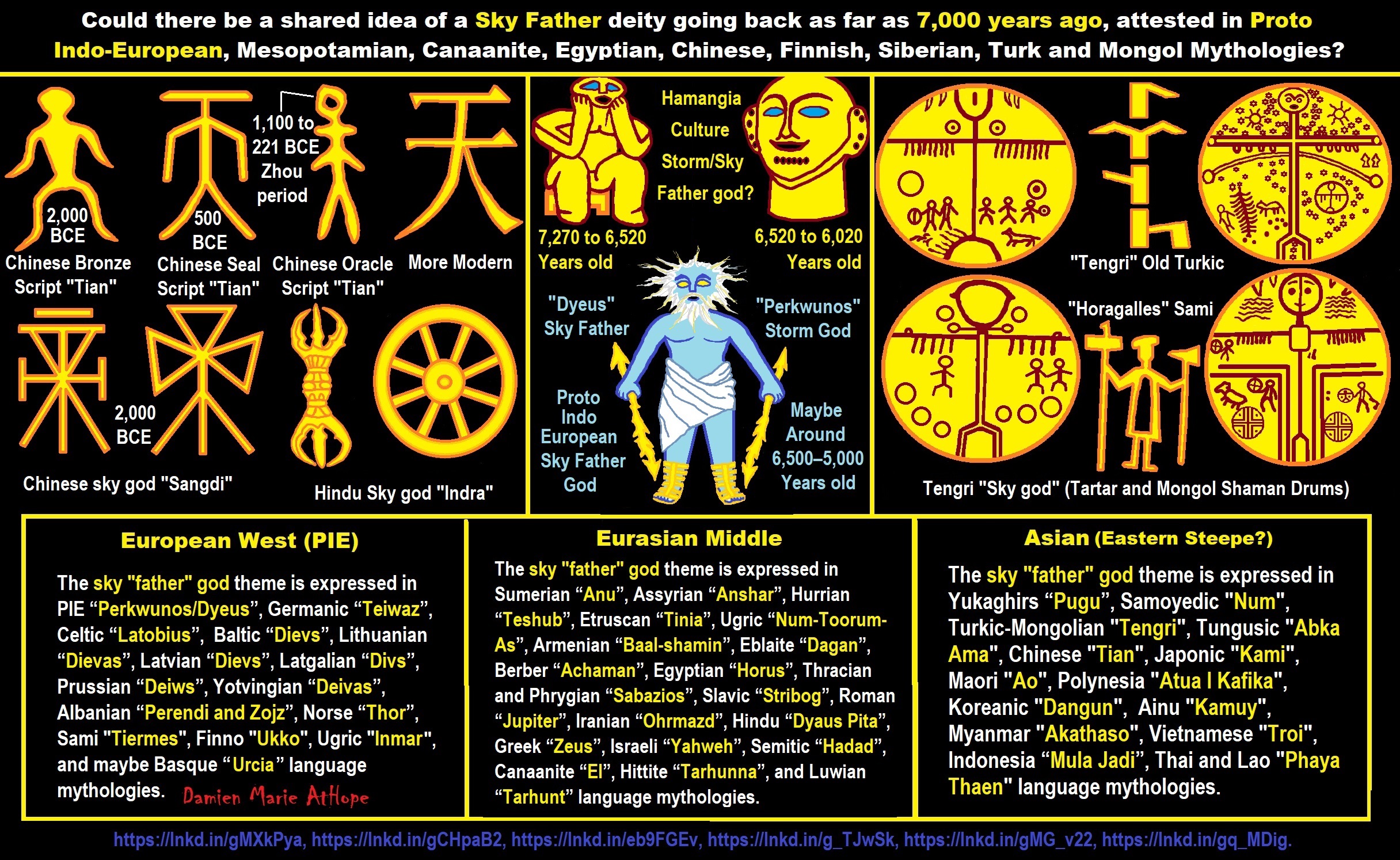

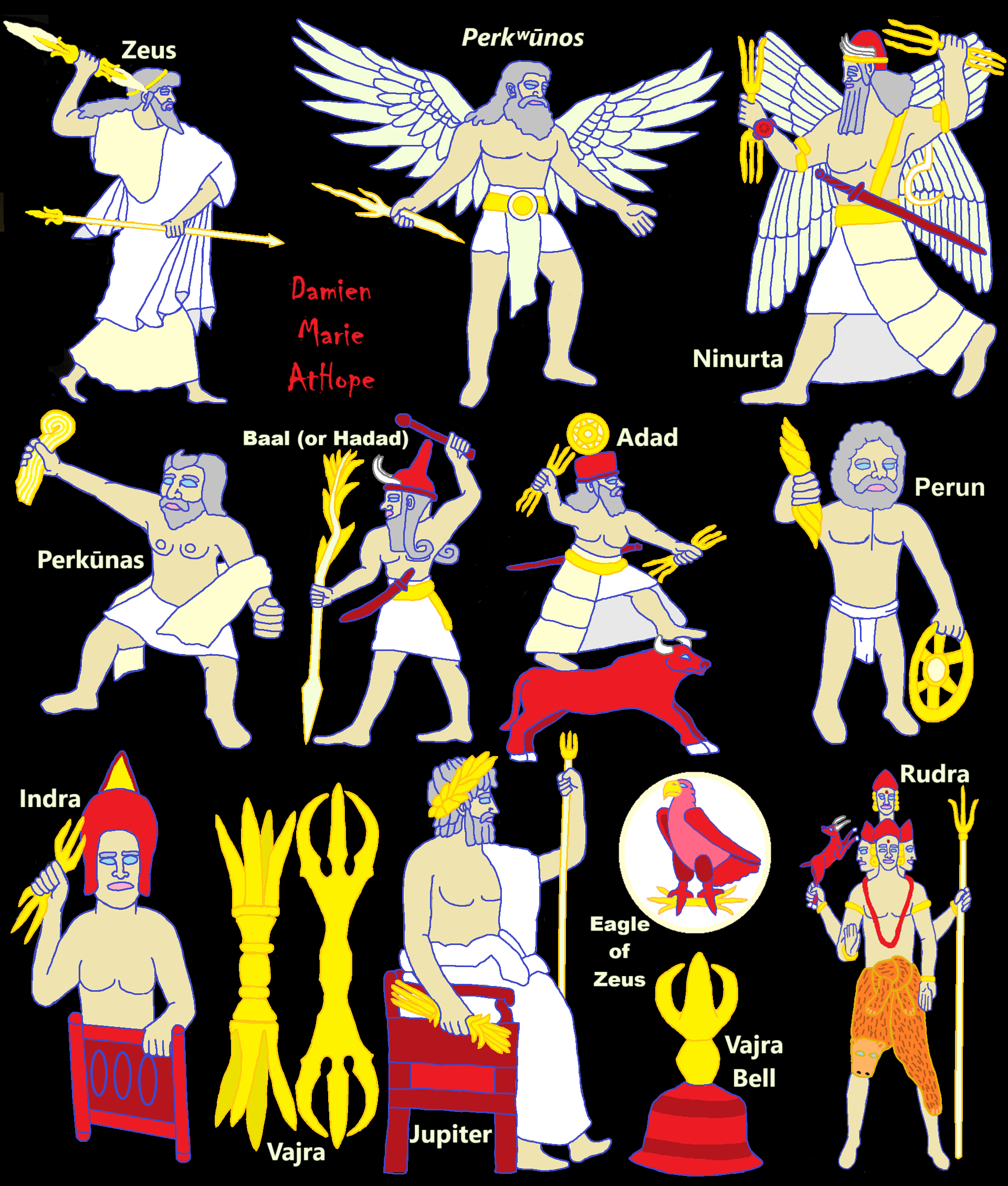

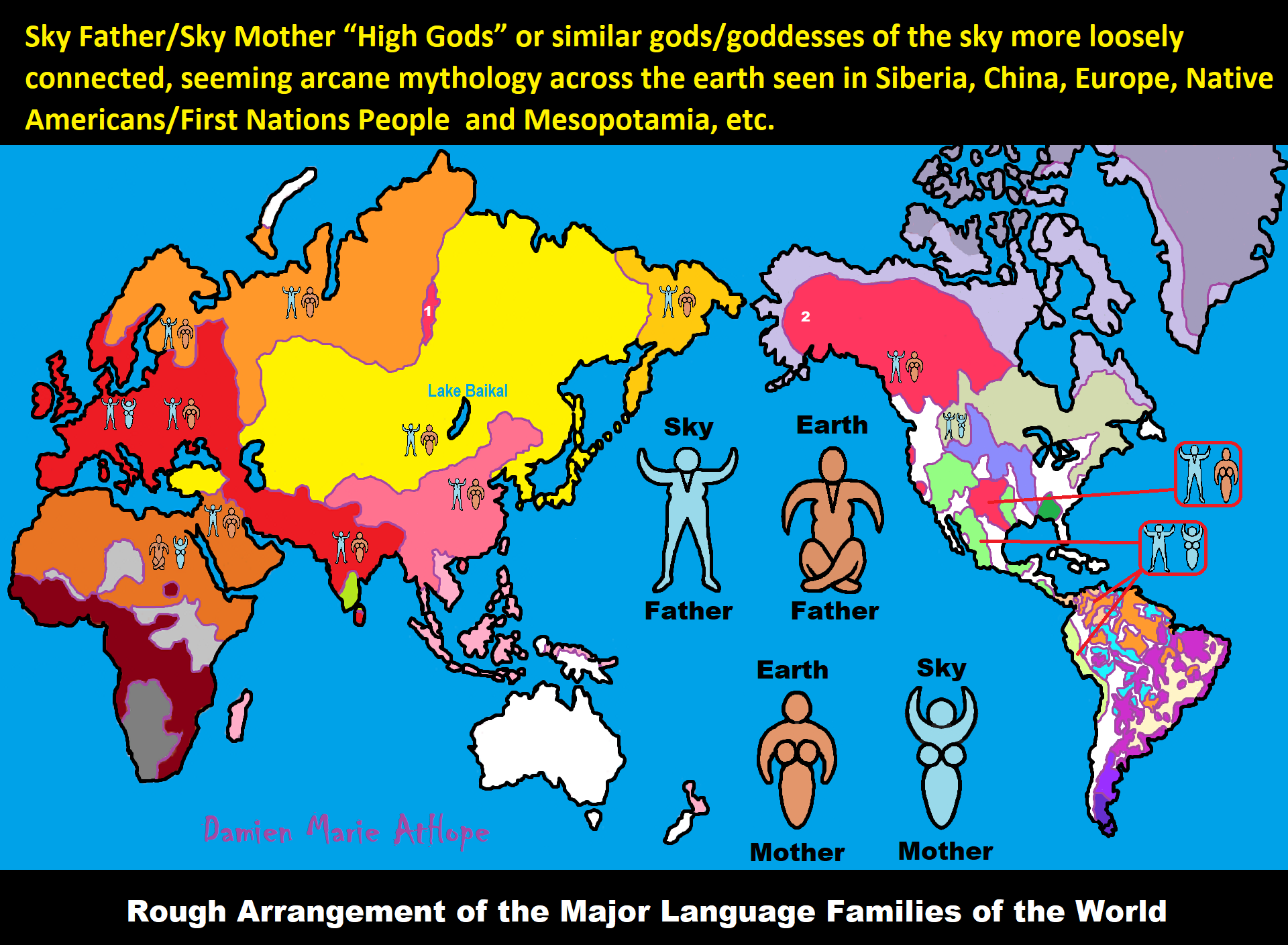

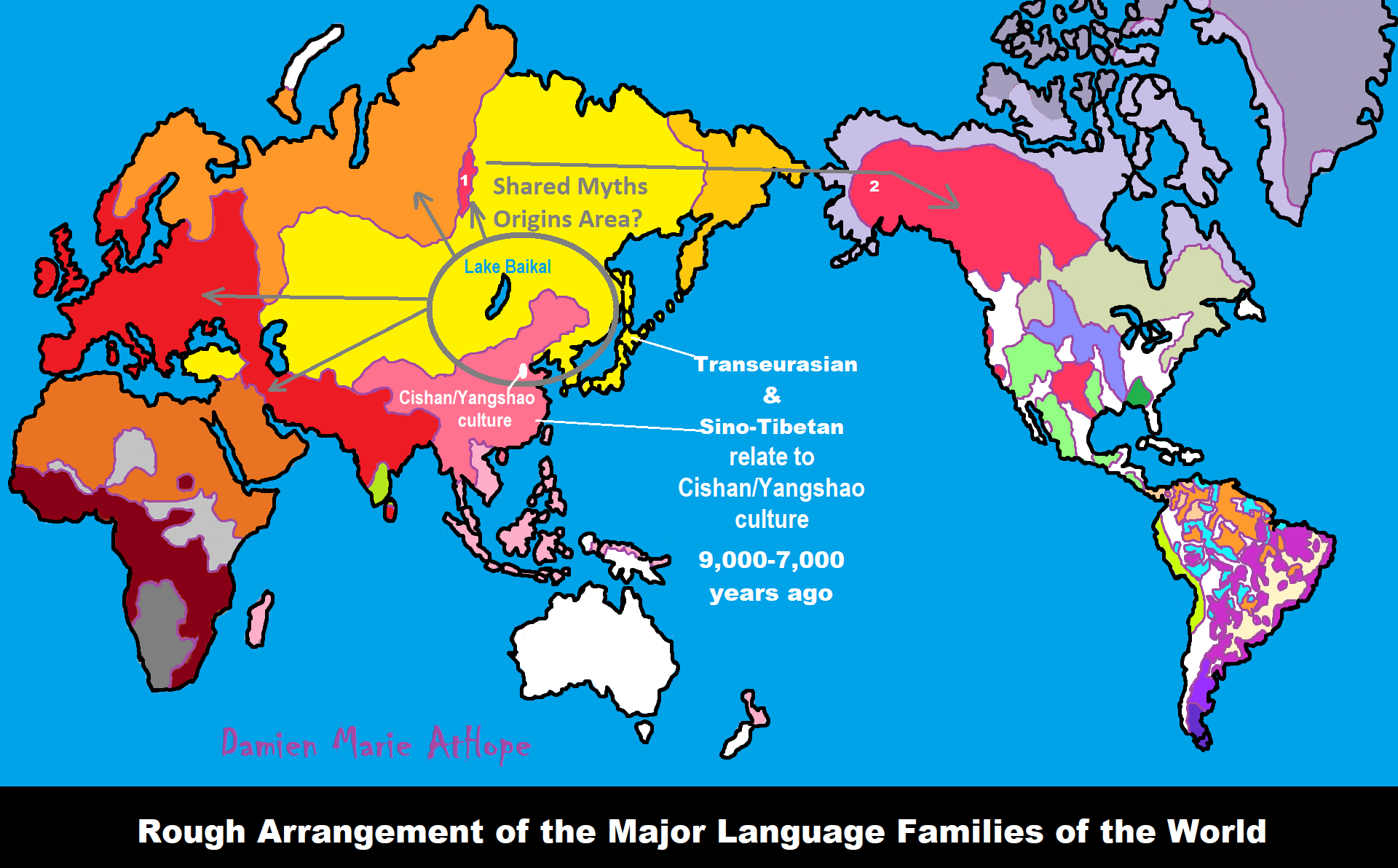

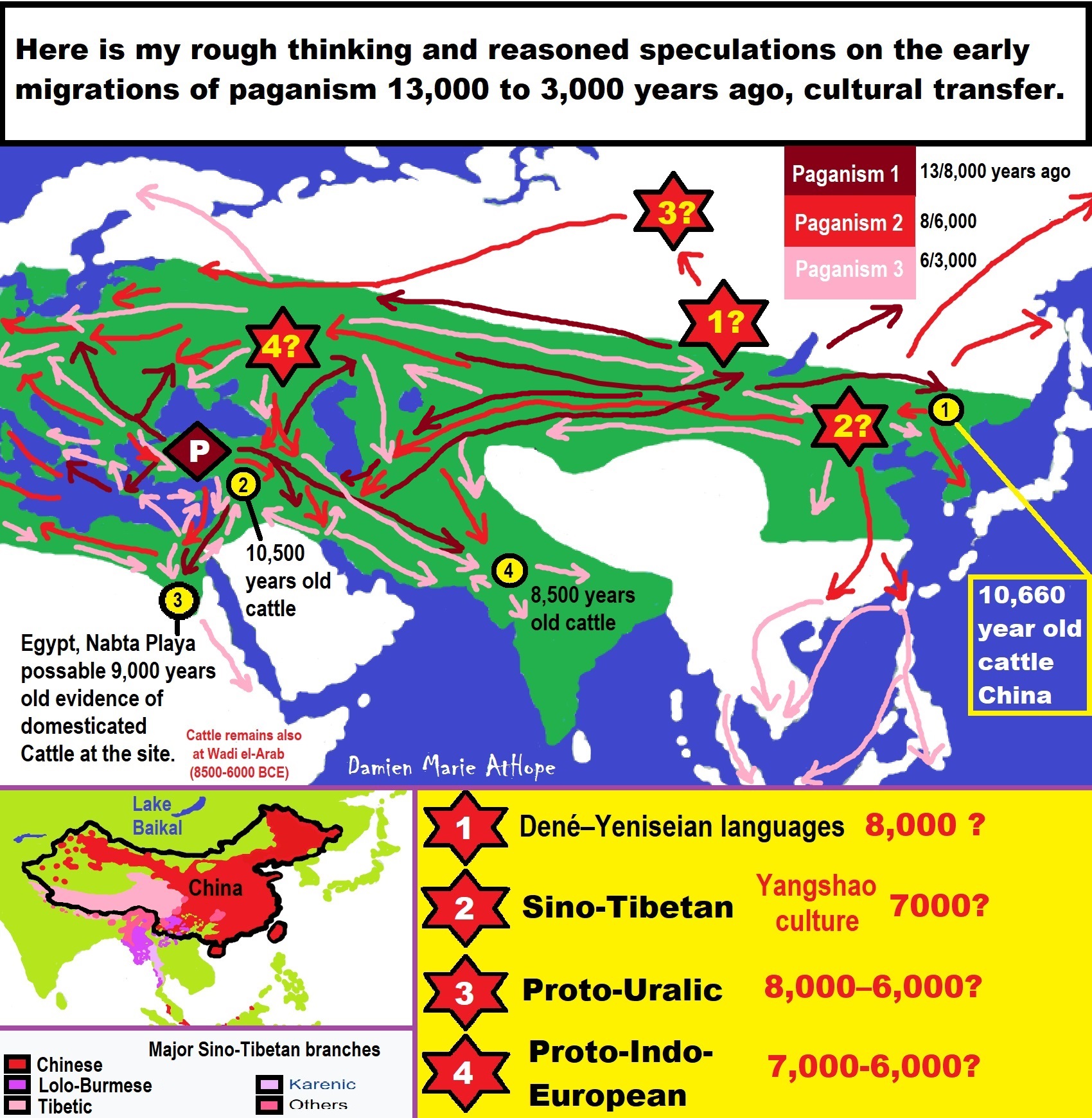

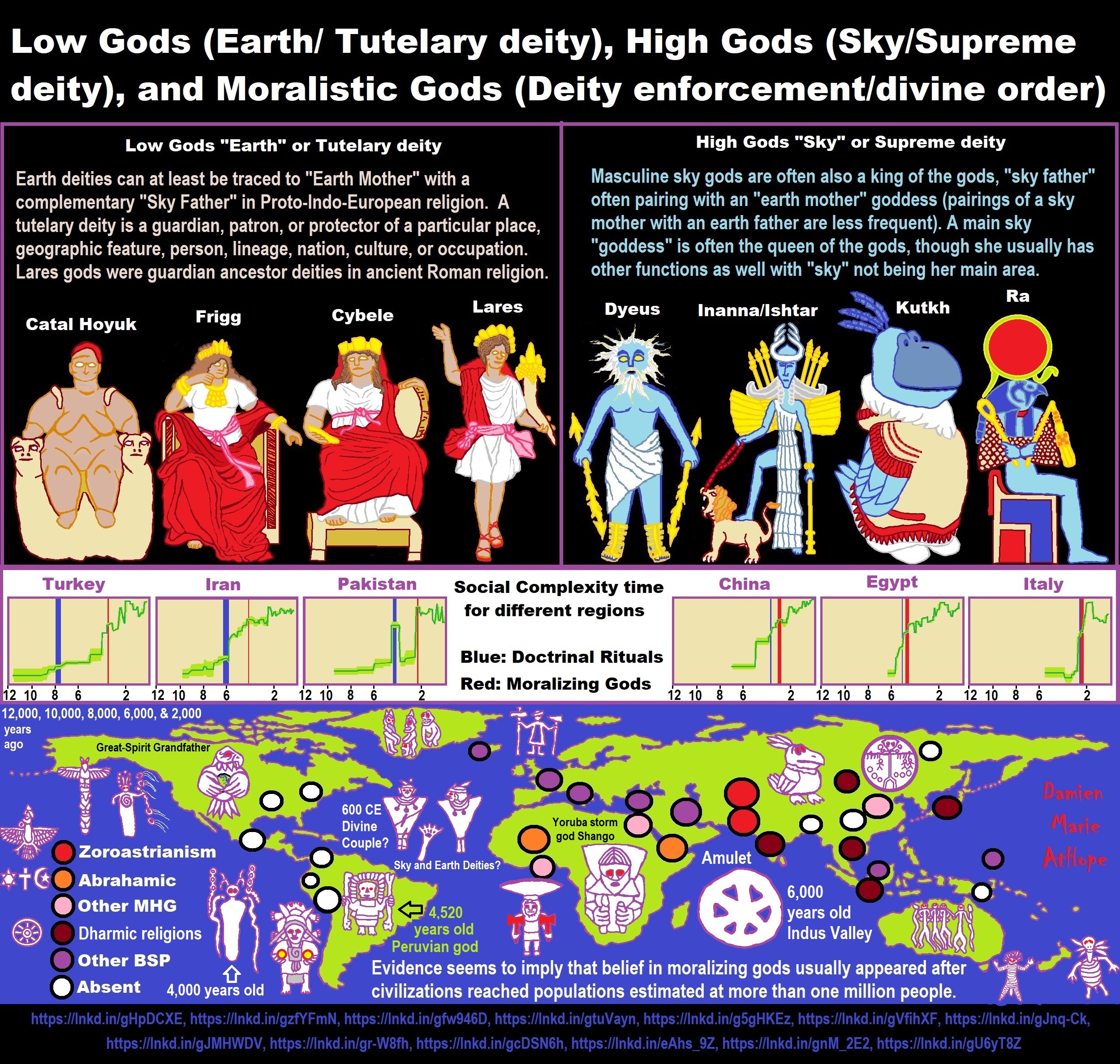

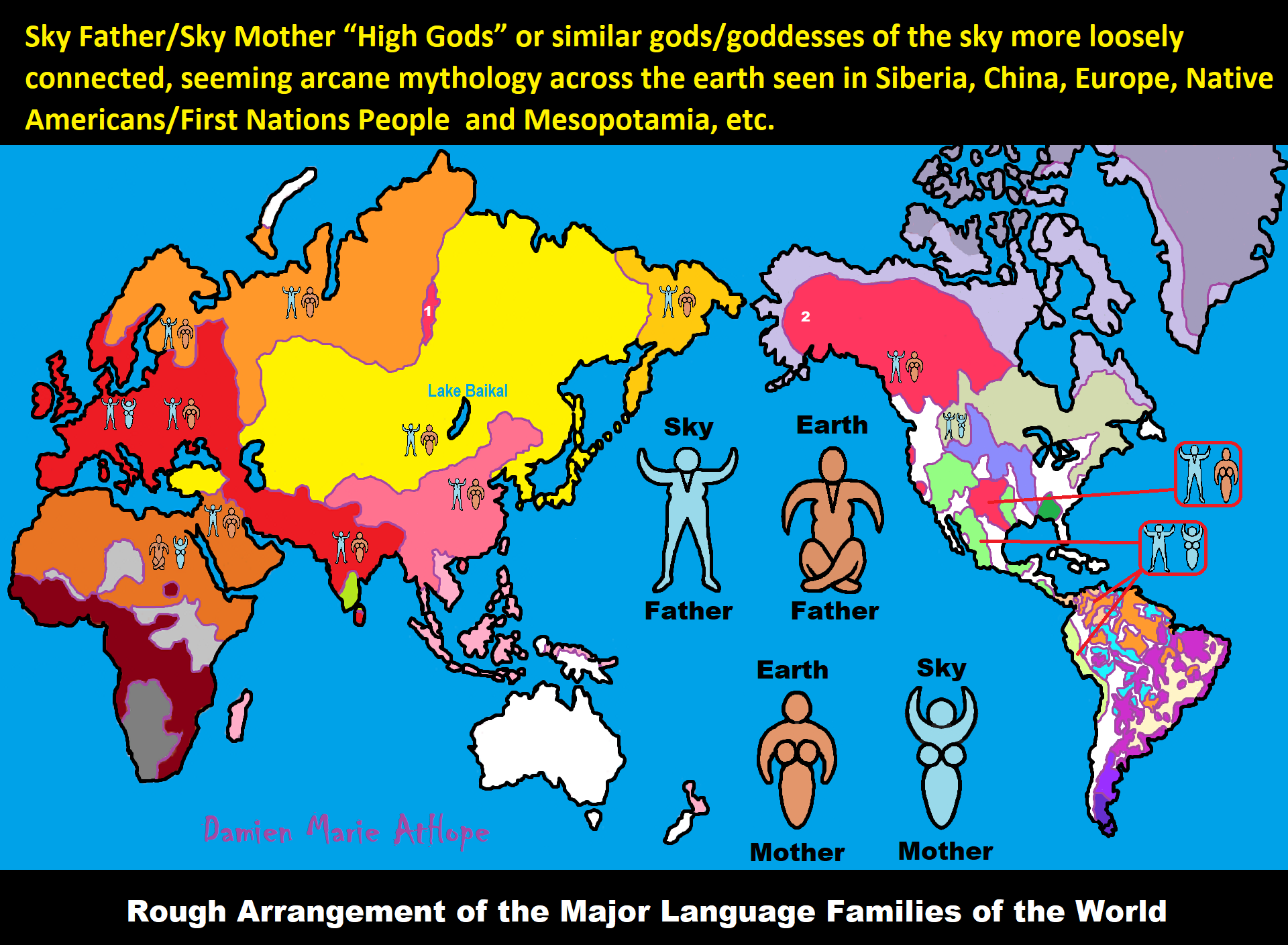

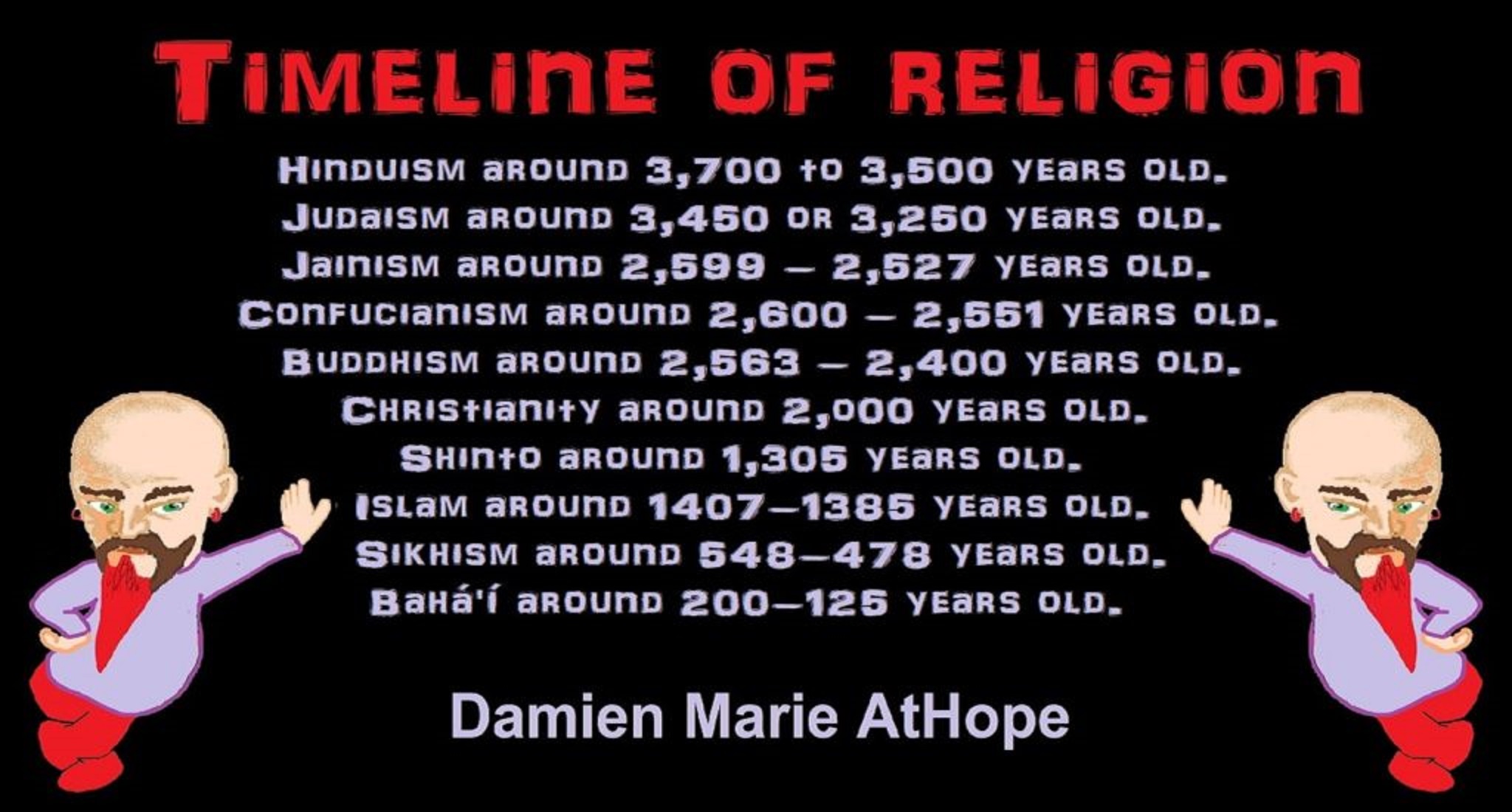

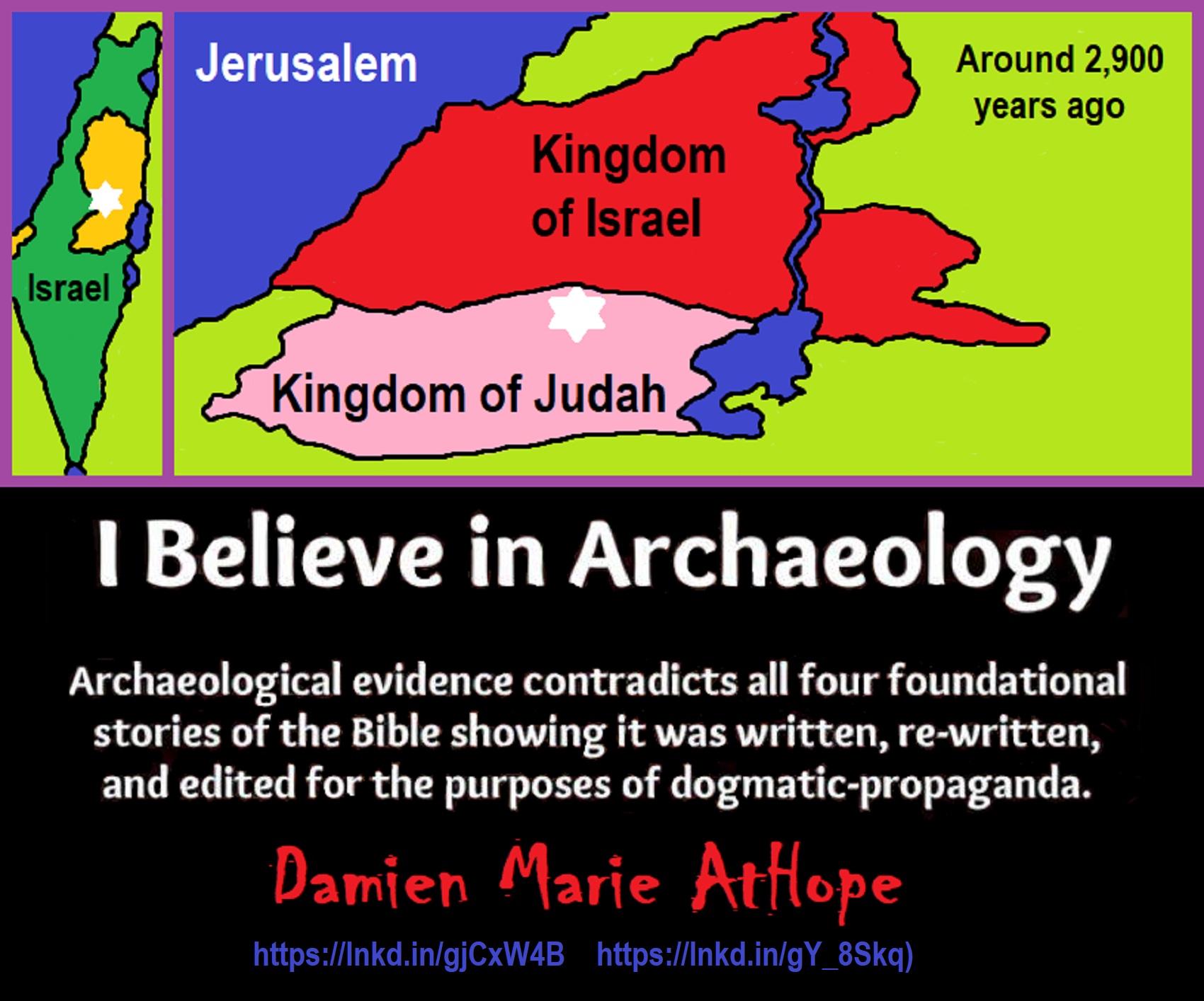

“Proto-Indo-European mythology is the myths and deities associated with speakers of the Indo-European, including Albanian, Armenian, Balto-Slavic, Celtic, Germanic, Hellenic, Indo-Iranian, Italic, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish, and Dutch. The Proto-Indo-European pantheon includes a number of securely reconstructed deities, since they are both cognates—linguistic siblings from a common origin—and associated with similar attributes and body of myths: such as *Dyḗws Ph₂tḗr, the daylight-sky god; his consort *Dʰéǵʰōm, the earth mother; his daughter *H₂éwsōs, the dawn goddess; his sons the Divine Twins; and *Seh₂ul and *Meh₁not, a solar deity and moon deity, respectively. Some deities, like the weather god *Perkʷunos or the herding-god *Péh₂usōn, are only attested in a limited number of traditions—Western (i.e. European) and Graeco-Aryan, respectively—and could therefore represent late additions that did not spread throughout the various Indo-European dialects.” ref, ref

