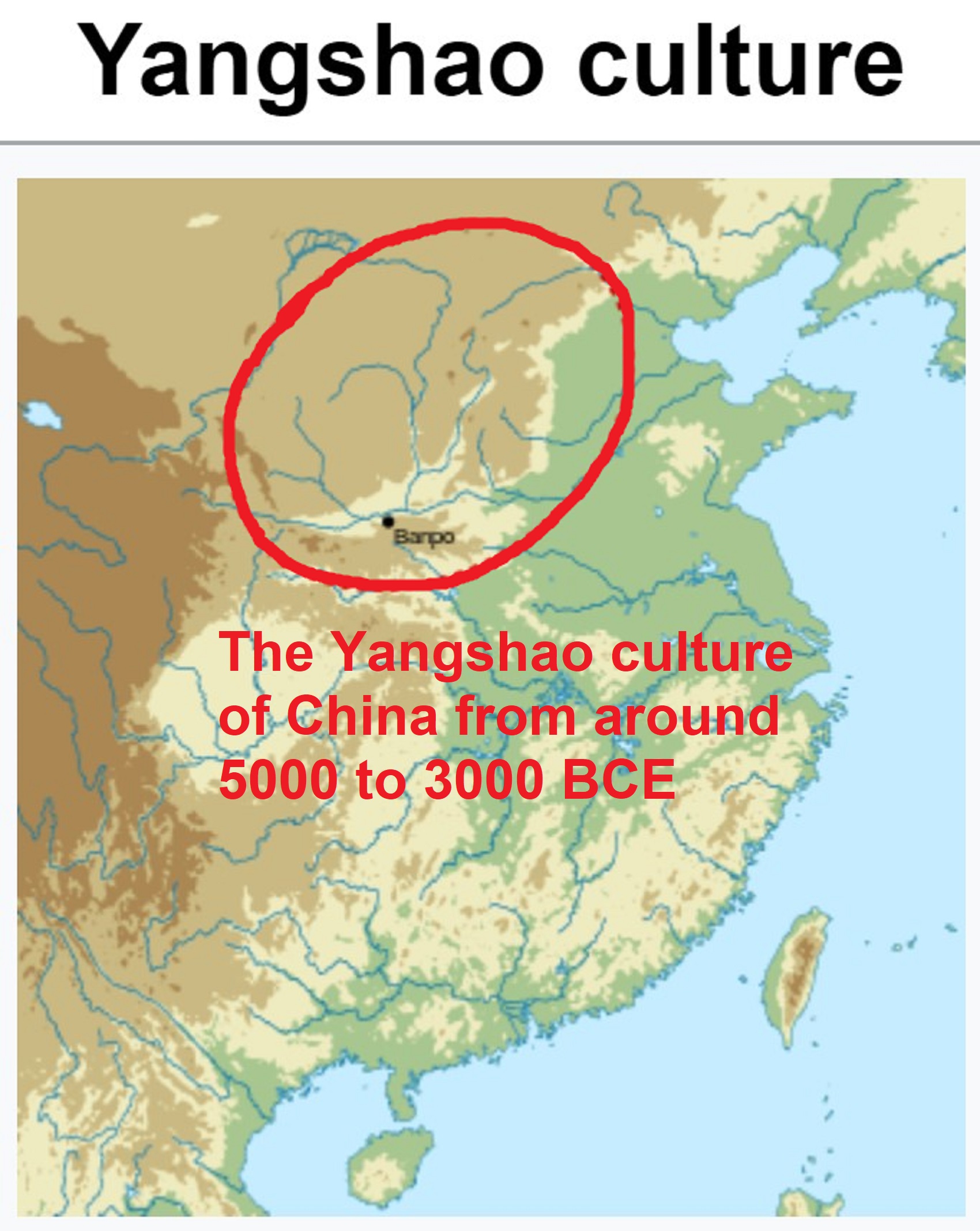

“Hemp use archaeologically dates back to the Neolithic Age in China, with hemp fiber imprints found on Yangshao culture pottery dating from the 5th millennium BCE or around 7,000 to 6,000 years ago.” ref

“Both hemp and psychoactive marijuana were used widely in ancient China, Warf wrote. The first record of the drug’s medicinal use dates to 4000 BCE or around 6,000 years ago. Burned cannabis seeds have also been found in kurgan burial mounds in Siberia dating back to 3,000 BCE or around 5,000 years ago.” ref

“The medicinal properties of the cannabis plant have been known for millennia. As far back as 2800 BCE or around 4,800 years ago, cannabis was used to treat a vast array of health problems and was listed in Emperor Shen Nung’s pharmacopoeia. Cannabis has a long and colorful history. The use of cannabis originated in central Asia or western China. Cannabis has been used for its alleged healing properties for millennia. The first documented case of its use dates back to 2800 BCE, when it was listed in the Emperor Shen Nung’s (regarded as the father of Chinese medicine) pharmacopoeia. Therapeutic indications of cannabis are mentioned in the texts of the Indian Hindus, Assyrians, Greeks and Romans. Hindu legend holds that Shiva, the supreme Godhead of many sects, was given the title ‘The Lord of Bhang’, because the cannabis plant was his favorite food. The ancient Hindus thought the medicinal benefits of cannabis were explained by pleasing the gods such as Shiva. Ancient Hindu texts attribute the onset of fever with the ‘hot breath of the gods’ who were angered by the afflicted person’s behavior. Using cannabis in religious rites appeased the gods and hence reduced the fever.” ref

“The herb was used, for instance, as an anesthetic during surgery, and stories say it was even used by the Chinese Emperor Shen Nung in 2737 BCE. (However, whether Shen Nung was a real or a mythical figure has been debated, as the first emperor of a unified China was born much later than the supposed Shen Nung.) And some of the tombs of noble people buried in Xinjiang region of China and Siberia around 2500 BCE have included large quantities of mummified psychoactive marijuana.” ref

“Historically, cannabis has been used in China for fiber, seeds, as a traditional medicine, as well as for some ritual purposes within Taoism. Má (Mandarin pronunciation: [mǎ]), a Chinese word for cannabis, is represented by the Han character 麻. The term ma, used to describe medical marijuana by 2700 BCE or around 4,700 years ago, is the oldest recorded name for the hemp plant. The word ma has been used to describe the cannabis plant since before the invention of writing five-thousand years ago. Ma might share a common root with the Proto-Semitic word mrr, meaning “bitter.” Evidence of the earliest human cultivation of cannabis was found in Taiwan. Ancient Chinese prose and poems, including poetry in the Shi jing (Book of Odes), mention the word ma many times. An early song refers to young women weaving ma into clothing. The word ma is often paired with the Chinese word for “big” or “great” to form the compound word dama or 大麻 (dàmá). Dama is sometimes used to describe industrial hemp, as there is a negative connotation meaning “numbness” associated with the word ma by itself.” ref

“The current highly-specialized hemp and drug varieties are thought to come from selective cultures initiated about 4,000 years ago, optimized for the production of fibers or cannabinoids. The selection led to unbranched, tall hemp plants with more fiber in the main stem, and well-branched, short marijuana plants with more flowers, maximizing resin production.” ref

Archaeobotanical evidence of the use of medicinal cannabis in a secular context unearthed from south China

Abstract: “As one of the first plants used by ancient people, cannabis has been used for medicinal purposes for thousands of years. The long history of medicinal cannabis use contrasts with the paucity of archaeobotanical records. Moreover, physical evidence of medicinal cannabis use in a secular context is much rarer than evidence of medicinal cannabis use in religious or ritual activities, which impedes our understanding of the history of medicinal cannabis use. Plant remains were collected from the Laoguanshan Cemetery of the Han Dynasty in Chengdu, South China. The botanical remains were accurately identified as cannabis. More than 120 thousand fruits were found, which represents the largest amount of cannabis fruit remains that have been statistically analyzed from any cemetery in the world thus far.” ref

“Charred cannabis seeds that are more than 4,000 years old have been found in special braziers from graves at Gurbanesti and the northern Caucasus region in Eastern Europe. These seeds may be the earliest evidence of the intentional burning of cannabis for psychoactive use and may thus represent the first physical evidence of medicinal cannabis use (the non-psychoactive cannabis seeds remain after the psychoactive inflorescences and leaves have been burnt away). In addition, some remains from Central Asia, such as nearly 13 whole cannabis plants from Jiayi Cemetery, female inflorescences of cannabis from Yanghai Cemetery in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, Northwest China, and cannabis fruits from Pazyryk Cemetery in East Siberia, are thought to indicate the use of cannabis for medical purposes.” ref

“From China, coastal farmers brought pot to Korea about 2000 BCE at around 4,000 years ago, or earlier, according to the book “The Archeology of Korea. Cannabis came to the South Asian subcontinent between 2000 to 1000 BCE, when the region was invaded by the Indo-Iranian speaking peoples — a group that spoke an archaic Indo-European language. The drug became widely used in India, where it was celebrated as one of “five kingdoms of herbs … which release us from anxiety” in one of the ancient Sanskrit Vedic poems whose name translate into “Science of Charms.” ref

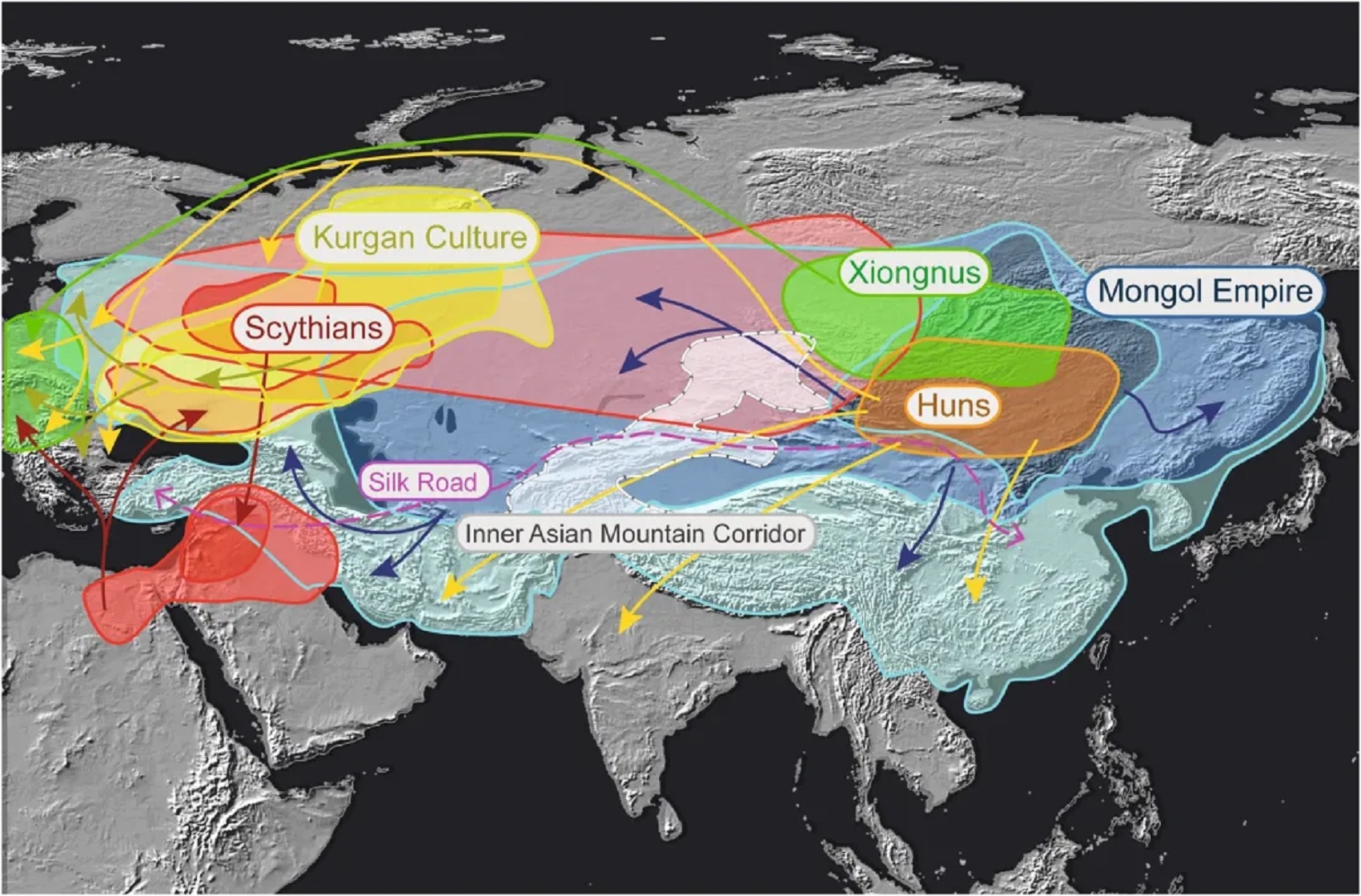

“From Asia to Europe, Cannabis came to the Middle East between 2000 to 1400 BCE or around 4,000 to 3,400 years ago, and it was probably used there by the Scythians, a nomadic Indo-European group. The Scythians also likely carried the drug into southeast Russia and Ukraine, as they occupied both territories for years, according to Warf’s report. Germanic tribes brought the drug into Germany, and marijuana went from there to Britain during the 5th century with the Anglo-Saxon invasions.” ref

“Different religions have varying stances on the use of cannabis, historically and presently. In ancient history some religions used cannabis as an entheogen, particularly in the Indian subcontinent where the tradition continues on a more limited basis. In Ancient Egypt there is a written record of the medicinal use of hemp. Thus the Ebers papyrus (written 1500 BCE or around 3,500 years ago) mentions the use of oil from hempseed to treat vaginal inflammation. Cannabis pollen was recovered from the tomb of Ramses II, who governed for sixty‐seven years during the 19th dynasty, and several mummies contain trace cannabinoids.” ref

“The Assyrians, Egyptians, and Hebrews, among other Semitic cultures of the Middle East, mostly acquired cannabis from Aryan cultures and have burned it as an incense as early as 1000 BCE or around 3,000 years ago. Cannabis has been used by shamanic and pagan cultures to ponder deeply religious and philosophical subjects related to their tribe or society, to achieve a form of enlightenment, to unravel unknown facts and realms of the human mind and subconscious, and also as an aphrodisiac during rituals or orgies. There are several references in Greek mythology to a powerful drug that eliminated anguish and sorrow. Herodotus wrote about early ceremonial practices by the Scythians, thought to have occurred from the 5th to 2nd century BCE or 2,500 to 2,200 years ago.” ref

“In addition, according to Herodotus, the Dacians and Scythians had a tradition where a fire was made in an enclosed space and cannabis seeds were burned and the resulting smoke ingested. In ancient Germanic paganism, cannabis was possibly associated with the Norse love goddess, Freya. Linguistics offers further evidence of prehistoric use of cannabis by Germanic peoples: The word hemp derives from Old English hænep, from Proto-Germanic *hanapiz. While *hanapiz has an unknown origin, some scholars believe it is a unreconstructed loanword of Scythian origin. The Greek word κάνναβις, which that cannabis derives from, is also thought to be a loanword of the same Scythian origin. While a loanword, *hanapiz was borrowed early enough to be affected by Grimm’s Law, by which Proto-Indo-European initial *k- becomes *h- in Germanic. The shift of *k→h indicates it was a loanword into the Germanic parent language at a time depth no later than the separation of Common Germanic from Proto-Indo-European, about 500 BCE or around 2,500 years ago.” ref

“People may have smoked marijuana in rituals 2,500 years ago in western China. Cannabis may have been altering minds at an ancient high-altitude cemetery, researchers say. Mourners gathered at a cemetery in what’s now western China around 2,500 years ago to inhale fumes of burning cannabis plants that wafted from small wooden containers. High levels of the psychoactive compound THC in those ignited plants, also known as marijuana, would have induced altered states of consciousness. Evidence of this practice comes from Jirzankal Cemetery in Central Asia’s Pamir Mountains, says a team led by archaeologist Yimin Yang of the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing. Chemical residues on wooden burners unearthed in tombs there provide some of the oldest evidence to date of smoking or inhaling cannabis fumes, the researchers report online June 12 in Science Advances.” ref

“Rituals aimed at communicating with the dead or a spirit world likely included cannabis smoking, the team speculates. Cannabis remains of comparable age have been found in several other Central Asian tombs, including a site in Russia’s Altai Mountains located about 3,000 kilometers northwest of the Pamir Mountains. But the discoveries at Jirzankal Cemetery offer an unprecedented look at how cannabis was initially used as a mind-altering substance, the researchers say. East Asians grew cannabis starting at least 6,000 years ago, but only to consume the plants’ oily seeds and make clothing and rope out of cannabis fibers. Early cultivated cannabis varieties in East Asia and elsewhere, like most wild forms of the plant, contained low levels of THC and other mind-altering compounds.” ref

“Some of the earliest evidence for people smoking marijuana comes from the Greek historian Herodotus, who wrote of cannabis smoking roughly 2,500 years ago on the Central Asian steppes, about 2,000 kilometers west of the Pamir Mountains. But a determination of exactly when and where high-THC cannabis plants first developed and which people first smoked cannabis has long eluded scientists. Archaeological finds indicate that many burial practices had spread across Central and East Asia by around 2,500 years ago. So cannabis smoking at graveside ceremonies was likely part of that process, says archaeologist Michael Frachetti of Washington University in St. Louis, who did not participate in the new study. “At that time, the early Silk Road connected populations from Beijing to Venice,” he says.” ref

“People have been smoking pot to get high for at least 2,500 years. Chinese archaeologists found signs of that when they studied the char on a set of wooden bowls from an ancient cemetery in western China. The findings are some of the earliest evidence of cannabis used as a drug.” ref

“Historical Chinese medical texts (c. 200 CE) through contemporary twentieth century Chinese medical literature discuss individual terms for ma, including mafen (麻蕡), mahua (麻花), and mabo (麻勃), referring to specific parts of the male and female flowers of a cannabis plant with differing cannabinoid ratios. Beginning around the 4th century, Taoist texts mentioned using cannabis in censers.” ref

“Needham cited the (ca. 570 CE) Taoist encyclopedia Wushang Biyao 無上秘要 (“Supreme Secret Essentials”) that cannabis was added into ritual incense-burners, and suggested the ancient Taoists experimented systematically with “hallucinogenic smokes”. Joseph Needham connected myths about Magu, “the Hemp Damsel”, with early Daoist religious usages of cannabis, pointing out that Magu was goddess of Shandong’s sacred Mount Tai, where cannabis “was supposed to be gathered on the seventh day of the seventh month, a day of séance banquets in the Taoist communities.” ref

|

8500–7700 |

Nanzhuangtou culture |

南莊頭遺址 |

Yellow River region in southern Hebei |

|

7500–6100 |

Pengtoushan culture |

彭頭山文化 |

|

|

7000–5000 |

裴李崗文化 |

Yi-Luo river basin valley in Henan |

|

|

6500–5500 |

後李文化 |

||

|

6200–5400 |

興隆洼文化 |

Inner Mongolia–Liaoning border |

|

|

6000–5000 |

Kuahuqiao culture |

跨湖桥文化 |

|

|

6000–5500 |

磁山文化 |

southern Hebei |

|

|

5800–5400 |

大地灣文化 |

||

|

5500–4800 |

新樂文化 |

lower Liao River on the Liaodong Peninsula |

|

|

5400–4500 |

趙宝溝文化 |

Luan River valley in Inner Mongolia and northern Hebei |

|

|

5300–4100 |

北辛文化 |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Neolithic_cultures_of_China

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

1. Kebaran culture 23,022-16,522 Years Ago, 2. Kortik Tepe 12,422-11,722 Years Ago, 3. Jerf el-Ahmar 11,222 -10,722 Years Ago, 4. Gobekli Tepe 11,152-9,392 Years Ago, 5. Tell Al-‘abrUbaid and Uruk Periods, 6. Nevali Cori 10,422 -10,122 Years Ago, 7. Catal Hoyuk 9,522-7,722 Years Ago