“Some myths are also securely dated to Proto-Indo-European times, since they feature both linguistic and thematic evidence of an inherited motif: a story portraying a mythical figure associated with thunder and slaying a multi-headed serpent to release torrents of water that had previously been pent up; a creation myth involving two brothers, one of whom sacrifices the other in order to create the world; and probably the belief that the Otherworld was guarded by a watchdog and could only be reached by crossing a river. Various schools of thought exist regarding possible interpretations of the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European mythology. One of the earliest attested and thus one of the most important of all Indo-European mythologies is Vedic mythology, especially the mythology of the Rigveda, the oldest of the Vedas. The main mythologies used in comparative reconstruction are Iranian, Baltic, Roman, Norse, Celtic, Greek, Slavic, Hittite, Armenian, and Albanian.” ref

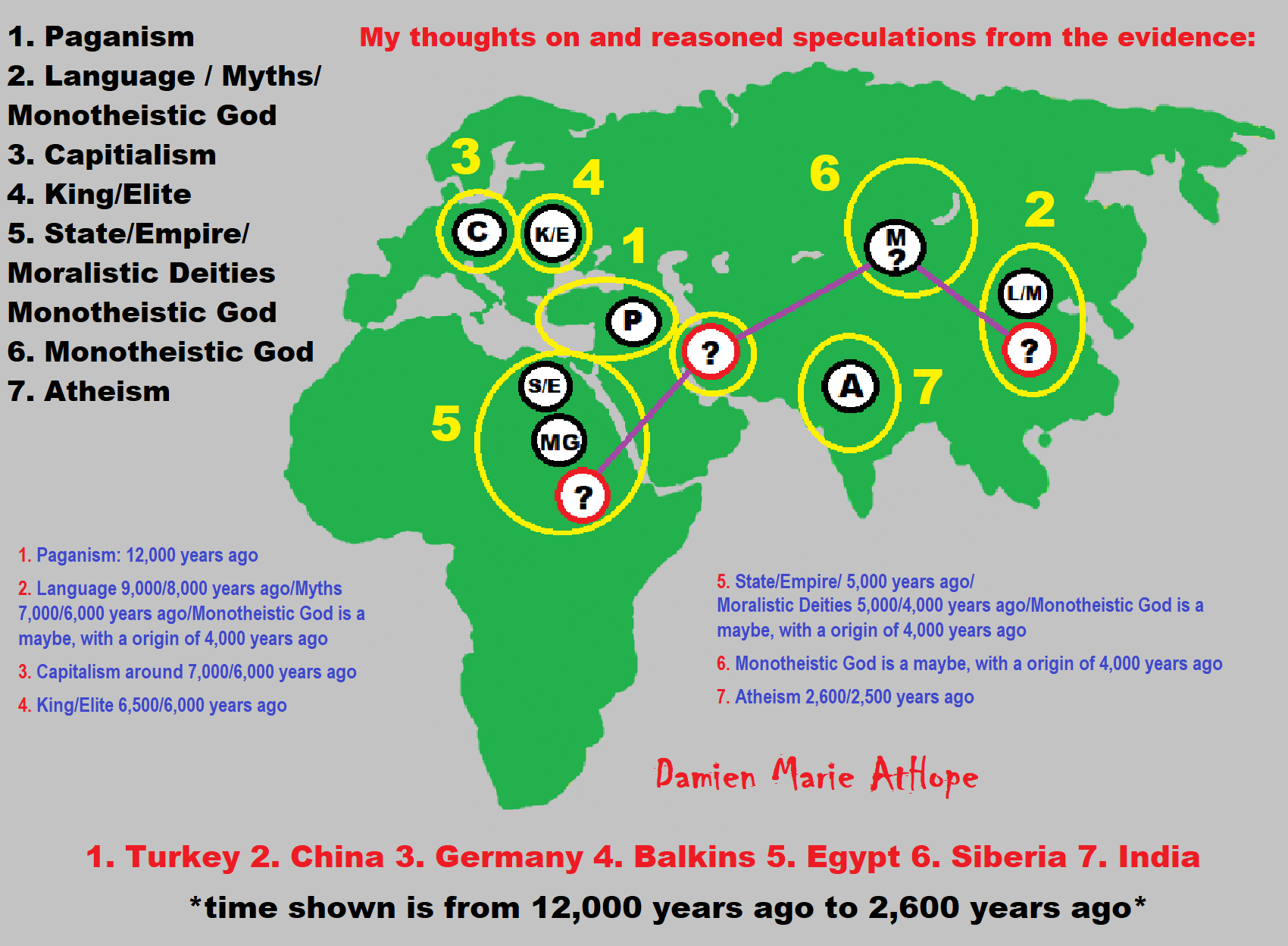