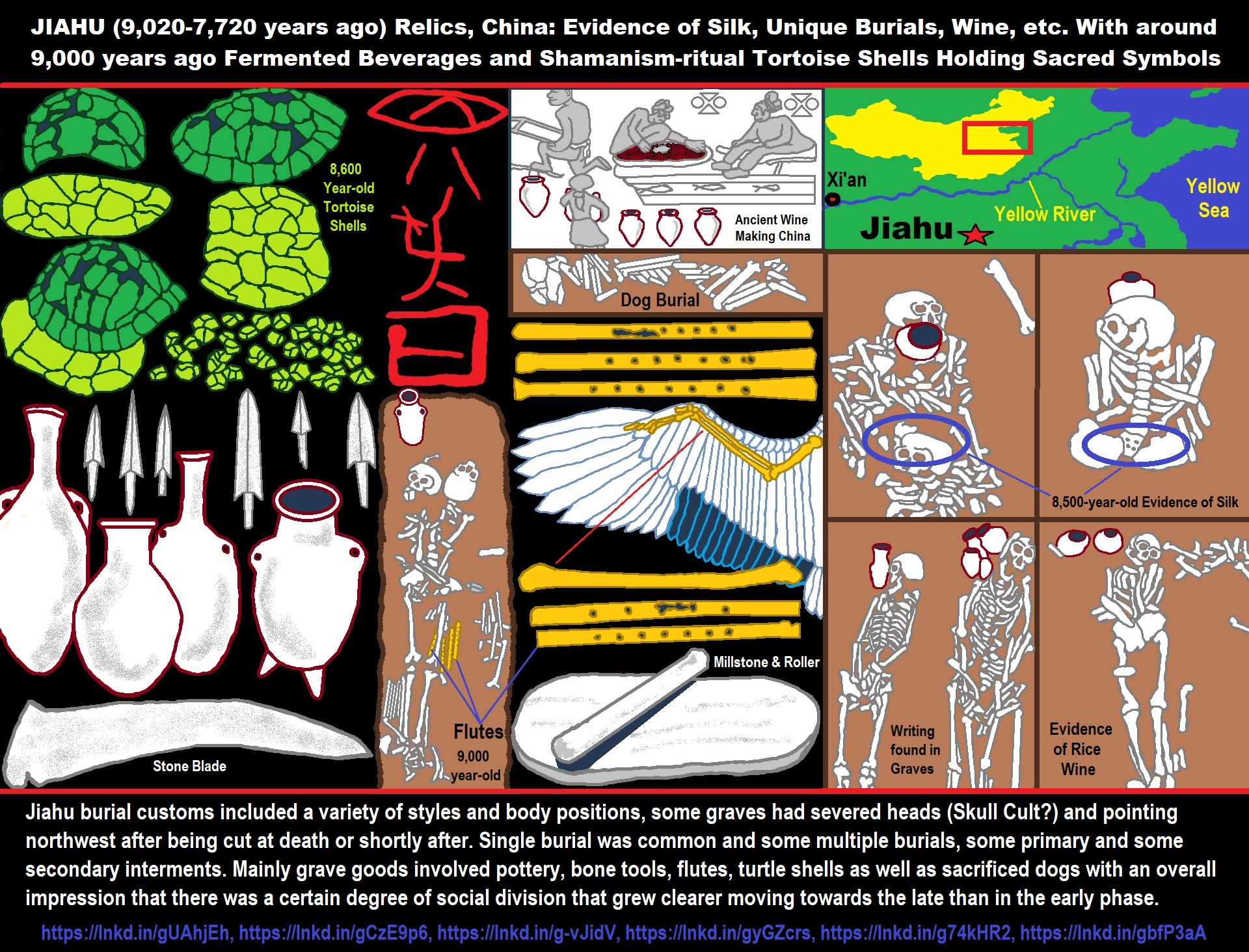

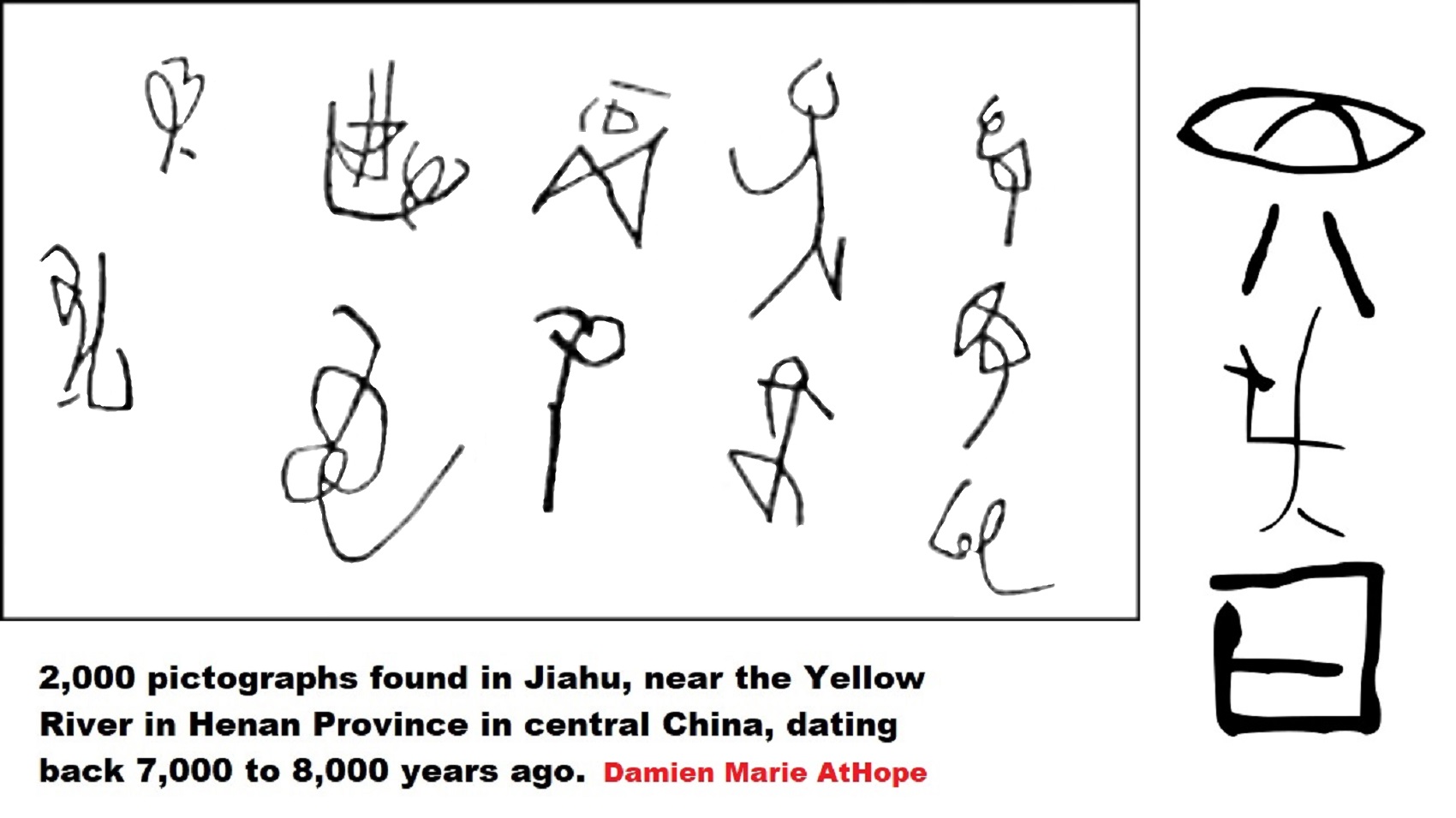

“Jiahu was the site of a Neolithic settlement based in the central plain of ancient China, near the Yellow River. Settled around 7000 BCE, the site was later flooded and abandoned around 5700 BCE. Jiahu symbols, possibly an early proto-writing.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jiahu

“The Jiahu symbols consist of 16 distinct markings on prehistoric artifacts found in Jiahu, a neolithic Peiligang culture site found in Henan, China, and excavated in 1989. The Jiahu symbols are dated to around 6000 BCE.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jiahu_symbols

Pic ref

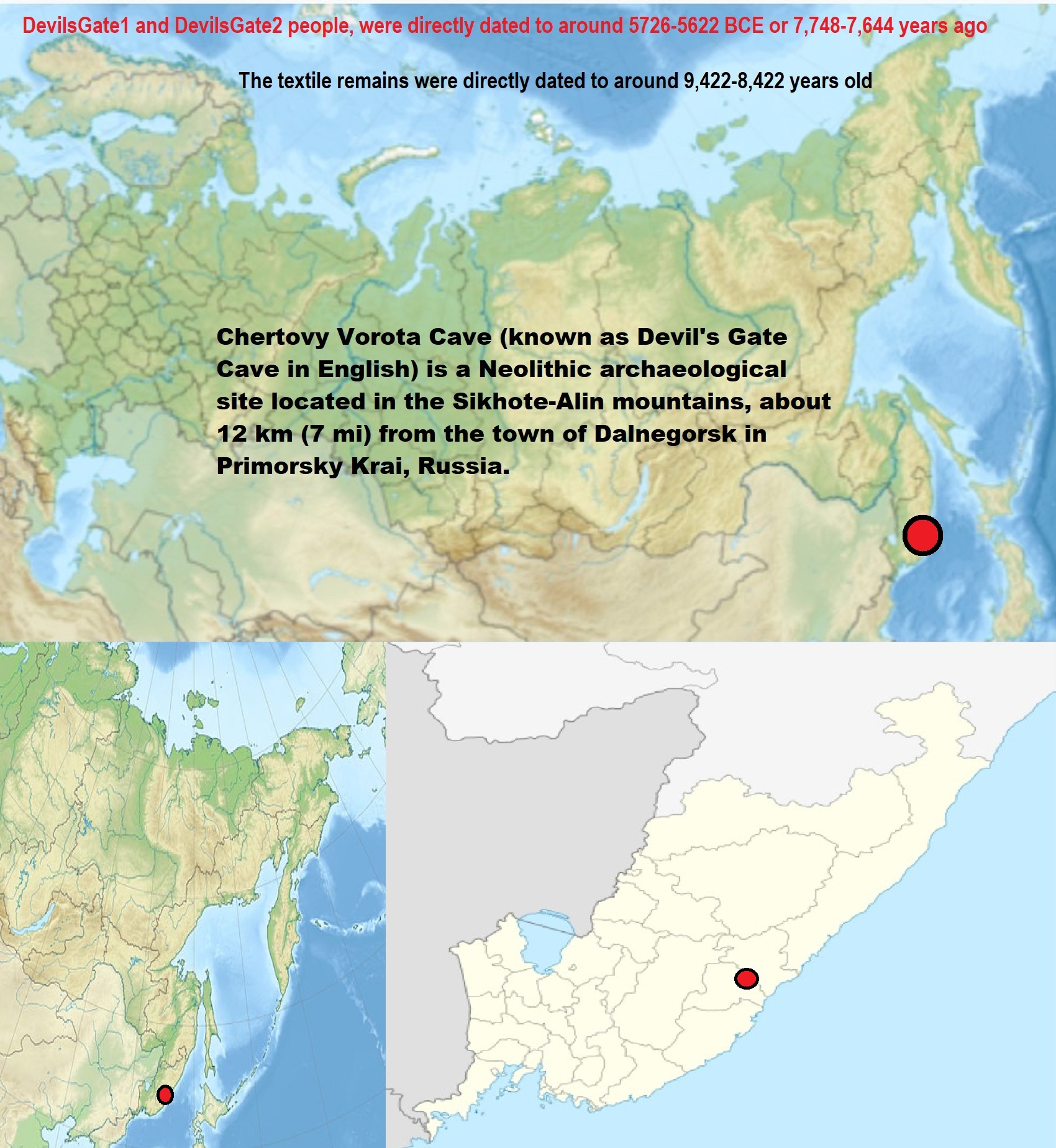

Ancient Women Found in a Russian Cave Turn Out to Be Closely Related to The Modern Population https://www.sciencealert.com/ancient-women-found-in-a-russian-cave-turn-out-to-be-closely-related-to-the-modern-population

Abstract

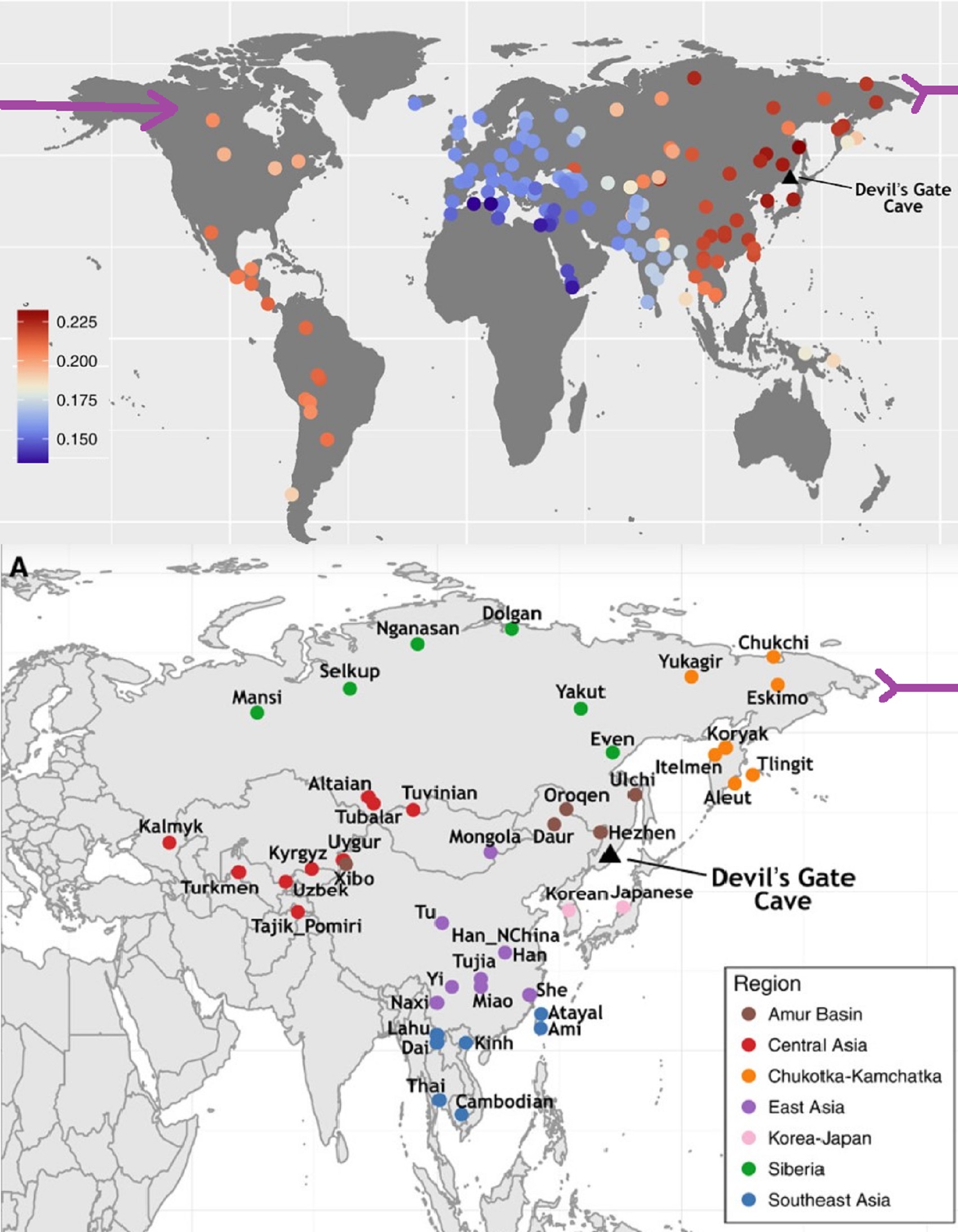

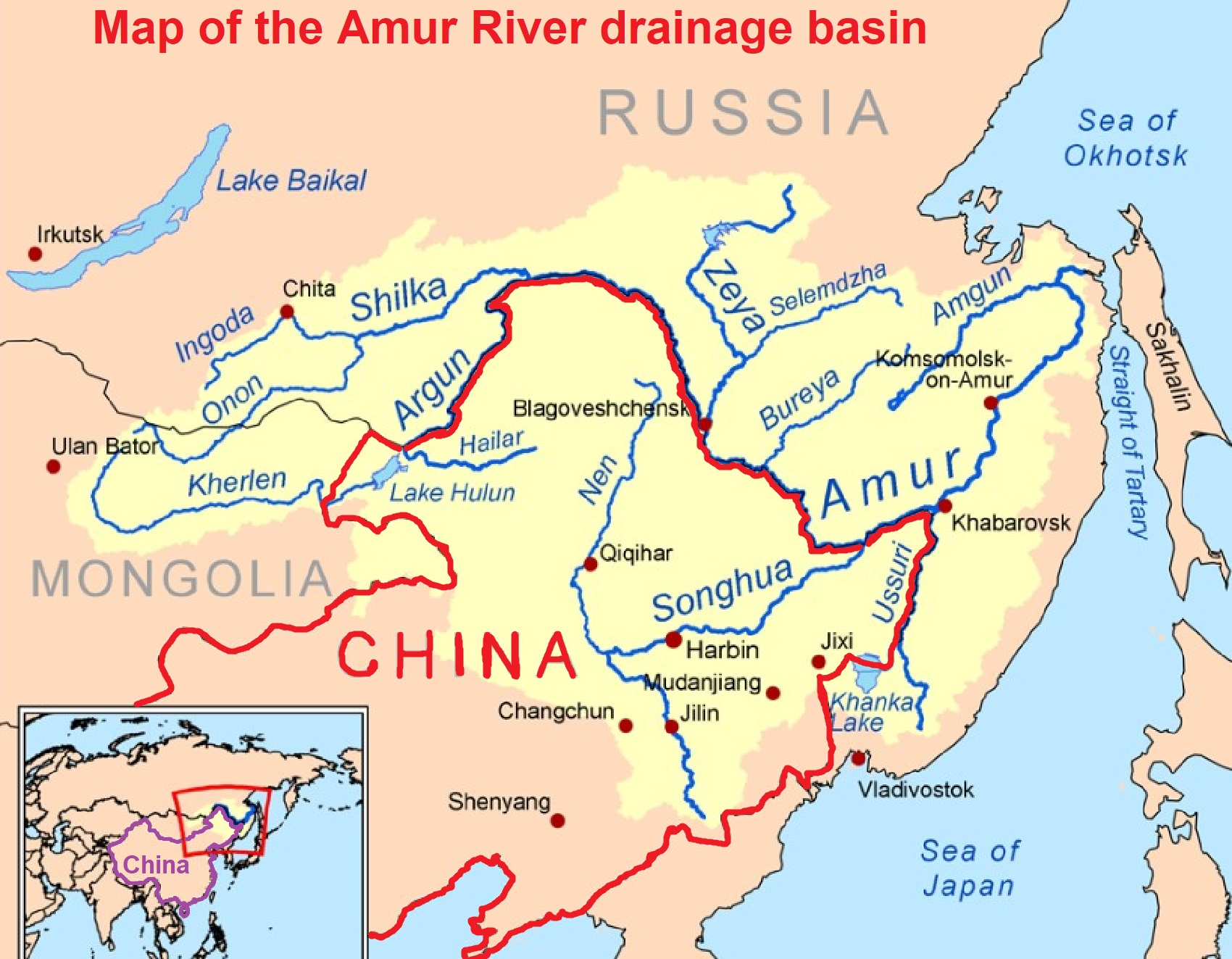

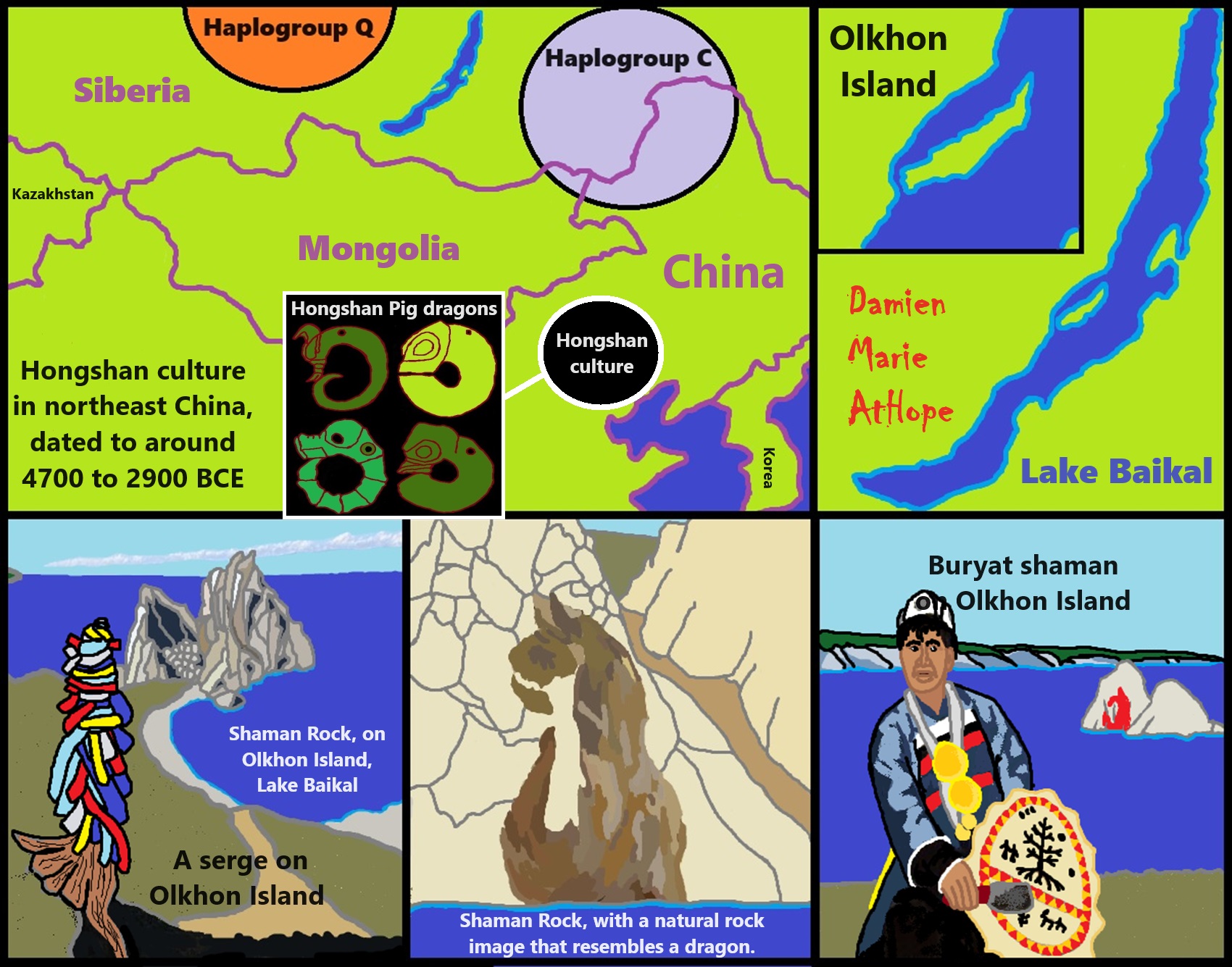

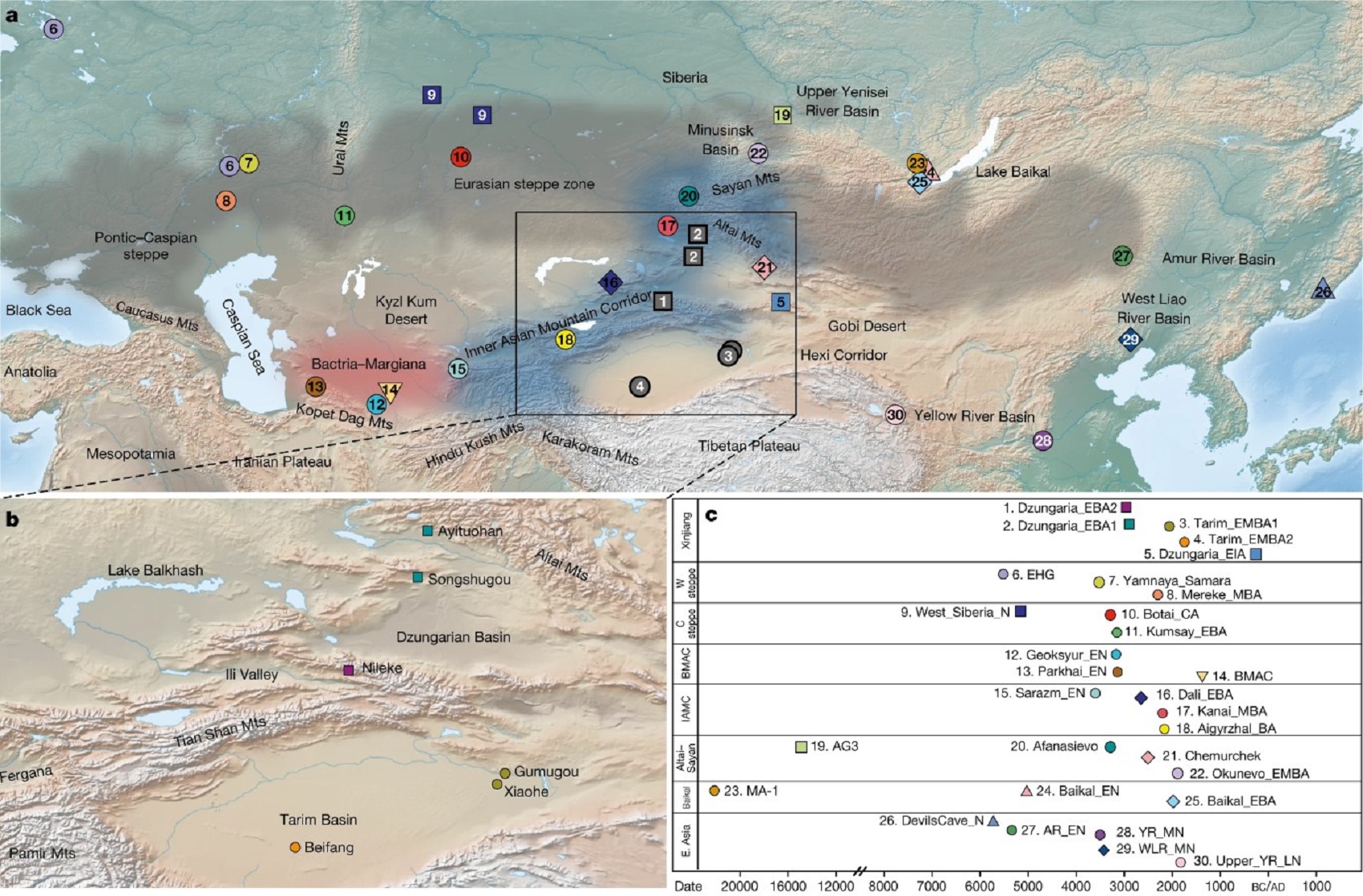

“Ancient genomes have revolutionized our understanding of Holocene prehistory and, particularly, the Neolithic transition in western Eurasia. In contrast, East Asia has so far received little attention, despite representing a core region at which the Neolithic transition took place independently ~3 millennia after its onset in the Near East. We report genome-wide data from two hunter-gatherers from Devil’s Gate, an early Neolithic cave site (dated to ~7.7 thousand years ago) located in East Asia, on the border between Russia and Korea. Both of these individuals are genetically most similar to geographically close modern populations from the Amur Basin, all speaking Tungusic languages, and, in particular, to the Ulchi. The similarity to nearby modern populations and the low levels of additional genetic material in the Ulchi imply a high level of genetic continuity in this region during the Holocene, a pattern that markedly contrasts with that reported for Europe.” ref

“Six of seven individuals whose remains have been recovered from the cave have been DNA tested. Originally, three of the specimens were thought to be adult males, two were thought to be adult females, one was thought to be a sub-adult of about 12-13 years of age, and one was thought to be a juvenile of about 6-7 years of age based on the skeletal morphology of the remains. Results of genetic analysis of the sub-adult individual have not yet been published. However, two specimens, NEO236 (Skull B, DevilsGate2) and NEO235 (Skull G), who had been presumed to be adult males according to a forensic morphological assessment of their remains, were discovered through genetic analysis to actually be females. The juvenile specimen also has been determined to be female through genetic analysis. Three of the specimens (including the only adult male plus NEO235/Skull G and another adult female, labeled as Skull Е, DevilsGate1, or NEO240, who has been genetically determined to be a first-degree relative of NEO235/Skull G) have been assigned to mtDNA haplogroup D4m; a previous genetic analysis of one of these adult female specimens determined her mtDNA haplogroup to be D4. Another three specimens (including the juvenile female, the DevilsGate2 specimen, and another adult female; both the juvenile female and the DevilsGate2 specimen have been determined to be first-degree relatives of the other adult female, and the juvenile female and the DevilsGate2 specimen also have been determined to be second-degree relatives of each other) have been assigned to haplogroup D4; a previous genetic analysis of the DevilsGate2 specimen determined her mtDNA haplogroup to be M. The only specimen from the cave who has been confirmed to be male through genetic analysis has been assigned to Y-DNAhaplogroup C2b-F6273/Y6704/Y6708, equivalent to C2b-L1373, the northern (Central Asian, Siberian, and indigenous American) branch of haplogroup C2-M217.” ref

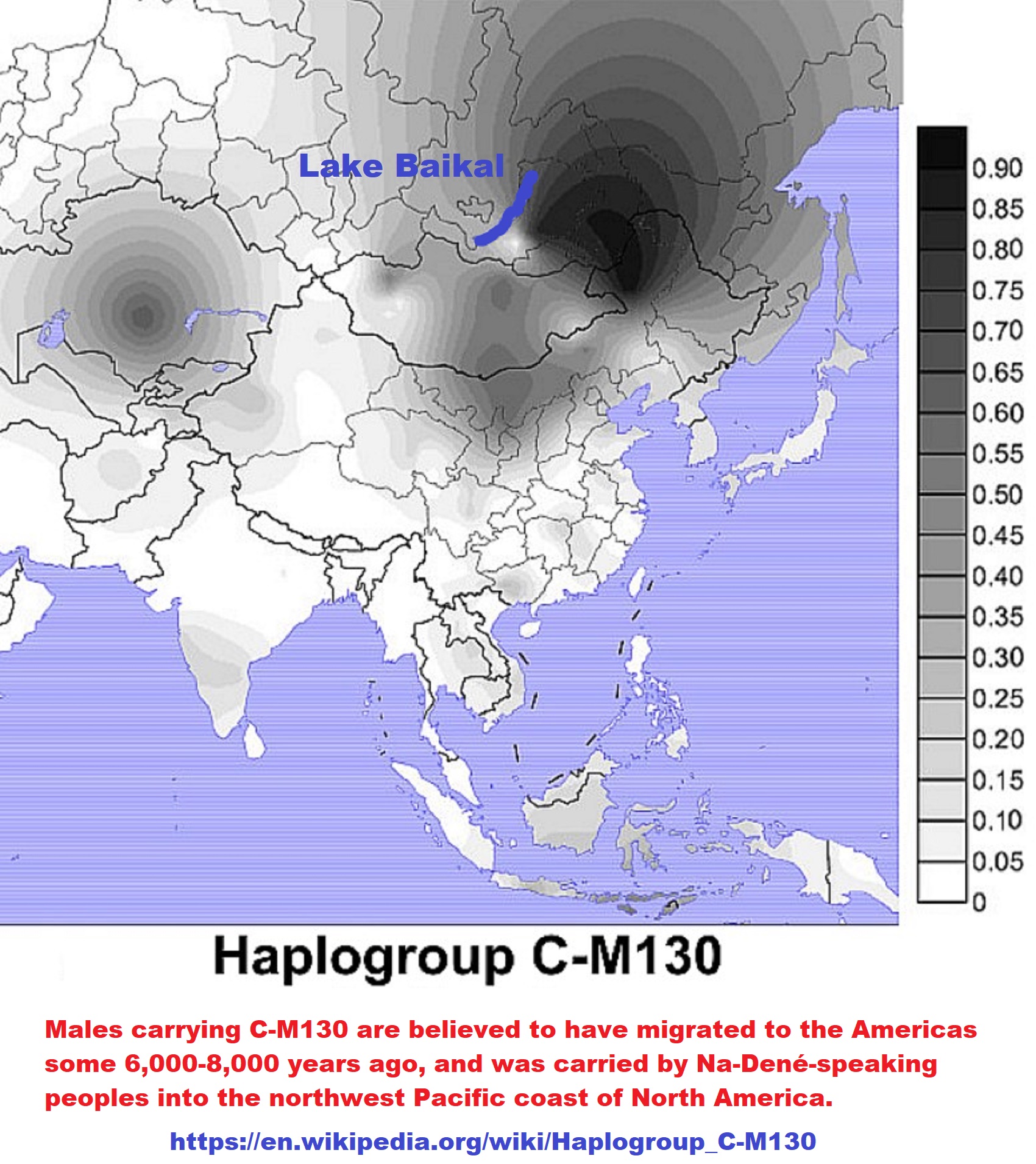

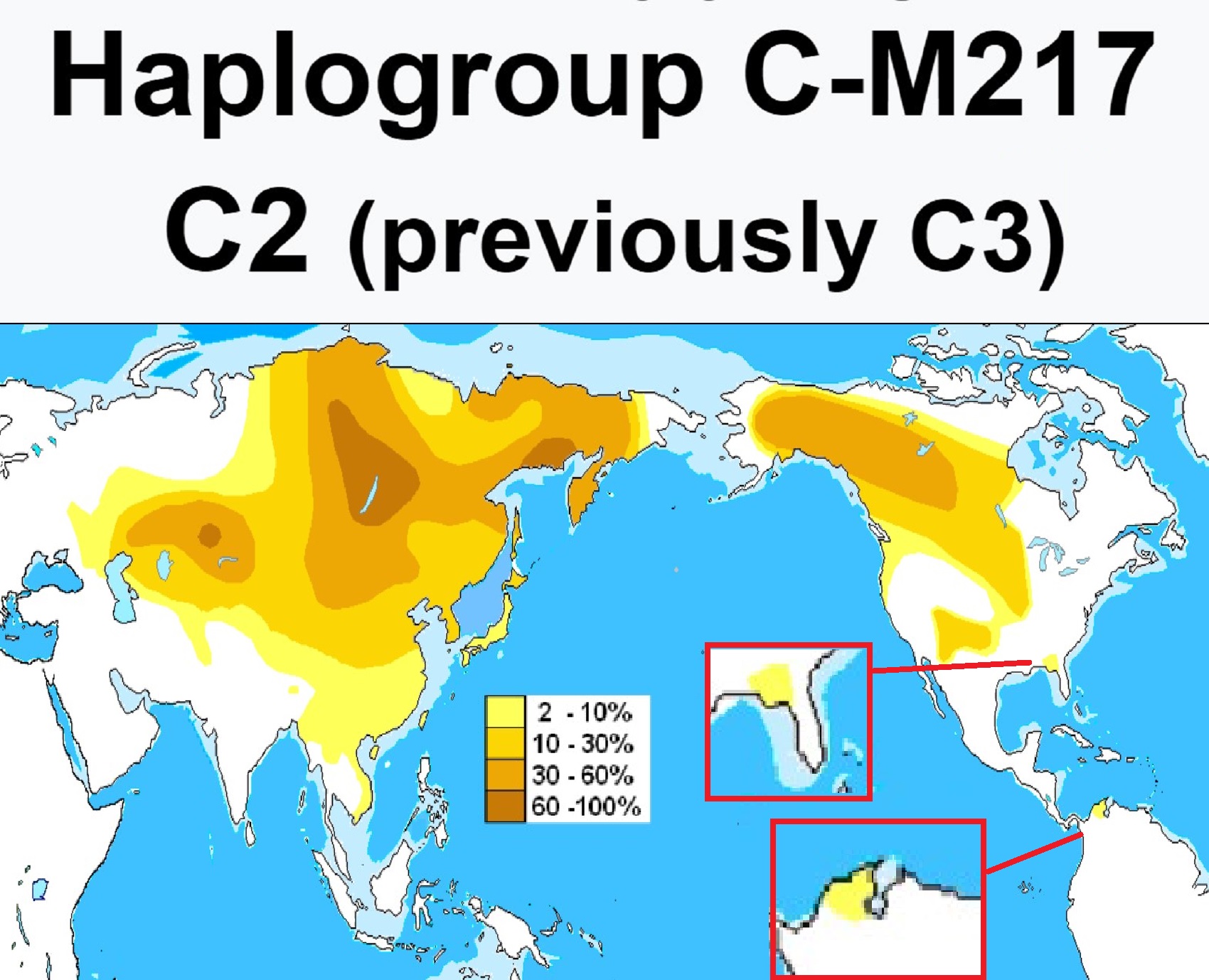

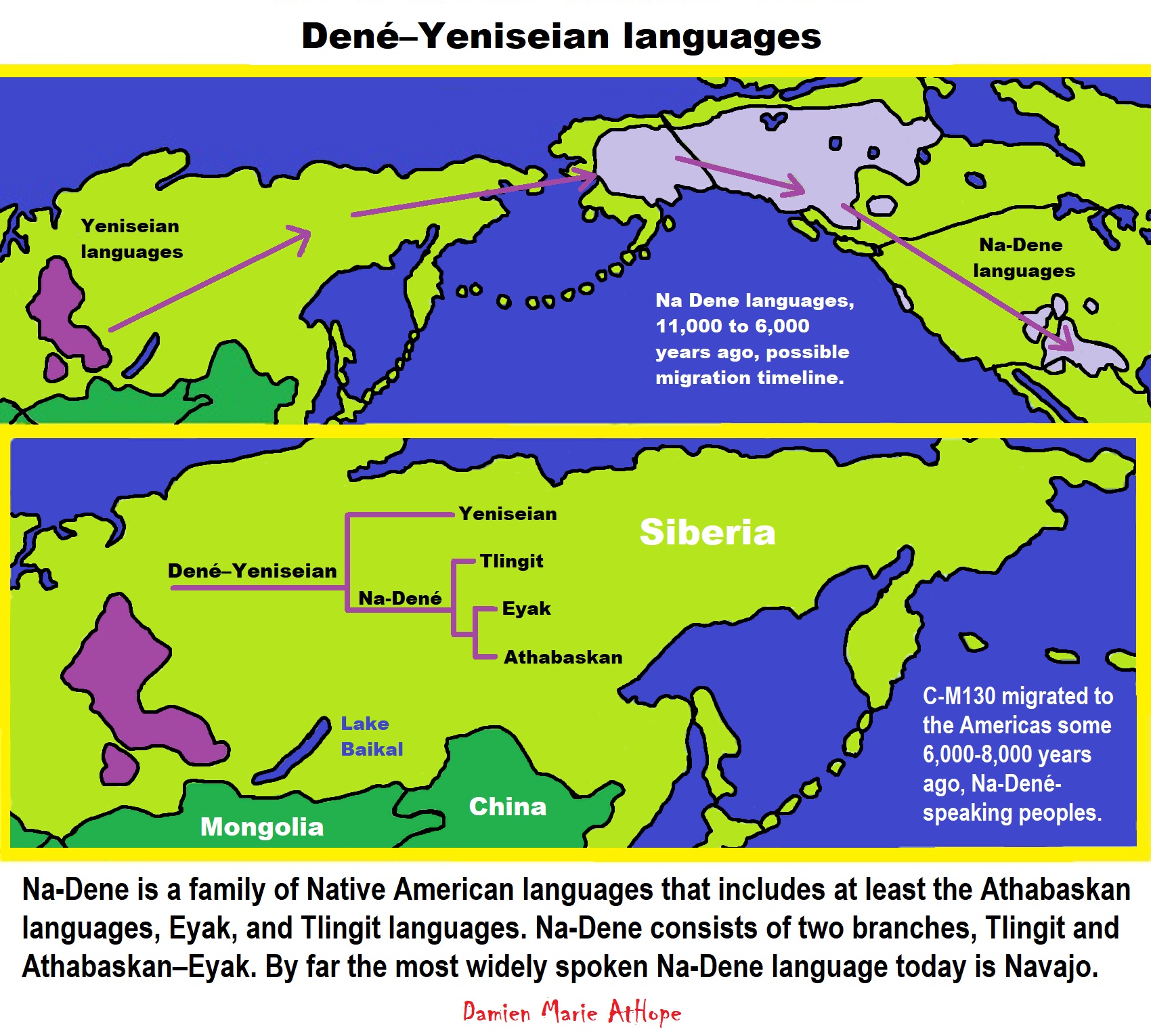

“The haplogroup C-M217 is now found at high frequencies among Central Asian peoples, indigenous Siberians, and some Native peoples of North America. Haplogroup C-M217 is the modal haplogroup among Mongolians and most indigenous populations of the Russian Far East, such as the Buryats, Northern Tungusic peoples, Nivkhs, Koryaks, and Itelmens. The subclade C-P39 is common among males of the indigenous North American peoples whose languages belong to the Na-Dené phylum. C2b1a1a P39 Canada,USA(Found in several indigenous peoples of North America, including some Na-Dené-,Algonquian-, orSiouan-speaking populations).” ref

“Males carrying C-M130 are believed to have migrated to the Americas some 6,000-8,000 years ago, and was carried by Na-Dené-speaking peoples into the northwest Pacific coast of North America. The distribution of Haplogroup C-M130 is generally limited to populations of Siberia, parts of East Asia, Oceania, and the Americas. Haplogroup C2 (M217) – the most numerous and widely dispersed C lineage – was once believed to have originated in Central Asia, spread from there into Northern Asia and the Americas while other theory it originated from East Asia. C-M217 stretches longitudinally from Central Europe and Turkey, to the Wayuu people of Colombia and Venezuela, and latitudinally from the Athabaskan peoples of Alaska to Vietnam to the Malay Archipelago. The highest frequencies of Haplogroup C-M217 are found among the populations of Mongolia and Far East Russia, where it is the modal haplogroup. Haplogroup C-M217 is the only variety of Haplogroup C-M130 to be found among Native Americans, among whom it reaches its highest frequency in Na-Dené populations.” ref