It is a typical atheist movement thinking that “fear of lightning created religion and/or deities,” this is not true of religion or deities as a group, which emerged due to lightning; it seems to have been a later myth after there were already sky deities.

Deities in the main art:

- Zeus (Greek mythology)

- Perkwunos (Proto-Indo-European mythology)

- Ninurta (ancient Mesopotamian mythology)

- Perkūnas (Baltic mythology)

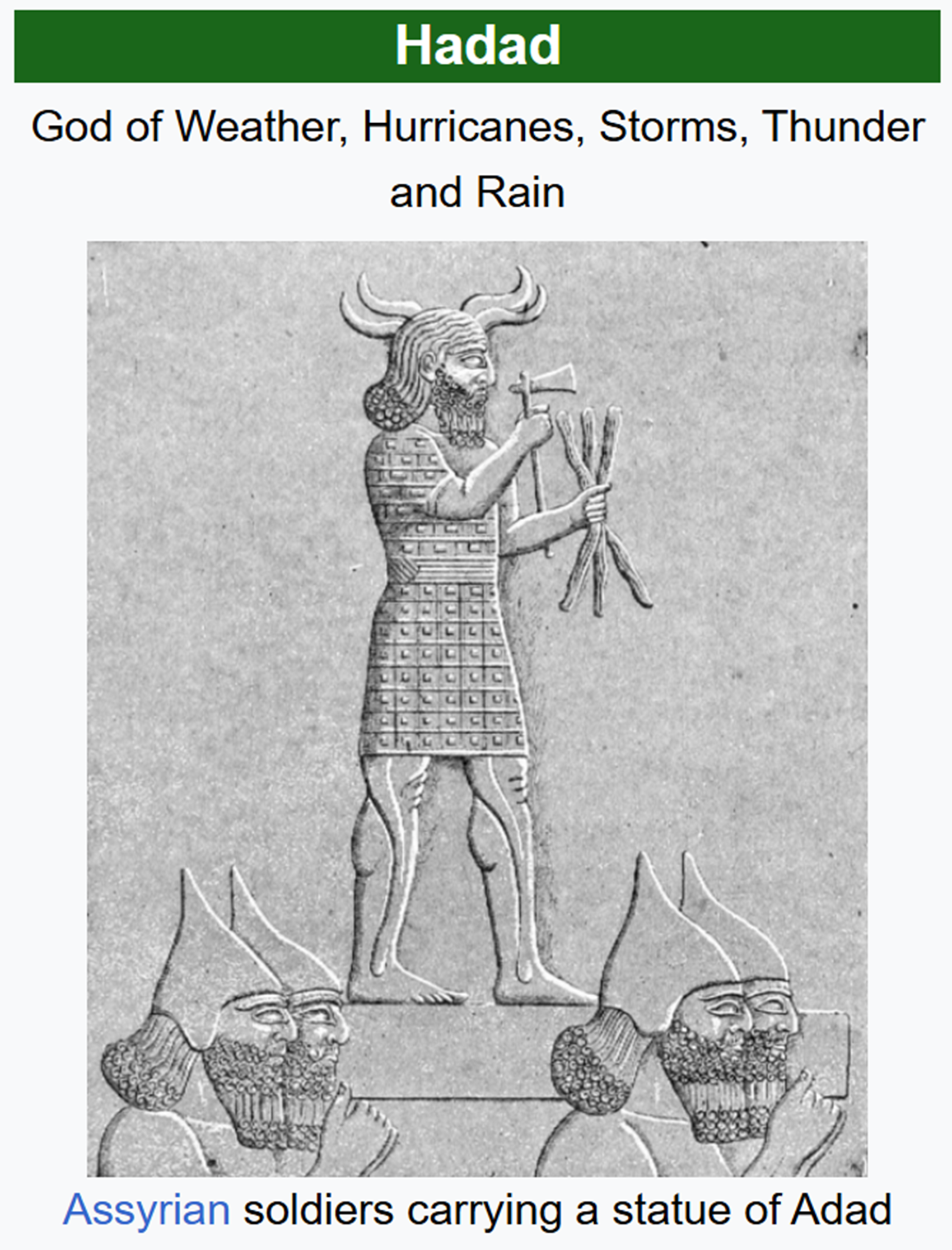

- Baʿal, Hadad (Canaanite and Phoenician mythology)

- Hadad, Adad (Canaanite and ancient Mesopotamian religions)

- Perun (Slavic mythology)

- Indra (Vedic, Hindu mythology and Buddhist mythology)

- Jupiter, Summanus (Roman mythology)

- Rudra, Shiva (Rigvedic deity and Hindu scriptures)

“Polytheistic peoples from many cultures have postulated a thunder deity, the creator or personification of the forces of thunder and lightning; a lightning god does not have a typical depiction and will vary based on the culture. In Indo-European cultures, the thunder god is frequently depicted as male and known as the chief or King of the Gods, e.g.: Indra in Hinduism, Zeus in Greek mythology, Zojz in Albanian mythology, and Perun in ancient Slavic religion.” ref