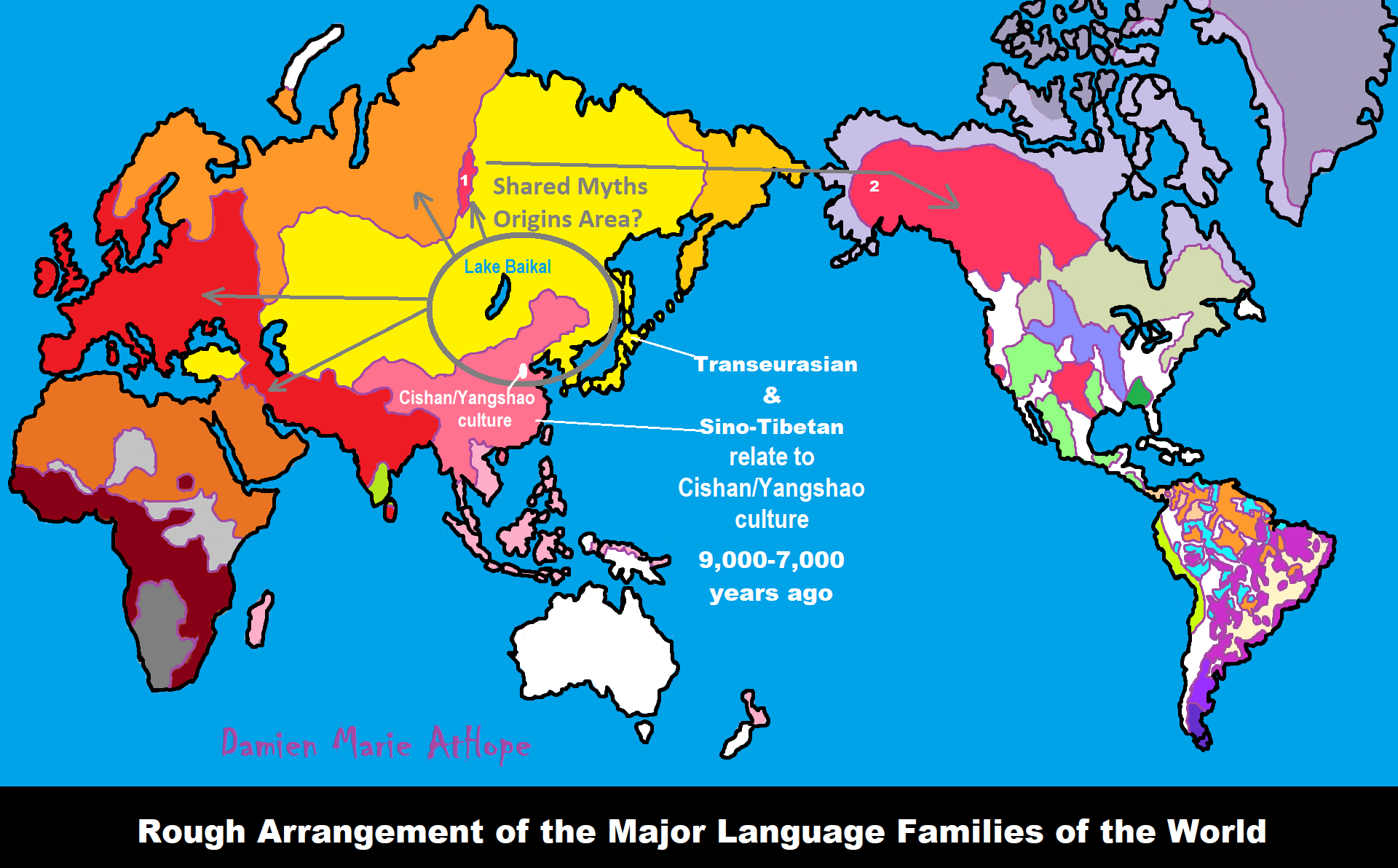

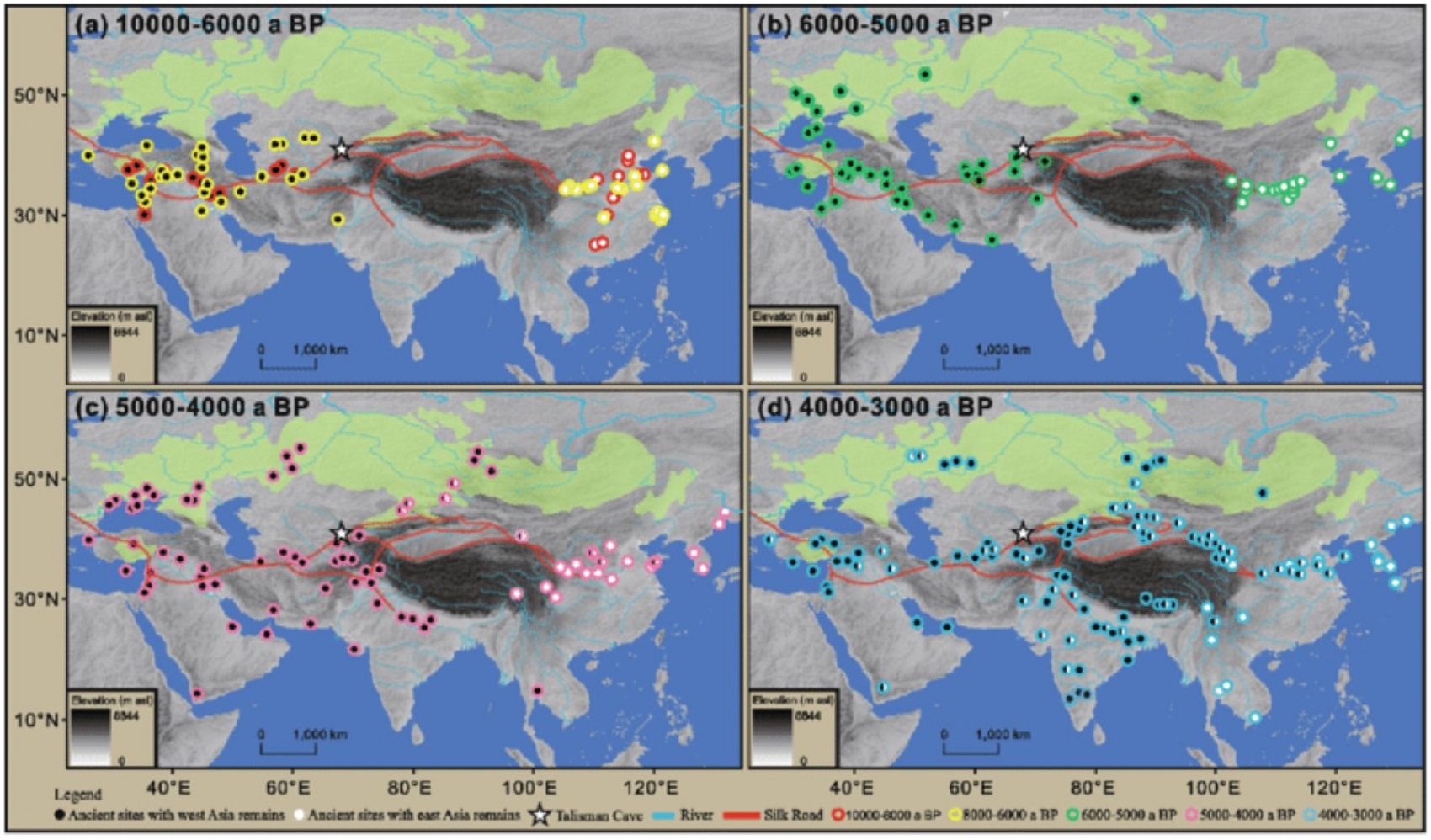

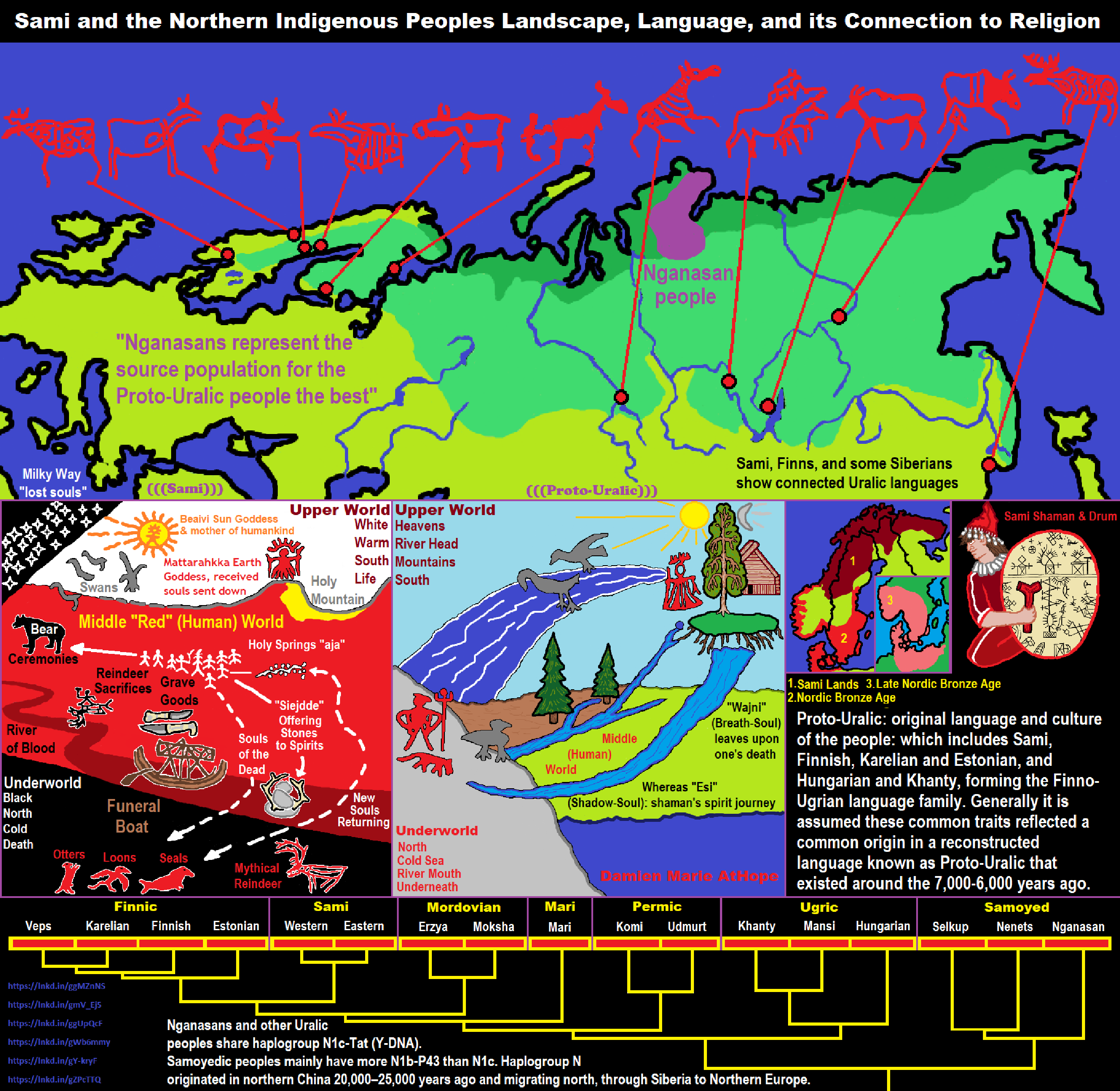

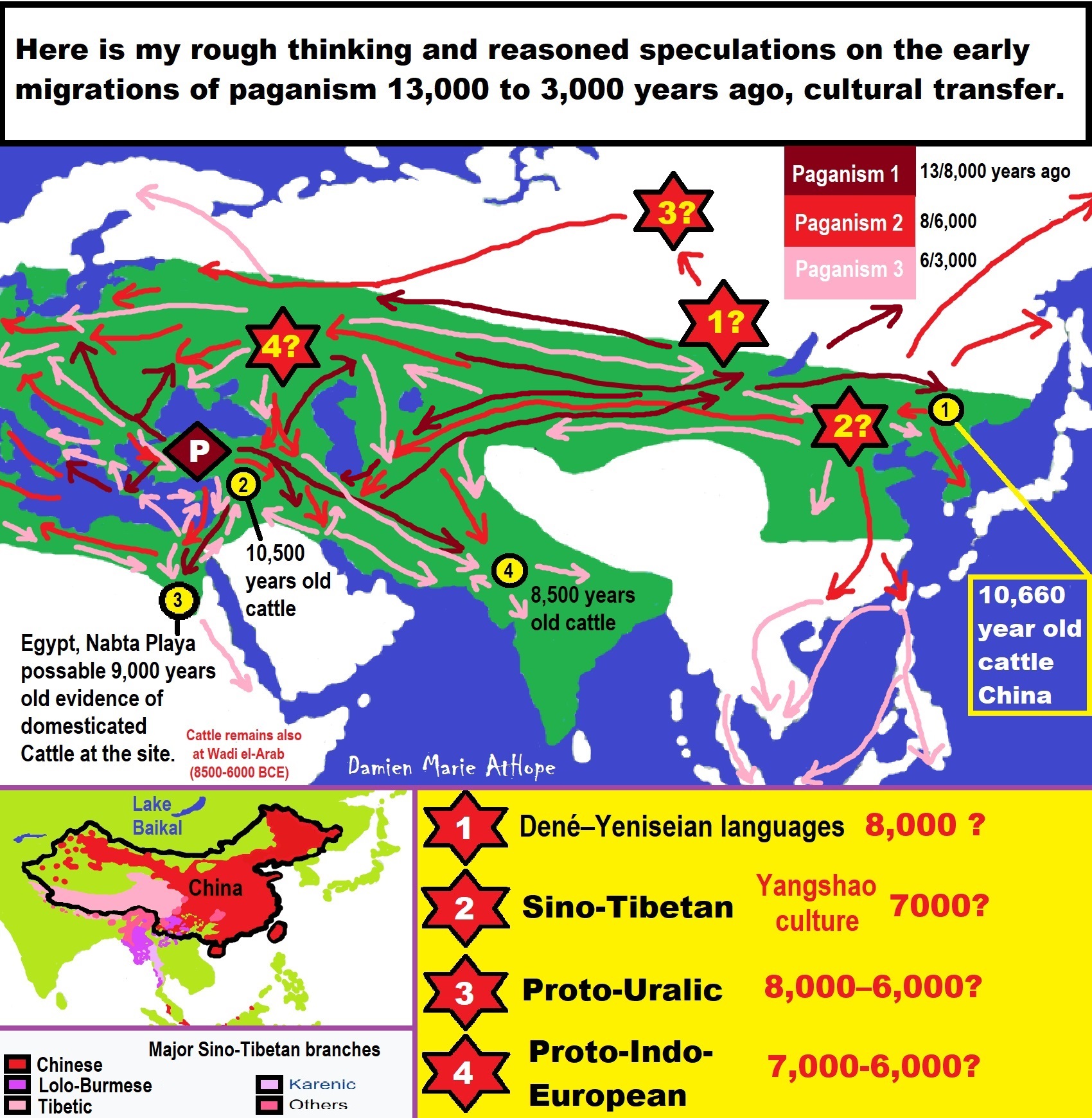

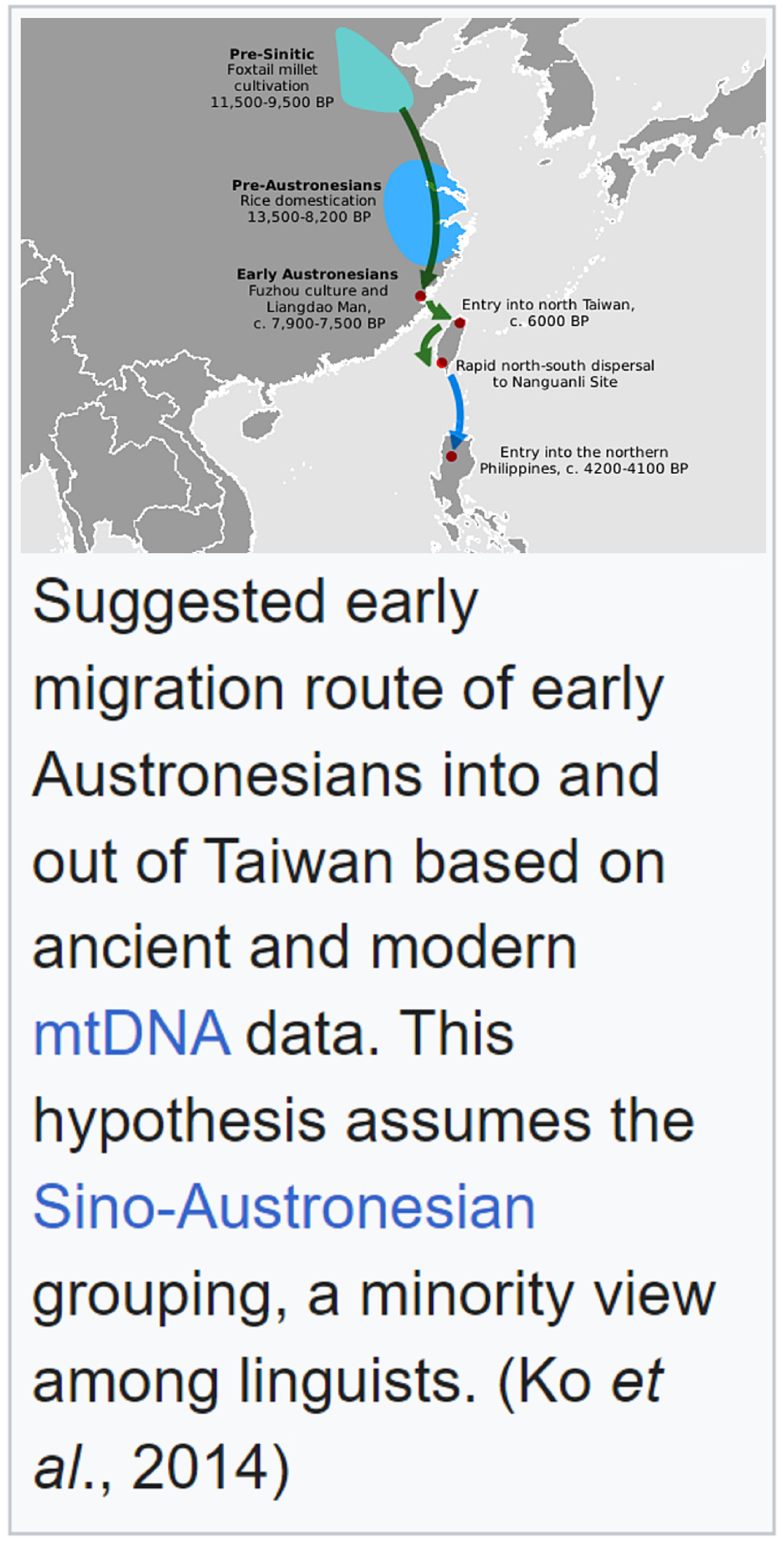

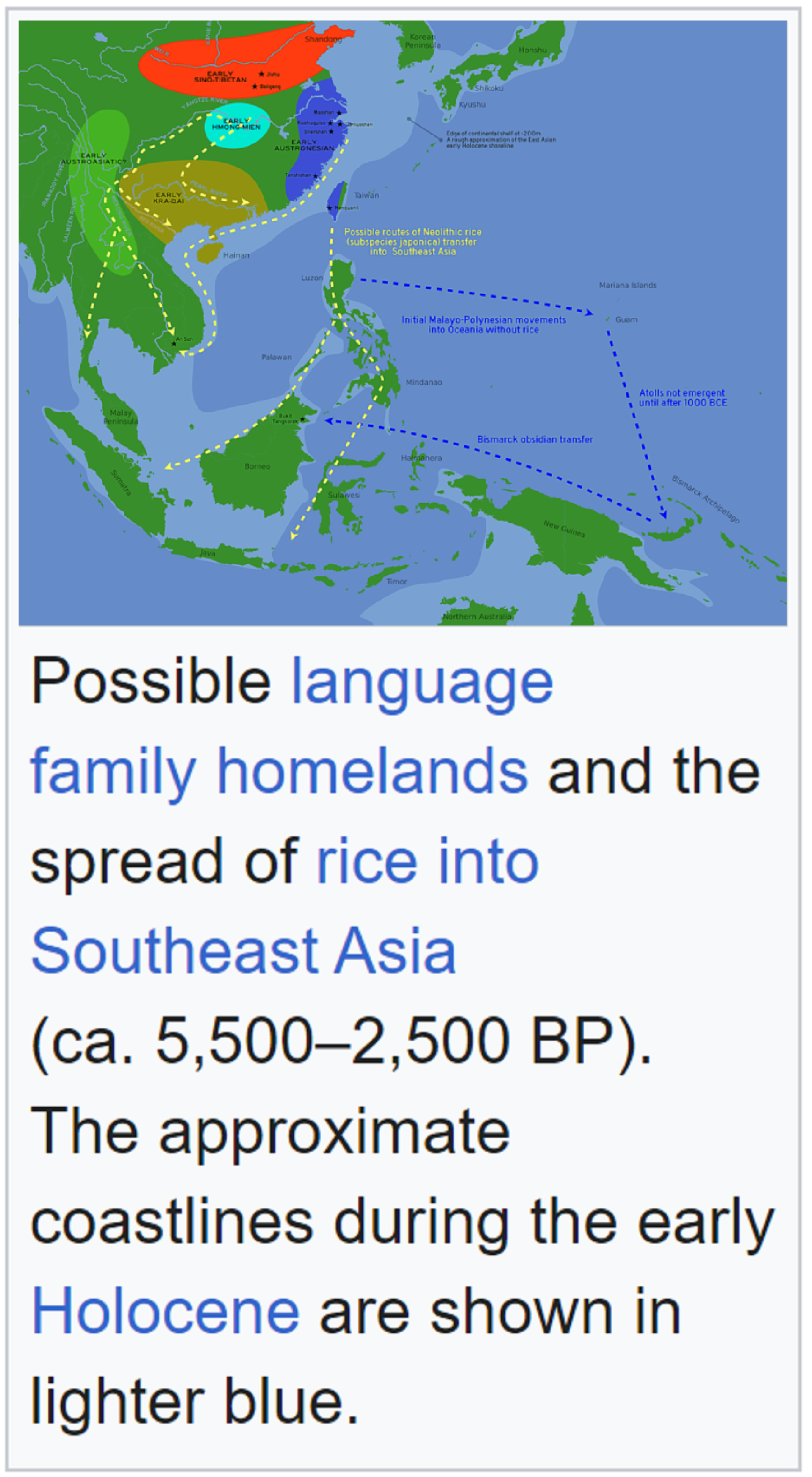

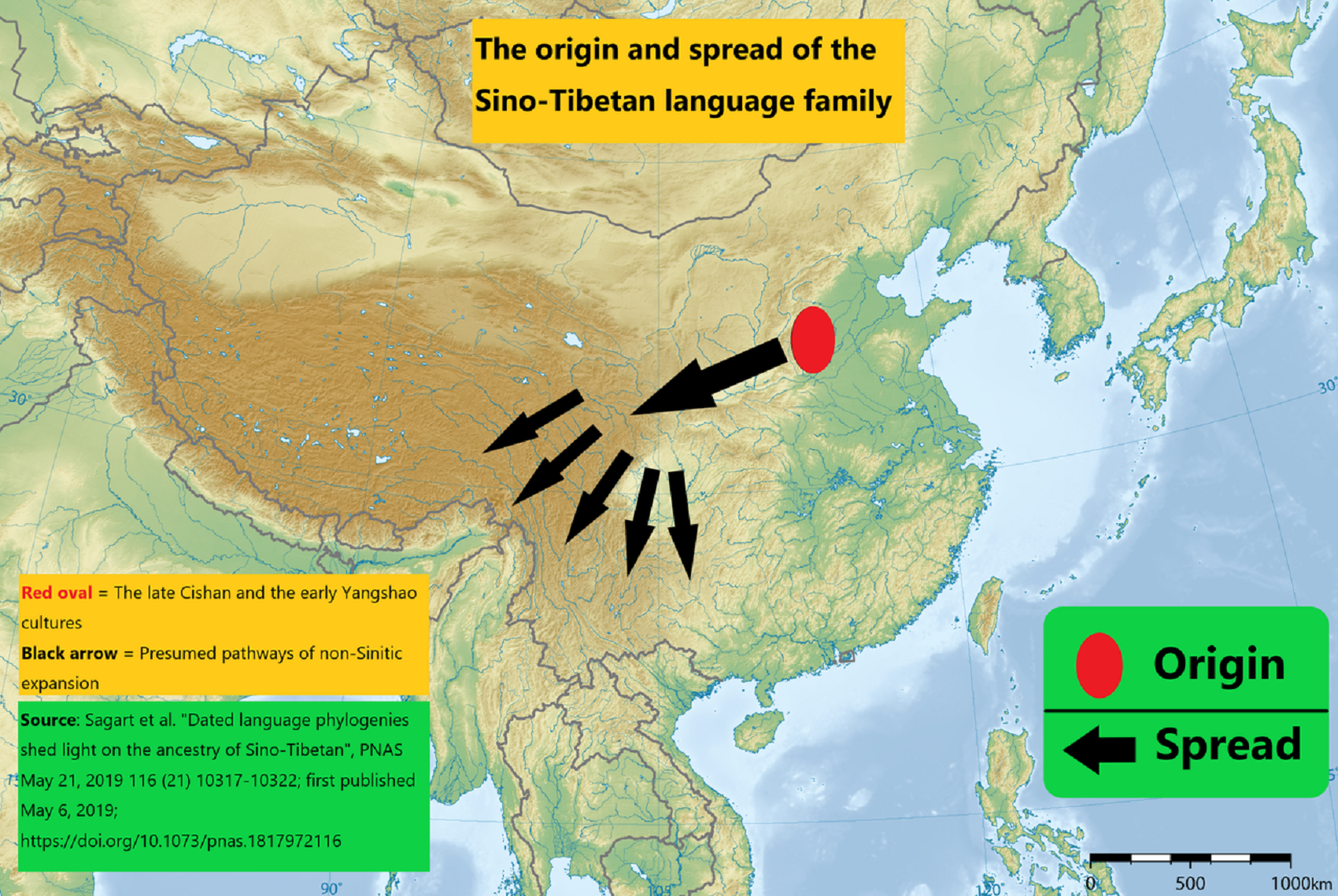