“The Hindu God Indra was the chief deity and at his prime during the Vedic period, where he was considered to be the supreme God. Indra was initially recorded in the Rigveda, the first of the religious scriptures that comprise the Vedas. Indra continued to play a prominent role throughout the evolution of Hinduism and played a pivotal role in the two Sanskrit epics that comprise the Itihasas, appearing in both the Ramayana and Mahabharata. Although the importance of Indra has since been subsided in favor of other Gods in contemporary Hinduism, he is still venerated and worshipped.” ref

“In Greek mythology, the Elysian Fields, or the Elysian Plains, was the final resting places of the souls of the heroic and the virtuous, evolved from a designation of a place or person struck by lightning, enelysion, enelysios. This could be a reference to Zeus, the god of lightning, so “lightning-struck” could be saying that the person was blessed (struck) by Zeus (/lightning/fortune). Egyptologist Jan Assmann has also suggested that Greek Elysion may have instead been derived from the Egyptian term ialu (older iaru), meaning “reeds,” with specific reference to the “Reed fields” (Egyptian: sekhet iaru / ialu), a paradisiacal land of plenty where the dead hoped to spend eternity.” ref

“The linguistic evidence for the worship of a thunder god under the name *Perkʷūnos as far back as Proto-Indo-European times (4500–2500 BCE) is therefore less secure.” ref

“*Perkʷūnos (Proto-Indo-European: ‘the Striker’ or ‘the Lord of Oaks’) is the reconstructed name of the weather god in Proto-Indo-European mythology. The deity was connected with fructifying rains, and his name was probably invoked in times of drought. In a widespread Indo-European myth, the thunder-deity fights a multi-headed water-serpent during an epic battle in order to release torrents of water that had previously been pent up. The name of his weapon, *mel-d-(n)-, which denoted both “lightning” and “hammer”, can be reconstructed from the attested traditions.” ref

*Perkʷūnos was often associated with oaks, probably because such tall trees are frequently struck by lightning, and his realm was located in the wooded mountains, *Perkʷūnyós. A term for the sky, *h₂éḱmō, apparently denoted a “heavenly vault of stone”, but also “thunderbolt” or “stone-made weapon”, in which case it was sometimes also used to refer to the thunder-god’s weapon. Contrary to other deities of the Proto-Indo-European pantheon, such as *Dyēus (the sky-god), or *H₂éwsōs (the dawn-goddess), widely accepted cognates stemming from the theonym *Perkʷūnos are only attested in Western Indo-European traditions.” ref

“The name *Perkʷunos is generally regarded as stemming from the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) verbal root *per- (‘to strike’). An alternative etymology is the PIE noun *pérkʷus (‘the oak‘), attached to the divine nomenclature *-nos (‘master of’). Various cognates can be found in the Latin oak-nymphs Querquetulanae (from quercus ‘oak-tree’), the Germanic *ferhwaz (‘oak’), the Gaulish erc- (‘oak’) and Quaquerni (a tribal name), the Punjabi pargāi (‘sacred oak’), and perhaps in the Greek spring-nymph Herkyna. The theonym *Perkʷunos thus either meant “the Striker” or “the Lord of Oaks.” ref

“A theory uniting those two etymologies has been proposed in the mythological association of oaks with thunder, suggested by the frequency with which such tall trees are struck by lightning. The existence of a female consort is suggested by gendered doublet-forms such as those found in Old Norse Fjörgyn–Fjörgynn and Lithuanian Perkūnas–Perkūnija. The South Slavic link Perun–Perperuna is not secure. The noun *perkʷunos also gave birth to a group of cognates for the ordinary word “thunder”, including Old Prussian percunis, Polish piorun (“thunderbolt”), Latvian pērkauns (“thunderbolt”), or Lithuanian perkūnas (“thunder”) and perkūnija (“thunderstorm”). On a Thracian enlightenment inscription is mentioned Hero Perkonei (Ηρωεη Περκωνει), an epithet of the god Ares (Mars), a Thracian horseman. Perkʷūnos is also the reflexive name of the god Mars (Ares).” ref

“Other Indo-European theonyms related to ‘thunder’, through another root *(s)tenh₂-, are found in the Germanic Þunraz (Thor), the Celtic Taranis (from an earlier *Tonaros), and the Latin epithet Tonans (attached to Jupiter). According to scholar Peter Jackson, “they may have arisen as the result of fossilization of an original epithet or epiclesis” of Perkʷunos, since the Vedic weather-god Parjanya is also called stanayitnú- (“Thunderer”). Another possible epithet was *tr̥h₂wónts “conquering”, from *térh₂uti “to overcome”, with its descendants being Hittite god Tarḫunna, Luwian Tarḫunz, and Sanskrit तूर्वत् (tūrvat), epithet of a storm-god Indra. George E. Dunkel regarded Perkʷunos as an original epithet of Dyēus, the Sky-God. It has also been postulated that Perkʷunos was referred to as *Diwós Putlós (‘son of Dyēus’), although this is based on the Vedic poetic tradition alone.” ref

Perkʷunos: Weapon

“Perkʷunos is usually depicted as holding a weapon, named *meld-n- in the Baltic and Old Norse traditions, which personifies lightning and is generally conceived as a club, mace, or hammer made of stone or metal. In the Latvian poetic expression Pērkōns met savu milnu (“Pērkōn throws his mace”), the mace (milna) is cognate with the Old Norse mjölnir, the hammer thrown by the thunder god Thor, and also with the word for ‘lightning’ in the Old Prussian mealde, the Old Church Slavonic *mlъni, or the Welsh mellt.” ref

Perkʷunos: Fructifying rains

“While his thunder and lightning had a destructive connotation, they could also be seen as a regenerative force since they were often accompanied by fructifying rains. Parjanya is depicted as a rain god in the Vedas, and Latvian prayers included a call for Pērkōns to bring rain in times of drought. The Balkan Slavs worshipped Perun along with his female counterpart Perperuna, the name of a ritual prayer calling for fructifying rains and centred on the dance of a naked virgin who had not yet had her first monthly period. The earth is likewise referred to as “menstruating” in a Vedic hymn to Parjanya, a possible cognate of Perperuna. The alternative name of Perperuna, Dodola, also recalls Perkūnas‘ pseudonym Dundulis, and Zeus’ oak oracle located at Dodona.” ref

“Perëndi – a name that is used in Albanian for “god, sky”, but considered by some scholars to be an Albanian thunder-god, cognate to Proto-Indo-European *Perkʷūnos – is especially invoked by Albanians in incantations and ritual songs praying for rain. Rituals were performed in times of summer drought to make it rain, usually in June and July, but sometimes also in the spring months when there was severe drought. In different Albanian regions, for rainmaking purposes, people threw water upwards to make it subsequently fall to the ground in the form of rain. This was an imitative type of magic practice with ritual songs.” ref

“A mythical multi-headed water-serpent is connected with the thunder-deity in an epic battle. The monstrous foe is a “blocker of waters”, and his heads are eventually smashed by the thunder-deity to release the pent-up torrents of rain. The myth has numerous reflexes in mythical stories of battles between a serpent and a god or mythical hero, who is not necessarily etymologically related to *Perkʷunos, but always associated with thunder. For example, the Vedic Indra and Vṛtra (the personification of drought), the Iranian Tištry/Sirius and Apaoša (a demon of drought), the Albanian Drangue and Kulshedra (an amphibious serpent who causes streams to dry up), the Armenian Vahagn and Vishap, the Greek Zeus and Typhoeus as well as Heracles and the Hydra, Heracles and Ladon, Apollo, and Python, or the Norse Thor and Miðgarðsormr.” ref

Perkʷunos: Striker and god of oaks

“The association of Perkʷunos with the oak is attested in various formulaic expressions from the Balto-Slavic languages: Lithuanian Perkūno ąžuolas (Perkūnas‘s oak), Latvian Pērkōna uōzuōls (‘Pērkōn’s oak’), or Old Russian Perunovŭ dubŭ (‘Perun‘s oak’). In the Albanian language, a word to refer to the lightning—considered in folk beliefs as the “fire of the sky”—is shkreptimë, a formation of shkrep meaning “to flash, tone, to strike (till sparks fly off)”. An association between strike, stones, and fire, can be related to the observation that one can kindle fire by striking stones against each other. The act of producing fire through a strike—reflected also in the belief that fire is residual within the oak trees after the thunder-god strikes them—indicates the potential of lightning in the myth of creation.” ref

“The Slavic thunder-god Perūn is said to frequently strike oaks to put fire within them, and the Norse thunder-god Thor to strike his foes the giants when they hide under an oak. Thor famously also had at least one sacred oak dedicated to him. According to Belarusian folklore, Piarun made the first fire ever by striking a tree in which the Demon was hiding. The striking of devils, demons, or evildoers by Perkʷunos is another motif in the myths surrounding the Baltic Perkūnas and the Vedic Parjanya. In Lithuanian and Latvian folkloric material, Perkunas/Perkons is invoked to protect against snakes and illness.” ref

Perkʷunos: Wooded mountains

“Perkʷunos is often portrayed in connection with stone and (wooded) mountains; mountainous forests were considered to be his realm. A cognate relationship has been noted between the Germanic *fergunja (‘[mountainous] forest’) and the Gaulish (h)ercunia (‘[oaks] forests’). The Old Russian chronicles describes wooden idols of Perūn on hills overlooking Kiev and Novgorod, and both the Belarusian Piarun and the Lithuanian Perkūnas were said to dwell on lofty mountaintops. Such places are called perkūnkalnis in Lithuanian, meaning the “summit of Perkūnas”, while the Slavic word perynja designated the hill over Novgorod where the sanctuary of Perun was located. Prince Vladimir the Great had an idol of Perūn cast down into the Dnepr river during the Christianization of Kievan Rus’.” ref

“In Germanic mythology, Fjörgynn was used as a poetic synonym for ‘the land, the earth’, and she could have originally been the mistress of the wooded mountains, the personification of what appears in Gothic as fairguni (‘wooded mountain’). Additionally, the Baltic tradition mentions a perpetual sacred fire dedicated to Perkūnas and fuelled by oakwood in the forests or on hilltops. Pagans believed that Perkūnas would freeze if Christians extinguished those fires. Words from a stem *pér-ur- are also attested in the Hittite pēru (‘rock, cliff, boulder’), the Avestan pauruuatā (‘mountains’), as well as in the Sanskrit goddess Parvati and the epithet Parvateshwara (‘lord of mountains’), attached to her father Himavat.” ref

Perkʷunos: Stony skies

“A term for the sky, *h₂ekmōn, denoted both ‘stone’ and ‘heaven’, possibly a ‘heavenly vault of stone’ akin to the biblical firmament. The motif of the stony skies can be found in the story of the Greek Akmon (‘anvil’), the father of Ouranos and the personified Heaven. The term akmon was also used with the meaning ‘thunderbolt’ in Homeric and Hesiodic diction. Other cognates appear in the Vedic áśman (‘stone’), the Iranian deity Asman (‘stone, heaven’), the Lithuanian god Akmo (mentioned alongside Perkūnas himself), and also in the Germanic *hemina (German: Himmel, English: heaven) and *hamara (cf. Old Norse: hamarr, which could mean ‘rock, boulder, cliff’ or ‘hammer’). Akmo is described in a 16th-century treatise as a saxum grandius, ‘a sizeable stone’, which was still worshipped in Samogitia.” ref

“Albanians believed in the supreme powers of thunder-stones (kokrra e rrufesë or guri i rejës), which were believed to be formed during lightning strikes and to be fallen from the sky. Thunder-stones were preserved in family life as important cult objects. It was believed that bringing them inside the house could bring good fortune, prosperity and progress in people, in livestock and in agriculture, or that rifle bullets would not hit the owners of the thunder-stones. A common practice was to hang a thunder-stone pendant on the body of the cattle or on the pregnant woman for good luck and to counteract the evil eye.” ref

“The mythological association can be explained by the observation (e.g., meteorites) or the belief that thunderstones (polished ones for axes in particular) had fallen from the sky. Indeed, the Vedic word áśman is the name of the weapon thrown by Indra, Thor’s weapon is also called hamarr, and the thunder-stone can be named Perkūno akmuõ (‘Perkuna‘s stone’) in the Lithuanian tradition. Scholars have also noted that Perkūnas and Piarun are said to strike rocks instead of oaks in some themes of the Lithuanian and Belarusian folklores, and that the Slavic Perūn sends his axe or arrow from a mountain or the sky. The original meaning of *h₂ekmōn could thus have been ‘stone-made weapon’, then ‘sky’ or ‘lightning’.” ref

“The following deities are cognates stemming from *Perkʷunos or related names in Western Indo-European mythologies:

- PIE: *per-, ‘to strike’ (or *pérkʷus, the ‘oak‘),

- PIE: *per-kʷun-os, the weather god,

- Baltic:

- Yotvingian: Parkuns (or Parcuns),

- Latgalian: Pārkiuņs (ltg);

- Lithuanian: Perkūnas, the god of rain and thunder, depicted as an angry-looking man with a tawny beard,

- Latvian: Pērkōns, whose functions are occasionally merged with those of Dievs (the sky-god) in the Latvian dainas (folk songs),

- Percunatele or Perkunatele, a female deity associated with Perkunas, as mother or wife;

- Baltic:

- PIE: *per-uh₁n-os, the ‘one with the thunder stone’,

- Slavic: *perunъ

- Old Church Slavonic: Perūn (Перýн), the ‘maker of the lightning’,

- Old East Slavic: Perunŭ, Belarusian: Piarun (Пярун), Czech: Peraun,

- Slovak: Perún; Parom;

- Bulgarian: Perun (Перун);

- Polish: Piorun (“lightning”);

- Russian: Peryn, a peninsula in Novgorod, Russia, connected to a historical worship of Slavic Perun.

- South Slavic: Perun

- Slavic: *perunъ

- PIE: *per-kʷun-iyo (feminine *per-kʷun-iyā, the ‘realm of Perkʷunos’, i.e. the [wooded] mountains),

- Celtic: *ferkunyā,

- Gaulish: the Hercynian (Hercynia) forest or mountains, ancient name of the Ardennes and the Black Forest, which was also known as Arkunia by the time of Aristotle; Hercuniates (‘Ερκουνιατες; attached to the suffix –atis ‘belonging to’), the name of a Celtic tribe from Pannonia, as described by Pliny and Ptolemy.

- Germanic: *fergunja, meaning ‘mountain’, perhaps ‘mountainous forest’ (or the feminine equivalent of *ferga, ‘god’),

- Old Norse: Fjörgyn, the mother of the thunder-god Thor, the goddess of the wooded landscape and a poetic synonym for ‘land’ or ‘the earth’,

- Gothic: fairguni (𐍆𐌰𐌹𐍂𐌲𐌿𐌽𐌹), ‘(wooded) mountain’, and fairhus, ‘world’, Old English: firgen, ‘mountain’, ‘wooded hill’,

- Old High German: Firgunnea, the Ore Mountains, and Virgundia Waldus, Virgunnia, ‘oaks forest’,

- Slavic: *per(g)ynja, ‘wooded hills’ (perhaps an early borrowing from Germanic),

- Old Church Slavonic: prӗgynja, Old East Slavic: peregynja, ‘wooded hills’; Polish: przeginia (toponym)” ref

- Celtic: *ferkunyā,

- PIE: *per-kʷun-os, the weather god,

“The name of Perkʷunos’ weapon *meld-n- is attested by a group of cognates alternatively denoting ‘hammer’ or ‘lightning’ in the following traditions:

- PIE: *melh₂-, ‘to grind’,

- Northern PIE: *mel-d-(n)-, ‘thunder-god’s hammer > lightning’,

- Germanic: *melðunija,

- Balto-Slavic: *mild-n-,

- Slavic: *mlъldni,

- Old Church Slavonic: mlъni or mlъnii, Serbo-Croatian: múnja (муња), Slovene mółnja, Bulgarian: мълния, Macedonian: молња, ‘lightning’,

- Russian: mólnija (молния), ‘lightning’, Ukrainian maladnjá (dial.) ‘lightning without thunder’, Belarusian: маланка, ‘lightning’,

- Czech: mlna (arch.), Polish mełnia (dial.), Lusatian: milina (arch.) ‘lightning’ (modern ‘electricity’),

- Baltic: *mildnā,

- Old Prussian: mealde, ‘lightning bolt’,

- Latvian: milna, the ‘hammer of the Thunderer’, Pērkōns,

- Slavic: *mlъldni,

- Celtic: *meldo-,

- Gaulish: Meldos, an epithet of thunder divinity Loucetios; as well as Meldi (*Meldoi), a tribal name, and Meldio, a personal name.

- Welsh: mellt, ‘lightning, thunderbolts’ (sing. mellten, ‘bolt of lightning’), and Mabon am Melld or Mabon fab Mellt (‘Mabon son of Mellt’),

- Breton: mell, ‘hammer’,

- Middle Irish: mell, ’rounded summit, small hill’, possibly via semantic contamination from *ferkunyā, ‘(wooded) mountains’.” ref

- Northern PIE: *mel-d-(n)-, ‘thunder-god’s hammer > lightning’,

“Another PIE term derived from the verbal root *melh₂- (‘to grind’), *molh₁-tlo- (‘grinding device’), also served as a common word for ‘hammer’, as in Old Church Slavonic mlatъ, Latin malleus, and Hittite malatt (‘sledgehammer, bludgeon’). 19th-century scholar Francis Hindes Groome cited the existence of the Romani word malúna as a loanword from Slavic molnija. The Komi word molńi or molńij (‘lightning’) has also been borrowed from Slavic.” ref

“Heavenly vault of stone: PIE: *h₂eḱ-, ‘sharp’,

-

- PIE: *h₂éḱmōn (gen. *h₂ḱmnós; loc. *h₂ḱméni), ‘stone, stone-made weapon’ > ‘heavenly vault of stone’,

- Indo-Aryan: *Haćman,

- Greek: ákmōn (ἄκμων), ‘anvil, meteoric stone, thunderbolt, heaven’,

- Balto-Slavic: *akmen-,

- Lithuanian: akmuõ, ‘stone’,

- Latvian: akmens, ‘stone’,

- Germanic: *hemō (gen.*hemnaz, dat. *hemeni), ‘heaven’,

- Gothic: himins, ‘heaven’,

- Old English: heofon, Old Frisian: himel, Old Saxon: heƀan, Old Dutch: himil, Old High German: himil, ‘heaven’,

- Old Norse: himinn, ‘heaven’,

- PIE: *h₂éḱmōn (gen. *h₂ḱmnós; loc. *h₂ḱméni), ‘stone, stone-made weapon’ > ‘heavenly vault of stone’,

A metathesized stem *ḱ(e)h₂-m-(r)- can also be reconstructed from Slavic *kamy (‘stone’), Germanic *hamaraz (‘hammer’), and Greek kamára (‘vault’).

Other possible cognates

-

- Albanian:

- Perëndi “god, deity, sky”, considered by some scholars to be an Albanian sky and thunder god (from per-en-, an extension of PIE *per-, ‘to strike’, attached to -di, the sky-god Dyēus, thus related to *per-uhₓn-os (see above); although the Albanian perëndoj, ‘to set (of the sun)’, from Latin parentare, ‘a sacrifice (to the dead), to satisfy’, has also been proposed as the origin of the theonym,

- Greek: keraunos (κεραυνός), the name of Zeus‘s thunderbolt, which was sometimes also deified (by metathesis of *per(k)aunos; although the root *ḱerh₂-, ‘shatter, smash’ has also been proposed), and the Herkyna spring-nymph, associated with a river of the same name and identified with Demeter (the name could be a borrowing as it rather follows Celtic sound laws),

- Thracian: Perkos/Perkon (Περκος/Περκων), a horseman hero depicted as facing a tree surrounded by a snake. His name is also attested as Ήρω Περκω and Περκώνει “in Odessos and the vicinities”.

- Albanian:

- Indo-Iranian:

- Vedic: Parjanya, the god of rain, thunder and lightning (although Sanskrit sound laws rather predict a parkūn(y)a form; an intermediate form *pergʷenyo- has therefore been postulated, possibly descending from *per-kʷun-(y)o-).

- Nuristani: Pärun (or Pērūneî), a war god worshipped in Kafiristan (present-day Nuristan Province, Afghanistan),

- Persian: Piran (Viseh), a heroic figure present in the Shahnameh, the national epic of Greater Iran; it has been suggested his name might be related to the Slavic deity Perun,

- Scythian: in the 19th century, Russian folklorist Alexander Afanasyev and French philologist Frédéric-Guillaume Bergmann (fr) mentioned the existence of a Scythian deity named Pirkunas or Pirchunas, an epithet attached to the “Scythian Divus” and meaning ‘rainy’.

- Celtic *(h)erku- (‘oak‘),

- Hispano-Celtic: Erguena (ERGVENA), a personal name thought to mean ‘oak-born’ (*pérkʷu-genā) or to derive from *pérkʷu-niya ‘wooded mountain’.

- Celtiberian: berkunetakam (‘Perkunetaka’), a word attested in the Botorrita Plate I and interpreted as a sacred oak grove,

- Pyrenees: the theonym Expercennius, attested in an inscription found in Cathervielle and possibly referring to an oak god. His name might mean ‘six oaks’.

- Gaulish: ercos (‘oak’),

- Gallo-Roman: references to ‘Deus Ercus’ (in Aquitania), ‘Nymphae Percernae’ (Narbonensis), and a deity named ‘Hercura’ (or Erecura) which appears throughout the provinces of the Roman Empire. Patrizia de Bernardo Stempel argues that Aerecura/Hercura derives from a Celtic *perk(w)ura.

- Irish: Erc (mac Cairpri), mentioned at the end of Táin Bó Cúailnge, and placed on the throne of Tara by Conchobar mac Nessa in Cath Ruis na Ríg for Bóinn; although an alternative etymology from PIE *perk- (‘color’) > *perk-no (‘[spotted] fish’) has been proposed by Hamp and Matasović.

- Hittite: the words perunas and peruni are attested in a Hittite text of The Song of Ullikummi, and refer to a female being made of ‘Rock’ or ‘Stone’ who gives birth to a rocky creature.

- Italic:

- Italian: porca, a word meaning ‘fir tree’ in the Trentino dialect. Mallory and Adams suppose it is a loanword from Raetic.

- Slavic

- Pomeranian: Porenut, Latinized as Porenutius in the work of Saxo Grammaticus. The name is believed to refer to a deity worshipped in the port city of Rügen in ancient times as a possible son of Perun.

- (?) Perperuna, figure invoked in rainmaking in Southeast Europe, which is of obscure etymology, but considered by some as a reduplicated feminine derivative from Perun’s name, which would parallel the Old Norse couple Fjörgyn–Fjörgynn and the Lithuanian Perkūnas–Perkūnija,

- Romano-Germanic: inscriptions to the Matronae ‘Ala-ferhuiae’ found in Bonn, Altdorf, or Dormagen.

- Caucasus: it has been suggested that the characters Пиръон (Piryon) and Пиръа (Pirya) may attest the presence of the thunder god’s name in the Caucasus.” ref

“Louis Léger stated that the Polabians adopted Perun as their name for Thursday (Perendan or Peräunedån), which is likely a calque of German Donnerstag. Some scholars argue that the functions of the Luwian and Hittite weather gods Tarḫunz and Tarḫunna ultimately stem from those of Perkʷunos. Anatolians may have dropped the old name in order to adopt the epithet *Tṛḫu-ent- (‘conquering’, from PIE Proto-Indo-European: *terh₂-, ‘to cross over, pass through, overcome’), which sounded closer to the name of the Hattian Storm-god Taru. According to scholarship, the name Tarhunt- is also cognate to the Vedic present participle tū́rvant- (‘vanquishing, conquering’), an epithet of the weather-god Indra.” ref

“Scholarship indicates the existence of a holdover of the theonym in European toponymy, specially in Eastern European and Slavic-speaking regions. In the territory that encompasses the modern day city of Kaštela existed the ancient Dalmatian city of Salona. Near Salona, in Late Antiquity, there was a hill named Perun. Likewise, the ancient oronym Borun (monte Borun) has been interpreted as a deformation of the theonym Perun. Their possible connection is further reinforced by the proximity of a mountain named Dobrava, a widespread word in Slavic-speaking regions that means ‘oak grove’. Places in South-Slavic-speaking lands are considered to be reflexes of Slavic god Perun, such as Perunac, Perunovac, Perunika, Perunićka Glava, Peruni Vrh, Perunja Ves, Peruna Dubrava, Perunuša, Perušice, Perudina, and Perutovac.” ref

“Scholar Marija Gimbutas cited the existence of the place names Perunowa gora (Poland), Perun Gora (Serbia), Gora Perun (Romania), and Porun hill (Istria). Patrice Lajoye associates place names in the Balkans with the Slavic god Perun: the city of Pernik and the mountain range Pirin (in Bulgaria). He also proposes that the German city of Pronstorf is also related to Perun, since it is located near Segeberg, whose former name was Perone in 1199. The name of the Baltic deity Perkunas is also attested in Baltic toponyms and hydronyms: a village called Perkūniškės in Žemaitija, north-west of Kaunas, and the place name Perkunlauken (‘Perkuns Fields’) near modern Gusev.” ref

Smith god?

“Although the name of a particular smith god cannot be linguistically reconstructed, smith gods of various names are found in most Proto-Indo-European daughter languages. There is not a strong argument for a single mythic prototype. Mallory notes that “deities specifically concerned with particular craft specializations may be expected in any ideological system whose people have achieved an appropriate level of social complexity”. Nonetheless, two motifs recur frequently in Indo-European traditions: the making of the chief god’s distinctive weapon (Indra‘s and Zeus‘ bolt; Lugh‘s and Odin‘s spear and Thor‘s hammer) by a special artificer, and the craftsman god’s association with the immortals’ drinking.” ref

Perkūnas

“Perkūnas (Lithuanian: Perkūnas, Latvian: Pērkons, Old Prussian: Perkūns, Perkunos, Yotvingian: Parkuns, Latgalian: Pārkiuņs) was the common Baltic god of thunder, and the second most important deity in the Baltic pantheon after Dievas. In both Lithuanian and Latvian mythology, he is documented as the god of sky, thunder, lightning, storms, rain, fire, war, law, order, fertility, mountains, and oak trees. The name continues PIE *Perkwunos, cognate to *perkwus, a word for “oak”, “fir” or “wooded mountain”. The Proto-Baltic name *Perkūnas can be reconstructed with certainty. Slavic Perun is a related god, but not an etymologically precise match. Finnish Perkele, a name of Ukko, is considered a loan from Baltic. Another connection is that of terpikeraunos, an epithet of Zeus meaning “who enjoys lightning.” ref

“Perkūnas is the god of lightning, thunder, and storms. In a triad of gods Perkūnas symbolizes the creative forces (including vegetative), courage, success, the top of the world, the sky, rain, thunder, heavenly fire (lightning) and celestial elements, while Potrimpo is involved with the seas, ground, crops, and cereals and Velnias/Patulas, with hell, and death. As a heavenly (atmospheric) deity Perkūnas, apparently, is the assistant and executor of Dievas‘s will. However, Perkūnas tends to surpass Dievas, deus otiosus, because he can be actually seen and has defined mythological functions. In the Latvian dainas, the functions of Pērkons and Dievs can occasionally merge: Pērkons is called Pērkona tēvs (‘Father or God of Thunder’) or Dieviņš, a diminutive form of Dievs.” ref

“Because most of them were collected rather late in the 19th century, they represent only some fragments of the whole mythology. Lithuanian Perkūnas has many alternative onomatopoeic names, like Dundulis, Dindutis, Dūdų senis, Tarškulis, Tarškutis, Blizgulis, etc. The earliest attestation of Perkūnas seems to be in the Ruthenian translation of the Chronicle of John Malalas (1261) where it speaks about the worship of “Перкоунови рекше громоу”, and in the Livonian Rhymed Chronicle (around 1290) which mentions the idol Perkūnė. In the Constitutiones Synodales (1530) Perkūnas is mentioned in a list of gods before the god of hell Pikuls and is identified with the Roman Jove (Jupiter). In the Sudovian Book Perkūnas (Parkuns) is mentioned in connection with a ritual involving a goat. In Christian compositions, Perkūnas is a malicious spirit, a demon, as in the Chronicle of John Malalas or in the 15th-century writings of Polish chronicler Jan Długosz.” ref

“Pērkons was strongly associated with Dievs, though the two were clearly different. The people sacrificed black calves, goats, and roosters to Pērkons, especially during droughts. The surrounding peoples came to these sacrifices to eat and drink together, after pouring beer onto the ground or into the fire for him. The Latvians also sacrificed cooked food before meals to Pērkons, in order to prevent thunderstorms, during which honeycombs were placed into fires to disperse the clouds. Pērkons’ family included sons that symbolized various aspects of thunderstorms (such as thunder, lightning, lightning strikes) and daughters that symbolized various kinds of rain. Pērkons appeared on a golden horse, wielding a sword, iron club, golden whip and a knife. Ancient Latvians wore tiny axes on their clothing in his honor.” ref

“Lithuanian Dievas, Latvian Dievs and Debestēvs (“Sky-Father“), Latgalian Dīvs, Old Prussian Diews, Yotvingian Deivas was the primordial supreme god in the Baltic mythology, one of the most important deities together with Perkūnas, and the brother of Potrimpo. He was the god of light, sky, prosperity, wealth, ruler of gods, and the creator of the universe. Dievas is a direct successor of the Proto-Indo-European supreme sky father god *Dyēus of the root *deiwo-. Its Proto-Baltic form was *Deivas. Dievas had two sons Dievo sūneliai (Lithuanian) or Dieva dēli (Latvian) known as the Heavenly Twins.” ref