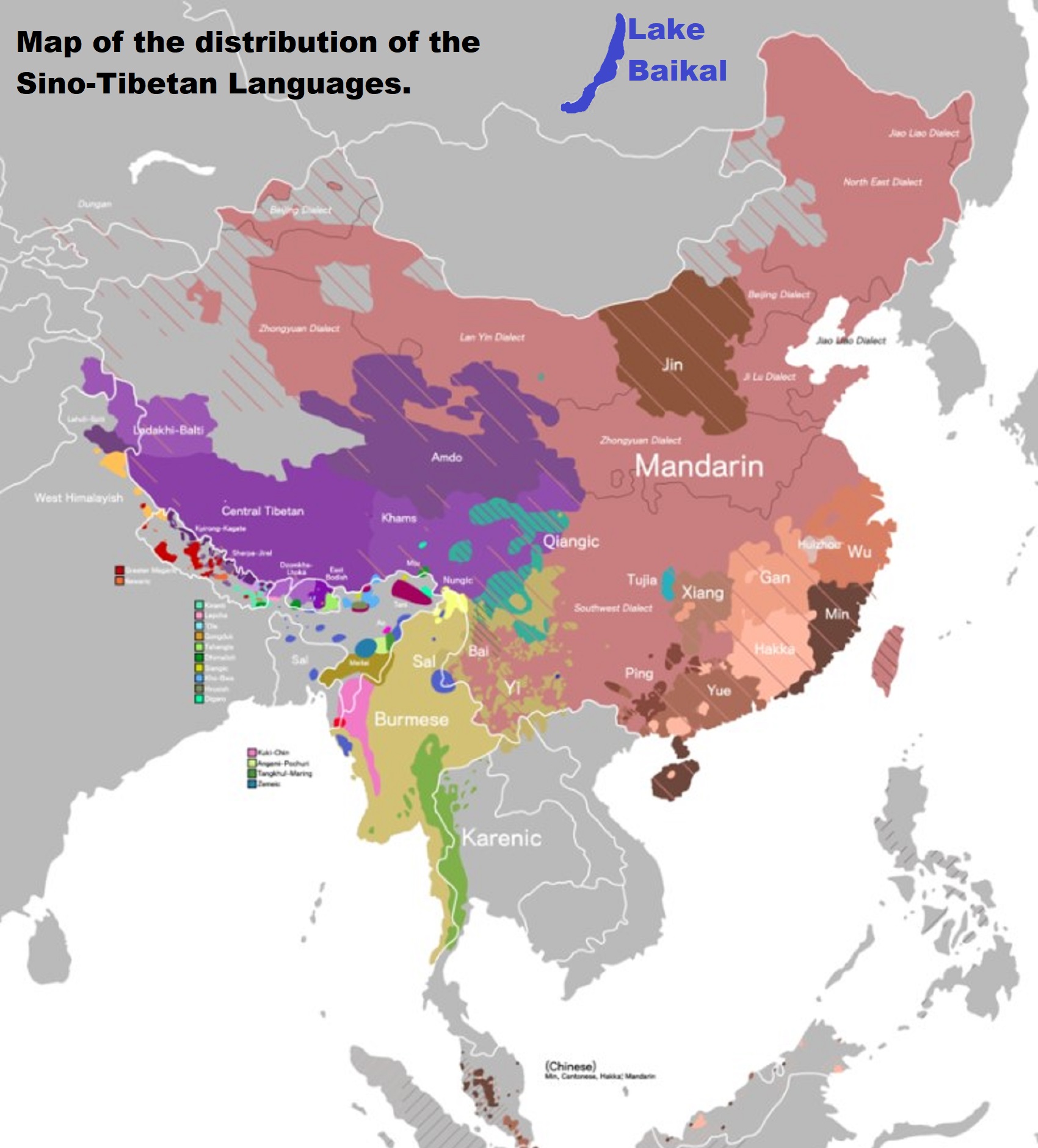

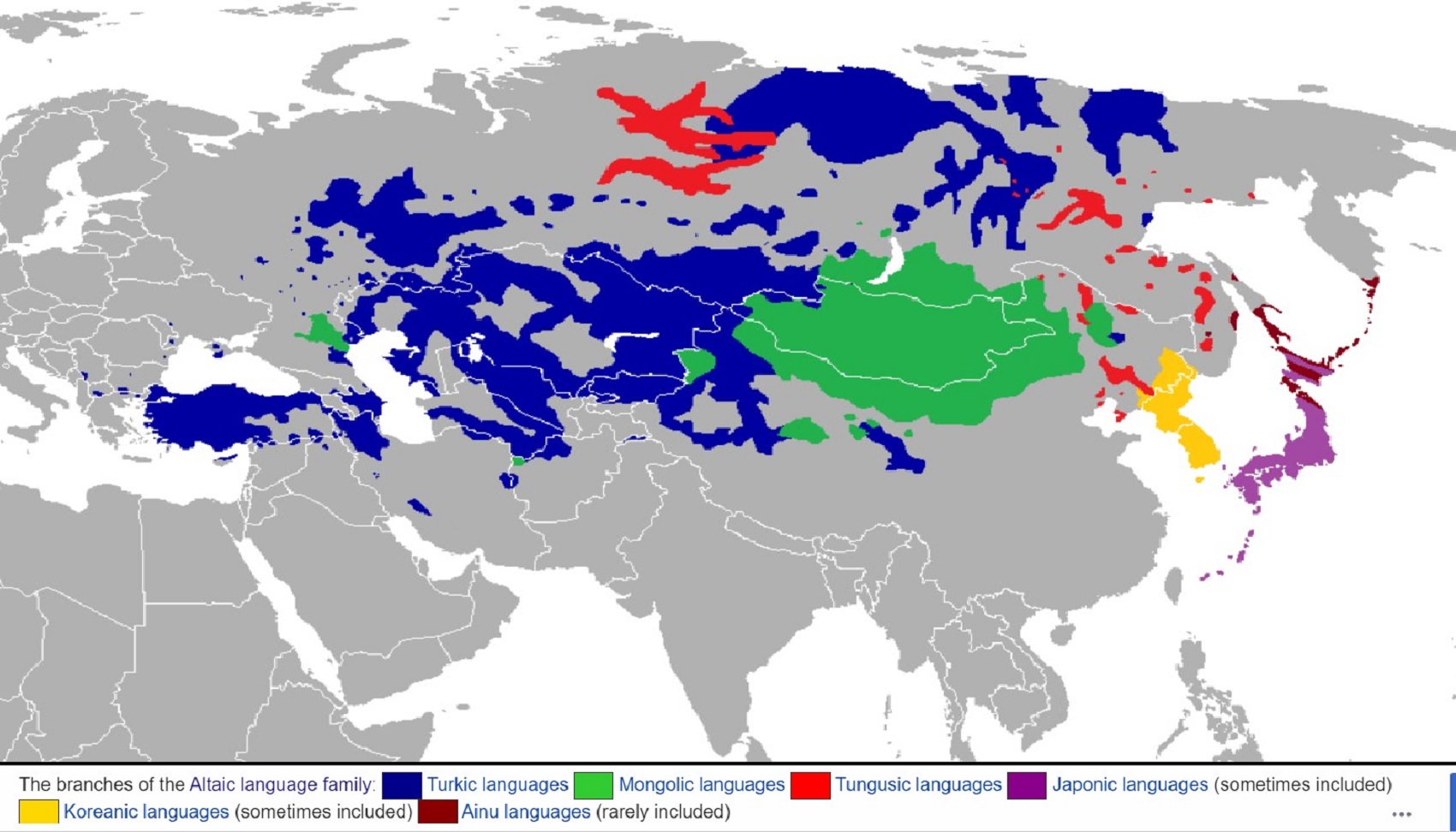

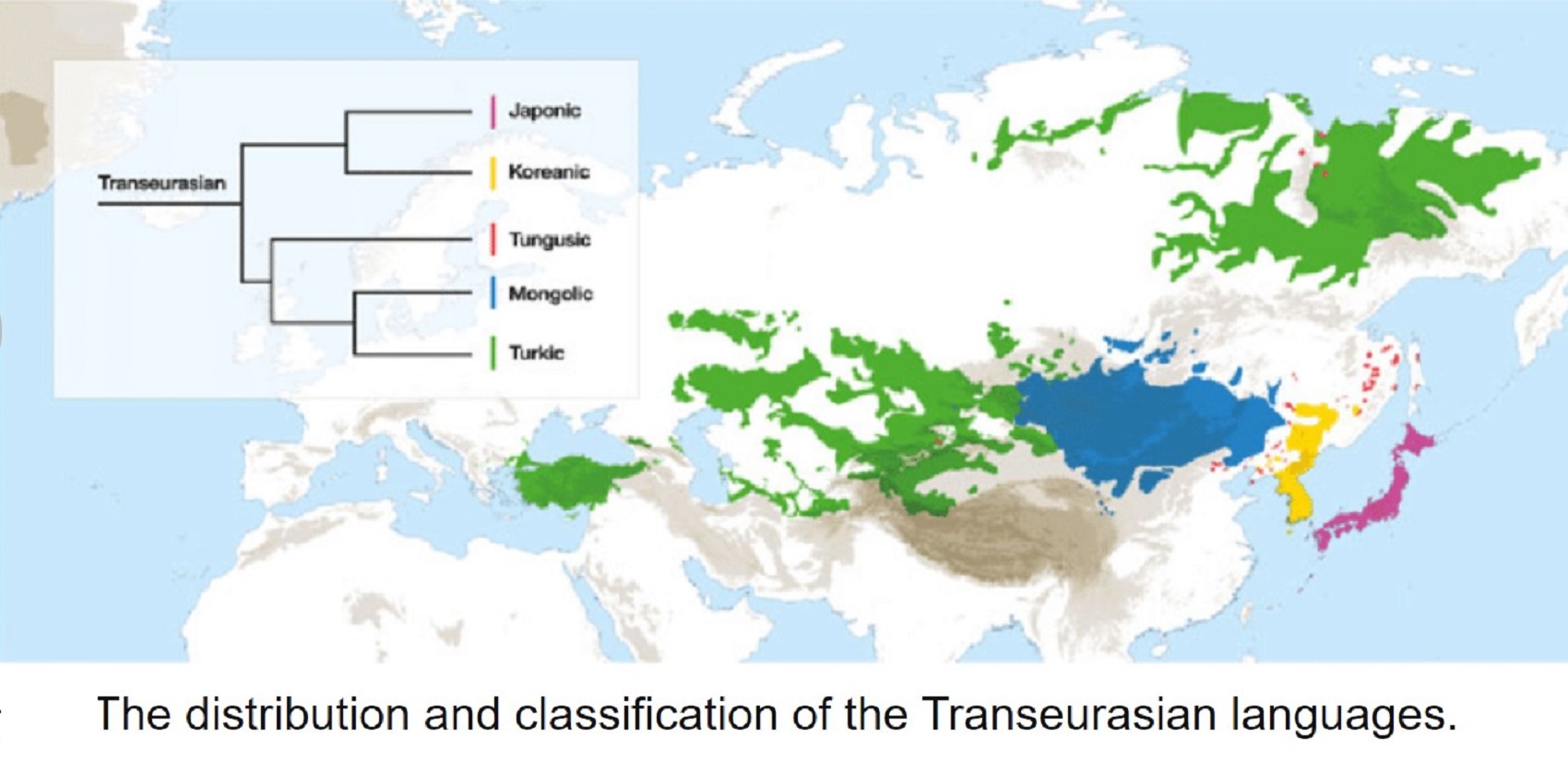

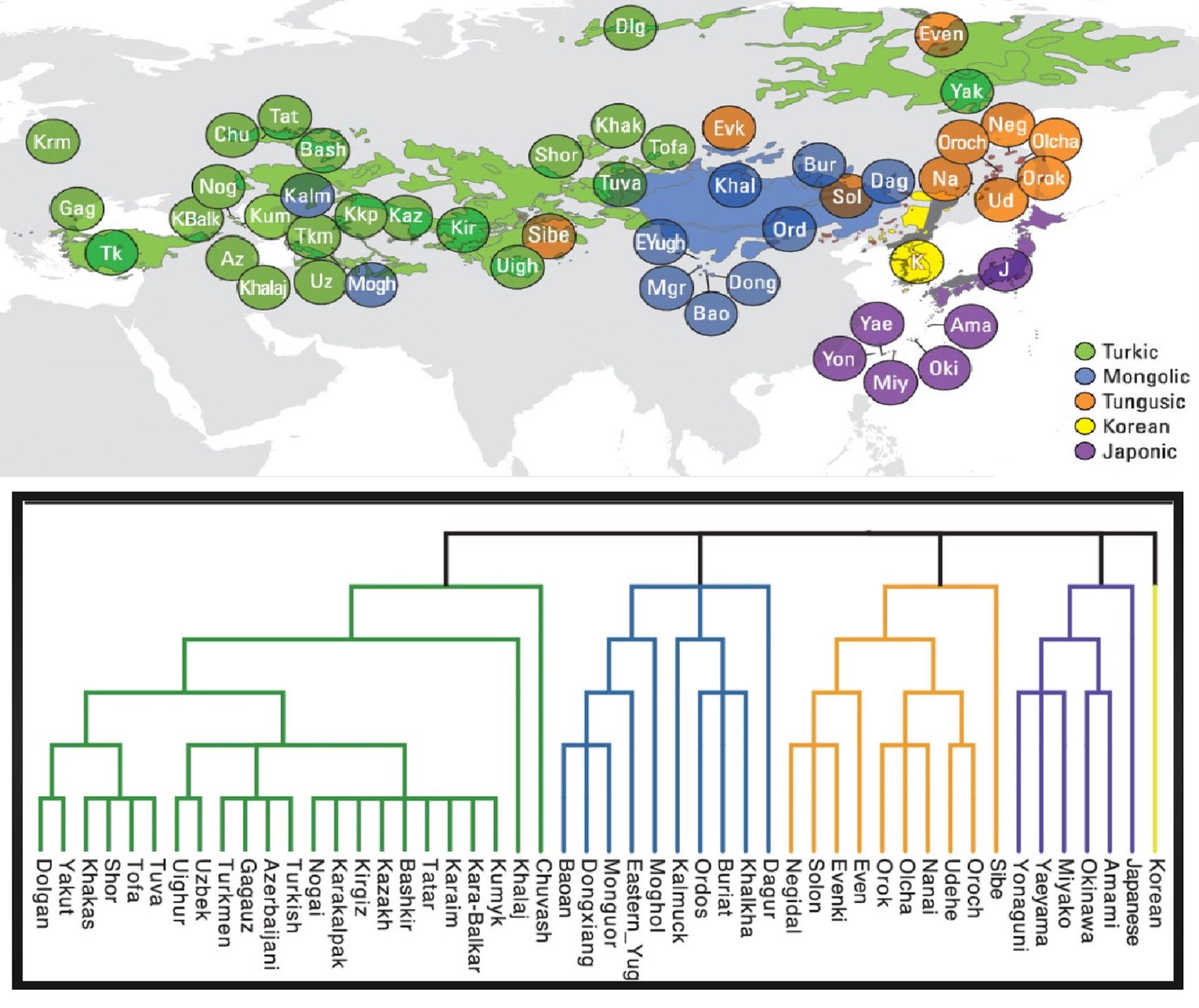

Origins of ‘Transeurasian’ languages traced to Neolithic millet farmers in north-eastern China about 9,000 years ago

“A study combining linguistic, genetic, and archaeological evidence has traced the origins of a family of languages including modern Japanese, Korean, Turkish and Mongolian and the people who speak them to millet farmers who inhabited a region in north-eastern China about 9,000 years ago. The findings outlined on Wednesday document a shared genetic ancestry for the hundreds of millions of people who speak what the researchers call Transeurasian languages across an area stretching more than 5,000 miles (8,000km).” ref

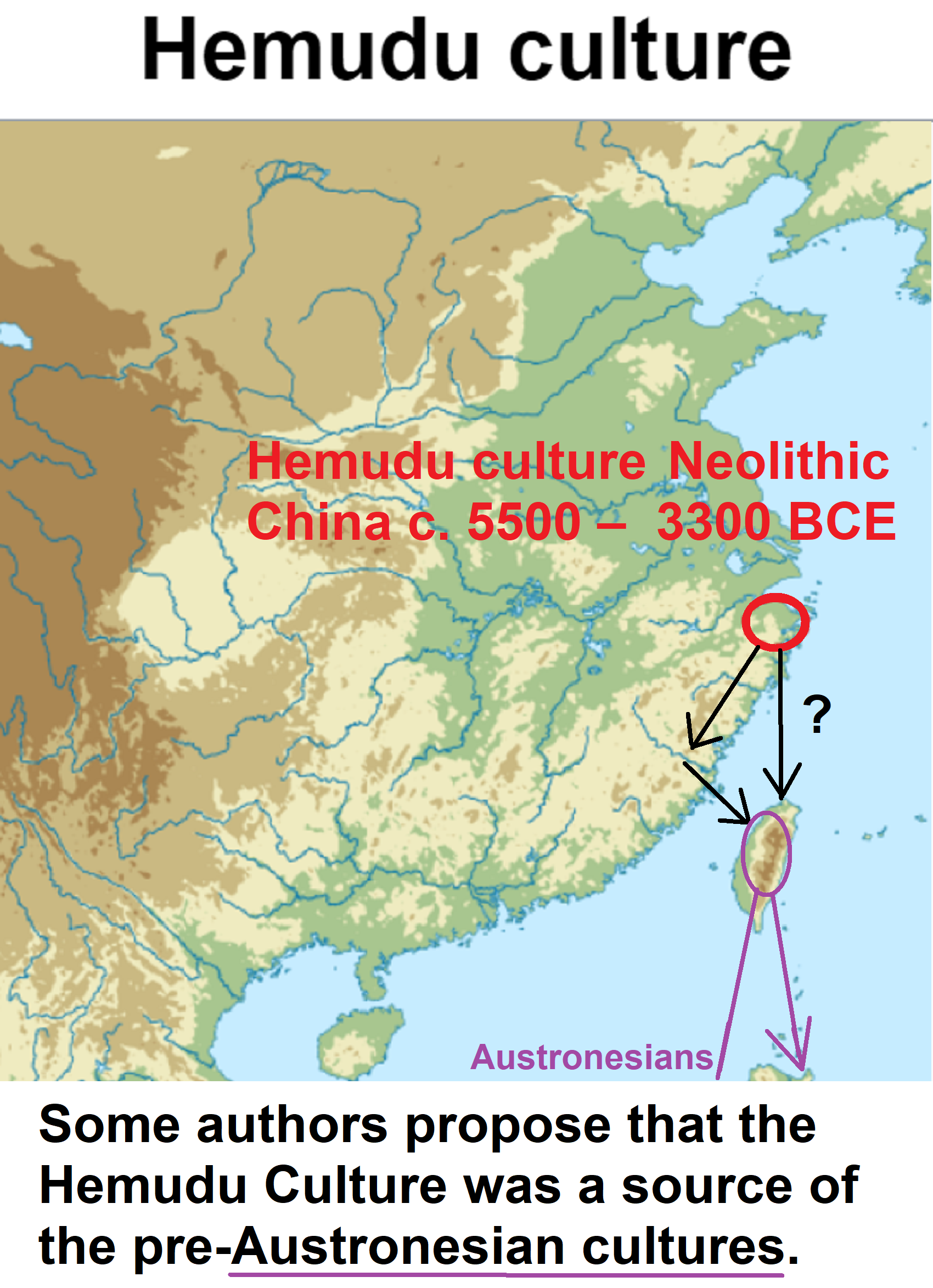

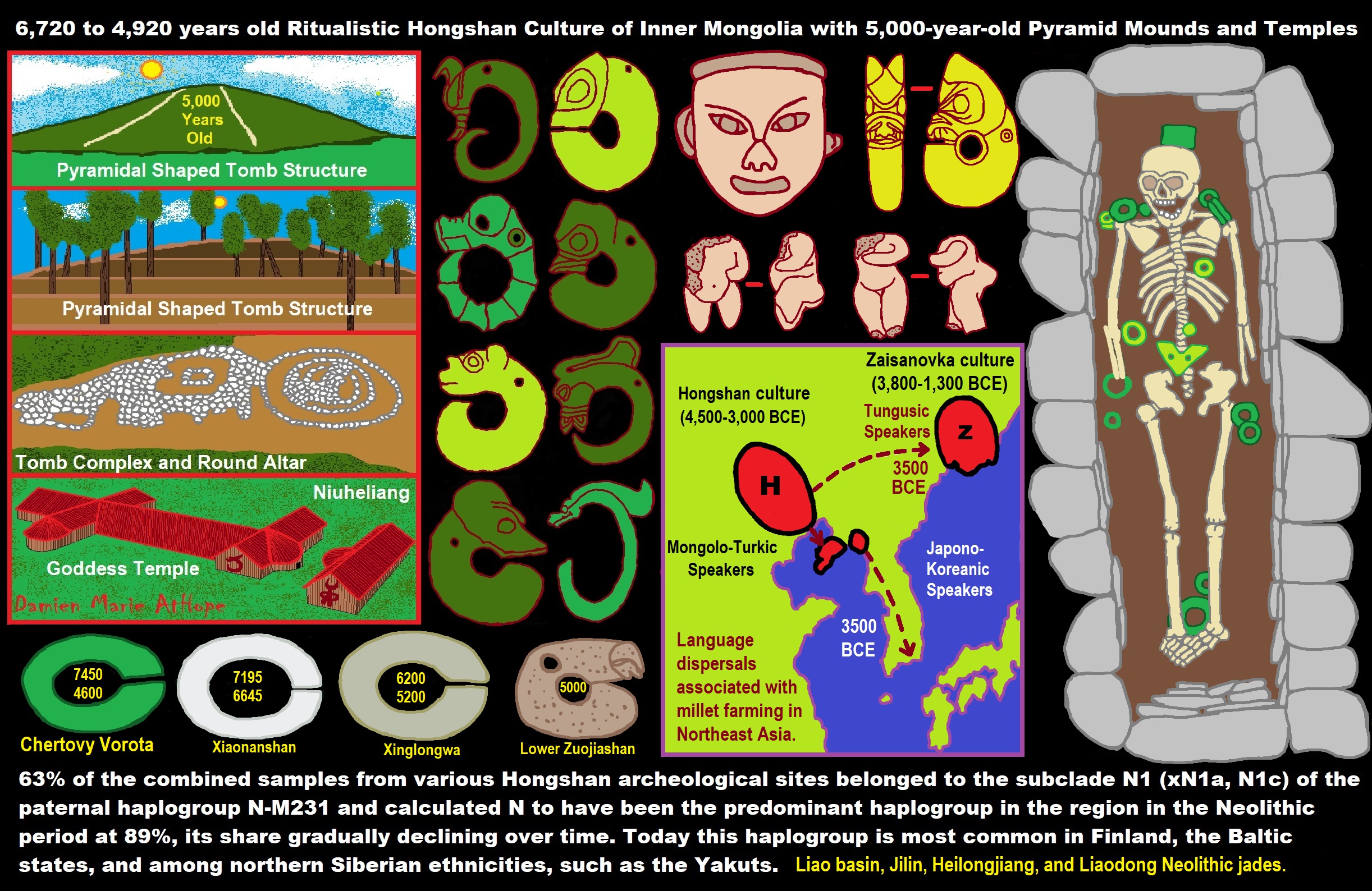

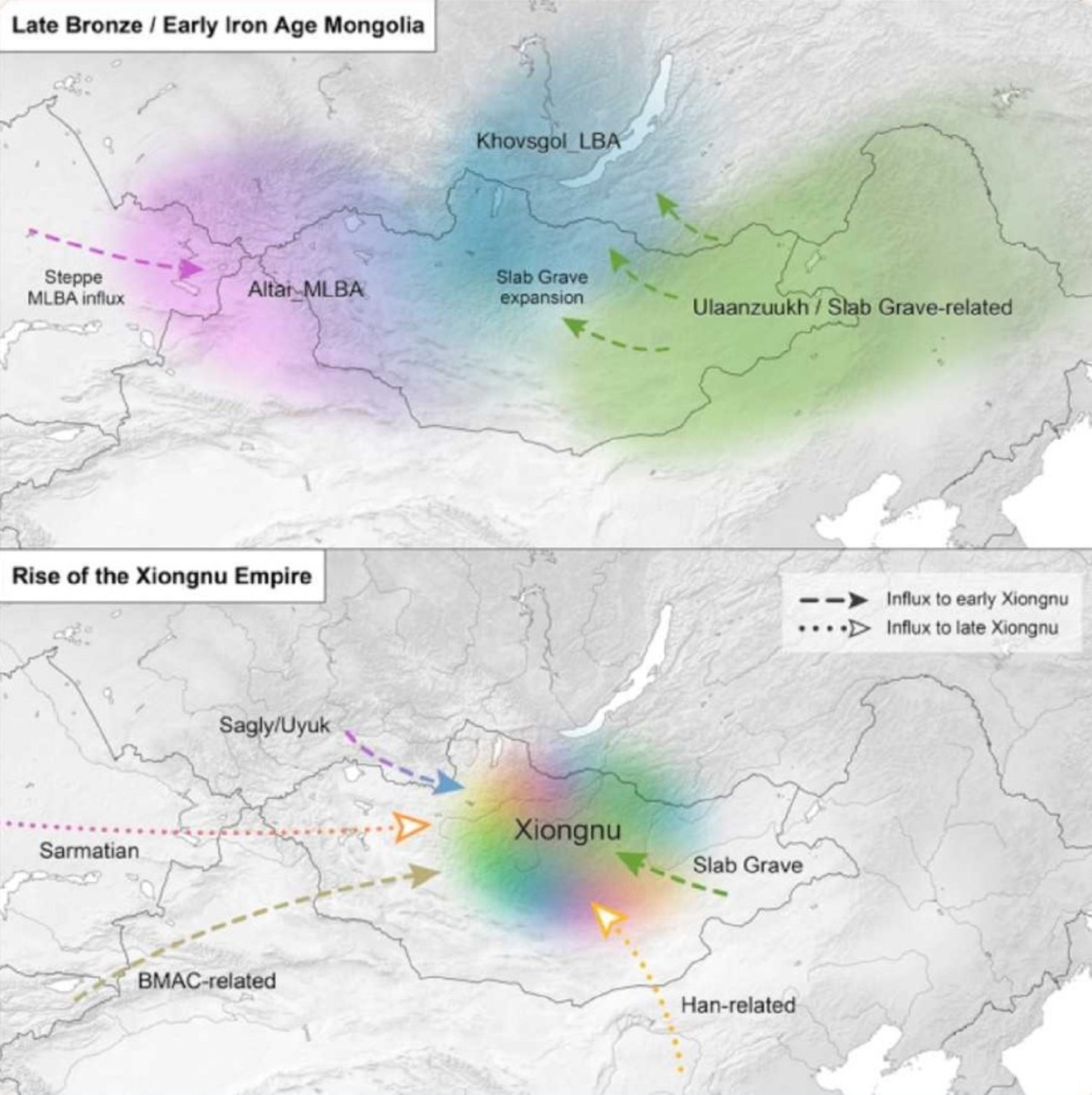

“Millet was an important early crop as hunter-gatherers transitioned to an agricultural lifestyle. There are 98 Transeurasian languages, including Korean, Japanese, and various Turkic languages in parts of Europe, Anatolia, Central Asia, and Siberia, various Mongolic languages, and various Tungusic languages in Manchuria and Siberia. This language family’s beginnings were traced to Neolithic millet farmers in the Liao River valley, an area encompassing parts of the Chinese provinces of Liaoning and Jilin and the region of Inner Mongolia. As these farmers moved across north-eastern Asia over thousands of years, the descendant languages spread north and west into Siberia and the steppes and east into the Korean peninsula and over the sea to the Japanese archipelago.” ref

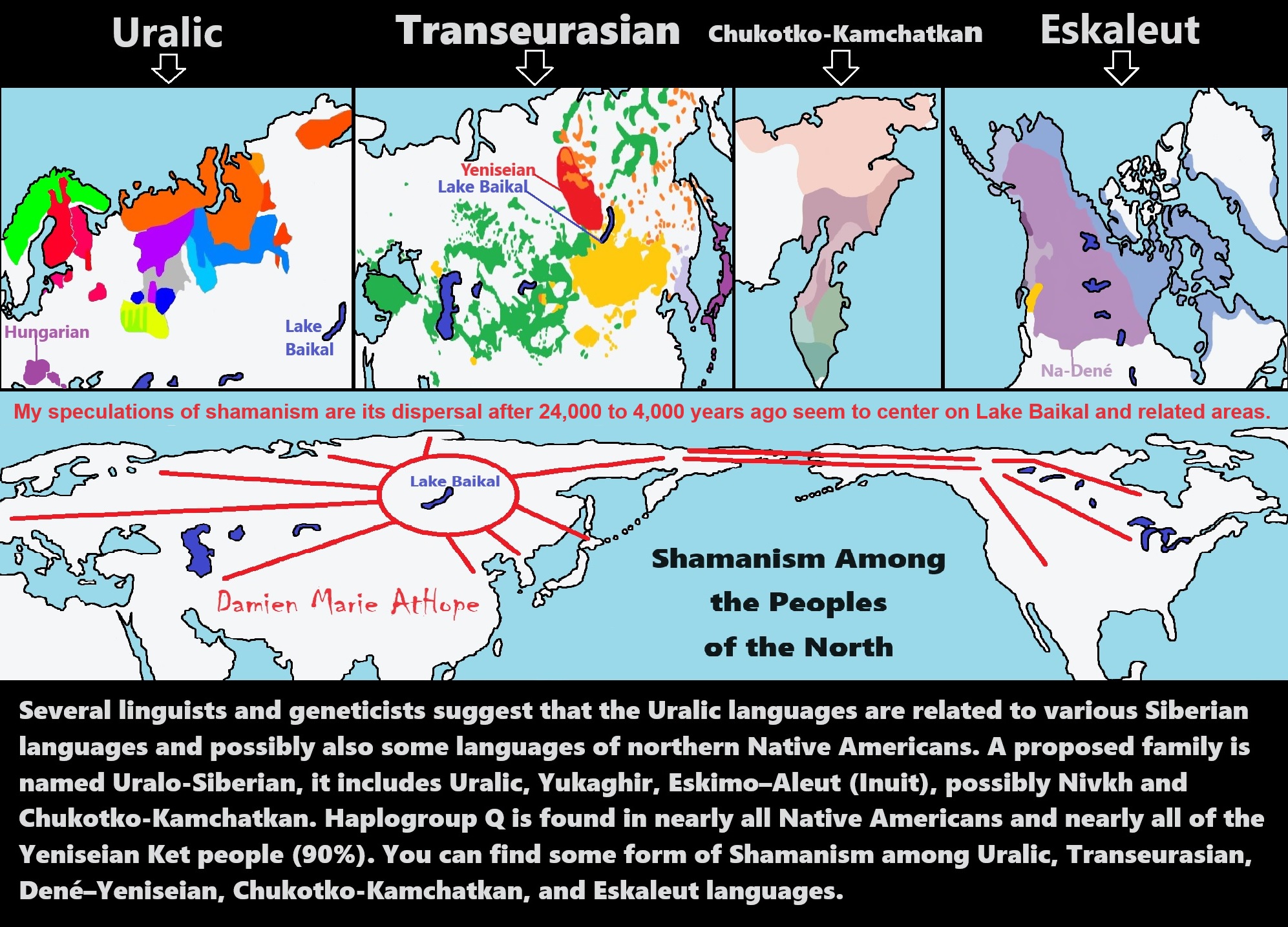

“Eurasiatic is a proposed language with many language families historically spoken in northern, western, and southern Eurasia; which typically include Altaic (Mongolic, Tungusic, and Turkic), Chukchi-Kamchatkan, Eskimo–Aleut, Indo-European, and Uralic.” ref

“Voiced stops such as /d/ occur in the Indo-European, Yeniseian, Turkic, Mongolian, Tungusic, Japonic and Sino-Tibetan languages. They have also later arisen in several branches of Uralic.” ref

“Uralo-Siberian is a hypothetical language family of Uralic, Yukaghir, Eskimo–Aleut and besides linguistic evidence, several genetic studies, support a common origin in Northeast Asia.” ref

“The Paleolithic dog was a Late Pleistocene canine. They were directly associated with human hunting camps in Europe over 30,000 years ago and it is proposed that these were domesticated. They are further proposed to be either a proto-dog and the ancestor of the domestic dog or an extinct, morphologically and genetically divergent wolf population. There are a number of recently discovered specimens which are proposed as being Paleolithic dogs, however, their taxonomy is debated. These have been found in either Europe or Siberia and date 40,000–17,000 years ago. They include Hohle Fels in Germany, Goyet Caves in Belgium, Predmosti in the Czech Republic, and four sites in Russia: Razboinichya Cave in the Altai Republic, Kostyonki-8, Ulakhan Sular in the Sakha Republic, and Eliseevichi 1 on the Russian plain.” ref

1. 40,000–35,500 years ago Hohle Fels, Schelklingen, Germany

2. 36,500 years ago Goyet Caves, Samson River Valley, Belgium

3. 33,500 years ago Razboinichya Cave, Altai Mountains, (Russia/Siberia)

4. 33,500–26,500 years ago Kostyonki-Borshchyovo archaeological complex, (Kostenki site) Voronezh, Russia

5. 31,000 years ago Predmostí, Moravia, Czech Republic

6. 26,000 years ago Chauvet Cave, Vallon-Pont-d’Arc, Ardèche region, France

7. 17,300–14,100 years ago Dyuktai Cave, northern Yakutia, Siberia

8. 17,000–16,000 years ago Eliseevichi-I site, Bryansk Region, Russian Plain, Russia

9. 16,900 years ago Afontova Gora-1, Yenisei River, southern Siberia

10. 14,223 years ago Bonn–Oberkassel, Germany

11. 13,500 years ago Mezine, Chernigov region, Ukraine

12. 13,000 years ago Palegawra, (Zarzian culture) Iraq

13. 12,800 years ago Ushki I, Kamchatka, eastern Siberia

14. 12,790 years ago Nanzhuangtou, China

15. 12,300 years ago Ust’-Khaita site, Baikal region, Siberia

16. 12,000 years ago Ain Mallaha (Eynan) and HaYonim terrace, Israel

17. 10,150 years ago Lawyer’s Cave, Alaska, USA

18. 9,000 years ago Jiahu site, China

19. 8,000 years ago Svaerdborg site, Denmark

20. 7,425 years ago Lake Baikal region, Siberia

21. 7,000 years ago Tianluoshan archaeological site, Zhejiang province, China ref

1. 40,000–35,500 years ago Hohle Fels, Schelklingen, Germany

“Canid maxillary fragment. The size of the molars matches those of a wolf, the morphology matches a dog. Proposed as a Paleolithic dog. The figurine Venus of Hohle Fels was discovered in this cave and dated to this time.” ref

2. 36,500 years ago Goyet Caves, Samson River Valley, Belgium

“The “Goyet dog” is proposed as being a Paleolithic dog. The Goyet skull is very similar in shape to that of the Eliseevichi-I dog skulls (16,900 years ago) and to the Epigravettian Mezin 5490 and Mezhirich dog skulls (13,500 years ago), which are about 18,000 years younger. The dog-like skull was found in a side gallery of the cave, and Palaeolithic artifacts in this system of caves date from the Mousterian, Aurignacian, Gravettian, and Magdalenian, which indicates recurrent occupations of the cave from the Pleniglacial until the Late Glacial. The Goyet dog left no descendants, and its genetic classification is inconclusive because its mitochondrial DNA (mDNA) does not match any living wolf nor dog. It may represent an aborted domestication event or phenotypically and genetically distinct wolves. A genome-wide study of a 35,000-year-old Pleistocene wolf fossil from northern Siberia indicates that the dog and the modern grey wolf genetically diverged from a common ancestor between 27,000 and 40,000 years ago.” ref

3. 33,500 years ago Razboinichya Cave, Altai Mountains, (Russia/Siberia)

“The “Altai dog” is proposed as being a Paleolithic dog. The specimens discovered were a dog-like skull, mandibles (both sides), and teeth. The morphological classification, and an initial mDNA analysis, found it to be a dog. A later study of its mDNA was inconclusive, with 2 analyses indicating dog and another 2 indicating wolf. In 2017, two prominent evolutionary biologists reviewed the evidence and supported the Altai dog as being a dog from a lineage that is now extinct and that was derived from a population of small wolves that are also now extinct.” ref