“In English, Dievas may be used as a word to describe the God (or, the supreme god) in the pre-Christian Baltic religion, where Dievas was understood to be the supreme being of the world. In Lithuanian and Latvian, it is also used to describe God as it is understood by major world religions today. Earlier *Deivas simply denoted the shining sunlit dome of the sky, as in other Indo-European mythologies. The celestial aspect is still apparent in phrases such as Saule noiet dievā (“The sun goes down to god”), from Latvian folksongs. In Hinduism, a group of celestial deities are called the devas, a result of shared Proto-Indo-European roots.” ref

Perun

“In Slavic mythology, Perun (Cyrillic: Перун) is the highest god of the pantheon and the god of sky, thunder, lightning, storms, rain, law, war, fertility and oak trees. His other attributes were fire, mountains, wind, iris, eagle, firmament (in Indo-European languages, this was joined with the notion of the sky of stone), horses and carts, and weapons (hammer, axe (Axe of Perun), and arrow). The supreme god in the Kievan Rus’ during the 9th-10th centuries, Perun was first associated with weapons made of stone and later with those of metal. Of all historic records describing Slavic gods, those mentioning Perun are the most numerous. As early as the 6th century, he was mentioned in De Bello Gothico, a historical source written by the Eastern Roman historian Procopius. A short note describing beliefs of a certain South Slavic tribe states they acknowledge that one god, creator of lightning, is the only lord of all: to him do they sacrifice an ox and all sacrificial animals. While the name of the god is not mentioned here explicitly, 20th century research has established beyond doubt that the god of thunder and lightning in Slavic mythology is Perun. To this day, the word perun in a number of Slavic languages means “thunder,” or “lightning bolt.” ref

“The Primary Chronicle relates that in the year 6415 (907 CE) prince Oleg (Old Norse: Helgi) made a peace treaty with the Byzantine Empire and by taking his men to the shrines and swearing by their weapons and by their god Perun, and by Volos, the god of cattle, they confirmed the treaty. We find the same form of confirmation of a peace treaty by prince Igor in 945. In 980, when prince Vladimir the Great came to the throne of Kiev, he erected statues of five pagan gods in front of his palace which he soon thereafter discarded after his Christianization in 988. Perun was chief among these, represented with a silver head and a golden moustache. Vladimir’s uncle Dobrynya also had a shrine of Perun established in his city of Novgorod. After the Christianization of Kievan Rus, this place became a monastery, which, quite remarkably, continued to bear the name of Perun.” ref

“Perun is not mentioned directly in any of the records of Western Slavic traditional religion, but a reference to him is perhaps made in a short note in Helmold‘s Chronica Slavorum, written in the latter half of the 12th century, which states (quite similarly to Procopius some six centuries earlier) that Slavic tribes, even though they worship many various gods, all agree there is a supreme god in heaven which rules over all other on earth. This could be a reference to Perun, but since he is not named, nor any of his chief attributes (thunder or lightning) mentioned, we cannot be certain. Slavic traditions preserved very ancient elements and intermingled with those of neighbouring European peoples. An exemplary case are the South Slavic still-living rain rituals Perperuna and Dodola of the couple Perun–Perperuna/Perunika, Lord and Lady Thunder, shared with the neighbouring Albanians, Greeks and Arumanians, corresponding to the Germanic Fjörgynn–Fjörgyn, the Lithuanian and Latvian Perkūnas/Dundulis–Perkūna/Pērkons, and finding similarities in the Vedic hymns to Parjanya.” ref

“Perun is strongly correlated with the near-identical Perkūnas/Pērkons from Baltic mythology, suggesting either a common derivative of the Proto-Indo European thunder god (whose original name has been reconstructed as *Perkʷūnos), or that one of these cultures borrowed the deity from the other. The root *perkwu originally probably meant oak, but in Proto-Slavic this evolved into *per- meaning “to strike, to slay”. The Lithuanian word “Perkūnas” has two meanings: “thunder” and the name of the god of thunder and lightning. From this root comes one of the names attributed to the Finnish deity Ukko, Perkele which has a Balto-Slavic origin. Artifacts, traditions and toponyms show the presence of the cult of Perun among all Slavic, Baltic and Finnic peoples. Perun was also related to an archaic form of astronomy – the Pole star was called Perun’s eye and countless Polish and Hungarian astronomers continued this tradition – most known well known is Nicolaus Copernicus.” ref

“Similarly to Perkūnas of Baltic mythology, Perun was considered to have multiple aspects. In one Lithuanian song, it is said there are in fact nine versions of Perkūnas. From comparison to the Baltic mythology, and also from additional sources in Slavic folklore, it can also be shown that Perun was married to the Sun. He, however, shared his wife with his enemy Veles, as each night the Sun was thought of as diving behind the horizon and into the underworld, the realm of the dead over which Veles ruled. Like many other Indo-European thunder gods, Perun’s vegetative hypostasis was the oak, especially a particularly distinctive or prominent one. In South Slavic traditions, marked oaks stood on country borders; communities at these positions were visited during village holidays in the late spring and during the summer. Shrines of Perun were located either on top of mountains or hills, or in sacred groves underneath ancient oaks. These were general places of worship and sacrifices (with a bull, an ox, a ram, and eggs). In addition to the tree association, Perun had a day association (Thursday) as well as the material association (tin).” ref

Thunderstones, Battle axe stones, Double axe or labrys (religion and folklore related)

“A thunderstone is a prehistoric hand axe, stone tool, or fossil which was used as an amulet to protect a person or a building. The name derives from the ancient belief that the object was found at a place where lightning had struck. They were also called ceraunia (a Latin word, derived from the Greek word κεραυνός, both of which mean “thunderbolt”). Albanians believed in the supreme powers of thunderstones (kokrra e rrufesë or guri i rejës), which were believed to be formed during lightning strikes and to fall from the sky. Thunderstones were preserved in family life as important cult objects. It was believed that bringing them inside the house would bring good fortune, prosperity, and progress to people, especially in livestock and agriculture, or that rifle bullets would not hit the owners of thunderstones. Thunderstone pendants were believed to have protective powers against the negative effects of the evil eye and were used as talismans for both cattle and pregnant women. The Greeks and Romans, at least from the Hellenistic period onward, used Neolithic stone axeheads for the apotropaic protection of buildings. A 1985 survey of the use of prehistoric axes in Romano-British contexts found forty examples, of which twenty-nine were associated with buildings including villas, military structures such as barracks, temples, and kilns.” ref

“In Scandinavia thunderstones were frequently worshiped as family gods who kept off spells and witchcraft. Beer was poured over them as an offering, and they were sometimes anointed with butter. In Switzerland the owner of a thunderstone whirls it, on the end of a thong, three times around his head, and throws it at the door of his dwelling at the approach of a storm to prevent lightning from striking the house. In Italy they are hung around children’s necks to protect them from illness and to ward off the Evil eye. In Roman times, they were sewn inside dog collars along with a little piece of coral to keep the dogs from going mad. In Sweden they offer protection from elves. Up until the 19th century it was common practice in Limburg to sew thunderstones into cloth bags and carried over the chest, in the belief that it would soothe stomach ailments. In some parts of Spain for example the province of Salamanca it was believed that by rubbing the thunderstones on the joints it would help prevent rheumatic diseases. In the French Alps they protect sheep, while elsewhere in France they are thought to ease childbirth. Among the Slavs they cure warts on man and beast, and during Passion Week they have the property to reveal hidden treasure.” ref

“The Slavic mythology, the highest god and the god of sky, thunder, lightning, storms, rain, law, war, fertility, as well as oak trees, “Perun” was first associated with weapons made of stone and later with those of metal.” ref

“Axes of Perun, also called “hatchet amulets”, are archaeological artifacts worn as a pendant and shaped like a battle axe in honor of Perun, the supreme deity of Slavic religion. They are counterparts to Nordic Mjolnir amulets. They are mostly found in modern-day Serbia, Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, and parts of Scandinavia. Connection with the Slavic pre-Christian god Perun was made by V. P. Darkevich, although some authors prefer the association with Norse material culture. The axes range in length from 4 to 5.5 cm (1.6 to 2.2 in), and blade width from 2.8 to 4 cm (1.1 to 1.6 in). Bronze is the most common material of their construction. Most have been dated between the 11th and 12th century, and over 60 specimens have been collected. Two basic designs of the axe have been found throughout Russia and its boundaries. Specimens of both designs include a hole in the centre of the blade, and both have been decorated with zigzag lines, representing lightning or more likely imitating inlaid ornamentation patterns of real axes, near the edge of the blade.” ref

- Type 1

- “The first type is a bearded axe (lower side of the blade is elongated) with a flat upper side. It resembles a battle axe. A knob-like protrusion is usually present on the lower side of the axe. These axes have been decorated with circles, believed to represent celestial bodies.” ref

- Type 2

- “The second type is distinguished by its symmetrical shape and broad blade. Similar to the knob of the first type, the second has two horn-like protrusions diametrically opposite on the upper and lower side.” ref

“Fulgurites (from Latin fulgur ‘lightning‘ and -ite), commonly called “fossilized lightning“, are natural tubes, clumps, or masses of sintered, vitrified, or fused soil, sand, rock, organic debris and other sediments that sometimes form when lightning discharges into ground. When composed of silica, fulgurites are classified as a variety of the mineraloid lechatelierite. The presence of fulgurites in an area can be used to estimate the frequency of lightning over a period of time, which can help to understand past regional climates. Paleolightning is the study of various indicators of past lightning strikes, primarily in the form of fulgurites and lightning-induced remanent magnetization signatures. Fulgurite tubes have been mentioned already by Persian polymaths Avicenna and Al-Biruni in the 11th century, without knowing their true origination. Over the following centuries fulgurites have been described but missinterpreted as a result of subterrestrial fires, falsely attributing curative powers to them, e.g. by Leonhard David Hermann 1711 in his Maslographia. Other famous natural scientists, among them Charles Darwin, Horace Bénédict de Saussure and Alexander von Humboldt gave attention to fulgurites, without discovering the relationship to lightning.” ref

“The axe is one of the oldest tools used by mankind. The oldest axes were known as hand axes/non-shaft-hole axes: the non-shaft-hole axes had no hole for the handle and were generally made from flint, greenstone, or slate. The thin-butted axe is usually made from flint, but some versions in other stones occur in both flint-rich and flint-poor areas. They tend to be seen as a working axe, and originate from roughly 3700–3200 BCE. The older types are generally longer and broader and have a thinner butt than the later thick-butted axe. The thin-butted axe was good for forest clearing, probably in the context of ring-barking. The shaft-hole axes were made using various stones, although not flint, and were more likely to be status weapons or ceremonial objects. Examples of these include the boat axes used in the Battle Axe cultures of Europe in around 3200–1800 BCE (read more about the Battle Axe culture below).” ref

- “The polygonal axe is a kind of battle axe that belongs to the Late Stone Age and dates to around 3000–3400 BCE. It is usually made from greenstone or some other exclusive stone, and is fitted with a shaft hole. It also tends to have various special features, such as a flared edge, an arched butt, an angled body, grooves and ridges. The features are hammered out and then polished across the whole surface. The polygonal axe is seen as a copy of the Central European copper axes, but even in these areas, polygonal axes of various kinds have been found.

- The double-headed battle axe is a shaft-hole axe from around 3400–2900 BCE. It occurred mainly around Rügen in Germany and on Zealand in Denmark, as the Battle Axe culture established itself in the surrounding areas. The axe has a flared edge that became very prominent among the later types, which also gained a flared butt. The double-edged axes were always made from hard and homogeneous stones such as porphyry, and they were also finely polished.

- The boat axe is an old name for the shaft-hole axe of the Swedish-Norwegian Battle Axe culture that is now simply referred to as the battle axe. In recent years, the purpose of the battle axe as a weapon has been called into question, not least because the shaft hole is sometimes so small that it could not be attached to a sufficiently strong handle. It may then have served a ceremonial purpose and as an identity marker for the upper echelons of society. Similar axes appeared across a large swathe of North-Eastern Europe, although there are clear differences in the details between different cultural areas.” ref

“The Battle Axe culture (c. 3200–1800 BCE), also referred to as the Boat Axe culture in older literature, is a relatively uniform archaeological culture that occurs in an area of Southern Sweden-Norway that stretches from Bornholm and Skåne in the south up to Uppland in the north and along the Norwegian coast up to Central Norway. It is a regional variant of the Corded Ware culture that occurred in North-Eastern Europe during the third century BCE. In addition to the battle axes that gave the culture its name and the typical ceramic pots, there are a number of other objects that are characteristic of the culture. These include flint adzes and chisels, which are commonly hollow-edged. During the Bronze Age (2000 BC – 500 CE for Northern Europe), stone axes began giving way to axes with a head made of copper and bronze. Initially, these were often pure copies of stone axes. The bronze axe head was cast in moulds, allowing the design to be copied and mass produced.” ref

“One type of Bronze Age axe is the Socketed Axe, or Celt, a wedge-shaped axe head with no shaft hole. The handle is instead fixed into a socket at the butt end. Since the axe is made hollow and the handle is inserted into the head, a perfectly functional working axe can be made with minimal materials. The older socketed axes were quite long, but they were gradually replaced with smaller types, where a flared edge compensated for the smaller size. The Palstave is another type of bronze axe that occurred for a short period during the Early Bronze Age (1500 – 1000 BCE). The characteristic of this axe type is the narrow butt, which inserts into a split wooden handle. The blade is often flared, and the sides may be decorated with spiral or angular patterns. The Palstave was mounted in the split end of a wooden handle and then tied in place with leather straps. In Scandinavia, axes in copper and bronze have been found in the Early Bronze Age (c. 2000 BCE). At the beginning of the Iron Age (from c. 500 BCE in Northern Europe) the old axe types, such as the socketed axe, were simply reproduced in iron, but the possibilities of the new material led the appearance of the axes to change gradually. The non-shaft-hole axes disappeared and were replaced by axes with a hole for a handle. The axe heads also became larger, with broader blades. In Scandinavia it has been found iron axes from the first century CE. In Scandinavia, the Battle axe rose in popularity during the Viking Age (c. 800–1100 CE), when the axe became something of a weapon of choice. During this time, the Nordic smiths developed axes with longer handles and thinner blades, making the axe head extra light for use in battle. This type of axe was very common at the Battle of Hastings in 1066, for example, as documented in the Bayeux tapestry.” ref

Double axe or labrys

“Labrys (Greek: λάβρυς, romanized: lábrys) is, according to Plutarch (Quaestiones Graecae 2.302a), the Lydian word for the double-bitted axe. Lydian is an extinct Indo-European Anatolian language spoken in the region of Lydia, in western Anatolia (now in Turkey). In Greek, it was called πέλεκυς (pélekys). The plural of labrys is labryes (λάβρυες). Plutarch relates that the word labrys was a Lydian word for ‘axe’: Λυδοὶ γὰρ ‘λάβρυν’ τὸν πέλεκυν ὀνομάζουσι. (“For Lydians name the double-edged axe ‘Labrys‘“). Many scholars including Arthur Evans assert that the word labyrinth is derived from labrys and thus implies ‘house of the double axe’. A priestly corporation in Delphi was named Labyades; the original name was probably Labryades, servants of the double axe. In the Roman era at Patrai and Messene, a goddess Laphria was worshipped, commonly identified with Artemis. Her name was said to be derived from the region around Delphi. In Crete, the “double axe” is not a weapon, and it always accompanies female goddesses, not male gods, referring to the male bull god itself. Robert S. P. Beekes regards the relation of labyrinth with labrys as speculative, and rather proposes a relation with laura (λαύρα), ‘narrow street’, or to the Carian theonym Dabraundos (Δαβραυνδος).” ref, ref