4. 33,500–26,500 years ago Kostyonki-Borshchyovo archaeological complex, (Kostenki site) Voronezh, Russia

“One left mandible paired with the right maxilla, proposed as a Paleolithic dog.” ref

5. 31,000 years ago Predmostí, Moravia, Czech Republic

“Three dog-like skulls proposed as being Paleolithic dogs. Predmostí is a Gravettian site. The skulls were found in the human burial zone and identified as Palaeolithic dogs, characterized by – compared to wolves – short skulls, short snouts, wide palates and braincases, and even-sized carnassials. Wolf skulls were also found at the site. One dog had been buried with a bone placed carefully in its mouth. The presence of dogs buried with humans at this Gravettian site corroborates the hypothesis that domestication began long before the Late Glacial. Further analysis of bone collagen and dental microwear on tooth enamel indicates that these canines had a different diet when compared with wolves (refer under diet).” ref

6. 26,000 years ago Chauvet Cave, Vallon-Pont-d’Arc, Ardèche region, France

“50-metre trail of footprints made by a boy of about ten years of age alongside those of a large canid. The size and position of the canid’s shortened middle toe in relation to its pads indicate a dog rather than a wolf. The footprints have been dated by soot deposited from the torch the child was carrying. The cave is famous for its cave paintings. A later study using geometric morphometric analysis to compare modern wolves with modern dog tracks proposes that these are wolf tracks.” ref

7. 17,300–14,100 years ago Dyuktai Cave, northern Yakutia, Siberia

“Large canid remains along with human artifacts. And from a nearby site dating to around 17,200–16,800 Ulakhan Sular, northern Yakutia, Siberia held a fossil dog-like skull similar in size to the “Altai dog”, proposed as a Paleolithic dog.” ref

8. 17,000–16,000 years ago Eliseevichi-I site, Bryansk Region, Russian Plain, Russia

“Two fossil canine skulls proposed as being Paleolithic dogs. In 2002, a study looked at the fossil skulls of two large canids that had been found buried 2 meters and 7 meters from what was once a mammoth-bone hut at this Upper Paleolithic site, and using an accepted morphologically based definition of domestication declared them to be “Ice Age dogs”. The carbon dating gave a calendar-year age estimate that ranged between 16,945 and 13,905 years ago. The Eliseevichi-1 skull is very similar in shape to the Goyet skull (36,000 years ago), the Mezine dog skull (13,500 years ago) and Mezhirich dog skull (13,500 years ago). In 2013, a study looked at the mDNA sequence for one of these skulls and identified it as Canis lupus familiaris i.e. dog. However, in 2015 a study using three-dimensional geometric morphometric analyses indicated the skull is more likely from a wolf. These animals were larger in size than most grey wolves and approached the size of a Great Dane.” ref

9. 16,900 years ago Afontova Gora-1, Yenisei River, southern Siberia

“Fossil dog-like tibia, proposed as a Paleolithic dog. The site is on the western bank of the Yenisei River about 2,500 km southwest of Ulakhan Sular, and shares a similar timeframe to that canid. A skull from this site described as dog-like has been lost in the past, but there exists a written description of it possessing a wide snout and a clear stop, with a skull length of 23 cm that falls outside of those of wolves.” ref

“Afontova Gora is a Late Upper Paleolithic and Mesolithic Siberian complex of archaeological sites located on the left bank of the Yenisei River near the city of Krasnoyarsk, Russia. Afontova Gora 3 carries are at the root of the classic European blond hair mutation, as massive population migrations from the Eurasian steppe, by a people who had substantial Ancient North Eurasian ancestry, entered continental Europe. Afontova Gora has cultural and genetic links to the people from Mal’ta-Buret’ culture. In a 2016 study, researchers determined that Afontova Gora 2, Afontova Gora 3, and Mal’ta 1 (Mal’ta boy) shared common descent and were clustered together in a Mal’ta cluster. The individual showed close genetic affinities to Mal’ta 1 (Mal’ta boy). Afontova Gora 2 also showed greater genetic affinity for the Karitiana people an indigenous people of Brazil, than for the Han Chinese.” ref

“Since the term ‘Ancient North Eurasian’ refers to a genetic bridge of connected mating networks, scholars of comparative mythology have argued that they probably shared myths and beliefs that could be reconstructed via the comparison of stories attested within cultures that were not in contact for millennia and stretched from the Pontic–Caspian steppe to the American continent. The mytheme of the dog guarding the Otherworld possibly stems from an older Ancient North Eurasian belief, as suggested by similar motifs found in Indo-European, Native American and Siberian mythology. In Siouan, Algonquian, Iroquoian, and in Central and South American beliefs, a fierce guard dog was located in the Milky Way, perceived as the path of souls in the afterlife, and getting past it was a test. The Siberian Chukchi and Tungus believed in a guardian-of-the-afterlife dog and a spirit dog that would absorb the dead man’s soul and act as a guide in the afterlife. In Indo-European myths, the figure of the dog is embodied by Cerberus, Sarvarā, and Garmr. In Zoroastrianism, two four-eyed dogs guard the bridge to the afterlife called Chinvat Bridge. Anthony and Brown note that it might be one of the oldest mythemes recoverable through comparative mythology. A second canid-related series of beliefs, myths and rituals connected dogs with healing rather than death. For instance, Ancient Near Eastern and Turkic–Kipchaq myths are prone to associate dogs with healing and generally categorised dogs as impure. A similar myth-pattern is assumed for the Eneolithic site of Botai in Kazakhstan, dated to 3500 BCE, which might represent the dog as absorber of illness and guardian of the household against disease and evil. In Mesopotamia, the goddess Nintinugga, associated with healing, was accompanied or symbolized by dogs. Similar absorbent-puppy healing and sacrifice rituals were practiced in Greece and Italy, among the Hittites, again possibly influenced by Near Eastern traditions.” ref

10. 14,223 years ago Bonn–Oberkassel, Germany

“The “Bonn-Oberkassel dog“. Undisputed dog skeleton buried with a man and woman. All three skeletal remains were found sprayed with red hematite powder. The consensus is that a dog was buried along with two humans. Analysis of mDNA indicates that this dog was a direct ancestor of modern dogs. Domestic dog.” ref

11. 13,500 years ago Mezine, Chernigov region, Ukraine

“Ancient dog-like skull proposed as being a Paleolithic dog. Additionally, ancient wolf specimens were found at the site. Dated to the Epigravettian period (17,000–10,000 years ago). The Mezine skull is very similar in shape to the Goyet skull (36,000 years ago), the Eliseevichi-1 dog skulls (16,900 years ago), and the Mezhirich dog skull (13,500 years ago). The Epigravettian Mezine site is well known for its round mammoth bone dwelling. Taxonomy uncertain.” ref

12. 13,000 years ago Palegawra, (Zarzian culture) Iraq

“The fossil jaw and teeth of a domesticated dog, recovered from a cave in Iraq, have been found to be about 14,000 years old. The bone was found in a shallow cave with a number of stone tools suggesting that its keepers were hunters. The scientists who found and studied the bone speculated that the animal served either as a hunting dog in the field or as a watchdog back at the cave or perhaps as both.” ref, ref

13. 12,800 years ago Ushki I, Kamchatka, eastern Siberia

“Complete skeleton buried in a buried dwelling. Located 1,800 km to the southeast from Ulakhan Sular. Domestic dog.” ref

14. 12,790 years ago Nanzhuangtou, China

“31 fragments including a complete dog mandible.” ref

“Nanzhuangtou, dated to 12,600–11,300 years ago an Initial Neolithic site near Lake Baiyangdian in Xushui County, Hebei, China. The site was discovered under a peat bog. Over 47 pieces of pottery were discovered at the site. Nanzhuangtou is also the earliest Neolithic site yet discovered in northern China. There is evidence that the people at Nanzhuangtou had domestic dogs 10,000 years ago. Stone grinding slabs and rollers and bone artifacts were also discovered at the site. It is one of the earliest sites showing evidence of millet cultivation dating to 10,500 years ago. Pottery can also be dated to 10,200 years ago.” ref

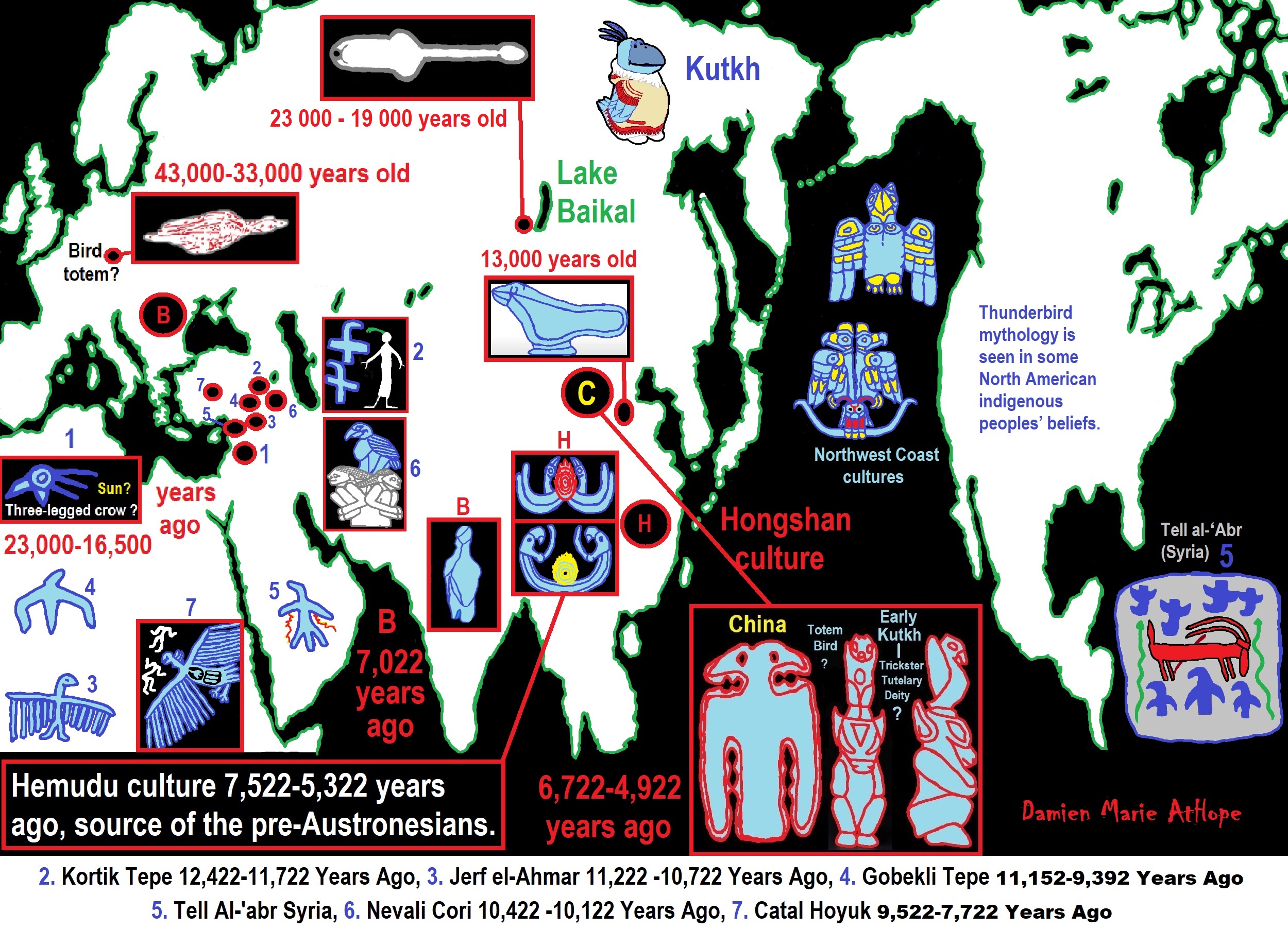

“At a nearby location of Lingjing (Henan, China) was found bird carving, with a probable age estimated to 13,500 years old. The carving, which predates previously known comparable instances from this region by 8,500 years.” ref

Damien finds both the dogs likely from Siberia and possibly the bird mythology that came to inspire the bird art.