“It is also possible that the word labyrinth is derived from the Egyptian, meaning: “the temple at the entrance of the lake”. The Egyptian labyrinth near Lake Moeris is described by Herodotus and Strabo. The inscription in Linear B, on tablet ΚΝ Gg 702, reads 𐀅𐁆𐀪𐀵𐀍𐀡𐀴𐀛𐀊 (da-pu2-ri-to-jo-po-ti-ni-ja). The conventional reading is λαβυρίνθοιο πότνια (labyrinthoio potnia; ‘mistress of the labyrinth’). According to some modern scholars it could read *δαφυρίνθοιο (*daphyrinthoio), or something similar, and hence be without a certain link with either the λάβρυς or the labyrinth. A link has also been posited with the double axe symbols at Çatalhöyük, dating to the Neolithic age. In Labraunda in Caria, as well as in the coinage of the Hecatomnid rulers of Caria, the double axe accompanies the storm god Zeus Labraundos. Arthur Evans notes, It seems natural to interpret names of Carian sanctuaries such as Labranda in the most literal sense as the place of the sacred labrys, which was the Lydian (or Carian) name for the Greek πέλεκυς [pelekys], or double-edged axe and on Carian coins, indeed of quite late date, the labrys, set up on its long pillar-like handle, with two dependent fillets, has much the appearance of a cult image.” ref

“In ancient Crete, the double axe was an important sacred symbol of the Minoan religion. In Crete, the double axe only accompanies goddesses, never gods. It seems that it was the symbol of the arche of the creation (Mater-arche).(p 161) Small versions were used as votive offerings and have been found in considerable numbers; the Arkalochori Axe is a famous and rather larger example. Minoan double axes have also recently been found in the prehistoric town of Akrotiri (Santorini Island) along with other objects of apparent religious significance. The double axe apparently carried important symbolism the ancient Thracian Odrysian kingdom related to the Thracian religion and to royal power. It is argued that in ancient Thrace the double axe was an attribute of Zalmoxis. The double axe appears on coins from Thrace and is believed to be the symbol of the kings of the Odrysae, who believed they could trace their lineage to Zalmoxis. A fresco from the Thracian tomb near Aleksandrovo in south-east Bulgaria, dated to c. 4th c. BCE, depicts a large-size naked man wielding a double axe.” ref

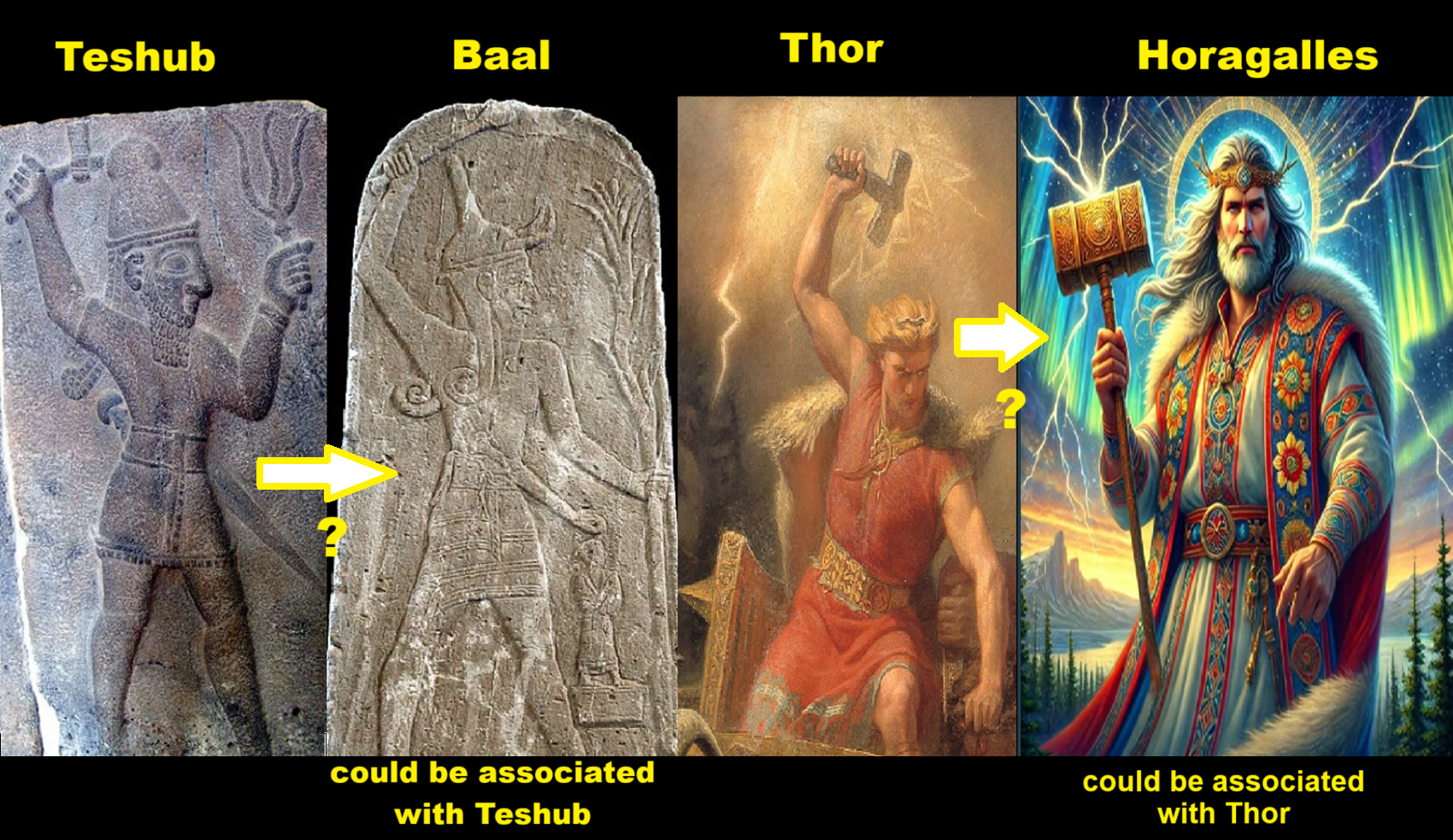

“In the Near East and other parts of the region, eventually, axes of this sort often are wielded by male divinities and appear to become symbols of the thunderbolt, a symbol often found associated with the axe symbol. In Labraunda of Caria the double-axe accompanies the storm-god Zeus Labraundos. Similar symbols have been found on plates of Linear pottery culture in Romania. The double-axe is associated with the Hurrian god of sky and storm Teshub. His Hittite and Luwian name was Tarhun. Both are depicted holding a triple thunderbolt in one hand and a double axe in the other hand. Similarly, Zeus throws his thunderbolt to bring a storm. The labrys, or pelekys, is the double axe Zeus uses to invoke storm and, the relatively modern Greek word for lightning is “star-axe” (ἀστροπελέκι astropeleki) The worship of the double axe was kept up in the Greek island of Tenedos and in several cities in the south-west of Asia Minor, and it appears in later historical times in the cult of the thunder god of Asia Minor (Zeus Labrayndeus).” ref

“In the context of the mythical Attic king Theseus, the labyrinth of Greek mythology is frequently associated with the Minoan palace of Knossos. This is based on the reading of Linear B da-pu2-ri-to-jo-po-ti-ni-ja as λαβυρίνθοιο πότνια (“mistress of the labyrinth”). It is uncertain, however, that labyrinth can be interpreted as “place of the double axes” and moreover that this should be Knossos; many more have been found, for example, at the Arkalachori Cave, where the famous Arkalochori Axe was found. On Greek coins of the classical period (e.g. Pixodauros) a type of Zeus venerated at Labraunda in Caria that numismatists call Zeus Labrandeus (Ζεὺς Λαβρανδεύς) stands with a sceptre upright in his left hand and the double-headed axe over his shoulder. In Roman Crete, the labrys was often associated with the mythological Amazons.” ref

Marija Gimbutas: Battle Axe or Cult Axe?

“This document discusses whether Neolithic axes were weapons or religious symbols. It notes that “battle axes” were common across northern and eastern Europe in Late Neolithic cultures. However, these axes coincided with cultural changes thought to result from migrations, so they have been interpreted as weapons. The author argues that these could instead have been tools or religious symbols. Axes with drooping blades date back to the 4th millennium BCE in Mesopotamia and spread across Europe in the Late Neolithic. Decorated axes appearing in the Middle Neolithic may have had symbolic meanings. So the term “battle axe” for Late Neolithic axes may be a misnomer.” ref

Funnelbeaker culture with 6,000-year-old axes

“The Funnel(-neck-)beaker culture, in short TRB or TBK (German: Trichter(-rand-)becherkultur, Dutch: Trechterbekercultuur; Danish: Tragtbægerkultur; c. 4300–2800 BCE), was an archaeological culture in north-central Europe, and in northern modern-day Germany c. 4100 BCE. A single-sided Copper axe from Lüstringen, Germany, c. 4000 BCE, and a double axe found in a megalithic tomb, as well as Copper axe, Denmark, c. 3750-3300 BCE. The oldest graves consisted of wooden chambered cairns inside long barrows, but were later made in the form of passage graves and dolmens. Originally, the structures were probably covered with a mound of earth, and the entrance was blocked by a stone. The Funnelbeaker culture marks the appearance of megalithic tombs at the coasts of the Baltic and of the North sea, an example of which are the Sieben Steinhäuser in northern Germany. The megalithic structures of Ireland, France, and Portugal are somewhat older and have been connected to earlier archeological cultures of those areas. At graves, the people sacrificed ceramic vessels that contained food along with amber jewelry and flint-axes. Genetic analysis of several dozen individuals found in the Funnelbeaker passage grave Frälsegården in Sweden suggests that these burials were based on a patrilineal social organisation, with the vast majority of males being ultimately descended from a single male ancestor, while the women were mostly unrelated and presumably married into the family.” ref

“Flint-axes and vessels were also deposited in streams and lakes near the farmlands, and virtually all of Sweden’s 10,000 flint axes that have been found from this culture were probably sacrificed in water. They also constructed large cult centres surrounded by palisades, earthworks, and moats. Ancient DNA analysis has found the people who produced the Funnelbeaker culture to be genetically different from earlier hunter-gather inhabitants of the region, and are instead closely related to other European Neolithic farmers, who ultimately traced most of their ancestry from early farmers in Anatolia, with some admixture from European hunter-gatherer groups. Genetic analysis suggests that there was some minor gene flow between the producers of the Funnelbeaker culture and those of the hunter-gatherer Pitted Ware culture (which descended from earlier Scandinavian hunter-gather groups) to the north. A total of 62 males from sites attributed to the Funnelbeaker culture in Scandinavia and Germany have been sequenced for ancient DNA. Most belonged to haplogroup I2, while a smaller number belonged to R1b-V88, Q-FTF30, and G2a. MtDNA haplogroups included U, H, T, R, and K.” ref

Battle Axe

“A battle axe (also battle-axe, battle ax, or battle-ax) is an axe specifically designed for combat. Battle axes were designed differently to utility axes, with blades more akin to cleavers than to wood axes. Many were suitable for use in one hand, while others were larger and were deployed two-handed. Stone hand axes were in use in the Paleolithic period for hundreds of thousands of years. The first hafted stone axes appear to have been produced about 6000 BCE during the Mesolithic period. Technological development continued in the Neolithic period with the much wider usage of hard stones in addition to flint and chert and the widespread use of polishing to improve axe properties. The axes proved critical in wood working and became cult objects (for example, the entry for the Battle-axe people of Scandinavia, treated their axes as high-status cultural objects). Such stone axes were made from a wide variety of tough rocks such as picrite and other igneous or metamorphic rocks, and were widespread in the Neolithic period. Many axe heads found were probably used primarily as mauls to split wood beams, and as sledgehammers for construction purposes (such hammering stakes into the ground, for example). The tabarzin (Persian: تبرزین, lit. “saddle axe” or “saddle hatchet”) is the traditional battle axe of Persia. It bears one or two crescent-shaped blades. The long form of the tabar was about seven feet long, while a shorter version was about three feet long. What made the Persian axe unique is the very thin handle, which is very light and always metallic.” ref

“Narrow axe heads made of cast metals were subsequently manufactured by artisans in the Middle East and then Europe during the Copper Age and the Bronze Age. The earliest specimens were socket-less. More specifically, bronze battle-axe heads are attested in the archaeological record from ancient China and the New Kingdom of ancient Egypt. Some of them were suited for practical use as infantry weapons while others were clearly intended to be brandished as symbols of status and authority, judging by the quality of their decoration. The epsilon axe was widely used during the Bronze Age by irregular infantry unable to afford better weapons. Its use was limited to Europe and the Middle East. In the eastern Mediterranean Basin during the Iron Age, the double-bladed labrys axe was prevalent, and a hafted, single-bitted axe made of bronze or later iron was sometimes used as a weapon of war by the heavy infantry of ancient Greece, especially when confronted with thickly-armored opponents. The sagaris—described as either single bitted or double bitted—became associated by the Greeks with the mythological Amazons, though these were generally ceremonial axes rather than practical implements. The Barbarian tribes that the Romans encountered north of the Alps did include iron war axes in their armories, alongside swords and spears. The Cantabri from the Iberian peninsula also used battle axes. Different types of battleaxes may be found in ancient China. In Chinese mythology, Xingtian (刑天), a deity, uses a battle axe against other gods. The battle axe of ancient India was known as a parashu (or farasa in some dialects). The parashu is often depicted in religious art as one of the weapons of Hindu deities such as Shiva and Durga. The sixth avatar of Lord Vishnu, Parashurama, is named after the weapon.” ref

Battle Axe culture

“The Battle Axe culture, also called Boat Axe culture, is a Chalcolithic culture that flourished in the coastal areas of the south of the Scandinavian Peninsula and southwest Finland, from c. 2800 – c. 2300 BCE. It was an offshoot of the Corded Ware culture, and replaced the Funnelbeaker culture in southern Scandinavia, probably through a process of mass migration and population replacement. It is thought to have been responsible for spreading Indo-European languages and other elements of Indo-European culture to the region. It co-existed for a time with the hunter-gatherer Pitted Ware culture, which it eventually absorbed, developing into the Nordic Bronze Age. The Nordic Bronze Age has, in turn, been considered ancestral to the Germanic peoples. The Battle Axe culture emerged in the south of the Scandinavian Peninsula about 2800 BCE. It was an offshoot of the Corded Ware culture, which was itself largely an offshoot of the Yamnaya culture of the Pontic–Caspian steppe. Modern genetic studies show that its emergence was accompanied by large-scale migrations and genetic displacement. The Battle Axe culture initially absorbed the agricultural Funnelbeaker culture.” ref

“The concentration of the Battle Axe culture was in Scania. Sites of the Battle Axe culture have been found throughout the coastal areas of southern Scandinavia and southwest Finland. The immediate coastline was, however, occupied by the Pitted Ware culture. By 2300 BCE, the Battle Axe culture had absorbed the Pitted Ware culture. Throughout its existence, the Battle Axe culture appears to have expanded into coastal Norway, accompanied by dramatic cultural changes. Einar Østmo reports sites of the Battle Axe culture inside the Norwegian Arctic Circle in the Lofoten, and as far north as the present city of Tromsø. The Battle Axe culture ended around 2300 BCE. It was eventually succeeded by the Nordic Bronze Age, which appears to be a fusion of elements from the Battle Axe culture and the Pitted Ware culture.” ref

“The Battle Axe culture is mostly known for its burials. Around 250 Battle Axe burials have been found in Sweden. They are quite different from those found in the Single Grave culture of Denmark. In the Battle Axe culture, the deceased were usually placed in a single flat grave with no barrow. Graves were typically oriented north-south, with the body in a flexed position facing towards the east. Men were placed on their left sides, while women were placed on their right sides. As regards both objects and placement, the grave goods are quite standardized. Axes of flint are found in both male and female burials. Battle axes are placed with males close to the head. These battle axes appear to have been status symbols, and it is from them that the culture is named. About 3000 battle axes have been found, in sites distributed over all of Scandinavia, but they are sparse in Norrland and northern Norway.” ref

“The polished flint axes of the Battle Axe culture and the Pitted Ware culture trace a common origin in southwest Scania and Denmark. Corded Ware ceramics were also common grave goods in Battle Axe burials. They were usually placed near the head or feet. Other grave goods include arrowheads, weapons of antler, amber beads, and polished flint axes and chisels. Faunal remains from burials include red deer, sheep, and goat. A new aspect was given to the Battle Axe culture in 1993, when a death house in Turinge, in Södermanland was excavated. Along the once heavily timbered walls were found the remains of about twenty clay vessels, six work axes, and a battle axe, which all came from the last period of the culture. There were also the cremated remains of at least six people. It is the earliest find of cremation in Scandinavia, and it shows close contacts with Central Europe. The social system of the Battle Axe culture was markedly different than that of the Funnelbeaker culture, shown by the fact that the Funnelbeaker culture had collective megalithic graves, each containing numerous sacrifices, while the Battle Axe culture had individual graves, with a single sacrifice each. Individualism appears to have played a much more prominent part in the Battle Axe culture than among its predecessors.” ref

“The Battle Axe culture is believed to have brought Indo-European languages and Indo-European culture to southern Scandinavia. The fusion of the Battle Axe culture with the native agricultural and hunter-gatherer cultures of the region spawned the Nordic Bronze Age, which is considered one of the ancestral civilizations of the Germanic peoples. A genetic study published in Nature in June 2015 examined the remains of a Battle Axe male buried in Viby, Sweden ca. 2621–2472 BCE. He was found to be a carrier of the paternal haplogroup R1a1a1 and the maternal haplogroup K1a2a. People of the Late Neolithic and Bronze Age cultures of Scandinavia were found to be very closely related to people of the Corded Ware culture, Bell Beaker culture, and Únětice culture, all of whom shared genetic affinity with the Yamnaya culture. The Sintashta culture and Andronovo culture of Central Asia also displayed close genetic relations to the Corded Ware culture.” ref

“A genetic study published in Nature Communications in January 2018 examined a male buried in Ölsund in northern Sweden, ca. 2570–2140 BCE. Although buried without artifacts, he was found close to an archaeological site containing both hunter-gatherer and Corded Ware artifacts. He was found to be a carrier of the paternal haplogroup R1a1a1b and the maternal haplogroup U4c2a. He was found to be genetically similar to peoples of the Battle Axe culture, carrying a large amount of steppe-related ancestry. The paternal haplogroup R1a1a1b was also found to be the predominant lineage among Corded Ware and Bronze Age males of the eastern Baltic. A genetic study published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B examined the remains of 2 Battle Axe individuals buried in Bergsgraven in central Sweden. The male carried the paternal haplogroup R1a-Z283 and the maternal haplogroup U4c1a, while the female carried the maternal haplogroup N1a1a1a1.” ref

“Haplogroup R1a is the most common paternal haplogroup among males from other cultures of the Corded Ware horizon, and has earlier been found among Eastern Hunter-Gatherers (EHGs). Interestingly, the Yamnaya culture is on the other hand dominated by the paternal haplogroup R1b. The two Battle Axe individuals examined were found to be closely related to peoples from other parts of the Corded Ware horizon. They were mostly of Western Steppe Herder (WSH) descent, although with slight Western Hunter-Gatherer (WHG) and Early European Farmer (EEF) admixture. The admixture appears to have occurred through mating of WSH males with EEF and WHG females. The ancestry of the Battle Axe individuals was markedly different from that of previous Neolithic populations, suggesting stratification among the cultural groups. WSH ancestry has not been detected among previous populations of the area. The results further underpinned the notion that the Battle Axe culture emerged as a result of migrations from southeast of the Baltic.” ref

“The study also examined a female buried in a Funnelbeaker megalith in Öllsjö, Sweden c. 2860–2500 BCE, during which the area was part of the Battle Axe culture. She carried the maternal haplogroup H6a1b3, and was found to be closely genetically related to other people of the Battle Axe culture. Two individuals buried in the same megalith during the Late Neolithic were likewise closely related to peoples of the Corded Ware culture. Malmström et al. (2020) examined Pitted Ware culture individuals of Gotland. Several of their burials contained typical Battle Axe artifacts. However, none of these individuals harbored any admixture from the Battle Axe culture, suggesting that peoples of the two cultures interacted without interbreeding. Modern Northern Europeans were found to be still closely genetically related to people of the Battle Axe culture.” ref

Rudra

“Rudra (/ɾud̪ɾə/; Sanskrit: रुद्र) is a Rigvedic deity associated with Shiva, the wind or storms, Vayu, medicine, and the hunt. One translation of the name is ‘the roarer’. In the Rigveda, Rudra is praised as the “mightiest of the mighty”. Rudra means “who eradicates problems from their roots”. Depending upon the period, the name Rudra can be interpreted as ‘the most severe roarer/howler’ or ‘the most frightening one’. This name appears in the Shiva Sahasranama, and R. K. Sharma notes that it is often used as a name of Shiva in later languages. The “Shri Rudram” hymn from the Yajurveda is dedicated to Rudra and is important in the Shaivite sect. In the Prathama Anuvaka of Namakam (Taittiriya Samhita 4.5), Rudra is revered as Sadasiva (meaning ‘mighty Shiva’) and Mahadeva. Sadashiva is the Supreme Being, Paramashiva, in the Siddhanta sect of Shaivism.” ref

“The etymology of the theonym Rudra is uncertain. It is usually derived from the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root rud- (related to English rude), which means ‘to cry, howl’. The name Rudra may thus be translated as ‘the roarer’. An alternative etymology interprets Rudra as the ‘red one’, the ‘brilliant one’, possibly derived from a lost root rud-, ‘red’ or ‘ruddy’, or alternatively, according to Grassman, ‘shining’. Stella Kramrisch notes a different etymology connected with the adjectival form raudra, which means ‘wild’, i.e., of rude (untamed) nature, and translates the name Rudra as ‘the wild one’ or ‘the fierce god’. R. K. Śarmā follows this alternative etymology and translates the name as ‘the terrible’ in his glossary for the Shiva Sahasranama. Rudra is used both as a name of Shiva and collectively (‘the Rudras‘) as the name for the Maruts. Maruts are ‘storm gods’ associated with the atmosphere. They are a group of gods whose number varies from two to sixty, sometimes also rendered as eleven, thirty-three or a hundred and eighty in number (i. e., three times sixty. See RV 8.96.8.).” ref

“Mallory and Adams also mention a comparison with the Old Russian deity Rŭglŭ to reconstruct a Proto-Indo-European wild-god named *Rudlos, though they remind that the issue of the etymology remains problematic: from PIE *reud- (‘rend, tear apart’; cf. Latin rullus, ‘rustic’), or *reu- (‘howl’). The commentator Sāyaṇa suggests six possible derivations for rudra. However, another reference states that Sayana suggested ten derivations. The adjective śiva (shiva) in the sense of ‘propitious’ or ‘kind’ is first applied to the Rudra in RV 10.92.9. Rudra is called ‘the archer’ (Sanskrit: Śarva) and the arrow is an essential attribute of Rudra. This name appears in the Shiva Sahasranama, and R. K. Śarmā notes that it is used as a name of Shiva often in later languages. The word is derived from the Sanskrit root śarv– which means ‘to injure’ or ‘to kill’, and Śarmā uses that general sense in his interpretive translation of the name Śarva as ‘One who can kill the forces of darkness’.” ref

“The names Dhanvin (‘bowman’) and Bāṇahasta (‘archer’, literally ‘Armed with a hand-full of arrows’) also refer to archery. In other contexts the word rudra can simply mean ‘the number eleven’. The word rudraksha (Sanskrit: rudrākṣa = rudra and akṣa ‘eye’ or tear), or ‘eye or tears of Rudra’, is used as a name for both the berry of the rudraksha tree and a name for a string of the prayer beads made from those seeds. Rudra is one of the names of Vishnu in Vishnu Sahasranama. Adi Shankara in his commentary to Vishnu Sahasranama defined the name Rudra as ‘One who makes all beings cry at the time of cosmic dissolution’. Author D. A. Desai in his glossary for the Vishnu Sahasranama says Vishnu in the form of Rudra is the one who does the total destruction at the time of great dissolution. This is only the context known where Vishnu is revered as Rudra.” ref

“In the Rigveda, Rudra’s role as a frightening god is apparent in references to him as ghora (‘extremely terrifying’), or simply as asau devam (‘that god’). He is ‘fierce like a terrific wild beast’ (RV 2.33.11). Chakravarti sums up the perception of Rudra by saying: ‘Rudra is thus regarded with a kind of cringing fear, as a deity whose wrath is to be deprecated and whose favor curried’. RV 1.114 is an appeal to Rudra for mercy, where he is referred to as ‘mighty Rudra, the god with braided hair’. In RV 7.46, Rudra is described as armed with a bow and fast-flying arrows, although many other weapons are known to exist. As quoted by R. G. Bhandarkar, the hymn declares that Rudra discharges ‘brilliant shafts which run about the heaven and the earth’ (RV 7.46.3), which may be a reference to lightning. Another verse (Yajurveda 16.46) locates Rudra in the heart of the gods, showing that he is the inner Self of all, even the gods: “Salutations to him who is in the heart of the gods.” ref

Indra

“Indra (/ˈɪndrə/; Sanskrit: इन्द्र) is the Hindu god of weather, considered the king of the Devas and Svarga in Hinduism. He is associated with the sky, lightning, weather, thunder, storms, rains, river flows, and war. Indra is the most frequently mentioned deity in the Rigveda. He is celebrated for his powers based on his status as a god of order, and as the one who killed the great evil, an asura named Vritra, who obstructed human prosperity and happiness. Indra destroys Vritra and his “deceiving forces”, and thereby brings rain and sunshine as the saviour of mankind. Indra’s significance diminishes in the post-Vedic Indian literature, but he still plays an important role in various mythological events. He is depicted as a powerful hero. According to the Vishnu Purana, Indra is the title borne by the king of the gods, which changes every Manvantara – a cyclic period of time in Hindu cosmology.” ref

“Each Manvantara has its own Indra and the Indra of the current Manvantara is called Purandhara. Indra is also depicted in Buddhist (Pali: Indā) and Jain mythologies. Indra rules over the much-sought Devas realm of rebirth within the Samsara doctrine of Buddhist traditions. However, like the post-Vedic Hindu texts, Indra is also a subject of ridicule and reduced to a figurehead status in Buddhist texts, shown as a god who suffers rebirth. In Jain traditions, unlike Buddhism and Hinduism, Indra is not the king of gods, but the king of superhumans residing in Svarga-Loka, and very much a part of Jain rebirth cosmology. Indra was a prominent deity in the Historical Vedic religion. In Vedic times Indra was described in Rig Veda 6.30.4 as superior to any other god. Sayana in his commentary on Rig Veda 6.47.18 described Indra as assuming many forms, making Agni, Vishnu, and Rudra his illusory forms.” ref

“He is also the one who appears with his consort Indrani to celebrate the auspicious moments in the life of a Jain Tirthankara, an iconography that suggests the king and queen of superhumans residing in Svarga reverentially marking the spiritual journey of a Jain. He is a rough equivalent to Zeus in Greek mythology, or Jupiter in Roman mythology. Indra’s powers are similar to other Indo-European deities such as Norse Odin, Perun, Perkūnas, Zalmoxis, Taranis, and Thor, part of the greater Proto-Indo-European mythology. Indra’s iconography shows him wielding his Vajra and riding his vahana, Airavata. Indra’s abode is in the capital city of Svarga, Amaravati, though he is also associated with Mount Meru (also called Sumeru).” ref

“The etymological roots of Indra are unclear, and it has been a contested topic among scholars since the 19th-century, one with many proposals. The significant proposals have been:

- root ind-u, or “spirit”, based on the Vedic mythology that he conquered rain and brought it down to earth.

- root ind, or “equipped with great power”. This was proposed by Vopadeva.

- root idh or “spirit”, and ina or “strong”.

- root indha, or “igniter”, for his ability to bring light and power (indriya) that ignites the vital forces of life (prana). This is based on Shatapatha Brahmana.

- root idam-dra, or “It seeing” which is a reference to the one who first perceived the self-sufficient metaphysical Brahman. This is based on Aitareya Upanishad.

- roots in ancient Indo-European, Indo-Aryan deities. For example, states John Colarusso, as a reflex of proto-Indo-European *h₂nḗr-, Greek anēr, Sabine nerō, Avestan nar-, Umbrian nerus, Old Irish nert, Pashto nər, Ossetic nart, and others which all refer to “most manly” or “hero”.

- roots in ancient Proto-Uralic paganism, possibly coming from the old Uralic sky-god Ilmarinen.” ref

“Colonial era scholarship proposed that Indra shares etymological roots with Avestan Andra, Old High German *antra (“giant”), or Old Church Slavonic jedru (“strong”), but Max Muller critiqued these proposals as untenable. Later scholarship has linked Vedic Indra to Aynar (the Great One) of Circassian, Abaza and Ubykh mythology, and Innara of Hittite mythology. Colarusso suggests a Pontic origin and that both the phonology and the context of Indra in Indian religions is best explained from Indo-Aryan roots and a Circassian etymology (i.e. *inra). Modern scholarship suggests the name originated at the Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex where the Aryans lived before settling in India.” ref