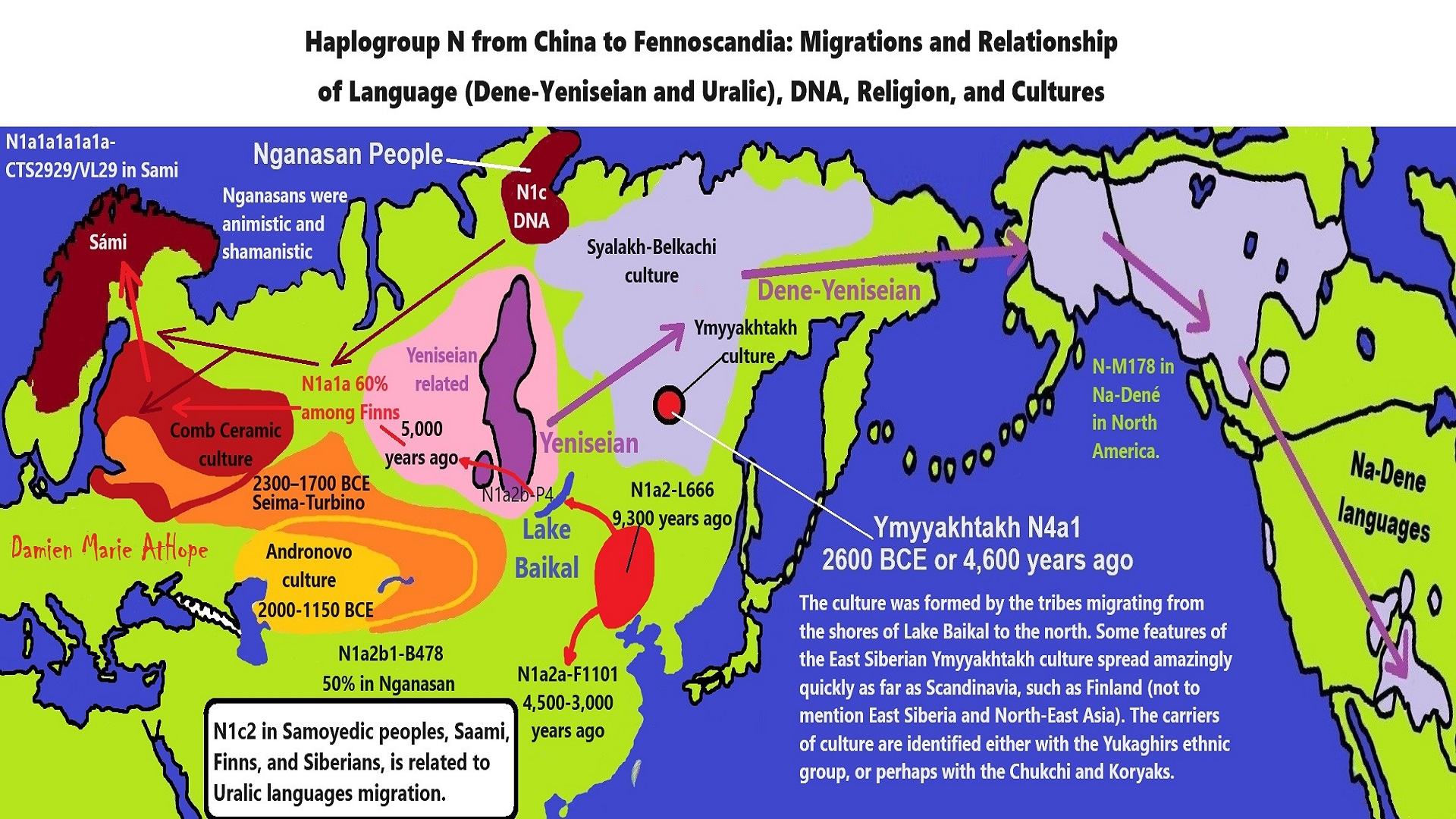

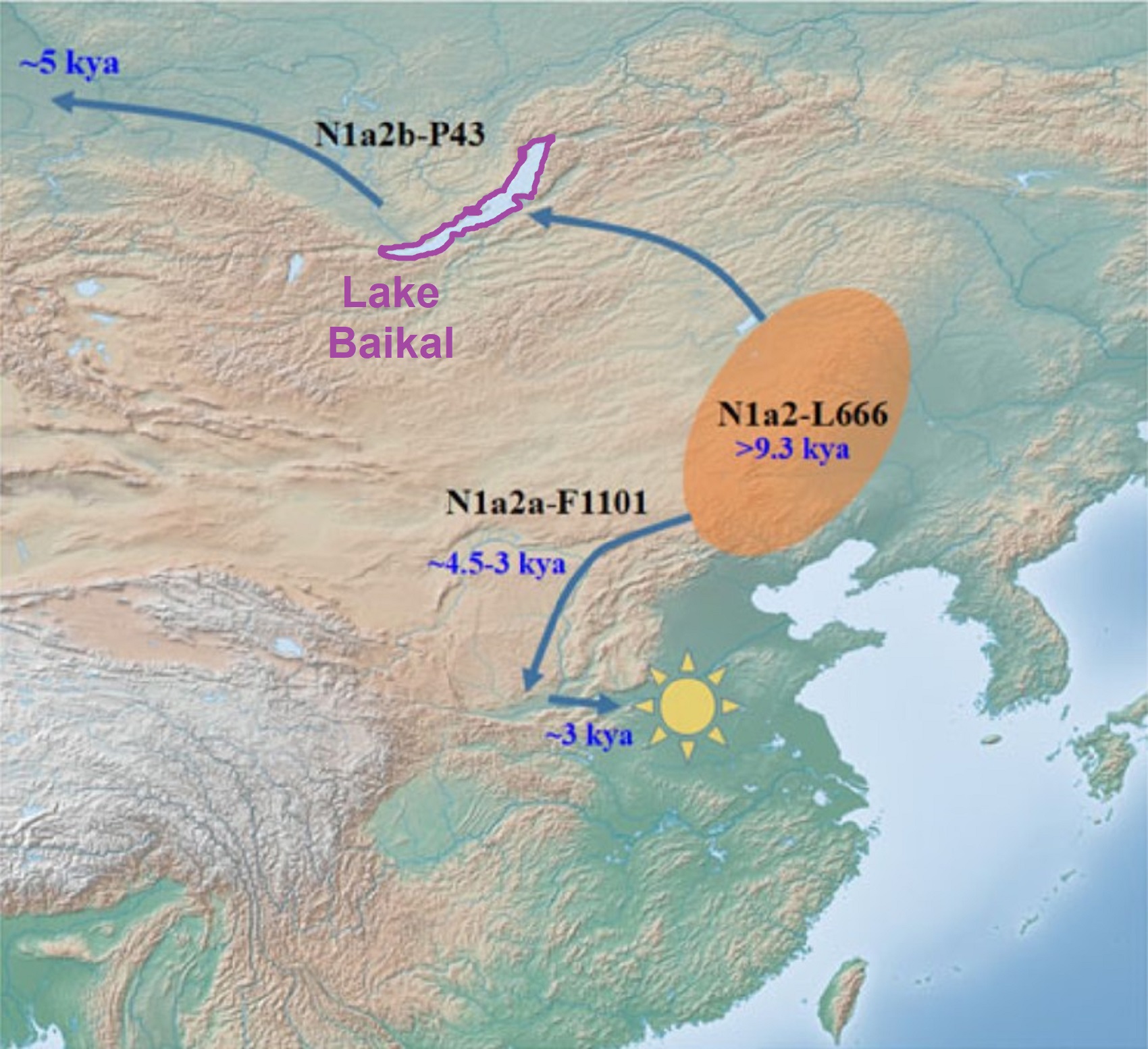

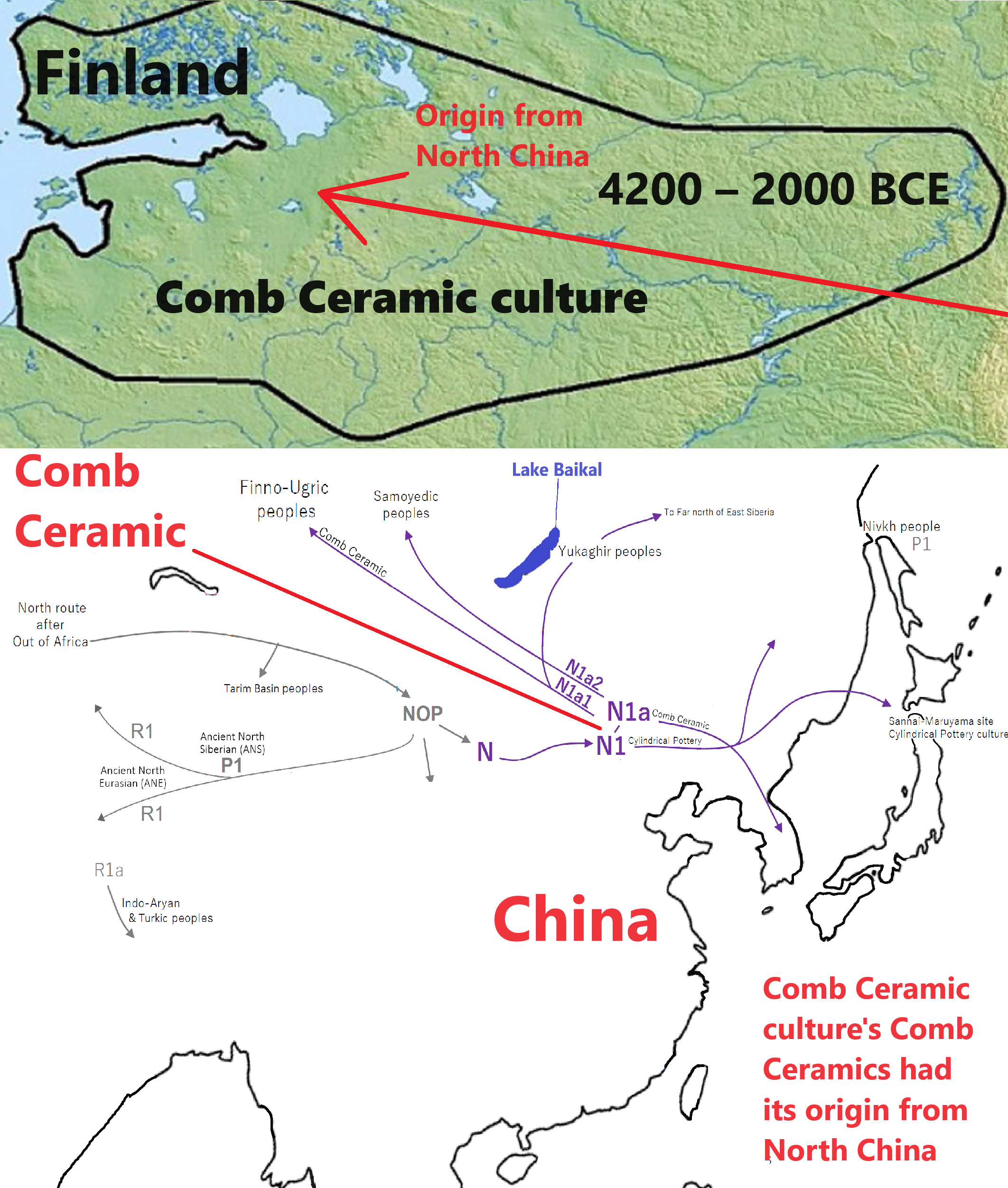

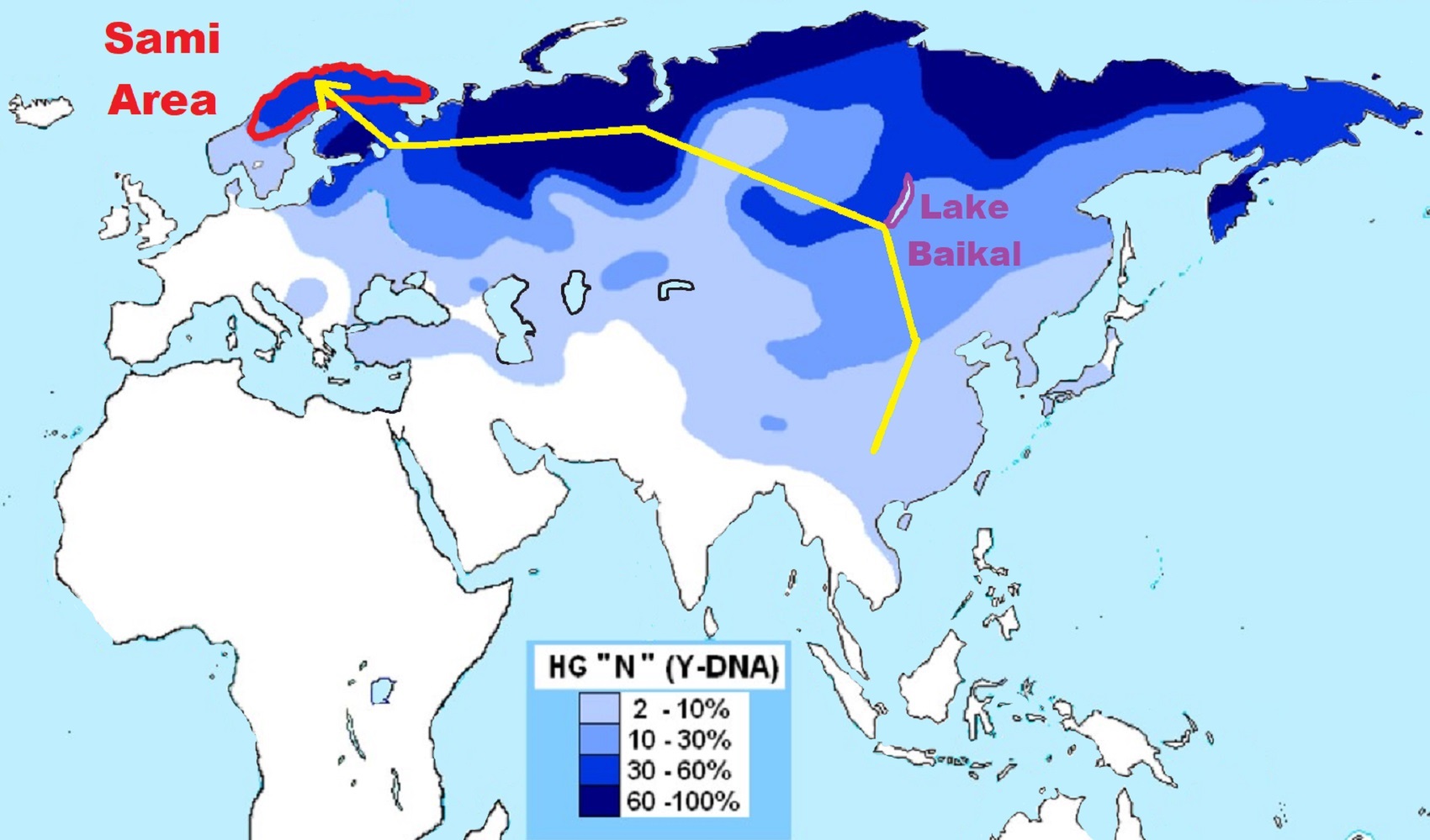

“N moved from southern China 20,000 years ago involving the earliest pottery, then spreading pottery into Siberia starting around 14,000 years ago, and N has experienced serial bottlenecks in Siberia and secondary expansions in eastern Europe. Haplogroup N-M46 is approximately 14,000 years old. In Siberia, haplogroup N-M46 reaches a maximum frequency of approximately 90% among the Yakuts, a Turkic people who live mainly in the Sakha (Yakutia) Republic. However, N-M46 is present with much lower frequency among many of the Yakuts’ neighbors, such as Evenks and Evens. The haplogroup N-M46 has a low diversity among Yakuts suggestive of a population bottleneck or founder effect. This was confirmed by a study of ancient DNA which traced the origins of the male Yakut lineages to a small group of horse-riders from the Cis-Baikal area.” ref

15. 12,300 years ago Ust’-Khaita site, Baikal region, Siberia

“Sub-adult skull located 2,400 km southwest of Ulakhan Sular and proposed as a Paleolithic dog. Also a somewhat close find at 12,450 years old mummified dog carcass. The “Black Dog of Tumat” was found frozen into the ice core of an oxbow lake steep ravine at the middle course of the Syalaah River in the Ust-Yana region. DNA analysis confirmed it as an early dog.” ref The Archaeology of Ushki Lake, Kamchatka, and the Pleistocene Peopling of the Americas: The Ushki Paleolithic sites of Kamchatka, Russia, have long been thought to contain information critical to the peopling of the Americas, especially the origins of Clovis. New radiocarbon dates indicate that human occupation of Ushki began only 13,000 calendar years ago-nearly 4000 years later than previously thought. Although biface industries were widespread across Beringia contemporaneous to the time of Clovis in western North America, these data suggest that late-glacial Siberians did not spread into Beringia until the end of the Pleistocene, perhaps too recently to have been ancestral to proposed pre-Clovis populations in the Americas.” ref

16. 12,000 years ago Ain Mallaha (Eynan) and HaYonim terrace, Israel

“Three canid finds. A diminutive carnassial and a mandible, and a wolf or dog puppy skeleton buried with a human during the Natufian culture. These Natufian dogs did not exhibit tooth-crowding. The Natufian culture occupied the Levant, and had earlier interred a fox together with a human in the Uyun al-Hammam burial site, Jordan dated 17,700–14,750 years ago.” ref

17. 10,150 years ago Lawyer’s Cave, Alaska, USA

“Bone of a dog, oldest find in North America. DNA indicates a split from Siberian relatives 16,500 years ago, indicating that dogs may have been in Beringia earlier. Lawyer’s Cave is on the Alaskan mainland east of Wrangell Island in the Alexander Archipelago of southeast Alaska.” ref

18. 9,000 years ago Jiahu site, China

“Eleven dog interments. Jaihu is a Neolithic site 22 kilometers north of Wuyang in Henan Province.” ref Most archaeologists consider the Jaihu site to be one of the earliest examples of the Peiligang culture. Settled around 7000 BCE or around 9,000 years ago, the site was later flooded and abandoned around 5700 BCE or around 7,700 years ago. At one time, it was “a complex, highly organized Chinese Neolithic society”, home to at least 250 people and perhaps as many as 800. The important discoveries of the Jiahu archaeological site include the Jiahu symbols, possibly an early example of proto-writing, carved into tortoise shells and bones; the thirty-three Jiahu flutes carved from the wing bones of cranes, believed to be among the oldest playable musical instruments in the world; and evidence of alcohol fermented from rice, honey and hawthorn leaves.” ref

19. 8,000 years ago Svaerdborg site, Denmark

“Three different sized dog types recorded at this Maglemosian culture site. Maglemosian (c. 9000 – c. 6000 BCE or around 11,000 to 8,000 years ago) is the name given to a culture of the early Mesolithic period in Northern Europe. In Scandinavia, the culture was succeeded by the Kongemose culture. It appears that they had domesticated the dog. Similar settlements were excavated from England to Poland and from Skåne in Sweden to northern France.” ref, ref

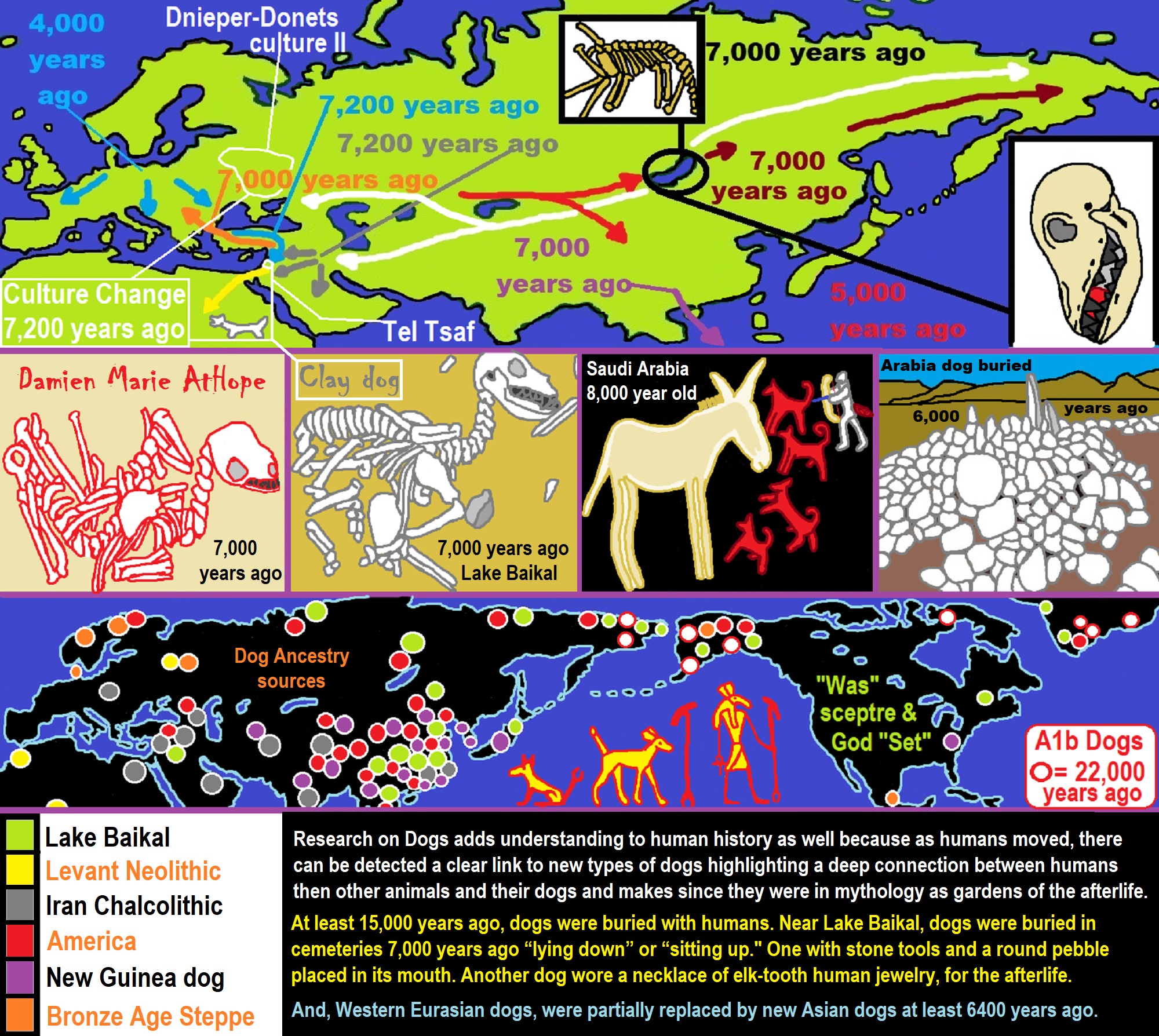

20. 7,425 years ago Lake Baikal region, Siberia

“Dog buried in a human burial ground. Additionally, a human skull was found buried between the legs of a “tundra wolf” dated 8,320 years ago (but it does not match any known wolf DNA). The evidence indicates that as soon as formal cemeteries developed in Baikal, some canids began to receive mortuary treatments that closely paralleled those of humans. One dog was found buried with four red deer canine pendants around its neck dated 5,770 years ago. Many burials of dogs continued in this region with the latest finding at 3,760 years ago, and they were buried lying on their right side and facing towards the east as did their humans. Some were buried with artifacts, e.g., stone blades, birch bark, and antler bone.” ref

21. 7,000 years ago Tianluoshan archaeological site, Zhejiang province, China

“In 2020, an mDNA study of ancient dog fossils from the Yellow River and Yangtze River basins of southern China showed that most of the ancient dogs fell within haplogroup A1b, as do the Australian dingoes and the pre-colonial dogs of the Pacific, but in low frequency in China today. The specimen from the Tianluoshan archaeological site is basal to the entire lineage. The dogs belonging to this haplogroup were once widely distributed in southern China, then dispersed through Southeast Asia into New Guinea and Oceania, but were replaced in China 2,000 years ago by dogs of other lineages.” ref

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

Based on the seeming evidence, I speculate that around 14,000 years ago, it could be possible Siberian Shamanism (along with dogs and a bird carving, different but yet possibly related to the bird carvings in Siberia dating from 24,000 to 15,000 years ago) was transferred to China, after “N” DNA reached Siberia bringing them pottery. Bird sculptures through ethnographic comparison at 24,000–15,000 years old Mal’ta with objects used by Siberian shamans, suggest a fully developed shamanism.

ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref, ref

“These ideas are my speculations from the evidence.”

I am still researching the “god‘s origins” all over the world. So you know, it is very complicated but I am smart and willing to look, DEEP, if necessary, which going very deep does seem to be needed here, when trying to actually understand the evolution of gods and goddesses. I am sure of a few things and less sure of others, but even in stuff I am not fully grasping I still am slowly figuring it out, to explain it to others. But as I research more I am understanding things a little better, though I am still working on understanding it all or something close and thus always figuring out more.

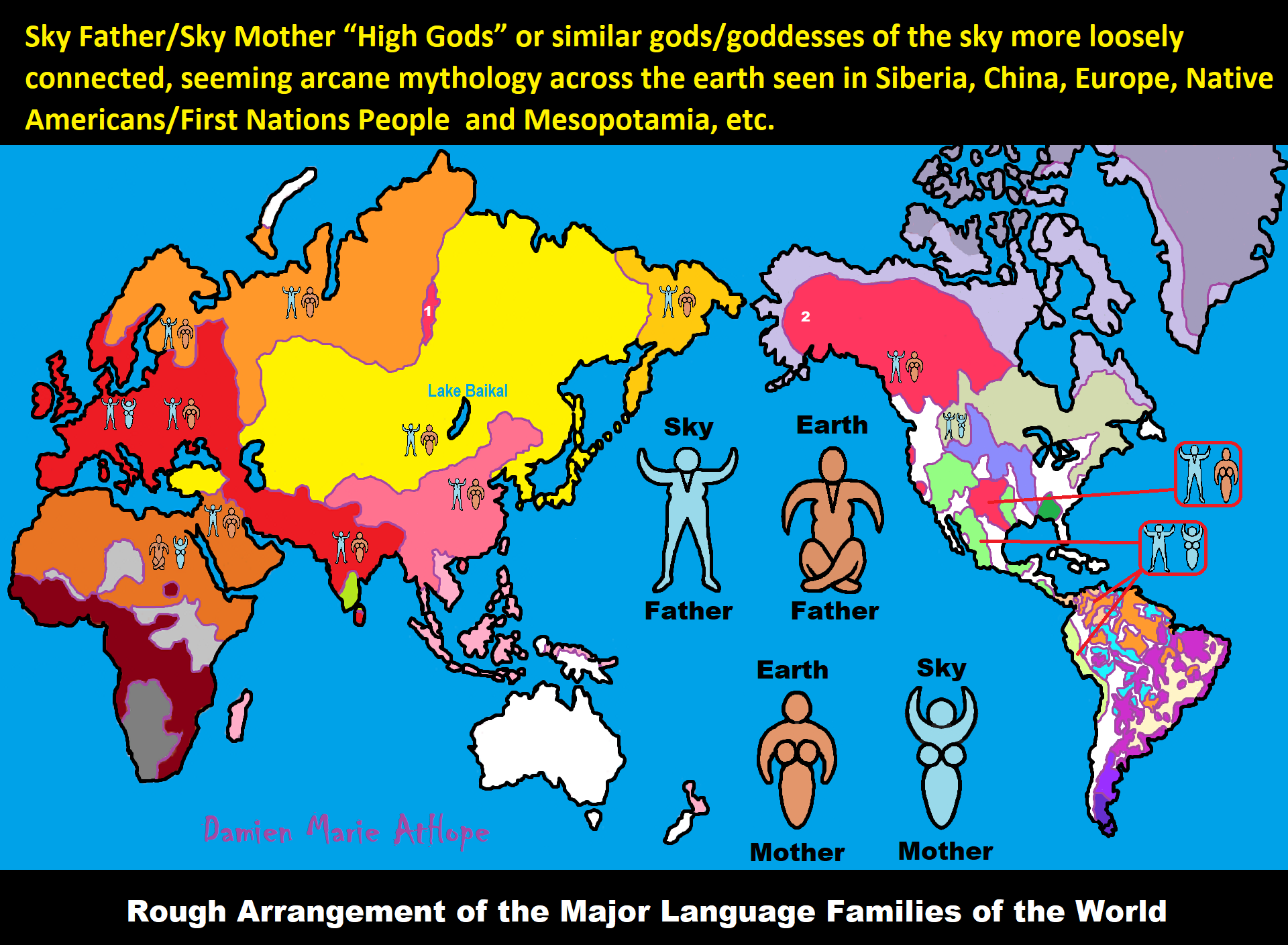

Sky Father/Sky God?

“Egyptian: (Nut) Sky Mother and (Geb) Earth Father” (Egypt is different but similar)

Turkic/Mongolic: (Tengri/Tenger Etseg) Sky Father and (Eje/Gazar Eej) Earth Mother *Transeurasian*

Hawaiian: (Wākea) Sky Father and (Papahānaumoku) Earth Mother *Austronesian*

New Zealand/ Māori: (Ranginui) Sky Father and (Papatūānuku) Earth Mother *Austronesian*

Proto-Indo-European: (Dyḗus/Dyḗus ph₂tḗr) Sky Father and (Dʰéǵʰōm/Pleth₂wih₁) Earth Mother